User login

Catherine Cooper Nellist is editor of Pediatric News and Ob. Gyn. News. She has more than 30 years of experience reporting, writing, and editing stories about clinical medicine and the U.S. health care industry. Prior to taking the helm of these award-winning publications, Catherine covered major medical research meetings throughout the United States and Canada, and had been editor of Clinical Psychiatry News, and Dermatology News. She joined the company in 1984 after graduating magna cum laude from Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pa., with a BA in English.

Learn how to manage your patients’ behavior problems

One of the presentations you’ll definitely want to attend is Dr. Barbara J. Howard’s “As Easy as A-B-C-G: Office Management of Behavior Problems in Children.”

She’ll teach you the A, B, C, and G of managing behavior problems:

- A = Antecedents/meaning

- B = Behavior

- C = Consequences

- G = Gap in skills

Dr. Howard, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, will use case presentations to show you how this model works in detail. She’ll describe how best to organize a session with a patient, how to engage the family, and how to approach the objectives of family interviewing.

Dr. Howard goes into much more detail, giving examples in each case, explaining how to assist the parent-child relationship, providing parents with bypass strategies for various issues, and teaching behavior modification for dysfunctional patterns.

That is just one case presentation. Others detail how to handle a toddler who refuses to go to bed, an aggressive 5-year-old, a clingy 9-year-old suffering from anxiety, and a 12-year-old who has recently begun wetting the bed and stealing from her mother.

At the American Academy of Pediatrics’ annual meeting in Chicago, Dr. Howard will be presenting Sunday, Sept. 17, from 4 p.m. to 5:30 p.m., and Monday, Sept. 18, from 8:30 a.m. to 10 a.m. You don’t want to miss it!

One of the presentations you’ll definitely want to attend is Dr. Barbara J. Howard’s “As Easy as A-B-C-G: Office Management of Behavior Problems in Children.”

She’ll teach you the A, B, C, and G of managing behavior problems:

- A = Antecedents/meaning

- B = Behavior

- C = Consequences

- G = Gap in skills

Dr. Howard, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, will use case presentations to show you how this model works in detail. She’ll describe how best to organize a session with a patient, how to engage the family, and how to approach the objectives of family interviewing.

Dr. Howard goes into much more detail, giving examples in each case, explaining how to assist the parent-child relationship, providing parents with bypass strategies for various issues, and teaching behavior modification for dysfunctional patterns.

That is just one case presentation. Others detail how to handle a toddler who refuses to go to bed, an aggressive 5-year-old, a clingy 9-year-old suffering from anxiety, and a 12-year-old who has recently begun wetting the bed and stealing from her mother.

At the American Academy of Pediatrics’ annual meeting in Chicago, Dr. Howard will be presenting Sunday, Sept. 17, from 4 p.m. to 5:30 p.m., and Monday, Sept. 18, from 8:30 a.m. to 10 a.m. You don’t want to miss it!

One of the presentations you’ll definitely want to attend is Dr. Barbara J. Howard’s “As Easy as A-B-C-G: Office Management of Behavior Problems in Children.”

She’ll teach you the A, B, C, and G of managing behavior problems:

- A = Antecedents/meaning

- B = Behavior

- C = Consequences

- G = Gap in skills

Dr. Howard, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, will use case presentations to show you how this model works in detail. She’ll describe how best to organize a session with a patient, how to engage the family, and how to approach the objectives of family interviewing.

Dr. Howard goes into much more detail, giving examples in each case, explaining how to assist the parent-child relationship, providing parents with bypass strategies for various issues, and teaching behavior modification for dysfunctional patterns.

That is just one case presentation. Others detail how to handle a toddler who refuses to go to bed, an aggressive 5-year-old, a clingy 9-year-old suffering from anxiety, and a 12-year-old who has recently begun wetting the bed and stealing from her mother.

At the American Academy of Pediatrics’ annual meeting in Chicago, Dr. Howard will be presenting Sunday, Sept. 17, from 4 p.m. to 5:30 p.m., and Monday, Sept. 18, from 8:30 a.m. to 10 a.m. You don’t want to miss it!

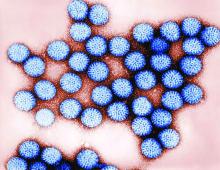

PD3 G1 SNA found to correlate with pentavalent rotavirus vaccine efficacy

(RV5), reported G. Frank Liu, PhD, and his associates at Merck in Kenilworth, N.J.

The researchers discovered this by analyzing data from five clinical trials of RV5 at both the individual and aggregated population level. Also, by looking at immunogenicity measures and case status of individuals from phase 2 and 3 trials of RV5, they found that “higher PD3 G1 SNA titers are associated with lower odds of contracting any [rotavirus gastroenteritis].”

Read more at (Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1356522).

[email protected]

(RV5), reported G. Frank Liu, PhD, and his associates at Merck in Kenilworth, N.J.

The researchers discovered this by analyzing data from five clinical trials of RV5 at both the individual and aggregated population level. Also, by looking at immunogenicity measures and case status of individuals from phase 2 and 3 trials of RV5, they found that “higher PD3 G1 SNA titers are associated with lower odds of contracting any [rotavirus gastroenteritis].”

Read more at (Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1356522).

[email protected]

(RV5), reported G. Frank Liu, PhD, and his associates at Merck in Kenilworth, N.J.

The researchers discovered this by analyzing data from five clinical trials of RV5 at both the individual and aggregated population level. Also, by looking at immunogenicity measures and case status of individuals from phase 2 and 3 trials of RV5, they found that “higher PD3 G1 SNA titers are associated with lower odds of contracting any [rotavirus gastroenteritis].”

Read more at (Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1356522).

[email protected]

FROM HUMAN VACCINES & IMMUNOTHERAPEUTICS

Real-world adverse events reported after bivalent MenB vaccination in college students

, said Theresa M. Fiorito, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her associates.

In February 2015, two unlinked, culture-confirmed cases of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B (MenB) disease occurred at a local college in Rhode Island, and a bivalent MenB vaccine subsequently was administered. After the first-dose vaccination clinic, a 94% coverage rate was achieved, and there were no other cases of MenB disease. Injection site pain occurred in 78% of 1,736 students after dose one, in 64% of 1,395 after dose two, and in 71% of 609 students after dose three.

Serious adverse events, such as any allergic reaction; difficulty breathing; hives, welts, or a severe rash; and swelling of the face, mouth, or throat occurred in fewer than 5% of students after any of the three doses, the investigators reported.

“We found an overall lower rate of headache within our sample relative to the rates in reported clinical trials. The rates of injection site pain, fatigue, thermometer-confirmed fevers (100.4° F or higher), and chills were approximately similar in our study as in clinical trials. The rate of myalgia was higher for our sample than in clinical trials following the first and second doses of the vaccine, but similar after the third dose of vaccine,” Dr. Fiorito and her associates wrote.

Read more at (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001742).

, said Theresa M. Fiorito, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her associates.

In February 2015, two unlinked, culture-confirmed cases of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B (MenB) disease occurred at a local college in Rhode Island, and a bivalent MenB vaccine subsequently was administered. After the first-dose vaccination clinic, a 94% coverage rate was achieved, and there were no other cases of MenB disease. Injection site pain occurred in 78% of 1,736 students after dose one, in 64% of 1,395 after dose two, and in 71% of 609 students after dose three.

Serious adverse events, such as any allergic reaction; difficulty breathing; hives, welts, or a severe rash; and swelling of the face, mouth, or throat occurred in fewer than 5% of students after any of the three doses, the investigators reported.

“We found an overall lower rate of headache within our sample relative to the rates in reported clinical trials. The rates of injection site pain, fatigue, thermometer-confirmed fevers (100.4° F or higher), and chills were approximately similar in our study as in clinical trials. The rate of myalgia was higher for our sample than in clinical trials following the first and second doses of the vaccine, but similar after the third dose of vaccine,” Dr. Fiorito and her associates wrote.

Read more at (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001742).

, said Theresa M. Fiorito, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her associates.

In February 2015, two unlinked, culture-confirmed cases of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B (MenB) disease occurred at a local college in Rhode Island, and a bivalent MenB vaccine subsequently was administered. After the first-dose vaccination clinic, a 94% coverage rate was achieved, and there were no other cases of MenB disease. Injection site pain occurred in 78% of 1,736 students after dose one, in 64% of 1,395 after dose two, and in 71% of 609 students after dose three.

Serious adverse events, such as any allergic reaction; difficulty breathing; hives, welts, or a severe rash; and swelling of the face, mouth, or throat occurred in fewer than 5% of students after any of the three doses, the investigators reported.

“We found an overall lower rate of headache within our sample relative to the rates in reported clinical trials. The rates of injection site pain, fatigue, thermometer-confirmed fevers (100.4° F or higher), and chills were approximately similar in our study as in clinical trials. The rate of myalgia was higher for our sample than in clinical trials following the first and second doses of the vaccine, but similar after the third dose of vaccine,” Dr. Fiorito and her associates wrote.

Read more at (Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001742).

FROM THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASE JOURNAL

Pediatric News welcomes Dr. Lenore Jarvis

Pediatric News welcomes Lenore Jarvis MD, MEd, to its editorial advisory board.

Dr. Jarvis is a pediatric emergency medicine physician at Children’s National Health System, and assistant professor of pediatrics at George Washington University, both in Washington.

Pediatric News welcomes Lenore Jarvis MD, MEd, to its editorial advisory board.

Dr. Jarvis is a pediatric emergency medicine physician at Children’s National Health System, and assistant professor of pediatrics at George Washington University, both in Washington.

Pediatric News welcomes Lenore Jarvis MD, MEd, to its editorial advisory board.

Dr. Jarvis is a pediatric emergency medicine physician at Children’s National Health System, and assistant professor of pediatrics at George Washington University, both in Washington.

Cerebral palsy rate down in children born very or moderately preterm

, even in children who were born moderately preterm.

The researchers gathered data for cerebral palsy from the medical questionnaire, including information on head control, sitting, standing, walking, and quality of gait; trunk and limb tone; and any abnormal neurologic signs. Development was assessed using the second version of the 24-month Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ), which is completed by parents.

Of 4,199 neonates born between 22 and 34 weeks’ gestation in 2011 enrolled in the EPIPAGE-2 study who lived until a median of 24.2 months corrected age, the rate of cerebral palsy dropped from 7% to 4% in those born between 24-26 and 27-31 weeks’ gestation, reported Véronique Pierrat, MD, PhD, of the Epidemiology and Biostatistics Sorbonne Paris Cité Research Center, INSERM, in Paris, and her associates. At 32-34 weeks’ gestation, the cerebral palsy rate was 1%. Only one child born at 22-23 weeks’ gestation lived beyond the neonatal period. Fewer than 1% of the children overall had severe auditory or visual impairment.

ASQ analysis was considered for 2,506 children, after excluding children with cerebral palsy, deafness or blindness, or severe congenital brain malformations. ASQ scores were below threshold in 50%, 41%, and 36% of children born at 24-26, 27-31, and 32-34 weeks’ gestation, respectively. “The domains most frequently scoring below threshold were communication and personal-social in all gestational age groups. Proportions of children scoring below the threshold in either of these domains decreased with increasing gestational age but still were 18% and 13%, respectively, at 32-34 weeks’ gestation,” the investigators said.

Only 1% or fewer of the children in this cohort had severe gastrointestinal or respiratory disabilities.

In a comparison of 1997 data and this 2011 data after adjustment for baseline characteristics in children born at 22-31 weeks’ gestation, survival increased by a mean 6% , and survival without neuromotor or sensory impairment by 7%; in children born at 24-31 weeks’ gestation, cerebral palsy decreased by a mean 3%. No statistically significant changes were found between the two periods for survival, survival without neuromotor or sensory disabilities, and rates of cerebral palsy in children born at 24 weeks’ gestation, but “noticeable improvements were seen at 25-26 weeks and, to a lesser extent, at 27-31 weeks,” Dr. Pierrat and her associates said. At 32-34 weeks’ gestation, the cerebral palsy rate dropped by 3%, but survival and survival without severe neuromotor or sensory impairment were similar between the two time periods.

In regard to the 2011 data, “the proportion of infants at risk of developmental delay was high, even for those born at 32-34 weeks’ gestation. Our results invite questioning perinatal strategies in France, and in countries with similar recommendations. However, improving outcomes at extremely low gestational age requires a complex change in philosophy of care and close cooperation not only between obstetricians and neonatologists, but also developmental specialists, parent associations, and policy makers,” Dr. Pierrat and her associates concluded.

The investigators said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the French Institute of Public Health Research/Institute of Public Health and several of its partners, the PREMUP Foundation, Fondation de France, and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

, even in children who were born moderately preterm.

The researchers gathered data for cerebral palsy from the medical questionnaire, including information on head control, sitting, standing, walking, and quality of gait; trunk and limb tone; and any abnormal neurologic signs. Development was assessed using the second version of the 24-month Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ), which is completed by parents.

Of 4,199 neonates born between 22 and 34 weeks’ gestation in 2011 enrolled in the EPIPAGE-2 study who lived until a median of 24.2 months corrected age, the rate of cerebral palsy dropped from 7% to 4% in those born between 24-26 and 27-31 weeks’ gestation, reported Véronique Pierrat, MD, PhD, of the Epidemiology and Biostatistics Sorbonne Paris Cité Research Center, INSERM, in Paris, and her associates. At 32-34 weeks’ gestation, the cerebral palsy rate was 1%. Only one child born at 22-23 weeks’ gestation lived beyond the neonatal period. Fewer than 1% of the children overall had severe auditory or visual impairment.

ASQ analysis was considered for 2,506 children, after excluding children with cerebral palsy, deafness or blindness, or severe congenital brain malformations. ASQ scores were below threshold in 50%, 41%, and 36% of children born at 24-26, 27-31, and 32-34 weeks’ gestation, respectively. “The domains most frequently scoring below threshold were communication and personal-social in all gestational age groups. Proportions of children scoring below the threshold in either of these domains decreased with increasing gestational age but still were 18% and 13%, respectively, at 32-34 weeks’ gestation,” the investigators said.

Only 1% or fewer of the children in this cohort had severe gastrointestinal or respiratory disabilities.

In a comparison of 1997 data and this 2011 data after adjustment for baseline characteristics in children born at 22-31 weeks’ gestation, survival increased by a mean 6% , and survival without neuromotor or sensory impairment by 7%; in children born at 24-31 weeks’ gestation, cerebral palsy decreased by a mean 3%. No statistically significant changes were found between the two periods for survival, survival without neuromotor or sensory disabilities, and rates of cerebral palsy in children born at 24 weeks’ gestation, but “noticeable improvements were seen at 25-26 weeks and, to a lesser extent, at 27-31 weeks,” Dr. Pierrat and her associates said. At 32-34 weeks’ gestation, the cerebral palsy rate dropped by 3%, but survival and survival without severe neuromotor or sensory impairment were similar between the two time periods.

In regard to the 2011 data, “the proportion of infants at risk of developmental delay was high, even for those born at 32-34 weeks’ gestation. Our results invite questioning perinatal strategies in France, and in countries with similar recommendations. However, improving outcomes at extremely low gestational age requires a complex change in philosophy of care and close cooperation not only between obstetricians and neonatologists, but also developmental specialists, parent associations, and policy makers,” Dr. Pierrat and her associates concluded.

The investigators said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the French Institute of Public Health Research/Institute of Public Health and several of its partners, the PREMUP Foundation, Fondation de France, and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

, even in children who were born moderately preterm.

The researchers gathered data for cerebral palsy from the medical questionnaire, including information on head control, sitting, standing, walking, and quality of gait; trunk and limb tone; and any abnormal neurologic signs. Development was assessed using the second version of the 24-month Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ), which is completed by parents.

Of 4,199 neonates born between 22 and 34 weeks’ gestation in 2011 enrolled in the EPIPAGE-2 study who lived until a median of 24.2 months corrected age, the rate of cerebral palsy dropped from 7% to 4% in those born between 24-26 and 27-31 weeks’ gestation, reported Véronique Pierrat, MD, PhD, of the Epidemiology and Biostatistics Sorbonne Paris Cité Research Center, INSERM, in Paris, and her associates. At 32-34 weeks’ gestation, the cerebral palsy rate was 1%. Only one child born at 22-23 weeks’ gestation lived beyond the neonatal period. Fewer than 1% of the children overall had severe auditory or visual impairment.

ASQ analysis was considered for 2,506 children, after excluding children with cerebral palsy, deafness or blindness, or severe congenital brain malformations. ASQ scores were below threshold in 50%, 41%, and 36% of children born at 24-26, 27-31, and 32-34 weeks’ gestation, respectively. “The domains most frequently scoring below threshold were communication and personal-social in all gestational age groups. Proportions of children scoring below the threshold in either of these domains decreased with increasing gestational age but still were 18% and 13%, respectively, at 32-34 weeks’ gestation,” the investigators said.

Only 1% or fewer of the children in this cohort had severe gastrointestinal or respiratory disabilities.

In a comparison of 1997 data and this 2011 data after adjustment for baseline characteristics in children born at 22-31 weeks’ gestation, survival increased by a mean 6% , and survival without neuromotor or sensory impairment by 7%; in children born at 24-31 weeks’ gestation, cerebral palsy decreased by a mean 3%. No statistically significant changes were found between the two periods for survival, survival without neuromotor or sensory disabilities, and rates of cerebral palsy in children born at 24 weeks’ gestation, but “noticeable improvements were seen at 25-26 weeks and, to a lesser extent, at 27-31 weeks,” Dr. Pierrat and her associates said. At 32-34 weeks’ gestation, the cerebral palsy rate dropped by 3%, but survival and survival without severe neuromotor or sensory impairment were similar between the two time periods.

In regard to the 2011 data, “the proportion of infants at risk of developmental delay was high, even for those born at 32-34 weeks’ gestation. Our results invite questioning perinatal strategies in France, and in countries with similar recommendations. However, improving outcomes at extremely low gestational age requires a complex change in philosophy of care and close cooperation not only between obstetricians and neonatologists, but also developmental specialists, parent associations, and policy makers,” Dr. Pierrat and her associates concluded.

The investigators said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the French Institute of Public Health Research/Institute of Public Health and several of its partners, the PREMUP Foundation, Fondation de France, and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

FROM BMJ

Key clinical point: Cerebral palsy rates are down in children born very and moderately preterm, but the risk of developmental delay remains high.

Major finding: ASQ scores were below threshold in 50%, 41%, and 36% of children born at 24-26, 27-31, and 32-34 weeks’ gestation, respectively.

Data source: A national population study of 4,199 French neonates born between 22 and 34 weeks’ gestation in 2011.

Disclosures: The investigators said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded by the French Institute of Public Health Research/Institute of Public Health and several of its partners, the PREMUP Foundation, Fondation de France, and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

Why three strategies to correct vaccination hesitancy failed

, supporting findings in the literature that misinformation tends to linger in the memory and efforts to dislodge it may in fact reinforce it.

In a study of 120 students recruited from diverse departments of the University of Edinburgh, the Suor Orsola Benincasa University of Naples, and the Second University of Naples, 61% were women, and the mean age was 25 years. Most students had a bachelor’s (38%) or master’s degree (53%), while 11 were PhD students, reported Sara Pluviano, PhD, of the University of Edinburgh, and her associates.

The participants completed a baseline questionnaire assessing their beliefs and attitudes about immunization, and twice completed a questionnaire that had focused on general misperceptions about vaccines causing autism, vaccine side effects, and how likely they would be to give MMR vaccine to their children – immediately after an intervention and after a 7-day delay.

Students were exposed to one of four correction interventions.

In the first, participants were given a booklet confronting 10 “myths” with a number of “facts” about vaccines (myths vs. facts group). In the second, students were presented with a series of tables comparing the potential problems caused by measles, mumps, and rubella with the potential side effects caused by the MMR vaccine (graphics group). In the third intervention, participants were shown photos of unvaccinated children with measles, mumps, and rubella, in addition to the symptoms of each disease and warnings about vaccinating one’s own child (fear group). The fourth was the control condition, where participants were given two unrelated fact sheets with tips to help prevent medical errors and get safer health care (control group).

“The myths vs. facts format, at odds with its aims, induced stronger beliefs in the vaccine/autism link and in vaccines side effects over time, lending credit to the literature showing that countering false information in ways that repeat it may further contribute to its dissemination,” the researchers said. Also, “the exposure to fear appeals through images of sick children led to more increased misperceptions about vaccines causing autism. Moreover, this corrective strategy induced the strongest beliefs in vaccines side effects.

“The usage of fact/icon boxes resulted in less damage but did not bring any effective result,” they said.

“Our pattern of results thus confirms that there should be more testing of public health campaign messages,” Dr. Pluviano and her associates cautioned. “This is especially true because corrective strategies may appear effective immediately, yet backfire even after a short delay when the message they tried to convey gradually fades from memory, allowing common misconceptions to be more easily remembered and identified as true.”

Read more in PLOS One (2017 Jul 27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181640).

, supporting findings in the literature that misinformation tends to linger in the memory and efforts to dislodge it may in fact reinforce it.

In a study of 120 students recruited from diverse departments of the University of Edinburgh, the Suor Orsola Benincasa University of Naples, and the Second University of Naples, 61% were women, and the mean age was 25 years. Most students had a bachelor’s (38%) or master’s degree (53%), while 11 were PhD students, reported Sara Pluviano, PhD, of the University of Edinburgh, and her associates.

The participants completed a baseline questionnaire assessing their beliefs and attitudes about immunization, and twice completed a questionnaire that had focused on general misperceptions about vaccines causing autism, vaccine side effects, and how likely they would be to give MMR vaccine to their children – immediately after an intervention and after a 7-day delay.

Students were exposed to one of four correction interventions.

In the first, participants were given a booklet confronting 10 “myths” with a number of “facts” about vaccines (myths vs. facts group). In the second, students were presented with a series of tables comparing the potential problems caused by measles, mumps, and rubella with the potential side effects caused by the MMR vaccine (graphics group). In the third intervention, participants were shown photos of unvaccinated children with measles, mumps, and rubella, in addition to the symptoms of each disease and warnings about vaccinating one’s own child (fear group). The fourth was the control condition, where participants were given two unrelated fact sheets with tips to help prevent medical errors and get safer health care (control group).

“The myths vs. facts format, at odds with its aims, induced stronger beliefs in the vaccine/autism link and in vaccines side effects over time, lending credit to the literature showing that countering false information in ways that repeat it may further contribute to its dissemination,” the researchers said. Also, “the exposure to fear appeals through images of sick children led to more increased misperceptions about vaccines causing autism. Moreover, this corrective strategy induced the strongest beliefs in vaccines side effects.

“The usage of fact/icon boxes resulted in less damage but did not bring any effective result,” they said.

“Our pattern of results thus confirms that there should be more testing of public health campaign messages,” Dr. Pluviano and her associates cautioned. “This is especially true because corrective strategies may appear effective immediately, yet backfire even after a short delay when the message they tried to convey gradually fades from memory, allowing common misconceptions to be more easily remembered and identified as true.”

Read more in PLOS One (2017 Jul 27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181640).

, supporting findings in the literature that misinformation tends to linger in the memory and efforts to dislodge it may in fact reinforce it.

In a study of 120 students recruited from diverse departments of the University of Edinburgh, the Suor Orsola Benincasa University of Naples, and the Second University of Naples, 61% were women, and the mean age was 25 years. Most students had a bachelor’s (38%) or master’s degree (53%), while 11 were PhD students, reported Sara Pluviano, PhD, of the University of Edinburgh, and her associates.

The participants completed a baseline questionnaire assessing their beliefs and attitudes about immunization, and twice completed a questionnaire that had focused on general misperceptions about vaccines causing autism, vaccine side effects, and how likely they would be to give MMR vaccine to their children – immediately after an intervention and after a 7-day delay.

Students were exposed to one of four correction interventions.

In the first, participants were given a booklet confronting 10 “myths” with a number of “facts” about vaccines (myths vs. facts group). In the second, students were presented with a series of tables comparing the potential problems caused by measles, mumps, and rubella with the potential side effects caused by the MMR vaccine (graphics group). In the third intervention, participants were shown photos of unvaccinated children with measles, mumps, and rubella, in addition to the symptoms of each disease and warnings about vaccinating one’s own child (fear group). The fourth was the control condition, where participants were given two unrelated fact sheets with tips to help prevent medical errors and get safer health care (control group).

“The myths vs. facts format, at odds with its aims, induced stronger beliefs in the vaccine/autism link and in vaccines side effects over time, lending credit to the literature showing that countering false information in ways that repeat it may further contribute to its dissemination,” the researchers said. Also, “the exposure to fear appeals through images of sick children led to more increased misperceptions about vaccines causing autism. Moreover, this corrective strategy induced the strongest beliefs in vaccines side effects.

“The usage of fact/icon boxes resulted in less damage but did not bring any effective result,” they said.

“Our pattern of results thus confirms that there should be more testing of public health campaign messages,” Dr. Pluviano and her associates cautioned. “This is especially true because corrective strategies may appear effective immediately, yet backfire even after a short delay when the message they tried to convey gradually fades from memory, allowing common misconceptions to be more easily remembered and identified as true.”

Read more in PLOS One (2017 Jul 27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181640).

FROM PLOS ONE

Extreme caffeine use in early pregnancy risks offspring behavioral disorders

, Susanne Hvolgaard Mikkelsen, PhD, of Aarhus (Denmark) University and her associates said.

“Caffeine metabolism is delayed during pregnancy, allowing longer opportunities for absorption. Caffeine increases dopamine levels by slowing down the rate of dopamine reabsorption, and this dysfunction of the dopaminergic system is thought to explain part of the association between caffeine consumption and offspring behavioral disorders,” the investigators said.

From 1996 to 2002, Danish physicians recruited women during their first pregnancy visit to participate in a study evaluating daily coffee and tea consumption during pregnancy, with follow-up of the children at age 11 years using the Danish National Birth Cohort. A follow-up questionnaire, including the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire, was completed by the children, their parents, and their teachers; the results were paired with data on coffee and tea consumption by the mothers of 47,491 children. At 15 weeks’ gestation, 12% of the women had consumed more than three cups/day of coffee, and 3% ingested eight or more cups/day of coffee; 19% of the women drank more than three cups/day of tea, and 4% drank eight or more cups/day of tea. The amount of coffee and tea consumed at 30 weeks’ gestation was only slightly less.

The percentage of children predicted to have “possible/probable” ADHD was 5%, conduct-oppositional disorders was 7%, anxiety-depressive disorders was 7%, and any psychiatric disorder was 14%.

A statistically significant association was found between maternal consumption of eight or more cups of coffee at 15 weeks’ gestation and greater risk of ADHD (a risk ratio [RR] of 1.47), conduct-oppositional disorder (RR, 1.22), and any psychiatric disorder (RR, 1.23). A statistically significant link was found between maternal consumption of eight or more cups of tea at 15 weeks’ gestation and greater risk of conduct-oppositional disorder (RR, 1.21). There was a statistically significant association between maternal consumption of eight or more cups of tea at 15 weeks’ gestation and a higher risk of anxiety-depressive disorder (RR, 1.28), but not for coffee. These significant relationships were not found again at 30 weeks’ gestation.

“The period of greatest prenatal brain development is 10-26 weeks after conception,which may explain our results suggesting the fetus to be more vulnerable to caffeine in first and second trimester, compared with the third trimester,” the researchers said.

There was no information available about caffeine consumption by chocolate, energy drinks, or medication; the measure of cola consumption also was not taken into account. Confounding by genetics or socioeconomic factors may affect these findings, Dr. Mikkelsen and her associates said.

Read more at (J Pediatr. 2017 Jul 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.051).

, Susanne Hvolgaard Mikkelsen, PhD, of Aarhus (Denmark) University and her associates said.

“Caffeine metabolism is delayed during pregnancy, allowing longer opportunities for absorption. Caffeine increases dopamine levels by slowing down the rate of dopamine reabsorption, and this dysfunction of the dopaminergic system is thought to explain part of the association between caffeine consumption and offspring behavioral disorders,” the investigators said.

From 1996 to 2002, Danish physicians recruited women during their first pregnancy visit to participate in a study evaluating daily coffee and tea consumption during pregnancy, with follow-up of the children at age 11 years using the Danish National Birth Cohort. A follow-up questionnaire, including the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire, was completed by the children, their parents, and their teachers; the results were paired with data on coffee and tea consumption by the mothers of 47,491 children. At 15 weeks’ gestation, 12% of the women had consumed more than three cups/day of coffee, and 3% ingested eight or more cups/day of coffee; 19% of the women drank more than three cups/day of tea, and 4% drank eight or more cups/day of tea. The amount of coffee and tea consumed at 30 weeks’ gestation was only slightly less.

The percentage of children predicted to have “possible/probable” ADHD was 5%, conduct-oppositional disorders was 7%, anxiety-depressive disorders was 7%, and any psychiatric disorder was 14%.

A statistically significant association was found between maternal consumption of eight or more cups of coffee at 15 weeks’ gestation and greater risk of ADHD (a risk ratio [RR] of 1.47), conduct-oppositional disorder (RR, 1.22), and any psychiatric disorder (RR, 1.23). A statistically significant link was found between maternal consumption of eight or more cups of tea at 15 weeks’ gestation and greater risk of conduct-oppositional disorder (RR, 1.21). There was a statistically significant association between maternal consumption of eight or more cups of tea at 15 weeks’ gestation and a higher risk of anxiety-depressive disorder (RR, 1.28), but not for coffee. These significant relationships were not found again at 30 weeks’ gestation.

“The period of greatest prenatal brain development is 10-26 weeks after conception,which may explain our results suggesting the fetus to be more vulnerable to caffeine in first and second trimester, compared with the third trimester,” the researchers said.

There was no information available about caffeine consumption by chocolate, energy drinks, or medication; the measure of cola consumption also was not taken into account. Confounding by genetics or socioeconomic factors may affect these findings, Dr. Mikkelsen and her associates said.

Read more at (J Pediatr. 2017 Jul 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.051).

, Susanne Hvolgaard Mikkelsen, PhD, of Aarhus (Denmark) University and her associates said.

“Caffeine metabolism is delayed during pregnancy, allowing longer opportunities for absorption. Caffeine increases dopamine levels by slowing down the rate of dopamine reabsorption, and this dysfunction of the dopaminergic system is thought to explain part of the association between caffeine consumption and offspring behavioral disorders,” the investigators said.

From 1996 to 2002, Danish physicians recruited women during their first pregnancy visit to participate in a study evaluating daily coffee and tea consumption during pregnancy, with follow-up of the children at age 11 years using the Danish National Birth Cohort. A follow-up questionnaire, including the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire, was completed by the children, their parents, and their teachers; the results were paired with data on coffee and tea consumption by the mothers of 47,491 children. At 15 weeks’ gestation, 12% of the women had consumed more than three cups/day of coffee, and 3% ingested eight or more cups/day of coffee; 19% of the women drank more than three cups/day of tea, and 4% drank eight or more cups/day of tea. The amount of coffee and tea consumed at 30 weeks’ gestation was only slightly less.

The percentage of children predicted to have “possible/probable” ADHD was 5%, conduct-oppositional disorders was 7%, anxiety-depressive disorders was 7%, and any psychiatric disorder was 14%.

A statistically significant association was found between maternal consumption of eight or more cups of coffee at 15 weeks’ gestation and greater risk of ADHD (a risk ratio [RR] of 1.47), conduct-oppositional disorder (RR, 1.22), and any psychiatric disorder (RR, 1.23). A statistically significant link was found between maternal consumption of eight or more cups of tea at 15 weeks’ gestation and greater risk of conduct-oppositional disorder (RR, 1.21). There was a statistically significant association between maternal consumption of eight or more cups of tea at 15 weeks’ gestation and a higher risk of anxiety-depressive disorder (RR, 1.28), but not for coffee. These significant relationships were not found again at 30 weeks’ gestation.

“The period of greatest prenatal brain development is 10-26 weeks after conception,which may explain our results suggesting the fetus to be more vulnerable to caffeine in first and second trimester, compared with the third trimester,” the researchers said.

There was no information available about caffeine consumption by chocolate, energy drinks, or medication; the measure of cola consumption also was not taken into account. Confounding by genetics or socioeconomic factors may affect these findings, Dr. Mikkelsen and her associates said.

Read more at (J Pediatr. 2017 Jul 18. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.051).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Statewide QI learning collaboratives improve asthma care

Care of children with asthma can be improved using statewide quality improvement (QI) learning collaboratives, said Judith C. Dolins, of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Elk Grove Village, Ill., and her associates.

AAP chapters demonstrated this through their implementation of the Chapter Quality Network (CQN) project, which was supported by the national organization. This project sought to encourage practice changes in asthma care in a number of states using statewide QI learning collaboratives and lead practices to implement the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s (NHLBI) 2007 asthma guidelines over the course of four time periods, which the researchers referred to as waves. In nine states, 19 AAP chapters engaged 180 practices to participate, and involved 749 pediatricians treating 45,431 patients (Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1612).

Across all waves, practices had reasonably high baseline use of the stepwise approach (81%-89%) and a controller medication for patients with persistent asthma (74%-88%). The patients with a current written asthma action plan increased from 49%-57% to 75%-91%. Physicians’ and parents’ ratings of asthma in children as “well controlled” rose modestly from 58%-63% to 71%-74% and from 67%-73% to 78%-87%, respectively. Patients receiving self-management materials increased from 57%-62% to 62%-88%.

Here’s how the project worked. The CQN had three linked frameworks.: One provided a methodology for spreading practice changes, another outlined the elements of care, and a third provided a framework so the practices could test, implement, and adapt changes.

A national AAP leadership team of experts in asthma care, QI, and primary care practice systems developed a set of key drivers and interventions, and an implementation guide that included resources, tools and methods, and a set of measures for the chapters. They also designed reporting tools and a curriculum fostering QI learning by chapter leaders. Then, in a state chapter leadership learning network and a practice collaborative model in each state, there were “multiple in-person learning sessions and defined action periods, best practices, and tests of change that were spread and incorporated” for the chapters to use, according to the study report.

Chapters in each state had monthly webinars and two in-person learning sessions for participating practices. They also reviewed data reports at the state and practice level and provided coaching for practices.

Practices were asked to “incorporate optimal NHLBI asthma care practices, including assessment of control, a stepwise approach to treatment, appropriate use of controller medication, and an updated asthma action plan for self-management.” Other interventions included use of an asthma encounter form (which collected 16 measures, including outcome and process measures that were entered into a national database at least monthly); introduction of population registries; workflow assessment; motivational interviews; plan-do-study-act cycles for QI; and review of data for QI.

All the physicians were eligible to earn MOC part 4 credit and continuing medical education credit, and 80% of the physicians did get MOC credit across the 4 waves.

“Our findings are notable for achieving improvement in asthma care through training multiple state coordinating entities instead of directly leading the learning collaborative itself. Few other projects have achieved this level of results in pediatric practice improvement in asthma care on such a widespread scale across multiple states. This project may serve as a model for other statewide and national organizations attempting to achieve improvements in population health through support and training for statewide organizations that, in turn, support individual health care providers and practices,” Ms. Dolins and her associates said. “Although none of the waves achieved the preset goal of 90%, all showed substantial improvement and remarkable consistency in the rate of improvement. We, therefore, regarded the project as an overall success.”

The study was funded by the Merck Childhood Asthma Network, American Board of Pediatrics Foundation, American Academy of Pediatrics Friends of Children Fund, the JPB Foundation, and GlaxoSmithKline. Ms. Dolins and Mr. Wise received salary support. Ms. Powell and Dr. Stemmler received consulting fees.

We can do a better job of taking care of our patients. And in no other area is there more room for quality improvement (QI) than in ambulatory care. In the article by Dolins et al., substantial improvements were reported in outpatient management meeting the standard of care for asthma. In my experience, doing so not only gives children a better functional outcome but also saves costs by avoiding unnecessary ED visits and hospitalization and generates new dollars for pediatric offices through the additional services they provide. We have seen similar improvements in our own work in South Carolina and Tennessee. The practices that have wanted to become involved in our asthma QI are those that are already doing a better than average job. Yet, they still generate substantial additional improvements.

The AAP study relied heavily on national experts and standards. Although their input is valued, the true advantage of QI is the opportunity for pediatricians and their staff at the service delivery level to generate their own changes within the context of a learning collaborative. True improvement and innovation is facilitated by allowing flexibility at the local level and sharing the ideas that result. Those that design the QI efforts of the future need to make sure they allow for local expertise rather than leaning too heavily on centrally predetermined change concepts.

Part IV Maintenance of Certification requirements from the American Board of Pediatrics help provide momentum for successful pediatric QI. The National Improvement Partnership Network has formed pediatric outpatient learning collaboratives to share ideas. As we identify more successes with ambulatory care QI, as more and more organizations like AAP state chapters become involved, as all practices – rather than just the best – recognize the obligation to promote quality, we have a tremendous opportunity to improve the developmental and health outcomes of the children. QI can promote work and cost efficiencies that facilitate our work as pediatricians, making our lives more productive and rewarding.

Francis E. Rushton Jr, MD, is a pediatrician and medical director of South Carolina’s QTIP (Quality Through Innovation in Pediatrics) network and the Quality Director for PHIIT (Pediatric Health Improvement In Tennessee). He reported not having any relevant financial disclosures.

We can do a better job of taking care of our patients. And in no other area is there more room for quality improvement (QI) than in ambulatory care. In the article by Dolins et al., substantial improvements were reported in outpatient management meeting the standard of care for asthma. In my experience, doing so not only gives children a better functional outcome but also saves costs by avoiding unnecessary ED visits and hospitalization and generates new dollars for pediatric offices through the additional services they provide. We have seen similar improvements in our own work in South Carolina and Tennessee. The practices that have wanted to become involved in our asthma QI are those that are already doing a better than average job. Yet, they still generate substantial additional improvements.

The AAP study relied heavily on national experts and standards. Although their input is valued, the true advantage of QI is the opportunity for pediatricians and their staff at the service delivery level to generate their own changes within the context of a learning collaborative. True improvement and innovation is facilitated by allowing flexibility at the local level and sharing the ideas that result. Those that design the QI efforts of the future need to make sure they allow for local expertise rather than leaning too heavily on centrally predetermined change concepts.

Part IV Maintenance of Certification requirements from the American Board of Pediatrics help provide momentum for successful pediatric QI. The National Improvement Partnership Network has formed pediatric outpatient learning collaboratives to share ideas. As we identify more successes with ambulatory care QI, as more and more organizations like AAP state chapters become involved, as all practices – rather than just the best – recognize the obligation to promote quality, we have a tremendous opportunity to improve the developmental and health outcomes of the children. QI can promote work and cost efficiencies that facilitate our work as pediatricians, making our lives more productive and rewarding.

Francis E. Rushton Jr, MD, is a pediatrician and medical director of South Carolina’s QTIP (Quality Through Innovation in Pediatrics) network and the Quality Director for PHIIT (Pediatric Health Improvement In Tennessee). He reported not having any relevant financial disclosures.

We can do a better job of taking care of our patients. And in no other area is there more room for quality improvement (QI) than in ambulatory care. In the article by Dolins et al., substantial improvements were reported in outpatient management meeting the standard of care for asthma. In my experience, doing so not only gives children a better functional outcome but also saves costs by avoiding unnecessary ED visits and hospitalization and generates new dollars for pediatric offices through the additional services they provide. We have seen similar improvements in our own work in South Carolina and Tennessee. The practices that have wanted to become involved in our asthma QI are those that are already doing a better than average job. Yet, they still generate substantial additional improvements.

The AAP study relied heavily on national experts and standards. Although their input is valued, the true advantage of QI is the opportunity for pediatricians and their staff at the service delivery level to generate their own changes within the context of a learning collaborative. True improvement and innovation is facilitated by allowing flexibility at the local level and sharing the ideas that result. Those that design the QI efforts of the future need to make sure they allow for local expertise rather than leaning too heavily on centrally predetermined change concepts.

Part IV Maintenance of Certification requirements from the American Board of Pediatrics help provide momentum for successful pediatric QI. The National Improvement Partnership Network has formed pediatric outpatient learning collaboratives to share ideas. As we identify more successes with ambulatory care QI, as more and more organizations like AAP state chapters become involved, as all practices – rather than just the best – recognize the obligation to promote quality, we have a tremendous opportunity to improve the developmental and health outcomes of the children. QI can promote work and cost efficiencies that facilitate our work as pediatricians, making our lives more productive and rewarding.

Francis E. Rushton Jr, MD, is a pediatrician and medical director of South Carolina’s QTIP (Quality Through Innovation in Pediatrics) network and the Quality Director for PHIIT (Pediatric Health Improvement In Tennessee). He reported not having any relevant financial disclosures.

Care of children with asthma can be improved using statewide quality improvement (QI) learning collaboratives, said Judith C. Dolins, of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Elk Grove Village, Ill., and her associates.

AAP chapters demonstrated this through their implementation of the Chapter Quality Network (CQN) project, which was supported by the national organization. This project sought to encourage practice changes in asthma care in a number of states using statewide QI learning collaboratives and lead practices to implement the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s (NHLBI) 2007 asthma guidelines over the course of four time periods, which the researchers referred to as waves. In nine states, 19 AAP chapters engaged 180 practices to participate, and involved 749 pediatricians treating 45,431 patients (Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1612).

Across all waves, practices had reasonably high baseline use of the stepwise approach (81%-89%) and a controller medication for patients with persistent asthma (74%-88%). The patients with a current written asthma action plan increased from 49%-57% to 75%-91%. Physicians’ and parents’ ratings of asthma in children as “well controlled” rose modestly from 58%-63% to 71%-74% and from 67%-73% to 78%-87%, respectively. Patients receiving self-management materials increased from 57%-62% to 62%-88%.

Here’s how the project worked. The CQN had three linked frameworks.: One provided a methodology for spreading practice changes, another outlined the elements of care, and a third provided a framework so the practices could test, implement, and adapt changes.

A national AAP leadership team of experts in asthma care, QI, and primary care practice systems developed a set of key drivers and interventions, and an implementation guide that included resources, tools and methods, and a set of measures for the chapters. They also designed reporting tools and a curriculum fostering QI learning by chapter leaders. Then, in a state chapter leadership learning network and a practice collaborative model in each state, there were “multiple in-person learning sessions and defined action periods, best practices, and tests of change that were spread and incorporated” for the chapters to use, according to the study report.

Chapters in each state had monthly webinars and two in-person learning sessions for participating practices. They also reviewed data reports at the state and practice level and provided coaching for practices.

Practices were asked to “incorporate optimal NHLBI asthma care practices, including assessment of control, a stepwise approach to treatment, appropriate use of controller medication, and an updated asthma action plan for self-management.” Other interventions included use of an asthma encounter form (which collected 16 measures, including outcome and process measures that were entered into a national database at least monthly); introduction of population registries; workflow assessment; motivational interviews; plan-do-study-act cycles for QI; and review of data for QI.

All the physicians were eligible to earn MOC part 4 credit and continuing medical education credit, and 80% of the physicians did get MOC credit across the 4 waves.

“Our findings are notable for achieving improvement in asthma care through training multiple state coordinating entities instead of directly leading the learning collaborative itself. Few other projects have achieved this level of results in pediatric practice improvement in asthma care on such a widespread scale across multiple states. This project may serve as a model for other statewide and national organizations attempting to achieve improvements in population health through support and training for statewide organizations that, in turn, support individual health care providers and practices,” Ms. Dolins and her associates said. “Although none of the waves achieved the preset goal of 90%, all showed substantial improvement and remarkable consistency in the rate of improvement. We, therefore, regarded the project as an overall success.”

The study was funded by the Merck Childhood Asthma Network, American Board of Pediatrics Foundation, American Academy of Pediatrics Friends of Children Fund, the JPB Foundation, and GlaxoSmithKline. Ms. Dolins and Mr. Wise received salary support. Ms. Powell and Dr. Stemmler received consulting fees.

Care of children with asthma can be improved using statewide quality improvement (QI) learning collaboratives, said Judith C. Dolins, of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Elk Grove Village, Ill., and her associates.

AAP chapters demonstrated this through their implementation of the Chapter Quality Network (CQN) project, which was supported by the national organization. This project sought to encourage practice changes in asthma care in a number of states using statewide QI learning collaboratives and lead practices to implement the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s (NHLBI) 2007 asthma guidelines over the course of four time periods, which the researchers referred to as waves. In nine states, 19 AAP chapters engaged 180 practices to participate, and involved 749 pediatricians treating 45,431 patients (Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1612).

Across all waves, practices had reasonably high baseline use of the stepwise approach (81%-89%) and a controller medication for patients with persistent asthma (74%-88%). The patients with a current written asthma action plan increased from 49%-57% to 75%-91%. Physicians’ and parents’ ratings of asthma in children as “well controlled” rose modestly from 58%-63% to 71%-74% and from 67%-73% to 78%-87%, respectively. Patients receiving self-management materials increased from 57%-62% to 62%-88%.

Here’s how the project worked. The CQN had three linked frameworks.: One provided a methodology for spreading practice changes, another outlined the elements of care, and a third provided a framework so the practices could test, implement, and adapt changes.

A national AAP leadership team of experts in asthma care, QI, and primary care practice systems developed a set of key drivers and interventions, and an implementation guide that included resources, tools and methods, and a set of measures for the chapters. They also designed reporting tools and a curriculum fostering QI learning by chapter leaders. Then, in a state chapter leadership learning network and a practice collaborative model in each state, there were “multiple in-person learning sessions and defined action periods, best practices, and tests of change that were spread and incorporated” for the chapters to use, according to the study report.

Chapters in each state had monthly webinars and two in-person learning sessions for participating practices. They also reviewed data reports at the state and practice level and provided coaching for practices.

Practices were asked to “incorporate optimal NHLBI asthma care practices, including assessment of control, a stepwise approach to treatment, appropriate use of controller medication, and an updated asthma action plan for self-management.” Other interventions included use of an asthma encounter form (which collected 16 measures, including outcome and process measures that were entered into a national database at least monthly); introduction of population registries; workflow assessment; motivational interviews; plan-do-study-act cycles for QI; and review of data for QI.

All the physicians were eligible to earn MOC part 4 credit and continuing medical education credit, and 80% of the physicians did get MOC credit across the 4 waves.

“Our findings are notable for achieving improvement in asthma care through training multiple state coordinating entities instead of directly leading the learning collaborative itself. Few other projects have achieved this level of results in pediatric practice improvement in asthma care on such a widespread scale across multiple states. This project may serve as a model for other statewide and national organizations attempting to achieve improvements in population health through support and training for statewide organizations that, in turn, support individual health care providers and practices,” Ms. Dolins and her associates said. “Although none of the waves achieved the preset goal of 90%, all showed substantial improvement and remarkable consistency in the rate of improvement. We, therefore, regarded the project as an overall success.”

The study was funded by the Merck Childhood Asthma Network, American Board of Pediatrics Foundation, American Academy of Pediatrics Friends of Children Fund, the JPB Foundation, and GlaxoSmithKline. Ms. Dolins and Mr. Wise received salary support. Ms. Powell and Dr. Stemmler received consulting fees.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In wave 4, during which data were collected for 9 months, the rate of optimal asthma care at each encounter improved from 38% to 72%.

Data source: In nine states, 19 AAP chapters engaged 180 practices to participate in quality improvement learning collaboratives, which involved 749 pediatricians treating 45,431 patients.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Merck Childhood Asthma Network, American Board of Pediatrics Foundation, American Academy of Pediatrics Friends of Children Fund, the JPB Foundation, and GlaxoSmithKline. Ms. Dolins and Mr. Wise received salary support. Ms. Powell and Dr. Stemmler received consulting fees.

ATV use by children still leads to significant trauma center admittance

The incidence of children admitted to Pennsylvania trauma centers because of accidents while riding all-terrain vehicles (ATV) fell 13% from the first 5 years to the last 6 years of a 2004-2014 study – but that decrease was not statistically or clinically significant, reported Mariano Garay, MD, of Pennsylvania State University, Hershey, and his associates.

In the American Academy of Pediatrics’ most recent policy statement in 2000, the academy recommended that use of ATVs be restricted to people older than 16 years and to off-road use only, with no passengers.

The median age of patients was 14 years, with a range of 1-17 years. Boys accounted for three-quarters of the patients. Being a passenger or being pulled behind the ATVs accounted for 24% of the injured patients. Of the crashes, 15% occurred on a street or roadway, and 49% of the riders reportedly wore a helmet. The majority of children who died were age 12-15 years, 25% were passengers, and 32% were injured while the ATV was being used on a street or roadway.

“Researchers in numerous studies, as well as professional organizations and ATV manufacturers, have concluded that children less than 16 years of age do not have the capacity to safely operate ATVs,” Dr. Garay and associates cautioned. “We advise primary care providers to be the forefront of the prevention effort and to continue to provide families with safety information and recommendations of age restrictions for ATV use by children.”

The incidence of children admitted to Pennsylvania trauma centers because of accidents while riding all-terrain vehicles (ATV) fell 13% from the first 5 years to the last 6 years of a 2004-2014 study – but that decrease was not statistically or clinically significant, reported Mariano Garay, MD, of Pennsylvania State University, Hershey, and his associates.

In the American Academy of Pediatrics’ most recent policy statement in 2000, the academy recommended that use of ATVs be restricted to people older than 16 years and to off-road use only, with no passengers.

The median age of patients was 14 years, with a range of 1-17 years. Boys accounted for three-quarters of the patients. Being a passenger or being pulled behind the ATVs accounted for 24% of the injured patients. Of the crashes, 15% occurred on a street or roadway, and 49% of the riders reportedly wore a helmet. The majority of children who died were age 12-15 years, 25% were passengers, and 32% were injured while the ATV was being used on a street or roadway.

“Researchers in numerous studies, as well as professional organizations and ATV manufacturers, have concluded that children less than 16 years of age do not have the capacity to safely operate ATVs,” Dr. Garay and associates cautioned. “We advise primary care providers to be the forefront of the prevention effort and to continue to provide families with safety information and recommendations of age restrictions for ATV use by children.”

The incidence of children admitted to Pennsylvania trauma centers because of accidents while riding all-terrain vehicles (ATV) fell 13% from the first 5 years to the last 6 years of a 2004-2014 study – but that decrease was not statistically or clinically significant, reported Mariano Garay, MD, of Pennsylvania State University, Hershey, and his associates.

In the American Academy of Pediatrics’ most recent policy statement in 2000, the academy recommended that use of ATVs be restricted to people older than 16 years and to off-road use only, with no passengers.

The median age of patients was 14 years, with a range of 1-17 years. Boys accounted for three-quarters of the patients. Being a passenger or being pulled behind the ATVs accounted for 24% of the injured patients. Of the crashes, 15% occurred on a street or roadway, and 49% of the riders reportedly wore a helmet. The majority of children who died were age 12-15 years, 25% were passengers, and 32% were injured while the ATV was being used on a street or roadway.

“Researchers in numerous studies, as well as professional organizations and ATV manufacturers, have concluded that children less than 16 years of age do not have the capacity to safely operate ATVs,” Dr. Garay and associates cautioned. “We advise primary care providers to be the forefront of the prevention effort and to continue to provide families with safety information and recommendations of age restrictions for ATV use by children.”

FROM PEDIATRICS

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines modestly reduce complex acute otitis media

Incidence rate ratios of children hospitalized with acute otitis media (hAOM) or more advanced stages, such as mastoidismus and acute mastoiditis (M+AM) declined by 10% and 20%, respectively, after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) in the central region of Denmark, reported Bjarke B. Laursen of Aarhus University in Denmark, and associates.

The use of antibiotics for AOM prior to hospitalization increased markedly during the study period, and that may have impacted the modest reduction in hAOM and M+AM, the researchers said.

Incidence of Streptococcus pneumoniae cases decreased from 38% in the prevaccine era to 31% in the PCV-7 era and decreased even more to 16% in the PCV-13 era. The incidence of the second most frequently isolated bacteria, group A streptococcus (GAS), fell from 17% in the prevaccine era to 16% in the PCV-13 era, becoming equal to S. pneumoniae. The “no growth” results rose from 12% in the prevaccine era to 38% and 44% in the PCV-7 and PCV-13 eras, respectively (Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Jul 4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.07.002) .

In the M+AM group, S. pneumoniae–positive cases fell to 10% in the PCV-13 era, compared with 44% in the prevaccine era and 41% in the PCV-7 era. A rise in GAS-positive cultures was seen in the M+AM group, from 15% in the prevaccine era to 30% in the PCV-13 era. The “no growth” group rose in incidence from 13% of cases in the prevaccine era to 26% in the PCV-7 era and 33% in the PCV-13 era.

“This microbiological shift is worrisome, because GAS may cause very serious infections due to its invasive nature,” Dr. Laursen and associates wrote. “An increase in GAS as described in this study has not been demonstrated elsewhere so far. In contrast to our findings, the most common species to ‘take over’ in the United States was Haemophilus influenzae.

“As [S. pneumoniae] and GAS are potentially invasive pathogens causing more severe clinical signs and symptoms, such cases are more likely to be admitted compared to cases caused by non-typable Haemophilus influenzae that gives rise to more subtle middle ear infections and clinical pictures,” the researchers noted.

Considering how many patients received antibiotics prior to admission in the hAOM group, there was a slight increase from 45% in the prevaccine era to 54% in the PCV-13 era, but a “more pronounced increase was found in the M+AM group, from 27% in the prevaccine era to 46% in the PCV-13 era,” they said.

The investigators called for continued surveillance of the microbiology associated with complex AOM.

No study funding or investigator disclosure information was provided.

Incidence rate ratios of children hospitalized with acute otitis media (hAOM) or more advanced stages, such as mastoidismus and acute mastoiditis (M+AM) declined by 10% and 20%, respectively, after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) in the central region of Denmark, reported Bjarke B. Laursen of Aarhus University in Denmark, and associates.

The use of antibiotics for AOM prior to hospitalization increased markedly during the study period, and that may have impacted the modest reduction in hAOM and M+AM, the researchers said.

Incidence of Streptococcus pneumoniae cases decreased from 38% in the prevaccine era to 31% in the PCV-7 era and decreased even more to 16% in the PCV-13 era. The incidence of the second most frequently isolated bacteria, group A streptococcus (GAS), fell from 17% in the prevaccine era to 16% in the PCV-13 era, becoming equal to S. pneumoniae. The “no growth” results rose from 12% in the prevaccine era to 38% and 44% in the PCV-7 and PCV-13 eras, respectively (Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Jul 4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.07.002) .

In the M+AM group, S. pneumoniae–positive cases fell to 10% in the PCV-13 era, compared with 44% in the prevaccine era and 41% in the PCV-7 era. A rise in GAS-positive cultures was seen in the M+AM group, from 15% in the prevaccine era to 30% in the PCV-13 era. The “no growth” group rose in incidence from 13% of cases in the prevaccine era to 26% in the PCV-7 era and 33% in the PCV-13 era.

“This microbiological shift is worrisome, because GAS may cause very serious infections due to its invasive nature,” Dr. Laursen and associates wrote. “An increase in GAS as described in this study has not been demonstrated elsewhere so far. In contrast to our findings, the most common species to ‘take over’ in the United States was Haemophilus influenzae.

“As [S. pneumoniae] and GAS are potentially invasive pathogens causing more severe clinical signs and symptoms, such cases are more likely to be admitted compared to cases caused by non-typable Haemophilus influenzae that gives rise to more subtle middle ear infections and clinical pictures,” the researchers noted.

Considering how many patients received antibiotics prior to admission in the hAOM group, there was a slight increase from 45% in the prevaccine era to 54% in the PCV-13 era, but a “more pronounced increase was found in the M+AM group, from 27% in the prevaccine era to 46% in the PCV-13 era,” they said.

The investigators called for continued surveillance of the microbiology associated with complex AOM.

No study funding or investigator disclosure information was provided.

Incidence rate ratios of children hospitalized with acute otitis media (hAOM) or more advanced stages, such as mastoidismus and acute mastoiditis (M+AM) declined by 10% and 20%, respectively, after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV) in the central region of Denmark, reported Bjarke B. Laursen of Aarhus University in Denmark, and associates.

The use of antibiotics for AOM prior to hospitalization increased markedly during the study period, and that may have impacted the modest reduction in hAOM and M+AM, the researchers said.

Incidence of Streptococcus pneumoniae cases decreased from 38% in the prevaccine era to 31% in the PCV-7 era and decreased even more to 16% in the PCV-13 era. The incidence of the second most frequently isolated bacteria, group A streptococcus (GAS), fell from 17% in the prevaccine era to 16% in the PCV-13 era, becoming equal to S. pneumoniae. The “no growth” results rose from 12% in the prevaccine era to 38% and 44% in the PCV-7 and PCV-13 eras, respectively (Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Jul 4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.07.002) .

In the M+AM group, S. pneumoniae–positive cases fell to 10% in the PCV-13 era, compared with 44% in the prevaccine era and 41% in the PCV-7 era. A rise in GAS-positive cultures was seen in the M+AM group, from 15% in the prevaccine era to 30% in the PCV-13 era. The “no growth” group rose in incidence from 13% of cases in the prevaccine era to 26% in the PCV-7 era and 33% in the PCV-13 era.

“This microbiological shift is worrisome, because GAS may cause very serious infections due to its invasive nature,” Dr. Laursen and associates wrote. “An increase in GAS as described in this study has not been demonstrated elsewhere so far. In contrast to our findings, the most common species to ‘take over’ in the United States was Haemophilus influenzae.

“As [S. pneumoniae] and GAS are potentially invasive pathogens causing more severe clinical signs and symptoms, such cases are more likely to be admitted compared to cases caused by non-typable Haemophilus influenzae that gives rise to more subtle middle ear infections and clinical pictures,” the researchers noted.

Considering how many patients received antibiotics prior to admission in the hAOM group, there was a slight increase from 45% in the prevaccine era to 54% in the PCV-13 era, but a “more pronounced increase was found in the M+AM group, from 27% in the prevaccine era to 46% in the PCV-13 era,” they said.

The investigators called for continued surveillance of the microbiology associated with complex AOM.

No study funding or investigator disclosure information was provided.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall incidence in hAOM decreased numerically from 6.45/100,000 annually in the prevaccine era to 2.43/100,000 in the PCV-7 era, and to 5.88/100,000 annually in the PCV-13 era.

Data source: A retrospective study of 246 cases of children hospitalized with acute otitis media.

Disclosures: No study funding or investigator disclosure information was provided.