User login

Painful Fungating Perianal Mass

The Diagnosis: Condyloma Latum

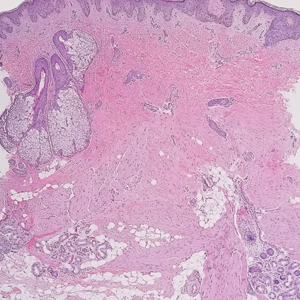

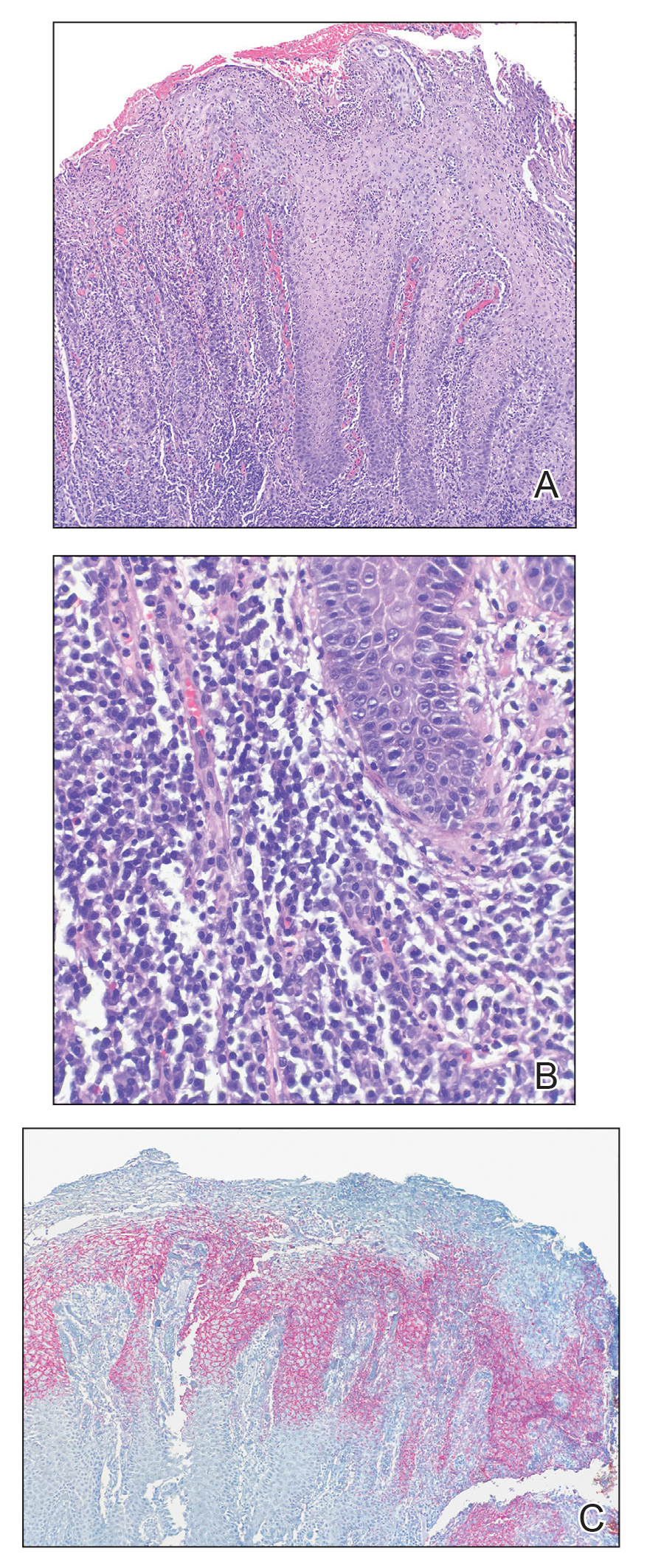

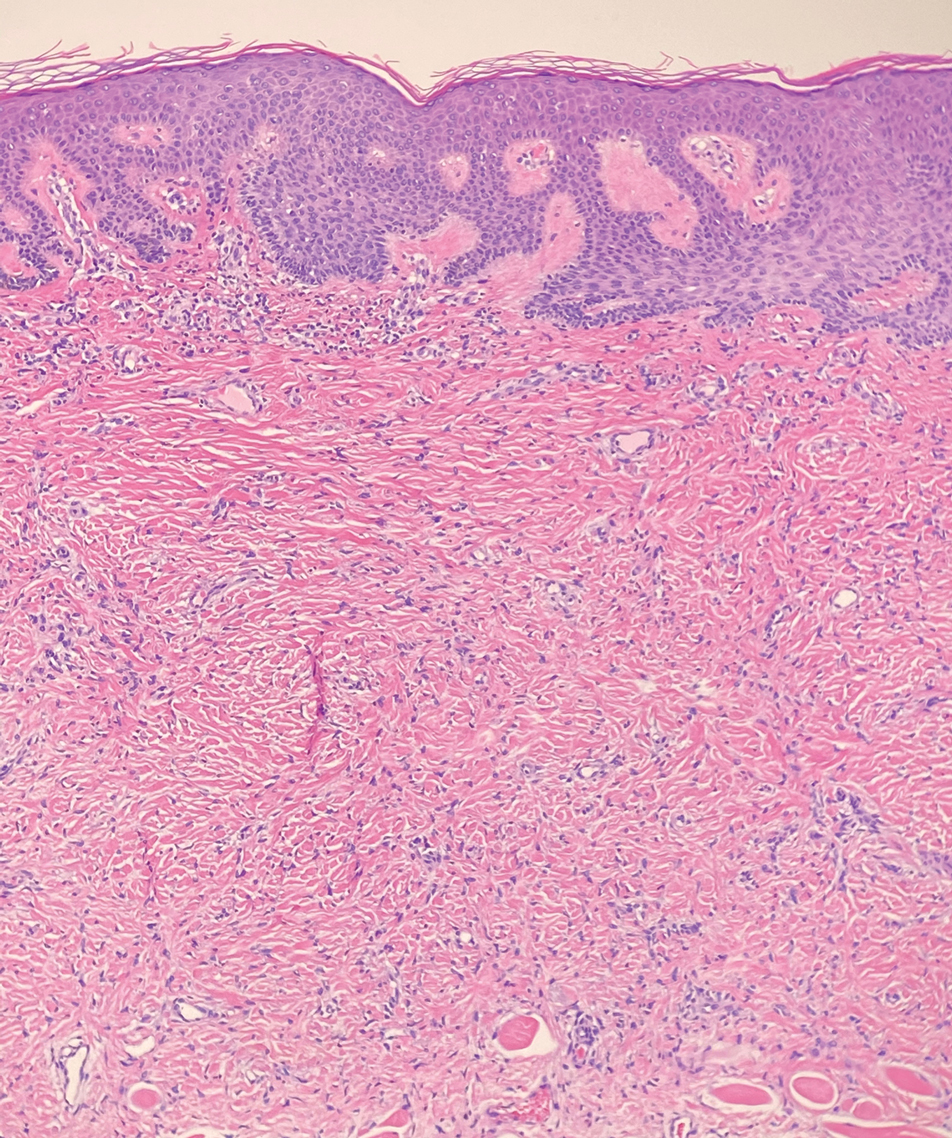

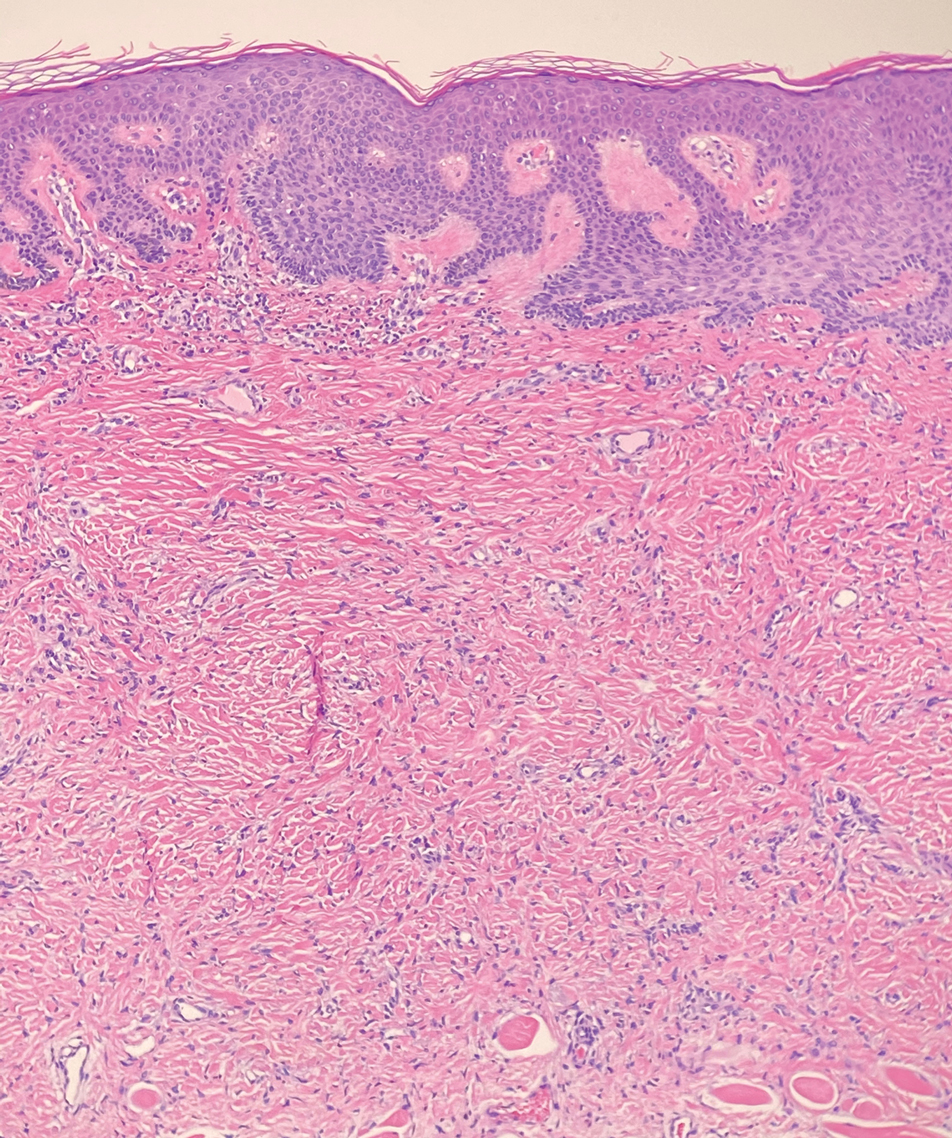

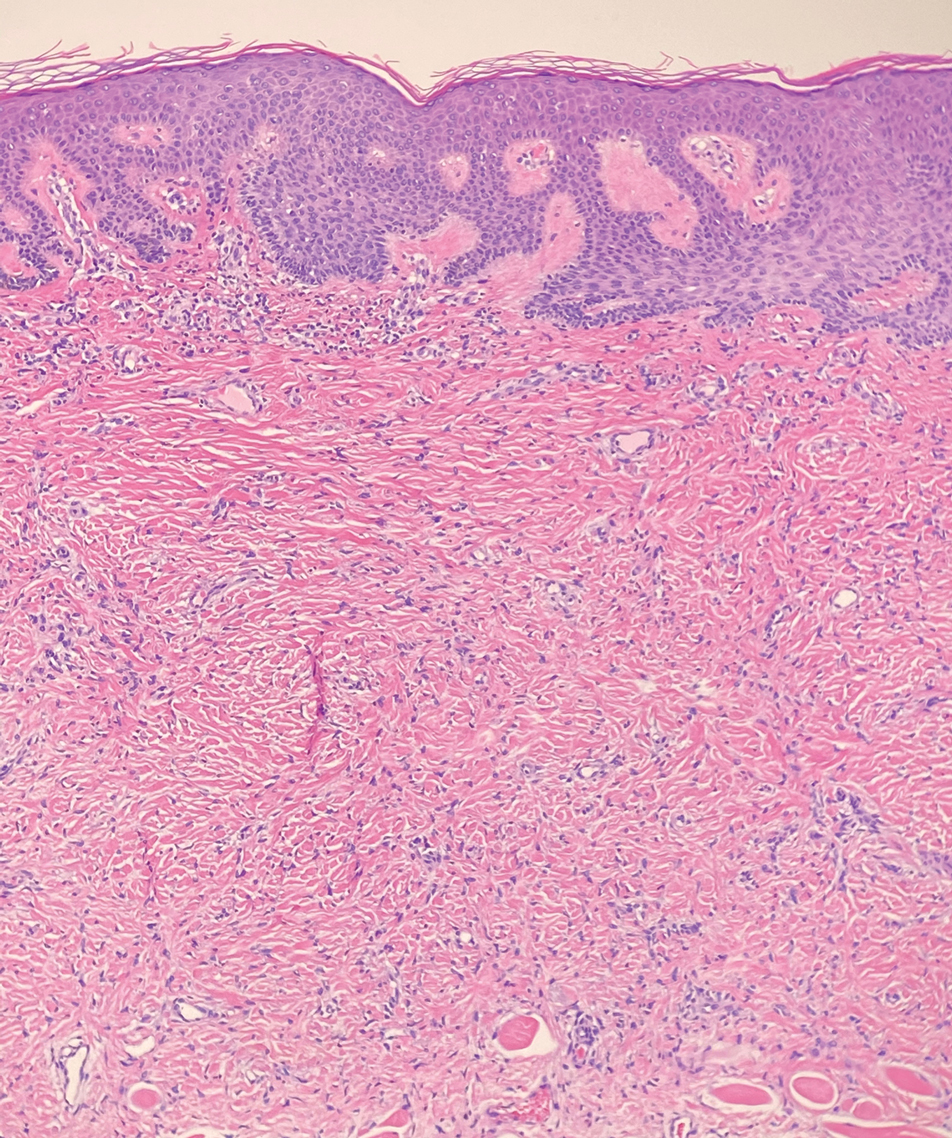

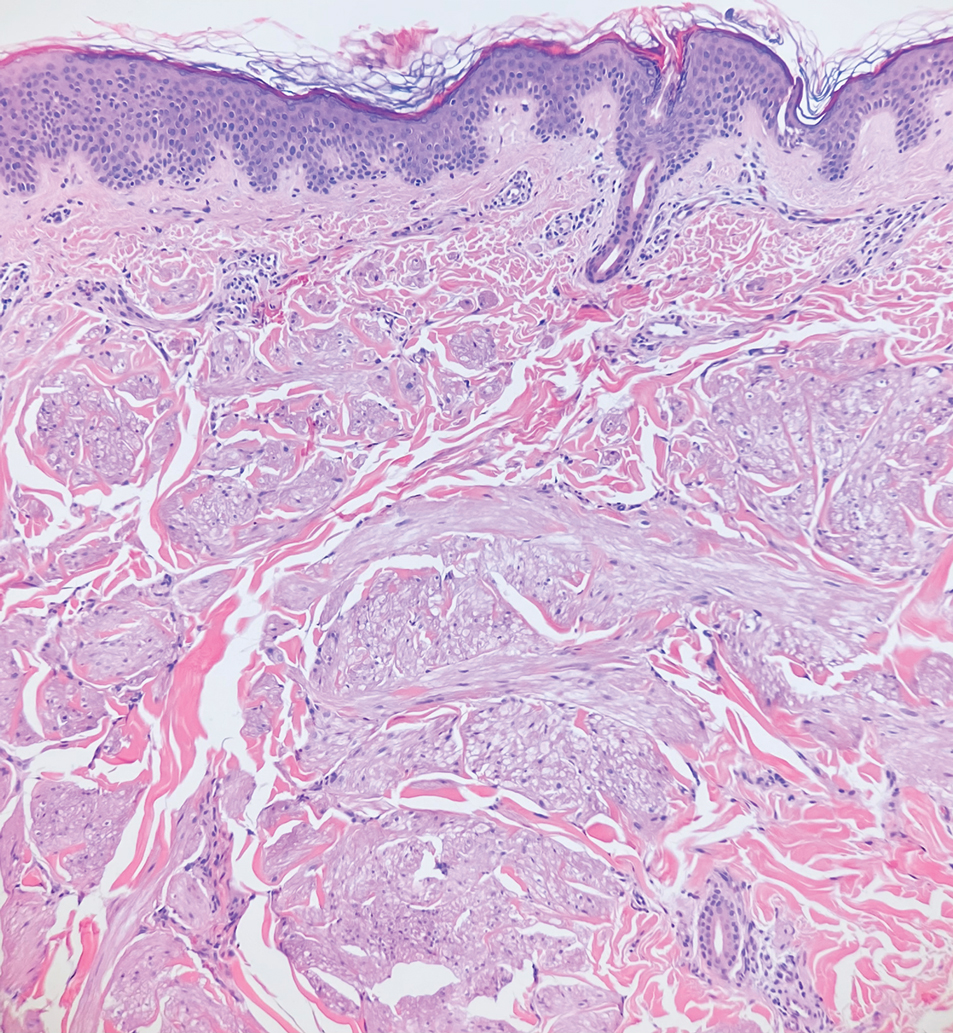

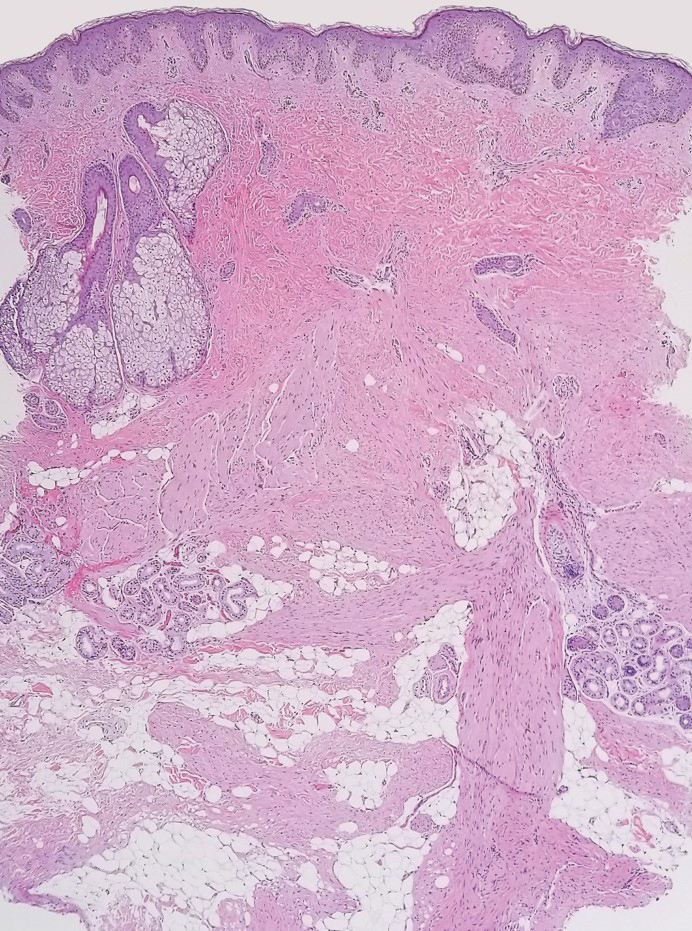

A punch biopsy of the perianal mass revealed epidermal acanthosis with elongated slender rete ridges, scattered intraepidermal neutrophils, and a dense dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure, A) with a prominent plasma cell component (Figure, B). A treponemal immunohistochemical stain revealed numerous coiled spirochetes concentrated in the lower epidermis (Figure, C). Serologic test results including rapid plasma reagin (titer 1:1024) and Treponema pallidum antibody were reactive, confirming the diagnosis of secondary syphilis with condyloma latum. The patient was treated with intramuscular penicillin G with resolution of the lesion 2 weeks later.

Syphilis, a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete T pallidum, reached historically low rates in the United States in the early 2000s due to the widespread use of penicillin and effective public health efforts.1 However, the rates of primary and secondary syphilis infections recently have markedly increased, resulting in the current epidemic of syphilis in the United States and Europe.1,2 Its wide variety of clinical and histopathologic manifestations make recognition challenging and lend it the moniker “the great imitator.”

Secondary syphilis results from the systemic spread of T pallidum and classically is characterized by the triad of a skin rash that frequently involves the palms and soles, mucosal ulceration such as condyloma latum, and lymphadenopathy.2,3 However, condyloma latum may represent the only manifestation of secondary syphilis in a subset of patients,4 as observed in our patient.

In the 2 months prior to diagnosis, our patient was evaluated at multiple emergency departments and primary care clinics, receiving diagnoses of condyloma acuminatum, genital herpes simplex virus, hemorrhoids, and suspicion for malignancy—entities that comprise the differential diagnosis for condyloma latum.2,5 Despite some degree of overlap in patient populations, risk factors, and presentations between these diagnostic considerations, recognition of certain clinical features, in addition to histopathologic evaluation, may facilitate navigation of this differential diagnosis.

Primary and secondary syphilis infections have been predominantly observed in men, mostly men who have sex with men and/or those who are infected with HIV.1 Condyloma acuminata, genital herpes simplex virus, and chancroid also are seen in younger individuals, more commonly in those with multiple sexual partners, but show a more even gender distribution and are not restricted to those partaking in anal intercourse. The clinical presentation of condyloma latum can be differentiated by its painless, flat, smooth, and commonly hypopigmented appearance, often with associated surface erosion and a gray exudate, in contrast to condyloma acuminatum, which typically presents as nontender, flesh-colored or hyperpigmented, exophytic papules that may coalesce into plaques.2,3,6 Genital herpes simplex virus infection presents with multiple small papulovesicular lesions with ulceration, most commonly on the tip or shaft of the penis, though perianal lesions may be seen in men who have sex with men.7 Similarly, chancroid presents with painful necrotizing genital ulcers most commonly on the penis, though perianal lesions also may be seen.8 Hemorrhoids classically are seen in middle-aged adults with a history of constipation, present with rectal bleeding, and may be associated with pain in the setting of thrombosis or ulceration.9 Finally, perianal squamous cell carcinoma primarily occurs in older adults, typically in the sixth decade of life. Verrucous carcinoma most commonly arises in the oropharynx or anogenital region in sites of chronic irritation and presents as a slow-growing exophytic mass. Classic squamous cell carcinoma most commonly occurs in association with human papillomavirus infection and presents with scaly erythematous papules or plaques.10

Our case highlighted the clinical difficulty in recognizing condyloma latum, as this lesion remained undiagnosed for 2 months, and our patient presumptively was treated for multiple perianal pathologies prior to a biopsy being performed. Due to the clinical similarity of various perianal lesions, the diagnosis of condyloma latum should be considered, and serologic studies should be performed in fitting clinical contexts, especially in light of recently rising rates of syphilis infection.1,2

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Tayal S, Shaban F, Dasgupta K, et al. A case of syphilitic anal condylomata lata mimicking malignancy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015; 17:69-71.

- Aung PP, Wimmer DB, Lester TR, et al. Perianal condylomata lata mimicking carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:209-214.

- Pourang A, Fung MA, Tartar D, et al. Condyloma lata in secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:18-21.

- Bruins FG, van Deudekom FJ, de Vries HJ. Syphilitic condylomata lata mimicking anogenital warts. BMJ. 2015;350:h1259.

- Leslie SW, Sajjad H, Kumar S. Genital warts. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Groves MJ. Genital herpes: a review. Am Fam Physician. 2016; 93:928-934.

- Irizarry L, Velasquez J, Wray AA. Chancroid. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Mounsey AL, Halladay J, Sadiq TS. Hemorrhoids. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:204-210.

- Abbass MA, Valente MA. Premalignant and malignant perianal lesions. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32:386-393.

The Diagnosis: Condyloma Latum

A punch biopsy of the perianal mass revealed epidermal acanthosis with elongated slender rete ridges, scattered intraepidermal neutrophils, and a dense dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure, A) with a prominent plasma cell component (Figure, B). A treponemal immunohistochemical stain revealed numerous coiled spirochetes concentrated in the lower epidermis (Figure, C). Serologic test results including rapid plasma reagin (titer 1:1024) and Treponema pallidum antibody were reactive, confirming the diagnosis of secondary syphilis with condyloma latum. The patient was treated with intramuscular penicillin G with resolution of the lesion 2 weeks later.

Syphilis, a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete T pallidum, reached historically low rates in the United States in the early 2000s due to the widespread use of penicillin and effective public health efforts.1 However, the rates of primary and secondary syphilis infections recently have markedly increased, resulting in the current epidemic of syphilis in the United States and Europe.1,2 Its wide variety of clinical and histopathologic manifestations make recognition challenging and lend it the moniker “the great imitator.”

Secondary syphilis results from the systemic spread of T pallidum and classically is characterized by the triad of a skin rash that frequently involves the palms and soles, mucosal ulceration such as condyloma latum, and lymphadenopathy.2,3 However, condyloma latum may represent the only manifestation of secondary syphilis in a subset of patients,4 as observed in our patient.

In the 2 months prior to diagnosis, our patient was evaluated at multiple emergency departments and primary care clinics, receiving diagnoses of condyloma acuminatum, genital herpes simplex virus, hemorrhoids, and suspicion for malignancy—entities that comprise the differential diagnosis for condyloma latum.2,5 Despite some degree of overlap in patient populations, risk factors, and presentations between these diagnostic considerations, recognition of certain clinical features, in addition to histopathologic evaluation, may facilitate navigation of this differential diagnosis.

Primary and secondary syphilis infections have been predominantly observed in men, mostly men who have sex with men and/or those who are infected with HIV.1 Condyloma acuminata, genital herpes simplex virus, and chancroid also are seen in younger individuals, more commonly in those with multiple sexual partners, but show a more even gender distribution and are not restricted to those partaking in anal intercourse. The clinical presentation of condyloma latum can be differentiated by its painless, flat, smooth, and commonly hypopigmented appearance, often with associated surface erosion and a gray exudate, in contrast to condyloma acuminatum, which typically presents as nontender, flesh-colored or hyperpigmented, exophytic papules that may coalesce into plaques.2,3,6 Genital herpes simplex virus infection presents with multiple small papulovesicular lesions with ulceration, most commonly on the tip or shaft of the penis, though perianal lesions may be seen in men who have sex with men.7 Similarly, chancroid presents with painful necrotizing genital ulcers most commonly on the penis, though perianal lesions also may be seen.8 Hemorrhoids classically are seen in middle-aged adults with a history of constipation, present with rectal bleeding, and may be associated with pain in the setting of thrombosis or ulceration.9 Finally, perianal squamous cell carcinoma primarily occurs in older adults, typically in the sixth decade of life. Verrucous carcinoma most commonly arises in the oropharynx or anogenital region in sites of chronic irritation and presents as a slow-growing exophytic mass. Classic squamous cell carcinoma most commonly occurs in association with human papillomavirus infection and presents with scaly erythematous papules or plaques.10

Our case highlighted the clinical difficulty in recognizing condyloma latum, as this lesion remained undiagnosed for 2 months, and our patient presumptively was treated for multiple perianal pathologies prior to a biopsy being performed. Due to the clinical similarity of various perianal lesions, the diagnosis of condyloma latum should be considered, and serologic studies should be performed in fitting clinical contexts, especially in light of recently rising rates of syphilis infection.1,2

The Diagnosis: Condyloma Latum

A punch biopsy of the perianal mass revealed epidermal acanthosis with elongated slender rete ridges, scattered intraepidermal neutrophils, and a dense dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure, A) with a prominent plasma cell component (Figure, B). A treponemal immunohistochemical stain revealed numerous coiled spirochetes concentrated in the lower epidermis (Figure, C). Serologic test results including rapid plasma reagin (titer 1:1024) and Treponema pallidum antibody were reactive, confirming the diagnosis of secondary syphilis with condyloma latum. The patient was treated with intramuscular penicillin G with resolution of the lesion 2 weeks later.

Syphilis, a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete T pallidum, reached historically low rates in the United States in the early 2000s due to the widespread use of penicillin and effective public health efforts.1 However, the rates of primary and secondary syphilis infections recently have markedly increased, resulting in the current epidemic of syphilis in the United States and Europe.1,2 Its wide variety of clinical and histopathologic manifestations make recognition challenging and lend it the moniker “the great imitator.”

Secondary syphilis results from the systemic spread of T pallidum and classically is characterized by the triad of a skin rash that frequently involves the palms and soles, mucosal ulceration such as condyloma latum, and lymphadenopathy.2,3 However, condyloma latum may represent the only manifestation of secondary syphilis in a subset of patients,4 as observed in our patient.

In the 2 months prior to diagnosis, our patient was evaluated at multiple emergency departments and primary care clinics, receiving diagnoses of condyloma acuminatum, genital herpes simplex virus, hemorrhoids, and suspicion for malignancy—entities that comprise the differential diagnosis for condyloma latum.2,5 Despite some degree of overlap in patient populations, risk factors, and presentations between these diagnostic considerations, recognition of certain clinical features, in addition to histopathologic evaluation, may facilitate navigation of this differential diagnosis.

Primary and secondary syphilis infections have been predominantly observed in men, mostly men who have sex with men and/or those who are infected with HIV.1 Condyloma acuminata, genital herpes simplex virus, and chancroid also are seen in younger individuals, more commonly in those with multiple sexual partners, but show a more even gender distribution and are not restricted to those partaking in anal intercourse. The clinical presentation of condyloma latum can be differentiated by its painless, flat, smooth, and commonly hypopigmented appearance, often with associated surface erosion and a gray exudate, in contrast to condyloma acuminatum, which typically presents as nontender, flesh-colored or hyperpigmented, exophytic papules that may coalesce into plaques.2,3,6 Genital herpes simplex virus infection presents with multiple small papulovesicular lesions with ulceration, most commonly on the tip or shaft of the penis, though perianal lesions may be seen in men who have sex with men.7 Similarly, chancroid presents with painful necrotizing genital ulcers most commonly on the penis, though perianal lesions also may be seen.8 Hemorrhoids classically are seen in middle-aged adults with a history of constipation, present with rectal bleeding, and may be associated with pain in the setting of thrombosis or ulceration.9 Finally, perianal squamous cell carcinoma primarily occurs in older adults, typically in the sixth decade of life. Verrucous carcinoma most commonly arises in the oropharynx or anogenital region in sites of chronic irritation and presents as a slow-growing exophytic mass. Classic squamous cell carcinoma most commonly occurs in association with human papillomavirus infection and presents with scaly erythematous papules or plaques.10

Our case highlighted the clinical difficulty in recognizing condyloma latum, as this lesion remained undiagnosed for 2 months, and our patient presumptively was treated for multiple perianal pathologies prior to a biopsy being performed. Due to the clinical similarity of various perianal lesions, the diagnosis of condyloma latum should be considered, and serologic studies should be performed in fitting clinical contexts, especially in light of recently rising rates of syphilis infection.1,2

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Tayal S, Shaban F, Dasgupta K, et al. A case of syphilitic anal condylomata lata mimicking malignancy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015; 17:69-71.

- Aung PP, Wimmer DB, Lester TR, et al. Perianal condylomata lata mimicking carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:209-214.

- Pourang A, Fung MA, Tartar D, et al. Condyloma lata in secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:18-21.

- Bruins FG, van Deudekom FJ, de Vries HJ. Syphilitic condylomata lata mimicking anogenital warts. BMJ. 2015;350:h1259.

- Leslie SW, Sajjad H, Kumar S. Genital warts. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Groves MJ. Genital herpes: a review. Am Fam Physician. 2016; 93:928-934.

- Irizarry L, Velasquez J, Wray AA. Chancroid. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Mounsey AL, Halladay J, Sadiq TS. Hemorrhoids. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:204-210.

- Abbass MA, Valente MA. Premalignant and malignant perianal lesions. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32:386-393.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Tayal S, Shaban F, Dasgupta K, et al. A case of syphilitic anal condylomata lata mimicking malignancy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015; 17:69-71.

- Aung PP, Wimmer DB, Lester TR, et al. Perianal condylomata lata mimicking carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:209-214.

- Pourang A, Fung MA, Tartar D, et al. Condyloma lata in secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:18-21.

- Bruins FG, van Deudekom FJ, de Vries HJ. Syphilitic condylomata lata mimicking anogenital warts. BMJ. 2015;350:h1259.

- Leslie SW, Sajjad H, Kumar S. Genital warts. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Groves MJ. Genital herpes: a review. Am Fam Physician. 2016; 93:928-934.

- Irizarry L, Velasquez J, Wray AA. Chancroid. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Mounsey AL, Halladay J, Sadiq TS. Hemorrhoids. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:204-210.

- Abbass MA, Valente MA. Premalignant and malignant perianal lesions. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32:386-393.

A 21-year-old man presented to our clinic with rectal pain of 2 months’ duration that occurred in association with bowel movements and rectal bleeding in the setting of constipation. The patient’s symptoms had persisted despite multiple clinical encounters and treatment with sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, clotrimazole, valacyclovir, topical hydrocortisone and pramoxine, topical lidocaine, imiquimod, and psyllium seed. The patient denied engaging in receptive anal intercourse and had no notable medical or surgical history. Physical examination revealed a 6-cm hypopigmented fungating mass on the left gluteal cleft just external to the anal verge; there were no other abnormal findings. The patient denied any other systemic symptoms.

Tender Subcutaneous Nodule in a Prepubescent Boy

The Diagnosis: Dermatomyofibroma

Dermatomyofibroma is an uncommon, benign, cutaneous mesenchymal neoplasm composed of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.1-3 This skin tumor was first described in 1991 by Hugel4 in the German literature as plaquelike fibromatosis. Pediatric dermatomyofibromas are exceedingly rare, with pediatric patients ranging in age from infants to teenagers.1

Clinically, dermatomyofibromas appear as long-standing, isolated, ill-demarcated, flesh-colored, slightly hyperpigmented or erythematous nodules or plaques that may be raised or indurated.1 Dermatomyofibromas may present with constant mild pain or pruritus, though in most cases the lesions are asymptomatic.1,3 The clinical presentation of dermatomyofibroma has a few distinct differences in children compared to adults. In adulthood, dermatomyofibroma has a strong female predominance and most commonly is located on the shoulder and adjacent upper body regions, including the axilla, neck, upper arm, and upper trunk.1-3 In childhood, the majority of dermatomyofibromas occur in young boys and usually are located on the neck with other upper body regions occurring less frequently.1,2 A shared characteristic includes the tendency for dermatomyofibromas to have an initial period of enlargement followed by stabilization or slow growth.1 Reported pediatric lesions have ranged in size from 4 to 60 mm with an average size of 14.9 mm (median, 12 mm).2

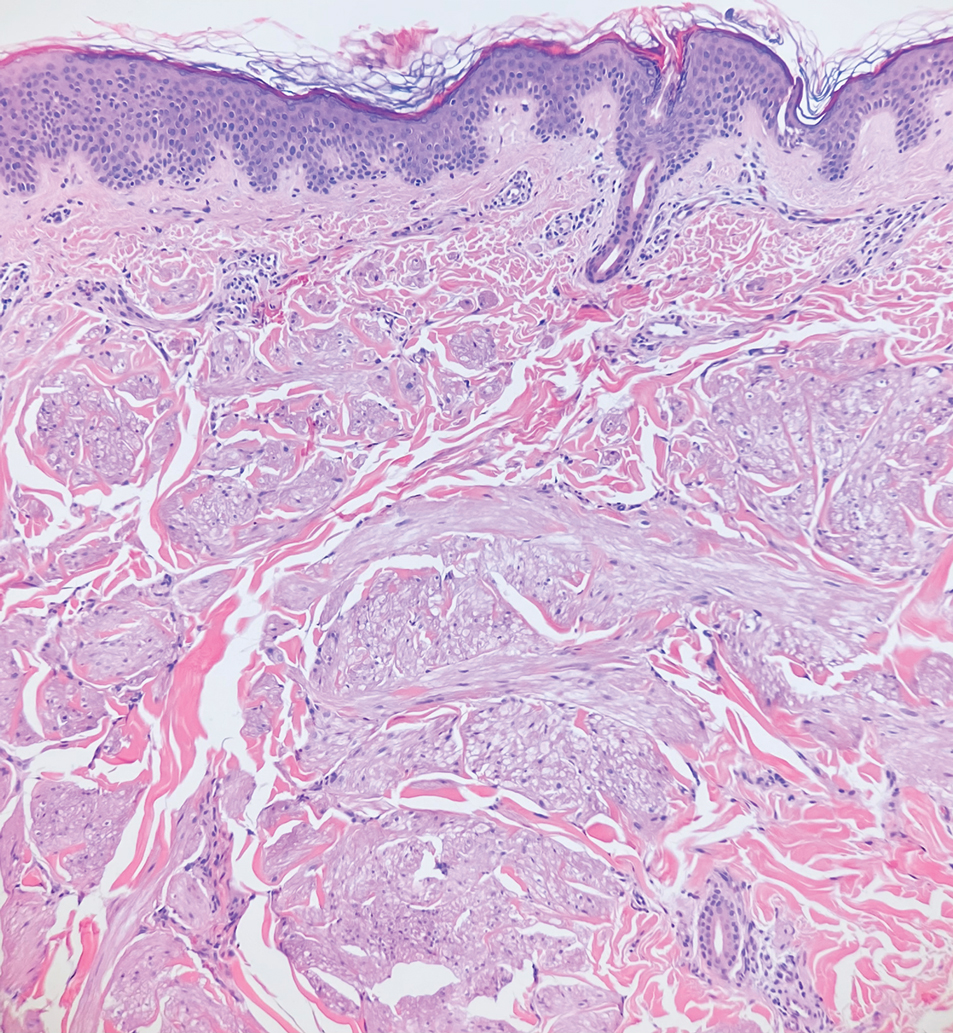

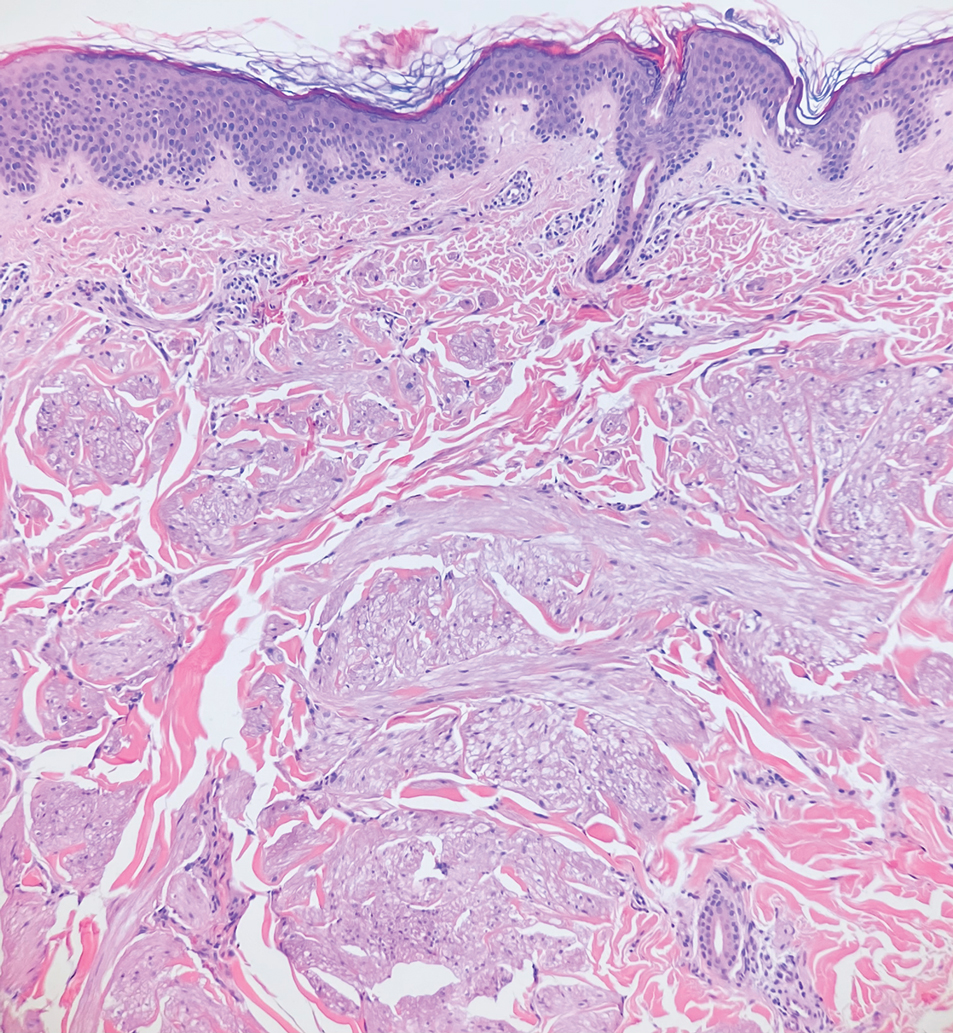

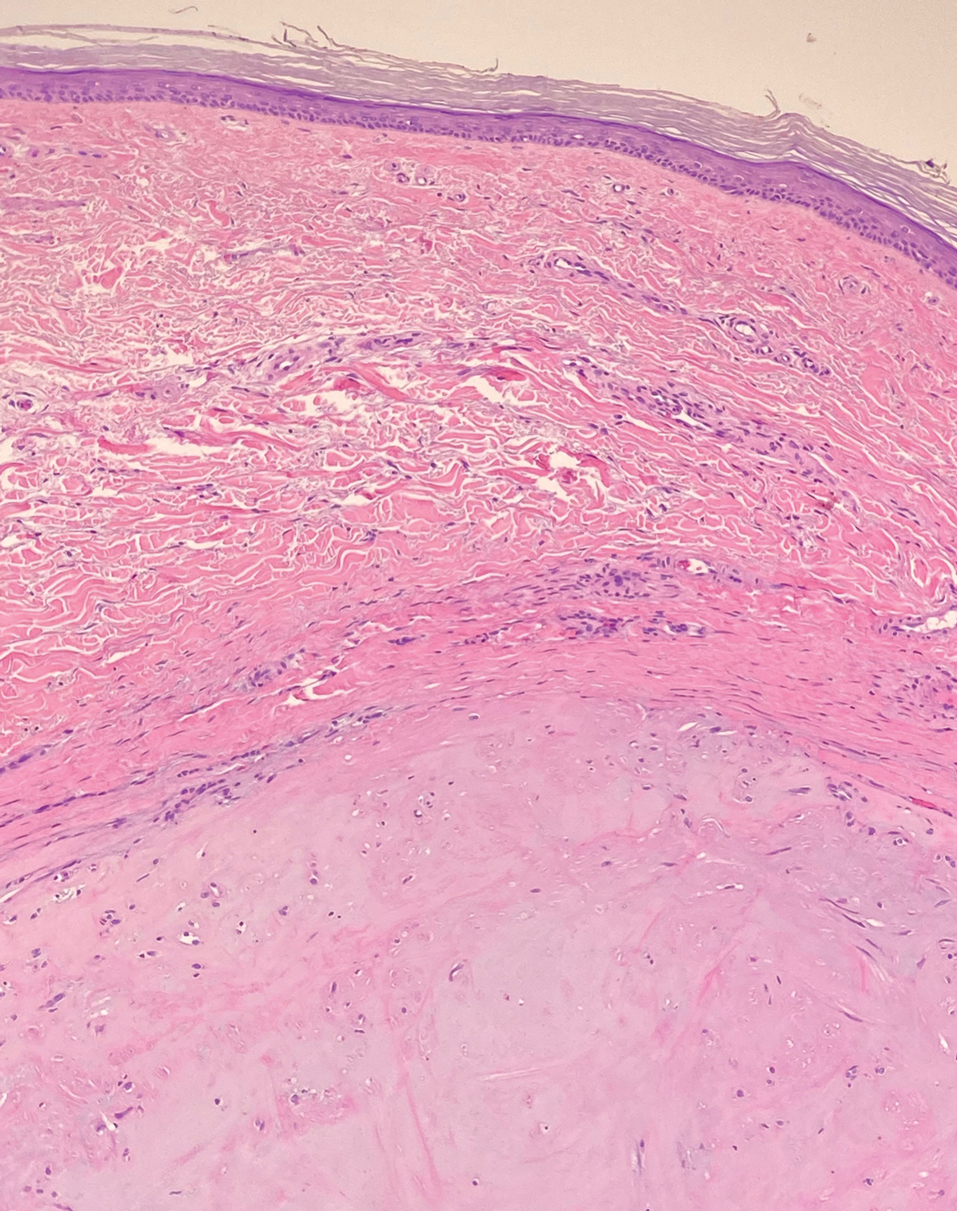

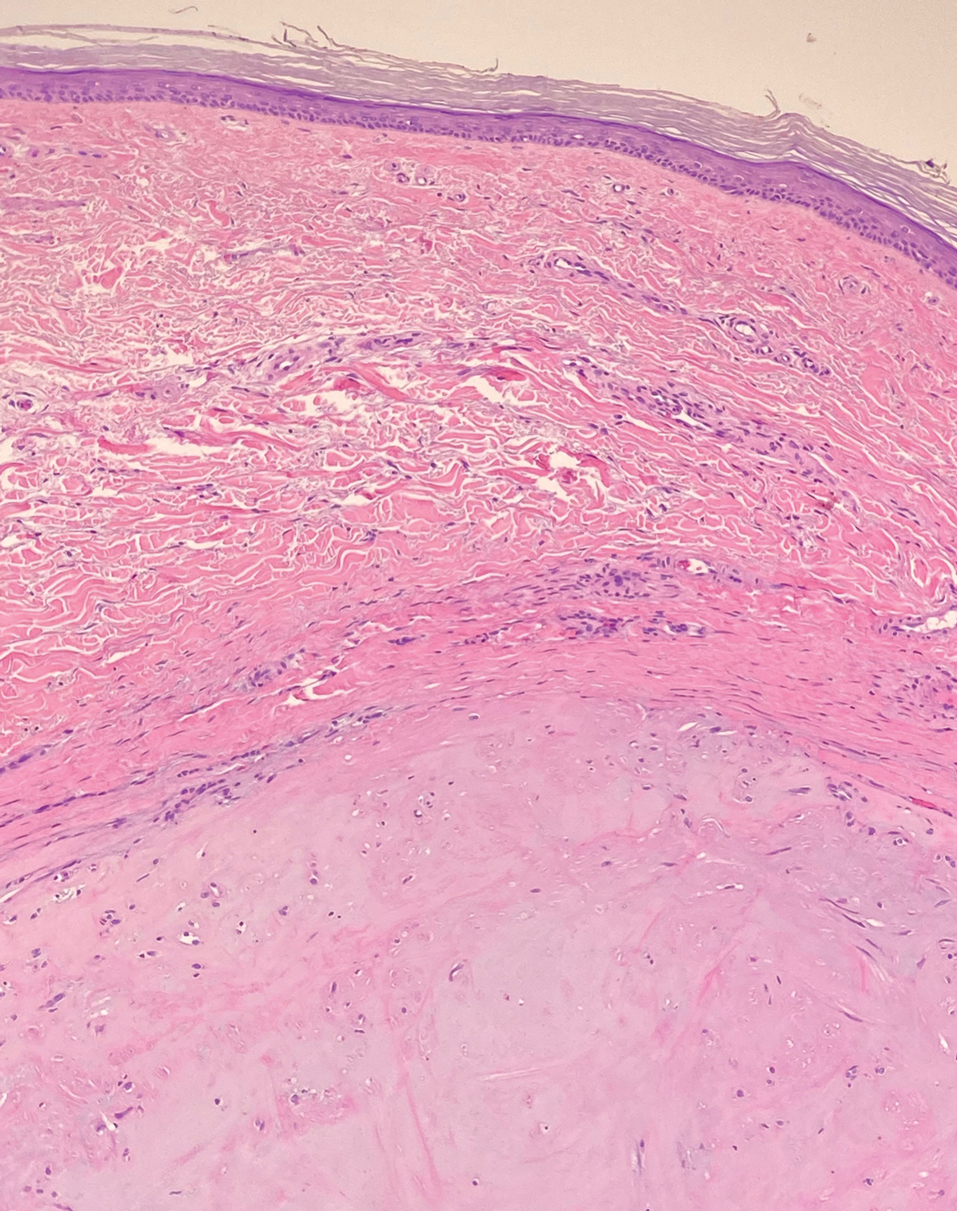

The diagnosis of dermatomyofibroma is based on histopathologic features in addition to clinical presentation. Histology from punch biopsy usually reveals a noninvasive dermal proliferation of bland, uniform, slender spindle cells oriented parallel to the overlying epidermis with increased and fragmented elastic fibers.1,3 Infiltration into the mid or deep dermis is common. The adnexal structures usually are spared; the stroma contains collagen and increased small blood vessels; and there typically is no inflammatory infiltrate, except for occasional scattered mast cells.2 Cytologically, the monomorphic spindleshaped tumor cells have an ill-defined, pale, eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclei that are elongated with tapered edges.3 Dermatomyofibroma has a variable immunohistochemical profile, as it may stain focally positive for CD34 or smooth muscle actin, with occasional staining of factor XIIIa, desmin, calponin, or vimentin.1-3 Normal to increased levels of often fragmented elastic fibers is a helpful clue in distinguishing dermatomyofibroma from dermatofibroma, hypertrophic scar, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and pilar leiomyoma, in which elastic fibers typically are reduced.3 Differential diagnoses of mesenchymal tumors in children include desmoid fibromatosis, connective tissue nevus, myofibromatosis, and smooth muscle hamartoma.1

A punch biopsy with clinical observation and followup is recommended for the management of lesions in cosmetically sensitive areas or in very young children who may not tolerate surgery. In symptomatic or cosmetically unappealing cases of dermatomyofibroma, simple surgical excision remains a viable treatment option. Recurrence is uncommon, even if only partially excised, and no instances of metastasis have been reported.1-5

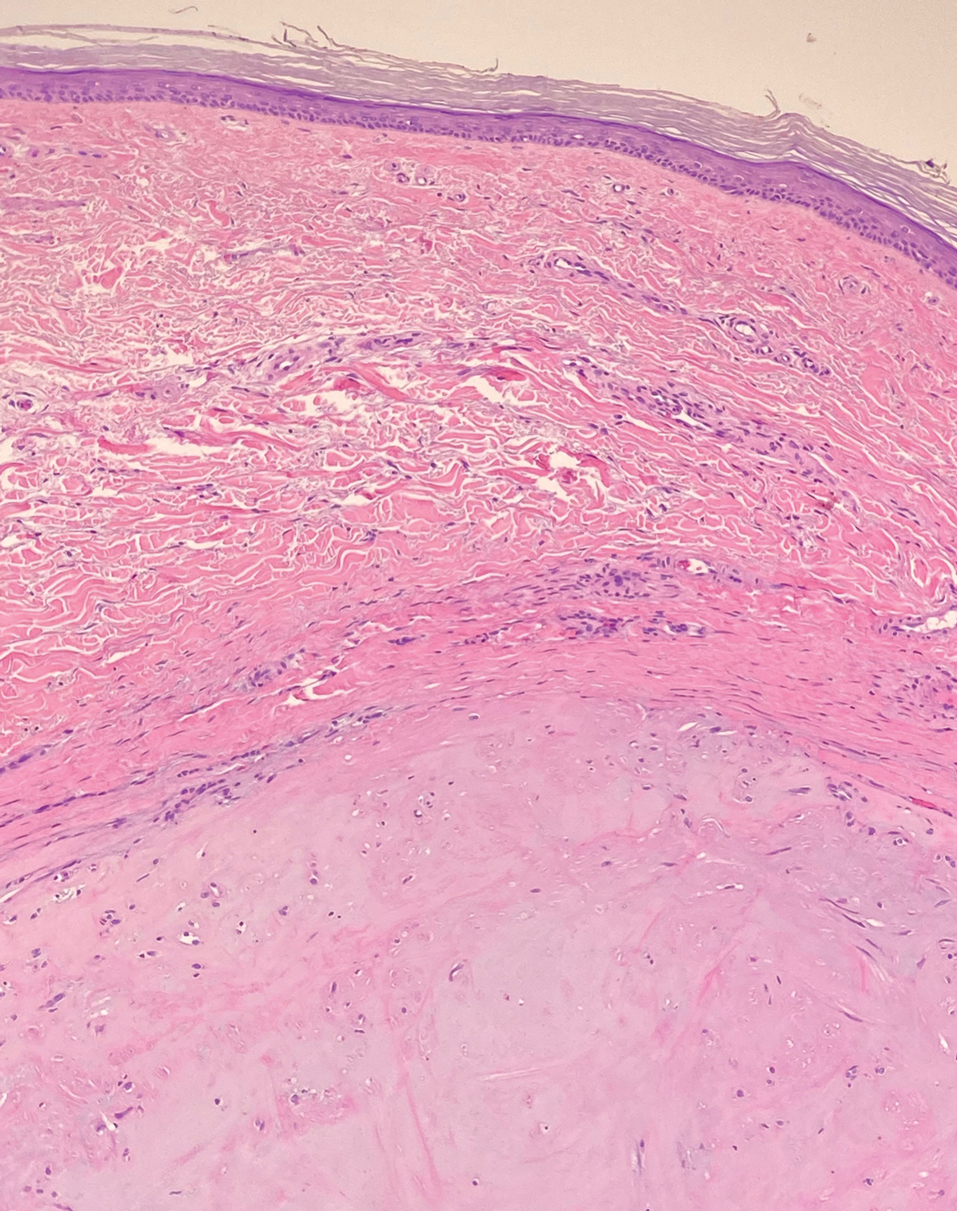

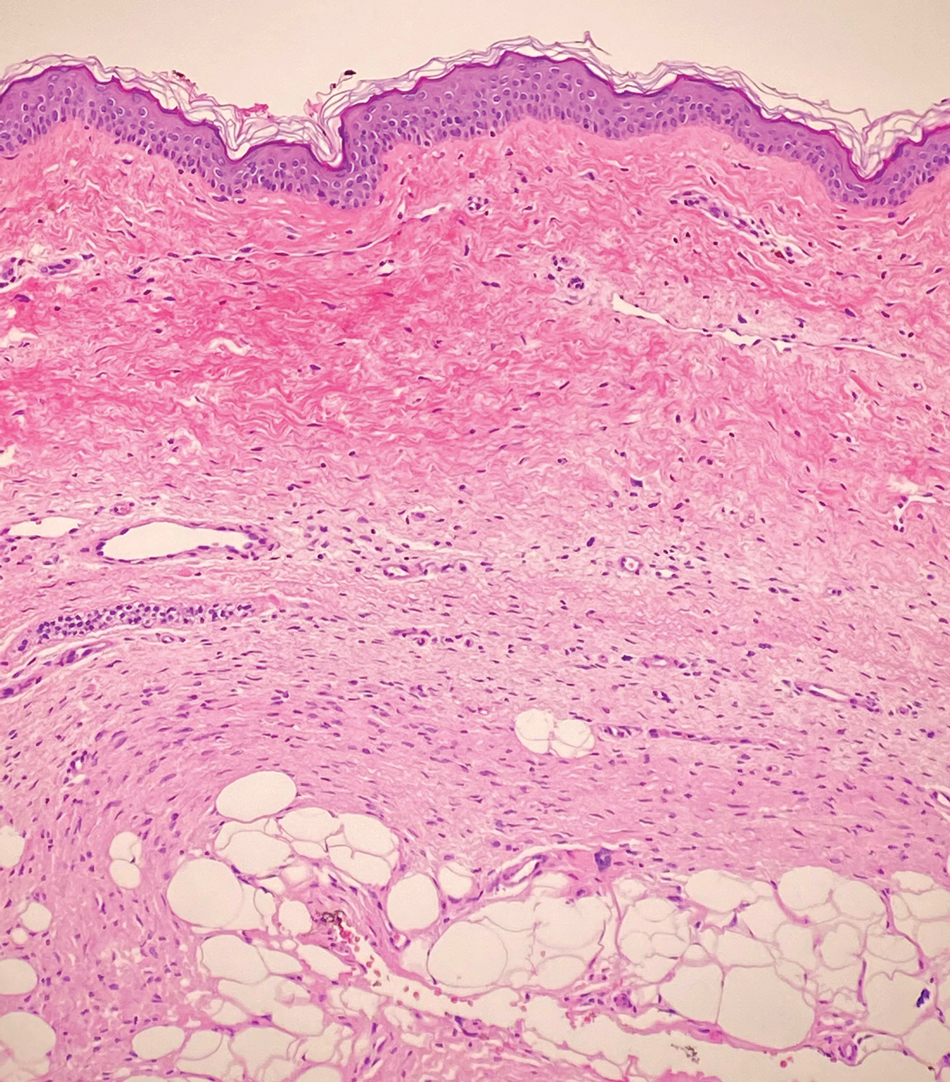

Dermatomyofibromas may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant. For example, the benign dermatofibroma is the second most common fibrohistiocytic tumor of the skin and presents as a firm, nontender, minimally elevated to dome-shaped papule that usually measures less than or equal to 1 cm in diameter with or without overlying skin changes.5,6 It primarily is seen in adults with a slight female predominance and favors the lower extremities.5 Patients usually are asymptomatic but often report a history of local trauma at the lesion site.6 Histologically, dermatofibroma is characterized by a nodular dermal proliferation of spindleshaped fibrous cells and histiocytes in a storiform pattern (Figure 1).6 Epidermal induction with acanthosis overlying the tumor often is found with occasional basilar hyperpigmentation.5 Dermatofibroma also characteristically has trapped collagen (“collagen balls”) seen at the periphery.5,6

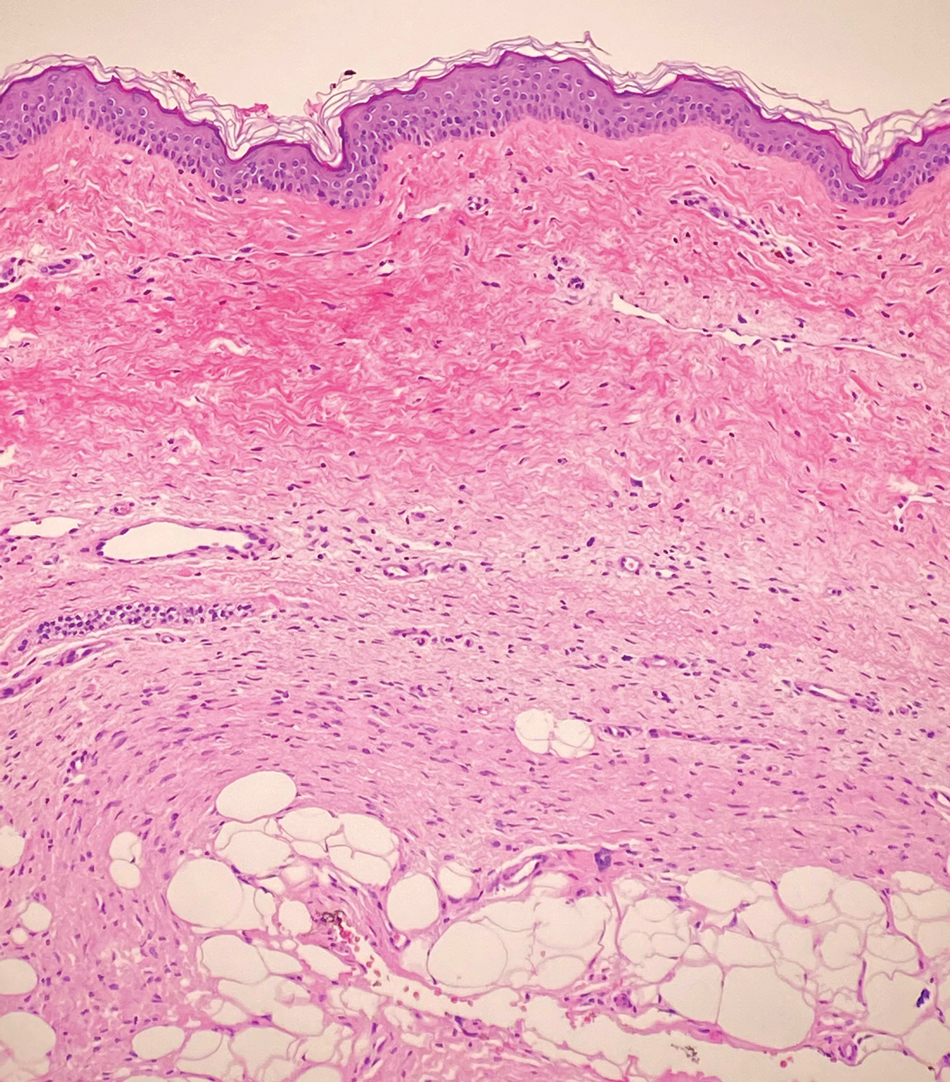

Piloleiomyomas are benign smooth muscle tumors arising from arrector pili muscles that may be solitary or multiple.5 Clinically, they typically present as firm, reddish-brown to flesh-colored papules or nodules that develop more commonly in adulthood.5,7 Piloleiomyomas favor the extremities and trunk, particularly the shoulder, and can be associated with spontaneous or induced pain. Histologically, piloleiomyomas are well circumscribed and centered within the reticular dermis situated closely to hair follicles (Figure 2).5 They are composed of numerous interlacing fascicles or whorls of smooth muscle cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and blunt-ended, cigar-shaped nuclei.5,7

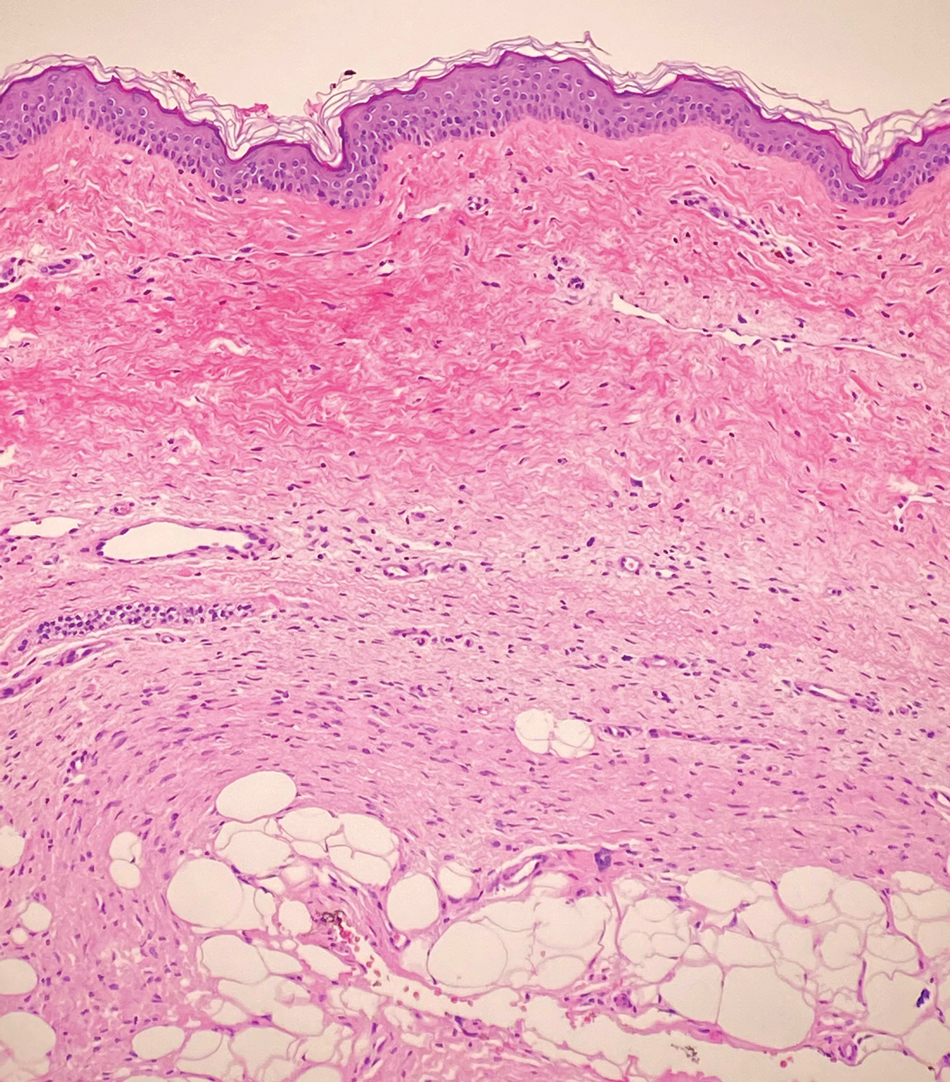

Solitary cutaneous myofibroma is a benign fibrous tumor found in adolescents and adults and is the counterpart to infantile myofibromatosis.8 Clinically, myofibromas typically present as painless, slow-growing, firm nodules with an occasional bluish hue. Histologically, solitary cutaneous myofibromas appear in a biphasic pattern, with hemangiopericytomatous components as well as spindle cells arranged in short bundles and fascicles resembling leiomyoma (Figure 3). The spindle cells also have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with short plump nuclei; the random, irregularly intersecting angles can be used to help differentiate myofibromas from smooth muscle lesions.8 Solitary cutaneous myofibroma is in the differential diagnosis for dermatomyofibroma because of their shared myofibroblastic nature.9

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is an uncommon, locally invasive sarcoma with a high recurrence rate that favors young to middle-aged adults, with rare childhood onset reported.5,10,11 Clinically, DFSP typically presents as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, firm, flesh-colored, indurated plaque that develops into a violaceous to reddish-brown nodule.5 The atrophic variant of DFSP is characterized by a nonprotuberant lesion and can be especially difficult to distinguish from other entities such as dermatomyofibroma.11 The majority of DFSP lesions occur on the trunk, particularly in the shoulder or pelvic region.5 Histologically, early plaque lesions are comprised of monomorphic spindle cells arranged in long fascicles (parallel to the skin surface), infiltrating adnexal structures, and subcutaneous adipocytes in a multilayered honeycomb pattern; the spindle cells of late nodular lesions are arranged in short fascicles in a matted or storiform pattern (Figure 4).5,10 Early stages of DFSP as well as variations in childhood-onset DFSP can easily be misdiagnosed and incompletely excised.5

- Ma JE, Wieland CN, Tollefson MM. Dermatomyofibromas arising in children: report of two new cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:347-351.

- Tardio JC, Azorin D, Hernandez-Nunez A, et al. Dermatomyofibromas presenting in pediatric patients: clinicopathologic characteristics and differential diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:967-972.

- Mentzel T, Kutzner H. Dermatomyofibroma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 56 cases and reappraisal of a rare and distinct cutaneous neoplasm. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:44-49.

- Hugel H. Plaque-like dermal fibromatosis. Hautarzt. 1991;42:223-226.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. WB Saunders Co; 2012.

- Myers DJ, Fillman EP. Dermatofibroma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Dilek N, Yuksel D, Sehitoglu I, et al. Cutaneous leiomyoma in a child: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:1163-1164.

- Roh HS, Paek JO, Yu HJ, et al. Solitary cutaneous myofibroma on the sole: an unusual localization. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:220-222.

- Weedon D, Strutton G, Rubin AI, et al. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

- Mendenhall WM, Zlotecki RA, Scarborough MT. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Cancer. 2004;101:2503-2508.

- Akay BN, Unlu E, Erdem C, et al. Dermatoscopic findings of atrophic dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:71-73.

The Diagnosis: Dermatomyofibroma

Dermatomyofibroma is an uncommon, benign, cutaneous mesenchymal neoplasm composed of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.1-3 This skin tumor was first described in 1991 by Hugel4 in the German literature as plaquelike fibromatosis. Pediatric dermatomyofibromas are exceedingly rare, with pediatric patients ranging in age from infants to teenagers.1

Clinically, dermatomyofibromas appear as long-standing, isolated, ill-demarcated, flesh-colored, slightly hyperpigmented or erythematous nodules or plaques that may be raised or indurated.1 Dermatomyofibromas may present with constant mild pain or pruritus, though in most cases the lesions are asymptomatic.1,3 The clinical presentation of dermatomyofibroma has a few distinct differences in children compared to adults. In adulthood, dermatomyofibroma has a strong female predominance and most commonly is located on the shoulder and adjacent upper body regions, including the axilla, neck, upper arm, and upper trunk.1-3 In childhood, the majority of dermatomyofibromas occur in young boys and usually are located on the neck with other upper body regions occurring less frequently.1,2 A shared characteristic includes the tendency for dermatomyofibromas to have an initial period of enlargement followed by stabilization or slow growth.1 Reported pediatric lesions have ranged in size from 4 to 60 mm with an average size of 14.9 mm (median, 12 mm).2

The diagnosis of dermatomyofibroma is based on histopathologic features in addition to clinical presentation. Histology from punch biopsy usually reveals a noninvasive dermal proliferation of bland, uniform, slender spindle cells oriented parallel to the overlying epidermis with increased and fragmented elastic fibers.1,3 Infiltration into the mid or deep dermis is common. The adnexal structures usually are spared; the stroma contains collagen and increased small blood vessels; and there typically is no inflammatory infiltrate, except for occasional scattered mast cells.2 Cytologically, the monomorphic spindleshaped tumor cells have an ill-defined, pale, eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclei that are elongated with tapered edges.3 Dermatomyofibroma has a variable immunohistochemical profile, as it may stain focally positive for CD34 or smooth muscle actin, with occasional staining of factor XIIIa, desmin, calponin, or vimentin.1-3 Normal to increased levels of often fragmented elastic fibers is a helpful clue in distinguishing dermatomyofibroma from dermatofibroma, hypertrophic scar, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and pilar leiomyoma, in which elastic fibers typically are reduced.3 Differential diagnoses of mesenchymal tumors in children include desmoid fibromatosis, connective tissue nevus, myofibromatosis, and smooth muscle hamartoma.1

A punch biopsy with clinical observation and followup is recommended for the management of lesions in cosmetically sensitive areas or in very young children who may not tolerate surgery. In symptomatic or cosmetically unappealing cases of dermatomyofibroma, simple surgical excision remains a viable treatment option. Recurrence is uncommon, even if only partially excised, and no instances of metastasis have been reported.1-5

Dermatomyofibromas may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant. For example, the benign dermatofibroma is the second most common fibrohistiocytic tumor of the skin and presents as a firm, nontender, minimally elevated to dome-shaped papule that usually measures less than or equal to 1 cm in diameter with or without overlying skin changes.5,6 It primarily is seen in adults with a slight female predominance and favors the lower extremities.5 Patients usually are asymptomatic but often report a history of local trauma at the lesion site.6 Histologically, dermatofibroma is characterized by a nodular dermal proliferation of spindleshaped fibrous cells and histiocytes in a storiform pattern (Figure 1).6 Epidermal induction with acanthosis overlying the tumor often is found with occasional basilar hyperpigmentation.5 Dermatofibroma also characteristically has trapped collagen (“collagen balls”) seen at the periphery.5,6

Piloleiomyomas are benign smooth muscle tumors arising from arrector pili muscles that may be solitary or multiple.5 Clinically, they typically present as firm, reddish-brown to flesh-colored papules or nodules that develop more commonly in adulthood.5,7 Piloleiomyomas favor the extremities and trunk, particularly the shoulder, and can be associated with spontaneous or induced pain. Histologically, piloleiomyomas are well circumscribed and centered within the reticular dermis situated closely to hair follicles (Figure 2).5 They are composed of numerous interlacing fascicles or whorls of smooth muscle cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and blunt-ended, cigar-shaped nuclei.5,7

Solitary cutaneous myofibroma is a benign fibrous tumor found in adolescents and adults and is the counterpart to infantile myofibromatosis.8 Clinically, myofibromas typically present as painless, slow-growing, firm nodules with an occasional bluish hue. Histologically, solitary cutaneous myofibromas appear in a biphasic pattern, with hemangiopericytomatous components as well as spindle cells arranged in short bundles and fascicles resembling leiomyoma (Figure 3). The spindle cells also have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with short plump nuclei; the random, irregularly intersecting angles can be used to help differentiate myofibromas from smooth muscle lesions.8 Solitary cutaneous myofibroma is in the differential diagnosis for dermatomyofibroma because of their shared myofibroblastic nature.9

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is an uncommon, locally invasive sarcoma with a high recurrence rate that favors young to middle-aged adults, with rare childhood onset reported.5,10,11 Clinically, DFSP typically presents as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, firm, flesh-colored, indurated plaque that develops into a violaceous to reddish-brown nodule.5 The atrophic variant of DFSP is characterized by a nonprotuberant lesion and can be especially difficult to distinguish from other entities such as dermatomyofibroma.11 The majority of DFSP lesions occur on the trunk, particularly in the shoulder or pelvic region.5 Histologically, early plaque lesions are comprised of monomorphic spindle cells arranged in long fascicles (parallel to the skin surface), infiltrating adnexal structures, and subcutaneous adipocytes in a multilayered honeycomb pattern; the spindle cells of late nodular lesions are arranged in short fascicles in a matted or storiform pattern (Figure 4).5,10 Early stages of DFSP as well as variations in childhood-onset DFSP can easily be misdiagnosed and incompletely excised.5

The Diagnosis: Dermatomyofibroma

Dermatomyofibroma is an uncommon, benign, cutaneous mesenchymal neoplasm composed of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.1-3 This skin tumor was first described in 1991 by Hugel4 in the German literature as plaquelike fibromatosis. Pediatric dermatomyofibromas are exceedingly rare, with pediatric patients ranging in age from infants to teenagers.1

Clinically, dermatomyofibromas appear as long-standing, isolated, ill-demarcated, flesh-colored, slightly hyperpigmented or erythematous nodules or plaques that may be raised or indurated.1 Dermatomyofibromas may present with constant mild pain or pruritus, though in most cases the lesions are asymptomatic.1,3 The clinical presentation of dermatomyofibroma has a few distinct differences in children compared to adults. In adulthood, dermatomyofibroma has a strong female predominance and most commonly is located on the shoulder and adjacent upper body regions, including the axilla, neck, upper arm, and upper trunk.1-3 In childhood, the majority of dermatomyofibromas occur in young boys and usually are located on the neck with other upper body regions occurring less frequently.1,2 A shared characteristic includes the tendency for dermatomyofibromas to have an initial period of enlargement followed by stabilization or slow growth.1 Reported pediatric lesions have ranged in size from 4 to 60 mm with an average size of 14.9 mm (median, 12 mm).2

The diagnosis of dermatomyofibroma is based on histopathologic features in addition to clinical presentation. Histology from punch biopsy usually reveals a noninvasive dermal proliferation of bland, uniform, slender spindle cells oriented parallel to the overlying epidermis with increased and fragmented elastic fibers.1,3 Infiltration into the mid or deep dermis is common. The adnexal structures usually are spared; the stroma contains collagen and increased small blood vessels; and there typically is no inflammatory infiltrate, except for occasional scattered mast cells.2 Cytologically, the monomorphic spindleshaped tumor cells have an ill-defined, pale, eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclei that are elongated with tapered edges.3 Dermatomyofibroma has a variable immunohistochemical profile, as it may stain focally positive for CD34 or smooth muscle actin, with occasional staining of factor XIIIa, desmin, calponin, or vimentin.1-3 Normal to increased levels of often fragmented elastic fibers is a helpful clue in distinguishing dermatomyofibroma from dermatofibroma, hypertrophic scar, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and pilar leiomyoma, in which elastic fibers typically are reduced.3 Differential diagnoses of mesenchymal tumors in children include desmoid fibromatosis, connective tissue nevus, myofibromatosis, and smooth muscle hamartoma.1

A punch biopsy with clinical observation and followup is recommended for the management of lesions in cosmetically sensitive areas or in very young children who may not tolerate surgery. In symptomatic or cosmetically unappealing cases of dermatomyofibroma, simple surgical excision remains a viable treatment option. Recurrence is uncommon, even if only partially excised, and no instances of metastasis have been reported.1-5

Dermatomyofibromas may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant. For example, the benign dermatofibroma is the second most common fibrohistiocytic tumor of the skin and presents as a firm, nontender, minimally elevated to dome-shaped papule that usually measures less than or equal to 1 cm in diameter with or without overlying skin changes.5,6 It primarily is seen in adults with a slight female predominance and favors the lower extremities.5 Patients usually are asymptomatic but often report a history of local trauma at the lesion site.6 Histologically, dermatofibroma is characterized by a nodular dermal proliferation of spindleshaped fibrous cells and histiocytes in a storiform pattern (Figure 1).6 Epidermal induction with acanthosis overlying the tumor often is found with occasional basilar hyperpigmentation.5 Dermatofibroma also characteristically has trapped collagen (“collagen balls”) seen at the periphery.5,6

Piloleiomyomas are benign smooth muscle tumors arising from arrector pili muscles that may be solitary or multiple.5 Clinically, they typically present as firm, reddish-brown to flesh-colored papules or nodules that develop more commonly in adulthood.5,7 Piloleiomyomas favor the extremities and trunk, particularly the shoulder, and can be associated with spontaneous or induced pain. Histologically, piloleiomyomas are well circumscribed and centered within the reticular dermis situated closely to hair follicles (Figure 2).5 They are composed of numerous interlacing fascicles or whorls of smooth muscle cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and blunt-ended, cigar-shaped nuclei.5,7

Solitary cutaneous myofibroma is a benign fibrous tumor found in adolescents and adults and is the counterpart to infantile myofibromatosis.8 Clinically, myofibromas typically present as painless, slow-growing, firm nodules with an occasional bluish hue. Histologically, solitary cutaneous myofibromas appear in a biphasic pattern, with hemangiopericytomatous components as well as spindle cells arranged in short bundles and fascicles resembling leiomyoma (Figure 3). The spindle cells also have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with short plump nuclei; the random, irregularly intersecting angles can be used to help differentiate myofibromas from smooth muscle lesions.8 Solitary cutaneous myofibroma is in the differential diagnosis for dermatomyofibroma because of their shared myofibroblastic nature.9

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is an uncommon, locally invasive sarcoma with a high recurrence rate that favors young to middle-aged adults, with rare childhood onset reported.5,10,11 Clinically, DFSP typically presents as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, firm, flesh-colored, indurated plaque that develops into a violaceous to reddish-brown nodule.5 The atrophic variant of DFSP is characterized by a nonprotuberant lesion and can be especially difficult to distinguish from other entities such as dermatomyofibroma.11 The majority of DFSP lesions occur on the trunk, particularly in the shoulder or pelvic region.5 Histologically, early plaque lesions are comprised of monomorphic spindle cells arranged in long fascicles (parallel to the skin surface), infiltrating adnexal structures, and subcutaneous adipocytes in a multilayered honeycomb pattern; the spindle cells of late nodular lesions are arranged in short fascicles in a matted or storiform pattern (Figure 4).5,10 Early stages of DFSP as well as variations in childhood-onset DFSP can easily be misdiagnosed and incompletely excised.5

- Ma JE, Wieland CN, Tollefson MM. Dermatomyofibromas arising in children: report of two new cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:347-351.

- Tardio JC, Azorin D, Hernandez-Nunez A, et al. Dermatomyofibromas presenting in pediatric patients: clinicopathologic characteristics and differential diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:967-972.

- Mentzel T, Kutzner H. Dermatomyofibroma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 56 cases and reappraisal of a rare and distinct cutaneous neoplasm. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:44-49.

- Hugel H. Plaque-like dermal fibromatosis. Hautarzt. 1991;42:223-226.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. WB Saunders Co; 2012.

- Myers DJ, Fillman EP. Dermatofibroma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Dilek N, Yuksel D, Sehitoglu I, et al. Cutaneous leiomyoma in a child: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:1163-1164.

- Roh HS, Paek JO, Yu HJ, et al. Solitary cutaneous myofibroma on the sole: an unusual localization. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:220-222.

- Weedon D, Strutton G, Rubin AI, et al. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

- Mendenhall WM, Zlotecki RA, Scarborough MT. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Cancer. 2004;101:2503-2508.

- Akay BN, Unlu E, Erdem C, et al. Dermatoscopic findings of atrophic dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:71-73.

- Ma JE, Wieland CN, Tollefson MM. Dermatomyofibromas arising in children: report of two new cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:347-351.

- Tardio JC, Azorin D, Hernandez-Nunez A, et al. Dermatomyofibromas presenting in pediatric patients: clinicopathologic characteristics and differential diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:967-972.

- Mentzel T, Kutzner H. Dermatomyofibroma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 56 cases and reappraisal of a rare and distinct cutaneous neoplasm. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:44-49.

- Hugel H. Plaque-like dermal fibromatosis. Hautarzt. 1991;42:223-226.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. WB Saunders Co; 2012.

- Myers DJ, Fillman EP. Dermatofibroma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Dilek N, Yuksel D, Sehitoglu I, et al. Cutaneous leiomyoma in a child: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:1163-1164.

- Roh HS, Paek JO, Yu HJ, et al. Solitary cutaneous myofibroma on the sole: an unusual localization. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:220-222.

- Weedon D, Strutton G, Rubin AI, et al. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

- Mendenhall WM, Zlotecki RA, Scarborough MT. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Cancer. 2004;101:2503-2508.

- Akay BN, Unlu E, Erdem C, et al. Dermatoscopic findings of atrophic dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:71-73.

A 12-year-old boy with olive skin presented with a tender subcutaneous nodule on the back of 6 months’ duration. He reported the lesion initially grew rapidly with increasing pain for approximately 3 months with subsequent stabilization in size and modest resolution of his symptoms. Physical examination revealed a solitary, 15-mm, ill-defined, indurated, tender, subcutaneous nodule with subtle overlying hyperpigmentation on the left side of the upper back. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of a 4-mm punch biopsy revealed a nonencapsulated mass of monomorphic eosinophilic spindle cells organized into fascicles arranged predominantly parallel to the skin surface. The mass extended from the mid reticular dermis to the upper subcutis, sparing adnexal structures.

From Buns to Braids and Ponytails: Entering a New Era of Female Military Hair-Grooming Standards

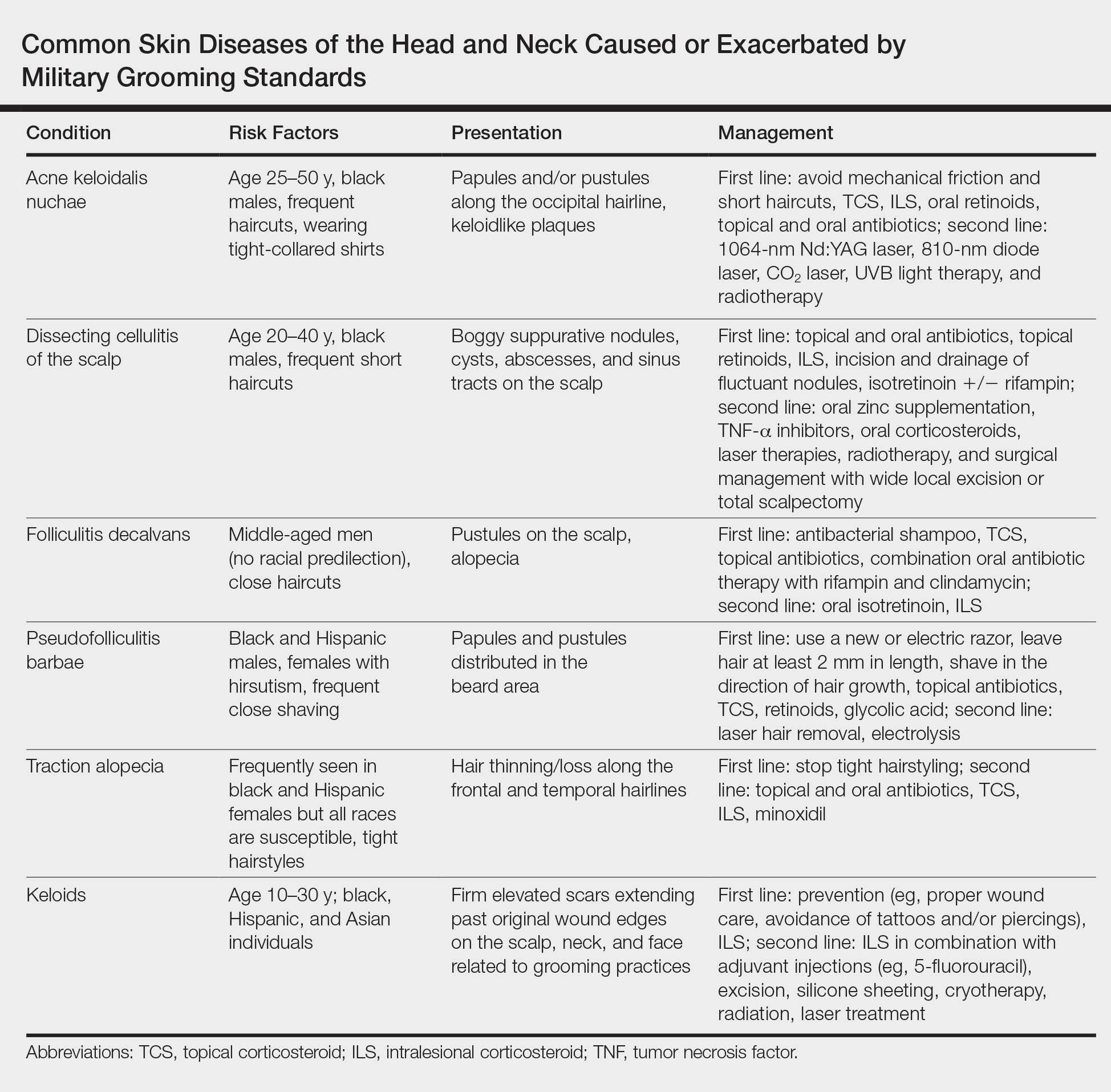

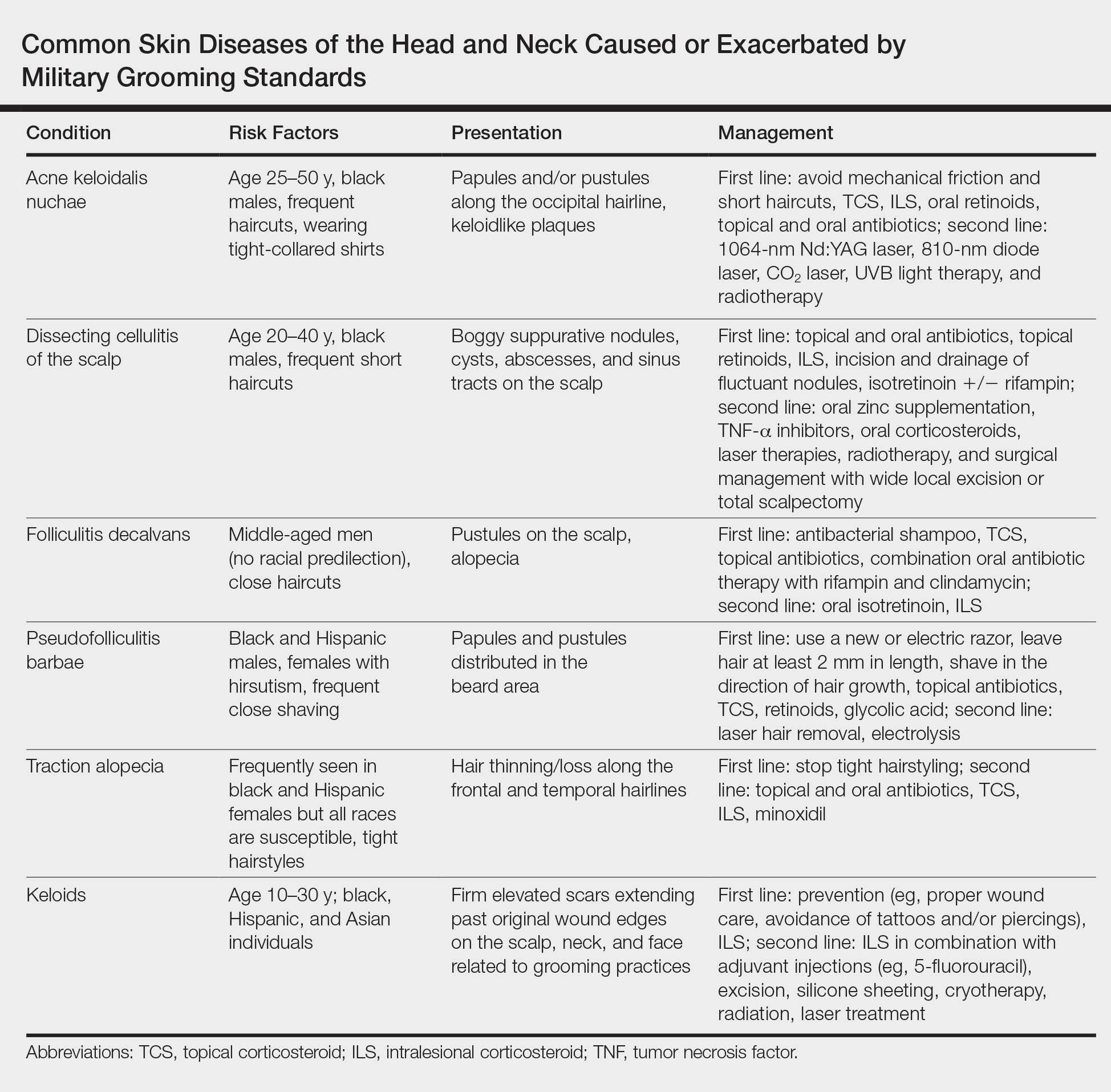

Professional appearance of servicemembers has been a long-standing custom in the US Military. Specific standards are determined by each branch. Initially, men dominated the military.1,2 As the number of women as well as racial diversity increased in the military, modifications to grooming standards were slow to change and resulted in female hair standards requiring a uniform tight and sleek style or short haircut. Clinicians can be attuned to these occupational standards and their implications on the diagnosis and management of common diseases of the hair and scalp.

History of Hairstyle Standards for Female Servicemembers

For half a century, female servicemembers had limited hairstyle choices. They were not authorized to have hair shorter than one-quarter inch in length. They could choose either short hair worn down or long hair with neatly secured loose ends in the form of a bun or a tucked braid—both of which could not extend past the bottom edge of the uniform collar.3-5 Female navy sailors and air force airmen with long hair were only allowed to wear ponytails during physical training; however, army soldiers previously were limited to wearing a bun.3,6,7 Cornrows and microbraids were authorized in the mid-1990s for the US Air Force, but policy stated that locs were prohibited due to their “unkempt” and “matted” nature. Furthermore, the size of hair bulk in the air force was restricted to no more than 3 inches and could not obstruct wear of the uniform cap.5 Based on these regulations, female servicemembers with longer hair had to utilize tight hairstyles that caused prolonged traction and pressure along the scalp, which contributed to headaches, a sore scalp, and alopecia over time. Normalization of these symptoms led to underreporting, as women lived with the consequences or turned to shorter hairstyles.

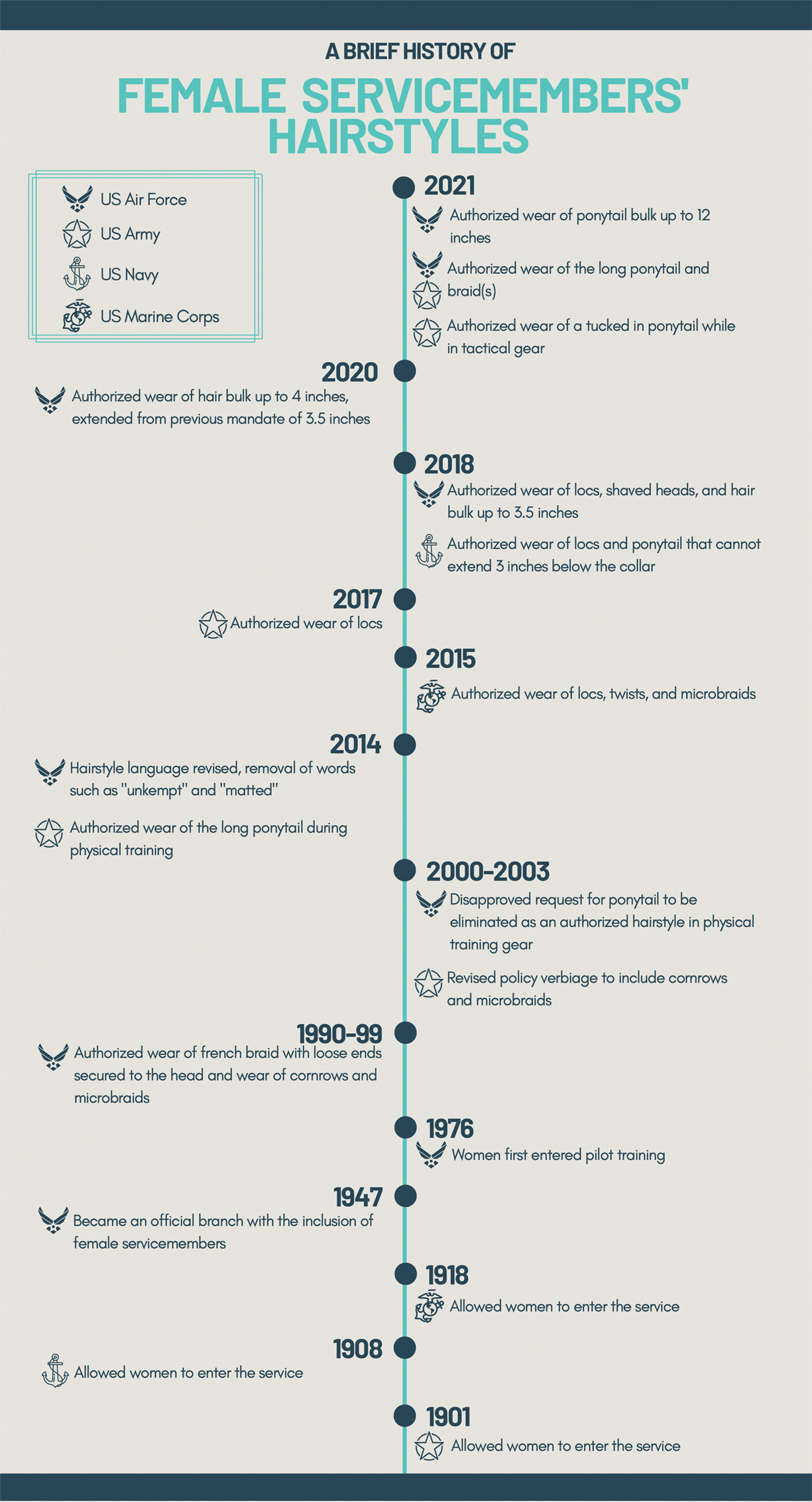

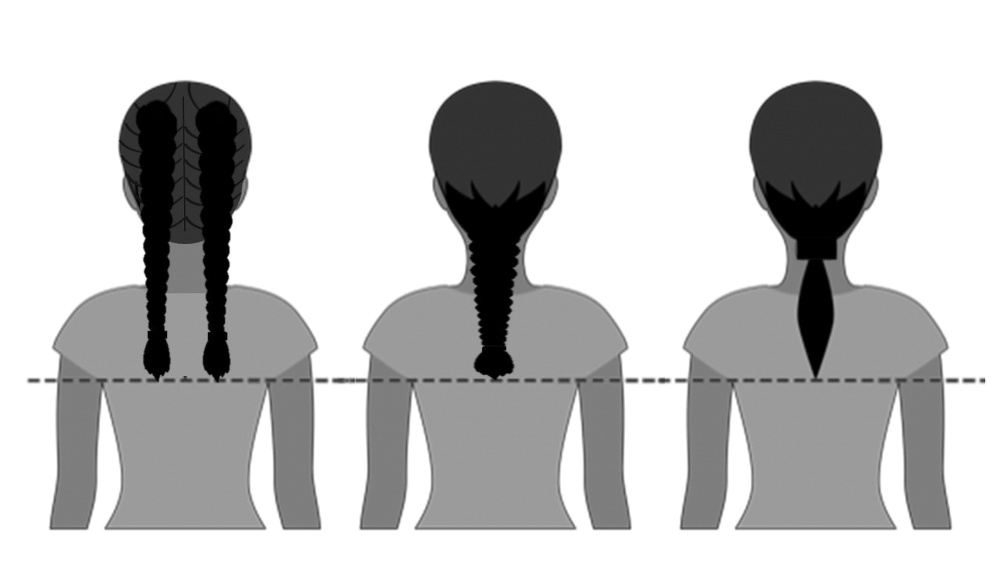

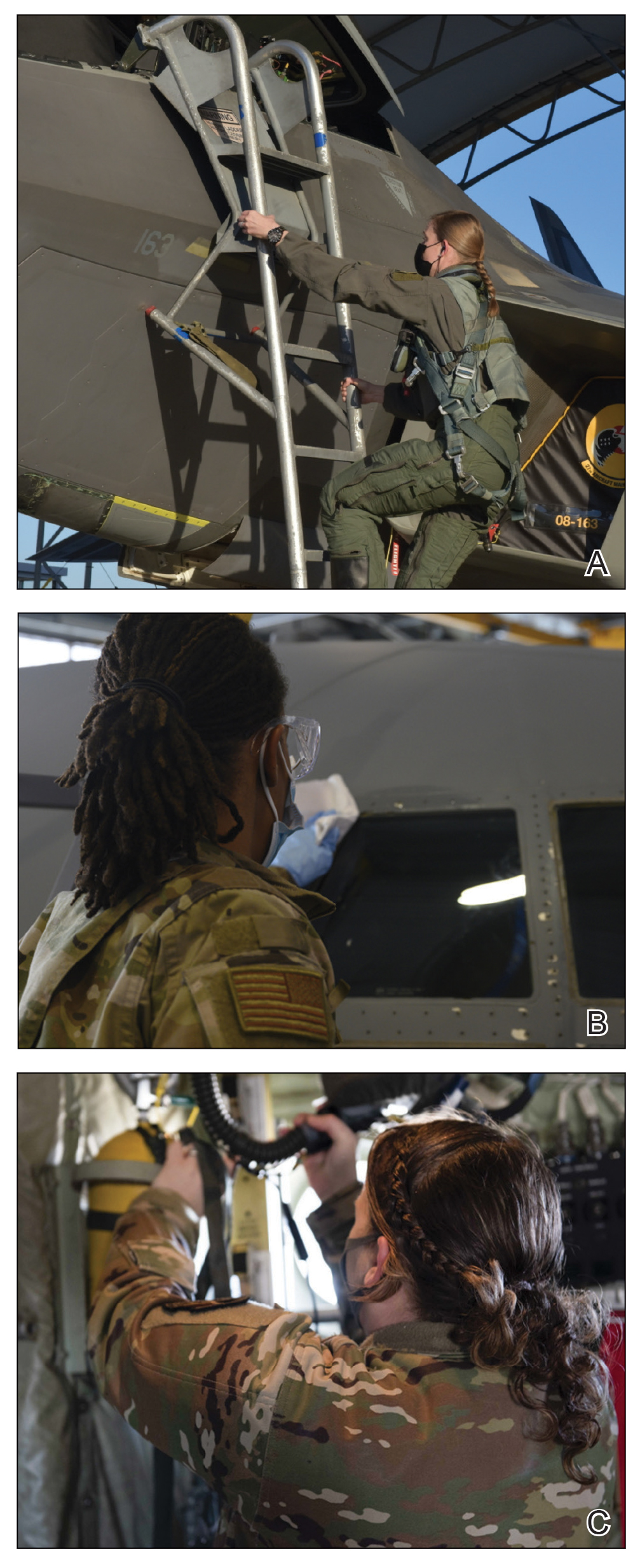

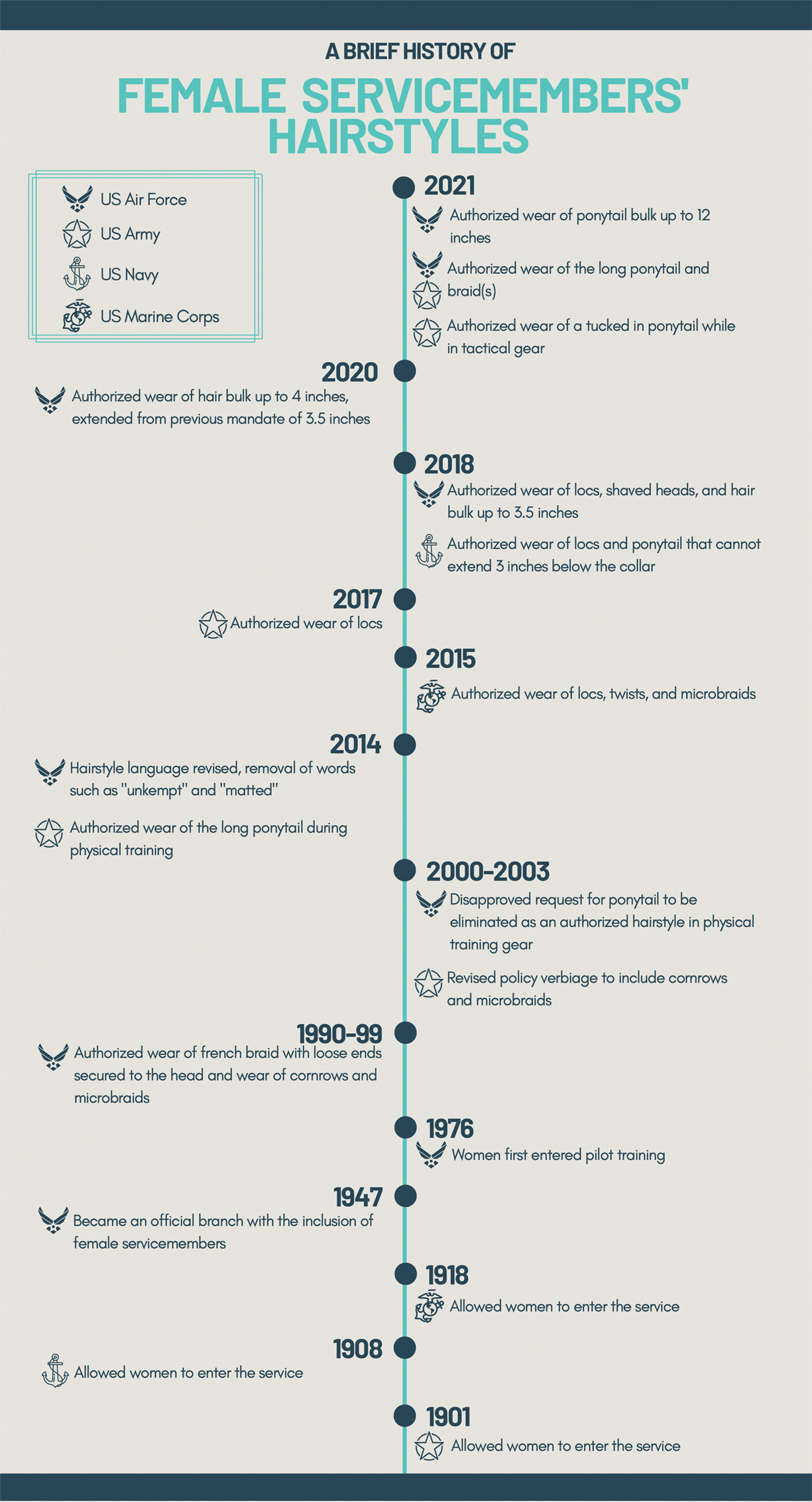

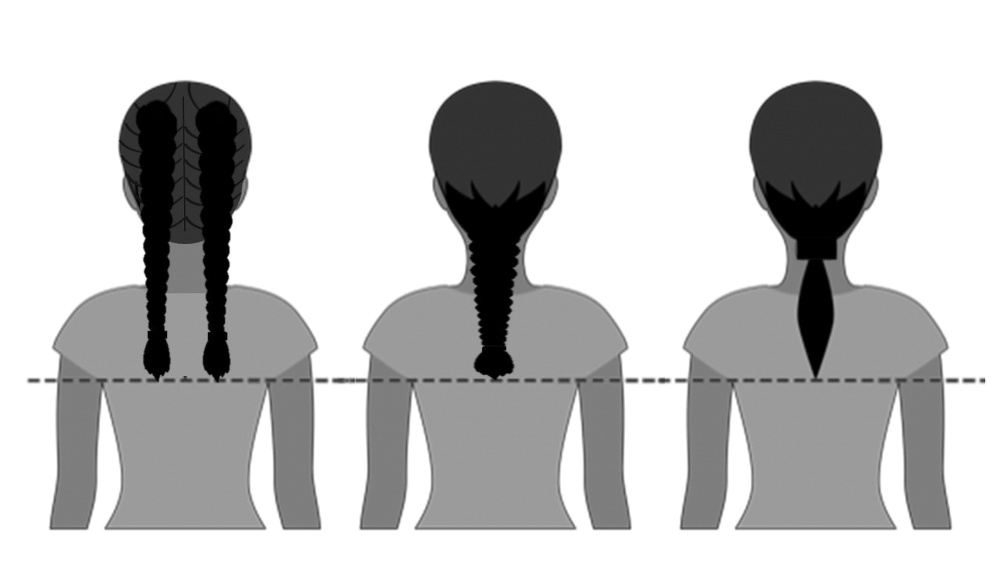

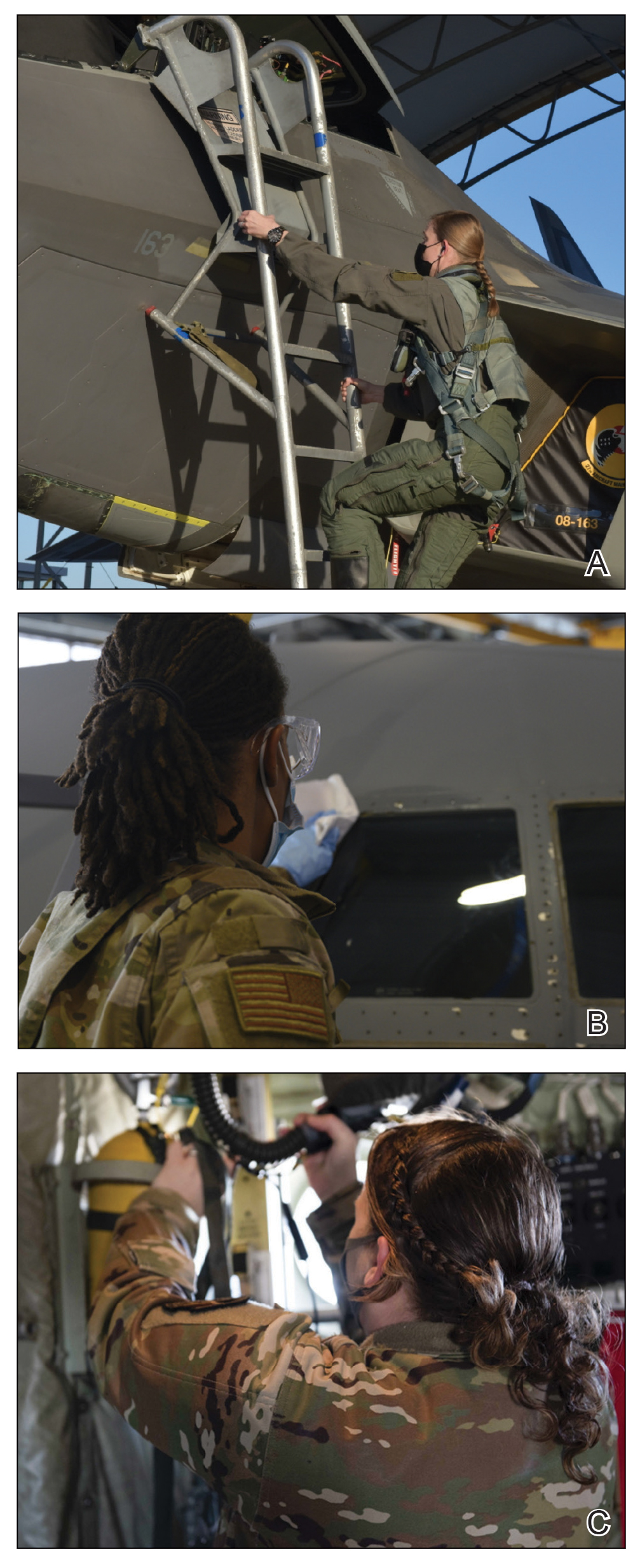

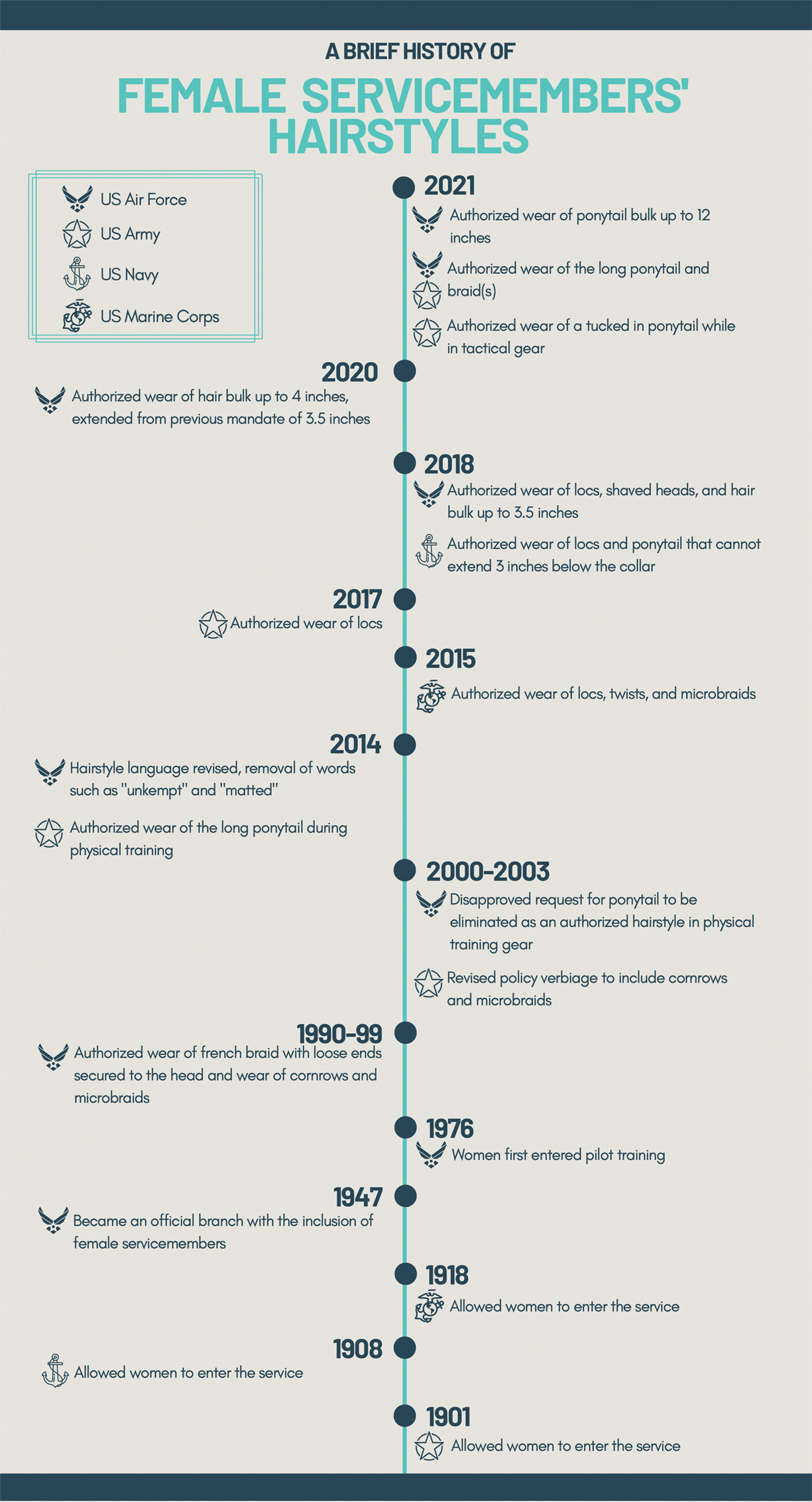

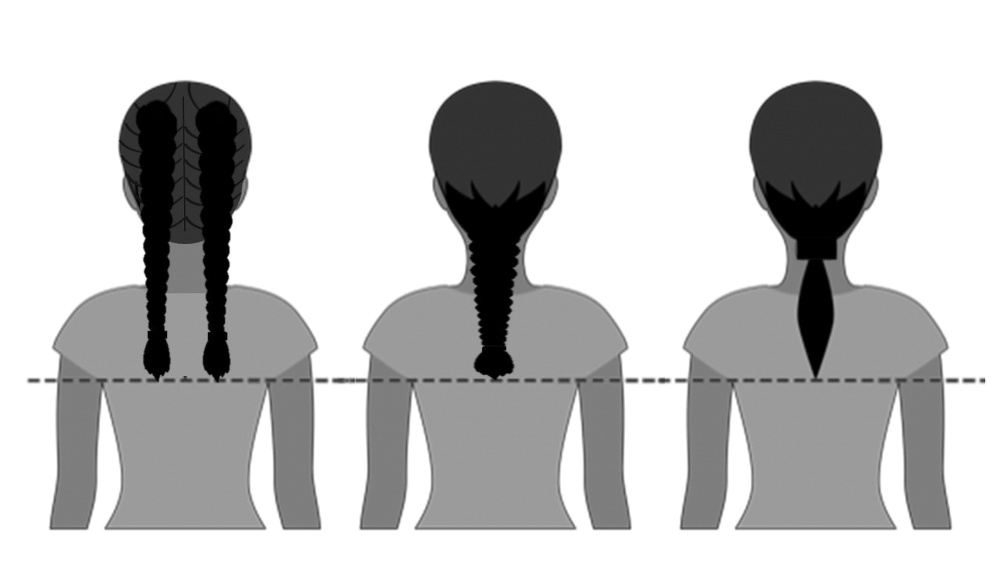

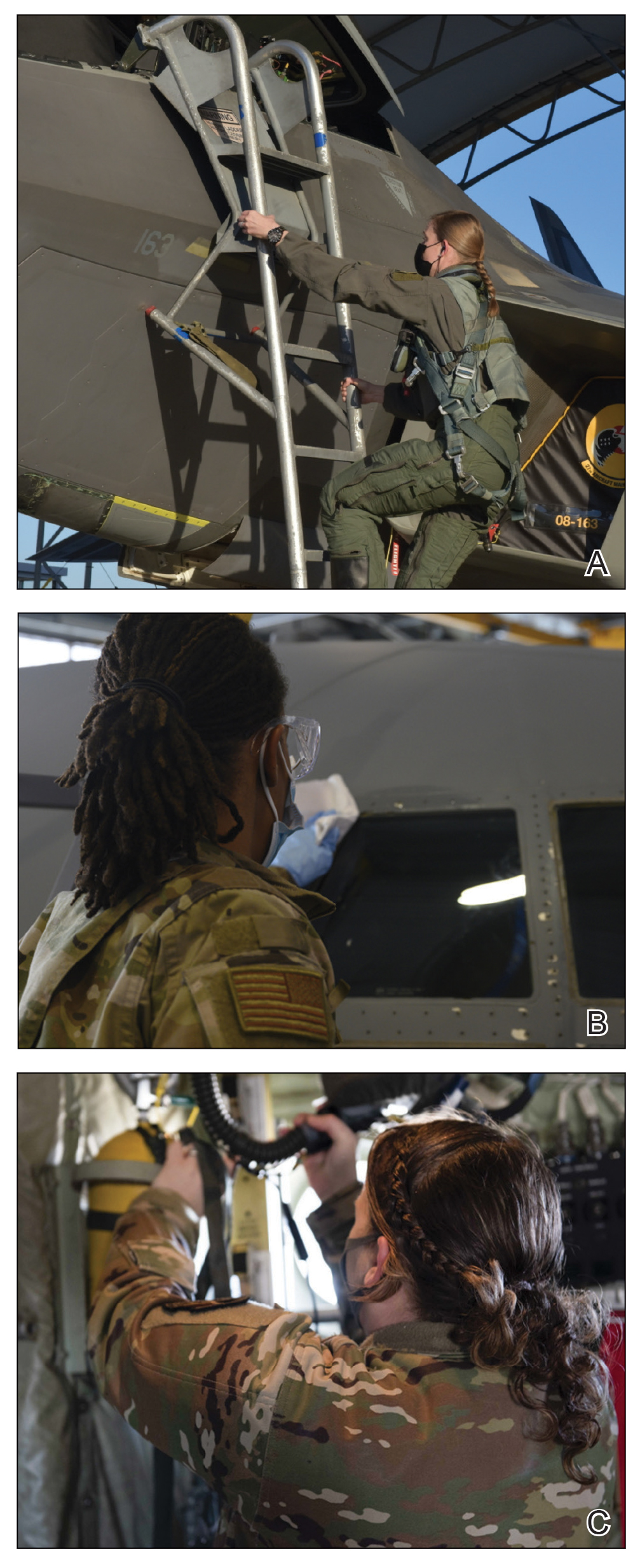

In the last decade alone, female servicemembers have witnessed the greatest number of changes in authorized hairstyles despite being part of the military for more than 50 years (Figure 1).1-11 In 2014, the language used in the air force instructions to describe locs was revised to remove ethnically offensive terms.4,5 This same year, the army allowed female soldiers to wear ponytails during physical training, a privilege that had been authorized by other services years prior.3,6,7 By the end of 2018, locs were authorized by all services, and female sailors could wear a ponytail in all navy uniforms as long as it did not extend 3 inches below the collar.3,4,6-8 In 2018, the air force increased authorized hair bulk up to 3.5 inches from the previous mandate of 3 inches and approved female buzz cuts6,9; in 2020, it allowed hair bulk up to 4 inches. As of 2021, female airmen can wear a ponytail and/or braid(s) as long as it starts below the crown of the head and the length does not extend below a horizontal line running between the top of each sleeve inseam at the underarm (Figures 2–4).6 In an ongoing effort to be more inclusive of hair density differences, female airmen will be authorized to wear a ponytail not exceeding a maximum width bulk of 1 ft starting June 25, 2021, so long as they can comply with the above regulations.11 The army now allows ponytails and braids across all uniforms, as long they do not extend past the bottom of the shoulder blades. This change came just months after authorizing the wearing of ponytails tucked under the uniform blouse with tactical headgear.10 These changes allow for a variety of hairstyles for members to practice while avoiding the physical consequences that develop from repetitive traction and pressure along the same areas of the hair and scalp.

Common Hair Disorders in Female Servicemembers

Herein, we discuss 3 of the most common hair and scalp disorders linked to grooming practices utilized by women to meet prior military regulations: trichorrhexis nodosa (TN), extracranial headaches, and traction alopecia (TA). It is essential that health care providers are able to promptly recognize these conditions, understand their risk factors, and be familiar with first-line treatment options. With these new standards, the hope is that the incidence of the following conditions decreases, thus improving servicemembers’ medical readiness and overall quality of life.

Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Acquired TN is a defect in the hair shaft that causes the hair to break easily secondary to chemical, thermal, or mechanical trauma. This can include but is not limited to chemical relaxers, blow-dryers, excessive brushing or styling, flat irons, and tightly packed hairstyles. The condition is characterized by a thickened hair diameter and splitting at the tip. Clinically, it may present as brittle, lusterless, broken hair with split ends, as well as a positive tug test.14 Management includes gentle hair care and avoidance of harsh hair care practices and treatments.

Extracranial Headaches

Headaches are a common concern among military servicemembers15 and generally are classified as primary or secondary. A less commonly discussed primary headache disorder includes external-pressure headaches, which result from either sustained compression or traction of the soft tissues of the scalp, usually from wearing headbands, helmets, or tight hairstyles.16 Additional at-risk groups include those who chronically wear surgical scrub caps or flight caps, especially if clipped or pinned to the hair. In our 38 years of combined military clinical experience, we can attest that these types of headaches are common among female servicemembers. The diagnostic criteria for an external-pressure headache, commonly referred to by patients as a “ponytail headache,” includes at least 2 headache episodes triggered within 1 hour of sustained traction on the scalp, maximal at the site of traction and resolving within 1 hour after relieving the traction.16 Management includes removal of the pressure-causing source, usually a tight ponytail or bun.

Traction Alopecia

Traction alopecia is hair loss caused by repetitive or prolonged tension on the hair secondary to tight hairstyles. It can be clinically classified into 2 types: marginal and nonmarginal patchy alopecia (Figure 5).13,17,18 Traction alopecia most commonly is found in individuals with ethnic hair, predominantly Black women. Hairstyles with the highest risk for causing TA include tight buns, ponytails, cornrows, weaves, and locs—all of which are utilized by female servicemembers to maintain a professional appearance and adhere to grooming regulations.13,18 Other groups at risk include athletes (eg, ballerinas, gymnasts) and those with chronic headwear use (eg, turbans, helmets, nurse caps, wigs).18 Early TA typically presents with perifollicular erythema followed by follicular-based papules or pustules.13,18 Marginal TA classically includes frontotemporal hair loss or thinning with or without a fringe sign.17,18 Nonmarginal TA includes patchy alopecia most commonly involving the parietal or occipital scalp, seen with chignons, buns, ponytails, or the use of clips, extensions, or bobby pins.18 The first line in management is avoidance of traction-causing hairstyles or headgear. Medical therapy may be warranted and consists of a single agent or combination regimen to include oral or topical antibiotics, topical or intralesional steroids, and topical minoxidil.13,18

Final Thoughts

Military hair-grooming standards have evolved over time. Recent changes show that the US Department of Defense is seriously evaluating policies that may be inherently exclusive. Prior grooming standards resulted in the widespread use of tight hairstyles and harsh hair treatments among female servicemembers with long hair. These practices resulted in TN, extracranial headaches, and TA, among other hair and scalp disorders. These occupational-related hair conditions impact female servicemembers’ mental and physical well-being and thus impact military readiness. Physicians should recognize that these conditions can be related to occupational grooming standards that may impact hair care practices.

The challenge that remains is a lack of standardized documentation for hair and scalp symptoms in the medical record. Due to a paucity in reporting and documentation, limited objective data exist to guide future recommendations for military grooming standards. Another obstacle is the lack of knowledge of hair diseases among primary care providers and patients, especially due to the underrepresentation of ethnic hair in medical textbooks.19 As a result, women frequently accept their hair symptoms as normal and either suffer through them, cut their hair short, or wear wigs before considering a visit to the doctor. Furthermore, hair-grooming standards can expose racial disparities, which are the driving force behind the current policy changes. Clinicians can strive to ask about hair and scalp symptoms and document the following in relation to hair and scalp disorders: occupational grooming requirements; skin and hair type; location, number, and size of scalp lesion(s); onset; duration; current and prior hair care practices; history of treatment; and clinical course accompanied with photographic documentation. Ultimately, improved awareness in patients, collaboration between physicians, and consistent clinical documentation can help create positive change and continued improvement in hair-grooming standards within the military. Improved reporting and documentation will facilitate further study into the effectiveness of the updated hair-grooming standards in female servicemembers.

- United States Air Force Statistical Digest FY 1999. United States Air Force; 2000. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://media.defense.gov/2011/Apr/14/2001330240/-1/-1/0/AFD-110414-048.pdf

- Air Force demographics. Air Force Personnel Center website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.afpc.af.mil/About/Air-Force-Demographics/

- US Department of the Army. Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia: Army Regulation 670-1. Department of the Army; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN30302-AR_670-1-000-WEB-1.pdf

- Losey S. Loc hairstyles, off-duty earrings for men ok’d in new dress regs. Air Force Times. Published July 16, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2018/07/16/loc-hairstyles-off-duty-earrings-for-men-okd-in-new-dress-regs/

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2011. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.uc.edu/content/dam/uc/afrotc/docs/Documents/AFI36-2903.pdf

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a1/publication/afi36-2903/afi36-2903.pdf

- U.S. Navy uniform regulations: summary of changes (26 February 2020). Navy Personnel Command website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Navy%20Uniforms/Uniform%20Regulations/Documents/SOC_2020_02_26.pdf?ver=y8Wd0ykVXgISfFpOy8qHkg%3d%3d

- US Headquarters Marine Corps. Marine Corps Uniform Regulations: Marine Corps Order 1020.34H. United States Marine Corps, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/MCO%201020.34H%20v2.pdf?ver=2018-06-26-094038-137

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force to allow longer braids, ponytails, bangs for women. United States Air Force website. Published January 21, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2478173/air-force-to-allow-longer-braids-ponytails-bangs-for-women/

- Britzky H. The Army will now allow women to wear ponytails in all uniforms. Task & Purpose. Published May 6, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://taskandpurpose.com/news/army-women-ponytails-all-uniforms/

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force readdresses women’s hair standard after feedback. US Air Force website. Published June 11, 2021. Accessed June 27, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2654774/air-force-readdresses-womens-hair-standard-after-feedback/

- Myers M. Esper direct services to review racial bias in grooming standards, training and more. Air Force Times. Published July 15, 2020. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-military/2020/07/15/esper-directs-services-to-review-racial-bias-in-grooming-standards-training-and-more/

- Madu P, Kundu RV. Follicular and scarring disorders in skin of color: presentation and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:307-321.

- Quaresma M, Martinez Velasco M, Tosti A. Hair breakage in patients of African descent: role of dermoscopy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:99-104.

- Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, et al. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015;55:21-34.

- Kararizou E, Bougea AM, Giotopoulou D, et al. An update on the less-known group of other primary headaches—a review. Eur Neurol Rev. 2014;9:71-77.

- Sperling L, Cowper S, Knopp E. An Atlas of Hair Pathology with Clinical Correlations. CRC Press; 2012:67-68.

- Billero V, Miteva M. Traction alopecia: the root of the problem. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:149-159.

- Adelekun A, Onyekaba G, Lipoff JB. Skin color in dermatology textbooks: an updated evaluation and analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:194-196.

Professional appearance of servicemembers has been a long-standing custom in the US Military. Specific standards are determined by each branch. Initially, men dominated the military.1,2 As the number of women as well as racial diversity increased in the military, modifications to grooming standards were slow to change and resulted in female hair standards requiring a uniform tight and sleek style or short haircut. Clinicians can be attuned to these occupational standards and their implications on the diagnosis and management of common diseases of the hair and scalp.

History of Hairstyle Standards for Female Servicemembers

For half a century, female servicemembers had limited hairstyle choices. They were not authorized to have hair shorter than one-quarter inch in length. They could choose either short hair worn down or long hair with neatly secured loose ends in the form of a bun or a tucked braid—both of which could not extend past the bottom edge of the uniform collar.3-5 Female navy sailors and air force airmen with long hair were only allowed to wear ponytails during physical training; however, army soldiers previously were limited to wearing a bun.3,6,7 Cornrows and microbraids were authorized in the mid-1990s for the US Air Force, but policy stated that locs were prohibited due to their “unkempt” and “matted” nature. Furthermore, the size of hair bulk in the air force was restricted to no more than 3 inches and could not obstruct wear of the uniform cap.5 Based on these regulations, female servicemembers with longer hair had to utilize tight hairstyles that caused prolonged traction and pressure along the scalp, which contributed to headaches, a sore scalp, and alopecia over time. Normalization of these symptoms led to underreporting, as women lived with the consequences or turned to shorter hairstyles.

In the last decade alone, female servicemembers have witnessed the greatest number of changes in authorized hairstyles despite being part of the military for more than 50 years (Figure 1).1-11 In 2014, the language used in the air force instructions to describe locs was revised to remove ethnically offensive terms.4,5 This same year, the army allowed female soldiers to wear ponytails during physical training, a privilege that had been authorized by other services years prior.3,6,7 By the end of 2018, locs were authorized by all services, and female sailors could wear a ponytail in all navy uniforms as long as it did not extend 3 inches below the collar.3,4,6-8 In 2018, the air force increased authorized hair bulk up to 3.5 inches from the previous mandate of 3 inches and approved female buzz cuts6,9; in 2020, it allowed hair bulk up to 4 inches. As of 2021, female airmen can wear a ponytail and/or braid(s) as long as it starts below the crown of the head and the length does not extend below a horizontal line running between the top of each sleeve inseam at the underarm (Figures 2–4).6 In an ongoing effort to be more inclusive of hair density differences, female airmen will be authorized to wear a ponytail not exceeding a maximum width bulk of 1 ft starting June 25, 2021, so long as they can comply with the above regulations.11 The army now allows ponytails and braids across all uniforms, as long they do not extend past the bottom of the shoulder blades. This change came just months after authorizing the wearing of ponytails tucked under the uniform blouse with tactical headgear.10 These changes allow for a variety of hairstyles for members to practice while avoiding the physical consequences that develop from repetitive traction and pressure along the same areas of the hair and scalp.

Common Hair Disorders in Female Servicemembers

Herein, we discuss 3 of the most common hair and scalp disorders linked to grooming practices utilized by women to meet prior military regulations: trichorrhexis nodosa (TN), extracranial headaches, and traction alopecia (TA). It is essential that health care providers are able to promptly recognize these conditions, understand their risk factors, and be familiar with first-line treatment options. With these new standards, the hope is that the incidence of the following conditions decreases, thus improving servicemembers’ medical readiness and overall quality of life.

Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Acquired TN is a defect in the hair shaft that causes the hair to break easily secondary to chemical, thermal, or mechanical trauma. This can include but is not limited to chemical relaxers, blow-dryers, excessive brushing or styling, flat irons, and tightly packed hairstyles. The condition is characterized by a thickened hair diameter and splitting at the tip. Clinically, it may present as brittle, lusterless, broken hair with split ends, as well as a positive tug test.14 Management includes gentle hair care and avoidance of harsh hair care practices and treatments.

Extracranial Headaches

Headaches are a common concern among military servicemembers15 and generally are classified as primary or secondary. A less commonly discussed primary headache disorder includes external-pressure headaches, which result from either sustained compression or traction of the soft tissues of the scalp, usually from wearing headbands, helmets, or tight hairstyles.16 Additional at-risk groups include those who chronically wear surgical scrub caps or flight caps, especially if clipped or pinned to the hair. In our 38 years of combined military clinical experience, we can attest that these types of headaches are common among female servicemembers. The diagnostic criteria for an external-pressure headache, commonly referred to by patients as a “ponytail headache,” includes at least 2 headache episodes triggered within 1 hour of sustained traction on the scalp, maximal at the site of traction and resolving within 1 hour after relieving the traction.16 Management includes removal of the pressure-causing source, usually a tight ponytail or bun.

Traction Alopecia

Traction alopecia is hair loss caused by repetitive or prolonged tension on the hair secondary to tight hairstyles. It can be clinically classified into 2 types: marginal and nonmarginal patchy alopecia (Figure 5).13,17,18 Traction alopecia most commonly is found in individuals with ethnic hair, predominantly Black women. Hairstyles with the highest risk for causing TA include tight buns, ponytails, cornrows, weaves, and locs—all of which are utilized by female servicemembers to maintain a professional appearance and adhere to grooming regulations.13,18 Other groups at risk include athletes (eg, ballerinas, gymnasts) and those with chronic headwear use (eg, turbans, helmets, nurse caps, wigs).18 Early TA typically presents with perifollicular erythema followed by follicular-based papules or pustules.13,18 Marginal TA classically includes frontotemporal hair loss or thinning with or without a fringe sign.17,18 Nonmarginal TA includes patchy alopecia most commonly involving the parietal or occipital scalp, seen with chignons, buns, ponytails, or the use of clips, extensions, or bobby pins.18 The first line in management is avoidance of traction-causing hairstyles or headgear. Medical therapy may be warranted and consists of a single agent or combination regimen to include oral or topical antibiotics, topical or intralesional steroids, and topical minoxidil.13,18

Final Thoughts

Military hair-grooming standards have evolved over time. Recent changes show that the US Department of Defense is seriously evaluating policies that may be inherently exclusive. Prior grooming standards resulted in the widespread use of tight hairstyles and harsh hair treatments among female servicemembers with long hair. These practices resulted in TN, extracranial headaches, and TA, among other hair and scalp disorders. These occupational-related hair conditions impact female servicemembers’ mental and physical well-being and thus impact military readiness. Physicians should recognize that these conditions can be related to occupational grooming standards that may impact hair care practices.

The challenge that remains is a lack of standardized documentation for hair and scalp symptoms in the medical record. Due to a paucity in reporting and documentation, limited objective data exist to guide future recommendations for military grooming standards. Another obstacle is the lack of knowledge of hair diseases among primary care providers and patients, especially due to the underrepresentation of ethnic hair in medical textbooks.19 As a result, women frequently accept their hair symptoms as normal and either suffer through them, cut their hair short, or wear wigs before considering a visit to the doctor. Furthermore, hair-grooming standards can expose racial disparities, which are the driving force behind the current policy changes. Clinicians can strive to ask about hair and scalp symptoms and document the following in relation to hair and scalp disorders: occupational grooming requirements; skin and hair type; location, number, and size of scalp lesion(s); onset; duration; current and prior hair care practices; history of treatment; and clinical course accompanied with photographic documentation. Ultimately, improved awareness in patients, collaboration between physicians, and consistent clinical documentation can help create positive change and continued improvement in hair-grooming standards within the military. Improved reporting and documentation will facilitate further study into the effectiveness of the updated hair-grooming standards in female servicemembers.

Professional appearance of servicemembers has been a long-standing custom in the US Military. Specific standards are determined by each branch. Initially, men dominated the military.1,2 As the number of women as well as racial diversity increased in the military, modifications to grooming standards were slow to change and resulted in female hair standards requiring a uniform tight and sleek style or short haircut. Clinicians can be attuned to these occupational standards and their implications on the diagnosis and management of common diseases of the hair and scalp.

History of Hairstyle Standards for Female Servicemembers

For half a century, female servicemembers had limited hairstyle choices. They were not authorized to have hair shorter than one-quarter inch in length. They could choose either short hair worn down or long hair with neatly secured loose ends in the form of a bun or a tucked braid—both of which could not extend past the bottom edge of the uniform collar.3-5 Female navy sailors and air force airmen with long hair were only allowed to wear ponytails during physical training; however, army soldiers previously were limited to wearing a bun.3,6,7 Cornrows and microbraids were authorized in the mid-1990s for the US Air Force, but policy stated that locs were prohibited due to their “unkempt” and “matted” nature. Furthermore, the size of hair bulk in the air force was restricted to no more than 3 inches and could not obstruct wear of the uniform cap.5 Based on these regulations, female servicemembers with longer hair had to utilize tight hairstyles that caused prolonged traction and pressure along the scalp, which contributed to headaches, a sore scalp, and alopecia over time. Normalization of these symptoms led to underreporting, as women lived with the consequences or turned to shorter hairstyles.

In the last decade alone, female servicemembers have witnessed the greatest number of changes in authorized hairstyles despite being part of the military for more than 50 years (Figure 1).1-11 In 2014, the language used in the air force instructions to describe locs was revised to remove ethnically offensive terms.4,5 This same year, the army allowed female soldiers to wear ponytails during physical training, a privilege that had been authorized by other services years prior.3,6,7 By the end of 2018, locs were authorized by all services, and female sailors could wear a ponytail in all navy uniforms as long as it did not extend 3 inches below the collar.3,4,6-8 In 2018, the air force increased authorized hair bulk up to 3.5 inches from the previous mandate of 3 inches and approved female buzz cuts6,9; in 2020, it allowed hair bulk up to 4 inches. As of 2021, female airmen can wear a ponytail and/or braid(s) as long as it starts below the crown of the head and the length does not extend below a horizontal line running between the top of each sleeve inseam at the underarm (Figures 2–4).6 In an ongoing effort to be more inclusive of hair density differences, female airmen will be authorized to wear a ponytail not exceeding a maximum width bulk of 1 ft starting June 25, 2021, so long as they can comply with the above regulations.11 The army now allows ponytails and braids across all uniforms, as long they do not extend past the bottom of the shoulder blades. This change came just months after authorizing the wearing of ponytails tucked under the uniform blouse with tactical headgear.10 These changes allow for a variety of hairstyles for members to practice while avoiding the physical consequences that develop from repetitive traction and pressure along the same areas of the hair and scalp.

Common Hair Disorders in Female Servicemembers

Herein, we discuss 3 of the most common hair and scalp disorders linked to grooming practices utilized by women to meet prior military regulations: trichorrhexis nodosa (TN), extracranial headaches, and traction alopecia (TA). It is essential that health care providers are able to promptly recognize these conditions, understand their risk factors, and be familiar with first-line treatment options. With these new standards, the hope is that the incidence of the following conditions decreases, thus improving servicemembers’ medical readiness and overall quality of life.

Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Acquired TN is a defect in the hair shaft that causes the hair to break easily secondary to chemical, thermal, or mechanical trauma. This can include but is not limited to chemical relaxers, blow-dryers, excessive brushing or styling, flat irons, and tightly packed hairstyles. The condition is characterized by a thickened hair diameter and splitting at the tip. Clinically, it may present as brittle, lusterless, broken hair with split ends, as well as a positive tug test.14 Management includes gentle hair care and avoidance of harsh hair care practices and treatments.

Extracranial Headaches

Headaches are a common concern among military servicemembers15 and generally are classified as primary or secondary. A less commonly discussed primary headache disorder includes external-pressure headaches, which result from either sustained compression or traction of the soft tissues of the scalp, usually from wearing headbands, helmets, or tight hairstyles.16 Additional at-risk groups include those who chronically wear surgical scrub caps or flight caps, especially if clipped or pinned to the hair. In our 38 years of combined military clinical experience, we can attest that these types of headaches are common among female servicemembers. The diagnostic criteria for an external-pressure headache, commonly referred to by patients as a “ponytail headache,” includes at least 2 headache episodes triggered within 1 hour of sustained traction on the scalp, maximal at the site of traction and resolving within 1 hour after relieving the traction.16 Management includes removal of the pressure-causing source, usually a tight ponytail or bun.

Traction Alopecia

Traction alopecia is hair loss caused by repetitive or prolonged tension on the hair secondary to tight hairstyles. It can be clinically classified into 2 types: marginal and nonmarginal patchy alopecia (Figure 5).13,17,18 Traction alopecia most commonly is found in individuals with ethnic hair, predominantly Black women. Hairstyles with the highest risk for causing TA include tight buns, ponytails, cornrows, weaves, and locs—all of which are utilized by female servicemembers to maintain a professional appearance and adhere to grooming regulations.13,18 Other groups at risk include athletes (eg, ballerinas, gymnasts) and those with chronic headwear use (eg, turbans, helmets, nurse caps, wigs).18 Early TA typically presents with perifollicular erythema followed by follicular-based papules or pustules.13,18 Marginal TA classically includes frontotemporal hair loss or thinning with or without a fringe sign.17,18 Nonmarginal TA includes patchy alopecia most commonly involving the parietal or occipital scalp, seen with chignons, buns, ponytails, or the use of clips, extensions, or bobby pins.18 The first line in management is avoidance of traction-causing hairstyles or headgear. Medical therapy may be warranted and consists of a single agent or combination regimen to include oral or topical antibiotics, topical or intralesional steroids, and topical minoxidil.13,18

Final Thoughts

Military hair-grooming standards have evolved over time. Recent changes show that the US Department of Defense is seriously evaluating policies that may be inherently exclusive. Prior grooming standards resulted in the widespread use of tight hairstyles and harsh hair treatments among female servicemembers with long hair. These practices resulted in TN, extracranial headaches, and TA, among other hair and scalp disorders. These occupational-related hair conditions impact female servicemembers’ mental and physical well-being and thus impact military readiness. Physicians should recognize that these conditions can be related to occupational grooming standards that may impact hair care practices.

The challenge that remains is a lack of standardized documentation for hair and scalp symptoms in the medical record. Due to a paucity in reporting and documentation, limited objective data exist to guide future recommendations for military grooming standards. Another obstacle is the lack of knowledge of hair diseases among primary care providers and patients, especially due to the underrepresentation of ethnic hair in medical textbooks.19 As a result, women frequently accept their hair symptoms as normal and either suffer through them, cut their hair short, or wear wigs before considering a visit to the doctor. Furthermore, hair-grooming standards can expose racial disparities, which are the driving force behind the current policy changes. Clinicians can strive to ask about hair and scalp symptoms and document the following in relation to hair and scalp disorders: occupational grooming requirements; skin and hair type; location, number, and size of scalp lesion(s); onset; duration; current and prior hair care practices; history of treatment; and clinical course accompanied with photographic documentation. Ultimately, improved awareness in patients, collaboration between physicians, and consistent clinical documentation can help create positive change and continued improvement in hair-grooming standards within the military. Improved reporting and documentation will facilitate further study into the effectiveness of the updated hair-grooming standards in female servicemembers.

- United States Air Force Statistical Digest FY 1999. United States Air Force; 2000. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://media.defense.gov/2011/Apr/14/2001330240/-1/-1/0/AFD-110414-048.pdf

- Air Force demographics. Air Force Personnel Center website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.afpc.af.mil/About/Air-Force-Demographics/

- US Department of the Army. Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia: Army Regulation 670-1. Department of the Army; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN30302-AR_670-1-000-WEB-1.pdf

- Losey S. Loc hairstyles, off-duty earrings for men ok’d in new dress regs. Air Force Times. Published July 16, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2018/07/16/loc-hairstyles-off-duty-earrings-for-men-okd-in-new-dress-regs/

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2011. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.uc.edu/content/dam/uc/afrotc/docs/Documents/AFI36-2903.pdf

- Department of the Air Force. AFT 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of Air Force Personnel. Department of the Air Force; 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a1/publication/afi36-2903/afi36-2903.pdf

- U.S. Navy uniform regulations: summary of changes (26 February 2020). Navy Personnel Command website. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Navy%20Uniforms/Uniform%20Regulations/Documents/SOC_2020_02_26.pdf?ver=y8Wd0ykVXgISfFpOy8qHkg%3d%3d

- US Headquarters Marine Corps. Marine Corps Uniform Regulations: Marine Corps Order 1020.34H. United States Marine Corps, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/MCO%201020.34H%20v2.pdf?ver=2018-06-26-094038-137

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force to allow longer braids, ponytails, bangs for women. United States Air Force website. Published January 21, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2478173/air-force-to-allow-longer-braids-ponytails-bangs-for-women/

- Britzky H. The Army will now allow women to wear ponytails in all uniforms. Task & Purpose. Published May 6, 2021. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://taskandpurpose.com/news/army-women-ponytails-all-uniforms/

- Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs. Air Force readdresses women’s hair standard after feedback. US Air Force website. Published June 11, 2021. Accessed June 27, 2021. https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2654774/air-force-readdresses-womens-hair-standard-after-feedback/

- Myers M. Esper direct services to review racial bias in grooming standards, training and more. Air Force Times. Published July 15, 2020. Accessed June 8, 2021. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-military/2020/07/15/esper-directs-services-to-review-racial-bias-in-grooming-standards-training-and-more/

- Madu P, Kundu RV. Follicular and scarring disorders in skin of color: presentation and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:307-321.

- Quaresma M, Martinez Velasco M, Tosti A. Hair breakage in patients of African descent: role of dermoscopy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:99-104.

- Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, et al. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015;55:21-34.