User login

Worsening motor function tied to post COVID syndrome in Parkinson’s disease

, new research suggests.

Results from a small, international retrospective case study show that about half of participants with Parkinson’s disease who developed post–COVID-19 syndrome experienced a worsening of motor symptoms and that their need for anti-Parkinson’s medication increased.

“In our series of 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease, 85% developed post–COVID-19 symptoms,” said lead investigator Valentina Leta, MD, Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence, Kings College Hospital, London.

The most common long-term effects were worsening of motor function and an increase in the need for daily levodopa. Other adverse effects included fatigue; cognitive disturbances, including brain fog, loss of concentration, and memory deficits; and sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, Dr. Leta said.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Long-term sequelae

Previous studies have documented worsening of motor and nonmotor symptoms among patients with Parkinson’s disease in the acute phase of COVID-19. Results of these studies suggest that mortality may be higher among patients with more advanced Parkinson’s disease, comorbidities, and frailty.

Dr. Leta noted that long-term sequelae with so-called long COVID have not been adequately explored, prompting the current study.

The case series included 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease in the United Kingdom, Italy, Romania, and Mexico who were also affected by COVID-19. The investigators defined post–COVID-19 syndrome as “signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks, and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis.”

Because some of the symptoms are also associated with Parkinson’s disease, symptoms were attributed to post–COVID-19 only if they occurred after a confirmed severe acute respiratory infection with SARS-CoV-2 or if patients experienced an acute or subacute worsening of a pre-existing symptom that had previously been stable.

Among the participants, 59.3% were men. The mean age at the time of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis was 59.0 ± 12.7 years, and the mean Parkinson’s disease duration was 9.2 ± 7.8 years. The patients were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 2.0 ± 1.0 at the time of their COVID-19 diagnosis.

Charlson Comorbidity Index score at COVID-19 diagnosis was 2.0 ± 1.5, and the levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was 1053.5 ± 842.4 mg.

Symptom worsening

“Cognitive disturbances” were defined as brain fog, concentration difficulty, or memory problems. “Peripheral neuropathy symptoms” were defined as having feelings of pins and needles or numbness.

By far, the most prevalent sequelae were worsening motor symptoms and increased need for anti-Parkinson’s medications. Each affected about half of the study cohort, the investigators noted.

Dr. Leta added the non-Parkinson’s disease-specific findings are in line with the existing literature on long COVID in the general population. The severity of COVID-19, as indicated by a history of hospitalization, did not seem to correlate with development of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

In this series, few patients had respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or dermatologic symptoms. Interestingly, only four patients reported a loss of taste or smell.

The investigators noted that in addition to viral illness, the stress of prolonged lockdown during the pandemic and reduced access to health care and rehabilitation programs may contribute to the burden of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Study limitations cited include the relatively small sample size and the lack of a control group. The researchers noted the need for larger studies to elucidate the natural history of COVID-19 among patients with Parkinson’s disease in order to raise awareness of their needs and to help develop personalized management strategies.

Meaningful addition

Commenting on the findings, Kyle Mitchell, MD, movement disorders neurologist, Duke University, Durham, N.C., said he found the study to be a meaningful addition in light of the fact that data on the challenges that patients with Parkinson’s disease may face after having COVID-19 are limited.

“What I liked about this study was there’s data from multiple countries, what looks like a diverse population of study participants, and really just addressing a question that we get asked a lot in clinic and we see a fair amount, but we don’t really know a lot about: how people with Parkinson’s disease will do during and post COVID-19 infection,” said Dr. Mitchell, who was not involved with the research.

He said the worsening of motor symptoms and the need for increased dopaminergic medication brought some questions to mind.

“Is this increase in medications permanent, or is it temporary until post-COVID resolves? Or is it truly something where they stay on a higher dose?” he asked.

Dr. Mitchell said he does not believe the worsening of symptoms is specific to COVID-19 and that he sees individuals with Parkinson’s disease who experience setbacks “from any number of infections.” These include urinary tract infections and influenza, which are associated with worsening mobility, rigidity, tremor, fatigue, and cognition.

“People with Parkinson’s disease seem to get hit harder by infections in general,” he said.

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Leta and Dr. Mitchell have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Results from a small, international retrospective case study show that about half of participants with Parkinson’s disease who developed post–COVID-19 syndrome experienced a worsening of motor symptoms and that their need for anti-Parkinson’s medication increased.

“In our series of 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease, 85% developed post–COVID-19 symptoms,” said lead investigator Valentina Leta, MD, Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence, Kings College Hospital, London.

The most common long-term effects were worsening of motor function and an increase in the need for daily levodopa. Other adverse effects included fatigue; cognitive disturbances, including brain fog, loss of concentration, and memory deficits; and sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, Dr. Leta said.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Long-term sequelae

Previous studies have documented worsening of motor and nonmotor symptoms among patients with Parkinson’s disease in the acute phase of COVID-19. Results of these studies suggest that mortality may be higher among patients with more advanced Parkinson’s disease, comorbidities, and frailty.

Dr. Leta noted that long-term sequelae with so-called long COVID have not been adequately explored, prompting the current study.

The case series included 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease in the United Kingdom, Italy, Romania, and Mexico who were also affected by COVID-19. The investigators defined post–COVID-19 syndrome as “signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks, and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis.”

Because some of the symptoms are also associated with Parkinson’s disease, symptoms were attributed to post–COVID-19 only if they occurred after a confirmed severe acute respiratory infection with SARS-CoV-2 or if patients experienced an acute or subacute worsening of a pre-existing symptom that had previously been stable.

Among the participants, 59.3% were men. The mean age at the time of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis was 59.0 ± 12.7 years, and the mean Parkinson’s disease duration was 9.2 ± 7.8 years. The patients were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 2.0 ± 1.0 at the time of their COVID-19 diagnosis.

Charlson Comorbidity Index score at COVID-19 diagnosis was 2.0 ± 1.5, and the levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was 1053.5 ± 842.4 mg.

Symptom worsening

“Cognitive disturbances” were defined as brain fog, concentration difficulty, or memory problems. “Peripheral neuropathy symptoms” were defined as having feelings of pins and needles or numbness.

By far, the most prevalent sequelae were worsening motor symptoms and increased need for anti-Parkinson’s medications. Each affected about half of the study cohort, the investigators noted.

Dr. Leta added the non-Parkinson’s disease-specific findings are in line with the existing literature on long COVID in the general population. The severity of COVID-19, as indicated by a history of hospitalization, did not seem to correlate with development of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

In this series, few patients had respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or dermatologic symptoms. Interestingly, only four patients reported a loss of taste or smell.

The investigators noted that in addition to viral illness, the stress of prolonged lockdown during the pandemic and reduced access to health care and rehabilitation programs may contribute to the burden of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Study limitations cited include the relatively small sample size and the lack of a control group. The researchers noted the need for larger studies to elucidate the natural history of COVID-19 among patients with Parkinson’s disease in order to raise awareness of their needs and to help develop personalized management strategies.

Meaningful addition

Commenting on the findings, Kyle Mitchell, MD, movement disorders neurologist, Duke University, Durham, N.C., said he found the study to be a meaningful addition in light of the fact that data on the challenges that patients with Parkinson’s disease may face after having COVID-19 are limited.

“What I liked about this study was there’s data from multiple countries, what looks like a diverse population of study participants, and really just addressing a question that we get asked a lot in clinic and we see a fair amount, but we don’t really know a lot about: how people with Parkinson’s disease will do during and post COVID-19 infection,” said Dr. Mitchell, who was not involved with the research.

He said the worsening of motor symptoms and the need for increased dopaminergic medication brought some questions to mind.

“Is this increase in medications permanent, or is it temporary until post-COVID resolves? Or is it truly something where they stay on a higher dose?” he asked.

Dr. Mitchell said he does not believe the worsening of symptoms is specific to COVID-19 and that he sees individuals with Parkinson’s disease who experience setbacks “from any number of infections.” These include urinary tract infections and influenza, which are associated with worsening mobility, rigidity, tremor, fatigue, and cognition.

“People with Parkinson’s disease seem to get hit harder by infections in general,” he said.

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Leta and Dr. Mitchell have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Results from a small, international retrospective case study show that about half of participants with Parkinson’s disease who developed post–COVID-19 syndrome experienced a worsening of motor symptoms and that their need for anti-Parkinson’s medication increased.

“In our series of 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease, 85% developed post–COVID-19 symptoms,” said lead investigator Valentina Leta, MD, Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence, Kings College Hospital, London.

The most common long-term effects were worsening of motor function and an increase in the need for daily levodopa. Other adverse effects included fatigue; cognitive disturbances, including brain fog, loss of concentration, and memory deficits; and sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, Dr. Leta said.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Long-term sequelae

Previous studies have documented worsening of motor and nonmotor symptoms among patients with Parkinson’s disease in the acute phase of COVID-19. Results of these studies suggest that mortality may be higher among patients with more advanced Parkinson’s disease, comorbidities, and frailty.

Dr. Leta noted that long-term sequelae with so-called long COVID have not been adequately explored, prompting the current study.

The case series included 27 patients with Parkinson’s disease in the United Kingdom, Italy, Romania, and Mexico who were also affected by COVID-19. The investigators defined post–COVID-19 syndrome as “signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks, and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis.”

Because some of the symptoms are also associated with Parkinson’s disease, symptoms were attributed to post–COVID-19 only if they occurred after a confirmed severe acute respiratory infection with SARS-CoV-2 or if patients experienced an acute or subacute worsening of a pre-existing symptom that had previously been stable.

Among the participants, 59.3% were men. The mean age at the time of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis was 59.0 ± 12.7 years, and the mean Parkinson’s disease duration was 9.2 ± 7.8 years. The patients were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 2.0 ± 1.0 at the time of their COVID-19 diagnosis.

Charlson Comorbidity Index score at COVID-19 diagnosis was 2.0 ± 1.5, and the levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was 1053.5 ± 842.4 mg.

Symptom worsening

“Cognitive disturbances” were defined as brain fog, concentration difficulty, or memory problems. “Peripheral neuropathy symptoms” were defined as having feelings of pins and needles or numbness.

By far, the most prevalent sequelae were worsening motor symptoms and increased need for anti-Parkinson’s medications. Each affected about half of the study cohort, the investigators noted.

Dr. Leta added the non-Parkinson’s disease-specific findings are in line with the existing literature on long COVID in the general population. The severity of COVID-19, as indicated by a history of hospitalization, did not seem to correlate with development of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

In this series, few patients had respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or dermatologic symptoms. Interestingly, only four patients reported a loss of taste or smell.

The investigators noted that in addition to viral illness, the stress of prolonged lockdown during the pandemic and reduced access to health care and rehabilitation programs may contribute to the burden of post–COVID-19 syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Study limitations cited include the relatively small sample size and the lack of a control group. The researchers noted the need for larger studies to elucidate the natural history of COVID-19 among patients with Parkinson’s disease in order to raise awareness of their needs and to help develop personalized management strategies.

Meaningful addition

Commenting on the findings, Kyle Mitchell, MD, movement disorders neurologist, Duke University, Durham, N.C., said he found the study to be a meaningful addition in light of the fact that data on the challenges that patients with Parkinson’s disease may face after having COVID-19 are limited.

“What I liked about this study was there’s data from multiple countries, what looks like a diverse population of study participants, and really just addressing a question that we get asked a lot in clinic and we see a fair amount, but we don’t really know a lot about: how people with Parkinson’s disease will do during and post COVID-19 infection,” said Dr. Mitchell, who was not involved with the research.

He said the worsening of motor symptoms and the need for increased dopaminergic medication brought some questions to mind.

“Is this increase in medications permanent, or is it temporary until post-COVID resolves? Or is it truly something where they stay on a higher dose?” he asked.

Dr. Mitchell said he does not believe the worsening of symptoms is specific to COVID-19 and that he sees individuals with Parkinson’s disease who experience setbacks “from any number of infections.” These include urinary tract infections and influenza, which are associated with worsening mobility, rigidity, tremor, fatigue, and cognition.

“People with Parkinson’s disease seem to get hit harder by infections in general,” he said.

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Leta and Dr. Mitchell have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MDS VIRTUAL CONGRESS 2021

Novel drug effective for essential tremor, but with significant side effects

new research suggests.

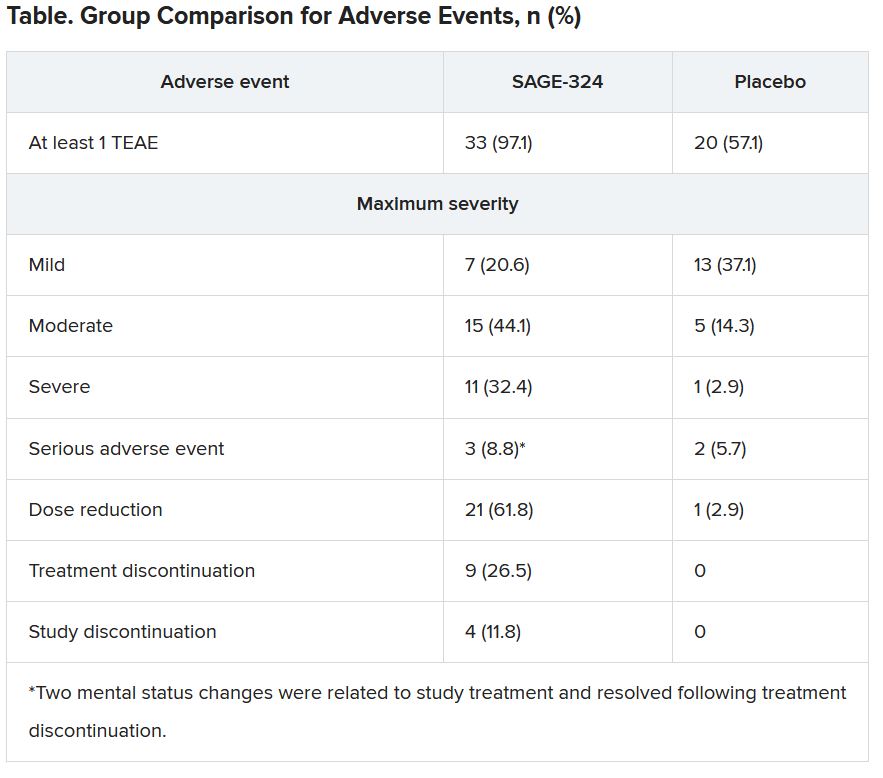

The phase 2 KINETIC trial involved patients with essential tremor. Among patients treated with SAGE-324 for 28 days, there was a statistically significant reduction in upper-limb tremors on day 29 – meeting the primary endpoint of the study.

However, moderate to severe treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) led to many treatment and/or study discontinuations, the investigators reported.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Mechanism of action

Essential tremor affects an estimated 6.4 million adults in the United States. Available drugs are not helpful for 30%-50% of these patients. No new drug for this condition has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the past 50 years. Of the several drugs used to treat essential tremor, propranolol is the only one that has been approved, according to the American Academy of Neurology.

Deficits in inhibitory signaling via the gamma-aminobutyric acid system may have a role in the pathophysiology of essential tremor because the GABAergic system is the major neuroinhibitory system in the brain.

SAGE-324 is a steroid-positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor. It acts on the receptor distant from the neuronal synapse to enhance GABAergic (inhibitory) signaling.

In the phase 2 multicenter KINETIC trial, investigators enrolled 69 patients aged 18-80 years. The patients had moderate to severe essential tremor, as determined on the basis of their having a score of 10 or higher on item 4 of the Essential Tremor Rating Assessment Scale (TETRAS) on screening day and at baseline/day 1 of the trial.

Participants did not take medications for essential tremor during the 28-day washout period. They were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive SAGE-324 60 mg (n = 34) or placebo (n = 35) once daily. Dose reductions were allowed.

The groups were reasonably matched for age (mean, 69.4 years for SAGE-324 vs. 64.7 years for placebo) and dominant hand (right, 85.3% for SAGE-324 vs. 88.6% for placebo). Women composed 35.3% of the drug group and 57.1% of the placebo group.

The primary endpoint of the trial was change from baseline for the active drug in comparison with placebo on day 29 (1 day after the final dose) for upper-limb tremor, as measured by item 4 of TETRAS. There was also a 2-week follow-up with assessments on day 42.

Primary endpoint met, high dropout rate

Baseline mean TETRAS Performance Subscale item 4 scores were 12.82 for the SAGE-324 group and 12.28 for the placebo group.

On day 29, the least squares mean difference from baseline was –2.31 with SAGE-324 (n = 21) versus –1.24 with placebo (n = 33; P = .049). There was no difference between the SAGE-324 and placebo groups on day 42.

“Their significant reduction in upper-limb tremor score at day 29 corresponds to a 36% reduction from baseline in tremor amplitude in patients receiving SAGE-324, compared with a 21% reduction in tremor amplitude in patients receiving a placebo,” said lead investigator Kemi Bankole, MBBCh, of Sage Therapeutics.

“A reduction in tremor amplitude of 36% is a clinically significant improvement for most patients with essential tremor. For patients with moderate-severe tremor, a 41% improvement would be clinically noticeable and appreciated,” said Helen Colquhoun, MBChB, vice president at Sage.

“We believe patients with more severe tremor, that is, a TETRAS score of greater than 12, represent the majority of [essential tremor] patients getting diagnosed and seeking treatment today,” Dr. Colquhoun said.

There was an even greater reduction in tremor amplitude for the subgroup of patients with more severe tremor at baseline, meaning those with a median TETRAS score of 12 or greater (–2.75 for SAGE-324 vs. –1.05 for placebo; P = .0066).

These figures represented a 41% reduction from baseline in tremor amplitude for the SAGE-324 group, versus an 18% reduction in the placebo group. Again, the effect had disappeared in comparison with placebo at the 2-week off-drug follow-up on day 42.

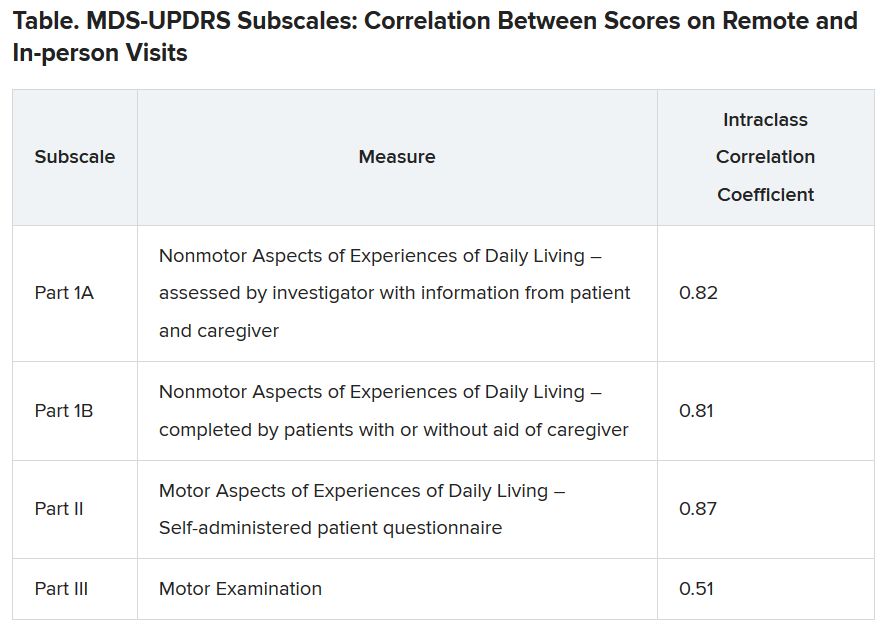

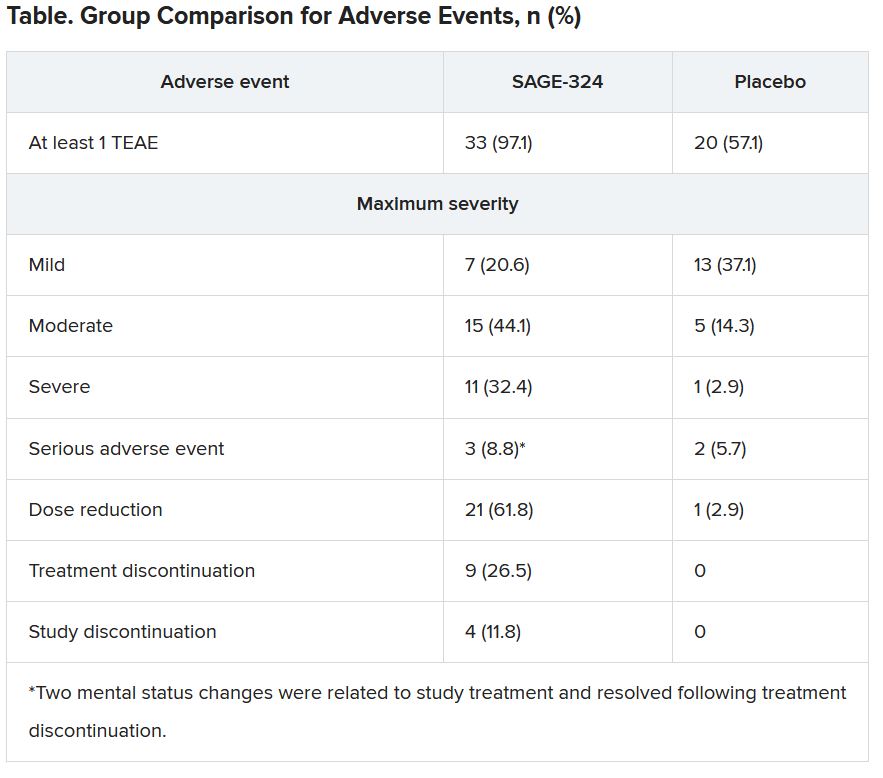

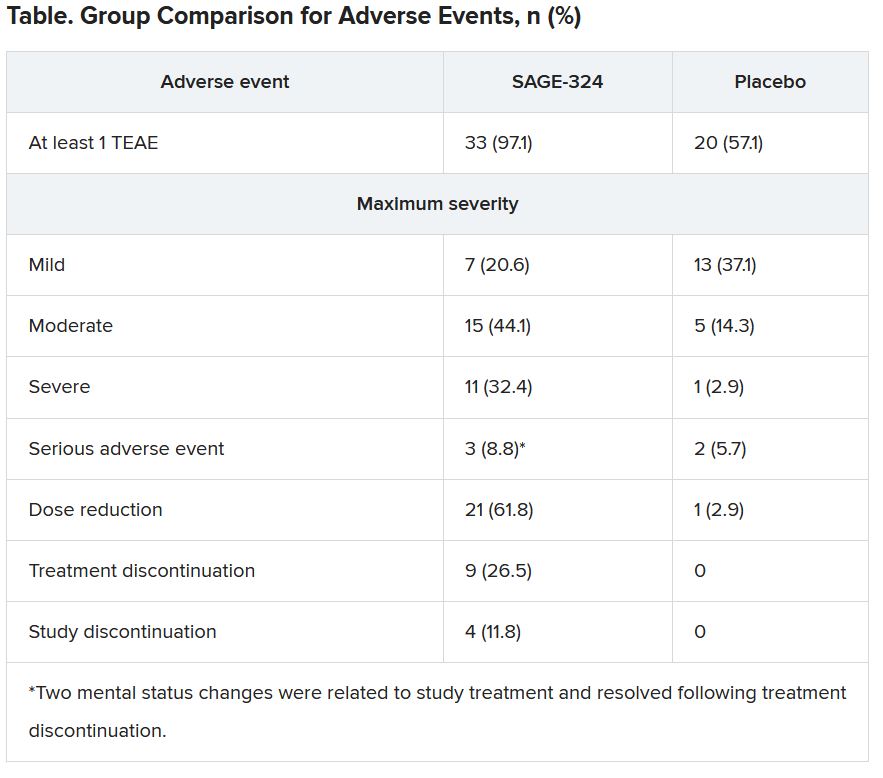

Tolerability of SAGE-324 was a major problem, leading to dose reductions, treatment discontinuations, and study discontinuations. Of the 34 patients who received SAGE-324, 13 dropped out of the study, compared with 2 of 35 patients who received placebo.

Most TEAEs were moderate or severe in the SAGE-324 group, whereas most were mild in the placebo group.

The most common TEAEs for participants who received SAGE-324 were somnolence (67.6%) and dizziness (38.2%), followed by balance problems, diplopia, dysarthria, and gait disturbance. In the placebo group, somnolence affected 5.7%, and dizziness affected 11.4%. There were no deaths in either group.

Dr. Colquhoun said these findings “are in line with our expectations for the 60-mg dose.”

More than one-third of the SAGE-324 group discontinued treatment before the end of the trial, and continuing treatment often required dose reductions. Only 24% completed the trial while taking the 60-mg dose; 15% completed the trial while taking 45 mg; and 24% did so while taking 30 mg.

Dr. Colquhoun noted that the company plans to initiate a phase 2b dose-ranging study later this year to optimize the dosing regimen with regard to tolerability and sustained tremor control.

No advantage over older drugs?

Commenting on the findings, Michele Tagliati, MD, director of the movement disorders program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said he had been aware of the study and was interested in seeing the results. However, he does not see an advantage with this drug, compared with what is already used for essential tremor.

“The response of people is not that different than when we treat them with the old barbiturates and benzodiazepines,” said Dr. Tagliati, who was not involved with the research.

He also noted the high rate of adverse events, particularly somnolence, and said that in his experience with current treatments, some patients prefer to live with their tremors rather than be sleepy and not thinking well.

Dr. Tagliati said he thinks use of SAGE-324 is going to be limited to patients who can tolerate it, “which was not that many.”

In addition, the trial was limited by its relatively small size, a “huge placebo effect,” and a high dropout rate in the active treatment arm, he concluded.

The study was funded by Sage Therapeutics and Biogen. Dr. Bankole and Dr. Calquhoun are employees of Sage. Dr. Tagliati reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

The phase 2 KINETIC trial involved patients with essential tremor. Among patients treated with SAGE-324 for 28 days, there was a statistically significant reduction in upper-limb tremors on day 29 – meeting the primary endpoint of the study.

However, moderate to severe treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) led to many treatment and/or study discontinuations, the investigators reported.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Mechanism of action

Essential tremor affects an estimated 6.4 million adults in the United States. Available drugs are not helpful for 30%-50% of these patients. No new drug for this condition has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the past 50 years. Of the several drugs used to treat essential tremor, propranolol is the only one that has been approved, according to the American Academy of Neurology.

Deficits in inhibitory signaling via the gamma-aminobutyric acid system may have a role in the pathophysiology of essential tremor because the GABAergic system is the major neuroinhibitory system in the brain.

SAGE-324 is a steroid-positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor. It acts on the receptor distant from the neuronal synapse to enhance GABAergic (inhibitory) signaling.

In the phase 2 multicenter KINETIC trial, investigators enrolled 69 patients aged 18-80 years. The patients had moderate to severe essential tremor, as determined on the basis of their having a score of 10 or higher on item 4 of the Essential Tremor Rating Assessment Scale (TETRAS) on screening day and at baseline/day 1 of the trial.

Participants did not take medications for essential tremor during the 28-day washout period. They were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive SAGE-324 60 mg (n = 34) or placebo (n = 35) once daily. Dose reductions were allowed.

The groups were reasonably matched for age (mean, 69.4 years for SAGE-324 vs. 64.7 years for placebo) and dominant hand (right, 85.3% for SAGE-324 vs. 88.6% for placebo). Women composed 35.3% of the drug group and 57.1% of the placebo group.

The primary endpoint of the trial was change from baseline for the active drug in comparison with placebo on day 29 (1 day after the final dose) for upper-limb tremor, as measured by item 4 of TETRAS. There was also a 2-week follow-up with assessments on day 42.

Primary endpoint met, high dropout rate

Baseline mean TETRAS Performance Subscale item 4 scores were 12.82 for the SAGE-324 group and 12.28 for the placebo group.

On day 29, the least squares mean difference from baseline was –2.31 with SAGE-324 (n = 21) versus –1.24 with placebo (n = 33; P = .049). There was no difference between the SAGE-324 and placebo groups on day 42.

“Their significant reduction in upper-limb tremor score at day 29 corresponds to a 36% reduction from baseline in tremor amplitude in patients receiving SAGE-324, compared with a 21% reduction in tremor amplitude in patients receiving a placebo,” said lead investigator Kemi Bankole, MBBCh, of Sage Therapeutics.

“A reduction in tremor amplitude of 36% is a clinically significant improvement for most patients with essential tremor. For patients with moderate-severe tremor, a 41% improvement would be clinically noticeable and appreciated,” said Helen Colquhoun, MBChB, vice president at Sage.

“We believe patients with more severe tremor, that is, a TETRAS score of greater than 12, represent the majority of [essential tremor] patients getting diagnosed and seeking treatment today,” Dr. Colquhoun said.

There was an even greater reduction in tremor amplitude for the subgroup of patients with more severe tremor at baseline, meaning those with a median TETRAS score of 12 or greater (–2.75 for SAGE-324 vs. –1.05 for placebo; P = .0066).

These figures represented a 41% reduction from baseline in tremor amplitude for the SAGE-324 group, versus an 18% reduction in the placebo group. Again, the effect had disappeared in comparison with placebo at the 2-week off-drug follow-up on day 42.

Tolerability of SAGE-324 was a major problem, leading to dose reductions, treatment discontinuations, and study discontinuations. Of the 34 patients who received SAGE-324, 13 dropped out of the study, compared with 2 of 35 patients who received placebo.

Most TEAEs were moderate or severe in the SAGE-324 group, whereas most were mild in the placebo group.

The most common TEAEs for participants who received SAGE-324 were somnolence (67.6%) and dizziness (38.2%), followed by balance problems, diplopia, dysarthria, and gait disturbance. In the placebo group, somnolence affected 5.7%, and dizziness affected 11.4%. There were no deaths in either group.

Dr. Colquhoun said these findings “are in line with our expectations for the 60-mg dose.”

More than one-third of the SAGE-324 group discontinued treatment before the end of the trial, and continuing treatment often required dose reductions. Only 24% completed the trial while taking the 60-mg dose; 15% completed the trial while taking 45 mg; and 24% did so while taking 30 mg.

Dr. Colquhoun noted that the company plans to initiate a phase 2b dose-ranging study later this year to optimize the dosing regimen with regard to tolerability and sustained tremor control.

No advantage over older drugs?

Commenting on the findings, Michele Tagliati, MD, director of the movement disorders program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said he had been aware of the study and was interested in seeing the results. However, he does not see an advantage with this drug, compared with what is already used for essential tremor.

“The response of people is not that different than when we treat them with the old barbiturates and benzodiazepines,” said Dr. Tagliati, who was not involved with the research.

He also noted the high rate of adverse events, particularly somnolence, and said that in his experience with current treatments, some patients prefer to live with their tremors rather than be sleepy and not thinking well.

Dr. Tagliati said he thinks use of SAGE-324 is going to be limited to patients who can tolerate it, “which was not that many.”

In addition, the trial was limited by its relatively small size, a “huge placebo effect,” and a high dropout rate in the active treatment arm, he concluded.

The study was funded by Sage Therapeutics and Biogen. Dr. Bankole and Dr. Calquhoun are employees of Sage. Dr. Tagliati reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

The phase 2 KINETIC trial involved patients with essential tremor. Among patients treated with SAGE-324 for 28 days, there was a statistically significant reduction in upper-limb tremors on day 29 – meeting the primary endpoint of the study.

However, moderate to severe treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) led to many treatment and/or study discontinuations, the investigators reported.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Mechanism of action

Essential tremor affects an estimated 6.4 million adults in the United States. Available drugs are not helpful for 30%-50% of these patients. No new drug for this condition has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the past 50 years. Of the several drugs used to treat essential tremor, propranolol is the only one that has been approved, according to the American Academy of Neurology.

Deficits in inhibitory signaling via the gamma-aminobutyric acid system may have a role in the pathophysiology of essential tremor because the GABAergic system is the major neuroinhibitory system in the brain.

SAGE-324 is a steroid-positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor. It acts on the receptor distant from the neuronal synapse to enhance GABAergic (inhibitory) signaling.

In the phase 2 multicenter KINETIC trial, investigators enrolled 69 patients aged 18-80 years. The patients had moderate to severe essential tremor, as determined on the basis of their having a score of 10 or higher on item 4 of the Essential Tremor Rating Assessment Scale (TETRAS) on screening day and at baseline/day 1 of the trial.

Participants did not take medications for essential tremor during the 28-day washout period. They were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive SAGE-324 60 mg (n = 34) or placebo (n = 35) once daily. Dose reductions were allowed.

The groups were reasonably matched for age (mean, 69.4 years for SAGE-324 vs. 64.7 years for placebo) and dominant hand (right, 85.3% for SAGE-324 vs. 88.6% for placebo). Women composed 35.3% of the drug group and 57.1% of the placebo group.

The primary endpoint of the trial was change from baseline for the active drug in comparison with placebo on day 29 (1 day after the final dose) for upper-limb tremor, as measured by item 4 of TETRAS. There was also a 2-week follow-up with assessments on day 42.

Primary endpoint met, high dropout rate

Baseline mean TETRAS Performance Subscale item 4 scores were 12.82 for the SAGE-324 group and 12.28 for the placebo group.

On day 29, the least squares mean difference from baseline was –2.31 with SAGE-324 (n = 21) versus –1.24 with placebo (n = 33; P = .049). There was no difference between the SAGE-324 and placebo groups on day 42.

“Their significant reduction in upper-limb tremor score at day 29 corresponds to a 36% reduction from baseline in tremor amplitude in patients receiving SAGE-324, compared with a 21% reduction in tremor amplitude in patients receiving a placebo,” said lead investigator Kemi Bankole, MBBCh, of Sage Therapeutics.

“A reduction in tremor amplitude of 36% is a clinically significant improvement for most patients with essential tremor. For patients with moderate-severe tremor, a 41% improvement would be clinically noticeable and appreciated,” said Helen Colquhoun, MBChB, vice president at Sage.

“We believe patients with more severe tremor, that is, a TETRAS score of greater than 12, represent the majority of [essential tremor] patients getting diagnosed and seeking treatment today,” Dr. Colquhoun said.

There was an even greater reduction in tremor amplitude for the subgroup of patients with more severe tremor at baseline, meaning those with a median TETRAS score of 12 or greater (–2.75 for SAGE-324 vs. –1.05 for placebo; P = .0066).

These figures represented a 41% reduction from baseline in tremor amplitude for the SAGE-324 group, versus an 18% reduction in the placebo group. Again, the effect had disappeared in comparison with placebo at the 2-week off-drug follow-up on day 42.

Tolerability of SAGE-324 was a major problem, leading to dose reductions, treatment discontinuations, and study discontinuations. Of the 34 patients who received SAGE-324, 13 dropped out of the study, compared with 2 of 35 patients who received placebo.

Most TEAEs were moderate or severe in the SAGE-324 group, whereas most were mild in the placebo group.

The most common TEAEs for participants who received SAGE-324 were somnolence (67.6%) and dizziness (38.2%), followed by balance problems, diplopia, dysarthria, and gait disturbance. In the placebo group, somnolence affected 5.7%, and dizziness affected 11.4%. There were no deaths in either group.

Dr. Colquhoun said these findings “are in line with our expectations for the 60-mg dose.”

More than one-third of the SAGE-324 group discontinued treatment before the end of the trial, and continuing treatment often required dose reductions. Only 24% completed the trial while taking the 60-mg dose; 15% completed the trial while taking 45 mg; and 24% did so while taking 30 mg.

Dr. Colquhoun noted that the company plans to initiate a phase 2b dose-ranging study later this year to optimize the dosing regimen with regard to tolerability and sustained tremor control.

No advantage over older drugs?

Commenting on the findings, Michele Tagliati, MD, director of the movement disorders program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said he had been aware of the study and was interested in seeing the results. However, he does not see an advantage with this drug, compared with what is already used for essential tremor.

“The response of people is not that different than when we treat them with the old barbiturates and benzodiazepines,” said Dr. Tagliati, who was not involved with the research.

He also noted the high rate of adverse events, particularly somnolence, and said that in his experience with current treatments, some patients prefer to live with their tremors rather than be sleepy and not thinking well.

Dr. Tagliati said he thinks use of SAGE-324 is going to be limited to patients who can tolerate it, “which was not that many.”

In addition, the trial was limited by its relatively small size, a “huge placebo effect,” and a high dropout rate in the active treatment arm, he concluded.

The study was funded by Sage Therapeutics and Biogen. Dr. Bankole and Dr. Calquhoun are employees of Sage. Dr. Tagliati reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MDS VIRTUAL CONGRESS 2021

Apple devices identify early Parkinson’s disease

, new research shows. Results from the WATCH-PD study show clear differences in a finger-tapping task in the Parkinson’s disease versus control group. The finger-tapping task also correlated with “traditional measures,” such as the Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), investigators reported.

“And then the smartphone and smartwatch also showed differences in gait between groups,” said lead investigator Jamie Adams, MD, University of Rochester, New York.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

WATCH-PD

The 12-month WATCH-PD study included 132 individuals at 17 Parkinson’s Study Group sites, 82 with Parkinson’s disease and 50 controls.

Participants with Parkinson’s disease were untreated, were no more than 2 years out from diagnosis (mean disease duration, 10.0 ±7.3 months), and were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 1 or 2.

Apple Watches and iPhones were provided to participants, all of whom underwent in-clinic assessments at baseline and at months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12. The assessments included motor and cognitive tasks using the devices, which contained motion sensors.

The phone also contained an app that could assess verbal, cognitive, and other abilities. Participants wore a set of inertial sensors (APDM Mobility Lab) while performing the MDS-UPDRS Part III motor examination.

In addition, there were biweekly at-home tasks. Questions and tests on the watch assessed symptoms of mood, fatigue, cognition, and falls as well as cognitive performance involving perceptual, verbal, visual spatial, and fine motor abilities. Both the watch and iPhone were used to gauge gait, balance, and tremor.

Ages of the participants were approximately the same in the Parkinson’s disease and control groups (63.3 years vs. 60.2 years, respectively), but male to female ratios differed between the groups. There were more men in the Parkinson’s disease cohort (56% men vs. 44% women) and more women in the control cohort (36% vs. 64%; P =.03).

Between-group differences

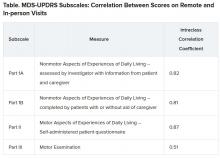

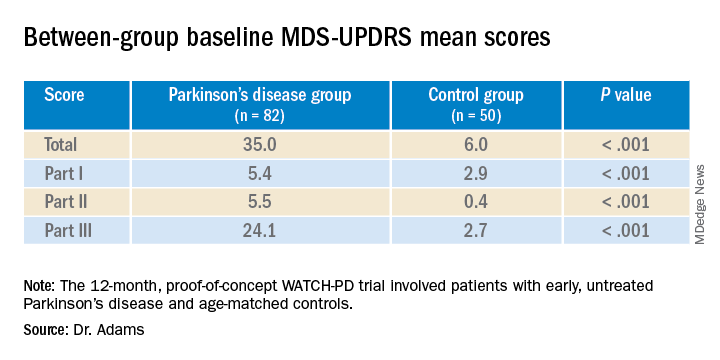

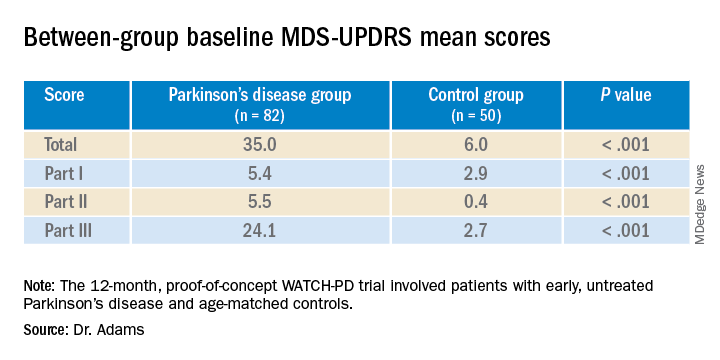

Results showed that MDS-UPDRS total scores and on all individual parts of the rating scale were significantly better for the control group (lower scores are better), as shown in the following table.

Similarly, the control group performed better than the Parkinson’s disease group on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), with higher scores showing better performance on the 0 to 30 scale (28.1 vs. 27.6, respectively).

Touchscreen assessments on the phone also showed group differences in a finger-tapping task, with more taps by the control group than by the Parkinson’s disease group. The difference was more pronounced when the dominant hand was used.

The median numbers of taps in 20 seconds for the dominant hand were 103.7 for the Parkinson’s disease cohort versus 131.9 for control cohort (P < .005); and for the nondominant hand the numbers of taps were 106.6 versus 122.1 (P < .05), respectively. The control group also scored better on tests of hand fine-motor control (P < .01) and on the mobile digit symbols modalities test (P < .05)

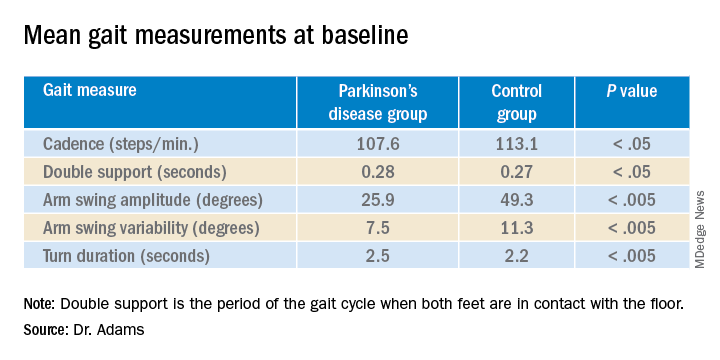

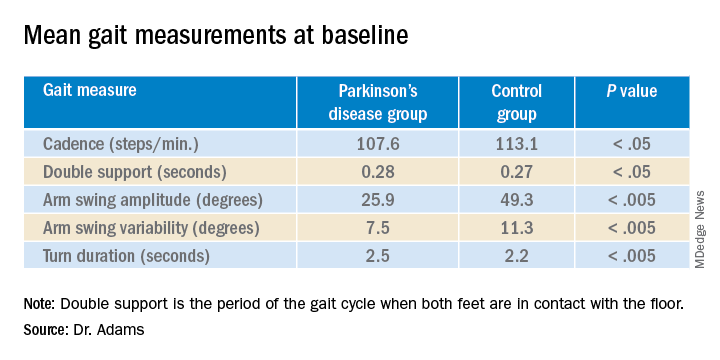

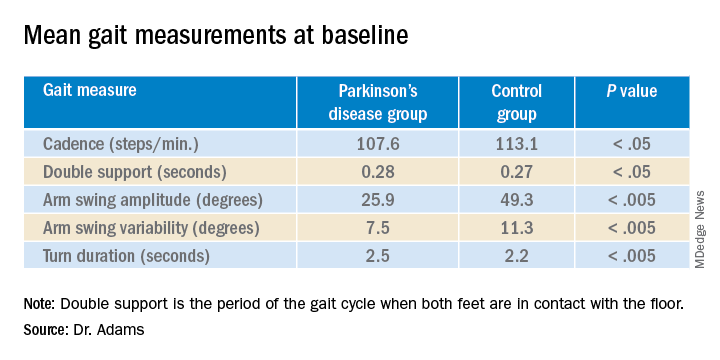

Measures of gait in a 1-minute walk test also showed group differences.

“The five gait measures that differed most were cadence, which is steps per minute, double support, arm swing amplitude, arm swing variation, and turn duration,” Dr. Adams said.

‘Tremendous interest’

Commenting on the findings, Ludy Shih, MD, MMSc, of Boston University, noted that in the future, devices such as the ones used in this study may help clinicians remotely monitor their patients’ Parkinson’s disease conditions and response to therapy.

That would “eliminate some of the transportation barrier for people with Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Shih, who was not involved with the research.

The devices can give objective measurements, reducing inter-rater variability in assessment of movements, she noted.

“I think there’s tremendous interest in using digital measures to pick up on subtle disease phenotypes earlier than a clinical diagnosis can be made,” Dr. Shih said.

She also referred to literature “going back a few decades” showing that finger tapping can be used as a pharmacodynamic measure of how well a patient’s dopaminergic medications are working, so the devices may be a way to remotely assess treatment efficacy and decide when it is time to make adjustments.

Dr. Shih said she thinks regulatory agencies are now open “to consider these as part of the totality of evidence that a therapeutic [device] might be working.”

Whether these would need to be professional grade and approved as medical devices or if patients could just buy smartwatches and smartphones to generate useful data is still a question, she said. Already, there are several Parkinson’s apps that the public can download to track symptoms, improve voice, provide exercises, find support groups or research studies, and more.

Dr. Shih predicted that the biweekly at-home tasks, as in the current protocol, could be a burden to some people. If only a segment of the population were willing to comply, it could call into question how generalizable the results were, she added.

“There’s even a prior publication showing that compliance rate really dropped like a rock,” she noted. However, for those people willing to perform the tasks on a regular schedule, the results could be valuable, Dr. Shih said.

Dr. Adams concurred, saying that she had received feedback from some of her study participants that the biweekly tasks were a bit much.

The study was supported by Biogen and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Adams receives research support from Biogen. Dr. Shih has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows. Results from the WATCH-PD study show clear differences in a finger-tapping task in the Parkinson’s disease versus control group. The finger-tapping task also correlated with “traditional measures,” such as the Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), investigators reported.

“And then the smartphone and smartwatch also showed differences in gait between groups,” said lead investigator Jamie Adams, MD, University of Rochester, New York.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

WATCH-PD

The 12-month WATCH-PD study included 132 individuals at 17 Parkinson’s Study Group sites, 82 with Parkinson’s disease and 50 controls.

Participants with Parkinson’s disease were untreated, were no more than 2 years out from diagnosis (mean disease duration, 10.0 ±7.3 months), and were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 1 or 2.

Apple Watches and iPhones were provided to participants, all of whom underwent in-clinic assessments at baseline and at months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12. The assessments included motor and cognitive tasks using the devices, which contained motion sensors.

The phone also contained an app that could assess verbal, cognitive, and other abilities. Participants wore a set of inertial sensors (APDM Mobility Lab) while performing the MDS-UPDRS Part III motor examination.

In addition, there were biweekly at-home tasks. Questions and tests on the watch assessed symptoms of mood, fatigue, cognition, and falls as well as cognitive performance involving perceptual, verbal, visual spatial, and fine motor abilities. Both the watch and iPhone were used to gauge gait, balance, and tremor.

Ages of the participants were approximately the same in the Parkinson’s disease and control groups (63.3 years vs. 60.2 years, respectively), but male to female ratios differed between the groups. There were more men in the Parkinson’s disease cohort (56% men vs. 44% women) and more women in the control cohort (36% vs. 64%; P =.03).

Between-group differences

Results showed that MDS-UPDRS total scores and on all individual parts of the rating scale were significantly better for the control group (lower scores are better), as shown in the following table.

Similarly, the control group performed better than the Parkinson’s disease group on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), with higher scores showing better performance on the 0 to 30 scale (28.1 vs. 27.6, respectively).

Touchscreen assessments on the phone also showed group differences in a finger-tapping task, with more taps by the control group than by the Parkinson’s disease group. The difference was more pronounced when the dominant hand was used.

The median numbers of taps in 20 seconds for the dominant hand were 103.7 for the Parkinson’s disease cohort versus 131.9 for control cohort (P < .005); and for the nondominant hand the numbers of taps were 106.6 versus 122.1 (P < .05), respectively. The control group also scored better on tests of hand fine-motor control (P < .01) and on the mobile digit symbols modalities test (P < .05)

Measures of gait in a 1-minute walk test also showed group differences.

“The five gait measures that differed most were cadence, which is steps per minute, double support, arm swing amplitude, arm swing variation, and turn duration,” Dr. Adams said.

‘Tremendous interest’

Commenting on the findings, Ludy Shih, MD, MMSc, of Boston University, noted that in the future, devices such as the ones used in this study may help clinicians remotely monitor their patients’ Parkinson’s disease conditions and response to therapy.

That would “eliminate some of the transportation barrier for people with Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Shih, who was not involved with the research.

The devices can give objective measurements, reducing inter-rater variability in assessment of movements, she noted.

“I think there’s tremendous interest in using digital measures to pick up on subtle disease phenotypes earlier than a clinical diagnosis can be made,” Dr. Shih said.

She also referred to literature “going back a few decades” showing that finger tapping can be used as a pharmacodynamic measure of how well a patient’s dopaminergic medications are working, so the devices may be a way to remotely assess treatment efficacy and decide when it is time to make adjustments.

Dr. Shih said she thinks regulatory agencies are now open “to consider these as part of the totality of evidence that a therapeutic [device] might be working.”

Whether these would need to be professional grade and approved as medical devices or if patients could just buy smartwatches and smartphones to generate useful data is still a question, she said. Already, there are several Parkinson’s apps that the public can download to track symptoms, improve voice, provide exercises, find support groups or research studies, and more.

Dr. Shih predicted that the biweekly at-home tasks, as in the current protocol, could be a burden to some people. If only a segment of the population were willing to comply, it could call into question how generalizable the results were, she added.

“There’s even a prior publication showing that compliance rate really dropped like a rock,” she noted. However, for those people willing to perform the tasks on a regular schedule, the results could be valuable, Dr. Shih said.

Dr. Adams concurred, saying that she had received feedback from some of her study participants that the biweekly tasks were a bit much.

The study was supported by Biogen and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Adams receives research support from Biogen. Dr. Shih has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows. Results from the WATCH-PD study show clear differences in a finger-tapping task in the Parkinson’s disease versus control group. The finger-tapping task also correlated with “traditional measures,” such as the Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), investigators reported.

“And then the smartphone and smartwatch also showed differences in gait between groups,” said lead investigator Jamie Adams, MD, University of Rochester, New York.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

WATCH-PD

The 12-month WATCH-PD study included 132 individuals at 17 Parkinson’s Study Group sites, 82 with Parkinson’s disease and 50 controls.

Participants with Parkinson’s disease were untreated, were no more than 2 years out from diagnosis (mean disease duration, 10.0 ±7.3 months), and were in Hoehn and Yahr stage 1 or 2.

Apple Watches and iPhones were provided to participants, all of whom underwent in-clinic assessments at baseline and at months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12. The assessments included motor and cognitive tasks using the devices, which contained motion sensors.

The phone also contained an app that could assess verbal, cognitive, and other abilities. Participants wore a set of inertial sensors (APDM Mobility Lab) while performing the MDS-UPDRS Part III motor examination.

In addition, there were biweekly at-home tasks. Questions and tests on the watch assessed symptoms of mood, fatigue, cognition, and falls as well as cognitive performance involving perceptual, verbal, visual spatial, and fine motor abilities. Both the watch and iPhone were used to gauge gait, balance, and tremor.

Ages of the participants were approximately the same in the Parkinson’s disease and control groups (63.3 years vs. 60.2 years, respectively), but male to female ratios differed between the groups. There were more men in the Parkinson’s disease cohort (56% men vs. 44% women) and more women in the control cohort (36% vs. 64%; P =.03).

Between-group differences

Results showed that MDS-UPDRS total scores and on all individual parts of the rating scale were significantly better for the control group (lower scores are better), as shown in the following table.

Similarly, the control group performed better than the Parkinson’s disease group on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), with higher scores showing better performance on the 0 to 30 scale (28.1 vs. 27.6, respectively).

Touchscreen assessments on the phone also showed group differences in a finger-tapping task, with more taps by the control group than by the Parkinson’s disease group. The difference was more pronounced when the dominant hand was used.

The median numbers of taps in 20 seconds for the dominant hand were 103.7 for the Parkinson’s disease cohort versus 131.9 for control cohort (P < .005); and for the nondominant hand the numbers of taps were 106.6 versus 122.1 (P < .05), respectively. The control group also scored better on tests of hand fine-motor control (P < .01) and on the mobile digit symbols modalities test (P < .05)

Measures of gait in a 1-minute walk test also showed group differences.

“The five gait measures that differed most were cadence, which is steps per minute, double support, arm swing amplitude, arm swing variation, and turn duration,” Dr. Adams said.

‘Tremendous interest’

Commenting on the findings, Ludy Shih, MD, MMSc, of Boston University, noted that in the future, devices such as the ones used in this study may help clinicians remotely monitor their patients’ Parkinson’s disease conditions and response to therapy.

That would “eliminate some of the transportation barrier for people with Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Shih, who was not involved with the research.

The devices can give objective measurements, reducing inter-rater variability in assessment of movements, she noted.

“I think there’s tremendous interest in using digital measures to pick up on subtle disease phenotypes earlier than a clinical diagnosis can be made,” Dr. Shih said.

She also referred to literature “going back a few decades” showing that finger tapping can be used as a pharmacodynamic measure of how well a patient’s dopaminergic medications are working, so the devices may be a way to remotely assess treatment efficacy and decide when it is time to make adjustments.

Dr. Shih said she thinks regulatory agencies are now open “to consider these as part of the totality of evidence that a therapeutic [device] might be working.”

Whether these would need to be professional grade and approved as medical devices or if patients could just buy smartwatches and smartphones to generate useful data is still a question, she said. Already, there are several Parkinson’s apps that the public can download to track symptoms, improve voice, provide exercises, find support groups or research studies, and more.

Dr. Shih predicted that the biweekly at-home tasks, as in the current protocol, could be a burden to some people. If only a segment of the population were willing to comply, it could call into question how generalizable the results were, she added.

“There’s even a prior publication showing that compliance rate really dropped like a rock,” she noted. However, for those people willing to perform the tasks on a regular schedule, the results could be valuable, Dr. Shih said.

Dr. Adams concurred, saying that she had received feedback from some of her study participants that the biweekly tasks were a bit much.

The study was supported by Biogen and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Adams receives research support from Biogen. Dr. Shih has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MDS VIRTUAL CONGRESS 2021

Surge in new-onset tics in adults tied to COVID-19 stress

, new research suggests.

Results from a large, single-center study show several cases of tic-like movements and vocalizations with abrupt onset among older adolescents and adults during the pandemic. None had a previous diagnosis of a tic disorder. Among 10 patients, two were diagnosed with a purely functional movement disorder, four with an organic tic disorder, and four with both.

“Within our movement disorders clinic specifically ... we’ve been seeing an increased number of patients with an almost explosive onset of these tic-like movements and vocalizations later in life than what is typically seen with organic tic disorders and Tourette syndrome, which is typically in school-aged children,” said study investigator Caroline Olvera, MD, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

“Abrupt onset of symptoms can be seen in patients with tic disorders, although this is typically quoted as less than 10%, or even 5% is more characteristic of functional neurological disorders in general and also with psychogenic tics,” she added.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Anxiety, other psychiatric conditions

Tic disorders typically start in childhood. However, the researchers observed an increase in the number of patients with abrupt onset of tic-like movements and vocalizations later in life, which is more often characteristic of functional neurological disorders.

To examine the profile, associated conditions, and risk factors in this population, the investigators conducted a thorough chart review of patients attending movement disorder clinics between March 2020, when the COVID pandemic was officially declared, and March 2021.

Patients with acute onset of tics were identified using the International Classification of Diseases codes for behavioral tics, tic vocalizations, and Tourette syndrome.

The charts were then narrowed down to patients with no previous diagnosis of these conditions. Most patients were videotaped for assessment by the rest of the movement disorder neurologists in the practice. Since the end of the study inclusion period in March 2021, Dr. Olvera estimates that the clinic experienced a doubling or tripling of the number of similar patients.

In the study cohort of 10 patients, the median age at presentation was 19 years (range, 15-41 years), nine were female, the gender of the other one was unknown, and the duration of tics was 8 weeks (range, 1-24 weeks) by the time they were first seen in the clinic. Four patients reported having COVID infection before tic onset.

All exhibited motor tics and nine had vocal tics. Two were diagnosed with a purely functional neurologic disorder, four with only an organic tic disorder, and four with organic tics with a functional overlay.

“All patients, including those with organic tic disorders, had a history of anxiety and also reported worsening anxiety in the setting of the COVID pandemic,” Dr. Olvera said.

The majority of patients were on a psychotropic medication prior to coming to the clinic, and these were primarily for anxiety and depression. Three patients had a history of suicidality, often very severe and leading to hospitalization, she noted.

“In terms of our conclusions from the project, we feel that this phenotype of acute explosive onset of tic-like movements and vocalizations in this older population of adults, compared with typical organic tic disorders and Tourette syndrome, appears novel to the pandemic,” she said.

She cautioned that functional and organic tics share many characteristics and therefore may be difficult to differentiate.

COVID stress

Commenting on the findings, Michele Tagliati, MD, director of the movement disorders program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said the research highlights how clinicians’ understanding of particular diseases can be challenged during extraordinary events such as COVID-19 and the heightened stress it causes.

“I’m not surprised that these [disorders] might have had a spike during a stressful time as COVID,” he said.

Patients are “really scared and really anxious, they’re afraid to die, and they’re afraid that their life will be over. So they might express their psychological difficulty, their discomfort, with these calls for help that look like tics. But they’re not what we consider physiological or organic things,” he added.

Dr. Tagliati added that he doesn’t believe rapid tic onset in adults is not a complication of the coronavirus infection, but rather a consequence of psychological pressure brought on by the pandemic.

Treating underlying anxiety may be a useful approach, possibly with the support of psychiatrists, which in many cases is enough to relieve the conditions and overcome the symptoms, he noted.

However, at other times, it’s not that simple, he added. Sometimes patients “fall through the cracks between neurology and psychiatry,” Dr. Tagliati said.

Dr. Olvera and Dr. Tagliati have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Results from a large, single-center study show several cases of tic-like movements and vocalizations with abrupt onset among older adolescents and adults during the pandemic. None had a previous diagnosis of a tic disorder. Among 10 patients, two were diagnosed with a purely functional movement disorder, four with an organic tic disorder, and four with both.

“Within our movement disorders clinic specifically ... we’ve been seeing an increased number of patients with an almost explosive onset of these tic-like movements and vocalizations later in life than what is typically seen with organic tic disorders and Tourette syndrome, which is typically in school-aged children,” said study investigator Caroline Olvera, MD, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

“Abrupt onset of symptoms can be seen in patients with tic disorders, although this is typically quoted as less than 10%, or even 5% is more characteristic of functional neurological disorders in general and also with psychogenic tics,” she added.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Anxiety, other psychiatric conditions

Tic disorders typically start in childhood. However, the researchers observed an increase in the number of patients with abrupt onset of tic-like movements and vocalizations later in life, which is more often characteristic of functional neurological disorders.

To examine the profile, associated conditions, and risk factors in this population, the investigators conducted a thorough chart review of patients attending movement disorder clinics between March 2020, when the COVID pandemic was officially declared, and March 2021.

Patients with acute onset of tics were identified using the International Classification of Diseases codes for behavioral tics, tic vocalizations, and Tourette syndrome.

The charts were then narrowed down to patients with no previous diagnosis of these conditions. Most patients were videotaped for assessment by the rest of the movement disorder neurologists in the practice. Since the end of the study inclusion period in March 2021, Dr. Olvera estimates that the clinic experienced a doubling or tripling of the number of similar patients.

In the study cohort of 10 patients, the median age at presentation was 19 years (range, 15-41 years), nine were female, the gender of the other one was unknown, and the duration of tics was 8 weeks (range, 1-24 weeks) by the time they were first seen in the clinic. Four patients reported having COVID infection before tic onset.

All exhibited motor tics and nine had vocal tics. Two were diagnosed with a purely functional neurologic disorder, four with only an organic tic disorder, and four with organic tics with a functional overlay.

“All patients, including those with organic tic disorders, had a history of anxiety and also reported worsening anxiety in the setting of the COVID pandemic,” Dr. Olvera said.

The majority of patients were on a psychotropic medication prior to coming to the clinic, and these were primarily for anxiety and depression. Three patients had a history of suicidality, often very severe and leading to hospitalization, she noted.

“In terms of our conclusions from the project, we feel that this phenotype of acute explosive onset of tic-like movements and vocalizations in this older population of adults, compared with typical organic tic disorders and Tourette syndrome, appears novel to the pandemic,” she said.

She cautioned that functional and organic tics share many characteristics and therefore may be difficult to differentiate.

COVID stress

Commenting on the findings, Michele Tagliati, MD, director of the movement disorders program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said the research highlights how clinicians’ understanding of particular diseases can be challenged during extraordinary events such as COVID-19 and the heightened stress it causes.

“I’m not surprised that these [disorders] might have had a spike during a stressful time as COVID,” he said.

Patients are “really scared and really anxious, they’re afraid to die, and they’re afraid that their life will be over. So they might express their psychological difficulty, their discomfort, with these calls for help that look like tics. But they’re not what we consider physiological or organic things,” he added.

Dr. Tagliati added that he doesn’t believe rapid tic onset in adults is not a complication of the coronavirus infection, but rather a consequence of psychological pressure brought on by the pandemic.

Treating underlying anxiety may be a useful approach, possibly with the support of psychiatrists, which in many cases is enough to relieve the conditions and overcome the symptoms, he noted.

However, at other times, it’s not that simple, he added. Sometimes patients “fall through the cracks between neurology and psychiatry,” Dr. Tagliati said.

Dr. Olvera and Dr. Tagliati have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Results from a large, single-center study show several cases of tic-like movements and vocalizations with abrupt onset among older adolescents and adults during the pandemic. None had a previous diagnosis of a tic disorder. Among 10 patients, two were diagnosed with a purely functional movement disorder, four with an organic tic disorder, and four with both.

“Within our movement disorders clinic specifically ... we’ve been seeing an increased number of patients with an almost explosive onset of these tic-like movements and vocalizations later in life than what is typically seen with organic tic disorders and Tourette syndrome, which is typically in school-aged children,” said study investigator Caroline Olvera, MD, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

“Abrupt onset of symptoms can be seen in patients with tic disorders, although this is typically quoted as less than 10%, or even 5% is more characteristic of functional neurological disorders in general and also with psychogenic tics,” she added.

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

Anxiety, other psychiatric conditions

Tic disorders typically start in childhood. However, the researchers observed an increase in the number of patients with abrupt onset of tic-like movements and vocalizations later in life, which is more often characteristic of functional neurological disorders.

To examine the profile, associated conditions, and risk factors in this population, the investigators conducted a thorough chart review of patients attending movement disorder clinics between March 2020, when the COVID pandemic was officially declared, and March 2021.

Patients with acute onset of tics were identified using the International Classification of Diseases codes for behavioral tics, tic vocalizations, and Tourette syndrome.

The charts were then narrowed down to patients with no previous diagnosis of these conditions. Most patients were videotaped for assessment by the rest of the movement disorder neurologists in the practice. Since the end of the study inclusion period in March 2021, Dr. Olvera estimates that the clinic experienced a doubling or tripling of the number of similar patients.

In the study cohort of 10 patients, the median age at presentation was 19 years (range, 15-41 years), nine were female, the gender of the other one was unknown, and the duration of tics was 8 weeks (range, 1-24 weeks) by the time they were first seen in the clinic. Four patients reported having COVID infection before tic onset.

All exhibited motor tics and nine had vocal tics. Two were diagnosed with a purely functional neurologic disorder, four with only an organic tic disorder, and four with organic tics with a functional overlay.

“All patients, including those with organic tic disorders, had a history of anxiety and also reported worsening anxiety in the setting of the COVID pandemic,” Dr. Olvera said.

The majority of patients were on a psychotropic medication prior to coming to the clinic, and these were primarily for anxiety and depression. Three patients had a history of suicidality, often very severe and leading to hospitalization, she noted.

“In terms of our conclusions from the project, we feel that this phenotype of acute explosive onset of tic-like movements and vocalizations in this older population of adults, compared with typical organic tic disorders and Tourette syndrome, appears novel to the pandemic,” she said.

She cautioned that functional and organic tics share many characteristics and therefore may be difficult to differentiate.

COVID stress

Commenting on the findings, Michele Tagliati, MD, director of the movement disorders program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said the research highlights how clinicians’ understanding of particular diseases can be challenged during extraordinary events such as COVID-19 and the heightened stress it causes.

“I’m not surprised that these [disorders] might have had a spike during a stressful time as COVID,” he said.

Patients are “really scared and really anxious, they’re afraid to die, and they’re afraid that their life will be over. So they might express their psychological difficulty, their discomfort, with these calls for help that look like tics. But they’re not what we consider physiological or organic things,” he added.

Dr. Tagliati added that he doesn’t believe rapid tic onset in adults is not a complication of the coronavirus infection, but rather a consequence of psychological pressure brought on by the pandemic.

Treating underlying anxiety may be a useful approach, possibly with the support of psychiatrists, which in many cases is enough to relieve the conditions and overcome the symptoms, he noted.

However, at other times, it’s not that simple, he added. Sometimes patients “fall through the cracks between neurology and psychiatry,” Dr. Tagliati said.

Dr. Olvera and Dr. Tagliati have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MDS VIRTUAL CONGRESS 2021

Sublingual film well tolerated for Parkinson ‘off’ episodes

new research shows.

“The bottom line was that the majority of patients did not have dose-limiting nausea or vomiting,” said coinvestigator William Ondo, MD, from Houston Methodist Neurological Institute. “And although it really did not compare in a prospective, placebo-controlled manner use of [trimethobenzamide antiemetic] ... versus not using [it], anecdotally and based on historic data, nausea really seemed to be about the same even without the antinausea medication.”

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

This study was the dose-titration phase to determine the effective and tolerable dose of the drug as part of a longer study looking at safety and efficacy.

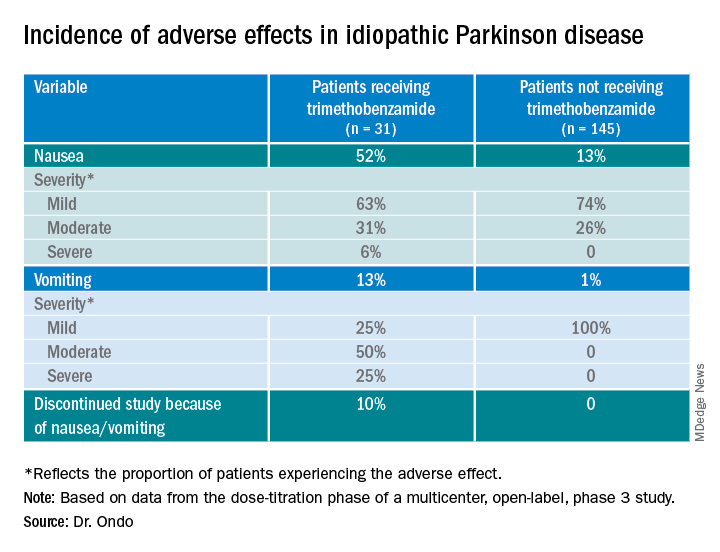

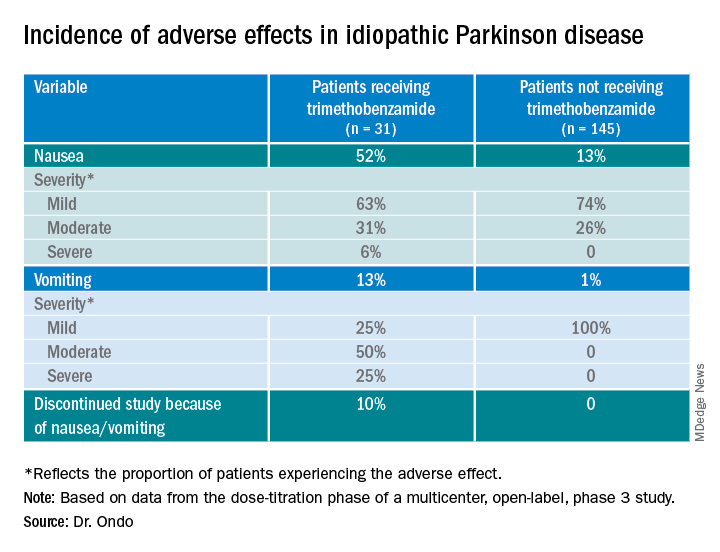

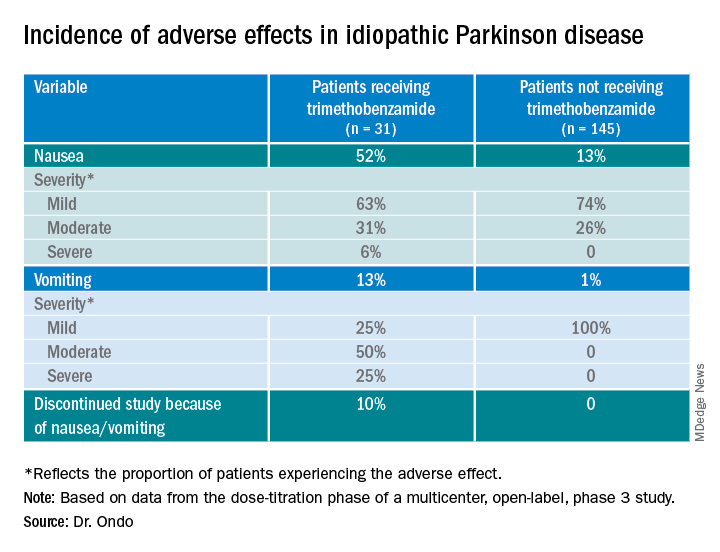

Only 13% of patients experienced nausea and/or vomiting, and of those, 74% cases were of mild severity and 26% were of moderate severity. These rates of nausea/vomiting were lower than those seen when trimethobenzamide (Tigan, Pfizer) was needed to be administered during the titration period, at the discretion of the investigator.

This multicenter, ongoing, open-label, phase 3 study enrolled 176 patients (mean age, 64.4 years) who had idiopathic Parkinson’s disease for a mean of 8.0 years and had no prior exposure to SL-apo, with modified Hoehn and Yahr stage 1-3 disease (83% stage 2 or 2.5 during “on” time).

Study participants had Mini-Mental State Examination scores greater than 25, were receiving stable doses of levodopa/carbidopa, and had 1 or more (mean, 4.2) “off” episodes per day with a total daily “off” time of 2 hours or more. Patients with mouth cankers or sores within 30 days of screening were excluded.

Open-label dose titration occurred during sequential office visits while patients were “off,” with escalating doses of 10-35 mg in 5-mg increments to determine a tolerable dose leading to a full “on” period within 45 minutes. Patients self-administered this achieved dose of SL-apo for up to five “off” episodes per day with a minimum of 2 hours between doses for the full 48-week study period.

The study protocol prohibited antiemetic use except when clinically warranted at the investigator’s discretion. Of the 176 patients, 31 (18%) received the antiemetic trimethobenzamide and 145 (82%) did not.

Of the 176 patients, 76% received their effective and tolerated dose within the first three doses. Just over half (55%) received 10 mg or 15 mg. Only 24% received the highest doses of 25 mg or 30 mg.

About 52%of patients who received trimethobenzamide experienced treatment-related nausea and 13% experienced vomiting; in comparison, 13% not receiving trimethobenzamide had nausea and 1% had vomiting. About 10%of patients in the former group and none in the latter discontinued the study because of nausea and/or vomiting.

The apomorphine sublingual film has “the advantage of ease of use compared to the injectable form,” Dr. Ondo said. “I think the injectable form, purely based on anecdotal experience, might start to work a minute or 2 faster than the sublingual form, but overall I would say efficacy as far as potency of turning ‘on’ and consistency of turning ‘on’ is comparable.”

In addition to the known adverse effects of nausea, vomiting, and hypotension with the use of any apomorphine, he said that long-term use of the sublingual form can lead to gingival irritation. Two recommendations are to place the film in a different site and to use a more basic toothpaste, such as one containing baking powder, because irritation may result from the acidity of the apomorphine.

Good news

Commenting on the study, Ludy Shih, MD, MMSc, from Boston University, noted that the drug label reports that “13%-15% had oropharyngeal soft tissue swelling or pain ... and 7% had oral ulcers and stomatitis.”

In addition, oral trimethobenzamide has been discontinued, although an injectable form is still available. This situation may present a problem, she said. “Most antinausea drugs block dopamine, so ... I would say they’re contraindicated for treating people with Parkinson’s disease. But trimethobenzamide in particular is one that we often reach for. ... But that appears to be constrained and may, in fact, be expensive for patients.”

Turning to the study findings, she said they suggest that “not everyone needs prophylactic use of trimethobenzamide before they take the apomorphine sublingual film, which is good news that helps doctors try to decide whether or not it’s reasonable to recommend people trying it without the trimethobenzamide.”

Although some patients did experience mild nausea, she said the fact that no needle is involved may attract some patients. Moreover, taking this medication may be easier than administering an injection during an “off” episode.

Dr. Ondo is a consultant for Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, which sponsored the study. Dr. Shih had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research shows.

“The bottom line was that the majority of patients did not have dose-limiting nausea or vomiting,” said coinvestigator William Ondo, MD, from Houston Methodist Neurological Institute. “And although it really did not compare in a prospective, placebo-controlled manner use of [trimethobenzamide antiemetic] ... versus not using [it], anecdotally and based on historic data, nausea really seemed to be about the same even without the antinausea medication.”

The findings were presented at the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

This study was the dose-titration phase to determine the effective and tolerable dose of the drug as part of a longer study looking at safety and efficacy.

Only 13% of patients experienced nausea and/or vomiting, and of those, 74% cases were of mild severity and 26% were of moderate severity. These rates of nausea/vomiting were lower than those seen when trimethobenzamide (Tigan, Pfizer) was needed to be administered during the titration period, at the discretion of the investigator.

This multicenter, ongoing, open-label, phase 3 study enrolled 176 patients (mean age, 64.4 years) who had idiopathic Parkinson’s disease for a mean of 8.0 years and had no prior exposure to SL-apo, with modified Hoehn and Yahr stage 1-3 disease (83% stage 2 or 2.5 during “on” time).

Study participants had Mini-Mental State Examination scores greater than 25, were receiving stable doses of levodopa/carbidopa, and had 1 or more (mean, 4.2) “off” episodes per day with a total daily “off” time of 2 hours or more. Patients with mouth cankers or sores within 30 days of screening were excluded.

Open-label dose titration occurred during sequential office visits while patients were “off,” with escalating doses of 10-35 mg in 5-mg increments to determine a tolerable dose leading to a full “on” period within 45 minutes. Patients self-administered this achieved dose of SL-apo for up to five “off” episodes per day with a minimum of 2 hours between doses for the full 48-week study period.

The study protocol prohibited antiemetic use except when clinically warranted at the investigator’s discretion. Of the 176 patients, 31 (18%) received the antiemetic trimethobenzamide and 145 (82%) did not.

Of the 176 patients, 76% received their effective and tolerated dose within the first three doses. Just over half (55%) received 10 mg or 15 mg. Only 24% received the highest doses of 25 mg or 30 mg.

About 52%of patients who received trimethobenzamide experienced treatment-related nausea and 13% experienced vomiting; in comparison, 13% not receiving trimethobenzamide had nausea and 1% had vomiting. About 10%of patients in the former group and none in the latter discontinued the study because of nausea and/or vomiting.

The apomorphine sublingual film has “the advantage of ease of use compared to the injectable form,” Dr. Ondo said. “I think the injectable form, purely based on anecdotal experience, might start to work a minute or 2 faster than the sublingual form, but overall I would say efficacy as far as potency of turning ‘on’ and consistency of turning ‘on’ is comparable.”