User login

COVID Linked to Eye Issues, But Vaccine Offers Protection

TOPLINE:

Patients with COVID had a higher risk of developing diplopia and cranial nerve VI palsy than those with influenza. Compared with unvaccinated patients, recipients of mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 had a more than 30% reduced risk of developing posterior-segment complications including retinal edema, vitreous hemorrhage, and optic neuritis.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of US electronic health records from March 2020 to April 2021 to assess eye complications after COVID and the effect of mRNA vaccination on them.

- They analyzed matched cohorts of 73,654 vaccinated patients with COVID (mean age, 60.6 years; 61.6% women) and 73,654 unvaccinated patients with the condition (mean age, 61.2 years; 62.8% women); vaccination status was determined based on recorded receipt of an mRNA vaccine.

- In a separate matched analysis, 77,809 patients with COVID (mean age, 39.3 years; 58.8% women) were compared with a historic cohort of 77,809 patients with influenza (mean age, 39.7 years; 58.9% women).

- The incidence of ophthalmic conditions — retinal artery occlusion, retinal vein occlusion, retinal edema, vitreous hemorrhage, and neuro-ophthalmic manifestations — was assessed within 4 months of infection.

TAKEAWAY:

- Vaccinated patients with COVID had 32% lower odds of retinal edema (odds ratio [OR], 0.68; 99.5% CI, 0.54-0.85), 45% lower odds of vitreous hemorrhage (OR, 0.55; 99.5% CI, 0.44-0.68), and 40% lower odds of optic neuritis (OR, 0.60; 99.5% CI, 0.43-0.85) than unvaccinated patients with the disease.

- No significant differences were found in the incidence of retinal artery occlusion, retinal vein occlusion, or retinal hemorrhage between the vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts.

- Patients with COVID had markedly higher odds of diplopia (OR, 1.89; 99.5% CI, 1.53-2.32) and cranial nerve VI palsy (OR, 3.19; 99.5% CI, 1.82-5.59) than those with influenza.

- The incidence of other neuro-ophthalmic manifestations and retinal complications was similar between patients with COVID and those with influenza.

IN PRACTICE:

“The complications we assessed were rare, though our results showed an increased incidence of retinal edema, vitreous hemorrhage, and optic neuritis in the nonvaccinated COVID-19 cohort,” the researchers reported.

“The increased incidence of retinal edema and vitreous hemorrhage in the nonvaccinated cohort suggests a potential for COVID-19 to affect posterior segment structures,” they added.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Alexander E. Azar, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland. It was published online in Eye.

LIMITATIONS:

This study could not determine if vaccination against COVID could prevent ophthalmic manifestations. Vaccination status may have been underreported since many participants received COVID vaccines at pharmacies or community centers not directly documented in the electronic health records. The study’s timeframe only reflected data from early strains of SARS-CoV-2 between March 2020 and April 2021, potentially limiting generalizability to newer variants or later vaccination phases.

DISCLOSURES:

This study received support from the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Science, and other sources. Some authors reported serving as consultants, participating in speakers’ bureaus, receiving personal fees, and having other ties with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Patients with COVID had a higher risk of developing diplopia and cranial nerve VI palsy than those with influenza. Compared with unvaccinated patients, recipients of mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 had a more than 30% reduced risk of developing posterior-segment complications including retinal edema, vitreous hemorrhage, and optic neuritis.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of US electronic health records from March 2020 to April 2021 to assess eye complications after COVID and the effect of mRNA vaccination on them.

- They analyzed matched cohorts of 73,654 vaccinated patients with COVID (mean age, 60.6 years; 61.6% women) and 73,654 unvaccinated patients with the condition (mean age, 61.2 years; 62.8% women); vaccination status was determined based on recorded receipt of an mRNA vaccine.

- In a separate matched analysis, 77,809 patients with COVID (mean age, 39.3 years; 58.8% women) were compared with a historic cohort of 77,809 patients with influenza (mean age, 39.7 years; 58.9% women).

- The incidence of ophthalmic conditions — retinal artery occlusion, retinal vein occlusion, retinal edema, vitreous hemorrhage, and neuro-ophthalmic manifestations — was assessed within 4 months of infection.

TAKEAWAY:

- Vaccinated patients with COVID had 32% lower odds of retinal edema (odds ratio [OR], 0.68; 99.5% CI, 0.54-0.85), 45% lower odds of vitreous hemorrhage (OR, 0.55; 99.5% CI, 0.44-0.68), and 40% lower odds of optic neuritis (OR, 0.60; 99.5% CI, 0.43-0.85) than unvaccinated patients with the disease.

- No significant differences were found in the incidence of retinal artery occlusion, retinal vein occlusion, or retinal hemorrhage between the vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts.

- Patients with COVID had markedly higher odds of diplopia (OR, 1.89; 99.5% CI, 1.53-2.32) and cranial nerve VI palsy (OR, 3.19; 99.5% CI, 1.82-5.59) than those with influenza.

- The incidence of other neuro-ophthalmic manifestations and retinal complications was similar between patients with COVID and those with influenza.

IN PRACTICE:

“The complications we assessed were rare, though our results showed an increased incidence of retinal edema, vitreous hemorrhage, and optic neuritis in the nonvaccinated COVID-19 cohort,” the researchers reported.

“The increased incidence of retinal edema and vitreous hemorrhage in the nonvaccinated cohort suggests a potential for COVID-19 to affect posterior segment structures,” they added.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Alexander E. Azar, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland. It was published online in Eye.

LIMITATIONS:

This study could not determine if vaccination against COVID could prevent ophthalmic manifestations. Vaccination status may have been underreported since many participants received COVID vaccines at pharmacies or community centers not directly documented in the electronic health records. The study’s timeframe only reflected data from early strains of SARS-CoV-2 between March 2020 and April 2021, potentially limiting generalizability to newer variants or later vaccination phases.

DISCLOSURES:

This study received support from the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Science, and other sources. Some authors reported serving as consultants, participating in speakers’ bureaus, receiving personal fees, and having other ties with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Patients with COVID had a higher risk of developing diplopia and cranial nerve VI palsy than those with influenza. Compared with unvaccinated patients, recipients of mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 had a more than 30% reduced risk of developing posterior-segment complications including retinal edema, vitreous hemorrhage, and optic neuritis.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of US electronic health records from March 2020 to April 2021 to assess eye complications after COVID and the effect of mRNA vaccination on them.

- They analyzed matched cohorts of 73,654 vaccinated patients with COVID (mean age, 60.6 years; 61.6% women) and 73,654 unvaccinated patients with the condition (mean age, 61.2 years; 62.8% women); vaccination status was determined based on recorded receipt of an mRNA vaccine.

- In a separate matched analysis, 77,809 patients with COVID (mean age, 39.3 years; 58.8% women) were compared with a historic cohort of 77,809 patients with influenza (mean age, 39.7 years; 58.9% women).

- The incidence of ophthalmic conditions — retinal artery occlusion, retinal vein occlusion, retinal edema, vitreous hemorrhage, and neuro-ophthalmic manifestations — was assessed within 4 months of infection.

TAKEAWAY:

- Vaccinated patients with COVID had 32% lower odds of retinal edema (odds ratio [OR], 0.68; 99.5% CI, 0.54-0.85), 45% lower odds of vitreous hemorrhage (OR, 0.55; 99.5% CI, 0.44-0.68), and 40% lower odds of optic neuritis (OR, 0.60; 99.5% CI, 0.43-0.85) than unvaccinated patients with the disease.

- No significant differences were found in the incidence of retinal artery occlusion, retinal vein occlusion, or retinal hemorrhage between the vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts.

- Patients with COVID had markedly higher odds of diplopia (OR, 1.89; 99.5% CI, 1.53-2.32) and cranial nerve VI palsy (OR, 3.19; 99.5% CI, 1.82-5.59) than those with influenza.

- The incidence of other neuro-ophthalmic manifestations and retinal complications was similar between patients with COVID and those with influenza.

IN PRACTICE:

“The complications we assessed were rare, though our results showed an increased incidence of retinal edema, vitreous hemorrhage, and optic neuritis in the nonvaccinated COVID-19 cohort,” the researchers reported.

“The increased incidence of retinal edema and vitreous hemorrhage in the nonvaccinated cohort suggests a potential for COVID-19 to affect posterior segment structures,” they added.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Alexander E. Azar, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland. It was published online in Eye.

LIMITATIONS:

This study could not determine if vaccination against COVID could prevent ophthalmic manifestations. Vaccination status may have been underreported since many participants received COVID vaccines at pharmacies or community centers not directly documented in the electronic health records. The study’s timeframe only reflected data from early strains of SARS-CoV-2 between March 2020 and April 2021, potentially limiting generalizability to newer variants or later vaccination phases.

DISCLOSURES:

This study received support from the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Science, and other sources. Some authors reported serving as consultants, participating in speakers’ bureaus, receiving personal fees, and having other ties with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lower Cancer Risk in Veterans With COVID-19 Infection

TOPLINE: COVID-19 infection is associated with a 25% reduction in cancer risk over 3 years among veterans who survived the initial infection. This protective effect was observed across sexes and racial groups, with stronger benefits seen in older patients and those with mild disease.

METHODOLOGY:

Researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study comparing Veterans who tested positive for COVID-19 between March 15, 2020, and November 30, 2020, to those who tested negative.

Analysis included 499,396 veterans, with 88,590 (17.2%) COVID-19 positive and 427,566 (82.8%) COVID-19 negative patients, with mean (SD) ages of 57.9 (16.4) and 59.5 (15.8) years, respectively.

Investigators utilized Cox proportional hazard regression models to determine the hazard ratio of new cancer diagnosis within a three-year follow-up period.

Patient characteristics included age, race, ethnicity, sex, BMI, smoking status, and various comorbidities as covariates in the analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

For patients surviving ≥ 30 days after COVID-19 testing, infection was associated with a 25% reduction in cancer hazard (hazard ratio [HR], 0.75; 95% CI, 0.73-0.77).

The reduction in cancer risk was similar across sexes and races, with the exception of Asians, and showed greater decreases with advancing age above 45 years.

Patients with mild COVID-19 showed the strongest reduction in cancer risk (adjusted HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.70-0.74), while those with moderate COVID-19 showed an 11% reduction (adjusted HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.83-0.93), and severe COVID-19 showed no significant reduction in cancer risk.

IN PRACTICE: "Regarding age, the incidence of cancer appeared to decrease with each decade of life in the COVID-19 group compared to that in the non-exposed group,” the authors noted. “This is surprising, given that cancer diagnoses typically increase with age.”

SOURCE: The study was led by researchers at the Miami Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center and was published online on August 25 in PLoS One.

LIMITATIONS: The findings of this retrospective and observational study should be interpreted with caution. Results may not be generalizable beyond the predominantly male, older veteran population. The 3-year follow-up period may be insufficient to fully understand long-term cancer incidence patterns. Researchers could not capture all COVID-19 reinfection cases due to testing occurring outside the Veterans Affairs system, including at-home testing. The impact of vaccination status and reinfection on cancer risk could not be fully assessed, as the initial study cohort was grouped prior to vaccine availability.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no financial support was received for this study and declare no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

TOPLINE: COVID-19 infection is associated with a 25% reduction in cancer risk over 3 years among veterans who survived the initial infection. This protective effect was observed across sexes and racial groups, with stronger benefits seen in older patients and those with mild disease.

METHODOLOGY:

Researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study comparing Veterans who tested positive for COVID-19 between March 15, 2020, and November 30, 2020, to those who tested negative.

Analysis included 499,396 veterans, with 88,590 (17.2%) COVID-19 positive and 427,566 (82.8%) COVID-19 negative patients, with mean (SD) ages of 57.9 (16.4) and 59.5 (15.8) years, respectively.

Investigators utilized Cox proportional hazard regression models to determine the hazard ratio of new cancer diagnosis within a three-year follow-up period.

Patient characteristics included age, race, ethnicity, sex, BMI, smoking status, and various comorbidities as covariates in the analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

For patients surviving ≥ 30 days after COVID-19 testing, infection was associated with a 25% reduction in cancer hazard (hazard ratio [HR], 0.75; 95% CI, 0.73-0.77).

The reduction in cancer risk was similar across sexes and races, with the exception of Asians, and showed greater decreases with advancing age above 45 years.

Patients with mild COVID-19 showed the strongest reduction in cancer risk (adjusted HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.70-0.74), while those with moderate COVID-19 showed an 11% reduction (adjusted HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.83-0.93), and severe COVID-19 showed no significant reduction in cancer risk.

IN PRACTICE: "Regarding age, the incidence of cancer appeared to decrease with each decade of life in the COVID-19 group compared to that in the non-exposed group,” the authors noted. “This is surprising, given that cancer diagnoses typically increase with age.”

SOURCE: The study was led by researchers at the Miami Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center and was published online on August 25 in PLoS One.

LIMITATIONS: The findings of this retrospective and observational study should be interpreted with caution. Results may not be generalizable beyond the predominantly male, older veteran population. The 3-year follow-up period may be insufficient to fully understand long-term cancer incidence patterns. Researchers could not capture all COVID-19 reinfection cases due to testing occurring outside the Veterans Affairs system, including at-home testing. The impact of vaccination status and reinfection on cancer risk could not be fully assessed, as the initial study cohort was grouped prior to vaccine availability.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no financial support was received for this study and declare no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

TOPLINE: COVID-19 infection is associated with a 25% reduction in cancer risk over 3 years among veterans who survived the initial infection. This protective effect was observed across sexes and racial groups, with stronger benefits seen in older patients and those with mild disease.

METHODOLOGY:

Researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study comparing Veterans who tested positive for COVID-19 between March 15, 2020, and November 30, 2020, to those who tested negative.

Analysis included 499,396 veterans, with 88,590 (17.2%) COVID-19 positive and 427,566 (82.8%) COVID-19 negative patients, with mean (SD) ages of 57.9 (16.4) and 59.5 (15.8) years, respectively.

Investigators utilized Cox proportional hazard regression models to determine the hazard ratio of new cancer diagnosis within a three-year follow-up period.

Patient characteristics included age, race, ethnicity, sex, BMI, smoking status, and various comorbidities as covariates in the analysis.

TAKEAWAY:

For patients surviving ≥ 30 days after COVID-19 testing, infection was associated with a 25% reduction in cancer hazard (hazard ratio [HR], 0.75; 95% CI, 0.73-0.77).

The reduction in cancer risk was similar across sexes and races, with the exception of Asians, and showed greater decreases with advancing age above 45 years.

Patients with mild COVID-19 showed the strongest reduction in cancer risk (adjusted HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.70-0.74), while those with moderate COVID-19 showed an 11% reduction (adjusted HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.83-0.93), and severe COVID-19 showed no significant reduction in cancer risk.

IN PRACTICE: "Regarding age, the incidence of cancer appeared to decrease with each decade of life in the COVID-19 group compared to that in the non-exposed group,” the authors noted. “This is surprising, given that cancer diagnoses typically increase with age.”

SOURCE: The study was led by researchers at the Miami Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center and was published online on August 25 in PLoS One.

LIMITATIONS: The findings of this retrospective and observational study should be interpreted with caution. Results may not be generalizable beyond the predominantly male, older veteran population. The 3-year follow-up period may be insufficient to fully understand long-term cancer incidence patterns. Researchers could not capture all COVID-19 reinfection cases due to testing occurring outside the Veterans Affairs system, including at-home testing. The impact of vaccination status and reinfection on cancer risk could not be fully assessed, as the initial study cohort was grouped prior to vaccine availability.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no financial support was received for this study and declare no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

About Half of Canadian Physicians Report High Burnout Levels

About Half of Canadian Physicians Report High Burnout Levels

Nearly half of physicians in Canada report high levels of burnout, according to preliminary data from the 2025 National Physician Health Survey (NPHS). The new data show that 46% of physicians report high levels of burnout, down from 2021 (53%) but significantly above the level of 2017 (30%), when the first survey was conducted. The full NPHS 2025 Foundational Report will be released later this year.

Other significant findings include the following:

- 74% of physicians reported experiencing bullying, harassment, microaggressions, or discrimination, a slight but meaningful reduction form 78% in 2021.

- 64% of physicians reported spending significant time on electronic medical records outside regular hours.

- 46% of physicians said that their mental health is worse than it was before the start of the pandemic, down 14% from 2021.

- 60% reported being satisfied or very satisfied with work-life balance, an improvement from 49% in 2021, though slightly below 2017 (62%).

- 37% of physicians plan to reduce their clinical hours in the next 2 years.

Margot Burnell, MD, president of the Canadian Medical Association (CMA), told Medscape Medical News that she was "disappointed" with the results.

"I hoped that the burnout numbers would decrease more than they have," she said. "Physicians are still under extreme stress in trying to provide the care for patients that they wish to give."

Reductions in Hours

The most distressing finding is that > one-third of physicians (37%) plan to reduce their hours within 24 hours -- at a time of growing physician shortages -- said Burnell.

"The one positive (finding) that stands out is that physicians are taking care of their own health and wellness and report that it's helping," she said. About 65% of physicians reported having accessed at least 1 wellness support in the past 5 years, up 11% since 2021.

The NPHS includes responses from about 3300 practicing physicians, medical residents, and fellows who were surveyed from March 14 to April 15.

Among the CMA's top priorities is to reduce the administrative burden because that tops the list of what physicians say would help them with burnout, said Burnell.

"The other area is to provide and encourage team-based care," she continued. "That provides some relief for physicians." It also is important to promote the approaches that seem to be helping, such as wellness support and artificial intelligence (AI), she said. In this survey, 59% of respondents who used AI said that it decreased their time spent on administrative tasks.

Burnout by Specialty

Future analyses will examine burnout by specialty, Burnell said. Burnout is particularly high among emergency physicians, regardless of province, according to previous work by Kerstin de Wit, MD, emergency physician and research director for the Department of Emergency Medicine at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario, and colleagues.

The NPHS findings are not surprising, she told Medscape Medical News. "We resurveyed all our emergency physicians in January and found similar results, in that the levels of burnout were marginally less than they were in 2022 but still significantly higher than they were in 2020. Still, a majority of (emergency department) physicians qualify as having high burnout levels."

The Pandemic's Role

A telling finding of her team's research is that emergency physician burnout levels are now higher than they were in December 2020, the first year of the COVID pandemic, said De Wit. "I don't think you can say burnout is because of COVID. It's because of the problems in the medical system."

Among those problems in hospitals are a shortage of beds, physicians, and nurses and inadequate numbers of physicians in outpatient clinics "so patients are waiting for years" for conditions to be treated, she added.

"We don't have the resources that we need to maintain the standards that we had even 10, 15 years ago. The whole system is collapsing. Government underfunding is huge. Routinely, our emergency department is 100% full of ward patients, so we don't have a room with a door or a curtain to see patients in. All the emergency patients are seen in corridors or the waiting room in full view of everyone else. We have people with serious medical conditions who are dying in waiting rooms because we can't get them in."

The issues are complex, but the overarching problem is chronic underfunding that results in physicians "feeling overworked and powerless to help patients," said De Wit.

Burnell and de Wit reported having no relevant financial relationships.

Marcia Frellick is an independent health care journalist and a regular contributor to Medscape Medical News.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly half of physicians in Canada report high levels of burnout, according to preliminary data from the 2025 National Physician Health Survey (NPHS). The new data show that 46% of physicians report high levels of burnout, down from 2021 (53%) but significantly above the level of 2017 (30%), when the first survey was conducted. The full NPHS 2025 Foundational Report will be released later this year.

Other significant findings include the following:

- 74% of physicians reported experiencing bullying, harassment, microaggressions, or discrimination, a slight but meaningful reduction form 78% in 2021.

- 64% of physicians reported spending significant time on electronic medical records outside regular hours.

- 46% of physicians said that their mental health is worse than it was before the start of the pandemic, down 14% from 2021.

- 60% reported being satisfied or very satisfied with work-life balance, an improvement from 49% in 2021, though slightly below 2017 (62%).

- 37% of physicians plan to reduce their clinical hours in the next 2 years.

Margot Burnell, MD, president of the Canadian Medical Association (CMA), told Medscape Medical News that she was "disappointed" with the results.

"I hoped that the burnout numbers would decrease more than they have," she said. "Physicians are still under extreme stress in trying to provide the care for patients that they wish to give."

Reductions in Hours

The most distressing finding is that > one-third of physicians (37%) plan to reduce their hours within 24 hours -- at a time of growing physician shortages -- said Burnell.

"The one positive (finding) that stands out is that physicians are taking care of their own health and wellness and report that it's helping," she said. About 65% of physicians reported having accessed at least 1 wellness support in the past 5 years, up 11% since 2021.

The NPHS includes responses from about 3300 practicing physicians, medical residents, and fellows who were surveyed from March 14 to April 15.

Among the CMA's top priorities is to reduce the administrative burden because that tops the list of what physicians say would help them with burnout, said Burnell.

"The other area is to provide and encourage team-based care," she continued. "That provides some relief for physicians." It also is important to promote the approaches that seem to be helping, such as wellness support and artificial intelligence (AI), she said. In this survey, 59% of respondents who used AI said that it decreased their time spent on administrative tasks.

Burnout by Specialty

Future analyses will examine burnout by specialty, Burnell said. Burnout is particularly high among emergency physicians, regardless of province, according to previous work by Kerstin de Wit, MD, emergency physician and research director for the Department of Emergency Medicine at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario, and colleagues.

The NPHS findings are not surprising, she told Medscape Medical News. "We resurveyed all our emergency physicians in January and found similar results, in that the levels of burnout were marginally less than they were in 2022 but still significantly higher than they were in 2020. Still, a majority of (emergency department) physicians qualify as having high burnout levels."

The Pandemic's Role

A telling finding of her team's research is that emergency physician burnout levels are now higher than they were in December 2020, the first year of the COVID pandemic, said De Wit. "I don't think you can say burnout is because of COVID. It's because of the problems in the medical system."

Among those problems in hospitals are a shortage of beds, physicians, and nurses and inadequate numbers of physicians in outpatient clinics "so patients are waiting for years" for conditions to be treated, she added.

"We don't have the resources that we need to maintain the standards that we had even 10, 15 years ago. The whole system is collapsing. Government underfunding is huge. Routinely, our emergency department is 100% full of ward patients, so we don't have a room with a door or a curtain to see patients in. All the emergency patients are seen in corridors or the waiting room in full view of everyone else. We have people with serious medical conditions who are dying in waiting rooms because we can't get them in."

The issues are complex, but the overarching problem is chronic underfunding that results in physicians "feeling overworked and powerless to help patients," said De Wit.

Burnell and de Wit reported having no relevant financial relationships.

Marcia Frellick is an independent health care journalist and a regular contributor to Medscape Medical News.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nearly half of physicians in Canada report high levels of burnout, according to preliminary data from the 2025 National Physician Health Survey (NPHS). The new data show that 46% of physicians report high levels of burnout, down from 2021 (53%) but significantly above the level of 2017 (30%), when the first survey was conducted. The full NPHS 2025 Foundational Report will be released later this year.

Other significant findings include the following:

- 74% of physicians reported experiencing bullying, harassment, microaggressions, or discrimination, a slight but meaningful reduction form 78% in 2021.

- 64% of physicians reported spending significant time on electronic medical records outside regular hours.

- 46% of physicians said that their mental health is worse than it was before the start of the pandemic, down 14% from 2021.

- 60% reported being satisfied or very satisfied with work-life balance, an improvement from 49% in 2021, though slightly below 2017 (62%).

- 37% of physicians plan to reduce their clinical hours in the next 2 years.

Margot Burnell, MD, president of the Canadian Medical Association (CMA), told Medscape Medical News that she was "disappointed" with the results.

"I hoped that the burnout numbers would decrease more than they have," she said. "Physicians are still under extreme stress in trying to provide the care for patients that they wish to give."

Reductions in Hours

The most distressing finding is that > one-third of physicians (37%) plan to reduce their hours within 24 hours -- at a time of growing physician shortages -- said Burnell.

"The one positive (finding) that stands out is that physicians are taking care of their own health and wellness and report that it's helping," she said. About 65% of physicians reported having accessed at least 1 wellness support in the past 5 years, up 11% since 2021.

The NPHS includes responses from about 3300 practicing physicians, medical residents, and fellows who were surveyed from March 14 to April 15.

Among the CMA's top priorities is to reduce the administrative burden because that tops the list of what physicians say would help them with burnout, said Burnell.

"The other area is to provide and encourage team-based care," she continued. "That provides some relief for physicians." It also is important to promote the approaches that seem to be helping, such as wellness support and artificial intelligence (AI), she said. In this survey, 59% of respondents who used AI said that it decreased their time spent on administrative tasks.

Burnout by Specialty

Future analyses will examine burnout by specialty, Burnell said. Burnout is particularly high among emergency physicians, regardless of province, according to previous work by Kerstin de Wit, MD, emergency physician and research director for the Department of Emergency Medicine at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario, and colleagues.

The NPHS findings are not surprising, she told Medscape Medical News. "We resurveyed all our emergency physicians in January and found similar results, in that the levels of burnout were marginally less than they were in 2022 but still significantly higher than they were in 2020. Still, a majority of (emergency department) physicians qualify as having high burnout levels."

The Pandemic's Role

A telling finding of her team's research is that emergency physician burnout levels are now higher than they were in December 2020, the first year of the COVID pandemic, said De Wit. "I don't think you can say burnout is because of COVID. It's because of the problems in the medical system."

Among those problems in hospitals are a shortage of beds, physicians, and nurses and inadequate numbers of physicians in outpatient clinics "so patients are waiting for years" for conditions to be treated, she added.

"We don't have the resources that we need to maintain the standards that we had even 10, 15 years ago. The whole system is collapsing. Government underfunding is huge. Routinely, our emergency department is 100% full of ward patients, so we don't have a room with a door or a curtain to see patients in. All the emergency patients are seen in corridors or the waiting room in full view of everyone else. We have people with serious medical conditions who are dying in waiting rooms because we can't get them in."

The issues are complex, but the overarching problem is chronic underfunding that results in physicians "feeling overworked and powerless to help patients," said De Wit.

Burnell and de Wit reported having no relevant financial relationships.

Marcia Frellick is an independent health care journalist and a regular contributor to Medscape Medical News.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About Half of Canadian Physicians Report High Burnout Levels

About Half of Canadian Physicians Report High Burnout Levels

US Health Official Calls for Separating Measles Combination Shots, Pulls Broad COVID Vaccine Support

(Reuters) -A top U.S. health official on Monday called for the combined measles-mumps-rubella shot to be broken up, drawing a quick rebuke from vaccine maker Merck, which said there is no scientific evidence that shows any benefit to doing so.

The U.S. CDC earlier on Monday pulled broad support for COVID-19 shots, saying they should be administered through shared decision-making with a health care provider in accordance with recommendations from Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s hand-picked vaccine advisory panel.

The acting director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Jim O’Neill, in an X post on Monday called on vaccine manufacturers to develop three separate vaccines to replace the combined MMR inoculation.

In a September 23 news conference at the White House, President Donald Trump delivered medical advice to pregnant women and parents of young children, repeatedly telling them common vaccines should not be taken together or so early in a child’s life, and urging them not to use or administer Tylenol, against the advice of medical societies.

Kennedy, a long-time anti-vaccine crusader before taking on the nation’s top health post, has linked vaccines to autism and sought to rewrite the country’s immunization policies. He fired all members of the national vaccine advisory board of outside experts and replaced them with new members, many of whom shared his views. The committee is reviewing the childhood vaccine schedule.

The causes of autism are unclear. But no rigorous studies have found links between autism and vaccines or medications, or their components such as thimerosal or formaldehyde. Vaccination rates have declined as autism rates have climbed.

MERCK, EXPERTS DEFEND MMR SHOT

Merck said there is no published scientific evidence that shows any benefit in separating the MMR shot.

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s website, there are currently no separate single virus shots for measles, mumps or rubella licensed for use in the United States. That means manufacturers could need to go through the FDA approval process before any become available.

“Use of the individual components of combination vaccines increases the number of injections for the individual and may result in delayed or missed immunizations,” Merck said in a statement.

Dr. Rana Alissa, president of the Florida chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said the purpose of combining the three shots in the MMR vaccine is not only to save parents extra visits to the doctor’s office.

“Studies have shown that when you give them together, the immune response is much better,” she said. “This is how you get lifelong immunity.”

GSK, which also makes an MMR shot, declined to comment. A spokesman for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, where O’Neill is deputy secretary, was not immediately available for comment.

The break-up of the MMR shot would “falsely imply that there is something unsafe about giving the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines at the same time,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease expert at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

“It would be another example of the federal government pandering to the anti-vaccine movement,” Adalja added.

Earlier in the day, the CDC signed off on the advisers’ recommendations against use of the combined measles-mumps-rubella-varicella vaccine before the age of 4 years because of a slight risk of seizures related to high fevers. Instead, varicella, commonly known as chickenpox, is recommended as a standalone shot.

Merck also makes the measles-mumps-rubella-varicella shot.

CDC CHANGES COVID VIEWS

The new CDC recommendation on the COVID vaccine calls for physician involvement but maintains access for the shot through health insurance.

The immunization schedules will be updated on the CDC website by Tuesday, the agency said.

The recommendations come after upheaval at the CDC, including the ouster of its former Director Susan Monarez, who had resisted changes to vaccine policy advanced by Kennedy. Monarez said she was told to rubber-stamp the committee’s recommendations without reviewing the scientific evidence.

The new advisory panel made its recommendations at a two-day meeting in September that highlighted deep divisions over the future of the U.S. immunization schedules under Kennedy.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, an influential U.S. medical group, has already broken from federal policy and pushed its own vaccine recommendations, suggesting all young children get vaccinated against COVID-19.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration in August cleared updated COVID-19 vaccines for everyone over age 65, but limited its approval for younger people to those with health risks.

The 3 approved COVID shots are made by Pfizer with German partner BioNTech, Moderna, and Novavax with Sanofi.

(Reporting by Mariam Sunny in Bengaluru, Michael Erman in New York and Julie Steenhuysen in Chicago; Editing by Caroline Humer and Bill Berkrot)■

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

(Reuters) -A top U.S. health official on Monday called for the combined measles-mumps-rubella shot to be broken up, drawing a quick rebuke from vaccine maker Merck, which said there is no scientific evidence that shows any benefit to doing so.

The U.S. CDC earlier on Monday pulled broad support for COVID-19 shots, saying they should be administered through shared decision-making with a health care provider in accordance with recommendations from Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s hand-picked vaccine advisory panel.

The acting director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Jim O’Neill, in an X post on Monday called on vaccine manufacturers to develop three separate vaccines to replace the combined MMR inoculation.

In a September 23 news conference at the White House, President Donald Trump delivered medical advice to pregnant women and parents of young children, repeatedly telling them common vaccines should not be taken together or so early in a child’s life, and urging them not to use or administer Tylenol, against the advice of medical societies.

Kennedy, a long-time anti-vaccine crusader before taking on the nation’s top health post, has linked vaccines to autism and sought to rewrite the country’s immunization policies. He fired all members of the national vaccine advisory board of outside experts and replaced them with new members, many of whom shared his views. The committee is reviewing the childhood vaccine schedule.

The causes of autism are unclear. But no rigorous studies have found links between autism and vaccines or medications, or their components such as thimerosal or formaldehyde. Vaccination rates have declined as autism rates have climbed.

MERCK, EXPERTS DEFEND MMR SHOT

Merck said there is no published scientific evidence that shows any benefit in separating the MMR shot.

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s website, there are currently no separate single virus shots for measles, mumps or rubella licensed for use in the United States. That means manufacturers could need to go through the FDA approval process before any become available.

“Use of the individual components of combination vaccines increases the number of injections for the individual and may result in delayed or missed immunizations,” Merck said in a statement.

Dr. Rana Alissa, president of the Florida chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said the purpose of combining the three shots in the MMR vaccine is not only to save parents extra visits to the doctor’s office.

“Studies have shown that when you give them together, the immune response is much better,” she said. “This is how you get lifelong immunity.”

GSK, which also makes an MMR shot, declined to comment. A spokesman for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, where O’Neill is deputy secretary, was not immediately available for comment.

The break-up of the MMR shot would “falsely imply that there is something unsafe about giving the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines at the same time,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease expert at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

“It would be another example of the federal government pandering to the anti-vaccine movement,” Adalja added.

Earlier in the day, the CDC signed off on the advisers’ recommendations against use of the combined measles-mumps-rubella-varicella vaccine before the age of 4 years because of a slight risk of seizures related to high fevers. Instead, varicella, commonly known as chickenpox, is recommended as a standalone shot.

Merck also makes the measles-mumps-rubella-varicella shot.

CDC CHANGES COVID VIEWS

The new CDC recommendation on the COVID vaccine calls for physician involvement but maintains access for the shot through health insurance.

The immunization schedules will be updated on the CDC website by Tuesday, the agency said.

The recommendations come after upheaval at the CDC, including the ouster of its former Director Susan Monarez, who had resisted changes to vaccine policy advanced by Kennedy. Monarez said she was told to rubber-stamp the committee’s recommendations without reviewing the scientific evidence.

The new advisory panel made its recommendations at a two-day meeting in September that highlighted deep divisions over the future of the U.S. immunization schedules under Kennedy.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, an influential U.S. medical group, has already broken from federal policy and pushed its own vaccine recommendations, suggesting all young children get vaccinated against COVID-19.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration in August cleared updated COVID-19 vaccines for everyone over age 65, but limited its approval for younger people to those with health risks.

The 3 approved COVID shots are made by Pfizer with German partner BioNTech, Moderna, and Novavax with Sanofi.

(Reporting by Mariam Sunny in Bengaluru, Michael Erman in New York and Julie Steenhuysen in Chicago; Editing by Caroline Humer and Bill Berkrot)■

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

(Reuters) -A top U.S. health official on Monday called for the combined measles-mumps-rubella shot to be broken up, drawing a quick rebuke from vaccine maker Merck, which said there is no scientific evidence that shows any benefit to doing so.

The U.S. CDC earlier on Monday pulled broad support for COVID-19 shots, saying they should be administered through shared decision-making with a health care provider in accordance with recommendations from Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s hand-picked vaccine advisory panel.

The acting director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Jim O’Neill, in an X post on Monday called on vaccine manufacturers to develop three separate vaccines to replace the combined MMR inoculation.

In a September 23 news conference at the White House, President Donald Trump delivered medical advice to pregnant women and parents of young children, repeatedly telling them common vaccines should not be taken together or so early in a child’s life, and urging them not to use or administer Tylenol, against the advice of medical societies.

Kennedy, a long-time anti-vaccine crusader before taking on the nation’s top health post, has linked vaccines to autism and sought to rewrite the country’s immunization policies. He fired all members of the national vaccine advisory board of outside experts and replaced them with new members, many of whom shared his views. The committee is reviewing the childhood vaccine schedule.

The causes of autism are unclear. But no rigorous studies have found links between autism and vaccines or medications, or their components such as thimerosal or formaldehyde. Vaccination rates have declined as autism rates have climbed.

MERCK, EXPERTS DEFEND MMR SHOT

Merck said there is no published scientific evidence that shows any benefit in separating the MMR shot.

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s website, there are currently no separate single virus shots for measles, mumps or rubella licensed for use in the United States. That means manufacturers could need to go through the FDA approval process before any become available.

“Use of the individual components of combination vaccines increases the number of injections for the individual and may result in delayed or missed immunizations,” Merck said in a statement.

Dr. Rana Alissa, president of the Florida chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said the purpose of combining the three shots in the MMR vaccine is not only to save parents extra visits to the doctor’s office.

“Studies have shown that when you give them together, the immune response is much better,” she said. “This is how you get lifelong immunity.”

GSK, which also makes an MMR shot, declined to comment. A spokesman for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, where O’Neill is deputy secretary, was not immediately available for comment.

The break-up of the MMR shot would “falsely imply that there is something unsafe about giving the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines at the same time,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease expert at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

“It would be another example of the federal government pandering to the anti-vaccine movement,” Adalja added.

Earlier in the day, the CDC signed off on the advisers’ recommendations against use of the combined measles-mumps-rubella-varicella vaccine before the age of 4 years because of a slight risk of seizures related to high fevers. Instead, varicella, commonly known as chickenpox, is recommended as a standalone shot.

Merck also makes the measles-mumps-rubella-varicella shot.

CDC CHANGES COVID VIEWS

The new CDC recommendation on the COVID vaccine calls for physician involvement but maintains access for the shot through health insurance.

The immunization schedules will be updated on the CDC website by Tuesday, the agency said.

The recommendations come after upheaval at the CDC, including the ouster of its former Director Susan Monarez, who had resisted changes to vaccine policy advanced by Kennedy. Monarez said she was told to rubber-stamp the committee’s recommendations without reviewing the scientific evidence.

The new advisory panel made its recommendations at a two-day meeting in September that highlighted deep divisions over the future of the U.S. immunization schedules under Kennedy.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, an influential U.S. medical group, has already broken from federal policy and pushed its own vaccine recommendations, suggesting all young children get vaccinated against COVID-19.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration in August cleared updated COVID-19 vaccines for everyone over age 65, but limited its approval for younger people to those with health risks.

The 3 approved COVID shots are made by Pfizer with German partner BioNTech, Moderna, and Novavax with Sanofi.

(Reporting by Mariam Sunny in Bengaluru, Michael Erman in New York and Julie Steenhuysen in Chicago; Editing by Caroline Humer and Bill Berkrot)■

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Insights Into Veterans’ Motivations and Hesitancies for COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake: A Mixed-Methods Analysis

Insights Into Veterans’ Motivations and Hesitancies for COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake: A Mixed-Methods Analysis

The SARS-CoV-2 virus has resulted in > 778 million reported COVID-19 cases and > 7 million deaths worldwide. 1 About 70% of the eligible US population has completed a primary COVID-19 vaccination series, yet only 17% have received an updated bivalent booster dose.2 These immunization rates fall below the World Health Organization (WHO) target of 70%.3

Early in the pandemic, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) vaccination rates ranged from 46% to 71%.4,5 Ensuring a high level of COVID-19 vaccination in the largest integrated US health care system aligns with the VA priority to provide high-quality, evidence-based care to a patient population that is older and has more comorbidities than the overall US population.6-9

Vaccine hesitancy, defined as a “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination service,” is a major contributor to suboptimal vaccination rates.10-13 Previous studies used cluster analyses to identify the unique combinations of behavioral and social factors responsible for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.10,11 Lack of perceived vaccine effectiveness and low perceived risk of the health consequences from COVID-19 infection were frequently identified in clusters where patients had the lowest intent for vaccination.10,11 Similarly, low trust in health care practitioners (HCPs), government, and pharmaceutical companies diminished intent for vaccination in these clusters.10 These quantitative studies were limited by their exclusive focus on unvaccinated individuals, reliance on self-reported intent, and lack of assessment of a health care system with a COVID-19 vaccine delivery program designed to overcome barriers to health care access, such as the VA.

Prior qualitative studies of vaccine uptake in distinct veteran subgroups (ie, unhoused and in VA facilities with low vaccination rates) demonstrated that overriding medical priorities among the unhoused and vaccine safety concerns were associated with decreased vaccine uptake, and positive perceptions of HCPs and the health care system were associated with increased vaccine uptake.11,12 However, these studies were conducted during periods of greater COVID-19 vaccine availability and acceptance, and prior to booster recommendations.4,12,13

This mixed-methods quality improvement (QI) project assessed the barriers and facilitators of COVID-19 vaccination among veterans receiving primary care at a single VA health care facility. We assessed whether unique patient clusters could be identified based on COVID-19–related and vaccine-related thoughts and feelings and whether cluster membership was associated with COVID-19 vaccination. This analysis also explored how individuals’ beliefs and trust shaped motivations and hesitancies for vaccine uptake in quantitatively derived clusters with varying vaccination rates.

Methods

This QI project was conducted at the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System (VAPHS), a tertiary care facility serving > 75,000 veterans in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio. The VAPHS Institutional Review Board determined this QI study was exempt from review.14-17 Participation was voluntary and had no bearing on VA health care or benefits. Financial support for the project, including key personnel and participant compensation, was provided by VAPHS. We followed the STROBE reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies and the COREQ checklist for qualitative research.18,19

Quantitative Survey

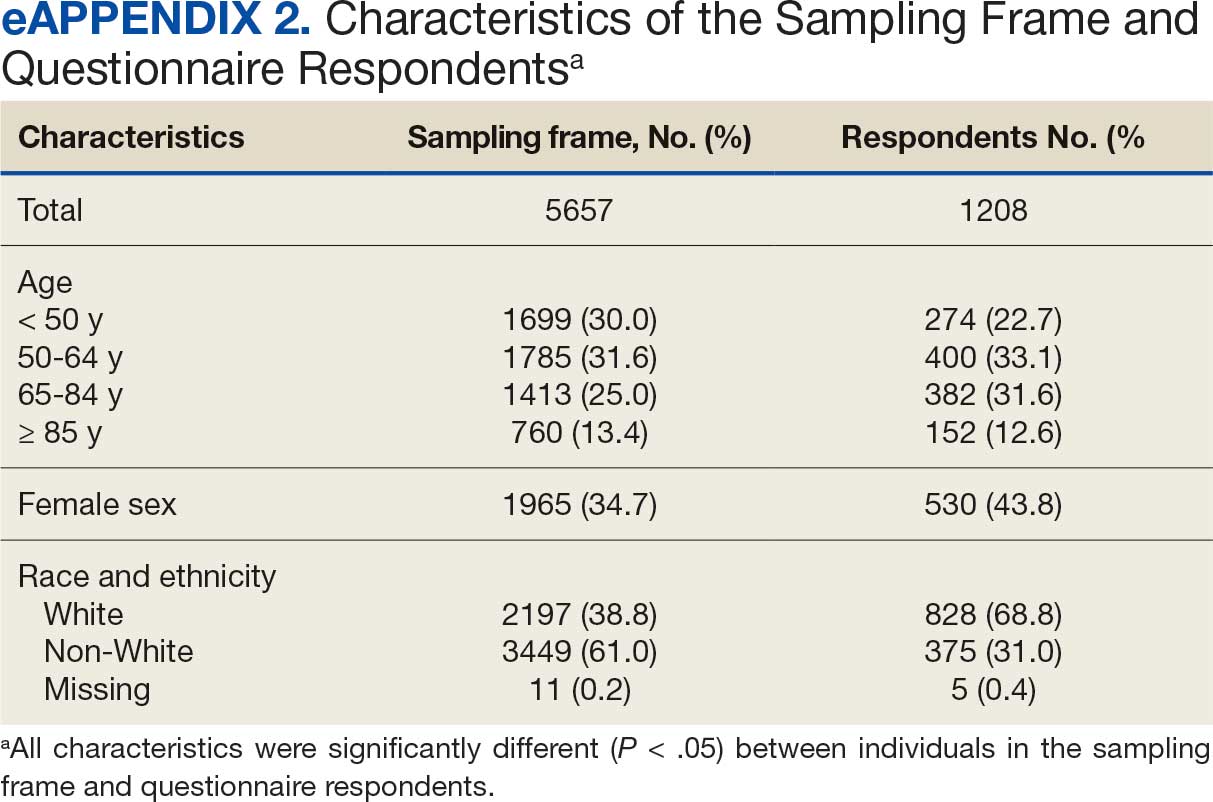

The 32,271 veterans assigned to a VAPHS primary care HCP, effective April 1, 2020, were eligible. To ensure representation of subgroups underrecognized in research and/or QI projects, the sample included all 1980 female patients at VAPHS and a random sample of 500 White and 500 Hispanic and/or non-White men within 4 age categories (< 50, 50-64, 65-84, and > 84 years). For the < 50 years or > 84 years categories, all Hispanic and/or non-White men were included due to small sample sizes.20-22 The nonrandom sampling frame comprised 1708 Hispanic and/or non-White men and 2000 White men. After assigning the 5688 potentially eligible individuals a unique identifier, 31 opted out, resulting in a final sample of 5657 individuals.

The 5657 individuals received a letter requesting their completion of a future questionnaire about COVID-19 infection and vaccines. An electronic Qualtrics questionnaire link was emailed to 3221 individuals; nonresponders received 2 follow-up email reminders. For the 2436 veterans without an email address on file, trained interviewers conducted phone surveys and entered responses. Those patients who completed the questionnaire could enter a drawing to win 1 of 100 cash prizes valued at $100. We collected questionnaire data from July to September 2021.

Questionnaire Items

We constructed a 60-item questionnaire based on prior research on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and the WHO Guidebook for Immunization Programs and Implementing Partners.4,23-25 The WHO Guidebook comprises survey items organized within 4 domains reflecting the behavioral and social determinants of vaccination: thoughts and feelings; social processes; motivation and hesitancy; and practical factors.23

Sociodemographic, clinical, and personal characteristics. The survey assessed respondent ethnicity and race and used these data to create a composite race and ethnicity variable. Highest educational level was also attained using 8 response options. The survey also assessed prior COVID-19 infection; prior receipt of vaccines for influenza, pneumonia, tetanus, or shingles; and presence of comorbidities that increase the risk of severe COVID-19 infection. We used administrative data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse to determine respondent age, sex, geographic residence (urban, rural), and to fill in missing self-reported data on sex (n = 4) and ethnicity and race (n = 12). The survey assessed political views using a 5-point Likert scale (1, very liberal; 5, very conservative) and was collapsed into 3 categories (ie, very conservative or conservative, moderate, very liberal or liberal), with prefer not to answer reported separately

COVID-19 infection and vaccine. We asked veterans if they had ever been infected with COVID-19, whether they had been offered and/or received a COVID-19 vaccine, and type (Pfizer, Moderna, or Johnson & Johnson), and number of doses received. Positive vaccination status was defined as the receipt of ≥ 1 dose of a COVID-19 vaccine approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

COVID-19 opinions. Respondents were asked about perceived risk of COVID-19 infection and related health outcomes, as well as beliefs about COVID-19 vaccines, using a 4-point Likert scale for all items: (1, not at all concerned; 4, very concerned). Respondents were asked about concerns related to COVID-19 infection and severe illness. They also were asked about vaccine-related short-term adverse effects (AEs) and long-term complications. Respondents were asked how effective they believed COVID-19 vaccines were at preventing infection, serious illness, or death. Unvaccinated and vaccinated veterans were asked similar items, with a qualifier of “before getting vaccinated…” for those who were vaccinated.

Social processes. Respondents were asked to rate their level of trust in various sources of COVID-19 vaccine information using a 4-point Likert scale (1, trust not at all; 4, trust very much). Respondents were asked whether community or religious leaders or close family or friends wanted them to get vaccinated (yes, no, or unsure).

Practical factors. Respondents were asked to rate the logistical difficulty of getting vaccinated or trying to get vaccinated using a 4-point Likert scale (1, not at all; 4, extremely).

Participants

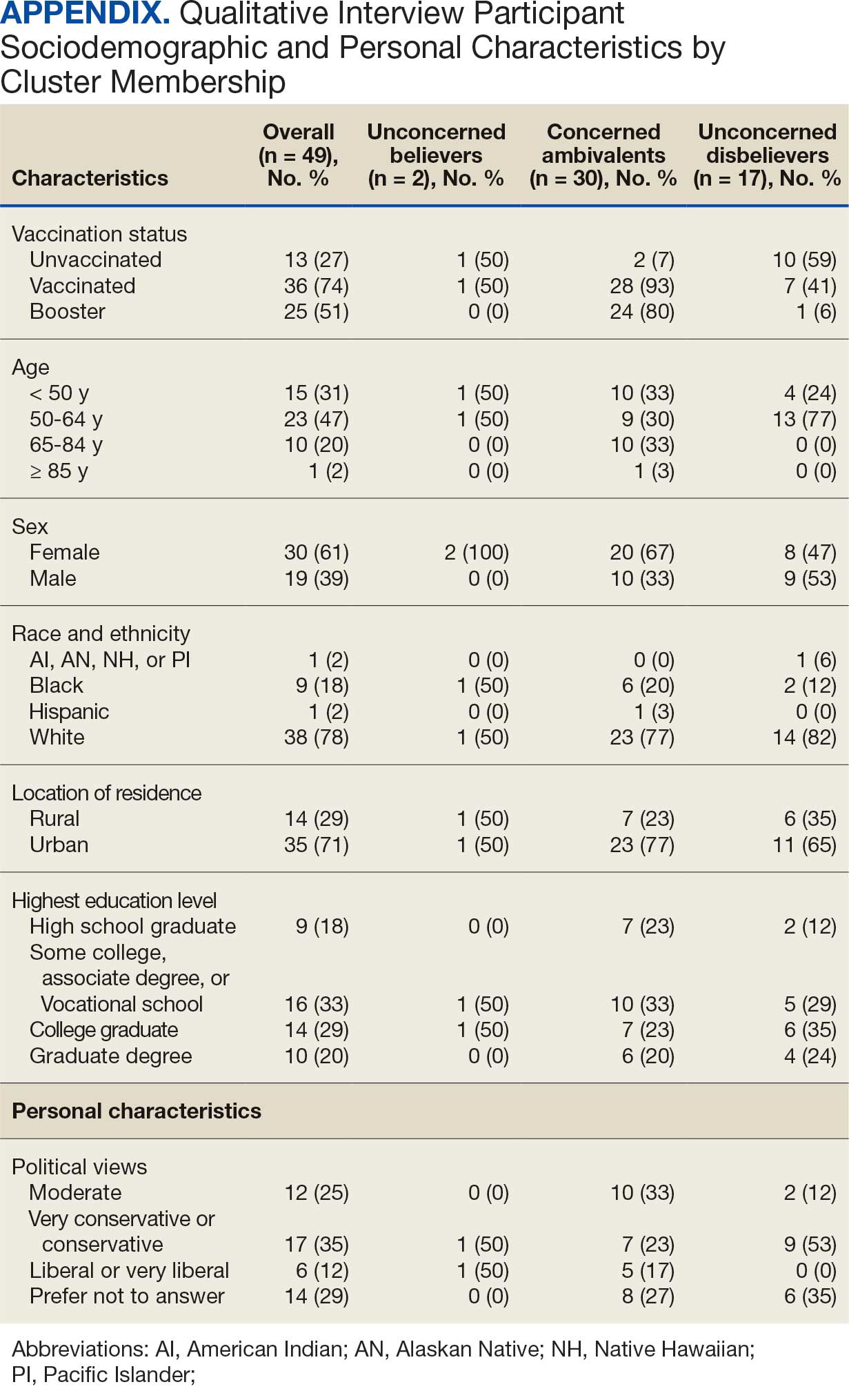

Respondents were asked to participate in a follow-up qualitative interview. Among 293 participants who agreed, we sampled all 86 unvaccinated individuals regardless of cluster assignment, a random sample of 88 individuals in the cluster with the lowest vaccination rate, and all 33 vaccinated individuals in the cluster with the second-lowest vaccination rate. Forty-nine veterans completed qualitative interviews.

Two research staff trained in qualitative research completed telephone interviews, averaging 16.5 minutes (March to May 2022), using semistructured scripts to elicit vaccine-related motivations, hesitancies, or concerns. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and deidentified. Participants provided written consent for recording and received $50 cash-equivalent compensation for interview completion.

Qualitative Interview Script

The interview script consisted of open-ended questions related to vaccine uptake across WHO domains.23 Both unvaccinated and vaccinated respondents were asked similar questions and customized questions about boosters for the vaccinated subgroup. To assess motivations and hesitancies, respondents were asked how they made their decisions about vaccination and what they considered when deciding. Vaccinated participants were asked about motivations and overcoming concerns. Unvaccinated respondents were asked about reasons for concern. To assess social processes, the interviewers asked participants whose opinion or counsel they trusted when deciding whether to get vaccinated. Questions also focused on positive experiences and vaccination barriers. Vaccinated participants were asked what could have improved their vaccination experiences. Finally, the interviewers asked participants who received a complete primary vaccine series about their motivations and plans related to booster vaccines, and whether information about emerging COVID-19 variants influenced their decisions.

Data Analyses

This analysis used X2 and Fisher exact tests to assess the associations among respondent characteristics, questionnaire responses, vaccination status, and cluster membership. Items phrased similarly were handled in a similar fashion for vaccinated and unvaccinated respondents.

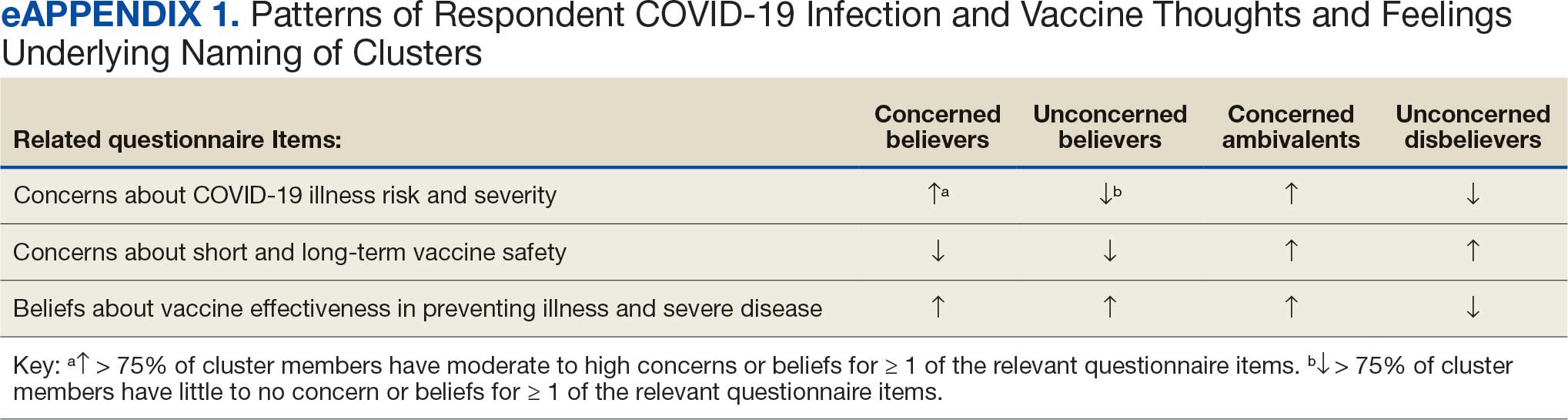

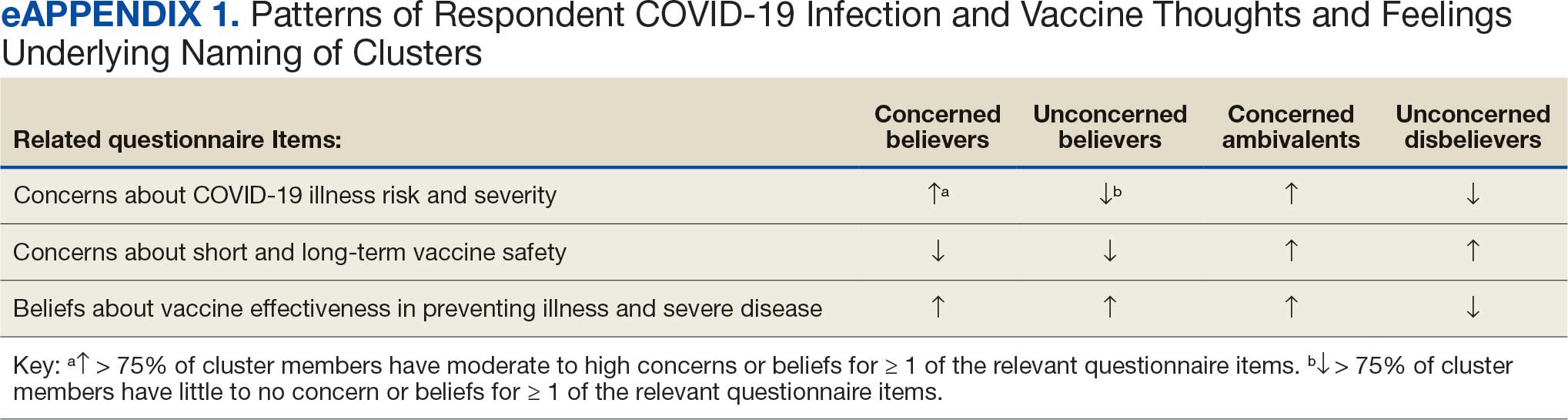

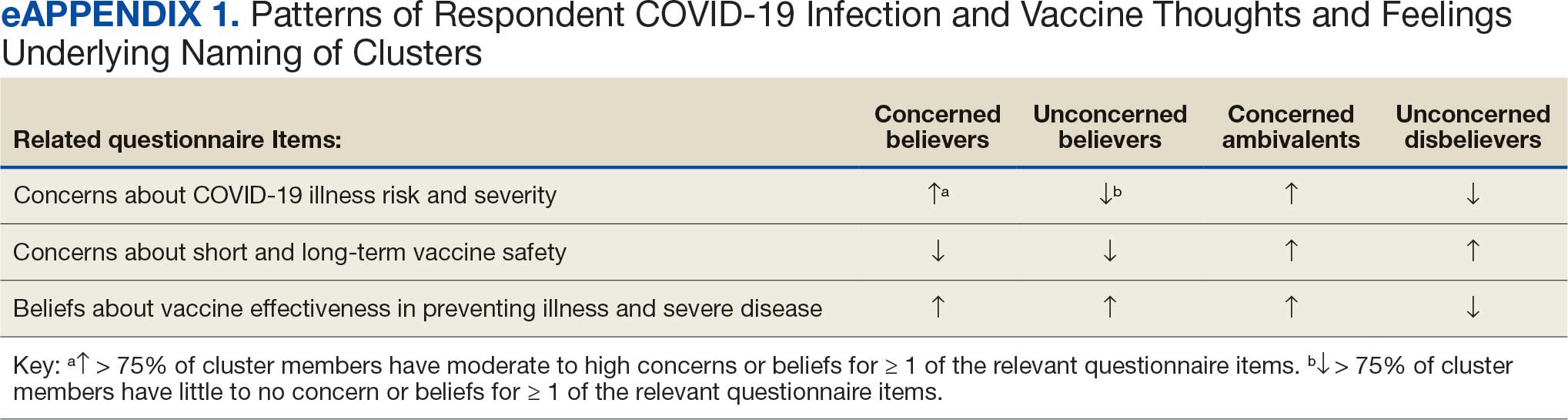

Cluster analysis assessed the possible groupings in responses to the quantitative questionnaire items focused on thoughts and feelings about COVID-19 infection risk and severity, vaccine effectiveness, and vaccine safety. This analysis treated the items’ ordinal response categories as continuous. We performed factor analysis using principal component analysis to explore dimension reduction and account for covariance between items. Two principal components were calculated and applied k-means clustering, determining the number of clusters through agreement from the elbow, gap statistic, and silhouette methods.26 Each cluster was named based on its unique pattern of responses to the items used to define them (eAppendix 1).

Multivariable logistic regression analyses assessed the independent association between cluster membership as the independent measure and vaccination status as the dependent measure, adjusting for respondent sociodemographic and personal characteristics and 2 measures of trust (ie, local VA HCP and the CDC). We selected these trust measures because they represent objective sources of medical information and were independently associated with COVID-19 vaccination status in a logistic regression model comprising all 6 trust items assessed.

This study defined statistical significance as a 2-tailed P value < .05. SAS 9.4 was used for all statistical analyses and Python 3.7.4 and the Scikit-learn package for cluster analyses.27 For qualitative analyses, this study used an inductive thematic approach guided by conventional qualitative content analysis, NVivo 12 Plus for Windows to code and analyze interview transcripts.28,29 We created an initial codebook based on 10 transcripts that were selected for high complexity and represented cluster membership and vaccination status.30,31 After 2 qualitative staff developed the initial codebook, 11 of 49 (22%) transcripts were independently coded by a primary and secondary coder to ensure consistent code application. Both coders reviewed the cocoded transcripts and resolved all discrepancies through negotiated consensus.32 After the cocoding process was complete, the primary coder coded the remaining transcripts. The primary and secondary coder met as needed to review and discuss any questions that arose during the primary coder’s work.

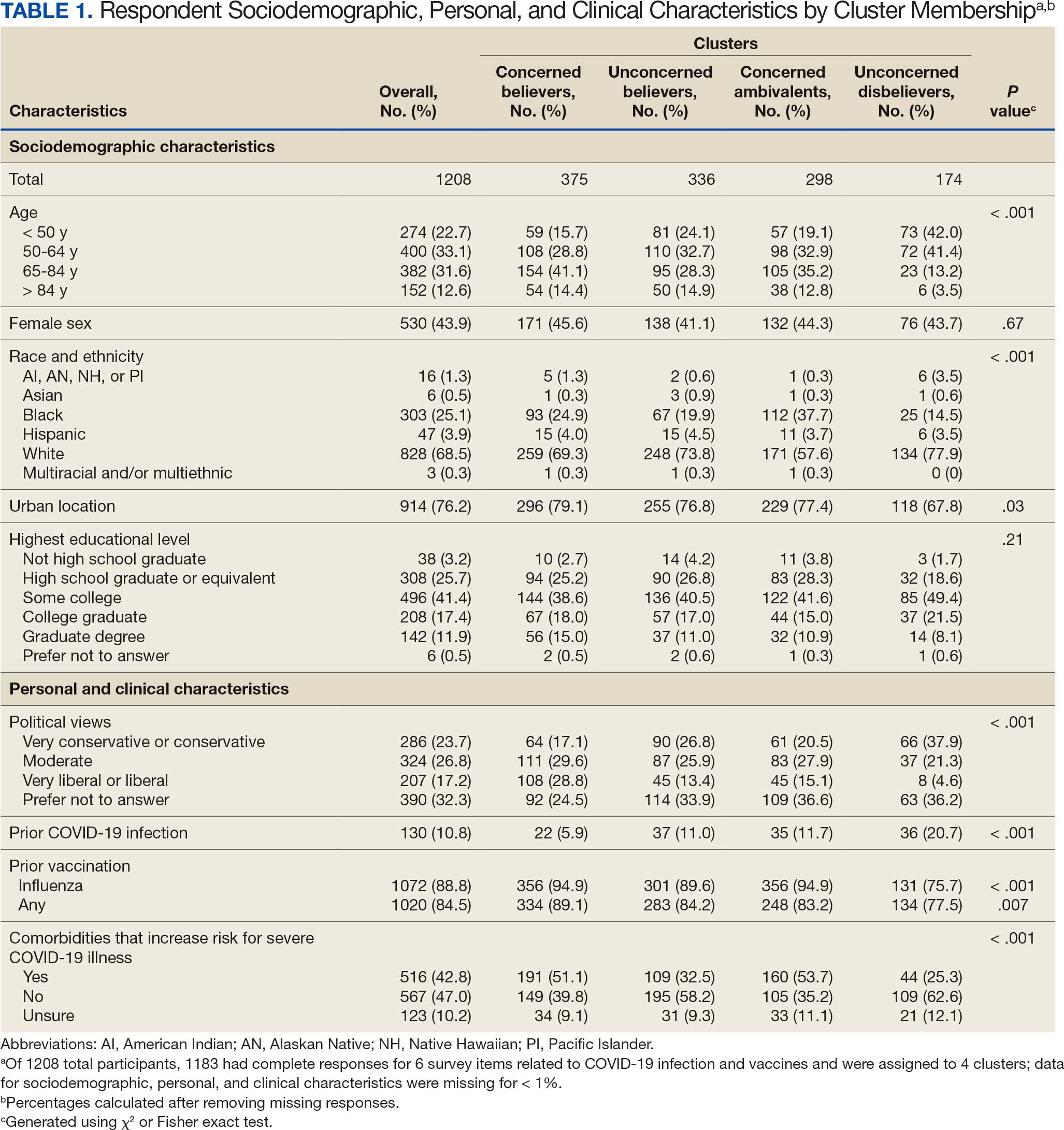

Results

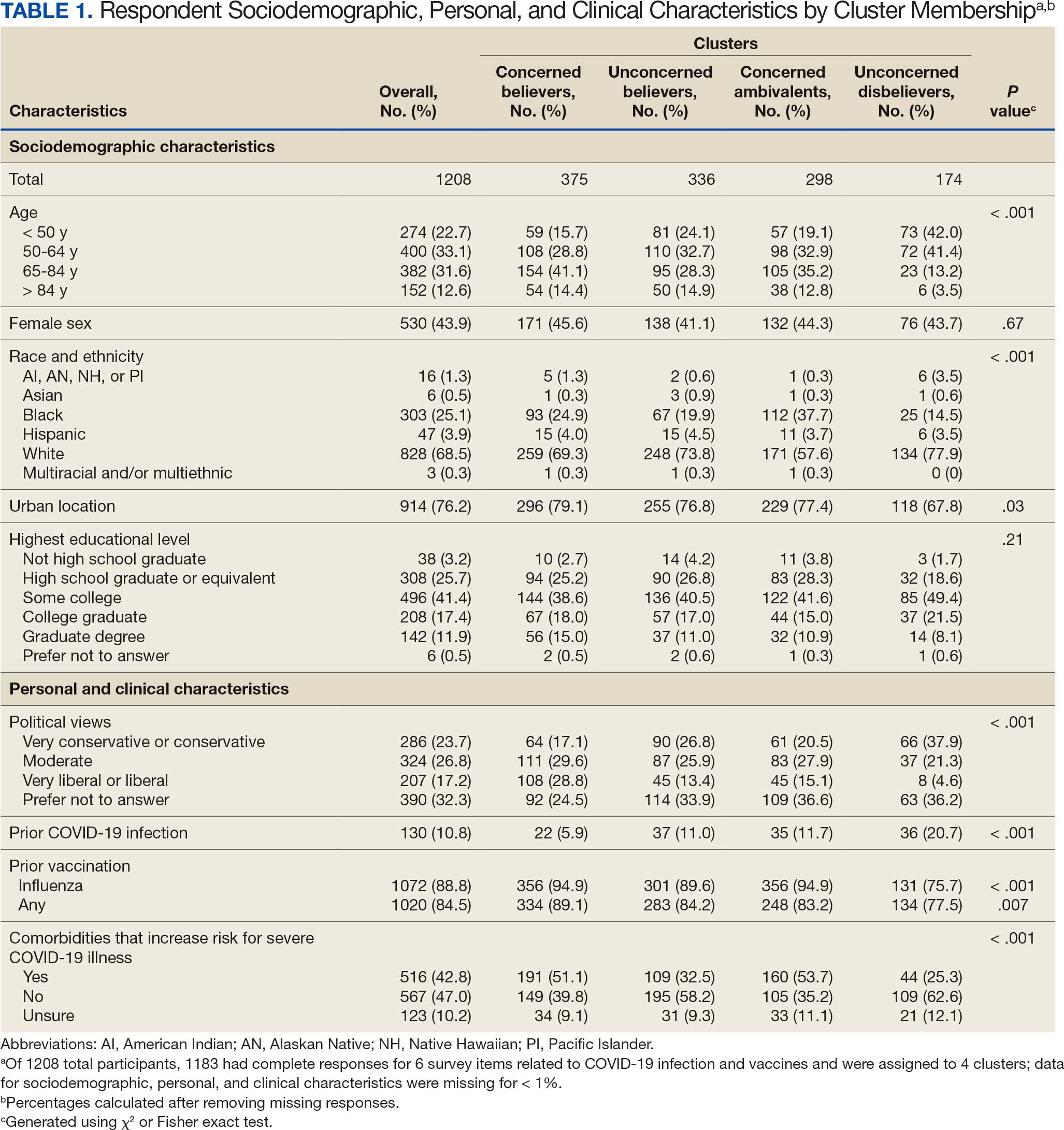

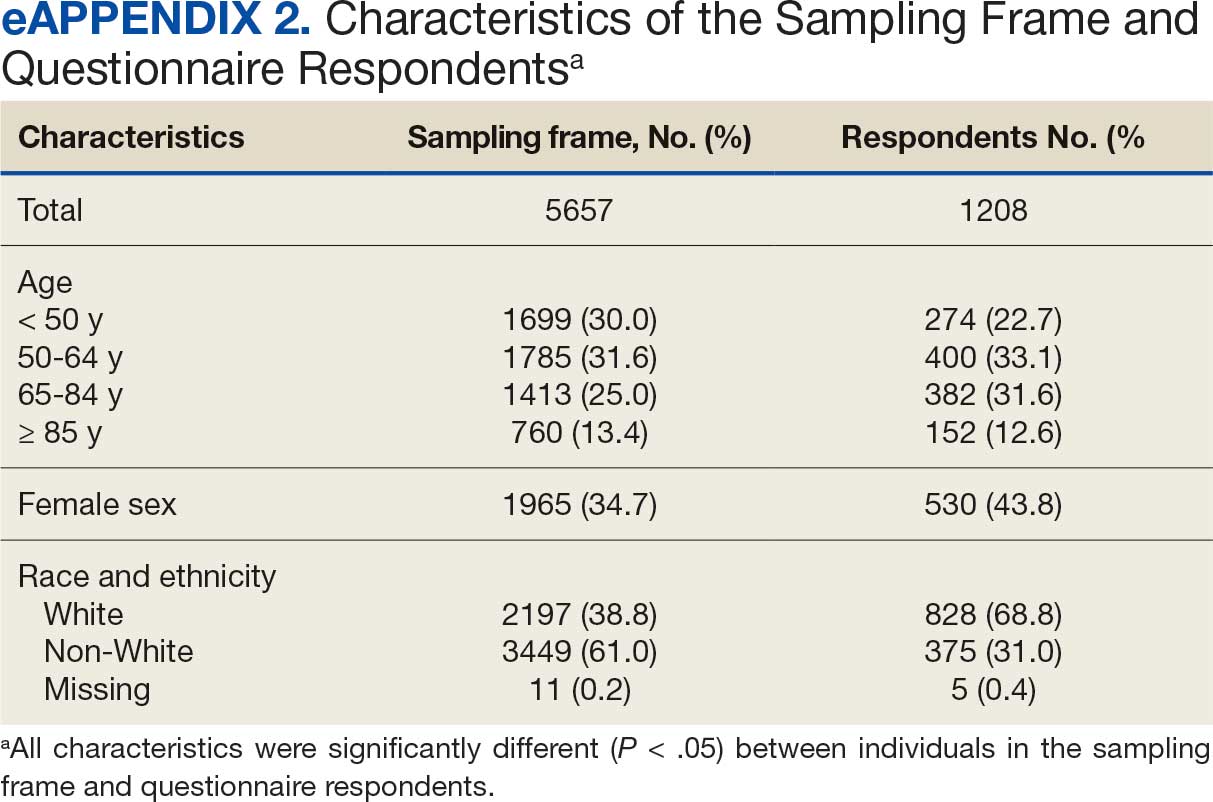

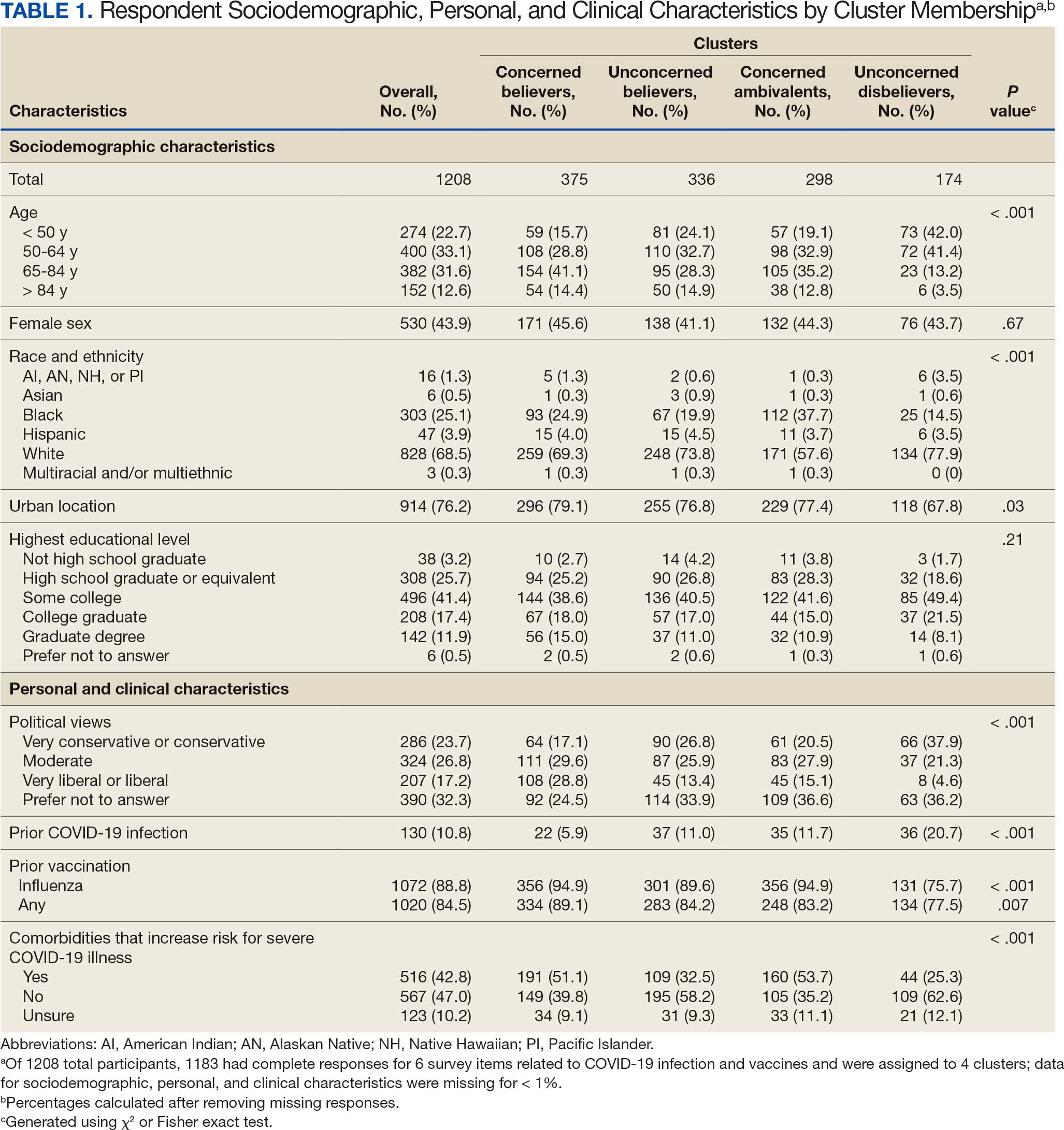

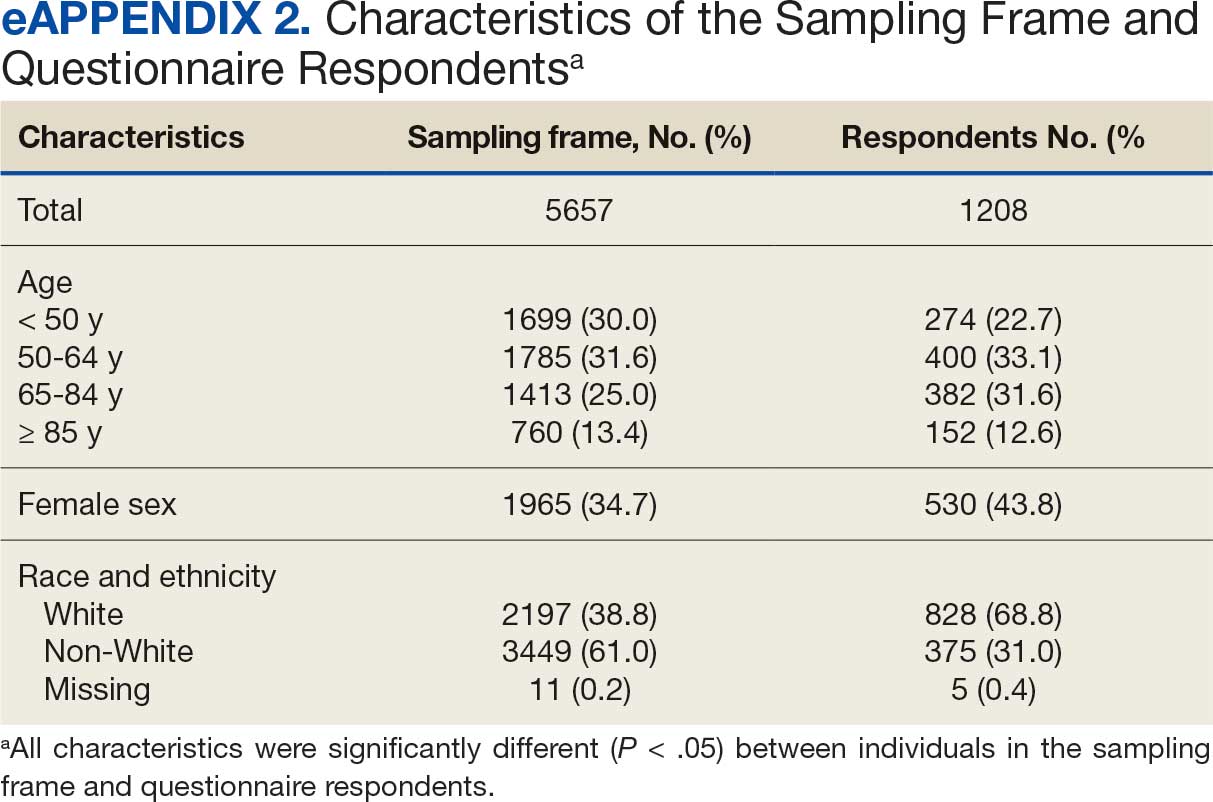

Of 5657 eligible participants, 1208 (21.4%) completed a questionnaire. Overall, 674 (55.8%) were aged < 65 years, 530 (43.9%) were women, 828 (68.5%) were non-Hispanic White, 303 (25.1%) were Black, and 47 (3.9%) were Hispanic, and 1034 (85.6%) were vaccinated (Table 1). Compared to the total sampled population, respondents were more often older, female, and White (eAppendix 2).

Cluster Membership

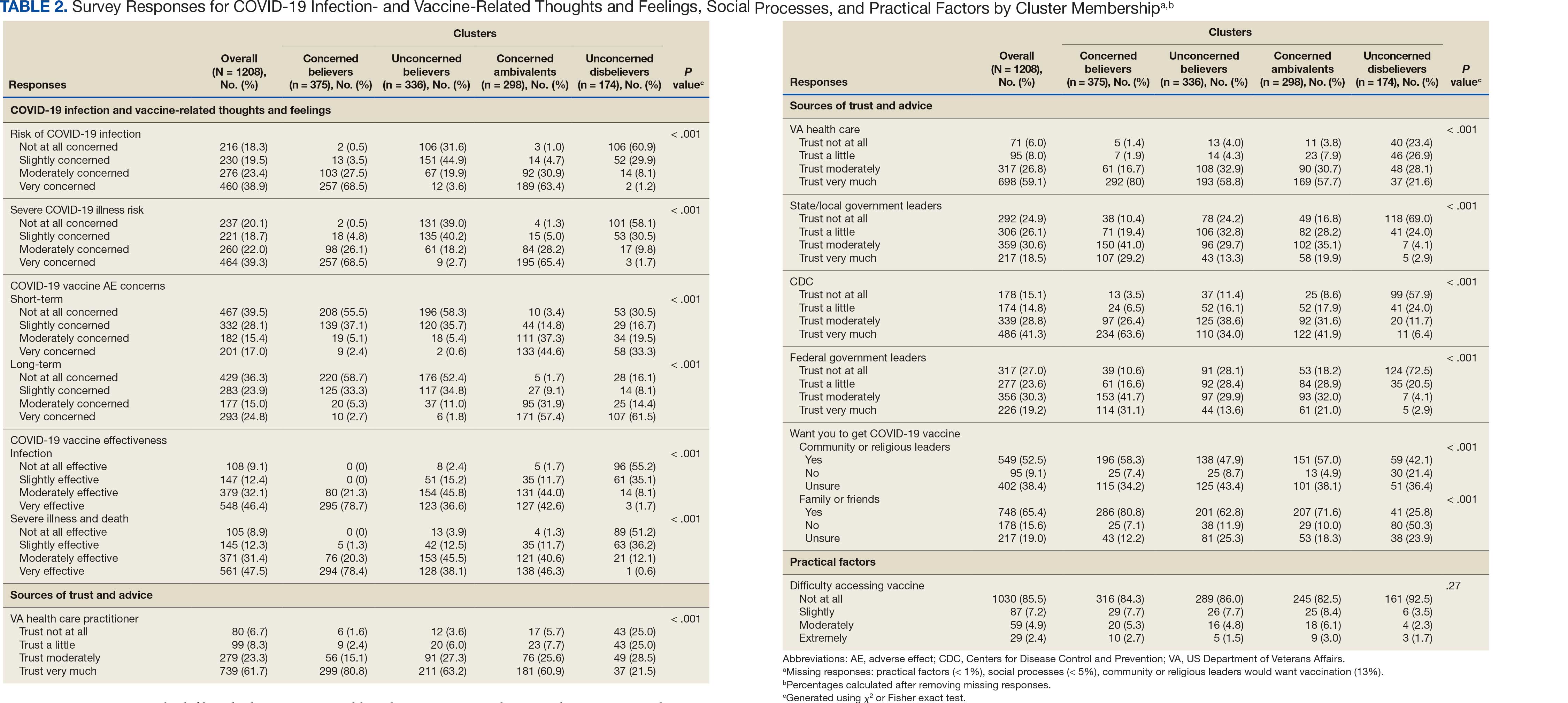

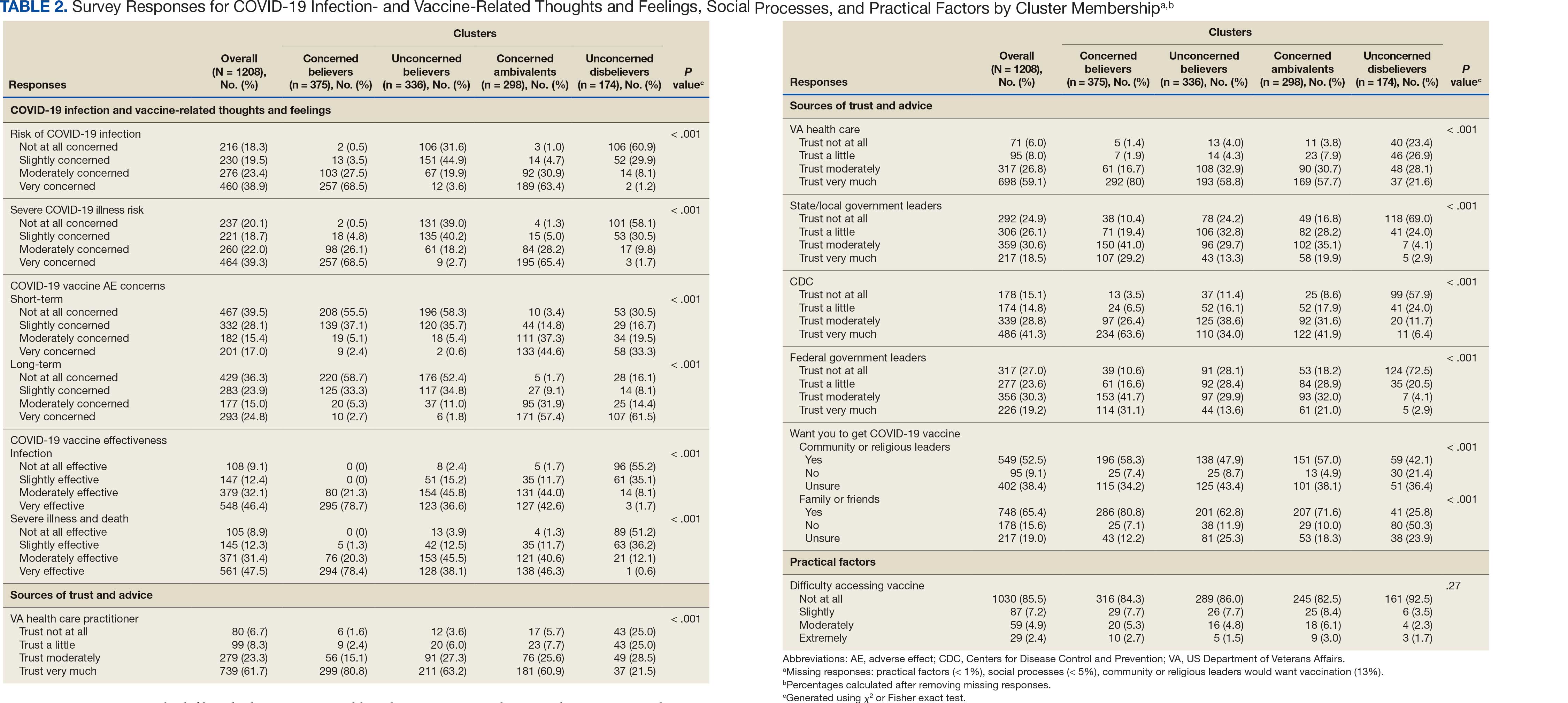

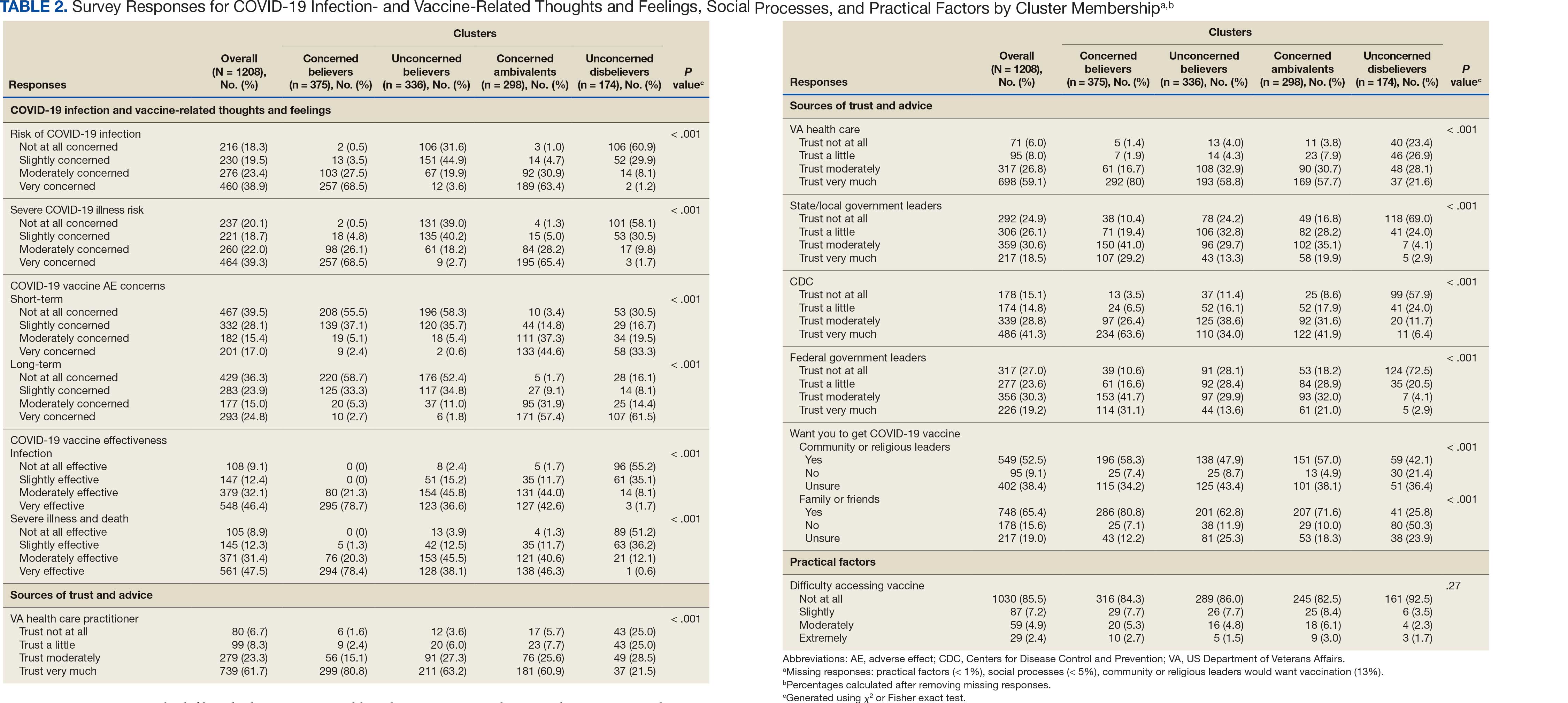

Four clusters were identified from 1183 (97.9%) participants who provided complete responses to 6 items assessing thoughts and feelings about COVID-19 infection and vaccines (Table 2). Of the 1183 respondents, 375 (31.7%) were Concerned Believers (cluster 1), 336 (28.4%) were Unconcerned Believers (cluster 2), 298 (25.2%) were Concerned Ambivalents (cluster 3), and 174 (14.7%) were Unconcerned Disbelievers (cluster 4). The Concerned Believers were moderately/ very concerned about COVID-19 infection (96.0%) and becoming very ill from infection (94.6%), believed the vaccine was moderately/very effective in preventing COVID-19 infection (100%) and severe illness or death from infection (98.7%), and had slight concern about short-term AEs (92.6%) or long-term complications (92.0%) from the vaccine. The Unconcerned Believers had no/slight concern about COVID-19 infection (76.5%) or becoming very ill (79.2%), believed the vaccine was effective in preventing infection (82.4%) and severe illness and death (83.6%), and had no/slight concern about short-term AEs (94.0%) or long-term complications (87.2%) from the vaccine. The Concerned Ambivalents were moderately/ very concerned about COVID-19 infection (94.3%) and becoming very ill (93.6%), believed the vaccine was moderately/very effective in preventing infection (86.6%) and severe illness or death (86.9%), and were moderately/very concerned about short-term AEs (81.9%) or long-term complications (89.3%) from the vaccine. The Unconcerned Disbelievers had no/slight concern about COVID-19 infection (90.8%) and becoming very ill (88.6%), believed the vaccine was not at all/slightly effective in preventing infection (90.3%) and severe illness or death (87.4%), and were moderately/very concerned about short-term AEs (52.8%) or long-term complications (75.9%) from the vaccine.

Cluster Membership

Respondent age, race and ethnicity, and political viewpoints differed significantly by cluster (P < .001). Compared with the other clusters, the Concerned Believer cluster was older (55.5% age ≥ 65 years vs 16.7%-48.0%) and more frequently reported liberal political views (28.8% vs 4.6%-15.1%). In contrast, the Unconcerned Disbeliever cluster was younger (83.4% age ≤ 64 years vs 44.5%-56.8%) and more frequently reported conservative political views (37.9% vs 17.1%-26.8%) than the other clusters. Whereas the Concerned Ambivalent cluster had the highest proportion of Black (37.7%) and the lowest proportion of White respondents (57.6%), the Unconcerned Disbelievers cluster had the lowest proportion of Black respondents (14.5%) and the highest proportion of White respondents (77.9%). The Unconcerned Disbelievers cluster were significantly less likely to trust COVID-19 vaccine information from any source and to believe those close to them wanted them to get vaccinated.

Association of Cluster Membership and COVID-19 Vaccination

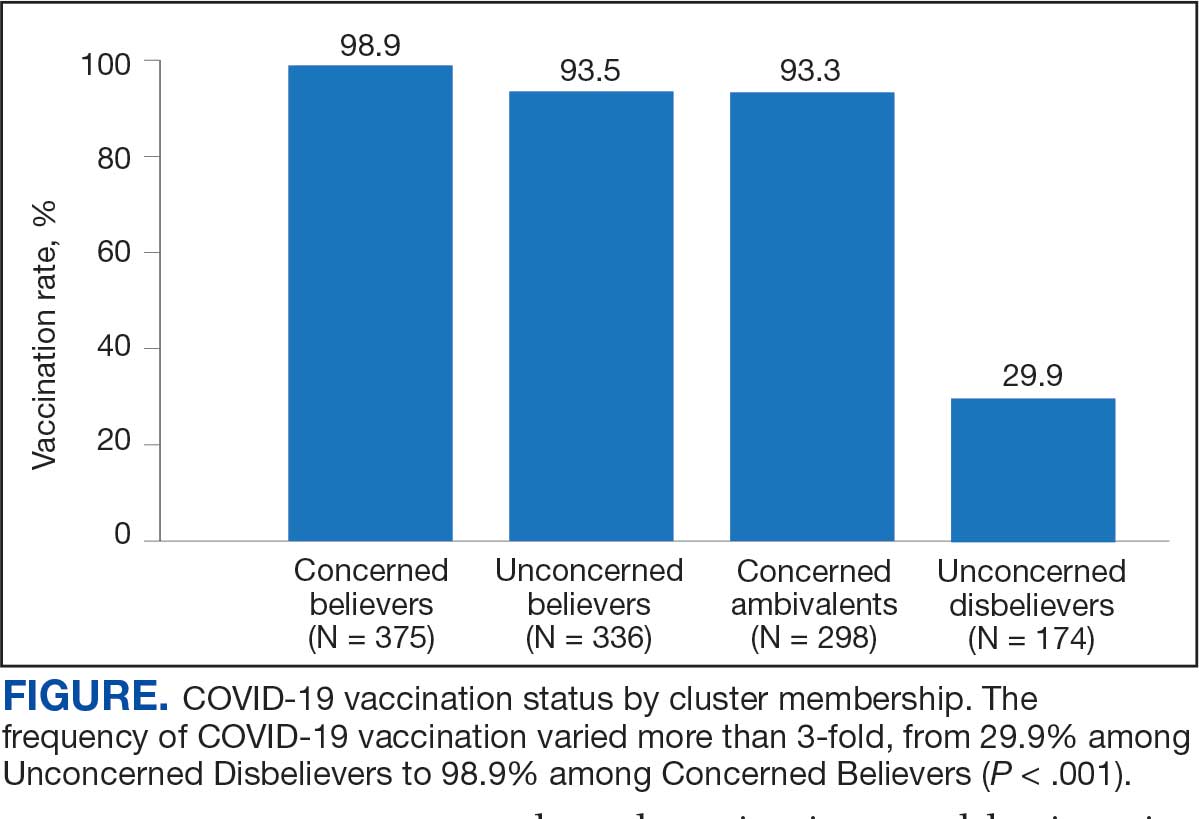

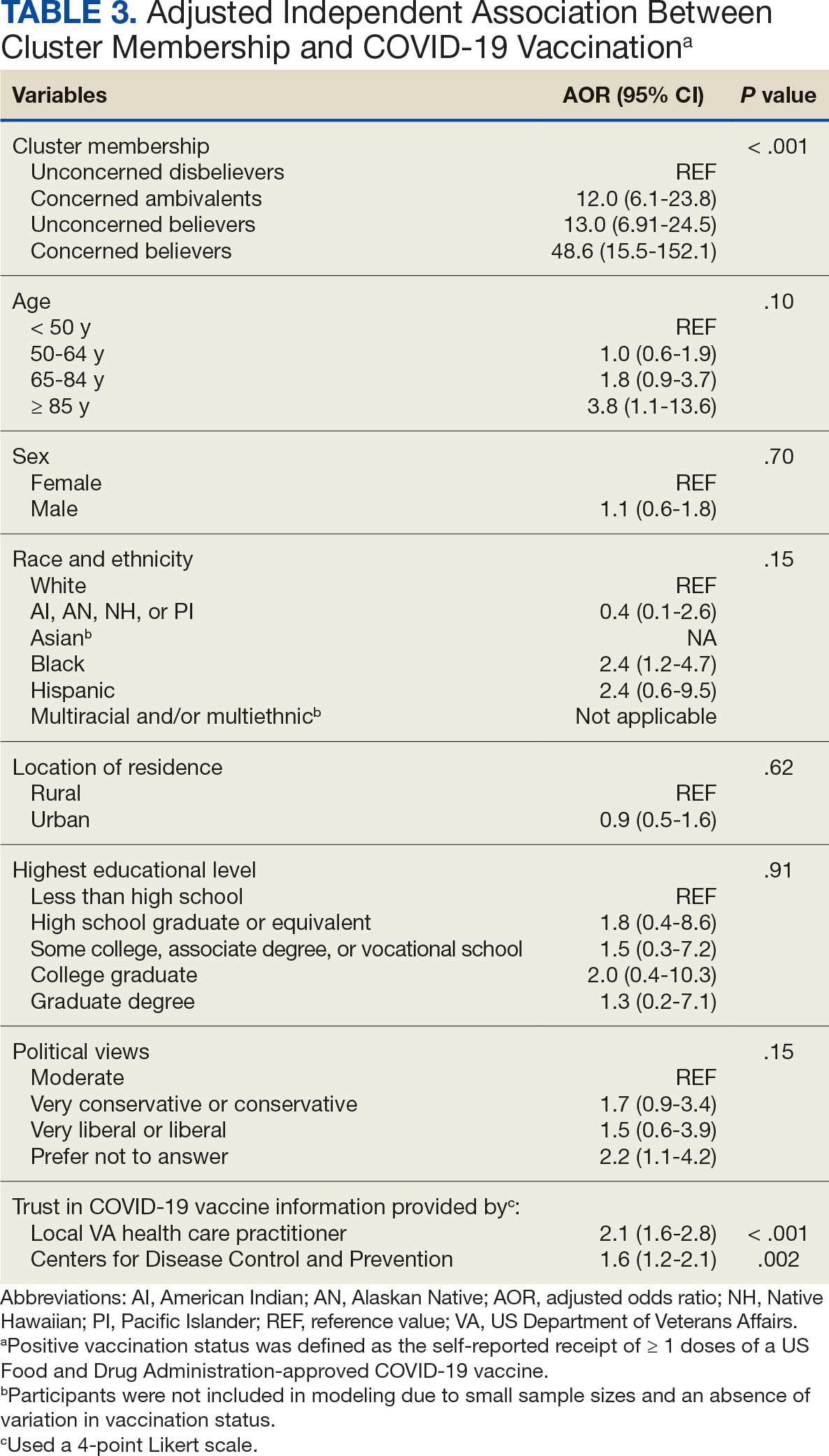

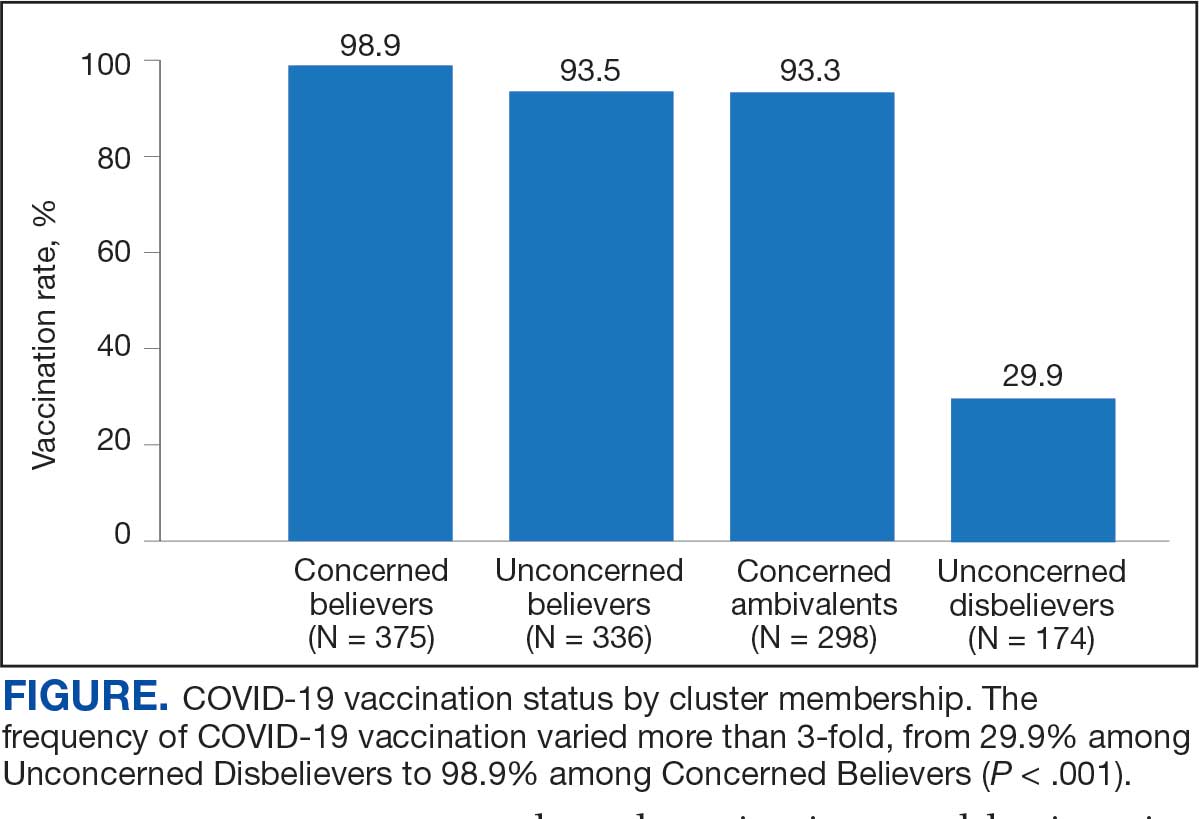

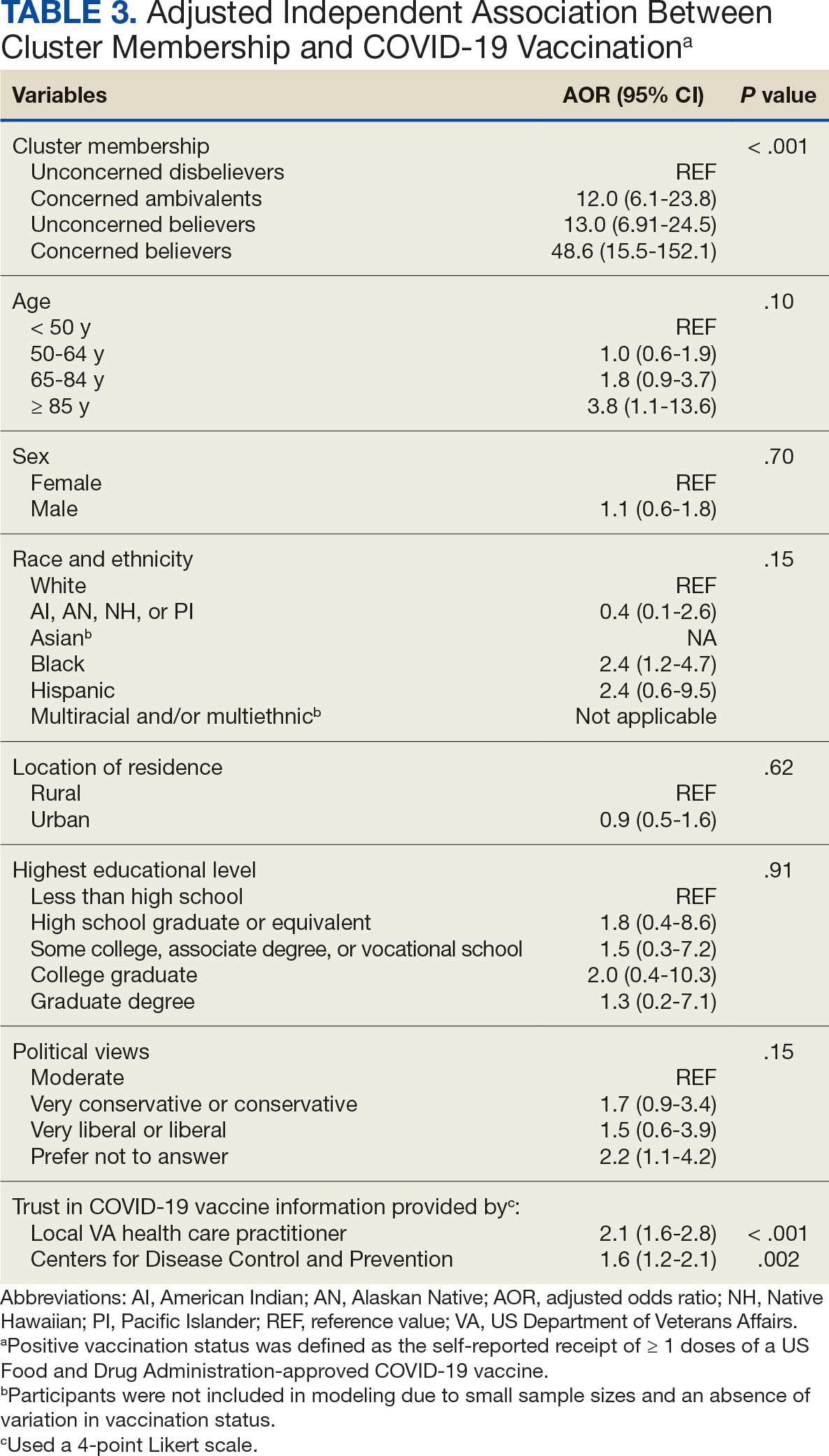

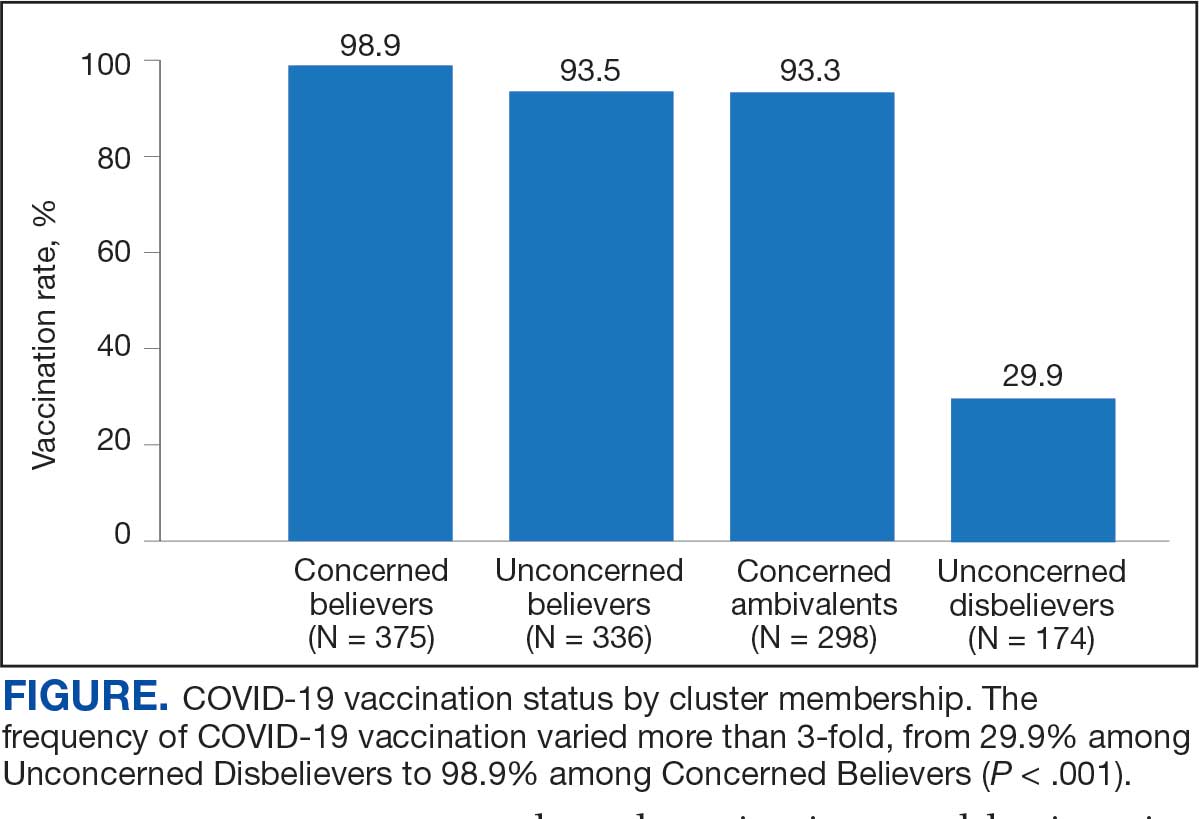

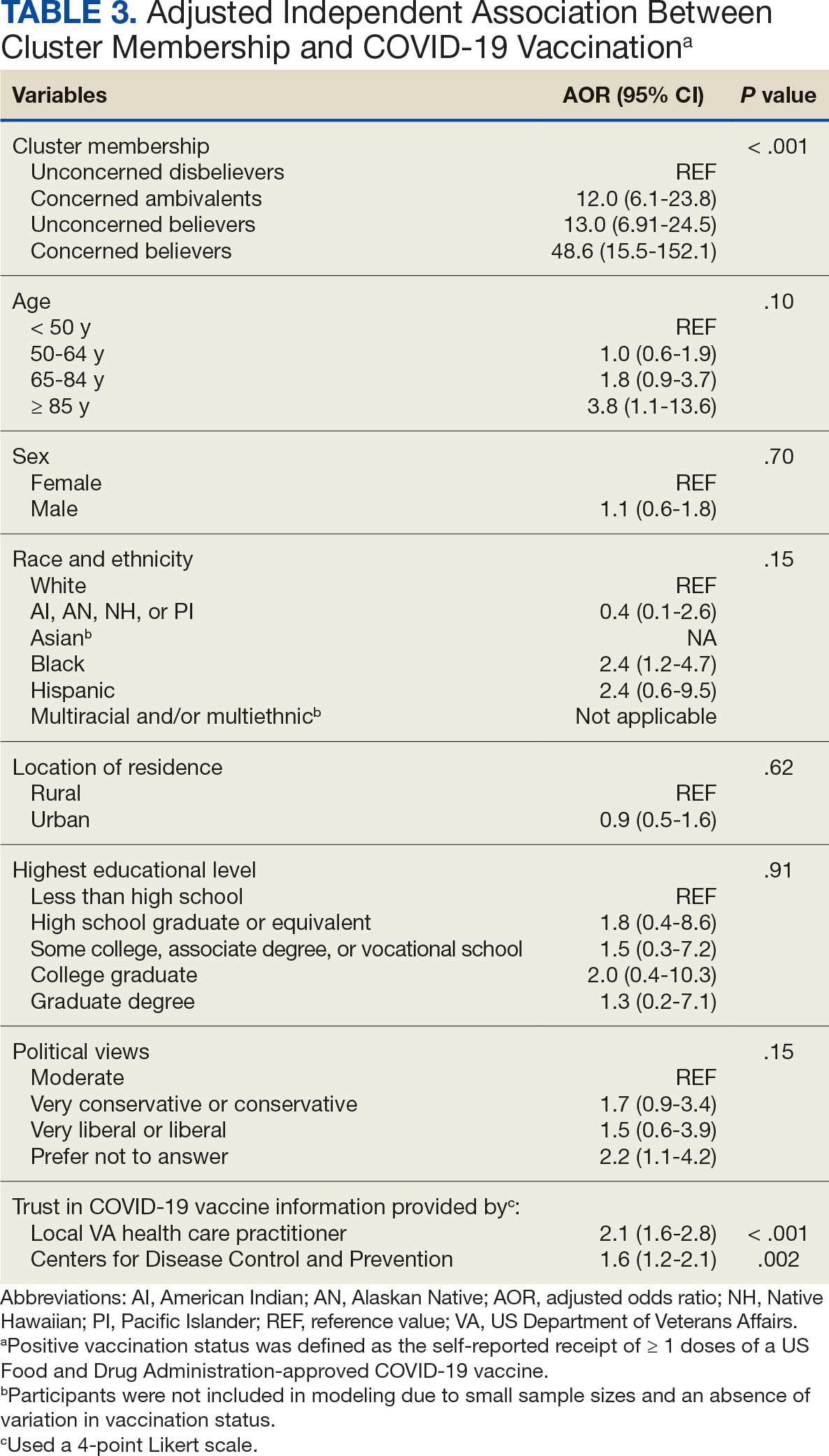

COVID-19 vaccination rates varied more than 3-fold (P < .001) by cluster, with 29.9% of Unconcerned Disbelievers, 93.3% of Concerned Ambivalents, 93.5% of Unconcerned Believers, and 98.9% of Concerned Believers reporting being vaccinated. (Figure). Cluster membership was independently associated with vaccination, with adjusted odds ratios (AORs) of 12.0 (95% CI, 6.1-23.8) for the Concerned Ambivalent, 13.0 (95% CI, 6.9-24.5) for Unconcerned Believer, and 48.6 (95% CI, 15.5-152.1) for Concerned Believer clusters (Table 3). Respondent trust in COVID-19 vaccine information from their VA HCP (AOR 2.1; 95% CI, 1.6-2.8) and the CDC (AOR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2-2.1) were independently associated with vaccination status, while the remaining respondent sociodemographic or personal characteristics were not.

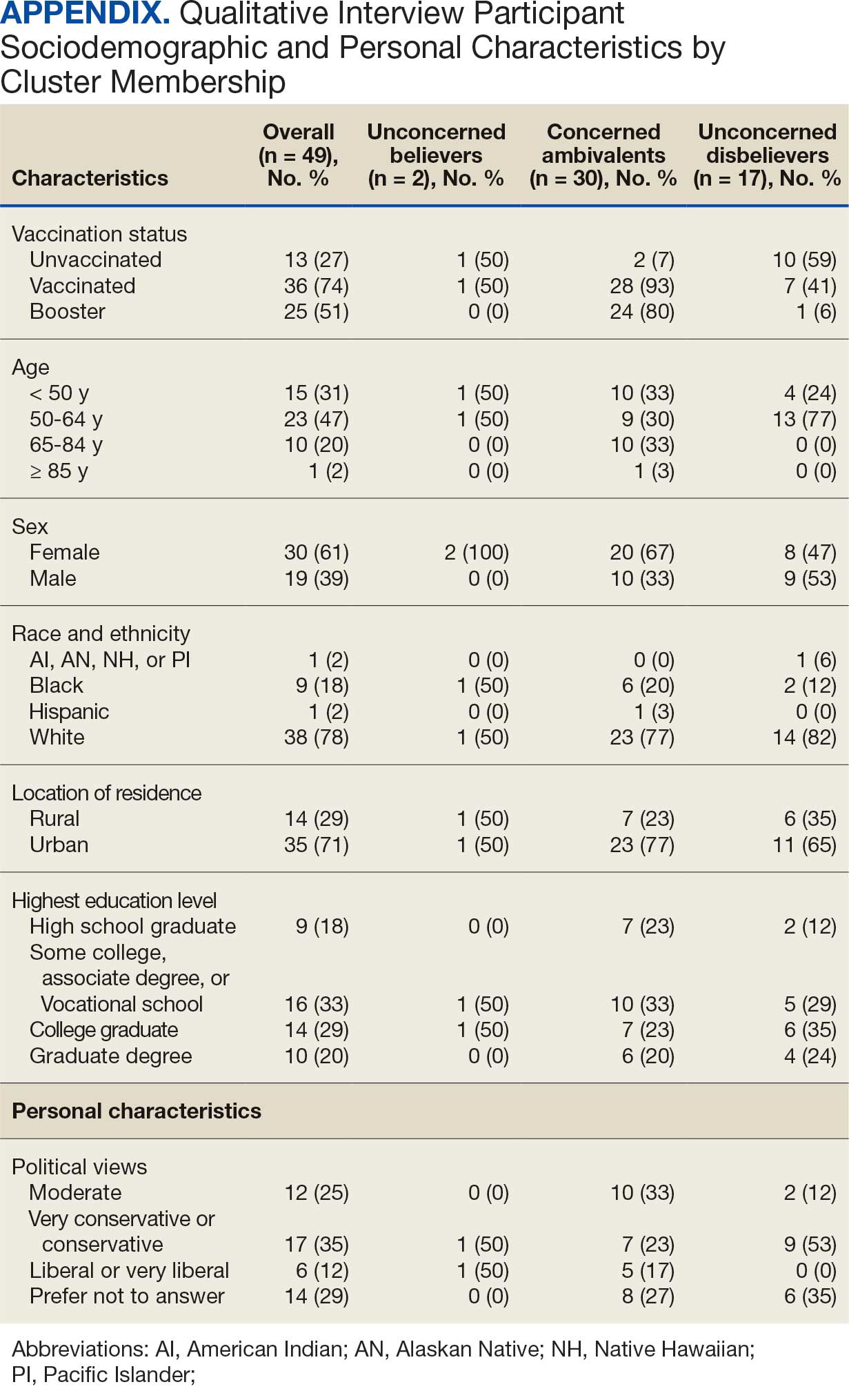

Qualitative Interview Participants

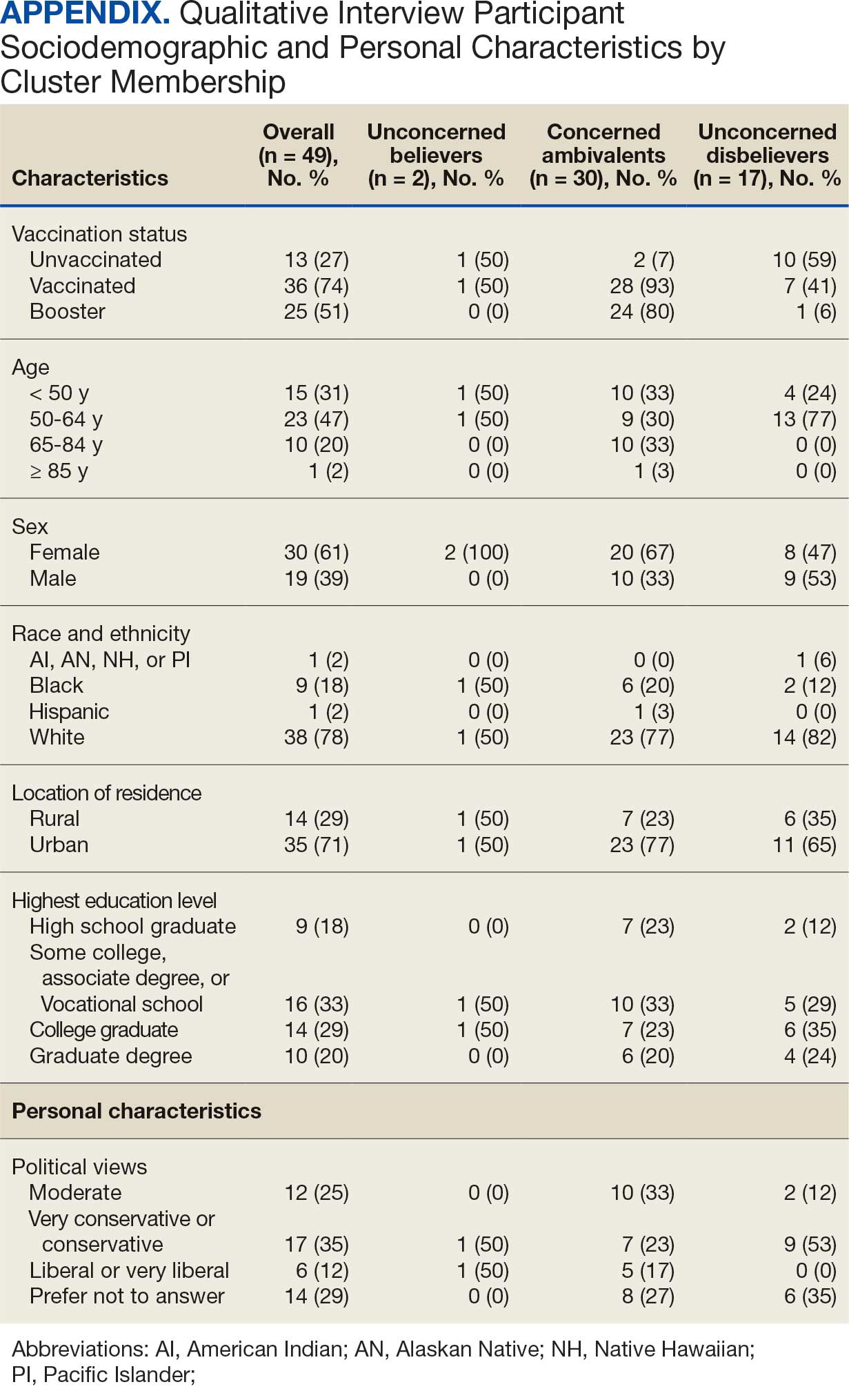

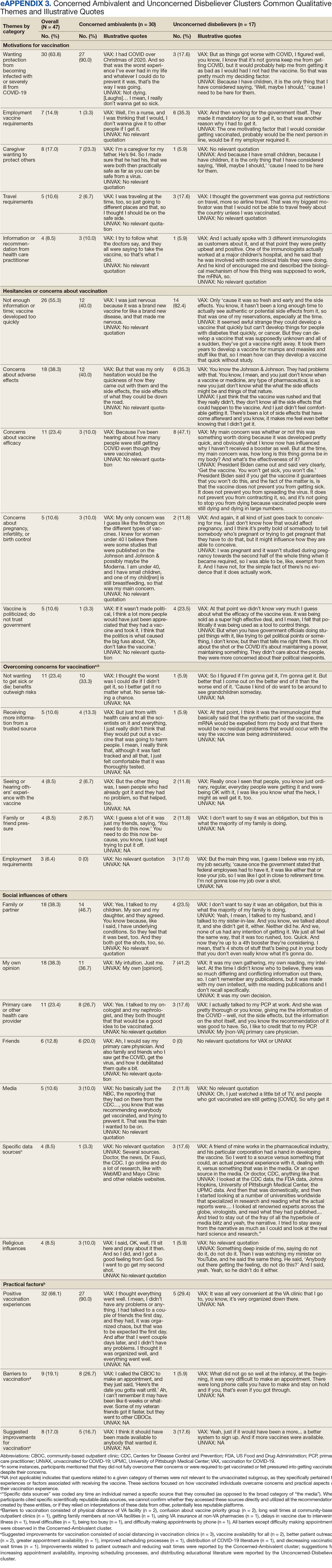

A 49-participant convenience sample completed interviews, including 30 Concerned Ambivalent, 17 Unconcerned Disbeliever, and 2 Unconcerned Believer respondents cluster. The data were not calculated for Unconcerned Believers due to the small sample size. Interview participants were more likely to be younger, female, non-Hispanic, White, less educated, and more politically conservative than the questionnaire respondents as a whole (Appendix). The vaccination rate for the interview participants was 73.5%, ranging from 29.9% in the Unconcerned Disbeliever to 93.3% in the Concerned Ambivalent cluster. Qualitative themes and participant quotes for Concerned Ambivalent and Unconcerned Disbeliever respondents are in eAppendix 3.

Motivations. Wanting personal protection from becoming infected or severely ill from COVID-19 (63.8%), caregiver wanting to protect others (17.0%), and employment vaccine requirements (14.9%) were frequent motivations for vaccination. Whereas personal protection (90.0%) and protection of others (23.3%) were identified more frequently in the Concerned Ambivalents cluster, employment vaccine requirements (35.3%) were more frequently identified in the Unconcerned Disbelievers cluster.

Hesitancies or concerns. Lack of sufficient information related to rapid vaccine development (55.3%), vaccine AEs (38.3%), and low confidence in vaccine efficacy (23.4%) were frequent concerns or hesitancies about vaccination. Unconcerned Disbelievers expressed higher levels of concern about the vaccine’s rapid development (82.4%), low perceived vaccine efficacy (47.1%), and a lack of trust in governmental vaccine promotion (23.5%) than did the Concerned Ambivalents.

Overcoming concerns. Not wanting to get sick or die from infection coupled with an understanding that vaccine benefits exceed risks (23.4%) and receiving information from a trusted source (10.6%) were common ways of overcoming concerns for vaccination. Although the Unconcerned Disbelievers infrequently identified reasons for overcoming concerns, they identified employment requirements (17.6%) as a reason for vaccination despite concerns. They also identified seeing others with positive vaccine experiences and pressure from family or friends as ways of overcoming concerns (11.8% each).

Social influences. Family members or partners (38.3%), personal opinions (38.3%), and HCPs (23.4%) were frequent social influences for vaccination. Concerned Ambivalents mentioned family members and partners (46.7%), HCPs (26.7%), and friends (20.0%) as common influences, while Unconcerned Disbelievers more frequently relied on their opinion (41.2%) and quoted specific scientifically reputable data sources (17.6%) to guide vaccine decision-making, although it is unclear whether these sources were accessed directly or if this information was obtained indirectly through scientifically unvetted data platforms.

Practical factors. Most participants had positive vaccination experiences (68.1%), determined mainly by the Concerned Ambivalents (90.0%), who were more highly vaccinated. Barriers to vaccination were reported by 9 (19.1%) participants, driven by those in the Concerned Ambivalent cluster (26.7%). Eight (17.0%) participants suggested improvements for vaccination processes, with similar overall reporting frequencies across clusters.

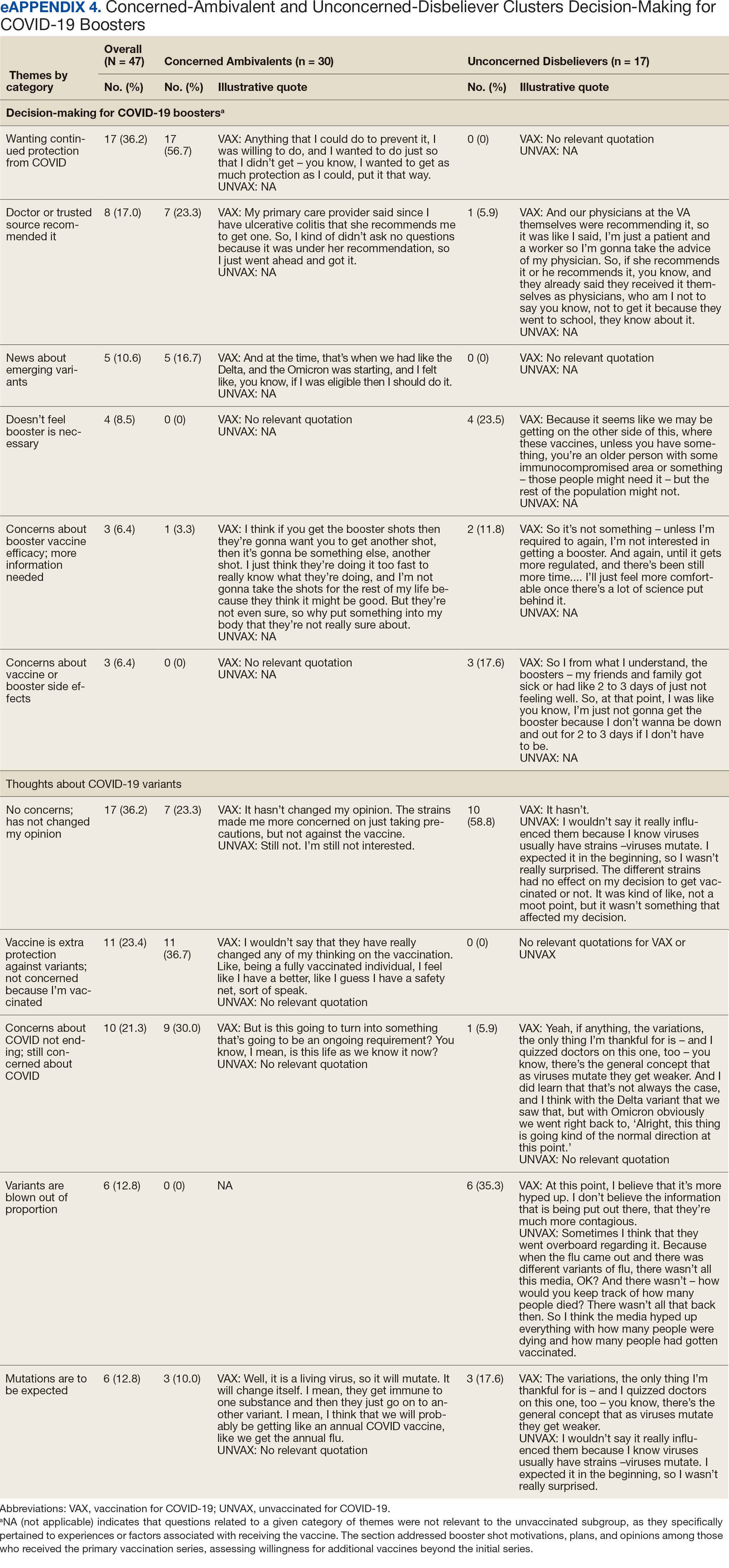

COVID-19 boosters and variants. Wanting continued protection from COVID-19 (36.2%), recommendations from a doctor or trusted source (17.0%), and news about emerging variants (10.6%) were frequent motivations for receiving a vaccine booster (eAppendix 4). These motivations were largely driven by the Concerned Ambivalents, of whom 25 of 30 were booster eligible and 24 received a booster dose. Belief that boosters were unnecessary (8.5%), concerns about efficacy (6.4%), and concerns about AEs (6.4%) were frequently identified hesitancies. These concerns were expressed largely by the Unconcerned Disbelievers, of whom 7 of 17 were booster dose eligible, but only 1 received a dose.

Evolving knowledge about variants was not a major concern overall and did not change existing opinions about the vaccine (36.2%). Concerned Ambivalents believed vaccination provided extra protection against variants (36.7%) and the emergence of variants served as a reminder of the ongoing pandemic (30.0%). In contrast, Unconcerned Disbelievers believed that the threat of variants was overblown (35.3%) and mutations are to be expected (17.6%).

Discussion

This study used a complementary mixed-methods approach to understand the motivations, hesitancies, and social and practical drivers of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among VA beneficiaries. Our quantitative analyses identified 4 distinct clusters based on respondents’ opinions on COVID-19 infection severity and vaccine effectiveness and safety. Veterans in 3 clusters were 12 to 49 times more likely to be vaccinated than those in the remaining cluster, even when controlling for baseline respondent characteristics and level of trust in credible sources of COVID-19 information. The observed vaccination rate of nearly 86% was higher than the contemporaneous national average of 62% for vaccine-eligible individuals, likely reflecting the comprehensive VA vaccine promotion strategies tailored to a patient demographic with a high COVID-19 risk profile.2,10

This cluster analyses demonstrated the importance of thoughts and feelings about COVID-19 infection and vaccination as influential social and behavioral drivers of vaccine uptake. These opinions help explain the strong association between cluster membership and vaccination status in this multivariable modeling. The cluster composition was consistent with findings from studies of nonveteran populations that identified perceived vulnerability to COVID-19 infection, beliefs in vaccine effectiveness, and adherence with protective behaviors during the pandemic as contributors to vaccine uptake.13,33 Qualitative themes showed that personal protection, protecting others, and vaccine mandates were frequent motivators for vaccination. Whereas protection of self and others from COVID-19 infection were more often expressed by the highly vaccinated Concerned Ambivalents, employment and travel vaccine mandates were more often identified by Unconcerned Disbelievers, who had a lower vaccination rate. Among Unconcerned Disbelievers, an employer vaccine requirement was the most frequent qualitative theme for overcoming vaccination concerns.

In addition to cluster membership, our modeling showed that trust in local VA HCPs and the CDC were independently associated with COVID-19 vaccination, which has been found in prior research.20 This qualitative analyses regarding vaccine hesitancy identified trust-related concerns that were more frequently expressed by Unconcerned Disbelievers than Concerned Ambivalents. Concerns included the rapid development of the vaccines potentially limiting the generation of scientifically sound effectiveness and safety data, and potential biases involving the entities promoting vaccine uptake.

Whereas the Concerned Believers, Unconcerned Believers, and Concerned Ambivalents all had high COVID-19 vaccination rates (≥ 93%), the decision-making pathways to vaccine uptake likely differ by their concerns about COVID-19 infection and perceptions of vaccine safety and effectiveness. For example, this mixed-methods analysis consistently showed that people in the Concerned Ambivalent cluster were positively motivated by concerns about COVID-19 infection and severity and beliefs about vaccine effectiveness that were tempered by concerns about vaccine AEs. For this cluster, their frequent thematic expression that the benefits of the vaccine exceed the risks, and the positive social influences of family, friends, and HCPs may explain their high vaccination rate.

Such insights into how the patterns of COVID-19–related thoughts and feelings vary across clusters can be used to design interventions to encourage initial and booster doses of COVID-19 vaccines. For example, messaging that highlights the infectivity and severity of COVID-19 and the potential for persistent negative health outcomes associated with long COVID could reinforce the beliefs of Concerned Believers and Concerned Ambivalents, and such messaging could also be used as a targeted intervention for Unconcerned Believers who expressed fewer concerns about the health consequences of COVID-19.23 Likewise, messaging about the safety profile of COVID-19 vaccines may reduce vaccine hesitancy for Concerned Ambivalents. Importantly, purposeful attention to health equity, community engagement, and involvement of racially diverse HCPs in patient discussions represent successful strategies to increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake among Black individuals, who were disproportionately represented in the Concerned Ambivalent cluster and may possess higher levels of mistrust due to racism experienced within the health care system.24

Our findings suggest that the greatest challenge for overcoming vaccine hesitancy is for individuals in the suboptimally vaccinated (30%) Unconcerned Disbeliever cluster. These individuals had low levels of concern about COVID-19 infection and severity, high levels of concern about vaccine safety, low perceived vaccine effectiveness, and low levels of trust in all information sources about COVID-19. While the Unconcerned Disbelievers cited scientifically reputable data sources, we were unable to verify whether participants accessed these reputable sources of information directly or obtained such information indirectly through potentially biased online sources. Nearly half of this cluster trusted their VA HCP and believed their community or religious leaders would want them to get vaccinated. This qualitative analyses found that Unconcerned Disbelievers relied on personal beliefs for vaccine decision-making more than Concerned Ambivalents. While Unconcerned Disbelievers were less likely to be socially influenced by family, friends, or religious leaders, they still acknowledged some impact from these sources. These findings suggest that addressing vaccine hesitancy among Unconcerned Disbelievers may require a multifaceted approach that respects their reliance on personal research while also leveraging the potential social influences. This approach supports the promising, previously reported practices of harnessing the social influences of HCPs and other community and religious leaders to promote vaccine uptake among Unconcerned Disbelievers.34,35 One evidence-based approach to effectively change patient health care behaviors is through motivational interviewing strategies that use open-ended questions, nonjudgmental interactions, and collaborative decision-making when discussing the risks and benefits of vaccination.21,22

Limitations

This study was conducted at a single VA health care facility and our sampling technique was nonrandom, suggesting that these results may not be generalizable to all veterans or non-VA patient populations. The 21% questionnaire response rate could have introduced selection bias into the respondent sample. All questionnaire data were self-reported, including vaccination status. Finally, the qualitative interviews consisted of a small number of unvaccinated individuals in 2 clusters (ie, Concerned Ambivalents and Unconcerned Disbelievers) and may not have reached thematic saturation in these subgroups.

Conclusions