User login

Flying toward equity and inclusion

Diversity is a ‘team sport’

These are challenging, and sometimes tragic, times in the history of the United States. The image of a father and child face down in the Rio Grande River, drowning as they tried to cross from Mexico into Texas, is heart breaking. Irrespective of your political affiliation, we can agree that the immigration process is far from ideal and that no one should die in pursuit of a better life.

The United States has a complicated history with equity and inclusion, for all persons, and we are now living in times when the scab is being ripped off and these wounds are raw. What role can the Society of Hospital Medicine play to help heal these wounds?

I am a first-generation immigrant to the United States. I remember walking down the streets of my neighborhood in Uganda when my attention was drawn to a plane flying overhead. I thought to myself, “Some lucky duck is going to the U.S.” The United States was the land of opportunity and I was determined to come here. Through hard work and some luck, I arrived in the United States on June 15, 1991, with a single suitcase packed full of hope, dreams, and $3,000.

Fast-forward 28 years. I am now a hospitalist and faculty at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, the associate director of the division of hospital medicine, and the vice chair for clinical operations at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. I learned about hospital medicine during my third year of medical school at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. While I loved general medicine, I could not see myself practicing anywhere outside of the hospital.

Following residency at Johns Hopkins Bayview, I still felt that a hospital-based practice was tailor-made for me. As I matured professionally, I worked to improve the provision of care within my hospital, and then started developing educational and practice programs in hospital medicine, both locally and internationally. My passion for hospital medicine led me to serve on committees for SHM, and this year, I was honored to join the SHM Board of Directors.

It is hard to answer the question of why, or how, one person immigrates to the United States and finds success while another loses their life. A quote attributed to Edmund Burke says, “the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good [wo]men to do nothing.” One of SHM’s core values is to promote diversity and inclusion. A major step taken by the society to promote work in this area was to establish the diversity and inclusion Special Interest Group in 2018. I am the board liaison for the diversity and inclusion SIG and will work alongside this group, which aims to:

- Foster diversity, equity, and inclusion in SHM.

- Increase visibility of diversity, equity, and inclusion to the broader hospital medicine community.

- Support hospital medicine groups in matching their work forces to their diverse patient populations.

- Develop tool kits to improve the provision of care for our diverse patient population.

- Engender diversity among hospitalists.

- Develop opportunities for expanding the fund of knowledge on diversity in hospital medicine through research and discovery.

- Participate in SHM’s advocacy efforts related to diversity and inclusion.

- Develop partnerships with other key organizations to advance diversity, equity, and inclusion platforms so as to increase the scalability of SHM’s efforts.

We have been successful at Hopkins with diversity and inclusion, but that did not occur by chance. I believe that diversity and inclusion is a team sport and that everyone can be an important part of that team. In my hospitalist group, we actively engage women, men, doctors, NPs, PAs, administrators, minorities, and nonminorities. We recruit to – and cherish members of – our group irrespective of religious beliefs or sexual orientation. We believe that a heterogeneous group of people leads to an engaged and high-performing culture.

I have traveled a convoluted path since my arrival in 1991. Along the way, I was blessed with a husband and son who anchor me. Every day they remind me that the hard work I do is to build on the past to improve the future. My husband, an immigrant from Uganda like me, reminds me that we are lucky to have made it to the United States and that the ability and freedom to work hard and be rewarded for that hard work is a great privilege. My son reminds me of the many other children who look at me and know that they too can dare to dream. Occasionally, I still look up and see a plane, and I am reminded of that day many years ago. Hospital medicine is my suitcase packed with hopes and dreams for me, for this specialty, and for this country.

Dr. Kisuule is associate director of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview and assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore, and a member of the SHM Board of Directors.

Diversity is a ‘team sport’

Diversity is a ‘team sport’

These are challenging, and sometimes tragic, times in the history of the United States. The image of a father and child face down in the Rio Grande River, drowning as they tried to cross from Mexico into Texas, is heart breaking. Irrespective of your political affiliation, we can agree that the immigration process is far from ideal and that no one should die in pursuit of a better life.

The United States has a complicated history with equity and inclusion, for all persons, and we are now living in times when the scab is being ripped off and these wounds are raw. What role can the Society of Hospital Medicine play to help heal these wounds?

I am a first-generation immigrant to the United States. I remember walking down the streets of my neighborhood in Uganda when my attention was drawn to a plane flying overhead. I thought to myself, “Some lucky duck is going to the U.S.” The United States was the land of opportunity and I was determined to come here. Through hard work and some luck, I arrived in the United States on June 15, 1991, with a single suitcase packed full of hope, dreams, and $3,000.

Fast-forward 28 years. I am now a hospitalist and faculty at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, the associate director of the division of hospital medicine, and the vice chair for clinical operations at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. I learned about hospital medicine during my third year of medical school at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. While I loved general medicine, I could not see myself practicing anywhere outside of the hospital.

Following residency at Johns Hopkins Bayview, I still felt that a hospital-based practice was tailor-made for me. As I matured professionally, I worked to improve the provision of care within my hospital, and then started developing educational and practice programs in hospital medicine, both locally and internationally. My passion for hospital medicine led me to serve on committees for SHM, and this year, I was honored to join the SHM Board of Directors.

It is hard to answer the question of why, or how, one person immigrates to the United States and finds success while another loses their life. A quote attributed to Edmund Burke says, “the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good [wo]men to do nothing.” One of SHM’s core values is to promote diversity and inclusion. A major step taken by the society to promote work in this area was to establish the diversity and inclusion Special Interest Group in 2018. I am the board liaison for the diversity and inclusion SIG and will work alongside this group, which aims to:

- Foster diversity, equity, and inclusion in SHM.

- Increase visibility of diversity, equity, and inclusion to the broader hospital medicine community.

- Support hospital medicine groups in matching their work forces to their diverse patient populations.

- Develop tool kits to improve the provision of care for our diverse patient population.

- Engender diversity among hospitalists.

- Develop opportunities for expanding the fund of knowledge on diversity in hospital medicine through research and discovery.

- Participate in SHM’s advocacy efforts related to diversity and inclusion.

- Develop partnerships with other key organizations to advance diversity, equity, and inclusion platforms so as to increase the scalability of SHM’s efforts.

We have been successful at Hopkins with diversity and inclusion, but that did not occur by chance. I believe that diversity and inclusion is a team sport and that everyone can be an important part of that team. In my hospitalist group, we actively engage women, men, doctors, NPs, PAs, administrators, minorities, and nonminorities. We recruit to – and cherish members of – our group irrespective of religious beliefs or sexual orientation. We believe that a heterogeneous group of people leads to an engaged and high-performing culture.

I have traveled a convoluted path since my arrival in 1991. Along the way, I was blessed with a husband and son who anchor me. Every day they remind me that the hard work I do is to build on the past to improve the future. My husband, an immigrant from Uganda like me, reminds me that we are lucky to have made it to the United States and that the ability and freedom to work hard and be rewarded for that hard work is a great privilege. My son reminds me of the many other children who look at me and know that they too can dare to dream. Occasionally, I still look up and see a plane, and I am reminded of that day many years ago. Hospital medicine is my suitcase packed with hopes and dreams for me, for this specialty, and for this country.

Dr. Kisuule is associate director of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview and assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore, and a member of the SHM Board of Directors.

These are challenging, and sometimes tragic, times in the history of the United States. The image of a father and child face down in the Rio Grande River, drowning as they tried to cross from Mexico into Texas, is heart breaking. Irrespective of your political affiliation, we can agree that the immigration process is far from ideal and that no one should die in pursuit of a better life.

The United States has a complicated history with equity and inclusion, for all persons, and we are now living in times when the scab is being ripped off and these wounds are raw. What role can the Society of Hospital Medicine play to help heal these wounds?

I am a first-generation immigrant to the United States. I remember walking down the streets of my neighborhood in Uganda when my attention was drawn to a plane flying overhead. I thought to myself, “Some lucky duck is going to the U.S.” The United States was the land of opportunity and I was determined to come here. Through hard work and some luck, I arrived in the United States on June 15, 1991, with a single suitcase packed full of hope, dreams, and $3,000.

Fast-forward 28 years. I am now a hospitalist and faculty at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, the associate director of the division of hospital medicine, and the vice chair for clinical operations at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. I learned about hospital medicine during my third year of medical school at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. While I loved general medicine, I could not see myself practicing anywhere outside of the hospital.

Following residency at Johns Hopkins Bayview, I still felt that a hospital-based practice was tailor-made for me. As I matured professionally, I worked to improve the provision of care within my hospital, and then started developing educational and practice programs in hospital medicine, both locally and internationally. My passion for hospital medicine led me to serve on committees for SHM, and this year, I was honored to join the SHM Board of Directors.

It is hard to answer the question of why, or how, one person immigrates to the United States and finds success while another loses their life. A quote attributed to Edmund Burke says, “the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good [wo]men to do nothing.” One of SHM’s core values is to promote diversity and inclusion. A major step taken by the society to promote work in this area was to establish the diversity and inclusion Special Interest Group in 2018. I am the board liaison for the diversity and inclusion SIG and will work alongside this group, which aims to:

- Foster diversity, equity, and inclusion in SHM.

- Increase visibility of diversity, equity, and inclusion to the broader hospital medicine community.

- Support hospital medicine groups in matching their work forces to their diverse patient populations.

- Develop tool kits to improve the provision of care for our diverse patient population.

- Engender diversity among hospitalists.

- Develop opportunities for expanding the fund of knowledge on diversity in hospital medicine through research and discovery.

- Participate in SHM’s advocacy efforts related to diversity and inclusion.

- Develop partnerships with other key organizations to advance diversity, equity, and inclusion platforms so as to increase the scalability of SHM’s efforts.

We have been successful at Hopkins with diversity and inclusion, but that did not occur by chance. I believe that diversity and inclusion is a team sport and that everyone can be an important part of that team. In my hospitalist group, we actively engage women, men, doctors, NPs, PAs, administrators, minorities, and nonminorities. We recruit to – and cherish members of – our group irrespective of religious beliefs or sexual orientation. We believe that a heterogeneous group of people leads to an engaged and high-performing culture.

I have traveled a convoluted path since my arrival in 1991. Along the way, I was blessed with a husband and son who anchor me. Every day they remind me that the hard work I do is to build on the past to improve the future. My husband, an immigrant from Uganda like me, reminds me that we are lucky to have made it to the United States and that the ability and freedom to work hard and be rewarded for that hard work is a great privilege. My son reminds me of the many other children who look at me and know that they too can dare to dream. Occasionally, I still look up and see a plane, and I am reminded of that day many years ago. Hospital medicine is my suitcase packed with hopes and dreams for me, for this specialty, and for this country.

Dr. Kisuule is associate director of the division of hospital medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview and assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University, both in Baltimore, and a member of the SHM Board of Directors.

The Current State of Advanced Practice Provider Fellowships in Hospital Medicine: A Survey of Program Directors

Postgraduate training for physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) is a rapidly evolving field. It has been estimated that the number of these advanced practice providers (APPs) almost doubled between 2000 and 2016 (from 15.3 to 28.2 per 100 physicians) and is expected to double again by 2030.

Historically, postgraduate APP fellowships have functioned to help bridge the gap in clinical practice experience between physicians and APPs.

First described in 2010 by the Mayo Clinic,

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study of all APP adult and pediatric fellowships in hospital medicine, in the United States, that were identifiable through May 2018. Multiple methods were used to identify all active fellowships. First, all training programs offering a Hospital Medicine Fellowship in the ARC-PA and Association of Postgraduate PA Programs databases were noted. Second, questionnaires were given out at the NP/PA forum at the national SHM conference in 2018 to gather information on existing APP fellowships. Third, similar online requests to identify known programs were posted to the SHM web forum Hospital Medicine Exchange (HMX). Fourth, Internet searches were used to discover additional programs. Once those fellowships were identified, surveys were sent to their program directors (PDs). These surveys not only asked the PDs about their fellowship but also asked them to identify additional APP fellowships beyond those that we had captured. Once additional programs were identified, a second round of surveys was sent to their PDs. This was performed in an iterative fashion until no additional fellowships were discovered.

The survey tool was developed and validated internally in the AAMC Survey Development style18 and was influenced by prior validated surveys of postgraduate medical fellowships.10,

A web-based survey format (Qualtrics) was used to distribute the questionnaire e-mail to the PDs. Follow up e-mail reminders were sent to all nonresponders to encourage full participation. Survey completion was voluntary; no financial incentives or gifts were offered. IRB approval was obtained at Johns Hopkins Bayview (IRB number 00181629). Descriptive statistics (proportions, means, and ranges as appropriate) were calculated for all variables. Stata 13 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, Texas. StataCorp LP) was used for data analysis.

RESULTS

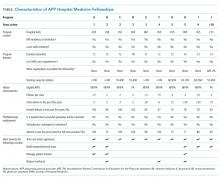

In total, 11 fellowships were identified using our multimethod approach. We found four (36%) programs by utilizing existing online databases, two (18%) through the SHM questionnaire and HMX forum, three (27%) through internet searches, and the remaining two (18%) were referred to us by the other PDs who were surveyed. Of the programs surveyed, 10 were adult programs and one was a pediatric program. Surveys were sent to the PDs of the 11 fellowships, and all but one of them (10/11, 91%) responded. Respondent programs were given alphabetical designations A through J (Table).

Fellowship and Individual Characteristics

Most programs have been in existence for five years or fewer. Eighty percent of the programs are about one year in duration; two outlier programs have fellowship lengths of six months and 18 months. The main hospital where training occurs has a mean of 496 beds (range 213 to 900). Ninety percent of the hospitals also have physician residency training programs. Sixty percent of programs enroll two to four fellows per year while 40% enroll five or more. The salary range paid by the programs is $55,000 to >$70,000, and half the programs pay more than $65,000.

The majority of fellows accepted into APP fellowships in hospital medicine are women. Eighty percent of fellows are 26-30 years old, and 90% of fellows have been out of NP or PA school for one year or less. Both NP and PA applicants are accepted in 80% of fellowships.

Program Rationales

All programs reported that training and retaining applicants is the main driver for developing their fellowship, and 50% of them offer financial incentives for retention upon successful completion of the program. Forty percent of PDs stated that there is an implicit or explicit understanding that successful completion of the fellowship would result in further employment. Over the last five years, 89% (range: 71%-100%) of graduates were asked to remain for a full-time position after program completion.

In addition to training and retention, building an interprofessional team (50%), managing patient volume (30%), and reducing overhead (20%) were also reported as rationales for program development. The majority of programs (80%) have fellows bill for clinical services, and five of those eight programs do so after their fellows become more clinically competent.

Curricula

Of the nine adult programs, 67% teach explicitly to SHM core competencies and 33% send their fellows to the SHM NP/PA Boot Camp. Thirty percent of fellowships partner formally with either a physician residency or a local PA program to develop educational content. Six of the nine programs with active physician residencies, including the pediatric fellowship, offer shared educational experiences for the residents and APPs.

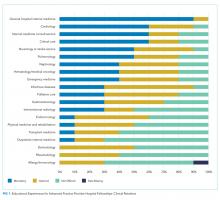

There are notable differences in clinical rotations between the programs (Figure 1). No single rotation is universally required, although general hospital internal medicine is required in all adult fellowships. The majority (80%) of programs offer at least one elective. Six programs reported mandatory rotations outside the department of medicine, most commonly neurology or the stroke service (four programs). Only one program reported only general medicine rotations, with no subspecialty electives.

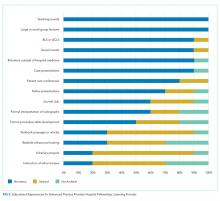

There are also differences between programs with respect to educational experiences and learning formats (Figure 2). Each fellowship takes a unique approach to clinical instruction; teaching rounds and lecture attendance are the only experiences that are mandatory across the board. Grand rounds are available, but not required, in all programs. Ninety percent of programs offer or require fellow presentations, journal clubs, reading assignments, or scholarly projects. Fellow presentations (70%) and journal club attendance (60%) are required in more than half the programs; however, reading assignments (30%) and scholarly projects (20%) are rarely required.

Methods of Fellow Assessment

Each program surveyed has a unique method of fellow assessment. Ninety percent of the programs use more than one method to assess their fellows. Faculty reviews are most commonly used and are conducted in all rotations in 80% of fellowships. Both self-assessment exercises and written examinations are used in some rotations by the majority of programs. Capstone projects are required infrequently (30%).

DISCUSSION

We found several commonalities between the fellowships surveyed. Many of the program characteristics, such as years in operation, salary, duration, and lack of accreditation, are quite similar. Most fellowships also have a similar rationale for building their programs and use resources from the SHM to inform their curricula. Fellows, on average, share several demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, and time out of schooling. Conversely, we found wide variability in clinical rotations, the general teaching structure, and methods of fellow evaluation.

There have been several publications detailing successful individual APP fellowships in medical subspecialties,

It is noteworthy that every program surveyed was created with training and retention in mind, rather than other factors like decreasing overhead or managing patient volume. Training one’s own APPs so that they can learn on the job, come to understand expectations within a group, and witness the culture is extremely valuable. From a patient safety standpoint, it has been documented that physician hospitalists straight out of residency have a higher patient mortality compared with more experienced providers.

Several limitations to this study should be considered. While we used multiple strategies to locate as many fellowships as possible, it is unlikely that we successfully captured all existing programs, and new programs are being developed annually. We also relied on self-reported data from PDs. While we would expect PDs to provide accurate data, we could not externally validate their answers. Additionally, although our survey tool was reviewed extensively and validated internally, it was developed de novo for this study.

CONCLUSION

APP fellowships in hospital medicine have experienced marked growth since the first program was described in 2010. The majority of programs are 12 months long, operate in existing teaching centers, and are intended to further enhance the training and retention of newly graduated PAs and NPs. Despite their similarities, fellowships have striking variability in their methods of teaching and assessing their learners. Best practices have yet to be identified, and further study is required to determine how to standardize curricula across the board.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This project was supported by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Data Management (BEAD) Core. Dr. Wright is the Anne Gaines and G. Thomas Miller Professor of Medicine, which is supported through the Johns Hopkins’ Center for Innovative Medicine.

1. Auerbach DI, Staiger DO, Buerhaus PI. Growing ranks of advanced practice clinicians — implications for the physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):2358-2360. doi: 10.1056/nejmp1801869. PubMed

2. Darves B. Midlevels make a rocky entrance into hospital medicine. Todays Hospitalist. 2007;5(1):28-32.

3. Polansky M. A historical perspective on postgraduate physician assistant education and the association of postgraduate physician assistant programs. J Physician Assist Educ. 2007;18(3):100-108. doi: 10.1097/01367895-200718030-00014.

4. FNP & AGNP Certification Candidate Handbook. The American Academy of Nurse Practitioners National Certification Board, Inc; 2018. https://www.aanpcert.org/resource/documents/AGNP FNP Candidate Handbook.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2018

5. Become a PA: Getting Your Prerequisites and Certification. AAPA. https://www.aapa.org/career-central/become-a-pa/. Accessed December 20, 2018.

6. ACGME Common Program Requirements. ACGME; 2017. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2018

7. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America; Institute of Medicine, Smith MD, Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, McGinnis JM. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. PubMed

8. The Future of Nursing LEADING CHANGE, ADVANCING HEALTH. THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS; 2014. https://www.nap.edu/read/12956/chapter/1. Accessed December 16, 2018.

9. Hussaini SS, Bushardt RL, Gonsalves WC, et al. Accreditation and implications of clinical postgraduate pa training programs. JAAPA. 2016:29:1-7. doi: 10.1097/01.jaa.0000482298.17821.fb. PubMed

10. Polansky M, Garver GJH, Hilton G. Postgraduate clinical education of physician assistants. J Physician Assist Educ. 2012;23(1):39-45. doi: 10.1097/01367895-201223010-00008.

11. Will KK, Budavari AI, Wilkens JA, Mishark K, Hartsell ZC. A hospitalist postgraduate training program for physician assistants. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(2):94-98. doi: 10.1002/jhm.619. PubMed

12. Kartha A, Restuccia JD, Burgess JF, et al. Nurse practitioner and physician assistant scope of practice in 118 acute care hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(10):615-620. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2231. PubMed

13. Singh S, Fletcher KE, Schapira MM, et al. A comparison of outcomes of general medical inpatient care provided by a hospitalist-physician assistant model vs a traditional resident-based model. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):122-130. doi: 10.1002/jhm.826. PubMed

14. Hussaini SS, Bushardt RL, Gonsalves WC, et al. Accreditation and implications of clinical postgraduate PA training programs. JAAPA. 2016;29(5):1-7. doi: 10.1097/01.jaa.0000482298.17821.fb. PubMed

15. Postgraduate Programs. ARC-PA. http://www.arc-pa.org/accreditation/postgraduate-programs. Accessed September 13, 2018.

16. National Nurse Practitioner Residency & Fellowship Training Consortium: Mission. https://www.nppostgradtraining.com/About-Us/Mission. Accessed September 27, 2018.

17. NP/PA Boot Camp. State of Hospital Medicine | Society of Hospital Medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/events/nppa-boot-camp. Accessed September 13, 2018.

18. Gehlbach H, Artino Jr AR, Durning SJ. AM last page: survey development guidance for medical education researchers. Acad Med. 2010;85(5):925. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181dd3e88.” Accessed March 10, 2018. PubMed

19. Kraus C, Carlisle T, Carney D. Emergency Medicine Physician Assistant (EMPA) post-graduate training programs: program characteristics and training curricula. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(5):803-807. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2018.6.37892.

20. Shah NH, Rhim HJH, Maniscalco J, Wilson K, Rassbach C. The current state of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships: A survey of program directors. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):324-328. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2571. PubMed

21. Thompson BM, Searle NS, Gruppen LD, Hatem CJ, Nelson E. A national survey of medical education fellowships. Med Educ Online. 2011;16(1):5642. doi: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.5642. PubMed

22. Hooker R. A physician assistant rheumatology fellowship. JAAPA. 2013;26(6):49-52. doi: 10.1097/01.jaa.0000430346.04435.e4 PubMed

23. Keizer T, Trangle M. the benefits of a physician assistant and/or nurse practitioner psychiatric postgraduate training program. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):691-694. doi: 10.1007/s40596-015-0331-z. PubMed

24. Miller A, Weiss J, Hill V, Lindaman K, Emory C. Implementation of a postgraduate orthopaedic physician assistant fellowship for improved specialty training. JBJS Journal of Orthopaedics for Physician Assistants. 2017:1. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.jopa.17.00021.

25. Sharma P, Brooks M, Roomiany P, Verma L, Criscione-Schreiber L. physician assistant student training for the inpatient setting. J Physician Assist Educ. 2017;28(4):189-195. doi: 10.1097/jpa.0000000000000174. PubMed

26. Goodwin JS, Salameh H, Zhou J, Singh S, Kuo Y-F, Nattinger AB. Association of hospitalist years of experience with mortality in the hospitalized medicare population. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):196. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7049. PubMed

27. Barnes H. Exploring the factors that influence nurse practitioner role transition. J Nurse Pract. 2015;11(2):178-183. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2014.11.004. PubMed

28. Will K, Williams J, Hilton G, Wilson L, Geyer H. Perceived efficacy and utility of postgraduate physician assistant training programs. JAAPA. 2016;29(3):46-48. doi: 10.1097/01.jaa.0000480569.39885.c8. PubMed

29. Torok H, Lackner C, Landis R, Wright S. Learning needs of physician assistants working in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2011;7(3):190-194. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1001. PubMed

30. Cate O. Competency-based postgraduate medical education: past, present and future. GMS J Med Educ. 2017:34(5). doi: 10.3205/zma001146. PubMed

31. Exploring the ACGME Core Competencies (Part 1 of 7). NEJM Knowledge. https://knowledgeplus.nejm.org/blog/exploring-acgme-core-competencies/. Accessed October 24, 2018.

32. Core Competencies. Core Competencies | Society of Hospital Medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/professional-development/core-competencies/. Accessed October 24, 2018.

Postgraduate training for physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) is a rapidly evolving field. It has been estimated that the number of these advanced practice providers (APPs) almost doubled between 2000 and 2016 (from 15.3 to 28.2 per 100 physicians) and is expected to double again by 2030.

Historically, postgraduate APP fellowships have functioned to help bridge the gap in clinical practice experience between physicians and APPs.

First described in 2010 by the Mayo Clinic,

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study of all APP adult and pediatric fellowships in hospital medicine, in the United States, that were identifiable through May 2018. Multiple methods were used to identify all active fellowships. First, all training programs offering a Hospital Medicine Fellowship in the ARC-PA and Association of Postgraduate PA Programs databases were noted. Second, questionnaires were given out at the NP/PA forum at the national SHM conference in 2018 to gather information on existing APP fellowships. Third, similar online requests to identify known programs were posted to the SHM web forum Hospital Medicine Exchange (HMX). Fourth, Internet searches were used to discover additional programs. Once those fellowships were identified, surveys were sent to their program directors (PDs). These surveys not only asked the PDs about their fellowship but also asked them to identify additional APP fellowships beyond those that we had captured. Once additional programs were identified, a second round of surveys was sent to their PDs. This was performed in an iterative fashion until no additional fellowships were discovered.

The survey tool was developed and validated internally in the AAMC Survey Development style18 and was influenced by prior validated surveys of postgraduate medical fellowships.10,

A web-based survey format (Qualtrics) was used to distribute the questionnaire e-mail to the PDs. Follow up e-mail reminders were sent to all nonresponders to encourage full participation. Survey completion was voluntary; no financial incentives or gifts were offered. IRB approval was obtained at Johns Hopkins Bayview (IRB number 00181629). Descriptive statistics (proportions, means, and ranges as appropriate) were calculated for all variables. Stata 13 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, Texas. StataCorp LP) was used for data analysis.

RESULTS

In total, 11 fellowships were identified using our multimethod approach. We found four (36%) programs by utilizing existing online databases, two (18%) through the SHM questionnaire and HMX forum, three (27%) through internet searches, and the remaining two (18%) were referred to us by the other PDs who were surveyed. Of the programs surveyed, 10 were adult programs and one was a pediatric program. Surveys were sent to the PDs of the 11 fellowships, and all but one of them (10/11, 91%) responded. Respondent programs were given alphabetical designations A through J (Table).

Fellowship and Individual Characteristics

Most programs have been in existence for five years or fewer. Eighty percent of the programs are about one year in duration; two outlier programs have fellowship lengths of six months and 18 months. The main hospital where training occurs has a mean of 496 beds (range 213 to 900). Ninety percent of the hospitals also have physician residency training programs. Sixty percent of programs enroll two to four fellows per year while 40% enroll five or more. The salary range paid by the programs is $55,000 to >$70,000, and half the programs pay more than $65,000.

The majority of fellows accepted into APP fellowships in hospital medicine are women. Eighty percent of fellows are 26-30 years old, and 90% of fellows have been out of NP or PA school for one year or less. Both NP and PA applicants are accepted in 80% of fellowships.

Program Rationales

All programs reported that training and retaining applicants is the main driver for developing their fellowship, and 50% of them offer financial incentives for retention upon successful completion of the program. Forty percent of PDs stated that there is an implicit or explicit understanding that successful completion of the fellowship would result in further employment. Over the last five years, 89% (range: 71%-100%) of graduates were asked to remain for a full-time position after program completion.

In addition to training and retention, building an interprofessional team (50%), managing patient volume (30%), and reducing overhead (20%) were also reported as rationales for program development. The majority of programs (80%) have fellows bill for clinical services, and five of those eight programs do so after their fellows become more clinically competent.

Curricula

Of the nine adult programs, 67% teach explicitly to SHM core competencies and 33% send their fellows to the SHM NP/PA Boot Camp. Thirty percent of fellowships partner formally with either a physician residency or a local PA program to develop educational content. Six of the nine programs with active physician residencies, including the pediatric fellowship, offer shared educational experiences for the residents and APPs.

There are notable differences in clinical rotations between the programs (Figure 1). No single rotation is universally required, although general hospital internal medicine is required in all adult fellowships. The majority (80%) of programs offer at least one elective. Six programs reported mandatory rotations outside the department of medicine, most commonly neurology or the stroke service (four programs). Only one program reported only general medicine rotations, with no subspecialty electives.

There are also differences between programs with respect to educational experiences and learning formats (Figure 2). Each fellowship takes a unique approach to clinical instruction; teaching rounds and lecture attendance are the only experiences that are mandatory across the board. Grand rounds are available, but not required, in all programs. Ninety percent of programs offer or require fellow presentations, journal clubs, reading assignments, or scholarly projects. Fellow presentations (70%) and journal club attendance (60%) are required in more than half the programs; however, reading assignments (30%) and scholarly projects (20%) are rarely required.

Methods of Fellow Assessment

Each program surveyed has a unique method of fellow assessment. Ninety percent of the programs use more than one method to assess their fellows. Faculty reviews are most commonly used and are conducted in all rotations in 80% of fellowships. Both self-assessment exercises and written examinations are used in some rotations by the majority of programs. Capstone projects are required infrequently (30%).

DISCUSSION

We found several commonalities between the fellowships surveyed. Many of the program characteristics, such as years in operation, salary, duration, and lack of accreditation, are quite similar. Most fellowships also have a similar rationale for building their programs and use resources from the SHM to inform their curricula. Fellows, on average, share several demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, and time out of schooling. Conversely, we found wide variability in clinical rotations, the general teaching structure, and methods of fellow evaluation.

There have been several publications detailing successful individual APP fellowships in medical subspecialties,

It is noteworthy that every program surveyed was created with training and retention in mind, rather than other factors like decreasing overhead or managing patient volume. Training one’s own APPs so that they can learn on the job, come to understand expectations within a group, and witness the culture is extremely valuable. From a patient safety standpoint, it has been documented that physician hospitalists straight out of residency have a higher patient mortality compared with more experienced providers.

Several limitations to this study should be considered. While we used multiple strategies to locate as many fellowships as possible, it is unlikely that we successfully captured all existing programs, and new programs are being developed annually. We also relied on self-reported data from PDs. While we would expect PDs to provide accurate data, we could not externally validate their answers. Additionally, although our survey tool was reviewed extensively and validated internally, it was developed de novo for this study.

CONCLUSION

APP fellowships in hospital medicine have experienced marked growth since the first program was described in 2010. The majority of programs are 12 months long, operate in existing teaching centers, and are intended to further enhance the training and retention of newly graduated PAs and NPs. Despite their similarities, fellowships have striking variability in their methods of teaching and assessing their learners. Best practices have yet to be identified, and further study is required to determine how to standardize curricula across the board.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This project was supported by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Data Management (BEAD) Core. Dr. Wright is the Anne Gaines and G. Thomas Miller Professor of Medicine, which is supported through the Johns Hopkins’ Center for Innovative Medicine.

Postgraduate training for physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) is a rapidly evolving field. It has been estimated that the number of these advanced practice providers (APPs) almost doubled between 2000 and 2016 (from 15.3 to 28.2 per 100 physicians) and is expected to double again by 2030.

Historically, postgraduate APP fellowships have functioned to help bridge the gap in clinical practice experience between physicians and APPs.

First described in 2010 by the Mayo Clinic,

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study of all APP adult and pediatric fellowships in hospital medicine, in the United States, that were identifiable through May 2018. Multiple methods were used to identify all active fellowships. First, all training programs offering a Hospital Medicine Fellowship in the ARC-PA and Association of Postgraduate PA Programs databases were noted. Second, questionnaires were given out at the NP/PA forum at the national SHM conference in 2018 to gather information on existing APP fellowships. Third, similar online requests to identify known programs were posted to the SHM web forum Hospital Medicine Exchange (HMX). Fourth, Internet searches were used to discover additional programs. Once those fellowships were identified, surveys were sent to their program directors (PDs). These surveys not only asked the PDs about their fellowship but also asked them to identify additional APP fellowships beyond those that we had captured. Once additional programs were identified, a second round of surveys was sent to their PDs. This was performed in an iterative fashion until no additional fellowships were discovered.

The survey tool was developed and validated internally in the AAMC Survey Development style18 and was influenced by prior validated surveys of postgraduate medical fellowships.10,

A web-based survey format (Qualtrics) was used to distribute the questionnaire e-mail to the PDs. Follow up e-mail reminders were sent to all nonresponders to encourage full participation. Survey completion was voluntary; no financial incentives or gifts were offered. IRB approval was obtained at Johns Hopkins Bayview (IRB number 00181629). Descriptive statistics (proportions, means, and ranges as appropriate) were calculated for all variables. Stata 13 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, Texas. StataCorp LP) was used for data analysis.

RESULTS

In total, 11 fellowships were identified using our multimethod approach. We found four (36%) programs by utilizing existing online databases, two (18%) through the SHM questionnaire and HMX forum, three (27%) through internet searches, and the remaining two (18%) were referred to us by the other PDs who were surveyed. Of the programs surveyed, 10 were adult programs and one was a pediatric program. Surveys were sent to the PDs of the 11 fellowships, and all but one of them (10/11, 91%) responded. Respondent programs were given alphabetical designations A through J (Table).

Fellowship and Individual Characteristics

Most programs have been in existence for five years or fewer. Eighty percent of the programs are about one year in duration; two outlier programs have fellowship lengths of six months and 18 months. The main hospital where training occurs has a mean of 496 beds (range 213 to 900). Ninety percent of the hospitals also have physician residency training programs. Sixty percent of programs enroll two to four fellows per year while 40% enroll five or more. The salary range paid by the programs is $55,000 to >$70,000, and half the programs pay more than $65,000.

The majority of fellows accepted into APP fellowships in hospital medicine are women. Eighty percent of fellows are 26-30 years old, and 90% of fellows have been out of NP or PA school for one year or less. Both NP and PA applicants are accepted in 80% of fellowships.

Program Rationales

All programs reported that training and retaining applicants is the main driver for developing their fellowship, and 50% of them offer financial incentives for retention upon successful completion of the program. Forty percent of PDs stated that there is an implicit or explicit understanding that successful completion of the fellowship would result in further employment. Over the last five years, 89% (range: 71%-100%) of graduates were asked to remain for a full-time position after program completion.

In addition to training and retention, building an interprofessional team (50%), managing patient volume (30%), and reducing overhead (20%) were also reported as rationales for program development. The majority of programs (80%) have fellows bill for clinical services, and five of those eight programs do so after their fellows become more clinically competent.

Curricula

Of the nine adult programs, 67% teach explicitly to SHM core competencies and 33% send their fellows to the SHM NP/PA Boot Camp. Thirty percent of fellowships partner formally with either a physician residency or a local PA program to develop educational content. Six of the nine programs with active physician residencies, including the pediatric fellowship, offer shared educational experiences for the residents and APPs.

There are notable differences in clinical rotations between the programs (Figure 1). No single rotation is universally required, although general hospital internal medicine is required in all adult fellowships. The majority (80%) of programs offer at least one elective. Six programs reported mandatory rotations outside the department of medicine, most commonly neurology or the stroke service (four programs). Only one program reported only general medicine rotations, with no subspecialty electives.

There are also differences between programs with respect to educational experiences and learning formats (Figure 2). Each fellowship takes a unique approach to clinical instruction; teaching rounds and lecture attendance are the only experiences that are mandatory across the board. Grand rounds are available, but not required, in all programs. Ninety percent of programs offer or require fellow presentations, journal clubs, reading assignments, or scholarly projects. Fellow presentations (70%) and journal club attendance (60%) are required in more than half the programs; however, reading assignments (30%) and scholarly projects (20%) are rarely required.

Methods of Fellow Assessment

Each program surveyed has a unique method of fellow assessment. Ninety percent of the programs use more than one method to assess their fellows. Faculty reviews are most commonly used and are conducted in all rotations in 80% of fellowships. Both self-assessment exercises and written examinations are used in some rotations by the majority of programs. Capstone projects are required infrequently (30%).

DISCUSSION

We found several commonalities between the fellowships surveyed. Many of the program characteristics, such as years in operation, salary, duration, and lack of accreditation, are quite similar. Most fellowships also have a similar rationale for building their programs and use resources from the SHM to inform their curricula. Fellows, on average, share several demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, and time out of schooling. Conversely, we found wide variability in clinical rotations, the general teaching structure, and methods of fellow evaluation.

There have been several publications detailing successful individual APP fellowships in medical subspecialties,

It is noteworthy that every program surveyed was created with training and retention in mind, rather than other factors like decreasing overhead or managing patient volume. Training one’s own APPs so that they can learn on the job, come to understand expectations within a group, and witness the culture is extremely valuable. From a patient safety standpoint, it has been documented that physician hospitalists straight out of residency have a higher patient mortality compared with more experienced providers.

Several limitations to this study should be considered. While we used multiple strategies to locate as many fellowships as possible, it is unlikely that we successfully captured all existing programs, and new programs are being developed annually. We also relied on self-reported data from PDs. While we would expect PDs to provide accurate data, we could not externally validate their answers. Additionally, although our survey tool was reviewed extensively and validated internally, it was developed de novo for this study.

CONCLUSION

APP fellowships in hospital medicine have experienced marked growth since the first program was described in 2010. The majority of programs are 12 months long, operate in existing teaching centers, and are intended to further enhance the training and retention of newly graduated PAs and NPs. Despite their similarities, fellowships have striking variability in their methods of teaching and assessing their learners. Best practices have yet to be identified, and further study is required to determine how to standardize curricula across the board.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This project was supported by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Data Management (BEAD) Core. Dr. Wright is the Anne Gaines and G. Thomas Miller Professor of Medicine, which is supported through the Johns Hopkins’ Center for Innovative Medicine.

1. Auerbach DI, Staiger DO, Buerhaus PI. Growing ranks of advanced practice clinicians — implications for the physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):2358-2360. doi: 10.1056/nejmp1801869. PubMed

2. Darves B. Midlevels make a rocky entrance into hospital medicine. Todays Hospitalist. 2007;5(1):28-32.

3. Polansky M. A historical perspective on postgraduate physician assistant education and the association of postgraduate physician assistant programs. J Physician Assist Educ. 2007;18(3):100-108. doi: 10.1097/01367895-200718030-00014.

4. FNP & AGNP Certification Candidate Handbook. The American Academy of Nurse Practitioners National Certification Board, Inc; 2018. https://www.aanpcert.org/resource/documents/AGNP FNP Candidate Handbook.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2018

5. Become a PA: Getting Your Prerequisites and Certification. AAPA. https://www.aapa.org/career-central/become-a-pa/. Accessed December 20, 2018.

6. ACGME Common Program Requirements. ACGME; 2017. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2018

7. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America; Institute of Medicine, Smith MD, Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, McGinnis JM. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. PubMed

8. The Future of Nursing LEADING CHANGE, ADVANCING HEALTH. THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS; 2014. https://www.nap.edu/read/12956/chapter/1. Accessed December 16, 2018.

9. Hussaini SS, Bushardt RL, Gonsalves WC, et al. Accreditation and implications of clinical postgraduate pa training programs. JAAPA. 2016:29:1-7. doi: 10.1097/01.jaa.0000482298.17821.fb. PubMed

10. Polansky M, Garver GJH, Hilton G. Postgraduate clinical education of physician assistants. J Physician Assist Educ. 2012;23(1):39-45. doi: 10.1097/01367895-201223010-00008.

11. Will KK, Budavari AI, Wilkens JA, Mishark K, Hartsell ZC. A hospitalist postgraduate training program for physician assistants. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(2):94-98. doi: 10.1002/jhm.619. PubMed

12. Kartha A, Restuccia JD, Burgess JF, et al. Nurse practitioner and physician assistant scope of practice in 118 acute care hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(10):615-620. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2231. PubMed

13. Singh S, Fletcher KE, Schapira MM, et al. A comparison of outcomes of general medical inpatient care provided by a hospitalist-physician assistant model vs a traditional resident-based model. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):122-130. doi: 10.1002/jhm.826. PubMed

14. Hussaini SS, Bushardt RL, Gonsalves WC, et al. Accreditation and implications of clinical postgraduate PA training programs. JAAPA. 2016;29(5):1-7. doi: 10.1097/01.jaa.0000482298.17821.fb. PubMed

15. Postgraduate Programs. ARC-PA. http://www.arc-pa.org/accreditation/postgraduate-programs. Accessed September 13, 2018.

16. National Nurse Practitioner Residency & Fellowship Training Consortium: Mission. https://www.nppostgradtraining.com/About-Us/Mission. Accessed September 27, 2018.

17. NP/PA Boot Camp. State of Hospital Medicine | Society of Hospital Medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/events/nppa-boot-camp. Accessed September 13, 2018.

18. Gehlbach H, Artino Jr AR, Durning SJ. AM last page: survey development guidance for medical education researchers. Acad Med. 2010;85(5):925. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181dd3e88.” Accessed March 10, 2018. PubMed

19. Kraus C, Carlisle T, Carney D. Emergency Medicine Physician Assistant (EMPA) post-graduate training programs: program characteristics and training curricula. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(5):803-807. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2018.6.37892.

20. Shah NH, Rhim HJH, Maniscalco J, Wilson K, Rassbach C. The current state of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships: A survey of program directors. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):324-328. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2571. PubMed

21. Thompson BM, Searle NS, Gruppen LD, Hatem CJ, Nelson E. A national survey of medical education fellowships. Med Educ Online. 2011;16(1):5642. doi: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.5642. PubMed

22. Hooker R. A physician assistant rheumatology fellowship. JAAPA. 2013;26(6):49-52. doi: 10.1097/01.jaa.0000430346.04435.e4 PubMed

23. Keizer T, Trangle M. the benefits of a physician assistant and/or nurse practitioner psychiatric postgraduate training program. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):691-694. doi: 10.1007/s40596-015-0331-z. PubMed

24. Miller A, Weiss J, Hill V, Lindaman K, Emory C. Implementation of a postgraduate orthopaedic physician assistant fellowship for improved specialty training. JBJS Journal of Orthopaedics for Physician Assistants. 2017:1. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.jopa.17.00021.

25. Sharma P, Brooks M, Roomiany P, Verma L, Criscione-Schreiber L. physician assistant student training for the inpatient setting. J Physician Assist Educ. 2017;28(4):189-195. doi: 10.1097/jpa.0000000000000174. PubMed

26. Goodwin JS, Salameh H, Zhou J, Singh S, Kuo Y-F, Nattinger AB. Association of hospitalist years of experience with mortality in the hospitalized medicare population. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):196. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7049. PubMed

27. Barnes H. Exploring the factors that influence nurse practitioner role transition. J Nurse Pract. 2015;11(2):178-183. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2014.11.004. PubMed

28. Will K, Williams J, Hilton G, Wilson L, Geyer H. Perceived efficacy and utility of postgraduate physician assistant training programs. JAAPA. 2016;29(3):46-48. doi: 10.1097/01.jaa.0000480569.39885.c8. PubMed

29. Torok H, Lackner C, Landis R, Wright S. Learning needs of physician assistants working in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2011;7(3):190-194. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1001. PubMed

30. Cate O. Competency-based postgraduate medical education: past, present and future. GMS J Med Educ. 2017:34(5). doi: 10.3205/zma001146. PubMed

31. Exploring the ACGME Core Competencies (Part 1 of 7). NEJM Knowledge. https://knowledgeplus.nejm.org/blog/exploring-acgme-core-competencies/. Accessed October 24, 2018.

32. Core Competencies. Core Competencies | Society of Hospital Medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/professional-development/core-competencies/. Accessed October 24, 2018.

1. Auerbach DI, Staiger DO, Buerhaus PI. Growing ranks of advanced practice clinicians — implications for the physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):2358-2360. doi: 10.1056/nejmp1801869. PubMed

2. Darves B. Midlevels make a rocky entrance into hospital medicine. Todays Hospitalist. 2007;5(1):28-32.

3. Polansky M. A historical perspective on postgraduate physician assistant education and the association of postgraduate physician assistant programs. J Physician Assist Educ. 2007;18(3):100-108. doi: 10.1097/01367895-200718030-00014.

4. FNP & AGNP Certification Candidate Handbook. The American Academy of Nurse Practitioners National Certification Board, Inc; 2018. https://www.aanpcert.org/resource/documents/AGNP FNP Candidate Handbook.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2018

5. Become a PA: Getting Your Prerequisites and Certification. AAPA. https://www.aapa.org/career-central/become-a-pa/. Accessed December 20, 2018.

6. ACGME Common Program Requirements. ACGME; 2017. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2018

7. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America; Institute of Medicine, Smith MD, Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, McGinnis JM. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. PubMed

8. The Future of Nursing LEADING CHANGE, ADVANCING HEALTH. THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS; 2014. https://www.nap.edu/read/12956/chapter/1. Accessed December 16, 2018.

9. Hussaini SS, Bushardt RL, Gonsalves WC, et al. Accreditation and implications of clinical postgraduate pa training programs. JAAPA. 2016:29:1-7. doi: 10.1097/01.jaa.0000482298.17821.fb. PubMed

10. Polansky M, Garver GJH, Hilton G. Postgraduate clinical education of physician assistants. J Physician Assist Educ. 2012;23(1):39-45. doi: 10.1097/01367895-201223010-00008.

11. Will KK, Budavari AI, Wilkens JA, Mishark K, Hartsell ZC. A hospitalist postgraduate training program for physician assistants. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(2):94-98. doi: 10.1002/jhm.619. PubMed

12. Kartha A, Restuccia JD, Burgess JF, et al. Nurse practitioner and physician assistant scope of practice in 118 acute care hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(10):615-620. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2231. PubMed

13. Singh S, Fletcher KE, Schapira MM, et al. A comparison of outcomes of general medical inpatient care provided by a hospitalist-physician assistant model vs a traditional resident-based model. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):122-130. doi: 10.1002/jhm.826. PubMed

14. Hussaini SS, Bushardt RL, Gonsalves WC, et al. Accreditation and implications of clinical postgraduate PA training programs. JAAPA. 2016;29(5):1-7. doi: 10.1097/01.jaa.0000482298.17821.fb. PubMed

15. Postgraduate Programs. ARC-PA. http://www.arc-pa.org/accreditation/postgraduate-programs. Accessed September 13, 2018.

16. National Nurse Practitioner Residency & Fellowship Training Consortium: Mission. https://www.nppostgradtraining.com/About-Us/Mission. Accessed September 27, 2018.

17. NP/PA Boot Camp. State of Hospital Medicine | Society of Hospital Medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/events/nppa-boot-camp. Accessed September 13, 2018.

18. Gehlbach H, Artino Jr AR, Durning SJ. AM last page: survey development guidance for medical education researchers. Acad Med. 2010;85(5):925. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181dd3e88.” Accessed March 10, 2018. PubMed

19. Kraus C, Carlisle T, Carney D. Emergency Medicine Physician Assistant (EMPA) post-graduate training programs: program characteristics and training curricula. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(5):803-807. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2018.6.37892.

20. Shah NH, Rhim HJH, Maniscalco J, Wilson K, Rassbach C. The current state of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships: A survey of program directors. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):324-328. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2571. PubMed

21. Thompson BM, Searle NS, Gruppen LD, Hatem CJ, Nelson E. A national survey of medical education fellowships. Med Educ Online. 2011;16(1):5642. doi: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.5642. PubMed

22. Hooker R. A physician assistant rheumatology fellowship. JAAPA. 2013;26(6):49-52. doi: 10.1097/01.jaa.0000430346.04435.e4 PubMed

23. Keizer T, Trangle M. the benefits of a physician assistant and/or nurse practitioner psychiatric postgraduate training program. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(6):691-694. doi: 10.1007/s40596-015-0331-z. PubMed

24. Miller A, Weiss J, Hill V, Lindaman K, Emory C. Implementation of a postgraduate orthopaedic physician assistant fellowship for improved specialty training. JBJS Journal of Orthopaedics for Physician Assistants. 2017:1. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.jopa.17.00021.

25. Sharma P, Brooks M, Roomiany P, Verma L, Criscione-Schreiber L. physician assistant student training for the inpatient setting. J Physician Assist Educ. 2017;28(4):189-195. doi: 10.1097/jpa.0000000000000174. PubMed

26. Goodwin JS, Salameh H, Zhou J, Singh S, Kuo Y-F, Nattinger AB. Association of hospitalist years of experience with mortality in the hospitalized medicare population. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):196. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7049. PubMed

27. Barnes H. Exploring the factors that influence nurse practitioner role transition. J Nurse Pract. 2015;11(2):178-183. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2014.11.004. PubMed

28. Will K, Williams J, Hilton G, Wilson L, Geyer H. Perceived efficacy and utility of postgraduate physician assistant training programs. JAAPA. 2016;29(3):46-48. doi: 10.1097/01.jaa.0000480569.39885.c8. PubMed

29. Torok H, Lackner C, Landis R, Wright S. Learning needs of physician assistants working in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2011;7(3):190-194. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1001. PubMed

30. Cate O. Competency-based postgraduate medical education: past, present and future. GMS J Med Educ. 2017:34(5). doi: 10.3205/zma001146. PubMed

31. Exploring the ACGME Core Competencies (Part 1 of 7). NEJM Knowledge. https://knowledgeplus.nejm.org/blog/exploring-acgme-core-competencies/. Accessed October 24, 2018.

32. Core Competencies. Core Competencies | Society of Hospital Medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/professional-development/core-competencies/. Accessed October 24, 2018.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine