User login

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM's "Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program" course. Write to him at [email protected].

Farewell to Larry Wellikson, MD, MHM

SHM cofounders praise the Society’s outgoing CEO

Setting the table for over 2 decades

I first met Larry in the spring of 1998 after I had made a presentation to the American College of Physicians’ Board of Regents on the Society for Hospital Medicine’s (then the National Association of Inpatient Physicians) new position statement that referral to hospitalists by primary care physicians should be voluntary. At the time, a number of managed care companies around the United States were compelling primary care physicians to use hospitalists to care for their hospitalized patients apparently because they felt hospitalists could do it more efficiently. SHM became the first professional society to voice the position which in turn was broadly endorsed by physician organizations, including the American Medical Association and the ACP.

Larry sought me out, engaged with me, and handed me his business card. He seemed keen on becoming a part of the rapidly accelerating hospitalist movement and, in retrospect, putting his signature on it. He had recently built and exited from a very large and successful independent physician association during the heyday of California managed care and was eager for a new challenge.

Unlike me, who was just a few years out of residency, Larry was at the height of his professional powers, with the right blend of experience on the one hand and energy on the other to take on a project like SHM.

Larry’s first contribution came in the form of facilitating a 2-day strategic planning meeting with the SHM board in the fall of 1998. John Nelson, MD, had moved to Philadelphia for 3 months to establish the operational foundation of SHM and guide SHM’s first staff member, Angela Musial. One of the most notable achievements during that time was a strategic planning board meeting, which largely set the course for SHM’s early years. Larry was a taskmaster, forcing us to make tough choices about what we wanted to accomplish and to establish concrete goals with timelines and milestones. The adult supervision Larry brought was a new and vital thing for us.

There was a lot at stake in ’97, ‘98, and ‘99. The demand for hospitalists across the nation was skyrocketing and there was a strong need for leadership and bold direction. Academics, community-based hospitalists, pediatricians, entrepreneurs, nonphysician hospital team members, heads of organized medicine, and government and industry leaders were just some of the key stakeholders looking for a seat at the HM table. That table would go on to be set for some 2 decades by Larry Wellikson.

From the beginning, many observers remarked that SHM had established an aggressive agenda. There was an unrelenting need to erect a big tent as a home for diverse stakeholders. John and I and the SHM board were doing all we could to continue to build momentum while also leading our local hospitalist groups and trying to maintain a semblance of balance with our young families back home.

It was against this backdrop, in late 1999, while on yet another flight crisscrossing the country to promote HM and SHM, that John; Bob Wachter, MD (who had by that time replaced John and I as SHM president); and I decided we needed a full-time CEO. By that time, each of us had participated in conversations with Larry. We rapidly decided, with buy-in from the board, that we would offer Larry the position. He accepted and became CEO in January 2000.

To list here all of Larry’s accomplishments since taking the helm at SHM would be impossible. Indeed, all that SHM has achieved is closely tied to Larry. Instead, I would like to call out character traits Larry brought to SHM that are now part of SHM’s DNA and a large part of the reason SHM has been so successful over the past 20 years.

Solution oriented. SHM’s culture has always been to take conditions as they are and work to make things better. There is no place for excessively airing grievances and complaining about “what is being done to us.”

Eschewing the status quo. We can do better. There is too much that needs to be done to wait.

Appropriately irreverent of the norms of the medical establishment. Physicians are by nature careful, plodding, considered, cautious, and methodical. The velocity of change in HM called for a different approach in order to be relevant, one better characterized as the move-fast-and-break-things ethos of a Silicon Valley startup.

Bringing diverse stakeholders to the table. A signature move has been to assemble influential people to lay out the issues before setting a course of action.

Strong bias to action. There is a time to analyze and discuss, but all of this ultimately is in service of taking action to achieve a tangible result.

Working to achieve consensus to a point, then moving forward. Considerable resources have been put into bringing stakeholders together, studying problems, and gaining a common understanding of issues. But this has never been at the expense of taking bold action, even if controversial at times.

Involving industry in creative ways to the benefit of patients. SHM pioneered an approach to use resources gained through industry partnerships to perform national scale improvement activities with groups of hospitalist mentor-experts working with local teams to make care more reliable for patients.

Tirelessly connecting to frontline hospitalists. The lifeblood of SHM is frontline hospitalists. Larry has taken the time to develop relationships with as many as possible, often through personally visiting their communities.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn., and cofounder and past president of SHM.

Dynamism

By John Nelson, MD, MHM

You probably know a few people with a magnetic personality. Larry Wellikson is the neodymium variety. Boundless energy, confidence that he has the answer or knows exactly where to find it, and ability to instantly recall every conversation he’s had with you, are traits that have energized his years leading SHM and have led countless people to regard him as friend and mentor.

Watch him at the SHM annual conference. There he goes, fast walking to his next commitment while facing backward to complete from a growing distance the conversation with a person he just bumped into along the way. It is like this for Larry from 6 a.m. until midnight. Like Alexander Hamilton, “the man is nonstop.”

Bill Campbell was the “Trillion Dollar Coach” who had his own success as a business leader, but is best known for mentoring Steve Jobs, the Google founders, and many others who went on to become titans of tech. Larry is hospital medicine’s “Coach,” and has inspired and guided the careers of so many clinicians, administrators, and entrepreneurs in hospital medicine and health care more broadly.

The biggest difference between these two highly effective leaders and mentors might be money; SHM has paid him pretty well, but alas, no stock options.

Larry is a great storyteller, and it doesn’t take long for a conversation with him to arrive at the point where he cites the example of how issues faced by someone else have parallels to your situation, the advice he gave that person, and how things turned out. Mostly this advice is about navigating professional life, but he is also happy to share wisdom about parenting, marriage, money, and sports. And most any other topic.

Larry was very accomplished even prior to connecting with SHM. He had a thriving clinical career, and though he left practice long ago he has maintained a close connection with many people he first met when they were his patients. I was surprised years ago when he drove up a new top-of-the-line Lexus – the two-seater with the solid convertible roof that folded into the trunk with the push of a button. I expressed surprise that he’d buy such a swanky car and he explained that a former patient, now long-time friend, was a Lexus distributor and arranged for Larry to drive it away for something like the cost of a Camry.

He also had terrific success forming and leading a large California independent physician association prior to connecting with SHM. Just ask him to show you the magazine with him on the cover and a glowing article detailing his accomplishments. Seriously, ask him, there’s a good chance he’ll have a copy with him.

When Dr. Win Whitcomb and I were trying to figure out how to start a new medical society and position our field to mature into a real specialty we were lucky enough to connect with many health care leaders who we thought could help. Most tended to pat us on the shoulder and say something along the lines of “good luck with your little hobby, now I have to get back to my important work.” But here was Larry with his impressive resume, having served as one of the leaders who crafted the merger of two giant medical societies (ACP and the American Society of Internal Medicine), keenly interested in our tiny new organization, and excited to serve as facilitator for our first strategic planning session.

SHM got a turbocharger when Larry signed on. For me it has felt like speeding down a highway, top down, radio blasting great music, and happy anticipation of what is around the next corner. I have never been disappointed, and certainly don’t plan to get out of Larry’s car just because he’s retiring as CEO.

Dr. Nelson is cofounder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif.

SHM cofounders praise the Society’s outgoing CEO

SHM cofounders praise the Society’s outgoing CEO

Setting the table for over 2 decades

I first met Larry in the spring of 1998 after I had made a presentation to the American College of Physicians’ Board of Regents on the Society for Hospital Medicine’s (then the National Association of Inpatient Physicians) new position statement that referral to hospitalists by primary care physicians should be voluntary. At the time, a number of managed care companies around the United States were compelling primary care physicians to use hospitalists to care for their hospitalized patients apparently because they felt hospitalists could do it more efficiently. SHM became the first professional society to voice the position which in turn was broadly endorsed by physician organizations, including the American Medical Association and the ACP.

Larry sought me out, engaged with me, and handed me his business card. He seemed keen on becoming a part of the rapidly accelerating hospitalist movement and, in retrospect, putting his signature on it. He had recently built and exited from a very large and successful independent physician association during the heyday of California managed care and was eager for a new challenge.

Unlike me, who was just a few years out of residency, Larry was at the height of his professional powers, with the right blend of experience on the one hand and energy on the other to take on a project like SHM.

Larry’s first contribution came in the form of facilitating a 2-day strategic planning meeting with the SHM board in the fall of 1998. John Nelson, MD, had moved to Philadelphia for 3 months to establish the operational foundation of SHM and guide SHM’s first staff member, Angela Musial. One of the most notable achievements during that time was a strategic planning board meeting, which largely set the course for SHM’s early years. Larry was a taskmaster, forcing us to make tough choices about what we wanted to accomplish and to establish concrete goals with timelines and milestones. The adult supervision Larry brought was a new and vital thing for us.

There was a lot at stake in ’97, ‘98, and ‘99. The demand for hospitalists across the nation was skyrocketing and there was a strong need for leadership and bold direction. Academics, community-based hospitalists, pediatricians, entrepreneurs, nonphysician hospital team members, heads of organized medicine, and government and industry leaders were just some of the key stakeholders looking for a seat at the HM table. That table would go on to be set for some 2 decades by Larry Wellikson.

From the beginning, many observers remarked that SHM had established an aggressive agenda. There was an unrelenting need to erect a big tent as a home for diverse stakeholders. John and I and the SHM board were doing all we could to continue to build momentum while also leading our local hospitalist groups and trying to maintain a semblance of balance with our young families back home.

It was against this backdrop, in late 1999, while on yet another flight crisscrossing the country to promote HM and SHM, that John; Bob Wachter, MD (who had by that time replaced John and I as SHM president); and I decided we needed a full-time CEO. By that time, each of us had participated in conversations with Larry. We rapidly decided, with buy-in from the board, that we would offer Larry the position. He accepted and became CEO in January 2000.

To list here all of Larry’s accomplishments since taking the helm at SHM would be impossible. Indeed, all that SHM has achieved is closely tied to Larry. Instead, I would like to call out character traits Larry brought to SHM that are now part of SHM’s DNA and a large part of the reason SHM has been so successful over the past 20 years.

Solution oriented. SHM’s culture has always been to take conditions as they are and work to make things better. There is no place for excessively airing grievances and complaining about “what is being done to us.”

Eschewing the status quo. We can do better. There is too much that needs to be done to wait.

Appropriately irreverent of the norms of the medical establishment. Physicians are by nature careful, plodding, considered, cautious, and methodical. The velocity of change in HM called for a different approach in order to be relevant, one better characterized as the move-fast-and-break-things ethos of a Silicon Valley startup.

Bringing diverse stakeholders to the table. A signature move has been to assemble influential people to lay out the issues before setting a course of action.

Strong bias to action. There is a time to analyze and discuss, but all of this ultimately is in service of taking action to achieve a tangible result.

Working to achieve consensus to a point, then moving forward. Considerable resources have been put into bringing stakeholders together, studying problems, and gaining a common understanding of issues. But this has never been at the expense of taking bold action, even if controversial at times.

Involving industry in creative ways to the benefit of patients. SHM pioneered an approach to use resources gained through industry partnerships to perform national scale improvement activities with groups of hospitalist mentor-experts working with local teams to make care more reliable for patients.

Tirelessly connecting to frontline hospitalists. The lifeblood of SHM is frontline hospitalists. Larry has taken the time to develop relationships with as many as possible, often through personally visiting their communities.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn., and cofounder and past president of SHM.

Dynamism

By John Nelson, MD, MHM

You probably know a few people with a magnetic personality. Larry Wellikson is the neodymium variety. Boundless energy, confidence that he has the answer or knows exactly where to find it, and ability to instantly recall every conversation he’s had with you, are traits that have energized his years leading SHM and have led countless people to regard him as friend and mentor.

Watch him at the SHM annual conference. There he goes, fast walking to his next commitment while facing backward to complete from a growing distance the conversation with a person he just bumped into along the way. It is like this for Larry from 6 a.m. until midnight. Like Alexander Hamilton, “the man is nonstop.”

Bill Campbell was the “Trillion Dollar Coach” who had his own success as a business leader, but is best known for mentoring Steve Jobs, the Google founders, and many others who went on to become titans of tech. Larry is hospital medicine’s “Coach,” and has inspired and guided the careers of so many clinicians, administrators, and entrepreneurs in hospital medicine and health care more broadly.

The biggest difference between these two highly effective leaders and mentors might be money; SHM has paid him pretty well, but alas, no stock options.

Larry is a great storyteller, and it doesn’t take long for a conversation with him to arrive at the point where he cites the example of how issues faced by someone else have parallels to your situation, the advice he gave that person, and how things turned out. Mostly this advice is about navigating professional life, but he is also happy to share wisdom about parenting, marriage, money, and sports. And most any other topic.

Larry was very accomplished even prior to connecting with SHM. He had a thriving clinical career, and though he left practice long ago he has maintained a close connection with many people he first met when they were his patients. I was surprised years ago when he drove up a new top-of-the-line Lexus – the two-seater with the solid convertible roof that folded into the trunk with the push of a button. I expressed surprise that he’d buy such a swanky car and he explained that a former patient, now long-time friend, was a Lexus distributor and arranged for Larry to drive it away for something like the cost of a Camry.

He also had terrific success forming and leading a large California independent physician association prior to connecting with SHM. Just ask him to show you the magazine with him on the cover and a glowing article detailing his accomplishments. Seriously, ask him, there’s a good chance he’ll have a copy with him.

When Dr. Win Whitcomb and I were trying to figure out how to start a new medical society and position our field to mature into a real specialty we were lucky enough to connect with many health care leaders who we thought could help. Most tended to pat us on the shoulder and say something along the lines of “good luck with your little hobby, now I have to get back to my important work.” But here was Larry with his impressive resume, having served as one of the leaders who crafted the merger of two giant medical societies (ACP and the American Society of Internal Medicine), keenly interested in our tiny new organization, and excited to serve as facilitator for our first strategic planning session.

SHM got a turbocharger when Larry signed on. For me it has felt like speeding down a highway, top down, radio blasting great music, and happy anticipation of what is around the next corner. I have never been disappointed, and certainly don’t plan to get out of Larry’s car just because he’s retiring as CEO.

Dr. Nelson is cofounder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif.

Setting the table for over 2 decades

I first met Larry in the spring of 1998 after I had made a presentation to the American College of Physicians’ Board of Regents on the Society for Hospital Medicine’s (then the National Association of Inpatient Physicians) new position statement that referral to hospitalists by primary care physicians should be voluntary. At the time, a number of managed care companies around the United States were compelling primary care physicians to use hospitalists to care for their hospitalized patients apparently because they felt hospitalists could do it more efficiently. SHM became the first professional society to voice the position which in turn was broadly endorsed by physician organizations, including the American Medical Association and the ACP.

Larry sought me out, engaged with me, and handed me his business card. He seemed keen on becoming a part of the rapidly accelerating hospitalist movement and, in retrospect, putting his signature on it. He had recently built and exited from a very large and successful independent physician association during the heyday of California managed care and was eager for a new challenge.

Unlike me, who was just a few years out of residency, Larry was at the height of his professional powers, with the right blend of experience on the one hand and energy on the other to take on a project like SHM.

Larry’s first contribution came in the form of facilitating a 2-day strategic planning meeting with the SHM board in the fall of 1998. John Nelson, MD, had moved to Philadelphia for 3 months to establish the operational foundation of SHM and guide SHM’s first staff member, Angela Musial. One of the most notable achievements during that time was a strategic planning board meeting, which largely set the course for SHM’s early years. Larry was a taskmaster, forcing us to make tough choices about what we wanted to accomplish and to establish concrete goals with timelines and milestones. The adult supervision Larry brought was a new and vital thing for us.

There was a lot at stake in ’97, ‘98, and ‘99. The demand for hospitalists across the nation was skyrocketing and there was a strong need for leadership and bold direction. Academics, community-based hospitalists, pediatricians, entrepreneurs, nonphysician hospital team members, heads of organized medicine, and government and industry leaders were just some of the key stakeholders looking for a seat at the HM table. That table would go on to be set for some 2 decades by Larry Wellikson.

From the beginning, many observers remarked that SHM had established an aggressive agenda. There was an unrelenting need to erect a big tent as a home for diverse stakeholders. John and I and the SHM board were doing all we could to continue to build momentum while also leading our local hospitalist groups and trying to maintain a semblance of balance with our young families back home.

It was against this backdrop, in late 1999, while on yet another flight crisscrossing the country to promote HM and SHM, that John; Bob Wachter, MD (who had by that time replaced John and I as SHM president); and I decided we needed a full-time CEO. By that time, each of us had participated in conversations with Larry. We rapidly decided, with buy-in from the board, that we would offer Larry the position. He accepted and became CEO in January 2000.

To list here all of Larry’s accomplishments since taking the helm at SHM would be impossible. Indeed, all that SHM has achieved is closely tied to Larry. Instead, I would like to call out character traits Larry brought to SHM that are now part of SHM’s DNA and a large part of the reason SHM has been so successful over the past 20 years.

Solution oriented. SHM’s culture has always been to take conditions as they are and work to make things better. There is no place for excessively airing grievances and complaining about “what is being done to us.”

Eschewing the status quo. We can do better. There is too much that needs to be done to wait.

Appropriately irreverent of the norms of the medical establishment. Physicians are by nature careful, plodding, considered, cautious, and methodical. The velocity of change in HM called for a different approach in order to be relevant, one better characterized as the move-fast-and-break-things ethos of a Silicon Valley startup.

Bringing diverse stakeholders to the table. A signature move has been to assemble influential people to lay out the issues before setting a course of action.

Strong bias to action. There is a time to analyze and discuss, but all of this ultimately is in service of taking action to achieve a tangible result.

Working to achieve consensus to a point, then moving forward. Considerable resources have been put into bringing stakeholders together, studying problems, and gaining a common understanding of issues. But this has never been at the expense of taking bold action, even if controversial at times.

Involving industry in creative ways to the benefit of patients. SHM pioneered an approach to use resources gained through industry partnerships to perform national scale improvement activities with groups of hospitalist mentor-experts working with local teams to make care more reliable for patients.

Tirelessly connecting to frontline hospitalists. The lifeblood of SHM is frontline hospitalists. Larry has taken the time to develop relationships with as many as possible, often through personally visiting their communities.

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, Conn., and cofounder and past president of SHM.

Dynamism

By John Nelson, MD, MHM

You probably know a few people with a magnetic personality. Larry Wellikson is the neodymium variety. Boundless energy, confidence that he has the answer or knows exactly where to find it, and ability to instantly recall every conversation he’s had with you, are traits that have energized his years leading SHM and have led countless people to regard him as friend and mentor.

Watch him at the SHM annual conference. There he goes, fast walking to his next commitment while facing backward to complete from a growing distance the conversation with a person he just bumped into along the way. It is like this for Larry from 6 a.m. until midnight. Like Alexander Hamilton, “the man is nonstop.”

Bill Campbell was the “Trillion Dollar Coach” who had his own success as a business leader, but is best known for mentoring Steve Jobs, the Google founders, and many others who went on to become titans of tech. Larry is hospital medicine’s “Coach,” and has inspired and guided the careers of so many clinicians, administrators, and entrepreneurs in hospital medicine and health care more broadly.

The biggest difference between these two highly effective leaders and mentors might be money; SHM has paid him pretty well, but alas, no stock options.

Larry is a great storyteller, and it doesn’t take long for a conversation with him to arrive at the point where he cites the example of how issues faced by someone else have parallels to your situation, the advice he gave that person, and how things turned out. Mostly this advice is about navigating professional life, but he is also happy to share wisdom about parenting, marriage, money, and sports. And most any other topic.

Larry was very accomplished even prior to connecting with SHM. He had a thriving clinical career, and though he left practice long ago he has maintained a close connection with many people he first met when they were his patients. I was surprised years ago when he drove up a new top-of-the-line Lexus – the two-seater with the solid convertible roof that folded into the trunk with the push of a button. I expressed surprise that he’d buy such a swanky car and he explained that a former patient, now long-time friend, was a Lexus distributor and arranged for Larry to drive it away for something like the cost of a Camry.

He also had terrific success forming and leading a large California independent physician association prior to connecting with SHM. Just ask him to show you the magazine with him on the cover and a glowing article detailing his accomplishments. Seriously, ask him, there’s a good chance he’ll have a copy with him.

When Dr. Win Whitcomb and I were trying to figure out how to start a new medical society and position our field to mature into a real specialty we were lucky enough to connect with many health care leaders who we thought could help. Most tended to pat us on the shoulder and say something along the lines of “good luck with your little hobby, now I have to get back to my important work.” But here was Larry with his impressive resume, having served as one of the leaders who crafted the merger of two giant medical societies (ACP and the American Society of Internal Medicine), keenly interested in our tiny new organization, and excited to serve as facilitator for our first strategic planning session.

SHM got a turbocharger when Larry signed on. For me it has felt like speeding down a highway, top down, radio blasting great music, and happy anticipation of what is around the next corner. I have never been disappointed, and certainly don’t plan to get out of Larry’s car just because he’s retiring as CEO.

Dr. Nelson is cofounder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif.

The past and future of hospital medicine

Challenges faced, and overcome

While I hope I’ll still be doing much the same work for many more years, I’m clearly at a stage of life that most of my career is behind me. So I guess it’s natural that I think about the past a little more than I used to. And one of the things that makes me smile is how I’m like George Costanza in The Comeback episode of “Seinfeld.”

In 1997 I had just delivered a presentation about what the future might hold for hospitalists to the roughly 110 attendees at the first in-person meeting of SHM (then known as the National Association of Inpatient Physicians). During the Q&A that followed, someone asked me what clinical content I would include in the hospitalist-specific test or board exam that I had speculated might be in our future. I took his tone and body language to suggest his main intent was to convey that I was crazy to think that such a test might ever be worthwhile.

A pregnant silence followed his question, after which I gave a tentative response that I worried made me sound dumb. So like George in “Seinfeld,” I continued to think about this, and days later came up with what I’m sure would have been a terrific comeback that would have gotten a robust laugh from the audience without being demeaning to the questioner. For the last 22 years I’ve been waiting for someone to ask me the same question so I can finally deliver my winner of a response.

There have been other missed opportunities, but when I think about the past and future of our field and our Society, I’m reminded of many past accomplishments and a promising future.

When Dr. Win Whitcomb and I founded SHM, I had the idea that, among its most important roles, would be serving as a forum for exchange of ideas among hospitalists and providing robust practice management resources for hospitalist groups. Through the efforts of so many people, including Angela Musial, the first SHM staff person, and so many other staff and members, we now have dozens of active special interest groups, informative publications, an active online discussion forum, and blogs. And our annual conference has grown a lot from that first meeting of 110 people; HM19 will bring together nearly 5,000 of us to educate, inspire, and support one another. Collectively, there are a lot of ideas being exchanged through SHM.

When SHM was brand new I had hope that it would grow. But I never guessed that hospital medicine would become the fastest-growing field in the history of U.S. health care.

I also never guessed that the term “nocturnist” would become a standard part of our field’s lexicon. I used it solely as a reliable way to get a laugh and find it really funny and delightful that it caught on.

And OB hospitalists? Neurohospitalists? I never saw these and the many other variations coming at all. But I see it as validating an idea first adopted by medicine and pediatrics. But dermatology hospitalists? Yep, that’s a thing too. The hospitalist model has been adopted, in at least a few places, by nearly every specialty in medicine.

And it is terrific that March 7, 2019, is the first National Hospitalist Day. SHM made this happen too.

I also think about the future of our field and see some pretty big challenges, though our past success as a field makes me confident we’ll navigate them effectively.

The burden of administrative, regulatory, and EHR-related tasks just keeps growing for hospitalists. This often means it is difficult or impossible see as many patients in a day as might have been reasonable in the past. In the near term, the only solution might be to reduce patient loads, but that isn’t a sustainable solution in the long term. I’m convinced we need to offload much of the work we do today that isn’t purely clinical, so that a typical hospitalist in the future can see more patients each day without working harder or longer.

I imagine a future in which the typical hospitalist goes home after seeing 20 or more patients in a day and isn’t completely exhausted and stressed, but sees it as a good day at work. I’m not sure exactly how we’ll get there, but it will probably include things like no longer having to devote any time or attention to whether the patient is inpatient or observation status, or whether they have had a qualifying 3-midnight stay so Medicare will cover a skilled nursing facility. I’m excited to see how this will evolve.

Dr. Nelson is cofounder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses.

Challenges faced, and overcome

Challenges faced, and overcome

While I hope I’ll still be doing much the same work for many more years, I’m clearly at a stage of life that most of my career is behind me. So I guess it’s natural that I think about the past a little more than I used to. And one of the things that makes me smile is how I’m like George Costanza in The Comeback episode of “Seinfeld.”

In 1997 I had just delivered a presentation about what the future might hold for hospitalists to the roughly 110 attendees at the first in-person meeting of SHM (then known as the National Association of Inpatient Physicians). During the Q&A that followed, someone asked me what clinical content I would include in the hospitalist-specific test or board exam that I had speculated might be in our future. I took his tone and body language to suggest his main intent was to convey that I was crazy to think that such a test might ever be worthwhile.

A pregnant silence followed his question, after which I gave a tentative response that I worried made me sound dumb. So like George in “Seinfeld,” I continued to think about this, and days later came up with what I’m sure would have been a terrific comeback that would have gotten a robust laugh from the audience without being demeaning to the questioner. For the last 22 years I’ve been waiting for someone to ask me the same question so I can finally deliver my winner of a response.

There have been other missed opportunities, but when I think about the past and future of our field and our Society, I’m reminded of many past accomplishments and a promising future.

When Dr. Win Whitcomb and I founded SHM, I had the idea that, among its most important roles, would be serving as a forum for exchange of ideas among hospitalists and providing robust practice management resources for hospitalist groups. Through the efforts of so many people, including Angela Musial, the first SHM staff person, and so many other staff and members, we now have dozens of active special interest groups, informative publications, an active online discussion forum, and blogs. And our annual conference has grown a lot from that first meeting of 110 people; HM19 will bring together nearly 5,000 of us to educate, inspire, and support one another. Collectively, there are a lot of ideas being exchanged through SHM.

When SHM was brand new I had hope that it would grow. But I never guessed that hospital medicine would become the fastest-growing field in the history of U.S. health care.

I also never guessed that the term “nocturnist” would become a standard part of our field’s lexicon. I used it solely as a reliable way to get a laugh and find it really funny and delightful that it caught on.

And OB hospitalists? Neurohospitalists? I never saw these and the many other variations coming at all. But I see it as validating an idea first adopted by medicine and pediatrics. But dermatology hospitalists? Yep, that’s a thing too. The hospitalist model has been adopted, in at least a few places, by nearly every specialty in medicine.

And it is terrific that March 7, 2019, is the first National Hospitalist Day. SHM made this happen too.

I also think about the future of our field and see some pretty big challenges, though our past success as a field makes me confident we’ll navigate them effectively.

The burden of administrative, regulatory, and EHR-related tasks just keeps growing for hospitalists. This often means it is difficult or impossible see as many patients in a day as might have been reasonable in the past. In the near term, the only solution might be to reduce patient loads, but that isn’t a sustainable solution in the long term. I’m convinced we need to offload much of the work we do today that isn’t purely clinical, so that a typical hospitalist in the future can see more patients each day without working harder or longer.

I imagine a future in which the typical hospitalist goes home after seeing 20 or more patients in a day and isn’t completely exhausted and stressed, but sees it as a good day at work. I’m not sure exactly how we’ll get there, but it will probably include things like no longer having to devote any time or attention to whether the patient is inpatient or observation status, or whether they have had a qualifying 3-midnight stay so Medicare will cover a skilled nursing facility. I’m excited to see how this will evolve.

Dr. Nelson is cofounder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses.

While I hope I’ll still be doing much the same work for many more years, I’m clearly at a stage of life that most of my career is behind me. So I guess it’s natural that I think about the past a little more than I used to. And one of the things that makes me smile is how I’m like George Costanza in The Comeback episode of “Seinfeld.”

In 1997 I had just delivered a presentation about what the future might hold for hospitalists to the roughly 110 attendees at the first in-person meeting of SHM (then known as the National Association of Inpatient Physicians). During the Q&A that followed, someone asked me what clinical content I would include in the hospitalist-specific test or board exam that I had speculated might be in our future. I took his tone and body language to suggest his main intent was to convey that I was crazy to think that such a test might ever be worthwhile.

A pregnant silence followed his question, after which I gave a tentative response that I worried made me sound dumb. So like George in “Seinfeld,” I continued to think about this, and days later came up with what I’m sure would have been a terrific comeback that would have gotten a robust laugh from the audience without being demeaning to the questioner. For the last 22 years I’ve been waiting for someone to ask me the same question so I can finally deliver my winner of a response.

There have been other missed opportunities, but when I think about the past and future of our field and our Society, I’m reminded of many past accomplishments and a promising future.

When Dr. Win Whitcomb and I founded SHM, I had the idea that, among its most important roles, would be serving as a forum for exchange of ideas among hospitalists and providing robust practice management resources for hospitalist groups. Through the efforts of so many people, including Angela Musial, the first SHM staff person, and so many other staff and members, we now have dozens of active special interest groups, informative publications, an active online discussion forum, and blogs. And our annual conference has grown a lot from that first meeting of 110 people; HM19 will bring together nearly 5,000 of us to educate, inspire, and support one another. Collectively, there are a lot of ideas being exchanged through SHM.

When SHM was brand new I had hope that it would grow. But I never guessed that hospital medicine would become the fastest-growing field in the history of U.S. health care.

I also never guessed that the term “nocturnist” would become a standard part of our field’s lexicon. I used it solely as a reliable way to get a laugh and find it really funny and delightful that it caught on.

And OB hospitalists? Neurohospitalists? I never saw these and the many other variations coming at all. But I see it as validating an idea first adopted by medicine and pediatrics. But dermatology hospitalists? Yep, that’s a thing too. The hospitalist model has been adopted, in at least a few places, by nearly every specialty in medicine.

And it is terrific that March 7, 2019, is the first National Hospitalist Day. SHM made this happen too.

I also think about the future of our field and see some pretty big challenges, though our past success as a field makes me confident we’ll navigate them effectively.

The burden of administrative, regulatory, and EHR-related tasks just keeps growing for hospitalists. This often means it is difficult or impossible see as many patients in a day as might have been reasonable in the past. In the near term, the only solution might be to reduce patient loads, but that isn’t a sustainable solution in the long term. I’m convinced we need to offload much of the work we do today that isn’t purely clinical, so that a typical hospitalist in the future can see more patients each day without working harder or longer.

I imagine a future in which the typical hospitalist goes home after seeing 20 or more patients in a day and isn’t completely exhausted and stressed, but sees it as a good day at work. I’m not sure exactly how we’ll get there, but it will probably include things like no longer having to devote any time or attention to whether the patient is inpatient or observation status, or whether they have had a qualifying 3-midnight stay so Medicare will cover a skilled nursing facility. I’m excited to see how this will evolve.

Dr. Nelson is cofounder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses.

Hospitalist burnout

Some things I’ve been thinking about:

- Physician well-being, morale, and burnout seem to be getting more attention in both the medical and the lay press.

- Leaders from 10 prestigious health systems and the CEO of the American Medical Association wrote a March 2017 post in the Health Affairs Blog titled “Physician Burnout is a Public Health Crisis: A Message To Our Fellow Health Care CEOs.”

- I’m now regularly hearing and reading mention of the “Quadruple Aim.” The “Triple Aim,” first described in 2008, is the pursuit of excellence in 1) patient experience – both quality of care and patient satisfaction; 2) population health; and 3) cost reduction. The November/December 2014 Annals of Family Medicine included an article recommending “that the Triple Aim be expanded to a Quadruple Aim by adding the goal of improving the work life of health care providers, including clinicians and staff.”1

- The CEO at a community hospital near me chose to make addressing physician burnout one of his top priorities and tied success in the effort to his own compensation bonus.

- In the course of my consulting work with hospitalist groups across the country, I’ve noticed a meaningful increase in the number of our colleagues who seem deeply unhappy with their work and/or burned out. The “Hospitalist Morale Index” may be a worthwhile way for a group to conduct an assessment.2

- I’m concerned that many other hospital care givers, including RNs, social workers, and others, are experiencing levels of distress and/or burnout that might be similar to that of physicians. From where I sit, they seem to be getting less attention, and I can’t tell if that is just because I’m not as immersed in their world or if it reflects reality. It’s pretty disappointing if it’s the latter.

For the most part, I think the causes of hospitalist distress and burnout are very similar to that of doctors in other specialties, and interventions to address the problem can be similar across specialties. Yet, each specialty probably differs in ways that are important to keep in mind.

Hospitalists also bear a huge burden related to observation status. Doctors in most other specialties rarely face complex decisions regarding whether observation is the right choice and are not so often the target of patient/family frustration and anger related to it.

Those seeking to address hospitalist burnout and well-being specifically should keep in mind these uniquely hospitalist issues. I think of them as a chronic disease to manage and mitigate, since “curing” them (making them go away entirely) is probably impossible for the foreseeable future.

What to do?

An Internet search on physician burnout, or other terms related to well-being, will yield more articles with advice to address the problem than you’ll ever have time to read. Trying to read all of them would likely lead to burnout! I think interventions can be divided into two broad categories: organizational efforts and personal efforts.

Like the 10 CEOs mentioned above, health care leaders should acknowledge physician distress and burnout as a meaningful issue that can impede organizational performance and that investments to address it can have a meaningful return on investment. The Health Affairs Blog post listed 11 things the CEOs committed to doing. It’s a list anyone working on this issue should review.

Doctors at The Mayo Clinic have published a great deal of research on physician burnout. In the March 7, 2017, JAMA, (summarized in a YouTube video) they describe several worthwhile organizational changes, as well as some personal strategies.3 They wrote about their experiences with interventions such as a deliberate curriculum to train doctors in self-care (self-reflection, mindfulness, etc.) in a series of one-hour lectures over several months.4 In November 2016, they published a meta-analysis of interventions to address burnout.5

In total, all of the worthwhile recommendations to address burnout leave me feeling like they’re a lot of work, and any individual intervention may not be as helpful as hoped, so that the best way to approach this is with a collection of interventions. In many ways, it is similar to the problem of readmissions: There is a lot of research out there, it’s hard to prove that any single intervention really works, and success lies in implementing a broad set of interventions. And success doesn’t equate to eliminating readmissions, only reducing them.

Coda: Is a sabbatical uniquely valuable for hospitalists?

I think a sabbatical might be a good idea for hospitalists. It also seems practical for other doctors, such as radiologists, anesthesiologists, and ED doctors, who don’t have 1:1 continuity relationships with patients. However, it is problematic for primary care doctors and specialists who need to maintain continuity relationships with patients and referring doctors that could be disrupted by a lengthy absence.

I’m not sure a sabbatical would reduce burnout much on its own, but, if properly structured, it seems very likely to reduce staffing turnover, and the sabbatical could be spent in ways that help rejuvenate interest and satisfaction in our work rather than simply taking a long vacation to travel and play golf, etc. It should probably be at least 3 months and better if it lasts a year. A common arrangement is that a doctor becomes eligible for the sabbatical after 10 years and is paid half of her usual compensation while away. I’d like to see more hospitalist groups do this.

Dr. Nelson has had a career in clinical practice as a hospitalist starting in 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses. Write to [email protected].

References

1. Bodenheimer, T and Sninsky, C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann Fam Med. Nov/Dec 2014.

2. Chandra, S et al. Introducing the Hospitalist Morale Index: A New Tool That May Be Relevant for Improving Provider Retention. JHM. June 2016.

3. Shanafelt, T, Dyrbye, L, West, C. Addressing Physician Burnout: The Way Forward. JAMA. March 7, 2017.

4. West, C et al. Intervention to Promote Physician Well-being, Job Satisfaction, and Professionalism: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-33.

5. West, C et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Nov 5, 2016.

Some things I’ve been thinking about:

- Physician well-being, morale, and burnout seem to be getting more attention in both the medical and the lay press.

- Leaders from 10 prestigious health systems and the CEO of the American Medical Association wrote a March 2017 post in the Health Affairs Blog titled “Physician Burnout is a Public Health Crisis: A Message To Our Fellow Health Care CEOs.”

- I’m now regularly hearing and reading mention of the “Quadruple Aim.” The “Triple Aim,” first described in 2008, is the pursuit of excellence in 1) patient experience – both quality of care and patient satisfaction; 2) population health; and 3) cost reduction. The November/December 2014 Annals of Family Medicine included an article recommending “that the Triple Aim be expanded to a Quadruple Aim by adding the goal of improving the work life of health care providers, including clinicians and staff.”1

- The CEO at a community hospital near me chose to make addressing physician burnout one of his top priorities and tied success in the effort to his own compensation bonus.

- In the course of my consulting work with hospitalist groups across the country, I’ve noticed a meaningful increase in the number of our colleagues who seem deeply unhappy with their work and/or burned out. The “Hospitalist Morale Index” may be a worthwhile way for a group to conduct an assessment.2

- I’m concerned that many other hospital care givers, including RNs, social workers, and others, are experiencing levels of distress and/or burnout that might be similar to that of physicians. From where I sit, they seem to be getting less attention, and I can’t tell if that is just because I’m not as immersed in their world or if it reflects reality. It’s pretty disappointing if it’s the latter.

For the most part, I think the causes of hospitalist distress and burnout are very similar to that of doctors in other specialties, and interventions to address the problem can be similar across specialties. Yet, each specialty probably differs in ways that are important to keep in mind.

Hospitalists also bear a huge burden related to observation status. Doctors in most other specialties rarely face complex decisions regarding whether observation is the right choice and are not so often the target of patient/family frustration and anger related to it.

Those seeking to address hospitalist burnout and well-being specifically should keep in mind these uniquely hospitalist issues. I think of them as a chronic disease to manage and mitigate, since “curing” them (making them go away entirely) is probably impossible for the foreseeable future.

What to do?

An Internet search on physician burnout, or other terms related to well-being, will yield more articles with advice to address the problem than you’ll ever have time to read. Trying to read all of them would likely lead to burnout! I think interventions can be divided into two broad categories: organizational efforts and personal efforts.

Like the 10 CEOs mentioned above, health care leaders should acknowledge physician distress and burnout as a meaningful issue that can impede organizational performance and that investments to address it can have a meaningful return on investment. The Health Affairs Blog post listed 11 things the CEOs committed to doing. It’s a list anyone working on this issue should review.

Doctors at The Mayo Clinic have published a great deal of research on physician burnout. In the March 7, 2017, JAMA, (summarized in a YouTube video) they describe several worthwhile organizational changes, as well as some personal strategies.3 They wrote about their experiences with interventions such as a deliberate curriculum to train doctors in self-care (self-reflection, mindfulness, etc.) in a series of one-hour lectures over several months.4 In November 2016, they published a meta-analysis of interventions to address burnout.5

In total, all of the worthwhile recommendations to address burnout leave me feeling like they’re a lot of work, and any individual intervention may not be as helpful as hoped, so that the best way to approach this is with a collection of interventions. In many ways, it is similar to the problem of readmissions: There is a lot of research out there, it’s hard to prove that any single intervention really works, and success lies in implementing a broad set of interventions. And success doesn’t equate to eliminating readmissions, only reducing them.

Coda: Is a sabbatical uniquely valuable for hospitalists?

I think a sabbatical might be a good idea for hospitalists. It also seems practical for other doctors, such as radiologists, anesthesiologists, and ED doctors, who don’t have 1:1 continuity relationships with patients. However, it is problematic for primary care doctors and specialists who need to maintain continuity relationships with patients and referring doctors that could be disrupted by a lengthy absence.

I’m not sure a sabbatical would reduce burnout much on its own, but, if properly structured, it seems very likely to reduce staffing turnover, and the sabbatical could be spent in ways that help rejuvenate interest and satisfaction in our work rather than simply taking a long vacation to travel and play golf, etc. It should probably be at least 3 months and better if it lasts a year. A common arrangement is that a doctor becomes eligible for the sabbatical after 10 years and is paid half of her usual compensation while away. I’d like to see more hospitalist groups do this.

Dr. Nelson has had a career in clinical practice as a hospitalist starting in 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses. Write to [email protected].

References

1. Bodenheimer, T and Sninsky, C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann Fam Med. Nov/Dec 2014.

2. Chandra, S et al. Introducing the Hospitalist Morale Index: A New Tool That May Be Relevant for Improving Provider Retention. JHM. June 2016.

3. Shanafelt, T, Dyrbye, L, West, C. Addressing Physician Burnout: The Way Forward. JAMA. March 7, 2017.

4. West, C et al. Intervention to Promote Physician Well-being, Job Satisfaction, and Professionalism: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-33.

5. West, C et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Nov 5, 2016.

Some things I’ve been thinking about:

- Physician well-being, morale, and burnout seem to be getting more attention in both the medical and the lay press.

- Leaders from 10 prestigious health systems and the CEO of the American Medical Association wrote a March 2017 post in the Health Affairs Blog titled “Physician Burnout is a Public Health Crisis: A Message To Our Fellow Health Care CEOs.”

- I’m now regularly hearing and reading mention of the “Quadruple Aim.” The “Triple Aim,” first described in 2008, is the pursuit of excellence in 1) patient experience – both quality of care and patient satisfaction; 2) population health; and 3) cost reduction. The November/December 2014 Annals of Family Medicine included an article recommending “that the Triple Aim be expanded to a Quadruple Aim by adding the goal of improving the work life of health care providers, including clinicians and staff.”1

- The CEO at a community hospital near me chose to make addressing physician burnout one of his top priorities and tied success in the effort to his own compensation bonus.

- In the course of my consulting work with hospitalist groups across the country, I’ve noticed a meaningful increase in the number of our colleagues who seem deeply unhappy with their work and/or burned out. The “Hospitalist Morale Index” may be a worthwhile way for a group to conduct an assessment.2

- I’m concerned that many other hospital care givers, including RNs, social workers, and others, are experiencing levels of distress and/or burnout that might be similar to that of physicians. From where I sit, they seem to be getting less attention, and I can’t tell if that is just because I’m not as immersed in their world or if it reflects reality. It’s pretty disappointing if it’s the latter.

For the most part, I think the causes of hospitalist distress and burnout are very similar to that of doctors in other specialties, and interventions to address the problem can be similar across specialties. Yet, each specialty probably differs in ways that are important to keep in mind.

Hospitalists also bear a huge burden related to observation status. Doctors in most other specialties rarely face complex decisions regarding whether observation is the right choice and are not so often the target of patient/family frustration and anger related to it.

Those seeking to address hospitalist burnout and well-being specifically should keep in mind these uniquely hospitalist issues. I think of them as a chronic disease to manage and mitigate, since “curing” them (making them go away entirely) is probably impossible for the foreseeable future.

What to do?

An Internet search on physician burnout, or other terms related to well-being, will yield more articles with advice to address the problem than you’ll ever have time to read. Trying to read all of them would likely lead to burnout! I think interventions can be divided into two broad categories: organizational efforts and personal efforts.

Like the 10 CEOs mentioned above, health care leaders should acknowledge physician distress and burnout as a meaningful issue that can impede organizational performance and that investments to address it can have a meaningful return on investment. The Health Affairs Blog post listed 11 things the CEOs committed to doing. It’s a list anyone working on this issue should review.

Doctors at The Mayo Clinic have published a great deal of research on physician burnout. In the March 7, 2017, JAMA, (summarized in a YouTube video) they describe several worthwhile organizational changes, as well as some personal strategies.3 They wrote about their experiences with interventions such as a deliberate curriculum to train doctors in self-care (self-reflection, mindfulness, etc.) in a series of one-hour lectures over several months.4 In November 2016, they published a meta-analysis of interventions to address burnout.5

In total, all of the worthwhile recommendations to address burnout leave me feeling like they’re a lot of work, and any individual intervention may not be as helpful as hoped, so that the best way to approach this is with a collection of interventions. In many ways, it is similar to the problem of readmissions: There is a lot of research out there, it’s hard to prove that any single intervention really works, and success lies in implementing a broad set of interventions. And success doesn’t equate to eliminating readmissions, only reducing them.

Coda: Is a sabbatical uniquely valuable for hospitalists?

I think a sabbatical might be a good idea for hospitalists. It also seems practical for other doctors, such as radiologists, anesthesiologists, and ED doctors, who don’t have 1:1 continuity relationships with patients. However, it is problematic for primary care doctors and specialists who need to maintain continuity relationships with patients and referring doctors that could be disrupted by a lengthy absence.

I’m not sure a sabbatical would reduce burnout much on its own, but, if properly structured, it seems very likely to reduce staffing turnover, and the sabbatical could be spent in ways that help rejuvenate interest and satisfaction in our work rather than simply taking a long vacation to travel and play golf, etc. It should probably be at least 3 months and better if it lasts a year. A common arrangement is that a doctor becomes eligible for the sabbatical after 10 years and is paid half of her usual compensation while away. I’d like to see more hospitalist groups do this.

Dr. Nelson has had a career in clinical practice as a hospitalist starting in 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses. Write to [email protected].

References

1. Bodenheimer, T and Sninsky, C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann Fam Med. Nov/Dec 2014.

2. Chandra, S et al. Introducing the Hospitalist Morale Index: A New Tool That May Be Relevant for Improving Provider Retention. JHM. June 2016.

3. Shanafelt, T, Dyrbye, L, West, C. Addressing Physician Burnout: The Way Forward. JAMA. March 7, 2017.

4. West, C et al. Intervention to Promote Physician Well-being, Job Satisfaction, and Professionalism: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-33.

5. West, C et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Nov 5, 2016.

On 15 years: Celebrating a nocturnist’s career longevity

“Nocturnist years are like dog years. So really we’re celebrating you for 105 years of service!”

Shawn Lee, MD, a day shift hospitalist at Overlake Medical Center in Bellevue, Wash. (where I work), said this about our colleague, Arash Nadershahi, MD, on the occasion of his 15th anniversary as a nocturnist with our group. Every hospitalist group should be so lucky to have someone like Arash among them, whether working nights or days.

When Arash joined our group the job simply entailed turning on the pager at 9 p.m. and coming in to the hospital only when the need arose. Some nights meant only answering some “cross-cover” calls from home, while other nights started with one or more patients needing admission right at the start of the shift.

As the months went by, patient volume climbed rapidly and Arash, as well as the nocturnists who joined us subsequently, began arriving at the hospital no later than the 9:00 p.m. shift start and staying in-house until 7 a.m. We never had a meeting or contentious conversation to make it official that the night shift changed to in-house all night instead of call-from-home. It just evolved that way to meet the need.

We all value Arash’s steady demeanor, excellent clinical skills, and good relationships with ED staff and nurses as well as patients. And for many years he and our other two nocturnists have covered all night shifts, including filling in when one of them is unexpectedly out for the birth of a child, illness, or other reason. The day doctors have never been called upon to work night shifts to cover an unexpected nocturnist absence.

Configuring the nocturnist position

A full-time nocturnist in our group works ten 10-hour night shifts and two 6-hour evening shifts (5-11 p.m.) per month. I like to think this has contributed to longevity for our nocturnists. One left last year after working nights for 10 years, and another just started his 9th year in the group.

The three nocturnists can work any schedule they like as long as one of them is on duty each night. For more than 10 years they’ve worked 7 consecutive night shifts followed by 14 off (that is sometimes interrupted by an evening shift). To my way of thinking, though, they’re essentially devoting 9 days to the practice for every seven consecutive shifts. The days before they start their rotation and after they complete it are spent preparing/recovering by adjusting their sleep, so aren’t really days of R&R.

For this work their compensation is very similar to that of full-time day shift doctors. The idea is that their compensation premium for working nights comes in the form of less work rather than more money; they work fewer and shorter shifts than their daytime counterparts. And we discourage moonlighting during all those days off. We want to provide the conditions for a healthy lifestyle to offset night work.

The longest-tenured nocturnist?

At 15 years of full-time work as a nocturnist, Arash may be one of the longest-tenured doctors in this role nationally. (I would love to hear about others who’ve been at it longer.) I like to think that our “pay ’em the same and work ’em less” approach may be a meaningful contributor to his longevity in the role, but I’m convinced his personal attributes are also a big factor.

His interests and creativity find their way into our workplace. For a while the day shift doctors would arrive to find our office full of motorcycle parts in various stages of assembly. Many of his doodles and drawings and witty writings are taped to the walls and cabinets. A few years ago he started writing haikus and before long everyone in the group joined in. This even led to one of our docs hosting a really fun party at which every guest wrote haikus and all had to guess the author of each one.

Other groups can’t count on finding someone as valuable as Arash, but they’ll have the best chance of it if they think carefully about how the nocturnist role is configured.

Dr. Nelson has had a career in clinical practice as a hospitalist starting in 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses.

“Nocturnist years are like dog years. So really we’re celebrating you for 105 years of service!”

Shawn Lee, MD, a day shift hospitalist at Overlake Medical Center in Bellevue, Wash. (where I work), said this about our colleague, Arash Nadershahi, MD, on the occasion of his 15th anniversary as a nocturnist with our group. Every hospitalist group should be so lucky to have someone like Arash among them, whether working nights or days.

When Arash joined our group the job simply entailed turning on the pager at 9 p.m. and coming in to the hospital only when the need arose. Some nights meant only answering some “cross-cover” calls from home, while other nights started with one or more patients needing admission right at the start of the shift.

As the months went by, patient volume climbed rapidly and Arash, as well as the nocturnists who joined us subsequently, began arriving at the hospital no later than the 9:00 p.m. shift start and staying in-house until 7 a.m. We never had a meeting or contentious conversation to make it official that the night shift changed to in-house all night instead of call-from-home. It just evolved that way to meet the need.

We all value Arash’s steady demeanor, excellent clinical skills, and good relationships with ED staff and nurses as well as patients. And for many years he and our other two nocturnists have covered all night shifts, including filling in when one of them is unexpectedly out for the birth of a child, illness, or other reason. The day doctors have never been called upon to work night shifts to cover an unexpected nocturnist absence.

Configuring the nocturnist position

A full-time nocturnist in our group works ten 10-hour night shifts and two 6-hour evening shifts (5-11 p.m.) per month. I like to think this has contributed to longevity for our nocturnists. One left last year after working nights for 10 years, and another just started his 9th year in the group.

The three nocturnists can work any schedule they like as long as one of them is on duty each night. For more than 10 years they’ve worked 7 consecutive night shifts followed by 14 off (that is sometimes interrupted by an evening shift). To my way of thinking, though, they’re essentially devoting 9 days to the practice for every seven consecutive shifts. The days before they start their rotation and after they complete it are spent preparing/recovering by adjusting their sleep, so aren’t really days of R&R.

For this work their compensation is very similar to that of full-time day shift doctors. The idea is that their compensation premium for working nights comes in the form of less work rather than more money; they work fewer and shorter shifts than their daytime counterparts. And we discourage moonlighting during all those days off. We want to provide the conditions for a healthy lifestyle to offset night work.

The longest-tenured nocturnist?

At 15 years of full-time work as a nocturnist, Arash may be one of the longest-tenured doctors in this role nationally. (I would love to hear about others who’ve been at it longer.) I like to think that our “pay ’em the same and work ’em less” approach may be a meaningful contributor to his longevity in the role, but I’m convinced his personal attributes are also a big factor.

His interests and creativity find their way into our workplace. For a while the day shift doctors would arrive to find our office full of motorcycle parts in various stages of assembly. Many of his doodles and drawings and witty writings are taped to the walls and cabinets. A few years ago he started writing haikus and before long everyone in the group joined in. This even led to one of our docs hosting a really fun party at which every guest wrote haikus and all had to guess the author of each one.

Other groups can’t count on finding someone as valuable as Arash, but they’ll have the best chance of it if they think carefully about how the nocturnist role is configured.

Dr. Nelson has had a career in clinical practice as a hospitalist starting in 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses.

“Nocturnist years are like dog years. So really we’re celebrating you for 105 years of service!”

Shawn Lee, MD, a day shift hospitalist at Overlake Medical Center in Bellevue, Wash. (where I work), said this about our colleague, Arash Nadershahi, MD, on the occasion of his 15th anniversary as a nocturnist with our group. Every hospitalist group should be so lucky to have someone like Arash among them, whether working nights or days.

When Arash joined our group the job simply entailed turning on the pager at 9 p.m. and coming in to the hospital only when the need arose. Some nights meant only answering some “cross-cover” calls from home, while other nights started with one or more patients needing admission right at the start of the shift.

As the months went by, patient volume climbed rapidly and Arash, as well as the nocturnists who joined us subsequently, began arriving at the hospital no later than the 9:00 p.m. shift start and staying in-house until 7 a.m. We never had a meeting or contentious conversation to make it official that the night shift changed to in-house all night instead of call-from-home. It just evolved that way to meet the need.

We all value Arash’s steady demeanor, excellent clinical skills, and good relationships with ED staff and nurses as well as patients. And for many years he and our other two nocturnists have covered all night shifts, including filling in when one of them is unexpectedly out for the birth of a child, illness, or other reason. The day doctors have never been called upon to work night shifts to cover an unexpected nocturnist absence.

Configuring the nocturnist position

A full-time nocturnist in our group works ten 10-hour night shifts and two 6-hour evening shifts (5-11 p.m.) per month. I like to think this has contributed to longevity for our nocturnists. One left last year after working nights for 10 years, and another just started his 9th year in the group.

The three nocturnists can work any schedule they like as long as one of them is on duty each night. For more than 10 years they’ve worked 7 consecutive night shifts followed by 14 off (that is sometimes interrupted by an evening shift). To my way of thinking, though, they’re essentially devoting 9 days to the practice for every seven consecutive shifts. The days before they start their rotation and after they complete it are spent preparing/recovering by adjusting their sleep, so aren’t really days of R&R.

For this work their compensation is very similar to that of full-time day shift doctors. The idea is that their compensation premium for working nights comes in the form of less work rather than more money; they work fewer and shorter shifts than their daytime counterparts. And we discourage moonlighting during all those days off. We want to provide the conditions for a healthy lifestyle to offset night work.

The longest-tenured nocturnist?

At 15 years of full-time work as a nocturnist, Arash may be one of the longest-tenured doctors in this role nationally. (I would love to hear about others who’ve been at it longer.) I like to think that our “pay ’em the same and work ’em less” approach may be a meaningful contributor to his longevity in the role, but I’m convinced his personal attributes are also a big factor.

His interests and creativity find their way into our workplace. For a while the day shift doctors would arrive to find our office full of motorcycle parts in various stages of assembly. Many of his doodles and drawings and witty writings are taped to the walls and cabinets. A few years ago he started writing haikus and before long everyone in the group joined in. This even led to one of our docs hosting a really fun party at which every guest wrote haikus and all had to guess the author of each one.

Other groups can’t count on finding someone as valuable as Arash, but they’ll have the best chance of it if they think carefully about how the nocturnist role is configured.

Dr. Nelson has had a career in clinical practice as a hospitalist starting in 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is codirector for SHM’s practice management courses.

Revisiting citizenship bonus and surge capacity

I devoted an entire column to the idea of a citizenship bonus in November 2011. At that time I expressed some ambivalence about its effectiveness. Since then I’ve become disenchanted and think it may do more harm than good.

SHM’s 2016 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) Report, based on 2015 data, shows that 46% of Hospital Medicine Groups (HMGs) connect some portion of bonus dollars to a provider’s citizenship.1 This is a relatively new phenomenon in the last 5 years or so. My anecdotal experience is that it isn’t limited to hospitalists; it is pretty common for doctors in any specialty who are employed by a hospital or other large organization.

HMGs vary in their definitions of what constitutes citizenship, but usually include things like committee participation, lectures, grand rounds presentations, community talks, research publications.

Our hospitalist group at my hospital has well-defined criteria that require attendance at more than 75% of meetings as a “light switch” (pays nothing itself, but “turns on” availability to citizenship bonus). Bonus dollars are paid for success in any one of several activities, such as making an in-person visit to two PCP offices or completing a meaningful project related to practice operations or clinical care.

I’ve been a supporter of a citizenship bonus for a long time, but two things have made me ambivalent or even opposed to it. The first is a book by Daniel Pink titled Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. It’s a short and very thought-provoking book summarizing research that suggests the effect of providing external rewards like compensation is to “…extinguish intrinsic motivation, diminish performance, crush creativity, and crowd out good behavior.”

The second reason for my ambivalence is my experience working with a lot of HMGs around the country. Those that have a citizenship bonus don’t seem to realize improved operations, more engaged doctors, or lower turnover, and so on. In fact, my experience is that the bonus tends to do exactly what Pink says – steer individuals and the group as a whole away from what is desired.

I’m not ready to say a citizenship bonus is always a bad idea. But it sure seems like it works out badly for many or most groups.

But if you do have a citizenship bonus, then don’t make the mistake of tying it to very basic expectations of the job, like attending group meetings or completing chart documentation on time. Doing those things should never be seen as a reason for a bonus.

Jeopardy (‘surge’) staffing: Not catching on?

As I write, influenza has swept through our region, and my hospital – like most along the west coast – is experiencing incredibly high volumes. I enter the building through a patient care unit that has been mothballed for several years, but today people from building maintenance were busy getting it ready for patients. The hospital is offering various incentives for patient care staff to work extra shifts to manage this volume surge, and our hospitalists have days with encounters near or at our highest-ever level. So surge capacity is once again on my mind.

But if every hospitalist in the group went from, say, 156 to 190 shifts annually, the practice might be able to staff every day with an additional provider without adding staff or spending more money. And a doc’s average day would be less busy, which for some people (okay, not very many) would be a worthwhile trade-off. I realize this is a tough sell and to many people it sounds crazy.

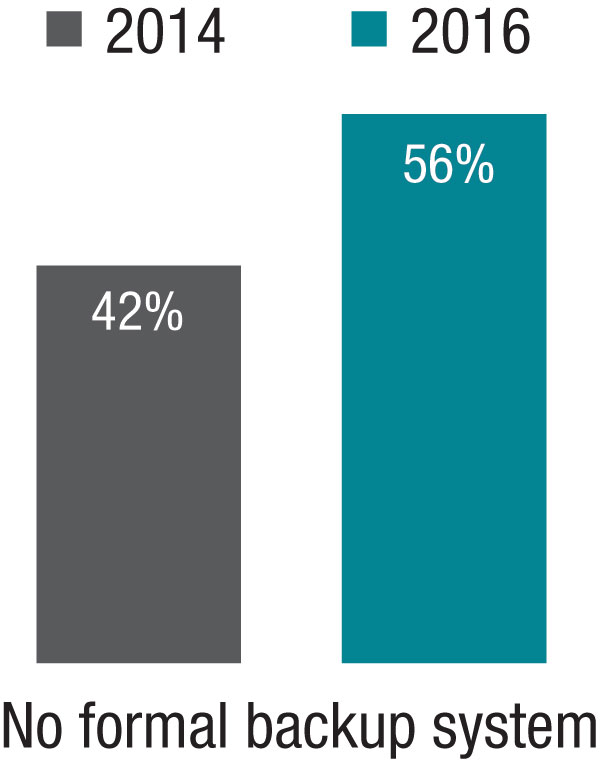

The 2014 SOHM showed 42% of HMGs had “no formal backup system,” and this had climbed to 58% in the 2016 Report. I don’t know if jeopardy or surge backup systems are really becoming less common, but it seems pretty clear they aren’t becoming more common. So it’s worth thinking about whether there is a practical way to remove inhibitors of surge capacity.