User login

Patients with challenging behaviors: Communication strategies

From time to time, all physicians encounter patients whose behavior evokes negative emotions. In 1978, in an article titled “Taking care of the hateful patient,”1 Groves detailed 4 types of patients—“dependent clingers, entitled demanders, manipulative help-rejecters, and self-destructive deniers”1—that even the most seasoned physicians dread, and provided suggestions for managing interactions with them. The topic was revisited and updated in 2006 by Strous et al.2

Now, more than 10 years later, the challenge of how to interact with difficult patients is more relevant than ever. A cultural environment in which every patient can become an “expert” via the Internet has added new challenges. Patients who are especially time-consuming and emotionally draining exacerbate the many other pressures physicians face today (eg, increased paperwork, cost-consciousness, shortened appointment times, and the move to electronic medical records), contributing to physician burnout.

This article further updates the topic of managing challenging patients to reflect the current practice climate. We provide a more modern view of challenging patients and provide guidance on handling them. Although it may be tempting to diagnose some of these patients as having a personality disorder, it can often be more helpful to recognize patterns of behavior and have a clear plan for management. We also discuss general coping strategies for avoiding physician burnout.

INTERNET-SEEKING, QUESTIONING

A 45-year-old man carries in an overstuffed briefcase for his first primary care visit. He is a medical editor for a national journal and recently worked on a case study involving a rare cancer. As he edited, he recognized that he had the same symptoms and diagnosed himself with the same disease. He has brought with him a sheaf of articles he found on the Internet detailing clinical trials for experimental treatments. When the doctor begins to ask questions, he says the answers are irrelevant: he explains that he would have gone straight to an oncologist, but his insurance policy requires that he also have a primary care physician. He now expects the doctor to order magnetic resonance imaging, refer him to an oncologist, and support his request for the treatment he has identified as best.

The Internet: A blessing and a curse

Patients now have access to enormous amounts of information of variable accuracy. As in this case, patients may come to an appointment carrying early research studies that the physician has not yet reviewed. Others get their information from patient blogs that frequently offer opinions without evidence. Often, based on an advertisement or Internet reading, a patient requests a particular medication or test that may not be cost-effective or medically justified.

In a survey more than 10 years ago, more than 75% of physicians reported that they had patients who brought in information from online sources.3 Hu et al4 reported that 70% of patients who had online information planned to discuss it with their physicians. This practice is only growing, including in older patients.5

Physicians may feel confused and frustrated by patients who come armed with information. They may infer that patients do not trust them to diagnose correctly or treat optimally. In addition, discussing such information takes time, causing others on the schedule to wait, adding to the stress of coping with over-booked appointments.

Why so overprepared?

Patients who have or fear that they have cancer may be particularly worried that an important treatment will be overlooked.6 Since they feel that their life is hanging in the balance, their search for a definitive cure is understandable.

Internet-seeking, intensely questioning patients clearly want more information about the treatments they are receiving, alternative medical or procedural options, and complementary therapies.7 The response to their desire for more information affects their impression of physician empathy.8

Adapting to a more informed patient

Approaching these patients as an opportunity to educate may result in a more trusting patient and one more likely to be open to physician guidance and more likely to adhere to an advised treatment plan. Triangulation of the 3 actors—the physician, the patient, and the Web—can help patients to make more-informed choices and foster an attitude of partnership with the physician to lead them to optimal healthcare.

In a review of the impact of Internet use on healthcare and the physician-patient relationship, Wald et al9 urged physicians to:

- Adopt a positive attitude toward discussing Internet contributions

- Encourage patients to take an active role in maintaining health

- Acknowledge patient concerns and fears

- Avoid becoming defensive

- Recommend credible Internet sources.

Laing et al10 urged physicians to recognize rather than deny the effects of patients’ online searching for information and support, and not to ignore the potential impact on treatment. Consumers are gaining autonomy and self-efficacy, and Laing et al encouraged healthcare providers to develop ways to incorporate this new reality into the services they provide.10

How Web-based interaction can assist in patient decision-making for colorectal cancer screening is being explored.11 Patients at home can use an online tool to learn about screening choices and would be more knowledgable and comfortable discussing the options with their care provider. The hope is to build in an automatic reminder for the clinician, who would better understand the patient’s preference before the office visit.

One approach to our patient is to say, “I can see how worried you are about having the same type of cancer you read about, and I want to help you. It is clear to me that you know a lot about healthcare, and I appreciate your engagement in your health. How about starting over? Let me ask a few questions so I can get a better perspective on your symptoms?” Many times, this strategy can help patients reframe their view and accept help.

DEMANDING, LITIGATION-THREATENING

A 60-year-old lawyer is admitted to the hospital for evaluation of abdominal pain. His physician recommends placing a nasogastric tube to provide nutrition while the evaluation is completed. His wife, a former nurse practitioner, insists that a nasogastric tube would be too dangerous and demands that he be allowed to eat instead. The couple declares the primary internal medicine physician incompetent, does not want any residents to be involved in his care, and antagonizes the nurses with constant demands. Soon, the entire team avoids the patient’s room.

Why so hostile?

People with demanding behavior often have a hostile and confrontational manner. They may use medical jargon and appear to believe that they know more than their healthcare team. Many demand to know why they have not been offered a particular test, diagnosis, or treatment, especially if they or a family member has a healthcare background. Such patients appear to feel that they are being treated incorrectly and leave us feeling vulnerable, wondering whether the patient might one day come back to haunt us with a lawsuit, especially if the medical outcome is unfavorable.

Understanding the motivation for the behavior can help a physician to empathize with the demanding patient.12 Although it may seem that the demanding patient is trying to intimidate the physician, the goal is usually the same: to find the best possible treatment. Anger and hostility are often motivated by fear and a sense of losing control.

Ironically, this maladaptive coping style may alienate the very people who can help the patient. Hostile behavior evokes defensiveness and resentment in others. A power struggle may ensue: as the patient makes more unreasonable demands and threats, the physician reacts by asserting his or her views in an attempt to maintain control. Or the physician and the rest of the healthcare team may simply avoid the patient as much as possible.

Collaboration can defuse anger

The best strategy is often to steer the encounter away from a power struggle by legitimizing the patient’s feeling of entitlement to the best possible treatment.13 Take a collaborative stance with the patient, with the common goal of finding and implementing the most effective and lowest-risk diagnostic and treatment plan. Empathy and exploration of the patient’s concerns are always in order.

Physicians can try several strategies to improve interactions with demanding patients and caregivers:

Be consistent. All members of the healthcare team, including nurses and specialists, should convey consistent messages regarding diagnostic testing and treatment plans.

Don’t play the game. Demanding patients often complain about being mistreated by other healthcare providers. When confronted with such complaints, acknowledge the patient’s feelings while refraining from blaming or criticizing other members of the healthcare team.

Clarify expectations. Clarifying expectations from the initial patient encounter can prevent conflicts later. Support a patient who must accept a diagnosis of a terminal illness, and then when appropriate, discuss goals moving forward. Collaboration within the framework of reasonable expectations is key.

For our case, the physician could say, “We want to work with you together as a team. We will work hard to address your concerns, but our nurses must have a safe environment in which to help you.” Such a statement highlights shared goals and expression of concern without judgment. The next step is to clarify expectations by describing the hospital routine and how decisions are made.

Offer choices. Offering choices whenever possible can help a demanding patient feel more in control. Rather than dismiss a patient’s ideas, explore the alternatives. While effective patient communication is preferable to repeated referrals to specialists,14 judicious referral can engender trust in the physician’s competence if a diagnosis is not forthcoming.15

A unique challenge in teaching hospitals is the patient who refuses to interact with residents and students. It is best to acknowledge the patient’s concerns and offer alternative options:

- If the patient is worried about lack of completed training, then clarify the residents’ roles and reassure the patient that you communicate with residents and supervisors regarding any clinical decisions

- If possible, offer to see the patient alone or have the resident interact only on an as-needed basis

- Consider transferring the patient to a nonteaching service or to another hospital.

Admit failings. Although not easy, admitting to and apologizing for things that have gone wrong can help to calm a demanding patient and even reduce the likelihood of a lawsuit.16 The physician should not convey defensiveness and instead should acknowledge the limitations of the healthcare system.

Legitimize concerns—to an extent. Legitimizing a demanding patient’s concerns is important, but never be bullied into taking actions that create unnecessary risk. Upsetting a demanding patient is better than ordering tests or providing treatments that are potentially harmful. Good physician-patient communication can go a long way toward preventing adverse outcomes.

CONSTANTLY SEEKING REASSURANCE

A 25-year-old professional presents to a new primary care provider concerned about a mole on her back. She discusses her sun exposure and family history of skin cancer and produces photographs documenting changes in the mole over time. Impressed with this level of detail, the physician takes time to explain his concerns before referring her to a dermatologist. Later that day, she calls to let the doctor know that her procedure has been scheduled and to thank him for his care. A few weeks after the mole is removed, she returns to discuss treatment options for the small remaining scar.

After this appointment, she calls the office repeatedly with a wide array of concerns, including an isolated symptom of fatigue that could indicate cancer and the relative merits of different sunscreens. She also sends the physician frequent e-mail messages through the personal health record system with pictures of inconsequential marks on her skin.

Needing reassurance is normal—to a point

Many patients seek reassurance from their physicians, and this can be done in a healthy and respectful manner. But requests for reassurance may escalate to becoming repeated, insistent, and even aggressive.1 This can elicit reactions from physicians ranging from feeling annoyed and burdened to feeling angry and overwhelmed.17 This can lead to significant stress, which, if not managed well, can lead to excessively control of physician behavior and substandard care.18

Reassurance-seeking behavior can manifest anywhere along the spectrum of health and disease.19 It may be a symptom of health anxiety (ie, an exaggerated fear of illness) or hypochondria (ie, the persistent conviction that one is currently or likely to become ill).20,21

Why so needy?

Attachment theory may help explain neediness. Parental bonding during childhood is associated with mental and physical health and health-related behaviors in adults.22,23 People with insecure-preoccupied attachment styles tend to be overly emotionally dependent on the acceptance of others and may exhibit dependent and care-seeking behaviors with a physician.24

Needy patients are often genuinely grateful for the care and attention from a physician.1 In the beginning, the doctor may appreciate the patient’s validation of care provided, but this positive feeling wanes as calls and requests become incessant. As the physician’s exhaustion increases with each request, the care and well-being of the patient may no longer be the primary focus.1

Set boundaries

Be alert to signs that a patient is crossing the line to an unhealthy need for reassurance. Address medical concerns appropriately, then institute clear guidelines for follow-up, which should be reinforced by the entire care team if necessary.22

The following strategies can be useful for defining boundaries:

- Instruct the patient to come to the office only for scheduled follow-up visits and to call only during office hours or in an emergency

- Be up-front about the time allowed for each appointment and ask the patient to help focus the discussion according to his or her main concerns25

- Consider telling the patient, “You seem really worried about a lot of physical symptoms. I want to reassure you that I find no evidence of a medical illness that would require intervention. I am concerned about your phone calls and e-mails, and I wonder what would be helpful at this point to address your concerns?”

- Consider treating the patient for anxiety.

It is important to remain responsive to all types of patient concerns. Setting boundaries will guide patients to express health concerns in an appropriate manner so that they can be heard and managed.18,19

SELF-INJURY

A 22-year-old woman presents to the emergency department complaining of abdominal pain. After a full workup, the physician clears her medically and orders a few laboratory tests. As the nurse draws blood samples, she notices multiple fresh cuts on the patient’s arm and informs the physician. The patient is questioned and examined again and acknowledges occasional thoughts of self-harm.

Her parents arrive and appear appropriately concerned. They report that she has been “cutting” for 4 years and is regularly seeing a therapist. However, they say that they are not worried for her safety and that she has an appointment with her therapist this week. Based on this, the emergency department physician discharges her.

Two weeks later, the patient returns to the emergency department with continued cutting and apparent cellulitis, prompting medical admission.

Self-injury presents in many ways

Self-injurious behaviors come in many forms other than the easily recognized one presented in this case: eg, a patient with cirrhosis who continues to drink, a patient with severe epilepsy who forgets to take medications and lands in the emergency department every week for status epilepticus, a patient with diabetes who eats a high-sugar diet, a patient with renal insufficiency who ignores water restrictions, or a patient with an organ transplant who misses medications and relapses.

There is an important psychological difference between patients who knowingly continue to challenge their luck and those who do not fully understand the severity of their condition and the consequences of their actions. The patient who simply does not “get it” can sometimes be managed effectively with education and by working with family members to create an environment to facilitate critical healthy behaviors.

Patients who willfully self-inflict injury are asking for help while doing everything to avoid being helped. They typically come to the office or the emergency department with assorted complaints, not divulging the real reason for their visit until the last minute as they are leaving. Then they drop a clue to the real concern, leaving the physician confused and frustrated.

Why deny an obvious problem?

Fear of the stigma of mental illness can be a major barrier to full disclosure of symptoms of psychological distress, and this especially tends to be the case for patients from some ethnic minorities.26

On the other hand, patients with borderline or antisocial personality disorder (and less often, schizotypal or narcissistic personality disorder) frequently use denial as their primary psychological defense. Self-destructive denial is sometimes associated with traumatic memories, feelings of worthlessness, or a desire to reduce self-awareness and rationalize harmful behaviors. Such patients usually need lengthy treatment, and although the likelihood of cure is low, therapy can be helpful.27–29

Lessons from psychiatry

It can be difficult to maintain empathy for patients who intentionally harm themselves. It is helpful to think of these patients as having a terminal illness and to recognize that they are suffering.

Different interventions have been studied for such patients. Dialectical behavior therapy, an approach that teaches patients better coping skills for regulating emotions, can help reduce maladaptive emotional distress and self-destructive behaviors.30–32 Lessons from this approach can be applied by general practitioners:

- Engage the patient and together establish an effective crisis management plan

- With patient permission, involve the family in the treatment plan

- Set clear limits about self-harm: once the patient values interaction with the doctor, he or she will be less likely to break the agreement.

Patients with severe or continuing issues can be referred to appropriate services that offer dialectical behavior therapy or other intensive outpatient programs.

To handle our patient, one might start by saying, “I am sorry to see you back in the ER. We need to treat the cellulitis and get your outpatient behavioral team on board, so we know the plan.” Then, it is critical that the entire team keep to that plan.

HOW TO STAY IN CONTROL AND IMPROVE INTERACTIONS

Patients with challenging behaviors will always be part of medical practice. Physicians should be aware of their reactions and feelings towards a patient (known in psychiatry as countertransference), as they can increase physician stress and interfere with providing optimal care. Finding effective ways to work with difficult patients will avoid these outcomes.

Physicians also feel loss of control

Most physicians are resilient, but they can feel overwhelmed under certain circumstances. According to Scudder and Shanafelt,33 a physician’s sense of well-being is influenced by several factors, including feelings of control in the workplace. It is easy to imagine how one or more difficult patients can create a sense of overwhelming demand and loss of control.

These tips can help maintain a sense of control and improve interactions with patients:

Have a plan for effective communication. Not having a plan for communicating in a difficult situation can contribute to loss of control in a hectic schedule that is already stretched to its limits. Practicing responses with a colleague for especially difficult patients or using a team approach can be helpful. Remaining compassionate while setting boundaries will result in the best outcome for the patient and physician.

Stop to analyze the situation. One of the tenets of cognitive-behavioral therapy is recognizing that negative thoughts can quickly take us down a dangerous path. Feeling angry and resentful without stopping to think and reflect on the causes can lead to the physician feeling victimized (just like many difficult patients feel).

It is important to step back and think, not just feel. While difficult patients present in different ways, all are reacting to losing control of their situation and want support. During a difficult interaction with a patient, pause to consider, “Why is he behaving this way? Is he afraid? Does he feel that no one cares?”

When a patient verbally attacks beyond what is appropriate, recognize that this is probably due less to anything the physician did than to the patient’s internal issues. Identifying the driver of a patient’s behavior makes it easier to control our own emotions.

Practice empathy. Difficult patients usually have something in their background that can help explain their inappropriate behavior, such as a lack of parental support or abuse. Being open to hearing their story facilitates an empathetic connection.

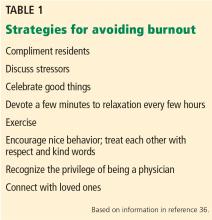

AVOIDING BURNOUT

Discuss problems

Sadly, physicians often neglect to talk with each other and with trainees about issues leading to burnout, thereby missing important opportunities for empathy, objectivity, reflection, and teaching moments.

Lessons can be gleaned from training in psychiatry, a field in which one must learn methods for working effectively in challenging situations. Dozens of scenarios are practiced using videotapes or observation through one-way mirrors. While not everyone has such opportunities, everyone can discuss issues with one another. Regularly scheduled facilitated groups devoted to discussing problems with colleagues can be enormously helpful.

Schedule quiet times

Mindfulness is an excellent way to spend a few minutes out of every 3- to 4-hour block. There are many ways to help facilitate such moments. Residents and students can be provided with a small book, Mindfulness on the Go,37 aimed for the busy person.

Deep, slow breathing can bring rapid relief to intense negative feelings. Not only does it reduce anxiety faster than medication, but it is also free, is easily taught to others, and can be done unobtrusively. A short description of the role of the blood pH in managing the locus ceruleus and vagus nerve’s balance of sympathetic and parasympathetic activity may capture the curiosity of someone who may otherwise be resistant to the exercise.

Increasingly, hospitals are developing mindfulness sessions and offering a variety of skills physicians can put into their toolbox. Lessons from cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, imagery, and muscle relaxation can help physicians in responding to patients. Investing in communication skills training specific to challenging behaviors seen in different specialties better equips physicians with more effective strategies.

- Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med 1978; 298:883–887.

- Strous RD, Ulman AM, Kotler M. The hateful patient revisited: relevance for 21st century medicine. Eur J Intern Med 2006; 17:387–393.

- Malone M, Mathes L, Dooley J, While AE. Health information seeking and its effect on the doctor-patient digital divide. J Telemed Telecare 2005; 11(suppl1):25–28.

- Hu X, Bell RA, Kravitz RL, Orrange S. The prepared patient: information seeking of online support group members before their medical appointments. J Health Commun 2012; 17:960–978.

- Tse MM, Choi KC, Leung RS. E-health for older people: the use of technology in health promotion. Cyberpsychol Behav 2008; 11:475–479.

- Pereira JL, Koski S, Hanson J, Bruera ED, Mackey JR. Internet usage among women with breast cancer: an exploratory study. Clin Breast Cancer 2000; 1:148–153.

- Brauer JA, El Sehamy A, Metz JN, Mao JJ. Complementary and alternative and supportive care at leading cancer centers: a systematic analysis of websites. J Altern Complement Med 2010; 16:183–186.

- Smith SG, Pandit A, Rush SR, Wolf MS, Simon C. The association between patient activation and accessing online health information: results from a national survey of US adults. Health Expect 2015; 18:3262–3273.

- Wald HS, Dube CE, Anthony DC. Untangling the Web—the impact of Internet use on health care and the physician-patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns 2007; 68:218–224.

- Laing A, Hogg G, Winkelman D. Healthcare and the information revolution: re-configuring the healthcare service encounter. Health Serv Manage Res 2004; 17:188–199.

- Jimbo M, Shultz CG, Nease DE, Fetters MD, Power D, Ruffin MT 4th. Perceived barriers and facilitators of using a Web-based interactive decision aid for colorectal cancer screening in community practice settings: findings from focus groups with primary care clinicians and medical office staff. J Med Internet Res 2013; 15:e286.

- Steinmetz D, Tabenkin H. The ‘difficult patient’ as perceived by family physicians. Fam Pract 2001; 18:495–500.

- Arciniegas DB, Beresford TP. Managing difficult interactions with patients in neurology practices: a practical approach. Neurology 2010; 75(suppl 1):S39–S44.

- Gallagher TH, Lo B, Chesney M, Christensen K. How do physicians respond to patient’s requests for costly, unindicated services? J Gen Intern Med 1997; 12:663–668.

- Breen KJ, Greenberg PB. Difficult physician-patient encounters. Intern Med J 2010; 40:682–688.

- Huntington B, Kuhn N. Communication gaffes: a root cause of malpractice claims. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2003; 16:157–161.

- Maunder RG, Panzer A, Viljoen M, Owen J, Human S, Hunter JJ. Physicians’ difficulty with emergency department patients is related to patients’ attachment style. Soc Sci Med 2006; 63:552–562.

- Thompson D, Ciechanowski PS. Attaching a new understanding to the patient-physician relationship in family practice. J Am Board Fam Pract 2003; 16:219–226.

- Groves M, Muskin P. Psychological responses to illness. In: Levenson JL, ed. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychosomatic Medicine. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2004:68–88.

- Görgen SM, Hiller W, Witthöft M. Health anxiety, cognitive coping, and emotion regulation: a latent variable approach. Int J Behav Med 2014; 21:364–374.

- Strand J, Goulding A, Tidefors I. Attachment styles and symptoms in individuals with psychosis. Nord J Psychiatry 2015; 69:67–72.

- Hooper LM, Tomek S, Newman CR. Using attachment theory in medical settings: implications for primary care physicians. J Ment Health 2012; 21:23–37.

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. 1. Attachment. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1969.

- Fuertes JN, Anand P, Haggerty G, Kestenbaum M, Rosenblum GC. The physician-patient working alliance and patient psychological attachment, adherence, outcome expectations, and satisfaction in a sample of rheumatology patients. Behav Med 2015; 41:60–68.

- Frederiksen HB, Kragstrup J, Dehlholm-Lambertsen B. Attachment in the doctor-patient relationship in general practice: a qualitative study. Scand J Prim Health Care 2010; 28:185–190.

- Rastogi P, Khushalani S, Dhawan S, et al. Understanding clinician perception of common presentations in South Asians seeking mental health treatment and determining barriers and facilitators to treatment. Asian J Psychiatr 2014; 7:15–21.

- van der Kolk BA, Perry JC, Herman JL. Childhood origins of self-destructive behavior. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1665–1671.

- Gacono CB, Meloy JR, Berg JL. Object relations, defensive operations, and affective states in narcissistic, borderline, and antisocial personality disorder. J Pers Assess 1992; 59:32–49.

- Perry JC, Presniak MD, Olson TR. Defense mechanisms in schizotypal, borderline, antisocial, and narcissistic personality disorders. Psychiatry 2013; 76:32–52.

- Gibson J, Booth R, Davenport J, Keogh K, Owens T. Dialectical behaviour therapy-informed skills training for deliberate self-harm: a controlled trial with 3-month follow-up data. Behav Res Ther 2014; 60:8–14.

- Fischer S, Peterson C. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescent binge eating, purging, suicidal behavior, and non-suicidal self-injury: a pilot study. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2015; 52:78–92.

- Booth R, Keogh K, Doyle J, Owens T. Living through distress: a skills training group for reducing deliberate self-harm. Behav Cogn Psychother 2014; 42:156–165.

- Scudder L, Shanafelt TD. Two sides of the physician coin: burnout and well-being. Medscape. Feb 09, 2015. http://nbpsa.org/images/PRP/PhysicianBurnoutMedscape.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2017.

- McAbee JH, Ragel BT, McCartney S, et al. Factors associated with career satisfaction and burnout among US neurosurgeons: results of a nationwide survey. J Neurosurg 2015; 123:161–173.

- Schneider S, Kingsolver K, Rosdahl J. Can physician self-care enhance patient-centered healthcare? Qualitative findings from a physician well-being coaching program. J Fam Med 2015; 2:6.

- Simonds G, Sotile W. Building Resilience in Neurosurgical Residents: A Primer. B Wright Publishing; 2015.

- Bays JC. Mindfulness on the Go: Simple Meditation Practices You Can Do Anywhere. Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications; 2014.

From time to time, all physicians encounter patients whose behavior evokes negative emotions. In 1978, in an article titled “Taking care of the hateful patient,”1 Groves detailed 4 types of patients—“dependent clingers, entitled demanders, manipulative help-rejecters, and self-destructive deniers”1—that even the most seasoned physicians dread, and provided suggestions for managing interactions with them. The topic was revisited and updated in 2006 by Strous et al.2

Now, more than 10 years later, the challenge of how to interact with difficult patients is more relevant than ever. A cultural environment in which every patient can become an “expert” via the Internet has added new challenges. Patients who are especially time-consuming and emotionally draining exacerbate the many other pressures physicians face today (eg, increased paperwork, cost-consciousness, shortened appointment times, and the move to electronic medical records), contributing to physician burnout.

This article further updates the topic of managing challenging patients to reflect the current practice climate. We provide a more modern view of challenging patients and provide guidance on handling them. Although it may be tempting to diagnose some of these patients as having a personality disorder, it can often be more helpful to recognize patterns of behavior and have a clear plan for management. We also discuss general coping strategies for avoiding physician burnout.

INTERNET-SEEKING, QUESTIONING

A 45-year-old man carries in an overstuffed briefcase for his first primary care visit. He is a medical editor for a national journal and recently worked on a case study involving a rare cancer. As he edited, he recognized that he had the same symptoms and diagnosed himself with the same disease. He has brought with him a sheaf of articles he found on the Internet detailing clinical trials for experimental treatments. When the doctor begins to ask questions, he says the answers are irrelevant: he explains that he would have gone straight to an oncologist, but his insurance policy requires that he also have a primary care physician. He now expects the doctor to order magnetic resonance imaging, refer him to an oncologist, and support his request for the treatment he has identified as best.

The Internet: A blessing and a curse

Patients now have access to enormous amounts of information of variable accuracy. As in this case, patients may come to an appointment carrying early research studies that the physician has not yet reviewed. Others get their information from patient blogs that frequently offer opinions without evidence. Often, based on an advertisement or Internet reading, a patient requests a particular medication or test that may not be cost-effective or medically justified.

In a survey more than 10 years ago, more than 75% of physicians reported that they had patients who brought in information from online sources.3 Hu et al4 reported that 70% of patients who had online information planned to discuss it with their physicians. This practice is only growing, including in older patients.5

Physicians may feel confused and frustrated by patients who come armed with information. They may infer that patients do not trust them to diagnose correctly or treat optimally. In addition, discussing such information takes time, causing others on the schedule to wait, adding to the stress of coping with over-booked appointments.

Why so overprepared?

Patients who have or fear that they have cancer may be particularly worried that an important treatment will be overlooked.6 Since they feel that their life is hanging in the balance, their search for a definitive cure is understandable.

Internet-seeking, intensely questioning patients clearly want more information about the treatments they are receiving, alternative medical or procedural options, and complementary therapies.7 The response to their desire for more information affects their impression of physician empathy.8

Adapting to a more informed patient

Approaching these patients as an opportunity to educate may result in a more trusting patient and one more likely to be open to physician guidance and more likely to adhere to an advised treatment plan. Triangulation of the 3 actors—the physician, the patient, and the Web—can help patients to make more-informed choices and foster an attitude of partnership with the physician to lead them to optimal healthcare.

In a review of the impact of Internet use on healthcare and the physician-patient relationship, Wald et al9 urged physicians to:

- Adopt a positive attitude toward discussing Internet contributions

- Encourage patients to take an active role in maintaining health

- Acknowledge patient concerns and fears

- Avoid becoming defensive

- Recommend credible Internet sources.

Laing et al10 urged physicians to recognize rather than deny the effects of patients’ online searching for information and support, and not to ignore the potential impact on treatment. Consumers are gaining autonomy and self-efficacy, and Laing et al encouraged healthcare providers to develop ways to incorporate this new reality into the services they provide.10

How Web-based interaction can assist in patient decision-making for colorectal cancer screening is being explored.11 Patients at home can use an online tool to learn about screening choices and would be more knowledgable and comfortable discussing the options with their care provider. The hope is to build in an automatic reminder for the clinician, who would better understand the patient’s preference before the office visit.

One approach to our patient is to say, “I can see how worried you are about having the same type of cancer you read about, and I want to help you. It is clear to me that you know a lot about healthcare, and I appreciate your engagement in your health. How about starting over? Let me ask a few questions so I can get a better perspective on your symptoms?” Many times, this strategy can help patients reframe their view and accept help.

DEMANDING, LITIGATION-THREATENING

A 60-year-old lawyer is admitted to the hospital for evaluation of abdominal pain. His physician recommends placing a nasogastric tube to provide nutrition while the evaluation is completed. His wife, a former nurse practitioner, insists that a nasogastric tube would be too dangerous and demands that he be allowed to eat instead. The couple declares the primary internal medicine physician incompetent, does not want any residents to be involved in his care, and antagonizes the nurses with constant demands. Soon, the entire team avoids the patient’s room.

Why so hostile?

People with demanding behavior often have a hostile and confrontational manner. They may use medical jargon and appear to believe that they know more than their healthcare team. Many demand to know why they have not been offered a particular test, diagnosis, or treatment, especially if they or a family member has a healthcare background. Such patients appear to feel that they are being treated incorrectly and leave us feeling vulnerable, wondering whether the patient might one day come back to haunt us with a lawsuit, especially if the medical outcome is unfavorable.

Understanding the motivation for the behavior can help a physician to empathize with the demanding patient.12 Although it may seem that the demanding patient is trying to intimidate the physician, the goal is usually the same: to find the best possible treatment. Anger and hostility are often motivated by fear and a sense of losing control.

Ironically, this maladaptive coping style may alienate the very people who can help the patient. Hostile behavior evokes defensiveness and resentment in others. A power struggle may ensue: as the patient makes more unreasonable demands and threats, the physician reacts by asserting his or her views in an attempt to maintain control. Or the physician and the rest of the healthcare team may simply avoid the patient as much as possible.

Collaboration can defuse anger

The best strategy is often to steer the encounter away from a power struggle by legitimizing the patient’s feeling of entitlement to the best possible treatment.13 Take a collaborative stance with the patient, with the common goal of finding and implementing the most effective and lowest-risk diagnostic and treatment plan. Empathy and exploration of the patient’s concerns are always in order.

Physicians can try several strategies to improve interactions with demanding patients and caregivers:

Be consistent. All members of the healthcare team, including nurses and specialists, should convey consistent messages regarding diagnostic testing and treatment plans.

Don’t play the game. Demanding patients often complain about being mistreated by other healthcare providers. When confronted with such complaints, acknowledge the patient’s feelings while refraining from blaming or criticizing other members of the healthcare team.

Clarify expectations. Clarifying expectations from the initial patient encounter can prevent conflicts later. Support a patient who must accept a diagnosis of a terminal illness, and then when appropriate, discuss goals moving forward. Collaboration within the framework of reasonable expectations is key.

For our case, the physician could say, “We want to work with you together as a team. We will work hard to address your concerns, but our nurses must have a safe environment in which to help you.” Such a statement highlights shared goals and expression of concern without judgment. The next step is to clarify expectations by describing the hospital routine and how decisions are made.

Offer choices. Offering choices whenever possible can help a demanding patient feel more in control. Rather than dismiss a patient’s ideas, explore the alternatives. While effective patient communication is preferable to repeated referrals to specialists,14 judicious referral can engender trust in the physician’s competence if a diagnosis is not forthcoming.15

A unique challenge in teaching hospitals is the patient who refuses to interact with residents and students. It is best to acknowledge the patient’s concerns and offer alternative options:

- If the patient is worried about lack of completed training, then clarify the residents’ roles and reassure the patient that you communicate with residents and supervisors regarding any clinical decisions

- If possible, offer to see the patient alone or have the resident interact only on an as-needed basis

- Consider transferring the patient to a nonteaching service or to another hospital.

Admit failings. Although not easy, admitting to and apologizing for things that have gone wrong can help to calm a demanding patient and even reduce the likelihood of a lawsuit.16 The physician should not convey defensiveness and instead should acknowledge the limitations of the healthcare system.

Legitimize concerns—to an extent. Legitimizing a demanding patient’s concerns is important, but never be bullied into taking actions that create unnecessary risk. Upsetting a demanding patient is better than ordering tests or providing treatments that are potentially harmful. Good physician-patient communication can go a long way toward preventing adverse outcomes.

CONSTANTLY SEEKING REASSURANCE

A 25-year-old professional presents to a new primary care provider concerned about a mole on her back. She discusses her sun exposure and family history of skin cancer and produces photographs documenting changes in the mole over time. Impressed with this level of detail, the physician takes time to explain his concerns before referring her to a dermatologist. Later that day, she calls to let the doctor know that her procedure has been scheduled and to thank him for his care. A few weeks after the mole is removed, she returns to discuss treatment options for the small remaining scar.

After this appointment, she calls the office repeatedly with a wide array of concerns, including an isolated symptom of fatigue that could indicate cancer and the relative merits of different sunscreens. She also sends the physician frequent e-mail messages through the personal health record system with pictures of inconsequential marks on her skin.

Needing reassurance is normal—to a point

Many patients seek reassurance from their physicians, and this can be done in a healthy and respectful manner. But requests for reassurance may escalate to becoming repeated, insistent, and even aggressive.1 This can elicit reactions from physicians ranging from feeling annoyed and burdened to feeling angry and overwhelmed.17 This can lead to significant stress, which, if not managed well, can lead to excessively control of physician behavior and substandard care.18

Reassurance-seeking behavior can manifest anywhere along the spectrum of health and disease.19 It may be a symptom of health anxiety (ie, an exaggerated fear of illness) or hypochondria (ie, the persistent conviction that one is currently or likely to become ill).20,21

Why so needy?

Attachment theory may help explain neediness. Parental bonding during childhood is associated with mental and physical health and health-related behaviors in adults.22,23 People with insecure-preoccupied attachment styles tend to be overly emotionally dependent on the acceptance of others and may exhibit dependent and care-seeking behaviors with a physician.24

Needy patients are often genuinely grateful for the care and attention from a physician.1 In the beginning, the doctor may appreciate the patient’s validation of care provided, but this positive feeling wanes as calls and requests become incessant. As the physician’s exhaustion increases with each request, the care and well-being of the patient may no longer be the primary focus.1

Set boundaries

Be alert to signs that a patient is crossing the line to an unhealthy need for reassurance. Address medical concerns appropriately, then institute clear guidelines for follow-up, which should be reinforced by the entire care team if necessary.22

The following strategies can be useful for defining boundaries:

- Instruct the patient to come to the office only for scheduled follow-up visits and to call only during office hours or in an emergency

- Be up-front about the time allowed for each appointment and ask the patient to help focus the discussion according to his or her main concerns25

- Consider telling the patient, “You seem really worried about a lot of physical symptoms. I want to reassure you that I find no evidence of a medical illness that would require intervention. I am concerned about your phone calls and e-mails, and I wonder what would be helpful at this point to address your concerns?”

- Consider treating the patient for anxiety.

It is important to remain responsive to all types of patient concerns. Setting boundaries will guide patients to express health concerns in an appropriate manner so that they can be heard and managed.18,19

SELF-INJURY

A 22-year-old woman presents to the emergency department complaining of abdominal pain. After a full workup, the physician clears her medically and orders a few laboratory tests. As the nurse draws blood samples, she notices multiple fresh cuts on the patient’s arm and informs the physician. The patient is questioned and examined again and acknowledges occasional thoughts of self-harm.

Her parents arrive and appear appropriately concerned. They report that she has been “cutting” for 4 years and is regularly seeing a therapist. However, they say that they are not worried for her safety and that she has an appointment with her therapist this week. Based on this, the emergency department physician discharges her.

Two weeks later, the patient returns to the emergency department with continued cutting and apparent cellulitis, prompting medical admission.

Self-injury presents in many ways

Self-injurious behaviors come in many forms other than the easily recognized one presented in this case: eg, a patient with cirrhosis who continues to drink, a patient with severe epilepsy who forgets to take medications and lands in the emergency department every week for status epilepticus, a patient with diabetes who eats a high-sugar diet, a patient with renal insufficiency who ignores water restrictions, or a patient with an organ transplant who misses medications and relapses.

There is an important psychological difference between patients who knowingly continue to challenge their luck and those who do not fully understand the severity of their condition and the consequences of their actions. The patient who simply does not “get it” can sometimes be managed effectively with education and by working with family members to create an environment to facilitate critical healthy behaviors.

Patients who willfully self-inflict injury are asking for help while doing everything to avoid being helped. They typically come to the office or the emergency department with assorted complaints, not divulging the real reason for their visit until the last minute as they are leaving. Then they drop a clue to the real concern, leaving the physician confused and frustrated.

Why deny an obvious problem?

Fear of the stigma of mental illness can be a major barrier to full disclosure of symptoms of psychological distress, and this especially tends to be the case for patients from some ethnic minorities.26

On the other hand, patients with borderline or antisocial personality disorder (and less often, schizotypal or narcissistic personality disorder) frequently use denial as their primary psychological defense. Self-destructive denial is sometimes associated with traumatic memories, feelings of worthlessness, or a desire to reduce self-awareness and rationalize harmful behaviors. Such patients usually need lengthy treatment, and although the likelihood of cure is low, therapy can be helpful.27–29

Lessons from psychiatry

It can be difficult to maintain empathy for patients who intentionally harm themselves. It is helpful to think of these patients as having a terminal illness and to recognize that they are suffering.

Different interventions have been studied for such patients. Dialectical behavior therapy, an approach that teaches patients better coping skills for regulating emotions, can help reduce maladaptive emotional distress and self-destructive behaviors.30–32 Lessons from this approach can be applied by general practitioners:

- Engage the patient and together establish an effective crisis management plan

- With patient permission, involve the family in the treatment plan

- Set clear limits about self-harm: once the patient values interaction with the doctor, he or she will be less likely to break the agreement.

Patients with severe or continuing issues can be referred to appropriate services that offer dialectical behavior therapy or other intensive outpatient programs.

To handle our patient, one might start by saying, “I am sorry to see you back in the ER. We need to treat the cellulitis and get your outpatient behavioral team on board, so we know the plan.” Then, it is critical that the entire team keep to that plan.

HOW TO STAY IN CONTROL AND IMPROVE INTERACTIONS

Patients with challenging behaviors will always be part of medical practice. Physicians should be aware of their reactions and feelings towards a patient (known in psychiatry as countertransference), as they can increase physician stress and interfere with providing optimal care. Finding effective ways to work with difficult patients will avoid these outcomes.

Physicians also feel loss of control

Most physicians are resilient, but they can feel overwhelmed under certain circumstances. According to Scudder and Shanafelt,33 a physician’s sense of well-being is influenced by several factors, including feelings of control in the workplace. It is easy to imagine how one or more difficult patients can create a sense of overwhelming demand and loss of control.

These tips can help maintain a sense of control and improve interactions with patients:

Have a plan for effective communication. Not having a plan for communicating in a difficult situation can contribute to loss of control in a hectic schedule that is already stretched to its limits. Practicing responses with a colleague for especially difficult patients or using a team approach can be helpful. Remaining compassionate while setting boundaries will result in the best outcome for the patient and physician.

Stop to analyze the situation. One of the tenets of cognitive-behavioral therapy is recognizing that negative thoughts can quickly take us down a dangerous path. Feeling angry and resentful without stopping to think and reflect on the causes can lead to the physician feeling victimized (just like many difficult patients feel).

It is important to step back and think, not just feel. While difficult patients present in different ways, all are reacting to losing control of their situation and want support. During a difficult interaction with a patient, pause to consider, “Why is he behaving this way? Is he afraid? Does he feel that no one cares?”

When a patient verbally attacks beyond what is appropriate, recognize that this is probably due less to anything the physician did than to the patient’s internal issues. Identifying the driver of a patient’s behavior makes it easier to control our own emotions.

Practice empathy. Difficult patients usually have something in their background that can help explain their inappropriate behavior, such as a lack of parental support or abuse. Being open to hearing their story facilitates an empathetic connection.

AVOIDING BURNOUT

Discuss problems

Sadly, physicians often neglect to talk with each other and with trainees about issues leading to burnout, thereby missing important opportunities for empathy, objectivity, reflection, and teaching moments.

Lessons can be gleaned from training in psychiatry, a field in which one must learn methods for working effectively in challenging situations. Dozens of scenarios are practiced using videotapes or observation through one-way mirrors. While not everyone has such opportunities, everyone can discuss issues with one another. Regularly scheduled facilitated groups devoted to discussing problems with colleagues can be enormously helpful.

Schedule quiet times

Mindfulness is an excellent way to spend a few minutes out of every 3- to 4-hour block. There are many ways to help facilitate such moments. Residents and students can be provided with a small book, Mindfulness on the Go,37 aimed for the busy person.

Deep, slow breathing can bring rapid relief to intense negative feelings. Not only does it reduce anxiety faster than medication, but it is also free, is easily taught to others, and can be done unobtrusively. A short description of the role of the blood pH in managing the locus ceruleus and vagus nerve’s balance of sympathetic and parasympathetic activity may capture the curiosity of someone who may otherwise be resistant to the exercise.

Increasingly, hospitals are developing mindfulness sessions and offering a variety of skills physicians can put into their toolbox. Lessons from cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, imagery, and muscle relaxation can help physicians in responding to patients. Investing in communication skills training specific to challenging behaviors seen in different specialties better equips physicians with more effective strategies.

From time to time, all physicians encounter patients whose behavior evokes negative emotions. In 1978, in an article titled “Taking care of the hateful patient,”1 Groves detailed 4 types of patients—“dependent clingers, entitled demanders, manipulative help-rejecters, and self-destructive deniers”1—that even the most seasoned physicians dread, and provided suggestions for managing interactions with them. The topic was revisited and updated in 2006 by Strous et al.2

Now, more than 10 years later, the challenge of how to interact with difficult patients is more relevant than ever. A cultural environment in which every patient can become an “expert” via the Internet has added new challenges. Patients who are especially time-consuming and emotionally draining exacerbate the many other pressures physicians face today (eg, increased paperwork, cost-consciousness, shortened appointment times, and the move to electronic medical records), contributing to physician burnout.

This article further updates the topic of managing challenging patients to reflect the current practice climate. We provide a more modern view of challenging patients and provide guidance on handling them. Although it may be tempting to diagnose some of these patients as having a personality disorder, it can often be more helpful to recognize patterns of behavior and have a clear plan for management. We also discuss general coping strategies for avoiding physician burnout.

INTERNET-SEEKING, QUESTIONING

A 45-year-old man carries in an overstuffed briefcase for his first primary care visit. He is a medical editor for a national journal and recently worked on a case study involving a rare cancer. As he edited, he recognized that he had the same symptoms and diagnosed himself with the same disease. He has brought with him a sheaf of articles he found on the Internet detailing clinical trials for experimental treatments. When the doctor begins to ask questions, he says the answers are irrelevant: he explains that he would have gone straight to an oncologist, but his insurance policy requires that he also have a primary care physician. He now expects the doctor to order magnetic resonance imaging, refer him to an oncologist, and support his request for the treatment he has identified as best.

The Internet: A blessing and a curse

Patients now have access to enormous amounts of information of variable accuracy. As in this case, patients may come to an appointment carrying early research studies that the physician has not yet reviewed. Others get their information from patient blogs that frequently offer opinions without evidence. Often, based on an advertisement or Internet reading, a patient requests a particular medication or test that may not be cost-effective or medically justified.

In a survey more than 10 years ago, more than 75% of physicians reported that they had patients who brought in information from online sources.3 Hu et al4 reported that 70% of patients who had online information planned to discuss it with their physicians. This practice is only growing, including in older patients.5

Physicians may feel confused and frustrated by patients who come armed with information. They may infer that patients do not trust them to diagnose correctly or treat optimally. In addition, discussing such information takes time, causing others on the schedule to wait, adding to the stress of coping with over-booked appointments.

Why so overprepared?

Patients who have or fear that they have cancer may be particularly worried that an important treatment will be overlooked.6 Since they feel that their life is hanging in the balance, their search for a definitive cure is understandable.

Internet-seeking, intensely questioning patients clearly want more information about the treatments they are receiving, alternative medical or procedural options, and complementary therapies.7 The response to their desire for more information affects their impression of physician empathy.8

Adapting to a more informed patient

Approaching these patients as an opportunity to educate may result in a more trusting patient and one more likely to be open to physician guidance and more likely to adhere to an advised treatment plan. Triangulation of the 3 actors—the physician, the patient, and the Web—can help patients to make more-informed choices and foster an attitude of partnership with the physician to lead them to optimal healthcare.

In a review of the impact of Internet use on healthcare and the physician-patient relationship, Wald et al9 urged physicians to:

- Adopt a positive attitude toward discussing Internet contributions

- Encourage patients to take an active role in maintaining health

- Acknowledge patient concerns and fears

- Avoid becoming defensive

- Recommend credible Internet sources.

Laing et al10 urged physicians to recognize rather than deny the effects of patients’ online searching for information and support, and not to ignore the potential impact on treatment. Consumers are gaining autonomy and self-efficacy, and Laing et al encouraged healthcare providers to develop ways to incorporate this new reality into the services they provide.10

How Web-based interaction can assist in patient decision-making for colorectal cancer screening is being explored.11 Patients at home can use an online tool to learn about screening choices and would be more knowledgable and comfortable discussing the options with their care provider. The hope is to build in an automatic reminder for the clinician, who would better understand the patient’s preference before the office visit.

One approach to our patient is to say, “I can see how worried you are about having the same type of cancer you read about, and I want to help you. It is clear to me that you know a lot about healthcare, and I appreciate your engagement in your health. How about starting over? Let me ask a few questions so I can get a better perspective on your symptoms?” Many times, this strategy can help patients reframe their view and accept help.

DEMANDING, LITIGATION-THREATENING

A 60-year-old lawyer is admitted to the hospital for evaluation of abdominal pain. His physician recommends placing a nasogastric tube to provide nutrition while the evaluation is completed. His wife, a former nurse practitioner, insists that a nasogastric tube would be too dangerous and demands that he be allowed to eat instead. The couple declares the primary internal medicine physician incompetent, does not want any residents to be involved in his care, and antagonizes the nurses with constant demands. Soon, the entire team avoids the patient’s room.

Why so hostile?

People with demanding behavior often have a hostile and confrontational manner. They may use medical jargon and appear to believe that they know more than their healthcare team. Many demand to know why they have not been offered a particular test, diagnosis, or treatment, especially if they or a family member has a healthcare background. Such patients appear to feel that they are being treated incorrectly and leave us feeling vulnerable, wondering whether the patient might one day come back to haunt us with a lawsuit, especially if the medical outcome is unfavorable.

Understanding the motivation for the behavior can help a physician to empathize with the demanding patient.12 Although it may seem that the demanding patient is trying to intimidate the physician, the goal is usually the same: to find the best possible treatment. Anger and hostility are often motivated by fear and a sense of losing control.

Ironically, this maladaptive coping style may alienate the very people who can help the patient. Hostile behavior evokes defensiveness and resentment in others. A power struggle may ensue: as the patient makes more unreasonable demands and threats, the physician reacts by asserting his or her views in an attempt to maintain control. Or the physician and the rest of the healthcare team may simply avoid the patient as much as possible.

Collaboration can defuse anger

The best strategy is often to steer the encounter away from a power struggle by legitimizing the patient’s feeling of entitlement to the best possible treatment.13 Take a collaborative stance with the patient, with the common goal of finding and implementing the most effective and lowest-risk diagnostic and treatment plan. Empathy and exploration of the patient’s concerns are always in order.

Physicians can try several strategies to improve interactions with demanding patients and caregivers:

Be consistent. All members of the healthcare team, including nurses and specialists, should convey consistent messages regarding diagnostic testing and treatment plans.

Don’t play the game. Demanding patients often complain about being mistreated by other healthcare providers. When confronted with such complaints, acknowledge the patient’s feelings while refraining from blaming or criticizing other members of the healthcare team.

Clarify expectations. Clarifying expectations from the initial patient encounter can prevent conflicts later. Support a patient who must accept a diagnosis of a terminal illness, and then when appropriate, discuss goals moving forward. Collaboration within the framework of reasonable expectations is key.

For our case, the physician could say, “We want to work with you together as a team. We will work hard to address your concerns, but our nurses must have a safe environment in which to help you.” Such a statement highlights shared goals and expression of concern without judgment. The next step is to clarify expectations by describing the hospital routine and how decisions are made.

Offer choices. Offering choices whenever possible can help a demanding patient feel more in control. Rather than dismiss a patient’s ideas, explore the alternatives. While effective patient communication is preferable to repeated referrals to specialists,14 judicious referral can engender trust in the physician’s competence if a diagnosis is not forthcoming.15

A unique challenge in teaching hospitals is the patient who refuses to interact with residents and students. It is best to acknowledge the patient’s concerns and offer alternative options:

- If the patient is worried about lack of completed training, then clarify the residents’ roles and reassure the patient that you communicate with residents and supervisors regarding any clinical decisions

- If possible, offer to see the patient alone or have the resident interact only on an as-needed basis

- Consider transferring the patient to a nonteaching service or to another hospital.

Admit failings. Although not easy, admitting to and apologizing for things that have gone wrong can help to calm a demanding patient and even reduce the likelihood of a lawsuit.16 The physician should not convey defensiveness and instead should acknowledge the limitations of the healthcare system.

Legitimize concerns—to an extent. Legitimizing a demanding patient’s concerns is important, but never be bullied into taking actions that create unnecessary risk. Upsetting a demanding patient is better than ordering tests or providing treatments that are potentially harmful. Good physician-patient communication can go a long way toward preventing adverse outcomes.

CONSTANTLY SEEKING REASSURANCE

A 25-year-old professional presents to a new primary care provider concerned about a mole on her back. She discusses her sun exposure and family history of skin cancer and produces photographs documenting changes in the mole over time. Impressed with this level of detail, the physician takes time to explain his concerns before referring her to a dermatologist. Later that day, she calls to let the doctor know that her procedure has been scheduled and to thank him for his care. A few weeks after the mole is removed, she returns to discuss treatment options for the small remaining scar.

After this appointment, she calls the office repeatedly with a wide array of concerns, including an isolated symptom of fatigue that could indicate cancer and the relative merits of different sunscreens. She also sends the physician frequent e-mail messages through the personal health record system with pictures of inconsequential marks on her skin.

Needing reassurance is normal—to a point

Many patients seek reassurance from their physicians, and this can be done in a healthy and respectful manner. But requests for reassurance may escalate to becoming repeated, insistent, and even aggressive.1 This can elicit reactions from physicians ranging from feeling annoyed and burdened to feeling angry and overwhelmed.17 This can lead to significant stress, which, if not managed well, can lead to excessively control of physician behavior and substandard care.18

Reassurance-seeking behavior can manifest anywhere along the spectrum of health and disease.19 It may be a symptom of health anxiety (ie, an exaggerated fear of illness) or hypochondria (ie, the persistent conviction that one is currently or likely to become ill).20,21

Why so needy?

Attachment theory may help explain neediness. Parental bonding during childhood is associated with mental and physical health and health-related behaviors in adults.22,23 People with insecure-preoccupied attachment styles tend to be overly emotionally dependent on the acceptance of others and may exhibit dependent and care-seeking behaviors with a physician.24

Needy patients are often genuinely grateful for the care and attention from a physician.1 In the beginning, the doctor may appreciate the patient’s validation of care provided, but this positive feeling wanes as calls and requests become incessant. As the physician’s exhaustion increases with each request, the care and well-being of the patient may no longer be the primary focus.1

Set boundaries

Be alert to signs that a patient is crossing the line to an unhealthy need for reassurance. Address medical concerns appropriately, then institute clear guidelines for follow-up, which should be reinforced by the entire care team if necessary.22

The following strategies can be useful for defining boundaries:

- Instruct the patient to come to the office only for scheduled follow-up visits and to call only during office hours or in an emergency

- Be up-front about the time allowed for each appointment and ask the patient to help focus the discussion according to his or her main concerns25

- Consider telling the patient, “You seem really worried about a lot of physical symptoms. I want to reassure you that I find no evidence of a medical illness that would require intervention. I am concerned about your phone calls and e-mails, and I wonder what would be helpful at this point to address your concerns?”

- Consider treating the patient for anxiety.

It is important to remain responsive to all types of patient concerns. Setting boundaries will guide patients to express health concerns in an appropriate manner so that they can be heard and managed.18,19

SELF-INJURY

A 22-year-old woman presents to the emergency department complaining of abdominal pain. After a full workup, the physician clears her medically and orders a few laboratory tests. As the nurse draws blood samples, she notices multiple fresh cuts on the patient’s arm and informs the physician. The patient is questioned and examined again and acknowledges occasional thoughts of self-harm.

Her parents arrive and appear appropriately concerned. They report that she has been “cutting” for 4 years and is regularly seeing a therapist. However, they say that they are not worried for her safety and that she has an appointment with her therapist this week. Based on this, the emergency department physician discharges her.

Two weeks later, the patient returns to the emergency department with continued cutting and apparent cellulitis, prompting medical admission.

Self-injury presents in many ways

Self-injurious behaviors come in many forms other than the easily recognized one presented in this case: eg, a patient with cirrhosis who continues to drink, a patient with severe epilepsy who forgets to take medications and lands in the emergency department every week for status epilepticus, a patient with diabetes who eats a high-sugar diet, a patient with renal insufficiency who ignores water restrictions, or a patient with an organ transplant who misses medications and relapses.

There is an important psychological difference between patients who knowingly continue to challenge their luck and those who do not fully understand the severity of their condition and the consequences of their actions. The patient who simply does not “get it” can sometimes be managed effectively with education and by working with family members to create an environment to facilitate critical healthy behaviors.

Patients who willfully self-inflict injury are asking for help while doing everything to avoid being helped. They typically come to the office or the emergency department with assorted complaints, not divulging the real reason for their visit until the last minute as they are leaving. Then they drop a clue to the real concern, leaving the physician confused and frustrated.

Why deny an obvious problem?

Fear of the stigma of mental illness can be a major barrier to full disclosure of symptoms of psychological distress, and this especially tends to be the case for patients from some ethnic minorities.26

On the other hand, patients with borderline or antisocial personality disorder (and less often, schizotypal or narcissistic personality disorder) frequently use denial as their primary psychological defense. Self-destructive denial is sometimes associated with traumatic memories, feelings of worthlessness, or a desire to reduce self-awareness and rationalize harmful behaviors. Such patients usually need lengthy treatment, and although the likelihood of cure is low, therapy can be helpful.27–29

Lessons from psychiatry

It can be difficult to maintain empathy for patients who intentionally harm themselves. It is helpful to think of these patients as having a terminal illness and to recognize that they are suffering.

Different interventions have been studied for such patients. Dialectical behavior therapy, an approach that teaches patients better coping skills for regulating emotions, can help reduce maladaptive emotional distress and self-destructive behaviors.30–32 Lessons from this approach can be applied by general practitioners:

- Engage the patient and together establish an effective crisis management plan

- With patient permission, involve the family in the treatment plan

- Set clear limits about self-harm: once the patient values interaction with the doctor, he or she will be less likely to break the agreement.

Patients with severe or continuing issues can be referred to appropriate services that offer dialectical behavior therapy or other intensive outpatient programs.

To handle our patient, one might start by saying, “I am sorry to see you back in the ER. We need to treat the cellulitis and get your outpatient behavioral team on board, so we know the plan.” Then, it is critical that the entire team keep to that plan.

HOW TO STAY IN CONTROL AND IMPROVE INTERACTIONS

Patients with challenging behaviors will always be part of medical practice. Physicians should be aware of their reactions and feelings towards a patient (known in psychiatry as countertransference), as they can increase physician stress and interfere with providing optimal care. Finding effective ways to work with difficult patients will avoid these outcomes.

Physicians also feel loss of control

Most physicians are resilient, but they can feel overwhelmed under certain circumstances. According to Scudder and Shanafelt,33 a physician’s sense of well-being is influenced by several factors, including feelings of control in the workplace. It is easy to imagine how one or more difficult patients can create a sense of overwhelming demand and loss of control.

These tips can help maintain a sense of control and improve interactions with patients:

Have a plan for effective communication. Not having a plan for communicating in a difficult situation can contribute to loss of control in a hectic schedule that is already stretched to its limits. Practicing responses with a colleague for especially difficult patients or using a team approach can be helpful. Remaining compassionate while setting boundaries will result in the best outcome for the patient and physician.

Stop to analyze the situation. One of the tenets of cognitive-behavioral therapy is recognizing that negative thoughts can quickly take us down a dangerous path. Feeling angry and resentful without stopping to think and reflect on the causes can lead to the physician feeling victimized (just like many difficult patients feel).

It is important to step back and think, not just feel. While difficult patients present in different ways, all are reacting to losing control of their situation and want support. During a difficult interaction with a patient, pause to consider, “Why is he behaving this way? Is he afraid? Does he feel that no one cares?”

When a patient verbally attacks beyond what is appropriate, recognize that this is probably due less to anything the physician did than to the patient’s internal issues. Identifying the driver of a patient’s behavior makes it easier to control our own emotions.

Practice empathy. Difficult patients usually have something in their background that can help explain their inappropriate behavior, such as a lack of parental support or abuse. Being open to hearing their story facilitates an empathetic connection.

AVOIDING BURNOUT

Discuss problems

Sadly, physicians often neglect to talk with each other and with trainees about issues leading to burnout, thereby missing important opportunities for empathy, objectivity, reflection, and teaching moments.

Lessons can be gleaned from training in psychiatry, a field in which one must learn methods for working effectively in challenging situations. Dozens of scenarios are practiced using videotapes or observation through one-way mirrors. While not everyone has such opportunities, everyone can discuss issues with one another. Regularly scheduled facilitated groups devoted to discussing problems with colleagues can be enormously helpful.

Schedule quiet times

Mindfulness is an excellent way to spend a few minutes out of every 3- to 4-hour block. There are many ways to help facilitate such moments. Residents and students can be provided with a small book, Mindfulness on the Go,37 aimed for the busy person.

Deep, slow breathing can bring rapid relief to intense negative feelings. Not only does it reduce anxiety faster than medication, but it is also free, is easily taught to others, and can be done unobtrusively. A short description of the role of the blood pH in managing the locus ceruleus and vagus nerve’s balance of sympathetic and parasympathetic activity may capture the curiosity of someone who may otherwise be resistant to the exercise.

Increasingly, hospitals are developing mindfulness sessions and offering a variety of skills physicians can put into their toolbox. Lessons from cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, imagery, and muscle relaxation can help physicians in responding to patients. Investing in communication skills training specific to challenging behaviors seen in different specialties better equips physicians with more effective strategies.

- Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med 1978; 298:883–887.

- Strous RD, Ulman AM, Kotler M. The hateful patient revisited: relevance for 21st century medicine. Eur J Intern Med 2006; 17:387–393.

- Malone M, Mathes L, Dooley J, While AE. Health information seeking and its effect on the doctor-patient digital divide. J Telemed Telecare 2005; 11(suppl1):25–28.

- Hu X, Bell RA, Kravitz RL, Orrange S. The prepared patient: information seeking of online support group members before their medical appointments. J Health Commun 2012; 17:960–978.

- Tse MM, Choi KC, Leung RS. E-health for older people: the use of technology in health promotion. Cyberpsychol Behav 2008; 11:475–479.

- Pereira JL, Koski S, Hanson J, Bruera ED, Mackey JR. Internet usage among women with breast cancer: an exploratory study. Clin Breast Cancer 2000; 1:148–153.

- Brauer JA, El Sehamy A, Metz JN, Mao JJ. Complementary and alternative and supportive care at leading cancer centers: a systematic analysis of websites. J Altern Complement Med 2010; 16:183–186.

- Smith SG, Pandit A, Rush SR, Wolf MS, Simon C. The association between patient activation and accessing online health information: results from a national survey of US adults. Health Expect 2015; 18:3262–3273.