User login

ESIR and Peripheral Insulin Resistance

A 34‐year‐old man was admitted for evaluation of elevated blood glucose despite extremely high subcutaneous (SQ) insulin requirements. He had a 12‐year history of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) without episodes of ketoacidosis, managed initially with oral medications (metformin with various sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones). Three months prior to admission, he was transitioned to SQ insulin and thereafter his requirements escalated rapidly. By the time of his admission, his blood glucose measurements were consistently above 300 mg/dL despite injecting more than 4100 units of insulin daily. His regimen included 300 units of insulin glargine (Lantus) 2 times per day (BID) and 1.75 mL of Humilin U‐500 Insulin (875 units) 4 times per day (QID). Past medical history included metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and diabetic neuropathy. Physical exam was remarkable for centripetal obesity (body mass index [BMI] = 38.9 kg/m2), acanthosis nigricans, and necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) (Figure 1).

We undertook an investigation to characterize this extreme insulin resistance. After 24 hours without insulin supplementation, and 12 hours of nothing by mouth (NPO), his blood glucose level was 280 mg/dL and his serum insulin was 133.5 IU/mL. We injected 12 units of insulin Aspart and subsequently measured his serum glucose and insulin once more. His blood glucose level had risen to 289 mg/dL and his serum insulin fell to 110.7 IU/mL. We then transitioned the patient to intravenous (IV) insulin. After a series of boluses totaling 400 units, his blood glucose normalized (90 mg/dL) and was maintained in normal range on a rate of 48 units per hour. Over 24 hours, we had infused over 1400 units.

During this time, we also drew several labs. Serum antiinsulin antibodies were undetectable (ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT). A full rheumatologic workup was negative for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid factor, Sjgren's syndrome (SS)‐A and SS‐B. Androgen levels were normal, as were 24‐hour urine collections for cortisol and metanephrines. The patient was discharged on a regimen of U‐500 without glargine.

By 5 months after discharge, his blood glucose remained uncontrolled despite increasing doses of U‐500 (with or without metformin and thiazolidinediones). The patient was offered a gastric bypass operation. Now, 4 months postoperative, his blood glucose is controlled, no greater than 90 mg/dL in the morning and 125 mg/dL in the evening. He is off insulin, taking 30 mg pioglitazone (Actos) daily and 500 mg metformin 3 times per day (TID).

Discussion

Extreme insulin resistance (EIR), defined by daily insulin requirements in excess of 200 U, is a rare and frustrating condition.1 Rarer still is extreme subcutaneous insulin resistance (ESIR). A systematic Medline review revealed only 29 reported cases of ESIR, all of which involved patients that maintained IV sensitivity to insulin. Classic diagnostic criteria for ESIR include preserved sensitivity to IV insulin, failure to increase serum insulin with subcutaneous injection, and insulin degrading activity of subcutaneous tissue.2, 3 However, there are, at present, no laboratory tests that can test the final criterion. Indeed, very few of the published reports of ESIR satisfy it, with most studies considering as diagnostic of ESIR the constellation of EIR with failure to raise serum insulin after injection and preserved intravenous insulin sensitivity.

As was evident in the high doses of IV insulin required for blood glucose normalization, our patient also had a proven receptor‐level peripheral resistance. Beyond the common, multifactorial insulin resistance of T2DM, the published reports of patients with extreme peripheral resistance are of 2 types: (A) genetic (eg, Leprechaunism) and (B) acquired autoimmune (Table 1).4 This patient fits neither category. Patients with Type A are very sick, with a syndromic disease that sharply curtails their life expectancy. Patients with Type B acquire antibodies directed against their insulin receptors and are almost invariably elderly African‐American women with severe rheumatological disease, namely SLE. We could not test our patient for an insulin‐receptor antibody secondary to prohibitive cost. This is probably moot, given that his autoimmune workup was negative and, as above, patients with such antibodies are vastly different compared to our patients.

| Class of Insulin Resistance | Mechanism | Incidence | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Multifactorial | 3% of total population | Many |

| Type A receptor‐level insulin resistance | Congenital receptor defect | 86 cases | U‐500, insulin‐like growth factor‐1 |

| Type B receptor‐level insulin resistance | Antiinsulin receptor antibody | 50 cases | U‐500, immune modulation |

| Subcutaneous insulin resistance | Unknown; SQ protease? | 30 cases | U‐500, intraperitoneal insulin delivery, other |

Based on SQ insulin requirements, our patient had EIR. As his insulin levels failed to rise following an insulin injection, his EIR is thus subcutaneous in nature. However, among patients with this condition his failure to respond to IV insulin is unique. He does not fit criteria for types A or B insulin resistance; his condition is likely also due to an extreme version of the more common, multifactorial peripheral insulin resistance. This is supported by his successful response to the gastric bypass operation.5

The standard treatments for ESIR include: (1) concentrated regular insulin (U‐500) and (2) implantable intraperitoneal delivery; our patient received the former.6 U‐500 use in EIR has been shown to be more cost‐effective.1 Several reports have suggested success with protease inhibitors (aprotinin, nafamostat ointment), plasmapheresis, and intravenous immunoglobulin for extreme SQ resistance. Our case also represents the first treated successfully with a gastric bypass operation.

CONCLUSIONS

EIR can present a significant challenge for both the patient and hospitalist. The approach to this condition should begin with the determination of 24‐hour IV insulin requirement utilizing an insulin drip; serum insulin antibody evaluation; and endocrinology consultation. Our case also highlights a few important points about the broader management of diabetes mellitus. First, there are dermatological manifestations of diabetes that serve as potential markers for disease (namely acanthosis nigricans and NLD). Second, for patients with extreme insulin requirements, an extensive workup should be initiated and the patient should be transitioned to a concentrated regular insulin or intraperitoneal delivery. Third, our experience suggests a role for other measures such as gastric bypass that ought to be studied further.

- ,,.The use of U‐500 in patients with extreme insulin resistance.Diabetes Care.2005;28:1240–1244.

- ,.Impaired absorption of insulin as a cause insulin resistance.Diabetes.1975;24:443.

- ,,.Insulin resistance caused by massive degradation of subcutaneous insulin.Diabetes.1979;28:640–645.

- ,,, et al.Clinical course of genetic diseases of the insulin receptor: a 30‐year prospective.Medicine.2004;83:209–222.

- ,,, et al.Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult‐onset diabetes mellitus.Ann Surg.1995;222:339–352.

- ,,,,,.Extreme subcutaneous insulin resistance: a misunderstood syndrome.Diabetes Metab.2003;29:539–546.

A 34‐year‐old man was admitted for evaluation of elevated blood glucose despite extremely high subcutaneous (SQ) insulin requirements. He had a 12‐year history of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) without episodes of ketoacidosis, managed initially with oral medications (metformin with various sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones). Three months prior to admission, he was transitioned to SQ insulin and thereafter his requirements escalated rapidly. By the time of his admission, his blood glucose measurements were consistently above 300 mg/dL despite injecting more than 4100 units of insulin daily. His regimen included 300 units of insulin glargine (Lantus) 2 times per day (BID) and 1.75 mL of Humilin U‐500 Insulin (875 units) 4 times per day (QID). Past medical history included metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and diabetic neuropathy. Physical exam was remarkable for centripetal obesity (body mass index [BMI] = 38.9 kg/m2), acanthosis nigricans, and necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) (Figure 1).

We undertook an investigation to characterize this extreme insulin resistance. After 24 hours without insulin supplementation, and 12 hours of nothing by mouth (NPO), his blood glucose level was 280 mg/dL and his serum insulin was 133.5 IU/mL. We injected 12 units of insulin Aspart and subsequently measured his serum glucose and insulin once more. His blood glucose level had risen to 289 mg/dL and his serum insulin fell to 110.7 IU/mL. We then transitioned the patient to intravenous (IV) insulin. After a series of boluses totaling 400 units, his blood glucose normalized (90 mg/dL) and was maintained in normal range on a rate of 48 units per hour. Over 24 hours, we had infused over 1400 units.

During this time, we also drew several labs. Serum antiinsulin antibodies were undetectable (ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT). A full rheumatologic workup was negative for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid factor, Sjgren's syndrome (SS)‐A and SS‐B. Androgen levels were normal, as were 24‐hour urine collections for cortisol and metanephrines. The patient was discharged on a regimen of U‐500 without glargine.

By 5 months after discharge, his blood glucose remained uncontrolled despite increasing doses of U‐500 (with or without metformin and thiazolidinediones). The patient was offered a gastric bypass operation. Now, 4 months postoperative, his blood glucose is controlled, no greater than 90 mg/dL in the morning and 125 mg/dL in the evening. He is off insulin, taking 30 mg pioglitazone (Actos) daily and 500 mg metformin 3 times per day (TID).

Discussion

Extreme insulin resistance (EIR), defined by daily insulin requirements in excess of 200 U, is a rare and frustrating condition.1 Rarer still is extreme subcutaneous insulin resistance (ESIR). A systematic Medline review revealed only 29 reported cases of ESIR, all of which involved patients that maintained IV sensitivity to insulin. Classic diagnostic criteria for ESIR include preserved sensitivity to IV insulin, failure to increase serum insulin with subcutaneous injection, and insulin degrading activity of subcutaneous tissue.2, 3 However, there are, at present, no laboratory tests that can test the final criterion. Indeed, very few of the published reports of ESIR satisfy it, with most studies considering as diagnostic of ESIR the constellation of EIR with failure to raise serum insulin after injection and preserved intravenous insulin sensitivity.

As was evident in the high doses of IV insulin required for blood glucose normalization, our patient also had a proven receptor‐level peripheral resistance. Beyond the common, multifactorial insulin resistance of T2DM, the published reports of patients with extreme peripheral resistance are of 2 types: (A) genetic (eg, Leprechaunism) and (B) acquired autoimmune (Table 1).4 This patient fits neither category. Patients with Type A are very sick, with a syndromic disease that sharply curtails their life expectancy. Patients with Type B acquire antibodies directed against their insulin receptors and are almost invariably elderly African‐American women with severe rheumatological disease, namely SLE. We could not test our patient for an insulin‐receptor antibody secondary to prohibitive cost. This is probably moot, given that his autoimmune workup was negative and, as above, patients with such antibodies are vastly different compared to our patients.

| Class of Insulin Resistance | Mechanism | Incidence | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Multifactorial | 3% of total population | Many |

| Type A receptor‐level insulin resistance | Congenital receptor defect | 86 cases | U‐500, insulin‐like growth factor‐1 |

| Type B receptor‐level insulin resistance | Antiinsulin receptor antibody | 50 cases | U‐500, immune modulation |

| Subcutaneous insulin resistance | Unknown; SQ protease? | 30 cases | U‐500, intraperitoneal insulin delivery, other |

Based on SQ insulin requirements, our patient had EIR. As his insulin levels failed to rise following an insulin injection, his EIR is thus subcutaneous in nature. However, among patients with this condition his failure to respond to IV insulin is unique. He does not fit criteria for types A or B insulin resistance; his condition is likely also due to an extreme version of the more common, multifactorial peripheral insulin resistance. This is supported by his successful response to the gastric bypass operation.5

The standard treatments for ESIR include: (1) concentrated regular insulin (U‐500) and (2) implantable intraperitoneal delivery; our patient received the former.6 U‐500 use in EIR has been shown to be more cost‐effective.1 Several reports have suggested success with protease inhibitors (aprotinin, nafamostat ointment), plasmapheresis, and intravenous immunoglobulin for extreme SQ resistance. Our case also represents the first treated successfully with a gastric bypass operation.

CONCLUSIONS

EIR can present a significant challenge for both the patient and hospitalist. The approach to this condition should begin with the determination of 24‐hour IV insulin requirement utilizing an insulin drip; serum insulin antibody evaluation; and endocrinology consultation. Our case also highlights a few important points about the broader management of diabetes mellitus. First, there are dermatological manifestations of diabetes that serve as potential markers for disease (namely acanthosis nigricans and NLD). Second, for patients with extreme insulin requirements, an extensive workup should be initiated and the patient should be transitioned to a concentrated regular insulin or intraperitoneal delivery. Third, our experience suggests a role for other measures such as gastric bypass that ought to be studied further.

A 34‐year‐old man was admitted for evaluation of elevated blood glucose despite extremely high subcutaneous (SQ) insulin requirements. He had a 12‐year history of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) without episodes of ketoacidosis, managed initially with oral medications (metformin with various sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones). Three months prior to admission, he was transitioned to SQ insulin and thereafter his requirements escalated rapidly. By the time of his admission, his blood glucose measurements were consistently above 300 mg/dL despite injecting more than 4100 units of insulin daily. His regimen included 300 units of insulin glargine (Lantus) 2 times per day (BID) and 1.75 mL of Humilin U‐500 Insulin (875 units) 4 times per day (QID). Past medical history included metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and diabetic neuropathy. Physical exam was remarkable for centripetal obesity (body mass index [BMI] = 38.9 kg/m2), acanthosis nigricans, and necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) (Figure 1).

We undertook an investigation to characterize this extreme insulin resistance. After 24 hours without insulin supplementation, and 12 hours of nothing by mouth (NPO), his blood glucose level was 280 mg/dL and his serum insulin was 133.5 IU/mL. We injected 12 units of insulin Aspart and subsequently measured his serum glucose and insulin once more. His blood glucose level had risen to 289 mg/dL and his serum insulin fell to 110.7 IU/mL. We then transitioned the patient to intravenous (IV) insulin. After a series of boluses totaling 400 units, his blood glucose normalized (90 mg/dL) and was maintained in normal range on a rate of 48 units per hour. Over 24 hours, we had infused over 1400 units.

During this time, we also drew several labs. Serum antiinsulin antibodies were undetectable (ARUP Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT). A full rheumatologic workup was negative for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid factor, Sjgren's syndrome (SS)‐A and SS‐B. Androgen levels were normal, as were 24‐hour urine collections for cortisol and metanephrines. The patient was discharged on a regimen of U‐500 without glargine.

By 5 months after discharge, his blood glucose remained uncontrolled despite increasing doses of U‐500 (with or without metformin and thiazolidinediones). The patient was offered a gastric bypass operation. Now, 4 months postoperative, his blood glucose is controlled, no greater than 90 mg/dL in the morning and 125 mg/dL in the evening. He is off insulin, taking 30 mg pioglitazone (Actos) daily and 500 mg metformin 3 times per day (TID).

Discussion

Extreme insulin resistance (EIR), defined by daily insulin requirements in excess of 200 U, is a rare and frustrating condition.1 Rarer still is extreme subcutaneous insulin resistance (ESIR). A systematic Medline review revealed only 29 reported cases of ESIR, all of which involved patients that maintained IV sensitivity to insulin. Classic diagnostic criteria for ESIR include preserved sensitivity to IV insulin, failure to increase serum insulin with subcutaneous injection, and insulin degrading activity of subcutaneous tissue.2, 3 However, there are, at present, no laboratory tests that can test the final criterion. Indeed, very few of the published reports of ESIR satisfy it, with most studies considering as diagnostic of ESIR the constellation of EIR with failure to raise serum insulin after injection and preserved intravenous insulin sensitivity.

As was evident in the high doses of IV insulin required for blood glucose normalization, our patient also had a proven receptor‐level peripheral resistance. Beyond the common, multifactorial insulin resistance of T2DM, the published reports of patients with extreme peripheral resistance are of 2 types: (A) genetic (eg, Leprechaunism) and (B) acquired autoimmune (Table 1).4 This patient fits neither category. Patients with Type A are very sick, with a syndromic disease that sharply curtails their life expectancy. Patients with Type B acquire antibodies directed against their insulin receptors and are almost invariably elderly African‐American women with severe rheumatological disease, namely SLE. We could not test our patient for an insulin‐receptor antibody secondary to prohibitive cost. This is probably moot, given that his autoimmune workup was negative and, as above, patients with such antibodies are vastly different compared to our patients.

| Class of Insulin Resistance | Mechanism | Incidence | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Multifactorial | 3% of total population | Many |

| Type A receptor‐level insulin resistance | Congenital receptor defect | 86 cases | U‐500, insulin‐like growth factor‐1 |

| Type B receptor‐level insulin resistance | Antiinsulin receptor antibody | 50 cases | U‐500, immune modulation |

| Subcutaneous insulin resistance | Unknown; SQ protease? | 30 cases | U‐500, intraperitoneal insulin delivery, other |

Based on SQ insulin requirements, our patient had EIR. As his insulin levels failed to rise following an insulin injection, his EIR is thus subcutaneous in nature. However, among patients with this condition his failure to respond to IV insulin is unique. He does not fit criteria for types A or B insulin resistance; his condition is likely also due to an extreme version of the more common, multifactorial peripheral insulin resistance. This is supported by his successful response to the gastric bypass operation.5

The standard treatments for ESIR include: (1) concentrated regular insulin (U‐500) and (2) implantable intraperitoneal delivery; our patient received the former.6 U‐500 use in EIR has been shown to be more cost‐effective.1 Several reports have suggested success with protease inhibitors (aprotinin, nafamostat ointment), plasmapheresis, and intravenous immunoglobulin for extreme SQ resistance. Our case also represents the first treated successfully with a gastric bypass operation.

CONCLUSIONS

EIR can present a significant challenge for both the patient and hospitalist. The approach to this condition should begin with the determination of 24‐hour IV insulin requirement utilizing an insulin drip; serum insulin antibody evaluation; and endocrinology consultation. Our case also highlights a few important points about the broader management of diabetes mellitus. First, there are dermatological manifestations of diabetes that serve as potential markers for disease (namely acanthosis nigricans and NLD). Second, for patients with extreme insulin requirements, an extensive workup should be initiated and the patient should be transitioned to a concentrated regular insulin or intraperitoneal delivery. Third, our experience suggests a role for other measures such as gastric bypass that ought to be studied further.

- ,,.The use of U‐500 in patients with extreme insulin resistance.Diabetes Care.2005;28:1240–1244.

- ,.Impaired absorption of insulin as a cause insulin resistance.Diabetes.1975;24:443.

- ,,.Insulin resistance caused by massive degradation of subcutaneous insulin.Diabetes.1979;28:640–645.

- ,,, et al.Clinical course of genetic diseases of the insulin receptor: a 30‐year prospective.Medicine.2004;83:209–222.

- ,,, et al.Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult‐onset diabetes mellitus.Ann Surg.1995;222:339–352.

- ,,,,,.Extreme subcutaneous insulin resistance: a misunderstood syndrome.Diabetes Metab.2003;29:539–546.

- ,,.The use of U‐500 in patients with extreme insulin resistance.Diabetes Care.2005;28:1240–1244.

- ,.Impaired absorption of insulin as a cause insulin resistance.Diabetes.1975;24:443.

- ,,.Insulin resistance caused by massive degradation of subcutaneous insulin.Diabetes.1979;28:640–645.

- ,,, et al.Clinical course of genetic diseases of the insulin receptor: a 30‐year prospective.Medicine.2004;83:209–222.

- ,,, et al.Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult‐onset diabetes mellitus.Ann Surg.1995;222:339–352.

- ,,,,,.Extreme subcutaneous insulin resistance: a misunderstood syndrome.Diabetes Metab.2003;29:539–546.

Recommendations for Hospitalist Handoffs

Handoffs during hospitalization from one provider to another represent critical transition points in patient care.1 In‐hospital handoffs are a frequent occurrence, with 1 teaching hospital reporting 4000 handoffs daily for a total of 1.6 million per year.2

Incomplete or poor‐quality handoffs have been implicated as a source of adverse events and near misses in hospitalized patients.35 Standardizing the handoff process may improve patient safety during care transitions.6 In 2006, the Joint Commission issued a National Patient Safety Goal that requires care providers to adopt a standardized approach for handoff communications, including an opportunity to ask and respond to questions about a patient's care.7 The reductions in resident work hours by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has also resulted in a greater number and greater scrutiny of handoffs in teaching hospitals.8, 9

In response to these issues, and because handoffs are a core competency for hospitalists, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM)convened a task force.10 Our goal was to develop a set of recommendations for handoffs that would be applicable in both community and academic settings; among physicians (hospitalists, internists, subspecialists, residents), nurse practitioners, and physicians assistants; and across roles including serving as the primary provider of hospital care, comanager, or consultant. This work focuses on handoffs that occur at shift change and service change.11 Shift changes are transitions of care between an outgoing provider and an incoming provider that occur at the end of the outgoing provider's continuous on‐duty period. Service changesa special type of shift changeare transitions of care between an outgoing provider and an incoming provider that occur when an outgoing provider is leaving a rotation or period of consecutive daily care for patients on the same service.

For this initiative, transfers of care in which the patient is moving from one patient area to another (eg, Emergency Department to inpatient floor, or floor to intensive care unit [ICU]) were excluded since they likely require unique consideration given their cross‐disciplinary and multispecialty nature. Likewise, transitions of care at hospital admission and discharge were also excluded because recommendations for discharge are already summarized in 2 complementary reports.12, 13

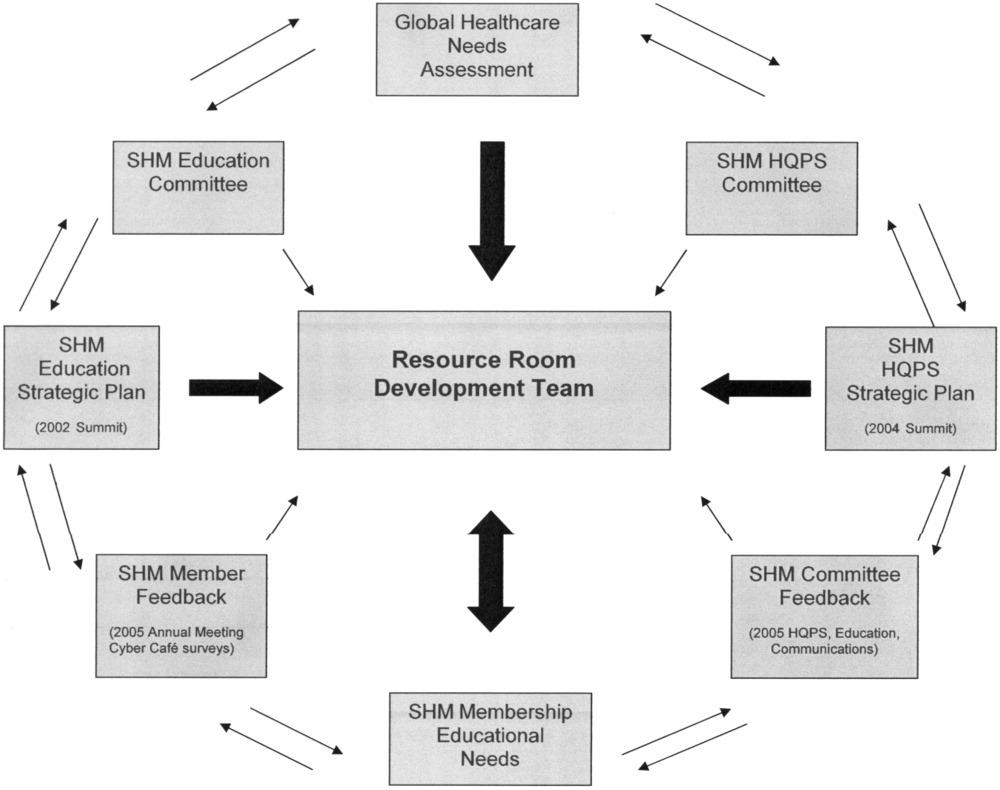

To develop recommendations for handoffs at routine shift change and service changes, the Handoff Task Force performed a systematic review of the literature to develop initial recommendations, obtained feedback from hospital‐based clinicians in addition to a panel of handoff experts, and finalized handoff recommendations, as well as a proposed research agenda, for the SHM.

Methods

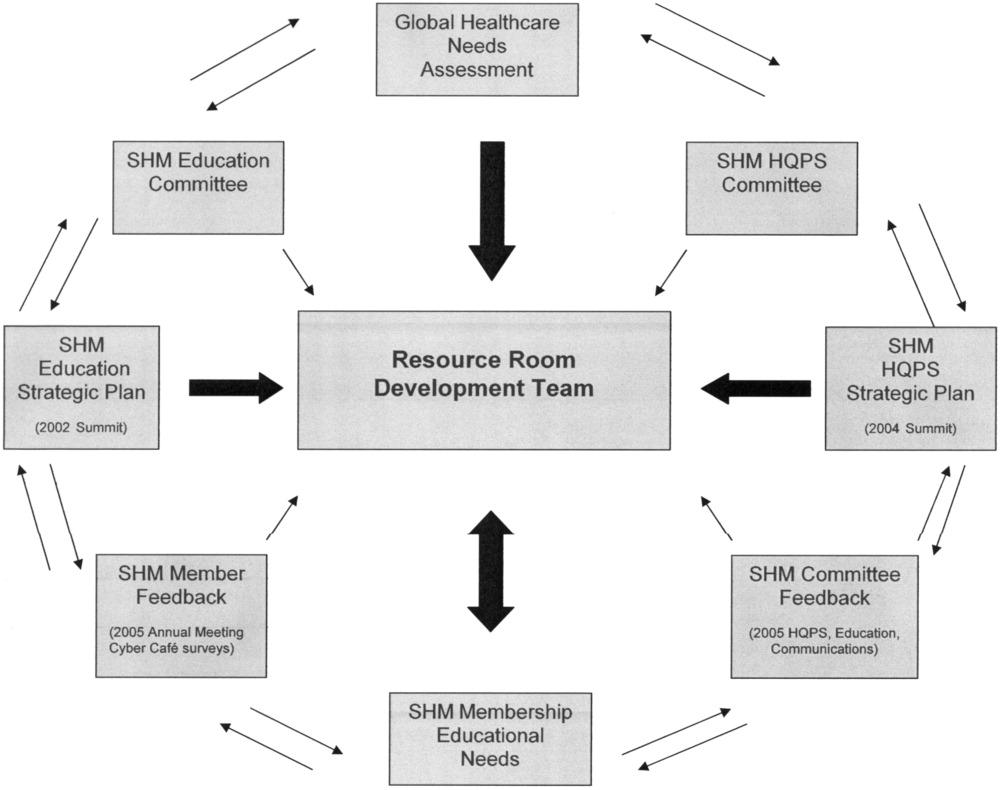

The SHM Healthcare Quality and Patient Safety (HQPS) Committee convened the Handoff Task Force, which was comprised of 6 geographically diverse, predominantly academic hospitalists with backgrounds in education, patient safety, health communication, evidence‐based medicine, and handoffs. The Task Force then engaged a panel of 4 content experts selected for their work on handoffs in the fields of nursing, information technology, human factors engineering, and hospital medicine. Similar to clinical guideline development by professional societies, the Task Force used a combination of evidence‐based review and expert opinions to propose recommendations.

Literature Review

A PubMed search was performed for English language articles published from January 1975 to January 2007, using the following keywords: handover or handoff or hand‐off or shift change or signout or sign‐out. Articles were eligible if they presented results from a controlled intervention to improve handoffs at shift change or service change, by any health profession. Articles that appeared potentially relevant based on their title were retrieved for full‐text review and included if deemed eligible by at least 2 reviewers. Additional studies were obtained through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Patient Safety Network,14 using the category Safety target and subcategory Discontinuities, gaps, and hand‐off problems. Finally, the expert panel reviewed the results of the literature review and suggested additional articles.

Eligible studies were abstracted by individual members of the Handoff Task Force using a structured form (Appendix Figure 1), and abstractions were verified by a second member. Handoff‐related outcome measures were categorized as referring to (1) patient outcomes, (2) staff outcomes, or (3) system outcomes. Because studies included those from nursing and other industries, interventions were evaluated by abstractors for their applicability to routine hospitalist handoffs. The literature review was supplemented by review of expert consensus or policy white papers that described recommendations for handoffs. The list of white papers was generated utilizing a common internet search engine (Google;

Peer and Expert Panel Review

The Task Force generated draft recommendations, which were revised through interactive discussions until consensus was achieved. These recommendations were then presented at a workshop to an audience of approximately 300 hospitalists, case managers, nurses, and pharmacists at the 2007 SHM Annual Meeting.

During the workshop, participants were asked to cast up to 3 votes for recommendations that should be removed. Those recommendations that received more than 20 votes for removal were then discussed. Participants also had the opportunity to anonymously suggest new recommendations or revisions using index cards, which were reviewed by 2 workshop faculty, assembled into themes, and immediately presented to the group. Through group discussion of prevalent themes, additional recommendations were developed.

Four content experts were then asked to review a draft paper that summarized the literature review, discussion at the SHM meeting, and handoff recommendations. Their input regarding the process, potential gaps in the literature, and additional items of relevance, was incorporated into this final manuscript.

Final Review by SHM Board and Rating each Recommendation

A working paper was reviewed and approved by the Board of the SHM in early January 2008. With Board input, the Task Force adopted the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) framework to rate each recommendation because of its appropriateness, ease of use, and familiarity to hospital‐based physicians.15 Recommendations are rated as Class I (effective), IIa (conflicting findings but weight of evidence supports use), IIb (conflicting findings but weight of evidence does not support use), or III (not effective). The Level of Evidence behind each recommendation is graded as A (from multiple large randomized controlled trials), B (from smaller or limited randomized trials, or nonrandomized studies), or C (based primarily on expert consensus). A recommendation with Level of Evidence B or C should not imply that the recommendation is not supported.15

Results

Literature Review

Of the 374 articles identified by the electronic search of PubMed and the AHRQ Patient Safety Network, 109 were retrieved for detailed review, and 10 of these met the criteria for inclusion (Figure 1). Of these studies, 3 were derived from nursing literature and the remaining were tests of technology solutions or structured templates (Table 1).1618, 20, 22, 3842 No studies examined hospitalist handoffs. All eligible studies concerned shift change. There were no studies of service change. Only 1 study was a randomized controlled trial; the rest were pre‐post studies with historical controls or a controlled simulation. All reports were single‐site studies. Most outcomes were staff‐related or system‐related, with only 2 studies using patient outcomes.

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Intervention | Setting and Study Population | Target | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Nursing | |||||

| Kelly22 (2005) | Pre‐post | Change to walk‐round handover (at bedside) from baseline (control) | 12‐bed rehab unit with 18 nurses and 10 patients | Staff, patient | 11/18 nurses felt more or much more informed and involved; 8/10 patients felt more involved |

| Pothier et al.20 (2005) | Controlled simulation | Compared pure verbal to verbal with note‐taking to verbal plus typed content | Handover of 12 simulated patients over 5 cycles | System (data loss) | Minimal data loss with typed content, compared to 31% data retained with note‐taking, and no data retained with verbal only |

| Wallum38 (1995) | Pre‐post | Change from oral handover (baseline) to written template read with exchange | 20 nurses in a geriatric dementia ward | Staff | 83% of nurses felt care plans followed better; 88% knew care plans better |

| Technology or structured template | |||||

| Cheah et al.39 (2005) | Pre‐post | Electronic template with free‐text entry compared to baseline | 14 UK Surgery residents | Staff | 100% (14) of residents rated electronic system as desirable, but 7 (50%) reported that information was not updated |

| Lee et al.40 (1996) | Pre‐post | Standardized signout card for interns to transmit information during handoffs compared to handwritten (baseline) | Inpatient cardiology service at IM residency program in Minnesota with 19 new interns over a 3‐month period | Staff | Intervention interns (n = 10) reported poor sign‐out less often than controls (n = 9) [intervention 8 nights (5.8%) vs. control 17 nights (14.9%); P = 0.016] |

| Kannry and Moore18 (1999) | Pre‐post | Compared web‐based signout program to usual system (baseline) | An academic teaching hospital in New York (34 patients admitted in 1997; 40 patients admitted in 1998) | System | Improved provider identification (86% web signout vs. 57% hospital census) |

| Petersen et al.17 (1998) | Pre‐post | 4 months of computerized signouts compared to baseline period (control) | 3747 patients admitted to the medical service at an academic teaching hospital | Patient | Preventable adverse events (ADE) decreased (1.7% to 1.2%, P 0.10); risk of cross‐cover physician for ADE eliminated |

| Ram and Block41 (1993) | Pre‐post | Compared handwritten (baseline) to computer‐generated | Family medicine residents at 2 academic teaching hospitals [Buffalo (n = 16) and Pittsburgh (n = 16)] | Staff | Higher satisfaction after electronic signout, but complaints with burden of data entry and need to keep information updated |

| Van Eaton et al.42 (2004) | Pre‐post | Use of UW Cores links sign‐out to list for rounds and IS data | 28 surgical and medical residents at 2 teaching hospitals | System | At 6 months, 66% of patients entered in system (adoption) |

| Van Eaton et al.16 (2005) | Prospective, randomized, crossover study. | Compared UW Cores* integrated system compared to usual system | 14 inpatient resident teams (6 surgery, 8 IM) at 2 teaching hospitals for 5 months | Staff, system | 50% reduction in the perceived time spent copying data [from 24% to 12% (P 0.0001)] and number of patients missed on rounds (2.5 vs. 5 patients/team/month, P = 0.0001); improved signout quality (69.6% agree or strongly agree); and improved continuity of care (66.1% agree or strongly agree) |

Overall, the literature presented supports the use of a verbal handoff supplemented with written documentation in a structured format or technology solution. The 2 most rigorous studies were led by Van Eaton et al.16 and Petersen et al.17 and focused on evaluating technology solutions. Van Eaton et al.16 performed a randomized controlled trial of a locally created rounding template with 161 surgical residents. This template downloads certain information (lab values and recent vital signs) from the hospital system into a sign‐out sheet and allows residents to enter notes about diagnoses, allergies, medications and to‐do items. When implemented, the investigators found the number of patients missed on rounds decreased by 50%. Residents reported an increase of 40% in the amount of time available to pre‐round, due largely to not having to copy data such as vital signs. They reported a decrease in rounding time by 3 hours per week, and this was perceived as helping them meet the ACGME 80 hours work rules. Lastly, the residents reported a higher quality of sign‐outs from their peers and perceived an overall improvement in continuity of care. Petersen and colleagues implemented a computerized sign‐out (auto‐imported medications, name, room number) in an internal medicine residency to improve continuity of care during cross‐coverage and decrease adverse events.17 Prior to the intervention, the frequency of preventable adverse events was 1.7% and it was significantly associated with cross‐coverage. Preventable adverse events were identified using a confidential self‐report system that was also validated by clinician review. After the intervention, the frequency of preventable adverse events dropped to 1.2% (P 0.1), and cross‐coverage was no longer associated with preventable adverse events. In other studies, technological solutions also improved provider identification and staff communication.18, 19 Together, these technology‐based intervention studies suggest that a computerized sign‐out with auto‐imported fields has the ability to improve physician efficiency and also improve inpatient care (reduction in number of patients missed on rounds, decrease in preventable adverse events).

Studies from nursing demonstrated that supplementing a verbal exchange with written information improved transfer of information, compared to verbal exchange alone.20 One of these studies rated the transfer of information using videotaped simulated handoff cases.21 Last, 1 nursing study that more directly involved patients in the handoff process resulted in improved nursing knowledge and greater patient empowerment (Table 1).22

White papers or consensus statements originated from international and national consortia in patient safety including the Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Healthcare,23 the Junior Doctors Committee of the British Medical Association,24 University Health Consortium,25 the Department of Defense Patient Safety Program,26 and The Joint Commission.27 Several common themes were prevalent in all white papers. First, there exists a need to train new personnel on how to perform an effective handoff. Second, efforts should be undertaken to ensure adequate time for handoffs and reduce interruptions during handoffs. Third, several of the papers supported verbal exchange that facilitates interactive questioning, focuses on ill patients, and delineates actions to be taken. Lastly, content should be updated to ensure transfer of the latest clinical information.

Peer Review at SHM Meeting of Preliminary Handoff Recommendations

In the presentation of preliminary handoff recommendations to over 300 attendees at the SHM Annual Meeting in 2007, 2 recommendations were supported unanimously: (1) a formal recognized handoff plan should be instituted at end of shift or change in service; and (2) ill patients should be given priority during verbal exchange.

During the workshop, discussion focused on three recommendations of concern, or those that received greater than 20 negative votes by participants. The proposed recommendation that raised the most objections (48 negative votes) was that interruptions be limited. Audience members expressed that it was hard to expect that interruptions would be limited given the busy workplace in the absence of endorsing a separate room and time. This recommendation was ultimately deleted.

The 2 other debated recommendations, which were retained after discussion, were ensuring adequate time for handoffs and using an interactive process during verbal communication. Several attendees stated that ensuring adequate time for handoffs may be difficult without setting a specific time. Others questioned the need for interactive verbal communication, and endorsed leaving a handoff by voicemail with a phone number or pager to answer questions. However, this type of asynchronous communication (senders and receivers not present at the same time) was not desirable or consistent with the Joint Commission's National Patient Safety Goal.

Two new recommendations were proposed from anonymous input and incorporated in the final recommendations, including (a) all patients should be on the sign‐out, and (b) sign‐outs should be accessible from a centralized location. Another recommendation proposed at the Annual Meeting was to institute feedback for poor sign‐outs, but this was not added to the final recommendations after discussion at the meeting and with content experts about the difficulty of maintaining anonymity in small hospitalist groups. Nevertheless, this should not preclude informal feedback among practitioners.

Anonymous commentary also yielded several major themes regarding handoff improvements and areas of uncertainty that merit future work. Several hospitalists described the need to delineate specific content domains for handoffs including, for example, code status, allergies, discharge plan, and parental contact information in the case of pediatric care. However, due to the variability in hospitalist programs and health systems and the general lack of evidence in this area, the Task Force opted to avoid recommending specific content domains which may have limited applicability in certain settings and little support from the literature. Several questions were raised regarding the legal status of written sign‐outs, and whether sign‐outs, especially those that are web‐based, are compliant with the Healthcare Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Hospitalists also questioned the appropriate number of patients to be handed off safely. Promoting efficient technology solutions that reduce documentation burden, such as linking the most current progress note to the sign‐out, was also proposed. Concerns were also raised about promoting safe handoffs when using moonlighting or rotating physicians, who may be less invested in the continuity of the patients' overall care.

Expert Panel Review

The final version of the Task Force recommendations incorporates feedback provided by the expert panel. In particular, the expert panel favored the use of the term, recommendations, rather than standards, minimum acceptable practices, or best practices. While the distinction may appear semantic, the Task Force and expert panel acknowledge that the current state of scientific knowledge regarding hospital handoffs is limited. Although an evidence‐based process informed the development of these recommendations, they are not a legal standard for practice. Additional research may allow for refinement of recommendations and development of more formal handoff standards.

The expert panel also highlighted the need to provide tools to hospitalist programs to facilitate the adoption of these recommendations. For example, recommendations for content exchange are difficult to adopt if groups do not already use a written template. The panel also commented on the need to consider the possible consequences if efforts are undertaken to include handoff documents (whether paper or electronic) as part of the medical record. While formalizing handoff documents may raise their quality, it is also possible that handoff documents become less helpful by either excluding the most candid impression regarding a patient's status or by encouraging hospitalists to provide too much detail. Privacy and confidentiality of paper‐based systems, in particular, were also questioned.

Additional Recommendations for Service Change

Patient handoffs during a change of service are a routine part of hospitalist care. Since service change is a type of shift change, the handoff recommendations for shift change do apply. Unlike shift change, service changes involve a more significant transfer of responsibility. Therefore, the Task Force recommends also that the incoming hospitalist be readily identified in the medical record or chart as the new provider, so that relevant clinical information can be communicated to the correct physician. This program‐level recommendation can be met by an electronic or paper‐based system that correctly identifies the current primary inpatient physician.

Final Handoff Recommendations

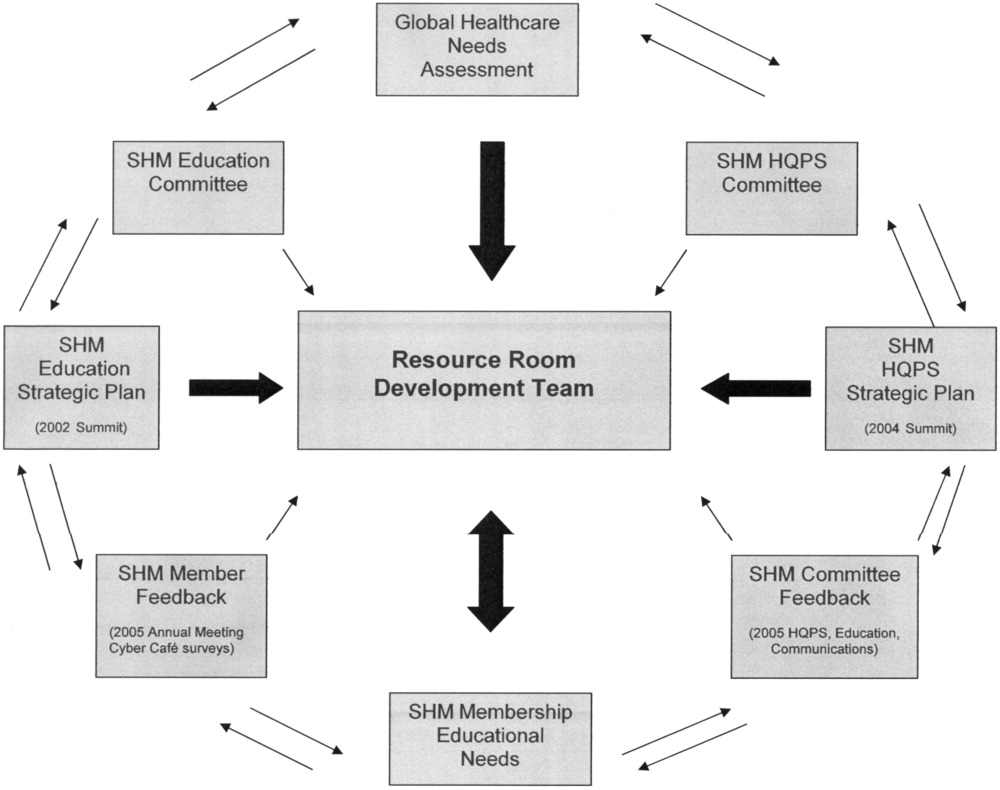

The final handoff recommendations are shown in Figure 2. The recommendations were designed to be consistent with the overall finding of the literature review, which supports the use of a verbal handoff supplemented with written documentation or a technological solution in a structured format. With the exception of 1 recommendation that is specific to service changes, all recommendations are designed to refer to shift changes and service changes. One overarching recommendation refers to the need for a formally recognized handoff plan at a shift change or change of service. The remaining 12 recommendations are divided into 4 that refer to hospitalist groups or programs, 3 that refer to verbal exchange, and 5 that refer to content exchange. The distinction is an important one because program‐level recommendations require organizational support and buy‐in to promote clinician participation and adherence. The 4 program recommendations also form the necessary framework for the remaining recommendations. For example, the second program recommendation describes the need for a standardized template or technology solution for accessing and recording patient information during the handoff. After a program adopts such a mechanism for exchanging patient information, the specific details for use and maintenance are outlined in greater detail in content exchange recommendations.

Because of the limited trials of handoff strategies, none of the recommendations are supported with level of evidence A (multiple numerous randomized controlled trials). In fact, with the exception of using a template or technology solution which was supported with level of evidence B, all handoff recommendations were supported with C level of evidence. The recommendations, however, were rated as Class I (effective) because there were no conflicting expert opinions or studies (Figure 2).

Discussion

In summary, our review of the literature supports the use of face‐to‐face verbal handoffs that are aided by the use of structured template to guide exchange of information. Furthermore, the development of these recommendations is the first effort of its kind for hospitalist handoffs and a movement towards standardizing the handoff process. While these recommendations are meant to provide structure to the hospitalist handoff process, the use and implementation by individual hospitalist programs may require more specific detail than these recommendations provide. Local modifications can allow for improved acceptance and adoption by practicing hospitalists. These recommendations can also help guide teaching efforts for academic hospitalists who are responsible for supervising residents.

The limitations of these recommendations related to lack of evidence in this field. Studies suffered from small size, poor description of methods, and a paucity of controlled interventions. The described technology solutions are not standardized or commercially available. Only 1 study included patient outcomes.28 There are no multicenter studies, studies of hospitalist handoffs, or studies to guide inclusion of specific content. Randomized controlled trials, interrupted time series analyses, and other rigorous study designs are needed in both teaching and non‐teaching settings to evaluate these recommendations and other approaches to improving handoffs. Ideally, these studies would occur through multicenter collaboratives and with human factors researchers familiar with mixed methods approaches to evaluate how and why interventions work.29 Efforts should focus on developing surrogate measures that are sensitive to handoff quality and related to important patient outcomes. The results of future studies should be used to refine the present recommendations. Locating new literature could be facilitated through the introduction of Medical Subject Heading for the term handoff by the National Library of Medicine. After completing this systematic review and developing the handoff recommendations described here, a few other noteworthy articles have been published on this topic, to which we refer interested readers. Several of these studies demonstrate that standardizing content and process during medical or surgical intern sign‐out improves resident confidence with handoffs,30 resident perceptions of accuracy and completeness of signout,31 and perceptions of patient safety.32 Another prospective audiotape study of 12 days of resident signout of clinical information demonstrated that poor quality oral sign‐outs was associated with an increased risk of post‐call resident reported signout‐related problems.5 Lastly, 1 nursing study demonstrated improved staff reports of safety, efficiency, and teamwork after a change from verbal reporting in an isolated room to bedside handover.33 Overall, these additional studies continue to support the current recommendations presented in this paper and do not significantly impact the conclusions of our literature review.

While lacking specific content domain recommendations, this report can be used as a starting point to guide development of self and peer assessment of hospitalist handoff quality. Development and validation of such assessments is especially important and can be incorporated into efforts to certify hospitalists through the recently approved certificate of focused practice in hospital medicine by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM). Initiatives by several related organizations may help guide these effortsThe Joint Commission, the ABIM's Stepping Up to the Plate (SUTTP) Alliance, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the Information Transfer and Communication Practices (ITCP) Project for surgical care transitions, and the Hospital at Night (H@N) Program sponsored by the United Kingdom's National Health Service.3437 Professional medical organizations can also serve as powerful mediators of change in this area, not only by raising the visibility of handoffs, but also by mobilizing research funding. Patients and their caregivers may also play an important role in increasing awareness and education in this area. Future efforts should target handoffs not addressed in this initiative, such as transfers from emergency departments to inpatient care units, or between ICUs and the medical floor.

Conclusion

With the growth of hospital medicine and the increased acuity of inpatients, improving handoffs becomes an important part of ensuring patient safety. The goal of the SHM Handoffs Task Force was to begin to standardize handoffs at change of shift and change of servicea fundamental activity of hospitalists. These recommendations build on the limited literature in surgery, nursing, and medical informatics and provide a starting point for promoting safe and seamless in‐hospital handoffs for practitioners of Hospital Medicine.

Acknowledgements

The authors also acknowledge Tina Budnitz and the Healthcare Quality and Safety Committee of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Last, they are indebted to the staff support provided by Shannon Roach from the Society of Hospital Medicine.

- ,,,.Lost in translation: challenges and opportunities in physician‐to‐physician communication during patient handoffs.Acad Med.2005;80(12):1094–1099.

- ... AHRQ WebM167(19):2030–2036.

- ,,,,.Communication failures in patient signout and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis.Qual Saf Health Care.2005;14:401–407.

- ,,,,.Consequences of inadequate sign‐out for patient care.Arch Intern Med.2008;168(16):1755–1760.

- ,,, et al.Handoff strategies in settings with high consequences for failure: lessons for health care operations.Int J Qual Health Care.2004;16:125–132.

- Joint Commission. 2006 Critical Access Hospital and Hospital National Patient Safety Goals. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/06_npsg_cah.htm. Accessed June2009.

- ,,,.Transfers of patient care between house staff on internal medicine wards: a national survey.Arch Intern Med.2006;166(11):1173–1177.

- ,.Re‐framing continuity of care for this century.Qual Saf Health Care.2005;14(6):394–396.

- ,,,,.Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology.J Hosp Med.2006;1(suppl 1):48–56.

- ,,, et al.Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign‐out.J Hosp Med.2006;1(4):257–266.

- ,,, et al.Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary‐care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care.JAMA.2007;297(8):831–841.

- ,,, et al.Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients: development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2006;1(6):354–360.

- Discontinuities, Gaps, and Hand‐Off Problems. AHRQ PSNet Patient Safety Network. Available at: http://www.psnet.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?taxonomyID=412. Accessed June2009.

- Manual for ACC/AHA Guideline Writing Committees. Methodologies and Policies from the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Available at: http://circ.ahajournals.org/manual/manual_IIstep6.shtml. Accessed June2009.

- ,,,,.A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign‐out system on continuity of care and resident work hours.J Am Coll Surg.2005;200(4):538–545.

- ,,,,.Using a computerized sign‐out program to improve continuity of inpatient care and prevent adverse events.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1998;24(2):77–87.

- ,.MediSign: using a web‐based SignOut System to improve provider identification.Proc AMIA Symp.1999:550–554.

- ,.Using a computerized sign‐out system to improve physician‐nurse communication.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2006;32(1):32–36.

- ,,,.Pilot study to show the loss of important data in nursing handover.Br J Nurs.2005;14(20):1090–1093.

- .Using care plans to replace the handover.Nurs Stand.1995;9(32):24–26.

- .Change from an office‐based to a walk‐around handover system.Nurs Times.2005;101(10):34–35.

- Clinical Handover and Patient Safety. Literature review report. Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care. Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/safety/publishing.nsf/Content/AA1369AD4AC5FC2ACA2571BF0081CD95/$File/clinhovrlitrev.pdf. Accessed June2009.

- Safe Handover: Safe Patients. Guidance on clinical handover for clinicians and managers. Junior Doctors Committee, British Medical Association. Available at: http://www.bma.org.uk/ap.nsf/AttachmentsByTitle/PDFsafehandover/$FILE/safehandover.pdf. Accessed June2009.

- University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC).UHC Best Practice Recommendation: Patient Hand Off Communication White Paper, May 2006.Oak Brook, IL:University HealthSystem Consortium;2006.

- Healthcare Communications Toolkit to Improve Transitions in Care. Department of Defense Patient Safety Program. Available at: http://dodpatientsafety.usuhs.mil/files/Handoff_Toolkit.pdf. Accessed June2009.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Joint Commission announces 2006 national patient safety goals for ambulatory care and office‐based surgery organizations. Available at: http://www.jcaho.org/news+room/news+release+archives/06_npsg_amb_obs.htm. Accessed June2009.

- ,,,,.Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events?Ann Intern Med.1994;121(11):866–872.

- .Communication strategies from high‐reliability organizations: translation is hard work.Ann Surg.2007;245(2):170–172.

- ,,, et al.A structured handoff program for interns.Acad Med.2009;84(3):347–352.

- ,,, et al.Simple standardized patient handoff system that increases accuracy and completeness.J Surg Educ.2008;65(6):476–485.

- ,,.Standardized sign‐out reduces intern perception of medical errors on the general internal medicine ward.Teach Learn Med.2009;21(2):121–126.

- ,,,,,.Bedside handover: quality improvement strategy to “transform care at the bedside”.J Nurs Care Qual.2009;24(2):136–142.

- Pillow M, ed.Improving Handoff Communications.Chicago:Joint Commission Resources;2007.

- American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Step Up To The Plate. Available at: http://www.abimfoundation.org/quality/suttp.shtm. Accessed June2009.

- ,,, et al.Surgeon information transfer and communication: factors affecting quality and efficiency of inpatient care.Ann Surg.2007;245(2):159–169.

- Hospital at Night. Available at: http://www.healthcareworkforce.nhs.uk/hospitalatnight.html. Accessed June2009.

- .Using care plans to replace the handover.Nurs Stand.1995;9(32):24–26.

- ,,,.Electronic medical handover: towards safer medical care.Med J Aust.2005;183(7):369–372.

- ,,.Utility of a standardized sign‐out card for new medical interns.J Gen Intern Med.1996;11(12):753–755.

- ,.Signing out patients for off‐hours coverage: comparison of manual and computer‐aided methods.Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care.1992:114–118.

- ,,,.Organizing the transfer of patient care information: the development of a computerized resident sign‐out system.Surgery.2004;136(1):5–13.

Handoffs during hospitalization from one provider to another represent critical transition points in patient care.1 In‐hospital handoffs are a frequent occurrence, with 1 teaching hospital reporting 4000 handoffs daily for a total of 1.6 million per year.2

Incomplete or poor‐quality handoffs have been implicated as a source of adverse events and near misses in hospitalized patients.35 Standardizing the handoff process may improve patient safety during care transitions.6 In 2006, the Joint Commission issued a National Patient Safety Goal that requires care providers to adopt a standardized approach for handoff communications, including an opportunity to ask and respond to questions about a patient's care.7 The reductions in resident work hours by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has also resulted in a greater number and greater scrutiny of handoffs in teaching hospitals.8, 9

In response to these issues, and because handoffs are a core competency for hospitalists, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM)convened a task force.10 Our goal was to develop a set of recommendations for handoffs that would be applicable in both community and academic settings; among physicians (hospitalists, internists, subspecialists, residents), nurse practitioners, and physicians assistants; and across roles including serving as the primary provider of hospital care, comanager, or consultant. This work focuses on handoffs that occur at shift change and service change.11 Shift changes are transitions of care between an outgoing provider and an incoming provider that occur at the end of the outgoing provider's continuous on‐duty period. Service changesa special type of shift changeare transitions of care between an outgoing provider and an incoming provider that occur when an outgoing provider is leaving a rotation or period of consecutive daily care for patients on the same service.

For this initiative, transfers of care in which the patient is moving from one patient area to another (eg, Emergency Department to inpatient floor, or floor to intensive care unit [ICU]) were excluded since they likely require unique consideration given their cross‐disciplinary and multispecialty nature. Likewise, transitions of care at hospital admission and discharge were also excluded because recommendations for discharge are already summarized in 2 complementary reports.12, 13

To develop recommendations for handoffs at routine shift change and service changes, the Handoff Task Force performed a systematic review of the literature to develop initial recommendations, obtained feedback from hospital‐based clinicians in addition to a panel of handoff experts, and finalized handoff recommendations, as well as a proposed research agenda, for the SHM.

Methods

The SHM Healthcare Quality and Patient Safety (HQPS) Committee convened the Handoff Task Force, which was comprised of 6 geographically diverse, predominantly academic hospitalists with backgrounds in education, patient safety, health communication, evidence‐based medicine, and handoffs. The Task Force then engaged a panel of 4 content experts selected for their work on handoffs in the fields of nursing, information technology, human factors engineering, and hospital medicine. Similar to clinical guideline development by professional societies, the Task Force used a combination of evidence‐based review and expert opinions to propose recommendations.

Literature Review

A PubMed search was performed for English language articles published from January 1975 to January 2007, using the following keywords: handover or handoff or hand‐off or shift change or signout or sign‐out. Articles were eligible if they presented results from a controlled intervention to improve handoffs at shift change or service change, by any health profession. Articles that appeared potentially relevant based on their title were retrieved for full‐text review and included if deemed eligible by at least 2 reviewers. Additional studies were obtained through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Patient Safety Network,14 using the category Safety target and subcategory Discontinuities, gaps, and hand‐off problems. Finally, the expert panel reviewed the results of the literature review and suggested additional articles.

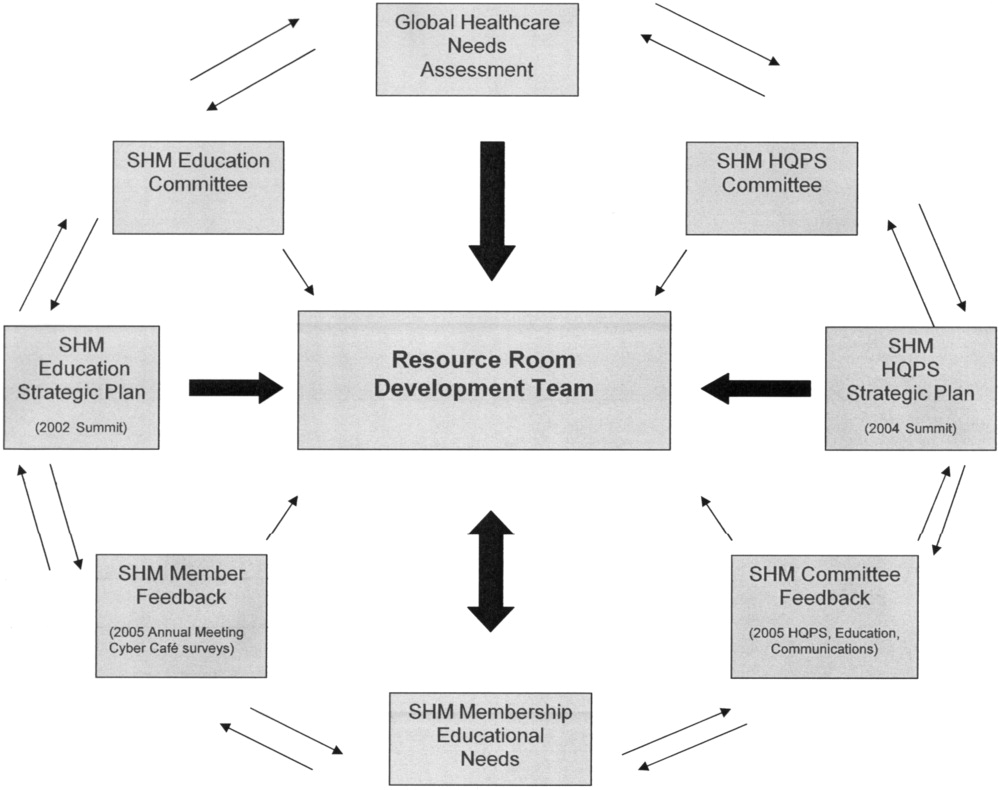

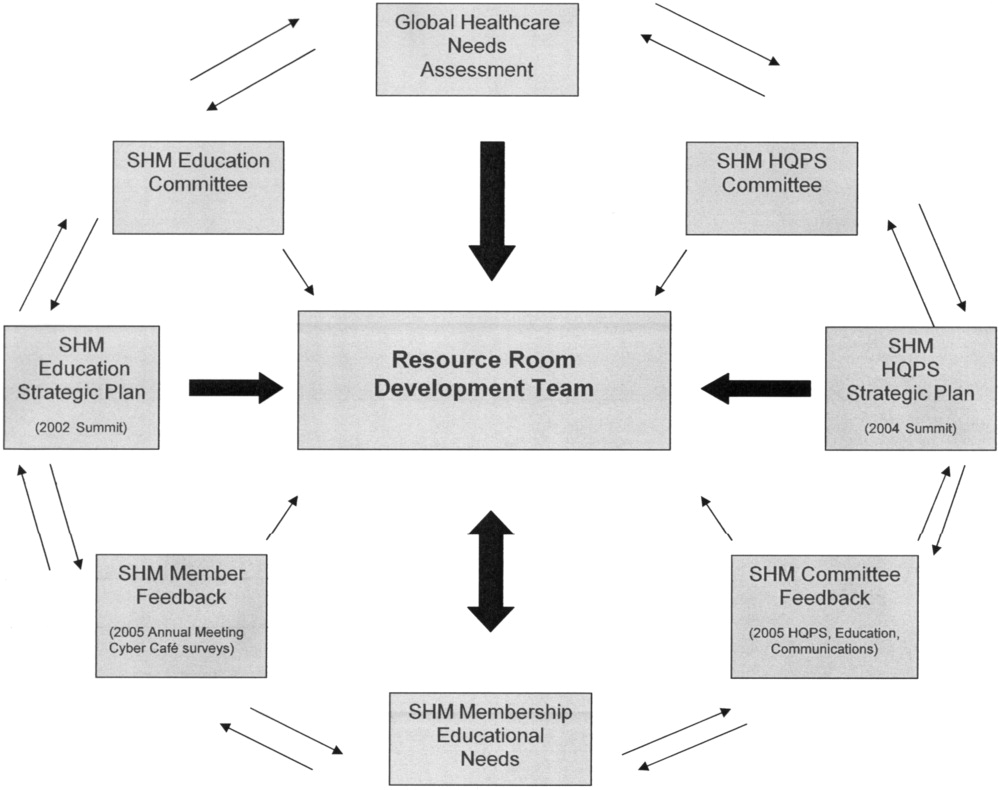

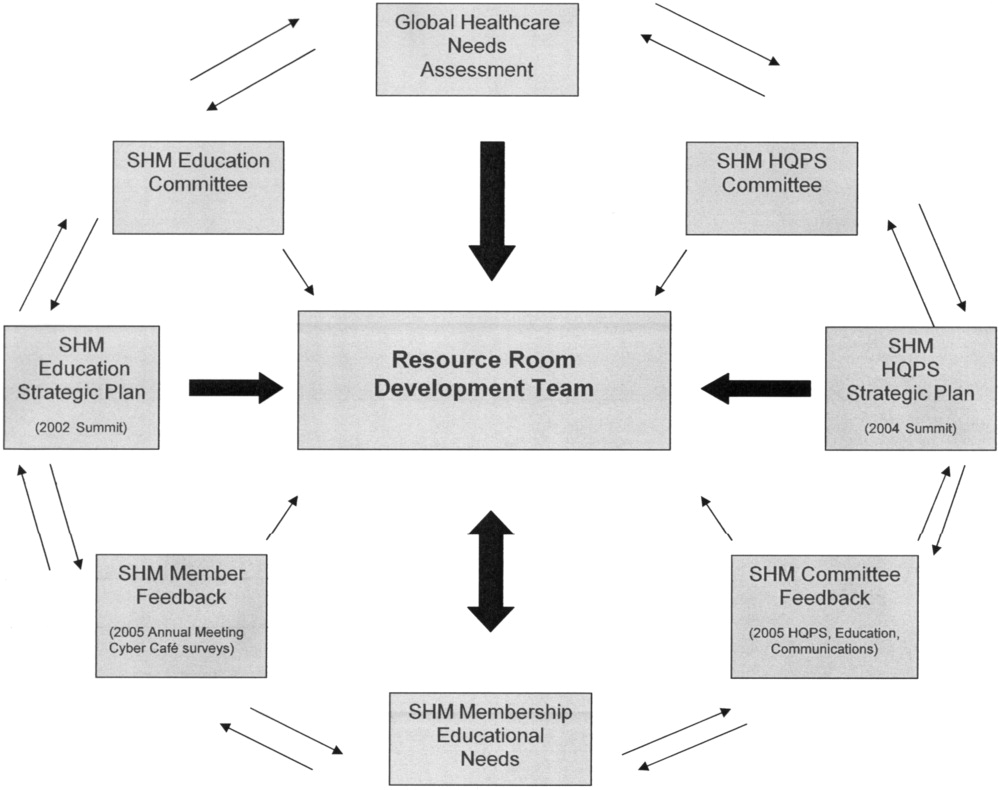

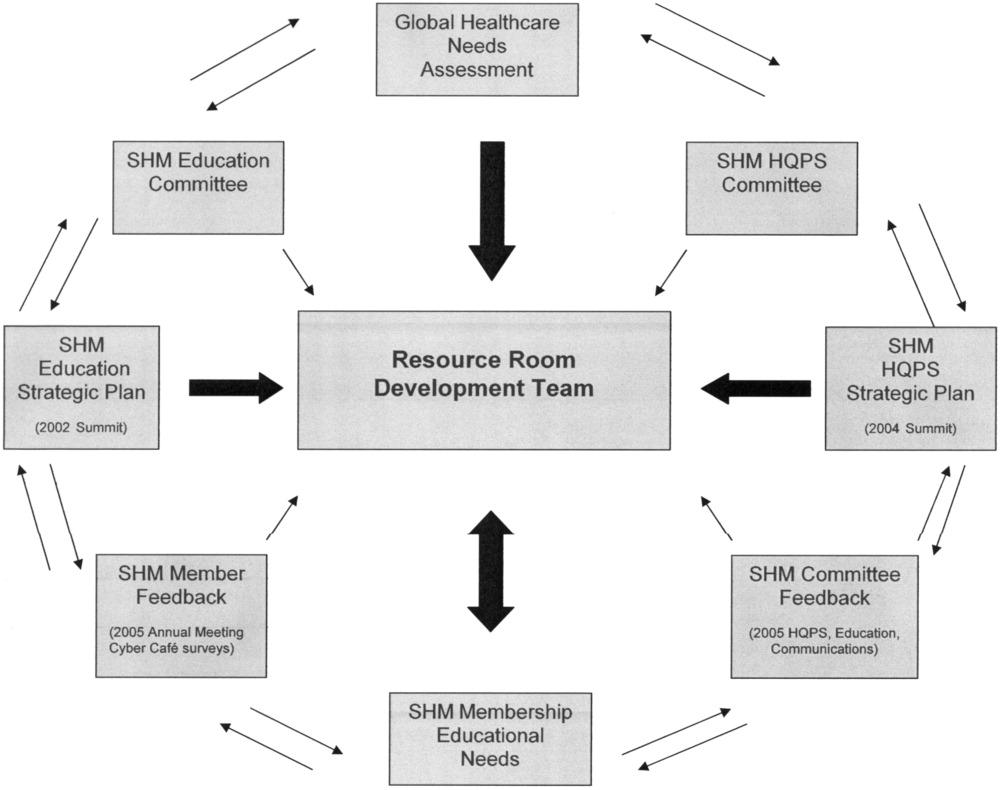

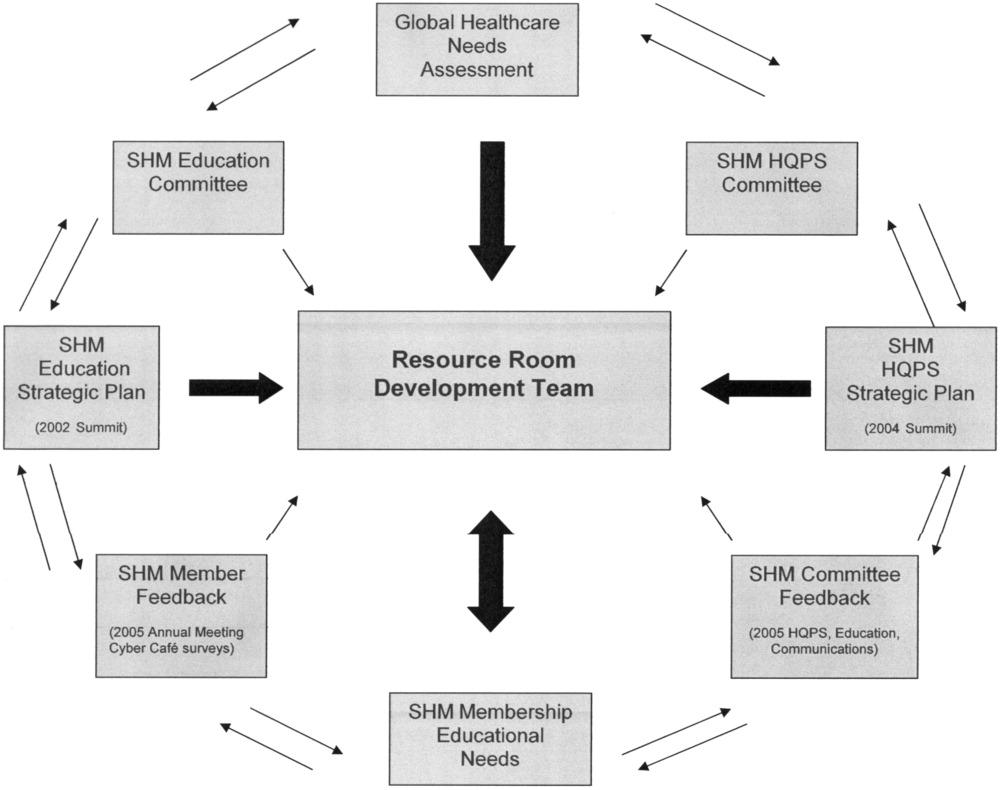

Eligible studies were abstracted by individual members of the Handoff Task Force using a structured form (Appendix Figure 1), and abstractions were verified by a second member. Handoff‐related outcome measures were categorized as referring to (1) patient outcomes, (2) staff outcomes, or (3) system outcomes. Because studies included those from nursing and other industries, interventions were evaluated by abstractors for their applicability to routine hospitalist handoffs. The literature review was supplemented by review of expert consensus or policy white papers that described recommendations for handoffs. The list of white papers was generated utilizing a common internet search engine (Google;

Peer and Expert Panel Review

The Task Force generated draft recommendations, which were revised through interactive discussions until consensus was achieved. These recommendations were then presented at a workshop to an audience of approximately 300 hospitalists, case managers, nurses, and pharmacists at the 2007 SHM Annual Meeting.

During the workshop, participants were asked to cast up to 3 votes for recommendations that should be removed. Those recommendations that received more than 20 votes for removal were then discussed. Participants also had the opportunity to anonymously suggest new recommendations or revisions using index cards, which were reviewed by 2 workshop faculty, assembled into themes, and immediately presented to the group. Through group discussion of prevalent themes, additional recommendations were developed.

Four content experts were then asked to review a draft paper that summarized the literature review, discussion at the SHM meeting, and handoff recommendations. Their input regarding the process, potential gaps in the literature, and additional items of relevance, was incorporated into this final manuscript.

Final Review by SHM Board and Rating each Recommendation

A working paper was reviewed and approved by the Board of the SHM in early January 2008. With Board input, the Task Force adopted the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) framework to rate each recommendation because of its appropriateness, ease of use, and familiarity to hospital‐based physicians.15 Recommendations are rated as Class I (effective), IIa (conflicting findings but weight of evidence supports use), IIb (conflicting findings but weight of evidence does not support use), or III (not effective). The Level of Evidence behind each recommendation is graded as A (from multiple large randomized controlled trials), B (from smaller or limited randomized trials, or nonrandomized studies), or C (based primarily on expert consensus). A recommendation with Level of Evidence B or C should not imply that the recommendation is not supported.15

Results

Literature Review

Of the 374 articles identified by the electronic search of PubMed and the AHRQ Patient Safety Network, 109 were retrieved for detailed review, and 10 of these met the criteria for inclusion (Figure 1). Of these studies, 3 were derived from nursing literature and the remaining were tests of technology solutions or structured templates (Table 1).1618, 20, 22, 3842 No studies examined hospitalist handoffs. All eligible studies concerned shift change. There were no studies of service change. Only 1 study was a randomized controlled trial; the rest were pre‐post studies with historical controls or a controlled simulation. All reports were single‐site studies. Most outcomes were staff‐related or system‐related, with only 2 studies using patient outcomes.

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Intervention | Setting and Study Population | Target | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Nursing | |||||

| Kelly22 (2005) | Pre‐post | Change to walk‐round handover (at bedside) from baseline (control) | 12‐bed rehab unit with 18 nurses and 10 patients | Staff, patient | 11/18 nurses felt more or much more informed and involved; 8/10 patients felt more involved |

| Pothier et al.20 (2005) | Controlled simulation | Compared pure verbal to verbal with note‐taking to verbal plus typed content | Handover of 12 simulated patients over 5 cycles | System (data loss) | Minimal data loss with typed content, compared to 31% data retained with note‐taking, and no data retained with verbal only |

| Wallum38 (1995) | Pre‐post | Change from oral handover (baseline) to written template read with exchange | 20 nurses in a geriatric dementia ward | Staff | 83% of nurses felt care plans followed better; 88% knew care plans better |

| Technology or structured template | |||||

| Cheah et al.39 (2005) | Pre‐post | Electronic template with free‐text entry compared to baseline | 14 UK Surgery residents | Staff | 100% (14) of residents rated electronic system as desirable, but 7 (50%) reported that information was not updated |

| Lee et al.40 (1996) | Pre‐post | Standardized signout card for interns to transmit information during handoffs compared to handwritten (baseline) | Inpatient cardiology service at IM residency program in Minnesota with 19 new interns over a 3‐month period | Staff | Intervention interns (n = 10) reported poor sign‐out less often than controls (n = 9) [intervention 8 nights (5.8%) vs. control 17 nights (14.9%); P = 0.016] |

| Kannry and Moore18 (1999) | Pre‐post | Compared web‐based signout program to usual system (baseline) | An academic teaching hospital in New York (34 patients admitted in 1997; 40 patients admitted in 1998) | System | Improved provider identification (86% web signout vs. 57% hospital census) |

| Petersen et al.17 (1998) | Pre‐post | 4 months of computerized signouts compared to baseline period (control) | 3747 patients admitted to the medical service at an academic teaching hospital | Patient | Preventable adverse events (ADE) decreased (1.7% to 1.2%, P 0.10); risk of cross‐cover physician for ADE eliminated |

| Ram and Block41 (1993) | Pre‐post | Compared handwritten (baseline) to computer‐generated | Family medicine residents at 2 academic teaching hospitals [Buffalo (n = 16) and Pittsburgh (n = 16)] | Staff | Higher satisfaction after electronic signout, but complaints with burden of data entry and need to keep information updated |

| Van Eaton et al.42 (2004) | Pre‐post | Use of UW Cores links sign‐out to list for rounds and IS data | 28 surgical and medical residents at 2 teaching hospitals | System | At 6 months, 66% of patients entered in system (adoption) |

| Van Eaton et al.16 (2005) | Prospective, randomized, crossover study. | Compared UW Cores* integrated system compared to usual system | 14 inpatient resident teams (6 surgery, 8 IM) at 2 teaching hospitals for 5 months | Staff, system | 50% reduction in the perceived time spent copying data [from 24% to 12% (P 0.0001)] and number of patients missed on rounds (2.5 vs. 5 patients/team/month, P = 0.0001); improved signout quality (69.6% agree or strongly agree); and improved continuity of care (66.1% agree or strongly agree) |

Overall, the literature presented supports the use of a verbal handoff supplemented with written documentation in a structured format or technology solution. The 2 most rigorous studies were led by Van Eaton et al.16 and Petersen et al.17 and focused on evaluating technology solutions. Van Eaton et al.16 performed a randomized controlled trial of a locally created rounding template with 161 surgical residents. This template downloads certain information (lab values and recent vital signs) from the hospital system into a sign‐out sheet and allows residents to enter notes about diagnoses, allergies, medications and to‐do items. When implemented, the investigators found the number of patients missed on rounds decreased by 50%. Residents reported an increase of 40% in the amount of time available to pre‐round, due largely to not having to copy data such as vital signs. They reported a decrease in rounding time by 3 hours per week, and this was perceived as helping them meet the ACGME 80 hours work rules. Lastly, the residents reported a higher quality of sign‐outs from their peers and perceived an overall improvement in continuity of care. Petersen and colleagues implemented a computerized sign‐out (auto‐imported medications, name, room number) in an internal medicine residency to improve continuity of care during cross‐coverage and decrease adverse events.17 Prior to the intervention, the frequency of preventable adverse events was 1.7% and it was significantly associated with cross‐coverage. Preventable adverse events were identified using a confidential self‐report system that was also validated by clinician review. After the intervention, the frequency of preventable adverse events dropped to 1.2% (P 0.1), and cross‐coverage was no longer associated with preventable adverse events. In other studies, technological solutions also improved provider identification and staff communication.18, 19 Together, these technology‐based intervention studies suggest that a computerized sign‐out with auto‐imported fields has the ability to improve physician efficiency and also improve inpatient care (reduction in number of patients missed on rounds, decrease in preventable adverse events).

Studies from nursing demonstrated that supplementing a verbal exchange with written information improved transfer of information, compared to verbal exchange alone.20 One of these studies rated the transfer of information using videotaped simulated handoff cases.21 Last, 1 nursing study that more directly involved patients in the handoff process resulted in improved nursing knowledge and greater patient empowerment (Table 1).22

White papers or consensus statements originated from international and national consortia in patient safety including the Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Healthcare,23 the Junior Doctors Committee of the British Medical Association,24 University Health Consortium,25 the Department of Defense Patient Safety Program,26 and The Joint Commission.27 Several common themes were prevalent in all white papers. First, there exists a need to train new personnel on how to perform an effective handoff. Second, efforts should be undertaken to ensure adequate time for handoffs and reduce interruptions during handoffs. Third, several of the papers supported verbal exchange that facilitates interactive questioning, focuses on ill patients, and delineates actions to be taken. Lastly, content should be updated to ensure transfer of the latest clinical information.

Peer Review at SHM Meeting of Preliminary Handoff Recommendations

In the presentation of preliminary handoff recommendations to over 300 attendees at the SHM Annual Meeting in 2007, 2 recommendations were supported unanimously: (1) a formal recognized handoff plan should be instituted at end of shift or change in service; and (2) ill patients should be given priority during verbal exchange.

During the workshop, discussion focused on three recommendations of concern, or those that received greater than 20 negative votes by participants. The proposed recommendation that raised the most objections (48 negative votes) was that interruptions be limited. Audience members expressed that it was hard to expect that interruptions would be limited given the busy workplace in the absence of endorsing a separate room and time. This recommendation was ultimately deleted.

The 2 other debated recommendations, which were retained after discussion, were ensuring adequate time for handoffs and using an interactive process during verbal communication. Several attendees stated that ensuring adequate time for handoffs may be difficult without setting a specific time. Others questioned the need for interactive verbal communication, and endorsed leaving a handoff by voicemail with a phone number or pager to answer questions. However, this type of asynchronous communication (senders and receivers not present at the same time) was not desirable or consistent with the Joint Commission's National Patient Safety Goal.

Two new recommendations were proposed from anonymous input and incorporated in the final recommendations, including (a) all patients should be on the sign‐out, and (b) sign‐outs should be accessible from a centralized location. Another recommendation proposed at the Annual Meeting was to institute feedback for poor sign‐outs, but this was not added to the final recommendations after discussion at the meeting and with content experts about the difficulty of maintaining anonymity in small hospitalist groups. Nevertheless, this should not preclude informal feedback among practitioners.

Anonymous commentary also yielded several major themes regarding handoff improvements and areas of uncertainty that merit future work. Several hospitalists described the need to delineate specific content domains for handoffs including, for example, code status, allergies, discharge plan, and parental contact information in the case of pediatric care. However, due to the variability in hospitalist programs and health systems and the general lack of evidence in this area, the Task Force opted to avoid recommending specific content domains which may have limited applicability in certain settings and little support from the literature. Several questions were raised regarding the legal status of written sign‐outs, and whether sign‐outs, especially those that are web‐based, are compliant with the Healthcare Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Hospitalists also questioned the appropriate number of patients to be handed off safely. Promoting efficient technology solutions that reduce documentation burden, such as linking the most current progress note to the sign‐out, was also proposed. Concerns were also raised about promoting safe handoffs when using moonlighting or rotating physicians, who may be less invested in the continuity of the patients' overall care.

Expert Panel Review

The final version of the Task Force recommendations incorporates feedback provided by the expert panel. In particular, the expert panel favored the use of the term, recommendations, rather than standards, minimum acceptable practices, or best practices. While the distinction may appear semantic, the Task Force and expert panel acknowledge that the current state of scientific knowledge regarding hospital handoffs is limited. Although an evidence‐based process informed the development of these recommendations, they are not a legal standard for practice. Additional research may allow for refinement of recommendations and development of more formal handoff standards.

The expert panel also highlighted the need to provide tools to hospitalist programs to facilitate the adoption of these recommendations. For example, recommendations for content exchange are difficult to adopt if groups do not already use a written template. The panel also commented on the need to consider the possible consequences if efforts are undertaken to include handoff documents (whether paper or electronic) as part of the medical record. While formalizing handoff documents may raise their quality, it is also possible that handoff documents become less helpful by either excluding the most candid impression regarding a patient's status or by encouraging hospitalists to provide too much detail. Privacy and confidentiality of paper‐based systems, in particular, were also questioned.

Additional Recommendations for Service Change

Patient handoffs during a change of service are a routine part of hospitalist care. Since service change is a type of shift change, the handoff recommendations for shift change do apply. Unlike shift change, service changes involve a more significant transfer of responsibility. Therefore, the Task Force recommends also that the incoming hospitalist be readily identified in the medical record or chart as the new provider, so that relevant clinical information can be communicated to the correct physician. This program‐level recommendation can be met by an electronic or paper‐based system that correctly identifies the current primary inpatient physician.

Final Handoff Recommendations

The final handoff recommendations are shown in Figure 2. The recommendations were designed to be consistent with the overall finding of the literature review, which supports the use of a verbal handoff supplemented with written documentation or a technological solution in a structured format. With the exception of 1 recommendation that is specific to service changes, all recommendations are designed to refer to shift changes and service changes. One overarching recommendation refers to the need for a formally recognized handoff plan at a shift change or change of service. The remaining 12 recommendations are divided into 4 that refer to hospitalist groups or programs, 3 that refer to verbal exchange, and 5 that refer to content exchange. The distinction is an important one because program‐level recommendations require organizational support and buy‐in to promote clinician participation and adherence. The 4 program recommendations also form the necessary framework for the remaining recommendations. For example, the second program recommendation describes the need for a standardized template or technology solution for accessing and recording patient information during the handoff. After a program adopts such a mechanism for exchanging patient information, the specific details for use and maintenance are outlined in greater detail in content exchange recommendations.

Because of the limited trials of handoff strategies, none of the recommendations are supported with level of evidence A (multiple numerous randomized controlled trials). In fact, with the exception of using a template or technology solution which was supported with level of evidence B, all handoff recommendations were supported with C level of evidence. The recommendations, however, were rated as Class I (effective) because there were no conflicting expert opinions or studies (Figure 2).

Discussion