User login

Pruritic Eruption on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Grover Disease

Grover disease (also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis) was first described by Ralph W. Grover in 1970 as an idiopathic, acquired, monomorphous, papulovesicular eruption. Although originally characterized by solely transient acantholytic dermatosis, over time the term Grover disease has been expanded to include persistent acantholytic dermatoses. Grover disease chiefly affects white adults older than 40 years and is more prevalent in males than females. Cases generally are self-limited but correlate with age, as older adults are more likely to have prolonged eruptions.1

Grover disease typically erupts with discrete, erythematous, edematous, acneform, red-brown or flesh-colored papules, papulovesicles, or keratotic papules that primarily are seen on the trunk and anterior portion of the chest. As the rash spreads, it can erupt on the neck and thighs. The etiology of Grover disease is unknown, but many factors have been associated with the condition in a limited number of patients, including exposure to UV radiation, excessive heat or sweating, use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and recombinant human IL-4, and infection with Malassezia furfur and Demodex folliculorum.1 Grover disease also has been associated with other conditions such as asteatotic eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis.2

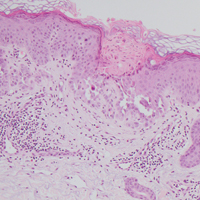

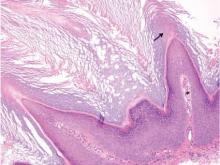

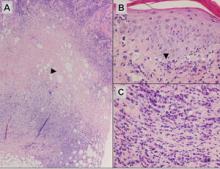

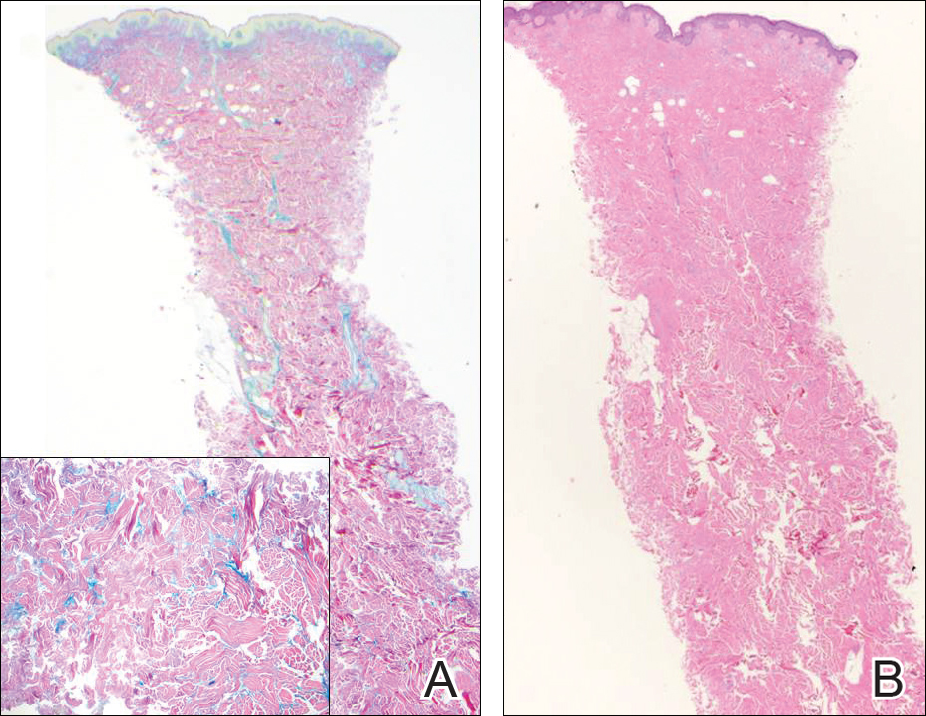

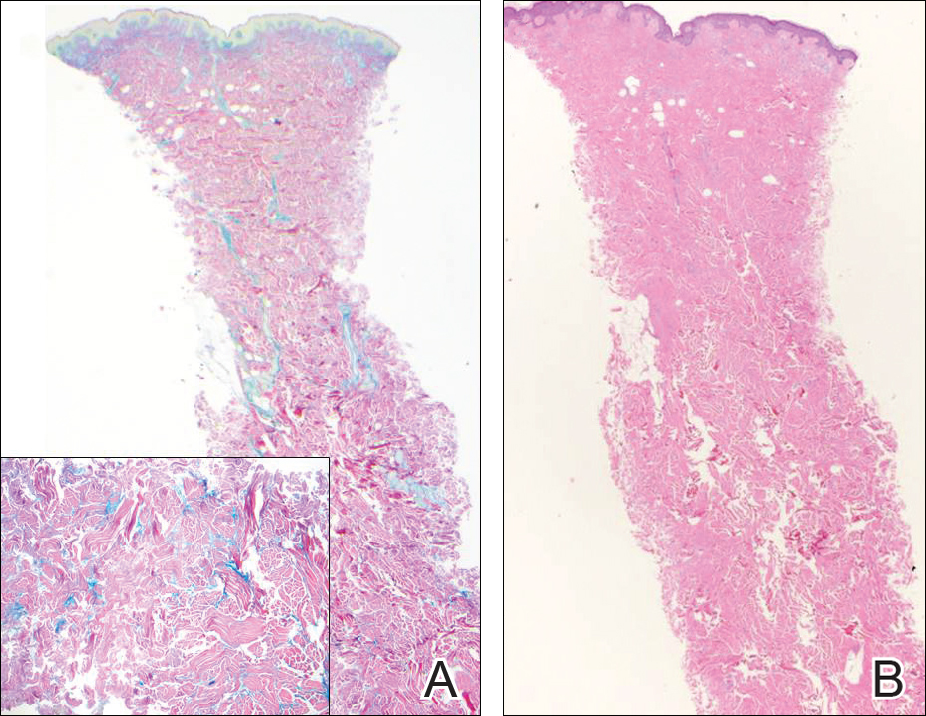

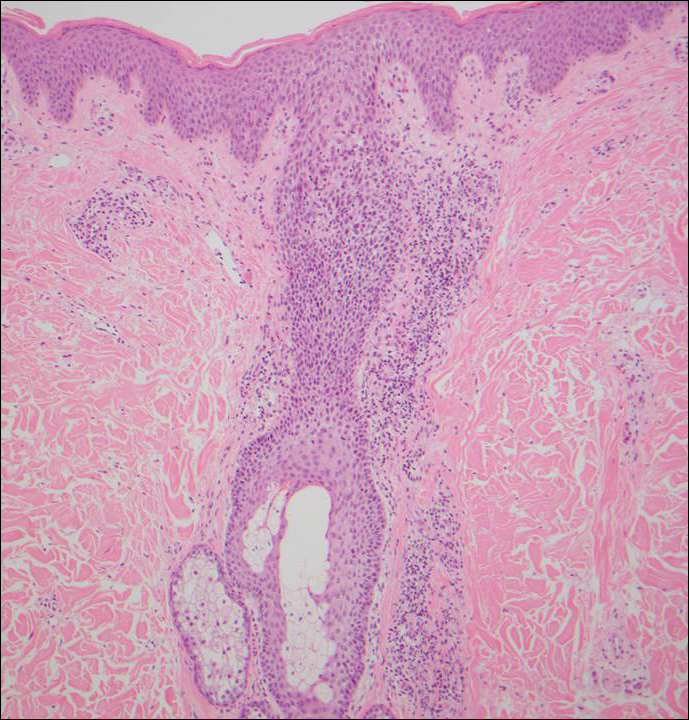

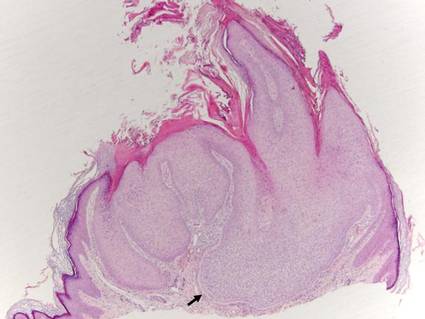

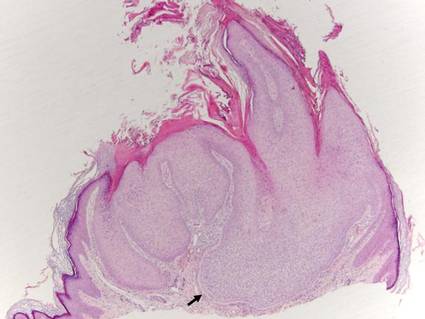

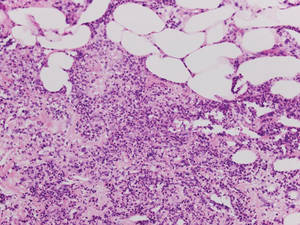

Histologically, Grover disease (Figure 1) is an acantholytic process that can exhibit dyskeratosis (corps ronds and grains). Foci often are small and multiple foci are seen on shave biopsy. There also may be spongiotic changes when associated with an eczematous element. A perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils usually is seen.3 Basket weave keratin may be seen; however, as the lesions cause pruritus, erosions and ulcerations often are present.4

Grover disease has multiple histologic variants that may resemble Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and spongiotic dermatitis and can present in combination.5

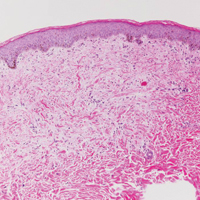

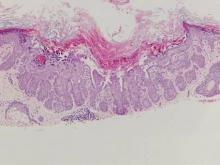

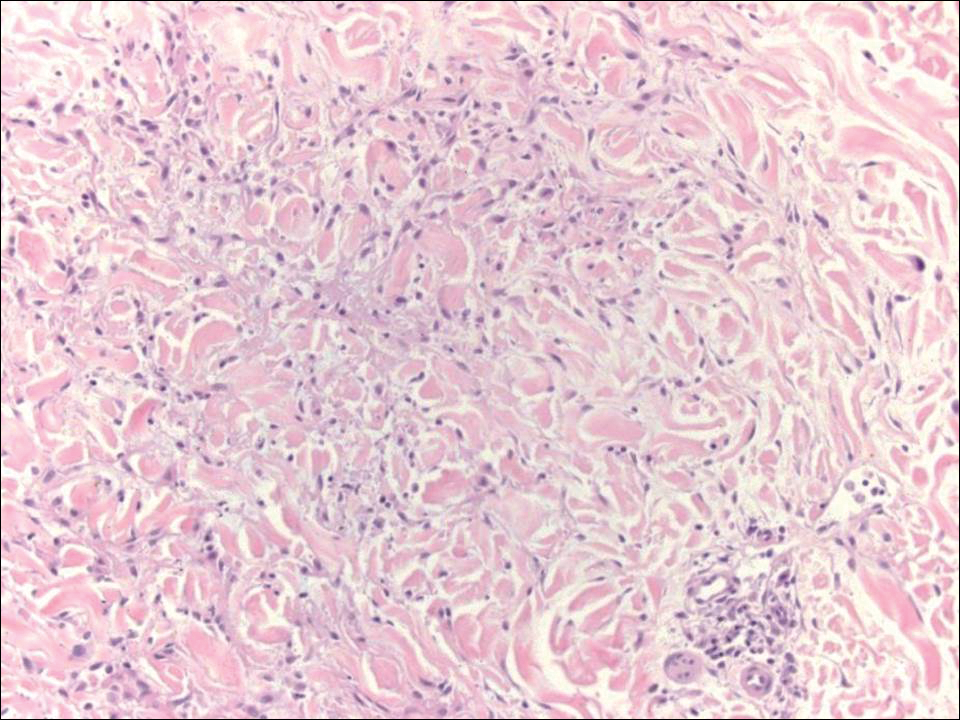

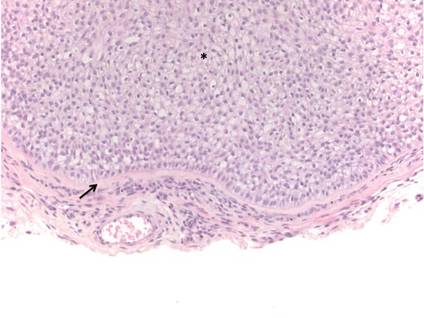

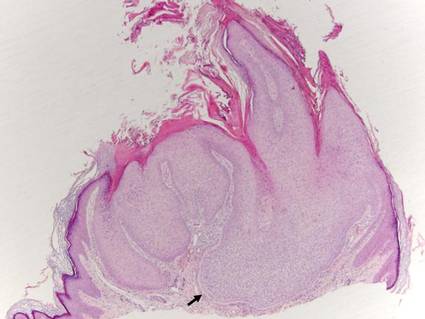

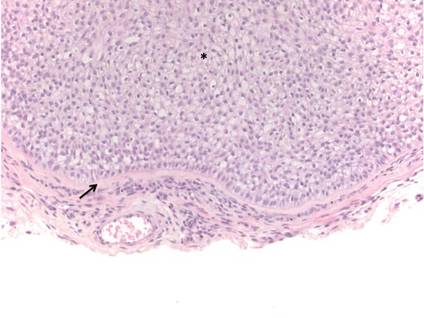

The variant of Grover disease that has a Darier-like pattern is difficult to distinguish from Darier disease, an autosomal-dominant-inherited disorder classified by small papules that emerge in seborrheic areas during childhood and adolescence. Histologically, Darier disease (Figure 2) shows broad areas of dyskeratosis and acantholysis that lead to suprabasal cleavage. Follicular extension may be present. In addition, there often is prominent vertical parakeratosis in Darier disease.6 Histologic features that favor Darier disease over the Darier-like variant of Grover disease include a broad focus of acanthotic dyskeratosis with follicular extension; the presence of a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum; and a lack of spongiosis and eosinophils, which are notably absent in Darier disease but may be present in Grover disease.4

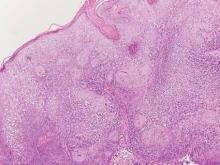

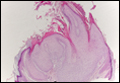

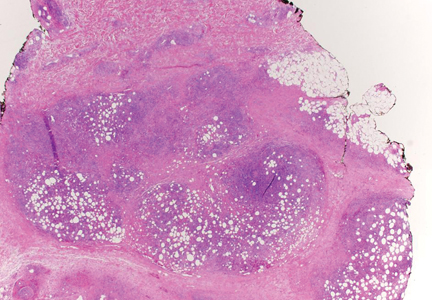

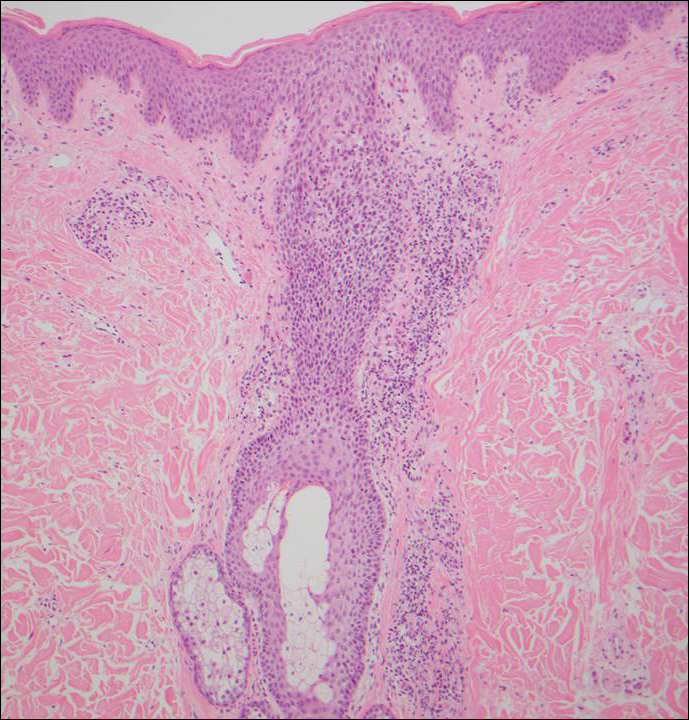

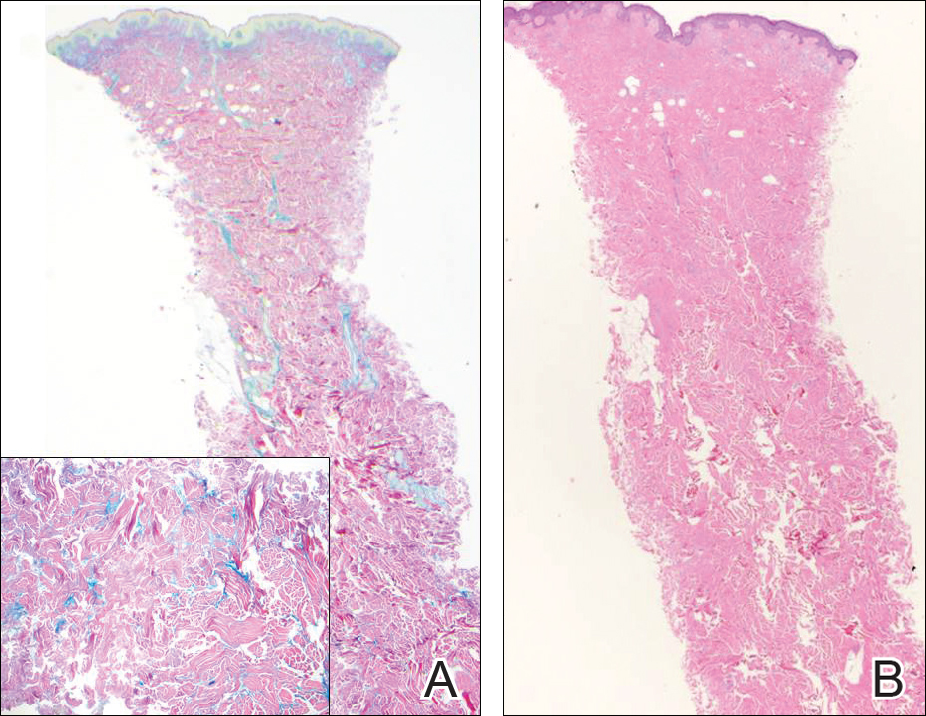

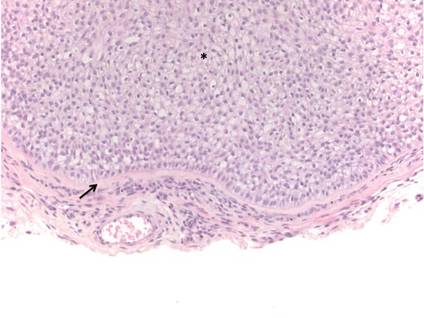

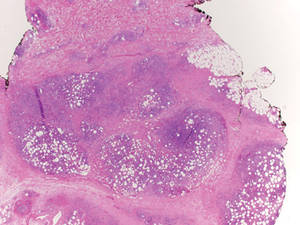

Another variant of Grover disease has a Hailey-Hailey-like pattern, which is characterized by Hailey-Hailey disease's dilapidated brick wall appearance or the diffuse suprabasal acantholysis of all epidermal layers without notable dyskeratosis.4 Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as familial benign pemphigus, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that presents with erythematous vesicular plaques in flexural areas. The plaques progress to flaccid bullae with rupture and crusting and spread peripherally.7 Pathology shows suprabasilar clefts and numerous acantholytic cells (Figure 3). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are rare with infrequent corps ronds and rare grains. The epidermis also is less hyperplastic in Grover disease than in Hailey-Hailey disease.1

Grover disease also may present histologically with a pemphiguslike pattern, mimicking pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris; however, direct immunofluorescence studies are negative in Grover disease.

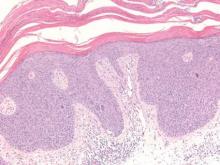

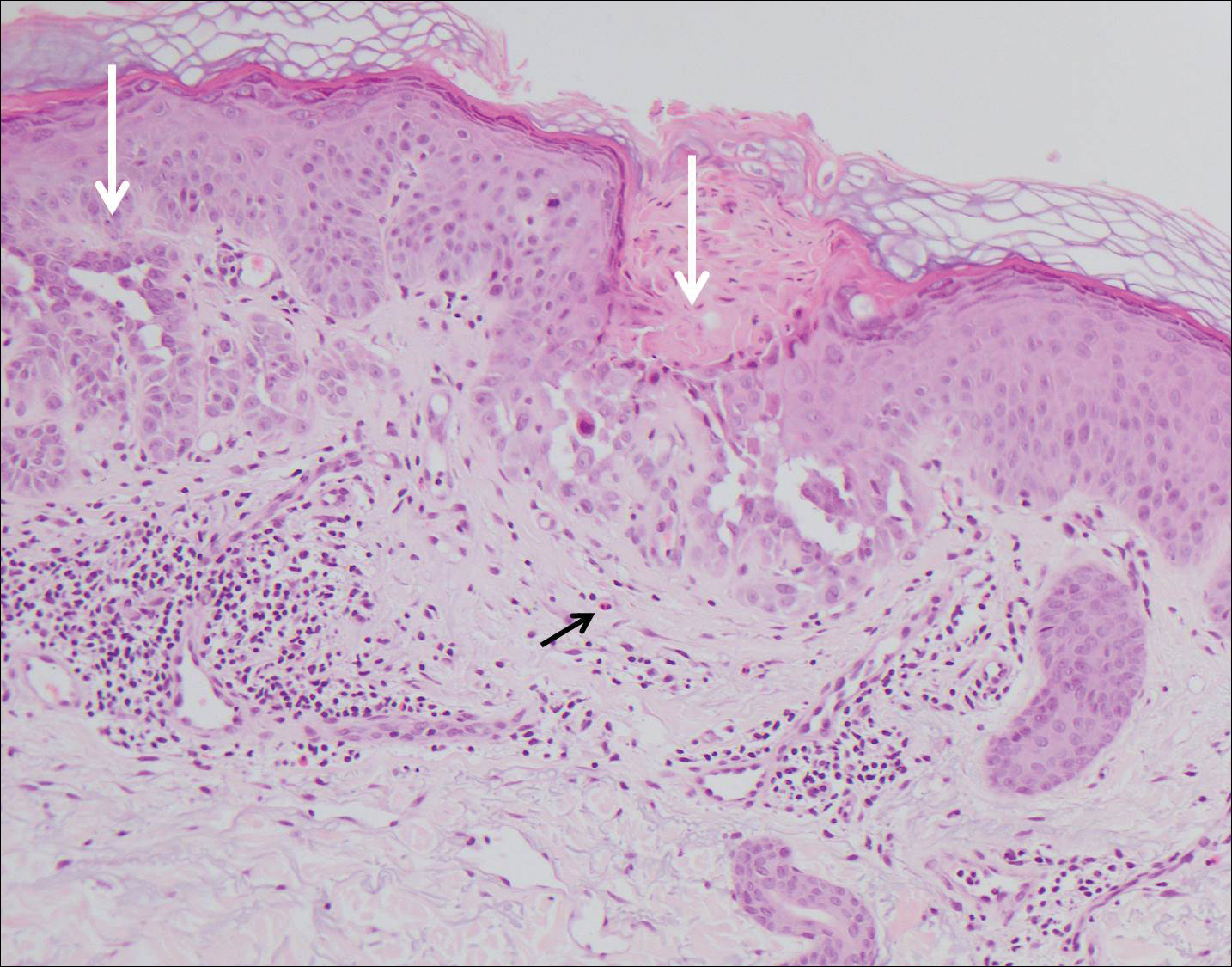

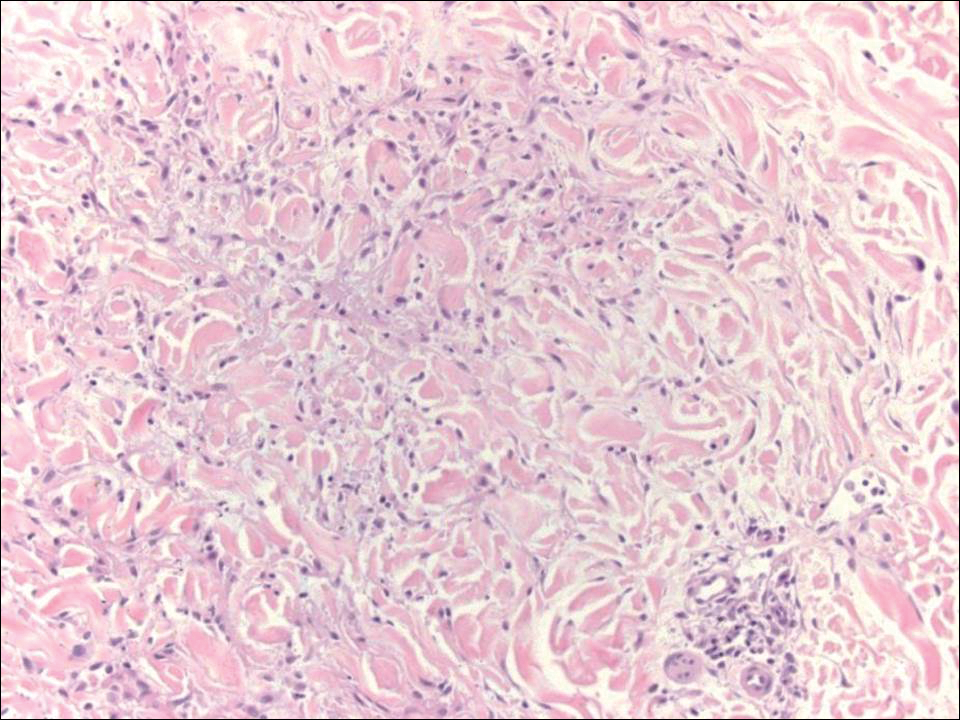

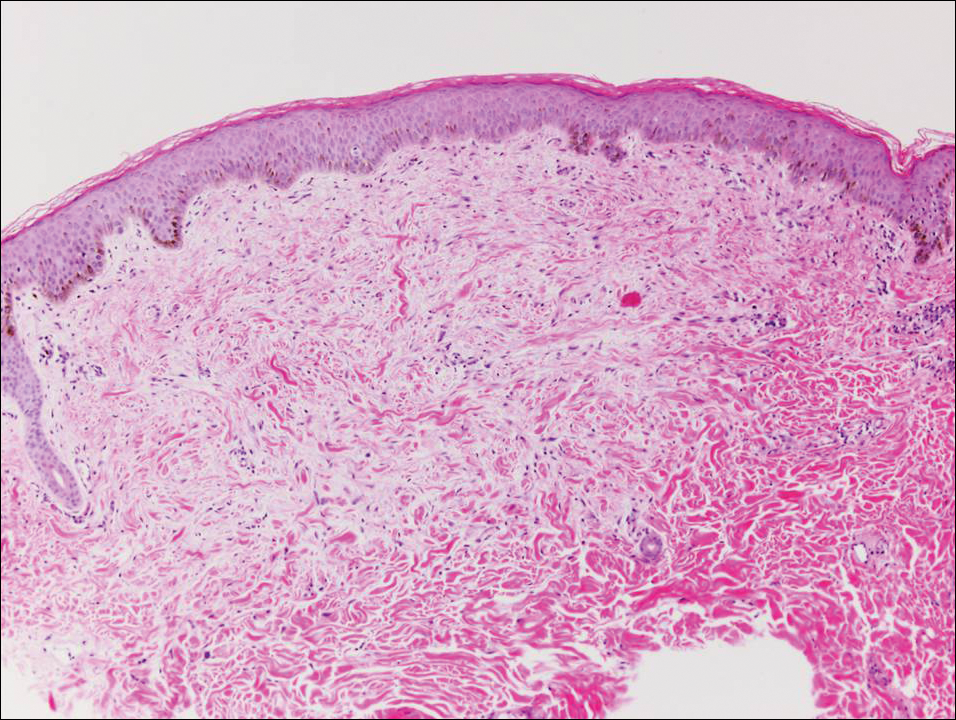

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies to desmoglein 1, which are present on the surfaces of keratinocytes, and is characterized by scaly crusts and blisters.8 Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus (Figure 4) shows a superficial epidermal blistering process. The acantholysis may be subtle and is commonly localized to the stratum granulosum, extending into the stratum corneum. Complete loss of the stratum corneum can be seen, resulting in only scattered acantholytic cells. Spongiosis also may be seen. The dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate that often contains eosinophils. Pemphigus foliaceus is confirmed by direct immunofluorescence.9

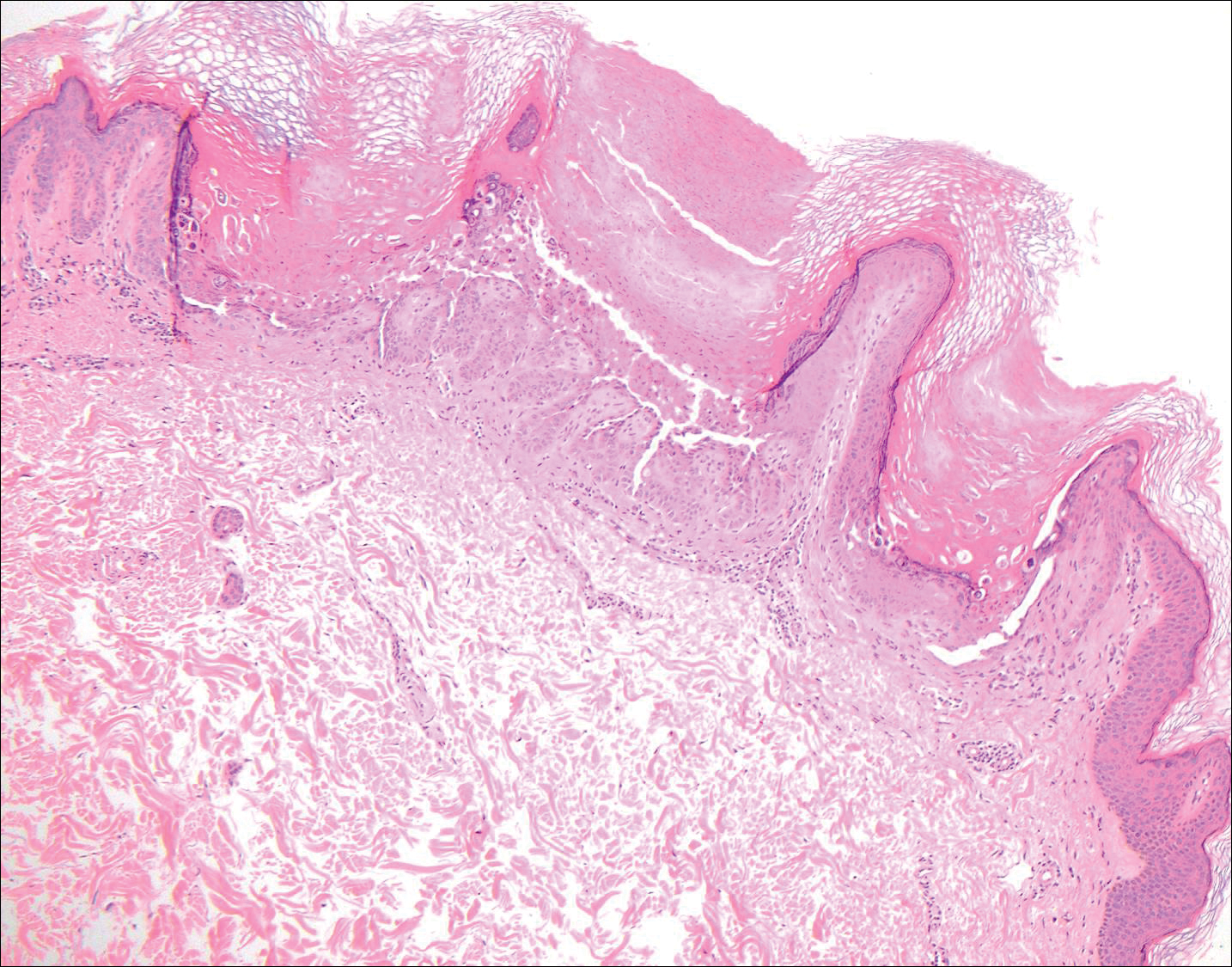

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disorder that is characterized by IgG autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a component of desmosomes that are involved in keratinocyte-to-keratinocyte adhesion. Clinically, patients present with flaccid fragile blisters on the skin and mucous membranes that rupture easily, leading to painful erosions.10 Intraepidermal blisters are seen histologically (Figure 5) with the loss of cohesion (acantholysis) seen classically in the lower portions of the epidermis where desmoglein 3 is most prominent. When only the basal layer remains, the histology has been likened to a tombstone row.11 Extension of the blister along the adnexa is common. The underlying dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate with eosinophils. Early lesions may show only eosinophilic spongiosis. Direct immunofluorescence studies show IgG and C3 in an intercellular pattern that resembles a fish net or chicken wire.4,11

The spongioticlike pattern of Grover disease is marked by epidermal edema with separation of the keratinocytes and the revelation of their intracellular bridges,4 which manifests as vesiculation in the stratum corneum or upper layers of the epidermis.12

Grover disease is self-limited and may spontaneously resolve; however, the disease may be responsive to topical and systemic steroids. Additionally, avoidance of aggravating factors such as sunlight, heat, and sweating can improve symptoms.2

- Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover's disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5, pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

- Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover's disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:83-86.

- Davis MD, Dinneen AM, Landa N, et al. Grover's disease: clinicopathologic review of 72 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:229-234.

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Chalet M, Grover R, Ackerman AB. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a reevaluation. Arch Dermatol. 1977;133:431-435.

- Takagi A, Kamijo M, Ikeda S. Darier disease. J Dermatol. 2016;43:275-279.

- Engin B, Kutlubay Z, Celik U, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:452-455.

- de Sena Nogueira Maehara L, Huizinga J, Jonkman MF. Rituximab therapy in pemphigus foliaceus: report of 12 cases and review of recent literature [published online March 31, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1420-1423.

- James KA, Culton DA, Diaz LA. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus foliaceus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:405-412.

- Black M, Mignogna MD, Scully C. Number II. pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Dis. 2005;11:119-130.

- Madke B, Doshi B, Khopkar U, et al. Appearances in dermatopathology: the diagnostic and the deceptive. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79:338-348.

- Motaparthi K. Pseudoherpetic transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease): case series and review of the literature [published online February 16, 2017]. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:486-489.

The Diagnosis: Grover Disease

Grover disease (also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis) was first described by Ralph W. Grover in 1970 as an idiopathic, acquired, monomorphous, papulovesicular eruption. Although originally characterized by solely transient acantholytic dermatosis, over time the term Grover disease has been expanded to include persistent acantholytic dermatoses. Grover disease chiefly affects white adults older than 40 years and is more prevalent in males than females. Cases generally are self-limited but correlate with age, as older adults are more likely to have prolonged eruptions.1

Grover disease typically erupts with discrete, erythematous, edematous, acneform, red-brown or flesh-colored papules, papulovesicles, or keratotic papules that primarily are seen on the trunk and anterior portion of the chest. As the rash spreads, it can erupt on the neck and thighs. The etiology of Grover disease is unknown, but many factors have been associated with the condition in a limited number of patients, including exposure to UV radiation, excessive heat or sweating, use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and recombinant human IL-4, and infection with Malassezia furfur and Demodex folliculorum.1 Grover disease also has been associated with other conditions such as asteatotic eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis.2

Histologically, Grover disease (Figure 1) is an acantholytic process that can exhibit dyskeratosis (corps ronds and grains). Foci often are small and multiple foci are seen on shave biopsy. There also may be spongiotic changes when associated with an eczematous element. A perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils usually is seen.3 Basket weave keratin may be seen; however, as the lesions cause pruritus, erosions and ulcerations often are present.4

Grover disease has multiple histologic variants that may resemble Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and spongiotic dermatitis and can present in combination.5

The variant of Grover disease that has a Darier-like pattern is difficult to distinguish from Darier disease, an autosomal-dominant-inherited disorder classified by small papules that emerge in seborrheic areas during childhood and adolescence. Histologically, Darier disease (Figure 2) shows broad areas of dyskeratosis and acantholysis that lead to suprabasal cleavage. Follicular extension may be present. In addition, there often is prominent vertical parakeratosis in Darier disease.6 Histologic features that favor Darier disease over the Darier-like variant of Grover disease include a broad focus of acanthotic dyskeratosis with follicular extension; the presence of a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum; and a lack of spongiosis and eosinophils, which are notably absent in Darier disease but may be present in Grover disease.4

Another variant of Grover disease has a Hailey-Hailey-like pattern, which is characterized by Hailey-Hailey disease's dilapidated brick wall appearance or the diffuse suprabasal acantholysis of all epidermal layers without notable dyskeratosis.4 Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as familial benign pemphigus, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that presents with erythematous vesicular plaques in flexural areas. The plaques progress to flaccid bullae with rupture and crusting and spread peripherally.7 Pathology shows suprabasilar clefts and numerous acantholytic cells (Figure 3). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are rare with infrequent corps ronds and rare grains. The epidermis also is less hyperplastic in Grover disease than in Hailey-Hailey disease.1

Grover disease also may present histologically with a pemphiguslike pattern, mimicking pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris; however, direct immunofluorescence studies are negative in Grover disease.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies to desmoglein 1, which are present on the surfaces of keratinocytes, and is characterized by scaly crusts and blisters.8 Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus (Figure 4) shows a superficial epidermal blistering process. The acantholysis may be subtle and is commonly localized to the stratum granulosum, extending into the stratum corneum. Complete loss of the stratum corneum can be seen, resulting in only scattered acantholytic cells. Spongiosis also may be seen. The dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate that often contains eosinophils. Pemphigus foliaceus is confirmed by direct immunofluorescence.9

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disorder that is characterized by IgG autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a component of desmosomes that are involved in keratinocyte-to-keratinocyte adhesion. Clinically, patients present with flaccid fragile blisters on the skin and mucous membranes that rupture easily, leading to painful erosions.10 Intraepidermal blisters are seen histologically (Figure 5) with the loss of cohesion (acantholysis) seen classically in the lower portions of the epidermis where desmoglein 3 is most prominent. When only the basal layer remains, the histology has been likened to a tombstone row.11 Extension of the blister along the adnexa is common. The underlying dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate with eosinophils. Early lesions may show only eosinophilic spongiosis. Direct immunofluorescence studies show IgG and C3 in an intercellular pattern that resembles a fish net or chicken wire.4,11

The spongioticlike pattern of Grover disease is marked by epidermal edema with separation of the keratinocytes and the revelation of their intracellular bridges,4 which manifests as vesiculation in the stratum corneum or upper layers of the epidermis.12

Grover disease is self-limited and may spontaneously resolve; however, the disease may be responsive to topical and systemic steroids. Additionally, avoidance of aggravating factors such as sunlight, heat, and sweating can improve symptoms.2

The Diagnosis: Grover Disease

Grover disease (also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis) was first described by Ralph W. Grover in 1970 as an idiopathic, acquired, monomorphous, papulovesicular eruption. Although originally characterized by solely transient acantholytic dermatosis, over time the term Grover disease has been expanded to include persistent acantholytic dermatoses. Grover disease chiefly affects white adults older than 40 years and is more prevalent in males than females. Cases generally are self-limited but correlate with age, as older adults are more likely to have prolonged eruptions.1

Grover disease typically erupts with discrete, erythematous, edematous, acneform, red-brown or flesh-colored papules, papulovesicles, or keratotic papules that primarily are seen on the trunk and anterior portion of the chest. As the rash spreads, it can erupt on the neck and thighs. The etiology of Grover disease is unknown, but many factors have been associated with the condition in a limited number of patients, including exposure to UV radiation, excessive heat or sweating, use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and recombinant human IL-4, and infection with Malassezia furfur and Demodex folliculorum.1 Grover disease also has been associated with other conditions such as asteatotic eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis.2

Histologically, Grover disease (Figure 1) is an acantholytic process that can exhibit dyskeratosis (corps ronds and grains). Foci often are small and multiple foci are seen on shave biopsy. There also may be spongiotic changes when associated with an eczematous element. A perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils usually is seen.3 Basket weave keratin may be seen; however, as the lesions cause pruritus, erosions and ulcerations often are present.4

Grover disease has multiple histologic variants that may resemble Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and spongiotic dermatitis and can present in combination.5

The variant of Grover disease that has a Darier-like pattern is difficult to distinguish from Darier disease, an autosomal-dominant-inherited disorder classified by small papules that emerge in seborrheic areas during childhood and adolescence. Histologically, Darier disease (Figure 2) shows broad areas of dyskeratosis and acantholysis that lead to suprabasal cleavage. Follicular extension may be present. In addition, there often is prominent vertical parakeratosis in Darier disease.6 Histologic features that favor Darier disease over the Darier-like variant of Grover disease include a broad focus of acanthotic dyskeratosis with follicular extension; the presence of a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum; and a lack of spongiosis and eosinophils, which are notably absent in Darier disease but may be present in Grover disease.4

Another variant of Grover disease has a Hailey-Hailey-like pattern, which is characterized by Hailey-Hailey disease's dilapidated brick wall appearance or the diffuse suprabasal acantholysis of all epidermal layers without notable dyskeratosis.4 Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as familial benign pemphigus, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that presents with erythematous vesicular plaques in flexural areas. The plaques progress to flaccid bullae with rupture and crusting and spread peripherally.7 Pathology shows suprabasilar clefts and numerous acantholytic cells (Figure 3). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are rare with infrequent corps ronds and rare grains. The epidermis also is less hyperplastic in Grover disease than in Hailey-Hailey disease.1

Grover disease also may present histologically with a pemphiguslike pattern, mimicking pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus vulgaris; however, direct immunofluorescence studies are negative in Grover disease.

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies to desmoglein 1, which are present on the surfaces of keratinocytes, and is characterized by scaly crusts and blisters.8 Histologically, pemphigus foliaceus (Figure 4) shows a superficial epidermal blistering process. The acantholysis may be subtle and is commonly localized to the stratum granulosum, extending into the stratum corneum. Complete loss of the stratum corneum can be seen, resulting in only scattered acantholytic cells. Spongiosis also may be seen. The dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate that often contains eosinophils. Pemphigus foliaceus is confirmed by direct immunofluorescence.9

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune blistering disorder that is characterized by IgG autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a component of desmosomes that are involved in keratinocyte-to-keratinocyte adhesion. Clinically, patients present with flaccid fragile blisters on the skin and mucous membranes that rupture easily, leading to painful erosions.10 Intraepidermal blisters are seen histologically (Figure 5) with the loss of cohesion (acantholysis) seen classically in the lower portions of the epidermis where desmoglein 3 is most prominent. When only the basal layer remains, the histology has been likened to a tombstone row.11 Extension of the blister along the adnexa is common. The underlying dermis shows a perivascular infiltrate with eosinophils. Early lesions may show only eosinophilic spongiosis. Direct immunofluorescence studies show IgG and C3 in an intercellular pattern that resembles a fish net or chicken wire.4,11

The spongioticlike pattern of Grover disease is marked by epidermal edema with separation of the keratinocytes and the revelation of their intracellular bridges,4 which manifests as vesiculation in the stratum corneum or upper layers of the epidermis.12

Grover disease is self-limited and may spontaneously resolve; however, the disease may be responsive to topical and systemic steroids. Additionally, avoidance of aggravating factors such as sunlight, heat, and sweating can improve symptoms.2

- Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover's disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5, pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

- Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover's disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:83-86.

- Davis MD, Dinneen AM, Landa N, et al. Grover's disease: clinicopathologic review of 72 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:229-234.

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Chalet M, Grover R, Ackerman AB. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a reevaluation. Arch Dermatol. 1977;133:431-435.

- Takagi A, Kamijo M, Ikeda S. Darier disease. J Dermatol. 2016;43:275-279.

- Engin B, Kutlubay Z, Celik U, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:452-455.

- de Sena Nogueira Maehara L, Huizinga J, Jonkman MF. Rituximab therapy in pemphigus foliaceus: report of 12 cases and review of recent literature [published online March 31, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1420-1423.

- James KA, Culton DA, Diaz LA. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus foliaceus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:405-412.

- Black M, Mignogna MD, Scully C. Number II. pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Dis. 2005;11:119-130.

- Madke B, Doshi B, Khopkar U, et al. Appearances in dermatopathology: the diagnostic and the deceptive. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79:338-348.

- Motaparthi K. Pseudoherpetic transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease): case series and review of the literature [published online February 16, 2017]. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:486-489.

- Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover's disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5, pt 1):653-666; quiz 667-670.

- Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover's disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:83-86.

- Davis MD, Dinneen AM, Landa N, et al. Grover's disease: clinicopathologic review of 72 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:229-234.

- Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1490-1494.

- Chalet M, Grover R, Ackerman AB. Transient acantholytic dermatosis: a reevaluation. Arch Dermatol. 1977;133:431-435.

- Takagi A, Kamijo M, Ikeda S. Darier disease. J Dermatol. 2016;43:275-279.

- Engin B, Kutlubay Z, Celik U, et al. Hailey-Hailey disease: a fold (intertriginous) dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:452-455.

- de Sena Nogueira Maehara L, Huizinga J, Jonkman MF. Rituximab therapy in pemphigus foliaceus: report of 12 cases and review of recent literature [published online March 31, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1420-1423.

- James KA, Culton DA, Diaz LA. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus foliaceus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:405-412.

- Black M, Mignogna MD, Scully C. Number II. pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Dis. 2005;11:119-130.

- Madke B, Doshi B, Khopkar U, et al. Appearances in dermatopathology: the diagnostic and the deceptive. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79:338-348.

- Motaparthi K. Pseudoherpetic transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover disease): case series and review of the literature [published online February 16, 2017]. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:486-489.

A 55-year-old man presented with small, erythematous, nonfollicular, pruritic papules on the mid chest.

Flesh-Colored Papular Eruption

Papular Mucinosis/Scleromyxedema

Papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema, also known as generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a rare dermal mucinosis characterized by a papular eruption that can have an associated IgG λ paraproteinemia. The clinical presentation is gradual with the development of firm, flesh-colored, 2- to 3-mm papules often involving the hands, face, and neck that can progress to plaques that cover the entire body. Skin stiffening also can be seen.1 Extracutaneous symptoms are common and include dysphagia, arthralgia, myopathy, and cardiac dysfunction.2 Occasionally, central nervous system involvement can lead to the often fatal dermato-neuro syndrome.3,4

Histologically, papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema demonstrates increased, irregularly arranged fibroblasts in the reticular dermis with increased dermal mucin deposition (quiz image and Figure 1). The epidermis is normal or slightly thinned due to pressure from dermal changes. There may be a mild superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and atrophy of hair follicles.5 In this case, the clinical and histologic findings best supported a diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema.

Infundibulofolliculitis is a pruritic follicular papular eruption typically involving the neck, trunk, and proximal upper arms and shoulders. It is most common in black men who reside in hot and humid climates. Although infundibulofolliculitis would be included in the clinical differential diagnosis for the current patient, the histopathologic findings were quite distinct for the correct diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Infundibulofolliculitis shows widening of the upper part of the hair follicle (infundibulum) and infundibular inflammatory infiltrate with follicular spongiosis (Figure 2). Neither mucin deposition nor fibroblast proliferation is appreciated in infundibulofolliculitis.6,7

Granuloma annulare (GA) often can be distinguished clinically from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema due to the annular appearance of papules and plaques in GA and the lack of stiffness of underlying skin. Interstitial granuloma annulare is a histologic variant of GA that can be included in the histologic differential diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Histologically, there is an interstitial infiltrate of cytologically bland histiocytes dissecting between collagen bundles in interstitial GA (Figure 3). Necrobiosis and collections of mucin often are inconspicuous. Occasionally, the presence of eosinophils can be a helpful clue.8 A fibroblast proliferation is not a feature of GA.

Reticular erythematous mucinosis also is a type of cutaneous mucinosis but with a classic clinical appearance of a reticulated erythematous plaque on the chest or back, making it clinically distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema and the presentation described in the current patient. Reticular erythematous mucinosis can be histologically distinguished from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema by the presence of a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with increased dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4). It often shows a positive IgM deposition on the basement membrane on direct immunofluorescence.9

Similar to papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema, scleredema shows thickening of the skin with decreased movement of involved areas. Scleredema often involves the upper back, shoulders, and neck where affected areas often have a peau d'orange appearance. Scleredema is classified into 3 clinical forms based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, classically Streptococcus pyogenes. Type 2 is associated with a hematologic dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma, or it can have an associated paraproteinemia that is typically of the IgA κ type, which is distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema where IgG λ paraproteinemia typically is seen. Type 3 is associated with diabetes mellitus. Histologically, scleredema also is distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Although increased mucin is seen in the dermis, the mucin is classically more prominent in the deep reticular dermis as compared with papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema (Figure 5). Additionally, collagen bundles are thickened with clear separation between them. Hyperplasia of fibroblasts in the dermis that is a characteristic feature of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema is not observed in scleredema.10

- Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, et al. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:493-497.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Fleming KE, Virmani D, Sutton E, et al. Scleromyxedema and the dermato-neuro syndrome: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:508-517.

- Hummers LK. Scleromyxedema. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:658-662.

- Rongioleti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus, and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;5:174-175.

- Soyinka F. Recurrent disseminated infundibulofolliculitis. Int J Dermatol. 1973;12:314-317.

- Keimig EL. Granuloma annulare. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:315-329.

- Thareja S, Paghdal K, Lein MH, et al. Reticular erythematous mucinosis--a review. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:903-909.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

Papular Mucinosis/Scleromyxedema

Papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema, also known as generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a rare dermal mucinosis characterized by a papular eruption that can have an associated IgG λ paraproteinemia. The clinical presentation is gradual with the development of firm, flesh-colored, 2- to 3-mm papules often involving the hands, face, and neck that can progress to plaques that cover the entire body. Skin stiffening also can be seen.1 Extracutaneous symptoms are common and include dysphagia, arthralgia, myopathy, and cardiac dysfunction.2 Occasionally, central nervous system involvement can lead to the often fatal dermato-neuro syndrome.3,4

Histologically, papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema demonstrates increased, irregularly arranged fibroblasts in the reticular dermis with increased dermal mucin deposition (quiz image and Figure 1). The epidermis is normal or slightly thinned due to pressure from dermal changes. There may be a mild superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and atrophy of hair follicles.5 In this case, the clinical and histologic findings best supported a diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema.

Infundibulofolliculitis is a pruritic follicular papular eruption typically involving the neck, trunk, and proximal upper arms and shoulders. It is most common in black men who reside in hot and humid climates. Although infundibulofolliculitis would be included in the clinical differential diagnosis for the current patient, the histopathologic findings were quite distinct for the correct diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Infundibulofolliculitis shows widening of the upper part of the hair follicle (infundibulum) and infundibular inflammatory infiltrate with follicular spongiosis (Figure 2). Neither mucin deposition nor fibroblast proliferation is appreciated in infundibulofolliculitis.6,7

Granuloma annulare (GA) often can be distinguished clinically from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema due to the annular appearance of papules and plaques in GA and the lack of stiffness of underlying skin. Interstitial granuloma annulare is a histologic variant of GA that can be included in the histologic differential diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Histologically, there is an interstitial infiltrate of cytologically bland histiocytes dissecting between collagen bundles in interstitial GA (Figure 3). Necrobiosis and collections of mucin often are inconspicuous. Occasionally, the presence of eosinophils can be a helpful clue.8 A fibroblast proliferation is not a feature of GA.

Reticular erythematous mucinosis also is a type of cutaneous mucinosis but with a classic clinical appearance of a reticulated erythematous plaque on the chest or back, making it clinically distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema and the presentation described in the current patient. Reticular erythematous mucinosis can be histologically distinguished from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema by the presence of a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with increased dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4). It often shows a positive IgM deposition on the basement membrane on direct immunofluorescence.9

Similar to papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema, scleredema shows thickening of the skin with decreased movement of involved areas. Scleredema often involves the upper back, shoulders, and neck where affected areas often have a peau d'orange appearance. Scleredema is classified into 3 clinical forms based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, classically Streptococcus pyogenes. Type 2 is associated with a hematologic dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma, or it can have an associated paraproteinemia that is typically of the IgA κ type, which is distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema where IgG λ paraproteinemia typically is seen. Type 3 is associated with diabetes mellitus. Histologically, scleredema also is distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Although increased mucin is seen in the dermis, the mucin is classically more prominent in the deep reticular dermis as compared with papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema (Figure 5). Additionally, collagen bundles are thickened with clear separation between them. Hyperplasia of fibroblasts in the dermis that is a characteristic feature of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema is not observed in scleredema.10

Papular Mucinosis/Scleromyxedema

Papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema, also known as generalized lichen myxedematosus, is a rare dermal mucinosis characterized by a papular eruption that can have an associated IgG λ paraproteinemia. The clinical presentation is gradual with the development of firm, flesh-colored, 2- to 3-mm papules often involving the hands, face, and neck that can progress to plaques that cover the entire body. Skin stiffening also can be seen.1 Extracutaneous symptoms are common and include dysphagia, arthralgia, myopathy, and cardiac dysfunction.2 Occasionally, central nervous system involvement can lead to the often fatal dermato-neuro syndrome.3,4

Histologically, papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema demonstrates increased, irregularly arranged fibroblasts in the reticular dermis with increased dermal mucin deposition (quiz image and Figure 1). The epidermis is normal or slightly thinned due to pressure from dermal changes. There may be a mild superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and atrophy of hair follicles.5 In this case, the clinical and histologic findings best supported a diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema.

Infundibulofolliculitis is a pruritic follicular papular eruption typically involving the neck, trunk, and proximal upper arms and shoulders. It is most common in black men who reside in hot and humid climates. Although infundibulofolliculitis would be included in the clinical differential diagnosis for the current patient, the histopathologic findings were quite distinct for the correct diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Infundibulofolliculitis shows widening of the upper part of the hair follicle (infundibulum) and infundibular inflammatory infiltrate with follicular spongiosis (Figure 2). Neither mucin deposition nor fibroblast proliferation is appreciated in infundibulofolliculitis.6,7

Granuloma annulare (GA) often can be distinguished clinically from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema due to the annular appearance of papules and plaques in GA and the lack of stiffness of underlying skin. Interstitial granuloma annulare is a histologic variant of GA that can be included in the histologic differential diagnosis of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Histologically, there is an interstitial infiltrate of cytologically bland histiocytes dissecting between collagen bundles in interstitial GA (Figure 3). Necrobiosis and collections of mucin often are inconspicuous. Occasionally, the presence of eosinophils can be a helpful clue.8 A fibroblast proliferation is not a feature of GA.

Reticular erythematous mucinosis also is a type of cutaneous mucinosis but with a classic clinical appearance of a reticulated erythematous plaque on the chest or back, making it clinically distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema and the presentation described in the current patient. Reticular erythematous mucinosis can be histologically distinguished from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema by the presence of a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with increased dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4). It often shows a positive IgM deposition on the basement membrane on direct immunofluorescence.9

Similar to papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema, scleredema shows thickening of the skin with decreased movement of involved areas. Scleredema often involves the upper back, shoulders, and neck where affected areas often have a peau d'orange appearance. Scleredema is classified into 3 clinical forms based on clinical associations. Type 1 often is preceded by an infection, classically Streptococcus pyogenes. Type 2 is associated with a hematologic dyscrasia such as multiple myeloma, or it can have an associated paraproteinemia that is typically of the IgA κ type, which is distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema where IgG λ paraproteinemia typically is seen. Type 3 is associated with diabetes mellitus. Histologically, scleredema also is distinct from papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema. Although increased mucin is seen in the dermis, the mucin is classically more prominent in the deep reticular dermis as compared with papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema (Figure 5). Additionally, collagen bundles are thickened with clear separation between them. Hyperplasia of fibroblasts in the dermis that is a characteristic feature of papular mucinosis/scleromyxedema is not observed in scleredema.10

- Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, et al. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:493-497.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Fleming KE, Virmani D, Sutton E, et al. Scleromyxedema and the dermato-neuro syndrome: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:508-517.

- Hummers LK. Scleromyxedema. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:658-662.

- Rongioleti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus, and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;5:174-175.

- Soyinka F. Recurrent disseminated infundibulofolliculitis. Int J Dermatol. 1973;12:314-317.

- Keimig EL. Granuloma annulare. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:315-329.

- Thareja S, Paghdal K, Lein MH, et al. Reticular erythematous mucinosis--a review. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:903-909.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, et al. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:493-497.

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72.

- Fleming KE, Virmani D, Sutton E, et al. Scleromyxedema and the dermato-neuro syndrome: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:508-517.

- Hummers LK. Scleromyxedema. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:658-662.

- Rongioleti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus, and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Owen WR, Wood C. Disseminate and recurrent infundibulofolliculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;5:174-175.

- Soyinka F. Recurrent disseminated infundibulofolliculitis. Int J Dermatol. 1973;12:314-317.

- Keimig EL. Granuloma annulare. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:315-329.

- Thareja S, Paghdal K, Lein MH, et al. Reticular erythematous mucinosis--a review. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:903-909.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

A 48-year-old black man presented with a rash of 7 months' duration that started on the face and spread to the body. He had extreme pruritus, increased stiffness in the hands and joints, and paresthesia. Physical examination revealed an eruption of 2- to 4-mm, flesh-colored papules with follicular accentuation on the face, neck, bilateral upper extremities, back, and thighs.

Trichilemmoma

Trichilemmomas are benign follicular neoplasms that exhibit differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the pilosebaceous follicular epithelium.1 Trichilemmomas clinically present as individual or multiple, slowly growing, verrucous papules appearing most commonly on the face or neck. The lesions may coalesce to form small plaques. Although trichilemmomas typically are isolated, patients with multiple trichilemmomas require a cancer screening workup due to their association with Cowden disease, which results from a mutation in the phosphatase and tensin homolog tumor suppressor gene, PTEN.2 An easy way to remember the association between trichilemmomas and Cowden disease is to alter the spelling to “trichile-moo-moo,” using the “moo moo” sound of an animal cow as a clue linking the tumor to Cowden disease.

Histologically, trichilemmomas exhibit a lobular epidermal downgrowth into the dermis (Figure 1). The surface of the lesion may be hyperkeratotic and somewhat papillomatous. Cells toward the center of the lobule are pale staining, periodic acid–Schiff positive, and diastase labile due to high levels of intracellular glycogen (Figure 2). Cells toward the periphery of the lobule usually appear basophilic with a palisading arrangement of the peripheral cells. The entire lobule is enclosed within an eosinophilic basement membrane that stains positively with periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 2).1 Consistent with the tumor’s differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, trichilemmomas have been reported to express CD34 focally or diffusely.3

|

|

Similar to trichilemmoma, inverted follicular keratosis (IFK) commonly presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule on the face. Inverted follicular keratosis is a somewhat controversial entity, with some authorities arguing IFK is a variant of verruca vulgaris or seborrheic keratosis. Histologically, IFKs can be differentiated by the presence of squamous eddies (concentric layers of squamous cells in a whorled pattern), which are diagnostic, and central longitudinal crypts that contain keratin and are lined by squamous epithelium.4 Basaloid cells can be seen at the periphery of the tumors; however, IFKs lack an eosinophilic basement membrane surrounding the tumor (Figure 3).

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ classically appears as an erythematous hyperkeratotic papule or plaque on sun-exposed sites that can become crusted or ulcerated. Microscopically, squamous cell carcinoma in situ displays full-thickness disorderly maturation of keratinocytes. The keratinocytes exhibit nuclear pleomorphism. Atypical mitotic figures and dyskeratotic keratinocytes also can be seen throughout the full thickness of the epidermis (Figure 4).5

Verruca vulgaris (Figure 5) histologically demonstrates hyperkeratosis with tiers of parakeratosis, digitated epidermal hyperplasia, and dilated tortuous capillaries within the dermal papillae. At the edges of the lesion there often is inward turning of elongated rete ridges,6,7 which can be thought of as the rete reaching out for a hug of sorts to spread the human papillomavirus infection. Although the surface of a trichilemmoma can bear resemblance to a verruca vulgaris, the remainder of the histologic features can be used to help differentiate these tumors. Additionally, there has been no evidence suggestive of a viral etiology for trichilemmomas.8

Warty dyskeratoma features an umbilicated papule, usually on the face, head, or neck, that is associated with a follicular unit. The papule shows a cup-shaped, keratin-filled invagination; suprabasilar clefting; and acantholytic dyskeratotic cells, which are features that are not seen in trichilemmomas (Figure 6).9

Acknowledgment—The authors would like to thank Brandon Litzner, MD, St Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

1. Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Trichilemmoma: analysis of 40 new cases. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:866-869.

2. Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg J, Prieto V, et al. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:493-499.

3. Tardío JC. CD34-reactive tumors of the skin. an updated review of an ever-growing list of lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:89-102.

4. Mehregan A. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

5. Cockerell CJ. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 2):11-17.

6. Jabłonska S, Majewski S, Obalek S, et al. Cutaneous warts. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:309-319.

7. Hardin J, Gardner J, Colome M, et al. Verrucous cyst with melanocytic and sebaceous differentiation. Arch Path Lab Med. 2013;137:576-579.

8. Johnson BL, Kramer EM, Lavker RM. The keratotic tumors of Cowden’s disease: an electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:291-298.

9. Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma—“follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

Trichilemmomas are benign follicular neoplasms that exhibit differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the pilosebaceous follicular epithelium.1 Trichilemmomas clinically present as individual or multiple, slowly growing, verrucous papules appearing most commonly on the face or neck. The lesions may coalesce to form small plaques. Although trichilemmomas typically are isolated, patients with multiple trichilemmomas require a cancer screening workup due to their association with Cowden disease, which results from a mutation in the phosphatase and tensin homolog tumor suppressor gene, PTEN.2 An easy way to remember the association between trichilemmomas and Cowden disease is to alter the spelling to “trichile-moo-moo,” using the “moo moo” sound of an animal cow as a clue linking the tumor to Cowden disease.

Histologically, trichilemmomas exhibit a lobular epidermal downgrowth into the dermis (Figure 1). The surface of the lesion may be hyperkeratotic and somewhat papillomatous. Cells toward the center of the lobule are pale staining, periodic acid–Schiff positive, and diastase labile due to high levels of intracellular glycogen (Figure 2). Cells toward the periphery of the lobule usually appear basophilic with a palisading arrangement of the peripheral cells. The entire lobule is enclosed within an eosinophilic basement membrane that stains positively with periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 2).1 Consistent with the tumor’s differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, trichilemmomas have been reported to express CD34 focally or diffusely.3

|

|

Similar to trichilemmoma, inverted follicular keratosis (IFK) commonly presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule on the face. Inverted follicular keratosis is a somewhat controversial entity, with some authorities arguing IFK is a variant of verruca vulgaris or seborrheic keratosis. Histologically, IFKs can be differentiated by the presence of squamous eddies (concentric layers of squamous cells in a whorled pattern), which are diagnostic, and central longitudinal crypts that contain keratin and are lined by squamous epithelium.4 Basaloid cells can be seen at the periphery of the tumors; however, IFKs lack an eosinophilic basement membrane surrounding the tumor (Figure 3).

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ classically appears as an erythematous hyperkeratotic papule or plaque on sun-exposed sites that can become crusted or ulcerated. Microscopically, squamous cell carcinoma in situ displays full-thickness disorderly maturation of keratinocytes. The keratinocytes exhibit nuclear pleomorphism. Atypical mitotic figures and dyskeratotic keratinocytes also can be seen throughout the full thickness of the epidermis (Figure 4).5

Verruca vulgaris (Figure 5) histologically demonstrates hyperkeratosis with tiers of parakeratosis, digitated epidermal hyperplasia, and dilated tortuous capillaries within the dermal papillae. At the edges of the lesion there often is inward turning of elongated rete ridges,6,7 which can be thought of as the rete reaching out for a hug of sorts to spread the human papillomavirus infection. Although the surface of a trichilemmoma can bear resemblance to a verruca vulgaris, the remainder of the histologic features can be used to help differentiate these tumors. Additionally, there has been no evidence suggestive of a viral etiology for trichilemmomas.8

Warty dyskeratoma features an umbilicated papule, usually on the face, head, or neck, that is associated with a follicular unit. The papule shows a cup-shaped, keratin-filled invagination; suprabasilar clefting; and acantholytic dyskeratotic cells, which are features that are not seen in trichilemmomas (Figure 6).9

Acknowledgment—The authors would like to thank Brandon Litzner, MD, St Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

Trichilemmomas are benign follicular neoplasms that exhibit differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the pilosebaceous follicular epithelium.1 Trichilemmomas clinically present as individual or multiple, slowly growing, verrucous papules appearing most commonly on the face or neck. The lesions may coalesce to form small plaques. Although trichilemmomas typically are isolated, patients with multiple trichilemmomas require a cancer screening workup due to their association with Cowden disease, which results from a mutation in the phosphatase and tensin homolog tumor suppressor gene, PTEN.2 An easy way to remember the association between trichilemmomas and Cowden disease is to alter the spelling to “trichile-moo-moo,” using the “moo moo” sound of an animal cow as a clue linking the tumor to Cowden disease.

Histologically, trichilemmomas exhibit a lobular epidermal downgrowth into the dermis (Figure 1). The surface of the lesion may be hyperkeratotic and somewhat papillomatous. Cells toward the center of the lobule are pale staining, periodic acid–Schiff positive, and diastase labile due to high levels of intracellular glycogen (Figure 2). Cells toward the periphery of the lobule usually appear basophilic with a palisading arrangement of the peripheral cells. The entire lobule is enclosed within an eosinophilic basement membrane that stains positively with periodic acid–Schiff (Figure 2).1 Consistent with the tumor’s differentiation toward the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, trichilemmomas have been reported to express CD34 focally or diffusely.3

|

|

Similar to trichilemmoma, inverted follicular keratosis (IFK) commonly presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule on the face. Inverted follicular keratosis is a somewhat controversial entity, with some authorities arguing IFK is a variant of verruca vulgaris or seborrheic keratosis. Histologically, IFKs can be differentiated by the presence of squamous eddies (concentric layers of squamous cells in a whorled pattern), which are diagnostic, and central longitudinal crypts that contain keratin and are lined by squamous epithelium.4 Basaloid cells can be seen at the periphery of the tumors; however, IFKs lack an eosinophilic basement membrane surrounding the tumor (Figure 3).

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ classically appears as an erythematous hyperkeratotic papule or plaque on sun-exposed sites that can become crusted or ulcerated. Microscopically, squamous cell carcinoma in situ displays full-thickness disorderly maturation of keratinocytes. The keratinocytes exhibit nuclear pleomorphism. Atypical mitotic figures and dyskeratotic keratinocytes also can be seen throughout the full thickness of the epidermis (Figure 4).5

Verruca vulgaris (Figure 5) histologically demonstrates hyperkeratosis with tiers of parakeratosis, digitated epidermal hyperplasia, and dilated tortuous capillaries within the dermal papillae. At the edges of the lesion there often is inward turning of elongated rete ridges,6,7 which can be thought of as the rete reaching out for a hug of sorts to spread the human papillomavirus infection. Although the surface of a trichilemmoma can bear resemblance to a verruca vulgaris, the remainder of the histologic features can be used to help differentiate these tumors. Additionally, there has been no evidence suggestive of a viral etiology for trichilemmomas.8

Warty dyskeratoma features an umbilicated papule, usually on the face, head, or neck, that is associated with a follicular unit. The papule shows a cup-shaped, keratin-filled invagination; suprabasilar clefting; and acantholytic dyskeratotic cells, which are features that are not seen in trichilemmomas (Figure 6).9

Acknowledgment—The authors would like to thank Brandon Litzner, MD, St Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

1. Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Trichilemmoma: analysis of 40 new cases. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:866-869.

2. Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg J, Prieto V, et al. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:493-499.

3. Tardío JC. CD34-reactive tumors of the skin. an updated review of an ever-growing list of lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:89-102.

4. Mehregan A. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

5. Cockerell CJ. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 2):11-17.

6. Jabłonska S, Majewski S, Obalek S, et al. Cutaneous warts. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:309-319.

7. Hardin J, Gardner J, Colome M, et al. Verrucous cyst with melanocytic and sebaceous differentiation. Arch Path Lab Med. 2013;137:576-579.

8. Johnson BL, Kramer EM, Lavker RM. The keratotic tumors of Cowden’s disease: an electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:291-298.

9. Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma—“follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

1. Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Trichilemmoma: analysis of 40 new cases. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:866-869.

2. Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg J, Prieto V, et al. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:493-499.

3. Tardío JC. CD34-reactive tumors of the skin. an updated review of an ever-growing list of lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:89-102.

4. Mehregan A. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

5. Cockerell CJ. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1, pt 2):11-17.

6. Jabłonska S, Majewski S, Obalek S, et al. Cutaneous warts. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:309-319.

7. Hardin J, Gardner J, Colome M, et al. Verrucous cyst with melanocytic and sebaceous differentiation. Arch Path Lab Med. 2013;137:576-579.

8. Johnson BL, Kramer EM, Lavker RM. The keratotic tumors of Cowden’s disease: an electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:291-298.

9. Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma—“follicular dyskeratoma”: analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

Subcutaneous Panniculitislike T-Cell Lymphoma

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma (SPTL) is a cutaneous lymphoma of α and β phenotype cytotoxic T cells in which the neoplastic cells are found almost exclusively in the subcutaneous layer and resemble a panniculitis.1 It affects males and females with equal incidence and is seen in both adults and children. Clinically, this disease presents as a nonspecific panniculitis with indurated but typically nonulcerated erythematous plaques and nodules most commonly located on the extremities. Plaques and nodules may appear on other body sites and may be generalized.1 In some cases, patients present with associated systemic symptoms including fever, malaise, weight loss, and fatigue.2

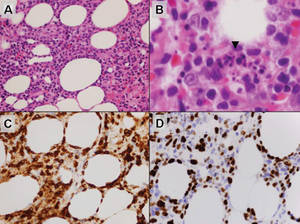

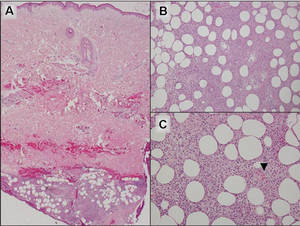

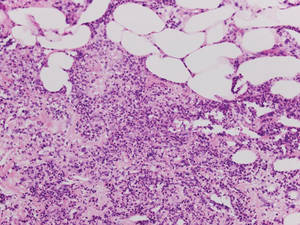

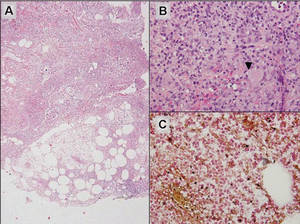

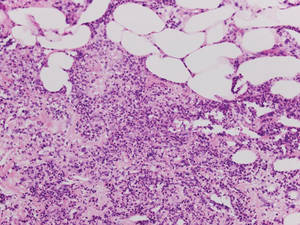

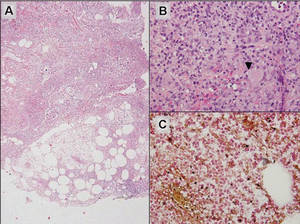

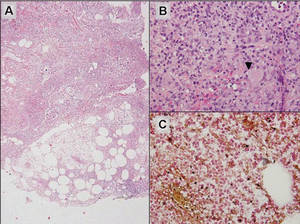

Histologically, SPTL presents as a predominantly lobular panniculitis (Figure 1) with rimming of adipocytes by neoplastic cells that appear as small and medium-sized atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 2A). A less dominant septal component may be present, and neoplastic cells may encroach into the lower reticular dermis, rarely involving the papillary dermis or epidermis.2 Although rimming of adipocytes is classic, it is not specific to this entity, as rimming also can be found in other lymphomas and infectious panniculitis. Reactive lymphocytes and macrophages with ingested lipid material also are seen intermixed with neoplastic cells.2 Necrosis is a common finding, including destructive fragmentation of the nucleus, known as karyorrhexis. If necrosis is extensive, appreciation of other histologic features may be hindered.3 Histiocytes engulfing the nuclear debris known as beanbag cells also can be seen (Figure 2B). The diagnosis can be made on immunohistologic analysis demonstrating neoplastic cells with a cytotoxic α and β T-suppressor phenotype centered around and rimming the adipocytes in the subcutaneous fat.3 Immunohistochemistry reveals positive CD3, CD8 (Figure 2C), and βF1 markers, as well as T-cell intracellular antigen 1 (TIA-1), granzyme B, and perforin.1,2 The neoplastic cells often have a high proliferation index as evidenced by MIB-1 (Ki-67) labeling (Figure 2D). The neoplastic cells are negative for CD4, CD56, and CD30.1,2 Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma cells are negative for Epstein-Barr virus by in situ hybridization.2

|

| Figure 1. Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma showing a predominantly lobular panniculitis (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

| Figure 2. Rimming of adipocytes by hyperchromatic lymphocytes (A)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Arrowhead indicates a histiocyte (ie, beanbag cell) that has undergone cytophagocytosis of nuclear debris (B)(H&E, original magnification ×600). Immunohistochemistry with CD8 highlights the cells rimming the adipocytes (C)(original magnification ×600). Immunohistochemistry with MIB-1 shows an increased proliferative rate in the lymphocytes rimming the adipocytes (D)(original magnification ×600). |

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma must be distinguished from lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP) and other cutaneous lymphomas. Importantly, LEP and SPTL clinically may appear similar and are not mutually exclusive diagnoses.2 On histology, they may look similar, showing T cell aggregates and necrosis; however, thickening of the basement membrane, vacuolar change at the dermoepidermal junction, plasma cells, hyaline sclerosis, mucin deposition, a lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate, and nodular aggregates of B cells are more common in LEP (Figure 3).2,4 Additionally, in LEP the T cell aggregates typically will not have a high proliferative rate as evidenced by MIB-1.3

Additionally, other lobular panniculitides can be considered in the differential diagnosis, including erythema induratum (EI), α1-antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis (A1ATDP), and infectious panniculitis. Histologically, EI (Figure 4), also known as nodular vasculitis when not associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has a lobular pattern of inflammation. Early in the disease process there are discrete collections of neutrophils; later, granulomas with histiocytes, giant cells, and foamy macrophages are seen.4 The reactive infiltrate of EI is more mixed than in SPTL, with small lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis and extravascular caseous or fibrinoid necrosis also may be present.4,5 Substantial caseous necrosis may extend to the dermis and epidermis with EI. Importantly, EI lacks true tuberculoid granulomas and stains negative for acid-fast bacilli, as it is a reactive rather than a local infectious process, but a history of M tuberculosis exposure is common.4 α1-Antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis results from a deficiency of proteinase activity and can be distinguished from SPTL by a neutrophil-rich panniculitis (Figure 5) as well as the classic appearance of splaying of neutrophils between collagen bundles in the deep reticular dermis. Additionally, the panniculitis is characterized by focal areas of necrotic lobules and septa with an infiltrate of neutrophils and macrophages that abut areas of normal-appearing subcutaneous fat without infiltrate.6 Clinically, the A1ATDP lesions may have ulceration and express an oily substance from fat necrosis. Panniculitis with A1ATDP may precede liver and lung disease.4 Panniculitis from bacterial or fungal infection is more common in immunocompromised patients but should be considered when subcutaneous inflammation and/or necrosis is present. Depending on the responsible organism and the status of a patient’s immune system, infectious panniculitis can have variable presentations, including suppurative granulomas with mycobacterial organisms, a dermal focus of infection if the primary source is cutaneous, or a deeper reticular and subcuticular focus in the subcutaneous fat if the infectious panniculitis occurs from hematogenous spread.4 An example of an infectious panniculitis having more of a granulomatous pattern secondary to Cryptococcus can be seen in Figure 6. Ultimately, special stains to identify infectious organisms (eg, Gram, periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen) can be ordered to aid in the diagnosis if a responsible organism is not visible on hematoxylin and eosin staining.

|

Figure 4. Erythema induratum is characterized by a lobular panniculitis (A and B)(both H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×200). Vascular changes (arrowhead) are present in a majority of cases with endothelial swelling and extravasation of erythrocytes (C)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

| Figure 5. Neutrophilic panniculitis that can be seen in α1-antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis (H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

Figure 6. Infectious panniculitis secondary to Cryptococcus showing a granulomatous reaction in the subcutis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). Closer inspection shows a dense infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells including numerous histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Some of the giant cells contain refractile organisms (arrowhead)(B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Mucicarmine histochemical stain highlights the capsule of the organism (C)(original magnification ×400). |

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Drake Poeschl, MD, St. Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

1. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3765-3785.

2. Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: definition, classification, and prognostic factors: an EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008;111:838-845.

3. Cerroni L, Gatter K, Kerl H. Subcutaneous “panniculitis-like” T-cell lymphoma. In: Cerroni L, Gatter K, Kerl H. Skin Lymphoma: The Illustrated Guide. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2011:87-96.

4. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

5. Sharon V, Goodarzi H, Chambers CJ, et al. Erythema induratum of Bazin. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:1.

6. Rajagopal R, Malik AK, Murthy PS, et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:362-364.

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma (SPTL) is a cutaneous lymphoma of α and β phenotype cytotoxic T cells in which the neoplastic cells are found almost exclusively in the subcutaneous layer and resemble a panniculitis.1 It affects males and females with equal incidence and is seen in both adults and children. Clinically, this disease presents as a nonspecific panniculitis with indurated but typically nonulcerated erythematous plaques and nodules most commonly located on the extremities. Plaques and nodules may appear on other body sites and may be generalized.1 In some cases, patients present with associated systemic symptoms including fever, malaise, weight loss, and fatigue.2

Histologically, SPTL presents as a predominantly lobular panniculitis (Figure 1) with rimming of adipocytes by neoplastic cells that appear as small and medium-sized atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 2A). A less dominant septal component may be present, and neoplastic cells may encroach into the lower reticular dermis, rarely involving the papillary dermis or epidermis.2 Although rimming of adipocytes is classic, it is not specific to this entity, as rimming also can be found in other lymphomas and infectious panniculitis. Reactive lymphocytes and macrophages with ingested lipid material also are seen intermixed with neoplastic cells.2 Necrosis is a common finding, including destructive fragmentation of the nucleus, known as karyorrhexis. If necrosis is extensive, appreciation of other histologic features may be hindered.3 Histiocytes engulfing the nuclear debris known as beanbag cells also can be seen (Figure 2B). The diagnosis can be made on immunohistologic analysis demonstrating neoplastic cells with a cytotoxic α and β T-suppressor phenotype centered around and rimming the adipocytes in the subcutaneous fat.3 Immunohistochemistry reveals positive CD3, CD8 (Figure 2C), and βF1 markers, as well as T-cell intracellular antigen 1 (TIA-1), granzyme B, and perforin.1,2 The neoplastic cells often have a high proliferation index as evidenced by MIB-1 (Ki-67) labeling (Figure 2D). The neoplastic cells are negative for CD4, CD56, and CD30.1,2 Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma cells are negative for Epstein-Barr virus by in situ hybridization.2

|

| Figure 1. Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma showing a predominantly lobular panniculitis (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

| Figure 2. Rimming of adipocytes by hyperchromatic lymphocytes (A)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Arrowhead indicates a histiocyte (ie, beanbag cell) that has undergone cytophagocytosis of nuclear debris (B)(H&E, original magnification ×600). Immunohistochemistry with CD8 highlights the cells rimming the adipocytes (C)(original magnification ×600). Immunohistochemistry with MIB-1 shows an increased proliferative rate in the lymphocytes rimming the adipocytes (D)(original magnification ×600). |

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma must be distinguished from lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP) and other cutaneous lymphomas. Importantly, LEP and SPTL clinically may appear similar and are not mutually exclusive diagnoses.2 On histology, they may look similar, showing T cell aggregates and necrosis; however, thickening of the basement membrane, vacuolar change at the dermoepidermal junction, plasma cells, hyaline sclerosis, mucin deposition, a lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate, and nodular aggregates of B cells are more common in LEP (Figure 3).2,4 Additionally, in LEP the T cell aggregates typically will not have a high proliferative rate as evidenced by MIB-1.3

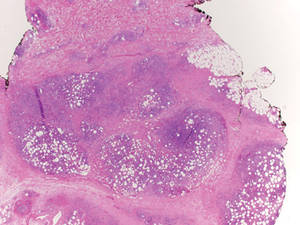

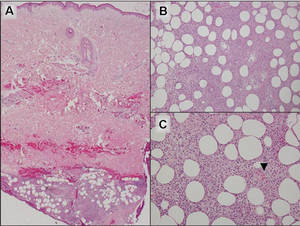

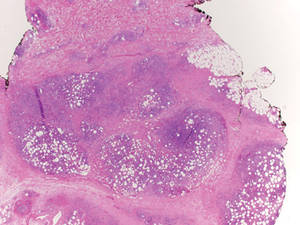

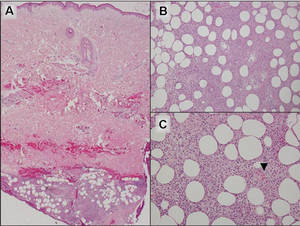

Additionally, other lobular panniculitides can be considered in the differential diagnosis, including erythema induratum (EI), α1-antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis (A1ATDP), and infectious panniculitis. Histologically, EI (Figure 4), also known as nodular vasculitis when not associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has a lobular pattern of inflammation. Early in the disease process there are discrete collections of neutrophils; later, granulomas with histiocytes, giant cells, and foamy macrophages are seen.4 The reactive infiltrate of EI is more mixed than in SPTL, with small lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis and extravascular caseous or fibrinoid necrosis also may be present.4,5 Substantial caseous necrosis may extend to the dermis and epidermis with EI. Importantly, EI lacks true tuberculoid granulomas and stains negative for acid-fast bacilli, as it is a reactive rather than a local infectious process, but a history of M tuberculosis exposure is common.4 α1-Antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis results from a deficiency of proteinase activity and can be distinguished from SPTL by a neutrophil-rich panniculitis (Figure 5) as well as the classic appearance of splaying of neutrophils between collagen bundles in the deep reticular dermis. Additionally, the panniculitis is characterized by focal areas of necrotic lobules and septa with an infiltrate of neutrophils and macrophages that abut areas of normal-appearing subcutaneous fat without infiltrate.6 Clinically, the A1ATDP lesions may have ulceration and express an oily substance from fat necrosis. Panniculitis with A1ATDP may precede liver and lung disease.4 Panniculitis from bacterial or fungal infection is more common in immunocompromised patients but should be considered when subcutaneous inflammation and/or necrosis is present. Depending on the responsible organism and the status of a patient’s immune system, infectious panniculitis can have variable presentations, including suppurative granulomas with mycobacterial organisms, a dermal focus of infection if the primary source is cutaneous, or a deeper reticular and subcuticular focus in the subcutaneous fat if the infectious panniculitis occurs from hematogenous spread.4 An example of an infectious panniculitis having more of a granulomatous pattern secondary to Cryptococcus can be seen in Figure 6. Ultimately, special stains to identify infectious organisms (eg, Gram, periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen) can be ordered to aid in the diagnosis if a responsible organism is not visible on hematoxylin and eosin staining.

|

Figure 4. Erythema induratum is characterized by a lobular panniculitis (A and B)(both H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×200). Vascular changes (arrowhead) are present in a majority of cases with endothelial swelling and extravasation of erythrocytes (C)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

| Figure 5. Neutrophilic panniculitis that can be seen in α1-antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis (H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

Figure 6. Infectious panniculitis secondary to Cryptococcus showing a granulomatous reaction in the subcutis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). Closer inspection shows a dense infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells including numerous histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Some of the giant cells contain refractile organisms (arrowhead)(B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Mucicarmine histochemical stain highlights the capsule of the organism (C)(original magnification ×400). |

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Drake Poeschl, MD, St. Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma (SPTL) is a cutaneous lymphoma of α and β phenotype cytotoxic T cells in which the neoplastic cells are found almost exclusively in the subcutaneous layer and resemble a panniculitis.1 It affects males and females with equal incidence and is seen in both adults and children. Clinically, this disease presents as a nonspecific panniculitis with indurated but typically nonulcerated erythematous plaques and nodules most commonly located on the extremities. Plaques and nodules may appear on other body sites and may be generalized.1 In some cases, patients present with associated systemic symptoms including fever, malaise, weight loss, and fatigue.2

Histologically, SPTL presents as a predominantly lobular panniculitis (Figure 1) with rimming of adipocytes by neoplastic cells that appear as small and medium-sized atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 2A). A less dominant septal component may be present, and neoplastic cells may encroach into the lower reticular dermis, rarely involving the papillary dermis or epidermis.2 Although rimming of adipocytes is classic, it is not specific to this entity, as rimming also can be found in other lymphomas and infectious panniculitis. Reactive lymphocytes and macrophages with ingested lipid material also are seen intermixed with neoplastic cells.2 Necrosis is a common finding, including destructive fragmentation of the nucleus, known as karyorrhexis. If necrosis is extensive, appreciation of other histologic features may be hindered.3 Histiocytes engulfing the nuclear debris known as beanbag cells also can be seen (Figure 2B). The diagnosis can be made on immunohistologic analysis demonstrating neoplastic cells with a cytotoxic α and β T-suppressor phenotype centered around and rimming the adipocytes in the subcutaneous fat.3 Immunohistochemistry reveals positive CD3, CD8 (Figure 2C), and βF1 markers, as well as T-cell intracellular antigen 1 (TIA-1), granzyme B, and perforin.1,2 The neoplastic cells often have a high proliferation index as evidenced by MIB-1 (Ki-67) labeling (Figure 2D). The neoplastic cells are negative for CD4, CD56, and CD30.1,2 Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma cells are negative for Epstein-Barr virus by in situ hybridization.2

|

| Figure 1. Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma showing a predominantly lobular panniculitis (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

| Figure 2. Rimming of adipocytes by hyperchromatic lymphocytes (A)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Arrowhead indicates a histiocyte (ie, beanbag cell) that has undergone cytophagocytosis of nuclear debris (B)(H&E, original magnification ×600). Immunohistochemistry with CD8 highlights the cells rimming the adipocytes (C)(original magnification ×600). Immunohistochemistry with MIB-1 shows an increased proliferative rate in the lymphocytes rimming the adipocytes (D)(original magnification ×600). |

Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma must be distinguished from lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP) and other cutaneous lymphomas. Importantly, LEP and SPTL clinically may appear similar and are not mutually exclusive diagnoses.2 On histology, they may look similar, showing T cell aggregates and necrosis; however, thickening of the basement membrane, vacuolar change at the dermoepidermal junction, plasma cells, hyaline sclerosis, mucin deposition, a lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate, and nodular aggregates of B cells are more common in LEP (Figure 3).2,4 Additionally, in LEP the T cell aggregates typically will not have a high proliferative rate as evidenced by MIB-1.3

Additionally, other lobular panniculitides can be considered in the differential diagnosis, including erythema induratum (EI), α1-antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis (A1ATDP), and infectious panniculitis. Histologically, EI (Figure 4), also known as nodular vasculitis when not associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has a lobular pattern of inflammation. Early in the disease process there are discrete collections of neutrophils; later, granulomas with histiocytes, giant cells, and foamy macrophages are seen.4 The reactive infiltrate of EI is more mixed than in SPTL, with small lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis and extravascular caseous or fibrinoid necrosis also may be present.4,5 Substantial caseous necrosis may extend to the dermis and epidermis with EI. Importantly, EI lacks true tuberculoid granulomas and stains negative for acid-fast bacilli, as it is a reactive rather than a local infectious process, but a history of M tuberculosis exposure is common.4 α1-Antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis results from a deficiency of proteinase activity and can be distinguished from SPTL by a neutrophil-rich panniculitis (Figure 5) as well as the classic appearance of splaying of neutrophils between collagen bundles in the deep reticular dermis. Additionally, the panniculitis is characterized by focal areas of necrotic lobules and septa with an infiltrate of neutrophils and macrophages that abut areas of normal-appearing subcutaneous fat without infiltrate.6 Clinically, the A1ATDP lesions may have ulceration and express an oily substance from fat necrosis. Panniculitis with A1ATDP may precede liver and lung disease.4 Panniculitis from bacterial or fungal infection is more common in immunocompromised patients but should be considered when subcutaneous inflammation and/or necrosis is present. Depending on the responsible organism and the status of a patient’s immune system, infectious panniculitis can have variable presentations, including suppurative granulomas with mycobacterial organisms, a dermal focus of infection if the primary source is cutaneous, or a deeper reticular and subcuticular focus in the subcutaneous fat if the infectious panniculitis occurs from hematogenous spread.4 An example of an infectious panniculitis having more of a granulomatous pattern secondary to Cryptococcus can be seen in Figure 6. Ultimately, special stains to identify infectious organisms (eg, Gram, periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen) can be ordered to aid in the diagnosis if a responsible organism is not visible on hematoxylin and eosin staining.

|

Figure 4. Erythema induratum is characterized by a lobular panniculitis (A and B)(both H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×200). Vascular changes (arrowhead) are present in a majority of cases with endothelial swelling and extravasation of erythrocytes (C)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

| Figure 5. Neutrophilic panniculitis that can be seen in α1-antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis (H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

Figure 6. Infectious panniculitis secondary to Cryptococcus showing a granulomatous reaction in the subcutis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). Closer inspection shows a dense infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells including numerous histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Some of the giant cells contain refractile organisms (arrowhead)(B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Mucicarmine histochemical stain highlights the capsule of the organism (C)(original magnification ×400). |

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Drake Poeschl, MD, St. Louis, Missouri, for proofreading the manuscript.

1. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3765-3785.

2. Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: definition, classification, and prognostic factors: an EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008;111:838-845.

3. Cerroni L, Gatter K, Kerl H. Subcutaneous “panniculitis-like” T-cell lymphoma. In: Cerroni L, Gatter K, Kerl H. Skin Lymphoma: The Illustrated Guide. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2011:87-96.

4. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.