User login

Paronychia and Target Lesions After Hematopoietic Cell Transplant

The Diagnosis: Fusariosis

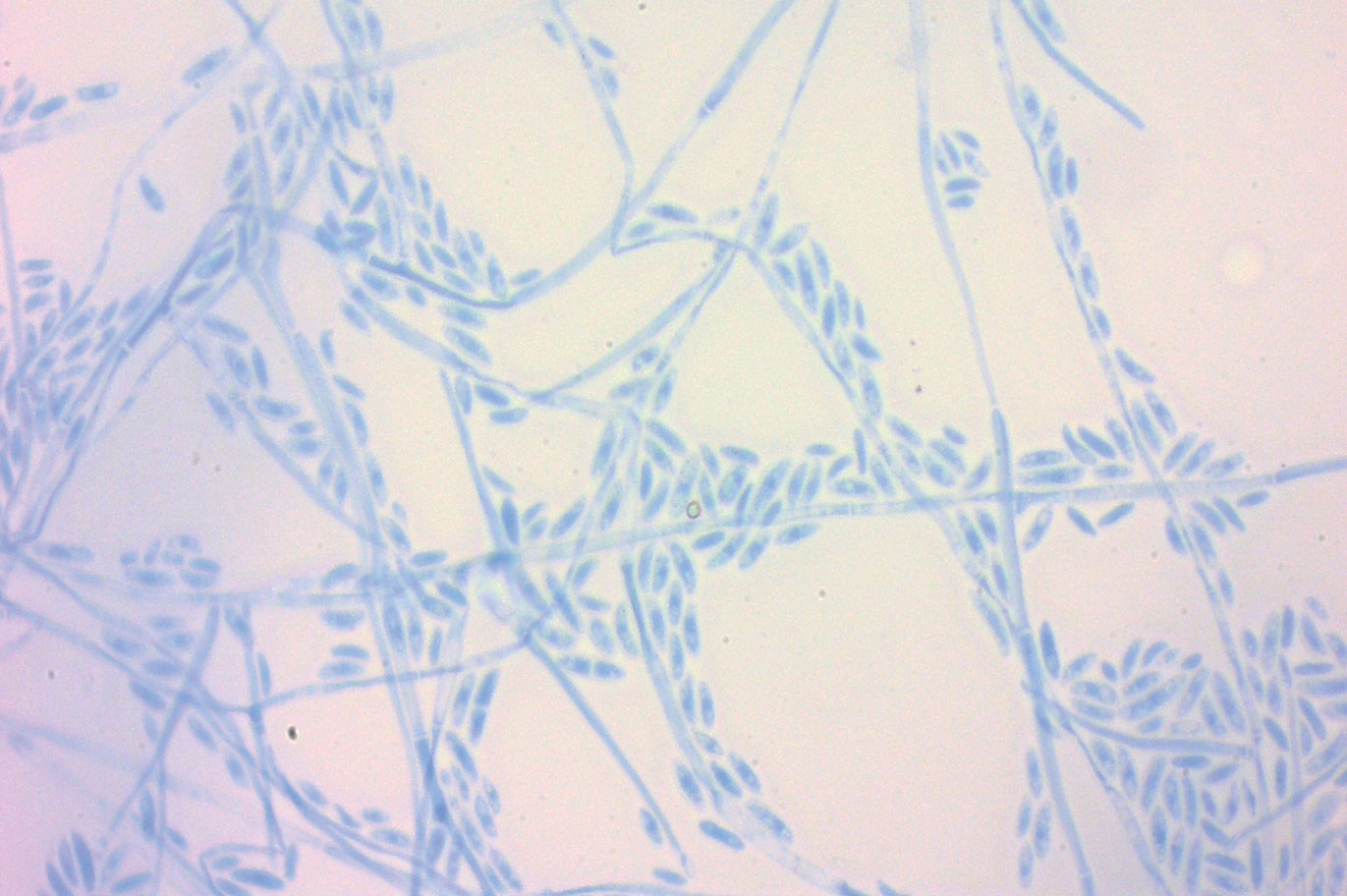

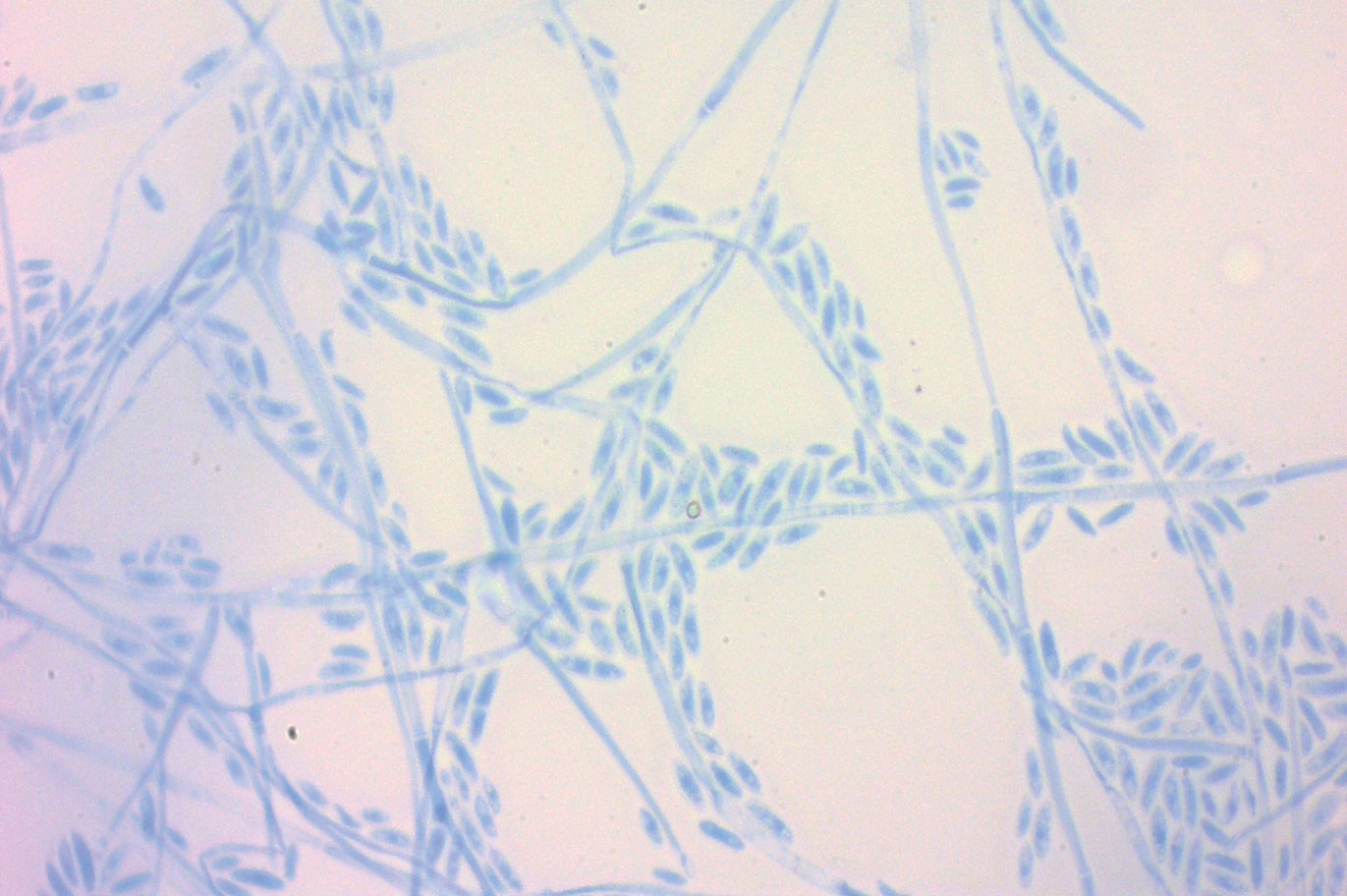

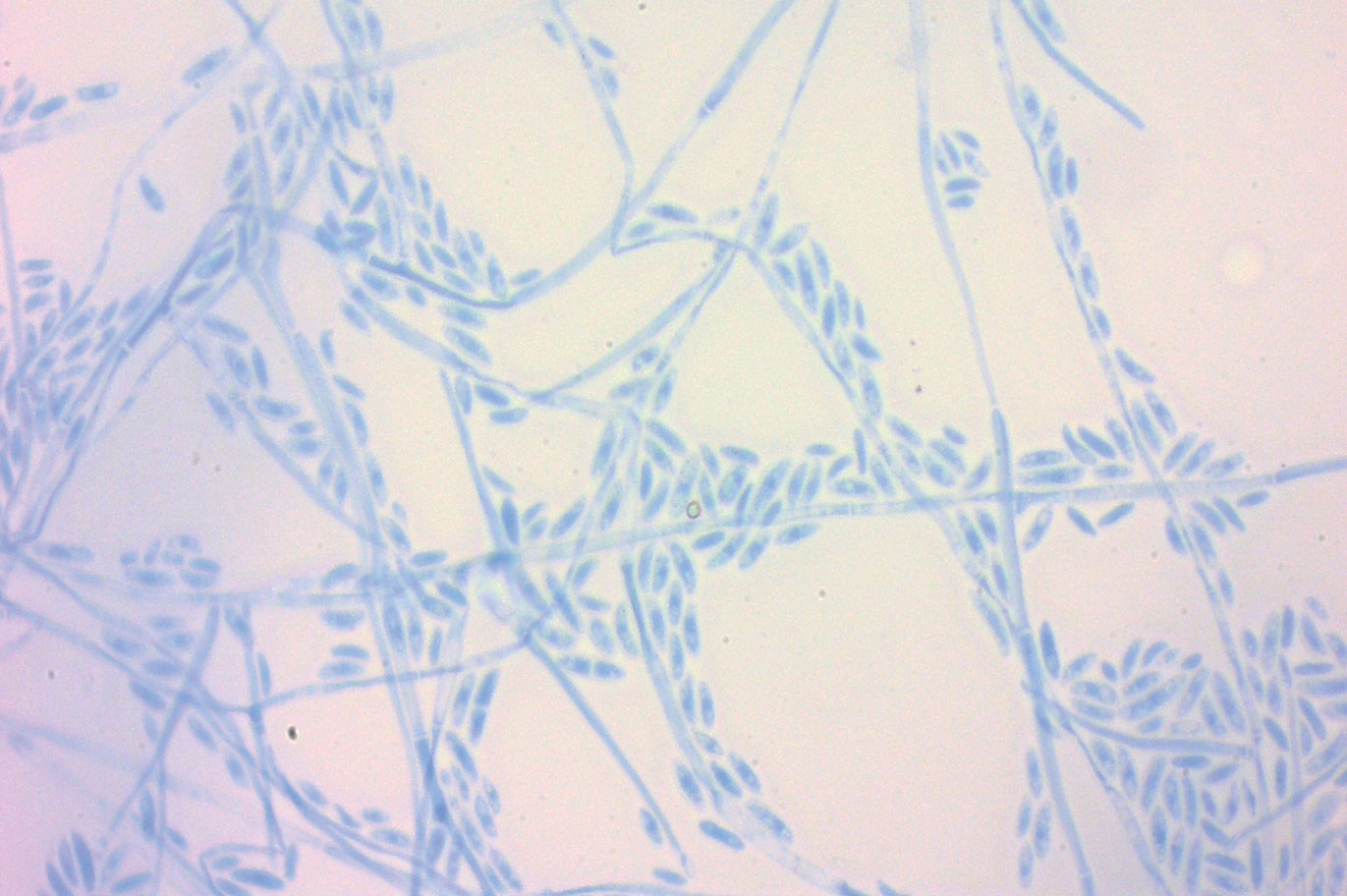

A periodic acid-Schiff stain of the seropurulent drainage from a skin nodule revealed neutrophils and scarce branching hyaline hyphae. Skin and blood cultures grew a white cottony colony. Microscopic examination showed sickle-shaped macroconidia and septate hyaline hyphae with branching acute angles (Figure). Molecular analysis by polymerase chain reaction yielded Fusarium solani species complex. Histopathology as well as culture and molecular findings were consistent with a diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis. Amphotericin B was started with rapid clinical improvement. The patient was asymptomatic upon discharge with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily.

Fusariosis is an emerging, opportunistic, and life-threatening mycosis. In immunocompetent patients it may cause onychomycosis and keratitis.1 Invasive fusariosis predominantly is caused by the F solani species complex and affects immunocompromised patients, especially those with neutropenia or acute leukemia or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.2

Before invasion, the infection frequently may begin by affecting the nail apparatus as onychomycosis or paronychia of the skin. As in our case, trauma or manipulation of the nail favors dissemination.3 Skin manifestations include erythematous to violaceous papules, macules, and nodules with central necrosis or crust; some may exhibit target morphology. Other organs may be affected, including the sinuses, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. A comprehensive clinical examination before hematopoietic cell transplant and during fever and neutropenia may opportunely identify these potential infective foci.3,4

The differential diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis includes bacterial infections, especially Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other invasive fungal infections, particularly aspergillosis, mucormycosis, and candidiasis.5 Symptom persistence after broad-spectrum antibiotic initiation should raise diagnostic suspicion of systemic mycosis or mycobacterial infection. Mucormycosis and candidiasis have histopathologic profiles that differ from fusariosis, presenting with broad ribbonlike hyphae with 90° angulation and pseudohyphae with budding yeast cells, respectively. Differentiation of disseminated fusariosis and aspergillosis in neutropenic patients is difficult. Hyphae cannot be differentiated from those of Aspergillus species on histology.6 Furthermore, serologic assays, such as galactomannan and (1,3)-β-D-glucan, cross-react with both genera. Clinically, Fusarium species exhibit metastatic skin lesions, cellulitis, and positive blood cultures due to adventitious sporulation more frequently than Aspergillus species. Patients with aspergillosis more commonly present with sinusitis, pneumonia, and pulmonary macronodules with the halo sign.6 Although nocardiosis presents with disseminated subcutaneous nodules with pulmonary affection in immunocompromised patients, its morphology is very different from fusariosis. Nocardia presents with a gram-positive bacillus with the microscopic appearance of branching filaments. Yeastlike microorganisms with morphology ranging from oval to sausagelike are found in talaromycosis, an uncommon fungal infection predominantly caused by Talaromyces marneffei. Fusarium species culture reveals white cottony colonies with characteristic hyaline, canoe-shaped or sickle-shaped (banana-shaped), multicellular macroconidia, and microconidia. Precise species identification requires molecular analyses such as polymerase chain reaction.

Mortality is high, ranging from 50% to 70% of cases.5 Voriconazole or lipid-based amphotericin B are considered first-line treatments. Posaconazole may be employed as a second-line alternative. Surgical debridement of infected tissues and removal of colonized venous catheters is recommended. Secondary prophylaxis should be considered with agents such as voriconazole, posaconazole, or amphotericin B.5 Resolution of immunosuppression and neutropenia is an important factor to reduce the mortality rate.

- Ranawaka RR, Nagahawatte A, Gunasekara TA. Fusarium onychomycosis: prevalence, clinical presentations, response toitraconazole and terbinafine pulse therapy, and 1-year follow-up in nine cases. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1275-1282.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Fusariosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:706-714.

- Varon AG, Nouer SA, Barreiros G, et al. Superficial skin lesions positive for Fusarium are associated with subsequent development of invasive fusariosis. J Infect. 2014;68:85-89.

- Hay RJ. Fusarium infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:115-117.

- Tortorano AM, Richardson M, Roilides E, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:27-46.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Invasive mould disease in haematologic patients: comparison between fusariosis and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:1105.e1-1105.e4.

The Diagnosis: Fusariosis

A periodic acid-Schiff stain of the seropurulent drainage from a skin nodule revealed neutrophils and scarce branching hyaline hyphae. Skin and blood cultures grew a white cottony colony. Microscopic examination showed sickle-shaped macroconidia and septate hyaline hyphae with branching acute angles (Figure). Molecular analysis by polymerase chain reaction yielded Fusarium solani species complex. Histopathology as well as culture and molecular findings were consistent with a diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis. Amphotericin B was started with rapid clinical improvement. The patient was asymptomatic upon discharge with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily.

Fusariosis is an emerging, opportunistic, and life-threatening mycosis. In immunocompetent patients it may cause onychomycosis and keratitis.1 Invasive fusariosis predominantly is caused by the F solani species complex and affects immunocompromised patients, especially those with neutropenia or acute leukemia or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.2

Before invasion, the infection frequently may begin by affecting the nail apparatus as onychomycosis or paronychia of the skin. As in our case, trauma or manipulation of the nail favors dissemination.3 Skin manifestations include erythematous to violaceous papules, macules, and nodules with central necrosis or crust; some may exhibit target morphology. Other organs may be affected, including the sinuses, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. A comprehensive clinical examination before hematopoietic cell transplant and during fever and neutropenia may opportunely identify these potential infective foci.3,4

The differential diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis includes bacterial infections, especially Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other invasive fungal infections, particularly aspergillosis, mucormycosis, and candidiasis.5 Symptom persistence after broad-spectrum antibiotic initiation should raise diagnostic suspicion of systemic mycosis or mycobacterial infection. Mucormycosis and candidiasis have histopathologic profiles that differ from fusariosis, presenting with broad ribbonlike hyphae with 90° angulation and pseudohyphae with budding yeast cells, respectively. Differentiation of disseminated fusariosis and aspergillosis in neutropenic patients is difficult. Hyphae cannot be differentiated from those of Aspergillus species on histology.6 Furthermore, serologic assays, such as galactomannan and (1,3)-β-D-glucan, cross-react with both genera. Clinically, Fusarium species exhibit metastatic skin lesions, cellulitis, and positive blood cultures due to adventitious sporulation more frequently than Aspergillus species. Patients with aspergillosis more commonly present with sinusitis, pneumonia, and pulmonary macronodules with the halo sign.6 Although nocardiosis presents with disseminated subcutaneous nodules with pulmonary affection in immunocompromised patients, its morphology is very different from fusariosis. Nocardia presents with a gram-positive bacillus with the microscopic appearance of branching filaments. Yeastlike microorganisms with morphology ranging from oval to sausagelike are found in talaromycosis, an uncommon fungal infection predominantly caused by Talaromyces marneffei. Fusarium species culture reveals white cottony colonies with characteristic hyaline, canoe-shaped or sickle-shaped (banana-shaped), multicellular macroconidia, and microconidia. Precise species identification requires molecular analyses such as polymerase chain reaction.

Mortality is high, ranging from 50% to 70% of cases.5 Voriconazole or lipid-based amphotericin B are considered first-line treatments. Posaconazole may be employed as a second-line alternative. Surgical debridement of infected tissues and removal of colonized venous catheters is recommended. Secondary prophylaxis should be considered with agents such as voriconazole, posaconazole, or amphotericin B.5 Resolution of immunosuppression and neutropenia is an important factor to reduce the mortality rate.

The Diagnosis: Fusariosis

A periodic acid-Schiff stain of the seropurulent drainage from a skin nodule revealed neutrophils and scarce branching hyaline hyphae. Skin and blood cultures grew a white cottony colony. Microscopic examination showed sickle-shaped macroconidia and septate hyaline hyphae with branching acute angles (Figure). Molecular analysis by polymerase chain reaction yielded Fusarium solani species complex. Histopathology as well as culture and molecular findings were consistent with a diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis. Amphotericin B was started with rapid clinical improvement. The patient was asymptomatic upon discharge with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily.

Fusariosis is an emerging, opportunistic, and life-threatening mycosis. In immunocompetent patients it may cause onychomycosis and keratitis.1 Invasive fusariosis predominantly is caused by the F solani species complex and affects immunocompromised patients, especially those with neutropenia or acute leukemia or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.2

Before invasion, the infection frequently may begin by affecting the nail apparatus as onychomycosis or paronychia of the skin. As in our case, trauma or manipulation of the nail favors dissemination.3 Skin manifestations include erythematous to violaceous papules, macules, and nodules with central necrosis or crust; some may exhibit target morphology. Other organs may be affected, including the sinuses, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. A comprehensive clinical examination before hematopoietic cell transplant and during fever and neutropenia may opportunely identify these potential infective foci.3,4

The differential diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis includes bacterial infections, especially Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other invasive fungal infections, particularly aspergillosis, mucormycosis, and candidiasis.5 Symptom persistence after broad-spectrum antibiotic initiation should raise diagnostic suspicion of systemic mycosis or mycobacterial infection. Mucormycosis and candidiasis have histopathologic profiles that differ from fusariosis, presenting with broad ribbonlike hyphae with 90° angulation and pseudohyphae with budding yeast cells, respectively. Differentiation of disseminated fusariosis and aspergillosis in neutropenic patients is difficult. Hyphae cannot be differentiated from those of Aspergillus species on histology.6 Furthermore, serologic assays, such as galactomannan and (1,3)-β-D-glucan, cross-react with both genera. Clinically, Fusarium species exhibit metastatic skin lesions, cellulitis, and positive blood cultures due to adventitious sporulation more frequently than Aspergillus species. Patients with aspergillosis more commonly present with sinusitis, pneumonia, and pulmonary macronodules with the halo sign.6 Although nocardiosis presents with disseminated subcutaneous nodules with pulmonary affection in immunocompromised patients, its morphology is very different from fusariosis. Nocardia presents with a gram-positive bacillus with the microscopic appearance of branching filaments. Yeastlike microorganisms with morphology ranging from oval to sausagelike are found in talaromycosis, an uncommon fungal infection predominantly caused by Talaromyces marneffei. Fusarium species culture reveals white cottony colonies with characteristic hyaline, canoe-shaped or sickle-shaped (banana-shaped), multicellular macroconidia, and microconidia. Precise species identification requires molecular analyses such as polymerase chain reaction.

Mortality is high, ranging from 50% to 70% of cases.5 Voriconazole or lipid-based amphotericin B are considered first-line treatments. Posaconazole may be employed as a second-line alternative. Surgical debridement of infected tissues and removal of colonized venous catheters is recommended. Secondary prophylaxis should be considered with agents such as voriconazole, posaconazole, or amphotericin B.5 Resolution of immunosuppression and neutropenia is an important factor to reduce the mortality rate.

- Ranawaka RR, Nagahawatte A, Gunasekara TA. Fusarium onychomycosis: prevalence, clinical presentations, response toitraconazole and terbinafine pulse therapy, and 1-year follow-up in nine cases. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1275-1282.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Fusariosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:706-714.

- Varon AG, Nouer SA, Barreiros G, et al. Superficial skin lesions positive for Fusarium are associated with subsequent development of invasive fusariosis. J Infect. 2014;68:85-89.

- Hay RJ. Fusarium infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:115-117.

- Tortorano AM, Richardson M, Roilides E, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:27-46.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Invasive mould disease in haematologic patients: comparison between fusariosis and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:1105.e1-1105.e4.

- Ranawaka RR, Nagahawatte A, Gunasekara TA. Fusarium onychomycosis: prevalence, clinical presentations, response toitraconazole and terbinafine pulse therapy, and 1-year follow-up in nine cases. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1275-1282.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Fusariosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:706-714.

- Varon AG, Nouer SA, Barreiros G, et al. Superficial skin lesions positive for Fusarium are associated with subsequent development of invasive fusariosis. J Infect. 2014;68:85-89.

- Hay RJ. Fusarium infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:115-117.

- Tortorano AM, Richardson M, Roilides E, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:27-46.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Invasive mould disease in haematologic patients: comparison between fusariosis and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:1105.e1-1105.e4.

A 19-year-old man with acute lymphoblastic leukemia was admitted for an allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. On the 11th day of hospitalization, he experienced a right toe trauma in his hospital room and subsequently developed edema, erythema, and pain on the right hallux (top). The next day, a general surgeon performed a minor incision and drainage of the affected area. After 2 days, the patient developed a fever and a disseminated dermatosis located on the arms and legs characterized by target lesions with a necrotic center and erythematous papules and macules (bottom). On day 3, he developed severe neutropenia (0.042×109 cells/L [reference range, 2.0–6.9×109 cells/L]). Broad-spectrum antibiotics were initiated without clinical improvement. The patient developed dyspnea on day 5. Skin, nail, and blood cultures were obtained. High-resolution computed tomography of the chest displayed multiple small pulmonary nodules, ground-glass opacities, and the tree-in-bud sign.