User login

Primary Cutaneous Marginal Zone B-Cell Lymphoma Discovered During Mohs Surgery for Basal Cell Carcinoma

Primary Cutaneous Marginal Zone B-Cell Lymphoma Discovered During Mohs Surgery for Basal Cell Carcinoma

To the Editor:

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (pcBCLs) can clinically mimic basal cell carcinomas (BCCs); however, histopathologic examination typically demonstrates features of lymphoma without evidence of an epithelial tumor. We present the case of a patient who demonstrated histologic features of both pcBCL and BCC in the same lesion, which was discovered during Mohs micrographic surgery.

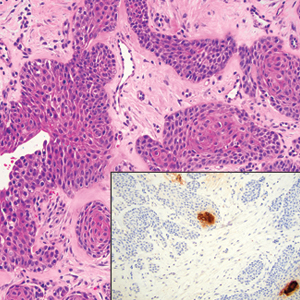

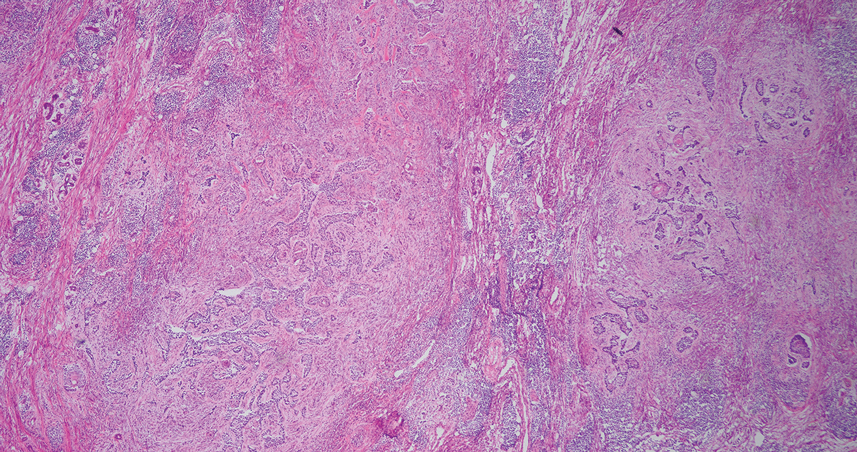

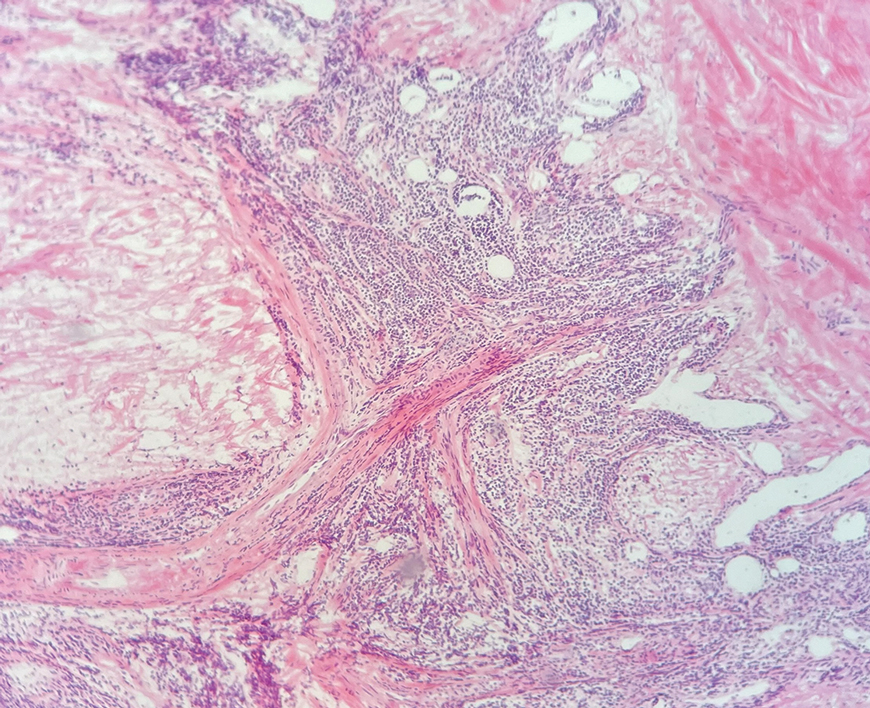

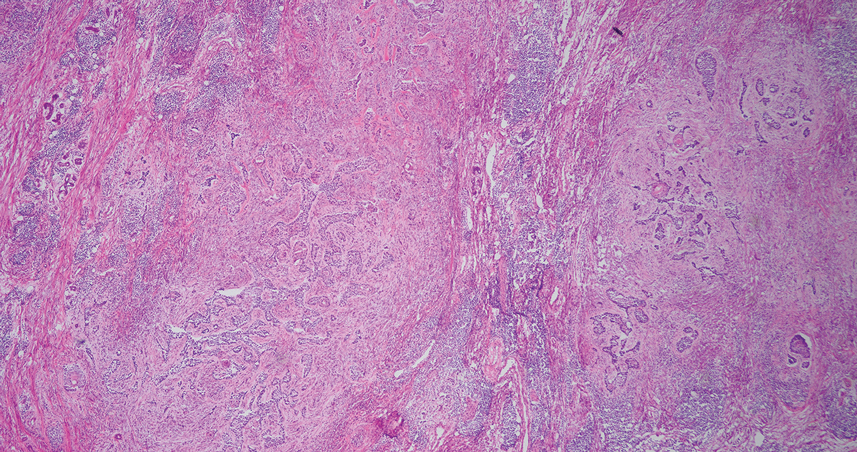

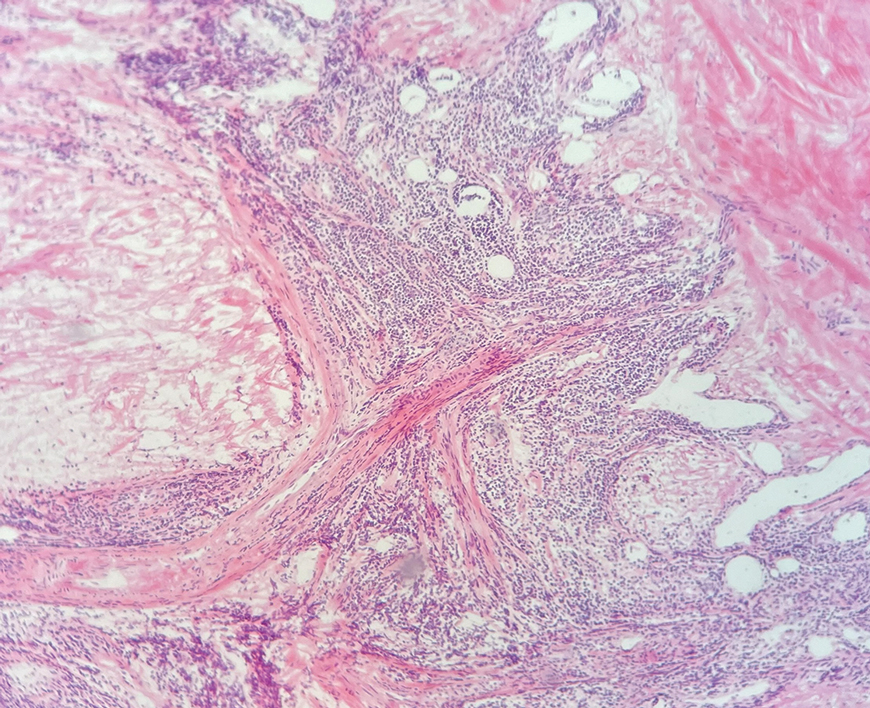

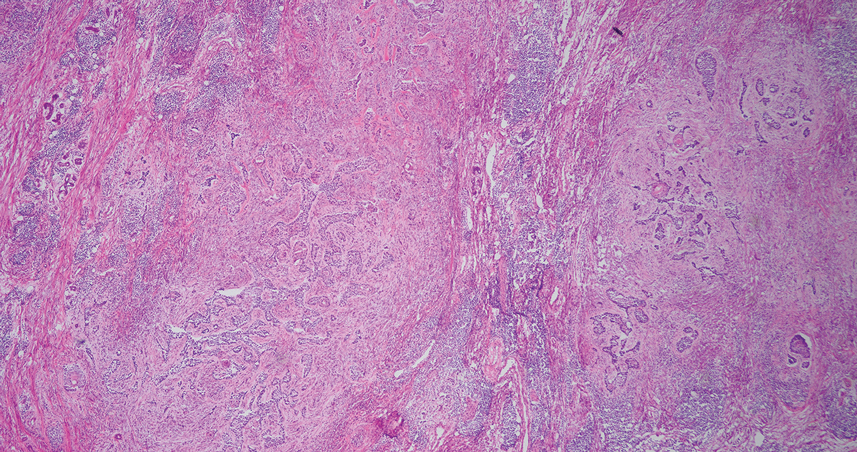

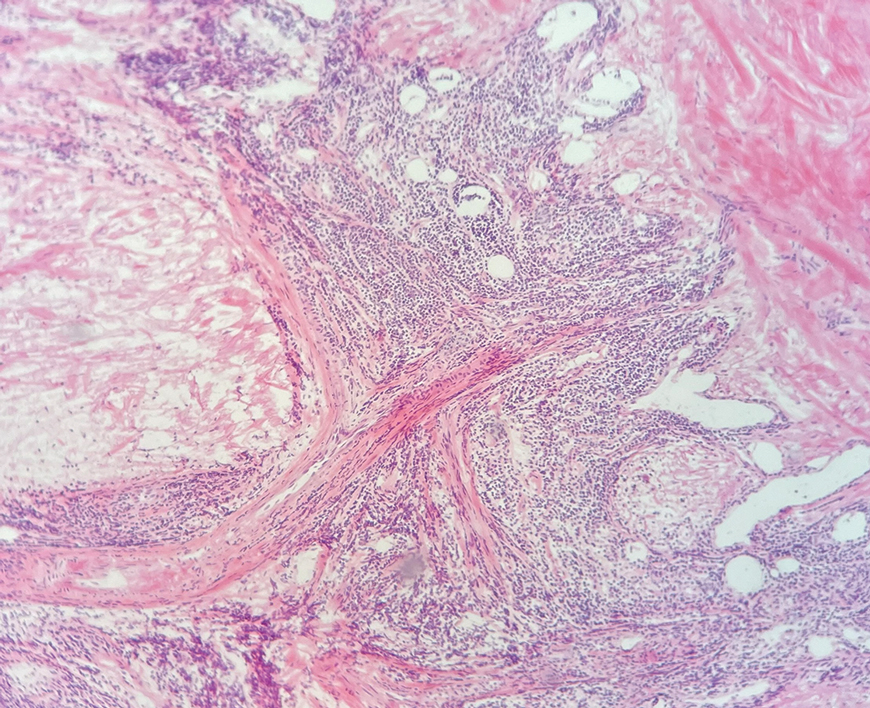

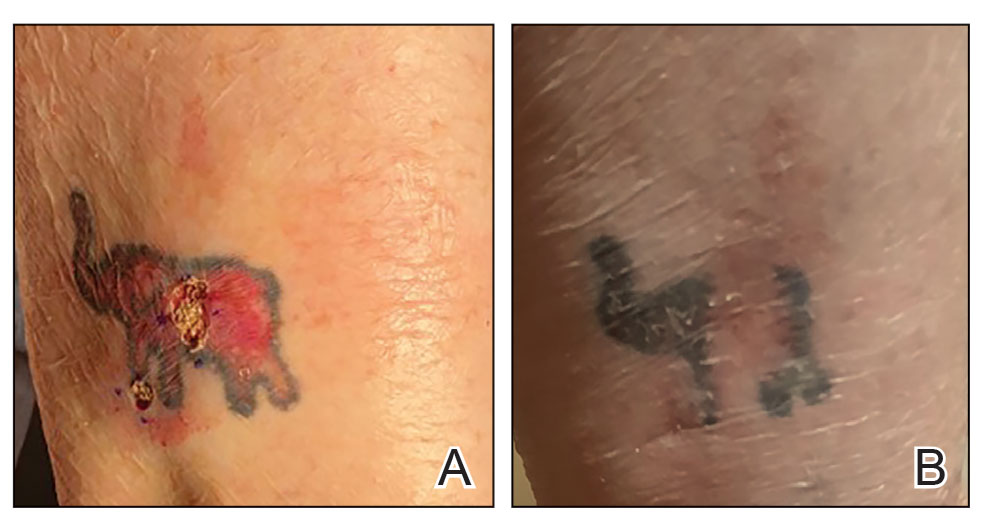

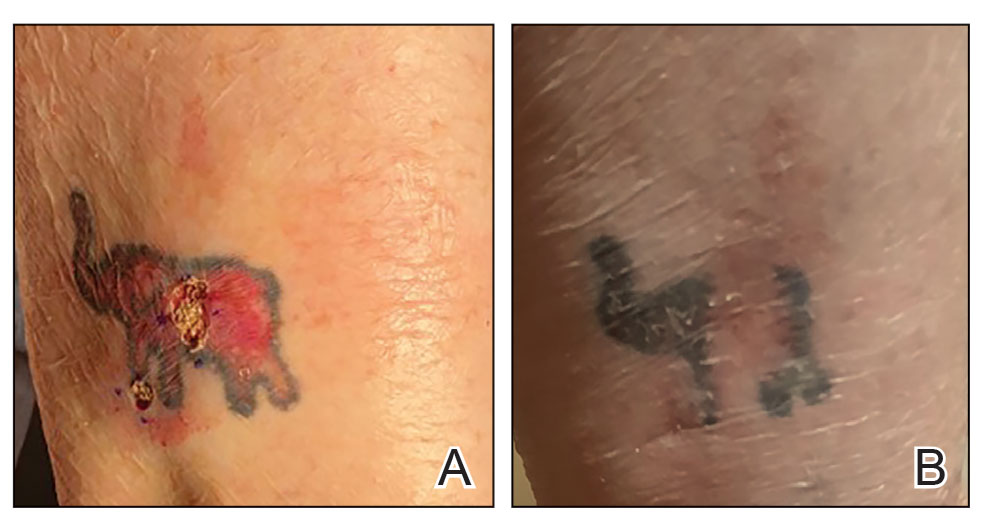

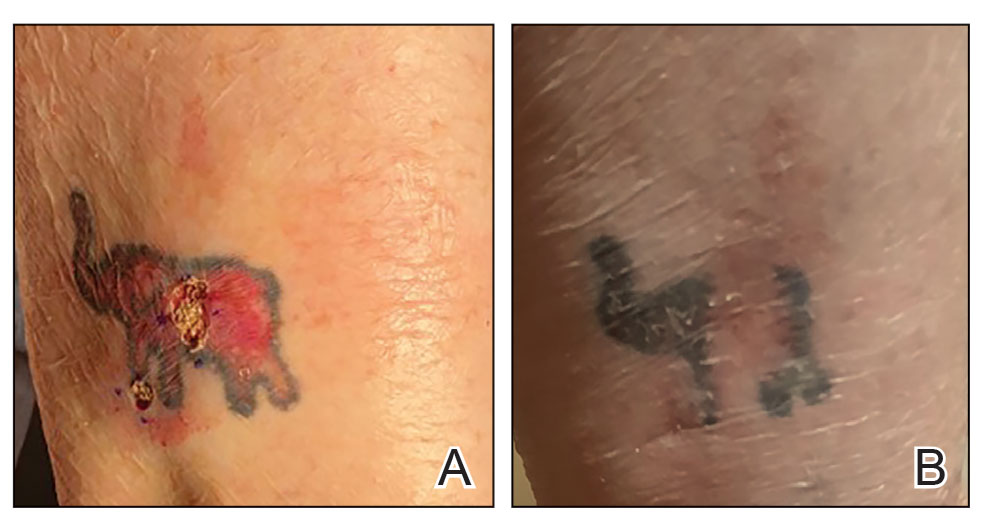

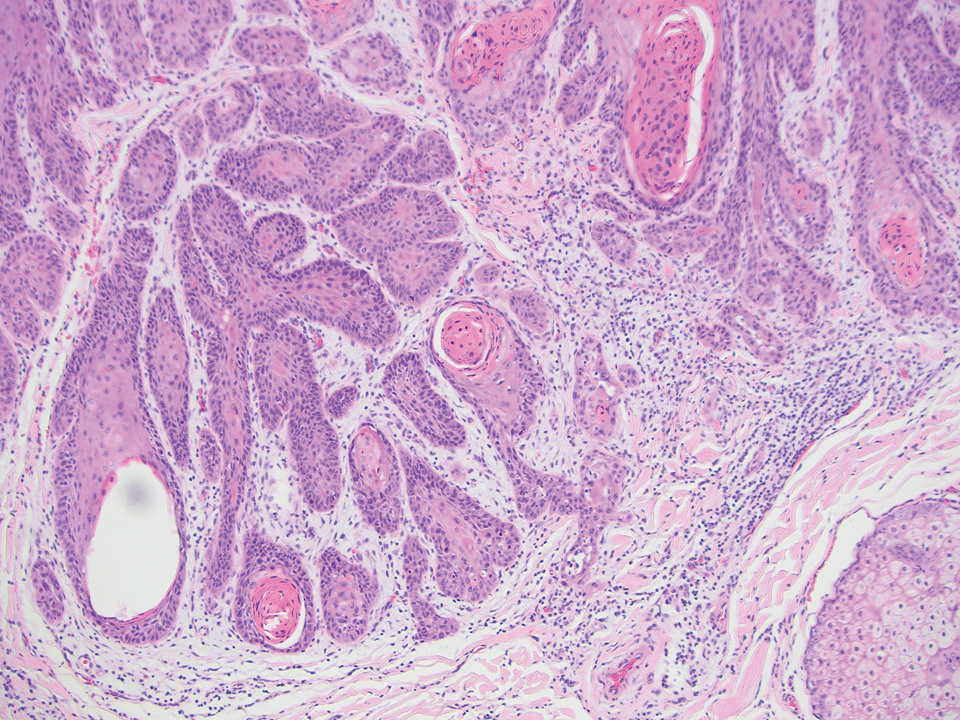

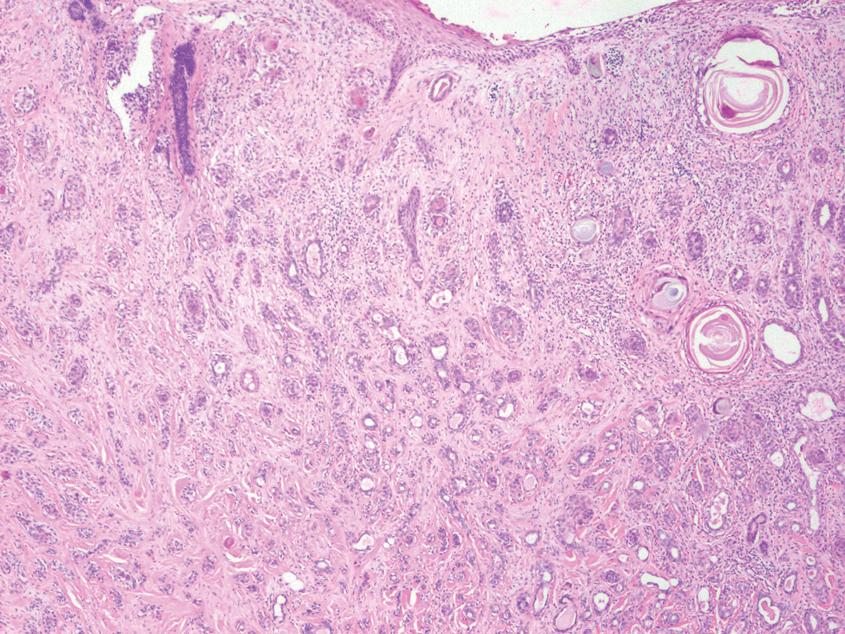

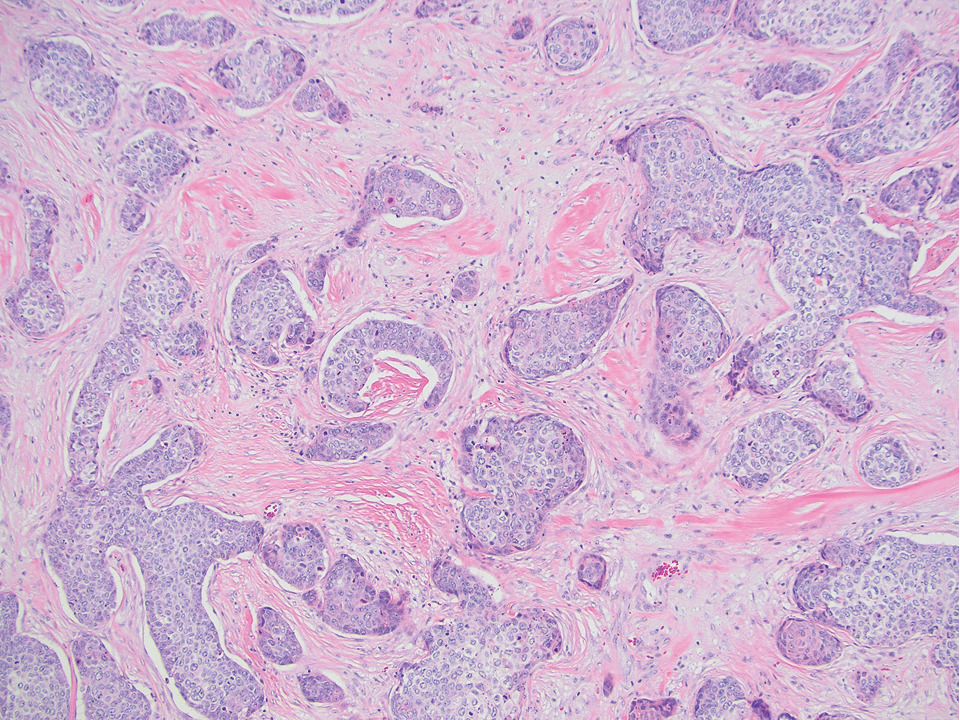

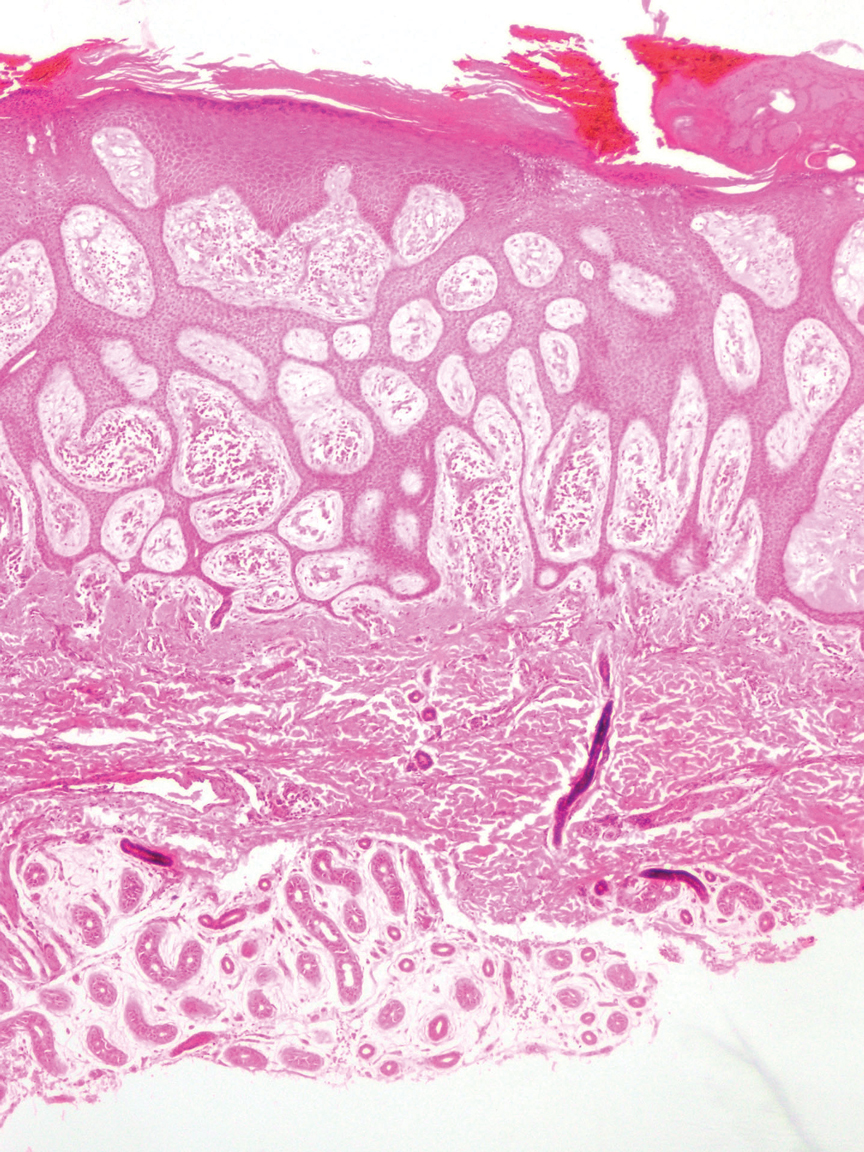

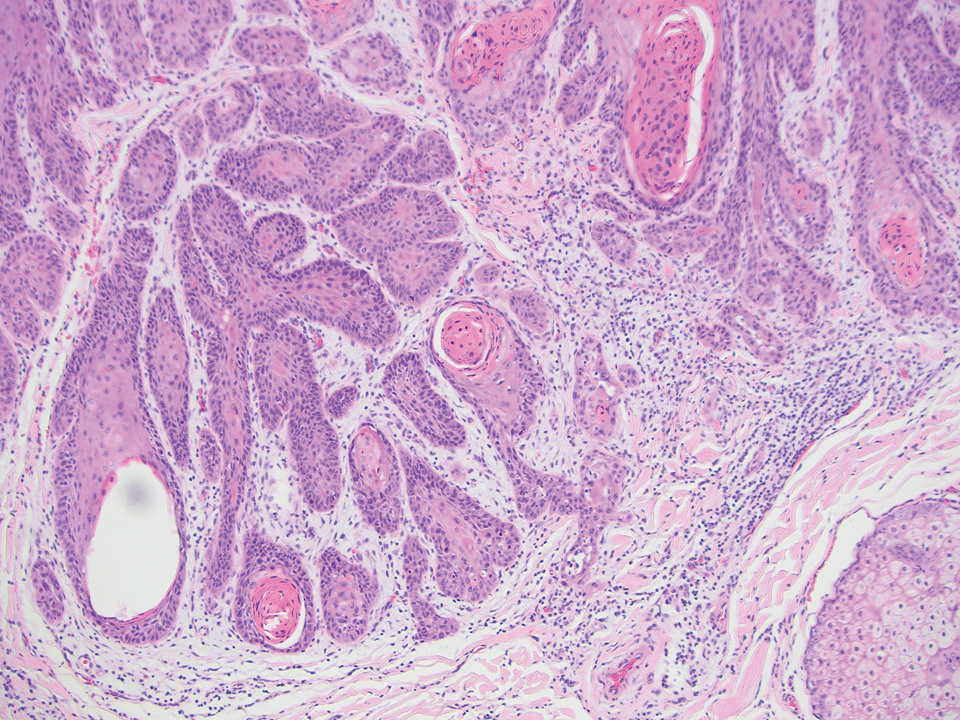

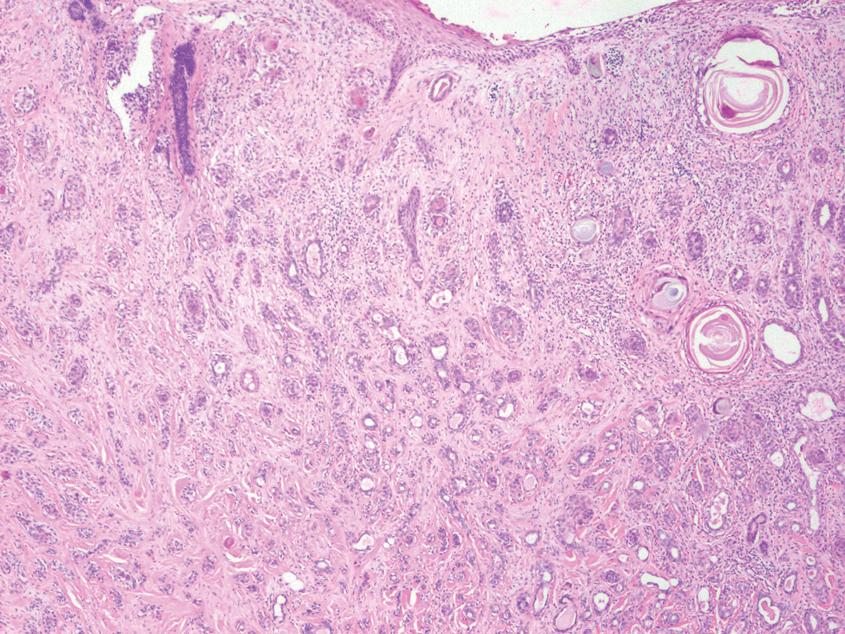

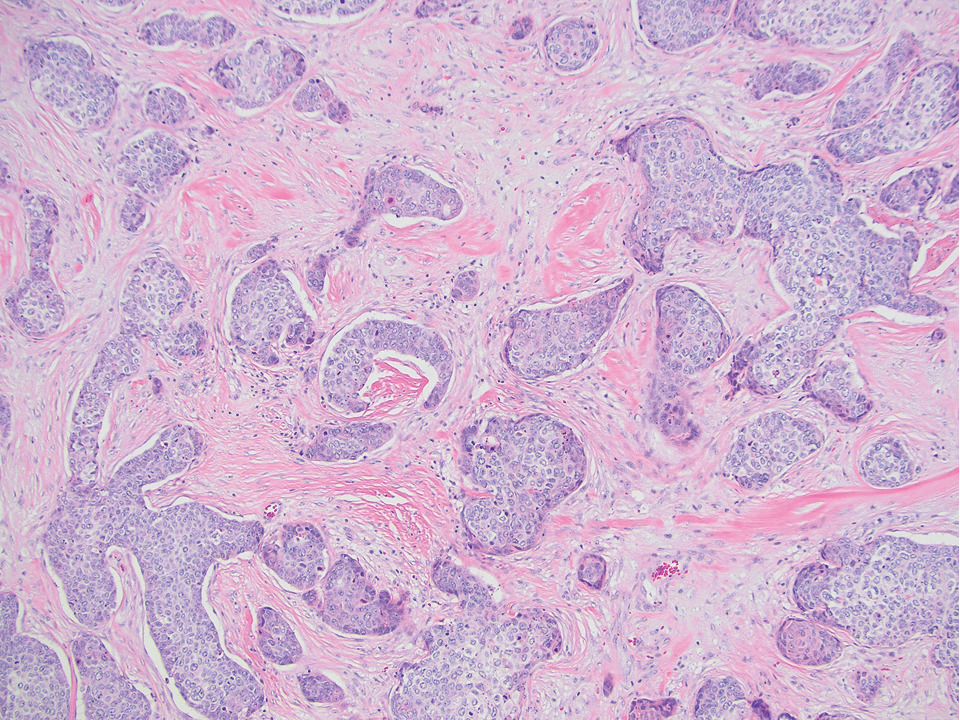

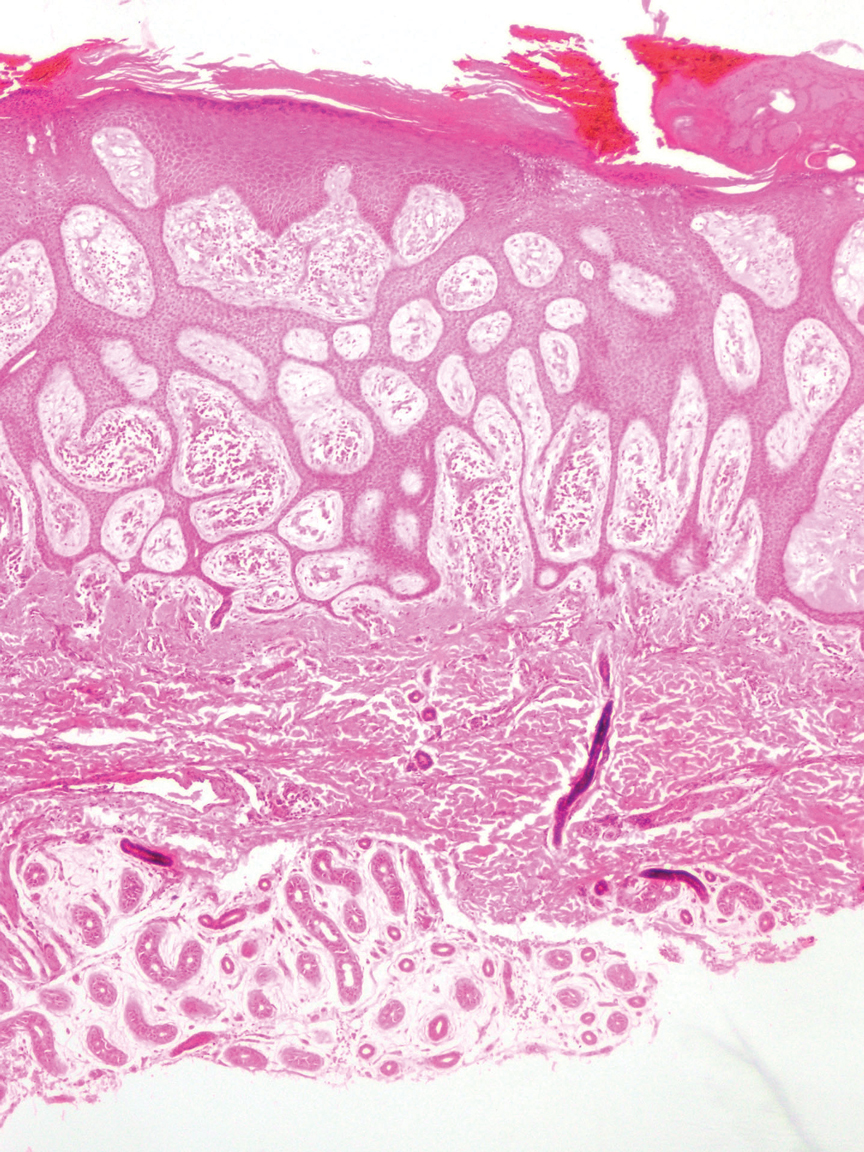

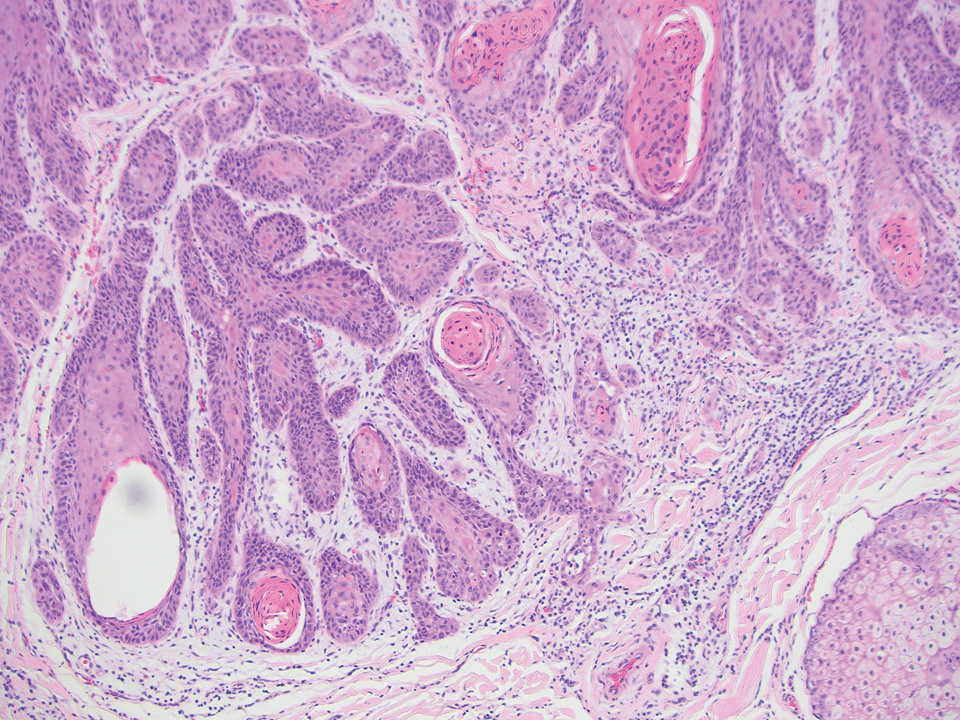

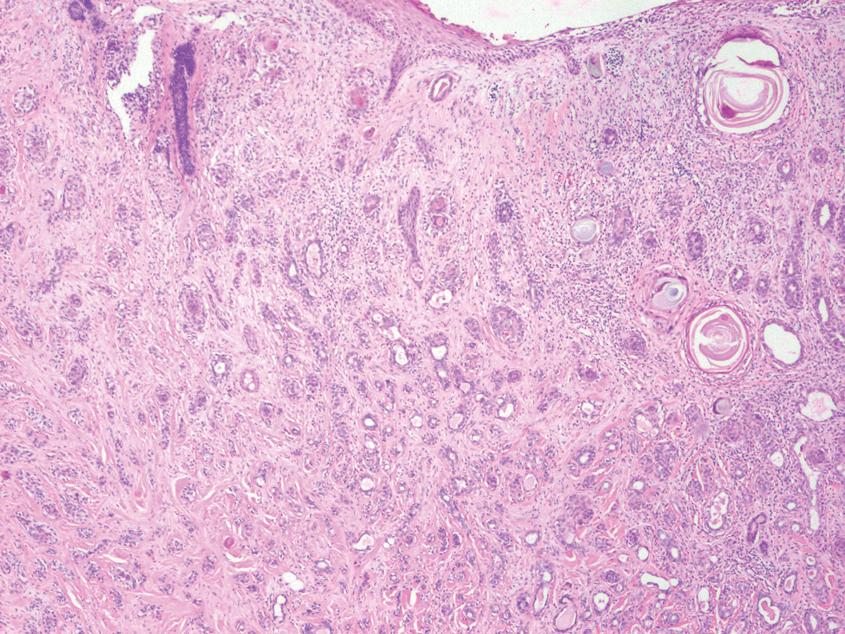

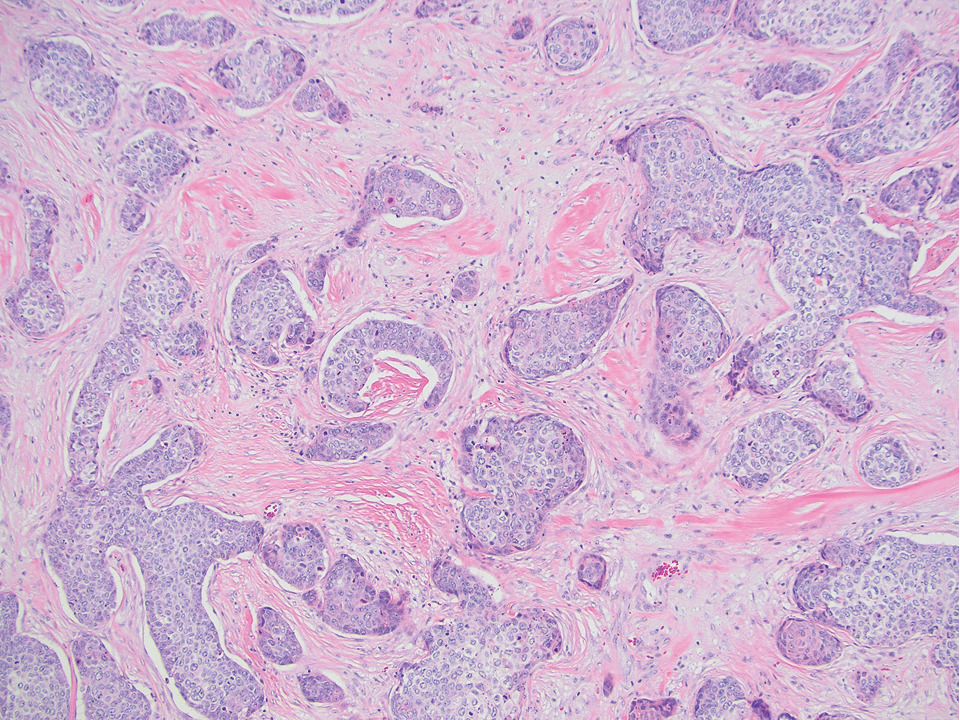

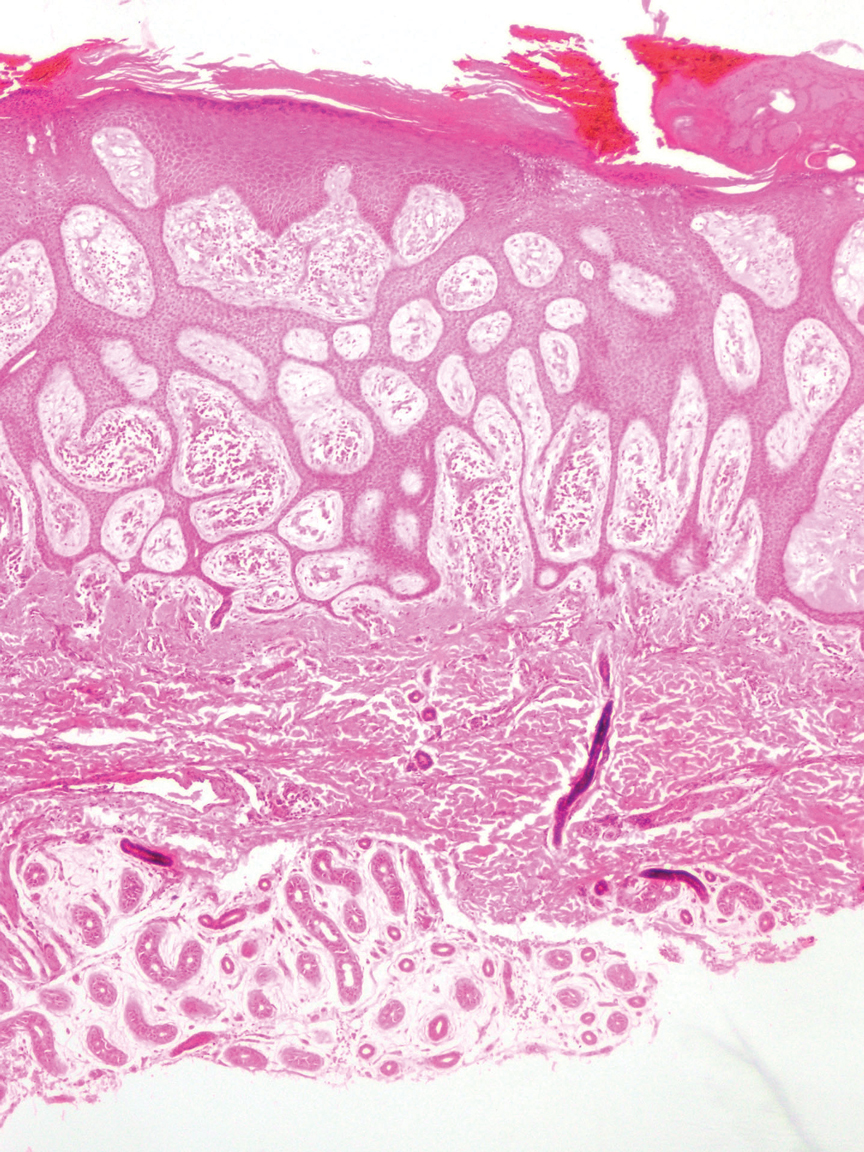

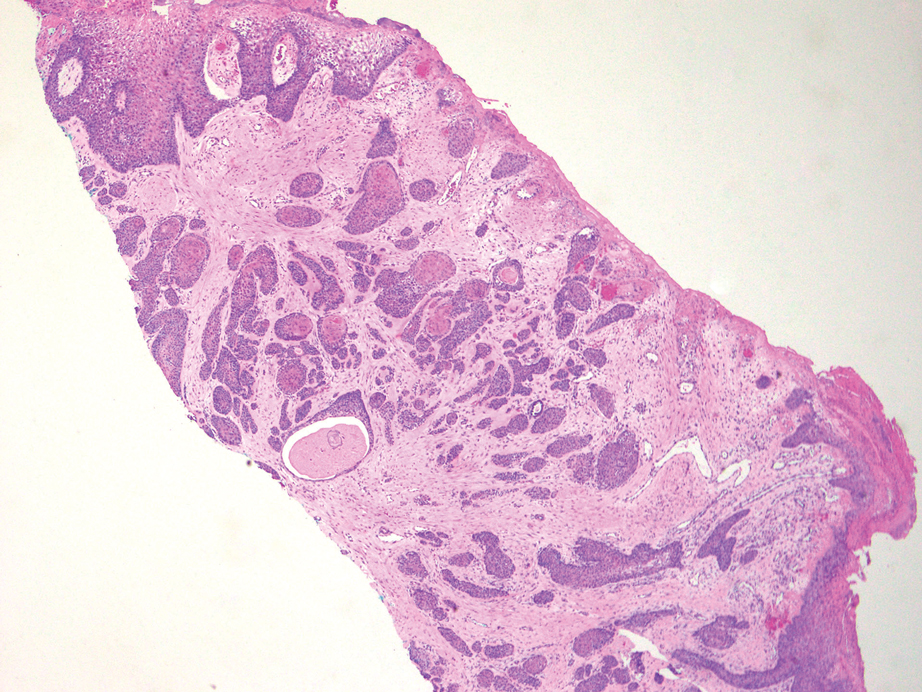

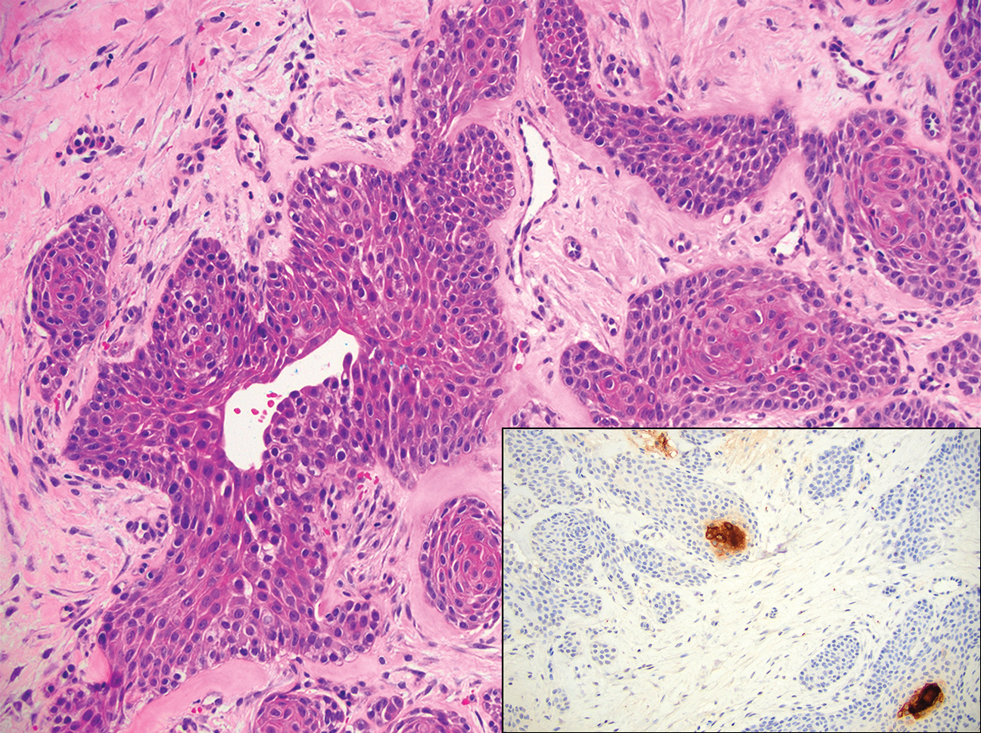

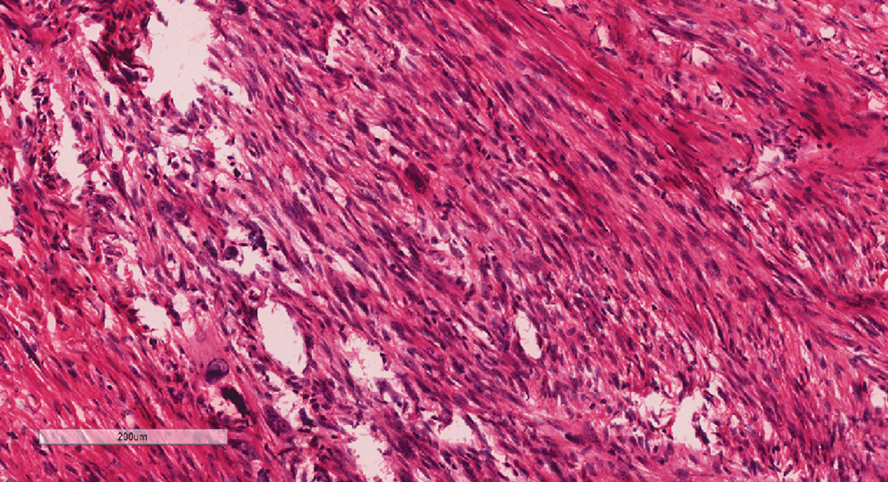

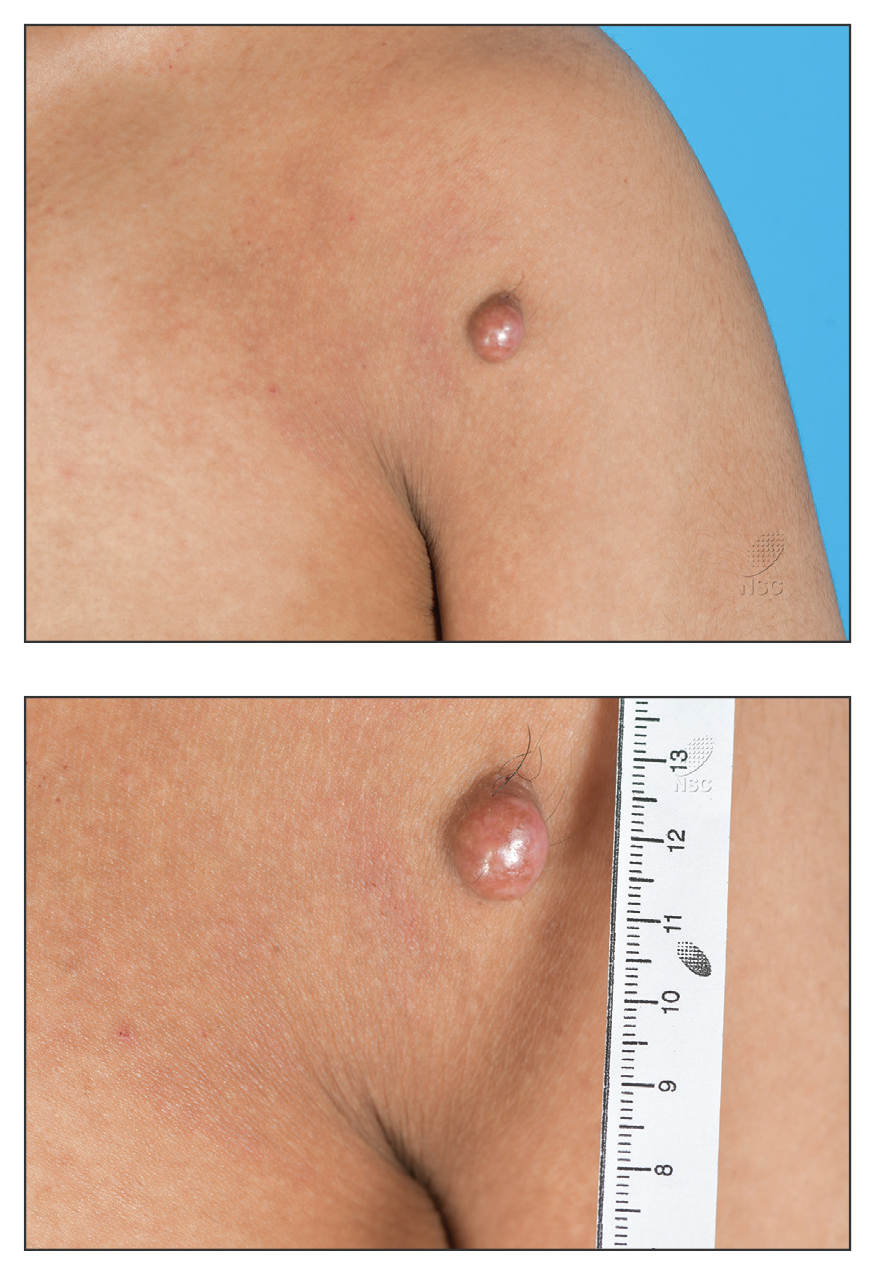

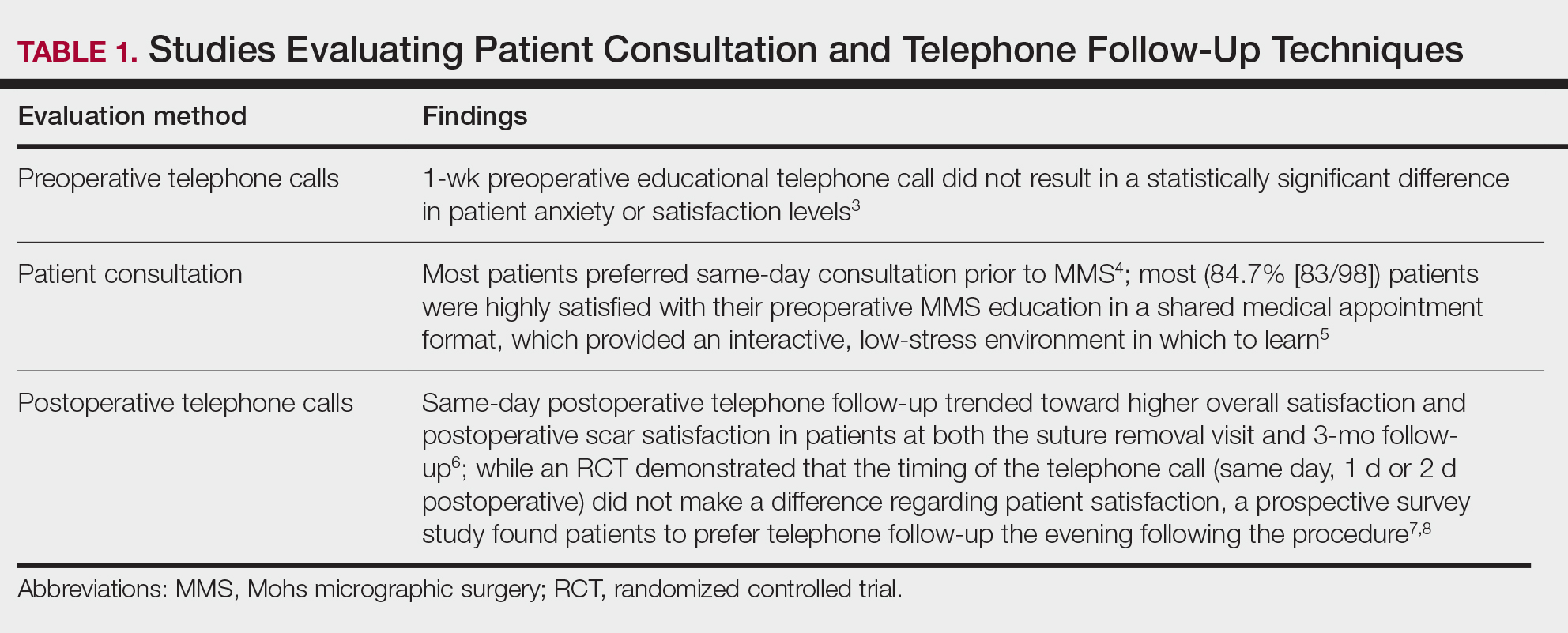

An 84-year-old man presented for Mohs surgery for a biopsy-proven nodular and infiltrative BCC on the right superior helix of the ear of 1 year’s duration. Physical examination of the ear revealed a 1.0×1.3–cm ulcerated indurated plaque with rolled borders and a central hyperkeratotic crust (Figure 1). Frozen sections from the first Mohs stage demonstrated residual superficial, infiltrative, and basosquamous BCC (Figure 2). In addition, there was a brisk inflammatory infiltrate throughout the deep margins. The second stage showed no residual BCC, but there still was a brisk atypical lymphocytic infiltrate, with some areas showing lymphocytes in a linear cordlike distribution (Figure 3). Permanent sections demonstrated infiltration of small to medium lymphoid cells. Immunohistochemistry stains were positive for CD20 and BCL2 and negative for CD5, CD10, BCL6, and CD43; a low Ki-67 proliferation fraction also was observed. B-cell clonality studies and polymerase chain reaction demonstrated rearrangements of the IgH and IgK genes, consistent with primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma (pcMZL). Positron emission tomography showed no spread of malignancy; therefore, medical oncology recommended observation and close monitoring.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma accounts for approximately 25% of all cutaneous lymphomas.1 Three main cutaneous subtypes exist: pcMZL; primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma; and primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. The second most common type of cutaneous lymphoma, pcMZL, accounts for 25% of cases of pcBCL.1 Primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma makes up 60% of cutaneous lymphomas, and the remainder are primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. All share a notable male predominance and onset most commonly in the sixth through eighth decades of life, although they also can occur in younger patients.1

Histologically, pcMZL has 2 distinct subtypes: one resembling mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas and a more clinically aggressive subtype with heavy chain class switching, although intermediate forms also exist. Both are characterized by diffuse and/or nodular infiltrates in the subcutis and dermis with sparing of the epidermis. Often, these infiltrates are more prominent in the deeper sections examined, and occasionally they may be accompanied by germinal center follicles. Immunohistochemical stains are key in determining the pcBCL subtype. Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma will most commonly show a BCL2+, BCL6–, CD20+, and CD10– immunophenotype, as in our case. If a majority of cells have undergone plasmacytoid differentiation, loss of CD20 can occur, but retention of other B-cell markers, such as CD79a and CD19, will be seen. Proliferation fraction via Ki-67 commonly is low, reflecting the indolence of this subtype of lymphoma.1

Monoclonal rearrangement of immunoglobulins also can occur, with IgH rearrangements detected in 60% to 80% of cases of pcMZL. Translocations are not a reliable method of diagnosis for pcMZL but can be present in a variable manner, with t(14;18), t(3;14), and t(11;18) reported in a subset of cases.2 Leukemic infiltrates encountered on frozen sections should prompt the Mohs surgeon to consider the possibility of a concomitant leukemia or lymphoma. In one study, 36% (20/55) of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) were found to have predominantly leukemic B-cell infiltrates on frozen sections.3 Numerous reports also exist of asymptomatic patients being diagnosed with CLL due to leukemic infiltrates identified during Mohs surgery.4,5 Patients with systemic hematologic malignancies, including CLL and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, also are known to be at an increased risk for skin cancers, including keratinocyte cancers, melanoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma. This can be attributed partially to immunosuppression, a well-known risk factor for development of cutaneous malignancies.5 Padgett et al5 speculated that local immune suppression due to underlying pcBCL and reaction of lymphocytes to tumor antigens could have played a role in the development of BCC at this site. If a leukemic infiltrate is demonstrated, the surgeon should consider sending tissue for permanent section and immunostaining. This can be helpful to determine if it is a reactive or neoplastic process and aid in characterizing the leukemic infiltrate if it is suspected to be neoplastic in nature.

There are numerous reports of pcBCL imitating the cutaneous findings of BCC clinically, but this is quite uncommon on histopathology. As in our case, findings of sheets of dense, monomorphic lymphocytes; inability to clear inflammation on deeper Mohs sections; presence of primordial follicles; and atypical cytology, including predominance of blastic forms, plasmacytoid cells, or cleaved lymphocytes, should give the clinician pause to consider further evaluation through permanent sections as well as genetic and immunoglobulin studies by a dermatopathologist. This case highlights the importance of further evaluation when an atypical finding is encountered during Mohs surgery.

- Goyal A, LeBlanc RE, Carter JB. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:149-161. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.006

- Vitiello P, Sica A, Ronchi A, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: an update. Front Oncol. 2020;10:651. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.00651

- Mehrany K, Byrd DR, Roenigk RK, et al. Lymphocytic infiltrates and subclinical epithelial tumor extension in patients with chronic leukemia and solid-organ transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:129-134. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29034.x

- Walters M, Chang C, Castillo JR. Diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia during Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;33:1-3. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.12.012

- Padgett JK, Parlette HL, English JC. A diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia prompted by cutaneous lymphocytic infiltrates present in mohs micrographic surgery frozen sections. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:769-771. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29194.x

To the Editor:

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (pcBCLs) can clinically mimic basal cell carcinomas (BCCs); however, histopathologic examination typically demonstrates features of lymphoma without evidence of an epithelial tumor. We present the case of a patient who demonstrated histologic features of both pcBCL and BCC in the same lesion, which was discovered during Mohs micrographic surgery.

An 84-year-old man presented for Mohs surgery for a biopsy-proven nodular and infiltrative BCC on the right superior helix of the ear of 1 year’s duration. Physical examination of the ear revealed a 1.0×1.3–cm ulcerated indurated plaque with rolled borders and a central hyperkeratotic crust (Figure 1). Frozen sections from the first Mohs stage demonstrated residual superficial, infiltrative, and basosquamous BCC (Figure 2). In addition, there was a brisk inflammatory infiltrate throughout the deep margins. The second stage showed no residual BCC, but there still was a brisk atypical lymphocytic infiltrate, with some areas showing lymphocytes in a linear cordlike distribution (Figure 3). Permanent sections demonstrated infiltration of small to medium lymphoid cells. Immunohistochemistry stains were positive for CD20 and BCL2 and negative for CD5, CD10, BCL6, and CD43; a low Ki-67 proliferation fraction also was observed. B-cell clonality studies and polymerase chain reaction demonstrated rearrangements of the IgH and IgK genes, consistent with primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma (pcMZL). Positron emission tomography showed no spread of malignancy; therefore, medical oncology recommended observation and close monitoring.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma accounts for approximately 25% of all cutaneous lymphomas.1 Three main cutaneous subtypes exist: pcMZL; primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma; and primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. The second most common type of cutaneous lymphoma, pcMZL, accounts for 25% of cases of pcBCL.1 Primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma makes up 60% of cutaneous lymphomas, and the remainder are primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. All share a notable male predominance and onset most commonly in the sixth through eighth decades of life, although they also can occur in younger patients.1

Histologically, pcMZL has 2 distinct subtypes: one resembling mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas and a more clinically aggressive subtype with heavy chain class switching, although intermediate forms also exist. Both are characterized by diffuse and/or nodular infiltrates in the subcutis and dermis with sparing of the epidermis. Often, these infiltrates are more prominent in the deeper sections examined, and occasionally they may be accompanied by germinal center follicles. Immunohistochemical stains are key in determining the pcBCL subtype. Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma will most commonly show a BCL2+, BCL6–, CD20+, and CD10– immunophenotype, as in our case. If a majority of cells have undergone plasmacytoid differentiation, loss of CD20 can occur, but retention of other B-cell markers, such as CD79a and CD19, will be seen. Proliferation fraction via Ki-67 commonly is low, reflecting the indolence of this subtype of lymphoma.1

Monoclonal rearrangement of immunoglobulins also can occur, with IgH rearrangements detected in 60% to 80% of cases of pcMZL. Translocations are not a reliable method of diagnosis for pcMZL but can be present in a variable manner, with t(14;18), t(3;14), and t(11;18) reported in a subset of cases.2 Leukemic infiltrates encountered on frozen sections should prompt the Mohs surgeon to consider the possibility of a concomitant leukemia or lymphoma. In one study, 36% (20/55) of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) were found to have predominantly leukemic B-cell infiltrates on frozen sections.3 Numerous reports also exist of asymptomatic patients being diagnosed with CLL due to leukemic infiltrates identified during Mohs surgery.4,5 Patients with systemic hematologic malignancies, including CLL and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, also are known to be at an increased risk for skin cancers, including keratinocyte cancers, melanoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma. This can be attributed partially to immunosuppression, a well-known risk factor for development of cutaneous malignancies.5 Padgett et al5 speculated that local immune suppression due to underlying pcBCL and reaction of lymphocytes to tumor antigens could have played a role in the development of BCC at this site. If a leukemic infiltrate is demonstrated, the surgeon should consider sending tissue for permanent section and immunostaining. This can be helpful to determine if it is a reactive or neoplastic process and aid in characterizing the leukemic infiltrate if it is suspected to be neoplastic in nature.

There are numerous reports of pcBCL imitating the cutaneous findings of BCC clinically, but this is quite uncommon on histopathology. As in our case, findings of sheets of dense, monomorphic lymphocytes; inability to clear inflammation on deeper Mohs sections; presence of primordial follicles; and atypical cytology, including predominance of blastic forms, plasmacytoid cells, or cleaved lymphocytes, should give the clinician pause to consider further evaluation through permanent sections as well as genetic and immunoglobulin studies by a dermatopathologist. This case highlights the importance of further evaluation when an atypical finding is encountered during Mohs surgery.

To the Editor:

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (pcBCLs) can clinically mimic basal cell carcinomas (BCCs); however, histopathologic examination typically demonstrates features of lymphoma without evidence of an epithelial tumor. We present the case of a patient who demonstrated histologic features of both pcBCL and BCC in the same lesion, which was discovered during Mohs micrographic surgery.

An 84-year-old man presented for Mohs surgery for a biopsy-proven nodular and infiltrative BCC on the right superior helix of the ear of 1 year’s duration. Physical examination of the ear revealed a 1.0×1.3–cm ulcerated indurated plaque with rolled borders and a central hyperkeratotic crust (Figure 1). Frozen sections from the first Mohs stage demonstrated residual superficial, infiltrative, and basosquamous BCC (Figure 2). In addition, there was a brisk inflammatory infiltrate throughout the deep margins. The second stage showed no residual BCC, but there still was a brisk atypical lymphocytic infiltrate, with some areas showing lymphocytes in a linear cordlike distribution (Figure 3). Permanent sections demonstrated infiltration of small to medium lymphoid cells. Immunohistochemistry stains were positive for CD20 and BCL2 and negative for CD5, CD10, BCL6, and CD43; a low Ki-67 proliferation fraction also was observed. B-cell clonality studies and polymerase chain reaction demonstrated rearrangements of the IgH and IgK genes, consistent with primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma (pcMZL). Positron emission tomography showed no spread of malignancy; therefore, medical oncology recommended observation and close monitoring.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma accounts for approximately 25% of all cutaneous lymphomas.1 Three main cutaneous subtypes exist: pcMZL; primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma; and primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. The second most common type of cutaneous lymphoma, pcMZL, accounts for 25% of cases of pcBCL.1 Primary cutaneous follicular center lymphoma makes up 60% of cutaneous lymphomas, and the remainder are primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. All share a notable male predominance and onset most commonly in the sixth through eighth decades of life, although they also can occur in younger patients.1

Histologically, pcMZL has 2 distinct subtypes: one resembling mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas and a more clinically aggressive subtype with heavy chain class switching, although intermediate forms also exist. Both are characterized by diffuse and/or nodular infiltrates in the subcutis and dermis with sparing of the epidermis. Often, these infiltrates are more prominent in the deeper sections examined, and occasionally they may be accompanied by germinal center follicles. Immunohistochemical stains are key in determining the pcBCL subtype. Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma will most commonly show a BCL2+, BCL6–, CD20+, and CD10– immunophenotype, as in our case. If a majority of cells have undergone plasmacytoid differentiation, loss of CD20 can occur, but retention of other B-cell markers, such as CD79a and CD19, will be seen. Proliferation fraction via Ki-67 commonly is low, reflecting the indolence of this subtype of lymphoma.1

Monoclonal rearrangement of immunoglobulins also can occur, with IgH rearrangements detected in 60% to 80% of cases of pcMZL. Translocations are not a reliable method of diagnosis for pcMZL but can be present in a variable manner, with t(14;18), t(3;14), and t(11;18) reported in a subset of cases.2 Leukemic infiltrates encountered on frozen sections should prompt the Mohs surgeon to consider the possibility of a concomitant leukemia or lymphoma. In one study, 36% (20/55) of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) were found to have predominantly leukemic B-cell infiltrates on frozen sections.3 Numerous reports also exist of asymptomatic patients being diagnosed with CLL due to leukemic infiltrates identified during Mohs surgery.4,5 Patients with systemic hematologic malignancies, including CLL and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, also are known to be at an increased risk for skin cancers, including keratinocyte cancers, melanoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma. This can be attributed partially to immunosuppression, a well-known risk factor for development of cutaneous malignancies.5 Padgett et al5 speculated that local immune suppression due to underlying pcBCL and reaction of lymphocytes to tumor antigens could have played a role in the development of BCC at this site. If a leukemic infiltrate is demonstrated, the surgeon should consider sending tissue for permanent section and immunostaining. This can be helpful to determine if it is a reactive or neoplastic process and aid in characterizing the leukemic infiltrate if it is suspected to be neoplastic in nature.

There are numerous reports of pcBCL imitating the cutaneous findings of BCC clinically, but this is quite uncommon on histopathology. As in our case, findings of sheets of dense, monomorphic lymphocytes; inability to clear inflammation on deeper Mohs sections; presence of primordial follicles; and atypical cytology, including predominance of blastic forms, plasmacytoid cells, or cleaved lymphocytes, should give the clinician pause to consider further evaluation through permanent sections as well as genetic and immunoglobulin studies by a dermatopathologist. This case highlights the importance of further evaluation when an atypical finding is encountered during Mohs surgery.

- Goyal A, LeBlanc RE, Carter JB. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:149-161. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.006

- Vitiello P, Sica A, Ronchi A, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: an update. Front Oncol. 2020;10:651. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.00651

- Mehrany K, Byrd DR, Roenigk RK, et al. Lymphocytic infiltrates and subclinical epithelial tumor extension in patients with chronic leukemia and solid-organ transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:129-134. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29034.x

- Walters M, Chang C, Castillo JR. Diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia during Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;33:1-3. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.12.012

- Padgett JK, Parlette HL, English JC. A diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia prompted by cutaneous lymphocytic infiltrates present in mohs micrographic surgery frozen sections. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:769-771. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29194.x

- Goyal A, LeBlanc RE, Carter JB. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:149-161. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.006

- Vitiello P, Sica A, Ronchi A, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: an update. Front Oncol. 2020;10:651. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.00651

- Mehrany K, Byrd DR, Roenigk RK, et al. Lymphocytic infiltrates and subclinical epithelial tumor extension in patients with chronic leukemia and solid-organ transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:129-134. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29034.x

- Walters M, Chang C, Castillo JR. Diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia during Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;33:1-3. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.12.012

- Padgett JK, Parlette HL, English JC. A diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia prompted by cutaneous lymphocytic infiltrates present in mohs micrographic surgery frozen sections. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:769-771. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29194.x

Primary Cutaneous Marginal Zone B-Cell Lymphoma Discovered During Mohs Surgery for Basal Cell Carcinoma

Primary Cutaneous Marginal Zone B-Cell Lymphoma Discovered During Mohs Surgery for Basal Cell Carcinoma

Practice Points

- Collision tumors of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma and basal cell carcinoma occurring within the same lesion are uncommon findings during Mohs surgery.

- Sheets of atypical monomorphic lymphocytes on deeper Mohs sections should prompt the surgeon to consider further evaluation, including sending tissue for permanent sections.

Intralesional Methotrexate: A Cost-Effective, High-Efficacy Alternative to Surgery for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Intralesional Methotrexate: A Cost-Effective, High-Efficacy Alternative to Surgery for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the malignant proliferation of keratinocytes in the epidermis of the skin. Most SCCs are caused by UV light exposure, with sex and increased age acting as the primary known risk factors: SCCs are nearly twice as prevalent in men vs women, and the average age of presentation is the middle of the seventh decade of life.1 In the United States, there are an estimated 1.8 million new SCC cases annually.2 Although not usually life threatening, if left untreated, SCC can metastasize, thereby reducing the 10-year survival rate from above 90% with treatment to 16%.3-6

Most invasive SCC lesions are treated surgically, but intralesional methotrexate (IL-MTX) has emerged as an alternative treatment for cutaneous SCC. It offers the potential for lower-cost, efficacious outpatient treatment.7-12 Methotrexate competitively inhibits the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase, which converts dihydrofolate into tetrahydrofolate.13 In doing so, MTX indirectly prevents the synthesis of thymine, a nucleotide required for DNA synthesis. Thus, MTX can halt DNA synthesis and consequently, cell division. Intralesional MTX has been shown to successfully treat keratoacanthomas, lymphomas, and various inflammatory dermatologic conditions.8-12

Surgical options include standard excision, Mohs micrographic surgery, or electrodesiccation and curettage. Surgical treatment has high (92% to 99%) cure rates and typically requires only 1 or 2 appointments.14,15 Although costs can vary, one 2012 study using Medicare fee schedules found that total costs (including primary procedure, biopsy, follow-up appointments through 2 months, and other associated costs) for cutaneous SCC were $475 for electrodesiccation and curettage, $1302.92 for excision, and $2093.14 for Mohs micrographic surgery.16 For some patients, surgery is not an ideal option due to the tumor location, poor wound healing, anticoagulation, and cost. In these patients, photodynamic therapy, topical therapy with 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod, radiation, and cryotherapy are options listed in the American Academy of Dermatology guidelines.15 Compared with surgery, radiation is more demanding on the patient, often requiring multiple visits a week and including common undesirable adverse effects such as radiation dermatitis and prolonged wounds on the lower legs.17 Radiation also can be costly, with one study reporting costs between $2559 and $3431 for SCC of the forearm.18 Furthermore, in young patients, radiotherapy can increase the risk for developing nonmelanoma skin cancer later in life.16

Intralesional MTX is a localized treatment option that avoids the high costs of surgery, the side effects of radiotherapy, prolonged healing, and the systemic effects of chemotherapy. Treatment with IL-MTX can vary depending on the number of treatments necessary but usually only costs a few hundred dollars, rarely costing more than $1000.7 Although IL-MTX is less expensive, it typically requires several follow-up visits, whereas surgical removal may only require 1 visit.

Prior research has noted the efficacy of IL-MTX as a neoadjuvant therapy, with one study finding that IL-MTX can reduce the size of SCC lesions by an average of 0.52 cm2 prior to surgery.19 Several case studies also have documented the effectiveness of IL-MTX as a treatment for SCC.20-22 However, larger studies involving multiple patients to evaluate the efficacy of IL-MTX as a sole treatment for SCC are lacking. Gualdi et al23 looked at the outcomes (complete resolution, partial response, or no response) for SCC treated with IL-MTX and found that 62% (13/21) of patients experienced improvement, with 48% (10/21) experiencing at least 50% improvement. Although these results are promising, further research is needed.

Our study sought to examine IL-MTX efficacy as well as evaluate the dosage and number of appointments/sessions needed to achieve resolution of the lesions.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients who received only IL-MTX for clinically evident or biopsy-proven SCC at US Dermatology Partners clinics in Phoenix, Arizona, from January 1, 2022, to June 30, 2023. Patients aged 18 to 89 years were included, and they had not received other treatment for their SCC lesions such as radiation or systemic chemotherapy. Each patient received at least 1 dose of IL-MTX, beginning with a concentration of 12.5 mg/mL and with all subsequent doses at a concentration of 25 mg/mL (low dose vs high dose). Lesion resolution was categorized as no gross clinical tumor on follow-up. Patients received additional doses of IL-MTX based on the clinical appearance of their lesion(s).

Patient-level descriptive statistics are reported as mean (SD) or median (interquartile range [IQR]) for continuous variables as well as frequency and percentage for categorical variables. To account for the correlation of multiple lesions within individual patients, marginal Cox proportional hazard models were used. Time as well as cumulative dose to lesion resolution were evaluated and presented via the cumulative hazard function, while differences in resolution were estimated using separate Cox models for age, sex, and initial dose.

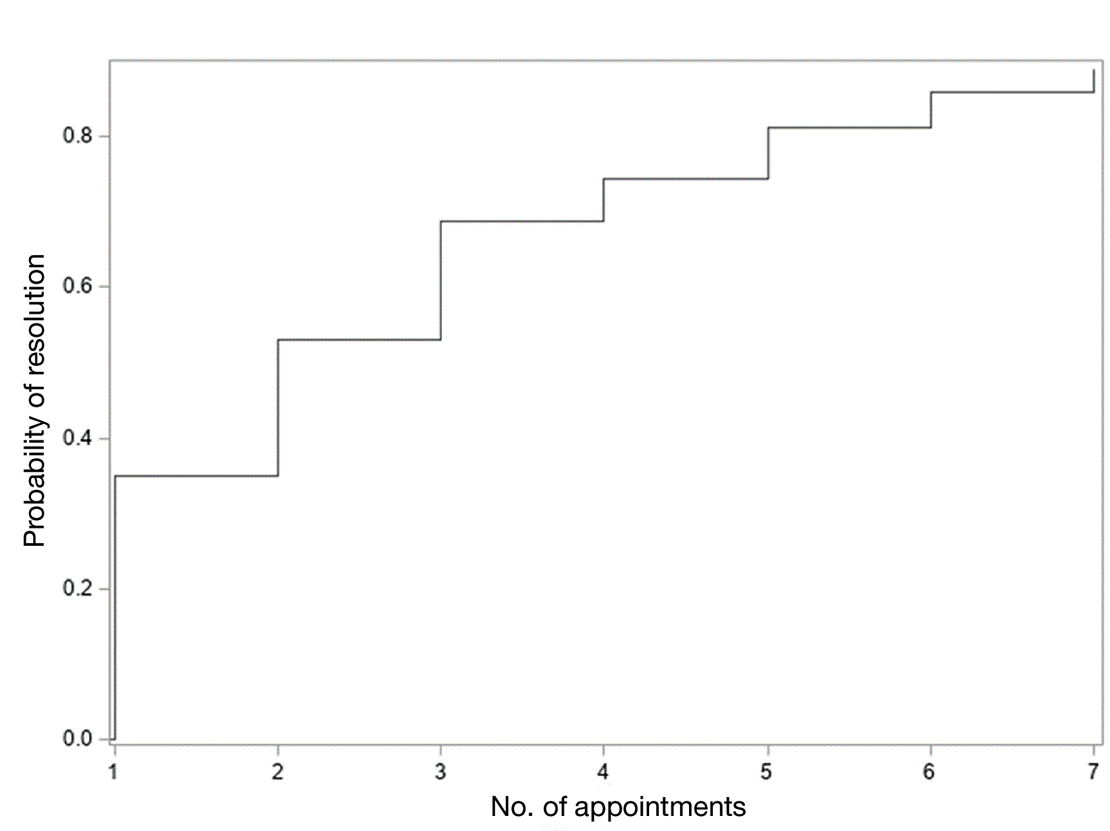

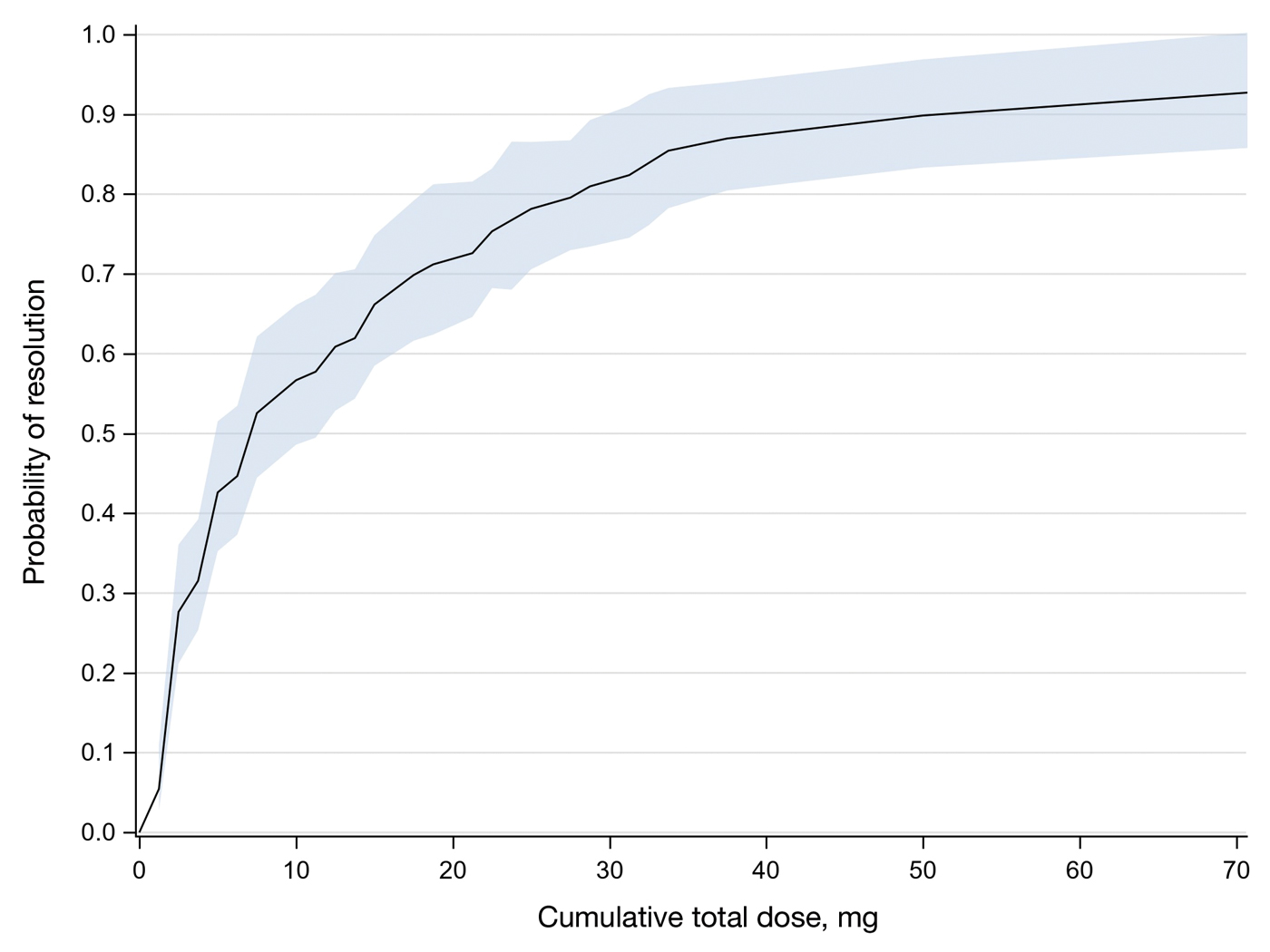

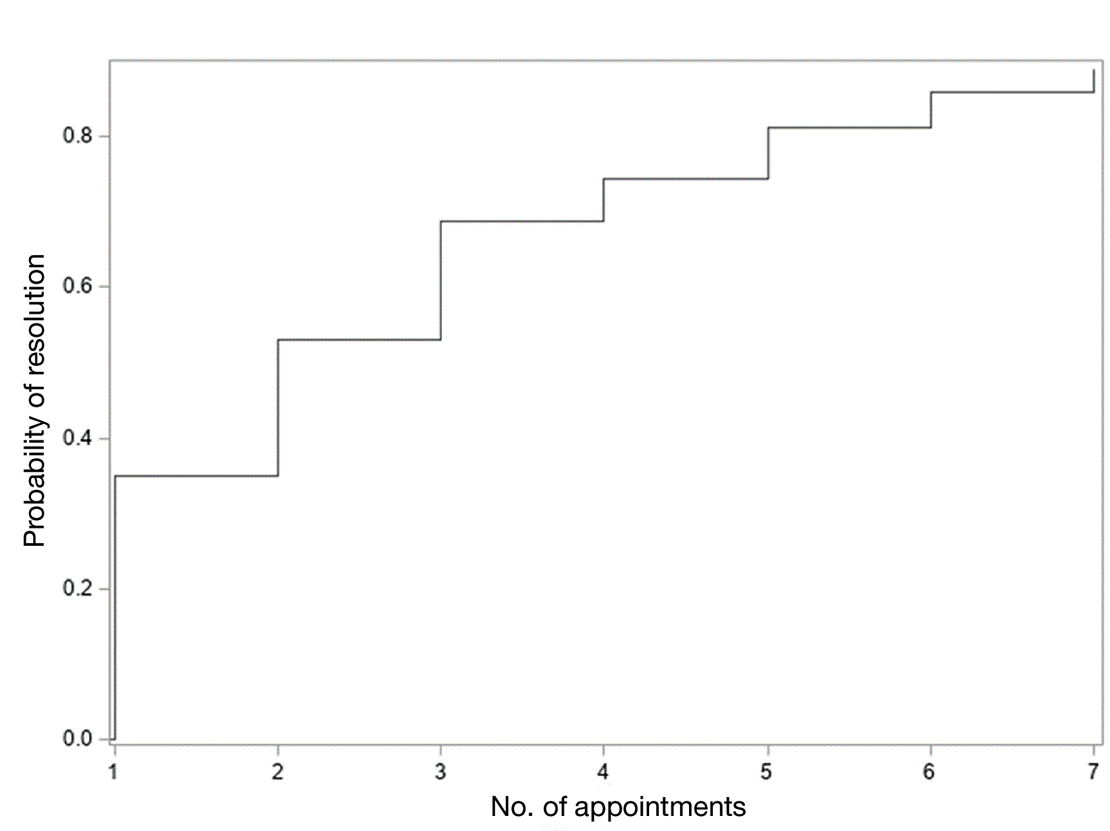

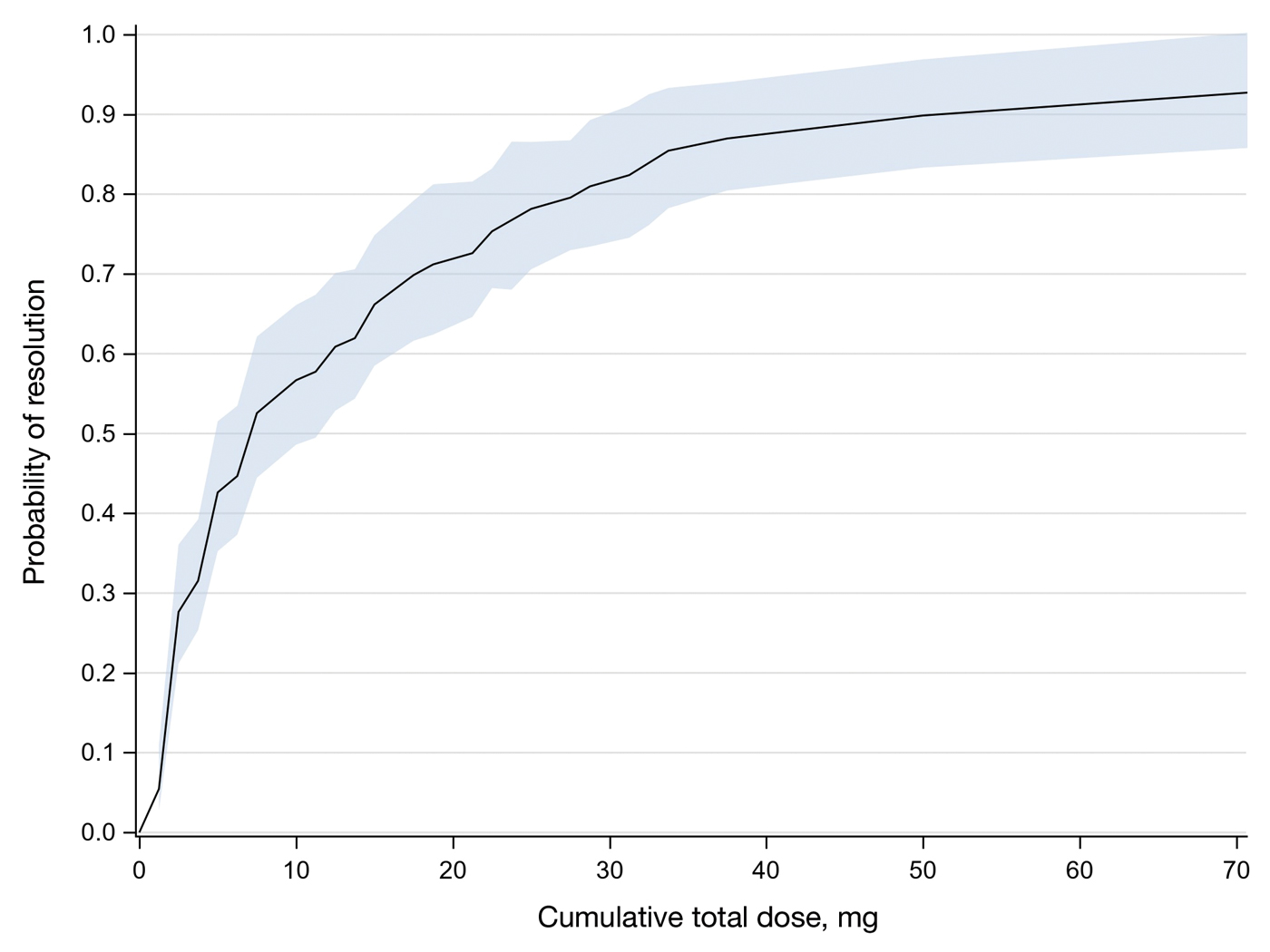

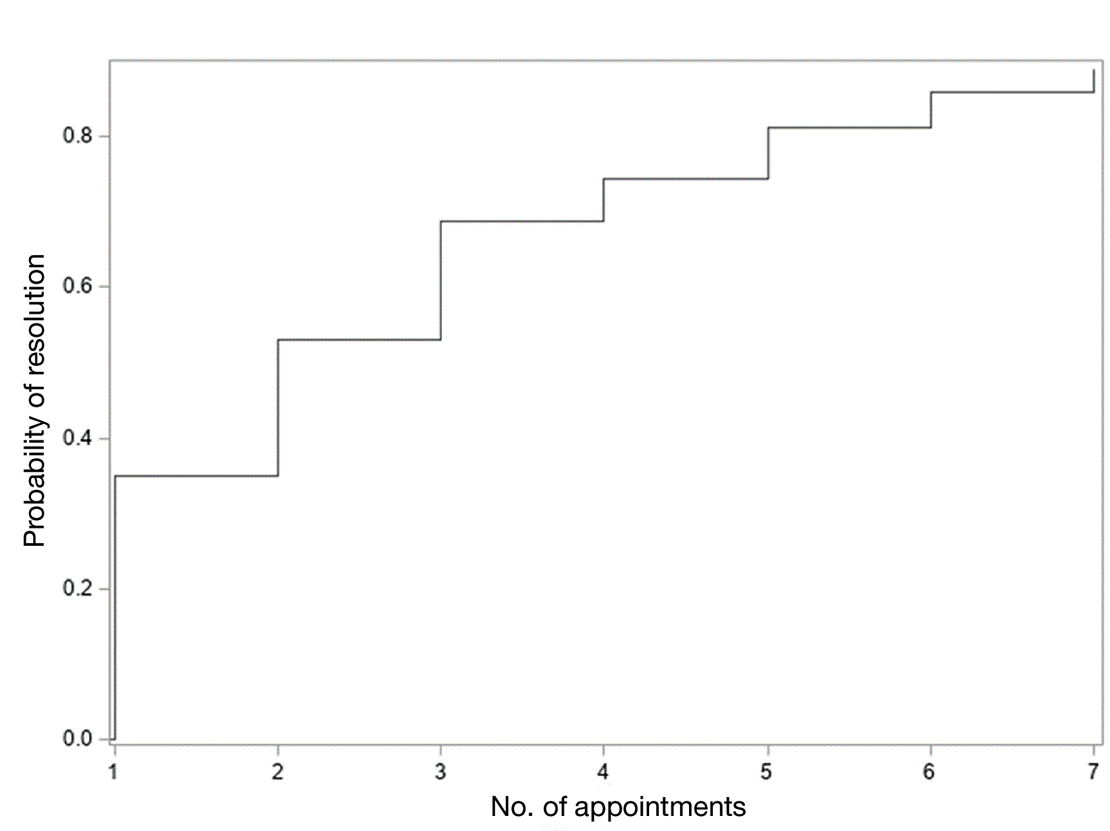

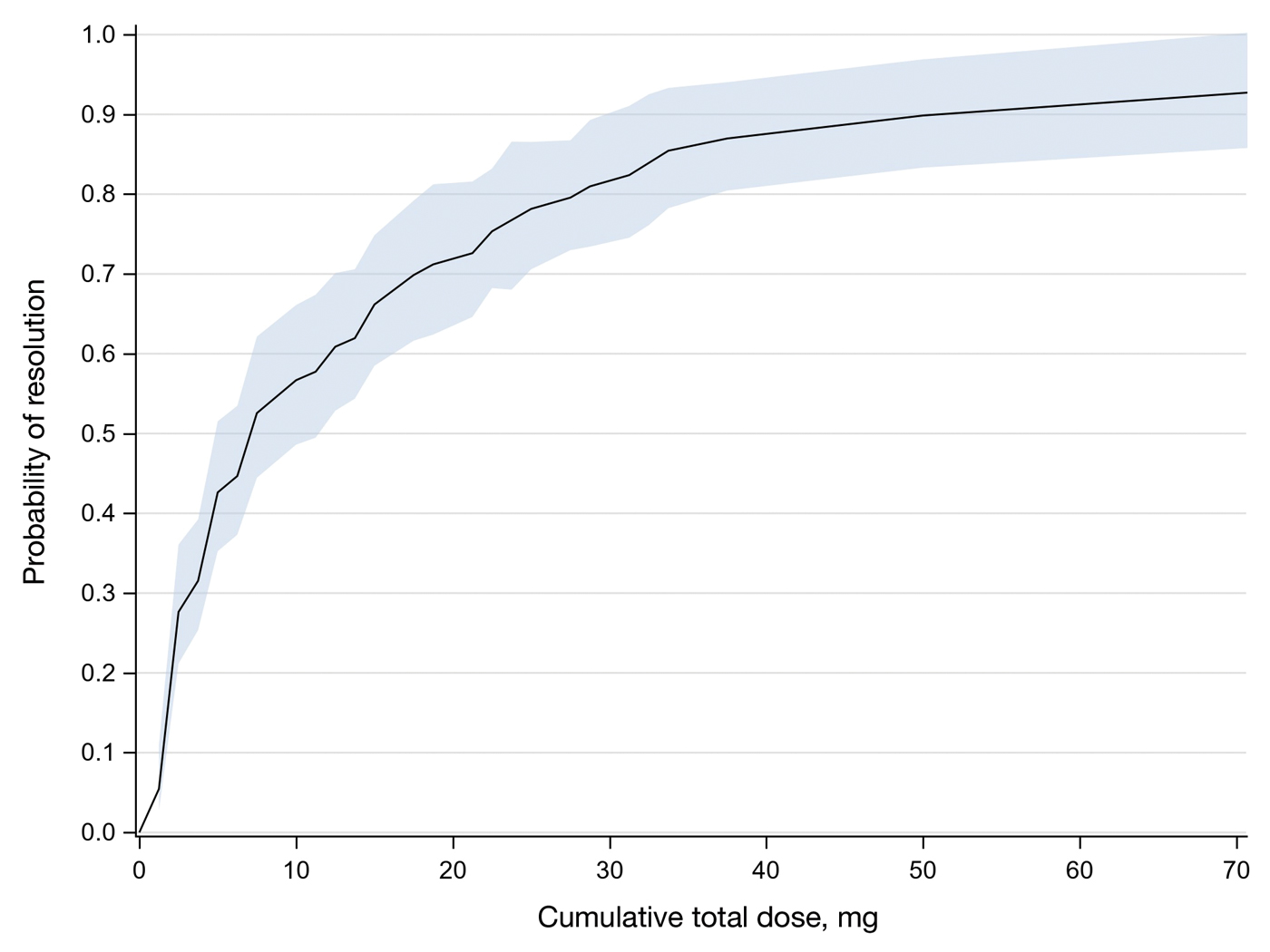

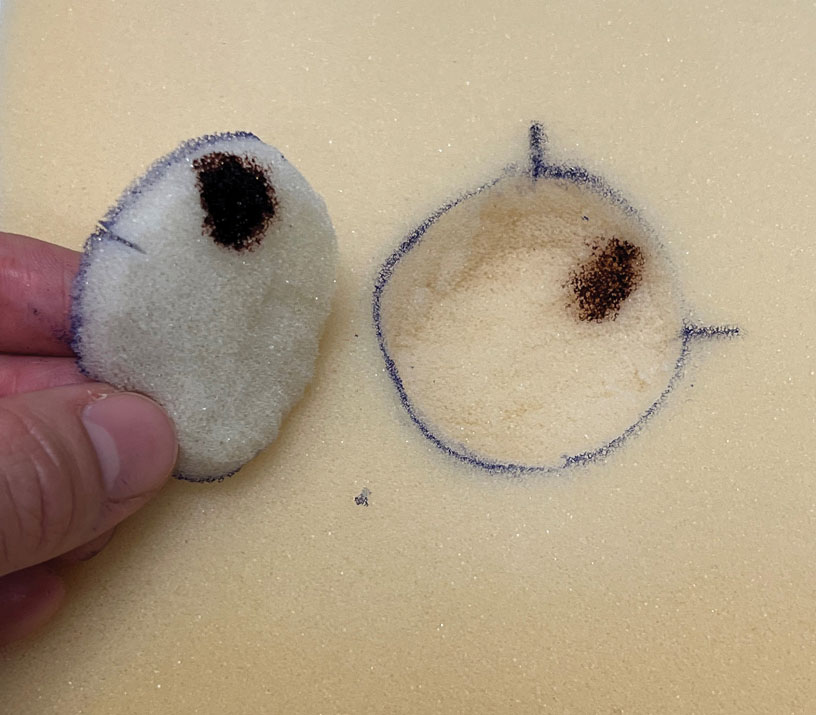

Results

In total, 107 different lesions from 21 patients were included in the analysis. The median number of lesions was 4 per patient (range, 1-15; IQR, 2-7), with a mean (SD) age of 80 (6) years. Patients were primarily female (81% [17/21]). From the data provided, the majority of lesions (83% [89/107]) resolved with IL-MTX. Of the 18 unresolved lesions, 5 (5%) were referred for a different procedure, and the remaining 13 (12%) were censored (lost to follow-up). Figure 1 provides the cumulative incidence function for lesion resolution. Approximately 50% of patient lesions resolved by the second appointment. Similarly, Figure 2 provides the cumulative dose function for lesion resolution; the median cumulative total dose for resolution was 5 mg (IQR, 2.5–12.5). Finally, concerning the ratio for case resolution, no difference in hazard ratio (HR) was observed for age (female vs male, HR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.96-1.06), biological sex (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.63-1.63), or initial dose (high vs low, HR: 1.13; 95% CI: 0.77-1.65).

Comment

Results of this study demonstrate the efficacy of IL-MTX for the treatment of cutaneous SCC. More than 80% of the lesions resolved by IL-MTX alone. This treatment approach is more cost-effective with fewer adverse effects when compared to other options. In our study, treatment with IL-MTX also proved to be reasonable in terms of the number of appointments and total dose required, with more than 50% of lesions resolving within 2 appointments and a median cumulative total dose of 5 mg. Intralesional MTX appears to be similarly efficacious in men and women, and the concentration of the initial dose (12.5 mg/mL vs 25 mg/mL) does not change the treatment outcome.

Although these data are encouraging for the use of IL-MTX in the treatment of SCC, future work should consider the relationships between lesion characteristics (such as size and location) and case resolution with IL-MTX as well as recurrence rates with lesions treated by IL-MTX compared to other treatment options.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the efficacy of IL-MTX as a treatment for SCC that is cost-effective, avoids bothersome side effects, and can be accomplished in relatively few appointments. However, more data are needed to characterize the lesion type best suited to this treatment.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- The Skin Cancer Foundation. Skin cancer facts & statistics: what you need to know. Updated January 2026. Accessed January 20, 2026. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/skin-cancer-facts

- Rees JR, Zens MS, Celaya MO, et al. Survival after squamous cell and basal cell carcinoma of the skin: a retrospective cohort analysis. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:878-884.

- Weinberg A, Ogle C, Shin E. Metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: an update. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:885-899.

- Varra V, Woody NM, Reddy C, et al. Suboptimal outcomes in cutaneous squamous cell cancer of the head and neck with nodal metastases. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:5825-5830. doi:10.21873/anticanres.12923

- Epstein E, Epstein NN, Bragg K, et al. Metastases from squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:245-251.

- Chitwood K, Etzkorn J, Cohen G. Topical and intralesional treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer: efficacy and cost comparisons. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1306-1316

- Scalvenzi M, Patrì A, Costa C, et al. Intralesional methotrexate for the treatment of keratoacanthoma: the Neapolitan experience. Dermatol Ther. 2019;9:369-372.

- Patel NP, Cervino AL. Treatment of keratoacanthoma: is intralesional methotrexate an option? Can J Plast Surg. 2011;19:E15-E18.

- Smith C, Srivastava D, Nijhawan RI. Intralesional methotrexate for keratoacanthomas: a retrospective cohort study. JAAD Int. 2020;83:904-905.

- Blume JE, Stoll HL, Cheney RT. Treatment of primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma with intralesional methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(5 Suppl):S229-S230.

- Nedelcu RI, Balaban M, Turcu G, et al. Efficacy of methotrexate as anti‑inflammatory and anti‑proliferative drug in dermatology: three case reports. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18:905-910.

- Lester RS. Methotrexate. Clin Dermatol. 1989;7:128-135.

- Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH. Current surgical management of skin cancer in dermatology. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990;16:136-151.

- Alam M, Armstrong A, Baum C, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:560-578.

- Wilson LS, Pregenzer M, Basu R, et al. Fee comparisons of treatments for nonmelanoma skin cancer in a private practice academic setting. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:570-584.

- DeConti RC. Chemotherapy of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Semin Oncol. 2012;39:145-149.

- Rogers HW, Coldiron BM. A relative value unit–based cost comparison of treatment modalities for nonmelanoma skin cancer: effect of the loss of the Mohs multiple surgery reduction exemption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:96-103.

- Salido-Vallejo R, Cuevas-Asencio I, Garnacho-Sucedo G, et al. Neoadjuvant intralesional methotrexate in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comparative cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1120-1124.

- Salido-Vallejo R, Garnacho-Saucedo G, Sánchez-Arca M, et al. Neoadjuvant intralesional methotrexate before surgical treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1849-1850.

- Vega-González LG, Morales-Pérez MI, Molina-Pérez T, et al. Successful treatment of squamous cell carcinoma with intralesional methotrexate. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;24:68-70.

- Moye MS, Clark AH, Legler AA, et al. Intralesional methotrexate for treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinomas in a patient taking vemurafenib for treatment of metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:E134-E136.

- Gualdi G, Caravello S, Frasci F, et al. Intralesional methotrexate for the treatment of advanced keratinocytic tumors: a multi-center retrospective study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:769-777.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the malignant proliferation of keratinocytes in the epidermis of the skin. Most SCCs are caused by UV light exposure, with sex and increased age acting as the primary known risk factors: SCCs are nearly twice as prevalent in men vs women, and the average age of presentation is the middle of the seventh decade of life.1 In the United States, there are an estimated 1.8 million new SCC cases annually.2 Although not usually life threatening, if left untreated, SCC can metastasize, thereby reducing the 10-year survival rate from above 90% with treatment to 16%.3-6

Most invasive SCC lesions are treated surgically, but intralesional methotrexate (IL-MTX) has emerged as an alternative treatment for cutaneous SCC. It offers the potential for lower-cost, efficacious outpatient treatment.7-12 Methotrexate competitively inhibits the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase, which converts dihydrofolate into tetrahydrofolate.13 In doing so, MTX indirectly prevents the synthesis of thymine, a nucleotide required for DNA synthesis. Thus, MTX can halt DNA synthesis and consequently, cell division. Intralesional MTX has been shown to successfully treat keratoacanthomas, lymphomas, and various inflammatory dermatologic conditions.8-12

Surgical options include standard excision, Mohs micrographic surgery, or electrodesiccation and curettage. Surgical treatment has high (92% to 99%) cure rates and typically requires only 1 or 2 appointments.14,15 Although costs can vary, one 2012 study using Medicare fee schedules found that total costs (including primary procedure, biopsy, follow-up appointments through 2 months, and other associated costs) for cutaneous SCC were $475 for electrodesiccation and curettage, $1302.92 for excision, and $2093.14 for Mohs micrographic surgery.16 For some patients, surgery is not an ideal option due to the tumor location, poor wound healing, anticoagulation, and cost. In these patients, photodynamic therapy, topical therapy with 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod, radiation, and cryotherapy are options listed in the American Academy of Dermatology guidelines.15 Compared with surgery, radiation is more demanding on the patient, often requiring multiple visits a week and including common undesirable adverse effects such as radiation dermatitis and prolonged wounds on the lower legs.17 Radiation also can be costly, with one study reporting costs between $2559 and $3431 for SCC of the forearm.18 Furthermore, in young patients, radiotherapy can increase the risk for developing nonmelanoma skin cancer later in life.16

Intralesional MTX is a localized treatment option that avoids the high costs of surgery, the side effects of radiotherapy, prolonged healing, and the systemic effects of chemotherapy. Treatment with IL-MTX can vary depending on the number of treatments necessary but usually only costs a few hundred dollars, rarely costing more than $1000.7 Although IL-MTX is less expensive, it typically requires several follow-up visits, whereas surgical removal may only require 1 visit.

Prior research has noted the efficacy of IL-MTX as a neoadjuvant therapy, with one study finding that IL-MTX can reduce the size of SCC lesions by an average of 0.52 cm2 prior to surgery.19 Several case studies also have documented the effectiveness of IL-MTX as a treatment for SCC.20-22 However, larger studies involving multiple patients to evaluate the efficacy of IL-MTX as a sole treatment for SCC are lacking. Gualdi et al23 looked at the outcomes (complete resolution, partial response, or no response) for SCC treated with IL-MTX and found that 62% (13/21) of patients experienced improvement, with 48% (10/21) experiencing at least 50% improvement. Although these results are promising, further research is needed.

Our study sought to examine IL-MTX efficacy as well as evaluate the dosage and number of appointments/sessions needed to achieve resolution of the lesions.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients who received only IL-MTX for clinically evident or biopsy-proven SCC at US Dermatology Partners clinics in Phoenix, Arizona, from January 1, 2022, to June 30, 2023. Patients aged 18 to 89 years were included, and they had not received other treatment for their SCC lesions such as radiation or systemic chemotherapy. Each patient received at least 1 dose of IL-MTX, beginning with a concentration of 12.5 mg/mL and with all subsequent doses at a concentration of 25 mg/mL (low dose vs high dose). Lesion resolution was categorized as no gross clinical tumor on follow-up. Patients received additional doses of IL-MTX based on the clinical appearance of their lesion(s).

Patient-level descriptive statistics are reported as mean (SD) or median (interquartile range [IQR]) for continuous variables as well as frequency and percentage for categorical variables. To account for the correlation of multiple lesions within individual patients, marginal Cox proportional hazard models were used. Time as well as cumulative dose to lesion resolution were evaluated and presented via the cumulative hazard function, while differences in resolution were estimated using separate Cox models for age, sex, and initial dose.

Results

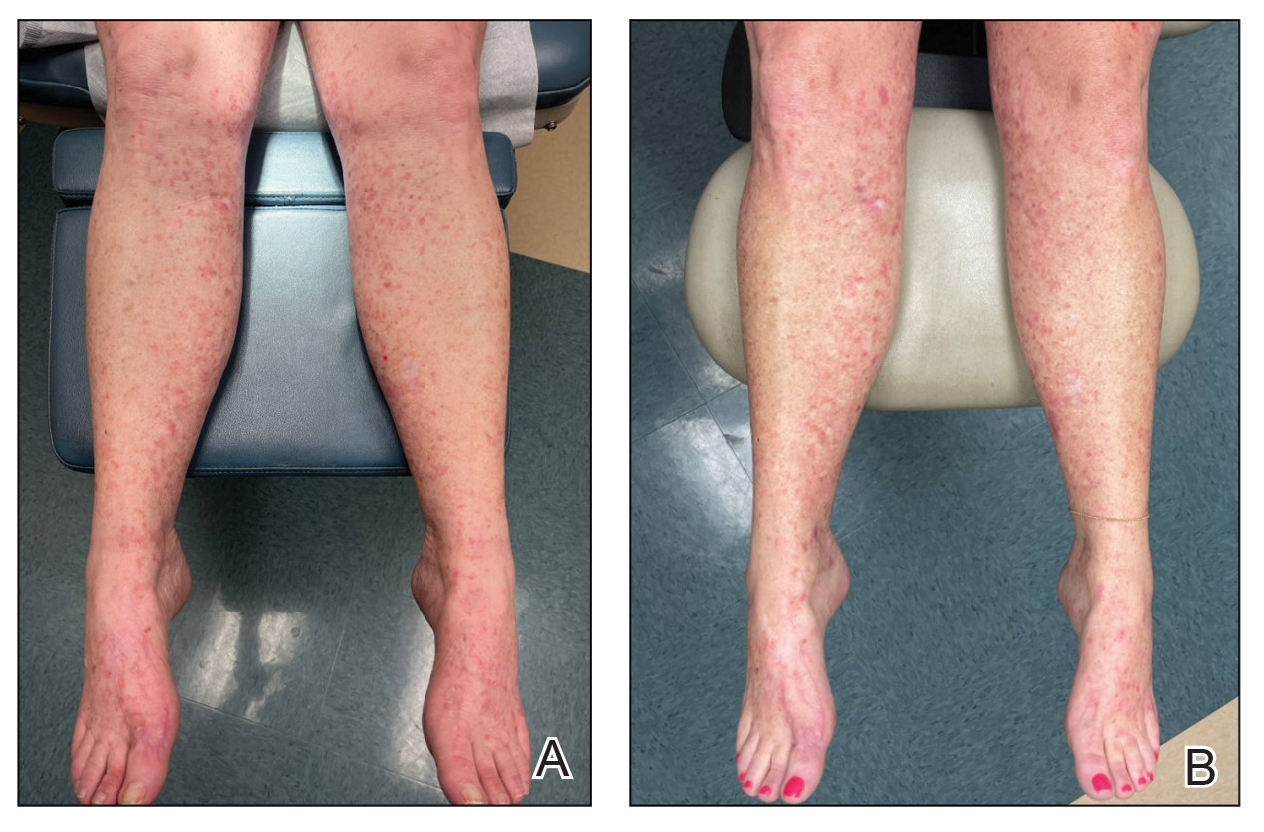

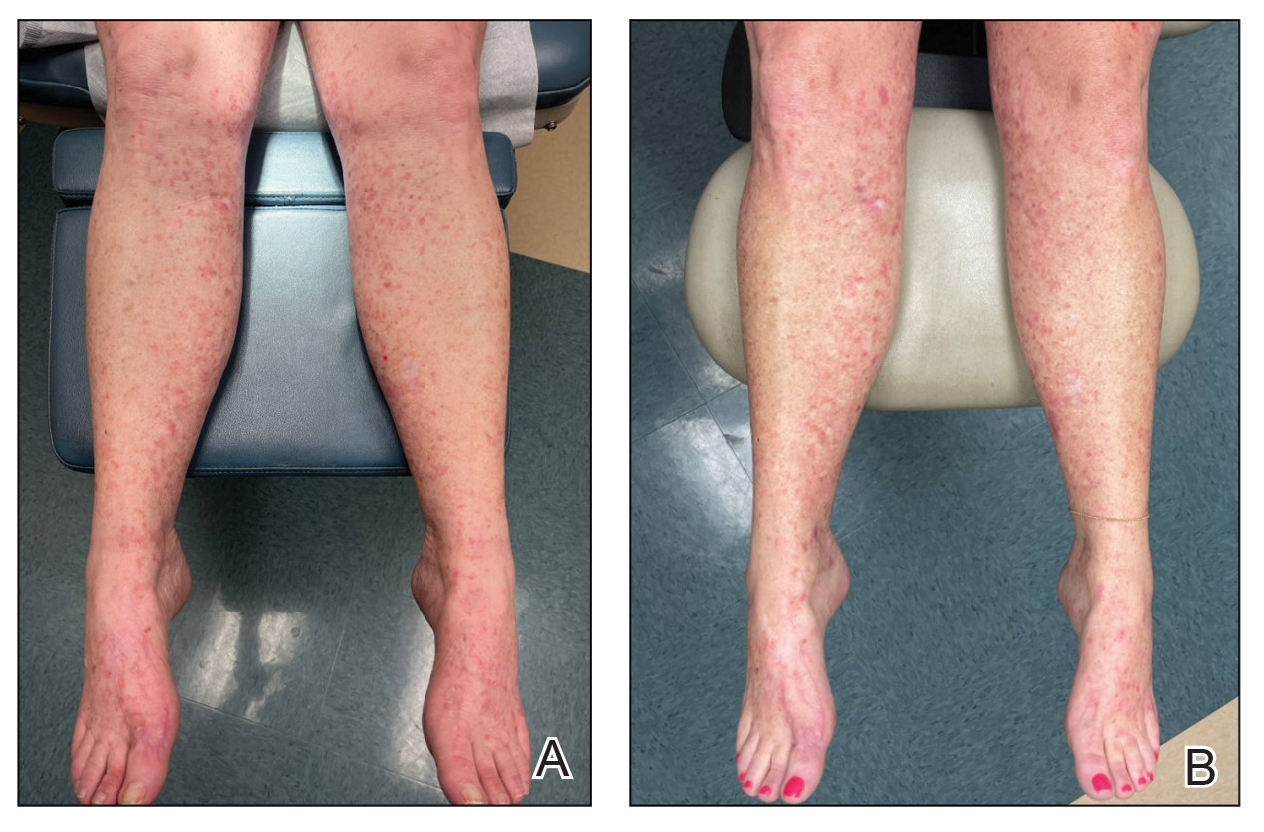

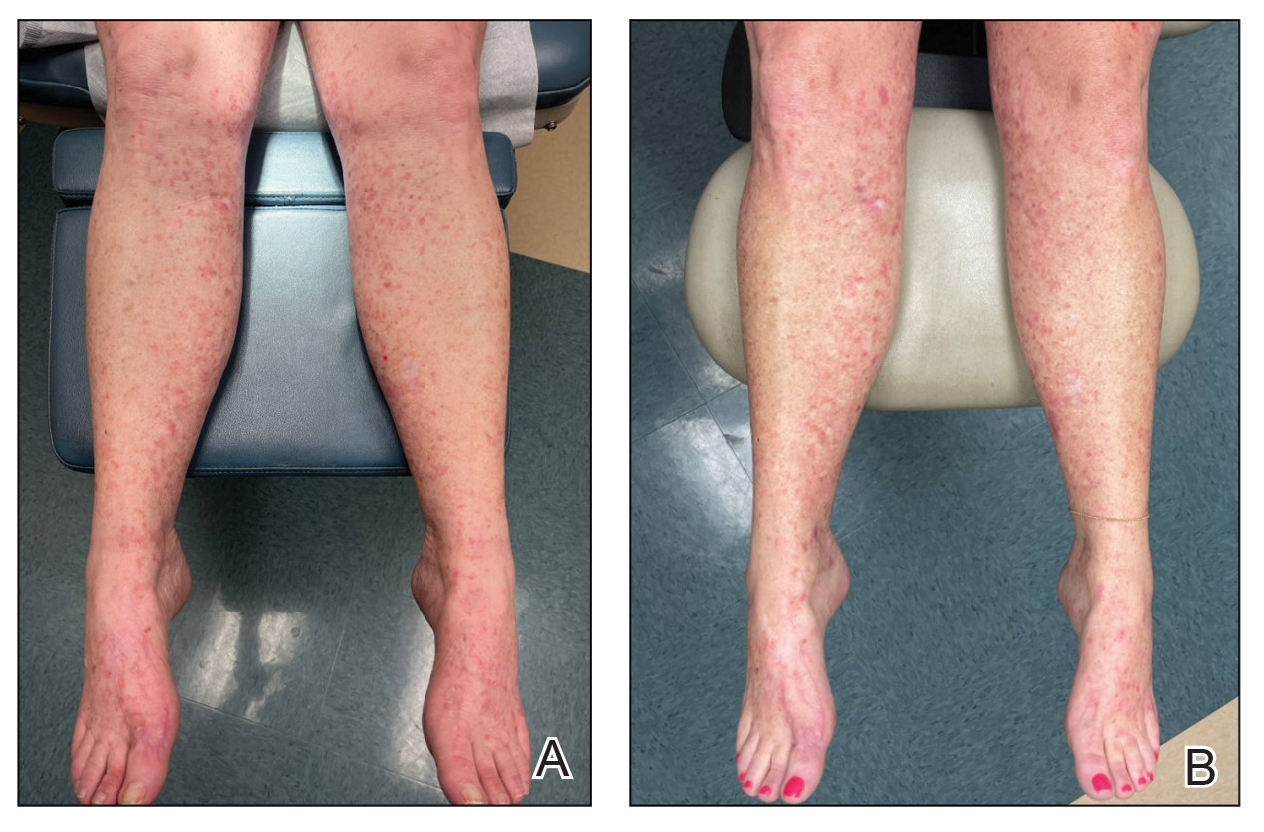

In total, 107 different lesions from 21 patients were included in the analysis. The median number of lesions was 4 per patient (range, 1-15; IQR, 2-7), with a mean (SD) age of 80 (6) years. Patients were primarily female (81% [17/21]). From the data provided, the majority of lesions (83% [89/107]) resolved with IL-MTX. Of the 18 unresolved lesions, 5 (5%) were referred for a different procedure, and the remaining 13 (12%) were censored (lost to follow-up). Figure 1 provides the cumulative incidence function for lesion resolution. Approximately 50% of patient lesions resolved by the second appointment. Similarly, Figure 2 provides the cumulative dose function for lesion resolution; the median cumulative total dose for resolution was 5 mg (IQR, 2.5–12.5). Finally, concerning the ratio for case resolution, no difference in hazard ratio (HR) was observed for age (female vs male, HR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.96-1.06), biological sex (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.63-1.63), or initial dose (high vs low, HR: 1.13; 95% CI: 0.77-1.65).

Comment

Results of this study demonstrate the efficacy of IL-MTX for the treatment of cutaneous SCC. More than 80% of the lesions resolved by IL-MTX alone. This treatment approach is more cost-effective with fewer adverse effects when compared to other options. In our study, treatment with IL-MTX also proved to be reasonable in terms of the number of appointments and total dose required, with more than 50% of lesions resolving within 2 appointments and a median cumulative total dose of 5 mg. Intralesional MTX appears to be similarly efficacious in men and women, and the concentration of the initial dose (12.5 mg/mL vs 25 mg/mL) does not change the treatment outcome.

Although these data are encouraging for the use of IL-MTX in the treatment of SCC, future work should consider the relationships between lesion characteristics (such as size and location) and case resolution with IL-MTX as well as recurrence rates with lesions treated by IL-MTX compared to other treatment options.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the efficacy of IL-MTX as a treatment for SCC that is cost-effective, avoids bothersome side effects, and can be accomplished in relatively few appointments. However, more data are needed to characterize the lesion type best suited to this treatment.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the malignant proliferation of keratinocytes in the epidermis of the skin. Most SCCs are caused by UV light exposure, with sex and increased age acting as the primary known risk factors: SCCs are nearly twice as prevalent in men vs women, and the average age of presentation is the middle of the seventh decade of life.1 In the United States, there are an estimated 1.8 million new SCC cases annually.2 Although not usually life threatening, if left untreated, SCC can metastasize, thereby reducing the 10-year survival rate from above 90% with treatment to 16%.3-6

Most invasive SCC lesions are treated surgically, but intralesional methotrexate (IL-MTX) has emerged as an alternative treatment for cutaneous SCC. It offers the potential for lower-cost, efficacious outpatient treatment.7-12 Methotrexate competitively inhibits the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase, which converts dihydrofolate into tetrahydrofolate.13 In doing so, MTX indirectly prevents the synthesis of thymine, a nucleotide required for DNA synthesis. Thus, MTX can halt DNA synthesis and consequently, cell division. Intralesional MTX has been shown to successfully treat keratoacanthomas, lymphomas, and various inflammatory dermatologic conditions.8-12

Surgical options include standard excision, Mohs micrographic surgery, or electrodesiccation and curettage. Surgical treatment has high (92% to 99%) cure rates and typically requires only 1 or 2 appointments.14,15 Although costs can vary, one 2012 study using Medicare fee schedules found that total costs (including primary procedure, biopsy, follow-up appointments through 2 months, and other associated costs) for cutaneous SCC were $475 for electrodesiccation and curettage, $1302.92 for excision, and $2093.14 for Mohs micrographic surgery.16 For some patients, surgery is not an ideal option due to the tumor location, poor wound healing, anticoagulation, and cost. In these patients, photodynamic therapy, topical therapy with 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod, radiation, and cryotherapy are options listed in the American Academy of Dermatology guidelines.15 Compared with surgery, radiation is more demanding on the patient, often requiring multiple visits a week and including common undesirable adverse effects such as radiation dermatitis and prolonged wounds on the lower legs.17 Radiation also can be costly, with one study reporting costs between $2559 and $3431 for SCC of the forearm.18 Furthermore, in young patients, radiotherapy can increase the risk for developing nonmelanoma skin cancer later in life.16

Intralesional MTX is a localized treatment option that avoids the high costs of surgery, the side effects of radiotherapy, prolonged healing, and the systemic effects of chemotherapy. Treatment with IL-MTX can vary depending on the number of treatments necessary but usually only costs a few hundred dollars, rarely costing more than $1000.7 Although IL-MTX is less expensive, it typically requires several follow-up visits, whereas surgical removal may only require 1 visit.

Prior research has noted the efficacy of IL-MTX as a neoadjuvant therapy, with one study finding that IL-MTX can reduce the size of SCC lesions by an average of 0.52 cm2 prior to surgery.19 Several case studies also have documented the effectiveness of IL-MTX as a treatment for SCC.20-22 However, larger studies involving multiple patients to evaluate the efficacy of IL-MTX as a sole treatment for SCC are lacking. Gualdi et al23 looked at the outcomes (complete resolution, partial response, or no response) for SCC treated with IL-MTX and found that 62% (13/21) of patients experienced improvement, with 48% (10/21) experiencing at least 50% improvement. Although these results are promising, further research is needed.

Our study sought to examine IL-MTX efficacy as well as evaluate the dosage and number of appointments/sessions needed to achieve resolution of the lesions.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients who received only IL-MTX for clinically evident or biopsy-proven SCC at US Dermatology Partners clinics in Phoenix, Arizona, from January 1, 2022, to June 30, 2023. Patients aged 18 to 89 years were included, and they had not received other treatment for their SCC lesions such as radiation or systemic chemotherapy. Each patient received at least 1 dose of IL-MTX, beginning with a concentration of 12.5 mg/mL and with all subsequent doses at a concentration of 25 mg/mL (low dose vs high dose). Lesion resolution was categorized as no gross clinical tumor on follow-up. Patients received additional doses of IL-MTX based on the clinical appearance of their lesion(s).

Patient-level descriptive statistics are reported as mean (SD) or median (interquartile range [IQR]) for continuous variables as well as frequency and percentage for categorical variables. To account for the correlation of multiple lesions within individual patients, marginal Cox proportional hazard models were used. Time as well as cumulative dose to lesion resolution were evaluated and presented via the cumulative hazard function, while differences in resolution were estimated using separate Cox models for age, sex, and initial dose.

Results

In total, 107 different lesions from 21 patients were included in the analysis. The median number of lesions was 4 per patient (range, 1-15; IQR, 2-7), with a mean (SD) age of 80 (6) years. Patients were primarily female (81% [17/21]). From the data provided, the majority of lesions (83% [89/107]) resolved with IL-MTX. Of the 18 unresolved lesions, 5 (5%) were referred for a different procedure, and the remaining 13 (12%) were censored (lost to follow-up). Figure 1 provides the cumulative incidence function for lesion resolution. Approximately 50% of patient lesions resolved by the second appointment. Similarly, Figure 2 provides the cumulative dose function for lesion resolution; the median cumulative total dose for resolution was 5 mg (IQR, 2.5–12.5). Finally, concerning the ratio for case resolution, no difference in hazard ratio (HR) was observed for age (female vs male, HR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.96-1.06), biological sex (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.63-1.63), or initial dose (high vs low, HR: 1.13; 95% CI: 0.77-1.65).

Comment

Results of this study demonstrate the efficacy of IL-MTX for the treatment of cutaneous SCC. More than 80% of the lesions resolved by IL-MTX alone. This treatment approach is more cost-effective with fewer adverse effects when compared to other options. In our study, treatment with IL-MTX also proved to be reasonable in terms of the number of appointments and total dose required, with more than 50% of lesions resolving within 2 appointments and a median cumulative total dose of 5 mg. Intralesional MTX appears to be similarly efficacious in men and women, and the concentration of the initial dose (12.5 mg/mL vs 25 mg/mL) does not change the treatment outcome.

Although these data are encouraging for the use of IL-MTX in the treatment of SCC, future work should consider the relationships between lesion characteristics (such as size and location) and case resolution with IL-MTX as well as recurrence rates with lesions treated by IL-MTX compared to other treatment options.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the efficacy of IL-MTX as a treatment for SCC that is cost-effective, avoids bothersome side effects, and can be accomplished in relatively few appointments. However, more data are needed to characterize the lesion type best suited to this treatment.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- The Skin Cancer Foundation. Skin cancer facts & statistics: what you need to know. Updated January 2026. Accessed January 20, 2026. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/skin-cancer-facts

- Rees JR, Zens MS, Celaya MO, et al. Survival after squamous cell and basal cell carcinoma of the skin: a retrospective cohort analysis. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:878-884.

- Weinberg A, Ogle C, Shin E. Metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: an update. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:885-899.

- Varra V, Woody NM, Reddy C, et al. Suboptimal outcomes in cutaneous squamous cell cancer of the head and neck with nodal metastases. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:5825-5830. doi:10.21873/anticanres.12923

- Epstein E, Epstein NN, Bragg K, et al. Metastases from squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:245-251.

- Chitwood K, Etzkorn J, Cohen G. Topical and intralesional treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer: efficacy and cost comparisons. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1306-1316

- Scalvenzi M, Patrì A, Costa C, et al. Intralesional methotrexate for the treatment of keratoacanthoma: the Neapolitan experience. Dermatol Ther. 2019;9:369-372.

- Patel NP, Cervino AL. Treatment of keratoacanthoma: is intralesional methotrexate an option? Can J Plast Surg. 2011;19:E15-E18.

- Smith C, Srivastava D, Nijhawan RI. Intralesional methotrexate for keratoacanthomas: a retrospective cohort study. JAAD Int. 2020;83:904-905.

- Blume JE, Stoll HL, Cheney RT. Treatment of primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma with intralesional methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(5 Suppl):S229-S230.

- Nedelcu RI, Balaban M, Turcu G, et al. Efficacy of methotrexate as anti‑inflammatory and anti‑proliferative drug in dermatology: three case reports. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18:905-910.

- Lester RS. Methotrexate. Clin Dermatol. 1989;7:128-135.

- Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH. Current surgical management of skin cancer in dermatology. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990;16:136-151.

- Alam M, Armstrong A, Baum C, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:560-578.

- Wilson LS, Pregenzer M, Basu R, et al. Fee comparisons of treatments for nonmelanoma skin cancer in a private practice academic setting. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:570-584.

- DeConti RC. Chemotherapy of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Semin Oncol. 2012;39:145-149.

- Rogers HW, Coldiron BM. A relative value unit–based cost comparison of treatment modalities for nonmelanoma skin cancer: effect of the loss of the Mohs multiple surgery reduction exemption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:96-103.

- Salido-Vallejo R, Cuevas-Asencio I, Garnacho-Sucedo G, et al. Neoadjuvant intralesional methotrexate in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comparative cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1120-1124.

- Salido-Vallejo R, Garnacho-Saucedo G, Sánchez-Arca M, et al. Neoadjuvant intralesional methotrexate before surgical treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1849-1850.

- Vega-González LG, Morales-Pérez MI, Molina-Pérez T, et al. Successful treatment of squamous cell carcinoma with intralesional methotrexate. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;24:68-70.

- Moye MS, Clark AH, Legler AA, et al. Intralesional methotrexate for treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinomas in a patient taking vemurafenib for treatment of metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:E134-E136.

- Gualdi G, Caravello S, Frasci F, et al. Intralesional methotrexate for the treatment of advanced keratinocytic tumors: a multi-center retrospective study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:769-777.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- The Skin Cancer Foundation. Skin cancer facts & statistics: what you need to know. Updated January 2026. Accessed January 20, 2026. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/skin-cancer-facts

- Rees JR, Zens MS, Celaya MO, et al. Survival after squamous cell and basal cell carcinoma of the skin: a retrospective cohort analysis. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:878-884.

- Weinberg A, Ogle C, Shin E. Metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: an update. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:885-899.

- Varra V, Woody NM, Reddy C, et al. Suboptimal outcomes in cutaneous squamous cell cancer of the head and neck with nodal metastases. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:5825-5830. doi:10.21873/anticanres.12923

- Epstein E, Epstein NN, Bragg K, et al. Metastases from squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:245-251.

- Chitwood K, Etzkorn J, Cohen G. Topical and intralesional treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer: efficacy and cost comparisons. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1306-1316

- Scalvenzi M, Patrì A, Costa C, et al. Intralesional methotrexate for the treatment of keratoacanthoma: the Neapolitan experience. Dermatol Ther. 2019;9:369-372.

- Patel NP, Cervino AL. Treatment of keratoacanthoma: is intralesional methotrexate an option? Can J Plast Surg. 2011;19:E15-E18.

- Smith C, Srivastava D, Nijhawan RI. Intralesional methotrexate for keratoacanthomas: a retrospective cohort study. JAAD Int. 2020;83:904-905.

- Blume JE, Stoll HL, Cheney RT. Treatment of primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma with intralesional methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(5 Suppl):S229-S230.

- Nedelcu RI, Balaban M, Turcu G, et al. Efficacy of methotrexate as anti‑inflammatory and anti‑proliferative drug in dermatology: three case reports. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18:905-910.

- Lester RS. Methotrexate. Clin Dermatol. 1989;7:128-135.

- Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH. Current surgical management of skin cancer in dermatology. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990;16:136-151.

- Alam M, Armstrong A, Baum C, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:560-578.

- Wilson LS, Pregenzer M, Basu R, et al. Fee comparisons of treatments for nonmelanoma skin cancer in a private practice academic setting. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:570-584.

- DeConti RC. Chemotherapy of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Semin Oncol. 2012;39:145-149.

- Rogers HW, Coldiron BM. A relative value unit–based cost comparison of treatment modalities for nonmelanoma skin cancer: effect of the loss of the Mohs multiple surgery reduction exemption. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:96-103.

- Salido-Vallejo R, Cuevas-Asencio I, Garnacho-Sucedo G, et al. Neoadjuvant intralesional methotrexate in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comparative cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1120-1124.

- Salido-Vallejo R, Garnacho-Saucedo G, Sánchez-Arca M, et al. Neoadjuvant intralesional methotrexate before surgical treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1849-1850.

- Vega-González LG, Morales-Pérez MI, Molina-Pérez T, et al. Successful treatment of squamous cell carcinoma with intralesional methotrexate. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;24:68-70.

- Moye MS, Clark AH, Legler AA, et al. Intralesional methotrexate for treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinomas in a patient taking vemurafenib for treatment of metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:E134-E136.

- Gualdi G, Caravello S, Frasci F, et al. Intralesional methotrexate for the treatment of advanced keratinocytic tumors: a multi-center retrospective study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:769-777.

Intralesional Methotrexate: A Cost-Effective, High-Efficacy Alternative to Surgery for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Intralesional Methotrexate: A Cost-Effective, High-Efficacy Alternative to Surgery for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

PRACTICE POINTS

- Intralesional methotrexate (IL-MTX) is an efficacious treatment option for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma lesions in patients who are not good candidates for surgical excision.

- The starting concentration of the initial IL-MTX dose did not substantially impact outcomes; however, a 25 mg/mL concentration is standard for subsequent treatments to maintain efficacy.

Screening for Meaning: Do Skin Cancer Screening Events Accomplish Anything?

Screening for Meaning: Do Skin Cancer Screening Events Accomplish Anything?

When Skin Cancer Awareness Month rolls around every May, my social media feed is inundated with posts extolling the benefits of total body skin examinations and the life-saving potential of skin cancer screenings; however, time and again the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)—the leading authority on evidence-based public health recommendations in the United States—has found the evidence supporting skin cancer screenings to be insufficient. The USPSTF has cited a lack of high-quality studies and inadequate data to recommend screening for the general population, excluding those at elevated risk due to personal, family, or occupational history.1 A 2019 Cochrane review went further, concluding that current evidence refutes the utility of population-based screening for melanoma.2

Despite these findings, skin cancer screenings and total body skin examinations remain popular among patients both with and without a personal or family history of cutaneous malignancy. Indeed, the anecdotal experience of dermatologists worldwide suggests an intangible benefit to screening that persists, even if robust data to support it remain elusive.

Putting aside studies that suggest these screenings help identify melanomas at earlier stages and with reduced Breslow thicknesses,3 there is a crucial benefit from face-to-face interaction between medical professionals and the public during skin cancer screening events or health fairs. This interaction has become especially important in an era when misinformation thrives online and so-called skin care “experts” with no formal training can amass tens of thousands—or even millions—of followers on social media.

So, what are the intangible benefits of the face-to-face interactions that occur naturally during skin cancer screenings? The most obvious is education. While the USPSTF may not recommend routine screening for skin cancer in the general population, it does endorse education for children, adolescents, and adults on the importance of minimizing exposure to UV radiation, particularly those with lighter skin tones.4 Publicly advertised skin cancer screenings at health fairs or other community events may offer an opportunity to raise awareness about sun safety and protection, including the value of peak UV avoidance, sun-protective clothing, and proper sunscreen use; these settings also serve as platforms for health care providers to counter misinformation, including concerns about sunscreen safety both for the patient and the environment, overhyped risks for vitamin D deficiency from sun avoidance, and myths about low skin cancer risk in patients with skin of color.

While the benefits of skin self-examination (SSE) remain uncertain, especially in low-risk populations, screening events provide an opportunity to educate patients on who is most likely to benefit from SSE and in whom the practice may cause more harm than good.5 For higher-risk individuals such as melanoma survivors or those with a strong family history, screening fairs can serve as meaningful touchpoints that reinforce the importance of sun protection and regular examinations with a health care provider. For those eager to perform SSEs, these events offer the chance to teach best practices—how to conduct SSEs effectively, what features to look for (eg, the ABCDE method or the ugly duckling sign), and when to seek professional care.

Finally (and importantly), skin cancer screening events provide peace of mind for patients. Reassurance from a professional about a benign skin lesion can alleviate anxiety that might otherwise lead to emergency or urgent care visits. While cellulitis and other skin infections are the most common dermatologic conditions seen in emergency settings, benign neoplasms and similar nonurgent conditions still contribute a substantial burden to urgent care systems in the United States.6 Outside emergency care, systems-level data support what many of us observe in practice: two of the most common reasons for referral to dermatology are benign neoplasms and epidermoid cysts, accounting for millions of visits annually.7 In fact, recent claims data suggest that the most common diagnosis made in US dermatology clinics in 2023 was (you guessed it!) seborrheic keratosis.8

What if instead of requiring a patient to wait weeks for a primary care appointment and months for a dermatology referral—all while worrying about a rapidly growing pigmented lesion and incurring costs in copays, travel, lost wages, and time away from work—we offered a fast, trustworthy, and free evaluation that meets the patient where they live, work, or socialize? An evaluation that not only eases their fears but also provides meaningful education about skin cancer prevention and screening guidelines? While precautions must of course be taken to ensure that the quality and completeness of such an examination equals that of an in-clinic evaluation, if services of this quality can be provided, public screening events may offer a simple, accessible, and valuable solution that delivers peace of mind and helps reduce unnecessary strain on emergency, primary, and specialty care networks.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, et al. Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2023;329:1290-1295. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.4342

- Johansson M, Brodersen J, Gøtzsche PC. Screening for reducing morbidity and mortality in malignant melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6:CD012352. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012352.pub2

- Matsumoto M, Wack S, Weinstock MA, et al. Five-year outcomes of a melanoma screening initiative in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:504-512. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0253

- Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1134-1142.

- Ersser SJ, Effah A, Dyson J, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to support the early detection of skin cancer through skin self‐examination: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1339-1347. doi:10.1111/bjd.17529

- Nadkarni A, Domeisen N, Hill D, et al. The most common dermatology diagnoses in the emergency department. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1261-1266. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.054

- Grada A, Muddasani S, Fleischer AB Jr. Trends in office visits for the five most common skin diseases in the United States. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:E82-E86.

- Definitive Healthcare. What are the most common diagnoses by dermatologists? Published January 31, 2024. Accessed May 5, 2025. https://www.definitivehc.com/resources/healthcare-insights/top-dermatologist-diagnoses

When Skin Cancer Awareness Month rolls around every May, my social media feed is inundated with posts extolling the benefits of total body skin examinations and the life-saving potential of skin cancer screenings; however, time and again the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)—the leading authority on evidence-based public health recommendations in the United States—has found the evidence supporting skin cancer screenings to be insufficient. The USPSTF has cited a lack of high-quality studies and inadequate data to recommend screening for the general population, excluding those at elevated risk due to personal, family, or occupational history.1 A 2019 Cochrane review went further, concluding that current evidence refutes the utility of population-based screening for melanoma.2

Despite these findings, skin cancer screenings and total body skin examinations remain popular among patients both with and without a personal or family history of cutaneous malignancy. Indeed, the anecdotal experience of dermatologists worldwide suggests an intangible benefit to screening that persists, even if robust data to support it remain elusive.

Putting aside studies that suggest these screenings help identify melanomas at earlier stages and with reduced Breslow thicknesses,3 there is a crucial benefit from face-to-face interaction between medical professionals and the public during skin cancer screening events or health fairs. This interaction has become especially important in an era when misinformation thrives online and so-called skin care “experts” with no formal training can amass tens of thousands—or even millions—of followers on social media.

So, what are the intangible benefits of the face-to-face interactions that occur naturally during skin cancer screenings? The most obvious is education. While the USPSTF may not recommend routine screening for skin cancer in the general population, it does endorse education for children, adolescents, and adults on the importance of minimizing exposure to UV radiation, particularly those with lighter skin tones.4 Publicly advertised skin cancer screenings at health fairs or other community events may offer an opportunity to raise awareness about sun safety and protection, including the value of peak UV avoidance, sun-protective clothing, and proper sunscreen use; these settings also serve as platforms for health care providers to counter misinformation, including concerns about sunscreen safety both for the patient and the environment, overhyped risks for vitamin D deficiency from sun avoidance, and myths about low skin cancer risk in patients with skin of color.

While the benefits of skin self-examination (SSE) remain uncertain, especially in low-risk populations, screening events provide an opportunity to educate patients on who is most likely to benefit from SSE and in whom the practice may cause more harm than good.5 For higher-risk individuals such as melanoma survivors or those with a strong family history, screening fairs can serve as meaningful touchpoints that reinforce the importance of sun protection and regular examinations with a health care provider. For those eager to perform SSEs, these events offer the chance to teach best practices—how to conduct SSEs effectively, what features to look for (eg, the ABCDE method or the ugly duckling sign), and when to seek professional care.

Finally (and importantly), skin cancer screening events provide peace of mind for patients. Reassurance from a professional about a benign skin lesion can alleviate anxiety that might otherwise lead to emergency or urgent care visits. While cellulitis and other skin infections are the most common dermatologic conditions seen in emergency settings, benign neoplasms and similar nonurgent conditions still contribute a substantial burden to urgent care systems in the United States.6 Outside emergency care, systems-level data support what many of us observe in practice: two of the most common reasons for referral to dermatology are benign neoplasms and epidermoid cysts, accounting for millions of visits annually.7 In fact, recent claims data suggest that the most common diagnosis made in US dermatology clinics in 2023 was (you guessed it!) seborrheic keratosis.8

What if instead of requiring a patient to wait weeks for a primary care appointment and months for a dermatology referral—all while worrying about a rapidly growing pigmented lesion and incurring costs in copays, travel, lost wages, and time away from work—we offered a fast, trustworthy, and free evaluation that meets the patient where they live, work, or socialize? An evaluation that not only eases their fears but also provides meaningful education about skin cancer prevention and screening guidelines? While precautions must of course be taken to ensure that the quality and completeness of such an examination equals that of an in-clinic evaluation, if services of this quality can be provided, public screening events may offer a simple, accessible, and valuable solution that delivers peace of mind and helps reduce unnecessary strain on emergency, primary, and specialty care networks.

When Skin Cancer Awareness Month rolls around every May, my social media feed is inundated with posts extolling the benefits of total body skin examinations and the life-saving potential of skin cancer screenings; however, time and again the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)—the leading authority on evidence-based public health recommendations in the United States—has found the evidence supporting skin cancer screenings to be insufficient. The USPSTF has cited a lack of high-quality studies and inadequate data to recommend screening for the general population, excluding those at elevated risk due to personal, family, or occupational history.1 A 2019 Cochrane review went further, concluding that current evidence refutes the utility of population-based screening for melanoma.2

Despite these findings, skin cancer screenings and total body skin examinations remain popular among patients both with and without a personal or family history of cutaneous malignancy. Indeed, the anecdotal experience of dermatologists worldwide suggests an intangible benefit to screening that persists, even if robust data to support it remain elusive.

Putting aside studies that suggest these screenings help identify melanomas at earlier stages and with reduced Breslow thicknesses,3 there is a crucial benefit from face-to-face interaction between medical professionals and the public during skin cancer screening events or health fairs. This interaction has become especially important in an era when misinformation thrives online and so-called skin care “experts” with no formal training can amass tens of thousands—or even millions—of followers on social media.

So, what are the intangible benefits of the face-to-face interactions that occur naturally during skin cancer screenings? The most obvious is education. While the USPSTF may not recommend routine screening for skin cancer in the general population, it does endorse education for children, adolescents, and adults on the importance of minimizing exposure to UV radiation, particularly those with lighter skin tones.4 Publicly advertised skin cancer screenings at health fairs or other community events may offer an opportunity to raise awareness about sun safety and protection, including the value of peak UV avoidance, sun-protective clothing, and proper sunscreen use; these settings also serve as platforms for health care providers to counter misinformation, including concerns about sunscreen safety both for the patient and the environment, overhyped risks for vitamin D deficiency from sun avoidance, and myths about low skin cancer risk in patients with skin of color.

While the benefits of skin self-examination (SSE) remain uncertain, especially in low-risk populations, screening events provide an opportunity to educate patients on who is most likely to benefit from SSE and in whom the practice may cause more harm than good.5 For higher-risk individuals such as melanoma survivors or those with a strong family history, screening fairs can serve as meaningful touchpoints that reinforce the importance of sun protection and regular examinations with a health care provider. For those eager to perform SSEs, these events offer the chance to teach best practices—how to conduct SSEs effectively, what features to look for (eg, the ABCDE method or the ugly duckling sign), and when to seek professional care.

Finally (and importantly), skin cancer screening events provide peace of mind for patients. Reassurance from a professional about a benign skin lesion can alleviate anxiety that might otherwise lead to emergency or urgent care visits. While cellulitis and other skin infections are the most common dermatologic conditions seen in emergency settings, benign neoplasms and similar nonurgent conditions still contribute a substantial burden to urgent care systems in the United States.6 Outside emergency care, systems-level data support what many of us observe in practice: two of the most common reasons for referral to dermatology are benign neoplasms and epidermoid cysts, accounting for millions of visits annually.7 In fact, recent claims data suggest that the most common diagnosis made in US dermatology clinics in 2023 was (you guessed it!) seborrheic keratosis.8

What if instead of requiring a patient to wait weeks for a primary care appointment and months for a dermatology referral—all while worrying about a rapidly growing pigmented lesion and incurring costs in copays, travel, lost wages, and time away from work—we offered a fast, trustworthy, and free evaluation that meets the patient where they live, work, or socialize? An evaluation that not only eases their fears but also provides meaningful education about skin cancer prevention and screening guidelines? While precautions must of course be taken to ensure that the quality and completeness of such an examination equals that of an in-clinic evaluation, if services of this quality can be provided, public screening events may offer a simple, accessible, and valuable solution that delivers peace of mind and helps reduce unnecessary strain on emergency, primary, and specialty care networks.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, et al. Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2023;329:1290-1295. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.4342

- Johansson M, Brodersen J, Gøtzsche PC. Screening for reducing morbidity and mortality in malignant melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6:CD012352. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012352.pub2

- Matsumoto M, Wack S, Weinstock MA, et al. Five-year outcomes of a melanoma screening initiative in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:504-512. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0253

- Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1134-1142.

- Ersser SJ, Effah A, Dyson J, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to support the early detection of skin cancer through skin self‐examination: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1339-1347. doi:10.1111/bjd.17529

- Nadkarni A, Domeisen N, Hill D, et al. The most common dermatology diagnoses in the emergency department. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1261-1266. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.054

- Grada A, Muddasani S, Fleischer AB Jr. Trends in office visits for the five most common skin diseases in the United States. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:E82-E86.

- Definitive Healthcare. What are the most common diagnoses by dermatologists? Published January 31, 2024. Accessed May 5, 2025. https://www.definitivehc.com/resources/healthcare-insights/top-dermatologist-diagnoses

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, et al. Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2023;329:1290-1295. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.4342

- Johansson M, Brodersen J, Gøtzsche PC. Screening for reducing morbidity and mortality in malignant melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6:CD012352. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012352.pub2

- Matsumoto M, Wack S, Weinstock MA, et al. Five-year outcomes of a melanoma screening initiative in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:504-512. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0253

- Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1134-1142.

- Ersser SJ, Effah A, Dyson J, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to support the early detection of skin cancer through skin self‐examination: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1339-1347. doi:10.1111/bjd.17529

- Nadkarni A, Domeisen N, Hill D, et al. The most common dermatology diagnoses in the emergency department. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1261-1266. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.054

- Grada A, Muddasani S, Fleischer AB Jr. Trends in office visits for the five most common skin diseases in the United States. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:E82-E86.

- Definitive Healthcare. What are the most common diagnoses by dermatologists? Published January 31, 2024. Accessed May 5, 2025. https://www.definitivehc.com/resources/healthcare-insights/top-dermatologist-diagnoses

Screening for Meaning: Do Skin Cancer Screening Events Accomplish Anything?

Screening for Meaning: Do Skin Cancer Screening Events Accomplish Anything?

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Practice Gap

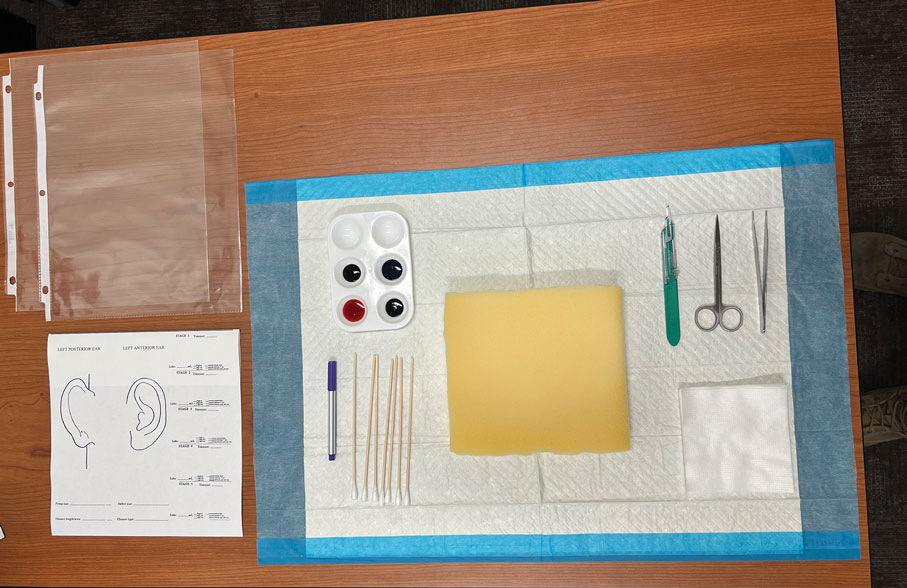

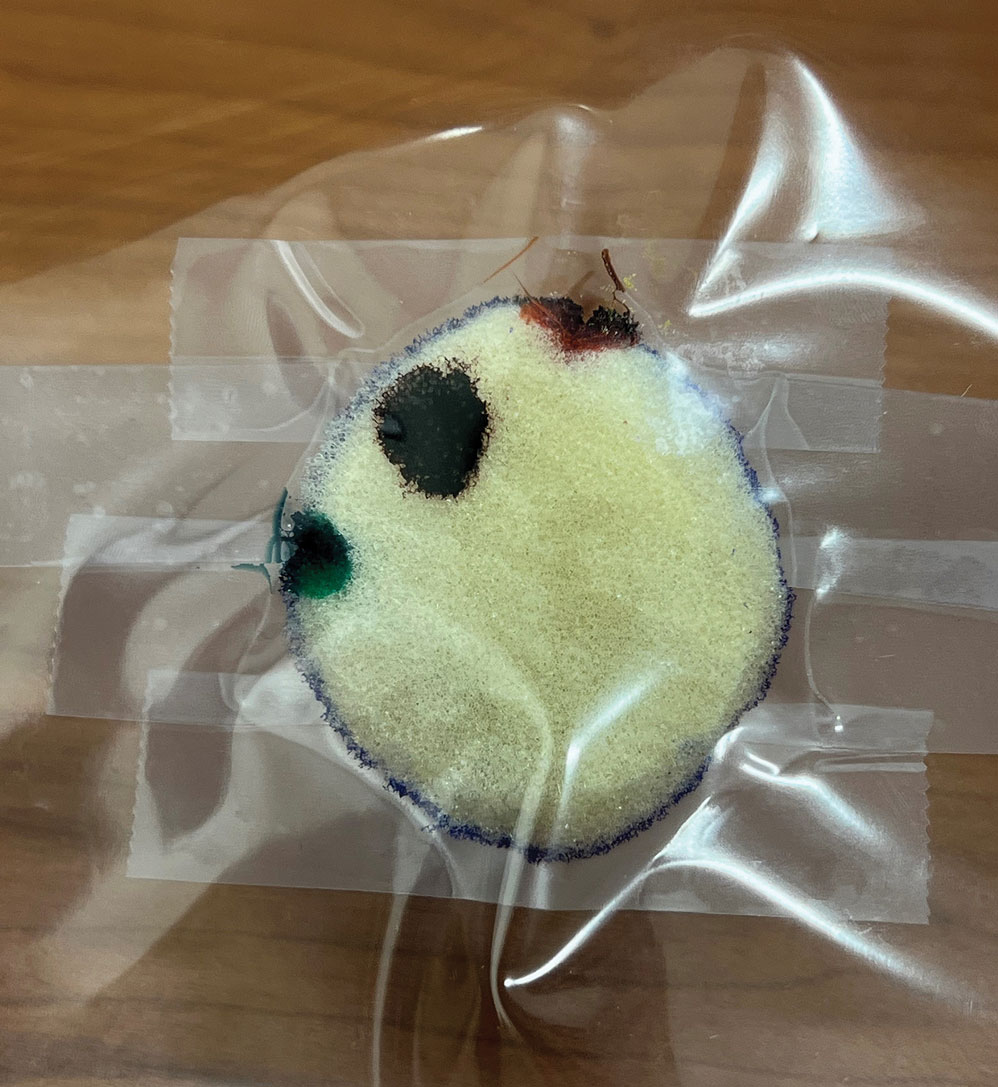

Tissue processing and complete margin assessment in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) are challenging concepts for residents, yet they are essential components of the dermatology residency curriculum. We propose a hands-on active teaching method using craft foam blocks to help residents master these techniques. Prior educational tools have included instructional videos1 as well as the peanut butter–cup and cantaloupe analogies.2,3 Specifically, our method utilizes inexpensive, readily available supplies that allow for repeated practice in a low-stakes environment without limitation of resources. This method provides an immersive, hands-on experience that allows residents to perform multiple practice excisions and simulate positive peripheral or deep margins, unlike tools that offer only fixed-depth or purely visual representations. Additionally, our learning model uniquely enables residents to flatten the simulated tissue, providing a clearer understanding of how a 3-dimensional specimen is transformed on a slide during histologic preparation. This step is particularly important, as tissue architecture can shift during processing, making it one of the most difficult concepts to grasp without hands-on experience. Having a multitude of teaching methods is crucial to accommodate various learning styles, and active learning has been shown to enhance retention for dermatology residents.4

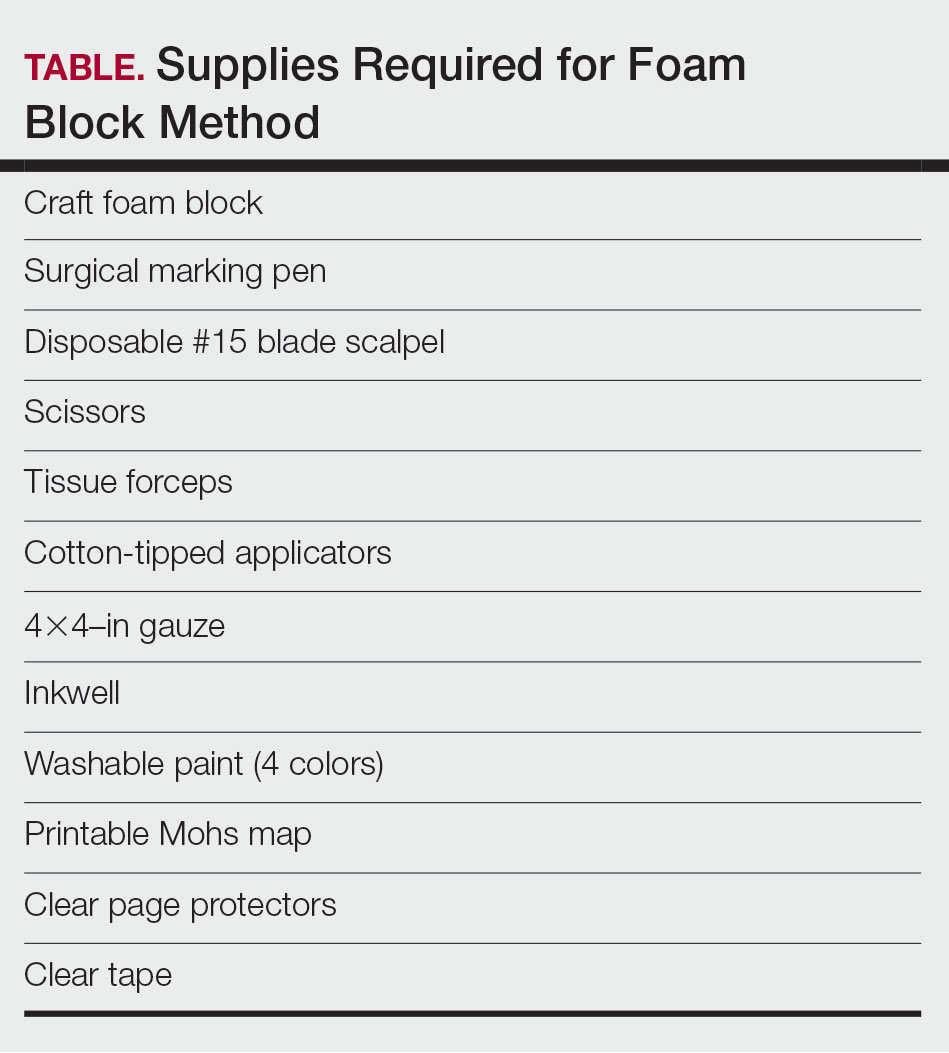

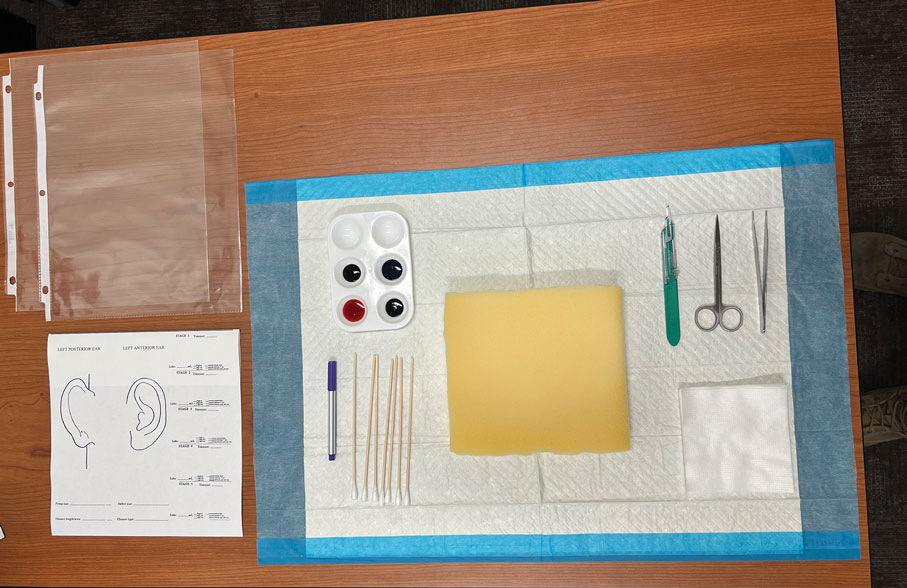

The Technique

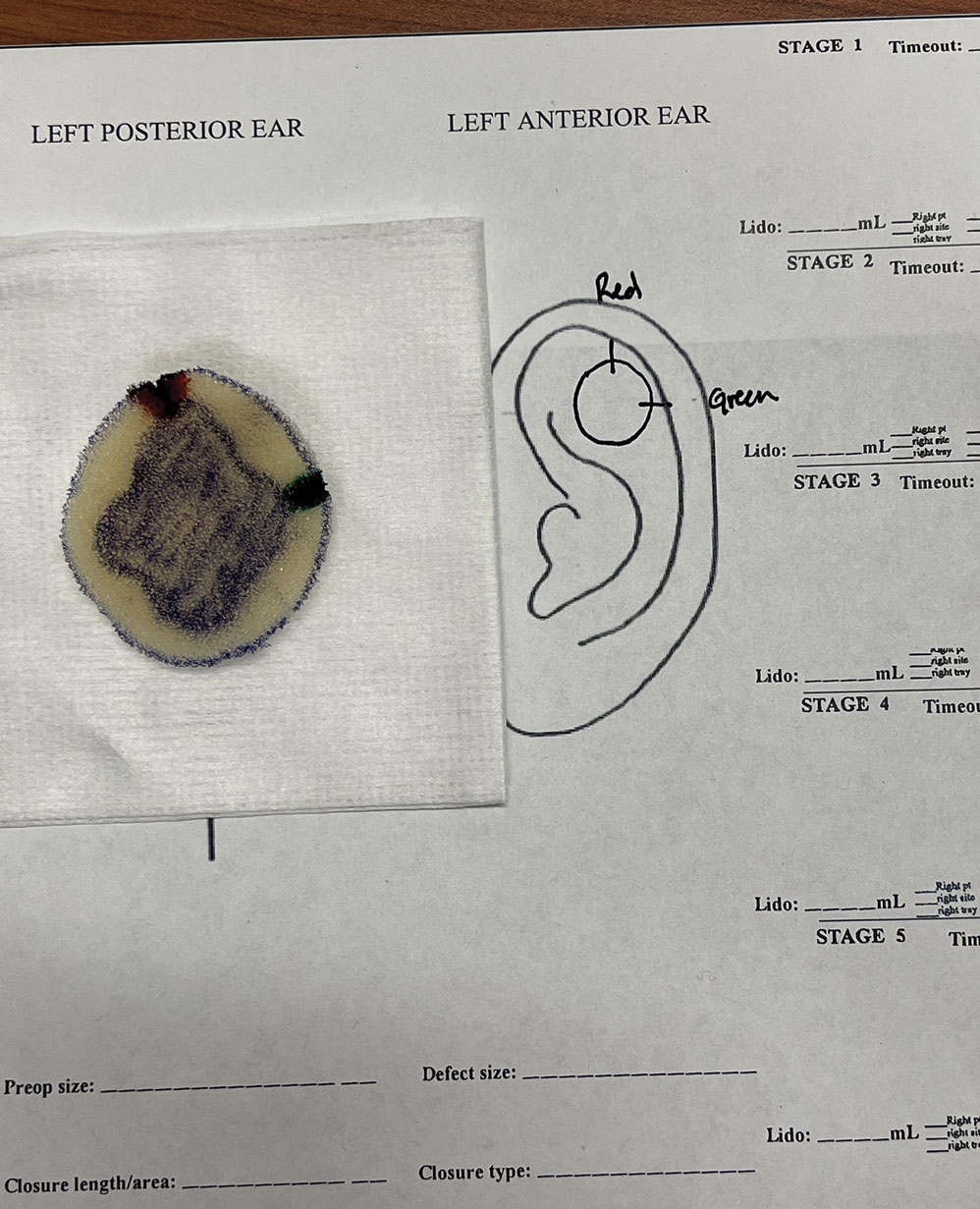

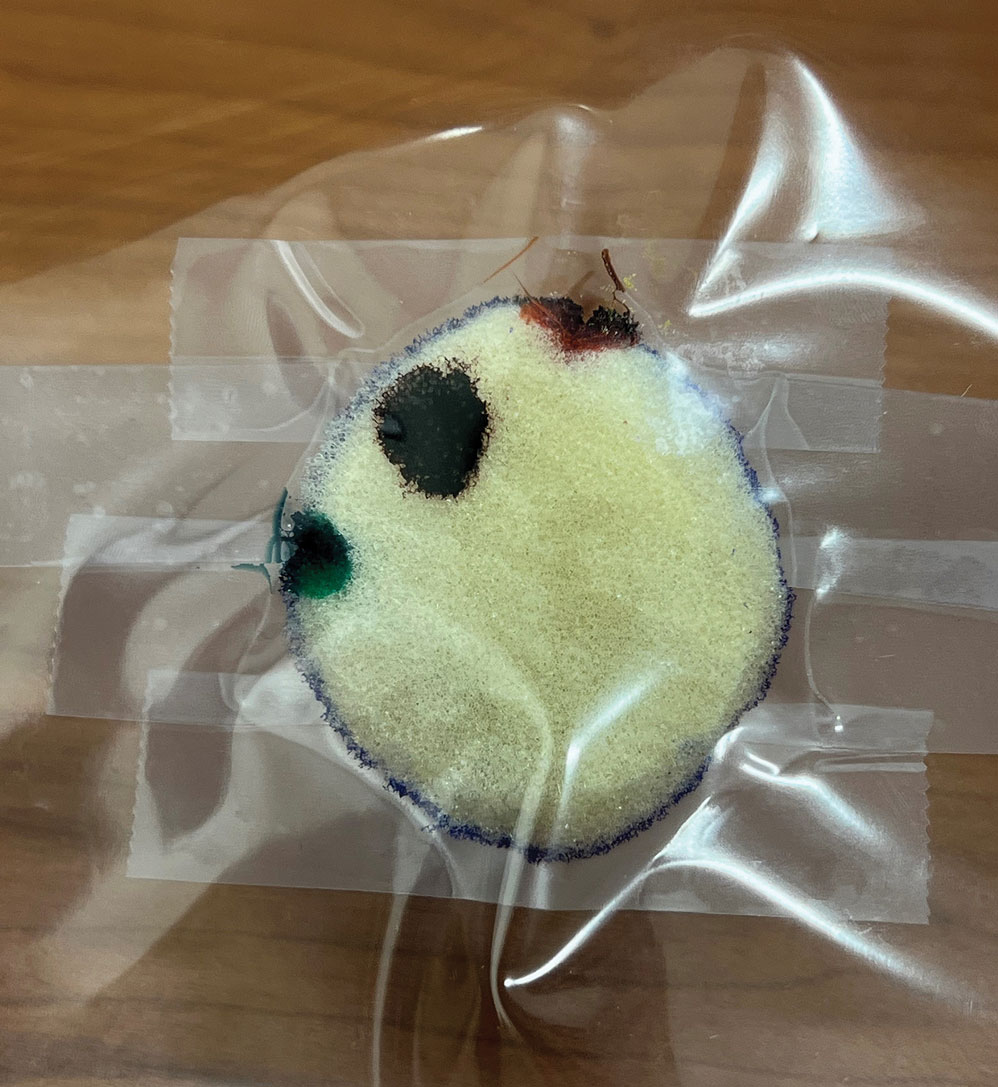

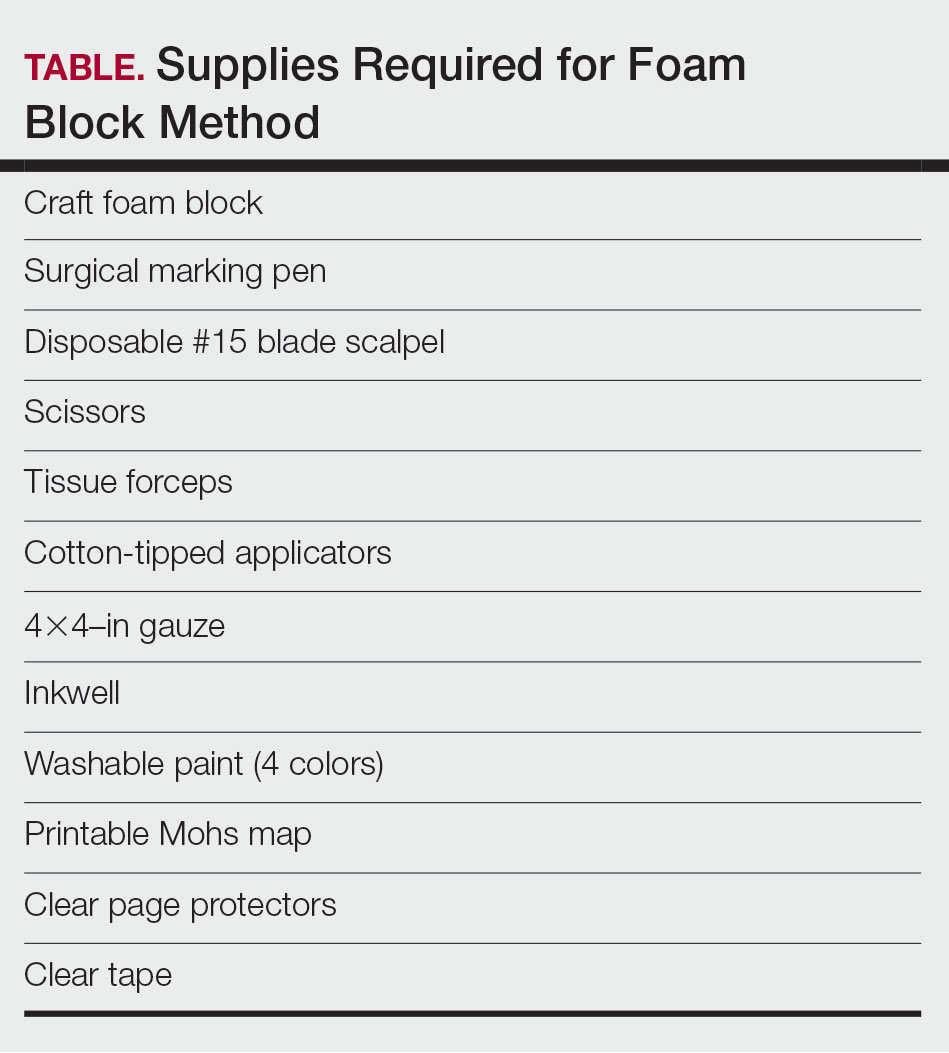

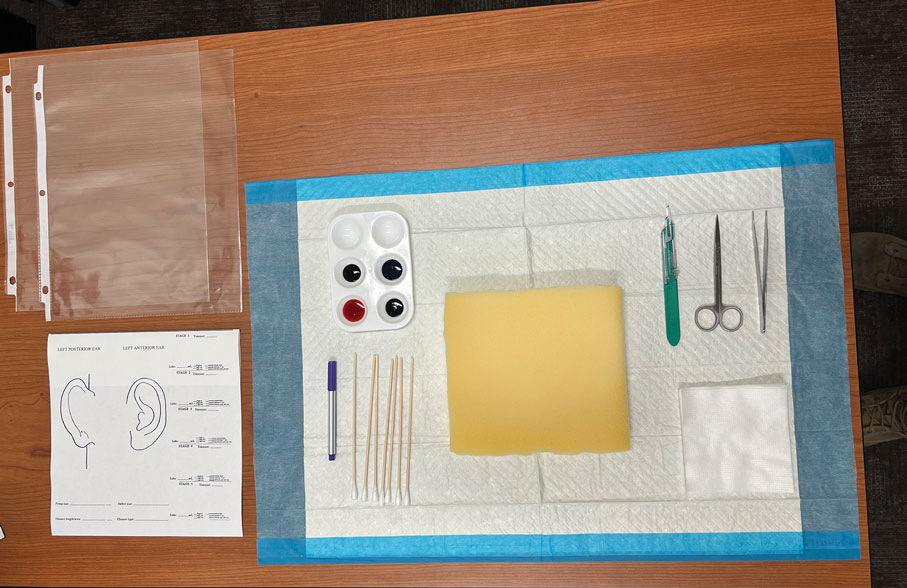

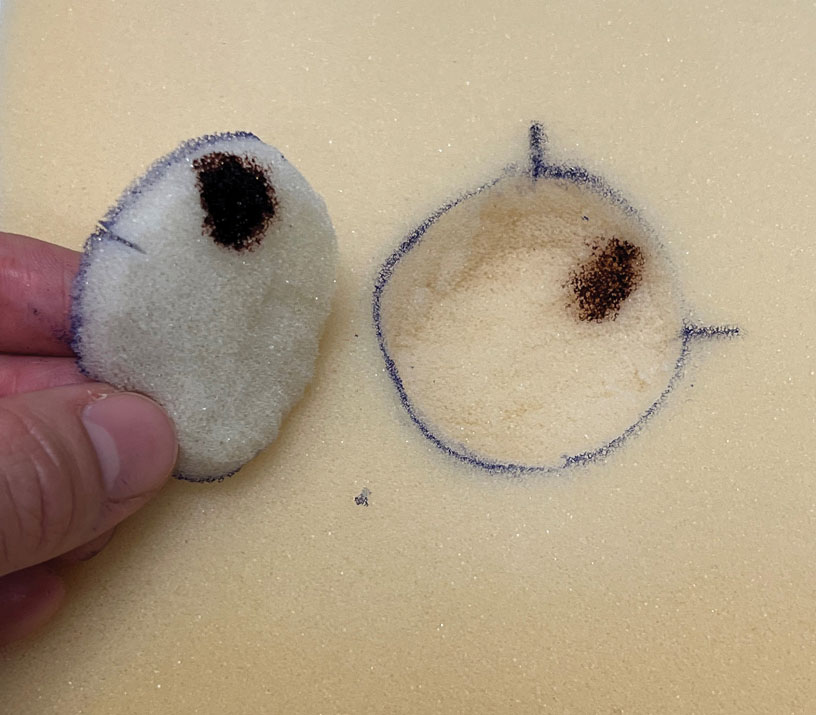

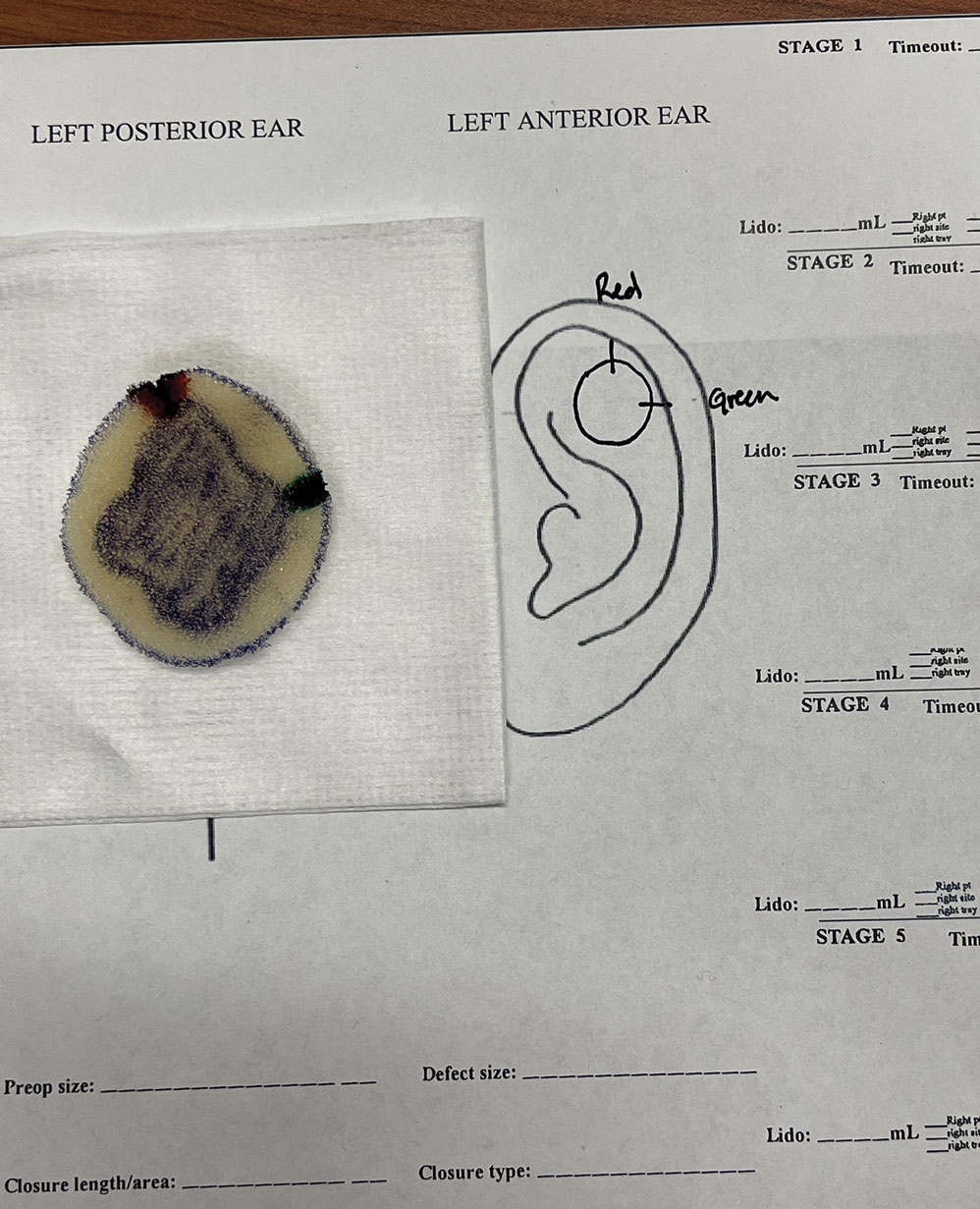

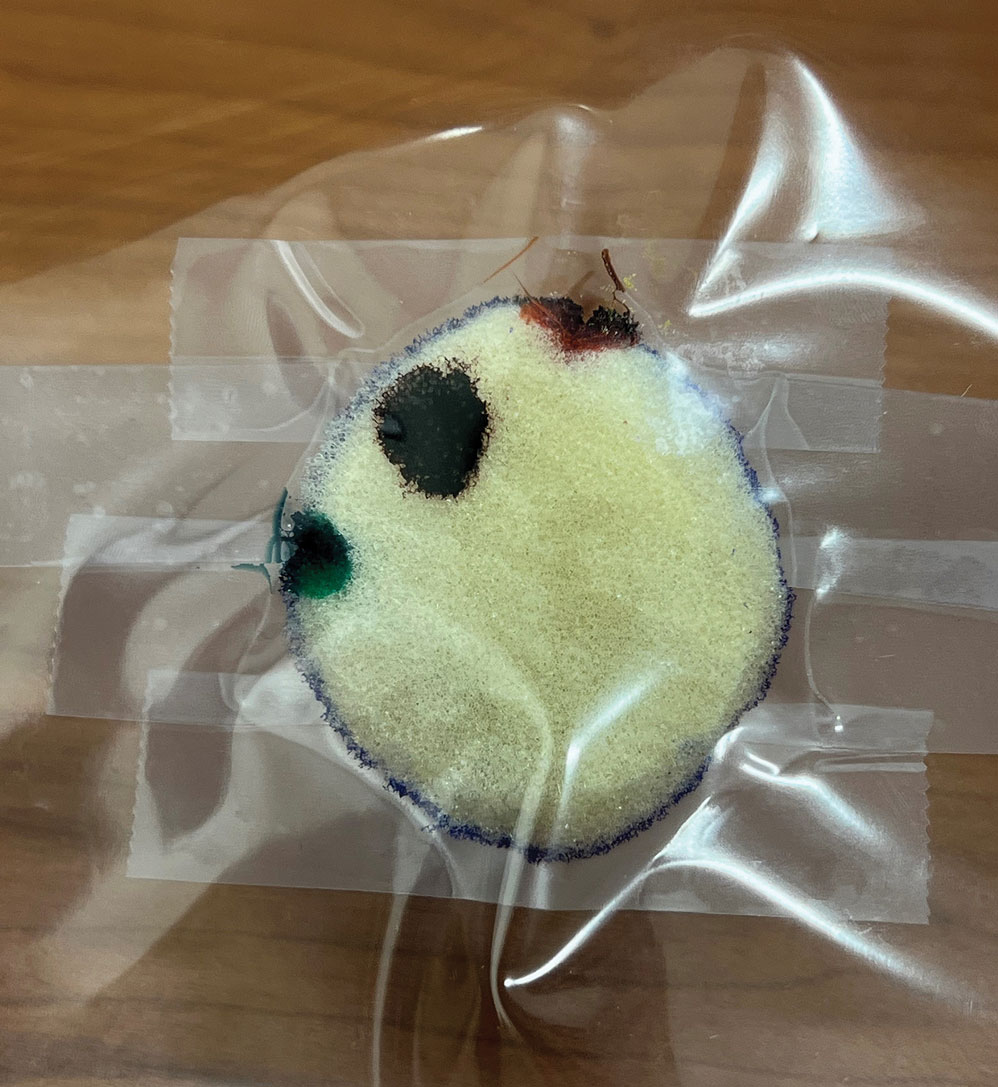

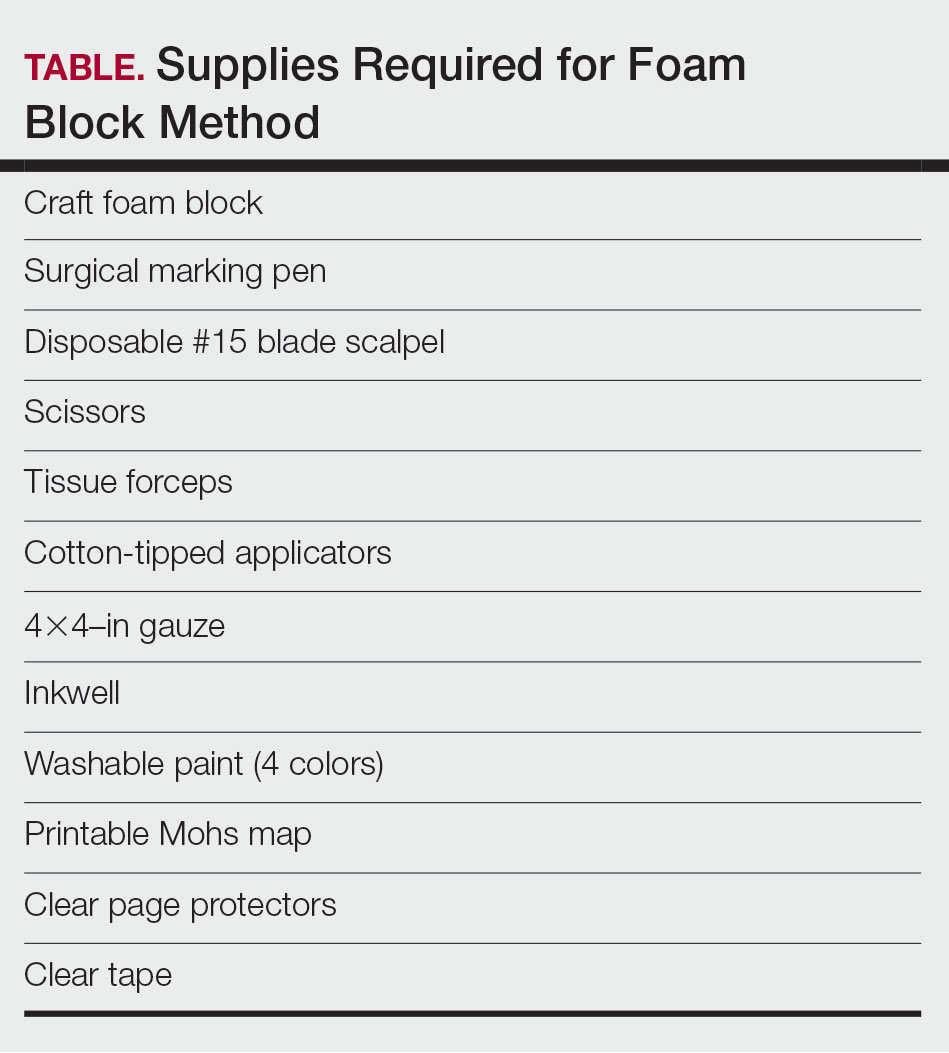

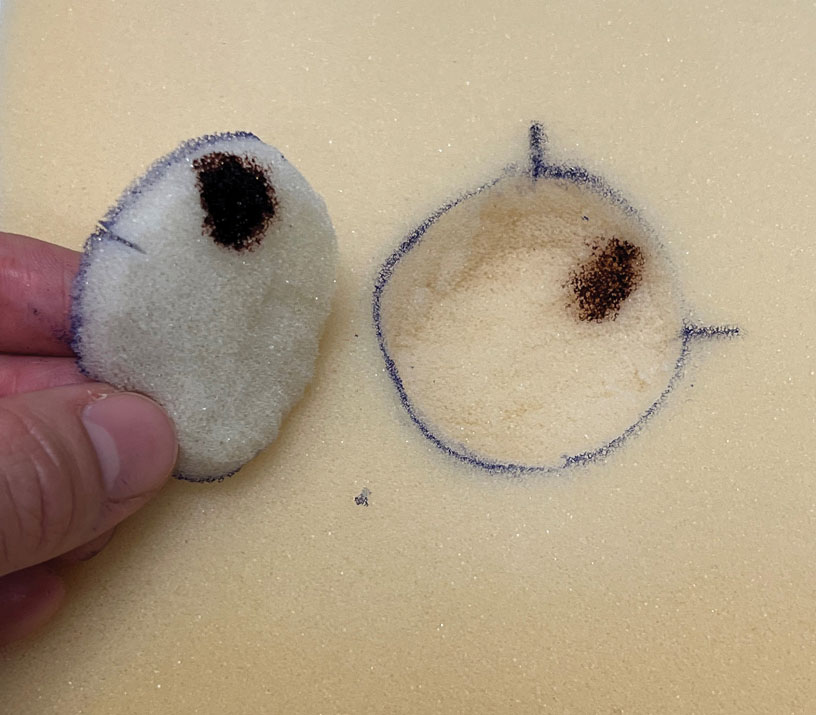

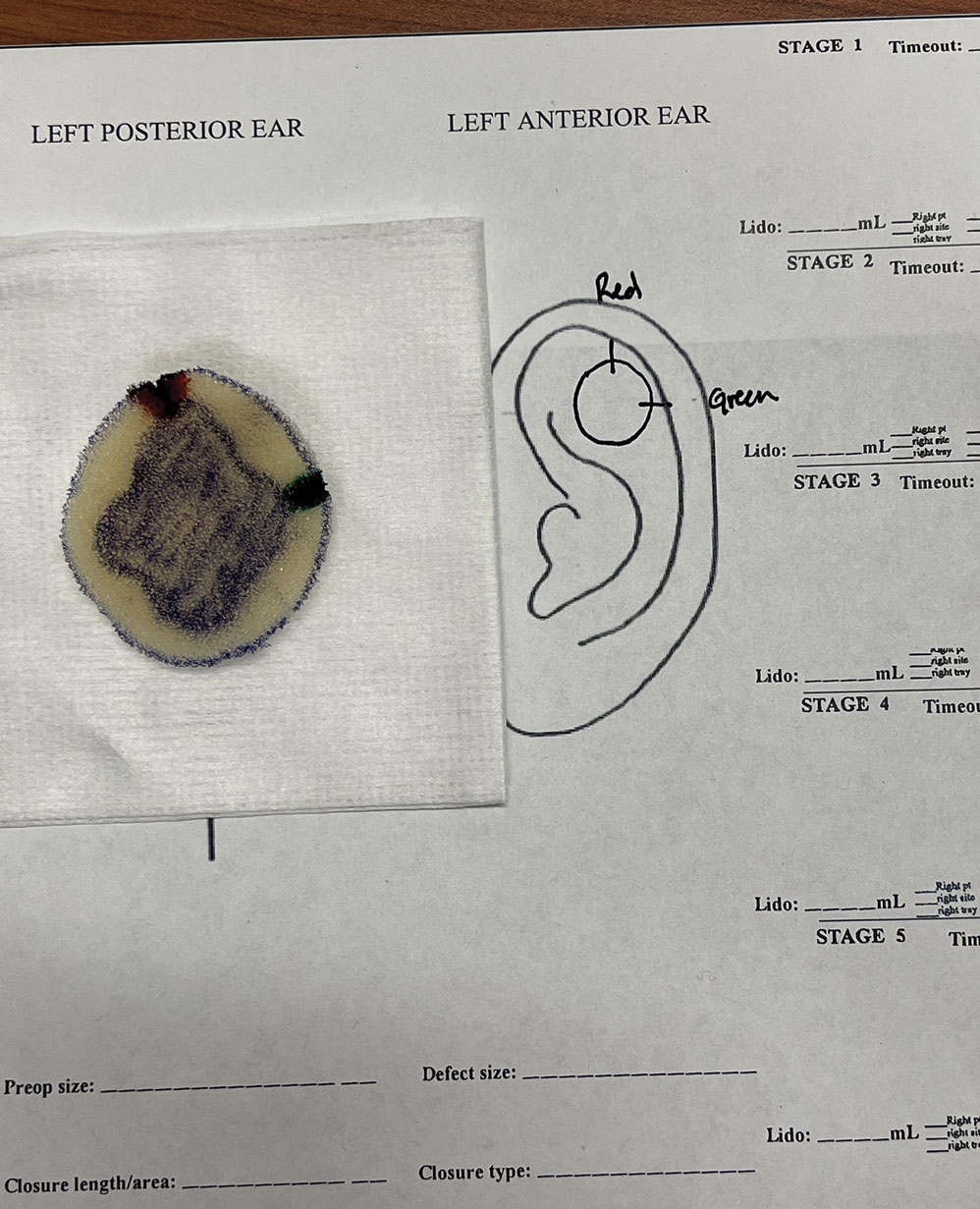

Residents use simple art supplies (including craft foam blocks and ink) and inexpensive, readily available surgical tools to simulate MMS (Table)(Figure 1). If desired, the resident can follow along with the comprehensive, stepwise textbook description of MMS, outlined by Benedetto et al5 to contextualize this hands-on exercise within a standardized didactic framework.

The foam block, which represents patient tissue, serves as the specimen. The resident begins by freehand drawing a simulated cutaneous tumor directly onto the foam using a surgical marking pen. At this point, the instructor discusses the advantages and limitations of tumor debulking with a sharp blade or curette. Residents then mark appropriate margins (1-3 mm) of normal-appearing “epidermis” on the foam block and add hash marks for orientation. This is another opportunity for the instructor to discuss common methods for marking tissue in vivo and to review situations when larger or smaller margins might be appropriate.