User login

When the patient wants to speak to a manager

A patient swore at me the other day. Not as in “she used a curse word.” As in she spewed fury, spitting out a vulgar, adverbial word before “... terrible doctor” while jabbing her finger toward me. In my 15 years of practice, I’d never had that happen before. Equally surprising, I was not surprised by her outburst. The level of incivility from patients is at an all-time high.

Her anger was misdirected. She wanted me to write a letter to her employer excusing her from getting a vaccine. It was neither indicated nor ethical for me to do so. I did my best to redirect her, but without success. As our chief of service, I often help with service concerns and am happy to see patients who want another opinion or want to speak with the department head (aka, “the manager”). Usually I can help. Lately, it’s become harder.

Not only are such rude incidents more frequent, but they are also more dramatic and inappropriate. For example, I cannot imagine writing a complaint against a doctor stating that she must be a foreign medical grad (as it happens, she’s Ivy League-trained) or demanding money back when a biopsy result turned out to be benign, or threatening to report a doctor to the medical board because he failed to schedule a follow-up appointment (that doctor had been retired for months). Patients have hung up on our staff mid-sentence and slammed a clinic door when they left in a huff. Why are so many previously sensible people throwing childlike tantrums?

It’s the same phenomenon happening to our fellow service agents across all industries. The Federal Aviation Administration’s graph of unruly passenger incidents is a flat line from 1995 to 2019, then it goes straight vertical. A recent survey showed that Americans’ sense of civility is low and worse, that people’s expectations that civility will improve is going down. It’s palpable. Last month, I witnessed a man and woman screaming at each other over Christmas lights in a busy store. An army of aproned walkie-talkie staff surrounded them and escorted them out – their coordination and efficiency clearly indicated they’d done this before. Customers everywhere are mad, frustrated, disenfranchised. Lately, a lot of things just are not working out for them. Supplies are out. Kids are sent home from school. No elective surgery appointments are available. The insta-gratification they’ve grown accustomed to from Amazon and DoorDash is colliding with the reality that not everything works that way.

The word “patient’’ you’ll recall comes from the Latin “patior,” meaning to suffer or bear. With virus variants raging, inflation growing, and call center wait times approaching infinity, many of our patients, it seems, cannot bear any more. I’m confident this situation will improve and our patients will be more reasonable in their expectations, but I am afraid that, in the end, we’ll have lost some decorum and dignity that we may never find again in medicine.

For my potty-mouthed patient, I made an excuse to leave the room to get my dermatoscope and walked out. It gave her time to calm down. I returned in a few minutes to do a skin exam. As I was wrapping up, I advised her that she cannot raise her voice or use offensive language and that she should know that I and everyone in our office cares about her and wants to help. She did apologize for her behavior, but then had to add that, if I really cared, I’d write the letter for her.

I guess the customer is not always right.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected]

A patient swore at me the other day. Not as in “she used a curse word.” As in she spewed fury, spitting out a vulgar, adverbial word before “... terrible doctor” while jabbing her finger toward me. In my 15 years of practice, I’d never had that happen before. Equally surprising, I was not surprised by her outburst. The level of incivility from patients is at an all-time high.

Her anger was misdirected. She wanted me to write a letter to her employer excusing her from getting a vaccine. It was neither indicated nor ethical for me to do so. I did my best to redirect her, but without success. As our chief of service, I often help with service concerns and am happy to see patients who want another opinion or want to speak with the department head (aka, “the manager”). Usually I can help. Lately, it’s become harder.

Not only are such rude incidents more frequent, but they are also more dramatic and inappropriate. For example, I cannot imagine writing a complaint against a doctor stating that she must be a foreign medical grad (as it happens, she’s Ivy League-trained) or demanding money back when a biopsy result turned out to be benign, or threatening to report a doctor to the medical board because he failed to schedule a follow-up appointment (that doctor had been retired for months). Patients have hung up on our staff mid-sentence and slammed a clinic door when they left in a huff. Why are so many previously sensible people throwing childlike tantrums?

It’s the same phenomenon happening to our fellow service agents across all industries. The Federal Aviation Administration’s graph of unruly passenger incidents is a flat line from 1995 to 2019, then it goes straight vertical. A recent survey showed that Americans’ sense of civility is low and worse, that people’s expectations that civility will improve is going down. It’s palpable. Last month, I witnessed a man and woman screaming at each other over Christmas lights in a busy store. An army of aproned walkie-talkie staff surrounded them and escorted them out – their coordination and efficiency clearly indicated they’d done this before. Customers everywhere are mad, frustrated, disenfranchised. Lately, a lot of things just are not working out for them. Supplies are out. Kids are sent home from school. No elective surgery appointments are available. The insta-gratification they’ve grown accustomed to from Amazon and DoorDash is colliding with the reality that not everything works that way.

The word “patient’’ you’ll recall comes from the Latin “patior,” meaning to suffer or bear. With virus variants raging, inflation growing, and call center wait times approaching infinity, many of our patients, it seems, cannot bear any more. I’m confident this situation will improve and our patients will be more reasonable in their expectations, but I am afraid that, in the end, we’ll have lost some decorum and dignity that we may never find again in medicine.

For my potty-mouthed patient, I made an excuse to leave the room to get my dermatoscope and walked out. It gave her time to calm down. I returned in a few minutes to do a skin exam. As I was wrapping up, I advised her that she cannot raise her voice or use offensive language and that she should know that I and everyone in our office cares about her and wants to help. She did apologize for her behavior, but then had to add that, if I really cared, I’d write the letter for her.

I guess the customer is not always right.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected]

A patient swore at me the other day. Not as in “she used a curse word.” As in she spewed fury, spitting out a vulgar, adverbial word before “... terrible doctor” while jabbing her finger toward me. In my 15 years of practice, I’d never had that happen before. Equally surprising, I was not surprised by her outburst. The level of incivility from patients is at an all-time high.

Her anger was misdirected. She wanted me to write a letter to her employer excusing her from getting a vaccine. It was neither indicated nor ethical for me to do so. I did my best to redirect her, but without success. As our chief of service, I often help with service concerns and am happy to see patients who want another opinion or want to speak with the department head (aka, “the manager”). Usually I can help. Lately, it’s become harder.

Not only are such rude incidents more frequent, but they are also more dramatic and inappropriate. For example, I cannot imagine writing a complaint against a doctor stating that she must be a foreign medical grad (as it happens, she’s Ivy League-trained) or demanding money back when a biopsy result turned out to be benign, or threatening to report a doctor to the medical board because he failed to schedule a follow-up appointment (that doctor had been retired for months). Patients have hung up on our staff mid-sentence and slammed a clinic door when they left in a huff. Why are so many previously sensible people throwing childlike tantrums?

It’s the same phenomenon happening to our fellow service agents across all industries. The Federal Aviation Administration’s graph of unruly passenger incidents is a flat line from 1995 to 2019, then it goes straight vertical. A recent survey showed that Americans’ sense of civility is low and worse, that people’s expectations that civility will improve is going down. It’s palpable. Last month, I witnessed a man and woman screaming at each other over Christmas lights in a busy store. An army of aproned walkie-talkie staff surrounded them and escorted them out – their coordination and efficiency clearly indicated they’d done this before. Customers everywhere are mad, frustrated, disenfranchised. Lately, a lot of things just are not working out for them. Supplies are out. Kids are sent home from school. No elective surgery appointments are available. The insta-gratification they’ve grown accustomed to from Amazon and DoorDash is colliding with the reality that not everything works that way.

The word “patient’’ you’ll recall comes from the Latin “patior,” meaning to suffer or bear. With virus variants raging, inflation growing, and call center wait times approaching infinity, many of our patients, it seems, cannot bear any more. I’m confident this situation will improve and our patients will be more reasonable in their expectations, but I am afraid that, in the end, we’ll have lost some decorum and dignity that we may never find again in medicine.

For my potty-mouthed patient, I made an excuse to leave the room to get my dermatoscope and walked out. It gave her time to calm down. I returned in a few minutes to do a skin exam. As I was wrapping up, I advised her that she cannot raise her voice or use offensive language and that she should know that I and everyone in our office cares about her and wants to help. She did apologize for her behavior, but then had to add that, if I really cared, I’d write the letter for her.

I guess the customer is not always right.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected]

My recommendations for the best books of 2018

There were .

“Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress,” by Steven Pinker, PhD (New York:Viking, 2018). Think life was better 50 years ago? 100? 500? Steven Pinker would say you’re wrong. Whether or not we feel it, empirically, life is better today than it ever has been. We are living longer, healthier lives, have better access to health care, have fewer war-related deaths and food shortages and higher levels of literacy and equal rights. However, Dr. Pinker acknowledges our shortcomings (e.g., providing a living wage) and potential societal pitfalls (e.g., increasing tribalism), although he could have addressed other crucial issues such as climate change more fully. If you’re looking for an optimistic, science-based outlook on humanity, look no further than this book.

“Aware: The Science and Practice of Presence – The Groundbreaking Meditation Practice,” by Daniel J. Siegel, MD (New York:TarcherPerigee, 2018). A clinical professor of psychiatry and director of the UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center, Dr. Siegel, in his latest book, constructs a compelling argument for practicing presence that is supported by ample scientific evidence. His “Wheel of Awareness” is a tool to cultivate presence, self-awareness, and compassion. He deftly shows how developing “open awareness” and “kind intention” has not only psychological benefits, but also physical ones, such as improving immune function and increasing neural integration in the brain. As he writes, “The scientific findings are now in: Your mind can change the health of your body and slow aging.” That’s a message both we physicians and our patients could benefit from hearing more often.

“When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing,” by Daniel H. Pink (New York: Riverhead Books, 2018). In his latest book, Mr. Pink delves into timing, and the evolving science of timing, which draws from fields that include biology, psychology, neuroscience, and economics. Through extensive research (he analyzed over 700 studies) and fascinating real-life examples, the data are clear: We overwhelmingly perform optimally in the morning, suffer a mid-day slump, then rally once more in the evening (of course, there are productive night owls too). These peaks and dips affect both our moods and decision-making abilities, resulting in real-world impact (judges, for example, are more lenient in sentencing following a break). With practical takeaways you can immediately incorporate into your daily routine, you can start to feel more productive, energized, and happy, which is good news for both you and your patients.

“Natural Causes An Epidemic of Wellness, the Certainty of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer,” by Barbara Ehrenreich, PhD (New York:Twelve, 2018). Infuriating, tender, disquieting, moving. Barbara Ehrenreich’s latest book is provocative. As a septuagenarian and cancer survivor who has forsworn most future medical measures, including Pap smears and cancer screenings (even though she has medical insurance), Dr. Ehrenreich castigates both the traditional medical and integrative holistic health establishments. Yes, she’s critical of us and nurses and fitness gurus and mindfulness coaches and Silicon Valley. Why should I read this you ask? Because it’s good to understand contrarian views, especially when they are thoughtfully articulated. Because there are many patients who share her beliefs, and understanding opposing perspectives might help us become better clinicians. Because she may cause you to be reflective. Do we order too many tests? Do we overprescribe meds? Are we setting up patients for false hopes of longevity? Is providing more care always the best option? This exercise is beneficial for all types of healers.

“Leadership in Turbulent Times,” by Doris Kearns Goodwin, PhD, (New York:Simon & Schuster, 2018). I’m a presidential biography junkie. As physicians in what some may rightly call a turbulent health care culture, we face challenges each day that require our best intentions, our best diagnostic skills, our best empathic efforts, our best selves. Dr. Goodwin, in her prototypical engaging and informative prose, shows us four American presidents, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Lyndon B. Johnson, who persevered through devastatingly turbulent times. While we don’t have to make decisions regarding warfare, we do have an unmistakable impact on the lives of thousands of patients, and this book provides insights that can help all of us become better informed, better prepared leaders for our patients, our coworkers, and our communities at large.

“You and I Eat the Same: On the Countless Ways Food and Cooking Connect Us to One Another,” edited by Chris Ying; foreword by René Redzepi (New York:Artisan, 2018). Open a newspaper or turn on the news, and it’s difficult not to feel as if we live in an alarmingly polarized society. We can find many issues that divide us, but as healers, I hope we also strive to find ways to connect us. In 19 engaging and thought-provoking essays, this book explores the various ways that food connects us as humans. Whether it’s an historical deep dive into our love of meat wrapped in flatbread (which we’ve been doing for over 1,000 years) or tackling philosophical questions like, “Is there such a thing as a ‘non-ethnic’ restaurant?” this book will inform, inspire, and delight, and provide delicious topics for a bite of small talk with your patients.

“The Great Alone,” by Kristin Hannah (New York:St. Martin’s Press, 2018). Lured by Alaska’s majestic splendor and remoteness, the Allbright family (former POW, Ernt; abused wife, Cora; and coming-of-age daughter, Leni) are happy with their new life. For a minute. What ensues, namely punishing 16-hour days of darkness punctuated by episodes of oppressive snowfall, paranoia, and domestic violence, is grueling: “Night swept in like nothing Leni had ever seen before, like the winged shadow of a creature too big and predatory to comprehend.” Yet, this book is also a story about the bonds of family, both those we are born into and those we choose, love, sacrifice, and resilience.

If you have any books you read over the last to year to add to this list, please write to me at [email protected].

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter.

There were .

“Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress,” by Steven Pinker, PhD (New York:Viking, 2018). Think life was better 50 years ago? 100? 500? Steven Pinker would say you’re wrong. Whether or not we feel it, empirically, life is better today than it ever has been. We are living longer, healthier lives, have better access to health care, have fewer war-related deaths and food shortages and higher levels of literacy and equal rights. However, Dr. Pinker acknowledges our shortcomings (e.g., providing a living wage) and potential societal pitfalls (e.g., increasing tribalism), although he could have addressed other crucial issues such as climate change more fully. If you’re looking for an optimistic, science-based outlook on humanity, look no further than this book.

“Aware: The Science and Practice of Presence – The Groundbreaking Meditation Practice,” by Daniel J. Siegel, MD (New York:TarcherPerigee, 2018). A clinical professor of psychiatry and director of the UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center, Dr. Siegel, in his latest book, constructs a compelling argument for practicing presence that is supported by ample scientific evidence. His “Wheel of Awareness” is a tool to cultivate presence, self-awareness, and compassion. He deftly shows how developing “open awareness” and “kind intention” has not only psychological benefits, but also physical ones, such as improving immune function and increasing neural integration in the brain. As he writes, “The scientific findings are now in: Your mind can change the health of your body and slow aging.” That’s a message both we physicians and our patients could benefit from hearing more often.

“When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing,” by Daniel H. Pink (New York: Riverhead Books, 2018). In his latest book, Mr. Pink delves into timing, and the evolving science of timing, which draws from fields that include biology, psychology, neuroscience, and economics. Through extensive research (he analyzed over 700 studies) and fascinating real-life examples, the data are clear: We overwhelmingly perform optimally in the morning, suffer a mid-day slump, then rally once more in the evening (of course, there are productive night owls too). These peaks and dips affect both our moods and decision-making abilities, resulting in real-world impact (judges, for example, are more lenient in sentencing following a break). With practical takeaways you can immediately incorporate into your daily routine, you can start to feel more productive, energized, and happy, which is good news for both you and your patients.

“Natural Causes An Epidemic of Wellness, the Certainty of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer,” by Barbara Ehrenreich, PhD (New York:Twelve, 2018). Infuriating, tender, disquieting, moving. Barbara Ehrenreich’s latest book is provocative. As a septuagenarian and cancer survivor who has forsworn most future medical measures, including Pap smears and cancer screenings (even though she has medical insurance), Dr. Ehrenreich castigates both the traditional medical and integrative holistic health establishments. Yes, she’s critical of us and nurses and fitness gurus and mindfulness coaches and Silicon Valley. Why should I read this you ask? Because it’s good to understand contrarian views, especially when they are thoughtfully articulated. Because there are many patients who share her beliefs, and understanding opposing perspectives might help us become better clinicians. Because she may cause you to be reflective. Do we order too many tests? Do we overprescribe meds? Are we setting up patients for false hopes of longevity? Is providing more care always the best option? This exercise is beneficial for all types of healers.

“Leadership in Turbulent Times,” by Doris Kearns Goodwin, PhD, (New York:Simon & Schuster, 2018). I’m a presidential biography junkie. As physicians in what some may rightly call a turbulent health care culture, we face challenges each day that require our best intentions, our best diagnostic skills, our best empathic efforts, our best selves. Dr. Goodwin, in her prototypical engaging and informative prose, shows us four American presidents, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Lyndon B. Johnson, who persevered through devastatingly turbulent times. While we don’t have to make decisions regarding warfare, we do have an unmistakable impact on the lives of thousands of patients, and this book provides insights that can help all of us become better informed, better prepared leaders for our patients, our coworkers, and our communities at large.

“You and I Eat the Same: On the Countless Ways Food and Cooking Connect Us to One Another,” edited by Chris Ying; foreword by René Redzepi (New York:Artisan, 2018). Open a newspaper or turn on the news, and it’s difficult not to feel as if we live in an alarmingly polarized society. We can find many issues that divide us, but as healers, I hope we also strive to find ways to connect us. In 19 engaging and thought-provoking essays, this book explores the various ways that food connects us as humans. Whether it’s an historical deep dive into our love of meat wrapped in flatbread (which we’ve been doing for over 1,000 years) or tackling philosophical questions like, “Is there such a thing as a ‘non-ethnic’ restaurant?” this book will inform, inspire, and delight, and provide delicious topics for a bite of small talk with your patients.

“The Great Alone,” by Kristin Hannah (New York:St. Martin’s Press, 2018). Lured by Alaska’s majestic splendor and remoteness, the Allbright family (former POW, Ernt; abused wife, Cora; and coming-of-age daughter, Leni) are happy with their new life. For a minute. What ensues, namely punishing 16-hour days of darkness punctuated by episodes of oppressive snowfall, paranoia, and domestic violence, is grueling: “Night swept in like nothing Leni had ever seen before, like the winged shadow of a creature too big and predatory to comprehend.” Yet, this book is also a story about the bonds of family, both those we are born into and those we choose, love, sacrifice, and resilience.

If you have any books you read over the last to year to add to this list, please write to me at [email protected].

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter.

There were .

“Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress,” by Steven Pinker, PhD (New York:Viking, 2018). Think life was better 50 years ago? 100? 500? Steven Pinker would say you’re wrong. Whether or not we feel it, empirically, life is better today than it ever has been. We are living longer, healthier lives, have better access to health care, have fewer war-related deaths and food shortages and higher levels of literacy and equal rights. However, Dr. Pinker acknowledges our shortcomings (e.g., providing a living wage) and potential societal pitfalls (e.g., increasing tribalism), although he could have addressed other crucial issues such as climate change more fully. If you’re looking for an optimistic, science-based outlook on humanity, look no further than this book.

“Aware: The Science and Practice of Presence – The Groundbreaking Meditation Practice,” by Daniel J. Siegel, MD (New York:TarcherPerigee, 2018). A clinical professor of psychiatry and director of the UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center, Dr. Siegel, in his latest book, constructs a compelling argument for practicing presence that is supported by ample scientific evidence. His “Wheel of Awareness” is a tool to cultivate presence, self-awareness, and compassion. He deftly shows how developing “open awareness” and “kind intention” has not only psychological benefits, but also physical ones, such as improving immune function and increasing neural integration in the brain. As he writes, “The scientific findings are now in: Your mind can change the health of your body and slow aging.” That’s a message both we physicians and our patients could benefit from hearing more often.

“When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing,” by Daniel H. Pink (New York: Riverhead Books, 2018). In his latest book, Mr. Pink delves into timing, and the evolving science of timing, which draws from fields that include biology, psychology, neuroscience, and economics. Through extensive research (he analyzed over 700 studies) and fascinating real-life examples, the data are clear: We overwhelmingly perform optimally in the morning, suffer a mid-day slump, then rally once more in the evening (of course, there are productive night owls too). These peaks and dips affect both our moods and decision-making abilities, resulting in real-world impact (judges, for example, are more lenient in sentencing following a break). With practical takeaways you can immediately incorporate into your daily routine, you can start to feel more productive, energized, and happy, which is good news for both you and your patients.

“Natural Causes An Epidemic of Wellness, the Certainty of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer,” by Barbara Ehrenreich, PhD (New York:Twelve, 2018). Infuriating, tender, disquieting, moving. Barbara Ehrenreich’s latest book is provocative. As a septuagenarian and cancer survivor who has forsworn most future medical measures, including Pap smears and cancer screenings (even though she has medical insurance), Dr. Ehrenreich castigates both the traditional medical and integrative holistic health establishments. Yes, she’s critical of us and nurses and fitness gurus and mindfulness coaches and Silicon Valley. Why should I read this you ask? Because it’s good to understand contrarian views, especially when they are thoughtfully articulated. Because there are many patients who share her beliefs, and understanding opposing perspectives might help us become better clinicians. Because she may cause you to be reflective. Do we order too many tests? Do we overprescribe meds? Are we setting up patients for false hopes of longevity? Is providing more care always the best option? This exercise is beneficial for all types of healers.

“Leadership in Turbulent Times,” by Doris Kearns Goodwin, PhD, (New York:Simon & Schuster, 2018). I’m a presidential biography junkie. As physicians in what some may rightly call a turbulent health care culture, we face challenges each day that require our best intentions, our best diagnostic skills, our best empathic efforts, our best selves. Dr. Goodwin, in her prototypical engaging and informative prose, shows us four American presidents, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Lyndon B. Johnson, who persevered through devastatingly turbulent times. While we don’t have to make decisions regarding warfare, we do have an unmistakable impact on the lives of thousands of patients, and this book provides insights that can help all of us become better informed, better prepared leaders for our patients, our coworkers, and our communities at large.

“You and I Eat the Same: On the Countless Ways Food and Cooking Connect Us to One Another,” edited by Chris Ying; foreword by René Redzepi (New York:Artisan, 2018). Open a newspaper or turn on the news, and it’s difficult not to feel as if we live in an alarmingly polarized society. We can find many issues that divide us, but as healers, I hope we also strive to find ways to connect us. In 19 engaging and thought-provoking essays, this book explores the various ways that food connects us as humans. Whether it’s an historical deep dive into our love of meat wrapped in flatbread (which we’ve been doing for over 1,000 years) or tackling philosophical questions like, “Is there such a thing as a ‘non-ethnic’ restaurant?” this book will inform, inspire, and delight, and provide delicious topics for a bite of small talk with your patients.

“The Great Alone,” by Kristin Hannah (New York:St. Martin’s Press, 2018). Lured by Alaska’s majestic splendor and remoteness, the Allbright family (former POW, Ernt; abused wife, Cora; and coming-of-age daughter, Leni) are happy with their new life. For a minute. What ensues, namely punishing 16-hour days of darkness punctuated by episodes of oppressive snowfall, paranoia, and domestic violence, is grueling: “Night swept in like nothing Leni had ever seen before, like the winged shadow of a creature too big and predatory to comprehend.” Yet, this book is also a story about the bonds of family, both those we are born into and those we choose, love, sacrifice, and resilience.

If you have any books you read over the last to year to add to this list, please write to me at [email protected].

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter.

Slowing down

This past Labor Day weekend, I did something radical. I slowed down. Way down. My wife slowed down with me, which helped. We spent the weekend close to home walking, talking, reading, contemplating, planning, assessing, doing puzzles and crosswords, and imbibing a craft beer or two, slowly, of course. Why? Because of Adam Grant, PhD, the organizational psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, Philadelphia. I had recently reread his 2016 book I’m a big fan; he’s one of those professors who makes you fervently wish you were a student again, someone who will provoke you and challenge your way of thinking.

Dr. Grant’s basic premise, which he has proved through research, is that procrastination boosts productivity. Here’s how: Let’s say you’re facing a challenge or difficult task. He says to start working on it immediately, then take some time away for reflection. This “quick to start and slow to finish” method allows your brain to continually percolate on the problem. An incomplete task stays partially active in your brain. When you come back to it you often see it with fresh eyes. You will experience your highest productivity when you are toggling between these two modes.

This makes sense, and Dr. Grant cites numerous examples from Leonardo da Vinci to the founders of Warby-Parker, as examples of success. But how can it benefit physicians? Many of us are “precrastinators,” people who tend to complete or at least begin tasks as soon as possible, even when it’s unnecessary or not urgent. Unlike some jobs in which it’s easier to take a break from a project and return to it with more creative solutions, we often are racing against a clock to see more patients, read more slides, answer more emails, and make more phone calls. We are perpetually frenetic, which is not conducive to original thinking.

If this sounds like you, then you are likely to benefit from deliberate procrastination. Here are a few ways to slow down:

- Put it on your calendar. Yes, I see the irony, but it works. Start by scheduling one hour a week where you are to accomplish nothing. You can fill this time with whatever your mind wants to do at that moment.

- When faced with a diagnostic dilemma or treatment failure, resist the urge to solve that problem in that moment. Save that note for later, tell the patient you will call him back or bring him back for a visit later. Even if you’re not actively working on it, it will incubate somewhere in your brain, allowing more divergent thought processes to take over. It’s a little like trying to solve a crossword that seems impossible in the moment and then answers suddenly appear without effort.

- Take up a hobby: Play the guitar, learn to make pasta, climb a big rock. When you are fully engaged in such pursuits it requires complete mental focus. When you revisit the difficult problem you’re working on, you will likely see it from different perspectives.

- Meditate: Meditation requires our brains and bodies to slow down. It can help reduce self-doubt and criticism which stifle problem solving.

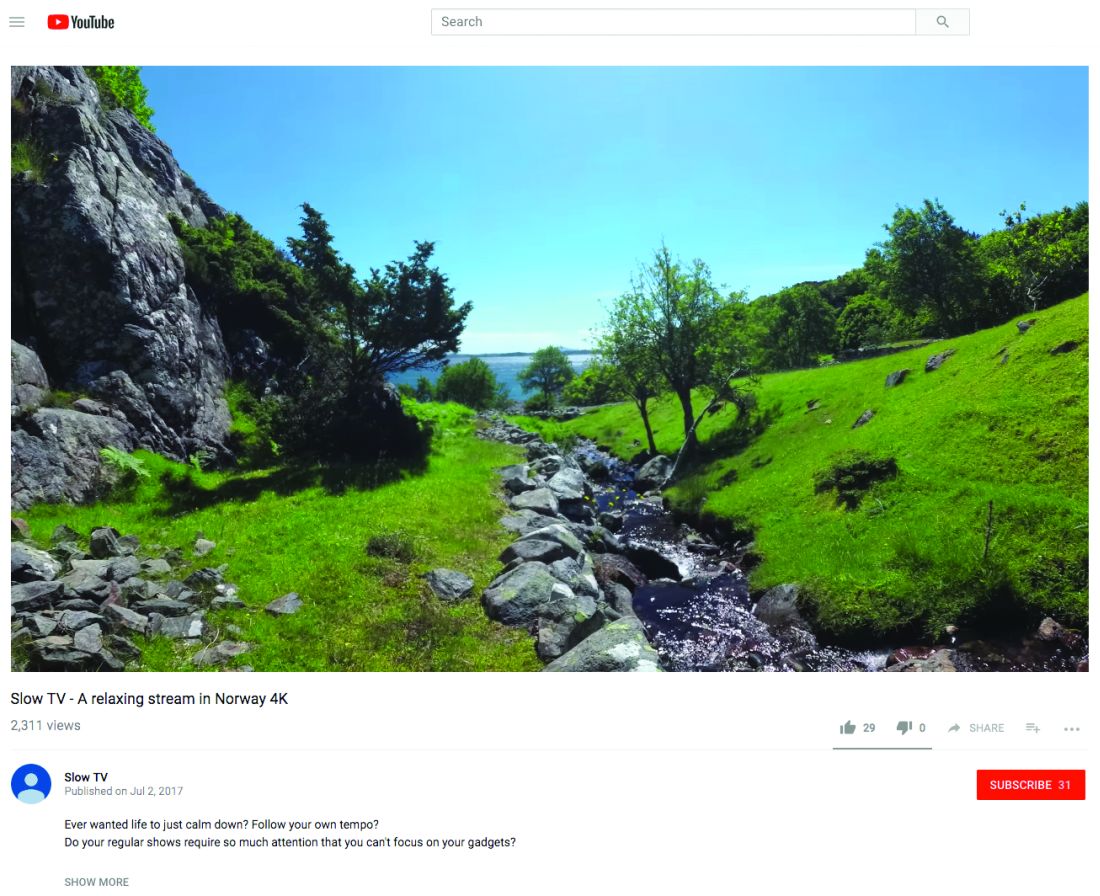

- Watch Slow TV. Slow TV is a Scandinavian phenomenon where you sit and watch meditative video such as a 7-hour train cam from Bergen, Norway, to Oslo. There’s no dialogue, no plot, no commercials. It’s just 7 hours of track and train and is weirdly comforting.

If you want to learn more, then when you get a chance, Google “slow living” and explore. Of course, some of you precrastinators probably have already started before finishing this column.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

This past Labor Day weekend, I did something radical. I slowed down. Way down. My wife slowed down with me, which helped. We spent the weekend close to home walking, talking, reading, contemplating, planning, assessing, doing puzzles and crosswords, and imbibing a craft beer or two, slowly, of course. Why? Because of Adam Grant, PhD, the organizational psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, Philadelphia. I had recently reread his 2016 book I’m a big fan; he’s one of those professors who makes you fervently wish you were a student again, someone who will provoke you and challenge your way of thinking.

Dr. Grant’s basic premise, which he has proved through research, is that procrastination boosts productivity. Here’s how: Let’s say you’re facing a challenge or difficult task. He says to start working on it immediately, then take some time away for reflection. This “quick to start and slow to finish” method allows your brain to continually percolate on the problem. An incomplete task stays partially active in your brain. When you come back to it you often see it with fresh eyes. You will experience your highest productivity when you are toggling between these two modes.

This makes sense, and Dr. Grant cites numerous examples from Leonardo da Vinci to the founders of Warby-Parker, as examples of success. But how can it benefit physicians? Many of us are “precrastinators,” people who tend to complete or at least begin tasks as soon as possible, even when it’s unnecessary or not urgent. Unlike some jobs in which it’s easier to take a break from a project and return to it with more creative solutions, we often are racing against a clock to see more patients, read more slides, answer more emails, and make more phone calls. We are perpetually frenetic, which is not conducive to original thinking.

If this sounds like you, then you are likely to benefit from deliberate procrastination. Here are a few ways to slow down:

- Put it on your calendar. Yes, I see the irony, but it works. Start by scheduling one hour a week where you are to accomplish nothing. You can fill this time with whatever your mind wants to do at that moment.

- When faced with a diagnostic dilemma or treatment failure, resist the urge to solve that problem in that moment. Save that note for later, tell the patient you will call him back or bring him back for a visit later. Even if you’re not actively working on it, it will incubate somewhere in your brain, allowing more divergent thought processes to take over. It’s a little like trying to solve a crossword that seems impossible in the moment and then answers suddenly appear without effort.

- Take up a hobby: Play the guitar, learn to make pasta, climb a big rock. When you are fully engaged in such pursuits it requires complete mental focus. When you revisit the difficult problem you’re working on, you will likely see it from different perspectives.

- Meditate: Meditation requires our brains and bodies to slow down. It can help reduce self-doubt and criticism which stifle problem solving.

- Watch Slow TV. Slow TV is a Scandinavian phenomenon where you sit and watch meditative video such as a 7-hour train cam from Bergen, Norway, to Oslo. There’s no dialogue, no plot, no commercials. It’s just 7 hours of track and train and is weirdly comforting.

If you want to learn more, then when you get a chance, Google “slow living” and explore. Of course, some of you precrastinators probably have already started before finishing this column.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

This past Labor Day weekend, I did something radical. I slowed down. Way down. My wife slowed down with me, which helped. We spent the weekend close to home walking, talking, reading, contemplating, planning, assessing, doing puzzles and crosswords, and imbibing a craft beer or two, slowly, of course. Why? Because of Adam Grant, PhD, the organizational psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, Philadelphia. I had recently reread his 2016 book I’m a big fan; he’s one of those professors who makes you fervently wish you were a student again, someone who will provoke you and challenge your way of thinking.

Dr. Grant’s basic premise, which he has proved through research, is that procrastination boosts productivity. Here’s how: Let’s say you’re facing a challenge or difficult task. He says to start working on it immediately, then take some time away for reflection. This “quick to start and slow to finish” method allows your brain to continually percolate on the problem. An incomplete task stays partially active in your brain. When you come back to it you often see it with fresh eyes. You will experience your highest productivity when you are toggling between these two modes.

This makes sense, and Dr. Grant cites numerous examples from Leonardo da Vinci to the founders of Warby-Parker, as examples of success. But how can it benefit physicians? Many of us are “precrastinators,” people who tend to complete or at least begin tasks as soon as possible, even when it’s unnecessary or not urgent. Unlike some jobs in which it’s easier to take a break from a project and return to it with more creative solutions, we often are racing against a clock to see more patients, read more slides, answer more emails, and make more phone calls. We are perpetually frenetic, which is not conducive to original thinking.

If this sounds like you, then you are likely to benefit from deliberate procrastination. Here are a few ways to slow down:

- Put it on your calendar. Yes, I see the irony, but it works. Start by scheduling one hour a week where you are to accomplish nothing. You can fill this time with whatever your mind wants to do at that moment.

- When faced with a diagnostic dilemma or treatment failure, resist the urge to solve that problem in that moment. Save that note for later, tell the patient you will call him back or bring him back for a visit later. Even if you’re not actively working on it, it will incubate somewhere in your brain, allowing more divergent thought processes to take over. It’s a little like trying to solve a crossword that seems impossible in the moment and then answers suddenly appear without effort.

- Take up a hobby: Play the guitar, learn to make pasta, climb a big rock. When you are fully engaged in such pursuits it requires complete mental focus. When you revisit the difficult problem you’re working on, you will likely see it from different perspectives.

- Meditate: Meditation requires our brains and bodies to slow down. It can help reduce self-doubt and criticism which stifle problem solving.

- Watch Slow TV. Slow TV is a Scandinavian phenomenon where you sit and watch meditative video such as a 7-hour train cam from Bergen, Norway, to Oslo. There’s no dialogue, no plot, no commercials. It’s just 7 hours of track and train and is weirdly comforting.

If you want to learn more, then when you get a chance, Google “slow living” and explore. Of course, some of you precrastinators probably have already started before finishing this column.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Creating positive patient experiences

Let’s start with an exercise, shall we? What was the last vacation you went on? How would you rate that vacation on a scale of 1-10?

How you came up with that score is likely not entirely reflective of your actual experience. Understanding how we remember experiences is critical for the work we do everyday.

My last vacation was in Alaska. I’d rate it a 9 out of 10. How did I come up with that score? It is not the mean score of the entire trip as you might expect. Rather, I took a shortcut and thought only about the highlights to come up with a number. We remember, and evaluate, our experiences as a series of discrete events. In considering these events, it is only the highs, the lows, and the transitions that matter. Think about the score you gave your vacation. What specific moments did you remember?

This phenomenon is not specific to vacations. It applies to all service experiences. When your patients evaluate you, they will ignore most of what occurred and focus on only a few moments. Fair or not, it is from these bits only that they will rate their entire experience. This information helps us devise strategies to achieve high satisfaction scores: Focus on the high points, address the low points, if any, and be sure the transitions are pleasant.

For example, a patient might come to see you for a procedure. It could be something positive, such as injection of cosmetic filler or something negative like a colonoscopy. Either way, being finished with the procedure will likely be the best part for them. Don’t rush this time; instead of quickly moving on, take a moment to acknowledge you’re done, how well the patient did, or how much better they will now look or feel. Engaging with your patient at this moment can improve the salience of their experience and increase the likelihood that she or he will remember the appointment favorably and rate you accordingly, if given the opportunity.

In the same way, if you are aware your patient has experienced something negative, try to respond to it right away. Acknowledge if she or he expressed frustration, such as a long wait or pain, then take a minute to address or reframe it. Blunting the severity of the service failure can blunt their recall of it. This will make it less likely that it becomes a memorable part of their experience.

Last, transitions matter. These are the moments when your patient shifts from one setting to another, such as arriving at your office, moving from the waiting room to the exam room, and wrapping up the visit with the receptionist. Many of these moments will be managed by your staff. Therefore, invest time reminding them of their importance and teaching them tips and techniques to help patients transition smoothly and to feel well cared for. There will likely be a wonderful return on investment for them, you and, most importantly, your patients.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Let’s start with an exercise, shall we? What was the last vacation you went on? How would you rate that vacation on a scale of 1-10?

How you came up with that score is likely not entirely reflective of your actual experience. Understanding how we remember experiences is critical for the work we do everyday.

My last vacation was in Alaska. I’d rate it a 9 out of 10. How did I come up with that score? It is not the mean score of the entire trip as you might expect. Rather, I took a shortcut and thought only about the highlights to come up with a number. We remember, and evaluate, our experiences as a series of discrete events. In considering these events, it is only the highs, the lows, and the transitions that matter. Think about the score you gave your vacation. What specific moments did you remember?

This phenomenon is not specific to vacations. It applies to all service experiences. When your patients evaluate you, they will ignore most of what occurred and focus on only a few moments. Fair or not, it is from these bits only that they will rate their entire experience. This information helps us devise strategies to achieve high satisfaction scores: Focus on the high points, address the low points, if any, and be sure the transitions are pleasant.

For example, a patient might come to see you for a procedure. It could be something positive, such as injection of cosmetic filler or something negative like a colonoscopy. Either way, being finished with the procedure will likely be the best part for them. Don’t rush this time; instead of quickly moving on, take a moment to acknowledge you’re done, how well the patient did, or how much better they will now look or feel. Engaging with your patient at this moment can improve the salience of their experience and increase the likelihood that she or he will remember the appointment favorably and rate you accordingly, if given the opportunity.

In the same way, if you are aware your patient has experienced something negative, try to respond to it right away. Acknowledge if she or he expressed frustration, such as a long wait or pain, then take a minute to address or reframe it. Blunting the severity of the service failure can blunt their recall of it. This will make it less likely that it becomes a memorable part of their experience.

Last, transitions matter. These are the moments when your patient shifts from one setting to another, such as arriving at your office, moving from the waiting room to the exam room, and wrapping up the visit with the receptionist. Many of these moments will be managed by your staff. Therefore, invest time reminding them of their importance and teaching them tips and techniques to help patients transition smoothly and to feel well cared for. There will likely be a wonderful return on investment for them, you and, most importantly, your patients.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Let’s start with an exercise, shall we? What was the last vacation you went on? How would you rate that vacation on a scale of 1-10?

How you came up with that score is likely not entirely reflective of your actual experience. Understanding how we remember experiences is critical for the work we do everyday.

My last vacation was in Alaska. I’d rate it a 9 out of 10. How did I come up with that score? It is not the mean score of the entire trip as you might expect. Rather, I took a shortcut and thought only about the highlights to come up with a number. We remember, and evaluate, our experiences as a series of discrete events. In considering these events, it is only the highs, the lows, and the transitions that matter. Think about the score you gave your vacation. What specific moments did you remember?

This phenomenon is not specific to vacations. It applies to all service experiences. When your patients evaluate you, they will ignore most of what occurred and focus on only a few moments. Fair or not, it is from these bits only that they will rate their entire experience. This information helps us devise strategies to achieve high satisfaction scores: Focus on the high points, address the low points, if any, and be sure the transitions are pleasant.

For example, a patient might come to see you for a procedure. It could be something positive, such as injection of cosmetic filler or something negative like a colonoscopy. Either way, being finished with the procedure will likely be the best part for them. Don’t rush this time; instead of quickly moving on, take a moment to acknowledge you’re done, how well the patient did, or how much better they will now look or feel. Engaging with your patient at this moment can improve the salience of their experience and increase the likelihood that she or he will remember the appointment favorably and rate you accordingly, if given the opportunity.

In the same way, if you are aware your patient has experienced something negative, try to respond to it right away. Acknowledge if she or he expressed frustration, such as a long wait or pain, then take a minute to address or reframe it. Blunting the severity of the service failure can blunt their recall of it. This will make it less likely that it becomes a memorable part of their experience.

Last, transitions matter. These are the moments when your patient shifts from one setting to another, such as arriving at your office, moving from the waiting room to the exam room, and wrapping up the visit with the receptionist. Many of these moments will be managed by your staff. Therefore, invest time reminding them of their importance and teaching them tips and techniques to help patients transition smoothly and to feel well cared for. There will likely be a wonderful return on investment for them, you and, most importantly, your patients.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Tabata training

I’m in really good shape. Well, more like really not bad shape. I eat healthy food (see my previous column on diet) and work out nearly every day. I have done so for years. I’ve learned that working out doesn’t make much difference with my weight, but it makes a huge difference with my mood, even more so than meditating. That’s why I’ll never give it up.

My approach is to vary my routine, typically by month. I’ve done “BUD/S qualification” months where I do only push-ups, sit-ups, pull-ups, and runs to meet the minimum requirements for the Navy Seal Training. (It’s not as hard as you might think, although I’m pretty lenient on form.)

When I have an hour to exercise and I’m deep into a podcast, then I’ll just keep going. If I’m trying to work out a piece I’m writing, like this one, then I’ll go for a run along the harbor here in San Diego. If I have to catch an early flight or drive to LA for the day, then I might have only 15 minutes. In that instance, I do high-intensity sprints, also known as high-intensity interval training (HIIT). Although it’s hard to break a good sweat, these workouts are both challenging and rewarding.

Recently, I participated in a wonderful physician wellness program at Kaiser Permanente, San Diego, where, over several weeks, we learned about nutrition, practiced meditation, and did Tabatas. What’s a Tabata you ask? It’s a kick in the butt.

. Yup, it’s a 4-minute workout that consists of 20 seconds of all-out, maximum effort, followed by 10 seconds of rest. The specific move you do for Tabatas is up to you, but it’s recommended that it be the same move for all 4 minutes. I like burpees which work your entire body – you jump, you drop into a push-up position, you pull your feet back in, and jump again. (Check out a video on YouTube.)

When we started the class, I thought Tabatas would be too easy for a gym rat like me. Plus, there were pediatricians, and even radiologists there, so how hard could they be? Let’s just say I couldn’t sit for 2 days after my first session: That’s how hard.

Tabatas are also a quick way to torch calories. A study published in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine in 2013 found subjects who performed a 20-minute Tabata session experienced improved cardiorespiratory endurance and increased calorie burn (J Sports Sci Med. 2013 Sep;12[3]: 612-3).

Sometimes on a Monday, which is typically my difficult day, I’ll break out a few burpees in my office between patients. The energy jolt is real, and unlike caffeine, doesn’t leave me shaky. Because Tabatas require physical and mental focus, they’re an effective way to clear your mind after a grueling patient visit or if you’re feeling distracted. You simply can’t be thinking about that late patient or angry email when you’re jumping and lunging at full speed.

All the physicians in our program liked the Tabatas; many were even better than me. (Turns out we have pediatricians and radiologists who do things like run the Boston marathon and win Spartan races).

And if you start doing Tabatas, feel free to email me if you need a recommendation for a standing desk – you might not be able to sit as much afterward.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

I’m in really good shape. Well, more like really not bad shape. I eat healthy food (see my previous column on diet) and work out nearly every day. I have done so for years. I’ve learned that working out doesn’t make much difference with my weight, but it makes a huge difference with my mood, even more so than meditating. That’s why I’ll never give it up.

My approach is to vary my routine, typically by month. I’ve done “BUD/S qualification” months where I do only push-ups, sit-ups, pull-ups, and runs to meet the minimum requirements for the Navy Seal Training. (It’s not as hard as you might think, although I’m pretty lenient on form.)

When I have an hour to exercise and I’m deep into a podcast, then I’ll just keep going. If I’m trying to work out a piece I’m writing, like this one, then I’ll go for a run along the harbor here in San Diego. If I have to catch an early flight or drive to LA for the day, then I might have only 15 minutes. In that instance, I do high-intensity sprints, also known as high-intensity interval training (HIIT). Although it’s hard to break a good sweat, these workouts are both challenging and rewarding.

Recently, I participated in a wonderful physician wellness program at Kaiser Permanente, San Diego, where, over several weeks, we learned about nutrition, practiced meditation, and did Tabatas. What’s a Tabata you ask? It’s a kick in the butt.

. Yup, it’s a 4-minute workout that consists of 20 seconds of all-out, maximum effort, followed by 10 seconds of rest. The specific move you do for Tabatas is up to you, but it’s recommended that it be the same move for all 4 minutes. I like burpees which work your entire body – you jump, you drop into a push-up position, you pull your feet back in, and jump again. (Check out a video on YouTube.)

When we started the class, I thought Tabatas would be too easy for a gym rat like me. Plus, there were pediatricians, and even radiologists there, so how hard could they be? Let’s just say I couldn’t sit for 2 days after my first session: That’s how hard.

Tabatas are also a quick way to torch calories. A study published in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine in 2013 found subjects who performed a 20-minute Tabata session experienced improved cardiorespiratory endurance and increased calorie burn (J Sports Sci Med. 2013 Sep;12[3]: 612-3).

Sometimes on a Monday, which is typically my difficult day, I’ll break out a few burpees in my office between patients. The energy jolt is real, and unlike caffeine, doesn’t leave me shaky. Because Tabatas require physical and mental focus, they’re an effective way to clear your mind after a grueling patient visit or if you’re feeling distracted. You simply can’t be thinking about that late patient or angry email when you’re jumping and lunging at full speed.

All the physicians in our program liked the Tabatas; many were even better than me. (Turns out we have pediatricians and radiologists who do things like run the Boston marathon and win Spartan races).

And if you start doing Tabatas, feel free to email me if you need a recommendation for a standing desk – you might not be able to sit as much afterward.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

I’m in really good shape. Well, more like really not bad shape. I eat healthy food (see my previous column on diet) and work out nearly every day. I have done so for years. I’ve learned that working out doesn’t make much difference with my weight, but it makes a huge difference with my mood, even more so than meditating. That’s why I’ll never give it up.

My approach is to vary my routine, typically by month. I’ve done “BUD/S qualification” months where I do only push-ups, sit-ups, pull-ups, and runs to meet the minimum requirements for the Navy Seal Training. (It’s not as hard as you might think, although I’m pretty lenient on form.)

When I have an hour to exercise and I’m deep into a podcast, then I’ll just keep going. If I’m trying to work out a piece I’m writing, like this one, then I’ll go for a run along the harbor here in San Diego. If I have to catch an early flight or drive to LA for the day, then I might have only 15 minutes. In that instance, I do high-intensity sprints, also known as high-intensity interval training (HIIT). Although it’s hard to break a good sweat, these workouts are both challenging and rewarding.

Recently, I participated in a wonderful physician wellness program at Kaiser Permanente, San Diego, where, over several weeks, we learned about nutrition, practiced meditation, and did Tabatas. What’s a Tabata you ask? It’s a kick in the butt.

. Yup, it’s a 4-minute workout that consists of 20 seconds of all-out, maximum effort, followed by 10 seconds of rest. The specific move you do for Tabatas is up to you, but it’s recommended that it be the same move for all 4 minutes. I like burpees which work your entire body – you jump, you drop into a push-up position, you pull your feet back in, and jump again. (Check out a video on YouTube.)

When we started the class, I thought Tabatas would be too easy for a gym rat like me. Plus, there were pediatricians, and even radiologists there, so how hard could they be? Let’s just say I couldn’t sit for 2 days after my first session: That’s how hard.

Tabatas are also a quick way to torch calories. A study published in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine in 2013 found subjects who performed a 20-minute Tabata session experienced improved cardiorespiratory endurance and increased calorie burn (J Sports Sci Med. 2013 Sep;12[3]: 612-3).

Sometimes on a Monday, which is typically my difficult day, I’ll break out a few burpees in my office between patients. The energy jolt is real, and unlike caffeine, doesn’t leave me shaky. Because Tabatas require physical and mental focus, they’re an effective way to clear your mind after a grueling patient visit or if you’re feeling distracted. You simply can’t be thinking about that late patient or angry email when you’re jumping and lunging at full speed.

All the physicians in our program liked the Tabatas; many were even better than me. (Turns out we have pediatricians and radiologists who do things like run the Boston marathon and win Spartan races).

And if you start doing Tabatas, feel free to email me if you need a recommendation for a standing desk – you might not be able to sit as much afterward.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Impostor syndrome

Why are you bothering to read this? What could I offer that could possibly be useful to you? In fact, I was invited to write this column simply because I happened to be at the right conference at the right time. Soon, if not already, you’ll discover I’m actually not that clever. I’m an impostor.

I’ve thought this while staring at the blank page that is to be my article for the month. Reflecting on it, I realize you’ve probably had the same feelings of fraud at one time or another. It often occurs at moments of transition, such as when you were accepted into medical school or matched into a competitive specialty. Looking at your peers, watching how your colleagues perform, you feel you just aren’t smart enough to be there; either someone made a mistake or you just got lucky.

There are potentially positive aspects of impostor syndrome: Humility can make us more effective over time and more tolerable to be around. It also, however, can be destructive. When we feel undeserving, we grow anxious and focus ever more tightly on ourselves. It can be paralyzing. When you think about how you are perceived, you fail to be present and attentive to others around you. Believing you lack innate ability, you can slip into a fixed mindset and fail to grow. Trying to keep your insecurities a secret from others, the foundation of impostor syndrome, is stressful and will stoke the fire of burnout which threatens us all. Fortunately, there is a cure.

The first step in escaping this maladaptive experience is to do what I’ve just done: Share it with others. Find colleagues or partners who care about you and who can speak frankly. By sharing how you feel with others, you banish any power that impostor syndrome might have over you. You can’t worry about being a fraud once you’ve just announced that you are a fraud; the gig is up! Choose your confidantes carefully, as not everyone is suitable to help. Avoid sharing such feelings with your patients; it can erode their confidence in you.

Reframe how you interpret situations when you feel like an impostor. Committing an error doesn’t mean you’re incompetent; moreover, you needn’t be supremely confident to be competent. Marveling at others’ abilities doesn’t mean you could not perform as well. Remember, you don’t know how much effort and time they’ve invested, and chances are you’re underestimating the work they’ve put forth.

Last, take the time to write about your success. Journaling can be a powerful tool to make your successes more salient and remind you that you are truly accomplished. Try writing in the third person, telling the story of your journey and the obstacles you’ve overcome to reach your current prestigious destination. If you still feel like a fake sometimes, there is good news. Having some self-doubt correlates with success, probably because it keeps you motivated to work hard.

Did this article resonate with you? It should. It took me lots of drafts before I got it right.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Why are you bothering to read this? What could I offer that could possibly be useful to you? In fact, I was invited to write this column simply because I happened to be at the right conference at the right time. Soon, if not already, you’ll discover I’m actually not that clever. I’m an impostor.

I’ve thought this while staring at the blank page that is to be my article for the month. Reflecting on it, I realize you’ve probably had the same feelings of fraud at one time or another. It often occurs at moments of transition, such as when you were accepted into medical school or matched into a competitive specialty. Looking at your peers, watching how your colleagues perform, you feel you just aren’t smart enough to be there; either someone made a mistake or you just got lucky.

There are potentially positive aspects of impostor syndrome: Humility can make us more effective over time and more tolerable to be around. It also, however, can be destructive. When we feel undeserving, we grow anxious and focus ever more tightly on ourselves. It can be paralyzing. When you think about how you are perceived, you fail to be present and attentive to others around you. Believing you lack innate ability, you can slip into a fixed mindset and fail to grow. Trying to keep your insecurities a secret from others, the foundation of impostor syndrome, is stressful and will stoke the fire of burnout which threatens us all. Fortunately, there is a cure.

The first step in escaping this maladaptive experience is to do what I’ve just done: Share it with others. Find colleagues or partners who care about you and who can speak frankly. By sharing how you feel with others, you banish any power that impostor syndrome might have over you. You can’t worry about being a fraud once you’ve just announced that you are a fraud; the gig is up! Choose your confidantes carefully, as not everyone is suitable to help. Avoid sharing such feelings with your patients; it can erode their confidence in you.

Reframe how you interpret situations when you feel like an impostor. Committing an error doesn’t mean you’re incompetent; moreover, you needn’t be supremely confident to be competent. Marveling at others’ abilities doesn’t mean you could not perform as well. Remember, you don’t know how much effort and time they’ve invested, and chances are you’re underestimating the work they’ve put forth.

Last, take the time to write about your success. Journaling can be a powerful tool to make your successes more salient and remind you that you are truly accomplished. Try writing in the third person, telling the story of your journey and the obstacles you’ve overcome to reach your current prestigious destination. If you still feel like a fake sometimes, there is good news. Having some self-doubt correlates with success, probably because it keeps you motivated to work hard.

Did this article resonate with you? It should. It took me lots of drafts before I got it right.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Why are you bothering to read this? What could I offer that could possibly be useful to you? In fact, I was invited to write this column simply because I happened to be at the right conference at the right time. Soon, if not already, you’ll discover I’m actually not that clever. I’m an impostor.

I’ve thought this while staring at the blank page that is to be my article for the month. Reflecting on it, I realize you’ve probably had the same feelings of fraud at one time or another. It often occurs at moments of transition, such as when you were accepted into medical school or matched into a competitive specialty. Looking at your peers, watching how your colleagues perform, you feel you just aren’t smart enough to be there; either someone made a mistake or you just got lucky.

There are potentially positive aspects of impostor syndrome: Humility can make us more effective over time and more tolerable to be around. It also, however, can be destructive. When we feel undeserving, we grow anxious and focus ever more tightly on ourselves. It can be paralyzing. When you think about how you are perceived, you fail to be present and attentive to others around you. Believing you lack innate ability, you can slip into a fixed mindset and fail to grow. Trying to keep your insecurities a secret from others, the foundation of impostor syndrome, is stressful and will stoke the fire of burnout which threatens us all. Fortunately, there is a cure.

The first step in escaping this maladaptive experience is to do what I’ve just done: Share it with others. Find colleagues or partners who care about you and who can speak frankly. By sharing how you feel with others, you banish any power that impostor syndrome might have over you. You can’t worry about being a fraud once you’ve just announced that you are a fraud; the gig is up! Choose your confidantes carefully, as not everyone is suitable to help. Avoid sharing such feelings with your patients; it can erode their confidence in you.

Reframe how you interpret situations when you feel like an impostor. Committing an error doesn’t mean you’re incompetent; moreover, you needn’t be supremely confident to be competent. Marveling at others’ abilities doesn’t mean you could not perform as well. Remember, you don’t know how much effort and time they’ve invested, and chances are you’re underestimating the work they’ve put forth.

Last, take the time to write about your success. Journaling can be a powerful tool to make your successes more salient and remind you that you are truly accomplished. Try writing in the third person, telling the story of your journey and the obstacles you’ve overcome to reach your current prestigious destination. If you still feel like a fake sometimes, there is good news. Having some self-doubt correlates with success, probably because it keeps you motivated to work hard.

Did this article resonate with you? It should. It took me lots of drafts before I got it right.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Handshake

There’s a simple act you’ve done with all your patients that you’ve probably been doing incorrectly. Yes, that is rather a bold assertion, but I’ll bet no one ever taught you the proper way. It’s only recently, after having done it thousands of times, that I came to realize there is a better way to give a handshake.

The first helps establish who you are as a doctor and reassures your patient that you’re both capable and trustworthy. At the end of the visit, it seals the agreement wherein they commit to take your advice (or at least try) and you commit to do whatever necessary to help them.

A poorly executed handshake, or worse, none at all, can erode trust or convey a lack of ability on your part. It’s true that handshakes aren’t always appropriate: For certain patients or disease states, they would be unsuitable. For the majority of patient visits, however, they are key. Here are some secrets to a good handshake:

- As you’ve probably experienced, timing is critical. A handshake requires someone to anticipate your action and to coordinate perfectly with you. When you enter the room, move toward your patient and put your hand forward just as you approach your patient. Too early and you look like an awkward high schooler eager for a Justin Bieber autograph. Too late and you’ll take your patient by surprise. The best position is to have your left foot forward as you reach for their hand. This gives you stability and allows you to convey confidence.

- As you approach your patient, make eye contact. Just a second or two as you cross the room is perfect. Then glance down at their now outstretched hand and connect web to web. Your arm should be tucked in and move straight toward their hand. Swinging out to come back in is great when you’re getting your new NBA jersey from the basketball commissioner, but not for getting patients comfortable with you.

- The grip depends on the patient. For most adults, a firm squeeze with two arm pumps is just right. For the hard-charging, testosterone-replacing ex-Marine, you can reciprocate the extra-firm grasp – let him win the grip contest though, that’s what he wants. For the freezing-in-her-gown great grandmother, an extra long hold, sometimes even double handed, is fine, even appreciated.

- No matter how firm, it is important to convey your enthusiasm and ability to your patient. This is done with a gentle push. As you shake hands, lightly push their arm back into them. This subtle transfer of energy from you to them is a little known tip that will make your handshake much more effective. Never push them off balance or worse, pull them toward you. Your objective is to create trust; making them unsteady will make that impossible.

- Finally, let go after two pumps. If you feel them holding on, then stay until they release. For the majority of patients, that will be a just a couple seconds.

For patients I’ve never met, I often proffer my hand turned slightly upward for our first handshake. This subtle sign of submission shows I’m open and committed to them. For our closing handshake, I have my hand turned slightly downward so that my hand is slightly over theirs. This conveys that I’m confident in what I’ve said and done and that now I want them to uphold their part in our agreement.

I’ve been using the above technique for a few years now with success. It has helped with my patient satisfaction scores, and importantly, has helped me manage difficult patients for whom trust in our relationship is invaluable.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

There’s a simple act you’ve done with all your patients that you’ve probably been doing incorrectly. Yes, that is rather a bold assertion, but I’ll bet no one ever taught you the proper way. It’s only recently, after having done it thousands of times, that I came to realize there is a better way to give a handshake.

The first helps establish who you are as a doctor and reassures your patient that you’re both capable and trustworthy. At the end of the visit, it seals the agreement wherein they commit to take your advice (or at least try) and you commit to do whatever necessary to help them.

A poorly executed handshake, or worse, none at all, can erode trust or convey a lack of ability on your part. It’s true that handshakes aren’t always appropriate: For certain patients or disease states, they would be unsuitable. For the majority of patient visits, however, they are key. Here are some secrets to a good handshake:

- As you’ve probably experienced, timing is critical. A handshake requires someone to anticipate your action and to coordinate perfectly with you. When you enter the room, move toward your patient and put your hand forward just as you approach your patient. Too early and you look like an awkward high schooler eager for a Justin Bieber autograph. Too late and you’ll take your patient by surprise. The best position is to have your left foot forward as you reach for their hand. This gives you stability and allows you to convey confidence.

- As you approach your patient, make eye contact. Just a second or two as you cross the room is perfect. Then glance down at their now outstretched hand and connect web to web. Your arm should be tucked in and move straight toward their hand. Swinging out to come back in is great when you’re getting your new NBA jersey from the basketball commissioner, but not for getting patients comfortable with you.

- The grip depends on the patient. For most adults, a firm squeeze with two arm pumps is just right. For the hard-charging, testosterone-replacing ex-Marine, you can reciprocate the extra-firm grasp – let him win the grip contest though, that’s what he wants. For the freezing-in-her-gown great grandmother, an extra long hold, sometimes even double handed, is fine, even appreciated.

- No matter how firm, it is important to convey your enthusiasm and ability to your patient. This is done with a gentle push. As you shake hands, lightly push their arm back into them. This subtle transfer of energy from you to them is a little known tip that will make your handshake much more effective. Never push them off balance or worse, pull them toward you. Your objective is to create trust; making them unsteady will make that impossible.

- Finally, let go after two pumps. If you feel them holding on, then stay until they release. For the majority of patients, that will be a just a couple seconds.