User login

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

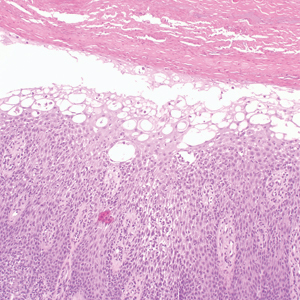

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

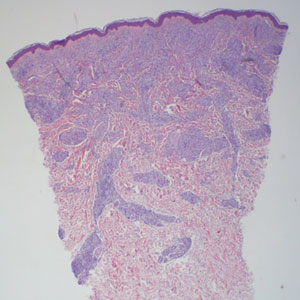

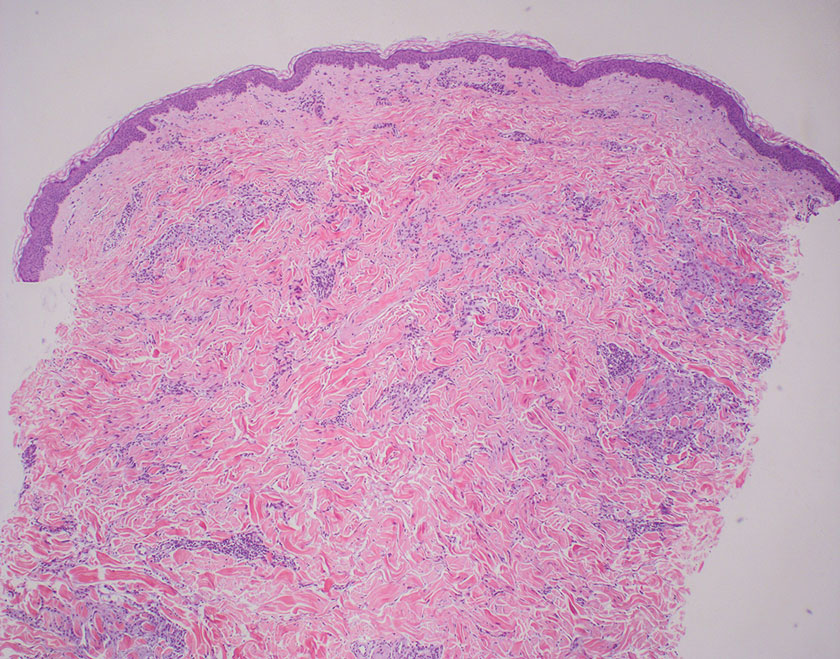

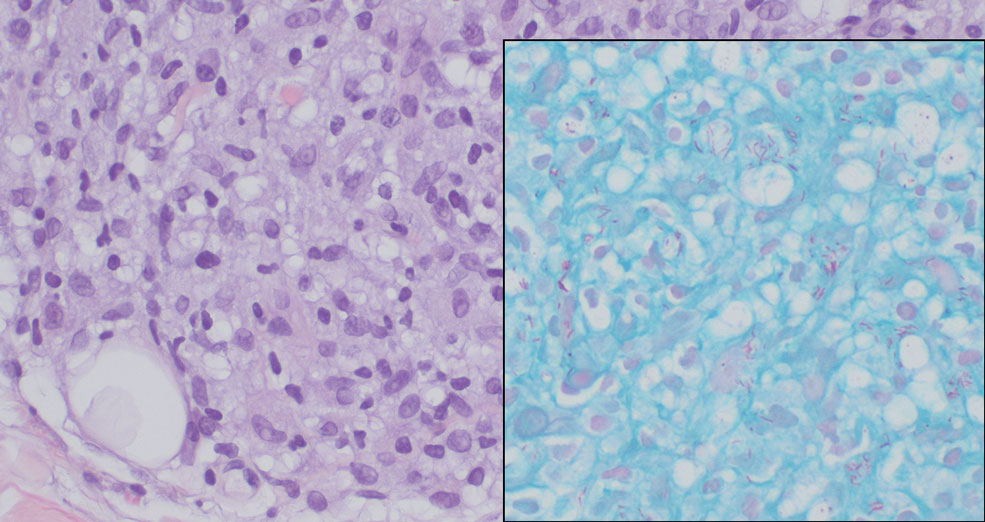

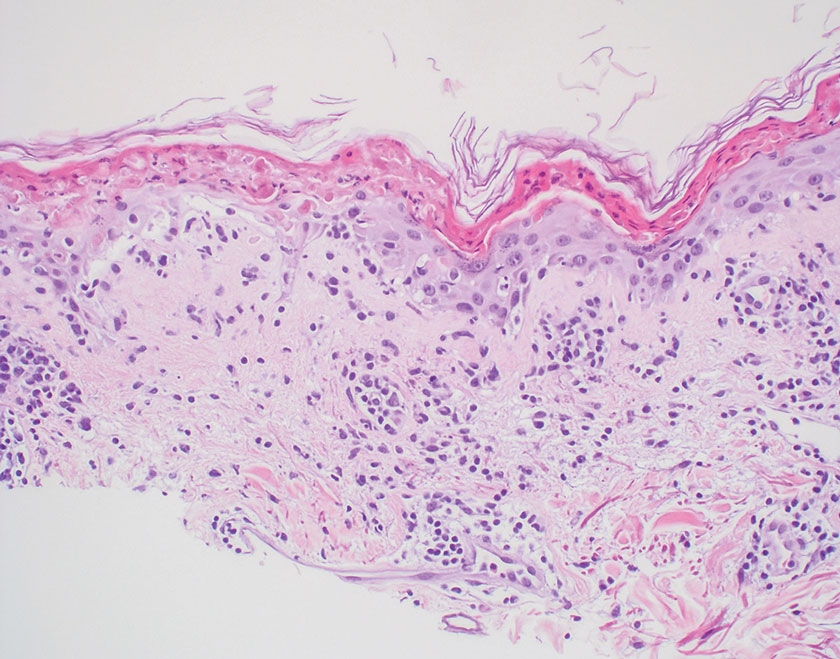

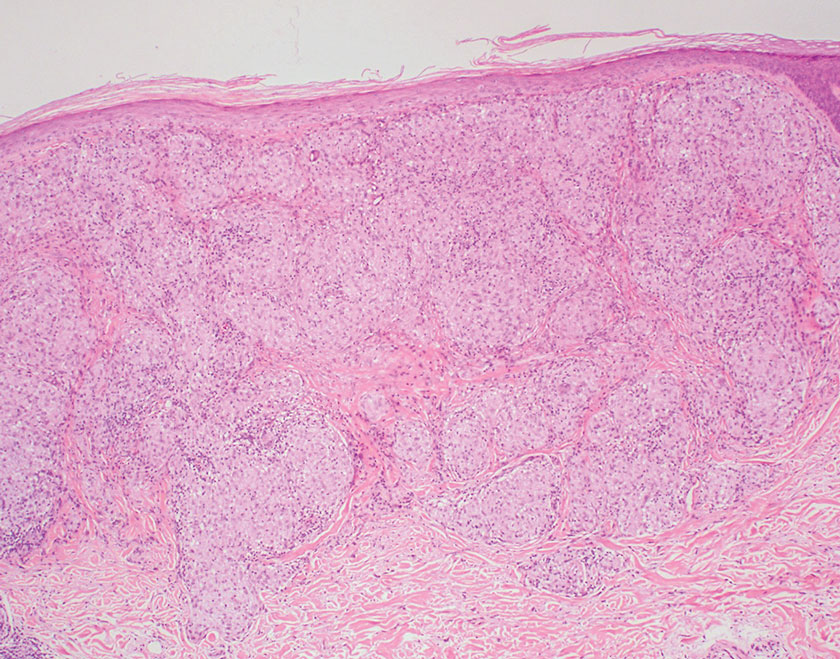

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

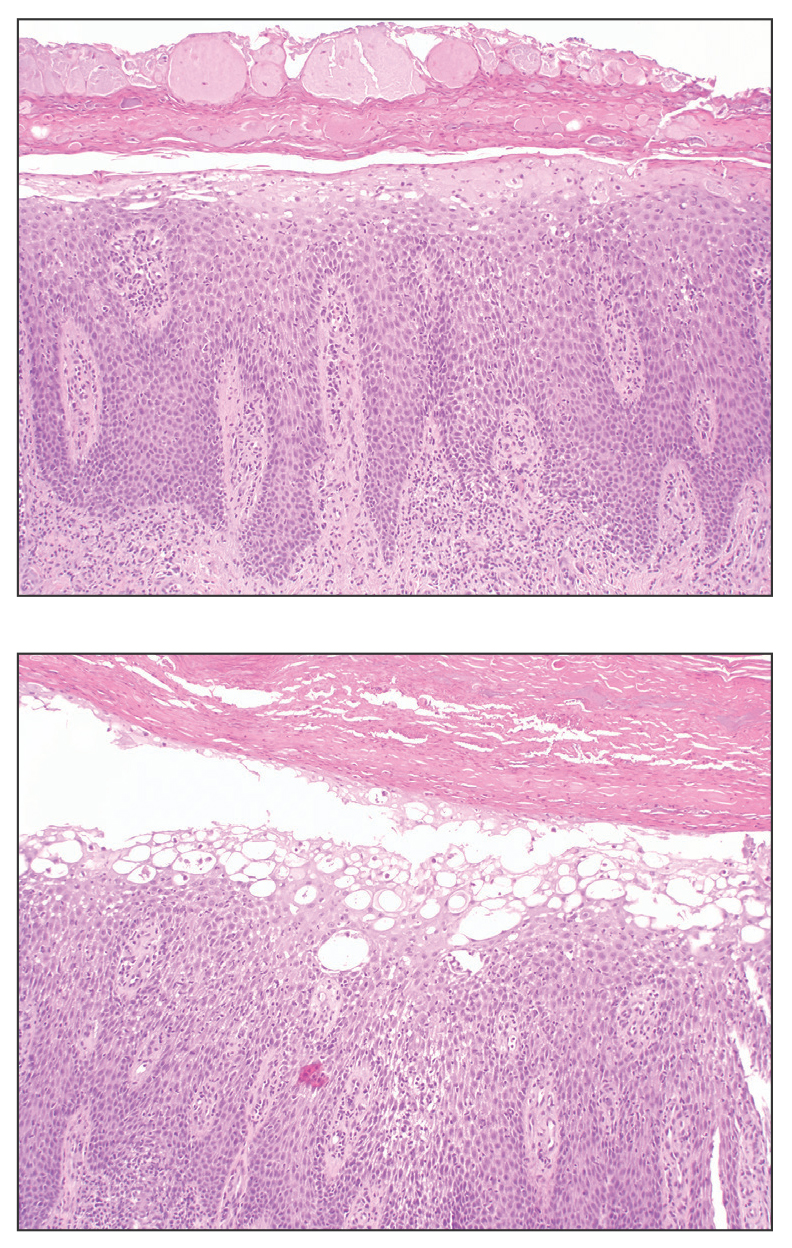

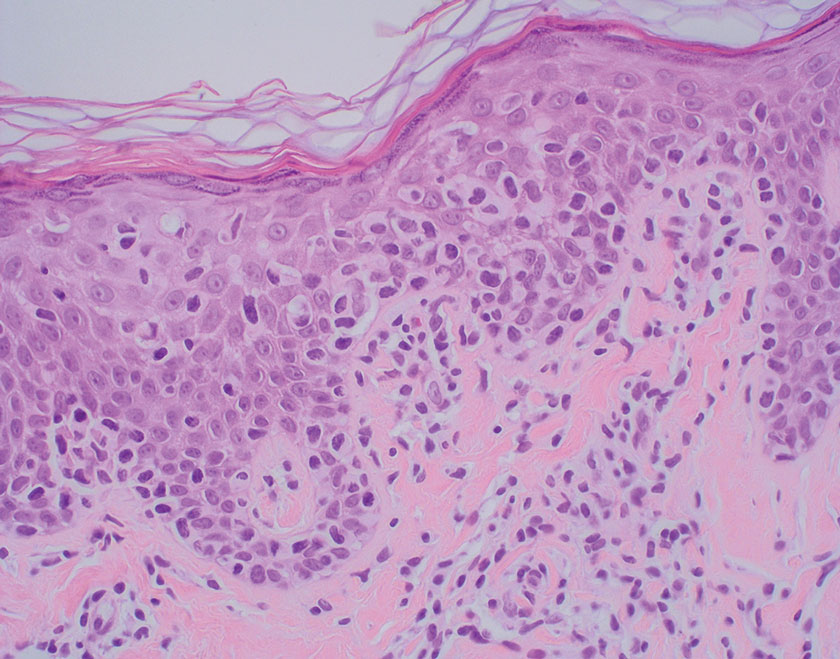

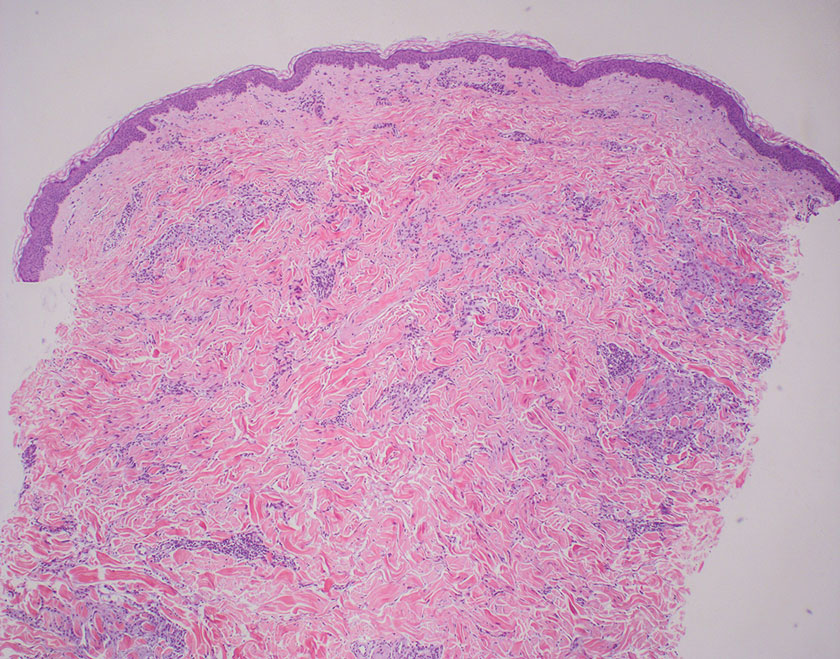

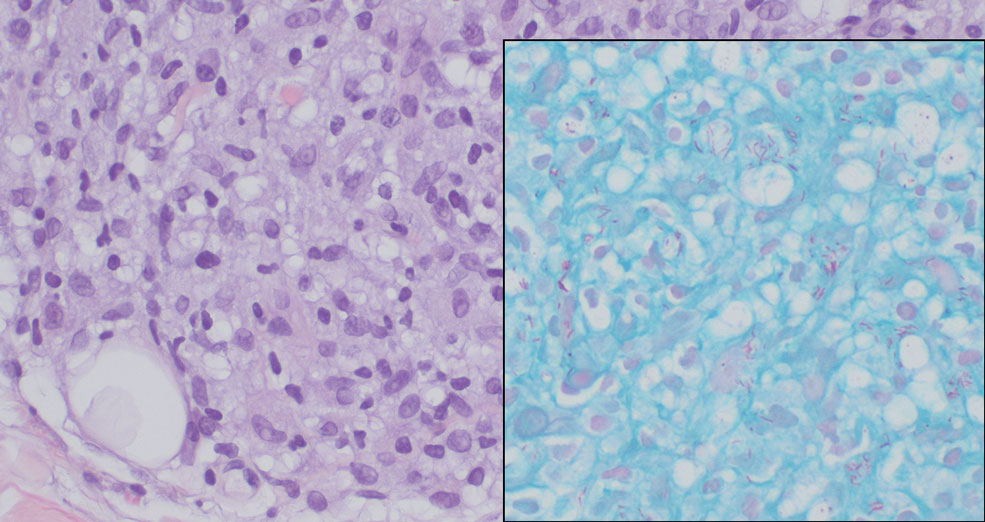

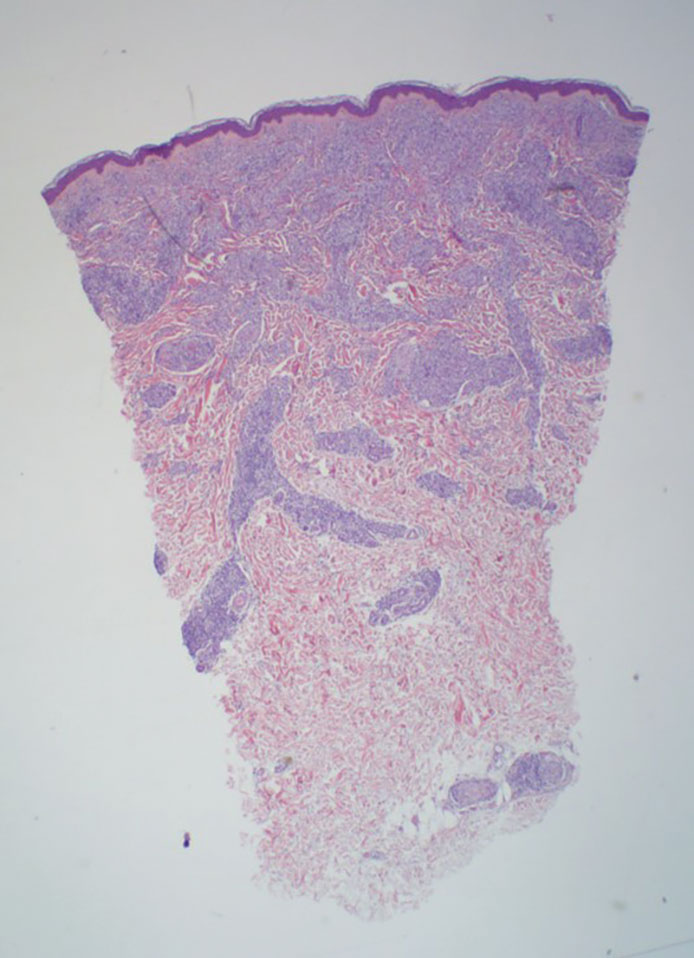

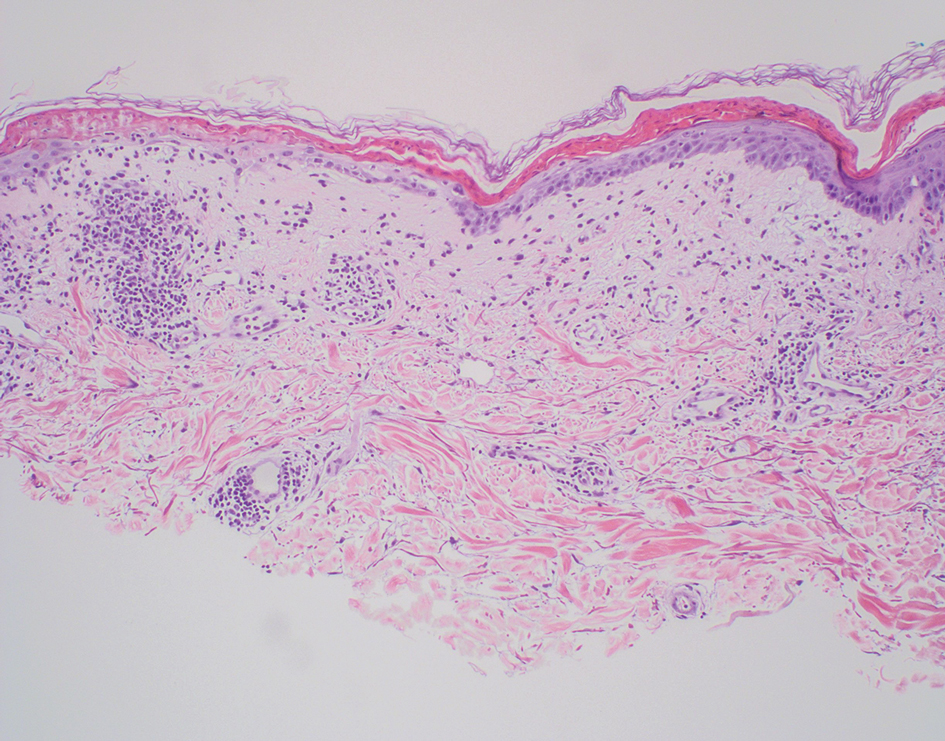

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

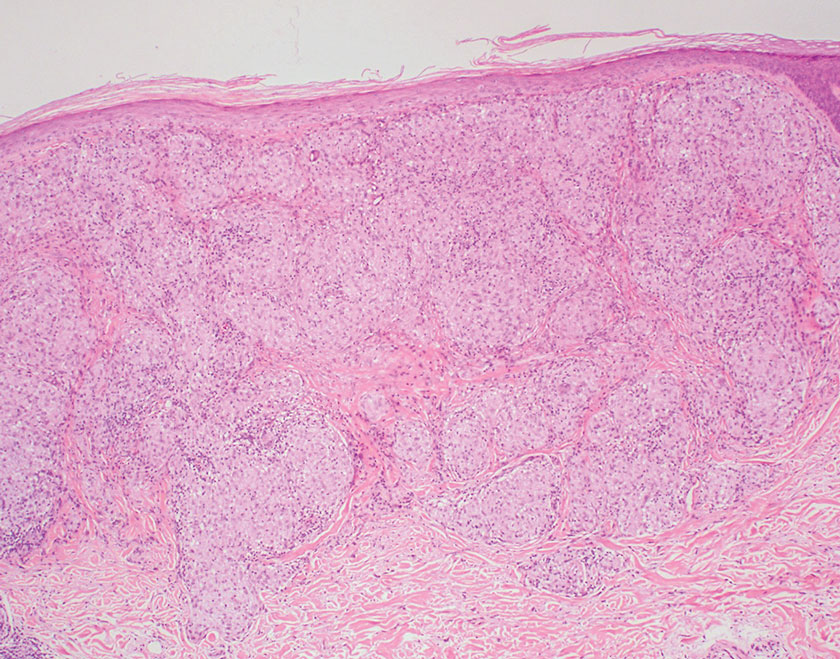

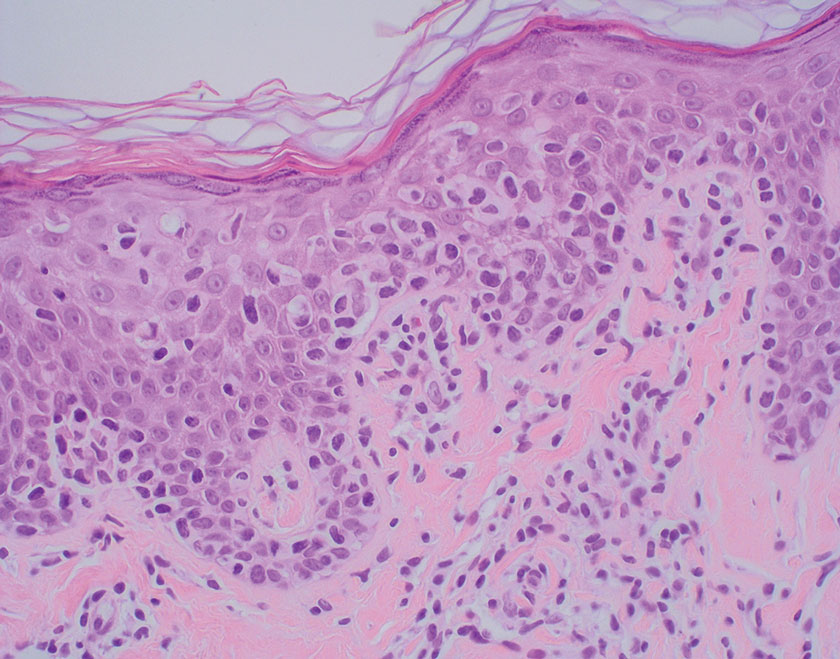

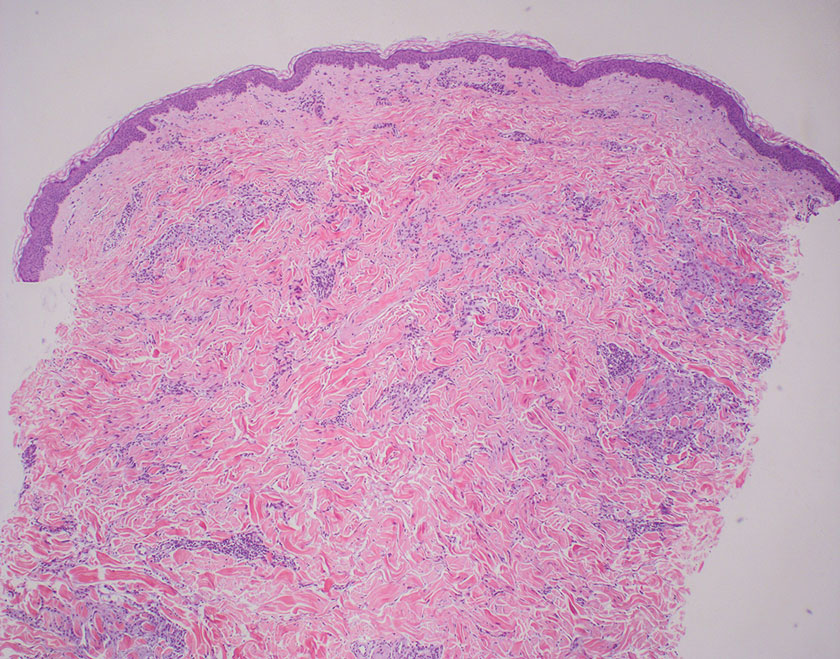

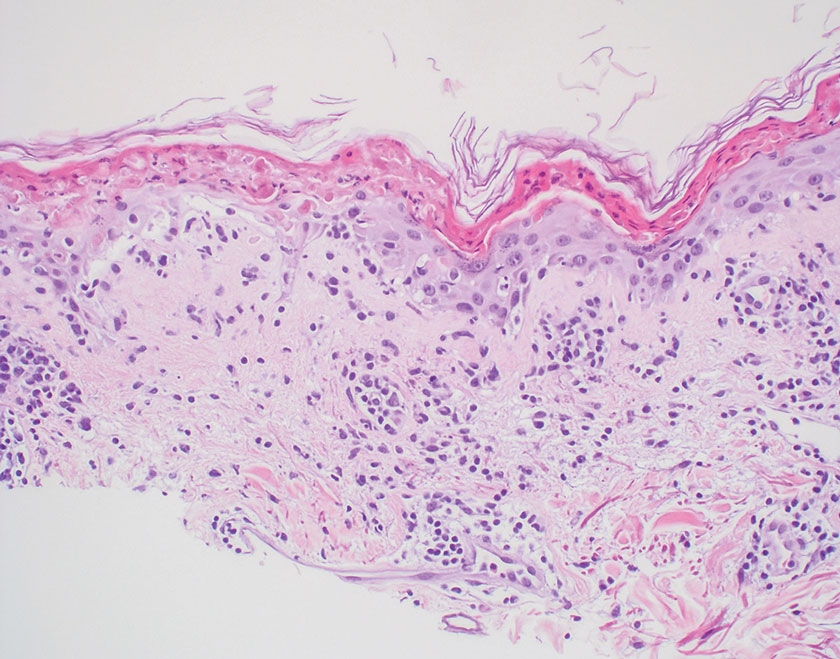

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

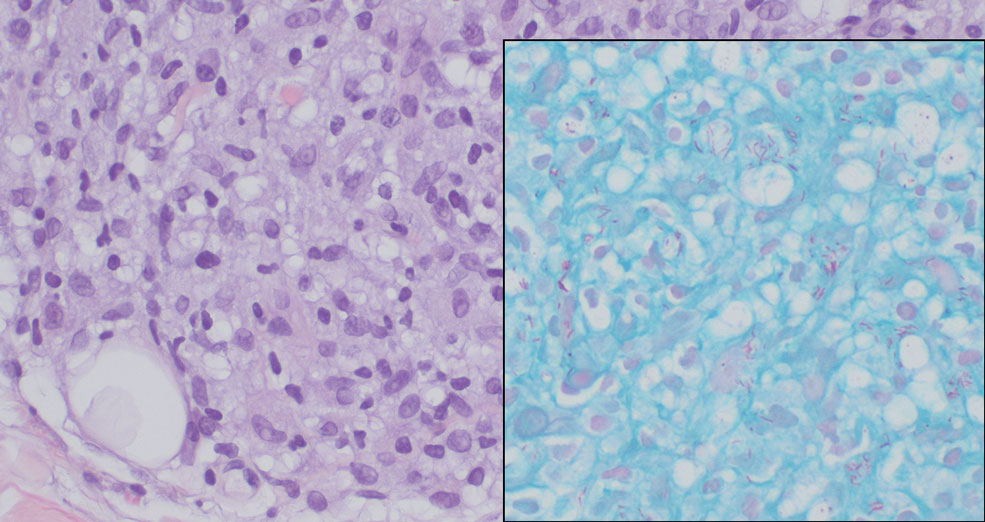

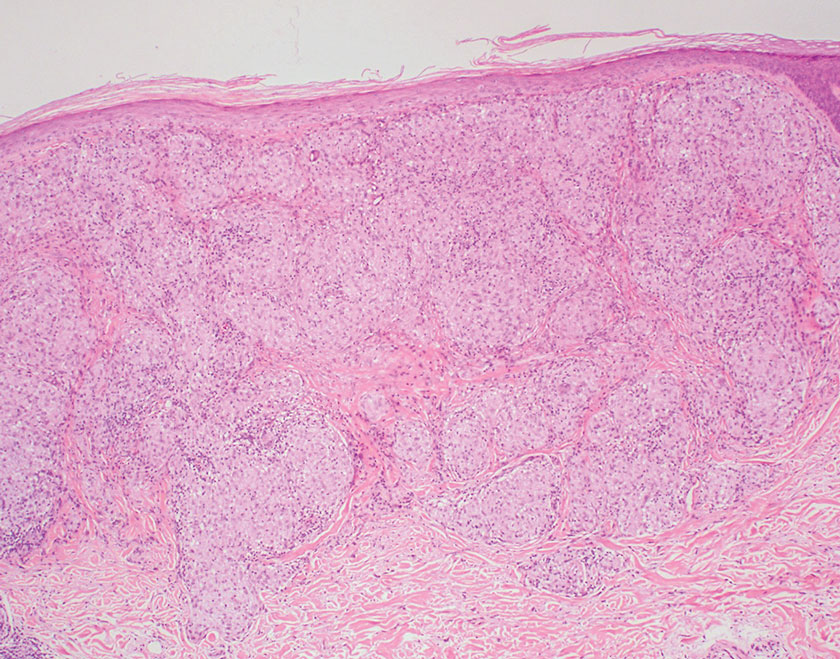

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

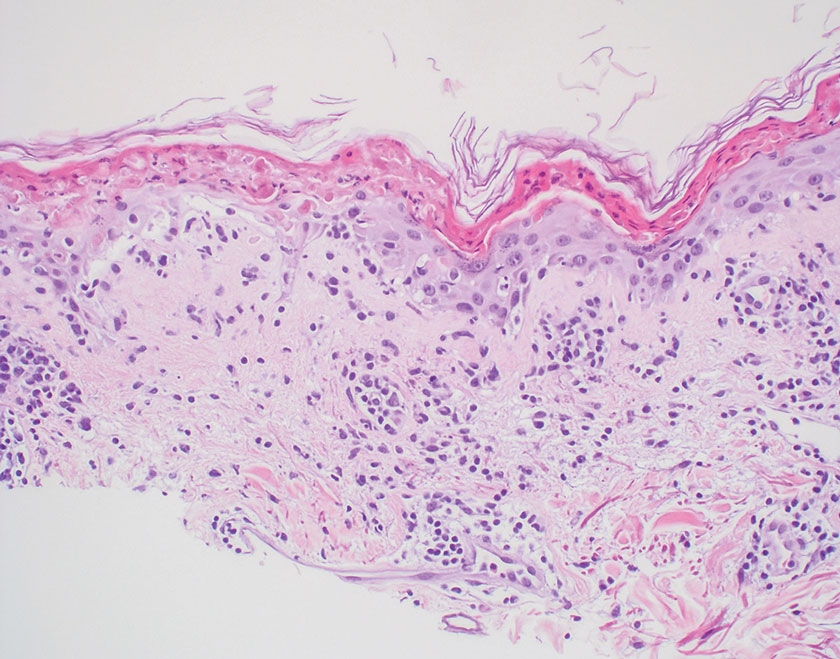

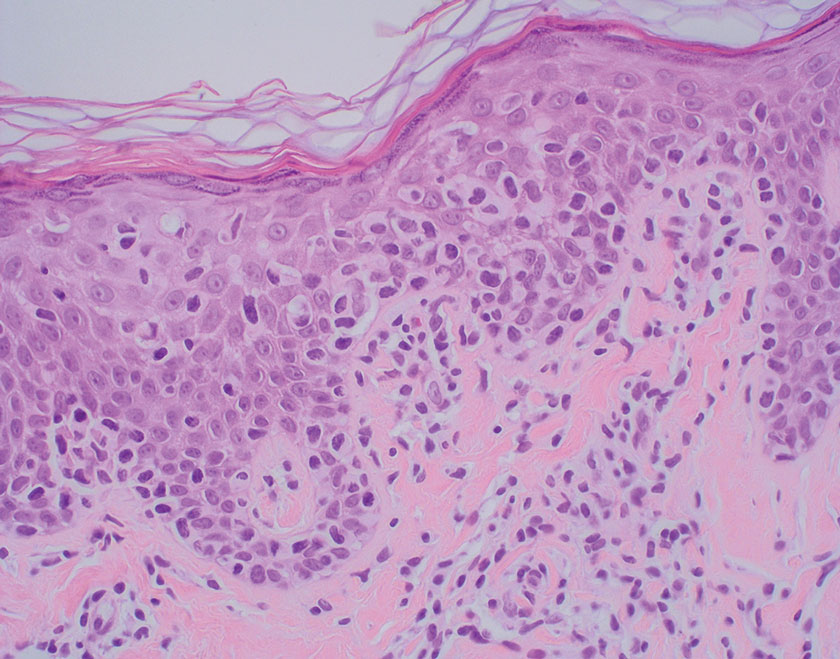

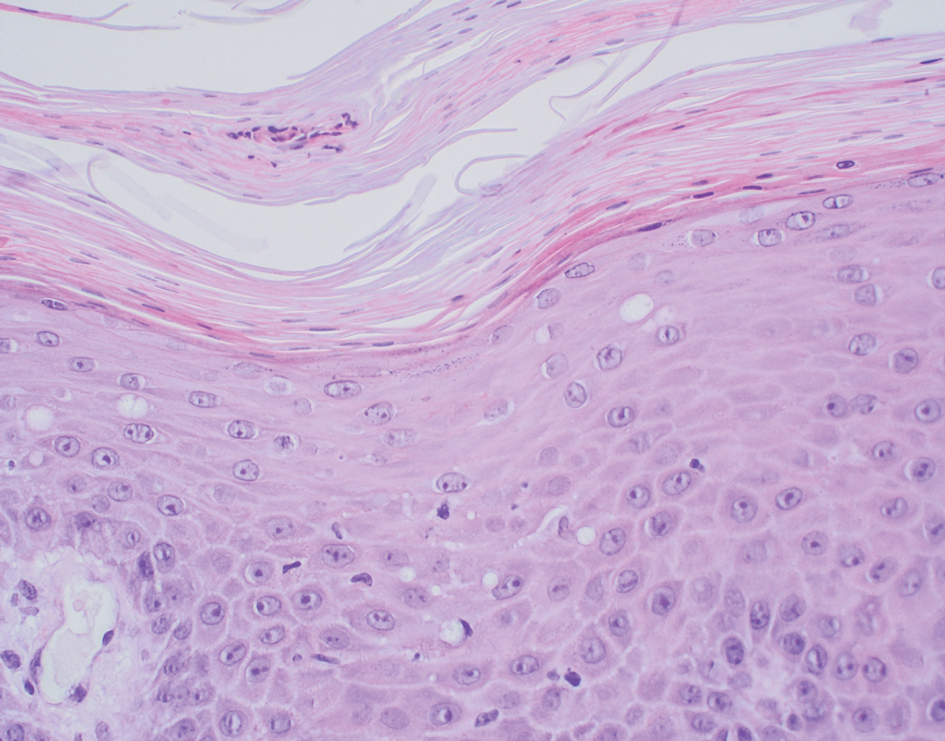

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E2773. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0002773

- Fischer M. Leprosy–an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827. doi:10.1111/ddg.13301

- Jolly M, Pickard SA, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Lupus QoL-US benchmarks for US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1828-1833. doi:10.3899/jrheum.091443

- Chan MMF, Smoller BR. Overview of the histopathology and other laboratory investigations in leprosy. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:131-137. doi:10.1007/s40475-016-0086-y

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of generalized granuloma annulare–a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1467-1480. doi:10.1111/jdv.12976

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933- 951. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohidrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:686. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.72470

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the cutaneous lymphoma histopathology task force group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.46

- Miyashiro D, Cardona C, Valente N, et al. Ulcers in leprosy patients, an unrecognized clinical manifestation: a report of 8 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4639-2

- Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:2-10. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.002

- Jain R, Yadav D, Puranik N, et al. Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1081. doi:10.3390 /jcm9041081

- Zÿ ychowska M, Reich A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4088. doi:10.3390/jcm11144088

- Lazar AL. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a facultative paraneoplastic dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:728-742. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2022.07.007

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

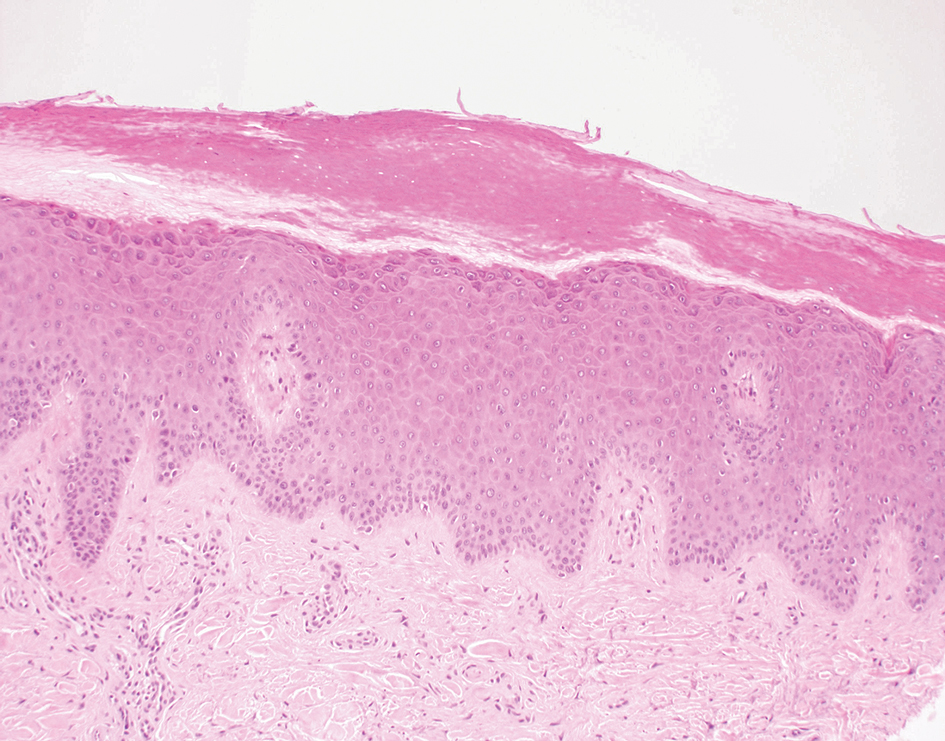

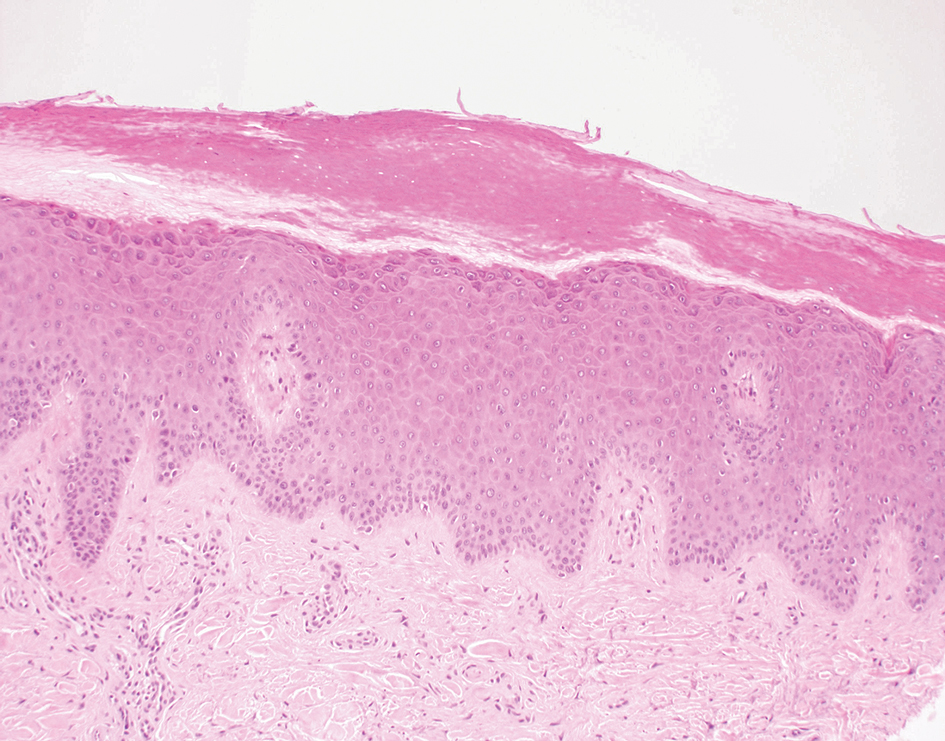

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

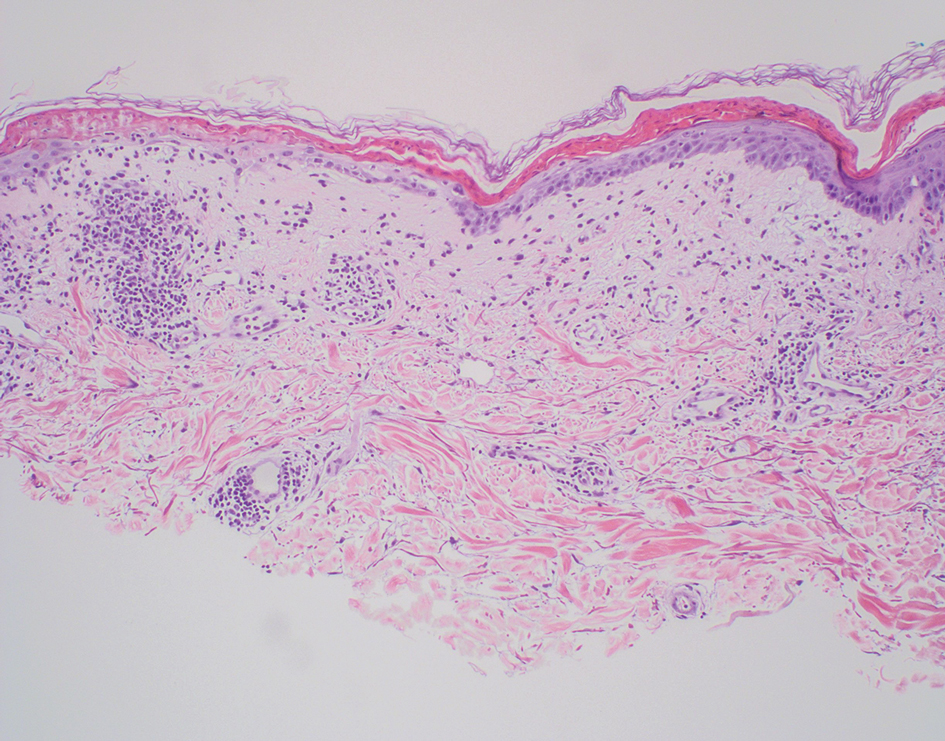

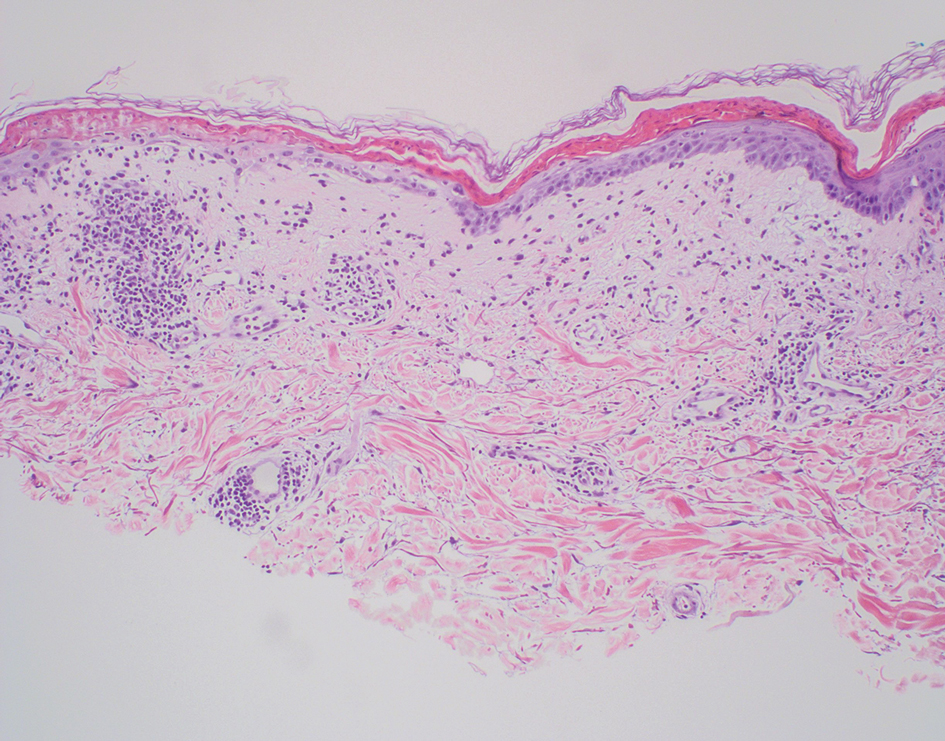

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

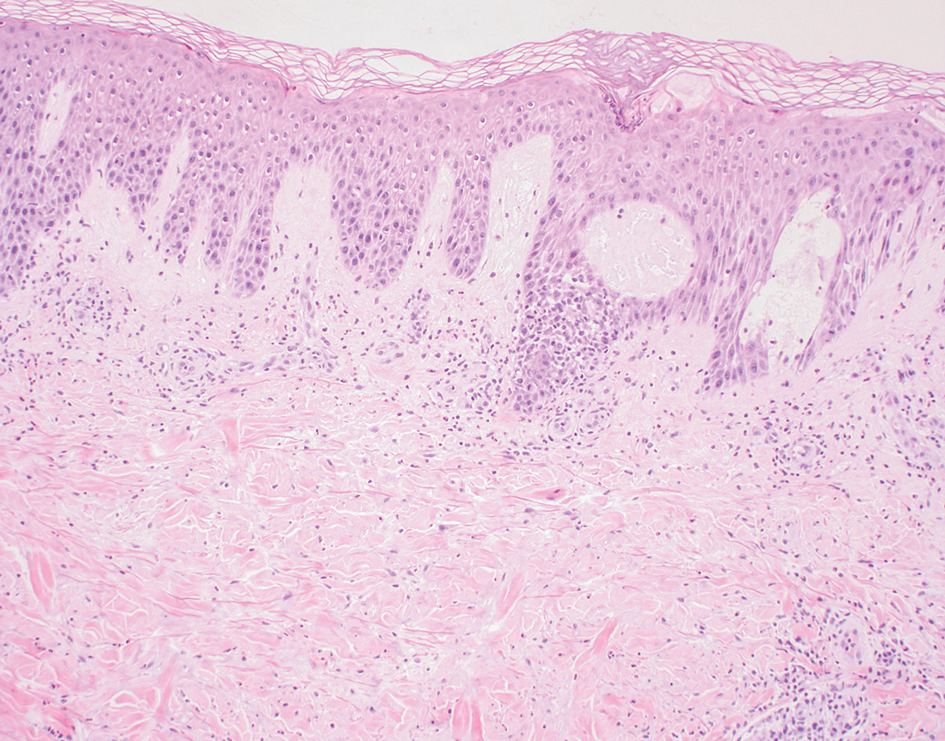

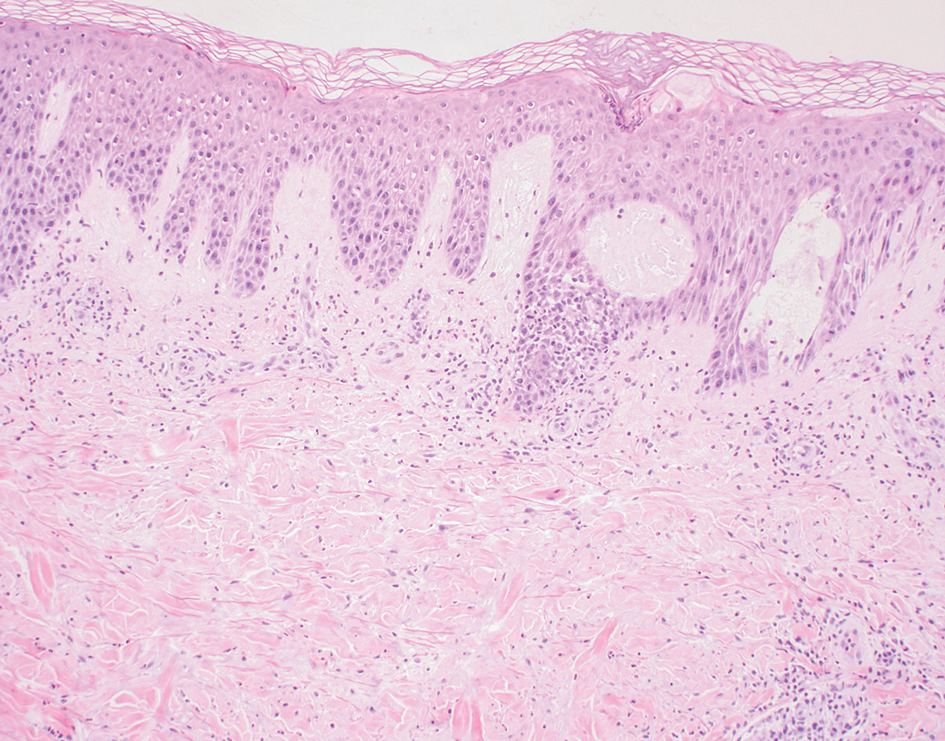

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E2773. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0002773

- Fischer M. Leprosy–an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827. doi:10.1111/ddg.13301

- Jolly M, Pickard SA, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Lupus QoL-US benchmarks for US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1828-1833. doi:10.3899/jrheum.091443

- Chan MMF, Smoller BR. Overview of the histopathology and other laboratory investigations in leprosy. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:131-137. doi:10.1007/s40475-016-0086-y

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of generalized granuloma annulare–a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1467-1480. doi:10.1111/jdv.12976

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933- 951. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohidrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:686. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.72470

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the cutaneous lymphoma histopathology task force group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.46

- Miyashiro D, Cardona C, Valente N, et al. Ulcers in leprosy patients, an unrecognized clinical manifestation: a report of 8 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4639-2

- Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:2-10. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.002

- Jain R, Yadav D, Puranik N, et al. Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1081. doi:10.3390 /jcm9041081

- Zÿ ychowska M, Reich A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4088. doi:10.3390/jcm11144088

- Lazar AL. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a facultative paraneoplastic dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:728-742. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2022.07.007

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E2773. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0002773

- Fischer M. Leprosy–an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827. doi:10.1111/ddg.13301

- Jolly M, Pickard SA, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Lupus QoL-US benchmarks for US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1828-1833. doi:10.3899/jrheum.091443

- Chan MMF, Smoller BR. Overview of the histopathology and other laboratory investigations in leprosy. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:131-137. doi:10.1007/s40475-016-0086-y

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of generalized granuloma annulare–a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1467-1480. doi:10.1111/jdv.12976

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933- 951. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohidrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:686. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.72470

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the cutaneous lymphoma histopathology task force group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.46

- Miyashiro D, Cardona C, Valente N, et al. Ulcers in leprosy patients, an unrecognized clinical manifestation: a report of 8 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4639-2

- Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:2-10. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.002

- Jain R, Yadav D, Puranik N, et al. Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1081. doi:10.3390 /jcm9041081

- Zÿ ychowska M, Reich A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4088. doi:10.3390/jcm11144088

- Lazar AL. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a facultative paraneoplastic dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:728-742. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2022.07.007

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

A 44-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a widespread red, itchy, bumpy rash of 1 year’s duration. Physical examination revealed smooth, coalescing, erythematous and edematous plaques on the face (notably the forehead, malar cheeks, and nose), back, arms, and legs. Several plaques on the back had central hypopigmentation. The patient also reported numbness and weakness in the fingers and toes, and hypoesthesia within the lesions was noted. A biopsy of one of the lesions on the left ventral forearm was performed.

Erythematous Flaky Rash on the Toe

The Diagnosis: Necrolytic Migratory Erythema

Necrolytic migratory erythema (NME) is a waxing and waning rash associated with rare pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors called glucagonomas. It is characterized by pruritic and painful, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques that manifest in the intertriginous areas and on the perineum and buttocks.1 Due to the evolving nature of the rash, the histopathologic findings in NME vary depending on the stage of the cutaneous lesions at the time of biopsy.2 Multiple dyskeratotic keratinocytes spanning all epidermal layers may be a diagnostic clue in early lesions of NME.3 Typical features of longstanding lesions include confluent parakeratosis, psoriasiform hyperplasia with mild or absent spongiosis, and upper epidermal necrosis with keratinocyte vacuolization and pallor.4 Morphologic features that are present prior to the development of epidermal vacuolation and necrosis frequently are misattributed to psoriasis or eczema. Long-standing lesions also may develop a neutrophilic infiltrate with subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules.2 Other common features include a discrete perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and an erosive or encrusted epidermis.5 Although direct immunofluorescence typically is negative, nonspecific findings can be seen, including apoptotic keratinocytes labeling with fibrinogen and C3, as well as scattered, clumped, IgM-positive cytoid bodies present at the dermal-epidermal junction (DEJ).6 Biopsies also have shown scattered, clumped, IgM-positive cytoid bodies present at the DEJ.5

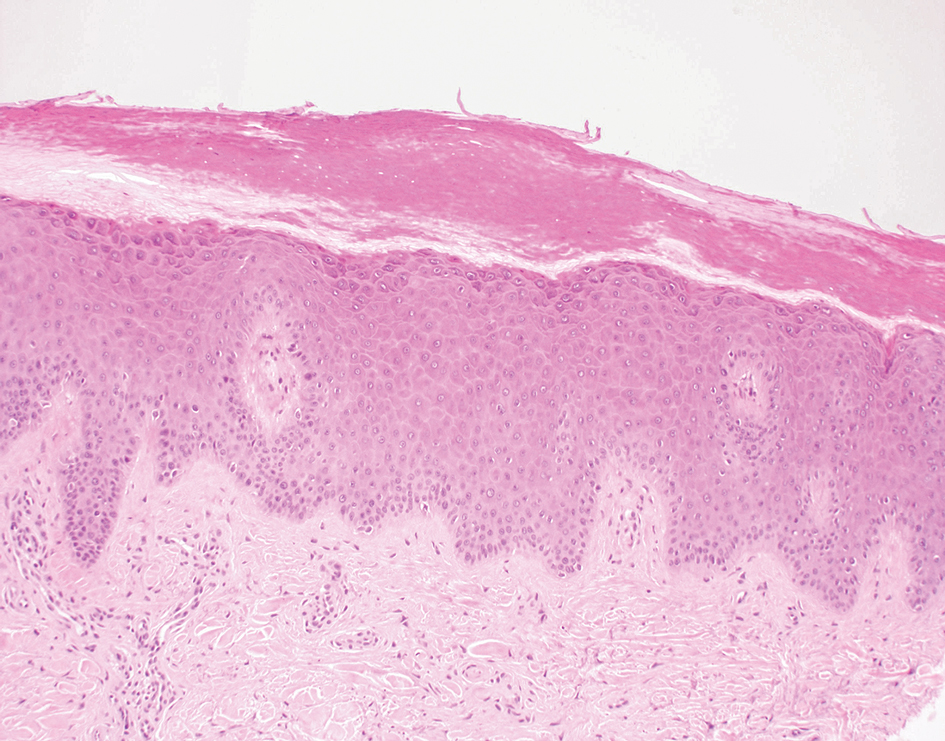

Psoriasis is a chronic relapsing papulosquamous disorder characterized by scaly erythematous plaques often overlying the extensor surfaces of the extremities. Histopathology shows a psoriasiform pattern of inflammation with thinning of the suprapapillary plates and elongation of the rete ridges. Further diagnostic clues of psoriasis include regular acanthosis, characteristic Munro microabscesses with neutrophils in a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum (Figure 1), hypogranulosis, and neutrophilic spongiform pustules of Kogoj in the stratum spinosum. Generally, there is a lack of the epidermal necrosis seen with NME.7,8

Lichen simplex chronicus manifests as pruritic, often hyperpigmented, well-defined, lichenified plaques with excoriation following repetitive mechanical trauma, commonly on the lower lateral legs, posterior neck, and flexural areas.9 The histologic landscape is marked by well-developed lesions evolving to show compact orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis, irregularly elongated rete ridges (ie, irregular acanthosis), and papillary dermal fibrosis with vertical streaking of collagen (Figure 2).9,10

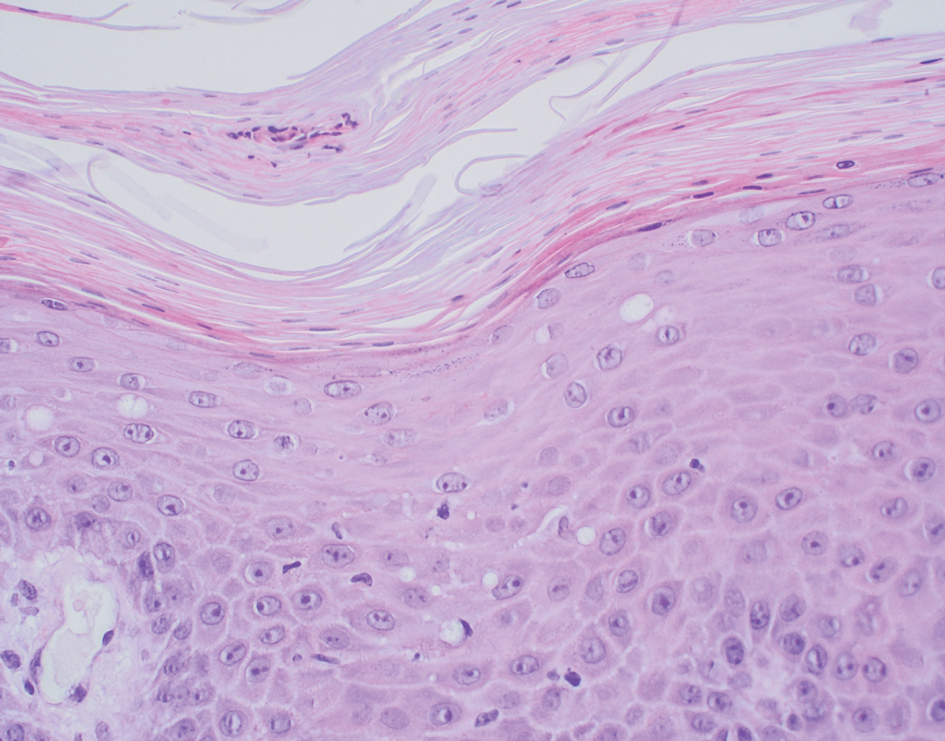

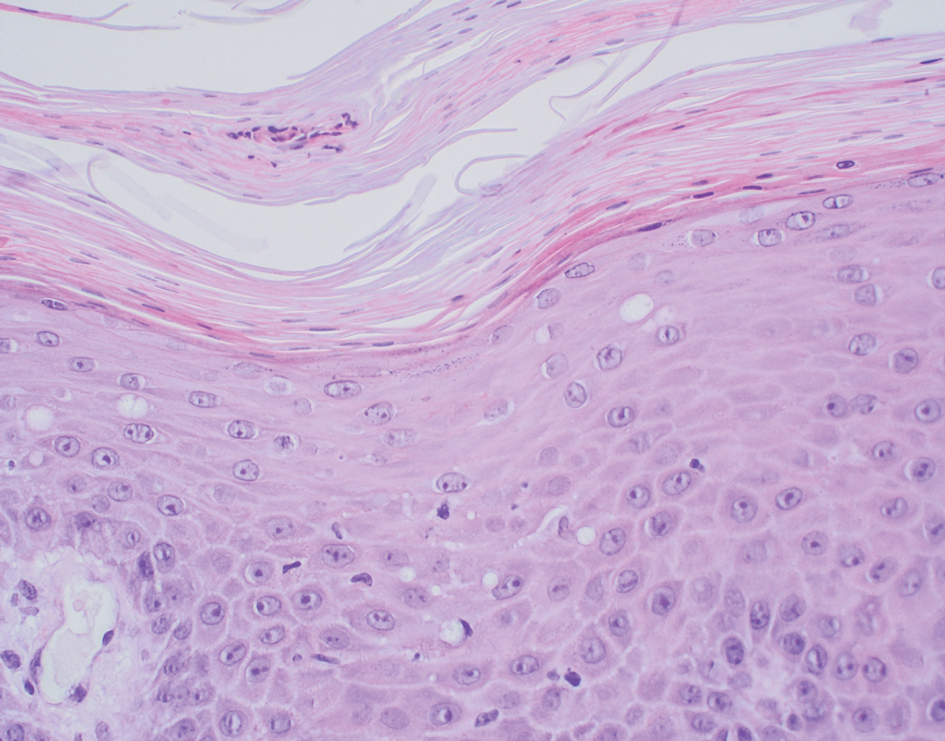

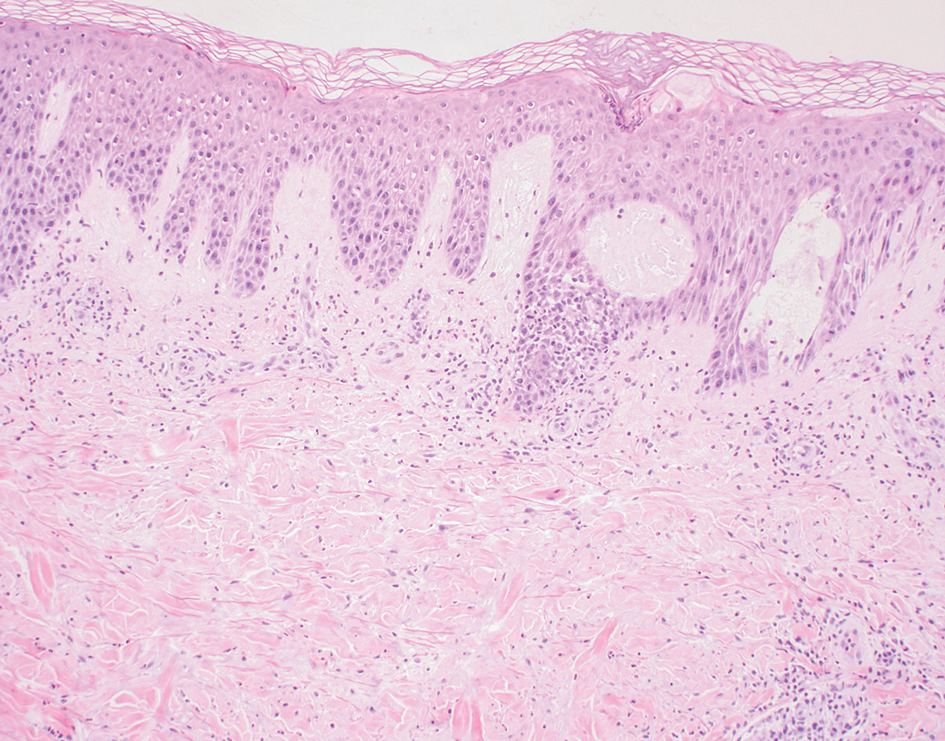

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is recognized clinically by scaly/psoriasiform and annular lesions with mild or absent systemic involvement. Common histopathologic findings include epidermal atrophy, vacuolar interface dermatitis with hydropic degeneration of the basal layer, a subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate, and a periadnexal and perivascular infiltrate (Figure 3).11 Upper dermal edema, spotty necrosis of individual cells in the epidermis, dermal-epidermal separation caused by prominent basal cell degeneration, and accumulation of acid mucopolysaccharides (mucin) are other histologic features associated with SCLE.12,13

The immunofluorescence pattern in SCLE features dustlike particles of IgG deposition in the epidermis, subepidermal region, and dermal cellular infiltrate. Lesions also may have granular deposition of immunoreactions at the DEJ.11,13

The manifestation of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome (also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome) is variable, with a morbilliform rash that spreads from the face to the entire body, urticaria, atypical target lesions, purpuriform lesions, lymphadenopathy, and exfoliative dermatitis.14 The nonspecific morphologic features of DRESS syndrome lesions are associated with variable histologic features, which include focal interface changes with vacuolar alteration of the basal layer; atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromic nuclei; and a superficial, inconsistently dense, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Other relatively common histopathologic patterns include an upper dermis with dilated blood vessels, spongiosis with exocytosis of lymphocytes (Figure 4), and necrotic keratinocytes. Although peripheral eosinophilia is an important diagnostic criterion and is observed consistently, eosinophils are variably present on skin biopsy.15,16 Given the histopathologic variability and nonspecific findings, clinical correlation is required when diagnosing DRESS syndrome.

- Halvorson SA, Gilbert E, Hopkins RS, et al. Putting the pieces together: necrolytic migratory erythema and the glucagonoma syndrome. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1525-1529. doi:10.1007 /s11606-013-2490-5

- Toberer F, Hartschuh W, Wiedemeyer K. Glucagonoma-associated necrolytic migratory erythema: the broad spectrum of the clinical and histopathological findings and clues to the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E29-E32. doi:10.1097DAD .0000000000001219

- Hunt SJ, Narus VT, Abell E. Necrolytic migratory erythema: dyskeratotic dermatitis, a clue to early diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991; 24:473-477. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70076-e

- van Beek AP, de Haas ER, van Vloten WA, et al. The glucagonoma syndrome and necrolytic migratory erythema: a clinical review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:531-537. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1510531

- Pujol RM, Wang C-Y E, el-Azhary RA, et al. Necrolytic migratory erythema: clinicopathologic study of 13 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:12- 18. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01844.x

- Johnson SM, Smoller BR, Lamps LW, et al. Necrolytic migratory erythema as the only presenting sign of a glucagonoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:325-328. doi:10.1067/s0190-9622(02)61774-8

- De Rosa G, Mignogna C. The histopathology of psoriasis. Reumatismo. 2007;59(suppl 1):46-48. doi:10.4081/reumatismo.2007.1s.46

- Kimmel GW, Lebwohl M. Psoriasis: overview and diagnosis. In: Bhutani T, Liao W, Nakamura M, eds. Evidence-Based Psoriasis. Springer; 2018:1-16. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-90107-7_1

- Balan R, Grigoras¸ A, Popovici D, et al. The histopathological landscape of the major psoriasiform dermatoses. Arch Clin Cases. 2021;6:59-68. doi:10.22551/2019.24.0603.10155

- O’Keefe RJ, Scurry JP, Dennerstein G, et al. Audit of 114 nonneoplastic vulvar biopsies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:780-786. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb10842.x

- Parodi A, Caproni M, Cardinali C, et al P. Clinical, histological and immunopathological features of 58 patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatology. 2000;200:6-10. doi:10.1159/000018307

- Lyon CC, Blewitt R, Harrison PV. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: two cases of delayed diagnosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:57-59. doi:10.1080/00015559850135869

- David-Bajar KM. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:2S-8S. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12355164

- Paulmann M, Mockenhaupt M. Severe drug-induced skin reactions: clinical features, diagnosis, etiology, and therapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:625-643. doi:10.1111/ddg.12747

- Borroni G, Torti S, Pezzini C, et al. Histopathologic spectrum of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a diagnosis that needs clinico-pathological correlation. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149:291-300.

- Ortonne N, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Histopathology of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome: a morphological and phenotypical study. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:50-58. doi:10.1111/bjd.13683

The Diagnosis: Necrolytic Migratory Erythema

Necrolytic migratory erythema (NME) is a waxing and waning rash associated with rare pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors called glucagonomas. It is characterized by pruritic and painful, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques that manifest in the intertriginous areas and on the perineum and buttocks.1 Due to the evolving nature of the rash, the histopathologic findings in NME vary depending on the stage of the cutaneous lesions at the time of biopsy.2 Multiple dyskeratotic keratinocytes spanning all epidermal layers may be a diagnostic clue in early lesions of NME.3 Typical features of longstanding lesions include confluent parakeratosis, psoriasiform hyperplasia with mild or absent spongiosis, and upper epidermal necrosis with keratinocyte vacuolization and pallor.4 Morphologic features that are present prior to the development of epidermal vacuolation and necrosis frequently are misattributed to psoriasis or eczema. Long-standing lesions also may develop a neutrophilic infiltrate with subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules.2 Other common features include a discrete perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and an erosive or encrusted epidermis.5 Although direct immunofluorescence typically is negative, nonspecific findings can be seen, including apoptotic keratinocytes labeling with fibrinogen and C3, as well as scattered, clumped, IgM-positive cytoid bodies present at the dermal-epidermal junction (DEJ).6 Biopsies also have shown scattered, clumped, IgM-positive cytoid bodies present at the DEJ.5

Psoriasis is a chronic relapsing papulosquamous disorder characterized by scaly erythematous plaques often overlying the extensor surfaces of the extremities. Histopathology shows a psoriasiform pattern of inflammation with thinning of the suprapapillary plates and elongation of the rete ridges. Further diagnostic clues of psoriasis include regular acanthosis, characteristic Munro microabscesses with neutrophils in a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum (Figure 1), hypogranulosis, and neutrophilic spongiform pustules of Kogoj in the stratum spinosum. Generally, there is a lack of the epidermal necrosis seen with NME.7,8

Lichen simplex chronicus manifests as pruritic, often hyperpigmented, well-defined, lichenified plaques with excoriation following repetitive mechanical trauma, commonly on the lower lateral legs, posterior neck, and flexural areas.9 The histologic landscape is marked by well-developed lesions evolving to show compact orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis, irregularly elongated rete ridges (ie, irregular acanthosis), and papillary dermal fibrosis with vertical streaking of collagen (Figure 2).9,10

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is recognized clinically by scaly/psoriasiform and annular lesions with mild or absent systemic involvement. Common histopathologic findings include epidermal atrophy, vacuolar interface dermatitis with hydropic degeneration of the basal layer, a subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate, and a periadnexal and perivascular infiltrate (Figure 3).11 Upper dermal edema, spotty necrosis of individual cells in the epidermis, dermal-epidermal separation caused by prominent basal cell degeneration, and accumulation of acid mucopolysaccharides (mucin) are other histologic features associated with SCLE.12,13

The immunofluorescence pattern in SCLE features dustlike particles of IgG deposition in the epidermis, subepidermal region, and dermal cellular infiltrate. Lesions also may have granular deposition of immunoreactions at the DEJ.11,13

The manifestation of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome (also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome) is variable, with a morbilliform rash that spreads from the face to the entire body, urticaria, atypical target lesions, purpuriform lesions, lymphadenopathy, and exfoliative dermatitis.14 The nonspecific morphologic features of DRESS syndrome lesions are associated with variable histologic features, which include focal interface changes with vacuolar alteration of the basal layer; atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromic nuclei; and a superficial, inconsistently dense, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Other relatively common histopathologic patterns include an upper dermis with dilated blood vessels, spongiosis with exocytosis of lymphocytes (Figure 4), and necrotic keratinocytes. Although peripheral eosinophilia is an important diagnostic criterion and is observed consistently, eosinophils are variably present on skin biopsy.15,16 Given the histopathologic variability and nonspecific findings, clinical correlation is required when diagnosing DRESS syndrome.

The Diagnosis: Necrolytic Migratory Erythema

Necrolytic migratory erythema (NME) is a waxing and waning rash associated with rare pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors called glucagonomas. It is characterized by pruritic and painful, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques that manifest in the intertriginous areas and on the perineum and buttocks.1 Due to the evolving nature of the rash, the histopathologic findings in NME vary depending on the stage of the cutaneous lesions at the time of biopsy.2 Multiple dyskeratotic keratinocytes spanning all epidermal layers may be a diagnostic clue in early lesions of NME.3 Typical features of longstanding lesions include confluent parakeratosis, psoriasiform hyperplasia with mild or absent spongiosis, and upper epidermal necrosis with keratinocyte vacuolization and pallor.4 Morphologic features that are present prior to the development of epidermal vacuolation and necrosis frequently are misattributed to psoriasis or eczema. Long-standing lesions also may develop a neutrophilic infiltrate with subcorneal and intraepidermal pustules.2 Other common features include a discrete perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and an erosive or encrusted epidermis.5 Although direct immunofluorescence typically is negative, nonspecific findings can be seen, including apoptotic keratinocytes labeling with fibrinogen and C3, as well as scattered, clumped, IgM-positive cytoid bodies present at the dermal-epidermal junction (DEJ).6 Biopsies also have shown scattered, clumped, IgM-positive cytoid bodies present at the DEJ.5

Psoriasis is a chronic relapsing papulosquamous disorder characterized by scaly erythematous plaques often overlying the extensor surfaces of the extremities. Histopathology shows a psoriasiform pattern of inflammation with thinning of the suprapapillary plates and elongation of the rete ridges. Further diagnostic clues of psoriasis include regular acanthosis, characteristic Munro microabscesses with neutrophils in a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum (Figure 1), hypogranulosis, and neutrophilic spongiform pustules of Kogoj in the stratum spinosum. Generally, there is a lack of the epidermal necrosis seen with NME.7,8

Lichen simplex chronicus manifests as pruritic, often hyperpigmented, well-defined, lichenified plaques with excoriation following repetitive mechanical trauma, commonly on the lower lateral legs, posterior neck, and flexural areas.9 The histologic landscape is marked by well-developed lesions evolving to show compact orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis, irregularly elongated rete ridges (ie, irregular acanthosis), and papillary dermal fibrosis with vertical streaking of collagen (Figure 2).9,10

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is recognized clinically by scaly/psoriasiform and annular lesions with mild or absent systemic involvement. Common histopathologic findings include epidermal atrophy, vacuolar interface dermatitis with hydropic degeneration of the basal layer, a subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate, and a periadnexal and perivascular infiltrate (Figure 3).11 Upper dermal edema, spotty necrosis of individual cells in the epidermis, dermal-epidermal separation caused by prominent basal cell degeneration, and accumulation of acid mucopolysaccharides (mucin) are other histologic features associated with SCLE.12,13

The immunofluorescence pattern in SCLE features dustlike particles of IgG deposition in the epidermis, subepidermal region, and dermal cellular infiltrate. Lesions also may have granular deposition of immunoreactions at the DEJ.11,13

The manifestation of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome (also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome) is variable, with a morbilliform rash that spreads from the face to the entire body, urticaria, atypical target lesions, purpuriform lesions, lymphadenopathy, and exfoliative dermatitis.14 The nonspecific morphologic features of DRESS syndrome lesions are associated with variable histologic features, which include focal interface changes with vacuolar alteration of the basal layer; atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromic nuclei; and a superficial, inconsistently dense, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Other relatively common histopathologic patterns include an upper dermis with dilated blood vessels, spongiosis with exocytosis of lymphocytes (Figure 4), and necrotic keratinocytes. Although peripheral eosinophilia is an important diagnostic criterion and is observed consistently, eosinophils are variably present on skin biopsy.15,16 Given the histopathologic variability and nonspecific findings, clinical correlation is required when diagnosing DRESS syndrome.

- Halvorson SA, Gilbert E, Hopkins RS, et al. Putting the pieces together: necrolytic migratory erythema and the glucagonoma syndrome. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1525-1529. doi:10.1007 /s11606-013-2490-5

- Toberer F, Hartschuh W, Wiedemeyer K. Glucagonoma-associated necrolytic migratory erythema: the broad spectrum of the clinical and histopathological findings and clues to the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E29-E32. doi:10.1097DAD .0000000000001219

- Hunt SJ, Narus VT, Abell E. Necrolytic migratory erythema: dyskeratotic dermatitis, a clue to early diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991; 24:473-477. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70076-e

- van Beek AP, de Haas ER, van Vloten WA, et al. The glucagonoma syndrome and necrolytic migratory erythema: a clinical review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:531-537. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1510531

- Pujol RM, Wang C-Y E, el-Azhary RA, et al. Necrolytic migratory erythema: clinicopathologic study of 13 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:12- 18. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01844.x

- Johnson SM, Smoller BR, Lamps LW, et al. Necrolytic migratory erythema as the only presenting sign of a glucagonoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:325-328. doi:10.1067/s0190-9622(02)61774-8

- De Rosa G, Mignogna C. The histopathology of psoriasis. Reumatismo. 2007;59(suppl 1):46-48. doi:10.4081/reumatismo.2007.1s.46

- Kimmel GW, Lebwohl M. Psoriasis: overview and diagnosis. In: Bhutani T, Liao W, Nakamura M, eds. Evidence-Based Psoriasis. Springer; 2018:1-16. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-90107-7_1

- Balan R, Grigoras¸ A, Popovici D, et al. The histopathological landscape of the major psoriasiform dermatoses. Arch Clin Cases. 2021;6:59-68. doi:10.22551/2019.24.0603.10155

- O’Keefe RJ, Scurry JP, Dennerstein G, et al. Audit of 114 nonneoplastic vulvar biopsies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:780-786. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb10842.x

- Parodi A, Caproni M, Cardinali C, et al P. Clinical, histological and immunopathological features of 58 patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatology. 2000;200:6-10. doi:10.1159/000018307

- Lyon CC, Blewitt R, Harrison PV. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: two cases of delayed diagnosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:57-59. doi:10.1080/00015559850135869

- David-Bajar KM. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:2S-8S. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12355164

- Paulmann M, Mockenhaupt M. Severe drug-induced skin reactions: clinical features, diagnosis, etiology, and therapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:625-643. doi:10.1111/ddg.12747

- Borroni G, Torti S, Pezzini C, et al. Histopathologic spectrum of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a diagnosis that needs clinico-pathological correlation. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149:291-300.

- Ortonne N, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Histopathology of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome: a morphological and phenotypical study. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:50-58. doi:10.1111/bjd.13683

- Halvorson SA, Gilbert E, Hopkins RS, et al. Putting the pieces together: necrolytic migratory erythema and the glucagonoma syndrome. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1525-1529. doi:10.1007 /s11606-013-2490-5

- Toberer F, Hartschuh W, Wiedemeyer K. Glucagonoma-associated necrolytic migratory erythema: the broad spectrum of the clinical and histopathological findings and clues to the diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:E29-E32. doi:10.1097DAD .0000000000001219

- Hunt SJ, Narus VT, Abell E. Necrolytic migratory erythema: dyskeratotic dermatitis, a clue to early diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991; 24:473-477. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70076-e

- van Beek AP, de Haas ER, van Vloten WA, et al. The glucagonoma syndrome and necrolytic migratory erythema: a clinical review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:531-537. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1510531

- Pujol RM, Wang C-Y E, el-Azhary RA, et al. Necrolytic migratory erythema: clinicopathologic study of 13 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:12- 18. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01844.x

- Johnson SM, Smoller BR, Lamps LW, et al. Necrolytic migratory erythema as the only presenting sign of a glucagonoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:325-328. doi:10.1067/s0190-9622(02)61774-8

- De Rosa G, Mignogna C. The histopathology of psoriasis. Reumatismo. 2007;59(suppl 1):46-48. doi:10.4081/reumatismo.2007.1s.46

- Kimmel GW, Lebwohl M. Psoriasis: overview and diagnosis. In: Bhutani T, Liao W, Nakamura M, eds. Evidence-Based Psoriasis. Springer; 2018:1-16. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-90107-7_1

- Balan R, Grigoras¸ A, Popovici D, et al. The histopathological landscape of the major psoriasiform dermatoses. Arch Clin Cases. 2021;6:59-68. doi:10.22551/2019.24.0603.10155

- O’Keefe RJ, Scurry JP, Dennerstein G, et al. Audit of 114 nonneoplastic vulvar biopsies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:780-786. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb10842.x

- Parodi A, Caproni M, Cardinali C, et al P. Clinical, histological and immunopathological features of 58 patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatology. 2000;200:6-10. doi:10.1159/000018307

- Lyon CC, Blewitt R, Harrison PV. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: two cases of delayed diagnosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:57-59. doi:10.1080/00015559850135869

- David-Bajar KM. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:2S-8S. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12355164

- Paulmann M, Mockenhaupt M. Severe drug-induced skin reactions: clinical features, diagnosis, etiology, and therapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:625-643. doi:10.1111/ddg.12747

- Borroni G, Torti S, Pezzini C, et al. Histopathologic spectrum of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a diagnosis that needs clinico-pathological correlation. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149:291-300.

- Ortonne N, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Histopathology of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome: a morphological and phenotypical study. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:50-58. doi:10.1111/bjd.13683

A 62-year-old man presented with an erythematous flaky rash associated with burning pain on the right medial second toe that persisted for several months. Prior treatment with econazole, ciclopirox, and oral amoxicillin had failed. A shave biopsy was performed.