User login

JAK inhibitor reduces GVHD in mice

An investigational JAK1/2 inhibitor can fight graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), according to preclinical research published in Leukemia.

The inhibitor, baricitinib, reduced GVHD in mice while preserving T-cell expansion and the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect.

Baricitinib proved more effective than ruxolitinib for the treatment and prevention of GVHD and enabled 100% survival in a mouse model of severe GVHD.

“We were surprised to achieve 100% survival of mice with the most severe model of graft-versus-host disease,” said study author Jaebok Choi, PhD, of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri.

“We are now studying the multi-pronged ways this drug behaves in an effort to develop an even better version for eventual use in clinical trials.”

For the current study, Dr Choi and his colleagues tested baricitinib and ruxolitinib in murine recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants (allo-HSCTs). Mice received either drug for 31 days post-HSCT.

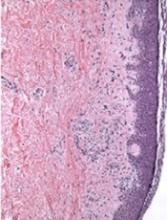

Mice treated with baricitinib had a significant reduction in intestinal GVHD compared to both ruxolitinib recipients and vehicle-treated controls (P=0.037).

In addition, 100% of baricitinib recipients were still alive at 60 days after HSCT, compared to about 60% of ruxolitinib recipients (P=0.0025) and almost none of the vehicle-treated controls.

The researchers found that baricitinib recipients had significantly better blood cell count recovery than control mice. Baricitinib recipients also had full donor chimerism and significantly higher percentages of donor bone marrow-derived B and T cells.

Furthermore, baricitinib recipients had higher levels of donor-derived regulatory T cells (Tregs) compared to vehicle- or ruxolitinib-treated mice.

However, the researchers noted that baricitinib recipients had a survival rate of about 70% even in the absence of donor Tregs. The team said this suggests baricitinib fights GVHD independently of the enhanced expansion of Tregs.

Further investigation revealed that baricitinib decreases helper T-cell 1 and 2 differentiation and reduces the expression of MHC II, CD80/86, and PD-L1 on allogeneic antigen-presenting cells.

The researchers also found that baricitinib could reverse ongoing GVHD. The team withheld baricitinib until mice developed GVHD, then tested the drug at doses of 200 μg and 400 μg per day.

Both doses reduced clinical GVHD scores and enabled 100% overall survival rates.

Finally, the researchers found that baricitinib “preserves and enhances” GVL effects. The team infused A20 cells and T-cell-depleted bone marrow cells into lethally irradiated mice, waited for the B-cell lymphoma to become established, and infused donor T cells.

The researchers found that baricitinib alone did not inhibit tumor growth, but it enhanced the GVL effects of donor T cells, significantly lowering the tumor burden.

“We don’t know yet exactly how this happens, but we’re working to understand it,” Dr Choi said. “We think at least part of the explanation is the drug strips the leukemia cells of their immune defenses, making them more vulnerable to attack by the donor T cells.”

“At the same time, the drug also stops the donor T cells from being able to make their way to important healthy tissues, such as the skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract, where they often do the most damage.”

An investigational JAK1/2 inhibitor can fight graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), according to preclinical research published in Leukemia.

The inhibitor, baricitinib, reduced GVHD in mice while preserving T-cell expansion and the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect.

Baricitinib proved more effective than ruxolitinib for the treatment and prevention of GVHD and enabled 100% survival in a mouse model of severe GVHD.

“We were surprised to achieve 100% survival of mice with the most severe model of graft-versus-host disease,” said study author Jaebok Choi, PhD, of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri.

“We are now studying the multi-pronged ways this drug behaves in an effort to develop an even better version for eventual use in clinical trials.”

For the current study, Dr Choi and his colleagues tested baricitinib and ruxolitinib in murine recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants (allo-HSCTs). Mice received either drug for 31 days post-HSCT.

Mice treated with baricitinib had a significant reduction in intestinal GVHD compared to both ruxolitinib recipients and vehicle-treated controls (P=0.037).

In addition, 100% of baricitinib recipients were still alive at 60 days after HSCT, compared to about 60% of ruxolitinib recipients (P=0.0025) and almost none of the vehicle-treated controls.

The researchers found that baricitinib recipients had significantly better blood cell count recovery than control mice. Baricitinib recipients also had full donor chimerism and significantly higher percentages of donor bone marrow-derived B and T cells.

Furthermore, baricitinib recipients had higher levels of donor-derived regulatory T cells (Tregs) compared to vehicle- or ruxolitinib-treated mice.

However, the researchers noted that baricitinib recipients had a survival rate of about 70% even in the absence of donor Tregs. The team said this suggests baricitinib fights GVHD independently of the enhanced expansion of Tregs.

Further investigation revealed that baricitinib decreases helper T-cell 1 and 2 differentiation and reduces the expression of MHC II, CD80/86, and PD-L1 on allogeneic antigen-presenting cells.

The researchers also found that baricitinib could reverse ongoing GVHD. The team withheld baricitinib until mice developed GVHD, then tested the drug at doses of 200 μg and 400 μg per day.

Both doses reduced clinical GVHD scores and enabled 100% overall survival rates.

Finally, the researchers found that baricitinib “preserves and enhances” GVL effects. The team infused A20 cells and T-cell-depleted bone marrow cells into lethally irradiated mice, waited for the B-cell lymphoma to become established, and infused donor T cells.

The researchers found that baricitinib alone did not inhibit tumor growth, but it enhanced the GVL effects of donor T cells, significantly lowering the tumor burden.

“We don’t know yet exactly how this happens, but we’re working to understand it,” Dr Choi said. “We think at least part of the explanation is the drug strips the leukemia cells of their immune defenses, making them more vulnerable to attack by the donor T cells.”

“At the same time, the drug also stops the donor T cells from being able to make their way to important healthy tissues, such as the skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract, where they often do the most damage.”

An investigational JAK1/2 inhibitor can fight graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), according to preclinical research published in Leukemia.

The inhibitor, baricitinib, reduced GVHD in mice while preserving T-cell expansion and the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect.

Baricitinib proved more effective than ruxolitinib for the treatment and prevention of GVHD and enabled 100% survival in a mouse model of severe GVHD.

“We were surprised to achieve 100% survival of mice with the most severe model of graft-versus-host disease,” said study author Jaebok Choi, PhD, of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri.

“We are now studying the multi-pronged ways this drug behaves in an effort to develop an even better version for eventual use in clinical trials.”

For the current study, Dr Choi and his colleagues tested baricitinib and ruxolitinib in murine recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants (allo-HSCTs). Mice received either drug for 31 days post-HSCT.

Mice treated with baricitinib had a significant reduction in intestinal GVHD compared to both ruxolitinib recipients and vehicle-treated controls (P=0.037).

In addition, 100% of baricitinib recipients were still alive at 60 days after HSCT, compared to about 60% of ruxolitinib recipients (P=0.0025) and almost none of the vehicle-treated controls.

The researchers found that baricitinib recipients had significantly better blood cell count recovery than control mice. Baricitinib recipients also had full donor chimerism and significantly higher percentages of donor bone marrow-derived B and T cells.

Furthermore, baricitinib recipients had higher levels of donor-derived regulatory T cells (Tregs) compared to vehicle- or ruxolitinib-treated mice.

However, the researchers noted that baricitinib recipients had a survival rate of about 70% even in the absence of donor Tregs. The team said this suggests baricitinib fights GVHD independently of the enhanced expansion of Tregs.

Further investigation revealed that baricitinib decreases helper T-cell 1 and 2 differentiation and reduces the expression of MHC II, CD80/86, and PD-L1 on allogeneic antigen-presenting cells.

The researchers also found that baricitinib could reverse ongoing GVHD. The team withheld baricitinib until mice developed GVHD, then tested the drug at doses of 200 μg and 400 μg per day.

Both doses reduced clinical GVHD scores and enabled 100% overall survival rates.

Finally, the researchers found that baricitinib “preserves and enhances” GVL effects. The team infused A20 cells and T-cell-depleted bone marrow cells into lethally irradiated mice, waited for the B-cell lymphoma to become established, and infused donor T cells.

The researchers found that baricitinib alone did not inhibit tumor growth, but it enhanced the GVL effects of donor T cells, significantly lowering the tumor burden.

“We don’t know yet exactly how this happens, but we’re working to understand it,” Dr Choi said. “We think at least part of the explanation is the drug strips the leukemia cells of their immune defenses, making them more vulnerable to attack by the donor T cells.”

“At the same time, the drug also stops the donor T cells from being able to make their way to important healthy tissues, such as the skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract, where they often do the most damage.”

FDA approves CAR T-cell therapy for lymphoma

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah®) for its second indication.

The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is now approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma after 2 or more lines of systemic therapy.

This includes patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, high grade B-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.

The application for tisagenlecleucel in B-cell lymphoma was granted priority review. The FDA aims to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

Tisagenlecleucel is also FDA-approved to treat patients age 25 and younger who have B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia that is refractory or in second or later relapse.

Access to tisagenlecleucel

The prescribing information for tisagenlecleucel includes a boxed warning detailing the risk of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurological toxicities for patients receiving tisagenlecleucel.

Because of these risks, tisagenlecleucel is only available through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program. The REMS program serves to inform and educate healthcare professionals about the risks associated with tisagenlecleucel treatment.

Novartis, the company marketing tisagenlecleucel, has established a network of certified treatment centers throughout the US. Staff at these centers are trained on the use of tisagenlecleucel and appropriate patient care.

Tisagenlecleucel is manufactured at a Novartis facility in Morris Plains, New Jersey. In the US, the target turnaround time for manufacturing tisagenlecleucel is 22 days.

Tisagenlecleucel costs $475,000 for a single course of treatment. However, Novartis said it is collaborating with the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on the creation of an appropriate value-based pricing approach.

The company also has a program called KYMRIAH CARES™, which offers financial assistance to eligible patients to help them gain access to tisagenlecleucel.

Phase 2 trial

The FDA approval of tisagenlecleucel for adults with relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphoma is based on results of the phase 2 JULIET trial.

The prescribing information for tisagenlecleucel includes data on 106 patients treated on this trial.

Only 68 of these patients were evaluable for efficacy. They had a median age of 56 (range, 22 to 74), and 71% were male.

Seventy-eight percent of patients had primary DLBCL not otherwise specified, and 22% had DLBCL following transformation from follicular lymphoma. Seventeen percent had high grade DLBCL.

Fifty-six percent of patients had refractory disease, and 44% had relapsed after their last therapy. The median number of prior therapies was 3 (range, 1 to 6), and 44% of patients had undergone autologous transplant.

Ninety percent of patients received lymphodepleting chemotherapy (66% fludarabine and 24% bendamustine) prior to tisagenlecleucel, and 10% did not. The median dose of tisagenlecleucel was 3.5 × 108 CAR+ T cells (range, 1.0 to 5.2 × 108).

The overall response rate was 50%, with 32% of patients achieving a complete response and 18% achieving a partial response. The median duration of response was not reached with a median follow-up of 9.4 months.

In all 106 patients infused with tisagenlecleucel, the most common grade 3/4 adverse events were infections (25%), CRS (23%), neurologic events (18%), febrile neutropenia (17%), encephalopathy (11%), lymphopenia (94%), neutropenia (81%), leukopenia (77%), anemia (58%), thrombocytopenia (54%), hypophosphatemia (24%), hypokalemia (12%), and hyponatremia (11%).

Three patients died within 30 days of tisagenlecleucel infusion. All of them had CRS and either stable or progressive disease. One of these patients developed bowel necrosis.

One patient died of infection. There were no deaths attributed to neurological events, and no fatal cases of cerebral edema.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah®) for its second indication.

The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is now approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma after 2 or more lines of systemic therapy.

This includes patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, high grade B-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.

The application for tisagenlecleucel in B-cell lymphoma was granted priority review. The FDA aims to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

Tisagenlecleucel is also FDA-approved to treat patients age 25 and younger who have B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia that is refractory or in second or later relapse.

Access to tisagenlecleucel

The prescribing information for tisagenlecleucel includes a boxed warning detailing the risk of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurological toxicities for patients receiving tisagenlecleucel.

Because of these risks, tisagenlecleucel is only available through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program. The REMS program serves to inform and educate healthcare professionals about the risks associated with tisagenlecleucel treatment.

Novartis, the company marketing tisagenlecleucel, has established a network of certified treatment centers throughout the US. Staff at these centers are trained on the use of tisagenlecleucel and appropriate patient care.

Tisagenlecleucel is manufactured at a Novartis facility in Morris Plains, New Jersey. In the US, the target turnaround time for manufacturing tisagenlecleucel is 22 days.

Tisagenlecleucel costs $475,000 for a single course of treatment. However, Novartis said it is collaborating with the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on the creation of an appropriate value-based pricing approach.

The company also has a program called KYMRIAH CARES™, which offers financial assistance to eligible patients to help them gain access to tisagenlecleucel.

Phase 2 trial

The FDA approval of tisagenlecleucel for adults with relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphoma is based on results of the phase 2 JULIET trial.

The prescribing information for tisagenlecleucel includes data on 106 patients treated on this trial.

Only 68 of these patients were evaluable for efficacy. They had a median age of 56 (range, 22 to 74), and 71% were male.

Seventy-eight percent of patients had primary DLBCL not otherwise specified, and 22% had DLBCL following transformation from follicular lymphoma. Seventeen percent had high grade DLBCL.

Fifty-six percent of patients had refractory disease, and 44% had relapsed after their last therapy. The median number of prior therapies was 3 (range, 1 to 6), and 44% of patients had undergone autologous transplant.

Ninety percent of patients received lymphodepleting chemotherapy (66% fludarabine and 24% bendamustine) prior to tisagenlecleucel, and 10% did not. The median dose of tisagenlecleucel was 3.5 × 108 CAR+ T cells (range, 1.0 to 5.2 × 108).

The overall response rate was 50%, with 32% of patients achieving a complete response and 18% achieving a partial response. The median duration of response was not reached with a median follow-up of 9.4 months.

In all 106 patients infused with tisagenlecleucel, the most common grade 3/4 adverse events were infections (25%), CRS (23%), neurologic events (18%), febrile neutropenia (17%), encephalopathy (11%), lymphopenia (94%), neutropenia (81%), leukopenia (77%), anemia (58%), thrombocytopenia (54%), hypophosphatemia (24%), hypokalemia (12%), and hyponatremia (11%).

Three patients died within 30 days of tisagenlecleucel infusion. All of them had CRS and either stable or progressive disease. One of these patients developed bowel necrosis.

One patient died of infection. There were no deaths attributed to neurological events, and no fatal cases of cerebral edema.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah®) for its second indication.

The chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is now approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma after 2 or more lines of systemic therapy.

This includes patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, high grade B-cell lymphoma, and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.

The application for tisagenlecleucel in B-cell lymphoma was granted priority review. The FDA aims to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

Tisagenlecleucel is also FDA-approved to treat patients age 25 and younger who have B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia that is refractory or in second or later relapse.

Access to tisagenlecleucel

The prescribing information for tisagenlecleucel includes a boxed warning detailing the risk of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurological toxicities for patients receiving tisagenlecleucel.

Because of these risks, tisagenlecleucel is only available through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program. The REMS program serves to inform and educate healthcare professionals about the risks associated with tisagenlecleucel treatment.

Novartis, the company marketing tisagenlecleucel, has established a network of certified treatment centers throughout the US. Staff at these centers are trained on the use of tisagenlecleucel and appropriate patient care.

Tisagenlecleucel is manufactured at a Novartis facility in Morris Plains, New Jersey. In the US, the target turnaround time for manufacturing tisagenlecleucel is 22 days.

Tisagenlecleucel costs $475,000 for a single course of treatment. However, Novartis said it is collaborating with the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on the creation of an appropriate value-based pricing approach.

The company also has a program called KYMRIAH CARES™, which offers financial assistance to eligible patients to help them gain access to tisagenlecleucel.

Phase 2 trial

The FDA approval of tisagenlecleucel for adults with relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphoma is based on results of the phase 2 JULIET trial.

The prescribing information for tisagenlecleucel includes data on 106 patients treated on this trial.

Only 68 of these patients were evaluable for efficacy. They had a median age of 56 (range, 22 to 74), and 71% were male.

Seventy-eight percent of patients had primary DLBCL not otherwise specified, and 22% had DLBCL following transformation from follicular lymphoma. Seventeen percent had high grade DLBCL.

Fifty-six percent of patients had refractory disease, and 44% had relapsed after their last therapy. The median number of prior therapies was 3 (range, 1 to 6), and 44% of patients had undergone autologous transplant.

Ninety percent of patients received lymphodepleting chemotherapy (66% fludarabine and 24% bendamustine) prior to tisagenlecleucel, and 10% did not. The median dose of tisagenlecleucel was 3.5 × 108 CAR+ T cells (range, 1.0 to 5.2 × 108).

The overall response rate was 50%, with 32% of patients achieving a complete response and 18% achieving a partial response. The median duration of response was not reached with a median follow-up of 9.4 months.

In all 106 patients infused with tisagenlecleucel, the most common grade 3/4 adverse events were infections (25%), CRS (23%), neurologic events (18%), febrile neutropenia (17%), encephalopathy (11%), lymphopenia (94%), neutropenia (81%), leukopenia (77%), anemia (58%), thrombocytopenia (54%), hypophosphatemia (24%), hypokalemia (12%), and hyponatremia (11%).

Three patients died within 30 days of tisagenlecleucel infusion. All of them had CRS and either stable or progressive disease. One of these patients developed bowel necrosis.

One patient died of infection. There were no deaths attributed to neurological events, and no fatal cases of cerebral edema.

Drug may alleviate CIPN in MM patients

Researchers say they’ve discovered why multiple myeloma (MM) patients may experience chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) when treated with bortezomib.

The group’s study also suggests fingolimod—a drug approved to treat multiple sclerosis—could mitigate CIPN without compromising the efficacy of bortezomib.

Daniela Salvemini, PhD, of the Saint Louis University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, and her colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The researchers said bortezomib causes CIPN in more than 40% of patients, but the reasons for this are unclear.

With their study, Dr Salvemini and her colleagues found that bortezomib accelerates the production of sphingolipids, which have been linked to neuropathic pain.

Rats treated with bortezomib began to accumulate 2 sphingolipid metabolites—sphingosine 1-phosphate and dihydrosphingosine 1-phosphate—in their spinal cords at the time they began to show signs of neuropathic pain.

Blocking the production of these molecules prevented the animals from developing CIPN in response to bortezomib.

Sphingosine 1-phosphate and dihydrosphingosine 1-phosphate can activate a cell surface receptor protein called S1PR1. Dr Salvemini and her colleagues determined that the 2 metabolites cause CIPN by activating S1PR1 on the surface of astrocytes, resulting in neuroinflammation and enhanced release of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate.

Drugs that inhibit S1PR1 prevented rats from developing CIPN in response to bortezomib. One such inhibitor was fingolimod, a drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat multiple sclerosis.

In addition to preventing CIPN, fingolimod did not inhibit bortezomib’s ability to kill MM cells. In fact, fingolimod has demonstrated anticancer activity in past studies.

“Because fingolimod shows promising anticancer potential and is already FDA-approved, we think that our findings in rats can be rapidly translated to the clinic to prevent and treat bortezomib-induced neuropathic pain,” Dr Salvemini said.

Researchers say they’ve discovered why multiple myeloma (MM) patients may experience chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) when treated with bortezomib.

The group’s study also suggests fingolimod—a drug approved to treat multiple sclerosis—could mitigate CIPN without compromising the efficacy of bortezomib.

Daniela Salvemini, PhD, of the Saint Louis University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, and her colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The researchers said bortezomib causes CIPN in more than 40% of patients, but the reasons for this are unclear.

With their study, Dr Salvemini and her colleagues found that bortezomib accelerates the production of sphingolipids, which have been linked to neuropathic pain.

Rats treated with bortezomib began to accumulate 2 sphingolipid metabolites—sphingosine 1-phosphate and dihydrosphingosine 1-phosphate—in their spinal cords at the time they began to show signs of neuropathic pain.

Blocking the production of these molecules prevented the animals from developing CIPN in response to bortezomib.

Sphingosine 1-phosphate and dihydrosphingosine 1-phosphate can activate a cell surface receptor protein called S1PR1. Dr Salvemini and her colleagues determined that the 2 metabolites cause CIPN by activating S1PR1 on the surface of astrocytes, resulting in neuroinflammation and enhanced release of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate.

Drugs that inhibit S1PR1 prevented rats from developing CIPN in response to bortezomib. One such inhibitor was fingolimod, a drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat multiple sclerosis.

In addition to preventing CIPN, fingolimod did not inhibit bortezomib’s ability to kill MM cells. In fact, fingolimod has demonstrated anticancer activity in past studies.

“Because fingolimod shows promising anticancer potential and is already FDA-approved, we think that our findings in rats can be rapidly translated to the clinic to prevent and treat bortezomib-induced neuropathic pain,” Dr Salvemini said.

Researchers say they’ve discovered why multiple myeloma (MM) patients may experience chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) when treated with bortezomib.

The group’s study also suggests fingolimod—a drug approved to treat multiple sclerosis—could mitigate CIPN without compromising the efficacy of bortezomib.

Daniela Salvemini, PhD, of the Saint Louis University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, and her colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The researchers said bortezomib causes CIPN in more than 40% of patients, but the reasons for this are unclear.

With their study, Dr Salvemini and her colleagues found that bortezomib accelerates the production of sphingolipids, which have been linked to neuropathic pain.

Rats treated with bortezomib began to accumulate 2 sphingolipid metabolites—sphingosine 1-phosphate and dihydrosphingosine 1-phosphate—in their spinal cords at the time they began to show signs of neuropathic pain.

Blocking the production of these molecules prevented the animals from developing CIPN in response to bortezomib.

Sphingosine 1-phosphate and dihydrosphingosine 1-phosphate can activate a cell surface receptor protein called S1PR1. Dr Salvemini and her colleagues determined that the 2 metabolites cause CIPN by activating S1PR1 on the surface of astrocytes, resulting in neuroinflammation and enhanced release of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate.

Drugs that inhibit S1PR1 prevented rats from developing CIPN in response to bortezomib. One such inhibitor was fingolimod, a drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat multiple sclerosis.

In addition to preventing CIPN, fingolimod did not inhibit bortezomib’s ability to kill MM cells. In fact, fingolimod has demonstrated anticancer activity in past studies.

“Because fingolimod shows promising anticancer potential and is already FDA-approved, we think that our findings in rats can be rapidly translated to the clinic to prevent and treat bortezomib-induced neuropathic pain,” Dr Salvemini said.

PI3K inhibitors could treat HHT

Preclinical research suggests PI3K inhibitors could treat hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT).

Experiments in mice and patient samples revealed that loss of ALK1 function induces vascular hyperplasia and increases activity of the PI3K pathway.

Pharmacological inhibition of PI3K was able to eliminate vascular hyperplasia in mouse models.

Francesc Viñals, PhD, of Institut Catala d’Oncologia in Barcelona, Spain, and his colleagues described this research in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology.

“Our group has been working with endothelial cells for a long time, focusing on how they are affected by changes in the TGF-beta signaling pathway from a basic research perspective,” Dr Viñals noted.

The group was especially interested in ALK1, a receptor for the TGF-beta factor BMP9 that is expressed by endothelial cells. Mutations in ALK1 have been associated with HHT.

The researchers developed a model for the formation of blood vessels in the retina of mice that lacked a copy of the gene for the ALK1 receptor. These models exhibited an excess of endothelial cells and errors in the formation of blood vessels.

These results corresponded with the researchers’ theory. The team thought that, if members of the TGF-beta family usually act as a “brake” for cellular proliferation, mutations in one of the family’s components should lead to uncontrolled proliferation. The researchers replicated and confirmed their results in in vitro cultures.

Further investigation revealed the role of the PI3K pathway. The researchers found that stimulation of PI3K acts as an “accelerator” for endothelial cells to proliferate.

BMP9 (through ALK1) acts as a brake, inhibiting VEGF-mediated PI3K signaling by increasing PTEN activity. When ALK1 is mutated, there is no brake, and endothelial cells proliferate more thanks to the PI3K pathway.

The researchers discovered this mechanism via experiments in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. However, experiments in HHT2 patient samples supported these findings.

The team found that mutations in ALK1 increased endothelial cell proliferation in vessels from patients with HHT2. The researchers also found overexpression of genes linked to PI3K/AKT signaling in telangiectasial tissue from patients with HHT2, as compared to normal tissue from either HHT2 patients or healthy individuals.

Going back to murine experiments, the researchers found that loss of both PI3K and ALK1 function stabilizes the proliferation of endothelial cells.

The team tested LY294002, a pan-PI3K inhibitor, in mice and found that PI3K inhibition can reverse the vascular hyperplasia induced by loss of ALK1 function.

“Now, the next step is clear,” Dr Viñals said. “We have to assess the effects of PI3K inhibitors in patients. PI3K inhibitors are currently used in the treatment of patients with cancer or patients who require immunosuppression after organ transplantation, and it has been observed that, in patients with these pathologies and HHT, treatment results in a reduction of the issues caused by HHT, which is a very encouraging fact.”

Preclinical research suggests PI3K inhibitors could treat hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT).

Experiments in mice and patient samples revealed that loss of ALK1 function induces vascular hyperplasia and increases activity of the PI3K pathway.

Pharmacological inhibition of PI3K was able to eliminate vascular hyperplasia in mouse models.

Francesc Viñals, PhD, of Institut Catala d’Oncologia in Barcelona, Spain, and his colleagues described this research in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology.

“Our group has been working with endothelial cells for a long time, focusing on how they are affected by changes in the TGF-beta signaling pathway from a basic research perspective,” Dr Viñals noted.

The group was especially interested in ALK1, a receptor for the TGF-beta factor BMP9 that is expressed by endothelial cells. Mutations in ALK1 have been associated with HHT.

The researchers developed a model for the formation of blood vessels in the retina of mice that lacked a copy of the gene for the ALK1 receptor. These models exhibited an excess of endothelial cells and errors in the formation of blood vessels.

These results corresponded with the researchers’ theory. The team thought that, if members of the TGF-beta family usually act as a “brake” for cellular proliferation, mutations in one of the family’s components should lead to uncontrolled proliferation. The researchers replicated and confirmed their results in in vitro cultures.

Further investigation revealed the role of the PI3K pathway. The researchers found that stimulation of PI3K acts as an “accelerator” for endothelial cells to proliferate.

BMP9 (through ALK1) acts as a brake, inhibiting VEGF-mediated PI3K signaling by increasing PTEN activity. When ALK1 is mutated, there is no brake, and endothelial cells proliferate more thanks to the PI3K pathway.

The researchers discovered this mechanism via experiments in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. However, experiments in HHT2 patient samples supported these findings.

The team found that mutations in ALK1 increased endothelial cell proliferation in vessels from patients with HHT2. The researchers also found overexpression of genes linked to PI3K/AKT signaling in telangiectasial tissue from patients with HHT2, as compared to normal tissue from either HHT2 patients or healthy individuals.

Going back to murine experiments, the researchers found that loss of both PI3K and ALK1 function stabilizes the proliferation of endothelial cells.

The team tested LY294002, a pan-PI3K inhibitor, in mice and found that PI3K inhibition can reverse the vascular hyperplasia induced by loss of ALK1 function.

“Now, the next step is clear,” Dr Viñals said. “We have to assess the effects of PI3K inhibitors in patients. PI3K inhibitors are currently used in the treatment of patients with cancer or patients who require immunosuppression after organ transplantation, and it has been observed that, in patients with these pathologies and HHT, treatment results in a reduction of the issues caused by HHT, which is a very encouraging fact.”

Preclinical research suggests PI3K inhibitors could treat hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT).

Experiments in mice and patient samples revealed that loss of ALK1 function induces vascular hyperplasia and increases activity of the PI3K pathway.

Pharmacological inhibition of PI3K was able to eliminate vascular hyperplasia in mouse models.

Francesc Viñals, PhD, of Institut Catala d’Oncologia in Barcelona, Spain, and his colleagues described this research in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology.

“Our group has been working with endothelial cells for a long time, focusing on how they are affected by changes in the TGF-beta signaling pathway from a basic research perspective,” Dr Viñals noted.

The group was especially interested in ALK1, a receptor for the TGF-beta factor BMP9 that is expressed by endothelial cells. Mutations in ALK1 have been associated with HHT.

The researchers developed a model for the formation of blood vessels in the retina of mice that lacked a copy of the gene for the ALK1 receptor. These models exhibited an excess of endothelial cells and errors in the formation of blood vessels.

These results corresponded with the researchers’ theory. The team thought that, if members of the TGF-beta family usually act as a “brake” for cellular proliferation, mutations in one of the family’s components should lead to uncontrolled proliferation. The researchers replicated and confirmed their results in in vitro cultures.

Further investigation revealed the role of the PI3K pathway. The researchers found that stimulation of PI3K acts as an “accelerator” for endothelial cells to proliferate.

BMP9 (through ALK1) acts as a brake, inhibiting VEGF-mediated PI3K signaling by increasing PTEN activity. When ALK1 is mutated, there is no brake, and endothelial cells proliferate more thanks to the PI3K pathway.

The researchers discovered this mechanism via experiments in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. However, experiments in HHT2 patient samples supported these findings.

The team found that mutations in ALK1 increased endothelial cell proliferation in vessels from patients with HHT2. The researchers also found overexpression of genes linked to PI3K/AKT signaling in telangiectasial tissue from patients with HHT2, as compared to normal tissue from either HHT2 patients or healthy individuals.

Going back to murine experiments, the researchers found that loss of both PI3K and ALK1 function stabilizes the proliferation of endothelial cells.

The team tested LY294002, a pan-PI3K inhibitor, in mice and found that PI3K inhibition can reverse the vascular hyperplasia induced by loss of ALK1 function.

“Now, the next step is clear,” Dr Viñals said. “We have to assess the effects of PI3K inhibitors in patients. PI3K inhibitors are currently used in the treatment of patients with cancer or patients who require immunosuppression after organ transplantation, and it has been observed that, in patients with these pathologies and HHT, treatment results in a reduction of the issues caused by HHT, which is a very encouraging fact.”

Predicting response to CAR T-cell therapy in CLL

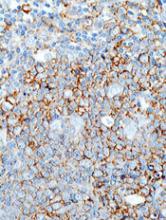

Researchers may have discovered why some patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) don’t respond to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

The team found that CLL patients with elevated levels of “early memory” T cells prior to receiving CAR T-cell therapy had a partial or complete response to treatment, while patients with lower levels of these T cells did not respond.

The early memory T cells were marked by the expression of CD8 and CD27, as well as the absence of CD45RO.

The researchers validated the association between the early memory T cells and response in a small group of patients, predicting with 100% accuracy which patients would achieve a complete response.

Joseph A. Fraietta, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature Medicine. This research was supported, in part, by Novartis.

For this study, the researchers retrospectively analyzed 41 patients with advanced, heavily pretreated, high-risk CLL who received at least 1 dose of CD19-directed CAR T cells.

Consistent with the team’s previously reported findings, they were not able to identify patient or disease-specific factors that predict who responds best to the therapy.

Therefore, the researchers compared the gene expression profiles and phenotypes of T cells in patients who had a complete response, partial response, or no response to therapy.

The CAR T cells that persisted and expanded in complete responders were enriched in genes that regulate early memory and effector T cells and possess the IL-6/STAT3 signature.

Non-responders, on the other hand, expressed genes involved in late T-cell differentiation, glycolysis, exhaustion, and apoptosis. These characteristics make for a weaker set of T cells to persist, expand, and fight the CLL.

“Pre-existing T-cell qualities have previously been associated with poor clinical response to cancer therapy, as well differentiation in the T cells,” Dr Fraietta said. “What is special about what we have done here is finding that critical cell subset and signature.”

Elevated levels of the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway in these early T cells correlated with clinical responses to CAR T-cell therapy.

To validate these findings, the researchers screened for the early memory T cells in a group of 8 CLL patients, before and after CAR T-cell therapy. The team identified the complete responders with 100% specificity and sensitivity.

“With a very robust biomarker like this, we can take a blood sample, measure the frequency of this T-cell population, and decide with a degree of confidence whether we can apply this therapy and know the patient would have a response,” Dr Fraietta said.

“The ability to select patients most likely to respond would have tremendous clinical impact, as this therapy would be applied only to patients most likely to benefit, allowing patients unlikely to respond to pursue other options.”

These findings also suggest the possibility of improving CAR T-cell therapy by selecting for cell manufacturing the subpopulation of T cells responsible for driving responses. However, this approach would come with challenges.

“What we’ve seen in these non-responders is that the frequency of these T cells is low, so it would be very hard to infuse them as starting populations,” said study author J. Joseph Melenhorst, PhD, also of the University of Pennsylvania.

“But one way to potentially boost their efficacy is by adding checkpoint inhibitors with the therapy to block the negative regulation prior to CAR T-cell therapy, which a past, separate study has shown can help elicit responses in these patients.”

The researchers also noted that it’s unclear why some patients’ T cells are suboptimal prior to treatment. However, the team believes this could have to do with prior therapies.

Future studies with a larger group of CLL patients should be conducted to help answer these questions and validate the findings from this study, the researchers said.

Researchers may have discovered why some patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) don’t respond to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

The team found that CLL patients with elevated levels of “early memory” T cells prior to receiving CAR T-cell therapy had a partial or complete response to treatment, while patients with lower levels of these T cells did not respond.

The early memory T cells were marked by the expression of CD8 and CD27, as well as the absence of CD45RO.

The researchers validated the association between the early memory T cells and response in a small group of patients, predicting with 100% accuracy which patients would achieve a complete response.

Joseph A. Fraietta, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature Medicine. This research was supported, in part, by Novartis.

For this study, the researchers retrospectively analyzed 41 patients with advanced, heavily pretreated, high-risk CLL who received at least 1 dose of CD19-directed CAR T cells.

Consistent with the team’s previously reported findings, they were not able to identify patient or disease-specific factors that predict who responds best to the therapy.

Therefore, the researchers compared the gene expression profiles and phenotypes of T cells in patients who had a complete response, partial response, or no response to therapy.

The CAR T cells that persisted and expanded in complete responders were enriched in genes that regulate early memory and effector T cells and possess the IL-6/STAT3 signature.

Non-responders, on the other hand, expressed genes involved in late T-cell differentiation, glycolysis, exhaustion, and apoptosis. These characteristics make for a weaker set of T cells to persist, expand, and fight the CLL.

“Pre-existing T-cell qualities have previously been associated with poor clinical response to cancer therapy, as well differentiation in the T cells,” Dr Fraietta said. “What is special about what we have done here is finding that critical cell subset and signature.”

Elevated levels of the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway in these early T cells correlated with clinical responses to CAR T-cell therapy.

To validate these findings, the researchers screened for the early memory T cells in a group of 8 CLL patients, before and after CAR T-cell therapy. The team identified the complete responders with 100% specificity and sensitivity.

“With a very robust biomarker like this, we can take a blood sample, measure the frequency of this T-cell population, and decide with a degree of confidence whether we can apply this therapy and know the patient would have a response,” Dr Fraietta said.

“The ability to select patients most likely to respond would have tremendous clinical impact, as this therapy would be applied only to patients most likely to benefit, allowing patients unlikely to respond to pursue other options.”

These findings also suggest the possibility of improving CAR T-cell therapy by selecting for cell manufacturing the subpopulation of T cells responsible for driving responses. However, this approach would come with challenges.

“What we’ve seen in these non-responders is that the frequency of these T cells is low, so it would be very hard to infuse them as starting populations,” said study author J. Joseph Melenhorst, PhD, also of the University of Pennsylvania.

“But one way to potentially boost their efficacy is by adding checkpoint inhibitors with the therapy to block the negative regulation prior to CAR T-cell therapy, which a past, separate study has shown can help elicit responses in these patients.”

The researchers also noted that it’s unclear why some patients’ T cells are suboptimal prior to treatment. However, the team believes this could have to do with prior therapies.

Future studies with a larger group of CLL patients should be conducted to help answer these questions and validate the findings from this study, the researchers said.

Researchers may have discovered why some patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) don’t respond to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

The team found that CLL patients with elevated levels of “early memory” T cells prior to receiving CAR T-cell therapy had a partial or complete response to treatment, while patients with lower levels of these T cells did not respond.

The early memory T cells were marked by the expression of CD8 and CD27, as well as the absence of CD45RO.

The researchers validated the association between the early memory T cells and response in a small group of patients, predicting with 100% accuracy which patients would achieve a complete response.

Joseph A. Fraietta, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature Medicine. This research was supported, in part, by Novartis.

For this study, the researchers retrospectively analyzed 41 patients with advanced, heavily pretreated, high-risk CLL who received at least 1 dose of CD19-directed CAR T cells.

Consistent with the team’s previously reported findings, they were not able to identify patient or disease-specific factors that predict who responds best to the therapy.

Therefore, the researchers compared the gene expression profiles and phenotypes of T cells in patients who had a complete response, partial response, or no response to therapy.

The CAR T cells that persisted and expanded in complete responders were enriched in genes that regulate early memory and effector T cells and possess the IL-6/STAT3 signature.

Non-responders, on the other hand, expressed genes involved in late T-cell differentiation, glycolysis, exhaustion, and apoptosis. These characteristics make for a weaker set of T cells to persist, expand, and fight the CLL.

“Pre-existing T-cell qualities have previously been associated with poor clinical response to cancer therapy, as well differentiation in the T cells,” Dr Fraietta said. “What is special about what we have done here is finding that critical cell subset and signature.”

Elevated levels of the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway in these early T cells correlated with clinical responses to CAR T-cell therapy.

To validate these findings, the researchers screened for the early memory T cells in a group of 8 CLL patients, before and after CAR T-cell therapy. The team identified the complete responders with 100% specificity and sensitivity.

“With a very robust biomarker like this, we can take a blood sample, measure the frequency of this T-cell population, and decide with a degree of confidence whether we can apply this therapy and know the patient would have a response,” Dr Fraietta said.

“The ability to select patients most likely to respond would have tremendous clinical impact, as this therapy would be applied only to patients most likely to benefit, allowing patients unlikely to respond to pursue other options.”

These findings also suggest the possibility of improving CAR T-cell therapy by selecting for cell manufacturing the subpopulation of T cells responsible for driving responses. However, this approach would come with challenges.

“What we’ve seen in these non-responders is that the frequency of these T cells is low, so it would be very hard to infuse them as starting populations,” said study author J. Joseph Melenhorst, PhD, also of the University of Pennsylvania.

“But one way to potentially boost their efficacy is by adding checkpoint inhibitors with the therapy to block the negative regulation prior to CAR T-cell therapy, which a past, separate study has shown can help elicit responses in these patients.”

The researchers also noted that it’s unclear why some patients’ T cells are suboptimal prior to treatment. However, the team believes this could have to do with prior therapies.

Future studies with a larger group of CLL patients should be conducted to help answer these questions and validate the findings from this study, the researchers said.

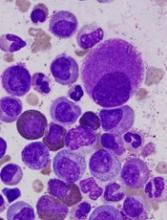

Team identifies 5 subtypes of DLBCL

New research has revealed 5 genetic subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Researchers identified a group of low-risk activated B-cell (ABC) DLBCLs, 2 subsets of germinal center B-cell (GCB) DLBCLs, a group of ABC/GCB-independent DLBCLs, and a group of ABC DLBCLs with genetic characteristics found in primary central nervous system lymphoma and testicular lymphoma.

The researchers believe these findings may have revealed new therapeutic targets for DLBCL, some of which could be inhibited by drugs that are already approved or under investigation in clinical trials.

Margaret Shipp, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, and her colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in Nature Medicine.

The team performed genetic analyses on samples from 304 DLBCL patients and observed great genetic diversity. The median number of genetic driver alterations in individual tumors was 17.

The researchers integrated data on 3 types of genetic alterations—recurrent mutations, somatic copy number alterations, and structural variants—to define previously unappreciated DLBCL subtypes.

“Specific genes that were perturbed by mutations could also be altered by changes in gene copy numbers or by chromosomal rearrangements, underscoring the importance of evaluating all 3 types of genetic alterations,” Dr Shipp noted.

“Most importantly, we saw that there were 5 discrete types of DLBCL that were distinguished one from another on the basis of the specific types of genetic alterations that occurred in combination.”

The researchers classified these subtypes as clusters (C) 1 to 5.

C1 consisted of largely ABC-DLBCLs with genetic features of an extra-follicular, possibly marginal zone origin.

C2 included both ABC and GCB DLBCLs with biallelic inactivation of TP53, 9p21.3/CDKN2A, and associated genomic instability.

Most DLBCLs in C3 were of the GCB subtype and were characterized by BCL2 structural variants and alterations of PTEN and epigenetic enzymes.

C4 consisted largely of GCB DLBCLs with alterations in BCR/PI3K, JAK/STAT, and BRAF pathway components and multiple histones.

Most C5 DLBCLs were of the ABC subtype, and the researchers said the major components of the C5 signature—BCL2 gain, concordant MYD88L265P/CD79B mutations, and mutations of ETV6, PIM1, GRHPR, TBL1XR1, and BTG1—were similar to those observed in primary central nervous system and testicular lymphoma.

Dr Shipp and her colleagues also identified a sixth cluster of DLBCLs (dubbed C0) that “lacked defining genetic drivers.”

Finally, the team found that patients with C0, C1, and C4 DLBCLs had more favorable outcomes, while patients with C2, C3, and C5 DLBCLs had less favorable outcomes.

“We feel this research opens the door to a whole series of additional investigations to understand how the combinations of these genetic alterations work together, and then to use that information to benefit patients with targeted therapies,” Dr Shipp said.

She and her colleagues are now working on creating a clinical tool to identify these genetic signatures in patients. The team is also developing clinical trials that will match patients with given genetic signatures to targeted treatments.

Another group of researchers recently identified 4 genetic subtypes of DLBCL.

New research has revealed 5 genetic subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Researchers identified a group of low-risk activated B-cell (ABC) DLBCLs, 2 subsets of germinal center B-cell (GCB) DLBCLs, a group of ABC/GCB-independent DLBCLs, and a group of ABC DLBCLs with genetic characteristics found in primary central nervous system lymphoma and testicular lymphoma.

The researchers believe these findings may have revealed new therapeutic targets for DLBCL, some of which could be inhibited by drugs that are already approved or under investigation in clinical trials.

Margaret Shipp, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, and her colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in Nature Medicine.

The team performed genetic analyses on samples from 304 DLBCL patients and observed great genetic diversity. The median number of genetic driver alterations in individual tumors was 17.

The researchers integrated data on 3 types of genetic alterations—recurrent mutations, somatic copy number alterations, and structural variants—to define previously unappreciated DLBCL subtypes.

“Specific genes that were perturbed by mutations could also be altered by changes in gene copy numbers or by chromosomal rearrangements, underscoring the importance of evaluating all 3 types of genetic alterations,” Dr Shipp noted.

“Most importantly, we saw that there were 5 discrete types of DLBCL that were distinguished one from another on the basis of the specific types of genetic alterations that occurred in combination.”

The researchers classified these subtypes as clusters (C) 1 to 5.

C1 consisted of largely ABC-DLBCLs with genetic features of an extra-follicular, possibly marginal zone origin.

C2 included both ABC and GCB DLBCLs with biallelic inactivation of TP53, 9p21.3/CDKN2A, and associated genomic instability.

Most DLBCLs in C3 were of the GCB subtype and were characterized by BCL2 structural variants and alterations of PTEN and epigenetic enzymes.

C4 consisted largely of GCB DLBCLs with alterations in BCR/PI3K, JAK/STAT, and BRAF pathway components and multiple histones.

Most C5 DLBCLs were of the ABC subtype, and the researchers said the major components of the C5 signature—BCL2 gain, concordant MYD88L265P/CD79B mutations, and mutations of ETV6, PIM1, GRHPR, TBL1XR1, and BTG1—were similar to those observed in primary central nervous system and testicular lymphoma.

Dr Shipp and her colleagues also identified a sixth cluster of DLBCLs (dubbed C0) that “lacked defining genetic drivers.”

Finally, the team found that patients with C0, C1, and C4 DLBCLs had more favorable outcomes, while patients with C2, C3, and C5 DLBCLs had less favorable outcomes.

“We feel this research opens the door to a whole series of additional investigations to understand how the combinations of these genetic alterations work together, and then to use that information to benefit patients with targeted therapies,” Dr Shipp said.

She and her colleagues are now working on creating a clinical tool to identify these genetic signatures in patients. The team is also developing clinical trials that will match patients with given genetic signatures to targeted treatments.

Another group of researchers recently identified 4 genetic subtypes of DLBCL.

New research has revealed 5 genetic subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Researchers identified a group of low-risk activated B-cell (ABC) DLBCLs, 2 subsets of germinal center B-cell (GCB) DLBCLs, a group of ABC/GCB-independent DLBCLs, and a group of ABC DLBCLs with genetic characteristics found in primary central nervous system lymphoma and testicular lymphoma.

The researchers believe these findings may have revealed new therapeutic targets for DLBCL, some of which could be inhibited by drugs that are already approved or under investigation in clinical trials.

Margaret Shipp, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, and her colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in Nature Medicine.

The team performed genetic analyses on samples from 304 DLBCL patients and observed great genetic diversity. The median number of genetic driver alterations in individual tumors was 17.

The researchers integrated data on 3 types of genetic alterations—recurrent mutations, somatic copy number alterations, and structural variants—to define previously unappreciated DLBCL subtypes.

“Specific genes that were perturbed by mutations could also be altered by changes in gene copy numbers or by chromosomal rearrangements, underscoring the importance of evaluating all 3 types of genetic alterations,” Dr Shipp noted.

“Most importantly, we saw that there were 5 discrete types of DLBCL that were distinguished one from another on the basis of the specific types of genetic alterations that occurred in combination.”

The researchers classified these subtypes as clusters (C) 1 to 5.

C1 consisted of largely ABC-DLBCLs with genetic features of an extra-follicular, possibly marginal zone origin.

C2 included both ABC and GCB DLBCLs with biallelic inactivation of TP53, 9p21.3/CDKN2A, and associated genomic instability.

Most DLBCLs in C3 were of the GCB subtype and were characterized by BCL2 structural variants and alterations of PTEN and epigenetic enzymes.

C4 consisted largely of GCB DLBCLs with alterations in BCR/PI3K, JAK/STAT, and BRAF pathway components and multiple histones.

Most C5 DLBCLs were of the ABC subtype, and the researchers said the major components of the C5 signature—BCL2 gain, concordant MYD88L265P/CD79B mutations, and mutations of ETV6, PIM1, GRHPR, TBL1XR1, and BTG1—were similar to those observed in primary central nervous system and testicular lymphoma.

Dr Shipp and her colleagues also identified a sixth cluster of DLBCLs (dubbed C0) that “lacked defining genetic drivers.”

Finally, the team found that patients with C0, C1, and C4 DLBCLs had more favorable outcomes, while patients with C2, C3, and C5 DLBCLs had less favorable outcomes.

“We feel this research opens the door to a whole series of additional investigations to understand how the combinations of these genetic alterations work together, and then to use that information to benefit patients with targeted therapies,” Dr Shipp said.

She and her colleagues are now working on creating a clinical tool to identify these genetic signatures in patients. The team is also developing clinical trials that will match patients with given genetic signatures to targeted treatments.

Another group of researchers recently identified 4 genetic subtypes of DLBCL.

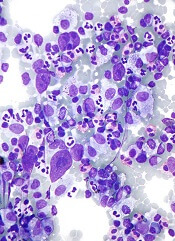

Fostamatinib produces responses in ITP

Fostamatinib has produced “clinically meaningful” responses in adults with persistent or chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), according to researchers.

In a pair of phase 3 trials, 18% of patients who received fostamatinib had a stable response, which was defined as having a platelet count of at least 50,000/µL for at least 4 of 6 clinic visits.

In comparison, 2% of patients who received placebo achieved a stable response.

The most common adverse events (AEs) in these trials were diarrhea, hypertension, and nausea. Most AEs were deemed mild or moderate.

These results were published in the American Journal of Hematology. The trials—known as FIT1 and FIT2—were sponsored by Rigel Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company marketing fostamatinib.

Fostamatinib is an oral Syk inhibitor that was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Patients and treatment

Researchers evaluated fostamatinib in the parallel FIT1 and FIT2 trials, which included 150 patients with persistent or chronic ITP who had an insufficient response to previous treatment.

In each study, patients were randomized 2:1 to receive fostamatinib or placebo for 24 weeks. In FIT1, 76 patients were randomized—51 to fostamatinib and 25 to placebo. In FIT2, 74 patients were randomized—50 to fostamatinib and 24 to placebo.

All patients initially received fostamatinib at 100 mg twice daily. Most (88%) were escalated to 150 mg twice daily at week 4 or later. Patients could also receive stable concurrent ITP therapy—glucocorticoids (< 20 mg prednisone equivalent per day), azathioprine, or danazol—and rescue therapy if needed.

The median age was 54 (range, 20-88) in the fostamatinib recipients and 53 (range, 20-78) in the placebo recipients. Sixty-one percent and 60%, respectively, were female. And 93% and 92%, respectively, were white.

The median duration of ITP was 8.7 years for fostamatinib recipients and 7.8 years for placebo recipients. Both fostamatinib and placebo recipients had a median of 3 prior unique treatments for ITP (range, 1-13 and 1-10, respectively).

Prior ITP treatments (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included corticosteroids (93% vs 96%), immunoglobulins (51% vs 55%), thrombopoietin receptor agonists (47% vs 51%), immunosuppressants (44% vs 45%), splenectomy (34% vs 39%), and rituximab (34% vs 29%), among other treatments.

Overall, the patients’ median platelet count at baseline was 16,000/µL. Mean baseline platelet counts were 16,052/µL (range, 1000-51,000) in fostamatinib recipients and 19,818/µL (range, 1000-156,000) in placebo recipients.

Response

The efficacy of fostamatinib was based on stable platelet response, defined as a platelet count of at least 50,000/µL on at least 4 of 6 biweekly clinic visits between weeks 14 and 24, without the use of rescue therapy.

Overall, 18% (18/101) of patients on fostamatinib and 2% (1/49) of those on placebo achieved this endpoint (P=0.0003).

In FIT1, 18% of patients in the fostamatinib arm and 0% of those in the placebo arm achieved a stable platelet response (P=0.026). In FIT2, rates of stable response were 18% and 4%, respectively (P=0.152).

A secondary endpoint was overall response, which was defined retrospectively as at least 1 platelet count ≥ 50,000/μL within the first 12 weeks on treatment.

Forty-three percent (43/101) of fostamatinib recipients achieved an overall response, as did 14% (7/49) of patients on placebo (P=0.0006).

In FIT1, the rate of overall response was 37% in the fostamatinib arm and 8% in the placebo arm (P=0.007). In FIT2, overall response rates were 48% and 21%, respectively (P=0.025).

The researchers said they observed responses to fostamatinib across all patient subgroups, regardless of age, sex, prior therapy, baseline platelet count, or duration of ITP at study entry.

Role of concomitant therapy

The researchers noted that 2 of the 18 patients with a stable platelet response were on concomitant treatment. Both were on steroids, one of them for 62 days before the first dose of fostamatinib and the other for 14 years.

Four of the 43 patients with an overall platelet response were on concomitant therapy. Three were on steroids—for 62 days, 67 days, and 14 years prior to first dose of fostamatinib—and 1 was on azathioprine—for 197 days prior to the first dose of fostamatinib.

The researchers said the effects of these therapies probably would have been evident prior to study entry, so they aren’t likely to have influenced the results.

Safety

In both trials, the rate of AEs was 83% in the fostamatinib recipients (32% mild, 35% moderate, and 16% severe AEs) and 75% in the placebo recipients (42% mild, 19% moderate, and 15% severe AEs.).

AEs occurring in at least 5% of patients (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included diarrhea (31% vs 15%), hypertension (28% vs 13%), nausea (19% vs 8%), dizziness (11% vs 8%), ALT increase (11% vs 0%), AST increase (9% vs 0%), respiratory infection (11% vs 6%), rash (9% vs 2%), abdominal pain (6% vs 2%), fatigue (6% vs 2%), chest pain (6% vs 2%), and neutropenia (6% vs 0%).

Moderate or severe bleeding-related AEs occurred in 9% of patients who had an overall response to fostamatinib and 16% of patients on placebo.

Serious AEs considered related to study drug occurred in 4 patients on fostamatinib and 1 patient on placebo. The placebo recipient experienced a bleeding event, and the fostamatinib-related events were consistent with the AE profile of the drug (hypertension, diarrhea, etc.), according to Rigel Pharmaceuticals.

There were 2 deaths. One placebo recipient died of probable sepsis 19 days after withdrawing from the study due to epistaxis. One fostamatinib recipient developed plasma cell myeloma, stopped treatment on day 19, and died 71 days later.

Fostamatinib has produced “clinically meaningful” responses in adults with persistent or chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), according to researchers.

In a pair of phase 3 trials, 18% of patients who received fostamatinib had a stable response, which was defined as having a platelet count of at least 50,000/µL for at least 4 of 6 clinic visits.

In comparison, 2% of patients who received placebo achieved a stable response.

The most common adverse events (AEs) in these trials were diarrhea, hypertension, and nausea. Most AEs were deemed mild or moderate.

These results were published in the American Journal of Hematology. The trials—known as FIT1 and FIT2—were sponsored by Rigel Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company marketing fostamatinib.

Fostamatinib is an oral Syk inhibitor that was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Patients and treatment

Researchers evaluated fostamatinib in the parallel FIT1 and FIT2 trials, which included 150 patients with persistent or chronic ITP who had an insufficient response to previous treatment.

In each study, patients were randomized 2:1 to receive fostamatinib or placebo for 24 weeks. In FIT1, 76 patients were randomized—51 to fostamatinib and 25 to placebo. In FIT2, 74 patients were randomized—50 to fostamatinib and 24 to placebo.

All patients initially received fostamatinib at 100 mg twice daily. Most (88%) were escalated to 150 mg twice daily at week 4 or later. Patients could also receive stable concurrent ITP therapy—glucocorticoids (< 20 mg prednisone equivalent per day), azathioprine, or danazol—and rescue therapy if needed.

The median age was 54 (range, 20-88) in the fostamatinib recipients and 53 (range, 20-78) in the placebo recipients. Sixty-one percent and 60%, respectively, were female. And 93% and 92%, respectively, were white.

The median duration of ITP was 8.7 years for fostamatinib recipients and 7.8 years for placebo recipients. Both fostamatinib and placebo recipients had a median of 3 prior unique treatments for ITP (range, 1-13 and 1-10, respectively).

Prior ITP treatments (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included corticosteroids (93% vs 96%), immunoglobulins (51% vs 55%), thrombopoietin receptor agonists (47% vs 51%), immunosuppressants (44% vs 45%), splenectomy (34% vs 39%), and rituximab (34% vs 29%), among other treatments.

Overall, the patients’ median platelet count at baseline was 16,000/µL. Mean baseline platelet counts were 16,052/µL (range, 1000-51,000) in fostamatinib recipients and 19,818/µL (range, 1000-156,000) in placebo recipients.

Response

The efficacy of fostamatinib was based on stable platelet response, defined as a platelet count of at least 50,000/µL on at least 4 of 6 biweekly clinic visits between weeks 14 and 24, without the use of rescue therapy.

Overall, 18% (18/101) of patients on fostamatinib and 2% (1/49) of those on placebo achieved this endpoint (P=0.0003).

In FIT1, 18% of patients in the fostamatinib arm and 0% of those in the placebo arm achieved a stable platelet response (P=0.026). In FIT2, rates of stable response were 18% and 4%, respectively (P=0.152).

A secondary endpoint was overall response, which was defined retrospectively as at least 1 platelet count ≥ 50,000/μL within the first 12 weeks on treatment.

Forty-three percent (43/101) of fostamatinib recipients achieved an overall response, as did 14% (7/49) of patients on placebo (P=0.0006).

In FIT1, the rate of overall response was 37% in the fostamatinib arm and 8% in the placebo arm (P=0.007). In FIT2, overall response rates were 48% and 21%, respectively (P=0.025).

The researchers said they observed responses to fostamatinib across all patient subgroups, regardless of age, sex, prior therapy, baseline platelet count, or duration of ITP at study entry.

Role of concomitant therapy

The researchers noted that 2 of the 18 patients with a stable platelet response were on concomitant treatment. Both were on steroids, one of them for 62 days before the first dose of fostamatinib and the other for 14 years.

Four of the 43 patients with an overall platelet response were on concomitant therapy. Three were on steroids—for 62 days, 67 days, and 14 years prior to first dose of fostamatinib—and 1 was on azathioprine—for 197 days prior to the first dose of fostamatinib.

The researchers said the effects of these therapies probably would have been evident prior to study entry, so they aren’t likely to have influenced the results.

Safety

In both trials, the rate of AEs was 83% in the fostamatinib recipients (32% mild, 35% moderate, and 16% severe AEs) and 75% in the placebo recipients (42% mild, 19% moderate, and 15% severe AEs.).

AEs occurring in at least 5% of patients (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included diarrhea (31% vs 15%), hypertension (28% vs 13%), nausea (19% vs 8%), dizziness (11% vs 8%), ALT increase (11% vs 0%), AST increase (9% vs 0%), respiratory infection (11% vs 6%), rash (9% vs 2%), abdominal pain (6% vs 2%), fatigue (6% vs 2%), chest pain (6% vs 2%), and neutropenia (6% vs 0%).

Moderate or severe bleeding-related AEs occurred in 9% of patients who had an overall response to fostamatinib and 16% of patients on placebo.

Serious AEs considered related to study drug occurred in 4 patients on fostamatinib and 1 patient on placebo. The placebo recipient experienced a bleeding event, and the fostamatinib-related events were consistent with the AE profile of the drug (hypertension, diarrhea, etc.), according to Rigel Pharmaceuticals.

There were 2 deaths. One placebo recipient died of probable sepsis 19 days after withdrawing from the study due to epistaxis. One fostamatinib recipient developed plasma cell myeloma, stopped treatment on day 19, and died 71 days later.

Fostamatinib has produced “clinically meaningful” responses in adults with persistent or chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), according to researchers.

In a pair of phase 3 trials, 18% of patients who received fostamatinib had a stable response, which was defined as having a platelet count of at least 50,000/µL for at least 4 of 6 clinic visits.

In comparison, 2% of patients who received placebo achieved a stable response.

The most common adverse events (AEs) in these trials were diarrhea, hypertension, and nausea. Most AEs were deemed mild or moderate.

These results were published in the American Journal of Hematology. The trials—known as FIT1 and FIT2—were sponsored by Rigel Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company marketing fostamatinib.

Fostamatinib is an oral Syk inhibitor that was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Patients and treatment

Researchers evaluated fostamatinib in the parallel FIT1 and FIT2 trials, which included 150 patients with persistent or chronic ITP who had an insufficient response to previous treatment.

In each study, patients were randomized 2:1 to receive fostamatinib or placebo for 24 weeks. In FIT1, 76 patients were randomized—51 to fostamatinib and 25 to placebo. In FIT2, 74 patients were randomized—50 to fostamatinib and 24 to placebo.

All patients initially received fostamatinib at 100 mg twice daily. Most (88%) were escalated to 150 mg twice daily at week 4 or later. Patients could also receive stable concurrent ITP therapy—glucocorticoids (< 20 mg prednisone equivalent per day), azathioprine, or danazol—and rescue therapy if needed.

The median age was 54 (range, 20-88) in the fostamatinib recipients and 53 (range, 20-78) in the placebo recipients. Sixty-one percent and 60%, respectively, were female. And 93% and 92%, respectively, were white.

The median duration of ITP was 8.7 years for fostamatinib recipients and 7.8 years for placebo recipients. Both fostamatinib and placebo recipients had a median of 3 prior unique treatments for ITP (range, 1-13 and 1-10, respectively).

Prior ITP treatments (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included corticosteroids (93% vs 96%), immunoglobulins (51% vs 55%), thrombopoietin receptor agonists (47% vs 51%), immunosuppressants (44% vs 45%), splenectomy (34% vs 39%), and rituximab (34% vs 29%), among other treatments.

Overall, the patients’ median platelet count at baseline was 16,000/µL. Mean baseline platelet counts were 16,052/µL (range, 1000-51,000) in fostamatinib recipients and 19,818/µL (range, 1000-156,000) in placebo recipients.

Response

The efficacy of fostamatinib was based on stable platelet response, defined as a platelet count of at least 50,000/µL on at least 4 of 6 biweekly clinic visits between weeks 14 and 24, without the use of rescue therapy.

Overall, 18% (18/101) of patients on fostamatinib and 2% (1/49) of those on placebo achieved this endpoint (P=0.0003).

In FIT1, 18% of patients in the fostamatinib arm and 0% of those in the placebo arm achieved a stable platelet response (P=0.026). In FIT2, rates of stable response were 18% and 4%, respectively (P=0.152).

A secondary endpoint was overall response, which was defined retrospectively as at least 1 platelet count ≥ 50,000/μL within the first 12 weeks on treatment.

Forty-three percent (43/101) of fostamatinib recipients achieved an overall response, as did 14% (7/49) of patients on placebo (P=0.0006).

In FIT1, the rate of overall response was 37% in the fostamatinib arm and 8% in the placebo arm (P=0.007). In FIT2, overall response rates were 48% and 21%, respectively (P=0.025).

The researchers said they observed responses to fostamatinib across all patient subgroups, regardless of age, sex, prior therapy, baseline platelet count, or duration of ITP at study entry.

Role of concomitant therapy

The researchers noted that 2 of the 18 patients with a stable platelet response were on concomitant treatment. Both were on steroids, one of them for 62 days before the first dose of fostamatinib and the other for 14 years.

Four of the 43 patients with an overall platelet response were on concomitant therapy. Three were on steroids—for 62 days, 67 days, and 14 years prior to first dose of fostamatinib—and 1 was on azathioprine—for 197 days prior to the first dose of fostamatinib.

The researchers said the effects of these therapies probably would have been evident prior to study entry, so they aren’t likely to have influenced the results.

Safety

In both trials, the rate of AEs was 83% in the fostamatinib recipients (32% mild, 35% moderate, and 16% severe AEs) and 75% in the placebo recipients (42% mild, 19% moderate, and 15% severe AEs.).

AEs occurring in at least 5% of patients (in the fostamatinib and placebo arms, respectively) included diarrhea (31% vs 15%), hypertension (28% vs 13%), nausea (19% vs 8%), dizziness (11% vs 8%), ALT increase (11% vs 0%), AST increase (9% vs 0%), respiratory infection (11% vs 6%), rash (9% vs 2%), abdominal pain (6% vs 2%), fatigue (6% vs 2%), chest pain (6% vs 2%), and neutropenia (6% vs 0%).

Moderate or severe bleeding-related AEs occurred in 9% of patients who had an overall response to fostamatinib and 16% of patients on placebo.

Serious AEs considered related to study drug occurred in 4 patients on fostamatinib and 1 patient on placebo. The placebo recipient experienced a bleeding event, and the fostamatinib-related events were consistent with the AE profile of the drug (hypertension, diarrhea, etc.), according to Rigel Pharmaceuticals.

There were 2 deaths. One placebo recipient died of probable sepsis 19 days after withdrawing from the study due to epistaxis. One fostamatinib recipient developed plasma cell myeloma, stopped treatment on day 19, and died 71 days later.

CHMP backs approval of dasatinib for kids

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended changes to the marketing authorization for dasatinib (Sprycel).

The CHMP is recommending approval for dasatinib as a treatment for pediatric patients with newly diagnosed, Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in chronic phase (CP) or Ph+ CML-CP that is resistant or intolerant to prior therapy, including imatinib.