User login

Intimate partner violence: Opening the door to a safer future

THE CASE

Louise T* is a 42-year-old woman who presented to her family medicine office for a routine annual visit. During the exam, her physician noticed bruises on Ms. T’s arms and back. Upon further inquiry, Ms. T reported that she and her husband had argued the night before the appointment. With some hesitancy, she went on to say that this was not the first time this had happened. She said that she and her husband had been arguing frequently for several years and that 6 months earlier, when he lost his job, he began hitting and pushing her.

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes physical, sexual, or psychological aggression or stalking perpetrated by a current or former relationship partner.1 IPV affects more than 12 million men and women living in the United States each year.2 According to a national survey of IPV, approximately one-third (35.6%) of women and one-quarter (28.5%) of men living in the United States experience rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime.2 Lifetime exposure to psychological IPV is even more prevalent, affecting nearly half of women and men (48.4% and 48.8%, respectively).2

Lifetime prevalence of any form of IPV is higher among women who identify as bisexual (59.8%) and lesbian (46.3%) compared with those who identify as heterosexual (37.2%); rates are comparable among men who identify as heterosexual (31.9%), bisexual (35.3%), and gay (35.1%).3 Preliminary data suggest that IPV may have increased in frequency and severity during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the context of mandated shelter-in-place and stay-at-home orders.4-6

IPV is associated with numerous negative health consequences. They include fear and concern for safety, mental health disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and physical health problems including physical injury, chronic pain, sleep disturbance, and frequent headaches.2 IPV is also associated with a greater number of missed days from school and work and increased utilization of legal, health care, and housing services.2,7 The overall annual cost of IPV against women is estimated at $5.8 billion, with health care costs accounting for approximately $4.1 billion.7 Family physicians can play an important role in curbing the devastating effects of IPV by screening patients and providing resources when needed.

Facilitate disclosure using screening tools and protocol

In Ms. T’s case, evidence of violence was clearly visible. However, not all instances of IPV leave physical marks. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all women of childbearing age be screened for IPV, whether or not they exhibit signs of violence.8 While the USPSTF has only published recommendations regarding screening women for IPV, there has been a recent push to screen all patients given that men also experience high rates of IPV.9

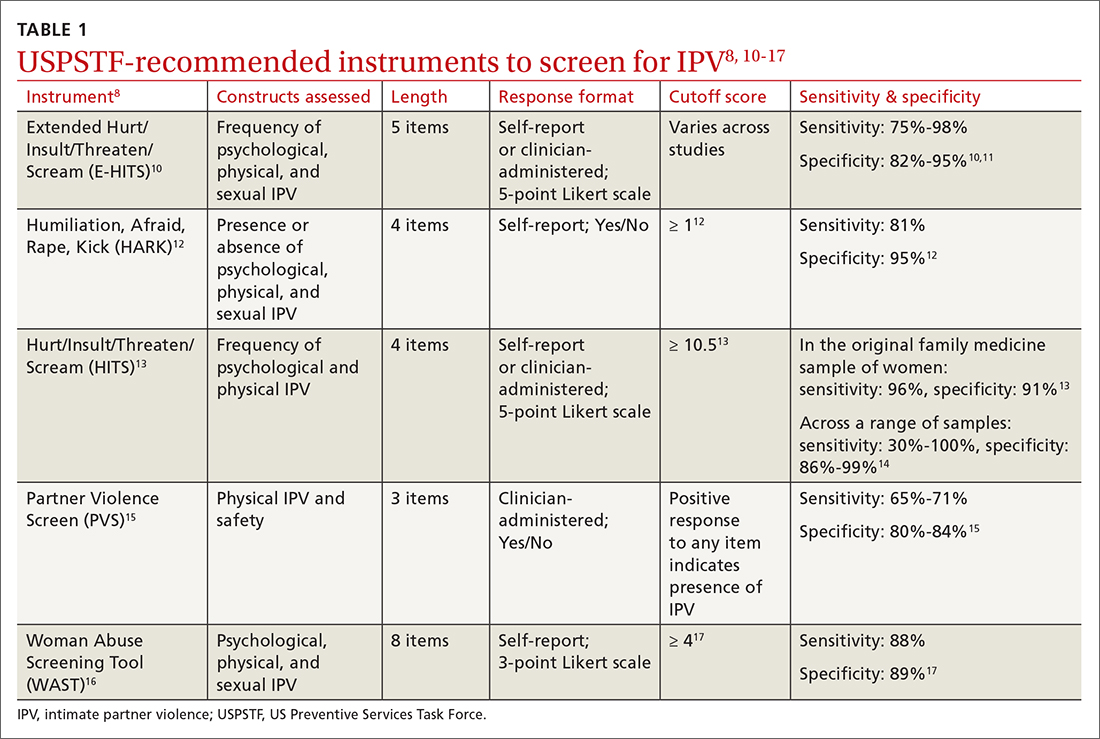

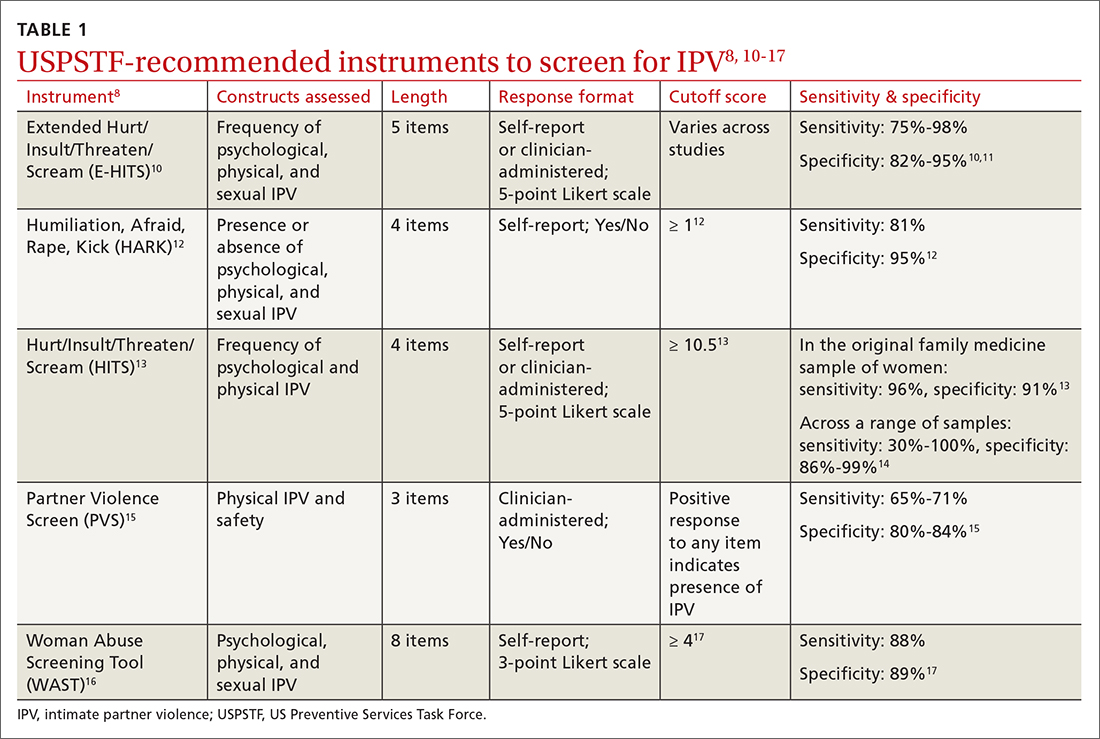

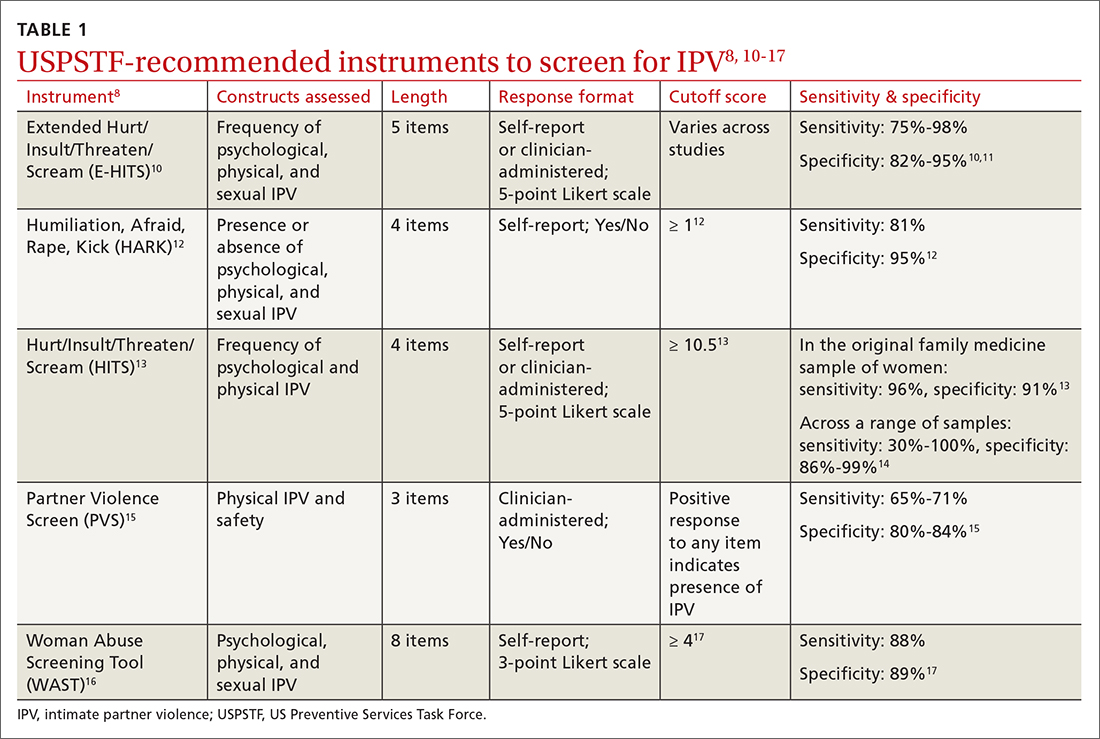

Utilize a brief screening tool. Directly ask patients about IPV; this can help reduce stigma, facilitate disclosure, and initiate the process of connecting patients to potentially lifesaving resources. The USPSTF lists several brief screening measures that can be used in primary care settings to assess exposure to IPV (TABLE 18,10-17). The brevity of these screening tools makes them well suited for busy physicians; cutoff scores facilitate the rapid identification of positive screens. While the USPSTF has not made specific recommendations regarding a screening interval, many studies examining the utility of these measures have reported on annual screenings.8 While there is limited evidence that brief screening alone leads to reductions in IPV,8 discussing IPV in a supportive and empathic manner and connecting patients to resources, such as supportive counseling, does have an important benefit: It can reduce symptoms of depression.18

Continue to: Screen patients in private; this protocol can help

Screen patients in private; this protocol can help. Given the sensitive nature of IPV and the potential danger some patients may be facing, it is important to screen patients in a safe and supportive environment.19,20 Screening should be conducted by the primary care clinician, ideally when a trusting relationship already has been formed. Screen patients only when they are alone in a private room; avoid screening in public spaces such as clinic waiting rooms or in the vicinity of the patient’s partner or children older than age 2 years.19,20

To provide all patients with an opportunity for private and safe IPV screening, clinics are encouraged to develop a clinic-wide policy whereby patients are routinely escorted to the exam room alone for the first portion of their visit, after which any accompanying individuals may be invited to join.21 Clinic staff can inform patients and accompanying individuals of this policy when they first arrive. Once in the exam room, and before the screening process begins, clearly state reporting requirements to ensure that patients can make an informed decision about whether to disclose IPV.19

Set a receptive tone. The manner in which clinicians discuss IPV with their patients is just as important as the setting. Demonstrating sensitivity and genuine concern for the patient’s safety and well-being may increase the patient’s comfort level throughout the screening process and may facilitate disclosures of IPV.19,22 When screening patients for IPV, sit face to face rather than standing over them, maintain warm and open body language, and speak in a soft tone of voice.22

Patients may feel more comfortable if you ask screening questions in a straightforward, nonjudgmental manner, as this helps to normalize the screening experience. We also recommend using behaviorally specific language (eg, “Do arguments [with your partner] ever result in hitting, kicking, or pushing?”16 or “How often does your partner scream or curse at you?”),13 as some patients who have experienced IPV will not label their experiences as “abuse” or “violence.” Not every patient who experiences IPV will be ready to disclose these events; however, maintaining a positive and supportive relationship during routine IPV screening and throughout the remainder of the medical visit may help facilitate future disclosures if, and when, a patient is ready to seek support.19

CRITICAL INTERVENTION ELEMENTS: EMPATHY AND SAFETY

A physician’s response to an IPV disclosure can have a lasting impact on the patient. We encourage family physicians to respond to IPV disclosures with empathy. Maintain eye contact and warm body language, validate the patient’s experiences (“I am sorry this happened to you,” “that must have been terrifying”), tell the patient that the violence was not their fault, and thank the patient for disclosing.23

Continue to: Assess patient safety

Assess patient safety. Another critical component of intervention is to assess the patient’s safety and engage in safety planning. If the patient agrees to this next step, you may wish to provide a warm handoff to a trained social worker, nurse, or psychologist in the clinic who can spend more time covering this information with the patient. Some key components of a safety assessment include determining whether the violence or threat of violence is ongoing and identifying who lives in the home (eg, the partner, children, and any pets). You and the patient can also discuss red flags that would indicate elevated risk. You should discuss red flags that are unique to the patient’s relationship as well as common factors that have been found to heighten risk for IPV (eg, partner engaging in heavy alcohol use).1

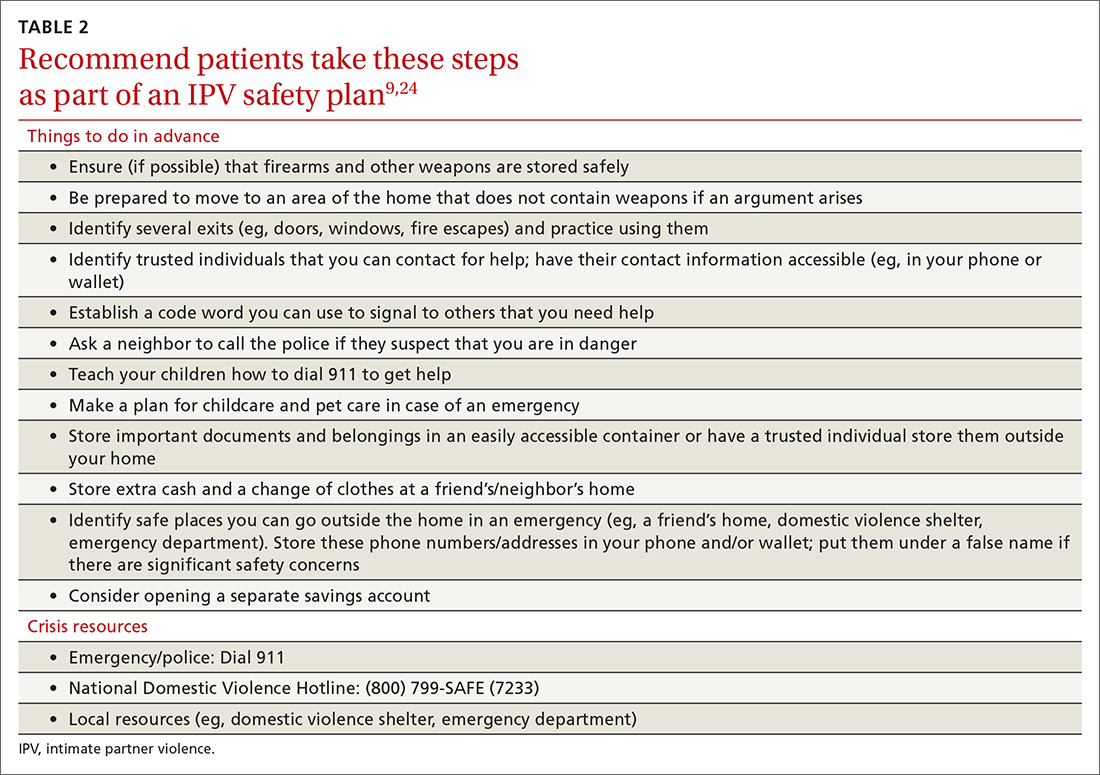

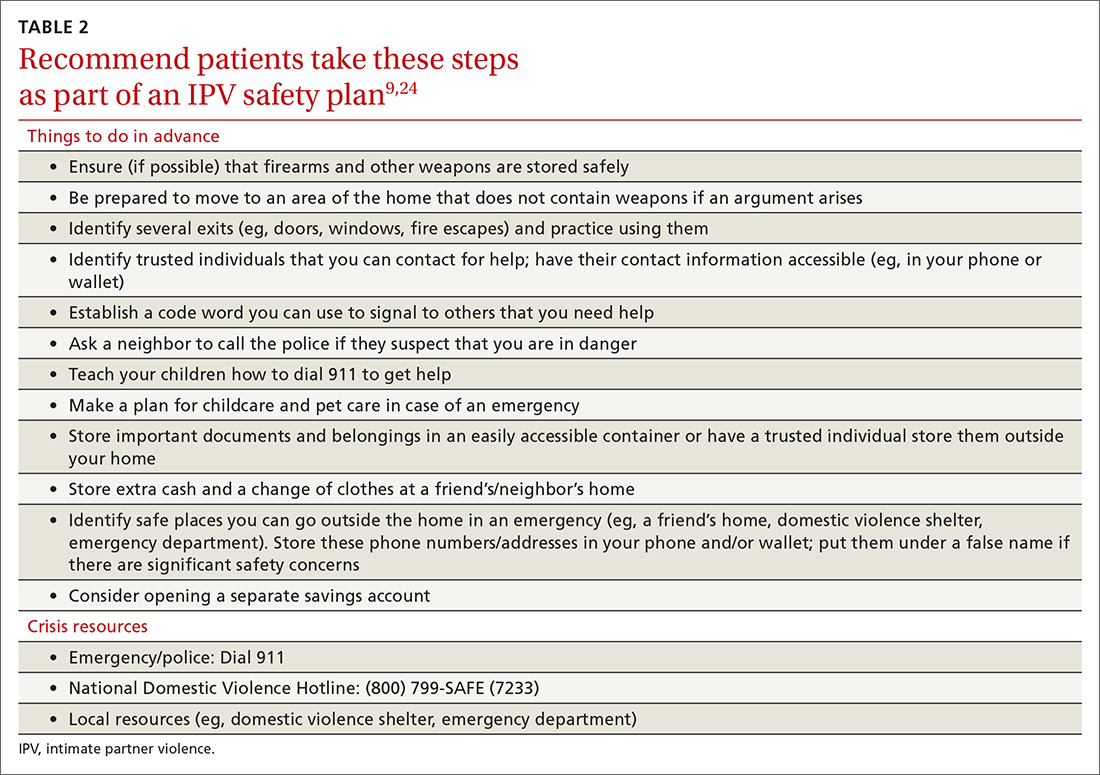

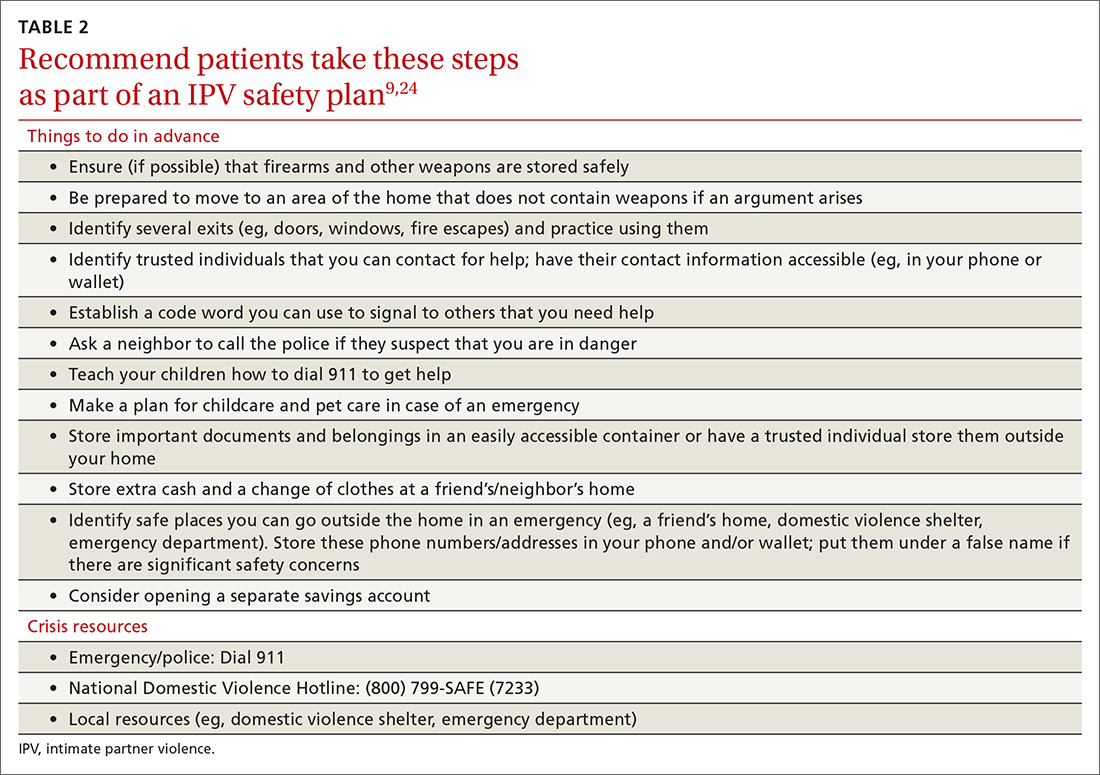

With the patient’s permission, collaboratively construct a safety plan that details how the patient can stay safe on a daily basis and how to safely leave should a dangerous situation arise (TABLE 29,24). The interactive safety planning tool available on the National Domestic Violence Hotline’s website can be a valuable resource (www.thehotline.org/plan-for-safety/).24 Finally, if a patient is experiencing mental health concerns associated with IPV (eg, PTSD, depression, substance misuse, suicidal ideation), consider a referral to a domestic violence counseling center or mental health provider.

Move at the patient’s pace. Even if patients are willing to disclose IPV, they will differ in their readiness to discuss psychoeducation, safety planning, and referrals. Similarly, even if a patient is experiencing severe violence, they may not be ready to leave the relationship. Thus, it’s important to ask the patient for permission before initiating each successive step of the follow-up intervention. You and the patient may wish to schedule additional appointments to discuss this information at a pace the patient finds appropriate.

You may need to spend some time helping the patient recognize the severity of their situation and to feel empowered to take action. In addition, offer information and resources to all patients, even those who do not disclose IPV. Some patients may want to receive this information even if they do not feel comfortable sharing their experiences during the appointment.20 You can also inform patients that they are welcome to bring up issues related to IPV at any future appointments in order to leave the door open to future disclosures.

THE CASE

The physician determined that Ms. T had been experiencing physical and psychological IPV in her current relationship. After responding empathically and obtaining the patient’s consent, the physician provided a warm handoff to the psychologist in the clinic. With Ms. T’s permission, the psychologist provided psychoeducation about IPV, and they discussed Ms. T’s current situation and risk level. They determined that Ms. T was at risk for subsequent episodes of IPV and they collaborated on a safety plan, making sure to discuss contact information for local and national crisis resources.

Continue to: Ms. T saved the phone number...

Ms. T saved the phone number for her local domestic violence shelter in her phone under a false name in case her husband looked through her phone. She said she planned to work on several safety plan items when her husband was away from the house and it was safe to do so. For example, she planned to identify additional ways to exit the house in an emergency and she was going to put together a bag with a change of clothes and some money and drop it off at a trusted friend’s house.

Ms. T and the psychologist agreed to follow up with an office visit in 1 week to discuss any additional safety concerns and to determine whether Ms. T could benefit from a referral to domestic violence counseling services or mental health treatment. The psychologist provided a summary of the topics she and Ms. T had discussed to the physician. The physician scheduled a follow-up appointment with Ms. T in 3 weeks to assess her current safety, troubleshoot any difficulties in implementing her safety plan, and offer additional resources, as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Andrea Massa, PhD, 125 Doughty Street, Suite 300, Charleston, SC 29403; [email protected]

1. CDC. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Preventing intimate partner violence. 2021. Accessed June 27, 2022. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html

2. CDC. Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report. Accessed June 27, 2022. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_executive_summary-a.pdf

3. Chen J, Walters ML, Gilbert LK, et al. Sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence by sexual orientation, United States. Psychol Violence. 2020;10:110-119. doi:10.1037/vio0000252

4. Kofman YB, Garfin DR. Home is not always a haven: the domestic violence crisis amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S199-S201. doi:10.1037/tra0000866

5. Lyons M, Brewer G. Experiences of intimate partner violence during lockdown and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Violence. 2021:1-9. doi:10.1007/s10896-021-00260-x

6. Parrott DJ, Halmos MB, Stappenbeck CA, et al. Intimate partner aggression during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with stress and heavy drinking. Psychol Violence. 2021;12:95-103. doi:10.1037/vio0000395

7. CDC. National Center for Injury Prevention and

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for intimate partner violence, elder abuse, and abuse of vulnerable adults: US Preventive Services Task Force final recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1678-1687. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14741

9. Sprunger JG, Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, et al. It’s time to start asking all patients about intimate partner violence. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:152-161.

10. Chan CC, Chan YC, Au A, et al. Reliability and validity of the “Extended - Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream” (E-HITS) screening tool in detecting intimate partner violence in hospital emergency departments in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2010;17:109-117. doi:10.1177/102490791001700202

11. Iverson KM, King MW, Gerber MR, et al. Accuracy of an intimate partner violence screening tool for female VHA patients: a replication and extension. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:79-82. doi:10.1002/jts.21985

12. Sohal H, Eldridge S, Feder G. The sensitivity and specificity of four questions (HARK) to identify intimate partner violence: a diagnostic accuracy study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:49. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-8-49

13. Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li X, et al. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:508-512.

14. Rabin RF, Jennings JM, Campbell JC, et al. Intimate partner violence screening tools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:439-445.e4. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.024

15. Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, et al. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA. 1997;277:1357-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03540410035027

16. Brown JB, Lent B, Schmidt G, et al. Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and WAST-short in the family practice setting. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:896-903.

17. Wathen CN, Jamieson E, MacMillan HL, MVAWRG. Who is identified by screening for intimate partner violence? Womens Health Issues. 2008;18:423-432. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2008.08.003

18. Hegarty K, O’Doherty L, Taft A, et al. Screening and counselling in the primary care setting for women who have experienced intimate partner violence (WEAVE): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:249-258. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60052-5

19. Correa NP, Cain CM, Bertenthal M, et al. Women’s experiences of being screened for intimate partner violence in the health care setting. Nurs Womens Health. 2020;24:185-196. doi:10.1016/j.nwh.2020.04.002

20. Chang JC, Decker MR, Moracco KE, et al. Asking about intimate partner violence: advice from female survivors to health care providers. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:141-147. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.008

21. Paterno MT, Draughon JE. Screening for intimate partner violence. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61:370-375. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12443

22. Iverson KM, Huang K, Wells SY, et al. Women veterans’ preferences for intimate partner violence screening and response procedures within the Veterans Health Administration. Res Nurs Health. 2014;37:302-311. doi:10.1002/nur.21602

23. National Sexual Violence Research Center. Assessing patients for sexual violence: A guide for health care providers. 2011. Accessed June 28, 2022. www.nsvrc.org/publications/assessing-patients-sexual-violence-guide-health-care-providers

24. National Domestic Violence Hotline. Interactive guide to safety planning. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.thehotline.org/plan-for-safety/create-a-safety-plan/

THE CASE

Louise T* is a 42-year-old woman who presented to her family medicine office for a routine annual visit. During the exam, her physician noticed bruises on Ms. T’s arms and back. Upon further inquiry, Ms. T reported that she and her husband had argued the night before the appointment. With some hesitancy, she went on to say that this was not the first time this had happened. She said that she and her husband had been arguing frequently for several years and that 6 months earlier, when he lost his job, he began hitting and pushing her.

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes physical, sexual, or psychological aggression or stalking perpetrated by a current or former relationship partner.1 IPV affects more than 12 million men and women living in the United States each year.2 According to a national survey of IPV, approximately one-third (35.6%) of women and one-quarter (28.5%) of men living in the United States experience rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime.2 Lifetime exposure to psychological IPV is even more prevalent, affecting nearly half of women and men (48.4% and 48.8%, respectively).2

Lifetime prevalence of any form of IPV is higher among women who identify as bisexual (59.8%) and lesbian (46.3%) compared with those who identify as heterosexual (37.2%); rates are comparable among men who identify as heterosexual (31.9%), bisexual (35.3%), and gay (35.1%).3 Preliminary data suggest that IPV may have increased in frequency and severity during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the context of mandated shelter-in-place and stay-at-home orders.4-6

IPV is associated with numerous negative health consequences. They include fear and concern for safety, mental health disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and physical health problems including physical injury, chronic pain, sleep disturbance, and frequent headaches.2 IPV is also associated with a greater number of missed days from school and work and increased utilization of legal, health care, and housing services.2,7 The overall annual cost of IPV against women is estimated at $5.8 billion, with health care costs accounting for approximately $4.1 billion.7 Family physicians can play an important role in curbing the devastating effects of IPV by screening patients and providing resources when needed.

Facilitate disclosure using screening tools and protocol

In Ms. T’s case, evidence of violence was clearly visible. However, not all instances of IPV leave physical marks. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all women of childbearing age be screened for IPV, whether or not they exhibit signs of violence.8 While the USPSTF has only published recommendations regarding screening women for IPV, there has been a recent push to screen all patients given that men also experience high rates of IPV.9

Utilize a brief screening tool. Directly ask patients about IPV; this can help reduce stigma, facilitate disclosure, and initiate the process of connecting patients to potentially lifesaving resources. The USPSTF lists several brief screening measures that can be used in primary care settings to assess exposure to IPV (TABLE 18,10-17). The brevity of these screening tools makes them well suited for busy physicians; cutoff scores facilitate the rapid identification of positive screens. While the USPSTF has not made specific recommendations regarding a screening interval, many studies examining the utility of these measures have reported on annual screenings.8 While there is limited evidence that brief screening alone leads to reductions in IPV,8 discussing IPV in a supportive and empathic manner and connecting patients to resources, such as supportive counseling, does have an important benefit: It can reduce symptoms of depression.18

Continue to: Screen patients in private; this protocol can help

Screen patients in private; this protocol can help. Given the sensitive nature of IPV and the potential danger some patients may be facing, it is important to screen patients in a safe and supportive environment.19,20 Screening should be conducted by the primary care clinician, ideally when a trusting relationship already has been formed. Screen patients only when they are alone in a private room; avoid screening in public spaces such as clinic waiting rooms or in the vicinity of the patient’s partner or children older than age 2 years.19,20

To provide all patients with an opportunity for private and safe IPV screening, clinics are encouraged to develop a clinic-wide policy whereby patients are routinely escorted to the exam room alone for the first portion of their visit, after which any accompanying individuals may be invited to join.21 Clinic staff can inform patients and accompanying individuals of this policy when they first arrive. Once in the exam room, and before the screening process begins, clearly state reporting requirements to ensure that patients can make an informed decision about whether to disclose IPV.19

Set a receptive tone. The manner in which clinicians discuss IPV with their patients is just as important as the setting. Demonstrating sensitivity and genuine concern for the patient’s safety and well-being may increase the patient’s comfort level throughout the screening process and may facilitate disclosures of IPV.19,22 When screening patients for IPV, sit face to face rather than standing over them, maintain warm and open body language, and speak in a soft tone of voice.22

Patients may feel more comfortable if you ask screening questions in a straightforward, nonjudgmental manner, as this helps to normalize the screening experience. We also recommend using behaviorally specific language (eg, “Do arguments [with your partner] ever result in hitting, kicking, or pushing?”16 or “How often does your partner scream or curse at you?”),13 as some patients who have experienced IPV will not label their experiences as “abuse” or “violence.” Not every patient who experiences IPV will be ready to disclose these events; however, maintaining a positive and supportive relationship during routine IPV screening and throughout the remainder of the medical visit may help facilitate future disclosures if, and when, a patient is ready to seek support.19

CRITICAL INTERVENTION ELEMENTS: EMPATHY AND SAFETY

A physician’s response to an IPV disclosure can have a lasting impact on the patient. We encourage family physicians to respond to IPV disclosures with empathy. Maintain eye contact and warm body language, validate the patient’s experiences (“I am sorry this happened to you,” “that must have been terrifying”), tell the patient that the violence was not their fault, and thank the patient for disclosing.23

Continue to: Assess patient safety

Assess patient safety. Another critical component of intervention is to assess the patient’s safety and engage in safety planning. If the patient agrees to this next step, you may wish to provide a warm handoff to a trained social worker, nurse, or psychologist in the clinic who can spend more time covering this information with the patient. Some key components of a safety assessment include determining whether the violence or threat of violence is ongoing and identifying who lives in the home (eg, the partner, children, and any pets). You and the patient can also discuss red flags that would indicate elevated risk. You should discuss red flags that are unique to the patient’s relationship as well as common factors that have been found to heighten risk for IPV (eg, partner engaging in heavy alcohol use).1

With the patient’s permission, collaboratively construct a safety plan that details how the patient can stay safe on a daily basis and how to safely leave should a dangerous situation arise (TABLE 29,24). The interactive safety planning tool available on the National Domestic Violence Hotline’s website can be a valuable resource (www.thehotline.org/plan-for-safety/).24 Finally, if a patient is experiencing mental health concerns associated with IPV (eg, PTSD, depression, substance misuse, suicidal ideation), consider a referral to a domestic violence counseling center or mental health provider.

Move at the patient’s pace. Even if patients are willing to disclose IPV, they will differ in their readiness to discuss psychoeducation, safety planning, and referrals. Similarly, even if a patient is experiencing severe violence, they may not be ready to leave the relationship. Thus, it’s important to ask the patient for permission before initiating each successive step of the follow-up intervention. You and the patient may wish to schedule additional appointments to discuss this information at a pace the patient finds appropriate.

You may need to spend some time helping the patient recognize the severity of their situation and to feel empowered to take action. In addition, offer information and resources to all patients, even those who do not disclose IPV. Some patients may want to receive this information even if they do not feel comfortable sharing their experiences during the appointment.20 You can also inform patients that they are welcome to bring up issues related to IPV at any future appointments in order to leave the door open to future disclosures.

THE CASE

The physician determined that Ms. T had been experiencing physical and psychological IPV in her current relationship. After responding empathically and obtaining the patient’s consent, the physician provided a warm handoff to the psychologist in the clinic. With Ms. T’s permission, the psychologist provided psychoeducation about IPV, and they discussed Ms. T’s current situation and risk level. They determined that Ms. T was at risk for subsequent episodes of IPV and they collaborated on a safety plan, making sure to discuss contact information for local and national crisis resources.

Continue to: Ms. T saved the phone number...

Ms. T saved the phone number for her local domestic violence shelter in her phone under a false name in case her husband looked through her phone. She said she planned to work on several safety plan items when her husband was away from the house and it was safe to do so. For example, she planned to identify additional ways to exit the house in an emergency and she was going to put together a bag with a change of clothes and some money and drop it off at a trusted friend’s house.

Ms. T and the psychologist agreed to follow up with an office visit in 1 week to discuss any additional safety concerns and to determine whether Ms. T could benefit from a referral to domestic violence counseling services or mental health treatment. The psychologist provided a summary of the topics she and Ms. T had discussed to the physician. The physician scheduled a follow-up appointment with Ms. T in 3 weeks to assess her current safety, troubleshoot any difficulties in implementing her safety plan, and offer additional resources, as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Andrea Massa, PhD, 125 Doughty Street, Suite 300, Charleston, SC 29403; [email protected]

THE CASE

Louise T* is a 42-year-old woman who presented to her family medicine office for a routine annual visit. During the exam, her physician noticed bruises on Ms. T’s arms and back. Upon further inquiry, Ms. T reported that she and her husband had argued the night before the appointment. With some hesitancy, she went on to say that this was not the first time this had happened. She said that she and her husband had been arguing frequently for several years and that 6 months earlier, when he lost his job, he began hitting and pushing her.

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes physical, sexual, or psychological aggression or stalking perpetrated by a current or former relationship partner.1 IPV affects more than 12 million men and women living in the United States each year.2 According to a national survey of IPV, approximately one-third (35.6%) of women and one-quarter (28.5%) of men living in the United States experience rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime.2 Lifetime exposure to psychological IPV is even more prevalent, affecting nearly half of women and men (48.4% and 48.8%, respectively).2

Lifetime prevalence of any form of IPV is higher among women who identify as bisexual (59.8%) and lesbian (46.3%) compared with those who identify as heterosexual (37.2%); rates are comparable among men who identify as heterosexual (31.9%), bisexual (35.3%), and gay (35.1%).3 Preliminary data suggest that IPV may have increased in frequency and severity during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the context of mandated shelter-in-place and stay-at-home orders.4-6

IPV is associated with numerous negative health consequences. They include fear and concern for safety, mental health disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and physical health problems including physical injury, chronic pain, sleep disturbance, and frequent headaches.2 IPV is also associated with a greater number of missed days from school and work and increased utilization of legal, health care, and housing services.2,7 The overall annual cost of IPV against women is estimated at $5.8 billion, with health care costs accounting for approximately $4.1 billion.7 Family physicians can play an important role in curbing the devastating effects of IPV by screening patients and providing resources when needed.

Facilitate disclosure using screening tools and protocol

In Ms. T’s case, evidence of violence was clearly visible. However, not all instances of IPV leave physical marks. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all women of childbearing age be screened for IPV, whether or not they exhibit signs of violence.8 While the USPSTF has only published recommendations regarding screening women for IPV, there has been a recent push to screen all patients given that men also experience high rates of IPV.9

Utilize a brief screening tool. Directly ask patients about IPV; this can help reduce stigma, facilitate disclosure, and initiate the process of connecting patients to potentially lifesaving resources. The USPSTF lists several brief screening measures that can be used in primary care settings to assess exposure to IPV (TABLE 18,10-17). The brevity of these screening tools makes them well suited for busy physicians; cutoff scores facilitate the rapid identification of positive screens. While the USPSTF has not made specific recommendations regarding a screening interval, many studies examining the utility of these measures have reported on annual screenings.8 While there is limited evidence that brief screening alone leads to reductions in IPV,8 discussing IPV in a supportive and empathic manner and connecting patients to resources, such as supportive counseling, does have an important benefit: It can reduce symptoms of depression.18

Continue to: Screen patients in private; this protocol can help

Screen patients in private; this protocol can help. Given the sensitive nature of IPV and the potential danger some patients may be facing, it is important to screen patients in a safe and supportive environment.19,20 Screening should be conducted by the primary care clinician, ideally when a trusting relationship already has been formed. Screen patients only when they are alone in a private room; avoid screening in public spaces such as clinic waiting rooms or in the vicinity of the patient’s partner or children older than age 2 years.19,20

To provide all patients with an opportunity for private and safe IPV screening, clinics are encouraged to develop a clinic-wide policy whereby patients are routinely escorted to the exam room alone for the first portion of their visit, after which any accompanying individuals may be invited to join.21 Clinic staff can inform patients and accompanying individuals of this policy when they first arrive. Once in the exam room, and before the screening process begins, clearly state reporting requirements to ensure that patients can make an informed decision about whether to disclose IPV.19

Set a receptive tone. The manner in which clinicians discuss IPV with their patients is just as important as the setting. Demonstrating sensitivity and genuine concern for the patient’s safety and well-being may increase the patient’s comfort level throughout the screening process and may facilitate disclosures of IPV.19,22 When screening patients for IPV, sit face to face rather than standing over them, maintain warm and open body language, and speak in a soft tone of voice.22

Patients may feel more comfortable if you ask screening questions in a straightforward, nonjudgmental manner, as this helps to normalize the screening experience. We also recommend using behaviorally specific language (eg, “Do arguments [with your partner] ever result in hitting, kicking, or pushing?”16 or “How often does your partner scream or curse at you?”),13 as some patients who have experienced IPV will not label their experiences as “abuse” or “violence.” Not every patient who experiences IPV will be ready to disclose these events; however, maintaining a positive and supportive relationship during routine IPV screening and throughout the remainder of the medical visit may help facilitate future disclosures if, and when, a patient is ready to seek support.19

CRITICAL INTERVENTION ELEMENTS: EMPATHY AND SAFETY

A physician’s response to an IPV disclosure can have a lasting impact on the patient. We encourage family physicians to respond to IPV disclosures with empathy. Maintain eye contact and warm body language, validate the patient’s experiences (“I am sorry this happened to you,” “that must have been terrifying”), tell the patient that the violence was not their fault, and thank the patient for disclosing.23

Continue to: Assess patient safety

Assess patient safety. Another critical component of intervention is to assess the patient’s safety and engage in safety planning. If the patient agrees to this next step, you may wish to provide a warm handoff to a trained social worker, nurse, or psychologist in the clinic who can spend more time covering this information with the patient. Some key components of a safety assessment include determining whether the violence or threat of violence is ongoing and identifying who lives in the home (eg, the partner, children, and any pets). You and the patient can also discuss red flags that would indicate elevated risk. You should discuss red flags that are unique to the patient’s relationship as well as common factors that have been found to heighten risk for IPV (eg, partner engaging in heavy alcohol use).1

With the patient’s permission, collaboratively construct a safety plan that details how the patient can stay safe on a daily basis and how to safely leave should a dangerous situation arise (TABLE 29,24). The interactive safety planning tool available on the National Domestic Violence Hotline’s website can be a valuable resource (www.thehotline.org/plan-for-safety/).24 Finally, if a patient is experiencing mental health concerns associated with IPV (eg, PTSD, depression, substance misuse, suicidal ideation), consider a referral to a domestic violence counseling center or mental health provider.

Move at the patient’s pace. Even if patients are willing to disclose IPV, they will differ in their readiness to discuss psychoeducation, safety planning, and referrals. Similarly, even if a patient is experiencing severe violence, they may not be ready to leave the relationship. Thus, it’s important to ask the patient for permission before initiating each successive step of the follow-up intervention. You and the patient may wish to schedule additional appointments to discuss this information at a pace the patient finds appropriate.

You may need to spend some time helping the patient recognize the severity of their situation and to feel empowered to take action. In addition, offer information and resources to all patients, even those who do not disclose IPV. Some patients may want to receive this information even if they do not feel comfortable sharing their experiences during the appointment.20 You can also inform patients that they are welcome to bring up issues related to IPV at any future appointments in order to leave the door open to future disclosures.

THE CASE

The physician determined that Ms. T had been experiencing physical and psychological IPV in her current relationship. After responding empathically and obtaining the patient’s consent, the physician provided a warm handoff to the psychologist in the clinic. With Ms. T’s permission, the psychologist provided psychoeducation about IPV, and they discussed Ms. T’s current situation and risk level. They determined that Ms. T was at risk for subsequent episodes of IPV and they collaborated on a safety plan, making sure to discuss contact information for local and national crisis resources.

Continue to: Ms. T saved the phone number...

Ms. T saved the phone number for her local domestic violence shelter in her phone under a false name in case her husband looked through her phone. She said she planned to work on several safety plan items when her husband was away from the house and it was safe to do so. For example, she planned to identify additional ways to exit the house in an emergency and she was going to put together a bag with a change of clothes and some money and drop it off at a trusted friend’s house.

Ms. T and the psychologist agreed to follow up with an office visit in 1 week to discuss any additional safety concerns and to determine whether Ms. T could benefit from a referral to domestic violence counseling services or mental health treatment. The psychologist provided a summary of the topics she and Ms. T had discussed to the physician. The physician scheduled a follow-up appointment with Ms. T in 3 weeks to assess her current safety, troubleshoot any difficulties in implementing her safety plan, and offer additional resources, as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Andrea Massa, PhD, 125 Doughty Street, Suite 300, Charleston, SC 29403; [email protected]

1. CDC. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Preventing intimate partner violence. 2021. Accessed June 27, 2022. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html

2. CDC. Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report. Accessed June 27, 2022. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_executive_summary-a.pdf

3. Chen J, Walters ML, Gilbert LK, et al. Sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence by sexual orientation, United States. Psychol Violence. 2020;10:110-119. doi:10.1037/vio0000252

4. Kofman YB, Garfin DR. Home is not always a haven: the domestic violence crisis amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S199-S201. doi:10.1037/tra0000866

5. Lyons M, Brewer G. Experiences of intimate partner violence during lockdown and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Violence. 2021:1-9. doi:10.1007/s10896-021-00260-x

6. Parrott DJ, Halmos MB, Stappenbeck CA, et al. Intimate partner aggression during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with stress and heavy drinking. Psychol Violence. 2021;12:95-103. doi:10.1037/vio0000395

7. CDC. National Center for Injury Prevention and

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for intimate partner violence, elder abuse, and abuse of vulnerable adults: US Preventive Services Task Force final recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1678-1687. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14741

9. Sprunger JG, Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, et al. It’s time to start asking all patients about intimate partner violence. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:152-161.

10. Chan CC, Chan YC, Au A, et al. Reliability and validity of the “Extended - Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream” (E-HITS) screening tool in detecting intimate partner violence in hospital emergency departments in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2010;17:109-117. doi:10.1177/102490791001700202

11. Iverson KM, King MW, Gerber MR, et al. Accuracy of an intimate partner violence screening tool for female VHA patients: a replication and extension. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:79-82. doi:10.1002/jts.21985

12. Sohal H, Eldridge S, Feder G. The sensitivity and specificity of four questions (HARK) to identify intimate partner violence: a diagnostic accuracy study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:49. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-8-49

13. Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li X, et al. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:508-512.

14. Rabin RF, Jennings JM, Campbell JC, et al. Intimate partner violence screening tools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:439-445.e4. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.024

15. Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, et al. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA. 1997;277:1357-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03540410035027

16. Brown JB, Lent B, Schmidt G, et al. Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and WAST-short in the family practice setting. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:896-903.

17. Wathen CN, Jamieson E, MacMillan HL, MVAWRG. Who is identified by screening for intimate partner violence? Womens Health Issues. 2008;18:423-432. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2008.08.003

18. Hegarty K, O’Doherty L, Taft A, et al. Screening and counselling in the primary care setting for women who have experienced intimate partner violence (WEAVE): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:249-258. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60052-5

19. Correa NP, Cain CM, Bertenthal M, et al. Women’s experiences of being screened for intimate partner violence in the health care setting. Nurs Womens Health. 2020;24:185-196. doi:10.1016/j.nwh.2020.04.002

20. Chang JC, Decker MR, Moracco KE, et al. Asking about intimate partner violence: advice from female survivors to health care providers. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:141-147. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.008

21. Paterno MT, Draughon JE. Screening for intimate partner violence. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61:370-375. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12443

22. Iverson KM, Huang K, Wells SY, et al. Women veterans’ preferences for intimate partner violence screening and response procedures within the Veterans Health Administration. Res Nurs Health. 2014;37:302-311. doi:10.1002/nur.21602

23. National Sexual Violence Research Center. Assessing patients for sexual violence: A guide for health care providers. 2011. Accessed June 28, 2022. www.nsvrc.org/publications/assessing-patients-sexual-violence-guide-health-care-providers

24. National Domestic Violence Hotline. Interactive guide to safety planning. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.thehotline.org/plan-for-safety/create-a-safety-plan/

1. CDC. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Preventing intimate partner violence. 2021. Accessed June 27, 2022. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html

2. CDC. Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report. Accessed June 27, 2022. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_executive_summary-a.pdf

3. Chen J, Walters ML, Gilbert LK, et al. Sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence by sexual orientation, United States. Psychol Violence. 2020;10:110-119. doi:10.1037/vio0000252

4. Kofman YB, Garfin DR. Home is not always a haven: the domestic violence crisis amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S199-S201. doi:10.1037/tra0000866

5. Lyons M, Brewer G. Experiences of intimate partner violence during lockdown and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Violence. 2021:1-9. doi:10.1007/s10896-021-00260-x

6. Parrott DJ, Halmos MB, Stappenbeck CA, et al. Intimate partner aggression during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with stress and heavy drinking. Psychol Violence. 2021;12:95-103. doi:10.1037/vio0000395

7. CDC. National Center for Injury Prevention and

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for intimate partner violence, elder abuse, and abuse of vulnerable adults: US Preventive Services Task Force final recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1678-1687. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14741

9. Sprunger JG, Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, et al. It’s time to start asking all patients about intimate partner violence. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:152-161.

10. Chan CC, Chan YC, Au A, et al. Reliability and validity of the “Extended - Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream” (E-HITS) screening tool in detecting intimate partner violence in hospital emergency departments in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2010;17:109-117. doi:10.1177/102490791001700202

11. Iverson KM, King MW, Gerber MR, et al. Accuracy of an intimate partner violence screening tool for female VHA patients: a replication and extension. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:79-82. doi:10.1002/jts.21985

12. Sohal H, Eldridge S, Feder G. The sensitivity and specificity of four questions (HARK) to identify intimate partner violence: a diagnostic accuracy study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:49. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-8-49

13. Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li X, et al. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:508-512.

14. Rabin RF, Jennings JM, Campbell JC, et al. Intimate partner violence screening tools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:439-445.e4. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.024

15. Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, et al. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA. 1997;277:1357-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03540410035027

16. Brown JB, Lent B, Schmidt G, et al. Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and WAST-short in the family practice setting. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:896-903.

17. Wathen CN, Jamieson E, MacMillan HL, MVAWRG. Who is identified by screening for intimate partner violence? Womens Health Issues. 2008;18:423-432. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2008.08.003

18. Hegarty K, O’Doherty L, Taft A, et al. Screening and counselling in the primary care setting for women who have experienced intimate partner violence (WEAVE): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:249-258. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60052-5

19. Correa NP, Cain CM, Bertenthal M, et al. Women’s experiences of being screened for intimate partner violence in the health care setting. Nurs Womens Health. 2020;24:185-196. doi:10.1016/j.nwh.2020.04.002

20. Chang JC, Decker MR, Moracco KE, et al. Asking about intimate partner violence: advice from female survivors to health care providers. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:141-147. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.008

21. Paterno MT, Draughon JE. Screening for intimate partner violence. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61:370-375. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12443

22. Iverson KM, Huang K, Wells SY, et al. Women veterans’ preferences for intimate partner violence screening and response procedures within the Veterans Health Administration. Res Nurs Health. 2014;37:302-311. doi:10.1002/nur.21602

23. National Sexual Violence Research Center. Assessing patients for sexual violence: A guide for health care providers. 2011. Accessed June 28, 2022. www.nsvrc.org/publications/assessing-patients-sexual-violence-guide-health-care-providers

24. National Domestic Violence Hotline. Interactive guide to safety planning. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.thehotline.org/plan-for-safety/create-a-safety-plan/

Youth e-cigarette use: Assessing for, and halting, the hidden habit

THE CASE

Joe, an 18-year-old, has been your patient for many years and has an uncomplicated medical history. He presents for his preparticipation sports examination for the upcoming high school baseball season. Joe’s mother, who arrives at the office with him, tells you she’s worried because she found an e-cigarette in his backpack last week. Joe says that many of the kids at his school vape and he tried it a while back and now vapes “a lot.”

After talking further with Joe, you realize that he is vaping every day, using a 5% nicotine pod. Based on previous consults with the behavioral health counselor in your clinic, you know that this level of vaping is about the same as smoking 1 pack of cigarettes per day in terms of nicotine exposure. Joe states that he often vapes in the bathroom at school because he cannot concentrate in class if he doesn’t vape. He also reports that he had previously used 1 pod per week but had recently started vaping more to help with his cravings.

You assess his withdrawal symptoms and learn that he feels on edge when he is not able to vape and that he vapes heavily before going into school because he knows he will not be able to vape again until his third passing period.

●

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes; also called “vapes”) are electronic nicotine delivery systems that heat and aerosolize e-liquid or “e-juice” that is inhaled by the user. The e-liquid is made up primarily of propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, and flavorings, and often includes nicotine. Nicotine levels in e-cigarettes can range from 0 mg/mL to 60 mg/mL (regular cigarettes contain ~12 mg of nicotine). The nicotine level of the pod available from e-cigarette company JUUL (50 mg/mL e-liquid) is equivalent to about 1 pack of cigarettes.1 E-cigarette devices are relatively affordable; popular brands cost $10 to $20, while the replacement pods or e-liquid are typically about $4 each.

The e-cigarette market is quickly evolving and diversifying. Originally, e-cigarettes looked similar to cigarettes (cig-a-likes) but did not efficiently deliver nicotine to the user.2 E-cigarettes have evolved and some now deliver cigarette-like levels of nicotine to the user.3,4 Youth and young adults primarily use pod-mod e-cigarettes, which have a sleek design and produce less vapor than older e-cigarettes, making them easier to conceal. They can look like a USB flash-drive or have a teardrop shape. Pod-mod e-cigarettes dominate the current market, led by companies such as JUUL, NJOY, and Vuse.5

E-cigarette use is proliferating in the United States, particularly among young people and facilitated by the introduction of pod-based e-cigarettes in appealing flavors.6,7 While rates of current e-cigarette use by US adults is around 5.5%,8 recent data show that 32.7% of US high school students say they’ve used an e-cigarette in the past 30 days.9

Continue to: A double-edged sword

A double-edged sword. E-cigarettes are less harmful than traditional cigarettes in the short term and likely benefit adult smokers who completely substitute e-cigarettes for their tobacco cigarettes.10 In randomized trials of adult smokers, e-cigarette use resulted in moderate combustible-cigarette cessation rates that rival or exceed rates achieved with traditional nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).11-13 However, most e-cigarettes contain addictive nicotine, can facilitate transitions to more harmful forms of tobacco use,10,14,15 and have unknown long-term health effects. Therefore, youth, young adults, and those who are otherwise tobacco naïve should not initiate e-cigarette use.

Moreover, cases of e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI)—a disease linked to vaping that causes cough, fever, shortness of breath, and death—were first identified in August 2019 and peaked in September 2019 before new cases decreased dramatically through January 2020.16 Since the initial cases of EVALI arose, product testing has shown that tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and vitamin E acetate are the main ingredients linked to EVALI cases.17 For this reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others strongly recommend against use of THC-containing e-cigarettes.18

Given the high rates of e-cigarette use among youth and young adults and its potential health harms, it is critical to inquire about e-cigarette use at primary care visits, and, as appropriate, to assess frequency and quantity of use. Patients who require intervention will be more likely to succeed in quitting if they are connected with behavioral health counseling and prescribed medication. This article offers evidence-based guidance to assess and advise teens and young adults regarding the potential health impact of e-cigarettes.

A NEW ICD-10-CM CODE AND A BRIEF ASSESSMENT TOOL

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5)19 and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10-CM),20 a tobacco use disorder is a problematic pattern of use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress. Associated features and behavioral markers of frequency and quantity include use within 30 minutes of waking, daily use, and increasing use. However, with youth, consider intervention for use of any nicotine or tobacco product, including e-cigarettes, regardless of whether it meets the threshold for diagnosis.21

The new code.

Continue to: As with other tobacco use...

As with other tobacco use, assess e-cigarette use patterns by asking questions about the frequency, duration, and quantity of use. Additionally, determine the level of nicotine in the e-liquid (discussed earlier) and evaluate whether the individual displays signs of physiologic dependence (eg, failed attempts to reduce or quit e-cigarette use, increased use, nicotine withdrawal symptoms).

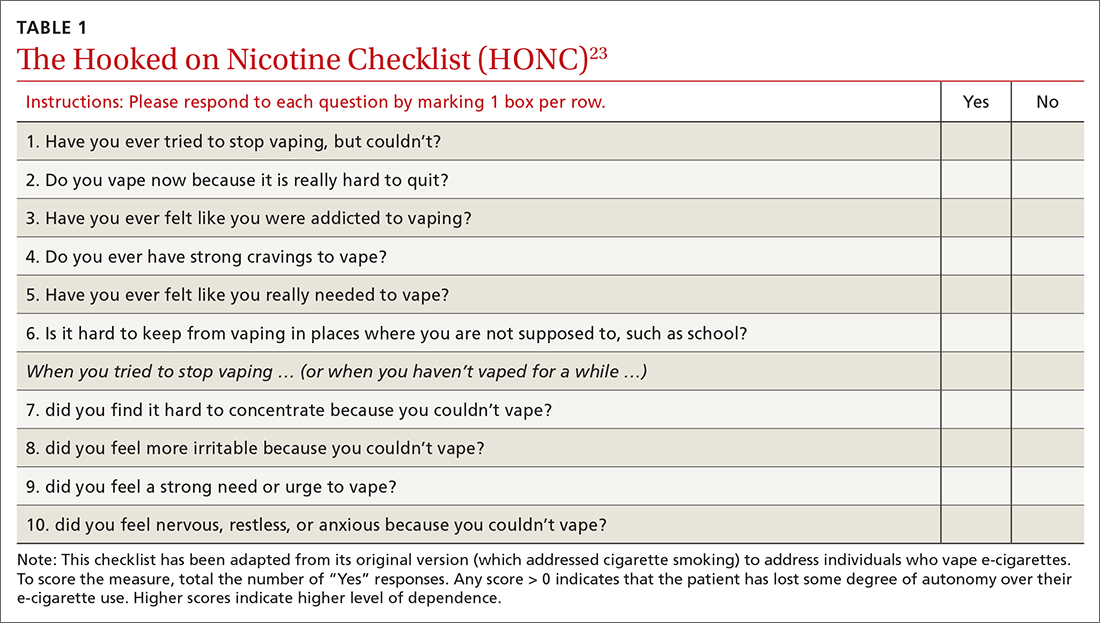

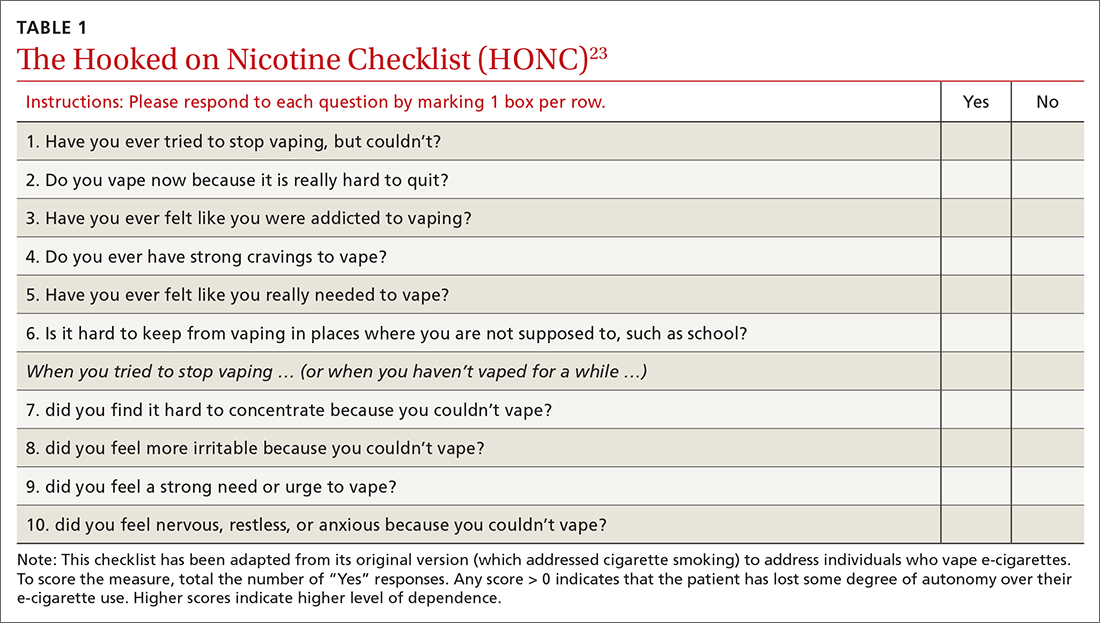

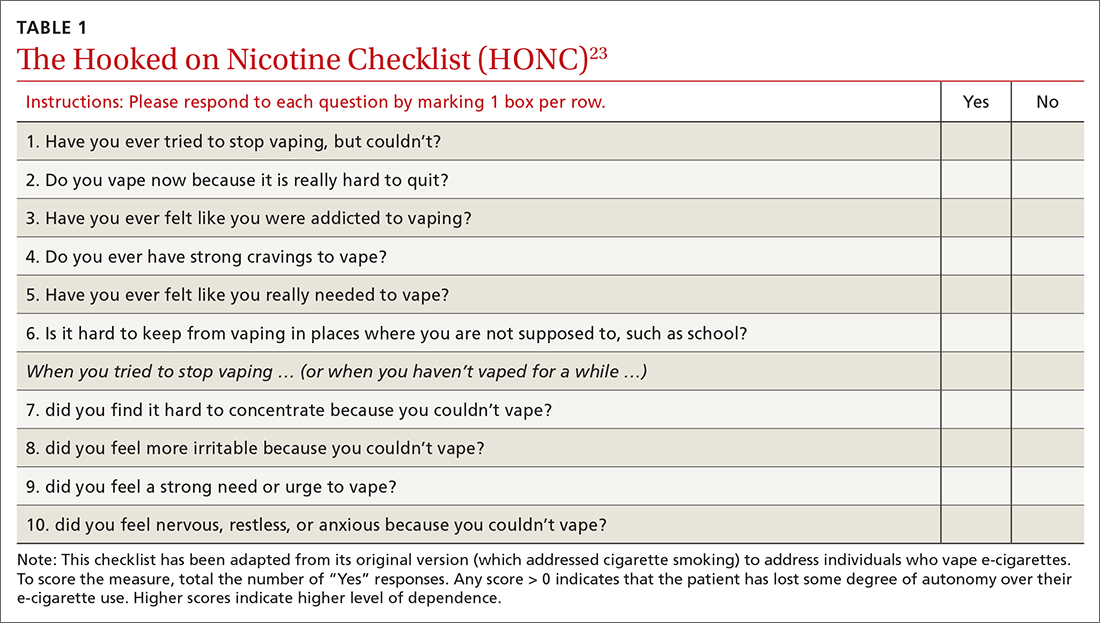

A useful assessment tool. While e-cigarette use is not often included on current substance use screening measures, the above questions can be added to the end of measures such as the CRAFFT (Car-Relax-Alone-Forget-Family and Friends-Trouble) test.22 Additionally, if an adolescent reports vaping, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends using a brief screening tool such as the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (HONC) to establish his or her level of dependence (TABLE 1).23

The HONC is ideal for a primary care setting because it is brief and has a high level of sensitivity, minimizing false-negative reports24; a patient’s acknowledgement of any item indicates a loss of autonomy over nicotine. Establishing the level of nicotine dependence is particularly pertinent when making decisions regarding the course of treatment and whether to prescribe NRT (eg, nicotine patch, gum, lozenge). Alternatively, you can quickly assess level of dependence by determining the time to first e-cigarette use in the morning. Tobacco guidelines suggest that if time to first use is > 30 minutes, the individual is “moderately dependent”; if time to first use is < 30 minutes after waking, the individual is “severely dependent.”25

COMBINATION TREATMENT IS MOST SUCCESSFUL

Studies have shown that the most effective treatment for tobacco cessation is pairing behavioral treatment with combination NRT (eg, nicotine gum + patch).25,26 The literature on e-cigarette cessation remains in its infancy, but techniques from traditional smoking cessation can be applied because the behaviors differ only in their mode of nicotine delivery.

Behavioral treatment. There are several options for behavioral treatment for tobacco cessation—and thus, e-cigarette cessation. The first step will depend on the patient’s level of motivation. If the patient is not yet ready to quit, consider using brief motivational interviewing. Once the patient is willing to engage in treatment, options include setting a mutually agreed upon quit date or planning for a reduction in the frequency and duration of vaping.

Continue to: Referrals to the Quitline...

Referrals to the Quitline (800-QUIT-NOW) have long been standard practice and can be used to extend primary care treatment.25 Studies show that it is more effective to connect patients directly to the Quitline at their primary care appointment27 than asking them to call after the visit.28,29 We suggest providing direct assistance in the office to patients as they initiate treatment with the Quitline.

Finally, if the level of dependence is severe or the patient is not motivated to quit, connect them with a behavioral health provider in your clinic or with an outside therapist skilled in cognitive behavioral techniques related to tobacco cessation. Discuss with the patient that quitting nicotine use is difficult for many people and that the best option for success is the combination of counseling and medication.25

Nicotine replacement therapy for e-cigarette use. While over-the-counter NRT (nicotine gum, patches, lozenges) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration only for sale to adults ≥ 18 years, the AAP issued guidance on prescribing NRT for those < 18 years who use e-cigarettes.30 While the AAP does not suggest a lower age limit for prescribing NRT, national data show that < 6% of middle schoolers report e-cigarette use and that e-cigarette use does not become common (~20% current use) until high school.31 It is therefore unlikely that a child < 14 years would require pharmacotherapy. On their fact sheet, the AAP includes the following guidance:

“Patients who are motivated to quit should use as much safe, FDA-approved NRT as needed to avoid smoking or vaping. When assessing a patient’s current level of nicotine use, it may be helpful to understand that using one JUUL pod per day is equivalent to one pack of cigarettes per day …. Pediatricians and other healthcare providers should work with each patient to determine a starting dosage of NRT that is most likely to help them quit successfully. Dosing is based on the patient’s level of nicotine dependence, which can be measured using a screening tool” (TABLE 123).32

The AAP NRT dosing guidelines can be found at downloads.aap.org/RCE/NRT_and_Adolescents_Pediatrician_Guidance_factsheet.pdf.32 Of note, the dosing guidelines for adolescents are the same as those for adults and are based on level of use and dependence. Moreover, the clinician and patient should work together to choose the initial dose and the plan for weaning NRT over time.

Continue to: THE CASE

Based on your conversation with Joe, you administer the HONC screening tool. He scores 9 out of 10, indicating significant loss of autonomy over nicotine. You consult with a behavioral health counselor, who believes that Joe would benefit from counseling and NRT. You discuss this treatment plan with Joe, who says he is ready to quit because he does not like feeling as if he depends on vaping. Your shared decision is to start the 21-mg patch and 4-mg gum with plans to step down from there.

Joe agrees to set a quit date in the following week. The behavioral health counselor then meets with Joe and they develop a quit plan, which is shared with you so you can follow up at the next visit. Joe also agrees to talk with his parents, who are unaware of his level of use and dependence. Everyone agrees on the quit plan, and a follow-up visit is scheduled.

At the follow-up visit 1 month later, Joe and his parents report that he has quit vaping but is still using the patch and gum. You instruct Joe to reduce his NRT use to the 14-mg patch and 2-mg gum and to stop using them over the next 2 to 3 weeks. Everyone is in agreement with the treatment plan. You also re-administer the HONC screening tool and see that Joe’s score has reduced by 7 points to just 2 out of 10. You recommend that Joe continue to see the behavioral health counselor and follow up as needed. (A noted benefit of having a behavioral health counselor in your clinic is the opportunity for informal briefings on patient progress.33,34)

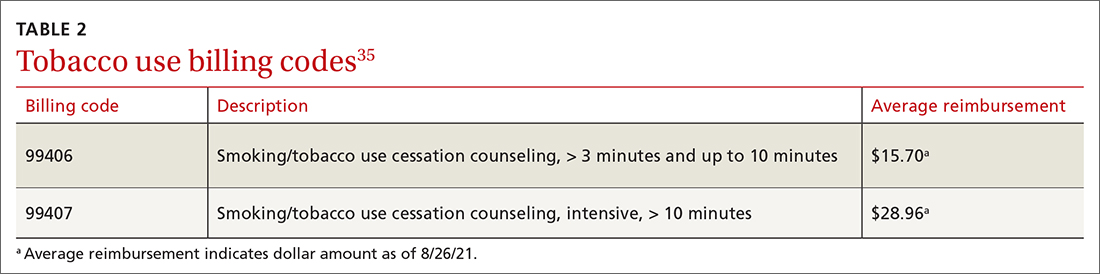

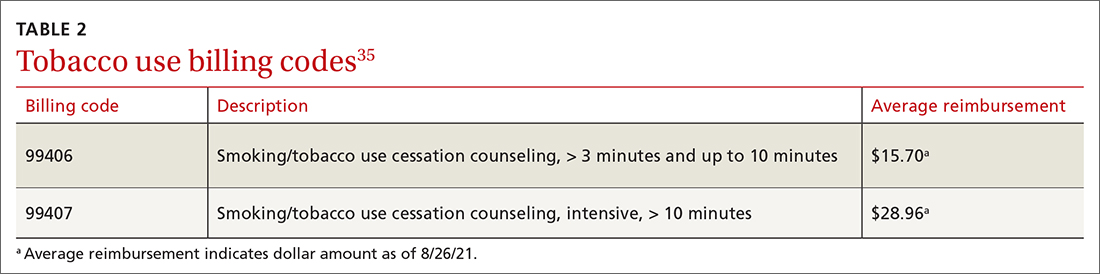

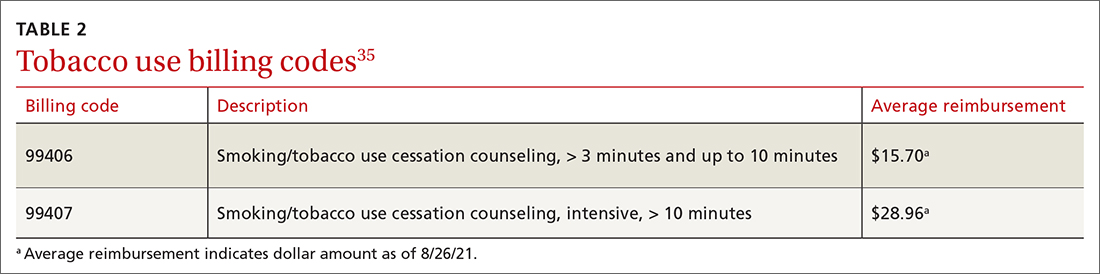

Following each visit with Joe, you make sure to complete documentation on (1) tobacco/e-cigarette use assessment, (2) diagnoses, (3) discussion of benefits of quitting,(4) assessment of readiness to quit, (5) creation and support of a quit plan, and (6) connection with a behavioral health counselor and planned follow-up. (See TABLE 235 for details onbilling codes.)

CORRESPONDENCE

Eleanor L. S. Leavens, PhD, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard, Mail Stop 1008, Kansas City, KS 66160; [email protected]

1. Prochaska JJ, Vogel EA, Benowitz N. Nicotine delivery and cigarette equivalents from vaping a JUULpod. Tob Control. Published online March 24, 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol- 2020-056367

2. Rüther T, Hagedorn D, Schiela K, et al. Nicotine delivery efficiency of first-and second-generation e-cigarettes and its impact on relief of craving during the acute phase of use. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2018;221:191-198. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.10.012

3. Hajek P, Pittaccio K, Pesola F, et al. Nicotine delivery and users’ reactions to Juul compared with cigarettes and other e‐cigarette products. Addiction. 2020;115:1141-1148. doi: 10.1111/add.14936

4. Wagener TL, Floyd EL, Stepanov I, et al. Have combustible cigarettes met their match? The nicotine delivery profiles and harmful constituent exposures of second-generation and third-generation electronic cigarette users. Tob control. 2017;26:e23-e28. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053041

5. Herzog B, Kanada P. Nielsen: Tobacco all channel data thru 8/11 - cig vol decelerates. Published August 21, 2018. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://athra.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Wells-Fargo-Nielsen-Tobacco-All-Channel-Report-Period-Ending-8.11.18.pdf

6. Harrell MB, Weaver SR, Loukas A, et al. Flavored e-cigarette use: characterizing youth, young adult, and adult users. Prev Med Rep. 2017;5:33-40. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.001

7. Morean ME, Butler ER, Bold KW, et al. Preferring more e-cigarette flavors is associated with e-cigarette use frequency among adolescents but not adults. PloS One. 2018;13:e0189015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189015

8. Obisesan OH, Osei AD, Iftekhar Uddin SM, et al. Trends in e-cigarette use in adults in the United States, 2016-2018. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1394-1398. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2817

9. Creamer MR, Wang TW, Babb S, et al. Tobacco product use and cessation indicators among adults—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1013-1019. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2

10. NASEM. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. National Academies Press; 2018. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507171/

11. Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:629-637. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808779

12. Pulvers K, Nollen NL, Rice M, et al. Effect of pod e-cigarettes vs cigarettes on carcinogen exposure among African American and Latinx smokers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2026324. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.26324

13. Wang RJ, Bhadriraju S, Glantz SA. E-cigarette use and adult cigarette smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2021;111:230-246. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305999

14. Barrington-Trimis JL, Urman R, Berhane K, et al. E-cigarettes and future cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160379. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0379

15. Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:788-797. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1488

16. Krishnasamy VP, Hallowell BD, Ko JY, et al. Update: characteristics of a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury—United States, August 2019–January 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:90-94. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6903e2

17. Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Shields PG, et al. Vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid associated with EVALI. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:697-705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916433

18. CDC. Outbreak of lung injury associated with use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Updated February 25, 2020. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

19. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

20. CDC. International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision. Updated July 30, 2021. Accessed August 31, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm

21. CDC. Surgeon General’s advisory on e-cigarette use among youth. Reviewed April 9, 2019. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/surgeon-general-advisory/index.html

22. Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, et al. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:607-614. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.607

23. DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, et al. Measuring the loss of autonomy over nicotine use in adolescents: the DANDY (Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youths) study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:397-403. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.397

24. Wellman RJ, Savageau JA, Godiwala S, et al. A comparison of the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist and the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence in adult smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:575-580. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789965

25. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Published May 2008. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/clinical_recommendations/TreatingTobaccoUseandDependence-2008Update.pdf

26. Shah SD, Wilken LA, Winkler SR, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of combination therapy for smoking cessation. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48:659-665. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07063

27. Vidrine JI, Shete S, Cao Y, et al. Ask-Advise-Connect: a new approach to smoking treatment delivery in health care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:458-464. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3751

28. Bentz CJ, Bayley KB, Bonin KE, et al. The feasibility of connecting physician offices to a state-level tobacco quit line. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:31-37. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.043

29. Borland R, Segan CJ. The potential of quitlines to increase smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25:73-78. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459537

30. Farber HJ, Walley SC, Groner JA, et al. Clinical practice policy to protect children from tobacco, nicotine, and tobacco smoke. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1008-1017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3108

31. Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1881-1888. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950a1

32. AAP. Nicotine replacement therapy and adolescent patients: information for pediatricians. Updated November 2019. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://downloads.aap.org/RCE/NRT_and_Adolescents_Pediatrician_Guidance_factsheet.pdf

33. Blasi PR, Cromp D, McDonald S, et al. Approaches to behavioral health integration at high performing primary care practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:691-701. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.05.170468

34. Jacobs C, Brieler JA, Salas J, et al. Integrated behavioral health care in family medicine residencies a CERA survey. Fam Med. 2018;50:380-384. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2018.639260

35. Oliverez M. Quick guide: billing for smoking cessation services. Capture Billing. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://capturebilling.com/how-bill-smoking-cessation-counseling-99406-99407/

THE CASE

Joe, an 18-year-old, has been your patient for many years and has an uncomplicated medical history. He presents for his preparticipation sports examination for the upcoming high school baseball season. Joe’s mother, who arrives at the office with him, tells you she’s worried because she found an e-cigarette in his backpack last week. Joe says that many of the kids at his school vape and he tried it a while back and now vapes “a lot.”

After talking further with Joe, you realize that he is vaping every day, using a 5% nicotine pod. Based on previous consults with the behavioral health counselor in your clinic, you know that this level of vaping is about the same as smoking 1 pack of cigarettes per day in terms of nicotine exposure. Joe states that he often vapes in the bathroom at school because he cannot concentrate in class if he doesn’t vape. He also reports that he had previously used 1 pod per week but had recently started vaping more to help with his cravings.

You assess his withdrawal symptoms and learn that he feels on edge when he is not able to vape and that he vapes heavily before going into school because he knows he will not be able to vape again until his third passing period.

●

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes; also called “vapes”) are electronic nicotine delivery systems that heat and aerosolize e-liquid or “e-juice” that is inhaled by the user. The e-liquid is made up primarily of propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, and flavorings, and often includes nicotine. Nicotine levels in e-cigarettes can range from 0 mg/mL to 60 mg/mL (regular cigarettes contain ~12 mg of nicotine). The nicotine level of the pod available from e-cigarette company JUUL (50 mg/mL e-liquid) is equivalent to about 1 pack of cigarettes.1 E-cigarette devices are relatively affordable; popular brands cost $10 to $20, while the replacement pods or e-liquid are typically about $4 each.

The e-cigarette market is quickly evolving and diversifying. Originally, e-cigarettes looked similar to cigarettes (cig-a-likes) but did not efficiently deliver nicotine to the user.2 E-cigarettes have evolved and some now deliver cigarette-like levels of nicotine to the user.3,4 Youth and young adults primarily use pod-mod e-cigarettes, which have a sleek design and produce less vapor than older e-cigarettes, making them easier to conceal. They can look like a USB flash-drive or have a teardrop shape. Pod-mod e-cigarettes dominate the current market, led by companies such as JUUL, NJOY, and Vuse.5

E-cigarette use is proliferating in the United States, particularly among young people and facilitated by the introduction of pod-based e-cigarettes in appealing flavors.6,7 While rates of current e-cigarette use by US adults is around 5.5%,8 recent data show that 32.7% of US high school students say they’ve used an e-cigarette in the past 30 days.9

Continue to: A double-edged sword

A double-edged sword. E-cigarettes are less harmful than traditional cigarettes in the short term and likely benefit adult smokers who completely substitute e-cigarettes for their tobacco cigarettes.10 In randomized trials of adult smokers, e-cigarette use resulted in moderate combustible-cigarette cessation rates that rival or exceed rates achieved with traditional nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).11-13 However, most e-cigarettes contain addictive nicotine, can facilitate transitions to more harmful forms of tobacco use,10,14,15 and have unknown long-term health effects. Therefore, youth, young adults, and those who are otherwise tobacco naïve should not initiate e-cigarette use.

Moreover, cases of e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI)—a disease linked to vaping that causes cough, fever, shortness of breath, and death—were first identified in August 2019 and peaked in September 2019 before new cases decreased dramatically through January 2020.16 Since the initial cases of EVALI arose, product testing has shown that tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and vitamin E acetate are the main ingredients linked to EVALI cases.17 For this reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others strongly recommend against use of THC-containing e-cigarettes.18

Given the high rates of e-cigarette use among youth and young adults and its potential health harms, it is critical to inquire about e-cigarette use at primary care visits, and, as appropriate, to assess frequency and quantity of use. Patients who require intervention will be more likely to succeed in quitting if they are connected with behavioral health counseling and prescribed medication. This article offers evidence-based guidance to assess and advise teens and young adults regarding the potential health impact of e-cigarettes.

A NEW ICD-10-CM CODE AND A BRIEF ASSESSMENT TOOL

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5)19 and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10-CM),20 a tobacco use disorder is a problematic pattern of use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress. Associated features and behavioral markers of frequency and quantity include use within 30 minutes of waking, daily use, and increasing use. However, with youth, consider intervention for use of any nicotine or tobacco product, including e-cigarettes, regardless of whether it meets the threshold for diagnosis.21

The new code.

Continue to: As with other tobacco use...

As with other tobacco use, assess e-cigarette use patterns by asking questions about the frequency, duration, and quantity of use. Additionally, determine the level of nicotine in the e-liquid (discussed earlier) and evaluate whether the individual displays signs of physiologic dependence (eg, failed attempts to reduce or quit e-cigarette use, increased use, nicotine withdrawal symptoms).

A useful assessment tool. While e-cigarette use is not often included on current substance use screening measures, the above questions can be added to the end of measures such as the CRAFFT (Car-Relax-Alone-Forget-Family and Friends-Trouble) test.22 Additionally, if an adolescent reports vaping, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends using a brief screening tool such as the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (HONC) to establish his or her level of dependence (TABLE 1).23

The HONC is ideal for a primary care setting because it is brief and has a high level of sensitivity, minimizing false-negative reports24; a patient’s acknowledgement of any item indicates a loss of autonomy over nicotine. Establishing the level of nicotine dependence is particularly pertinent when making decisions regarding the course of treatment and whether to prescribe NRT (eg, nicotine patch, gum, lozenge). Alternatively, you can quickly assess level of dependence by determining the time to first e-cigarette use in the morning. Tobacco guidelines suggest that if time to first use is > 30 minutes, the individual is “moderately dependent”; if time to first use is < 30 minutes after waking, the individual is “severely dependent.”25

COMBINATION TREATMENT IS MOST SUCCESSFUL

Studies have shown that the most effective treatment for tobacco cessation is pairing behavioral treatment with combination NRT (eg, nicotine gum + patch).25,26 The literature on e-cigarette cessation remains in its infancy, but techniques from traditional smoking cessation can be applied because the behaviors differ only in their mode of nicotine delivery.

Behavioral treatment. There are several options for behavioral treatment for tobacco cessation—and thus, e-cigarette cessation. The first step will depend on the patient’s level of motivation. If the patient is not yet ready to quit, consider using brief motivational interviewing. Once the patient is willing to engage in treatment, options include setting a mutually agreed upon quit date or planning for a reduction in the frequency and duration of vaping.

Continue to: Referrals to the Quitline...

Referrals to the Quitline (800-QUIT-NOW) have long been standard practice and can be used to extend primary care treatment.25 Studies show that it is more effective to connect patients directly to the Quitline at their primary care appointment27 than asking them to call after the visit.28,29 We suggest providing direct assistance in the office to patients as they initiate treatment with the Quitline.

Finally, if the level of dependence is severe or the patient is not motivated to quit, connect them with a behavioral health provider in your clinic or with an outside therapist skilled in cognitive behavioral techniques related to tobacco cessation. Discuss with the patient that quitting nicotine use is difficult for many people and that the best option for success is the combination of counseling and medication.25

Nicotine replacement therapy for e-cigarette use. While over-the-counter NRT (nicotine gum, patches, lozenges) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration only for sale to adults ≥ 18 years, the AAP issued guidance on prescribing NRT for those < 18 years who use e-cigarettes.30 While the AAP does not suggest a lower age limit for prescribing NRT, national data show that < 6% of middle schoolers report e-cigarette use and that e-cigarette use does not become common (~20% current use) until high school.31 It is therefore unlikely that a child < 14 years would require pharmacotherapy. On their fact sheet, the AAP includes the following guidance:

“Patients who are motivated to quit should use as much safe, FDA-approved NRT as needed to avoid smoking or vaping. When assessing a patient’s current level of nicotine use, it may be helpful to understand that using one JUUL pod per day is equivalent to one pack of cigarettes per day …. Pediatricians and other healthcare providers should work with each patient to determine a starting dosage of NRT that is most likely to help them quit successfully. Dosing is based on the patient’s level of nicotine dependence, which can be measured using a screening tool” (TABLE 123).32

The AAP NRT dosing guidelines can be found at downloads.aap.org/RCE/NRT_and_Adolescents_Pediatrician_Guidance_factsheet.pdf.32 Of note, the dosing guidelines for adolescents are the same as those for adults and are based on level of use and dependence. Moreover, the clinician and patient should work together to choose the initial dose and the plan for weaning NRT over time.

Continue to: THE CASE

Based on your conversation with Joe, you administer the HONC screening tool. He scores 9 out of 10, indicating significant loss of autonomy over nicotine. You consult with a behavioral health counselor, who believes that Joe would benefit from counseling and NRT. You discuss this treatment plan with Joe, who says he is ready to quit because he does not like feeling as if he depends on vaping. Your shared decision is to start the 21-mg patch and 4-mg gum with plans to step down from there.