User login

Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension

Hypertensive disorders represent one of the most common medical complications of pregnancy.1,2 Based on a nationwide inpatient sample examining more than 36 million deliveries in the United States, the prevalence of associated hypertensive disorders increased from 67.2 per 1,000 deliveries in 1998 to 83.4 per 1,000 deliveries in 2006.3Pregnancy-induced hypertension (also referred to as gestational hypertension or hypertensive disorder of pregnancy)4-6 is estimated to affect 6% to 8% of US pregnancies.1,2

Women who develop severe hypertension during pregnancy may experience adverse effects similar to those associated with mild preeclampsia.2,7,8 In the mother, these may range from elevated liver enzymes to renal dysfunction; and in the fetus, from preterm delivery to intrauterine restriction of fetal growth.7,8

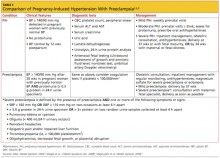

This article will review the risk factors, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of pregnancy-induced hypertension. A brief discussion of preeclampsia as it relates to gestational hypertension will be included (see Table 12,6,9).

Classification, Definitions

Pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) is classified as mild or severe. Mild PIH is defined as new-onset hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg), occurring after 20 weeks’ gestation. The majority of cases of mild PIH develop beyond 37 weeks’ gestation, and in these cases, pregnancy outcomes are comparable to those of normotensive pregnancies.2,7,8

Severe PIH is defined as sustained elevated blood pressures of ≥ 160 mm Hg systolic and ≥ 110 mm Hg diastolic. In prospective cohort studies in which calcium supplementation and low-dose aspirin use were being investigated for prevention of preeclampsia in healthy pregnant women, those who were severely hypertensive were found to be at increased risk for certain maternal comorbidities (eg, cesarean delivery, renal dysfunction, elevated liver enzymes, placental abruption) and perinatal morbidities (delivery before 37 weeks’ gestation, low birth weight, fetal growth restriction, and neonatal ICU admission), compared with patients who were normotensive or mildly hypertensive.7,8

The diagnosis of PIH may later be amended or replaced by one of the following diagnoses: preeclampsia, if proteinuria (to be defined and discussed later) develops; chronic hypertension, if blood pressure remains elevated past 12 weeks postpartum; or transient hypertension of pregnancy, if blood pressure normalizes by 12 weeks postpartum.5,6,10

Pathophysiology and Risk Factors

Although the pathophysiology of PIH is not well understood, the pathogenesis of preeclampsia likely involves abnormalities in the development, implantation, or perfusion of the placenta, and often leads to impaired maternal organ function.6,11 It is not clear whether PIH and preeclampsia are two different diseases that share a manifestation of elevated blood pressure or whether PIH represents an early stage of preeclampsia.4,12 However, women with preexisting hypertension, especially severe hypertension, are at increased risk for preeclampsia, placental abruption, and fetal growth restriction.2

There are some similarities and some distinct differences among the clinical features and risk factors associated with PIH, compared with those of preeclampsia. Risk factors for PIH include a pre-pregnancy BMI of 25 or greater, PIH and/or preeclampsia in previous pregnancies, and history of renal disease, cardiac disease, or diabetes. The most important risk factors for preeclampsia include preexisting diabetes or nephropathy, chronic hypertension, PIH or preeclampsia in a previous pregnancy, maternal age younger than 18 or older than 34, African-American ethnicity, first pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, history of preeclampsia in the patient’s mother or sister, obesity, autoimmune disease, and an interval between pregnancies longer than 10 years.4-6,13-15

The risk for preeclampsia in patients with PIH is approximately 15% to 25%12,16; according to Magee et al,6 35% of women with PIH onset before 37 weeks’ gestation develop preeclampsia.6,12,17 The risk for recurrence of PIH in subsequent pregnancies is about 26%, whereas women who experience preeclampsia in one pregnancy have a comparable risk for PIH or preeclampsia (about 14% each) in subsequent pregnancies.18

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Evaluation

Blood pressure should be measured and recorded at every prenatal visit, using the correct-sized cuff, with the patient in a seated position.5 Gestational hypertension is a clinical diagnosis confirmed by at least two accurate blood pressure measurements in the same arm in women without proteinuria, with readings of ≥ 140 mm Hg systolic and/or ≥ 90 mm Hg diastolic. It should then be determined whether the patient’s hypertension is mild or severe (ie, blood pressure > 160/110 mm Hg). The patient with severe PIH should be evaluated for signs of preeclampsia, as discussed below.

Patients with mild PIH are often asymptomatic, and the diagnosis is made at a prenatal visit as a result of routine blood pressure monitoring; this is one of many reasons to encourage early and regular prenatal care. Blood pressure may be higher at night in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.10

In contrast to patients with mild PIH, the clinical presentation of those with severe PIH or preeclampsia (and the potential for impending eclampsia) may include the following symptoms and signs:

- Generalized edema, including that of the face and hands

- Rapid weight gain

- Blurred vision or scotomata (ie, areas of diminished vision in the visual field)

- Severe, throbbing or pounding headaches

- Epigastric or right upper quadrant pain

- Oliguria (urinary output < 500 mL/d)

- Nausea, with or without vomiting

- Hyperactive reflexes

- Chest pain or tightness

- Shortness of breath.2,6,14

Medical History

Important questions to address in the patient’s medical history relate to risk factors for PIH, such as a history of renal disease, cardiac disease, or diabetes, previous history of PIH and/or preeclampsia, and abuse of cocaine or amphetamines—in addition to the specific aforementioned symptoms and signs of severe preeclampsia.5,6

Physical Examination

The clinician performing the physical exam should be attentive to accurate blood pressure measurements and any signs that suggest preeclampsia. Weight should be measured and BMI calculated at each prenatal visit.

If the patient’s blood pressure is markedly elevated, the focused physical examination should include an ophthalmologic examination for jaundice and for evidence of hypertensive retinopathy or papilledema; pulmonary and cardiac examination; abdominal examination, including palpation of the liver; examination of the face and extremities for edema; and a complete neurologic examination, including assessment of deep tendon reflexes and examination for clonus.

Laboratory Testing

In patients with PIH, laboratory evaluation should be focused to rule out preeclampsia. The potential for proteinuria (defined as ≥ 0.3 g/d in a 24-hour urine sample1,14) must be investigated at diagnosis and at regular visits during the pregnancy.1 At least two random urine samples, collected at least 6 hours apart, should be evaluated for protein. A spot (random) urine sample with a result of 2+ protein or greater is highly suggestive of proteinuria; a 24-hour urine collection is the gold standard by which such findings should be confirmed and protein levels in the urine quantified.1,14

Elevated blood pressure and proteinuria are the hallmarks of preeclampsia.6 Patients affected by these developments must be evaluated for signs and symptoms of severe preeclampsia. However, those with only mild elevations in blood pressure and little or no proteinuria may complain of sudden-onset throbbing or pounding headache, blurry vision, and severe epigastric pain—possibly indicating severe preeclampsia.5,10

In addition to laboratory evaluation for urinary protein excretion, the following tests are recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)14 to assess for end organ involvement, which is consistent with severe preeclampsia:

- Hematocrit, which may be either high, to suggest hemoconcentration; or low, indicating hemolysis

- Platelet count, which is normal in women with PIH and low in those with severe preeclampsia; if results are abnormal, this test should be followed by coagulation testing (international normalized ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen)

- Renal function testing (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine may be elevated in severe preeclampsia), and random urine testing for proteinuria, as explained earlier

- Liver enzymes (which are elevated in severe preeclampsia), and

- Lactate dehydrogenase (which is elevated in severe preeclampsia).1,14

Additionally, researchers conducting a small cohort study (n = 163) reported in 2009 that in women with PIH, serum uric acid levels exceeding 309 µmol/L were predictive of preeclampsia, with 87.7% sensitivity and 93.3% specificity.19 An increase from first-trimester serum uric acid levels was also a strong prognostic factor for preeclampsia. Earlier this year, a Canadian investigative team reported an increased risk for premature birth (odds ratio, 3.2) and small infant size for gestational age (odds ratio, 2.5) in women with PIH and hyperuricemia.20 While the predictive value of uric acid has been debated to some extent,14 measurement is often included in the workup of patients with hypertensive pregnancies.5,6

The frequency of prenatal visits, laboratory testing, and fetal monitoring should be adjusted according to the severity of PIH. In mildly hypertensive patients, the general recommendation is urine and blood testing at weekly prenatal visits.14 Fetal well-being must be monitored regularly, although neither the type nor frequency of such testing has been well established. Generally, patients should be advised to count daily fetal movements, and they should be scheduled for either a nonstress test (NST) or a biophysical profile as soon as a diagnosis of PIH is made.1,2,6,14

According to a 2010 guidance from the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE),13,21 pregnant women with mild to moderate hypertension should undergo an initial ultrasonographic assessment of fetal growth and amniotic fluid volume at the time of diagnosis, then serially every 3 to 4 weeks. If results from initial fetal testing are normal, patients with mild PIH do not require repeat testing after 34 weeks’ gestation, unless conditions change (eg, preeclampsia, worsening hypertension, and/or change in fetal movements).1,2,14 The NICE guidelines also recommend umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry.13,21

In patients with severe PIH, an NST ultrasound assessment of fetal growth and amniotic fluid volume and umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry should be performed at diagnosis to evaluate for placental dysfunction.6,21 If all test results are normal, the ultrasound and umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry need not be repeated more frequently than every two weeks, and the NST no more than once per week.13

Treatment/Management and Follow-Up

Regular prenatal monitoring to assess for worsening of PIH and/or development of preeclampsia is key to management. Figure 12 outlines an algorithm for managing PIH, which is guided by the severity of the condition. Patients with mild PIH can be managed with weekly outpatient visits and assessed for signs and symptoms of preeclampsia, monitoring of fetal movements, weight, blood pressure measurements, and urine and blood tests.2

At each visit, it is important to instruct patients to report immediately any of the following symptoms: new-onset severe headache, visual changes, epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, nausea or vomiting, difficulty breathing or chest tightness, as well as vaginal bleeding, decreased fetal movements, or uterine contractions.6,14

Generally, expectant management with delivery at term is recommended for women with mild PIH.2 Vaginal delivery (or cesarean delivery, if indicated) is recommended at 37 weeks or when fetal maturity is confirmed; and at 34 weeks if fetal or maternal distress is evident.2,6

Findings from the Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial At Term (HYPITAT),22 an open-label, randomized clinical trial in women with PIH or mild preeclampsia, suggested an association between induction of labor between 36 and 41 weeks’ gestation and improved maternal outcomes (specifically, reduced risk for severe hypertension), compared with expectant management. Similarly, in a literature review by Caughey et al,23 results from nine randomized controlled trials indicated a reduced risk for cesarean delivery in women who underwent induction of labor, compared with expectant management. Rates of “successful” induction of labor (ie, procedures resulting in vaginal rather than cesarean delivery) were greater in women with higher parity, a favorable cervix, and earlier gestational age.

Based on data from the HYPITAT trial,22 a cost-effectiveness analysis of induction of labor compared with expectant management revealed an 11% reduction in the average cost in delivery that followed induction of labor, compared with expectant management, in women with PIH or mild preeclampsia.24 Caughey et al23 reported similar savings, particularly when induction of labor was performed at 41 weeks’ gestation.

If induction of labor is being considered in a woman with an unfavorable cervix, administration of prostaglandins is recommended to enhance cervical ripening.6

Medication

Pregnant women should be advised to discontinue previously prescribed ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, or thiazide diuretics, which are associated with congenital abnormalities, intrauterine growth restriction, and/or neonatal nephropathy.5,6,13,21

Antihypertensive medication is not recommended for women with mild to moderate PIH, as it does not appear to improve outcomes. Evidence was found insufficient in a 2007 Cochrane review to determine the potential impact of antihypertensive medications for treatment of mild to moderate PIH on clinical outcomes such as preterm birth, infant mortality, and infant size relative to gestational age.25 A similar review conducted in 2011, with primary outcomes that included severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, and maternal death or perinatal death, concluded only that further study was needed to determine how tightly blood pressure must be controlled to improve maternal and fetal outcomes in patients with PIH.26

ACOG14 recommends antihypertensive therapy (eg, hydralazine, labetalol) only for women with diastolic blood pressure of 105 to 110 mm Hg or higher.1,2 There are several recommendations from different organizations regarding the choice of antihypertensive medications for PIH. In the UK’s NICE guidance,21 it is recommended that patients with moderate to severe PIH take oral labetalol as first-line treatment to keep systolic blood pressure below 150 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure between 80 and 100 mm Hg.

Like severe preeclampsia, severe PIH should be managed in an inpatient setting.6,14 IV labetalol or hydralazine is recommended to lower the blood pressure to less than 160/110 mm Hg, although current evidence is insufficient to identify a target blood pressure.6,26 A 2002 ACOG practice bulletin recommends one of the following:

- Hydralazine 5 to 10 mg IV every 15 to 20 minutes until the desired response is achieved; or

- Labetalol 20 mg IV bolus, followed by 40 mg if not effective within 10 minutes, then 80 mg every 10 minutes with maximum total dose of 220 mg.1,14

In women who have severe PIH or who develop severe preeclampsia or eclampsia, magnesium sulfate is administered to prevent or treat seizures.14 This agent should be used during labor and for at least 24 hours postpartum.2 Dosing of magnesium sulfate for this indication is 4 g IV bolus, followed by infusion of 1 g/h. It is important to monitor treated patients for signs of toxicity, including muscle weakness, loss of patellar reflexes, hypoventilation, pulmonary edema, hypotension, and bradycardia. IV calcium gluconate should be readily available for use as an antidote to life-threatening hypermagnesemia.27,28

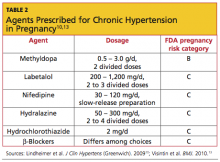

For chronic hypertension in pregnancy, the American Society of Hypertension10 has recommended several agents. There is no consensus on which medication is most appropriate (see Table 210,13).

Patient Education

Patient education is an important aspect of caring for women with PIH. The American Academy of Family Physicians29,30 provides a comprehensive patient education resource that defines the hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, explains the symptoms and signs of severe hypertension or preeclampsia, and describes appropriate diagnostic tests, monitoring, and treatment options. (See http://familydoctor.org/familydoctor/en/diseases-conditions/pregnancy-induced-hypertension.printerview.all.html.)

Patients who are considering pregnancy should be counseled to maintain a healthy weight prior to and during pregnancy. Adequate dietary calcium can reduce the risk for PIH, and calcium supplementation has been shown to reduce the risk for preeclampsia, especially in women at high risk.31 The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada recommends low-dose aspirin (75 mg/d) at bedtime for high-risk women, starting before pregnancy, or upon diagnosis of pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia.6 Although there is insufficient evidence to recommend dietary salt restriction, excess salt can increase fluid retention and possibly blood pressure. Patients should be urged to attend all scheduled prenatal visits and to review the warning signs and symptoms of severe hypertension and preeclampsia at each visit.

Mode of delivery may be discussed and will depend on the severity of hypertension, presence of preeclampsia, and fetal well-being. Vaginal delivery at term is considered optimal unless there are indications for cesarean delivery. Induction of labor may be considered at term in patients with PIH. Those with severe preeclampsia who may require preterm delivery must be prepared for potential issues associated with prematurity.

Follow-Up and Prognosis

Patients with PIH should be evaluated postpartum for persistent hypertension. Blood pressure in patients with PIH usually normalizes by day 7 postpartum.32 If blood pressure elevation persists past 12 weeks postpartum, the patient’s diagnosis is revised to chronic hypertension and managed accordingly.

In the patient with persistent hypertension who chooses breastfeeding, it is important to select an antihypertensive medication with low transfer into breast milk. Many β-adrenergic antagonists and calcium channel antagonists are considered “compatible” with breastfeeding by the American Academy of Pediatrics.33

In addition to the potential for recurrent PIH in subsequent pregnancies, women with PIH are at increased risk for hypertension later in life, and findings from several large cohort studies suggest increased cardiovascular risk in patients with hypertensive pregnancies.16,34 Magnussen et al,9 who followed more than 15,000 mothers of singleton infants for several years postpartum, found that those who experienced hypertensive disorders (particularly recurrent hypertensive disorders) during pregnancy were more likely than normotensive women to subsequently develop diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. Women who remained normotensive while pregnant generally had lower BMI measurements than those who experienced PIH or preeclampsia.

Conclusion

Hypertensive disorders commonly develop during pregnancy. It is important to diagnose and classify PIH during routine prenatal visits. Once the diagnosis is made, patients must be monitored closely for increasing blood pressure or development of preeclampsia. Urine protein testing is a key clinical test to detect preeclampsia, and positive findings on a random urine protein dipstick should be confirmed and quantified with a 24-hour urine collection.

In addition to undergoing frequent blood pressure measurements and urine protein tests, patients should be asked about signs and symptoms that suggest preeclampsia. Women with mild PIH can be managed as outpatients with prenatal visits at least weekly, followed by delivery at term. Severely hypertensive patients are managed in the hospital with antihypertensive medications and prompt delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation or beyond, should maternal or fetal distress become evident.

1. Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on high blood pressure in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(1):S1-S22.

2. Sibai BM. Diagnosis and management of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(1):181-192.

3. Kuklina EV, Ayala C, Callaghan WM. Hypertensive disorders and severe obstetric morbidity in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 113(6):1299-1306.

4. Villar J, Carroli, G, Wojdyla D, et al; World Health Organization Antenatal Care Trial Research Group. Preeclampsia, gestational hypertension and intrauterine growth restriction, related or independent conditions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(4):921-931.

5. Leeman L, Fontaine P. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(1):

93-100.

6. Magee LA, Helewa M, Moutquin JM, von Dadelszen P; Hypertension Guideline Committee; Strategic Training Initiative in Research in the Reproductive Health Sciences (STIRRHS) Scholars. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30(3 suppl):S1-S48.

7. Buchbinder A, Sibai BM, Caritis S, et al. Adverse perinatal outcomes are significantly higher in severe gestational hypertension than in mild preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(1):66-71.

8. Hauth JC, Ewell MG, Levine RJ, et al; Calcium for Preeclampsia Prevention Study Group. Pregnancy outcomes in healthy nulliparas who developed hypertension. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(1):24-28.

9. Magnussen EB, Vatten LJ, Smith GD, Romundstad PR. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and subsequently measured cardiovascular risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 114(5):961-970.

10. Lindheimer MD, Taler SJ, Cunningham FG; American Society of Hypertension (ASH). ASH position paper: hypertension in pregnancy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2009;11(4):214-225.

11. Roberts JM, Gammill HS. Preeclampsia: recent insights. Hypertension. 2005;46(6):

1243-1249.

12. Saudan P, Brown MA, Buddle ML, Jones M. Does gestational hypertension become pre-eclampsia? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105 (11):1177-1184.

13. Visintin C, Mugglestone MA, Almerie MQ, et al; Guideline Development Group. Management of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2010;341:c2207.

14. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician–Gynecologists. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia: ACOG practice bulletin No. 33. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:159-167.

15. Parazzini F, Bortolus R, Chatenoud L, et al; Italian Study of Aspirin in Pregnancy Group. Risk factors for pregnancy-induced hypertension in women at high risk for the condition. Epidemiology. 1996;7(3):306-308.

16. Hjartardottir S, Leifsson BG, Geirsson RT, Steinthorsdottir V. Recurrence of hypertensive disorder in second pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(4):916-920.

17. Barton JR, O’Brien JM, Bergauer NK, et al. Mild gestational hypertension remote from term: progression and outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(5):979-983.

18. Brown MA, Mackenzie C, Dunsmuir W, et al. Can we predict recurrence of pre-eclampsia or gestational hypertension? BJOG. 2007; 114(8):984-993.

19. Bellomo G, Venanzi S, Saronio P, et al. Prognostic significance of serum uric acid in women with gestational hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;58(4):704-708.

20. Hawkins TL, Roberts JM, Mangos GJ, et al. Plasma uric acid remains a marker of poor outcome in hypertensive pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2012;119(4):484-492.

21. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: the management of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13098/50418/50418.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2012.

22. Koopmans CM, Bijlenga D, Groen H, et al. Induction of labour versus expectant monitoring for gestational hypertension or mild pre-eclampsia after 36 weeks’ gestation (HYPITAT): a multicentre, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9694):979-988.

23. Caughey AB, Sundaram V, Kaimal AJ, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of elective induction of labor. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2009;(176):1-257.

24. Shennan A, Hezelgrave N. An economic analysis of induction of labour and expectant monitoring in women with gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia at term (HYPITAT trial). BJOG. 2010;117(13):1575-1576.

25. Abalos E, Duley L, Steyn DW, Henderson-Smart DJ. Antihypertensive drug therapy for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24;(1):CD002252.

26. Nabhan AF, Elsedawy MM. Tight control of mild-moderate pre-existing or non-proteinuric gestational hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jul 6;(7):CD006907.

27. Duley L, Gülmezoglu AM, Henderson-Smart DJ. Magnesium sulphate and other anticonvulsants for women with preeclampsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD000025.

28. Kraft MD, Btaiche IF, Sacks GS, Kudsk KA. Treatment of electrolyte disorders in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62(16):1663-1682.

29. FamilyDoctor.org. Pregnancy-induced hypertension (updated 2010). http://familydoctor.org/familydoctor/en/diseases-conditions/pregnancy-induced-hypertension.printerview

.all.html. Accessed April 16, 2012.

30. Zamorski MA, Green LA. NHBPEP report on high blood pressure in pregnancy: a summary for family physicians. Am Fam Physician. 2001; 64(2):263-270.

31. Hofmeyr GJ, Duley L, Atallah A. Dietary calcium supplementation for prevention of pre-eclampsia and related problems: a systematic review and commentary. BJOG. 2007;114(8): 933-943.

32. Ferrazzani S, De Carolis S, Pomini F, et al. The duration of hypertension in the puerperium of preeclamptic women: relationship with renal impairment and week of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(2):506-512.

33. Beardmore KS, Morris JM, Gallery ED. Excretion of antihypertensive medication into human breast milk: a systematic review. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2002;21(1):85-95.

34. Wilson BJ, Watson MS, Prescott GJ, et al. Hypertensive diseases of pregnancy and risk of hypertension and stroke in later life: results from cohort study. BMJ. 2003;326(7394):845.

Hypertensive disorders represent one of the most common medical complications of pregnancy.1,2 Based on a nationwide inpatient sample examining more than 36 million deliveries in the United States, the prevalence of associated hypertensive disorders increased from 67.2 per 1,000 deliveries in 1998 to 83.4 per 1,000 deliveries in 2006.3Pregnancy-induced hypertension (also referred to as gestational hypertension or hypertensive disorder of pregnancy)4-6 is estimated to affect 6% to 8% of US pregnancies.1,2

Women who develop severe hypertension during pregnancy may experience adverse effects similar to those associated with mild preeclampsia.2,7,8 In the mother, these may range from elevated liver enzymes to renal dysfunction; and in the fetus, from preterm delivery to intrauterine restriction of fetal growth.7,8

This article will review the risk factors, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of pregnancy-induced hypertension. A brief discussion of preeclampsia as it relates to gestational hypertension will be included (see Table 12,6,9).

Classification, Definitions

Pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) is classified as mild or severe. Mild PIH is defined as new-onset hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg), occurring after 20 weeks’ gestation. The majority of cases of mild PIH develop beyond 37 weeks’ gestation, and in these cases, pregnancy outcomes are comparable to those of normotensive pregnancies.2,7,8

Severe PIH is defined as sustained elevated blood pressures of ≥ 160 mm Hg systolic and ≥ 110 mm Hg diastolic. In prospective cohort studies in which calcium supplementation and low-dose aspirin use were being investigated for prevention of preeclampsia in healthy pregnant women, those who were severely hypertensive were found to be at increased risk for certain maternal comorbidities (eg, cesarean delivery, renal dysfunction, elevated liver enzymes, placental abruption) and perinatal morbidities (delivery before 37 weeks’ gestation, low birth weight, fetal growth restriction, and neonatal ICU admission), compared with patients who were normotensive or mildly hypertensive.7,8

The diagnosis of PIH may later be amended or replaced by one of the following diagnoses: preeclampsia, if proteinuria (to be defined and discussed later) develops; chronic hypertension, if blood pressure remains elevated past 12 weeks postpartum; or transient hypertension of pregnancy, if blood pressure normalizes by 12 weeks postpartum.5,6,10

Pathophysiology and Risk Factors

Although the pathophysiology of PIH is not well understood, the pathogenesis of preeclampsia likely involves abnormalities in the development, implantation, or perfusion of the placenta, and often leads to impaired maternal organ function.6,11 It is not clear whether PIH and preeclampsia are two different diseases that share a manifestation of elevated blood pressure or whether PIH represents an early stage of preeclampsia.4,12 However, women with preexisting hypertension, especially severe hypertension, are at increased risk for preeclampsia, placental abruption, and fetal growth restriction.2

There are some similarities and some distinct differences among the clinical features and risk factors associated with PIH, compared with those of preeclampsia. Risk factors for PIH include a pre-pregnancy BMI of 25 or greater, PIH and/or preeclampsia in previous pregnancies, and history of renal disease, cardiac disease, or diabetes. The most important risk factors for preeclampsia include preexisting diabetes or nephropathy, chronic hypertension, PIH or preeclampsia in a previous pregnancy, maternal age younger than 18 or older than 34, African-American ethnicity, first pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, history of preeclampsia in the patient’s mother or sister, obesity, autoimmune disease, and an interval between pregnancies longer than 10 years.4-6,13-15

The risk for preeclampsia in patients with PIH is approximately 15% to 25%12,16; according to Magee et al,6 35% of women with PIH onset before 37 weeks’ gestation develop preeclampsia.6,12,17 The risk for recurrence of PIH in subsequent pregnancies is about 26%, whereas women who experience preeclampsia in one pregnancy have a comparable risk for PIH or preeclampsia (about 14% each) in subsequent pregnancies.18

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Evaluation

Blood pressure should be measured and recorded at every prenatal visit, using the correct-sized cuff, with the patient in a seated position.5 Gestational hypertension is a clinical diagnosis confirmed by at least two accurate blood pressure measurements in the same arm in women without proteinuria, with readings of ≥ 140 mm Hg systolic and/or ≥ 90 mm Hg diastolic. It should then be determined whether the patient’s hypertension is mild or severe (ie, blood pressure > 160/110 mm Hg). The patient with severe PIH should be evaluated for signs of preeclampsia, as discussed below.

Patients with mild PIH are often asymptomatic, and the diagnosis is made at a prenatal visit as a result of routine blood pressure monitoring; this is one of many reasons to encourage early and regular prenatal care. Blood pressure may be higher at night in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.10

In contrast to patients with mild PIH, the clinical presentation of those with severe PIH or preeclampsia (and the potential for impending eclampsia) may include the following symptoms and signs:

- Generalized edema, including that of the face and hands

- Rapid weight gain

- Blurred vision or scotomata (ie, areas of diminished vision in the visual field)

- Severe, throbbing or pounding headaches

- Epigastric or right upper quadrant pain

- Oliguria (urinary output < 500 mL/d)

- Nausea, with or without vomiting

- Hyperactive reflexes

- Chest pain or tightness

- Shortness of breath.2,6,14

Medical History

Important questions to address in the patient’s medical history relate to risk factors for PIH, such as a history of renal disease, cardiac disease, or diabetes, previous history of PIH and/or preeclampsia, and abuse of cocaine or amphetamines—in addition to the specific aforementioned symptoms and signs of severe preeclampsia.5,6

Physical Examination

The clinician performing the physical exam should be attentive to accurate blood pressure measurements and any signs that suggest preeclampsia. Weight should be measured and BMI calculated at each prenatal visit.

If the patient’s blood pressure is markedly elevated, the focused physical examination should include an ophthalmologic examination for jaundice and for evidence of hypertensive retinopathy or papilledema; pulmonary and cardiac examination; abdominal examination, including palpation of the liver; examination of the face and extremities for edema; and a complete neurologic examination, including assessment of deep tendon reflexes and examination for clonus.

Laboratory Testing

In patients with PIH, laboratory evaluation should be focused to rule out preeclampsia. The potential for proteinuria (defined as ≥ 0.3 g/d in a 24-hour urine sample1,14) must be investigated at diagnosis and at regular visits during the pregnancy.1 At least two random urine samples, collected at least 6 hours apart, should be evaluated for protein. A spot (random) urine sample with a result of 2+ protein or greater is highly suggestive of proteinuria; a 24-hour urine collection is the gold standard by which such findings should be confirmed and protein levels in the urine quantified.1,14

Elevated blood pressure and proteinuria are the hallmarks of preeclampsia.6 Patients affected by these developments must be evaluated for signs and symptoms of severe preeclampsia. However, those with only mild elevations in blood pressure and little or no proteinuria may complain of sudden-onset throbbing or pounding headache, blurry vision, and severe epigastric pain—possibly indicating severe preeclampsia.5,10

In addition to laboratory evaluation for urinary protein excretion, the following tests are recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)14 to assess for end organ involvement, which is consistent with severe preeclampsia:

- Hematocrit, which may be either high, to suggest hemoconcentration; or low, indicating hemolysis

- Platelet count, which is normal in women with PIH and low in those with severe preeclampsia; if results are abnormal, this test should be followed by coagulation testing (international normalized ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen)

- Renal function testing (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine may be elevated in severe preeclampsia), and random urine testing for proteinuria, as explained earlier

- Liver enzymes (which are elevated in severe preeclampsia), and

- Lactate dehydrogenase (which is elevated in severe preeclampsia).1,14

Additionally, researchers conducting a small cohort study (n = 163) reported in 2009 that in women with PIH, serum uric acid levels exceeding 309 µmol/L were predictive of preeclampsia, with 87.7% sensitivity and 93.3% specificity.19 An increase from first-trimester serum uric acid levels was also a strong prognostic factor for preeclampsia. Earlier this year, a Canadian investigative team reported an increased risk for premature birth (odds ratio, 3.2) and small infant size for gestational age (odds ratio, 2.5) in women with PIH and hyperuricemia.20 While the predictive value of uric acid has been debated to some extent,14 measurement is often included in the workup of patients with hypertensive pregnancies.5,6

The frequency of prenatal visits, laboratory testing, and fetal monitoring should be adjusted according to the severity of PIH. In mildly hypertensive patients, the general recommendation is urine and blood testing at weekly prenatal visits.14 Fetal well-being must be monitored regularly, although neither the type nor frequency of such testing has been well established. Generally, patients should be advised to count daily fetal movements, and they should be scheduled for either a nonstress test (NST) or a biophysical profile as soon as a diagnosis of PIH is made.1,2,6,14

According to a 2010 guidance from the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE),13,21 pregnant women with mild to moderate hypertension should undergo an initial ultrasonographic assessment of fetal growth and amniotic fluid volume at the time of diagnosis, then serially every 3 to 4 weeks. If results from initial fetal testing are normal, patients with mild PIH do not require repeat testing after 34 weeks’ gestation, unless conditions change (eg, preeclampsia, worsening hypertension, and/or change in fetal movements).1,2,14 The NICE guidelines also recommend umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry.13,21

In patients with severe PIH, an NST ultrasound assessment of fetal growth and amniotic fluid volume and umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry should be performed at diagnosis to evaluate for placental dysfunction.6,21 If all test results are normal, the ultrasound and umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry need not be repeated more frequently than every two weeks, and the NST no more than once per week.13

Treatment/Management and Follow-Up

Regular prenatal monitoring to assess for worsening of PIH and/or development of preeclampsia is key to management. Figure 12 outlines an algorithm for managing PIH, which is guided by the severity of the condition. Patients with mild PIH can be managed with weekly outpatient visits and assessed for signs and symptoms of preeclampsia, monitoring of fetal movements, weight, blood pressure measurements, and urine and blood tests.2

At each visit, it is important to instruct patients to report immediately any of the following symptoms: new-onset severe headache, visual changes, epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, nausea or vomiting, difficulty breathing or chest tightness, as well as vaginal bleeding, decreased fetal movements, or uterine contractions.6,14

Generally, expectant management with delivery at term is recommended for women with mild PIH.2 Vaginal delivery (or cesarean delivery, if indicated) is recommended at 37 weeks or when fetal maturity is confirmed; and at 34 weeks if fetal or maternal distress is evident.2,6

Findings from the Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial At Term (HYPITAT),22 an open-label, randomized clinical trial in women with PIH or mild preeclampsia, suggested an association between induction of labor between 36 and 41 weeks’ gestation and improved maternal outcomes (specifically, reduced risk for severe hypertension), compared with expectant management. Similarly, in a literature review by Caughey et al,23 results from nine randomized controlled trials indicated a reduced risk for cesarean delivery in women who underwent induction of labor, compared with expectant management. Rates of “successful” induction of labor (ie, procedures resulting in vaginal rather than cesarean delivery) were greater in women with higher parity, a favorable cervix, and earlier gestational age.

Based on data from the HYPITAT trial,22 a cost-effectiveness analysis of induction of labor compared with expectant management revealed an 11% reduction in the average cost in delivery that followed induction of labor, compared with expectant management, in women with PIH or mild preeclampsia.24 Caughey et al23 reported similar savings, particularly when induction of labor was performed at 41 weeks’ gestation.

If induction of labor is being considered in a woman with an unfavorable cervix, administration of prostaglandins is recommended to enhance cervical ripening.6

Medication

Pregnant women should be advised to discontinue previously prescribed ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, or thiazide diuretics, which are associated with congenital abnormalities, intrauterine growth restriction, and/or neonatal nephropathy.5,6,13,21

Antihypertensive medication is not recommended for women with mild to moderate PIH, as it does not appear to improve outcomes. Evidence was found insufficient in a 2007 Cochrane review to determine the potential impact of antihypertensive medications for treatment of mild to moderate PIH on clinical outcomes such as preterm birth, infant mortality, and infant size relative to gestational age.25 A similar review conducted in 2011, with primary outcomes that included severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, and maternal death or perinatal death, concluded only that further study was needed to determine how tightly blood pressure must be controlled to improve maternal and fetal outcomes in patients with PIH.26

ACOG14 recommends antihypertensive therapy (eg, hydralazine, labetalol) only for women with diastolic blood pressure of 105 to 110 mm Hg or higher.1,2 There are several recommendations from different organizations regarding the choice of antihypertensive medications for PIH. In the UK’s NICE guidance,21 it is recommended that patients with moderate to severe PIH take oral labetalol as first-line treatment to keep systolic blood pressure below 150 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure between 80 and 100 mm Hg.

Like severe preeclampsia, severe PIH should be managed in an inpatient setting.6,14 IV labetalol or hydralazine is recommended to lower the blood pressure to less than 160/110 mm Hg, although current evidence is insufficient to identify a target blood pressure.6,26 A 2002 ACOG practice bulletin recommends one of the following:

- Hydralazine 5 to 10 mg IV every 15 to 20 minutes until the desired response is achieved; or

- Labetalol 20 mg IV bolus, followed by 40 mg if not effective within 10 minutes, then 80 mg every 10 minutes with maximum total dose of 220 mg.1,14

In women who have severe PIH or who develop severe preeclampsia or eclampsia, magnesium sulfate is administered to prevent or treat seizures.14 This agent should be used during labor and for at least 24 hours postpartum.2 Dosing of magnesium sulfate for this indication is 4 g IV bolus, followed by infusion of 1 g/h. It is important to monitor treated patients for signs of toxicity, including muscle weakness, loss of patellar reflexes, hypoventilation, pulmonary edema, hypotension, and bradycardia. IV calcium gluconate should be readily available for use as an antidote to life-threatening hypermagnesemia.27,28

For chronic hypertension in pregnancy, the American Society of Hypertension10 has recommended several agents. There is no consensus on which medication is most appropriate (see Table 210,13).

Patient Education

Patient education is an important aspect of caring for women with PIH. The American Academy of Family Physicians29,30 provides a comprehensive patient education resource that defines the hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, explains the symptoms and signs of severe hypertension or preeclampsia, and describes appropriate diagnostic tests, monitoring, and treatment options. (See http://familydoctor.org/familydoctor/en/diseases-conditions/pregnancy-induced-hypertension.printerview.all.html.)

Patients who are considering pregnancy should be counseled to maintain a healthy weight prior to and during pregnancy. Adequate dietary calcium can reduce the risk for PIH, and calcium supplementation has been shown to reduce the risk for preeclampsia, especially in women at high risk.31 The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada recommends low-dose aspirin (75 mg/d) at bedtime for high-risk women, starting before pregnancy, or upon diagnosis of pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia.6 Although there is insufficient evidence to recommend dietary salt restriction, excess salt can increase fluid retention and possibly blood pressure. Patients should be urged to attend all scheduled prenatal visits and to review the warning signs and symptoms of severe hypertension and preeclampsia at each visit.

Mode of delivery may be discussed and will depend on the severity of hypertension, presence of preeclampsia, and fetal well-being. Vaginal delivery at term is considered optimal unless there are indications for cesarean delivery. Induction of labor may be considered at term in patients with PIH. Those with severe preeclampsia who may require preterm delivery must be prepared for potential issues associated with prematurity.

Follow-Up and Prognosis

Patients with PIH should be evaluated postpartum for persistent hypertension. Blood pressure in patients with PIH usually normalizes by day 7 postpartum.32 If blood pressure elevation persists past 12 weeks postpartum, the patient’s diagnosis is revised to chronic hypertension and managed accordingly.

In the patient with persistent hypertension who chooses breastfeeding, it is important to select an antihypertensive medication with low transfer into breast milk. Many β-adrenergic antagonists and calcium channel antagonists are considered “compatible” with breastfeeding by the American Academy of Pediatrics.33

In addition to the potential for recurrent PIH in subsequent pregnancies, women with PIH are at increased risk for hypertension later in life, and findings from several large cohort studies suggest increased cardiovascular risk in patients with hypertensive pregnancies.16,34 Magnussen et al,9 who followed more than 15,000 mothers of singleton infants for several years postpartum, found that those who experienced hypertensive disorders (particularly recurrent hypertensive disorders) during pregnancy were more likely than normotensive women to subsequently develop diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. Women who remained normotensive while pregnant generally had lower BMI measurements than those who experienced PIH or preeclampsia.

Conclusion

Hypertensive disorders commonly develop during pregnancy. It is important to diagnose and classify PIH during routine prenatal visits. Once the diagnosis is made, patients must be monitored closely for increasing blood pressure or development of preeclampsia. Urine protein testing is a key clinical test to detect preeclampsia, and positive findings on a random urine protein dipstick should be confirmed and quantified with a 24-hour urine collection.

In addition to undergoing frequent blood pressure measurements and urine protein tests, patients should be asked about signs and symptoms that suggest preeclampsia. Women with mild PIH can be managed as outpatients with prenatal visits at least weekly, followed by delivery at term. Severely hypertensive patients are managed in the hospital with antihypertensive medications and prompt delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation or beyond, should maternal or fetal distress become evident.

Hypertensive disorders represent one of the most common medical complications of pregnancy.1,2 Based on a nationwide inpatient sample examining more than 36 million deliveries in the United States, the prevalence of associated hypertensive disorders increased from 67.2 per 1,000 deliveries in 1998 to 83.4 per 1,000 deliveries in 2006.3Pregnancy-induced hypertension (also referred to as gestational hypertension or hypertensive disorder of pregnancy)4-6 is estimated to affect 6% to 8% of US pregnancies.1,2

Women who develop severe hypertension during pregnancy may experience adverse effects similar to those associated with mild preeclampsia.2,7,8 In the mother, these may range from elevated liver enzymes to renal dysfunction; and in the fetus, from preterm delivery to intrauterine restriction of fetal growth.7,8

This article will review the risk factors, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of pregnancy-induced hypertension. A brief discussion of preeclampsia as it relates to gestational hypertension will be included (see Table 12,6,9).

Classification, Definitions

Pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) is classified as mild or severe. Mild PIH is defined as new-onset hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg), occurring after 20 weeks’ gestation. The majority of cases of mild PIH develop beyond 37 weeks’ gestation, and in these cases, pregnancy outcomes are comparable to those of normotensive pregnancies.2,7,8

Severe PIH is defined as sustained elevated blood pressures of ≥ 160 mm Hg systolic and ≥ 110 mm Hg diastolic. In prospective cohort studies in which calcium supplementation and low-dose aspirin use were being investigated for prevention of preeclampsia in healthy pregnant women, those who were severely hypertensive were found to be at increased risk for certain maternal comorbidities (eg, cesarean delivery, renal dysfunction, elevated liver enzymes, placental abruption) and perinatal morbidities (delivery before 37 weeks’ gestation, low birth weight, fetal growth restriction, and neonatal ICU admission), compared with patients who were normotensive or mildly hypertensive.7,8

The diagnosis of PIH may later be amended or replaced by one of the following diagnoses: preeclampsia, if proteinuria (to be defined and discussed later) develops; chronic hypertension, if blood pressure remains elevated past 12 weeks postpartum; or transient hypertension of pregnancy, if blood pressure normalizes by 12 weeks postpartum.5,6,10

Pathophysiology and Risk Factors

Although the pathophysiology of PIH is not well understood, the pathogenesis of preeclampsia likely involves abnormalities in the development, implantation, or perfusion of the placenta, and often leads to impaired maternal organ function.6,11 It is not clear whether PIH and preeclampsia are two different diseases that share a manifestation of elevated blood pressure or whether PIH represents an early stage of preeclampsia.4,12 However, women with preexisting hypertension, especially severe hypertension, are at increased risk for preeclampsia, placental abruption, and fetal growth restriction.2

There are some similarities and some distinct differences among the clinical features and risk factors associated with PIH, compared with those of preeclampsia. Risk factors for PIH include a pre-pregnancy BMI of 25 or greater, PIH and/or preeclampsia in previous pregnancies, and history of renal disease, cardiac disease, or diabetes. The most important risk factors for preeclampsia include preexisting diabetes or nephropathy, chronic hypertension, PIH or preeclampsia in a previous pregnancy, maternal age younger than 18 or older than 34, African-American ethnicity, first pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, history of preeclampsia in the patient’s mother or sister, obesity, autoimmune disease, and an interval between pregnancies longer than 10 years.4-6,13-15

The risk for preeclampsia in patients with PIH is approximately 15% to 25%12,16; according to Magee et al,6 35% of women with PIH onset before 37 weeks’ gestation develop preeclampsia.6,12,17 The risk for recurrence of PIH in subsequent pregnancies is about 26%, whereas women who experience preeclampsia in one pregnancy have a comparable risk for PIH or preeclampsia (about 14% each) in subsequent pregnancies.18

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Evaluation

Blood pressure should be measured and recorded at every prenatal visit, using the correct-sized cuff, with the patient in a seated position.5 Gestational hypertension is a clinical diagnosis confirmed by at least two accurate blood pressure measurements in the same arm in women without proteinuria, with readings of ≥ 140 mm Hg systolic and/or ≥ 90 mm Hg diastolic. It should then be determined whether the patient’s hypertension is mild or severe (ie, blood pressure > 160/110 mm Hg). The patient with severe PIH should be evaluated for signs of preeclampsia, as discussed below.

Patients with mild PIH are often asymptomatic, and the diagnosis is made at a prenatal visit as a result of routine blood pressure monitoring; this is one of many reasons to encourage early and regular prenatal care. Blood pressure may be higher at night in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.10

In contrast to patients with mild PIH, the clinical presentation of those with severe PIH or preeclampsia (and the potential for impending eclampsia) may include the following symptoms and signs:

- Generalized edema, including that of the face and hands

- Rapid weight gain

- Blurred vision or scotomata (ie, areas of diminished vision in the visual field)

- Severe, throbbing or pounding headaches

- Epigastric or right upper quadrant pain

- Oliguria (urinary output < 500 mL/d)

- Nausea, with or without vomiting

- Hyperactive reflexes

- Chest pain or tightness

- Shortness of breath.2,6,14

Medical History

Important questions to address in the patient’s medical history relate to risk factors for PIH, such as a history of renal disease, cardiac disease, or diabetes, previous history of PIH and/or preeclampsia, and abuse of cocaine or amphetamines—in addition to the specific aforementioned symptoms and signs of severe preeclampsia.5,6

Physical Examination

The clinician performing the physical exam should be attentive to accurate blood pressure measurements and any signs that suggest preeclampsia. Weight should be measured and BMI calculated at each prenatal visit.

If the patient’s blood pressure is markedly elevated, the focused physical examination should include an ophthalmologic examination for jaundice and for evidence of hypertensive retinopathy or papilledema; pulmonary and cardiac examination; abdominal examination, including palpation of the liver; examination of the face and extremities for edema; and a complete neurologic examination, including assessment of deep tendon reflexes and examination for clonus.

Laboratory Testing

In patients with PIH, laboratory evaluation should be focused to rule out preeclampsia. The potential for proteinuria (defined as ≥ 0.3 g/d in a 24-hour urine sample1,14) must be investigated at diagnosis and at regular visits during the pregnancy.1 At least two random urine samples, collected at least 6 hours apart, should be evaluated for protein. A spot (random) urine sample with a result of 2+ protein or greater is highly suggestive of proteinuria; a 24-hour urine collection is the gold standard by which such findings should be confirmed and protein levels in the urine quantified.1,14

Elevated blood pressure and proteinuria are the hallmarks of preeclampsia.6 Patients affected by these developments must be evaluated for signs and symptoms of severe preeclampsia. However, those with only mild elevations in blood pressure and little or no proteinuria may complain of sudden-onset throbbing or pounding headache, blurry vision, and severe epigastric pain—possibly indicating severe preeclampsia.5,10

In addition to laboratory evaluation for urinary protein excretion, the following tests are recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)14 to assess for end organ involvement, which is consistent with severe preeclampsia:

- Hematocrit, which may be either high, to suggest hemoconcentration; or low, indicating hemolysis

- Platelet count, which is normal in women with PIH and low in those with severe preeclampsia; if results are abnormal, this test should be followed by coagulation testing (international normalized ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen)

- Renal function testing (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine may be elevated in severe preeclampsia), and random urine testing for proteinuria, as explained earlier

- Liver enzymes (which are elevated in severe preeclampsia), and

- Lactate dehydrogenase (which is elevated in severe preeclampsia).1,14

Additionally, researchers conducting a small cohort study (n = 163) reported in 2009 that in women with PIH, serum uric acid levels exceeding 309 µmol/L were predictive of preeclampsia, with 87.7% sensitivity and 93.3% specificity.19 An increase from first-trimester serum uric acid levels was also a strong prognostic factor for preeclampsia. Earlier this year, a Canadian investigative team reported an increased risk for premature birth (odds ratio, 3.2) and small infant size for gestational age (odds ratio, 2.5) in women with PIH and hyperuricemia.20 While the predictive value of uric acid has been debated to some extent,14 measurement is often included in the workup of patients with hypertensive pregnancies.5,6

The frequency of prenatal visits, laboratory testing, and fetal monitoring should be adjusted according to the severity of PIH. In mildly hypertensive patients, the general recommendation is urine and blood testing at weekly prenatal visits.14 Fetal well-being must be monitored regularly, although neither the type nor frequency of such testing has been well established. Generally, patients should be advised to count daily fetal movements, and they should be scheduled for either a nonstress test (NST) or a biophysical profile as soon as a diagnosis of PIH is made.1,2,6,14

According to a 2010 guidance from the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE),13,21 pregnant women with mild to moderate hypertension should undergo an initial ultrasonographic assessment of fetal growth and amniotic fluid volume at the time of diagnosis, then serially every 3 to 4 weeks. If results from initial fetal testing are normal, patients with mild PIH do not require repeat testing after 34 weeks’ gestation, unless conditions change (eg, preeclampsia, worsening hypertension, and/or change in fetal movements).1,2,14 The NICE guidelines also recommend umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry.13,21

In patients with severe PIH, an NST ultrasound assessment of fetal growth and amniotic fluid volume and umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry should be performed at diagnosis to evaluate for placental dysfunction.6,21 If all test results are normal, the ultrasound and umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry need not be repeated more frequently than every two weeks, and the NST no more than once per week.13

Treatment/Management and Follow-Up

Regular prenatal monitoring to assess for worsening of PIH and/or development of preeclampsia is key to management. Figure 12 outlines an algorithm for managing PIH, which is guided by the severity of the condition. Patients with mild PIH can be managed with weekly outpatient visits and assessed for signs and symptoms of preeclampsia, monitoring of fetal movements, weight, blood pressure measurements, and urine and blood tests.2

At each visit, it is important to instruct patients to report immediately any of the following symptoms: new-onset severe headache, visual changes, epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, nausea or vomiting, difficulty breathing or chest tightness, as well as vaginal bleeding, decreased fetal movements, or uterine contractions.6,14

Generally, expectant management with delivery at term is recommended for women with mild PIH.2 Vaginal delivery (or cesarean delivery, if indicated) is recommended at 37 weeks or when fetal maturity is confirmed; and at 34 weeks if fetal or maternal distress is evident.2,6

Findings from the Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial At Term (HYPITAT),22 an open-label, randomized clinical trial in women with PIH or mild preeclampsia, suggested an association between induction of labor between 36 and 41 weeks’ gestation and improved maternal outcomes (specifically, reduced risk for severe hypertension), compared with expectant management. Similarly, in a literature review by Caughey et al,23 results from nine randomized controlled trials indicated a reduced risk for cesarean delivery in women who underwent induction of labor, compared with expectant management. Rates of “successful” induction of labor (ie, procedures resulting in vaginal rather than cesarean delivery) were greater in women with higher parity, a favorable cervix, and earlier gestational age.

Based on data from the HYPITAT trial,22 a cost-effectiveness analysis of induction of labor compared with expectant management revealed an 11% reduction in the average cost in delivery that followed induction of labor, compared with expectant management, in women with PIH or mild preeclampsia.24 Caughey et al23 reported similar savings, particularly when induction of labor was performed at 41 weeks’ gestation.

If induction of labor is being considered in a woman with an unfavorable cervix, administration of prostaglandins is recommended to enhance cervical ripening.6

Medication

Pregnant women should be advised to discontinue previously prescribed ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, or thiazide diuretics, which are associated with congenital abnormalities, intrauterine growth restriction, and/or neonatal nephropathy.5,6,13,21

Antihypertensive medication is not recommended for women with mild to moderate PIH, as it does not appear to improve outcomes. Evidence was found insufficient in a 2007 Cochrane review to determine the potential impact of antihypertensive medications for treatment of mild to moderate PIH on clinical outcomes such as preterm birth, infant mortality, and infant size relative to gestational age.25 A similar review conducted in 2011, with primary outcomes that included severe preeclampsia, eclampsia, and maternal death or perinatal death, concluded only that further study was needed to determine how tightly blood pressure must be controlled to improve maternal and fetal outcomes in patients with PIH.26

ACOG14 recommends antihypertensive therapy (eg, hydralazine, labetalol) only for women with diastolic blood pressure of 105 to 110 mm Hg or higher.1,2 There are several recommendations from different organizations regarding the choice of antihypertensive medications for PIH. In the UK’s NICE guidance,21 it is recommended that patients with moderate to severe PIH take oral labetalol as first-line treatment to keep systolic blood pressure below 150 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure between 80 and 100 mm Hg.

Like severe preeclampsia, severe PIH should be managed in an inpatient setting.6,14 IV labetalol or hydralazine is recommended to lower the blood pressure to less than 160/110 mm Hg, although current evidence is insufficient to identify a target blood pressure.6,26 A 2002 ACOG practice bulletin recommends one of the following:

- Hydralazine 5 to 10 mg IV every 15 to 20 minutes until the desired response is achieved; or

- Labetalol 20 mg IV bolus, followed by 40 mg if not effective within 10 minutes, then 80 mg every 10 minutes with maximum total dose of 220 mg.1,14

In women who have severe PIH or who develop severe preeclampsia or eclampsia, magnesium sulfate is administered to prevent or treat seizures.14 This agent should be used during labor and for at least 24 hours postpartum.2 Dosing of magnesium sulfate for this indication is 4 g IV bolus, followed by infusion of 1 g/h. It is important to monitor treated patients for signs of toxicity, including muscle weakness, loss of patellar reflexes, hypoventilation, pulmonary edema, hypotension, and bradycardia. IV calcium gluconate should be readily available for use as an antidote to life-threatening hypermagnesemia.27,28

For chronic hypertension in pregnancy, the American Society of Hypertension10 has recommended several agents. There is no consensus on which medication is most appropriate (see Table 210,13).

Patient Education

Patient education is an important aspect of caring for women with PIH. The American Academy of Family Physicians29,30 provides a comprehensive patient education resource that defines the hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, explains the symptoms and signs of severe hypertension or preeclampsia, and describes appropriate diagnostic tests, monitoring, and treatment options. (See http://familydoctor.org/familydoctor/en/diseases-conditions/pregnancy-induced-hypertension.printerview.all.html.)

Patients who are considering pregnancy should be counseled to maintain a healthy weight prior to and during pregnancy. Adequate dietary calcium can reduce the risk for PIH, and calcium supplementation has been shown to reduce the risk for preeclampsia, especially in women at high risk.31 The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada recommends low-dose aspirin (75 mg/d) at bedtime for high-risk women, starting before pregnancy, or upon diagnosis of pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia.6 Although there is insufficient evidence to recommend dietary salt restriction, excess salt can increase fluid retention and possibly blood pressure. Patients should be urged to attend all scheduled prenatal visits and to review the warning signs and symptoms of severe hypertension and preeclampsia at each visit.

Mode of delivery may be discussed and will depend on the severity of hypertension, presence of preeclampsia, and fetal well-being. Vaginal delivery at term is considered optimal unless there are indications for cesarean delivery. Induction of labor may be considered at term in patients with PIH. Those with severe preeclampsia who may require preterm delivery must be prepared for potential issues associated with prematurity.

Follow-Up and Prognosis

Patients with PIH should be evaluated postpartum for persistent hypertension. Blood pressure in patients with PIH usually normalizes by day 7 postpartum.32 If blood pressure elevation persists past 12 weeks postpartum, the patient’s diagnosis is revised to chronic hypertension and managed accordingly.

In the patient with persistent hypertension who chooses breastfeeding, it is important to select an antihypertensive medication with low transfer into breast milk. Many β-adrenergic antagonists and calcium channel antagonists are considered “compatible” with breastfeeding by the American Academy of Pediatrics.33

In addition to the potential for recurrent PIH in subsequent pregnancies, women with PIH are at increased risk for hypertension later in life, and findings from several large cohort studies suggest increased cardiovascular risk in patients with hypertensive pregnancies.16,34 Magnussen et al,9 who followed more than 15,000 mothers of singleton infants for several years postpartum, found that those who experienced hypertensive disorders (particularly recurrent hypertensive disorders) during pregnancy were more likely than normotensive women to subsequently develop diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. Women who remained normotensive while pregnant generally had lower BMI measurements than those who experienced PIH or preeclampsia.

Conclusion

Hypertensive disorders commonly develop during pregnancy. It is important to diagnose and classify PIH during routine prenatal visits. Once the diagnosis is made, patients must be monitored closely for increasing blood pressure or development of preeclampsia. Urine protein testing is a key clinical test to detect preeclampsia, and positive findings on a random urine protein dipstick should be confirmed and quantified with a 24-hour urine collection.

In addition to undergoing frequent blood pressure measurements and urine protein tests, patients should be asked about signs and symptoms that suggest preeclampsia. Women with mild PIH can be managed as outpatients with prenatal visits at least weekly, followed by delivery at term. Severely hypertensive patients are managed in the hospital with antihypertensive medications and prompt delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation or beyond, should maternal or fetal distress become evident.

1. Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on high blood pressure in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(1):S1-S22.

2. Sibai BM. Diagnosis and management of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(1):181-192.

3. Kuklina EV, Ayala C, Callaghan WM. Hypertensive disorders and severe obstetric morbidity in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 113(6):1299-1306.

4. Villar J, Carroli, G, Wojdyla D, et al; World Health Organization Antenatal Care Trial Research Group. Preeclampsia, gestational hypertension and intrauterine growth restriction, related or independent conditions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(4):921-931.

5. Leeman L, Fontaine P. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(1):

93-100.

6. Magee LA, Helewa M, Moutquin JM, von Dadelszen P; Hypertension Guideline Committee; Strategic Training Initiative in Research in the Reproductive Health Sciences (STIRRHS) Scholars. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30(3 suppl):S1-S48.

7. Buchbinder A, Sibai BM, Caritis S, et al. Adverse perinatal outcomes are significantly higher in severe gestational hypertension than in mild preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(1):66-71.

8. Hauth JC, Ewell MG, Levine RJ, et al; Calcium for Preeclampsia Prevention Study Group. Pregnancy outcomes in healthy nulliparas who developed hypertension. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(1):24-28.

9. Magnussen EB, Vatten LJ, Smith GD, Romundstad PR. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and subsequently measured cardiovascular risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 114(5):961-970.

10. Lindheimer MD, Taler SJ, Cunningham FG; American Society of Hypertension (ASH). ASH position paper: hypertension in pregnancy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2009;11(4):214-225.

11. Roberts JM, Gammill HS. Preeclampsia: recent insights. Hypertension. 2005;46(6):

1243-1249.

12. Saudan P, Brown MA, Buddle ML, Jones M. Does gestational hypertension become pre-eclampsia? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105 (11):1177-1184.

13. Visintin C, Mugglestone MA, Almerie MQ, et al; Guideline Development Group. Management of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2010;341:c2207.

14. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician–Gynecologists. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia: ACOG practice bulletin No. 33. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:159-167.

15. Parazzini F, Bortolus R, Chatenoud L, et al; Italian Study of Aspirin in Pregnancy Group. Risk factors for pregnancy-induced hypertension in women at high risk for the condition. Epidemiology. 1996;7(3):306-308.

16. Hjartardottir S, Leifsson BG, Geirsson RT, Steinthorsdottir V. Recurrence of hypertensive disorder in second pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(4):916-920.

17. Barton JR, O’Brien JM, Bergauer NK, et al. Mild gestational hypertension remote from term: progression and outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(5):979-983.

18. Brown MA, Mackenzie C, Dunsmuir W, et al. Can we predict recurrence of pre-eclampsia or gestational hypertension? BJOG. 2007; 114(8):984-993.

19. Bellomo G, Venanzi S, Saronio P, et al. Prognostic significance of serum uric acid in women with gestational hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;58(4):704-708.

20. Hawkins TL, Roberts JM, Mangos GJ, et al. Plasma uric acid remains a marker of poor outcome in hypertensive pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2012;119(4):484-492.

21. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: the management of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13098/50418/50418.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2012.

22. Koopmans CM, Bijlenga D, Groen H, et al. Induction of labour versus expectant monitoring for gestational hypertension or mild pre-eclampsia after 36 weeks’ gestation (HYPITAT): a multicentre, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9694):979-988.

23. Caughey AB, Sundaram V, Kaimal AJ, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of elective induction of labor. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2009;(176):1-257.

24. Shennan A, Hezelgrave N. An economic analysis of induction of labour and expectant monitoring in women with gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia at term (HYPITAT trial). BJOG. 2010;117(13):1575-1576.

25. Abalos E, Duley L, Steyn DW, Henderson-Smart DJ. Antihypertensive drug therapy for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24;(1):CD002252.

26. Nabhan AF, Elsedawy MM. Tight control of mild-moderate pre-existing or non-proteinuric gestational hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jul 6;(7):CD006907.

27. Duley L, Gülmezoglu AM, Henderson-Smart DJ. Magnesium sulphate and other anticonvulsants for women with preeclampsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD000025.

28. Kraft MD, Btaiche IF, Sacks GS, Kudsk KA. Treatment of electrolyte disorders in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62(16):1663-1682.

29. FamilyDoctor.org. Pregnancy-induced hypertension (updated 2010). http://familydoctor.org/familydoctor/en/diseases-conditions/pregnancy-induced-hypertension.printerview

.all.html. Accessed April 16, 2012.

30. Zamorski MA, Green LA. NHBPEP report on high blood pressure in pregnancy: a summary for family physicians. Am Fam Physician. 2001; 64(2):263-270.

31. Hofmeyr GJ, Duley L, Atallah A. Dietary calcium supplementation for prevention of pre-eclampsia and related problems: a systematic review and commentary. BJOG. 2007;114(8): 933-943.

32. Ferrazzani S, De Carolis S, Pomini F, et al. The duration of hypertension in the puerperium of preeclamptic women: relationship with renal impairment and week of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(2):506-512.

33. Beardmore KS, Morris JM, Gallery ED. Excretion of antihypertensive medication into human breast milk: a systematic review. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2002;21(1):85-95.

34. Wilson BJ, Watson MS, Prescott GJ, et al. Hypertensive diseases of pregnancy and risk of hypertension and stroke in later life: results from cohort study. BMJ. 2003;326(7394):845.

1. Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on high blood pressure in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(1):S1-S22.

2. Sibai BM. Diagnosis and management of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(1):181-192.

3. Kuklina EV, Ayala C, Callaghan WM. Hypertensive disorders and severe obstetric morbidity in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 113(6):1299-1306.

4. Villar J, Carroli, G, Wojdyla D, et al; World Health Organization Antenatal Care Trial Research Group. Preeclampsia, gestational hypertension and intrauterine growth restriction, related or independent conditions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(4):921-931.

5. Leeman L, Fontaine P. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(1):

93-100.

6. Magee LA, Helewa M, Moutquin JM, von Dadelszen P; Hypertension Guideline Committee; Strategic Training Initiative in Research in the Reproductive Health Sciences (STIRRHS) Scholars. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30(3 suppl):S1-S48.

7. Buchbinder A, Sibai BM, Caritis S, et al. Adverse perinatal outcomes are significantly higher in severe gestational hypertension than in mild preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(1):66-71.

8. Hauth JC, Ewell MG, Levine RJ, et al; Calcium for Preeclampsia Prevention Study Group. Pregnancy outcomes in healthy nulliparas who developed hypertension. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(1):24-28.

9. Magnussen EB, Vatten LJ, Smith GD, Romundstad PR. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and subsequently measured cardiovascular risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 114(5):961-970.

10. Lindheimer MD, Taler SJ, Cunningham FG; American Society of Hypertension (ASH). ASH position paper: hypertension in pregnancy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2009;11(4):214-225.

11. Roberts JM, Gammill HS. Preeclampsia: recent insights. Hypertension. 2005;46(6):

1243-1249.

12. Saudan P, Brown MA, Buddle ML, Jones M. Does gestational hypertension become pre-eclampsia? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105 (11):1177-1184.

13. Visintin C, Mugglestone MA, Almerie MQ, et al; Guideline Development Group. Management of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2010;341:c2207.

14. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician–Gynecologists. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia: ACOG practice bulletin No. 33. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:159-167.

15. Parazzini F, Bortolus R, Chatenoud L, et al; Italian Study of Aspirin in Pregnancy Group. Risk factors for pregnancy-induced hypertension in women at high risk for the condition. Epidemiology. 1996;7(3):306-308.

16. Hjartardottir S, Leifsson BG, Geirsson RT, Steinthorsdottir V. Recurrence of hypertensive disorder in second pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(4):916-920.

17. Barton JR, O’Brien JM, Bergauer NK, et al. Mild gestational hypertension remote from term: progression and outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(5):979-983.

18. Brown MA, Mackenzie C, Dunsmuir W, et al. Can we predict recurrence of pre-eclampsia or gestational hypertension? BJOG. 2007; 114(8):984-993.

19. Bellomo G, Venanzi S, Saronio P, et al. Prognostic significance of serum uric acid in women with gestational hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;58(4):704-708.

20. Hawkins TL, Roberts JM, Mangos GJ, et al. Plasma uric acid remains a marker of poor outcome in hypertensive pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2012;119(4):484-492.

21. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: the management of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13098/50418/50418.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2012.