User login

Less Lumens-Less Risk: A Pilot Intervention to Increase the Use of Single-Lumen Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters

Vascular access is a cornerstone of safe and effective medical care. The use of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) to meet vascular access needs has recently increased.1,2 PICCs offer several advantages over other central venous catheters. These advantages include increased reliability over intermediate to long-term use and reductions in complication rates during insertion.3,4

Multiple studies have suggested a strong association between the number of PICC lumens and risk of complications, such as central-line associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI), venous thrombosis, and catheter occlusion.5-8,9,10-12 These complications may lead to device failure, interrupt therapy, prolonged length of stay, and increased healthcare costs.13-15 Thus, available guidelines recommend using PICCs with the least clinically necessary number of lumens.1,16 Quality improvement strategies that have targeted decreasing the number of PICC lumens have reduced complications and healthcare costs.17-19 However, variability exists in the selection of the number of PICC lumens, and many providers request multilumen devices “just in case” additional lumens are needed.20,21 Such variation in device selection may stem from the paucity of information that defines the appropriate indications for the use of single- versus multi-lumen PICCs.

Therefore, to ensure appropriateness of PICC use, we designed an intervention to improve selection of the number of PICC lumens.

METHODS

We conducted this pre–post quasi-experimental study in accordance with SQUIRE guidelines.22 Details regarding clinical parameters associated with the decision to place a PICC, patient characteristics, comorbidities, complications, and laboratory values were collected from the medical records of patients. All PICCs were placed by the Vascular Access Service Team (VAST) during the study period.

Intervention

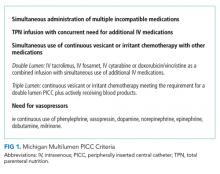

The intervention consisted of three components: first, all hospitalists, pharmacists, and VAST nurses received education in the form of a CME lecture that emphasized use of the Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC).1 These criteria define when use of a PICC is appropriate and emphasize how best to select the most appropriate device characteristics such as lumens and catheter gauge. Next, a multidisciplinary task force that consisted of hospitalists, VAST nurses, and pharmacists developed a list of indications specifying when use of a multilumen PICC was appropriate.1 Third, the order for a PICC in our electronic medical record (EMR) system was modified to set single-lumen PICCs as default. If a multilumen PICC was requested, text-based justification from the ordering clinician was required.

As an additional safeguard, a VAST nurse reviewed the number of lumens and clinical scenario for each PICC order prior to insertion. If the number of lumens ordered was considered inappropriate on the basis of the developed list of MAGIC recommendations, the case was referred to a pharmacist for additional review. The pharmacist then reviewed active and anticipated medications, explored options for adjusting the medication delivery plan, and discussed these options with the ordering clinician to determine the most appropriate number of lumens.

Measures and Definitions

In accordance with the criteria set by the Centers for Disease Control National Healthcare Safety Network,23 CLABSI was defined as a confirmed positive blood culture with a PICC in place for 48 hours or longer without another identified infection source or a positive PICC tip culture in the setting of clinically suspected infection. Venous thrombosis was defined as symptomatic upper extremity deep vein thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism that was radiographically confirmed after the placement of a PICC or within one week of device removal. Catheter occlusion was captured when documented or when tPA was administered for problems related to the PICC. The appropriateness of the number of PICC lumens was independently adjudicated by an attending physician and clinical pharmacist by comparing the indications of the device placed against predefined appropriateness criteria.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the change in the proportion of single-lumen PICCs placed. Secondary outcomes included (1) the placement of PICCs with an appropriate number of lumens, (2) the occurrence of PICC-related complications (CLABSI, venous thrombosis, and catheter occlusion), and (3) the need for a second procedure to place a multilumen device or additional vascular access.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to tabulate and summarize patient and PICC characteristics. Differences between pre- and postintervention populations were assessed using χ2, Fishers exact, t-, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Differences in complications were assessed using the two-sample tests of proportions. Results were reported as medians (IQR) and percentages with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. All statistical tests were two-sided, with P < .05 considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted with Stata v.14 (stataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Ethical and Regulatory Oversight

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan (IRB#HUM00118168).

RESULTS

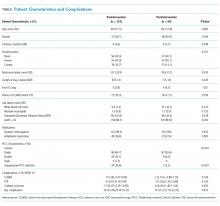

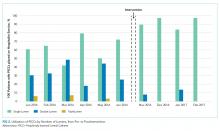

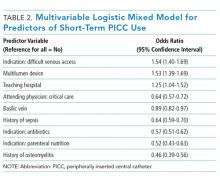

Of the 133 PICCs placed preintervention, 64.7% (n = 86) were single lumen, 33.1% (n = 44) were double lumen, and 2.3% (n = 3) were triple lumen. Compared with the preintervention period, the use of single-lumen PICCs significantly increased following the intervention (64.7% to 93.6%; P < .001; Figure 1). As well, the proportion of PICCs with an inappropriate number of lumens decreased from 25.6% to 2.2% (P < .001; Table 1).

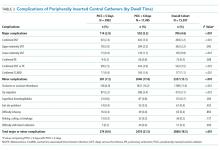

Preintervention, 14.3% (95% CI = 8.34-20.23) of the patients with PICCs experienced at least one complication (n = 19). Following the intervention, 15.1% (95% CI = 7.79-22.32) of the 93 patients with PICCs experienced at least one complication (absolute difference = 0.8%, P = .872). With respect to individual complications, CLABSI decreased from 5.3% (n = 7; 95% CI = 1.47-9.06) to 2.2% (n = 2; 95% CI = −0.80-5.10) (P = .239). Similarly, the incidence of catheter occlusion decreased from 8.3% (n = 11; 95% CI = 3.59-12.95) to 6.5% (n = 6; 95% CI = 1.46-11.44; P = .610; Table). Notably, only 12.1% (n = 21) of patients with a single-lumen PICC experienced any complication, whereas 20.0% (n = 10) of patients with a double lumen, and 66.7% (n = 2) with a triple lumen experienced a PICC-associated complication (P = .022). Patients with triple lumens had a significantly higher incidence of catheter occlusion compared with patients that received double- and single-lumen PICCs (66.7% vs. 12.0% and 5.2%, respectively; P = .003).

No patient who received a single-lumen device required a second procedure for the placement of a device with additional lumens. Similarly, no documentation suggesting an insufficient number of PICC lumens or the need for additional vascular access (eg, placement of additional PICCs) was found in medical records of patients postintervention. Pharmacists supporting the interventions and VAST team members reported no disagreements when discussing number of lumens or appropriateness of catheter choice.

DISCUSSION

In this single center, pre–post quasi-experimental study, a multimodal intervention based on the MAGIC criteria significantly reduced the use of multilumen PICCs. Additionally, a trend toward reductions in complications, including CLABSI and catheter occlusion, was also observed. Notably, these changes in ordering practices did not lead to requests for additional devices or replacement with a multilumen PICC when a single-lumen device was inserted. Collectively, our findings suggest that the use of single-lumen devices in a large direct care service can be feasibly and safely increased through this approach. Larger scale studies that implement MAGIC to inform placement of multilumen PICCs and reduce PICC-related complications now appear necessary.

The presence of a PICC, even for short periods, significantly increases the risk of CLABSI and is one of the strongest predictors of venous thrombosis risk in the hospital setting.19,24,25 Although some factors that lead to this increased risk are patient-related and not modifiable (eg, malignancy or intensive care unit status), increased risk linked to the gauge of PICCs and the number of PICC lumens can be modified by improving device selection.9,18,26 Deliberate use of PICCs with the least numbers of clinically necessary lumens decreases risk of CLABSI, venous thrombosis and overall cost.17,19,26 Additionally, greater rates of occlusion with each additional PICC lumen may result in the interruption of intravenous therapy, the administration of costly medications (eg, tissue plasminogen activator) to salvage the PICC, and premature removal of devices should the occlusion prove irreversible.8

We observed a trend toward decreased PICC complications following implementation of our criteria, especially for the outcomes of CLABSI and catheter occlusion. Given the pilot nature of this study, we were underpowered to detect a statistically significant change in PICC adverse events. However, we did observe a statistically significant increase in the rate of single-lumen PICC use following our intervention. Notably, this increase occurred in the setting of high rates of single-lumen PICC use at baseline (64%). Therefore, an important takeaway from our findings is that room for improving PICC appropriateness exists even among high performers. This finding In turn, high baseline use of single-lumen PICCs may also explain why a robust reduction in PICC complications was not observed in our study, given that other studies showing reduction in the rates of complications began with considerably low rates of single-lumen device use.19 Outcomes may improve, however, if we expand and sustain these changes or expand to larger settings. For example, (based on assumptions from a previously published simulation study and our average hospital medicine daily census of 98 patients) the increased use of single-over multilumen PICCs is expected to decrease CLABSI events and venous thrombosis episodes by 2.4-fold in our hospital medicine service with an associated cost savings of $74,300 each year.17 Additionally, we would also expect the increase in the proportion of single-lumen PICCs to reduce rates of catheter occlusion. This reduction, in turn, would lessen interruptions in intravenous therapy, the need for medications to treat occlusion, and the need for device replacement all leading to reduced costs.27 Overall, then, our intervention (informed by appropriateness criteria) provides substantial benefits to hospital savings and patient safety.

After our intervention, 98% of all PICCs placed were found to comply with appropriate criteria for multilumen PICC use. We unexpectedly found that the most important factor driving our findings was not oversight or order modification by the pharmacy team or VAST nurses, but rather better decisions made by physicians at the outset. Specifically, we did not find a single instance wherein the original PICC order was changed to a device with a different number of lumens after review from the VAST team. We attribute this finding to receptiveness of physicians to change ordering practices following education and the redesign of the default EMR PICC order, both of which provided a scientific rationale for multilumen PICC use. Clarifying the risk and criteria of the use of multilumen devices along with providing an EMR ordering process that supports best practice helped hospitalists “do the right thing”. Additionally, setting single-lumen devices as the preselected EMR order and requiring text-based justification for placement of a multilumen PICC helped provide a nudge to physicians, much as it has done with antibiotic choices.28

Our study has limitations. First, we were only able to identify complications that were captured by our EMR. Given that over 70% of the patients in our study were discharged with a PICC in place, we do not know whether complications may have developed outside the hospital. Second, our intervention was resource intensive and required partnership with pharmacy, VAST, and hospitalists. Thus, the generalizability of our intervention to other institutions without similar support is unclear. Third, despite an increase in the use of single-lumen PICCs and a decrease in multilumen devices, we did not observe a significant reduction in all types of complications. While our high rate of single-lumen PICC use may account for these findings, larger scale studies are needed to better study the impact of MAGIC and appropriateness criteria on PICC complications. Finally, given our approach, we cannot identify the most effective modality within our bundled intervention. Stepped wedge or single-component studies are needed to further address this question.

In conclusion, we piloted a multimodal intervention to promote the use of single-lumen PICCs while lowering the use of multilumen devices. By using MAGIC to create appropriate indications, the use of multilumen PICCs declined and complications trended downwards. Larger, multicenter studies to validate our findings and examine the sustainability of this intervention would be welcomed.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, et al. The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC): Results from a multispecialty panel using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6 Suppl):S1-S40. doi: 10.7326/M15-0744. PubMed

2. Taylor RW, Palagiri AV. Central venous catheterization. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(5):1390-1396. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000260241.80346.1B. PubMed

3. Pikwer A, Akeson J, Lindgren S. Complications associated with peripheral or central routes for central venous cannulation. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(1):65-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06911.x. PubMed

4. Johansson E, Hammarskjold F, Lundberg D, Arnlind MH. Advantages and disadvantages of peripherally inserted central venous catheters (PICC) compared to other central venous lines: a systematic review of the literature. Acta Onco. 2013;52(5):886-892. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.773072. PubMed

5. Pan L, Zhao Q, Yang X. Risk factors for venous thrombosis associated with peripherally inserted central venous catheters. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7(12):5814-5819. PubMed

6. Herc E, Patel P, Washer LL, Conlon A, Flanders SA, Chopra V. A model to predict central-line-associated bloodstream infection among patients with peripherally inserted central catheters: The MPC score. Infect Cont Hosp Ep. 2017;38(10):1155-1166. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.167. PubMed

7. Maki DG, Kluger DM, Crnich CJ. The risk of bloodstream infection in adults with different intravascular devices: a systematic review of 200 published prospective studies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(9):1159–1171. doi: 10.4065/81.9.1159. PubMed

8. Smith SN, Moureau N, Vaughn VM, et al. Patterns and predictors of peripherally inserted central catheter occlusion: The 3P-O study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28(5):749-756.e742. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.02.005. PubMed

9. Chopra V, Anand S, Hickner A, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with peripherally inserted central catheters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9889):311-325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60592-9. PubMed

10. Chopra V, Ratz D, Kuhn L, Lopus T, Lee A, Krein S. Peripherally inserted central catheter-related deep vein thrombosis: contemporary patterns and predictors. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(6):847-854. doi: 10.1111/jth.12549. PubMed

11. Carter JH, Langley JM, Kuhle S, Kirkland S. Risk factors for central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infection in pediatric patients: A cohort study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(8):939-945. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.83. PubMed

12. Chopra V, Ratz D, Kuhn L, Lopus T, Chenoweth C, Krein S. PICC-associated bloodstream infections: prevalence, patterns, and predictors. Am J Med. 2014;127(4):319-328. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.01.001. PubMed

13. O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(9):e162-e193. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir257. PubMed

14. Parkinson R, Gandhi M, Harper J, Archibald C. Establishing an ultrasound guided peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) insertion service. Clin Radiol. 1998;53(1):33-36. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(98)80031-7. PubMed

15. Shannon RP, Patel B, Cummins D, Shannon AH, Ganguli G, Lu Y. Economics of central line--associated bloodstream infections. Am J Med Qual. 2006;21(6 Suppl):7s–16s. doi: 10.1177/1062860606294631. PubMed

16. Mermis JD, Strom JC, Greenwood JP, et al. Quality improvement initiative to reduce deep vein thrombosis associated with peripherally inserted central catheters in adults with cystic fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(9):1404-1410. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201404-175OC. PubMed

17. Ratz D, Hofer T, Flanders SA, Saint S, Chopra V. Limiting the number of lumens in peripherally inserted central catheters to improve outcomes and reduce cost: A simulation study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(7):811-817. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.55. PubMed

18. Chopra V, Anand S, Krein SL, Chenoweth C, Saint S. Bloodstream infection, venous thrombosis, and peripherally inserted central catheters: reappraising the evidence. Am J Med. 2012;125(8):733-741. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.04.010. PubMed

19. O’Brien J, Paquet F, Lindsay R, Valenti D. Insertion of PICCs with minimum number of lumens reduces complications and costs. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;10(11):864-868. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.06.003. PubMed

20. Tiwari MM, Hermsen ED, Charlton ME, Anderson JR, Rupp ME. Inappropriate intravascular device use: a prospective study. J Hosp Infect. 2011;78(2):128-132. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.03.004. PubMed

21. Chopra V, Kuhn L, Flanders SA, Saint S, Krein SL. Hospitalist experiences, practice, opinions, and knowledge regarding peripherally inserted central catheters: results of a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):635-638. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2095. PubMed

22. Goodman D, Ogrinc G, Davies L, et al. Explanation and elaboration of the SQUIRE (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence) Guidelines, V.2.0: examples of SQUIRE elements in the healthcare improvement literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(12):e7. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004480. PubMed

23. CDC Bloodstream Infection/Device Associated Infection Module. https://wwwcdcgov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/4psc_clabscurrentpdf 2017. Accessed April 11, 2017.

24. Woller SC, Stevens SM, Jones JP, et al. Derivation and validation of a simple model to identify venous thromboembolism risk in medical patients. Am J Med. 2011;124(10):947-954.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.06.004. PubMed

25. Paje D, Conlon A, Kaatz S, et al. Patterns and predictors of short-term peripherally inserted central catheter use: A multicenter prospective cohort study. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(2):76-82. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2847. PubMed

26. Evans RS, Sharp JH, Linford LH, et al. Reduction of peripherally inserted central catheter-associated DVT. Chest. 2013;143(3):627-633. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0923. PubMed

27. Smith S, Moureau N, Vaughn VM, et al. Patterns and predictors of peripherally inserted central catheter occlusion: The 3P-O study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28(5):749-756.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.02.005. PubMed

28. Vaughn VM, Linder JA. Thoughtless design of the electronic health record drives overuse, but purposeful design can nudge improved patient care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(8):583-586. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007578. PubMed

Vascular access is a cornerstone of safe and effective medical care. The use of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) to meet vascular access needs has recently increased.1,2 PICCs offer several advantages over other central venous catheters. These advantages include increased reliability over intermediate to long-term use and reductions in complication rates during insertion.3,4

Multiple studies have suggested a strong association between the number of PICC lumens and risk of complications, such as central-line associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI), venous thrombosis, and catheter occlusion.5-8,9,10-12 These complications may lead to device failure, interrupt therapy, prolonged length of stay, and increased healthcare costs.13-15 Thus, available guidelines recommend using PICCs with the least clinically necessary number of lumens.1,16 Quality improvement strategies that have targeted decreasing the number of PICC lumens have reduced complications and healthcare costs.17-19 However, variability exists in the selection of the number of PICC lumens, and many providers request multilumen devices “just in case” additional lumens are needed.20,21 Such variation in device selection may stem from the paucity of information that defines the appropriate indications for the use of single- versus multi-lumen PICCs.

Therefore, to ensure appropriateness of PICC use, we designed an intervention to improve selection of the number of PICC lumens.

METHODS

We conducted this pre–post quasi-experimental study in accordance with SQUIRE guidelines.22 Details regarding clinical parameters associated with the decision to place a PICC, patient characteristics, comorbidities, complications, and laboratory values were collected from the medical records of patients. All PICCs were placed by the Vascular Access Service Team (VAST) during the study period.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of three components: first, all hospitalists, pharmacists, and VAST nurses received education in the form of a CME lecture that emphasized use of the Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC).1 These criteria define when use of a PICC is appropriate and emphasize how best to select the most appropriate device characteristics such as lumens and catheter gauge. Next, a multidisciplinary task force that consisted of hospitalists, VAST nurses, and pharmacists developed a list of indications specifying when use of a multilumen PICC was appropriate.1 Third, the order for a PICC in our electronic medical record (EMR) system was modified to set single-lumen PICCs as default. If a multilumen PICC was requested, text-based justification from the ordering clinician was required.

As an additional safeguard, a VAST nurse reviewed the number of lumens and clinical scenario for each PICC order prior to insertion. If the number of lumens ordered was considered inappropriate on the basis of the developed list of MAGIC recommendations, the case was referred to a pharmacist for additional review. The pharmacist then reviewed active and anticipated medications, explored options for adjusting the medication delivery plan, and discussed these options with the ordering clinician to determine the most appropriate number of lumens.

Measures and Definitions

In accordance with the criteria set by the Centers for Disease Control National Healthcare Safety Network,23 CLABSI was defined as a confirmed positive blood culture with a PICC in place for 48 hours or longer without another identified infection source or a positive PICC tip culture in the setting of clinically suspected infection. Venous thrombosis was defined as symptomatic upper extremity deep vein thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism that was radiographically confirmed after the placement of a PICC or within one week of device removal. Catheter occlusion was captured when documented or when tPA was administered for problems related to the PICC. The appropriateness of the number of PICC lumens was independently adjudicated by an attending physician and clinical pharmacist by comparing the indications of the device placed against predefined appropriateness criteria.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the change in the proportion of single-lumen PICCs placed. Secondary outcomes included (1) the placement of PICCs with an appropriate number of lumens, (2) the occurrence of PICC-related complications (CLABSI, venous thrombosis, and catheter occlusion), and (3) the need for a second procedure to place a multilumen device or additional vascular access.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to tabulate and summarize patient and PICC characteristics. Differences between pre- and postintervention populations were assessed using χ2, Fishers exact, t-, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Differences in complications were assessed using the two-sample tests of proportions. Results were reported as medians (IQR) and percentages with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. All statistical tests were two-sided, with P < .05 considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted with Stata v.14 (stataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Ethical and Regulatory Oversight

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan (IRB#HUM00118168).

RESULTS

Of the 133 PICCs placed preintervention, 64.7% (n = 86) were single lumen, 33.1% (n = 44) were double lumen, and 2.3% (n = 3) were triple lumen. Compared with the preintervention period, the use of single-lumen PICCs significantly increased following the intervention (64.7% to 93.6%; P < .001; Figure 1). As well, the proportion of PICCs with an inappropriate number of lumens decreased from 25.6% to 2.2% (P < .001; Table 1).

Preintervention, 14.3% (95% CI = 8.34-20.23) of the patients with PICCs experienced at least one complication (n = 19). Following the intervention, 15.1% (95% CI = 7.79-22.32) of the 93 patients with PICCs experienced at least one complication (absolute difference = 0.8%, P = .872). With respect to individual complications, CLABSI decreased from 5.3% (n = 7; 95% CI = 1.47-9.06) to 2.2% (n = 2; 95% CI = −0.80-5.10) (P = .239). Similarly, the incidence of catheter occlusion decreased from 8.3% (n = 11; 95% CI = 3.59-12.95) to 6.5% (n = 6; 95% CI = 1.46-11.44; P = .610; Table). Notably, only 12.1% (n = 21) of patients with a single-lumen PICC experienced any complication, whereas 20.0% (n = 10) of patients with a double lumen, and 66.7% (n = 2) with a triple lumen experienced a PICC-associated complication (P = .022). Patients with triple lumens had a significantly higher incidence of catheter occlusion compared with patients that received double- and single-lumen PICCs (66.7% vs. 12.0% and 5.2%, respectively; P = .003).

No patient who received a single-lumen device required a second procedure for the placement of a device with additional lumens. Similarly, no documentation suggesting an insufficient number of PICC lumens or the need for additional vascular access (eg, placement of additional PICCs) was found in medical records of patients postintervention. Pharmacists supporting the interventions and VAST team members reported no disagreements when discussing number of lumens or appropriateness of catheter choice.

DISCUSSION

In this single center, pre–post quasi-experimental study, a multimodal intervention based on the MAGIC criteria significantly reduced the use of multilumen PICCs. Additionally, a trend toward reductions in complications, including CLABSI and catheter occlusion, was also observed. Notably, these changes in ordering practices did not lead to requests for additional devices or replacement with a multilumen PICC when a single-lumen device was inserted. Collectively, our findings suggest that the use of single-lumen devices in a large direct care service can be feasibly and safely increased through this approach. Larger scale studies that implement MAGIC to inform placement of multilumen PICCs and reduce PICC-related complications now appear necessary.

The presence of a PICC, even for short periods, significantly increases the risk of CLABSI and is one of the strongest predictors of venous thrombosis risk in the hospital setting.19,24,25 Although some factors that lead to this increased risk are patient-related and not modifiable (eg, malignancy or intensive care unit status), increased risk linked to the gauge of PICCs and the number of PICC lumens can be modified by improving device selection.9,18,26 Deliberate use of PICCs with the least numbers of clinically necessary lumens decreases risk of CLABSI, venous thrombosis and overall cost.17,19,26 Additionally, greater rates of occlusion with each additional PICC lumen may result in the interruption of intravenous therapy, the administration of costly medications (eg, tissue plasminogen activator) to salvage the PICC, and premature removal of devices should the occlusion prove irreversible.8

We observed a trend toward decreased PICC complications following implementation of our criteria, especially for the outcomes of CLABSI and catheter occlusion. Given the pilot nature of this study, we were underpowered to detect a statistically significant change in PICC adverse events. However, we did observe a statistically significant increase in the rate of single-lumen PICC use following our intervention. Notably, this increase occurred in the setting of high rates of single-lumen PICC use at baseline (64%). Therefore, an important takeaway from our findings is that room for improving PICC appropriateness exists even among high performers. This finding In turn, high baseline use of single-lumen PICCs may also explain why a robust reduction in PICC complications was not observed in our study, given that other studies showing reduction in the rates of complications began with considerably low rates of single-lumen device use.19 Outcomes may improve, however, if we expand and sustain these changes or expand to larger settings. For example, (based on assumptions from a previously published simulation study and our average hospital medicine daily census of 98 patients) the increased use of single-over multilumen PICCs is expected to decrease CLABSI events and venous thrombosis episodes by 2.4-fold in our hospital medicine service with an associated cost savings of $74,300 each year.17 Additionally, we would also expect the increase in the proportion of single-lumen PICCs to reduce rates of catheter occlusion. This reduction, in turn, would lessen interruptions in intravenous therapy, the need for medications to treat occlusion, and the need for device replacement all leading to reduced costs.27 Overall, then, our intervention (informed by appropriateness criteria) provides substantial benefits to hospital savings and patient safety.

After our intervention, 98% of all PICCs placed were found to comply with appropriate criteria for multilumen PICC use. We unexpectedly found that the most important factor driving our findings was not oversight or order modification by the pharmacy team or VAST nurses, but rather better decisions made by physicians at the outset. Specifically, we did not find a single instance wherein the original PICC order was changed to a device with a different number of lumens after review from the VAST team. We attribute this finding to receptiveness of physicians to change ordering practices following education and the redesign of the default EMR PICC order, both of which provided a scientific rationale for multilumen PICC use. Clarifying the risk and criteria of the use of multilumen devices along with providing an EMR ordering process that supports best practice helped hospitalists “do the right thing”. Additionally, setting single-lumen devices as the preselected EMR order and requiring text-based justification for placement of a multilumen PICC helped provide a nudge to physicians, much as it has done with antibiotic choices.28

Our study has limitations. First, we were only able to identify complications that were captured by our EMR. Given that over 70% of the patients in our study were discharged with a PICC in place, we do not know whether complications may have developed outside the hospital. Second, our intervention was resource intensive and required partnership with pharmacy, VAST, and hospitalists. Thus, the generalizability of our intervention to other institutions without similar support is unclear. Third, despite an increase in the use of single-lumen PICCs and a decrease in multilumen devices, we did not observe a significant reduction in all types of complications. While our high rate of single-lumen PICC use may account for these findings, larger scale studies are needed to better study the impact of MAGIC and appropriateness criteria on PICC complications. Finally, given our approach, we cannot identify the most effective modality within our bundled intervention. Stepped wedge or single-component studies are needed to further address this question.

In conclusion, we piloted a multimodal intervention to promote the use of single-lumen PICCs while lowering the use of multilumen devices. By using MAGIC to create appropriate indications, the use of multilumen PICCs declined and complications trended downwards. Larger, multicenter studies to validate our findings and examine the sustainability of this intervention would be welcomed.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Vascular access is a cornerstone of safe and effective medical care. The use of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) to meet vascular access needs has recently increased.1,2 PICCs offer several advantages over other central venous catheters. These advantages include increased reliability over intermediate to long-term use and reductions in complication rates during insertion.3,4

Multiple studies have suggested a strong association between the number of PICC lumens and risk of complications, such as central-line associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI), venous thrombosis, and catheter occlusion.5-8,9,10-12 These complications may lead to device failure, interrupt therapy, prolonged length of stay, and increased healthcare costs.13-15 Thus, available guidelines recommend using PICCs with the least clinically necessary number of lumens.1,16 Quality improvement strategies that have targeted decreasing the number of PICC lumens have reduced complications and healthcare costs.17-19 However, variability exists in the selection of the number of PICC lumens, and many providers request multilumen devices “just in case” additional lumens are needed.20,21 Such variation in device selection may stem from the paucity of information that defines the appropriate indications for the use of single- versus multi-lumen PICCs.

Therefore, to ensure appropriateness of PICC use, we designed an intervention to improve selection of the number of PICC lumens.

METHODS

We conducted this pre–post quasi-experimental study in accordance with SQUIRE guidelines.22 Details regarding clinical parameters associated with the decision to place a PICC, patient characteristics, comorbidities, complications, and laboratory values were collected from the medical records of patients. All PICCs were placed by the Vascular Access Service Team (VAST) during the study period.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of three components: first, all hospitalists, pharmacists, and VAST nurses received education in the form of a CME lecture that emphasized use of the Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC).1 These criteria define when use of a PICC is appropriate and emphasize how best to select the most appropriate device characteristics such as lumens and catheter gauge. Next, a multidisciplinary task force that consisted of hospitalists, VAST nurses, and pharmacists developed a list of indications specifying when use of a multilumen PICC was appropriate.1 Third, the order for a PICC in our electronic medical record (EMR) system was modified to set single-lumen PICCs as default. If a multilumen PICC was requested, text-based justification from the ordering clinician was required.

As an additional safeguard, a VAST nurse reviewed the number of lumens and clinical scenario for each PICC order prior to insertion. If the number of lumens ordered was considered inappropriate on the basis of the developed list of MAGIC recommendations, the case was referred to a pharmacist for additional review. The pharmacist then reviewed active and anticipated medications, explored options for adjusting the medication delivery plan, and discussed these options with the ordering clinician to determine the most appropriate number of lumens.

Measures and Definitions

In accordance with the criteria set by the Centers for Disease Control National Healthcare Safety Network,23 CLABSI was defined as a confirmed positive blood culture with a PICC in place for 48 hours or longer without another identified infection source or a positive PICC tip culture in the setting of clinically suspected infection. Venous thrombosis was defined as symptomatic upper extremity deep vein thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism that was radiographically confirmed after the placement of a PICC or within one week of device removal. Catheter occlusion was captured when documented or when tPA was administered for problems related to the PICC. The appropriateness of the number of PICC lumens was independently adjudicated by an attending physician and clinical pharmacist by comparing the indications of the device placed against predefined appropriateness criteria.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the change in the proportion of single-lumen PICCs placed. Secondary outcomes included (1) the placement of PICCs with an appropriate number of lumens, (2) the occurrence of PICC-related complications (CLABSI, venous thrombosis, and catheter occlusion), and (3) the need for a second procedure to place a multilumen device or additional vascular access.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to tabulate and summarize patient and PICC characteristics. Differences between pre- and postintervention populations were assessed using χ2, Fishers exact, t-, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Differences in complications were assessed using the two-sample tests of proportions. Results were reported as medians (IQR) and percentages with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. All statistical tests were two-sided, with P < .05 considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted with Stata v.14 (stataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Ethical and Regulatory Oversight

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan (IRB#HUM00118168).

RESULTS

Of the 133 PICCs placed preintervention, 64.7% (n = 86) were single lumen, 33.1% (n = 44) were double lumen, and 2.3% (n = 3) were triple lumen. Compared with the preintervention period, the use of single-lumen PICCs significantly increased following the intervention (64.7% to 93.6%; P < .001; Figure 1). As well, the proportion of PICCs with an inappropriate number of lumens decreased from 25.6% to 2.2% (P < .001; Table 1).

Preintervention, 14.3% (95% CI = 8.34-20.23) of the patients with PICCs experienced at least one complication (n = 19). Following the intervention, 15.1% (95% CI = 7.79-22.32) of the 93 patients with PICCs experienced at least one complication (absolute difference = 0.8%, P = .872). With respect to individual complications, CLABSI decreased from 5.3% (n = 7; 95% CI = 1.47-9.06) to 2.2% (n = 2; 95% CI = −0.80-5.10) (P = .239). Similarly, the incidence of catheter occlusion decreased from 8.3% (n = 11; 95% CI = 3.59-12.95) to 6.5% (n = 6; 95% CI = 1.46-11.44; P = .610; Table). Notably, only 12.1% (n = 21) of patients with a single-lumen PICC experienced any complication, whereas 20.0% (n = 10) of patients with a double lumen, and 66.7% (n = 2) with a triple lumen experienced a PICC-associated complication (P = .022). Patients with triple lumens had a significantly higher incidence of catheter occlusion compared with patients that received double- and single-lumen PICCs (66.7% vs. 12.0% and 5.2%, respectively; P = .003).

No patient who received a single-lumen device required a second procedure for the placement of a device with additional lumens. Similarly, no documentation suggesting an insufficient number of PICC lumens or the need for additional vascular access (eg, placement of additional PICCs) was found in medical records of patients postintervention. Pharmacists supporting the interventions and VAST team members reported no disagreements when discussing number of lumens or appropriateness of catheter choice.

DISCUSSION

In this single center, pre–post quasi-experimental study, a multimodal intervention based on the MAGIC criteria significantly reduced the use of multilumen PICCs. Additionally, a trend toward reductions in complications, including CLABSI and catheter occlusion, was also observed. Notably, these changes in ordering practices did not lead to requests for additional devices or replacement with a multilumen PICC when a single-lumen device was inserted. Collectively, our findings suggest that the use of single-lumen devices in a large direct care service can be feasibly and safely increased through this approach. Larger scale studies that implement MAGIC to inform placement of multilumen PICCs and reduce PICC-related complications now appear necessary.

The presence of a PICC, even for short periods, significantly increases the risk of CLABSI and is one of the strongest predictors of venous thrombosis risk in the hospital setting.19,24,25 Although some factors that lead to this increased risk are patient-related and not modifiable (eg, malignancy or intensive care unit status), increased risk linked to the gauge of PICCs and the number of PICC lumens can be modified by improving device selection.9,18,26 Deliberate use of PICCs with the least numbers of clinically necessary lumens decreases risk of CLABSI, venous thrombosis and overall cost.17,19,26 Additionally, greater rates of occlusion with each additional PICC lumen may result in the interruption of intravenous therapy, the administration of costly medications (eg, tissue plasminogen activator) to salvage the PICC, and premature removal of devices should the occlusion prove irreversible.8

We observed a trend toward decreased PICC complications following implementation of our criteria, especially for the outcomes of CLABSI and catheter occlusion. Given the pilot nature of this study, we were underpowered to detect a statistically significant change in PICC adverse events. However, we did observe a statistically significant increase in the rate of single-lumen PICC use following our intervention. Notably, this increase occurred in the setting of high rates of single-lumen PICC use at baseline (64%). Therefore, an important takeaway from our findings is that room for improving PICC appropriateness exists even among high performers. This finding In turn, high baseline use of single-lumen PICCs may also explain why a robust reduction in PICC complications was not observed in our study, given that other studies showing reduction in the rates of complications began with considerably low rates of single-lumen device use.19 Outcomes may improve, however, if we expand and sustain these changes or expand to larger settings. For example, (based on assumptions from a previously published simulation study and our average hospital medicine daily census of 98 patients) the increased use of single-over multilumen PICCs is expected to decrease CLABSI events and venous thrombosis episodes by 2.4-fold in our hospital medicine service with an associated cost savings of $74,300 each year.17 Additionally, we would also expect the increase in the proportion of single-lumen PICCs to reduce rates of catheter occlusion. This reduction, in turn, would lessen interruptions in intravenous therapy, the need for medications to treat occlusion, and the need for device replacement all leading to reduced costs.27 Overall, then, our intervention (informed by appropriateness criteria) provides substantial benefits to hospital savings and patient safety.

After our intervention, 98% of all PICCs placed were found to comply with appropriate criteria for multilumen PICC use. We unexpectedly found that the most important factor driving our findings was not oversight or order modification by the pharmacy team or VAST nurses, but rather better decisions made by physicians at the outset. Specifically, we did not find a single instance wherein the original PICC order was changed to a device with a different number of lumens after review from the VAST team. We attribute this finding to receptiveness of physicians to change ordering practices following education and the redesign of the default EMR PICC order, both of which provided a scientific rationale for multilumen PICC use. Clarifying the risk and criteria of the use of multilumen devices along with providing an EMR ordering process that supports best practice helped hospitalists “do the right thing”. Additionally, setting single-lumen devices as the preselected EMR order and requiring text-based justification for placement of a multilumen PICC helped provide a nudge to physicians, much as it has done with antibiotic choices.28

Our study has limitations. First, we were only able to identify complications that were captured by our EMR. Given that over 70% of the patients in our study were discharged with a PICC in place, we do not know whether complications may have developed outside the hospital. Second, our intervention was resource intensive and required partnership with pharmacy, VAST, and hospitalists. Thus, the generalizability of our intervention to other institutions without similar support is unclear. Third, despite an increase in the use of single-lumen PICCs and a decrease in multilumen devices, we did not observe a significant reduction in all types of complications. While our high rate of single-lumen PICC use may account for these findings, larger scale studies are needed to better study the impact of MAGIC and appropriateness criteria on PICC complications. Finally, given our approach, we cannot identify the most effective modality within our bundled intervention. Stepped wedge or single-component studies are needed to further address this question.

In conclusion, we piloted a multimodal intervention to promote the use of single-lumen PICCs while lowering the use of multilumen devices. By using MAGIC to create appropriate indications, the use of multilumen PICCs declined and complications trended downwards. Larger, multicenter studies to validate our findings and examine the sustainability of this intervention would be welcomed.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, et al. The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC): Results from a multispecialty panel using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6 Suppl):S1-S40. doi: 10.7326/M15-0744. PubMed

2. Taylor RW, Palagiri AV. Central venous catheterization. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(5):1390-1396. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000260241.80346.1B. PubMed

3. Pikwer A, Akeson J, Lindgren S. Complications associated with peripheral or central routes for central venous cannulation. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(1):65-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06911.x. PubMed

4. Johansson E, Hammarskjold F, Lundberg D, Arnlind MH. Advantages and disadvantages of peripherally inserted central venous catheters (PICC) compared to other central venous lines: a systematic review of the literature. Acta Onco. 2013;52(5):886-892. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.773072. PubMed

5. Pan L, Zhao Q, Yang X. Risk factors for venous thrombosis associated with peripherally inserted central venous catheters. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7(12):5814-5819. PubMed

6. Herc E, Patel P, Washer LL, Conlon A, Flanders SA, Chopra V. A model to predict central-line-associated bloodstream infection among patients with peripherally inserted central catheters: The MPC score. Infect Cont Hosp Ep. 2017;38(10):1155-1166. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.167. PubMed

7. Maki DG, Kluger DM, Crnich CJ. The risk of bloodstream infection in adults with different intravascular devices: a systematic review of 200 published prospective studies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(9):1159–1171. doi: 10.4065/81.9.1159. PubMed

8. Smith SN, Moureau N, Vaughn VM, et al. Patterns and predictors of peripherally inserted central catheter occlusion: The 3P-O study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28(5):749-756.e742. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.02.005. PubMed

9. Chopra V, Anand S, Hickner A, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with peripherally inserted central catheters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9889):311-325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60592-9. PubMed

10. Chopra V, Ratz D, Kuhn L, Lopus T, Lee A, Krein S. Peripherally inserted central catheter-related deep vein thrombosis: contemporary patterns and predictors. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(6):847-854. doi: 10.1111/jth.12549. PubMed

11. Carter JH, Langley JM, Kuhle S, Kirkland S. Risk factors for central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infection in pediatric patients: A cohort study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(8):939-945. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.83. PubMed

12. Chopra V, Ratz D, Kuhn L, Lopus T, Chenoweth C, Krein S. PICC-associated bloodstream infections: prevalence, patterns, and predictors. Am J Med. 2014;127(4):319-328. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.01.001. PubMed

13. O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(9):e162-e193. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir257. PubMed

14. Parkinson R, Gandhi M, Harper J, Archibald C. Establishing an ultrasound guided peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) insertion service. Clin Radiol. 1998;53(1):33-36. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(98)80031-7. PubMed

15. Shannon RP, Patel B, Cummins D, Shannon AH, Ganguli G, Lu Y. Economics of central line--associated bloodstream infections. Am J Med Qual. 2006;21(6 Suppl):7s–16s. doi: 10.1177/1062860606294631. PubMed

16. Mermis JD, Strom JC, Greenwood JP, et al. Quality improvement initiative to reduce deep vein thrombosis associated with peripherally inserted central catheters in adults with cystic fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(9):1404-1410. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201404-175OC. PubMed

17. Ratz D, Hofer T, Flanders SA, Saint S, Chopra V. Limiting the number of lumens in peripherally inserted central catheters to improve outcomes and reduce cost: A simulation study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(7):811-817. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.55. PubMed

18. Chopra V, Anand S, Krein SL, Chenoweth C, Saint S. Bloodstream infection, venous thrombosis, and peripherally inserted central catheters: reappraising the evidence. Am J Med. 2012;125(8):733-741. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.04.010. PubMed

19. O’Brien J, Paquet F, Lindsay R, Valenti D. Insertion of PICCs with minimum number of lumens reduces complications and costs. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;10(11):864-868. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.06.003. PubMed

20. Tiwari MM, Hermsen ED, Charlton ME, Anderson JR, Rupp ME. Inappropriate intravascular device use: a prospective study. J Hosp Infect. 2011;78(2):128-132. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.03.004. PubMed

21. Chopra V, Kuhn L, Flanders SA, Saint S, Krein SL. Hospitalist experiences, practice, opinions, and knowledge regarding peripherally inserted central catheters: results of a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):635-638. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2095. PubMed

22. Goodman D, Ogrinc G, Davies L, et al. Explanation and elaboration of the SQUIRE (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence) Guidelines, V.2.0: examples of SQUIRE elements in the healthcare improvement literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(12):e7. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004480. PubMed

23. CDC Bloodstream Infection/Device Associated Infection Module. https://wwwcdcgov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/4psc_clabscurrentpdf 2017. Accessed April 11, 2017.

24. Woller SC, Stevens SM, Jones JP, et al. Derivation and validation of a simple model to identify venous thromboembolism risk in medical patients. Am J Med. 2011;124(10):947-954.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.06.004. PubMed

25. Paje D, Conlon A, Kaatz S, et al. Patterns and predictors of short-term peripherally inserted central catheter use: A multicenter prospective cohort study. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(2):76-82. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2847. PubMed

26. Evans RS, Sharp JH, Linford LH, et al. Reduction of peripherally inserted central catheter-associated DVT. Chest. 2013;143(3):627-633. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0923. PubMed

27. Smith S, Moureau N, Vaughn VM, et al. Patterns and predictors of peripherally inserted central catheter occlusion: The 3P-O study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28(5):749-756.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.02.005. PubMed

28. Vaughn VM, Linder JA. Thoughtless design of the electronic health record drives overuse, but purposeful design can nudge improved patient care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(8):583-586. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007578. PubMed

1. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, et al. The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC): Results from a multispecialty panel using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6 Suppl):S1-S40. doi: 10.7326/M15-0744. PubMed

2. Taylor RW, Palagiri AV. Central venous catheterization. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(5):1390-1396. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000260241.80346.1B. PubMed

3. Pikwer A, Akeson J, Lindgren S. Complications associated with peripheral or central routes for central venous cannulation. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(1):65-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06911.x. PubMed

4. Johansson E, Hammarskjold F, Lundberg D, Arnlind MH. Advantages and disadvantages of peripherally inserted central venous catheters (PICC) compared to other central venous lines: a systematic review of the literature. Acta Onco. 2013;52(5):886-892. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.773072. PubMed

5. Pan L, Zhao Q, Yang X. Risk factors for venous thrombosis associated with peripherally inserted central venous catheters. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7(12):5814-5819. PubMed

6. Herc E, Patel P, Washer LL, Conlon A, Flanders SA, Chopra V. A model to predict central-line-associated bloodstream infection among patients with peripherally inserted central catheters: The MPC score. Infect Cont Hosp Ep. 2017;38(10):1155-1166. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.167. PubMed

7. Maki DG, Kluger DM, Crnich CJ. The risk of bloodstream infection in adults with different intravascular devices: a systematic review of 200 published prospective studies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(9):1159–1171. doi: 10.4065/81.9.1159. PubMed

8. Smith SN, Moureau N, Vaughn VM, et al. Patterns and predictors of peripherally inserted central catheter occlusion: The 3P-O study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28(5):749-756.e742. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.02.005. PubMed

9. Chopra V, Anand S, Hickner A, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with peripherally inserted central catheters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9889):311-325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60592-9. PubMed

10. Chopra V, Ratz D, Kuhn L, Lopus T, Lee A, Krein S. Peripherally inserted central catheter-related deep vein thrombosis: contemporary patterns and predictors. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(6):847-854. doi: 10.1111/jth.12549. PubMed

11. Carter JH, Langley JM, Kuhle S, Kirkland S. Risk factors for central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infection in pediatric patients: A cohort study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(8):939-945. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.83. PubMed

12. Chopra V, Ratz D, Kuhn L, Lopus T, Chenoweth C, Krein S. PICC-associated bloodstream infections: prevalence, patterns, and predictors. Am J Med. 2014;127(4):319-328. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.01.001. PubMed

13. O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(9):e162-e193. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir257. PubMed

14. Parkinson R, Gandhi M, Harper J, Archibald C. Establishing an ultrasound guided peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) insertion service. Clin Radiol. 1998;53(1):33-36. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(98)80031-7. PubMed

15. Shannon RP, Patel B, Cummins D, Shannon AH, Ganguli G, Lu Y. Economics of central line--associated bloodstream infections. Am J Med Qual. 2006;21(6 Suppl):7s–16s. doi: 10.1177/1062860606294631. PubMed

16. Mermis JD, Strom JC, Greenwood JP, et al. Quality improvement initiative to reduce deep vein thrombosis associated with peripherally inserted central catheters in adults with cystic fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(9):1404-1410. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201404-175OC. PubMed

17. Ratz D, Hofer T, Flanders SA, Saint S, Chopra V. Limiting the number of lumens in peripherally inserted central catheters to improve outcomes and reduce cost: A simulation study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(7):811-817. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.55. PubMed

18. Chopra V, Anand S, Krein SL, Chenoweth C, Saint S. Bloodstream infection, venous thrombosis, and peripherally inserted central catheters: reappraising the evidence. Am J Med. 2012;125(8):733-741. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.04.010. PubMed

19. O’Brien J, Paquet F, Lindsay R, Valenti D. Insertion of PICCs with minimum number of lumens reduces complications and costs. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;10(11):864-868. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.06.003. PubMed

20. Tiwari MM, Hermsen ED, Charlton ME, Anderson JR, Rupp ME. Inappropriate intravascular device use: a prospective study. J Hosp Infect. 2011;78(2):128-132. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.03.004. PubMed

21. Chopra V, Kuhn L, Flanders SA, Saint S, Krein SL. Hospitalist experiences, practice, opinions, and knowledge regarding peripherally inserted central catheters: results of a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):635-638. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2095. PubMed

22. Goodman D, Ogrinc G, Davies L, et al. Explanation and elaboration of the SQUIRE (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence) Guidelines, V.2.0: examples of SQUIRE elements in the healthcare improvement literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(12):e7. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004480. PubMed

23. CDC Bloodstream Infection/Device Associated Infection Module. https://wwwcdcgov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/4psc_clabscurrentpdf 2017. Accessed April 11, 2017.

24. Woller SC, Stevens SM, Jones JP, et al. Derivation and validation of a simple model to identify venous thromboembolism risk in medical patients. Am J Med. 2011;124(10):947-954.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.06.004. PubMed

25. Paje D, Conlon A, Kaatz S, et al. Patterns and predictors of short-term peripherally inserted central catheter use: A multicenter prospective cohort study. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(2):76-82. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2847. PubMed

26. Evans RS, Sharp JH, Linford LH, et al. Reduction of peripherally inserted central catheter-associated DVT. Chest. 2013;143(3):627-633. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0923. PubMed

27. Smith S, Moureau N, Vaughn VM, et al. Patterns and predictors of peripherally inserted central catheter occlusion: The 3P-O study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28(5):749-756.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.02.005. PubMed

28. Vaughn VM, Linder JA. Thoughtless design of the electronic health record drives overuse, but purposeful design can nudge improved patient care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(8):583-586. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007578. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Patterns and Predictors of Short-Term Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study

Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) are integral to the care of hospitalized patients in the United States.1 Consequently, utilization of these devices in acutely ill patients has steadily increased in the past decade.2 Although originally designed to support the delivery of total parenteral nutrition, PICCs have found broader applications in the hospital setting given the ease and safety of placement, the advances in technology that facilitate insertion, and the growing availability of specially trained vascular nurses that place these devices at the bedside.3 Furthermore, because they are placed in deeper veins of the arm, PICCs are more durable than peripheral catheters and can support venous access for extended durations.4-6

However, the growing use of PICCs has led to the realization that these devices are not without attendant risks. For example, PICCs are associated with venous thromboembolism (VTE) and central-line associated blood stream infection (CLABSI).7,8 Additionally, complications such as catheter occlusion and tip migration commonly occur and may interrupt care or necessitate device removal.9-11 Hence, thoughtful weighing of the risks against the benefits of PICC use prior to placement is necessary. To facilitate such decision-making, we developed the Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous (IV) Catheters (MAGIC) criteria,12 which is an evidence-based tool that defines when the use of a PICC is appropriate in hospitalized adults.

The use of PICCs for infusion of peripherally compatible therapies for 5 or fewer days is rated as inappropriate by MAGIC.12 This strategy is also endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) guidelines for the prevention of catheter-related infections.13 Despite these recommendations, short-term PICC use remains common. For example, a study conducted at a tertiary pediatric care center reported a trend toward shorter PICC dwell times and increasing rates of early removal.2 However, factors that prompt such short-term PICC use are poorly understood. Without understanding drivers and outcomes of short-term PICC use, interventions to prevent such practice are unlikely to succeed.

Therefore, by using data from a multicenter cohort study, we examined patterns of short-term PICC use and sought to identify which patient, provider, and device factors were associated with such use. We hypothesized that short-term placement would be associated with difficult venous access and would also be associated with the risk of major and minor complications.

METHODS

Study Setting and Design

We used data from the Michigan Hospital Medicine Safety (HMS) Consortium to examine patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use.14 As a multi-institutional clinical quality initiative sponsored by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network, HMS aims to improve the quality of care by preventing adverse events in hospitalized medical patients.4,15-17 In January of 2014, dedicated, trained abstractors started collecting data on PICC placements at participating HMS hospitals by using a standard protocol and template for data collection. Patients who received PICCs while admitted to either a general medicine unit or an intensive care unit (ICU) during clinical care were eligible for inclusion. Patients were excluded if they were (a) under the age of 18 years, (b) pregnant, (c) admitted to a nonmedical service (eg, surgery), or (d) admitted under observation status.

Every 14 days, each hospital collected data on the first 17 eligible patients that received a PICC, with at least 7 of these placements occurring in an ICU setting. All patients were prospectively followed until the PICC was removed, death, or until 70 days after insertion, whichever occurred first. For patients who had their PICC removed prior to hospital discharge, follow-up occurred via a review of medical records. For those discharged with a PICC in place, both medical record review and telephone follow-up were performed. To ensure data quality, annual random audits at each participating hospital were performed by the coordinating center at the University of Michigan.

For this analysis, we included all available data as of June 30, 2016. However, HMS hospitals continue to collect data on PICC use and outcomes as part of an ongoing clinical quality initiative to reduce the incidence of PICC-related complications.

Patient, Provider, and Device Data

Patient characteristics, including demographics, detailed medical history, comorbidities, physical findings, laboratory results, and medications were abstracted directly from medical records. To estimate the comorbidity burden, the Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score was calculated for each patient by using data available in the medical record at the time of PICC placement.18 Data, such as the documented indication for PICC insertion and the reason for removal, were obtained directly from medical records. Provider characteristics, including the specialty of the attending physician at the time of insertion and the type of operator who inserted the PICC, were also collected. Institutional characteristics, such as total number of beds, teaching versus nonteaching, and urban versus rural, were obtained from hospital publicly reported data and semiannual surveys of HMS sites.19,20 Data on device characteristics, such as catheter gauge, coating, insertion attempts, tip location, and number of lumens, were abstracted from PICC insertion notes.

Outcomes of Interest

The outcome of interest was short-term PICC use, defined as PICCs removed within 5 days of insertion. Patients who expired with a PICC in situ were excluded. Secondary outcomes of interest included PICC-related complications, categorized as major (eg, symptomatic VTE and CLABSI) or minor (eg, catheter occlusion, superficial thrombosis, mechanical complications [kinking, coiling], exit site infection, and tip migration). Symptomatic VTE was defined as clinically diagnosed deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and/or pulmonary embolism (PE) not present at the time of PICC placement and confirmed via imaging (ultrasound or venogram for DVT; computed tomography scan, ventilation perfusion scan, or pulmonary angiogram for PE). CLABSI was defined in accordance with the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network criteria or according to Infectious Diseases Society of America recommendations.21,22 All minor PICC complications were defined in accordance with prior published definitions.4

Statistical Analysis

Cases of short-term PICC use were identified and compared with patients with a PICC dwell time of 6 or more days by patient, provider, and device characteristics. The initial analyses for the associations of putative factors with short-term PICC use were performed using χ2 or Wilcoxon tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Univariable mixed effect logistic regression models (with a random hospital-specific intercept) were then used to control for hospital-level clustering. Next, a mixed effects multivariable logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with short-term PICC use. Variables with P ≤ .25 were considered as candidate predictors for the final multivariable model, which was chosen through a stepwise variable selection algorithm performed on 1000 bootstrapped data sets.23 Variables in the final model were retained based on their frequency of selection in the bootstrapped samples, significance level, and contribution to the overall model likelihood. Results were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). SAS for Windows (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for analyses.

Ethical and Regulatory Oversight

The study was classified as “not regulated” by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan (HUM00078730).

RESULTS

Overall Characteristics of the Study Cohort

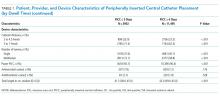

Characteristics of Short-Term Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use

Of the 15,397 PICCs included, we identified 3902 PICCs (25.3%) with a dwell time of ≤5 days (median = 3 days; IQR, 2-4 days). When compared to PICCs that were in place for longer durations, no significant differences in age or comorbidity scores were observed. Importantly, despite recommendations to avoid PICCs in patients with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate [GFR] ≤ 59 ml/min), 1292 (33.1%) short-term PICCs occurred in patients that met such criteria.

Among short-term PICCs, 3618 (92.7%) were power-capable devices, 2785 (71.4%) were 5-French, and 2813 (72.1%) were multilumen. Indications for the use of short-term PICCs differed from longer term devices in important ways (P < .001). For example, the most common documented indication for short-term PICC use was difficult venous access (28.2%), while for long-term PICCs, it was antibiotic administration (39.8%). General internists and hospitalists were the most common attending physicians for patients with short-term and long-term PICCs (65.1% and 65.5%, respectively [P = .73]). Also, the proportion of critical care physicians responsible for patients with short versus long-term PICC use was similar (14.0% vs 15.0%, respectively [P = .123]). Of the short-term PICCs, 2583 (66.2%) were inserted by vascular access nurses, 795 (20.4%) by interventional radiologists, and 439 (11.3%) by advance practice professionals. Almost all of the PICCs placed ≤5 days (95.5%) were removed during hospitalization.

Complications Associated with Short-Term Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use

DISCUSSION

This large, multisite prospective cohort study is the first to examine patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use in hospitalized adults. By examining clinically granular data derived from the medical records of patients across 52 hospitals, we found that short-term use was common, representing 25% of all PICCs placed. Almost all such PICCs were removed prior to discharge, suggesting that they were placed primarily to meet acute needs during hospitalization. Multivariable models indicated that patients with difficult venous access, multilumen devices, and teaching hospital settings were associated with short-term use. Given that (a) short term PICC use is not recommended by published evidence-based guidelines,12,13 (b) both major and minor complications were not uncommon despite brief exposure, and (c) specific factors might be targeted to avoid such use, strategies to improve PICC decision-making in the hospital appear increasingly necessary.

In our study, difficult venous access was the most common documented indication for short-term PICC placement. For patients in whom an anticipated catheter dwell time of 5 days or less is expected, MAGIC recommends the consideration of midline or peripheral IV catheters placed under ultrasound guidance.12 A midline is a type of peripheral IV catheter that is about 7.5 cm to 25 cm in length and is typically inserted in the larger diameter veins of the upper extremity, such as the cephalic or basilic veins, with the tip terminating distal to the subclavian vein.7,12 While there is a paucity of information that directly compares PICCs to midlines, some data suggest a lower risk of bloodstream infection and thrombosis associated with the latter.24-26 For example, at one quaternary teaching hospital, house staff who are trained to insert midline catheters under ultrasound guidance in critically ill patients with difficult venous access reported no CLABSI and DVT events.26

Interestingly, multilumen catheters were used twice as often as single lumen catheters in patients with short-term PICCs. In these instances, the use of additional lumens is questionable, as infusion of multiple incompatible fluids was not commonly listed as an indication prompting PICC use. Because multilumen PICCs are associated with higher risks of both VTE and CLABSI compared to single lumen devices, such use represents an important safety concern.27-29 Institutional efforts that not only limit the use of multilumen PICCs but also fundamentally define when use of a PICC is appropriate may substantially improve outcomes related to vascular access.28,30,31We observed that short-term PICCs were more common in teaching compared to nonteaching hospitals. While the design of the present study precludes understanding the reasons for such a difference, some plausible theories include the presence of physician trainees who may not appreciate the risks of PICC use, diminishing peripheral IV access securement skills, and the lack of alternatives to PICC use. Educating trainees who most often order PICCs in teaching settings as to when they should or should not consider this device may represent an important quality improvement opportunity.32 Similarly, auditing and assessing the clinical skills of those entrusted to place peripheral IVs might prove helpful.33,34 Finally, the introduction of a midline program, or similar programs that expand the scope of vascular access teams to place alternative devices, should be explored as a means to improve PICC use and patient safety.

Our study also found that a third of patients who received PICCs for 5 or fewer days had moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. In these patients who may require renal replacement therapy, prior PICC placement is among the strongest predictors of arteriovenous fistula failure.35,36 Therefore, even though national guidelines discourage the use of PICCs in these patients and recommend alternative routes of venous access,12,37,38 such practice is clearly not happening. System-based interventions that begin by identifying patients who require vein preservation (eg, those with a GFR < 45 ml/min) and are therefore not appropriate for a PICC would be a welcomed first step in improving care for such patients.37,38Our study has limitations. First, the observational nature of the study limits the ability to assess for causality or to account for the effects of unmeasured confounders. Second, while the use of medical records to collect granular data is valuable, differences in documentation patterns within and across hospitals, including patterns of missing data, may produce a misclassification of covariates or outcomes. Third, while we found that higher rates of short-term PICC use were associated with teaching hospitals and patients with difficult venous access, we were unable to determine the precise reasons for this practice trend. Qualitative or mixed-methods approaches to understand provider decision-making in these settings would be welcomed.

Our study also has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically describe and evaluate patterns and predictors of short-term PICC use. The finding that PICCs placed for difficult venous access is a dominant category of short-term placement confirms clinical suspicions regarding inappropriate use and strengthens the need for pathways or protocols to manage such patients. Second, the inclusion of medical patients in diverse institutions offers not only real-world insights related to PICC use, but also offers findings that should be generalizable to other hospitals and health systems. Third, the use of a robust data collection strategy that emphasized standardized data collection, dedicated trained abstractors, and random audits to ensure data quality strengthen the findings of this work. Finally, our findings highlight an urgent need to develop policies related to PICC use, including limiting the use of multiple lumens and avoidance in patients with moderate to severe kidney disease.

In conclusion, short-term use of PICCs is prevalent and associated with key patient, provider, and device factors. Such use is also associated with complications, such as catheter occlusion, tip migration, VTE, and CLABSI. Limiting the use of multiple-lumen PICCs, enhancing education for when a PICC should be used, and defining strategies for patients with difficult access may help reduce inappropriate PICC use and improve patient safety. Future studies to examine implementation of such interventions would be welcomed.

Disclosure: Drs. Paje, Conlon, Swaminathan, and Boldenow disclose no conflicts of interest. Dr. Chopra has received honoraria for talks at hospitals as a visiting professor. Dr. Flanders discloses consultancies for the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and the Society of Hospital Medicine, royalties from Wiley Publishing, honoraria for various talks at hospitals as a visiting professor, grants from the CDC Foundation, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM), and Michigan Hospital Association, and expert witness testimony. Dr. Bernstein discloses consultancies for Blue Care Network and grants from BCBSM, Department of Veterans Affairs, and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kaatz discloses no relevant conflicts of interest. BCBSM and Blue Care Network provided support for the Michigan HMS Consortium as part of the BCBSM Value Partnerships program. Although BCBSM and HMS work collaboratively, the opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs, and viewpoints of BCBSM or any of its employees. Dr. Chopra is supported by a career development award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1-K08-HS022835-01). BCBSM and Blue Care Network supported data collection at each participating site and funded the data coordinating center but had no role in study concept, interpretation of findings, or in the preparation, final approval, or decision to submit the manuscript.

1. Al Raiy B, Fakih MG, Bryan-Nomides N, et al. Peripherally inserted central venous catheters in the acute care setting: A safe alternative to high-risk short-term central venous catheters. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(2):149-153. PubMed

2. Gibson C, Connolly BL, Moineddin R, Mahant S, Filipescu D, Amaral JG. Peripherally inserted central catheters: use at a tertiary care pediatric center. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(9):1323-1331. PubMed

3. Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S. The problem with peripherally inserted central catheters. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1527-1528. PubMed

4. Chopra V, Smith S, Swaminathan L, et al. Variations in Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Use and Outcomes in Michigan Hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):548-551. PubMed

5. Cowl CT, Weinstock JV, Al-Jurf A, Ephgrave K, Murray JA, Dillon K. Complications and cost associated with parenteral nutrition delivered to hospitalized patients through either subclavian or peripherally-inserted central catheters. Clin Nutr. 2000;19(4):237-243. PubMed

6. MacDonald AS, Master SK, Moffitt EA. A comparative study of peripherally inserted silicone catheters for parenteral nutrition. Can J Anaesth. 1977;24(2):263-269. PubMed