User login

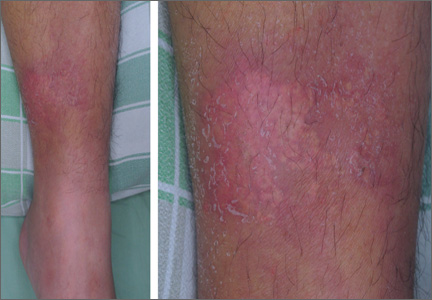

Erythematous plaque with yellowish papules on the shin

A 53-YEAR-OLD MAN with a 10-year history of poorly controlled hypertension was brought to our emergency department (ED) because he’d had a sudden loss of consciousness. The ED physicians discovered a spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage in his brainstem with fourth ventricle compression and immediately transferred him to the intensive care unit (ICU).

During the patient’s hospitalization, he was treated for ventilator-associated pneumonia and a gastric ulcer with cefepime 1 g IV 3 times daily and esomeprazole 40 mg/d IV via the long saphenous vein of his lower left leg. The patient subsequently developed acute renal failure with hyperkalemia and was treated with furosemide, glucose, and insulin. He also received parenteral calcium gluconate, also via the long saphenous vein in his left leg.

One week later, while still in the ICU, the patient developed an erythematous plaque with several firm yellowish papules on his lower left leg (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Iatrogenic calcinosis cutis

Calcinosis cutis is characterized by calcification of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It is categorized into 5 major types based on the etiology: dystrophic, metastatic, idiopathic, calciphylaxis, and iatrogenic.1 Calcification results from local tissue injury inducing alterations in collagen, subcutaneous fat, and elastic fibers. Typically, the ectopic calcification mass consists of amorphous calcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite. Serum levels of calcium and phosphate in these patients are typically in the normal range.2

Iatrogenic calcification typically occurs in patients who have received IV calcium chloride or calcium gluconate therapy.2 When extravasation of calcium gluconate occurs, the venipuncture site can rapidly become tender, warm, and swollen, with erythema and whitish papuloplaques; in severe cases, signs of soft tissue necrosis or infection may also be seen.3 The lesions appear about 13 days after the infusion of calcium gluconate.4 Radiographs are initially negative, but can show changes one to 3 weeks after the skin lesions appear.4

Not always obvious. Iatrogenic calcinosis cutis is easy to diagnose when a massive extravasation of calcium infusion is followed by tender, swollen whitish papuloplaques with surrounding erythema and skin necrosis.3 The diagnosis can be more challenging when the extravasation is not obvious. In such cases, a thorough history and careful exam will help distinguish it from 3 other conditions in the differential diagnosis.

Distinguishing calcinosis cutis from these conditions

The differential diagnosis includes cellulitis, eruptive xanthoma, and gouty tophus.

Patients with cellulitis will complain of areas of increased warmth, tenderness, redness, and swelling. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, and tachycardia may also be present. Laboratory results will reveal leukocytosis and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels.Radiographs are initially negative, but can show changes one to 3 weeks after the initial appearance of the skin lesions.

Eruptive xanthoma affects patients with hypertriglyceridemia with a sudden onset of monomorphous erythematous to yellowish papules over the buttocks, shoulders, and extensor surfaces of the extremities. High serum triglyceride levels confirm this diagnosis.

In gouty tophus, hyperuricemia is a key risk factor. Patients initially present with extreme pain and swelling in a single joint—especially the first metacarpophalangeal. When left untreated, the pain and swelling may extend to the soft tissue of other articular joints and the auricular helix. Hard yellowish to whitish papulonodules with an erythematous halo may also appear. A histopathologic examination will reveal granulomatous inflammation surrounding yellow-brown urate crystals; in contrast, you will see deposits of blue calcium phosphate with calcinosis cutis.2

A conservative approach to treatmentThere is no consensus on the management of calcinosis cutis, although it is typically managed conservatively.5 Progressive clearing of the calcification often occurs spontaneously 2 to 3 months after onset, with no evidence of tissue calcification after 5 or 6 months.6 When calcinosis cutis is complicated by serious extravasation injuries, such as secondary infection or skin necrosis, debridement, drainage, or skin grafting may be needed.

Our patient’s road to recoveryOur patient was transferred to the respiratory care unit after he was stabilized. His lesions improved gradually, without any treatment. One month after being hospitalized, he was discharged to an assisted living facility.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chien-Ping Chiang, MD, Department of Dermatology, Tri-Service General Hospital, No. 325, Sec. 2, Chenggong Road, Neihu District, Taipei City 114, Taiwan (ROC); [email protected]

1. Walsh JS, Fairley JA. Calcifying disorders of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:693-706.

2. Walsh JS, Fairley JA. Cutaneous mineralization and ossification. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. Columbus, Ohio: McGraw-Hill;2007:1293-1296.

3. Goldminz D, Barnhill R, McGuire J, et al. Calcinosis cutis following extravasation of calcium chloride. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:922-925.

4. Sonohata M, Akiyama T, Fujita I, et al. Neonate with calcinosis cutis following extravasation of calcium gluconate. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13:269-272.

5. Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, et al. Calcinosis cutis: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:15-22.

6. Ramamurthy RS, Harris V, Pildes RS. Subcutaneous calcium deposition in the neonate associated with intravenous administration of calcium gluconate. Pediatrics. 1975;55:802-806.

A 53-YEAR-OLD MAN with a 10-year history of poorly controlled hypertension was brought to our emergency department (ED) because he’d had a sudden loss of consciousness. The ED physicians discovered a spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage in his brainstem with fourth ventricle compression and immediately transferred him to the intensive care unit (ICU).

During the patient’s hospitalization, he was treated for ventilator-associated pneumonia and a gastric ulcer with cefepime 1 g IV 3 times daily and esomeprazole 40 mg/d IV via the long saphenous vein of his lower left leg. The patient subsequently developed acute renal failure with hyperkalemia and was treated with furosemide, glucose, and insulin. He also received parenteral calcium gluconate, also via the long saphenous vein in his left leg.

One week later, while still in the ICU, the patient developed an erythematous plaque with several firm yellowish papules on his lower left leg (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Iatrogenic calcinosis cutis

Calcinosis cutis is characterized by calcification of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It is categorized into 5 major types based on the etiology: dystrophic, metastatic, idiopathic, calciphylaxis, and iatrogenic.1 Calcification results from local tissue injury inducing alterations in collagen, subcutaneous fat, and elastic fibers. Typically, the ectopic calcification mass consists of amorphous calcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite. Serum levels of calcium and phosphate in these patients are typically in the normal range.2

Iatrogenic calcification typically occurs in patients who have received IV calcium chloride or calcium gluconate therapy.2 When extravasation of calcium gluconate occurs, the venipuncture site can rapidly become tender, warm, and swollen, with erythema and whitish papuloplaques; in severe cases, signs of soft tissue necrosis or infection may also be seen.3 The lesions appear about 13 days after the infusion of calcium gluconate.4 Radiographs are initially negative, but can show changes one to 3 weeks after the skin lesions appear.4

Not always obvious. Iatrogenic calcinosis cutis is easy to diagnose when a massive extravasation of calcium infusion is followed by tender, swollen whitish papuloplaques with surrounding erythema and skin necrosis.3 The diagnosis can be more challenging when the extravasation is not obvious. In such cases, a thorough history and careful exam will help distinguish it from 3 other conditions in the differential diagnosis.

Distinguishing calcinosis cutis from these conditions

The differential diagnosis includes cellulitis, eruptive xanthoma, and gouty tophus.

Patients with cellulitis will complain of areas of increased warmth, tenderness, redness, and swelling. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, and tachycardia may also be present. Laboratory results will reveal leukocytosis and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels.Radiographs are initially negative, but can show changes one to 3 weeks after the initial appearance of the skin lesions.

Eruptive xanthoma affects patients with hypertriglyceridemia with a sudden onset of monomorphous erythematous to yellowish papules over the buttocks, shoulders, and extensor surfaces of the extremities. High serum triglyceride levels confirm this diagnosis.

In gouty tophus, hyperuricemia is a key risk factor. Patients initially present with extreme pain and swelling in a single joint—especially the first metacarpophalangeal. When left untreated, the pain and swelling may extend to the soft tissue of other articular joints and the auricular helix. Hard yellowish to whitish papulonodules with an erythematous halo may also appear. A histopathologic examination will reveal granulomatous inflammation surrounding yellow-brown urate crystals; in contrast, you will see deposits of blue calcium phosphate with calcinosis cutis.2

A conservative approach to treatmentThere is no consensus on the management of calcinosis cutis, although it is typically managed conservatively.5 Progressive clearing of the calcification often occurs spontaneously 2 to 3 months after onset, with no evidence of tissue calcification after 5 or 6 months.6 When calcinosis cutis is complicated by serious extravasation injuries, such as secondary infection or skin necrosis, debridement, drainage, or skin grafting may be needed.

Our patient’s road to recoveryOur patient was transferred to the respiratory care unit after he was stabilized. His lesions improved gradually, without any treatment. One month after being hospitalized, he was discharged to an assisted living facility.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chien-Ping Chiang, MD, Department of Dermatology, Tri-Service General Hospital, No. 325, Sec. 2, Chenggong Road, Neihu District, Taipei City 114, Taiwan (ROC); [email protected]

A 53-YEAR-OLD MAN with a 10-year history of poorly controlled hypertension was brought to our emergency department (ED) because he’d had a sudden loss of consciousness. The ED physicians discovered a spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage in his brainstem with fourth ventricle compression and immediately transferred him to the intensive care unit (ICU).

During the patient’s hospitalization, he was treated for ventilator-associated pneumonia and a gastric ulcer with cefepime 1 g IV 3 times daily and esomeprazole 40 mg/d IV via the long saphenous vein of his lower left leg. The patient subsequently developed acute renal failure with hyperkalemia and was treated with furosemide, glucose, and insulin. He also received parenteral calcium gluconate, also via the long saphenous vein in his left leg.

One week later, while still in the ICU, the patient developed an erythematous plaque with several firm yellowish papules on his lower left leg (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Iatrogenic calcinosis cutis

Calcinosis cutis is characterized by calcification of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It is categorized into 5 major types based on the etiology: dystrophic, metastatic, idiopathic, calciphylaxis, and iatrogenic.1 Calcification results from local tissue injury inducing alterations in collagen, subcutaneous fat, and elastic fibers. Typically, the ectopic calcification mass consists of amorphous calcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite. Serum levels of calcium and phosphate in these patients are typically in the normal range.2

Iatrogenic calcification typically occurs in patients who have received IV calcium chloride or calcium gluconate therapy.2 When extravasation of calcium gluconate occurs, the venipuncture site can rapidly become tender, warm, and swollen, with erythema and whitish papuloplaques; in severe cases, signs of soft tissue necrosis or infection may also be seen.3 The lesions appear about 13 days after the infusion of calcium gluconate.4 Radiographs are initially negative, but can show changes one to 3 weeks after the skin lesions appear.4

Not always obvious. Iatrogenic calcinosis cutis is easy to diagnose when a massive extravasation of calcium infusion is followed by tender, swollen whitish papuloplaques with surrounding erythema and skin necrosis.3 The diagnosis can be more challenging when the extravasation is not obvious. In such cases, a thorough history and careful exam will help distinguish it from 3 other conditions in the differential diagnosis.

Distinguishing calcinosis cutis from these conditions

The differential diagnosis includes cellulitis, eruptive xanthoma, and gouty tophus.

Patients with cellulitis will complain of areas of increased warmth, tenderness, redness, and swelling. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, and tachycardia may also be present. Laboratory results will reveal leukocytosis and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels.Radiographs are initially negative, but can show changes one to 3 weeks after the initial appearance of the skin lesions.

Eruptive xanthoma affects patients with hypertriglyceridemia with a sudden onset of monomorphous erythematous to yellowish papules over the buttocks, shoulders, and extensor surfaces of the extremities. High serum triglyceride levels confirm this diagnosis.

In gouty tophus, hyperuricemia is a key risk factor. Patients initially present with extreme pain and swelling in a single joint—especially the first metacarpophalangeal. When left untreated, the pain and swelling may extend to the soft tissue of other articular joints and the auricular helix. Hard yellowish to whitish papulonodules with an erythematous halo may also appear. A histopathologic examination will reveal granulomatous inflammation surrounding yellow-brown urate crystals; in contrast, you will see deposits of blue calcium phosphate with calcinosis cutis.2

A conservative approach to treatmentThere is no consensus on the management of calcinosis cutis, although it is typically managed conservatively.5 Progressive clearing of the calcification often occurs spontaneously 2 to 3 months after onset, with no evidence of tissue calcification after 5 or 6 months.6 When calcinosis cutis is complicated by serious extravasation injuries, such as secondary infection or skin necrosis, debridement, drainage, or skin grafting may be needed.

Our patient’s road to recoveryOur patient was transferred to the respiratory care unit after he was stabilized. His lesions improved gradually, without any treatment. One month after being hospitalized, he was discharged to an assisted living facility.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chien-Ping Chiang, MD, Department of Dermatology, Tri-Service General Hospital, No. 325, Sec. 2, Chenggong Road, Neihu District, Taipei City 114, Taiwan (ROC); [email protected]

1. Walsh JS, Fairley JA. Calcifying disorders of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:693-706.

2. Walsh JS, Fairley JA. Cutaneous mineralization and ossification. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. Columbus, Ohio: McGraw-Hill;2007:1293-1296.

3. Goldminz D, Barnhill R, McGuire J, et al. Calcinosis cutis following extravasation of calcium chloride. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:922-925.

4. Sonohata M, Akiyama T, Fujita I, et al. Neonate with calcinosis cutis following extravasation of calcium gluconate. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13:269-272.

5. Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, et al. Calcinosis cutis: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:15-22.

6. Ramamurthy RS, Harris V, Pildes RS. Subcutaneous calcium deposition in the neonate associated with intravenous administration of calcium gluconate. Pediatrics. 1975;55:802-806.

1. Walsh JS, Fairley JA. Calcifying disorders of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:693-706.

2. Walsh JS, Fairley JA. Cutaneous mineralization and ossification. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. Columbus, Ohio: McGraw-Hill;2007:1293-1296.

3. Goldminz D, Barnhill R, McGuire J, et al. Calcinosis cutis following extravasation of calcium chloride. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:922-925.

4. Sonohata M, Akiyama T, Fujita I, et al. Neonate with calcinosis cutis following extravasation of calcium gluconate. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13:269-272.

5. Reiter N, El-Shabrawi L, Leinweber B, et al. Calcinosis cutis: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:15-22.

6. Ramamurthy RS, Harris V, Pildes RS. Subcutaneous calcium deposition in the neonate associated with intravenous administration of calcium gluconate. Pediatrics. 1975;55:802-806.

Acral papular rash in a 2-year-old boy

A 2-YEAR-OLD BOY was referred to our outpatient department in the spring with a mild pruritic rash that had appeared on his face, arms, and legs over the previous 2 weeks. His family said that the boy had developed an enteroviral infection the month before. Furthermore, he had a 6-month history of acute myeloid leukemia.

On examination, the child was afebrile, with numerous monomorphous flesh-colored to erythematous papules on his face and on the extensor sites of his limbs ( FIGURE ). However, his trunk, palms, and soles were spared.

FIGURE

Flesh-colored to erythematous papules with a monomorphous appearance

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Gianotti-Crosti syndrome

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS) is a pediatric disease whose incidence and prevalence are unknown. Children who have GCS may be given a diagnosis of “nonspecific viral exanthem” or “viral rash” and, as a result, the condition may be underdiagnosed.1

GCS—also known as papular acrodermatitis of childhood—affects children between the ages of 6 months and 12 years.2 The pathogenesis of GCS is unclear, but is believed to involve a cutaneous reaction pattern related to viral and bacterial infections or to vaccination.3 It is associated with the hepatitis B virus, Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, parainfluenza viruses, and other viral infections. The eruption has also occurred following vaccination (hepatitis A, others).4

GCS is usually diagnosed clinically. Physical examination typically shows discrete, monomorphous, flesh-colored or erythematous flat-topped papulovesicles distributed symmetrically on the cheeks and on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and the buttocks. The trunk, palms, and soles are usually spared. This distribution pattern is responsible for the name “papular acrodermatitis of childhood.” The lesions are usually asymptomatic, but may be accompanied by a low-grade fever, diarrhea, or malaise.5

Avoid confusing GCS with these 4 conditions

The differential diagnosis for GCS includes miliaria rubra, papular urticaria, lichen nitidus, and molluscum contagiosum.

Miliaria rubra (“prickly heat”) is caused when keratinous plugs occlude the sweat glands. Retrograde pressure may cause rupture of the sweat duct and leakage of sweat into the surrounding tissue, thereby inducing inflammation. Most cases of miliaria rubra occur in hot and humid conditions. However, infants may develop such eruptions in winter if they are dressed too warmly indoors.4

Miliaria rubra manifests as superficial, erythematous, minute papulovesicles with nonfollicular distribution. The lesions, which cause a prickly sensation, are typically localized in flexural regions such as the neck, groin, and axilla, and may be confused with candidiasis or folliculitis.

Cooling by regulation of environmental temperatures and removing excessive clothing can dramatically reduce miliaria rubra. Antipyretics can relieve the symptoms in febrile patients. Topical agents are not recommended because they may exacerbate the skin eruptions.4

Papular urticaria predominantly affects children and is caused by allergic hypersensitivity to insect bites.6 The skin lesions are intensely pruritic and are initially characterized by multiple small erythematous wheals and later progress to pruritic brownish papules.3 Some lesions may have a central punctum. The patient’s age and a history of symmetrically distributed lesions, hypersensitivity, and exposure to animals or insects can help diagnose papular urticaria.6 Lesions are typically observed on exposed areas, can persist for days or weeks, and usually occur in the summer.7

Management of papular urticaria includes the 3 Ps:

- Protection. Children should wear protective clothing for outdoor play and use insect repellent.

- Pruritus control. Topical high-potency steroids and antihistamines may help with individual lesions, but may be ineffective when the inflammatory process extends to the dermis and the fat.

- Patience. Although there is a chance that papular urticaria will be persistent and recurrent, it typically improves with time.6

Lichen nitidus is rare and when it does occur, it typically develops in children.8 Some lesions subside spontaneously, but others may persist for as long as several years.8

Lichen nitidus is clinically manifested as asymptomatic, discrete, flesh-colored, shiny, pinpoint-to-pinhead-sized papules; these papules are sharply demarcated and have fine scales. The most commonly affected sites are the genitalia, chest, abdomen, and upper extremities.8-10 The isomorphic condition called Koebner phenomenon is observed in most cases.3

Lichen nitidus is diagnosed on the basis of clinical presentation. Biopsy is indicated only when atypical morphology and distribution are observed. Histologically, the pathognomonic features of lichen nitidus include focal granulomas containing lymphohistiocytic cells in the papillary dermis.

Lichen nitidus usually regresses spontaneously and most patients do not require intervention; treatment is required only when the patient complains of pruritus or cosmetically undesirable effects.5 Topical glucocorticoid treatment may provide good results in such cases.8

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by poxvirus infection and generally affects young children. It is asymptomatic and presents with small pearly white or pink round/oval papules that may have umbilication. The papules are often 2 to 5 mm in diameter, but can be as large as 3 cm (a giant molluscum). Most papules appear in intertriginous sites such as the groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa.

Transmission occurs by direct mucous membrane or skin contact, leading to autoinoculation.11 Patients should not share towels or bath water and must avoid swimming in public pools to reduce the risk of spreading the infection.12

The individual lesions usually persist for 6 to 9 months but may last for years. Most lesions resolve spontaneously and heal without scarring. Active treatment is used for cosmetic and epidemiologic reasons and includes curettage, cryotherapy, cantharidin, and topical imiquimod.11 There is no consensus about the dosage and duration in current therapy modalities, but some experts suggest liquid cantharidin (0.7%-0.9%).3

Management of GCS? Let it run its course

Most patients with GCS do not need treatment because it is a self-limited benign disease. Although the course is variable and the skin lesions may persist for up to 60 days, the lesions will heal without scarring.2

Postinflammation hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation is rarely seen. In patients who have severe pruritus, topical antipruritic lotions or oral histamines can provide relief.5 Medium-potency topical steroids may have some benefits, but patients should be closely monitored because there have been reports of exacerbations of lesions with steroid use.2

A good outcome. In the case of our patient, the lesions resolved one week after applying 0.1% mometasone furoate cream once a day.

CORRESPONDENCE Chien-Ping Chiang, MD, Department of Dermatology, Tri-Service General Hospital, No. 325, Sec. 2, Chenggong Road, Neihu District, Taipei City 114, Taiwan R.O.C.; [email protected]

1. Jindal T, Arora VK. Gianotti-crosti syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37:683-684.

2. Brandt O, Abeck D, Gianotti R, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:136-145.

3. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2008.

4. Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, et al. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Pa: WB Saunders Co; 2007.

5. Wu CY, Huang WH. Question: can you identify this condition? Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:712-716.

6. Hernandez RG, Cohen BA. Insect bite-induced hypersensitivity and the SCRATCH principles: a new approach to papular urticaria. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e189-e196.

7. Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Urticarial lesions: if not urticaria, what else? The differential diagnosis of urticaria: part I. Cutaneous diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:541-555.

8. Tilly JJ, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Lichenoid eruptions in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:606-624.

9. Arizaga AT, Gaughan MD, Bang RH. Generalized lichen nitidus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:115-117.

10. Kim YC, Shim SD. Two cases of generalized lichen nitidus treated successfully with narrow-band UV-B phototherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:615-617.

11. Jones S, Kress D. Treatment of molluscum contagiosum and herpes simplex virus cutaneous infections. Cutis. 2007;79(4 suppl):11-17.

12. Silverberg NB. Warts and molluscum in children. Adv Dermatol. 2004;20:23-73.

A 2-YEAR-OLD BOY was referred to our outpatient department in the spring with a mild pruritic rash that had appeared on his face, arms, and legs over the previous 2 weeks. His family said that the boy had developed an enteroviral infection the month before. Furthermore, he had a 6-month history of acute myeloid leukemia.

On examination, the child was afebrile, with numerous monomorphous flesh-colored to erythematous papules on his face and on the extensor sites of his limbs ( FIGURE ). However, his trunk, palms, and soles were spared.

FIGURE

Flesh-colored to erythematous papules with a monomorphous appearance

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Gianotti-Crosti syndrome

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS) is a pediatric disease whose incidence and prevalence are unknown. Children who have GCS may be given a diagnosis of “nonspecific viral exanthem” or “viral rash” and, as a result, the condition may be underdiagnosed.1

GCS—also known as papular acrodermatitis of childhood—affects children between the ages of 6 months and 12 years.2 The pathogenesis of GCS is unclear, but is believed to involve a cutaneous reaction pattern related to viral and bacterial infections or to vaccination.3 It is associated with the hepatitis B virus, Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, parainfluenza viruses, and other viral infections. The eruption has also occurred following vaccination (hepatitis A, others).4

GCS is usually diagnosed clinically. Physical examination typically shows discrete, monomorphous, flesh-colored or erythematous flat-topped papulovesicles distributed symmetrically on the cheeks and on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and the buttocks. The trunk, palms, and soles are usually spared. This distribution pattern is responsible for the name “papular acrodermatitis of childhood.” The lesions are usually asymptomatic, but may be accompanied by a low-grade fever, diarrhea, or malaise.5

Avoid confusing GCS with these 4 conditions

The differential diagnosis for GCS includes miliaria rubra, papular urticaria, lichen nitidus, and molluscum contagiosum.

Miliaria rubra (“prickly heat”) is caused when keratinous plugs occlude the sweat glands. Retrograde pressure may cause rupture of the sweat duct and leakage of sweat into the surrounding tissue, thereby inducing inflammation. Most cases of miliaria rubra occur in hot and humid conditions. However, infants may develop such eruptions in winter if they are dressed too warmly indoors.4

Miliaria rubra manifests as superficial, erythematous, minute papulovesicles with nonfollicular distribution. The lesions, which cause a prickly sensation, are typically localized in flexural regions such as the neck, groin, and axilla, and may be confused with candidiasis or folliculitis.

Cooling by regulation of environmental temperatures and removing excessive clothing can dramatically reduce miliaria rubra. Antipyretics can relieve the symptoms in febrile patients. Topical agents are not recommended because they may exacerbate the skin eruptions.4

Papular urticaria predominantly affects children and is caused by allergic hypersensitivity to insect bites.6 The skin lesions are intensely pruritic and are initially characterized by multiple small erythematous wheals and later progress to pruritic brownish papules.3 Some lesions may have a central punctum. The patient’s age and a history of symmetrically distributed lesions, hypersensitivity, and exposure to animals or insects can help diagnose papular urticaria.6 Lesions are typically observed on exposed areas, can persist for days or weeks, and usually occur in the summer.7

Management of papular urticaria includes the 3 Ps:

- Protection. Children should wear protective clothing for outdoor play and use insect repellent.

- Pruritus control. Topical high-potency steroids and antihistamines may help with individual lesions, but may be ineffective when the inflammatory process extends to the dermis and the fat.

- Patience. Although there is a chance that papular urticaria will be persistent and recurrent, it typically improves with time.6

Lichen nitidus is rare and when it does occur, it typically develops in children.8 Some lesions subside spontaneously, but others may persist for as long as several years.8

Lichen nitidus is clinically manifested as asymptomatic, discrete, flesh-colored, shiny, pinpoint-to-pinhead-sized papules; these papules are sharply demarcated and have fine scales. The most commonly affected sites are the genitalia, chest, abdomen, and upper extremities.8-10 The isomorphic condition called Koebner phenomenon is observed in most cases.3

Lichen nitidus is diagnosed on the basis of clinical presentation. Biopsy is indicated only when atypical morphology and distribution are observed. Histologically, the pathognomonic features of lichen nitidus include focal granulomas containing lymphohistiocytic cells in the papillary dermis.

Lichen nitidus usually regresses spontaneously and most patients do not require intervention; treatment is required only when the patient complains of pruritus or cosmetically undesirable effects.5 Topical glucocorticoid treatment may provide good results in such cases.8

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by poxvirus infection and generally affects young children. It is asymptomatic and presents with small pearly white or pink round/oval papules that may have umbilication. The papules are often 2 to 5 mm in diameter, but can be as large as 3 cm (a giant molluscum). Most papules appear in intertriginous sites such as the groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa.

Transmission occurs by direct mucous membrane or skin contact, leading to autoinoculation.11 Patients should not share towels or bath water and must avoid swimming in public pools to reduce the risk of spreading the infection.12

The individual lesions usually persist for 6 to 9 months but may last for years. Most lesions resolve spontaneously and heal without scarring. Active treatment is used for cosmetic and epidemiologic reasons and includes curettage, cryotherapy, cantharidin, and topical imiquimod.11 There is no consensus about the dosage and duration in current therapy modalities, but some experts suggest liquid cantharidin (0.7%-0.9%).3

Management of GCS? Let it run its course

Most patients with GCS do not need treatment because it is a self-limited benign disease. Although the course is variable and the skin lesions may persist for up to 60 days, the lesions will heal without scarring.2

Postinflammation hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation is rarely seen. In patients who have severe pruritus, topical antipruritic lotions or oral histamines can provide relief.5 Medium-potency topical steroids may have some benefits, but patients should be closely monitored because there have been reports of exacerbations of lesions with steroid use.2

A good outcome. In the case of our patient, the lesions resolved one week after applying 0.1% mometasone furoate cream once a day.

CORRESPONDENCE Chien-Ping Chiang, MD, Department of Dermatology, Tri-Service General Hospital, No. 325, Sec. 2, Chenggong Road, Neihu District, Taipei City 114, Taiwan R.O.C.; [email protected]

A 2-YEAR-OLD BOY was referred to our outpatient department in the spring with a mild pruritic rash that had appeared on his face, arms, and legs over the previous 2 weeks. His family said that the boy had developed an enteroviral infection the month before. Furthermore, he had a 6-month history of acute myeloid leukemia.

On examination, the child was afebrile, with numerous monomorphous flesh-colored to erythematous papules on his face and on the extensor sites of his limbs ( FIGURE ). However, his trunk, palms, and soles were spared.

FIGURE

Flesh-colored to erythematous papules with a monomorphous appearance

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Gianotti-Crosti syndrome

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS) is a pediatric disease whose incidence and prevalence are unknown. Children who have GCS may be given a diagnosis of “nonspecific viral exanthem” or “viral rash” and, as a result, the condition may be underdiagnosed.1

GCS—also known as papular acrodermatitis of childhood—affects children between the ages of 6 months and 12 years.2 The pathogenesis of GCS is unclear, but is believed to involve a cutaneous reaction pattern related to viral and bacterial infections or to vaccination.3 It is associated with the hepatitis B virus, Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, parainfluenza viruses, and other viral infections. The eruption has also occurred following vaccination (hepatitis A, others).4

GCS is usually diagnosed clinically. Physical examination typically shows discrete, monomorphous, flesh-colored or erythematous flat-topped papulovesicles distributed symmetrically on the cheeks and on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and the buttocks. The trunk, palms, and soles are usually spared. This distribution pattern is responsible for the name “papular acrodermatitis of childhood.” The lesions are usually asymptomatic, but may be accompanied by a low-grade fever, diarrhea, or malaise.5

Avoid confusing GCS with these 4 conditions

The differential diagnosis for GCS includes miliaria rubra, papular urticaria, lichen nitidus, and molluscum contagiosum.

Miliaria rubra (“prickly heat”) is caused when keratinous plugs occlude the sweat glands. Retrograde pressure may cause rupture of the sweat duct and leakage of sweat into the surrounding tissue, thereby inducing inflammation. Most cases of miliaria rubra occur in hot and humid conditions. However, infants may develop such eruptions in winter if they are dressed too warmly indoors.4

Miliaria rubra manifests as superficial, erythematous, minute papulovesicles with nonfollicular distribution. The lesions, which cause a prickly sensation, are typically localized in flexural regions such as the neck, groin, and axilla, and may be confused with candidiasis or folliculitis.

Cooling by regulation of environmental temperatures and removing excessive clothing can dramatically reduce miliaria rubra. Antipyretics can relieve the symptoms in febrile patients. Topical agents are not recommended because they may exacerbate the skin eruptions.4

Papular urticaria predominantly affects children and is caused by allergic hypersensitivity to insect bites.6 The skin lesions are intensely pruritic and are initially characterized by multiple small erythematous wheals and later progress to pruritic brownish papules.3 Some lesions may have a central punctum. The patient’s age and a history of symmetrically distributed lesions, hypersensitivity, and exposure to animals or insects can help diagnose papular urticaria.6 Lesions are typically observed on exposed areas, can persist for days or weeks, and usually occur in the summer.7

Management of papular urticaria includes the 3 Ps:

- Protection. Children should wear protective clothing for outdoor play and use insect repellent.

- Pruritus control. Topical high-potency steroids and antihistamines may help with individual lesions, but may be ineffective when the inflammatory process extends to the dermis and the fat.

- Patience. Although there is a chance that papular urticaria will be persistent and recurrent, it typically improves with time.6

Lichen nitidus is rare and when it does occur, it typically develops in children.8 Some lesions subside spontaneously, but others may persist for as long as several years.8

Lichen nitidus is clinically manifested as asymptomatic, discrete, flesh-colored, shiny, pinpoint-to-pinhead-sized papules; these papules are sharply demarcated and have fine scales. The most commonly affected sites are the genitalia, chest, abdomen, and upper extremities.8-10 The isomorphic condition called Koebner phenomenon is observed in most cases.3

Lichen nitidus is diagnosed on the basis of clinical presentation. Biopsy is indicated only when atypical morphology and distribution are observed. Histologically, the pathognomonic features of lichen nitidus include focal granulomas containing lymphohistiocytic cells in the papillary dermis.

Lichen nitidus usually regresses spontaneously and most patients do not require intervention; treatment is required only when the patient complains of pruritus or cosmetically undesirable effects.5 Topical glucocorticoid treatment may provide good results in such cases.8

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by poxvirus infection and generally affects young children. It is asymptomatic and presents with small pearly white or pink round/oval papules that may have umbilication. The papules are often 2 to 5 mm in diameter, but can be as large as 3 cm (a giant molluscum). Most papules appear in intertriginous sites such as the groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa.

Transmission occurs by direct mucous membrane or skin contact, leading to autoinoculation.11 Patients should not share towels or bath water and must avoid swimming in public pools to reduce the risk of spreading the infection.12

The individual lesions usually persist for 6 to 9 months but may last for years. Most lesions resolve spontaneously and heal without scarring. Active treatment is used for cosmetic and epidemiologic reasons and includes curettage, cryotherapy, cantharidin, and topical imiquimod.11 There is no consensus about the dosage and duration in current therapy modalities, but some experts suggest liquid cantharidin (0.7%-0.9%).3

Management of GCS? Let it run its course

Most patients with GCS do not need treatment because it is a self-limited benign disease. Although the course is variable and the skin lesions may persist for up to 60 days, the lesions will heal without scarring.2

Postinflammation hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation is rarely seen. In patients who have severe pruritus, topical antipruritic lotions or oral histamines can provide relief.5 Medium-potency topical steroids may have some benefits, but patients should be closely monitored because there have been reports of exacerbations of lesions with steroid use.2

A good outcome. In the case of our patient, the lesions resolved one week after applying 0.1% mometasone furoate cream once a day.

CORRESPONDENCE Chien-Ping Chiang, MD, Department of Dermatology, Tri-Service General Hospital, No. 325, Sec. 2, Chenggong Road, Neihu District, Taipei City 114, Taiwan R.O.C.; [email protected]

1. Jindal T, Arora VK. Gianotti-crosti syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37:683-684.

2. Brandt O, Abeck D, Gianotti R, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:136-145.

3. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2008.

4. Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, et al. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Pa: WB Saunders Co; 2007.

5. Wu CY, Huang WH. Question: can you identify this condition? Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:712-716.

6. Hernandez RG, Cohen BA. Insect bite-induced hypersensitivity and the SCRATCH principles: a new approach to papular urticaria. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e189-e196.

7. Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Urticarial lesions: if not urticaria, what else? The differential diagnosis of urticaria: part I. Cutaneous diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:541-555.

8. Tilly JJ, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Lichenoid eruptions in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:606-624.

9. Arizaga AT, Gaughan MD, Bang RH. Generalized lichen nitidus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:115-117.

10. Kim YC, Shim SD. Two cases of generalized lichen nitidus treated successfully with narrow-band UV-B phototherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:615-617.

11. Jones S, Kress D. Treatment of molluscum contagiosum and herpes simplex virus cutaneous infections. Cutis. 2007;79(4 suppl):11-17.

12. Silverberg NB. Warts and molluscum in children. Adv Dermatol. 2004;20:23-73.

1. Jindal T, Arora VK. Gianotti-crosti syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37:683-684.

2. Brandt O, Abeck D, Gianotti R, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:136-145.

3. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2008.

4. Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, et al. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Pa: WB Saunders Co; 2007.

5. Wu CY, Huang WH. Question: can you identify this condition? Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:712-716.

6. Hernandez RG, Cohen BA. Insect bite-induced hypersensitivity and the SCRATCH principles: a new approach to papular urticaria. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e189-e196.

7. Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Urticarial lesions: if not urticaria, what else? The differential diagnosis of urticaria: part I. Cutaneous diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:541-555.

8. Tilly JJ, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Lichenoid eruptions in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:606-624.

9. Arizaga AT, Gaughan MD, Bang RH. Generalized lichen nitidus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:115-117.

10. Kim YC, Shim SD. Two cases of generalized lichen nitidus treated successfully with narrow-band UV-B phototherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:615-617.

11. Jones S, Kress D. Treatment of molluscum contagiosum and herpes simplex virus cutaneous infections. Cutis. 2007;79(4 suppl):11-17.

12. Silverberg NB. Warts and molluscum in children. Adv Dermatol. 2004;20:23-73.