User login

When vaccine misconceptions jeopardize public health

› Reassure parents that vaccines are some of the safest and most effective interventions we have to prevent infectious disease. A

› Advise parents that there are multiple systems in place to monitor vaccine safety. C

› Educate parents that lapses in immunization rates can put children at risk of resurgent cases of previously well-controlled diseases, like measles and Haemophilus influenza type b. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

When a public health intervention succeeds and achieves long-term suppression of the target problem, an unfortunate irony is that, with time, the intervention can seem less vital. So it is with vaccines. Many patients and physicians today have never experienced the infectious diseases that once caused millions of deaths and much disability each year, and they therefore do not appreciate the impact these diseases had when they were prevalent.

It is estimated that just 9 of the routinely recommended vaccines prevent 42,000 deaths and 20 million cases of disease in every birth cohort.1 With many of these diseases thus held at bay, attention shifted instead to the supposed risks of vaccines. Many people mistakenly believe a vaccine’s potential for harm is more likely than the chance of acquiring the disease it prevents, and they therefore refuse vaccines for themselves and their children, with little chance in the short term of suffering an adverse outcome for their decision.

In this review—which can inform primary care physicians’ discussions with vaccine-hesitant patients—we first highlight 2 preventable diseases, measles and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infection. Recent residency graduates may never see these diseases thanks to sustained vaccination programs. However, the risk of acquiring these infections has not disappeared entirely. After considering these examples, we examine the totality of the morbidity and mortality prevented by vaccination and describe the safety of current vaccines and the systems in place to assure their continued safety.

Measles: No longer endemic to the United States, but still a risk from importation

In the pre-vaccine era, measles (rubeola) infected more than 500,000 Americans annually and killed roughly 500.2 This highly communicable systemic acute viral infection was once considered universal in childhood. After vaccine licensure in 1963, widespread immunization reduced the incidence by more than 98%, and by 2000 it had eliminated endemic measles from the United States. However, the disease has now reappeared—largely due to international travel and neglect in becoming vaccinated. As of October 31, 2014, the United States had 20 outbreaks and 603 cases of measles reported in 2014—a dramatic increase over recent years.3

Clinical appearance. Acute measles infection is characterized by high fever, cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and rash. Koplik spots are a 24- to 72-hour pathognomonic exanthem of blue-white spots 1 to 3 mm in diameter on an erythematous base along the buccal mucosa. The resolving exanthem coincides with the eruption of a blanching, maculopapular exanthem originating at the hairline, progressing down the trunk and out to the limbs (sparing the palms and soles), coalescing, and then fading with a fine desquamation in the same order of appearance over 7 days. Additional associated symptoms include anorexia, diarrhea, and generalized lymphadenopathy.2,4

Complications are common with measles. Acute measles infection is rarely fatal. However, serious complications occur in nearly one-third of reported cases.2 During the 1989-1991 measles resurgence in the United States, more than 100 deaths occurred among the 55,000 cases reported.5-7 In early 2011, the United States saw the highest reported number of measles cases since 1996 due to importation. Of the 118 reported cases, 105 (89%) occurred in unvaccinated people, 47 (40%) required hospitalization, and 9 individuals developed pneumonia.8

Complications of measles infection are shown in TABLE 1.2,4 Pneumonia (viral or superimposed bacterial) accounts for 60% of measles-related deaths.2 Neurologic complications, while less frequent, can be severe.

Acute encephalitis occurs in 1 in 1000 to 2000 cases and presents within a week following the exanthem with fever, headache, vomiting, meningismus, change in mental status, convulsions, and coma.2 Encephalitis has a fatality rate of 15%, leaving another 25% with residual neurologic damage.2 Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) occurs in 5 to 10 cases per million (in the United States), on average 7 years after the initial measles infection.9,10 After an insidious onset, behavior and intellect deteriorate, followed by ataxia, myoclonic seizures, and ultimately death. In the United States, the number of reported cases of SSPE has declined with the reduction in measles cases. However, in countries with less robust measles immunization eradication programs, the risk of developing SSPE remains.9,10

Hib: Contained but not eradicated

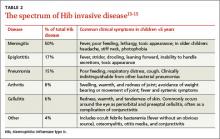

Hib was once the leading cause of meningitis and a major cause of other invasive bacterial diseases, but it has been greatly controlled since the advent of routine Hib vaccination in 1990.11 Hib is an encapsulated, gram-negative coccobacillus. There are 6 major capsular serotypes of Haemophilus influenzae, but serotype b was linked to major invasive disease in humans 95% of the time.12 The spectrum of diseases caused by Hib is seen in TABLE 2.13-15 Hib is transmitted by respiratory droplets from noninfected as well as infected carriers. Asymptomatic nasal carriage in the pre-vaccine era varied from 0.5% to 5%.12

Hib is primarily a disease of young children, with almost all cases occurring in children younger than 5 years of age (66% in those younger than 18 months). Other risk factors for invasive disease are those that increase the spread of respiratory droplets: crowding, lower socioeconomic status, day care attendance, large household size, and school-aged siblings. American Indian and Alaskan Native populations remain at higher risk due to incomplete vaccination rates and the sociodemographic risk factors noted above. Breastfeeding is protective.12

Three percent to 6% of cases of invasive Hib disease are fatal; another 20% can have long-term sequelae such as hearing loss. In the early 1990s, the peak incidence of Hib disease reached 41 cases per 100,000 population.12 The reduction in incidence of Hib disease brought about by universal vaccination has been attributed to individual immunity, decreased asymptomatic nasal carriage, and herd immunity.12

Despite this progress, Hib continues to evade eradication. In Minnesota in 2008, 5 children, ages 5 months to 3 years, contracted invasive Hib disease (3 with meningitis, 1 with pneumonia, 1 with epiglottitis).16 Of the 5, only one was up to date with Hib vaccination; the others had not received vaccine because of shortages or parent refusal. These children were unrelated and had not been in contact with each other.

In a daycare outbreak in the United Kingdom, 2 cases of Hib disease (meningitis and septic arthritis) were identified in fully immunized children younger than 18 months, presumably due to a lack of complete vaccine efficacy.17 A study of nasal carriage (performed just prior to rifampin prophylaxis) among other attendees and caregivers revealed 3 asymptomatic carriers.17 Although Hib is largely well-contained in developed countries due to vaccination policies, the burden of disease in developing countries is estimated to be approximately 8.1 million serious illnesses with 371,000 deaths annually.13

The totality of morbidity and mortality prevented by vaccines

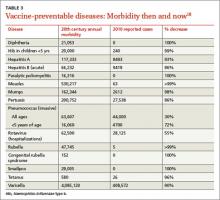

Measles and Hib are 2 examples of vaccine-preventable diseases and the reduction in morbidity and mortality achievable with vaccines. TABLE 318 summarizes the number of pre-vaccine era cases for selected diseases. Routine vaccination against 7 common childhood diseases not only prevents many thousands of deaths, as mentioned earlier,1 but it saves $13.5 billion in direct costs in each birth cohort and saves society $68.8 billion in costs that include disability and lost productivity of both patients and caregivers.1

Put simply, every dollar spent on the vaccination program saves $10 in direct and indirect costs to society.1 Sustaining these successes and averting the resurgence of contained diseases requires a commitment to high immunization rates without delays and lapses—an effort made more challenging in light of misinformation about vaccine safety and resultant parental vaccine hesitancy.

Vaccine safety is ensured by rigorous systems

Despite an impressive record of safety, vaccines still cause anxiety among patients and parents in family practices. A recent survey identified concerns of long-term complications, autism, and thimerosal effects to be foremost on the minds of parents, whereas short-term effects were of much less concern.19 Causation of autism related to vaccines has been dismissed; the initial linkages have been shown to be fraudulent.20 With the exception of some influenza vaccine preparations, thimerosal is no longer present in routinely administered children’s vaccines and has been shown not to be associated with autism.21,22 To address parents’ and patients’ concerns about vaccine safety, and especially those surrounding short- and long-term complications, physicians should have a general understanding of the pre- and post-licensure mechanisms in the United States.

Pre-licensure safety is under the purview of vaccine manufacturers and the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the US Food and Drug Administration (http://www.fda.gov/biologicsbloodvaccines/vaccines/default.htm). For licensure, manufacturers must provide clinical data to demonstrate sufficient safety and efficacy. Accordingly, pre-licensure assessments are conducted in a “closed system” under a research protocol. The vaccine recipients are volitional research subjects selected according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. They are also compensated. However, sample sizes are rarely large enough to exclude rare serious adverse events.

Once licensure has been granted, the focus of safety then shifts to the “open system” of usual clinical practice. Vaccine recipients are unselected members of the general population and may have underlying medical conditions, and sometimes—such as with school entry mandates—are less volitional. In this sphere, the responsible parties for safety include the government, manufacturers, and health care systems.

Three ongoing systems function to assure vaccine safety: the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network.23,24

VAERS serves as an early warning system for coincidental safety signals and can generate hypotheses for further investigation.24,25 It is characterized by high sensitivity but low specificity as it relies on voluntary reporting from health care personnel, parents, and others. This system was instrumental in identifying the initial cases of intussusception attributable to the rotavirus vaccine, RotaShield.26

The VSD is a network of 10 large, geographically diverse and linked health maintenance organizations that cover about 3% of the US population. Within this “real time” network, vaccination (exposure) can be compared with outpatient, emergency department, hospital, and laboratory data (health outcomes), while accounting for demographic variables (confounders).27,28 VSD studies linked the measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccine to febrile seizures29 and showed no relationship between cumulative vaccine antigen exposure and autism.30

The CISA was established in 2001 to investigate the pathophysiologic mechanisms and biologic risks of adverse effects following immunization and to provide evidence-based vaccine safety assessments.

Based on all available evidence, routinely recommended vaccines have attained a very high level of safety. As with other preventive services, immunizations are generally provided to healthy individuals to maintain good health; thus, a low tolerance for significant adverse events exists. Well over 100 million doses of vaccines are given each year, yet the VAERS receives, on average, only 28,000 adverse event reports per year.

These reports comprise mild, moderate, and severe reactions to vaccines, but also adverse events that may not be related in any way other than chronologically to the vaccine’s administration. Despite this relatively low number of real safety concerns, it is still more likely that patients will know someone who has had a vaccine-related adverse event than someone who has had some of the diseases the vaccines prevent.31

Final thoughts

Current anti-vaccine sentiments appear to arise from varying perspectives. Some are held by parents of children who have allegedly suffered a severe vaccine related adverse event; others by those opposed to government-mandated school immunization requirements; and some from those who have a dislike of vaccine manufacturers. These sentiments persist in part because of a low level of vaccine preventable diseases: When such illnesses are no longer deemed a threat, those who have concerns about vaccine safety, no matter how invalid, believe their concerns should trump all other considerations.

To appreciate the true benefit of vaccine acceptance, we need only look to Europe, where the anti-vaccine movement has led to high levels of vaccine refusal and a resurgence of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles, with their associated morbidity and mortality.32 In advocating for continued acceptance and widespread use of vaccines, family physicians can convey to patients and parents the magnitude of associated health benefits while confidently attesting to the effectiveness and safety of vaccines.

CORRESPONDENCE

John Epling, MD, MSEd, Department of Family Medicine, SUNY Upstate Medical University, 475 Irving Ave, Suite 200, Syracuse, NY 13210; [email protected]

1. Zhou F, Shefer A, Wenger J, et al. Economic evaluation of the routine childhood immunization program in the United States, 2009. Pediatrics. 2014;133:577-585.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. The Pink Book: Course Textbook. 12th ed. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/meas.html. Accessed March 4, 2012.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/measles/. Accessed November 19, 2014.

4. Measles. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, et al, eds. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:444-455.

5. Atkinson WL, Orenstein WA, Krugman S. The resurgence of measles in the United States, 1989-1990. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:451-463.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Measles--United States, 1990. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;40:369-372.

7. Gindler J, Tinker S, Markowitz L, et al. Acute measles mortality in the United States, 1987-2002. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(suppl 1): S69-S77.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Measles: United States, January-May 20, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:666-668.

9. Bernstein DI, Reuman PD, Schiff GM. Rubeola (measles) and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis virus. In: Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR (eds). Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1998:2135.

10. Bellini WJ, Rota JS, Lowe LE, et al. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: more cases of this fatal disease are prevented by measles immunization than was previously recognized. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1686-1693.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Progress toward elimination of Haemophilus influenza type b invasive disease among infants and children—United States, 1998-2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:234-237.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. The Pink Book, Course Textbook, 12th ed. Haemophilus influenzae type b. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/hib.html. Accessed March 4, 2012.

13. Watt JP, Wolfson LJ, O’Brien KL, et al; Hib and Pneumococcal Global Burden of Disease Study Team. Burden of disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374:903-911.

14. Agrawal A, Murphy TF. Haemophilus influenzae infections in the H. influenzae type b conjugate vaccine era. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3728-3732.

15. Chandran A, Watt JP, Santosham M. Prevention of Haemophilus influenza type b disease: past successes and future challenges. Informa Healthcare. 2005;4:819-827.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Invasive Haemophilus influenza Type B disease in five young children--Minnesota, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:58-60.

17. McVernon J, Morgan P, Mallaghan C, et al. Outbreak of Haemophilus influenzae type b disease among fully vaccinated children in a day-care center. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:38-41.

18. Hinman AR, Orenstein WA, Schuchat A; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine-preventable diseases, immunizations, and MMWR—1961-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60 suppl 4:49-57.

19. Kempe A, Daley MF, McCauley MM, et al. Prevalence of parental concerns about childhood vaccines: the experience of primary care physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:548-555.

20. Godlee F, Smith J, Marcovitch H. Wakefield’s article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent. BMJ. 2011;342:c7452.

21. Institute for Vaccine Safety. Thimerosal content in some US Licensed vaccines. Institute for Vaccine Safety Web site. Available at: http://www.vaccinesafety.edu/thi-table.htm. Accessed March 8, 2012.

22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Immunization safety and autism. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/00_pdf/CDCStudiesonVaccinesandAutism.pdf. Accessed September 23, 2013.

23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ensuring the safety of vaccines in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/patient-ed/conversations/downloads/vacsafe-ensuring-color-office.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2014.

24. Wharton M. Vaccine safety: current systems and recent findings. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:88-93.

25. US Food and Drug Administration. Understanding the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). US Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/SafetyAvailability/VaccineSafety/UCM298183.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2014.

26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Suspension of rotavirus vaccine after reports of intussusception--United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:786-789.

27. Greene SK, Kulldorff M, Lewis EM, et al. Near real-time surveillance for influenza vaccine safety: proof-of-concept in the Vaccine Safety Datalink Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:177-188.

28. Iskander J, Broder K. Monitoring the safety of annual and pandemic influenza vaccines: lessons from the US experience. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7:75-82.

29. Klein NP, Fireman B, Yih WK, et al. Measles-mumps-rubella-varicella combination vaccine and the risk of febrile seizures. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1-e8.

30. DeStefano F, Price CS, Weintraub ES. Increasing exposure to antibody-stimulating proteins and polysaccharides in vaccines is not associated with risk of autism. J Pediatr. 2013;163:561-567.

31. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. The Pink Book, Course Textbook, 12th ed. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/safety.html. Accessed November 17, 2014.

32. World Health Organization (WHO). Measles outbreak in Europe. Global alert and response. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2011_04_21/en/index.html. Accessed March 8, 2012.

› Reassure parents that vaccines are some of the safest and most effective interventions we have to prevent infectious disease. A

› Advise parents that there are multiple systems in place to monitor vaccine safety. C

› Educate parents that lapses in immunization rates can put children at risk of resurgent cases of previously well-controlled diseases, like measles and Haemophilus influenza type b. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

When a public health intervention succeeds and achieves long-term suppression of the target problem, an unfortunate irony is that, with time, the intervention can seem less vital. So it is with vaccines. Many patients and physicians today have never experienced the infectious diseases that once caused millions of deaths and much disability each year, and they therefore do not appreciate the impact these diseases had when they were prevalent.

It is estimated that just 9 of the routinely recommended vaccines prevent 42,000 deaths and 20 million cases of disease in every birth cohort.1 With many of these diseases thus held at bay, attention shifted instead to the supposed risks of vaccines. Many people mistakenly believe a vaccine’s potential for harm is more likely than the chance of acquiring the disease it prevents, and they therefore refuse vaccines for themselves and their children, with little chance in the short term of suffering an adverse outcome for their decision.

In this review—which can inform primary care physicians’ discussions with vaccine-hesitant patients—we first highlight 2 preventable diseases, measles and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infection. Recent residency graduates may never see these diseases thanks to sustained vaccination programs. However, the risk of acquiring these infections has not disappeared entirely. After considering these examples, we examine the totality of the morbidity and mortality prevented by vaccination and describe the safety of current vaccines and the systems in place to assure their continued safety.

Measles: No longer endemic to the United States, but still a risk from importation

In the pre-vaccine era, measles (rubeola) infected more than 500,000 Americans annually and killed roughly 500.2 This highly communicable systemic acute viral infection was once considered universal in childhood. After vaccine licensure in 1963, widespread immunization reduced the incidence by more than 98%, and by 2000 it had eliminated endemic measles from the United States. However, the disease has now reappeared—largely due to international travel and neglect in becoming vaccinated. As of October 31, 2014, the United States had 20 outbreaks and 603 cases of measles reported in 2014—a dramatic increase over recent years.3

Clinical appearance. Acute measles infection is characterized by high fever, cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and rash. Koplik spots are a 24- to 72-hour pathognomonic exanthem of blue-white spots 1 to 3 mm in diameter on an erythematous base along the buccal mucosa. The resolving exanthem coincides with the eruption of a blanching, maculopapular exanthem originating at the hairline, progressing down the trunk and out to the limbs (sparing the palms and soles), coalescing, and then fading with a fine desquamation in the same order of appearance over 7 days. Additional associated symptoms include anorexia, diarrhea, and generalized lymphadenopathy.2,4

Complications are common with measles. Acute measles infection is rarely fatal. However, serious complications occur in nearly one-third of reported cases.2 During the 1989-1991 measles resurgence in the United States, more than 100 deaths occurred among the 55,000 cases reported.5-7 In early 2011, the United States saw the highest reported number of measles cases since 1996 due to importation. Of the 118 reported cases, 105 (89%) occurred in unvaccinated people, 47 (40%) required hospitalization, and 9 individuals developed pneumonia.8

Complications of measles infection are shown in TABLE 1.2,4 Pneumonia (viral or superimposed bacterial) accounts for 60% of measles-related deaths.2 Neurologic complications, while less frequent, can be severe.

Acute encephalitis occurs in 1 in 1000 to 2000 cases and presents within a week following the exanthem with fever, headache, vomiting, meningismus, change in mental status, convulsions, and coma.2 Encephalitis has a fatality rate of 15%, leaving another 25% with residual neurologic damage.2 Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) occurs in 5 to 10 cases per million (in the United States), on average 7 years after the initial measles infection.9,10 After an insidious onset, behavior and intellect deteriorate, followed by ataxia, myoclonic seizures, and ultimately death. In the United States, the number of reported cases of SSPE has declined with the reduction in measles cases. However, in countries with less robust measles immunization eradication programs, the risk of developing SSPE remains.9,10

Hib: Contained but not eradicated

Hib was once the leading cause of meningitis and a major cause of other invasive bacterial diseases, but it has been greatly controlled since the advent of routine Hib vaccination in 1990.11 Hib is an encapsulated, gram-negative coccobacillus. There are 6 major capsular serotypes of Haemophilus influenzae, but serotype b was linked to major invasive disease in humans 95% of the time.12 The spectrum of diseases caused by Hib is seen in TABLE 2.13-15 Hib is transmitted by respiratory droplets from noninfected as well as infected carriers. Asymptomatic nasal carriage in the pre-vaccine era varied from 0.5% to 5%.12

Hib is primarily a disease of young children, with almost all cases occurring in children younger than 5 years of age (66% in those younger than 18 months). Other risk factors for invasive disease are those that increase the spread of respiratory droplets: crowding, lower socioeconomic status, day care attendance, large household size, and school-aged siblings. American Indian and Alaskan Native populations remain at higher risk due to incomplete vaccination rates and the sociodemographic risk factors noted above. Breastfeeding is protective.12

Three percent to 6% of cases of invasive Hib disease are fatal; another 20% can have long-term sequelae such as hearing loss. In the early 1990s, the peak incidence of Hib disease reached 41 cases per 100,000 population.12 The reduction in incidence of Hib disease brought about by universal vaccination has been attributed to individual immunity, decreased asymptomatic nasal carriage, and herd immunity.12

Despite this progress, Hib continues to evade eradication. In Minnesota in 2008, 5 children, ages 5 months to 3 years, contracted invasive Hib disease (3 with meningitis, 1 with pneumonia, 1 with epiglottitis).16 Of the 5, only one was up to date with Hib vaccination; the others had not received vaccine because of shortages or parent refusal. These children were unrelated and had not been in contact with each other.

In a daycare outbreak in the United Kingdom, 2 cases of Hib disease (meningitis and septic arthritis) were identified in fully immunized children younger than 18 months, presumably due to a lack of complete vaccine efficacy.17 A study of nasal carriage (performed just prior to rifampin prophylaxis) among other attendees and caregivers revealed 3 asymptomatic carriers.17 Although Hib is largely well-contained in developed countries due to vaccination policies, the burden of disease in developing countries is estimated to be approximately 8.1 million serious illnesses with 371,000 deaths annually.13

The totality of morbidity and mortality prevented by vaccines

Measles and Hib are 2 examples of vaccine-preventable diseases and the reduction in morbidity and mortality achievable with vaccines. TABLE 318 summarizes the number of pre-vaccine era cases for selected diseases. Routine vaccination against 7 common childhood diseases not only prevents many thousands of deaths, as mentioned earlier,1 but it saves $13.5 billion in direct costs in each birth cohort and saves society $68.8 billion in costs that include disability and lost productivity of both patients and caregivers.1

Put simply, every dollar spent on the vaccination program saves $10 in direct and indirect costs to society.1 Sustaining these successes and averting the resurgence of contained diseases requires a commitment to high immunization rates without delays and lapses—an effort made more challenging in light of misinformation about vaccine safety and resultant parental vaccine hesitancy.

Vaccine safety is ensured by rigorous systems

Despite an impressive record of safety, vaccines still cause anxiety among patients and parents in family practices. A recent survey identified concerns of long-term complications, autism, and thimerosal effects to be foremost on the minds of parents, whereas short-term effects were of much less concern.19 Causation of autism related to vaccines has been dismissed; the initial linkages have been shown to be fraudulent.20 With the exception of some influenza vaccine preparations, thimerosal is no longer present in routinely administered children’s vaccines and has been shown not to be associated with autism.21,22 To address parents’ and patients’ concerns about vaccine safety, and especially those surrounding short- and long-term complications, physicians should have a general understanding of the pre- and post-licensure mechanisms in the United States.

Pre-licensure safety is under the purview of vaccine manufacturers and the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the US Food and Drug Administration (http://www.fda.gov/biologicsbloodvaccines/vaccines/default.htm). For licensure, manufacturers must provide clinical data to demonstrate sufficient safety and efficacy. Accordingly, pre-licensure assessments are conducted in a “closed system” under a research protocol. The vaccine recipients are volitional research subjects selected according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. They are also compensated. However, sample sizes are rarely large enough to exclude rare serious adverse events.

Once licensure has been granted, the focus of safety then shifts to the “open system” of usual clinical practice. Vaccine recipients are unselected members of the general population and may have underlying medical conditions, and sometimes—such as with school entry mandates—are less volitional. In this sphere, the responsible parties for safety include the government, manufacturers, and health care systems.

Three ongoing systems function to assure vaccine safety: the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network.23,24

VAERS serves as an early warning system for coincidental safety signals and can generate hypotheses for further investigation.24,25 It is characterized by high sensitivity but low specificity as it relies on voluntary reporting from health care personnel, parents, and others. This system was instrumental in identifying the initial cases of intussusception attributable to the rotavirus vaccine, RotaShield.26

The VSD is a network of 10 large, geographically diverse and linked health maintenance organizations that cover about 3% of the US population. Within this “real time” network, vaccination (exposure) can be compared with outpatient, emergency department, hospital, and laboratory data (health outcomes), while accounting for demographic variables (confounders).27,28 VSD studies linked the measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccine to febrile seizures29 and showed no relationship between cumulative vaccine antigen exposure and autism.30

The CISA was established in 2001 to investigate the pathophysiologic mechanisms and biologic risks of adverse effects following immunization and to provide evidence-based vaccine safety assessments.

Based on all available evidence, routinely recommended vaccines have attained a very high level of safety. As with other preventive services, immunizations are generally provided to healthy individuals to maintain good health; thus, a low tolerance for significant adverse events exists. Well over 100 million doses of vaccines are given each year, yet the VAERS receives, on average, only 28,000 adverse event reports per year.

These reports comprise mild, moderate, and severe reactions to vaccines, but also adverse events that may not be related in any way other than chronologically to the vaccine’s administration. Despite this relatively low number of real safety concerns, it is still more likely that patients will know someone who has had a vaccine-related adverse event than someone who has had some of the diseases the vaccines prevent.31

Final thoughts

Current anti-vaccine sentiments appear to arise from varying perspectives. Some are held by parents of children who have allegedly suffered a severe vaccine related adverse event; others by those opposed to government-mandated school immunization requirements; and some from those who have a dislike of vaccine manufacturers. These sentiments persist in part because of a low level of vaccine preventable diseases: When such illnesses are no longer deemed a threat, those who have concerns about vaccine safety, no matter how invalid, believe their concerns should trump all other considerations.

To appreciate the true benefit of vaccine acceptance, we need only look to Europe, where the anti-vaccine movement has led to high levels of vaccine refusal and a resurgence of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles, with their associated morbidity and mortality.32 In advocating for continued acceptance and widespread use of vaccines, family physicians can convey to patients and parents the magnitude of associated health benefits while confidently attesting to the effectiveness and safety of vaccines.

CORRESPONDENCE

John Epling, MD, MSEd, Department of Family Medicine, SUNY Upstate Medical University, 475 Irving Ave, Suite 200, Syracuse, NY 13210; [email protected]

› Reassure parents that vaccines are some of the safest and most effective interventions we have to prevent infectious disease. A

› Advise parents that there are multiple systems in place to monitor vaccine safety. C

› Educate parents that lapses in immunization rates can put children at risk of resurgent cases of previously well-controlled diseases, like measles and Haemophilus influenza type b. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

When a public health intervention succeeds and achieves long-term suppression of the target problem, an unfortunate irony is that, with time, the intervention can seem less vital. So it is with vaccines. Many patients and physicians today have never experienced the infectious diseases that once caused millions of deaths and much disability each year, and they therefore do not appreciate the impact these diseases had when they were prevalent.

It is estimated that just 9 of the routinely recommended vaccines prevent 42,000 deaths and 20 million cases of disease in every birth cohort.1 With many of these diseases thus held at bay, attention shifted instead to the supposed risks of vaccines. Many people mistakenly believe a vaccine’s potential for harm is more likely than the chance of acquiring the disease it prevents, and they therefore refuse vaccines for themselves and their children, with little chance in the short term of suffering an adverse outcome for their decision.

In this review—which can inform primary care physicians’ discussions with vaccine-hesitant patients—we first highlight 2 preventable diseases, measles and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infection. Recent residency graduates may never see these diseases thanks to sustained vaccination programs. However, the risk of acquiring these infections has not disappeared entirely. After considering these examples, we examine the totality of the morbidity and mortality prevented by vaccination and describe the safety of current vaccines and the systems in place to assure their continued safety.

Measles: No longer endemic to the United States, but still a risk from importation

In the pre-vaccine era, measles (rubeola) infected more than 500,000 Americans annually and killed roughly 500.2 This highly communicable systemic acute viral infection was once considered universal in childhood. After vaccine licensure in 1963, widespread immunization reduced the incidence by more than 98%, and by 2000 it had eliminated endemic measles from the United States. However, the disease has now reappeared—largely due to international travel and neglect in becoming vaccinated. As of October 31, 2014, the United States had 20 outbreaks and 603 cases of measles reported in 2014—a dramatic increase over recent years.3

Clinical appearance. Acute measles infection is characterized by high fever, cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and rash. Koplik spots are a 24- to 72-hour pathognomonic exanthem of blue-white spots 1 to 3 mm in diameter on an erythematous base along the buccal mucosa. The resolving exanthem coincides with the eruption of a blanching, maculopapular exanthem originating at the hairline, progressing down the trunk and out to the limbs (sparing the palms and soles), coalescing, and then fading with a fine desquamation in the same order of appearance over 7 days. Additional associated symptoms include anorexia, diarrhea, and generalized lymphadenopathy.2,4

Complications are common with measles. Acute measles infection is rarely fatal. However, serious complications occur in nearly one-third of reported cases.2 During the 1989-1991 measles resurgence in the United States, more than 100 deaths occurred among the 55,000 cases reported.5-7 In early 2011, the United States saw the highest reported number of measles cases since 1996 due to importation. Of the 118 reported cases, 105 (89%) occurred in unvaccinated people, 47 (40%) required hospitalization, and 9 individuals developed pneumonia.8

Complications of measles infection are shown in TABLE 1.2,4 Pneumonia (viral or superimposed bacterial) accounts for 60% of measles-related deaths.2 Neurologic complications, while less frequent, can be severe.

Acute encephalitis occurs in 1 in 1000 to 2000 cases and presents within a week following the exanthem with fever, headache, vomiting, meningismus, change in mental status, convulsions, and coma.2 Encephalitis has a fatality rate of 15%, leaving another 25% with residual neurologic damage.2 Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) occurs in 5 to 10 cases per million (in the United States), on average 7 years after the initial measles infection.9,10 After an insidious onset, behavior and intellect deteriorate, followed by ataxia, myoclonic seizures, and ultimately death. In the United States, the number of reported cases of SSPE has declined with the reduction in measles cases. However, in countries with less robust measles immunization eradication programs, the risk of developing SSPE remains.9,10

Hib: Contained but not eradicated

Hib was once the leading cause of meningitis and a major cause of other invasive bacterial diseases, but it has been greatly controlled since the advent of routine Hib vaccination in 1990.11 Hib is an encapsulated, gram-negative coccobacillus. There are 6 major capsular serotypes of Haemophilus influenzae, but serotype b was linked to major invasive disease in humans 95% of the time.12 The spectrum of diseases caused by Hib is seen in TABLE 2.13-15 Hib is transmitted by respiratory droplets from noninfected as well as infected carriers. Asymptomatic nasal carriage in the pre-vaccine era varied from 0.5% to 5%.12

Hib is primarily a disease of young children, with almost all cases occurring in children younger than 5 years of age (66% in those younger than 18 months). Other risk factors for invasive disease are those that increase the spread of respiratory droplets: crowding, lower socioeconomic status, day care attendance, large household size, and school-aged siblings. American Indian and Alaskan Native populations remain at higher risk due to incomplete vaccination rates and the sociodemographic risk factors noted above. Breastfeeding is protective.12

Three percent to 6% of cases of invasive Hib disease are fatal; another 20% can have long-term sequelae such as hearing loss. In the early 1990s, the peak incidence of Hib disease reached 41 cases per 100,000 population.12 The reduction in incidence of Hib disease brought about by universal vaccination has been attributed to individual immunity, decreased asymptomatic nasal carriage, and herd immunity.12

Despite this progress, Hib continues to evade eradication. In Minnesota in 2008, 5 children, ages 5 months to 3 years, contracted invasive Hib disease (3 with meningitis, 1 with pneumonia, 1 with epiglottitis).16 Of the 5, only one was up to date with Hib vaccination; the others had not received vaccine because of shortages or parent refusal. These children were unrelated and had not been in contact with each other.

In a daycare outbreak in the United Kingdom, 2 cases of Hib disease (meningitis and septic arthritis) were identified in fully immunized children younger than 18 months, presumably due to a lack of complete vaccine efficacy.17 A study of nasal carriage (performed just prior to rifampin prophylaxis) among other attendees and caregivers revealed 3 asymptomatic carriers.17 Although Hib is largely well-contained in developed countries due to vaccination policies, the burden of disease in developing countries is estimated to be approximately 8.1 million serious illnesses with 371,000 deaths annually.13

The totality of morbidity and mortality prevented by vaccines

Measles and Hib are 2 examples of vaccine-preventable diseases and the reduction in morbidity and mortality achievable with vaccines. TABLE 318 summarizes the number of pre-vaccine era cases for selected diseases. Routine vaccination against 7 common childhood diseases not only prevents many thousands of deaths, as mentioned earlier,1 but it saves $13.5 billion in direct costs in each birth cohort and saves society $68.8 billion in costs that include disability and lost productivity of both patients and caregivers.1

Put simply, every dollar spent on the vaccination program saves $10 in direct and indirect costs to society.1 Sustaining these successes and averting the resurgence of contained diseases requires a commitment to high immunization rates without delays and lapses—an effort made more challenging in light of misinformation about vaccine safety and resultant parental vaccine hesitancy.

Vaccine safety is ensured by rigorous systems

Despite an impressive record of safety, vaccines still cause anxiety among patients and parents in family practices. A recent survey identified concerns of long-term complications, autism, and thimerosal effects to be foremost on the minds of parents, whereas short-term effects were of much less concern.19 Causation of autism related to vaccines has been dismissed; the initial linkages have been shown to be fraudulent.20 With the exception of some influenza vaccine preparations, thimerosal is no longer present in routinely administered children’s vaccines and has been shown not to be associated with autism.21,22 To address parents’ and patients’ concerns about vaccine safety, and especially those surrounding short- and long-term complications, physicians should have a general understanding of the pre- and post-licensure mechanisms in the United States.

Pre-licensure safety is under the purview of vaccine manufacturers and the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the US Food and Drug Administration (http://www.fda.gov/biologicsbloodvaccines/vaccines/default.htm). For licensure, manufacturers must provide clinical data to demonstrate sufficient safety and efficacy. Accordingly, pre-licensure assessments are conducted in a “closed system” under a research protocol. The vaccine recipients are volitional research subjects selected according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. They are also compensated. However, sample sizes are rarely large enough to exclude rare serious adverse events.

Once licensure has been granted, the focus of safety then shifts to the “open system” of usual clinical practice. Vaccine recipients are unselected members of the general population and may have underlying medical conditions, and sometimes—such as with school entry mandates—are less volitional. In this sphere, the responsible parties for safety include the government, manufacturers, and health care systems.

Three ongoing systems function to assure vaccine safety: the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network.23,24

VAERS serves as an early warning system for coincidental safety signals and can generate hypotheses for further investigation.24,25 It is characterized by high sensitivity but low specificity as it relies on voluntary reporting from health care personnel, parents, and others. This system was instrumental in identifying the initial cases of intussusception attributable to the rotavirus vaccine, RotaShield.26

The VSD is a network of 10 large, geographically diverse and linked health maintenance organizations that cover about 3% of the US population. Within this “real time” network, vaccination (exposure) can be compared with outpatient, emergency department, hospital, and laboratory data (health outcomes), while accounting for demographic variables (confounders).27,28 VSD studies linked the measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccine to febrile seizures29 and showed no relationship between cumulative vaccine antigen exposure and autism.30

The CISA was established in 2001 to investigate the pathophysiologic mechanisms and biologic risks of adverse effects following immunization and to provide evidence-based vaccine safety assessments.

Based on all available evidence, routinely recommended vaccines have attained a very high level of safety. As with other preventive services, immunizations are generally provided to healthy individuals to maintain good health; thus, a low tolerance for significant adverse events exists. Well over 100 million doses of vaccines are given each year, yet the VAERS receives, on average, only 28,000 adverse event reports per year.

These reports comprise mild, moderate, and severe reactions to vaccines, but also adverse events that may not be related in any way other than chronologically to the vaccine’s administration. Despite this relatively low number of real safety concerns, it is still more likely that patients will know someone who has had a vaccine-related adverse event than someone who has had some of the diseases the vaccines prevent.31

Final thoughts

Current anti-vaccine sentiments appear to arise from varying perspectives. Some are held by parents of children who have allegedly suffered a severe vaccine related adverse event; others by those opposed to government-mandated school immunization requirements; and some from those who have a dislike of vaccine manufacturers. These sentiments persist in part because of a low level of vaccine preventable diseases: When such illnesses are no longer deemed a threat, those who have concerns about vaccine safety, no matter how invalid, believe their concerns should trump all other considerations.

To appreciate the true benefit of vaccine acceptance, we need only look to Europe, where the anti-vaccine movement has led to high levels of vaccine refusal and a resurgence of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles, with their associated morbidity and mortality.32 In advocating for continued acceptance and widespread use of vaccines, family physicians can convey to patients and parents the magnitude of associated health benefits while confidently attesting to the effectiveness and safety of vaccines.

CORRESPONDENCE

John Epling, MD, MSEd, Department of Family Medicine, SUNY Upstate Medical University, 475 Irving Ave, Suite 200, Syracuse, NY 13210; [email protected]

1. Zhou F, Shefer A, Wenger J, et al. Economic evaluation of the routine childhood immunization program in the United States, 2009. Pediatrics. 2014;133:577-585.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. The Pink Book: Course Textbook. 12th ed. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/meas.html. Accessed March 4, 2012.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/measles/. Accessed November 19, 2014.

4. Measles. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, et al, eds. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:444-455.

5. Atkinson WL, Orenstein WA, Krugman S. The resurgence of measles in the United States, 1989-1990. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:451-463.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Measles--United States, 1990. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;40:369-372.

7. Gindler J, Tinker S, Markowitz L, et al. Acute measles mortality in the United States, 1987-2002. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(suppl 1): S69-S77.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Measles: United States, January-May 20, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:666-668.

9. Bernstein DI, Reuman PD, Schiff GM. Rubeola (measles) and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis virus. In: Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR (eds). Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1998:2135.

10. Bellini WJ, Rota JS, Lowe LE, et al. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: more cases of this fatal disease are prevented by measles immunization than was previously recognized. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1686-1693.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Progress toward elimination of Haemophilus influenza type b invasive disease among infants and children—United States, 1998-2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:234-237.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. The Pink Book, Course Textbook, 12th ed. Haemophilus influenzae type b. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/hib.html. Accessed March 4, 2012.

13. Watt JP, Wolfson LJ, O’Brien KL, et al; Hib and Pneumococcal Global Burden of Disease Study Team. Burden of disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374:903-911.

14. Agrawal A, Murphy TF. Haemophilus influenzae infections in the H. influenzae type b conjugate vaccine era. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3728-3732.

15. Chandran A, Watt JP, Santosham M. Prevention of Haemophilus influenza type b disease: past successes and future challenges. Informa Healthcare. 2005;4:819-827.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Invasive Haemophilus influenza Type B disease in five young children--Minnesota, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:58-60.

17. McVernon J, Morgan P, Mallaghan C, et al. Outbreak of Haemophilus influenzae type b disease among fully vaccinated children in a day-care center. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:38-41.

18. Hinman AR, Orenstein WA, Schuchat A; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine-preventable diseases, immunizations, and MMWR—1961-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60 suppl 4:49-57.

19. Kempe A, Daley MF, McCauley MM, et al. Prevalence of parental concerns about childhood vaccines: the experience of primary care physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:548-555.

20. Godlee F, Smith J, Marcovitch H. Wakefield’s article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent. BMJ. 2011;342:c7452.

21. Institute for Vaccine Safety. Thimerosal content in some US Licensed vaccines. Institute for Vaccine Safety Web site. Available at: http://www.vaccinesafety.edu/thi-table.htm. Accessed March 8, 2012.

22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Immunization safety and autism. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/00_pdf/CDCStudiesonVaccinesandAutism.pdf. Accessed September 23, 2013.

23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ensuring the safety of vaccines in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/patient-ed/conversations/downloads/vacsafe-ensuring-color-office.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2014.

24. Wharton M. Vaccine safety: current systems and recent findings. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:88-93.

25. US Food and Drug Administration. Understanding the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). US Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/SafetyAvailability/VaccineSafety/UCM298183.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2014.

26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Suspension of rotavirus vaccine after reports of intussusception--United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:786-789.

27. Greene SK, Kulldorff M, Lewis EM, et al. Near real-time surveillance for influenza vaccine safety: proof-of-concept in the Vaccine Safety Datalink Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:177-188.

28. Iskander J, Broder K. Monitoring the safety of annual and pandemic influenza vaccines: lessons from the US experience. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7:75-82.

29. Klein NP, Fireman B, Yih WK, et al. Measles-mumps-rubella-varicella combination vaccine and the risk of febrile seizures. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1-e8.

30. DeStefano F, Price CS, Weintraub ES. Increasing exposure to antibody-stimulating proteins and polysaccharides in vaccines is not associated with risk of autism. J Pediatr. 2013;163:561-567.

31. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. The Pink Book, Course Textbook, 12th ed. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/safety.html. Accessed November 17, 2014.

32. World Health Organization (WHO). Measles outbreak in Europe. Global alert and response. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2011_04_21/en/index.html. Accessed March 8, 2012.

1. Zhou F, Shefer A, Wenger J, et al. Economic evaluation of the routine childhood immunization program in the United States, 2009. Pediatrics. 2014;133:577-585.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. The Pink Book: Course Textbook. 12th ed. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/meas.html. Accessed March 4, 2012.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/measles/. Accessed November 19, 2014.

4. Measles. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, et al, eds. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:444-455.

5. Atkinson WL, Orenstein WA, Krugman S. The resurgence of measles in the United States, 1989-1990. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:451-463.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Measles--United States, 1990. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;40:369-372.

7. Gindler J, Tinker S, Markowitz L, et al. Acute measles mortality in the United States, 1987-2002. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(suppl 1): S69-S77.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Measles: United States, January-May 20, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:666-668.

9. Bernstein DI, Reuman PD, Schiff GM. Rubeola (measles) and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis virus. In: Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR (eds). Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1998:2135.

10. Bellini WJ, Rota JS, Lowe LE, et al. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: more cases of this fatal disease are prevented by measles immunization than was previously recognized. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1686-1693.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Progress toward elimination of Haemophilus influenza type b invasive disease among infants and children—United States, 1998-2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:234-237.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. The Pink Book, Course Textbook, 12th ed. Haemophilus influenzae type b. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/hib.html. Accessed March 4, 2012.

13. Watt JP, Wolfson LJ, O’Brien KL, et al; Hib and Pneumococcal Global Burden of Disease Study Team. Burden of disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374:903-911.

14. Agrawal A, Murphy TF. Haemophilus influenzae infections in the H. influenzae type b conjugate vaccine era. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3728-3732.

15. Chandran A, Watt JP, Santosham M. Prevention of Haemophilus influenza type b disease: past successes and future challenges. Informa Healthcare. 2005;4:819-827.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Invasive Haemophilus influenza Type B disease in five young children--Minnesota, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:58-60.

17. McVernon J, Morgan P, Mallaghan C, et al. Outbreak of Haemophilus influenzae type b disease among fully vaccinated children in a day-care center. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:38-41.

18. Hinman AR, Orenstein WA, Schuchat A; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine-preventable diseases, immunizations, and MMWR—1961-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60 suppl 4:49-57.

19. Kempe A, Daley MF, McCauley MM, et al. Prevalence of parental concerns about childhood vaccines: the experience of primary care physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:548-555.

20. Godlee F, Smith J, Marcovitch H. Wakefield’s article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent. BMJ. 2011;342:c7452.

21. Institute for Vaccine Safety. Thimerosal content in some US Licensed vaccines. Institute for Vaccine Safety Web site. Available at: http://www.vaccinesafety.edu/thi-table.htm. Accessed March 8, 2012.

22. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Immunization safety and autism. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/00_pdf/CDCStudiesonVaccinesandAutism.pdf. Accessed September 23, 2013.

23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ensuring the safety of vaccines in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/patient-ed/conversations/downloads/vacsafe-ensuring-color-office.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2014.

24. Wharton M. Vaccine safety: current systems and recent findings. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:88-93.

25. US Food and Drug Administration. Understanding the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). US Food and Drug Administration Web site. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/SafetyAvailability/VaccineSafety/UCM298183.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2014.

26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Suspension of rotavirus vaccine after reports of intussusception--United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:786-789.

27. Greene SK, Kulldorff M, Lewis EM, et al. Near real-time surveillance for influenza vaccine safety: proof-of-concept in the Vaccine Safety Datalink Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:177-188.

28. Iskander J, Broder K. Monitoring the safety of annual and pandemic influenza vaccines: lessons from the US experience. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7:75-82.

29. Klein NP, Fireman B, Yih WK, et al. Measles-mumps-rubella-varicella combination vaccine and the risk of febrile seizures. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1-e8.

30. DeStefano F, Price CS, Weintraub ES. Increasing exposure to antibody-stimulating proteins and polysaccharides in vaccines is not associated with risk of autism. J Pediatr. 2013;163:561-567.

31. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. The Pink Book, Course Textbook, 12th ed. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/safety.html. Accessed November 17, 2014.

32. World Health Organization (WHO). Measles outbreak in Europe. Global alert and response. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2011_04_21/en/index.html. Accessed March 8, 2012.

Rate of Case Reporting, Physician Compliance, and Practice Volume in a Practice-Based Research Network Study

STUDY DESIGN: This was a prospective observational cohort study of participants in a practice-based research network who submitted data on 231 patients with dyspepsia from a total of 45,337 patient encounters over a 53-week period. Reporting of individual cases involved use of a relatively high-burden data instrument. Outcome measures were compared using rank correlation.

POPULATION: We included 18 physicians in a Wisconsin research network study on initial management of dyspepsia in primary care settings.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The outcomes were the rate of dyspepsia visits, average weekly patient volume, and self-reported compliance with the study protocol for each physician.

RESULTS: A significant negative correlation existed between physician patient volume and the reported rate of dyspepsia visits. Self-reported compliance with the protocol was negatively correlated with patient volume and positively correlated with the reported rate of dyspepsia visits.

CONCLUSIONS: Practice volume may influence the results in practice-based research. Investigators using practice-base research networks need to consider the complexity of their protocols and should be cognizant of compliance-sensitive measures.

Common medical problems, especially those that are self-limited or in their early phases, can be best studied in community practice settings where they are usually diagnosed and managed. Practice-based research provides one method to conduct studies of these problems. Often practice-based research physicians are linked together in practice-based research networks (PBRNs), thus forming, in effect, laboratories of community practices.1-3

The methodologic limitations of these laboratories are of concern and have not been extensively explored. Although it has been adequately demonstrated that the patient populations and the problems addressed in participating practices are comparable to patients and problems in the general population,4-6 the question of the selection bias of the clinicians has been raised.4

As research involvement can be a costly endeavor for the individual physician,7 participation in a research protocol—to some extent—may be related to the intensity of practice (ie, the volume of patients seen and services provided). It has been shown that high-volume practices differ from low-volume practices8 in that high-volume practices provide lower rates of preventive services and generate lower patient satisfaction. One may anticipate that physicians with more discretionary time (ie, fewer patients) may be better able to fully participate in research activities. There have been no direct studies of the impact of practice volume on the reporting of medical problems and compliance in research studies. This study, conducted as part of a larger Wisconsin Research Network (WReN) study of dyspepsia in primary care settings, is a first step in that direction.

Methods

Eighteen family physicians, making up the Practice-Based Research Group of WReN practices, volunteered to participate in a study of the initial management of dyspepsia in primary care.9 As part of the study protocol, participants were requested to record the number of adult patients presenting with dyspepsia and the total number of patients seen in their clinic for each week of the 12-month study. Dyspepsia was defined as pain in the upper abdomen lasting for at least 2 weeks and not attributable to cardiac or pulmonary disease or trauma. Data was collected for both initial and follow-up visits. Participants were instructed to complete a 1-page data instrument for each dyspeptic patient at the time of the visit. Each instrument contained 68 data elements and took up to 5 minutes to complete. Data forms were mailed to the study coordinator on a monthly basis. Data collection began on January 30, 1995, and continued through February 2, 1996.

An average weekly patient volume was calculated for each physician, as was the reported rate of dyspepsia visits in their practice. The patient volume was estimated for each physician by summing the weekly patient totals and dividing by the number of weeks during which the physician saw patients in the clinic and participated in the study. The reported rate of dyspepsia visits for each physician was estimated as the total number of patient visits reported meeting the study criteria for dyspepsia divided by the total number of patients seen during the study period.

Following completion of primary data collection, a demographic questionnaire was sent out to all 18 participants. The questionnaire distribution occurred approximately 4 months after data collection and during a chart review phase of the primary study. The chart review was performed by a research assistant and did not involve the participating physicians. One question, included to assess compliance with the study protocol, asked, “On a 10-point scale, how compliant were you at recording data for all qualifying dyspepsia patients during the weeks that you were involved with this study?” Responses were circled on a scale from 1 (poor) to 10 (perfect). Type of practice (solo, group multispecialty, or academic) was also obtained. Seventeen of the 18 questionnaires were completed and returned.

MINITAB was used for statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the outcome variables. Because data for reported rate of dyspepsia visits and compliance were not normally distributed, Spearman rank correlation (“ = 0.05) was used to test the hypotheses that practice volume, protocol compliance, and reported rate of dyspepsia visits were correlated. The one solo practitioner was placed with the group practice physicians because of a high level of similarity in all outcome variables. Because differences were noted among the practice types, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess differences in patient volume, compliance, and reported rate of dyspepsia visits.

Results

The average participant in this study was a 46-year-old male physician who had been in practice for 17 years and saw 61.5 patients per week Table w1. Eight physicians were located in group practices, while 5 were in multispecialty and 3 were in academic practices. The mean reported rate of dyspepsia visits was 7.7 cases per 1000 patient visits. Initial dyspepsia visits accounted for 118 of the 231 reported visits for dyspepsia (0.51%), with a total of 45,337 patient visits recorded by participating physicians.

The average participant recorded visits over 43.2 weeks of the possible 53-week study (81.5% overall participation rate). The average self-reported compliance with the study protocol was 6.7 on a 10-point scale but with a very wide range (from 1 to 10). Significant differences among practice types were found in patient volume, reported rate of dyspepsia visits, and self-reported compliance Table 2. Participants from group practices had the highest patient volumes but the lowest rate of dyspepsia visits and compliance. Academic physicians saw the least number of patients but had the highest reported rate of dyspepsia visits and compliance.

Significant negative rank correlations were found to exist between patient volume and reported rate of dyspepsia visits (Figure 1: rs = -0.548; P .05) and between patient volume and compliance with protocol (Figure 2: rs = -0.490; P .05). A significant positive rank correlation was found between compliance with protocol and rate of dyspepsia visits (Figure 3 (: rs = 0.551; P .05). No significant correlation existed between the number of weeks of participation and patient volume (rs = -0.303), rate of dyspepsia visits (rs = 0.065), or compliance with protocol (rs = 0.415).

Discussion

Practice volume can have a significant effect on physicians’ reporting rates in practice-based studies. The rate of dyspepsia visits, as measured by the identification of patients meeting study criteria and having a completed data form, was negatively related to the number of patients seen per week by the physician. Practice volume appears to be linked to reporting by way of compliance. As an extension, it appears that physicians are generally accurate in self-assessment of their compliance with a protocol.

Although previous evaluations of PBRNs have demonstrated high levels of accuracy within reported data,10 the results reported here are somewhat disturbing. If other studies show similar results, the idea that PBRNs can assess prevalence of medical conditions could be called into question. Also, there may be a bias in the higher? volume practices for patients with more severe symptoms to be reported in preference to those with less “attention getting” symptoms, or in low-volume practices to seek out problems for which the patient did not seek attention. Consequently, even when a medical problem is identified, there may be patient selection bias toward those with more or less severe symptoms.

Additional burden and lack of practice support were common reasons for withdrawing from participation in PBRNs.11 Overall participation and compliance with a research protocol, therefore, is likely related to the complexity of that protocol. While the reported rate of dyspepsia visits was negatively related to practice volume, the simple reporting of a weekly tally of patients seen in clinic was not. Consequently, compliance-sensitive measurements (eg, prevalence) may need simple time-efficient protocols. For example, full compliance with the protocol for the approximately 1050 physicians currently involved in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention US Influenza Sentinel Physician Surveillance Network requires less than 3 minutes per week. This surveillance network for monitoring prevalence of influenza-like illness is a highly accurate, timely, and valued component of influenza surveillance.12 Other enhancements for study protocols may include decreased periods for data gathering, use of intermittent reporting, and use of other office staff for case identification.

Limitations

This study is limited by a potential lack of generalizability. It is an observational study of physician behavior around a complex and relatively high-burden data collection instrument. There were no true standards regarding prevalence of dyspepsia at any location, thus allowing for the possibility that patient populations differed significantly among sites. Self-reported compliance with the research protocol was based on recall 4 months after the end of the data collection period. Also, some of the effect attributable to patient volume could alternatively result from the types of physicians involved in this study.

Academic physicians, with low practice volumes, may be more likely to be compliant with research protocols in general, regardless of their practice volumes. Because of the small sample size, however, this alternate hypothesis cannot be examined independently. With the exclusion of the academic physicians, relationships between the variables demonstrated the same trends, but the Spearman rank correlations were no longer significant (n = 14; patient volume vs rate: rs = -0.345; patient volume vs compliance: rs = -0.187; compliance vs rate: rs = 0.379).

This study does, however, challenge other investigators using PBRNs to revisit suitable data to determine similar patterns. Also, a simple assessment of participant compliance might prove to be an essential enhancement of future practice-based research.

Conclusions

Even encumbered with potential methodologic dilemmas, practice-based research studies may be the only way to approach many common medical issues in the context of the communities in which they occur.1-3 For example, while selection bias in reporting of dyspepsia is clearly a problem in this example, the selection bias is still far less severe than it would be in the gastrointestinal specialty clinic of a referral center. Likewise, if nonreferred conditions are to be tracked over extensive periods of time, the use of community settings is essential, as was done with a recent longitudinal study of depression.13

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided through a grant from the American Academy of Family Physicians. We thank the following participants of the WReN Practice-Based Research Group: R. Baldwin, E. Barr, D. Baumgardner, A. Berlage, M. Chin, D. Erickson, R. Erickson, G. Gay, M. Grajewski, D. Hahn, T. Hankey, D. Madlon-Kay, A. Marquis, E. Ott, D. Pine, and L. Radant.

1. Nutting PA, Beasley JW, Werner JJ. Practice-based research networks answer primary care questions. JAMA 1999;281:686-88.

2. Nutting PA. Practice-based research networks: building the infrastructure of primary care research. J Fam Pract 1996;42:199-203.

3. Nutting PA, Green LA. Practice-based research networks: reuniting practice and research around the problems most of the people have most of the time. J Fam Pract 1994;38:335-36.

4. Nutting PA, Baier M, Werner JJ, Cutter G, Reed FM, Orzano J. Practice patterns of family physicians in practice-based research networks: a report from ASPN. J Am Board Fam Pract 1999;12:78-84.

5. Green LA, Miller RS, Reed FM, Iverson DC, Barley GE. How representative of typical practice are practice-based research networks? A report from the Ambulatory Sentinel Practice Network Inc (ASPN). Arch Fam Med 1993;2:939-49.

6. Hahn DL, Beasley JW. Diagnosed and possible undiagnosed asthma: a Wisconsin Research Network (WReN) study. J Fam Pract 1994;38:373-79.

7. Hahn DL. Physician opportunity costs for performing practice-based research. J Fam Pract 2000;49:983-84.

8. Zyzanski SJ, Stange KC, Langa D, Flocke SA. Trade-offs in high-volume primary care practice. J Fam Pract 1998;46:397-402.

9. Temte JL, Hankey T. Initial management of dyspepsia in primary care settings: the WReN practice-based research group dyspepsia study. Wis Med J 1998;97:48-49.

10. Green LA, Hames CG, Sr, Nutting PA. Potential of practice-based research networks: experiences from ASPN. J Fam Pract 1994;38:400-06.

11. Green LA, Niebauer LJ, Miller RS, Lutz LJ. An analysis of reasons for discontinuing participation in a practice-based research network. Fam Med 1991;23:447-49.

12. Buffington J, Chapman LE, Schmeltz LM, Kendal AP. Do family physicians make good sentinels for influenza? Arch Fam Med 1993;2:859-64.

13. van Weel-Baumgarten E, van den Bosch W, van den Hoogen H, Zitman FG. Ten-year follow-up of depression after diagnosis in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1643-46.

STUDY DESIGN: This was a prospective observational cohort study of participants in a practice-based research network who submitted data on 231 patients with dyspepsia from a total of 45,337 patient encounters over a 53-week period. Reporting of individual cases involved use of a relatively high-burden data instrument. Outcome measures were compared using rank correlation.

POPULATION: We included 18 physicians in a Wisconsin research network study on initial management of dyspepsia in primary care settings.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The outcomes were the rate of dyspepsia visits, average weekly patient volume, and self-reported compliance with the study protocol for each physician.

RESULTS: A significant negative correlation existed between physician patient volume and the reported rate of dyspepsia visits. Self-reported compliance with the protocol was negatively correlated with patient volume and positively correlated with the reported rate of dyspepsia visits.

CONCLUSIONS: Practice volume may influence the results in practice-based research. Investigators using practice-base research networks need to consider the complexity of their protocols and should be cognizant of compliance-sensitive measures.

Common medical problems, especially those that are self-limited or in their early phases, can be best studied in community practice settings where they are usually diagnosed and managed. Practice-based research provides one method to conduct studies of these problems. Often practice-based research physicians are linked together in practice-based research networks (PBRNs), thus forming, in effect, laboratories of community practices.1-3

The methodologic limitations of these laboratories are of concern and have not been extensively explored. Although it has been adequately demonstrated that the patient populations and the problems addressed in participating practices are comparable to patients and problems in the general population,4-6 the question of the selection bias of the clinicians has been raised.4