User login

Jennifer Smith is the editor of Oncology Practice, part of MDedge Hematology/Oncology. She was previously the editor of Hematology Times, an editor at Principal Investigators Association, and a reporter at The Oneida Daily Dispatch. She has a BS in journalism.

Elotuzumab under review for relapsed/refractory myeloma

The Food and Drug Administration has granted .

Bristol-Myers Squibb is seeking approval for elotuzumab in combination with pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone to treat patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who have received at least two prior therapies, including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor.

Elotuzumab is already approved for use in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone to treat multiple myeloma patients who have received between one and three prior therapies.

The elotuzumab application is supported by data from ELOQUENT-3, a randomized, phase 2 study that evaluated the addition of elotuzumab to pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.

Researchers presented findings from this study at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association in June 2018.

The overall response rate was 53% in the elotuzumab, pomalidomide, and low-dose dexamethasone (EPd) arm and 26% in the pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (Pd) arm. The median progression-free survival was 10.3 months in the EPd arm and 4.7 months in the Pd arm (hazard ratio, 0.54; P = .0078), the researchers reported.

The researchers also reported that adverse events in the EPd arm were consistent with expectations based on previous results with elotuzumab and pomalidomide regimens.

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions. The priority review typically shortens the time to an approval decision by a few months. The agency is expected to make a decision on elotuzumab by Dec. 27, 2018.

Bristol-Myers Squibb and AbbVie are codeveloping elotuzumab, with Bristol-Myers Squibb solely responsible for commercial activities.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted .

Bristol-Myers Squibb is seeking approval for elotuzumab in combination with pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone to treat patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who have received at least two prior therapies, including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor.

Elotuzumab is already approved for use in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone to treat multiple myeloma patients who have received between one and three prior therapies.

The elotuzumab application is supported by data from ELOQUENT-3, a randomized, phase 2 study that evaluated the addition of elotuzumab to pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.

Researchers presented findings from this study at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association in June 2018.

The overall response rate was 53% in the elotuzumab, pomalidomide, and low-dose dexamethasone (EPd) arm and 26% in the pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (Pd) arm. The median progression-free survival was 10.3 months in the EPd arm and 4.7 months in the Pd arm (hazard ratio, 0.54; P = .0078), the researchers reported.

The researchers also reported that adverse events in the EPd arm were consistent with expectations based on previous results with elotuzumab and pomalidomide regimens.

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions. The priority review typically shortens the time to an approval decision by a few months. The agency is expected to make a decision on elotuzumab by Dec. 27, 2018.

Bristol-Myers Squibb and AbbVie are codeveloping elotuzumab, with Bristol-Myers Squibb solely responsible for commercial activities.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted .

Bristol-Myers Squibb is seeking approval for elotuzumab in combination with pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone to treat patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who have received at least two prior therapies, including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor.

Elotuzumab is already approved for use in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone to treat multiple myeloma patients who have received between one and three prior therapies.

The elotuzumab application is supported by data from ELOQUENT-3, a randomized, phase 2 study that evaluated the addition of elotuzumab to pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.

Researchers presented findings from this study at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association in June 2018.

The overall response rate was 53% in the elotuzumab, pomalidomide, and low-dose dexamethasone (EPd) arm and 26% in the pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (Pd) arm. The median progression-free survival was 10.3 months in the EPd arm and 4.7 months in the Pd arm (hazard ratio, 0.54; P = .0078), the researchers reported.

The researchers also reported that adverse events in the EPd arm were consistent with expectations based on previous results with elotuzumab and pomalidomide regimens.

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions. The priority review typically shortens the time to an approval decision by a few months. The agency is expected to make a decision on elotuzumab by Dec. 27, 2018.

Bristol-Myers Squibb and AbbVie are codeveloping elotuzumab, with Bristol-Myers Squibb solely responsible for commercial activities.

Marzeptacog alfa reduces bleeding episodes in hemophilia with inhibitors

The activated factor VIIa variant according to researchers.

To date, the trial has enrolled five patients with hemophilia A or B and inhibitors. Catalyst would not disclose how many patients have hemophilia A and how many have hemophilia B. Three patients have completed dosing with marzeptacog alfa in a phase 2/3 study. None of these patients experienced bleeding during treatment, and none have developed antidrug antibodies or reported injection site reactions. As for the other two patients enrolled in this study, one withdrew consent, and one died of an adverse event unrelated to marzeptacog alfa.

Howard Levy, chief medical officer of Catalyst Biosciences, which has been developing this drug and sponsored the trial, presented these data at the 2018 Hemophilia Drug Development Summit in Boston.

The goal of this ongoing trial is to determine whether daily subcutaneous injections of marzeptacog alfa can eliminate or minimize spontaneous bleeding episodes. The primary endpoint is a reduction in annualized bleed rate (ABR), compared with each individual’s recorded historical ABR.

One patient with a historic ABR of 26.7 experienced a bleed on day 46 when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 mcg/kg but then had no bleeds after 50 days of treatment with marzeptacog alfa at 60 mcg/kg. This patient did experience a bleed 16 days after the end of dosing at 60 mcg/kg.

A second patient with a historic ABR of 16.6 had no bleeds when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 mcg/kg for 50 days.

And a third patient with a historic ABR of 15.9 had no bleeds when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 mcg/kg for 44 days.

“The data from these 3 individuals support the efficacy of [marzeptacog alfa] to reduce annualized bleed rates after daily subcutaneous injections,” said Nassim Usman, PhD, chief executive officer of Catalyst Biosciences. “Importantly, to date, we have not observed any injection site reactions nor any antidrug antibodies after more than 200 subcutaneous doses of [marzeptacog alfa].”

A fourth patient with a historic ABR of 18.3 had a fatal hemorrhagic stroke on day 11 that was considered unrelated to marzeptacog alfa. The patient had previously treated hypertension that was going untreated at the time of death.

A fifth patient with a historic ABR of 12.2 withdrew consent.

The activated factor VIIa variant according to researchers.

To date, the trial has enrolled five patients with hemophilia A or B and inhibitors. Catalyst would not disclose how many patients have hemophilia A and how many have hemophilia B. Three patients have completed dosing with marzeptacog alfa in a phase 2/3 study. None of these patients experienced bleeding during treatment, and none have developed antidrug antibodies or reported injection site reactions. As for the other two patients enrolled in this study, one withdrew consent, and one died of an adverse event unrelated to marzeptacog alfa.

Howard Levy, chief medical officer of Catalyst Biosciences, which has been developing this drug and sponsored the trial, presented these data at the 2018 Hemophilia Drug Development Summit in Boston.

The goal of this ongoing trial is to determine whether daily subcutaneous injections of marzeptacog alfa can eliminate or minimize spontaneous bleeding episodes. The primary endpoint is a reduction in annualized bleed rate (ABR), compared with each individual’s recorded historical ABR.

One patient with a historic ABR of 26.7 experienced a bleed on day 46 when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 mcg/kg but then had no bleeds after 50 days of treatment with marzeptacog alfa at 60 mcg/kg. This patient did experience a bleed 16 days after the end of dosing at 60 mcg/kg.

A second patient with a historic ABR of 16.6 had no bleeds when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 mcg/kg for 50 days.

And a third patient with a historic ABR of 15.9 had no bleeds when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 mcg/kg for 44 days.

“The data from these 3 individuals support the efficacy of [marzeptacog alfa] to reduce annualized bleed rates after daily subcutaneous injections,” said Nassim Usman, PhD, chief executive officer of Catalyst Biosciences. “Importantly, to date, we have not observed any injection site reactions nor any antidrug antibodies after more than 200 subcutaneous doses of [marzeptacog alfa].”

A fourth patient with a historic ABR of 18.3 had a fatal hemorrhagic stroke on day 11 that was considered unrelated to marzeptacog alfa. The patient had previously treated hypertension that was going untreated at the time of death.

A fifth patient with a historic ABR of 12.2 withdrew consent.

The activated factor VIIa variant according to researchers.

To date, the trial has enrolled five patients with hemophilia A or B and inhibitors. Catalyst would not disclose how many patients have hemophilia A and how many have hemophilia B. Three patients have completed dosing with marzeptacog alfa in a phase 2/3 study. None of these patients experienced bleeding during treatment, and none have developed antidrug antibodies or reported injection site reactions. As for the other two patients enrolled in this study, one withdrew consent, and one died of an adverse event unrelated to marzeptacog alfa.

Howard Levy, chief medical officer of Catalyst Biosciences, which has been developing this drug and sponsored the trial, presented these data at the 2018 Hemophilia Drug Development Summit in Boston.

The goal of this ongoing trial is to determine whether daily subcutaneous injections of marzeptacog alfa can eliminate or minimize spontaneous bleeding episodes. The primary endpoint is a reduction in annualized bleed rate (ABR), compared with each individual’s recorded historical ABR.

One patient with a historic ABR of 26.7 experienced a bleed on day 46 when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 mcg/kg but then had no bleeds after 50 days of treatment with marzeptacog alfa at 60 mcg/kg. This patient did experience a bleed 16 days after the end of dosing at 60 mcg/kg.

A second patient with a historic ABR of 16.6 had no bleeds when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 mcg/kg for 50 days.

And a third patient with a historic ABR of 15.9 had no bleeds when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 mcg/kg for 44 days.

“The data from these 3 individuals support the efficacy of [marzeptacog alfa] to reduce annualized bleed rates after daily subcutaneous injections,” said Nassim Usman, PhD, chief executive officer of Catalyst Biosciences. “Importantly, to date, we have not observed any injection site reactions nor any antidrug antibodies after more than 200 subcutaneous doses of [marzeptacog alfa].”

A fourth patient with a historic ABR of 18.3 had a fatal hemorrhagic stroke on day 11 that was considered unrelated to marzeptacog alfa. The patient had previously treated hypertension that was going untreated at the time of death.

A fifth patient with a historic ABR of 12.2 withdrew consent.

FDA grants orphan designation to DHODH inhibitor for AML

ASLAN003 is a small molecule inhibitor of the human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) enzyme. This second-generation DHODH inhibitor is being developed by Aslan Pharmaceuticals. The company is currently conducting a phase 2 trial (NCT03451084) of ASLAN003 in patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed/refractory AML. Aslan expects to report interim data from this trial in the second half of 2018.

Aslan has already completed a phase 1 trial (NCT01992367) of ASLAN003 in healthy volunteers. The results suggested that ASLAN003 has an “excellent” pharmacokinetic profile, according to Aslan, and the drug was considered well tolerated in the volunteers.

ASLAN003 has also demonstrated “potent” inhibition of DHODH, according to the drug sponsor. In fact, the company said the binding affinity of ASLAN003 to DHODH has proven to be up to two orders of magnitude stronger than first-generation DHODH inhibitors, such as leflunomide and teriflunomide, but it has less toxicity.

In addition, ASLAN003 has been shown to differentiate blast cells into granulocytes in AML cell lines that do not respond to all-trans retinoic acid. These results were published in Cell in 2016.

ASLAN003 is a small molecule inhibitor of the human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) enzyme. This second-generation DHODH inhibitor is being developed by Aslan Pharmaceuticals. The company is currently conducting a phase 2 trial (NCT03451084) of ASLAN003 in patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed/refractory AML. Aslan expects to report interim data from this trial in the second half of 2018.

Aslan has already completed a phase 1 trial (NCT01992367) of ASLAN003 in healthy volunteers. The results suggested that ASLAN003 has an “excellent” pharmacokinetic profile, according to Aslan, and the drug was considered well tolerated in the volunteers.

ASLAN003 has also demonstrated “potent” inhibition of DHODH, according to the drug sponsor. In fact, the company said the binding affinity of ASLAN003 to DHODH has proven to be up to two orders of magnitude stronger than first-generation DHODH inhibitors, such as leflunomide and teriflunomide, but it has less toxicity.

In addition, ASLAN003 has been shown to differentiate blast cells into granulocytes in AML cell lines that do not respond to all-trans retinoic acid. These results were published in Cell in 2016.

ASLAN003 is a small molecule inhibitor of the human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) enzyme. This second-generation DHODH inhibitor is being developed by Aslan Pharmaceuticals. The company is currently conducting a phase 2 trial (NCT03451084) of ASLAN003 in patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed/refractory AML. Aslan expects to report interim data from this trial in the second half of 2018.

Aslan has already completed a phase 1 trial (NCT01992367) of ASLAN003 in healthy volunteers. The results suggested that ASLAN003 has an “excellent” pharmacokinetic profile, according to Aslan, and the drug was considered well tolerated in the volunteers.

ASLAN003 has also demonstrated “potent” inhibition of DHODH, according to the drug sponsor. In fact, the company said the binding affinity of ASLAN003 to DHODH has proven to be up to two orders of magnitude stronger than first-generation DHODH inhibitors, such as leflunomide and teriflunomide, but it has less toxicity.

In addition, ASLAN003 has been shown to differentiate blast cells into granulocytes in AML cell lines that do not respond to all-trans retinoic acid. These results were published in Cell in 2016.

Some PE patients don’t require hospitalization

A new study suggests that

Researchers tested outpatient anticoagulant therapy in 200 patients with PE with a low mortality risk. At 90 days of follow-up, there were no deaths or recurrences of venous thromboembolism (VTE), but one patient experienced major bleeding after a traumatic injury.

A majority of patients said they were satisfied with outpatient care.

Joseph R. Bledsoe, MD, of Intermountain Medical Center in Salt Lake City, and his colleagues reported these results in Chest.

The researchers tracked patients who were treated for acute PE in five Intermountain Healthcare emergency departments (EDs) from 2013 to 2016. The patients had to have a low mortality risk according to the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (score less than 86), echocardiography (no signs of right heart strain), and whole-leg compression ultrasound. Patients could not have deep vein thrombosis proximal to the popliteal vein, hypoxia, hypotension, hepatic failure, or renal failure. They had to be eligible for therapeutic anticoagulation and could not have any condition requiring hospitalization.

With these criteria, the researchers selected 200 patients. They were observed in the ED or hospital for 12-24 hours and then discharged with anticoagulant therapy. Patients received rivaroxaban (n = 149), enoxaparin transitioned to warfarin (n = 26), apixaban (n = 24), or enoxaparin alone (n = 1).

Results

The study’s primary outcome was the 90-day composite rate of all-cause mortality, recurrent symptomatic VTE, and major bleeding. There were no deaths and no cases of recurrent VTE, but one patient did experience major bleeding at day 61 because of a traumatic thigh injury.

Within 7 days of study enrollment, there were 19 patients (9.5%) who returned to the ED and 2 patients (1%) who were admitted to the hospital. One patient with pulmonary infarct was admitted for pain control (day 2); the other was admitted for an elective coronary intervention (day 7) because of a positive cardiac stress test.

Within 30 days, 32 patients (16%) returned to the ED, and 5 (3%) were admitted to the hospital for events unrelated to their PE.

The study also showed that patients were largely satisfied with outpatient care. Of the 146 patients who completed a satisfaction survey at 90 days, 89% said they would choose outpatient management if they had another PE in the future.

“We found a large subset of patients with blood clots who’d do well at home; in fact, who probably did better at home,” Dr. Bledsoe said. “When patients are sent home versus staying in the hospital, they’re at lower risk of getting another infection. It’s a lot less expensive, too.”

Currently, the standard of care in the United States for acute PE is hospitalization for all patients. That’s recommended, in part, because their overall mortality rate is 17%. However, the lower mortality rate among some appropriately risk-stratified patients suggests that at-home care, which has become the norm in some European countries, leads to better outcomes for those patients overall and less chance of a hospital-introduced infection, according to Dr. Bledsoe. “Our findings show that if you appropriately risk-stratify patients, there are a lot of people with blood clots who are safe to go home.”

He added that similar research should be conducted outside of the Intermountain Healthcare system to confirm the results of this study and that a larger group of patients should be studied.

The investigators reported no conflicts related to this study.

SOURCE: Bledsoe JR et al. Chest. 2018 Aug;154(2):249-56.

A new study suggests that

Researchers tested outpatient anticoagulant therapy in 200 patients with PE with a low mortality risk. At 90 days of follow-up, there were no deaths or recurrences of venous thromboembolism (VTE), but one patient experienced major bleeding after a traumatic injury.

A majority of patients said they were satisfied with outpatient care.

Joseph R. Bledsoe, MD, of Intermountain Medical Center in Salt Lake City, and his colleagues reported these results in Chest.

The researchers tracked patients who were treated for acute PE in five Intermountain Healthcare emergency departments (EDs) from 2013 to 2016. The patients had to have a low mortality risk according to the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (score less than 86), echocardiography (no signs of right heart strain), and whole-leg compression ultrasound. Patients could not have deep vein thrombosis proximal to the popliteal vein, hypoxia, hypotension, hepatic failure, or renal failure. They had to be eligible for therapeutic anticoagulation and could not have any condition requiring hospitalization.

With these criteria, the researchers selected 200 patients. They were observed in the ED or hospital for 12-24 hours and then discharged with anticoagulant therapy. Patients received rivaroxaban (n = 149), enoxaparin transitioned to warfarin (n = 26), apixaban (n = 24), or enoxaparin alone (n = 1).

Results

The study’s primary outcome was the 90-day composite rate of all-cause mortality, recurrent symptomatic VTE, and major bleeding. There were no deaths and no cases of recurrent VTE, but one patient did experience major bleeding at day 61 because of a traumatic thigh injury.

Within 7 days of study enrollment, there were 19 patients (9.5%) who returned to the ED and 2 patients (1%) who were admitted to the hospital. One patient with pulmonary infarct was admitted for pain control (day 2); the other was admitted for an elective coronary intervention (day 7) because of a positive cardiac stress test.

Within 30 days, 32 patients (16%) returned to the ED, and 5 (3%) were admitted to the hospital for events unrelated to their PE.

The study also showed that patients were largely satisfied with outpatient care. Of the 146 patients who completed a satisfaction survey at 90 days, 89% said they would choose outpatient management if they had another PE in the future.

“We found a large subset of patients with blood clots who’d do well at home; in fact, who probably did better at home,” Dr. Bledsoe said. “When patients are sent home versus staying in the hospital, they’re at lower risk of getting another infection. It’s a lot less expensive, too.”

Currently, the standard of care in the United States for acute PE is hospitalization for all patients. That’s recommended, in part, because their overall mortality rate is 17%. However, the lower mortality rate among some appropriately risk-stratified patients suggests that at-home care, which has become the norm in some European countries, leads to better outcomes for those patients overall and less chance of a hospital-introduced infection, according to Dr. Bledsoe. “Our findings show that if you appropriately risk-stratify patients, there are a lot of people with blood clots who are safe to go home.”

He added that similar research should be conducted outside of the Intermountain Healthcare system to confirm the results of this study and that a larger group of patients should be studied.

The investigators reported no conflicts related to this study.

SOURCE: Bledsoe JR et al. Chest. 2018 Aug;154(2):249-56.

A new study suggests that

Researchers tested outpatient anticoagulant therapy in 200 patients with PE with a low mortality risk. At 90 days of follow-up, there were no deaths or recurrences of venous thromboembolism (VTE), but one patient experienced major bleeding after a traumatic injury.

A majority of patients said they were satisfied with outpatient care.

Joseph R. Bledsoe, MD, of Intermountain Medical Center in Salt Lake City, and his colleagues reported these results in Chest.

The researchers tracked patients who were treated for acute PE in five Intermountain Healthcare emergency departments (EDs) from 2013 to 2016. The patients had to have a low mortality risk according to the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (score less than 86), echocardiography (no signs of right heart strain), and whole-leg compression ultrasound. Patients could not have deep vein thrombosis proximal to the popliteal vein, hypoxia, hypotension, hepatic failure, or renal failure. They had to be eligible for therapeutic anticoagulation and could not have any condition requiring hospitalization.

With these criteria, the researchers selected 200 patients. They were observed in the ED or hospital for 12-24 hours and then discharged with anticoagulant therapy. Patients received rivaroxaban (n = 149), enoxaparin transitioned to warfarin (n = 26), apixaban (n = 24), or enoxaparin alone (n = 1).

Results

The study’s primary outcome was the 90-day composite rate of all-cause mortality, recurrent symptomatic VTE, and major bleeding. There were no deaths and no cases of recurrent VTE, but one patient did experience major bleeding at day 61 because of a traumatic thigh injury.

Within 7 days of study enrollment, there were 19 patients (9.5%) who returned to the ED and 2 patients (1%) who were admitted to the hospital. One patient with pulmonary infarct was admitted for pain control (day 2); the other was admitted for an elective coronary intervention (day 7) because of a positive cardiac stress test.

Within 30 days, 32 patients (16%) returned to the ED, and 5 (3%) were admitted to the hospital for events unrelated to their PE.

The study also showed that patients were largely satisfied with outpatient care. Of the 146 patients who completed a satisfaction survey at 90 days, 89% said they would choose outpatient management if they had another PE in the future.

“We found a large subset of patients with blood clots who’d do well at home; in fact, who probably did better at home,” Dr. Bledsoe said. “When patients are sent home versus staying in the hospital, they’re at lower risk of getting another infection. It’s a lot less expensive, too.”

Currently, the standard of care in the United States for acute PE is hospitalization for all patients. That’s recommended, in part, because their overall mortality rate is 17%. However, the lower mortality rate among some appropriately risk-stratified patients suggests that at-home care, which has become the norm in some European countries, leads to better outcomes for those patients overall and less chance of a hospital-introduced infection, according to Dr. Bledsoe. “Our findings show that if you appropriately risk-stratify patients, there are a lot of people with blood clots who are safe to go home.”

He added that similar research should be conducted outside of the Intermountain Healthcare system to confirm the results of this study and that a larger group of patients should be studied.

The investigators reported no conflicts related to this study.

SOURCE: Bledsoe JR et al. Chest. 2018 Aug;154(2):249-56.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: There were no deaths or recurrences of pulmonary embolism at 90 days in a group of patients stratified by criteria for low risk.

Major finding: At 90 days of follow-up, there were no deaths or recurrences of venous thromboembolism.

Study details: Researchers tested outpatient anticoagulant therapy in 200 patients with pulmonary embolism with a low mortality risk.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no conflicts related to this study.

Source: Bledsoe JR et al. Chest. 2018 Aug;154(2):249-56.

FDA puts partial hold on trial of vascular agent for AML, MDS

The Food and Drug Administration has placed a partial clinical hold on a phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503, a vascular disrupting agent.

In this trial (NCT02576301), researchers are evaluating OXi4503 alone and in combination with cytarabine in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The partial clinical hold applies to the 12.2 mg/m2 dose of OXi4503. The FDA is allowing the continued treatment and enrollment of patients using a dose of 9.76 mg/m2. Additional data on patients receiving OXi4503 at 9.76 mg/m2 must be evaluated before dosing at 12.2 mg/m2 can be resumed.

The partial clinical hold is a result of two potential dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) observed at the 12.2-mg/m2 dose level: hypotension, which occurred shortly after initial treatment with OXi4503, and acute hypoxic respiratory failure, which occurred approximately 2 weeks after receiving OXi4503 and cytarabine.

Both events were deemed “possibly related” to OXi4503, and both patients recovered following treatment.

“Although it is disappointing that we are not currently continuing with the higher dose of OXi4503, we look forward to gathering more safety and efficacy data at the previous dose level, where we observed 2 complete remissions in the 4 patients that we treated,” William D. Schwieterman, MD, chief executive officer of Mateon Therapeutics Inc., the company developing OXi4503, said in a statement.

In preclinical research, OXi4503 demonstrated activity against AML, both when given alone and in combination with bevacizumab. These results were published in Blood in 2010.

In a phase 1 trial (NCT01085656), researchers evaluated OXi4503 in patients with relapsed or refractory AML or MDS. OXi4503 demonstrated preliminary evidence of disease response in heavily pretreated, refractory AML and advanced MDS.

The maximum tolerated dose of OXi4503 was not identified, but adverse events attributable to the drug included hypertension, bone pain, fever, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and coagulopathies.

Results from this study were presented at the 2013 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In 2015, Mateon Therapeutics initiated the phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503 (NCT02576301) that is now on partial clinical hold.

The phase 1 portion of this study was designed to assess the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy of single-agent OXi4503 in patients with relapsed/refractory AML and MDS. It is also aimed at determining the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of OXi4503 plus intermediate-dose cytarabine.

The goal of the phase 2 portion is to assess the preliminary efficacy of OXi4503 and cytarabine in patients with AML and MDS.

The Food and Drug Administration has placed a partial clinical hold on a phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503, a vascular disrupting agent.

In this trial (NCT02576301), researchers are evaluating OXi4503 alone and in combination with cytarabine in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The partial clinical hold applies to the 12.2 mg/m2 dose of OXi4503. The FDA is allowing the continued treatment and enrollment of patients using a dose of 9.76 mg/m2. Additional data on patients receiving OXi4503 at 9.76 mg/m2 must be evaluated before dosing at 12.2 mg/m2 can be resumed.

The partial clinical hold is a result of two potential dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) observed at the 12.2-mg/m2 dose level: hypotension, which occurred shortly after initial treatment with OXi4503, and acute hypoxic respiratory failure, which occurred approximately 2 weeks after receiving OXi4503 and cytarabine.

Both events were deemed “possibly related” to OXi4503, and both patients recovered following treatment.

“Although it is disappointing that we are not currently continuing with the higher dose of OXi4503, we look forward to gathering more safety and efficacy data at the previous dose level, where we observed 2 complete remissions in the 4 patients that we treated,” William D. Schwieterman, MD, chief executive officer of Mateon Therapeutics Inc., the company developing OXi4503, said in a statement.

In preclinical research, OXi4503 demonstrated activity against AML, both when given alone and in combination with bevacizumab. These results were published in Blood in 2010.

In a phase 1 trial (NCT01085656), researchers evaluated OXi4503 in patients with relapsed or refractory AML or MDS. OXi4503 demonstrated preliminary evidence of disease response in heavily pretreated, refractory AML and advanced MDS.

The maximum tolerated dose of OXi4503 was not identified, but adverse events attributable to the drug included hypertension, bone pain, fever, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and coagulopathies.

Results from this study were presented at the 2013 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In 2015, Mateon Therapeutics initiated the phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503 (NCT02576301) that is now on partial clinical hold.

The phase 1 portion of this study was designed to assess the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy of single-agent OXi4503 in patients with relapsed/refractory AML and MDS. It is also aimed at determining the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of OXi4503 plus intermediate-dose cytarabine.

The goal of the phase 2 portion is to assess the preliminary efficacy of OXi4503 and cytarabine in patients with AML and MDS.

The Food and Drug Administration has placed a partial clinical hold on a phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503, a vascular disrupting agent.

In this trial (NCT02576301), researchers are evaluating OXi4503 alone and in combination with cytarabine in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The partial clinical hold applies to the 12.2 mg/m2 dose of OXi4503. The FDA is allowing the continued treatment and enrollment of patients using a dose of 9.76 mg/m2. Additional data on patients receiving OXi4503 at 9.76 mg/m2 must be evaluated before dosing at 12.2 mg/m2 can be resumed.

The partial clinical hold is a result of two potential dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) observed at the 12.2-mg/m2 dose level: hypotension, which occurred shortly after initial treatment with OXi4503, and acute hypoxic respiratory failure, which occurred approximately 2 weeks after receiving OXi4503 and cytarabine.

Both events were deemed “possibly related” to OXi4503, and both patients recovered following treatment.

“Although it is disappointing that we are not currently continuing with the higher dose of OXi4503, we look forward to gathering more safety and efficacy data at the previous dose level, where we observed 2 complete remissions in the 4 patients that we treated,” William D. Schwieterman, MD, chief executive officer of Mateon Therapeutics Inc., the company developing OXi4503, said in a statement.

In preclinical research, OXi4503 demonstrated activity against AML, both when given alone and in combination with bevacizumab. These results were published in Blood in 2010.

In a phase 1 trial (NCT01085656), researchers evaluated OXi4503 in patients with relapsed or refractory AML or MDS. OXi4503 demonstrated preliminary evidence of disease response in heavily pretreated, refractory AML and advanced MDS.

The maximum tolerated dose of OXi4503 was not identified, but adverse events attributable to the drug included hypertension, bone pain, fever, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and coagulopathies.

Results from this study were presented at the 2013 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In 2015, Mateon Therapeutics initiated the phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503 (NCT02576301) that is now on partial clinical hold.

The phase 1 portion of this study was designed to assess the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy of single-agent OXi4503 in patients with relapsed/refractory AML and MDS. It is also aimed at determining the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of OXi4503 plus intermediate-dose cytarabine.

The goal of the phase 2 portion is to assess the preliminary efficacy of OXi4503 and cytarabine in patients with AML and MDS.

CPI-613 receives orphan designation for PTCL

The Food and Drug Administration has granted orphan drug designation to CPI-613 for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

CPI-613 is a novel lipoic acid analogue that inhibits multiple enzyme targets within the tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Rafael Pharmaceuticals is developing CPI-613 as a treatment for hematologic malignancies and solid tumors.

CPI-613 is currently under investigation in combination with bendamustine in a phase 1 study of patients with relapsed or refractory T-cell lymphoma or classical Hodgkin lymphoma, according to the press release from the company.

Results from this trial were presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

CPI-613 was given at escalating doses starting at 2,000 mg/m2 over 2 hours on days 1-4 as well as on days 8, 11, 15, and 18. Bendamustine was infused at 90 mg/m2 on days 4 and 5 of each 4-week treatment cycle. The treatment cycles were repeated for up to six cycles. There was no intrapatient dose escalation.

The ASH presentation included safety data on eight patients. The most common grade 3 or higher toxicities – lymphopenia and neutropenia – occurred in four patients.

A patient dosed at 2,750 mg/m2 had a dose-limiting toxicity of grade 3 acute kidney injury and grade 4 lactic acidosis. Because of this, the study protocol was amended to discontinue dose escalation at doses of 2,750 mg/m2 or higher and to expand the 2,500 mg/m2 cohort.

Six patients were evaluable for efficacy, and the overall response rate was 83% (5/6).

There were three complete responses in patients with PTCL not otherwise specified, a partial response in a patient with mycosis fungoides, and a partial response in a patient with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma.

One patient with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia experienced progressive disease.

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the United States.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted orphan drug designation to CPI-613 for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

CPI-613 is a novel lipoic acid analogue that inhibits multiple enzyme targets within the tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Rafael Pharmaceuticals is developing CPI-613 as a treatment for hematologic malignancies and solid tumors.

CPI-613 is currently under investigation in combination with bendamustine in a phase 1 study of patients with relapsed or refractory T-cell lymphoma or classical Hodgkin lymphoma, according to the press release from the company.

Results from this trial were presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

CPI-613 was given at escalating doses starting at 2,000 mg/m2 over 2 hours on days 1-4 as well as on days 8, 11, 15, and 18. Bendamustine was infused at 90 mg/m2 on days 4 and 5 of each 4-week treatment cycle. The treatment cycles were repeated for up to six cycles. There was no intrapatient dose escalation.

The ASH presentation included safety data on eight patients. The most common grade 3 or higher toxicities – lymphopenia and neutropenia – occurred in four patients.

A patient dosed at 2,750 mg/m2 had a dose-limiting toxicity of grade 3 acute kidney injury and grade 4 lactic acidosis. Because of this, the study protocol was amended to discontinue dose escalation at doses of 2,750 mg/m2 or higher and to expand the 2,500 mg/m2 cohort.

Six patients were evaluable for efficacy, and the overall response rate was 83% (5/6).

There were three complete responses in patients with PTCL not otherwise specified, a partial response in a patient with mycosis fungoides, and a partial response in a patient with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma.

One patient with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia experienced progressive disease.

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the United States.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted orphan drug designation to CPI-613 for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

CPI-613 is a novel lipoic acid analogue that inhibits multiple enzyme targets within the tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Rafael Pharmaceuticals is developing CPI-613 as a treatment for hematologic malignancies and solid tumors.

CPI-613 is currently under investigation in combination with bendamustine in a phase 1 study of patients with relapsed or refractory T-cell lymphoma or classical Hodgkin lymphoma, according to the press release from the company.

Results from this trial were presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

CPI-613 was given at escalating doses starting at 2,000 mg/m2 over 2 hours on days 1-4 as well as on days 8, 11, 15, and 18. Bendamustine was infused at 90 mg/m2 on days 4 and 5 of each 4-week treatment cycle. The treatment cycles were repeated for up to six cycles. There was no intrapatient dose escalation.

The ASH presentation included safety data on eight patients. The most common grade 3 or higher toxicities – lymphopenia and neutropenia – occurred in four patients.

A patient dosed at 2,750 mg/m2 had a dose-limiting toxicity of grade 3 acute kidney injury and grade 4 lactic acidosis. Because of this, the study protocol was amended to discontinue dose escalation at doses of 2,750 mg/m2 or higher and to expand the 2,500 mg/m2 cohort.

Six patients were evaluable for efficacy, and the overall response rate was 83% (5/6).

There were three complete responses in patients with PTCL not otherwise specified, a partial response in a patient with mycosis fungoides, and a partial response in a patient with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma.

One patient with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia experienced progressive disease.

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the United States.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

FDA approves biologic for mycosis fungoides, Sézary syndrome

The Food and Drug Administration has approved mogamulizumab-kpkc (Poteligeo) for the treatment of adults with relapsed or refractory mycosis fungoides (MF) or Sézary syndrome (SS) who have received at least one prior systemic therapy.

Mogamulizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against CC chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4). It is the first biologic agent targeting CCR4 to be approved for patients in the United States.

Mogamulizumab is expected to be commercially available in the fourth quarter of 2018.

The FDA previously granted mogamulizumab breakthrough therapy and orphan drug designations, as well as priority review.

The approval is supported by the phase 3 MAVORIC trial. Results from this trial were presented at the 10th Annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum in February 2018.

MAVORIC enrolled 372 adults with histologically confirmed MF or SS who had failed at least one systemic therapy. They were randomized to receive mogamulizumab at 1.0 mg/kg (weekly for the first 4-week cycle and then every 2 weeks) or vorinostat at 400 mg daily. Patients were treated until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Those receiving vorinostat could cross over to mogamulizumab if they progressed or experienced intolerable toxicity. Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The study’s primary endpoint was progression-free survival. The median progression-free survival was 7.7 months with mogamulizumab and 3.1 months with vorinostat (hazard ratio, 0.53; P less than .0001).

The global overall response rate was 28% (52/189) in the mogamulizumab arm and 5% (9/186) in the vorinostat arm (P less than .0001). For patients with MF, the ORR was 21% with mogamulizumab and 7% with vorinostat; for patients with SS, the ORR was 37% and 2%, respectively. After crossover, the ORR in the mogamulizumab arm was 30% (41/136).

The median duration of response (DOR) was 14 months in the mogamulizumab arm and 9 months in the vorinostat arm. For MF patients, the median DOR was 13 months with mogamulizumab and 9 months with vorinostat; for SS patients, the median DOR was 17 months and 7 months, respectively.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), which occurred in at least 20% of patients in either arm (mogamulizumab and vorinostat, respectively), included the following:

- Infusion-related reactions (33.2% vs. 0.5%).

- Drug eruptions (23.9% vs. 0.5%).

- Diarrhea (23.4% vs. 61.8%).

- Nausea (15.2% vs. 42.5%).

- Thrombocytopenia (11.4% vs. 30.6%).

- Dysgeusia (3.3% vs. 28.0%).

- Increased blood creatinine (3.3% vs. 28.0%).

- Decreased appetite (7.6% vs. 24.7%).

There were no grade 4 AEs in the mogamulizumab arm. Grade 3 AEs in mogamulizumab recipients included drug eruptions (n = 8), infusion-related reactions (n = 3), fatigue (n = 3), decreased appetite (n = 2), nausea (n = 1), pyrexia (n = 1), and diarrhea (n = 1).

The drug is marketed by Kyowa Kirin.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved mogamulizumab-kpkc (Poteligeo) for the treatment of adults with relapsed or refractory mycosis fungoides (MF) or Sézary syndrome (SS) who have received at least one prior systemic therapy.

Mogamulizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against CC chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4). It is the first biologic agent targeting CCR4 to be approved for patients in the United States.

Mogamulizumab is expected to be commercially available in the fourth quarter of 2018.

The FDA previously granted mogamulizumab breakthrough therapy and orphan drug designations, as well as priority review.

The approval is supported by the phase 3 MAVORIC trial. Results from this trial were presented at the 10th Annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum in February 2018.

MAVORIC enrolled 372 adults with histologically confirmed MF or SS who had failed at least one systemic therapy. They were randomized to receive mogamulizumab at 1.0 mg/kg (weekly for the first 4-week cycle and then every 2 weeks) or vorinostat at 400 mg daily. Patients were treated until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Those receiving vorinostat could cross over to mogamulizumab if they progressed or experienced intolerable toxicity. Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The study’s primary endpoint was progression-free survival. The median progression-free survival was 7.7 months with mogamulizumab and 3.1 months with vorinostat (hazard ratio, 0.53; P less than .0001).

The global overall response rate was 28% (52/189) in the mogamulizumab arm and 5% (9/186) in the vorinostat arm (P less than .0001). For patients with MF, the ORR was 21% with mogamulizumab and 7% with vorinostat; for patients with SS, the ORR was 37% and 2%, respectively. After crossover, the ORR in the mogamulizumab arm was 30% (41/136).

The median duration of response (DOR) was 14 months in the mogamulizumab arm and 9 months in the vorinostat arm. For MF patients, the median DOR was 13 months with mogamulizumab and 9 months with vorinostat; for SS patients, the median DOR was 17 months and 7 months, respectively.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), which occurred in at least 20% of patients in either arm (mogamulizumab and vorinostat, respectively), included the following:

- Infusion-related reactions (33.2% vs. 0.5%).

- Drug eruptions (23.9% vs. 0.5%).

- Diarrhea (23.4% vs. 61.8%).

- Nausea (15.2% vs. 42.5%).

- Thrombocytopenia (11.4% vs. 30.6%).

- Dysgeusia (3.3% vs. 28.0%).

- Increased blood creatinine (3.3% vs. 28.0%).

- Decreased appetite (7.6% vs. 24.7%).

There were no grade 4 AEs in the mogamulizumab arm. Grade 3 AEs in mogamulizumab recipients included drug eruptions (n = 8), infusion-related reactions (n = 3), fatigue (n = 3), decreased appetite (n = 2), nausea (n = 1), pyrexia (n = 1), and diarrhea (n = 1).

The drug is marketed by Kyowa Kirin.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved mogamulizumab-kpkc (Poteligeo) for the treatment of adults with relapsed or refractory mycosis fungoides (MF) or Sézary syndrome (SS) who have received at least one prior systemic therapy.

Mogamulizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against CC chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4). It is the first biologic agent targeting CCR4 to be approved for patients in the United States.

Mogamulizumab is expected to be commercially available in the fourth quarter of 2018.

The FDA previously granted mogamulizumab breakthrough therapy and orphan drug designations, as well as priority review.

The approval is supported by the phase 3 MAVORIC trial. Results from this trial were presented at the 10th Annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum in February 2018.

MAVORIC enrolled 372 adults with histologically confirmed MF or SS who had failed at least one systemic therapy. They were randomized to receive mogamulizumab at 1.0 mg/kg (weekly for the first 4-week cycle and then every 2 weeks) or vorinostat at 400 mg daily. Patients were treated until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Those receiving vorinostat could cross over to mogamulizumab if they progressed or experienced intolerable toxicity. Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The study’s primary endpoint was progression-free survival. The median progression-free survival was 7.7 months with mogamulizumab and 3.1 months with vorinostat (hazard ratio, 0.53; P less than .0001).

The global overall response rate was 28% (52/189) in the mogamulizumab arm and 5% (9/186) in the vorinostat arm (P less than .0001). For patients with MF, the ORR was 21% with mogamulizumab and 7% with vorinostat; for patients with SS, the ORR was 37% and 2%, respectively. After crossover, the ORR in the mogamulizumab arm was 30% (41/136).

The median duration of response (DOR) was 14 months in the mogamulizumab arm and 9 months in the vorinostat arm. For MF patients, the median DOR was 13 months with mogamulizumab and 9 months with vorinostat; for SS patients, the median DOR was 17 months and 7 months, respectively.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), which occurred in at least 20% of patients in either arm (mogamulizumab and vorinostat, respectively), included the following:

- Infusion-related reactions (33.2% vs. 0.5%).

- Drug eruptions (23.9% vs. 0.5%).

- Diarrhea (23.4% vs. 61.8%).

- Nausea (15.2% vs. 42.5%).

- Thrombocytopenia (11.4% vs. 30.6%).

- Dysgeusia (3.3% vs. 28.0%).

- Increased blood creatinine (3.3% vs. 28.0%).

- Decreased appetite (7.6% vs. 24.7%).

There were no grade 4 AEs in the mogamulizumab arm. Grade 3 AEs in mogamulizumab recipients included drug eruptions (n = 8), infusion-related reactions (n = 3), fatigue (n = 3), decreased appetite (n = 2), nausea (n = 1), pyrexia (n = 1), and diarrhea (n = 1).

The drug is marketed by Kyowa Kirin.

Tobacco, Alcohol, and Drug Use Among Hospital Patients

Population‐based surveys of the adult US population estimate a prevalence of smoking of 25% and a prevalence of hazardous alcohol or illegal drug use of 23% and 8% respectively,1 with frequent concurrent use of these substances.2 The mortality associated with smoking and substance use is extremely high with tobacco first, alcohol third, and illicit drug use ninth as the leading causes of death in the US.3 Worldwide, the burden of disease from tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs accounts for almost 10% of all disability‐adjusted life years.4 Despite the availability of effective treatments,57 many patients do not receive professional intervention and few are offered comprehensive programs that address all of their harmful substance use.

Interventions have been successfully implemented for hospitalized smokers. Earlier work by Emmons8 and Orleans9 suggests that many smokers seek assistance to quit smoking during hospitalization. Over the past 15 years, hospital‐based smoking cessation interventions have been successfully implemented.10 Although mute on hospital‐based settings, the United States Preventive Service Task Force recommends screening and counseling interventions to reduce alcohol misuse among adults seen in primary care settings (B recommendation).6 Referral to specialized care is the accepted standard for most patients with substance dependence disorders7 regardless of the medical setting in which the diagnosis is made. Hospitalization provides a unique opportunity to initiate change in harmful substance use and smoking;11 however, interventions rarely are coordinated.

A high prevalence of smoking among substance users has been reported from population‐based surveys1215 and among patients in substance use treatment facilities.1618 Rates of concurrent smoking and substance use range from 35%44% in population‐based studies and may reach 80% in populations seeking substance use treatment.19 A recent hospital‐based study found at‐risk alcohol users were 3 times more likely to smoke.20 There are limited data describing concurrent smoking and substance use in the hospital population,15 and no reports describing the association between patients' willingness to quit smoking and readiness to change substance use behavior.

To better inform hospital‐based smoking and substance use intervention strategies, the epidemiology of smoking and substance use in the hospital population needs to be better described. Furthermore, there may be opportunities for synergy between these programs. In this study, we screened inpatients from multiple services at 2 hospitals for tobacco, alcohol, and illicit substance use. We report the prevalence and co‐occurrence of these behaviors and willingness to quit smoking among patients with and without at‐risk substance use.

METHODS

Data for this study were obtained for a 5‐year Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) grant to the Illinois Office of the Governor. The grant was awarded to implement screening, brief intervention, brief treatment, and referral to treatment programs for patients of the Cook County Bureau of Health Services who had alcohol or other drug use disorders. We analyzed data collected from nonIntensive Care Unit patients who had been hospitalized on the internal medicine, family practice, HIV, or surgery services at John H. Stroger Jr Hospital of Cook County (formerly Cook County Hospital, a 464‐bed public, tertiary‐care hospital) or Provident Hospital of Cook County (a 100‐bed public community hospital), in Chicago, Illinois. Because internal medicine and family practice patients were similar in demographic characteristics and interview responses, we considered these as a single service. There is an HIV service at Stroger Hospital; all HIV‐infected patients are admitted or transferred to this service. For each patient, we used data collected from their initial hospitalization during a 9‐month study period (April 1, 2006 through December 31, 2006). Using hospital admission data, we estimated that 65% of patients were interviewed by a counselor; only 5% of patients could not be interviewed due to patient refusal or mental status changes.

Patients were screened for alcohol use, drug use, and smoking history by bedside interview. We defined at‐risk substance use as any illicit drug use within the previous 3 months or alcohol use that exceeded the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) guidelines for low‐risk drinking (no more than 5 drinks per day or 14 drinks per week for men up to age 65; no more than 3 drinks per day or 7 drinks per week for men over 65 and women). Based on their responses to questions about smoking history, patients were categorized into the following 4 groups: current smokers (ie, smoked within the previous 7 days), recent quitters (ie, quit within 8 days and 6 months), ex‐smokers (quit more than 6 months ago), or never smokers. Current smokers were also asked about their heaviness of smoking and willingness to quit. All smokers received a counseling session during hospitalization. All smokers who indicated a desire to quit were encouraged to call the Illinois Quitline after hospital discharge. Individuals who smoked between 10‐14 cigarettes per day and smoked their first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking or who smoked 15 or more cigarettes per day were classified as moderate or heavy smokers; all other smokers were classified as light smokers. We established these cut‐points by modifying the Public Health Service guideline and Heaviness of Smoking Index.5, 21, 22 The heaviness of smoking classification was used to guide recommendations to the primary service regarding the appropriateness of nicotine patch therapy during and after hospitalization. For moderate to heavy smokers who were willing to quit, the recommendation was to continue nicotine replacement after hospitalization.5

Patients were considered low health risk if their alcohol use did not exceed NIAAA guidelines and they reported no recent drug use. For all patients who reported alcohol use that exceeded the NIAAA guidelines or recent drug use, we administered the Texas Christian University Drug Screen II (TCU)23 to further characterize the severity of their use. Patients who had a TCU score of 3 were considered at‐risk substance users with substance dependence disorder; patients with scores of 2 or less were considered at‐risk substance users without dependence. Among all at‐risk substance users, we used a 10‐point visual analog scale to assess their readiness to change substance use. After evaluating the distribution and clustering of scores, we prespecified that a score 8 was indicative of a patient being ready to change their substance use behavior. This ruler has been successfully implemented as part of the Brief Negotiated Interview and Active Referral to Treatment Institute toolbox.24

Analysis

To facilitate comparison with other data sources, we used the same age categories as the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.1 Differences between proportions were evaluated by the chi‐squared test. We analyzed the trend in smoking behavior across the strata of substance use (ie, number of substances used and severity of use) using the Cochrane‐Armitage test for trend. To evaluate the association between substance use and smoking, multivariable models were constructed that included terms to adjust for age, race, gender, and hospital service; potential confounders (eg, age, race, gender, and service) were included in the final model if they significantly contributed to the outcome variable (P < 0.1). From these multivariable models, prevalence ratios were estimated using the binary log transformation in PROC GENMOD.25, 26 All data were analyzed using SAS version 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Of the 7,714 unique patients interviewed at the 2 hospitals, we had data on smoking status for 7,391 (96%) (Table 1). The mean age was 50 years, most were male, cared for by the internal medicine or family practice service, and the most common racial/ethnic category was non‐Hispanic Black, followed by Hispanic, non‐Hispanic White, and Asian (Table 1). More than one‐quarter of patients reported at‐risk substance use other than tobacco; the most common substance used was alcohol followed by cocaine, marijuana, and then heroin (Table 1). Most patients who were at‐risk substance users (52%) met criteria for substance dependence disorder.23

| Characteristic | N | (%) | Smoking prevalence* (%) | Prevalence ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Age category | |||||

| 18‐25 | 479 | (6) | 35 | 2.6 | (2.1 to 3.1) |

| 26‐34 | 664 | (9) | 38 | 2.8 | (2.4 to 3.4) |

| 35‐44 | 1306 | (18) | 46 | 3.4 | (2.9 to 4.0) |

| 45‐54 | 2182 | (30) | 46 | 3.4 | (2.9 to 4.0) |

| 55‐64 | 1563 | (21) | 31 | 2.3 | (2.0 to 2.7) |

| 65 and older | 1185 | (16) | 13 | ref | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non Hispanic Black | 4990 | (68) | 45 | 3.0 | (2.2 to 4.0) |

| Non Hispanic White | 850 | (12) | 40 | 2.7 | (2.0 to 3.6) |

| Hispanic | 1222 | (17) | 19 | 1.3 | (0.9 to 1.7) |

| Asian | 253 | (3) | 15 | ref | |

| Other | 27 | (<1) | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 4279 | (58) | 42 | 1.5 | (1.4 to 1.6) |

| Female | 3099 | (42) | 29 | ref | |

| Service | |||||

| HIV | 227 | (3) | 52 | 1.7 | (1.5 to 2.0) |

| Internal medicine or | 6278 | (85) | 36 | 1.2 | (1.1 to 1.3) |

| family practice | |||||

| Surgery | 886 | (12) | 31 | ref | |

Tobacco Use

Many hospitalized patients were current smokers (36%) and 35% of current smokers were moderate to heavy smokers. The prevalence of smoking varied significantly by age category, race, gender, and service. By age category, the prevalence of smoking peaked at 3554 years with lower rates of smoking at either extreme of age (Table 1). Non‐Hispanic Blacks and Whites had a prevalence of smoking 3‐fold higher than Asians; Hispanics were less likely to smoke than non‐Hispanic Whites or Blacks. Men were more likely to smoke than women, and patients on the HIV or internal medicine/family practice services had a higher prevalence of smoking compared to patients on the surgery service (Table 1).

The proportion of current smokers who were moderate to heavy smokers was similar between patients with no‐risk or low‐risk substance use and those who had at‐risk substance use without dependence (32% versus 34%, respectively); however, current smokers who were substance‐dependent were 40% more likely to be moderate to heavy smokers (48%) (prevalence ratio [PR]: 1.4, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1 to 1.9).

Concurrent Tobacco and Substance Use

Compared to patients who reported low‐risk substance use, patients with at‐risk substance use had a dramatically higher prevalence of smoking (Table 2). In addition, there was a significant increase in the likelihood of smoking across the 3 levels of substance use and the number of substances used (Table 2).

| N | (%) | Smoking prevalence (%) | Adjusted prevalence ratio (95% CI)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Risk Index | |||||

| Low Health Risk | 5419 | (73) | 24 | ref | |

| At‐Risk, not dependent | 945 | (13) | 64 | 2.2 | (2.0 to 2.3) |

| At‐Risk, dependent | 1027 | (14) | 75 | 2.5 | (2.3 to 2.6) |

| Specific substance use | |||||

| Low Health Risk | 5419 | (73) | 24 | ref | |

| At‐Risk Alcohol Use | 1171 | (16) | 68 | 2.2 | (2.1 to 2.4) |

| At‐ Risk Marijuana Use | 688 | (9) | 70 | 2.1 | (2.0 to 2.3) |

| At‐Risk Cocaine Use | 503 | (7) | 79 | 2.4 | (2.2 to 2.6) |

| At‐Risk Heroin Use | 448 | (6) | 82 | 2.4 | (2.2 to 2.6) |

| Number of drugs | |||||

| None | 5419 | (73) | 24 | ref | |

| One | 1284 | (17) | 64 | 2.2 | (2.0 to 2.3) |

| Two or more | 688 | (9) | 81 | 2.6 | (2.5 to 2.8) |

Willingness to Quit

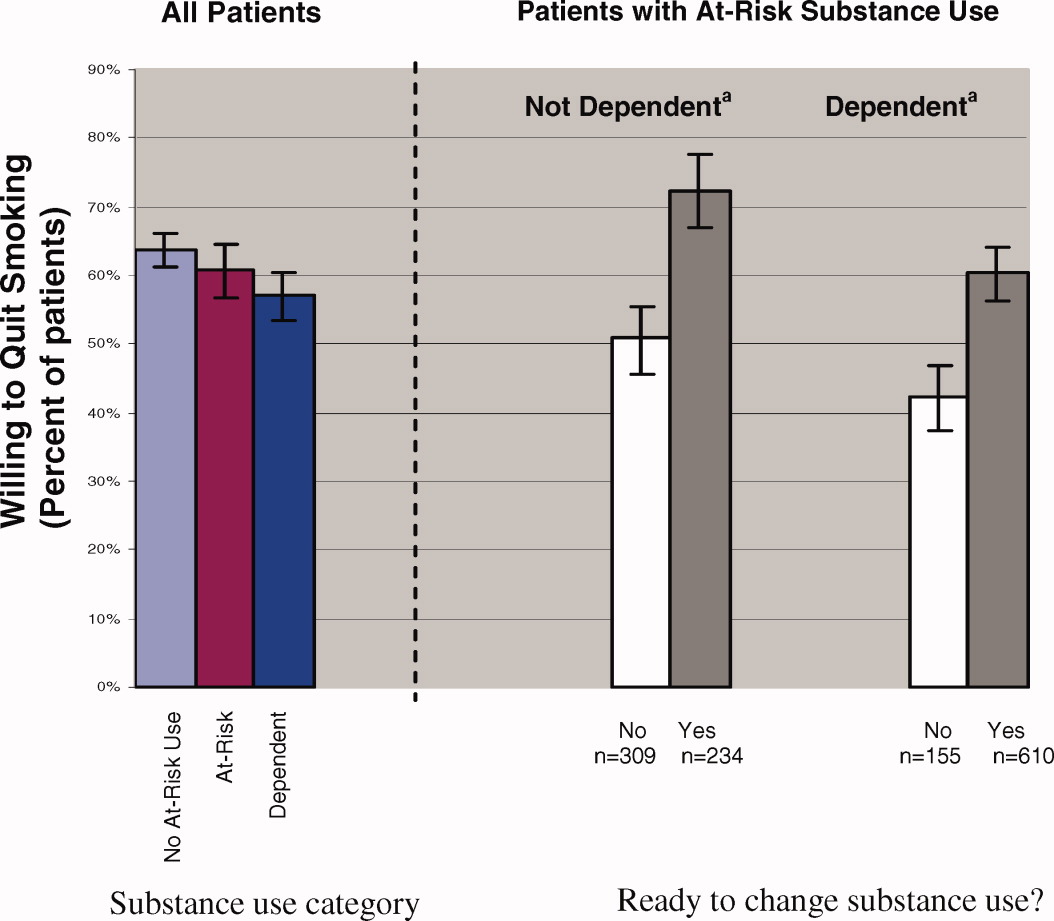

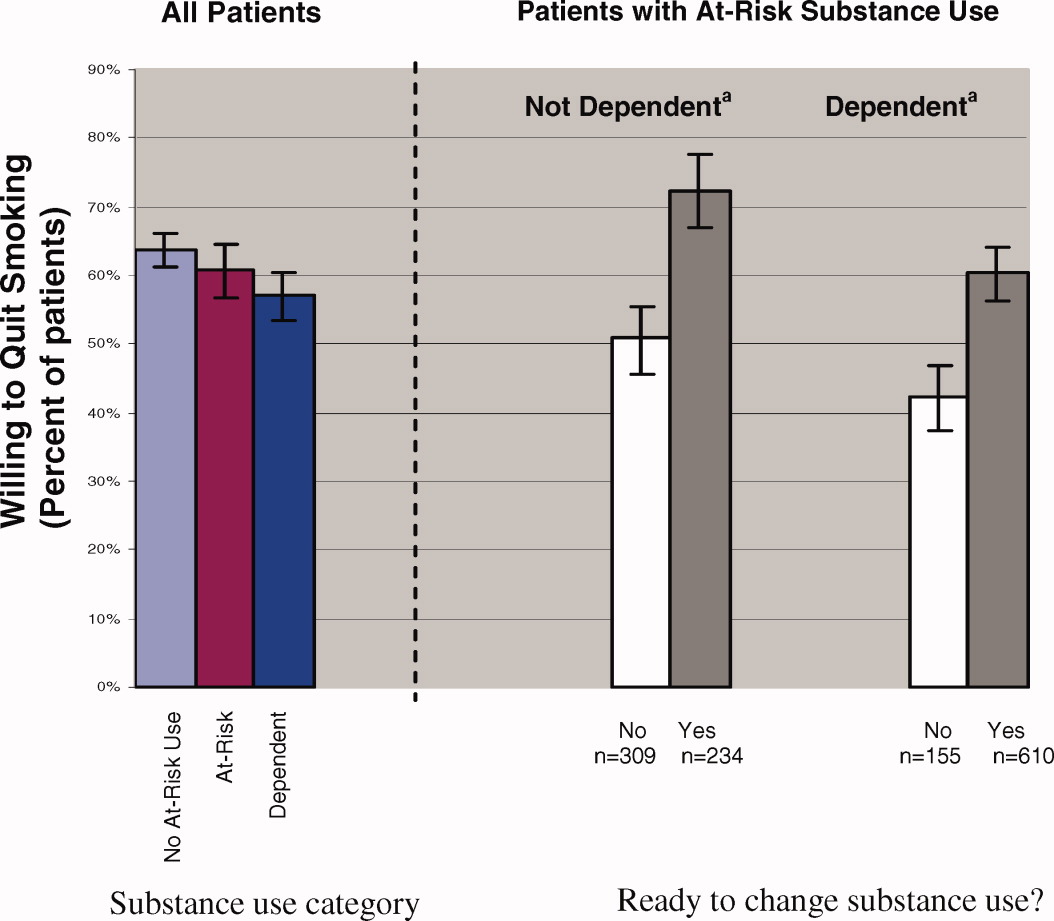

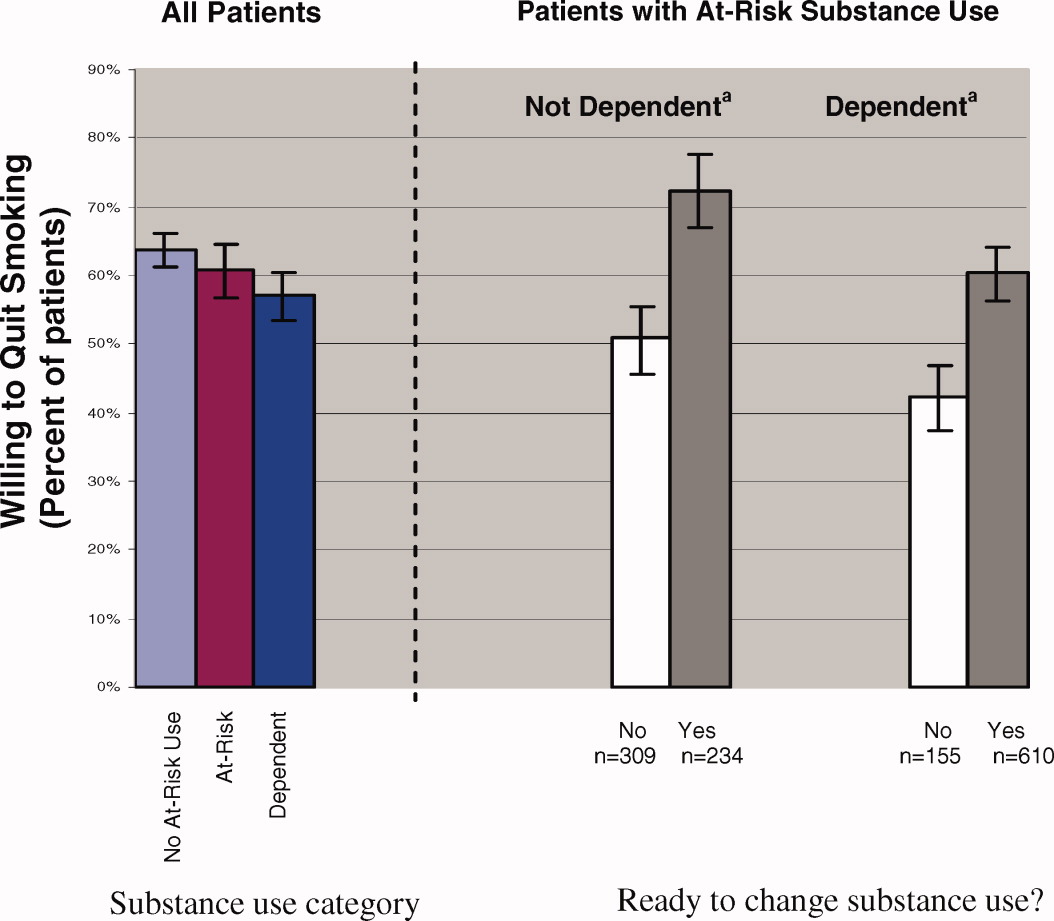

Most patients (61%) who smoked were willing to immediately quit smoking. After adjusting for other demographic confounders, non‐Hispanic Blacks and the elderly (age > 65) were more willing to quit (P < 0.05, data not shown). The substance use risk categories of low risk, at‐risk, and dependence were not associated with willingness to quit tobacco (Fig. 1, left panel).

Regardless of substance use category, most patients were ready to change their substance use behavior (Fig. 1). Those patients who were ready to change their substance use behavior, regardless of whether they were substance‐dependent, were significantly more likely to report a willingness to quit smoking than those who were not ready to change (Fig. 1, right panel). In fact, at‐risk substance users without dependence who were ready to change their substance use were more willing to quit smoking than patients without at‐risk substance use (72% versus 64%; P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Among hospital patients, we found a 46% absolute increase in the prevalence of smoking among those who used illicit substances or alcohol above NIAAA guidelines compared to those who did not report such use. The prevalence of smoking increased across the spectrum of substance use, being highest for patients who met criteria for dependence. Also, patients who were substance dependent were more likely to be moderate to heavy smokers, suggesting an association between alcohol or other drug dependence disorders and nicotine dependence. Regardless of their patterns of substance use, most patients expressed a desire to immediately quit smoking and there was a strong association between willingness to quit smoking and readiness to reduce substance use.

In our hospital population, the prevalence of smoking among patients who use illicit drugs or at‐risk quantities of alcohol far exceeds estimates obtained from population‐based surveys. In addition to the relatively high prevalence of smoking, focusing attention on hospital patients who use substances is important for several other reasons. Individuals who use substances are less likely to receive health care from a primary care physician.28 Also, most patients who have substance use disorders do not enter treatment programs,1 even after hospitalization.29 Further, hospitals provide a setting that facilitates change; patients are temporarily required to stop smoking, and often they are available for relatively long counseling sessions. Finally, for patients without substance use disorders, hospital‐based smoking cessation intervention programs have been proven to be successful in several randomized controlled trials.10, 30

Because alcohol and drug use are so common among hospitalized smokers, it is unfortunate that there is little evidence from clinical trials to inform intervention strategies for patients with concurrent use. The clinical trials that form the evidence base for intervention among hospitalized smokers10 either have explicitly excluded patients who reported substance use,10, 15, 3133 did not assess baseline substance use,34, 35 or were underpowered to perform subgroup analyses on this population.36 Awaiting better evidence, we have chosen to routinely screen hospital patients for tobacco, alcohol, and drug use. For treatment strategies, we extrapolate the findings from successful interventions in the ambulatory setting37 or among hospital patients who do not use substances to our population. We offer smoking cessation interventions to patients regardless of other substance use.

Understanding the similarities and differences between smokers who use substances and those who do not is important in implementing successful strategies for smoking cessation. Rather than a step‐wise increase in heaviness of smoking across substance use categories (ie, no‐risk or low‐risk use, at‐risk use without dependence, and substance dependence), we found an increased heaviness of smoking only among substance‐dependent smokers; there was no difference in heaviness of smoking between those with at‐risk use without dependence and those with no‐risk or low‐risk use. Because interventions for patients who have nicotine dependence are more likely to succeed when pharmacotherapy is offered as an adjunct to behavior therapy,38 smokers who also are substance‐dependent likely will benefit from the addition of pharmacotherapy. One similarity is that all patients, regardless of substance use category, were willing to quit smoking. In fact, hospitalized smokers who were ready to change at‐risk substance use were more willing to quit smoking than patients who had no‐risk or low‐risk substance use. Previous investigators have found that smokers who use substances have fewer quit attempts,39 higher nicotine dependence,37, 39 and lower enrollment in smoking cessation interventions.38

Our study only includes data from patients at 2 public hospitals; therefore, our findings may not generalize to populations of higher socioeconomic status. Also, our smoking screening tool had relatively low sensitivity for categorizing current smokers as moderate to heavy smokers; therefore, we may have underestimated the number of moderate to heavy smokers.5, 22 Further, given our cross‐sectional study design, we were unable to evaluate whether patients who have at‐risk substance use remain willing to quit smoking after hospital discharge or to the effectiveness of our smoking cessation program. Finally, socially desirable responses may have caused patients to overstate their willingness to quit tobacco and readiness to change substance use. Additional research is needed to determine whether post‐hospitalization quit rates are similar between smokers with and without at‐risk substance use, and the optimal timing for smoking cessation interventions in relation to substance dependence treatment.40

Hospital patients who have substance use disorders are also highly likely to smoke, and these patients express a willingness to quit smoking. Given the frequency of concurrent smoking and other substance misuse and patients' desire to change both behaviors, there is a role for coordination of substance use and smoking cessation intervention programs.

- US Department of Health 24:201–208.

- ,,,.Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000.JAMA.2004;291:1238–1245.

- ,,.Global burden of disease from alcohol, illicit drugs and tobacco.Drug Alcohol Rev.2006;25:503–513.

- A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence,:A US Public Health Service report. The tobacco use and dependence clinical practice guideline panel, staff, and consortium representatives.JAMA.2000;283:3244–3254.

- ,,,,,U.S.Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.Ann Intern Med.2004;140:557–568.

- Work Group on Substance Use Disorders,,, et al.Treatment of patients with substance use disorders, second edition. American Psychiatic Association.Am J Psych.2006;163(8 Suppl):75–82.

- ,.Smokers who are hospitalized: a window of opportunity for cessation interventions.Prev Med.1992;21;262–269.

- ,,.Helping hospitalized smokers quit: new directions for treatment and research.J Consult Clin Psychol.1993;61:778–89.

- ,,.Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalised patients.Cochrane Database Sys Rev.2007;3(3);CD001837.

- ,,,.Expanding the roles of hospitalists physicians to include public health.J Hosp Med.2007;2:93–101.

- ,,,,.Smoking status as a clinical indicator for alcohol misuse in US adults.Arch Intern Med.2007;167:716–721.

- ,,,,.Alcohol high risk drinking, abuse and dependence among tobacco smoking medical care patients and the general population.Drug Alcohol Depend.2003;69:189–195.

- ,,,,.Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions.Arch Gen Psychiatry.2004;61:1107–1115.

- ,,,,,.Smoking and mental illness: A population‐based prevalence study.JAMA.2000;284:2606–2610.

- .Clinical Implications of the association between smoking and alcoholism. In:Fertig JB,Allen JP, eds.Alcohol and Tobacco: From Basic Science to Clinical Practice.Bethesda, MD:NIAAA Research;1995:171–185.

- ,,,,,.Smoking and drinking among alcoholics in treatment: cross‐sectional and longitudinal relationships.J Stud Alcohol.2000;61:157–163.

- ,,, et al.Interrelationship of smoking and alcohol dependence, use and urges to use.J Stud Alcohol.1995;56:202–206.

- ,,.Tobacco cessation treatment for alcohol‐dependent smokers: when is the best time?Alcohol Res Health.2006;29:203–207.

- ,,, et al.Substance use in the general hospital.Addict Behav.2003;28:483–499.

- ,,,,.Measuring the heaviness of smoking: Using self‐reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day.Br J Addict.1989;84:791–799.

- ,,,.The Heaviness of Smoking Index as a predictor of smoking cessation in Canada.Addict Behav.2007;32:1031–1042.

- ,,, et al.Effectiveness of screening instruments in detecting substance use disorders among prisoners.J Subst Abuse Treat.2000;18:349–358.

- Th BNI‐ART Institute, Readiness Ruler. http://www.ed.bmc.org/sbirt/techniques.php. Accessed August 20,2008.

- .A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data.Am J Epidemiol.2004;159:702–706.

- ,,,.Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes.Am J Epidemiol.2003;157:940–943.

- ,.Do smokers with alcohol problems have more difficulty quitting?Drug Alcohol Depend.2006;82:91–102.

- .Emergency room and primary care services utilization and associated alcohol and drug use in the United States general population.Alcohol Alcohol.1999;34:581–589.

- ,,, et al.Brief intervention for medical inpatients with unhealthy alcohol use: a randomized, controlled trial.Ann Intern Med.2007;146:167–176.

- ,,.Smoking cessation interventions among hospitalized patients: what have we learned?Prev Med.2001;32:376–388.

- ,,, et al.Smoking cessation and severity of disease: the Coronary Artery Smoking Intervention Study.Health Psychol.1992;11:119–126.

- ,,,,.A randomized controlled trial of smoking cessation counseling after myocardial infarction.Prev Med.2000;30:261–268.

- ,.Comorbid cigarette and alcohol addiction: epidemiology and treatment.J Addict Dis.1998;17:55–66.

- ,,, et al.A case‐management system for coronary risk factor modification after acute myocardial infarction.Ann Intern Med.1994;120:721–729.

- ,,, et al.A nurse‐managed smoking cessation program for hospitalized smokers.Am J Public Health.1996;86:1557–1560.

- ,,,.Smoking cessation after surgery. A randomized trial.Arch Intern Med.1997;157:1371–1376.

- ,,,,.Efficacy of nicotine patch in smokers with a history of alcoholism.Alcohol Clin Exp Res.2003;27:946–954.

- ,,,.Predictors of tobacco quit attempts among recovering alcoholics.J Subst Abuse.1996;8:431–443.

- ,,.Is dependence on one drug associated with dependence on other drugs? The cases of alcohol, caffeine and nicotine.Am J Addict.2000;9:196–201.

- .Nicotine interventions with comorbid populations.Am J Prev Med.2007;33:S406–S413.

Population‐based surveys of the adult US population estimate a prevalence of smoking of 25% and a prevalence of hazardous alcohol or illegal drug use of 23% and 8% respectively,1 with frequent concurrent use of these substances.2 The mortality associated with smoking and substance use is extremely high with tobacco first, alcohol third, and illicit drug use ninth as the leading causes of death in the US.3 Worldwide, the burden of disease from tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs accounts for almost 10% of all disability‐adjusted life years.4 Despite the availability of effective treatments,57 many patients do not receive professional intervention and few are offered comprehensive programs that address all of their harmful substance use.

Interventions have been successfully implemented for hospitalized smokers. Earlier work by Emmons8 and Orleans9 suggests that many smokers seek assistance to quit smoking during hospitalization. Over the past 15 years, hospital‐based smoking cessation interventions have been successfully implemented.10 Although mute on hospital‐based settings, the United States Preventive Service Task Force recommends screening and counseling interventions to reduce alcohol misuse among adults seen in primary care settings (B recommendation).6 Referral to specialized care is the accepted standard for most patients with substance dependence disorders7 regardless of the medical setting in which the diagnosis is made. Hospitalization provides a unique opportunity to initiate change in harmful substance use and smoking;11 however, interventions rarely are coordinated.

A high prevalence of smoking among substance users has been reported from population‐based surveys1215 and among patients in substance use treatment facilities.1618 Rates of concurrent smoking and substance use range from 35%44% in population‐based studies and may reach 80% in populations seeking substance use treatment.19 A recent hospital‐based study found at‐risk alcohol users were 3 times more likely to smoke.20 There are limited data describing concurrent smoking and substance use in the hospital population,15 and no reports describing the association between patients' willingness to quit smoking and readiness to change substance use behavior.

To better inform hospital‐based smoking and substance use intervention strategies, the epidemiology of smoking and substance use in the hospital population needs to be better described. Furthermore, there may be opportunities for synergy between these programs. In this study, we screened inpatients from multiple services at 2 hospitals for tobacco, alcohol, and illicit substance use. We report the prevalence and co‐occurrence of these behaviors and willingness to quit smoking among patients with and without at‐risk substance use.

METHODS