User login

Severe GI distress: Is clozapine to blame?

CASE GI distress while taking clozapine

Mr. F, age 29, has a history of psychiatric hospitalizations for psychotic episodes. It took a herculean effort to get him to agree to try clozapine, to which he has experienced a modest to good response. Unfortunately, recently he has been experiencing significant upper gastrointestinal (GI) distress. He attributes this to clozapine, and asks if he can discontinue this medication.

HISTORY Nausea becomes severe

Mr. F, age 29, resides in a long-term residential setting for patients with serious mental illness who need additional support following acute hospitalization. He has treatment-refractory schizophrenia. He first developed symptoms at age 18, and experienced multiple psychotic episodes requiring psychiatric hospitalizations that lasted for months. He has had numerous antipsychotic trials and a course of electroconvulsive therapy, with limited benefit.

More recently, Mr. F’s symptoms began to stabilize on a medication regimen that includes clozapine, 350 mg/d at bedtime, and haloperidol, 2 mg/d. He has not required psychiatric hospitalization for the past year.

Within months of initiating clozapine, Mr. F starts to complain daily about symptoms of worsening abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, nausea, intermittent episodes of emesis, and heartburn. The symptoms begin when he wakes up, are worse in the morning, and persist throughout the morning. He has experienced occasional mild constipation, but no diarrhea or weight loss. There have been no major changes in his diet, addition of new medications, or significant use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Mr. F’s nausea worsens over the next several weeks, to the point he begins to significantly limit how much he eats to cope with it. His GI symptoms are also impacting his mood and daily functioning.

This is not Mr. F’s first experience with significant GI distress. A few months before his first psychotic episode, Mr. F began developing vision problems, joint and abdominal pain, and a general decline in social and academic functioning. At that time, he underwent a significant workup by both GI and integrative medicine, including stool testing, upper endoscopy, and a Cyrex panel (a complementary medicine approach to exploring for specific autoimmune conditions). Results were largely within expected parameters, though a hydrogen breath test was suggestive of possible small intestine bowel overgrowth. More recently, he has been adhering to a gluten-free diet, which his family felt may help prevent some of his physical symptoms as well as mitigate some of his psychotic symptoms. He now asks if he can stop taking clozapine.

[polldaddy:11008393]

EVALUATION Establishing the correct diagnosis

Initially, Mr. F is diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and attempts to manage his symptoms with pharmacologic and diet-based interventions. He significantly cuts down on soda consumption, and undergoes trials of calcium carbonate, antiemetics, and a PPI. Unfortunately, no material improvements are noted, and he continued to experience significant upper GI distress, especially after meals.

The psychiatric treatment team, Mr. F, and his family seek consultation with a GI specialist, who recommends that Mr. F. undergo a nuclear medicine solid gastric emptying scintigraphy study to evaluate for gastroparesis (delayed gastric emptying).1 Results demonstrate grade 3 gastroparesis, with 56% radiotracer retainment at 4 hours. Mr. F is relieved to finally have an explanation for his persistent GI symptoms, and discusses his treatment options with the GI consultant and psychiatry team.

Continue to: The authors’ observations...

The authors’ observations

Mr. F and his family are opposed to starting a dopamine antagonist such as metoclopramide or domperidone (the latter is not FDA-approved but is available by special application to the FDA). These are first-line treatments for gastroparesis, but Mr. F and his family do not want them because of the risk of tardive dyskinesia. This is consistent with their previously expressed concerns regarding first-generation antipsychotics, and is why Mr. F has only been treated with a very low dose of haloperidol while the clozapine was titrated. Instead, Mr. F, his family, the psychiatry treatment team, and the GI specialist agree to pursue a combination of a GI hypomotility diet—which includes frequent small meals (4 to 6 per day), ideally with low fiber, low fat, and increased fluid intake—and a trial of the second line agent for gastroparesis, erythromycin, a medication with known hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) drug-drug interactions that impacts the clearance of clozapine.

Shared decision making is an evidence-based approach to engaging patients in medical decision making. It allows clinicians to provide education on potential treatment options and includes a discussion of risks and benefits. It also includes an assessment of the patient’s understanding of their condition, explores attitudes towards treatment, and elicits patient values specific to the desired outcome. Even in very ill patients with schizophrenia, shared decision making has been demonstrated to increase patient perception of involvement in their own care and knowledge about their condition.2 Using this framework, Mr. F and his family, as well as the GI and psychiatric teams, felt confident that the agreed-upon approach was the best one for Mr. F.

TREATMENT Erythromycin and continued clozapine

Mr. F. is started on erythromycin, 100 mg 3 times a day. Erythromycin is a prokinetic agent that acts as a motilin agonist and increases the rate of gastric emptying. The liquid formulation of the medication is a suspension typically taken in 3- to 4-week courses, with 1 week “off” to prevent tachyphylaxis.3 Compared to the tablet, the liquid suspension has higher bioavailability, allows for easier dose adjustment, and takes less time to reach peak serum concentrations, which make it the preferred formulation for gastroparesis treatment.

Per the GI consultant’s recommendation, Mr. F receives a total of 3 courses of erythromycin, with some improvement in the frequency of his nausea noted only during the third erythromycin course. His clozapine levels are closely monitored during this time, as well as symptoms of clozapine toxicity (ie, sedation, confusion, hypersalivation, seizures, myoclonic jerks), because erythromycin can directly affect clozapine levels.4,5 Case reports suggest that when these 2 medications are taken concomitantly, erythromycin inhibits the metabolism of hepatic enzyme CYP3A4, causing increased plasma concentrations of clozapine. Before starting erythromycin, Mr. F’s clozapine levels were 809 ng/mL at 350 mg/d. During the erythromycin courses, his levels are 1,043 to 1,074 ng/mL, despite reducing clozapine to 300 mg/d. However, he does not experience any adverse effects of clozapine (including seizures), which were being monitored closely.

The authors’ observations

Clozapine is the most effective medication for treatment-refractory schizophrenia.6 Compared to the other second-generation antipsychotics, it is associated with a lower risk of rehospitalization and treatment discontinuation, a significant decrease of positive symptom burden, and a reduction in suicidality.7,8 Unfortunately, clozapine use is not without significant risk. FDA black box warnings highlight severe neutropenia, myocarditis, seizures, and hypotension as potentially life-threatening adverse effects that require close monitoring.9

Recently, clinicians have increasingly focused on the underrecognized but well-established finding that clozapine can cause significant GI adverse effects. While constipation is a known adverse effect of other antipsychotics, a 2016 meta-analysis of 32 studies estimated that the pooled prevalence of clozapine-associated constipation was 31.2%, and showed that patients receiving clozapine were 3 times more likely to be constipated than patients receiving other antipsychotics (odds ratio 3.02, CI 1.91-4.77, P < .001, n = 11 studies).10 A 2012 review of 16 studies involving potentially lethal adverse effects of clozapine demonstrated that rates of agranulocytosis and GI hypomotility were nearly identical, but that mortality from constipation was 3.6 to 12.5 times higher than mortality from agranulocytosis.11

In 2020, the FDA issued an increased warning regarding severe bowel-related complications in patients receiving clozapine, ranging in severity from mild discomfort to ileus, bowel obstruction, toxic megacolon, and death.9

As exemplified by Mr. F’s case, upper GI symptoms associated with clozapine also are distressing and can have a significant impact on quality of life. Dyspepsia is a common complaint in patients with chronic psychiatric illness. A study of 79 psychiatric inpatients hospitalized long-term found that 80% reported at least 1 symptom of dyspepsia.12 There are few older studies describing the effect of clozapine on the upper GI system. We and others previously reported on significantly increased use of—not only antacids—but also H2 blockers and prokinetic agents after initiating clozapine, but sample sizes are small.13-15 These older data and newer studies suggest that GERD is a common upper GI disorder diagnosis following clozapine initiation, perhaps reflecting a knowledge gap and infrequent use of the more complex testing required to confirm a diagnosis of GI motility disorders such as gastroparesis.

In a study of 17 patients receiving clozapine, wireless motility capsules were used to measure whole gut motility, including gastric emptying time, small bowel transit time, and colonic transit time. In 82% of patients, there was demonstrated GI hypomotility in at least 1 region, and 41% of participants exhibited delayed gastric emptying, with a cut-off time of >5 hours required for a gastroparesis diagnosis.16 This is significantly higher than the prevalence of gastroparesis observed in studies of the general community.17 The Table18,19 summarizes the differences between GERD and gastroparesis.

OUTCOME Some improvement

Mr. F experiences limited improvement of some of his nausea symptoms during the third erythromycin cycle and returns to the gastroenterologist for a follow-up appointment. The GI specialist decides to discontinue erythromycin in view of potential drug-drug interactions and Mr. F’s elevated clozapine levels and the associated risks that might entail. Mr. F is again offered the D2 dopamine antagonist metoclopramide, but again refuses due to the risk for tardive dyskinesia. He is asked to continue the GI dysmotility diet. Mr. F finds some relief of nausea symptoms from an over-the-counter product for nausea (a nasal inhalant containing essential oils) and is advised to follow up with the GI specialist in 3 months. Shortly thereafter, he is discharged to live in a less restrictive supportive housing environment, and his follow-up psychiatric care is provided by an assertive community treatment team. Over the next several months, the dosage of clozapine is decreased to 250 mg/d. Mr. F initially experiences worsening psychiatric symptoms, but stabilizes thereafter. He then moves out of state to be closer to his family.

Bottom Line

In patients receiving clozapine, frequent nausea along with clustering of heartburn, abdominal pain, bloating, early satiety, and vomiting (especially after meals) may signal gastroparesis rather than gastroesophageal reflux disease. Such patients may require consultation with a gastroenterologist, a scintigraphy-based gastric emptying test, and treatment if gastroparesis is confirmed.

1. Camilleri M, Chedid V, Ford AC, et al. Gastroparesis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):41. doi:10.1038/s41572-018-0038-z

2. Hamann J, Langer B, Winkler V, et al. Shared decision making for in-patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(4):265-273. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00798.x

3. Maganti K, Onyemere K, Jones MP. Oral erythromycin and symptomatic relief of gastroparesis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):259-263. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07167.x

4. Taylor D. Pharmacokinetic interactions involving clozapine. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:109-112. doi:10.1192/bjp.171.2.109

5. Edge SC, Markowitz JS, Devane CL. Clozapine drug-drug interactions: a review of the literature. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 1997;12(1):5-20.

6. Vanasse A, Blais L, Courteau J, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia treatment: a real-world observational study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134(5):374-384. doi:10.1111/acps.12621

7. Siskind D, McCartney L, Goldschlager R, et al. Clozapine v. first- and second-generation antipsychotics in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(5):385-392. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.115.177261

8. Azorin JM, Spiegel R, Remington G, et al. A double-blind comparative study of clozapine and risperidone in the management of severe chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1305-1313. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1305

9. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Clozapine. Accessed June 13, 2021. https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Treatments/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Clozapine-(Clozaril-and-FazaClo)

10. Shirazi A, Stubbs B, Gomez L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of clozapine-associated constipation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(6):863. doi:10.3390/ijms17060863

11. Cohen D, Bogers JP, van Dijk D, et al. Beyond white blood cell monitoring: screening in the initial phase of clozapine therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(10):1307-1312. doi:10.4088/JCP.11r06977

12. Mookhoek EJ, Meijs VM, Loonen AJ, et al. Dyspepsia in chronic psychiatric patients. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2005;38(3):125-127. doi:10.1055/s-2005-864123

13. John JP, Chengappa KN, Baker RW, et al. Assessment of changes in both weight and frequency of use of medications for the treatment of gastrointestinal symptoms among clozapine-treated patients. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1995;7(3):119-125. doi: 10.3109/10401239509149038

14. Schwartz BJ, Frisolone JA. A case report of clozapine-induced gastric outlet obstruction. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(10):1563. doi:10.1176/ajp.150.10.1563a

15. Taylor D, Olofinjana O, Rahimi T. Use of antacid medication in patients receiving clozapine: a comparison with other second-generation antipsychotics. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(4):460-461. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181e5c0f7

16. Every-Palmer S, Inns SJ, Grant E, et al. Effects of clozapine on the gut: cross-sectional study of delayed gastric emptying and small and large intestinal dysmotility. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(1):81-91. doi:10.1007/s40263-018-0587-4

17. Jung HK, Choung RS, Locke GR 3rd, et al. The incidence, prevalence, and outcomes of patients with gastroparesis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1996 to 2006. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1225-1233. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.047

18. Antunes C, Aleem A, Curtis SA. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 7, 2021. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441938/

19. Reddivari AKR, Mehta P. Gastroparesis. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 30, 2021. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551528/

CASE GI distress while taking clozapine

Mr. F, age 29, has a history of psychiatric hospitalizations for psychotic episodes. It took a herculean effort to get him to agree to try clozapine, to which he has experienced a modest to good response. Unfortunately, recently he has been experiencing significant upper gastrointestinal (GI) distress. He attributes this to clozapine, and asks if he can discontinue this medication.

HISTORY Nausea becomes severe

Mr. F, age 29, resides in a long-term residential setting for patients with serious mental illness who need additional support following acute hospitalization. He has treatment-refractory schizophrenia. He first developed symptoms at age 18, and experienced multiple psychotic episodes requiring psychiatric hospitalizations that lasted for months. He has had numerous antipsychotic trials and a course of electroconvulsive therapy, with limited benefit.

More recently, Mr. F’s symptoms began to stabilize on a medication regimen that includes clozapine, 350 mg/d at bedtime, and haloperidol, 2 mg/d. He has not required psychiatric hospitalization for the past year.

Within months of initiating clozapine, Mr. F starts to complain daily about symptoms of worsening abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, nausea, intermittent episodes of emesis, and heartburn. The symptoms begin when he wakes up, are worse in the morning, and persist throughout the morning. He has experienced occasional mild constipation, but no diarrhea or weight loss. There have been no major changes in his diet, addition of new medications, or significant use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Mr. F’s nausea worsens over the next several weeks, to the point he begins to significantly limit how much he eats to cope with it. His GI symptoms are also impacting his mood and daily functioning.

This is not Mr. F’s first experience with significant GI distress. A few months before his first psychotic episode, Mr. F began developing vision problems, joint and abdominal pain, and a general decline in social and academic functioning. At that time, he underwent a significant workup by both GI and integrative medicine, including stool testing, upper endoscopy, and a Cyrex panel (a complementary medicine approach to exploring for specific autoimmune conditions). Results were largely within expected parameters, though a hydrogen breath test was suggestive of possible small intestine bowel overgrowth. More recently, he has been adhering to a gluten-free diet, which his family felt may help prevent some of his physical symptoms as well as mitigate some of his psychotic symptoms. He now asks if he can stop taking clozapine.

[polldaddy:11008393]

EVALUATION Establishing the correct diagnosis

Initially, Mr. F is diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and attempts to manage his symptoms with pharmacologic and diet-based interventions. He significantly cuts down on soda consumption, and undergoes trials of calcium carbonate, antiemetics, and a PPI. Unfortunately, no material improvements are noted, and he continued to experience significant upper GI distress, especially after meals.

The psychiatric treatment team, Mr. F, and his family seek consultation with a GI specialist, who recommends that Mr. F. undergo a nuclear medicine solid gastric emptying scintigraphy study to evaluate for gastroparesis (delayed gastric emptying).1 Results demonstrate grade 3 gastroparesis, with 56% radiotracer retainment at 4 hours. Mr. F is relieved to finally have an explanation for his persistent GI symptoms, and discusses his treatment options with the GI consultant and psychiatry team.

Continue to: The authors’ observations...

The authors’ observations

Mr. F and his family are opposed to starting a dopamine antagonist such as metoclopramide or domperidone (the latter is not FDA-approved but is available by special application to the FDA). These are first-line treatments for gastroparesis, but Mr. F and his family do not want them because of the risk of tardive dyskinesia. This is consistent with their previously expressed concerns regarding first-generation antipsychotics, and is why Mr. F has only been treated with a very low dose of haloperidol while the clozapine was titrated. Instead, Mr. F, his family, the psychiatry treatment team, and the GI specialist agree to pursue a combination of a GI hypomotility diet—which includes frequent small meals (4 to 6 per day), ideally with low fiber, low fat, and increased fluid intake—and a trial of the second line agent for gastroparesis, erythromycin, a medication with known hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) drug-drug interactions that impacts the clearance of clozapine.

Shared decision making is an evidence-based approach to engaging patients in medical decision making. It allows clinicians to provide education on potential treatment options and includes a discussion of risks and benefits. It also includes an assessment of the patient’s understanding of their condition, explores attitudes towards treatment, and elicits patient values specific to the desired outcome. Even in very ill patients with schizophrenia, shared decision making has been demonstrated to increase patient perception of involvement in their own care and knowledge about their condition.2 Using this framework, Mr. F and his family, as well as the GI and psychiatric teams, felt confident that the agreed-upon approach was the best one for Mr. F.

TREATMENT Erythromycin and continued clozapine

Mr. F. is started on erythromycin, 100 mg 3 times a day. Erythromycin is a prokinetic agent that acts as a motilin agonist and increases the rate of gastric emptying. The liquid formulation of the medication is a suspension typically taken in 3- to 4-week courses, with 1 week “off” to prevent tachyphylaxis.3 Compared to the tablet, the liquid suspension has higher bioavailability, allows for easier dose adjustment, and takes less time to reach peak serum concentrations, which make it the preferred formulation for gastroparesis treatment.

Per the GI consultant’s recommendation, Mr. F receives a total of 3 courses of erythromycin, with some improvement in the frequency of his nausea noted only during the third erythromycin course. His clozapine levels are closely monitored during this time, as well as symptoms of clozapine toxicity (ie, sedation, confusion, hypersalivation, seizures, myoclonic jerks), because erythromycin can directly affect clozapine levels.4,5 Case reports suggest that when these 2 medications are taken concomitantly, erythromycin inhibits the metabolism of hepatic enzyme CYP3A4, causing increased plasma concentrations of clozapine. Before starting erythromycin, Mr. F’s clozapine levels were 809 ng/mL at 350 mg/d. During the erythromycin courses, his levels are 1,043 to 1,074 ng/mL, despite reducing clozapine to 300 mg/d. However, he does not experience any adverse effects of clozapine (including seizures), which were being monitored closely.

The authors’ observations

Clozapine is the most effective medication for treatment-refractory schizophrenia.6 Compared to the other second-generation antipsychotics, it is associated with a lower risk of rehospitalization and treatment discontinuation, a significant decrease of positive symptom burden, and a reduction in suicidality.7,8 Unfortunately, clozapine use is not without significant risk. FDA black box warnings highlight severe neutropenia, myocarditis, seizures, and hypotension as potentially life-threatening adverse effects that require close monitoring.9

Recently, clinicians have increasingly focused on the underrecognized but well-established finding that clozapine can cause significant GI adverse effects. While constipation is a known adverse effect of other antipsychotics, a 2016 meta-analysis of 32 studies estimated that the pooled prevalence of clozapine-associated constipation was 31.2%, and showed that patients receiving clozapine were 3 times more likely to be constipated than patients receiving other antipsychotics (odds ratio 3.02, CI 1.91-4.77, P < .001, n = 11 studies).10 A 2012 review of 16 studies involving potentially lethal adverse effects of clozapine demonstrated that rates of agranulocytosis and GI hypomotility were nearly identical, but that mortality from constipation was 3.6 to 12.5 times higher than mortality from agranulocytosis.11

In 2020, the FDA issued an increased warning regarding severe bowel-related complications in patients receiving clozapine, ranging in severity from mild discomfort to ileus, bowel obstruction, toxic megacolon, and death.9

As exemplified by Mr. F’s case, upper GI symptoms associated with clozapine also are distressing and can have a significant impact on quality of life. Dyspepsia is a common complaint in patients with chronic psychiatric illness. A study of 79 psychiatric inpatients hospitalized long-term found that 80% reported at least 1 symptom of dyspepsia.12 There are few older studies describing the effect of clozapine on the upper GI system. We and others previously reported on significantly increased use of—not only antacids—but also H2 blockers and prokinetic agents after initiating clozapine, but sample sizes are small.13-15 These older data and newer studies suggest that GERD is a common upper GI disorder diagnosis following clozapine initiation, perhaps reflecting a knowledge gap and infrequent use of the more complex testing required to confirm a diagnosis of GI motility disorders such as gastroparesis.

In a study of 17 patients receiving clozapine, wireless motility capsules were used to measure whole gut motility, including gastric emptying time, small bowel transit time, and colonic transit time. In 82% of patients, there was demonstrated GI hypomotility in at least 1 region, and 41% of participants exhibited delayed gastric emptying, with a cut-off time of >5 hours required for a gastroparesis diagnosis.16 This is significantly higher than the prevalence of gastroparesis observed in studies of the general community.17 The Table18,19 summarizes the differences between GERD and gastroparesis.

OUTCOME Some improvement

Mr. F experiences limited improvement of some of his nausea symptoms during the third erythromycin cycle and returns to the gastroenterologist for a follow-up appointment. The GI specialist decides to discontinue erythromycin in view of potential drug-drug interactions and Mr. F’s elevated clozapine levels and the associated risks that might entail. Mr. F is again offered the D2 dopamine antagonist metoclopramide, but again refuses due to the risk for tardive dyskinesia. He is asked to continue the GI dysmotility diet. Mr. F finds some relief of nausea symptoms from an over-the-counter product for nausea (a nasal inhalant containing essential oils) and is advised to follow up with the GI specialist in 3 months. Shortly thereafter, he is discharged to live in a less restrictive supportive housing environment, and his follow-up psychiatric care is provided by an assertive community treatment team. Over the next several months, the dosage of clozapine is decreased to 250 mg/d. Mr. F initially experiences worsening psychiatric symptoms, but stabilizes thereafter. He then moves out of state to be closer to his family.

Bottom Line

In patients receiving clozapine, frequent nausea along with clustering of heartburn, abdominal pain, bloating, early satiety, and vomiting (especially after meals) may signal gastroparesis rather than gastroesophageal reflux disease. Such patients may require consultation with a gastroenterologist, a scintigraphy-based gastric emptying test, and treatment if gastroparesis is confirmed.

CASE GI distress while taking clozapine

Mr. F, age 29, has a history of psychiatric hospitalizations for psychotic episodes. It took a herculean effort to get him to agree to try clozapine, to which he has experienced a modest to good response. Unfortunately, recently he has been experiencing significant upper gastrointestinal (GI) distress. He attributes this to clozapine, and asks if he can discontinue this medication.

HISTORY Nausea becomes severe

Mr. F, age 29, resides in a long-term residential setting for patients with serious mental illness who need additional support following acute hospitalization. He has treatment-refractory schizophrenia. He first developed symptoms at age 18, and experienced multiple psychotic episodes requiring psychiatric hospitalizations that lasted for months. He has had numerous antipsychotic trials and a course of electroconvulsive therapy, with limited benefit.

More recently, Mr. F’s symptoms began to stabilize on a medication regimen that includes clozapine, 350 mg/d at bedtime, and haloperidol, 2 mg/d. He has not required psychiatric hospitalization for the past year.

Within months of initiating clozapine, Mr. F starts to complain daily about symptoms of worsening abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, nausea, intermittent episodes of emesis, and heartburn. The symptoms begin when he wakes up, are worse in the morning, and persist throughout the morning. He has experienced occasional mild constipation, but no diarrhea or weight loss. There have been no major changes in his diet, addition of new medications, or significant use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Mr. F’s nausea worsens over the next several weeks, to the point he begins to significantly limit how much he eats to cope with it. His GI symptoms are also impacting his mood and daily functioning.

This is not Mr. F’s first experience with significant GI distress. A few months before his first psychotic episode, Mr. F began developing vision problems, joint and abdominal pain, and a general decline in social and academic functioning. At that time, he underwent a significant workup by both GI and integrative medicine, including stool testing, upper endoscopy, and a Cyrex panel (a complementary medicine approach to exploring for specific autoimmune conditions). Results were largely within expected parameters, though a hydrogen breath test was suggestive of possible small intestine bowel overgrowth. More recently, he has been adhering to a gluten-free diet, which his family felt may help prevent some of his physical symptoms as well as mitigate some of his psychotic symptoms. He now asks if he can stop taking clozapine.

[polldaddy:11008393]

EVALUATION Establishing the correct diagnosis

Initially, Mr. F is diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and attempts to manage his symptoms with pharmacologic and diet-based interventions. He significantly cuts down on soda consumption, and undergoes trials of calcium carbonate, antiemetics, and a PPI. Unfortunately, no material improvements are noted, and he continued to experience significant upper GI distress, especially after meals.

The psychiatric treatment team, Mr. F, and his family seek consultation with a GI specialist, who recommends that Mr. F. undergo a nuclear medicine solid gastric emptying scintigraphy study to evaluate for gastroparesis (delayed gastric emptying).1 Results demonstrate grade 3 gastroparesis, with 56% radiotracer retainment at 4 hours. Mr. F is relieved to finally have an explanation for his persistent GI symptoms, and discusses his treatment options with the GI consultant and psychiatry team.

Continue to: The authors’ observations...

The authors’ observations

Mr. F and his family are opposed to starting a dopamine antagonist such as metoclopramide or domperidone (the latter is not FDA-approved but is available by special application to the FDA). These are first-line treatments for gastroparesis, but Mr. F and his family do not want them because of the risk of tardive dyskinesia. This is consistent with their previously expressed concerns regarding first-generation antipsychotics, and is why Mr. F has only been treated with a very low dose of haloperidol while the clozapine was titrated. Instead, Mr. F, his family, the psychiatry treatment team, and the GI specialist agree to pursue a combination of a GI hypomotility diet—which includes frequent small meals (4 to 6 per day), ideally with low fiber, low fat, and increased fluid intake—and a trial of the second line agent for gastroparesis, erythromycin, a medication with known hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) drug-drug interactions that impacts the clearance of clozapine.

Shared decision making is an evidence-based approach to engaging patients in medical decision making. It allows clinicians to provide education on potential treatment options and includes a discussion of risks and benefits. It also includes an assessment of the patient’s understanding of their condition, explores attitudes towards treatment, and elicits patient values specific to the desired outcome. Even in very ill patients with schizophrenia, shared decision making has been demonstrated to increase patient perception of involvement in their own care and knowledge about their condition.2 Using this framework, Mr. F and his family, as well as the GI and psychiatric teams, felt confident that the agreed-upon approach was the best one for Mr. F.

TREATMENT Erythromycin and continued clozapine

Mr. F. is started on erythromycin, 100 mg 3 times a day. Erythromycin is a prokinetic agent that acts as a motilin agonist and increases the rate of gastric emptying. The liquid formulation of the medication is a suspension typically taken in 3- to 4-week courses, with 1 week “off” to prevent tachyphylaxis.3 Compared to the tablet, the liquid suspension has higher bioavailability, allows for easier dose adjustment, and takes less time to reach peak serum concentrations, which make it the preferred formulation for gastroparesis treatment.

Per the GI consultant’s recommendation, Mr. F receives a total of 3 courses of erythromycin, with some improvement in the frequency of his nausea noted only during the third erythromycin course. His clozapine levels are closely monitored during this time, as well as symptoms of clozapine toxicity (ie, sedation, confusion, hypersalivation, seizures, myoclonic jerks), because erythromycin can directly affect clozapine levels.4,5 Case reports suggest that when these 2 medications are taken concomitantly, erythromycin inhibits the metabolism of hepatic enzyme CYP3A4, causing increased plasma concentrations of clozapine. Before starting erythromycin, Mr. F’s clozapine levels were 809 ng/mL at 350 mg/d. During the erythromycin courses, his levels are 1,043 to 1,074 ng/mL, despite reducing clozapine to 300 mg/d. However, he does not experience any adverse effects of clozapine (including seizures), which were being monitored closely.

The authors’ observations

Clozapine is the most effective medication for treatment-refractory schizophrenia.6 Compared to the other second-generation antipsychotics, it is associated with a lower risk of rehospitalization and treatment discontinuation, a significant decrease of positive symptom burden, and a reduction in suicidality.7,8 Unfortunately, clozapine use is not without significant risk. FDA black box warnings highlight severe neutropenia, myocarditis, seizures, and hypotension as potentially life-threatening adverse effects that require close monitoring.9

Recently, clinicians have increasingly focused on the underrecognized but well-established finding that clozapine can cause significant GI adverse effects. While constipation is a known adverse effect of other antipsychotics, a 2016 meta-analysis of 32 studies estimated that the pooled prevalence of clozapine-associated constipation was 31.2%, and showed that patients receiving clozapine were 3 times more likely to be constipated than patients receiving other antipsychotics (odds ratio 3.02, CI 1.91-4.77, P < .001, n = 11 studies).10 A 2012 review of 16 studies involving potentially lethal adverse effects of clozapine demonstrated that rates of agranulocytosis and GI hypomotility were nearly identical, but that mortality from constipation was 3.6 to 12.5 times higher than mortality from agranulocytosis.11

In 2020, the FDA issued an increased warning regarding severe bowel-related complications in patients receiving clozapine, ranging in severity from mild discomfort to ileus, bowel obstruction, toxic megacolon, and death.9

As exemplified by Mr. F’s case, upper GI symptoms associated with clozapine also are distressing and can have a significant impact on quality of life. Dyspepsia is a common complaint in patients with chronic psychiatric illness. A study of 79 psychiatric inpatients hospitalized long-term found that 80% reported at least 1 symptom of dyspepsia.12 There are few older studies describing the effect of clozapine on the upper GI system. We and others previously reported on significantly increased use of—not only antacids—but also H2 blockers and prokinetic agents after initiating clozapine, but sample sizes are small.13-15 These older data and newer studies suggest that GERD is a common upper GI disorder diagnosis following clozapine initiation, perhaps reflecting a knowledge gap and infrequent use of the more complex testing required to confirm a diagnosis of GI motility disorders such as gastroparesis.

In a study of 17 patients receiving clozapine, wireless motility capsules were used to measure whole gut motility, including gastric emptying time, small bowel transit time, and colonic transit time. In 82% of patients, there was demonstrated GI hypomotility in at least 1 region, and 41% of participants exhibited delayed gastric emptying, with a cut-off time of >5 hours required for a gastroparesis diagnosis.16 This is significantly higher than the prevalence of gastroparesis observed in studies of the general community.17 The Table18,19 summarizes the differences between GERD and gastroparesis.

OUTCOME Some improvement

Mr. F experiences limited improvement of some of his nausea symptoms during the third erythromycin cycle and returns to the gastroenterologist for a follow-up appointment. The GI specialist decides to discontinue erythromycin in view of potential drug-drug interactions and Mr. F’s elevated clozapine levels and the associated risks that might entail. Mr. F is again offered the D2 dopamine antagonist metoclopramide, but again refuses due to the risk for tardive dyskinesia. He is asked to continue the GI dysmotility diet. Mr. F finds some relief of nausea symptoms from an over-the-counter product for nausea (a nasal inhalant containing essential oils) and is advised to follow up with the GI specialist in 3 months. Shortly thereafter, he is discharged to live in a less restrictive supportive housing environment, and his follow-up psychiatric care is provided by an assertive community treatment team. Over the next several months, the dosage of clozapine is decreased to 250 mg/d. Mr. F initially experiences worsening psychiatric symptoms, but stabilizes thereafter. He then moves out of state to be closer to his family.

Bottom Line

In patients receiving clozapine, frequent nausea along with clustering of heartburn, abdominal pain, bloating, early satiety, and vomiting (especially after meals) may signal gastroparesis rather than gastroesophageal reflux disease. Such patients may require consultation with a gastroenterologist, a scintigraphy-based gastric emptying test, and treatment if gastroparesis is confirmed.

1. Camilleri M, Chedid V, Ford AC, et al. Gastroparesis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):41. doi:10.1038/s41572-018-0038-z

2. Hamann J, Langer B, Winkler V, et al. Shared decision making for in-patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(4):265-273. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00798.x

3. Maganti K, Onyemere K, Jones MP. Oral erythromycin and symptomatic relief of gastroparesis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):259-263. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07167.x

4. Taylor D. Pharmacokinetic interactions involving clozapine. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:109-112. doi:10.1192/bjp.171.2.109

5. Edge SC, Markowitz JS, Devane CL. Clozapine drug-drug interactions: a review of the literature. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 1997;12(1):5-20.

6. Vanasse A, Blais L, Courteau J, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia treatment: a real-world observational study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134(5):374-384. doi:10.1111/acps.12621

7. Siskind D, McCartney L, Goldschlager R, et al. Clozapine v. first- and second-generation antipsychotics in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(5):385-392. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.115.177261

8. Azorin JM, Spiegel R, Remington G, et al. A double-blind comparative study of clozapine and risperidone in the management of severe chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1305-1313. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1305

9. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Clozapine. Accessed June 13, 2021. https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Treatments/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Clozapine-(Clozaril-and-FazaClo)

10. Shirazi A, Stubbs B, Gomez L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of clozapine-associated constipation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(6):863. doi:10.3390/ijms17060863

11. Cohen D, Bogers JP, van Dijk D, et al. Beyond white blood cell monitoring: screening in the initial phase of clozapine therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(10):1307-1312. doi:10.4088/JCP.11r06977

12. Mookhoek EJ, Meijs VM, Loonen AJ, et al. Dyspepsia in chronic psychiatric patients. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2005;38(3):125-127. doi:10.1055/s-2005-864123

13. John JP, Chengappa KN, Baker RW, et al. Assessment of changes in both weight and frequency of use of medications for the treatment of gastrointestinal symptoms among clozapine-treated patients. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1995;7(3):119-125. doi: 10.3109/10401239509149038

14. Schwartz BJ, Frisolone JA. A case report of clozapine-induced gastric outlet obstruction. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(10):1563. doi:10.1176/ajp.150.10.1563a

15. Taylor D, Olofinjana O, Rahimi T. Use of antacid medication in patients receiving clozapine: a comparison with other second-generation antipsychotics. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(4):460-461. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181e5c0f7

16. Every-Palmer S, Inns SJ, Grant E, et al. Effects of clozapine on the gut: cross-sectional study of delayed gastric emptying and small and large intestinal dysmotility. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(1):81-91. doi:10.1007/s40263-018-0587-4

17. Jung HK, Choung RS, Locke GR 3rd, et al. The incidence, prevalence, and outcomes of patients with gastroparesis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1996 to 2006. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1225-1233. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.047

18. Antunes C, Aleem A, Curtis SA. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 7, 2021. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441938/

19. Reddivari AKR, Mehta P. Gastroparesis. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 30, 2021. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551528/

1. Camilleri M, Chedid V, Ford AC, et al. Gastroparesis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):41. doi:10.1038/s41572-018-0038-z

2. Hamann J, Langer B, Winkler V, et al. Shared decision making for in-patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(4):265-273. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00798.x

3. Maganti K, Onyemere K, Jones MP. Oral erythromycin and symptomatic relief of gastroparesis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):259-263. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07167.x

4. Taylor D. Pharmacokinetic interactions involving clozapine. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:109-112. doi:10.1192/bjp.171.2.109

5. Edge SC, Markowitz JS, Devane CL. Clozapine drug-drug interactions: a review of the literature. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 1997;12(1):5-20.

6. Vanasse A, Blais L, Courteau J, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia treatment: a real-world observational study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134(5):374-384. doi:10.1111/acps.12621

7. Siskind D, McCartney L, Goldschlager R, et al. Clozapine v. first- and second-generation antipsychotics in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(5):385-392. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.115.177261

8. Azorin JM, Spiegel R, Remington G, et al. A double-blind comparative study of clozapine and risperidone in the management of severe chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1305-1313. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1305

9. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Clozapine. Accessed June 13, 2021. https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Treatments/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Clozapine-(Clozaril-and-FazaClo)

10. Shirazi A, Stubbs B, Gomez L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of clozapine-associated constipation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(6):863. doi:10.3390/ijms17060863

11. Cohen D, Bogers JP, van Dijk D, et al. Beyond white blood cell monitoring: screening in the initial phase of clozapine therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(10):1307-1312. doi:10.4088/JCP.11r06977

12. Mookhoek EJ, Meijs VM, Loonen AJ, et al. Dyspepsia in chronic psychiatric patients. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2005;38(3):125-127. doi:10.1055/s-2005-864123

13. John JP, Chengappa KN, Baker RW, et al. Assessment of changes in both weight and frequency of use of medications for the treatment of gastrointestinal symptoms among clozapine-treated patients. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1995;7(3):119-125. doi: 10.3109/10401239509149038

14. Schwartz BJ, Frisolone JA. A case report of clozapine-induced gastric outlet obstruction. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(10):1563. doi:10.1176/ajp.150.10.1563a

15. Taylor D, Olofinjana O, Rahimi T. Use of antacid medication in patients receiving clozapine: a comparison with other second-generation antipsychotics. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(4):460-461. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181e5c0f7

16. Every-Palmer S, Inns SJ, Grant E, et al. Effects of clozapine on the gut: cross-sectional study of delayed gastric emptying and small and large intestinal dysmotility. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(1):81-91. doi:10.1007/s40263-018-0587-4

17. Jung HK, Choung RS, Locke GR 3rd, et al. The incidence, prevalence, and outcomes of patients with gastroparesis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1996 to 2006. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(4):1225-1233. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.047

18. Antunes C, Aleem A, Curtis SA. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 7, 2021. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441938/

19. Reddivari AKR, Mehta P. Gastroparesis. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 30, 2021. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551528/

Command hallucinations, but is it really psychosis?

CASE Frequent hospitalizations

Ms. D, age 26, presents to the emergency department (ED) after drinking a bottle of hand sanitizer in a suicide attempt. She is admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where she spends 50 days, followed by a transfer to a step-down unit, where she spends 26 days. Upon discharge, her diagnosis is schizoaffective disorder–bipolar type.

Shortly before this, Ms. D had intentionally ingested 20 vitamin pills to “make her heart stop” after a conflict at home. After ingesting the pills, Ms. D presented to the ED, where she stated that if she were discharged, she would kill herself by taking “better pills.” She was then admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where she spent 60 days before being moved to an extended-care step-down facility, where she resided for 42 days.

HISTORY A challenging past

Ms. D has a history of >25 psychiatric hospitalizations with varying discharge diagnoses, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, borderline personality disorder (BPD), and borderline intellectual functioning.

Ms. D was raised in a 2-parent home with 3 older half-brothers and 3 sisters. She was sexually assaulted by a cousin when she was 12. Ms. D recalls one event of self-injury/cutting behavior at age 15 after she was bullied by peers. Her family history is significant for schizophrenia (mother), alcohol use disorder (both parents), and bipolar disorder (sister). Her mother, who is now deceased, was admitted to state psychiatric hospitals for extended periods.

Her medication regimen has changed with nearly every hospitalization but generally has included ≥1 antipsychotic, a mood stabilizer, an antidepressant, and a benzodiazepine (often prescribed on an as-needed basis). Ms. D is obese and has difficulty sleeping, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), hypertension, and iron deficiency anemia. She receives medications to manage each of these conditions.

Ms. D’s previous psychotic symptoms included auditory command hallucinations. These occurred under stressful circumstances, such as during severe family conflicts that often led to her feeling abandoned. She reported that the “voice” she heard was usually her own instructing her to “take pills.” There was no prior evidence of bizarre delusions, negative symptoms, or disorganized thoughts or speech.

During episodes of decompensation, Ms. D did not report symptoms of mania, sustained depressed mood, or anxiety, nor were these symptoms observed. Although Ms. D endorsed suicidal ideation with a plan, intent, and means, during several of her previous ED presentations, she told clinicians that her intent was not to end her life but rather to evoke concern in her family members.

Continue to: After her mother died...

After her mother died when Ms. D was 19, she began to have nightmares of wanting to hurt herself and others and began experiencing multiple hospitalizations. In 2010, Ms. D was referred to an assertive community treatment (ACT) program for individuals age 16 to 27 because of her inability to participate in traditional community-based services and her historical need for advanced services, in order to provide psychiatric care in the least restrictive means possible.

Despite receiving intensive ACT services, and in addition to the numerous inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, over 7 years, Ms. D accumulated 8 additional general-medical hospitalizations and >50 visits to hospital EDs and urgent care facilities. These hospitalizations typically followed arguments at home, strained family dynamics, and not feeling wanted. Ms. D would ingest large quantities of prescription or over-the-counter medications as a way of coping, which often occurred while she was residing in a step-down facility after hospital discharge.

[polldaddy:10528342]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team decided to transition Ms. D to an LTSR with full continuum of treatment. While some clinicians might be concerned with potential iatrogenic harm of LTSR placement and might instead recommend less restrictive residential support and an IOP. However, in Ms. D’s case, her numerous admissions to EDs, urgent care facilities, and medical and psychiatric hospitals, her failed step-down facility placements, and her family conflicts and poor dynamics limited the efficacy of her natural support system and drove the recommendation for an LTSR.

Previously, Ms. D’s experience with ACT services had centered on managing acute crises, with brief periods of stabilization that insufficiently engaged her in a consistent and meaningful treatment plan. Ms. D’s insurance company agreed to pay for the LTSR after lengthy discussions with the clinical leadership at the ACT program and the LTSR demonstrated that she was a high utilizer of health care services. They concluded that Ms. D’s stay at the LTSR would be less expensive than the frequent use of expensive hospital services and care.

EVALUATION A consensus on the diagnosis

During the first few weeks of Ms. D’s admission to the LTSR, the treatment team takes a thorough history and reviews her medical records, which they obtained from several past inpatient admissions and therapists who previously treated Ms. D. The team also collects collateral information from Ms. D’s family members. Based on this information, interviews, and composite behavioral observations from the first few weeks of Ms. D’s time at the LTSR, the psychiatrists and treatment team at the LTSR and ACT program determine that Ms. D meets the criteria for a primary diagnosis of BPD. Previous discharge diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder–bipolar type (Table 11), schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder could not be affirmed.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

During Ms. D’s LTSR placement, it became clear that her self-harm behaviors and numerous visits to the ED and urgent care facilities involved severe and intense emotional dysregulation and maladaptive behaviors. These behaviors had developed over time in response to acute stressors and past trauma, and not as a result of a sustained mood or psychotic disorder. Before her LTSR placement, Ms. D was unable to use more adaptive coping skills, such as skills building, learning, and coaching. Ms. D typically “thrived” with medical attention in the ED or hospital, and once the stressor dissipated, she was discharged back to the same stressful living environment associated with her maladaptive coping.

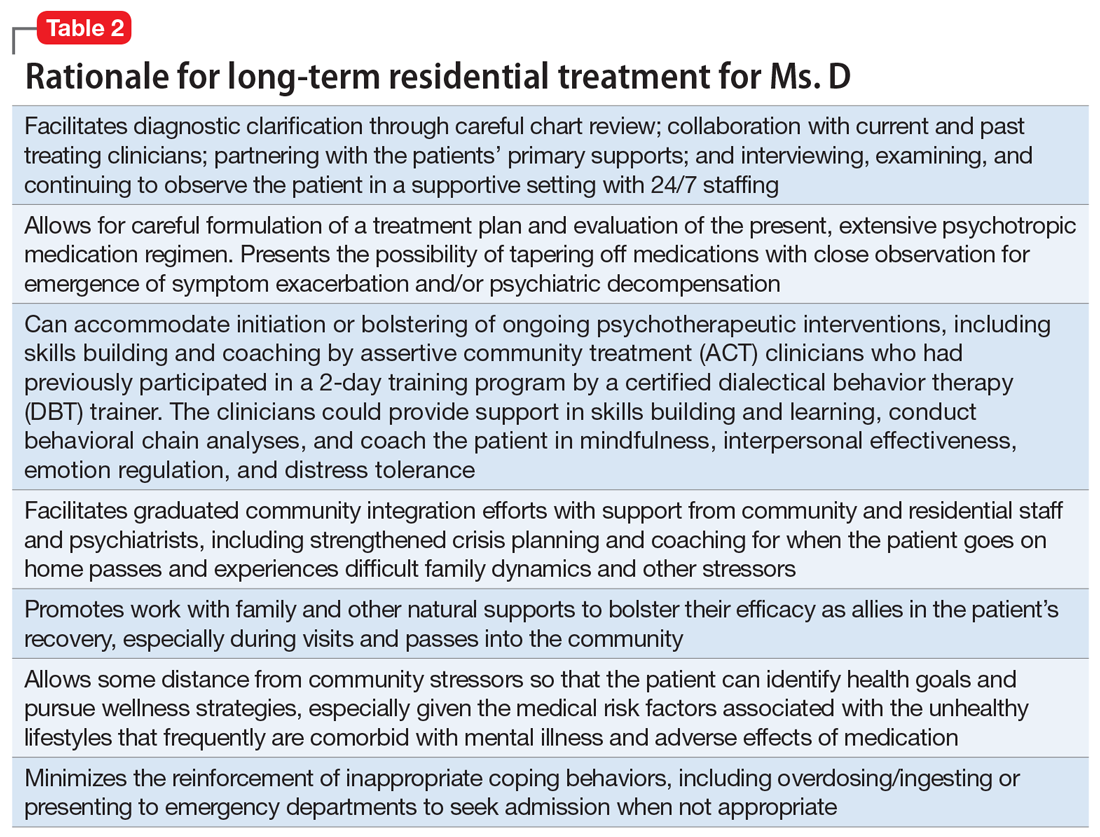

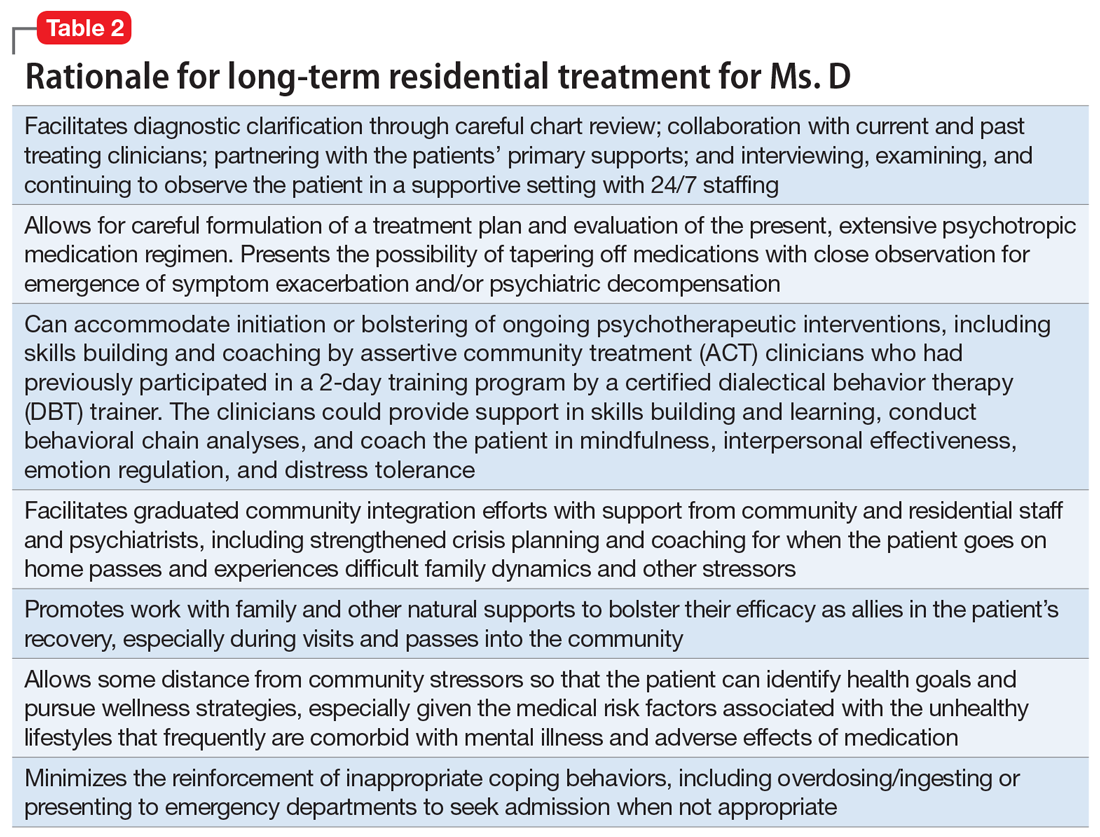

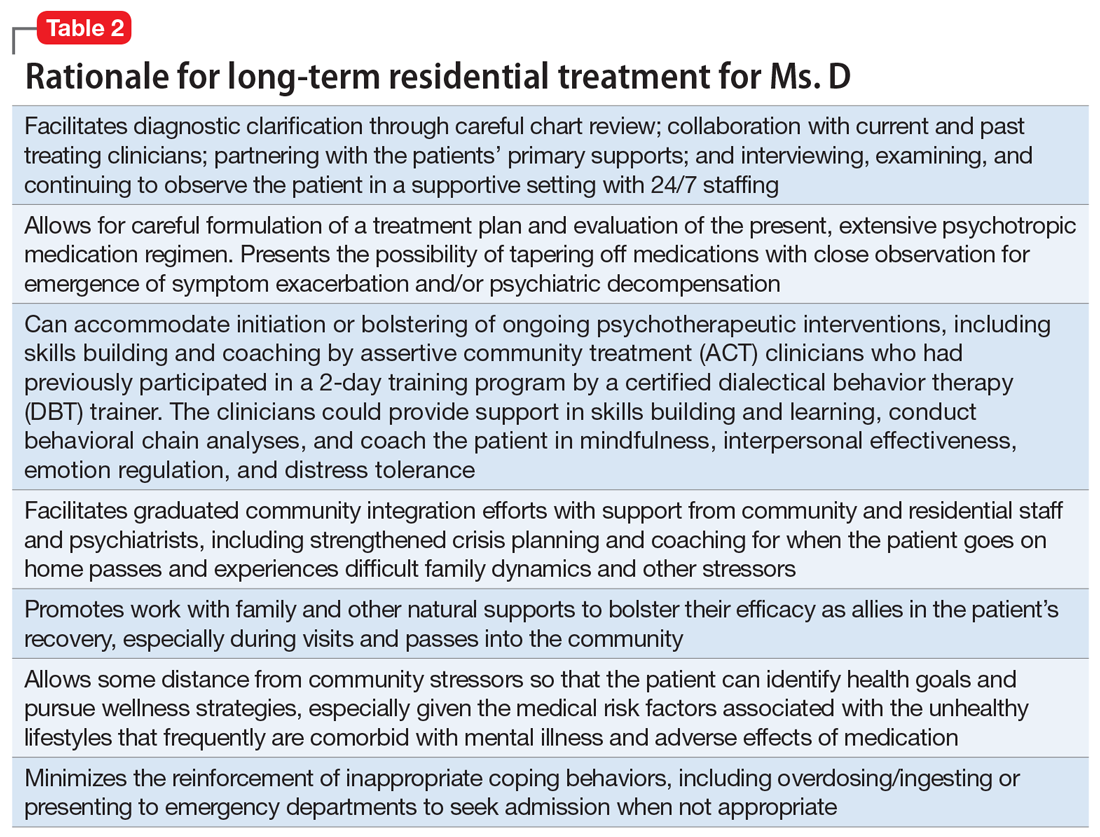

Table 2 outlines the rationale for long-term residential treatment for Ms. D.

TREATMENT Developing more effective skills

Bolstered by a clearer diagnostic formulation of BPD, Ms. D’s initial treatment goals at the LTSR include developing effective skills (eg, mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, emotion regulation, and distress tolerance) to cope with family conflicts and other stressors while she is outside the facility on a therapeutic pass. Ms. D’s treatment focuses on skills learning and coaching, and behavior chain analyses, which are conducted by her therapist from the ACT program.

Ms. D remains clinically stable throughout her LTSR placement, and benefits from ongoing skills building and learning, coaching, and community integration efforts.

[polldaddy:10528348]

The authors’ observations

Several systematic reviews2-5 have found that there is a lack of high-quality evidence for the use of various psychotropic medications for patients with BPD, yet polypharmacy is common. Many patients with BPD receive ≥2 medications and >25% of patients receive ≥4 medications, typically for prolonged periods. Stoffers et al4 suggested that FGAs and antidepressants have marginal effects of for patients with BPD; however, their use cannot be ruled out because they may be helpful for comorbid symptoms that are often observed in patients with BPD. There is better evidence for SGAs, mood stabilizers, and omega-3 fatty acids; however, most effect estimates were based on single studies, and there is minimal data on long-term use of these agents.4

Continue to: A recent review highlighted...

A recent review highlighted 2 trends in medication prescribing for individuals with BPD3:

- a decrease in the use of benzodiazepines and antidepressants

- an increase in or preference for mood stabilizers and SGAs, especially valproate and quetiapine.

In terms of which medications can be used to target specific symptoms, the same researchers also noted from previous studies3:

- The prior use of SSRIs to target affective dysregulation, anxiety, and impulsive- behavior dyscontrol

- mood stabilizers (notably anticonvulsants) and SGAs to target “core symptoms” of BPD, including affective dysregulation, impulsive-behavioral dyscontrol, and cognitive-perceptual distortions

- omega-3 fatty acids for mood stabilization, impulsive-behavior dyscontrol, and possibly to reduce self-harm behaviors.

TREATMENT Medication adjustments

The treatment team reviews the lack of evidence for the long-term use of psychotropic medications in the treatment of BPD with Ms. D and her relatives,2-5 and develops a medication regimen that is clinically appropriate for managing the symptoms of BPD, while also being mindful of adverse effects.

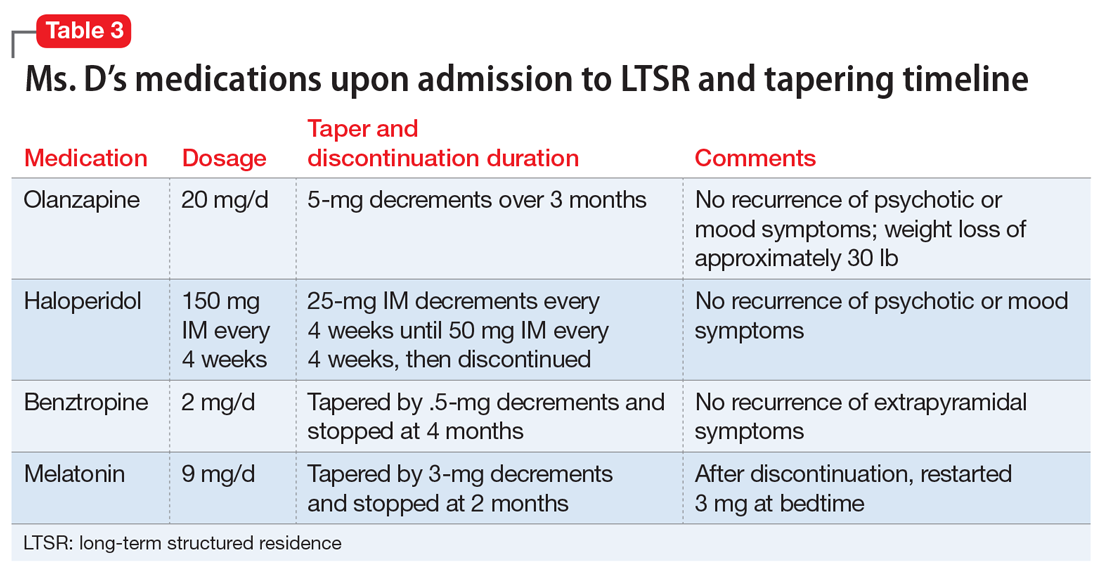

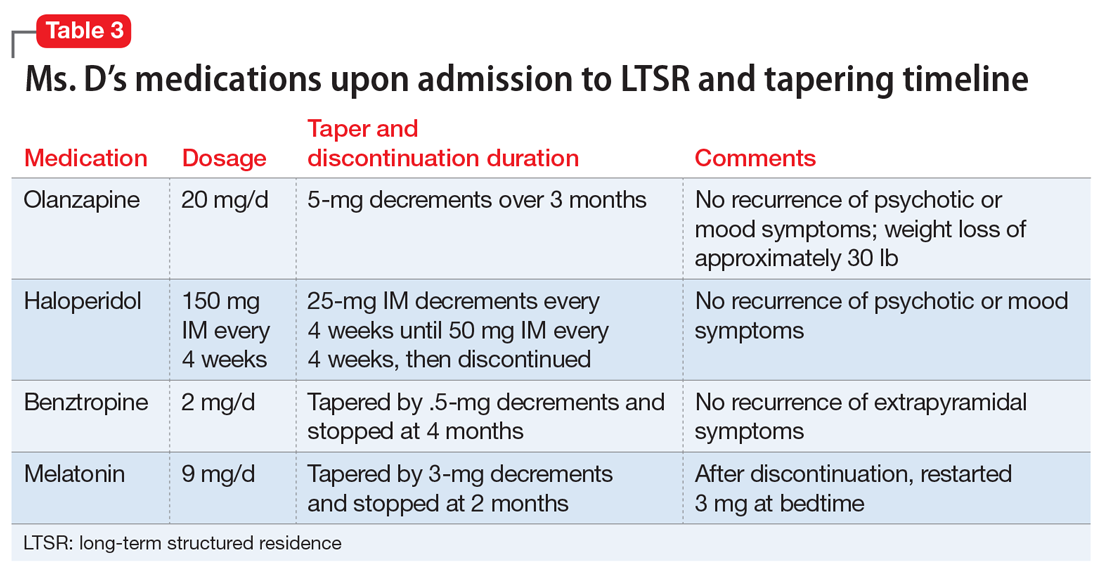

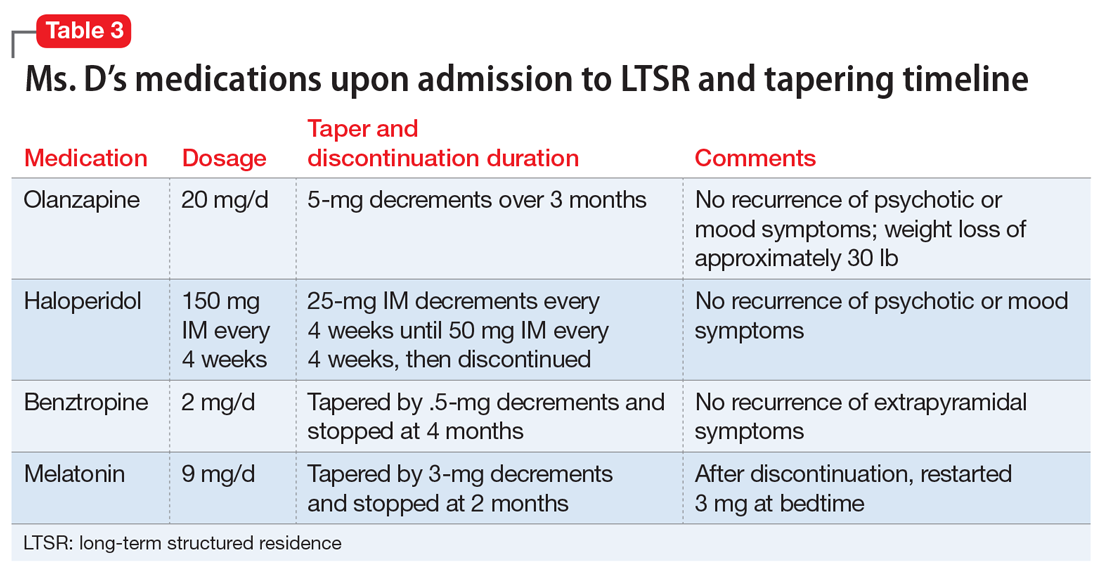

When Ms. D was admitted to the LTSR from the hospital, her psychotropic medication regimen included haloperidol, 150 mg IM every month; olanzapine, 20 mg at bedtime; benztropine, 1 mg twice daily; and melatonin, 9 mg at bedtime.

Following discussions with Ms. D and her older sister, the team initiates a taper of olanzapine because of metabolic concerns. Ms. D has gained >40 lb while receiving this medication and had hypertension. Olanzapine was tapered and discontinued over the course of 3 months with no reemergence of sustained mood or psychotic symptoms (Table 3). During this period, Ms. D also participates in dietary counselling, follows a portion-controlled regimen, and loses >30 lb. Her wellness plan focuses on nutrition and exercise to improve her overall physical health.

Continue to: Six months into her stay...

Six months into her stay at the LTSR, Ms. D remains clinically stable and is able to leave the LTSR placement to go on home passes. At this time, the team begins to taper the haloperidol long-acting injection. One month prior to discharge from the LTSR, haloperidol is discontinued entirely. The treatment team simultaneously tapers and discontinues benztropine. No recurrence of extrapyramidal symptoms is observed by staff or noted by the patient.

A treatment plan is developed to address Ms. D’s medical conditions, including hypothyroidism, GERD, and obesity. Ms. D does not appear to have difficulty sleeping at the LTSR, so melatonin is tapered by 3-mg decrements and stopped after 2 months. However, shortly thereafter, she develops insomnia, so a 3-mg dose is re-initiated, and her complaints abate. Her primary care physician discontinues hydrochlorothiazide, an antihypertensive medication.

Ms. D’s medication regimen consists of melatonin, 3 mg at bedtime; pantoprazole, 40 mg before breakfast, for GERD; senna, 8.6 mg at bedtime, and polyethylene glycol, 17 gm/d, for constipation; levothyroxine, 125 mcg/d, for hypothyroidism; metoprolol extended-release, 50 mg/d, for hypertension; and ferrous sulfate, 325 mg/d, for iron deficiency anemia.

OUTCOME Improved functioning

After 11 months at the LTSR, Ms. D is discharged home. She continues to receive outpatient services in the community through the ACT program, meeting with her therapist for cognitive-behavioral therapy, skills building and learning, and integration.

Approximately 9 months later, Ms. D is re-started on an SSRI (sertraline, 50 mg/d, which is increased to 100 mg/d 9 months later) to target symptoms of anxiety, which primarily manifest as excessive worrying. Hydroxyzine, 50 mg 3 times daily as needed, is added to this regimen, for breakthrough anxiety symptoms. Hydroxyzine is prescribed instead of a benzodiazepine to avoid potential addiction and abuse.

Continue to: Oral ziprasidone...

Oral ziprasidone, 20 mg/d twice daily, is initiated during 2 brief inpatient psychiatric admissions; however, it is successfully tapered within 1 week of discharge, in partnership with the ACT program.

In the 23 months after her discharge, Ms. D has had 1 ED visit and 2 brief inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, which is markedly fewer encounters than she had in the 2 years before her LTSR placement. She has also lost an additional 30 lb since her LTSR discharge through a healthy diet and exercise.

Ms. D is now considering transitioning to living independently in the community through a residential supported housing program.

Bottom Line

Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) are typically fleeting and mostly occur in the context of intense interpersonal conflicts and real or imagined abandonment. Long-term structured residence placement for patients with BPD can allow for careful formulation of a treatment plan, and help patients gain effective skills to cope with difficult family dynamics and other stressors, with the ultimate goal of gradual community integration.

Related Resource

- National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder. https://www.borderlinepersonalitydisorder.org.

Drug Brand Names

Benztropine • Cogentin

Haloperidol • Haldol

Hydrochlorothiazide • Microzide, HydroDiuril

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Levothyroxine • Synthroid,

Metoprolol ER • Toprol XL

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Pantoprazole • Protonix

Polyethylene glycol • MiraLax, Glycolax

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Senna • Senokot

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproate • Depakene, Depakote

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Hancock-Johnson E, Griffiths C, Picchioni M. A focused systematic review of pharmacological treatment for borderline personality disorder. CNS Drugs. 2017;31:345-356.

3. Starcevic V, Janca A. Pharmacotherapy of borderline personality disorder: replacing confusion with prudent pragmatism. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31(1):69-73.

4. Stoffers J, Völlm BA, Rücker G, et al. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;6:CD005653. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005653.pub2.

5. Stoffers-Winterling JM, Storebo OJ, Völlm BA, et al. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD012956. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012956.

CASE Frequent hospitalizations

Ms. D, age 26, presents to the emergency department (ED) after drinking a bottle of hand sanitizer in a suicide attempt. She is admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where she spends 50 days, followed by a transfer to a step-down unit, where she spends 26 days. Upon discharge, her diagnosis is schizoaffective disorder–bipolar type.

Shortly before this, Ms. D had intentionally ingested 20 vitamin pills to “make her heart stop” after a conflict at home. After ingesting the pills, Ms. D presented to the ED, where she stated that if she were discharged, she would kill herself by taking “better pills.” She was then admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where she spent 60 days before being moved to an extended-care step-down facility, where she resided for 42 days.

HISTORY A challenging past

Ms. D has a history of >25 psychiatric hospitalizations with varying discharge diagnoses, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, borderline personality disorder (BPD), and borderline intellectual functioning.

Ms. D was raised in a 2-parent home with 3 older half-brothers and 3 sisters. She was sexually assaulted by a cousin when she was 12. Ms. D recalls one event of self-injury/cutting behavior at age 15 after she was bullied by peers. Her family history is significant for schizophrenia (mother), alcohol use disorder (both parents), and bipolar disorder (sister). Her mother, who is now deceased, was admitted to state psychiatric hospitals for extended periods.

Her medication regimen has changed with nearly every hospitalization but generally has included ≥1 antipsychotic, a mood stabilizer, an antidepressant, and a benzodiazepine (often prescribed on an as-needed basis). Ms. D is obese and has difficulty sleeping, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), hypertension, and iron deficiency anemia. She receives medications to manage each of these conditions.

Ms. D’s previous psychotic symptoms included auditory command hallucinations. These occurred under stressful circumstances, such as during severe family conflicts that often led to her feeling abandoned. She reported that the “voice” she heard was usually her own instructing her to “take pills.” There was no prior evidence of bizarre delusions, negative symptoms, or disorganized thoughts or speech.

During episodes of decompensation, Ms. D did not report symptoms of mania, sustained depressed mood, or anxiety, nor were these symptoms observed. Although Ms. D endorsed suicidal ideation with a plan, intent, and means, during several of her previous ED presentations, she told clinicians that her intent was not to end her life but rather to evoke concern in her family members.

Continue to: After her mother died...

After her mother died when Ms. D was 19, she began to have nightmares of wanting to hurt herself and others and began experiencing multiple hospitalizations. In 2010, Ms. D was referred to an assertive community treatment (ACT) program for individuals age 16 to 27 because of her inability to participate in traditional community-based services and her historical need for advanced services, in order to provide psychiatric care in the least restrictive means possible.

Despite receiving intensive ACT services, and in addition to the numerous inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, over 7 years, Ms. D accumulated 8 additional general-medical hospitalizations and >50 visits to hospital EDs and urgent care facilities. These hospitalizations typically followed arguments at home, strained family dynamics, and not feeling wanted. Ms. D would ingest large quantities of prescription or over-the-counter medications as a way of coping, which often occurred while she was residing in a step-down facility after hospital discharge.

[polldaddy:10528342]

The authors’ observations

The treatment team decided to transition Ms. D to an LTSR with full continuum of treatment. While some clinicians might be concerned with potential iatrogenic harm of LTSR placement and might instead recommend less restrictive residential support and an IOP. However, in Ms. D’s case, her numerous admissions to EDs, urgent care facilities, and medical and psychiatric hospitals, her failed step-down facility placements, and her family conflicts and poor dynamics limited the efficacy of her natural support system and drove the recommendation for an LTSR.

Previously, Ms. D’s experience with ACT services had centered on managing acute crises, with brief periods of stabilization that insufficiently engaged her in a consistent and meaningful treatment plan. Ms. D’s insurance company agreed to pay for the LTSR after lengthy discussions with the clinical leadership at the ACT program and the LTSR demonstrated that she was a high utilizer of health care services. They concluded that Ms. D’s stay at the LTSR would be less expensive than the frequent use of expensive hospital services and care.

EVALUATION A consensus on the diagnosis

During the first few weeks of Ms. D’s admission to the LTSR, the treatment team takes a thorough history and reviews her medical records, which they obtained from several past inpatient admissions and therapists who previously treated Ms. D. The team also collects collateral information from Ms. D’s family members. Based on this information, interviews, and composite behavioral observations from the first few weeks of Ms. D’s time at the LTSR, the psychiatrists and treatment team at the LTSR and ACT program determine that Ms. D meets the criteria for a primary diagnosis of BPD. Previous discharge diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder–bipolar type (Table 11), schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder could not be affirmed.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

During Ms. D’s LTSR placement, it became clear that her self-harm behaviors and numerous visits to the ED and urgent care facilities involved severe and intense emotional dysregulation and maladaptive behaviors. These behaviors had developed over time in response to acute stressors and past trauma, and not as a result of a sustained mood or psychotic disorder. Before her LTSR placement, Ms. D was unable to use more adaptive coping skills, such as skills building, learning, and coaching. Ms. D typically “thrived” with medical attention in the ED or hospital, and once the stressor dissipated, she was discharged back to the same stressful living environment associated with her maladaptive coping.

Table 2 outlines the rationale for long-term residential treatment for Ms. D.

TREATMENT Developing more effective skills

Bolstered by a clearer diagnostic formulation of BPD, Ms. D’s initial treatment goals at the LTSR include developing effective skills (eg, mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, emotion regulation, and distress tolerance) to cope with family conflicts and other stressors while she is outside the facility on a therapeutic pass. Ms. D’s treatment focuses on skills learning and coaching, and behavior chain analyses, which are conducted by her therapist from the ACT program.

Ms. D remains clinically stable throughout her LTSR placement, and benefits from ongoing skills building and learning, coaching, and community integration efforts.

[polldaddy:10528348]

The authors’ observations

Several systematic reviews2-5 have found that there is a lack of high-quality evidence for the use of various psychotropic medications for patients with BPD, yet polypharmacy is common. Many patients with BPD receive ≥2 medications and >25% of patients receive ≥4 medications, typically for prolonged periods. Stoffers et al4 suggested that FGAs and antidepressants have marginal effects of for patients with BPD; however, their use cannot be ruled out because they may be helpful for comorbid symptoms that are often observed in patients with BPD. There is better evidence for SGAs, mood stabilizers, and omega-3 fatty acids; however, most effect estimates were based on single studies, and there is minimal data on long-term use of these agents.4

Continue to: A recent review highlighted...

A recent review highlighted 2 trends in medication prescribing for individuals with BPD3:

- a decrease in the use of benzodiazepines and antidepressants

- an increase in or preference for mood stabilizers and SGAs, especially valproate and quetiapine.

In terms of which medications can be used to target specific symptoms, the same researchers also noted from previous studies3:

- The prior use of SSRIs to target affective dysregulation, anxiety, and impulsive- behavior dyscontrol

- mood stabilizers (notably anticonvulsants) and SGAs to target “core symptoms” of BPD, including affective dysregulation, impulsive-behavioral dyscontrol, and cognitive-perceptual distortions

- omega-3 fatty acids for mood stabilization, impulsive-behavior dyscontrol, and possibly to reduce self-harm behaviors.

TREATMENT Medication adjustments

The treatment team reviews the lack of evidence for the long-term use of psychotropic medications in the treatment of BPD with Ms. D and her relatives,2-5 and develops a medication regimen that is clinically appropriate for managing the symptoms of BPD, while also being mindful of adverse effects.

When Ms. D was admitted to the LTSR from the hospital, her psychotropic medication regimen included haloperidol, 150 mg IM every month; olanzapine, 20 mg at bedtime; benztropine, 1 mg twice daily; and melatonin, 9 mg at bedtime.

Following discussions with Ms. D and her older sister, the team initiates a taper of olanzapine because of metabolic concerns. Ms. D has gained >40 lb while receiving this medication and had hypertension. Olanzapine was tapered and discontinued over the course of 3 months with no reemergence of sustained mood or psychotic symptoms (Table 3). During this period, Ms. D also participates in dietary counselling, follows a portion-controlled regimen, and loses >30 lb. Her wellness plan focuses on nutrition and exercise to improve her overall physical health.

Continue to: Six months into her stay...

Six months into her stay at the LTSR, Ms. D remains clinically stable and is able to leave the LTSR placement to go on home passes. At this time, the team begins to taper the haloperidol long-acting injection. One month prior to discharge from the LTSR, haloperidol is discontinued entirely. The treatment team simultaneously tapers and discontinues benztropine. No recurrence of extrapyramidal symptoms is observed by staff or noted by the patient.

A treatment plan is developed to address Ms. D’s medical conditions, including hypothyroidism, GERD, and obesity. Ms. D does not appear to have difficulty sleeping at the LTSR, so melatonin is tapered by 3-mg decrements and stopped after 2 months. However, shortly thereafter, she develops insomnia, so a 3-mg dose is re-initiated, and her complaints abate. Her primary care physician discontinues hydrochlorothiazide, an antihypertensive medication.

Ms. D’s medication regimen consists of melatonin, 3 mg at bedtime; pantoprazole, 40 mg before breakfast, for GERD; senna, 8.6 mg at bedtime, and polyethylene glycol, 17 gm/d, for constipation; levothyroxine, 125 mcg/d, for hypothyroidism; metoprolol extended-release, 50 mg/d, for hypertension; and ferrous sulfate, 325 mg/d, for iron deficiency anemia.

OUTCOME Improved functioning

After 11 months at the LTSR, Ms. D is discharged home. She continues to receive outpatient services in the community through the ACT program, meeting with her therapist for cognitive-behavioral therapy, skills building and learning, and integration.

Approximately 9 months later, Ms. D is re-started on an SSRI (sertraline, 50 mg/d, which is increased to 100 mg/d 9 months later) to target symptoms of anxiety, which primarily manifest as excessive worrying. Hydroxyzine, 50 mg 3 times daily as needed, is added to this regimen, for breakthrough anxiety symptoms. Hydroxyzine is prescribed instead of a benzodiazepine to avoid potential addiction and abuse.

Continue to: Oral ziprasidone...

Oral ziprasidone, 20 mg/d twice daily, is initiated during 2 brief inpatient psychiatric admissions; however, it is successfully tapered within 1 week of discharge, in partnership with the ACT program.

In the 23 months after her discharge, Ms. D has had 1 ED visit and 2 brief inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, which is markedly fewer encounters than she had in the 2 years before her LTSR placement. She has also lost an additional 30 lb since her LTSR discharge through a healthy diet and exercise.

Ms. D is now considering transitioning to living independently in the community through a residential supported housing program.

Bottom Line

Psychotic symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) are typically fleeting and mostly occur in the context of intense interpersonal conflicts and real or imagined abandonment. Long-term structured residence placement for patients with BPD can allow for careful formulation of a treatment plan, and help patients gain effective skills to cope with difficult family dynamics and other stressors, with the ultimate goal of gradual community integration.

Related Resource

- National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder. https://www.borderlinepersonalitydisorder.org.

Drug Brand Names

Benztropine • Cogentin

Haloperidol • Haldol

Hydrochlorothiazide • Microzide, HydroDiuril

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Levothyroxine • Synthroid,

Metoprolol ER • Toprol XL

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Pantoprazole • Protonix

Polyethylene glycol • MiraLax, Glycolax

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Senna • Senokot

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproate • Depakene, Depakote

Ziprasidone • Geodon

CASE Frequent hospitalizations

Ms. D, age 26, presents to the emergency department (ED) after drinking a bottle of hand sanitizer in a suicide attempt. She is admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where she spends 50 days, followed by a transfer to a step-down unit, where she spends 26 days. Upon discharge, her diagnosis is schizoaffective disorder–bipolar type.

Shortly before this, Ms. D had intentionally ingested 20 vitamin pills to “make her heart stop” after a conflict at home. After ingesting the pills, Ms. D presented to the ED, where she stated that if she were discharged, she would kill herself by taking “better pills.” She was then admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where she spent 60 days before being moved to an extended-care step-down facility, where she resided for 42 days.

HISTORY A challenging past

Ms. D has a history of >25 psychiatric hospitalizations with varying discharge diagnoses, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, borderline personality disorder (BPD), and borderline intellectual functioning.

Ms. D was raised in a 2-parent home with 3 older half-brothers and 3 sisters. She was sexually assaulted by a cousin when she was 12. Ms. D recalls one event of self-injury/cutting behavior at age 15 after she was bullied by peers. Her family history is significant for schizophrenia (mother), alcohol use disorder (both parents), and bipolar disorder (sister). Her mother, who is now deceased, was admitted to state psychiatric hospitals for extended periods.

Her medication regimen has changed with nearly every hospitalization but generally has included ≥1 antipsychotic, a mood stabilizer, an antidepressant, and a benzodiazepine (often prescribed on an as-needed basis). Ms. D is obese and has difficulty sleeping, hypothyroidism, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), hypertension, and iron deficiency anemia. She receives medications to manage each of these conditions.

Ms. D’s previous psychotic symptoms included auditory command hallucinations. These occurred under stressful circumstances, such as during severe family conflicts that often led to her feeling abandoned. She reported that the “voice” she heard was usually her own instructing her to “take pills.” There was no prior evidence of bizarre delusions, negative symptoms, or disorganized thoughts or speech.

During episodes of decompensation, Ms. D did not report symptoms of mania, sustained depressed mood, or anxiety, nor were these symptoms observed. Although Ms. D endorsed suicidal ideation with a plan, intent, and means, during several of her previous ED presentations, she told clinicians that her intent was not to end her life but rather to evoke concern in her family members.

Continue to: After her mother died...

After her mother died when Ms. D was 19, she began to have nightmares of wanting to hurt herself and others and began experiencing multiple hospitalizations. In 2010, Ms. D was referred to an assertive community treatment (ACT) program for individuals age 16 to 27 because of her inability to participate in traditional community-based services and her historical need for advanced services, in order to provide psychiatric care in the least restrictive means possible.

Despite receiving intensive ACT services, and in addition to the numerous inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations, over 7 years, Ms. D accumulated 8 additional general-medical hospitalizations and >50 visits to hospital EDs and urgent care facilities. These hospitalizations typically followed arguments at home, strained family dynamics, and not feeling wanted. Ms. D would ingest large quantities of prescription or over-the-counter medications as a way of coping, which often occurred while she was residing in a step-down facility after hospital discharge.

[polldaddy:10528342]

The authors’ observations