User login

Suicide Risk in Older Adults: The Role and Responsibility of Primary Care

From the Primary Care Institute, Gainesville, FL.

Abstract

- Objective: To provide primary care practitioners with the knowledge required to identify and address older adult suicide risk in their practice.

- Methods: Review of the literature and good clinical practices.

- Results: Primary care practitioners play an important role in older adult suicide prevention and must have knowledge about older adult suicide risk, including risk factors and warning signs in this age-group. Practitioners also must appropriately screen for and manage suicide risk. Older adults, particularly older men, are at high risk for suicide, though they may be less likely to report suicide ideation. Additionally, older adults frequently see primary care practitioners within a month prior to death by suicide. A number of older adult–specific risk factors are reviewed, and appropriate screening and intervention for the primary care setting are discussed.

- Conclusion: Primary care practitioners are uniquely qualified to address a broad range of potential risk factors and should be prepared to identify risk factors and warning signs for older adult suicide, ask appropriate questions to screen for suicide risk, and intervene to prevent suicide.

Key words: suicide; older adults; risk factors; screening; safety planning.

Primary care practitioners play an important role in older adult suicide prevention and have a responsibility to identify and address suicide risk among older adults. To do so, practitioners must understand the problem of older adult suicide, recognize risk factors for suicide in older adults, screen for suicide risk, and appropriately assess and manage suicide risk. Primary care practitioners may face challenges in completing these tasks; the goal of this article is to assist practitioners in addressing these challenges.

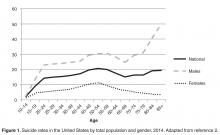

Suicide in Older Adults

The United States has recently seen increases in suicide rates across the lifespan; from 1999 to 2014, the suicide rate rose by 24% across all ages [3]. Among both men and women aged 65 to 74, the suicide rate increased in this time period [3]. The high suicide rate among older adults is particularly important to address given the increasing numbers of older adults in the United States. By 2050, the older adult population in the United States is expected to reach 88.5 million, more than double the older adult population in 2010 [4]. Additionally, the generation that is currently aging into older adulthood has historically had higher rates of suicide across their lifespan [5]. Given that suicide rates also increase in older adulthood for men, the coming decades may evidence even higher rates of suicide among older adults than previously and it is critical that older adult suicide prevention becomes a public health priority.

It is also essential to discuss other suicide-related outcomes among older adults, including suicide attempts and suicide ideation. This is critical particularly because the ratio of suicide attempts to deaths by suicide in this age-group is 4 to 1 [1]. This is in contrast to the ratio of attempts to deaths across all ages, which is 25 suicide attempts per death by suicide [1]. This means that suicide prevention must occur before a first suicide attempt is made; suicide attempts cannot be used a marker of elevated suicide risk in older adults or an indication that intervention is needed. Intervention is required prior to suicide risk becoming elevated to the point of a suicide attempt.

It is also critical to recognize that despite the fact that suicide rates rise with age, reports of suicide ideation decrease with age [7,8]. Across all ages, 3.9% of Americans report past-year suicide ideation; however, only 2.7% of older adults report thoughts of suicide [9]. The discrepancy with the increasing rates of death by suicide with age suggest that suicide risk, and thereby opportunities for intervention, may be missed in this age-group [10].

However, older adults may be more willing to report death ideation, as research has found that over 15% of older adults endorse death ideation [11–13]. Death ideation is a desire for death without a specific desire to end one’s own life, and is an important suicide-related outcome, as older adults with death ideation appear the same as those with suicide ideation in terms of depression, hopelessness, and history of suicidal behavior [14]. Additionally, older adults with death ideation had more hospitalizations, more outpatient visits, and more medical issues than older adults with suicide ideation [15]. Therefore, death ideation should be taken as seriously as suicide ideation in older adults [14]. In sum, the high rates of death by suicide, the likelihood of death on a first or early suicide attempt, and the discrepancy between decreasing reports of suicide ideation and increasing rates of death by suicide among older adults indicate that older adult suicide is an important public health problem.

Suicide Prevention Strategies

Many suicide prevention strategies to date have focused on indicated prevention, which concentrates on individuals already identified at high risk (eg, those with suicide ideation or who have made a suicide attempt) [16]. However, because older adults may not report suicide ideation or survive a first suicide attempt, indicated prevention is likely not enough to be effective in older adult suicide prevention. A multilevel suicide prevention strategy [17] is required to prevent older adult suicide [18]. Older adult suicide prevention must include indicated prevention but must also include selective and universal prevention [16]. Selective prevention focuses on groups who may be at risk for suicide (eg, individuals with depression, older adults) and universal prevention focuses on the entire population (eg, interventions to reduce mental health stigma) [16]. To prevent older adult suicide, crisis intervention is critical, but suicide prevention efforts upstream of the development of a suicidal crisis are also essential.

The Importance of Primary Care

Research indicates that primary care is one of the best settings in which to engage in older adult suicide prevention [18]. Older adults are significantly less likely to receive specialty mental health care than younger adults, even when they have depressive symptoms [19]. Additionally, among older adults who died by suicide, 58% had contact with a primary care provider within a month of their deaths, compared to only 11% who had contact with a mental health specialist [20]. Among older adults who died by suicide, 67% saw any provider in the 4 weeks prior to their death [21]. Approximately 10% of older adults saw an outpatient mental health provider, 11% saw a primary care physician for a mental health issue, and 40% saw a primary care physician for a non-mental health issue [21]. Therefore, because older adults are less likely to receive specialty mental health treatment and so often seen a primary care practitioner prior to death by suicide, primary care may be the ideal place for older adult suicide risk to be detected and addressed, especially as many older adults visit primary care without a mental health presenting concern prior to their death by suicide.

Additionally, older adults may be more likely to disclose suicide ideation to primary care practitioners, with whom they are more familiar, than physicians in other settings (eg, emergency departments). Research has shown that familiarity with a primary care physician significantly increases the likelihood of patient disclosure of psychosocial issues to the physician [22]. Primary care providers also have a critical role as care coordinators; many older adults also see specialty physicians and use the emergency department. In fact, older adults are more likely to use the emergency department than younger adults, but emergency departments are not equipped to navigate the complex care needs of this population [23]. Primary care practitioners are important in ensuring that health issues of older adults are addressed by coordinating with specialists, hospitals (eg, inpatient stays, emergency department visits, surgery) and other health services (eg, home health care, physical therapy). Approximately 35% of older adults in the United States experience a lack of care coordination [24], which can negatively impact their health and leave issues such as suicide ideation unaddressed. Primary care practitioners may be critical in screening for mental health issues and suicide risk during even routine visits because of their familiarity with patients, and also play an important role in coordinating care for older adults to improve well-being and to ensure that critical issues, such as suicide ideation, are appropriately addressed.

Primary care practitioners can also be key in upstream prevention. Primary care practitioners are in a unique role to address risk factors for suicide prior to the development of a suicidal crisis. Because older adults frequently see primary care practitioners, such practitioners may have more opportunities to identify risk factors (eg, chronic pain, depression). Primary care practitioners are also trained to treat a broad range of conditions, providing the skills to address many different risk factors.

Finally, primary care is a setting in which screening for depression and suicide ideation among older adults is recommended. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for depression in all adults and older adults and provides recommended screening instruments, some of which include questions about self-harm or suicide risk [25]. However, this same group has concluded that there is insufficient evidence to support a recommendation for suicide risk screening [26]. Despite this, the Joint Commission recently released an alert that recommends screening for suicide risk in all settings, including primary care [27]. The Joint Commission requirement for ambulatory care that is relevant to suicide is PC.04.01.01: The organization has a process that addresses the patient’s need for continuing care, treatment, or services after discharge or transfer; behavioral health settings have additional suicide-specific requirements. The recommendations, though, go far beyond this requirement for primary care. The Joint Commission specifically notes that primary care clinicians play an important role in detecting suicide ideation and recommends that primary care practitioners review each patient’s history for suicide risk factors, screen all patients for suicide risk, review screenings before patients leave appointments, and take appropriate actions to address suicide risk when needed [27]. Further details are available in the Joint Commission’s Sentinel Event Alert titled, “Detecting and treating suicide ideation in all settings” [27]. Given these recommendations, primary care is an important setting in which to identify and address suicide risk.

Risk Factors for Older Adult Suicide

Numerous reviews exist that cover many risk factors for suicide in older adults [18,28]. This article will focus briefly on risk factors that are likely to be recognized and potentially addressed by primary care practitioners. Risk factors that apply across the lifespan can be recalled through a mnemonic: IS PATH WARM [29]. These risk factors include suicide Ideation, Substance abuse, Purposelessness, Anxiety (including agitation and poor sleep), feeling Trapped, Hopelessness, social Withdrawal, Anger or rage, Recklessness (ie, engaging in risky activities), and Mood changes. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline also includes being in unbearable physical pain, perceiving one’s self as a burden to others, and seeking revenge on others as risk factors [30]. More specific to older adults, Conwell notes 5 categories or domains of risk factors with strong research support: psychiatric symptoms, somatic illness, functional impairment, social integration, and personality traits and coping [18,31].

Affective or mood disorders, particularly depression and depressive symptoms, are some of the most well-studied and strongest risk factors for older adult suicide [31]; 71% to 97% of all older adults who die by suicide have psychiatric illnesses [28]. Mood disorders, including major depressive episodes, are most consistently linked to older adult suicide risk; there is evidence as well for anxiety disorders and substance abuse disorders as risk factors, though it is somewhat mixed [28]. Therefore, screening for depression, anxiety, and substance abuse may be key to recognizing potential suicide risk. However, depression and anxiety do not present similarly in younger and older adults [32,33]. Depressive symptoms in older adults may be more somatic (eg, agitation, gastrointestinal symptoms) [32] and may reflect more anhedonia than mood changes [33]. Anxiety in older adults tends to be reported as stress or tension, whereas younger adults report feeling anxious or worried [33]. Additionally, substance abuse is often underrecognized, underdiagnosed, and undertreated in older adults [34]. Proactive screening for substance abuse is important as it may not interfere with work or other obligations in older adults, and therefore substance abuse may not be identified by older adults or others in their lives.

Physical illness may also be a risk factor for suicide [28,31]. Numerous diagnoses have been linked to suicide risk, including cancers, neurodegenerative diseases (eg, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington disease), spinal cord injury, cardiovascular disease, and pulmonary disease [28,35]. However, overall illness burden (ie, number of chronic illnesses) [28] and self-perceived health [36] appear to be stronger risk factors than any specific illness. Additionally, authors have suggested that illness itself may not be a particularly strong risk factor, but the effect of illness on depressive symptoms [35], functioning, pain, or hopelessness due to the potential for decline over time [28] may increase suicide risk in older adults. Pain itself has been identified as a risk factor for suicide, as have perceptions of burden to others, hopelessness, and functional impairment [28].

In terms of functional impairment, research has shown that impairment in completing instrumental activities of daily living is associated with higher risk for death by suicide, and cognitive impairment may also be associated with elevated suicide risk [28]. However, there are some discrepant findings regarding the role of dementia in suicide risk, which may reflect medical and psychiatric comorbidities, as well as different stages of dementia or levels of cognitive impairment (eg, hopelessness about cognitive decline may increase suicide risk shortly after diagnosis, whereas lack of insight may decrease risk later in the course of the illness) [37]. Related to functional or cognitive impairment is perceived burdensomeness (ie, the perception that one is a liability or burden to others, to the point that others would be better off if one was gone) [38], which may also be associated with suicide risk in older adults [39,40]. Researchers have found that the interaction between perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (ie, a belief that one lacks reciprocal caring relationships and does not belong) identified older adults who were likely experiencing suicide ideation but did not report it [41]. These findings indicate that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness may be key in identifying older adults at risk for suicide.

Thwarted belongingness has also been linked to suicide ideation in older adults [41]. In fact, studies suggest that social integration is especially important for reducing suicide risk in this population [28,31,42]. A larger social network, living with others, and being active in the community are each protective against suicide [28]. Bereavement, which can reduce social connectedness and acts as a significant life stressor, is also an important risk factor [31]. Retirement may also reduce social connectedness, and employment changes have been identified as a suicide risk factor for older adults [28]. Retirement has been linked to risk for death by suicide in this population [43], and may not only serve to reduce social connectedness, but for some older adults may also be a significant role loss or loss of sense of purpose that can influence suicide risk.

Finally, rigid personality traits or coping styles are a risk factor for suicide among older adults [28,31]. As older adults face potential losses, health changes, and functional decline, effective positive coping strategies and flexibility are key to maintaining well-being. If older adults are unable to flexibly cope with these challenges, their risk for suicide increases [28].

In addition to risk factors, which confer suicide risk but do not necessarily suggest that an older adult is thinking about suicide, warning signs exist that indicate that suicide risk is imminent. These include suicidal communication (ie, talking or writing about suicide), seeking access to means, and making preparations for suicide (eg, ensuring a will is in place, giving away prized possessions). One important note is that discussing and preparing for death may be developmentally appropriate for older adults, particularly those with chronic illnesses; however, such appropriate preparation is critically different from talking about suicide or a desire for death.

Additionally, a lack of planning for the future may be a warning sign. For example, older adults who decline to schedule medical follow-up or do not wish to refill needed prescriptions may be exhibiting warning signs that should be addressed. Similarly, not following needed medical regimens (eg, an older adult with diabetes no longer taking insulin) is also a warning sign. Other, potentially more subtle warning signs may include significant changes in mood, sleep, or social interactions. Older adults may become agitated and sleep less when they are considering suicide, or may feel more at ease after they have made the decision to die by suicide and their sleep or mood may improve. Withdrawing from valued others may also be a warning sign. Finally, recent major changes (eg, loss of a spouse, moving to an assisted living facility) may be triggers for suicide risk and can serve as warning signs themselves.

Specific Screening Strategies

Given the numerous risk factors and warning signs for older adult suicide, as well as the time limitations that primary care practitioners face [44,45], it would be impractical to comprehensively assess each older adult who presents at a primary care practice. Therefore, more specific screening is necessary. Most importantly, every older adult should be screened for suicide ideation and death ideation at every visit. Screening at every visit is critical because suicide ideation may develop at any point. Previous research has included screening of over 29,000 older adults in 11 primary care settings for suicide ideation, risk of alcohol misuse, and mental health disorders [15], suggesting that suicide risk screening is feasible. Other studies have also successfully used widespread screening for depression and suicide ideation among older adults in primary care [46–48]. Additionally, in an emergency department setting, universal suicide risk screening has been associated with significantly improved risk detection [49], indicating that improved screening may be beneficial in identifying suicide risk. Importantly, asking about suicide does not cause thoughts of suicide [50]. Additionally, it is a myth that those who talk about suicide ideation will not act on these thoughts [51].

When primary care practitioners inquire about suicide ideation, they should also ask about death ideation; though some may believe that death ideation is not as significant in terms of suicide risk as suicide ideation, recall that research has not found differences in previous suicide attempts or current hopelessness among older adults with death ideation versus suicide ideation [14]. Therefore, screening for death ideation should be completed as part of every suicide risk screening.

Screening can take many forms. Screening may be oral; asking an older adult if he or she is having thoughts of suicide or is experiencing a desire to die is a brief, 2-question screening that may provide valuable information (eg, “Are you having thoughts about your own death or wanting to die?”, “Are you having thoughts of killing yourself or thinking about suicide?”). This screening may be conducted by medical assistants, nurses, care managers, or physicians, with the patient’s responses documented. Importantly, a standard procedure should be implemented to ensure older adults are consistently asked about suicide risk at each visit, but do not feel inundated by such questions from numerous staff.

If verbal questions are asked, they must be asked appropriately. Euphemisms or indirect language should not be used during a screening; older adults should be directly asked about thoughts of death and suicide, not simply asked questions such as, “Have you ever had thoughts of harming or hurting yourself?” A question like this does not adequately assess current suicide risk, as it does not assess current thoughts, nor does it specifically inquire about suicide ideation (ie, killing one’s self). It is also important to phrase questions in a manner that invites honest responses and conveys an openness to listening. For example, asking, “You’re not thinking about suicide, are you?” suggests that the practitioner wants the older adult to say no and is not comfortable with the older adult endorsing suicide ideation. Open questions that allow endorsement or denial (eg, “Are you having thoughts of killing yourself?”) imply that the practitioner is receptive to either an endorsement or denial of suicide ideation.

Alternatively, a written screening can be used; older adults may complete a questionnaire prior to their appointment or while waiting to see their practitioner. Such an assessment may be a brief screening (eg, using similar yes/no questions to an oral screening), or may be a standardized measure. For example, the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale [52] is a 31-item self-report measure that provides scores for suicide ideation, death ideation, loss of personal and social worth, and perceived meaning in life. Though there are not standard cutoffs that suggest high versus low suicide risk, responses can be reviewed to identify whether older adults are reporting suicide ideation or death ideation, and can also be compared to norms (ie, average scores) from other older adults [52]. This measure also has the benefit of 2 subscales that do not specifically require reporting thoughts of suicide or death (ie, loss of personal and social worth, perceived meaning in life), which may give practitioners an indication of an older adult’s suicide risk even if the older adult is not comfortable disclosing suicide ideation, as has been shown in previous research [7,8].

Similarly, the Geriatric Depression Scale, which has a validated 15-item version [53], does not directly ask about suicide ideation but has a 5-item subscale that has been found to be highly correlated with reported suicide ideation [54]. When administered to older adult primary care patients, this subscale was an effective measure of suicide ideation; a score of ≥ 1 was the best cutoff for determining whether an older adult reported suicide ideation [55].

Additionally, as noted previously, the interaction between perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness may identify older adults who are potentially experiencing, but not reporting, suicide ideation [41]. The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire [56] is the validated assessment for both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. Perceived burdensomeness is assessed via 6 self-report items, and thwarted belongingness is assessed via 9 self-report items on this measure [56]. There are not specific cutoffs that determine high versus low perceived burdensomeness or thwarted belongingness, but older adults’ responses can provide information about their experiences of these constructs. Administration of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire can provide information about potential risk for suicide among older adults who may otherwise deny thoughts of suicide or death.

If the screening for suicide ideation or death ideation is positive (ie, the older adult endorses thoughts of suicide or death), the treating primary care practitioner must then follow up with additional questions to determine current level of suicide risk. To make this determination, at a minimum, follow-up questions should focus on whether the older adult has any intent to die by suicide (eg, “Do you have any intent to act on your thoughts of suicide?”), as well as whether he or she has a plan to die by suicide (eg, “Have you begun formulating a plan to die by suicide?”). When asking about a plan, it is important to determine how specific the plan is. For example, an older adult with a specific method identified and date selected to implement the plan is at much higher risk than an older adult with a relatively vague idea. It is also critical to assess for the older adult’s access to means for suicide. If an older adult has a specific plan and has the capability to carry out the plan (eg, plans to overdose on prescription medication and has large quantities of medication or high-lethality medication at home), he or she is more likely to die by suicide than an older adult who does not have access to means (eg, only has small quantities of low-lethality medication available). A general assessment of risk factors and previous suicidal behavior (ie, any previous suicide attempts) also informs decisions about level of risk and interventions.

After a screening or assessment is completed, a risk determination must be made and documented. Acute suicide risk can be categorized as low, moderate, or high. It is not appropriate to say that there is “no” suicide risk present. Low risk occurs when there is no current suicide ideation, no plan to die by suicide, and no intent to act on suicidal thoughts, especially when the patient has no history of suicidal behavior and few risk factors [57]. Moderate risk is evident when there is current suicide ideation, but no specific plan to die by suicide or intent to act on suicidal thoughts. There are likely warning signs or risk factors, which may include previous suicidal behaviors, present in moderate suicide risk [57]. High risk is indicated by current suicide ideation with plan to die by suicide and suicidal intent. There are significant warning signs and risk factors present; there may also be a recent suicide attempt, though this is not a requirement for a high risk determination [57]. Undetermined suicide risk occurs when a practitioner cannot accurately assess risk, but concern regarding suicide is present; this is primarily used when a patient refuses to answer questions about suicide. Undetermined risk should be treated as at least moderate risk. Because research shows that death ideation has similar outcomes to suicide ideation in older adults [14], death ideation should also be factored into determinations of suicide risk; reports of death ideation may indicate low or moderate risk in older adults, dependent upon other risk factors, suicidal intent, and plan.

After a risk determination is made, it must be documented in the medical record. The level of risk and rationale for that determination must be included [58]. Stating only the level of risk without a rationale (ie, the older adult’s responses to questions) is not adequate, and documenting only the older adult’s responses without a determination of risk is also not sufficient. Finally, it is critical to document the intervention that occurred or steps taken after the level of risk was determined.

Critically, stating only that there was no indication of suicide risk is inadequate. For example, documenting “No evidence of suicide risk” is not appropriate. This documentation does not indicate that the older adult was specifically asked about suicide ideation, death ideation, suicidal intent, or plan to die by suicide. It also does not indicate a level of suicide risk. Examples of appropriate documentation include:

Patient was asked about suicide risk. She denied current suicide ideation but reported death ideation. She denied any current suicidal intent or plan. She also denied any previous suicide attempts. Therefore, acute suicide risk was deemed to be low. Provided patient with wallet card about the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Also called the Friendship Line while in the room with the patient to connect her with services. Finally, provided a brief list of local mental health professionals to patient; the patient reported she would like to see Dr. Smith. Called and left a message for Dr. Smith with referral information with patient during appointment.

Patient was asked about suicide risk. He reported both death ideation and suicide ideation. He also reported a nonspecific plan (ie, causing a single-vehicle motor vehicle accident, with no specific plan for the motor vehicle accident or timeframe) and denied any intent to act on his thoughts of suicide. He reported one previous suicide attempt, at age 22, by overdose on over-the-counter medication. He reported that this attempt did not require medical attention. Therefore, acute suicide risk was determined to be moderate. Patient was introduced to the behavioral health specialist, who met with the patient during the appointment to conduct further assessment and intervention.

Specific Intervention Strategies

Despite the fact that the pace of the primary care setting often does not allow for time-intensive intervention, there are ways to address suicide risk in this setting. Importantly, no-suicide contracts should not be used at any time [59,60]. No-suicide contracts are documents that patients who are experiencing suicide ideation are required to sign that state that they will not die by suicide while under the care of the practitioner. These contracts have no evidence of effectiveness, and some researchers argue that they may in fact damage the relationship with patients and serve the practitioner’s needs more than the patient’s needs [59].

One of the best options for older adults at low acute suicide risk is to provide resources and referrals. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be reached at 1-800-273-TALK (8255); trained counselors are available to speak to patients at all times. Wallet cards with information about the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline are available at no charge from the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration online store. The Friendship Line is another service available free to adults ages 60 and older, 24 hours per day, 7 days per week; this line can be reached at 1-800-971-0016. The Friendship Line, which is managed by the Institute on Aging, also provides outreach calls to older adults who may be isolated or lonely, increasing connectedness and potentially reducing suicide risk.

Having a ready list of local mental health professionals with expertise in geriatrics and suicide risk to provide to the patient is also beneficial. Recall, though, that older adults are less likely to seek out and receive mental health services [19]; therefore, connecting the patient with resources or referrals during the appointment is critical. If the practitioner does not have time to do this, having a medical assistant or other staff member that the patient knows engage in this step may be appropriate. For example, the patient can call the Friendship Line or National Suicide Prevention Lifeline while in the room with the practitioner, which may reduce anxiety or stigma about doing so and connect the patient with services. Similarly, calling a local mental health professional to make a referral during the appointment may increase the likelihood that the older adult will follow up on the referral.

The most ideal method of intervention for moderate or high acute suicide risk is a warm handoff to a behavioral or mental health specialist. As primary care and behavioral health become more integrated and financially viable as reimbursement through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services improves [61], it is becoming increasingly likely that such a specialist will be on-site and available. Research has found that collaborative care in primary care reduces suicide risk in older adults [46–48,62]. Mental health specialists can conduct more comprehensive assessments and spend more time intervening to reduce suicide risk among older adults with death or suicide ideation. If an on-site behavioral health specialist is not available, older adults at high suicide risk may need to be referred to an emergency department for further evaluation and follow-up. Each state has its own laws and procedures regarding this process, which should be incorporated into a practice’s procedures for addressing high suicide risk. The procedure often involves ensuring that the older adult is accompanied at all times (ie, not left alone in a room), alerting emergency services (usually via phone call to an emergency line, such as 911), and completion of paperwork by a practitioner asserting that the patient is a danger to self. Police or other emergency personnel are then responsible for transporting the patient for further evaluation and determination of whether hospitalization is required.

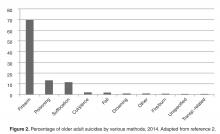

If more time is available, either via the treating primary care practitioner or other patient care staff in the office, other brief interventions may be beneficial. First, means safety discussions are critical, particularly for older adults with plans for suicide or access to highly lethal means. In such discussions, patients are encouraged to restrict access to the methods that they may use to die by suicide. Plans for restricting access are developed, and when possible, a support person is enlisted to ensure that the plans are carried out. For example, if an older adult has access to firearms (eg, keeps a loaded weapon in his or her nightstand), he or she is encouraged to restrict his or her access to it. Ideally, this is through removing the weapon from the home, either permanently or until suicide risk reduces (eg, giving it to a friend, turning it over to police), but more safe storage may also be an option if the older adult is not willing to remove the weapon from the home. This may mean using a gun lock or storing the weapon in a gun safe, storing ammunition separately from an unloaded weapon, removing the firing pin, or otherwise disassembling the weapon. Means safety counseling has been shown to be effective in reducing suicide rates [63] and is acceptable to patients [64]. Studies indicate that over 90% of individuals who make a suicide attempt and survive do not go on to die by suicide [65]; therefore, reducing access to highly lethal means during a suicidal crisis may be key in reducing suicide rates. Though an in-depth review of means safety counseling is outside the scope of this article, readers are directed to Bryan, Stone, and Rudd’s article for a practical overview of means safety discussions [66].

Second, safety planning is a brief intervention that may be beneficial in the primary care setting [67,68]. The goal of a safety plan is to create an individualized plan to remain safe during a suicidal crisis. Means safety discussion is the last of 6 steps in the safety plan [68]. The first 5 steps include identifying warning signs, using internal coping strategies, social connectedness as distraction, social support for the crisis, and professionals that can be used as resources. When patients can identify specific, individualized warning signs that occur prior to a crisis, they can then use strategies to cope and prevent the crisis from worsening. Coping strategies that are encouraged are first internal (ie, those that can be done without relying on anyone else), such as exercise or journaling. If those do not improve the patient’s mood, then he or she is encouraged to use people or social settings as a distraction (eg, people watching at the mall, calling an acquaintance to chat), and if he or she is still feeling bad, encouraged to get social support for the crisis (eg, calling a family member to discuss the crisis and get support). Finally, if all of these steps are not effective, the older adult is encouraged to reach out to professional supports, such as a mental health provider, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, or 911 (or go to an emergency room). Readers are encouraged to review Stanley and Brown’s articles for comprehensive details about safety planning as an intervention [67,68]. Additionally, an article with specific adaptations for safety planning with older adults is forthcoming [69].

Conclusion

Older adults, particularly older men, are at high risk for suicide [1,2], and primary care practitioners are a critical component of older adult suicide prevention. Older adults frequently see primary care practitioners within a month prior to death by suicide [20,21]; primary care practitioners are uniquely qualified to address a broad range of potential risk factors, and may have more interactions and familiarity with older adults at risk for suicide than other medical professionals [20–22]. Primary care practitioners should be prepared to identify risk factors and warning signs for older adult suicide, ask appropriate questions to screen for suicide risk, and intervene to prevent suicide. Screening can consist of standardized written questionnaires or oral questioning, and interventions may include providing resources and referrals, discussions about means safety, safety planning, and handoff to a mental health specialist. Interventions for suicide risk are likely feasible and acceptable in primary care [46–48]. Primary care practitioners have an important role to play in older adult suicide prevention, and must be prepared to interact with older adults who may be at risk for suicide.

Corresponding author: Danielle R. Jahn, PhD, Primary Care Institute, 605 NE 1st St, Gainesville, FL 32605, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None reported.

1. American Association of Suicidology. U.S.A. suicide: 2014official final data. 2016. Accessed at www.suicidology.org/Portals/14/docs/Resources/FactSheets/2014/2014datapgsv1b.pdf.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading causes of death reports, national and regional, 1999-2015. 2016. Accessed at https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcaus10_us.html.

3. Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999-2014. NCHS Data Brief, No 241. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016.

4. US Census Bureau. The next four decades. The older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. 2010. Accessed at www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p25-1138.pdf.

5. Phillips JA, Robin AV, Nugent CN, Idler EL. Understanding recent changes in suicide rates among the middle-aged: period or cohort effects? Public Health Rep 2010;125:680–8.

6. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Issue brief 4: preventing suicide in older adults. 2012. Accessed at https://aoa.acl.gov/AoA_Programs/HPW/Behavioral/docs2/Issue%20Brief%204%20Preventing%20Suicide.pdf.

7. Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Seidlitz L, et al. Age and suicidal ideation in older depressed inpatients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999;7:289–96.

8. Lynch TR, Johnson CS, Mendelson T, et al. Correlates of suicidal ideation among an elderly depressed sample. J Affect Disord 1999;56:9–15.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide: facts at a glance 2015. 2015. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicide-datasheet-a.pdf.

10. Cukrowicz KC, Duberstein PR, Vannoy SD, et al. What factors determine disclosure of suicide ideation in adults 60 and older to a treatment provider? Suicide Life Threat Behav 2014;44:331–7.

11. Kim YA, Bogner HR, Brown GK, Gallo JJ. Chronic medical conditions and wishes to die among older primary care patients. Int J Psychiatry Med 2006;36:183–98.

12. Scocco P, Fantoni G, Rapattoni M, et al. Death ideas, suicidal thoughts, and plans among nursing home residents. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2009;22:141–8.

13. Scocco P, Meneghel G, Caon F, et al. Death ideation and its correlates: survey of an over-65-year-old population. J Nerv Ment Dis 2001;189:210–8.

14. Szanto K, Reynolds III CF, Frank E, et al. Suicide in elderly patients: is active vs. passive suicidal ideation a clinically valid distinction? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2002;4:197–207.

15. Bartels SJ, Coakley E, Oxman TE, et al. Suicidal and death ideation in older primary care patients with depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;10:417–27.

16. Yip PSF. A public health approach to suicide prevention. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2005;15:29–31.

17. van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Sarchiapone M, Postuvan V, et al. Best practice elements of multilevel suicide prevention strategies: a review of systematic reviews. Crisis 2011;32:319–33.

18. Conwell Y. Suicide and suicide prevention in later life. Focus 2013;11:39–47.

19. Crabb R, Hunsley J. Utilization of mental health services among older adults with depression. J Clin Psychol 2006;62:299–312.

20. Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:909–16.

21. Ahmedani BK, Simon GE, Stewart C, et al. Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:870–7.

22. Robinson JW, Roter DL. Psychosocial problem disclosure by primary care patients. Soc Sci Med 1999;48:1353–62.

23. Aminzadeh F, Dalziel WB. Older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review of patterns of use, adverse outcomes, and effectiveness of interventions. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:238–47.

24. Osborn R, Moulds D, Squires D, et al. International survey of older adults finds shortcomings in access, coordination, and patient-centered care. Health Aff 2014;33:2247–55.

25. Siu AL, US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2016;315:380–7.

26. LeFevre ML, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for suicide risk in adolescents, adults, and older adults in primary care: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:719–26.

27. The Joint Commission. Detecting and treating suicide risk in all settings. Sentinel Event Alert 2016;56:1–7.

28. Conwell Y, Van Orden K, Caine ED. Suicide in older adults. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2011;34:451–68.

29. American Association of Suicidology. Know the warning signs of suicide. 2016. Accessed at www.suicidology.org/resources/warning-signs.

30. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Suicide warning signs. 2011. Accessed at www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org/App_Files/Media/PDF/NSPL_WalletCard.pdf.

31. Conwell Y. Suicide later in life: challenges and priorities for prevention. Am J Prev Med 2014;47:S244–50.

32. Hegeman JM, Kok RM, van der Mast RC, Giltay EJ. Phenomenology of depression in older compared with younger adults: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2012;200:275–81.

33. Wuthrich VM, Johnco CJ, Wetherell JL. Differences in anxiety and depression symptoms: comparison between older and younger clinical samples. Int Psychogeriatr 2015;27:1523–32.

34. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Substance abuse among older adults. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 26. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-3918. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 1998.

35. Fiske A, O’Riley AA, Widoe RK. Physical health and suicide in late life: an evaluative review. Clin Gerontologist 2008;31:31–50.

36. Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Conner KR, et al. Suicide at 50 years of age and older: perceived physical illness, family discord, and financial strain. Psychol Med 2004;34:137–46.

37. Draper B, Peisah C, Snowdon J, Brodaty H. Early dementia diagnosis and the risk of suicide and euthanasia. Alzheimers Dement 2010;6:75–82.

38. Joiner T. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2005.

39. Jahn DR, Cukrowicz KC. The impact of the nature of relationships on perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation in a community sample of older adults. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2011;41:635–49.

40. Jahn DR, Cukrowicz KC, Linton K, Prabhu F. The mediating effect of perceived burdensomeness on the relation between depressive symptoms and suicide ideation in a community sample of older adults. Aging Ment Health 2011;15:214–20.

41. Cukrowicz KC, Jahn DR, Graham RD, et al. Suicide risk in older adults: evaluating models of risk and predicting excess zeros in a primary care sample. J Abnorm Psychol 2013;122:1021–30.

42. Fassberg MM, Van Orden KA, Duberstein, P, et al. A systematic review of social factors and suicidal behavior in older adulthood. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012;9:722–45.

43. Pompili M, Innamorati M, Masotti V, et al. Suicide in the elderly: a psychological autopsy study in a north Italy area (1994-2004). Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008;16:727–35.

44. Konrad TR, Link CL, Shackelton RJ, et al. It’s about time: physicians’ perceptions of time constraints in primary medical practice in three national healthcare systems. Med Care 2010;48:95–100.

45. Tai-Seale M, McGuire TG, Zhang W. Time allocation in primary care office visits. Health Serv Res 2006;42:1871–94.

46. Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds III CF, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc 2004;291:1081–91.

47. Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF III, Bruce ML, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT study. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:882–90.

48. Unutzer J, Tang L, Oishi S, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation in depressed older primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1550–6.

49. Boudreaux ED, Camargo Jr CA, Arias SA, et al. Improving suicide risk screening and detection in the emergency department. Am J Prev Med 2016;50:445–53.

50. Mathias CW, Furr RM, Sheftall AH, et al. What’s the harm in asking about suicidal ideation? Suicide Life Threat Behav 2012;42:341–51.

51. Joiner T. Myths about suicide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2011.

52. Heisel MJ, Flett GL. The development and initial validation of the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14:742–51.

53. Sheikh JL, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale: recent evidence and development of a shorter version. In: Brink TL, editor. Clinical gerontology: a guide to assessment and intervention. New York: Howarth Press; 1986: 165–73.

54. Heisel MJ, Flett GL, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Does the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) distinguish between older adults with high versus low levels of suicidal ideation? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;13:876–83.

55. Heisel MJ, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM, Feldman MD. Screening for suicide ideation among older primary care patients. J Am Board Fam Med 2010;23:260–9.

56. Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, Joiner Jr TE. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychol Assess 2012;24;197–215.

57. Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide. 2013. Accessed at www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/srb/VADODCP_SuicideRisk_Full.pdf.

58. Freedenthal S. Documentation: do it well, for the client’s sake and yours. 2013. Accessed at www.speakingofsuicide.com/2013/05/25/documentation/.

59. McMyler C, Pryjmachuk S. Do ‘no-suicide’ contracts work? J Psychiatr Ment Hlt 2008;15:512–22.

60. Rudd MD, Mandrusiak M, Joiner Jr TE. The case against no-suicide contracts: the commitment to treatment statement as a practice alternative. J Clin Psychol 2006;62:243–51.

61. National Institute of Mental Health. Adding better mental health care to primary care: a new era of behavioral health integration. 2016. Accessed at www.nimh.nih.gov/news/science-news/2016/adding-better-mental-health-care-to-primary-care.shtml.

62. Lapierre S, Erlangsen A, Waern M, et al. A systematic review of elderly suicide prevention programs. Crisis 2011;32;88–98.

63. Hawton K. Restricting access to methods of suicide: rationale and evaluation of this approach to suicide prevention. Crisis 2007;28:4–9.

64. Walters H, Kulkarni M, Forman J, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of interventions to delay gun access in VA mental health settings. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2012;34:692–8.

65. Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm: systematic review. Brit J Psychiatry 2002;181:193–9.

66. Bryan CJ, Stone SL, Rudd MD. A practical, evidence-based approach for means-restriction counseling with suicidal patients. Prof Psychol Res Pr 2011;42:339–46.

67. Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety plan treatment manual to reduce suicide risk: veteran version. 2008. Accessed at www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/va_safety_planning_manual.pdf.

68. Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety planning intervention: a brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cogn Behav Pract 2012;19:256–64.

69. Jahn DR, Conti EC, Simons KV, et al. Evidence and considerations for safety planning as a suicide prevention strategy for older adults. 2017. Manuscript in preparation.

70. Knox KL, Stanley B, Currier GW, et al. An emergency department-based brief intervention for veterans at risk for suicide (SAFE VET). Am J Public Health 2012;102:S33–7.

From the Primary Care Institute, Gainesville, FL.

Abstract

- Objective: To provide primary care practitioners with the knowledge required to identify and address older adult suicide risk in their practice.

- Methods: Review of the literature and good clinical practices.

- Results: Primary care practitioners play an important role in older adult suicide prevention and must have knowledge about older adult suicide risk, including risk factors and warning signs in this age-group. Practitioners also must appropriately screen for and manage suicide risk. Older adults, particularly older men, are at high risk for suicide, though they may be less likely to report suicide ideation. Additionally, older adults frequently see primary care practitioners within a month prior to death by suicide. A number of older adult–specific risk factors are reviewed, and appropriate screening and intervention for the primary care setting are discussed.

- Conclusion: Primary care practitioners are uniquely qualified to address a broad range of potential risk factors and should be prepared to identify risk factors and warning signs for older adult suicide, ask appropriate questions to screen for suicide risk, and intervene to prevent suicide.

Key words: suicide; older adults; risk factors; screening; safety planning.

Primary care practitioners play an important role in older adult suicide prevention and have a responsibility to identify and address suicide risk among older adults. To do so, practitioners must understand the problem of older adult suicide, recognize risk factors for suicide in older adults, screen for suicide risk, and appropriately assess and manage suicide risk. Primary care practitioners may face challenges in completing these tasks; the goal of this article is to assist practitioners in addressing these challenges.

Suicide in Older Adults

The United States has recently seen increases in suicide rates across the lifespan; from 1999 to 2014, the suicide rate rose by 24% across all ages [3]. Among both men and women aged 65 to 74, the suicide rate increased in this time period [3]. The high suicide rate among older adults is particularly important to address given the increasing numbers of older adults in the United States. By 2050, the older adult population in the United States is expected to reach 88.5 million, more than double the older adult population in 2010 [4]. Additionally, the generation that is currently aging into older adulthood has historically had higher rates of suicide across their lifespan [5]. Given that suicide rates also increase in older adulthood for men, the coming decades may evidence even higher rates of suicide among older adults than previously and it is critical that older adult suicide prevention becomes a public health priority.

It is also essential to discuss other suicide-related outcomes among older adults, including suicide attempts and suicide ideation. This is critical particularly because the ratio of suicide attempts to deaths by suicide in this age-group is 4 to 1 [1]. This is in contrast to the ratio of attempts to deaths across all ages, which is 25 suicide attempts per death by suicide [1]. This means that suicide prevention must occur before a first suicide attempt is made; suicide attempts cannot be used a marker of elevated suicide risk in older adults or an indication that intervention is needed. Intervention is required prior to suicide risk becoming elevated to the point of a suicide attempt.

It is also critical to recognize that despite the fact that suicide rates rise with age, reports of suicide ideation decrease with age [7,8]. Across all ages, 3.9% of Americans report past-year suicide ideation; however, only 2.7% of older adults report thoughts of suicide [9]. The discrepancy with the increasing rates of death by suicide with age suggest that suicide risk, and thereby opportunities for intervention, may be missed in this age-group [10].

However, older adults may be more willing to report death ideation, as research has found that over 15% of older adults endorse death ideation [11–13]. Death ideation is a desire for death without a specific desire to end one’s own life, and is an important suicide-related outcome, as older adults with death ideation appear the same as those with suicide ideation in terms of depression, hopelessness, and history of suicidal behavior [14]. Additionally, older adults with death ideation had more hospitalizations, more outpatient visits, and more medical issues than older adults with suicide ideation [15]. Therefore, death ideation should be taken as seriously as suicide ideation in older adults [14]. In sum, the high rates of death by suicide, the likelihood of death on a first or early suicide attempt, and the discrepancy between decreasing reports of suicide ideation and increasing rates of death by suicide among older adults indicate that older adult suicide is an important public health problem.

Suicide Prevention Strategies

Many suicide prevention strategies to date have focused on indicated prevention, which concentrates on individuals already identified at high risk (eg, those with suicide ideation or who have made a suicide attempt) [16]. However, because older adults may not report suicide ideation or survive a first suicide attempt, indicated prevention is likely not enough to be effective in older adult suicide prevention. A multilevel suicide prevention strategy [17] is required to prevent older adult suicide [18]. Older adult suicide prevention must include indicated prevention but must also include selective and universal prevention [16]. Selective prevention focuses on groups who may be at risk for suicide (eg, individuals with depression, older adults) and universal prevention focuses on the entire population (eg, interventions to reduce mental health stigma) [16]. To prevent older adult suicide, crisis intervention is critical, but suicide prevention efforts upstream of the development of a suicidal crisis are also essential.

The Importance of Primary Care

Research indicates that primary care is one of the best settings in which to engage in older adult suicide prevention [18]. Older adults are significantly less likely to receive specialty mental health care than younger adults, even when they have depressive symptoms [19]. Additionally, among older adults who died by suicide, 58% had contact with a primary care provider within a month of their deaths, compared to only 11% who had contact with a mental health specialist [20]. Among older adults who died by suicide, 67% saw any provider in the 4 weeks prior to their death [21]. Approximately 10% of older adults saw an outpatient mental health provider, 11% saw a primary care physician for a mental health issue, and 40% saw a primary care physician for a non-mental health issue [21]. Therefore, because older adults are less likely to receive specialty mental health treatment and so often seen a primary care practitioner prior to death by suicide, primary care may be the ideal place for older adult suicide risk to be detected and addressed, especially as many older adults visit primary care without a mental health presenting concern prior to their death by suicide.

Additionally, older adults may be more likely to disclose suicide ideation to primary care practitioners, with whom they are more familiar, than physicians in other settings (eg, emergency departments). Research has shown that familiarity with a primary care physician significantly increases the likelihood of patient disclosure of psychosocial issues to the physician [22]. Primary care providers also have a critical role as care coordinators; many older adults also see specialty physicians and use the emergency department. In fact, older adults are more likely to use the emergency department than younger adults, but emergency departments are not equipped to navigate the complex care needs of this population [23]. Primary care practitioners are important in ensuring that health issues of older adults are addressed by coordinating with specialists, hospitals (eg, inpatient stays, emergency department visits, surgery) and other health services (eg, home health care, physical therapy). Approximately 35% of older adults in the United States experience a lack of care coordination [24], which can negatively impact their health and leave issues such as suicide ideation unaddressed. Primary care practitioners may be critical in screening for mental health issues and suicide risk during even routine visits because of their familiarity with patients, and also play an important role in coordinating care for older adults to improve well-being and to ensure that critical issues, such as suicide ideation, are appropriately addressed.

Primary care practitioners can also be key in upstream prevention. Primary care practitioners are in a unique role to address risk factors for suicide prior to the development of a suicidal crisis. Because older adults frequently see primary care practitioners, such practitioners may have more opportunities to identify risk factors (eg, chronic pain, depression). Primary care practitioners are also trained to treat a broad range of conditions, providing the skills to address many different risk factors.

Finally, primary care is a setting in which screening for depression and suicide ideation among older adults is recommended. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for depression in all adults and older adults and provides recommended screening instruments, some of which include questions about self-harm or suicide risk [25]. However, this same group has concluded that there is insufficient evidence to support a recommendation for suicide risk screening [26]. Despite this, the Joint Commission recently released an alert that recommends screening for suicide risk in all settings, including primary care [27]. The Joint Commission requirement for ambulatory care that is relevant to suicide is PC.04.01.01: The organization has a process that addresses the patient’s need for continuing care, treatment, or services after discharge or transfer; behavioral health settings have additional suicide-specific requirements. The recommendations, though, go far beyond this requirement for primary care. The Joint Commission specifically notes that primary care clinicians play an important role in detecting suicide ideation and recommends that primary care practitioners review each patient’s history for suicide risk factors, screen all patients for suicide risk, review screenings before patients leave appointments, and take appropriate actions to address suicide risk when needed [27]. Further details are available in the Joint Commission’s Sentinel Event Alert titled, “Detecting and treating suicide ideation in all settings” [27]. Given these recommendations, primary care is an important setting in which to identify and address suicide risk.

Risk Factors for Older Adult Suicide

Numerous reviews exist that cover many risk factors for suicide in older adults [18,28]. This article will focus briefly on risk factors that are likely to be recognized and potentially addressed by primary care practitioners. Risk factors that apply across the lifespan can be recalled through a mnemonic: IS PATH WARM [29]. These risk factors include suicide Ideation, Substance abuse, Purposelessness, Anxiety (including agitation and poor sleep), feeling Trapped, Hopelessness, social Withdrawal, Anger or rage, Recklessness (ie, engaging in risky activities), and Mood changes. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline also includes being in unbearable physical pain, perceiving one’s self as a burden to others, and seeking revenge on others as risk factors [30]. More specific to older adults, Conwell notes 5 categories or domains of risk factors with strong research support: psychiatric symptoms, somatic illness, functional impairment, social integration, and personality traits and coping [18,31].

Affective or mood disorders, particularly depression and depressive symptoms, are some of the most well-studied and strongest risk factors for older adult suicide [31]; 71% to 97% of all older adults who die by suicide have psychiatric illnesses [28]. Mood disorders, including major depressive episodes, are most consistently linked to older adult suicide risk; there is evidence as well for anxiety disorders and substance abuse disorders as risk factors, though it is somewhat mixed [28]. Therefore, screening for depression, anxiety, and substance abuse may be key to recognizing potential suicide risk. However, depression and anxiety do not present similarly in younger and older adults [32,33]. Depressive symptoms in older adults may be more somatic (eg, agitation, gastrointestinal symptoms) [32] and may reflect more anhedonia than mood changes [33]. Anxiety in older adults tends to be reported as stress or tension, whereas younger adults report feeling anxious or worried [33]. Additionally, substance abuse is often underrecognized, underdiagnosed, and undertreated in older adults [34]. Proactive screening for substance abuse is important as it may not interfere with work or other obligations in older adults, and therefore substance abuse may not be identified by older adults or others in their lives.

Physical illness may also be a risk factor for suicide [28,31]. Numerous diagnoses have been linked to suicide risk, including cancers, neurodegenerative diseases (eg, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington disease), spinal cord injury, cardiovascular disease, and pulmonary disease [28,35]. However, overall illness burden (ie, number of chronic illnesses) [28] and self-perceived health [36] appear to be stronger risk factors than any specific illness. Additionally, authors have suggested that illness itself may not be a particularly strong risk factor, but the effect of illness on depressive symptoms [35], functioning, pain, or hopelessness due to the potential for decline over time [28] may increase suicide risk in older adults. Pain itself has been identified as a risk factor for suicide, as have perceptions of burden to others, hopelessness, and functional impairment [28].

In terms of functional impairment, research has shown that impairment in completing instrumental activities of daily living is associated with higher risk for death by suicide, and cognitive impairment may also be associated with elevated suicide risk [28]. However, there are some discrepant findings regarding the role of dementia in suicide risk, which may reflect medical and psychiatric comorbidities, as well as different stages of dementia or levels of cognitive impairment (eg, hopelessness about cognitive decline may increase suicide risk shortly after diagnosis, whereas lack of insight may decrease risk later in the course of the illness) [37]. Related to functional or cognitive impairment is perceived burdensomeness (ie, the perception that one is a liability or burden to others, to the point that others would be better off if one was gone) [38], which may also be associated with suicide risk in older adults [39,40]. Researchers have found that the interaction between perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (ie, a belief that one lacks reciprocal caring relationships and does not belong) identified older adults who were likely experiencing suicide ideation but did not report it [41]. These findings indicate that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness may be key in identifying older adults at risk for suicide.

Thwarted belongingness has also been linked to suicide ideation in older adults [41]. In fact, studies suggest that social integration is especially important for reducing suicide risk in this population [28,31,42]. A larger social network, living with others, and being active in the community are each protective against suicide [28]. Bereavement, which can reduce social connectedness and acts as a significant life stressor, is also an important risk factor [31]. Retirement may also reduce social connectedness, and employment changes have been identified as a suicide risk factor for older adults [28]. Retirement has been linked to risk for death by suicide in this population [43], and may not only serve to reduce social connectedness, but for some older adults may also be a significant role loss or loss of sense of purpose that can influence suicide risk.

Finally, rigid personality traits or coping styles are a risk factor for suicide among older adults [28,31]. As older adults face potential losses, health changes, and functional decline, effective positive coping strategies and flexibility are key to maintaining well-being. If older adults are unable to flexibly cope with these challenges, their risk for suicide increases [28].

In addition to risk factors, which confer suicide risk but do not necessarily suggest that an older adult is thinking about suicide, warning signs exist that indicate that suicide risk is imminent. These include suicidal communication (ie, talking or writing about suicide), seeking access to means, and making preparations for suicide (eg, ensuring a will is in place, giving away prized possessions). One important note is that discussing and preparing for death may be developmentally appropriate for older adults, particularly those with chronic illnesses; however, such appropriate preparation is critically different from talking about suicide or a desire for death.

Additionally, a lack of planning for the future may be a warning sign. For example, older adults who decline to schedule medical follow-up or do not wish to refill needed prescriptions may be exhibiting warning signs that should be addressed. Similarly, not following needed medical regimens (eg, an older adult with diabetes no longer taking insulin) is also a warning sign. Other, potentially more subtle warning signs may include significant changes in mood, sleep, or social interactions. Older adults may become agitated and sleep less when they are considering suicide, or may feel more at ease after they have made the decision to die by suicide and their sleep or mood may improve. Withdrawing from valued others may also be a warning sign. Finally, recent major changes (eg, loss of a spouse, moving to an assisted living facility) may be triggers for suicide risk and can serve as warning signs themselves.

Specific Screening Strategies

Given the numerous risk factors and warning signs for older adult suicide, as well as the time limitations that primary care practitioners face [44,45], it would be impractical to comprehensively assess each older adult who presents at a primary care practice. Therefore, more specific screening is necessary. Most importantly, every older adult should be screened for suicide ideation and death ideation at every visit. Screening at every visit is critical because suicide ideation may develop at any point. Previous research has included screening of over 29,000 older adults in 11 primary care settings for suicide ideation, risk of alcohol misuse, and mental health disorders [15], suggesting that suicide risk screening is feasible. Other studies have also successfully used widespread screening for depression and suicide ideation among older adults in primary care [46–48]. Additionally, in an emergency department setting, universal suicide risk screening has been associated with significantly improved risk detection [49], indicating that improved screening may be beneficial in identifying suicide risk. Importantly, asking about suicide does not cause thoughts of suicide [50]. Additionally, it is a myth that those who talk about suicide ideation will not act on these thoughts [51].

When primary care practitioners inquire about suicide ideation, they should also ask about death ideation; though some may believe that death ideation is not as significant in terms of suicide risk as suicide ideation, recall that research has not found differences in previous suicide attempts or current hopelessness among older adults with death ideation versus suicide ideation [14]. Therefore, screening for death ideation should be completed as part of every suicide risk screening.

Screening can take many forms. Screening may be oral; asking an older adult if he or she is having thoughts of suicide or is experiencing a desire to die is a brief, 2-question screening that may provide valuable information (eg, “Are you having thoughts about your own death or wanting to die?”, “Are you having thoughts of killing yourself or thinking about suicide?”). This screening may be conducted by medical assistants, nurses, care managers, or physicians, with the patient’s responses documented. Importantly, a standard procedure should be implemented to ensure older adults are consistently asked about suicide risk at each visit, but do not feel inundated by such questions from numerous staff.

If verbal questions are asked, they must be asked appropriately. Euphemisms or indirect language should not be used during a screening; older adults should be directly asked about thoughts of death and suicide, not simply asked questions such as, “Have you ever had thoughts of harming or hurting yourself?” A question like this does not adequately assess current suicide risk, as it does not assess current thoughts, nor does it specifically inquire about suicide ideation (ie, killing one’s self). It is also important to phrase questions in a manner that invites honest responses and conveys an openness to listening. For example, asking, “You’re not thinking about suicide, are you?” suggests that the practitioner wants the older adult to say no and is not comfortable with the older adult endorsing suicide ideation. Open questions that allow endorsement or denial (eg, “Are you having thoughts of killing yourself?”) imply that the practitioner is receptive to either an endorsement or denial of suicide ideation.

Alternatively, a written screening can be used; older adults may complete a questionnaire prior to their appointment or while waiting to see their practitioner. Such an assessment may be a brief screening (eg, using similar yes/no questions to an oral screening), or may be a standardized measure. For example, the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale [52] is a 31-item self-report measure that provides scores for suicide ideation, death ideation, loss of personal and social worth, and perceived meaning in life. Though there are not standard cutoffs that suggest high versus low suicide risk, responses can be reviewed to identify whether older adults are reporting suicide ideation or death ideation, and can also be compared to norms (ie, average scores) from other older adults [52]. This measure also has the benefit of 2 subscales that do not specifically require reporting thoughts of suicide or death (ie, loss of personal and social worth, perceived meaning in life), which may give practitioners an indication of an older adult’s suicide risk even if the older adult is not comfortable disclosing suicide ideation, as has been shown in previous research [7,8].

Similarly, the Geriatric Depression Scale, which has a validated 15-item version [53], does not directly ask about suicide ideation but has a 5-item subscale that has been found to be highly correlated with reported suicide ideation [54]. When administered to older adult primary care patients, this subscale was an effective measure of suicide ideation; a score of ≥ 1 was the best cutoff for determining whether an older adult reported suicide ideation [55].

Additionally, as noted previously, the interaction between perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness may identify older adults who are potentially experiencing, but not reporting, suicide ideation [41]. The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire [56] is the validated assessment for both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. Perceived burdensomeness is assessed via 6 self-report items, and thwarted belongingness is assessed via 9 self-report items on this measure [56]. There are not specific cutoffs that determine high versus low perceived burdensomeness or thwarted belongingness, but older adults’ responses can provide information about their experiences of these constructs. Administration of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire can provide information about potential risk for suicide among older adults who may otherwise deny thoughts of suicide or death.

If the screening for suicide ideation or death ideation is positive (ie, the older adult endorses thoughts of suicide or death), the treating primary care practitioner must then follow up with additional questions to determine current level of suicide risk. To make this determination, at a minimum, follow-up questions should focus on whether the older adult has any intent to die by suicide (eg, “Do you have any intent to act on your thoughts of suicide?”), as well as whether he or she has a plan to die by suicide (eg, “Have you begun formulating a plan to die by suicide?”). When asking about a plan, it is important to determine how specific the plan is. For example, an older adult with a specific method identified and date selected to implement the plan is at much higher risk than an older adult with a relatively vague idea. It is also critical to assess for the older adult’s access to means for suicide. If an older adult has a specific plan and has the capability to carry out the plan (eg, plans to overdose on prescription medication and has large quantities of medication or high-lethality medication at home), he or she is more likely to die by suicide than an older adult who does not have access to means (eg, only has small quantities of low-lethality medication available). A general assessment of risk factors and previous suicidal behavior (ie, any previous suicide attempts) also informs decisions about level of risk and interventions.

After a screening or assessment is completed, a risk determination must be made and documented. Acute suicide risk can be categorized as low, moderate, or high. It is not appropriate to say that there is “no” suicide risk present. Low risk occurs when there is no current suicide ideation, no plan to die by suicide, and no intent to act on suicidal thoughts, especially when the patient has no history of suicidal behavior and few risk factors [57]. Moderate risk is evident when there is current suicide ideation, but no specific plan to die by suicide or intent to act on suicidal thoughts. There are likely warning signs or risk factors, which may include previous suicidal behaviors, present in moderate suicide risk [57]. High risk is indicated by current suicide ideation with plan to die by suicide and suicidal intent. There are significant warning signs and risk factors present; there may also be a recent suicide attempt, though this is not a requirement for a high risk determination [57]. Undetermined suicide risk occurs when a practitioner cannot accurately assess risk, but concern regarding suicide is present; this is primarily used when a patient refuses to answer questions about suicide. Undetermined risk should be treated as at least moderate risk. Because research shows that death ideation has similar outcomes to suicide ideation in older adults [14], death ideation should also be factored into determinations of suicide risk; reports of death ideation may indicate low or moderate risk in older adults, dependent upon other risk factors, suicidal intent, and plan.

After a risk determination is made, it must be documented in the medical record. The level of risk and rationale for that determination must be included [58]. Stating only the level of risk without a rationale (ie, the older adult’s responses to questions) is not adequate, and documenting only the older adult’s responses without a determination of risk is also not sufficient. Finally, it is critical to document the intervention that occurred or steps taken after the level of risk was determined.

Critically, stating only that there was no indication of suicide risk is inadequate. For example, documenting “No evidence of suicide risk” is not appropriate. This documentation does not indicate that the older adult was specifically asked about suicide ideation, death ideation, suicidal intent, or plan to die by suicide. It also does not indicate a level of suicide risk. Examples of appropriate documentation include: