User login

Whole Health(y) Aging With Gerofit: The Development of a Pilot Wellness Program for Older Veterans

Whole Health(y) Aging With Gerofit: The Development of a Pilot Wellness Program for Older Veterans

About half of the > 9 million veterans served by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) are aged ≥ 65 years.1 Veterans are at a higher risk for comorbidities, which may contribute to increased health care costs, mobility limitations and disability, poor quality of life, and mortality. 2-5 Programs and policies that promote health maintenance, independent living, and quality of life are needed among older veterans. To support veterans’ overall health and well-being, the VHA has shifted to whole health, a patient-centered care model.6

The whole health paradigm employs personalized, proactive, and patient-driven care, emphasizing complementary and integrative health practices, and prioritizing health promotion and disease prevention over disease treatment.7 The veteran is empowered to decide “what matters to [me],” reflect on life and health, and define mission, aspiration, and purpose. This approach gives veterans a more active and direct role in their care, distinguishing it from traditional care models. In turn, it helps reduce the burden on clinicians and fosters a more collaborative environment in which both the clinician and veteran work together to shape the care process.7 Veterans utilize the Circle of Health to identify skills and support needed to implement changes in self-care. The Circle of Health includes 8 self-care components: moving the body; surroundings; personal development; food and drink; recharge; family, friends, and coworkers; spirit and soul; and power of the mind.6 This process drives the creation of a personal health plan, creating opportunities for individuals to engage in well-being programs that matter to them and help them meet their goals.

Gerofit is a VHA best practice and whole health outpatient exercise program for veterans aged ≥65 years.8 Gerofit has focused primarily on exercise within the moving the body self-care component.9 A longitudinal study followed 691 Gerofit participants across 6 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers who on average were 73 years old, had 16 different medical conditions, and took 10 medications. Most were obese and had a mean gait speed of 1.04 m/s, suggesting functional impairment.10 Prior studies have shown that Gerofit participation is associated with a range of health benefits. Two studies reported improvements in psychological well-being and sustained gains in endurance, strength, and flexibility following early Gerofit program participation. 11,12 A 10-year analysis of 115 veterans found that long-term Gerofit participation reduced mortality risk, while another study of 452 veterans showed decreased medication use following 1 year in the program.13,14

The VHA whole health model comprises 3 components: (1) The Pathway, (2) well-being programs, and (3) whole health clinical care.6 The Pathway engages veterans in identifying personal health goals, while well-being programs offer selfcare and skill-building activities. Traditional clinical settings often focus primarily on the third component due to time and resource constraints. The Gerofit platform addresses all 3 components. Its existing infrastructure, including a supportive community and dedicated facilities, provides a setting for implementing The Pathway and well-being programs. The Gerofit structure allows for the time and continuity necessary for these components, which are often limited during standard clinical visits.

By expanding the Gerofit exercise regimen to include additional wellness activities, it can holistically support older veterans. Research supports this integrative approach. For example, a 2020 study found that incorporating a holistic health program into an existing exercise program within a church setting led to improved physical activity and overall health among women participants.15 This article describes the integration of Whole Health(y) Aging with Gerofit (WHAG), a pilot program in Baltimore, Maryland, that integrates whole health components into the established Gerofit framework to enhance the overall well-being of participating veterans (Figure 1).

WHOLE HEALTH(Y) AGING WITH GEROFIT

Gerofit enrollment has been described elsewhere in detail.16 Patients aged ≥ 65 years are eligible to participate with clinician approval if they are medically stable. Following VHA clinician referral and primary care approval, veterans completed a telephone visit to determine eligibility and discuss their exercise history, goals, and preferences. Veterans dependent in activities of daily living and those with cognitive impairment, unstable angina, active proliferative diabetic retinopathy, oxygen dependence, frank incontinence, active open wounds, active substance abuse, volatile behavioral issues, or who are experiencing homelessness are not eligible for Gerofit.

The exercise physiologist identified veteran barriers and incentives to participation and assisted with a plan to maximize SMART goals (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound). Veterans then completed an assessment visit, either in person or virtually, depending on the selected programming. Functional assessments conducted by trained Gerofit exercise physiologists include testing of lower and upper body strength and submaximal endurance.9,17,18 Participation in Gerofit is voluntary and not time limited.

Prior to these newly expanded offerings, veterans could only enroll in a personalized, structured exercise program. Based on feedback from Gerofit participants indicating areas of interest, WHAG was developed to provide additional wellness offerings aligned with other Circle of Health components.6 This included virtual group nutrition education and cooking interventions with optional fresh produce delivery; wellness classes, the Companion Dog Fostering & Adoption program, and Gerofit in the Mind, which included mindfulness classes and relaxation seminars (Figure 1). Programs were virtual (except dog fostering and adoption) and rotated throughout the year. Not all programs are offered simultaneously.

Attendance, completion of selected questions from the individual Personal Health Inventory (PHI) Short Form, measured physical function, self-reported physical activity levels, physical and mental health status, and program satisfaction were measured for all WHAG subprograms.18 Selected questions from the PHI Short Form use a 5-point Likert scale to rate the following whole health components: physical activity; sleep, relaxation, and recovery; healthy eating habits; and positive outlook, healthy relationships, and caring for mental health. Physical function was assessed using 30-second arm curls (upper body strength), 30-second chair stands (lower body strength), and the 2-minute step test (virtual) or 6-minute walk test (in person) (submaximal cardiovascular endurance).

Self-reported physical activity was assessed by asking frequency (days per week) and duration (minutes per session) of cardiovascular and strength exercises to calculate total minutes per week. Physical and mental health status was assessed using the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Health Scale.19 Demographic data included sex, race and ethnicity, and age at baseline visit. Mean (SD) was calculated for continuous variables and presented unless otherwise specified, and frequencies were calculated for categorical variables. Subsequent reports will describe additional assessments and detailed outcomes unique to individual programs.

Overview

Veterans chose the programs that best suited their needs without limitations.7 Staff provided guidance on newly available programs based on an individual’s specified goals. Gerofit staff assisted veterans with development of individualized personal health plans, monitoring progress towards their goals, supporting program participation, and connecting veterans with additional whole health resources.

Gerofit Exercise Group. Exercise was designed to address the Moving the Body component of whole health. Veterans could elect to schedule 1-hour, 3-times-weekly in-person gym appointments, participate in 3-times-weekly livestreamed virtual group exercise classes through VA Video Connect, or receive a self-directed at-home exercise plan.

Gerofit Learning Opportunities for Wellness Classes. These virtual health education sessions addressed the personal development component of whole health and were designed to increase self-efficacy and empower veterans to take an active role in their health care. Topics focused broadly on issues related to healthy aging (eg, importance of sleep, goal setting, self-care, and comorbidity education). Veterans could participate in any classes of interest, which were led by health care professionals and offered twice monthly. Sessions encouraged participant questions and peer interaction.

Nutrition. Improving dietary quality is a frequently reported goal of Gerofit participants. WHAG incorporated multiple strategies to assist veterans in meeting these goals. For example, through a partnership with Therapeutic Alternative of Maryland Farm, Gerofit provided veterans free, locally grown fresh produce. This initiative addressed barriers to healthy eating by improving access to fresh produce, which has been shown to influence cooking frequency and diet quality.20-22 Participation in nutrition classes was not required. In 2021, veterans received produce weekly; however, many reported excess quantities. Beginning in 2022, veterans could select both produce items and quantities desired.

In addition, a registered dietitian led a 14-week virtual nutrition education program guided by the social cognitive theory framework and focused on self-regulation skills such as goal setting, overcoming barriers, and identifying triggers.23 Prior research highlighted low health literacy as a common barrier among older veterans, which informed several key components of the curriculum.24 These included how to read and interpret nutrition labels, define balanced meals and snacks, and understand the classification of various food groups such as fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. The online program curriculum included an instructor guide and participant materials for each individual lesson, including an educational handout on the specific week’s topic, applied activity (group or individual), and recipes related to the produce shares. Structured group discussion promoted camaraderie and recipe sharing, and additional instruction on produce preparation and storage.

Reported lack of self-efficacy and knowledge regarding produce preparation prompted a 5-week virtual cooking series, led by a medical student and supervised by a registered dietitian. Sessions combined brief nutrition education with live cooking demonstrations adapted from the VA Healthy Teaching Kitchen curriculum. Recipes emphasized low-cost, commonly found food items. The Healthy Teaching Kitchen modifications focused on Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diets, diabetes, and the importance of protein for older adults. Participants were allowed time to discuss recipes and food preparation tips, and other household members were allowed to observe.

Dog Fostering and Adoption. Veterans could foster or adopt a rescue dog through a partnership with local rescue groups. This program allowed participating veterans to have a companion, which addressed the surroundings, moving the body, and spirit and soul whole health components. The Companion Dog Fostering and Adoption Program and results on physical function and daily physical activity from the first 3 months were recently published. Positive effects on physical activity, physical function, and quality of life were observed at 3 months as compared to baseline in veterans who received a companion dog.25

Gerofit in the Garden. Veterans could opt to receive an EarthBox containing soil and seedlings for 1 vegetable and 1 herb. The boxes are designed to fit on a small tabletop, regardless of home type or availability of backyard. In-person instruction for veterans on care and maintenance was provided by a farm employee with experience in gardening and farming practices.

Gerofit in the Mind. Online relaxation seminars were offered twice monthly for 4 months. Led by a certified sound health guide, sessions incorporated sound baths, crystal bowls, Tibetan bowls, tuning forks, and breath work. Virtual mindfulness classes led by a certified yoga instructor were offered weekly for 1 month. Veterans could drop in and participate based on their availability. Classes were designed to introduce veterans to the practice of mindfulness, improve mood, and lower stress and anxiety.

Pilot Program Outcomes

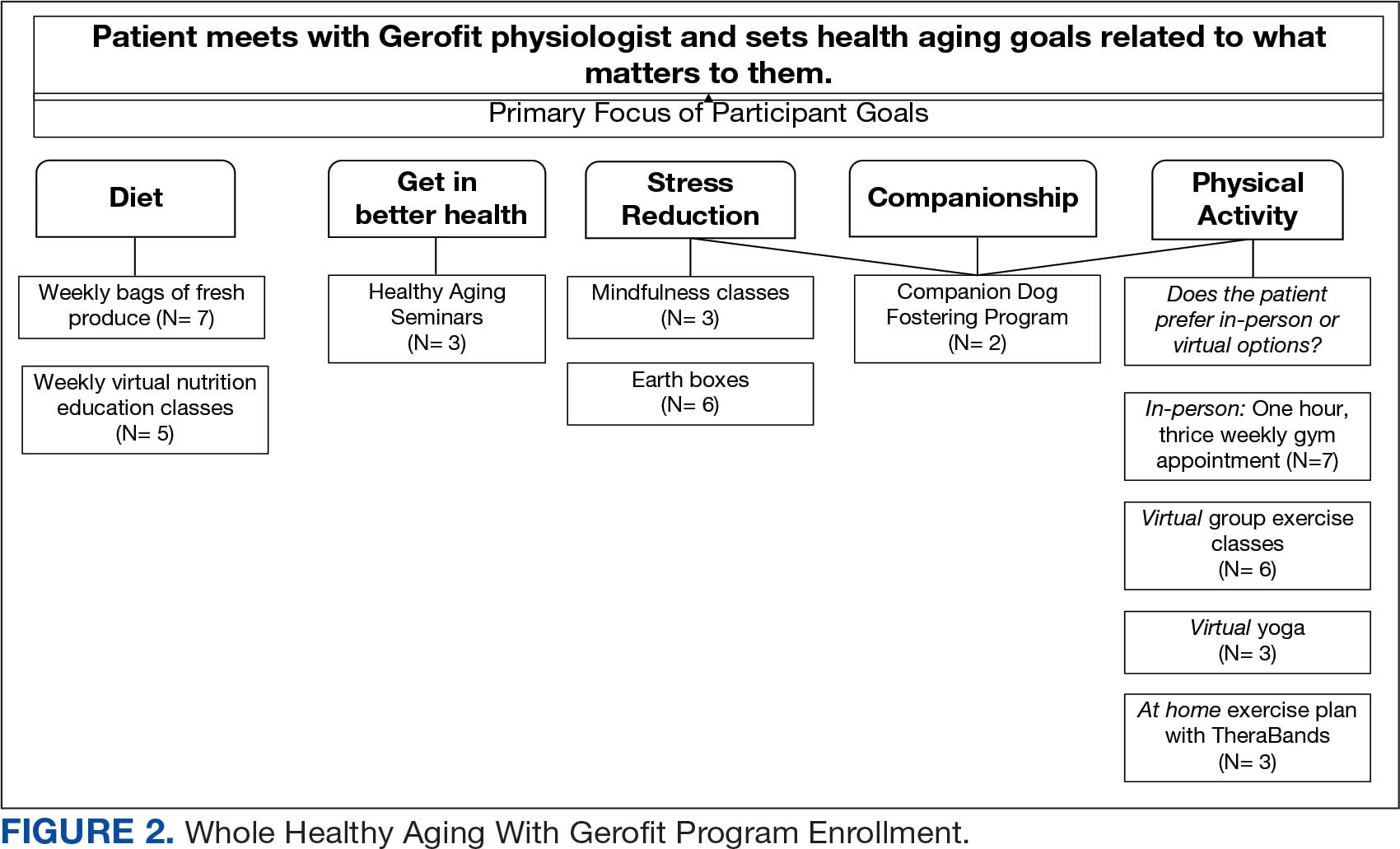

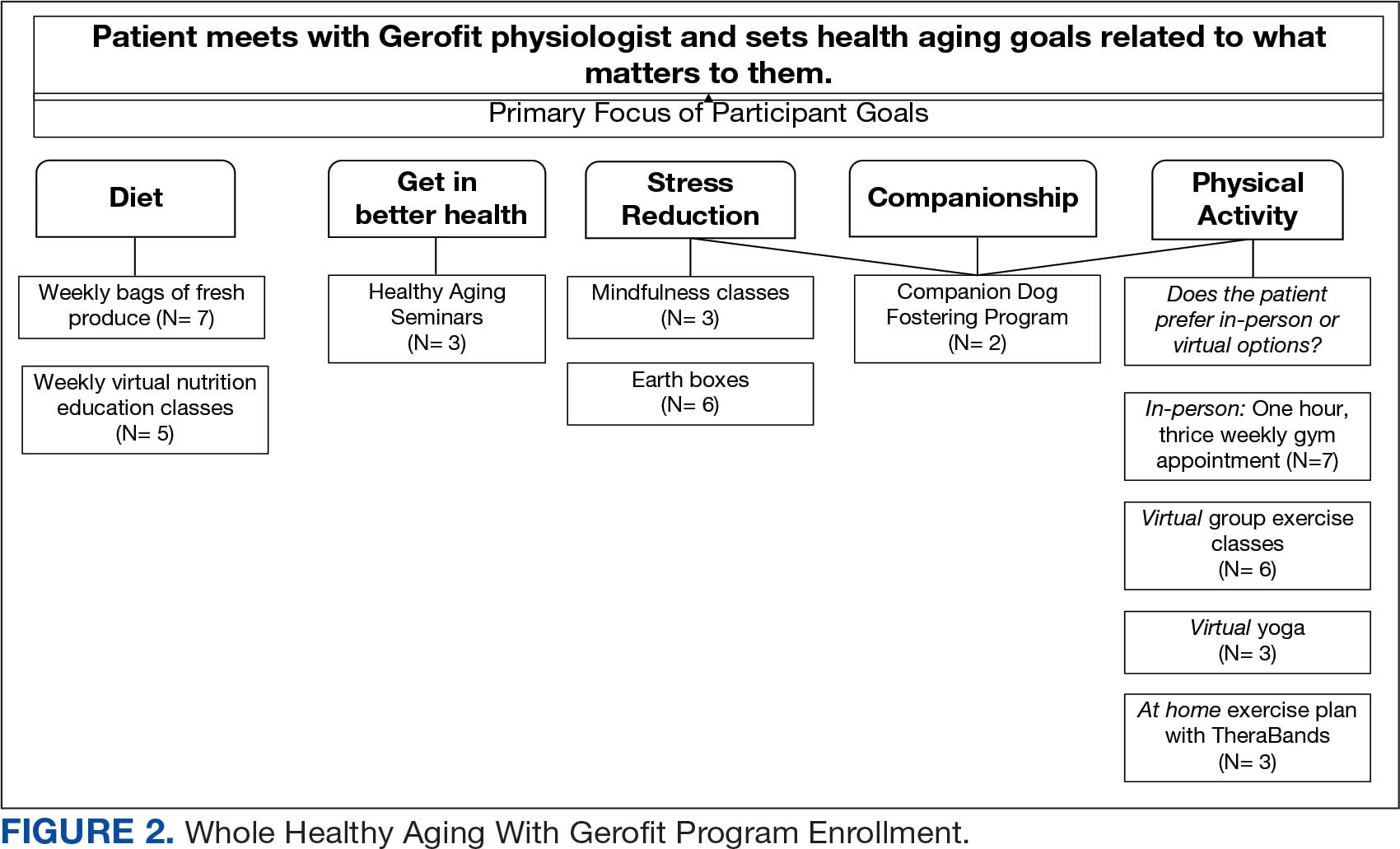

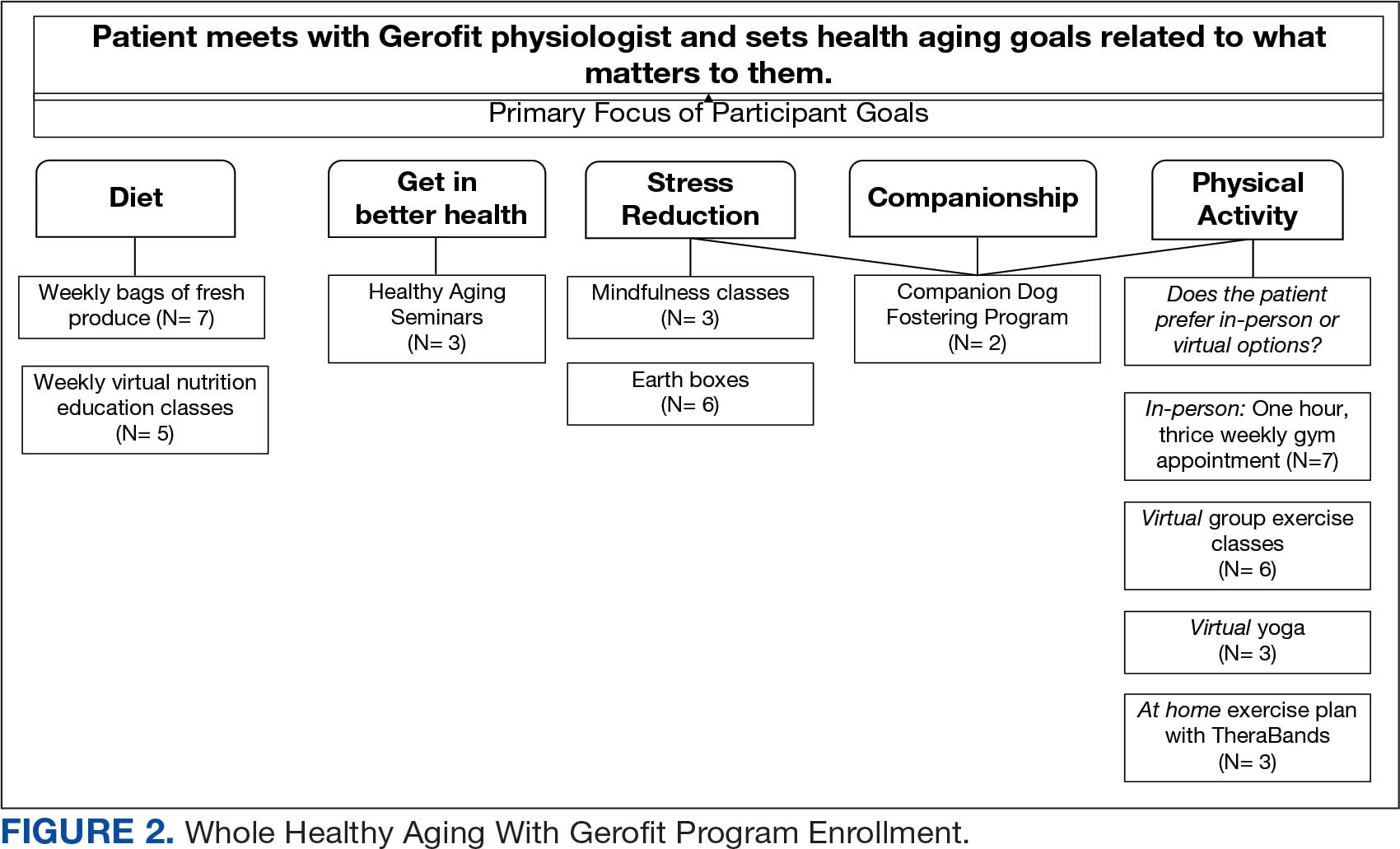

Sixteen male veterans participated in WHAG. Participants were 62% Black, with a mean age of 76 years. Veterans collaborated with Gerofit staff to develop personal health plans, which ultimately guided program participation (Figure 2).

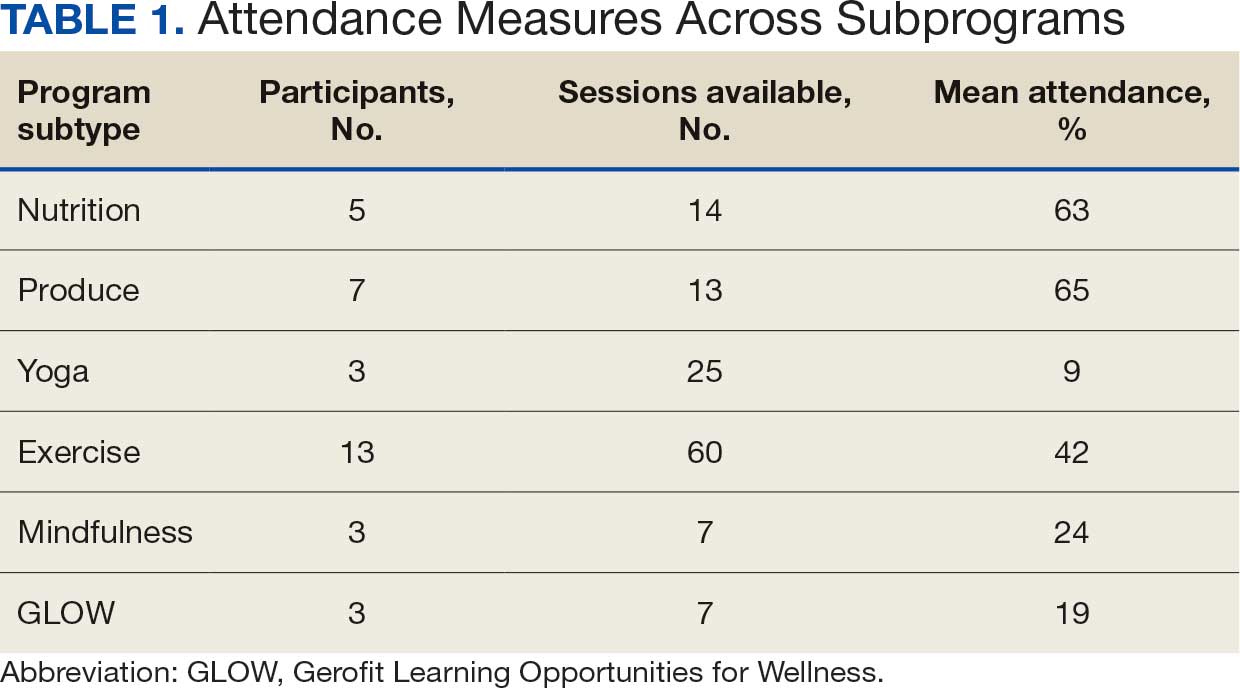

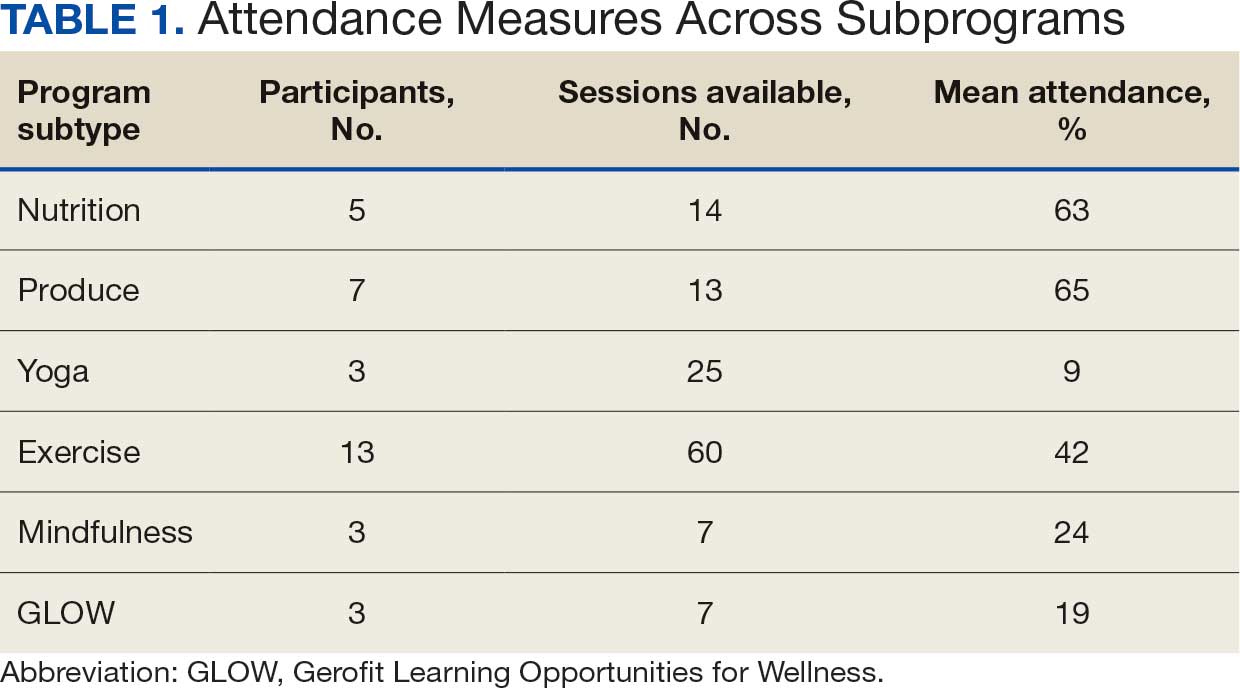

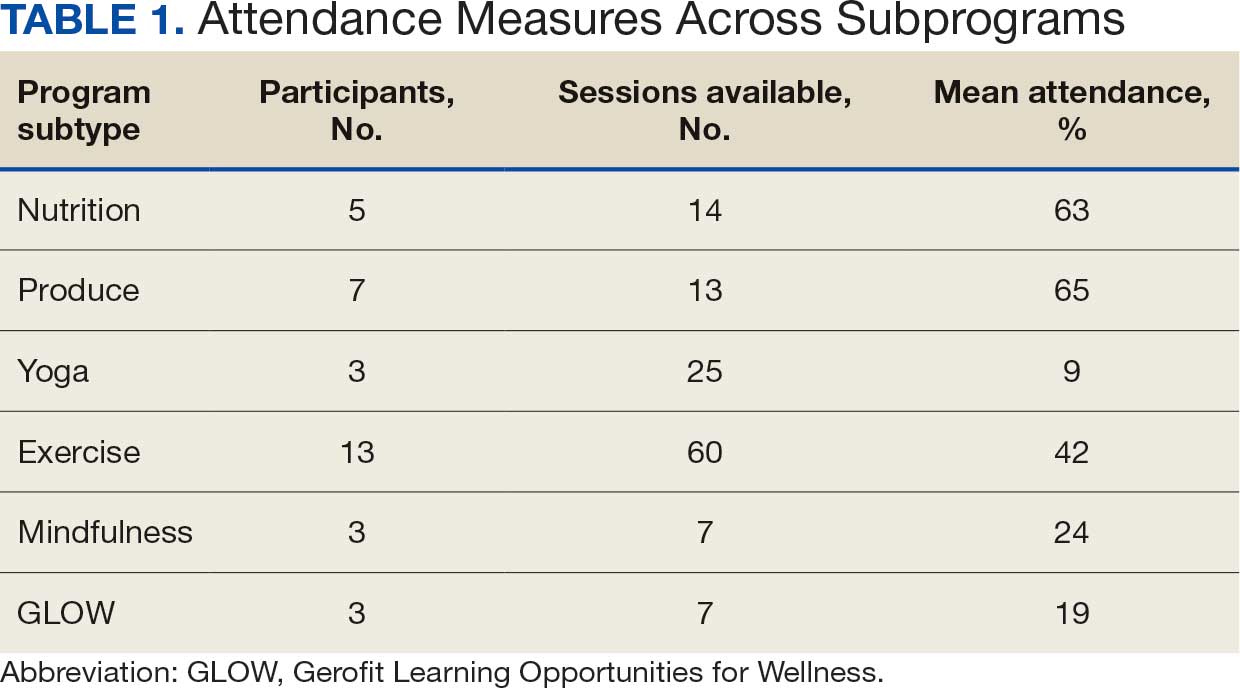

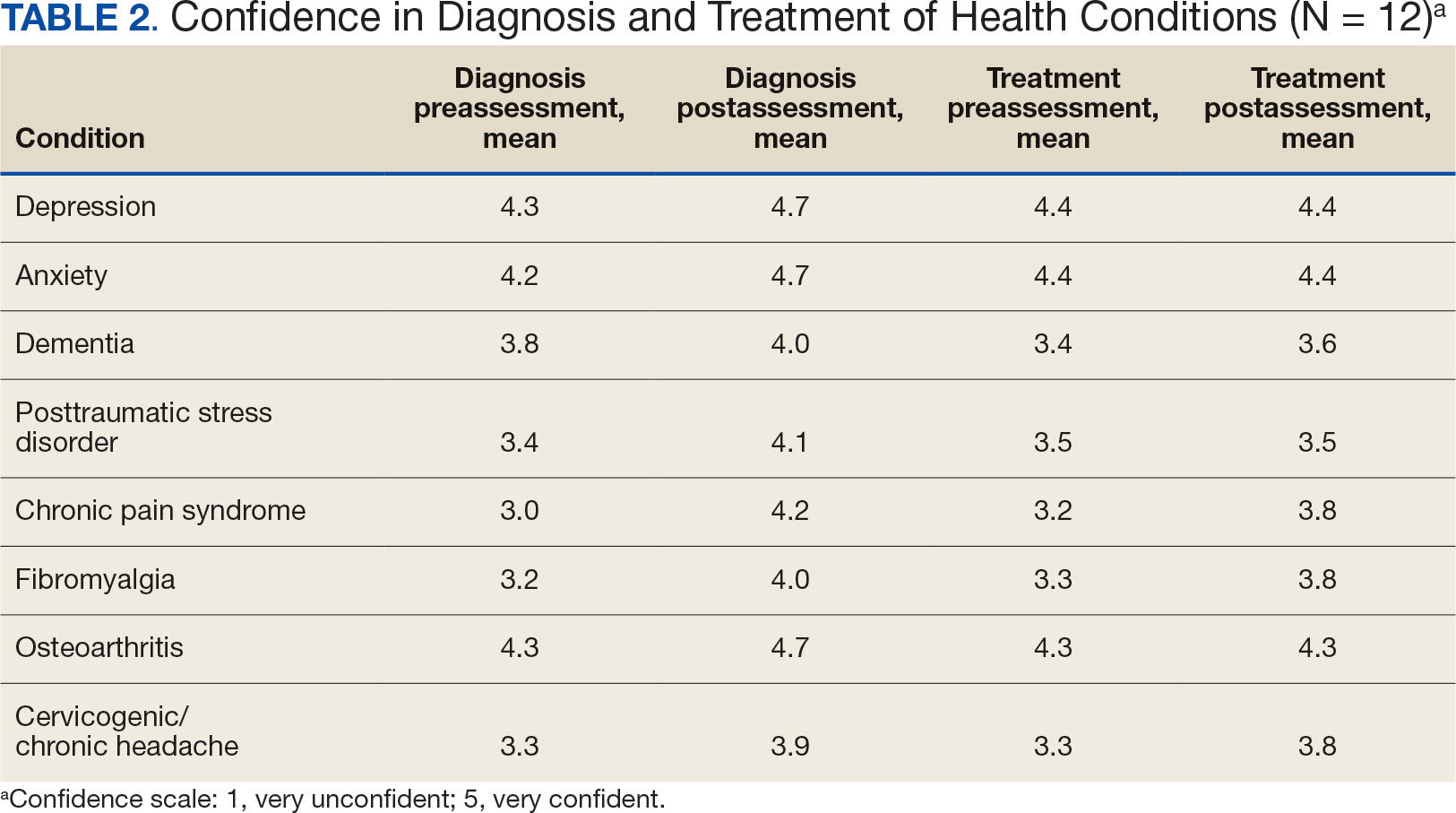

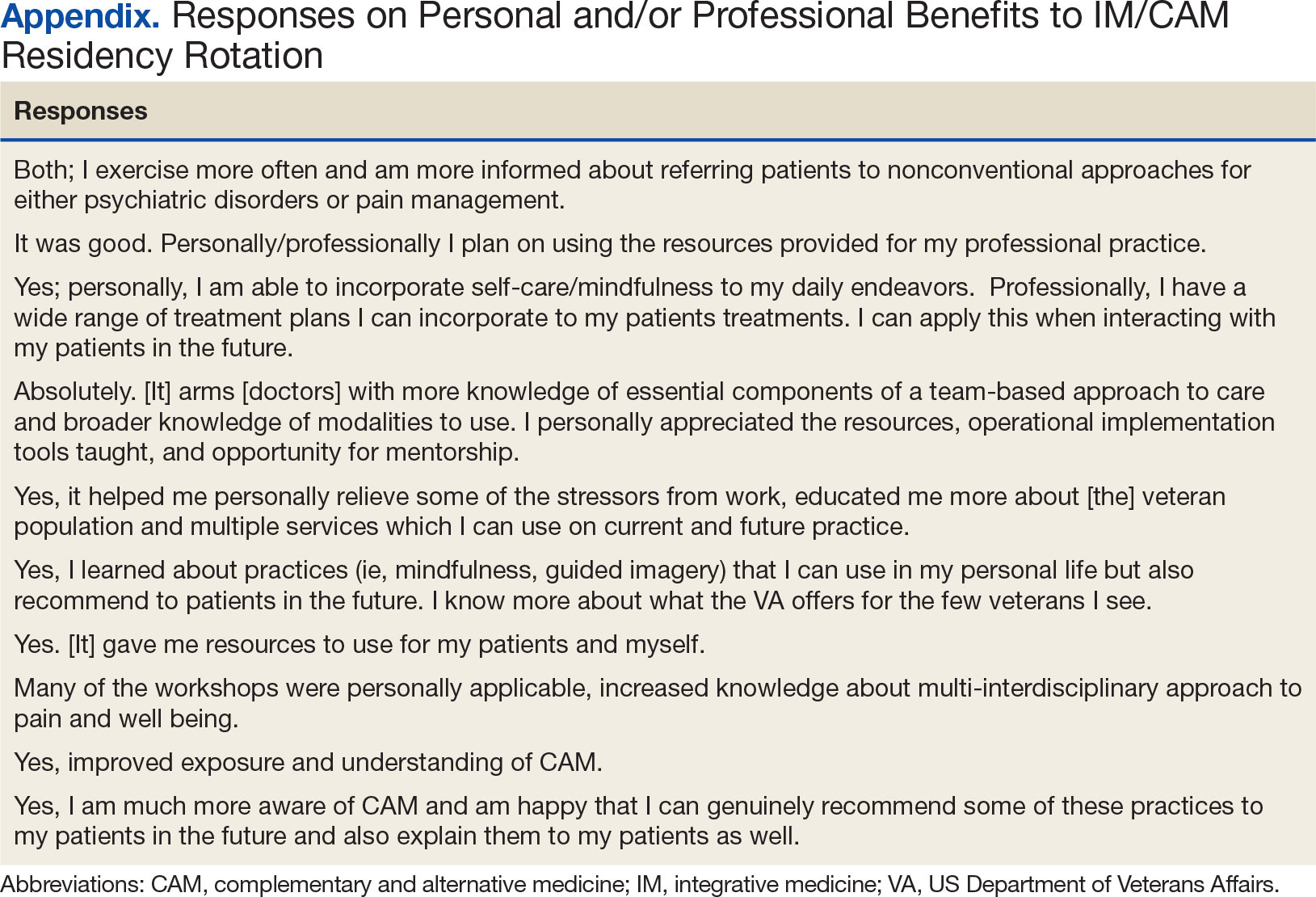

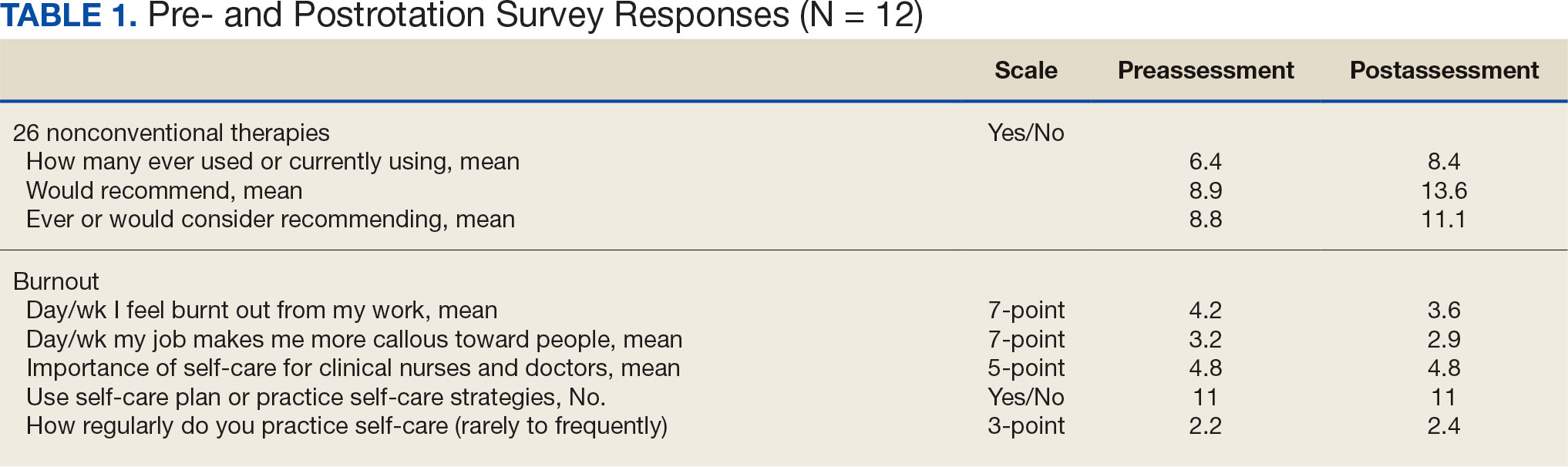

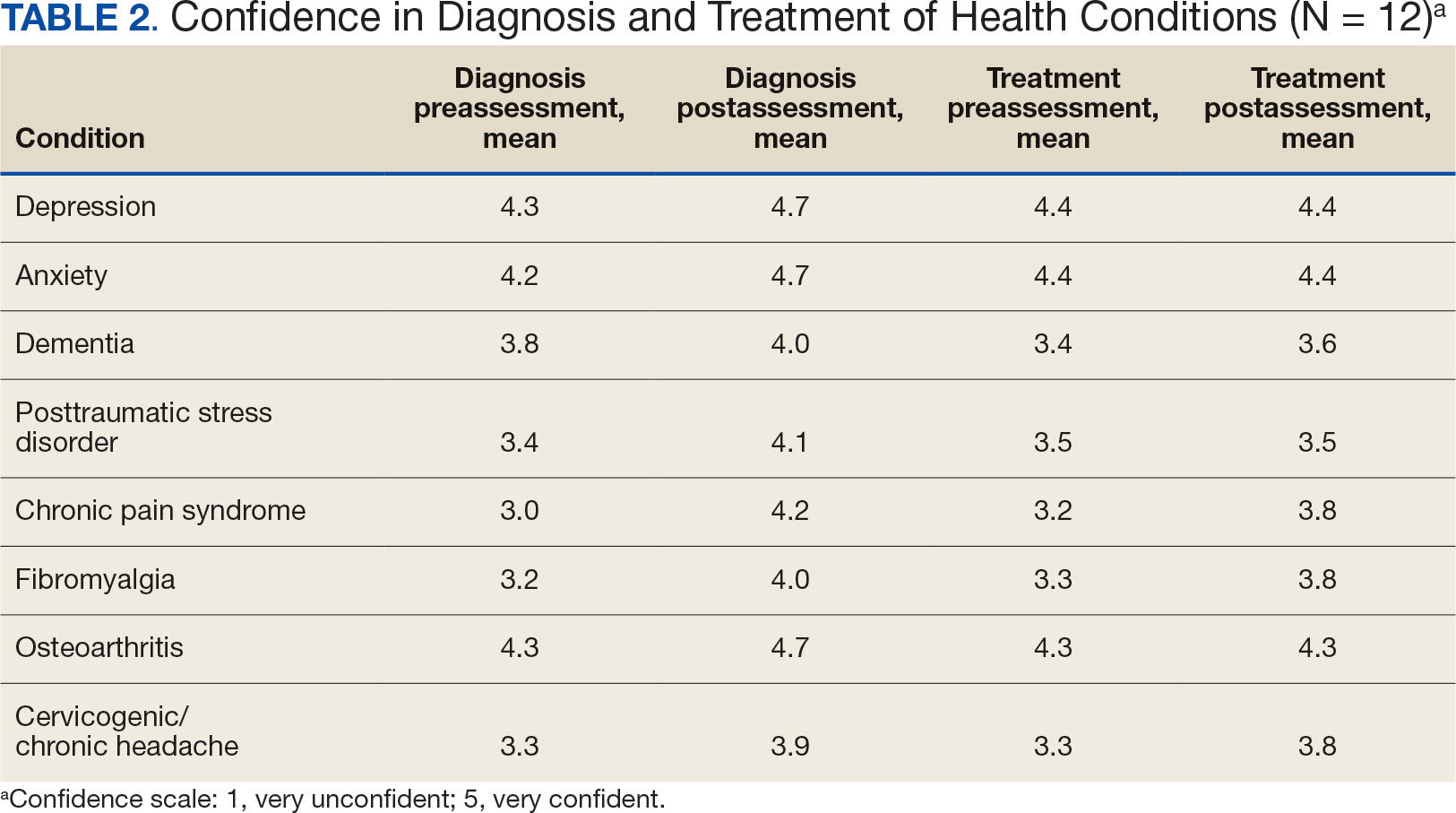

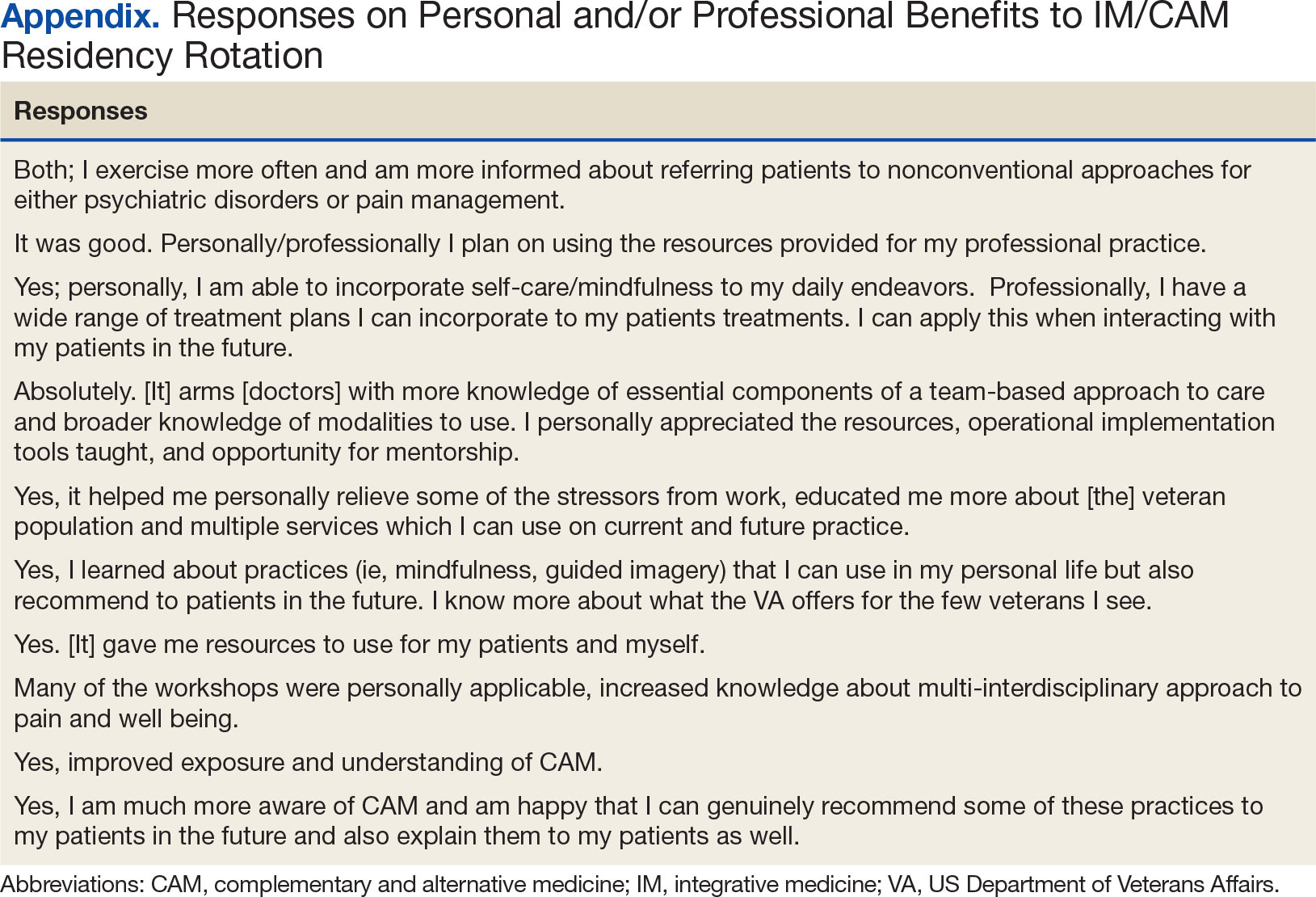

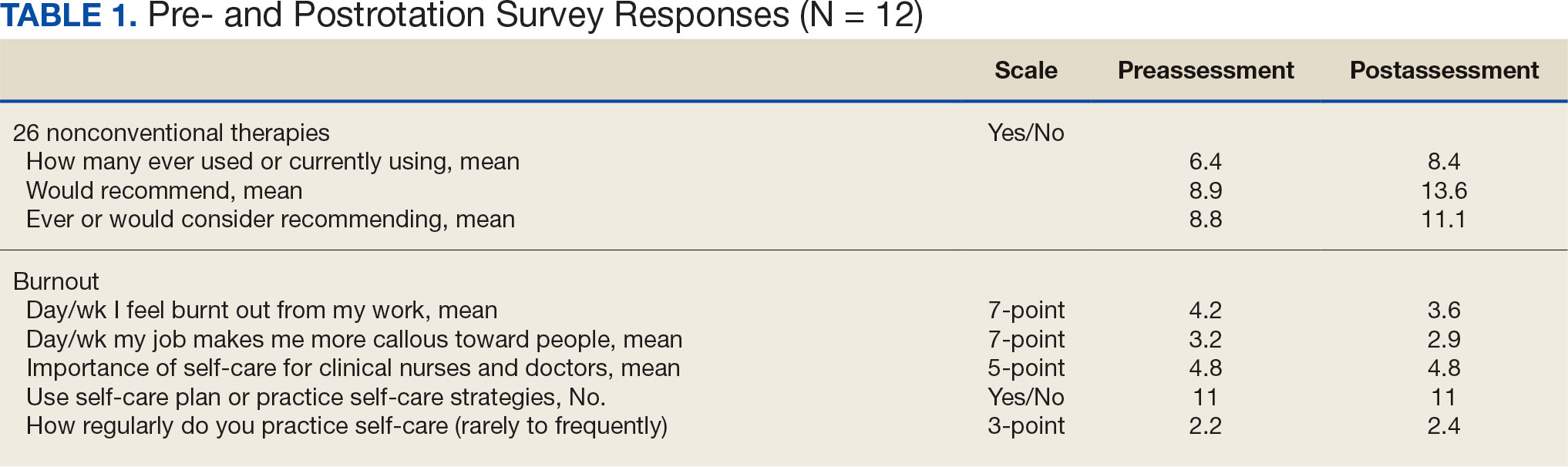

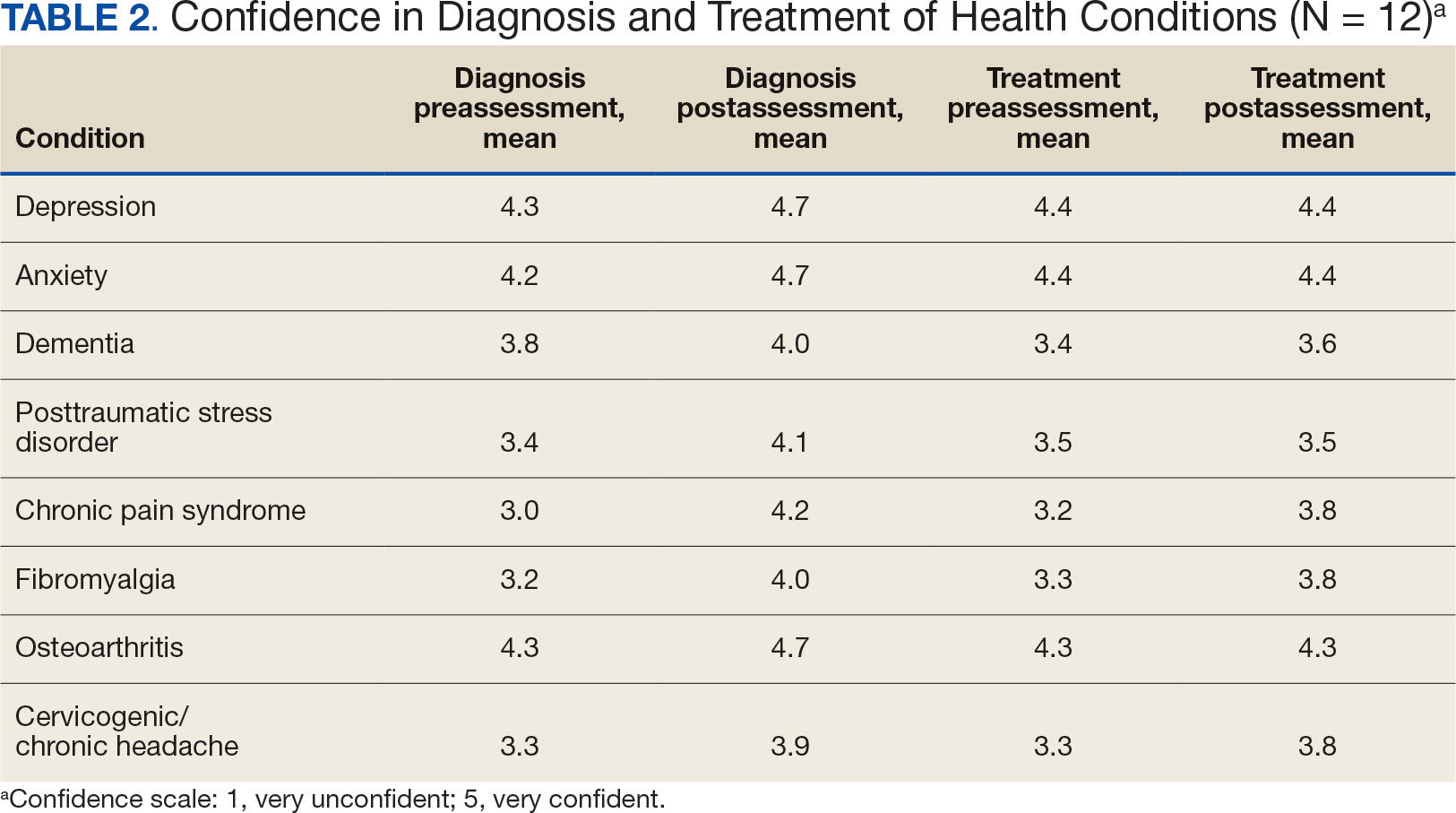

Five participants enrolled in 1 WHAG program, 11 enrolled in 2, and 8 enrolled in ≥ 3 (Table 1). Sixteen veterans completed baseline testing and 12 completed 3-month follow-up assessments (Table 2). At baseline, participants were below the reference range for physical functioning and physical activity levels. After 3 months, improvements were observed in endurance self-reported physical activity, and strength with many values in the reference range. However, physical and mental global health scores did not change.

Ten veterans completed the PHI Short Form. Veterans most frequently identified multiple areas they wished to improve, including moving the body (n = 10), recharge (n = 10), food and drink (n = 9), and power of the mind (n = 7). Baseline self-ratings on each whole health component, along with follow-up ratings at the program’s conclusion, are presented in Figure 3. Some participants aimed to maintain current levels rather than seek improvement. At the 3-month mark, most veterans perceived themselves as improving in ≥1 health component.

Discussion Programs that target holistic wellness are needed to ensure the health of a rapidly aging population. The WHAG pilot program is an example of a comprehensive, patient-centered wellness program that supports participants in defining personal wellness goals to promote healthy aging. Gerofit addresses the continuum by beginning with goal-oriented discussions with veterans to guide program participation and support desired outcomes.

Gerofit provided a strong pre-existing framework of virtual social support and physical infrastructure for the addition of WHAG. Gerofit staff were responsible for recruitment and engagement, program oversight, and outcome data collection. Additionally, VHA facilities provide physical space for in-person and virtual programming. Integrating WHAG into Gerofit allows veterans to prioritize “what matters” and engage with peers in a nontraditional way, such as the dog fostering and adoption program provides veterans with an opportunity to increase physical activity levels and improve mental and physical health through the human-animal bond.25

By providing virtual options, WHAG enhances access to health care in medically underserved areas. WHAG also improves the veteran experience with the VA, building on Gerofit’s track record of high patient satisfaction, strong adherence, high retention, and consistent consults for veterans to join.10 The program allows veterans to be at the forefront of their VHA care, choosing to participate in the various offerings based on their personal preferences.

In this population of older veterans from Baltimore, Maryland, the majority of whom reside in disadvantaged areas, we observed that the programs with the highest participation were related to diet, stress reduction, and physical activity. These 3 areas align with common barriers faced by individuals in underserved communities. Many of these communities are food deserts, lack space or resources for gardening, and have limited or unsafe access to opportunities for physical activity, making gyms or even neighborhood exercise difficult to access.26-28 Offering produce delivery and virtual nutrition classes may potentially alleviate this barrier by providing economic stability by increasing access to healthy foods paired with nutrition education to promote use of free, fresh food. Teaching older adults with impaired mobility how to overcome barriers to consuming a healthy diet may improve their dietary intake.23,29,30 Future evaluations aim to examine how these various nutrition programs impact dietary intake and how changes in dietary intake may impact functional outcomes among this group.

Group classes provide opportunities for social connection and mutual support, both of which are powerful motivators for older adults. Frequent contact with others may help reduce the risk of depression, loneliness, and social isolation.28 Routine contact with staff allows for observation of short-term changes in behavior and mood, giving staff the chance to follow up when needed. The addition of these new programs gives participants more opportunities to engage with Gerofit staff and fellow veterans beyond traditional exercise sessions. This WHAG model could expand to other Gerofit sites; however, future whole health programs should take into account the unique needs and barriers specific to each location. Doing so will help ensure offerings align with participant preferences. Programs should be thoughtfully selected and designed to directly address local challenges to promote optimal engagement and support the greatest potential for success.

CONCLUSIONS

Programs that promote and support functional independence in older adults are needed, particularly given the rapidly growing and aging population. Identifying comprehensive strategies that promote healthy aging is likely to be beneficial not only for chronic disease management and social engagement but may also promote functional independence and reduce the risk of further functional decline.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration– About VHA. Veterans Health Administration. 2023. Accessed December 4, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp

- Nelson KM. The burden of obesity among a national probability sample of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:915- 919. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00526.x

- Koepsell TD, Forsberg CW, Littman AJ. Obesity, overweight, and weight control practices in U.S. veterans. Prev Med. 2009;48:267-271. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.01.008

- Das SR, Kinsinger LS, Yancy WS Jr, et al. Obesity prevalence among veterans at Veterans Affairs medical facilities. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:291-294. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.007

- Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, et al. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

- Bokhour BG, Haun JN, Hyde J, et al. Transforming the Veterans Affairs to a whole health system of care: time for action and research. Med Care. 2020;58:295-300. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001316

- Marchand WR, Beckstrom J, Nazarenko E, et al. The Veterans Health Administration whole health model of care: early implementation and utilization at a large healthcare system. Mil Med. 2020;185:2150-2157. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa198

- Shulkin D, Elnahal S, Maddock E, Shaheen M. Best Care Everywhere by VA Professionals Across the Nation. US Dept of Veterans Affairs; 2017.

- Morey MC, Lee CC, Castle S, et al. Should structured exercise be promoted as a model of care? Dissemination of the Department of Veterans Affairs Gerofit Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1009-1016. doi:10.1111/jgs.15276

- Cowper PA, Morey MC, Bearon LB, et al. The impact of supervised exercise on the psychological well-being and health status of older veterans. J Appl Gerontol. 1991;10:469-485. doi:10.1177/073346489101000408

- Pepin MJ, Valencia WM, Bettger JP, et al. Impact of supervised exercise on one-year medication use in older veterans with multiple morbidities. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420956751. doi:10.1177/073346489101000408

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Sullivan RJ Jr, et al. Fiveyear performance trends for older exercisers: a hierarchical model of endurance, strength, and flexibility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1226-1231. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01374.x

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Crowley GM, et al. Exercise adherence and 10-year mortality in chronically ill older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1929-1933. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50602.x

- Jorna M, Ball K, Salmon J. Effects of a holistic health program on women’s physical activity and mental and spiritual health. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9:395-401. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2006.06.011

- Jennings SC, Manning KM, Bettger JP, et al. Rapid transition to telehealth group exercise and functional assessments in response to COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420980313. doi:10.1177/2333721420980313

- Morey MC, Crowley GM, Robbins MS, et al. The Gerofit program: a VA innovation. South Med J. 1994;87:S83-87.

- Addison O, Serra MC, Katzel L, et al. Mobility improvements are found in older veterans after 6 months of Gerofit regardless of BMI classification. J Aging Phys Act. 2019;27:848-854. doi:10.1123/japa.2018-0317

- Veterans Health Administration Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation. Making your plan— whole health. November 14, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2025. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/phi.asp

- Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:873-880. doi:10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9

- Aktary ML, Caron-Roy S, Sajobi T, et al. Impact of a farmers’ market nutrition coupon programme on diet quality and psychosocial well-being among low-income adults: protocol for a randomised controlled trial and a longitudinal qualitative investigation. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e035143. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035143

- Afshin A, Penalvo JL, Del Gobbo L, et al. The prospective impact of food pricing on improving dietary consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172277. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172277

- Singleton CR, Kessee N, Chatman C, et al. Racial/ ethnic differences in the shopping behaviors and fruit and vegetable consumption of farmers’ market incentive program users in Illinois. Ethn Dis. 2020;30:109. doi:10.18865/ed.30.1.109

- Cassatt S, Giffuni J, Ortmeyer H, et al. A pilot study to evaluate the development and implementation of a virtual nutrition education program in older veterans. Abstract presented at: American Heart Association Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health 2022 Scientific Sessions; March 1-4, 2022; Chicago, IL. https:// www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circ.145.suppl_1.P002

- Parker EA, Perez WJ, Phipps B, et al. Dietary quality and perceived barriers to weight loss among older overweight veterans with dysmobility. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:9153. doi:10.3390/ijerph19159153

- Ortmeyer HK, Giffuni J, Etchberger D, et al. The role of companion dogs in the VA Maryland Health Care System Whole Health(y) GeroFit Program. Animals (Basel). 2023;13:19. doi:10.3390/ani13193047

- Milaneschi Y, Tanaka T, Ferrucci L. Nutritional determinants of mobility. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:625- 629.

- Lane JM, Davis BA. Food, physical activity, and health deserts in Alabama: the spatial link between healthy eating, exercise, and socioeconomic factors. GeoJournal. 2022;87:5229-5249.

- Komatsu H, Yagasaki K, Saito Y, et al. Regular group exercise contributes to balanced health in older adults in Japan: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:190. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0584-3

- Komatsu H, Yagasaki K, Saito Y, et al. Regular group exercise contributes to balanced health in older adults in Japan: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:190. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0584-3

- Wolfson JA, Ramsing R, Richardson CR, et al. Barriers to healthy food access: associations with household income and cooking behavior. Prev Med Rep. 2019;13:298-305. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.01.023

About half of the > 9 million veterans served by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) are aged ≥ 65 years.1 Veterans are at a higher risk for comorbidities, which may contribute to increased health care costs, mobility limitations and disability, poor quality of life, and mortality. 2-5 Programs and policies that promote health maintenance, independent living, and quality of life are needed among older veterans. To support veterans’ overall health and well-being, the VHA has shifted to whole health, a patient-centered care model.6

The whole health paradigm employs personalized, proactive, and patient-driven care, emphasizing complementary and integrative health practices, and prioritizing health promotion and disease prevention over disease treatment.7 The veteran is empowered to decide “what matters to [me],” reflect on life and health, and define mission, aspiration, and purpose. This approach gives veterans a more active and direct role in their care, distinguishing it from traditional care models. In turn, it helps reduce the burden on clinicians and fosters a more collaborative environment in which both the clinician and veteran work together to shape the care process.7 Veterans utilize the Circle of Health to identify skills and support needed to implement changes in self-care. The Circle of Health includes 8 self-care components: moving the body; surroundings; personal development; food and drink; recharge; family, friends, and coworkers; spirit and soul; and power of the mind.6 This process drives the creation of a personal health plan, creating opportunities for individuals to engage in well-being programs that matter to them and help them meet their goals.

Gerofit is a VHA best practice and whole health outpatient exercise program for veterans aged ≥65 years.8 Gerofit has focused primarily on exercise within the moving the body self-care component.9 A longitudinal study followed 691 Gerofit participants across 6 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers who on average were 73 years old, had 16 different medical conditions, and took 10 medications. Most were obese and had a mean gait speed of 1.04 m/s, suggesting functional impairment.10 Prior studies have shown that Gerofit participation is associated with a range of health benefits. Two studies reported improvements in psychological well-being and sustained gains in endurance, strength, and flexibility following early Gerofit program participation. 11,12 A 10-year analysis of 115 veterans found that long-term Gerofit participation reduced mortality risk, while another study of 452 veterans showed decreased medication use following 1 year in the program.13,14

The VHA whole health model comprises 3 components: (1) The Pathway, (2) well-being programs, and (3) whole health clinical care.6 The Pathway engages veterans in identifying personal health goals, while well-being programs offer selfcare and skill-building activities. Traditional clinical settings often focus primarily on the third component due to time and resource constraints. The Gerofit platform addresses all 3 components. Its existing infrastructure, including a supportive community and dedicated facilities, provides a setting for implementing The Pathway and well-being programs. The Gerofit structure allows for the time and continuity necessary for these components, which are often limited during standard clinical visits.

By expanding the Gerofit exercise regimen to include additional wellness activities, it can holistically support older veterans. Research supports this integrative approach. For example, a 2020 study found that incorporating a holistic health program into an existing exercise program within a church setting led to improved physical activity and overall health among women participants.15 This article describes the integration of Whole Health(y) Aging with Gerofit (WHAG), a pilot program in Baltimore, Maryland, that integrates whole health components into the established Gerofit framework to enhance the overall well-being of participating veterans (Figure 1).

WHOLE HEALTH(Y) AGING WITH GEROFIT

Gerofit enrollment has been described elsewhere in detail.16 Patients aged ≥ 65 years are eligible to participate with clinician approval if they are medically stable. Following VHA clinician referral and primary care approval, veterans completed a telephone visit to determine eligibility and discuss their exercise history, goals, and preferences. Veterans dependent in activities of daily living and those with cognitive impairment, unstable angina, active proliferative diabetic retinopathy, oxygen dependence, frank incontinence, active open wounds, active substance abuse, volatile behavioral issues, or who are experiencing homelessness are not eligible for Gerofit.

The exercise physiologist identified veteran barriers and incentives to participation and assisted with a plan to maximize SMART goals (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound). Veterans then completed an assessment visit, either in person or virtually, depending on the selected programming. Functional assessments conducted by trained Gerofit exercise physiologists include testing of lower and upper body strength and submaximal endurance.9,17,18 Participation in Gerofit is voluntary and not time limited.

Prior to these newly expanded offerings, veterans could only enroll in a personalized, structured exercise program. Based on feedback from Gerofit participants indicating areas of interest, WHAG was developed to provide additional wellness offerings aligned with other Circle of Health components.6 This included virtual group nutrition education and cooking interventions with optional fresh produce delivery; wellness classes, the Companion Dog Fostering & Adoption program, and Gerofit in the Mind, which included mindfulness classes and relaxation seminars (Figure 1). Programs were virtual (except dog fostering and adoption) and rotated throughout the year. Not all programs are offered simultaneously.

Attendance, completion of selected questions from the individual Personal Health Inventory (PHI) Short Form, measured physical function, self-reported physical activity levels, physical and mental health status, and program satisfaction were measured for all WHAG subprograms.18 Selected questions from the PHI Short Form use a 5-point Likert scale to rate the following whole health components: physical activity; sleep, relaxation, and recovery; healthy eating habits; and positive outlook, healthy relationships, and caring for mental health. Physical function was assessed using 30-second arm curls (upper body strength), 30-second chair stands (lower body strength), and the 2-minute step test (virtual) or 6-minute walk test (in person) (submaximal cardiovascular endurance).

Self-reported physical activity was assessed by asking frequency (days per week) and duration (minutes per session) of cardiovascular and strength exercises to calculate total minutes per week. Physical and mental health status was assessed using the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Health Scale.19 Demographic data included sex, race and ethnicity, and age at baseline visit. Mean (SD) was calculated for continuous variables and presented unless otherwise specified, and frequencies were calculated for categorical variables. Subsequent reports will describe additional assessments and detailed outcomes unique to individual programs.

Overview

Veterans chose the programs that best suited their needs without limitations.7 Staff provided guidance on newly available programs based on an individual’s specified goals. Gerofit staff assisted veterans with development of individualized personal health plans, monitoring progress towards their goals, supporting program participation, and connecting veterans with additional whole health resources.

Gerofit Exercise Group. Exercise was designed to address the Moving the Body component of whole health. Veterans could elect to schedule 1-hour, 3-times-weekly in-person gym appointments, participate in 3-times-weekly livestreamed virtual group exercise classes through VA Video Connect, or receive a self-directed at-home exercise plan.

Gerofit Learning Opportunities for Wellness Classes. These virtual health education sessions addressed the personal development component of whole health and were designed to increase self-efficacy and empower veterans to take an active role in their health care. Topics focused broadly on issues related to healthy aging (eg, importance of sleep, goal setting, self-care, and comorbidity education). Veterans could participate in any classes of interest, which were led by health care professionals and offered twice monthly. Sessions encouraged participant questions and peer interaction.

Nutrition. Improving dietary quality is a frequently reported goal of Gerofit participants. WHAG incorporated multiple strategies to assist veterans in meeting these goals. For example, through a partnership with Therapeutic Alternative of Maryland Farm, Gerofit provided veterans free, locally grown fresh produce. This initiative addressed barriers to healthy eating by improving access to fresh produce, which has been shown to influence cooking frequency and diet quality.20-22 Participation in nutrition classes was not required. In 2021, veterans received produce weekly; however, many reported excess quantities. Beginning in 2022, veterans could select both produce items and quantities desired.

In addition, a registered dietitian led a 14-week virtual nutrition education program guided by the social cognitive theory framework and focused on self-regulation skills such as goal setting, overcoming barriers, and identifying triggers.23 Prior research highlighted low health literacy as a common barrier among older veterans, which informed several key components of the curriculum.24 These included how to read and interpret nutrition labels, define balanced meals and snacks, and understand the classification of various food groups such as fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. The online program curriculum included an instructor guide and participant materials for each individual lesson, including an educational handout on the specific week’s topic, applied activity (group or individual), and recipes related to the produce shares. Structured group discussion promoted camaraderie and recipe sharing, and additional instruction on produce preparation and storage.

Reported lack of self-efficacy and knowledge regarding produce preparation prompted a 5-week virtual cooking series, led by a medical student and supervised by a registered dietitian. Sessions combined brief nutrition education with live cooking demonstrations adapted from the VA Healthy Teaching Kitchen curriculum. Recipes emphasized low-cost, commonly found food items. The Healthy Teaching Kitchen modifications focused on Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diets, diabetes, and the importance of protein for older adults. Participants were allowed time to discuss recipes and food preparation tips, and other household members were allowed to observe.

Dog Fostering and Adoption. Veterans could foster or adopt a rescue dog through a partnership with local rescue groups. This program allowed participating veterans to have a companion, which addressed the surroundings, moving the body, and spirit and soul whole health components. The Companion Dog Fostering and Adoption Program and results on physical function and daily physical activity from the first 3 months were recently published. Positive effects on physical activity, physical function, and quality of life were observed at 3 months as compared to baseline in veterans who received a companion dog.25

Gerofit in the Garden. Veterans could opt to receive an EarthBox containing soil and seedlings for 1 vegetable and 1 herb. The boxes are designed to fit on a small tabletop, regardless of home type or availability of backyard. In-person instruction for veterans on care and maintenance was provided by a farm employee with experience in gardening and farming practices.

Gerofit in the Mind. Online relaxation seminars were offered twice monthly for 4 months. Led by a certified sound health guide, sessions incorporated sound baths, crystal bowls, Tibetan bowls, tuning forks, and breath work. Virtual mindfulness classes led by a certified yoga instructor were offered weekly for 1 month. Veterans could drop in and participate based on their availability. Classes were designed to introduce veterans to the practice of mindfulness, improve mood, and lower stress and anxiety.

Pilot Program Outcomes

Sixteen male veterans participated in WHAG. Participants were 62% Black, with a mean age of 76 years. Veterans collaborated with Gerofit staff to develop personal health plans, which ultimately guided program participation (Figure 2).

Five participants enrolled in 1 WHAG program, 11 enrolled in 2, and 8 enrolled in ≥ 3 (Table 1). Sixteen veterans completed baseline testing and 12 completed 3-month follow-up assessments (Table 2). At baseline, participants were below the reference range for physical functioning and physical activity levels. After 3 months, improvements were observed in endurance self-reported physical activity, and strength with many values in the reference range. However, physical and mental global health scores did not change.

Ten veterans completed the PHI Short Form. Veterans most frequently identified multiple areas they wished to improve, including moving the body (n = 10), recharge (n = 10), food and drink (n = 9), and power of the mind (n = 7). Baseline self-ratings on each whole health component, along with follow-up ratings at the program’s conclusion, are presented in Figure 3. Some participants aimed to maintain current levels rather than seek improvement. At the 3-month mark, most veterans perceived themselves as improving in ≥1 health component.

Discussion Programs that target holistic wellness are needed to ensure the health of a rapidly aging population. The WHAG pilot program is an example of a comprehensive, patient-centered wellness program that supports participants in defining personal wellness goals to promote healthy aging. Gerofit addresses the continuum by beginning with goal-oriented discussions with veterans to guide program participation and support desired outcomes.

Gerofit provided a strong pre-existing framework of virtual social support and physical infrastructure for the addition of WHAG. Gerofit staff were responsible for recruitment and engagement, program oversight, and outcome data collection. Additionally, VHA facilities provide physical space for in-person and virtual programming. Integrating WHAG into Gerofit allows veterans to prioritize “what matters” and engage with peers in a nontraditional way, such as the dog fostering and adoption program provides veterans with an opportunity to increase physical activity levels and improve mental and physical health through the human-animal bond.25

By providing virtual options, WHAG enhances access to health care in medically underserved areas. WHAG also improves the veteran experience with the VA, building on Gerofit’s track record of high patient satisfaction, strong adherence, high retention, and consistent consults for veterans to join.10 The program allows veterans to be at the forefront of their VHA care, choosing to participate in the various offerings based on their personal preferences.

In this population of older veterans from Baltimore, Maryland, the majority of whom reside in disadvantaged areas, we observed that the programs with the highest participation were related to diet, stress reduction, and physical activity. These 3 areas align with common barriers faced by individuals in underserved communities. Many of these communities are food deserts, lack space or resources for gardening, and have limited or unsafe access to opportunities for physical activity, making gyms or even neighborhood exercise difficult to access.26-28 Offering produce delivery and virtual nutrition classes may potentially alleviate this barrier by providing economic stability by increasing access to healthy foods paired with nutrition education to promote use of free, fresh food. Teaching older adults with impaired mobility how to overcome barriers to consuming a healthy diet may improve their dietary intake.23,29,30 Future evaluations aim to examine how these various nutrition programs impact dietary intake and how changes in dietary intake may impact functional outcomes among this group.

Group classes provide opportunities for social connection and mutual support, both of which are powerful motivators for older adults. Frequent contact with others may help reduce the risk of depression, loneliness, and social isolation.28 Routine contact with staff allows for observation of short-term changes in behavior and mood, giving staff the chance to follow up when needed. The addition of these new programs gives participants more opportunities to engage with Gerofit staff and fellow veterans beyond traditional exercise sessions. This WHAG model could expand to other Gerofit sites; however, future whole health programs should take into account the unique needs and barriers specific to each location. Doing so will help ensure offerings align with participant preferences. Programs should be thoughtfully selected and designed to directly address local challenges to promote optimal engagement and support the greatest potential for success.

CONCLUSIONS

Programs that promote and support functional independence in older adults are needed, particularly given the rapidly growing and aging population. Identifying comprehensive strategies that promote healthy aging is likely to be beneficial not only for chronic disease management and social engagement but may also promote functional independence and reduce the risk of further functional decline.

About half of the > 9 million veterans served by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) are aged ≥ 65 years.1 Veterans are at a higher risk for comorbidities, which may contribute to increased health care costs, mobility limitations and disability, poor quality of life, and mortality. 2-5 Programs and policies that promote health maintenance, independent living, and quality of life are needed among older veterans. To support veterans’ overall health and well-being, the VHA has shifted to whole health, a patient-centered care model.6

The whole health paradigm employs personalized, proactive, and patient-driven care, emphasizing complementary and integrative health practices, and prioritizing health promotion and disease prevention over disease treatment.7 The veteran is empowered to decide “what matters to [me],” reflect on life and health, and define mission, aspiration, and purpose. This approach gives veterans a more active and direct role in their care, distinguishing it from traditional care models. In turn, it helps reduce the burden on clinicians and fosters a more collaborative environment in which both the clinician and veteran work together to shape the care process.7 Veterans utilize the Circle of Health to identify skills and support needed to implement changes in self-care. The Circle of Health includes 8 self-care components: moving the body; surroundings; personal development; food and drink; recharge; family, friends, and coworkers; spirit and soul; and power of the mind.6 This process drives the creation of a personal health plan, creating opportunities for individuals to engage in well-being programs that matter to them and help them meet their goals.

Gerofit is a VHA best practice and whole health outpatient exercise program for veterans aged ≥65 years.8 Gerofit has focused primarily on exercise within the moving the body self-care component.9 A longitudinal study followed 691 Gerofit participants across 6 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers who on average were 73 years old, had 16 different medical conditions, and took 10 medications. Most were obese and had a mean gait speed of 1.04 m/s, suggesting functional impairment.10 Prior studies have shown that Gerofit participation is associated with a range of health benefits. Two studies reported improvements in psychological well-being and sustained gains in endurance, strength, and flexibility following early Gerofit program participation. 11,12 A 10-year analysis of 115 veterans found that long-term Gerofit participation reduced mortality risk, while another study of 452 veterans showed decreased medication use following 1 year in the program.13,14

The VHA whole health model comprises 3 components: (1) The Pathway, (2) well-being programs, and (3) whole health clinical care.6 The Pathway engages veterans in identifying personal health goals, while well-being programs offer selfcare and skill-building activities. Traditional clinical settings often focus primarily on the third component due to time and resource constraints. The Gerofit platform addresses all 3 components. Its existing infrastructure, including a supportive community and dedicated facilities, provides a setting for implementing The Pathway and well-being programs. The Gerofit structure allows for the time and continuity necessary for these components, which are often limited during standard clinical visits.

By expanding the Gerofit exercise regimen to include additional wellness activities, it can holistically support older veterans. Research supports this integrative approach. For example, a 2020 study found that incorporating a holistic health program into an existing exercise program within a church setting led to improved physical activity and overall health among women participants.15 This article describes the integration of Whole Health(y) Aging with Gerofit (WHAG), a pilot program in Baltimore, Maryland, that integrates whole health components into the established Gerofit framework to enhance the overall well-being of participating veterans (Figure 1).

WHOLE HEALTH(Y) AGING WITH GEROFIT

Gerofit enrollment has been described elsewhere in detail.16 Patients aged ≥ 65 years are eligible to participate with clinician approval if they are medically stable. Following VHA clinician referral and primary care approval, veterans completed a telephone visit to determine eligibility and discuss their exercise history, goals, and preferences. Veterans dependent in activities of daily living and those with cognitive impairment, unstable angina, active proliferative diabetic retinopathy, oxygen dependence, frank incontinence, active open wounds, active substance abuse, volatile behavioral issues, or who are experiencing homelessness are not eligible for Gerofit.

The exercise physiologist identified veteran barriers and incentives to participation and assisted with a plan to maximize SMART goals (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound). Veterans then completed an assessment visit, either in person or virtually, depending on the selected programming. Functional assessments conducted by trained Gerofit exercise physiologists include testing of lower and upper body strength and submaximal endurance.9,17,18 Participation in Gerofit is voluntary and not time limited.

Prior to these newly expanded offerings, veterans could only enroll in a personalized, structured exercise program. Based on feedback from Gerofit participants indicating areas of interest, WHAG was developed to provide additional wellness offerings aligned with other Circle of Health components.6 This included virtual group nutrition education and cooking interventions with optional fresh produce delivery; wellness classes, the Companion Dog Fostering & Adoption program, and Gerofit in the Mind, which included mindfulness classes and relaxation seminars (Figure 1). Programs were virtual (except dog fostering and adoption) and rotated throughout the year. Not all programs are offered simultaneously.

Attendance, completion of selected questions from the individual Personal Health Inventory (PHI) Short Form, measured physical function, self-reported physical activity levels, physical and mental health status, and program satisfaction were measured for all WHAG subprograms.18 Selected questions from the PHI Short Form use a 5-point Likert scale to rate the following whole health components: physical activity; sleep, relaxation, and recovery; healthy eating habits; and positive outlook, healthy relationships, and caring for mental health. Physical function was assessed using 30-second arm curls (upper body strength), 30-second chair stands (lower body strength), and the 2-minute step test (virtual) or 6-minute walk test (in person) (submaximal cardiovascular endurance).

Self-reported physical activity was assessed by asking frequency (days per week) and duration (minutes per session) of cardiovascular and strength exercises to calculate total minutes per week. Physical and mental health status was assessed using the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Health Scale.19 Demographic data included sex, race and ethnicity, and age at baseline visit. Mean (SD) was calculated for continuous variables and presented unless otherwise specified, and frequencies were calculated for categorical variables. Subsequent reports will describe additional assessments and detailed outcomes unique to individual programs.

Overview

Veterans chose the programs that best suited their needs without limitations.7 Staff provided guidance on newly available programs based on an individual’s specified goals. Gerofit staff assisted veterans with development of individualized personal health plans, monitoring progress towards their goals, supporting program participation, and connecting veterans with additional whole health resources.

Gerofit Exercise Group. Exercise was designed to address the Moving the Body component of whole health. Veterans could elect to schedule 1-hour, 3-times-weekly in-person gym appointments, participate in 3-times-weekly livestreamed virtual group exercise classes through VA Video Connect, or receive a self-directed at-home exercise plan.

Gerofit Learning Opportunities for Wellness Classes. These virtual health education sessions addressed the personal development component of whole health and were designed to increase self-efficacy and empower veterans to take an active role in their health care. Topics focused broadly on issues related to healthy aging (eg, importance of sleep, goal setting, self-care, and comorbidity education). Veterans could participate in any classes of interest, which were led by health care professionals and offered twice monthly. Sessions encouraged participant questions and peer interaction.

Nutrition. Improving dietary quality is a frequently reported goal of Gerofit participants. WHAG incorporated multiple strategies to assist veterans in meeting these goals. For example, through a partnership with Therapeutic Alternative of Maryland Farm, Gerofit provided veterans free, locally grown fresh produce. This initiative addressed barriers to healthy eating by improving access to fresh produce, which has been shown to influence cooking frequency and diet quality.20-22 Participation in nutrition classes was not required. In 2021, veterans received produce weekly; however, many reported excess quantities. Beginning in 2022, veterans could select both produce items and quantities desired.

In addition, a registered dietitian led a 14-week virtual nutrition education program guided by the social cognitive theory framework and focused on self-regulation skills such as goal setting, overcoming barriers, and identifying triggers.23 Prior research highlighted low health literacy as a common barrier among older veterans, which informed several key components of the curriculum.24 These included how to read and interpret nutrition labels, define balanced meals and snacks, and understand the classification of various food groups such as fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. The online program curriculum included an instructor guide and participant materials for each individual lesson, including an educational handout on the specific week’s topic, applied activity (group or individual), and recipes related to the produce shares. Structured group discussion promoted camaraderie and recipe sharing, and additional instruction on produce preparation and storage.

Reported lack of self-efficacy and knowledge regarding produce preparation prompted a 5-week virtual cooking series, led by a medical student and supervised by a registered dietitian. Sessions combined brief nutrition education with live cooking demonstrations adapted from the VA Healthy Teaching Kitchen curriculum. Recipes emphasized low-cost, commonly found food items. The Healthy Teaching Kitchen modifications focused on Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diets, diabetes, and the importance of protein for older adults. Participants were allowed time to discuss recipes and food preparation tips, and other household members were allowed to observe.

Dog Fostering and Adoption. Veterans could foster or adopt a rescue dog through a partnership with local rescue groups. This program allowed participating veterans to have a companion, which addressed the surroundings, moving the body, and spirit and soul whole health components. The Companion Dog Fostering and Adoption Program and results on physical function and daily physical activity from the first 3 months were recently published. Positive effects on physical activity, physical function, and quality of life were observed at 3 months as compared to baseline in veterans who received a companion dog.25

Gerofit in the Garden. Veterans could opt to receive an EarthBox containing soil and seedlings for 1 vegetable and 1 herb. The boxes are designed to fit on a small tabletop, regardless of home type or availability of backyard. In-person instruction for veterans on care and maintenance was provided by a farm employee with experience in gardening and farming practices.

Gerofit in the Mind. Online relaxation seminars were offered twice monthly for 4 months. Led by a certified sound health guide, sessions incorporated sound baths, crystal bowls, Tibetan bowls, tuning forks, and breath work. Virtual mindfulness classes led by a certified yoga instructor were offered weekly for 1 month. Veterans could drop in and participate based on their availability. Classes were designed to introduce veterans to the practice of mindfulness, improve mood, and lower stress and anxiety.

Pilot Program Outcomes

Sixteen male veterans participated in WHAG. Participants were 62% Black, with a mean age of 76 years. Veterans collaborated with Gerofit staff to develop personal health plans, which ultimately guided program participation (Figure 2).

Five participants enrolled in 1 WHAG program, 11 enrolled in 2, and 8 enrolled in ≥ 3 (Table 1). Sixteen veterans completed baseline testing and 12 completed 3-month follow-up assessments (Table 2). At baseline, participants were below the reference range for physical functioning and physical activity levels. After 3 months, improvements were observed in endurance self-reported physical activity, and strength with many values in the reference range. However, physical and mental global health scores did not change.

Ten veterans completed the PHI Short Form. Veterans most frequently identified multiple areas they wished to improve, including moving the body (n = 10), recharge (n = 10), food and drink (n = 9), and power of the mind (n = 7). Baseline self-ratings on each whole health component, along with follow-up ratings at the program’s conclusion, are presented in Figure 3. Some participants aimed to maintain current levels rather than seek improvement. At the 3-month mark, most veterans perceived themselves as improving in ≥1 health component.

Discussion Programs that target holistic wellness are needed to ensure the health of a rapidly aging population. The WHAG pilot program is an example of a comprehensive, patient-centered wellness program that supports participants in defining personal wellness goals to promote healthy aging. Gerofit addresses the continuum by beginning with goal-oriented discussions with veterans to guide program participation and support desired outcomes.

Gerofit provided a strong pre-existing framework of virtual social support and physical infrastructure for the addition of WHAG. Gerofit staff were responsible for recruitment and engagement, program oversight, and outcome data collection. Additionally, VHA facilities provide physical space for in-person and virtual programming. Integrating WHAG into Gerofit allows veterans to prioritize “what matters” and engage with peers in a nontraditional way, such as the dog fostering and adoption program provides veterans with an opportunity to increase physical activity levels and improve mental and physical health through the human-animal bond.25

By providing virtual options, WHAG enhances access to health care in medically underserved areas. WHAG also improves the veteran experience with the VA, building on Gerofit’s track record of high patient satisfaction, strong adherence, high retention, and consistent consults for veterans to join.10 The program allows veterans to be at the forefront of their VHA care, choosing to participate in the various offerings based on their personal preferences.

In this population of older veterans from Baltimore, Maryland, the majority of whom reside in disadvantaged areas, we observed that the programs with the highest participation were related to diet, stress reduction, and physical activity. These 3 areas align with common barriers faced by individuals in underserved communities. Many of these communities are food deserts, lack space or resources for gardening, and have limited or unsafe access to opportunities for physical activity, making gyms or even neighborhood exercise difficult to access.26-28 Offering produce delivery and virtual nutrition classes may potentially alleviate this barrier by providing economic stability by increasing access to healthy foods paired with nutrition education to promote use of free, fresh food. Teaching older adults with impaired mobility how to overcome barriers to consuming a healthy diet may improve their dietary intake.23,29,30 Future evaluations aim to examine how these various nutrition programs impact dietary intake and how changes in dietary intake may impact functional outcomes among this group.

Group classes provide opportunities for social connection and mutual support, both of which are powerful motivators for older adults. Frequent contact with others may help reduce the risk of depression, loneliness, and social isolation.28 Routine contact with staff allows for observation of short-term changes in behavior and mood, giving staff the chance to follow up when needed. The addition of these new programs gives participants more opportunities to engage with Gerofit staff and fellow veterans beyond traditional exercise sessions. This WHAG model could expand to other Gerofit sites; however, future whole health programs should take into account the unique needs and barriers specific to each location. Doing so will help ensure offerings align with participant preferences. Programs should be thoughtfully selected and designed to directly address local challenges to promote optimal engagement and support the greatest potential for success.

CONCLUSIONS

Programs that promote and support functional independence in older adults are needed, particularly given the rapidly growing and aging population. Identifying comprehensive strategies that promote healthy aging is likely to be beneficial not only for chronic disease management and social engagement but may also promote functional independence and reduce the risk of further functional decline.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration– About VHA. Veterans Health Administration. 2023. Accessed December 4, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp

- Nelson KM. The burden of obesity among a national probability sample of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:915- 919. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00526.x

- Koepsell TD, Forsberg CW, Littman AJ. Obesity, overweight, and weight control practices in U.S. veterans. Prev Med. 2009;48:267-271. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.01.008

- Das SR, Kinsinger LS, Yancy WS Jr, et al. Obesity prevalence among veterans at Veterans Affairs medical facilities. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:291-294. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.007

- Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, et al. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

- Bokhour BG, Haun JN, Hyde J, et al. Transforming the Veterans Affairs to a whole health system of care: time for action and research. Med Care. 2020;58:295-300. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001316

- Marchand WR, Beckstrom J, Nazarenko E, et al. The Veterans Health Administration whole health model of care: early implementation and utilization at a large healthcare system. Mil Med. 2020;185:2150-2157. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa198

- Shulkin D, Elnahal S, Maddock E, Shaheen M. Best Care Everywhere by VA Professionals Across the Nation. US Dept of Veterans Affairs; 2017.

- Morey MC, Lee CC, Castle S, et al. Should structured exercise be promoted as a model of care? Dissemination of the Department of Veterans Affairs Gerofit Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1009-1016. doi:10.1111/jgs.15276

- Cowper PA, Morey MC, Bearon LB, et al. The impact of supervised exercise on the psychological well-being and health status of older veterans. J Appl Gerontol. 1991;10:469-485. doi:10.1177/073346489101000408

- Pepin MJ, Valencia WM, Bettger JP, et al. Impact of supervised exercise on one-year medication use in older veterans with multiple morbidities. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420956751. doi:10.1177/073346489101000408

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Sullivan RJ Jr, et al. Fiveyear performance trends for older exercisers: a hierarchical model of endurance, strength, and flexibility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1226-1231. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01374.x

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Crowley GM, et al. Exercise adherence and 10-year mortality in chronically ill older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1929-1933. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50602.x

- Jorna M, Ball K, Salmon J. Effects of a holistic health program on women’s physical activity and mental and spiritual health. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9:395-401. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2006.06.011

- Jennings SC, Manning KM, Bettger JP, et al. Rapid transition to telehealth group exercise and functional assessments in response to COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420980313. doi:10.1177/2333721420980313

- Morey MC, Crowley GM, Robbins MS, et al. The Gerofit program: a VA innovation. South Med J. 1994;87:S83-87.

- Addison O, Serra MC, Katzel L, et al. Mobility improvements are found in older veterans after 6 months of Gerofit regardless of BMI classification. J Aging Phys Act. 2019;27:848-854. doi:10.1123/japa.2018-0317

- Veterans Health Administration Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation. Making your plan— whole health. November 14, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2025. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/phi.asp

- Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:873-880. doi:10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9

- Aktary ML, Caron-Roy S, Sajobi T, et al. Impact of a farmers’ market nutrition coupon programme on diet quality and psychosocial well-being among low-income adults: protocol for a randomised controlled trial and a longitudinal qualitative investigation. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e035143. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035143

- Afshin A, Penalvo JL, Del Gobbo L, et al. The prospective impact of food pricing on improving dietary consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172277. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172277

- Singleton CR, Kessee N, Chatman C, et al. Racial/ ethnic differences in the shopping behaviors and fruit and vegetable consumption of farmers’ market incentive program users in Illinois. Ethn Dis. 2020;30:109. doi:10.18865/ed.30.1.109

- Cassatt S, Giffuni J, Ortmeyer H, et al. A pilot study to evaluate the development and implementation of a virtual nutrition education program in older veterans. Abstract presented at: American Heart Association Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health 2022 Scientific Sessions; March 1-4, 2022; Chicago, IL. https:// www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circ.145.suppl_1.P002

- Parker EA, Perez WJ, Phipps B, et al. Dietary quality and perceived barriers to weight loss among older overweight veterans with dysmobility. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:9153. doi:10.3390/ijerph19159153

- Ortmeyer HK, Giffuni J, Etchberger D, et al. The role of companion dogs in the VA Maryland Health Care System Whole Health(y) GeroFit Program. Animals (Basel). 2023;13:19. doi:10.3390/ani13193047

- Milaneschi Y, Tanaka T, Ferrucci L. Nutritional determinants of mobility. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:625- 629.

- Lane JM, Davis BA. Food, physical activity, and health deserts in Alabama: the spatial link between healthy eating, exercise, and socioeconomic factors. GeoJournal. 2022;87:5229-5249.

- Komatsu H, Yagasaki K, Saito Y, et al. Regular group exercise contributes to balanced health in older adults in Japan: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:190. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0584-3

- Komatsu H, Yagasaki K, Saito Y, et al. Regular group exercise contributes to balanced health in older adults in Japan: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:190. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0584-3

- Wolfson JA, Ramsing R, Richardson CR, et al. Barriers to healthy food access: associations with household income and cooking behavior. Prev Med Rep. 2019;13:298-305. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.01.023

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration– About VHA. Veterans Health Administration. 2023. Accessed December 4, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp

- Nelson KM. The burden of obesity among a national probability sample of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:915- 919. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00526.x

- Koepsell TD, Forsberg CW, Littman AJ. Obesity, overweight, and weight control practices in U.S. veterans. Prev Med. 2009;48:267-271. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.01.008

- Das SR, Kinsinger LS, Yancy WS Jr, et al. Obesity prevalence among veterans at Veterans Affairs medical facilities. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:291-294. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.007

- Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, et al. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

- Bokhour BG, Haun JN, Hyde J, et al. Transforming the Veterans Affairs to a whole health system of care: time for action and research. Med Care. 2020;58:295-300. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001316

- Marchand WR, Beckstrom J, Nazarenko E, et al. The Veterans Health Administration whole health model of care: early implementation and utilization at a large healthcare system. Mil Med. 2020;185:2150-2157. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa198

- Shulkin D, Elnahal S, Maddock E, Shaheen M. Best Care Everywhere by VA Professionals Across the Nation. US Dept of Veterans Affairs; 2017.

- Morey MC, Lee CC, Castle S, et al. Should structured exercise be promoted as a model of care? Dissemination of the Department of Veterans Affairs Gerofit Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1009-1016. doi:10.1111/jgs.15276

- Cowper PA, Morey MC, Bearon LB, et al. The impact of supervised exercise on the psychological well-being and health status of older veterans. J Appl Gerontol. 1991;10:469-485. doi:10.1177/073346489101000408

- Pepin MJ, Valencia WM, Bettger JP, et al. Impact of supervised exercise on one-year medication use in older veterans with multiple morbidities. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420956751. doi:10.1177/073346489101000408

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Sullivan RJ Jr, et al. Fiveyear performance trends for older exercisers: a hierarchical model of endurance, strength, and flexibility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1226-1231. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01374.x

- Morey MC, Pieper CF, Crowley GM, et al. Exercise adherence and 10-year mortality in chronically ill older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1929-1933. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50602.x

- Jorna M, Ball K, Salmon J. Effects of a holistic health program on women’s physical activity and mental and spiritual health. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9:395-401. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2006.06.011

- Jennings SC, Manning KM, Bettger JP, et al. Rapid transition to telehealth group exercise and functional assessments in response to COVID-19. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420980313. doi:10.1177/2333721420980313

- Morey MC, Crowley GM, Robbins MS, et al. The Gerofit program: a VA innovation. South Med J. 1994;87:S83-87.

- Addison O, Serra MC, Katzel L, et al. Mobility improvements are found in older veterans after 6 months of Gerofit regardless of BMI classification. J Aging Phys Act. 2019;27:848-854. doi:10.1123/japa.2018-0317

- Veterans Health Administration Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation. Making your plan— whole health. November 14, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2025. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/phi.asp

- Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:873-880. doi:10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9

- Aktary ML, Caron-Roy S, Sajobi T, et al. Impact of a farmers’ market nutrition coupon programme on diet quality and psychosocial well-being among low-income adults: protocol for a randomised controlled trial and a longitudinal qualitative investigation. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e035143. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035143

- Afshin A, Penalvo JL, Del Gobbo L, et al. The prospective impact of food pricing on improving dietary consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172277. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172277

- Singleton CR, Kessee N, Chatman C, et al. Racial/ ethnic differences in the shopping behaviors and fruit and vegetable consumption of farmers’ market incentive program users in Illinois. Ethn Dis. 2020;30:109. doi:10.18865/ed.30.1.109

- Cassatt S, Giffuni J, Ortmeyer H, et al. A pilot study to evaluate the development and implementation of a virtual nutrition education program in older veterans. Abstract presented at: American Heart Association Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health 2022 Scientific Sessions; March 1-4, 2022; Chicago, IL. https:// www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circ.145.suppl_1.P002

- Parker EA, Perez WJ, Phipps B, et al. Dietary quality and perceived barriers to weight loss among older overweight veterans with dysmobility. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:9153. doi:10.3390/ijerph19159153

- Ortmeyer HK, Giffuni J, Etchberger D, et al. The role of companion dogs in the VA Maryland Health Care System Whole Health(y) GeroFit Program. Animals (Basel). 2023;13:19. doi:10.3390/ani13193047

- Milaneschi Y, Tanaka T, Ferrucci L. Nutritional determinants of mobility. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:625- 629.

- Lane JM, Davis BA. Food, physical activity, and health deserts in Alabama: the spatial link between healthy eating, exercise, and socioeconomic factors. GeoJournal. 2022;87:5229-5249.

- Komatsu H, Yagasaki K, Saito Y, et al. Regular group exercise contributes to balanced health in older adults in Japan: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:190. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0584-3

- Komatsu H, Yagasaki K, Saito Y, et al. Regular group exercise contributes to balanced health in older adults in Japan: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:190. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0584-3

- Wolfson JA, Ramsing R, Richardson CR, et al. Barriers to healthy food access: associations with household income and cooking behavior. Prev Med Rep. 2019;13:298-305. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.01.023

Whole Health(y) Aging With Gerofit: The Development of a Pilot Wellness Program for Older Veterans

Whole Health(y) Aging With Gerofit: The Development of a Pilot Wellness Program for Older Veterans

Development of an Integrative Medicine Rotation for Family Medicine and Preventive Medicine Residency

Development of an Integrative Medicine Rotation for Family Medicine and Preventive Medicine Residency

Integrative medicine or complementary alternative medicine (IM/CAM) is increasingly being recognized as an integral part of optimal health and healing. IM/CAM “reaffirms the importance of the relationship between practitioner and patient, focuses on the whole person, is informed by evidence, and makes use of all appropriate therapeutic approaches, healthcare professionals and disciplines.”1 IM/CAM encompasses a wide range of therapies, conceptual frameworks, and health care-related professions, such as acupuncture, massage, dietary supplements, mindfulness, yoga, meditation and guided imagery.1 Research has found that 30% to 98% of patients with chronic conditions seek IM/CAM therapies.1-3

Despite the high prevalence of patients utilizing IM/CAM therapies and the National Institutes of Health grants for IM/CAM education, implementation of IM/CAM instruction in graduate medical education programs remains inconsistent.1 Barriers cited by programs include a lack of IM/CAM experts in the program, faculty training, competing financial resources, and an already full resident education schedule.4 As a result, many physicians have limited or no training in IM/CAM.1,5

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) offers IM/CAM health programs to veterans and caregivers as part of its whole health care initiative.6 Several VA health care systems have adopted whole health and IM/CAM through programs for mental health integration into primary care; women’s health; integrative pain care; geriatrics, through adoption of Age-Friendly Health Systems standards; and nutrition and physical activity.7-13 The VA provides training to more medical students than any other health system: > 95% of US medical schools are affiliated with a VA medical center (VAMC).14 As part of the training mission, VA seeks to encourage students of diverse professions to consider careers in the VA.14

Residency is a time for newly licensed physicians to acquire additional experience and training to translate knowledge and skills acquired during medical school directly to patient care.15 However, residency curricula have limited time to incorporate IM/CAM training. Residency training is also physically and psychosocially demanding, often resulting in inadequate self-care, poor work-life balance, and disrupted sleep.16-18 Resident wellness is at a historic low, resulting in high rates of burnout during training.4,15

Residency programs are required to provide wellness education; however, most programs include minimal content.19 Despite high rates of burnout, formal curricula on the topic have not been established. 20 IM/CAM education also can provide a path for residents to learn about and engage in mindfulness-based training or cognitive stress reduction for self-care.

INTEGRATIVE WHOLE HEALTH ROTATION

In 2017, the Baltimore Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) established an IM/whole health residency rotation and created a structured curriculum incorporating self-assessment, active reflection, and self-care to complement training in specific IM/CAM modalities for residents in family medicine. The curriculum evaluated how this training improved residents’ perceptions of IM/CAM and how it personally and professionally impacted the practice of self-care as a strategy to decrease burnout. We hypothesized that this structured experience would increase IM/CAM knowledge among clinicians while promoting the importance and practice of self-care to reduce burnout.

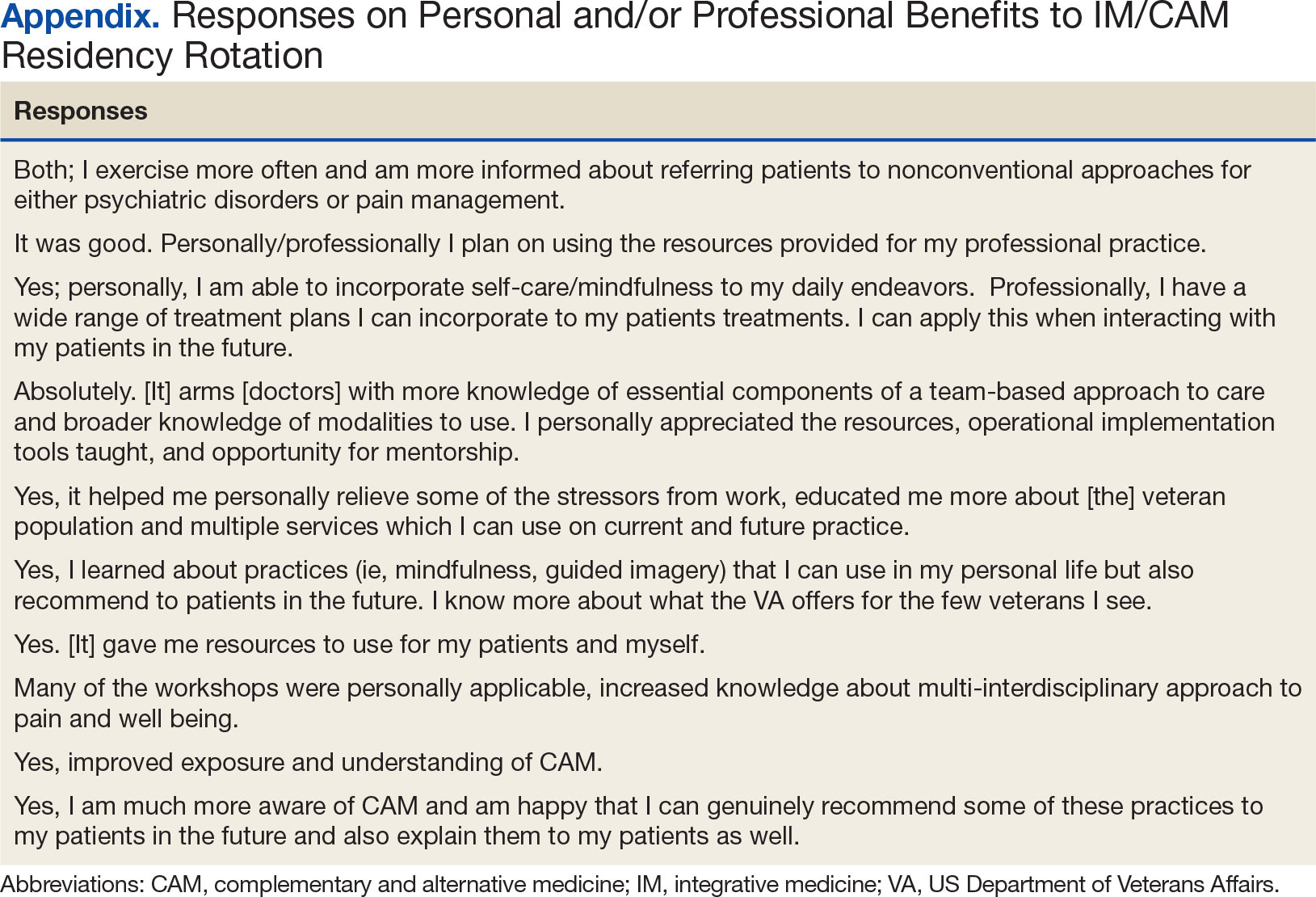

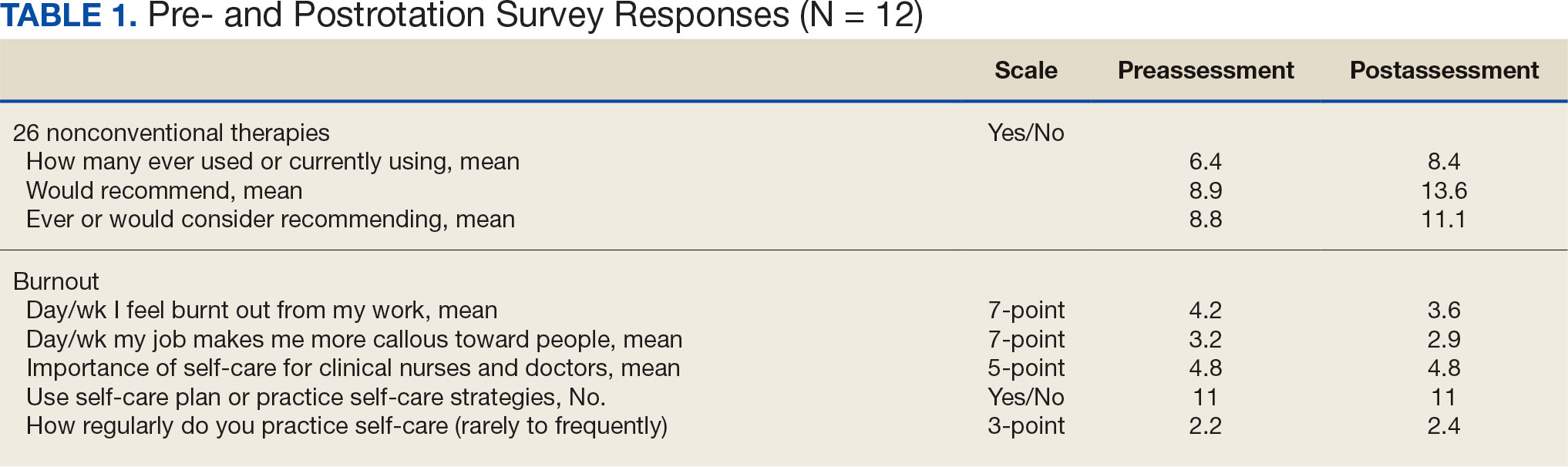

The 2-week IM/CAM curriculum was developed by University of Maryland School of Medicine faculty in partnership with the Baltimore GRECC and staff at the VA Maryland Health Care System. The curriculum was designed to expose residents to the 8 components of the whole health Circle of Health (moving the body; surroundings; personal development; food and drink; recharge; family, friends, and coworkers; spirit and soul; and power of the mind) in addition to IM/ CAM modalities the VA is mandated to offer to veterans (acupuncture, chiropractic, meditation, massage therapy, biofeedback, clinical hypnosis, guided imagery, yoga, and tai chi).21 Twelve residents (1 preventive medicine and 11 third-year family medicine residents) rotated individually throughout the year as part of their behavioral health block rotation. All residents completed the 2-week curriculum as their schedules allowed. The curriculum consisted of didactics sessions and activities at the Baltimore, Loch Raven, and Perry Point VAMCs. Residents completed evaluations before and after the rotation. The experience described in this article by the residents and the survey data were collected from the 2018/2019 training year. A rotation syllabus, competencies adapted from Locke and colleagues and skills residents obtain during this rotation that support these competencies, as well as a resident sample schedule were developed (eAppendix is available at doi:10.12788/fp.0544).1

Rotation Overview