User login

AD Myths in Healthcare Debate

All new legislation concerning advance care planning was removed from the Affordable Care Act, signed into law in March 2010. However, through a Medicare payment regulation, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) was able to add a provision allowing compensation to physicians for advance directive (AD) discussions as part of the annual Medicare wellness exam. Previously, under President George W. Bush, funding for AD discussions was already part of the Welcome to Medicare visit. Once again, the provision was misrepresented and distorted in the media, talk radio shows, and social networking sites. Within days of the announcement, the White House removed the regulation stating that the controversy surrounding the provision was distracting from the overall debate about healthcare. The term death panels has now entered our national lexicon and serves to undermine the efforts of the palliative care field which, through discussions with patients and families, attempts to provide care consistent with patients' goals.

In fact, ADs have been a cornerstone of ethical decision making, by supporting patient autonomy and allowing patient wishes to be respected when decisional capacity is lacking. Advance directives may include a living will, a Medical Durable Power of Attorney, or may be a broader more comprehensive document outlining goals, values, and preferences for care in the event of decisional incapacity. ADs allow patients to express preferences that incorporate both quantity and quality of life, as there are times when interventions at the end of life may increase length of life to the detriment of quality of life. In this context, patients may chose to value quality of life and request the interventions be withdrawn that focus on maintaining life without hope for quality of life. ADs also permit patients who prefer quantity over quality of life to communicate these wishes. These conversations are complex and time‐consuming. Patients may have profound misperceptions about the benefits offered by interventions at the end of life. Having detailed conversations with healthcare providers about actual benefits, risks, and alternatives has been shown to impact that decision‐making process.1 In our current payment system, these time‐consuming conversations are not compensated by private or public insurers, and are incompatible with 20‐minute appointments, so they rarely occur.24 While Nancy Cruzan and Terri Schiavo brought national attention to the issue for a brief time, recent data suggest that only 30% of adults have completed an AD,57 however, 93% of adults would like to discuss ADs with their physician.8 Furthermore, Silveira et al. showed that older adults with ADs are more likely than those without ADs to receive care that is consistent with their preferences at the end of life.9 ADs were the sole predictor of concordance between preferred and actual site of death in a cohort of seriously ill, hospitalized patients.10 Patients with advanced cancer who discussed their end of life wishes with their physician were more likely to receive care consistent with their preferences.11

Advance directives are based on the ethical principle of autonomy and, with the growing evidence that ADs may improve care at the end of life, public understanding of the issue is critical. We had presented early preliminary data in a letter to the editor showing that having had an advance directive discussion or an AD in the medical record was not associated with an increased risk of death.12 This research, along with the work of Silveira and colleagues,9 was cited by the Obama administration when they decided to add the regulation for including advance care planning as part of the annual Medicare wellness exams. This brief report presents a more comprehensive examination of the relationship of AD discussions and AD documentation with survival in a group of hospitalized patients.

METHODS

Study Sites and Participant Recruitment

This was a multisite, prospective study of patients admitted to the hospital for medical illness. The Colorado Multi‐Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Over a 17‐month period starting in February 2004, participants were recruited from 3 hospitals affiliated with the University of ColoradoDenver Internal Medicine Residency program: the Denver Veterans' Administration Center (DVAMC); Denver Health Medical Center (DHMC), the city's safety net hospital; and University of Colorado Hospital (UCH), an academic tertiary, specialty care and referral center. Exclusion criteria included: admission <24 hours, pregnancy, age <18 years, incarceration, spoke neither English nor Spanish, lack of decisional capacity. Recruitment was done on the day following admission to the hospital throughout the year, to reduce potential bias due to seasonal trends. A trained assistant recruited on variable weekdays (to allow inclusion of weekend admissions). Of 842 admissions occurring during the recruitment, 331 (39%) were ineligible (175 discharged and 2 died within 24 hours postadmission; 76 lacked decisional capacity; and 78 met other exclusion criteria listed above). All other patients (n = 511) were invited to participate and 458 patients consented.

Participant Interview and Measures

Fifty‐three (10%) refused; 458 gave informed consent and participated in a bedside interview, including questions related to advance care planning. In this interview, participants were first asked to define an AD. Their response was either confirmed or corrected using a standard simple explanation that defined and described ADs:

An advance directive is a document that lets your healthcare providers know who you would want to make decisions for you if you were unable to make them for yourself. It can also tell your healthcare providers what types of medical treatments you would and would not want if you were unable to speak for yourself.

They were then asked if any healthcare provider had ever discussed ADs with them (AD discussion is a primary variable of interest).

Chart Review and Vital Records Data Collection

We reviewed each medical record to determine admitting diagnoses, CARING criteria (a set of simple criteria developed by our group to score the need for palliative care, which has been shown to predict death at 1 year),13 socioeconomic and demographic information, and the presence of ADs in the medical record (documentation of AD is a primary variable of interest). We defined ADs broadly, including: living will, durable power of attorney for healthcare, or a comprehensive advance care planning document (eg, Five Wishes). The CARING criteria are validated criteria that accurately predict death at 1 year, and were developed to identify patients who would be appropriate for a palliative care intervention. It is based on the following variables: Cancer as a primary admitting diagnosis, Admitted 2 times to the hospital in the past year for a chronic medical illness, Resident of a nursing home, ICU admission with >2 organ systems in failure, and 2 Non‐Cancer hospice Guidelines as well as age. Scores range from 4 = low risk of death, 5‐12 = medium risk of death, and 13 = high risk of death at 1 year. We accessed hospital records and state Vital Records from 2003 to 2009 to determine which patients died within a 12‐month follow‐up period, and their date of death (primary outcome).

Cohort Risk Stratification

Based on their CARING score, participants were classified as being at low, medium, or high risk of death at 1 year.13 The probability of imminent death in the group of high‐risk patients is the main indication for an advance directive, and therefore the analysis of this high‐risk group would be confounded. Therefore, those at high (and unclassified) risk of death (89 [and 13] out of 458 interviewed patients) were excluded from the survival analysis. Including persons at high risk of death in this analysis would lead to confounding by indicationthat physicians are most likely to address ADs with patients that they perceive are likely to die in the near future. An example of this in the literature is the timing of do‐not‐attempt‐resuscitation orders (DNAR). It is well documented that most DNAR orders are written within 1 to 2 days of death.1416 The DNAR orders do not cause or lead to death, they are simply finally written for patients that are actively dying.

Statistical Analysis

SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. Survival analysis was conducted to examine time to death. Interaction effects of the variable of interest with patient risk were assessed by estimating Kaplan‐Meier survival curves for low and medium risk groups separately. The Wilcoxon and log‐rank tests were employed to compare those with and without AD discussions (and accounting for clustering within hospitals) and documentation. Since the stratification into risk groups involves the use of the CARING criteria, which were the main confounders, additional risk adjustment in each risk group was not performed. Post hoc power analysis showed an ability to detect a 13 percentage points difference in mortality rate, with 80% power for a 2‐sided test and alpha = 0.05, assuming a 20% death rate for the group without AD discussion (adjusting for the covariate distribution difference between those with and without AD discussion).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the 356 study subjects are listed in Table 1. Overall, the sample population was ethnically diverse, slightly above middle‐aged, mostly male, and of lower socioeconomic status, reflecting the hospitals' populations. Using the CARING criteria, 297 subjects were found to be at low risk, and 59 subjects at medium risk, of death at 1 year.

| Percent (n) or Mean SD | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 19% (69) |

| Caucasian | 55% (194) |

| Latino | 19% (66) |

| Other | 8% (27) |

| Age (years) | 57.2 15 |

| Female gender | 34% (122) |

| Admitted to | |

| DVAMC | 41% (147) |

| DHMC | 34% (122) |

| UCH | 24% (87) |

| CARING criteria | |

| Cancer diagnosis | 4% (15) |

| Admitted to hospital 2 times in the past year for chronic illness | 31% (109) |

| Resident in a nursing home | 2% (7) |

| Non‐cancer hospice guidelines (meeting 2) | 1% (4) |

| Income less than $30,000/yr | 81% (284) |

| No greater than high school education | 53% (188) |

| Living situation | |

| Home owner | 36% (125) |

| Rents home | 38% (132) |

| Unstable living situation | 27% (94) |

| Low social support | 37% (169) |

| Uninsured | 14% (51) |

| Regular primary care provider | 72% (254) |

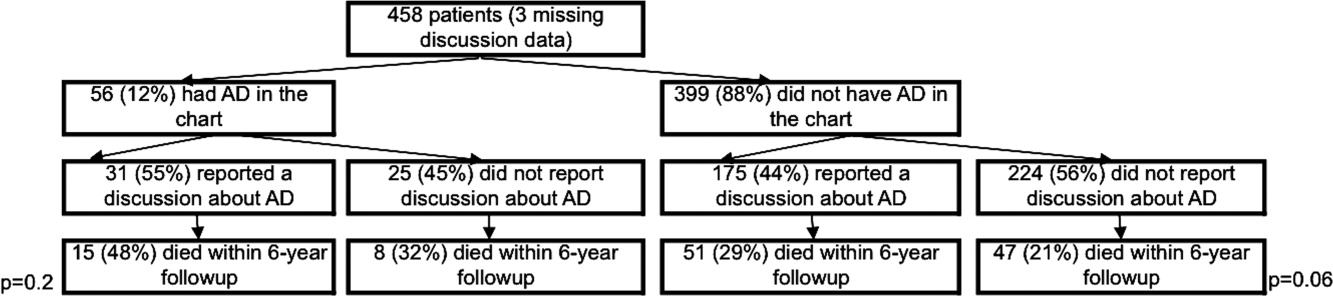

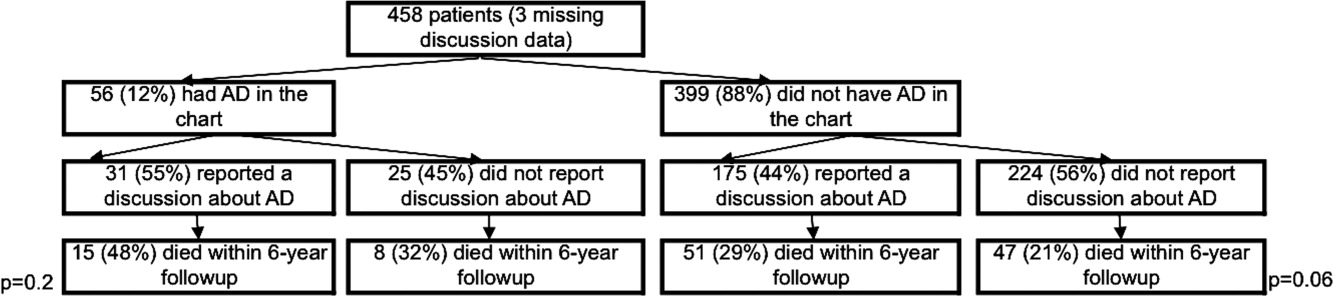

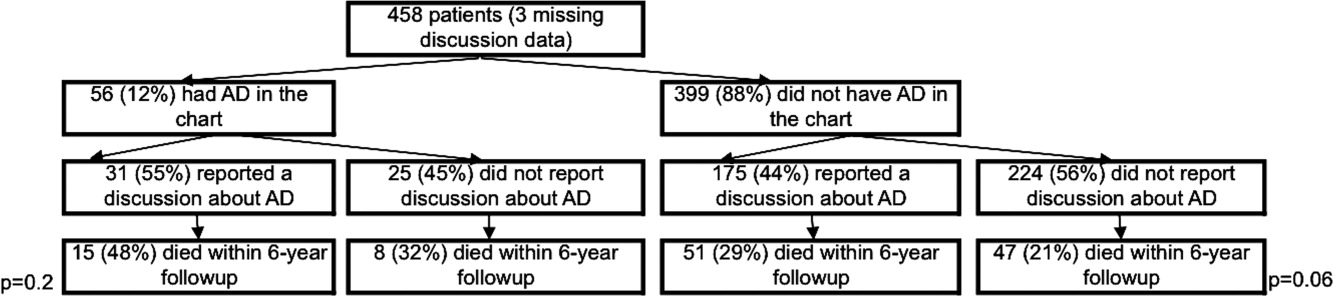

Overall, 206 (45%) reported a discussion about ADs with a healthcare provider. However, we found that only 56 (10%) had an AD document on their chart. Twenty‐eight (6%) had a living will, 43 (9%) had a durable power of attorney, and 30 (7%) had a broader AD document. Between 2003 and 2009, 121 (26%) patients died. Unadjusted mortality rates for those with and without documentation and discussions of ADs are displayed in Figure 1.

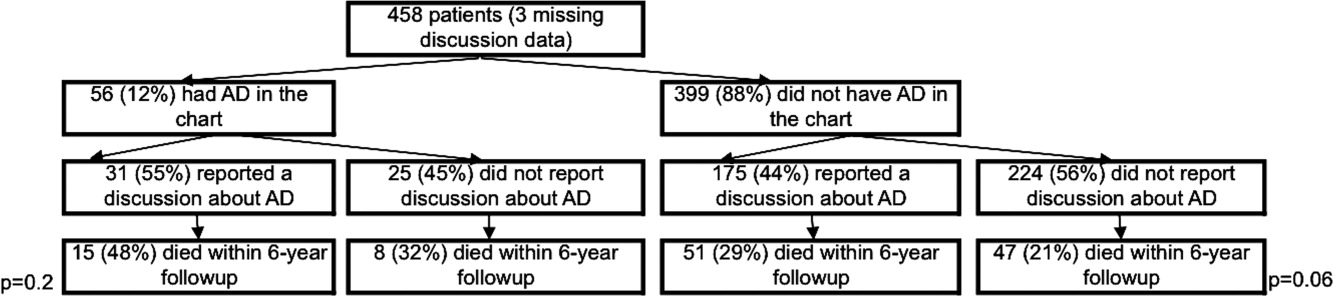

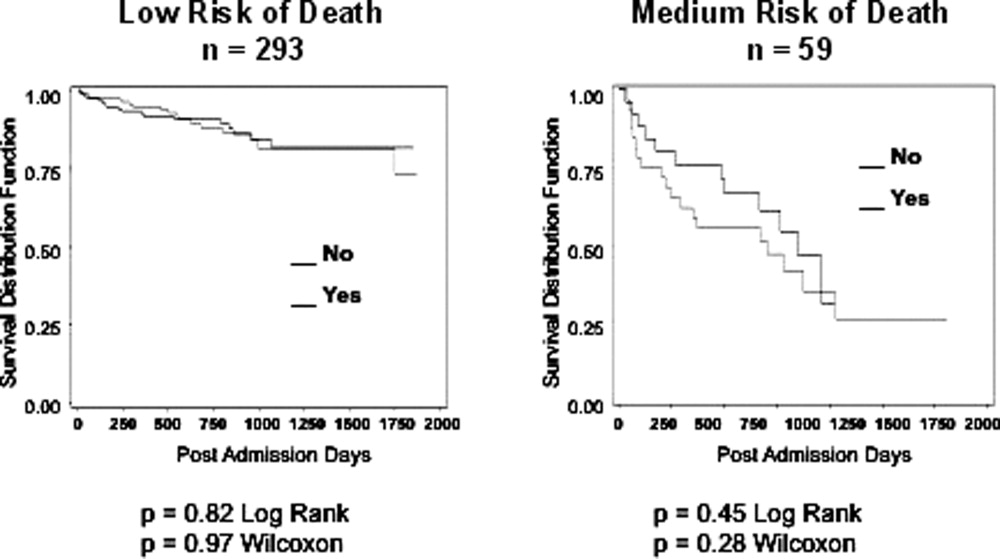

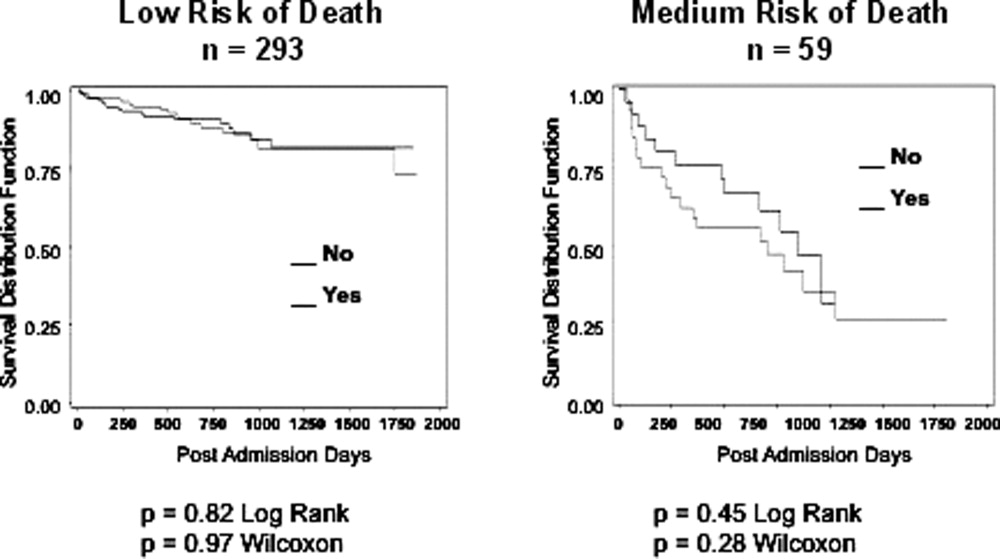

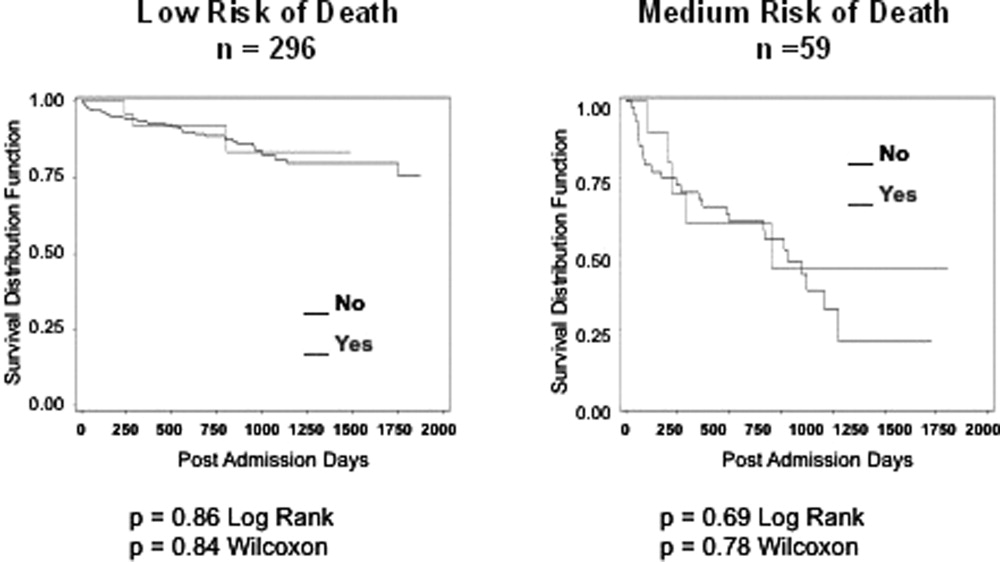

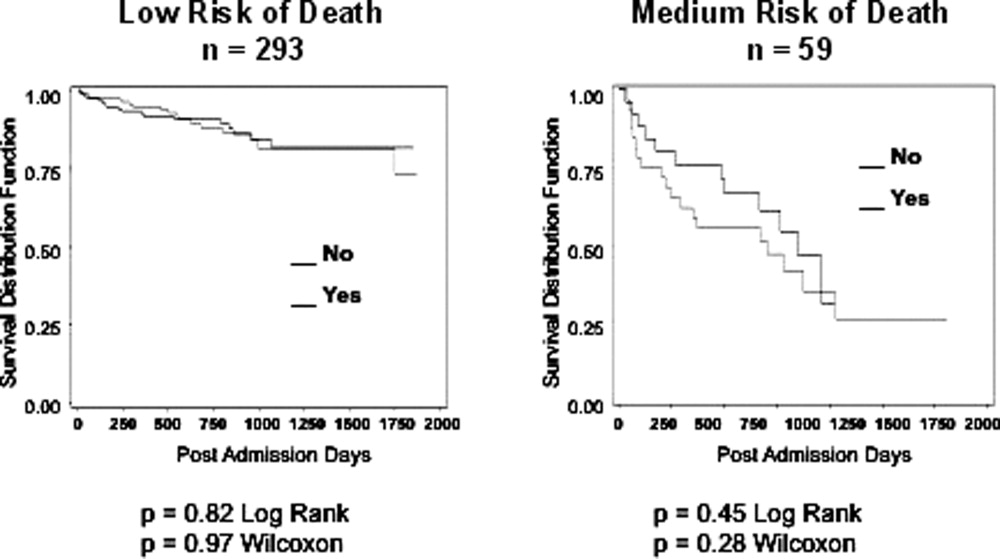

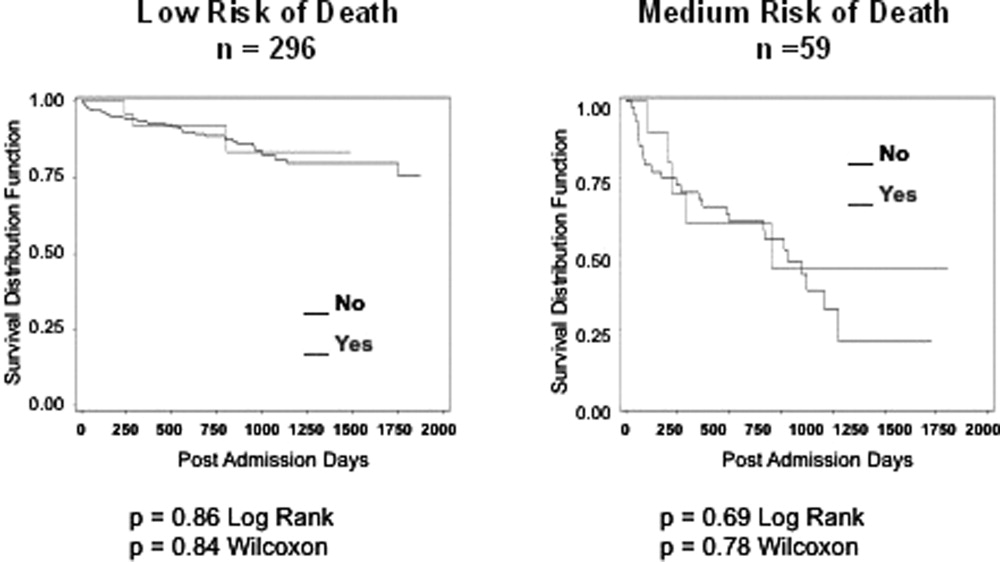

Kaplan‐Meier survival curves showed that, for subjects with a low or medium risk of death at 1 year, having had an AD discussion or having an AD in the medical record did not affect survival in subjects (Figures 2 and 3). Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for other covariates confirmed the results of the survival analysis (data not shown). Minimal intraclass correlation coefficients (0.005) were observed for the outcomes. Therefore, no models accounting for clustering within hospitals were developed.

DISCUSSION

We found no decrease in survival for patients at low and medium 1‐year risk of death who reported having discussed ADs or who had an AD in their medical record, providing important evidence that having advance care planning discussions do not hasten death in this group of adults. However, it is possible that ADs, when implemented properly, may dictate withdrawal or withholding of interventions that may extend quantity of life at a quality unacceptable for the person executing the directive. For example, a feeding tube delivering artificial nutrition and hydration may grant years to someone in a persistent vegetative state, but those years, without the ability to be aware or interact with surroundings and loved ones, may not be a life worth living for some individuals. One explanation for our negative findings may be that the circumstances in which an AD may have an effect on outcomes may not yet have occurred among this lower risk population.

Opposition to the process of advance care planning may be considered unethical, by removing the opportunity for individuals to express their desires in the event of decisional incapacity, therefore disregarding patient autonomy. Furthermore, with the growing evidence that AD discussions and documentation help patients achieve care consistent with their wishes at the end of life,9, 11, 17 preventing advance care planning may worsen end of life outcomes.

Another important finding in our study was that only about 10% of the patients interviewed had completed an AD document, although nearly half reported they had discussed ADs with a healthcare provider. The patients we interviewed in this study had been admitted to the hospital in the previous 24 hours. As part of the Patient Self‐Determination Act, all patients admitted to a healthcare facility should receive information and counseling on AD. Less than half of our cohort reported any discussions about ADs and only 10% had completed an AD, suggesting that huge opportunities exist for improvement in advance care planning. As this study demonstrates, there was no increased mortality from advance care planning among those at low and medium risk of death, and others have shown benefits from the process. AD discussions and documentation should be fostered, especially as the burden of chronic disease increases and the population ages. In targeted studies to improve advance care planning, completion rates of up to 85% have been achieved.17

Our decision to focus solely on patients at low or medium risk of death, and exclude those at a high risk of death, is based on both clinical and methodological judgment. First, it is important to note that ADs are important even for those at lower risk of deaththe 3 critical cases that have shaped AD policy in this country, Karen Ann Quinlan, Nancy Cruzan, and Terry Schiavo, were all otherwise healthy young women.

Our study does have limitations. First, the sample size is small and not powered to detect small differences in survival. In addition, we only examined Vital Records within Colorado, although all participants had either a date of death or recent date of last contact. It is also conceivable that some patients discussed or completed ADs at a later time in their illness trajectory. However, the generalizability of this study is a major strength, by including a population and healthcare settings that are ethnically and socioeconomically diverse. Generalization of results beyond the three types of hospitals should be limited even with the low intraclass correlation. The major limitation of this research is that we do not have data on participant quality of life or whether completing an AD led to increased use of palliative care. During the time the research was conducted, 2 of the 3 hospitals involved had small palliative care services and the third remains without a palliative care service.

In conclusion, our study provides limited data to counteract the misleading claims of those opposed to the advance care planning process. Our results underscore the importance of educating the public on the importance of ADs and cast doubt on the death myth surrounding advance care planning. However, further, preferably longitudinal, study is needed to prospectively understand both the benefits and risks of advance care planning.

- ,,.The influence of the probability of survival on patient's preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation.N Engl J Med.1994;330:545–549.

- ,,.Physician reluctance to discuss advance directives. An empiric investigation of potential barriers.Arch Intern Med.1994;154(20):2311–2318.

- Advance directives and advance care planning: report to Congress. US Department of Health 82(12):1487–1490.

- Facts on dying: policy relevant data on care at the end of life, USA and state statistics. Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Web site. Available at: http://www.chcr.brown.edu/dying/usastatistics.htm. Accessed September 20,2010.

- ,.The quest to reform end of life care: rethinking assumptions and setting new directions.Hastings Cent Rep. November—December2005;S52–S57.

- ,,, et al.End‐of‐life care and outcomes.Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 110.Rockville, MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; December2004;1–6.

- ,,,,.Advance directives for medical care—a case for greater use.N Engl J Med.1991;324(13):889–895.

- ,,.Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death.N Engl J Med.2010;362(13):1211–1218.

- ,,.Advance directives: the best predictor of congruence between preferred and actual site of death [Research Poster Abstracts].Journal of Hospital Medicine2010;5(S1):1–81.

- ,,,,.End‐of‐life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences.J Clin Oncol2010;28(7):1203–1208.

- ,,.Advance directive discussions do not lead to death.J Am Geriatr Soc.2010;58(2):400–401.

- ,,,,,.Practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: the CARING criteria.J Pain Symptom Manage.2005;31(4):285–292.

- ,,.Do not resuscitate orders and the cost of death.Arch Intern Med.1993;153(10):1249–1253.

- ,,,,.The do‐not‐resuscitate order: associations with advance directives, physician specialty and documentation of discussion 15 years after the Patient Self‐Determination Act.J Med Ethics.2008;34(9):642–647.

- ,,, et al.Factors associated with do‐not‐resuscitate orders: patients' preferences, prognoses, and physicians' judgments. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment.Ann Intern Med.1996;125(4):284–293.

- ,.Death and end‐of‐life planning in one midwestern community.Arch Intern Med.1998;158(4):383–390.

All new legislation concerning advance care planning was removed from the Affordable Care Act, signed into law in March 2010. However, through a Medicare payment regulation, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) was able to add a provision allowing compensation to physicians for advance directive (AD) discussions as part of the annual Medicare wellness exam. Previously, under President George W. Bush, funding for AD discussions was already part of the Welcome to Medicare visit. Once again, the provision was misrepresented and distorted in the media, talk radio shows, and social networking sites. Within days of the announcement, the White House removed the regulation stating that the controversy surrounding the provision was distracting from the overall debate about healthcare. The term death panels has now entered our national lexicon and serves to undermine the efforts of the palliative care field which, through discussions with patients and families, attempts to provide care consistent with patients' goals.

In fact, ADs have been a cornerstone of ethical decision making, by supporting patient autonomy and allowing patient wishes to be respected when decisional capacity is lacking. Advance directives may include a living will, a Medical Durable Power of Attorney, or may be a broader more comprehensive document outlining goals, values, and preferences for care in the event of decisional incapacity. ADs allow patients to express preferences that incorporate both quantity and quality of life, as there are times when interventions at the end of life may increase length of life to the detriment of quality of life. In this context, patients may chose to value quality of life and request the interventions be withdrawn that focus on maintaining life without hope for quality of life. ADs also permit patients who prefer quantity over quality of life to communicate these wishes. These conversations are complex and time‐consuming. Patients may have profound misperceptions about the benefits offered by interventions at the end of life. Having detailed conversations with healthcare providers about actual benefits, risks, and alternatives has been shown to impact that decision‐making process.1 In our current payment system, these time‐consuming conversations are not compensated by private or public insurers, and are incompatible with 20‐minute appointments, so they rarely occur.24 While Nancy Cruzan and Terri Schiavo brought national attention to the issue for a brief time, recent data suggest that only 30% of adults have completed an AD,57 however, 93% of adults would like to discuss ADs with their physician.8 Furthermore, Silveira et al. showed that older adults with ADs are more likely than those without ADs to receive care that is consistent with their preferences at the end of life.9 ADs were the sole predictor of concordance between preferred and actual site of death in a cohort of seriously ill, hospitalized patients.10 Patients with advanced cancer who discussed their end of life wishes with their physician were more likely to receive care consistent with their preferences.11

Advance directives are based on the ethical principle of autonomy and, with the growing evidence that ADs may improve care at the end of life, public understanding of the issue is critical. We had presented early preliminary data in a letter to the editor showing that having had an advance directive discussion or an AD in the medical record was not associated with an increased risk of death.12 This research, along with the work of Silveira and colleagues,9 was cited by the Obama administration when they decided to add the regulation for including advance care planning as part of the annual Medicare wellness exams. This brief report presents a more comprehensive examination of the relationship of AD discussions and AD documentation with survival in a group of hospitalized patients.

METHODS

Study Sites and Participant Recruitment

This was a multisite, prospective study of patients admitted to the hospital for medical illness. The Colorado Multi‐Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Over a 17‐month period starting in February 2004, participants were recruited from 3 hospitals affiliated with the University of ColoradoDenver Internal Medicine Residency program: the Denver Veterans' Administration Center (DVAMC); Denver Health Medical Center (DHMC), the city's safety net hospital; and University of Colorado Hospital (UCH), an academic tertiary, specialty care and referral center. Exclusion criteria included: admission <24 hours, pregnancy, age <18 years, incarceration, spoke neither English nor Spanish, lack of decisional capacity. Recruitment was done on the day following admission to the hospital throughout the year, to reduce potential bias due to seasonal trends. A trained assistant recruited on variable weekdays (to allow inclusion of weekend admissions). Of 842 admissions occurring during the recruitment, 331 (39%) were ineligible (175 discharged and 2 died within 24 hours postadmission; 76 lacked decisional capacity; and 78 met other exclusion criteria listed above). All other patients (n = 511) were invited to participate and 458 patients consented.

Participant Interview and Measures

Fifty‐three (10%) refused; 458 gave informed consent and participated in a bedside interview, including questions related to advance care planning. In this interview, participants were first asked to define an AD. Their response was either confirmed or corrected using a standard simple explanation that defined and described ADs:

An advance directive is a document that lets your healthcare providers know who you would want to make decisions for you if you were unable to make them for yourself. It can also tell your healthcare providers what types of medical treatments you would and would not want if you were unable to speak for yourself.

They were then asked if any healthcare provider had ever discussed ADs with them (AD discussion is a primary variable of interest).

Chart Review and Vital Records Data Collection

We reviewed each medical record to determine admitting diagnoses, CARING criteria (a set of simple criteria developed by our group to score the need for palliative care, which has been shown to predict death at 1 year),13 socioeconomic and demographic information, and the presence of ADs in the medical record (documentation of AD is a primary variable of interest). We defined ADs broadly, including: living will, durable power of attorney for healthcare, or a comprehensive advance care planning document (eg, Five Wishes). The CARING criteria are validated criteria that accurately predict death at 1 year, and were developed to identify patients who would be appropriate for a palliative care intervention. It is based on the following variables: Cancer as a primary admitting diagnosis, Admitted 2 times to the hospital in the past year for a chronic medical illness, Resident of a nursing home, ICU admission with >2 organ systems in failure, and 2 Non‐Cancer hospice Guidelines as well as age. Scores range from 4 = low risk of death, 5‐12 = medium risk of death, and 13 = high risk of death at 1 year. We accessed hospital records and state Vital Records from 2003 to 2009 to determine which patients died within a 12‐month follow‐up period, and their date of death (primary outcome).

Cohort Risk Stratification

Based on their CARING score, participants were classified as being at low, medium, or high risk of death at 1 year.13 The probability of imminent death in the group of high‐risk patients is the main indication for an advance directive, and therefore the analysis of this high‐risk group would be confounded. Therefore, those at high (and unclassified) risk of death (89 [and 13] out of 458 interviewed patients) were excluded from the survival analysis. Including persons at high risk of death in this analysis would lead to confounding by indicationthat physicians are most likely to address ADs with patients that they perceive are likely to die in the near future. An example of this in the literature is the timing of do‐not‐attempt‐resuscitation orders (DNAR). It is well documented that most DNAR orders are written within 1 to 2 days of death.1416 The DNAR orders do not cause or lead to death, they are simply finally written for patients that are actively dying.

Statistical Analysis

SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. Survival analysis was conducted to examine time to death. Interaction effects of the variable of interest with patient risk were assessed by estimating Kaplan‐Meier survival curves for low and medium risk groups separately. The Wilcoxon and log‐rank tests were employed to compare those with and without AD discussions (and accounting for clustering within hospitals) and documentation. Since the stratification into risk groups involves the use of the CARING criteria, which were the main confounders, additional risk adjustment in each risk group was not performed. Post hoc power analysis showed an ability to detect a 13 percentage points difference in mortality rate, with 80% power for a 2‐sided test and alpha = 0.05, assuming a 20% death rate for the group without AD discussion (adjusting for the covariate distribution difference between those with and without AD discussion).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the 356 study subjects are listed in Table 1. Overall, the sample population was ethnically diverse, slightly above middle‐aged, mostly male, and of lower socioeconomic status, reflecting the hospitals' populations. Using the CARING criteria, 297 subjects were found to be at low risk, and 59 subjects at medium risk, of death at 1 year.

| Percent (n) or Mean SD | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 19% (69) |

| Caucasian | 55% (194) |

| Latino | 19% (66) |

| Other | 8% (27) |

| Age (years) | 57.2 15 |

| Female gender | 34% (122) |

| Admitted to | |

| DVAMC | 41% (147) |

| DHMC | 34% (122) |

| UCH | 24% (87) |

| CARING criteria | |

| Cancer diagnosis | 4% (15) |

| Admitted to hospital 2 times in the past year for chronic illness | 31% (109) |

| Resident in a nursing home | 2% (7) |

| Non‐cancer hospice guidelines (meeting 2) | 1% (4) |

| Income less than $30,000/yr | 81% (284) |

| No greater than high school education | 53% (188) |

| Living situation | |

| Home owner | 36% (125) |

| Rents home | 38% (132) |

| Unstable living situation | 27% (94) |

| Low social support | 37% (169) |

| Uninsured | 14% (51) |

| Regular primary care provider | 72% (254) |

Overall, 206 (45%) reported a discussion about ADs with a healthcare provider. However, we found that only 56 (10%) had an AD document on their chart. Twenty‐eight (6%) had a living will, 43 (9%) had a durable power of attorney, and 30 (7%) had a broader AD document. Between 2003 and 2009, 121 (26%) patients died. Unadjusted mortality rates for those with and without documentation and discussions of ADs are displayed in Figure 1.

Kaplan‐Meier survival curves showed that, for subjects with a low or medium risk of death at 1 year, having had an AD discussion or having an AD in the medical record did not affect survival in subjects (Figures 2 and 3). Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for other covariates confirmed the results of the survival analysis (data not shown). Minimal intraclass correlation coefficients (0.005) were observed for the outcomes. Therefore, no models accounting for clustering within hospitals were developed.

DISCUSSION

We found no decrease in survival for patients at low and medium 1‐year risk of death who reported having discussed ADs or who had an AD in their medical record, providing important evidence that having advance care planning discussions do not hasten death in this group of adults. However, it is possible that ADs, when implemented properly, may dictate withdrawal or withholding of interventions that may extend quantity of life at a quality unacceptable for the person executing the directive. For example, a feeding tube delivering artificial nutrition and hydration may grant years to someone in a persistent vegetative state, but those years, without the ability to be aware or interact with surroundings and loved ones, may not be a life worth living for some individuals. One explanation for our negative findings may be that the circumstances in which an AD may have an effect on outcomes may not yet have occurred among this lower risk population.

Opposition to the process of advance care planning may be considered unethical, by removing the opportunity for individuals to express their desires in the event of decisional incapacity, therefore disregarding patient autonomy. Furthermore, with the growing evidence that AD discussions and documentation help patients achieve care consistent with their wishes at the end of life,9, 11, 17 preventing advance care planning may worsen end of life outcomes.

Another important finding in our study was that only about 10% of the patients interviewed had completed an AD document, although nearly half reported they had discussed ADs with a healthcare provider. The patients we interviewed in this study had been admitted to the hospital in the previous 24 hours. As part of the Patient Self‐Determination Act, all patients admitted to a healthcare facility should receive information and counseling on AD. Less than half of our cohort reported any discussions about ADs and only 10% had completed an AD, suggesting that huge opportunities exist for improvement in advance care planning. As this study demonstrates, there was no increased mortality from advance care planning among those at low and medium risk of death, and others have shown benefits from the process. AD discussions and documentation should be fostered, especially as the burden of chronic disease increases and the population ages. In targeted studies to improve advance care planning, completion rates of up to 85% have been achieved.17

Our decision to focus solely on patients at low or medium risk of death, and exclude those at a high risk of death, is based on both clinical and methodological judgment. First, it is important to note that ADs are important even for those at lower risk of deaththe 3 critical cases that have shaped AD policy in this country, Karen Ann Quinlan, Nancy Cruzan, and Terry Schiavo, were all otherwise healthy young women.

Our study does have limitations. First, the sample size is small and not powered to detect small differences in survival. In addition, we only examined Vital Records within Colorado, although all participants had either a date of death or recent date of last contact. It is also conceivable that some patients discussed or completed ADs at a later time in their illness trajectory. However, the generalizability of this study is a major strength, by including a population and healthcare settings that are ethnically and socioeconomically diverse. Generalization of results beyond the three types of hospitals should be limited even with the low intraclass correlation. The major limitation of this research is that we do not have data on participant quality of life or whether completing an AD led to increased use of palliative care. During the time the research was conducted, 2 of the 3 hospitals involved had small palliative care services and the third remains without a palliative care service.

In conclusion, our study provides limited data to counteract the misleading claims of those opposed to the advance care planning process. Our results underscore the importance of educating the public on the importance of ADs and cast doubt on the death myth surrounding advance care planning. However, further, preferably longitudinal, study is needed to prospectively understand both the benefits and risks of advance care planning.

All new legislation concerning advance care planning was removed from the Affordable Care Act, signed into law in March 2010. However, through a Medicare payment regulation, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) was able to add a provision allowing compensation to physicians for advance directive (AD) discussions as part of the annual Medicare wellness exam. Previously, under President George W. Bush, funding for AD discussions was already part of the Welcome to Medicare visit. Once again, the provision was misrepresented and distorted in the media, talk radio shows, and social networking sites. Within days of the announcement, the White House removed the regulation stating that the controversy surrounding the provision was distracting from the overall debate about healthcare. The term death panels has now entered our national lexicon and serves to undermine the efforts of the palliative care field which, through discussions with patients and families, attempts to provide care consistent with patients' goals.

In fact, ADs have been a cornerstone of ethical decision making, by supporting patient autonomy and allowing patient wishes to be respected when decisional capacity is lacking. Advance directives may include a living will, a Medical Durable Power of Attorney, or may be a broader more comprehensive document outlining goals, values, and preferences for care in the event of decisional incapacity. ADs allow patients to express preferences that incorporate both quantity and quality of life, as there are times when interventions at the end of life may increase length of life to the detriment of quality of life. In this context, patients may chose to value quality of life and request the interventions be withdrawn that focus on maintaining life without hope for quality of life. ADs also permit patients who prefer quantity over quality of life to communicate these wishes. These conversations are complex and time‐consuming. Patients may have profound misperceptions about the benefits offered by interventions at the end of life. Having detailed conversations with healthcare providers about actual benefits, risks, and alternatives has been shown to impact that decision‐making process.1 In our current payment system, these time‐consuming conversations are not compensated by private or public insurers, and are incompatible with 20‐minute appointments, so they rarely occur.24 While Nancy Cruzan and Terri Schiavo brought national attention to the issue for a brief time, recent data suggest that only 30% of adults have completed an AD,57 however, 93% of adults would like to discuss ADs with their physician.8 Furthermore, Silveira et al. showed that older adults with ADs are more likely than those without ADs to receive care that is consistent with their preferences at the end of life.9 ADs were the sole predictor of concordance between preferred and actual site of death in a cohort of seriously ill, hospitalized patients.10 Patients with advanced cancer who discussed their end of life wishes with their physician were more likely to receive care consistent with their preferences.11

Advance directives are based on the ethical principle of autonomy and, with the growing evidence that ADs may improve care at the end of life, public understanding of the issue is critical. We had presented early preliminary data in a letter to the editor showing that having had an advance directive discussion or an AD in the medical record was not associated with an increased risk of death.12 This research, along with the work of Silveira and colleagues,9 was cited by the Obama administration when they decided to add the regulation for including advance care planning as part of the annual Medicare wellness exams. This brief report presents a more comprehensive examination of the relationship of AD discussions and AD documentation with survival in a group of hospitalized patients.

METHODS

Study Sites and Participant Recruitment

This was a multisite, prospective study of patients admitted to the hospital for medical illness. The Colorado Multi‐Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Over a 17‐month period starting in February 2004, participants were recruited from 3 hospitals affiliated with the University of ColoradoDenver Internal Medicine Residency program: the Denver Veterans' Administration Center (DVAMC); Denver Health Medical Center (DHMC), the city's safety net hospital; and University of Colorado Hospital (UCH), an academic tertiary, specialty care and referral center. Exclusion criteria included: admission <24 hours, pregnancy, age <18 years, incarceration, spoke neither English nor Spanish, lack of decisional capacity. Recruitment was done on the day following admission to the hospital throughout the year, to reduce potential bias due to seasonal trends. A trained assistant recruited on variable weekdays (to allow inclusion of weekend admissions). Of 842 admissions occurring during the recruitment, 331 (39%) were ineligible (175 discharged and 2 died within 24 hours postadmission; 76 lacked decisional capacity; and 78 met other exclusion criteria listed above). All other patients (n = 511) were invited to participate and 458 patients consented.

Participant Interview and Measures

Fifty‐three (10%) refused; 458 gave informed consent and participated in a bedside interview, including questions related to advance care planning. In this interview, participants were first asked to define an AD. Their response was either confirmed or corrected using a standard simple explanation that defined and described ADs:

An advance directive is a document that lets your healthcare providers know who you would want to make decisions for you if you were unable to make them for yourself. It can also tell your healthcare providers what types of medical treatments you would and would not want if you were unable to speak for yourself.

They were then asked if any healthcare provider had ever discussed ADs with them (AD discussion is a primary variable of interest).

Chart Review and Vital Records Data Collection

We reviewed each medical record to determine admitting diagnoses, CARING criteria (a set of simple criteria developed by our group to score the need for palliative care, which has been shown to predict death at 1 year),13 socioeconomic and demographic information, and the presence of ADs in the medical record (documentation of AD is a primary variable of interest). We defined ADs broadly, including: living will, durable power of attorney for healthcare, or a comprehensive advance care planning document (eg, Five Wishes). The CARING criteria are validated criteria that accurately predict death at 1 year, and were developed to identify patients who would be appropriate for a palliative care intervention. It is based on the following variables: Cancer as a primary admitting diagnosis, Admitted 2 times to the hospital in the past year for a chronic medical illness, Resident of a nursing home, ICU admission with >2 organ systems in failure, and 2 Non‐Cancer hospice Guidelines as well as age. Scores range from 4 = low risk of death, 5‐12 = medium risk of death, and 13 = high risk of death at 1 year. We accessed hospital records and state Vital Records from 2003 to 2009 to determine which patients died within a 12‐month follow‐up period, and their date of death (primary outcome).

Cohort Risk Stratification

Based on their CARING score, participants were classified as being at low, medium, or high risk of death at 1 year.13 The probability of imminent death in the group of high‐risk patients is the main indication for an advance directive, and therefore the analysis of this high‐risk group would be confounded. Therefore, those at high (and unclassified) risk of death (89 [and 13] out of 458 interviewed patients) were excluded from the survival analysis. Including persons at high risk of death in this analysis would lead to confounding by indicationthat physicians are most likely to address ADs with patients that they perceive are likely to die in the near future. An example of this in the literature is the timing of do‐not‐attempt‐resuscitation orders (DNAR). It is well documented that most DNAR orders are written within 1 to 2 days of death.1416 The DNAR orders do not cause or lead to death, they are simply finally written for patients that are actively dying.

Statistical Analysis

SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. Survival analysis was conducted to examine time to death. Interaction effects of the variable of interest with patient risk were assessed by estimating Kaplan‐Meier survival curves for low and medium risk groups separately. The Wilcoxon and log‐rank tests were employed to compare those with and without AD discussions (and accounting for clustering within hospitals) and documentation. Since the stratification into risk groups involves the use of the CARING criteria, which were the main confounders, additional risk adjustment in each risk group was not performed. Post hoc power analysis showed an ability to detect a 13 percentage points difference in mortality rate, with 80% power for a 2‐sided test and alpha = 0.05, assuming a 20% death rate for the group without AD discussion (adjusting for the covariate distribution difference between those with and without AD discussion).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the 356 study subjects are listed in Table 1. Overall, the sample population was ethnically diverse, slightly above middle‐aged, mostly male, and of lower socioeconomic status, reflecting the hospitals' populations. Using the CARING criteria, 297 subjects were found to be at low risk, and 59 subjects at medium risk, of death at 1 year.

| Percent (n) or Mean SD | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 19% (69) |

| Caucasian | 55% (194) |

| Latino | 19% (66) |

| Other | 8% (27) |

| Age (years) | 57.2 15 |

| Female gender | 34% (122) |

| Admitted to | |

| DVAMC | 41% (147) |

| DHMC | 34% (122) |

| UCH | 24% (87) |

| CARING criteria | |

| Cancer diagnosis | 4% (15) |

| Admitted to hospital 2 times in the past year for chronic illness | 31% (109) |

| Resident in a nursing home | 2% (7) |

| Non‐cancer hospice guidelines (meeting 2) | 1% (4) |

| Income less than $30,000/yr | 81% (284) |

| No greater than high school education | 53% (188) |

| Living situation | |

| Home owner | 36% (125) |

| Rents home | 38% (132) |

| Unstable living situation | 27% (94) |

| Low social support | 37% (169) |

| Uninsured | 14% (51) |

| Regular primary care provider | 72% (254) |

Overall, 206 (45%) reported a discussion about ADs with a healthcare provider. However, we found that only 56 (10%) had an AD document on their chart. Twenty‐eight (6%) had a living will, 43 (9%) had a durable power of attorney, and 30 (7%) had a broader AD document. Between 2003 and 2009, 121 (26%) patients died. Unadjusted mortality rates for those with and without documentation and discussions of ADs are displayed in Figure 1.

Kaplan‐Meier survival curves showed that, for subjects with a low or medium risk of death at 1 year, having had an AD discussion or having an AD in the medical record did not affect survival in subjects (Figures 2 and 3). Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for other covariates confirmed the results of the survival analysis (data not shown). Minimal intraclass correlation coefficients (0.005) were observed for the outcomes. Therefore, no models accounting for clustering within hospitals were developed.

DISCUSSION

We found no decrease in survival for patients at low and medium 1‐year risk of death who reported having discussed ADs or who had an AD in their medical record, providing important evidence that having advance care planning discussions do not hasten death in this group of adults. However, it is possible that ADs, when implemented properly, may dictate withdrawal or withholding of interventions that may extend quantity of life at a quality unacceptable for the person executing the directive. For example, a feeding tube delivering artificial nutrition and hydration may grant years to someone in a persistent vegetative state, but those years, without the ability to be aware or interact with surroundings and loved ones, may not be a life worth living for some individuals. One explanation for our negative findings may be that the circumstances in which an AD may have an effect on outcomes may not yet have occurred among this lower risk population.

Opposition to the process of advance care planning may be considered unethical, by removing the opportunity for individuals to express their desires in the event of decisional incapacity, therefore disregarding patient autonomy. Furthermore, with the growing evidence that AD discussions and documentation help patients achieve care consistent with their wishes at the end of life,9, 11, 17 preventing advance care planning may worsen end of life outcomes.

Another important finding in our study was that only about 10% of the patients interviewed had completed an AD document, although nearly half reported they had discussed ADs with a healthcare provider. The patients we interviewed in this study had been admitted to the hospital in the previous 24 hours. As part of the Patient Self‐Determination Act, all patients admitted to a healthcare facility should receive information and counseling on AD. Less than half of our cohort reported any discussions about ADs and only 10% had completed an AD, suggesting that huge opportunities exist for improvement in advance care planning. As this study demonstrates, there was no increased mortality from advance care planning among those at low and medium risk of death, and others have shown benefits from the process. AD discussions and documentation should be fostered, especially as the burden of chronic disease increases and the population ages. In targeted studies to improve advance care planning, completion rates of up to 85% have been achieved.17

Our decision to focus solely on patients at low or medium risk of death, and exclude those at a high risk of death, is based on both clinical and methodological judgment. First, it is important to note that ADs are important even for those at lower risk of deaththe 3 critical cases that have shaped AD policy in this country, Karen Ann Quinlan, Nancy Cruzan, and Terry Schiavo, were all otherwise healthy young women.

Our study does have limitations. First, the sample size is small and not powered to detect small differences in survival. In addition, we only examined Vital Records within Colorado, although all participants had either a date of death or recent date of last contact. It is also conceivable that some patients discussed or completed ADs at a later time in their illness trajectory. However, the generalizability of this study is a major strength, by including a population and healthcare settings that are ethnically and socioeconomically diverse. Generalization of results beyond the three types of hospitals should be limited even with the low intraclass correlation. The major limitation of this research is that we do not have data on participant quality of life or whether completing an AD led to increased use of palliative care. During the time the research was conducted, 2 of the 3 hospitals involved had small palliative care services and the third remains without a palliative care service.

In conclusion, our study provides limited data to counteract the misleading claims of those opposed to the advance care planning process. Our results underscore the importance of educating the public on the importance of ADs and cast doubt on the death myth surrounding advance care planning. However, further, preferably longitudinal, study is needed to prospectively understand both the benefits and risks of advance care planning.

- ,,.The influence of the probability of survival on patient's preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation.N Engl J Med.1994;330:545–549.

- ,,.Physician reluctance to discuss advance directives. An empiric investigation of potential barriers.Arch Intern Med.1994;154(20):2311–2318.

- Advance directives and advance care planning: report to Congress. US Department of Health 82(12):1487–1490.

- Facts on dying: policy relevant data on care at the end of life, USA and state statistics. Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Web site. Available at: http://www.chcr.brown.edu/dying/usastatistics.htm. Accessed September 20,2010.

- ,.The quest to reform end of life care: rethinking assumptions and setting new directions.Hastings Cent Rep. November—December2005;S52–S57.

- ,,, et al.End‐of‐life care and outcomes.Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 110.Rockville, MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; December2004;1–6.

- ,,,,.Advance directives for medical care—a case for greater use.N Engl J Med.1991;324(13):889–895.

- ,,.Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death.N Engl J Med.2010;362(13):1211–1218.

- ,,.Advance directives: the best predictor of congruence between preferred and actual site of death [Research Poster Abstracts].Journal of Hospital Medicine2010;5(S1):1–81.

- ,,,,.End‐of‐life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences.J Clin Oncol2010;28(7):1203–1208.

- ,,.Advance directive discussions do not lead to death.J Am Geriatr Soc.2010;58(2):400–401.

- ,,,,,.Practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: the CARING criteria.J Pain Symptom Manage.2005;31(4):285–292.

- ,,.Do not resuscitate orders and the cost of death.Arch Intern Med.1993;153(10):1249–1253.

- ,,,,.The do‐not‐resuscitate order: associations with advance directives, physician specialty and documentation of discussion 15 years after the Patient Self‐Determination Act.J Med Ethics.2008;34(9):642–647.

- ,,, et al.Factors associated with do‐not‐resuscitate orders: patients' preferences, prognoses, and physicians' judgments. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment.Ann Intern Med.1996;125(4):284–293.

- ,.Death and end‐of‐life planning in one midwestern community.Arch Intern Med.1998;158(4):383–390.

- ,,.The influence of the probability of survival on patient's preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation.N Engl J Med.1994;330:545–549.

- ,,.Physician reluctance to discuss advance directives. An empiric investigation of potential barriers.Arch Intern Med.1994;154(20):2311–2318.

- Advance directives and advance care planning: report to Congress. US Department of Health 82(12):1487–1490.

- Facts on dying: policy relevant data on care at the end of life, USA and state statistics. Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Web site. Available at: http://www.chcr.brown.edu/dying/usastatistics.htm. Accessed September 20,2010.

- ,.The quest to reform end of life care: rethinking assumptions and setting new directions.Hastings Cent Rep. November—December2005;S52–S57.

- ,,, et al.End‐of‐life care and outcomes.Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 110.Rockville, MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; December2004;1–6.

- ,,,,.Advance directives for medical care—a case for greater use.N Engl J Med.1991;324(13):889–895.

- ,,.Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death.N Engl J Med.2010;362(13):1211–1218.

- ,,.Advance directives: the best predictor of congruence between preferred and actual site of death [Research Poster Abstracts].Journal of Hospital Medicine2010;5(S1):1–81.

- ,,,,.End‐of‐life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences.J Clin Oncol2010;28(7):1203–1208.

- ,,.Advance directive discussions do not lead to death.J Am Geriatr Soc.2010;58(2):400–401.

- ,,,,,.Practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: the CARING criteria.J Pain Symptom Manage.2005;31(4):285–292.

- ,,.Do not resuscitate orders and the cost of death.Arch Intern Med.1993;153(10):1249–1253.

- ,,,,.The do‐not‐resuscitate order: associations with advance directives, physician specialty and documentation of discussion 15 years after the Patient Self‐Determination Act.J Med Ethics.2008;34(9):642–647.

- ,,, et al.Factors associated with do‐not‐resuscitate orders: patients' preferences, prognoses, and physicians' judgments. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment.Ann Intern Med.1996;125(4):284–293.

- ,.Death and end‐of‐life planning in one midwestern community.Arch Intern Med.1998;158(4):383–390.

Copyright © 2011 Society of Hospital Medicine

Characteristics of High Cost/LOS Patients

Patients with advanced illness frequently do not receive care that meets their physical and emotional needs at the end of life,1 despite significant expenditures. Palliative care has been recommended as an approach to improve the quality of care for patients with advanced illness,26 while achieving hospital cost savings.7 Studies show that palliative care consults are associated with decreased hospitalization cost712 and length of stay13, 14 in the acute care setting.

Identifying which hospitalized patients are likely to benefit most from palliative care has not been well defined. The Hamilton Chart Audit tool was developed to estimate the number of patients that would benefit from a palliative care consult, in order to determine hospital palliative care staffing and financial needs.15 The CARING criteria identifies patients on admission to the hospital who are at high risk of death within one year and may, therefore, benefit from palliative care.16 The literature from the medical intensive care unit (MICU) identifies palliative care core competencies and quality measures, but does not describe patient factors that should trigger a palliative care consult.1719 Norton et al. studied proactive palliative care consultation in the MICU, finding that palliative care consultation in the high‐risk group (serious illness and high risk of dying) was associated with a shorter MICU length of stay without a significant difference in mortality rates.14

The most specific triggers for a palliative care consult comes from the surgical intensive care guidelines. The American College of Surgeons Surgical Palliative Care Task Force published a consensus guideline based on expert opinion identifying the top ten triggers for a palliative care consultation in the surgical intensive care unit (SICU).20 The top 10 criteria to identify SICU patients for palliative care consultation listed in order of priority were: 1) family request; 2) futility considered or declared by the medical team; 3) family disagreement with the team, advance directive, or each other lasting greater than seven days; 4) death expected during the same SICU stay; 5) SICU stay of greater than one month; 6) diagnosis with a median survival of less than six months; 7) greater than three SICU admissions during the same hospitalization; 8) Glasgow Coma Score of less than eight for greater than one week in a patient greater than 75 years old; 9) Glasgow Outcome Score of less than three (i.e., persistent vegetative state); and 10) multisystem organ failure of greater than three systems.

Studies are lacking that identify hospitalized patients who are more likely to have higher cost per day or length of stay, as these are patients who may benefit from palliative care. We sought to identify patient characteristics that are associated with higher cost per day or longer length of stay in hospitalized patients who died during the hospitalization or were discharged to hospicepatients likely to benefit from targeted palliative care services. We hypothesized that hospitalized patients with the following characteristics who died during the hospitalization or were discharged to hospice would have a higher cost per day or longer length of stay: older patients, lack of insurance, and patients receiving care from a critical care specialty.

METHODS

Study Design

We analyzed administrative data from a single academic hospital, the University of Colorado Hospital, a tertiary care, academic hospital with approximately 400 beds. The study population consisted of hospitalized adult patients (age 18 years) who died during hospitalization or were discharged to hospice in 2006 and 2007. We included both patients discharged to hospice and those who died during hospitalization, as we were seeking to identify a hospitalized patient population who might be expected to benefit from palliative care: those at high risk of death in the near future. Predictors were selected on the basis of clinical experience and the literature. Cost per day and length of stay were the outcome variables. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not necessary because all of the study patients were deceased at the time of analysis.

Due to resource limitations, we were only able to gather clinical information (presence of organ failure [cardiac, respiratory, renal, hepatic, neurologic] or sepsis on admission, and presence or absence of palliative care consultation during hospitalization) from chart review in a subset of the sample population: those that had the highest 10% total hospitalization costs (n = 115). Organ failure was defined as chart documentation of any of the following: 1) cardiac: ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, non‐ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, heart failure (n = 28); 2) respiratory: respiratory failure (n = 36); 3) renal: acute kidney injury, acute renal failure, chronic renal failure, dialysis, end‐stage renal disease (n = 42); 4) hepatic: hepatic failure, end‐stage liver disease (n = 10); and 5) neurologic: altered mental status, delirium (n = 4). Sepsis was defined as chart documentation of any of the following: sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock.

Outcomes

We found total cost and length of stay to be correlated. Therefore, we used cost per day in lieu of total cost as the primary outcome. Length of stay was the secondary outcome. Using cost per day as the primary outcome reduced the correlation between our primary and secondary outcomes.

Predictors

Potential predictors (age, insurance status, and attending physician specialty) were selected on the basis of clinical experience, the literature, and patient variables available from the administrative data. We also considered diagnosis‐related group (DRG), however, the wide range of unique DRGs for this population did not allow for sensible groupings, so DRG was excluded from further analyses. For descriptive purposes, mean (standard deviation, SD) age was reported. For modeling, age was centered at 65 years, because this is the age of Medicare eligibility and thus a likely point at which insurance status would change. Sixty‐five was also close to the mean age of the full population, 62 years, therefore ensuring that interactions were assessed over the bulk of the data, rather than at outlying points. We also divided age into ten‐year increments for easier interpretation of model estimates. The relationship between age and primary and secondary outcomes differed among younger vs older patients. Therefore, age was included as a piecewise term in the final multivariate linear model which allowed a separate slope to be fit for patients age <65 years vs those 65 years.

Insurance status was dichotomized as insured vs uninsured. Attending physician specialty categories (internal medicine, pulmonary critical care, neurosurgery, surgical oncology, and cardiothoracic surgery) were selected because they were the five most common specialties. The remaining specialties were grouped together as other, which was used as a reference group in the multivariate analyses as it constituted a nontrivial proportion of the study population.

Statistical Analyses

Univariate analyses were performed separately for the primary and secondary outcomes. Univariate associations between the outcomes and categorical predictors were tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA) models with adjustment for multiple comparisons. Associations between the outcomes and the binary predictors were assessed with t‐tests. Predictors that were significant at the 0.10 level and considered clinically relevant were included in the multivariate model. Interaction terms between predictors were examined and included in the final multivariate piecewise linear models, when inclusion of the interaction terms altered the magnitude of the model estimates.

RESULTS

The study population comprised 1155 hospitalizations. Nine hospitalizations were excluded from analysis (five for organ donation, three were erroneousthe patients were not discharged to hospice or did not die during the hospitalization, and one was a pediatric patient), resulting in a study population of n = 1146 hospitalizations.

Table 1 depicts study population characteristics. The average patient age was 62 years (SD = 16), and 96% of patients were insured. The average length of stay was 10.7 days (SD = 14.1), with an average total cost per admission of $44,410 (SD = 76,355), as compared to an overall hospital admission (excluding obstetrics/neonatology) average length of stay of 5.7 days (SD = 8.5) and average total cost per admission of $17,410 (SD = 36,633) during the same time period. The average cost per day was $5095 (SD = $8546). About one‐third of patients were admitted to internal medicine, 20% to pulmonary critical care, and 18% to surgical specialties. The remaining 29% belonged to other specialties.

| Number of patients, n (%) | 1146 |

| Death in hospital | 730 (63.7) |

| Discharged with hospice | 416 (36.3) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 61.7 (15.9) |

| Insurance, n (%) | |

| Uninsured | 52 (4.5) |

| Insured | 1,094 (95.5) |

| Length of stay (days), mean (SD) | 10.7 (14.1) |

| Total cost, mean (SD) | $44,410 (76,355) |

| Cost per day, mean (SD) | $5,095 (8,546) |

| Attending MD specialty, n (%) | |

| Cardiothoracic Surgery | 56 (4.9) |

| Pulmonary Critical Care | 230 (20.1) |

| Surgical Oncology | 70 (6.1) |

| Internal Medicine | 383 (33.4) |

| Neurosurgery | 77 (6.7) |

| Other | 330 (28.8) |

Univariate Analyses

Overall, younger patients had a higher cost per day (Pearson 0.09; P = 0.02) and longer length of stay (Pearson 0.15; P < 0.0001) than older patients (data not shown). According to age groups defined by quartiles, patients who were age <51 and between 61‐72 years had significantly higher cost per day than patients age 73 years ($5787 and $5826 vs $3649, respectively; ANOVA P = 0.005; pairwise P < 0.05). The length of stay for the age groups under 73 years of age were significantly longer than for the patients who were 73 years of age and older (11.9, 11.9, and 11.2 vs 8.0 days, respectively; ANOVA P = 0.001; pairwise P < 0.05; Table 2). Uninsured patients had a higher cost per day ($6618 vs $5023; P = 0.02) than insured patients. In pairwise comparisons, patients on the cardiothoracic surgery service had a higher cost per day ($17,942) than any other specialty (ANOVA P < 0.0001; pairwise P < 0.05). Neurosurgery patients had a higher cost per day ($7089) than the internal medicine patients ($3173; pairwise P < 0.05). Cardiothoracic surgery patients also had a significantly higher LOS (18.3 days) than internal medicine (8.0 days), critical care (11.6 days), neurosurgery (10.0 days), and the other (10.9 days) specialties (ANOVA P < 0.0001; pairwise P < 0.05). The LOS for internal medicine (8.0 days) was significantly lower than critical care (11.6 days), surgical oncology (15.9 days), and cardiothoracic surgery (18.3 days; pairwise P < 0.05).

| Variable | N | Cost per day [$] (mean [SD]) | P Value | Length of stay [days] (mean [SD]) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| 1146 | |||||

| Age group, quartiles | |||||

| <51 years | 281 | 5,787 (8,008) | 0.005 | 11.9 (16.4) | 0.001 |

| 51‐60 | 264 | 5,202 (7,643) | 11.9 (15.4) | ||

| 61‐72 | 297 | 5,826 (12,272) | 11.2 (14.1) | ||

| 73 | 304 | 3,649 (3,978) | 8.0 (9.7) | ||

| Insurance | |||||

| Insured | 1094 | 5,023 (8,691) | 0.02 | 10.8 (14.2) | 0.23 |

| Uninsured | 52 | 6,618 (4,297) | 8.4 (13.5) | ||

| Attending MD specialty | |||||

| Internal Medicine | 383 | 3,173 (2,647) | <0.0001* | 8.0 (11.0) | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary Critical Care | 230 | 4,671 (2,734) | 11.6 (14.3) | ||

| Neurosurgery | 77 | 7,089 (6,103) | 10.0 (13.5) | ||

| Surgical Oncology | 70 | 5,768 (3,521) | 15.9 (17.9) | ||

| Cardiothoracic Surgery | 56 | 17,942 (26,943) | 18.3 (23.6) | ||

| Other | 330 | 4,833 (8,641) | 10.9 (13.6) | ||

Multivariate Analyses

Cost per Day

The final multivariate linear model included age and attending physician specialty. Insurance status was excluded because it lost significant association with cost per day when it was added to the model (Table 3). Compared to the other specialty, internal medicine decreased cost per day by $1531 (P = 0.01), neurosurgery increased cost per day by $2255 (P = 0.03), and cardiothoracic surgery increased cost per day by $12,937 (P < 0.0001). Cost per day decreased by $811 (SE = 349; P = 0.02) for each age decade 65 years, however, no effect was observed on cost per day for those younger than 65 years.

| Predictors | Estimated Effect ($) | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value to Test if = 0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Other specialty (reference group at 65 yr) | 5209 | (4,133, 6,284) | |

| Internal Medicine | 1,531 | (2,709, 353) | 0.01 |

| Pulmonary Critical Care | 217 | (1,562, 1,128) | 0.75 |

| Neurosurgery | 2255 | (278, 4,232) | 0.03 |

| Surgical Oncology | 1064 | (994, 3,122) | 0.31 |

| Cardiothoracic Surgery | 12937 | (10,676, 15,198) | <0.0001 |

| Age per 10 yr/age <65 | 7 | (506, 519) | 0.98 |

| Age per 10 yr/age 65 | 811 | (1,497, 125) | 0.02 |

Length of Stay

Because age and attending physician specialty had a significant effect on length of stay, multivariate analyses were performed with these two predictor variables (Table 4). Compared to the other specialty, internal medicine decreased length of stay by 2.4 days (P = 0.02), surgical oncology increased LOS by 5.3 days (P = 0.003), and cardiothoracic surgery increased length of stay by 6.9 days (P = 0.001). Length of stay was significantly decreased by 1.8 days (SE = 0.61; P = 0.003) for each age decade 65 years.

| Predictors | Estimated Effect (days) | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value to Test if = 0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Other specialty (reference group at 65 yr) | 11 | (9.1, 12.9) | |

| Internal Medicine | 2.4 | (4.4, 0.3) | 0.02 |

| Pulmonary Critical Care | 0.5 | (1.9, 2.8) | 0.7 |

| Neurosurgery | 0.9 | (4.3, 2.6) | 0.62 |

| Surgical Oncology | 5.3 | (1.8, 8.9) | 0.003 |

| Cardiothoracic Surgery | 6.9 | (3.0, 10.9) | 0.001 |

| Age per 10 yr/age <65 | 0.8 | (1.7, 0.1) | 0.08 |

| Age per 10 yr/age 65 | 1.8 | (3.0, 0.6) | 0.003 |

DISCUSSION

We found several characteristics that were significantly associated with higher cost per day or longer length of stay in patients who died during hospitalization or were discharged to hospice. Among this patient population, the surgical specialty services had overall higher cost per day and length of stay than other services. Patients cared for on the cardiothoracic surgery service had higher cost per day and length of stay; in contrast, internal medicine patients had lower cost per day and length of stay. Neurosurgery patients had higher cost per day, while surgical oncology patients had higher length of stay. Patients age 65 years and older had a significantly lower cost per day and shorter length of stay than those less than 65 years of age.

Higher cost per day for cardiothoracic surgery and neurosurgery patients may partially be explained by cardiothoracic surgery patients' usage of clinical services, including operating room services, which are higher in costs compared with those of nonsurgical specialties. Some patients may require repeat surgeries in the same hospitalization which further increases the cost per day. Longer length of stay in surgical oncology patients may be related to complex surgeries and possible postoperative complications that may take longer to recover from than standard surgeries.

Our findings that older patients have lower cost per day and shorter length of stay are corroborated by other studies. Lubitz and Riley21 found that in 1976 and 1988, Medicare payments per person year decreased with age. Levinsky et al.22 had similar findings in a review of Medicare data in 2001, but noted smaller reductions in total costabout $400 decrease for each year above 65. Their explanation of the lower cost is that older patients receive less aggressive care. Physicians, as well as patients and families, may continue to pursue expensive, invasive therapies for terminally ill patients who are younger for a longer period of time than with older patients, which would increase cost per day as well as length of stay.

The finding that patients on the surgical specialty services may be a focus for active palliative care intervention has many implications. The American College of Surgeons Surgical Palliative Care Task Force consensus guideline triggers for a palliative care consultation in SICU applied clinically did not result in a change in palliative care consultation rate.23 The use of triggers for palliative care consultation may be an ineffective approach because knowledge and application of the triggers did not change behavior. Focusing on integrating palliative care interventions or consultation for all high‐risk surgical patients, as opposed to relying upon triggers, may be a more effective approach to meeting these patients' palliative care needs while lowering cost per day and length of stay and warrants further study. For instance, palliative care consult teams may consider routine or daily rounds with the surgical specialty services in order to effectively integrate palliative care for these patients. Such an integrative approach may foster familiarity and comfort with palliative care approaches, facilitating access to palliative care services for those patients with palliative needs.

Our study is limited in that it is a retrospective, single‐center study. Our results may not be applicable to the general population. The experience of additional centers analyzed prospectively would provide additional context. The available administrative data limited the analyses to only a small number of predictors. In the subset population with the highest 10% total hospitalization costs, from which clinical information was gathered, the presence of respiratory failure was associated with shorter LOS (33 days vs 42 days; P = 0.03), but not associated with cost per day. Having sepsis at admission was associated with lower cost per day ($5783 vs $10,071; P = 0.04); however, this finding was based on only four patients with sepsis at admission. Patients who were evaluated by the palliative care service (n = 35) had a significantly lower cost per day ($4896 vs $12,210; P = 0.01) but longer LOS (46.5 vs 35.7 days; P = 0.03) than those who were not. These, and other, clinical characteristics need further testing in larger samples. An additional limitation is that we combined hospital decedents with patients discharged to hospice as our study population. These groups were combined since they are both at high risk of death in the near future; the median hospice length of stay in Colorado is 20 days.24 There may exist important differences in these populations that are not accounted for in our findings. Despite these unidentified differences, both populations are at high risk of death in the near future, making it likely that they would benefit from palliative care. Those who died during hospitalization did have a longer LOS (11.5 vs 9.2 days; P = 0.003) and higher cost per day ($6734 vs $2221; P < 0.0001) than those who were discharged to hospice.

Palliative care consultations can lead to improved quality of care for patients and families by addressing suffering and addressing quality of life measures (2, 4, 5, 6). We sought to identify characteristics associated with high cost and prolonged hospitalizations in patients who died during hospitalization, or were discharged to hospice, in order to inform targeting of palliative care services. Our data suggest that younger patients and those cared for by surgical specialty services may have the most palliative needs. Palliative care teams may consider focusing efforts at integrating palliative care with surgical specialty services to address these needs. These findings need to be corroborated in other centers, and include clinical outcomes.

- ,,, et al.Family perspectives on end‐of‐life care at the last place of care.JAMA.2004;291:88–93.

- ,.Do specialist palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients? A systematic literature review.Palliat Med.1998;12:317–332.

- ,,, et al.Evidence‐based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians.Ann Intern Med.2008;148:141–146.

- ,,, et al.Do palliative consultations improve patient outcomes?JAGS.2008;56:593–599.

- ,,, et al.Effects of a palliative cafe intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer.JAMA.2009;302:741–749.

- ,,, et al.Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer.N Engl J Med.2010;363:733–742.

- ,,, et al.Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs.Arch Intern Med.2008;168(16):1783–1790.

- ,,.Impact of palliative care case management on resource use by patients dying of cancer at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center.J Palliat Med.2005;8(1):26–35.

- ,,, et al.Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital‐based palliative care consultation.J Palliat Med.2006;9(4):855–860.

- ,,, et al.A high‐volume specialist palliative care unit and team may reduce in‐hospital end‐of‐life care costs.J Palliat Med.2003;6(5):699–705.

- ,,, et al.The economic and clinical impact of an inpatient palliative care consultation service: a multifaceted approach.J Palliat Med.2007;10(6):1347–1355.

- ,,, et al.Hospital‐based palliative care consultation: effects on hospital cost.J Palliat Med.2010;13(8):1–7.

- ,.Impact of a proactive approach to improve end‐of‐life care in a medical ICU.Chest.2003;123:266–271.

- ,,, et al.Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: effects on length of stay for selected high‐risk patients.Crit Care Med.2007;35:1530–1535.

- ,,,,.Who needs a palliative care consult? The Hamilton Chart Audit tool.J Palliat Med.2007;10(2):304–307.

- ,,,,,.A practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative care approach: the CARING criteria.J Pain Symptom Manage.2006;31:285–292.

- ,,, et al.An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Policy Statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2008;177:912–927.

- ,,, et al.Proposed quality measures for palliative care in the critically ill: a consensus from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care Workgroup.Crit Care Med.2006;34:S404–S411.

- ,,, et al.Recommendations for end‐of‐life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American Academy of Critical Care Medicine.Crit Care Med.2008;36:953–963.

- ,.Developing guidelines that identify patients who would benefit from palliative care services in the surgical intensive care unit.Crit Care Med.2009;37:946–950.

- ,.Trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life.N Engl J Med.1993;328:1092–1096.

- ,,, et al.Influence of age on Medicare expenditures and medical care in the last year of life.JAMA.2001;286:1349–1355.