User login

Implementation of an Interfacility Telehealth Cancer Genetics Clinic

BACKGROUND

Cancer risk assessment and genetic counseling are the processes to identify and counsel people at risk for familial or hereditary cancer syndromes. They serve to inform, educate and empower patients and family members to make informed decisions about testing, cancer screening, and prevention. Additionally, genetic testing can also provide therapeutic options and opportunities for research.

METHODS

Prior to this program initiative, there were no cancer genetics services available at the VA Pittsburgh Medical Center (VAPHS) and 100% of genetics consults were referred to the community. Each year over $100,000 was spent outside of VAPHS on genetic testing and counseling. Community care referral resulted in fragmented care, prolonged wait times of 3 to 5 months, communication issues, and added financial cost to the institution. Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center (CMCVAMC) had previously created a genetics consultation service staffed with an advanced practice nurse that increased access to genetics services and testing rates at the facility-level. VAPHS recently established an interfacility telegenetics clinic with CMCVAMC to provide virtual genetic counseling services to Veterans at VAPHS. Under this program, VAPHS providers place an interfacility consult for Veterans who need cancer genetics services. The consult is received and reviewed by the CMCVAMC team. VAPHS patients are then seen by CMCVAMC providers via VVC or CVT and provide recommendations regarding additional genetic testing and follow-up.

RESULTS

The telegenetics clinic opened in October 2022. The clinic initially focused on patients with metastatic prostate cancer but has since expanded to provide care for all patients for whom genetics testing and/ or counseling is recommended by NCCN guidelines. Since initiation, 29 consults have been placed and 26 have been completed or are in process (89.6%). In the year prior to creation of the clinic, only 31 of 67 (46%) of referred patients completed genetics evaluation.

CONCLUSIONS

Due to the success of the clinic, plans to expand services to the VISN-level and within VAPHS to include high risk breast cancer assessment are underway. Efforts to provide genetic counseling services via virtual care modalities have the potential to increase access to care and to improve outcomes for veterans with cancer.

BACKGROUND

Cancer risk assessment and genetic counseling are the processes to identify and counsel people at risk for familial or hereditary cancer syndromes. They serve to inform, educate and empower patients and family members to make informed decisions about testing, cancer screening, and prevention. Additionally, genetic testing can also provide therapeutic options and opportunities for research.

METHODS

Prior to this program initiative, there were no cancer genetics services available at the VA Pittsburgh Medical Center (VAPHS) and 100% of genetics consults were referred to the community. Each year over $100,000 was spent outside of VAPHS on genetic testing and counseling. Community care referral resulted in fragmented care, prolonged wait times of 3 to 5 months, communication issues, and added financial cost to the institution. Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center (CMCVAMC) had previously created a genetics consultation service staffed with an advanced practice nurse that increased access to genetics services and testing rates at the facility-level. VAPHS recently established an interfacility telegenetics clinic with CMCVAMC to provide virtual genetic counseling services to Veterans at VAPHS. Under this program, VAPHS providers place an interfacility consult for Veterans who need cancer genetics services. The consult is received and reviewed by the CMCVAMC team. VAPHS patients are then seen by CMCVAMC providers via VVC or CVT and provide recommendations regarding additional genetic testing and follow-up.

RESULTS

The telegenetics clinic opened in October 2022. The clinic initially focused on patients with metastatic prostate cancer but has since expanded to provide care for all patients for whom genetics testing and/ or counseling is recommended by NCCN guidelines. Since initiation, 29 consults have been placed and 26 have been completed or are in process (89.6%). In the year prior to creation of the clinic, only 31 of 67 (46%) of referred patients completed genetics evaluation.

CONCLUSIONS

Due to the success of the clinic, plans to expand services to the VISN-level and within VAPHS to include high risk breast cancer assessment are underway. Efforts to provide genetic counseling services via virtual care modalities have the potential to increase access to care and to improve outcomes for veterans with cancer.

BACKGROUND

Cancer risk assessment and genetic counseling are the processes to identify and counsel people at risk for familial or hereditary cancer syndromes. They serve to inform, educate and empower patients and family members to make informed decisions about testing, cancer screening, and prevention. Additionally, genetic testing can also provide therapeutic options and opportunities for research.

METHODS

Prior to this program initiative, there were no cancer genetics services available at the VA Pittsburgh Medical Center (VAPHS) and 100% of genetics consults were referred to the community. Each year over $100,000 was spent outside of VAPHS on genetic testing and counseling. Community care referral resulted in fragmented care, prolonged wait times of 3 to 5 months, communication issues, and added financial cost to the institution. Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center (CMCVAMC) had previously created a genetics consultation service staffed with an advanced practice nurse that increased access to genetics services and testing rates at the facility-level. VAPHS recently established an interfacility telegenetics clinic with CMCVAMC to provide virtual genetic counseling services to Veterans at VAPHS. Under this program, VAPHS providers place an interfacility consult for Veterans who need cancer genetics services. The consult is received and reviewed by the CMCVAMC team. VAPHS patients are then seen by CMCVAMC providers via VVC or CVT and provide recommendations regarding additional genetic testing and follow-up.

RESULTS

The telegenetics clinic opened in October 2022. The clinic initially focused on patients with metastatic prostate cancer but has since expanded to provide care for all patients for whom genetics testing and/ or counseling is recommended by NCCN guidelines. Since initiation, 29 consults have been placed and 26 have been completed or are in process (89.6%). In the year prior to creation of the clinic, only 31 of 67 (46%) of referred patients completed genetics evaluation.

CONCLUSIONS

Due to the success of the clinic, plans to expand services to the VISN-level and within VAPHS to include high risk breast cancer assessment are underway. Efforts to provide genetic counseling services via virtual care modalities have the potential to increase access to care and to improve outcomes for veterans with cancer.

The Effect of Radium-223 Therapy in Agent Orange-Related Prostate Carcinoma

Patients with metastatic castrate resistant prostate carcinoma (CRPC) have several treatment options, including radium-223 dichloride (Ra-223) radionuclide therapy, abiraterone, enzalutamide, and cabazitaxel. Ra-223 therapy has been reported to increase median survival in patients with bone metastatic prostate carcinoma.1,2 However, ERA 223 trial data showed an increase of bone fractures with combination of Ra-223 and abiraterone.3

Agent Orange (AO) exposure has been studied as a potential risk factor for development of prostate carcinoma. AO was a commercially manufactured defoliate that was sprayed extensively during the Vietnam War. Due to a side product of chemical manufacturing, AO was contaminated with the toxin 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, a putative carcinogen. These dioxins can enter the food chain through soil contamination. There is enough evidence to link AO to hematologic malignancies and several solid tumors, including prostate carcinoma.4 Although no real estimates exist for what percentage of Vietnam veterans experienced AO exposure, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data showed that about 3 million veterans served in Southeast Asia where AO was used extensively in the combat theater. AO has been reported to be positively associated with a 52% increase in risk of prostate carcinoma detection at initial prostate biopsy.5

There has been no reported study of treatment efficacy in veterans with AO-related prostate carcinoma. We present a retrospective study of Ra-223 and other therapies in metastatic CRPC. The purpose of this study was to compare response to therapy and survival in veterans exposed to agent orange (AO+) vs veterans who were not exposed to (AO-) in a single US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) medical center.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of veterans with metastatic CRPC to bones who received Ra-223 radionuclide therapy with standard dose of 50 kBq per kg of body weight and other sequential therapies at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System (VAPHS) from January 2014 to January 2019. The purpose of this study was to measure difference in treatment outcome between AO+ veterans and AO- veterans.

Eligibility Criteria

All veterans had a history that included bone metastasis CRPC. They could have 2 to 3 small lymphadenopathies but not visceral metastasis. They received a minimum of 3 cycles and a maximum of 6 cycles of Ra-223 therapy, which was given in 4-week intervals. Pretreatment criteria was hemoglobin > 10 g/dL, platelet > 100

Statistics

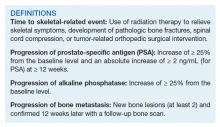

Time to study was calculated from the initiation of Ra-223 therapy. Time to skeletal-related events (SRE), progression of prostate specific antigen (PSA), bone metastasis, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) were calculated in months, using unpaired t test with 2-tailed P value. Median survival was calculated in months by Kaplan Meier R log-rank test Definition).

Results

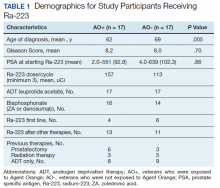

Forty-eight veterans with bone metastasis CRPC received Ra-223 therapy. Of those, 34 veterans were eligible for this retrospective study: 17 AO+ veterans and 17 AO- veterans. Mean age of diagnosis was 62 years (AO+) and 69 years (AO-) (P = .005). Mean Gleason score was 8.2 (AO+) and 8.0 (AO-) (P = .705). Veterans received initial therapy at diagnosis of prostate carcinoma, including radical prostatectomy (6 AO+ and 3 AO-), localized radiation therapy (3 AO+ and 5 AO-), and ADT (8 AO+ and 9 AO-) (Table 1).

Mean PSA at the initiation of Ra-223 therapy for AO+ was 92.8 (range, 2-551) and for AO- was 102.3 (range, 4-639; P = .86). Mean Ra-223 dose per cycle for AO+ and AO- was 157 uCi and 113 uCi, respectively. All 34 veterans received ADT (leuprolide acetate), and 30 veterans (16 AO+ and 14 AO-) received bisphosphonates (zoledronic acid or denosumab). A total of 10 veterans (29%) received Ra-223 as a first-line therapy (4 AO+ and 6 AO-), and 24 veterans (71%) received Ra-223 after hormonal or chemotherapy (13 AO+ and 11 AO-).

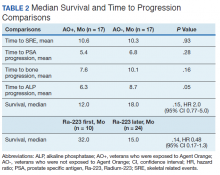

There were 12 SRE (8 AO+ and 4 AO-). Mean time to SRE for AO+ was 10.6 months and AO- was 10.3 months (P = .93). Three veterans received concurrent Ra-223 and abiraterone (participated in ERA 223 trial). Two AO+ veterans experienced SRE at 7 months and 11 months, respectively. Mean time to PSA progression for AO+ was 5.4 months and for AO- was 6.8 months (P = .28). Mean time to bone progression for AO+ and for AO- were 7.6 months and 10.1 months, respectively (P = .16). Mean time to ALP progression for AO+ and AO- were 6.3 months and 8.7 months, respectively (P = .05). (Table 2). The treatment pattern of AO+ and AO- is depicted on a swimmer plot (Figures 1 and 2).

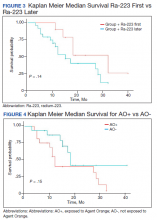

Twenty veterans (58%) had died: 13 AO+ and 7 AO- veterans. Median survival for Ra-223 first and Ra-223 later was was 32 months and 15 months, respectively (P = .14; hazard ratio [HR], 0.48). Overall median survival for AO+ veterans and AO- veterans were 12 months and 18 months, respectively (P = .15; HR, 2.0) (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussions

There has been no reported VA study of using Ra-223 and other therapies (hormonal and chemotherapy) in veterans exposed to AO. This is the first retrospective study to compare the response and survival between AO+ and AO- veterans. Even though this study featured a small sample, it is interesting to note the difference between those 2 populations. There was 1 prior study in veterans with prostate carcinoma using radiotherapy (brachytherapy) in early-stage disease. Everly and colleagues reported that AO+ veterans were less likely to remain biochemically controlled compared with AO- and nonveteran patients with prostate carcinoma.4

Ansbaugh and colleagues reported that AO was associated with a 75% increase in the risk of Gleason ≥ 7 and a 110% increase in Gleason ≥ 8. AO+ veterans are at risk for the detection of high-grade prostate carcinoma. They also tend to have an average age of diagnosis that is 4 to 5 years younger than AO- veterans.6

Our study revealed that AO+ veterans were diagnosed at a younger age (mean 62 years) compared with that of AO- veterans (mean 69 years, P = .005). We also proved that AO veterans have a higher mean Gleason score (8.2) compared with that of AO- veterans (8.0). Veterans received therapy at the time of diagnosis of prostate carcinoma with either radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy, or ADT with leuprolide acetate. Mean PSA at the start of Ra-223 therapy for AO+ was 92.8 (range, 2-551); for AO- was 102.3 (range, 4-639), which is not statistically significant.

Ra-223, an

In a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study by Parker and colleagues (ALSYMPCA study), 921 patients who had received, were not eligible to receive, or declined docetaxel, in a 2:1 ratio, were randomized to receive 6 injections of Ra-223 or matching placebo.2 Ra-223 significantly improved overall survival (OS) (median, 14.9 months vs 11.3 months) compared with that of placebo. Ra-223 also prolonged the time to the first symptomatic SRE (median, 15.6 months vs 9.8 months), the time to an increase in the total ALP level (median 7.4 months vs 3.8 months), and the time to an increase in the PSA level (median 3.6 months vs 3.4 months).2

In our study, the mean time to SRE for AO+ was 10.6 months and AO- was 10.3 months (P = .93). Mean time to PSA progression for AO+ was 5.4 months and for AO- was 6.8 months (P = .28). Mean time to bone progression for AO+ and for AO- were 7.6 months and 10.1 months respectively (P = .16). Mean time to ALP progression for AO+ and AO- were 6.3 months and 8.7 months respectively (P = .05). There is a trend of shorter PSA progression, bone progression, and ALP progression in AO+ veterans, though these were not statistically significant due to small sample population. In our study the median survival in for AO- was 18 months and for AO+ was 12 months, which is comparable with median survival of 14.9 months from the ALSYMPCA study.

There were 12 veterans who developed SREs. All received radiation therapy due to bone progression or impending fracture. AO+ veterans developed more SREs (n = 8) when compared with AO- veterans (n = 4). There were more AO- veterans alive (n = 10) than there were AO+ veterans (n = 4). The plausible explanation of this may be due to the aggressive pattern of prostate carcinoma in AO+ veterans (younger age and higher Gleason score).

VAPHS participated in the ERA trial between 2014 and 2016. The trial enrolled 806 patients who were randomly assigned to receive first-line Ra-223 or placebo in addition to abiraterone acetate plus prednisone.3 The study was unblinded prematurely after more fractures and deaths were noted in the Ra-223 and abiraterone group than there were in the placebo and abiraterone group. Median symptomatic SRE was 22.3 months in the Ra-223 group and 26.0 months in the placebo group. Fractures (any grade) occurred in 29% in the Ra-223 group and 11% in the placebo group. It was suggested that Ra-223 could contribute to the risk of osteoporotic fractures in patients with bone metastatic prostate carcinoma. Median OS was 30.7 months in the Ra-223 group and 33.3 months in the placebo group.

We enrolled 3 veterans in the ERA clinical trial. Two AO+ veterans had SREs at 7 months and 11 months. In our study, the median OS for Ra-223 first line was 32 months, which is comparable with median survival of 30.7 months from ERA-223 study. Median survival for Ra-223 later was only 15 months. We recommend veterans with at least 2 to 3-bone metastasis receive Ra-223 in the first-line setting rather than second- or third-line setting. In this retrospective study with Ra-223 and other therapies, we proved that AO+ veterans have a worse response and OS when compared with that of AO- veterans.

Conclusions

This is the first VA study to compare the efficacy of Ra-223 and other therapies in metastatic CRPC between AO+ and AO- veterans. AO+ veterans were diagnosed at a younger age and had higher Gleason scores. There was no statistical difference between AO+ and AO- veterans in terms of time to SRE, PSA progression, and bone and ALP progression even though there was a trend of shorter duration in AO+ veterans. There was no median survival difference between veterans who received Ra-223 first vs Ra-223 later as well as between AO+ and AO- veterans, but there was a trend of worse survival in veteran who received Ra-223 later and AO+ veterans.

This study showed that AO+ veterans have a shorter duration of response to therapy and shorter median survival compared with that of AO- veterans. We recommend that veterans should get Ra-223 in the first-line setting rather than after hormonal therapy and chemotherapy because their marrows are still intact. We need to investigate further whether veterans that exposed to carcinogen 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) may have different molecular biology and as such may cause inferior efficacy in the treatment of prostate carcinoma.

1. Shore ND. Radium-223 dichloride for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: the urologist’s perspective. Urology. 2015;85(4):717-724. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.11.031

2. Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al; ALSYMPCA Investigators. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(3):213-223. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1213755

3. Smith M, Parker C, Saad F, et al. Addition of radium-223 to abiraterone acetate and prednisone or prednisolone in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases (ERA 223): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2019 Oct;20(10):e559]. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(3):408-419. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30860-X

4. Everly L, Merrick GS, Allen ZA, et al. Prostate cancer control and survival in Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange. Brachytherapy. 2009;8(1):57-62. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2008.08.001

5. Altekruse S. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2017 Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. 2009. 6. Ansbaugh N, Shannon J, Mori M, Farris PE, Garzotto M. Agent Orange as a risk factor for high-grade prostate cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(13):2399-2404. doi:10.1002/cncr.27941

7. Jadvar H, Quinn DI. Targeted α-particle therapy of bone metastases in prostate cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2013;38(12):966-971. doi:10.1097/RLU.0000000000000290

Patients with metastatic castrate resistant prostate carcinoma (CRPC) have several treatment options, including radium-223 dichloride (Ra-223) radionuclide therapy, abiraterone, enzalutamide, and cabazitaxel. Ra-223 therapy has been reported to increase median survival in patients with bone metastatic prostate carcinoma.1,2 However, ERA 223 trial data showed an increase of bone fractures with combination of Ra-223 and abiraterone.3

Agent Orange (AO) exposure has been studied as a potential risk factor for development of prostate carcinoma. AO was a commercially manufactured defoliate that was sprayed extensively during the Vietnam War. Due to a side product of chemical manufacturing, AO was contaminated with the toxin 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, a putative carcinogen. These dioxins can enter the food chain through soil contamination. There is enough evidence to link AO to hematologic malignancies and several solid tumors, including prostate carcinoma.4 Although no real estimates exist for what percentage of Vietnam veterans experienced AO exposure, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data showed that about 3 million veterans served in Southeast Asia where AO was used extensively in the combat theater. AO has been reported to be positively associated with a 52% increase in risk of prostate carcinoma detection at initial prostate biopsy.5

There has been no reported study of treatment efficacy in veterans with AO-related prostate carcinoma. We present a retrospective study of Ra-223 and other therapies in metastatic CRPC. The purpose of this study was to compare response to therapy and survival in veterans exposed to agent orange (AO+) vs veterans who were not exposed to (AO-) in a single US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) medical center.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of veterans with metastatic CRPC to bones who received Ra-223 radionuclide therapy with standard dose of 50 kBq per kg of body weight and other sequential therapies at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System (VAPHS) from January 2014 to January 2019. The purpose of this study was to measure difference in treatment outcome between AO+ veterans and AO- veterans.

Eligibility Criteria

All veterans had a history that included bone metastasis CRPC. They could have 2 to 3 small lymphadenopathies but not visceral metastasis. They received a minimum of 3 cycles and a maximum of 6 cycles of Ra-223 therapy, which was given in 4-week intervals. Pretreatment criteria was hemoglobin > 10 g/dL, platelet > 100

Statistics

Time to study was calculated from the initiation of Ra-223 therapy. Time to skeletal-related events (SRE), progression of prostate specific antigen (PSA), bone metastasis, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) were calculated in months, using unpaired t test with 2-tailed P value. Median survival was calculated in months by Kaplan Meier R log-rank test Definition).

Results

Forty-eight veterans with bone metastasis CRPC received Ra-223 therapy. Of those, 34 veterans were eligible for this retrospective study: 17 AO+ veterans and 17 AO- veterans. Mean age of diagnosis was 62 years (AO+) and 69 years (AO-) (P = .005). Mean Gleason score was 8.2 (AO+) and 8.0 (AO-) (P = .705). Veterans received initial therapy at diagnosis of prostate carcinoma, including radical prostatectomy (6 AO+ and 3 AO-), localized radiation therapy (3 AO+ and 5 AO-), and ADT (8 AO+ and 9 AO-) (Table 1).

Mean PSA at the initiation of Ra-223 therapy for AO+ was 92.8 (range, 2-551) and for AO- was 102.3 (range, 4-639; P = .86). Mean Ra-223 dose per cycle for AO+ and AO- was 157 uCi and 113 uCi, respectively. All 34 veterans received ADT (leuprolide acetate), and 30 veterans (16 AO+ and 14 AO-) received bisphosphonates (zoledronic acid or denosumab). A total of 10 veterans (29%) received Ra-223 as a first-line therapy (4 AO+ and 6 AO-), and 24 veterans (71%) received Ra-223 after hormonal or chemotherapy (13 AO+ and 11 AO-).

There were 12 SRE (8 AO+ and 4 AO-). Mean time to SRE for AO+ was 10.6 months and AO- was 10.3 months (P = .93). Three veterans received concurrent Ra-223 and abiraterone (participated in ERA 223 trial). Two AO+ veterans experienced SRE at 7 months and 11 months, respectively. Mean time to PSA progression for AO+ was 5.4 months and for AO- was 6.8 months (P = .28). Mean time to bone progression for AO+ and for AO- were 7.6 months and 10.1 months, respectively (P = .16). Mean time to ALP progression for AO+ and AO- were 6.3 months and 8.7 months, respectively (P = .05). (Table 2). The treatment pattern of AO+ and AO- is depicted on a swimmer plot (Figures 1 and 2).

Twenty veterans (58%) had died: 13 AO+ and 7 AO- veterans. Median survival for Ra-223 first and Ra-223 later was was 32 months and 15 months, respectively (P = .14; hazard ratio [HR], 0.48). Overall median survival for AO+ veterans and AO- veterans were 12 months and 18 months, respectively (P = .15; HR, 2.0) (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussions

There has been no reported VA study of using Ra-223 and other therapies (hormonal and chemotherapy) in veterans exposed to AO. This is the first retrospective study to compare the response and survival between AO+ and AO- veterans. Even though this study featured a small sample, it is interesting to note the difference between those 2 populations. There was 1 prior study in veterans with prostate carcinoma using radiotherapy (brachytherapy) in early-stage disease. Everly and colleagues reported that AO+ veterans were less likely to remain biochemically controlled compared with AO- and nonveteran patients with prostate carcinoma.4

Ansbaugh and colleagues reported that AO was associated with a 75% increase in the risk of Gleason ≥ 7 and a 110% increase in Gleason ≥ 8. AO+ veterans are at risk for the detection of high-grade prostate carcinoma. They also tend to have an average age of diagnosis that is 4 to 5 years younger than AO- veterans.6

Our study revealed that AO+ veterans were diagnosed at a younger age (mean 62 years) compared with that of AO- veterans (mean 69 years, P = .005). We also proved that AO veterans have a higher mean Gleason score (8.2) compared with that of AO- veterans (8.0). Veterans received therapy at the time of diagnosis of prostate carcinoma with either radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy, or ADT with leuprolide acetate. Mean PSA at the start of Ra-223 therapy for AO+ was 92.8 (range, 2-551); for AO- was 102.3 (range, 4-639), which is not statistically significant.

Ra-223, an

In a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study by Parker and colleagues (ALSYMPCA study), 921 patients who had received, were not eligible to receive, or declined docetaxel, in a 2:1 ratio, were randomized to receive 6 injections of Ra-223 or matching placebo.2 Ra-223 significantly improved overall survival (OS) (median, 14.9 months vs 11.3 months) compared with that of placebo. Ra-223 also prolonged the time to the first symptomatic SRE (median, 15.6 months vs 9.8 months), the time to an increase in the total ALP level (median 7.4 months vs 3.8 months), and the time to an increase in the PSA level (median 3.6 months vs 3.4 months).2

In our study, the mean time to SRE for AO+ was 10.6 months and AO- was 10.3 months (P = .93). Mean time to PSA progression for AO+ was 5.4 months and for AO- was 6.8 months (P = .28). Mean time to bone progression for AO+ and for AO- were 7.6 months and 10.1 months respectively (P = .16). Mean time to ALP progression for AO+ and AO- were 6.3 months and 8.7 months respectively (P = .05). There is a trend of shorter PSA progression, bone progression, and ALP progression in AO+ veterans, though these were not statistically significant due to small sample population. In our study the median survival in for AO- was 18 months and for AO+ was 12 months, which is comparable with median survival of 14.9 months from the ALSYMPCA study.

There were 12 veterans who developed SREs. All received radiation therapy due to bone progression or impending fracture. AO+ veterans developed more SREs (n = 8) when compared with AO- veterans (n = 4). There were more AO- veterans alive (n = 10) than there were AO+ veterans (n = 4). The plausible explanation of this may be due to the aggressive pattern of prostate carcinoma in AO+ veterans (younger age and higher Gleason score).

VAPHS participated in the ERA trial between 2014 and 2016. The trial enrolled 806 patients who were randomly assigned to receive first-line Ra-223 or placebo in addition to abiraterone acetate plus prednisone.3 The study was unblinded prematurely after more fractures and deaths were noted in the Ra-223 and abiraterone group than there were in the placebo and abiraterone group. Median symptomatic SRE was 22.3 months in the Ra-223 group and 26.0 months in the placebo group. Fractures (any grade) occurred in 29% in the Ra-223 group and 11% in the placebo group. It was suggested that Ra-223 could contribute to the risk of osteoporotic fractures in patients with bone metastatic prostate carcinoma. Median OS was 30.7 months in the Ra-223 group and 33.3 months in the placebo group.

We enrolled 3 veterans in the ERA clinical trial. Two AO+ veterans had SREs at 7 months and 11 months. In our study, the median OS for Ra-223 first line was 32 months, which is comparable with median survival of 30.7 months from ERA-223 study. Median survival for Ra-223 later was only 15 months. We recommend veterans with at least 2 to 3-bone metastasis receive Ra-223 in the first-line setting rather than second- or third-line setting. In this retrospective study with Ra-223 and other therapies, we proved that AO+ veterans have a worse response and OS when compared with that of AO- veterans.

Conclusions

This is the first VA study to compare the efficacy of Ra-223 and other therapies in metastatic CRPC between AO+ and AO- veterans. AO+ veterans were diagnosed at a younger age and had higher Gleason scores. There was no statistical difference between AO+ and AO- veterans in terms of time to SRE, PSA progression, and bone and ALP progression even though there was a trend of shorter duration in AO+ veterans. There was no median survival difference between veterans who received Ra-223 first vs Ra-223 later as well as between AO+ and AO- veterans, but there was a trend of worse survival in veteran who received Ra-223 later and AO+ veterans.

This study showed that AO+ veterans have a shorter duration of response to therapy and shorter median survival compared with that of AO- veterans. We recommend that veterans should get Ra-223 in the first-line setting rather than after hormonal therapy and chemotherapy because their marrows are still intact. We need to investigate further whether veterans that exposed to carcinogen 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) may have different molecular biology and as such may cause inferior efficacy in the treatment of prostate carcinoma.

Patients with metastatic castrate resistant prostate carcinoma (CRPC) have several treatment options, including radium-223 dichloride (Ra-223) radionuclide therapy, abiraterone, enzalutamide, and cabazitaxel. Ra-223 therapy has been reported to increase median survival in patients with bone metastatic prostate carcinoma.1,2 However, ERA 223 trial data showed an increase of bone fractures with combination of Ra-223 and abiraterone.3

Agent Orange (AO) exposure has been studied as a potential risk factor for development of prostate carcinoma. AO was a commercially manufactured defoliate that was sprayed extensively during the Vietnam War. Due to a side product of chemical manufacturing, AO was contaminated with the toxin 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, a putative carcinogen. These dioxins can enter the food chain through soil contamination. There is enough evidence to link AO to hematologic malignancies and several solid tumors, including prostate carcinoma.4 Although no real estimates exist for what percentage of Vietnam veterans experienced AO exposure, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data showed that about 3 million veterans served in Southeast Asia where AO was used extensively in the combat theater. AO has been reported to be positively associated with a 52% increase in risk of prostate carcinoma detection at initial prostate biopsy.5

There has been no reported study of treatment efficacy in veterans with AO-related prostate carcinoma. We present a retrospective study of Ra-223 and other therapies in metastatic CRPC. The purpose of this study was to compare response to therapy and survival in veterans exposed to agent orange (AO+) vs veterans who were not exposed to (AO-) in a single US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) medical center.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of veterans with metastatic CRPC to bones who received Ra-223 radionuclide therapy with standard dose of 50 kBq per kg of body weight and other sequential therapies at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System (VAPHS) from January 2014 to January 2019. The purpose of this study was to measure difference in treatment outcome between AO+ veterans and AO- veterans.

Eligibility Criteria

All veterans had a history that included bone metastasis CRPC. They could have 2 to 3 small lymphadenopathies but not visceral metastasis. They received a minimum of 3 cycles and a maximum of 6 cycles of Ra-223 therapy, which was given in 4-week intervals. Pretreatment criteria was hemoglobin > 10 g/dL, platelet > 100

Statistics

Time to study was calculated from the initiation of Ra-223 therapy. Time to skeletal-related events (SRE), progression of prostate specific antigen (PSA), bone metastasis, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) were calculated in months, using unpaired t test with 2-tailed P value. Median survival was calculated in months by Kaplan Meier R log-rank test Definition).

Results

Forty-eight veterans with bone metastasis CRPC received Ra-223 therapy. Of those, 34 veterans were eligible for this retrospective study: 17 AO+ veterans and 17 AO- veterans. Mean age of diagnosis was 62 years (AO+) and 69 years (AO-) (P = .005). Mean Gleason score was 8.2 (AO+) and 8.0 (AO-) (P = .705). Veterans received initial therapy at diagnosis of prostate carcinoma, including radical prostatectomy (6 AO+ and 3 AO-), localized radiation therapy (3 AO+ and 5 AO-), and ADT (8 AO+ and 9 AO-) (Table 1).

Mean PSA at the initiation of Ra-223 therapy for AO+ was 92.8 (range, 2-551) and for AO- was 102.3 (range, 4-639; P = .86). Mean Ra-223 dose per cycle for AO+ and AO- was 157 uCi and 113 uCi, respectively. All 34 veterans received ADT (leuprolide acetate), and 30 veterans (16 AO+ and 14 AO-) received bisphosphonates (zoledronic acid or denosumab). A total of 10 veterans (29%) received Ra-223 as a first-line therapy (4 AO+ and 6 AO-), and 24 veterans (71%) received Ra-223 after hormonal or chemotherapy (13 AO+ and 11 AO-).

There were 12 SRE (8 AO+ and 4 AO-). Mean time to SRE for AO+ was 10.6 months and AO- was 10.3 months (P = .93). Three veterans received concurrent Ra-223 and abiraterone (participated in ERA 223 trial). Two AO+ veterans experienced SRE at 7 months and 11 months, respectively. Mean time to PSA progression for AO+ was 5.4 months and for AO- was 6.8 months (P = .28). Mean time to bone progression for AO+ and for AO- were 7.6 months and 10.1 months, respectively (P = .16). Mean time to ALP progression for AO+ and AO- were 6.3 months and 8.7 months, respectively (P = .05). (Table 2). The treatment pattern of AO+ and AO- is depicted on a swimmer plot (Figures 1 and 2).

Twenty veterans (58%) had died: 13 AO+ and 7 AO- veterans. Median survival for Ra-223 first and Ra-223 later was was 32 months and 15 months, respectively (P = .14; hazard ratio [HR], 0.48). Overall median survival for AO+ veterans and AO- veterans were 12 months and 18 months, respectively (P = .15; HR, 2.0) (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussions

There has been no reported VA study of using Ra-223 and other therapies (hormonal and chemotherapy) in veterans exposed to AO. This is the first retrospective study to compare the response and survival between AO+ and AO- veterans. Even though this study featured a small sample, it is interesting to note the difference between those 2 populations. There was 1 prior study in veterans with prostate carcinoma using radiotherapy (brachytherapy) in early-stage disease. Everly and colleagues reported that AO+ veterans were less likely to remain biochemically controlled compared with AO- and nonveteran patients with prostate carcinoma.4

Ansbaugh and colleagues reported that AO was associated with a 75% increase in the risk of Gleason ≥ 7 and a 110% increase in Gleason ≥ 8. AO+ veterans are at risk for the detection of high-grade prostate carcinoma. They also tend to have an average age of diagnosis that is 4 to 5 years younger than AO- veterans.6

Our study revealed that AO+ veterans were diagnosed at a younger age (mean 62 years) compared with that of AO- veterans (mean 69 years, P = .005). We also proved that AO veterans have a higher mean Gleason score (8.2) compared with that of AO- veterans (8.0). Veterans received therapy at the time of diagnosis of prostate carcinoma with either radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy, or ADT with leuprolide acetate. Mean PSA at the start of Ra-223 therapy for AO+ was 92.8 (range, 2-551); for AO- was 102.3 (range, 4-639), which is not statistically significant.

Ra-223, an

In a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study by Parker and colleagues (ALSYMPCA study), 921 patients who had received, were not eligible to receive, or declined docetaxel, in a 2:1 ratio, were randomized to receive 6 injections of Ra-223 or matching placebo.2 Ra-223 significantly improved overall survival (OS) (median, 14.9 months vs 11.3 months) compared with that of placebo. Ra-223 also prolonged the time to the first symptomatic SRE (median, 15.6 months vs 9.8 months), the time to an increase in the total ALP level (median 7.4 months vs 3.8 months), and the time to an increase in the PSA level (median 3.6 months vs 3.4 months).2

In our study, the mean time to SRE for AO+ was 10.6 months and AO- was 10.3 months (P = .93). Mean time to PSA progression for AO+ was 5.4 months and for AO- was 6.8 months (P = .28). Mean time to bone progression for AO+ and for AO- were 7.6 months and 10.1 months respectively (P = .16). Mean time to ALP progression for AO+ and AO- were 6.3 months and 8.7 months respectively (P = .05). There is a trend of shorter PSA progression, bone progression, and ALP progression in AO+ veterans, though these were not statistically significant due to small sample population. In our study the median survival in for AO- was 18 months and for AO+ was 12 months, which is comparable with median survival of 14.9 months from the ALSYMPCA study.

There were 12 veterans who developed SREs. All received radiation therapy due to bone progression or impending fracture. AO+ veterans developed more SREs (n = 8) when compared with AO- veterans (n = 4). There were more AO- veterans alive (n = 10) than there were AO+ veterans (n = 4). The plausible explanation of this may be due to the aggressive pattern of prostate carcinoma in AO+ veterans (younger age and higher Gleason score).

VAPHS participated in the ERA trial between 2014 and 2016. The trial enrolled 806 patients who were randomly assigned to receive first-line Ra-223 or placebo in addition to abiraterone acetate plus prednisone.3 The study was unblinded prematurely after more fractures and deaths were noted in the Ra-223 and abiraterone group than there were in the placebo and abiraterone group. Median symptomatic SRE was 22.3 months in the Ra-223 group and 26.0 months in the placebo group. Fractures (any grade) occurred in 29% in the Ra-223 group and 11% in the placebo group. It was suggested that Ra-223 could contribute to the risk of osteoporotic fractures in patients with bone metastatic prostate carcinoma. Median OS was 30.7 months in the Ra-223 group and 33.3 months in the placebo group.

We enrolled 3 veterans in the ERA clinical trial. Two AO+ veterans had SREs at 7 months and 11 months. In our study, the median OS for Ra-223 first line was 32 months, which is comparable with median survival of 30.7 months from ERA-223 study. Median survival for Ra-223 later was only 15 months. We recommend veterans with at least 2 to 3-bone metastasis receive Ra-223 in the first-line setting rather than second- or third-line setting. In this retrospective study with Ra-223 and other therapies, we proved that AO+ veterans have a worse response and OS when compared with that of AO- veterans.

Conclusions

This is the first VA study to compare the efficacy of Ra-223 and other therapies in metastatic CRPC between AO+ and AO- veterans. AO+ veterans were diagnosed at a younger age and had higher Gleason scores. There was no statistical difference between AO+ and AO- veterans in terms of time to SRE, PSA progression, and bone and ALP progression even though there was a trend of shorter duration in AO+ veterans. There was no median survival difference between veterans who received Ra-223 first vs Ra-223 later as well as between AO+ and AO- veterans, but there was a trend of worse survival in veteran who received Ra-223 later and AO+ veterans.

This study showed that AO+ veterans have a shorter duration of response to therapy and shorter median survival compared with that of AO- veterans. We recommend that veterans should get Ra-223 in the first-line setting rather than after hormonal therapy and chemotherapy because their marrows are still intact. We need to investigate further whether veterans that exposed to carcinogen 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) may have different molecular biology and as such may cause inferior efficacy in the treatment of prostate carcinoma.

1. Shore ND. Radium-223 dichloride for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: the urologist’s perspective. Urology. 2015;85(4):717-724. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.11.031

2. Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al; ALSYMPCA Investigators. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(3):213-223. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1213755

3. Smith M, Parker C, Saad F, et al. Addition of radium-223 to abiraterone acetate and prednisone or prednisolone in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases (ERA 223): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2019 Oct;20(10):e559]. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(3):408-419. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30860-X

4. Everly L, Merrick GS, Allen ZA, et al. Prostate cancer control and survival in Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange. Brachytherapy. 2009;8(1):57-62. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2008.08.001

5. Altekruse S. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2017 Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. 2009. 6. Ansbaugh N, Shannon J, Mori M, Farris PE, Garzotto M. Agent Orange as a risk factor for high-grade prostate cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(13):2399-2404. doi:10.1002/cncr.27941

7. Jadvar H, Quinn DI. Targeted α-particle therapy of bone metastases in prostate cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2013;38(12):966-971. doi:10.1097/RLU.0000000000000290

1. Shore ND. Radium-223 dichloride for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: the urologist’s perspective. Urology. 2015;85(4):717-724. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.11.031

2. Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al; ALSYMPCA Investigators. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(3):213-223. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1213755

3. Smith M, Parker C, Saad F, et al. Addition of radium-223 to abiraterone acetate and prednisone or prednisolone in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases (ERA 223): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2019 Oct;20(10):e559]. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(3):408-419. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30860-X

4. Everly L, Merrick GS, Allen ZA, et al. Prostate cancer control and survival in Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange. Brachytherapy. 2009;8(1):57-62. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2008.08.001

5. Altekruse S. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2017 Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. 2009. 6. Ansbaugh N, Shannon J, Mori M, Farris PE, Garzotto M. Agent Orange as a risk factor for high-grade prostate cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(13):2399-2404. doi:10.1002/cncr.27941

7. Jadvar H, Quinn DI. Targeted α-particle therapy of bone metastases in prostate cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2013;38(12):966-971. doi:10.1097/RLU.0000000000000290