User login

Safety and Efficacy of Ezetimibe in Patients With and Without Chronic Kidney Disease at a Pharmacist-Managed Clinic

Statins are widely used to reduce low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and non-high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels for the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).1 However, despite maximally tolerated statin therapy, many patients may not reach their LDL and non-HDL goals. Some patients may experience adverse events (AEs), particularly muscle-related AEs, which can limit the use of these medications.

The 2022 American College of Cardiology (ACC) expert consensus pathway recommends a goal LDL of < 55 mg/dL in very high-risk patients, defined as those with a history of multiple major ASCVD events or 1 major ASCVD event and multiple high-risk conditions.2 Major ASCVD events include acute coronary syndrome within 12 months, history of myocardial infarction (MI) or ischemic stroke, and symptomatic peripheral arterial disease (ie, claudication with ankle-brachial index < 0.85 or previous revascularization or amputation). Factors for being considered high risk include age > 65 years, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, history of prior coronary artery bypass surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention outside the major ASCVD events, diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] 15-59 mL/min/1.73 m2), current smoking, persistently elevated LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) levels despite maximally tolerated statin therapy and ezetimibe, and history of congestive heart failure.2 For these patients, statin therapy alone may not achieve LDL goal.

The ACC recommends ezetimibe as the initial nonstatin therapy in patients who are not at their goal LDL.2 Ezetimibe works by inhibiting Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 protein, which causes reduced cholesterol absorption in the small intestine.2,3 Previous studies have shown the benefit of ezetimibe for LDL reduction and ASCVD prevention.4-7 The 2015 IMPROVE-IT study found the combination of simvastatin and ezetimibe resulted in a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular events than simvastatin monotherapy. IMPROVE-IT also reported a further clinical benefit when lower LDL targets (ie, < 55 mg/dL) are achieved, which aligns with the expert consensus pathway recommendations for a lower LDL goal for very high-risk patients.2,5

The RACING trial found that treatment with a moderate-intensity statin and ezetimibe was noninferior to treatment with a high-intensity statin for the primary outcome of occurrence of cardiovascular death, major cardiovascular events, or nonfatal stroke within 3 years. The combination of moderate-intensity statin and ezetimibe achieved lower LDL-C levels and lower incidence of drug intolerance compared to high intensity statin monotherapy.6 The SHARP-CKD study assessed major atherosclerotic events in patients with CKD who had no history of MI or coronary revascularization. The study found that lowering LDL-C with the combination of simvastatin plus ezetimibe safely reduces the risk of major atherosclerotic events in a wide range of patients with CKD.7

Lastly, the 2019 EWTOPIA 75 study found that ezetimibe noted a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of the composite of sudden cardiac death, MI, coronary revascularization, or stroke compared to placebo. Ezetimibe showed benefits in preventing ASCVD events independently of statin therapy.8 These clinical trials provided evidence for the efficacy of ezetimibe for secondary or primary prevention of ASCVD, patients with CKD, and patients who are not at their LDL goal despite maximally tolerated statin therapy.

Reductions in LDL levels with ezetimibe are reported to be 15% to 19% for monotherapy and 13% to 25% when used in combination with a statin.4 Given that the ACC now recommends lower LDL goals, patients may need additional lowering despite taking maximally tolerated statin therapy.2 Additionally, the package insert for ezetimibe reports increased area under the curve (AUC) values of ezetimibe and its metabolites in patients with severe renal disease. It is anticipated that ezetimibe may show an increased reduction of LDL and non-HDL, but there may also be an increased risk for muscle-related AEs.3

This quality-assurance quality improvement project investigated the use of ezetimibe in patients with CKD to determine whether there is further LDL and non-HDL reduction in this patient population. It sought to determine the LDL and non-HDL percentage reduction in patients with and without CKD at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WBVAMC) and whether there is an increased risk for muscle-related AEs. Determining the percentage reduction of LDL and non-HDL within this population can help increase use of ezetimibe in patients not at their LDL or non-HDL goal or for those patients unable to tolerate statin therapy.

Methods

This single-center retrospective chart review investigated patients prescribed ezetimibe by a patient aligned care team (PACT) pharmacist at WBVAMC between September 1, 2021, and September 1, 2023. This project was determined to be nonresearch by the Veterans Integrated Service Network 4 multisite institutional review board. Patients were excluded from the review if they started taking ezetimibe outside of the prespecified time frame, if ezetimibe was initiated by a non-WBVAMC PACT pharmacist, or if there was no follow-up lipid panel obtained within 6 months of initiation of ezetimibe.

The primary outcomes were to determine the percentage mean change in LDL and non-HDL reduction and the incidence of muscle-related AEs after initiation of ezetimibe in patients without CKD. The secondary outcomes were to determine the percentage mean change in LDL and non-HDL levels and the incidence of muscle-related AEs after initiation of ezetimibe in patients with CKD. For this study, CKD was defined as a patient having an eGFR 15 to 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Non-HDL is the combination of LDL-C and very LDL-C and represents all potentially atherogenic particles. The 2022 Expert Consensus Pathway included non-HDL goals in addition to LDL goals.2 Non-HDL cholesterol levels can be used for patients with elevated triglycerides where LDL levels may not be as accurate. To account for instances of elevated triglycerides, this study assessed changes in both LDL and non-HDL levels.

Data were collected from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and recorded in a spreadsheet. Collected data included age, sex, race, concomitant cholesterol-lowering medications (statin, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 [PCSK9] inhibitor, bempedoic acid, fish oil, niacin, bile acid sequestrants, and fibrates), baseline lipid panel, lipid panel within 6 months of ezetimibe initiation, and eGFR level. If the patient’s LDL or non-HDL levels worsened on the follow-up lipid panel, their baseline LDL and non-HDL levels were used to calculate the percentage reduction; thus, the percentage reduction would be 0%. This strategy was used in prior research, notably the IMPROVE-IT and SHARP-CKD trials.

Ezetimibe 5 mg once daily was used in this study based on a 2008 VA study that evaluated the use of ezetimibe 5 mg vs ezetimibe 10 mg and the percentage reduction of LDL with each dose. The study found no significant difference between the 5 mg and 10 mg dose.9 Most patients included in this study received the 5 mg dose.

Results

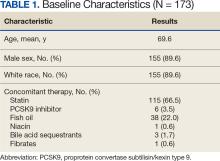

This retrospective chart review consisted of 173 patients, 137 (79.2%) without CKD and 36 (20.8%) with CKD at baseline. The mean age was 69.6 years, 155 (89.6%) patients were male, and 18 (10.4%) were female. There were 164 concomitant medications, including 115 patients prescribed a statin and 38 patients prescribed fish oil (Table 1).

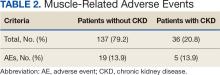

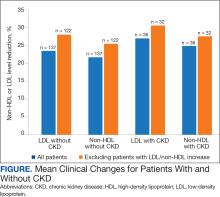

Patients without CKD had mean reductions in LDL levels of 23.5% and non-HDL levels of 21.7% (Figure). Patients who had an increase in LDL and non-HDL levels were excluded to control for potential confounding factors such as dietary changes, discontinuation of ezetimibe therapy, nonadherence to ezetimibe, and medication changes that impacted follow-up laboratory tests such as discontinuation of a statin. Fifteen patients experienced an increase in LDL or non-HDL levels. After excluding these patients, those without CKD had a mean reduction in LDL levels of 28.0% and non-HDL levels of 25.5%. Nineteen (13.9%) patients without CKD experienced a muscle-related AE (Table 2). One patient discontinued ezetimibe and statin use following a Lyme disease diagnosis due to concerns over potential muscle-related AEs.

Patients with CKD had a mean reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels of 27.0% and 24.8%, respectively. Patients with an increase in LDL or non-HDL levels were also excluded to help control for potential confounding factors. After excluding 4 patients with increased LDL and non-HDL levels, the mean reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels was 30.5% and 27.5%, respectively. Five (13.9%) patients with CKD experienced muscle-related AEs thought to be due to ezetimibe. Other AEs (eg, urticaria, diarrhea, reflux, dizziness, headache, upset stomach) were reported that led to discontinuation of ezetimibe, but only muscle-related AEs were analyzed.

Discussion

This retrospective chart review found larger reductions in LDL and non-HDL levels for patients with CKD than reported in the literature.4 Based on the findings that indicate a greater cholesterol reduction with ezetimibe, the results suggest an underutilization of ezetimibe in clinical practice, which may be due to clinicians favoring statin therapy and overlooking ezetimibe as a viable option based on recommendation in earlier guidelines. The 2022 guidelines transitioned from a statin focus to a focus on LDL targets and goals.2

According to the ACC, there is evidence to support a direct relationship between LDL-C levels, atherosclerosis progression, and ASCVD event risk.2 Absolute LDL-C level reduction is directly associated with ASCVD risk reduction which supports the LDL hypothesis. There appears to be no specific LDL-C level below which benefit ceases.2 This suggests that lower LDL-C targets (< 55 mg/dL) should be used when clinically indicated. Many patients are either unable to reach their goal LDL levels with statin monotherapy or are unable to tolerate statin therapy at higher doses, which may require additional pharmacotherapy to reach goal LDL-C. The ACC expert consensus pathway recommends ezetimibe as the initial add-on treatment to statins.2 The RACING trial showed the benefit of adding ezetimibe to a moderate-intensity statin vs increasing to a high-intensity statin dose. This trial found patients had lower LDL levels and lower rates of intolerances, which further supports ezetimibe use.6

This quality improvement project assessed LDL and non-HDL level reduction in patients with CKD. As anticipated, there was greater reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels seen in patients with CKD. The SHARP-CKD trial also found reductions in LDL levels with ezetimibe in patients with CKD.7 Given the reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels with ezetimibe in patients with or without CKD, add-on therapy of ezetimibe should be recommended for patients who do not achieve their LDL goals with statin therapy or for patients who intolerant to statin therapy.

The ezetimibe package insert reports myalgias incidence to be < 5% in patients and research has shown up to a 20% incidence of muscle-related AEs with statin therapy.3,10 Based on the package information reporting increased AUC values of ezetimibe and its metabolites in patients with severe renal disease, it was anticipated there may be an increased risk of muscle-related AEs in patients with CKD.3 However, this study found the same incidence of muscle-related AEs in patients with and without CKD. Previous research on statin-intolerant patients found the incidence of muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe to be 23.0% and 28.8%.11,12 This increased incidence of muscle-related AEs may be the result of including patients with a history of statin intolerance. Collectively, data from clinical trials and this study indicate that patients with prior intolerances to statins appear to have a higher likelihood of developing a muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe.11,12 Clinicians and patients should be educated on the potential for these AEs and be aware that the likelihood may be greater if there is a history of statin intolerance. To our knowledge, this was the first study to evaluate muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe in patients with and without CKD.

Limitations

This retrospective chart review was performed over a prespecified period and only patients initiated on ezetimibe by a PACT pharmacist were included. This study did not assess the percentage of LDL reduction in patients on concomitant statins vs those who were not on concomitant statins. The study only included 173 patients. Additionally, the study was primarily composed of White men and may not be representative of other populations. In addition, veterans may not be representative of the general population given their high comorbidity burden and other exposures. Some reported muscle-related AEs associated with ezetimibe may be attributed to the nocebo effect.

Conclusions

The results of this retrospective chart review suggest there may be a larger mean reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels seen with ezetimibe therapy than reported within the literature. There was a larger mean reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels in patients with CKD than in patients without CKD. Additionally, there were the same rates of muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe therapy in patients with and without CKD. The rates of muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe therapy were higher than reported in the medication’s package insert, but lower than reported in literature that included statin-intolerant patients. These results indicate there may be a benefit to an increase in use of ezetimibe in clinical practice due to its increased effectiveness and safety in patients with and without CKD. Ultimately, this can help patients achieve their LDL goals as recommended by ACC clinical practice guidelines.

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(24) e285-e350. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003

Writing Committee, Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, et al. 2022 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the role of nonstatin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(14):1366-1418. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.07.006

US Food and Drug Administration. Ezetimibe. 2007. Accessed April 1, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/021445s019lbl.pdf

Singh A, Cho LS. Nonstatin therapy to reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and improve cardiovascular outcomes. Cleve Clin J Med. 2024;91(1):53-63. doi:10.3949/ccjm.91a.23058

Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2387-2397. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1410489

Kim B, Hong S, Lee Y, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe combination therapy versus high-intensity statin monotherapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (RACING): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10349):380-390. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00916-3

Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9784):2181-2192. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60739-3

Ouchi Y, Sasaki J, Arai H, et al. Ezetimibe lipid-lowering trial on prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in 75 or older (EWTOPIA 75): a randomized, controlled trial. Circulation. 2019;140:992-1003. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.039415

Baruch L, Gupta B, Lieberman-Blum SS, Agarwal S, Eng C. Ezetimibe 5 and 10 mg for lowering LDL-C: potential billion-dollar savings with improved tolerability. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(10):637-641. https://www.ajmc.com/view/oct08-3644p637-641

Stroes ES, Thompson PD, Corsini A, et al. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: impact on statin therapy-European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel Statement on Assessment, Aetiology and Management. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(17):1012-1022. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv043

Stroes E, Colquhoun D, Sullivan D, et al. Anti-PCSK9 antibody effectively lowers cholesterol in patients with statin intolerance: the GAUSS-2 randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial of evolocumab. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(23):2541-2548. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.019

Nissen SE, Stroes E, Dent-Acosta RE, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of evolocumab vs ezetimibe in patients with muscle-related statin intolerance: the GAUSS-3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1580-1590. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.3608

Statins are widely used to reduce low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and non-high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels for the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).1 However, despite maximally tolerated statin therapy, many patients may not reach their LDL and non-HDL goals. Some patients may experience adverse events (AEs), particularly muscle-related AEs, which can limit the use of these medications.

The 2022 American College of Cardiology (ACC) expert consensus pathway recommends a goal LDL of < 55 mg/dL in very high-risk patients, defined as those with a history of multiple major ASCVD events or 1 major ASCVD event and multiple high-risk conditions.2 Major ASCVD events include acute coronary syndrome within 12 months, history of myocardial infarction (MI) or ischemic stroke, and symptomatic peripheral arterial disease (ie, claudication with ankle-brachial index < 0.85 or previous revascularization or amputation). Factors for being considered high risk include age > 65 years, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, history of prior coronary artery bypass surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention outside the major ASCVD events, diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] 15-59 mL/min/1.73 m2), current smoking, persistently elevated LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) levels despite maximally tolerated statin therapy and ezetimibe, and history of congestive heart failure.2 For these patients, statin therapy alone may not achieve LDL goal.

The ACC recommends ezetimibe as the initial nonstatin therapy in patients who are not at their goal LDL.2 Ezetimibe works by inhibiting Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 protein, which causes reduced cholesterol absorption in the small intestine.2,3 Previous studies have shown the benefit of ezetimibe for LDL reduction and ASCVD prevention.4-7 The 2015 IMPROVE-IT study found the combination of simvastatin and ezetimibe resulted in a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular events than simvastatin monotherapy. IMPROVE-IT also reported a further clinical benefit when lower LDL targets (ie, < 55 mg/dL) are achieved, which aligns with the expert consensus pathway recommendations for a lower LDL goal for very high-risk patients.2,5

The RACING trial found that treatment with a moderate-intensity statin and ezetimibe was noninferior to treatment with a high-intensity statin for the primary outcome of occurrence of cardiovascular death, major cardiovascular events, or nonfatal stroke within 3 years. The combination of moderate-intensity statin and ezetimibe achieved lower LDL-C levels and lower incidence of drug intolerance compared to high intensity statin monotherapy.6 The SHARP-CKD study assessed major atherosclerotic events in patients with CKD who had no history of MI or coronary revascularization. The study found that lowering LDL-C with the combination of simvastatin plus ezetimibe safely reduces the risk of major atherosclerotic events in a wide range of patients with CKD.7

Lastly, the 2019 EWTOPIA 75 study found that ezetimibe noted a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of the composite of sudden cardiac death, MI, coronary revascularization, or stroke compared to placebo. Ezetimibe showed benefits in preventing ASCVD events independently of statin therapy.8 These clinical trials provided evidence for the efficacy of ezetimibe for secondary or primary prevention of ASCVD, patients with CKD, and patients who are not at their LDL goal despite maximally tolerated statin therapy.

Reductions in LDL levels with ezetimibe are reported to be 15% to 19% for monotherapy and 13% to 25% when used in combination with a statin.4 Given that the ACC now recommends lower LDL goals, patients may need additional lowering despite taking maximally tolerated statin therapy.2 Additionally, the package insert for ezetimibe reports increased area under the curve (AUC) values of ezetimibe and its metabolites in patients with severe renal disease. It is anticipated that ezetimibe may show an increased reduction of LDL and non-HDL, but there may also be an increased risk for muscle-related AEs.3

This quality-assurance quality improvement project investigated the use of ezetimibe in patients with CKD to determine whether there is further LDL and non-HDL reduction in this patient population. It sought to determine the LDL and non-HDL percentage reduction in patients with and without CKD at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WBVAMC) and whether there is an increased risk for muscle-related AEs. Determining the percentage reduction of LDL and non-HDL within this population can help increase use of ezetimibe in patients not at their LDL or non-HDL goal or for those patients unable to tolerate statin therapy.

Methods

This single-center retrospective chart review investigated patients prescribed ezetimibe by a patient aligned care team (PACT) pharmacist at WBVAMC between September 1, 2021, and September 1, 2023. This project was determined to be nonresearch by the Veterans Integrated Service Network 4 multisite institutional review board. Patients were excluded from the review if they started taking ezetimibe outside of the prespecified time frame, if ezetimibe was initiated by a non-WBVAMC PACT pharmacist, or if there was no follow-up lipid panel obtained within 6 months of initiation of ezetimibe.

The primary outcomes were to determine the percentage mean change in LDL and non-HDL reduction and the incidence of muscle-related AEs after initiation of ezetimibe in patients without CKD. The secondary outcomes were to determine the percentage mean change in LDL and non-HDL levels and the incidence of muscle-related AEs after initiation of ezetimibe in patients with CKD. For this study, CKD was defined as a patient having an eGFR 15 to 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Non-HDL is the combination of LDL-C and very LDL-C and represents all potentially atherogenic particles. The 2022 Expert Consensus Pathway included non-HDL goals in addition to LDL goals.2 Non-HDL cholesterol levels can be used for patients with elevated triglycerides where LDL levels may not be as accurate. To account for instances of elevated triglycerides, this study assessed changes in both LDL and non-HDL levels.

Data were collected from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and recorded in a spreadsheet. Collected data included age, sex, race, concomitant cholesterol-lowering medications (statin, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 [PCSK9] inhibitor, bempedoic acid, fish oil, niacin, bile acid sequestrants, and fibrates), baseline lipid panel, lipid panel within 6 months of ezetimibe initiation, and eGFR level. If the patient’s LDL or non-HDL levels worsened on the follow-up lipid panel, their baseline LDL and non-HDL levels were used to calculate the percentage reduction; thus, the percentage reduction would be 0%. This strategy was used in prior research, notably the IMPROVE-IT and SHARP-CKD trials.

Ezetimibe 5 mg once daily was used in this study based on a 2008 VA study that evaluated the use of ezetimibe 5 mg vs ezetimibe 10 mg and the percentage reduction of LDL with each dose. The study found no significant difference between the 5 mg and 10 mg dose.9 Most patients included in this study received the 5 mg dose.

Results

This retrospective chart review consisted of 173 patients, 137 (79.2%) without CKD and 36 (20.8%) with CKD at baseline. The mean age was 69.6 years, 155 (89.6%) patients were male, and 18 (10.4%) were female. There were 164 concomitant medications, including 115 patients prescribed a statin and 38 patients prescribed fish oil (Table 1).

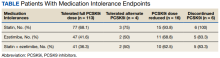

Patients without CKD had mean reductions in LDL levels of 23.5% and non-HDL levels of 21.7% (Figure). Patients who had an increase in LDL and non-HDL levels were excluded to control for potential confounding factors such as dietary changes, discontinuation of ezetimibe therapy, nonadherence to ezetimibe, and medication changes that impacted follow-up laboratory tests such as discontinuation of a statin. Fifteen patients experienced an increase in LDL or non-HDL levels. After excluding these patients, those without CKD had a mean reduction in LDL levels of 28.0% and non-HDL levels of 25.5%. Nineteen (13.9%) patients without CKD experienced a muscle-related AE (Table 2). One patient discontinued ezetimibe and statin use following a Lyme disease diagnosis due to concerns over potential muscle-related AEs.

Patients with CKD had a mean reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels of 27.0% and 24.8%, respectively. Patients with an increase in LDL or non-HDL levels were also excluded to help control for potential confounding factors. After excluding 4 patients with increased LDL and non-HDL levels, the mean reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels was 30.5% and 27.5%, respectively. Five (13.9%) patients with CKD experienced muscle-related AEs thought to be due to ezetimibe. Other AEs (eg, urticaria, diarrhea, reflux, dizziness, headache, upset stomach) were reported that led to discontinuation of ezetimibe, but only muscle-related AEs were analyzed.

Discussion

This retrospective chart review found larger reductions in LDL and non-HDL levels for patients with CKD than reported in the literature.4 Based on the findings that indicate a greater cholesterol reduction with ezetimibe, the results suggest an underutilization of ezetimibe in clinical practice, which may be due to clinicians favoring statin therapy and overlooking ezetimibe as a viable option based on recommendation in earlier guidelines. The 2022 guidelines transitioned from a statin focus to a focus on LDL targets and goals.2

According to the ACC, there is evidence to support a direct relationship between LDL-C levels, atherosclerosis progression, and ASCVD event risk.2 Absolute LDL-C level reduction is directly associated with ASCVD risk reduction which supports the LDL hypothesis. There appears to be no specific LDL-C level below which benefit ceases.2 This suggests that lower LDL-C targets (< 55 mg/dL) should be used when clinically indicated. Many patients are either unable to reach their goal LDL levels with statin monotherapy or are unable to tolerate statin therapy at higher doses, which may require additional pharmacotherapy to reach goal LDL-C. The ACC expert consensus pathway recommends ezetimibe as the initial add-on treatment to statins.2 The RACING trial showed the benefit of adding ezetimibe to a moderate-intensity statin vs increasing to a high-intensity statin dose. This trial found patients had lower LDL levels and lower rates of intolerances, which further supports ezetimibe use.6

This quality improvement project assessed LDL and non-HDL level reduction in patients with CKD. As anticipated, there was greater reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels seen in patients with CKD. The SHARP-CKD trial also found reductions in LDL levels with ezetimibe in patients with CKD.7 Given the reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels with ezetimibe in patients with or without CKD, add-on therapy of ezetimibe should be recommended for patients who do not achieve their LDL goals with statin therapy or for patients who intolerant to statin therapy.

The ezetimibe package insert reports myalgias incidence to be < 5% in patients and research has shown up to a 20% incidence of muscle-related AEs with statin therapy.3,10 Based on the package information reporting increased AUC values of ezetimibe and its metabolites in patients with severe renal disease, it was anticipated there may be an increased risk of muscle-related AEs in patients with CKD.3 However, this study found the same incidence of muscle-related AEs in patients with and without CKD. Previous research on statin-intolerant patients found the incidence of muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe to be 23.0% and 28.8%.11,12 This increased incidence of muscle-related AEs may be the result of including patients with a history of statin intolerance. Collectively, data from clinical trials and this study indicate that patients with prior intolerances to statins appear to have a higher likelihood of developing a muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe.11,12 Clinicians and patients should be educated on the potential for these AEs and be aware that the likelihood may be greater if there is a history of statin intolerance. To our knowledge, this was the first study to evaluate muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe in patients with and without CKD.

Limitations

This retrospective chart review was performed over a prespecified period and only patients initiated on ezetimibe by a PACT pharmacist were included. This study did not assess the percentage of LDL reduction in patients on concomitant statins vs those who were not on concomitant statins. The study only included 173 patients. Additionally, the study was primarily composed of White men and may not be representative of other populations. In addition, veterans may not be representative of the general population given their high comorbidity burden and other exposures. Some reported muscle-related AEs associated with ezetimibe may be attributed to the nocebo effect.

Conclusions

The results of this retrospective chart review suggest there may be a larger mean reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels seen with ezetimibe therapy than reported within the literature. There was a larger mean reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels in patients with CKD than in patients without CKD. Additionally, there were the same rates of muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe therapy in patients with and without CKD. The rates of muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe therapy were higher than reported in the medication’s package insert, but lower than reported in literature that included statin-intolerant patients. These results indicate there may be a benefit to an increase in use of ezetimibe in clinical practice due to its increased effectiveness and safety in patients with and without CKD. Ultimately, this can help patients achieve their LDL goals as recommended by ACC clinical practice guidelines.

Statins are widely used to reduce low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and non-high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels for the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).1 However, despite maximally tolerated statin therapy, many patients may not reach their LDL and non-HDL goals. Some patients may experience adverse events (AEs), particularly muscle-related AEs, which can limit the use of these medications.

The 2022 American College of Cardiology (ACC) expert consensus pathway recommends a goal LDL of < 55 mg/dL in very high-risk patients, defined as those with a history of multiple major ASCVD events or 1 major ASCVD event and multiple high-risk conditions.2 Major ASCVD events include acute coronary syndrome within 12 months, history of myocardial infarction (MI) or ischemic stroke, and symptomatic peripheral arterial disease (ie, claudication with ankle-brachial index < 0.85 or previous revascularization or amputation). Factors for being considered high risk include age > 65 years, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, history of prior coronary artery bypass surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention outside the major ASCVD events, diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] 15-59 mL/min/1.73 m2), current smoking, persistently elevated LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) levels despite maximally tolerated statin therapy and ezetimibe, and history of congestive heart failure.2 For these patients, statin therapy alone may not achieve LDL goal.

The ACC recommends ezetimibe as the initial nonstatin therapy in patients who are not at their goal LDL.2 Ezetimibe works by inhibiting Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 protein, which causes reduced cholesterol absorption in the small intestine.2,3 Previous studies have shown the benefit of ezetimibe for LDL reduction and ASCVD prevention.4-7 The 2015 IMPROVE-IT study found the combination of simvastatin and ezetimibe resulted in a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular events than simvastatin monotherapy. IMPROVE-IT also reported a further clinical benefit when lower LDL targets (ie, < 55 mg/dL) are achieved, which aligns with the expert consensus pathway recommendations for a lower LDL goal for very high-risk patients.2,5

The RACING trial found that treatment with a moderate-intensity statin and ezetimibe was noninferior to treatment with a high-intensity statin for the primary outcome of occurrence of cardiovascular death, major cardiovascular events, or nonfatal stroke within 3 years. The combination of moderate-intensity statin and ezetimibe achieved lower LDL-C levels and lower incidence of drug intolerance compared to high intensity statin monotherapy.6 The SHARP-CKD study assessed major atherosclerotic events in patients with CKD who had no history of MI or coronary revascularization. The study found that lowering LDL-C with the combination of simvastatin plus ezetimibe safely reduces the risk of major atherosclerotic events in a wide range of patients with CKD.7

Lastly, the 2019 EWTOPIA 75 study found that ezetimibe noted a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of the composite of sudden cardiac death, MI, coronary revascularization, or stroke compared to placebo. Ezetimibe showed benefits in preventing ASCVD events independently of statin therapy.8 These clinical trials provided evidence for the efficacy of ezetimibe for secondary or primary prevention of ASCVD, patients with CKD, and patients who are not at their LDL goal despite maximally tolerated statin therapy.

Reductions in LDL levels with ezetimibe are reported to be 15% to 19% for monotherapy and 13% to 25% when used in combination with a statin.4 Given that the ACC now recommends lower LDL goals, patients may need additional lowering despite taking maximally tolerated statin therapy.2 Additionally, the package insert for ezetimibe reports increased area under the curve (AUC) values of ezetimibe and its metabolites in patients with severe renal disease. It is anticipated that ezetimibe may show an increased reduction of LDL and non-HDL, but there may also be an increased risk for muscle-related AEs.3

This quality-assurance quality improvement project investigated the use of ezetimibe in patients with CKD to determine whether there is further LDL and non-HDL reduction in this patient population. It sought to determine the LDL and non-HDL percentage reduction in patients with and without CKD at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WBVAMC) and whether there is an increased risk for muscle-related AEs. Determining the percentage reduction of LDL and non-HDL within this population can help increase use of ezetimibe in patients not at their LDL or non-HDL goal or for those patients unable to tolerate statin therapy.

Methods

This single-center retrospective chart review investigated patients prescribed ezetimibe by a patient aligned care team (PACT) pharmacist at WBVAMC between September 1, 2021, and September 1, 2023. This project was determined to be nonresearch by the Veterans Integrated Service Network 4 multisite institutional review board. Patients were excluded from the review if they started taking ezetimibe outside of the prespecified time frame, if ezetimibe was initiated by a non-WBVAMC PACT pharmacist, or if there was no follow-up lipid panel obtained within 6 months of initiation of ezetimibe.

The primary outcomes were to determine the percentage mean change in LDL and non-HDL reduction and the incidence of muscle-related AEs after initiation of ezetimibe in patients without CKD. The secondary outcomes were to determine the percentage mean change in LDL and non-HDL levels and the incidence of muscle-related AEs after initiation of ezetimibe in patients with CKD. For this study, CKD was defined as a patient having an eGFR 15 to 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Non-HDL is the combination of LDL-C and very LDL-C and represents all potentially atherogenic particles. The 2022 Expert Consensus Pathway included non-HDL goals in addition to LDL goals.2 Non-HDL cholesterol levels can be used for patients with elevated triglycerides where LDL levels may not be as accurate. To account for instances of elevated triglycerides, this study assessed changes in both LDL and non-HDL levels.

Data were collected from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and recorded in a spreadsheet. Collected data included age, sex, race, concomitant cholesterol-lowering medications (statin, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 [PCSK9] inhibitor, bempedoic acid, fish oil, niacin, bile acid sequestrants, and fibrates), baseline lipid panel, lipid panel within 6 months of ezetimibe initiation, and eGFR level. If the patient’s LDL or non-HDL levels worsened on the follow-up lipid panel, their baseline LDL and non-HDL levels were used to calculate the percentage reduction; thus, the percentage reduction would be 0%. This strategy was used in prior research, notably the IMPROVE-IT and SHARP-CKD trials.

Ezetimibe 5 mg once daily was used in this study based on a 2008 VA study that evaluated the use of ezetimibe 5 mg vs ezetimibe 10 mg and the percentage reduction of LDL with each dose. The study found no significant difference between the 5 mg and 10 mg dose.9 Most patients included in this study received the 5 mg dose.

Results

This retrospective chart review consisted of 173 patients, 137 (79.2%) without CKD and 36 (20.8%) with CKD at baseline. The mean age was 69.6 years, 155 (89.6%) patients were male, and 18 (10.4%) were female. There were 164 concomitant medications, including 115 patients prescribed a statin and 38 patients prescribed fish oil (Table 1).

Patients without CKD had mean reductions in LDL levels of 23.5% and non-HDL levels of 21.7% (Figure). Patients who had an increase in LDL and non-HDL levels were excluded to control for potential confounding factors such as dietary changes, discontinuation of ezetimibe therapy, nonadherence to ezetimibe, and medication changes that impacted follow-up laboratory tests such as discontinuation of a statin. Fifteen patients experienced an increase in LDL or non-HDL levels. After excluding these patients, those without CKD had a mean reduction in LDL levels of 28.0% and non-HDL levels of 25.5%. Nineteen (13.9%) patients without CKD experienced a muscle-related AE (Table 2). One patient discontinued ezetimibe and statin use following a Lyme disease diagnosis due to concerns over potential muscle-related AEs.

Patients with CKD had a mean reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels of 27.0% and 24.8%, respectively. Patients with an increase in LDL or non-HDL levels were also excluded to help control for potential confounding factors. After excluding 4 patients with increased LDL and non-HDL levels, the mean reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels was 30.5% and 27.5%, respectively. Five (13.9%) patients with CKD experienced muscle-related AEs thought to be due to ezetimibe. Other AEs (eg, urticaria, diarrhea, reflux, dizziness, headache, upset stomach) were reported that led to discontinuation of ezetimibe, but only muscle-related AEs were analyzed.

Discussion

This retrospective chart review found larger reductions in LDL and non-HDL levels for patients with CKD than reported in the literature.4 Based on the findings that indicate a greater cholesterol reduction with ezetimibe, the results suggest an underutilization of ezetimibe in clinical practice, which may be due to clinicians favoring statin therapy and overlooking ezetimibe as a viable option based on recommendation in earlier guidelines. The 2022 guidelines transitioned from a statin focus to a focus on LDL targets and goals.2

According to the ACC, there is evidence to support a direct relationship between LDL-C levels, atherosclerosis progression, and ASCVD event risk.2 Absolute LDL-C level reduction is directly associated with ASCVD risk reduction which supports the LDL hypothesis. There appears to be no specific LDL-C level below which benefit ceases.2 This suggests that lower LDL-C targets (< 55 mg/dL) should be used when clinically indicated. Many patients are either unable to reach their goal LDL levels with statin monotherapy or are unable to tolerate statin therapy at higher doses, which may require additional pharmacotherapy to reach goal LDL-C. The ACC expert consensus pathway recommends ezetimibe as the initial add-on treatment to statins.2 The RACING trial showed the benefit of adding ezetimibe to a moderate-intensity statin vs increasing to a high-intensity statin dose. This trial found patients had lower LDL levels and lower rates of intolerances, which further supports ezetimibe use.6

This quality improvement project assessed LDL and non-HDL level reduction in patients with CKD. As anticipated, there was greater reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels seen in patients with CKD. The SHARP-CKD trial also found reductions in LDL levels with ezetimibe in patients with CKD.7 Given the reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels with ezetimibe in patients with or without CKD, add-on therapy of ezetimibe should be recommended for patients who do not achieve their LDL goals with statin therapy or for patients who intolerant to statin therapy.

The ezetimibe package insert reports myalgias incidence to be < 5% in patients and research has shown up to a 20% incidence of muscle-related AEs with statin therapy.3,10 Based on the package information reporting increased AUC values of ezetimibe and its metabolites in patients with severe renal disease, it was anticipated there may be an increased risk of muscle-related AEs in patients with CKD.3 However, this study found the same incidence of muscle-related AEs in patients with and without CKD. Previous research on statin-intolerant patients found the incidence of muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe to be 23.0% and 28.8%.11,12 This increased incidence of muscle-related AEs may be the result of including patients with a history of statin intolerance. Collectively, data from clinical trials and this study indicate that patients with prior intolerances to statins appear to have a higher likelihood of developing a muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe.11,12 Clinicians and patients should be educated on the potential for these AEs and be aware that the likelihood may be greater if there is a history of statin intolerance. To our knowledge, this was the first study to evaluate muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe in patients with and without CKD.

Limitations

This retrospective chart review was performed over a prespecified period and only patients initiated on ezetimibe by a PACT pharmacist were included. This study did not assess the percentage of LDL reduction in patients on concomitant statins vs those who were not on concomitant statins. The study only included 173 patients. Additionally, the study was primarily composed of White men and may not be representative of other populations. In addition, veterans may not be representative of the general population given their high comorbidity burden and other exposures. Some reported muscle-related AEs associated with ezetimibe may be attributed to the nocebo effect.

Conclusions

The results of this retrospective chart review suggest there may be a larger mean reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels seen with ezetimibe therapy than reported within the literature. There was a larger mean reduction in LDL and non-HDL levels in patients with CKD than in patients without CKD. Additionally, there were the same rates of muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe therapy in patients with and without CKD. The rates of muscle-related AEs with ezetimibe therapy were higher than reported in the medication’s package insert, but lower than reported in literature that included statin-intolerant patients. These results indicate there may be a benefit to an increase in use of ezetimibe in clinical practice due to its increased effectiveness and safety in patients with and without CKD. Ultimately, this can help patients achieve their LDL goals as recommended by ACC clinical practice guidelines.

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(24) e285-e350. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003

Writing Committee, Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, et al. 2022 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the role of nonstatin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(14):1366-1418. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.07.006

US Food and Drug Administration. Ezetimibe. 2007. Accessed April 1, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/021445s019lbl.pdf

Singh A, Cho LS. Nonstatin therapy to reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and improve cardiovascular outcomes. Cleve Clin J Med. 2024;91(1):53-63. doi:10.3949/ccjm.91a.23058

Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2387-2397. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1410489

Kim B, Hong S, Lee Y, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe combination therapy versus high-intensity statin monotherapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (RACING): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10349):380-390. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00916-3

Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9784):2181-2192. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60739-3

Ouchi Y, Sasaki J, Arai H, et al. Ezetimibe lipid-lowering trial on prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in 75 or older (EWTOPIA 75): a randomized, controlled trial. Circulation. 2019;140:992-1003. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.039415

Baruch L, Gupta B, Lieberman-Blum SS, Agarwal S, Eng C. Ezetimibe 5 and 10 mg for lowering LDL-C: potential billion-dollar savings with improved tolerability. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(10):637-641. https://www.ajmc.com/view/oct08-3644p637-641

Stroes ES, Thompson PD, Corsini A, et al. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: impact on statin therapy-European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel Statement on Assessment, Aetiology and Management. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(17):1012-1022. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv043

Stroes E, Colquhoun D, Sullivan D, et al. Anti-PCSK9 antibody effectively lowers cholesterol in patients with statin intolerance: the GAUSS-2 randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial of evolocumab. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(23):2541-2548. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.019

Nissen SE, Stroes E, Dent-Acosta RE, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of evolocumab vs ezetimibe in patients with muscle-related statin intolerance: the GAUSS-3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1580-1590. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.3608

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(24) e285-e350. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003

Writing Committee, Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, et al. 2022 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the role of nonstatin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(14):1366-1418. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.07.006

US Food and Drug Administration. Ezetimibe. 2007. Accessed April 1, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/021445s019lbl.pdf

Singh A, Cho LS. Nonstatin therapy to reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and improve cardiovascular outcomes. Cleve Clin J Med. 2024;91(1):53-63. doi:10.3949/ccjm.91a.23058

Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2387-2397. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1410489

Kim B, Hong S, Lee Y, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of moderate-intensity statin with ezetimibe combination therapy versus high-intensity statin monotherapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (RACING): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10349):380-390. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00916-3

Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9784):2181-2192. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60739-3

Ouchi Y, Sasaki J, Arai H, et al. Ezetimibe lipid-lowering trial on prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in 75 or older (EWTOPIA 75): a randomized, controlled trial. Circulation. 2019;140:992-1003. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.039415

Baruch L, Gupta B, Lieberman-Blum SS, Agarwal S, Eng C. Ezetimibe 5 and 10 mg for lowering LDL-C: potential billion-dollar savings with improved tolerability. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(10):637-641. https://www.ajmc.com/view/oct08-3644p637-641

Stroes ES, Thompson PD, Corsini A, et al. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: impact on statin therapy-European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel Statement on Assessment, Aetiology and Management. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(17):1012-1022. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv043

Stroes E, Colquhoun D, Sullivan D, et al. Anti-PCSK9 antibody effectively lowers cholesterol in patients with statin intolerance: the GAUSS-2 randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial of evolocumab. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(23):2541-2548. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.019

Nissen SE, Stroes E, Dent-Acosta RE, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of evolocumab vs ezetimibe in patients with muscle-related statin intolerance: the GAUSS-3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1580-1590. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.3608

Reducing or Discontinuing Insulin or Sulfonylurea When Initiating a Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Agonist

Hypoglycemia and weight gain are well-known adverse effects that can result from insulin and sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1,2 Insulin and sulfonylurea medications can cause additional weight gain in patients who are overweight or obese, which can increase the burden of diabetes therapy with added medications, raise the risk of hypoglycemia complications, and raise atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors.3 Although increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option health care practitioners or pharmacists have, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in older adults, such as the veteran population, which could lead to complications, such as falls.2

Previous studies focusing on hypoglycemic events in patients with T2DM showed that glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist monotherapy has a low incidence of a hypoglycemic events. However, when a GLP-1 agonist is combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, patients have an increased chance of a hypoglycemic event.3-8 According to the prescribing information for semaglutide, 1.6% to 3.8% of patients on a GLP-1 agonist monotherapy reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event (blood glucose ≤ 70 mg/dL), based on semaglutide dosing. 9 Patients on combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist and basal insulin and a GLP-1 agonist and a sulfonylurea reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event ranging from 16.7% to 29.8% and 17.3% to 24.4%, respectively.9 The incidences of hypoglycemia thus dramatically increase with combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist plus insulin or a sulfonylurea.

When adding a GLP-1 agonist to insulin or a sulfonylurea, clinicians must be mindful of the increased risk of hypoglycemia. Per the warnings and precautions in the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists, concomitant use with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia, and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 According to the American College of Cardiology guidelines, when starting a GLP-1 agonist, the insulin dose should be decreased by about 20% in patients with a well-controlled hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).12

This study aimed to determine the percentage of patients who required dose reductions or discontinuations of insulin and sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist. Understanding necessary dose reductions or discontinuations of these concomitant diabetes agents can assist pharmacists in preventing hypoglycemia and minimizing weight gain.

Methods

This clinical review was a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed a GLP-1 agonist while on insulin or a sulfonylurea between January 1, 2019, and September 30, 2022, at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WBVAMC) in Pennsylvania and managed in a pharmacist-led patient aligned care team (PACT) clinic. It was determined by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development that an institutional review board or other review committee approval was not needed for this nonresearch Veterans Health Administration quality assurance and improvement project. Patients aged ≥ 18 years were included in this study. Patients were excluded if they were not on insulin or a sulfonylurea when starting a GLP-1 agonist, started a GLP-1 agonist outside of the retrospective chart review dates, or were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by anyone other than a pharmacist in their PACT clinic. This included if a GLP-1 agonist was prescribed by a primary care physician, endocrinologist, or someone outside the VA system.

The primary study outcomes were to determine the percentage of patients with a dose reduction of insulin or sulfonylurea and discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea at intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months. Secondary outcomes included changes in HbA1c and body weight measured at the same intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months.

Data were collected using the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and stored in a locked spreadsheet. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. Patient data included the number of patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea when initiating a GLP-1 agonist, the percentage of patients started on a certain GLP-1 agonist (dulaglutide, liraglutide, exenatide, and semaglutide), and the percentage of patients with a baseline HbA1c of < 8%, 8% to 10%, and > 10%. The GLP-1 agonist formulary was adjusted during the time of this retrospective chart review. Patients who were not on semaglutide were switched over if they were on another GLP-1 agonist as semaglutide became the preferred GLP-1 agonist.

Patients were considered to have a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea if the dose or medication they were on decreased or was discontinued permanently within 12 months of starting a GLP-1 agonist. For example, if a patient who was administering 10 units of insulin daily was decreased to 8 but later increased back to 10, this was not counted as a dose reduction. If a patient discontinued insulin or a sulfonylurea and then restarted it within 12 months of initiating a GLP-1 agonist, this was not counted as a discontinuation.

Results

This retrospective review included 136 patients; 96 patients taking insulin and 54 taking a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist. Fourteen patients were on both. Criteria for use, which are clinical criteria to determine if a patient is eligible for the use of a given medication, are used within the VA. The inclusion criteria for a patient initiating a GLP-1 agonist is that the patient must have atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or chronic kidney disease with the patient receiving metformin (unless unable to use metformin) and empagliflozin (unless unable to use empagliflozin).

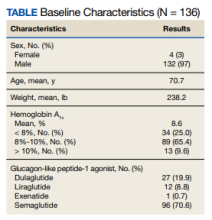

The baseline mean age and weight for the patient population in this retrospective chart review was 70.7 years and 238.2 lb, respectively. Ninety-six patients (70.6%) were started on semaglutide, 27 (19.9%) on dulaglutide, 12 (8.8%) on liraglutide, and 1 (0.7%) on exenatide. The mean HbA1c when patients initiated a GLP-1 agonist was 8.6%. When starting a GLP-1 agonist, 34 patients (25.0%) had an HbA1c < 8%, 89 (65.4%) had an HbA1c between 8% to 10%, and 13 (9.6%) had an HbA1c > 10% (Table).

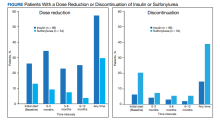

For the primary results, 25 patients (26.0%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 55 patients (57.3%) had at least 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Seven patients (13.0%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 16 patients (29.6%) had at least 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Six patients (6.3%) discontinued insulin use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 14 patients (14.6%) discontinued insulin use within the year follow-up. Eleven patients (20.4%) discontinued sulfonylurea use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 21 patients (38.9%) discontinued sulfonylurea use within the year follow-up (Figure).

Fourteen patients were on both insulin and a sulfonylurea. Two patients (14.3%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 5 (35.7%) had ≥ 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Three patients (21.4%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 6 (42.9%) had ≥ 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Seven patients (50.0%) discontinued sulfonylurea and 3 (21.4%) discontinued insulin at any time throughout the year. The majority of the discontinuations were at the initial start of GLP-1 agonist therapy.

The mean HbA1c for patients on GLP-1 agonist was 8.6% at baseline, 8.0% at 0 to 3 months, 7.6% at 3 to 6 months, and 7.5% at 12 months. Patients experienced a mean HbA1c reduction of 1.1%. The mean weight when a GLP-1 agonist was started was 238.2 lb, 236.0 lb at 0 to 3 months, 223.8 lb at 3 to 6 months, and 224.3 lb after 12 months. Study participants lost a mean weight of 13.9 lb while on a GLP-1 agonist.

Discussion

While this study did not examine why there were dose reductions or discontinuations, we can hypothesize that insulin or sulfonylureas were reduced or discontinued due to a myriad of reasons, such as prophylactic dosing per guidelines, patients having a hypoglycemic event, or pharmacists anticipating potential low blood glucose trends. Also, there could have been numerous reasons GLP-1 agonists were started in patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea, such as HbA1c not being within goal range, cardiovascular benefits (reduce risk of stroke, heart attack, and death), weight loss, and renal protection, such as preventing albuminuria.13,14

This retrospective chart review found a large proportion of patients had a dose reduction of insulin (57.3%) or sulfonylurea (29.6%). The percentage of patients with a dose reduction was potentially underestimated as patients were not counted if they discontinued insulin or sulfonylurea. Concomitant use of GLP-1 agonists with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 The dose reductions in this study show that pharmacists within pharmacy-led PACT clinics monitor for or attempt to prevent hypoglycemia, which aligns with the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists. While increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option for patients, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in an older population, like this one with a mean age > 70 years. The large proportions of patients with dose reductions or insulin and sulfonylurea discontinuations suggest that pharmacists may need to take a more cautious approach when initiating a GLP-1 agonist to prevent adverse health outcomes related to low blood sugar for older adults, such as falls and fractures.

Insulin was discontinued in 20.4% of patients and sulfonylurea was discontinued in 38.9% of patients within 12 months after starting a GLP-1 agonist. When a patient was on both insulin and a sulfonylurea, the percentage of patients who discontinued insulin (21.4%) or a sulfonylurea (50.0%) was higher compared with patients just on insulin (14.6%) or a sulfonylurea (38.9%) alone. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to a higher incidence of discontinuations when these diabetes agents are administered in combination.

Within 12 months of patients receiving a GLP-1 agonist, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.1%, which is comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. For semaglutide 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.4% and 1.6%, respectively.9 For dulaglutide 0.75 mg and 1.5 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 0.7% to 1.6% and 0.8% to 1.6%, respectively.10 For liraglutide 1.8 mg dosage, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 1.0% to 1.5%.11 The mean weight loss in this study was 13.9 lb. Along with HbA1c, weight loss in this review was comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. Patients administering semaglutide lost up to 14 lb, patients taking dulaglutide lost up to 10.1 lb, and patients on liraglutide lost on average 6.2 lb.9-11 Even with medications such as insulin and sulfonylurea that have the side effects of hypoglycemia and weight gain, adding a GLP-1 agonist showed a reduction in HbA1c and weight loss relatively similar to previous clinical trials.

A study on the effects of adding semaglutide to insulin regimens in March 2023 by Meyer and colleagues displayed similar results to this retrospective chart review. That study concluded that there was blood glucose improvement (HbA1c reduction of 1.3%) in patients after 6 months despite a decrease in the insulin dose. Also, patients lost a mean weight of 11 lb during the 6-month trial.3 This retrospective chart review at the WBVAMC adds to the body of research that supports potential reductions or discontinuations of insulin and/or sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be considered when evaluating the results. This review was comprised of a mostly older, male population, which results in a low generalizability to organizations other than VA medical centers. In addition, this study only evaluated patients on a GLP-1 agonist followed in a pharmacist-led PACT clinic. This study excluded patients who were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by an endocrinologist or a pharmacist at one of the community-based outpatient clinics affiliated with WBVAMC, or a pharmacist or clinician outside the VA. The sole focus of this study was patients in a pharmacist-led VAMC clinic. Not all patient data may have been included in the study. If a patient did not have an appointment at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months or did not obtain laboratory tests, HbA1c and weights were not recorded. Data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and in-person appointments were potentially switched to phone or video appointments. There were many instances during this chart review where a weight was not recorded at each time interval. Also, this study did not consider any other diabetes medications the patient was taking. There were many instances where the patient was taking metformin and/or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors. These medications along with diet could have affected the weight results as metformin is weight neutral and SGLT-2 inhibitors promote weight loss.15 Lastly, this study did not evaluate the amount of insulin reduced, only if there was a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin and/or a sulfonylurea.

Conclusions

Dose reductions and a discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist may be needed. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to the higher incidences of discontinuations compared with patients on just 1 of these agents. Dose reductions or discontinuations of these diabetic agents can promote positive patient outcomes, such as preventing hypoglycemia, minimizing weight gain, increasing weight loss, and reducing HbA1c levels.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Pennsylvania.

1. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 8. Obesity and weight management for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S128-S139. doi:10.2337/dc23-S008

2. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VE, et al. Older adults: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S216-S229. doi:10.2337/dc23-S013

3. Meyer J, Dreischmeier E, Lehmann M, Phelan J. The effects of adding semaglutide to high daily dose insulin regimens in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Pharmacother. 2023;57(3):241-250. doi:10.1177/10600280221107381

4. Rodbard HW, Lingvay I, Reed J, et al. Semaglutide added to basal insulin in type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 5): a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(6):2291-2301. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00070

5. Anderson SL, Trujillo JM. Basal insulin use with GLP-1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Spectr. 2016;29(3):152-160. doi:10.2337/diaspect.29.3.152

6. Castek SL, Healey LC, Kania DS, Vernon VP, Dawson AJ. Assessment of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in veterans taking basal/bolus insulin regimens. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 5):S18-S23. doi:10.12788/fp.0317

7. Chen M, Vider E, Plakogiannis R. Insulin dosage adjustments after initiation of GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Pharm Pract. 2022;35(4):511-517. doi:10.1177/0897190021993625

8. Seino Y, Min KW, Niemoeller E, Takami A; EFC10887 GETGOAL-L Asia Study Investigators. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on basal insulin with or without a sulfonylurea (GetGoal-L-Asia). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(10):910-917. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01618.x.

9. Ozempic (semaglutide) injection. Package insert. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. https://www.ozempic.com/prescribing-information.html

10. Trulicity (dulaglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://pi.lilly.com/us/trulicity-uspi.pdf

11. Victoza (liraglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://www.novo-pi.com/victoza.pdf

12. Das SR, Everett BM, Birtcher KK, et al. 2020 expert consensus decision pathway on novel therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(9):1117-1145. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.037

13. Granata A, Maccarrone R, Anzaldi M, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and renal outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 and diabetic kidney disease: state of the art. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(9):1657-1665. Published 2022 Mar 12. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfac069

14. Marx N, Husain M, Lehrke M, Verma S, Sattar N. GLP-1 receptor agonists for the reduction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Circulation. 2022;146(24):1882-1894. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.059595

15. Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2022;65(12):1925-1966. doi:10.1007/s00125-022-05787-2

Hypoglycemia and weight gain are well-known adverse effects that can result from insulin and sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1,2 Insulin and sulfonylurea medications can cause additional weight gain in patients who are overweight or obese, which can increase the burden of diabetes therapy with added medications, raise the risk of hypoglycemia complications, and raise atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors.3 Although increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option health care practitioners or pharmacists have, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in older adults, such as the veteran population, which could lead to complications, such as falls.2

Previous studies focusing on hypoglycemic events in patients with T2DM showed that glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist monotherapy has a low incidence of a hypoglycemic events. However, when a GLP-1 agonist is combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, patients have an increased chance of a hypoglycemic event.3-8 According to the prescribing information for semaglutide, 1.6% to 3.8% of patients on a GLP-1 agonist monotherapy reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event (blood glucose ≤ 70 mg/dL), based on semaglutide dosing. 9 Patients on combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist and basal insulin and a GLP-1 agonist and a sulfonylurea reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event ranging from 16.7% to 29.8% and 17.3% to 24.4%, respectively.9 The incidences of hypoglycemia thus dramatically increase with combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist plus insulin or a sulfonylurea.

When adding a GLP-1 agonist to insulin or a sulfonylurea, clinicians must be mindful of the increased risk of hypoglycemia. Per the warnings and precautions in the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists, concomitant use with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia, and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 According to the American College of Cardiology guidelines, when starting a GLP-1 agonist, the insulin dose should be decreased by about 20% in patients with a well-controlled hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).12

This study aimed to determine the percentage of patients who required dose reductions or discontinuations of insulin and sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist. Understanding necessary dose reductions or discontinuations of these concomitant diabetes agents can assist pharmacists in preventing hypoglycemia and minimizing weight gain.

Methods

This clinical review was a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed a GLP-1 agonist while on insulin or a sulfonylurea between January 1, 2019, and September 30, 2022, at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WBVAMC) in Pennsylvania and managed in a pharmacist-led patient aligned care team (PACT) clinic. It was determined by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development that an institutional review board or other review committee approval was not needed for this nonresearch Veterans Health Administration quality assurance and improvement project. Patients aged ≥ 18 years were included in this study. Patients were excluded if they were not on insulin or a sulfonylurea when starting a GLP-1 agonist, started a GLP-1 agonist outside of the retrospective chart review dates, or were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by anyone other than a pharmacist in their PACT clinic. This included if a GLP-1 agonist was prescribed by a primary care physician, endocrinologist, or someone outside the VA system.

The primary study outcomes were to determine the percentage of patients with a dose reduction of insulin or sulfonylurea and discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea at intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months. Secondary outcomes included changes in HbA1c and body weight measured at the same intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months.

Data were collected using the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and stored in a locked spreadsheet. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. Patient data included the number of patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea when initiating a GLP-1 agonist, the percentage of patients started on a certain GLP-1 agonist (dulaglutide, liraglutide, exenatide, and semaglutide), and the percentage of patients with a baseline HbA1c of < 8%, 8% to 10%, and > 10%. The GLP-1 agonist formulary was adjusted during the time of this retrospective chart review. Patients who were not on semaglutide were switched over if they were on another GLP-1 agonist as semaglutide became the preferred GLP-1 agonist.

Patients were considered to have a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea if the dose or medication they were on decreased or was discontinued permanently within 12 months of starting a GLP-1 agonist. For example, if a patient who was administering 10 units of insulin daily was decreased to 8 but later increased back to 10, this was not counted as a dose reduction. If a patient discontinued insulin or a sulfonylurea and then restarted it within 12 months of initiating a GLP-1 agonist, this was not counted as a discontinuation.

Results

This retrospective review included 136 patients; 96 patients taking insulin and 54 taking a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist. Fourteen patients were on both. Criteria for use, which are clinical criteria to determine if a patient is eligible for the use of a given medication, are used within the VA. The inclusion criteria for a patient initiating a GLP-1 agonist is that the patient must have atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or chronic kidney disease with the patient receiving metformin (unless unable to use metformin) and empagliflozin (unless unable to use empagliflozin).

The baseline mean age and weight for the patient population in this retrospective chart review was 70.7 years and 238.2 lb, respectively. Ninety-six patients (70.6%) were started on semaglutide, 27 (19.9%) on dulaglutide, 12 (8.8%) on liraglutide, and 1 (0.7%) on exenatide. The mean HbA1c when patients initiated a GLP-1 agonist was 8.6%. When starting a GLP-1 agonist, 34 patients (25.0%) had an HbA1c < 8%, 89 (65.4%) had an HbA1c between 8% to 10%, and 13 (9.6%) had an HbA1c > 10% (Table).

For the primary results, 25 patients (26.0%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 55 patients (57.3%) had at least 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Seven patients (13.0%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 16 patients (29.6%) had at least 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Six patients (6.3%) discontinued insulin use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 14 patients (14.6%) discontinued insulin use within the year follow-up. Eleven patients (20.4%) discontinued sulfonylurea use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 21 patients (38.9%) discontinued sulfonylurea use within the year follow-up (Figure).

Fourteen patients were on both insulin and a sulfonylurea. Two patients (14.3%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 5 (35.7%) had ≥ 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Three patients (21.4%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 6 (42.9%) had ≥ 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Seven patients (50.0%) discontinued sulfonylurea and 3 (21.4%) discontinued insulin at any time throughout the year. The majority of the discontinuations were at the initial start of GLP-1 agonist therapy.

The mean HbA1c for patients on GLP-1 agonist was 8.6% at baseline, 8.0% at 0 to 3 months, 7.6% at 3 to 6 months, and 7.5% at 12 months. Patients experienced a mean HbA1c reduction of 1.1%. The mean weight when a GLP-1 agonist was started was 238.2 lb, 236.0 lb at 0 to 3 months, 223.8 lb at 3 to 6 months, and 224.3 lb after 12 months. Study participants lost a mean weight of 13.9 lb while on a GLP-1 agonist.

Discussion

While this study did not examine why there were dose reductions or discontinuations, we can hypothesize that insulin or sulfonylureas were reduced or discontinued due to a myriad of reasons, such as prophylactic dosing per guidelines, patients having a hypoglycemic event, or pharmacists anticipating potential low blood glucose trends. Also, there could have been numerous reasons GLP-1 agonists were started in patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea, such as HbA1c not being within goal range, cardiovascular benefits (reduce risk of stroke, heart attack, and death), weight loss, and renal protection, such as preventing albuminuria.13,14