User login

Using CBT effectively for treating depression and anxiety

Fewer than 20% of people seeking help for depression and anxiety disorders receive cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), the most established evidence-based psychotherapeutic treatment.1 Efforts are being made to increase access to CBT,2 but a substantial barrier remains: therapist training is a strong predictor of treatment outcome, and many therapists offering CBT services are not sufficiently trained to deliver multiple manual-based interventions with adequate fidelity to the model. Proposed solutions to this barrier include:

• abbreviated versions of CBT training for practitioners in primary care and community settings

• culturally adapted CBT training for community health workers3

• Internet-based CBT and telemedicine (telephone and video conferencing)2

• mobile phone applications that use text messaging, social support, and physiological monitoring as adjuncts to clinical practice or stand-alone interventions.4

New models of CBT also are emerging, including transdiagnostic CBT and metacognitive approaches (mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy), and several new foci for exposure therapy.

In light of these ongoing modulations, this article is intended to help clinicians make informed decisions about CBT when selecting treatment for patients with depressive and anxiety disorders (Box5 ). We review the evidence of CBT’s efficacy for acute-phase treatment and relapse prevention; explain the common elements considered essential to CBT practice; describe CBT adaptations for specific anxiety disorders; and provide an overview of recent advances in conceptualizing and adapting CBT.

Efficacy for mood and anxiety disorders

Depression. Dozens of randomized controlled trials (RCT) and other studies support CBT’s efficacy in treating major depressive disorder (MDD). For acute treatment:

• CBT is more effective in producing remission when compared with no treatment, treatment as usual, or nonspecific psychotherapy.

• For mild to moderate depression, CBT is equivalent to antidepressant medication in terms of response and remission rates.

• Combining antidepressant therapy with CBT increases treatment adherence.6

Less well known may be that a successful response to CBT in the acute phase may have a protective effect against depression recurrences. A 2013 meta-analysis that totaled 506 individuals with depressive disorders found a trend toward significantly lower relapse rates when CBT was discontinued after acute therapy, compared with antidepressant therapy that continued beyond the acute phase.7

Anxiety. Among psychotherapies, CBT’s superior efficacy for anxiety disorders is well-established. CBT and its specific-disorder adaptations are considered first-line treatment.8

CBT’s essential elements

CBT focuses on distorted cognitions about the self, the world, and the future, and on behaviors that lead to or maintain symptoms.

Cognitive interventions seek to identify thoughts and beliefs that trigger emotional and behavioral reactions. A person with social anxiety disorder, for example, might believe that people will notice if he makes even a minor social mistake and then reject him, which will make him feel worthless. CBT can help him subject these beliefs to rational analysis and develop more adaptive beliefs, such as: “It is not certain that I will behave so badly that people would notice, but if that happened, the likelihood of being outright rejected is probably low. If—in the worst-case scenario—I was rejected, I am not worthless; I’m just a fallible human being.”

CBT’s behavioral component can be conceptualized as behavioral activation (BA), a structured approach to help the patient:

• increase behaviors and experiences that are rewarding

• overcome barriers to engaging in these new behaviors

• and decrease behaviors that maintain symptoms.

BA can be a useful intervention for individuals with depression characterized by lack of engagement or capacity for pleasurable experiences. During pregnancy and the postpartum period, for example, a woman undergoes physical, social, and environmental changes that might gradually deprive her of sources of pleasure and other reinforcing activities. BA would focus on developing creative solutions to regain access to or create new opportunities for rewarding experiences and to avoid behaviors (such as social withdrawal or physical activity restriction) that perpetuate depressed mood.

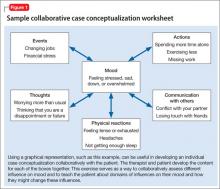

Common elements. Cognitive and behavioral interventions focus on problem solving, individualized case conceptualization (Figure 1), and collaborative empiricism.9

Individualized case conceptualization lays the foundation for the course of CBT, and may be thought of as a map for therapy. Case conceptualization brings in several domains of assessment including symptoms and diagnosis, the patient’s strengths, formative experiences (including biopsychosocial aspects), contextual factors, and cognitive factors that influence diagnosis and treatment, such as automatic thoughts or schemas. The case formulation leads to a working hypothesis about the optimal course and focus of CBT.

Collaborative empiricism is the way in which the patient and therapist work together to continually refine this working hypothesis. The pair works together to investigate the hypotheses and all aspects of the therapeutic relationship.

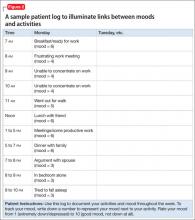

Although no specific technique defines CBT, a common practice is to educate a person about interrelationships between behaviors/activities, thoughts, and mood. A mood activity log (Figure 2) can illuminate links between moods and activities and be useful with targeting interventions. For a person with social anxiety, for example, a mood activity log could assist in developing a hierarchy of feared social situations and avoidance intensity. Systematic exposure therapy would follow, beginning with the least frightening/intense situation, accompanied by teaching new coping skills (such as relaxation strategies).

CBT adaptations for anxiety disorders

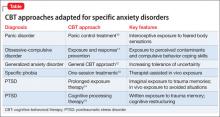

Elements of CBT have been adapted for a variety of anxiety disorders, based on specific symptoms and features (Table).10-15

Panic disorder. Panic control treatment is considered the first-line intervention for panic disorder’s defining features: spontaneous panic attacks, worry about future occurrence of attacks, and perceived catastrophic consequences (such as heart attack, fainting).10 This CBT adaptation includes:

• patient education about the nature of panic

• breathing retraining to foster exposure to feared bodily sensations and avoided activities and places

• cognitive restructuring of danger-related thoughts (such as “I’m going to faint,” or “It would be catastrophic if I did”).

Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the first-line treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).11 In traditional therapist-guided ERP, patients expose themselves to perceived contaminants while refraining from inappropriate compulsive behaviors (such as hand washing).

Cognitive interventions also can be an effective treatment of obsessions, without patients having to engage in exposure to their horrific thoughts and images.16 Consider, for example, a new mother who upon seeing the kitchen knife has the intrusive thought, “What if I stabbed my baby?” Instead of the traditional exposure approach for OCD (ie, having her vividly imagine stabbing her baby until her anxiety level subsided), the cognitive intervention would be to educate her about the normalcy of intrusive thoughts, particularly in the postpartum period.

Generalized anxiety disorder. CBT for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) targets patients’ overestimation of the likelihood of negative events and the belief that these events, should they occur, would be catastrophic and render them unable to cope.12

Motivational interviewing (MI) appears to be a useful adjunct to precede traditional CBT, particularly for severe worriers.17 MI attempts to help individuals with GAD recognize their ambivalence about giving up worry. This technique acknowledges and validates perceived benefits of worry (eg, “It helps me prepare for the worst, so I won’t be emotionally devastated if it happens”), but also explores how worry is destructive.

Emerging CBT models for anxiety disorders

Metacognitive treatment. Evidence, such as presented by Dobson,18 suggests that the field of CBT is shifting towards a metacognitive model of change and treatment. A metacognitive approach goes beyond changing thinking and emphasizes thoughts about thoughts and experiences. Examples include mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT).

MBCT typically consists of an 8-week program of 2-hour sessions each week and 1 full-day retreat. MBCT is modeled after Kabat-Zinn’s widely disseminated and empirically supported mindfulness based stress reduction course.19 MBCT was developed as a relapse prevention program for patients who had recovered from depression. Unlike traditional cognitive therapy for depression that targets changing the content of automatic thoughts and core beliefs, in MBCT patients are aware of negative automatic thoughts and find ways to change their relationship with these thoughts, learning that thoughts are not facts. This process mainly is carried out by practicing mindfulness meditation exercises. Importantly, MBCT goes beyond mindful acceptance of negative thoughts and teaches patients mindful acceptance of all internal experiences.

A fundamental difference between ACT and traditional CBT is the approach to cognitions.20 Although CBT focuses on changing the content of maladaptive thoughts, such as “I am a worthless person,” ACT focuses on changing the function of thoughts. ACT strives to help patients to accept their internal experiences—whether unwanted thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, or memories—while committing themselves to pursuing their life goals and values. Strategies aim to help patients step back from their thoughts and observe them as just thoughts. The patient who thinks, “I am worthless” would be instructed to practice saying “I am having the thought I am worthless.” Therefore the thought no longer controls the person’s behavior.

These approaches train the patient to keenly observe distressing thoughts and experiences—not necessarily with the goal of changing them but to accept them and act in a way that is consistent with his (her) goals and values. A meta-analysis of 39 studies found mindfulness-based therapy effective in improving symptoms in participants with anxiety and mood disorders.21 Similarly, ACT has demonstrated efficacy with mixed anxiety disorders.22

Transdiagnostic CBT. Recent research18 suggests that mood and anxiety disorders may have more commonalities than differences in underlying biological and psychological traits. Because the symptoms of anxiety and depressive disorders tend to overlap, and their rate of comorbidity may be as high as 55%,23 so-called transdiagnostic treatments have been developed. Transdiagnostic treatments target impairing symptoms that cut across different diagnoses. For example, patients with depression, anxiety, or substance abuse might share a common difficulty with regulating and coping with negative emotions.

In a preliminary comparison trial,24 46 patients with social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or GAD were randomly assigned to transdiagnostic CBT (n = 23) or diagnosis-specific CBT (n = 23). Treatments were based on widely used manuals and offered in 2-hour group sessions across 12 weeks. Transdiagnostic CBT was found to be as effective as specific CBT protocols in terms of symptom improvement. Participants attended an average of 8.46 sessions, with similar attendance in each protocol. Fourteen participants (30%) discontinued treatment, similar to attrition rates reported in other trials of transdiagnostic and diagnosis-specific CBT.

Transdiagnostic treatments may facilitate the dissemination of empirically supported treatments because therapists would not be required to have training and supervision to competency in delivering multiple manuals for specific anxiety disorders. This could be attractive to busy practitioners with limited time to learn new treatments.

Bottom Line

Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for depression and anxiety is well established. Although no specific technique defines CBT, a common practice is to educate an individual about interrelationships between behaviors/activities, thoughts, and mood. CBT techniques can be customized to treat specific anxiety disorders, such as panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Collins K, Westra H, Dozois D, et al. Gaps in accessing treatment for anxiety and depressions: challenges for the delivery of care. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(5):583-616.

2. Foa EB, Gillihan SJ, Bryant RA. Challenges and successes in dissemination of evidence-based treatments for posttraumatic stress: lessons learned from prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2013;14(2):65-111.

3. Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):902-909.

4. Aguilera A, Muench F. There’s an app for that: information technology applications for cognitive behavioral practitioners. Behavior Therapist. 2012;35(4):65-73.

5. Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006; 74(4):658-670.

6. Hollon SD, Jarrett RB, Nierenberg AA, et al. Psychotherapy and medication in the treatment of adult and geriatric depression: which monotherapy or combined treatment? J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(4):455-468.

7. Cuijpers P, Hollon SD, van Straten A, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy have an enduring effect that is superior to keeping patients on continuation pharmacotherapy? A meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4):1-8.

8. Stewart R, Chambless D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: a meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(4): 595-606.

9. Wright JH, Basco MR, Thase M. Learning cognitive behavior therapy: an illustrated guide. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

10. Barlow DH, Craske MG. Mastery of your anxiety and panic. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2007.

11. Foa EB, Yadin E, Lichner TK. Exposure and response prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2012.

12. Dugas MJ, Robichaud M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder. New York, NY: Routledge; 2007.

13. Zlomke K, Davis TE. One-session treatment of specific phobias: a detailed description and review of treatment efficacy. Behav Ther. 2008;39(3):207-223.

14. Foa EB, Hembree E, Rothbaum B. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: emotional processing of traumatic experiences. Therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2007.

15. Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for rape victims. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications; 1996.

16. Whittal ML, Robichaud M, Woody SR. Cognitive treatment of obsessions: enhancing dissemination with video components. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17(1):1-8.

17. Westra H, Arkowitz H, Dozois D. Adding a motivational interviewing pretreatment to cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(2): 1106-1117.

18. Dobson KS. The science of CBT: toward a metacognitive model of change? Behav Ther. 2013;44(2):224-227.

19. Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living. Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Revised edition. New York, NY: Bantam Books; 2013.

20. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD. Acceptance and commitment therapy. The process and practice of mindful change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012.

21. Hofmann S, Sawyer A, Witt A, et al. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(2): 169-183.

22. Arch J, Eifert G, Davies C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for mixed anxiety disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):750-765.

23. Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, et al. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110(4):585-599.

24. Norton P, Barrera T. Transdiagnostic versus diagnosis-specific CBT for anxiety disorders: a preliminary randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(10):874-882.

Fewer than 20% of people seeking help for depression and anxiety disorders receive cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), the most established evidence-based psychotherapeutic treatment.1 Efforts are being made to increase access to CBT,2 but a substantial barrier remains: therapist training is a strong predictor of treatment outcome, and many therapists offering CBT services are not sufficiently trained to deliver multiple manual-based interventions with adequate fidelity to the model. Proposed solutions to this barrier include:

• abbreviated versions of CBT training for practitioners in primary care and community settings

• culturally adapted CBT training for community health workers3

• Internet-based CBT and telemedicine (telephone and video conferencing)2

• mobile phone applications that use text messaging, social support, and physiological monitoring as adjuncts to clinical practice or stand-alone interventions.4

New models of CBT also are emerging, including transdiagnostic CBT and metacognitive approaches (mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy), and several new foci for exposure therapy.

In light of these ongoing modulations, this article is intended to help clinicians make informed decisions about CBT when selecting treatment for patients with depressive and anxiety disorders (Box5 ). We review the evidence of CBT’s efficacy for acute-phase treatment and relapse prevention; explain the common elements considered essential to CBT practice; describe CBT adaptations for specific anxiety disorders; and provide an overview of recent advances in conceptualizing and adapting CBT.

Efficacy for mood and anxiety disorders

Depression. Dozens of randomized controlled trials (RCT) and other studies support CBT’s efficacy in treating major depressive disorder (MDD). For acute treatment:

• CBT is more effective in producing remission when compared with no treatment, treatment as usual, or nonspecific psychotherapy.

• For mild to moderate depression, CBT is equivalent to antidepressant medication in terms of response and remission rates.

• Combining antidepressant therapy with CBT increases treatment adherence.6

Less well known may be that a successful response to CBT in the acute phase may have a protective effect against depression recurrences. A 2013 meta-analysis that totaled 506 individuals with depressive disorders found a trend toward significantly lower relapse rates when CBT was discontinued after acute therapy, compared with antidepressant therapy that continued beyond the acute phase.7

Anxiety. Among psychotherapies, CBT’s superior efficacy for anxiety disorders is well-established. CBT and its specific-disorder adaptations are considered first-line treatment.8

CBT’s essential elements

CBT focuses on distorted cognitions about the self, the world, and the future, and on behaviors that lead to or maintain symptoms.

Cognitive interventions seek to identify thoughts and beliefs that trigger emotional and behavioral reactions. A person with social anxiety disorder, for example, might believe that people will notice if he makes even a minor social mistake and then reject him, which will make him feel worthless. CBT can help him subject these beliefs to rational analysis and develop more adaptive beliefs, such as: “It is not certain that I will behave so badly that people would notice, but if that happened, the likelihood of being outright rejected is probably low. If—in the worst-case scenario—I was rejected, I am not worthless; I’m just a fallible human being.”

CBT’s behavioral component can be conceptualized as behavioral activation (BA), a structured approach to help the patient:

• increase behaviors and experiences that are rewarding

• overcome barriers to engaging in these new behaviors

• and decrease behaviors that maintain symptoms.

BA can be a useful intervention for individuals with depression characterized by lack of engagement or capacity for pleasurable experiences. During pregnancy and the postpartum period, for example, a woman undergoes physical, social, and environmental changes that might gradually deprive her of sources of pleasure and other reinforcing activities. BA would focus on developing creative solutions to regain access to or create new opportunities for rewarding experiences and to avoid behaviors (such as social withdrawal or physical activity restriction) that perpetuate depressed mood.

Common elements. Cognitive and behavioral interventions focus on problem solving, individualized case conceptualization (Figure 1), and collaborative empiricism.9

Individualized case conceptualization lays the foundation for the course of CBT, and may be thought of as a map for therapy. Case conceptualization brings in several domains of assessment including symptoms and diagnosis, the patient’s strengths, formative experiences (including biopsychosocial aspects), contextual factors, and cognitive factors that influence diagnosis and treatment, such as automatic thoughts or schemas. The case formulation leads to a working hypothesis about the optimal course and focus of CBT.

Collaborative empiricism is the way in which the patient and therapist work together to continually refine this working hypothesis. The pair works together to investigate the hypotheses and all aspects of the therapeutic relationship.

Although no specific technique defines CBT, a common practice is to educate a person about interrelationships between behaviors/activities, thoughts, and mood. A mood activity log (Figure 2) can illuminate links between moods and activities and be useful with targeting interventions. For a person with social anxiety, for example, a mood activity log could assist in developing a hierarchy of feared social situations and avoidance intensity. Systematic exposure therapy would follow, beginning with the least frightening/intense situation, accompanied by teaching new coping skills (such as relaxation strategies).

CBT adaptations for anxiety disorders

Elements of CBT have been adapted for a variety of anxiety disorders, based on specific symptoms and features (Table).10-15

Panic disorder. Panic control treatment is considered the first-line intervention for panic disorder’s defining features: spontaneous panic attacks, worry about future occurrence of attacks, and perceived catastrophic consequences (such as heart attack, fainting).10 This CBT adaptation includes:

• patient education about the nature of panic

• breathing retraining to foster exposure to feared bodily sensations and avoided activities and places

• cognitive restructuring of danger-related thoughts (such as “I’m going to faint,” or “It would be catastrophic if I did”).

Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the first-line treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).11 In traditional therapist-guided ERP, patients expose themselves to perceived contaminants while refraining from inappropriate compulsive behaviors (such as hand washing).

Cognitive interventions also can be an effective treatment of obsessions, without patients having to engage in exposure to their horrific thoughts and images.16 Consider, for example, a new mother who upon seeing the kitchen knife has the intrusive thought, “What if I stabbed my baby?” Instead of the traditional exposure approach for OCD (ie, having her vividly imagine stabbing her baby until her anxiety level subsided), the cognitive intervention would be to educate her about the normalcy of intrusive thoughts, particularly in the postpartum period.

Generalized anxiety disorder. CBT for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) targets patients’ overestimation of the likelihood of negative events and the belief that these events, should they occur, would be catastrophic and render them unable to cope.12

Motivational interviewing (MI) appears to be a useful adjunct to precede traditional CBT, particularly for severe worriers.17 MI attempts to help individuals with GAD recognize their ambivalence about giving up worry. This technique acknowledges and validates perceived benefits of worry (eg, “It helps me prepare for the worst, so I won’t be emotionally devastated if it happens”), but also explores how worry is destructive.

Emerging CBT models for anxiety disorders

Metacognitive treatment. Evidence, such as presented by Dobson,18 suggests that the field of CBT is shifting towards a metacognitive model of change and treatment. A metacognitive approach goes beyond changing thinking and emphasizes thoughts about thoughts and experiences. Examples include mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT).

MBCT typically consists of an 8-week program of 2-hour sessions each week and 1 full-day retreat. MBCT is modeled after Kabat-Zinn’s widely disseminated and empirically supported mindfulness based stress reduction course.19 MBCT was developed as a relapse prevention program for patients who had recovered from depression. Unlike traditional cognitive therapy for depression that targets changing the content of automatic thoughts and core beliefs, in MBCT patients are aware of negative automatic thoughts and find ways to change their relationship with these thoughts, learning that thoughts are not facts. This process mainly is carried out by practicing mindfulness meditation exercises. Importantly, MBCT goes beyond mindful acceptance of negative thoughts and teaches patients mindful acceptance of all internal experiences.

A fundamental difference between ACT and traditional CBT is the approach to cognitions.20 Although CBT focuses on changing the content of maladaptive thoughts, such as “I am a worthless person,” ACT focuses on changing the function of thoughts. ACT strives to help patients to accept their internal experiences—whether unwanted thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, or memories—while committing themselves to pursuing their life goals and values. Strategies aim to help patients step back from their thoughts and observe them as just thoughts. The patient who thinks, “I am worthless” would be instructed to practice saying “I am having the thought I am worthless.” Therefore the thought no longer controls the person’s behavior.

These approaches train the patient to keenly observe distressing thoughts and experiences—not necessarily with the goal of changing them but to accept them and act in a way that is consistent with his (her) goals and values. A meta-analysis of 39 studies found mindfulness-based therapy effective in improving symptoms in participants with anxiety and mood disorders.21 Similarly, ACT has demonstrated efficacy with mixed anxiety disorders.22

Transdiagnostic CBT. Recent research18 suggests that mood and anxiety disorders may have more commonalities than differences in underlying biological and psychological traits. Because the symptoms of anxiety and depressive disorders tend to overlap, and their rate of comorbidity may be as high as 55%,23 so-called transdiagnostic treatments have been developed. Transdiagnostic treatments target impairing symptoms that cut across different diagnoses. For example, patients with depression, anxiety, or substance abuse might share a common difficulty with regulating and coping with negative emotions.

In a preliminary comparison trial,24 46 patients with social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or GAD were randomly assigned to transdiagnostic CBT (n = 23) or diagnosis-specific CBT (n = 23). Treatments were based on widely used manuals and offered in 2-hour group sessions across 12 weeks. Transdiagnostic CBT was found to be as effective as specific CBT protocols in terms of symptom improvement. Participants attended an average of 8.46 sessions, with similar attendance in each protocol. Fourteen participants (30%) discontinued treatment, similar to attrition rates reported in other trials of transdiagnostic and diagnosis-specific CBT.

Transdiagnostic treatments may facilitate the dissemination of empirically supported treatments because therapists would not be required to have training and supervision to competency in delivering multiple manuals for specific anxiety disorders. This could be attractive to busy practitioners with limited time to learn new treatments.

Bottom Line

Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for depression and anxiety is well established. Although no specific technique defines CBT, a common practice is to educate an individual about interrelationships between behaviors/activities, thoughts, and mood. CBT techniques can be customized to treat specific anxiety disorders, such as panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Fewer than 20% of people seeking help for depression and anxiety disorders receive cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), the most established evidence-based psychotherapeutic treatment.1 Efforts are being made to increase access to CBT,2 but a substantial barrier remains: therapist training is a strong predictor of treatment outcome, and many therapists offering CBT services are not sufficiently trained to deliver multiple manual-based interventions with adequate fidelity to the model. Proposed solutions to this barrier include:

• abbreviated versions of CBT training for practitioners in primary care and community settings

• culturally adapted CBT training for community health workers3

• Internet-based CBT and telemedicine (telephone and video conferencing)2

• mobile phone applications that use text messaging, social support, and physiological monitoring as adjuncts to clinical practice or stand-alone interventions.4

New models of CBT also are emerging, including transdiagnostic CBT and metacognitive approaches (mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy), and several new foci for exposure therapy.

In light of these ongoing modulations, this article is intended to help clinicians make informed decisions about CBT when selecting treatment for patients with depressive and anxiety disorders (Box5 ). We review the evidence of CBT’s efficacy for acute-phase treatment and relapse prevention; explain the common elements considered essential to CBT practice; describe CBT adaptations for specific anxiety disorders; and provide an overview of recent advances in conceptualizing and adapting CBT.

Efficacy for mood and anxiety disorders

Depression. Dozens of randomized controlled trials (RCT) and other studies support CBT’s efficacy in treating major depressive disorder (MDD). For acute treatment:

• CBT is more effective in producing remission when compared with no treatment, treatment as usual, or nonspecific psychotherapy.

• For mild to moderate depression, CBT is equivalent to antidepressant medication in terms of response and remission rates.

• Combining antidepressant therapy with CBT increases treatment adherence.6

Less well known may be that a successful response to CBT in the acute phase may have a protective effect against depression recurrences. A 2013 meta-analysis that totaled 506 individuals with depressive disorders found a trend toward significantly lower relapse rates when CBT was discontinued after acute therapy, compared with antidepressant therapy that continued beyond the acute phase.7

Anxiety. Among psychotherapies, CBT’s superior efficacy for anxiety disorders is well-established. CBT and its specific-disorder adaptations are considered first-line treatment.8

CBT’s essential elements

CBT focuses on distorted cognitions about the self, the world, and the future, and on behaviors that lead to or maintain symptoms.

Cognitive interventions seek to identify thoughts and beliefs that trigger emotional and behavioral reactions. A person with social anxiety disorder, for example, might believe that people will notice if he makes even a minor social mistake and then reject him, which will make him feel worthless. CBT can help him subject these beliefs to rational analysis and develop more adaptive beliefs, such as: “It is not certain that I will behave so badly that people would notice, but if that happened, the likelihood of being outright rejected is probably low. If—in the worst-case scenario—I was rejected, I am not worthless; I’m just a fallible human being.”

CBT’s behavioral component can be conceptualized as behavioral activation (BA), a structured approach to help the patient:

• increase behaviors and experiences that are rewarding

• overcome barriers to engaging in these new behaviors

• and decrease behaviors that maintain symptoms.

BA can be a useful intervention for individuals with depression characterized by lack of engagement or capacity for pleasurable experiences. During pregnancy and the postpartum period, for example, a woman undergoes physical, social, and environmental changes that might gradually deprive her of sources of pleasure and other reinforcing activities. BA would focus on developing creative solutions to regain access to or create new opportunities for rewarding experiences and to avoid behaviors (such as social withdrawal or physical activity restriction) that perpetuate depressed mood.

Common elements. Cognitive and behavioral interventions focus on problem solving, individualized case conceptualization (Figure 1), and collaborative empiricism.9

Individualized case conceptualization lays the foundation for the course of CBT, and may be thought of as a map for therapy. Case conceptualization brings in several domains of assessment including symptoms and diagnosis, the patient’s strengths, formative experiences (including biopsychosocial aspects), contextual factors, and cognitive factors that influence diagnosis and treatment, such as automatic thoughts or schemas. The case formulation leads to a working hypothesis about the optimal course and focus of CBT.

Collaborative empiricism is the way in which the patient and therapist work together to continually refine this working hypothesis. The pair works together to investigate the hypotheses and all aspects of the therapeutic relationship.

Although no specific technique defines CBT, a common practice is to educate a person about interrelationships between behaviors/activities, thoughts, and mood. A mood activity log (Figure 2) can illuminate links between moods and activities and be useful with targeting interventions. For a person with social anxiety, for example, a mood activity log could assist in developing a hierarchy of feared social situations and avoidance intensity. Systematic exposure therapy would follow, beginning with the least frightening/intense situation, accompanied by teaching new coping skills (such as relaxation strategies).

CBT adaptations for anxiety disorders

Elements of CBT have been adapted for a variety of anxiety disorders, based on specific symptoms and features (Table).10-15

Panic disorder. Panic control treatment is considered the first-line intervention for panic disorder’s defining features: spontaneous panic attacks, worry about future occurrence of attacks, and perceived catastrophic consequences (such as heart attack, fainting).10 This CBT adaptation includes:

• patient education about the nature of panic

• breathing retraining to foster exposure to feared bodily sensations and avoided activities and places

• cognitive restructuring of danger-related thoughts (such as “I’m going to faint,” or “It would be catastrophic if I did”).

Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the first-line treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).11 In traditional therapist-guided ERP, patients expose themselves to perceived contaminants while refraining from inappropriate compulsive behaviors (such as hand washing).

Cognitive interventions also can be an effective treatment of obsessions, without patients having to engage in exposure to their horrific thoughts and images.16 Consider, for example, a new mother who upon seeing the kitchen knife has the intrusive thought, “What if I stabbed my baby?” Instead of the traditional exposure approach for OCD (ie, having her vividly imagine stabbing her baby until her anxiety level subsided), the cognitive intervention would be to educate her about the normalcy of intrusive thoughts, particularly in the postpartum period.

Generalized anxiety disorder. CBT for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) targets patients’ overestimation of the likelihood of negative events and the belief that these events, should they occur, would be catastrophic and render them unable to cope.12

Motivational interviewing (MI) appears to be a useful adjunct to precede traditional CBT, particularly for severe worriers.17 MI attempts to help individuals with GAD recognize their ambivalence about giving up worry. This technique acknowledges and validates perceived benefits of worry (eg, “It helps me prepare for the worst, so I won’t be emotionally devastated if it happens”), but also explores how worry is destructive.

Emerging CBT models for anxiety disorders

Metacognitive treatment. Evidence, such as presented by Dobson,18 suggests that the field of CBT is shifting towards a metacognitive model of change and treatment. A metacognitive approach goes beyond changing thinking and emphasizes thoughts about thoughts and experiences. Examples include mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT).

MBCT typically consists of an 8-week program of 2-hour sessions each week and 1 full-day retreat. MBCT is modeled after Kabat-Zinn’s widely disseminated and empirically supported mindfulness based stress reduction course.19 MBCT was developed as a relapse prevention program for patients who had recovered from depression. Unlike traditional cognitive therapy for depression that targets changing the content of automatic thoughts and core beliefs, in MBCT patients are aware of negative automatic thoughts and find ways to change their relationship with these thoughts, learning that thoughts are not facts. This process mainly is carried out by practicing mindfulness meditation exercises. Importantly, MBCT goes beyond mindful acceptance of negative thoughts and teaches patients mindful acceptance of all internal experiences.

A fundamental difference between ACT and traditional CBT is the approach to cognitions.20 Although CBT focuses on changing the content of maladaptive thoughts, such as “I am a worthless person,” ACT focuses on changing the function of thoughts. ACT strives to help patients to accept their internal experiences—whether unwanted thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, or memories—while committing themselves to pursuing their life goals and values. Strategies aim to help patients step back from their thoughts and observe them as just thoughts. The patient who thinks, “I am worthless” would be instructed to practice saying “I am having the thought I am worthless.” Therefore the thought no longer controls the person’s behavior.

These approaches train the patient to keenly observe distressing thoughts and experiences—not necessarily with the goal of changing them but to accept them and act in a way that is consistent with his (her) goals and values. A meta-analysis of 39 studies found mindfulness-based therapy effective in improving symptoms in participants with anxiety and mood disorders.21 Similarly, ACT has demonstrated efficacy with mixed anxiety disorders.22

Transdiagnostic CBT. Recent research18 suggests that mood and anxiety disorders may have more commonalities than differences in underlying biological and psychological traits. Because the symptoms of anxiety and depressive disorders tend to overlap, and their rate of comorbidity may be as high as 55%,23 so-called transdiagnostic treatments have been developed. Transdiagnostic treatments target impairing symptoms that cut across different diagnoses. For example, patients with depression, anxiety, or substance abuse might share a common difficulty with regulating and coping with negative emotions.

In a preliminary comparison trial,24 46 patients with social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or GAD were randomly assigned to transdiagnostic CBT (n = 23) or diagnosis-specific CBT (n = 23). Treatments were based on widely used manuals and offered in 2-hour group sessions across 12 weeks. Transdiagnostic CBT was found to be as effective as specific CBT protocols in terms of symptom improvement. Participants attended an average of 8.46 sessions, with similar attendance in each protocol. Fourteen participants (30%) discontinued treatment, similar to attrition rates reported in other trials of transdiagnostic and diagnosis-specific CBT.

Transdiagnostic treatments may facilitate the dissemination of empirically supported treatments because therapists would not be required to have training and supervision to competency in delivering multiple manuals for specific anxiety disorders. This could be attractive to busy practitioners with limited time to learn new treatments.

Bottom Line

Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for depression and anxiety is well established. Although no specific technique defines CBT, a common practice is to educate an individual about interrelationships between behaviors/activities, thoughts, and mood. CBT techniques can be customized to treat specific anxiety disorders, such as panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Collins K, Westra H, Dozois D, et al. Gaps in accessing treatment for anxiety and depressions: challenges for the delivery of care. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(5):583-616.

2. Foa EB, Gillihan SJ, Bryant RA. Challenges and successes in dissemination of evidence-based treatments for posttraumatic stress: lessons learned from prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2013;14(2):65-111.

3. Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):902-909.

4. Aguilera A, Muench F. There’s an app for that: information technology applications for cognitive behavioral practitioners. Behavior Therapist. 2012;35(4):65-73.

5. Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006; 74(4):658-670.

6. Hollon SD, Jarrett RB, Nierenberg AA, et al. Psychotherapy and medication in the treatment of adult and geriatric depression: which monotherapy or combined treatment? J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(4):455-468.

7. Cuijpers P, Hollon SD, van Straten A, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy have an enduring effect that is superior to keeping patients on continuation pharmacotherapy? A meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4):1-8.

8. Stewart R, Chambless D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: a meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(4): 595-606.

9. Wright JH, Basco MR, Thase M. Learning cognitive behavior therapy: an illustrated guide. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

10. Barlow DH, Craske MG. Mastery of your anxiety and panic. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2007.

11. Foa EB, Yadin E, Lichner TK. Exposure and response prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2012.

12. Dugas MJ, Robichaud M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder. New York, NY: Routledge; 2007.

13. Zlomke K, Davis TE. One-session treatment of specific phobias: a detailed description and review of treatment efficacy. Behav Ther. 2008;39(3):207-223.

14. Foa EB, Hembree E, Rothbaum B. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: emotional processing of traumatic experiences. Therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2007.

15. Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for rape victims. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications; 1996.

16. Whittal ML, Robichaud M, Woody SR. Cognitive treatment of obsessions: enhancing dissemination with video components. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17(1):1-8.

17. Westra H, Arkowitz H, Dozois D. Adding a motivational interviewing pretreatment to cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(2): 1106-1117.

18. Dobson KS. The science of CBT: toward a metacognitive model of change? Behav Ther. 2013;44(2):224-227.

19. Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living. Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Revised edition. New York, NY: Bantam Books; 2013.

20. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD. Acceptance and commitment therapy. The process and practice of mindful change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012.

21. Hofmann S, Sawyer A, Witt A, et al. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(2): 169-183.

22. Arch J, Eifert G, Davies C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for mixed anxiety disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):750-765.

23. Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, et al. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110(4):585-599.

24. Norton P, Barrera T. Transdiagnostic versus diagnosis-specific CBT for anxiety disorders: a preliminary randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(10):874-882.

1. Collins K, Westra H, Dozois D, et al. Gaps in accessing treatment for anxiety and depressions: challenges for the delivery of care. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24(5):583-616.

2. Foa EB, Gillihan SJ, Bryant RA. Challenges and successes in dissemination of evidence-based treatments for posttraumatic stress: lessons learned from prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2013;14(2):65-111.

3. Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):902-909.

4. Aguilera A, Muench F. There’s an app for that: information technology applications for cognitive behavioral practitioners. Behavior Therapist. 2012;35(4):65-73.

5. Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006; 74(4):658-670.

6. Hollon SD, Jarrett RB, Nierenberg AA, et al. Psychotherapy and medication in the treatment of adult and geriatric depression: which monotherapy or combined treatment? J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(4):455-468.

7. Cuijpers P, Hollon SD, van Straten A, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy have an enduring effect that is superior to keeping patients on continuation pharmacotherapy? A meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4):1-8.

8. Stewart R, Chambless D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: a meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(4): 595-606.

9. Wright JH, Basco MR, Thase M. Learning cognitive behavior therapy: an illustrated guide. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

10. Barlow DH, Craske MG. Mastery of your anxiety and panic. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2007.

11. Foa EB, Yadin E, Lichner TK. Exposure and response prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2012.

12. Dugas MJ, Robichaud M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder. New York, NY: Routledge; 2007.

13. Zlomke K, Davis TE. One-session treatment of specific phobias: a detailed description and review of treatment efficacy. Behav Ther. 2008;39(3):207-223.

14. Foa EB, Hembree E, Rothbaum B. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: emotional processing of traumatic experiences. Therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2007.

15. Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for rape victims. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications; 1996.

16. Whittal ML, Robichaud M, Woody SR. Cognitive treatment of obsessions: enhancing dissemination with video components. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17(1):1-8.

17. Westra H, Arkowitz H, Dozois D. Adding a motivational interviewing pretreatment to cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(2): 1106-1117.

18. Dobson KS. The science of CBT: toward a metacognitive model of change? Behav Ther. 2013;44(2):224-227.

19. Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living. Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Revised edition. New York, NY: Bantam Books; 2013.

20. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD. Acceptance and commitment therapy. The process and practice of mindful change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012.

21. Hofmann S, Sawyer A, Witt A, et al. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(2): 169-183.

22. Arch J, Eifert G, Davies C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for mixed anxiety disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):750-765.

23. Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, et al. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110(4):585-599.

24. Norton P, Barrera T. Transdiagnostic versus diagnosis-specific CBT for anxiety disorders: a preliminary randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(10):874-882.