User login

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

How to Handle Medicare Documentation Audits

The recent announcement of a settlement by a physician firm should cause the HM community to pause and take inventory. The settlement “addressed allegations that, between 2004 and 2012, [the firm] knowingly submitted to federal health benefits programs inflated claims on behalf of its hospitalist employees for higher and more expensive levels of service than were documented by hospitalists in patient medical records.”1

This civil settlement highlights the vigilance being exercised against healthcare fraud and demonstrates the coordinated efforts in place to tackle the issue. To put the weight of this case in perspective, consider the breadth of legal entities involved: the U.S. Department of Justice; the U.S. Attorney’s Office; the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; the U.S. Department of Defense; the U.S. Office of Personnel Management; the U.S. Department of Veterans’ Affairs; and the TRICARE Management Activity Office of General Counsel.1

The underlying factor in the settlement is a common issue routinely identified by Medicare-initiated review programs such as CERT (Comprehensive Error Rate Testing). CERT selects a stratified, random sample of approximately 40,000 claims submitted to Part A/B Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) and Durable Medical Equipment MACs (DME MACs) during each reporting period and allows the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to calculate a national improper payment rate and contractor- and service-specific improper payment rates.2 The CERT-determined improper payment rate identifies services that have not satisfied Medicare requirements, but it cannot label a claim fraudulent.2

Incorrect coding errors involving hospitalists are related to inpatient evaluation and management (E/M) services that do not adequately reflect the documentation in the medical record. For example, WPS Medicare identified the following error rates for claims submitted 7/1/11 to 6/30/12: 45% of 99223 (initial hospital care, per day, for the evaluation and management of a patient, which requires these three key components: a comprehensive history, a comprehensive exam, and medical decision-making of high complexity); and 34% of 99233 (subsequent hospital care, per day, for the evaluation and management of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: a detailed interval history, a detailed examination, and medical decision-making of high complexity).3,4 More recent WPS Medicare data in first quarter of FY2013 reveals a continuing problem but an improved error rate.5 Novitas Solutions offers additional support of these findings.6

Based on efforts that identify improper payments, MACs are encouraged to initiate targeted service-specific prepayment review to prevent improper payments for services identified by CERT or recovery audit contractors (RACs) as problem areas, as well as problem areas identified by their own data analysis.7 For this reason, hospitalists may see prepayment requests for documentation by Medicare for services that are most “problematic” (e.g., 99223 and 99233). This occurs when a claim involving these services is submitted to Medicare. The MAC suspends all or part of a claim so that a trained clinician or claims analyst can review the claim and associated documentation in order to make determinations about coverage and payment.7 Responding to these requests in a timely manner is crucial in preventing claim denials.

Responding to Requests

When documentation is requested by the payor, take note of the date and the provider for whom the service is requested. Be certain to include all pertinent information in support of the claim. The payor request letter will typically include a generic list of items that should be submitted with the documentation request. Consider these particular items when submitting documentation for targeted services typically provided by hospitalists:

- Initial Hospital Care (99223)

- Physician notes (including resident, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant notes);

- Identify any referenced sources of information (e.g., physician referencing a family history documented in the ED record);

- Dictations, when performed;

- Admitting orders; and

- Labs or diagnostic test reports performed on admission.

- Subsequent Hospital Care (99233)

- Physician notes (including resident, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant notes);

- Identify multiple encounters/entries recorded on a given date;

- Physician orders; and

- Labs or diagnostic test reports performed on the requested date.

Documentation Tips

Because it is the primary communication tool for providers involved in the patient’s care, documentation must be entered in a timely manner and must be decipherable to members of the healthcare team as well as other individuals who may need to review the information (e.g., auditors). Proper credit cannot be given for documentation that is difficult to read.

Information should include historical review of past/interim events, a physical exam, medical decision-making as related to the patient’s progress/response to intervention, and modification of the care plan (as necessary). The reason for the encounter should be evident to support the medical necessity of the service. Because various specialists may participate in patient care, documentation for each provider’s encounter should demonstrate personalized and non-duplicative care.

Each individual provider must exhibit a personal contribution to the case to prevent payors from viewing the documentation as overlapping and indistinguishable from care already provided by another physician. Each entry should be dated and signed with a legible identifier (i.e., signature with a printed name).

The next several articles will address each of the key components (history, exam, and decision-making) and serve as a “documentation refresher” for providers who wish to compare their documentation to current standards.

References

- Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. Tacoma, Wash., Medical Firm to Pay $14.5 Million to Settle Overbilling Allegations. Available at: www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2013/July/13-civ-758.html. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT). Available at: www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Monitoring-Programs/CERT/index.html?redirect=/cert. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- WPS Medicare, Legacy Part B. Are you billing these evaluation and management (e/m) services correctly? Available at: http://www.wpsmedicare.com/j5macpartb/departments/cert/2011-0912-billemservices.shtml. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis, L. Current Procedural Terminology 2013 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2012:15-17.

- WPS Medicare, Legacy Part B. 1st Qtr. 2013 (Jan. - Mar.) - CERT Error Summary. Available at: http://www.wpsmedicare.com/j5macpartb/departments/cert/2013-1st-quarter-summary.shtml. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Novitas Solutions. Analysis of JL Part B Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT) Data - January thru March 2013. Available at: https://www.novitas-solutions.com/cert/errors/2013/b-jan-mar-j12.html. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Program Integrity Manual, Chapter 3, Section 3.2. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/pim83c03.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 11, Section 40.1.2 Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c11.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2013.

The recent announcement of a settlement by a physician firm should cause the HM community to pause and take inventory. The settlement “addressed allegations that, between 2004 and 2012, [the firm] knowingly submitted to federal health benefits programs inflated claims on behalf of its hospitalist employees for higher and more expensive levels of service than were documented by hospitalists in patient medical records.”1

This civil settlement highlights the vigilance being exercised against healthcare fraud and demonstrates the coordinated efforts in place to tackle the issue. To put the weight of this case in perspective, consider the breadth of legal entities involved: the U.S. Department of Justice; the U.S. Attorney’s Office; the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; the U.S. Department of Defense; the U.S. Office of Personnel Management; the U.S. Department of Veterans’ Affairs; and the TRICARE Management Activity Office of General Counsel.1

The underlying factor in the settlement is a common issue routinely identified by Medicare-initiated review programs such as CERT (Comprehensive Error Rate Testing). CERT selects a stratified, random sample of approximately 40,000 claims submitted to Part A/B Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) and Durable Medical Equipment MACs (DME MACs) during each reporting period and allows the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to calculate a national improper payment rate and contractor- and service-specific improper payment rates.2 The CERT-determined improper payment rate identifies services that have not satisfied Medicare requirements, but it cannot label a claim fraudulent.2

Incorrect coding errors involving hospitalists are related to inpatient evaluation and management (E/M) services that do not adequately reflect the documentation in the medical record. For example, WPS Medicare identified the following error rates for claims submitted 7/1/11 to 6/30/12: 45% of 99223 (initial hospital care, per day, for the evaluation and management of a patient, which requires these three key components: a comprehensive history, a comprehensive exam, and medical decision-making of high complexity); and 34% of 99233 (subsequent hospital care, per day, for the evaluation and management of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: a detailed interval history, a detailed examination, and medical decision-making of high complexity).3,4 More recent WPS Medicare data in first quarter of FY2013 reveals a continuing problem but an improved error rate.5 Novitas Solutions offers additional support of these findings.6

Based on efforts that identify improper payments, MACs are encouraged to initiate targeted service-specific prepayment review to prevent improper payments for services identified by CERT or recovery audit contractors (RACs) as problem areas, as well as problem areas identified by their own data analysis.7 For this reason, hospitalists may see prepayment requests for documentation by Medicare for services that are most “problematic” (e.g., 99223 and 99233). This occurs when a claim involving these services is submitted to Medicare. The MAC suspends all or part of a claim so that a trained clinician or claims analyst can review the claim and associated documentation in order to make determinations about coverage and payment.7 Responding to these requests in a timely manner is crucial in preventing claim denials.

Responding to Requests

When documentation is requested by the payor, take note of the date and the provider for whom the service is requested. Be certain to include all pertinent information in support of the claim. The payor request letter will typically include a generic list of items that should be submitted with the documentation request. Consider these particular items when submitting documentation for targeted services typically provided by hospitalists:

- Initial Hospital Care (99223)

- Physician notes (including resident, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant notes);

- Identify any referenced sources of information (e.g., physician referencing a family history documented in the ED record);

- Dictations, when performed;

- Admitting orders; and

- Labs or diagnostic test reports performed on admission.

- Subsequent Hospital Care (99233)

- Physician notes (including resident, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant notes);

- Identify multiple encounters/entries recorded on a given date;

- Physician orders; and

- Labs or diagnostic test reports performed on the requested date.

Documentation Tips

Because it is the primary communication tool for providers involved in the patient’s care, documentation must be entered in a timely manner and must be decipherable to members of the healthcare team as well as other individuals who may need to review the information (e.g., auditors). Proper credit cannot be given for documentation that is difficult to read.

Information should include historical review of past/interim events, a physical exam, medical decision-making as related to the patient’s progress/response to intervention, and modification of the care plan (as necessary). The reason for the encounter should be evident to support the medical necessity of the service. Because various specialists may participate in patient care, documentation for each provider’s encounter should demonstrate personalized and non-duplicative care.

Each individual provider must exhibit a personal contribution to the case to prevent payors from viewing the documentation as overlapping and indistinguishable from care already provided by another physician. Each entry should be dated and signed with a legible identifier (i.e., signature with a printed name).

The next several articles will address each of the key components (history, exam, and decision-making) and serve as a “documentation refresher” for providers who wish to compare their documentation to current standards.

References

- Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. Tacoma, Wash., Medical Firm to Pay $14.5 Million to Settle Overbilling Allegations. Available at: www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2013/July/13-civ-758.html. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT). Available at: www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Monitoring-Programs/CERT/index.html?redirect=/cert. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- WPS Medicare, Legacy Part B. Are you billing these evaluation and management (e/m) services correctly? Available at: http://www.wpsmedicare.com/j5macpartb/departments/cert/2011-0912-billemservices.shtml. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis, L. Current Procedural Terminology 2013 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2012:15-17.

- WPS Medicare, Legacy Part B. 1st Qtr. 2013 (Jan. - Mar.) - CERT Error Summary. Available at: http://www.wpsmedicare.com/j5macpartb/departments/cert/2013-1st-quarter-summary.shtml. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Novitas Solutions. Analysis of JL Part B Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT) Data - January thru March 2013. Available at: https://www.novitas-solutions.com/cert/errors/2013/b-jan-mar-j12.html. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Program Integrity Manual, Chapter 3, Section 3.2. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/pim83c03.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 11, Section 40.1.2 Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c11.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2013.

The recent announcement of a settlement by a physician firm should cause the HM community to pause and take inventory. The settlement “addressed allegations that, between 2004 and 2012, [the firm] knowingly submitted to federal health benefits programs inflated claims on behalf of its hospitalist employees for higher and more expensive levels of service than were documented by hospitalists in patient medical records.”1

This civil settlement highlights the vigilance being exercised against healthcare fraud and demonstrates the coordinated efforts in place to tackle the issue. To put the weight of this case in perspective, consider the breadth of legal entities involved: the U.S. Department of Justice; the U.S. Attorney’s Office; the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; the U.S. Department of Defense; the U.S. Office of Personnel Management; the U.S. Department of Veterans’ Affairs; and the TRICARE Management Activity Office of General Counsel.1

The underlying factor in the settlement is a common issue routinely identified by Medicare-initiated review programs such as CERT (Comprehensive Error Rate Testing). CERT selects a stratified, random sample of approximately 40,000 claims submitted to Part A/B Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) and Durable Medical Equipment MACs (DME MACs) during each reporting period and allows the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to calculate a national improper payment rate and contractor- and service-specific improper payment rates.2 The CERT-determined improper payment rate identifies services that have not satisfied Medicare requirements, but it cannot label a claim fraudulent.2

Incorrect coding errors involving hospitalists are related to inpatient evaluation and management (E/M) services that do not adequately reflect the documentation in the medical record. For example, WPS Medicare identified the following error rates for claims submitted 7/1/11 to 6/30/12: 45% of 99223 (initial hospital care, per day, for the evaluation and management of a patient, which requires these three key components: a comprehensive history, a comprehensive exam, and medical decision-making of high complexity); and 34% of 99233 (subsequent hospital care, per day, for the evaluation and management of a patient, which requires at least two of these three key components: a detailed interval history, a detailed examination, and medical decision-making of high complexity).3,4 More recent WPS Medicare data in first quarter of FY2013 reveals a continuing problem but an improved error rate.5 Novitas Solutions offers additional support of these findings.6

Based on efforts that identify improper payments, MACs are encouraged to initiate targeted service-specific prepayment review to prevent improper payments for services identified by CERT or recovery audit contractors (RACs) as problem areas, as well as problem areas identified by their own data analysis.7 For this reason, hospitalists may see prepayment requests for documentation by Medicare for services that are most “problematic” (e.g., 99223 and 99233). This occurs when a claim involving these services is submitted to Medicare. The MAC suspends all or part of a claim so that a trained clinician or claims analyst can review the claim and associated documentation in order to make determinations about coverage and payment.7 Responding to these requests in a timely manner is crucial in preventing claim denials.

Responding to Requests

When documentation is requested by the payor, take note of the date and the provider for whom the service is requested. Be certain to include all pertinent information in support of the claim. The payor request letter will typically include a generic list of items that should be submitted with the documentation request. Consider these particular items when submitting documentation for targeted services typically provided by hospitalists:

- Initial Hospital Care (99223)

- Physician notes (including resident, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant notes);

- Identify any referenced sources of information (e.g., physician referencing a family history documented in the ED record);

- Dictations, when performed;

- Admitting orders; and

- Labs or diagnostic test reports performed on admission.

- Subsequent Hospital Care (99233)

- Physician notes (including resident, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant notes);

- Identify multiple encounters/entries recorded on a given date;

- Physician orders; and

- Labs or diagnostic test reports performed on the requested date.

Documentation Tips

Because it is the primary communication tool for providers involved in the patient’s care, documentation must be entered in a timely manner and must be decipherable to members of the healthcare team as well as other individuals who may need to review the information (e.g., auditors). Proper credit cannot be given for documentation that is difficult to read.

Information should include historical review of past/interim events, a physical exam, medical decision-making as related to the patient’s progress/response to intervention, and modification of the care plan (as necessary). The reason for the encounter should be evident to support the medical necessity of the service. Because various specialists may participate in patient care, documentation for each provider’s encounter should demonstrate personalized and non-duplicative care.

Each individual provider must exhibit a personal contribution to the case to prevent payors from viewing the documentation as overlapping and indistinguishable from care already provided by another physician. Each entry should be dated and signed with a legible identifier (i.e., signature with a printed name).

The next several articles will address each of the key components (history, exam, and decision-making) and serve as a “documentation refresher” for providers who wish to compare their documentation to current standards.

References

- Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. Tacoma, Wash., Medical Firm to Pay $14.5 Million to Settle Overbilling Allegations. Available at: www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2013/July/13-civ-758.html. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT). Available at: www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Monitoring-Programs/CERT/index.html?redirect=/cert. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- WPS Medicare, Legacy Part B. Are you billing these evaluation and management (e/m) services correctly? Available at: http://www.wpsmedicare.com/j5macpartb/departments/cert/2011-0912-billemservices.shtml. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis, L. Current Procedural Terminology 2013 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2012:15-17.

- WPS Medicare, Legacy Part B. 1st Qtr. 2013 (Jan. - Mar.) - CERT Error Summary. Available at: http://www.wpsmedicare.com/j5macpartb/departments/cert/2013-1st-quarter-summary.shtml. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Novitas Solutions. Analysis of JL Part B Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT) Data - January thru March 2013. Available at: https://www.novitas-solutions.com/cert/errors/2013/b-jan-mar-j12.html. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Program Integrity Manual, Chapter 3, Section 3.2. Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/pim83c03.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 11, Section 40.1.2 Available at: www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c11.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2013.

How To Avoid Medicare Denials for Critical-Care Billing

Are your critical-care claims at risk for denial or repayment upon review? Several payors have identified increased potential for critical-care reporting discrepancies, which has resulted in targeted prepayment reviews of this code.1 Some payors have implemented 100% review when critical care is reported in settings other than inpatient hospitals, outpatient hospitals, or emergency departments.2 To ensure a successful outcome, make sure the documentation meets the basic principles of the critical-care guidelines.

Defining Critical Illness/Injury

CPT and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g. central-nervous-system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).3 The provider’s time must be solely directed toward the critically ill patient. Highly complex decision-making and interventions of high intensity are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline if left untreated. Payment may be made for critical-care services provided in any reasonable location, as long as the care provided meets the definition of critical care. Critical-care services cannot be reported for a patient who is not critically ill but happens to be in a critical-care unit, or when a particular physician is only treating one of the patient’s conditions that is not considered the critical illness.4

Examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical-necessity criteria, do not meet critical-care criteria, or who do not have a critical-care illness or injury and therefore are not eligible for critical-care payment:

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g. drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g. insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical-care unit; and

- Care of only a chronic illness in the absence of caring for a critical illness (e.g. daily management of a chronic ventilator patient; management of or care related to dialysis for an ESRD).

These circumstances would require using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233), initial hospital care codes (99221-99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251-99255) when applicable.3,5

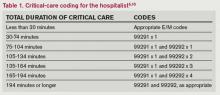

Because critical-care time is a cumulative service, providers keep track of their total time throughout a single calendar day. For each date and encounter entry, the physician’s progress notes shall document the total time that critical-care services were provided (e.g. 45 minutes).4 Some payors impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g. 10 to 10:45 a.m.).

Code This Case

Consider the following scenario: A hospitalist admits a 75-year-old patient to the ICU with acute respiratory failure. He spends 45 minutes in critical-care time. The patient’s family arrives soon thereafter to discuss the patient’s condition with a second hospitalist. The discussion lasts an additional 20 minutes, and the decision regarding the patient’s DNR status is made.

Family meetings must take place at the bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate, unless they are medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. A notation in the chart should indicate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason. Meeting time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or the limitations of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.5,6 Meetings that take place for family grief counseling (90846, 90847, 90849) are not included in critical-care time and cannot be billed separately.

Do not count time associated with periodic condition updates to the family or answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision-making.

Family discussions can take place via phone as long as the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.6

Critically ill patients often require the care of multiple providers.3 Payors implement code logic in their systems that allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical-care hours. Documentation must demonstrate that care is not duplicative of other specialists and does not overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical-care services.

Same-specialty physicians (two hospitalists from the same group practice) bill and are paid as one physician. The initial critical-care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical-care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. Cumulative physician time should be reported under one provider number on a single invoice in order to prevent denials from billing 99292 independently (see “Critical-Care Services: Time Reminders,”).

When a physician and a nurse practitioner (NP) see a patient on the same calendar day, critical-care reporting is handled differently. A single unit of critical-care time cannot be split or shared between a physician and a qualified NP. One individual must meet the entire time requirement of the reported service code.

More specifically, the hospitalist must individually meet the criteria for the first critical-care hour before reporting 99291, and the NP must individually meet the criteria for an additional 30 minutes of critical care before reporting 99292. The same is true if the NP provided the initial hour while the hospitalist provided the additional critical-care time.

Payors who recognize NPs as independent billing providers (e.g. Medicare and Aetna) require a “split” invoice: an invoice for 99291 with the hospitalist NPI and an invoice for 99292 with the NP’s NPI.9 This ensures reimbursement-rate accuracy, as the physician receives 100% of the allowable rate while the NP receives 85%. If the 99292 invoice is denied due to the payor’s system edits disallowing separate invoicing of add-on codes, appeal with documentation by both the hospitalist and NP to identify the circumstances and reclaim payment.

References

- Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC. Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC website. Available at: http://www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed May 4, 2013.

- First Coast Service Options Inc. Prepayment edit of evaluation and management (E/M) code 99291. First Coast Service Options Inc. website. Available at: http://medicare.fcso.com/Medical_documentation/249650.asp. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12A. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12B. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12E. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis L. Current Procedural Terminology 2013 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2012.

- Novitas Solutions Inc. Evaluation & management: service-specific coding instructions. Novitas Solutions Inc. website. Available at: http://www.novitas-solutions.com/em/coding.html. Accessed May 7, 2013.

- United Healthcare. Same day same service policy—adding edits. United Healthcare website. Available at: http://www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ ProviderII/ UHC/en-US/Assets/ProviderStaticFiles/ProviderStaticFilesPdf/News/Network_Bulletin_November _2012_Volume_52.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12G. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2013.

Are your critical-care claims at risk for denial or repayment upon review? Several payors have identified increased potential for critical-care reporting discrepancies, which has resulted in targeted prepayment reviews of this code.1 Some payors have implemented 100% review when critical care is reported in settings other than inpatient hospitals, outpatient hospitals, or emergency departments.2 To ensure a successful outcome, make sure the documentation meets the basic principles of the critical-care guidelines.

Defining Critical Illness/Injury

CPT and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g. central-nervous-system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).3 The provider’s time must be solely directed toward the critically ill patient. Highly complex decision-making and interventions of high intensity are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline if left untreated. Payment may be made for critical-care services provided in any reasonable location, as long as the care provided meets the definition of critical care. Critical-care services cannot be reported for a patient who is not critically ill but happens to be in a critical-care unit, or when a particular physician is only treating one of the patient’s conditions that is not considered the critical illness.4

Examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical-necessity criteria, do not meet critical-care criteria, or who do not have a critical-care illness or injury and therefore are not eligible for critical-care payment:

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g. drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g. insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical-care unit; and

- Care of only a chronic illness in the absence of caring for a critical illness (e.g. daily management of a chronic ventilator patient; management of or care related to dialysis for an ESRD).

These circumstances would require using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233), initial hospital care codes (99221-99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251-99255) when applicable.3,5

Because critical-care time is a cumulative service, providers keep track of their total time throughout a single calendar day. For each date and encounter entry, the physician’s progress notes shall document the total time that critical-care services were provided (e.g. 45 minutes).4 Some payors impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g. 10 to 10:45 a.m.).

Code This Case

Consider the following scenario: A hospitalist admits a 75-year-old patient to the ICU with acute respiratory failure. He spends 45 minutes in critical-care time. The patient’s family arrives soon thereafter to discuss the patient’s condition with a second hospitalist. The discussion lasts an additional 20 minutes, and the decision regarding the patient’s DNR status is made.

Family meetings must take place at the bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate, unless they are medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. A notation in the chart should indicate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason. Meeting time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or the limitations of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.5,6 Meetings that take place for family grief counseling (90846, 90847, 90849) are not included in critical-care time and cannot be billed separately.

Do not count time associated with periodic condition updates to the family or answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision-making.

Family discussions can take place via phone as long as the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.6

Critically ill patients often require the care of multiple providers.3 Payors implement code logic in their systems that allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical-care hours. Documentation must demonstrate that care is not duplicative of other specialists and does not overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical-care services.

Same-specialty physicians (two hospitalists from the same group practice) bill and are paid as one physician. The initial critical-care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical-care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. Cumulative physician time should be reported under one provider number on a single invoice in order to prevent denials from billing 99292 independently (see “Critical-Care Services: Time Reminders,”).

When a physician and a nurse practitioner (NP) see a patient on the same calendar day, critical-care reporting is handled differently. A single unit of critical-care time cannot be split or shared between a physician and a qualified NP. One individual must meet the entire time requirement of the reported service code.

More specifically, the hospitalist must individually meet the criteria for the first critical-care hour before reporting 99291, and the NP must individually meet the criteria for an additional 30 minutes of critical care before reporting 99292. The same is true if the NP provided the initial hour while the hospitalist provided the additional critical-care time.

Payors who recognize NPs as independent billing providers (e.g. Medicare and Aetna) require a “split” invoice: an invoice for 99291 with the hospitalist NPI and an invoice for 99292 with the NP’s NPI.9 This ensures reimbursement-rate accuracy, as the physician receives 100% of the allowable rate while the NP receives 85%. If the 99292 invoice is denied due to the payor’s system edits disallowing separate invoicing of add-on codes, appeal with documentation by both the hospitalist and NP to identify the circumstances and reclaim payment.

References

- Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC. Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC website. Available at: http://www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed May 4, 2013.

- First Coast Service Options Inc. Prepayment edit of evaluation and management (E/M) code 99291. First Coast Service Options Inc. website. Available at: http://medicare.fcso.com/Medical_documentation/249650.asp. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12A. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12B. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12E. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis L. Current Procedural Terminology 2013 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2012.

- Novitas Solutions Inc. Evaluation & management: service-specific coding instructions. Novitas Solutions Inc. website. Available at: http://www.novitas-solutions.com/em/coding.html. Accessed May 7, 2013.

- United Healthcare. Same day same service policy—adding edits. United Healthcare website. Available at: http://www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ ProviderII/ UHC/en-US/Assets/ProviderStaticFiles/ProviderStaticFilesPdf/News/Network_Bulletin_November _2012_Volume_52.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12G. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2013.

Are your critical-care claims at risk for denial or repayment upon review? Several payors have identified increased potential for critical-care reporting discrepancies, which has resulted in targeted prepayment reviews of this code.1 Some payors have implemented 100% review when critical care is reported in settings other than inpatient hospitals, outpatient hospitals, or emergency departments.2 To ensure a successful outcome, make sure the documentation meets the basic principles of the critical-care guidelines.

Defining Critical Illness/Injury

CPT and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define “critical illness or injury” as a condition that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition (e.g. central-nervous-system failure; circulatory failure; shock; renal, hepatic, metabolic, and/or respiratory failure).3 The provider’s time must be solely directed toward the critically ill patient. Highly complex decision-making and interventions of high intensity are required to prevent the patient’s inevitable decline if left untreated. Payment may be made for critical-care services provided in any reasonable location, as long as the care provided meets the definition of critical care. Critical-care services cannot be reported for a patient who is not critically ill but happens to be in a critical-care unit, or when a particular physician is only treating one of the patient’s conditions that is not considered the critical illness.4

Examples of patients who may not satisfy Medicare medical-necessity criteria, do not meet critical-care criteria, or who do not have a critical-care illness or injury and therefore are not eligible for critical-care payment:

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because no other hospital beds were available;

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit for close nursing observation and/or frequent monitoring of vital signs (e.g. drug toxicity or overdose);

- Patients admitted to a critical-care unit because hospital rules require certain treatments (e.g. insulin infusions) to be administered in the critical-care unit; and

- Care of only a chronic illness in the absence of caring for a critical illness (e.g. daily management of a chronic ventilator patient; management of or care related to dialysis for an ESRD).

These circumstances would require using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233), initial hospital care codes (99221-99223), or hospital consultation codes (99251-99255) when applicable.3,5

Because critical-care time is a cumulative service, providers keep track of their total time throughout a single calendar day. For each date and encounter entry, the physician’s progress notes shall document the total time that critical-care services were provided (e.g. 45 minutes).4 Some payors impose the notation of “start-and-stop time” per encounter (e.g. 10 to 10:45 a.m.).

Code This Case

Consider the following scenario: A hospitalist admits a 75-year-old patient to the ICU with acute respiratory failure. He spends 45 minutes in critical-care time. The patient’s family arrives soon thereafter to discuss the patient’s condition with a second hospitalist. The discussion lasts an additional 20 minutes, and the decision regarding the patient’s DNR status is made.

Family meetings must take place at the bedside or on the patient’s unit/floor. The patient must participate, unless they are medically unable or clinically incompetent to participate. A notation in the chart should indicate the patient’s inability to participate and the reason. Meeting time can only involve obtaining a medical history and/or discussing treatment options or the limitations of treatment. The conversation must bear directly on patient management.5,6 Meetings that take place for family grief counseling (90846, 90847, 90849) are not included in critical-care time and cannot be billed separately.

Do not count time associated with periodic condition updates to the family or answering questions about the patient’s condition that are unrelated to decision-making.

Family discussions can take place via phone as long as the physician is calling from the patient’s unit/floor and the conversation involves the same criterion identified for face-to-face family meetings.6

Critically ill patients often require the care of multiple providers.3 Payors implement code logic in their systems that allow reimbursement for 99291 once per day when reported by physicians of the same group and specialty.8 Physicians of different specialties can separately report critical-care hours. Documentation must demonstrate that care is not duplicative of other specialists and does not overlap the same time period of any other physician reporting critical-care services.

Same-specialty physicians (two hospitalists from the same group practice) bill and are paid as one physician. The initial critical-care hour (99291) must be met by a single physician. Medically necessary critical-care time beyond the first hour (99292) may be met individually by the same physician or collectively with another physician from the same group. Cumulative physician time should be reported under one provider number on a single invoice in order to prevent denials from billing 99292 independently (see “Critical-Care Services: Time Reminders,”).

When a physician and a nurse practitioner (NP) see a patient on the same calendar day, critical-care reporting is handled differently. A single unit of critical-care time cannot be split or shared between a physician and a qualified NP. One individual must meet the entire time requirement of the reported service code.

More specifically, the hospitalist must individually meet the criteria for the first critical-care hour before reporting 99291, and the NP must individually meet the criteria for an additional 30 minutes of critical care before reporting 99292. The same is true if the NP provided the initial hour while the hospitalist provided the additional critical-care time.

Payors who recognize NPs as independent billing providers (e.g. Medicare and Aetna) require a “split” invoice: an invoice for 99291 with the hospitalist NPI and an invoice for 99292 with the NP’s NPI.9 This ensures reimbursement-rate accuracy, as the physician receives 100% of the allowable rate while the NP receives 85%. If the 99292 invoice is denied due to the payor’s system edits disallowing separate invoicing of add-on codes, appeal with documentation by both the hospitalist and NP to identify the circumstances and reclaim payment.

References

- Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC. Widespread prepayment targeted review notification—CPT 99291. Cahaba Government Benefit Administrators LLC website. Available at: http://www.cahabagba.com/news/widespread-prepayment-targeted-review-notification-part-b/. Accessed May 4, 2013.

- First Coast Service Options Inc. Prepayment edit of evaluation and management (E/M) code 99291. First Coast Service Options Inc. website. Available at: http://medicare.fcso.com/Medical_documentation/249650.asp. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12A. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12B. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12E. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Boudreau A, Connelly J, Levreau-Davis L. Current Procedural Terminology 2013 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2012.

- Novitas Solutions Inc. Evaluation & management: service-specific coding instructions. Novitas Solutions Inc. website. Available at: http://www.novitas-solutions.com/em/coding.html. Accessed May 7, 2013.

- United Healthcare. Same day same service policy—adding edits. United Healthcare website. Available at: http://www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ ProviderII/ UHC/en-US/Assets/ProviderStaticFiles/ProviderStaticFilesPdf/News/Network_Bulletin_November _2012_Volume_52.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.12G. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2013.

Documentation, CMS-Approved Language Key to Getting Paid for Hospitalist Teaching Services

When hospitalists work in academic centers, medical and surgical services are furnished, in part, by a resident within the scope of the hospitalists’ training program. A resident is “an individual who participates in an approved graduate medical education (GME) program or a physician who is not in an approved GME program but who is authorized to practice only in a hospital setting.”1 Resident services are covered by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and paid by the Fiscal Intermediary through direct GME and Indirect Medical Education (IME) payments. These services are not billed or paid using the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. The teaching physician is responsible for supervising the resident’s health-care delivery but is not paid for the resident’s work. The teaching physician is paid for their personal and medically necessary service in providing patient care. The teaching physician has the option to perform the entire service, or perform the self-determined critical or key portion(s) of the service.

Comprehensive Service

Teaching physicians independently see the patient and perform all required elements to support the visit level (e.g. 99233: subsequent hospital care, per day, which requires at least two of the following three key components: a detailed interval history, a detailed examination, or high-complexity medical decision-making).2 The teaching physician writes a note independent of a resident encounter with the patient or documentation. The teaching physician note “stands alone” and does not rely on the resident’s documentation. If the resident saw the patient and documented the encounter, the teaching physician might choose to “link to” the resident note in lieu of personally documenting the entire service. The linking statement must demonstrate teaching physician involvement in the patient encounter and participation in patient management. Use of CMS-approved statements is best to meet these requirements. Statement examples include:3

- “I performed a history and physical examination of the patient and discussed his management with the resident. I reviewed the resident’s note and agree with the documented findings and plan of care.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. I agree with the findings and the plan of care as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “I saw and examined the patient. I agree with the resident’s note, except the heart murmur is louder, so I will obtain an echo to evaluate.”

Each of these statements meets the minimum requirements for billing. However, teaching physicians should offer more information in support of other clinical, quality, and regulatory initiatives and mandates, better exemplified in the last example. The reported visit level will be supported by the combined documentation (teaching physician and resident).

The teaching physician submits a claim in their name and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99223-GC). This alerts the Medicare contractor that services were provided under teaching physician rules. Requests for documentation should include a response with medical record entries from the teaching physician and resident.

Critical/Key Portion

“Supervised” service: The resident and teaching physician can round together; they can see the patient at the same time. The teaching physician observes the resident’s performance during the patient encounter, or personally performs self-determined elements of patient care. The resident documents their patient care. The attending must still note their presence in the medical record, performance of the critical or key portions of the service, and involvement in patient management. CMS-accepted statements include:3

- “I was present with the resident during the history and exam. I discussed the case with the resident and agree with the findings and plan as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “I saw the patient with the resident and agree with the resident’s findings and plan.”

Although these statements demonstrate acceptable billing language, they lack patient-specific details that support the teaching physician’s personal contribution to patient care and the quality of their expertise. The teaching physician selects the visit level that represents the combined documentation and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99232-GC).

“Shared” service: The resident sees the patient unaccompanied and documents the corresponding care provided. The teaching physician sees the patient at a different time but performs only the critical or key portions of the service. The case is subsequently discussed with the resident. The teaching physician must document their presence and performance of the critical or key portions of the service, along with any patient management. Using CMS-quoted statements ensures regulatory compliance:3

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. I reviewed the resident’s note and agree, except that the picture is more consistent with pericarditis than myocardial ischemia. Will begin NSAIDs.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. Discussed with resident and agree with resident’s findings and plan as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “See resident’s note for details. I saw and evaluated the patient and agree with the resident’s finding and plans as written.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. Agree with resident’s note, but lower extremities are weaker, now 3/5; MRI of L/S spine today.”

Once again, the teaching physician selects the visit level that represents the combined documentation and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99233-GC).

EHR Considerations

When seeing patients independent of one another, the timing of the teaching physician and resident encounters does not impact billing. However, the time that the resident encounter is documented in the medical record can significantly impact the payment when reviewed by external auditors. When the resident note is dated and timed later than the teaching physician’s entry, the teaching physician cannot consider the resident’s note for visit-level selection. The teaching physician should not “link to” a resident note that is viewed as “not having been written” prior to the teaching physician note. This would not fulfill the requirements represented in the CMS-approved language “I reviewed the resident’s note and agree.”

Electronic health record (EHR) systems sometimes hinder compliance. If the resident completes the note but does not “finalize” or “close” the encounter until after the teaching physician documents their own note, it can falsely appear that the resident note did not exist at the time the teaching physician created their entry. Because an auditor can only view the finalized entries, the timing of each entry might be erroneously represented. Proper training and closing of encounters can diminish these issues.

Additionally, scribing the attestation is not permitted. Residents cannot document the teaching physician attestation on behalf of the physician under any circumstance. CMS rules require the teaching physician to document their presence, participation, and management of the patient. In an EHR, the teaching physician must document this entry under his/her own log-in and password, which is not to be shared with anyone.

Students

CMS defines student as “an individual who participates in an accredited educational program [e.g. a medical school] that is not an approved GME program.”1 A student is not regarded as a “physician in training,” and the service is not eligible for reimbursement consideration under the teaching physician rules.

Per CMS guidelines, students can document services in the medical record, but the teaching physician may only refer to the student’s systems review and past/family/social history entries. The teaching physician must verify and redocument the history of present illness. A student’s physical exam findings or medical decision-making are not suitable for tethering, and the teaching physician must personally perform and redocument the physical exam and medical decision-making. The visit level reflects only the teaching physician’s personally performed and documented service.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Guidelines for Teaching Physicians, Interns, Residents. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/downloads/gdelinesteachgresfctsht.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 100. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15, Section 30.2. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

When hospitalists work in academic centers, medical and surgical services are furnished, in part, by a resident within the scope of the hospitalists’ training program. A resident is “an individual who participates in an approved graduate medical education (GME) program or a physician who is not in an approved GME program but who is authorized to practice only in a hospital setting.”1 Resident services are covered by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and paid by the Fiscal Intermediary through direct GME and Indirect Medical Education (IME) payments. These services are not billed or paid using the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. The teaching physician is responsible for supervising the resident’s health-care delivery but is not paid for the resident’s work. The teaching physician is paid for their personal and medically necessary service in providing patient care. The teaching physician has the option to perform the entire service, or perform the self-determined critical or key portion(s) of the service.

Comprehensive Service

Teaching physicians independently see the patient and perform all required elements to support the visit level (e.g. 99233: subsequent hospital care, per day, which requires at least two of the following three key components: a detailed interval history, a detailed examination, or high-complexity medical decision-making).2 The teaching physician writes a note independent of a resident encounter with the patient or documentation. The teaching physician note “stands alone” and does not rely on the resident’s documentation. If the resident saw the patient and documented the encounter, the teaching physician might choose to “link to” the resident note in lieu of personally documenting the entire service. The linking statement must demonstrate teaching physician involvement in the patient encounter and participation in patient management. Use of CMS-approved statements is best to meet these requirements. Statement examples include:3

- “I performed a history and physical examination of the patient and discussed his management with the resident. I reviewed the resident’s note and agree with the documented findings and plan of care.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. I agree with the findings and the plan of care as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “I saw and examined the patient. I agree with the resident’s note, except the heart murmur is louder, so I will obtain an echo to evaluate.”

Each of these statements meets the minimum requirements for billing. However, teaching physicians should offer more information in support of other clinical, quality, and regulatory initiatives and mandates, better exemplified in the last example. The reported visit level will be supported by the combined documentation (teaching physician and resident).

The teaching physician submits a claim in their name and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99223-GC). This alerts the Medicare contractor that services were provided under teaching physician rules. Requests for documentation should include a response with medical record entries from the teaching physician and resident.

Critical/Key Portion

“Supervised” service: The resident and teaching physician can round together; they can see the patient at the same time. The teaching physician observes the resident’s performance during the patient encounter, or personally performs self-determined elements of patient care. The resident documents their patient care. The attending must still note their presence in the medical record, performance of the critical or key portions of the service, and involvement in patient management. CMS-accepted statements include:3

- “I was present with the resident during the history and exam. I discussed the case with the resident and agree with the findings and plan as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “I saw the patient with the resident and agree with the resident’s findings and plan.”

Although these statements demonstrate acceptable billing language, they lack patient-specific details that support the teaching physician’s personal contribution to patient care and the quality of their expertise. The teaching physician selects the visit level that represents the combined documentation and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99232-GC).

“Shared” service: The resident sees the patient unaccompanied and documents the corresponding care provided. The teaching physician sees the patient at a different time but performs only the critical or key portions of the service. The case is subsequently discussed with the resident. The teaching physician must document their presence and performance of the critical or key portions of the service, along with any patient management. Using CMS-quoted statements ensures regulatory compliance:3

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. I reviewed the resident’s note and agree, except that the picture is more consistent with pericarditis than myocardial ischemia. Will begin NSAIDs.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. Discussed with resident and agree with resident’s findings and plan as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “See resident’s note for details. I saw and evaluated the patient and agree with the resident’s finding and plans as written.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. Agree with resident’s note, but lower extremities are weaker, now 3/5; MRI of L/S spine today.”

Once again, the teaching physician selects the visit level that represents the combined documentation and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99233-GC).

EHR Considerations

When seeing patients independent of one another, the timing of the teaching physician and resident encounters does not impact billing. However, the time that the resident encounter is documented in the medical record can significantly impact the payment when reviewed by external auditors. When the resident note is dated and timed later than the teaching physician’s entry, the teaching physician cannot consider the resident’s note for visit-level selection. The teaching physician should not “link to” a resident note that is viewed as “not having been written” prior to the teaching physician note. This would not fulfill the requirements represented in the CMS-approved language “I reviewed the resident’s note and agree.”

Electronic health record (EHR) systems sometimes hinder compliance. If the resident completes the note but does not “finalize” or “close” the encounter until after the teaching physician documents their own note, it can falsely appear that the resident note did not exist at the time the teaching physician created their entry. Because an auditor can only view the finalized entries, the timing of each entry might be erroneously represented. Proper training and closing of encounters can diminish these issues.

Additionally, scribing the attestation is not permitted. Residents cannot document the teaching physician attestation on behalf of the physician under any circumstance. CMS rules require the teaching physician to document their presence, participation, and management of the patient. In an EHR, the teaching physician must document this entry under his/her own log-in and password, which is not to be shared with anyone.

Students

CMS defines student as “an individual who participates in an accredited educational program [e.g. a medical school] that is not an approved GME program.”1 A student is not regarded as a “physician in training,” and the service is not eligible for reimbursement consideration under the teaching physician rules.

Per CMS guidelines, students can document services in the medical record, but the teaching physician may only refer to the student’s systems review and past/family/social history entries. The teaching physician must verify and redocument the history of present illness. A student’s physical exam findings or medical decision-making are not suitable for tethering, and the teaching physician must personally perform and redocument the physical exam and medical decision-making. The visit level reflects only the teaching physician’s personally performed and documented service.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Guidelines for Teaching Physicians, Interns, Residents. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/downloads/gdelinesteachgresfctsht.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 100. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual: Chapter 15, Section 30.2. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c15.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

When hospitalists work in academic centers, medical and surgical services are furnished, in part, by a resident within the scope of the hospitalists’ training program. A resident is “an individual who participates in an approved graduate medical education (GME) program or a physician who is not in an approved GME program but who is authorized to practice only in a hospital setting.”1 Resident services are covered by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and paid by the Fiscal Intermediary through direct GME and Indirect Medical Education (IME) payments. These services are not billed or paid using the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. The teaching physician is responsible for supervising the resident’s health-care delivery but is not paid for the resident’s work. The teaching physician is paid for their personal and medically necessary service in providing patient care. The teaching physician has the option to perform the entire service, or perform the self-determined critical or key portion(s) of the service.

Comprehensive Service

Teaching physicians independently see the patient and perform all required elements to support the visit level (e.g. 99233: subsequent hospital care, per day, which requires at least two of the following three key components: a detailed interval history, a detailed examination, or high-complexity medical decision-making).2 The teaching physician writes a note independent of a resident encounter with the patient or documentation. The teaching physician note “stands alone” and does not rely on the resident’s documentation. If the resident saw the patient and documented the encounter, the teaching physician might choose to “link to” the resident note in lieu of personally documenting the entire service. The linking statement must demonstrate teaching physician involvement in the patient encounter and participation in patient management. Use of CMS-approved statements is best to meet these requirements. Statement examples include:3

- “I performed a history and physical examination of the patient and discussed his management with the resident. I reviewed the resident’s note and agree with the documented findings and plan of care.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. I agree with the findings and the plan of care as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “I saw and examined the patient. I agree with the resident’s note, except the heart murmur is louder, so I will obtain an echo to evaluate.”

Each of these statements meets the minimum requirements for billing. However, teaching physicians should offer more information in support of other clinical, quality, and regulatory initiatives and mandates, better exemplified in the last example. The reported visit level will be supported by the combined documentation (teaching physician and resident).

The teaching physician submits a claim in their name and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99223-GC). This alerts the Medicare contractor that services were provided under teaching physician rules. Requests for documentation should include a response with medical record entries from the teaching physician and resident.

Critical/Key Portion

“Supervised” service: The resident and teaching physician can round together; they can see the patient at the same time. The teaching physician observes the resident’s performance during the patient encounter, or personally performs self-determined elements of patient care. The resident documents their patient care. The attending must still note their presence in the medical record, performance of the critical or key portions of the service, and involvement in patient management. CMS-accepted statements include:3

- “I was present with the resident during the history and exam. I discussed the case with the resident and agree with the findings and plan as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “I saw the patient with the resident and agree with the resident’s findings and plan.”

Although these statements demonstrate acceptable billing language, they lack patient-specific details that support the teaching physician’s personal contribution to patient care and the quality of their expertise. The teaching physician selects the visit level that represents the combined documentation and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99232-GC).

“Shared” service: The resident sees the patient unaccompanied and documents the corresponding care provided. The teaching physician sees the patient at a different time but performs only the critical or key portions of the service. The case is subsequently discussed with the resident. The teaching physician must document their presence and performance of the critical or key portions of the service, along with any patient management. Using CMS-quoted statements ensures regulatory compliance:3

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. I reviewed the resident’s note and agree, except that the picture is more consistent with pericarditis than myocardial ischemia. Will begin NSAIDs.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. Discussed with resident and agree with resident’s findings and plan as documented in the resident’s note.”

- “See resident’s note for details. I saw and evaluated the patient and agree with the resident’s finding and plans as written.”

- “I saw and evaluated the patient. Agree with resident’s note, but lower extremities are weaker, now 3/5; MRI of L/S spine today.”

Once again, the teaching physician selects the visit level that represents the combined documentation and, if it is a Medicare claim, appends modifier GC to the selected visit level (e.g. 99233-GC).

EHR Considerations

When seeing patients independent of one another, the timing of the teaching physician and resident encounters does not impact billing. However, the time that the resident encounter is documented in the medical record can significantly impact the payment when reviewed by external auditors. When the resident note is dated and timed later than the teaching physician’s entry, the teaching physician cannot consider the resident’s note for visit-level selection. The teaching physician should not “link to” a resident note that is viewed as “not having been written” prior to the teaching physician note. This would not fulfill the requirements represented in the CMS-approved language “I reviewed the resident’s note and agree.”

Electronic health record (EHR) systems sometimes hinder compliance. If the resident completes the note but does not “finalize” or “close” the encounter until after the teaching physician documents their own note, it can falsely appear that the resident note did not exist at the time the teaching physician created their entry. Because an auditor can only view the finalized entries, the timing of each entry might be erroneously represented. Proper training and closing of encounters can diminish these issues.

Additionally, scribing the attestation is not permitted. Residents cannot document the teaching physician attestation on behalf of the physician under any circumstance. CMS rules require the teaching physician to document their presence, participation, and management of the patient. In an EHR, the teaching physician must document this entry under his/her own log-in and password, which is not to be shared with anyone.

Students

CMS defines student as “an individual who participates in an accredited educational program [e.g. a medical school] that is not an approved GME program.”1 A student is not regarded as a “physician in training,” and the service is not eligible for reimbursement consideration under the teaching physician rules.

Per CMS guidelines, students can document services in the medical record, but the teaching physician may only refer to the student’s systems review and past/family/social history entries. The teaching physician must verify and redocument the history of present illness. A student’s physical exam findings or medical decision-making are not suitable for tethering, and the teaching physician must personally perform and redocument the physical exam and medical decision-making. The visit level reflects only the teaching physician’s personally performed and documented service.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Guidelines for Teaching Physicians, Interns, Residents. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/MLNProducts/downloads/gdelinesteachgresfctsht.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 100. CMS website. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.