User login

Readmission Analysis Using Fault Tree

As physicians strive to increase the value of healthcare delivery, there has been increased focus on improving the quality of care that patients receive while lowering per capita costs. A provision of the Affordable Care Act implemented in 2012 identified all‐cause 30‐day readmission rates as a measure of hospital quality, and as part of the Act's Hospital Readmission and Reduction Program, Medicare now penalizes hospitals with higher than expected all‐cause readmissions rates for adult patients with certain conditions by lowering reimbursements.[1] Although readmissions are not yet commonly used to determine reimbursements for pediatric hospitals, several states are penalizing higher than expected readmission rates for Medicaid enrollees,[2, 3] using an imprecise algorithm to determine which readmissions resulted from low‐quality care during the index admission.[4, 5, 6]

There is growing concern, however, that readmission rates are not an accurate gauge of the quality of care patients receive while in the hospital or during the discharge process to prepare them for their transition home.[7, 8, 9, 10] This is especially true in pediatric settings, where overall readmission rates are much lower than in adult settings, many readmissions are expected as part of a patient's planned course of care, and variation in readmission rates between hospitals is correlated with the percentage of patients with certain complex chronic conditions.[1, 7, 11] Thus, there is increasing agreement that hospitals and external evaluators need to shift the focus from all‐cause readmissions to a reliable, consistent, and fair measure of potentially preventable readmissions.[12, 13] In addition to being a more useful quality metric, analyzing preventable readmissions will help hospitals focus resources on patients with potentially modifiable risk factors and develop meaningful quality‐improvement initiatives to improve inpatient care as well as the discharge process to prepare families for their transition to home.[14]

Although previous studies have attempted to distinguish preventable from nonpreventable readmissions, many reported significant challenges in completing reviews efficiently, achieving consistency in how readmissions were classified, and attaining consensus on final determinations.[12, 13, 14] Studies have also demonstrated that the algorithms some states are using to streamline preventability reviews and determine reimbursements overestimate the rate of potentially preventable readmissions.[4, 5, 6]

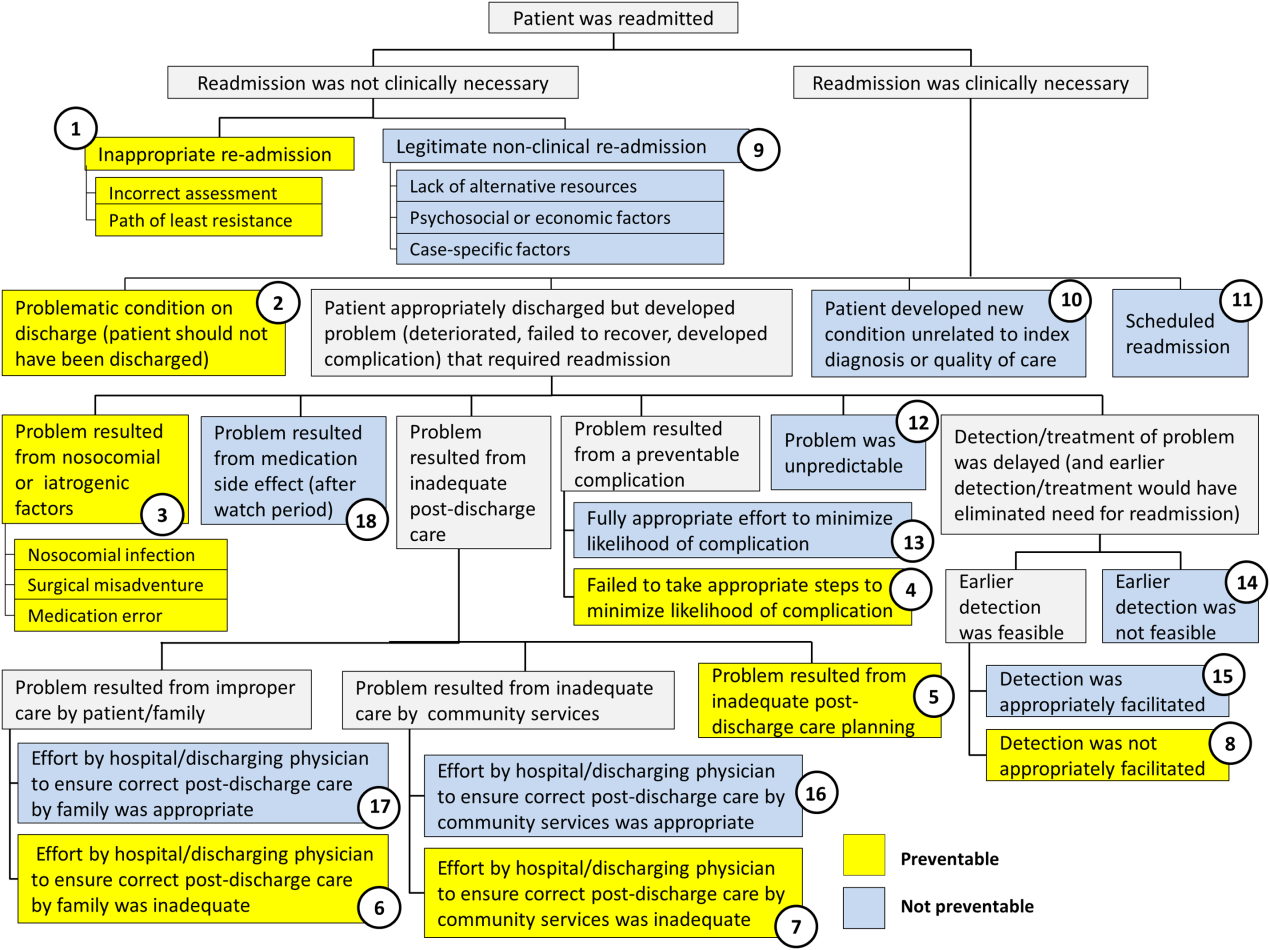

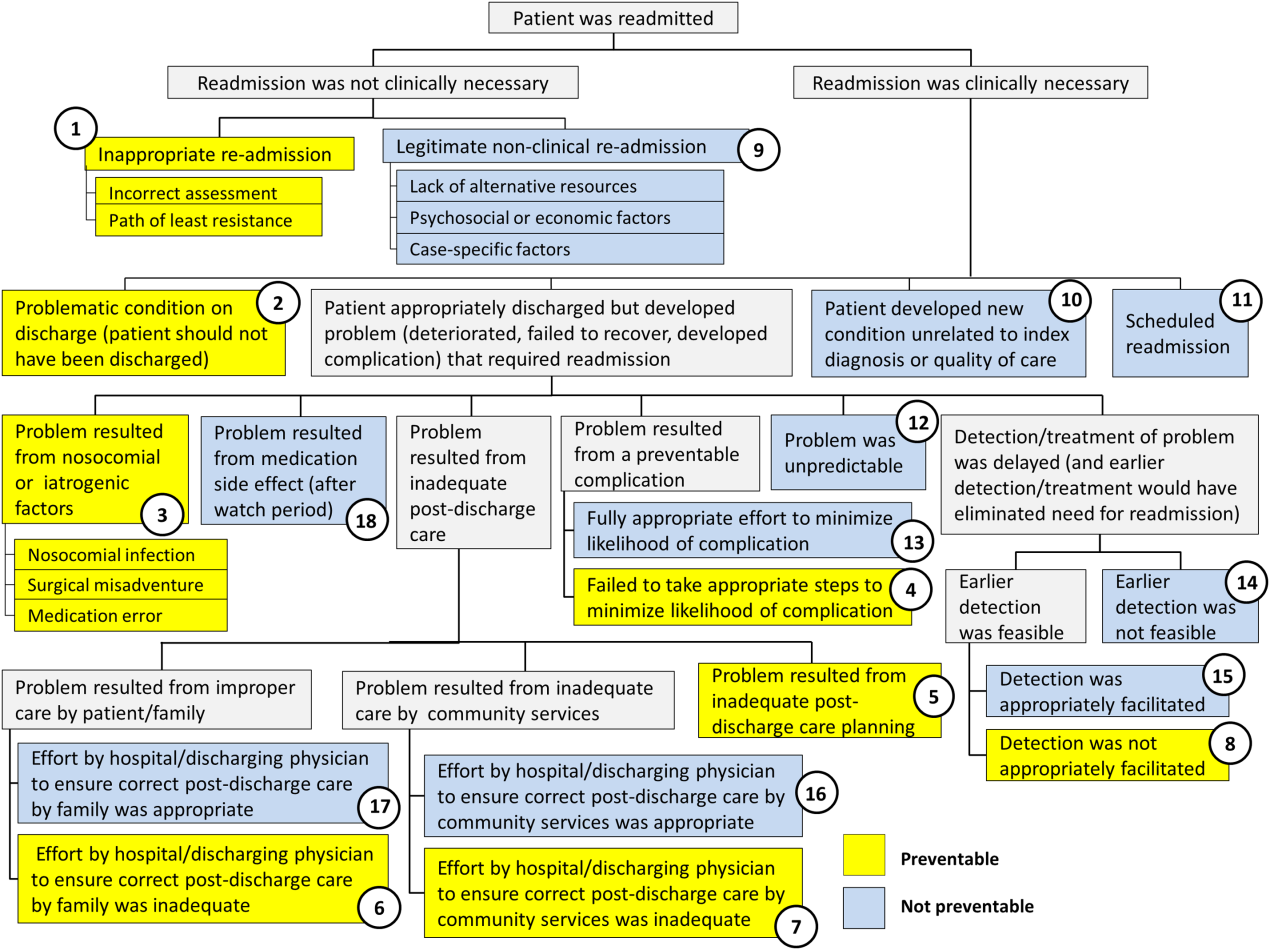

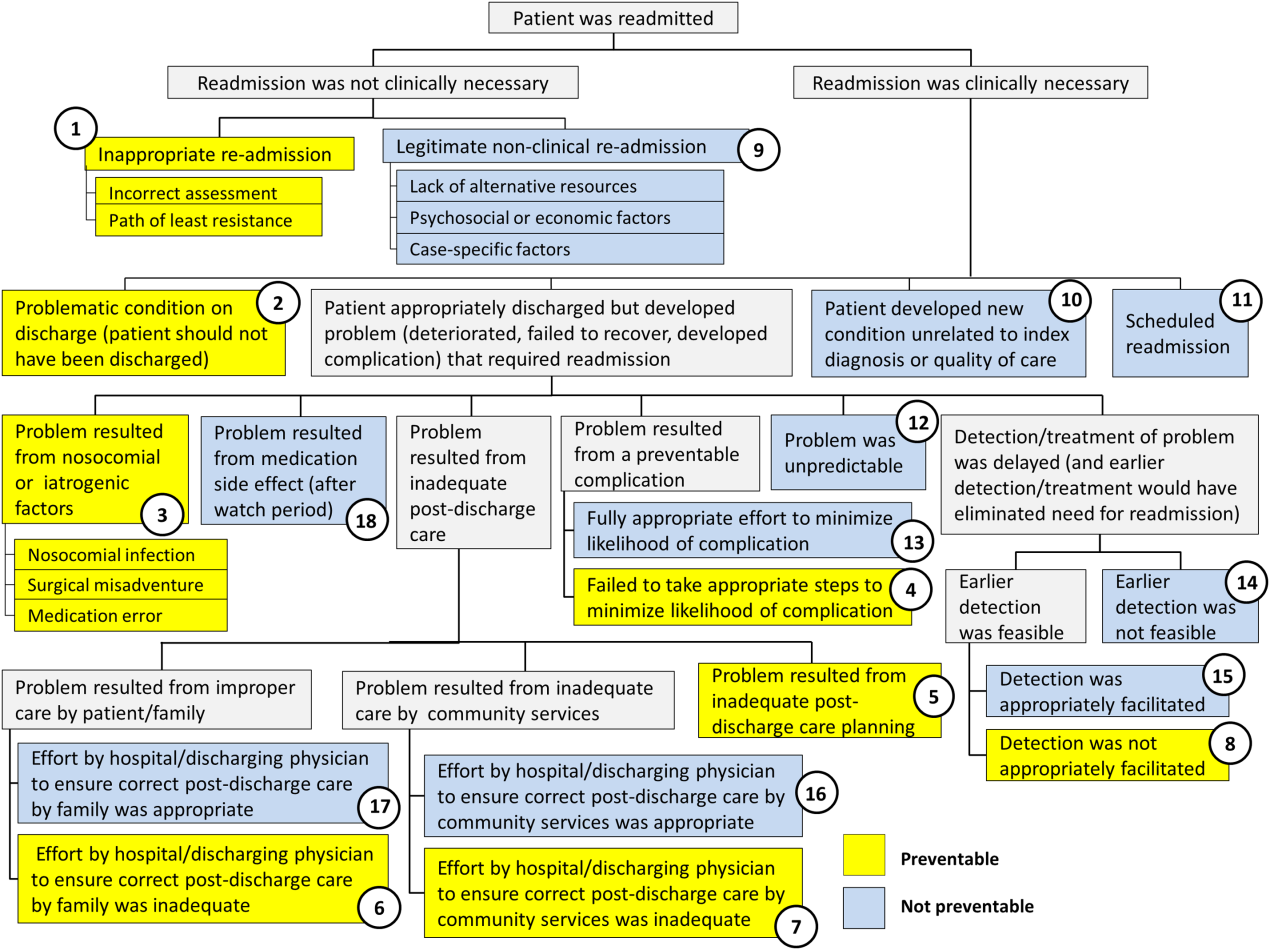

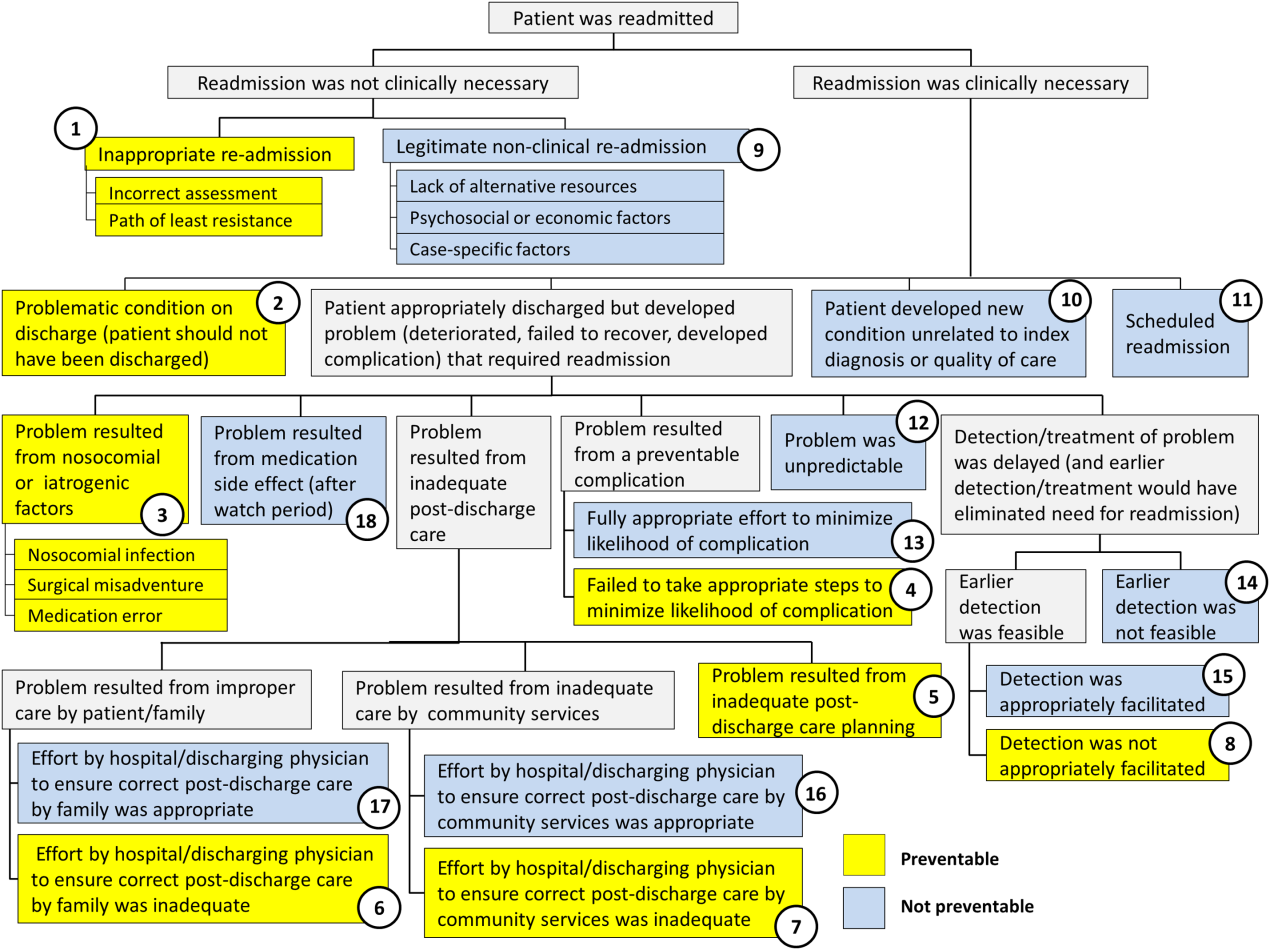

To increase the efficiency of preventability reviews and reduce the subjectivity involved in reaching final determinations, while still accounting for the nuances necessary to conduct a fair review, a quality‐improvement team from the Division of General Pediatrics at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) implemented a fault tree analysis tool based on a framework developed by Howard Parker at Intermountain Primary Children's Hospital. The CHOP team coded this framework into a secure Web‐based data‐collection tool in the form of a decision tree to guide reviewers through a logical progression of questions that result in 1 of 18 root causes of readmissions, 8 of which are considered potentially preventable. We hypothesized that this method would help reviewers efficiently reach consensus on the root causes of hospital readmissions, and thus help the division and the hospital focus efforts on developing relevant quality‐improvement initiatives.

METHODS

Inclusion Criteria and Study Design

This study was conducted at CHOP, a 535‐bed urban, tertiary‐care, freestanding children's hospital with approximately 29,000 annual discharges. Of those discharges, 7000 to 8000 are from the general pediatrics service, meaning that the attending of record was a general pediatrician. Patients were included in the study if (1) they were discharged from the general pediatrics service between January 2014 and December 2014, and (2) they were readmitted to the hospital, for any reason, within 15 days of discharge. Because this analysis was done as part of a quality‐improvement initiative, it focuses on 15‐day, early readmissions to target cases with a higher probability of being potentially preventable from the perspective of the hospital care team.[10, 12, 13] Patients under observation status during the index admission or the readmission were included. However, patients who returned to the emergency department but were not admitted to an inpatient unit were excluded. Objective details about each case, including the patient's name, demographics, chart number, and diagnosis code, were pre‐loaded from EPIC (Epic Systems Corp., Verona, WI) into REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture;

A panel of 10 general pediatricians divided up the cases to perform retrospective chart reviews. For each case, REDCap guided reviewers through the fault tree analysis. Reviewers met monthly to discuss difficult cases and reach consensus on any identified ambiguities in the process. After all cases were reviewed once, 3 panel members independently reviewed a random selection of cases to measure inter‐rater reliability and confirm reproducibility of final determinations. The inter‐rater reliability statistic was calculated using Stata 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). During chart reviews, panel members were not blinded to the identity of physicians and other staff members caring for the patients under review. CHOP's institutional review board determined this study to be exempt from ongoing review.

Fault Tree Analysis

Using the decision tree framework for analyzing readmissions that was developed at Intermountain Primary Children's Hospital, the REDCap tool prompted reviewers with a series of sequential questions, each with mutually exclusive options. Using imbedded branching logic to select follow‐up questions, the tool guided reviewers to 1 of 18 terminal nodes, each representing a potential root cause of the readmission. Of those 18 potential causes, 8 were considered potentially preventable. A diagram of the fault tree framework, color coded to indicate which nodes were considered potentially preventable, is shown in Figure 1.

RESULTS

In 2014, 7252 patients were discharged from the general pediatrics service at CHOP. Of those patients, 248 were readmitted within 15 days for an overall general pediatrics 15‐day readmission rate of 3.4%.

Preventability Analysis

Of the 248 readmissions, 233 (94.0%) were considered not preventable. The most common cause for readmission, which accounted for 145 cases (58.5%), was a patient developing an unpredictable problem related to the index diagnosis or a natural progression of the disease that required readmission. The second most common cause, which accounted for 53 cases (21.4%), was a patient developing a new condition unrelated to the index diagnosis or a readmission unrelated to the quality of care received during the index stay. The third most frequent cause, which accounted for 11 cases (4.4%), was a legitimate nonclinical readmission due to lack of alternative resources, psychosocial or economic factors, or case‐specific factors. Other nonpreventable causes of readmission, including scheduled readmissions, each accounted for 7 or fewer cases and <3% of total readmissions.

The 15 readmissions considered potentially preventable accounted for 6.0% of total readmissions and 0.2% of total discharges from the general pediatrics service in 2014. The most common cause of preventable readmissions, which accounted for 6 cases, was premature discharge. The second most common cause, which accounted for 4 cases, was a problem resulting from nosocomial or iatrogenic factors. Other potentially preventable causes included delayed detection of problem (3 cases), inappropriate readmission (1 case), and inadequate postdischarge care planning (1 case).

A breakdown of fault tree results, including examples of cases associated with each terminal node, is shown in Table 1. Information about general pediatrics patients and readmitted patients is included in Tables 2 and 3. A breakdown of determinations for each reviewer is included in Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article.

| Fault Tree Terminal Node | Root Cause of Readmission | No. of Cases | % of Total Readmissions | % Within Preventability Category | % of Total Discharges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| 2 (Potentially Preventable) | Problematic condition on discharge. Example:* Index admission: Infant with history of prematurity admitted with RSV and rhinovirus bronchiolitis. Had some waxing and waning symptoms. Just prior to discharge, noted to have increased work of breathing related to feeds. Readmission: 12 hours later with tachypnea, retractions, and hypoxia. | 6 | 2.4% | 40.0% | 0.08% |

| 3 (Potentially Preventable) | Nosocomial/Iatrogenic factors. Example*: Index admission: Toddler admitted with fever and neutropenia. Treated with antibiotics 24 hours. Diagnosed with viral illness and discharged home. Readmission: symptomatic Clostridum difficile infection. | 4 | 1.6% | 26.7% | 0.06% |

| 8 (Potentially Preventable) | Detection/treatment of problem was delayed and not appropriately facilitated. Example:* Index admission: Preteen admitted with abdominal pain, concern for appendicitis. Ultrasound and abdominal MRI negative for appendicitis. Symptoms improved. Tolerated PO. Readmission: 3 days later with similar abdominal pain. Diagnosed with constipation with significant improvement following clean‐out. | 3 | 1.2% | 20.0% | 0.04% |

| 1 (Potentially Preventable) | Inappropriate readmission. Example:* Index admission: Infant with laryngomalacia admitted with bronchiolitis. Readmission: Continued mild bronchiolitis symptoms but did not require oxygen or suctioning, normal CXR. | 1 | 0.4% | 6.7% | 0.01% |

| 5 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from inadequate postdischarge care planning. Example:* Index diagnosis: Infant with vomiting, prior admissions, and extensive evaluation, diagnosed with milk protein allergy and GERD. PPI increased. Readmission: Persistent symptoms, required NGT feeds supplementation. | 1 | 0.4% | 6.7% | 0.01% |

| 4 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from a preventable complication and hospital/physician did not take the appropriate steps to minimize likelihood of complication. | ||||

| 6 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from improper care by patient/family and effort by hospital/physician to ensure correct postdischarge care was inadequate. | ||||

| 7 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from inadequate care by community services and effort by hospital/physician to ensure correct postdischarge care was inadequate. | ||||

| 15 | 6.0% | 100% | 0.2% | ||

| 12 (Not Preventable) | Problem was unpredictable. Example:* Index admission: Infant admitted with gastroenteritis and dehydration with an anion gap metabolic acidosis. Vomiting and diarrhea improved, rehydrated, acidosis improved. Readmission: 1 day later, presented with emesis and fussiness. Readmitted for metabolic acidosis. | 145 | 58.5% | 62.2% | 2.00% |

| 10 (Not Preventable) | Patient developed new condition unrelated to index diagnosis or quality of care. Example:* Index admission: Toddler admitted with cellulitis. Readmission: Bronchiolitis (did not meet CDC guidelines for nosocomial infection). | 53 | 21.4% | 22.7% | 0.73% |

| 9 (Not Preventable) | Legitimate nonclinical readmission. Example:* Index admission: Infant admitted with second episode of bronchiolitis. Readmission: 4 days later with mild diarrhea. Tolerated PO challenge in emergency department. Admitted due to parental anxiety. | 11 | 4.4% | 4.7% | 0.15% |

| 17 (Not Preventable) | Problem resulted from improper care by patient/family but effort by hospital/physician to ensure correct postdischarge care was appropriate. Example:* Index admission: Infant admitted with diarrhea, diagnosed with milk protein allergy. Discharged on soy formula. Readmission: Developed vomiting and diarrhea with cow milk formula. | 7 | 2.8% | 3.0% | 0.10% |

| 11 (Not Preventable) | Scheduled readmission. Example:* Index admission: Infant with conjunctivitis and preseptal cellulitis with nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Readmission: Postoperatively following scheduled nasolacrimal duct repair. | 7 | 2.8% | 3.0% | 0.10% |

| 14 (Not Preventable) | Detection/treatment of problem was delayed, but earlier detection was not feasible. Example:* Index admission: Preteen admitted with fever, abdominal pain, and elevated inflammatory markers. Fever resolved and symptoms improved. Diagnosed with unspecified viral infection. Readmission: 4 days later with lower extremity pyomyositis and possible osteomyelitis. | 4 | 1.6% | 1.7% | 0.06% |

| 15 (Not Preventable) | Detection/treatment of problem was delayed, earlier detection was feasible, but detection was appropriately facilitated. Example:* Index admission: Infant with history of laryngomalacia and GER admitted with an ALTE. No events during hospitalization. Appropriate workup and cleared by consultants for discharge. Zantac increased. Readmission: Infant had similar ALTE events within a week after discharge. Ultimately underwent supraglottoplasty. | 2 | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.03% |

| 13 (Not Preventable) | Resulted from preventable complication but efforts to minimize likelihood were appropriate. Example:* Index admission: Patient on GJ feeds admitted for dislodged GJ. Extensive conversations between primary team and multiple consulting services regarding best type of tube. Determined that no other tube options were appropriate. Temporizing measures were initiated. Readmission: GJ tube dislodged again. | 2 | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.03% |

| 18 (Not Preventable) | Resulted from medication side effect (after watch period). Example:* Index admission: Preteen with MSSA bacteremia spread to other organs. Sent home on appropriate IV antibiotics. Readmission: Fever, rash, increased LFTs. Blood cultures negative. Presumed drug reaction. Fevers resolved with alternate medication. | 2 | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.03% |

| 16 (Not Preventable) | Resulted from inadequate care by community services, but effort by hospital/physician to ensure correct postdischarge care was appropriate. | ||||

| 233 | 94.0% | 100% | 3.2% | ||

| Fault Tree Terminal Node | Root Cause of Potentially Preventable Readmission with Case Descriptions* |

|---|---|

| |

| 2 (Potentially Preventable) | Problematic condition on discharge |

| Case 1: Index admission: Infant with history of prematurity admitted with RSV and rhinovirus bronchiolitis. Had some waxing and waning symptoms. Just prior to discharge, noted to have increased work of breathing related to feeds. Readmission: 12 hours later with tachypnea, retractions, and hypoxia. | |

| Case 2: Index admission: Toddler admitted with febrile seizure in setting of gastroenteritis. Poor PO intake during hospitalization. Readmission: 1 day later with dehydration. | |

| Case 3: Index admission: Infant admitted with a prolonged complex febrile seizure. Workup included an unremarkable lumbar puncture. No additional seizures. No inpatient imaging obtained. Readmission: Abnormal outpatient MRI requiring intervention. | |

| Case 4: Index admission: Teenager with wheezing and history of chronic daily symptoms. Discharged <24 hours later on albuterol every 4 hours and prednisone. Readmission: 1 day later, seen by primary care physician with persistent asthma flare. | |

| Case 5: Index admission: Exfull‐term infant admitted with bronchiolitis, early in course. At time of discharge, had been off oxygen for 24 hours, but last recorded respiratory rate was >70. Readmission: 1 day later due to continued tachypnea and increased work of breathing. No hypoxia. CXR normal. | |

| Case 6: Exfull‐term infant admitted with bilious emesis, diarrhea, and dehydration. Ultrasound of pylorus, UGI, and BMP all normal. Tolerated oral intake but had emesis and loose stools prior to discharge. Readmission: <48 hours later with severe metabolic acidosis. | |

| 3 (Potentially Preventable) | Nosocomial/ematrogenic factors |

| Case 1: Index admission: Toddler admitted with fever and neutropenia. Treated with antibiotics 24 hours. Diagnosed with viral illness and discharged home. Readmission: Symptomatic Clostridum difficile infection. | |

| Case 2: Index admission: Patient with autism admitted with viral gastroenteritis. Readmission: Presumed nosocominal upper respiratory infection. | |

| Case 3: Index admission: Infant admitted with bronchiolitis. Recovered from initial infection. Readmission: New upper respiratory infection and presumed nosocomial infection. | |

| Case 4: Index admission: <28‐day‐old full‐term neonate presenting with neonatal fever and rash. Full septic workup performed and all cultures negative at 24 hours. Readmission: CSF culture positive at 36 hours and readmitted while awaiting speciation. Discharged once culture grew out a contaminant. | |

| 8 (Potentially Preventable) | Detection/treatment of problem was delayed and/or not appropriately facilitated |

| Case 1: Index admission: Preteen admitted with abdominal pain, concern for appendicitis. Ultrasound and MRI abdomen negative for appendicitis. Symptoms improved. Tolerated PO. Readmission: 3 days later with similar abdominal pain. Diagnosed with constipation with significant improvement following clean‐out. | |

| Case 2: Index admission: Infant with history of macrocephaly presented with fever and full fontanelle. Head CT showed mild prominence of the extra‐axial space, and lumbar puncture was normal. Readmission: Patient developed torticollis. MRI demonstrated a malignant lesion. | |

| Case 3: Index admission: School‐age child with RLQ abdominal pain, fever, leukocytosis, and indeterminate RLQ abdominal ultrasound. Twelve‐hour observation with no further fevers. Pain and appetite improved. Readmission: 1 day later with fever, anorexia, and abdominal pain. RLQ ultrasound unchanged. Appendectomy performed with inflamed appendix. | |

| 1 (Potentially Preventable) | Inappropriate readmission |

| Case 1: Index admission: Infant with laryngomalacia admitted with bronchiolitis. Readmission: Continued mild bronchiolitis symptoms but did not require oxygen or suctioning. Normal CXR. | |

| 5 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from inadequate postdischarge care planning |

| Case 1: Index diagnosis: Infant with vomiting, prior admissions, and extensive evaluation, diagnosed with milk protein allergy and GERD. PPI increased. Readmission: Persistent symptoms, required NGT feeds supplementation. | |

| All General Pediatrics Patients in 2014 | General Pediatric Readmitted Patients in 2014 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Diagnosis Category at Index Admission | No. | % | Major Diagnosis Category at Index Admission | No. | % |

| |||||

| Respiratory | 2,723 | 37.5% | Respiratory | 79 | 31.9% |

| Digestive | 748 | 10.3% | Digestive | 41 | 16.5% |

| Ear, nose, mouth, throat | 675 | 9.3% | Ear, nose, mouth, throat | 24 | 9.7% |

| Skin, subcutaneous tissue | 480 | 6.6% | Musculoskeletal and connective tissue | 14 | 5.6% |

| Infectious, parasitic, systemic | 455 | 6.3% | Nervous | 13 | 5.2% |

| Factors influencing health status | 359 | 5.0% | Endocrine, nutritional, metabolic | 13 | 5.2% |

| Endocrine, nutritional, metabolic | 339 | 4.7% | Infectious, parasitic, systemic | 12 | 4.8% |

| Nervous | 239 | 3.3% | Newborn, neonate, perinatal period | 11 | 4.4% |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue | 228 | 3.1% | Hepatobiliary system and pancreas | 8 | 3.2% |

| Newborn, neonate, perinatal period | 206 | 2.8% | Skin, subcutaneous tissue | 8 | 3.2% |

| Other* | 800 | 11.0% | Other | 25 | 10.1% |

| Total | 7,252 | 100% | Total | 248 | 100% |

Inter‐Rater Reliability Analysis

A random selection of 50 cases (20% of total readmissions) was selected for a second review to test the tool's inter‐rater reliability. The second review resulted in the same terminal node for 44 (86%) of the cross‐checked files ( = 0.79; 95% confidence interval: 0.60‐0.98). Of the 6 cross‐checked files that ended at different nodes, 5 resulted in the same final determination about preventability. Only 1 of the cross‐checks (2% of total cross‐checked files) resulted in a different conclusion about preventability.

Efficiency Analysis

Reviewers reported that using the tool to reach a determination about preventability took approximately 20 minutes per case. Thus, initial reviews on the 248 cases required approximately 82.6 reviewer hours. Divided across 10 reviewers, this resulted in 8 to 9 hours of review time per reviewer over the year.

DISCUSSION

As part of an effort to direct quality‐improvement initiatives, this project used a Web‐based fault tree tool to identify root causes of general pediatrics readmissions at a freestanding children's hospital and classify them as either preventable or not preventable. The project also investigated the efficiency and inter‐rater reliability of the tool, which was designed to systematically guide physicians through the chart review process to a final determination about preventability. The project confirmed that using the tool helped reviewers reach final determinations about preventability efficiently with a high degree of consistency. It also confirmed that only a very small percentage of general pediatrics 15‐day readmissions are potentially preventable. Specifically, potentially preventable readmissions accounted for only 6.0% of total readmissions and 0.2% of general pediatrics discharges in 2014. Although our analysis focused on 15‐day readmissions, the fault tree methodology can be applied to any timeframe.

Previous studies attempting to distinguish preventable from nonpreventable readmissions, which used a range of methodologies to reach final determinations, reported that their review process was both time intensive and highly subjective. One study, which had 4 reviewers independently review charts and assign each case a preventability score on a 5‐point Likert scale, reported that reviewers disagreed on the final determination in 62.5% of cases.[12] Another study had 2 physicians independently review a selection of cases and assign a preventability score on a scale from 0 to 3. Scores for the 2 reviewers were added together, and cases above a certain composite threshold were classified as preventable. Despite being time‐intensive, this method resulted in only moderate agreement among physicians about the likelihood of preventability (weighted statistic of 0.44).[14] A more recent study, in which 2 physicians independently classified readmissions into 1 of 4 predefined categories, also reported only moderate agreement between reviewers ( = 0.44).[13] Other methods that have been reported include classifying readmissions as preventable only if multiple reviewers independently agreed, and using a third reviewer as a tie‐breaker.[14]

In an attempt to identify potentially preventable readmissions without using chart reviews, 3M (St. Paul, MN) developed its Potentially Preventable Readmissions software (3M‐PPR), which uses administrative data to identify which readmissions were potentially preventable. Although this automated approach is less time intensive, evidence suggests that due to a lack of nuance, the algorithm significantly overestimates the percentage of readmissions that are potentially preventable.[4, 5] A study that used 3M‐PPR to assess 1.7 million hospitalizations across 58 children's hospitals found that the algorithm classified 81% of sickle cell crisis and asthma readmissions, and 83% of bronchiolitis readmissions as potentially preventable.[10, 11] However, many readmissions for asthma and bronchiolitis are due to social factors that are outside of a hospital's direct control,[4, 5] and at many hospitals, readmissions for sickle cell crisis are part of a high‐value care model that weighs length of stay against potential readmissions. In addition, when assessing readmissions 7, 15, and 30 days after discharge, the algorithm classified almost the same percentage as potentially preventable, which is inconsistent with the notion that readmissions are more likely to have been preventable if they occurred closer to the initial discharge.[4, 13] Another study that assessed the performance of the software in the adult population reported that the algorithm performed with 85% sensitivity, but only 28% specificity.[5, 6]

The results of this quality‐improvement project indicate that using the fault tree tool to guide physicians through the chart review process helped address some of the shortcomings of methods reported in previous studies, by increasing the efficiency and reducing the subjectivity of final determinations, while still accounting for the nuances necessary to conduct a fair review. Because the tool provided a systematic framework for reviews, each case was completed in approximately 20 minutes, and because the process was the same for all reviewers, inter‐rater reliability was extremely high. In 86% of cross‐checked cases, the second reviewer ended at the same terminal node in the decision tree as the original reviewer, and in 98% of cross‐checked cases the second reviewer reached the same conclusion about preventability, even if they did not end at the same terminal node. Even accounting for agreement due to chance, the statistic of 0.79 confirmed that there was substantial agreement among reviewers about final determinations. Because the tool is easily adaptable, other hospitals can adopt this framework for their own preventability reviews and quality‐improvement initiatives.

Using the fault tree tool to access root causes of all 15‐day general pediatric readmissions helped the division focus quality‐improvement efforts on the most common causes of potentially preventable readmissions. Because 40% of potentially preventable readmissions were due to premature discharges, this prompted quality‐improvement teams to focus efforts on improving and clarifying the division's discharge criteria and clinical pathways. The division also initiated processes to improve discharge planning, including improved teaching of discharge instructions and having families pick up prescriptions prior to discharge.

Although these results did help the division identify a few areas of focus to potentially reduce readmissions, the fact that the overall 15‐day readmission rate for general pediatrics, as well as the percentage of readmissions and total discharges that were deemed potentially preventable, were so low (3.4%, 6.0%, and 0.2%, respectively), supports those who question whether prioritizing pediatric readmissions is the best place for hospitals to focus quality‐improvement efforts.[10, 12, 15, 16] As these results indicate, most pediatric readmissions are not preventable, and thus consistent with an efficient, effective, timely, patient‐centered, and equitable health system. Other studies have also shown that because overall and condition‐specific readmissions at pediatric hospitals are low, few pediatric hospitals are high or low performing for readmissions, and thus readmission rates are likely not a good measure of hospital quality.[8]

However, other condition‐specific studies of readmissions in pediatrics have indicated that there are some areas of opportunity to identify populations at high risk for readmission. One study found that although pneumonia‐specific 30‐day readmission rates in a national cohort of children hospitalized with pneumonia was only 3.1%, the chances of readmission were higher for children <1 year old, children with chronic comorbidities or complicated pneumonia, and children cared for in hospitals with lower volumes of pneumonia admissions.[17] Another study found that 17.1% of adolescents in a statewide database were readmitted post‐tonsillectomy for pain, nausea, and dehydration.[18] Thus, adapting the tool to identify root causes of condition‐specific or procedure‐specific readmissions, especially for surgical patients, may be an area of opportunity for future quality‐improvement efforts.[5] However, for general pediatrics, shifting the focus from reducing readmissions to improving the quality of care patients receive in the hospital, improving the discharge process, and adopting a population health approach to mitigate external risk factors, may be appropriate.

This project was subject to limitations. First, because it was conducted at a single site and only on general pediatrics patients, results may not be generalizable to other hospitals or other pediatric divisions. Thus, future studies might use the fault tree framework to assess preventability of pediatric readmissions in other divisions or specialties. Second, because readmissions to other hospitals were not included in the sample, the overall readmissions rate is likely underestimated.[19] However, it is unclear how this would affect the rate of potentially preventable readmissions. Third, although the fault tree framework reduced the subjectivity of the review process, there is still a degree of subjectivity inherent at each decision node. To minimize this, reviewers should try to discuss and come to consensus on how they are making determinations at each juncture in the decision tree. Similarly, because reviewers' answers to decision‐tree questions rely heavily on chart documentation, reviews may be compromised by unclear or incomplete documentation. For example, if information about steps the hospital team took to prepare a family for discharge were not properly documented, it would be difficult to determine whether appropriate steps were taken to minimize the likelihood of a complication. In the case of insufficient documentation of relevant social concerns, cases may be incorrectly classified as preventable, because addressing social issues is often not within a hospital's direct control. Finally, because reviewers were not blinded to the original discharging physician, there may have been some unconscious bias of unknown direction in the reviews.

CONCLUSION

Using the Web‐based fault tree tool helped physicians to identify the root causes of hospital readmissions and classify them as preventable or not preventable in a standardized, efficient, and consistent way, while still accounting for the nuances necessary to conduct a fair review. Thus, other hospitals should consider adopting this framework for their own preventability reviews and quality‐improvement initiatives. However, this project also confirmed that only a very small percentage of general pediatrics 15‐day readmissions are potentially preventable, suggesting that general pediatrics readmissions are not an appropriate measure of hospital quality. Instead, adapting the tool to identify root causes of condition‐specific or procedure‐specific readmission rates may be an area of opportunity for future quality‐improvement efforts.

Disclosures: This work was supported through internal funds from The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. The authors have no financial interests, relationships or affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the article to disclose. The authors have no potential conflicts of interest relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the article to disclose.

- , . Pediatric readmissions as a hospital quality measure. JAMA. 2013;309(4):396–398.

- Texas Health and Human Services Commission. Potentially preventable readmissions in the Texas Medicaid population, state fiscal year 2012. Available at: http://www.hhsc.state.tx.us/reports/2013/ppr‐report.pdf. Published November 2013. Accessed August 16, 2015.

- Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. Quality initiative to reduce hospital potentially preventable readmissions (PPR): Status update. Available at: http://www.illinois.gov/hfs/SiteCollectionDocuments/PPRPolicyStatusUpdate.pdf. Published September 3, 2014. Accessed August 16, 2015.

- , , , et al. Rates and impact of potentially preventable readmissions at children's hospitals. J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):613–619.e615.

- , . Preventing pediatric readmissions: which ones and how? J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):519–520.

- , , , , , . Manual and automated methods for identifying potentially preventable readmissions: a comparison in a large healthcare system. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:28.

- , . Section on hospital medicine leadership and staff. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(4):390–393.

- , , , et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429–436.

- , . Hospital readmissions—not just a measure of quality. JAMA. 2011;306(16):1796–1797.

- , . Preventing readmissions in children: how do we do that? Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):602–604.

- , , , et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372–380.

- , , , , , . Preventability of early readmissions at a children's hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171–e181.

- , , , et al. An examination of physician‐, caregiver‐, and disease‐related factors associated with readmission from a pediatric hospital medicine service. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):566–573.

- , , , et al. Clinical preventability of 30‐day readmission after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(5):e001290.

- . 3M algorithm overestimates preventable pediatric readmissions. Hospitalist News website. Available at: http://www.ehospitalistnews.com/specialty‐focus/pediatrics/single‐article‐page/3m‐algorithm‐overestimates‐preventable‐pediatric‐readmissions.html. Published August 16, 2013. Accessed August 16, 2015.

- . The 30‐day readmission rate: not a quality measure but an accountability measure. An Ounce of Evidence: Health Policy blog. Available at: https://blogs.sph.harvard.edu/ashish‐jha/?s=30‐day+readmission+rate. Published February 14, 2013. Accessed August 16, 2015.

- , , , et al. Readmissions among children previously hospitalized with pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2014;134(1):100–109.

- , , . A population‐based study of acute care revisits following tonsillectomy. J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):607–612.e605.

- , , , et al. Same‐hospital readmission rates as a measure of pediatric quality of care. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):905–912.

As physicians strive to increase the value of healthcare delivery, there has been increased focus on improving the quality of care that patients receive while lowering per capita costs. A provision of the Affordable Care Act implemented in 2012 identified all‐cause 30‐day readmission rates as a measure of hospital quality, and as part of the Act's Hospital Readmission and Reduction Program, Medicare now penalizes hospitals with higher than expected all‐cause readmissions rates for adult patients with certain conditions by lowering reimbursements.[1] Although readmissions are not yet commonly used to determine reimbursements for pediatric hospitals, several states are penalizing higher than expected readmission rates for Medicaid enrollees,[2, 3] using an imprecise algorithm to determine which readmissions resulted from low‐quality care during the index admission.[4, 5, 6]

There is growing concern, however, that readmission rates are not an accurate gauge of the quality of care patients receive while in the hospital or during the discharge process to prepare them for their transition home.[7, 8, 9, 10] This is especially true in pediatric settings, where overall readmission rates are much lower than in adult settings, many readmissions are expected as part of a patient's planned course of care, and variation in readmission rates between hospitals is correlated with the percentage of patients with certain complex chronic conditions.[1, 7, 11] Thus, there is increasing agreement that hospitals and external evaluators need to shift the focus from all‐cause readmissions to a reliable, consistent, and fair measure of potentially preventable readmissions.[12, 13] In addition to being a more useful quality metric, analyzing preventable readmissions will help hospitals focus resources on patients with potentially modifiable risk factors and develop meaningful quality‐improvement initiatives to improve inpatient care as well as the discharge process to prepare families for their transition to home.[14]

Although previous studies have attempted to distinguish preventable from nonpreventable readmissions, many reported significant challenges in completing reviews efficiently, achieving consistency in how readmissions were classified, and attaining consensus on final determinations.[12, 13, 14] Studies have also demonstrated that the algorithms some states are using to streamline preventability reviews and determine reimbursements overestimate the rate of potentially preventable readmissions.[4, 5, 6]

To increase the efficiency of preventability reviews and reduce the subjectivity involved in reaching final determinations, while still accounting for the nuances necessary to conduct a fair review, a quality‐improvement team from the Division of General Pediatrics at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) implemented a fault tree analysis tool based on a framework developed by Howard Parker at Intermountain Primary Children's Hospital. The CHOP team coded this framework into a secure Web‐based data‐collection tool in the form of a decision tree to guide reviewers through a logical progression of questions that result in 1 of 18 root causes of readmissions, 8 of which are considered potentially preventable. We hypothesized that this method would help reviewers efficiently reach consensus on the root causes of hospital readmissions, and thus help the division and the hospital focus efforts on developing relevant quality‐improvement initiatives.

METHODS

Inclusion Criteria and Study Design

This study was conducted at CHOP, a 535‐bed urban, tertiary‐care, freestanding children's hospital with approximately 29,000 annual discharges. Of those discharges, 7000 to 8000 are from the general pediatrics service, meaning that the attending of record was a general pediatrician. Patients were included in the study if (1) they were discharged from the general pediatrics service between January 2014 and December 2014, and (2) they were readmitted to the hospital, for any reason, within 15 days of discharge. Because this analysis was done as part of a quality‐improvement initiative, it focuses on 15‐day, early readmissions to target cases with a higher probability of being potentially preventable from the perspective of the hospital care team.[10, 12, 13] Patients under observation status during the index admission or the readmission were included. However, patients who returned to the emergency department but were not admitted to an inpatient unit were excluded. Objective details about each case, including the patient's name, demographics, chart number, and diagnosis code, were pre‐loaded from EPIC (Epic Systems Corp., Verona, WI) into REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture;

A panel of 10 general pediatricians divided up the cases to perform retrospective chart reviews. For each case, REDCap guided reviewers through the fault tree analysis. Reviewers met monthly to discuss difficult cases and reach consensus on any identified ambiguities in the process. After all cases were reviewed once, 3 panel members independently reviewed a random selection of cases to measure inter‐rater reliability and confirm reproducibility of final determinations. The inter‐rater reliability statistic was calculated using Stata 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). During chart reviews, panel members were not blinded to the identity of physicians and other staff members caring for the patients under review. CHOP's institutional review board determined this study to be exempt from ongoing review.

Fault Tree Analysis

Using the decision tree framework for analyzing readmissions that was developed at Intermountain Primary Children's Hospital, the REDCap tool prompted reviewers with a series of sequential questions, each with mutually exclusive options. Using imbedded branching logic to select follow‐up questions, the tool guided reviewers to 1 of 18 terminal nodes, each representing a potential root cause of the readmission. Of those 18 potential causes, 8 were considered potentially preventable. A diagram of the fault tree framework, color coded to indicate which nodes were considered potentially preventable, is shown in Figure 1.

RESULTS

In 2014, 7252 patients were discharged from the general pediatrics service at CHOP. Of those patients, 248 were readmitted within 15 days for an overall general pediatrics 15‐day readmission rate of 3.4%.

Preventability Analysis

Of the 248 readmissions, 233 (94.0%) were considered not preventable. The most common cause for readmission, which accounted for 145 cases (58.5%), was a patient developing an unpredictable problem related to the index diagnosis or a natural progression of the disease that required readmission. The second most common cause, which accounted for 53 cases (21.4%), was a patient developing a new condition unrelated to the index diagnosis or a readmission unrelated to the quality of care received during the index stay. The third most frequent cause, which accounted for 11 cases (4.4%), was a legitimate nonclinical readmission due to lack of alternative resources, psychosocial or economic factors, or case‐specific factors. Other nonpreventable causes of readmission, including scheduled readmissions, each accounted for 7 or fewer cases and <3% of total readmissions.

The 15 readmissions considered potentially preventable accounted for 6.0% of total readmissions and 0.2% of total discharges from the general pediatrics service in 2014. The most common cause of preventable readmissions, which accounted for 6 cases, was premature discharge. The second most common cause, which accounted for 4 cases, was a problem resulting from nosocomial or iatrogenic factors. Other potentially preventable causes included delayed detection of problem (3 cases), inappropriate readmission (1 case), and inadequate postdischarge care planning (1 case).

A breakdown of fault tree results, including examples of cases associated with each terminal node, is shown in Table 1. Information about general pediatrics patients and readmitted patients is included in Tables 2 and 3. A breakdown of determinations for each reviewer is included in Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article.

| Fault Tree Terminal Node | Root Cause of Readmission | No. of Cases | % of Total Readmissions | % Within Preventability Category | % of Total Discharges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| 2 (Potentially Preventable) | Problematic condition on discharge. Example:* Index admission: Infant with history of prematurity admitted with RSV and rhinovirus bronchiolitis. Had some waxing and waning symptoms. Just prior to discharge, noted to have increased work of breathing related to feeds. Readmission: 12 hours later with tachypnea, retractions, and hypoxia. | 6 | 2.4% | 40.0% | 0.08% |

| 3 (Potentially Preventable) | Nosocomial/Iatrogenic factors. Example*: Index admission: Toddler admitted with fever and neutropenia. Treated with antibiotics 24 hours. Diagnosed with viral illness and discharged home. Readmission: symptomatic Clostridum difficile infection. | 4 | 1.6% | 26.7% | 0.06% |

| 8 (Potentially Preventable) | Detection/treatment of problem was delayed and not appropriately facilitated. Example:* Index admission: Preteen admitted with abdominal pain, concern for appendicitis. Ultrasound and abdominal MRI negative for appendicitis. Symptoms improved. Tolerated PO. Readmission: 3 days later with similar abdominal pain. Diagnosed with constipation with significant improvement following clean‐out. | 3 | 1.2% | 20.0% | 0.04% |

| 1 (Potentially Preventable) | Inappropriate readmission. Example:* Index admission: Infant with laryngomalacia admitted with bronchiolitis. Readmission: Continued mild bronchiolitis symptoms but did not require oxygen or suctioning, normal CXR. | 1 | 0.4% | 6.7% | 0.01% |

| 5 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from inadequate postdischarge care planning. Example:* Index diagnosis: Infant with vomiting, prior admissions, and extensive evaluation, diagnosed with milk protein allergy and GERD. PPI increased. Readmission: Persistent symptoms, required NGT feeds supplementation. | 1 | 0.4% | 6.7% | 0.01% |

| 4 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from a preventable complication and hospital/physician did not take the appropriate steps to minimize likelihood of complication. | ||||

| 6 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from improper care by patient/family and effort by hospital/physician to ensure correct postdischarge care was inadequate. | ||||

| 7 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from inadequate care by community services and effort by hospital/physician to ensure correct postdischarge care was inadequate. | ||||

| 15 | 6.0% | 100% | 0.2% | ||

| 12 (Not Preventable) | Problem was unpredictable. Example:* Index admission: Infant admitted with gastroenteritis and dehydration with an anion gap metabolic acidosis. Vomiting and diarrhea improved, rehydrated, acidosis improved. Readmission: 1 day later, presented with emesis and fussiness. Readmitted for metabolic acidosis. | 145 | 58.5% | 62.2% | 2.00% |

| 10 (Not Preventable) | Patient developed new condition unrelated to index diagnosis or quality of care. Example:* Index admission: Toddler admitted with cellulitis. Readmission: Bronchiolitis (did not meet CDC guidelines for nosocomial infection). | 53 | 21.4% | 22.7% | 0.73% |

| 9 (Not Preventable) | Legitimate nonclinical readmission. Example:* Index admission: Infant admitted with second episode of bronchiolitis. Readmission: 4 days later with mild diarrhea. Tolerated PO challenge in emergency department. Admitted due to parental anxiety. | 11 | 4.4% | 4.7% | 0.15% |

| 17 (Not Preventable) | Problem resulted from improper care by patient/family but effort by hospital/physician to ensure correct postdischarge care was appropriate. Example:* Index admission: Infant admitted with diarrhea, diagnosed with milk protein allergy. Discharged on soy formula. Readmission: Developed vomiting and diarrhea with cow milk formula. | 7 | 2.8% | 3.0% | 0.10% |

| 11 (Not Preventable) | Scheduled readmission. Example:* Index admission: Infant with conjunctivitis and preseptal cellulitis with nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Readmission: Postoperatively following scheduled nasolacrimal duct repair. | 7 | 2.8% | 3.0% | 0.10% |

| 14 (Not Preventable) | Detection/treatment of problem was delayed, but earlier detection was not feasible. Example:* Index admission: Preteen admitted with fever, abdominal pain, and elevated inflammatory markers. Fever resolved and symptoms improved. Diagnosed with unspecified viral infection. Readmission: 4 days later with lower extremity pyomyositis and possible osteomyelitis. | 4 | 1.6% | 1.7% | 0.06% |

| 15 (Not Preventable) | Detection/treatment of problem was delayed, earlier detection was feasible, but detection was appropriately facilitated. Example:* Index admission: Infant with history of laryngomalacia and GER admitted with an ALTE. No events during hospitalization. Appropriate workup and cleared by consultants for discharge. Zantac increased. Readmission: Infant had similar ALTE events within a week after discharge. Ultimately underwent supraglottoplasty. | 2 | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.03% |

| 13 (Not Preventable) | Resulted from preventable complication but efforts to minimize likelihood were appropriate. Example:* Index admission: Patient on GJ feeds admitted for dislodged GJ. Extensive conversations between primary team and multiple consulting services regarding best type of tube. Determined that no other tube options were appropriate. Temporizing measures were initiated. Readmission: GJ tube dislodged again. | 2 | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.03% |

| 18 (Not Preventable) | Resulted from medication side effect (after watch period). Example:* Index admission: Preteen with MSSA bacteremia spread to other organs. Sent home on appropriate IV antibiotics. Readmission: Fever, rash, increased LFTs. Blood cultures negative. Presumed drug reaction. Fevers resolved with alternate medication. | 2 | 0.8% | 0.9% | 0.03% |

| 16 (Not Preventable) | Resulted from inadequate care by community services, but effort by hospital/physician to ensure correct postdischarge care was appropriate. | ||||

| 233 | 94.0% | 100% | 3.2% | ||

| Fault Tree Terminal Node | Root Cause of Potentially Preventable Readmission with Case Descriptions* |

|---|---|

| |

| 2 (Potentially Preventable) | Problematic condition on discharge |

| Case 1: Index admission: Infant with history of prematurity admitted with RSV and rhinovirus bronchiolitis. Had some waxing and waning symptoms. Just prior to discharge, noted to have increased work of breathing related to feeds. Readmission: 12 hours later with tachypnea, retractions, and hypoxia. | |

| Case 2: Index admission: Toddler admitted with febrile seizure in setting of gastroenteritis. Poor PO intake during hospitalization. Readmission: 1 day later with dehydration. | |

| Case 3: Index admission: Infant admitted with a prolonged complex febrile seizure. Workup included an unremarkable lumbar puncture. No additional seizures. No inpatient imaging obtained. Readmission: Abnormal outpatient MRI requiring intervention. | |

| Case 4: Index admission: Teenager with wheezing and history of chronic daily symptoms. Discharged <24 hours later on albuterol every 4 hours and prednisone. Readmission: 1 day later, seen by primary care physician with persistent asthma flare. | |

| Case 5: Index admission: Exfull‐term infant admitted with bronchiolitis, early in course. At time of discharge, had been off oxygen for 24 hours, but last recorded respiratory rate was >70. Readmission: 1 day later due to continued tachypnea and increased work of breathing. No hypoxia. CXR normal. | |

| Case 6: Exfull‐term infant admitted with bilious emesis, diarrhea, and dehydration. Ultrasound of pylorus, UGI, and BMP all normal. Tolerated oral intake but had emesis and loose stools prior to discharge. Readmission: <48 hours later with severe metabolic acidosis. | |

| 3 (Potentially Preventable) | Nosocomial/ematrogenic factors |

| Case 1: Index admission: Toddler admitted with fever and neutropenia. Treated with antibiotics 24 hours. Diagnosed with viral illness and discharged home. Readmission: Symptomatic Clostridum difficile infection. | |

| Case 2: Index admission: Patient with autism admitted with viral gastroenteritis. Readmission: Presumed nosocominal upper respiratory infection. | |

| Case 3: Index admission: Infant admitted with bronchiolitis. Recovered from initial infection. Readmission: New upper respiratory infection and presumed nosocomial infection. | |

| Case 4: Index admission: <28‐day‐old full‐term neonate presenting with neonatal fever and rash. Full septic workup performed and all cultures negative at 24 hours. Readmission: CSF culture positive at 36 hours and readmitted while awaiting speciation. Discharged once culture grew out a contaminant. | |

| 8 (Potentially Preventable) | Detection/treatment of problem was delayed and/or not appropriately facilitated |

| Case 1: Index admission: Preteen admitted with abdominal pain, concern for appendicitis. Ultrasound and MRI abdomen negative for appendicitis. Symptoms improved. Tolerated PO. Readmission: 3 days later with similar abdominal pain. Diagnosed with constipation with significant improvement following clean‐out. | |

| Case 2: Index admission: Infant with history of macrocephaly presented with fever and full fontanelle. Head CT showed mild prominence of the extra‐axial space, and lumbar puncture was normal. Readmission: Patient developed torticollis. MRI demonstrated a malignant lesion. | |

| Case 3: Index admission: School‐age child with RLQ abdominal pain, fever, leukocytosis, and indeterminate RLQ abdominal ultrasound. Twelve‐hour observation with no further fevers. Pain and appetite improved. Readmission: 1 day later with fever, anorexia, and abdominal pain. RLQ ultrasound unchanged. Appendectomy performed with inflamed appendix. | |

| 1 (Potentially Preventable) | Inappropriate readmission |

| Case 1: Index admission: Infant with laryngomalacia admitted with bronchiolitis. Readmission: Continued mild bronchiolitis symptoms but did not require oxygen or suctioning. Normal CXR. | |

| 5 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from inadequate postdischarge care planning |

| Case 1: Index diagnosis: Infant with vomiting, prior admissions, and extensive evaluation, diagnosed with milk protein allergy and GERD. PPI increased. Readmission: Persistent symptoms, required NGT feeds supplementation. | |

| All General Pediatrics Patients in 2014 | General Pediatric Readmitted Patients in 2014 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Diagnosis Category at Index Admission | No. | % | Major Diagnosis Category at Index Admission | No. | % |

| |||||

| Respiratory | 2,723 | 37.5% | Respiratory | 79 | 31.9% |

| Digestive | 748 | 10.3% | Digestive | 41 | 16.5% |

| Ear, nose, mouth, throat | 675 | 9.3% | Ear, nose, mouth, throat | 24 | 9.7% |

| Skin, subcutaneous tissue | 480 | 6.6% | Musculoskeletal and connective tissue | 14 | 5.6% |

| Infectious, parasitic, systemic | 455 | 6.3% | Nervous | 13 | 5.2% |

| Factors influencing health status | 359 | 5.0% | Endocrine, nutritional, metabolic | 13 | 5.2% |

| Endocrine, nutritional, metabolic | 339 | 4.7% | Infectious, parasitic, systemic | 12 | 4.8% |

| Nervous | 239 | 3.3% | Newborn, neonate, perinatal period | 11 | 4.4% |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue | 228 | 3.1% | Hepatobiliary system and pancreas | 8 | 3.2% |

| Newborn, neonate, perinatal period | 206 | 2.8% | Skin, subcutaneous tissue | 8 | 3.2% |

| Other* | 800 | 11.0% | Other | 25 | 10.1% |

| Total | 7,252 | 100% | Total | 248 | 100% |

Inter‐Rater Reliability Analysis

A random selection of 50 cases (20% of total readmissions) was selected for a second review to test the tool's inter‐rater reliability. The second review resulted in the same terminal node for 44 (86%) of the cross‐checked files ( = 0.79; 95% confidence interval: 0.60‐0.98). Of the 6 cross‐checked files that ended at different nodes, 5 resulted in the same final determination about preventability. Only 1 of the cross‐checks (2% of total cross‐checked files) resulted in a different conclusion about preventability.

Efficiency Analysis

Reviewers reported that using the tool to reach a determination about preventability took approximately 20 minutes per case. Thus, initial reviews on the 248 cases required approximately 82.6 reviewer hours. Divided across 10 reviewers, this resulted in 8 to 9 hours of review time per reviewer over the year.

DISCUSSION

As part of an effort to direct quality‐improvement initiatives, this project used a Web‐based fault tree tool to identify root causes of general pediatrics readmissions at a freestanding children's hospital and classify them as either preventable or not preventable. The project also investigated the efficiency and inter‐rater reliability of the tool, which was designed to systematically guide physicians through the chart review process to a final determination about preventability. The project confirmed that using the tool helped reviewers reach final determinations about preventability efficiently with a high degree of consistency. It also confirmed that only a very small percentage of general pediatrics 15‐day readmissions are potentially preventable. Specifically, potentially preventable readmissions accounted for only 6.0% of total readmissions and 0.2% of general pediatrics discharges in 2014. Although our analysis focused on 15‐day readmissions, the fault tree methodology can be applied to any timeframe.

Previous studies attempting to distinguish preventable from nonpreventable readmissions, which used a range of methodologies to reach final determinations, reported that their review process was both time intensive and highly subjective. One study, which had 4 reviewers independently review charts and assign each case a preventability score on a 5‐point Likert scale, reported that reviewers disagreed on the final determination in 62.5% of cases.[12] Another study had 2 physicians independently review a selection of cases and assign a preventability score on a scale from 0 to 3. Scores for the 2 reviewers were added together, and cases above a certain composite threshold were classified as preventable. Despite being time‐intensive, this method resulted in only moderate agreement among physicians about the likelihood of preventability (weighted statistic of 0.44).[14] A more recent study, in which 2 physicians independently classified readmissions into 1 of 4 predefined categories, also reported only moderate agreement between reviewers ( = 0.44).[13] Other methods that have been reported include classifying readmissions as preventable only if multiple reviewers independently agreed, and using a third reviewer as a tie‐breaker.[14]

In an attempt to identify potentially preventable readmissions without using chart reviews, 3M (St. Paul, MN) developed its Potentially Preventable Readmissions software (3M‐PPR), which uses administrative data to identify which readmissions were potentially preventable. Although this automated approach is less time intensive, evidence suggests that due to a lack of nuance, the algorithm significantly overestimates the percentage of readmissions that are potentially preventable.[4, 5] A study that used 3M‐PPR to assess 1.7 million hospitalizations across 58 children's hospitals found that the algorithm classified 81% of sickle cell crisis and asthma readmissions, and 83% of bronchiolitis readmissions as potentially preventable.[10, 11] However, many readmissions for asthma and bronchiolitis are due to social factors that are outside of a hospital's direct control,[4, 5] and at many hospitals, readmissions for sickle cell crisis are part of a high‐value care model that weighs length of stay against potential readmissions. In addition, when assessing readmissions 7, 15, and 30 days after discharge, the algorithm classified almost the same percentage as potentially preventable, which is inconsistent with the notion that readmissions are more likely to have been preventable if they occurred closer to the initial discharge.[4, 13] Another study that assessed the performance of the software in the adult population reported that the algorithm performed with 85% sensitivity, but only 28% specificity.[5, 6]

The results of this quality‐improvement project indicate that using the fault tree tool to guide physicians through the chart review process helped address some of the shortcomings of methods reported in previous studies, by increasing the efficiency and reducing the subjectivity of final determinations, while still accounting for the nuances necessary to conduct a fair review. Because the tool provided a systematic framework for reviews, each case was completed in approximately 20 minutes, and because the process was the same for all reviewers, inter‐rater reliability was extremely high. In 86% of cross‐checked cases, the second reviewer ended at the same terminal node in the decision tree as the original reviewer, and in 98% of cross‐checked cases the second reviewer reached the same conclusion about preventability, even if they did not end at the same terminal node. Even accounting for agreement due to chance, the statistic of 0.79 confirmed that there was substantial agreement among reviewers about final determinations. Because the tool is easily adaptable, other hospitals can adopt this framework for their own preventability reviews and quality‐improvement initiatives.

Using the fault tree tool to access root causes of all 15‐day general pediatric readmissions helped the division focus quality‐improvement efforts on the most common causes of potentially preventable readmissions. Because 40% of potentially preventable readmissions were due to premature discharges, this prompted quality‐improvement teams to focus efforts on improving and clarifying the division's discharge criteria and clinical pathways. The division also initiated processes to improve discharge planning, including improved teaching of discharge instructions and having families pick up prescriptions prior to discharge.

Although these results did help the division identify a few areas of focus to potentially reduce readmissions, the fact that the overall 15‐day readmission rate for general pediatrics, as well as the percentage of readmissions and total discharges that were deemed potentially preventable, were so low (3.4%, 6.0%, and 0.2%, respectively), supports those who question whether prioritizing pediatric readmissions is the best place for hospitals to focus quality‐improvement efforts.[10, 12, 15, 16] As these results indicate, most pediatric readmissions are not preventable, and thus consistent with an efficient, effective, timely, patient‐centered, and equitable health system. Other studies have also shown that because overall and condition‐specific readmissions at pediatric hospitals are low, few pediatric hospitals are high or low performing for readmissions, and thus readmission rates are likely not a good measure of hospital quality.[8]

However, other condition‐specific studies of readmissions in pediatrics have indicated that there are some areas of opportunity to identify populations at high risk for readmission. One study found that although pneumonia‐specific 30‐day readmission rates in a national cohort of children hospitalized with pneumonia was only 3.1%, the chances of readmission were higher for children <1 year old, children with chronic comorbidities or complicated pneumonia, and children cared for in hospitals with lower volumes of pneumonia admissions.[17] Another study found that 17.1% of adolescents in a statewide database were readmitted post‐tonsillectomy for pain, nausea, and dehydration.[18] Thus, adapting the tool to identify root causes of condition‐specific or procedure‐specific readmissions, especially for surgical patients, may be an area of opportunity for future quality‐improvement efforts.[5] However, for general pediatrics, shifting the focus from reducing readmissions to improving the quality of care patients receive in the hospital, improving the discharge process, and adopting a population health approach to mitigate external risk factors, may be appropriate.

This project was subject to limitations. First, because it was conducted at a single site and only on general pediatrics patients, results may not be generalizable to other hospitals or other pediatric divisions. Thus, future studies might use the fault tree framework to assess preventability of pediatric readmissions in other divisions or specialties. Second, because readmissions to other hospitals were not included in the sample, the overall readmissions rate is likely underestimated.[19] However, it is unclear how this would affect the rate of potentially preventable readmissions. Third, although the fault tree framework reduced the subjectivity of the review process, there is still a degree of subjectivity inherent at each decision node. To minimize this, reviewers should try to discuss and come to consensus on how they are making determinations at each juncture in the decision tree. Similarly, because reviewers' answers to decision‐tree questions rely heavily on chart documentation, reviews may be compromised by unclear or incomplete documentation. For example, if information about steps the hospital team took to prepare a family for discharge were not properly documented, it would be difficult to determine whether appropriate steps were taken to minimize the likelihood of a complication. In the case of insufficient documentation of relevant social concerns, cases may be incorrectly classified as preventable, because addressing social issues is often not within a hospital's direct control. Finally, because reviewers were not blinded to the original discharging physician, there may have been some unconscious bias of unknown direction in the reviews.

CONCLUSION

Using the Web‐based fault tree tool helped physicians to identify the root causes of hospital readmissions and classify them as preventable or not preventable in a standardized, efficient, and consistent way, while still accounting for the nuances necessary to conduct a fair review. Thus, other hospitals should consider adopting this framework for their own preventability reviews and quality‐improvement initiatives. However, this project also confirmed that only a very small percentage of general pediatrics 15‐day readmissions are potentially preventable, suggesting that general pediatrics readmissions are not an appropriate measure of hospital quality. Instead, adapting the tool to identify root causes of condition‐specific or procedure‐specific readmission rates may be an area of opportunity for future quality‐improvement efforts.

Disclosures: This work was supported through internal funds from The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. The authors have no financial interests, relationships or affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the article to disclose. The authors have no potential conflicts of interest relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the article to disclose.

As physicians strive to increase the value of healthcare delivery, there has been increased focus on improving the quality of care that patients receive while lowering per capita costs. A provision of the Affordable Care Act implemented in 2012 identified all‐cause 30‐day readmission rates as a measure of hospital quality, and as part of the Act's Hospital Readmission and Reduction Program, Medicare now penalizes hospitals with higher than expected all‐cause readmissions rates for adult patients with certain conditions by lowering reimbursements.[1] Although readmissions are not yet commonly used to determine reimbursements for pediatric hospitals, several states are penalizing higher than expected readmission rates for Medicaid enrollees,[2, 3] using an imprecise algorithm to determine which readmissions resulted from low‐quality care during the index admission.[4, 5, 6]

There is growing concern, however, that readmission rates are not an accurate gauge of the quality of care patients receive while in the hospital or during the discharge process to prepare them for their transition home.[7, 8, 9, 10] This is especially true in pediatric settings, where overall readmission rates are much lower than in adult settings, many readmissions are expected as part of a patient's planned course of care, and variation in readmission rates between hospitals is correlated with the percentage of patients with certain complex chronic conditions.[1, 7, 11] Thus, there is increasing agreement that hospitals and external evaluators need to shift the focus from all‐cause readmissions to a reliable, consistent, and fair measure of potentially preventable readmissions.[12, 13] In addition to being a more useful quality metric, analyzing preventable readmissions will help hospitals focus resources on patients with potentially modifiable risk factors and develop meaningful quality‐improvement initiatives to improve inpatient care as well as the discharge process to prepare families for their transition to home.[14]

Although previous studies have attempted to distinguish preventable from nonpreventable readmissions, many reported significant challenges in completing reviews efficiently, achieving consistency in how readmissions were classified, and attaining consensus on final determinations.[12, 13, 14] Studies have also demonstrated that the algorithms some states are using to streamline preventability reviews and determine reimbursements overestimate the rate of potentially preventable readmissions.[4, 5, 6]

To increase the efficiency of preventability reviews and reduce the subjectivity involved in reaching final determinations, while still accounting for the nuances necessary to conduct a fair review, a quality‐improvement team from the Division of General Pediatrics at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) implemented a fault tree analysis tool based on a framework developed by Howard Parker at Intermountain Primary Children's Hospital. The CHOP team coded this framework into a secure Web‐based data‐collection tool in the form of a decision tree to guide reviewers through a logical progression of questions that result in 1 of 18 root causes of readmissions, 8 of which are considered potentially preventable. We hypothesized that this method would help reviewers efficiently reach consensus on the root causes of hospital readmissions, and thus help the division and the hospital focus efforts on developing relevant quality‐improvement initiatives.

METHODS

Inclusion Criteria and Study Design

This study was conducted at CHOP, a 535‐bed urban, tertiary‐care, freestanding children's hospital with approximately 29,000 annual discharges. Of those discharges, 7000 to 8000 are from the general pediatrics service, meaning that the attending of record was a general pediatrician. Patients were included in the study if (1) they were discharged from the general pediatrics service between January 2014 and December 2014, and (2) they were readmitted to the hospital, for any reason, within 15 days of discharge. Because this analysis was done as part of a quality‐improvement initiative, it focuses on 15‐day, early readmissions to target cases with a higher probability of being potentially preventable from the perspective of the hospital care team.[10, 12, 13] Patients under observation status during the index admission or the readmission were included. However, patients who returned to the emergency department but were not admitted to an inpatient unit were excluded. Objective details about each case, including the patient's name, demographics, chart number, and diagnosis code, were pre‐loaded from EPIC (Epic Systems Corp., Verona, WI) into REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture;

A panel of 10 general pediatricians divided up the cases to perform retrospective chart reviews. For each case, REDCap guided reviewers through the fault tree analysis. Reviewers met monthly to discuss difficult cases and reach consensus on any identified ambiguities in the process. After all cases were reviewed once, 3 panel members independently reviewed a random selection of cases to measure inter‐rater reliability and confirm reproducibility of final determinations. The inter‐rater reliability statistic was calculated using Stata 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). During chart reviews, panel members were not blinded to the identity of physicians and other staff members caring for the patients under review. CHOP's institutional review board determined this study to be exempt from ongoing review.

Fault Tree Analysis

Using the decision tree framework for analyzing readmissions that was developed at Intermountain Primary Children's Hospital, the REDCap tool prompted reviewers with a series of sequential questions, each with mutually exclusive options. Using imbedded branching logic to select follow‐up questions, the tool guided reviewers to 1 of 18 terminal nodes, each representing a potential root cause of the readmission. Of those 18 potential causes, 8 were considered potentially preventable. A diagram of the fault tree framework, color coded to indicate which nodes were considered potentially preventable, is shown in Figure 1.

RESULTS

In 2014, 7252 patients were discharged from the general pediatrics service at CHOP. Of those patients, 248 were readmitted within 15 days for an overall general pediatrics 15‐day readmission rate of 3.4%.

Preventability Analysis

Of the 248 readmissions, 233 (94.0%) were considered not preventable. The most common cause for readmission, which accounted for 145 cases (58.5%), was a patient developing an unpredictable problem related to the index diagnosis or a natural progression of the disease that required readmission. The second most common cause, which accounted for 53 cases (21.4%), was a patient developing a new condition unrelated to the index diagnosis or a readmission unrelated to the quality of care received during the index stay. The third most frequent cause, which accounted for 11 cases (4.4%), was a legitimate nonclinical readmission due to lack of alternative resources, psychosocial or economic factors, or case‐specific factors. Other nonpreventable causes of readmission, including scheduled readmissions, each accounted for 7 or fewer cases and <3% of total readmissions.

The 15 readmissions considered potentially preventable accounted for 6.0% of total readmissions and 0.2% of total discharges from the general pediatrics service in 2014. The most common cause of preventable readmissions, which accounted for 6 cases, was premature discharge. The second most common cause, which accounted for 4 cases, was a problem resulting from nosocomial or iatrogenic factors. Other potentially preventable causes included delayed detection of problem (3 cases), inappropriate readmission (1 case), and inadequate postdischarge care planning (1 case).

A breakdown of fault tree results, including examples of cases associated with each terminal node, is shown in Table 1. Information about general pediatrics patients and readmitted patients is included in Tables 2 and 3. A breakdown of determinations for each reviewer is included in Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article.

| Fault Tree Terminal Node | Root Cause of Readmission | No. of Cases | % of Total Readmissions | % Within Preventability Category | % of Total Discharges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| 2 (Potentially Preventable) | Problematic condition on discharge. Example:* Index admission: Infant with history of prematurity admitted with RSV and rhinovirus bronchiolitis. Had some waxing and waning symptoms. Just prior to discharge, noted to have increased work of breathing related to feeds. Readmission: 12 hours later with tachypnea, retractions, and hypoxia. | 6 | 2.4% | 40.0% | 0.08% |

| 3 (Potentially Preventable) | Nosocomial/Iatrogenic factors. Example*: Index admission: Toddler admitted with fever and neutropenia. Treated with antibiotics 24 hours. Diagnosed with viral illness and discharged home. Readmission: symptomatic Clostridum difficile infection. | 4 | 1.6% | 26.7% | 0.06% |

| 8 (Potentially Preventable) | Detection/treatment of problem was delayed and not appropriately facilitated. Example:* Index admission: Preteen admitted with abdominal pain, concern for appendicitis. Ultrasound and abdominal MRI negative for appendicitis. Symptoms improved. Tolerated PO. Readmission: 3 days later with similar abdominal pain. Diagnosed with constipation with significant improvement following clean‐out. | 3 | 1.2% | 20.0% | 0.04% |

| 1 (Potentially Preventable) | Inappropriate readmission. Example:* Index admission: Infant with laryngomalacia admitted with bronchiolitis. Readmission: Continued mild bronchiolitis symptoms but did not require oxygen or suctioning, normal CXR. | 1 | 0.4% | 6.7% | 0.01% |

| 5 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from inadequate postdischarge care planning. Example:* Index diagnosis: Infant with vomiting, prior admissions, and extensive evaluation, diagnosed with milk protein allergy and GERD. PPI increased. Readmission: Persistent symptoms, required NGT feeds supplementation. | 1 | 0.4% | 6.7% | 0.01% |

| 4 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from a preventable complication and hospital/physician did not take the appropriate steps to minimize likelihood of complication. | ||||

| 6 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from improper care by patient/family and effort by hospital/physician to ensure correct postdischarge care was inadequate. | ||||

| 7 (Potentially Preventable) | Resulted from inadequate care by community services and effort by hospital/physician to ensure correct postdischarge care was inadequate. | ||||

| 15 | 6.0% | 100% | 0.2% | ||

| 12 (Not Preventable) | Problem was unpredictable. Example:* Index admission: Infant admitted with gastroenteritis and dehydration with an anion gap metabolic acidosis. Vomiting and diarrhea improved, rehydrated, acidosis improved. Readmission: 1 day later, presented with emesis and fussiness. Readmitted for metabolic acidosis. | 145 | 58.5% | 62.2% | 2.00% |

| 10 (Not Preventable) | Patient developed new condition unrelated to index diagnosis or quality of care. Example:* Index admission: Toddler admitted with cellulitis. Readmission: Bronchiolitis (did not meet CDC guidelines for nosocomial infection). | 53 | 21.4% | 22.7% | 0.73% |

| 9 (Not Preventable) | Legitimate nonclinical readmission. Example:* Index admission: Infant admitted with second episode of bronchiolitis. Readmission: 4 days later with mild diarrhea. Tolerated PO challenge in emergency department. Admitted due to parental anxiety. | 11 | 4.4% | 4.7% | 0.15% |

| 17 (Not Preventable) | Problem resulted from improper care by patient/family but effort by hospital/physician to ensure correct postdischarge care was appropriate. Example:* Index admission: Infant admitted with diarrhea, diagnosed with milk protein allergy. Discharged on soy formula. Readmission: Developed vomiting and diarrhea with cow milk formula. | 7 | 2.8% | 3.0% | 0.10% |

| 11 (Not Preventable) | Scheduled readmission. Example:* Index admission: Infant with conjunctivitis and preseptal cellulitis with nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Readmission: Postoperatively following scheduled nasolacrimal duct repair. | 7 | 2.8% | 3.0% | 0.10% |

| 14 (Not Preventable) | Detection/treatment of problem was delayed, but earlier detection was not feasible. Example:* Index admission: Preteen admitted with fever, abdominal pain, and elevated inflammatory markers. Fever resolved and symptoms improved. Diagnosed with unspecified viral infection. Readmission: 4 days later with lower extremity pyomyositis and possible osteomyelitis. | 4 | 1.6% | 1.7% | 0.06% |