User login

Evaluating Factors Impacting Hidradenitis Suppurativa Disease Severity in Patients With Darker Skin Types

Evaluating Factors Impacting Hidradenitis Suppurativa Disease Severity in Patients With Darker Skin Types

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a debilitating chronic skin disease that often affects apocrinebearing regions of the skin such as the axillae, perineum, and groin.1 Although current research on the etiology and pathogenesis of HS is limited, the disease is known to have a considerable psychosocial impact on patient quality of life.

Clinically, HS lesions manifest as tender subcutaneous nodules that rupture to form painful and deep dermal abscesses.2 These lesions typically develop due to hair follicle occlusion, followed by a cyclic process of inflammation, healing, re-inflammation, and scarring. Often, they are mistaken for cysts or a simple abscess in the early stages of the disease, leading to a delay in diagnosis.1 Disease severity is categorized based on Hurley staging: stage 1 involves abscess formation without scarring; stage 2 involves limited sinus tracts and recurrent abscesses with scarring and/or multiple separated lesions; and stage 3 is the most advanced stage, with diffuse involvement or multiple interconnected sinus tracts across an area with scarring. The condition primarily is medically managed with antibiotics and immunomodulators, but patients who have refractory disease can benefit from surgical excision.1,2

The prevalence of HS in the United States ranges from 0.77% to 1.19%, and individuals who self-identify as Black have 3-fold higher odds of having this condition compared with all other racial groups.3-5 Black patients also are thought to have a greater number and size of apocrine glands compared with patients who self-identify as White, suggesting an anatomic predisposition to developing HS and greater disease severity.6 However, despite HS disproportionately impacting individuals with skin of color (SOC), the majority of published HS research includes predominantly White patient cohorts.5 There is insufficient research assessing HS epidemiology, comorbidities, and treatment responses in patients with SOC.

A 2020 review reported the notable lack of clinical trials that sufficiently examine systemic medication treatment response in HS patients with SOC.7 Of the 15 HS treatment trials published from 2000 to 2019, only 16.4% (138/840) of the patient population were of African descent.7 Clinical trials investigating the efficacy of adalimumab in reducing HS burden also did not adequately evaluate clinical response in patients with SOC. One clinical trial did not include any Black patients as part of the cohort,8 and in 3 other studies, 80% to 85% of the study participants self-identified as White.9 The current literature does not reflect the patient populations most affected by HS, as several studies have reported that 65% of patients diagnosed with HS in the United States annually are Black.5,7 These results emphasize the underrepresentation of SOC populations in the current HS literature and the need for more research that investigates the disease processes, comorbidities, and treatment outcomes of the diverse patient population impacted by HS.

Methods

Study Population and Data Extraction—Following a protocol reviewed and approved by the MedStar Health/Georgetown University institutional review board (IRB #00006783), a retrospective chart review of 31 adult patients with HS who underwent surgery at a regional verified burn center from April 2014 to April 2023 was conducted. The following variables were collected from the electronic medical record (EMR): baseline demographics including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), obesity status, race, ethnicity, Fitzpatrick skin type, smoking status, substance use, employment status, and family history of HS; HS-specific details including Hurley staging, affected areas, and age at initial diagnosis; comorbidities such as dermatologic conditions, autoimmune disorders, infectious diseases, cardiovascular and associated diseases, ovarian disorders, gastrointestinal diseases, and othother common chronic comorbidities (psychiatric illness, kidney disease, type 2 diabetes [T2D], asthma, allergies, lymphedema, and inflammatory eye disease); and use of pharmacologics such as topical medications, oral antibiotics, immunomodulators, and steroids.

Study Definitions—Obesity was defined as both a continuous and categorical variable. Each patient’s BMI at the surgery date was recorded from the EMR as a continuous variable. Patients with obesity also had this condition listed under their complaints and problem list in the EMR, which was recorded as a categorical variable. Race and ethnicity were self-reported by patients. Comorbidity data, including T2D and hyperlipidemia, were defined by previously diagnosed diseases listed in the EMR. Pharmacologic medication data were included in the study if a patient was recommended/prescribed a medication and they had confirmed use of the medication in a subsequent office visit.

Statistical Analysis—Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographics, HS characteristics (eg, location, Hurley stage), and comorbidities. Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range and were evaluated using a t test or Mann-Whitney U test when appropriate. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and tested for associations using the X2 or Fisher exact test. Data analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

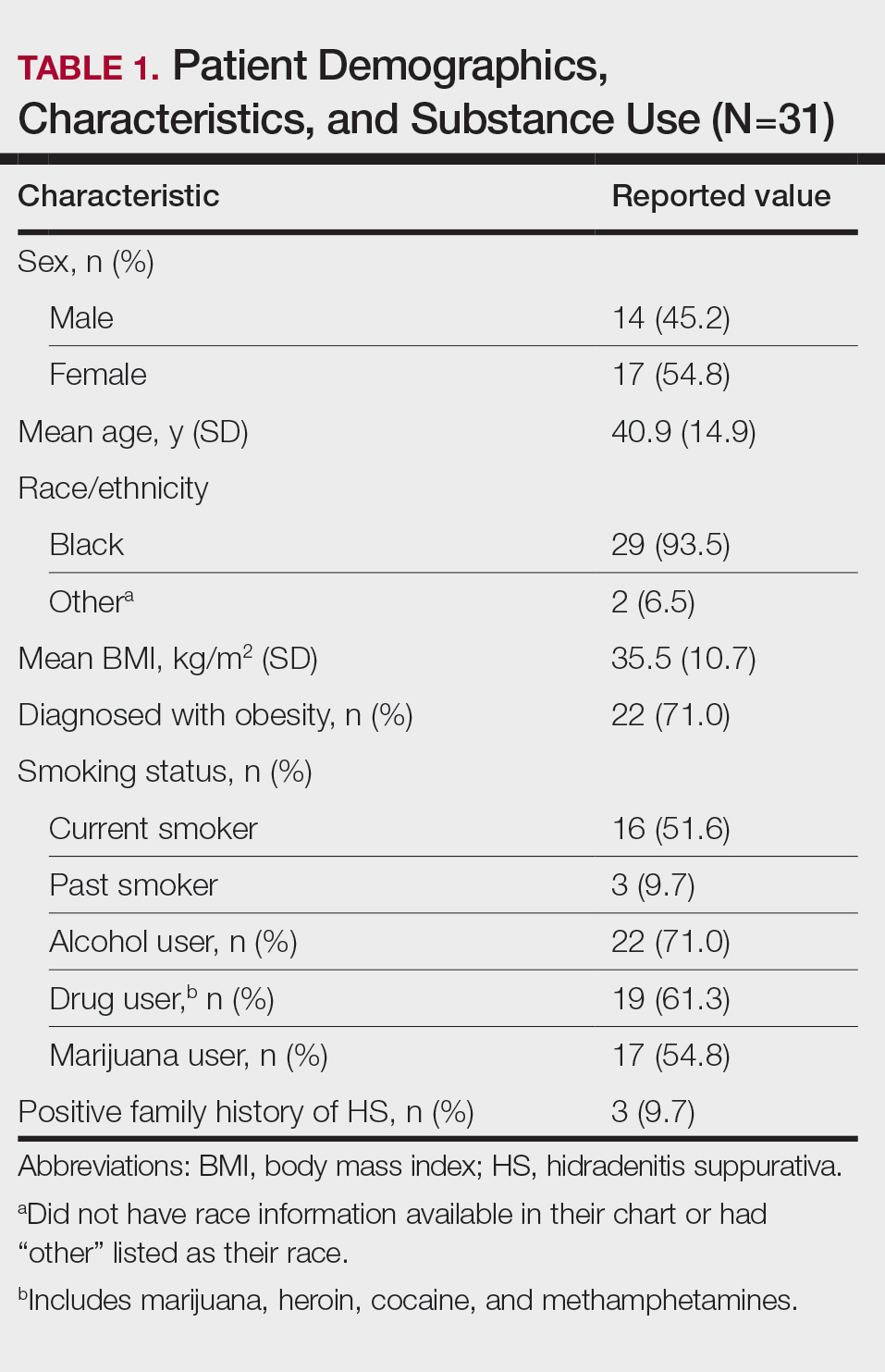

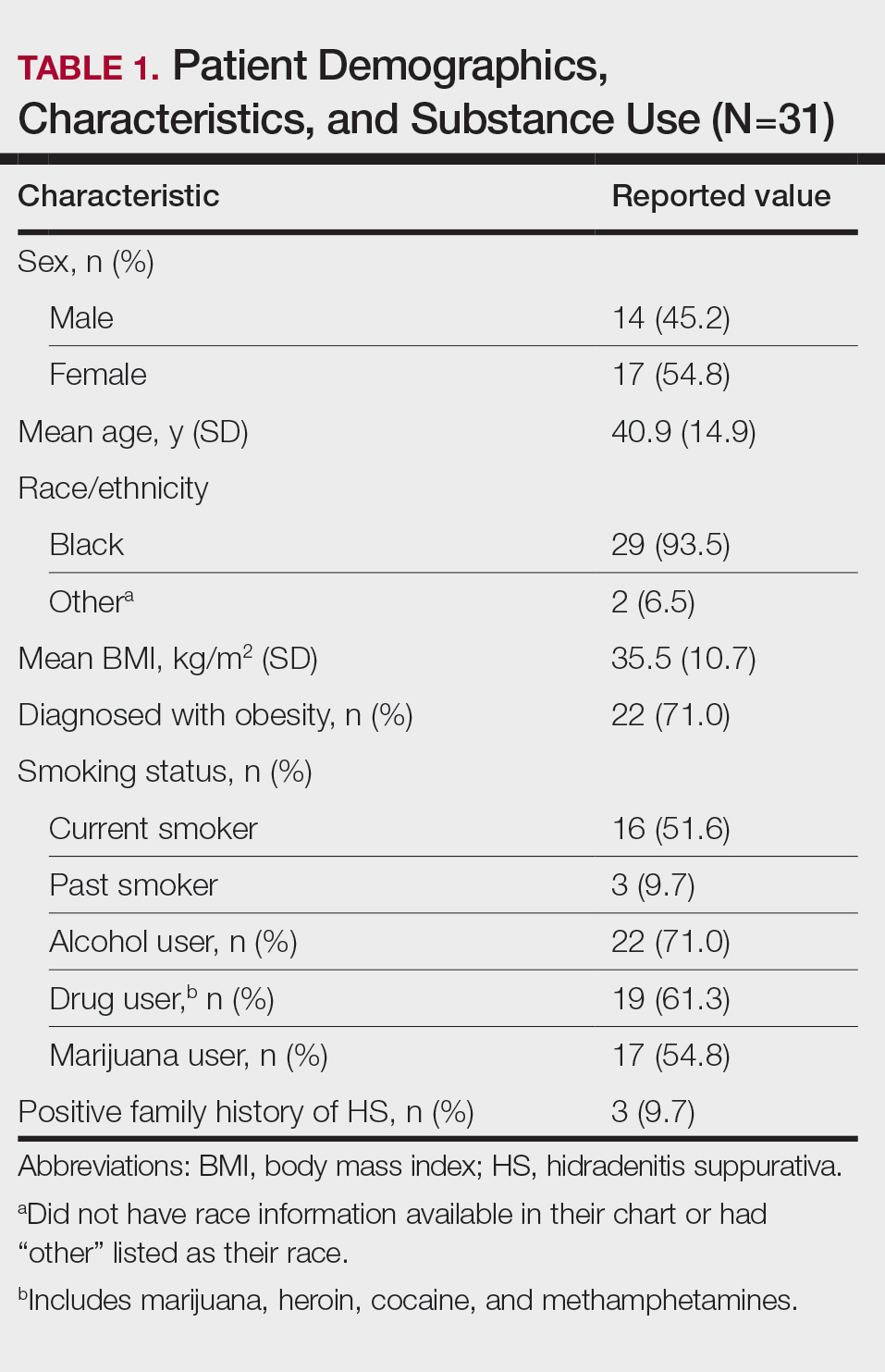

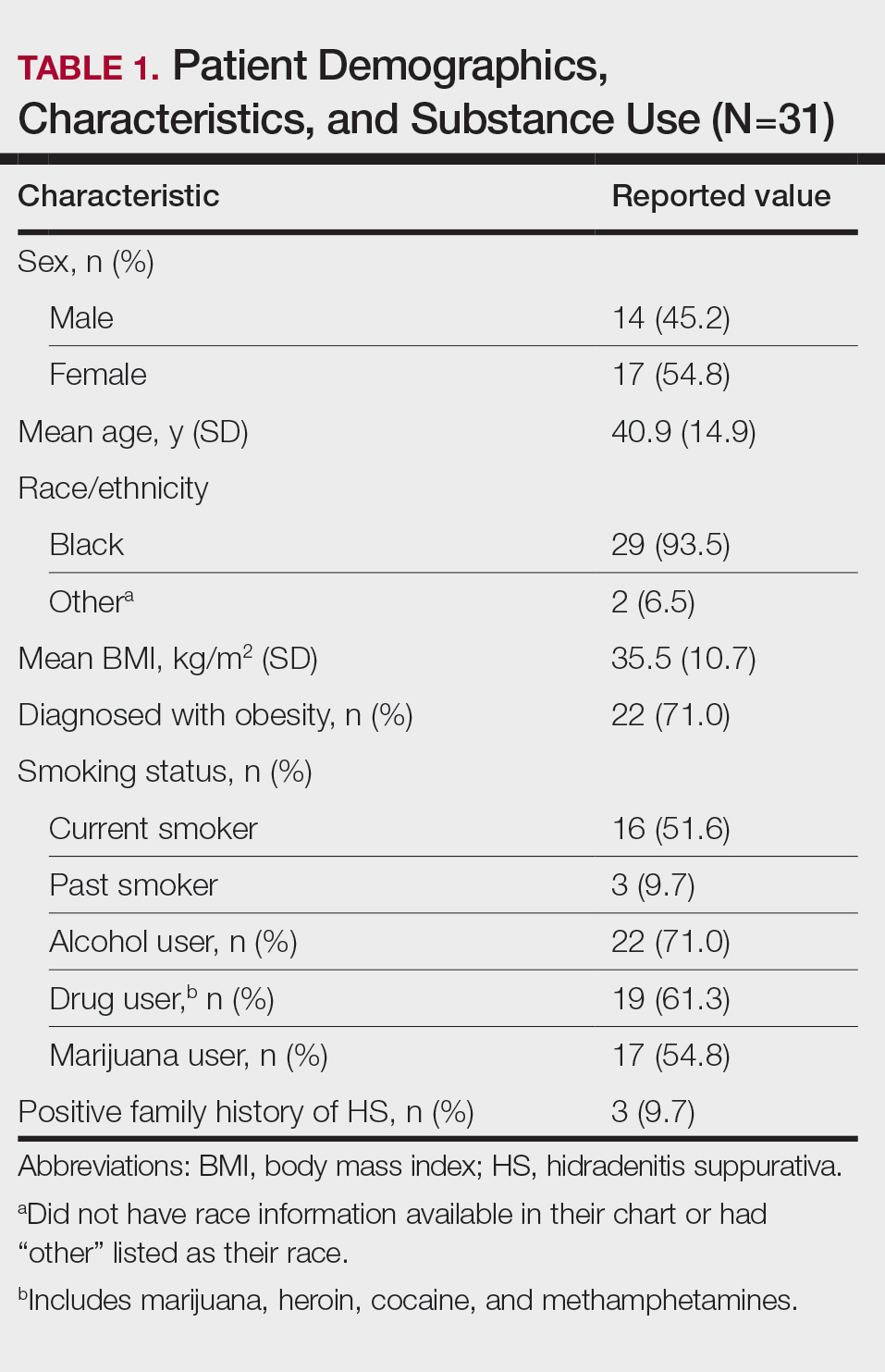

Thirty-one patients (17 females, 14 males; mean age, 40.9 years) were included in the study. Twenty-nine (93.5%) patients identified as Black. All study patients had at least 1 comorbidity. Obesity was diagnosed in 22 (71.0%) patients (mean BMI, 35.5 kg/m2). A total of 16 (51.6%) patients were current smokers, 3 (9.7%) were past smokers, 22 (71%) reported alcohol use, and 17 (54.8%) were active marijuana users. Only 3 (9.7%) patients had a family history of HS (Table 1).

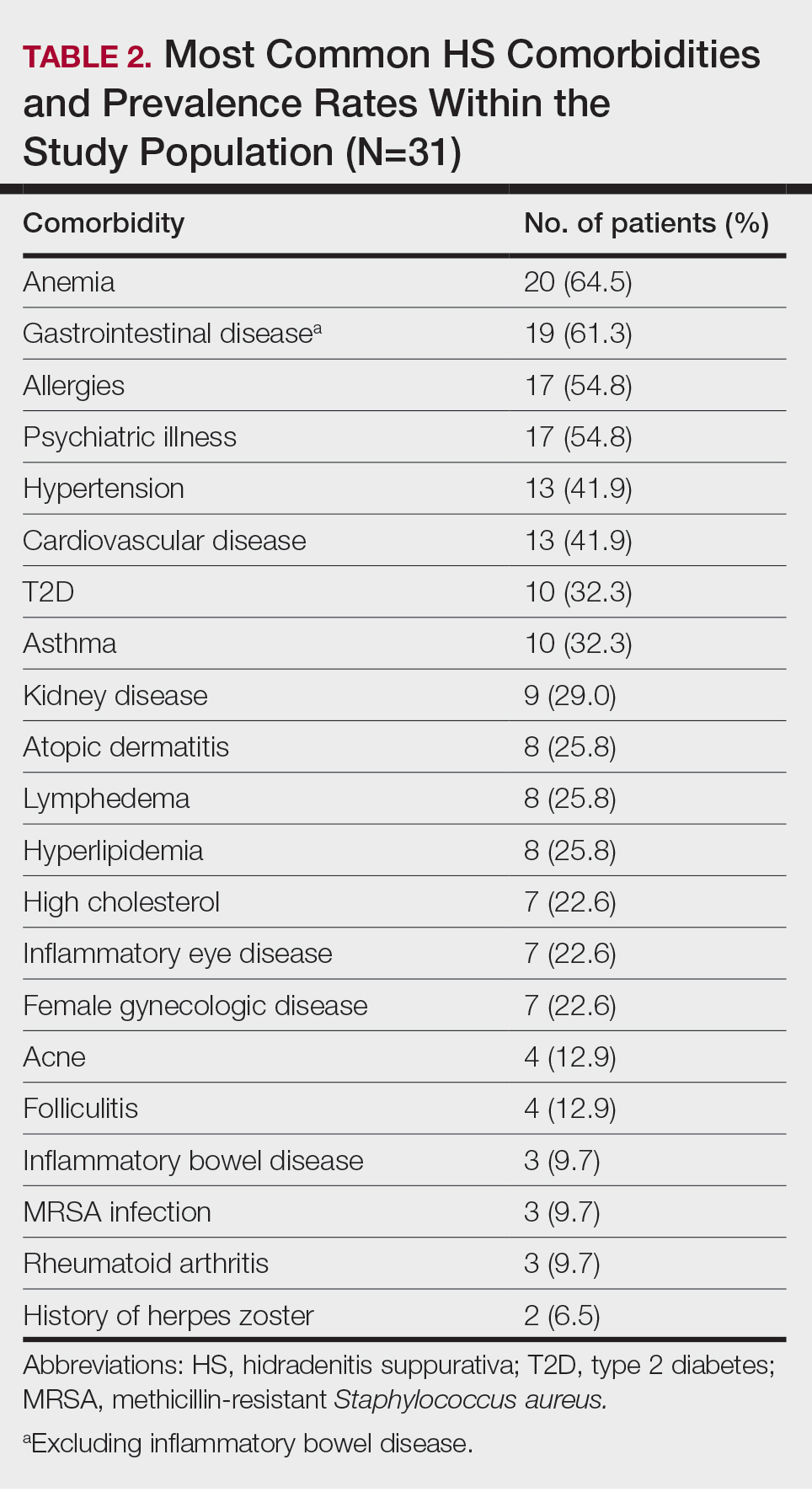

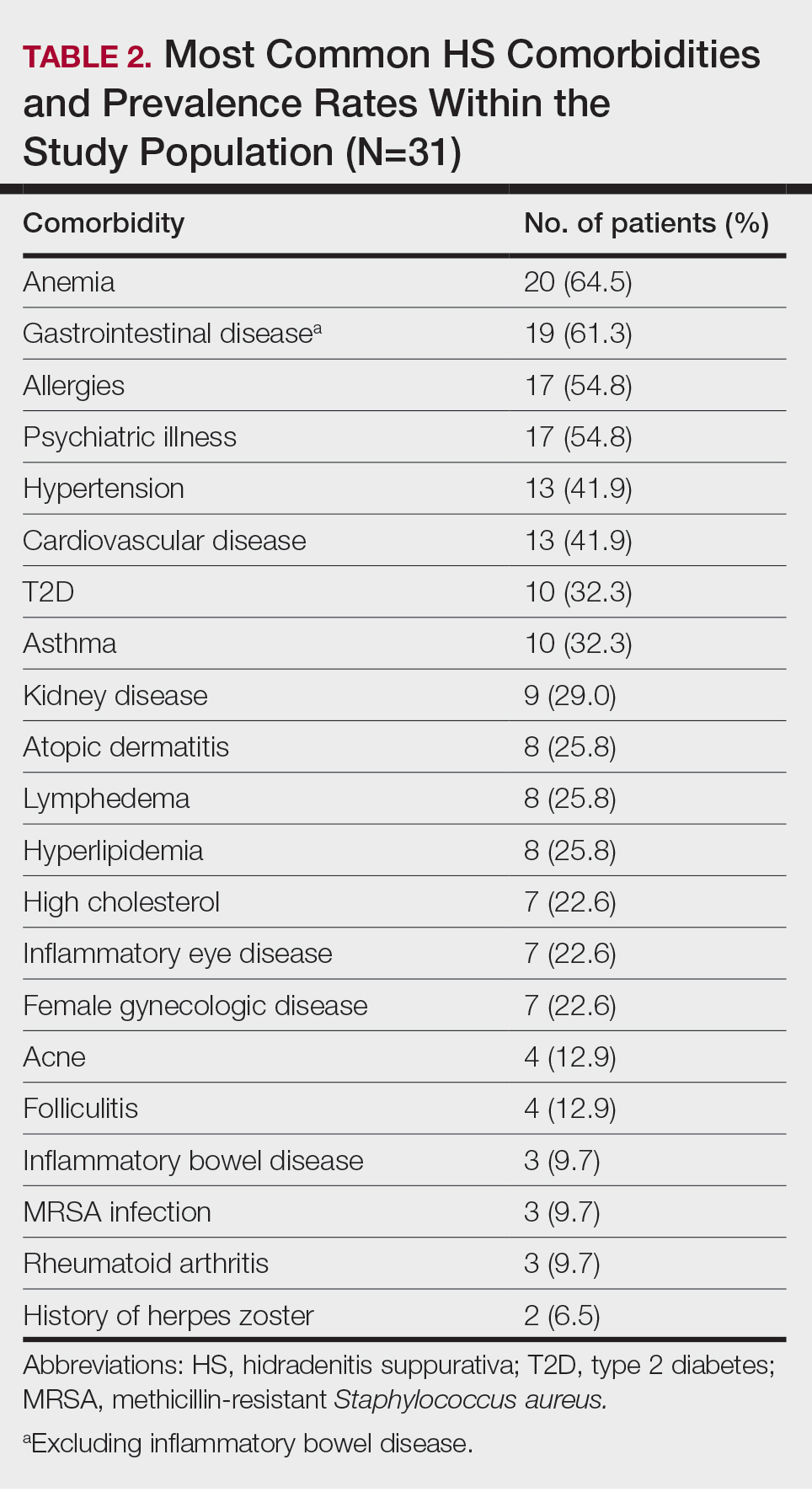

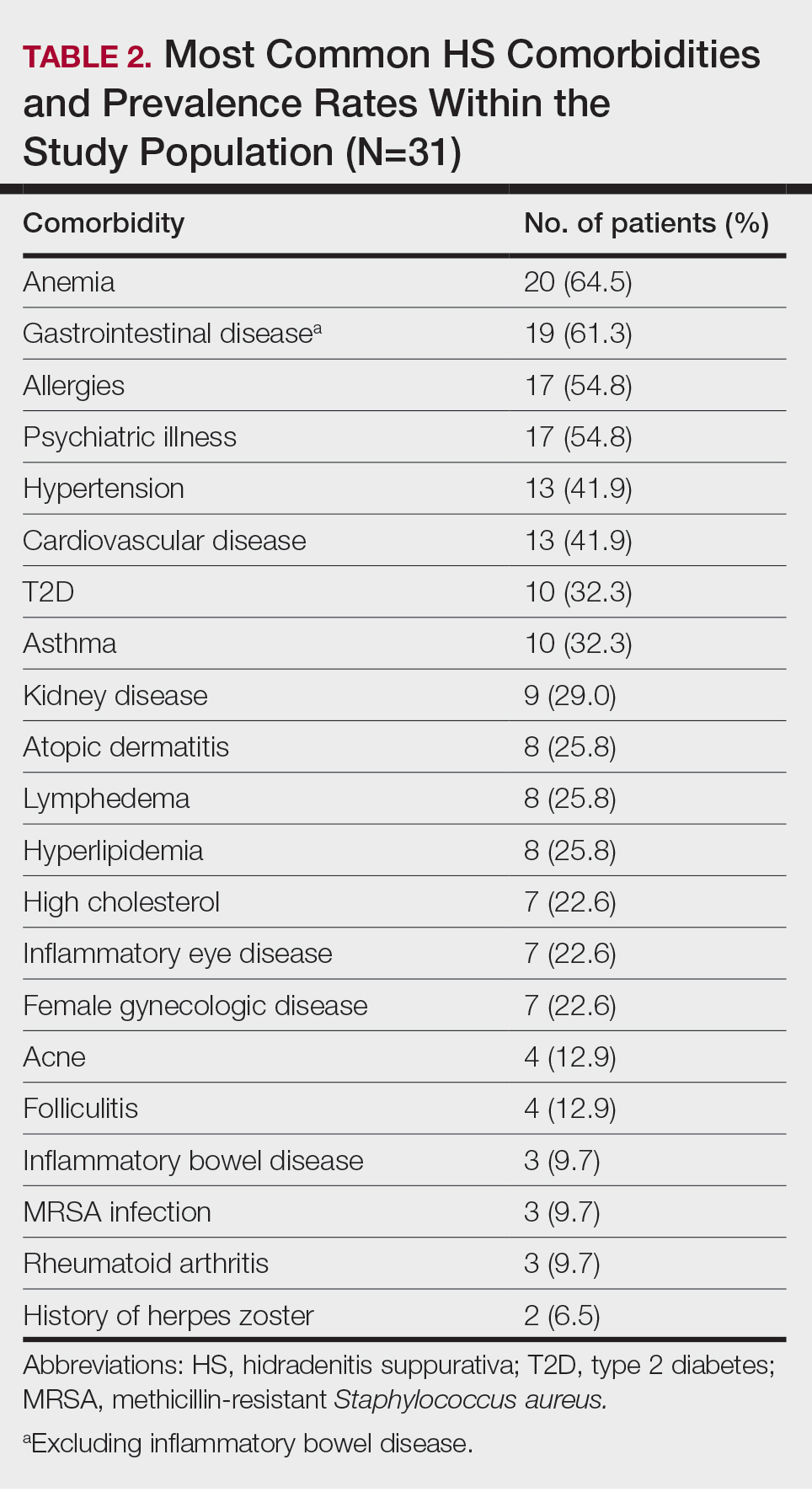

Other common comorbidities associated with HS were anemia (64.5% [20/31]), a non–inflammatory bowel disease gastrointestinal disease (61.3% [19/31]), allergies (54.8% [17/31]), hypertension (41.9% [13/31]), cardiovascular disease (41.9% [13/31]), T2D (32.3% [10/31]), asthma (32.3% [10/31]), kidney disease (29.0% [9/31]), and atopic dermatitis (25.8% [8/31]). More than half (54.8% [17/31]) of patients were diagnosed with psychiatric illnesses, including depression, anxiety, bipolar depression, psychosis, anorexia, impulsive anger, hallucinations, delusion, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, and panic disorder (Table 2). Depression was diagnosed in 38.7% (12/31) of patients, and 22.6% (7/31) were diagnosed with anxiety.

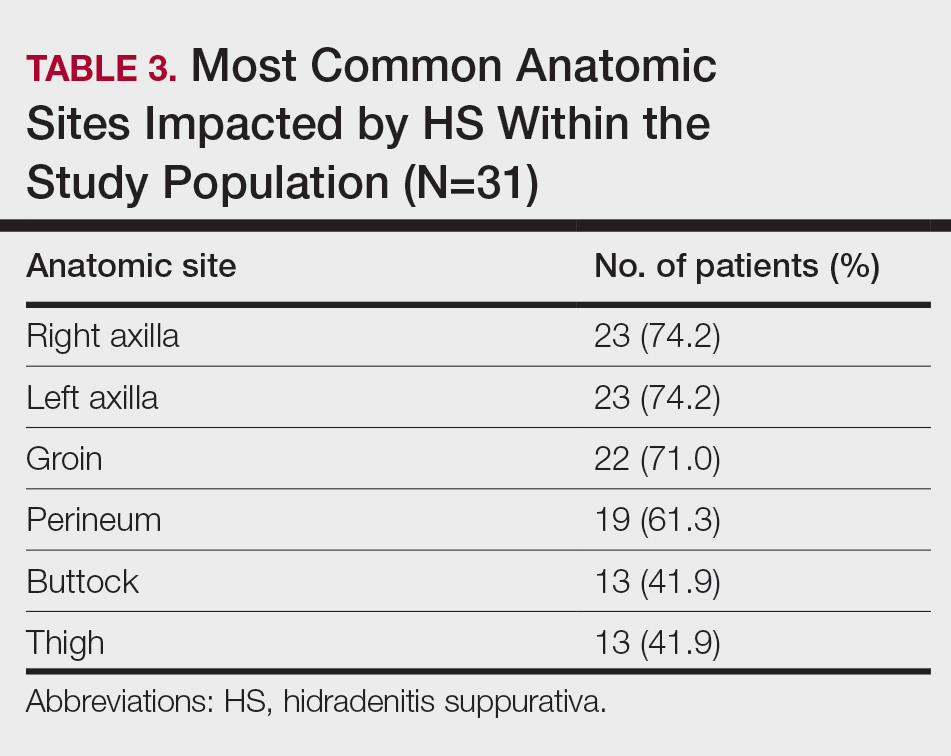

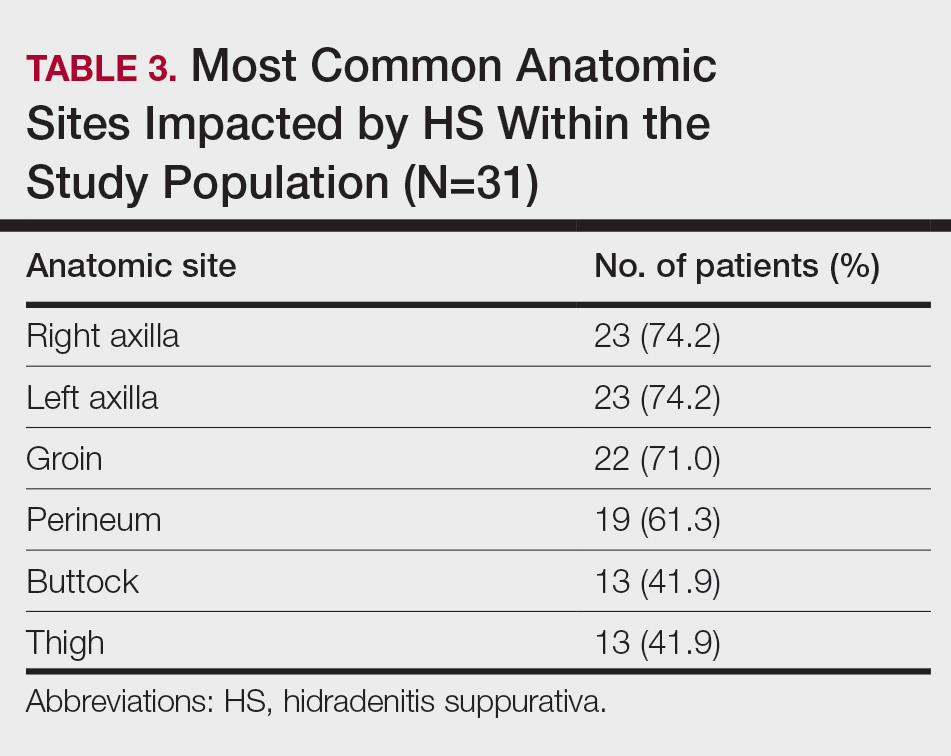

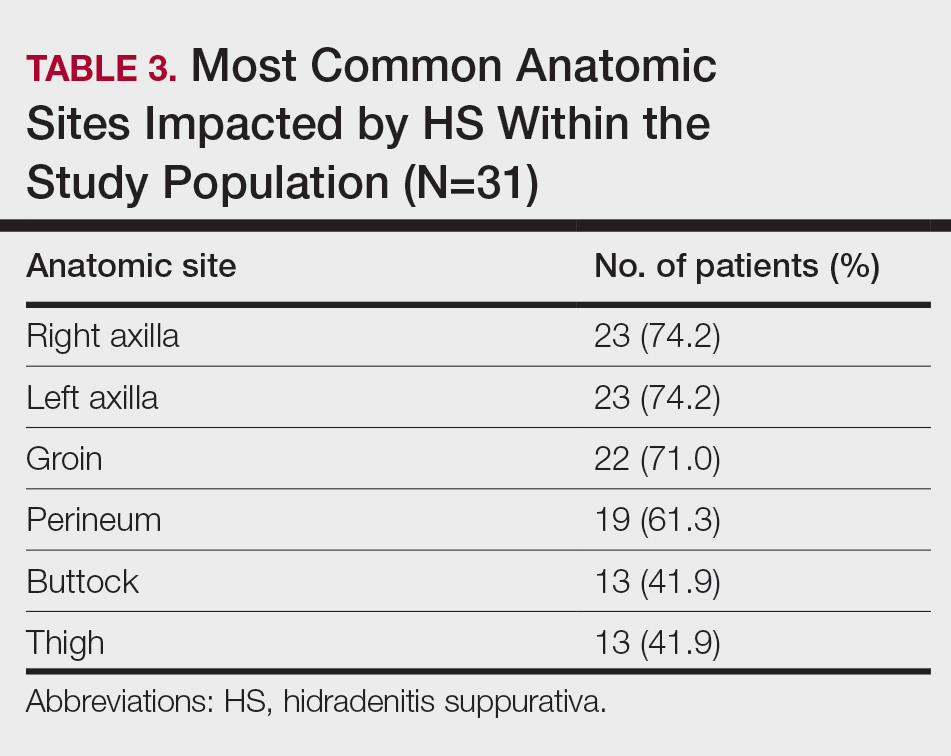

The most common anatomic locations for HS were the right axilla (74.2% [23/31]), left axilla (74.2% [23/31]), groin (71% [22/31]), perineum (61.3% [19/31]), buttocks (41.9% [13/31]), and thigh (41.9% [13/31]). Other locations included the breast, lower back, posterior neck, dorsal foot, and scalp (all 3.2% [1/31])(Table 3). Twenty (64.5%) patients had Hurley staging recorded in the EMR. Seventeen (54.8%) were categorized as Hurley stage 3, and 3 (9.7%) were categorized as Hurley stage 2.

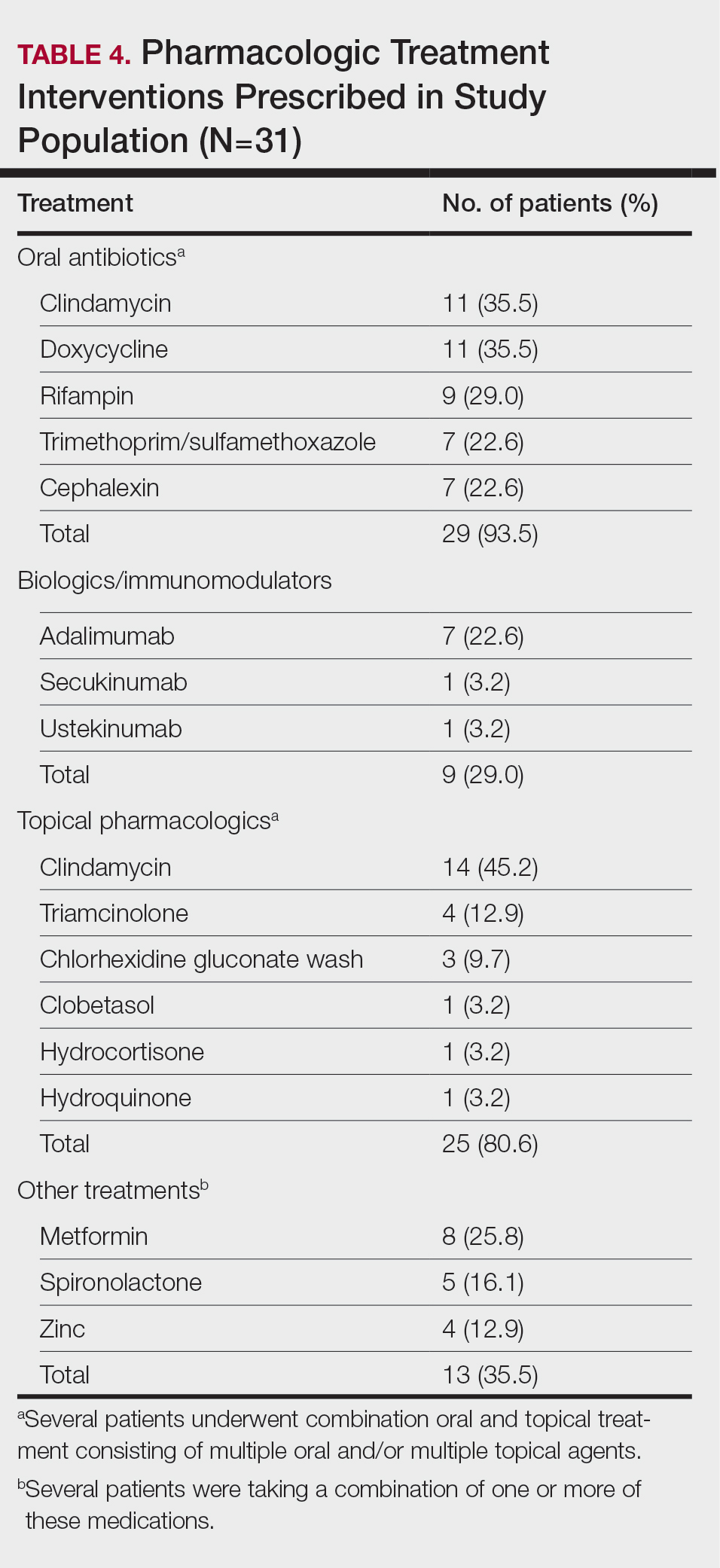

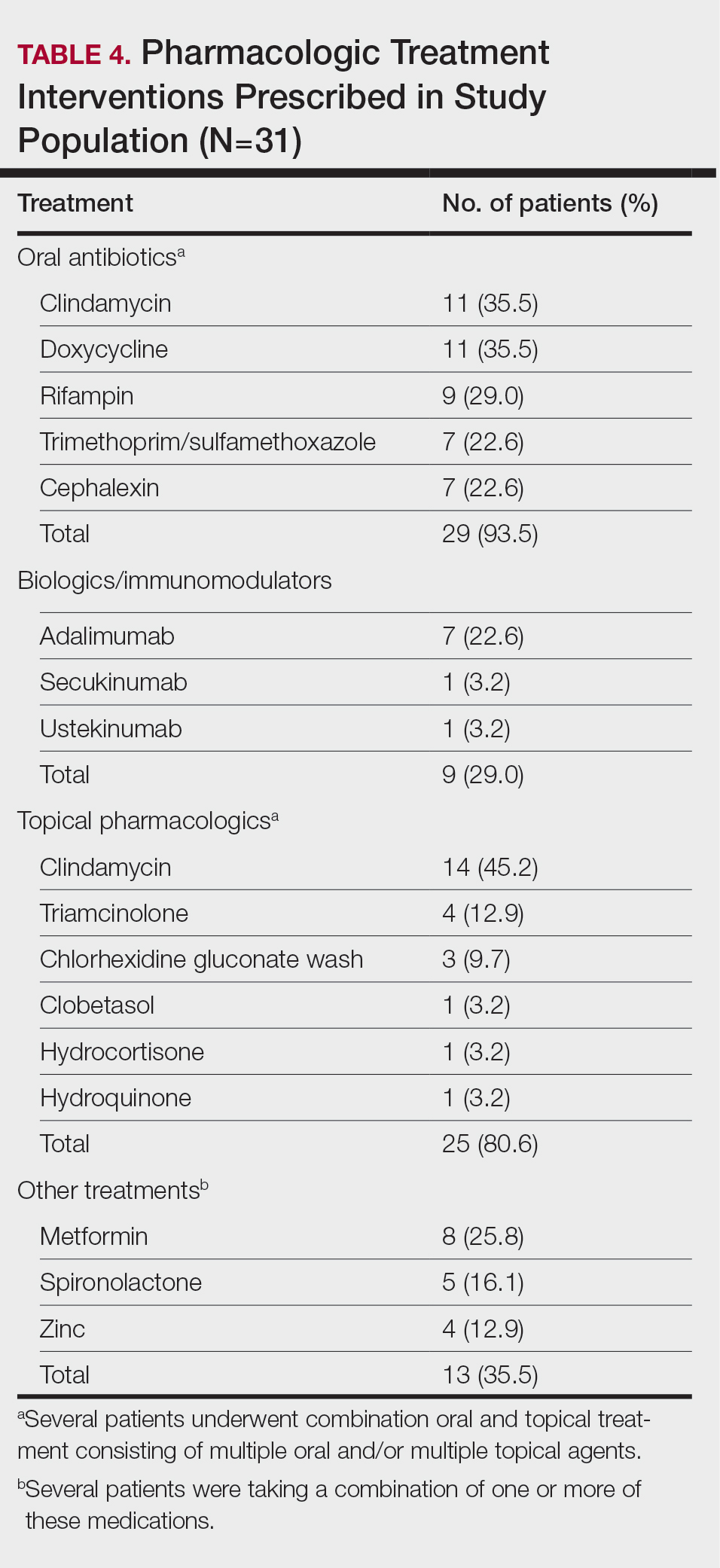

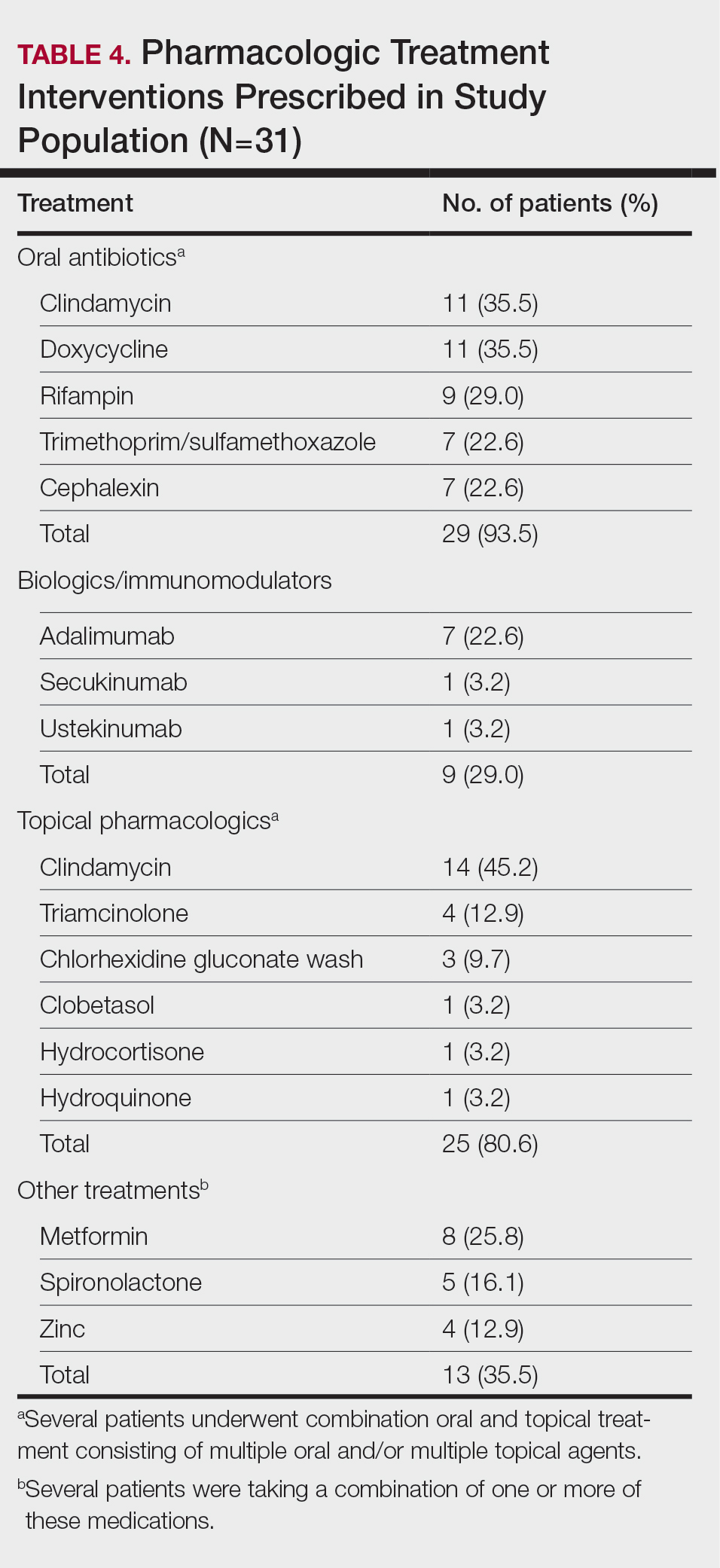

Twenty-nine (93.5%) patients were prescribed an oral antibiotic regimen. The most common oral antibiotics were clindamycin (35.5% [11/31]), doxycycline (35.5% [11/31]), rifampin (29% [9/31]), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (22.6% [7/31]), and cephalexin (22.6% [7/31]). Of the patients who were prescribed rifampin, 87.5% (8/9) also were prescribed an adjunct oral clindamycin regimen. Twenty-nine percent (9/31) of patients were prescribed a biologic regimen; 22.6% (7/31) were prescribed adalimumab, 3.2% (1/31) were prescribed secukinumab, and 3.2% (1/31) were prescribed ustekinumab (Table 4).

Twenty-five (80.6%) patients were prescribed a topical treatment regimen, the most common being topical clindamycin (45.2% [14/31]). Other topical medications included triamcinolone (12.9% [4/31]), chlorhexidine gluconate wash (9.7% [3/31]), clobetasol (3.2% [1/31]), hydrocortisone (3.2% [1/31]), and hydroquinone (3.2% [1/31])(Table 4).

Other medical treatments for HS included metformin (25.8% [8/31]), spironolactone (16.1% [5/31]), and zinc supplements (12.9% [4/31]). Four patients (12.9%) were prescribed clindamycin plus rifampin as well as a combination of metformin, spironolactone, and/or zinc (Table 4).

Twenty-two (71.0%) patients had a history of receiving incision and drainage procedures as treatment for HS. All 31 patients underwent excisional surgery followed by appropriate reconstruction. The total number of excisional surgeries a single patient underwent for HS treatment ranged from 1 to 9, with a mean of 2 excisional surgeries per patient.

Comment

Our regional verified burn center in Washington, DC, serves a large population of patients with SOC, making it a unique and important sample to study for HS. Our results suggest that Black patients with HS may be at a higher risk for depression and anxiety. Twelve (38.7%) of our patients were diagnosed with depression, which is substantially higher than the 17% to 21% depression prevalence rate among all HS patients reported in meta-analyses.10,11 Additionally, 22.6% (7/31) of our patients were diagnosed with anxiety, which is higher than the 5% to 12% prevalence rate of anxiety among HS patients reported in meta-analyses.10,11 The stress of chronic disease management, psychosocial impact of living with HS, social stigma, sexual dysfunction, pain, and financial concerns make mental illness a debilitating yet common comorbidity for patients with HS. The results of our study suggest that anxiety and depression are highly prevalent among Black patients with HS. It is important to identify if this finding is due to the interplay of health care disparities and social determinants of health; the cause likely is multifactorial, as race and ethnicity may be potential predictors for increased disease severity. Hidradenitis suppurativa is known to be a major economic burden on patients, and race-dependent structural and societal inequalities may be influencing the increased prevalence of anxiety and depression among Black patients with HS.12 Therefore, clinicians must be vigilant for the signs and symptoms of mental illnesses to refer patients for psychiatric treatment when appropriate. Implementing self-report Patient Health Questionnaire-9, General Anxiety Disorder-7 depression and anxiety screening tools, and Dermatology Life Quality Index questionnaires at primary care and dermatology office visits may be a beneficial step toward identifying patients who could benefit from additional mental health resources.13

The patients included in our study predominantly self-identified as Black, and the current smoker prevalence rate was 51.6% (16/31). This percentage is lower than the smoking rates of other published HS studies conducted in predominantly White patient populations, which report up to a 76.5% smoking prevalence rate.14-16 One review article published in 2022 reported that approximately 90% of HS patients are current or former smokers.17 Additionally, a retrospective cohort analysis identifying HS cases among 3,924,310 tobacco smokers in the United States reported that tobacco smokers diagnosed with HS most commonly racially self-identified as White (66.2%).18 Tobacco chemicals and smoke can increase inflammatory cytokine levels, and the activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors surrounding pilosebaceous-apocrine units can increase follicular occlusion.14 While several studies1-3,14,19,20 support the strong correlation between tobacco smoking and HS, there are very few that specifically investigate the association between smoking and HS disease in SOC populations. It is possible that smoking rates may be lower in Black patients with HS compared with White patients with HS, which would suggest a multifactorial nature of HS disease pathophysiology. Future large, multicenter studies are needed that investigate smoking rates and HS disease severity in patients across various racial groups.

Prior research has shown a strong correlation between cigarette smoking and HS, but there is minimal data on the role of use of marijuana and other illicit drugs in HS disease pathophysiology.21 A total of 54.8% of our patients were active marijuana users with daily or weekly usage. Further research is needed to investigate whether marijuana use is linked with HS disease pathophysiology and severity or if patients with HS may be using marijuana to relieve pain, anxiety, and depression. Additional studies that survey the method of marijuana use (eg, joint, vape devices, or edibles) would clarify the relationship between not only HS and marijuana but also a potential link between disease severity and the process of inhaling large amounts of smoke vs a link with the active ingredients in the marijuana plant itself.

Approximately 61% (19/31) of our patients were diagnosed with a gastrointestinal disease in addition to HS. Current research reports the link between HS and inflammatory bowel disease, but few studies have investigated if a relationship exists between the gut microbiome and HS, as well as the incidence of general gastrointestinal disease among Black patients with HS.14,22 Our patients were diagnosed with gastrointestinal conditions such as colonic polyps, gastroesophageal reflux disease, benign neoplasms of the cecum and sigmoid colons, small bowel obstruction and perforation, biliary tract diseases, ileus, abdominal hernia, peritonitis, and diverticulosis. Further research is warranted to identify if there is a true relationship between gastrointestinal disease, the gut microbiome, and skin conditions such as HS.22 Biochemical research on the common genetic and inflammatory cytokine pathways involved in HS and gastrointestinal manifestations could help predict disease severity and management in HS patients with SOC.

Several research studies have reported the association between obesity and HS, likely due to adipose cells producing increased estrogen and leading to an estrogen-dominant hormone profile and increased local androgen production in adipose tissue.14,23,24 Antiandrogenic drugs such as finasteride and spironolactone lead to positive results in HS treatment compared to oral antibiotics alone.24 While 71.9% (22/31) of our patients were diagnosed with obesity, only 16.1% (5/31) were prescribed antiandrogen therapy such as spironolactone. It is unclear if this result reflects a health disparity due to insufficient insurance coverage and low prescribing rates or if there is patient hesitancy to taking antiandrogen medications. Additional clinical trials are needed to investigate the efficacy of antiandrogen therapies for HS. If proven to be efficacious, providers should consider adding these medications to the pharmacologic regimen of HS patients with SOC prior to recommending wide-excision surgeries. Furthermore, in addition to antiandrogen medication, weight-management interventions may be helpful in reducing HS disease. The results of a survey conducted in 35 HS patients who underwent bariatric surgery reported 48.6% (17/35) experienced complete disease remission after more than a 15% weight reduction.25,26 Investigating the impact of weight-management practices on disease severity would be helpful in outlining nonpharmacologic treatments for patients with HS.

Limitations

Our study was limited by the constraints of a retrospective chart review and small sample size. Retrospective chart reviews are susceptible to recall bias, variability in providers’ charting practices, and human error from data collectors. We acknowledge that a control group of non-HS patients should be the next step in furthering our research on HS disease comorbidities. Also, since 35.5% (11/31) of our patients did not have Hurley staging recorded in the EMR, it would be beneficial to conduct a future study comprehensive of all 3 Hurley stages. Since 93.5% (29/31) of the patients in our study racially identified as Black, having a control group of racially diverse HS patients would help further our understanding of HS pathophysiology. Lastly, since the inclusion criteria required patients to have undergone excisional surgery for HS, future studies that consider comorbidities among both surgical and nonsurgical patients with HS will aid in our understanding of HS patients with SOC.

Conclusion

The results of our study demonstrate a descriptive analysis of the demographics, most common comorbidities, lesion sites, pharmacologic treatments, and surgical profiles in patients with SOC who underwent surgical treatment for HS. Our data show that HS patients with SOC may be more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and gastrointestinal disease than other HS patients. Additionally, our patients had a high prevalence of marijuana use but lower prevalence of current cigarette use compared to studies conducted in predominantly White HS patient populations, emphasizing the multifactorial nature of HS pathophysiology. Furthermore, despite published research on the efficacy of immunomodulator therapy for HS, most of our HS patients with SOC underwent surgical intervention without first attempting biologic treatment regimens, indicating possible gaps in health care access for minority patients that may be impacting disease severity and outcomes. Studies such as this one that investigate disease pathophysiology and risk factors in SOC patient populations with HS are imperative in minimizing the health care disparity gap, improving disease outcomes, and providing more equitable health care for all patients.

- Wieczorek M, Walecka I. Hidradenitis suppurativa—known and unknown disease. Reumatologia. 2018;56:337-339. doi:10.5114/reum.2018.80709

- Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:539-563. doi:10.1016/j. jaad.2008.11.911

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118-122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

- Ingram JR, Jenkins-Jones S, Knipe DW, et al. Population-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink study using algorithm modelling to identify the true burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:917-924. doi:10.1111/bjd.16101

- Lee DE, Clark AK, Shi VY. Hidradenitis suppurativa: disease burden and etiology in skin of color. Dermatology. 2017;233:456-461. doi:10.1159/000486741

- Brown-Korsah JB, McKenzie S, Omar D, et al. Variations in genetics, biology, and phenotype of cutaneous disorders in skin of color—part I: genetic, biologic, and structural differences in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1239-1258. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1193

- Narla S, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH. The most recent advances in understanding and managing hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res. 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-1049. doi:10.12688/f1000research.26083.1

- Arenbergerova M, Gkalpakiotis S, Arenberger P. Effective long-term control of refractory hidradenitis suppurativa with adalimumab after failure of conventional therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1445-1449. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04638.x

- Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:422-434. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504370

- Jalenques I, Ciortianu L, Pereira B, et al. The prevalence and odds of anxiety and depression in children and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:542-553. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.041

- Machado MO, Stergiopoulos V, Maes M, et al. Depression and anxiety in adults with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:939-945. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2019.0759

- Kilgour JM, Li S, Sarin KY. Hidradenitis suppurativa in patients of color is associated with increased disease severity and healthcare utilization: a retrospective analysis of 2 U.S. cohorts. JAAD Int. 2021;3:42-52. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.01.007

- Rymaszewska JE, Krajewski PK, Szcze² ch J, et al. Depression and anxiety in hidradenitis suppurativa patients: a cross-sectional study among Polish patients. Postep Dermatol Alergol. 2023;40:35-39. doi:10.5114ada.2022.119080

- Johnston LA, Alhusayen R, Bourcier M, et al. Practical guidelines for managing patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: an update. J Cutan Med Surg. 2022;26(2 suppl):2S-24S. doi:10.1177/12034754221116115

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population-based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97-103. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.255

- Seyed Jafari SM, Knüsel E, Cazzaniga S, et al. A retrospective cohort study on patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2018;234:71-78. doi:10.1159/000488344

- Lewandowski M, S´ wierczewska Z, Baran´ ska-Rybak W. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of current treatment options. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:1152-1164. doi:10.1111/ijd.16115

- Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa among tobacco smokers: a population-based retrospective analysis in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:709-714. doi:10.1111/bjd.15939

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Tzellos T, Zouboulis CC. Which hidradenitis suppurativa comorbidities should I take into account? Exp Dermatol. 2022;31(suppl 1):29-32. doi:10.1111/exd.14633

- Metko D, Mehta S, Piguet V. Cannabis usage among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a scoping review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2024;28:307-308. doi:10.1177/12034754241238719

- Mahmud MR, Akter S, Tamanna SK, et al. Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases. Gut Microbes. 2022;14:2096995. doi:10.1080/194 90976.2022.2096995

- Mair KM, Gaw R, MacLean MR. Obesity, estrogens and adipose tissue dysfunction—implications for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2020;10:2045894020952019. doi:10.1177/2045894020952023

- Abu Rached N, Gambichler T, Dietrich JW, et al. The role of hormones in hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:15250. doi:10.3390/ijms232315250

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2019.02.067

- Choi ECE, Phan PHC, Oon HH. Hidradenitis suppurativa: racial and socioeconomic considerations in management. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:1452-1457. doi:10.1111/ijd.16163

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a debilitating chronic skin disease that often affects apocrinebearing regions of the skin such as the axillae, perineum, and groin.1 Although current research on the etiology and pathogenesis of HS is limited, the disease is known to have a considerable psychosocial impact on patient quality of life.

Clinically, HS lesions manifest as tender subcutaneous nodules that rupture to form painful and deep dermal abscesses.2 These lesions typically develop due to hair follicle occlusion, followed by a cyclic process of inflammation, healing, re-inflammation, and scarring. Often, they are mistaken for cysts or a simple abscess in the early stages of the disease, leading to a delay in diagnosis.1 Disease severity is categorized based on Hurley staging: stage 1 involves abscess formation without scarring; stage 2 involves limited sinus tracts and recurrent abscesses with scarring and/or multiple separated lesions; and stage 3 is the most advanced stage, with diffuse involvement or multiple interconnected sinus tracts across an area with scarring. The condition primarily is medically managed with antibiotics and immunomodulators, but patients who have refractory disease can benefit from surgical excision.1,2

The prevalence of HS in the United States ranges from 0.77% to 1.19%, and individuals who self-identify as Black have 3-fold higher odds of having this condition compared with all other racial groups.3-5 Black patients also are thought to have a greater number and size of apocrine glands compared with patients who self-identify as White, suggesting an anatomic predisposition to developing HS and greater disease severity.6 However, despite HS disproportionately impacting individuals with skin of color (SOC), the majority of published HS research includes predominantly White patient cohorts.5 There is insufficient research assessing HS epidemiology, comorbidities, and treatment responses in patients with SOC.

A 2020 review reported the notable lack of clinical trials that sufficiently examine systemic medication treatment response in HS patients with SOC.7 Of the 15 HS treatment trials published from 2000 to 2019, only 16.4% (138/840) of the patient population were of African descent.7 Clinical trials investigating the efficacy of adalimumab in reducing HS burden also did not adequately evaluate clinical response in patients with SOC. One clinical trial did not include any Black patients as part of the cohort,8 and in 3 other studies, 80% to 85% of the study participants self-identified as White.9 The current literature does not reflect the patient populations most affected by HS, as several studies have reported that 65% of patients diagnosed with HS in the United States annually are Black.5,7 These results emphasize the underrepresentation of SOC populations in the current HS literature and the need for more research that investigates the disease processes, comorbidities, and treatment outcomes of the diverse patient population impacted by HS.

Methods

Study Population and Data Extraction—Following a protocol reviewed and approved by the MedStar Health/Georgetown University institutional review board (IRB #00006783), a retrospective chart review of 31 adult patients with HS who underwent surgery at a regional verified burn center from April 2014 to April 2023 was conducted. The following variables were collected from the electronic medical record (EMR): baseline demographics including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), obesity status, race, ethnicity, Fitzpatrick skin type, smoking status, substance use, employment status, and family history of HS; HS-specific details including Hurley staging, affected areas, and age at initial diagnosis; comorbidities such as dermatologic conditions, autoimmune disorders, infectious diseases, cardiovascular and associated diseases, ovarian disorders, gastrointestinal diseases, and othother common chronic comorbidities (psychiatric illness, kidney disease, type 2 diabetes [T2D], asthma, allergies, lymphedema, and inflammatory eye disease); and use of pharmacologics such as topical medications, oral antibiotics, immunomodulators, and steroids.

Study Definitions—Obesity was defined as both a continuous and categorical variable. Each patient’s BMI at the surgery date was recorded from the EMR as a continuous variable. Patients with obesity also had this condition listed under their complaints and problem list in the EMR, which was recorded as a categorical variable. Race and ethnicity were self-reported by patients. Comorbidity data, including T2D and hyperlipidemia, were defined by previously diagnosed diseases listed in the EMR. Pharmacologic medication data were included in the study if a patient was recommended/prescribed a medication and they had confirmed use of the medication in a subsequent office visit.

Statistical Analysis—Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographics, HS characteristics (eg, location, Hurley stage), and comorbidities. Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range and were evaluated using a t test or Mann-Whitney U test when appropriate. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and tested for associations using the X2 or Fisher exact test. Data analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Thirty-one patients (17 females, 14 males; mean age, 40.9 years) were included in the study. Twenty-nine (93.5%) patients identified as Black. All study patients had at least 1 comorbidity. Obesity was diagnosed in 22 (71.0%) patients (mean BMI, 35.5 kg/m2). A total of 16 (51.6%) patients were current smokers, 3 (9.7%) were past smokers, 22 (71%) reported alcohol use, and 17 (54.8%) were active marijuana users. Only 3 (9.7%) patients had a family history of HS (Table 1).

Other common comorbidities associated with HS were anemia (64.5% [20/31]), a non–inflammatory bowel disease gastrointestinal disease (61.3% [19/31]), allergies (54.8% [17/31]), hypertension (41.9% [13/31]), cardiovascular disease (41.9% [13/31]), T2D (32.3% [10/31]), asthma (32.3% [10/31]), kidney disease (29.0% [9/31]), and atopic dermatitis (25.8% [8/31]). More than half (54.8% [17/31]) of patients were diagnosed with psychiatric illnesses, including depression, anxiety, bipolar depression, psychosis, anorexia, impulsive anger, hallucinations, delusion, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, and panic disorder (Table 2). Depression was diagnosed in 38.7% (12/31) of patients, and 22.6% (7/31) were diagnosed with anxiety.

The most common anatomic locations for HS were the right axilla (74.2% [23/31]), left axilla (74.2% [23/31]), groin (71% [22/31]), perineum (61.3% [19/31]), buttocks (41.9% [13/31]), and thigh (41.9% [13/31]). Other locations included the breast, lower back, posterior neck, dorsal foot, and scalp (all 3.2% [1/31])(Table 3). Twenty (64.5%) patients had Hurley staging recorded in the EMR. Seventeen (54.8%) were categorized as Hurley stage 3, and 3 (9.7%) were categorized as Hurley stage 2.

Twenty-nine (93.5%) patients were prescribed an oral antibiotic regimen. The most common oral antibiotics were clindamycin (35.5% [11/31]), doxycycline (35.5% [11/31]), rifampin (29% [9/31]), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (22.6% [7/31]), and cephalexin (22.6% [7/31]). Of the patients who were prescribed rifampin, 87.5% (8/9) also were prescribed an adjunct oral clindamycin regimen. Twenty-nine percent (9/31) of patients were prescribed a biologic regimen; 22.6% (7/31) were prescribed adalimumab, 3.2% (1/31) were prescribed secukinumab, and 3.2% (1/31) were prescribed ustekinumab (Table 4).

Twenty-five (80.6%) patients were prescribed a topical treatment regimen, the most common being topical clindamycin (45.2% [14/31]). Other topical medications included triamcinolone (12.9% [4/31]), chlorhexidine gluconate wash (9.7% [3/31]), clobetasol (3.2% [1/31]), hydrocortisone (3.2% [1/31]), and hydroquinone (3.2% [1/31])(Table 4).

Other medical treatments for HS included metformin (25.8% [8/31]), spironolactone (16.1% [5/31]), and zinc supplements (12.9% [4/31]). Four patients (12.9%) were prescribed clindamycin plus rifampin as well as a combination of metformin, spironolactone, and/or zinc (Table 4).

Twenty-two (71.0%) patients had a history of receiving incision and drainage procedures as treatment for HS. All 31 patients underwent excisional surgery followed by appropriate reconstruction. The total number of excisional surgeries a single patient underwent for HS treatment ranged from 1 to 9, with a mean of 2 excisional surgeries per patient.

Comment

Our regional verified burn center in Washington, DC, serves a large population of patients with SOC, making it a unique and important sample to study for HS. Our results suggest that Black patients with HS may be at a higher risk for depression and anxiety. Twelve (38.7%) of our patients were diagnosed with depression, which is substantially higher than the 17% to 21% depression prevalence rate among all HS patients reported in meta-analyses.10,11 Additionally, 22.6% (7/31) of our patients were diagnosed with anxiety, which is higher than the 5% to 12% prevalence rate of anxiety among HS patients reported in meta-analyses.10,11 The stress of chronic disease management, psychosocial impact of living with HS, social stigma, sexual dysfunction, pain, and financial concerns make mental illness a debilitating yet common comorbidity for patients with HS. The results of our study suggest that anxiety and depression are highly prevalent among Black patients with HS. It is important to identify if this finding is due to the interplay of health care disparities and social determinants of health; the cause likely is multifactorial, as race and ethnicity may be potential predictors for increased disease severity. Hidradenitis suppurativa is known to be a major economic burden on patients, and race-dependent structural and societal inequalities may be influencing the increased prevalence of anxiety and depression among Black patients with HS.12 Therefore, clinicians must be vigilant for the signs and symptoms of mental illnesses to refer patients for psychiatric treatment when appropriate. Implementing self-report Patient Health Questionnaire-9, General Anxiety Disorder-7 depression and anxiety screening tools, and Dermatology Life Quality Index questionnaires at primary care and dermatology office visits may be a beneficial step toward identifying patients who could benefit from additional mental health resources.13

The patients included in our study predominantly self-identified as Black, and the current smoker prevalence rate was 51.6% (16/31). This percentage is lower than the smoking rates of other published HS studies conducted in predominantly White patient populations, which report up to a 76.5% smoking prevalence rate.14-16 One review article published in 2022 reported that approximately 90% of HS patients are current or former smokers.17 Additionally, a retrospective cohort analysis identifying HS cases among 3,924,310 tobacco smokers in the United States reported that tobacco smokers diagnosed with HS most commonly racially self-identified as White (66.2%).18 Tobacco chemicals and smoke can increase inflammatory cytokine levels, and the activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors surrounding pilosebaceous-apocrine units can increase follicular occlusion.14 While several studies1-3,14,19,20 support the strong correlation between tobacco smoking and HS, there are very few that specifically investigate the association between smoking and HS disease in SOC populations. It is possible that smoking rates may be lower in Black patients with HS compared with White patients with HS, which would suggest a multifactorial nature of HS disease pathophysiology. Future large, multicenter studies are needed that investigate smoking rates and HS disease severity in patients across various racial groups.

Prior research has shown a strong correlation between cigarette smoking and HS, but there is minimal data on the role of use of marijuana and other illicit drugs in HS disease pathophysiology.21 A total of 54.8% of our patients were active marijuana users with daily or weekly usage. Further research is needed to investigate whether marijuana use is linked with HS disease pathophysiology and severity or if patients with HS may be using marijuana to relieve pain, anxiety, and depression. Additional studies that survey the method of marijuana use (eg, joint, vape devices, or edibles) would clarify the relationship between not only HS and marijuana but also a potential link between disease severity and the process of inhaling large amounts of smoke vs a link with the active ingredients in the marijuana plant itself.

Approximately 61% (19/31) of our patients were diagnosed with a gastrointestinal disease in addition to HS. Current research reports the link between HS and inflammatory bowel disease, but few studies have investigated if a relationship exists between the gut microbiome and HS, as well as the incidence of general gastrointestinal disease among Black patients with HS.14,22 Our patients were diagnosed with gastrointestinal conditions such as colonic polyps, gastroesophageal reflux disease, benign neoplasms of the cecum and sigmoid colons, small bowel obstruction and perforation, biliary tract diseases, ileus, abdominal hernia, peritonitis, and diverticulosis. Further research is warranted to identify if there is a true relationship between gastrointestinal disease, the gut microbiome, and skin conditions such as HS.22 Biochemical research on the common genetic and inflammatory cytokine pathways involved in HS and gastrointestinal manifestations could help predict disease severity and management in HS patients with SOC.

Several research studies have reported the association between obesity and HS, likely due to adipose cells producing increased estrogen and leading to an estrogen-dominant hormone profile and increased local androgen production in adipose tissue.14,23,24 Antiandrogenic drugs such as finasteride and spironolactone lead to positive results in HS treatment compared to oral antibiotics alone.24 While 71.9% (22/31) of our patients were diagnosed with obesity, only 16.1% (5/31) were prescribed antiandrogen therapy such as spironolactone. It is unclear if this result reflects a health disparity due to insufficient insurance coverage and low prescribing rates or if there is patient hesitancy to taking antiandrogen medications. Additional clinical trials are needed to investigate the efficacy of antiandrogen therapies for HS. If proven to be efficacious, providers should consider adding these medications to the pharmacologic regimen of HS patients with SOC prior to recommending wide-excision surgeries. Furthermore, in addition to antiandrogen medication, weight-management interventions may be helpful in reducing HS disease. The results of a survey conducted in 35 HS patients who underwent bariatric surgery reported 48.6% (17/35) experienced complete disease remission after more than a 15% weight reduction.25,26 Investigating the impact of weight-management practices on disease severity would be helpful in outlining nonpharmacologic treatments for patients with HS.

Limitations

Our study was limited by the constraints of a retrospective chart review and small sample size. Retrospective chart reviews are susceptible to recall bias, variability in providers’ charting practices, and human error from data collectors. We acknowledge that a control group of non-HS patients should be the next step in furthering our research on HS disease comorbidities. Also, since 35.5% (11/31) of our patients did not have Hurley staging recorded in the EMR, it would be beneficial to conduct a future study comprehensive of all 3 Hurley stages. Since 93.5% (29/31) of the patients in our study racially identified as Black, having a control group of racially diverse HS patients would help further our understanding of HS pathophysiology. Lastly, since the inclusion criteria required patients to have undergone excisional surgery for HS, future studies that consider comorbidities among both surgical and nonsurgical patients with HS will aid in our understanding of HS patients with SOC.

Conclusion

The results of our study demonstrate a descriptive analysis of the demographics, most common comorbidities, lesion sites, pharmacologic treatments, and surgical profiles in patients with SOC who underwent surgical treatment for HS. Our data show that HS patients with SOC may be more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and gastrointestinal disease than other HS patients. Additionally, our patients had a high prevalence of marijuana use but lower prevalence of current cigarette use compared to studies conducted in predominantly White HS patient populations, emphasizing the multifactorial nature of HS pathophysiology. Furthermore, despite published research on the efficacy of immunomodulator therapy for HS, most of our HS patients with SOC underwent surgical intervention without first attempting biologic treatment regimens, indicating possible gaps in health care access for minority patients that may be impacting disease severity and outcomes. Studies such as this one that investigate disease pathophysiology and risk factors in SOC patient populations with HS are imperative in minimizing the health care disparity gap, improving disease outcomes, and providing more equitable health care for all patients.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a debilitating chronic skin disease that often affects apocrinebearing regions of the skin such as the axillae, perineum, and groin.1 Although current research on the etiology and pathogenesis of HS is limited, the disease is known to have a considerable psychosocial impact on patient quality of life.

Clinically, HS lesions manifest as tender subcutaneous nodules that rupture to form painful and deep dermal abscesses.2 These lesions typically develop due to hair follicle occlusion, followed by a cyclic process of inflammation, healing, re-inflammation, and scarring. Often, they are mistaken for cysts or a simple abscess in the early stages of the disease, leading to a delay in diagnosis.1 Disease severity is categorized based on Hurley staging: stage 1 involves abscess formation without scarring; stage 2 involves limited sinus tracts and recurrent abscesses with scarring and/or multiple separated lesions; and stage 3 is the most advanced stage, with diffuse involvement or multiple interconnected sinus tracts across an area with scarring. The condition primarily is medically managed with antibiotics and immunomodulators, but patients who have refractory disease can benefit from surgical excision.1,2

The prevalence of HS in the United States ranges from 0.77% to 1.19%, and individuals who self-identify as Black have 3-fold higher odds of having this condition compared with all other racial groups.3-5 Black patients also are thought to have a greater number and size of apocrine glands compared with patients who self-identify as White, suggesting an anatomic predisposition to developing HS and greater disease severity.6 However, despite HS disproportionately impacting individuals with skin of color (SOC), the majority of published HS research includes predominantly White patient cohorts.5 There is insufficient research assessing HS epidemiology, comorbidities, and treatment responses in patients with SOC.

A 2020 review reported the notable lack of clinical trials that sufficiently examine systemic medication treatment response in HS patients with SOC.7 Of the 15 HS treatment trials published from 2000 to 2019, only 16.4% (138/840) of the patient population were of African descent.7 Clinical trials investigating the efficacy of adalimumab in reducing HS burden also did not adequately evaluate clinical response in patients with SOC. One clinical trial did not include any Black patients as part of the cohort,8 and in 3 other studies, 80% to 85% of the study participants self-identified as White.9 The current literature does not reflect the patient populations most affected by HS, as several studies have reported that 65% of patients diagnosed with HS in the United States annually are Black.5,7 These results emphasize the underrepresentation of SOC populations in the current HS literature and the need for more research that investigates the disease processes, comorbidities, and treatment outcomes of the diverse patient population impacted by HS.

Methods

Study Population and Data Extraction—Following a protocol reviewed and approved by the MedStar Health/Georgetown University institutional review board (IRB #00006783), a retrospective chart review of 31 adult patients with HS who underwent surgery at a regional verified burn center from April 2014 to April 2023 was conducted. The following variables were collected from the electronic medical record (EMR): baseline demographics including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), obesity status, race, ethnicity, Fitzpatrick skin type, smoking status, substance use, employment status, and family history of HS; HS-specific details including Hurley staging, affected areas, and age at initial diagnosis; comorbidities such as dermatologic conditions, autoimmune disorders, infectious diseases, cardiovascular and associated diseases, ovarian disorders, gastrointestinal diseases, and othother common chronic comorbidities (psychiatric illness, kidney disease, type 2 diabetes [T2D], asthma, allergies, lymphedema, and inflammatory eye disease); and use of pharmacologics such as topical medications, oral antibiotics, immunomodulators, and steroids.

Study Definitions—Obesity was defined as both a continuous and categorical variable. Each patient’s BMI at the surgery date was recorded from the EMR as a continuous variable. Patients with obesity also had this condition listed under their complaints and problem list in the EMR, which was recorded as a categorical variable. Race and ethnicity were self-reported by patients. Comorbidity data, including T2D and hyperlipidemia, were defined by previously diagnosed diseases listed in the EMR. Pharmacologic medication data were included in the study if a patient was recommended/prescribed a medication and they had confirmed use of the medication in a subsequent office visit.

Statistical Analysis—Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographics, HS characteristics (eg, location, Hurley stage), and comorbidities. Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range and were evaluated using a t test or Mann-Whitney U test when appropriate. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and tested for associations using the X2 or Fisher exact test. Data analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Thirty-one patients (17 females, 14 males; mean age, 40.9 years) were included in the study. Twenty-nine (93.5%) patients identified as Black. All study patients had at least 1 comorbidity. Obesity was diagnosed in 22 (71.0%) patients (mean BMI, 35.5 kg/m2). A total of 16 (51.6%) patients were current smokers, 3 (9.7%) were past smokers, 22 (71%) reported alcohol use, and 17 (54.8%) were active marijuana users. Only 3 (9.7%) patients had a family history of HS (Table 1).

Other common comorbidities associated with HS were anemia (64.5% [20/31]), a non–inflammatory bowel disease gastrointestinal disease (61.3% [19/31]), allergies (54.8% [17/31]), hypertension (41.9% [13/31]), cardiovascular disease (41.9% [13/31]), T2D (32.3% [10/31]), asthma (32.3% [10/31]), kidney disease (29.0% [9/31]), and atopic dermatitis (25.8% [8/31]). More than half (54.8% [17/31]) of patients were diagnosed with psychiatric illnesses, including depression, anxiety, bipolar depression, psychosis, anorexia, impulsive anger, hallucinations, delusion, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, and panic disorder (Table 2). Depression was diagnosed in 38.7% (12/31) of patients, and 22.6% (7/31) were diagnosed with anxiety.

The most common anatomic locations for HS were the right axilla (74.2% [23/31]), left axilla (74.2% [23/31]), groin (71% [22/31]), perineum (61.3% [19/31]), buttocks (41.9% [13/31]), and thigh (41.9% [13/31]). Other locations included the breast, lower back, posterior neck, dorsal foot, and scalp (all 3.2% [1/31])(Table 3). Twenty (64.5%) patients had Hurley staging recorded in the EMR. Seventeen (54.8%) were categorized as Hurley stage 3, and 3 (9.7%) were categorized as Hurley stage 2.

Twenty-nine (93.5%) patients were prescribed an oral antibiotic regimen. The most common oral antibiotics were clindamycin (35.5% [11/31]), doxycycline (35.5% [11/31]), rifampin (29% [9/31]), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (22.6% [7/31]), and cephalexin (22.6% [7/31]). Of the patients who were prescribed rifampin, 87.5% (8/9) also were prescribed an adjunct oral clindamycin regimen. Twenty-nine percent (9/31) of patients were prescribed a biologic regimen; 22.6% (7/31) were prescribed adalimumab, 3.2% (1/31) were prescribed secukinumab, and 3.2% (1/31) were prescribed ustekinumab (Table 4).

Twenty-five (80.6%) patients were prescribed a topical treatment regimen, the most common being topical clindamycin (45.2% [14/31]). Other topical medications included triamcinolone (12.9% [4/31]), chlorhexidine gluconate wash (9.7% [3/31]), clobetasol (3.2% [1/31]), hydrocortisone (3.2% [1/31]), and hydroquinone (3.2% [1/31])(Table 4).

Other medical treatments for HS included metformin (25.8% [8/31]), spironolactone (16.1% [5/31]), and zinc supplements (12.9% [4/31]). Four patients (12.9%) were prescribed clindamycin plus rifampin as well as a combination of metformin, spironolactone, and/or zinc (Table 4).

Twenty-two (71.0%) patients had a history of receiving incision and drainage procedures as treatment for HS. All 31 patients underwent excisional surgery followed by appropriate reconstruction. The total number of excisional surgeries a single patient underwent for HS treatment ranged from 1 to 9, with a mean of 2 excisional surgeries per patient.

Comment

Our regional verified burn center in Washington, DC, serves a large population of patients with SOC, making it a unique and important sample to study for HS. Our results suggest that Black patients with HS may be at a higher risk for depression and anxiety. Twelve (38.7%) of our patients were diagnosed with depression, which is substantially higher than the 17% to 21% depression prevalence rate among all HS patients reported in meta-analyses.10,11 Additionally, 22.6% (7/31) of our patients were diagnosed with anxiety, which is higher than the 5% to 12% prevalence rate of anxiety among HS patients reported in meta-analyses.10,11 The stress of chronic disease management, psychosocial impact of living with HS, social stigma, sexual dysfunction, pain, and financial concerns make mental illness a debilitating yet common comorbidity for patients with HS. The results of our study suggest that anxiety and depression are highly prevalent among Black patients with HS. It is important to identify if this finding is due to the interplay of health care disparities and social determinants of health; the cause likely is multifactorial, as race and ethnicity may be potential predictors for increased disease severity. Hidradenitis suppurativa is known to be a major economic burden on patients, and race-dependent structural and societal inequalities may be influencing the increased prevalence of anxiety and depression among Black patients with HS.12 Therefore, clinicians must be vigilant for the signs and symptoms of mental illnesses to refer patients for psychiatric treatment when appropriate. Implementing self-report Patient Health Questionnaire-9, General Anxiety Disorder-7 depression and anxiety screening tools, and Dermatology Life Quality Index questionnaires at primary care and dermatology office visits may be a beneficial step toward identifying patients who could benefit from additional mental health resources.13

The patients included in our study predominantly self-identified as Black, and the current smoker prevalence rate was 51.6% (16/31). This percentage is lower than the smoking rates of other published HS studies conducted in predominantly White patient populations, which report up to a 76.5% smoking prevalence rate.14-16 One review article published in 2022 reported that approximately 90% of HS patients are current or former smokers.17 Additionally, a retrospective cohort analysis identifying HS cases among 3,924,310 tobacco smokers in the United States reported that tobacco smokers diagnosed with HS most commonly racially self-identified as White (66.2%).18 Tobacco chemicals and smoke can increase inflammatory cytokine levels, and the activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors surrounding pilosebaceous-apocrine units can increase follicular occlusion.14 While several studies1-3,14,19,20 support the strong correlation between tobacco smoking and HS, there are very few that specifically investigate the association between smoking and HS disease in SOC populations. It is possible that smoking rates may be lower in Black patients with HS compared with White patients with HS, which would suggest a multifactorial nature of HS disease pathophysiology. Future large, multicenter studies are needed that investigate smoking rates and HS disease severity in patients across various racial groups.

Prior research has shown a strong correlation between cigarette smoking and HS, but there is minimal data on the role of use of marijuana and other illicit drugs in HS disease pathophysiology.21 A total of 54.8% of our patients were active marijuana users with daily or weekly usage. Further research is needed to investigate whether marijuana use is linked with HS disease pathophysiology and severity or if patients with HS may be using marijuana to relieve pain, anxiety, and depression. Additional studies that survey the method of marijuana use (eg, joint, vape devices, or edibles) would clarify the relationship between not only HS and marijuana but also a potential link between disease severity and the process of inhaling large amounts of smoke vs a link with the active ingredients in the marijuana plant itself.

Approximately 61% (19/31) of our patients were diagnosed with a gastrointestinal disease in addition to HS. Current research reports the link between HS and inflammatory bowel disease, but few studies have investigated if a relationship exists between the gut microbiome and HS, as well as the incidence of general gastrointestinal disease among Black patients with HS.14,22 Our patients were diagnosed with gastrointestinal conditions such as colonic polyps, gastroesophageal reflux disease, benign neoplasms of the cecum and sigmoid colons, small bowel obstruction and perforation, biliary tract diseases, ileus, abdominal hernia, peritonitis, and diverticulosis. Further research is warranted to identify if there is a true relationship between gastrointestinal disease, the gut microbiome, and skin conditions such as HS.22 Biochemical research on the common genetic and inflammatory cytokine pathways involved in HS and gastrointestinal manifestations could help predict disease severity and management in HS patients with SOC.

Several research studies have reported the association between obesity and HS, likely due to adipose cells producing increased estrogen and leading to an estrogen-dominant hormone profile and increased local androgen production in adipose tissue.14,23,24 Antiandrogenic drugs such as finasteride and spironolactone lead to positive results in HS treatment compared to oral antibiotics alone.24 While 71.9% (22/31) of our patients were diagnosed with obesity, only 16.1% (5/31) were prescribed antiandrogen therapy such as spironolactone. It is unclear if this result reflects a health disparity due to insufficient insurance coverage and low prescribing rates or if there is patient hesitancy to taking antiandrogen medications. Additional clinical trials are needed to investigate the efficacy of antiandrogen therapies for HS. If proven to be efficacious, providers should consider adding these medications to the pharmacologic regimen of HS patients with SOC prior to recommending wide-excision surgeries. Furthermore, in addition to antiandrogen medication, weight-management interventions may be helpful in reducing HS disease. The results of a survey conducted in 35 HS patients who underwent bariatric surgery reported 48.6% (17/35) experienced complete disease remission after more than a 15% weight reduction.25,26 Investigating the impact of weight-management practices on disease severity would be helpful in outlining nonpharmacologic treatments for patients with HS.

Limitations

Our study was limited by the constraints of a retrospective chart review and small sample size. Retrospective chart reviews are susceptible to recall bias, variability in providers’ charting practices, and human error from data collectors. We acknowledge that a control group of non-HS patients should be the next step in furthering our research on HS disease comorbidities. Also, since 35.5% (11/31) of our patients did not have Hurley staging recorded in the EMR, it would be beneficial to conduct a future study comprehensive of all 3 Hurley stages. Since 93.5% (29/31) of the patients in our study racially identified as Black, having a control group of racially diverse HS patients would help further our understanding of HS pathophysiology. Lastly, since the inclusion criteria required patients to have undergone excisional surgery for HS, future studies that consider comorbidities among both surgical and nonsurgical patients with HS will aid in our understanding of HS patients with SOC.

Conclusion

The results of our study demonstrate a descriptive analysis of the demographics, most common comorbidities, lesion sites, pharmacologic treatments, and surgical profiles in patients with SOC who underwent surgical treatment for HS. Our data show that HS patients with SOC may be more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and gastrointestinal disease than other HS patients. Additionally, our patients had a high prevalence of marijuana use but lower prevalence of current cigarette use compared to studies conducted in predominantly White HS patient populations, emphasizing the multifactorial nature of HS pathophysiology. Furthermore, despite published research on the efficacy of immunomodulator therapy for HS, most of our HS patients with SOC underwent surgical intervention without first attempting biologic treatment regimens, indicating possible gaps in health care access for minority patients that may be impacting disease severity and outcomes. Studies such as this one that investigate disease pathophysiology and risk factors in SOC patient populations with HS are imperative in minimizing the health care disparity gap, improving disease outcomes, and providing more equitable health care for all patients.

- Wieczorek M, Walecka I. Hidradenitis suppurativa—known and unknown disease. Reumatologia. 2018;56:337-339. doi:10.5114/reum.2018.80709

- Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:539-563. doi:10.1016/j. jaad.2008.11.911

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118-122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

- Ingram JR, Jenkins-Jones S, Knipe DW, et al. Population-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink study using algorithm modelling to identify the true burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:917-924. doi:10.1111/bjd.16101

- Lee DE, Clark AK, Shi VY. Hidradenitis suppurativa: disease burden and etiology in skin of color. Dermatology. 2017;233:456-461. doi:10.1159/000486741

- Brown-Korsah JB, McKenzie S, Omar D, et al. Variations in genetics, biology, and phenotype of cutaneous disorders in skin of color—part I: genetic, biologic, and structural differences in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1239-1258. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1193

- Narla S, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH. The most recent advances in understanding and managing hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res. 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-1049. doi:10.12688/f1000research.26083.1

- Arenbergerova M, Gkalpakiotis S, Arenberger P. Effective long-term control of refractory hidradenitis suppurativa with adalimumab after failure of conventional therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1445-1449. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04638.x

- Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:422-434. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504370

- Jalenques I, Ciortianu L, Pereira B, et al. The prevalence and odds of anxiety and depression in children and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:542-553. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.041

- Machado MO, Stergiopoulos V, Maes M, et al. Depression and anxiety in adults with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:939-945. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2019.0759

- Kilgour JM, Li S, Sarin KY. Hidradenitis suppurativa in patients of color is associated with increased disease severity and healthcare utilization: a retrospective analysis of 2 U.S. cohorts. JAAD Int. 2021;3:42-52. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.01.007

- Rymaszewska JE, Krajewski PK, Szcze² ch J, et al. Depression and anxiety in hidradenitis suppurativa patients: a cross-sectional study among Polish patients. Postep Dermatol Alergol. 2023;40:35-39. doi:10.5114ada.2022.119080

- Johnston LA, Alhusayen R, Bourcier M, et al. Practical guidelines for managing patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: an update. J Cutan Med Surg. 2022;26(2 suppl):2S-24S. doi:10.1177/12034754221116115

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population-based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97-103. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.255

- Seyed Jafari SM, Knüsel E, Cazzaniga S, et al. A retrospective cohort study on patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2018;234:71-78. doi:10.1159/000488344

- Lewandowski M, S´ wierczewska Z, Baran´ ska-Rybak W. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of current treatment options. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:1152-1164. doi:10.1111/ijd.16115

- Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa among tobacco smokers: a population-based retrospective analysis in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:709-714. doi:10.1111/bjd.15939

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Tzellos T, Zouboulis CC. Which hidradenitis suppurativa comorbidities should I take into account? Exp Dermatol. 2022;31(suppl 1):29-32. doi:10.1111/exd.14633

- Metko D, Mehta S, Piguet V. Cannabis usage among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a scoping review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2024;28:307-308. doi:10.1177/12034754241238719

- Mahmud MR, Akter S, Tamanna SK, et al. Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases. Gut Microbes. 2022;14:2096995. doi:10.1080/194 90976.2022.2096995

- Mair KM, Gaw R, MacLean MR. Obesity, estrogens and adipose tissue dysfunction—implications for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2020;10:2045894020952019. doi:10.1177/2045894020952023

- Abu Rached N, Gambichler T, Dietrich JW, et al. The role of hormones in hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:15250. doi:10.3390/ijms232315250

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2019.02.067

- Choi ECE, Phan PHC, Oon HH. Hidradenitis suppurativa: racial and socioeconomic considerations in management. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:1452-1457. doi:10.1111/ijd.16163

- Wieczorek M, Walecka I. Hidradenitis suppurativa—known and unknown disease. Reumatologia. 2018;56:337-339. doi:10.5114/reum.2018.80709

- Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:539-563. doi:10.1016/j. jaad.2008.11.911

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118-122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

- Ingram JR, Jenkins-Jones S, Knipe DW, et al. Population-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink study using algorithm modelling to identify the true burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:917-924. doi:10.1111/bjd.16101

- Lee DE, Clark AK, Shi VY. Hidradenitis suppurativa: disease burden and etiology in skin of color. Dermatology. 2017;233:456-461. doi:10.1159/000486741

- Brown-Korsah JB, McKenzie S, Omar D, et al. Variations in genetics, biology, and phenotype of cutaneous disorders in skin of color—part I: genetic, biologic, and structural differences in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1239-1258. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1193

- Narla S, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH. The most recent advances in understanding and managing hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res. 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-1049. doi:10.12688/f1000research.26083.1

- Arenbergerova M, Gkalpakiotis S, Arenberger P. Effective long-term control of refractory hidradenitis suppurativa with adalimumab after failure of conventional therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1445-1449. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04638.x

- Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:422-434. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504370

- Jalenques I, Ciortianu L, Pereira B, et al. The prevalence and odds of anxiety and depression in children and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:542-553. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.041

- Machado MO, Stergiopoulos V, Maes M, et al. Depression and anxiety in adults with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:939-945. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2019.0759

- Kilgour JM, Li S, Sarin KY. Hidradenitis suppurativa in patients of color is associated with increased disease severity and healthcare utilization: a retrospective analysis of 2 U.S. cohorts. JAAD Int. 2021;3:42-52. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2021.01.007

- Rymaszewska JE, Krajewski PK, Szcze² ch J, et al. Depression and anxiety in hidradenitis suppurativa patients: a cross-sectional study among Polish patients. Postep Dermatol Alergol. 2023;40:35-39. doi:10.5114ada.2022.119080

- Johnston LA, Alhusayen R, Bourcier M, et al. Practical guidelines for managing patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: an update. J Cutan Med Surg. 2022;26(2 suppl):2S-24S. doi:10.1177/12034754221116115

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population-based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97-103. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.255

- Seyed Jafari SM, Knüsel E, Cazzaniga S, et al. A retrospective cohort study on patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2018;234:71-78. doi:10.1159/000488344

- Lewandowski M, S´ wierczewska Z, Baran´ ska-Rybak W. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a review of current treatment options. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:1152-1164. doi:10.1111/ijd.16115

- Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa among tobacco smokers: a population-based retrospective analysis in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:709-714. doi:10.1111/bjd.15939

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Tzellos T, Zouboulis CC. Which hidradenitis suppurativa comorbidities should I take into account? Exp Dermatol. 2022;31(suppl 1):29-32. doi:10.1111/exd.14633

- Metko D, Mehta S, Piguet V. Cannabis usage among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a scoping review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2024;28:307-308. doi:10.1177/12034754241238719

- Mahmud MR, Akter S, Tamanna SK, et al. Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases. Gut Microbes. 2022;14:2096995. doi:10.1080/194 90976.2022.2096995

- Mair KM, Gaw R, MacLean MR. Obesity, estrogens and adipose tissue dysfunction—implications for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2020;10:2045894020952019. doi:10.1177/2045894020952023

- Abu Rached N, Gambichler T, Dietrich JW, et al. The role of hormones in hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:15250. doi:10.3390/ijms232315250

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2019.02.067

- Choi ECE, Phan PHC, Oon HH. Hidradenitis suppurativa: racial and socioeconomic considerations in management. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:1452-1457. doi:10.1111/ijd.16163

Evaluating Factors Impacting Hidradenitis Suppurativa Disease Severity in Patients With Darker Skin Types

Evaluating Factors Impacting Hidradenitis Suppurativa Disease Severity in Patients With Darker Skin Types

PRACTICE POINTS

- Anxiety and depression are highly prevalent among Black patients with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Implementing self-report questionnaires at medical office visits are crucial to identifying patients who could benefit from additional psychiatric resources.

- Hidradenitis suppurativa patients with skin of color may have a higher incidence of comorbid gastrointestinal disease than other HS patients.

- Investigating the impact of weight-management practices on disease severity would be helpful in outlining nonpharmacologic treatments for patients with HS.

- The patient cohort described here had a high prevalence of marijuana use but lower prevalence of current cigarette use compared to studies conducted in predominantly White HS patient populations, emphasizing the multifactorial nature of HS pathophysiology.

Navigating Hair Loss in Medical School: Experiences of 2 Young Black Women

As medical students, we often assume we are exempt from the diagnoses we learn about. During the first 2 years of medical school, we learn about alopecia as a condition that may be associated with stress, hormonal imbalances, nutrient deficiencies, and aging. However, our curricula do not explore the subtypes, psychosocial impact, or even the overwhelming number of Black women who are disproportionately affected by alopecia. For Black women, hair is a colossal part of their cultural identity, learning from a young age how to nurture and style natural coils. It becomes devastating when women begin to lose them.

The diagnosis of alopecia subtypes in Black women has been explored in the literature; however, understanding the unique experiences of young Black women is an important part of patient care, as alopecia often is destructive to the patient’s self-image. Therefore, it is important to shed light on these experiences so others feel empowered and supported in their journeys. Herein, we share the experiences of 2 authors (J.D. and C.A.V.O.)—both young Black women—who navigated unexpected hair loss in medical school.

Jewell’s Story

During my first year of medical school, I noticed my hair was shedding more than usual, and my ponytail was not as thick as it once was. I also had an area in my crown that was abnormally thin. My parents suggested that it was a consequence of stress, but I knew something was not right. With only 1 Black dermatologist within 2 hours of Nashville, Tennessee, I remember worrying about seeing a dermatologist who did not understand Black hair. I still scheduled an appointment, but I remember debating if I should straighten my hair or wear my naturally curly Afro. The first dermatologist I saw diagnosed me with seborrheic dermatitis—without even examining my scalp. She told me that I had a “full head of hair” and that I had nothing to worry about. I was unconvinced. Weeks later, I met with another dermatologist who took the time to listen to my concerns. After a scalp biopsy and laboratory work, she diagnosed me with telogen effluvium and androgenetic alopecia. Months later, I had the opportunity to visit the Black dermatologist, and she diagnosed me with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. I am grateful for the earlier dermatologists I saw, but I finally feel at ease with my diagnosis and treatment plan after being seen by the latter.

Chidubem’s Story

From a young age, I was conditioned to think my hair was thick, unmanageable, and a nuisance. I grew accustomed to people yanking on my hair, and my gentle whispers of “this hurts” and “the braid is too tight” being ignored. That continued into adulthood. While studying for the US Medical Licensing Examination, I noticed a burning sensation on my scalp. I decided to ignore it. However, as the days progressed, the slight burning sensation turned into intense burning and itching. I still ignored it. Not only did I lack the funds for a dermatology appointment, but my licensing examination was approaching, and it was more important than anything related to my hair. After the examination, I eventually made an appointment with my primary care physician, who attributed my symptoms to the stressors of medical school. “I think you are having migraines,” she told me. So, I continued to ignore my symptoms. A year passed, and a hair braider pointed out that I had 2 well-defined bald patches on my scalp. I remember feeling angry and confused as to how I missed those findings. I could no longer ignore it—it bothered me less when no one else knew about it. I quickly made a dermatology appointment. Although I opted out of a biopsy, we decided to treat my hair loss empirically, and I have experienced drastic improvement.

Final Thoughts

We are 2 Black women living more than 500 miles away from each other at different medical institutions, yet we share the same experience, which many other women unfortunately face alone. It is not uncommon for us to feel unheard, dismissed, or misdiagnosed. We write this for the Black woman sorting through the feelings of confusion and shock as she traces the hairless spot on her scalp. We write this for the medical student ignoring their symptoms until after their examination. We even write this for any nondermatologists uncomfortable with diagnosing and treating textured hair. To improve patient satisfaction and overall health outcomes, physicians must approach patients with both knowledge and cultural competency. Most importantly, dermatologists (and other physicians) should be appropriately trained in not only the structural differences of textured hair but also the unique practices and beliefs among Black women in relation to their hair.

Acknowledgments—Jewell Dinkins is the inaugural recipient of the Janssen–Skin of Color Research Fellowship at Howard University (Washington, DC), and Chidubem A.V. Okeke is the inaugural recipient of the Women’s Dermatologic Society–La Roche-Posay dermatology fellowship at Howard University.

As medical students, we often assume we are exempt from the diagnoses we learn about. During the first 2 years of medical school, we learn about alopecia as a condition that may be associated with stress, hormonal imbalances, nutrient deficiencies, and aging. However, our curricula do not explore the subtypes, psychosocial impact, or even the overwhelming number of Black women who are disproportionately affected by alopecia. For Black women, hair is a colossal part of their cultural identity, learning from a young age how to nurture and style natural coils. It becomes devastating when women begin to lose them.

The diagnosis of alopecia subtypes in Black women has been explored in the literature; however, understanding the unique experiences of young Black women is an important part of patient care, as alopecia often is destructive to the patient’s self-image. Therefore, it is important to shed light on these experiences so others feel empowered and supported in their journeys. Herein, we share the experiences of 2 authors (J.D. and C.A.V.O.)—both young Black women—who navigated unexpected hair loss in medical school.

Jewell’s Story

During my first year of medical school, I noticed my hair was shedding more than usual, and my ponytail was not as thick as it once was. I also had an area in my crown that was abnormally thin. My parents suggested that it was a consequence of stress, but I knew something was not right. With only 1 Black dermatologist within 2 hours of Nashville, Tennessee, I remember worrying about seeing a dermatologist who did not understand Black hair. I still scheduled an appointment, but I remember debating if I should straighten my hair or wear my naturally curly Afro. The first dermatologist I saw diagnosed me with seborrheic dermatitis—without even examining my scalp. She told me that I had a “full head of hair” and that I had nothing to worry about. I was unconvinced. Weeks later, I met with another dermatologist who took the time to listen to my concerns. After a scalp biopsy and laboratory work, she diagnosed me with telogen effluvium and androgenetic alopecia. Months later, I had the opportunity to visit the Black dermatologist, and she diagnosed me with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. I am grateful for the earlier dermatologists I saw, but I finally feel at ease with my diagnosis and treatment plan after being seen by the latter.

Chidubem’s Story