User login

Self-criticism and self-compassion: Risk and resilience

Once thought to only be associated with depression, self-criticism is a transdiagnostic risk factor for diverse forms of psychopathology.1,2 However, research has shown that self-compassion is a robust resilience factor when faced with feelings of personal inadequacy.3,4

Self-critical individuals experience feelings of unworthiness, inferiority, failure, and guilt. They engage in constant and harsh self-scrutiny and evaluation, and fear being disapproved and criticized and losing the approval and acceptance of others.5 Self-compassion involves treating oneself with care and concern when confronted with personal inadequacies, mistakes, failures, and painful life situations.6,7

Although self-criticism is destructive across clinical disorders and interpersonal relationships, self-compassion is associated with healthy relationships, emotional well-being, and better treatment outcomes.

Recent research shows how clinicians can teach their patients how to be less self-critical and more self-compassionate. Neff6,7 proposes that self-compassion involves treating yourself with care and concern when being confronted with personal inadequacies, mistakes, failures, and painful life situations. It consists of 3 interacting components, each of which has a positive and negative pole:

- self-kindness vs self-judgment

- a sense of common humanity vs isolation

- mindfulness vs over-identification.

Self-kindness refers to being caring and understanding with oneself rather than harshly judgmental. Instead of attacking and berating oneself for personal shortcomings, the self is offered warmth and unconditional acceptance.

Humanity involves recognizing that humans are imperfect, that all people fail, make mistakes, and have serious life challenges. By remembering that imperfection is part of life, we feel less isolated when we are in pain.

Mindfulness in the context of self-compassion involves being aware of one’s painful experiences in a balanced way that neither ignores and avoids nor exaggerates painful thoughts and emotions.

Self-compassion is more than the absence of self-judgment, although a defining feature of self-compassion is the lack of self-judgment, and self-judgment overlaps with self-criticism. Rather, self-compassion provides several access points for reducing self-criticism. For example, being kind and understanding when confronting personal inadequacies (eg, “it’s okay not to be perfect”) can counter harsh self-talk (eg, “I’m not defective”). Mindfulness of emotional pain (eg, “this is hard”) can facilitate a kind and warm response (eg, “what can I do to take care of myself right now?”) and therefore lessen self-blame (eg, “blaming myself is just causing me more suffering”). Similarly, remembering that failure is part of the human experience (eg, “it’s normal to mess up sometimes”) can lessen egocentric feelings of isolation (eg, “it’s not just me”) and over-identification (eg, “it’s not the end of the world”), resulting in lessened self-criticism (eg, “maybe it’s not just because I’m a bad person”).

Depression

Several studies have found that self-criticism predicts depression. In 3 epidemiological studies, “feeling worthless” was among the top 2 symptoms predicting a depression diagnosis and later depressive episodes.10 Self-criticism in fourth-year medical students predicted depression 2 years later, and—in males—10 years later in their medical careers better than a history of depression.11 Self-critical perfectionism also is associated with suicidal ideation and lethality of suicide attempts.12

Self-criticism has been shown to predict depressive relapse and residual self-devaluative symptoms in recovered depressed patients.13 In one study, currently depressed and remitted depressed patients had higher self-criticism and lower self-compassion compared with healthy controls. Both factors were more strongly associated with depression status than higher perfectionistic beliefs and cognitions, rumination, and maladaptive emotional regulation.14

Self-criticism and response to treatment. In the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program,15 self-critical perfectionism predicted a poorer outcome across all 4 treatments (cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT], interpersonal psychotherapy [IPT], pharmacotherapy plus clinical management, and placebo plus clinical management). Subsequent studies found that self-criticism predicted poorer response to CBT16 and IPT.17 The authors suggest that self-criticism could interfere with treatment because self-critical patients might have difficulty developing a strong therapeutic alliance.18,19

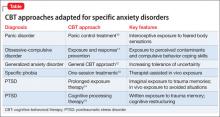

Anxiety disorders

Self-criticism is common across psychiatric disorders. In a study of 5,877 respondents in the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), self-criticism was associated with social phobia, findings that were significant after controlling for current emotional distress, neuroticism, and lifetime history of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders.20 Further, in a CBT treatment study, baseline self-criticism was associated with severity of social phobia and changes in self-criticism predicted treatment outcome.21 Self-criticism might be an important core psychological process in the development, maintenance, and course of social phobia. Patients with social anxiety disorder have less self-compassion than healthy controls and greater fear of negative evaluation.

In the NCS, self-criticism was associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) even after controlling for lifetime history of affective and anxiety disorders.20 Self-criticism predicted greater severity of combat-related PTSD in hospitalized male veterans,22 and those with PTSD had higher scores on self-criticism scales than those with major depressive disorder.23 In a study of Holocaust survivors, those with PTSD scored higher on self-criticism than survivors without PTSD.24 Self-criticism also distinguished between female victims of domestic violence with and without PTSD.25

Self-compassion could be a protective factor for posttraumatic stress.26 Combat veterans with higher levels of self-compassion showed lower levels of psychopathology, better functioning in daily life, and fewer symptoms of posttraumatic stress.27 In fact, self-compassion has been found to be a stronger predictor of PTSD than level of combat exposure.28

In an early study, self-criticism scores were higher in patients with panic disorder than in healthy controls, but lower than in patients with depression.29 In a study of a mixed sample of anxiety disorder patients, symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder were associated with shame proneness.30 Consistent with these results, Hoge et al31 found that self-compassion was lower in generalized anxiety disorder patients compared with healthy controls with elevated stress. Low self-compassion has been associated with severity of obsessive-compulsive disorder.32

Eating disorders

Self-criticism is correlated with eating disorder severity.33 In a study of patients with binge eating disorder, Dunkley and Grilo34 found that self-criticism was associated with the over-evaluation of shape and weight independently of self-esteem and depression. Self-criticism also is associated with body dissatisfaction, independent of self-esteem and depression. Dunkley et al35 found that self-criticism, but not global self-esteem, in patients with binge eating disorder mediated the relationship between childhood abuse and body dissatisfaction and depression. Numerous studies have shown that shame is associated with more severe eating disorder pathology.33

Self-compassion seems to buffer against body image concerns. It is associated with less body dissatisfaction, body preoccupation, and weight worries,36 greater body appreciation37 and less disordered eating.37-39 Early decreases in shame during eating disorder treatment was associated with more rapid reduction in eating disorder symptoms.40

Interpersonal relationships

Several studies have shown that self-criticism has negative effects on interpersonal relationships throughout life.5,41,42

- Self-criticism at age 12 predicted less involvement in high school activities and, at age 31, personal and social maladjustment.43

- High school students with high self-criticism reported more interpersonal problems.44

- Self-criticism was associated with loneliness, depression, and lack of intimacy with opposite sex friends or partners during the transition to college.45

- In a study of college roommates,46 self-criticism was associated with increased likelihood of rejection.

- Whiffen and Aube47 found that self-criticism was associated with marital dissatisfaction and depression.

- Self-critical mothers with postpartum depression were less satisfied with social support and were more vulnerable to depression.48

Self-compassion appears to enhance interpersonal relationships. In a study of heterosexual couples,49 self-compassionate individuals were described by their partners as being more emotionally connected, as well as accepting and supporting autonomy, while being less detached, controlling, and verbally or physically aggressive than those lacking self-compassion. Because self-compassionate people give themselves care and support, they seem to have more emotional resources available to give to others.

See the Box examining the evidence on the role of self-compassion in borderline personality disorder and non-suicidal self-injury.

Achieving goals

Powers et al50 suggest that self-critics approach goals based on motivation to avoid failure and disapproval, rather than on intrinsic interest and personal meaning. In studies of college students pursuing academic, social, or weight loss goals, self-criticism was associated with less progress to that goal. Self-criticism was associated with rumination and procrastination, which the authors suggest might have focused the self-critic on potential failure, negative evaluation from others, and loss of self-esteem. Additional studies showed the deleterious effects of self-criticism on college students’ progress on obtaining academic or music performance goals and on community residents’ weight loss goals.51

Not surprisingly, self-compassion is associated with successful goal pursuit and resilience when goals are not met52 and less procrastination and academic worry.53 Self-compassion also is associated with intrinsic motivation, goals based on mastery rather than performance, and less fear of academic failure.54

How self-criticism and self-compassion develop

Studies have explored the impact of early relationships with parents and development of self-criticism. Parental overcontrol and restrictiveness and lack of warmth consistently have been identified as parenting styles associated with development of self-criticism in children.55 One study found that self-criticism fully mediated the relationship between childhood verbal abuse from parents and depression and anxiety in adulthood.56 Reports from parents on their current parenting styles are consistent with these studies.57 Amitay et al57 states that “[s]elf-critics’ negative childhood experiences thus seem to contribute to a pattern of entering, creating, or manipulating subsequent interpersonal environments in ways that perpetuate their negative self-image and increase vulnerability to depression.” Not surprisingly, self-criticism is associated with a fearful avoidant attachment style.58 Review of the developmental origins of self-criticism confirms these factors and presents findings that peer relationships also are important factors in the development of self-criticism.59,60

Early positive relationships with caregivers are associated with self-compassion. Recollections of maternal support are correlated with self-compassion and secure attachment styles in adolescents and adults.61 Pepping et al62 found that retrospective reports of parental rejection, overprotection, and low parental warmth was associated with low self-compassion.

Benefits of self-compassion

A growing body of research suggests that self-compassion is strongly linked to mental health. Greater self-compassion consistently has been associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety,3 with a large effect size.4 Of course, central to self-compassion is the lack of self-criticism, but self-compassion still protects against anxiety and depression when controlling for self-criticism and negative affect.6,63 Self-compassion is a strong predictor of symptom severity and quality of life among individuals with anxious distress.64

The benefits of self-compassion stem partly from a greater ability to cope with negative emotions.6,63,65 Self-compassionate people are less likely to ruminate on their negative thoughts and emotions or suppress them,6,66 which helps to explain why self-compassion is a negative predictor of depression.67

Self-compassion also enhances positive mind states. A number of studies have found links between self-compassion and positive psychological qualities, such as happiness, optimism, wisdom, curiosity, and exploration, and personal initiative.63,65,68,69 By embracing one’s suffering with compassion, negative states are ameliorated when positive emotions of kindness, connectedness, and mindful presence are generated.

Misconceptions about self-compassion

A common misconception is that abandoning self-criticism in favor of self-compassion will undermine motivation70; however, research indicates the opposite. Although self-compassion is negatively associated with maladaptive perfectionism, it is not correlated with self-adopted performance standards.6 Self-compassionate people have less fear of failure54 and, when they do fail, they are more likely to try again.71 Breines and Chen72 found in a series of experimental studies that engendering feelings of self-compassion for personal weaknesses, failures, and past transgressions resulted in more motivation to change, to try harder to learn, and to avoid repeating past mistakes.

Another common misunderstanding is that self-compassion is a weakness. In fact, research suggests that self-compassion is a powerful way to cope with life challenges.73

Although some fear that self-compassion leads to self-indulgence, there is evidence that self-compassion promotes health-related behaviors. Self-compassionate individuals are more likely to seek medical treatment when needed,74 exercise for intrinsic reasons,75 and drink less alcohol.76 Inducing self-compassion has been found to help people stick to their diets77 and quit smoking.78

Self-compassion interventions

Individuals can develop self-compassion. Shapira and Mongrain79 found that adults who wrote a compassionate letter to themselves once a day for a week about the distressing events they were experiencing showed significant reductions in depression up to 3 months and significant increases in happiness up to 6 months compared with a control group who wrote about early memories. Albertson et al80 found that, compared with a wait-list control group, 3 weeks of self-compassion meditation training improved body dissatisfaction, body shame, and body appreciation among women with body image concerns. Similarly, Smeets et al81 found that 3 weeks of self-compassion training for female college students led to significantly greater increases in mindfulness, optimism, and self-efficacy, as well as greater decreases in rumination compared with a time management control group.

The Box6,70,82-86 describes rating scales that can measure self-compassion and self-criticism.

Mindful self-compassion (MSC), developed by Neff and Germer,87 is an 8-week group intervention designed to teach people how to be more self-compassionate through meditation and informal practices in daily life. Results of a randomized controlled trial found that, compared with a wait-list control group, participants using MSC reported significantly greater increases in self-compassion, compassion for others, mindfulness, and life satisfaction, and greater decreases in depression, anxiety, stress, and emotional avoidance, with large effect sizes indicated. These results were maintained up to 1 year.

Compassion-focused therapy (CFT) is designed to enhance self-compassion in clinical populations.88 The approach uses a number of imagery and experiential exercises to enhance patients’ abilities to extend feelings of reassurance, safeness, and understanding toward themselves. CFT has shown promise in treating a diverse group of clinical disorders such as depression and shame,8,89 social anxiety and shame,90 eating disorders,91 psychosis,92 and patients with acquired brain injury.93 A group-based CFT intervention with a heterogeneous group of community mental health patients led to significant reductions in depression, anxiety, stress, and self-criticism.94 See Leaviss and Utley95 for a review of the benefits of CFT.

Fears of developing self-compassion

It is important to note that some people can access self-compassion more easily than others. Highly self-critical patients could feel anxious when learning to be compassionate to themselves, a phenomenon known as “fear of compassion”96 or “backdraft.”97 Backdraft occurs when a firefighter opens a door with a hot fire behind it. Oxygen rushes in, causing a burst of flame. Similarly, when the door of the heart is opened with compassion, intense pain could be released. Unconditional love reveals the conditions under which we were unloved in the past. Some individuals, especially those with a history of childhood abuse or neglect, are fearful of compassion because it activates grief associated with feelings of wanting, but not receiving, affection and care from significant others in childhood.

Clinicians should be aware that anxiety could arise and should help patients learn how to go slowly and stabilize themselves if overwhelming emotions occur as a part of self-compassion practice. Both CFT and MSC have processes to deal with fear of compassion in their protocols,98,99 with the focus on explaining to individuals that although such fears may occur, they are a normal and necessary part of the healing process. Individuals also are taught to focus on the breath, feeling the sensations in the soles of their feet, or other mindfulness practices to ground and stabilize attention when overwhelming feelings arise.

Clinical interventions

Self-compassion interventions that I (R.W.) find most helpful, in the order I administer them, are:

- exploring perceived advantages and disadvantages of self-criticism

- presenting self-compassion as a way to get the perceived advantages of self-criticism without the disadvantages

- discussing what it means to be compassionate for someone else who is suffering, and then asking what it would be like if they treated themselves with the same compassion

- exploring patients’ misconceptions and fears of self-compassion

- directing patients to the self-compassion Web site to get an understanding of what self-compassion is and how it differs from self-esteem

- taking an example of a recent situation in which the patient was self-critical and exploring how a self-compassionate response would differ.

Asking what they would say to a friend often is an effective way to get at this. In a later therapy session, self-compassionate imagery is a useful way to get the patient to experience self-compassion on an emotional level. See Neff100 and Gilbert98 for other techniques to enhance self-compassion.

1. Shahar B, Doron G, Ohad S. Childhood maltreatment, shame-proneness and self-criticism in social anxiety disorder: a sequential mediational model. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2015:22(6):570-579.

2. Kannan D, Levitt HM. A review of client self-criticism in psychotherapy. J Psychother Integr. 2013;23(2):166-178.

3. Barnard LK, Curry JF. Self-compassion: conceptualizations, correlates, and interventions. Rev Gen Psychol. 2011;15(4):289-303.

4. MacBeth A, Gumley A. Exploring compassion: a meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(6):545-552

5. Blatt SJ, Zuroff DC. Interpersonal relatedness and self-definition: two prototypes for depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 1992;12(5):527-562.

6. Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2(2):223-250.

7. Neff KD. Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity. 2003;(2)2:85-101.

8. Gilbert P, Procter S. Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2006;13(6):353-379.

9. Dunkley DM, Zuroff DC, Blankstein KR. Specific perfectionism components versus self-criticism in predicting maladjustment. Pers Individ Dif. 2006;40(4):665-676.

10. Murphy JM, Nierenberg AA, Monson RR, et al. Self-disparagement as feature and forerunner of depression: Mindfindings from the Stirling County Study. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(1):13-21.

11. Brewin CR, Firth-Cozens J. Dependency and self-criticism as predictors of depression in young doctors. J Occup Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):242-246.

12. Fazaa N, Page S. Dependency and self-criticism as predictors of suicidal behavior. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2003;33(2):172-185.

13. Teasdale JD, Cox SG. Dysphoria: self-devaluative and affective components in recovered depressed patients and never depressed controls. Psychol Med. 2001;31(7):1311-1316.

14. Ehret AM, Joormann J, Berking M. Examining risk and resilience factors for depression: the role of self-criticism and self-compassion. Cogn Emot. 2015;29(8):1496-1504.

15. Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):971-982; discussion 983.

16. Rector NA, Bagby RM, Segal ZV, et al. Self-criticism and dependency in depressed patients treated with cognitive therapy or pharmacotherapy. Cognit Ther Res. 2000;24(5):571-584.

17. Marshall MB, Zuroff DC, McBride C, et al. Self-criticism predicts differential response to treatment for major depression. J Clin Psychol. 2008;64(3):231-244.

18. Zuroff DC, Blatt SJ, Sotsky SM, et al. Relation of therapeutic alliance and perfectionism to outcome in brief outpatient treatment of depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(1):114-124.

19. Whelton WJ, Greenberg LS. Emotion in self-criticism. Pers Individ Dif. 2005;38(7):1583-1595.

20. Cox BJ, Fleet C, Stein MB. Self-criticism and social phobia in the US national comorbidity survey. J Affect Disord. 2004;82(2):227-234.

21. Cox BJ, Walker JR, Enns MW, et al. Self-criticism in generalized social phobia and response to cognitive-behavioral treatment. Behav Ther. 2002;33(4):479-491.

22. McCranie EW, Hyer LA. Self-critical depressive experience in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Rep. 1995;77(3 pt 1):880-882.

23. Southwick SM, Yehuda R, Giller EL Jr. Characterization of depression in war-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(2):179-183.

24. Yehuda R, Kahana B, Southwick SM, et al. Depressive features in Holocaust survivors with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Traumatic Stress. 1994;7(4):699-704.

25. Sharhabani-Arzy R, Amir M, Swisa A. Self-criticism, dependency and posttraumatic stress disorder among a female group of help-seeking victims of domestic violence in Israel. Pers Individ Dif. 2005;38(5):1231-1240.

26. Beaumont E, Galpin A, Jenkins P. ‘Being kinder to myself’: a prospective comparative study, exploring post-trauma therapy outcome measures, for two groups of clients, receiving either cognitive behaviour therapy or cognitive behaviour therapy and compassionate mind training. Counselling Psychol Rev. 2012;27(1):31-43.

27. Dahm KA. Mindfulness and self-compassion as predictors of functional outcomes and psychopathology in OEF/OIF veterans exposed to trauma. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/21635. Published August 2013. Accessed November 8, 2016.

28. Hiraoka R, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, et al. Self-compassion as a prospective predictor of PTSD symptom severity among trauma-exposed US Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(2):127-133.

29. Bagby RM, Cox BJ, Schuller DR, et al. Diagnostic specificity of the dependent and self-critical personality dimensions in major depression. J Affect Disord. 1992;26(1):59-63.

30. Hedman E, Ström P, Stünkel A, et al. Shame and guilt in social anxiety disorder: effects of cognitive behavior therapy and association with social anxiety and depressive symptoms. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061713.

31. Hoge EA, Hölzel BK, Marques L, et al. Mindfulness and self-compassion in generalized anxiety disorder: examining predictors of disability. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:576258. doi: 10.1155/2013/576258.

32. Wetterneck CT, Lee EB, Smith AH, et al. Courage, self-compassion, and values in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2013;2(3-4):68-73.

33. Kelly AC, Carter JC. Why self-critical patients present with more severe eating disorder pathology: The mediating role of shame. Br J Clin Psychol. 2013;52(2):148-161.

34. Dunkley DM, Grilo CM. Self-criticism, low self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and over-evaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder patients. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(1):139-149.

35. Dunkley DM, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Childhood maltreatment, depressive symptoms, and body dissatisfaction in patients with binge eating disorder: the mediating role of self-criticism. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43(3):274-281.

36. Wasylkiw L, MacKinnon AL, MacLellan AM. Exploring the link between self-compassion and body image in university women. Body Image. 2012;9(2):236-245.

37. Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Duarte C. Self-compassion in the face of shame and body image dissatisfaction: implications for eating disorders. Eat Behavs. 2013;14(2):207-210.

38. Kelly AC, Carter JC, Zuroff DC, et al. Self-compassion and fear of self-compassion interact to predict response to eating disorders treatment: a preliminary investigation. Psychother Res. 2013;23(3):252-264.

39. Webb JB, Forman MJ. Evaluating the indirect effect of self-compassion on binge eating severity through cognitive-affective self-regulatory pathways. Eat Behavs. 2013;14(2):224-228.

40. Kelly AC, Carter JC, Borairi S. Are improvements in shame and self-compassion early in eating disorders treatment associated with better patient outcomes? Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(1):54-64.

41. Wiseman H, Raz A, Sharabany R. Depressive personality styles and interpersonal problems in young adults with difficulties in establishing long-term romantic relationships. Isr J Psychiatry Rel Sci. 2007;44(4):280-291.

42. Besser A, Priel B. A multisource approach to self-critical vulnerability to depression: the moderating role of attachment. J Pers. 2003;71(4):515-555.

43. Zuroff DC, Koestner R, Powers TA. Self-criticism at age 12: a longitudinal-study of adjustment. Cognit Ther Res. 1994;18(4):367-385.

44. Fichman L, Koestner R, Zuroff DC. Depressive styles in adolescence: Assessment, relation to social functioning, and developmental trends. J Youth Adolesc. 1994;23(3):315-330.

45. Wiseman H. Interpersonal relatedness and self-definition in the experience of loneliness during the transition to university. Personal Relationships. 1997;4(3):285-299.

46. Mongrain M, Lubbers R, Struthers W. The power of love: mediation of rejection in roommate relationships of dependents and self-critics. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30(1):94-105.

47. Whiffen VE, Aube JA. Personality, interpersonal context and depression in couples. J Soc Pers Relat. 1999;16(3):369-383.

48. Priel B, Besser A. Dependency and self-criticism among first-time mothers: the roles of global and specific support. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2000;19(4):437-450.

49. Neff KD, Beretvas SN. The role of self-compassion in romantic relationships. Self Identity. 2013;12(1):78-98.

50. Powers TA, Koestner R, Zuroff DC. Self-criticism, goal motivation, and goal progress. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2007;26(7):826-840.

51. Powers TA, Koestner R, Zuroff DC, et al. The effects of self-criticism and self-oriented perfectionism on goal pursuit. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2011;37(7):964-975.

52. Hope N, Koestner R, Milyavskaya M. The role of self-compassion in goal pursuit and well-being among university freshmen. Self Identity. 2014;13(5):579-593.

53. Williams JG, Stark SK, Foster EE. Start today or the very last day? The relationships among self-compassion, motivation, and procrastination. Am J Psychol Res. 2008;4(1):37-44.

54. Neff KD, Hseih Y, Dejittherat K. Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self Identity. 2005;4(3):263-287.

55. Campos RC, Besser A, Blatt SJ. The mediating role of self-criticism and dependency in the association between perceptions of maternal caring and depressive symptoms. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(12):1149-1157.

56. Sachs-Ericsson N, Verona E, Joiner T, et al. Parental verbal abuse and the mediating role of self-criticism in adult internalizing disorders. J Affect Disord. 2006;93(1-3):71-78.

57. Amitay OA, Mongrain M, Fazaa N. Love and control: self-criticism in parents and daughters and perceptions of relationship partners. Pers Individ Dif. 2008;44(1):75-85.

58. Zuroff DC, Fitzpatrick DK. Depressive personality styles: implications for adult attachment. Pers Individ Dif. 1995;18(2):253-265.

59. Kopala-Sibley DC, Zuroff DC. The developmental origins of personality factors from the self-definitional and relatedness domains: a review of theory and research. Rev Gen Psychol. 2014;18(3):137-155.

60. Kopala-Sibley DC, Zuroff DC, Leybman MJ, et al. Recalled peer relationship experiences and current levels of self-criticism and self-reassurance. Psychol Psychother. 2013;86(1):33-51.

61. Neff KD, McGehee P. Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self Identity. 2010;9(3):225-240.

62. Pepping CA, Davis PJ, O’Donovan A, et al. Individual differences in self-compassion: the role of attachment and experiences of parenting in childhood. Self Identity. 2015;14(1):104-117.

63. Neff KD, Rude SS, Kirkpatrick KL. An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. J Res Pers. 2007;41(4):908-916.

64. Van Dam NT, Sheppard SC, Forsyth JP, et al. Self-compassion is a better predictor than mindfulness of symptom severity and quality of life in mixed anxiety and depression. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(1):123-130.

65. Heffernan M, Quinn MT, McNulty SR, et al. Self-compassion and emotional intelligence in nurses. Int J Nursing Practice. 2010;16(4):366-373.

66. Neff KD, Kirkpatrick KL, Rude SS. Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. J Res Pers. 2007;41(1):139-154.

67. Krieger T, Altenstein D, Baettig I, et al. Self-compassion in depression: associations with depressive symptoms, rumination, and avoidance in depressed outpatients. Behav Ther. 2013;44(3):501-513.

68. Breen WE, Kashdan TB, Lenser ML, et al. Gratitude and forgiveness: convergence and divergence on self-report and informant ratings. Pers Individ Dif. 2010;49(8):932-937.

69. Hollis-Walker L, Colosimo K. Mindfulness, self-compassion, and happiness in non-meditators: A theoretical and empirical examination. Pers Individ Dif. 2011;50(2):222-227.

70. Gilbert P, McEwan K, Matos M, et al. Fears of compassion: development of three self-report measures. Psychol Psychother. 2011;84(3):239-255.

71. Neely ME, Schallert DL, Mohammed SS, et al. Self-kindness when facing stress: the role of self-compassion, goal regulation, and support in college students’ well-being. Motiv Emot. 2009;33(1):88-97.

72. Breines JG, Chen S. Self-compassion increases self-improvement motivation. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2012;38(9):1133-1143.

73. Allen AB, Leary MR. Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2010;4(2):107-118.

74. Terry ML, Leary MR. Self-compassion, self-regulation, and health. Self Identity. 2011;10(3):352-362.

75. Magnus CMR, Kowalski KC, McHugh TF. The role of self-compassion in women’s self-determined motives to exercise and exercise-related outcomes. Self Identity. 2010;9(4):363-382.

76. Brooks M, Kay-Lambkin F, Bowman J, et al. Self-compassion amongst clients with problematic alcohol use. Mindfulness. 2012;3(4):308-317.

77. Adams CE, Leary MR. Promoting self-compassionate attitudes toward eating among restrictive and guilty eaters. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2007;26(10):1120-1144.

78. Kelly AC, Zuroff DC, Foa CL, et al. Who benefits from training in self-compassionate self-regulation? A study of smoking reduction. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2010;29(7):727-755.

79. Shapira LB, Mongrain M. The benefits of self-compassion and optimism exercises for individuals vulnerable to depression. J Posit Psychol. 2010;5(5):377-389.

80. Albertson ER, Neff KD, Dill-Shackleford KE. Self-compassion and body dissatisfaction in women: a randomized controlled trial of a brief meditation intervention. Mindfulness. 2015;6(3):444-454.

81. Smeets E, Neff K, Alberts H, et al. Meeting suffering with kindness: effects of a brief self-compassion intervention for female college students. J Clinical Psychol. 2014;70(9):794-807.

82. Blatt SJ, D’Afflitti JP, Quinlan DM. Depressive experiences questionnaire. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1976.

83. Weissman AN, Beck AT. Development and validation of the dysfunctional attitude scale: a preliminary investigation. Paper presented at: 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Advanced Behavior Therapy; March 27-31, 1978; Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

84. Gilbert P, Clarke M, Hempel S, et al. Criticizing and reassuring oneself: an exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. Br J Clin Psychol. 2004;43(pt 1):31-50.

85. Baião R, Gilbert P, McEwan K, et al. Forms of self-criticising/attacking & self-reassuring scale: psychometric properties and normative study. Psychol Psychother. 2015;88(4):438-452.

86. Neff KD. The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness. 2016;7(1):264-274.

87. Neff KD, Germer CK. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. J Clinical Psychol. 2013;69(1):28-44.

88. Gilbert P. Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2009;15(3):199-208.

89. Kelly AC, Zuroff DC, Shapira LB. Soothing oneself and resisting self-attacks: the treatment of two intrapersonal deficits in depression vulnerability. Cognit Ther Res. 2009;33(3):301-313.

90. Boersma K, Hakanson A, Salomonsson E, et al. Compassion focused therapy to counteract shame, self-criticism and isolation. A replicated single case experimental study of individuals with social anxiety. J Contemp Psychother. 2015;45(2):89-98.

91. Gale C, Gilbert P, Read N, et al. An evaluation of the impact of introducing compassion focused therapy to a standard treatment programme for people with eating disorders. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2014;21(1):1-12.

92. Braehler C, Gumley A, Harper J, et al. Exploring change processes in compassion focused therapy in psychosis: results of a feasibility randomized controlled trial. Br J Clin Psychol. 2013;52(2):199-214.

93. Ashworth F, Clarke A, Jones L, et al. An exploration of compassion focused therapy following acquired brain injury. Psychol Psychother. 2014;88(2):143-162.

94. Judge L, Cleghorn A, McEwan K, et al. An exploration of group-based compassion focused therapy for a heterogeneous range of clients presenting to a community mental health team. Int J Cogn Ther. 2012;5(4):420-429.

95. Leaviss J, Utley L. Psychotherapeutic benefits of compassion-focused therapy: an early systematic review. Psychol Med. 2015;45(5):927-945.

96. Gilbert P, McEwan K, Gibbons L, et al. Fears of compassion and happiness in relation to alexithymia, mindfulness, and self‐criticism. Psychol Psychother. 2012;85(4):374-390.

97. Germer CK, Neff KD. Cultivating self-compassion in trauma survivors. In: Follette VM, Briere J, Rozelle D, et al, eds. Mindfulness-oriented interventions for trauma: integrating contemplative practices. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2015:43-58.

98. Gilbert P. Compassion focused therapy: the CBT distinctive features series. London, United Kingdom: Routledge; 2010.

99. Germer C, Neff K. The mindful self-compassion training program. In: Singer T, Bolz M, eds. Compassion: bridging theory and practice: a multimedia book. Leipzig, Germany: Max-Planck Institute; 2013:365-396.

100. Neff K. Self-compassion: the proven power of being kind to yourself. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 2015.

Once thought to only be associated with depression, self-criticism is a transdiagnostic risk factor for diverse forms of psychopathology.1,2 However, research has shown that self-compassion is a robust resilience factor when faced with feelings of personal inadequacy.3,4

Self-critical individuals experience feelings of unworthiness, inferiority, failure, and guilt. They engage in constant and harsh self-scrutiny and evaluation, and fear being disapproved and criticized and losing the approval and acceptance of others.5 Self-compassion involves treating oneself with care and concern when confronted with personal inadequacies, mistakes, failures, and painful life situations.6,7

Although self-criticism is destructive across clinical disorders and interpersonal relationships, self-compassion is associated with healthy relationships, emotional well-being, and better treatment outcomes.

Recent research shows how clinicians can teach their patients how to be less self-critical and more self-compassionate. Neff6,7 proposes that self-compassion involves treating yourself with care and concern when being confronted with personal inadequacies, mistakes, failures, and painful life situations. It consists of 3 interacting components, each of which has a positive and negative pole:

- self-kindness vs self-judgment

- a sense of common humanity vs isolation

- mindfulness vs over-identification.

Self-kindness refers to being caring and understanding with oneself rather than harshly judgmental. Instead of attacking and berating oneself for personal shortcomings, the self is offered warmth and unconditional acceptance.

Humanity involves recognizing that humans are imperfect, that all people fail, make mistakes, and have serious life challenges. By remembering that imperfection is part of life, we feel less isolated when we are in pain.

Mindfulness in the context of self-compassion involves being aware of one’s painful experiences in a balanced way that neither ignores and avoids nor exaggerates painful thoughts and emotions.

Self-compassion is more than the absence of self-judgment, although a defining feature of self-compassion is the lack of self-judgment, and self-judgment overlaps with self-criticism. Rather, self-compassion provides several access points for reducing self-criticism. For example, being kind and understanding when confronting personal inadequacies (eg, “it’s okay not to be perfect”) can counter harsh self-talk (eg, “I’m not defective”). Mindfulness of emotional pain (eg, “this is hard”) can facilitate a kind and warm response (eg, “what can I do to take care of myself right now?”) and therefore lessen self-blame (eg, “blaming myself is just causing me more suffering”). Similarly, remembering that failure is part of the human experience (eg, “it’s normal to mess up sometimes”) can lessen egocentric feelings of isolation (eg, “it’s not just me”) and over-identification (eg, “it’s not the end of the world”), resulting in lessened self-criticism (eg, “maybe it’s not just because I’m a bad person”).

Depression

Several studies have found that self-criticism predicts depression. In 3 epidemiological studies, “feeling worthless” was among the top 2 symptoms predicting a depression diagnosis and later depressive episodes.10 Self-criticism in fourth-year medical students predicted depression 2 years later, and—in males—10 years later in their medical careers better than a history of depression.11 Self-critical perfectionism also is associated with suicidal ideation and lethality of suicide attempts.12

Self-criticism has been shown to predict depressive relapse and residual self-devaluative symptoms in recovered depressed patients.13 In one study, currently depressed and remitted depressed patients had higher self-criticism and lower self-compassion compared with healthy controls. Both factors were more strongly associated with depression status than higher perfectionistic beliefs and cognitions, rumination, and maladaptive emotional regulation.14

Self-criticism and response to treatment. In the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program,15 self-critical perfectionism predicted a poorer outcome across all 4 treatments (cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT], interpersonal psychotherapy [IPT], pharmacotherapy plus clinical management, and placebo plus clinical management). Subsequent studies found that self-criticism predicted poorer response to CBT16 and IPT.17 The authors suggest that self-criticism could interfere with treatment because self-critical patients might have difficulty developing a strong therapeutic alliance.18,19

Anxiety disorders

Self-criticism is common across psychiatric disorders. In a study of 5,877 respondents in the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), self-criticism was associated with social phobia, findings that were significant after controlling for current emotional distress, neuroticism, and lifetime history of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders.20 Further, in a CBT treatment study, baseline self-criticism was associated with severity of social phobia and changes in self-criticism predicted treatment outcome.21 Self-criticism might be an important core psychological process in the development, maintenance, and course of social phobia. Patients with social anxiety disorder have less self-compassion than healthy controls and greater fear of negative evaluation.

In the NCS, self-criticism was associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) even after controlling for lifetime history of affective and anxiety disorders.20 Self-criticism predicted greater severity of combat-related PTSD in hospitalized male veterans,22 and those with PTSD had higher scores on self-criticism scales than those with major depressive disorder.23 In a study of Holocaust survivors, those with PTSD scored higher on self-criticism than survivors without PTSD.24 Self-criticism also distinguished between female victims of domestic violence with and without PTSD.25

Self-compassion could be a protective factor for posttraumatic stress.26 Combat veterans with higher levels of self-compassion showed lower levels of psychopathology, better functioning in daily life, and fewer symptoms of posttraumatic stress.27 In fact, self-compassion has been found to be a stronger predictor of PTSD than level of combat exposure.28

In an early study, self-criticism scores were higher in patients with panic disorder than in healthy controls, but lower than in patients with depression.29 In a study of a mixed sample of anxiety disorder patients, symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder were associated with shame proneness.30 Consistent with these results, Hoge et al31 found that self-compassion was lower in generalized anxiety disorder patients compared with healthy controls with elevated stress. Low self-compassion has been associated with severity of obsessive-compulsive disorder.32

Eating disorders

Self-criticism is correlated with eating disorder severity.33 In a study of patients with binge eating disorder, Dunkley and Grilo34 found that self-criticism was associated with the over-evaluation of shape and weight independently of self-esteem and depression. Self-criticism also is associated with body dissatisfaction, independent of self-esteem and depression. Dunkley et al35 found that self-criticism, but not global self-esteem, in patients with binge eating disorder mediated the relationship between childhood abuse and body dissatisfaction and depression. Numerous studies have shown that shame is associated with more severe eating disorder pathology.33

Self-compassion seems to buffer against body image concerns. It is associated with less body dissatisfaction, body preoccupation, and weight worries,36 greater body appreciation37 and less disordered eating.37-39 Early decreases in shame during eating disorder treatment was associated with more rapid reduction in eating disorder symptoms.40

Interpersonal relationships

Several studies have shown that self-criticism has negative effects on interpersonal relationships throughout life.5,41,42

- Self-criticism at age 12 predicted less involvement in high school activities and, at age 31, personal and social maladjustment.43

- High school students with high self-criticism reported more interpersonal problems.44

- Self-criticism was associated with loneliness, depression, and lack of intimacy with opposite sex friends or partners during the transition to college.45

- In a study of college roommates,46 self-criticism was associated with increased likelihood of rejection.

- Whiffen and Aube47 found that self-criticism was associated with marital dissatisfaction and depression.

- Self-critical mothers with postpartum depression were less satisfied with social support and were more vulnerable to depression.48

Self-compassion appears to enhance interpersonal relationships. In a study of heterosexual couples,49 self-compassionate individuals were described by their partners as being more emotionally connected, as well as accepting and supporting autonomy, while being less detached, controlling, and verbally or physically aggressive than those lacking self-compassion. Because self-compassionate people give themselves care and support, they seem to have more emotional resources available to give to others.

See the Box examining the evidence on the role of self-compassion in borderline personality disorder and non-suicidal self-injury.

Achieving goals

Powers et al50 suggest that self-critics approach goals based on motivation to avoid failure and disapproval, rather than on intrinsic interest and personal meaning. In studies of college students pursuing academic, social, or weight loss goals, self-criticism was associated with less progress to that goal. Self-criticism was associated with rumination and procrastination, which the authors suggest might have focused the self-critic on potential failure, negative evaluation from others, and loss of self-esteem. Additional studies showed the deleterious effects of self-criticism on college students’ progress on obtaining academic or music performance goals and on community residents’ weight loss goals.51

Not surprisingly, self-compassion is associated with successful goal pursuit and resilience when goals are not met52 and less procrastination and academic worry.53 Self-compassion also is associated with intrinsic motivation, goals based on mastery rather than performance, and less fear of academic failure.54

How self-criticism and self-compassion develop

Studies have explored the impact of early relationships with parents and development of self-criticism. Parental overcontrol and restrictiveness and lack of warmth consistently have been identified as parenting styles associated with development of self-criticism in children.55 One study found that self-criticism fully mediated the relationship between childhood verbal abuse from parents and depression and anxiety in adulthood.56 Reports from parents on their current parenting styles are consistent with these studies.57 Amitay et al57 states that “[s]elf-critics’ negative childhood experiences thus seem to contribute to a pattern of entering, creating, or manipulating subsequent interpersonal environments in ways that perpetuate their negative self-image and increase vulnerability to depression.” Not surprisingly, self-criticism is associated with a fearful avoidant attachment style.58 Review of the developmental origins of self-criticism confirms these factors and presents findings that peer relationships also are important factors in the development of self-criticism.59,60

Early positive relationships with caregivers are associated with self-compassion. Recollections of maternal support are correlated with self-compassion and secure attachment styles in adolescents and adults.61 Pepping et al62 found that retrospective reports of parental rejection, overprotection, and low parental warmth was associated with low self-compassion.

Benefits of self-compassion

A growing body of research suggests that self-compassion is strongly linked to mental health. Greater self-compassion consistently has been associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety,3 with a large effect size.4 Of course, central to self-compassion is the lack of self-criticism, but self-compassion still protects against anxiety and depression when controlling for self-criticism and negative affect.6,63 Self-compassion is a strong predictor of symptom severity and quality of life among individuals with anxious distress.64

The benefits of self-compassion stem partly from a greater ability to cope with negative emotions.6,63,65 Self-compassionate people are less likely to ruminate on their negative thoughts and emotions or suppress them,6,66 which helps to explain why self-compassion is a negative predictor of depression.67

Self-compassion also enhances positive mind states. A number of studies have found links between self-compassion and positive psychological qualities, such as happiness, optimism, wisdom, curiosity, and exploration, and personal initiative.63,65,68,69 By embracing one’s suffering with compassion, negative states are ameliorated when positive emotions of kindness, connectedness, and mindful presence are generated.

Misconceptions about self-compassion

A common misconception is that abandoning self-criticism in favor of self-compassion will undermine motivation70; however, research indicates the opposite. Although self-compassion is negatively associated with maladaptive perfectionism, it is not correlated with self-adopted performance standards.6 Self-compassionate people have less fear of failure54 and, when they do fail, they are more likely to try again.71 Breines and Chen72 found in a series of experimental studies that engendering feelings of self-compassion for personal weaknesses, failures, and past transgressions resulted in more motivation to change, to try harder to learn, and to avoid repeating past mistakes.

Another common misunderstanding is that self-compassion is a weakness. In fact, research suggests that self-compassion is a powerful way to cope with life challenges.73

Although some fear that self-compassion leads to self-indulgence, there is evidence that self-compassion promotes health-related behaviors. Self-compassionate individuals are more likely to seek medical treatment when needed,74 exercise for intrinsic reasons,75 and drink less alcohol.76 Inducing self-compassion has been found to help people stick to their diets77 and quit smoking.78

Self-compassion interventions

Individuals can develop self-compassion. Shapira and Mongrain79 found that adults who wrote a compassionate letter to themselves once a day for a week about the distressing events they were experiencing showed significant reductions in depression up to 3 months and significant increases in happiness up to 6 months compared with a control group who wrote about early memories. Albertson et al80 found that, compared with a wait-list control group, 3 weeks of self-compassion meditation training improved body dissatisfaction, body shame, and body appreciation among women with body image concerns. Similarly, Smeets et al81 found that 3 weeks of self-compassion training for female college students led to significantly greater increases in mindfulness, optimism, and self-efficacy, as well as greater decreases in rumination compared with a time management control group.

The Box6,70,82-86 describes rating scales that can measure self-compassion and self-criticism.

Mindful self-compassion (MSC), developed by Neff and Germer,87 is an 8-week group intervention designed to teach people how to be more self-compassionate through meditation and informal practices in daily life. Results of a randomized controlled trial found that, compared with a wait-list control group, participants using MSC reported significantly greater increases in self-compassion, compassion for others, mindfulness, and life satisfaction, and greater decreases in depression, anxiety, stress, and emotional avoidance, with large effect sizes indicated. These results were maintained up to 1 year.

Compassion-focused therapy (CFT) is designed to enhance self-compassion in clinical populations.88 The approach uses a number of imagery and experiential exercises to enhance patients’ abilities to extend feelings of reassurance, safeness, and understanding toward themselves. CFT has shown promise in treating a diverse group of clinical disorders such as depression and shame,8,89 social anxiety and shame,90 eating disorders,91 psychosis,92 and patients with acquired brain injury.93 A group-based CFT intervention with a heterogeneous group of community mental health patients led to significant reductions in depression, anxiety, stress, and self-criticism.94 See Leaviss and Utley95 for a review of the benefits of CFT.

Fears of developing self-compassion

It is important to note that some people can access self-compassion more easily than others. Highly self-critical patients could feel anxious when learning to be compassionate to themselves, a phenomenon known as “fear of compassion”96 or “backdraft.”97 Backdraft occurs when a firefighter opens a door with a hot fire behind it. Oxygen rushes in, causing a burst of flame. Similarly, when the door of the heart is opened with compassion, intense pain could be released. Unconditional love reveals the conditions under which we were unloved in the past. Some individuals, especially those with a history of childhood abuse or neglect, are fearful of compassion because it activates grief associated with feelings of wanting, but not receiving, affection and care from significant others in childhood.

Clinicians should be aware that anxiety could arise and should help patients learn how to go slowly and stabilize themselves if overwhelming emotions occur as a part of self-compassion practice. Both CFT and MSC have processes to deal with fear of compassion in their protocols,98,99 with the focus on explaining to individuals that although such fears may occur, they are a normal and necessary part of the healing process. Individuals also are taught to focus on the breath, feeling the sensations in the soles of their feet, or other mindfulness practices to ground and stabilize attention when overwhelming feelings arise.

Clinical interventions

Self-compassion interventions that I (R.W.) find most helpful, in the order I administer them, are:

- exploring perceived advantages and disadvantages of self-criticism

- presenting self-compassion as a way to get the perceived advantages of self-criticism without the disadvantages

- discussing what it means to be compassionate for someone else who is suffering, and then asking what it would be like if they treated themselves with the same compassion

- exploring patients’ misconceptions and fears of self-compassion

- directing patients to the self-compassion Web site to get an understanding of what self-compassion is and how it differs from self-esteem

- taking an example of a recent situation in which the patient was self-critical and exploring how a self-compassionate response would differ.

Asking what they would say to a friend often is an effective way to get at this. In a later therapy session, self-compassionate imagery is a useful way to get the patient to experience self-compassion on an emotional level. See Neff100 and Gilbert98 for other techniques to enhance self-compassion.

Once thought to only be associated with depression, self-criticism is a transdiagnostic risk factor for diverse forms of psychopathology.1,2 However, research has shown that self-compassion is a robust resilience factor when faced with feelings of personal inadequacy.3,4

Self-critical individuals experience feelings of unworthiness, inferiority, failure, and guilt. They engage in constant and harsh self-scrutiny and evaluation, and fear being disapproved and criticized and losing the approval and acceptance of others.5 Self-compassion involves treating oneself with care and concern when confronted with personal inadequacies, mistakes, failures, and painful life situations.6,7

Although self-criticism is destructive across clinical disorders and interpersonal relationships, self-compassion is associated with healthy relationships, emotional well-being, and better treatment outcomes.

Recent research shows how clinicians can teach their patients how to be less self-critical and more self-compassionate. Neff6,7 proposes that self-compassion involves treating yourself with care and concern when being confronted with personal inadequacies, mistakes, failures, and painful life situations. It consists of 3 interacting components, each of which has a positive and negative pole:

- self-kindness vs self-judgment

- a sense of common humanity vs isolation

- mindfulness vs over-identification.

Self-kindness refers to being caring and understanding with oneself rather than harshly judgmental. Instead of attacking and berating oneself for personal shortcomings, the self is offered warmth and unconditional acceptance.

Humanity involves recognizing that humans are imperfect, that all people fail, make mistakes, and have serious life challenges. By remembering that imperfection is part of life, we feel less isolated when we are in pain.

Mindfulness in the context of self-compassion involves being aware of one’s painful experiences in a balanced way that neither ignores and avoids nor exaggerates painful thoughts and emotions.

Self-compassion is more than the absence of self-judgment, although a defining feature of self-compassion is the lack of self-judgment, and self-judgment overlaps with self-criticism. Rather, self-compassion provides several access points for reducing self-criticism. For example, being kind and understanding when confronting personal inadequacies (eg, “it’s okay not to be perfect”) can counter harsh self-talk (eg, “I’m not defective”). Mindfulness of emotional pain (eg, “this is hard”) can facilitate a kind and warm response (eg, “what can I do to take care of myself right now?”) and therefore lessen self-blame (eg, “blaming myself is just causing me more suffering”). Similarly, remembering that failure is part of the human experience (eg, “it’s normal to mess up sometimes”) can lessen egocentric feelings of isolation (eg, “it’s not just me”) and over-identification (eg, “it’s not the end of the world”), resulting in lessened self-criticism (eg, “maybe it’s not just because I’m a bad person”).

Depression

Several studies have found that self-criticism predicts depression. In 3 epidemiological studies, “feeling worthless” was among the top 2 symptoms predicting a depression diagnosis and later depressive episodes.10 Self-criticism in fourth-year medical students predicted depression 2 years later, and—in males—10 years later in their medical careers better than a history of depression.11 Self-critical perfectionism also is associated with suicidal ideation and lethality of suicide attempts.12

Self-criticism has been shown to predict depressive relapse and residual self-devaluative symptoms in recovered depressed patients.13 In one study, currently depressed and remitted depressed patients had higher self-criticism and lower self-compassion compared with healthy controls. Both factors were more strongly associated with depression status than higher perfectionistic beliefs and cognitions, rumination, and maladaptive emotional regulation.14

Self-criticism and response to treatment. In the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program,15 self-critical perfectionism predicted a poorer outcome across all 4 treatments (cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT], interpersonal psychotherapy [IPT], pharmacotherapy plus clinical management, and placebo plus clinical management). Subsequent studies found that self-criticism predicted poorer response to CBT16 and IPT.17 The authors suggest that self-criticism could interfere with treatment because self-critical patients might have difficulty developing a strong therapeutic alliance.18,19

Anxiety disorders

Self-criticism is common across psychiatric disorders. In a study of 5,877 respondents in the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), self-criticism was associated with social phobia, findings that were significant after controlling for current emotional distress, neuroticism, and lifetime history of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders.20 Further, in a CBT treatment study, baseline self-criticism was associated with severity of social phobia and changes in self-criticism predicted treatment outcome.21 Self-criticism might be an important core psychological process in the development, maintenance, and course of social phobia. Patients with social anxiety disorder have less self-compassion than healthy controls and greater fear of negative evaluation.

In the NCS, self-criticism was associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) even after controlling for lifetime history of affective and anxiety disorders.20 Self-criticism predicted greater severity of combat-related PTSD in hospitalized male veterans,22 and those with PTSD had higher scores on self-criticism scales than those with major depressive disorder.23 In a study of Holocaust survivors, those with PTSD scored higher on self-criticism than survivors without PTSD.24 Self-criticism also distinguished between female victims of domestic violence with and without PTSD.25

Self-compassion could be a protective factor for posttraumatic stress.26 Combat veterans with higher levels of self-compassion showed lower levels of psychopathology, better functioning in daily life, and fewer symptoms of posttraumatic stress.27 In fact, self-compassion has been found to be a stronger predictor of PTSD than level of combat exposure.28

In an early study, self-criticism scores were higher in patients with panic disorder than in healthy controls, but lower than in patients with depression.29 In a study of a mixed sample of anxiety disorder patients, symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder were associated with shame proneness.30 Consistent with these results, Hoge et al31 found that self-compassion was lower in generalized anxiety disorder patients compared with healthy controls with elevated stress. Low self-compassion has been associated with severity of obsessive-compulsive disorder.32

Eating disorders

Self-criticism is correlated with eating disorder severity.33 In a study of patients with binge eating disorder, Dunkley and Grilo34 found that self-criticism was associated with the over-evaluation of shape and weight independently of self-esteem and depression. Self-criticism also is associated with body dissatisfaction, independent of self-esteem and depression. Dunkley et al35 found that self-criticism, but not global self-esteem, in patients with binge eating disorder mediated the relationship between childhood abuse and body dissatisfaction and depression. Numerous studies have shown that shame is associated with more severe eating disorder pathology.33

Self-compassion seems to buffer against body image concerns. It is associated with less body dissatisfaction, body preoccupation, and weight worries,36 greater body appreciation37 and less disordered eating.37-39 Early decreases in shame during eating disorder treatment was associated with more rapid reduction in eating disorder symptoms.40

Interpersonal relationships

Several studies have shown that self-criticism has negative effects on interpersonal relationships throughout life.5,41,42

- Self-criticism at age 12 predicted less involvement in high school activities and, at age 31, personal and social maladjustment.43

- High school students with high self-criticism reported more interpersonal problems.44

- Self-criticism was associated with loneliness, depression, and lack of intimacy with opposite sex friends or partners during the transition to college.45

- In a study of college roommates,46 self-criticism was associated with increased likelihood of rejection.

- Whiffen and Aube47 found that self-criticism was associated with marital dissatisfaction and depression.

- Self-critical mothers with postpartum depression were less satisfied with social support and were more vulnerable to depression.48

Self-compassion appears to enhance interpersonal relationships. In a study of heterosexual couples,49 self-compassionate individuals were described by their partners as being more emotionally connected, as well as accepting and supporting autonomy, while being less detached, controlling, and verbally or physically aggressive than those lacking self-compassion. Because self-compassionate people give themselves care and support, they seem to have more emotional resources available to give to others.

See the Box examining the evidence on the role of self-compassion in borderline personality disorder and non-suicidal self-injury.

Achieving goals

Powers et al50 suggest that self-critics approach goals based on motivation to avoid failure and disapproval, rather than on intrinsic interest and personal meaning. In studies of college students pursuing academic, social, or weight loss goals, self-criticism was associated with less progress to that goal. Self-criticism was associated with rumination and procrastination, which the authors suggest might have focused the self-critic on potential failure, negative evaluation from others, and loss of self-esteem. Additional studies showed the deleterious effects of self-criticism on college students’ progress on obtaining academic or music performance goals and on community residents’ weight loss goals.51

Not surprisingly, self-compassion is associated with successful goal pursuit and resilience when goals are not met52 and less procrastination and academic worry.53 Self-compassion also is associated with intrinsic motivation, goals based on mastery rather than performance, and less fear of academic failure.54

How self-criticism and self-compassion develop

Studies have explored the impact of early relationships with parents and development of self-criticism. Parental overcontrol and restrictiveness and lack of warmth consistently have been identified as parenting styles associated with development of self-criticism in children.55 One study found that self-criticism fully mediated the relationship between childhood verbal abuse from parents and depression and anxiety in adulthood.56 Reports from parents on their current parenting styles are consistent with these studies.57 Amitay et al57 states that “[s]elf-critics’ negative childhood experiences thus seem to contribute to a pattern of entering, creating, or manipulating subsequent interpersonal environments in ways that perpetuate their negative self-image and increase vulnerability to depression.” Not surprisingly, self-criticism is associated with a fearful avoidant attachment style.58 Review of the developmental origins of self-criticism confirms these factors and presents findings that peer relationships also are important factors in the development of self-criticism.59,60

Early positive relationships with caregivers are associated with self-compassion. Recollections of maternal support are correlated with self-compassion and secure attachment styles in adolescents and adults.61 Pepping et al62 found that retrospective reports of parental rejection, overprotection, and low parental warmth was associated with low self-compassion.

Benefits of self-compassion

A growing body of research suggests that self-compassion is strongly linked to mental health. Greater self-compassion consistently has been associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety,3 with a large effect size.4 Of course, central to self-compassion is the lack of self-criticism, but self-compassion still protects against anxiety and depression when controlling for self-criticism and negative affect.6,63 Self-compassion is a strong predictor of symptom severity and quality of life among individuals with anxious distress.64

The benefits of self-compassion stem partly from a greater ability to cope with negative emotions.6,63,65 Self-compassionate people are less likely to ruminate on their negative thoughts and emotions or suppress them,6,66 which helps to explain why self-compassion is a negative predictor of depression.67

Self-compassion also enhances positive mind states. A number of studies have found links between self-compassion and positive psychological qualities, such as happiness, optimism, wisdom, curiosity, and exploration, and personal initiative.63,65,68,69 By embracing one’s suffering with compassion, negative states are ameliorated when positive emotions of kindness, connectedness, and mindful presence are generated.

Misconceptions about self-compassion

A common misconception is that abandoning self-criticism in favor of self-compassion will undermine motivation70; however, research indicates the opposite. Although self-compassion is negatively associated with maladaptive perfectionism, it is not correlated with self-adopted performance standards.6 Self-compassionate people have less fear of failure54 and, when they do fail, they are more likely to try again.71 Breines and Chen72 found in a series of experimental studies that engendering feelings of self-compassion for personal weaknesses, failures, and past transgressions resulted in more motivation to change, to try harder to learn, and to avoid repeating past mistakes.

Another common misunderstanding is that self-compassion is a weakness. In fact, research suggests that self-compassion is a powerful way to cope with life challenges.73

Although some fear that self-compassion leads to self-indulgence, there is evidence that self-compassion promotes health-related behaviors. Self-compassionate individuals are more likely to seek medical treatment when needed,74 exercise for intrinsic reasons,75 and drink less alcohol.76 Inducing self-compassion has been found to help people stick to their diets77 and quit smoking.78

Self-compassion interventions

Individuals can develop self-compassion. Shapira and Mongrain79 found that adults who wrote a compassionate letter to themselves once a day for a week about the distressing events they were experiencing showed significant reductions in depression up to 3 months and significant increases in happiness up to 6 months compared with a control group who wrote about early memories. Albertson et al80 found that, compared with a wait-list control group, 3 weeks of self-compassion meditation training improved body dissatisfaction, body shame, and body appreciation among women with body image concerns. Similarly, Smeets et al81 found that 3 weeks of self-compassion training for female college students led to significantly greater increases in mindfulness, optimism, and self-efficacy, as well as greater decreases in rumination compared with a time management control group.

The Box6,70,82-86 describes rating scales that can measure self-compassion and self-criticism.

Mindful self-compassion (MSC), developed by Neff and Germer,87 is an 8-week group intervention designed to teach people how to be more self-compassionate through meditation and informal practices in daily life. Results of a randomized controlled trial found that, compared with a wait-list control group, participants using MSC reported significantly greater increases in self-compassion, compassion for others, mindfulness, and life satisfaction, and greater decreases in depression, anxiety, stress, and emotional avoidance, with large effect sizes indicated. These results were maintained up to 1 year.

Compassion-focused therapy (CFT) is designed to enhance self-compassion in clinical populations.88 The approach uses a number of imagery and experiential exercises to enhance patients’ abilities to extend feelings of reassurance, safeness, and understanding toward themselves. CFT has shown promise in treating a diverse group of clinical disorders such as depression and shame,8,89 social anxiety and shame,90 eating disorders,91 psychosis,92 and patients with acquired brain injury.93 A group-based CFT intervention with a heterogeneous group of community mental health patients led to significant reductions in depression, anxiety, stress, and self-criticism.94 See Leaviss and Utley95 for a review of the benefits of CFT.

Fears of developing self-compassion

It is important to note that some people can access self-compassion more easily than others. Highly self-critical patients could feel anxious when learning to be compassionate to themselves, a phenomenon known as “fear of compassion”96 or “backdraft.”97 Backdraft occurs when a firefighter opens a door with a hot fire behind it. Oxygen rushes in, causing a burst of flame. Similarly, when the door of the heart is opened with compassion, intense pain could be released. Unconditional love reveals the conditions under which we were unloved in the past. Some individuals, especially those with a history of childhood abuse or neglect, are fearful of compassion because it activates grief associated with feelings of wanting, but not receiving, affection and care from significant others in childhood.

Clinicians should be aware that anxiety could arise and should help patients learn how to go slowly and stabilize themselves if overwhelming emotions occur as a part of self-compassion practice. Both CFT and MSC have processes to deal with fear of compassion in their protocols,98,99 with the focus on explaining to individuals that although such fears may occur, they are a normal and necessary part of the healing process. Individuals also are taught to focus on the breath, feeling the sensations in the soles of their feet, or other mindfulness practices to ground and stabilize attention when overwhelming feelings arise.

Clinical interventions

Self-compassion interventions that I (R.W.) find most helpful, in the order I administer them, are:

- exploring perceived advantages and disadvantages of self-criticism

- presenting self-compassion as a way to get the perceived advantages of self-criticism without the disadvantages

- discussing what it means to be compassionate for someone else who is suffering, and then asking what it would be like if they treated themselves with the same compassion

- exploring patients’ misconceptions and fears of self-compassion

- directing patients to the self-compassion Web site to get an understanding of what self-compassion is and how it differs from self-esteem

- taking an example of a recent situation in which the patient was self-critical and exploring how a self-compassionate response would differ.

Asking what they would say to a friend often is an effective way to get at this. In a later therapy session, self-compassionate imagery is a useful way to get the patient to experience self-compassion on an emotional level. See Neff100 and Gilbert98 for other techniques to enhance self-compassion.

1. Shahar B, Doron G, Ohad S. Childhood maltreatment, shame-proneness and self-criticism in social anxiety disorder: a sequential mediational model. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2015:22(6):570-579.

2. Kannan D, Levitt HM. A review of client self-criticism in psychotherapy. J Psychother Integr. 2013;23(2):166-178.

3. Barnard LK, Curry JF. Self-compassion: conceptualizations, correlates, and interventions. Rev Gen Psychol. 2011;15(4):289-303.

4. MacBeth A, Gumley A. Exploring compassion: a meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(6):545-552

5. Blatt SJ, Zuroff DC. Interpersonal relatedness and self-definition: two prototypes for depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 1992;12(5):527-562.

6. Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2(2):223-250.

7. Neff KD. Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity. 2003;(2)2:85-101.

8. Gilbert P, Procter S. Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2006;13(6):353-379.

9. Dunkley DM, Zuroff DC, Blankstein KR. Specific perfectionism components versus self-criticism in predicting maladjustment. Pers Individ Dif. 2006;40(4):665-676.

10. Murphy JM, Nierenberg AA, Monson RR, et al. Self-disparagement as feature and forerunner of depression: Mindfindings from the Stirling County Study. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(1):13-21.

11. Brewin CR, Firth-Cozens J. Dependency and self-criticism as predictors of depression in young doctors. J Occup Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):242-246.

12. Fazaa N, Page S. Dependency and self-criticism as predictors of suicidal behavior. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2003;33(2):172-185.

13. Teasdale JD, Cox SG. Dysphoria: self-devaluative and affective components in recovered depressed patients and never depressed controls. Psychol Med. 2001;31(7):1311-1316.

14. Ehret AM, Joormann J, Berking M. Examining risk and resilience factors for depression: the role of self-criticism and self-compassion. Cogn Emot. 2015;29(8):1496-1504.

15. Elkin I, Shea MT, Watkins JT, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):971-982; discussion 983.