User login

Passing the ‘baton’ with pride

I was honored to be the third Editor-in-Chief of GIHN, from 2016 through 2021. GIHN is the official newspaper of the American Gastroenterological Association and has the widest readership of any AGA publication and is one that readers told us they read cover to cover. As such, each EIC and their Board of Editors must ensure balanced content that holds the interest of a diverse readership. I was privileged to work with a talented editorial board who reviewed articles, attended leadership meetings, and offered terrific suggestions throughout our tenure. I treasured their support and friendship.

Within each of the 60 monthly issues, we sought to highlight science, practice operations, national trends, and opinions and reviews that would be most important to basic scientists, clinical researchers, and academic and community clinicians, primarily from the United States but also from a worldwide readership. I was given a 300-word section to create editorial comments on pertinent topics that were important to gastroenterologists. Having a background in both community and academic practice, I tried to bring a balanced perspective to areas that often seem worlds apart.

The period between 2016 and 2021 also was a time of political upheaval in this country – something we could not ignore. I attempted to write about current events in a balanced way that kept a focus on patients and AGA’s core constituency. Not always an easy task. Sustainability of the Affordable Care Act was very much in question because of judicial and legislative challenges; had the ACA been overturned, our practices would be very different now.

In 2016, the first private equity–backed practice platform was created in south Florida. Little did we know how much that model would change community practice. Then, on Jan. 21, 2020, the first case of COVID 19 was diagnosed in Seattle (although earlier cases likely occurred). By March, many clinics and practices were closing, and we were altering our care delivery infrastructure in ways that would forever change practice. Trying to keep current with ever-changing science and policies was a challenge.

I will always treasure my time as EIC. I was happy (and proud) to pass this baton to Megan A. Adams MD, JD, MSc, my colleague and mentee at the University of Michigan. The partnership between AGA and Frontline Medical Communications has been successful for 15 years and will continue to be so.

Dr. Allen, now retired, was professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He is secretary/treasurer for the American Gastroenterological Association, and declares no relevant conflicts of interest.

I was honored to be the third Editor-in-Chief of GIHN, from 2016 through 2021. GIHN is the official newspaper of the American Gastroenterological Association and has the widest readership of any AGA publication and is one that readers told us they read cover to cover. As such, each EIC and their Board of Editors must ensure balanced content that holds the interest of a diverse readership. I was privileged to work with a talented editorial board who reviewed articles, attended leadership meetings, and offered terrific suggestions throughout our tenure. I treasured their support and friendship.

Within each of the 60 monthly issues, we sought to highlight science, practice operations, national trends, and opinions and reviews that would be most important to basic scientists, clinical researchers, and academic and community clinicians, primarily from the United States but also from a worldwide readership. I was given a 300-word section to create editorial comments on pertinent topics that were important to gastroenterologists. Having a background in both community and academic practice, I tried to bring a balanced perspective to areas that often seem worlds apart.

The period between 2016 and 2021 also was a time of political upheaval in this country – something we could not ignore. I attempted to write about current events in a balanced way that kept a focus on patients and AGA’s core constituency. Not always an easy task. Sustainability of the Affordable Care Act was very much in question because of judicial and legislative challenges; had the ACA been overturned, our practices would be very different now.

In 2016, the first private equity–backed practice platform was created in south Florida. Little did we know how much that model would change community practice. Then, on Jan. 21, 2020, the first case of COVID 19 was diagnosed in Seattle (although earlier cases likely occurred). By March, many clinics and practices were closing, and we were altering our care delivery infrastructure in ways that would forever change practice. Trying to keep current with ever-changing science and policies was a challenge.

I will always treasure my time as EIC. I was happy (and proud) to pass this baton to Megan A. Adams MD, JD, MSc, my colleague and mentee at the University of Michigan. The partnership between AGA and Frontline Medical Communications has been successful for 15 years and will continue to be so.

Dr. Allen, now retired, was professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He is secretary/treasurer for the American Gastroenterological Association, and declares no relevant conflicts of interest.

I was honored to be the third Editor-in-Chief of GIHN, from 2016 through 2021. GIHN is the official newspaper of the American Gastroenterological Association and has the widest readership of any AGA publication and is one that readers told us they read cover to cover. As such, each EIC and their Board of Editors must ensure balanced content that holds the interest of a diverse readership. I was privileged to work with a talented editorial board who reviewed articles, attended leadership meetings, and offered terrific suggestions throughout our tenure. I treasured their support and friendship.

Within each of the 60 monthly issues, we sought to highlight science, practice operations, national trends, and opinions and reviews that would be most important to basic scientists, clinical researchers, and academic and community clinicians, primarily from the United States but also from a worldwide readership. I was given a 300-word section to create editorial comments on pertinent topics that were important to gastroenterologists. Having a background in both community and academic practice, I tried to bring a balanced perspective to areas that often seem worlds apart.

The period between 2016 and 2021 also was a time of political upheaval in this country – something we could not ignore. I attempted to write about current events in a balanced way that kept a focus on patients and AGA’s core constituency. Not always an easy task. Sustainability of the Affordable Care Act was very much in question because of judicial and legislative challenges; had the ACA been overturned, our practices would be very different now.

In 2016, the first private equity–backed practice platform was created in south Florida. Little did we know how much that model would change community practice. Then, on Jan. 21, 2020, the first case of COVID 19 was diagnosed in Seattle (although earlier cases likely occurred). By March, many clinics and practices were closing, and we were altering our care delivery infrastructure in ways that would forever change practice. Trying to keep current with ever-changing science and policies was a challenge.

I will always treasure my time as EIC. I was happy (and proud) to pass this baton to Megan A. Adams MD, JD, MSc, my colleague and mentee at the University of Michigan. The partnership between AGA and Frontline Medical Communications has been successful for 15 years and will continue to be so.

Dr. Allen, now retired, was professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He is secretary/treasurer for the American Gastroenterological Association, and declares no relevant conflicts of interest.

What to keep in mind as 2021 begins

As 2020 comes to a close, most of us are looking forward to a (hopefully) brighter 2021. This year has been full of challenges and new experiences, but we have learned a lot. Pandemic or not, there are some things that you and your practice can do to ensure that you are prepared to make 2021 a success.

Tips for your practice

Assess staff morale: It seems simple but checking in with your staff can go a long way. Everyone is dealing with challenges both in and out of the workplace. Check in, show them you care, and think of ways that you can make their work a positive experience in the new year. During our May 2020 GI division chief townhall, John Inadomi, MD, gave a great presentation on the importance of staff morale during the pandemic.

Listen to colleagues: Find out about their experiences, challenges, and solutions. In October, the American Gastroenterological Association held a town hall with some great information and resources called “Adapting to Changing Practice Paradigms.” The agenda covered topics from telehealth to private equity and planning for the next potential wave of COVID-19.

Celebrate the wins: It can often feel like not much went right in 2020, but we did accomplish significant wins for GIs, including achieving payment parity for telephone evaluation and management (E/M) visits with video visits, increases in digestive disease and GI cancer research funding, and inclusion/expansion of GI cancers research opportunities. We couldn’t have done it without you, though, and we will continue to need your help to move important issues forward in 2021. Get involved today! Visit “Get Involved” under Advocacy and Policy on www.gastro.org.

Prepare for E/M changes: The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) E/M for new and established patient office/outpatient codes (99201-99205, 99211-99215), guidelines, and Medicare payments will undergo major changes beginning Jan. 1, 2021. See the AGA’s coding and reimbursement experts’ article from the March 2020 issue of GI & Hepatology News, “Prepare for major changes to E/M coding starting in 2021,” to learn about the changes and get resources to help practices prepare.

Keep up with new Medicare payment rules: The release of the 2021 physician payments and rules for the Medicare program was delayed this year because of the COVID-19 public health emergency. We were dismayed to learn that Medicare did not make any changes that substantively mitigated the expected cuts to most specialties. Instead of a 5% cut for GI, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services now projects GI will experience a 4% payment cut for 2021. AGA is calling on Congress to pass legislation to stop the cuts. This situation is evolving quickly. Watch for AGA member alerts for breaking news and resources, including the AGA’s “Medicare plans significant payment cuts for 2021.”

Stay current on telehealth and telephone E/M coverage: The commercial payer community came together to cover telehealth (video visits) and telephone E/M at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic but have since regularly teased the end of coverage only to extend it just before it expires. It’s impossible to predict what each payer will do, but you can use the following resources to keep current on most payers’ policies and correct coding/reporting for telehealth and telephone E/M:

- “Current State Laws & Reimbursement Policies ” from the Center for Connected Health.

- “Coding for Telehealth & Virtual Visits During COVID-19” from the AGA University.

Check to see if you can report on additional quality measures: AGA has expanded the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) measure portfolio by assuming ownership and stewardship of two hepatitis C virus (HCV) measures from PCPI, including annually checking for HCV in active injection drug users (measure 387) and performing a one-time screening for HCV among patients at risk (measure 400). As a result, gastroenterologists can now report on even more GI-specific measures. There have been the following two changes to GI-specific measures in 2021:

- Measure 275: “Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Assessment of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Status Before Initiating Anti-TNF (Tumor Necrosis Factor) Therapy” now includes coding to allow reporting for all age groups, including pediatric populations.

- Measure 439: “Age Appropriate Screening Colonoscopy” now includes all colonoscopies for patients 50 years and older; however, there’s an exclusion for those patients between the ages of 50 and 85 years.

These changes will help more gastroenterologists qualify for these measures.

Dates and deadlines to remember

January 2021

- Jan. 1 – MIPS Performance Year 2021 begins.

- Jan. 4 – Submission window opens for MIPS Performance Year 2020.

- Changes to Improvement Activity category go into effect (if approved in final rule).

March 2021

- March 31 – First snapshot for Qualifying Participant (QP) determinations and MIPS APM participation.

April 2021

- April 1 – Registration begins for CMS web interface and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) for MIPS survey.

June 2021

- June 30 – Second snapshot for QP determinations and MIPS APM participation.

- June 30 – Registration ends for CMS web interface and CAHPS for MIPS survey.

July 2021

- CMS publishes proposed reimbursement values for 2022 in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule.

- CMS “Targeted Review” opens once CMS makes your MIPS payment adjustment available.

- July 1 - MIPS Performance Feedback Available. CMS will provide you with performance feedback based on the data you submitted for Performance Year 2020. You can use this feedback to improve your care and optimize the payments you receive from CMS in the future.

August 2021

- Aug. 31 - Targeted Review period closes (appeals process).

September 2021

- AMA releases CPT 2022 book, including a new CPT code for Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM).

October 2021

- Oct. 3 - Last day to start a 90-day performance period for promoting Interoperability and Improvement Activities.

November 2021

- CMS finalizes reimbursement values for 2022 in the MPFS final rule. New payment rates take effect Jan. 1, 2022.

December 2021

- Dec. 31 – Quality Payment Program Exception Applications window closes.

- Dec. 31 – MIPS Performance year 2020 ends.

- Dec. 31 – Fourth snapshot for full TIN APMs (Medicare Shared Savings Program).

G. Anton Decker, MD, is chair of the AGA Practice Management and Economics Committee, Mayo Clinic International; Dawn Francis, MD, is chair-elect of the AGA Practice Management and Economics Committee, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla.

They have no conflicts of interest.

As 2020 comes to a close, most of us are looking forward to a (hopefully) brighter 2021. This year has been full of challenges and new experiences, but we have learned a lot. Pandemic or not, there are some things that you and your practice can do to ensure that you are prepared to make 2021 a success.

Tips for your practice

Assess staff morale: It seems simple but checking in with your staff can go a long way. Everyone is dealing with challenges both in and out of the workplace. Check in, show them you care, and think of ways that you can make their work a positive experience in the new year. During our May 2020 GI division chief townhall, John Inadomi, MD, gave a great presentation on the importance of staff morale during the pandemic.

Listen to colleagues: Find out about their experiences, challenges, and solutions. In October, the American Gastroenterological Association held a town hall with some great information and resources called “Adapting to Changing Practice Paradigms.” The agenda covered topics from telehealth to private equity and planning for the next potential wave of COVID-19.

Celebrate the wins: It can often feel like not much went right in 2020, but we did accomplish significant wins for GIs, including achieving payment parity for telephone evaluation and management (E/M) visits with video visits, increases in digestive disease and GI cancer research funding, and inclusion/expansion of GI cancers research opportunities. We couldn’t have done it without you, though, and we will continue to need your help to move important issues forward in 2021. Get involved today! Visit “Get Involved” under Advocacy and Policy on www.gastro.org.

Prepare for E/M changes: The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) E/M for new and established patient office/outpatient codes (99201-99205, 99211-99215), guidelines, and Medicare payments will undergo major changes beginning Jan. 1, 2021. See the AGA’s coding and reimbursement experts’ article from the March 2020 issue of GI & Hepatology News, “Prepare for major changes to E/M coding starting in 2021,” to learn about the changes and get resources to help practices prepare.

Keep up with new Medicare payment rules: The release of the 2021 physician payments and rules for the Medicare program was delayed this year because of the COVID-19 public health emergency. We were dismayed to learn that Medicare did not make any changes that substantively mitigated the expected cuts to most specialties. Instead of a 5% cut for GI, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services now projects GI will experience a 4% payment cut for 2021. AGA is calling on Congress to pass legislation to stop the cuts. This situation is evolving quickly. Watch for AGA member alerts for breaking news and resources, including the AGA’s “Medicare plans significant payment cuts for 2021.”

Stay current on telehealth and telephone E/M coverage: The commercial payer community came together to cover telehealth (video visits) and telephone E/M at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic but have since regularly teased the end of coverage only to extend it just before it expires. It’s impossible to predict what each payer will do, but you can use the following resources to keep current on most payers’ policies and correct coding/reporting for telehealth and telephone E/M:

- “Current State Laws & Reimbursement Policies ” from the Center for Connected Health.

- “Coding for Telehealth & Virtual Visits During COVID-19” from the AGA University.

Check to see if you can report on additional quality measures: AGA has expanded the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) measure portfolio by assuming ownership and stewardship of two hepatitis C virus (HCV) measures from PCPI, including annually checking for HCV in active injection drug users (measure 387) and performing a one-time screening for HCV among patients at risk (measure 400). As a result, gastroenterologists can now report on even more GI-specific measures. There have been the following two changes to GI-specific measures in 2021:

- Measure 275: “Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Assessment of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Status Before Initiating Anti-TNF (Tumor Necrosis Factor) Therapy” now includes coding to allow reporting for all age groups, including pediatric populations.

- Measure 439: “Age Appropriate Screening Colonoscopy” now includes all colonoscopies for patients 50 years and older; however, there’s an exclusion for those patients between the ages of 50 and 85 years.

These changes will help more gastroenterologists qualify for these measures.

Dates and deadlines to remember

January 2021

- Jan. 1 – MIPS Performance Year 2021 begins.

- Jan. 4 – Submission window opens for MIPS Performance Year 2020.

- Changes to Improvement Activity category go into effect (if approved in final rule).

March 2021

- March 31 – First snapshot for Qualifying Participant (QP) determinations and MIPS APM participation.

April 2021

- April 1 – Registration begins for CMS web interface and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) for MIPS survey.

June 2021

- June 30 – Second snapshot for QP determinations and MIPS APM participation.

- June 30 – Registration ends for CMS web interface and CAHPS for MIPS survey.

July 2021

- CMS publishes proposed reimbursement values for 2022 in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule.

- CMS “Targeted Review” opens once CMS makes your MIPS payment adjustment available.

- July 1 - MIPS Performance Feedback Available. CMS will provide you with performance feedback based on the data you submitted for Performance Year 2020. You can use this feedback to improve your care and optimize the payments you receive from CMS in the future.

August 2021

- Aug. 31 - Targeted Review period closes (appeals process).

September 2021

- AMA releases CPT 2022 book, including a new CPT code for Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM).

October 2021

- Oct. 3 - Last day to start a 90-day performance period for promoting Interoperability and Improvement Activities.

November 2021

- CMS finalizes reimbursement values for 2022 in the MPFS final rule. New payment rates take effect Jan. 1, 2022.

December 2021

- Dec. 31 – Quality Payment Program Exception Applications window closes.

- Dec. 31 – MIPS Performance year 2020 ends.

- Dec. 31 – Fourth snapshot for full TIN APMs (Medicare Shared Savings Program).

G. Anton Decker, MD, is chair of the AGA Practice Management and Economics Committee, Mayo Clinic International; Dawn Francis, MD, is chair-elect of the AGA Practice Management and Economics Committee, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla.

They have no conflicts of interest.

As 2020 comes to a close, most of us are looking forward to a (hopefully) brighter 2021. This year has been full of challenges and new experiences, but we have learned a lot. Pandemic or not, there are some things that you and your practice can do to ensure that you are prepared to make 2021 a success.

Tips for your practice

Assess staff morale: It seems simple but checking in with your staff can go a long way. Everyone is dealing with challenges both in and out of the workplace. Check in, show them you care, and think of ways that you can make their work a positive experience in the new year. During our May 2020 GI division chief townhall, John Inadomi, MD, gave a great presentation on the importance of staff morale during the pandemic.

Listen to colleagues: Find out about their experiences, challenges, and solutions. In October, the American Gastroenterological Association held a town hall with some great information and resources called “Adapting to Changing Practice Paradigms.” The agenda covered topics from telehealth to private equity and planning for the next potential wave of COVID-19.

Celebrate the wins: It can often feel like not much went right in 2020, but we did accomplish significant wins for GIs, including achieving payment parity for telephone evaluation and management (E/M) visits with video visits, increases in digestive disease and GI cancer research funding, and inclusion/expansion of GI cancers research opportunities. We couldn’t have done it without you, though, and we will continue to need your help to move important issues forward in 2021. Get involved today! Visit “Get Involved” under Advocacy and Policy on www.gastro.org.

Prepare for E/M changes: The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) E/M for new and established patient office/outpatient codes (99201-99205, 99211-99215), guidelines, and Medicare payments will undergo major changes beginning Jan. 1, 2021. See the AGA’s coding and reimbursement experts’ article from the March 2020 issue of GI & Hepatology News, “Prepare for major changes to E/M coding starting in 2021,” to learn about the changes and get resources to help practices prepare.

Keep up with new Medicare payment rules: The release of the 2021 physician payments and rules for the Medicare program was delayed this year because of the COVID-19 public health emergency. We were dismayed to learn that Medicare did not make any changes that substantively mitigated the expected cuts to most specialties. Instead of a 5% cut for GI, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services now projects GI will experience a 4% payment cut for 2021. AGA is calling on Congress to pass legislation to stop the cuts. This situation is evolving quickly. Watch for AGA member alerts for breaking news and resources, including the AGA’s “Medicare plans significant payment cuts for 2021.”

Stay current on telehealth and telephone E/M coverage: The commercial payer community came together to cover telehealth (video visits) and telephone E/M at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic but have since regularly teased the end of coverage only to extend it just before it expires. It’s impossible to predict what each payer will do, but you can use the following resources to keep current on most payers’ policies and correct coding/reporting for telehealth and telephone E/M:

- “Current State Laws & Reimbursement Policies ” from the Center for Connected Health.

- “Coding for Telehealth & Virtual Visits During COVID-19” from the AGA University.

Check to see if you can report on additional quality measures: AGA has expanded the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) measure portfolio by assuming ownership and stewardship of two hepatitis C virus (HCV) measures from PCPI, including annually checking for HCV in active injection drug users (measure 387) and performing a one-time screening for HCV among patients at risk (measure 400). As a result, gastroenterologists can now report on even more GI-specific measures. There have been the following two changes to GI-specific measures in 2021:

- Measure 275: “Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Assessment of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Status Before Initiating Anti-TNF (Tumor Necrosis Factor) Therapy” now includes coding to allow reporting for all age groups, including pediatric populations.

- Measure 439: “Age Appropriate Screening Colonoscopy” now includes all colonoscopies for patients 50 years and older; however, there’s an exclusion for those patients between the ages of 50 and 85 years.

These changes will help more gastroenterologists qualify for these measures.

Dates and deadlines to remember

January 2021

- Jan. 1 – MIPS Performance Year 2021 begins.

- Jan. 4 – Submission window opens for MIPS Performance Year 2020.

- Changes to Improvement Activity category go into effect (if approved in final rule).

March 2021

- March 31 – First snapshot for Qualifying Participant (QP) determinations and MIPS APM participation.

April 2021

- April 1 – Registration begins for CMS web interface and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) for MIPS survey.

June 2021

- June 30 – Second snapshot for QP determinations and MIPS APM participation.

- June 30 – Registration ends for CMS web interface and CAHPS for MIPS survey.

July 2021

- CMS publishes proposed reimbursement values for 2022 in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule.

- CMS “Targeted Review” opens once CMS makes your MIPS payment adjustment available.

- July 1 - MIPS Performance Feedback Available. CMS will provide you with performance feedback based on the data you submitted for Performance Year 2020. You can use this feedback to improve your care and optimize the payments you receive from CMS in the future.

August 2021

- Aug. 31 - Targeted Review period closes (appeals process).

September 2021

- AMA releases CPT 2022 book, including a new CPT code for Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM).

October 2021

- Oct. 3 - Last day to start a 90-day performance period for promoting Interoperability and Improvement Activities.

November 2021

- CMS finalizes reimbursement values for 2022 in the MPFS final rule. New payment rates take effect Jan. 1, 2022.

December 2021

- Dec. 31 – Quality Payment Program Exception Applications window closes.

- Dec. 31 – MIPS Performance year 2020 ends.

- Dec. 31 – Fourth snapshot for full TIN APMs (Medicare Shared Savings Program).

G. Anton Decker, MD, is chair of the AGA Practice Management and Economics Committee, Mayo Clinic International; Dawn Francis, MD, is chair-elect of the AGA Practice Management and Economics Committee, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla.

They have no conflicts of interest.

New models of gastroenterology practice

The variety of employment models available to gastroenterologists reflects the dynamic changes we are experiencing in medicine today. Delivery of gastrointestinal (GI) care in the United States continues to evolve in light of health care reform and the Affordable Care Act.1 Within the past decade, as health systems and payers continue to consolidate, regulatory pressures have increased steadily and new policies such as electronic documentation and mandatory quality metrics reporting have added new challenges to the emerging generation of gastroenterologists.2 Although the lay press tends to focus on health care costs, coverage, physician reimbursement, provider burnout, health system consolidation, and value-based payment models, relatively less has been published about emerging employment and practice models.

Here,

Background

When the senior author graduated from fellowship in 1983 (J.I.A.), gastroenterology practice model choices were limited to essentially 4: independent community-based, single-specialty, physician-owned practice (solo or small group); independent multispecialty physician-owned practice; hospital or health system–owned multispecialty practice; and academic practice (including the Veterans Administration Medical Centers).

In the private sector, young community gastroenterologists typically would join a physician-owned practice and spend time (2–5 y) as an employed physician in a partnership track. During this time, his/her salary was subsidized while he/she built a practice base. Then, they would buy into the Professional Association with cash or equity equivalents and become a partner. As a partner, he/she then had the opportunity to share in ancillary revenue streams such as facility fees derived from a practice-owned ambulatory endoscopy center (AEC). By contrast, young academic faculty would be hired as an instructor and, if successful, climb the traditional ladder track to assistant, associate, and professor of medicine in an academic medical center (AMC).

In the 1980s, a typical community GI practice comprised 1 to 8 physicians, with most having been formed by 1 or 2 male gastroenterologists in the early 1970s when flexible endoscopy moved into clinical practice. The three practices that eventually would become Minnesota Gastroenterology (where J.I.A. practiced) opened in 1972. In 1996, the three practices merged into a single group of 38 physicians with ownership in three AECs. Advanced practice nurses and physician assistants were not yet part of the equation. Colonoscopy represented 48% of procedure volume, accounts receivable (time between submitting an insurance claim and being paid) averaged 88 days, and physicians averaged 9000 work relative value units (wRVUs) per partner annually. By comparison, median wRVUs for a full-time community GI in 1996 was 10,422 according to the Medical Group Management Association.3 Annual gross revenue (before expenses) per physician was approximately $400,000, and overhead reached 38% and 47% of revenue (there were 2 divisions). Partner incomes were at the 12% level of the Medical Group Management Association for gastroenterologists (personal management notes of J.I.A.). Minnesota Gastroenterology was the largest single-specialty GI practice in 1996 and its consolidation foreshadowed a trend that has accelerated over the ensuing generation.

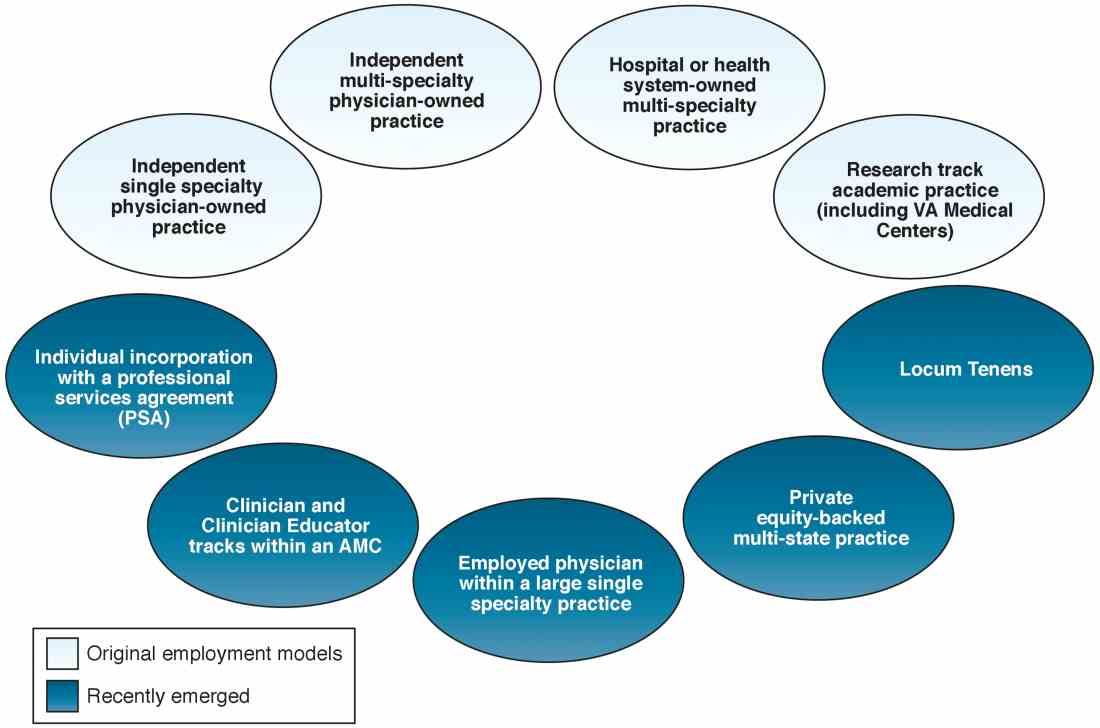

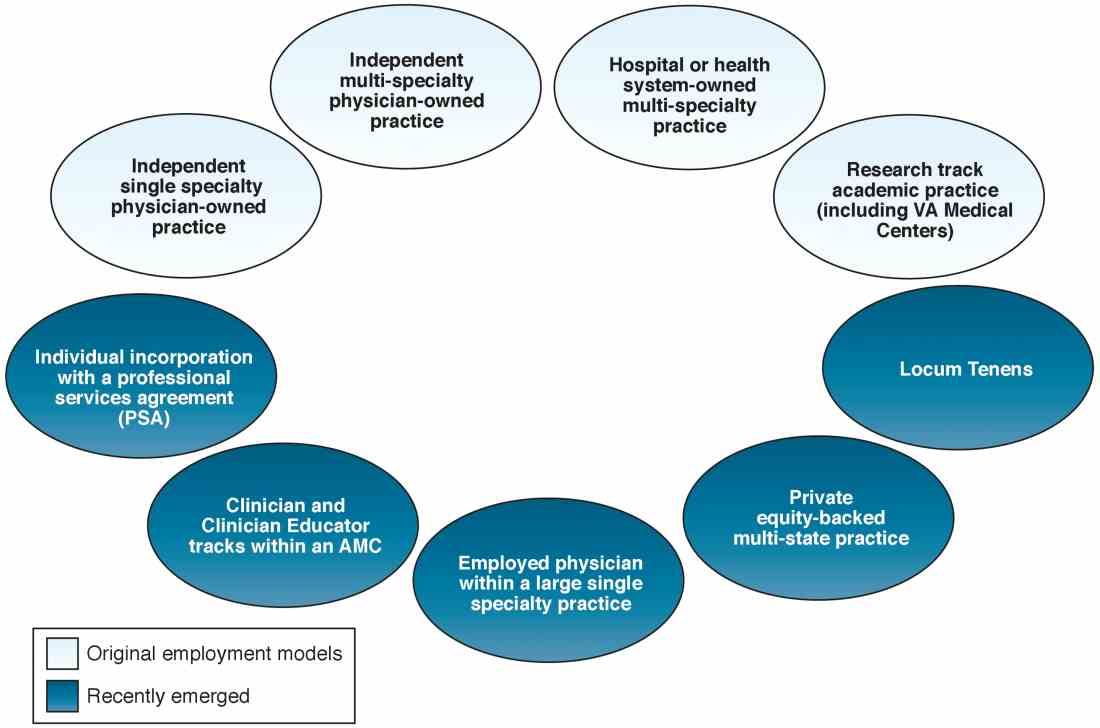

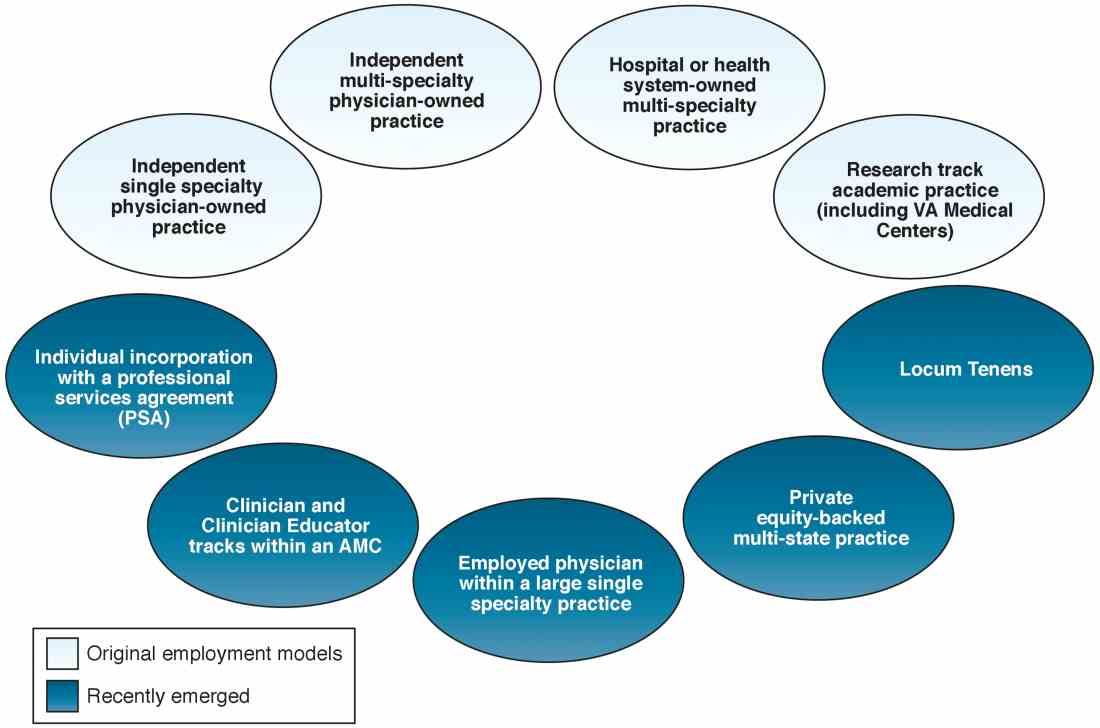

When one of the authors (N.K.) graduated from the University of California Los Angeles in 2017, the GI employment landscape had evolved considerably. At least five new models of GI practice had emerged: individual incorporation with a Professional Services Agreement (PSA), a clinician track within an AMC, large single-specialty group practice (partnership or employee), private equity-backed multistate practice, and locum tenens (Figure 1).

Employment models (light blue) available in the 1980s and those that have emerged as common models in the last decade (dark blue).

An individual corporation with a professional services agreement

For gastroenterologists at any career stage, the prospect of employment within a corporate entity, be it an academic university, hospital system, or private practice group, can be daunting. To that end, one central question facing nearly all gastroenterologists is: how much independence and flexibility, both clinically and financially, do I really want, and what can I do to realize my ideal job description?

An interesting alternative to direct health system employment occurs when a physician forms a solo corporation and then contracts with a hospital or health system under a PSA. Here, the physician provides professional services on a contractual basis, but retains control of finances and has more autonomy compared with employment. Essentially, the physician is a corporation of one, with hospital alignment rather than employment. For full disclosure, this is the employment model of one of the authors (N.K.).

A PSA arrangement is common for larger independent GI practices. Many practices have PSA arrangements with hospitals ranging from call coverage to full professional services. For an individual working within a PSA, income is not the traditional W-2 Internal Revenue Service arrangement in which taxes are removed automatically. Income derived from a PSA usually falls under an Internal Revenue Service Form 1099. The physician actually is employed through their practice corporation and relates to the hospital as an independent contractor.

There are four common variants of the PSA model.4 A Global Payment PSA is when a hospital contracts with the physician practice for specific services and pays a global rate linked to wRVUs. The rate is negotiated to encompass physician compensation, benefits, and practice overhead. The practice retains control of its own office functions and staff.

In a traditional PSA, the hospital contracts with physicians and pays them based on RVU production, but the hospital owns the administrative part of the practice (staff, billing, collections, equipment, and supplies).

A practice management arrangement occurs when the hospital employs the physician who provides professional services and a separate third party manages the practice via a separate management contract. Finally, a Carve-Out PSA can use any of the earlier-described PSA arrangements and certain services are carved out under line-item provisions. For example, a hospital could contract with a private GI group for endoscopic services or night call and write a PSA expressly for these purposes.

Some notable benefits of the PSA are that physicians can maintain financial and employment independence from the hospital and have more control over benefits packages, retirement savings options, and health insurance. Physicians also can provide services outside of the hospital (e.g., telemedicine or locums tenens — see later) without institutional restrictions or conflicts. Finally, physicians benefit from tax advantages of self-employment (with associated business-related tax deductions) through their corporation. The potential downsides of a PSA contract are the subtle expansion of services demanded (known as scope creep) or the possibility of contract termination (or nonrenewal) by the hospital. In addition, medical training does not equip physicians with the knowledge to navigate personal and corporate finances, benefits packages, and tax structures, so the learning curve can be quite steep. Nevertheless, PSAs can be an innovative employment model for gastroenterologists who wish to preserve autonomy and financial flexibility. In this model, legal advice by an attorney skilled in employment law is mandatory.

Academic clinicians track

Until recently, clinically oriented academic faculty were channeled into the traditional ladder faculty model in which advancement was contingent on publications, national recognition, grant support, and teaching. As competition for market share has intensified among regional health systems, many AMCs have developed purely clinical tracks in which research, publication, and teaching are not expected; salaries are linked to clinical productivity; and income may approximate the professional (but not ancillary) income of a community gastroenterologist.

Various models of this arrangement exist as well. For example, clinicians can be employed within a group that has a board and management structure distinct from the faculty group practice, as in the case of the Northeast Medical Group at Yale New Haven Health System5 and the University of Maryland Community Medical Group. In addition, clinicians can form an operating group separate from the faculty practice but as a controlled subsidiary (such as the University of Pittsburgh Community Medicine), separate operating group for primary care but specialists are employed within their respective departments (Emory Specialty Associates) or as a distinct clinical department within a faculty practice (University of California Los Angeles Medical Group Staff Physicians).

Irrespective of the employment model, these clinicians essentially work similar to community gastroenterologists but within the umbrella of an AMC. For young faculty whose interest is not in research or teaching, this can be an attractive option that maintains a tie to a university health system. For a seasoned clinician in community practice, this is an option to return to an academic environment. Usually, productivity expectations within the clinician track approximate those of a community practice gastroenterologist, but again total compensation may not be as great because ancillary income streams usually are not available. We expect this AMC employment track to become more prevalent as universities expand their footprints and acquire practices, hospitals, and ambulatory facilities distant from the main campus.

Large single-specialty practice

Consolidation of independent practices has been evident for 20 years and has accelerated as physicians in smaller practices have aged and burdens of practice have increased. Now, most urban centers have large mega-sized practices or super groups that have grown through practice mergers, acquisitions, and successful recruitment. Large practices can be modeled as a single integrated corporation (with ancillary components such as an AEC or infusion center) or as individual business units that are grouped under a single corporate entity.6

Within these large and mega-sized practices, differing employment options have emerged in addition to the traditional partnership track. These include payment on a per-diem basis, annual salary, or a mix of both. As opposed to partnership, the employment track avoids responsibility for governance and corporate liability, although not individual liability, and usually does not involve after-hours call. An employed physician usually does not benefit from ancillary income that derives from AEC facility fees, infusion centers, and pathology and anesthesia services.

Private equity ownership of gastroenterology practices

In June 2016, private equity entered the GI space with the investment of the Audax Group in a community GI practice based in Miami, Florida. The term private equity refers to capital that is not reported in public forums and comprises funds that investors directly invest into private companies or use to buy out public companies and turn them private.

According to their website, when the Audax Group invests in a medical practice, they provide capital for substantial infrastructure support, business experience, and acumen, but retain medical practice leaders as their clinical decision makers. They also bring proven expertise and economies of scale to resource-intensive aspects of a medical practice including information technology, regulation compliance, human resources, revenue cycle management, payroll, benefits, rents, and lease as examples. These components can be difficult to manage efficiently within independent medical practices, so many maturing practices are selling their practices to regional health systems. This multistate equity-backed medical practice is an alternative to health system acquisition, and may help physicians feel more in control of their practices and potentially share in the equity investment.

It is important to understand the employment structure and associations of any practice you are contemplating joining. The model devised by this group is meant to retain physician authority and responsibility while providing capital to support innovation and the development of needed infrastructure. Growth of market share and revenues can accrue back to physician owners. This is distinct from practices that are part of a health system in which there may be more of a corporate feeling and centralized governance.

Locum tenens

Locum tenens is a Latin phrase that means “to hold the place of.” According to the website of a large locum tenens company, this practice model originated in the 1970s when the federal government provided a grant to the University of Utah to provide physician services for underserved areas in the Western United States. The program proved so successful that hospital administrators who had difficulty recruiting staff physicians began asking for staffing assistance.

Today, a substantial number of physicians at all stages of their careers are working as locum tenens. They work as independent contractors so that income taxes are not withheld and benefits are the responsibility of the individual. As with the PSA arrangement, a physician would meet with both an accountant and labor lawyer to establish him or herself as a corporate entity for tax advantages and limited liability from litigation.

Early stage physicians who might be following a significant other or spouse to specific locations sometimes consider a locum tenens as a bridge to permanent positions. Late-stage physicians who no longer want to be tied to a small group or solo practice have become locum tenens physicians who enjoy multiple temporary employment positions nationwide. This pathway no longer is unusual and can be a satisfying means to expand employment horizons. As with all employment situations, due diligence is mandatory before signing with any locum tenens company.

Conclusions

The employment spectrum for gastroenterologists and other medical professionals has expanded greatly between the time the senior author and the junior author entered the workforce. Change is now the one constant in medicine, and medicine today largely is fast-paced, corporatized, and highly regulated. Finding an employment model that is comfortable for current physicians, whose life situations are quite diverse, can be challenging. but a variety of opportunities now exist.

Think carefully about what you truly desire as a medical professional and how you might shape your employment to realize your goals. Options are available for those with an open mind and persistence.

References

1. Sheen E, Dorn SD, Brill JV, et al. Health care reform and the road ahead for gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1062-5.

2. Kosinski LR. Meaningful use and electronic medical records for the gastroenterology practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:494-7.

3. Medical Group Management Association (MGMA). Accessed January 20, 2017.

4. The Coker Group. PSAs as an Alternative to Employment: A Contemporary Option for Alignment and Integration. In: The Coker Group Thought Leadership – White Papers. March 2016.

5. Houston R, McGinnis T. Accountable care organizations: looking back and moving forward. Centers for Health Care Strategies Inc. Brief. January 2016. Accessed January 20, 2017.

6. Pallardy C. 7 gastroenterologists leading GI mega-practices. Becker’s GI and endoscopy 2015. Accessed January 20, 2017.

Dr. Allen is in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor; he is also the Editor in Chief of GI & Hepatology News. Dr. Kaushal is in the division of gastroenterology, Adventist Health Systems, Sonora, Calif. The authors disclose no conflicts.

The variety of employment models available to gastroenterologists reflects the dynamic changes we are experiencing in medicine today. Delivery of gastrointestinal (GI) care in the United States continues to evolve in light of health care reform and the Affordable Care Act.1 Within the past decade, as health systems and payers continue to consolidate, regulatory pressures have increased steadily and new policies such as electronic documentation and mandatory quality metrics reporting have added new challenges to the emerging generation of gastroenterologists.2 Although the lay press tends to focus on health care costs, coverage, physician reimbursement, provider burnout, health system consolidation, and value-based payment models, relatively less has been published about emerging employment and practice models.

Here,

Background

When the senior author graduated from fellowship in 1983 (J.I.A.), gastroenterology practice model choices were limited to essentially 4: independent community-based, single-specialty, physician-owned practice (solo or small group); independent multispecialty physician-owned practice; hospital or health system–owned multispecialty practice; and academic practice (including the Veterans Administration Medical Centers).

In the private sector, young community gastroenterologists typically would join a physician-owned practice and spend time (2–5 y) as an employed physician in a partnership track. During this time, his/her salary was subsidized while he/she built a practice base. Then, they would buy into the Professional Association with cash or equity equivalents and become a partner. As a partner, he/she then had the opportunity to share in ancillary revenue streams such as facility fees derived from a practice-owned ambulatory endoscopy center (AEC). By contrast, young academic faculty would be hired as an instructor and, if successful, climb the traditional ladder track to assistant, associate, and professor of medicine in an academic medical center (AMC).

In the 1980s, a typical community GI practice comprised 1 to 8 physicians, with most having been formed by 1 or 2 male gastroenterologists in the early 1970s when flexible endoscopy moved into clinical practice. The three practices that eventually would become Minnesota Gastroenterology (where J.I.A. practiced) opened in 1972. In 1996, the three practices merged into a single group of 38 physicians with ownership in three AECs. Advanced practice nurses and physician assistants were not yet part of the equation. Colonoscopy represented 48% of procedure volume, accounts receivable (time between submitting an insurance claim and being paid) averaged 88 days, and physicians averaged 9000 work relative value units (wRVUs) per partner annually. By comparison, median wRVUs for a full-time community GI in 1996 was 10,422 according to the Medical Group Management Association.3 Annual gross revenue (before expenses) per physician was approximately $400,000, and overhead reached 38% and 47% of revenue (there were 2 divisions). Partner incomes were at the 12% level of the Medical Group Management Association for gastroenterologists (personal management notes of J.I.A.). Minnesota Gastroenterology was the largest single-specialty GI practice in 1996 and its consolidation foreshadowed a trend that has accelerated over the ensuing generation.

When one of the authors (N.K.) graduated from the University of California Los Angeles in 2017, the GI employment landscape had evolved considerably. At least five new models of GI practice had emerged: individual incorporation with a Professional Services Agreement (PSA), a clinician track within an AMC, large single-specialty group practice (partnership or employee), private equity-backed multistate practice, and locum tenens (Figure 1).

Employment models (light blue) available in the 1980s and those that have emerged as common models in the last decade (dark blue).

An individual corporation with a professional services agreement

For gastroenterologists at any career stage, the prospect of employment within a corporate entity, be it an academic university, hospital system, or private practice group, can be daunting. To that end, one central question facing nearly all gastroenterologists is: how much independence and flexibility, both clinically and financially, do I really want, and what can I do to realize my ideal job description?

An interesting alternative to direct health system employment occurs when a physician forms a solo corporation and then contracts with a hospital or health system under a PSA. Here, the physician provides professional services on a contractual basis, but retains control of finances and has more autonomy compared with employment. Essentially, the physician is a corporation of one, with hospital alignment rather than employment. For full disclosure, this is the employment model of one of the authors (N.K.).

A PSA arrangement is common for larger independent GI practices. Many practices have PSA arrangements with hospitals ranging from call coverage to full professional services. For an individual working within a PSA, income is not the traditional W-2 Internal Revenue Service arrangement in which taxes are removed automatically. Income derived from a PSA usually falls under an Internal Revenue Service Form 1099. The physician actually is employed through their practice corporation and relates to the hospital as an independent contractor.

There are four common variants of the PSA model.4 A Global Payment PSA is when a hospital contracts with the physician practice for specific services and pays a global rate linked to wRVUs. The rate is negotiated to encompass physician compensation, benefits, and practice overhead. The practice retains control of its own office functions and staff.

In a traditional PSA, the hospital contracts with physicians and pays them based on RVU production, but the hospital owns the administrative part of the practice (staff, billing, collections, equipment, and supplies).

A practice management arrangement occurs when the hospital employs the physician who provides professional services and a separate third party manages the practice via a separate management contract. Finally, a Carve-Out PSA can use any of the earlier-described PSA arrangements and certain services are carved out under line-item provisions. For example, a hospital could contract with a private GI group for endoscopic services or night call and write a PSA expressly for these purposes.

Some notable benefits of the PSA are that physicians can maintain financial and employment independence from the hospital and have more control over benefits packages, retirement savings options, and health insurance. Physicians also can provide services outside of the hospital (e.g., telemedicine or locums tenens — see later) without institutional restrictions or conflicts. Finally, physicians benefit from tax advantages of self-employment (with associated business-related tax deductions) through their corporation. The potential downsides of a PSA contract are the subtle expansion of services demanded (known as scope creep) or the possibility of contract termination (or nonrenewal) by the hospital. In addition, medical training does not equip physicians with the knowledge to navigate personal and corporate finances, benefits packages, and tax structures, so the learning curve can be quite steep. Nevertheless, PSAs can be an innovative employment model for gastroenterologists who wish to preserve autonomy and financial flexibility. In this model, legal advice by an attorney skilled in employment law is mandatory.

Academic clinicians track

Until recently, clinically oriented academic faculty were channeled into the traditional ladder faculty model in which advancement was contingent on publications, national recognition, grant support, and teaching. As competition for market share has intensified among regional health systems, many AMCs have developed purely clinical tracks in which research, publication, and teaching are not expected; salaries are linked to clinical productivity; and income may approximate the professional (but not ancillary) income of a community gastroenterologist.

Various models of this arrangement exist as well. For example, clinicians can be employed within a group that has a board and management structure distinct from the faculty group practice, as in the case of the Northeast Medical Group at Yale New Haven Health System5 and the University of Maryland Community Medical Group. In addition, clinicians can form an operating group separate from the faculty practice but as a controlled subsidiary (such as the University of Pittsburgh Community Medicine), separate operating group for primary care but specialists are employed within their respective departments (Emory Specialty Associates) or as a distinct clinical department within a faculty practice (University of California Los Angeles Medical Group Staff Physicians).

Irrespective of the employment model, these clinicians essentially work similar to community gastroenterologists but within the umbrella of an AMC. For young faculty whose interest is not in research or teaching, this can be an attractive option that maintains a tie to a university health system. For a seasoned clinician in community practice, this is an option to return to an academic environment. Usually, productivity expectations within the clinician track approximate those of a community practice gastroenterologist, but again total compensation may not be as great because ancillary income streams usually are not available. We expect this AMC employment track to become more prevalent as universities expand their footprints and acquire practices, hospitals, and ambulatory facilities distant from the main campus.

Large single-specialty practice

Consolidation of independent practices has been evident for 20 years and has accelerated as physicians in smaller practices have aged and burdens of practice have increased. Now, most urban centers have large mega-sized practices or super groups that have grown through practice mergers, acquisitions, and successful recruitment. Large practices can be modeled as a single integrated corporation (with ancillary components such as an AEC or infusion center) or as individual business units that are grouped under a single corporate entity.6

Within these large and mega-sized practices, differing employment options have emerged in addition to the traditional partnership track. These include payment on a per-diem basis, annual salary, or a mix of both. As opposed to partnership, the employment track avoids responsibility for governance and corporate liability, although not individual liability, and usually does not involve after-hours call. An employed physician usually does not benefit from ancillary income that derives from AEC facility fees, infusion centers, and pathology and anesthesia services.

Private equity ownership of gastroenterology practices

In June 2016, private equity entered the GI space with the investment of the Audax Group in a community GI practice based in Miami, Florida. The term private equity refers to capital that is not reported in public forums and comprises funds that investors directly invest into private companies or use to buy out public companies and turn them private.

According to their website, when the Audax Group invests in a medical practice, they provide capital for substantial infrastructure support, business experience, and acumen, but retain medical practice leaders as their clinical decision makers. They also bring proven expertise and economies of scale to resource-intensive aspects of a medical practice including information technology, regulation compliance, human resources, revenue cycle management, payroll, benefits, rents, and lease as examples. These components can be difficult to manage efficiently within independent medical practices, so many maturing practices are selling their practices to regional health systems. This multistate equity-backed medical practice is an alternative to health system acquisition, and may help physicians feel more in control of their practices and potentially share in the equity investment.

It is important to understand the employment structure and associations of any practice you are contemplating joining. The model devised by this group is meant to retain physician authority and responsibility while providing capital to support innovation and the development of needed infrastructure. Growth of market share and revenues can accrue back to physician owners. This is distinct from practices that are part of a health system in which there may be more of a corporate feeling and centralized governance.

Locum tenens

Locum tenens is a Latin phrase that means “to hold the place of.” According to the website of a large locum tenens company, this practice model originated in the 1970s when the federal government provided a grant to the University of Utah to provide physician services for underserved areas in the Western United States. The program proved so successful that hospital administrators who had difficulty recruiting staff physicians began asking for staffing assistance.

Today, a substantial number of physicians at all stages of their careers are working as locum tenens. They work as independent contractors so that income taxes are not withheld and benefits are the responsibility of the individual. As with the PSA arrangement, a physician would meet with both an accountant and labor lawyer to establish him or herself as a corporate entity for tax advantages and limited liability from litigation.

Early stage physicians who might be following a significant other or spouse to specific locations sometimes consider a locum tenens as a bridge to permanent positions. Late-stage physicians who no longer want to be tied to a small group or solo practice have become locum tenens physicians who enjoy multiple temporary employment positions nationwide. This pathway no longer is unusual and can be a satisfying means to expand employment horizons. As with all employment situations, due diligence is mandatory before signing with any locum tenens company.

Conclusions

The employment spectrum for gastroenterologists and other medical professionals has expanded greatly between the time the senior author and the junior author entered the workforce. Change is now the one constant in medicine, and medicine today largely is fast-paced, corporatized, and highly regulated. Finding an employment model that is comfortable for current physicians, whose life situations are quite diverse, can be challenging. but a variety of opportunities now exist.

Think carefully about what you truly desire as a medical professional and how you might shape your employment to realize your goals. Options are available for those with an open mind and persistence.

References

1. Sheen E, Dorn SD, Brill JV, et al. Health care reform and the road ahead for gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1062-5.

2. Kosinski LR. Meaningful use and electronic medical records for the gastroenterology practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:494-7.

3. Medical Group Management Association (MGMA). Accessed January 20, 2017.

4. The Coker Group. PSAs as an Alternative to Employment: A Contemporary Option for Alignment and Integration. In: The Coker Group Thought Leadership – White Papers. March 2016.

5. Houston R, McGinnis T. Accountable care organizations: looking back and moving forward. Centers for Health Care Strategies Inc. Brief. January 2016. Accessed January 20, 2017.

6. Pallardy C. 7 gastroenterologists leading GI mega-practices. Becker’s GI and endoscopy 2015. Accessed January 20, 2017.

Dr. Allen is in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor; he is also the Editor in Chief of GI & Hepatology News. Dr. Kaushal is in the division of gastroenterology, Adventist Health Systems, Sonora, Calif. The authors disclose no conflicts.

The variety of employment models available to gastroenterologists reflects the dynamic changes we are experiencing in medicine today. Delivery of gastrointestinal (GI) care in the United States continues to evolve in light of health care reform and the Affordable Care Act.1 Within the past decade, as health systems and payers continue to consolidate, regulatory pressures have increased steadily and new policies such as electronic documentation and mandatory quality metrics reporting have added new challenges to the emerging generation of gastroenterologists.2 Although the lay press tends to focus on health care costs, coverage, physician reimbursement, provider burnout, health system consolidation, and value-based payment models, relatively less has been published about emerging employment and practice models.

Here,

Background

When the senior author graduated from fellowship in 1983 (J.I.A.), gastroenterology practice model choices were limited to essentially 4: independent community-based, single-specialty, physician-owned practice (solo or small group); independent multispecialty physician-owned practice; hospital or health system–owned multispecialty practice; and academic practice (including the Veterans Administration Medical Centers).

In the private sector, young community gastroenterologists typically would join a physician-owned practice and spend time (2–5 y) as an employed physician in a partnership track. During this time, his/her salary was subsidized while he/she built a practice base. Then, they would buy into the Professional Association with cash or equity equivalents and become a partner. As a partner, he/she then had the opportunity to share in ancillary revenue streams such as facility fees derived from a practice-owned ambulatory endoscopy center (AEC). By contrast, young academic faculty would be hired as an instructor and, if successful, climb the traditional ladder track to assistant, associate, and professor of medicine in an academic medical center (AMC).

In the 1980s, a typical community GI practice comprised 1 to 8 physicians, with most having been formed by 1 or 2 male gastroenterologists in the early 1970s when flexible endoscopy moved into clinical practice. The three practices that eventually would become Minnesota Gastroenterology (where J.I.A. practiced) opened in 1972. In 1996, the three practices merged into a single group of 38 physicians with ownership in three AECs. Advanced practice nurses and physician assistants were not yet part of the equation. Colonoscopy represented 48% of procedure volume, accounts receivable (time between submitting an insurance claim and being paid) averaged 88 days, and physicians averaged 9000 work relative value units (wRVUs) per partner annually. By comparison, median wRVUs for a full-time community GI in 1996 was 10,422 according to the Medical Group Management Association.3 Annual gross revenue (before expenses) per physician was approximately $400,000, and overhead reached 38% and 47% of revenue (there were 2 divisions). Partner incomes were at the 12% level of the Medical Group Management Association for gastroenterologists (personal management notes of J.I.A.). Minnesota Gastroenterology was the largest single-specialty GI practice in 1996 and its consolidation foreshadowed a trend that has accelerated over the ensuing generation.

When one of the authors (N.K.) graduated from the University of California Los Angeles in 2017, the GI employment landscape had evolved considerably. At least five new models of GI practice had emerged: individual incorporation with a Professional Services Agreement (PSA), a clinician track within an AMC, large single-specialty group practice (partnership or employee), private equity-backed multistate practice, and locum tenens (Figure 1).

Employment models (light blue) available in the 1980s and those that have emerged as common models in the last decade (dark blue).

An individual corporation with a professional services agreement

For gastroenterologists at any career stage, the prospect of employment within a corporate entity, be it an academic university, hospital system, or private practice group, can be daunting. To that end, one central question facing nearly all gastroenterologists is: how much independence and flexibility, both clinically and financially, do I really want, and what can I do to realize my ideal job description?

An interesting alternative to direct health system employment occurs when a physician forms a solo corporation and then contracts with a hospital or health system under a PSA. Here, the physician provides professional services on a contractual basis, but retains control of finances and has more autonomy compared with employment. Essentially, the physician is a corporation of one, with hospital alignment rather than employment. For full disclosure, this is the employment model of one of the authors (N.K.).

A PSA arrangement is common for larger independent GI practices. Many practices have PSA arrangements with hospitals ranging from call coverage to full professional services. For an individual working within a PSA, income is not the traditional W-2 Internal Revenue Service arrangement in which taxes are removed automatically. Income derived from a PSA usually falls under an Internal Revenue Service Form 1099. The physician actually is employed through their practice corporation and relates to the hospital as an independent contractor.

There are four common variants of the PSA model.4 A Global Payment PSA is when a hospital contracts with the physician practice for specific services and pays a global rate linked to wRVUs. The rate is negotiated to encompass physician compensation, benefits, and practice overhead. The practice retains control of its own office functions and staff.

In a traditional PSA, the hospital contracts with physicians and pays them based on RVU production, but the hospital owns the administrative part of the practice (staff, billing, collections, equipment, and supplies).

A practice management arrangement occurs when the hospital employs the physician who provides professional services and a separate third party manages the practice via a separate management contract. Finally, a Carve-Out PSA can use any of the earlier-described PSA arrangements and certain services are carved out under line-item provisions. For example, a hospital could contract with a private GI group for endoscopic services or night call and write a PSA expressly for these purposes.

Some notable benefits of the PSA are that physicians can maintain financial and employment independence from the hospital and have more control over benefits packages, retirement savings options, and health insurance. Physicians also can provide services outside of the hospital (e.g., telemedicine or locums tenens — see later) without institutional restrictions or conflicts. Finally, physicians benefit from tax advantages of self-employment (with associated business-related tax deductions) through their corporation. The potential downsides of a PSA contract are the subtle expansion of services demanded (known as scope creep) or the possibility of contract termination (or nonrenewal) by the hospital. In addition, medical training does not equip physicians with the knowledge to navigate personal and corporate finances, benefits packages, and tax structures, so the learning curve can be quite steep. Nevertheless, PSAs can be an innovative employment model for gastroenterologists who wish to preserve autonomy and financial flexibility. In this model, legal advice by an attorney skilled in employment law is mandatory.

Academic clinicians track

Until recently, clinically oriented academic faculty were channeled into the traditional ladder faculty model in which advancement was contingent on publications, national recognition, grant support, and teaching. As competition for market share has intensified among regional health systems, many AMCs have developed purely clinical tracks in which research, publication, and teaching are not expected; salaries are linked to clinical productivity; and income may approximate the professional (but not ancillary) income of a community gastroenterologist.

Various models of this arrangement exist as well. For example, clinicians can be employed within a group that has a board and management structure distinct from the faculty group practice, as in the case of the Northeast Medical Group at Yale New Haven Health System5 and the University of Maryland Community Medical Group. In addition, clinicians can form an operating group separate from the faculty practice but as a controlled subsidiary (such as the University of Pittsburgh Community Medicine), separate operating group for primary care but specialists are employed within their respective departments (Emory Specialty Associates) or as a distinct clinical department within a faculty practice (University of California Los Angeles Medical Group Staff Physicians).

Irrespective of the employment model, these clinicians essentially work similar to community gastroenterologists but within the umbrella of an AMC. For young faculty whose interest is not in research or teaching, this can be an attractive option that maintains a tie to a university health system. For a seasoned clinician in community practice, this is an option to return to an academic environment. Usually, productivity expectations within the clinician track approximate those of a community practice gastroenterologist, but again total compensation may not be as great because ancillary income streams usually are not available. We expect this AMC employment track to become more prevalent as universities expand their footprints and acquire practices, hospitals, and ambulatory facilities distant from the main campus.

Large single-specialty practice

Consolidation of independent practices has been evident for 20 years and has accelerated as physicians in smaller practices have aged and burdens of practice have increased. Now, most urban centers have large mega-sized practices or super groups that have grown through practice mergers, acquisitions, and successful recruitment. Large practices can be modeled as a single integrated corporation (with ancillary components such as an AEC or infusion center) or as individual business units that are grouped under a single corporate entity.6

Within these large and mega-sized practices, differing employment options have emerged in addition to the traditional partnership track. These include payment on a per-diem basis, annual salary, or a mix of both. As opposed to partnership, the employment track avoids responsibility for governance and corporate liability, although not individual liability, and usually does not involve after-hours call. An employed physician usually does not benefit from ancillary income that derives from AEC facility fees, infusion centers, and pathology and anesthesia services.

Private equity ownership of gastroenterology practices

In June 2016, private equity entered the GI space with the investment of the Audax Group in a community GI practice based in Miami, Florida. The term private equity refers to capital that is not reported in public forums and comprises funds that investors directly invest into private companies or use to buy out public companies and turn them private.

According to their website, when the Audax Group invests in a medical practice, they provide capital for substantial infrastructure support, business experience, and acumen, but retain medical practice leaders as their clinical decision makers. They also bring proven expertise and economies of scale to resource-intensive aspects of a medical practice including information technology, regulation compliance, human resources, revenue cycle management, payroll, benefits, rents, and lease as examples. These components can be difficult to manage efficiently within independent medical practices, so many maturing practices are selling their practices to regional health systems. This multistate equity-backed medical practice is an alternative to health system acquisition, and may help physicians feel more in control of their practices and potentially share in the equity investment.

It is important to understand the employment structure and associations of any practice you are contemplating joining. The model devised by this group is meant to retain physician authority and responsibility while providing capital to support innovation and the development of needed infrastructure. Growth of market share and revenues can accrue back to physician owners. This is distinct from practices that are part of a health system in which there may be more of a corporate feeling and centralized governance.

Locum tenens

Locum tenens is a Latin phrase that means “to hold the place of.” According to the website of a large locum tenens company, this practice model originated in the 1970s when the federal government provided a grant to the University of Utah to provide physician services for underserved areas in the Western United States. The program proved so successful that hospital administrators who had difficulty recruiting staff physicians began asking for staffing assistance.

Today, a substantial number of physicians at all stages of their careers are working as locum tenens. They work as independent contractors so that income taxes are not withheld and benefits are the responsibility of the individual. As with the PSA arrangement, a physician would meet with both an accountant and labor lawyer to establish him or herself as a corporate entity for tax advantages and limited liability from litigation.

Early stage physicians who might be following a significant other or spouse to specific locations sometimes consider a locum tenens as a bridge to permanent positions. Late-stage physicians who no longer want to be tied to a small group or solo practice have become locum tenens physicians who enjoy multiple temporary employment positions nationwide. This pathway no longer is unusual and can be a satisfying means to expand employment horizons. As with all employment situations, due diligence is mandatory before signing with any locum tenens company.

Conclusions

The employment spectrum for gastroenterologists and other medical professionals has expanded greatly between the time the senior author and the junior author entered the workforce. Change is now the one constant in medicine, and medicine today largely is fast-paced, corporatized, and highly regulated. Finding an employment model that is comfortable for current physicians, whose life situations are quite diverse, can be challenging. but a variety of opportunities now exist.

Think carefully about what you truly desire as a medical professional and how you might shape your employment to realize your goals. Options are available for those with an open mind and persistence.

References

1. Sheen E, Dorn SD, Brill JV, et al. Health care reform and the road ahead for gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1062-5.

2. Kosinski LR. Meaningful use and electronic medical records for the gastroenterology practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:494-7.

3. Medical Group Management Association (MGMA). Accessed January 20, 2017.

4. The Coker Group. PSAs as an Alternative to Employment: A Contemporary Option for Alignment and Integration. In: The Coker Group Thought Leadership – White Papers. March 2016.

5. Houston R, McGinnis T. Accountable care organizations: looking back and moving forward. Centers for Health Care Strategies Inc. Brief. January 2016. Accessed January 20, 2017.

6. Pallardy C. 7 gastroenterologists leading GI mega-practices. Becker’s GI and endoscopy 2015. Accessed January 20, 2017.

Dr. Allen is in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor; he is also the Editor in Chief of GI & Hepatology News. Dr. Kaushal is in the division of gastroenterology, Adventist Health Systems, Sonora, Calif. The authors disclose no conflicts.

From Obamacare to Trumpcare – implications for gastroenterologists

The June issue of CGH was the final column under my management. I have enjoyed the opportunity to provide you with information about practice management and health care reform. I also have enjoyed working with the Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology board of editors, and Erin Landis and Brook Simpson from AGA headquarters. Beginning in July 2017, this section will become the responsibility of Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF, from Duke University. I have worked with Ziad for many years, and he serves on my board of editors for GI & Hepatology News. I have great confidence in his knowledge and ability.

During the last 5 years, we have published 58 columns beginning with an article where I made several broad predictions. I have tried to present important concepts and management tools related to private and academic clinical practice, health care reform, and health economics. This article was written in early January 2017 just before the inauguration of Donald Trump. As I wrote, we did not know the full extent or the pace of “Repeal and Replace,” as Obamacare becomes Trumpcare (www.healthaffairs.org/obamacare-to-trumpcare).