User login

Rounding up the usual suspects

A 76‐year‐old white male presented to his primary care physician with a 40‐pound weight loss and gradual decline in function over the prior 6 months. In addition, over the previous 2 months, he had begun to suffer a constant, non‐bloody, and non‐productive cough accompanied by night sweats. Associated complaints included a decline in physical activity, increased sleep needs, decreased appetite, irritability, and generalized body aches.

The patient, an elderly man, presents with a subacute, progressive systemic illness, which appears to have a pulmonary component. Broad disease categories meriting consideration include infections such as tuberculosis, endemic fungi, and infectious endocarditis; malignancies including bronchogenic carcinoma, as well as a variety of other neoplasms; and rheumatologic conditions including temporal arteritis/polymyalgia rheumatica and Wegener's granulomatosis. His complaints of anhedonia, somnolence, and irritability, while decidedly nonspecific, raise the possibility of central nervous system involvement.

His past medical history was notable for coronary artery disease, moderate aortic stenosis, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and chronic sinusitis. Two years ago, he had unexplained kidney failure. Anti‐neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) were present, and indirect immunoflorescence revealed a peri‐nuclear (P‐ANCA) pattern on kidney biopsy. The patient had been empirically placed on azathioprine for presumed focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and his renal function remained stable at an estimated glomerular filtrate rate ranging from 15 to 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. His other medications included nifedipine, metoprolol, aspirin, isosorbide mononitrate, atorvastatin, calcitriol, and docusate. His family and social histories were unremarkable, including no history of tobacco. He had no pets and denied illicit drug use. He admitted to spending a considerable amount of time gardening, including working in his yard in bare feet.

The associations of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, if indeed this diagnosis is correct, include lupus, vasculitis, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. The nephrotic syndrome is a frequent manifestation of this entity, although, based on limited information, this patient does not appear to be clinically nephrotic. If possible, the biopsy pathology should be reviewed by a pathologist with interest in the kidney. The report of a positive P‐ANCA may not be particularly helpful here, given the frequency of false‐positive results, and in any event, P‐ANCAs have been associated with a host of conditions other than vasculitis.

The patient's gardening exposure, in bare feet no less, is intriguing. This potentially places him at risk for fungal infections including blastomycosis, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, and sporotrichosis. Gardening without shoes is a somewhat different enterprise in northeast Ohio than, say, Mississippi, and it will be helpful to know where this took place. Exposure in Appalachia or the South should prompt consideration of disseminated strongyloidiasis, given his azathioprine use.

Vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 151/76 mmHg, pulse 67 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, temperature 35.6C, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. On examination, he appeared very thin but not in distress. Examination of the skin did not reveal rashes or lesions, and there was no lymphadenopathy. His thyroid was symmetric and normal in size. Lungs were clear to auscultation, and cardiac exam revealed a regular rate with a previously documented III/VI holosystolic murmur over the aortic auscultatory area. Abdominal exam revealed no organomegaly or tenderness. Joints were noted to be non‐inflamed, and extremities non‐edematous. Radial, brachial, popliteal, and dorsalis pedis pulses were normal bilaterally. A neurological exam revealed no focal deficits.

The physical examination does not help to substantively narrow or redirect the differential diagnosis. Although he appears to be tachypneic, this may simply reflect charting artifact. At this point, I would like to proceed with a number of basic diagnostic studies. In addition to complete blood count with differential, chemistries, and liver function panel, I would also obtain a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) assay, urinalysis, blood cultures, erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C‐reactive protein, a HIV enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), chest radiograph, and a repeat ANCA panel. A purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test should be placed.

Blood chemistries were as follows: glucose 88 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 48 mg/dL, creatinine 2.71 mg/dL, sodium 139 mmol/L, potassium 5.5 mmol/L, chloride 103 mmol/L, CO2 28 mmol/L, and anion gap 8 mmol/L. TSH, urinalysis, and PPD tests were unremarkable. His white blood cell count (WBC) was 33.62 K/L with 94% eosinophils and an absolute eosinophil count of 31.6 K/L. His platelet count was 189 K/L, hemoglobin 12.1 g/dL, and hematocrit 36.9%. A chest x‐ray revealed reticular opacities in the mid‐to‐lower lungs, and subsequent computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest demonstrated multiple bilateral indeterminate nodules and right axillary adenopathy.

The patient's strikingly elevated absolute eosinophil count is a very important clue that helps to significantly focus the diagnostic possibilities. In general, an eosinophilia this pronounced signifies one of several possibilities, including primary hypereosinophilic syndrome, ChurgStrauss syndrome, parasitic infection with an active tissue migration phase, eosinophilic leukemia, and perhaps chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. In addition, Wegener's granulomatosis still merits consideration, although an eosinophil count this high would certainly be unusual.

Of the above possibilities, ChurgStrauss seems less likely given his apparent absence of a history of asthma. Parasitic infections, particularly ascariasis but also strongyloidiasis, hookworm, and even visceral larva migrans are possible, although we have not been told whether geographical exposure exists to support the first 3 of these. Hypereosinophilic syndrome remains a strong consideration, although the patient does not yet clearly meet criteria for this diagnosis.

At this juncture, I would send stool and sputum for ova and parasite exam, and order Strongyloides serology, have the peripheral smear reviewed by a pathologist, await the repeat ANCA studies, and consider obtaining hematology consultation.

Tests for anti‐Smith, anti‐ribonuclear (RNP), anti‐SSA, anti‐SSB, anti‐centromere, anti‐Scl 70, and anti‐Jo antibodies were negative. Repeat ANCA testing was positive with P‐ANCA pattern on indirect immunofluorescence. His erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C‐reactive Protein (CRP) were mildly elevated at 29 mm/hr and 1.1 mg/dL, respectively. An immunodeficiency panel work‐up consisting of CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, T‐cell, B‐cell, and natural killer (NK) cell differential counts demonstrated CD8 T‐cell depletion. Blood cultures demonstrated no growth at 72 hours. No definite M protein was identified on serum and urine protein electrophoresis. Strongyloides IgG was negative. HIV ELISA was negative. A serologic fungal battery to measure antibodies against Aspergillus, Blastomyces, Histoplasma, and Coccidiodes was negative. A microscopic examination of stool and sputum for ova and parasites was also negative. A peripheral blood smear showed anisocytosis and confirmed the elevated eosinophil count.

The preceding wealth of information helps to further refine the picture. The positive P‐ANCA by ELISA as well as immunofluorescence suggests this is a real phenomenon, and makes ChurgStrauss syndrome more likely, despite the absence of preceding or concurrent asthma. I am not aware of an association between P‐ANCA and hypereosinophilic syndrome, nor of a similar link to either chronic eosinophilic pneumonia or hematological malignancies. Although I would like to see 2 additional stool studies for ova and parasites performed by an experienced laboratory technician before discarding the diagnosis of parasitic infection entirely, I am increasingly suspicious that this patient has a prednisone‐deficient state, most likely ChurgStrauss syndrome. I am uncertain of the relationship between his more recent symptoms and his pre‐existing kidney disease, but proceeding to lung biopsy appears to be appropriate.

Bronchoscopic examination with accompanying bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and transbronchial biopsy were performed. The BAL showed many Aspergillus fumigatus as well as hemosiderin‐laden macrophages, and the biopsy demonstrated an eosinophilic infiltrate throughout the interstitia, alveolar spaces, and bronchiolar walls. However, the airways did not show features of asthma, capillaritis, vasculitis, or granulomas. A bone marrow biopsy showed no evidence of clonal hematologic disease.

The Aspergillus recovered from BAL, although unexpected, probably does not adequately explain the picture. I am not convinced that the patient has invasive aspergillosis, and although components of the case are consistent with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, the absence of an asthma history and the extreme degree of peripheral eosinophilia seem to speak against this diagnosis. The biopsy does not corroborate a vasculitic process, but the yield of transbronchial biopsy is relatively low in this setting, and the pulmonary vasculitides remain in play unless a more substantial biopsy specimen is obtained. It is worth noting that high‐dose corticosteroids are a risk factor for the conversion of Aspergillus colonization to invasive aspergillosis, and treatment with voriconazole would certainly be appropriate if prednisone was to be initiated.

I believe ChurgStrauss syndrome, hypereosinophilic syndrome, and chronic eosinophilic pneumonia remain the leading diagnostic possibilities, with the P‐ANCA likely serving as a red herring if the diagnosis turns out to be one of the latter entities. An open lung biopsy would be an appropriate next step, after first obtaining those additional ova and parasite exams for completeness.

An infectious diseases specialist recommended that the patient be discharged on voriconazole 300 mg PO bid for Aspergillus colonization with an underlying lung disease and likely allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis or invasive aspergillosis. Steroid therapy was contemplated but not initiated.

Three weeks later, the patient re‐presented with worsening of fatigue and cognitive deterioration marked by episodes of confusion and word‐finding difficulties. His WBC had increased to 45.67 K/L (94% eosinophils). He had now lost a total of 70 pounds, and an increase in generalized weakness was apparent. His blood pressure on presentation was 120/63 mmHg, pulse rate 75 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, temperature 35.8C, and oxygen saturation 97% on room air. He appeared cachectic, but not in overt distress. His skin, head, neck, chest, cardiac, abdominal, peripheral vascular, and neurological exam demonstrated no change from the last admission. A follow‐up chest x‐ray showed mild pulmonary edema and new poorly defined pulmonary nodules in the right upper lobe. A repeat CT scan of the thorax demonstrated interval progression of ground‐glass attenuation nodules, which were now more solid‐appearing and increased in number, and present in all lobes of the lung. A CT of the brain did not reveal acute processes such as intracranial hemorrhage, infarction, or mass lesions. Lumbar puncture was performed, with a normal opening pressure. Analysis of the clear and colorless cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed 1 red blood cell count (RBC)/L, 2 WBC/L with 92% lymphocytes, glucose 68 mg/dL, and protein 39 mg/dL. CSF fungal cultures, routine cultures, venereal disease reaction level (VDRL), and cryptococcal antigen were negative. CSF cytology did not demonstrate malignant cells. Multiple ova and parasite exams obtained from the previous admission were confirmed to be negative.

The patient's continued deterioration points to either ChurgStrauss syndrome or hypereosinophilic syndrome, I believe. His renal function and P‐ANCA (if related) support the former possibility, while the development of what now appear to be clear encephalopathic symptoms are more in favor of the latter. I would initiate steroid therapy while proceeding to an open lung biopsy in an effort to secure a definitive diagnosis, again under the cover of voriconazole, and would ask for hematology input if this had not already been obtained.

A video‐assisted right thoracoscopy with wedge resection of 2 visible nodules in the right lower lobe was performed. The biopsy conclusively diagnosed a peripheral T‐cell lymphoma. The patient's condition deteriorated, and ultimately he and his family chose a palliative approach.

COMMENTARY

Eosinophils are cells of myeloid lineage that contain cationic‐rich protein granules that mediate allergic response, reaction to parasitic infections, tissue inflammation, and immune modulation.1, 2 Eosinophilia (absolute eosinophil count 600 cells/L) suggests the possibility of a wide array of disorders. The degree of eosinophilia can be categorized as mild (6001500 cells/L), moderate (15005000 cells/L), or severe (>5000 cells/L).3 It may signify a reactive phenomenon (secondary) or, less commonly, either an underlying hematological neoplasm (primary) or an idiopathic process.2 Clinicians faced with an unexplained eosinophilia should seek the most frequent causes first.

Initial investigation should include a careful travel history; consideration of both prescription and over‐the‐counter medications, especially non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), with withdrawal of non‐essential agents; serology for Strongyloides stercoralis antibodies (and possibly other helminths, depending on potential exposure) should be assessed; and stool examinations for ova and parasites should be obtained. The possibility of a wide variety of other potential causes of eosinophilia (Table 1) should be entertained,413 and a careful search for end‐organ damage related to eosinophilic infiltration should be performed if eosinophilia is moderate or severe.1

| Differential Diagnoses | Comments |

|---|---|

| Asthma and common allergic diseases (atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis) | Levels >1500 cell/l are uncommon |

| Paraneoplastic eosinophilia | Associated with adenocarcinomas, Hodgkin disease, T‐cell lymphomas, and systemic mastocytosis |

| Drugs and drug‐associated eosinophilic syndromes | Commonly associated with antibiotics (especially B‐lactams) and anti‐epileptic drugs |

| Immunodeficiency disorders | Hyper‐IgE syndrome and Omenn syndrome are rare causes of eosinophilia |

| Adrenal insufficiency | Important consideration in the critical care setting because endogenous glucocorticoids are involved in the stimulation of eosinophil apoptosis |

| Organ‐specific eosinophilic disorders | Examples: acute and chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, gastrointestinal eosinophilic disorders (esophagitis, colitis) |

| Primary eosinophilia: clonal or idiopathic | Clonal eosinophilia has histologic, cytogenetic, or molecular evidence of an underlying myeloid malignancy |

| Helminthic infections | An active tissue migration phase may manifest with hypereosinophilia |

| Hypereosinophilic syndrome | Classic criteria: hypereosinophilia for at least 6 mo, exclusion of both secondary and clonal eosinophilia, and evidence of organ involvement |

| ChurgStrauss syndrome | Hypereosinophilia with asthma, systemic vasculitis, migratory pulmonary infiltrates, sinusitis, and extravascular eosinophils |

| Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) | Major criteria: history of asthma, central bronchiectasis, immediate skin reactivity to Aspergillus, elevated total serum IgE (>1000 ng/mL), elevated IgE or IgG to Aspergillus |

Hypereosinophilia is defined as an eosinophil level greater than 1500 cells/L. These levels may be associated with end‐organ damage regardless of the underlying etiology, although the degree of eosinophilia frequently does not correlate closely with eosinophilic tissue infiltration. As a result, relatively modest degrees of peripheral eosinophilia may be seen in association with end‐organ damage, while severe eosinophilia may be tolerated well for prolonged periods in other cases.1 The most serious complications of hypereosinophilia are myocardial damage with ultimate development of cardiac fibrosis and refractory heart failure; pulmonary involvement with hypoxia; and involvement of both the central and peripheral nervous systems including stroke, encephalopathy, and mononeuritis multiplex. A number of studies should be considered to help evaluate for the possibility of end‐organ damage as well as to assess for the presence of primary and idiopathic causes of hypereosinophilia. These include peripheral blood smear looking particularly for dysplastic eosinophils or blasts, serum tryptase, serum vitamin B12, serum IgE, cardiac troponin levels, anti‐neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, electrocardiography, echocardiography, pulmonary function tests, and thoracoabdominal CT scanning. Endoscopic studies with esophageal, duodenal, and colonic biopsy should be performed if eosinophilic gastroenteritis is suspected.1, 7, 10

While more modest degrees of eosinophilia are associated with a plethora of conditions, severe eosinophilia, especially that approaching the levels displayed by this patient, suggests a much more circumscribed differential diagnosis. This should prompt consideration of ChurgStrauss syndrome, parasitic infection with an active tissue migration phase, and hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES).4 HES has classically been characterized by hypereosinophilia for at least 6 months, exclusion of both secondary and clonal eosinophilia, and evidence of end‐organ involvement. More recently, however, a revised definition consisting of marked eosinophilia with reasonable exclusion of other causes has gained favor.1, 7, 10, 1416 While perhaps as many as 75% of cases of HES continue to be considered idiopathic at present, 2 subtypes have now been recognized, with important prognostic and therapeutic implications. Myeloproliferative HES has a strong male predominance, is frequently associated with elevated serum tryptase and B12 levels, often manifests with hepatosplenomegaly, and displays a characteristic gene mutation, FIP1L1/PDGFRA. Lymphocytic HES is typified by polyclonal eosinophilic expansion in response to elevated IL‐5 levels, is associated with less cardiac involvement and a somewhat more favorable prognosis in the absence of therapy, and has been associated with transformation into T‐cell lymphoma.1, 1417 We suspect, though we are unable to prove, that our patient was finally diagnosed at the end of a journey that began as lymphocytic HES and ultimately progressed to T‐cell lymphoma. T‐cell lymphoma has rarely been associated with profound eosinophilia. This appears to reflect disordered production of IL‐5, as was true of this patient, and many of these cases may represent transformed lymphocytic HES.14

Specific therapy exists for the myeloproliferative subtype of HES, consisting of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib, with excellent response in typical cases. Initial treatment of most other extreme eosinophilic syndromes not caused by parasitic infection, including lymphocytic and idiopathic HES as well as ChurgStrauss syndrome, consists of high‐dose corticosteroids, with a variety of other agents used as second‐line and steroid‐sparing treatments. The urgency of therapy is dictated by the presence and severity of end‐organ damage, and in some instances corticosteroids may need to be given before the diagnosis is fully secure. When S. stercoralis infection has not been ruled out, concurrent therapy with ivermectin should be given to prevent triggering Strongyloides hyperinfection. Hematology input is critical when HES is under serious consideration, with bone marrow examination, cytogenetic studies, T‐cell phenotyping and T‐cell receptor rearrangement studies essential in helping to establish the correct diagnosis.10, 17

The differential diagnosis of peripheral eosinophilia is broad and requires a thorough, stepwise approach. Although profound eosinophilia is usually caused by a limited number of diseases, this patient reminds us that Captain Renault's advice in the film Casablanca to round up the usual suspects does not always suffice, as the diagnosis of T‐cell lymphoma was not considered by either the clinicians or the discussant until lung biopsy results became available. Most patients with hypereosinophilia not caused by parasitic infection will ultimately require an invasive procedure to establish a diagnosis, which is essential before embarking on an often‐toxic course of therapy, as well as for providing an accurate prognosis.

TEACHING POINTS

-

The most common causes of eosinophilia include helminthic infections (the leading cause worldwide), asthma, allergic conditions (the leading cause in the United States), malignancies, and drugs.

-

Hypereosinophilia may lead to end‐organ damage. The most important etiologies include ChurgStrauss Syndrome, HES, or a helminthic infection in the larval migration phase.

-

The mainstay of therapy for most cases of HES is corticosteroids. The goal of therapy is to prevent, or ameliorate, end‐organ damage.

- ,.Practical approach to the patient with hypereosinophilia.J Allergy Clin Immunol.2010;126(1):39–44.

- ,,.Eosinophilia: secondary, clonal and idiopathic.Br J Haematol.2006;133(5):468–492.

- .Blood eosinophilia: a new paradigm in disease classification, diagnosis, and treatment.Mayo Clin Proc.2005;80(1):75–83.

- ,,,.Clinical manifestations and treatment of Churg‐Strauss syndrome.Rheum Dis Clin North Am.2010;36(3):527–543.

- ,,,.Relative eosinophilia and functional adrenal insufficiency in critically ill patients.Lancet.1999;353(9165):1675–1676.

- ,,,.Opposing effects of glucocorticoids on the rate of apoptosis in neutrophilic and eosinophilic granulocytes.J Immunol.1996;156(10):4422–4428.

- ,.Eosinophilic disorders.J Allergy Clin Immunol.2007;119(6):1291–1300; quiz 1301–1302.

- ,.Pulmonary eosinophilia.Clin Rev Allergy Immunol.2008;34(3):367–371.

- .Eosinophilic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract.Scand J Gastroenterol.2010;45(9):1013–1021.

- ,,.Hypereosinophilic syndrome and clonal eosinophilia: point‐of‐care diagnostic algorithm and treatment update.Mayo Clin Proc.2010;85(2):158–164.

- ,,,,,.Eosinophilia as a predictor of food allergy in atopic dermatitis.Allergy Asthma Proc.2010;31(2):e18–e24.

- ,,, et al.The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg‐Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis).Arthritis Rheum.1990;33(8):1094–1100.

- .Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. In: Adkinson NF, Yunginger JW, Busse WW, et al, eds. Middleton's Allergy Principles 2003:1353–1371.

- ,,, et al.TARC and IL‐5 expression correlates with tissue eosinophilia in peripheral T‐cell lymphomas.Leuk Res.2008;32(9):1431–1438.

- ,,.Hypereosinophilic syndrome and proliferative diseases.Acta Dermatovenerol Croat.2009;17(4):323–330.

- ,.The hypereosinophilic syndromes: current concepts and treatments.Br J Haematol.2009;145(3):271–285.

- ,,.Lymphocytic variant hypereosinophilic syndromes.Immunol Allergy Clin North Am.2007;27(3):389–413.

A 76‐year‐old white male presented to his primary care physician with a 40‐pound weight loss and gradual decline in function over the prior 6 months. In addition, over the previous 2 months, he had begun to suffer a constant, non‐bloody, and non‐productive cough accompanied by night sweats. Associated complaints included a decline in physical activity, increased sleep needs, decreased appetite, irritability, and generalized body aches.

The patient, an elderly man, presents with a subacute, progressive systemic illness, which appears to have a pulmonary component. Broad disease categories meriting consideration include infections such as tuberculosis, endemic fungi, and infectious endocarditis; malignancies including bronchogenic carcinoma, as well as a variety of other neoplasms; and rheumatologic conditions including temporal arteritis/polymyalgia rheumatica and Wegener's granulomatosis. His complaints of anhedonia, somnolence, and irritability, while decidedly nonspecific, raise the possibility of central nervous system involvement.

His past medical history was notable for coronary artery disease, moderate aortic stenosis, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and chronic sinusitis. Two years ago, he had unexplained kidney failure. Anti‐neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) were present, and indirect immunoflorescence revealed a peri‐nuclear (P‐ANCA) pattern on kidney biopsy. The patient had been empirically placed on azathioprine for presumed focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and his renal function remained stable at an estimated glomerular filtrate rate ranging from 15 to 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. His other medications included nifedipine, metoprolol, aspirin, isosorbide mononitrate, atorvastatin, calcitriol, and docusate. His family and social histories were unremarkable, including no history of tobacco. He had no pets and denied illicit drug use. He admitted to spending a considerable amount of time gardening, including working in his yard in bare feet.

The associations of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, if indeed this diagnosis is correct, include lupus, vasculitis, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. The nephrotic syndrome is a frequent manifestation of this entity, although, based on limited information, this patient does not appear to be clinically nephrotic. If possible, the biopsy pathology should be reviewed by a pathologist with interest in the kidney. The report of a positive P‐ANCA may not be particularly helpful here, given the frequency of false‐positive results, and in any event, P‐ANCAs have been associated with a host of conditions other than vasculitis.

The patient's gardening exposure, in bare feet no less, is intriguing. This potentially places him at risk for fungal infections including blastomycosis, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, and sporotrichosis. Gardening without shoes is a somewhat different enterprise in northeast Ohio than, say, Mississippi, and it will be helpful to know where this took place. Exposure in Appalachia or the South should prompt consideration of disseminated strongyloidiasis, given his azathioprine use.

Vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 151/76 mmHg, pulse 67 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, temperature 35.6C, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. On examination, he appeared very thin but not in distress. Examination of the skin did not reveal rashes or lesions, and there was no lymphadenopathy. His thyroid was symmetric and normal in size. Lungs were clear to auscultation, and cardiac exam revealed a regular rate with a previously documented III/VI holosystolic murmur over the aortic auscultatory area. Abdominal exam revealed no organomegaly or tenderness. Joints were noted to be non‐inflamed, and extremities non‐edematous. Radial, brachial, popliteal, and dorsalis pedis pulses were normal bilaterally. A neurological exam revealed no focal deficits.

The physical examination does not help to substantively narrow or redirect the differential diagnosis. Although he appears to be tachypneic, this may simply reflect charting artifact. At this point, I would like to proceed with a number of basic diagnostic studies. In addition to complete blood count with differential, chemistries, and liver function panel, I would also obtain a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) assay, urinalysis, blood cultures, erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C‐reactive protein, a HIV enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), chest radiograph, and a repeat ANCA panel. A purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test should be placed.

Blood chemistries were as follows: glucose 88 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 48 mg/dL, creatinine 2.71 mg/dL, sodium 139 mmol/L, potassium 5.5 mmol/L, chloride 103 mmol/L, CO2 28 mmol/L, and anion gap 8 mmol/L. TSH, urinalysis, and PPD tests were unremarkable. His white blood cell count (WBC) was 33.62 K/L with 94% eosinophils and an absolute eosinophil count of 31.6 K/L. His platelet count was 189 K/L, hemoglobin 12.1 g/dL, and hematocrit 36.9%. A chest x‐ray revealed reticular opacities in the mid‐to‐lower lungs, and subsequent computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest demonstrated multiple bilateral indeterminate nodules and right axillary adenopathy.

The patient's strikingly elevated absolute eosinophil count is a very important clue that helps to significantly focus the diagnostic possibilities. In general, an eosinophilia this pronounced signifies one of several possibilities, including primary hypereosinophilic syndrome, ChurgStrauss syndrome, parasitic infection with an active tissue migration phase, eosinophilic leukemia, and perhaps chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. In addition, Wegener's granulomatosis still merits consideration, although an eosinophil count this high would certainly be unusual.

Of the above possibilities, ChurgStrauss seems less likely given his apparent absence of a history of asthma. Parasitic infections, particularly ascariasis but also strongyloidiasis, hookworm, and even visceral larva migrans are possible, although we have not been told whether geographical exposure exists to support the first 3 of these. Hypereosinophilic syndrome remains a strong consideration, although the patient does not yet clearly meet criteria for this diagnosis.

At this juncture, I would send stool and sputum for ova and parasite exam, and order Strongyloides serology, have the peripheral smear reviewed by a pathologist, await the repeat ANCA studies, and consider obtaining hematology consultation.

Tests for anti‐Smith, anti‐ribonuclear (RNP), anti‐SSA, anti‐SSB, anti‐centromere, anti‐Scl 70, and anti‐Jo antibodies were negative. Repeat ANCA testing was positive with P‐ANCA pattern on indirect immunofluorescence. His erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C‐reactive Protein (CRP) were mildly elevated at 29 mm/hr and 1.1 mg/dL, respectively. An immunodeficiency panel work‐up consisting of CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, T‐cell, B‐cell, and natural killer (NK) cell differential counts demonstrated CD8 T‐cell depletion. Blood cultures demonstrated no growth at 72 hours. No definite M protein was identified on serum and urine protein electrophoresis. Strongyloides IgG was negative. HIV ELISA was negative. A serologic fungal battery to measure antibodies against Aspergillus, Blastomyces, Histoplasma, and Coccidiodes was negative. A microscopic examination of stool and sputum for ova and parasites was also negative. A peripheral blood smear showed anisocytosis and confirmed the elevated eosinophil count.

The preceding wealth of information helps to further refine the picture. The positive P‐ANCA by ELISA as well as immunofluorescence suggests this is a real phenomenon, and makes ChurgStrauss syndrome more likely, despite the absence of preceding or concurrent asthma. I am not aware of an association between P‐ANCA and hypereosinophilic syndrome, nor of a similar link to either chronic eosinophilic pneumonia or hematological malignancies. Although I would like to see 2 additional stool studies for ova and parasites performed by an experienced laboratory technician before discarding the diagnosis of parasitic infection entirely, I am increasingly suspicious that this patient has a prednisone‐deficient state, most likely ChurgStrauss syndrome. I am uncertain of the relationship between his more recent symptoms and his pre‐existing kidney disease, but proceeding to lung biopsy appears to be appropriate.

Bronchoscopic examination with accompanying bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and transbronchial biopsy were performed. The BAL showed many Aspergillus fumigatus as well as hemosiderin‐laden macrophages, and the biopsy demonstrated an eosinophilic infiltrate throughout the interstitia, alveolar spaces, and bronchiolar walls. However, the airways did not show features of asthma, capillaritis, vasculitis, or granulomas. A bone marrow biopsy showed no evidence of clonal hematologic disease.

The Aspergillus recovered from BAL, although unexpected, probably does not adequately explain the picture. I am not convinced that the patient has invasive aspergillosis, and although components of the case are consistent with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, the absence of an asthma history and the extreme degree of peripheral eosinophilia seem to speak against this diagnosis. The biopsy does not corroborate a vasculitic process, but the yield of transbronchial biopsy is relatively low in this setting, and the pulmonary vasculitides remain in play unless a more substantial biopsy specimen is obtained. It is worth noting that high‐dose corticosteroids are a risk factor for the conversion of Aspergillus colonization to invasive aspergillosis, and treatment with voriconazole would certainly be appropriate if prednisone was to be initiated.

I believe ChurgStrauss syndrome, hypereosinophilic syndrome, and chronic eosinophilic pneumonia remain the leading diagnostic possibilities, with the P‐ANCA likely serving as a red herring if the diagnosis turns out to be one of the latter entities. An open lung biopsy would be an appropriate next step, after first obtaining those additional ova and parasite exams for completeness.

An infectious diseases specialist recommended that the patient be discharged on voriconazole 300 mg PO bid for Aspergillus colonization with an underlying lung disease and likely allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis or invasive aspergillosis. Steroid therapy was contemplated but not initiated.

Three weeks later, the patient re‐presented with worsening of fatigue and cognitive deterioration marked by episodes of confusion and word‐finding difficulties. His WBC had increased to 45.67 K/L (94% eosinophils). He had now lost a total of 70 pounds, and an increase in generalized weakness was apparent. His blood pressure on presentation was 120/63 mmHg, pulse rate 75 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, temperature 35.8C, and oxygen saturation 97% on room air. He appeared cachectic, but not in overt distress. His skin, head, neck, chest, cardiac, abdominal, peripheral vascular, and neurological exam demonstrated no change from the last admission. A follow‐up chest x‐ray showed mild pulmonary edema and new poorly defined pulmonary nodules in the right upper lobe. A repeat CT scan of the thorax demonstrated interval progression of ground‐glass attenuation nodules, which were now more solid‐appearing and increased in number, and present in all lobes of the lung. A CT of the brain did not reveal acute processes such as intracranial hemorrhage, infarction, or mass lesions. Lumbar puncture was performed, with a normal opening pressure. Analysis of the clear and colorless cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed 1 red blood cell count (RBC)/L, 2 WBC/L with 92% lymphocytes, glucose 68 mg/dL, and protein 39 mg/dL. CSF fungal cultures, routine cultures, venereal disease reaction level (VDRL), and cryptococcal antigen were negative. CSF cytology did not demonstrate malignant cells. Multiple ova and parasite exams obtained from the previous admission were confirmed to be negative.

The patient's continued deterioration points to either ChurgStrauss syndrome or hypereosinophilic syndrome, I believe. His renal function and P‐ANCA (if related) support the former possibility, while the development of what now appear to be clear encephalopathic symptoms are more in favor of the latter. I would initiate steroid therapy while proceeding to an open lung biopsy in an effort to secure a definitive diagnosis, again under the cover of voriconazole, and would ask for hematology input if this had not already been obtained.

A video‐assisted right thoracoscopy with wedge resection of 2 visible nodules in the right lower lobe was performed. The biopsy conclusively diagnosed a peripheral T‐cell lymphoma. The patient's condition deteriorated, and ultimately he and his family chose a palliative approach.

COMMENTARY

Eosinophils are cells of myeloid lineage that contain cationic‐rich protein granules that mediate allergic response, reaction to parasitic infections, tissue inflammation, and immune modulation.1, 2 Eosinophilia (absolute eosinophil count 600 cells/L) suggests the possibility of a wide array of disorders. The degree of eosinophilia can be categorized as mild (6001500 cells/L), moderate (15005000 cells/L), or severe (>5000 cells/L).3 It may signify a reactive phenomenon (secondary) or, less commonly, either an underlying hematological neoplasm (primary) or an idiopathic process.2 Clinicians faced with an unexplained eosinophilia should seek the most frequent causes first.

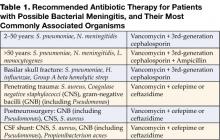

Initial investigation should include a careful travel history; consideration of both prescription and over‐the‐counter medications, especially non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), with withdrawal of non‐essential agents; serology for Strongyloides stercoralis antibodies (and possibly other helminths, depending on potential exposure) should be assessed; and stool examinations for ova and parasites should be obtained. The possibility of a wide variety of other potential causes of eosinophilia (Table 1) should be entertained,413 and a careful search for end‐organ damage related to eosinophilic infiltration should be performed if eosinophilia is moderate or severe.1

| Differential Diagnoses | Comments |

|---|---|

| Asthma and common allergic diseases (atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis) | Levels >1500 cell/l are uncommon |

| Paraneoplastic eosinophilia | Associated with adenocarcinomas, Hodgkin disease, T‐cell lymphomas, and systemic mastocytosis |

| Drugs and drug‐associated eosinophilic syndromes | Commonly associated with antibiotics (especially B‐lactams) and anti‐epileptic drugs |

| Immunodeficiency disorders | Hyper‐IgE syndrome and Omenn syndrome are rare causes of eosinophilia |

| Adrenal insufficiency | Important consideration in the critical care setting because endogenous glucocorticoids are involved in the stimulation of eosinophil apoptosis |

| Organ‐specific eosinophilic disorders | Examples: acute and chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, gastrointestinal eosinophilic disorders (esophagitis, colitis) |

| Primary eosinophilia: clonal or idiopathic | Clonal eosinophilia has histologic, cytogenetic, or molecular evidence of an underlying myeloid malignancy |

| Helminthic infections | An active tissue migration phase may manifest with hypereosinophilia |

| Hypereosinophilic syndrome | Classic criteria: hypereosinophilia for at least 6 mo, exclusion of both secondary and clonal eosinophilia, and evidence of organ involvement |

| ChurgStrauss syndrome | Hypereosinophilia with asthma, systemic vasculitis, migratory pulmonary infiltrates, sinusitis, and extravascular eosinophils |

| Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) | Major criteria: history of asthma, central bronchiectasis, immediate skin reactivity to Aspergillus, elevated total serum IgE (>1000 ng/mL), elevated IgE or IgG to Aspergillus |

Hypereosinophilia is defined as an eosinophil level greater than 1500 cells/L. These levels may be associated with end‐organ damage regardless of the underlying etiology, although the degree of eosinophilia frequently does not correlate closely with eosinophilic tissue infiltration. As a result, relatively modest degrees of peripheral eosinophilia may be seen in association with end‐organ damage, while severe eosinophilia may be tolerated well for prolonged periods in other cases.1 The most serious complications of hypereosinophilia are myocardial damage with ultimate development of cardiac fibrosis and refractory heart failure; pulmonary involvement with hypoxia; and involvement of both the central and peripheral nervous systems including stroke, encephalopathy, and mononeuritis multiplex. A number of studies should be considered to help evaluate for the possibility of end‐organ damage as well as to assess for the presence of primary and idiopathic causes of hypereosinophilia. These include peripheral blood smear looking particularly for dysplastic eosinophils or blasts, serum tryptase, serum vitamin B12, serum IgE, cardiac troponin levels, anti‐neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, electrocardiography, echocardiography, pulmonary function tests, and thoracoabdominal CT scanning. Endoscopic studies with esophageal, duodenal, and colonic biopsy should be performed if eosinophilic gastroenteritis is suspected.1, 7, 10

While more modest degrees of eosinophilia are associated with a plethora of conditions, severe eosinophilia, especially that approaching the levels displayed by this patient, suggests a much more circumscribed differential diagnosis. This should prompt consideration of ChurgStrauss syndrome, parasitic infection with an active tissue migration phase, and hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES).4 HES has classically been characterized by hypereosinophilia for at least 6 months, exclusion of both secondary and clonal eosinophilia, and evidence of end‐organ involvement. More recently, however, a revised definition consisting of marked eosinophilia with reasonable exclusion of other causes has gained favor.1, 7, 10, 1416 While perhaps as many as 75% of cases of HES continue to be considered idiopathic at present, 2 subtypes have now been recognized, with important prognostic and therapeutic implications. Myeloproliferative HES has a strong male predominance, is frequently associated with elevated serum tryptase and B12 levels, often manifests with hepatosplenomegaly, and displays a characteristic gene mutation, FIP1L1/PDGFRA. Lymphocytic HES is typified by polyclonal eosinophilic expansion in response to elevated IL‐5 levels, is associated with less cardiac involvement and a somewhat more favorable prognosis in the absence of therapy, and has been associated with transformation into T‐cell lymphoma.1, 1417 We suspect, though we are unable to prove, that our patient was finally diagnosed at the end of a journey that began as lymphocytic HES and ultimately progressed to T‐cell lymphoma. T‐cell lymphoma has rarely been associated with profound eosinophilia. This appears to reflect disordered production of IL‐5, as was true of this patient, and many of these cases may represent transformed lymphocytic HES.14

Specific therapy exists for the myeloproliferative subtype of HES, consisting of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib, with excellent response in typical cases. Initial treatment of most other extreme eosinophilic syndromes not caused by parasitic infection, including lymphocytic and idiopathic HES as well as ChurgStrauss syndrome, consists of high‐dose corticosteroids, with a variety of other agents used as second‐line and steroid‐sparing treatments. The urgency of therapy is dictated by the presence and severity of end‐organ damage, and in some instances corticosteroids may need to be given before the diagnosis is fully secure. When S. stercoralis infection has not been ruled out, concurrent therapy with ivermectin should be given to prevent triggering Strongyloides hyperinfection. Hematology input is critical when HES is under serious consideration, with bone marrow examination, cytogenetic studies, T‐cell phenotyping and T‐cell receptor rearrangement studies essential in helping to establish the correct diagnosis.10, 17

The differential diagnosis of peripheral eosinophilia is broad and requires a thorough, stepwise approach. Although profound eosinophilia is usually caused by a limited number of diseases, this patient reminds us that Captain Renault's advice in the film Casablanca to round up the usual suspects does not always suffice, as the diagnosis of T‐cell lymphoma was not considered by either the clinicians or the discussant until lung biopsy results became available. Most patients with hypereosinophilia not caused by parasitic infection will ultimately require an invasive procedure to establish a diagnosis, which is essential before embarking on an often‐toxic course of therapy, as well as for providing an accurate prognosis.

TEACHING POINTS

-

The most common causes of eosinophilia include helminthic infections (the leading cause worldwide), asthma, allergic conditions (the leading cause in the United States), malignancies, and drugs.

-

Hypereosinophilia may lead to end‐organ damage. The most important etiologies include ChurgStrauss Syndrome, HES, or a helminthic infection in the larval migration phase.

-

The mainstay of therapy for most cases of HES is corticosteroids. The goal of therapy is to prevent, or ameliorate, end‐organ damage.

A 76‐year‐old white male presented to his primary care physician with a 40‐pound weight loss and gradual decline in function over the prior 6 months. In addition, over the previous 2 months, he had begun to suffer a constant, non‐bloody, and non‐productive cough accompanied by night sweats. Associated complaints included a decline in physical activity, increased sleep needs, decreased appetite, irritability, and generalized body aches.

The patient, an elderly man, presents with a subacute, progressive systemic illness, which appears to have a pulmonary component. Broad disease categories meriting consideration include infections such as tuberculosis, endemic fungi, and infectious endocarditis; malignancies including bronchogenic carcinoma, as well as a variety of other neoplasms; and rheumatologic conditions including temporal arteritis/polymyalgia rheumatica and Wegener's granulomatosis. His complaints of anhedonia, somnolence, and irritability, while decidedly nonspecific, raise the possibility of central nervous system involvement.

His past medical history was notable for coronary artery disease, moderate aortic stenosis, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and chronic sinusitis. Two years ago, he had unexplained kidney failure. Anti‐neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) were present, and indirect immunoflorescence revealed a peri‐nuclear (P‐ANCA) pattern on kidney biopsy. The patient had been empirically placed on azathioprine for presumed focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and his renal function remained stable at an estimated glomerular filtrate rate ranging from 15 to 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. His other medications included nifedipine, metoprolol, aspirin, isosorbide mononitrate, atorvastatin, calcitriol, and docusate. His family and social histories were unremarkable, including no history of tobacco. He had no pets and denied illicit drug use. He admitted to spending a considerable amount of time gardening, including working in his yard in bare feet.

The associations of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, if indeed this diagnosis is correct, include lupus, vasculitis, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. The nephrotic syndrome is a frequent manifestation of this entity, although, based on limited information, this patient does not appear to be clinically nephrotic. If possible, the biopsy pathology should be reviewed by a pathologist with interest in the kidney. The report of a positive P‐ANCA may not be particularly helpful here, given the frequency of false‐positive results, and in any event, P‐ANCAs have been associated with a host of conditions other than vasculitis.

The patient's gardening exposure, in bare feet no less, is intriguing. This potentially places him at risk for fungal infections including blastomycosis, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, and sporotrichosis. Gardening without shoes is a somewhat different enterprise in northeast Ohio than, say, Mississippi, and it will be helpful to know where this took place. Exposure in Appalachia or the South should prompt consideration of disseminated strongyloidiasis, given his azathioprine use.

Vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 151/76 mmHg, pulse 67 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, temperature 35.6C, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. On examination, he appeared very thin but not in distress. Examination of the skin did not reveal rashes or lesions, and there was no lymphadenopathy. His thyroid was symmetric and normal in size. Lungs were clear to auscultation, and cardiac exam revealed a regular rate with a previously documented III/VI holosystolic murmur over the aortic auscultatory area. Abdominal exam revealed no organomegaly or tenderness. Joints were noted to be non‐inflamed, and extremities non‐edematous. Radial, brachial, popliteal, and dorsalis pedis pulses were normal bilaterally. A neurological exam revealed no focal deficits.

The physical examination does not help to substantively narrow or redirect the differential diagnosis. Although he appears to be tachypneic, this may simply reflect charting artifact. At this point, I would like to proceed with a number of basic diagnostic studies. In addition to complete blood count with differential, chemistries, and liver function panel, I would also obtain a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) assay, urinalysis, blood cultures, erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C‐reactive protein, a HIV enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), chest radiograph, and a repeat ANCA panel. A purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test should be placed.

Blood chemistries were as follows: glucose 88 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 48 mg/dL, creatinine 2.71 mg/dL, sodium 139 mmol/L, potassium 5.5 mmol/L, chloride 103 mmol/L, CO2 28 mmol/L, and anion gap 8 mmol/L. TSH, urinalysis, and PPD tests were unremarkable. His white blood cell count (WBC) was 33.62 K/L with 94% eosinophils and an absolute eosinophil count of 31.6 K/L. His platelet count was 189 K/L, hemoglobin 12.1 g/dL, and hematocrit 36.9%. A chest x‐ray revealed reticular opacities in the mid‐to‐lower lungs, and subsequent computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest demonstrated multiple bilateral indeterminate nodules and right axillary adenopathy.

The patient's strikingly elevated absolute eosinophil count is a very important clue that helps to significantly focus the diagnostic possibilities. In general, an eosinophilia this pronounced signifies one of several possibilities, including primary hypereosinophilic syndrome, ChurgStrauss syndrome, parasitic infection with an active tissue migration phase, eosinophilic leukemia, and perhaps chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. In addition, Wegener's granulomatosis still merits consideration, although an eosinophil count this high would certainly be unusual.

Of the above possibilities, ChurgStrauss seems less likely given his apparent absence of a history of asthma. Parasitic infections, particularly ascariasis but also strongyloidiasis, hookworm, and even visceral larva migrans are possible, although we have not been told whether geographical exposure exists to support the first 3 of these. Hypereosinophilic syndrome remains a strong consideration, although the patient does not yet clearly meet criteria for this diagnosis.

At this juncture, I would send stool and sputum for ova and parasite exam, and order Strongyloides serology, have the peripheral smear reviewed by a pathologist, await the repeat ANCA studies, and consider obtaining hematology consultation.

Tests for anti‐Smith, anti‐ribonuclear (RNP), anti‐SSA, anti‐SSB, anti‐centromere, anti‐Scl 70, and anti‐Jo antibodies were negative. Repeat ANCA testing was positive with P‐ANCA pattern on indirect immunofluorescence. His erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C‐reactive Protein (CRP) were mildly elevated at 29 mm/hr and 1.1 mg/dL, respectively. An immunodeficiency panel work‐up consisting of CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, T‐cell, B‐cell, and natural killer (NK) cell differential counts demonstrated CD8 T‐cell depletion. Blood cultures demonstrated no growth at 72 hours. No definite M protein was identified on serum and urine protein electrophoresis. Strongyloides IgG was negative. HIV ELISA was negative. A serologic fungal battery to measure antibodies against Aspergillus, Blastomyces, Histoplasma, and Coccidiodes was negative. A microscopic examination of stool and sputum for ova and parasites was also negative. A peripheral blood smear showed anisocytosis and confirmed the elevated eosinophil count.

The preceding wealth of information helps to further refine the picture. The positive P‐ANCA by ELISA as well as immunofluorescence suggests this is a real phenomenon, and makes ChurgStrauss syndrome more likely, despite the absence of preceding or concurrent asthma. I am not aware of an association between P‐ANCA and hypereosinophilic syndrome, nor of a similar link to either chronic eosinophilic pneumonia or hematological malignancies. Although I would like to see 2 additional stool studies for ova and parasites performed by an experienced laboratory technician before discarding the diagnosis of parasitic infection entirely, I am increasingly suspicious that this patient has a prednisone‐deficient state, most likely ChurgStrauss syndrome. I am uncertain of the relationship between his more recent symptoms and his pre‐existing kidney disease, but proceeding to lung biopsy appears to be appropriate.

Bronchoscopic examination with accompanying bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and transbronchial biopsy were performed. The BAL showed many Aspergillus fumigatus as well as hemosiderin‐laden macrophages, and the biopsy demonstrated an eosinophilic infiltrate throughout the interstitia, alveolar spaces, and bronchiolar walls. However, the airways did not show features of asthma, capillaritis, vasculitis, or granulomas. A bone marrow biopsy showed no evidence of clonal hematologic disease.

The Aspergillus recovered from BAL, although unexpected, probably does not adequately explain the picture. I am not convinced that the patient has invasive aspergillosis, and although components of the case are consistent with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, the absence of an asthma history and the extreme degree of peripheral eosinophilia seem to speak against this diagnosis. The biopsy does not corroborate a vasculitic process, but the yield of transbronchial biopsy is relatively low in this setting, and the pulmonary vasculitides remain in play unless a more substantial biopsy specimen is obtained. It is worth noting that high‐dose corticosteroids are a risk factor for the conversion of Aspergillus colonization to invasive aspergillosis, and treatment with voriconazole would certainly be appropriate if prednisone was to be initiated.

I believe ChurgStrauss syndrome, hypereosinophilic syndrome, and chronic eosinophilic pneumonia remain the leading diagnostic possibilities, with the P‐ANCA likely serving as a red herring if the diagnosis turns out to be one of the latter entities. An open lung biopsy would be an appropriate next step, after first obtaining those additional ova and parasite exams for completeness.

An infectious diseases specialist recommended that the patient be discharged on voriconazole 300 mg PO bid for Aspergillus colonization with an underlying lung disease and likely allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis or invasive aspergillosis. Steroid therapy was contemplated but not initiated.

Three weeks later, the patient re‐presented with worsening of fatigue and cognitive deterioration marked by episodes of confusion and word‐finding difficulties. His WBC had increased to 45.67 K/L (94% eosinophils). He had now lost a total of 70 pounds, and an increase in generalized weakness was apparent. His blood pressure on presentation was 120/63 mmHg, pulse rate 75 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, temperature 35.8C, and oxygen saturation 97% on room air. He appeared cachectic, but not in overt distress. His skin, head, neck, chest, cardiac, abdominal, peripheral vascular, and neurological exam demonstrated no change from the last admission. A follow‐up chest x‐ray showed mild pulmonary edema and new poorly defined pulmonary nodules in the right upper lobe. A repeat CT scan of the thorax demonstrated interval progression of ground‐glass attenuation nodules, which were now more solid‐appearing and increased in number, and present in all lobes of the lung. A CT of the brain did not reveal acute processes such as intracranial hemorrhage, infarction, or mass lesions. Lumbar puncture was performed, with a normal opening pressure. Analysis of the clear and colorless cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed 1 red blood cell count (RBC)/L, 2 WBC/L with 92% lymphocytes, glucose 68 mg/dL, and protein 39 mg/dL. CSF fungal cultures, routine cultures, venereal disease reaction level (VDRL), and cryptococcal antigen were negative. CSF cytology did not demonstrate malignant cells. Multiple ova and parasite exams obtained from the previous admission were confirmed to be negative.

The patient's continued deterioration points to either ChurgStrauss syndrome or hypereosinophilic syndrome, I believe. His renal function and P‐ANCA (if related) support the former possibility, while the development of what now appear to be clear encephalopathic symptoms are more in favor of the latter. I would initiate steroid therapy while proceeding to an open lung biopsy in an effort to secure a definitive diagnosis, again under the cover of voriconazole, and would ask for hematology input if this had not already been obtained.

A video‐assisted right thoracoscopy with wedge resection of 2 visible nodules in the right lower lobe was performed. The biopsy conclusively diagnosed a peripheral T‐cell lymphoma. The patient's condition deteriorated, and ultimately he and his family chose a palliative approach.

COMMENTARY

Eosinophils are cells of myeloid lineage that contain cationic‐rich protein granules that mediate allergic response, reaction to parasitic infections, tissue inflammation, and immune modulation.1, 2 Eosinophilia (absolute eosinophil count 600 cells/L) suggests the possibility of a wide array of disorders. The degree of eosinophilia can be categorized as mild (6001500 cells/L), moderate (15005000 cells/L), or severe (>5000 cells/L).3 It may signify a reactive phenomenon (secondary) or, less commonly, either an underlying hematological neoplasm (primary) or an idiopathic process.2 Clinicians faced with an unexplained eosinophilia should seek the most frequent causes first.

Initial investigation should include a careful travel history; consideration of both prescription and over‐the‐counter medications, especially non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), with withdrawal of non‐essential agents; serology for Strongyloides stercoralis antibodies (and possibly other helminths, depending on potential exposure) should be assessed; and stool examinations for ova and parasites should be obtained. The possibility of a wide variety of other potential causes of eosinophilia (Table 1) should be entertained,413 and a careful search for end‐organ damage related to eosinophilic infiltration should be performed if eosinophilia is moderate or severe.1

| Differential Diagnoses | Comments |

|---|---|

| Asthma and common allergic diseases (atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis) | Levels >1500 cell/l are uncommon |

| Paraneoplastic eosinophilia | Associated with adenocarcinomas, Hodgkin disease, T‐cell lymphomas, and systemic mastocytosis |

| Drugs and drug‐associated eosinophilic syndromes | Commonly associated with antibiotics (especially B‐lactams) and anti‐epileptic drugs |

| Immunodeficiency disorders | Hyper‐IgE syndrome and Omenn syndrome are rare causes of eosinophilia |

| Adrenal insufficiency | Important consideration in the critical care setting because endogenous glucocorticoids are involved in the stimulation of eosinophil apoptosis |

| Organ‐specific eosinophilic disorders | Examples: acute and chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, gastrointestinal eosinophilic disorders (esophagitis, colitis) |

| Primary eosinophilia: clonal or idiopathic | Clonal eosinophilia has histologic, cytogenetic, or molecular evidence of an underlying myeloid malignancy |

| Helminthic infections | An active tissue migration phase may manifest with hypereosinophilia |

| Hypereosinophilic syndrome | Classic criteria: hypereosinophilia for at least 6 mo, exclusion of both secondary and clonal eosinophilia, and evidence of organ involvement |

| ChurgStrauss syndrome | Hypereosinophilia with asthma, systemic vasculitis, migratory pulmonary infiltrates, sinusitis, and extravascular eosinophils |

| Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) | Major criteria: history of asthma, central bronchiectasis, immediate skin reactivity to Aspergillus, elevated total serum IgE (>1000 ng/mL), elevated IgE or IgG to Aspergillus |

Hypereosinophilia is defined as an eosinophil level greater than 1500 cells/L. These levels may be associated with end‐organ damage regardless of the underlying etiology, although the degree of eosinophilia frequently does not correlate closely with eosinophilic tissue infiltration. As a result, relatively modest degrees of peripheral eosinophilia may be seen in association with end‐organ damage, while severe eosinophilia may be tolerated well for prolonged periods in other cases.1 The most serious complications of hypereosinophilia are myocardial damage with ultimate development of cardiac fibrosis and refractory heart failure; pulmonary involvement with hypoxia; and involvement of both the central and peripheral nervous systems including stroke, encephalopathy, and mononeuritis multiplex. A number of studies should be considered to help evaluate for the possibility of end‐organ damage as well as to assess for the presence of primary and idiopathic causes of hypereosinophilia. These include peripheral blood smear looking particularly for dysplastic eosinophils or blasts, serum tryptase, serum vitamin B12, serum IgE, cardiac troponin levels, anti‐neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, electrocardiography, echocardiography, pulmonary function tests, and thoracoabdominal CT scanning. Endoscopic studies with esophageal, duodenal, and colonic biopsy should be performed if eosinophilic gastroenteritis is suspected.1, 7, 10

While more modest degrees of eosinophilia are associated with a plethora of conditions, severe eosinophilia, especially that approaching the levels displayed by this patient, suggests a much more circumscribed differential diagnosis. This should prompt consideration of ChurgStrauss syndrome, parasitic infection with an active tissue migration phase, and hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES).4 HES has classically been characterized by hypereosinophilia for at least 6 months, exclusion of both secondary and clonal eosinophilia, and evidence of end‐organ involvement. More recently, however, a revised definition consisting of marked eosinophilia with reasonable exclusion of other causes has gained favor.1, 7, 10, 1416 While perhaps as many as 75% of cases of HES continue to be considered idiopathic at present, 2 subtypes have now been recognized, with important prognostic and therapeutic implications. Myeloproliferative HES has a strong male predominance, is frequently associated with elevated serum tryptase and B12 levels, often manifests with hepatosplenomegaly, and displays a characteristic gene mutation, FIP1L1/PDGFRA. Lymphocytic HES is typified by polyclonal eosinophilic expansion in response to elevated IL‐5 levels, is associated with less cardiac involvement and a somewhat more favorable prognosis in the absence of therapy, and has been associated with transformation into T‐cell lymphoma.1, 1417 We suspect, though we are unable to prove, that our patient was finally diagnosed at the end of a journey that began as lymphocytic HES and ultimately progressed to T‐cell lymphoma. T‐cell lymphoma has rarely been associated with profound eosinophilia. This appears to reflect disordered production of IL‐5, as was true of this patient, and many of these cases may represent transformed lymphocytic HES.14

Specific therapy exists for the myeloproliferative subtype of HES, consisting of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib, with excellent response in typical cases. Initial treatment of most other extreme eosinophilic syndromes not caused by parasitic infection, including lymphocytic and idiopathic HES as well as ChurgStrauss syndrome, consists of high‐dose corticosteroids, with a variety of other agents used as second‐line and steroid‐sparing treatments. The urgency of therapy is dictated by the presence and severity of end‐organ damage, and in some instances corticosteroids may need to be given before the diagnosis is fully secure. When S. stercoralis infection has not been ruled out, concurrent therapy with ivermectin should be given to prevent triggering Strongyloides hyperinfection. Hematology input is critical when HES is under serious consideration, with bone marrow examination, cytogenetic studies, T‐cell phenotyping and T‐cell receptor rearrangement studies essential in helping to establish the correct diagnosis.10, 17

The differential diagnosis of peripheral eosinophilia is broad and requires a thorough, stepwise approach. Although profound eosinophilia is usually caused by a limited number of diseases, this patient reminds us that Captain Renault's advice in the film Casablanca to round up the usual suspects does not always suffice, as the diagnosis of T‐cell lymphoma was not considered by either the clinicians or the discussant until lung biopsy results became available. Most patients with hypereosinophilia not caused by parasitic infection will ultimately require an invasive procedure to establish a diagnosis, which is essential before embarking on an often‐toxic course of therapy, as well as for providing an accurate prognosis.

TEACHING POINTS

-

The most common causes of eosinophilia include helminthic infections (the leading cause worldwide), asthma, allergic conditions (the leading cause in the United States), malignancies, and drugs.

-

Hypereosinophilia may lead to end‐organ damage. The most important etiologies include ChurgStrauss Syndrome, HES, or a helminthic infection in the larval migration phase.

-

The mainstay of therapy for most cases of HES is corticosteroids. The goal of therapy is to prevent, or ameliorate, end‐organ damage.

- ,.Practical approach to the patient with hypereosinophilia.J Allergy Clin Immunol.2010;126(1):39–44.

- ,,.Eosinophilia: secondary, clonal and idiopathic.Br J Haematol.2006;133(5):468–492.

- .Blood eosinophilia: a new paradigm in disease classification, diagnosis, and treatment.Mayo Clin Proc.2005;80(1):75–83.

- ,,,.Clinical manifestations and treatment of Churg‐Strauss syndrome.Rheum Dis Clin North Am.2010;36(3):527–543.

- ,,,.Relative eosinophilia and functional adrenal insufficiency in critically ill patients.Lancet.1999;353(9165):1675–1676.

- ,,,.Opposing effects of glucocorticoids on the rate of apoptosis in neutrophilic and eosinophilic granulocytes.J Immunol.1996;156(10):4422–4428.

- ,.Eosinophilic disorders.J Allergy Clin Immunol.2007;119(6):1291–1300; quiz 1301–1302.

- ,.Pulmonary eosinophilia.Clin Rev Allergy Immunol.2008;34(3):367–371.

- .Eosinophilic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract.Scand J Gastroenterol.2010;45(9):1013–1021.

- ,,.Hypereosinophilic syndrome and clonal eosinophilia: point‐of‐care diagnostic algorithm and treatment update.Mayo Clin Proc.2010;85(2):158–164.

- ,,,,,.Eosinophilia as a predictor of food allergy in atopic dermatitis.Allergy Asthma Proc.2010;31(2):e18–e24.

- ,,, et al.The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg‐Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis).Arthritis Rheum.1990;33(8):1094–1100.

- .Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. In: Adkinson NF, Yunginger JW, Busse WW, et al, eds. Middleton's Allergy Principles 2003:1353–1371.

- ,,, et al.TARC and IL‐5 expression correlates with tissue eosinophilia in peripheral T‐cell lymphomas.Leuk Res.2008;32(9):1431–1438.

- ,,.Hypereosinophilic syndrome and proliferative diseases.Acta Dermatovenerol Croat.2009;17(4):323–330.

- ,.The hypereosinophilic syndromes: current concepts and treatments.Br J Haematol.2009;145(3):271–285.

- ,,.Lymphocytic variant hypereosinophilic syndromes.Immunol Allergy Clin North Am.2007;27(3):389–413.

- ,.Practical approach to the patient with hypereosinophilia.J Allergy Clin Immunol.2010;126(1):39–44.

- ,,.Eosinophilia: secondary, clonal and idiopathic.Br J Haematol.2006;133(5):468–492.

- .Blood eosinophilia: a new paradigm in disease classification, diagnosis, and treatment.Mayo Clin Proc.2005;80(1):75–83.

- ,,,.Clinical manifestations and treatment of Churg‐Strauss syndrome.Rheum Dis Clin North Am.2010;36(3):527–543.

- ,,,.Relative eosinophilia and functional adrenal insufficiency in critically ill patients.Lancet.1999;353(9165):1675–1676.

- ,,,.Opposing effects of glucocorticoids on the rate of apoptosis in neutrophilic and eosinophilic granulocytes.J Immunol.1996;156(10):4422–4428.

- ,.Eosinophilic disorders.J Allergy Clin Immunol.2007;119(6):1291–1300; quiz 1301–1302.

- ,.Pulmonary eosinophilia.Clin Rev Allergy Immunol.2008;34(3):367–371.

- .Eosinophilic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract.Scand J Gastroenterol.2010;45(9):1013–1021.

- ,,.Hypereosinophilic syndrome and clonal eosinophilia: point‐of‐care diagnostic algorithm and treatment update.Mayo Clin Proc.2010;85(2):158–164.

- ,,,,,.Eosinophilia as a predictor of food allergy in atopic dermatitis.Allergy Asthma Proc.2010;31(2):e18–e24.

- ,,, et al.The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg‐Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis).Arthritis Rheum.1990;33(8):1094–1100.

- .Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. In: Adkinson NF, Yunginger JW, Busse WW, et al, eds. Middleton's Allergy Principles 2003:1353–1371.

- ,,, et al.TARC and IL‐5 expression correlates with tissue eosinophilia in peripheral T‐cell lymphomas.Leuk Res.2008;32(9):1431–1438.

- ,,.Hypereosinophilic syndrome and proliferative diseases.Acta Dermatovenerol Croat.2009;17(4):323–330.

- ,.The hypereosinophilic syndromes: current concepts and treatments.Br J Haematol.2009;145(3):271–285.

- ,,.Lymphocytic variant hypereosinophilic syndromes.Immunol Allergy Clin North Am.2007;27(3):389–413.

Acute Bacterial Meningitis in Adults

Background Acute bacterial meningitis is an inflammation of the meninges, which results from bacterially mediated recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Bacterial meningitis was an almost invariably fatal disease at the start of the 20th century. With the development of and advancements in antimicrobial therapy, however, there has been a significant reduction in the mortality rate, although this has remained stable during the past 20 years (1). One large study of adults with community-acquired bacterial meningitis reported an overall mortality rate of 21%, including a 30% mortality rate associated with Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis and a 7% mortality rate for Neisseria meningitidis (2). In adults, the most commonly identified organisms are S. pneumoniae (40–50%), Neisseria meningitidis (14–37%), and Listeria monocytogenes (4–10%) (2-4).

Clinical Presentation

Bacterial meningitis is a serious illness that often progresses rapidly. The classic clinical presentation consists of fever, nuchal rigidity, and mental status change (3). One large review of 10 critically appraised studies showed that almost all (99–100%) of the patients with bacterial meningitis presented with at least one of these clinical findings; and 95% of the patients had at least 2 of the clinical findings (5). In contrast, less than half of the patients presented with all 3 findings. Thus, in the absence of all 3 of these classic findings, the diagnosis of meningitis can virtually be dismissed, and further evaluation for meningitis need not be pursued. Individually, fever was the most common presenting finding, with a sensitivity of 85%. Nuchal rigidity had a sensitivity of 70%, and mental status change was 67%. While these physical examination findings may be of value in determining the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis, the accuracy of the clinical history including features such as headache, nausea and vomiting, and neck pain was too low to be of use clinically.

Signs of meningeal irritation may be of benefit in the clinical diagnosis of bacterial meningitis. Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs were first described nearly a century ago and have been used by most clinicians in the clinical realm; however, their diagnostic utility has been evaluated only in a limited number of studies. Kernig’s sign is positive when a patient in the supine position with his/her hips flexed at 90 degrees develops pain in the lower back or posterior thigh during an attempt to extend the knee. Brudzinski’s sign is positive when a patient in the supine position whose neck is passively flexed responds with flexion of his/her knees and hips. Recently, a bedside maneuver called jolt accentuation of headache was found to be potentially useful. In this maneuver, the patient is asked to turn his/her head horizontally 2–3 times per second, and a worsening headache is considered a positive sign. A small study showed that this maneuver had 97% sensitivity and 60% specificity for patients with CSF pleocytosis (6).

Other clinical manifestations in patients with bacterial meningitis include photophobia, seizure, rash, focal neurologic deficits, and signs of increased intracranial pressure. While these various findings may be present in many patients with bacterial meningitis, their sensitivities have been found to be low. Thus, their clinical utility in ruling out the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis is limited (5).

Laboratory Findings

Any patient who presents with a reasonable likelihood of having bacterial meningitis should undergo a lumbar puncture (LP) to evaluate the CSF as soon as possible. The initial CSF study should measure the opening pressure. One study demonstrated that 39% of patients with bacterial meningitis had opening pressures greater than 300 mg H20 (3). Other CSF laboratory studies should be sent for analysis in 4 sterile tubes filled with approximately 1 mL of CSF each. The first tube is typically reserved for gram stain and culture. The gram stain is positive in about 70% of patients with bacterial meningitis, and the culture will be positive in about 80% of cases. The second tube is sent for protein and glucose levels. Patients who have markedly elevated CSF protein counts (>500 mg/dL) and low glucose levels (<45 mg/dL, or ratio of serum: CSF glucose levels <0.4) are likely to have bacterial meningitis. The third tube is sent for cell count and differential. Patients with bacterial meningitis are likely to have >10 WBC/μL that are predominantly polymorphonucleocytes and have few or no red blood cells in the absence of a traumatic LP. We recommend the fourth tube be used for any viral, fungal, or other miscellaneous studies. In addition to the CSF studies, other diagnostic evaluations should include blood cultures, complete blood count with platelets and differential (CBCPD), and basic chemistry labs.

The CSF studies described above are the primary tools in diagnosing bacterial meningitis; however, there are other studies that may be helpful in certain clinical settings. Latex agglutination tests for bacterial antigens may be used in cases in which bacterial meningitis remains a possible diagnosis despite negative CSF studies. This test is available for S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, H. influenzae type B, group B Streptococcus, and E. coli. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test of the CSF has been developed for some bacterial pathogens including S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, H. influenzae type B, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The limulus amebocyte lysate assay is a very sensitive test for gram-negative endotoxins, which may aid in identifying gram-negative organisms as potential pathogens in the CSF. While these alternative CSF diagnostic tests are available, many laboratories do not perform the tests on site and require send-out to a specialty laboratory. The time required for this may negate the clinical utility of these tests.

Role of Brain Imaging

The decision to obtain a brain imaging study prior to performing an LP has been a controversial issue for both patient safety and medical-legal reasons. Two large studies have been published in an attempt to derive a clinically useful decision analysis tool (7,8). In summary, the studies found that 5 clinical features were associated with an abnormal head cranial tomography (CT) scan. These were:

- Age >60 years

- Immunocompromised state

- Any history of central nervous system (CNS) disease

- A history of seizure within 1 week prior to presentation

- Presence of a focal neurologic abnormality, including altered level of consciousness, inability to answer or follow 2 consecutive requests, gaze palsy, abnormal visual fields, facial palsy, arm or leg drift, and abnormal language.

In patients with none of these findings, there was a 97% negative predictive value of having an abnormal CT scan, with the few patients with positive scans nonetheless tolerating LP without adverse effects. Thus, in patients with none of these findings, it appears that an LP can safely be performed without obtaining a CT scan. One study also demonstrated that patients who underwent a CT scan prior to their LP waited, on average, 2 hours longer to get an LP; with antibiotic administration delayed by an average of 1 hour (8). Antibiotic administration should not be delayed in any patient suspected of having bacterial meningitis, whether brain imaging is performed or not.

Differential Diagnosis