User login

PCP Communication at Discharge

Transitions of care from hospital to home are high‐risk times for patients.[1, 2] Increasing complexity of hospital admissions and shorter lengths of stay demand more effective coordination of care between hospitalists and outpatient clinicians.[3, 4, 5] Inaccurate, delayed, or incomplete clinical handoversthat is, transfer of information and professional responsibility and accountability[6]can lead to patient harm, and has been recognized as a key cause of preventable morbidity by the World Health Organization and The Joint Commission.[6, 7, 8] Conversely, when done effectively, transitions can result in improved patient health outcomes, reduced readmission rates, and higher patient and provider satisfaction.3

Previous studies note deficits in communication at discharge and primary care provider (PCP) dissatisfaction with discharge practices.[4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13] In studies at academic medical centers, there were low rates of direct communication between inpatient and outpatient providers, mainly because of providers' belief that the discharge summary was adequate and the presence of significant barriers to direct communication.[14, 15] However, studies have shown that discharge summaries often omit critical information, and often are not available to PCPs in a timely manner.[10, 11, 12, 16] In response, the Society of Hospital Medicine developed a discharge checklist to aide in standardization of safe discharge practices.[1, 5] Discharge summary templates further attempt to improve documentation of patients' hospital courses. An electronic medical record (EMR) system shared by both inpatient and outpatient clinicians should impart several advantages: (1) automated alerts provide timely notification to PCPs regarding admission and discharge, (2) discharge summaries are available to the PCP as soon as they are written, and (3) all patient information pertaining to the hospitalization is available to the PCP.

Although it is plausible that shared EMRs should facilitate transitions of care by streamlining communication between hospitalists and PCPs, guidelines on format and content of PCP communication at discharge in the era of a shared EMR have yet to be defined. In this study, we sought to understand current discharge communication practices and PCP satisfaction within a shared EMR at our institution, and to identify key areas in which communication can be improved.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

We surveyed all resident and attending PCPs (n=124) working in the Division of General Internal Medicine (DGIM) Outpatient Practice at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). In June 2012, the outpatient and inpatient practices of UCSF transitioned from having separate medical record systems to a shared EMR (Epic Systems Corp., Verona, WI) where all informationboth inpatient and outpatientis accessible among healthcare professionals. The EMR provides automated notifications of admission and discharge to PCPs, allows for review of inpatient notes, labs, and studies, and immediate access to templated discharge summaries (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). The EMR also enables secure communication between clinicians. At our institution, over 90% of discharge summaries are completed within 24 hours of discharge.[17]

Study Design and Analysis

We developed a survey about the discharge communication practices of inpatient medicine patients based on a previously described survey in the literature (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article).[9] The anonymous, 17‐question survey was electronically distributed to resident and attending PCPs at the DGIM practice. The survey was designed to determine: (1) overall PCP satisfaction with current communication practices from the inpatient team at patient discharge, (2) perceived adequacy of automatic discharge notifications, and (3) perception of the types of patients and hospitalizations requiring additional high‐touch communication at discharge.

We analyzed results of our survey using descriptive statistics. Differences in resident and attending responses were analyzed by 2tests.

RESULTS

Seventy‐five of 124 (60%) clinicians (46% residents, 54% attendings) completed the survey. Thirty‐nine (52%) PCPs were satisfied or very satisfied with communication at patient discharge. Although most reported receiving automated discharge notifications (71%), only 39% felt that the notifications plus the discharge summaries were adequate communication for safe transition of care from hospital to community. Fifty‐one percent desired direct contact beyond a discharge summary. There were no differences in preferences on discharge communication between resident and attending PCPs (P>0.05).

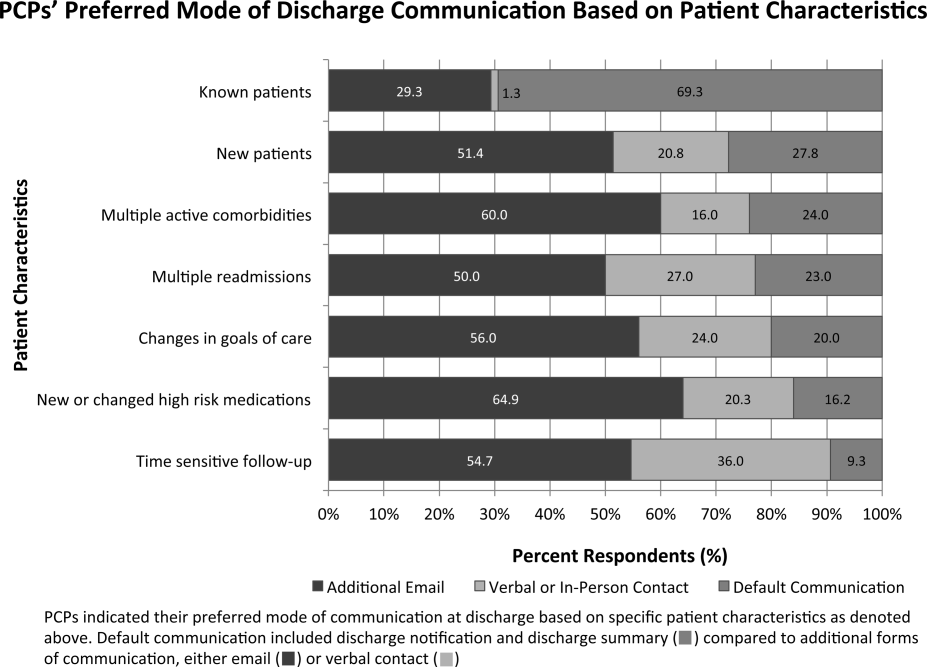

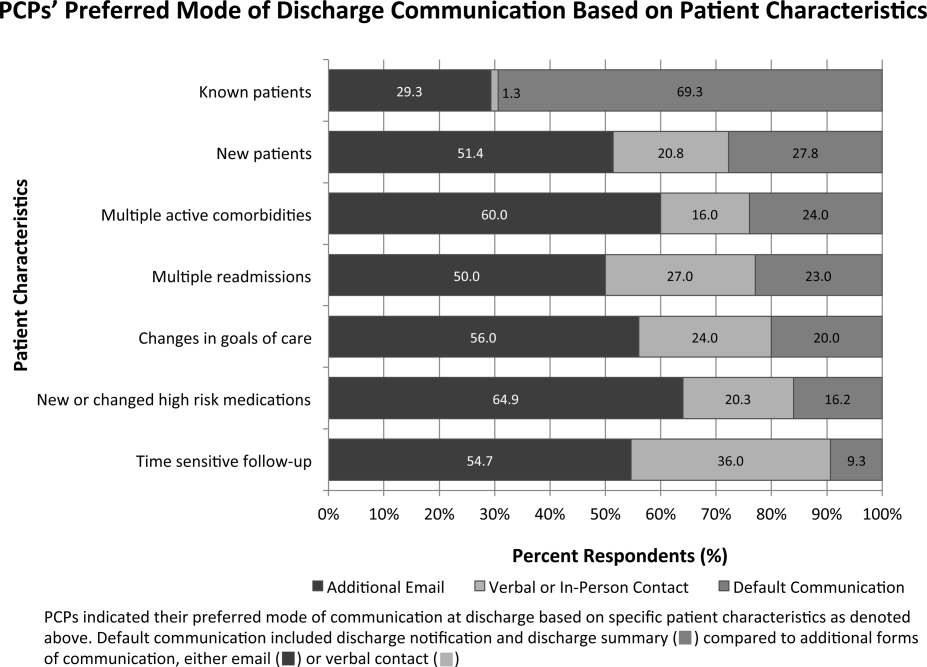

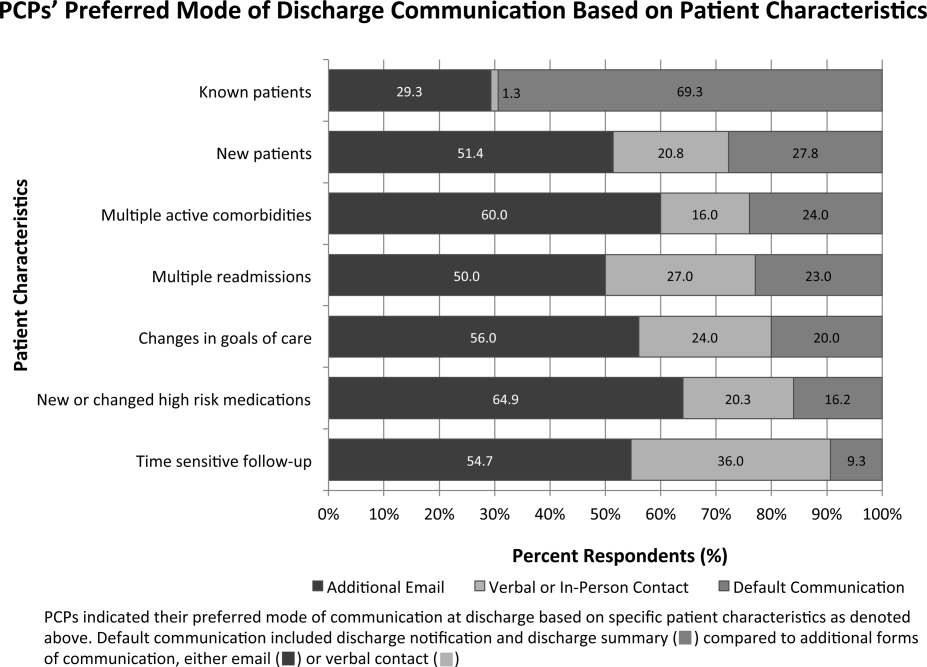

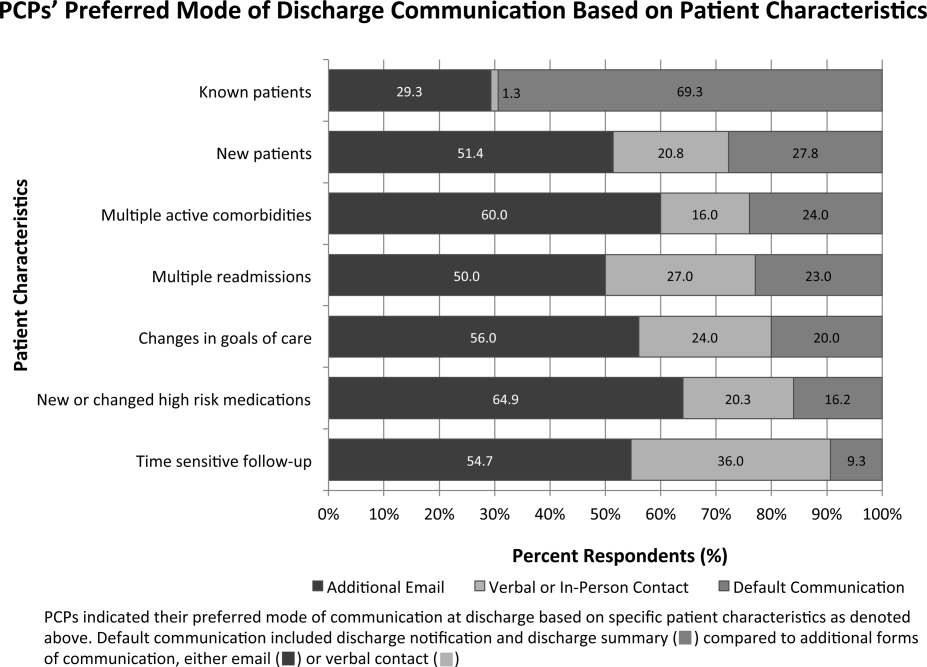

Over three‐fourths of PCPs surveyed preferred that for patients with complex hospitalizations (multiple readmissions, multiple active comorbidities, goals of care changes, high‐risk medication changes, time‐sensitive follow‐up needs), an additional e‐mail or verbal communication was needed to augment the information in the discharge summary (Figure 1). Only 31% reported receiving such communication.

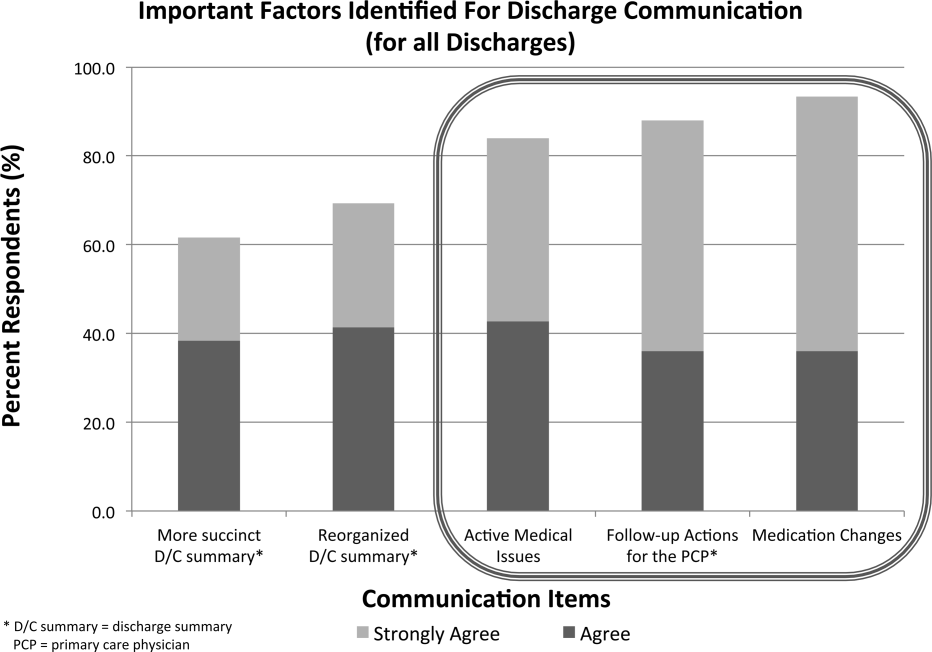

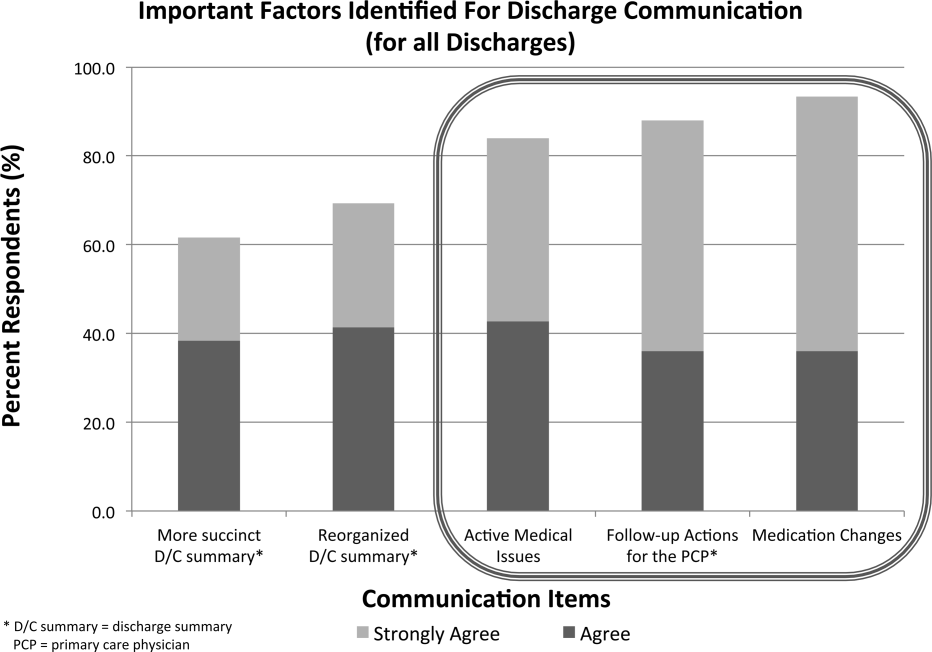

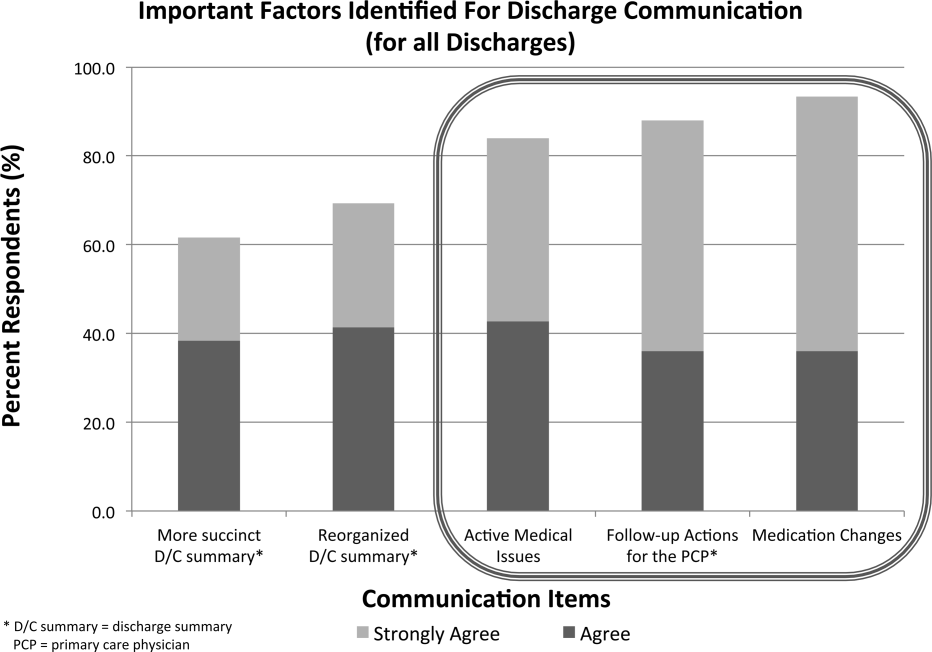

When asked about important items to communicate for safer transitions of care, PCPs reported finding the following elements most critical: (1) medication changes (93%), (2) follow‐up actions for the PCP (88%), and (3) active medical issues (84%) (Figure 2).

CONCLUSIONS

In the era of shared EMRs, real‐time access to medication lists, pending test results, and discharge summaries should facilitate care transitions at discharge.[18, 19] We conducted a study to determine PCP perceptions of discharge communication after implementation of a shared EMR. We found that although PCPs largely acknowledged timely receipt of automated discharge notifications and discharge summaries, the majority of PCPs felt that most discharges required additional communication to ensure safe transition of care.

Guidelines for discharge communication emphasize timely communication with the PCP, primarily through discharge summaries containing key safety elements.[1, 5, 10] At our institution, we have improved the timeliness and quality of discharge summaries according to guideline recommendations,[17] and conducted quality improvement projects to improve rates of direct communication with PCPs.[9] In addition, the shared EMR provides automated notifications to PCPs when their patients are discharged. Despite these interventions, our survey shows that PCP satisfaction with discharge communication is still inadequate. PCPs desired direct communication that highlights active medical issues, medication changes, and specific follow‐up actions. Although all of these topics are included in our discharge summary template (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article), it is possible that the templated discharge summaries lend themselves to longer documents and information overload, as prior studies have documented the desire for more succinct discharge summaries.[18] We also found that automated notifications of discharge were less reliable and useful for PCPs than anticipated. There were several reasons for this: (1) discharge summaries sometimes were sent to PCPs uncoupled from the discharge notification, (2) there were errors with the generation and delivery of automated messages at the rollout of the new system, and (3) PCPs received many other automated system messages, meaning that discharge notifications could be easily missed. These factors all likely contribute to PCPs' desire for high‐touch communication that highlights the most salient aspects of each patient's hospitalization. It is also possible that automated notifications and depersonalized discharge summaries create distance and a less‐collaborative feeling to patient care. PCPs want more direct communication, and desire to play a more active role in inpatient management, especially for complex hospitalizations.[18] This emphasis on direct communication resonates with previous studies conducted before shared EMRs existed.[9, 12, 19]

Our study had several limitations. First, because this is a single‐institution study at a tertiary care academic setting, the results may not be generalizable to all shared EMR settings, and may not reflect all the challenges of communication with the wider community of outpatient providers. One can postulate that inpatient and outpatient clinician relationships are stronger in an academic setting than in other more disparate environments, where direct communication may happen even less frequently. Of note, our low rates of direct communication are consistent with other single‐ and multi‐institution studies, suggesting that our findings are generalizable.[14, 15] Second, our survey is limited in its ability to distinguish those patients who require high‐touch communication and those who do not. Third, although we have used the survey to assess PCP satisfaction in previous studies, it is not a validated instrument, and therefore we cannot reliably say that increasing direct PCP communication would increase their satisfaction around discharge. Last, the PCP‐reported rates of discharge communication are subjective and may be influenced by recall bias. We did not have a systematic way to confirm the actual rates of communication at discharge, which could have occurred through EMR messages, e‐mails, phone calls, or pages.

Although a shared EMR allows for real‐time access to patient data, it does not eliminate PCPs' desire for direct 2‐way dialogue at discharge, especially for complex patients. Key information desired in such communication should include active medical issues, medication changes, and follow‐up needs, which is consistent with prior studies. Standardizing this direct communication process in an efficient way can be challenging. Further elucidation of PCP preferences around which patients necessitate higher‐level communication and preferred methods and timing of communication is needed, as well as determining the most efficient and effective method for hospitalists to provide such communication. Improving communication between hospitalists and PCPs requires not just the presence of a shared EMR, but additional, systematic efforts to engage both inpatient and outpatient clinicians in collaborative care.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , et al. Development of a checklist of safe discharge practices for hospital patients. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):444–449.

- , , , , The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167.

- , , , et al. Improving patient handovers from hospital to primary care: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(6):417–428.

- , , , , “Did I do as best as the system would let me?” Healthcare professional views on hospital to home care transitions. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(12):1649–1656.

- , , , et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients—development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):354−660.

- , , , , Improving measurement in clinical handover. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:272–277.

- World Health Organization. Patient safety: action on patient safety: high 5s. 2007. Available at: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/solutions/high5s/en/index.html. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Hand‐off communications. 2012. Available at: http://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/projects/detail.aspx?Project=1. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- , , , et al. The effect of a resident‐led quality improvement project on improving communication between hospital‐based and outpatient physicians. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28(6):472–479.

- , , , Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314–323.

- , , , , , Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841.

- , , , Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Am J Med. 2001;111(9B):15S–20S.

- , , , et al. Searching for the missing pieces between the hospital and primary care: mapping the patient process during care transitions. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:i97–i105.

- , , , et al. Association of self‐reported hospital discharge handoffs with 30‐day readmissions. JAMA. 2013;173(8):624–629.

- , , , et al. Association of communication between hospital‐based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):381–386.

- , , , Effect of discharge summary availability during post‐discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):186–192.

- , , , , The Housestaff Incentive Program: improving the timeliness and quality of discharge summaries by engaging residents in quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(9):768–774.

- , , , et al. A Failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations [published online ahead of print October 15, 2014]. J Gen Intern Med. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3056-x.

- , , , et al. Pediatric hospitalists and primary care providers: a communication needs assessment. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):187–193.

Transitions of care from hospital to home are high‐risk times for patients.[1, 2] Increasing complexity of hospital admissions and shorter lengths of stay demand more effective coordination of care between hospitalists and outpatient clinicians.[3, 4, 5] Inaccurate, delayed, or incomplete clinical handoversthat is, transfer of information and professional responsibility and accountability[6]can lead to patient harm, and has been recognized as a key cause of preventable morbidity by the World Health Organization and The Joint Commission.[6, 7, 8] Conversely, when done effectively, transitions can result in improved patient health outcomes, reduced readmission rates, and higher patient and provider satisfaction.3

Previous studies note deficits in communication at discharge and primary care provider (PCP) dissatisfaction with discharge practices.[4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13] In studies at academic medical centers, there were low rates of direct communication between inpatient and outpatient providers, mainly because of providers' belief that the discharge summary was adequate and the presence of significant barriers to direct communication.[14, 15] However, studies have shown that discharge summaries often omit critical information, and often are not available to PCPs in a timely manner.[10, 11, 12, 16] In response, the Society of Hospital Medicine developed a discharge checklist to aide in standardization of safe discharge practices.[1, 5] Discharge summary templates further attempt to improve documentation of patients' hospital courses. An electronic medical record (EMR) system shared by both inpatient and outpatient clinicians should impart several advantages: (1) automated alerts provide timely notification to PCPs regarding admission and discharge, (2) discharge summaries are available to the PCP as soon as they are written, and (3) all patient information pertaining to the hospitalization is available to the PCP.

Although it is plausible that shared EMRs should facilitate transitions of care by streamlining communication between hospitalists and PCPs, guidelines on format and content of PCP communication at discharge in the era of a shared EMR have yet to be defined. In this study, we sought to understand current discharge communication practices and PCP satisfaction within a shared EMR at our institution, and to identify key areas in which communication can be improved.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

We surveyed all resident and attending PCPs (n=124) working in the Division of General Internal Medicine (DGIM) Outpatient Practice at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). In June 2012, the outpatient and inpatient practices of UCSF transitioned from having separate medical record systems to a shared EMR (Epic Systems Corp., Verona, WI) where all informationboth inpatient and outpatientis accessible among healthcare professionals. The EMR provides automated notifications of admission and discharge to PCPs, allows for review of inpatient notes, labs, and studies, and immediate access to templated discharge summaries (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). The EMR also enables secure communication between clinicians. At our institution, over 90% of discharge summaries are completed within 24 hours of discharge.[17]

Study Design and Analysis

We developed a survey about the discharge communication practices of inpatient medicine patients based on a previously described survey in the literature (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article).[9] The anonymous, 17‐question survey was electronically distributed to resident and attending PCPs at the DGIM practice. The survey was designed to determine: (1) overall PCP satisfaction with current communication practices from the inpatient team at patient discharge, (2) perceived adequacy of automatic discharge notifications, and (3) perception of the types of patients and hospitalizations requiring additional high‐touch communication at discharge.

We analyzed results of our survey using descriptive statistics. Differences in resident and attending responses were analyzed by 2tests.

RESULTS

Seventy‐five of 124 (60%) clinicians (46% residents, 54% attendings) completed the survey. Thirty‐nine (52%) PCPs were satisfied or very satisfied with communication at patient discharge. Although most reported receiving automated discharge notifications (71%), only 39% felt that the notifications plus the discharge summaries were adequate communication for safe transition of care from hospital to community. Fifty‐one percent desired direct contact beyond a discharge summary. There were no differences in preferences on discharge communication between resident and attending PCPs (P>0.05).

Over three‐fourths of PCPs surveyed preferred that for patients with complex hospitalizations (multiple readmissions, multiple active comorbidities, goals of care changes, high‐risk medication changes, time‐sensitive follow‐up needs), an additional e‐mail or verbal communication was needed to augment the information in the discharge summary (Figure 1). Only 31% reported receiving such communication.

When asked about important items to communicate for safer transitions of care, PCPs reported finding the following elements most critical: (1) medication changes (93%), (2) follow‐up actions for the PCP (88%), and (3) active medical issues (84%) (Figure 2).

CONCLUSIONS

In the era of shared EMRs, real‐time access to medication lists, pending test results, and discharge summaries should facilitate care transitions at discharge.[18, 19] We conducted a study to determine PCP perceptions of discharge communication after implementation of a shared EMR. We found that although PCPs largely acknowledged timely receipt of automated discharge notifications and discharge summaries, the majority of PCPs felt that most discharges required additional communication to ensure safe transition of care.

Guidelines for discharge communication emphasize timely communication with the PCP, primarily through discharge summaries containing key safety elements.[1, 5, 10] At our institution, we have improved the timeliness and quality of discharge summaries according to guideline recommendations,[17] and conducted quality improvement projects to improve rates of direct communication with PCPs.[9] In addition, the shared EMR provides automated notifications to PCPs when their patients are discharged. Despite these interventions, our survey shows that PCP satisfaction with discharge communication is still inadequate. PCPs desired direct communication that highlights active medical issues, medication changes, and specific follow‐up actions. Although all of these topics are included in our discharge summary template (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article), it is possible that the templated discharge summaries lend themselves to longer documents and information overload, as prior studies have documented the desire for more succinct discharge summaries.[18] We also found that automated notifications of discharge were less reliable and useful for PCPs than anticipated. There were several reasons for this: (1) discharge summaries sometimes were sent to PCPs uncoupled from the discharge notification, (2) there were errors with the generation and delivery of automated messages at the rollout of the new system, and (3) PCPs received many other automated system messages, meaning that discharge notifications could be easily missed. These factors all likely contribute to PCPs' desire for high‐touch communication that highlights the most salient aspects of each patient's hospitalization. It is also possible that automated notifications and depersonalized discharge summaries create distance and a less‐collaborative feeling to patient care. PCPs want more direct communication, and desire to play a more active role in inpatient management, especially for complex hospitalizations.[18] This emphasis on direct communication resonates with previous studies conducted before shared EMRs existed.[9, 12, 19]

Our study had several limitations. First, because this is a single‐institution study at a tertiary care academic setting, the results may not be generalizable to all shared EMR settings, and may not reflect all the challenges of communication with the wider community of outpatient providers. One can postulate that inpatient and outpatient clinician relationships are stronger in an academic setting than in other more disparate environments, where direct communication may happen even less frequently. Of note, our low rates of direct communication are consistent with other single‐ and multi‐institution studies, suggesting that our findings are generalizable.[14, 15] Second, our survey is limited in its ability to distinguish those patients who require high‐touch communication and those who do not. Third, although we have used the survey to assess PCP satisfaction in previous studies, it is not a validated instrument, and therefore we cannot reliably say that increasing direct PCP communication would increase their satisfaction around discharge. Last, the PCP‐reported rates of discharge communication are subjective and may be influenced by recall bias. We did not have a systematic way to confirm the actual rates of communication at discharge, which could have occurred through EMR messages, e‐mails, phone calls, or pages.

Although a shared EMR allows for real‐time access to patient data, it does not eliminate PCPs' desire for direct 2‐way dialogue at discharge, especially for complex patients. Key information desired in such communication should include active medical issues, medication changes, and follow‐up needs, which is consistent with prior studies. Standardizing this direct communication process in an efficient way can be challenging. Further elucidation of PCP preferences around which patients necessitate higher‐level communication and preferred methods and timing of communication is needed, as well as determining the most efficient and effective method for hospitalists to provide such communication. Improving communication between hospitalists and PCPs requires not just the presence of a shared EMR, but additional, systematic efforts to engage both inpatient and outpatient clinicians in collaborative care.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Transitions of care from hospital to home are high‐risk times for patients.[1, 2] Increasing complexity of hospital admissions and shorter lengths of stay demand more effective coordination of care between hospitalists and outpatient clinicians.[3, 4, 5] Inaccurate, delayed, or incomplete clinical handoversthat is, transfer of information and professional responsibility and accountability[6]can lead to patient harm, and has been recognized as a key cause of preventable morbidity by the World Health Organization and The Joint Commission.[6, 7, 8] Conversely, when done effectively, transitions can result in improved patient health outcomes, reduced readmission rates, and higher patient and provider satisfaction.3

Previous studies note deficits in communication at discharge and primary care provider (PCP) dissatisfaction with discharge practices.[4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13] In studies at academic medical centers, there were low rates of direct communication between inpatient and outpatient providers, mainly because of providers' belief that the discharge summary was adequate and the presence of significant barriers to direct communication.[14, 15] However, studies have shown that discharge summaries often omit critical information, and often are not available to PCPs in a timely manner.[10, 11, 12, 16] In response, the Society of Hospital Medicine developed a discharge checklist to aide in standardization of safe discharge practices.[1, 5] Discharge summary templates further attempt to improve documentation of patients' hospital courses. An electronic medical record (EMR) system shared by both inpatient and outpatient clinicians should impart several advantages: (1) automated alerts provide timely notification to PCPs regarding admission and discharge, (2) discharge summaries are available to the PCP as soon as they are written, and (3) all patient information pertaining to the hospitalization is available to the PCP.

Although it is plausible that shared EMRs should facilitate transitions of care by streamlining communication between hospitalists and PCPs, guidelines on format and content of PCP communication at discharge in the era of a shared EMR have yet to be defined. In this study, we sought to understand current discharge communication practices and PCP satisfaction within a shared EMR at our institution, and to identify key areas in which communication can be improved.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

We surveyed all resident and attending PCPs (n=124) working in the Division of General Internal Medicine (DGIM) Outpatient Practice at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). In June 2012, the outpatient and inpatient practices of UCSF transitioned from having separate medical record systems to a shared EMR (Epic Systems Corp., Verona, WI) where all informationboth inpatient and outpatientis accessible among healthcare professionals. The EMR provides automated notifications of admission and discharge to PCPs, allows for review of inpatient notes, labs, and studies, and immediate access to templated discharge summaries (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). The EMR also enables secure communication between clinicians. At our institution, over 90% of discharge summaries are completed within 24 hours of discharge.[17]

Study Design and Analysis

We developed a survey about the discharge communication practices of inpatient medicine patients based on a previously described survey in the literature (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article).[9] The anonymous, 17‐question survey was electronically distributed to resident and attending PCPs at the DGIM practice. The survey was designed to determine: (1) overall PCP satisfaction with current communication practices from the inpatient team at patient discharge, (2) perceived adequacy of automatic discharge notifications, and (3) perception of the types of patients and hospitalizations requiring additional high‐touch communication at discharge.

We analyzed results of our survey using descriptive statistics. Differences in resident and attending responses were analyzed by 2tests.

RESULTS

Seventy‐five of 124 (60%) clinicians (46% residents, 54% attendings) completed the survey. Thirty‐nine (52%) PCPs were satisfied or very satisfied with communication at patient discharge. Although most reported receiving automated discharge notifications (71%), only 39% felt that the notifications plus the discharge summaries were adequate communication for safe transition of care from hospital to community. Fifty‐one percent desired direct contact beyond a discharge summary. There were no differences in preferences on discharge communication between resident and attending PCPs (P>0.05).

Over three‐fourths of PCPs surveyed preferred that for patients with complex hospitalizations (multiple readmissions, multiple active comorbidities, goals of care changes, high‐risk medication changes, time‐sensitive follow‐up needs), an additional e‐mail or verbal communication was needed to augment the information in the discharge summary (Figure 1). Only 31% reported receiving such communication.

When asked about important items to communicate for safer transitions of care, PCPs reported finding the following elements most critical: (1) medication changes (93%), (2) follow‐up actions for the PCP (88%), and (3) active medical issues (84%) (Figure 2).

CONCLUSIONS

In the era of shared EMRs, real‐time access to medication lists, pending test results, and discharge summaries should facilitate care transitions at discharge.[18, 19] We conducted a study to determine PCP perceptions of discharge communication after implementation of a shared EMR. We found that although PCPs largely acknowledged timely receipt of automated discharge notifications and discharge summaries, the majority of PCPs felt that most discharges required additional communication to ensure safe transition of care.

Guidelines for discharge communication emphasize timely communication with the PCP, primarily through discharge summaries containing key safety elements.[1, 5, 10] At our institution, we have improved the timeliness and quality of discharge summaries according to guideline recommendations,[17] and conducted quality improvement projects to improve rates of direct communication with PCPs.[9] In addition, the shared EMR provides automated notifications to PCPs when their patients are discharged. Despite these interventions, our survey shows that PCP satisfaction with discharge communication is still inadequate. PCPs desired direct communication that highlights active medical issues, medication changes, and specific follow‐up actions. Although all of these topics are included in our discharge summary template (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article), it is possible that the templated discharge summaries lend themselves to longer documents and information overload, as prior studies have documented the desire for more succinct discharge summaries.[18] We also found that automated notifications of discharge were less reliable and useful for PCPs than anticipated. There were several reasons for this: (1) discharge summaries sometimes were sent to PCPs uncoupled from the discharge notification, (2) there were errors with the generation and delivery of automated messages at the rollout of the new system, and (3) PCPs received many other automated system messages, meaning that discharge notifications could be easily missed. These factors all likely contribute to PCPs' desire for high‐touch communication that highlights the most salient aspects of each patient's hospitalization. It is also possible that automated notifications and depersonalized discharge summaries create distance and a less‐collaborative feeling to patient care. PCPs want more direct communication, and desire to play a more active role in inpatient management, especially for complex hospitalizations.[18] This emphasis on direct communication resonates with previous studies conducted before shared EMRs existed.[9, 12, 19]

Our study had several limitations. First, because this is a single‐institution study at a tertiary care academic setting, the results may not be generalizable to all shared EMR settings, and may not reflect all the challenges of communication with the wider community of outpatient providers. One can postulate that inpatient and outpatient clinician relationships are stronger in an academic setting than in other more disparate environments, where direct communication may happen even less frequently. Of note, our low rates of direct communication are consistent with other single‐ and multi‐institution studies, suggesting that our findings are generalizable.[14, 15] Second, our survey is limited in its ability to distinguish those patients who require high‐touch communication and those who do not. Third, although we have used the survey to assess PCP satisfaction in previous studies, it is not a validated instrument, and therefore we cannot reliably say that increasing direct PCP communication would increase their satisfaction around discharge. Last, the PCP‐reported rates of discharge communication are subjective and may be influenced by recall bias. We did not have a systematic way to confirm the actual rates of communication at discharge, which could have occurred through EMR messages, e‐mails, phone calls, or pages.

Although a shared EMR allows for real‐time access to patient data, it does not eliminate PCPs' desire for direct 2‐way dialogue at discharge, especially for complex patients. Key information desired in such communication should include active medical issues, medication changes, and follow‐up needs, which is consistent with prior studies. Standardizing this direct communication process in an efficient way can be challenging. Further elucidation of PCP preferences around which patients necessitate higher‐level communication and preferred methods and timing of communication is needed, as well as determining the most efficient and effective method for hospitalists to provide such communication. Improving communication between hospitalists and PCPs requires not just the presence of a shared EMR, but additional, systematic efforts to engage both inpatient and outpatient clinicians in collaborative care.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , et al. Development of a checklist of safe discharge practices for hospital patients. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):444–449.

- , , , , The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167.

- , , , et al. Improving patient handovers from hospital to primary care: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(6):417–428.

- , , , , “Did I do as best as the system would let me?” Healthcare professional views on hospital to home care transitions. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(12):1649–1656.

- , , , et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients—development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):354−660.

- , , , , Improving measurement in clinical handover. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:272–277.

- World Health Organization. Patient safety: action on patient safety: high 5s. 2007. Available at: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/solutions/high5s/en/index.html. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Hand‐off communications. 2012. Available at: http://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/projects/detail.aspx?Project=1. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- , , , et al. The effect of a resident‐led quality improvement project on improving communication between hospital‐based and outpatient physicians. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28(6):472–479.

- , , , Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314–323.

- , , , , , Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841.

- , , , Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Am J Med. 2001;111(9B):15S–20S.

- , , , et al. Searching for the missing pieces between the hospital and primary care: mapping the patient process during care transitions. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:i97–i105.

- , , , et al. Association of self‐reported hospital discharge handoffs with 30‐day readmissions. JAMA. 2013;173(8):624–629.

- , , , et al. Association of communication between hospital‐based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):381–386.

- , , , Effect of discharge summary availability during post‐discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):186–192.

- , , , , The Housestaff Incentive Program: improving the timeliness and quality of discharge summaries by engaging residents in quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(9):768–774.

- , , , et al. A Failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations [published online ahead of print October 15, 2014]. J Gen Intern Med. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3056-x.

- , , , et al. Pediatric hospitalists and primary care providers: a communication needs assessment. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):187–193.

- , , , et al. Development of a checklist of safe discharge practices for hospital patients. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):444–449.

- , , , , The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167.

- , , , et al. Improving patient handovers from hospital to primary care: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(6):417–428.

- , , , , “Did I do as best as the system would let me?” Healthcare professional views on hospital to home care transitions. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(12):1649–1656.

- , , , et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients—development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):354−660.

- , , , , Improving measurement in clinical handover. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:272–277.

- World Health Organization. Patient safety: action on patient safety: high 5s. 2007. Available at: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/solutions/high5s/en/index.html. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Hand‐off communications. 2012. Available at: http://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/projects/detail.aspx?Project=1. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- , , , et al. The effect of a resident‐led quality improvement project on improving communication between hospital‐based and outpatient physicians. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28(6):472–479.

- , , , Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314–323.

- , , , , , Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841.

- , , , Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Am J Med. 2001;111(9B):15S–20S.

- , , , et al. Searching for the missing pieces between the hospital and primary care: mapping the patient process during care transitions. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:i97–i105.

- , , , et al. Association of self‐reported hospital discharge handoffs with 30‐day readmissions. JAMA. 2013;173(8):624–629.

- , , , et al. Association of communication between hospital‐based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):381–386.

- , , , Effect of discharge summary availability during post‐discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):186–192.

- , , , , The Housestaff Incentive Program: improving the timeliness and quality of discharge summaries by engaging residents in quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(9):768–774.

- , , , et al. A Failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations [published online ahead of print October 15, 2014]. J Gen Intern Med. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3056-x.

- , , , et al. Pediatric hospitalists and primary care providers: a communication needs assessment. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):187–193.

Hospitalists' Role in the Ebola Response

Concern and fear over an infection and how best to contain its spread is a well‐known storyline dating back centuries before the germ theory was hypothesized. During the Plague of Athens in the fourth century bc, upon noticing that physicians and caregivers of the sick were most at risk of dying, the Greek historian and philosopher Thucydides wrote that thwarting the disease likely required more practical measures than simple prayer to the gods.[1] To this day, the fears of contracting disease often outstripor worse, overrideour practical or scientific understanding.

Ebola has rekindled past concerns about disease transmission, whether real or imagined. In this article we will describe the history of Ebola outside the United States as well as recent events in US hospitals. We will review guidelines for how to prepare hospitals to treat potential Ebola patients and highlight the key role that hospitalists can have in ensuring the safety of their patients and coworkers. We will also describe the emerging role of global health hospitalists, whose numbers are growing and whose expertise is ideally suited to improving hospital care in developing countries.

EBOLA EPIDEMICS AND HEALTH EQUITY

In the first identified Ebola outbreak in 1976 in Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, patients arrived at local hospitals with symptoms that resembled common endemic illnesses like malaria, typhoid, and yellow fever. The ensuing deaths of 11 of the 17 staff members at 1 hospital were only an introduction to the deadly consequences of Ebola and the necessity of vigilant infection control. Unfortunately, not much has changed with each subsequent outbreak; to this day the heralding of an Ebola outbreak denotes the death of healthcare workers. Since the discovery of the Ebola virus 38 years ago, there have been nearly 30 recorded Ebola outbreaks. The mortality rates of prior outbreaks range widely between 25% and 90%; reports of the current outbreak's mortality falls within that range, between 50% and 70%. It is important to note that despite this high mortality, there had been no more than 1600 Ebola deaths worldwide before the 2014 West African pandemic.[2] In comparison, the number of deaths in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia approaches 6000.[3]

Although these disturbing figures have fueled public fear and panic in the United States, we wonder how many of these deaths were actually preventable. At the epicenter of the current Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak are 3 countries especially vulnerable to epidemics, with armed conflict recently crippling the health systems that have now just started to rebuild. When Liberia emerged from its second civil war in 2003, they had barely 50 physicians caring for a country of nearly 4 million.[4] In contrast with the devastating death toll in Liberia, it perhaps should not come as a surprise that out of the 10 known cases of Ebola that were treated in the United States and caught early, none have resulted in death. With an advanced healthcare infrastructure in place, the mortality rate for EVD in the United States has been close to zero. Although the true unpreventable case fatality rate in West Africa is unknown, the positive outcomes in the United States cases illustrate that hospitals can treat EVD successfully, provided that they are well staffed, supplied, and prepared.

Furthermore, the stark difference in access to quality healthcare between nations suggests that combating the virus should not be our only concern. In fact, EVD itself is only an acute symptom of a much larger, chronic problem with the health systems in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. Western countries must direct more resources and attention to improving the overall quality of care in these countries, for although the underlying inequities may be limited to places like Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, the resulting threat is a global one.

PREPARING FOR THE FIGHT AGAINST EBOLA IN THE UNITED STATES

On September 25, 2014, Thomas Eric Duncan presented to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital with fever, abdominal pain, and headache 11 days after transporting a pregnant neighbor in his home country of Liberia who later died of EVD. Duncan was discharged from the emergency room without admission. Three days later, on September 28, 2014, an ambulance was called and transported him to Texas Health where he was admitted. He was isolated and the hospital followed existing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for infection control. He was confirmed to have EVD on September 30, 2014. He was cared for by the healthcare providers at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, but despite their care, his condition deteriorated. Eric Duncan died on October 8, 2014. About 120 healthcare workers came into contact with the patient. None of his 48 contacts prior to admission to the hospital contracted the disease. However, 2 nurses who cared for him during his admission developed symptoms and were confirmed to have Ebola. An alarm was sounded across the United States, awakening hospitals to the reality of their vulnerability and need for preparedness.[5]

For any healthcare worker treating EVD, whether working in a hospital here in the United States or an Ebola treatment unit (ETU) in West Africa, intensive training is necessary to keep oneself safe. Although infection control is not a novel concept, the stakes have undoubtedly been raised, as even the smallest misstep can be deadly when dealing with the Ebola virus. We were participants in a 3‐day infection control training program conducted by the CDC in Anniston, Alabama, which aimed to prepare healthcare workers to assist with the Ebola response in West Africa. Throughout the training, we repeatedly donned and doffed personal protective equipment (PPE), following protocols established by the World Health Organization and Doctors Without Borders (Mdecins Sans Frontires):

- Use a combination of contact, droplet, and standard precautions, ensuring no area of skin is left uncovered.

- Enter and exit with a buddy; inspect one another for breaches at each step of donning, caring for the patient, and doffing.

- Wash gloved hands with 0.5% chlorine bleach between tasks and patients.

- Exit at the slightest breach of infection protocol.

- Doff PPE per protocol and under supervision; take great care not to contaminate oneself.

Doffing is considered the most difficult and also the most important part, with 7 pieces to remove and no less than 20 steps to do so. After 3 full days of training, although we felt more confident with the carefully choreographed movements of donning and doffing, we were also more aware of the many opportunities during which a breach could occur. Despite our repeated practice, the training staff was firm in telling us that we were still not prepared to work in an ETU. We had only undergone what could be called a cold training. To work in the hot zone of the ETUs, it is essential to undergo additional mentorship and training once in the field. We believe a similar approach to extensive training should be employed for all healthcare workers on the front lines of an Ebola response, both in the United States and abroad.

Given the complexity of the infection control practices above, questions have appropriately been raised about US healthcare facilities' aptitude at providing care for patients with EVD. Although hospitals have historically been focal point(s) for dissemination of infection of Ebola, this does not have to be the case.[6] With appropriate preparedness, training, and understanding of facility limitations, hospitals can also be places of confidence and healing.

Both Emory University and the University of Nebraska have successfully treated multiple Ebola patients without incurring further transmission.[7, 8] Much of their success comes from the work of longitudinal teams that are trained in infectious disease response on a regular basis, despite the rare occurrence of a serious outbreak. When Emory scaled up this team upon receiving a confirmed EVD patient, new members were required to pass a proficiency test prior to providing care. Emory's strict adherence to infection control and advanced preparation serve as a model for other institutions.

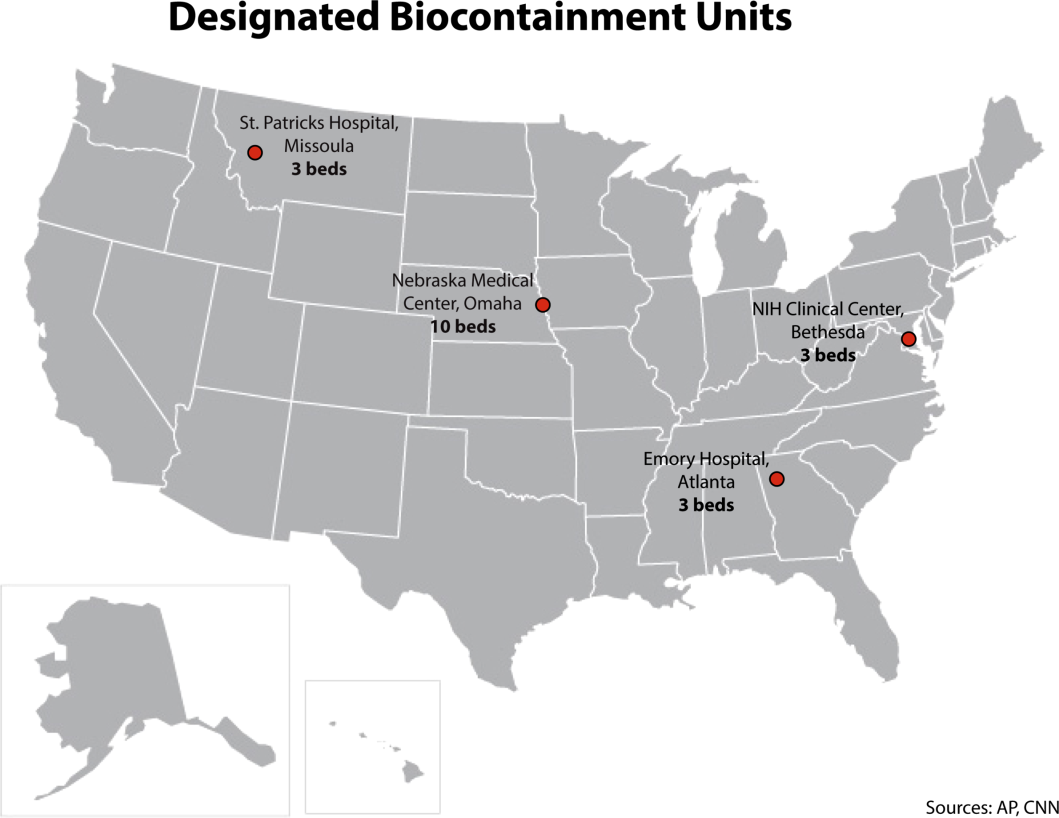

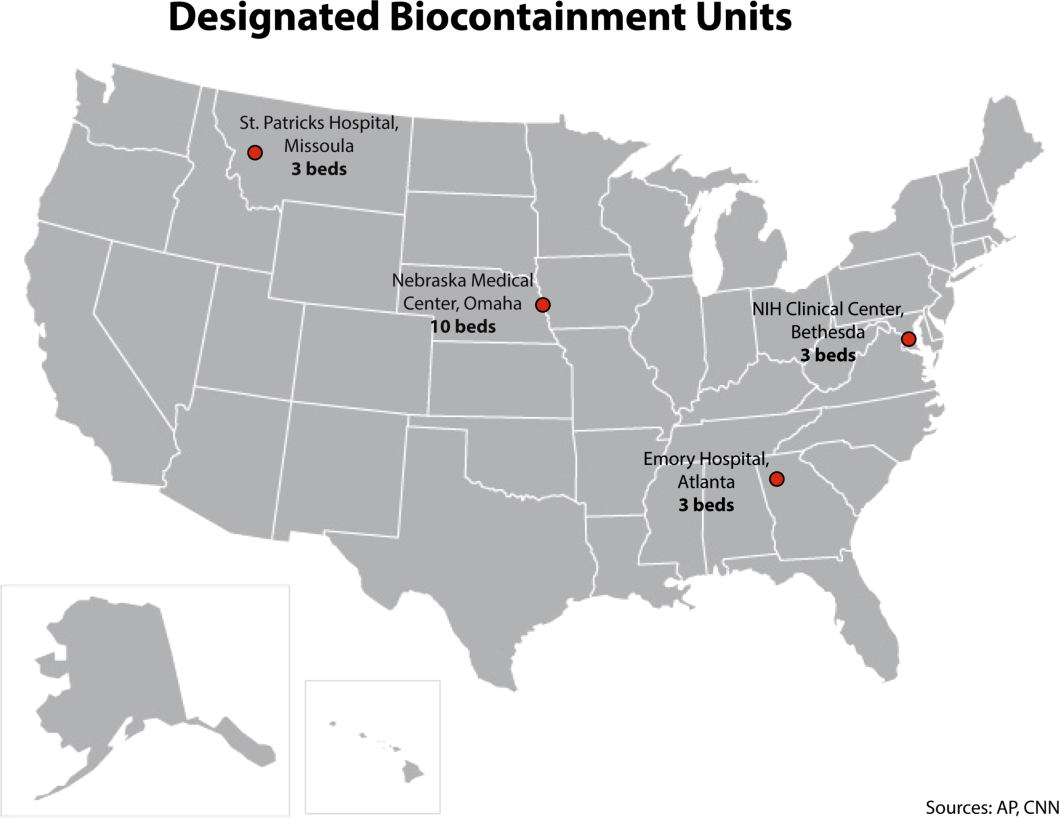

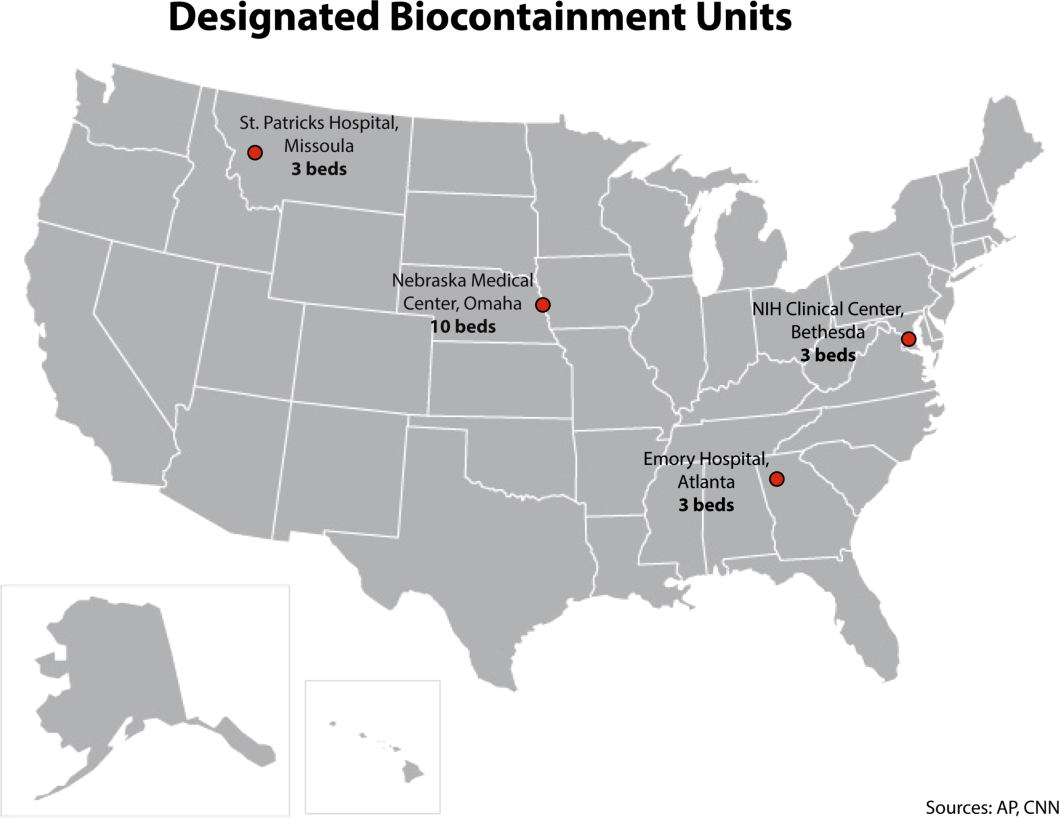

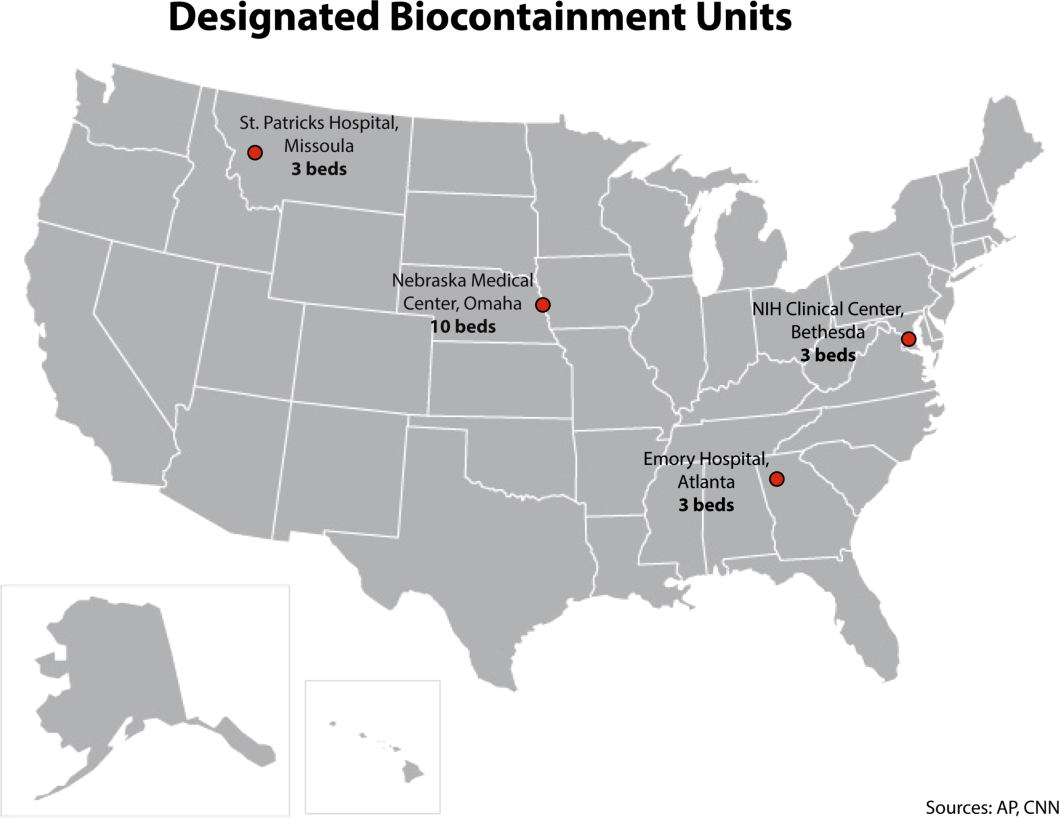

It is important to recognize that not all hospitals should be fully equipped and staffed for safe care of a patient with EVD. Much like in cases of high‐level trauma, regional centers should be identified, prepared, and available to be called upon in a time of need (Figure 1). At the writing of this article, guidelines for hospitals are evolving; most states, with input from federal and local officials, are moving toward designating regional referral centers. Although the number of designated facilities and standards for each vary by state, general preparedness for care of a patient with suspected or confirmed EVD should include: (1) a designated and trained care team, (2) appropriate and vetted operational protocols, (3) an assigned isolation unit with adequate space for the necessary specialized precautions, (4) separate laboratory and diagnostic capabilities, and (5) a working waste management plan.[9] Although not all facilities throughout the United States will have the capability to care for a patient with EVD, all hospitals must have an action plan.

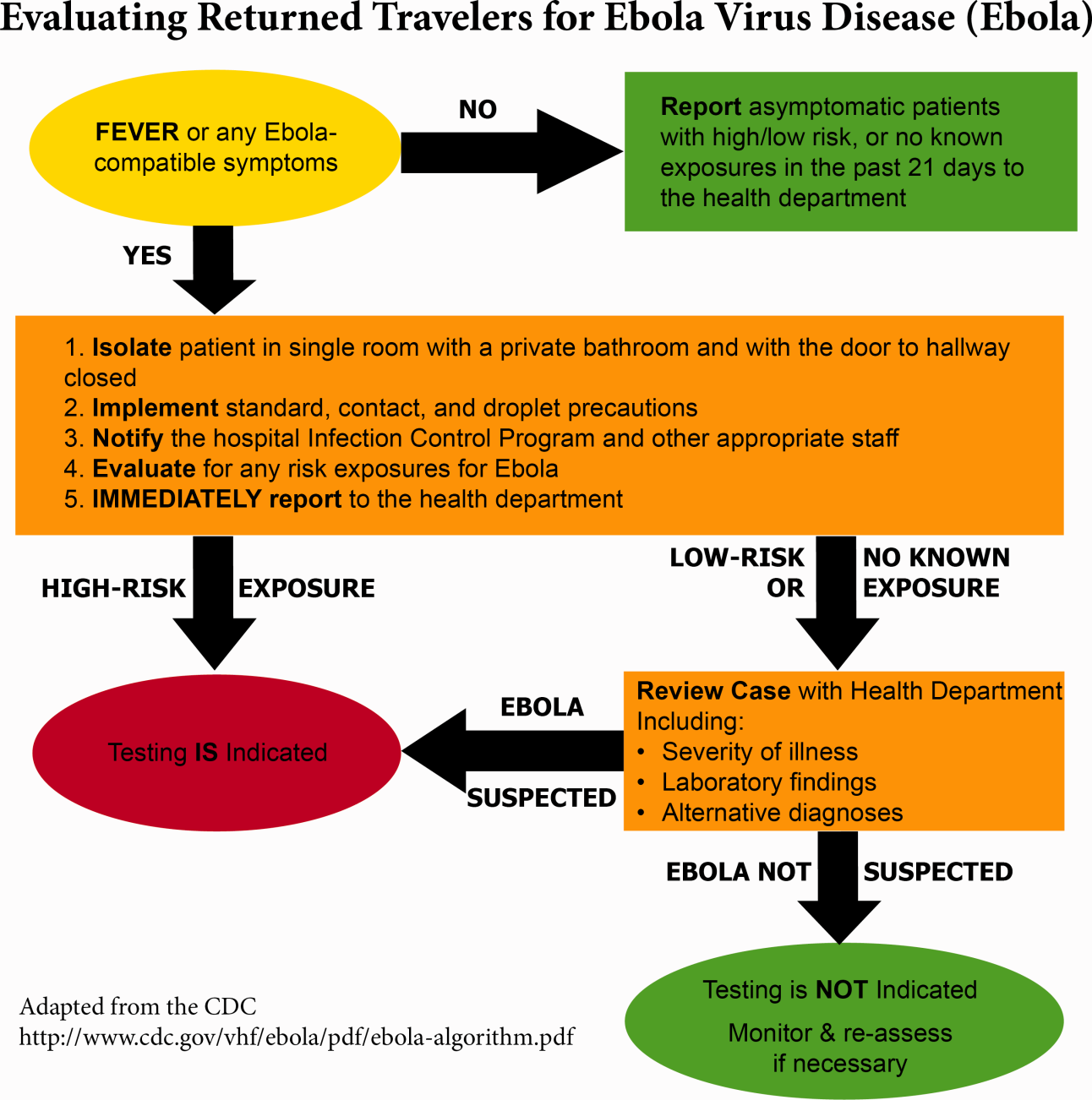

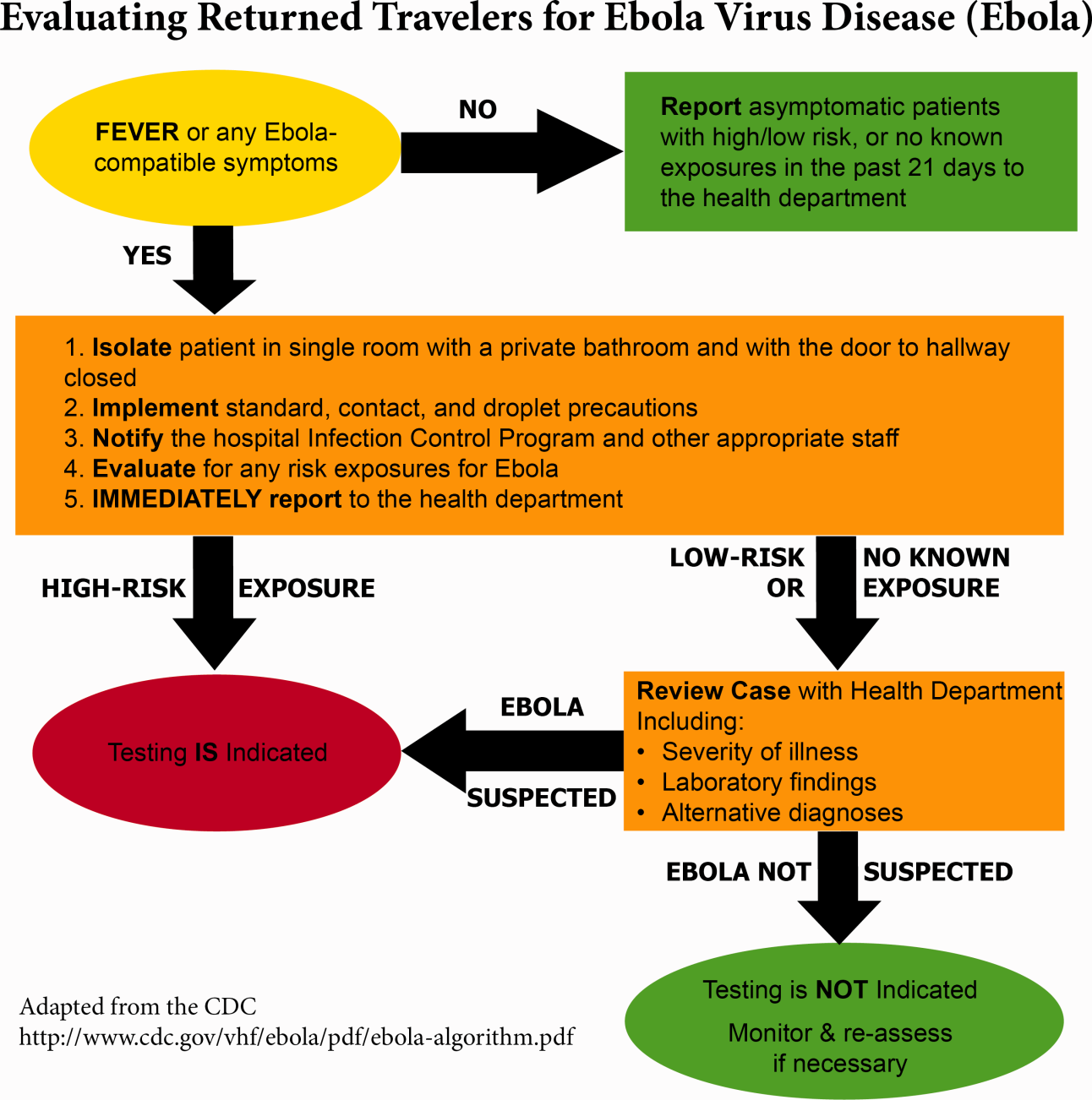

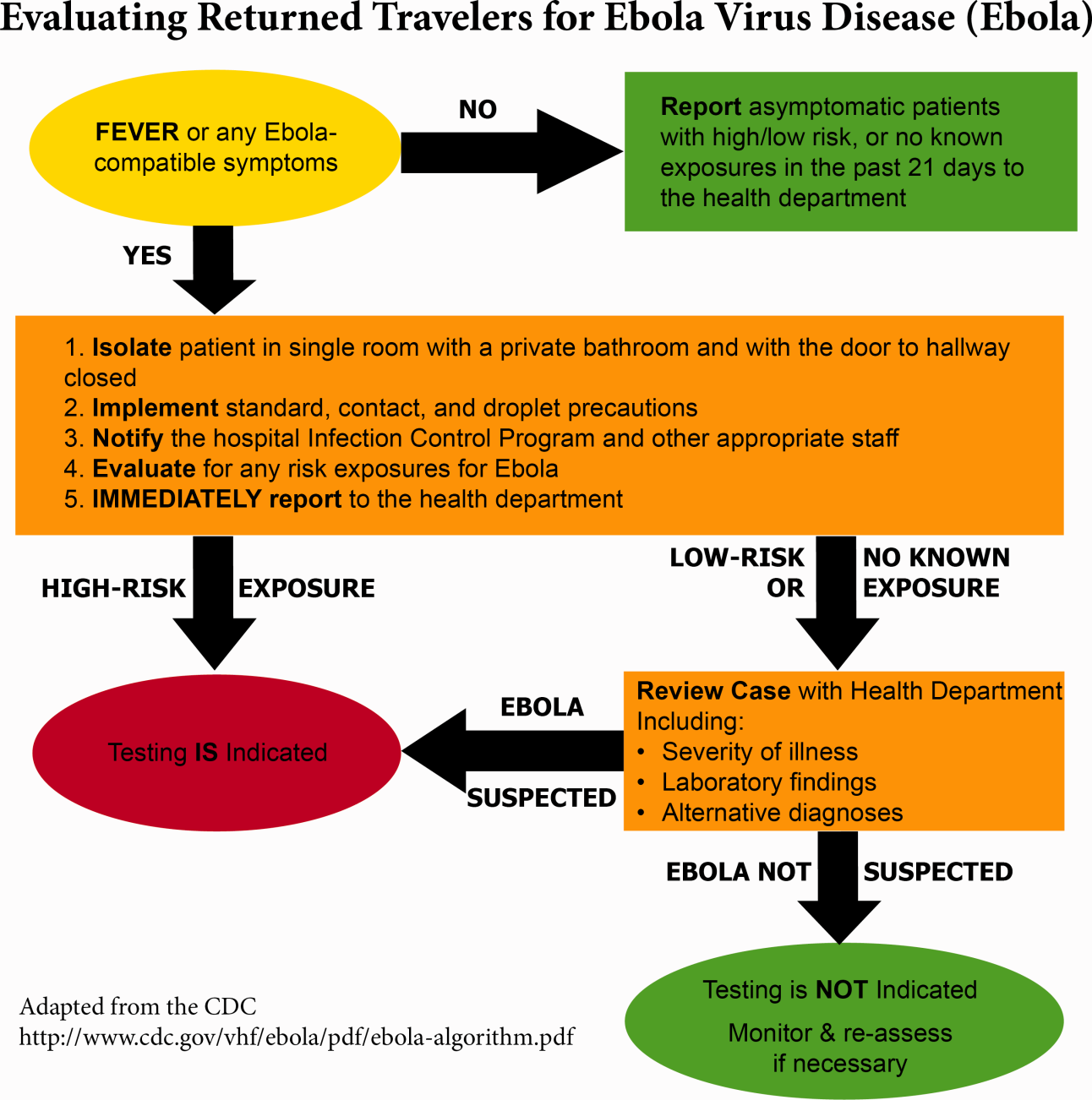

Triage is the first step; facilities should have well‐informed and trained staff prepared to perform assessments of potential cases safely (Figure 2). The ability to temporarily isolate and then efficiently transfer suspected or confirmed EVD patients to an appropriate facility also requires careful planning. Prompt identification, constant vigilance, and accurate histories all serve as stepping stones to a successful outcome and can protect employees and other patients in the process.

Within this proposed structure, hospitalists are uniquely equipped to play a leading role in EVD response. First, hospitalists are frequently responsible for interfacility transfer. Their intimate knowledge of this process and the collegiality they have fostered through its use are both assets in navigating the tiered referral system outlined above. Furthermore, as point people in the acute‐care setting who accept patients from emergency medicine colleagues, discuss cases with various consultants, and coordinate discharges with multidisciplinary teams on a daily basis, hospitalists have honed communication and leadership skills that are highly valuable in collaborative efforts. Finally, many hospitalists are also champions of quality and safety in their institutions. The focus on the process of continuous improvement is critical in the face of evolving challenges such as EVD.

GLOBAL HEALTH HOSPITALISTS

The Ebola outbreak is a global crisis that clearly illustrates the challenges of addressing highly infectious diseases in modern times. We have outlined the role of hospitalists and defined the steps toward adequate preparedness within our facilities. By following the measured and practical actions Thucydides advised, we can further strengthen our health systems and work toward the control of this outbreak in the United States. The important role of hospitalists can and should be extended to serve those in poor countries.

Over the last decade, health systems strengthening, health workforce training, and patient safety have come to the forefront of global health priorities, the same priorities that are also at the forefront of many hospitalists' aspirations. Shoeb et al. recently conducted a survey of global health hospitalists. They found that within the framework of global health, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to contribute to this growing field, particularly in areas such as quality improvement, safety, systems thinking, and medical education, all strengths of the hospital medicine model that could be translated to resource‐limited settings.[10]

We believe that hospitalists, with their unique positions and skills, are natural and necessary agents of action in this time of need. Our ultimate aim is for hospitalists to become actively engaged in addressing not only the current Ebola outbreak, but also the extreme inequity of healthcare globallyan inequity that lies at the heart of the current devastation in West Africa. We call upon hospital medicine leaders, from division chiefs to chairs of medicine to chief medical officers to support, encourage, and incentivize their staff and faculty to join the ranks of global health hospitalists as they work to both end gross inequities in healthcare abroad and protect our patients and ourselves back home.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for Brett Lewis' assistance in the preparation of this article.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- . Infection control throughout history. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(4):280.

- , . Ebola then and now. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1663–1666.

- World Health Organization. Ebola response roadmap—situation report. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/situation‐reports/en/. Accessed November 2014.

- , . Effect of civil war on medical education in Liberia. Int J Emerg Med. 2011;4:6.

- , . Is the U.S. prepared for an Ebola outbreak? New York Times. October 10, 2014. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/10/09/us/is-the-us-prepared-for-an-ebola-outbreak.html?module=Search61(6):997–1003.

- . With good hospital practices, Emory rises to Ebola challenge. Kaiser Health News. U.S. News 8(3):162–163.

Concern and fear over an infection and how best to contain its spread is a well‐known storyline dating back centuries before the germ theory was hypothesized. During the Plague of Athens in the fourth century bc, upon noticing that physicians and caregivers of the sick were most at risk of dying, the Greek historian and philosopher Thucydides wrote that thwarting the disease likely required more practical measures than simple prayer to the gods.[1] To this day, the fears of contracting disease often outstripor worse, overrideour practical or scientific understanding.

Ebola has rekindled past concerns about disease transmission, whether real or imagined. In this article we will describe the history of Ebola outside the United States as well as recent events in US hospitals. We will review guidelines for how to prepare hospitals to treat potential Ebola patients and highlight the key role that hospitalists can have in ensuring the safety of their patients and coworkers. We will also describe the emerging role of global health hospitalists, whose numbers are growing and whose expertise is ideally suited to improving hospital care in developing countries.

EBOLA EPIDEMICS AND HEALTH EQUITY

In the first identified Ebola outbreak in 1976 in Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, patients arrived at local hospitals with symptoms that resembled common endemic illnesses like malaria, typhoid, and yellow fever. The ensuing deaths of 11 of the 17 staff members at 1 hospital were only an introduction to the deadly consequences of Ebola and the necessity of vigilant infection control. Unfortunately, not much has changed with each subsequent outbreak; to this day the heralding of an Ebola outbreak denotes the death of healthcare workers. Since the discovery of the Ebola virus 38 years ago, there have been nearly 30 recorded Ebola outbreaks. The mortality rates of prior outbreaks range widely between 25% and 90%; reports of the current outbreak's mortality falls within that range, between 50% and 70%. It is important to note that despite this high mortality, there had been no more than 1600 Ebola deaths worldwide before the 2014 West African pandemic.[2] In comparison, the number of deaths in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia approaches 6000.[3]

Although these disturbing figures have fueled public fear and panic in the United States, we wonder how many of these deaths were actually preventable. At the epicenter of the current Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak are 3 countries especially vulnerable to epidemics, with armed conflict recently crippling the health systems that have now just started to rebuild. When Liberia emerged from its second civil war in 2003, they had barely 50 physicians caring for a country of nearly 4 million.[4] In contrast with the devastating death toll in Liberia, it perhaps should not come as a surprise that out of the 10 known cases of Ebola that were treated in the United States and caught early, none have resulted in death. With an advanced healthcare infrastructure in place, the mortality rate for EVD in the United States has been close to zero. Although the true unpreventable case fatality rate in West Africa is unknown, the positive outcomes in the United States cases illustrate that hospitals can treat EVD successfully, provided that they are well staffed, supplied, and prepared.

Furthermore, the stark difference in access to quality healthcare between nations suggests that combating the virus should not be our only concern. In fact, EVD itself is only an acute symptom of a much larger, chronic problem with the health systems in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. Western countries must direct more resources and attention to improving the overall quality of care in these countries, for although the underlying inequities may be limited to places like Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, the resulting threat is a global one.

PREPARING FOR THE FIGHT AGAINST EBOLA IN THE UNITED STATES

On September 25, 2014, Thomas Eric Duncan presented to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital with fever, abdominal pain, and headache 11 days after transporting a pregnant neighbor in his home country of Liberia who later died of EVD. Duncan was discharged from the emergency room without admission. Three days later, on September 28, 2014, an ambulance was called and transported him to Texas Health where he was admitted. He was isolated and the hospital followed existing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for infection control. He was confirmed to have EVD on September 30, 2014. He was cared for by the healthcare providers at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, but despite their care, his condition deteriorated. Eric Duncan died on October 8, 2014. About 120 healthcare workers came into contact with the patient. None of his 48 contacts prior to admission to the hospital contracted the disease. However, 2 nurses who cared for him during his admission developed symptoms and were confirmed to have Ebola. An alarm was sounded across the United States, awakening hospitals to the reality of their vulnerability and need for preparedness.[5]

For any healthcare worker treating EVD, whether working in a hospital here in the United States or an Ebola treatment unit (ETU) in West Africa, intensive training is necessary to keep oneself safe. Although infection control is not a novel concept, the stakes have undoubtedly been raised, as even the smallest misstep can be deadly when dealing with the Ebola virus. We were participants in a 3‐day infection control training program conducted by the CDC in Anniston, Alabama, which aimed to prepare healthcare workers to assist with the Ebola response in West Africa. Throughout the training, we repeatedly donned and doffed personal protective equipment (PPE), following protocols established by the World Health Organization and Doctors Without Borders (Mdecins Sans Frontires):

- Use a combination of contact, droplet, and standard precautions, ensuring no area of skin is left uncovered.

- Enter and exit with a buddy; inspect one another for breaches at each step of donning, caring for the patient, and doffing.

- Wash gloved hands with 0.5% chlorine bleach between tasks and patients.

- Exit at the slightest breach of infection protocol.

- Doff PPE per protocol and under supervision; take great care not to contaminate oneself.

Doffing is considered the most difficult and also the most important part, with 7 pieces to remove and no less than 20 steps to do so. After 3 full days of training, although we felt more confident with the carefully choreographed movements of donning and doffing, we were also more aware of the many opportunities during which a breach could occur. Despite our repeated practice, the training staff was firm in telling us that we were still not prepared to work in an ETU. We had only undergone what could be called a cold training. To work in the hot zone of the ETUs, it is essential to undergo additional mentorship and training once in the field. We believe a similar approach to extensive training should be employed for all healthcare workers on the front lines of an Ebola response, both in the United States and abroad.

Given the complexity of the infection control practices above, questions have appropriately been raised about US healthcare facilities' aptitude at providing care for patients with EVD. Although hospitals have historically been focal point(s) for dissemination of infection of Ebola, this does not have to be the case.[6] With appropriate preparedness, training, and understanding of facility limitations, hospitals can also be places of confidence and healing.

Both Emory University and the University of Nebraska have successfully treated multiple Ebola patients without incurring further transmission.[7, 8] Much of their success comes from the work of longitudinal teams that are trained in infectious disease response on a regular basis, despite the rare occurrence of a serious outbreak. When Emory scaled up this team upon receiving a confirmed EVD patient, new members were required to pass a proficiency test prior to providing care. Emory's strict adherence to infection control and advanced preparation serve as a model for other institutions.

It is important to recognize that not all hospitals should be fully equipped and staffed for safe care of a patient with EVD. Much like in cases of high‐level trauma, regional centers should be identified, prepared, and available to be called upon in a time of need (Figure 1). At the writing of this article, guidelines for hospitals are evolving; most states, with input from federal and local officials, are moving toward designating regional referral centers. Although the number of designated facilities and standards for each vary by state, general preparedness for care of a patient with suspected or confirmed EVD should include: (1) a designated and trained care team, (2) appropriate and vetted operational protocols, (3) an assigned isolation unit with adequate space for the necessary specialized precautions, (4) separate laboratory and diagnostic capabilities, and (5) a working waste management plan.[9] Although not all facilities throughout the United States will have the capability to care for a patient with EVD, all hospitals must have an action plan.

Triage is the first step; facilities should have well‐informed and trained staff prepared to perform assessments of potential cases safely (Figure 2). The ability to temporarily isolate and then efficiently transfer suspected or confirmed EVD patients to an appropriate facility also requires careful planning. Prompt identification, constant vigilance, and accurate histories all serve as stepping stones to a successful outcome and can protect employees and other patients in the process.

Within this proposed structure, hospitalists are uniquely equipped to play a leading role in EVD response. First, hospitalists are frequently responsible for interfacility transfer. Their intimate knowledge of this process and the collegiality they have fostered through its use are both assets in navigating the tiered referral system outlined above. Furthermore, as point people in the acute‐care setting who accept patients from emergency medicine colleagues, discuss cases with various consultants, and coordinate discharges with multidisciplinary teams on a daily basis, hospitalists have honed communication and leadership skills that are highly valuable in collaborative efforts. Finally, many hospitalists are also champions of quality and safety in their institutions. The focus on the process of continuous improvement is critical in the face of evolving challenges such as EVD.

GLOBAL HEALTH HOSPITALISTS

The Ebola outbreak is a global crisis that clearly illustrates the challenges of addressing highly infectious diseases in modern times. We have outlined the role of hospitalists and defined the steps toward adequate preparedness within our facilities. By following the measured and practical actions Thucydides advised, we can further strengthen our health systems and work toward the control of this outbreak in the United States. The important role of hospitalists can and should be extended to serve those in poor countries.

Over the last decade, health systems strengthening, health workforce training, and patient safety have come to the forefront of global health priorities, the same priorities that are also at the forefront of many hospitalists' aspirations. Shoeb et al. recently conducted a survey of global health hospitalists. They found that within the framework of global health, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to contribute to this growing field, particularly in areas such as quality improvement, safety, systems thinking, and medical education, all strengths of the hospital medicine model that could be translated to resource‐limited settings.[10]

We believe that hospitalists, with their unique positions and skills, are natural and necessary agents of action in this time of need. Our ultimate aim is for hospitalists to become actively engaged in addressing not only the current Ebola outbreak, but also the extreme inequity of healthcare globallyan inequity that lies at the heart of the current devastation in West Africa. We call upon hospital medicine leaders, from division chiefs to chairs of medicine to chief medical officers to support, encourage, and incentivize their staff and faculty to join the ranks of global health hospitalists as they work to both end gross inequities in healthcare abroad and protect our patients and ourselves back home.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for Brett Lewis' assistance in the preparation of this article.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Concern and fear over an infection and how best to contain its spread is a well‐known storyline dating back centuries before the germ theory was hypothesized. During the Plague of Athens in the fourth century bc, upon noticing that physicians and caregivers of the sick were most at risk of dying, the Greek historian and philosopher Thucydides wrote that thwarting the disease likely required more practical measures than simple prayer to the gods.[1] To this day, the fears of contracting disease often outstripor worse, overrideour practical or scientific understanding.

Ebola has rekindled past concerns about disease transmission, whether real or imagined. In this article we will describe the history of Ebola outside the United States as well as recent events in US hospitals. We will review guidelines for how to prepare hospitals to treat potential Ebola patients and highlight the key role that hospitalists can have in ensuring the safety of their patients and coworkers. We will also describe the emerging role of global health hospitalists, whose numbers are growing and whose expertise is ideally suited to improving hospital care in developing countries.

EBOLA EPIDEMICS AND HEALTH EQUITY

In the first identified Ebola outbreak in 1976 in Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, patients arrived at local hospitals with symptoms that resembled common endemic illnesses like malaria, typhoid, and yellow fever. The ensuing deaths of 11 of the 17 staff members at 1 hospital were only an introduction to the deadly consequences of Ebola and the necessity of vigilant infection control. Unfortunately, not much has changed with each subsequent outbreak; to this day the heralding of an Ebola outbreak denotes the death of healthcare workers. Since the discovery of the Ebola virus 38 years ago, there have been nearly 30 recorded Ebola outbreaks. The mortality rates of prior outbreaks range widely between 25% and 90%; reports of the current outbreak's mortality falls within that range, between 50% and 70%. It is important to note that despite this high mortality, there had been no more than 1600 Ebola deaths worldwide before the 2014 West African pandemic.[2] In comparison, the number of deaths in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia approaches 6000.[3]

Although these disturbing figures have fueled public fear and panic in the United States, we wonder how many of these deaths were actually preventable. At the epicenter of the current Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak are 3 countries especially vulnerable to epidemics, with armed conflict recently crippling the health systems that have now just started to rebuild. When Liberia emerged from its second civil war in 2003, they had barely 50 physicians caring for a country of nearly 4 million.[4] In contrast with the devastating death toll in Liberia, it perhaps should not come as a surprise that out of the 10 known cases of Ebola that were treated in the United States and caught early, none have resulted in death. With an advanced healthcare infrastructure in place, the mortality rate for EVD in the United States has been close to zero. Although the true unpreventable case fatality rate in West Africa is unknown, the positive outcomes in the United States cases illustrate that hospitals can treat EVD successfully, provided that they are well staffed, supplied, and prepared.

Furthermore, the stark difference in access to quality healthcare between nations suggests that combating the virus should not be our only concern. In fact, EVD itself is only an acute symptom of a much larger, chronic problem with the health systems in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. Western countries must direct more resources and attention to improving the overall quality of care in these countries, for although the underlying inequities may be limited to places like Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, the resulting threat is a global one.

PREPARING FOR THE FIGHT AGAINST EBOLA IN THE UNITED STATES

On September 25, 2014, Thomas Eric Duncan presented to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital with fever, abdominal pain, and headache 11 days after transporting a pregnant neighbor in his home country of Liberia who later died of EVD. Duncan was discharged from the emergency room without admission. Three days later, on September 28, 2014, an ambulance was called and transported him to Texas Health where he was admitted. He was isolated and the hospital followed existing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for infection control. He was confirmed to have EVD on September 30, 2014. He was cared for by the healthcare providers at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, but despite their care, his condition deteriorated. Eric Duncan died on October 8, 2014. About 120 healthcare workers came into contact with the patient. None of his 48 contacts prior to admission to the hospital contracted the disease. However, 2 nurses who cared for him during his admission developed symptoms and were confirmed to have Ebola. An alarm was sounded across the United States, awakening hospitals to the reality of their vulnerability and need for preparedness.[5]

For any healthcare worker treating EVD, whether working in a hospital here in the United States or an Ebola treatment unit (ETU) in West Africa, intensive training is necessary to keep oneself safe. Although infection control is not a novel concept, the stakes have undoubtedly been raised, as even the smallest misstep can be deadly when dealing with the Ebola virus. We were participants in a 3‐day infection control training program conducted by the CDC in Anniston, Alabama, which aimed to prepare healthcare workers to assist with the Ebola response in West Africa. Throughout the training, we repeatedly donned and doffed personal protective equipment (PPE), following protocols established by the World Health Organization and Doctors Without Borders (Mdecins Sans Frontires):

- Use a combination of contact, droplet, and standard precautions, ensuring no area of skin is left uncovered.

- Enter and exit with a buddy; inspect one another for breaches at each step of donning, caring for the patient, and doffing.

- Wash gloved hands with 0.5% chlorine bleach between tasks and patients.

- Exit at the slightest breach of infection protocol.

- Doff PPE per protocol and under supervision; take great care not to contaminate oneself.

Doffing is considered the most difficult and also the most important part, with 7 pieces to remove and no less than 20 steps to do so. After 3 full days of training, although we felt more confident with the carefully choreographed movements of donning and doffing, we were also more aware of the many opportunities during which a breach could occur. Despite our repeated practice, the training staff was firm in telling us that we were still not prepared to work in an ETU. We had only undergone what could be called a cold training. To work in the hot zone of the ETUs, it is essential to undergo additional mentorship and training once in the field. We believe a similar approach to extensive training should be employed for all healthcare workers on the front lines of an Ebola response, both in the United States and abroad.

Given the complexity of the infection control practices above, questions have appropriately been raised about US healthcare facilities' aptitude at providing care for patients with EVD. Although hospitals have historically been focal point(s) for dissemination of infection of Ebola, this does not have to be the case.[6] With appropriate preparedness, training, and understanding of facility limitations, hospitals can also be places of confidence and healing.

Both Emory University and the University of Nebraska have successfully treated multiple Ebola patients without incurring further transmission.[7, 8] Much of their success comes from the work of longitudinal teams that are trained in infectious disease response on a regular basis, despite the rare occurrence of a serious outbreak. When Emory scaled up this team upon receiving a confirmed EVD patient, new members were required to pass a proficiency test prior to providing care. Emory's strict adherence to infection control and advanced preparation serve as a model for other institutions.

It is important to recognize that not all hospitals should be fully equipped and staffed for safe care of a patient with EVD. Much like in cases of high‐level trauma, regional centers should be identified, prepared, and available to be called upon in a time of need (Figure 1). At the writing of this article, guidelines for hospitals are evolving; most states, with input from federal and local officials, are moving toward designating regional referral centers. Although the number of designated facilities and standards for each vary by state, general preparedness for care of a patient with suspected or confirmed EVD should include: (1) a designated and trained care team, (2) appropriate and vetted operational protocols, (3) an assigned isolation unit with adequate space for the necessary specialized precautions, (4) separate laboratory and diagnostic capabilities, and (5) a working waste management plan.[9] Although not all facilities throughout the United States will have the capability to care for a patient with EVD, all hospitals must have an action plan.

Triage is the first step; facilities should have well‐informed and trained staff prepared to perform assessments of potential cases safely (Figure 2). The ability to temporarily isolate and then efficiently transfer suspected or confirmed EVD patients to an appropriate facility also requires careful planning. Prompt identification, constant vigilance, and accurate histories all serve as stepping stones to a successful outcome and can protect employees and other patients in the process.

Within this proposed structure, hospitalists are uniquely equipped to play a leading role in EVD response. First, hospitalists are frequently responsible for interfacility transfer. Their intimate knowledge of this process and the collegiality they have fostered through its use are both assets in navigating the tiered referral system outlined above. Furthermore, as point people in the acute‐care setting who accept patients from emergency medicine colleagues, discuss cases with various consultants, and coordinate discharges with multidisciplinary teams on a daily basis, hospitalists have honed communication and leadership skills that are highly valuable in collaborative efforts. Finally, many hospitalists are also champions of quality and safety in their institutions. The focus on the process of continuous improvement is critical in the face of evolving challenges such as EVD.

GLOBAL HEALTH HOSPITALISTS

The Ebola outbreak is a global crisis that clearly illustrates the challenges of addressing highly infectious diseases in modern times. We have outlined the role of hospitalists and defined the steps toward adequate preparedness within our facilities. By following the measured and practical actions Thucydides advised, we can further strengthen our health systems and work toward the control of this outbreak in the United States. The important role of hospitalists can and should be extended to serve those in poor countries.

Over the last decade, health systems strengthening, health workforce training, and patient safety have come to the forefront of global health priorities, the same priorities that are also at the forefront of many hospitalists' aspirations. Shoeb et al. recently conducted a survey of global health hospitalists. They found that within the framework of global health, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to contribute to this growing field, particularly in areas such as quality improvement, safety, systems thinking, and medical education, all strengths of the hospital medicine model that could be translated to resource‐limited settings.[10]