User login

Cutaneous Insulin-Derived Amyloidosis Presenting as Hyperkeratotic Nodules

Amyloidosis consists of approximately 30 protein-folding disorders sharing the common feature of abnormal extracellular amyloid deposition. In each condition, a specific soluble precursor protein aggregates to form the insoluble fibrils of amyloid, characterized by the beta-pleated sheet structure.1 Amyloidosis occurs as either a systemic or localized process. Insulin-derived (AIns) amyloidosis, a localized process occurring at insulin injection sites, was first reported in 1983.2 There were fewer than 20 reported cases until 2014, when 57 additional cases were reported by just 2 institutions,3,4 indicating that AIns amyloidosis may be more common than previously thought.3,5

Despite the increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus and insulin use, there is a paucity of published cases of AIns amyloidosis. The lack of awareness of this condition among both dermatologists and general practitioners may be in part due to its variable clinical manifestations. We describe 2 patients with unique presentations of localized amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 39-year-old man with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus presented with 4 asymptomatic nodules on the lateral thighs in areas of previous insulin injection. He first noticed the lesions 9 months prior to presentation and subsequently switched the injection site to the abdomen without development of new nodules. Despite being compliant with his insulin regimen, he had a long history of irregular glucose control, including frequent hypoglycemic episodes. The patient was using regular and neutral protamine hagedorn insulin.

On physical examination, 2 soft, nontender, exophytic nodules were noted on each upper thigh with surrounding hyperpigmented and hyperkeratotic collarettes (Figure 1). The nodules ranged in size from 2 to 3.5 cm in diameter.

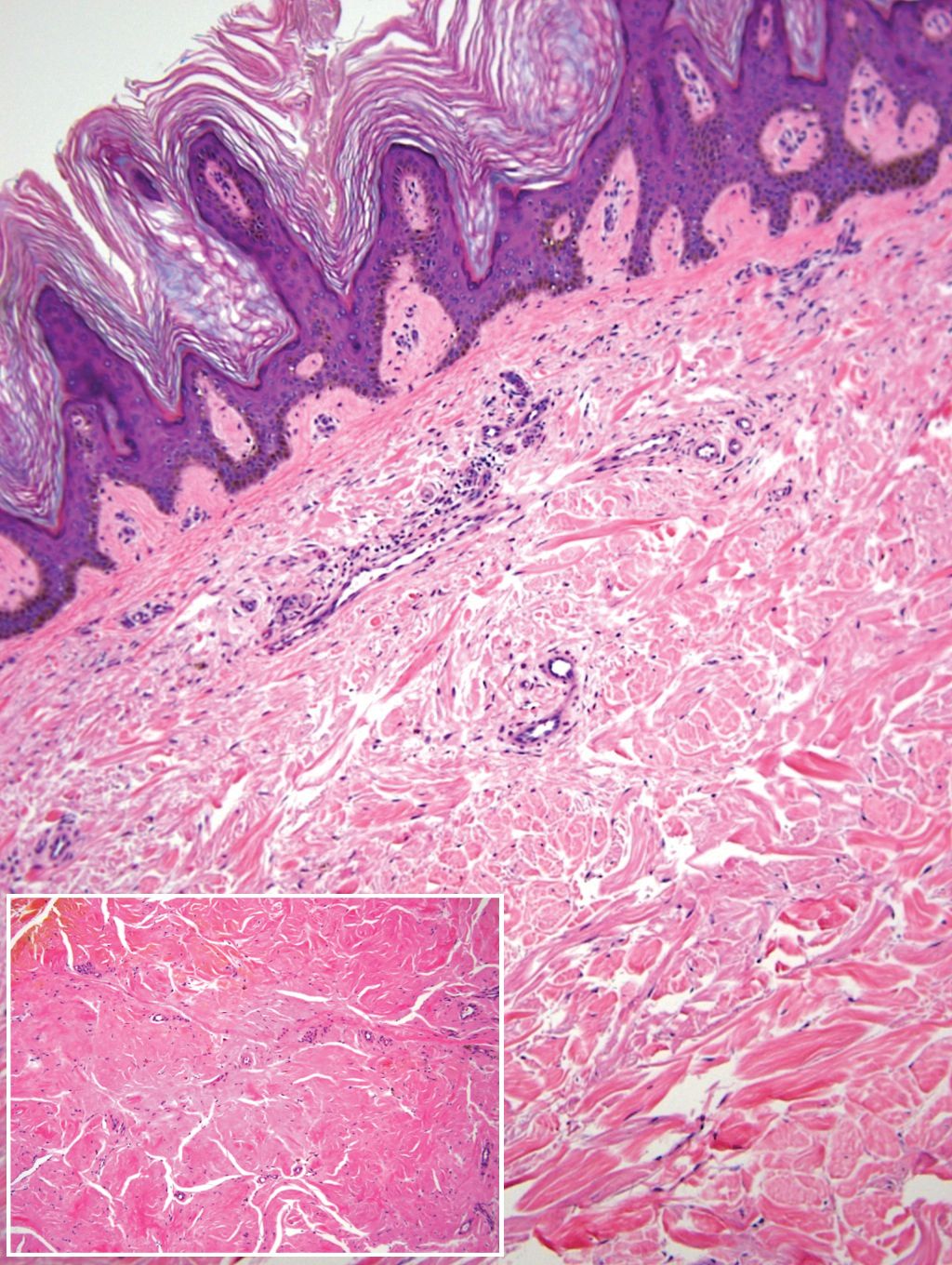

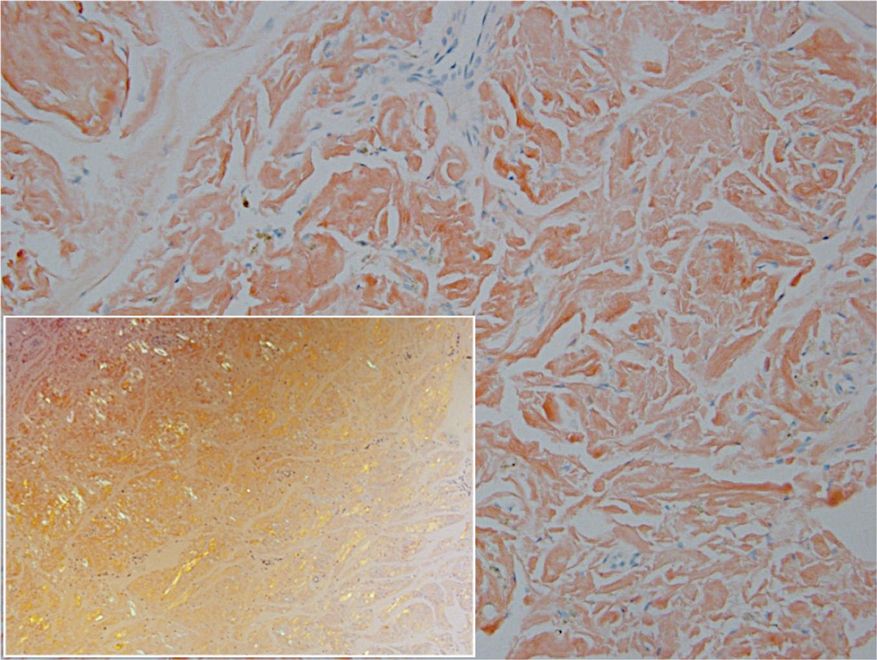

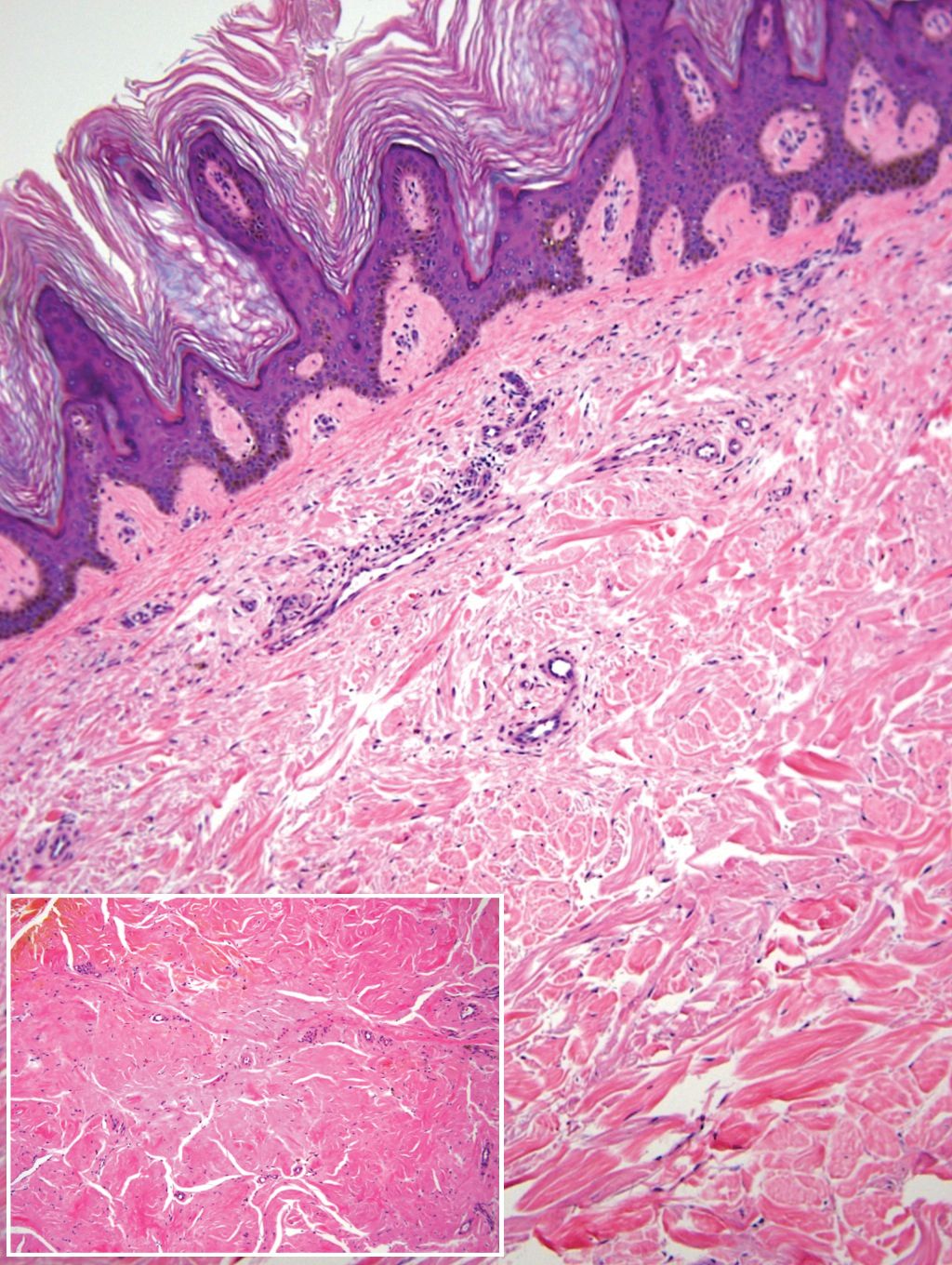

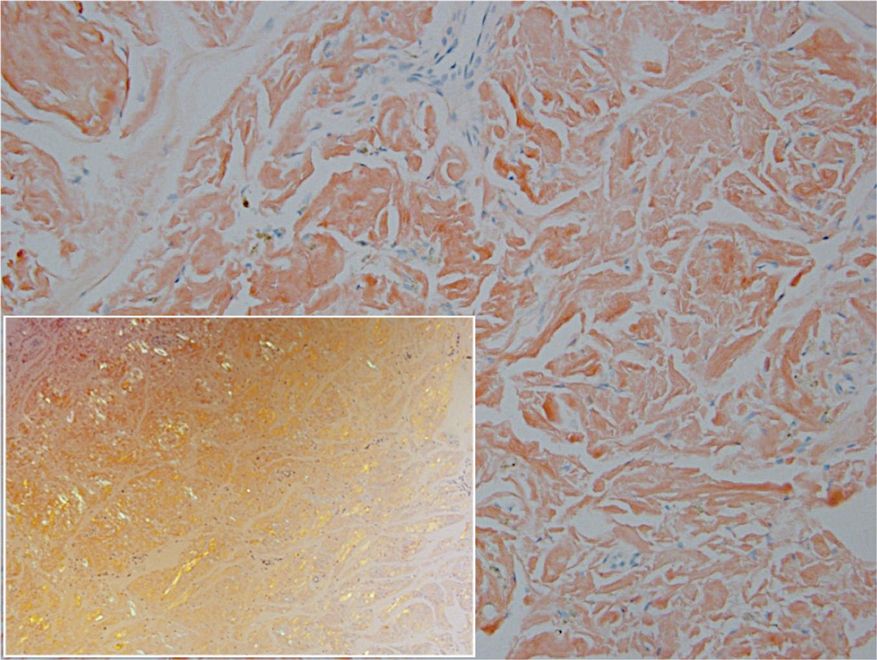

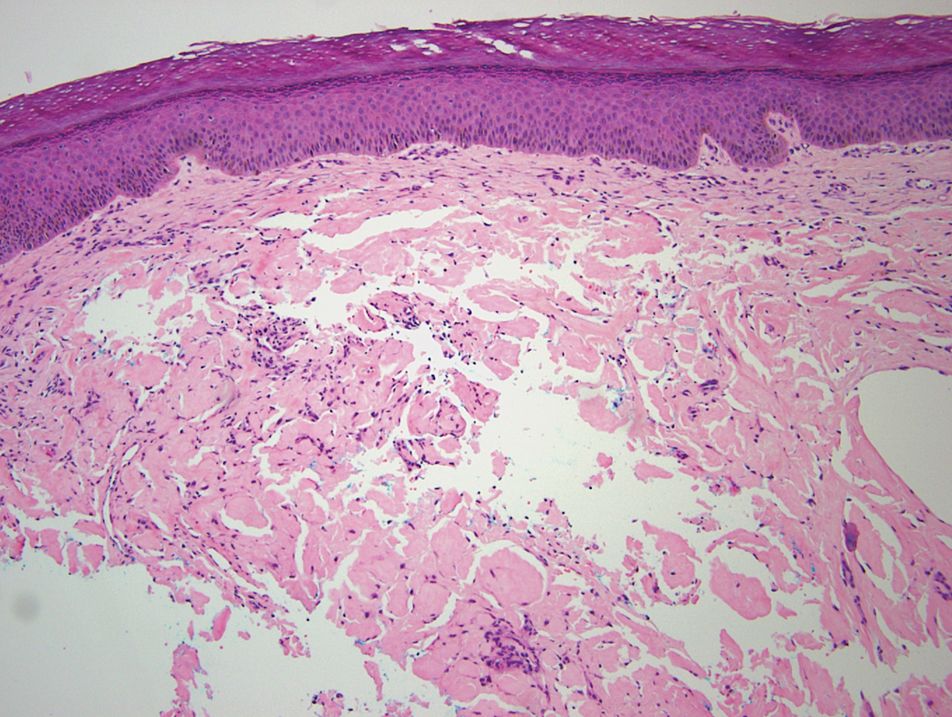

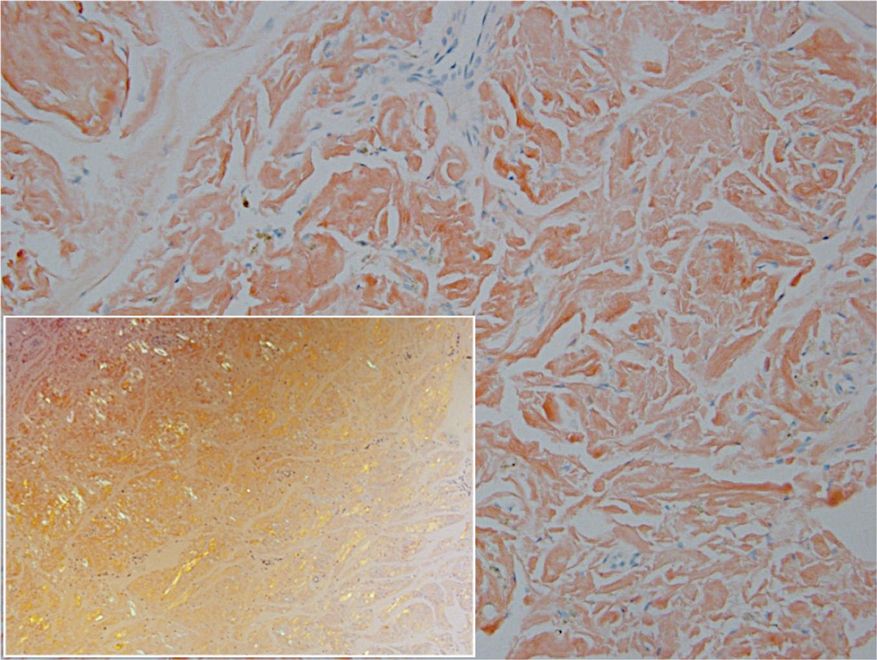

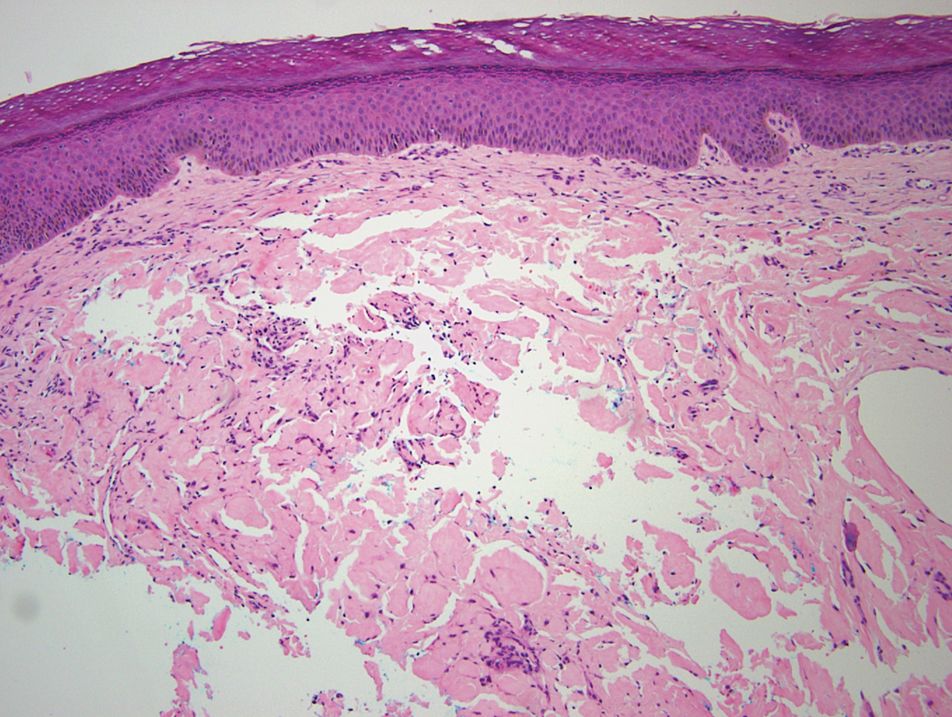

Remarkable laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 207 mg/dL (reference range, 70–110 mg/dL) and a glycohemoglobin of 8.8% (reference range, <5.7%). Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation were normal. Histopathology of the lesions demonstrated diffuse deposition of pink amorphous material associated with prominent papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Congo red staining was positive with green birefringence under polarized light, indicative of amyloid deposits (Figure 3). Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimens was consistent with deposition of AIns amyloidosis.

Due to the size and persistent nature of the lesions, the nodules were removed by tangential excision. In addition, the patient was advised to continue rotating injection sites frequently. His blood glucose levels are now well controlled, and he has not developed any new nodules.

Patient 2

A 53-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with painful subcutaneous nodules on the lower abdomen at sites of previous insulin injections. The nodules developed approximately 1 month after she started treatment with neutral protamine hagedorn insulin and had been slowly enlarging over the past year. She tried switching injection sites after noticing the lesions, but the nodules persisted. The patient had a long history of poor glucose control with chronically elevated glycohemoglobin and blood glucose levels.

On physical examination, 2 hyperpigmented, exophytic, smooth nodules were noted on the right and left lower abdomen, ranging in size from 2.5 to 5.5 cm in diameter (Figure 4).

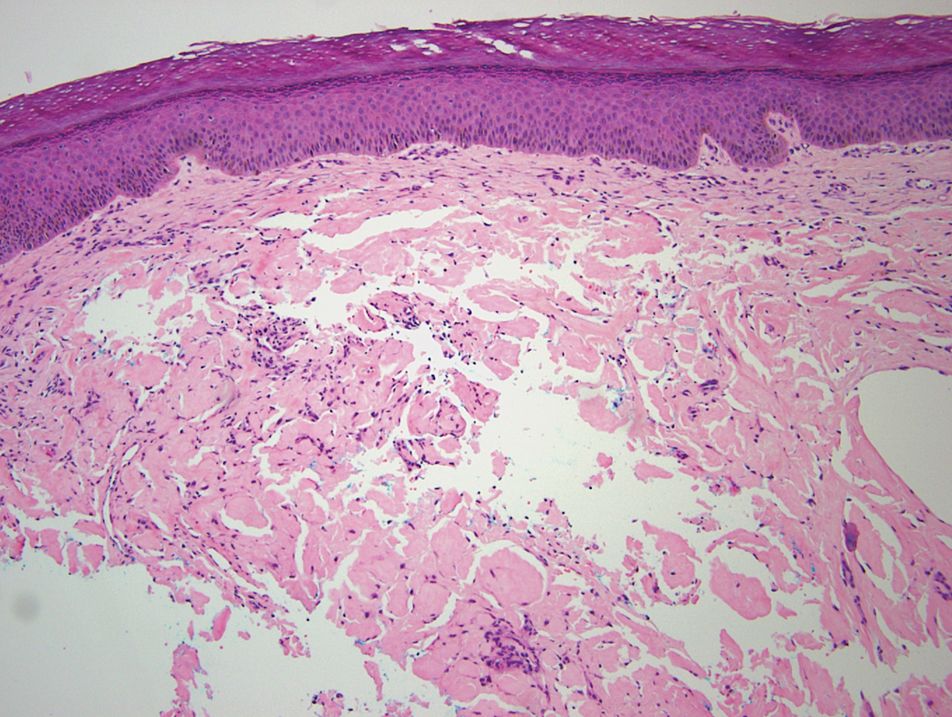

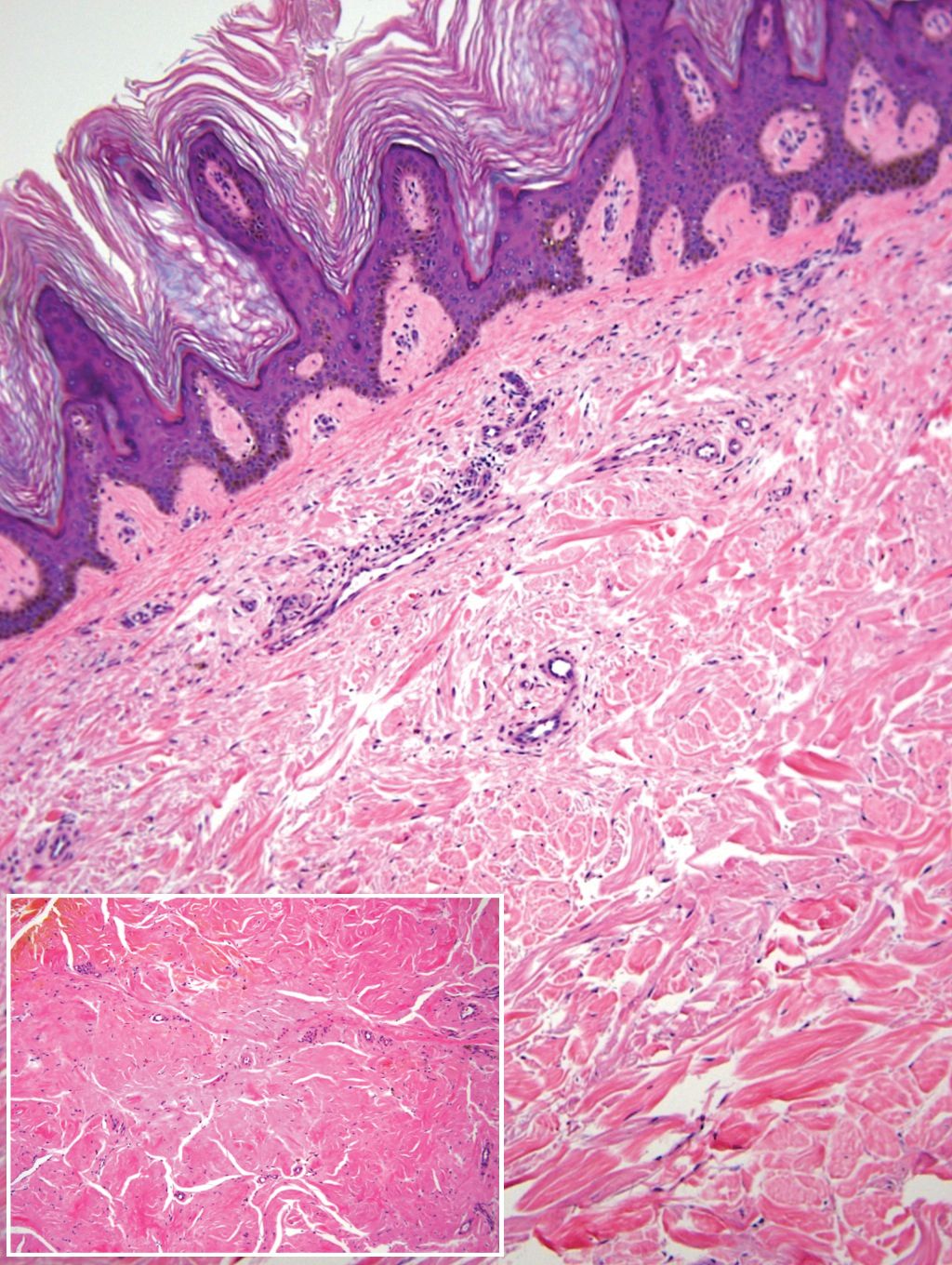

Relevant laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 197 mg/dL and a glycohemoglobin of 9.3%. A biopsy of the lesion on the left lower abdomen revealed eosinophilic amorphous deposits with fissuring in the dermis (Figure 5). Congo red stain was positive with green birefringence under polarized light. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimen showed deposition of AIns amyloid. The patient began injecting away from the amyloid nodules without development of any new lesions. The original nodules have persisted, and surgical excision is planned.

Comment

Insulin is the suspected precursor protein in AIns amyloidosis, but the exact pathogenesis is unknown. The protein that is derived from insulin in these tumors is now identified as AIns amyloidosis.5,6 It is hypothesized that insulin accumulates locally and is converted to amyloid by an unknown mechanism.7 Other potential contributory factors include chronic inflammation and foreign body reactions developing around amyloid deposits, as well as repeated trauma from injections into a single site.4,5 It appears that lesions may derive from a wide range of insulin types and occur after variable time periods.

A majority of cases of iatrogenic amyloid have been described as single, firm, subcutaneous masses at an injection site that commonly are misdiagnosed as lipomas or lipohypertrophy.7-11 To our knowledge, none of the reported cases resembled the multiple, discrete, exophytic nodules seen in our patients.3,4 The surrounding hyperkeratosis noted in patient 1 is another uncommon feature of AIns amyloidosis (Figures 1 and 2). Only 3 AIns amyloidosis cases described lesions with acanthosis nigricans–like changes, only 1 of which provided a clinical image.6,7,12The mechanism for the acanthosis nigricans–like changes may have been due to the high levels of insulin at the injection site. It has been suggested that the activation of insulinlike growth factor receptor by insulin leads to the proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts.6 Histologic examination of AIns amyloidosis lesions generally demonstrates deposition of homogenous eosinophilic material consistent with amyloid, as well as positive Congo red staining with green birefringence by polarization. Immunohistologic staining with insulin antibody with or without proteomic analysis of the amyloid deposits can confirm the diagnosis. In both of our patients’ specimens, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry was performed for proteomic analysis, and results were consistent with AIns amyloidosis.

Reports in the literature have suggested that the deposition of amyloid at insulin injection sites has the potential to interfere with insulin absorption, leading to poor glucose control.4,11,13 Hence, injection site rotation is a crucial aspect of treatment and prevention of AIns amyloidosis. In their study of 4 patients, Nagase et al4 compared serum insulin levels after insulin injection into amyloid nodules vs insulin levels after injection into normal skin. Insulin absorption at the amyloid sites was 34% of that at normal sites. Given these results, patients should be instructed to inject away from the amyloid deposit once it is identified.6 Glucose levels should be monitored closely when patients first inject away from the amyloid mass, as injection of the same dosage to an area of normal skin can lead to increased insulin absorption and hypoglycemia.4,6 It is possible that the frequent hypoglycemic episodes noted in patient 1 were due to increased insulin sensitivity after switching to injection sites away from amyloid lesions.

Conclusion

Our patients demonstrate unique presentations of localized cutaneous amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites. We report these cases to complement the current data of iatrogenic amyloidosis and provide insight into this likely underreported phenomenon.

- Hazenberg BPC. Amyloidosis: a clinical overview. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:323-345.

- Storkel S, Schneider HM, Muntefering H, et al. Iatrogenic, insulin-dependent, local amyloidosis. Lab Invest. 1983;48:108-111.

- D’souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, et al. Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration. Amyloid. 2014;21:71-75.

- Nagase T, Iwaya K, Iwaki Y, et al. Insulin-derived amyloidosis and poor glycemic control: a case series. Am J Med. 2014;127:450-454.

- Gupta Y, Singla G, Singla R. Insulin-derived amyloidosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:174-177.

- Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, et al. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:25-29.

- Yumlu S, Barany R, Eriksson M, et al. Localized insulin-derived amyloidosis in patients with diabetes mellitus: a case report. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1655-1660.

- Okamura S, Hayashino Y, Kore-Eda S, et al. Localized amyloidosis at the site of repeated insulin injection in a patient with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:E200.

- Dische FE, Wernstedt C, Westermark GT, et al. Insulin as an amyloid-fibril protein at sites of repeated insulin injections in a diabetic patient. Diabetologia. 1988;31:158-161.

- Swift B, Hawkins PN, Richards C, et al. Examination of insulin injection sites: an unexpected finding of localized amyloidosis. Diabetic Med. 2002;19:881-882.

- Albert SG, Obadiah J, Parseghian SA, et al. Severe insulin resistance associated with subcutaneous amyloid deposition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:374-376.

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:127-129.

- Endo JO, Rocken C, Lamb S, et al. Nodular amyloidosis in a diabetic patient with frequent hypoglycemia: sequelae of repeatedly injecting insulin without site rotation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:E113-E114.

Amyloidosis consists of approximately 30 protein-folding disorders sharing the common feature of abnormal extracellular amyloid deposition. In each condition, a specific soluble precursor protein aggregates to form the insoluble fibrils of amyloid, characterized by the beta-pleated sheet structure.1 Amyloidosis occurs as either a systemic or localized process. Insulin-derived (AIns) amyloidosis, a localized process occurring at insulin injection sites, was first reported in 1983.2 There were fewer than 20 reported cases until 2014, when 57 additional cases were reported by just 2 institutions,3,4 indicating that AIns amyloidosis may be more common than previously thought.3,5

Despite the increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus and insulin use, there is a paucity of published cases of AIns amyloidosis. The lack of awareness of this condition among both dermatologists and general practitioners may be in part due to its variable clinical manifestations. We describe 2 patients with unique presentations of localized amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 39-year-old man with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus presented with 4 asymptomatic nodules on the lateral thighs in areas of previous insulin injection. He first noticed the lesions 9 months prior to presentation and subsequently switched the injection site to the abdomen without development of new nodules. Despite being compliant with his insulin regimen, he had a long history of irregular glucose control, including frequent hypoglycemic episodes. The patient was using regular and neutral protamine hagedorn insulin.

On physical examination, 2 soft, nontender, exophytic nodules were noted on each upper thigh with surrounding hyperpigmented and hyperkeratotic collarettes (Figure 1). The nodules ranged in size from 2 to 3.5 cm in diameter.

Remarkable laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 207 mg/dL (reference range, 70–110 mg/dL) and a glycohemoglobin of 8.8% (reference range, <5.7%). Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation were normal. Histopathology of the lesions demonstrated diffuse deposition of pink amorphous material associated with prominent papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Congo red staining was positive with green birefringence under polarized light, indicative of amyloid deposits (Figure 3). Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimens was consistent with deposition of AIns amyloidosis.

Due to the size and persistent nature of the lesions, the nodules were removed by tangential excision. In addition, the patient was advised to continue rotating injection sites frequently. His blood glucose levels are now well controlled, and he has not developed any new nodules.

Patient 2

A 53-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with painful subcutaneous nodules on the lower abdomen at sites of previous insulin injections. The nodules developed approximately 1 month after she started treatment with neutral protamine hagedorn insulin and had been slowly enlarging over the past year. She tried switching injection sites after noticing the lesions, but the nodules persisted. The patient had a long history of poor glucose control with chronically elevated glycohemoglobin and blood glucose levels.

On physical examination, 2 hyperpigmented, exophytic, smooth nodules were noted on the right and left lower abdomen, ranging in size from 2.5 to 5.5 cm in diameter (Figure 4).

Relevant laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 197 mg/dL and a glycohemoglobin of 9.3%. A biopsy of the lesion on the left lower abdomen revealed eosinophilic amorphous deposits with fissuring in the dermis (Figure 5). Congo red stain was positive with green birefringence under polarized light. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimen showed deposition of AIns amyloid. The patient began injecting away from the amyloid nodules without development of any new lesions. The original nodules have persisted, and surgical excision is planned.

Comment

Insulin is the suspected precursor protein in AIns amyloidosis, but the exact pathogenesis is unknown. The protein that is derived from insulin in these tumors is now identified as AIns amyloidosis.5,6 It is hypothesized that insulin accumulates locally and is converted to amyloid by an unknown mechanism.7 Other potential contributory factors include chronic inflammation and foreign body reactions developing around amyloid deposits, as well as repeated trauma from injections into a single site.4,5 It appears that lesions may derive from a wide range of insulin types and occur after variable time periods.

A majority of cases of iatrogenic amyloid have been described as single, firm, subcutaneous masses at an injection site that commonly are misdiagnosed as lipomas or lipohypertrophy.7-11 To our knowledge, none of the reported cases resembled the multiple, discrete, exophytic nodules seen in our patients.3,4 The surrounding hyperkeratosis noted in patient 1 is another uncommon feature of AIns amyloidosis (Figures 1 and 2). Only 3 AIns amyloidosis cases described lesions with acanthosis nigricans–like changes, only 1 of which provided a clinical image.6,7,12The mechanism for the acanthosis nigricans–like changes may have been due to the high levels of insulin at the injection site. It has been suggested that the activation of insulinlike growth factor receptor by insulin leads to the proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts.6 Histologic examination of AIns amyloidosis lesions generally demonstrates deposition of homogenous eosinophilic material consistent with amyloid, as well as positive Congo red staining with green birefringence by polarization. Immunohistologic staining with insulin antibody with or without proteomic analysis of the amyloid deposits can confirm the diagnosis. In both of our patients’ specimens, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry was performed for proteomic analysis, and results were consistent with AIns amyloidosis.

Reports in the literature have suggested that the deposition of amyloid at insulin injection sites has the potential to interfere with insulin absorption, leading to poor glucose control.4,11,13 Hence, injection site rotation is a crucial aspect of treatment and prevention of AIns amyloidosis. In their study of 4 patients, Nagase et al4 compared serum insulin levels after insulin injection into amyloid nodules vs insulin levels after injection into normal skin. Insulin absorption at the amyloid sites was 34% of that at normal sites. Given these results, patients should be instructed to inject away from the amyloid deposit once it is identified.6 Glucose levels should be monitored closely when patients first inject away from the amyloid mass, as injection of the same dosage to an area of normal skin can lead to increased insulin absorption and hypoglycemia.4,6 It is possible that the frequent hypoglycemic episodes noted in patient 1 were due to increased insulin sensitivity after switching to injection sites away from amyloid lesions.

Conclusion

Our patients demonstrate unique presentations of localized cutaneous amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites. We report these cases to complement the current data of iatrogenic amyloidosis and provide insight into this likely underreported phenomenon.

Amyloidosis consists of approximately 30 protein-folding disorders sharing the common feature of abnormal extracellular amyloid deposition. In each condition, a specific soluble precursor protein aggregates to form the insoluble fibrils of amyloid, characterized by the beta-pleated sheet structure.1 Amyloidosis occurs as either a systemic or localized process. Insulin-derived (AIns) amyloidosis, a localized process occurring at insulin injection sites, was first reported in 1983.2 There were fewer than 20 reported cases until 2014, when 57 additional cases were reported by just 2 institutions,3,4 indicating that AIns amyloidosis may be more common than previously thought.3,5

Despite the increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus and insulin use, there is a paucity of published cases of AIns amyloidosis. The lack of awareness of this condition among both dermatologists and general practitioners may be in part due to its variable clinical manifestations. We describe 2 patients with unique presentations of localized amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 39-year-old man with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus presented with 4 asymptomatic nodules on the lateral thighs in areas of previous insulin injection. He first noticed the lesions 9 months prior to presentation and subsequently switched the injection site to the abdomen without development of new nodules. Despite being compliant with his insulin regimen, he had a long history of irregular glucose control, including frequent hypoglycemic episodes. The patient was using regular and neutral protamine hagedorn insulin.

On physical examination, 2 soft, nontender, exophytic nodules were noted on each upper thigh with surrounding hyperpigmented and hyperkeratotic collarettes (Figure 1). The nodules ranged in size from 2 to 3.5 cm in diameter.

Remarkable laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 207 mg/dL (reference range, 70–110 mg/dL) and a glycohemoglobin of 8.8% (reference range, <5.7%). Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation were normal. Histopathology of the lesions demonstrated diffuse deposition of pink amorphous material associated with prominent papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Congo red staining was positive with green birefringence under polarized light, indicative of amyloid deposits (Figure 3). Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimens was consistent with deposition of AIns amyloidosis.

Due to the size and persistent nature of the lesions, the nodules were removed by tangential excision. In addition, the patient was advised to continue rotating injection sites frequently. His blood glucose levels are now well controlled, and he has not developed any new nodules.

Patient 2

A 53-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with painful subcutaneous nodules on the lower abdomen at sites of previous insulin injections. The nodules developed approximately 1 month after she started treatment with neutral protamine hagedorn insulin and had been slowly enlarging over the past year. She tried switching injection sites after noticing the lesions, but the nodules persisted. The patient had a long history of poor glucose control with chronically elevated glycohemoglobin and blood glucose levels.

On physical examination, 2 hyperpigmented, exophytic, smooth nodules were noted on the right and left lower abdomen, ranging in size from 2.5 to 5.5 cm in diameter (Figure 4).

Relevant laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 197 mg/dL and a glycohemoglobin of 9.3%. A biopsy of the lesion on the left lower abdomen revealed eosinophilic amorphous deposits with fissuring in the dermis (Figure 5). Congo red stain was positive with green birefringence under polarized light. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimen showed deposition of AIns amyloid. The patient began injecting away from the amyloid nodules without development of any new lesions. The original nodules have persisted, and surgical excision is planned.

Comment

Insulin is the suspected precursor protein in AIns amyloidosis, but the exact pathogenesis is unknown. The protein that is derived from insulin in these tumors is now identified as AIns amyloidosis.5,6 It is hypothesized that insulin accumulates locally and is converted to amyloid by an unknown mechanism.7 Other potential contributory factors include chronic inflammation and foreign body reactions developing around amyloid deposits, as well as repeated trauma from injections into a single site.4,5 It appears that lesions may derive from a wide range of insulin types and occur after variable time periods.

A majority of cases of iatrogenic amyloid have been described as single, firm, subcutaneous masses at an injection site that commonly are misdiagnosed as lipomas or lipohypertrophy.7-11 To our knowledge, none of the reported cases resembled the multiple, discrete, exophytic nodules seen in our patients.3,4 The surrounding hyperkeratosis noted in patient 1 is another uncommon feature of AIns amyloidosis (Figures 1 and 2). Only 3 AIns amyloidosis cases described lesions with acanthosis nigricans–like changes, only 1 of which provided a clinical image.6,7,12The mechanism for the acanthosis nigricans–like changes may have been due to the high levels of insulin at the injection site. It has been suggested that the activation of insulinlike growth factor receptor by insulin leads to the proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts.6 Histologic examination of AIns amyloidosis lesions generally demonstrates deposition of homogenous eosinophilic material consistent with amyloid, as well as positive Congo red staining with green birefringence by polarization. Immunohistologic staining with insulin antibody with or without proteomic analysis of the amyloid deposits can confirm the diagnosis. In both of our patients’ specimens, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry was performed for proteomic analysis, and results were consistent with AIns amyloidosis.

Reports in the literature have suggested that the deposition of amyloid at insulin injection sites has the potential to interfere with insulin absorption, leading to poor glucose control.4,11,13 Hence, injection site rotation is a crucial aspect of treatment and prevention of AIns amyloidosis. In their study of 4 patients, Nagase et al4 compared serum insulin levels after insulin injection into amyloid nodules vs insulin levels after injection into normal skin. Insulin absorption at the amyloid sites was 34% of that at normal sites. Given these results, patients should be instructed to inject away from the amyloid deposit once it is identified.6 Glucose levels should be monitored closely when patients first inject away from the amyloid mass, as injection of the same dosage to an area of normal skin can lead to increased insulin absorption and hypoglycemia.4,6 It is possible that the frequent hypoglycemic episodes noted in patient 1 were due to increased insulin sensitivity after switching to injection sites away from amyloid lesions.

Conclusion

Our patients demonstrate unique presentations of localized cutaneous amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites. We report these cases to complement the current data of iatrogenic amyloidosis and provide insight into this likely underreported phenomenon.

- Hazenberg BPC. Amyloidosis: a clinical overview. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:323-345.

- Storkel S, Schneider HM, Muntefering H, et al. Iatrogenic, insulin-dependent, local amyloidosis. Lab Invest. 1983;48:108-111.

- D’souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, et al. Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration. Amyloid. 2014;21:71-75.

- Nagase T, Iwaya K, Iwaki Y, et al. Insulin-derived amyloidosis and poor glycemic control: a case series. Am J Med. 2014;127:450-454.

- Gupta Y, Singla G, Singla R. Insulin-derived amyloidosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:174-177.

- Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, et al. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:25-29.

- Yumlu S, Barany R, Eriksson M, et al. Localized insulin-derived amyloidosis in patients with diabetes mellitus: a case report. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1655-1660.

- Okamura S, Hayashino Y, Kore-Eda S, et al. Localized amyloidosis at the site of repeated insulin injection in a patient with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:E200.

- Dische FE, Wernstedt C, Westermark GT, et al. Insulin as an amyloid-fibril protein at sites of repeated insulin injections in a diabetic patient. Diabetologia. 1988;31:158-161.

- Swift B, Hawkins PN, Richards C, et al. Examination of insulin injection sites: an unexpected finding of localized amyloidosis. Diabetic Med. 2002;19:881-882.

- Albert SG, Obadiah J, Parseghian SA, et al. Severe insulin resistance associated with subcutaneous amyloid deposition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:374-376.

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:127-129.

- Endo JO, Rocken C, Lamb S, et al. Nodular amyloidosis in a diabetic patient with frequent hypoglycemia: sequelae of repeatedly injecting insulin without site rotation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:E113-E114.

- Hazenberg BPC. Amyloidosis: a clinical overview. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:323-345.

- Storkel S, Schneider HM, Muntefering H, et al. Iatrogenic, insulin-dependent, local amyloidosis. Lab Invest. 1983;48:108-111.

- D’souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, et al. Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration. Amyloid. 2014;21:71-75.

- Nagase T, Iwaya K, Iwaki Y, et al. Insulin-derived amyloidosis and poor glycemic control: a case series. Am J Med. 2014;127:450-454.

- Gupta Y, Singla G, Singla R. Insulin-derived amyloidosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:174-177.

- Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, et al. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:25-29.

- Yumlu S, Barany R, Eriksson M, et al. Localized insulin-derived amyloidosis in patients with diabetes mellitus: a case report. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1655-1660.

- Okamura S, Hayashino Y, Kore-Eda S, et al. Localized amyloidosis at the site of repeated insulin injection in a patient with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:E200.

- Dische FE, Wernstedt C, Westermark GT, et al. Insulin as an amyloid-fibril protein at sites of repeated insulin injections in a diabetic patient. Diabetologia. 1988;31:158-161.

- Swift B, Hawkins PN, Richards C, et al. Examination of insulin injection sites: an unexpected finding of localized amyloidosis. Diabetic Med. 2002;19:881-882.

- Albert SG, Obadiah J, Parseghian SA, et al. Severe insulin resistance associated with subcutaneous amyloid deposition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:374-376.

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:127-129.

- Endo JO, Rocken C, Lamb S, et al. Nodular amyloidosis in a diabetic patient with frequent hypoglycemia: sequelae of repeatedly injecting insulin without site rotation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:E113-E114.

Practice Points

- Deposition of amyloid at insulin injection sites has the potential to interfere with insulin absorption, leading to poor glucose control.

- Patients with insulin-derived (AIns) amyloidosis may initially present after noticing nodular deposits.

- Insulin injection site rotation is a crucial aspect of treatment and prevention of AIns amyloidosis.

Prednisone and Vardenafil Hydrochloride for Refractory Levamisole-Induced Vasculitis

Levamisole is an immunomodulatory drug that had been used to treat various medical conditions, including parasitic infections, nephrotic syndrome, and colorectal cancer,1 before being withdrawn from the US market in 2000. The most common reasons for levamisole discontinuation were leukopenia and rashes (1%–2%),1 many of which included leg ulcers and necrotizing purpura of the ears.1,2 The drug is currently available only as a deworming agent in veterinary medicine.

Since 2007, increasing amounts of levamisole have been used as an adulterant in cocaine. In 2007, less than 10% of cocaine was contaminated with levamisole, with an increase to 77% by 2010.3 In addition, 78% of 249 urine toxicology screens that were positive for cocaine in an inner city hospital also tested positive for levamisole.4 Levamisole-cut cocaine has become a concern because it is associated with a life-threatening syndrome involving a necrotizing purpuric rash, autoantibody production, and leukopenia.5

Levamisole-induced vasculitis is an independent entity from cocaine-induced vasculitis, which is associated with skin findings ranging from palpable purpura and chronic ulcers to digital infarction secondary to its vasospastic activity.6-8 Cocaine-induced vasculopathy has been related to cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positivity and often resembles Wegener granulomatosis.6 Although both cocaine and levamisole have reportedly caused acrally distributed purpura and vasculopathy, levamisole is specifically associated with retiform purpura, ear involvement, and leukopenia.6,9 In addition, levamisole-induced skin reactions have been linked to specific antibodies, including antinuclear, antiphospholipid, and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA).2,5-7,9-14

We present a case of refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis and review its clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, laboratory findings, histology, and management. Furthermore, we discuss the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients with refractory disease or for patients who continue to use levamisole.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with a history of polysubstance abuse presented with intermittent fevers and painful swollen ears as well as joint pain of 3 weeks’ duration. One week after the lesions developed on the ears, similar lesions were seen on the legs, arms, and trunk. He admitted to cocaine use 3 weeks prior to presentation when the symptoms began.

On physical examination, violaceous patches with necrotic bleeding edges and overlying black eschars were noted on the helices, antihelices, and ear lobules bilaterally (Figure 1). Retiform, purpuric to dark brown patches, some with signs of epidermal necrosis, were scattered on the arms, legs, and chest (Figure 2).

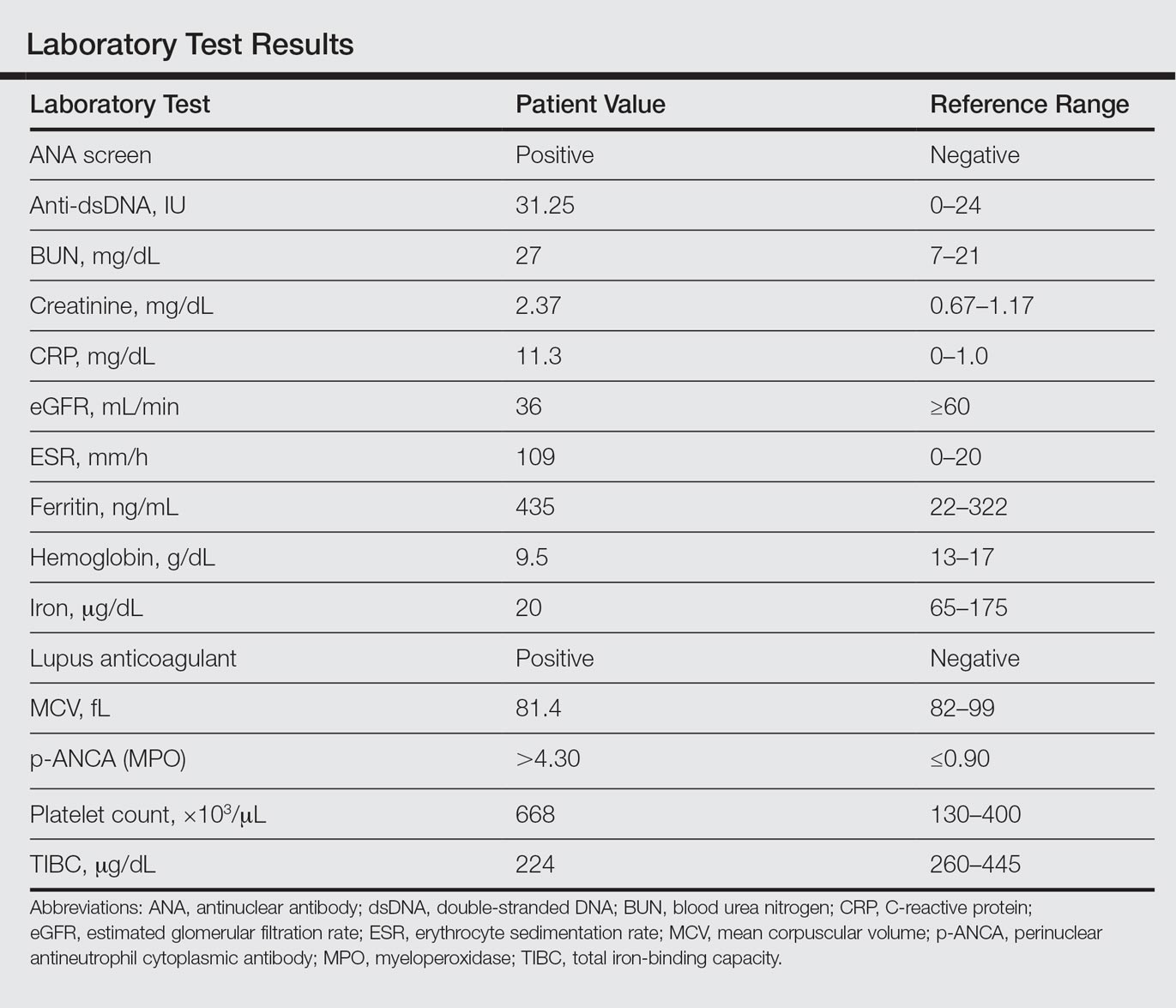

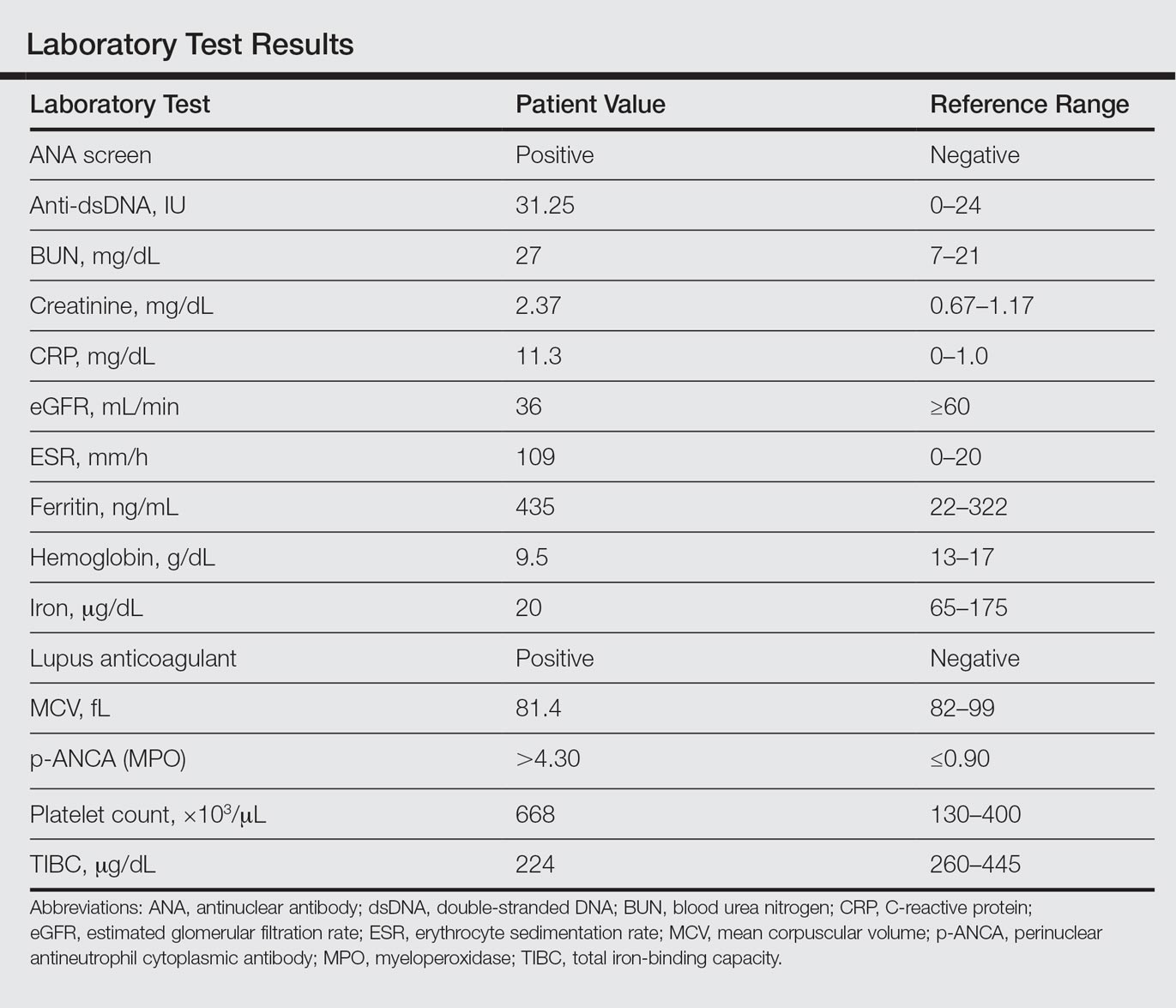

Laboratory examination revealed renal failure, anemia of chronic disease, and thrombocytosis (Table). The patient also screened positive for lupus anticoagulant and antinuclear antibodies and had elevated p-ANCA and anti–double-stranded DNA (Table). He also had an elevated sedimentation rate (109 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (11.3 mg/dL [reference range, 0–1.0 mg/dL])(Table). Urine toxicology was positive for cocaine.

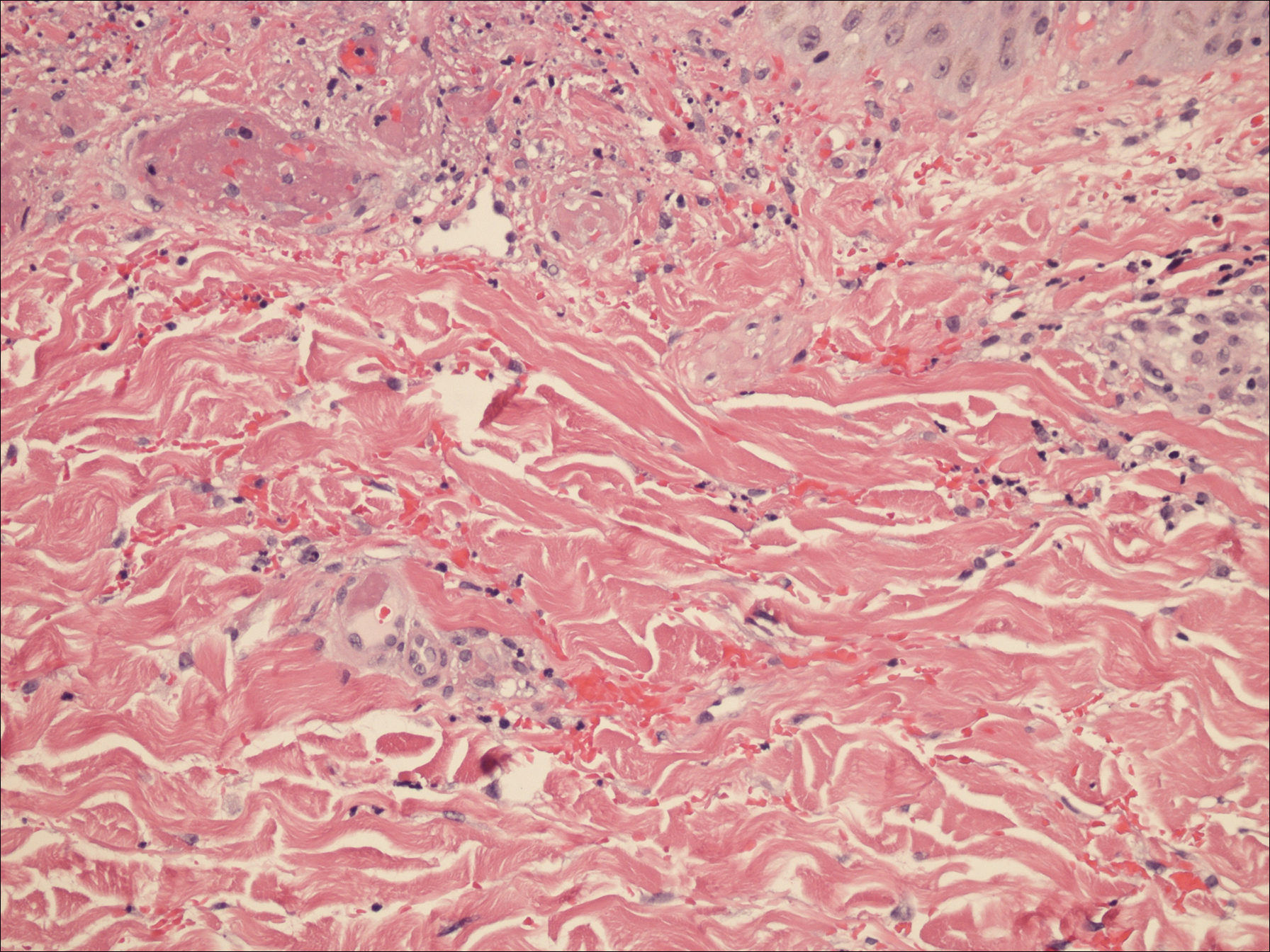

A punch biopsy of the left thigh was performed on the edge of a retiform purpuric patch. Histopathologic examination revealed epidermal necrosis with subjacent intraluminal vascular thrombi along with extravasated red blood cells and neutrophilic debris (leukocytoclasis) and fibrin in and around vessel walls, consistent with vasculitis (Figure 3).

The patient was admitted to the hospital for pain management and wound care. Despite cocaine cessation and oral prednisone taper, the lesions on the legs worsened over the next several weeks. His condition was further complicated by wound infections, nonhealing ulcers, and subjective fevers and chills requiring frequent hospitalization. The patient was managed by the dermatology department as an outpatient and in clinic between hospital visits. He was treated with antibiotics, ulcer debridement, compression wraps, and aspirin (81 mg once daily) with moderate improvement.

Ten weeks after the first visit, the patient returned with worsening and recurrent leg and ear lesions. He denied any cocaine use since the initial hospital admission; however, a toxicology screen was never obtained. It was decided that the patient would need additional treatment along with traditional trigger (cocaine) avoidance and wound care. Combined treatment with aspirin (81 mg once daily), oral prednisone (40 mg once daily), and vardenafil hydrochloride (20 mg twice weekly) was initiated. At the end of week 1, the patient began to exhibit signs of improvement, which continued over the next 4 weeks. He was then lost to follow-up.

Comment

Our patient presented with severe necrotizing cutaneous vasculitis, likely secondary to levamisole exposure. Some of our patient’s cutaneous findings may be explained exclusively on the basis of cocaine exposure, but the characteristic lesion distribution and histopathologic findings along with the evidence of autoantibody positivity and concurrent arthralgias make the combination of levamisole and cocaine a more likely cause. Similar skin lesions were first described in children treated with levamisole for nephrotic syndrome.2 The most common site of clinical involvement in these children was the ears, as seen in our patient. Our patient tested positive for p-ANCA, which is the most commonly reported autoantibody associated with this patient population. Sixty-one percent (20/33) of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis from 2 separate reviews showed p-ANCA positivity.7,10

On histopathology, our patient’s skin biopsy findings were consistent with those of prior reports of levamisole-induced vasculitis, which describe patterns of thrombotic vasculitis, leukocytoclasis, and fibrin deposition or occlusive disease.2,6,7,9-14 Mixed histologic findings of vasculitis and thrombosis, usually with varying ages of thrombi, are characteristic of levamisole-induced purpura. In addition, the disease can present nonspecifically with pure microvascular thrombosis without vasculitis, especially later in the course.9

The recommended management of levamisole-induced vasculitis currently involves the withdrawal of the culprit adulterated cocaine along with supportive treatment. Spontaneous and complete clinical resolution of lesions has been reported within 2 to 3 weeks and serology normalization within 2 to 14 months of levamisole cessation.2,6 A 2011 review of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis reported 66% (19/29) of cases with either full cutaneous resolution after levamisole withdrawal or recurrence with resumed use, supporting a causal relationship.7 Walsh et al9 described 2 patients with recurrent and exacerbated retiform purpura following cocaine binges. Both of these patients had urine samples that tested positive for levamisole.9 In more severe cases, medications shown to be effective include colchicine, polidocanol, antibiotics, methotrexate, anticoagulants, and most commonly systemic corticosteroids.7,10,11,15 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were successful in treating lesions in 2 patients with concurrent arthralgia.7 Rarely, patients have required surgical debridement or skin grafting due to advanced disease at initial presentation.9,12-14 One of the most severe cases of levamisole-induced vasculitis reported in the literature involved 52% of the patient’s total body surface area with skin, soft tissue, and bony necrosis requiring nasal amputation, upper lip excision, skin grafting, and extremity amputation.14 Another severe case with widespread skin involvement was recently reported.16

For unclear reasons, our patient continued to develop cutaneous lesions despite self-reported cocaine cessation. Complete resolution required the combination of vardenafil, prednisone, and aspirin, along with debridement and wound care. Vardenafil, a selective phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor, enhances the effect of nitrous oxide by increasing levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate,17 which results in smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilatation. The primary indication for vardenafil is the treatment of erectile dysfunction, but it often is used off label in diseases that may benefit from vasodilatation. Because of its mechanism of action, it is understandable that a vasodilator such as vardenafil could be therapeutic in a condition associated with thrombosis. Moreover, the autoinflammatory nature of levamisole-induced vasculitis makes corticosteroid treatment effective. Given the 10-week delay in improvement, we suspect that it was the combination of treatment or an individual agent that led to our patient’s eventual recovery.

There are few reports in the literature focusing on optimal treatment of levamisole-induced vasculitis and none that mention alternative management for patients who continue to develop new lesions despite cocaine avoidance. Although the discontinuation of levamisole seems to be imperative for resolution of cutaneous lesions, it may not always be enough. It is possible that there is a subpopulation of patients that may not respond to the simple withdrawal of cocaine. It also should be mentioned that there was no urine toxicology screen obtained to support our patient’s reported cocaine cessation. Therefore, it is possible that his worsening condition was secondary to continued cocaine use. However, the patient successfully responded to the combination of vardenafil and prednisone, regardless of whether his condition persisted due to continued use of cocaine or not. This case suggests the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients who continue to use levamisole despite instruction for cessation or for patients with refractory disease.

Conclusion

A trial of prednisone and vardenafil should be considered for patients with refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis. Further studies and discussions of disease course are needed to identify the best treatment of this skin condition, especially for patients with refractory lesions.

- Scheinfeld N, Rosenberg JD, Weinberg JM. Levamisole in dermatology: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:97-104.

- Rongioletti F, Ghio L, Ginevri F, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948-951.

- National Drug Threat Assessment 2011. US Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center website. https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44849/44849p.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed August 7, 2016.

- Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

- Gross RL, Brucker J, Bahce-Altuntas A, et al. A novel cutaneous vasculitis syndrome induced by levamisole-contaminated cocaine. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1385-1392.

- Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

- Poon SH, Baliog CR, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leukopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

- Brewer JD, Meves A, Bostwick JM, et al. Cocaine abuse: dermatologic manifestations and therapeutic approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:483-487.

- Walsh NMG, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia—a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole adultered cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

- Kahn TA, Cuchacovich R, Espinoza LR, et al. Vasculopathy, hematological, and immune abnormalities associated with levamisole-contaminated cocaine use. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:445-454.

- Graf J, Lynch K, Yeh CL, et al. Purpura, cutaneous necrosis, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3998-4001.

- Farmer RW, Malhotra PS, Mays MP, et al. Necrotizing peripheral vasculitis/vasculopathy following the use of cocaine laced with levamisole. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e6-e11.

- Ching JA, Smith DJ Jr. Levamisole-induced skin necrosis of skin, soft tissue, and bone: case report and review of literature. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e1-e5.

- Buchanan JA, Vogel JA, Eberhardt AM. Levamisole-induced occlusive necrotizing vasculitis of the ears after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7:83-84.

- Graff N, Whitworth K, Trigger C. Purpuric skin eruption in an illicit drug user: levamisole-induced vasculitis. Am J Emer Med. 2016;34:1321.

- Schwartz BG, Kloner RA. Drug interactions with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors used for the treatment of erectile dysfunction or pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122:88-95.

Levamisole is an immunomodulatory drug that had been used to treat various medical conditions, including parasitic infections, nephrotic syndrome, and colorectal cancer,1 before being withdrawn from the US market in 2000. The most common reasons for levamisole discontinuation were leukopenia and rashes (1%–2%),1 many of which included leg ulcers and necrotizing purpura of the ears.1,2 The drug is currently available only as a deworming agent in veterinary medicine.

Since 2007, increasing amounts of levamisole have been used as an adulterant in cocaine. In 2007, less than 10% of cocaine was contaminated with levamisole, with an increase to 77% by 2010.3 In addition, 78% of 249 urine toxicology screens that were positive for cocaine in an inner city hospital also tested positive for levamisole.4 Levamisole-cut cocaine has become a concern because it is associated with a life-threatening syndrome involving a necrotizing purpuric rash, autoantibody production, and leukopenia.5

Levamisole-induced vasculitis is an independent entity from cocaine-induced vasculitis, which is associated with skin findings ranging from palpable purpura and chronic ulcers to digital infarction secondary to its vasospastic activity.6-8 Cocaine-induced vasculopathy has been related to cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positivity and often resembles Wegener granulomatosis.6 Although both cocaine and levamisole have reportedly caused acrally distributed purpura and vasculopathy, levamisole is specifically associated with retiform purpura, ear involvement, and leukopenia.6,9 In addition, levamisole-induced skin reactions have been linked to specific antibodies, including antinuclear, antiphospholipid, and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA).2,5-7,9-14

We present a case of refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis and review its clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, laboratory findings, histology, and management. Furthermore, we discuss the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients with refractory disease or for patients who continue to use levamisole.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with a history of polysubstance abuse presented with intermittent fevers and painful swollen ears as well as joint pain of 3 weeks’ duration. One week after the lesions developed on the ears, similar lesions were seen on the legs, arms, and trunk. He admitted to cocaine use 3 weeks prior to presentation when the symptoms began.

On physical examination, violaceous patches with necrotic bleeding edges and overlying black eschars were noted on the helices, antihelices, and ear lobules bilaterally (Figure 1). Retiform, purpuric to dark brown patches, some with signs of epidermal necrosis, were scattered on the arms, legs, and chest (Figure 2).

Laboratory examination revealed renal failure, anemia of chronic disease, and thrombocytosis (Table). The patient also screened positive for lupus anticoagulant and antinuclear antibodies and had elevated p-ANCA and anti–double-stranded DNA (Table). He also had an elevated sedimentation rate (109 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (11.3 mg/dL [reference range, 0–1.0 mg/dL])(Table). Urine toxicology was positive for cocaine.

A punch biopsy of the left thigh was performed on the edge of a retiform purpuric patch. Histopathologic examination revealed epidermal necrosis with subjacent intraluminal vascular thrombi along with extravasated red blood cells and neutrophilic debris (leukocytoclasis) and fibrin in and around vessel walls, consistent with vasculitis (Figure 3).

The patient was admitted to the hospital for pain management and wound care. Despite cocaine cessation and oral prednisone taper, the lesions on the legs worsened over the next several weeks. His condition was further complicated by wound infections, nonhealing ulcers, and subjective fevers and chills requiring frequent hospitalization. The patient was managed by the dermatology department as an outpatient and in clinic between hospital visits. He was treated with antibiotics, ulcer debridement, compression wraps, and aspirin (81 mg once daily) with moderate improvement.

Ten weeks after the first visit, the patient returned with worsening and recurrent leg and ear lesions. He denied any cocaine use since the initial hospital admission; however, a toxicology screen was never obtained. It was decided that the patient would need additional treatment along with traditional trigger (cocaine) avoidance and wound care. Combined treatment with aspirin (81 mg once daily), oral prednisone (40 mg once daily), and vardenafil hydrochloride (20 mg twice weekly) was initiated. At the end of week 1, the patient began to exhibit signs of improvement, which continued over the next 4 weeks. He was then lost to follow-up.

Comment

Our patient presented with severe necrotizing cutaneous vasculitis, likely secondary to levamisole exposure. Some of our patient’s cutaneous findings may be explained exclusively on the basis of cocaine exposure, but the characteristic lesion distribution and histopathologic findings along with the evidence of autoantibody positivity and concurrent arthralgias make the combination of levamisole and cocaine a more likely cause. Similar skin lesions were first described in children treated with levamisole for nephrotic syndrome.2 The most common site of clinical involvement in these children was the ears, as seen in our patient. Our patient tested positive for p-ANCA, which is the most commonly reported autoantibody associated with this patient population. Sixty-one percent (20/33) of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis from 2 separate reviews showed p-ANCA positivity.7,10

On histopathology, our patient’s skin biopsy findings were consistent with those of prior reports of levamisole-induced vasculitis, which describe patterns of thrombotic vasculitis, leukocytoclasis, and fibrin deposition or occlusive disease.2,6,7,9-14 Mixed histologic findings of vasculitis and thrombosis, usually with varying ages of thrombi, are characteristic of levamisole-induced purpura. In addition, the disease can present nonspecifically with pure microvascular thrombosis without vasculitis, especially later in the course.9

The recommended management of levamisole-induced vasculitis currently involves the withdrawal of the culprit adulterated cocaine along with supportive treatment. Spontaneous and complete clinical resolution of lesions has been reported within 2 to 3 weeks and serology normalization within 2 to 14 months of levamisole cessation.2,6 A 2011 review of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis reported 66% (19/29) of cases with either full cutaneous resolution after levamisole withdrawal or recurrence with resumed use, supporting a causal relationship.7 Walsh et al9 described 2 patients with recurrent and exacerbated retiform purpura following cocaine binges. Both of these patients had urine samples that tested positive for levamisole.9 In more severe cases, medications shown to be effective include colchicine, polidocanol, antibiotics, methotrexate, anticoagulants, and most commonly systemic corticosteroids.7,10,11,15 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were successful in treating lesions in 2 patients with concurrent arthralgia.7 Rarely, patients have required surgical debridement or skin grafting due to advanced disease at initial presentation.9,12-14 One of the most severe cases of levamisole-induced vasculitis reported in the literature involved 52% of the patient’s total body surface area with skin, soft tissue, and bony necrosis requiring nasal amputation, upper lip excision, skin grafting, and extremity amputation.14 Another severe case with widespread skin involvement was recently reported.16

For unclear reasons, our patient continued to develop cutaneous lesions despite self-reported cocaine cessation. Complete resolution required the combination of vardenafil, prednisone, and aspirin, along with debridement and wound care. Vardenafil, a selective phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor, enhances the effect of nitrous oxide by increasing levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate,17 which results in smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilatation. The primary indication for vardenafil is the treatment of erectile dysfunction, but it often is used off label in diseases that may benefit from vasodilatation. Because of its mechanism of action, it is understandable that a vasodilator such as vardenafil could be therapeutic in a condition associated with thrombosis. Moreover, the autoinflammatory nature of levamisole-induced vasculitis makes corticosteroid treatment effective. Given the 10-week delay in improvement, we suspect that it was the combination of treatment or an individual agent that led to our patient’s eventual recovery.

There are few reports in the literature focusing on optimal treatment of levamisole-induced vasculitis and none that mention alternative management for patients who continue to develop new lesions despite cocaine avoidance. Although the discontinuation of levamisole seems to be imperative for resolution of cutaneous lesions, it may not always be enough. It is possible that there is a subpopulation of patients that may not respond to the simple withdrawal of cocaine. It also should be mentioned that there was no urine toxicology screen obtained to support our patient’s reported cocaine cessation. Therefore, it is possible that his worsening condition was secondary to continued cocaine use. However, the patient successfully responded to the combination of vardenafil and prednisone, regardless of whether his condition persisted due to continued use of cocaine or not. This case suggests the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients who continue to use levamisole despite instruction for cessation or for patients with refractory disease.

Conclusion

A trial of prednisone and vardenafil should be considered for patients with refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis. Further studies and discussions of disease course are needed to identify the best treatment of this skin condition, especially for patients with refractory lesions.

Levamisole is an immunomodulatory drug that had been used to treat various medical conditions, including parasitic infections, nephrotic syndrome, and colorectal cancer,1 before being withdrawn from the US market in 2000. The most common reasons for levamisole discontinuation were leukopenia and rashes (1%–2%),1 many of which included leg ulcers and necrotizing purpura of the ears.1,2 The drug is currently available only as a deworming agent in veterinary medicine.

Since 2007, increasing amounts of levamisole have been used as an adulterant in cocaine. In 2007, less than 10% of cocaine was contaminated with levamisole, with an increase to 77% by 2010.3 In addition, 78% of 249 urine toxicology screens that were positive for cocaine in an inner city hospital also tested positive for levamisole.4 Levamisole-cut cocaine has become a concern because it is associated with a life-threatening syndrome involving a necrotizing purpuric rash, autoantibody production, and leukopenia.5

Levamisole-induced vasculitis is an independent entity from cocaine-induced vasculitis, which is associated with skin findings ranging from palpable purpura and chronic ulcers to digital infarction secondary to its vasospastic activity.6-8 Cocaine-induced vasculopathy has been related to cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positivity and often resembles Wegener granulomatosis.6 Although both cocaine and levamisole have reportedly caused acrally distributed purpura and vasculopathy, levamisole is specifically associated with retiform purpura, ear involvement, and leukopenia.6,9 In addition, levamisole-induced skin reactions have been linked to specific antibodies, including antinuclear, antiphospholipid, and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA).2,5-7,9-14

We present a case of refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis and review its clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, laboratory findings, histology, and management. Furthermore, we discuss the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients with refractory disease or for patients who continue to use levamisole.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with a history of polysubstance abuse presented with intermittent fevers and painful swollen ears as well as joint pain of 3 weeks’ duration. One week after the lesions developed on the ears, similar lesions were seen on the legs, arms, and trunk. He admitted to cocaine use 3 weeks prior to presentation when the symptoms began.

On physical examination, violaceous patches with necrotic bleeding edges and overlying black eschars were noted on the helices, antihelices, and ear lobules bilaterally (Figure 1). Retiform, purpuric to dark brown patches, some with signs of epidermal necrosis, were scattered on the arms, legs, and chest (Figure 2).

Laboratory examination revealed renal failure, anemia of chronic disease, and thrombocytosis (Table). The patient also screened positive for lupus anticoagulant and antinuclear antibodies and had elevated p-ANCA and anti–double-stranded DNA (Table). He also had an elevated sedimentation rate (109 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (11.3 mg/dL [reference range, 0–1.0 mg/dL])(Table). Urine toxicology was positive for cocaine.

A punch biopsy of the left thigh was performed on the edge of a retiform purpuric patch. Histopathologic examination revealed epidermal necrosis with subjacent intraluminal vascular thrombi along with extravasated red blood cells and neutrophilic debris (leukocytoclasis) and fibrin in and around vessel walls, consistent with vasculitis (Figure 3).

The patient was admitted to the hospital for pain management and wound care. Despite cocaine cessation and oral prednisone taper, the lesions on the legs worsened over the next several weeks. His condition was further complicated by wound infections, nonhealing ulcers, and subjective fevers and chills requiring frequent hospitalization. The patient was managed by the dermatology department as an outpatient and in clinic between hospital visits. He was treated with antibiotics, ulcer debridement, compression wraps, and aspirin (81 mg once daily) with moderate improvement.

Ten weeks after the first visit, the patient returned with worsening and recurrent leg and ear lesions. He denied any cocaine use since the initial hospital admission; however, a toxicology screen was never obtained. It was decided that the patient would need additional treatment along with traditional trigger (cocaine) avoidance and wound care. Combined treatment with aspirin (81 mg once daily), oral prednisone (40 mg once daily), and vardenafil hydrochloride (20 mg twice weekly) was initiated. At the end of week 1, the patient began to exhibit signs of improvement, which continued over the next 4 weeks. He was then lost to follow-up.

Comment

Our patient presented with severe necrotizing cutaneous vasculitis, likely secondary to levamisole exposure. Some of our patient’s cutaneous findings may be explained exclusively on the basis of cocaine exposure, but the characteristic lesion distribution and histopathologic findings along with the evidence of autoantibody positivity and concurrent arthralgias make the combination of levamisole and cocaine a more likely cause. Similar skin lesions were first described in children treated with levamisole for nephrotic syndrome.2 The most common site of clinical involvement in these children was the ears, as seen in our patient. Our patient tested positive for p-ANCA, which is the most commonly reported autoantibody associated with this patient population. Sixty-one percent (20/33) of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis from 2 separate reviews showed p-ANCA positivity.7,10

On histopathology, our patient’s skin biopsy findings were consistent with those of prior reports of levamisole-induced vasculitis, which describe patterns of thrombotic vasculitis, leukocytoclasis, and fibrin deposition or occlusive disease.2,6,7,9-14 Mixed histologic findings of vasculitis and thrombosis, usually with varying ages of thrombi, are characteristic of levamisole-induced purpura. In addition, the disease can present nonspecifically with pure microvascular thrombosis without vasculitis, especially later in the course.9

The recommended management of levamisole-induced vasculitis currently involves the withdrawal of the culprit adulterated cocaine along with supportive treatment. Spontaneous and complete clinical resolution of lesions has been reported within 2 to 3 weeks and serology normalization within 2 to 14 months of levamisole cessation.2,6 A 2011 review of patients with levamisole-induced vasculitis reported 66% (19/29) of cases with either full cutaneous resolution after levamisole withdrawal or recurrence with resumed use, supporting a causal relationship.7 Walsh et al9 described 2 patients with recurrent and exacerbated retiform purpura following cocaine binges. Both of these patients had urine samples that tested positive for levamisole.9 In more severe cases, medications shown to be effective include colchicine, polidocanol, antibiotics, methotrexate, anticoagulants, and most commonly systemic corticosteroids.7,10,11,15 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were successful in treating lesions in 2 patients with concurrent arthralgia.7 Rarely, patients have required surgical debridement or skin grafting due to advanced disease at initial presentation.9,12-14 One of the most severe cases of levamisole-induced vasculitis reported in the literature involved 52% of the patient’s total body surface area with skin, soft tissue, and bony necrosis requiring nasal amputation, upper lip excision, skin grafting, and extremity amputation.14 Another severe case with widespread skin involvement was recently reported.16

For unclear reasons, our patient continued to develop cutaneous lesions despite self-reported cocaine cessation. Complete resolution required the combination of vardenafil, prednisone, and aspirin, along with debridement and wound care. Vardenafil, a selective phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor, enhances the effect of nitrous oxide by increasing levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate,17 which results in smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilatation. The primary indication for vardenafil is the treatment of erectile dysfunction, but it often is used off label in diseases that may benefit from vasodilatation. Because of its mechanism of action, it is understandable that a vasodilator such as vardenafil could be therapeutic in a condition associated with thrombosis. Moreover, the autoinflammatory nature of levamisole-induced vasculitis makes corticosteroid treatment effective. Given the 10-week delay in improvement, we suspect that it was the combination of treatment or an individual agent that led to our patient’s eventual recovery.

There are few reports in the literature focusing on optimal treatment of levamisole-induced vasculitis and none that mention alternative management for patients who continue to develop new lesions despite cocaine avoidance. Although the discontinuation of levamisole seems to be imperative for resolution of cutaneous lesions, it may not always be enough. It is possible that there is a subpopulation of patients that may not respond to the simple withdrawal of cocaine. It also should be mentioned that there was no urine toxicology screen obtained to support our patient’s reported cocaine cessation. Therefore, it is possible that his worsening condition was secondary to continued cocaine use. However, the patient successfully responded to the combination of vardenafil and prednisone, regardless of whether his condition persisted due to continued use of cocaine or not. This case suggests the possibility of a new treatment option for levamisole-induced vasculitis for patients who continue to use levamisole despite instruction for cessation or for patients with refractory disease.

Conclusion

A trial of prednisone and vardenafil should be considered for patients with refractory levamisole-induced vasculitis. Further studies and discussions of disease course are needed to identify the best treatment of this skin condition, especially for patients with refractory lesions.

- Scheinfeld N, Rosenberg JD, Weinberg JM. Levamisole in dermatology: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:97-104.

- Rongioletti F, Ghio L, Ginevri F, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948-951.

- National Drug Threat Assessment 2011. US Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center website. https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44849/44849p.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed August 7, 2016.

- Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

- Gross RL, Brucker J, Bahce-Altuntas A, et al. A novel cutaneous vasculitis syndrome induced by levamisole-contaminated cocaine. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1385-1392.

- Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

- Poon SH, Baliog CR, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leukopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

- Brewer JD, Meves A, Bostwick JM, et al. Cocaine abuse: dermatologic manifestations and therapeutic approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:483-487.

- Walsh NMG, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia—a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole adultered cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

- Kahn TA, Cuchacovich R, Espinoza LR, et al. Vasculopathy, hematological, and immune abnormalities associated with levamisole-contaminated cocaine use. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:445-454.

- Graf J, Lynch K, Yeh CL, et al. Purpura, cutaneous necrosis, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3998-4001.

- Farmer RW, Malhotra PS, Mays MP, et al. Necrotizing peripheral vasculitis/vasculopathy following the use of cocaine laced with levamisole. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e6-e11.

- Ching JA, Smith DJ Jr. Levamisole-induced skin necrosis of skin, soft tissue, and bone: case report and review of literature. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e1-e5.

- Buchanan JA, Vogel JA, Eberhardt AM. Levamisole-induced occlusive necrotizing vasculitis of the ears after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7:83-84.

- Graff N, Whitworth K, Trigger C. Purpuric skin eruption in an illicit drug user: levamisole-induced vasculitis. Am J Emer Med. 2016;34:1321.

- Schwartz BG, Kloner RA. Drug interactions with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors used for the treatment of erectile dysfunction or pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122:88-95.

- Scheinfeld N, Rosenberg JD, Weinberg JM. Levamisole in dermatology: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:97-104.

- Rongioletti F, Ghio L, Ginevri F, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948-951.

- National Drug Threat Assessment 2011. US Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center website. https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44849/44849p.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed August 7, 2016.

- Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

- Gross RL, Brucker J, Bahce-Altuntas A, et al. A novel cutaneous vasculitis syndrome induced by levamisole-contaminated cocaine. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1385-1392.

- Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530-535.

- Poon SH, Baliog CR, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leukopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

- Brewer JD, Meves A, Bostwick JM, et al. Cocaine abuse: dermatologic manifestations and therapeutic approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:483-487.

- Walsh NMG, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia—a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole adultered cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:722-725.

- Kahn TA, Cuchacovich R, Espinoza LR, et al. Vasculopathy, hematological, and immune abnormalities associated with levamisole-contaminated cocaine use. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:445-454.

- Graf J, Lynch K, Yeh CL, et al. Purpura, cutaneous necrosis, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3998-4001.

- Farmer RW, Malhotra PS, Mays MP, et al. Necrotizing peripheral vasculitis/vasculopathy following the use of cocaine laced with levamisole. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e6-e11.

- Ching JA, Smith DJ Jr. Levamisole-induced skin necrosis of skin, soft tissue, and bone: case report and review of literature. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e1-e5.

- Buchanan JA, Vogel JA, Eberhardt AM. Levamisole-induced occlusive necrotizing vasculitis of the ears after use of cocaine contaminated with levamisole. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7:83-84.

- Graff N, Whitworth K, Trigger C. Purpuric skin eruption in an illicit drug user: levamisole-induced vasculitis. Am J Emer Med. 2016;34:1321.

- Schwartz BG, Kloner RA. Drug interactions with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors used for the treatment of erectile dysfunction or pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122:88-95.

Practice Points

- Levamisole is an immunomodulatory drug that, before being withdrawn from the US market in 2000, was previously used to treat various medical conditions.

- A majority of the cocaine in the United States is contaminated with levamisole, which is added as an adulterant or bulking agent.

- Levamisole-cut cocaine is a concern because it is associated with a life-threatening syndrome involving a necrotizing purpuric rash, autoantibody production, and leukopenia.

- Although treatment of levamisole toxicity is primarily supportive and includes cessation of levamisole-cut cocaine, a trial of prednisone and vardenafil hydrochloride can be considered for refractory levamisole-induced vasculopathy or for patients who continue to use the drug.