User login

In reply: Colorectal cancer screening

In Reply: We thank the readers for their interest in our paper.

Drs. Goldstein, Mascitelli, and Rauf point out the concerning epidemiologic increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) among individuals under the age of 50 and suggest folate as a potential cause.1

The underlying cause of the rise in incidence is unknown, and many environmental and lifestyle risk factors have been proposed.2–4 Black men have historically had and continue to have the highest incidence of and stage-adjusted mortality from CRC, but the rise of CRC in the young is a phenomenon in whites.1 Furthermore, these cancers are left-sided. Other known and proposed risk factors associated with this phenomenon include dietary and lifestyle factors such as alcohol consumption, smoking, obesity, and consumption of processed and red meat.5–7

The cohort effect of rising colon and rectal cancer incidence in younger individuals is likely due to changes in the microbiome. Antibiotic exposure is widespread and has been conjectured as a cause, as has folate supplementation, which began in the United States in 1998. Folic acid has been shown to be associated with both protective and harmful effects on colorectal neoplasia.8,9 While Goldstein et al recommend CRC screening starting at an early age in countries with folate supplementation, countries without folate supplementation have also noted a rise in early-onset CRC. For example, in Azerbaijan, the mean age at diagnosis of CRC in 546 individuals was 55.2 ± 11.5, and 23% had an age lower than 40 years. Nearly 60% presented at an advanced stage, and the majority of lesions were in the rectum.10

The impact of the confounding variables and risk factors resulting in the epidemiologic shift in young patients with CRC, along with the biology of the cancers, should be teased out. Once these are known, population screening guidelines can be adjusted. Until then, practitioners should personalize recommendations based on individual risk factors and promptly investigate colonic symptoms, no matter the age of the patient.

We also thank Drs. Joseph Weiss, Nancy Cetel, and Danielle Weiss for their thoughtful analysis of our article. Our intent was to highlight 2 of the most utilized options available for CRC screening and surveillance in the United States. As we pointed out, the choice of test depends on patient preference, family history, and the likelihood of compliance. The goal of any screening program is outreach and adherence, which is optimized when patients are offered a choice of tests.11–13 Table 1 from our article shows the options available.14

When discussing these options with patients, several factors should be taken into consideration. It is important that patients have an understanding of how tests are performed: stool-based vs imaging, bowel prep vs no prep, and frequency of testing.15 Any screening test short of colonoscopy that is positive leads to colonoscopy. Also, programmatic noncolonoscopic screening tests require a system of patient navigation for both positive and negative results. An individual may be more likely to complete 1 test such as screening colonoscopy every 10 years vs another test annually.

A common misconception about computed tomography colonography is that it is similar to computed tomography of the abdomen with a focus on the colon. Individuals may still have to undergo a bowel preparation and dietary restrictions before the procedure. Furthermore, a rectal catheter is used to insufflate and distend the colon prior to capturing images, which many patients find uncomfortable.16 Finally, the incidental discovery of extracolonic lesions may result in unnecessary testing.17

The sensitivity and specificity of each test and operator variability in accuracy and quality should also be highlighted. For example, the sensitivity of a one-time fecal immunochemical test to detect an advanced adenoma may be as low as 25%.18 All testing modalities are diagnostic, but only colonoscopy is therapeutic.

We agree that clinicians who perform CRC screening have an armamentarium of tests to offer, and the advantages and disadvantages of each should be carefully considered and individualized.

- Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017:109(8). doi:10.1093/jnci/djw322

- Rosato V, Bosetti C, Levi F, et al. Risk factors for young-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2013; 24(2):335–341. doi:10.1007/s10552-012-0119-3

- Pearlman R, Frankel WL, Swanson B, et al. Prevalence and spectrum of germline cancer susceptibility gene mutations among patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(4):464–471. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5194

- Stoffel EM, Koeppe E, Everett J, et al. Germline genetic features of young individuals with colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2018; 154(4):897–905. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.004

- Huxley RR, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Clifton P, Czernichow S, Parr CL, Woodward M. The impact of dietary and lifestyle risk factors on risk of colorectal cancer: a quantitative overview of the epidemiological evidence. Int J Cancer 2009; 125(1):171–180. doi:10.1002/ijc.24343

- Yuhara H, Steinmaus C, Cohen SE, et al. Is diabetes mellitus an independent risk factor for colon cancer and rectal cancer? Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106(11):1911–1921. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.301

- Chan DS, Lau R, Aune D, et al. Red and processed meat and colorectal cancer incidence: meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2011; 6(6):e20456. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020456

- Lee JE, Willett WC, Fuchs CS, et al. Folate intake and risk of colorectal cancer and adenoma: modification by time. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 93(4):817–825. doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.007781

- Cole BF, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2007; 297(21):2351–2359. doi:10.1001/jama.297.21.2351

- Mahmodlou R, Mohammadi P, Sepehrvand N. Colorectal cancer in northwestern Iran. ISRN Gastroenterol 2012; 2012:968560. doi:10.5402/2012/968560

- Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172(7):575–582. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.332

- Steinwachs D, Allen JD, Barlow WE, et al. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement: enhancing use and quality of colorectal cancer screening. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152(10):663–667. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-10-201005180-00237

- Subramanian S, Klosterman M, Amonkar MM, Hunt TL. Adherence with colorectal cancer screening guidelines: a review. Prev Med 2004; 38(5):536–550. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.011

- Mankaney G, Sutton RA, Burke CA. Colorectal cancer screening: choosing the right test. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(6):385–392. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.17125

- Tiro JA, Kamineni A, Levin TR, et al. The colorectal cancer screening process in community settings: a conceptual model for the population-based research optimizing screening through personalized regimens consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014; 23(7):1147–1158. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1217

- Plumb A, Ghanouni A, Rees CJ, et al. Patient experience of CT colonography and colonoscopy after fecal occult blood test in a national screening programme. Eur Radiol 2017; 27(3):1052–1063. doi:10.1007/s00330-016-4428-x

- Macari M, Nevsky G, Bonavita J, Kim DC, Megibow AJ, Babb JS. CT colonography in senior versus nonsenior patients: extracolonic findings, recommendations for additional imaging, and polyp prevalence. Radiology 2011; 259(3):767–774. doi:10.1148/radiol.11102144

- Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, et al. Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 85(1):2–21.e3. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.025

In Reply: We thank the readers for their interest in our paper.

Drs. Goldstein, Mascitelli, and Rauf point out the concerning epidemiologic increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) among individuals under the age of 50 and suggest folate as a potential cause.1

The underlying cause of the rise in incidence is unknown, and many environmental and lifestyle risk factors have been proposed.2–4 Black men have historically had and continue to have the highest incidence of and stage-adjusted mortality from CRC, but the rise of CRC in the young is a phenomenon in whites.1 Furthermore, these cancers are left-sided. Other known and proposed risk factors associated with this phenomenon include dietary and lifestyle factors such as alcohol consumption, smoking, obesity, and consumption of processed and red meat.5–7

The cohort effect of rising colon and rectal cancer incidence in younger individuals is likely due to changes in the microbiome. Antibiotic exposure is widespread and has been conjectured as a cause, as has folate supplementation, which began in the United States in 1998. Folic acid has been shown to be associated with both protective and harmful effects on colorectal neoplasia.8,9 While Goldstein et al recommend CRC screening starting at an early age in countries with folate supplementation, countries without folate supplementation have also noted a rise in early-onset CRC. For example, in Azerbaijan, the mean age at diagnosis of CRC in 546 individuals was 55.2 ± 11.5, and 23% had an age lower than 40 years. Nearly 60% presented at an advanced stage, and the majority of lesions were in the rectum.10

The impact of the confounding variables and risk factors resulting in the epidemiologic shift in young patients with CRC, along with the biology of the cancers, should be teased out. Once these are known, population screening guidelines can be adjusted. Until then, practitioners should personalize recommendations based on individual risk factors and promptly investigate colonic symptoms, no matter the age of the patient.

We also thank Drs. Joseph Weiss, Nancy Cetel, and Danielle Weiss for their thoughtful analysis of our article. Our intent was to highlight 2 of the most utilized options available for CRC screening and surveillance in the United States. As we pointed out, the choice of test depends on patient preference, family history, and the likelihood of compliance. The goal of any screening program is outreach and adherence, which is optimized when patients are offered a choice of tests.11–13 Table 1 from our article shows the options available.14

When discussing these options with patients, several factors should be taken into consideration. It is important that patients have an understanding of how tests are performed: stool-based vs imaging, bowel prep vs no prep, and frequency of testing.15 Any screening test short of colonoscopy that is positive leads to colonoscopy. Also, programmatic noncolonoscopic screening tests require a system of patient navigation for both positive and negative results. An individual may be more likely to complete 1 test such as screening colonoscopy every 10 years vs another test annually.

A common misconception about computed tomography colonography is that it is similar to computed tomography of the abdomen with a focus on the colon. Individuals may still have to undergo a bowel preparation and dietary restrictions before the procedure. Furthermore, a rectal catheter is used to insufflate and distend the colon prior to capturing images, which many patients find uncomfortable.16 Finally, the incidental discovery of extracolonic lesions may result in unnecessary testing.17

The sensitivity and specificity of each test and operator variability in accuracy and quality should also be highlighted. For example, the sensitivity of a one-time fecal immunochemical test to detect an advanced adenoma may be as low as 25%.18 All testing modalities are diagnostic, but only colonoscopy is therapeutic.

We agree that clinicians who perform CRC screening have an armamentarium of tests to offer, and the advantages and disadvantages of each should be carefully considered and individualized.

In Reply: We thank the readers for their interest in our paper.

Drs. Goldstein, Mascitelli, and Rauf point out the concerning epidemiologic increase in the incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) among individuals under the age of 50 and suggest folate as a potential cause.1

The underlying cause of the rise in incidence is unknown, and many environmental and lifestyle risk factors have been proposed.2–4 Black men have historically had and continue to have the highest incidence of and stage-adjusted mortality from CRC, but the rise of CRC in the young is a phenomenon in whites.1 Furthermore, these cancers are left-sided. Other known and proposed risk factors associated with this phenomenon include dietary and lifestyle factors such as alcohol consumption, smoking, obesity, and consumption of processed and red meat.5–7

The cohort effect of rising colon and rectal cancer incidence in younger individuals is likely due to changes in the microbiome. Antibiotic exposure is widespread and has been conjectured as a cause, as has folate supplementation, which began in the United States in 1998. Folic acid has been shown to be associated with both protective and harmful effects on colorectal neoplasia.8,9 While Goldstein et al recommend CRC screening starting at an early age in countries with folate supplementation, countries without folate supplementation have also noted a rise in early-onset CRC. For example, in Azerbaijan, the mean age at diagnosis of CRC in 546 individuals was 55.2 ± 11.5, and 23% had an age lower than 40 years. Nearly 60% presented at an advanced stage, and the majority of lesions were in the rectum.10

The impact of the confounding variables and risk factors resulting in the epidemiologic shift in young patients with CRC, along with the biology of the cancers, should be teased out. Once these are known, population screening guidelines can be adjusted. Until then, practitioners should personalize recommendations based on individual risk factors and promptly investigate colonic symptoms, no matter the age of the patient.

We also thank Drs. Joseph Weiss, Nancy Cetel, and Danielle Weiss for their thoughtful analysis of our article. Our intent was to highlight 2 of the most utilized options available for CRC screening and surveillance in the United States. As we pointed out, the choice of test depends on patient preference, family history, and the likelihood of compliance. The goal of any screening program is outreach and adherence, which is optimized when patients are offered a choice of tests.11–13 Table 1 from our article shows the options available.14

When discussing these options with patients, several factors should be taken into consideration. It is important that patients have an understanding of how tests are performed: stool-based vs imaging, bowel prep vs no prep, and frequency of testing.15 Any screening test short of colonoscopy that is positive leads to colonoscopy. Also, programmatic noncolonoscopic screening tests require a system of patient navigation for both positive and negative results. An individual may be more likely to complete 1 test such as screening colonoscopy every 10 years vs another test annually.

A common misconception about computed tomography colonography is that it is similar to computed tomography of the abdomen with a focus on the colon. Individuals may still have to undergo a bowel preparation and dietary restrictions before the procedure. Furthermore, a rectal catheter is used to insufflate and distend the colon prior to capturing images, which many patients find uncomfortable.16 Finally, the incidental discovery of extracolonic lesions may result in unnecessary testing.17

The sensitivity and specificity of each test and operator variability in accuracy and quality should also be highlighted. For example, the sensitivity of a one-time fecal immunochemical test to detect an advanced adenoma may be as low as 25%.18 All testing modalities are diagnostic, but only colonoscopy is therapeutic.

We agree that clinicians who perform CRC screening have an armamentarium of tests to offer, and the advantages and disadvantages of each should be carefully considered and individualized.

- Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017:109(8). doi:10.1093/jnci/djw322

- Rosato V, Bosetti C, Levi F, et al. Risk factors for young-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2013; 24(2):335–341. doi:10.1007/s10552-012-0119-3

- Pearlman R, Frankel WL, Swanson B, et al. Prevalence and spectrum of germline cancer susceptibility gene mutations among patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(4):464–471. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5194

- Stoffel EM, Koeppe E, Everett J, et al. Germline genetic features of young individuals with colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2018; 154(4):897–905. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.004

- Huxley RR, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Clifton P, Czernichow S, Parr CL, Woodward M. The impact of dietary and lifestyle risk factors on risk of colorectal cancer: a quantitative overview of the epidemiological evidence. Int J Cancer 2009; 125(1):171–180. doi:10.1002/ijc.24343

- Yuhara H, Steinmaus C, Cohen SE, et al. Is diabetes mellitus an independent risk factor for colon cancer and rectal cancer? Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106(11):1911–1921. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.301

- Chan DS, Lau R, Aune D, et al. Red and processed meat and colorectal cancer incidence: meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2011; 6(6):e20456. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020456

- Lee JE, Willett WC, Fuchs CS, et al. Folate intake and risk of colorectal cancer and adenoma: modification by time. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 93(4):817–825. doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.007781

- Cole BF, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2007; 297(21):2351–2359. doi:10.1001/jama.297.21.2351

- Mahmodlou R, Mohammadi P, Sepehrvand N. Colorectal cancer in northwestern Iran. ISRN Gastroenterol 2012; 2012:968560. doi:10.5402/2012/968560

- Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172(7):575–582. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.332

- Steinwachs D, Allen JD, Barlow WE, et al. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement: enhancing use and quality of colorectal cancer screening. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152(10):663–667. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-10-201005180-00237

- Subramanian S, Klosterman M, Amonkar MM, Hunt TL. Adherence with colorectal cancer screening guidelines: a review. Prev Med 2004; 38(5):536–550. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.011

- Mankaney G, Sutton RA, Burke CA. Colorectal cancer screening: choosing the right test. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(6):385–392. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.17125

- Tiro JA, Kamineni A, Levin TR, et al. The colorectal cancer screening process in community settings: a conceptual model for the population-based research optimizing screening through personalized regimens consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014; 23(7):1147–1158. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1217

- Plumb A, Ghanouni A, Rees CJ, et al. Patient experience of CT colonography and colonoscopy after fecal occult blood test in a national screening programme. Eur Radiol 2017; 27(3):1052–1063. doi:10.1007/s00330-016-4428-x

- Macari M, Nevsky G, Bonavita J, Kim DC, Megibow AJ, Babb JS. CT colonography in senior versus nonsenior patients: extracolonic findings, recommendations for additional imaging, and polyp prevalence. Radiology 2011; 259(3):767–774. doi:10.1148/radiol.11102144

- Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, et al. Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 85(1):2–21.e3. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.025

- Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017:109(8). doi:10.1093/jnci/djw322

- Rosato V, Bosetti C, Levi F, et al. Risk factors for young-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2013; 24(2):335–341. doi:10.1007/s10552-012-0119-3

- Pearlman R, Frankel WL, Swanson B, et al. Prevalence and spectrum of germline cancer susceptibility gene mutations among patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(4):464–471. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5194

- Stoffel EM, Koeppe E, Everett J, et al. Germline genetic features of young individuals with colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2018; 154(4):897–905. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.004

- Huxley RR, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Clifton P, Czernichow S, Parr CL, Woodward M. The impact of dietary and lifestyle risk factors on risk of colorectal cancer: a quantitative overview of the epidemiological evidence. Int J Cancer 2009; 125(1):171–180. doi:10.1002/ijc.24343

- Yuhara H, Steinmaus C, Cohen SE, et al. Is diabetes mellitus an independent risk factor for colon cancer and rectal cancer? Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106(11):1911–1921. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.301

- Chan DS, Lau R, Aune D, et al. Red and processed meat and colorectal cancer incidence: meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2011; 6(6):e20456. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020456

- Lee JE, Willett WC, Fuchs CS, et al. Folate intake and risk of colorectal cancer and adenoma: modification by time. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 93(4):817–825. doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.007781

- Cole BF, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al. Folic acid for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2007; 297(21):2351–2359. doi:10.1001/jama.297.21.2351

- Mahmodlou R, Mohammadi P, Sepehrvand N. Colorectal cancer in northwestern Iran. ISRN Gastroenterol 2012; 2012:968560. doi:10.5402/2012/968560

- Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172(7):575–582. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.332

- Steinwachs D, Allen JD, Barlow WE, et al. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement: enhancing use and quality of colorectal cancer screening. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152(10):663–667. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-10-201005180-00237

- Subramanian S, Klosterman M, Amonkar MM, Hunt TL. Adherence with colorectal cancer screening guidelines: a review. Prev Med 2004; 38(5):536–550. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.011

- Mankaney G, Sutton RA, Burke CA. Colorectal cancer screening: choosing the right test. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(6):385–392. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.17125

- Tiro JA, Kamineni A, Levin TR, et al. The colorectal cancer screening process in community settings: a conceptual model for the population-based research optimizing screening through personalized regimens consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014; 23(7):1147–1158. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1217

- Plumb A, Ghanouni A, Rees CJ, et al. Patient experience of CT colonography and colonoscopy after fecal occult blood test in a national screening programme. Eur Radiol 2017; 27(3):1052–1063. doi:10.1007/s00330-016-4428-x

- Macari M, Nevsky G, Bonavita J, Kim DC, Megibow AJ, Babb JS. CT colonography in senior versus nonsenior patients: extracolonic findings, recommendations for additional imaging, and polyp prevalence. Radiology 2011; 259(3):767–774. doi:10.1148/radiol.11102144

- Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, et al. Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 85(1):2–21.e3. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.025

Colorectal cancer screening: Choosing the right test

Screening can help prevent colorectal cancer. The United States has seen a steady decline in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality, thanks in large part to screening. Screening rates can be increased with good patient-physician dialogue and by choosing a method the patient prefers and is most likely to complete.

In this article, we review a general approach to screening, focusing on the most commonly used methods in the United States, ie, the guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (FOBT), the fecal immunochemical test (FIT), and colonoscopy. We discuss current colorectal cancer incidence rates, screening recommendations, and how to choose the appropriate screening test.

This article does not discuss patients at high risk of polyps or cancer due to hereditary colon cancer syndromes, a personal history of colorectal neoplasia, inflammatory bowel disease, or primary sclerosing cholangitis.

TRENDS IN INCIDENCE

Colorectal cancer is the second most common type of cancer and cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, responsible for an estimated 50,000 deaths in 2017. The lifetime risk of its occurrence is estimated to be 1 in 21 men and 1 in 23 women.1 Encouragingly, the incidence has declined by 24% over the last 30 years,2 and by 3% per year from 2004 to 2013.1 Also, as a result of screening and advances in treatment, 5-year survival rates for patients with colorectal cancer have increased, from 48.6% in 1975 to 66.4% in 2009.2

When detected at a localized stage, the 5-year survival rate in colorectal cancer is greater than 90%. Unfortunately, it is diagnosed early in only 39% of patients. And despite advances in treatment and a doubling of the 5-year survival rate in patients with advanced cancers since 1990,3 the latter is only 14%. In most patients, cancer is diagnosed when it has spread to the lymph nodes (36%) or to distant organs (22%), and the survival rate declines to 71% after lymph-node spread, and 14% after metastasis to distant organs.

It is essential to screen people who have no symptoms, as symptoms such as gastrointestinal bleeding, unexplained abdominal pain or weight loss, a persistent change in bowel movements, and bowel obstruction typically do not arise until the disease is advanced and less amenable to cure.

Increasing prevalence in younger adults

Curiously, the incidence of colorectal cancer is increasing in white US adults under age 50. Over the last 30 years, incidence rates have increased from 1.0% to 2.4% annually in adults ages 20 to 39.4 Based on current trends, colon cancer rates are expected to increase by 90% for patients ages 20 to 34 and by 28% for patients 35 to 49 by 2030.5

Although recommendations vary for colorectal cancer screening in patients under age 50, clinicians should investigate symptoms such as rectal bleeding, unexplained iron deficiency anemia, progressive abdominal pain, and persistent changes in bowel movements.

Other challenges

Despite the benefits of screening, it is underutilized. Although rates of compliance with screening recommendations have increased 10% over the last 10 years, only 65% of eligible adults currently comply.1,6

Additionally, certain areas of the country such as Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta have not benefited from the decline in the national rate of colorectal cancer.7

SCREENING GUIDELINES

Most guidelines say that colorectal cancer screening should begin at age 50 in people at average risk with no symptoms. However, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommends beginning screening at age 45 in African Americans, as this group has higher incidence and mortality rates of colorectal cancer.8 Also, the American Cancer Society recently recommended beginning screening at age 45 for all individuals.9

Screening can stop at age 75 for most patients, according to the ACG,8 the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer,10 and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).11 However, the decision should be individualized for patients ages 76 to 85. Patients within that age group who are in good health and have not previously been screened are more likely to benefit than those who have previously been screened and had a negative screening test. Patients over age 85 should not begin or continue screening, because of diminished benefit of screening in this age group, shorter life expectancy, advanced comorbid conditions, and the risks of colonoscopy and cancer treatment.

Patients and clinicians are encouraged to collaborate in deciding which screening method is appropriate. Patients adhere better when they are given a choice in the matter.12–14 And adherence is the key to effective colorectal cancer screening.

Familiarity with the key characteristics of currently available colorectal cancer screening tests will facilitate discussion with patients.

Opportunistic vs programmatic screening

Screening can be classified according to the approach to the patient or population and the intent of the test. Most screening in the United States is opportunistic rather than programmatic—that is, the physician offers the patient screening at the point of service without systematic follow-up or patient re-engagement.

In a programmatic approach, the patient is offered screening through an organized program that streamlines services, reduces overscreening, and provides systematic follow-up of testing.

DISCUSSING THE OPTIONS

Stool studies such as FOBT and FIT do not reliably detect cancer precursors such as adenomas and serrated neoplasms. If an FOBT is positive, follow-up diagnostic colonoscopy is required. Unlike screening colonoscopy, diagnostic colonoscopy requires a copayment for Medicare patients, and this should be explained to the patient.

FIT and FOBT detect hemolyzed blood within a stool sample, FOBT by a chemical reaction, and FIT by detecting a globin-specific antibody. Colorectal cancer and some large adenomatous polyps may intermittently bleed and result in occult blood in the stool, iron deficiency anemia, or hematochezia.15

Fecal occult blood testing

Historically, FOBT was the stool test of choice for screening. It uses an indirect enzymatic reaction to detect hemolyzed blood in the stool. When a specimen containing hemoglobin is added to guaiac paper and a drop of hydrogen peroxide is added to “develop” it, the peroxidase activity of hemoglobin turns the guaiac blue.

Screening with FOBT involves annual testing of 3 consecutively passed stools from different days; FOBT should not be performed at the time of digital rectal examination or if the patient is having overt rectal, urinary, or menstrual bleeding.

Dietary and medication restrictions before and during the testing period are critical, as red meat contains hemoglobin, and certain vegetables (eg, radishes, turnips, cauliflower, cucumbers) contain peroxidase, all of which can cause a false-positive result. Waiting 3 days after the stool sample is collected to develop it can mitigate the peroxidase activity of vegetables.16 Vitamin C inhibits heme peroxidase activity and leads to false-negative results. Aspirin and high-dose nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can promote bleeding throughout the intestinal tract.17

In randomized controlled trials,18–21 screening with FOBT reduced colorectal cancer mortality rates by 15% to 33%. The 30-year follow-up of a large US trial22 found a 32% relative reduction in mortality rates in patients randomized to annual screening, and a 22% relative reduction in those randomized to screening every 2 years. Despite the many possibilities for false-positive results, the specificity for detecting cancer has ranged from 86.7% to 97.3%, and the sensitivity from 37.1% to 79.4%, highlighting the benefit of colorectal cancer screening programs in unscreened populations.23–26

FIT vs FOBT in current practice

FIT should replace FOBT as the preferred stool screening method. Instead of an enzymatic reaction that can be altered by food or medication, FIT utilizes an antibody specific to human globin to directly detect hemolyzed blood, thus eliminating the need to modify the diet or medications.27 Additionally, only 1 stool specimen is needed, which may explain why the adherence rate was about 20% higher with FIT than with FOBT in most studies.28–30

FIT has a sensitivity of 69% to 86% for colorectal cancer and a specificity of 92% to 95%.31 The sensitivity can be improved by lowering the threshold value for a positive test, but this is associated with a decrease in specificity. A single FIT has the same sensitivity and specificity as several samples.32

In a large retrospective US cohort study of programmatic screening with FIT, Jensen et al33 reported that 48% of 670,841 people who were offered testing actually did the test. Of the 48% who participated in the first round and remained eligible, 75% to 86% participated in subsequent rounds over 4 years. Those who had a positive result on FIT were supposed to undergo colonoscopy, but 22% did not.

The US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer34 suggests that FIT-based screening programs aim for a target FIT completion rate of more than 60% and a target colonoscopy completion rate of more than 80% of patients with positive FITs. These benchmarks were derived from adherence rates in international FIT screening studies in average-risk populations.35–39 (Note that the large US cohort described above33 did not meet these goals.) Ideally, every patient with a positive FIT should undergo diagnostic colonoscopy, but in reality only 50% to 83% actually do. Methods shown to improve adherence include structured screening programs with routine performance reports, provider feedback, and involvement of patient navigators.40–42

Accordingly, several aspects of stool-based testing need to be stressed with patients. Understanding that FOBT is recommended yearly is integral for optimal impact on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality rates.

Additionally, patients should be advised to undergo colonoscopy soon after a positive FIT, because delaying colonoscopy could give precancerous lesions time to progress in stage. The acceptable time between a positive FIT and colonoscopy has yet to be determined. However, a retrospective cohort study of 1.26 million screened patients with 107,000 positive FIT results demonstrated that the rates of cancer discovered on colonoscopy were similar when performed within 30 days or up to 10 months after a positive test. Detection rates increased from 3% to 4.8% at 10 months and to 7.9% at 12 months.43

In modeling studies, Meester et al44 showed the estimated lifetime risk and mortality rates from colorectal cancer and life-years gained from screening are significantly better when colonoscopy is completed within 2 weeks rather than 1 year after a positive FIT. Each additional month after 2 weeks incrementally affected these outcomes, with a 1.4% increase in cancer mortality. These data suggest that colonoscopy should be done soon after a positive FIT result and at a maximum of 10 months.43,44

Screening with FOBT is a multistep process for patients that includes receiving the test kit, collecting the sample, preparing it, returning it, undergoing colonoscopy after a positive test, and repeating in 1 year if negative. The screening program should identify patients at average risk in whom screening is appropriate, ensure delivery of the test, verify the quality of collected samples for laboratory testing against the manufacturer’s recommendations, and report results. Report of a positive FOBT result should provide recommendations for follow-up.

Though evidence clearly supports screening annually or biennially (every 2 years) with FOBT, the ideal interval for FIT is undetermined. Modeling studies utilized by the USPSTF and Multi-Society Task Force demonstrate that colonoscopy and annual FIT result in similar life-years gained, while 2 population-based screening programs have demonstrated that a 2- or 3-year interval may be equally efficacious by lowering the threshold for a positive test.38,45

Randomized controlled trials of screening colonoscopy vs annual and biennial FIT are currently under way. Cost-effectiveness analysis has shown that offering single-sample FITs at more frequent (annual) intervals performs better than multisample testing at less frequent intervals.45–47

Colonoscopy

Compared with stool-based screening, colonoscopy has advantages, including a 10-year screening interval if bowel preparation is adequate and the examination shows no neoplasia, the ability to inspect the entire colon, and the ability to diagnose and treat lesions in the same session.

Screening colonoscopy visualizes the entire colon in more than 98% of cases, although it requires adequate bowel preparation for maximal polyp detection. It can be done safely with or without sedation.48

While there are no available randomized controlled trial data on the impact of screening colonoscopy on cancer incidence or mortality, extensive case-control and cohort studies consistently show that screening colonoscopy reduces cancer incidence and mortality rates.49–54 A US Veterans Administration study of more than 32,000 patients reported a 50% reduction in overall colorectal cancer mortality.55 In a microsimulation modeling study that assumed 100% adherence, colonoscopy every 10 years and annual FIT in individuals ages 50 to 75 provided similar life-years gained per 1,000 people screened (270 for colonoscopy, 244 for FIT).56

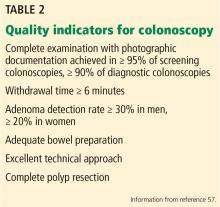

Well-established metrics for maximizing the effectiveness and quality of colonoscopy have been established (Table 2). The most important include the mucosa inspection time (withdrawal time) and adenoma detection rate.57 Withdrawal time is directly correlated with adenoma detection, and a 6-minute minimum withdrawal time is recommended in screening colonoscopy examinations of patients at average risk when no polyps are found.58 The adenoma detection rate is the strongest evidence-based metric, as each 1% increase in the adenoma detection rate over 19% is associated with a 3% decrease in the risk of colorectal cancer and a 5% decrease in death rate.59 The average-risk screening adenoma detection rate differs based on sex: the rate is greater than 20% for women and greater than 30% for men.

Complications from screening, diagnostic, or therapeutic colonoscopy are infrequent but include perforation (4/10,000) and significant intestinal bleeding (8/10,000).56–62

Patients with a first-degree relative under age 60 with advanced adenomas or colorectal cancer are considered at high risk and should begin screening colonoscopy at age 40, with repeat colonoscopy at 5-year intervals, given a trend toward advanced neoplasia detection compared with FIT.63

Guidelines recently published by the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology and endorsed by the American Gastroenterological Association also support starting screening in high-risk individuals at age 40, with a surveillance interval of 5 to 10 years based on the number of first-degree relatives with colorectal cancer or adenomas.64 Consensus statements were based on retrospective cohort, prospective case-controlled, and cross-sectional studies comparing the risk of colorectal cancer in individuals with a family history against those without a family history.

Randomized clinical trials comparing colonoscopy and FIT are under way. Interim analysis of a European trial in which asymptomatic adults ages 50 to 69 were randomized to 1-time colonoscopy (26,703 patients) vs FIT every 2 years (26,599 patients) found significantly higher participation rates in the FIT arm (34.2% vs 24.6%) but higher rates of nonadvanced adenomas (4.2% vs 0.4%) and advanced neoplasia (1.9% vs 0.9%) in the colonoscopy arm.65 Cancer was detected in 0.1% in each arm. These findings correlate with those of another study showing higher participation with FIT but higher advanced neoplasia detection rates with colonoscopy.66

Detection of precursor lesions is vital, as removing neoplasms is the main strategy to reduce colorectal cancer incidence. Accordingly, the advantage of colonoscopy was illustrated by a study that determined that 53 patients would need to undergo screening colonoscopy to detect 1 advanced adenoma or cancerous lesion, compared with 264 for FIT.67

STARTING SCREEING AT AGE 45

The American Cancer Society recently provided a qualified recommendation to start colorectal cancer screening in all individuals at age 45 rather than 50.9 This recommendation was based on modeling studies demonstrating that starting screening at age 45 with colonoscopy every 10 years resulted in 25 life-years gained at the cost of 610 colonoscopies per 1,000 individuals. Alternative strategies included FIT, which resulted in an additional 26 life-years gained per 1,000 individuals screened, flexible sigmoidoscopy (23 life-years gained), and computed tomographic colonoscopy (22 life-years gained).

Rates of colorectal cancer are rising in adults under age 50, and 10,000 new cases are anticipated this year.2,3 Currently, 22 million US adults are between the ages of 45 and 50. The system and support needed to perform screening in all adults over age 45 and a lack of direct evidence to support its benefits in the young population need to be considered before widespread acceptance of the American Cancer Society recommendations. However, if screening is considered, FIT with or without sigmoidoscopy may be appropriate, given that most cancers diagnosed in individuals under age 50 are left-sided.4,5

Screening has not been proven to reduce all-cause mortality. Randomized controlled trials of FOBT and observational studies of colonoscopy show that screening reduces cancer incidence and mortality. Until the currently ongoing randomized controlled trials comparing colonoscopy with FIT are completed, their comparative impact on colorectal cancer end points is unknown.

PATIENT ADHERENCE IS KEY

FIT and colonoscopy are the most prevalent screening methods in the United States. Careful attention should be given to offer the screening option the patient is most likely to complete, as adherence is key to the benefit from colorectal cancer screening.

The National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable (nccrt.org), established in 1997 by the American Cancer Society and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is a national coalition of public and private organizations dedicated to reducing colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. The Roundtable waged a national campaign to achieve a colorectal cancer screening rate of 80% in eligible adults by 2018, a goal that was not met. Still, the potential for a substantial impact is a compelling reason to endorse adherence to colorectal cancer screening. The Roundtable provides many resources for physicians to enhance screening in their practice.

The United States has seen a steady decline in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality, mainly as a result of screening. Colorectal cancer is preventable with ensuring patients’ adherence to screening. Screening rates have been shown to increase with patient-provider dialogue and with selection of a screening program the patient prefers and is most likely to complete.

- American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2017–2019. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2017. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures-2017-2019.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67(3):177–193. doi:10.3322/caac.21395

- Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(22):3677–3683. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278

- Siegel RL, Jemal A, Ward EM. Increase in incidence of colorectal cancer among young men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009; 18(6):1695–1698. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0186

- Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. JAMA Surg 2015; 150(1):17–22. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1756

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening test use—United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62(44):881–888. pmid:24196665

- Siegel RL, Sahar L, Robbins A, Jemal A. Where can colorectal cancer screening interventions have the most impact? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015; 24(8):1151–1156. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0082

- Agrawal S, Bhupinderjit A, Bhutani MS, et al; Committee of Minority Affairs and Cultural Diversity, American College of Gastroenterology. Colorectal cancer in African Americans. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100(3):515–523. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41829.x

- Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68(4):250–281. doi:10.3322/caac.21457

- Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112(7):1016–1030. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.174

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2016; 315(23):2564–2575. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.5989

- Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172(7):575–582. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.332

- Steinwachs D, Allen JD, Barlow WE, et al. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement: enhancing use and quality of colorectal cancer screening. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152(10):663–667. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-10-201005180-00237

- Subramanian S, Klosterman M, Amonkar MM, Hunt TL. Adherence with colorectal cancer screening guidelines: a review. Prev Med 2004; 38(5):536–550. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.011

- Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al; American Cancer Society Colorectal Cancer Advisory Group; US Multi-Society Task Force; American College of Radiology Colon Cancer Committee. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin 2008; 58(3):130–160. doi:10.3322/CA.2007.0018

- Sinatra MA, St John DJ, Young GP. Interference of plant peroxidases with guaiac-based fecal occult blood tests is avoidable. Clin Chem 1999; 45(1):123–126. pmid:9895348

- Allison JE, Sakoda LC, Levin TR, et al. Screening for colorectal neoplasms with new fecal occult blood tests: update on performance characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007; 99(19):1462–1470. doi:10.1093/jnci/djm150

- Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med 1993; 328(19):1365–1371. doi:10.1056/NEJM199305133281901

- Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet 1996; 348(9040):1472–1477. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7

- Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jørgensen OD, Søndergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet 1996; 348(9040):1467–1471. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7

- Wilson JMG, Junger G. Principles and practice of screening for disease. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1968. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/37650/WHO_PHP_34.pdf?sequence=17. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(12):1106–1114. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1300720

- Allison JE, Tekawa IS, Ransom LJ, Adrain AL. A comparison of fecal occult-blood tests for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 1996; 334(3):155–159. doi:10.1056/NEJM199601183340304

- Shapiro JA, Bobo JK, Church TR, et al. A comparison of fecal immunochemical and high-sensitivity guaiac tests for colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112(11):1728–1735. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.285

- Smith A, Young GP, Cole SR, Bampton P. Comparison of a brush-sampling fecal immunochemical test for hemoglobin with a sensitive guaiac-based fecal occult blood test in detection of colorectal neoplasia. Cancer 2006; 107(9):2152–2159. doi:10.1002/cncr.22230

- Brenner H, Tao S. Superior diagnostic performance of faecal immunochemical tests for haemoglobin in a head-to-head comparison with guaiac based faecal occult blood test among 2235 participants of screening colonoscopy. Eur J Cancer 2013; 49(14):3049–3054. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2013.04.023

- Young GP, Cole S. New stool screening tests for colorectal cancer. Digestion 2007; 76(1):26–33. doi:10.1159/000108391

- van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, Laheij RJ, et al. Random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer in a screening population. Gastroenterology 2008; 135(1):82–90. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.040

- Hassan C, Giorgi Rossi P, Camilloni L, et al. Meta-analysis: adherence to colorectal cancer screening and the detection rate for advanced neoplasia, according to the type of screening test. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 36(10):929–940. doi:10.1111/apt.12071

- Vart G, Banzi R, Minozzi S. Comparing participation rates between immunochemical and guaiac faecal occult blood tests: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 2012; 55(2):87–92. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.05.006

- Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(14):1287–1297. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1311194

- Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, Levin TR, Corley DA. Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160(3):171. doi:10.7326/M13-1484

- Jensen CD, Corley DA, Quinn VP, et al. Fecal immunochemical test program performance over 4 rounds of annual screening: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2016; 164(7):456–463. doi:10.7326/M15-0983

- Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, et al. Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2017; 152(5):1217–1237.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.08.053

- Rabeneck L, Rumble RB, Thompson F, et al. Fecal immunochemical tests compared with guaiac fecal occult blood tests for population-based colorectal cancer screening. Can J Gastroenterol 2012; 26(3):131–147. pmid:22408764

- Logan RF, Patnick J, Nickerson C, Coleman L, Rutter MD, von Wagner C; English Bowel Cancer Screening Evaluation Committee. Outcomes of the Bowel Cancer Screening Programme (BCSP) in England after the first 1 million tests. Gut 2012; 61(10):1439–1446. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300843

- Malila N, Oivanen T, Malminiemi O, Hakama M. Test, episode, and programme sensitivities of screening for colorectal cancer as a public health policy in Finland: experimental design. BMJ 2008; 337:a2261. doi:10.1136/bmj.a2261

- Denters MJ, Deutekom M, Bossuyt PM, Stroobants AK, Fockens P, Dekker E. Lower risk of advanced neoplasia among patients with a previous negative result from a fecal test for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2012; 142(3):497–504. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.024

- van Roon AH, Goede SL, van Ballegooijen M, et al. Random comparison of repeated faecal immunochemical testing at different intervals for population-based colorectal cancer screening. Gut 2013; 62(3):409–415. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301583

- Chubak J, Garcia MP, Burnett-Hartman AN, et al; PROSPR consortium. Time to colonoscopy after positive fecal blood test in four US health care systems. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2016; 25(2):344–350. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0470

- Carlson CM, Kirby KA, Casadei MA, Partin MR, Kistler CE, Walter LC. Lack of follow-up after fecal occult blood testing in older adults: inappropriate screening or failure to follow up? Arch Intern Med 2011; 171(3):249–256. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.372

- Selby K, Baumgartner C, Levin TR, et al. Interventions to improve follow-up of positive results on fecal blood tests: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2017; 167(8):565–575. doi:10.7326/M17-1361

- Corley DA, Jensen CD, Quinn VP, et al. Association between time to colonoscopy after a positive fecal test result and risk of colorectal cancer and cancer stage at diagnosis. JAMA 2017; 317(16):1631–1641. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.3634

- Meester RG, Zauber AG, Doubeni CA, et al. Consequences of increasing time to colonoscopy examination after positive result from fecal colorectal cancer screening test. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 14(10):1445–1451.e8. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2016.05.017

- Haug U, Grobbee EJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Spaander MCW, Kuipers EJ. Immunochemical faecal occult blood testing to screen for colorectal cancer: can the screening interval be extended? Gut 2017; 66(7):1262–1267. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310102

- Goede SL, van Roon AH, Reijerink JC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of one versus two sample faecal immunochemical testing for colorectal cancer screening. Gut 2013; 62(5):727–734. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301917

- Digby J, Fraser CG, Carey FA, Steele RJC. Can the performance of a quantitative FIT-based colorectal cancer screening programme be enhanced by lowering the threshold and increasing the interval? Gut 2018; 67(5):993–994. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314862

- Hoffman MS, Butler TW, Shaver T. Colonoscopy without sedation. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998; 26(4):279–282. pmid:9649011

- Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med 2012; 366(8):687–696. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1100370

- Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(12):1095–1105. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1301969

- Løberg M, Kalager M, Holme Ø, Hoff G, Adami HO, Bretthauer M. Long-term colorectal-cancer mortality after adenoma removal. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(9):799–807. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1315870

- Manser CN, Bachmann LM, Brunner J, Hunold F, Bauerfeind P, Marbet UA. Colonoscopy screening markedly reduces the occurrence of colon carcinomas and carcinoma-related death: a closed cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 76(1):110–117. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2012.02.040

- Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med 1993; 329(27):1977–1981. doi:10.1056/NEJM199312303292701

- Citarda F, Tomaselli G, Capocaccia R, Barcherini S, Crespi M; Italian Multicentre Study Group. Efficacy in standard clinical practice of colonoscopic polypectomy in reducing colorectal cancer incidence. Gut 2001; 48(6):812–815. pmid:11358901

- Muller AD, Sonnenberg A. Prevention of colorectal cancer by flexible endoscopy and polypectomy. A case-control study of 32,702 veterans. Ann Intern Med 1995; 123(12):904–910. pmid:7486484

- Knudsen AB, Zauber AG, Rutter CM, et al. Estimation of benefits, burden, and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2016; 315(23):2595–2609. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.6828

- Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81(1):31–53. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2014.07.058

- Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, Johanson JF, Greenlaw RL. Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(24):2533–2541. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055498

- Corley DA, Levin TR, Doubeni CA. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(26):2541. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1405329

- Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2016; 315(23):2576–2594. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.3332

- Gatto NM, Frucht H, Sundararajan V, Jacobson JS, Grann VR, Neugut AI. Risk of perforation after colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy: a population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003; 95(3):230–236. pmid:12569145

- Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Mariotto AB, et al. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150(12):849–857, W152. pmid:19528563

- Quintero E, Carrillo M, Gimeno-García AZ, et al. Equivalency of fecal immunochemical tests and colonoscopy in familial colorectal cancer screening. Gastroenterology 2014; 147(5):1021–130.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.004

- Leddin D, Lieberman DA, Tse F, et al. Clinical practice guideline on screening for colorectal cancer in individuals with a family history of nonhereditary colorectal cancer or adenoma: the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Banff Consensus. Gastroenterology 2018; 155(5):1325–1347.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.017

- Quintero E, Castells A, Bujanda L, et al; COLONPREV Study Investigators. Colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical testing in colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 2012; 366(8):697–706. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1108895

- Gupta S, Halm EA, Rockey DC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of fecal immunochemical test outreach, colonoscopy outreach, and usual care for boosting colorectal cancer screening among the underserved: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173(18):1725–1732. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9294

- Segnan N, Senore C, Andreoni B, et al; SCORE3 Working Group-Italy. Comparing attendance and detection rate of colonoscopy with sigmoidoscopy and FIT for colorectal cancer screening. Gastroenterology 2007; 132(7):2304–2312. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.030

Screening can help prevent colorectal cancer. The United States has seen a steady decline in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality, thanks in large part to screening. Screening rates can be increased with good patient-physician dialogue and by choosing a method the patient prefers and is most likely to complete.

In this article, we review a general approach to screening, focusing on the most commonly used methods in the United States, ie, the guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (FOBT), the fecal immunochemical test (FIT), and colonoscopy. We discuss current colorectal cancer incidence rates, screening recommendations, and how to choose the appropriate screening test.

This article does not discuss patients at high risk of polyps or cancer due to hereditary colon cancer syndromes, a personal history of colorectal neoplasia, inflammatory bowel disease, or primary sclerosing cholangitis.

TRENDS IN INCIDENCE

Colorectal cancer is the second most common type of cancer and cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, responsible for an estimated 50,000 deaths in 2017. The lifetime risk of its occurrence is estimated to be 1 in 21 men and 1 in 23 women.1 Encouragingly, the incidence has declined by 24% over the last 30 years,2 and by 3% per year from 2004 to 2013.1 Also, as a result of screening and advances in treatment, 5-year survival rates for patients with colorectal cancer have increased, from 48.6% in 1975 to 66.4% in 2009.2

When detected at a localized stage, the 5-year survival rate in colorectal cancer is greater than 90%. Unfortunately, it is diagnosed early in only 39% of patients. And despite advances in treatment and a doubling of the 5-year survival rate in patients with advanced cancers since 1990,3 the latter is only 14%. In most patients, cancer is diagnosed when it has spread to the lymph nodes (36%) or to distant organs (22%), and the survival rate declines to 71% after lymph-node spread, and 14% after metastasis to distant organs.

It is essential to screen people who have no symptoms, as symptoms such as gastrointestinal bleeding, unexplained abdominal pain or weight loss, a persistent change in bowel movements, and bowel obstruction typically do not arise until the disease is advanced and less amenable to cure.

Increasing prevalence in younger adults

Curiously, the incidence of colorectal cancer is increasing in white US adults under age 50. Over the last 30 years, incidence rates have increased from 1.0% to 2.4% annually in adults ages 20 to 39.4 Based on current trends, colon cancer rates are expected to increase by 90% for patients ages 20 to 34 and by 28% for patients 35 to 49 by 2030.5

Although recommendations vary for colorectal cancer screening in patients under age 50, clinicians should investigate symptoms such as rectal bleeding, unexplained iron deficiency anemia, progressive abdominal pain, and persistent changes in bowel movements.

Other challenges

Despite the benefits of screening, it is underutilized. Although rates of compliance with screening recommendations have increased 10% over the last 10 years, only 65% of eligible adults currently comply.1,6

Additionally, certain areas of the country such as Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta have not benefited from the decline in the national rate of colorectal cancer.7

SCREENING GUIDELINES

Most guidelines say that colorectal cancer screening should begin at age 50 in people at average risk with no symptoms. However, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommends beginning screening at age 45 in African Americans, as this group has higher incidence and mortality rates of colorectal cancer.8 Also, the American Cancer Society recently recommended beginning screening at age 45 for all individuals.9

Screening can stop at age 75 for most patients, according to the ACG,8 the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer,10 and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).11 However, the decision should be individualized for patients ages 76 to 85. Patients within that age group who are in good health and have not previously been screened are more likely to benefit than those who have previously been screened and had a negative screening test. Patients over age 85 should not begin or continue screening, because of diminished benefit of screening in this age group, shorter life expectancy, advanced comorbid conditions, and the risks of colonoscopy and cancer treatment.

Patients and clinicians are encouraged to collaborate in deciding which screening method is appropriate. Patients adhere better when they are given a choice in the matter.12–14 And adherence is the key to effective colorectal cancer screening.

Familiarity with the key characteristics of currently available colorectal cancer screening tests will facilitate discussion with patients.

Opportunistic vs programmatic screening

Screening can be classified according to the approach to the patient or population and the intent of the test. Most screening in the United States is opportunistic rather than programmatic—that is, the physician offers the patient screening at the point of service without systematic follow-up or patient re-engagement.

In a programmatic approach, the patient is offered screening through an organized program that streamlines services, reduces overscreening, and provides systematic follow-up of testing.

DISCUSSING THE OPTIONS

Stool studies such as FOBT and FIT do not reliably detect cancer precursors such as adenomas and serrated neoplasms. If an FOBT is positive, follow-up diagnostic colonoscopy is required. Unlike screening colonoscopy, diagnostic colonoscopy requires a copayment for Medicare patients, and this should be explained to the patient.

FIT and FOBT detect hemolyzed blood within a stool sample, FOBT by a chemical reaction, and FIT by detecting a globin-specific antibody. Colorectal cancer and some large adenomatous polyps may intermittently bleed and result in occult blood in the stool, iron deficiency anemia, or hematochezia.15

Fecal occult blood testing

Historically, FOBT was the stool test of choice for screening. It uses an indirect enzymatic reaction to detect hemolyzed blood in the stool. When a specimen containing hemoglobin is added to guaiac paper and a drop of hydrogen peroxide is added to “develop” it, the peroxidase activity of hemoglobin turns the guaiac blue.

Screening with FOBT involves annual testing of 3 consecutively passed stools from different days; FOBT should not be performed at the time of digital rectal examination or if the patient is having overt rectal, urinary, or menstrual bleeding.

Dietary and medication restrictions before and during the testing period are critical, as red meat contains hemoglobin, and certain vegetables (eg, radishes, turnips, cauliflower, cucumbers) contain peroxidase, all of which can cause a false-positive result. Waiting 3 days after the stool sample is collected to develop it can mitigate the peroxidase activity of vegetables.16 Vitamin C inhibits heme peroxidase activity and leads to false-negative results. Aspirin and high-dose nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can promote bleeding throughout the intestinal tract.17

In randomized controlled trials,18–21 screening with FOBT reduced colorectal cancer mortality rates by 15% to 33%. The 30-year follow-up of a large US trial22 found a 32% relative reduction in mortality rates in patients randomized to annual screening, and a 22% relative reduction in those randomized to screening every 2 years. Despite the many possibilities for false-positive results, the specificity for detecting cancer has ranged from 86.7% to 97.3%, and the sensitivity from 37.1% to 79.4%, highlighting the benefit of colorectal cancer screening programs in unscreened populations.23–26

FIT vs FOBT in current practice

FIT should replace FOBT as the preferred stool screening method. Instead of an enzymatic reaction that can be altered by food or medication, FIT utilizes an antibody specific to human globin to directly detect hemolyzed blood, thus eliminating the need to modify the diet or medications.27 Additionally, only 1 stool specimen is needed, which may explain why the adherence rate was about 20% higher with FIT than with FOBT in most studies.28–30

FIT has a sensitivity of 69% to 86% for colorectal cancer and a specificity of 92% to 95%.31 The sensitivity can be improved by lowering the threshold value for a positive test, but this is associated with a decrease in specificity. A single FIT has the same sensitivity and specificity as several samples.32

In a large retrospective US cohort study of programmatic screening with FIT, Jensen et al33 reported that 48% of 670,841 people who were offered testing actually did the test. Of the 48% who participated in the first round and remained eligible, 75% to 86% participated in subsequent rounds over 4 years. Those who had a positive result on FIT were supposed to undergo colonoscopy, but 22% did not.

The US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer34 suggests that FIT-based screening programs aim for a target FIT completion rate of more than 60% and a target colonoscopy completion rate of more than 80% of patients with positive FITs. These benchmarks were derived from adherence rates in international FIT screening studies in average-risk populations.35–39 (Note that the large US cohort described above33 did not meet these goals.) Ideally, every patient with a positive FIT should undergo diagnostic colonoscopy, but in reality only 50% to 83% actually do. Methods shown to improve adherence include structured screening programs with routine performance reports, provider feedback, and involvement of patient navigators.40–42

Accordingly, several aspects of stool-based testing need to be stressed with patients. Understanding that FOBT is recommended yearly is integral for optimal impact on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality rates.

Additionally, patients should be advised to undergo colonoscopy soon after a positive FIT, because delaying colonoscopy could give precancerous lesions time to progress in stage. The acceptable time between a positive FIT and colonoscopy has yet to be determined. However, a retrospective cohort study of 1.26 million screened patients with 107,000 positive FIT results demonstrated that the rates of cancer discovered on colonoscopy were similar when performed within 30 days or up to 10 months after a positive test. Detection rates increased from 3% to 4.8% at 10 months and to 7.9% at 12 months.43

In modeling studies, Meester et al44 showed the estimated lifetime risk and mortality rates from colorectal cancer and life-years gained from screening are significantly better when colonoscopy is completed within 2 weeks rather than 1 year after a positive FIT. Each additional month after 2 weeks incrementally affected these outcomes, with a 1.4% increase in cancer mortality. These data suggest that colonoscopy should be done soon after a positive FIT result and at a maximum of 10 months.43,44

Screening with FOBT is a multistep process for patients that includes receiving the test kit, collecting the sample, preparing it, returning it, undergoing colonoscopy after a positive test, and repeating in 1 year if negative. The screening program should identify patients at average risk in whom screening is appropriate, ensure delivery of the test, verify the quality of collected samples for laboratory testing against the manufacturer’s recommendations, and report results. Report of a positive FOBT result should provide recommendations for follow-up.

Though evidence clearly supports screening annually or biennially (every 2 years) with FOBT, the ideal interval for FIT is undetermined. Modeling studies utilized by the USPSTF and Multi-Society Task Force demonstrate that colonoscopy and annual FIT result in similar life-years gained, while 2 population-based screening programs have demonstrated that a 2- or 3-year interval may be equally efficacious by lowering the threshold for a positive test.38,45

Randomized controlled trials of screening colonoscopy vs annual and biennial FIT are currently under way. Cost-effectiveness analysis has shown that offering single-sample FITs at more frequent (annual) intervals performs better than multisample testing at less frequent intervals.45–47

Colonoscopy

Compared with stool-based screening, colonoscopy has advantages, including a 10-year screening interval if bowel preparation is adequate and the examination shows no neoplasia, the ability to inspect the entire colon, and the ability to diagnose and treat lesions in the same session.

Screening colonoscopy visualizes the entire colon in more than 98% of cases, although it requires adequate bowel preparation for maximal polyp detection. It can be done safely with or without sedation.48

While there are no available randomized controlled trial data on the impact of screening colonoscopy on cancer incidence or mortality, extensive case-control and cohort studies consistently show that screening colonoscopy reduces cancer incidence and mortality rates.49–54 A US Veterans Administration study of more than 32,000 patients reported a 50% reduction in overall colorectal cancer mortality.55 In a microsimulation modeling study that assumed 100% adherence, colonoscopy every 10 years and annual FIT in individuals ages 50 to 75 provided similar life-years gained per 1,000 people screened (270 for colonoscopy, 244 for FIT).56

Well-established metrics for maximizing the effectiveness and quality of colonoscopy have been established (Table 2). The most important include the mucosa inspection time (withdrawal time) and adenoma detection rate.57 Withdrawal time is directly correlated with adenoma detection, and a 6-minute minimum withdrawal time is recommended in screening colonoscopy examinations of patients at average risk when no polyps are found.58 The adenoma detection rate is the strongest evidence-based metric, as each 1% increase in the adenoma detection rate over 19% is associated with a 3% decrease in the risk of colorectal cancer and a 5% decrease in death rate.59 The average-risk screening adenoma detection rate differs based on sex: the rate is greater than 20% for women and greater than 30% for men.

Complications from screening, diagnostic, or therapeutic colonoscopy are infrequent but include perforation (4/10,000) and significant intestinal bleeding (8/10,000).56–62

Patients with a first-degree relative under age 60 with advanced adenomas or colorectal cancer are considered at high risk and should begin screening colonoscopy at age 40, with repeat colonoscopy at 5-year intervals, given a trend toward advanced neoplasia detection compared with FIT.63

Guidelines recently published by the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology and endorsed by the American Gastroenterological Association also support starting screening in high-risk individuals at age 40, with a surveillance interval of 5 to 10 years based on the number of first-degree relatives with colorectal cancer or adenomas.64 Consensus statements were based on retrospective cohort, prospective case-controlled, and cross-sectional studies comparing the risk of colorectal cancer in individuals with a family history against those without a family history.

Randomized clinical trials comparing colonoscopy and FIT are under way. Interim analysis of a European trial in which asymptomatic adults ages 50 to 69 were randomized to 1-time colonoscopy (26,703 patients) vs FIT every 2 years (26,599 patients) found significantly higher participation rates in the FIT arm (34.2% vs 24.6%) but higher rates of nonadvanced adenomas (4.2% vs 0.4%) and advanced neoplasia (1.9% vs 0.9%) in the colonoscopy arm.65 Cancer was detected in 0.1% in each arm. These findings correlate with those of another study showing higher participation with FIT but higher advanced neoplasia detection rates with colonoscopy.66

Detection of precursor lesions is vital, as removing neoplasms is the main strategy to reduce colorectal cancer incidence. Accordingly, the advantage of colonoscopy was illustrated by a study that determined that 53 patients would need to undergo screening colonoscopy to detect 1 advanced adenoma or cancerous lesion, compared with 264 for FIT.67

STARTING SCREEING AT AGE 45

The American Cancer Society recently provided a qualified recommendation to start colorectal cancer screening in all individuals at age 45 rather than 50.9 This recommendation was based on modeling studies demonstrating that starting screening at age 45 with colonoscopy every 10 years resulted in 25 life-years gained at the cost of 610 colonoscopies per 1,000 individuals. Alternative strategies included FIT, which resulted in an additional 26 life-years gained per 1,000 individuals screened, flexible sigmoidoscopy (23 life-years gained), and computed tomographic colonoscopy (22 life-years gained).

Rates of colorectal cancer are rising in adults under age 50, and 10,000 new cases are anticipated this year.2,3 Currently, 22 million US adults are between the ages of 45 and 50. The system and support needed to perform screening in all adults over age 45 and a lack of direct evidence to support its benefits in the young population need to be considered before widespread acceptance of the American Cancer Society recommendations. However, if screening is considered, FIT with or without sigmoidoscopy may be appropriate, given that most cancers diagnosed in individuals under age 50 are left-sided.4,5

Screening has not been proven to reduce all-cause mortality. Randomized controlled trials of FOBT and observational studies of colonoscopy show that screening reduces cancer incidence and mortality. Until the currently ongoing randomized controlled trials comparing colonoscopy with FIT are completed, their comparative impact on colorectal cancer end points is unknown.

PATIENT ADHERENCE IS KEY

FIT and colonoscopy are the most prevalent screening methods in the United States. Careful attention should be given to offer the screening option the patient is most likely to complete, as adherence is key to the benefit from colorectal cancer screening.

The National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable (nccrt.org), established in 1997 by the American Cancer Society and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is a national coalition of public and private organizations dedicated to reducing colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. The Roundtable waged a national campaign to achieve a colorectal cancer screening rate of 80% in eligible adults by 2018, a goal that was not met. Still, the potential for a substantial impact is a compelling reason to endorse adherence to colorectal cancer screening. The Roundtable provides many resources for physicians to enhance screening in their practice.

The United States has seen a steady decline in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality, mainly as a result of screening. Colorectal cancer is preventable with ensuring patients’ adherence to screening. Screening rates have been shown to increase with patient-provider dialogue and with selection of a screening program the patient prefers and is most likely to complete.

Screening can help prevent colorectal cancer. The United States has seen a steady decline in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality, thanks in large part to screening. Screening rates can be increased with good patient-physician dialogue and by choosing a method the patient prefers and is most likely to complete.

In this article, we review a general approach to screening, focusing on the most commonly used methods in the United States, ie, the guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (FOBT), the fecal immunochemical test (FIT), and colonoscopy. We discuss current colorectal cancer incidence rates, screening recommendations, and how to choose the appropriate screening test.

This article does not discuss patients at high risk of polyps or cancer due to hereditary colon cancer syndromes, a personal history of colorectal neoplasia, inflammatory bowel disease, or primary sclerosing cholangitis.

TRENDS IN INCIDENCE