User login

Dysphagia in a patient with schizophrenia: Is the antipsychotic the culprit?

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Mr. N, age 58, has a history of schizophrenia, tobacco use disorder, and alcohol use disorder. For many years, Mr. N has been receiving IM olanzapine 2.5 mg/d to treat his schizophrenia. He lives in a psychiatric hospital but was sent to our hospital after being found to have severe oropharyngeal dysphasia on a modified barium swallow study. There was concern for aspiration due to a history of choking episodes, which had been occurring for almost 1 month. During the modified barium swallow study, Mr. N was noted to have aspiration with deep laryngeal penetration during the pharyngeal stages of swallowing to all consistencies; this did not improve with the chin-tuck maneuver. In addition, during a CT scan of the cervical spine, an osteophyte was noted at the C5-C6 level, with possible impingement of the cervical esophagus and decreased upper esophageal sphincter opening.

Due to these findings, Mr. N was sent to our emergency department (ED) for further evaluation. In the ED, his vital signs were stable. He endorsed having a cough after eating, a sensation of having food stuck in his throat, and some hoarseness. His physical examination was notable for poor dentition. Results of a standard laboratory workup were all within normal limits. X-ray was notable for hazy opacities in the right upper to mid lung zones. Mr. N was admitted to the medical unit for further evaluation and management.

Narrowing the diagnosis

Because Mr. N was aspirating both liquids and solids, it was imperative that we identify the cause as soon as possible. The consultations that followed slowly guided the treatment team toward a diagnosis of antipsychotic-induced dysphagia. Otolaryngology identified insensate larynx during a flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy exam, which was highly suggestive of a neurological dysfunction such as dystonia. Furthermore, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy found no structural abnormalities to explain Mr. N’s dysphagia, which ruled out impingement of the cervical esophagus by the osteophyte. An MRI of the brain ruled out structural abnormalities or evidence of stroke. Finally, a speech and language pathologist confirmed decreased laryngeal closure and airway protection with a repeat modified barium swallow, which led to aspiration during swallowing. Psychiatry recommended starting diphenhydramine to treat Mr. N’s extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). A 6-day trial was initiated, with a single 50 mg IV dose on the first day followed by 25 mL oral twice daily for the remaining 5 days. In addition, olanzapine was discontinued.

Switching to a different diet and antipsychotic

Two days after starting diphenhydramine, Mr. N was switched to a puree diet. His ability to swallow improved, and he no longer coughed. However, on repeat modified barium swallow, aspiration was still noted for all types of liquids and solids. No structural improvements were seen.

Mr. N was discharged back to his psychiatric hospital, and his antipsychotic was changed from olanzapine to oral aripiprazole 2 mg/d. The aripiprazole dose was kept low to prevent the recurrence of dystonia and because at the time, his schizophrenia was asymptomatic. Mr. N was also prescribed oral diphenhydramine 25 mL twice daily.

At a 2-week follow-up appointment, Mr. N continued to show clinical improvement on the puree diet with thin liquids and continued the prescribed medication regimen.

Dysphagia as a manifestation of EPS

All antipsychotics, and particularly first-generation agents, are associated with EPS.1 These symptoms may be the result of antagonistic binding of dopaminergic D2 receptors within mesolimbic and mesocortical pathways of the brain, as well as parts of basal ganglia such as the caudate nucleus.2

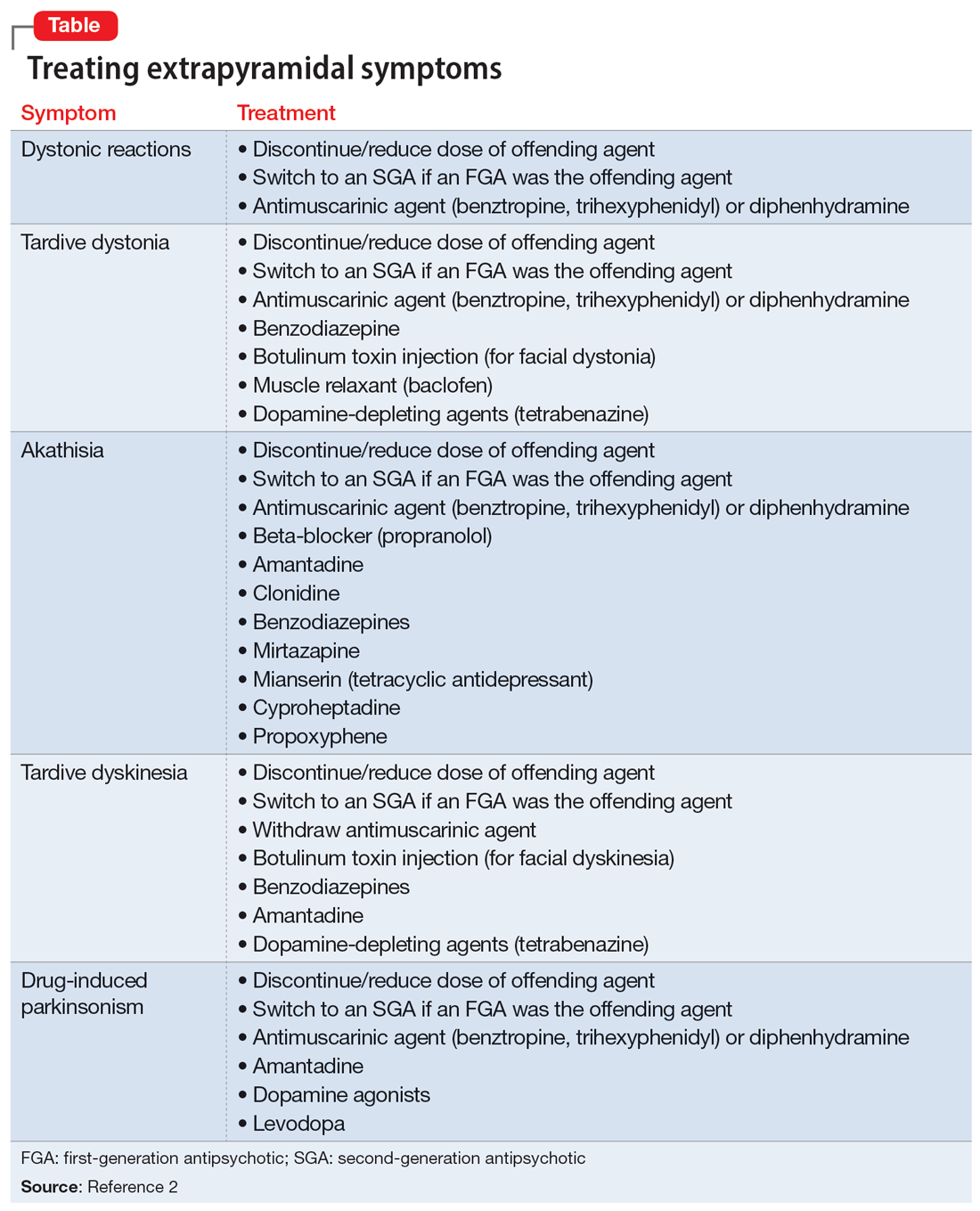

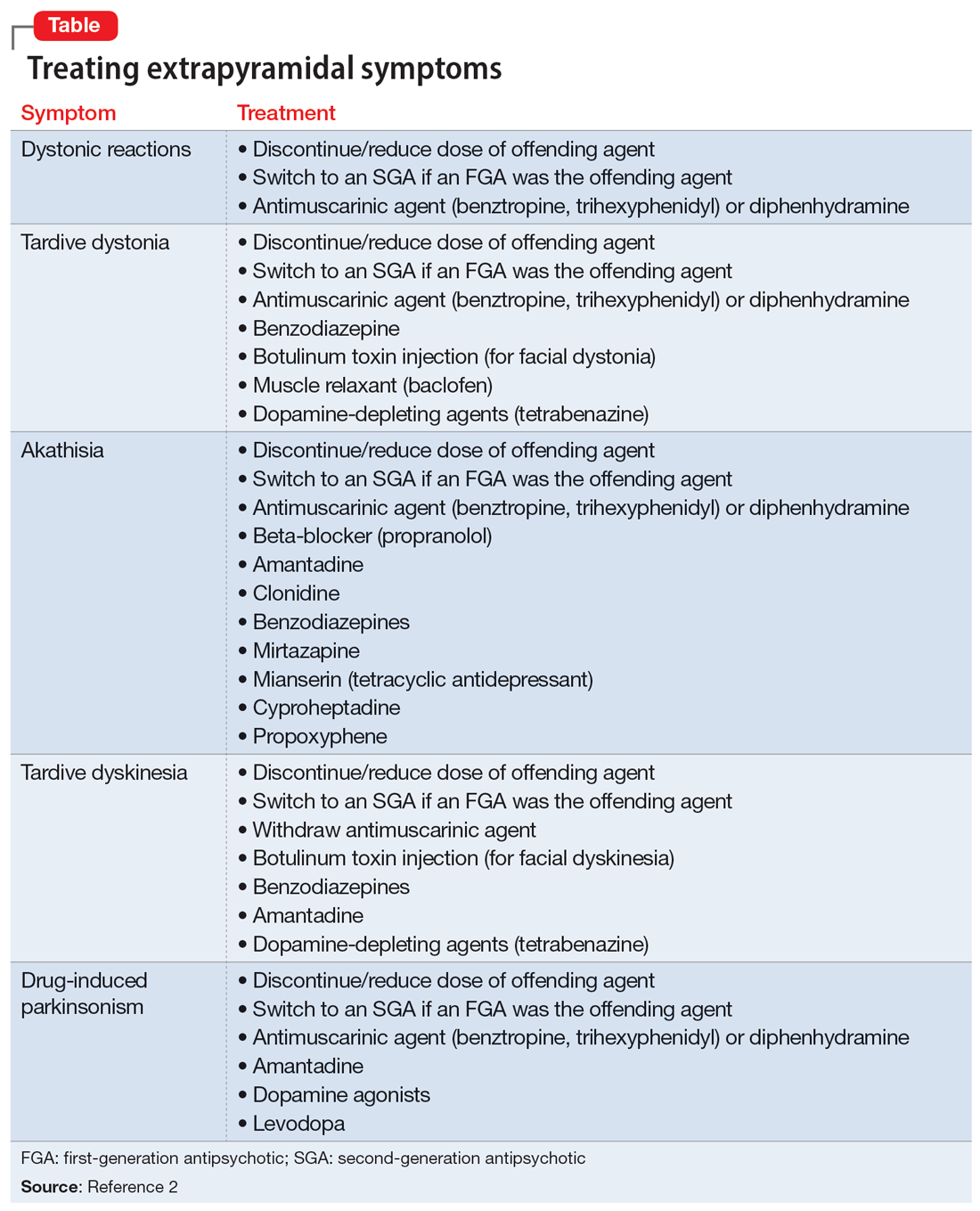

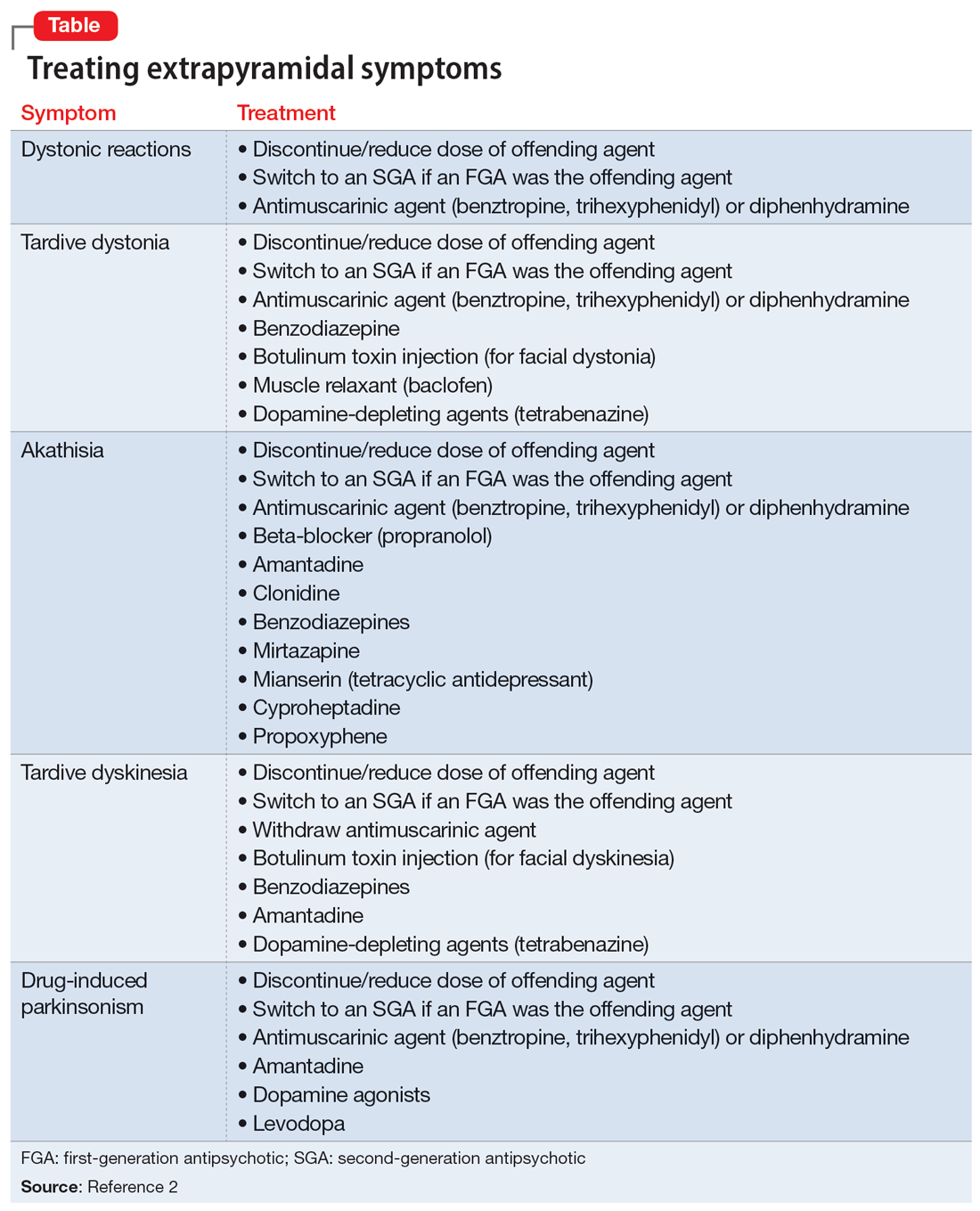

In addition to the examples listed in the Table,2 EPS can present as dysphagia, esophageal dysmotility, or aspiration, none of which may be recognized as EPS. Research has found haloperidol, loxapine, trifluoperazine, olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, clozapine, and aripiprazole are associated with dysphagia.3-6 Strategies to treat antipsychotic-induced dysphagia include discontinuing the antipsychotic, lowering the dose, and changing to another medication.7

1. Crouse EL, Alastanos JN, Bozymski KM, et al. Dysphagia with second-generation antipsychotics: a case report and review of the literature. Ment Health Clin. 2018;7(2):56-64. doi:10.9740/mhc.2017.03.056

2. D’Souza RS, Hooten WM. Extrapyramidal symptoms. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated January 8, 2023. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534115/

3. Dziewas R, Warnecke T, Schnabel M, et al. Neuroleptic-induced dysphagia: case report and literature review. Dysphagia. 2007;22(1):63-67. doi:10.1007/s00455-006-9032-9

4. Kalf JG, de Swart BJ, Bloem BR, et al. Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(4):311-315. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.11.006

5. Lin TW, Lee BS, Liao YC, et al. High dosage of aripiprazole-induced dysphagia. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(2):305-306. doi:10.1002/eat.20934

6. Stewart JT. Dysphagia associated with risperidone therapy. Dysphagia. 2003;18(4):274-275. doi:10.1007/s00455-003-0006-x

7. Lee JC, Takeshita J. Antipsychotic-induced dysphagia: a case report. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(5):10.4088/PCC.15I01792. doi:10.4088/PCC.15I01792

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Mr. N, age 58, has a history of schizophrenia, tobacco use disorder, and alcohol use disorder. For many years, Mr. N has been receiving IM olanzapine 2.5 mg/d to treat his schizophrenia. He lives in a psychiatric hospital but was sent to our hospital after being found to have severe oropharyngeal dysphasia on a modified barium swallow study. There was concern for aspiration due to a history of choking episodes, which had been occurring for almost 1 month. During the modified barium swallow study, Mr. N was noted to have aspiration with deep laryngeal penetration during the pharyngeal stages of swallowing to all consistencies; this did not improve with the chin-tuck maneuver. In addition, during a CT scan of the cervical spine, an osteophyte was noted at the C5-C6 level, with possible impingement of the cervical esophagus and decreased upper esophageal sphincter opening.

Due to these findings, Mr. N was sent to our emergency department (ED) for further evaluation. In the ED, his vital signs were stable. He endorsed having a cough after eating, a sensation of having food stuck in his throat, and some hoarseness. His physical examination was notable for poor dentition. Results of a standard laboratory workup were all within normal limits. X-ray was notable for hazy opacities in the right upper to mid lung zones. Mr. N was admitted to the medical unit for further evaluation and management.

Narrowing the diagnosis

Because Mr. N was aspirating both liquids and solids, it was imperative that we identify the cause as soon as possible. The consultations that followed slowly guided the treatment team toward a diagnosis of antipsychotic-induced dysphagia. Otolaryngology identified insensate larynx during a flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy exam, which was highly suggestive of a neurological dysfunction such as dystonia. Furthermore, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy found no structural abnormalities to explain Mr. N’s dysphagia, which ruled out impingement of the cervical esophagus by the osteophyte. An MRI of the brain ruled out structural abnormalities or evidence of stroke. Finally, a speech and language pathologist confirmed decreased laryngeal closure and airway protection with a repeat modified barium swallow, which led to aspiration during swallowing. Psychiatry recommended starting diphenhydramine to treat Mr. N’s extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). A 6-day trial was initiated, with a single 50 mg IV dose on the first day followed by 25 mL oral twice daily for the remaining 5 days. In addition, olanzapine was discontinued.

Switching to a different diet and antipsychotic

Two days after starting diphenhydramine, Mr. N was switched to a puree diet. His ability to swallow improved, and he no longer coughed. However, on repeat modified barium swallow, aspiration was still noted for all types of liquids and solids. No structural improvements were seen.

Mr. N was discharged back to his psychiatric hospital, and his antipsychotic was changed from olanzapine to oral aripiprazole 2 mg/d. The aripiprazole dose was kept low to prevent the recurrence of dystonia and because at the time, his schizophrenia was asymptomatic. Mr. N was also prescribed oral diphenhydramine 25 mL twice daily.

At a 2-week follow-up appointment, Mr. N continued to show clinical improvement on the puree diet with thin liquids and continued the prescribed medication regimen.

Dysphagia as a manifestation of EPS

All antipsychotics, and particularly first-generation agents, are associated with EPS.1 These symptoms may be the result of antagonistic binding of dopaminergic D2 receptors within mesolimbic and mesocortical pathways of the brain, as well as parts of basal ganglia such as the caudate nucleus.2

In addition to the examples listed in the Table,2 EPS can present as dysphagia, esophageal dysmotility, or aspiration, none of which may be recognized as EPS. Research has found haloperidol, loxapine, trifluoperazine, olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, clozapine, and aripiprazole are associated with dysphagia.3-6 Strategies to treat antipsychotic-induced dysphagia include discontinuing the antipsychotic, lowering the dose, and changing to another medication.7

Editor’s note: Readers’ Forum is a department for correspondence from readers that is not in response to articles published in

Mr. N, age 58, has a history of schizophrenia, tobacco use disorder, and alcohol use disorder. For many years, Mr. N has been receiving IM olanzapine 2.5 mg/d to treat his schizophrenia. He lives in a psychiatric hospital but was sent to our hospital after being found to have severe oropharyngeal dysphasia on a modified barium swallow study. There was concern for aspiration due to a history of choking episodes, which had been occurring for almost 1 month. During the modified barium swallow study, Mr. N was noted to have aspiration with deep laryngeal penetration during the pharyngeal stages of swallowing to all consistencies; this did not improve with the chin-tuck maneuver. In addition, during a CT scan of the cervical spine, an osteophyte was noted at the C5-C6 level, with possible impingement of the cervical esophagus and decreased upper esophageal sphincter opening.

Due to these findings, Mr. N was sent to our emergency department (ED) for further evaluation. In the ED, his vital signs were stable. He endorsed having a cough after eating, a sensation of having food stuck in his throat, and some hoarseness. His physical examination was notable for poor dentition. Results of a standard laboratory workup were all within normal limits. X-ray was notable for hazy opacities in the right upper to mid lung zones. Mr. N was admitted to the medical unit for further evaluation and management.

Narrowing the diagnosis

Because Mr. N was aspirating both liquids and solids, it was imperative that we identify the cause as soon as possible. The consultations that followed slowly guided the treatment team toward a diagnosis of antipsychotic-induced dysphagia. Otolaryngology identified insensate larynx during a flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy exam, which was highly suggestive of a neurological dysfunction such as dystonia. Furthermore, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy found no structural abnormalities to explain Mr. N’s dysphagia, which ruled out impingement of the cervical esophagus by the osteophyte. An MRI of the brain ruled out structural abnormalities or evidence of stroke. Finally, a speech and language pathologist confirmed decreased laryngeal closure and airway protection with a repeat modified barium swallow, which led to aspiration during swallowing. Psychiatry recommended starting diphenhydramine to treat Mr. N’s extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). A 6-day trial was initiated, with a single 50 mg IV dose on the first day followed by 25 mL oral twice daily for the remaining 5 days. In addition, olanzapine was discontinued.

Switching to a different diet and antipsychotic

Two days after starting diphenhydramine, Mr. N was switched to a puree diet. His ability to swallow improved, and he no longer coughed. However, on repeat modified barium swallow, aspiration was still noted for all types of liquids and solids. No structural improvements were seen.

Mr. N was discharged back to his psychiatric hospital, and his antipsychotic was changed from olanzapine to oral aripiprazole 2 mg/d. The aripiprazole dose was kept low to prevent the recurrence of dystonia and because at the time, his schizophrenia was asymptomatic. Mr. N was also prescribed oral diphenhydramine 25 mL twice daily.

At a 2-week follow-up appointment, Mr. N continued to show clinical improvement on the puree diet with thin liquids and continued the prescribed medication regimen.

Dysphagia as a manifestation of EPS

All antipsychotics, and particularly first-generation agents, are associated with EPS.1 These symptoms may be the result of antagonistic binding of dopaminergic D2 receptors within mesolimbic and mesocortical pathways of the brain, as well as parts of basal ganglia such as the caudate nucleus.2

In addition to the examples listed in the Table,2 EPS can present as dysphagia, esophageal dysmotility, or aspiration, none of which may be recognized as EPS. Research has found haloperidol, loxapine, trifluoperazine, olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, clozapine, and aripiprazole are associated with dysphagia.3-6 Strategies to treat antipsychotic-induced dysphagia include discontinuing the antipsychotic, lowering the dose, and changing to another medication.7

1. Crouse EL, Alastanos JN, Bozymski KM, et al. Dysphagia with second-generation antipsychotics: a case report and review of the literature. Ment Health Clin. 2018;7(2):56-64. doi:10.9740/mhc.2017.03.056

2. D’Souza RS, Hooten WM. Extrapyramidal symptoms. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated January 8, 2023. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534115/

3. Dziewas R, Warnecke T, Schnabel M, et al. Neuroleptic-induced dysphagia: case report and literature review. Dysphagia. 2007;22(1):63-67. doi:10.1007/s00455-006-9032-9

4. Kalf JG, de Swart BJ, Bloem BR, et al. Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(4):311-315. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.11.006

5. Lin TW, Lee BS, Liao YC, et al. High dosage of aripiprazole-induced dysphagia. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(2):305-306. doi:10.1002/eat.20934

6. Stewart JT. Dysphagia associated with risperidone therapy. Dysphagia. 2003;18(4):274-275. doi:10.1007/s00455-003-0006-x

7. Lee JC, Takeshita J. Antipsychotic-induced dysphagia: a case report. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(5):10.4088/PCC.15I01792. doi:10.4088/PCC.15I01792

1. Crouse EL, Alastanos JN, Bozymski KM, et al. Dysphagia with second-generation antipsychotics: a case report and review of the literature. Ment Health Clin. 2018;7(2):56-64. doi:10.9740/mhc.2017.03.056

2. D’Souza RS, Hooten WM. Extrapyramidal symptoms. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated January 8, 2023. Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534115/

3. Dziewas R, Warnecke T, Schnabel M, et al. Neuroleptic-induced dysphagia: case report and literature review. Dysphagia. 2007;22(1):63-67. doi:10.1007/s00455-006-9032-9

4. Kalf JG, de Swart BJ, Bloem BR, et al. Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(4):311-315. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.11.006

5. Lin TW, Lee BS, Liao YC, et al. High dosage of aripiprazole-induced dysphagia. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45(2):305-306. doi:10.1002/eat.20934

6. Stewart JT. Dysphagia associated with risperidone therapy. Dysphagia. 2003;18(4):274-275. doi:10.1007/s00455-003-0006-x

7. Lee JC, Takeshita J. Antipsychotic-induced dysphagia: a case report. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(5):10.4088/PCC.15I01792. doi:10.4088/PCC.15I01792

When the worry is worse than the actual illness

CASE Distraught over a medical illness

Ms. S, age 16, presents to the emergency department (ED) accompanied by her mother with superficial lacerations on her arm. Ms. S states, “I cut my arm because I was afraid I was going to do something serious if I didn’t get to go to the ED.” She says that 6 months earlier, she was diagnosed with superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS), a rare, potentially life-threatening condition that occurs when the duodenum is compressed between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery, causing a partial or complete blockage of the duodenum. Since receiving this diagnosis, Ms. S reports feeling anxious, depressed, and overwhelmed by both the pain she is experiencing from her illness and uncertainty about her prognosis.

HISTORY In pain and isolated

Since being diagnosed with SMAS, Ms. S has had approximately 30 medical and 7 ED visits for SMAS-related pain. Ms. S was referred to the outpatient clinic for ongoing support and treatment for SMAS.

Because of her pain and anxiety, Ms. S, a junior in high school, no longer attends school but has been working with a tutor. Ms. S says that some of her loneliness and hopelessness are due to the social isolation of being tutored at home. She states that she has been “out of sight and out of mind” from her friends. She also reports feeling different from them due to the pain brought on by SMAS.

Ms. S and her mother live in public housing. Ms. S says that overall, she has a good relationship with her mother, but that in certain situations, her mother’s anxiety causes her significant frustration and anxiety.

EVALUATION Transient suicidal thoughts

A physical examination reveals superficial lacerations to Ms. S’s left arm. Although she appears thin, her current body mass index (BMI) is 20.4 kg/m2, which is within normal range. She says she sees herself as “underweight” and “not fat at all.” Ms. S reports that she likes food and enjoyed eating until it became too painful following her SMAS diagnosis. Ms. S denies a history of binging or purging. Results from her laboratory workup and all values are within normal limits.

During the initial interview, Ms. S’s mother says they came to the ED because Ms. S urgently needs a psychiatric evaluation so she can be cleared for gastrointestinal (GI) surgery and placement of a nasogastric tube. Her mother says a surgeon from a different hospital told them that her insurance company required a psychiatric evaluation to rule out anorexia nervosa before they would authorize the GI surgery. When asked why psychiatry at this hospital was not consulted, Ms. S’s mother does not answer.

When asked about the symptoms she has been experiencing, Ms. S says that her sleep has been poor because of increased pain and excessive worrying about her health. She has limited her food intake. Ms. S reports that after eating, she lays on her left side to alleviate pain and help the food move through her body.

Continue to: Ms. S says...

Ms. S says she feels anxious and depressed due to her SMAS diagnosis, her mother’s online research and oversharing of poor prognoses, and being isolated from her friends. Most of her time outside the home is spent attending medical appointments with specialists. Several months ago, Ms. S had seen a psychotherapist, but her mother was unhappy with the treatment recommendations, which included seeking care from a nutritionist and joining group therapy. Ms. S’s mother says she ended her daughter’s psychotherapy because she was unable to obtain a signature ruling out anorexia nervosa within the first few appointments.

Ms. S also says she has had passive suicidal thoughts during the past month, usually twice a week. She reports that these thoughts lasted as long as several hours and were difficult to control, but she has no specific plan or intent. Ms. S denies current suicidal thoughts or ideation, and works with the treatment team to complete a safety plan, which she signs. Other than her recent visit to the ED, Ms. S denies any other thoughts or behaviors of self-injury or suicide.

[polldaddy:10586905]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team considered the following conditions as part of Ms. S’s differential diagnosis:

Major depressive disorder. The team was able to rule out MDD because Ms. S’s depression was attributed to SMAS. Ms. S reported that all depressive symptoms were manageable or nonexistent before the onset of pain from SMAS. There was no direct pathophysiological consequence of another medical condition. Ms. S was clear that her symptoms of anxiety and depression began after she was isolated from her friends and began having difficulty understanding her diagnosis and prognosis.

Anorexia nervosa also was ruled out. According to the DSM-5, a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa requires the following 3 criteria1:

- restriction of food intake resulting in significantly low body weight (defined as weight that is less than “minimally normal”) relative to age, gender, or development

- intense fear of gaining weight, or persistent behaviors that interfere with weight gain

- disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or lack of insight with regard to seriousness of current low body weight.

Continue to: Although Ms. S appeared...

Although Ms. S appeared thin, her BMI was within normal range. She added that she likes food and enjoyed eating, but that her medical condition made it too painful. Lastly, Ms. S denied a history of binging or purging.

Somatic symptom disorder.

Factitious disorder imposed on self. An individual with FDIS chronically stimulates, induces, or aggravates illnesses to gain the status of being a patient.

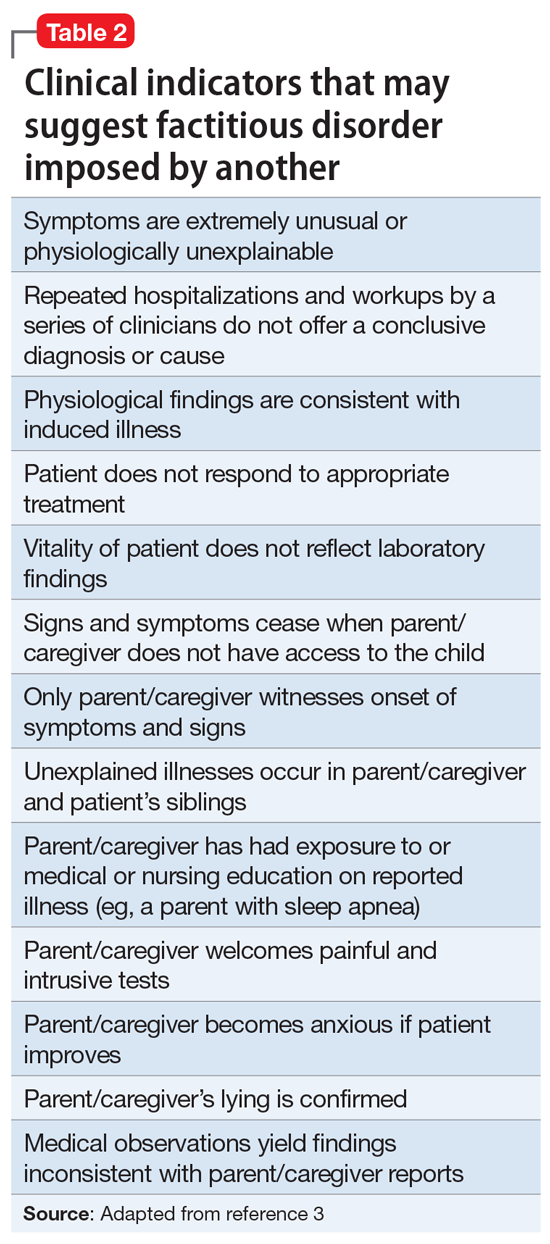

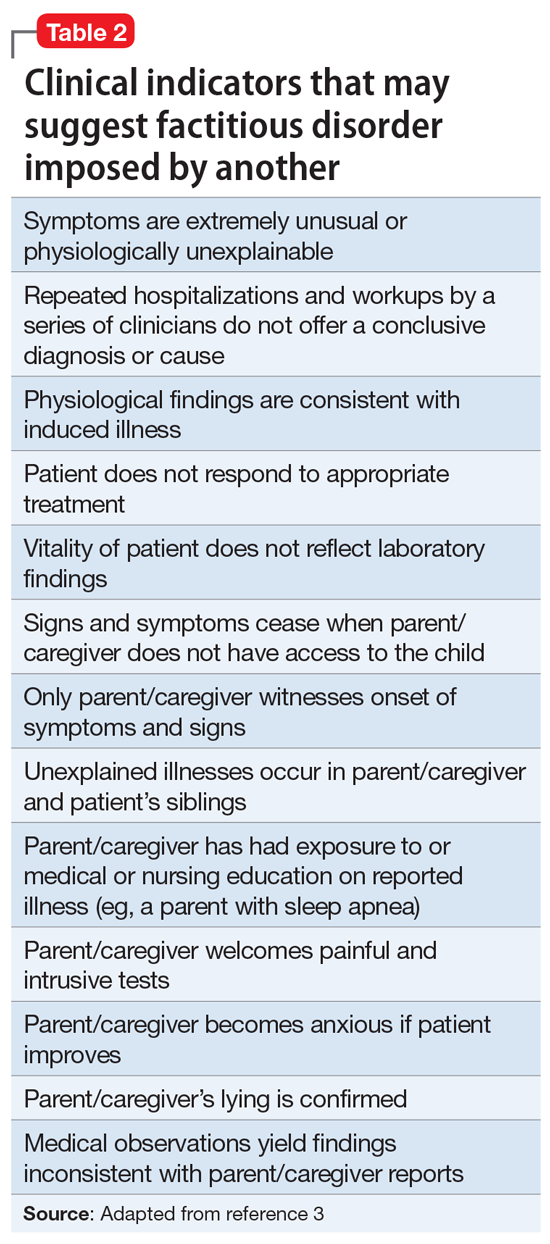

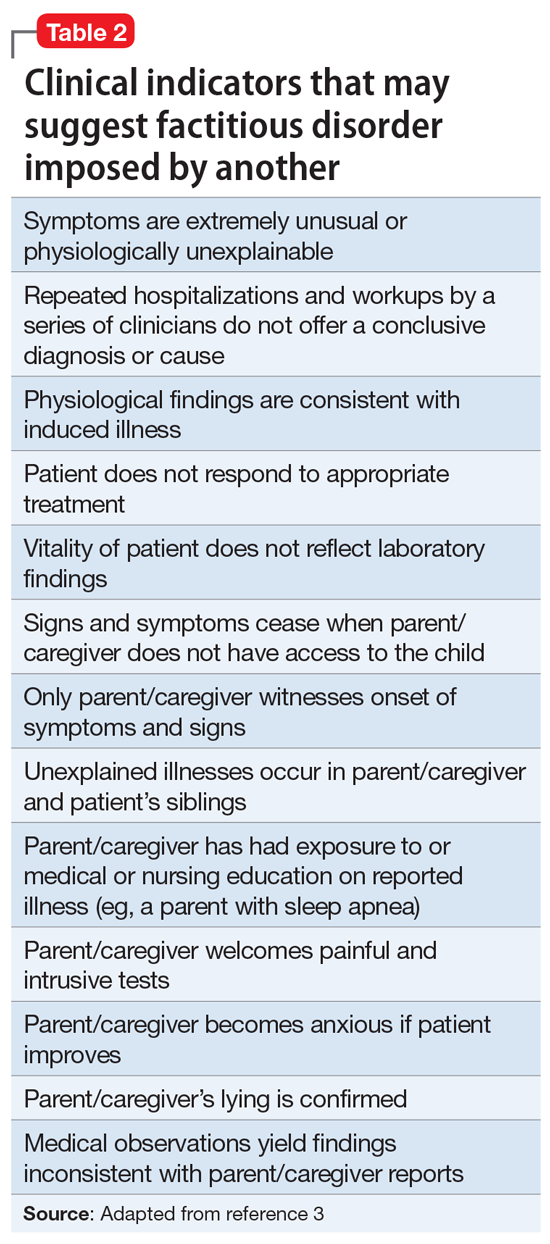

Factitious disorder imposed on another is the deliberate feigning or production of symptoms in another individual who is under the perpetrator’s supervision.1 Table 23 lists clinical indicators that raise suspicion for FDIA.

Before a diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder, FDIS, or FDIA could be established or ruled out, it was imperative to gather collateral information from other clinicians involved in Ms. S’s care. Ms. S and her mother had sought out help from a pediatric surgeon, a pediatric gastroenterologist, a pediatrician, and a psychotherapist.

Continue to: EVALUATION Collateral information

EVALUATION Collateral information

After Ms. S’s mother signs consent forms for exchange of information, the treatment team reaches out to the other clinicians. The therapist confirms that Ms. S’s mother had ended her daughter’s treatment after she was unable to quickly obtain documentation to rule out anorexia nervosa.

Both the pediatric surgeon and gastroenterologist report concerns of FDIA, which is why both clinicians had referred Ms. S and her mother to psychiatry. The pediatric surgeon states that on one occasion when he interviewed Ms. S separately from her mother, she seemed to be going down a checklist of symptoms. The surgeon reports that there was a partial occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery, confirming the diagnosis of SMAS, but he believed it was not severe enough to explain the symptoms Ms. S reported. The surgeon had scheduled another imaging appointment for 1 month later.

The pediatric gastroenterologist reports that Ms. S’s mother had demanded surgery and nasogastric tube placement for her daughter, which raised suspicion of FDIA. The gastroenterologist had convinced Ms. S and her mother to start low-dose doxepin, 20 mg twice a day, for anxiety, sleep, and abdominal pain.

Lastly, the pediatrician reports that she had not seen Ms. S for several months but stated that Ms. S always has been in the low normal BMI range. The pediatrician also reports that 6 months ago, the patient and her mother were frantically visiting EDs and scheduling doctor’s appointments.

[polldaddy:10586906]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team decided that Ms. S was not in imminent danger, and felt it was important to keep her in treatment without raising her mother’s suspicion. The team agreed to raise these concerns to the police, child protective services, and risk management if Ms. S’s health suddenly deteriorated or if her mother decided to remove Ms. S from our care.

Continue to: The treatment team...

The treatment team at the outpatient psychiatry clinic agreed that Ms. S did not currently meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, MDD, FDIS, or FDIA. However, Ms. S reported worries particular to persistent abdominal pain that was exacerbated by either eating or going to bed at night, which indicated that somatic symptom disorder was her likely diagnosis. Further, she endorsed a high level of anxiety and depression with regard to this somatic complaint that interfered with her daily activities and consumed an excessive amount of time, which also pointed to somatic symptom disorder. As a result of this diagnosis, the treatment team helped Ms. S manage her somatic symptoms and monitored for any other changes in her symptoms

Generally, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based therapy may help relieve symptoms associated with somatic symptom disorder.4

TREATMENT Therapy sessions and medication management

At the psychiatric clinic, Ms. S is scheduled for biweekly therapy sessions with a social worker and biweekly appointments with a senior psychiatry resident for medication management. At each visit, Ms. S’s vital signs, height, and weight are measured. In the therapy sessions, she is taught mindfulness skills as well as CBT. The senior psychiatry resident maintains regular communication with the other clinicians involved in Ms. S’s care.

After the first month of treatment, Ms. S undergoes repeat imaging at the gastroenterologist’s office that indicates her SMAS is no longer occluded. Ms. S continues to report somatic symptoms, but with mild improvement.

Over the course of approximately 4 months, Ms. S begins to show signs of improvement in her pain, anxiety, and depression. Ms. S begins to feel well enough to get a summer job at a nursing home and expresses enthusiasm when her weight begins to increase. Her mother also became enthused and verbalized her appreciation that her daughter appeared to be improving.

Continue to: In the fall...

In the fall, Ms. S returns to high school for her senior year but has difficulty getting back into the routine and relating to her old friends. Ms. S continues to perseverate on thoughts of getting sick and her physical symptoms become overwhelming once again. She continues to be focused on any new symptoms she experiences, and to limit the types of foods she eats due to fear of the abdominal pain returning.

After several more months of psychiatric treatment, Ms. S reports significant relief from her abdominal pain, and no longer seeks corrective surgery for her SMAS. Although she occasionally struggles with perseverating thoughts and anxiety about her somatic symptoms such as abdominal pain and worrying about the types of foods she eats and becoming ill, she continues to work through symptoms of her somatic symptom disorder.

The authors’ observations

The main challenge of somatic symptom disorder is the patient’s “abnormal illness behavior.”2,5,6 For pediatric patients, there may an association between a parent’s psychological status and the patient’s somatic symptoms. Abdominal symptoms in a pediatric patient have a strong association with a parent who presents with depression, anxiety, or somatization. The effects of the parent’s psychological status could also manifest in the form of modeling catastrophic thinking or through reinforcement. Parents with certain traits, such as disproportionate worry about pain, may pay more attention to their child’s symptoms, and hence, reward the child when he/she reports somatic symptoms.7,8 In the case of Ms. S, her mother did not participate in therapy and the mother’s psychiatric history was never obtained.

OUTCOMES Making personal strides

Ms. S continues to use mindfulness skills as well as CBT to manage her symptoms of somatic symptom disorder. She continues to celebrate her weight gains, denies any thoughts of suicide or self-harm behaviors, and prepares for college by scheduling campus visits and completing admissions applications.

Bottom Line

Patients with somatic symptom disorder tend to have very high levels of worry about illness. Somatic symptoms in such patients may or may not have a medical explanation. Accurate diagnosis and careful management are necessary to reduce patient distress. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based therapy may help relieve symptoms associated with this disorder.

Related Resources

- Henningsen P. Management of somatic symptom disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(1):23-91.

- Rosic T, Kalra S, Samaan Z. Somatic symptom disorder, a new DSM-5 diagnosis of an old clinical challenge. BMJ Case Rep. 2016: bcr2015212553. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-212553.

Drug Brand Name

Doxepin • Silenor

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Stern T, Freudenreich O, Smith F, et al. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry, 7th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017.

3. Feldman MD, Eisendrath SJ. The spectrum of factitious disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1997.

4. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry, 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014:470.

5. Pilowsky I. The concept of abnormal illness behavior. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(2):207-213.

6. Kirmayer LJ, Looper KJ. Abnormal illness behavior: physiological, psychological and social dimensions of coping with stress. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19(1):54-60.

7. Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Somatic complaints in pediatric patients: a prospective study of the role of negative life events, child social and academic competence, and parental somatic symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychology. 1994;62(6):1213-1221.

8. Van Oudenhove L, Levy RL, Crowell MD, et al. Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders: how central and environmental processes contribute to the development and expression of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1355-1367.

CASE Distraught over a medical illness

Ms. S, age 16, presents to the emergency department (ED) accompanied by her mother with superficial lacerations on her arm. Ms. S states, “I cut my arm because I was afraid I was going to do something serious if I didn’t get to go to the ED.” She says that 6 months earlier, she was diagnosed with superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS), a rare, potentially life-threatening condition that occurs when the duodenum is compressed between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery, causing a partial or complete blockage of the duodenum. Since receiving this diagnosis, Ms. S reports feeling anxious, depressed, and overwhelmed by both the pain she is experiencing from her illness and uncertainty about her prognosis.

HISTORY In pain and isolated

Since being diagnosed with SMAS, Ms. S has had approximately 30 medical and 7 ED visits for SMAS-related pain. Ms. S was referred to the outpatient clinic for ongoing support and treatment for SMAS.

Because of her pain and anxiety, Ms. S, a junior in high school, no longer attends school but has been working with a tutor. Ms. S says that some of her loneliness and hopelessness are due to the social isolation of being tutored at home. She states that she has been “out of sight and out of mind” from her friends. She also reports feeling different from them due to the pain brought on by SMAS.

Ms. S and her mother live in public housing. Ms. S says that overall, she has a good relationship with her mother, but that in certain situations, her mother’s anxiety causes her significant frustration and anxiety.

EVALUATION Transient suicidal thoughts

A physical examination reveals superficial lacerations to Ms. S’s left arm. Although she appears thin, her current body mass index (BMI) is 20.4 kg/m2, which is within normal range. She says she sees herself as “underweight” and “not fat at all.” Ms. S reports that she likes food and enjoyed eating until it became too painful following her SMAS diagnosis. Ms. S denies a history of binging or purging. Results from her laboratory workup and all values are within normal limits.

During the initial interview, Ms. S’s mother says they came to the ED because Ms. S urgently needs a psychiatric evaluation so she can be cleared for gastrointestinal (GI) surgery and placement of a nasogastric tube. Her mother says a surgeon from a different hospital told them that her insurance company required a psychiatric evaluation to rule out anorexia nervosa before they would authorize the GI surgery. When asked why psychiatry at this hospital was not consulted, Ms. S’s mother does not answer.

When asked about the symptoms she has been experiencing, Ms. S says that her sleep has been poor because of increased pain and excessive worrying about her health. She has limited her food intake. Ms. S reports that after eating, she lays on her left side to alleviate pain and help the food move through her body.

Continue to: Ms. S says...

Ms. S says she feels anxious and depressed due to her SMAS diagnosis, her mother’s online research and oversharing of poor prognoses, and being isolated from her friends. Most of her time outside the home is spent attending medical appointments with specialists. Several months ago, Ms. S had seen a psychotherapist, but her mother was unhappy with the treatment recommendations, which included seeking care from a nutritionist and joining group therapy. Ms. S’s mother says she ended her daughter’s psychotherapy because she was unable to obtain a signature ruling out anorexia nervosa within the first few appointments.

Ms. S also says she has had passive suicidal thoughts during the past month, usually twice a week. She reports that these thoughts lasted as long as several hours and were difficult to control, but she has no specific plan or intent. Ms. S denies current suicidal thoughts or ideation, and works with the treatment team to complete a safety plan, which she signs. Other than her recent visit to the ED, Ms. S denies any other thoughts or behaviors of self-injury or suicide.

[polldaddy:10586905]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team considered the following conditions as part of Ms. S’s differential diagnosis:

Major depressive disorder. The team was able to rule out MDD because Ms. S’s depression was attributed to SMAS. Ms. S reported that all depressive symptoms were manageable or nonexistent before the onset of pain from SMAS. There was no direct pathophysiological consequence of another medical condition. Ms. S was clear that her symptoms of anxiety and depression began after she was isolated from her friends and began having difficulty understanding her diagnosis and prognosis.

Anorexia nervosa also was ruled out. According to the DSM-5, a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa requires the following 3 criteria1:

- restriction of food intake resulting in significantly low body weight (defined as weight that is less than “minimally normal”) relative to age, gender, or development

- intense fear of gaining weight, or persistent behaviors that interfere with weight gain

- disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or lack of insight with regard to seriousness of current low body weight.

Continue to: Although Ms. S appeared...

Although Ms. S appeared thin, her BMI was within normal range. She added that she likes food and enjoyed eating, but that her medical condition made it too painful. Lastly, Ms. S denied a history of binging or purging.

Somatic symptom disorder.

Factitious disorder imposed on self. An individual with FDIS chronically stimulates, induces, or aggravates illnesses to gain the status of being a patient.

Factitious disorder imposed on another is the deliberate feigning or production of symptoms in another individual who is under the perpetrator’s supervision.1 Table 23 lists clinical indicators that raise suspicion for FDIA.

Before a diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder, FDIS, or FDIA could be established or ruled out, it was imperative to gather collateral information from other clinicians involved in Ms. S’s care. Ms. S and her mother had sought out help from a pediatric surgeon, a pediatric gastroenterologist, a pediatrician, and a psychotherapist.

Continue to: EVALUATION Collateral information

EVALUATION Collateral information

After Ms. S’s mother signs consent forms for exchange of information, the treatment team reaches out to the other clinicians. The therapist confirms that Ms. S’s mother had ended her daughter’s treatment after she was unable to quickly obtain documentation to rule out anorexia nervosa.

Both the pediatric surgeon and gastroenterologist report concerns of FDIA, which is why both clinicians had referred Ms. S and her mother to psychiatry. The pediatric surgeon states that on one occasion when he interviewed Ms. S separately from her mother, she seemed to be going down a checklist of symptoms. The surgeon reports that there was a partial occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery, confirming the diagnosis of SMAS, but he believed it was not severe enough to explain the symptoms Ms. S reported. The surgeon had scheduled another imaging appointment for 1 month later.

The pediatric gastroenterologist reports that Ms. S’s mother had demanded surgery and nasogastric tube placement for her daughter, which raised suspicion of FDIA. The gastroenterologist had convinced Ms. S and her mother to start low-dose doxepin, 20 mg twice a day, for anxiety, sleep, and abdominal pain.

Lastly, the pediatrician reports that she had not seen Ms. S for several months but stated that Ms. S always has been in the low normal BMI range. The pediatrician also reports that 6 months ago, the patient and her mother were frantically visiting EDs and scheduling doctor’s appointments.

[polldaddy:10586906]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team decided that Ms. S was not in imminent danger, and felt it was important to keep her in treatment without raising her mother’s suspicion. The team agreed to raise these concerns to the police, child protective services, and risk management if Ms. S’s health suddenly deteriorated or if her mother decided to remove Ms. S from our care.

Continue to: The treatment team...

The treatment team at the outpatient psychiatry clinic agreed that Ms. S did not currently meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, MDD, FDIS, or FDIA. However, Ms. S reported worries particular to persistent abdominal pain that was exacerbated by either eating or going to bed at night, which indicated that somatic symptom disorder was her likely diagnosis. Further, she endorsed a high level of anxiety and depression with regard to this somatic complaint that interfered with her daily activities and consumed an excessive amount of time, which also pointed to somatic symptom disorder. As a result of this diagnosis, the treatment team helped Ms. S manage her somatic symptoms and monitored for any other changes in her symptoms

Generally, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based therapy may help relieve symptoms associated with somatic symptom disorder.4

TREATMENT Therapy sessions and medication management

At the psychiatric clinic, Ms. S is scheduled for biweekly therapy sessions with a social worker and biweekly appointments with a senior psychiatry resident for medication management. At each visit, Ms. S’s vital signs, height, and weight are measured. In the therapy sessions, she is taught mindfulness skills as well as CBT. The senior psychiatry resident maintains regular communication with the other clinicians involved in Ms. S’s care.

After the first month of treatment, Ms. S undergoes repeat imaging at the gastroenterologist’s office that indicates her SMAS is no longer occluded. Ms. S continues to report somatic symptoms, but with mild improvement.

Over the course of approximately 4 months, Ms. S begins to show signs of improvement in her pain, anxiety, and depression. Ms. S begins to feel well enough to get a summer job at a nursing home and expresses enthusiasm when her weight begins to increase. Her mother also became enthused and verbalized her appreciation that her daughter appeared to be improving.

Continue to: In the fall...

In the fall, Ms. S returns to high school for her senior year but has difficulty getting back into the routine and relating to her old friends. Ms. S continues to perseverate on thoughts of getting sick and her physical symptoms become overwhelming once again. She continues to be focused on any new symptoms she experiences, and to limit the types of foods she eats due to fear of the abdominal pain returning.

After several more months of psychiatric treatment, Ms. S reports significant relief from her abdominal pain, and no longer seeks corrective surgery for her SMAS. Although she occasionally struggles with perseverating thoughts and anxiety about her somatic symptoms such as abdominal pain and worrying about the types of foods she eats and becoming ill, she continues to work through symptoms of her somatic symptom disorder.

The authors’ observations

The main challenge of somatic symptom disorder is the patient’s “abnormal illness behavior.”2,5,6 For pediatric patients, there may an association between a parent’s psychological status and the patient’s somatic symptoms. Abdominal symptoms in a pediatric patient have a strong association with a parent who presents with depression, anxiety, or somatization. The effects of the parent’s psychological status could also manifest in the form of modeling catastrophic thinking or through reinforcement. Parents with certain traits, such as disproportionate worry about pain, may pay more attention to their child’s symptoms, and hence, reward the child when he/she reports somatic symptoms.7,8 In the case of Ms. S, her mother did not participate in therapy and the mother’s psychiatric history was never obtained.

OUTCOMES Making personal strides

Ms. S continues to use mindfulness skills as well as CBT to manage her symptoms of somatic symptom disorder. She continues to celebrate her weight gains, denies any thoughts of suicide or self-harm behaviors, and prepares for college by scheduling campus visits and completing admissions applications.

Bottom Line

Patients with somatic symptom disorder tend to have very high levels of worry about illness. Somatic symptoms in such patients may or may not have a medical explanation. Accurate diagnosis and careful management are necessary to reduce patient distress. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based therapy may help relieve symptoms associated with this disorder.

Related Resources

- Henningsen P. Management of somatic symptom disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(1):23-91.

- Rosic T, Kalra S, Samaan Z. Somatic symptom disorder, a new DSM-5 diagnosis of an old clinical challenge. BMJ Case Rep. 2016: bcr2015212553. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-212553.

Drug Brand Name

Doxepin • Silenor

CASE Distraught over a medical illness

Ms. S, age 16, presents to the emergency department (ED) accompanied by her mother with superficial lacerations on her arm. Ms. S states, “I cut my arm because I was afraid I was going to do something serious if I didn’t get to go to the ED.” She says that 6 months earlier, she was diagnosed with superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS), a rare, potentially life-threatening condition that occurs when the duodenum is compressed between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery, causing a partial or complete blockage of the duodenum. Since receiving this diagnosis, Ms. S reports feeling anxious, depressed, and overwhelmed by both the pain she is experiencing from her illness and uncertainty about her prognosis.

HISTORY In pain and isolated

Since being diagnosed with SMAS, Ms. S has had approximately 30 medical and 7 ED visits for SMAS-related pain. Ms. S was referred to the outpatient clinic for ongoing support and treatment for SMAS.

Because of her pain and anxiety, Ms. S, a junior in high school, no longer attends school but has been working with a tutor. Ms. S says that some of her loneliness and hopelessness are due to the social isolation of being tutored at home. She states that she has been “out of sight and out of mind” from her friends. She also reports feeling different from them due to the pain brought on by SMAS.

Ms. S and her mother live in public housing. Ms. S says that overall, she has a good relationship with her mother, but that in certain situations, her mother’s anxiety causes her significant frustration and anxiety.

EVALUATION Transient suicidal thoughts

A physical examination reveals superficial lacerations to Ms. S’s left arm. Although she appears thin, her current body mass index (BMI) is 20.4 kg/m2, which is within normal range. She says she sees herself as “underweight” and “not fat at all.” Ms. S reports that she likes food and enjoyed eating until it became too painful following her SMAS diagnosis. Ms. S denies a history of binging or purging. Results from her laboratory workup and all values are within normal limits.

During the initial interview, Ms. S’s mother says they came to the ED because Ms. S urgently needs a psychiatric evaluation so she can be cleared for gastrointestinal (GI) surgery and placement of a nasogastric tube. Her mother says a surgeon from a different hospital told them that her insurance company required a psychiatric evaluation to rule out anorexia nervosa before they would authorize the GI surgery. When asked why psychiatry at this hospital was not consulted, Ms. S’s mother does not answer.

When asked about the symptoms she has been experiencing, Ms. S says that her sleep has been poor because of increased pain and excessive worrying about her health. She has limited her food intake. Ms. S reports that after eating, she lays on her left side to alleviate pain and help the food move through her body.

Continue to: Ms. S says...

Ms. S says she feels anxious and depressed due to her SMAS diagnosis, her mother’s online research and oversharing of poor prognoses, and being isolated from her friends. Most of her time outside the home is spent attending medical appointments with specialists. Several months ago, Ms. S had seen a psychotherapist, but her mother was unhappy with the treatment recommendations, which included seeking care from a nutritionist and joining group therapy. Ms. S’s mother says she ended her daughter’s psychotherapy because she was unable to obtain a signature ruling out anorexia nervosa within the first few appointments.

Ms. S also says she has had passive suicidal thoughts during the past month, usually twice a week. She reports that these thoughts lasted as long as several hours and were difficult to control, but she has no specific plan or intent. Ms. S denies current suicidal thoughts or ideation, and works with the treatment team to complete a safety plan, which she signs. Other than her recent visit to the ED, Ms. S denies any other thoughts or behaviors of self-injury or suicide.

[polldaddy:10586905]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team considered the following conditions as part of Ms. S’s differential diagnosis:

Major depressive disorder. The team was able to rule out MDD because Ms. S’s depression was attributed to SMAS. Ms. S reported that all depressive symptoms were manageable or nonexistent before the onset of pain from SMAS. There was no direct pathophysiological consequence of another medical condition. Ms. S was clear that her symptoms of anxiety and depression began after she was isolated from her friends and began having difficulty understanding her diagnosis and prognosis.

Anorexia nervosa also was ruled out. According to the DSM-5, a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa requires the following 3 criteria1:

- restriction of food intake resulting in significantly low body weight (defined as weight that is less than “minimally normal”) relative to age, gender, or development

- intense fear of gaining weight, or persistent behaviors that interfere with weight gain

- disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or lack of insight with regard to seriousness of current low body weight.

Continue to: Although Ms. S appeared...

Although Ms. S appeared thin, her BMI was within normal range. She added that she likes food and enjoyed eating, but that her medical condition made it too painful. Lastly, Ms. S denied a history of binging or purging.

Somatic symptom disorder.

Factitious disorder imposed on self. An individual with FDIS chronically stimulates, induces, or aggravates illnesses to gain the status of being a patient.

Factitious disorder imposed on another is the deliberate feigning or production of symptoms in another individual who is under the perpetrator’s supervision.1 Table 23 lists clinical indicators that raise suspicion for FDIA.

Before a diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder, FDIS, or FDIA could be established or ruled out, it was imperative to gather collateral information from other clinicians involved in Ms. S’s care. Ms. S and her mother had sought out help from a pediatric surgeon, a pediatric gastroenterologist, a pediatrician, and a psychotherapist.

Continue to: EVALUATION Collateral information

EVALUATION Collateral information

After Ms. S’s mother signs consent forms for exchange of information, the treatment team reaches out to the other clinicians. The therapist confirms that Ms. S’s mother had ended her daughter’s treatment after she was unable to quickly obtain documentation to rule out anorexia nervosa.

Both the pediatric surgeon and gastroenterologist report concerns of FDIA, which is why both clinicians had referred Ms. S and her mother to psychiatry. The pediatric surgeon states that on one occasion when he interviewed Ms. S separately from her mother, she seemed to be going down a checklist of symptoms. The surgeon reports that there was a partial occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery, confirming the diagnosis of SMAS, but he believed it was not severe enough to explain the symptoms Ms. S reported. The surgeon had scheduled another imaging appointment for 1 month later.

The pediatric gastroenterologist reports that Ms. S’s mother had demanded surgery and nasogastric tube placement for her daughter, which raised suspicion of FDIA. The gastroenterologist had convinced Ms. S and her mother to start low-dose doxepin, 20 mg twice a day, for anxiety, sleep, and abdominal pain.

Lastly, the pediatrician reports that she had not seen Ms. S for several months but stated that Ms. S always has been in the low normal BMI range. The pediatrician also reports that 6 months ago, the patient and her mother were frantically visiting EDs and scheduling doctor’s appointments.

[polldaddy:10586906]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team decided that Ms. S was not in imminent danger, and felt it was important to keep her in treatment without raising her mother’s suspicion. The team agreed to raise these concerns to the police, child protective services, and risk management if Ms. S’s health suddenly deteriorated or if her mother decided to remove Ms. S from our care.

Continue to: The treatment team...

The treatment team at the outpatient psychiatry clinic agreed that Ms. S did not currently meet criteria for anorexia nervosa, MDD, FDIS, or FDIA. However, Ms. S reported worries particular to persistent abdominal pain that was exacerbated by either eating or going to bed at night, which indicated that somatic symptom disorder was her likely diagnosis. Further, she endorsed a high level of anxiety and depression with regard to this somatic complaint that interfered with her daily activities and consumed an excessive amount of time, which also pointed to somatic symptom disorder. As a result of this diagnosis, the treatment team helped Ms. S manage her somatic symptoms and monitored for any other changes in her symptoms

Generally, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based therapy may help relieve symptoms associated with somatic symptom disorder.4

TREATMENT Therapy sessions and medication management

At the psychiatric clinic, Ms. S is scheduled for biweekly therapy sessions with a social worker and biweekly appointments with a senior psychiatry resident for medication management. At each visit, Ms. S’s vital signs, height, and weight are measured. In the therapy sessions, she is taught mindfulness skills as well as CBT. The senior psychiatry resident maintains regular communication with the other clinicians involved in Ms. S’s care.

After the first month of treatment, Ms. S undergoes repeat imaging at the gastroenterologist’s office that indicates her SMAS is no longer occluded. Ms. S continues to report somatic symptoms, but with mild improvement.

Over the course of approximately 4 months, Ms. S begins to show signs of improvement in her pain, anxiety, and depression. Ms. S begins to feel well enough to get a summer job at a nursing home and expresses enthusiasm when her weight begins to increase. Her mother also became enthused and verbalized her appreciation that her daughter appeared to be improving.

Continue to: In the fall...

In the fall, Ms. S returns to high school for her senior year but has difficulty getting back into the routine and relating to her old friends. Ms. S continues to perseverate on thoughts of getting sick and her physical symptoms become overwhelming once again. She continues to be focused on any new symptoms she experiences, and to limit the types of foods she eats due to fear of the abdominal pain returning.

After several more months of psychiatric treatment, Ms. S reports significant relief from her abdominal pain, and no longer seeks corrective surgery for her SMAS. Although she occasionally struggles with perseverating thoughts and anxiety about her somatic symptoms such as abdominal pain and worrying about the types of foods she eats and becoming ill, she continues to work through symptoms of her somatic symptom disorder.

The authors’ observations

The main challenge of somatic symptom disorder is the patient’s “abnormal illness behavior.”2,5,6 For pediatric patients, there may an association between a parent’s psychological status and the patient’s somatic symptoms. Abdominal symptoms in a pediatric patient have a strong association with a parent who presents with depression, anxiety, or somatization. The effects of the parent’s psychological status could also manifest in the form of modeling catastrophic thinking or through reinforcement. Parents with certain traits, such as disproportionate worry about pain, may pay more attention to their child’s symptoms, and hence, reward the child when he/she reports somatic symptoms.7,8 In the case of Ms. S, her mother did not participate in therapy and the mother’s psychiatric history was never obtained.

OUTCOMES Making personal strides

Ms. S continues to use mindfulness skills as well as CBT to manage her symptoms of somatic symptom disorder. She continues to celebrate her weight gains, denies any thoughts of suicide or self-harm behaviors, and prepares for college by scheduling campus visits and completing admissions applications.

Bottom Line

Patients with somatic symptom disorder tend to have very high levels of worry about illness. Somatic symptoms in such patients may or may not have a medical explanation. Accurate diagnosis and careful management are necessary to reduce patient distress. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based therapy may help relieve symptoms associated with this disorder.

Related Resources

- Henningsen P. Management of somatic symptom disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(1):23-91.

- Rosic T, Kalra S, Samaan Z. Somatic symptom disorder, a new DSM-5 diagnosis of an old clinical challenge. BMJ Case Rep. 2016: bcr2015212553. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-212553.

Drug Brand Name

Doxepin • Silenor

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Stern T, Freudenreich O, Smith F, et al. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry, 7th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017.

3. Feldman MD, Eisendrath SJ. The spectrum of factitious disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1997.

4. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry, 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014:470.

5. Pilowsky I. The concept of abnormal illness behavior. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(2):207-213.

6. Kirmayer LJ, Looper KJ. Abnormal illness behavior: physiological, psychological and social dimensions of coping with stress. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19(1):54-60.

7. Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Somatic complaints in pediatric patients: a prospective study of the role of negative life events, child social and academic competence, and parental somatic symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychology. 1994;62(6):1213-1221.

8. Van Oudenhove L, Levy RL, Crowell MD, et al. Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders: how central and environmental processes contribute to the development and expression of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1355-1367.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Stern T, Freudenreich O, Smith F, et al. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry, 7th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017.

3. Feldman MD, Eisendrath SJ. The spectrum of factitious disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1997.

4. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry, 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014:470.

5. Pilowsky I. The concept of abnormal illness behavior. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(2):207-213.

6. Kirmayer LJ, Looper KJ. Abnormal illness behavior: physiological, psychological and social dimensions of coping with stress. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19(1):54-60.

7. Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Somatic complaints in pediatric patients: a prospective study of the role of negative life events, child social and academic competence, and parental somatic symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychology. 1994;62(6):1213-1221.

8. Van Oudenhove L, Levy RL, Crowell MD, et al. Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders: how central and environmental processes contribute to the development and expression of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1355-1367.