User login

Doctor in a Bottle: Examining the Increase in Essential Oil Use

What Are Essential Oils?

Essential oils are aromatic volatile oils produced by medicinal plants that give them their distinct flavors and aromas. They are extracted using a variety of different techniques, such as microwave-assisted extraction, headspace extraction, and the most commonly employed hydrodistillation.1 Different parts of the plant are used for the specific oils; the shoots and leaves of Origanum vulgare are used for oregano oil, whereas the skins of Citrus limonum are used for lemon oil.2 Historically, essential oils have been used for cooking, food preservation, perfume, and medicine.3,4

Historical Uses for Essential Oils

Essential oils and their intact medicinal plants were among the first medicines widely available to the ancient world. The Ancient Greeks used topical and oral oregano as a cure-all for ailments including wounds, sore muscles, and diarrhea. Because of its use as a cure-all medicine, it remains a popular folk remedy in parts of Europe today.3 Lavender also has a long history of being a cure-all plant and oil. Some of the many claims behind this flower include treatment of burns, insect bites, parasites, muscle spasms, nausea, and anxiety/depression.5 With an extensive list of historical uses, many essential oils are being researched to determine if their acclaimed qualities have quantifiable properties.

Science Behind the Belief

In vitro experiments with oregano (O vulgare) have demonstrated notable antifungal and antimicrobial effects.6 Gas chromatographic analysis of the oil shows much of it is composed of phenolic monoterpenes, such as thymol and carvacrol. They exhibit strong antifungal effects with a slightly stronger effect on the dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum over other yeast species such as Candida.7,8 The full effect of the monoterpenes on fungi is not completely understood, but early data show it has a strong affinity for the ergosterol used in the cell-wall synthesis. Other effects demonstrated in in vitro studies include the ability to block drug efflux pumps, biofilm formation, cellular communication among bacteria, and mycotoxin production.9

A double-blind, randomized trial by Akhondzadeh et al10 demonstrated lavender (Lavandula officinalis) to have a mild antidepressant quality but a noticeably more potent effect when combined with imipramine. The effects of the lavender with imipramine were stronger and provided earlier improvement than imipramine alone for treatment of mild to moderate depression. The team concluded that lavender may be an effective adjunct therapy in treating depression.10

In a study by Mori et al,11 full-thickness circular wounds were made in rats and treated with either lavender oil (L officinalis), nothing, or a control oil. With the lavender oil being at only 1% solution, the wounds treated with lavender oil demonstrated earlier closure than the other 2 groups of wounds, where no major difference was noted. On cellular analysis, it was seen that the lavender had increased the rate of granulation as well as expression of types I and III collagen. The most striking result was the large expression of transforming growth factor β seen in the lavender group compared to the others. The final thoughts on this experiment were that lavender may provide new approaches to wound care in the future.11

Potential Problems With Purity

One major concern raised about essential oils is their purity and the fidelity of their chemical composition. The specific aromatic chemicals in each essential oil are maintained for each species, but the proportions of each change even with the time of year.12 Gas chromatograph analysis of the same oil distilled with different techniques showed that the proportions of aromatic chemicals varied with technique. However, the major constituents of the oil remained present in large quantities, just at different percentages.1 Even using the same distillation technique for different time periods can greatly affect the yield and composition of the oil. Although the percentage of each aromatic compound can be affected by distillation times, the antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of the oil remain constant regardless of these variables.2 There is clearly a lack in standardization in essential oil production, which may not be an issue for its use in complementary medicine if its properties are maintained regardless.

Safety Concerns and Regulations

With essential oils being a natural cure for everyday ailments, some people are turning first to oils for every cut and bruise. The danger in these natural cures is that essential oils can cause several types of dermatitis and allergic reactions. The development of allergies to essential oils is at an even higher risk, considering people frequently put them on wounds and rashes where the skin barrier is already weakened. Many essential oils fall into the fragrance category in patch tests, negating the widely circulating blogger and online reports that essential oils cannot cause allergies.

Some of the oils, although regarded safe by the US Food and Drug Administration for consumption, can cause dermatitis from simple contact or with sun exposure.13 Members of the citrus family are notorious for the phytophotodermatitis reaction, which can leave hyperpigmented scarring after exposure of the oils to sunlight.14 Most companies that sell essential oils are aware of this reaction and include it in the warning labels.

The legal problem with selling and classifying essential oils is that the US Food and Drug Administration requires products intended for treatment to be labeled as drugs, which hinders their sales on the open market.13 It all boils down to intended use, so some companies sell the oils under a food or fragrance classification with vague instructions on how to use said oil for medicinal purposes, which leads to lack of supervision, anecdotal cures, and false health claims. One company claims in their safety guide for topical applications of their oils that “[i]f a rash occurs, this may be a sign of detoxification.”15 If essential oils had only minimal absorption topically, their safety would be less concerning, but this does not appear to be the case.

Absorption and Systemics

The effects of essential oils on the skin is one aspect of their use to be studied; another is the more systemic effects from absorption through the skin. Most essential oils used in small quantities for fragrance in over-the-counter lotions prove only to be an issue for allergens in sensitive patient groups. However, topical applications of essential oils in their pure concentrated form get absorbed into the skin faster than if used with a carrier oil, emulsion, or solvent.16 For most minor uses of essential oils, the body can detoxify absorbed chemicals the same way it does when a person eats the plants the oils came from (eg, basil essential oils leaching from the leaves into a tomato sauce). A possible danger of the oils’ systemic properties lies in the pregnant patient population who use essential oils thinking that natural is safe.

Many essential oils, such as lavender (L officinalis), exhibit hormonal mimicry with phytoestrogens and can produce emmenagogue (increasing menstrual flow) effects in women. Other oils, such as those of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) and myrrh (Commiphora myrrha), can have abortifacient effects. These natural essential oils can lead to unintended health risks for mother and baby.17 With implications this serious, many essential oil companies put pregnancy warnings on most if not all of their products, but pregnant patients may not always note the risk.

Conclusion

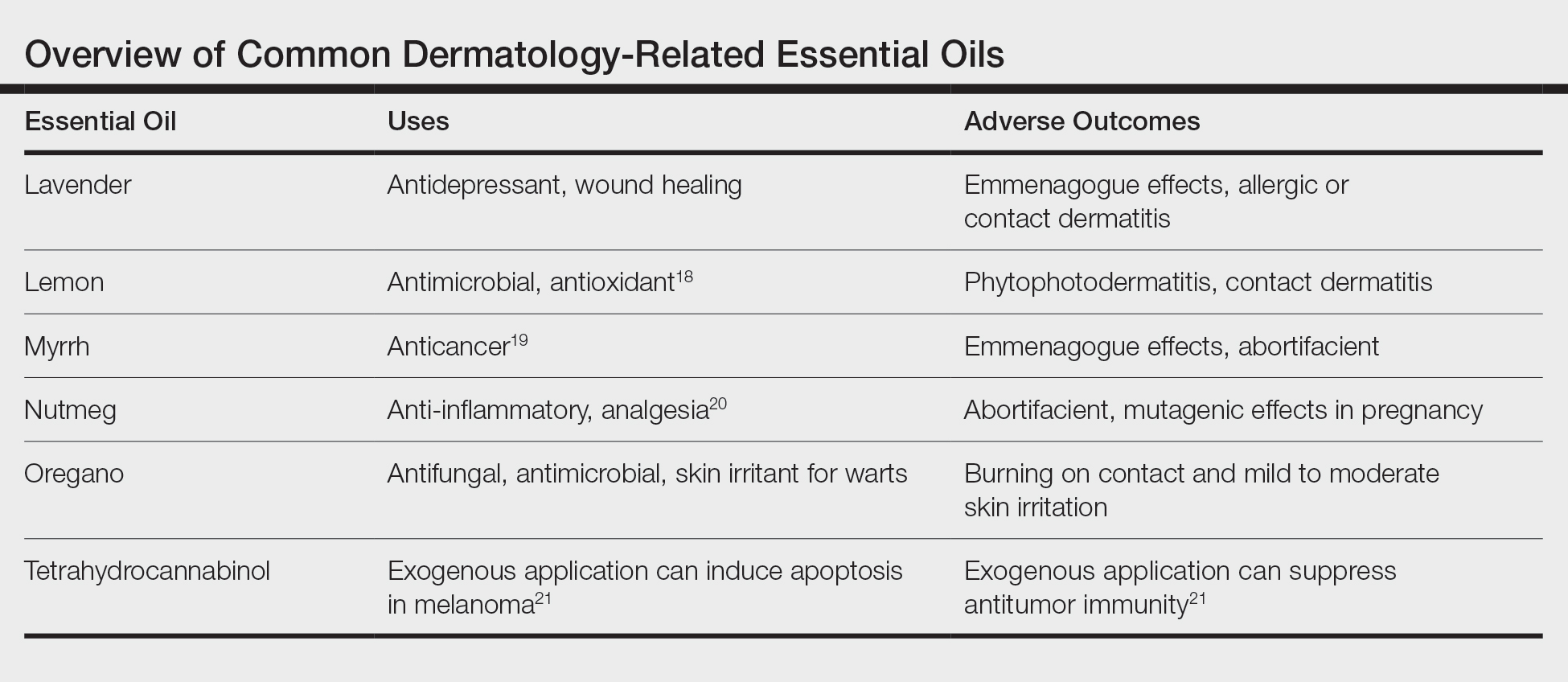

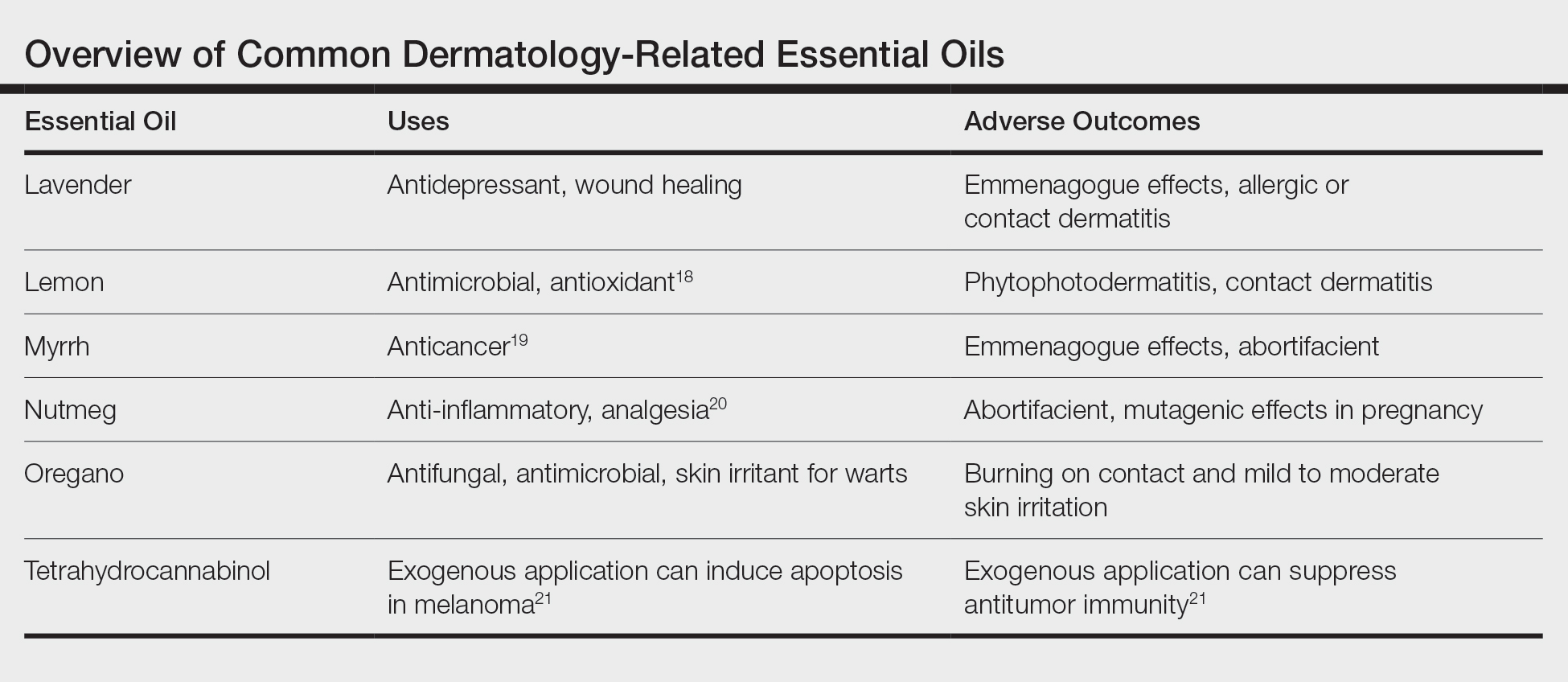

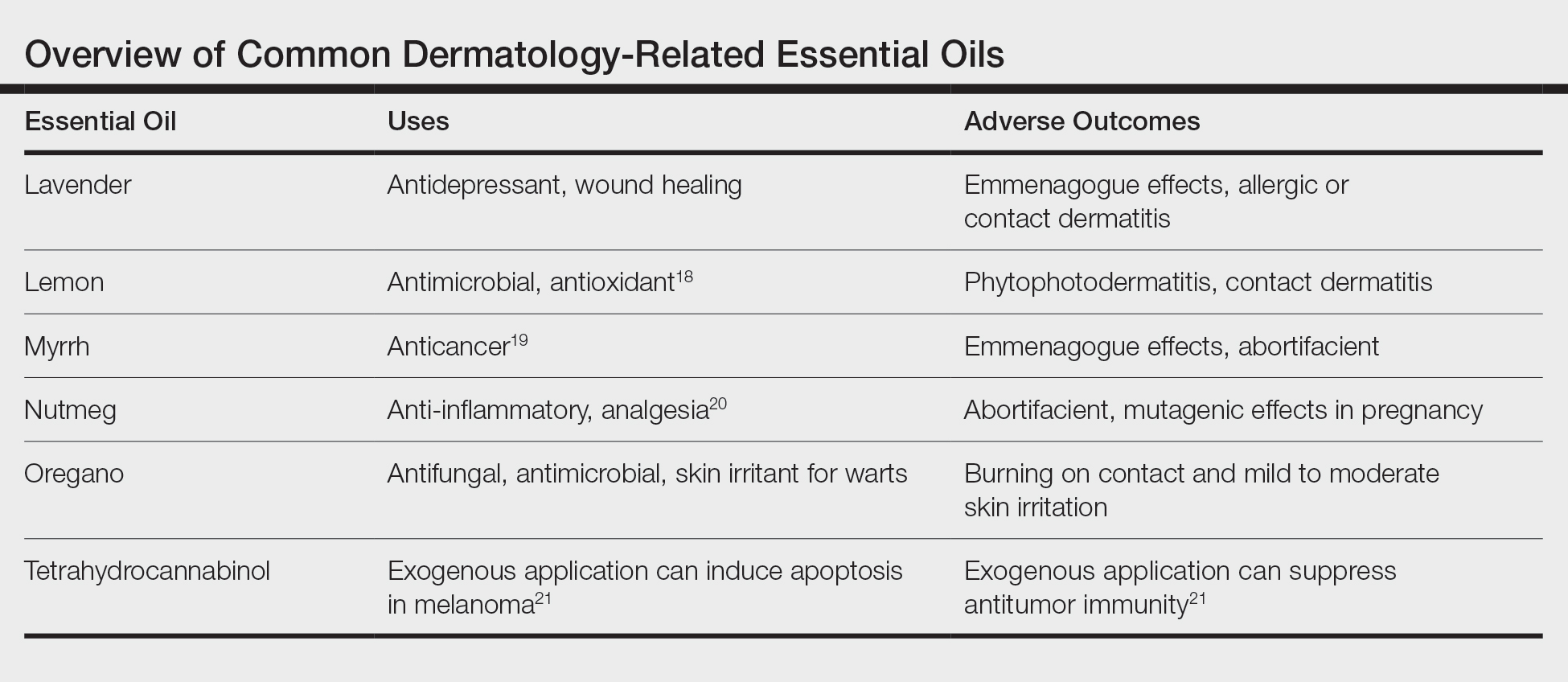

Essential oils are not the newest medical fad. They outdate every drug on the market and were used by some of the first physicians in history. It is important to continue research into the antimicrobial effects of essential oils, as they may hold the secret to treatment options with the continued rise of multidrug-resistant organisms. The danger of these oils lies not in their hidden potential but in the belief that natural things are safe. A few animal studies have been performed, but little is known about the full effects of essential oils in humans. Patients need to be educated that these are not panaceas with freedom from side effects and that treatment options backed by the scientific method should be their first choice under the supervision of trained physicians. The Table outlines the uses and side effects of the essential oils discussed here.

- Fan S, Chang J, Zong Y, et al. GC-MS analysis of the composition of the essential oil from Dendranthema indicum var. aromaticum using three extraction methods and two columns. Molecules. 2018;23:576.

- Zheljazkov VD, Astatkie T, Schlegel V. Distillation time changes oregano essential oil yields and composition but not the antioxidant or antimicrobial activities. HortScience. 2012;47:777-784.

- Singletary K. Oregano: overview of the literature on health benefits. Nutr Today. 2010;45:129-138.

- Cortés-Rojas DF, de Souza CRF, Oliveira WP. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): a precious spice. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4:90-96.

- Koulivand PH, Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Gorji A. Lavender and the nervous system. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:681304.

- Cleff MB, Meinerz AR, Xavier M, et al. In vitro activity of Origanum vulgare essential oil against Candida species. Brazilian J Microbiol. 2010;41:116-123.

- Adam K, Sivropoulou A, Kokkini S, et al. Antifungal activities of Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum, Mentha spicata, Lavandula angustifolia, and Salvia fruticosa essential oils against human pathogenic fungi. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:1739-1745.

- Miron D, Battisti F, Silva FK, et al. Antifungal activity and mechanism of action of monoterpenes against dermatophytes and yeasts. Brazil J Pharmacognosy. 2014;24:660-667.

- Nazzaro F, Fratianni F, Coppola R, et al. Essential oils and antifungal activity. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2017;10:86.

- Akhondzadeh S, Kashani L, Fotouhi A, et al. Comparison of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. tincture and imipramine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:123-127.

- Mori H-M, Kawanami H, Kawahata H, et al. Wound healing potential of lavender oil by acceleration of granulation and wound contraction through induction of TGF-β in a rat model. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:144.

- Vekiari SA, Protopapadakis EE, Papadopoulou P, et al. Composition and seasonal variation of the essential oil from leaves and peel of a cretan lemon variety. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:147-153.

- Aromatherapy. US Food & Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/productsingredients/products/ucm127054.htm. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Hankinson A, Lloyd B, Alweis R. Lime-induced phytophotodermatitis. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.25090.

- Essential Oil Safety Guide. Young Living Essential Oils website. https://www.youngliving.com/en_US/discover/essential-oil-safety. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Cal K. Skin penetration of terpenes from essential oils and topical vehicles. Planta Medica. 2006;72:311-316.

- Ernst E. Herbal medicinal products during pregnancy: are they safe? BJOG. 2002;109:227-235.

- Hsouna AB, Halima NB, Smaoui S, et al. Citrus lemon essential oil: chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities with its preservative effect against Listeria monocytogenes inoculated in minced beef meat. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16:146.

- Chen Y, Zhou C, Ge Z, et al. Composition and potential anticancer activities of essential oils obtained from myrrh and frankincense. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:1140-1146.

- Zhang WK, Tao S-S, Li T-T, et al. Nutmeg oil alleviates chronic inflammatory pain through inhibition of COX-2 expression and substance P release in vivo. Food Nutr Res. 2016;60:30849.

- Glodde N, Jakobs M, Bald T, et al. Differential role of cannabinoids in the pathogenesis of skin cancer. Life Sci. 2015;138:35-40.

What Are Essential Oils?

Essential oils are aromatic volatile oils produced by medicinal plants that give them their distinct flavors and aromas. They are extracted using a variety of different techniques, such as microwave-assisted extraction, headspace extraction, and the most commonly employed hydrodistillation.1 Different parts of the plant are used for the specific oils; the shoots and leaves of Origanum vulgare are used for oregano oil, whereas the skins of Citrus limonum are used for lemon oil.2 Historically, essential oils have been used for cooking, food preservation, perfume, and medicine.3,4

Historical Uses for Essential Oils

Essential oils and their intact medicinal plants were among the first medicines widely available to the ancient world. The Ancient Greeks used topical and oral oregano as a cure-all for ailments including wounds, sore muscles, and diarrhea. Because of its use as a cure-all medicine, it remains a popular folk remedy in parts of Europe today.3 Lavender also has a long history of being a cure-all plant and oil. Some of the many claims behind this flower include treatment of burns, insect bites, parasites, muscle spasms, nausea, and anxiety/depression.5 With an extensive list of historical uses, many essential oils are being researched to determine if their acclaimed qualities have quantifiable properties.

Science Behind the Belief

In vitro experiments with oregano (O vulgare) have demonstrated notable antifungal and antimicrobial effects.6 Gas chromatographic analysis of the oil shows much of it is composed of phenolic monoterpenes, such as thymol and carvacrol. They exhibit strong antifungal effects with a slightly stronger effect on the dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum over other yeast species such as Candida.7,8 The full effect of the monoterpenes on fungi is not completely understood, but early data show it has a strong affinity for the ergosterol used in the cell-wall synthesis. Other effects demonstrated in in vitro studies include the ability to block drug efflux pumps, biofilm formation, cellular communication among bacteria, and mycotoxin production.9

A double-blind, randomized trial by Akhondzadeh et al10 demonstrated lavender (Lavandula officinalis) to have a mild antidepressant quality but a noticeably more potent effect when combined with imipramine. The effects of the lavender with imipramine were stronger and provided earlier improvement than imipramine alone for treatment of mild to moderate depression. The team concluded that lavender may be an effective adjunct therapy in treating depression.10

In a study by Mori et al,11 full-thickness circular wounds were made in rats and treated with either lavender oil (L officinalis), nothing, or a control oil. With the lavender oil being at only 1% solution, the wounds treated with lavender oil demonstrated earlier closure than the other 2 groups of wounds, where no major difference was noted. On cellular analysis, it was seen that the lavender had increased the rate of granulation as well as expression of types I and III collagen. The most striking result was the large expression of transforming growth factor β seen in the lavender group compared to the others. The final thoughts on this experiment were that lavender may provide new approaches to wound care in the future.11

Potential Problems With Purity

One major concern raised about essential oils is their purity and the fidelity of their chemical composition. The specific aromatic chemicals in each essential oil are maintained for each species, but the proportions of each change even with the time of year.12 Gas chromatograph analysis of the same oil distilled with different techniques showed that the proportions of aromatic chemicals varied with technique. However, the major constituents of the oil remained present in large quantities, just at different percentages.1 Even using the same distillation technique for different time periods can greatly affect the yield and composition of the oil. Although the percentage of each aromatic compound can be affected by distillation times, the antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of the oil remain constant regardless of these variables.2 There is clearly a lack in standardization in essential oil production, which may not be an issue for its use in complementary medicine if its properties are maintained regardless.

Safety Concerns and Regulations

With essential oils being a natural cure for everyday ailments, some people are turning first to oils for every cut and bruise. The danger in these natural cures is that essential oils can cause several types of dermatitis and allergic reactions. The development of allergies to essential oils is at an even higher risk, considering people frequently put them on wounds and rashes where the skin barrier is already weakened. Many essential oils fall into the fragrance category in patch tests, negating the widely circulating blogger and online reports that essential oils cannot cause allergies.

Some of the oils, although regarded safe by the US Food and Drug Administration for consumption, can cause dermatitis from simple contact or with sun exposure.13 Members of the citrus family are notorious for the phytophotodermatitis reaction, which can leave hyperpigmented scarring after exposure of the oils to sunlight.14 Most companies that sell essential oils are aware of this reaction and include it in the warning labels.

The legal problem with selling and classifying essential oils is that the US Food and Drug Administration requires products intended for treatment to be labeled as drugs, which hinders their sales on the open market.13 It all boils down to intended use, so some companies sell the oils under a food or fragrance classification with vague instructions on how to use said oil for medicinal purposes, which leads to lack of supervision, anecdotal cures, and false health claims. One company claims in their safety guide for topical applications of their oils that “[i]f a rash occurs, this may be a sign of detoxification.”15 If essential oils had only minimal absorption topically, their safety would be less concerning, but this does not appear to be the case.

Absorption and Systemics

The effects of essential oils on the skin is one aspect of their use to be studied; another is the more systemic effects from absorption through the skin. Most essential oils used in small quantities for fragrance in over-the-counter lotions prove only to be an issue for allergens in sensitive patient groups. However, topical applications of essential oils in their pure concentrated form get absorbed into the skin faster than if used with a carrier oil, emulsion, or solvent.16 For most minor uses of essential oils, the body can detoxify absorbed chemicals the same way it does when a person eats the plants the oils came from (eg, basil essential oils leaching from the leaves into a tomato sauce). A possible danger of the oils’ systemic properties lies in the pregnant patient population who use essential oils thinking that natural is safe.

Many essential oils, such as lavender (L officinalis), exhibit hormonal mimicry with phytoestrogens and can produce emmenagogue (increasing menstrual flow) effects in women. Other oils, such as those of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) and myrrh (Commiphora myrrha), can have abortifacient effects. These natural essential oils can lead to unintended health risks for mother and baby.17 With implications this serious, many essential oil companies put pregnancy warnings on most if not all of their products, but pregnant patients may not always note the risk.

Conclusion

Essential oils are not the newest medical fad. They outdate every drug on the market and were used by some of the first physicians in history. It is important to continue research into the antimicrobial effects of essential oils, as they may hold the secret to treatment options with the continued rise of multidrug-resistant organisms. The danger of these oils lies not in their hidden potential but in the belief that natural things are safe. A few animal studies have been performed, but little is known about the full effects of essential oils in humans. Patients need to be educated that these are not panaceas with freedom from side effects and that treatment options backed by the scientific method should be their first choice under the supervision of trained physicians. The Table outlines the uses and side effects of the essential oils discussed here.

What Are Essential Oils?

Essential oils are aromatic volatile oils produced by medicinal plants that give them their distinct flavors and aromas. They are extracted using a variety of different techniques, such as microwave-assisted extraction, headspace extraction, and the most commonly employed hydrodistillation.1 Different parts of the plant are used for the specific oils; the shoots and leaves of Origanum vulgare are used for oregano oil, whereas the skins of Citrus limonum are used for lemon oil.2 Historically, essential oils have been used for cooking, food preservation, perfume, and medicine.3,4

Historical Uses for Essential Oils

Essential oils and their intact medicinal plants were among the first medicines widely available to the ancient world. The Ancient Greeks used topical and oral oregano as a cure-all for ailments including wounds, sore muscles, and diarrhea. Because of its use as a cure-all medicine, it remains a popular folk remedy in parts of Europe today.3 Lavender also has a long history of being a cure-all plant and oil. Some of the many claims behind this flower include treatment of burns, insect bites, parasites, muscle spasms, nausea, and anxiety/depression.5 With an extensive list of historical uses, many essential oils are being researched to determine if their acclaimed qualities have quantifiable properties.

Science Behind the Belief

In vitro experiments with oregano (O vulgare) have demonstrated notable antifungal and antimicrobial effects.6 Gas chromatographic analysis of the oil shows much of it is composed of phenolic monoterpenes, such as thymol and carvacrol. They exhibit strong antifungal effects with a slightly stronger effect on the dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum over other yeast species such as Candida.7,8 The full effect of the monoterpenes on fungi is not completely understood, but early data show it has a strong affinity for the ergosterol used in the cell-wall synthesis. Other effects demonstrated in in vitro studies include the ability to block drug efflux pumps, biofilm formation, cellular communication among bacteria, and mycotoxin production.9

A double-blind, randomized trial by Akhondzadeh et al10 demonstrated lavender (Lavandula officinalis) to have a mild antidepressant quality but a noticeably more potent effect when combined with imipramine. The effects of the lavender with imipramine were stronger and provided earlier improvement than imipramine alone for treatment of mild to moderate depression. The team concluded that lavender may be an effective adjunct therapy in treating depression.10

In a study by Mori et al,11 full-thickness circular wounds were made in rats and treated with either lavender oil (L officinalis), nothing, or a control oil. With the lavender oil being at only 1% solution, the wounds treated with lavender oil demonstrated earlier closure than the other 2 groups of wounds, where no major difference was noted. On cellular analysis, it was seen that the lavender had increased the rate of granulation as well as expression of types I and III collagen. The most striking result was the large expression of transforming growth factor β seen in the lavender group compared to the others. The final thoughts on this experiment were that lavender may provide new approaches to wound care in the future.11

Potential Problems With Purity

One major concern raised about essential oils is their purity and the fidelity of their chemical composition. The specific aromatic chemicals in each essential oil are maintained for each species, but the proportions of each change even with the time of year.12 Gas chromatograph analysis of the same oil distilled with different techniques showed that the proportions of aromatic chemicals varied with technique. However, the major constituents of the oil remained present in large quantities, just at different percentages.1 Even using the same distillation technique for different time periods can greatly affect the yield and composition of the oil. Although the percentage of each aromatic compound can be affected by distillation times, the antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of the oil remain constant regardless of these variables.2 There is clearly a lack in standardization in essential oil production, which may not be an issue for its use in complementary medicine if its properties are maintained regardless.

Safety Concerns and Regulations

With essential oils being a natural cure for everyday ailments, some people are turning first to oils for every cut and bruise. The danger in these natural cures is that essential oils can cause several types of dermatitis and allergic reactions. The development of allergies to essential oils is at an even higher risk, considering people frequently put them on wounds and rashes where the skin barrier is already weakened. Many essential oils fall into the fragrance category in patch tests, negating the widely circulating blogger and online reports that essential oils cannot cause allergies.

Some of the oils, although regarded safe by the US Food and Drug Administration for consumption, can cause dermatitis from simple contact or with sun exposure.13 Members of the citrus family are notorious for the phytophotodermatitis reaction, which can leave hyperpigmented scarring after exposure of the oils to sunlight.14 Most companies that sell essential oils are aware of this reaction and include it in the warning labels.

The legal problem with selling and classifying essential oils is that the US Food and Drug Administration requires products intended for treatment to be labeled as drugs, which hinders their sales on the open market.13 It all boils down to intended use, so some companies sell the oils under a food or fragrance classification with vague instructions on how to use said oil for medicinal purposes, which leads to lack of supervision, anecdotal cures, and false health claims. One company claims in their safety guide for topical applications of their oils that “[i]f a rash occurs, this may be a sign of detoxification.”15 If essential oils had only minimal absorption topically, their safety would be less concerning, but this does not appear to be the case.

Absorption and Systemics

The effects of essential oils on the skin is one aspect of their use to be studied; another is the more systemic effects from absorption through the skin. Most essential oils used in small quantities for fragrance in over-the-counter lotions prove only to be an issue for allergens in sensitive patient groups. However, topical applications of essential oils in their pure concentrated form get absorbed into the skin faster than if used with a carrier oil, emulsion, or solvent.16 For most minor uses of essential oils, the body can detoxify absorbed chemicals the same way it does when a person eats the plants the oils came from (eg, basil essential oils leaching from the leaves into a tomato sauce). A possible danger of the oils’ systemic properties lies in the pregnant patient population who use essential oils thinking that natural is safe.

Many essential oils, such as lavender (L officinalis), exhibit hormonal mimicry with phytoestrogens and can produce emmenagogue (increasing menstrual flow) effects in women. Other oils, such as those of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) and myrrh (Commiphora myrrha), can have abortifacient effects. These natural essential oils can lead to unintended health risks for mother and baby.17 With implications this serious, many essential oil companies put pregnancy warnings on most if not all of their products, but pregnant patients may not always note the risk.

Conclusion

Essential oils are not the newest medical fad. They outdate every drug on the market and were used by some of the first physicians in history. It is important to continue research into the antimicrobial effects of essential oils, as they may hold the secret to treatment options with the continued rise of multidrug-resistant organisms. The danger of these oils lies not in their hidden potential but in the belief that natural things are safe. A few animal studies have been performed, but little is known about the full effects of essential oils in humans. Patients need to be educated that these are not panaceas with freedom from side effects and that treatment options backed by the scientific method should be their first choice under the supervision of trained physicians. The Table outlines the uses and side effects of the essential oils discussed here.

- Fan S, Chang J, Zong Y, et al. GC-MS analysis of the composition of the essential oil from Dendranthema indicum var. aromaticum using three extraction methods and two columns. Molecules. 2018;23:576.

- Zheljazkov VD, Astatkie T, Schlegel V. Distillation time changes oregano essential oil yields and composition but not the antioxidant or antimicrobial activities. HortScience. 2012;47:777-784.

- Singletary K. Oregano: overview of the literature on health benefits. Nutr Today. 2010;45:129-138.

- Cortés-Rojas DF, de Souza CRF, Oliveira WP. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): a precious spice. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4:90-96.

- Koulivand PH, Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Gorji A. Lavender and the nervous system. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:681304.

- Cleff MB, Meinerz AR, Xavier M, et al. In vitro activity of Origanum vulgare essential oil against Candida species. Brazilian J Microbiol. 2010;41:116-123.

- Adam K, Sivropoulou A, Kokkini S, et al. Antifungal activities of Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum, Mentha spicata, Lavandula angustifolia, and Salvia fruticosa essential oils against human pathogenic fungi. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:1739-1745.

- Miron D, Battisti F, Silva FK, et al. Antifungal activity and mechanism of action of monoterpenes against dermatophytes and yeasts. Brazil J Pharmacognosy. 2014;24:660-667.

- Nazzaro F, Fratianni F, Coppola R, et al. Essential oils and antifungal activity. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2017;10:86.

- Akhondzadeh S, Kashani L, Fotouhi A, et al. Comparison of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. tincture and imipramine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:123-127.

- Mori H-M, Kawanami H, Kawahata H, et al. Wound healing potential of lavender oil by acceleration of granulation and wound contraction through induction of TGF-β in a rat model. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:144.

- Vekiari SA, Protopapadakis EE, Papadopoulou P, et al. Composition and seasonal variation of the essential oil from leaves and peel of a cretan lemon variety. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:147-153.

- Aromatherapy. US Food & Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/productsingredients/products/ucm127054.htm. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Hankinson A, Lloyd B, Alweis R. Lime-induced phytophotodermatitis. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.25090.

- Essential Oil Safety Guide. Young Living Essential Oils website. https://www.youngliving.com/en_US/discover/essential-oil-safety. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Cal K. Skin penetration of terpenes from essential oils and topical vehicles. Planta Medica. 2006;72:311-316.

- Ernst E. Herbal medicinal products during pregnancy: are they safe? BJOG. 2002;109:227-235.

- Hsouna AB, Halima NB, Smaoui S, et al. Citrus lemon essential oil: chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities with its preservative effect against Listeria monocytogenes inoculated in minced beef meat. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16:146.

- Chen Y, Zhou C, Ge Z, et al. Composition and potential anticancer activities of essential oils obtained from myrrh and frankincense. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:1140-1146.

- Zhang WK, Tao S-S, Li T-T, et al. Nutmeg oil alleviates chronic inflammatory pain through inhibition of COX-2 expression and substance P release in vivo. Food Nutr Res. 2016;60:30849.

- Glodde N, Jakobs M, Bald T, et al. Differential role of cannabinoids in the pathogenesis of skin cancer. Life Sci. 2015;138:35-40.

- Fan S, Chang J, Zong Y, et al. GC-MS analysis of the composition of the essential oil from Dendranthema indicum var. aromaticum using three extraction methods and two columns. Molecules. 2018;23:576.

- Zheljazkov VD, Astatkie T, Schlegel V. Distillation time changes oregano essential oil yields and composition but not the antioxidant or antimicrobial activities. HortScience. 2012;47:777-784.

- Singletary K. Oregano: overview of the literature on health benefits. Nutr Today. 2010;45:129-138.

- Cortés-Rojas DF, de Souza CRF, Oliveira WP. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): a precious spice. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4:90-96.

- Koulivand PH, Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Gorji A. Lavender and the nervous system. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:681304.

- Cleff MB, Meinerz AR, Xavier M, et al. In vitro activity of Origanum vulgare essential oil against Candida species. Brazilian J Microbiol. 2010;41:116-123.

- Adam K, Sivropoulou A, Kokkini S, et al. Antifungal activities of Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum, Mentha spicata, Lavandula angustifolia, and Salvia fruticosa essential oils against human pathogenic fungi. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:1739-1745.

- Miron D, Battisti F, Silva FK, et al. Antifungal activity and mechanism of action of monoterpenes against dermatophytes and yeasts. Brazil J Pharmacognosy. 2014;24:660-667.

- Nazzaro F, Fratianni F, Coppola R, et al. Essential oils and antifungal activity. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2017;10:86.

- Akhondzadeh S, Kashani L, Fotouhi A, et al. Comparison of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. tincture and imipramine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:123-127.

- Mori H-M, Kawanami H, Kawahata H, et al. Wound healing potential of lavender oil by acceleration of granulation and wound contraction through induction of TGF-β in a rat model. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:144.

- Vekiari SA, Protopapadakis EE, Papadopoulou P, et al. Composition and seasonal variation of the essential oil from leaves and peel of a cretan lemon variety. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:147-153.

- Aromatherapy. US Food & Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/productsingredients/products/ucm127054.htm. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Hankinson A, Lloyd B, Alweis R. Lime-induced phytophotodermatitis. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.25090.

- Essential Oil Safety Guide. Young Living Essential Oils website. https://www.youngliving.com/en_US/discover/essential-oil-safety. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- Cal K. Skin penetration of terpenes from essential oils and topical vehicles. Planta Medica. 2006;72:311-316.

- Ernst E. Herbal medicinal products during pregnancy: are they safe? BJOG. 2002;109:227-235.

- Hsouna AB, Halima NB, Smaoui S, et al. Citrus lemon essential oil: chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities with its preservative effect against Listeria monocytogenes inoculated in minced beef meat. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16:146.

- Chen Y, Zhou C, Ge Z, et al. Composition and potential anticancer activities of essential oils obtained from myrrh and frankincense. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:1140-1146.

- Zhang WK, Tao S-S, Li T-T, et al. Nutmeg oil alleviates chronic inflammatory pain through inhibition of COX-2 expression and substance P release in vivo. Food Nutr Res. 2016;60:30849.

- Glodde N, Jakobs M, Bald T, et al. Differential role of cannabinoids in the pathogenesis of skin cancer. Life Sci. 2015;138:35-40.

Practice Points

- Essential oils are a rising trend of nonprescribed topical supplements used by patients to self-treat.

- Research into historically medicinal essential oils may unlock treatment opportunities in the near future.

- Keeping an open-minded line of communication is critical for divulgence of potential home remedies that could be causing patients harm.

- Understanding the mindset of the essential oil–using community is key to building trust and treating these patients who are often distrusting of Western medicine.

Segmental distribution of nodules on trunk

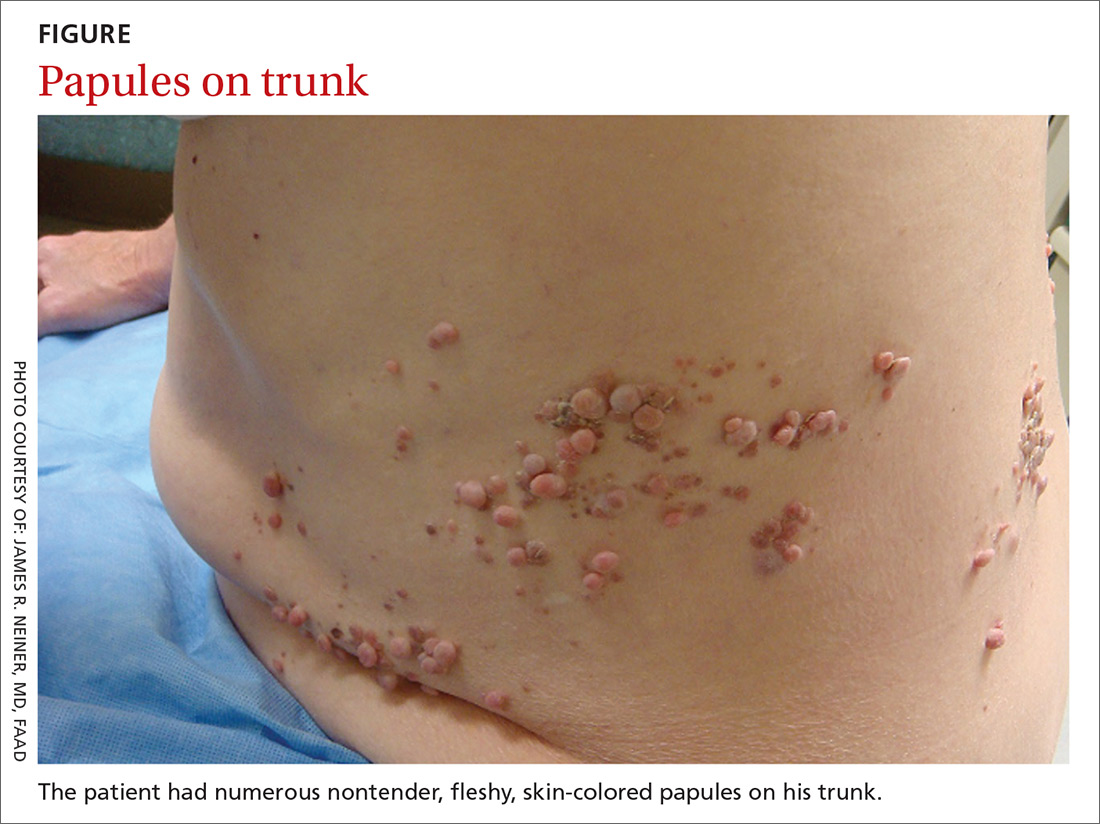

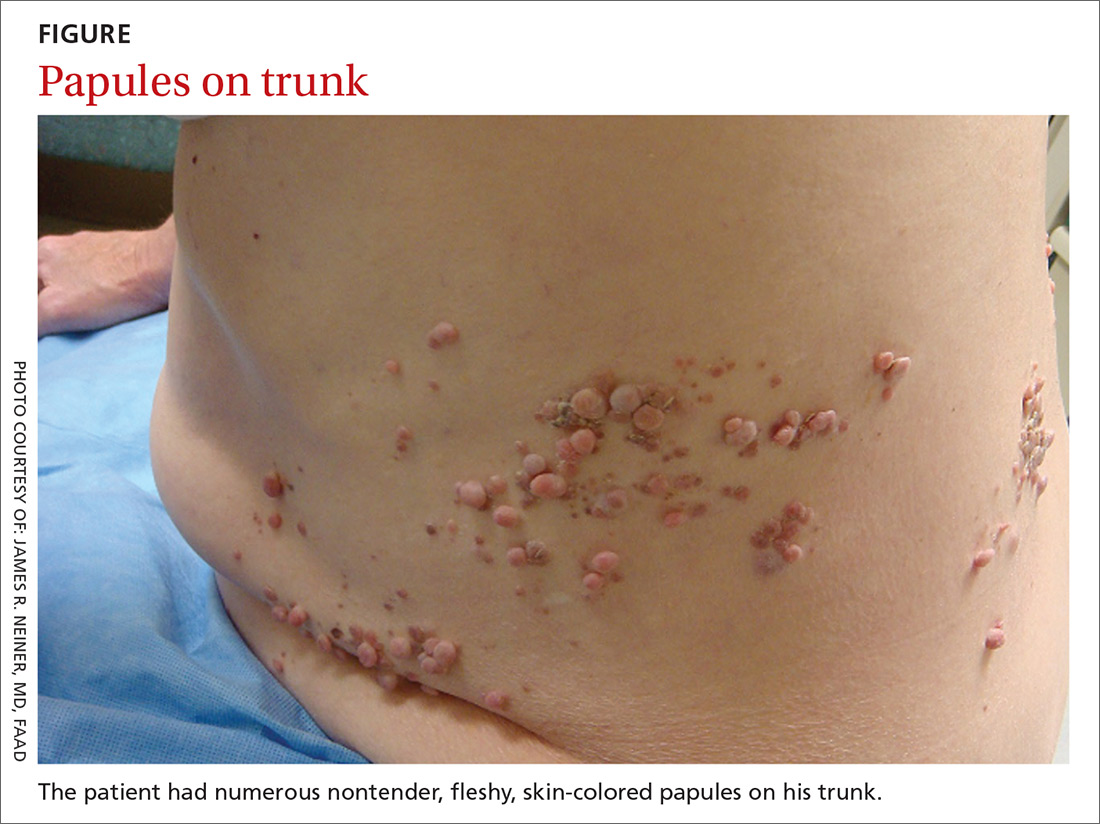

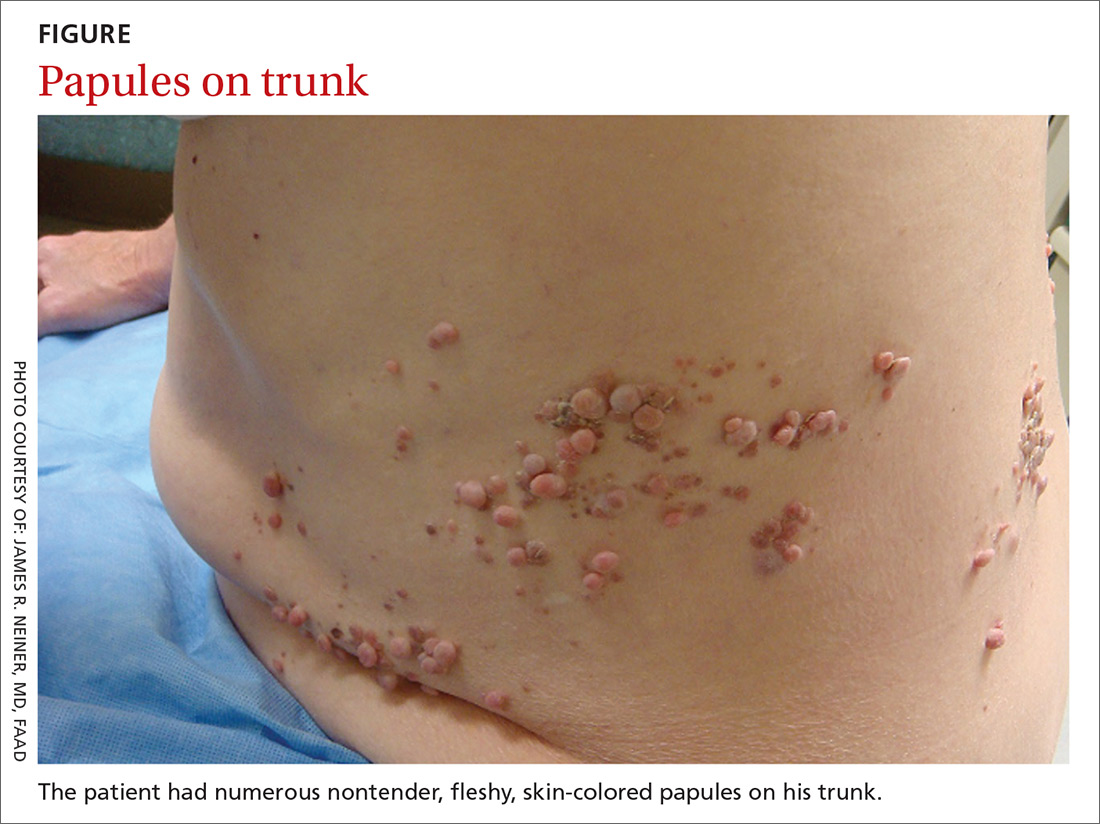

A 70-year-old Caucasian man presented with a longstanding history of numerous nontender, fleshy, skin-colored papules on his trunk, ranging from 3 to 8 mm in size (FIGURE). They were noted incidentally during an examination of unrelated nonhealing lesions on the patient’s left cheek. He said the lesions on his trunk first appeared when he was 28 years old and had continued to grow in size and number. The patient said his son had at least one similar lesion on his upper back, but otherwise there was no family history of these lesions.

A biopsy was performed on one of the nodules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Segmental neurofibromatosis

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical with biopsy to confirm the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of one in 3000,1 segmental NF is more rare, with an estimated prevalence of one in 40,000.2

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations.3 NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas).

Systemic findings that are associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy.3 While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of neurofibromas is often limited to one dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF.

Rule out these dermatomal lesions

This case highlights a unique pattern of neoplasm development along a dermatome, an area of skin where innervation derives from a single spinal nerve. Symptoms that follow a dermatome often point to a pathology involving the related nerve root.

This differs from Blaschko lines, which form a specific surface pattern that is believed to reflect the migration of embryonic skin cells. Blaschko lines do not follow any known vascular, nervous, or lymphatic structures of the skin. Interestingly, when patients with segmental NF have associated pigmentary lesions, such as café-au-lait macules, these lesions may border Blaschko lines.

Herpes zoster, also known as shingles, is the most common infectious process that presents in a dermatomal pattern. Herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, which lies within the dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. This condition commonly results in a dermatomal distribution of vesicles/bullae on an erythematous base.

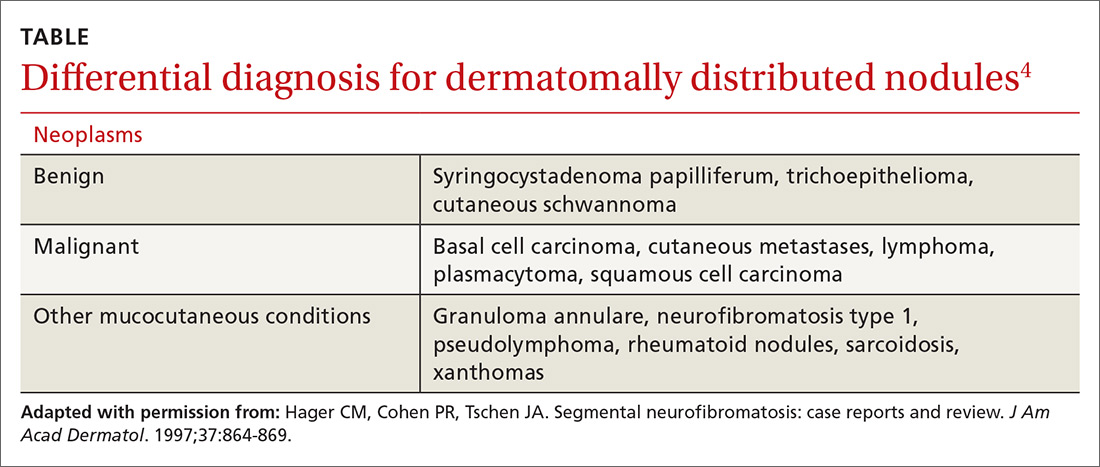

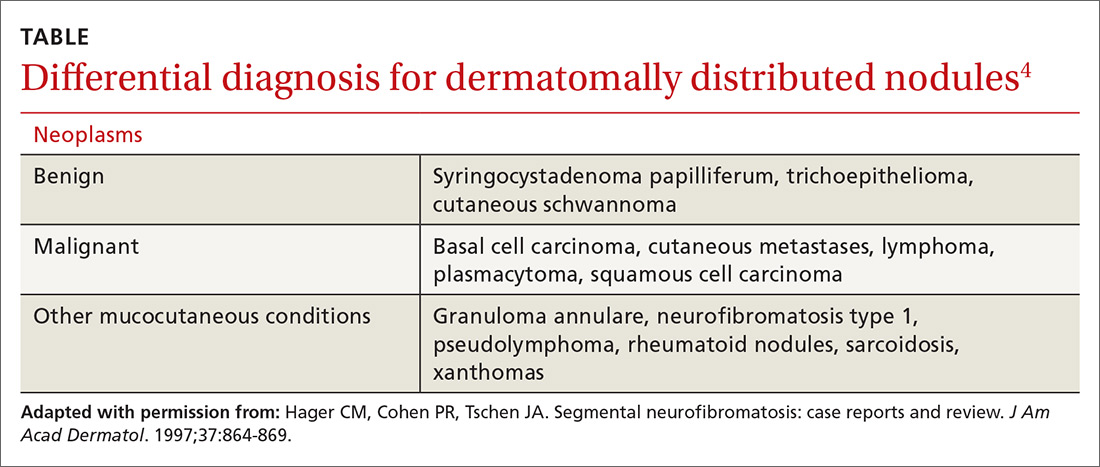

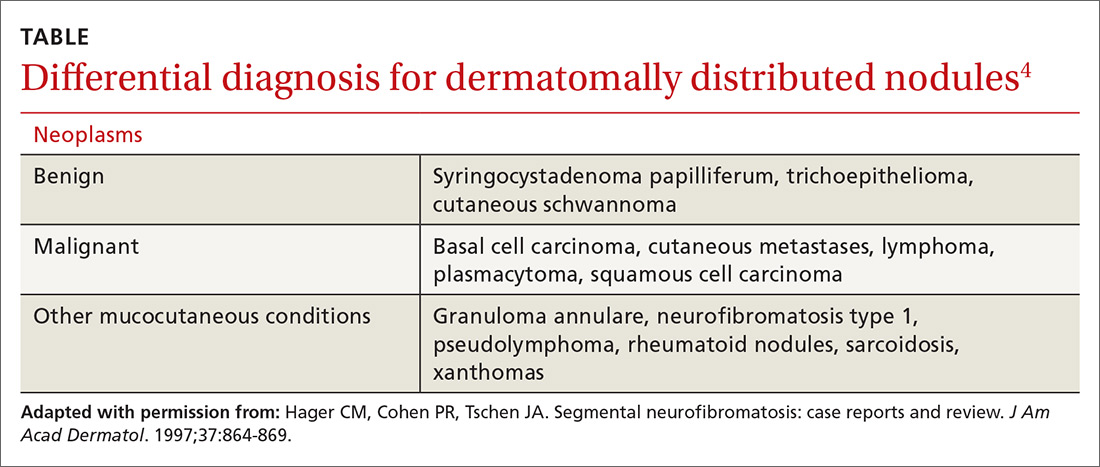

Neoplasms—including common cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma, as well as rare benign cutaneous conditions, such as cutaneous schwannoma, may have a distribution similar to that of segmental NF. A biopsy can help distinguish the diagnosis. See the TABLE4 for a complete differential diagnosis for dermatomally distributed nodules.

Classifying neurofibromatosis

It’s important to classify the type of NF in order to get a better handle on the patient’s prognosis and to facilitate genetic counseling. In particular, the much more common NF1 comes with an increased risk of systemic findings such as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, other gliomas, and leukemia. Few patients with segmental NF, on the other hand, will have these systemic findings.4 Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

Our patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF as discussed above, so no medical treatment was required. We informed him that the cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. Our patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so we recommended follow-up as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, FAAD, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, Brooke Army Medical Center, 3551 Roger Brooke Dr, Fort Sam Houston, TX 78234; [email protected].

1. Riccardi VM. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1617-1627.

2. Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

3. Jett K, Friedman JM. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med. 2010;12:1-11.

4. Hager CM, Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Segmental neurofibromatosis: case reports and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:864-869.

A 70-year-old Caucasian man presented with a longstanding history of numerous nontender, fleshy, skin-colored papules on his trunk, ranging from 3 to 8 mm in size (FIGURE). They were noted incidentally during an examination of unrelated nonhealing lesions on the patient’s left cheek. He said the lesions on his trunk first appeared when he was 28 years old and had continued to grow in size and number. The patient said his son had at least one similar lesion on his upper back, but otherwise there was no family history of these lesions.

A biopsy was performed on one of the nodules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Segmental neurofibromatosis

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical with biopsy to confirm the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of one in 3000,1 segmental NF is more rare, with an estimated prevalence of one in 40,000.2

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations.3 NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas).

Systemic findings that are associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy.3 While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of neurofibromas is often limited to one dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF.

Rule out these dermatomal lesions

This case highlights a unique pattern of neoplasm development along a dermatome, an area of skin where innervation derives from a single spinal nerve. Symptoms that follow a dermatome often point to a pathology involving the related nerve root.

This differs from Blaschko lines, which form a specific surface pattern that is believed to reflect the migration of embryonic skin cells. Blaschko lines do not follow any known vascular, nervous, or lymphatic structures of the skin. Interestingly, when patients with segmental NF have associated pigmentary lesions, such as café-au-lait macules, these lesions may border Blaschko lines.

Herpes zoster, also known as shingles, is the most common infectious process that presents in a dermatomal pattern. Herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, which lies within the dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. This condition commonly results in a dermatomal distribution of vesicles/bullae on an erythematous base.

Neoplasms—including common cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma, as well as rare benign cutaneous conditions, such as cutaneous schwannoma, may have a distribution similar to that of segmental NF. A biopsy can help distinguish the diagnosis. See the TABLE4 for a complete differential diagnosis for dermatomally distributed nodules.

Classifying neurofibromatosis

It’s important to classify the type of NF in order to get a better handle on the patient’s prognosis and to facilitate genetic counseling. In particular, the much more common NF1 comes with an increased risk of systemic findings such as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, other gliomas, and leukemia. Few patients with segmental NF, on the other hand, will have these systemic findings.4 Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

Our patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF as discussed above, so no medical treatment was required. We informed him that the cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. Our patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so we recommended follow-up as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, FAAD, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, Brooke Army Medical Center, 3551 Roger Brooke Dr, Fort Sam Houston, TX 78234; [email protected].

A 70-year-old Caucasian man presented with a longstanding history of numerous nontender, fleshy, skin-colored papules on his trunk, ranging from 3 to 8 mm in size (FIGURE). They were noted incidentally during an examination of unrelated nonhealing lesions on the patient’s left cheek. He said the lesions on his trunk first appeared when he was 28 years old and had continued to grow in size and number. The patient said his son had at least one similar lesion on his upper back, but otherwise there was no family history of these lesions.

A biopsy was performed on one of the nodules.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Segmental neurofibromatosis

Dermatopathologic evaluation of the tissue sample indicated that the lesion was a neurofibroma, and clinical correlation fine-tuned the diagnosis to segmental neurofibromatosis (NF). The diagnosis of segmental NF is clinical with biopsy to confirm the lesions are neurofibromas. Segmental NF is a mosaic form of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) that results from a postzygotic mutation of the NF1 gene. While NF1 is a relatively common neurocutaneous disorder that occurs with a frequency of one in 3000,1 segmental NF is more rare, with an estimated prevalence of one in 40,000.2

NF1 often follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, although up to 50% of patients with NF1 arise de novo from spontaneous mutations.3 NF1 is characterized by multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules (pigmented iris hamartomas).

Systemic findings that are associated with NF1 include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, and vasculopathy.3 While patients with segmental NF may exhibit some of these same findings, the distribution of neurofibromas is often limited to one dermatome. Additionally, patients with segmental NF typically do not exhibit extracutaneous lesions, systemic involvement, or a family history of NF.

Rule out these dermatomal lesions

This case highlights a unique pattern of neoplasm development along a dermatome, an area of skin where innervation derives from a single spinal nerve. Symptoms that follow a dermatome often point to a pathology involving the related nerve root.

This differs from Blaschko lines, which form a specific surface pattern that is believed to reflect the migration of embryonic skin cells. Blaschko lines do not follow any known vascular, nervous, or lymphatic structures of the skin. Interestingly, when patients with segmental NF have associated pigmentary lesions, such as café-au-lait macules, these lesions may border Blaschko lines.

Herpes zoster, also known as shingles, is the most common infectious process that presents in a dermatomal pattern. Herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, which lies within the dorsal root ganglion of a spinal nerve. This condition commonly results in a dermatomal distribution of vesicles/bullae on an erythematous base.

Neoplasms—including common cutaneous malignancies, such as basal cell carcinoma, as well as rare benign cutaneous conditions, such as cutaneous schwannoma, may have a distribution similar to that of segmental NF. A biopsy can help distinguish the diagnosis. See the TABLE4 for a complete differential diagnosis for dermatomally distributed nodules.

Classifying neurofibromatosis

It’s important to classify the type of NF in order to get a better handle on the patient’s prognosis and to facilitate genetic counseling. In particular, the much more common NF1 comes with an increased risk of systemic findings such as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, optic gliomas, other gliomas, and leukemia. Few patients with segmental NF, on the other hand, will have these systemic findings.4 Segmental NF treatment typically focuses on symptomatic management or cosmetic concerns.

Our patient did not have any of the systemic complications that occasionally occur with segmental NF as discussed above, so no medical treatment was required. We informed him that the cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas do not require removal unless there is pain, bleeding, disfigurement, or signs of malignant transformation. Our patient was not interested in removal of the nodules for cosmetic reasons, so we recommended follow-up as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, FAAD, San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium, Brooke Army Medical Center, 3551 Roger Brooke Dr, Fort Sam Houston, TX 78234; [email protected].

1. Riccardi VM. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1617-1627.

2. Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

3. Jett K, Friedman JM. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med. 2010;12:1-11.

4. Hager CM, Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Segmental neurofibromatosis: case reports and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:864-869.

1. Riccardi VM. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1617-1627.

2. Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

3. Jett K, Friedman JM. Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med. 2010;12:1-11.

4. Hager CM, Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Segmental neurofibromatosis: case reports and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:864-869.