User login

From Buns to Braids and Ponytails: Entering a New Era of Female Military Hair-Grooming Standards

Professional appearance of servicemembers has been a long-standing custom in the US Military. Specific standards are determined by each branch. Initially, men dominated the military.1,2 As the number of women as well as racial diversity increased in the military, modifications to grooming standards were slow to change and resulted in female hair standards requiring a uniform tight and sleek style or short haircut. Clinicians can be attuned to these occupational standards and their implications on the diagnosis and management of common diseases of the hair and scalp.

History of Hairstyle Standards for Female Servicemembers

For half a century, female servicemembers had limited hairstyle choices. They were not authorized to have hair shorter than one-quarter inch in length. They could choose either short hair worn down or long hair with neatly secured loose ends in the form of a bun or a tucked braid—both of which could not extend past the bottom edge of the uniform collar.3-5 Female navy sailors and air force airmen with long hair were only allowed to wear ponytails during physical training; however, army soldiers previously were limited to wearing a bun.3,6,7 Cornrows and microbraids were authorized in the mid-1990s for the US Air Force, but policy stated that locs were prohibited due to their “unkempt” and “matted” nature. Furthermore, the size of hair bulk in the air force was restricted to no more than 3 inches and could not obstruct wear of the uniform cap.5 Based on these regulations, female servicemembers with longer hair had to utilize tight hairstyles that caused prolonged traction and pressure along the scalp, which contributed to headaches, a sore scalp, and alopecia over time. Normalization of these symptoms led to underreporting, as women lived with the consequences or turned to shorter hairstyles.

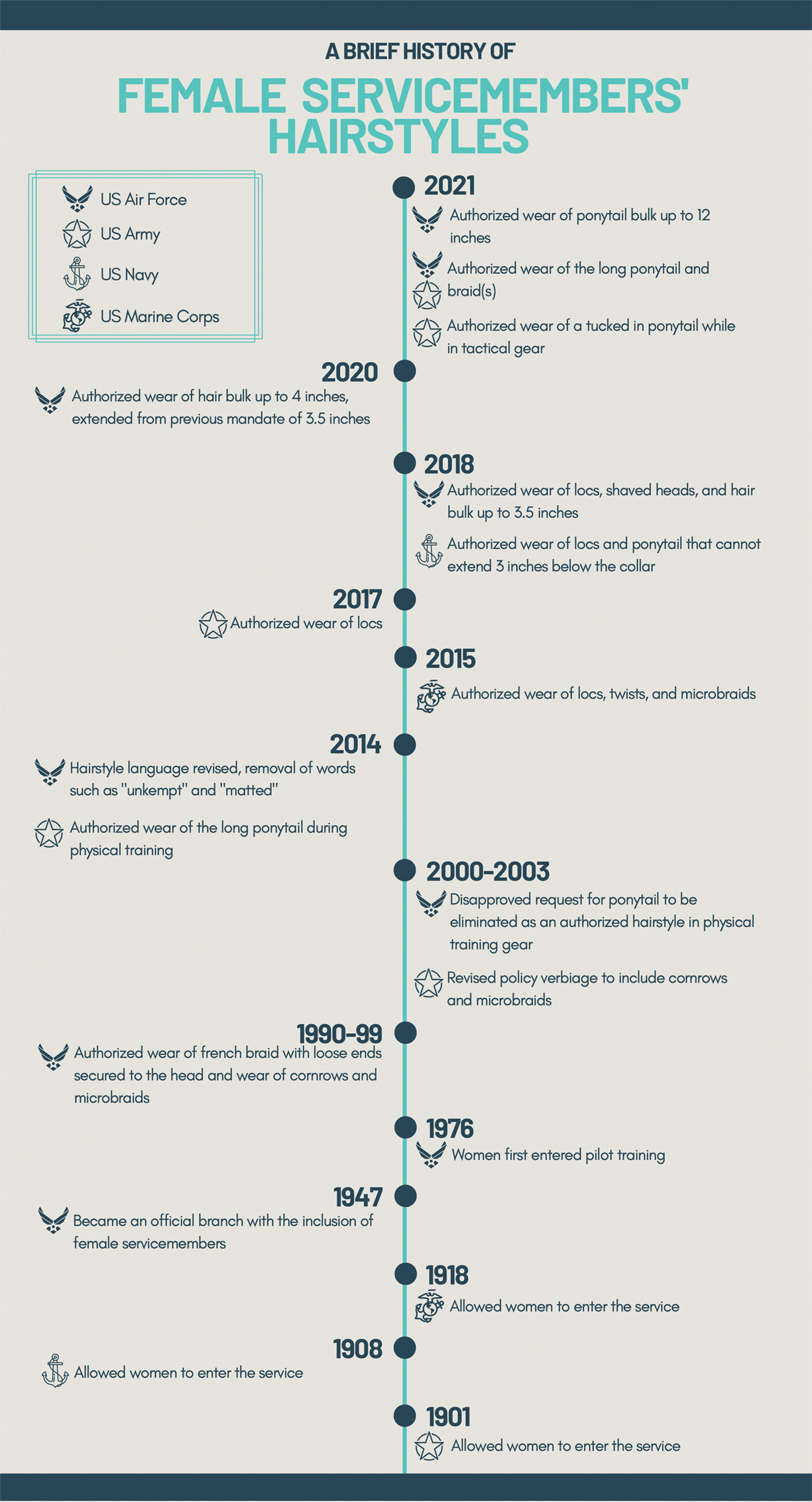

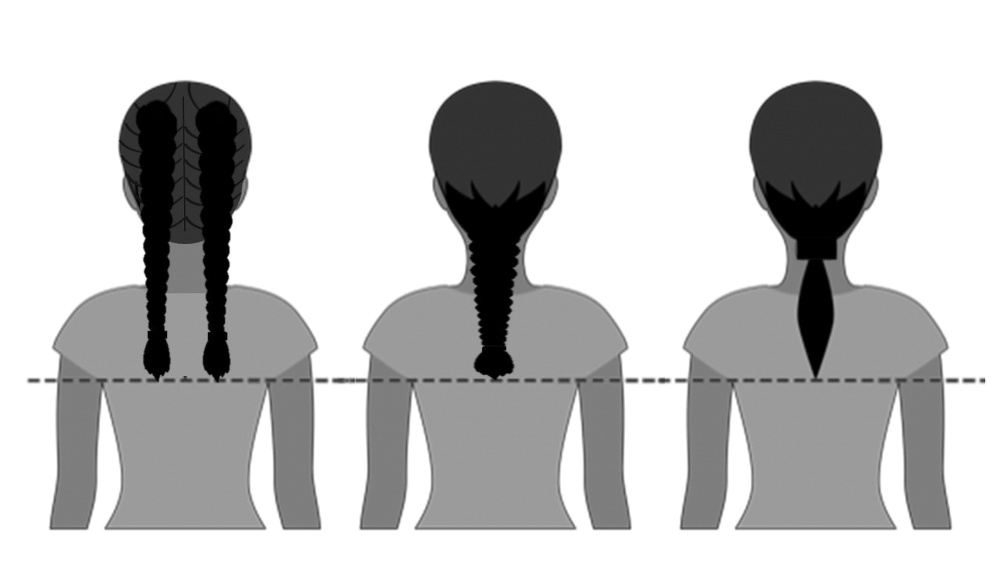

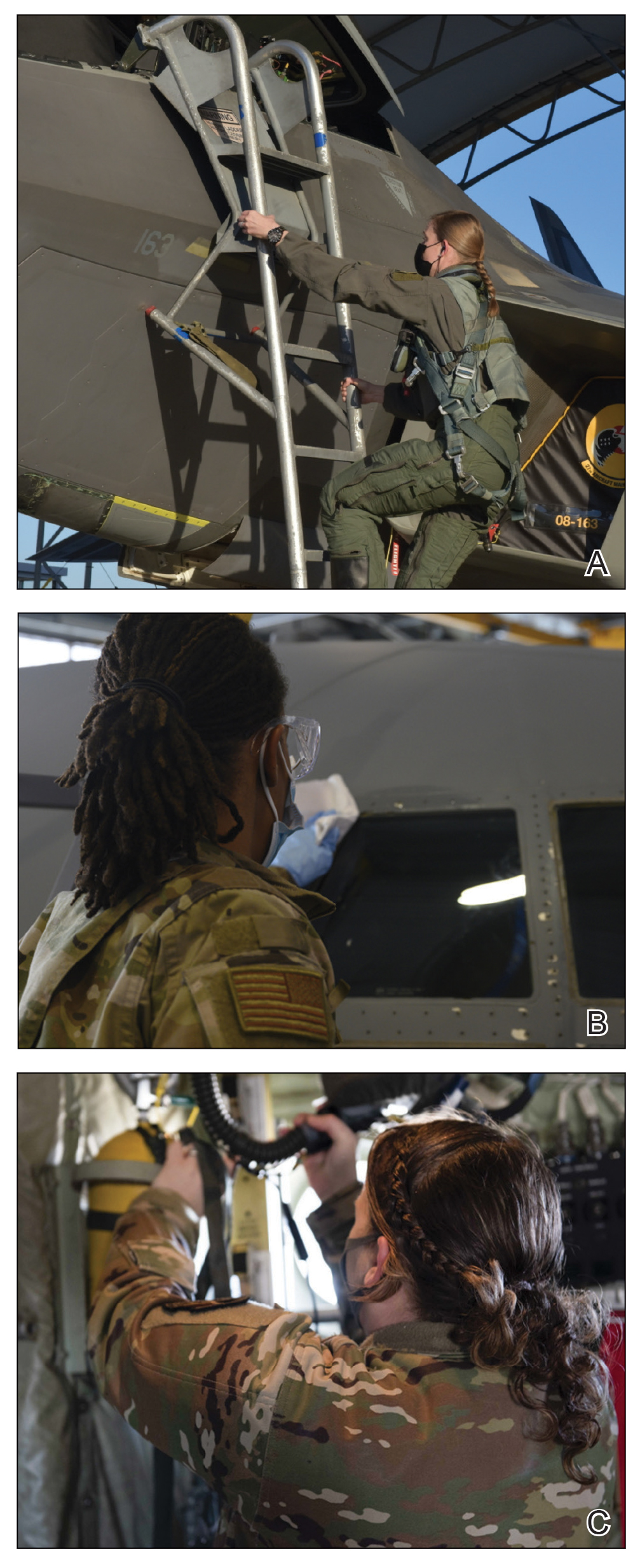

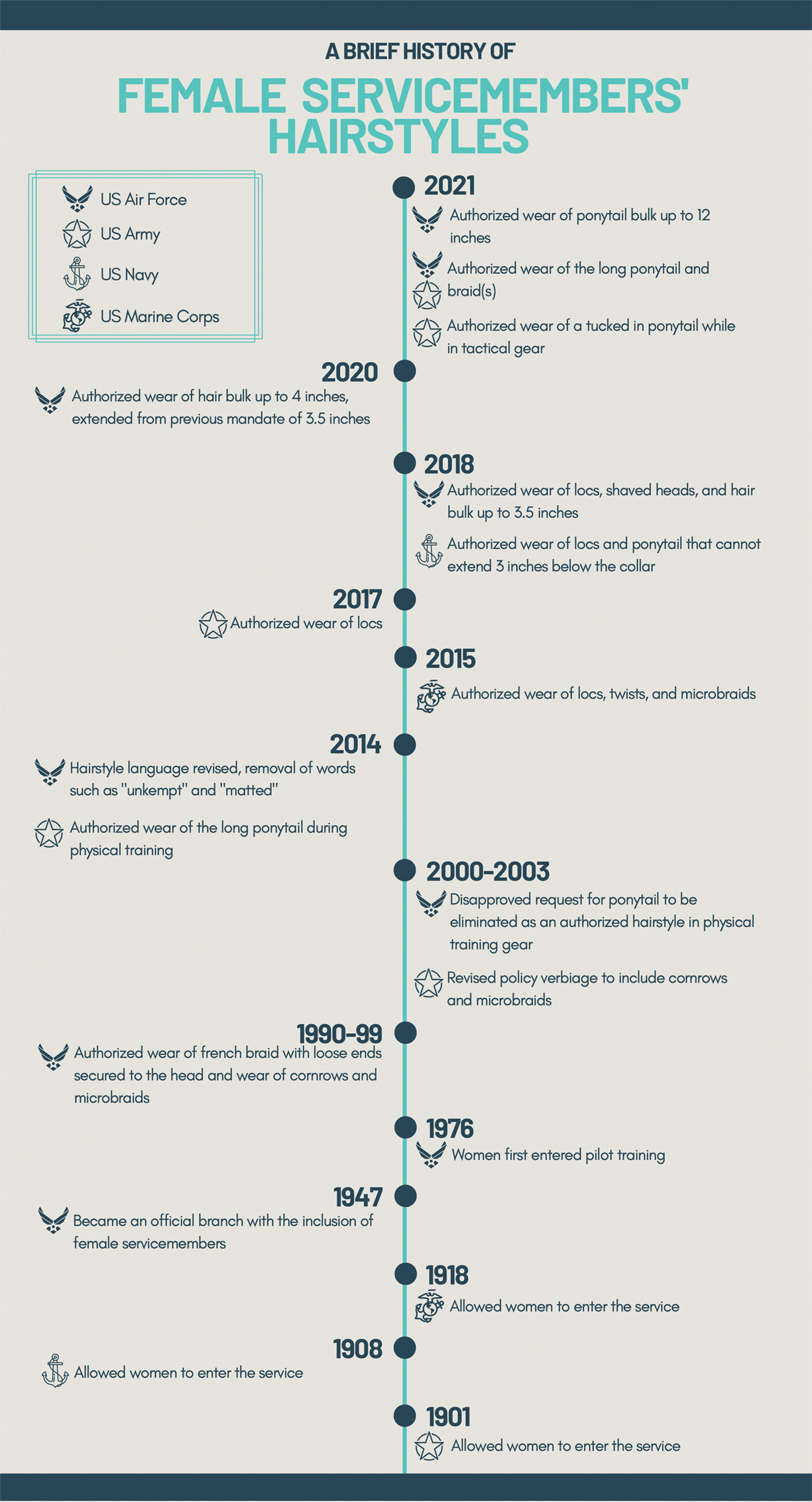

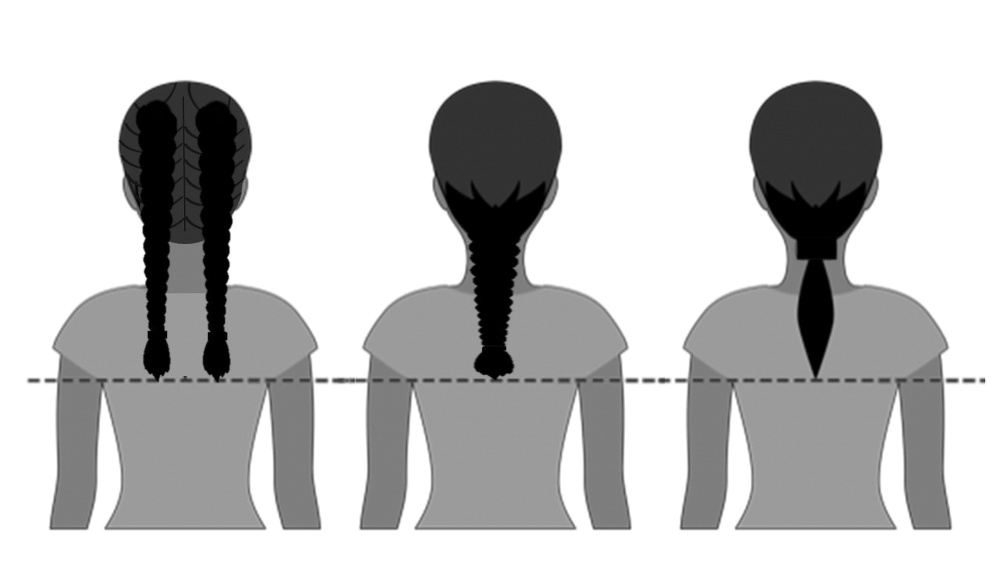

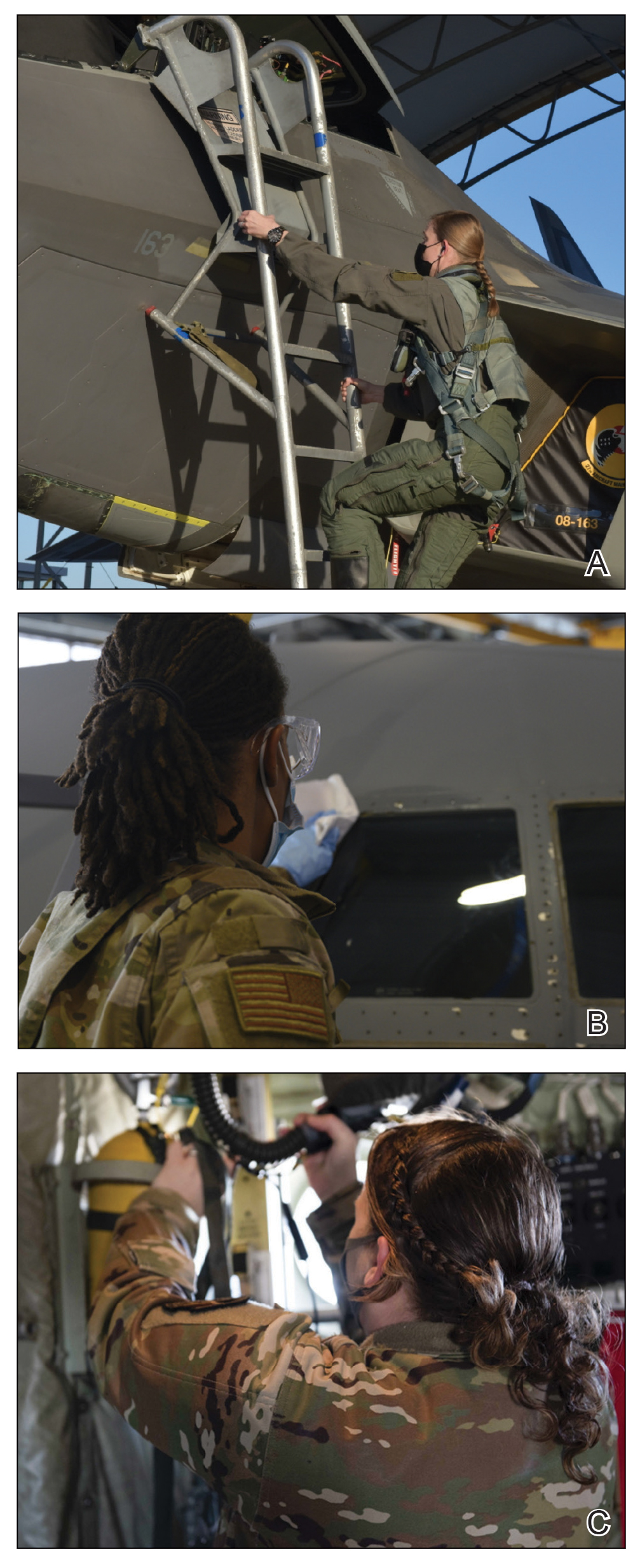

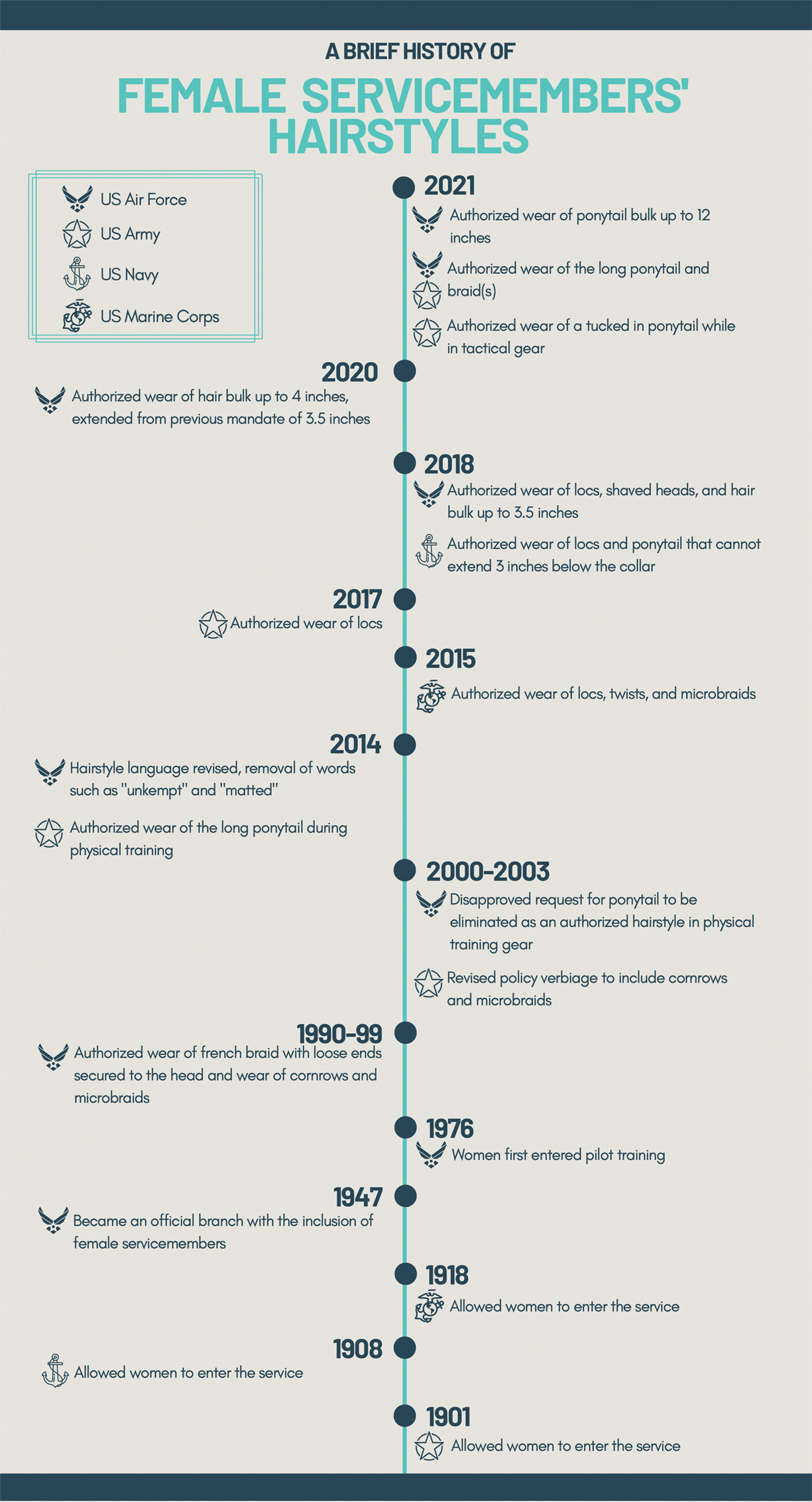

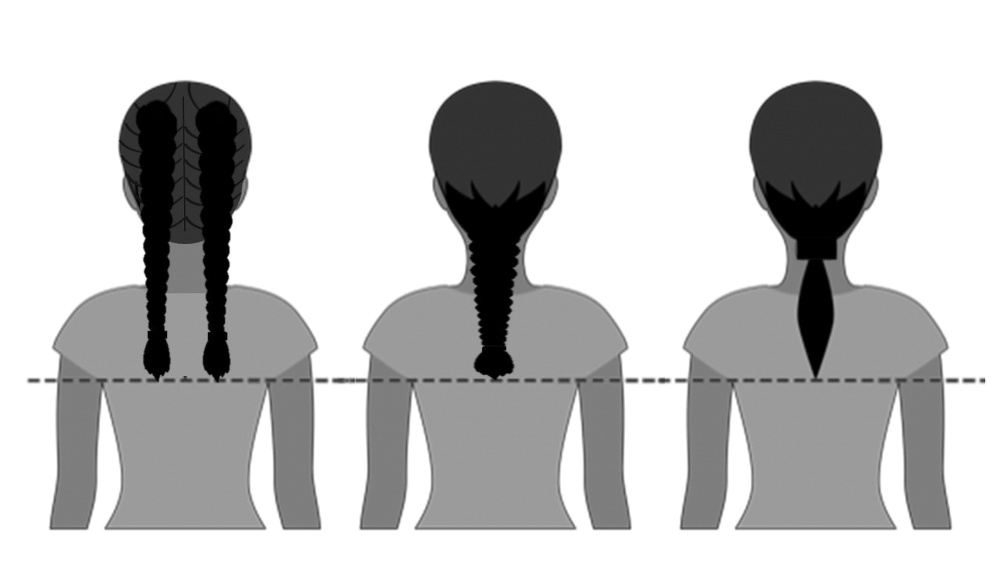

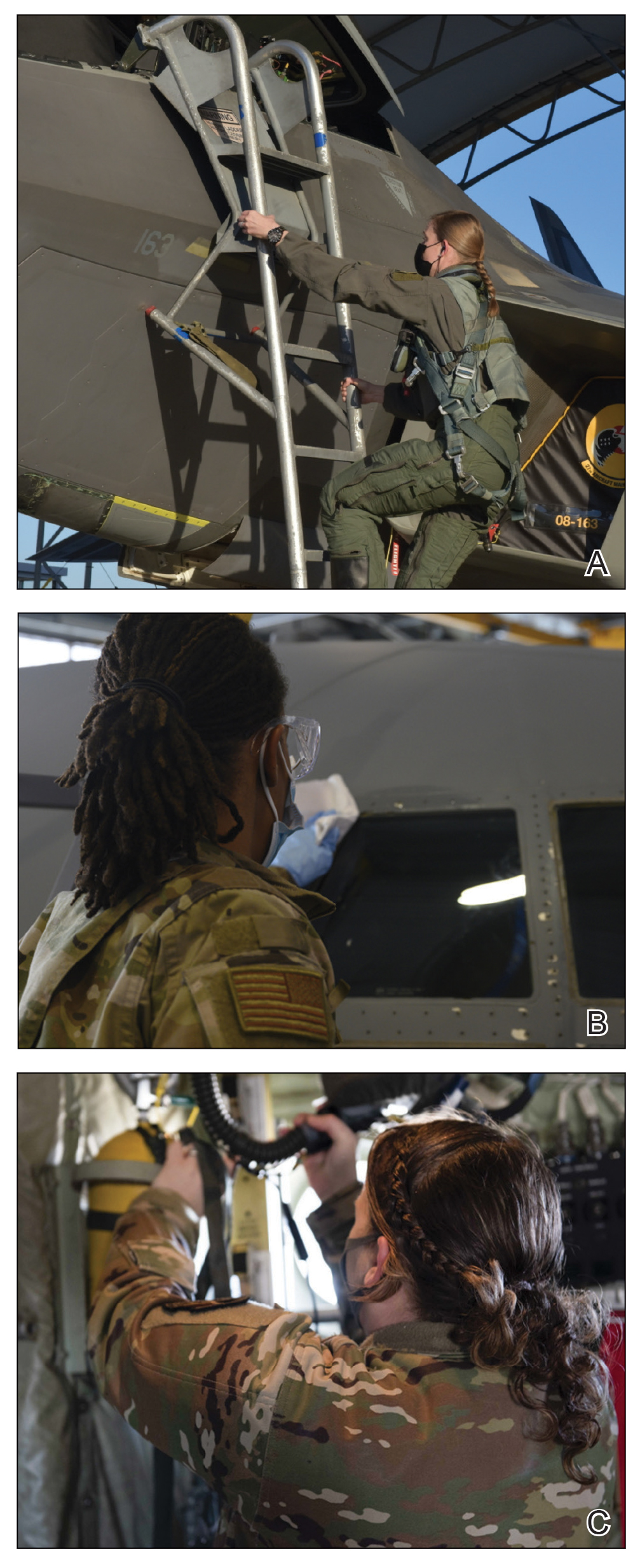

In the last decade alone, female servicemembers have witnessed the greatest number of changes in authorized hairstyles despite being part of the military for more than 50 years (Figure 1).1-11 In 2014, the language used in the air force instructions to describe locs was revised to remove ethnically offensive terms.4,5 This same year, the army allowed female soldiers to wear ponytails during physical training, a privilege that had been authorized by other services years prior.3,6,7 By the end of 2018, locs were authorized by all services, and female sailors could wear a ponytail in all navy uniforms as long as it did not extend 3 inches below the collar.3,4,6-8 In 2018, the air force increased authorized hair bulk up to 3.5 inches from the previous mandate of 3 inches and approved female buzz cuts6,9; in 2020, it allowed hair bulk up to 4 inches. As of 2021, female airmen can wear a ponytail and/or braid(s) as long as it starts below the crown of the head and the length does not extend below a horizontal line running between the top of each sleeve inseam at the underarm (Figures 2–4).6 In an ongoing effort to be more inclusive of hair density differences, female airmen will be authorized to wear a ponytail not exceeding a maximum width bulk of 1 ft starting June 25, 2021, so long as they can comply with the above regulations.11 The army now allows ponytails and braids across all uniforms, as long they do not extend past the bottom of the shoulder blades. This change came just months after authorizing the wearing of ponytails tucked under the uniform blouse with tactical headgear.10 These changes allow for a variety of hairstyles for members to practice while avoiding the physical consequences that develop from repetitive traction and pressure along the same areas of the hair and scalp.

Common Hair Disorders in Female Servicemembers

Herein, we discuss 3 of the most common hair and scalp disorders linked to grooming practices utilized by women to meet prior military regulations: trichorrhexis nodosa (TN), extracranial headaches, and traction alopecia (TA). It is essential that health care providers are able to promptly recognize these conditions, understand their risk factors, and be familiar with first-line treatment options. With these new standards, the hope is that the incidence of the following conditions decreases, thus improving servicemembers’ medical readiness and overall quality of life.

Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Acquired TN is a defect in the hair shaft that causes the hair to break easily secondary to chemical, thermal, or mechanical trauma. This can include but is not limited to chemical relaxers, blow-dryers, excessive brushing or styling, flat irons, and tightly packed hairstyles. The condition is characterized by a thickened hair diameter and splitting at the tip. Clinically, it may present as brittle, lusterless, broken hair with split ends, as well as a positive tug test.14 Management includes gentle hair care and avoidance of harsh hair care practices and treatments.

Extracranial Headaches

Headaches are a common concern among military servicemembers15 and generally are classified as primary or secondary. A less commonly discussed primary headache disorder includes external-pressure headaches, which result from either sustained compression or traction of the soft tissues of the scalp, usually from wearing headbands, helmets, or tight hairstyles.16 Additional at-risk groups include those who chronically wear surgical scrub caps or flight caps, especially if clipped or pinned to the hair. In our 38 years of combined military clinical experience, we can attest that these types of headaches are common among female servicemembers. The diagnostic criteria for an external-pressure headache, commonly referred to by patients as a “ponytail headache,” includes at least 2 headache episodes triggered within 1 hour of sustained traction on the scalp, maximal at the site of traction and resolving within 1 hour after relieving the traction.16 Management includes removal of the pressure-causing source, usually a tight ponytail or bun.

Traction Alopecia

Traction alopecia is hair loss caused by repetitive or prolonged tension on the hair secondary to tight hairstyles. It can be clinically classified into 2 types: marginal and nonmarginal patchy alopecia (Figure 5).13,17,18 Traction alopecia most commonly is found in individuals with ethnic hair, predominantly Black women. Hairstyles with the highest risk for causing TA include tight buns, ponytails, cornrows, weaves, and locs—all of which are utilized by female servicemembers to maintain a professional appearance and adhere to grooming regulations.13,18 Other groups at risk include athletes (eg, ballerinas, gymnasts) and those with chronic headwear use (eg, turbans, helmets, nurse caps, wigs).18 Early TA typically presents with perifollicular erythema followed by follicular-based papules or pustules.13,18 Marginal TA classically includes frontotemporal hair loss or thinning with or without a fringe sign.17,18 Nonmarginal TA includes patchy alopecia most commonly involving the parietal or occipital scalp, seen with chignons, buns, ponytails, or the use of clips, extensions, or bobby pins.18 The first line in management is avoidance of traction-causing hairstyles or headgear. Medical therapy may be warranted and consists of a single agent or combination regimen to include oral or topical antibiotics, topical or intralesional steroids, and topical minoxidil.13,18

Final Thoughts

Military hair-grooming standards have evolved over time. Recent changes show that the US Department of Defense is seriously evaluating policies that may be inherently exclusive. Prior grooming standards resulted in the widespread use of tight hairstyles and harsh hair treatments among female servicemembers with long hair. These practices resulted in TN, extracranial headaches, and TA, among other hair and scalp disorders. These occupational-related hair conditions impact female servicemembers’ mental and physical well-being and thus impact military readiness. Physicians should recognize that these conditions can be related to occupational grooming standards that may impact hair care practices.

The challenge that remains is a lack of standardized documentation for hair and scalp symptoms in the medical record. Due to a paucity in reporting and documentation, limited objective data exist to guide future recommendations for military grooming standards. Another obstacle is the lack of knowledge of hair diseases among primary care providers and patients, especially due to the underrepresentation of ethnic hair in medical textbooks.19 As a result, women frequently accept their hair symptoms as normal and either suffer through them, cut their hair short, or wear wigs before considering a visit to the doctor. Furthermore, hair-grooming standards can expose racial disparities, which are the driving force behind the current policy changes. Clinicians can strive to ask about hair and scalp symptoms and document the following in relation to hair and scalp disorders: occupational grooming requirements; skin and hair type; location, number, and size of scalp lesion(s); onset; duration; current and prior hair care practices; history of treatment; and clinical course accompanied with photographic documentation. Ultimately, improved awareness in patients, collaboration between physicians, and consistent clinical documentation can help create positive change and continued improvement in hair-grooming standards within the military. Improved reporting and documentation will facilitate further study into the effectiveness of the updated hair-grooming standards in female servicemembers.

- United States Air Force Statistical Digest FY 1999. United States Air Force; 2000. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://media.defense.gov/2011/Apr/14/2001330240/-1/-1/0/AFD-110414-048.pdf

- Air Force demographics. Air Force Personnel Center website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.afpc.af.mil/About/Air-Force-Demographics/

- US Department of the Army. Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia: Army Regulation 670-1. Department of the Army; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN30302-AR_670-1-000-WEB-1.pdf

- Losey S. Loc hairstyles, off-duty earrings for men ok’d in new dress regs. Air Force Times. Published July 16, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2018/07/16/loc-hairstyles-off-duty-earrings-for-men-okd-in-new-dress-regs/

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2011. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.uc.edu/content/dam/uc/afrotc/docs/Documents/AFI36-2903.pdf

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a1/publication/afi36-2903/afi36-2903.pdf

- U.S. Navy uniform regulations: summary of changes (26 February 2020). Navy Personnel Command website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Navy%20Uniforms/Uniform%20Regulations/Documents/SOC_2020_02_26.pdf?ver=y8Wd0ykVXgISfFpOy8qHkg%3d%3d

- US Headquarters Marine Corps. Marine Corps Uniform Regulations: Marine Corps Order 1020.34H. United States Marine Corps, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/MCO%201020.34H%20v2.pdf?ver=2018-06-26-094038-137

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force to allow longer braids, ponytails, bangs for women. United States Air Force website. Published January 21, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2478173/air-force-to-allow-longer-braids-ponytails-bangs-for-women/

- Britzky H. The Army will now allow women to wear ponytails in all uniforms. Task & Purpose. Published May 6, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://taskandpurpose.com/news/army-women-ponytails-all-uniforms/

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force readdresses women’s hair standard after feedback. US Air Force website. Published June 11, 2021. Accessed June 27, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2654774/air-force-readdresses-womens-hair-standard-after-feedback/

- Myers M. Esper direct services to review racial bias in grooming standards, training and more. Air Force Times. Published July 15, 2020. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-military/2020/07/15/esper-directs-services-to-review-racial-bias-in-grooming-standards-training-and-more/

- Madu P, Kundu RV. Follicular and scarring disorders in skin of color: presentation and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:307-321.

- Quaresma M, Martinez Velasco M, Tosti A. Hair breakage in patients of African descent: role of dermoscopy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:99-104.

- Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, et al. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015;55:21-34.

- Kararizou E, Bougea AM, Giotopoulou D, et al. An update on the less-known group of other primary headaches—a review. Eur Neurol Rev. 2014;9:71-77.

- Sperling L, Cowper S, Knopp E. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlations. CRC Press; 2012:67-68.

- Billero V, Miteva M. Traction alopecia: the root of the problem. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:149-159.

- Adelekun A, Onyekaba G, Lipoff JB. Skin color in dermatology textbooks: an updated evaluation and analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:194-196.

Professional appearance of servicemembers has been a long-standing custom in the US Military. Specific standards are determined by each branch. Initially, men dominated the military.1,2 As the number of women as well as racial diversity increased in the military, modifications to grooming standards were slow to change and resulted in female hair standards requiring a uniform tight and sleek style or short haircut. Clinicians can be attuned to these occupational standards and their implications on the diagnosis and management of common diseases of the hair and scalp.

History of Hairstyle Standards for Female Servicemembers

For half a century, female servicemembers had limited hairstyle choices. They were not authorized to have hair shorter than one-quarter inch in length. They could choose either short hair worn down or long hair with neatly secured loose ends in the form of a bun or a tucked braid—both of which could not extend past the bottom edge of the uniform collar.3-5 Female navy sailors and air force airmen with long hair were only allowed to wear ponytails during physical training; however, army soldiers previously were limited to wearing a bun.3,6,7 Cornrows and microbraids were authorized in the mid-1990s for the US Air Force, but policy stated that locs were prohibited due to their “unkempt” and “matted” nature. Furthermore, the size of hair bulk in the air force was restricted to no more than 3 inches and could not obstruct wear of the uniform cap.5 Based on these regulations, female servicemembers with longer hair had to utilize tight hairstyles that caused prolonged traction and pressure along the scalp, which contributed to headaches, a sore scalp, and alopecia over time. Normalization of these symptoms led to underreporting, as women lived with the consequences or turned to shorter hairstyles.

In the last decade alone, female servicemembers have witnessed the greatest number of changes in authorized hairstyles despite being part of the military for more than 50 years (Figure 1).1-11 In 2014, the language used in the air force instructions to describe locs was revised to remove ethnically offensive terms.4,5 This same year, the army allowed female soldiers to wear ponytails during physical training, a privilege that had been authorized by other services years prior.3,6,7 By the end of 2018, locs were authorized by all services, and female sailors could wear a ponytail in all navy uniforms as long as it did not extend 3 inches below the collar.3,4,6-8 In 2018, the air force increased authorized hair bulk up to 3.5 inches from the previous mandate of 3 inches and approved female buzz cuts6,9; in 2020, it allowed hair bulk up to 4 inches. As of 2021, female airmen can wear a ponytail and/or braid(s) as long as it starts below the crown of the head and the length does not extend below a horizontal line running between the top of each sleeve inseam at the underarm (Figures 2–4).6 In an ongoing effort to be more inclusive of hair density differences, female airmen will be authorized to wear a ponytail not exceeding a maximum width bulk of 1 ft starting June 25, 2021, so long as they can comply with the above regulations.11 The army now allows ponytails and braids across all uniforms, as long they do not extend past the bottom of the shoulder blades. This change came just months after authorizing the wearing of ponytails tucked under the uniform blouse with tactical headgear.10 These changes allow for a variety of hairstyles for members to practice while avoiding the physical consequences that develop from repetitive traction and pressure along the same areas of the hair and scalp.

Common Hair Disorders in Female Servicemembers

Herein, we discuss 3 of the most common hair and scalp disorders linked to grooming practices utilized by women to meet prior military regulations: trichorrhexis nodosa (TN), extracranial headaches, and traction alopecia (TA). It is essential that health care providers are able to promptly recognize these conditions, understand their risk factors, and be familiar with first-line treatment options. With these new standards, the hope is that the incidence of the following conditions decreases, thus improving servicemembers’ medical readiness and overall quality of life.

Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Acquired TN is a defect in the hair shaft that causes the hair to break easily secondary to chemical, thermal, or mechanical trauma. This can include but is not limited to chemical relaxers, blow-dryers, excessive brushing or styling, flat irons, and tightly packed hairstyles. The condition is characterized by a thickened hair diameter and splitting at the tip. Clinically, it may present as brittle, lusterless, broken hair with split ends, as well as a positive tug test.14 Management includes gentle hair care and avoidance of harsh hair care practices and treatments.

Extracranial Headaches

Headaches are a common concern among military servicemembers15 and generally are classified as primary or secondary. A less commonly discussed primary headache disorder includes external-pressure headaches, which result from either sustained compression or traction of the soft tissues of the scalp, usually from wearing headbands, helmets, or tight hairstyles.16 Additional at-risk groups include those who chronically wear surgical scrub caps or flight caps, especially if clipped or pinned to the hair. In our 38 years of combined military clinical experience, we can attest that these types of headaches are common among female servicemembers. The diagnostic criteria for an external-pressure headache, commonly referred to by patients as a “ponytail headache,” includes at least 2 headache episodes triggered within 1 hour of sustained traction on the scalp, maximal at the site of traction and resolving within 1 hour after relieving the traction.16 Management includes removal of the pressure-causing source, usually a tight ponytail or bun.

Traction Alopecia

Traction alopecia is hair loss caused by repetitive or prolonged tension on the hair secondary to tight hairstyles. It can be clinically classified into 2 types: marginal and nonmarginal patchy alopecia (Figure 5).13,17,18 Traction alopecia most commonly is found in individuals with ethnic hair, predominantly Black women. Hairstyles with the highest risk for causing TA include tight buns, ponytails, cornrows, weaves, and locs—all of which are utilized by female servicemembers to maintain a professional appearance and adhere to grooming regulations.13,18 Other groups at risk include athletes (eg, ballerinas, gymnasts) and those with chronic headwear use (eg, turbans, helmets, nurse caps, wigs).18 Early TA typically presents with perifollicular erythema followed by follicular-based papules or pustules.13,18 Marginal TA classically includes frontotemporal hair loss or thinning with or without a fringe sign.17,18 Nonmarginal TA includes patchy alopecia most commonly involving the parietal or occipital scalp, seen with chignons, buns, ponytails, or the use of clips, extensions, or bobby pins.18 The first line in management is avoidance of traction-causing hairstyles or headgear. Medical therapy may be warranted and consists of a single agent or combination regimen to include oral or topical antibiotics, topical or intralesional steroids, and topical minoxidil.13,18

Final Thoughts

Military hair-grooming standards have evolved over time. Recent changes show that the US Department of Defense is seriously evaluating policies that may be inherently exclusive. Prior grooming standards resulted in the widespread use of tight hairstyles and harsh hair treatments among female servicemembers with long hair. These practices resulted in TN, extracranial headaches, and TA, among other hair and scalp disorders. These occupational-related hair conditions impact female servicemembers’ mental and physical well-being and thus impact military readiness. Physicians should recognize that these conditions can be related to occupational grooming standards that may impact hair care practices.

The challenge that remains is a lack of standardized documentation for hair and scalp symptoms in the medical record. Due to a paucity in reporting and documentation, limited objective data exist to guide future recommendations for military grooming standards. Another obstacle is the lack of knowledge of hair diseases among primary care providers and patients, especially due to the underrepresentation of ethnic hair in medical textbooks.19 As a result, women frequently accept their hair symptoms as normal and either suffer through them, cut their hair short, or wear wigs before considering a visit to the doctor. Furthermore, hair-grooming standards can expose racial disparities, which are the driving force behind the current policy changes. Clinicians can strive to ask about hair and scalp symptoms and document the following in relation to hair and scalp disorders: occupational grooming requirements; skin and hair type; location, number, and size of scalp lesion(s); onset; duration; current and prior hair care practices; history of treatment; and clinical course accompanied with photographic documentation. Ultimately, improved awareness in patients, collaboration between physicians, and consistent clinical documentation can help create positive change and continued improvement in hair-grooming standards within the military. Improved reporting and documentation will facilitate further study into the effectiveness of the updated hair-grooming standards in female servicemembers.

Professional appearance of servicemembers has been a long-standing custom in the US Military. Specific standards are determined by each branch. Initially, men dominated the military.1,2 As the number of women as well as racial diversity increased in the military, modifications to grooming standards were slow to change and resulted in female hair standards requiring a uniform tight and sleek style or short haircut. Clinicians can be attuned to these occupational standards and their implications on the diagnosis and management of common diseases of the hair and scalp.

History of Hairstyle Standards for Female Servicemembers

For half a century, female servicemembers had limited hairstyle choices. They were not authorized to have hair shorter than one-quarter inch in length. They could choose either short hair worn down or long hair with neatly secured loose ends in the form of a bun or a tucked braid—both of which could not extend past the bottom edge of the uniform collar.3-5 Female navy sailors and air force airmen with long hair were only allowed to wear ponytails during physical training; however, army soldiers previously were limited to wearing a bun.3,6,7 Cornrows and microbraids were authorized in the mid-1990s for the US Air Force, but policy stated that locs were prohibited due to their “unkempt” and “matted” nature. Furthermore, the size of hair bulk in the air force was restricted to no more than 3 inches and could not obstruct wear of the uniform cap.5 Based on these regulations, female servicemembers with longer hair had to utilize tight hairstyles that caused prolonged traction and pressure along the scalp, which contributed to headaches, a sore scalp, and alopecia over time. Normalization of these symptoms led to underreporting, as women lived with the consequences or turned to shorter hairstyles.

In the last decade alone, female servicemembers have witnessed the greatest number of changes in authorized hairstyles despite being part of the military for more than 50 years (Figure 1).1-11 In 2014, the language used in the air force instructions to describe locs was revised to remove ethnically offensive terms.4,5 This same year, the army allowed female soldiers to wear ponytails during physical training, a privilege that had been authorized by other services years prior.3,6,7 By the end of 2018, locs were authorized by all services, and female sailors could wear a ponytail in all navy uniforms as long as it did not extend 3 inches below the collar.3,4,6-8 In 2018, the air force increased authorized hair bulk up to 3.5 inches from the previous mandate of 3 inches and approved female buzz cuts6,9; in 2020, it allowed hair bulk up to 4 inches. As of 2021, female airmen can wear a ponytail and/or braid(s) as long as it starts below the crown of the head and the length does not extend below a horizontal line running between the top of each sleeve inseam at the underarm (Figures 2–4).6 In an ongoing effort to be more inclusive of hair density differences, female airmen will be authorized to wear a ponytail not exceeding a maximum width bulk of 1 ft starting June 25, 2021, so long as they can comply with the above regulations.11 The army now allows ponytails and braids across all uniforms, as long they do not extend past the bottom of the shoulder blades. This change came just months after authorizing the wearing of ponytails tucked under the uniform blouse with tactical headgear.10 These changes allow for a variety of hairstyles for members to practice while avoiding the physical consequences that develop from repetitive traction and pressure along the same areas of the hair and scalp.

Common Hair Disorders in Female Servicemembers

Herein, we discuss 3 of the most common hair and scalp disorders linked to grooming practices utilized by women to meet prior military regulations: trichorrhexis nodosa (TN), extracranial headaches, and traction alopecia (TA). It is essential that health care providers are able to promptly recognize these conditions, understand their risk factors, and be familiar with first-line treatment options. With these new standards, the hope is that the incidence of the following conditions decreases, thus improving servicemembers’ medical readiness and overall quality of life.

Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Acquired TN is a defect in the hair shaft that causes the hair to break easily secondary to chemical, thermal, or mechanical trauma. This can include but is not limited to chemical relaxers, blow-dryers, excessive brushing or styling, flat irons, and tightly packed hairstyles. The condition is characterized by a thickened hair diameter and splitting at the tip. Clinically, it may present as brittle, lusterless, broken hair with split ends, as well as a positive tug test.14 Management includes gentle hair care and avoidance of harsh hair care practices and treatments.

Extracranial Headaches

Headaches are a common concern among military servicemembers15 and generally are classified as primary or secondary. A less commonly discussed primary headache disorder includes external-pressure headaches, which result from either sustained compression or traction of the soft tissues of the scalp, usually from wearing headbands, helmets, or tight hairstyles.16 Additional at-risk groups include those who chronically wear surgical scrub caps or flight caps, especially if clipped or pinned to the hair. In our 38 years of combined military clinical experience, we can attest that these types of headaches are common among female servicemembers. The diagnostic criteria for an external-pressure headache, commonly referred to by patients as a “ponytail headache,” includes at least 2 headache episodes triggered within 1 hour of sustained traction on the scalp, maximal at the site of traction and resolving within 1 hour after relieving the traction.16 Management includes removal of the pressure-causing source, usually a tight ponytail or bun.

Traction Alopecia

Traction alopecia is hair loss caused by repetitive or prolonged tension on the hair secondary to tight hairstyles. It can be clinically classified into 2 types: marginal and nonmarginal patchy alopecia (Figure 5).13,17,18 Traction alopecia most commonly is found in individuals with ethnic hair, predominantly Black women. Hairstyles with the highest risk for causing TA include tight buns, ponytails, cornrows, weaves, and locs—all of which are utilized by female servicemembers to maintain a professional appearance and adhere to grooming regulations.13,18 Other groups at risk include athletes (eg, ballerinas, gymnasts) and those with chronic headwear use (eg, turbans, helmets, nurse caps, wigs).18 Early TA typically presents with perifollicular erythema followed by follicular-based papules or pustules.13,18 Marginal TA classically includes frontotemporal hair loss or thinning with or without a fringe sign.17,18 Nonmarginal TA includes patchy alopecia most commonly involving the parietal or occipital scalp, seen with chignons, buns, ponytails, or the use of clips, extensions, or bobby pins.18 The first line in management is avoidance of traction-causing hairstyles or headgear. Medical therapy may be warranted and consists of a single agent or combination regimen to include oral or topical antibiotics, topical or intralesional steroids, and topical minoxidil.13,18

Final Thoughts

Military hair-grooming standards have evolved over time. Recent changes show that the US Department of Defense is seriously evaluating policies that may be inherently exclusive. Prior grooming standards resulted in the widespread use of tight hairstyles and harsh hair treatments among female servicemembers with long hair. These practices resulted in TN, extracranial headaches, and TA, among other hair and scalp disorders. These occupational-related hair conditions impact female servicemembers’ mental and physical well-being and thus impact military readiness. Physicians should recognize that these conditions can be related to occupational grooming standards that may impact hair care practices.

The challenge that remains is a lack of standardized documentation for hair and scalp symptoms in the medical record. Due to a paucity in reporting and documentation, limited objective data exist to guide future recommendations for military grooming standards. Another obstacle is the lack of knowledge of hair diseases among primary care providers and patients, especially due to the underrepresentation of ethnic hair in medical textbooks.19 As a result, women frequently accept their hair symptoms as normal and either suffer through them, cut their hair short, or wear wigs before considering a visit to the doctor. Furthermore, hair-grooming standards can expose racial disparities, which are the driving force behind the current policy changes. Clinicians can strive to ask about hair and scalp symptoms and document the following in relation to hair and scalp disorders: occupational grooming requirements; skin and hair type; location, number, and size of scalp lesion(s); onset; duration; current and prior hair care practices; history of treatment; and clinical course accompanied with photographic documentation. Ultimately, improved awareness in patients, collaboration between physicians, and consistent clinical documentation can help create positive change and continued improvement in hair-grooming standards within the military. Improved reporting and documentation will facilitate further study into the effectiveness of the updated hair-grooming standards in female servicemembers.

- United States Air Force Statistical Digest FY 1999. United States Air Force; 2000. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://media.defense.gov/2011/Apr/14/2001330240/-1/-1/0/AFD-110414-048.pdf

- Air Force demographics. Air Force Personnel Center website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.afpc.af.mil/About/Air-Force-Demographics/

- US Department of the Army. Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia: Army Regulation 670-1. Department of the Army; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN30302-AR_670-1-000-WEB-1.pdf

- Losey S. Loc hairstyles, off-duty earrings for men ok’d in new dress regs. Air Force Times. Published July 16, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2018/07/16/loc-hairstyles-off-duty-earrings-for-men-okd-in-new-dress-regs/

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2011. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.uc.edu/content/dam/uc/afrotc/docs/Documents/AFI36-2903.pdf

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a1/publication/afi36-2903/afi36-2903.pdf

- U.S. Navy uniform regulations: summary of changes (26 February 2020). Navy Personnel Command website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Navy%20Uniforms/Uniform%20Regulations/Documents/SOC_2020_02_26.pdf?ver=y8Wd0ykVXgISfFpOy8qHkg%3d%3d

- US Headquarters Marine Corps. Marine Corps Uniform Regulations: Marine Corps Order 1020.34H. United States Marine Corps, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/MCO%201020.34H%20v2.pdf?ver=2018-06-26-094038-137

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force to allow longer braids, ponytails, bangs for women. United States Air Force website. Published January 21, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2478173/air-force-to-allow-longer-braids-ponytails-bangs-for-women/

- Britzky H. The Army will now allow women to wear ponytails in all uniforms. Task & Purpose. Published May 6, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://taskandpurpose.com/news/army-women-ponytails-all-uniforms/

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force readdresses women’s hair standard after feedback. US Air Force website. Published June 11, 2021. Accessed June 27, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2654774/air-force-readdresses-womens-hair-standard-after-feedback/

- Myers M. Esper direct services to review racial bias in grooming standards, training and more. Air Force Times. Published July 15, 2020. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-military/2020/07/15/esper-directs-services-to-review-racial-bias-in-grooming-standards-training-and-more/

- Madu P, Kundu RV. Follicular and scarring disorders in skin of color: presentation and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:307-321.

- Quaresma M, Martinez Velasco M, Tosti A. Hair breakage in patients of African descent: role of dermoscopy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:99-104.

- Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, et al. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015;55:21-34.

- Kararizou E, Bougea AM, Giotopoulou D, et al. An update on the less-known group of other primary headaches—a review. Eur Neurol Rev. 2014;9:71-77.

- Sperling L, Cowper S, Knopp E. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlations. CRC Press; 2012:67-68.

- Billero V, Miteva M. Traction alopecia: the root of the problem. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:149-159.

- Adelekun A, Onyekaba G, Lipoff JB. Skin color in dermatology textbooks: an updated evaluation and analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:194-196.

- United States Air Force Statistical Digest FY 1999. United States Air Force; 2000. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://media.defense.gov/2011/Apr/14/2001330240/-1/-1/0/AFD-110414-048.pdf

- Air Force demographics. Air Force Personnel Center website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.afpc.af.mil/About/Air-Force-Demographics/

- US Department of the Army. Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia: Army Regulation 670-1. Department of the Army; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN30302-AR_670-1-000-WEB-1.pdf

- Losey S. Loc hairstyles, off-duty earrings for men ok’d in new dress regs. Air Force Times. Published July 16, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2018/07/16/loc-hairstyles-off-duty-earrings-for-men-okd-in-new-dress-regs/

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2011. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.uc.edu/content/dam/uc/afrotc/docs/Documents/AFI36-2903.pdf

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a1/publication/afi36-2903/afi36-2903.pdf

- U.S. Navy uniform regulations: summary of changes (26 February 2020). Navy Personnel Command website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Navy%20Uniforms/Uniform%20Regulations/Documents/SOC_2020_02_26.pdf?ver=y8Wd0ykVXgISfFpOy8qHkg%3d%3d

- US Headquarters Marine Corps. Marine Corps Uniform Regulations: Marine Corps Order 1020.34H. United States Marine Corps, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/MCO%201020.34H%20v2.pdf?ver=2018-06-26-094038-137

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force to allow longer braids, ponytails, bangs for women. United States Air Force website. Published January 21, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2478173/air-force-to-allow-longer-braids-ponytails-bangs-for-women/

- Britzky H. The Army will now allow women to wear ponytails in all uniforms. Task & Purpose. Published May 6, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://taskandpurpose.com/news/army-women-ponytails-all-uniforms/

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force readdresses women’s hair standard after feedback. US Air Force website. Published June 11, 2021. Accessed June 27, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2654774/air-force-readdresses-womens-hair-standard-after-feedback/

- Myers M. Esper direct services to review racial bias in grooming standards, training and more. Air Force Times. Published July 15, 2020. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-military/2020/07/15/esper-directs-services-to-review-racial-bias-in-grooming-standards-training-and-more/

- Madu P, Kundu RV. Follicular and scarring disorders in skin of color: presentation and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:307-321.

- Quaresma M, Martinez Velasco M, Tosti A. Hair breakage in patients of African descent: role of dermoscopy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:99-104.

- Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, et al. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015;55:21-34.

- Kararizou E, Bougea AM, Giotopoulou D, et al. An update on the less-known group of other primary headaches—a review. Eur Neurol Rev. 2014;9:71-77.

- Sperling L, Cowper S, Knopp E. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlations. CRC Press; 2012:67-68.

- Billero V, Miteva M. Traction alopecia: the root of the problem. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:149-159.

- Adelekun A, Onyekaba G, Lipoff JB. Skin color in dermatology textbooks: an updated evaluation and analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:194-196.

Practice Points

- Military hair-grooming standards have undergone considerable changes to foster inclusivity and acknowledge racial diversity in hair and skin types.

- The chronic wearing of tight hairstyles can lead to hair breakage, headaches, and traction alopecia.

- A deliberate focus on diversity and inclusivity has started to drive policy change that eliminates racial and gender bias.