User login

A Veteran Presenting With Symptomatic Postprandial Episodes

A Veteran Presenting With Symptomatic Postprandial Episodes

Idiopathic postprandial syndrome (IPP), initially termed reactive hypoglycemia, presents with hypoglycemic-like symptoms in the absence of biochemical hypoglycemia and remains a diagnosis of exclusion. Its pathophysiology is poorly understood. The diagnosis requires thorough evaluation of cardiac, metabolic, neurologic, and gastrointestinal causes, as well as Whipple triad criteria. Dietary modifications, including reduced carbohydrate intake, increased protein and fiber, and frequent small meals, remain the cornerstone of IPP management. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) may be a useful adjunct in correlating symptoms with glucose trends, but its role is still evolving.

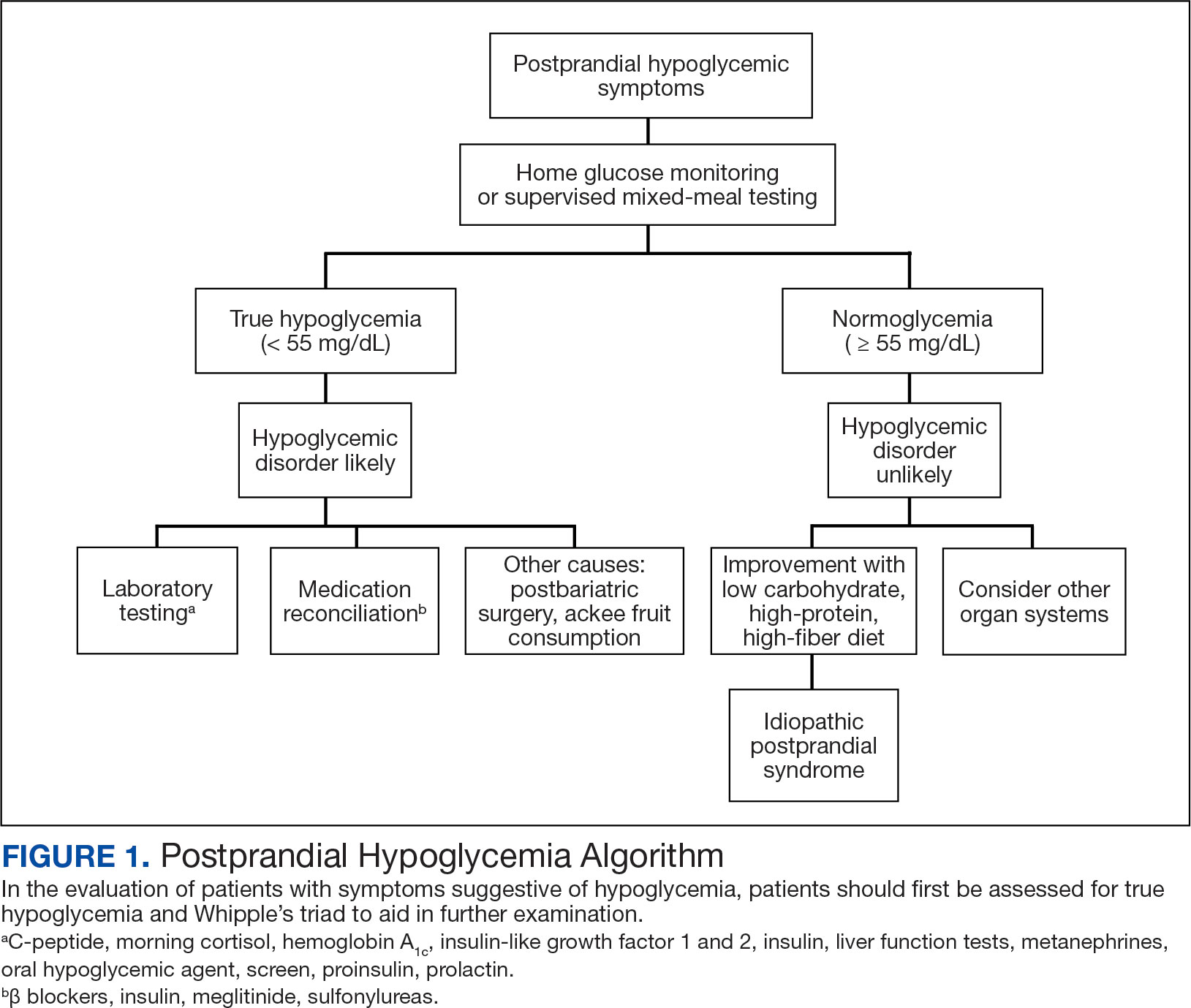

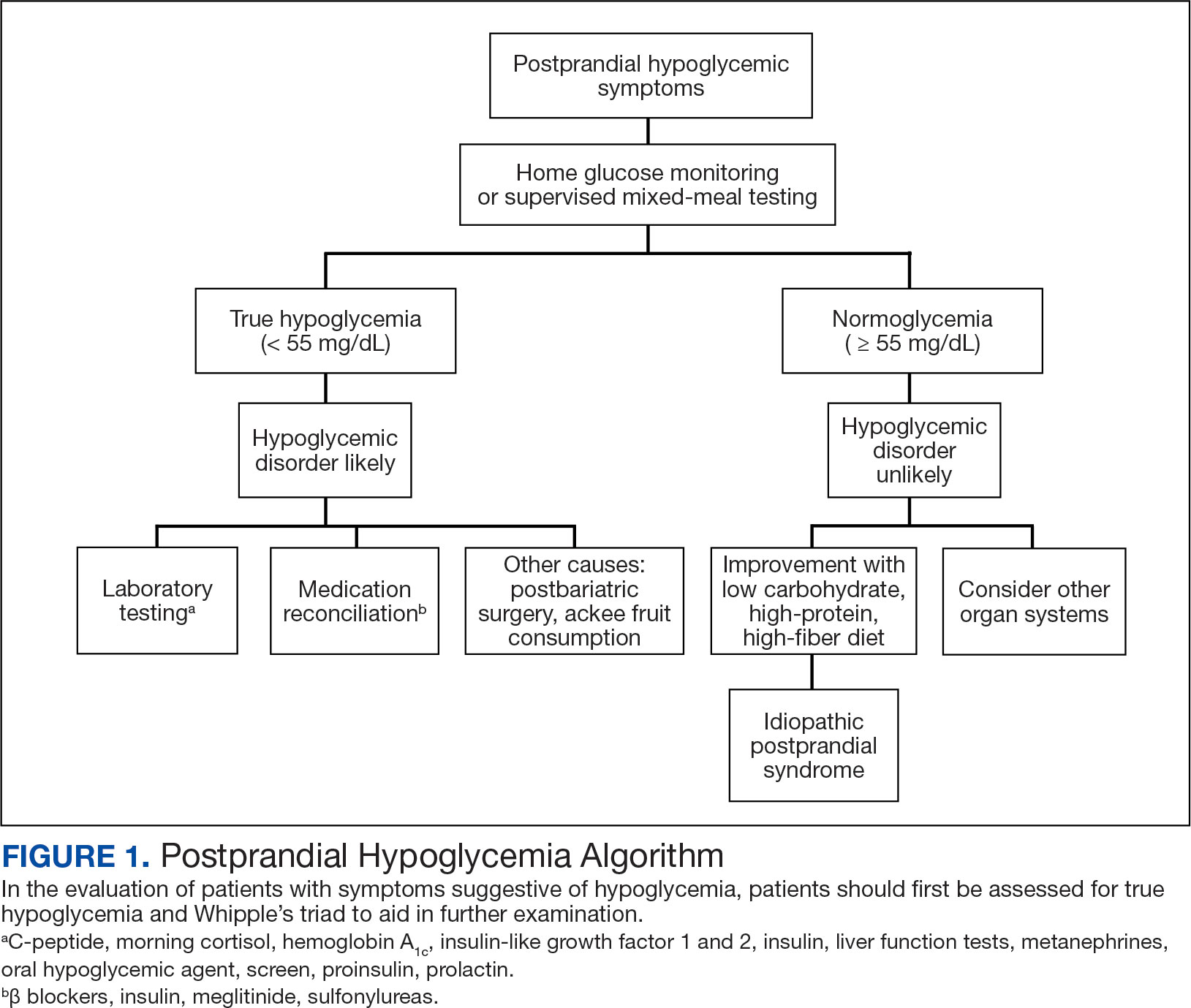

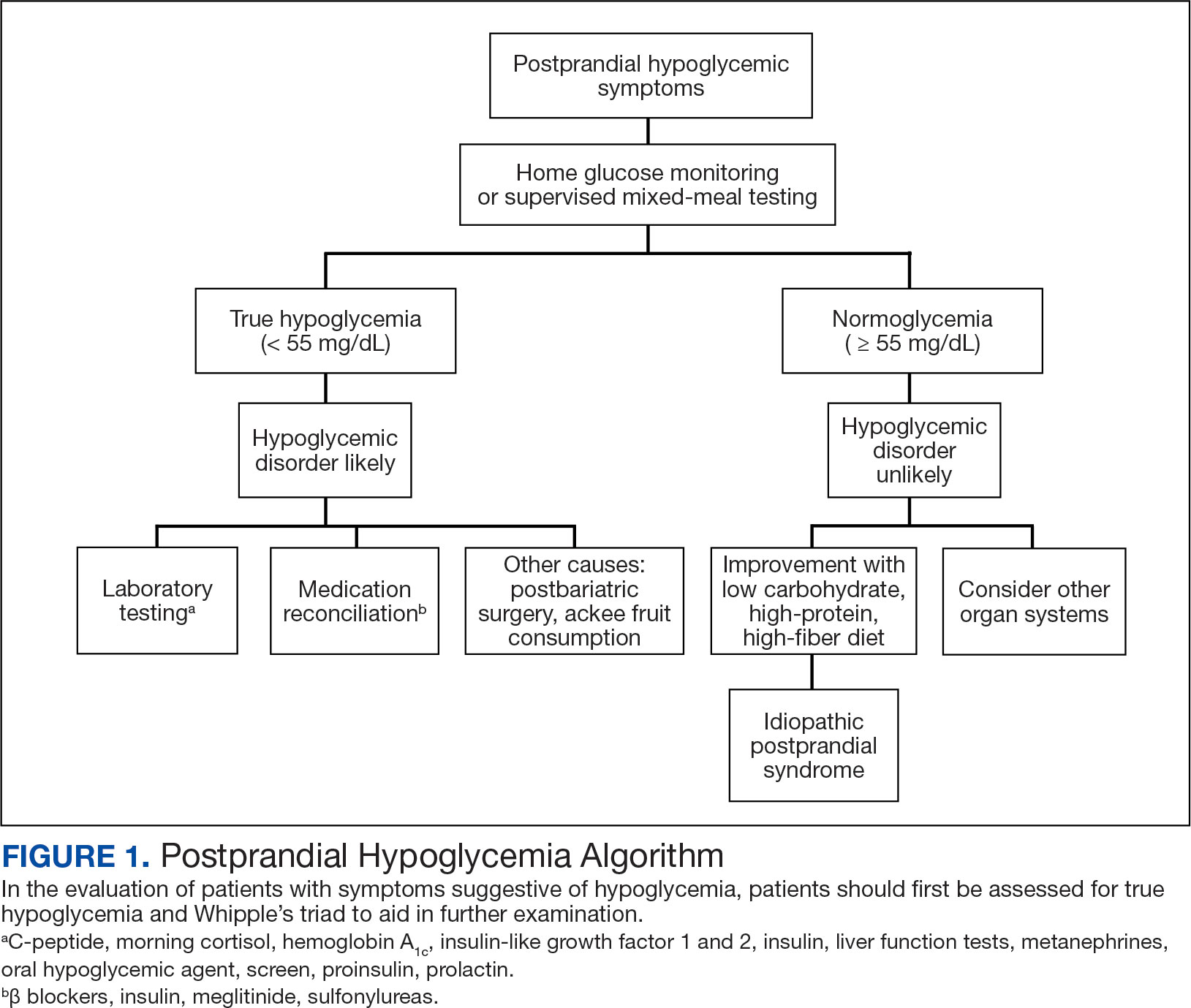

In the evaluation of patients with symptoms suggestive of hypoglycemia (Figure 1), patients should first be assessed for Whipple triad: symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia, blood glucose level < 55 mg/dL, and reversal of symptoms with glucose.1 Patients who meet Whipple triad criteria should be investigated to identify further etiologies of hypoglycemia. They may include insulinoma, medication-induced (insulin, sulfonylurea, meglitinide, or β blocker use), postbariatric surgery complications, noninsulinoma pancreatogenous hypoglycemia syndrome, ackee fruit consumption, or familial conditions.2 The presence of hypoglycemic symptoms in the postprandial or fasting state can provide valuable insights into underlying etiology.

Patients who do not meet Whipple triad criteria, but exhibit postprandial symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia, as in this case, present a diagnostic dilemma. IPP is defined as hypoglycemic symptoms occuring after carbohydrate ingestion without biochemical hypoglycemia. Initially termed reactive hypoglycemia, it was renamed in 1981to reflect the absence of low blood glucose levels.3

The understanding of this diagnosis has not significantly progressed since the 1980s. Its prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and societal burden remain unclear. IPP is a challenging diagnosis due to nonspecific symptoms that overlap with a myriad of conditions. These symptoms may include adrenergic symptoms such as diaphoresis, tremulousness, palpitations, anxiety, and hunger. Potentially severe neuroglycopenic symptoms, including weakness, dizziness, behavior changes, confusion, and coma, are not typically observed.4 Given that objective criteria are not well established, IPP remains a diagnosis of exclusion. It is imperative to rule out alternative etiologies, particularly cardiac, gastrointestinal, and neurologic causes.

CASE PRESENTATION

A male aged 41 years presented to primary care for evaluation of acute on chronic symptomatic postprandial episodes. He reported a history of symptomatic sinus bradycardia in the setting of sick sinus syndrome following dual-chamber pacemaker placement, posttraumatic stress disorder, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. He was a retired Navy sailor without any known occupational exposures who worked in the real estate industry. The patient reported feeling lightheaded, tremulous, and anxious most afternoons after lunch for several years. He also reported that meals heavy in carbohydrates exacerbated his symptoms, whereas skipping meals or lying down alleviated his symptoms. The patient also reported concomitant arm numbness, shortness of breath, palpitations, and nausea during these episodes. Review of systems was otherwise negative, including no weight changes, fever, chills, night sweats, chest pain, or syncope.

The patient’s medications included ferrous sulfate 325 mg once every other day, bupropion 200 mg once daily, metoprolol succinate 25 mg once daily, and as-needed lorazepam 1 mg once daily. The patient reported no current substance use but reported previous tobacco use 3 years prior (maximum 1 pack/week) and alcohol use 5 years prior (750 ml/day for 15 years). The patient did not exercise and typically ate oatmeal for breakfast, a sandwich or salad for lunch, and taquitos or salad for dinner, with snacks throughout the day. Notable family history included a maternal grandmother with colon cancer. The patient’s vital signs included a 36.8 °C temperature, heart rate 87 beats/min, 118/71 mm Hg blood pressure, oxygen saturation 98% on room air, 125.2 kg weight, and 38.5 body mass index. There were no orthostatic vital sign changes. A physical examination demonstrated obesity with an unremarkable cardiopulmonary and volume examination.

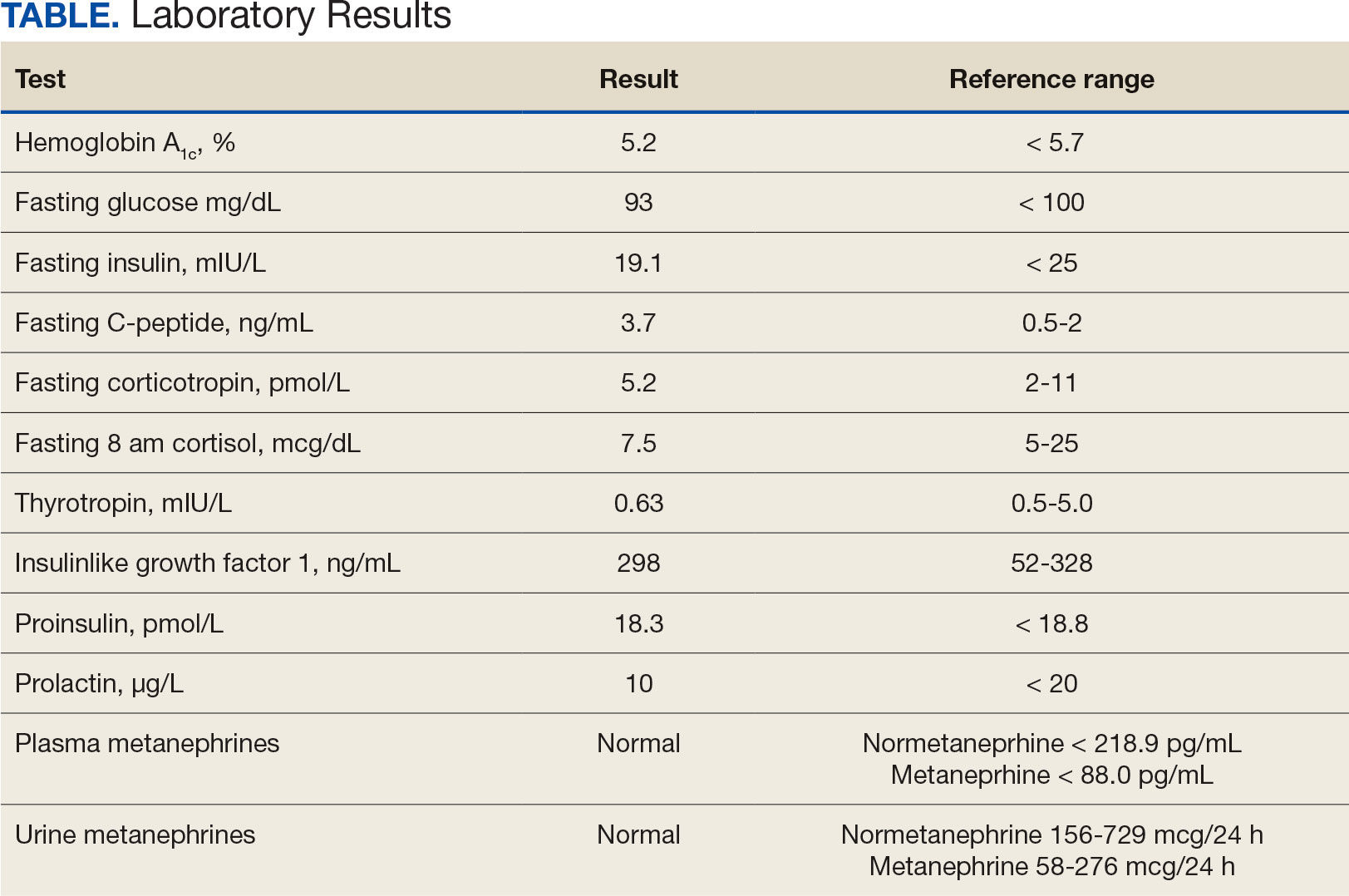

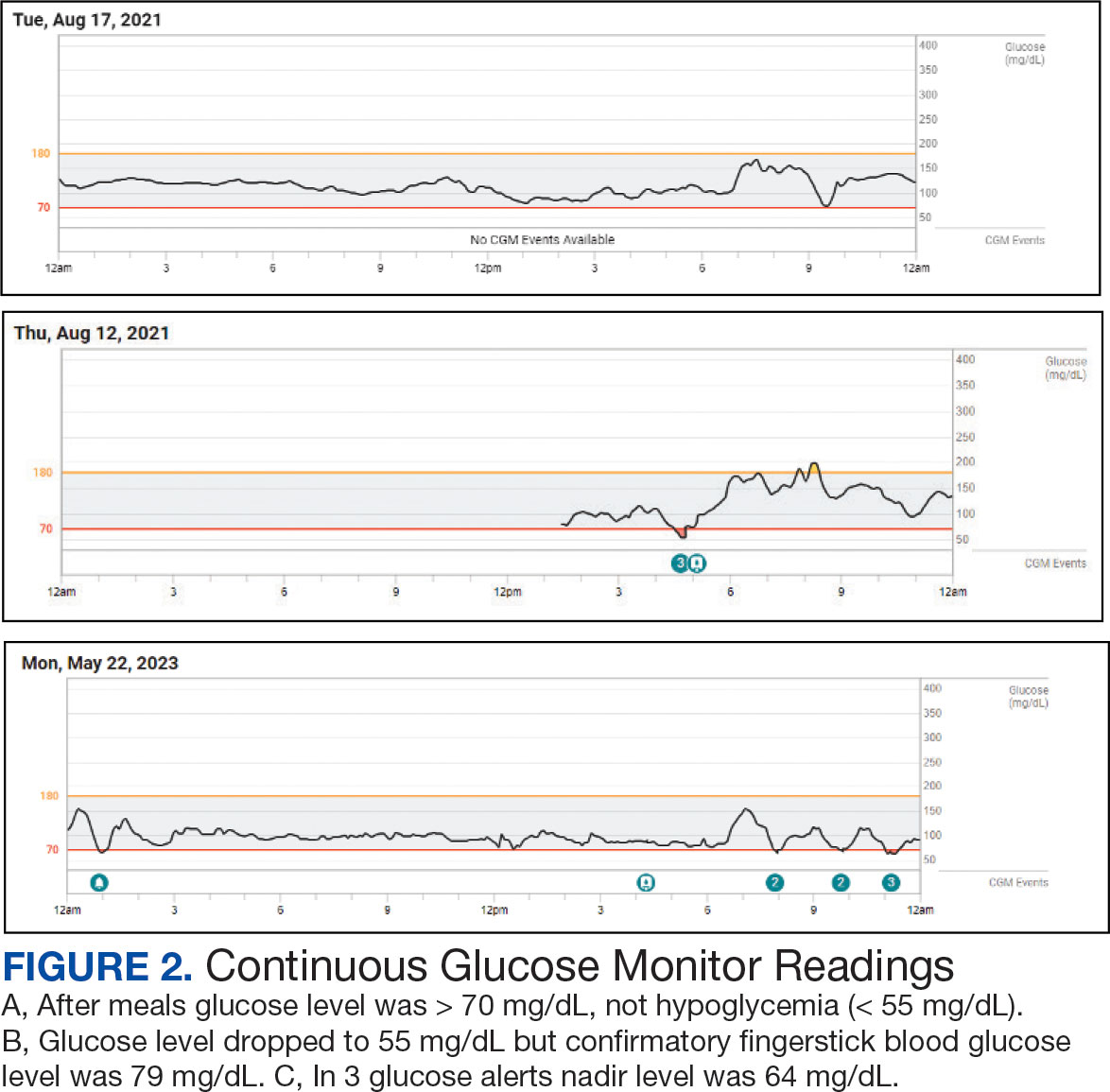

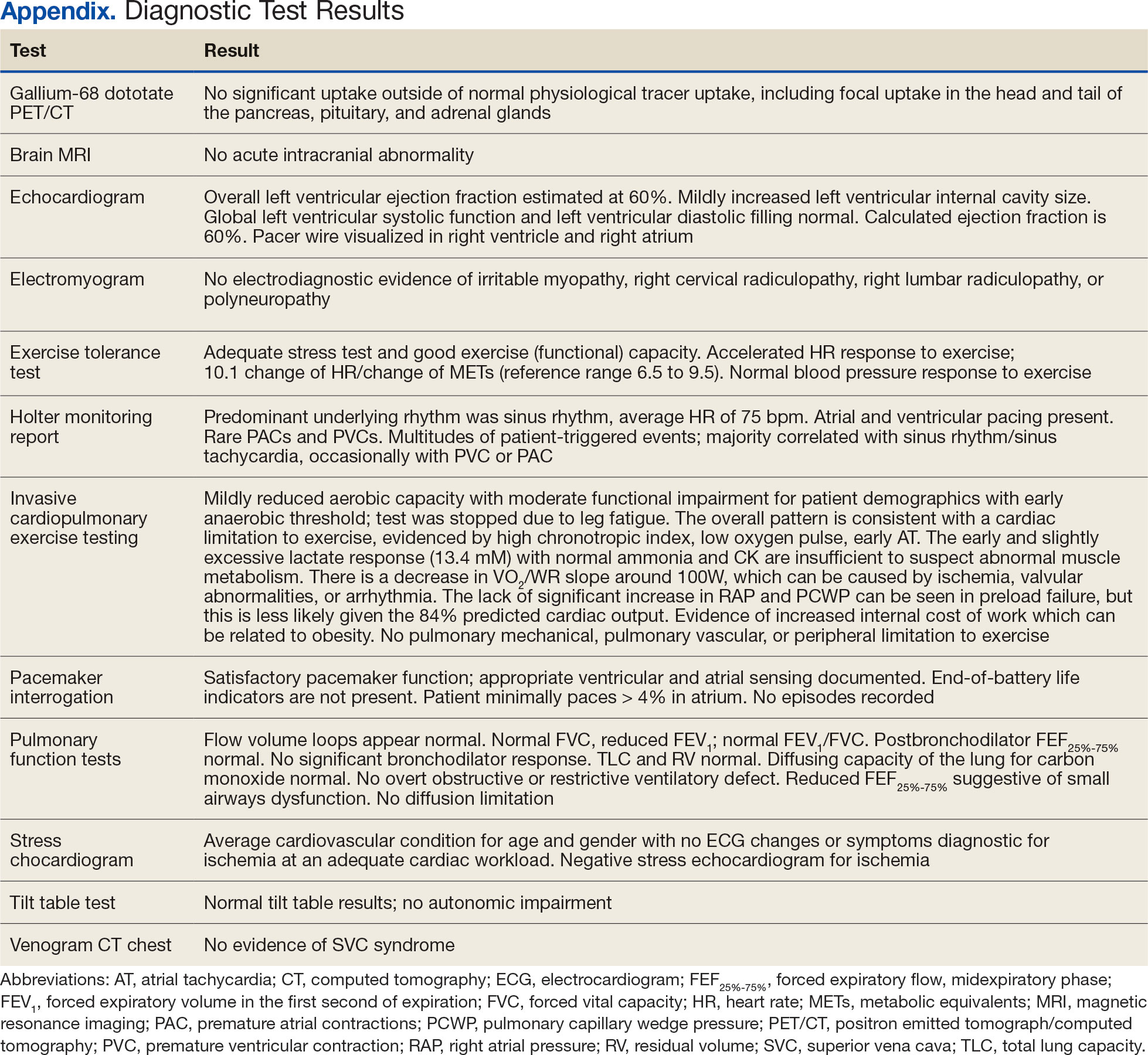

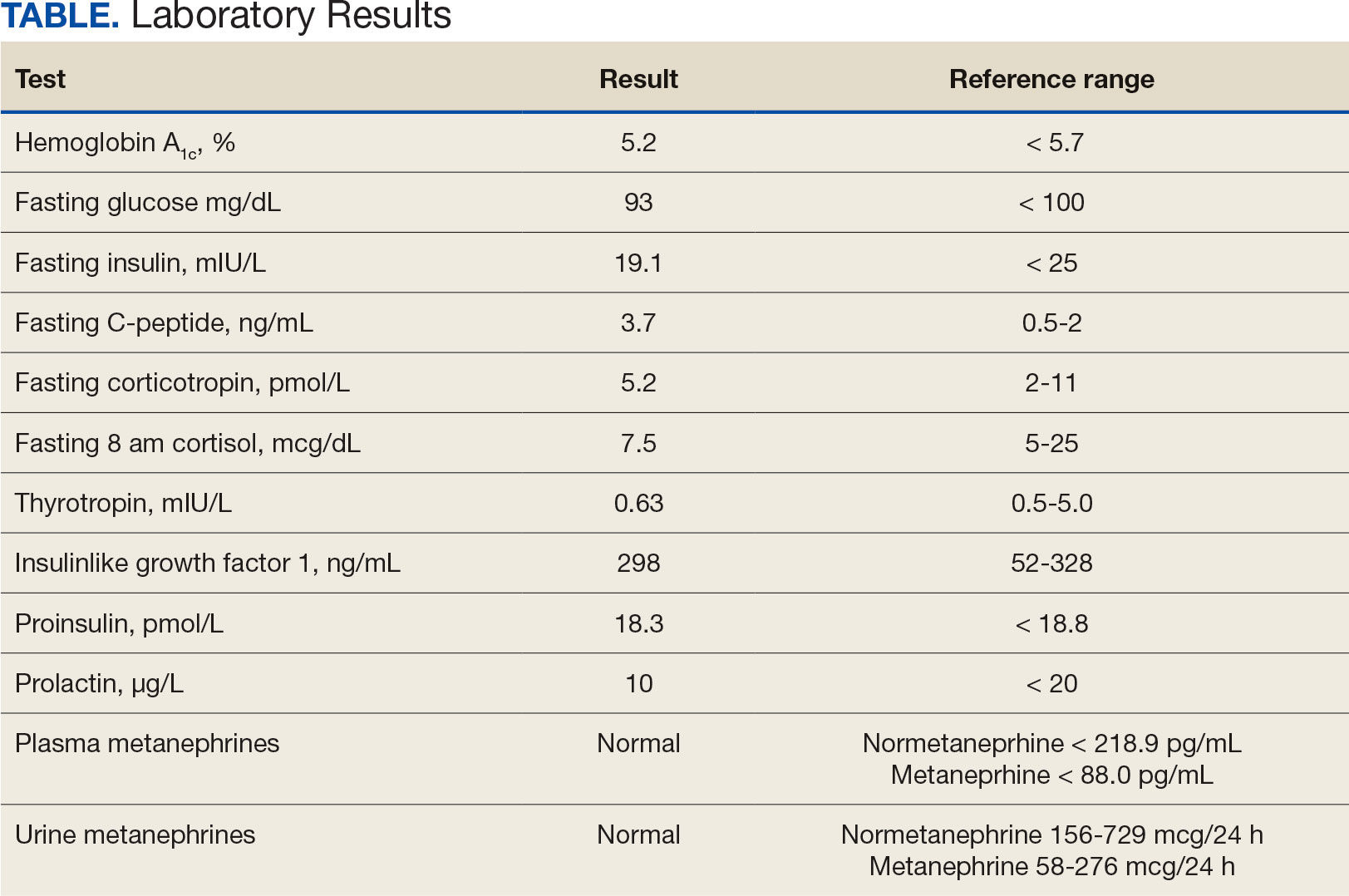

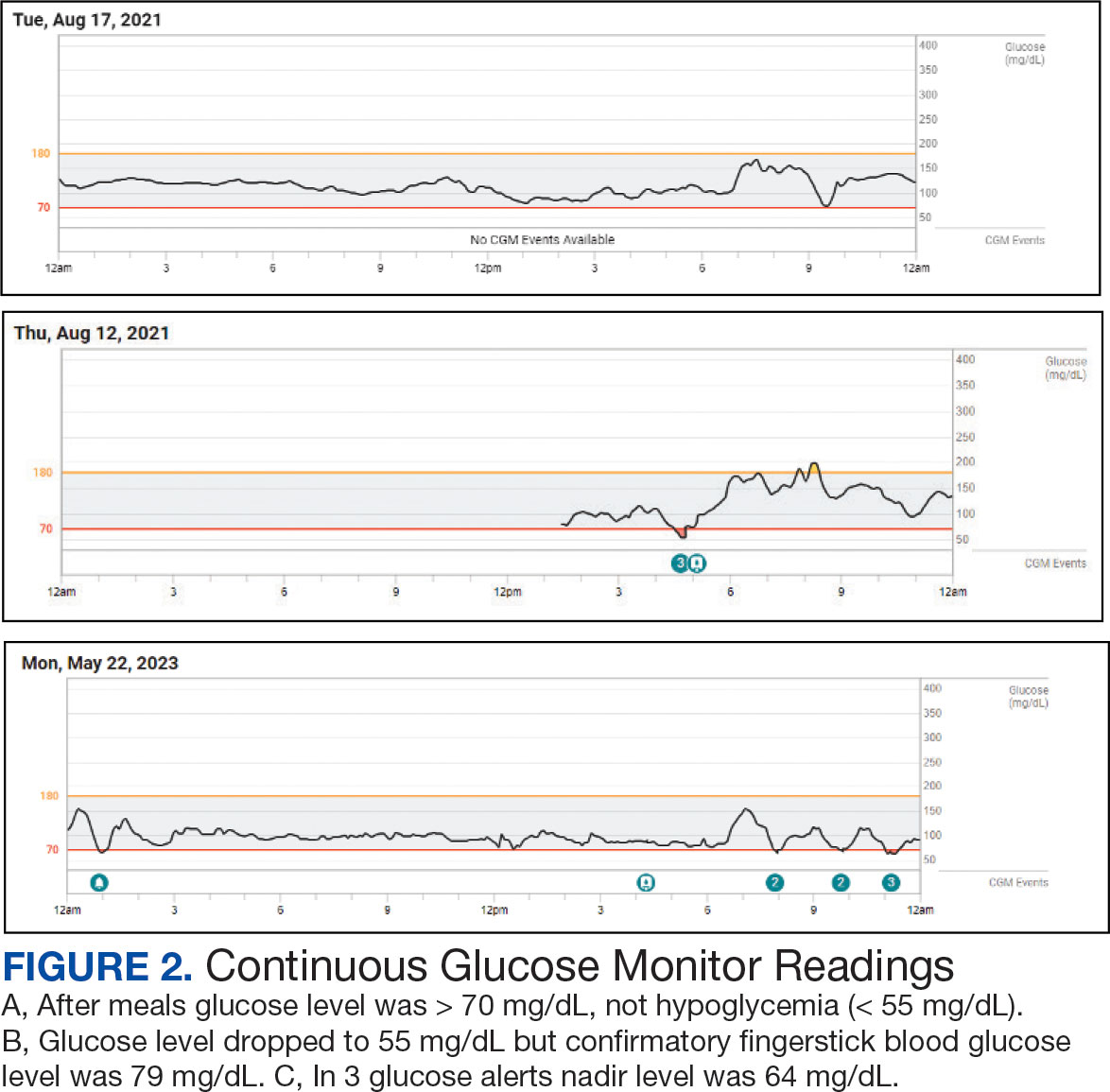

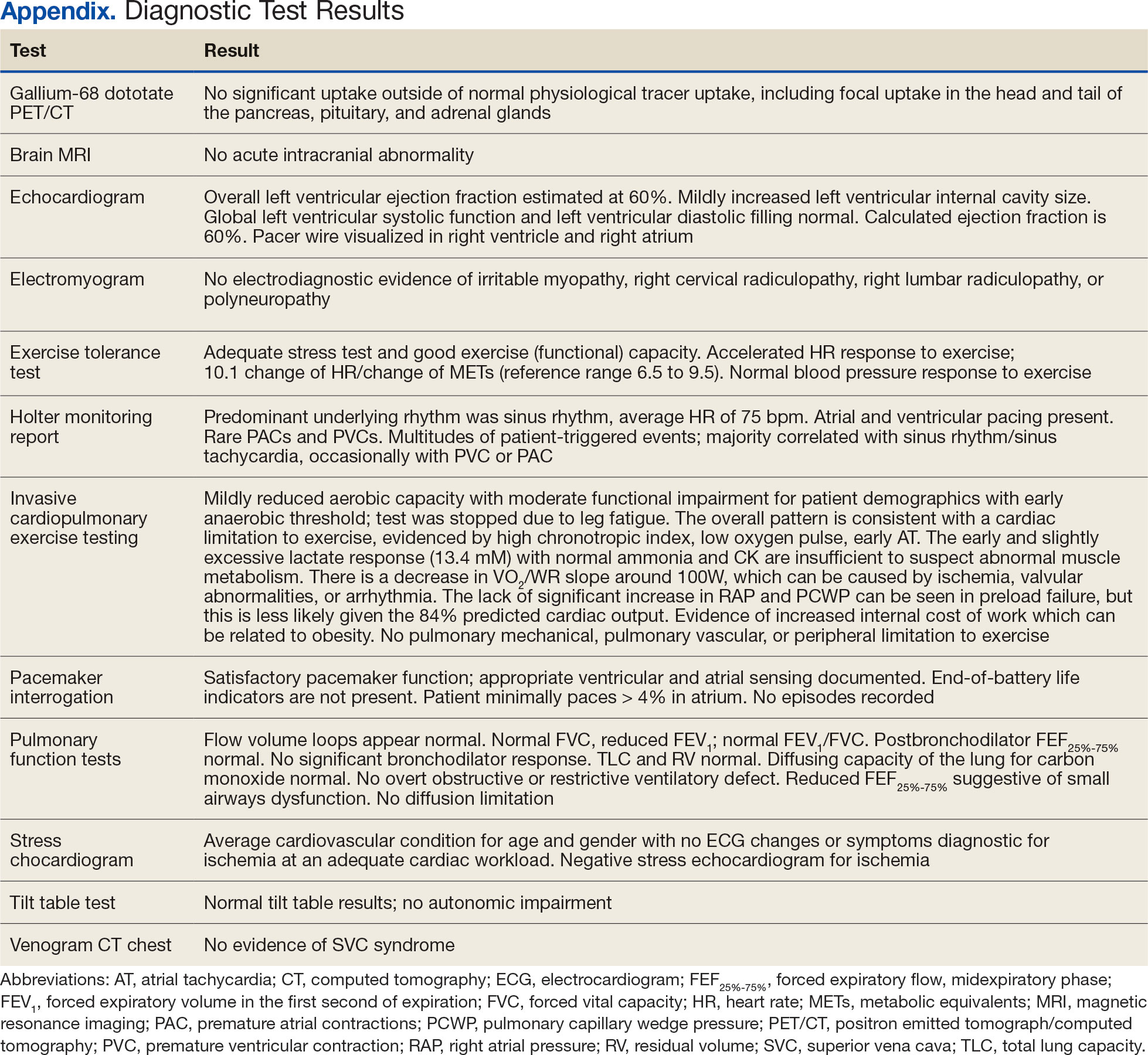

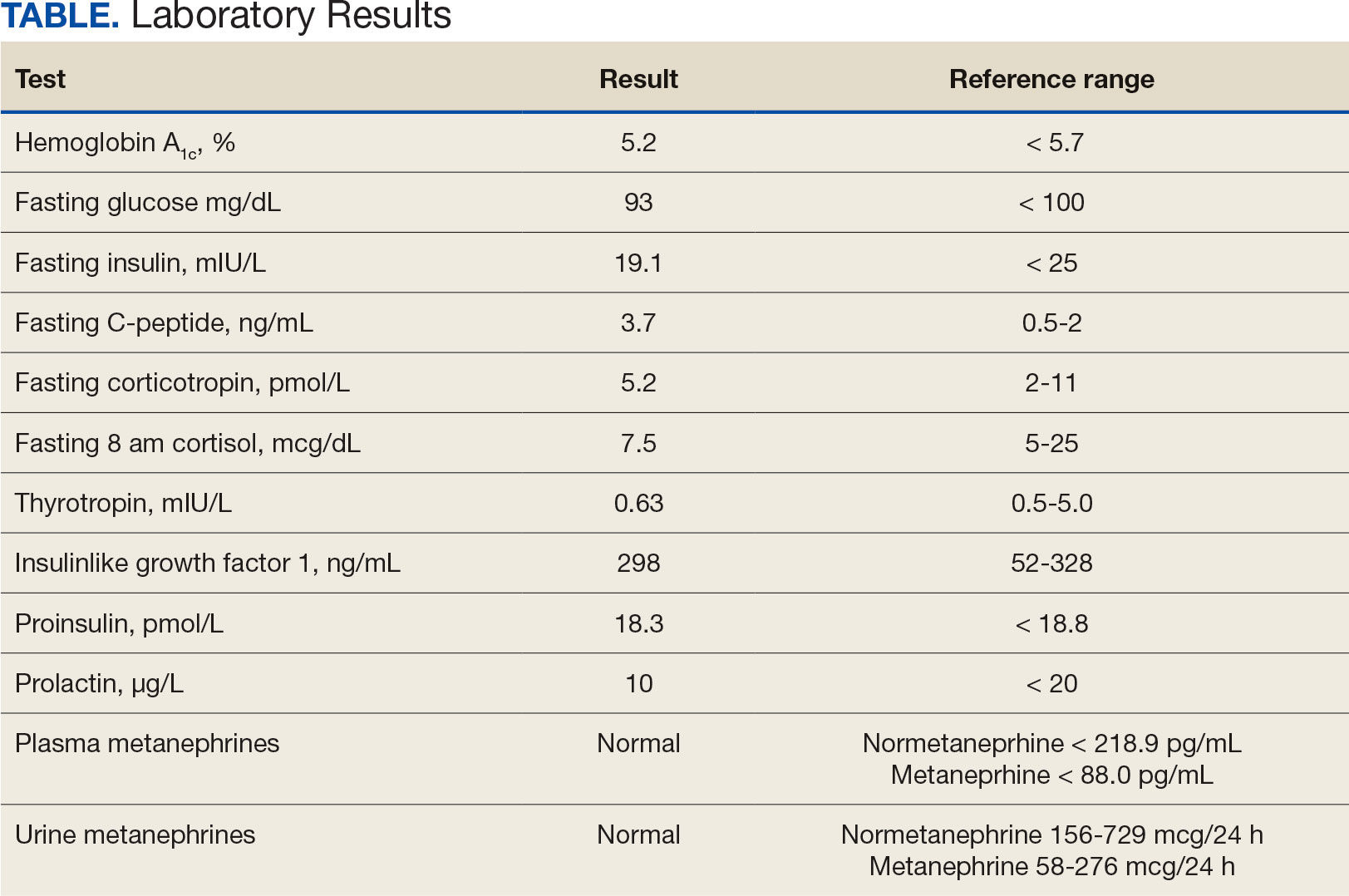

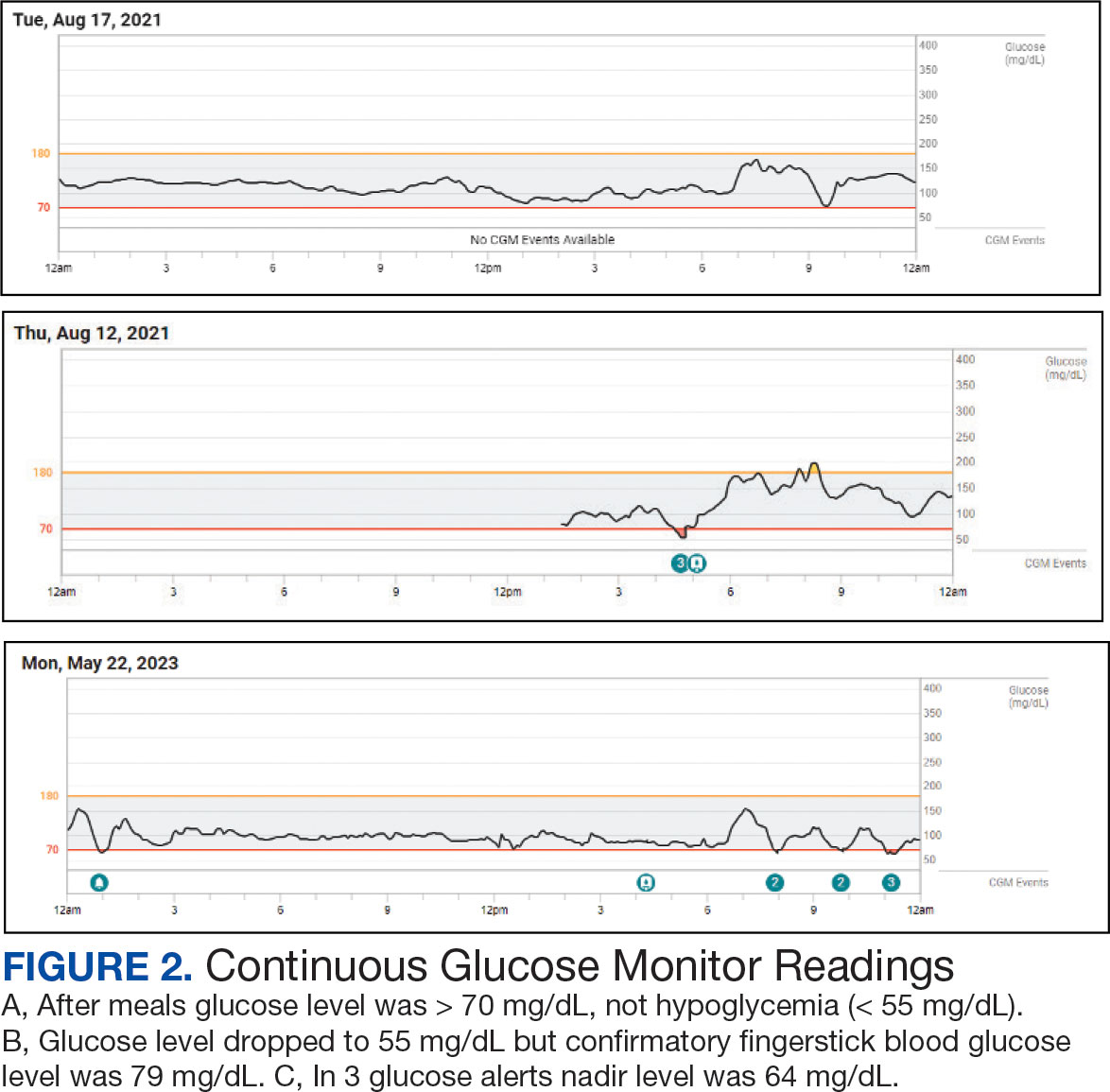

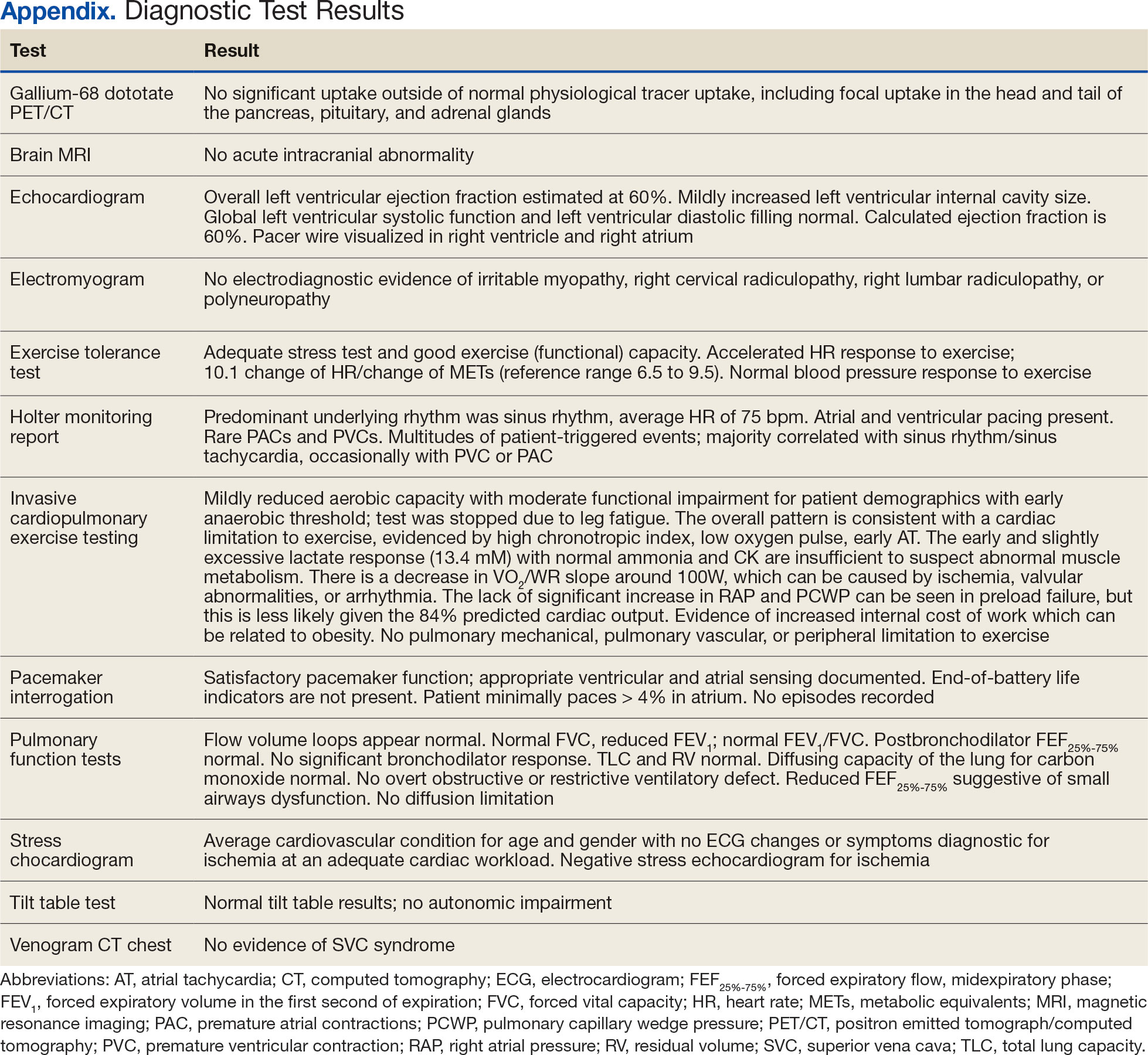

Additional testing included Gallium-68 dototate positron emission tomography/computed tomography, brain magnetic resonance imaging, echocardiogram, electromyogram, exercise tolerance test, Holter monitoring, invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing, pacemaker interrogation, pulmonary function testing, stress echocardiogram, tilt table test, and venogram computed tomography of the chest, but the results were unremarkable (Appendix). His afternoon nonfasting glucose level was 138 mg/dL with a concurrent hemoglobin A1c of 5.2%. The patient had a fasting C-peptide level of 3.7 ng/mL (reference range 0.5-2.0 ng/mL), fasting insulin level 19.1 mIU/L (reference range < 25 mIU/L), and a fasting glucose level of 93 mg/dL (reference range 70-99 mg/dL). The patient’s urine 5-HIAA, plasma metanephrines, urine metanephrines, insulin-like growth factor 1, prolactin, corticotropin, fasting cortisol, and thyrotropin yielded results within reference ranges (Table). The veteran was prescribed a CGM, which demonstrated normal glucose levels (≥ 55 mg/dL) during symptomatic episodes (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with IPP given normoglycemia, exclusion of alternative diagnoses, and symptomatic improvement with dietary changes. He was referred to a nutritionist for a high-protein, high-fiber, and low-carbohydrate diet.

DISCUSSION

Seemingly simple diagnostic tools can lead to diagnostic pitfalls. Home glucose monitoring with the use of a standard glucometer during an episode is the typical first step in identifying hypoglycemia, as it is both pragmatic and accurate, with a mean absolute relative difference (MARD) of about 10% in hypoglycemic ranges.5 While the advent of CGM provides real-time data and can reveal clinically relevant fluctuations, it reveals mild hypoglycemia (54 to 70 mg/dL) of no clinical significance in a large proportion of individuals.

Additionally, CGM is less accurate than glucometers with a MARD of about 20% in hypoglycemia ranges.6 CGM technology, however, is rapidly evolving and undergoing further investigation for hypoglycemia detection. Therefore, CGM may be considered in select patients as prospective study results are established; the newest CGMs have MARDs very similar to fingerstick blood glucose data.7,8 In the patient described in this case, CGM helped corroborate the diagnosis, given that symptomatic episodes correlated with lower glucose levels. Provocative testing with oral glucose tolerance testing can frequently result in false positive hypoglycemic readings and is not recommended.9 Supervised mixed meal testing can also be used, which entails monitoring after consuming a mixed macronutrient meal. The test concludes after hypoglycemic symptoms develop or 5 hours elapse, whichever occurs first.1

The pathophysiology of IPP is poorly understood. Proposed mechanisms include increased insulin sensitivity, increased adrenergic sensitivity, impaired glucagon regulation, emotional distress, insulin resistance, and increased glucagon-like peptide-1 production.10-13 Research suggests this may occur as pancreatic β cells fail in early type 2 diabetes mellitus, with diminished first-phase insulin release leading to an initial exuberant rise in blood glucose, an overshooting of the second phase of insulin secretion, and the feeling of the postprandial blood glucose falling, even though the final glucose level achieved is not truly low.13 There are contradictory studies in the literature demonstrating no association between insulin resistance and hypoglycemic symptoms.14 In 2022, Kosuda and colleagues looked at homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance in patients with postprandial syndrome. They found that the patients were slightly insulin resistant but had normal or exaggerated insulin secretory capacity compared to an oral glucose load, whereas glucagon levels were robustly suppressed by a glucose load. The observed hormonal responses may result in the glycemic patterns and symptoms observed; further study is warranted to elucidate the mechanism.15

Dietary modification is the cornerstone treatment for postprandial syndrome, including reduced carbohydrate intake, increased protein and fiber intake, and more frequent and smaller meals. There is also evidence that a Mediterranean diet may be beneficial for managing hypoglycemic symptoms.16 Furthermore, α-glucosidase inhibitors, whose mechanism of action delays the digestion of carbohydrates, have demonstrated promise. This medication class has demonstrated significance in raising postprandial glucose levels and alleviating hypoglycemic symptoms in patients with true postprandial hypoglycemia.17

CONCLUSIONS

IPP is a benign diagnosis encompassing hypoglycemic symptoms without biochemical hypoglycemia. It is not a true hypoglycemic disorder. IPP is challenging to diagnose, given that it is an interpretation of exclusion, supported by symptom improvement with dietary changes (ie, reduced carbohydrate intake, increased protein and fiber intake, and more frequent and smaller meals). Supervised mixed meal testing or CGM can be used to assist with diagnosis. Even though CGM is undergoing further study in this patient population, it corroborated the diagnosis in the patient described in this case.

For hypoglycemic symptoms, physicians should first assess for evidence of Whipple triad to evaluate for true biochemical hypoglycemia. For true hypoglycemia (< 55 mg/dL), physicians may conduct an examination in conjunction with an endocrinologist. For normoglycemia (≥ 55 mg/dL), physicians should first exclude alternative etiologies (including cardiac and neurologic), and subsequently consider IPP.

Bansal N, Weinstock RS. Non-Diabetic Hypoglycemia. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al, eds. Endotext. MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

Service FJ. Hypoglycemic disorders. New Engl J Med. 1995;332(17):1144-1152.doi:10.1056/NEJM199504273321707

Charles MA, Hofeldt F, Shackelford A, et al. Comparison of oral glucose tolerance tests and mixed meals in patients with apparent idiopathic postabsorptive hypoglycemia: absence of hypoglycemia after meals. Diabetes. 1981;30(6):465-470.

Douillard C, Jannin A, Vantyghem MC. Rare causes of hypoglycemia in adults. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2020;81(2-3):110-117. doi:10.1016/j.ando.2020.04.003

Ekhlaspour L, Mondesir D, Lautsch N, et al. Comparative accuracy of 17 point-of-care glucose meters. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11(3):558-566. doi:10.1177/1932296816672237

Alitta Q, Grino M, Adjemout L, Langar A, Retornaz F, Oliver C. Overestimation of hypoglycemia diagnosis by FreeStyle Libre continuous glucose monitoring in long-term care home residents with diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12(3):727-728. doi:10.1177/1932296817747887

Mongraw-Chaffin M, Beavers DP, McClain DA. Hypoglycemic symptoms in the absence of diabetes: pilot evidence of clinical hypoglycemia in young women. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2019;18:100202. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2019.100202

Shah VN, DuBose SN, Li Z, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring profiles in healthy nondiabetic participants: a multicenter prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(10):4356-4364. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-02763

Cryer PE, Axelrod L, Grossman AB, et al. Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(3):709-728. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-1410

Galati SJ, Rayfield EJ. Approach to the patient with postprandial hypoglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(4):331-340. doi:10.4158/EP13132.RA

Altuntas Y. Postprandial reactive hypoglycemia. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tip Bul. 2019;53(3):215-220.doi:10.14744/SEMB.2019.59455

HARRIS S. HYPERINSULINISM AND DYSINSULINISM. JAMA. 1924;83(10):729-733.doi:10.1001/jama.1924.02660100003002

Harris S. HYPERINSULINISM AND DYSINSULINISM (INSULOGENIC HYPOGLYCBMIA). Endocrinology. 1932;16(1):29-42. doi:10.1210/endo-16-1-29

Hall M, Walicka M, Panczyk M, Traczyk I. Metabolic parameters in patients with suspected reactive hypoglycemia. J Pers Med. 2021;11(4):276. doi:10.3390/jpm11040276

Kosuda M, Watanabe K, Koike M, et al. Glucagon response to glucose challenge in patients with idiopathic postprandial syndrome. J Nippon Med Sch. 2022;89(1):102-107. doi:10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2022_89-205

Hall M, Walicka M, Panczyk M, Traczyk I. Assessing long-term impact of dietary interventions on occurrence of symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia in patients without diabetes: a one-year follow-up study. Nutrients. 2022;14(3):497. doi:10.3390/nu14030497

Ozgen AG, Hamulu F, Bayraktar F, et al. Long-term treatment with acarbose for the treatment of reactive hypoglycemia. Eat Weight Disord. 1998;3(3):136-140. doi:10.1007/BF03340001

Idiopathic postprandial syndrome (IPP), initially termed reactive hypoglycemia, presents with hypoglycemic-like symptoms in the absence of biochemical hypoglycemia and remains a diagnosis of exclusion. Its pathophysiology is poorly understood. The diagnosis requires thorough evaluation of cardiac, metabolic, neurologic, and gastrointestinal causes, as well as Whipple triad criteria. Dietary modifications, including reduced carbohydrate intake, increased protein and fiber, and frequent small meals, remain the cornerstone of IPP management. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) may be a useful adjunct in correlating symptoms with glucose trends, but its role is still evolving.

In the evaluation of patients with symptoms suggestive of hypoglycemia (Figure 1), patients should first be assessed for Whipple triad: symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia, blood glucose level < 55 mg/dL, and reversal of symptoms with glucose.1 Patients who meet Whipple triad criteria should be investigated to identify further etiologies of hypoglycemia. They may include insulinoma, medication-induced (insulin, sulfonylurea, meglitinide, or β blocker use), postbariatric surgery complications, noninsulinoma pancreatogenous hypoglycemia syndrome, ackee fruit consumption, or familial conditions.2 The presence of hypoglycemic symptoms in the postprandial or fasting state can provide valuable insights into underlying etiology.

Patients who do not meet Whipple triad criteria, but exhibit postprandial symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia, as in this case, present a diagnostic dilemma. IPP is defined as hypoglycemic symptoms occuring after carbohydrate ingestion without biochemical hypoglycemia. Initially termed reactive hypoglycemia, it was renamed in 1981to reflect the absence of low blood glucose levels.3

The understanding of this diagnosis has not significantly progressed since the 1980s. Its prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and societal burden remain unclear. IPP is a challenging diagnosis due to nonspecific symptoms that overlap with a myriad of conditions. These symptoms may include adrenergic symptoms such as diaphoresis, tremulousness, palpitations, anxiety, and hunger. Potentially severe neuroglycopenic symptoms, including weakness, dizziness, behavior changes, confusion, and coma, are not typically observed.4 Given that objective criteria are not well established, IPP remains a diagnosis of exclusion. It is imperative to rule out alternative etiologies, particularly cardiac, gastrointestinal, and neurologic causes.

CASE PRESENTATION

A male aged 41 years presented to primary care for evaluation of acute on chronic symptomatic postprandial episodes. He reported a history of symptomatic sinus bradycardia in the setting of sick sinus syndrome following dual-chamber pacemaker placement, posttraumatic stress disorder, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. He was a retired Navy sailor without any known occupational exposures who worked in the real estate industry. The patient reported feeling lightheaded, tremulous, and anxious most afternoons after lunch for several years. He also reported that meals heavy in carbohydrates exacerbated his symptoms, whereas skipping meals or lying down alleviated his symptoms. The patient also reported concomitant arm numbness, shortness of breath, palpitations, and nausea during these episodes. Review of systems was otherwise negative, including no weight changes, fever, chills, night sweats, chest pain, or syncope.

The patient’s medications included ferrous sulfate 325 mg once every other day, bupropion 200 mg once daily, metoprolol succinate 25 mg once daily, and as-needed lorazepam 1 mg once daily. The patient reported no current substance use but reported previous tobacco use 3 years prior (maximum 1 pack/week) and alcohol use 5 years prior (750 ml/day for 15 years). The patient did not exercise and typically ate oatmeal for breakfast, a sandwich or salad for lunch, and taquitos or salad for dinner, with snacks throughout the day. Notable family history included a maternal grandmother with colon cancer. The patient’s vital signs included a 36.8 °C temperature, heart rate 87 beats/min, 118/71 mm Hg blood pressure, oxygen saturation 98% on room air, 125.2 kg weight, and 38.5 body mass index. There were no orthostatic vital sign changes. A physical examination demonstrated obesity with an unremarkable cardiopulmonary and volume examination.

Additional testing included Gallium-68 dototate positron emission tomography/computed tomography, brain magnetic resonance imaging, echocardiogram, electromyogram, exercise tolerance test, Holter monitoring, invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing, pacemaker interrogation, pulmonary function testing, stress echocardiogram, tilt table test, and venogram computed tomography of the chest, but the results were unremarkable (Appendix). His afternoon nonfasting glucose level was 138 mg/dL with a concurrent hemoglobin A1c of 5.2%. The patient had a fasting C-peptide level of 3.7 ng/mL (reference range 0.5-2.0 ng/mL), fasting insulin level 19.1 mIU/L (reference range < 25 mIU/L), and a fasting glucose level of 93 mg/dL (reference range 70-99 mg/dL). The patient’s urine 5-HIAA, plasma metanephrines, urine metanephrines, insulin-like growth factor 1, prolactin, corticotropin, fasting cortisol, and thyrotropin yielded results within reference ranges (Table). The veteran was prescribed a CGM, which demonstrated normal glucose levels (≥ 55 mg/dL) during symptomatic episodes (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with IPP given normoglycemia, exclusion of alternative diagnoses, and symptomatic improvement with dietary changes. He was referred to a nutritionist for a high-protein, high-fiber, and low-carbohydrate diet.

DISCUSSION

Seemingly simple diagnostic tools can lead to diagnostic pitfalls. Home glucose monitoring with the use of a standard glucometer during an episode is the typical first step in identifying hypoglycemia, as it is both pragmatic and accurate, with a mean absolute relative difference (MARD) of about 10% in hypoglycemic ranges.5 While the advent of CGM provides real-time data and can reveal clinically relevant fluctuations, it reveals mild hypoglycemia (54 to 70 mg/dL) of no clinical significance in a large proportion of individuals.

Additionally, CGM is less accurate than glucometers with a MARD of about 20% in hypoglycemia ranges.6 CGM technology, however, is rapidly evolving and undergoing further investigation for hypoglycemia detection. Therefore, CGM may be considered in select patients as prospective study results are established; the newest CGMs have MARDs very similar to fingerstick blood glucose data.7,8 In the patient described in this case, CGM helped corroborate the diagnosis, given that symptomatic episodes correlated with lower glucose levels. Provocative testing with oral glucose tolerance testing can frequently result in false positive hypoglycemic readings and is not recommended.9 Supervised mixed meal testing can also be used, which entails monitoring after consuming a mixed macronutrient meal. The test concludes after hypoglycemic symptoms develop or 5 hours elapse, whichever occurs first.1

The pathophysiology of IPP is poorly understood. Proposed mechanisms include increased insulin sensitivity, increased adrenergic sensitivity, impaired glucagon regulation, emotional distress, insulin resistance, and increased glucagon-like peptide-1 production.10-13 Research suggests this may occur as pancreatic β cells fail in early type 2 diabetes mellitus, with diminished first-phase insulin release leading to an initial exuberant rise in blood glucose, an overshooting of the second phase of insulin secretion, and the feeling of the postprandial blood glucose falling, even though the final glucose level achieved is not truly low.13 There are contradictory studies in the literature demonstrating no association between insulin resistance and hypoglycemic symptoms.14 In 2022, Kosuda and colleagues looked at homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance in patients with postprandial syndrome. They found that the patients were slightly insulin resistant but had normal or exaggerated insulin secretory capacity compared to an oral glucose load, whereas glucagon levels were robustly suppressed by a glucose load. The observed hormonal responses may result in the glycemic patterns and symptoms observed; further study is warranted to elucidate the mechanism.15

Dietary modification is the cornerstone treatment for postprandial syndrome, including reduced carbohydrate intake, increased protein and fiber intake, and more frequent and smaller meals. There is also evidence that a Mediterranean diet may be beneficial for managing hypoglycemic symptoms.16 Furthermore, α-glucosidase inhibitors, whose mechanism of action delays the digestion of carbohydrates, have demonstrated promise. This medication class has demonstrated significance in raising postprandial glucose levels and alleviating hypoglycemic symptoms in patients with true postprandial hypoglycemia.17

CONCLUSIONS

IPP is a benign diagnosis encompassing hypoglycemic symptoms without biochemical hypoglycemia. It is not a true hypoglycemic disorder. IPP is challenging to diagnose, given that it is an interpretation of exclusion, supported by symptom improvement with dietary changes (ie, reduced carbohydrate intake, increased protein and fiber intake, and more frequent and smaller meals). Supervised mixed meal testing or CGM can be used to assist with diagnosis. Even though CGM is undergoing further study in this patient population, it corroborated the diagnosis in the patient described in this case.

For hypoglycemic symptoms, physicians should first assess for evidence of Whipple triad to evaluate for true biochemical hypoglycemia. For true hypoglycemia (< 55 mg/dL), physicians may conduct an examination in conjunction with an endocrinologist. For normoglycemia (≥ 55 mg/dL), physicians should first exclude alternative etiologies (including cardiac and neurologic), and subsequently consider IPP.

Idiopathic postprandial syndrome (IPP), initially termed reactive hypoglycemia, presents with hypoglycemic-like symptoms in the absence of biochemical hypoglycemia and remains a diagnosis of exclusion. Its pathophysiology is poorly understood. The diagnosis requires thorough evaluation of cardiac, metabolic, neurologic, and gastrointestinal causes, as well as Whipple triad criteria. Dietary modifications, including reduced carbohydrate intake, increased protein and fiber, and frequent small meals, remain the cornerstone of IPP management. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) may be a useful adjunct in correlating symptoms with glucose trends, but its role is still evolving.

In the evaluation of patients with symptoms suggestive of hypoglycemia (Figure 1), patients should first be assessed for Whipple triad: symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia, blood glucose level < 55 mg/dL, and reversal of symptoms with glucose.1 Patients who meet Whipple triad criteria should be investigated to identify further etiologies of hypoglycemia. They may include insulinoma, medication-induced (insulin, sulfonylurea, meglitinide, or β blocker use), postbariatric surgery complications, noninsulinoma pancreatogenous hypoglycemia syndrome, ackee fruit consumption, or familial conditions.2 The presence of hypoglycemic symptoms in the postprandial or fasting state can provide valuable insights into underlying etiology.

Patients who do not meet Whipple triad criteria, but exhibit postprandial symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia, as in this case, present a diagnostic dilemma. IPP is defined as hypoglycemic symptoms occuring after carbohydrate ingestion without biochemical hypoglycemia. Initially termed reactive hypoglycemia, it was renamed in 1981to reflect the absence of low blood glucose levels.3

The understanding of this diagnosis has not significantly progressed since the 1980s. Its prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and societal burden remain unclear. IPP is a challenging diagnosis due to nonspecific symptoms that overlap with a myriad of conditions. These symptoms may include adrenergic symptoms such as diaphoresis, tremulousness, palpitations, anxiety, and hunger. Potentially severe neuroglycopenic symptoms, including weakness, dizziness, behavior changes, confusion, and coma, are not typically observed.4 Given that objective criteria are not well established, IPP remains a diagnosis of exclusion. It is imperative to rule out alternative etiologies, particularly cardiac, gastrointestinal, and neurologic causes.

CASE PRESENTATION

A male aged 41 years presented to primary care for evaluation of acute on chronic symptomatic postprandial episodes. He reported a history of symptomatic sinus bradycardia in the setting of sick sinus syndrome following dual-chamber pacemaker placement, posttraumatic stress disorder, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. He was a retired Navy sailor without any known occupational exposures who worked in the real estate industry. The patient reported feeling lightheaded, tremulous, and anxious most afternoons after lunch for several years. He also reported that meals heavy in carbohydrates exacerbated his symptoms, whereas skipping meals or lying down alleviated his symptoms. The patient also reported concomitant arm numbness, shortness of breath, palpitations, and nausea during these episodes. Review of systems was otherwise negative, including no weight changes, fever, chills, night sweats, chest pain, or syncope.

The patient’s medications included ferrous sulfate 325 mg once every other day, bupropion 200 mg once daily, metoprolol succinate 25 mg once daily, and as-needed lorazepam 1 mg once daily. The patient reported no current substance use but reported previous tobacco use 3 years prior (maximum 1 pack/week) and alcohol use 5 years prior (750 ml/day for 15 years). The patient did not exercise and typically ate oatmeal for breakfast, a sandwich or salad for lunch, and taquitos or salad for dinner, with snacks throughout the day. Notable family history included a maternal grandmother with colon cancer. The patient’s vital signs included a 36.8 °C temperature, heart rate 87 beats/min, 118/71 mm Hg blood pressure, oxygen saturation 98% on room air, 125.2 kg weight, and 38.5 body mass index. There were no orthostatic vital sign changes. A physical examination demonstrated obesity with an unremarkable cardiopulmonary and volume examination.

Additional testing included Gallium-68 dototate positron emission tomography/computed tomography, brain magnetic resonance imaging, echocardiogram, electromyogram, exercise tolerance test, Holter monitoring, invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing, pacemaker interrogation, pulmonary function testing, stress echocardiogram, tilt table test, and venogram computed tomography of the chest, but the results were unremarkable (Appendix). His afternoon nonfasting glucose level was 138 mg/dL with a concurrent hemoglobin A1c of 5.2%. The patient had a fasting C-peptide level of 3.7 ng/mL (reference range 0.5-2.0 ng/mL), fasting insulin level 19.1 mIU/L (reference range < 25 mIU/L), and a fasting glucose level of 93 mg/dL (reference range 70-99 mg/dL). The patient’s urine 5-HIAA, plasma metanephrines, urine metanephrines, insulin-like growth factor 1, prolactin, corticotropin, fasting cortisol, and thyrotropin yielded results within reference ranges (Table). The veteran was prescribed a CGM, which demonstrated normal glucose levels (≥ 55 mg/dL) during symptomatic episodes (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with IPP given normoglycemia, exclusion of alternative diagnoses, and symptomatic improvement with dietary changes. He was referred to a nutritionist for a high-protein, high-fiber, and low-carbohydrate diet.

DISCUSSION

Seemingly simple diagnostic tools can lead to diagnostic pitfalls. Home glucose monitoring with the use of a standard glucometer during an episode is the typical first step in identifying hypoglycemia, as it is both pragmatic and accurate, with a mean absolute relative difference (MARD) of about 10% in hypoglycemic ranges.5 While the advent of CGM provides real-time data and can reveal clinically relevant fluctuations, it reveals mild hypoglycemia (54 to 70 mg/dL) of no clinical significance in a large proportion of individuals.

Additionally, CGM is less accurate than glucometers with a MARD of about 20% in hypoglycemia ranges.6 CGM technology, however, is rapidly evolving and undergoing further investigation for hypoglycemia detection. Therefore, CGM may be considered in select patients as prospective study results are established; the newest CGMs have MARDs very similar to fingerstick blood glucose data.7,8 In the patient described in this case, CGM helped corroborate the diagnosis, given that symptomatic episodes correlated with lower glucose levels. Provocative testing with oral glucose tolerance testing can frequently result in false positive hypoglycemic readings and is not recommended.9 Supervised mixed meal testing can also be used, which entails monitoring after consuming a mixed macronutrient meal. The test concludes after hypoglycemic symptoms develop or 5 hours elapse, whichever occurs first.1

The pathophysiology of IPP is poorly understood. Proposed mechanisms include increased insulin sensitivity, increased adrenergic sensitivity, impaired glucagon regulation, emotional distress, insulin resistance, and increased glucagon-like peptide-1 production.10-13 Research suggests this may occur as pancreatic β cells fail in early type 2 diabetes mellitus, with diminished first-phase insulin release leading to an initial exuberant rise in blood glucose, an overshooting of the second phase of insulin secretion, and the feeling of the postprandial blood glucose falling, even though the final glucose level achieved is not truly low.13 There are contradictory studies in the literature demonstrating no association between insulin resistance and hypoglycemic symptoms.14 In 2022, Kosuda and colleagues looked at homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance in patients with postprandial syndrome. They found that the patients were slightly insulin resistant but had normal or exaggerated insulin secretory capacity compared to an oral glucose load, whereas glucagon levels were robustly suppressed by a glucose load. The observed hormonal responses may result in the glycemic patterns and symptoms observed; further study is warranted to elucidate the mechanism.15

Dietary modification is the cornerstone treatment for postprandial syndrome, including reduced carbohydrate intake, increased protein and fiber intake, and more frequent and smaller meals. There is also evidence that a Mediterranean diet may be beneficial for managing hypoglycemic symptoms.16 Furthermore, α-glucosidase inhibitors, whose mechanism of action delays the digestion of carbohydrates, have demonstrated promise. This medication class has demonstrated significance in raising postprandial glucose levels and alleviating hypoglycemic symptoms in patients with true postprandial hypoglycemia.17

CONCLUSIONS

IPP is a benign diagnosis encompassing hypoglycemic symptoms without biochemical hypoglycemia. It is not a true hypoglycemic disorder. IPP is challenging to diagnose, given that it is an interpretation of exclusion, supported by symptom improvement with dietary changes (ie, reduced carbohydrate intake, increased protein and fiber intake, and more frequent and smaller meals). Supervised mixed meal testing or CGM can be used to assist with diagnosis. Even though CGM is undergoing further study in this patient population, it corroborated the diagnosis in the patient described in this case.

For hypoglycemic symptoms, physicians should first assess for evidence of Whipple triad to evaluate for true biochemical hypoglycemia. For true hypoglycemia (< 55 mg/dL), physicians may conduct an examination in conjunction with an endocrinologist. For normoglycemia (≥ 55 mg/dL), physicians should first exclude alternative etiologies (including cardiac and neurologic), and subsequently consider IPP.

Bansal N, Weinstock RS. Non-Diabetic Hypoglycemia. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al, eds. Endotext. MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

Service FJ. Hypoglycemic disorders. New Engl J Med. 1995;332(17):1144-1152.doi:10.1056/NEJM199504273321707

Charles MA, Hofeldt F, Shackelford A, et al. Comparison of oral glucose tolerance tests and mixed meals in patients with apparent idiopathic postabsorptive hypoglycemia: absence of hypoglycemia after meals. Diabetes. 1981;30(6):465-470.

Douillard C, Jannin A, Vantyghem MC. Rare causes of hypoglycemia in adults. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2020;81(2-3):110-117. doi:10.1016/j.ando.2020.04.003

Ekhlaspour L, Mondesir D, Lautsch N, et al. Comparative accuracy of 17 point-of-care glucose meters. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11(3):558-566. doi:10.1177/1932296816672237

Alitta Q, Grino M, Adjemout L, Langar A, Retornaz F, Oliver C. Overestimation of hypoglycemia diagnosis by FreeStyle Libre continuous glucose monitoring in long-term care home residents with diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12(3):727-728. doi:10.1177/1932296817747887

Mongraw-Chaffin M, Beavers DP, McClain DA. Hypoglycemic symptoms in the absence of diabetes: pilot evidence of clinical hypoglycemia in young women. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2019;18:100202. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2019.100202

Shah VN, DuBose SN, Li Z, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring profiles in healthy nondiabetic participants: a multicenter prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(10):4356-4364. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-02763

Cryer PE, Axelrod L, Grossman AB, et al. Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(3):709-728. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-1410

Galati SJ, Rayfield EJ. Approach to the patient with postprandial hypoglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(4):331-340. doi:10.4158/EP13132.RA

Altuntas Y. Postprandial reactive hypoglycemia. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tip Bul. 2019;53(3):215-220.doi:10.14744/SEMB.2019.59455

HARRIS S. HYPERINSULINISM AND DYSINSULINISM. JAMA. 1924;83(10):729-733.doi:10.1001/jama.1924.02660100003002

Harris S. HYPERINSULINISM AND DYSINSULINISM (INSULOGENIC HYPOGLYCBMIA). Endocrinology. 1932;16(1):29-42. doi:10.1210/endo-16-1-29

Hall M, Walicka M, Panczyk M, Traczyk I. Metabolic parameters in patients with suspected reactive hypoglycemia. J Pers Med. 2021;11(4):276. doi:10.3390/jpm11040276

Kosuda M, Watanabe K, Koike M, et al. Glucagon response to glucose challenge in patients with idiopathic postprandial syndrome. J Nippon Med Sch. 2022;89(1):102-107. doi:10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2022_89-205

Hall M, Walicka M, Panczyk M, Traczyk I. Assessing long-term impact of dietary interventions on occurrence of symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia in patients without diabetes: a one-year follow-up study. Nutrients. 2022;14(3):497. doi:10.3390/nu14030497

Ozgen AG, Hamulu F, Bayraktar F, et al. Long-term treatment with acarbose for the treatment of reactive hypoglycemia. Eat Weight Disord. 1998;3(3):136-140. doi:10.1007/BF03340001

Bansal N, Weinstock RS. Non-Diabetic Hypoglycemia. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al, eds. Endotext. MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

Service FJ. Hypoglycemic disorders. New Engl J Med. 1995;332(17):1144-1152.doi:10.1056/NEJM199504273321707

Charles MA, Hofeldt F, Shackelford A, et al. Comparison of oral glucose tolerance tests and mixed meals in patients with apparent idiopathic postabsorptive hypoglycemia: absence of hypoglycemia after meals. Diabetes. 1981;30(6):465-470.

Douillard C, Jannin A, Vantyghem MC. Rare causes of hypoglycemia in adults. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2020;81(2-3):110-117. doi:10.1016/j.ando.2020.04.003

Ekhlaspour L, Mondesir D, Lautsch N, et al. Comparative accuracy of 17 point-of-care glucose meters. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11(3):558-566. doi:10.1177/1932296816672237

Alitta Q, Grino M, Adjemout L, Langar A, Retornaz F, Oliver C. Overestimation of hypoglycemia diagnosis by FreeStyle Libre continuous glucose monitoring in long-term care home residents with diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12(3):727-728. doi:10.1177/1932296817747887

Mongraw-Chaffin M, Beavers DP, McClain DA. Hypoglycemic symptoms in the absence of diabetes: pilot evidence of clinical hypoglycemia in young women. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2019;18:100202. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2019.100202

Shah VN, DuBose SN, Li Z, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring profiles in healthy nondiabetic participants: a multicenter prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(10):4356-4364. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-02763

Cryer PE, Axelrod L, Grossman AB, et al. Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(3):709-728. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-1410

Galati SJ, Rayfield EJ. Approach to the patient with postprandial hypoglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(4):331-340. doi:10.4158/EP13132.RA

Altuntas Y. Postprandial reactive hypoglycemia. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tip Bul. 2019;53(3):215-220.doi:10.14744/SEMB.2019.59455

HARRIS S. HYPERINSULINISM AND DYSINSULINISM. JAMA. 1924;83(10):729-733.doi:10.1001/jama.1924.02660100003002

Harris S. HYPERINSULINISM AND DYSINSULINISM (INSULOGENIC HYPOGLYCBMIA). Endocrinology. 1932;16(1):29-42. doi:10.1210/endo-16-1-29

Hall M, Walicka M, Panczyk M, Traczyk I. Metabolic parameters in patients with suspected reactive hypoglycemia. J Pers Med. 2021;11(4):276. doi:10.3390/jpm11040276

Kosuda M, Watanabe K, Koike M, et al. Glucagon response to glucose challenge in patients with idiopathic postprandial syndrome. J Nippon Med Sch. 2022;89(1):102-107. doi:10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2022_89-205

Hall M, Walicka M, Panczyk M, Traczyk I. Assessing long-term impact of dietary interventions on occurrence of symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia in patients without diabetes: a one-year follow-up study. Nutrients. 2022;14(3):497. doi:10.3390/nu14030497

Ozgen AG, Hamulu F, Bayraktar F, et al. Long-term treatment with acarbose for the treatment of reactive hypoglycemia. Eat Weight Disord. 1998;3(3):136-140. doi:10.1007/BF03340001

A Veteran Presenting With Symptomatic Postprandial Episodes

A Veteran Presenting With Symptomatic Postprandial Episodes