User login

A Veteran With a Solitary Pulmonary Nodule

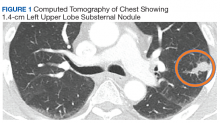

Case Presentation. A 69-year-old veteran presented with an intermittent, waxing and waning cough. He had never smoked and had no family history of lung cancer. His primary care physician ordered a chest radiograph, which revealed a nodular opacity within the lingula concerning for a parenchymal nodule. Further characterization with a chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 1.4-cm left upper lobe subpleural nodule with small satellite nodules (Figure 1). Given these imaging findings, the patient was referred to the pulmonary clinic.

►Lauren Kearney, MD, Medical Resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. What is the differential diagnosis of a solitary pulmonary nodule? What characteristics of the nodule do you consider to differentiate these diagnoses?

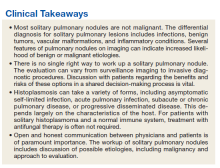

►Renda Wiener, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Pulmonary nodules are well-defined lesions < 3 cm in diameter that are surrounded by lung parenchyma. Although cancer is a possibility (including primary lung cancers, metastatic cancers, or carcinoid tumors), most small nodules do not turn out to be malignant.1 Benign etiologies include infections, benign tumors, vascular malformations, and inflammatory conditions. Infectious causes of nodules are often granulomatous in nature, including fungi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and nontuberculous mycobacteria. Benign tumors are most commonly hamartomas, and these may be clearly distinguished based on imaging characteristics. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, hematomas, and infarcts may present as nodules as well. Inflammatory causes of nodules are important and relatively common, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and rounded atelectasis.

To distinguish benign from malignant etiologies, we look for several features of pulmonary nodules on imaging. Larger size, irregular borders, and upper lobe location all increase the likelihood of cancer, whereas solid attenuation and calcification make cancer less likely. One of the most reassuring findings that suggests a benign etiology is lack of growth over a period of surveillance; after 2 years without growth we typically consider a nodule benign.1 And of course, we also consider the patient’s symptoms and risk factors: weight loss, hemoptysis, a history of cigarette smoking or asbestos exposure, or family history of cancer all increase the likelihood of malignancy.

►Dr. Kearney. Given that the differential diagnosis is so broad, how do you think about the next step in evaluating a pulmonary nodule? How do you approach shared decision making with the patient?

►Dr. Wiener. The characteristics of the patient, the nodule, and the circumstances in which the nodule were discovered are all important to consider. Incidental pulmonary nodules are often found on chest imaging. The imaging characteristics of the nodule are important, as are the patient’s risk factors. A similarly appearing nodule can have very different implications if the patient is a never-smoker exposed to endemic fungi, or a long-time smoker enrolled in a lung cancer screening program. Consultation with a pulmonologist is often appropriate.

It’s important to note that we lack high-quality evidence on the optimal strategy to evaluate pulmonary nodules, and there is no single “right answer“ for all patients. For patients with a low risk of malignancy (< 5%-10%)—which comprises the majority of the incidental nodules discovered—we typically favor serial CT surveillance of the nodule over a period of a few years, whereas for patients at high risk of malignancy (> 65%), we favor early surgical resection if the patient is able to tolerate that. For patients with an intermediate risk of malignancy (~5%-65%), we might consider serial CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or biopsy.1 The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for pulmonary nodule evaluation recommend discussing with patients the different options and the trade-offs of these options in a shared decision-making process.1

►Dr. Kearney. The patient’s pulmonologist laid out options, including monitoring with serial CT scans, obtaining a PET scan, performing CT-guided needle biopsy, or referring for surgical excision. In this case, the patient elected to undergo CT-guided needle biopsy. Dr. Huang, can you discuss the pathology results?

►Qin Huang, MD, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Pathology, Harvard Medical School (HMS). The microscopic examination of the needle biopsy of the lung mass revealed rare clusters of atypical cells with crushed cells adjacent to an extensive area of necrosis with scarring. The atypical cells were suspicious for carcinoma. The Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were negative for common bacterial and fungal microorganisms.

►Dr. Kearney. The tumor board, pulmonologist, and patient decide to move forward with video-assisted excisional biopsy with lymphadenectomy. Dr. Huang, can you interpret the pathology?

►Dr. Huang. Figure 2 showed an hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung resection tissue section with multiple caseating necrotic granulomas. No foreign bodies were identified. There was no evidence of malignancy. The GMS stain revealed a fungal microorganism oval with morphology typical of histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 3).

►Dr. Kearney. What are some of the different ways histoplasmosis can present? Which of these diagnoses fits this patient’s presentation?

►Judy Strymish, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, HMS. Most patients who inhale histoplasmosis spores develop asymptomatic or self-limited infection that is usually not detected. Patients at risk of symptomatic and clinically relevant disease include those who are immunocompromised, at extremes of ages, or exposed to larger inoculums. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can present with cough, shortness of breath, fever, chills, and less commonly, rheumatologic complaints such as erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme. Imaging often shows patchy infiltrates and enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Patients can go on to develop subacute or chronic pulmonary disease with focal opacities and mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Those with chronic disease can have cavitary lesions similar to patients with tuberculosis. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can develop in immunocompromised patients and disseminate through the reticuloendothelial system to other organs with the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and adrenal glands.2

Pulmonary nodules are common incidental finding on chest imaging of patients who reside in histoplasmosis endemic regions, and they are often hard to differentiate from malignancies. There are 3 mediastinal manifestations: adenitis, granuloma, and fibrosis. Usually the syndromes are subclinical, but occasionally the nodes cause symptoms by impinging on other structures.2

This patient had a solitary pulmonary nodule with none of the associated features mentioned above. Pathology showed caseating granuloma and confirmed histoplasmosis.

►Dr. Kearney. Given the diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma, how should this patient be managed?

►Dr. Strymish. The optimal therapy for histoplasmosis depends on the patient’s clinical syndrome. Most infections are self-limited and require no therapy. However, patients who are immunocompromised, exposed to large inoculum, and have progressive disease require antifungal treatment, usually with itraconazole for mild-to-moderate disease and a combination of azole therapy and amphotericin B with extensive disease. Patients with few solitary pulmonary nodules do not benefit from antifungal therapy as the nodule could represent quiescent disease that is unlikely to have clinical impact; in this case, the treatment would be higher risk than the nodule.3

►Dr. Kearney. While the discussion of the diagnosis is interesting, it is also important to acknowledge what the patient went through to arrive at this, an essentially benign diagnosis: 8 months, multiple imaging studies, and 2 invasive diagnostic procedures. Further, the patient had to grapple with the possibility of a diagnosis of cancer. Dr. Wiener, can you talk about the challenges in communicating with patients about pulmonary nodules when cancer is on the differential? What are some of the harms patients face and how can clinicians work to mitigate these harms?

►Dr. Wiener. My colleague Dr. Christopher Slatore of the Portland VA Medical Center and I studied communication about pulmonary nodules in a series of surveys and qualitative studies of patients with pulmonary nodules and the clinicians who take care of them. We found that there seems to be a disconnect between patients’ perceptions of pulmonary nodules and their clinicians, often due to inadequate communication about the nodule. Many clinicians indicated that they do not tell patients about the chance that a nodule may be cancer, because the clinicians know that cancer is unlikely (< 5% of incidentally detected pulmonary nodules turn out to be malignant), and they do not want to alarm patients unnecessarily. However, we found that patients almost immediately wondered about cancer when they learned about their pulmonary nodule, and without hearing explicitly from their clinician that cancer was unlikely, patients tended to overestimate the likelihood of a malignant nodule. Moreover, patients often were not told much about the evaluation plan for the nodule or the rationale for CT surveillance of small nodules instead of biopsy. This uncertainty about the risk of cancer and the plan for evaluating the nodule was difficult for some patients to live with; we found that about one-quarter of patients with a small pulmonary nodule experienced mild-moderate distress during the period of radiographic surveillance. Reassuringly, high-quality patient-clinician communication was associated with lower distress and higher adherence to pulmonary nodule evaluation.4

►Dr. Kearney. The patient was educated about his diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma. Given that the patient was otherwise well appearing with no complicating factors, he was not treated with antifungal therapy. After an 8-month-long workup, the patient was relieved to receive a diagnosis that excluded cancer and did not require any further treatment. His case provides a good example of how to proceed in the workup of a solitary pulmonary nodule and on the importance of communication and shared decision making with our patients.

1. Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(suppl 5):e93S-e120S.

2. Azar MM, Hage CA. Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):403-415.

3. Wheat LJ, Freifeld A, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807-825.

4. Slatore CG, Wiener RS. Pulmonary nodules: a small problem for many, severe distress for some, and how to communicate about it. Chest. 2018;153(4):1004-1015.

Case Presentation. A 69-year-old veteran presented with an intermittent, waxing and waning cough. He had never smoked and had no family history of lung cancer. His primary care physician ordered a chest radiograph, which revealed a nodular opacity within the lingula concerning for a parenchymal nodule. Further characterization with a chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 1.4-cm left upper lobe subpleural nodule with small satellite nodules (Figure 1). Given these imaging findings, the patient was referred to the pulmonary clinic.

►Lauren Kearney, MD, Medical Resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. What is the differential diagnosis of a solitary pulmonary nodule? What characteristics of the nodule do you consider to differentiate these diagnoses?

►Renda Wiener, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Pulmonary nodules are well-defined lesions < 3 cm in diameter that are surrounded by lung parenchyma. Although cancer is a possibility (including primary lung cancers, metastatic cancers, or carcinoid tumors), most small nodules do not turn out to be malignant.1 Benign etiologies include infections, benign tumors, vascular malformations, and inflammatory conditions. Infectious causes of nodules are often granulomatous in nature, including fungi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and nontuberculous mycobacteria. Benign tumors are most commonly hamartomas, and these may be clearly distinguished based on imaging characteristics. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, hematomas, and infarcts may present as nodules as well. Inflammatory causes of nodules are important and relatively common, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and rounded atelectasis.

To distinguish benign from malignant etiologies, we look for several features of pulmonary nodules on imaging. Larger size, irregular borders, and upper lobe location all increase the likelihood of cancer, whereas solid attenuation and calcification make cancer less likely. One of the most reassuring findings that suggests a benign etiology is lack of growth over a period of surveillance; after 2 years without growth we typically consider a nodule benign.1 And of course, we also consider the patient’s symptoms and risk factors: weight loss, hemoptysis, a history of cigarette smoking or asbestos exposure, or family history of cancer all increase the likelihood of malignancy.

►Dr. Kearney. Given that the differential diagnosis is so broad, how do you think about the next step in evaluating a pulmonary nodule? How do you approach shared decision making with the patient?

►Dr. Wiener. The characteristics of the patient, the nodule, and the circumstances in which the nodule were discovered are all important to consider. Incidental pulmonary nodules are often found on chest imaging. The imaging characteristics of the nodule are important, as are the patient’s risk factors. A similarly appearing nodule can have very different implications if the patient is a never-smoker exposed to endemic fungi, or a long-time smoker enrolled in a lung cancer screening program. Consultation with a pulmonologist is often appropriate.

It’s important to note that we lack high-quality evidence on the optimal strategy to evaluate pulmonary nodules, and there is no single “right answer“ for all patients. For patients with a low risk of malignancy (< 5%-10%)—which comprises the majority of the incidental nodules discovered—we typically favor serial CT surveillance of the nodule over a period of a few years, whereas for patients at high risk of malignancy (> 65%), we favor early surgical resection if the patient is able to tolerate that. For patients with an intermediate risk of malignancy (~5%-65%), we might consider serial CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or biopsy.1 The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for pulmonary nodule evaluation recommend discussing with patients the different options and the trade-offs of these options in a shared decision-making process.1

►Dr. Kearney. The patient’s pulmonologist laid out options, including monitoring with serial CT scans, obtaining a PET scan, performing CT-guided needle biopsy, or referring for surgical excision. In this case, the patient elected to undergo CT-guided needle biopsy. Dr. Huang, can you discuss the pathology results?

►Qin Huang, MD, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Pathology, Harvard Medical School (HMS). The microscopic examination of the needle biopsy of the lung mass revealed rare clusters of atypical cells with crushed cells adjacent to an extensive area of necrosis with scarring. The atypical cells were suspicious for carcinoma. The Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were negative for common bacterial and fungal microorganisms.

►Dr. Kearney. The tumor board, pulmonologist, and patient decide to move forward with video-assisted excisional biopsy with lymphadenectomy. Dr. Huang, can you interpret the pathology?

►Dr. Huang. Figure 2 showed an hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung resection tissue section with multiple caseating necrotic granulomas. No foreign bodies were identified. There was no evidence of malignancy. The GMS stain revealed a fungal microorganism oval with morphology typical of histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 3).

►Dr. Kearney. What are some of the different ways histoplasmosis can present? Which of these diagnoses fits this patient’s presentation?

►Judy Strymish, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, HMS. Most patients who inhale histoplasmosis spores develop asymptomatic or self-limited infection that is usually not detected. Patients at risk of symptomatic and clinically relevant disease include those who are immunocompromised, at extremes of ages, or exposed to larger inoculums. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can present with cough, shortness of breath, fever, chills, and less commonly, rheumatologic complaints such as erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme. Imaging often shows patchy infiltrates and enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Patients can go on to develop subacute or chronic pulmonary disease with focal opacities and mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Those with chronic disease can have cavitary lesions similar to patients with tuberculosis. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can develop in immunocompromised patients and disseminate through the reticuloendothelial system to other organs with the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and adrenal glands.2

Pulmonary nodules are common incidental finding on chest imaging of patients who reside in histoplasmosis endemic regions, and they are often hard to differentiate from malignancies. There are 3 mediastinal manifestations: adenitis, granuloma, and fibrosis. Usually the syndromes are subclinical, but occasionally the nodes cause symptoms by impinging on other structures.2

This patient had a solitary pulmonary nodule with none of the associated features mentioned above. Pathology showed caseating granuloma and confirmed histoplasmosis.

►Dr. Kearney. Given the diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma, how should this patient be managed?

►Dr. Strymish. The optimal therapy for histoplasmosis depends on the patient’s clinical syndrome. Most infections are self-limited and require no therapy. However, patients who are immunocompromised, exposed to large inoculum, and have progressive disease require antifungal treatment, usually with itraconazole for mild-to-moderate disease and a combination of azole therapy and amphotericin B with extensive disease. Patients with few solitary pulmonary nodules do not benefit from antifungal therapy as the nodule could represent quiescent disease that is unlikely to have clinical impact; in this case, the treatment would be higher risk than the nodule.3

►Dr. Kearney. While the discussion of the diagnosis is interesting, it is also important to acknowledge what the patient went through to arrive at this, an essentially benign diagnosis: 8 months, multiple imaging studies, and 2 invasive diagnostic procedures. Further, the patient had to grapple with the possibility of a diagnosis of cancer. Dr. Wiener, can you talk about the challenges in communicating with patients about pulmonary nodules when cancer is on the differential? What are some of the harms patients face and how can clinicians work to mitigate these harms?

►Dr. Wiener. My colleague Dr. Christopher Slatore of the Portland VA Medical Center and I studied communication about pulmonary nodules in a series of surveys and qualitative studies of patients with pulmonary nodules and the clinicians who take care of them. We found that there seems to be a disconnect between patients’ perceptions of pulmonary nodules and their clinicians, often due to inadequate communication about the nodule. Many clinicians indicated that they do not tell patients about the chance that a nodule may be cancer, because the clinicians know that cancer is unlikely (< 5% of incidentally detected pulmonary nodules turn out to be malignant), and they do not want to alarm patients unnecessarily. However, we found that patients almost immediately wondered about cancer when they learned about their pulmonary nodule, and without hearing explicitly from their clinician that cancer was unlikely, patients tended to overestimate the likelihood of a malignant nodule. Moreover, patients often were not told much about the evaluation plan for the nodule or the rationale for CT surveillance of small nodules instead of biopsy. This uncertainty about the risk of cancer and the plan for evaluating the nodule was difficult for some patients to live with; we found that about one-quarter of patients with a small pulmonary nodule experienced mild-moderate distress during the period of radiographic surveillance. Reassuringly, high-quality patient-clinician communication was associated with lower distress and higher adherence to pulmonary nodule evaluation.4

►Dr. Kearney. The patient was educated about his diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma. Given that the patient was otherwise well appearing with no complicating factors, he was not treated with antifungal therapy. After an 8-month-long workup, the patient was relieved to receive a diagnosis that excluded cancer and did not require any further treatment. His case provides a good example of how to proceed in the workup of a solitary pulmonary nodule and on the importance of communication and shared decision making with our patients.

Case Presentation. A 69-year-old veteran presented with an intermittent, waxing and waning cough. He had never smoked and had no family history of lung cancer. His primary care physician ordered a chest radiograph, which revealed a nodular opacity within the lingula concerning for a parenchymal nodule. Further characterization with a chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a 1.4-cm left upper lobe subpleural nodule with small satellite nodules (Figure 1). Given these imaging findings, the patient was referred to the pulmonary clinic.

►Lauren Kearney, MD, Medical Resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. What is the differential diagnosis of a solitary pulmonary nodule? What characteristics of the nodule do you consider to differentiate these diagnoses?

►Renda Wiener, MD, Pulmonary and Critical Care, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. Pulmonary nodules are well-defined lesions < 3 cm in diameter that are surrounded by lung parenchyma. Although cancer is a possibility (including primary lung cancers, metastatic cancers, or carcinoid tumors), most small nodules do not turn out to be malignant.1 Benign etiologies include infections, benign tumors, vascular malformations, and inflammatory conditions. Infectious causes of nodules are often granulomatous in nature, including fungi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and nontuberculous mycobacteria. Benign tumors are most commonly hamartomas, and these may be clearly distinguished based on imaging characteristics. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, hematomas, and infarcts may present as nodules as well. Inflammatory causes of nodules are important and relatively common, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and rounded atelectasis.

To distinguish benign from malignant etiologies, we look for several features of pulmonary nodules on imaging. Larger size, irregular borders, and upper lobe location all increase the likelihood of cancer, whereas solid attenuation and calcification make cancer less likely. One of the most reassuring findings that suggests a benign etiology is lack of growth over a period of surveillance; after 2 years without growth we typically consider a nodule benign.1 And of course, we also consider the patient’s symptoms and risk factors: weight loss, hemoptysis, a history of cigarette smoking or asbestos exposure, or family history of cancer all increase the likelihood of malignancy.

►Dr. Kearney. Given that the differential diagnosis is so broad, how do you think about the next step in evaluating a pulmonary nodule? How do you approach shared decision making with the patient?

►Dr. Wiener. The characteristics of the patient, the nodule, and the circumstances in which the nodule were discovered are all important to consider. Incidental pulmonary nodules are often found on chest imaging. The imaging characteristics of the nodule are important, as are the patient’s risk factors. A similarly appearing nodule can have very different implications if the patient is a never-smoker exposed to endemic fungi, or a long-time smoker enrolled in a lung cancer screening program. Consultation with a pulmonologist is often appropriate.

It’s important to note that we lack high-quality evidence on the optimal strategy to evaluate pulmonary nodules, and there is no single “right answer“ for all patients. For patients with a low risk of malignancy (< 5%-10%)—which comprises the majority of the incidental nodules discovered—we typically favor serial CT surveillance of the nodule over a period of a few years, whereas for patients at high risk of malignancy (> 65%), we favor early surgical resection if the patient is able to tolerate that. For patients with an intermediate risk of malignancy (~5%-65%), we might consider serial CT surveillance, positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or biopsy.1 The American College of Chest Physicians guidelines for pulmonary nodule evaluation recommend discussing with patients the different options and the trade-offs of these options in a shared decision-making process.1

►Dr. Kearney. The patient’s pulmonologist laid out options, including monitoring with serial CT scans, obtaining a PET scan, performing CT-guided needle biopsy, or referring for surgical excision. In this case, the patient elected to undergo CT-guided needle biopsy. Dr. Huang, can you discuss the pathology results?

►Qin Huang, MD, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Pathology, Harvard Medical School (HMS). The microscopic examination of the needle biopsy of the lung mass revealed rare clusters of atypical cells with crushed cells adjacent to an extensive area of necrosis with scarring. The atypical cells were suspicious for carcinoma. The Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were negative for common bacterial and fungal microorganisms.

►Dr. Kearney. The tumor board, pulmonologist, and patient decide to move forward with video-assisted excisional biopsy with lymphadenectomy. Dr. Huang, can you interpret the pathology?

►Dr. Huang. Figure 2 showed an hemotoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung resection tissue section with multiple caseating necrotic granulomas. No foreign bodies were identified. There was no evidence of malignancy. The GMS stain revealed a fungal microorganism oval with morphology typical of histoplasma capsulatum (Figure 3).

►Dr. Kearney. What are some of the different ways histoplasmosis can present? Which of these diagnoses fits this patient’s presentation?

►Judy Strymish, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, and Assistant Professor of Medicine, HMS. Most patients who inhale histoplasmosis spores develop asymptomatic or self-limited infection that is usually not detected. Patients at risk of symptomatic and clinically relevant disease include those who are immunocompromised, at extremes of ages, or exposed to larger inoculums. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis can present with cough, shortness of breath, fever, chills, and less commonly, rheumatologic complaints such as erythema nodosum or erythema multiforme. Imaging often shows patchy infiltrates and enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Patients can go on to develop subacute or chronic pulmonary disease with focal opacities and mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. Those with chronic disease can have cavitary lesions similar to patients with tuberculosis. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis can develop in immunocompromised patients and disseminate through the reticuloendothelial system to other organs with the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and adrenal glands.2

Pulmonary nodules are common incidental finding on chest imaging of patients who reside in histoplasmosis endemic regions, and they are often hard to differentiate from malignancies. There are 3 mediastinal manifestations: adenitis, granuloma, and fibrosis. Usually the syndromes are subclinical, but occasionally the nodes cause symptoms by impinging on other structures.2

This patient had a solitary pulmonary nodule with none of the associated features mentioned above. Pathology showed caseating granuloma and confirmed histoplasmosis.

►Dr. Kearney. Given the diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma, how should this patient be managed?

►Dr. Strymish. The optimal therapy for histoplasmosis depends on the patient’s clinical syndrome. Most infections are self-limited and require no therapy. However, patients who are immunocompromised, exposed to large inoculum, and have progressive disease require antifungal treatment, usually with itraconazole for mild-to-moderate disease and a combination of azole therapy and amphotericin B with extensive disease. Patients with few solitary pulmonary nodules do not benefit from antifungal therapy as the nodule could represent quiescent disease that is unlikely to have clinical impact; in this case, the treatment would be higher risk than the nodule.3

►Dr. Kearney. While the discussion of the diagnosis is interesting, it is also important to acknowledge what the patient went through to arrive at this, an essentially benign diagnosis: 8 months, multiple imaging studies, and 2 invasive diagnostic procedures. Further, the patient had to grapple with the possibility of a diagnosis of cancer. Dr. Wiener, can you talk about the challenges in communicating with patients about pulmonary nodules when cancer is on the differential? What are some of the harms patients face and how can clinicians work to mitigate these harms?

►Dr. Wiener. My colleague Dr. Christopher Slatore of the Portland VA Medical Center and I studied communication about pulmonary nodules in a series of surveys and qualitative studies of patients with pulmonary nodules and the clinicians who take care of them. We found that there seems to be a disconnect between patients’ perceptions of pulmonary nodules and their clinicians, often due to inadequate communication about the nodule. Many clinicians indicated that they do not tell patients about the chance that a nodule may be cancer, because the clinicians know that cancer is unlikely (< 5% of incidentally detected pulmonary nodules turn out to be malignant), and they do not want to alarm patients unnecessarily. However, we found that patients almost immediately wondered about cancer when they learned about their pulmonary nodule, and without hearing explicitly from their clinician that cancer was unlikely, patients tended to overestimate the likelihood of a malignant nodule. Moreover, patients often were not told much about the evaluation plan for the nodule or the rationale for CT surveillance of small nodules instead of biopsy. This uncertainty about the risk of cancer and the plan for evaluating the nodule was difficult for some patients to live with; we found that about one-quarter of patients with a small pulmonary nodule experienced mild-moderate distress during the period of radiographic surveillance. Reassuringly, high-quality patient-clinician communication was associated with lower distress and higher adherence to pulmonary nodule evaluation.4

►Dr. Kearney. The patient was educated about his diagnosis of solitary histoplasmoma. Given that the patient was otherwise well appearing with no complicating factors, he was not treated with antifungal therapy. After an 8-month-long workup, the patient was relieved to receive a diagnosis that excluded cancer and did not require any further treatment. His case provides a good example of how to proceed in the workup of a solitary pulmonary nodule and on the importance of communication and shared decision making with our patients.

1. Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(suppl 5):e93S-e120S.

2. Azar MM, Hage CA. Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):403-415.

3. Wheat LJ, Freifeld A, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807-825.

4. Slatore CG, Wiener RS. Pulmonary nodules: a small problem for many, severe distress for some, and how to communicate about it. Chest. 2018;153(4):1004-1015.

1. Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, et al. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(suppl 5):e93S-e120S.

2. Azar MM, Hage CA. Clinical perspectives in the diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(3):403-415.

3. Wheat LJ, Freifeld A, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):807-825.

4. Slatore CG, Wiener RS. Pulmonary nodules: a small problem for many, severe distress for some, and how to communicate about it. Chest. 2018;153(4):1004-1015.

A Veteran Presenting With Leg Swelling, Dyspnea, and Proteinuria

*This article has been corrected to include a missing author.

Case Presentation. A 63-year-old male with well-controlled HIV (CD4 count 757, undetectable viral load), epilepsy, and hypertension presented to the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) emergency department with 1 week of bilateral leg swelling and exertional shortness of breath. He reported having no fever, cough, chest pain, pain with inspiration and orthopnea. There was no personal or family history of pulmonary embolism. He reported weight gain but was unable to quantify how much. He also reported flare up of chronic knee pain, without swelling for which he had taken up to 4 tablets of naproxen daily for several weeks. His physical examination was notable for a heart rate of 105 beats per minute and bilateral pitting edema to his knees. Laboratory testing revealed a creatinine level of 2.5 mg/dL, which was increased from a baseline of 1.0 mg/dL (Table 1), and a urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 7.8 mg/mg (Table 2). A renal ultrasound showed normal-sized kidneys without hydronephrosis or obstructing renal calculi. The patient was admitted for further workup of his dyspnea and acute kidney injury.

► Jonathan Li, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). Dr. William, based on the degree of proteinuria and edema, a diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome was made. How is nephrotic syndrome defined, and how is it distinguished from glomerulonephritis?

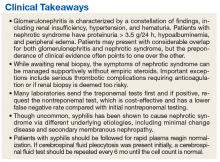

► Jeffrey William, MD, Nephrologist, BIDMC, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. The pathophysiology of nephrotic disease and glomerulonephritis are quite distinct, resulting in symptoms and systemic manifestations that only slightly overlap. Glomerulonephritis is characterized by inflammation of the endothelial cells of the trilayered glomerular capillary, with a resulting active urine sediment with red blood cells, white blood cells, and casts. Nephrotic syndrome mostly affects the visceral epithelial cells of the glomerular capillary, commonly referred to as podocytes, and hence, the urine sediment in nephrotic disease is often inactive. Patients with nephrotic syndrome have nephrotic-range proteinuria (excretion of > 3.5 g per 24 h or a spot urine protein-creatinine ratio > 3.5 g in the steady state) and both hypoalbuminemia (< 3 g/dL) and peripheral edema. Lipiduria and hyperlipidemia are common findings in nephrotic syndrome but are not required for a clinical diagnosis.1 In contrast, glomerulonephritis is defined by a constellation of findings that include renal insufficiency (often indicated by an elevation in blood urea nitrogen and creatinine), hypertension, hematuria, and subnephrotic range proteinuria. In practice, patients may fulfill criteria of both nephrotic and nephritic syndromes, but the preponderance of clinical evidence often points one way or the other. In this case, nephrotic syndrome was diagnosed based on the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 7.8 mg/mg, hypoalbuminemia, and edema.

► Dr. Li. What would be your first-line workup for evaluation of the etiology of this patient’s nephrotic syndrome?

► Dr. William. Rather than memorizing a list of etiologies of nephrotic syndrome, it is essential to consider the pathophysiology of heavy proteinuria. Though the glomerular filtration barrier is extremely complex and defects in any component can cause proteinuria, disruption of the podocyte is often involved. Common disease processes that chiefly target the podocyte include minimal change disease, primary focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and membranous nephropathy, all by differing mechanisms. Minimal change disease and idiopathic/primary FSGS are increasingly thought to be at differing points on a spectrum of the same disease.2 Secondary FSGS, on the other hand, is a progressive disease, commonly resulting from longstanding hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity in adults. Membranous nephropathy can also be either primary or secondary. Primary membranous nephropathy is chiefly caused by a circulating IgG4 antibody to the podocyte membrane antigen PLA2R (M-type phospholipase A2 receptor), whereas secondary membranous nephropathy can be caused by a variety of systemic etiologies, including autoimmune disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), certain malignancies, chronic infections (eg, hepatitis B and C), and many medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3-5 Paraprotein deposition diseases can also cause glomerular damage leading to nephrotic-range proteinuria.

Given these potential diagnoses, a careful history should be taken to assess exposures and recent medication use. Urine sediment evaluation is essential in the evaluation of nephrotic syndrome to determine if there is an underlying nephritic process. Select serologies may be sent to look for autoimmune disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and common viral exposures like hepatitis B or C. Serum and urine protein electrophoreses would be appropriate initial tests of suspected paraprotein-related diseases. Other serologies, such as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies or antiglomerular basement membrane antibodies, would not necessarily be indicated here given the lack of hematuria and presence of nephrotic-range proteinuria.

► Dr. Li. The initial evaluation was notable for an erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 120 (mm/h) and a weakly positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:40. The remainder of his initial workup did not reveal an etiology for his nephrotic syndrome (Table 3).

Dr. William, is there a role for starting urgent empiric steroids in nephrotic syndrome while workup is ongoing? If so, do the severity of proteinuria and/or symptoms play a role or is this determination based on something else?

► Dr. William. Edema is a primary symptom of nephrotic syndrome and can often be managed with diuretics alone. If a clear medication-mediated cause is suspected, discontinuation of this agent may result in spontaneous improvement without steroid treatment. However,in cases where an etiology is unclear and there are serious thrombotic complications requiring anticoagulation, and a renal biopsy is deemed to be too risky, then empiric steroid therapy may be necessary. Children with new-onset nephrotic syndrome are presumed to have minimal change disease, given its prevalence in this patient population, and are often given empiric steroids without obtaining a renal biopsy. However, in the adult population, a renal biopsy can typically be performed quickly and safely, with pathology results interpreted within days. In this patient, since a diagnosis was unclear and there was no contraindication to renal biopsy, a biopsy should be obtained before consideration of steroids.

► Dr. Li. Steroids were deferred in anticipation of renal biopsy, which showed stage I membranous nephropathy, suggestive of membranous lupus nephritis Class V. The deposits were strongly reactive for immunoglobuline G (IgG), IgA, and complement 1q (C1q), showed co-dominant staining for IgG1, IgG2, and IgG3, and were weakly positive for the PLA2 receptor. Focal intimal arteritis in a small interlobular vessel was seen.

Dr. William, the pathology returned suggestive of lupus nephritis. Does the overall clinical picture fit with lupus nephritis?

► Dr. William. Given the history and a rather low ANA, the diagnosis of lupus nephritis seems unlikely. The lack of IgG4 and PLA2R staining in the biopsy suggests that this membranous pattern on the biopsy is likely to be secondary to a systemic etiology, but further investigation should be pursued.

► Dr. Li. The patient was discharged after the biopsy with a planned outpatient nephrology follow-up to discuss results and treatment. He was prescribed an oral diuretic, and his symptoms improved. Several days after discharge, he developed blurry vision and was evaluated in the Ophthalmology clinic. On fundoscopy, he was found to have acute papillitis, a form of optic neuritis. As part of initial evaluation of infectious etiologies of papillitis, ophthalmology recommended testing for syphilis.

Dr. Strymish, when we are considering secondary syphilis, what is the recommended approach to diagnostic testing?

► Judith Strymish, MD, Infectious Diseases, BIDMC, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. The diagnosis of syphilis is usually made through serologic testing of blood specimens. Methods that detect the spirochete directly like dark-field smears are not readily available. Serologic tests include treponemal tests (eg, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay [TPPA]) and nontreponemal tests (eg, rapid plasma reagin [RPR]). One needs a confirmatory test because either test is associated with false positives. Either test can be done first. Most laboratories, including those at VABHS are now performing treponemal tests first as these have become more cost-effective.6 The TPPA treponemal test was found to have a lower false negative rate in primary syphilis compared with that of nontreponemal tests.7 Nontreponemal tests can be followed for response to therapy. If a patient has a history of treated syphilis, a nontreponemal test should be sent, since the treponemal test will remain positive for life.

If there is clinical concern for neurosyphilis, cerebrospinal fluid fluorescent (CSF) treponemal antibody needs to be sampled and sent for the nontreponemal venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test. The VDRL is highly specific for neurosyphilis but not as sensitive. Cerebrospinal fluid fluorescent treponemal antibody (CSF FTA) may also be sent; it is very sensitive but not very specific for neurosyphilis.

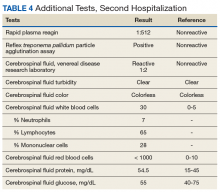

► Dr. Li. An RPR returned positive at 1:512 (was negative 14 months prior on a routine screening test), with positive reflex TPPA (Table 4). A diagnosis of secondary syphilis was made. Dr. Strymish, at this point, what additional testing and treatment is necessary?

► Dr. Strymish. With papillitis and a very high RPR, we need to assume that he has ophthalmic syphilis. This can occur in any stage of syphilis, but his eye findings and high RPR are consistent with secondary syphilis. Ophthalmic syphilis has been on the upswing, even more than is expected with recent increases in syphilis cases.8 Ophthalmic syphilis is considered a form of neurosyphilis. A lumbar puncture and treatment for neurosyphilis is recommended.9,10

► Dr. Li. A lumbar puncture was performed, and his CSF was VDRL positive. This confirmed a diagnosis of neurosyphilis (Table 4). The patient was treated for neurosyphilis with IV penicillin. The patient shared that he had episodes of unprotected oral sexual activity within the past year and approximately 1 year ago, he came in close contact (but no sexual activity) with a person who had a rash consistent with syphilis.Dr. William, syphilis would be a potential unifying diagnosis of his renal and ophthalmologic manifestations. Is syphilis known to cause membranous nephropathy?

► Dr. William. Though it is uncommon, the nephrotic syndrome is a well-described complication of secondary syphilis.11,12 Syphilis has been shown to cause nephrotic syndrome in a variety of ways. Case reports abound linking syphilis to minimal change disease and other glomerular diseases.13,14 A case report from 1993 shows a membranous pattern of glomerular disease similar to this case.15 As a form of secondary membranous nephropathy, the immunofluorescence pattern can demonstrate staining similar to the “full house” seen in lupus nephritis (IgA, IgM, and C1q, in addition to IgG and C3).16 This explains the initial interpretation of this patient’s biopsy, as lupus nephritis would be a much more common etiology of secondary membranous nephropathy than is acute syphilis with this immunofluorescence pattern. However, the data in this case are highly suggestive of a causal relationship between secondary syphilis and membranous nephropathy.

► Dr. Li. Dr. Strymish, how should this patient be screened for syphilis reinfection, and at what intervals would you recommend?

► Dr. Strymish. He will need follow-up testing to make sure that his syphilis is effectively treated. If CSF pleocytosis was present initially, a CSF examination should be repeated every 6 months until the cell count is normal. He will also need follow-up for normalization of his RPR. Persons with HIV infection and primary or secondary syphilis should be evaluated clinically and serologically for treatment failure at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months after therapy according to US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.9

His treponemal test for syphilis will likely stay positive for life. His RPR should decrease significantly with effective treatment. It makes sense to screen with RPR alone as long as he continues to have risk factors for acquiring syphilis. Routine syphilis testing is recommended for pregnant women, sexually active men who have sex with men, sexually active persons with HIV, and persons taking PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) for HIV prevention. He should be screened at least yearly for syphilis.

► Dr. Li. Over the next several months, the patient’s creatinine normalized and his proteinuria resolved. His vision recovered, and he has had no further ophthalmologic complications.

Dr. William, what is his long-term renal prognosis? Do you expect that his acute episode of membranous nephropathy will have permanent effects on his renal function?

► Dr. William. His rapid response to therapy for neurosyphilis provides evidence for this etiology of his renal dysfunction and glomerulonephritis. His long-term prognosis is quite good if the syphilis is the only reason for him to have renal disease. The renal damage is often reversible in these cases. However, given his prior extensive NSAID exposure and history of hypertension, he may be at higher risk for chronic kidney disease than an otherwise healthy patient, especially after an episode of acute kidney injury. Therefore, his renal function should continue to be monitored as an outpatient.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank this veteran for sharing his story and allowing us to learn from this unusual case for the benefit of our future patients.

1. Rennke H, Denker BM. Renal Pathophysiology: The Essentials. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014.

2. Maas RJ, Deegens JK, Smeets B, Moeller MJ, Wetzels JF. Minimal change disease and idiopathic FSGS: manifestations of the same disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(12):768-776.

3. Beck LH Jr, Bonegio RG, Lambeau G, et al. M-type phospholipase A2 receptor as target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):11-21.

4. Rennke HG. Secondary membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1995;47(2):643-656.

5. Nawaz FA, Larsen CP, Troxell ML. Membranous nephropathy and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(5):1012-1017.

6. Pillay A. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Syphilis Summit—Diagnostics and laboratory issues. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;45(9S)(suppl 1):S13-S16.

7. Levett PN, Fonseca K, Tsang RS, et al. Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network laboratory guidelines for the use of serological tests (excluding point-of-care tests) for the diagnosis of syphilis in Canada. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2015;26(suppl A):6A-12A.

8. Oliver SE, Aubin M, Atwell L, et al. Ocular syphilis—eight jurisdictions, United States, 2014-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(43):1185-1188.

9. Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recommendations and Reports 2015;64(RR3):1-137. [Erratum in MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(33):924.]

10. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical advisory: ocular syphilis in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/clinicaladvisoryos2015.htm. Updated March 24, 2016. Accessed August 12, 2019.

11. Braunstein GD, Lewis EJ, Galvanek EG, Hamilton A, Bell WR. The nephrotic syndrome associated with secondary syphilis: an immune deposit disease. Am J Med. 1970;48:643-648.1.

12. Handoko ML, Duijvestein M, Scheepstra CG, de Fijter CW. Syphilis: a reversible cause of nephrotic syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:pii:bcr2012008279

13. Krane NK, Espenan P, Walker PD, Bergman SM, Wallin JD. Renal disease and syphilis: a report of nephrotic syndrome with minimal change disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;9(2):176-179.

14. Bhorade MS, Carag HB, Lee HJ, Potter EV, Dunea G. Nephropathy of secondary syphilis: a clinical and pathological spectrum. JAMA. 1971;216(7):1159-1166.

15. Hunte W, al-Ghraoui F, Cohen RJ. Secondary syphilis and the nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;3(7):1351-1355.

16. Gamble CN, Reardan JB. Immunopathogenesis of syphilitic glomerulonephritis. Elution of antitreponemal antibody from glomerular immune-complex deposits. N Engl J Med. 1975;292(9):449-454.

*This article has been corrected to include a missing author.

Case Presentation. A 63-year-old male with well-controlled HIV (CD4 count 757, undetectable viral load), epilepsy, and hypertension presented to the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) emergency department with 1 week of bilateral leg swelling and exertional shortness of breath. He reported having no fever, cough, chest pain, pain with inspiration and orthopnea. There was no personal or family history of pulmonary embolism. He reported weight gain but was unable to quantify how much. He also reported flare up of chronic knee pain, without swelling for which he had taken up to 4 tablets of naproxen daily for several weeks. His physical examination was notable for a heart rate of 105 beats per minute and bilateral pitting edema to his knees. Laboratory testing revealed a creatinine level of 2.5 mg/dL, which was increased from a baseline of 1.0 mg/dL (Table 1), and a urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 7.8 mg/mg (Table 2). A renal ultrasound showed normal-sized kidneys without hydronephrosis or obstructing renal calculi. The patient was admitted for further workup of his dyspnea and acute kidney injury.

► Jonathan Li, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). Dr. William, based on the degree of proteinuria and edema, a diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome was made. How is nephrotic syndrome defined, and how is it distinguished from glomerulonephritis?

► Jeffrey William, MD, Nephrologist, BIDMC, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. The pathophysiology of nephrotic disease and glomerulonephritis are quite distinct, resulting in symptoms and systemic manifestations that only slightly overlap. Glomerulonephritis is characterized by inflammation of the endothelial cells of the trilayered glomerular capillary, with a resulting active urine sediment with red blood cells, white blood cells, and casts. Nephrotic syndrome mostly affects the visceral epithelial cells of the glomerular capillary, commonly referred to as podocytes, and hence, the urine sediment in nephrotic disease is often inactive. Patients with nephrotic syndrome have nephrotic-range proteinuria (excretion of > 3.5 g per 24 h or a spot urine protein-creatinine ratio > 3.5 g in the steady state) and both hypoalbuminemia (< 3 g/dL) and peripheral edema. Lipiduria and hyperlipidemia are common findings in nephrotic syndrome but are not required for a clinical diagnosis.1 In contrast, glomerulonephritis is defined by a constellation of findings that include renal insufficiency (often indicated by an elevation in blood urea nitrogen and creatinine), hypertension, hematuria, and subnephrotic range proteinuria. In practice, patients may fulfill criteria of both nephrotic and nephritic syndromes, but the preponderance of clinical evidence often points one way or the other. In this case, nephrotic syndrome was diagnosed based on the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 7.8 mg/mg, hypoalbuminemia, and edema.

► Dr. Li. What would be your first-line workup for evaluation of the etiology of this patient’s nephrotic syndrome?

► Dr. William. Rather than memorizing a list of etiologies of nephrotic syndrome, it is essential to consider the pathophysiology of heavy proteinuria. Though the glomerular filtration barrier is extremely complex and defects in any component can cause proteinuria, disruption of the podocyte is often involved. Common disease processes that chiefly target the podocyte include minimal change disease, primary focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and membranous nephropathy, all by differing mechanisms. Minimal change disease and idiopathic/primary FSGS are increasingly thought to be at differing points on a spectrum of the same disease.2 Secondary FSGS, on the other hand, is a progressive disease, commonly resulting from longstanding hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity in adults. Membranous nephropathy can also be either primary or secondary. Primary membranous nephropathy is chiefly caused by a circulating IgG4 antibody to the podocyte membrane antigen PLA2R (M-type phospholipase A2 receptor), whereas secondary membranous nephropathy can be caused by a variety of systemic etiologies, including autoimmune disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), certain malignancies, chronic infections (eg, hepatitis B and C), and many medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3-5 Paraprotein deposition diseases can also cause glomerular damage leading to nephrotic-range proteinuria.

Given these potential diagnoses, a careful history should be taken to assess exposures and recent medication use. Urine sediment evaluation is essential in the evaluation of nephrotic syndrome to determine if there is an underlying nephritic process. Select serologies may be sent to look for autoimmune disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and common viral exposures like hepatitis B or C. Serum and urine protein electrophoreses would be appropriate initial tests of suspected paraprotein-related diseases. Other serologies, such as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies or antiglomerular basement membrane antibodies, would not necessarily be indicated here given the lack of hematuria and presence of nephrotic-range proteinuria.

► Dr. Li. The initial evaluation was notable for an erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 120 (mm/h) and a weakly positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:40. The remainder of his initial workup did not reveal an etiology for his nephrotic syndrome (Table 3).

Dr. William, is there a role for starting urgent empiric steroids in nephrotic syndrome while workup is ongoing? If so, do the severity of proteinuria and/or symptoms play a role or is this determination based on something else?

► Dr. William. Edema is a primary symptom of nephrotic syndrome and can often be managed with diuretics alone. If a clear medication-mediated cause is suspected, discontinuation of this agent may result in spontaneous improvement without steroid treatment. However,in cases where an etiology is unclear and there are serious thrombotic complications requiring anticoagulation, and a renal biopsy is deemed to be too risky, then empiric steroid therapy may be necessary. Children with new-onset nephrotic syndrome are presumed to have minimal change disease, given its prevalence in this patient population, and are often given empiric steroids without obtaining a renal biopsy. However, in the adult population, a renal biopsy can typically be performed quickly and safely, with pathology results interpreted within days. In this patient, since a diagnosis was unclear and there was no contraindication to renal biopsy, a biopsy should be obtained before consideration of steroids.

► Dr. Li. Steroids were deferred in anticipation of renal biopsy, which showed stage I membranous nephropathy, suggestive of membranous lupus nephritis Class V. The deposits were strongly reactive for immunoglobuline G (IgG), IgA, and complement 1q (C1q), showed co-dominant staining for IgG1, IgG2, and IgG3, and were weakly positive for the PLA2 receptor. Focal intimal arteritis in a small interlobular vessel was seen.

Dr. William, the pathology returned suggestive of lupus nephritis. Does the overall clinical picture fit with lupus nephritis?

► Dr. William. Given the history and a rather low ANA, the diagnosis of lupus nephritis seems unlikely. The lack of IgG4 and PLA2R staining in the biopsy suggests that this membranous pattern on the biopsy is likely to be secondary to a systemic etiology, but further investigation should be pursued.

► Dr. Li. The patient was discharged after the biopsy with a planned outpatient nephrology follow-up to discuss results and treatment. He was prescribed an oral diuretic, and his symptoms improved. Several days after discharge, he developed blurry vision and was evaluated in the Ophthalmology clinic. On fundoscopy, he was found to have acute papillitis, a form of optic neuritis. As part of initial evaluation of infectious etiologies of papillitis, ophthalmology recommended testing for syphilis.

Dr. Strymish, when we are considering secondary syphilis, what is the recommended approach to diagnostic testing?

► Judith Strymish, MD, Infectious Diseases, BIDMC, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. The diagnosis of syphilis is usually made through serologic testing of blood specimens. Methods that detect the spirochete directly like dark-field smears are not readily available. Serologic tests include treponemal tests (eg, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay [TPPA]) and nontreponemal tests (eg, rapid plasma reagin [RPR]). One needs a confirmatory test because either test is associated with false positives. Either test can be done first. Most laboratories, including those at VABHS are now performing treponemal tests first as these have become more cost-effective.6 The TPPA treponemal test was found to have a lower false negative rate in primary syphilis compared with that of nontreponemal tests.7 Nontreponemal tests can be followed for response to therapy. If a patient has a history of treated syphilis, a nontreponemal test should be sent, since the treponemal test will remain positive for life.

If there is clinical concern for neurosyphilis, cerebrospinal fluid fluorescent (CSF) treponemal antibody needs to be sampled and sent for the nontreponemal venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test. The VDRL is highly specific for neurosyphilis but not as sensitive. Cerebrospinal fluid fluorescent treponemal antibody (CSF FTA) may also be sent; it is very sensitive but not very specific for neurosyphilis.

► Dr. Li. An RPR returned positive at 1:512 (was negative 14 months prior on a routine screening test), with positive reflex TPPA (Table 4). A diagnosis of secondary syphilis was made. Dr. Strymish, at this point, what additional testing and treatment is necessary?

► Dr. Strymish. With papillitis and a very high RPR, we need to assume that he has ophthalmic syphilis. This can occur in any stage of syphilis, but his eye findings and high RPR are consistent with secondary syphilis. Ophthalmic syphilis has been on the upswing, even more than is expected with recent increases in syphilis cases.8 Ophthalmic syphilis is considered a form of neurosyphilis. A lumbar puncture and treatment for neurosyphilis is recommended.9,10

► Dr. Li. A lumbar puncture was performed, and his CSF was VDRL positive. This confirmed a diagnosis of neurosyphilis (Table 4). The patient was treated for neurosyphilis with IV penicillin. The patient shared that he had episodes of unprotected oral sexual activity within the past year and approximately 1 year ago, he came in close contact (but no sexual activity) with a person who had a rash consistent with syphilis.Dr. William, syphilis would be a potential unifying diagnosis of his renal and ophthalmologic manifestations. Is syphilis known to cause membranous nephropathy?

► Dr. William. Though it is uncommon, the nephrotic syndrome is a well-described complication of secondary syphilis.11,12 Syphilis has been shown to cause nephrotic syndrome in a variety of ways. Case reports abound linking syphilis to minimal change disease and other glomerular diseases.13,14 A case report from 1993 shows a membranous pattern of glomerular disease similar to this case.15 As a form of secondary membranous nephropathy, the immunofluorescence pattern can demonstrate staining similar to the “full house” seen in lupus nephritis (IgA, IgM, and C1q, in addition to IgG and C3).16 This explains the initial interpretation of this patient’s biopsy, as lupus nephritis would be a much more common etiology of secondary membranous nephropathy than is acute syphilis with this immunofluorescence pattern. However, the data in this case are highly suggestive of a causal relationship between secondary syphilis and membranous nephropathy.

► Dr. Li. Dr. Strymish, how should this patient be screened for syphilis reinfection, and at what intervals would you recommend?

► Dr. Strymish. He will need follow-up testing to make sure that his syphilis is effectively treated. If CSF pleocytosis was present initially, a CSF examination should be repeated every 6 months until the cell count is normal. He will also need follow-up for normalization of his RPR. Persons with HIV infection and primary or secondary syphilis should be evaluated clinically and serologically for treatment failure at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months after therapy according to US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.9

His treponemal test for syphilis will likely stay positive for life. His RPR should decrease significantly with effective treatment. It makes sense to screen with RPR alone as long as he continues to have risk factors for acquiring syphilis. Routine syphilis testing is recommended for pregnant women, sexually active men who have sex with men, sexually active persons with HIV, and persons taking PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) for HIV prevention. He should be screened at least yearly for syphilis.

► Dr. Li. Over the next several months, the patient’s creatinine normalized and his proteinuria resolved. His vision recovered, and he has had no further ophthalmologic complications.

Dr. William, what is his long-term renal prognosis? Do you expect that his acute episode of membranous nephropathy will have permanent effects on his renal function?

► Dr. William. His rapid response to therapy for neurosyphilis provides evidence for this etiology of his renal dysfunction and glomerulonephritis. His long-term prognosis is quite good if the syphilis is the only reason for him to have renal disease. The renal damage is often reversible in these cases. However, given his prior extensive NSAID exposure and history of hypertension, he may be at higher risk for chronic kidney disease than an otherwise healthy patient, especially after an episode of acute kidney injury. Therefore, his renal function should continue to be monitored as an outpatient.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank this veteran for sharing his story and allowing us to learn from this unusual case for the benefit of our future patients.

*This article has been corrected to include a missing author.

Case Presentation. A 63-year-old male with well-controlled HIV (CD4 count 757, undetectable viral load), epilepsy, and hypertension presented to the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) emergency department with 1 week of bilateral leg swelling and exertional shortness of breath. He reported having no fever, cough, chest pain, pain with inspiration and orthopnea. There was no personal or family history of pulmonary embolism. He reported weight gain but was unable to quantify how much. He also reported flare up of chronic knee pain, without swelling for which he had taken up to 4 tablets of naproxen daily for several weeks. His physical examination was notable for a heart rate of 105 beats per minute and bilateral pitting edema to his knees. Laboratory testing revealed a creatinine level of 2.5 mg/dL, which was increased from a baseline of 1.0 mg/dL (Table 1), and a urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 7.8 mg/mg (Table 2). A renal ultrasound showed normal-sized kidneys without hydronephrosis or obstructing renal calculi. The patient was admitted for further workup of his dyspnea and acute kidney injury.

► Jonathan Li, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). Dr. William, based on the degree of proteinuria and edema, a diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome was made. How is nephrotic syndrome defined, and how is it distinguished from glomerulonephritis?

► Jeffrey William, MD, Nephrologist, BIDMC, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. The pathophysiology of nephrotic disease and glomerulonephritis are quite distinct, resulting in symptoms and systemic manifestations that only slightly overlap. Glomerulonephritis is characterized by inflammation of the endothelial cells of the trilayered glomerular capillary, with a resulting active urine sediment with red blood cells, white blood cells, and casts. Nephrotic syndrome mostly affects the visceral epithelial cells of the glomerular capillary, commonly referred to as podocytes, and hence, the urine sediment in nephrotic disease is often inactive. Patients with nephrotic syndrome have nephrotic-range proteinuria (excretion of > 3.5 g per 24 h or a spot urine protein-creatinine ratio > 3.5 g in the steady state) and both hypoalbuminemia (< 3 g/dL) and peripheral edema. Lipiduria and hyperlipidemia are common findings in nephrotic syndrome but are not required for a clinical diagnosis.1 In contrast, glomerulonephritis is defined by a constellation of findings that include renal insufficiency (often indicated by an elevation in blood urea nitrogen and creatinine), hypertension, hematuria, and subnephrotic range proteinuria. In practice, patients may fulfill criteria of both nephrotic and nephritic syndromes, but the preponderance of clinical evidence often points one way or the other. In this case, nephrotic syndrome was diagnosed based on the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 7.8 mg/mg, hypoalbuminemia, and edema.

► Dr. Li. What would be your first-line workup for evaluation of the etiology of this patient’s nephrotic syndrome?

► Dr. William. Rather than memorizing a list of etiologies of nephrotic syndrome, it is essential to consider the pathophysiology of heavy proteinuria. Though the glomerular filtration barrier is extremely complex and defects in any component can cause proteinuria, disruption of the podocyte is often involved. Common disease processes that chiefly target the podocyte include minimal change disease, primary focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and membranous nephropathy, all by differing mechanisms. Minimal change disease and idiopathic/primary FSGS are increasingly thought to be at differing points on a spectrum of the same disease.2 Secondary FSGS, on the other hand, is a progressive disease, commonly resulting from longstanding hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity in adults. Membranous nephropathy can also be either primary or secondary. Primary membranous nephropathy is chiefly caused by a circulating IgG4 antibody to the podocyte membrane antigen PLA2R (M-type phospholipase A2 receptor), whereas secondary membranous nephropathy can be caused by a variety of systemic etiologies, including autoimmune disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), certain malignancies, chronic infections (eg, hepatitis B and C), and many medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3-5 Paraprotein deposition diseases can also cause glomerular damage leading to nephrotic-range proteinuria.

Given these potential diagnoses, a careful history should be taken to assess exposures and recent medication use. Urine sediment evaluation is essential in the evaluation of nephrotic syndrome to determine if there is an underlying nephritic process. Select serologies may be sent to look for autoimmune disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and common viral exposures like hepatitis B or C. Serum and urine protein electrophoreses would be appropriate initial tests of suspected paraprotein-related diseases. Other serologies, such as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies or antiglomerular basement membrane antibodies, would not necessarily be indicated here given the lack of hematuria and presence of nephrotic-range proteinuria.

► Dr. Li. The initial evaluation was notable for an erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 120 (mm/h) and a weakly positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:40. The remainder of his initial workup did not reveal an etiology for his nephrotic syndrome (Table 3).

Dr. William, is there a role for starting urgent empiric steroids in nephrotic syndrome while workup is ongoing? If so, do the severity of proteinuria and/or symptoms play a role or is this determination based on something else?

► Dr. William. Edema is a primary symptom of nephrotic syndrome and can often be managed with diuretics alone. If a clear medication-mediated cause is suspected, discontinuation of this agent may result in spontaneous improvement without steroid treatment. However,in cases where an etiology is unclear and there are serious thrombotic complications requiring anticoagulation, and a renal biopsy is deemed to be too risky, then empiric steroid therapy may be necessary. Children with new-onset nephrotic syndrome are presumed to have minimal change disease, given its prevalence in this patient population, and are often given empiric steroids without obtaining a renal biopsy. However, in the adult population, a renal biopsy can typically be performed quickly and safely, with pathology results interpreted within days. In this patient, since a diagnosis was unclear and there was no contraindication to renal biopsy, a biopsy should be obtained before consideration of steroids.

► Dr. Li. Steroids were deferred in anticipation of renal biopsy, which showed stage I membranous nephropathy, suggestive of membranous lupus nephritis Class V. The deposits were strongly reactive for immunoglobuline G (IgG), IgA, and complement 1q (C1q), showed co-dominant staining for IgG1, IgG2, and IgG3, and were weakly positive for the PLA2 receptor. Focal intimal arteritis in a small interlobular vessel was seen.

Dr. William, the pathology returned suggestive of lupus nephritis. Does the overall clinical picture fit with lupus nephritis?

► Dr. William. Given the history and a rather low ANA, the diagnosis of lupus nephritis seems unlikely. The lack of IgG4 and PLA2R staining in the biopsy suggests that this membranous pattern on the biopsy is likely to be secondary to a systemic etiology, but further investigation should be pursued.

► Dr. Li. The patient was discharged after the biopsy with a planned outpatient nephrology follow-up to discuss results and treatment. He was prescribed an oral diuretic, and his symptoms improved. Several days after discharge, he developed blurry vision and was evaluated in the Ophthalmology clinic. On fundoscopy, he was found to have acute papillitis, a form of optic neuritis. As part of initial evaluation of infectious etiologies of papillitis, ophthalmology recommended testing for syphilis.

Dr. Strymish, when we are considering secondary syphilis, what is the recommended approach to diagnostic testing?

► Judith Strymish, MD, Infectious Diseases, BIDMC, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. The diagnosis of syphilis is usually made through serologic testing of blood specimens. Methods that detect the spirochete directly like dark-field smears are not readily available. Serologic tests include treponemal tests (eg, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay [TPPA]) and nontreponemal tests (eg, rapid plasma reagin [RPR]). One needs a confirmatory test because either test is associated with false positives. Either test can be done first. Most laboratories, including those at VABHS are now performing treponemal tests first as these have become more cost-effective.6 The TPPA treponemal test was found to have a lower false negative rate in primary syphilis compared with that of nontreponemal tests.7 Nontreponemal tests can be followed for response to therapy. If a patient has a history of treated syphilis, a nontreponemal test should be sent, since the treponemal test will remain positive for life.

If there is clinical concern for neurosyphilis, cerebrospinal fluid fluorescent (CSF) treponemal antibody needs to be sampled and sent for the nontreponemal venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test. The VDRL is highly specific for neurosyphilis but not as sensitive. Cerebrospinal fluid fluorescent treponemal antibody (CSF FTA) may also be sent; it is very sensitive but not very specific for neurosyphilis.

► Dr. Li. An RPR returned positive at 1:512 (was negative 14 months prior on a routine screening test), with positive reflex TPPA (Table 4). A diagnosis of secondary syphilis was made. Dr. Strymish, at this point, what additional testing and treatment is necessary?

► Dr. Strymish. With papillitis and a very high RPR, we need to assume that he has ophthalmic syphilis. This can occur in any stage of syphilis, but his eye findings and high RPR are consistent with secondary syphilis. Ophthalmic syphilis has been on the upswing, even more than is expected with recent increases in syphilis cases.8 Ophthalmic syphilis is considered a form of neurosyphilis. A lumbar puncture and treatment for neurosyphilis is recommended.9,10

► Dr. Li. A lumbar puncture was performed, and his CSF was VDRL positive. This confirmed a diagnosis of neurosyphilis (Table 4). The patient was treated for neurosyphilis with IV penicillin. The patient shared that he had episodes of unprotected oral sexual activity within the past year and approximately 1 year ago, he came in close contact (but no sexual activity) with a person who had a rash consistent with syphilis.Dr. William, syphilis would be a potential unifying diagnosis of his renal and ophthalmologic manifestations. Is syphilis known to cause membranous nephropathy?

► Dr. William. Though it is uncommon, the nephrotic syndrome is a well-described complication of secondary syphilis.11,12 Syphilis has been shown to cause nephrotic syndrome in a variety of ways. Case reports abound linking syphilis to minimal change disease and other glomerular diseases.13,14 A case report from 1993 shows a membranous pattern of glomerular disease similar to this case.15 As a form of secondary membranous nephropathy, the immunofluorescence pattern can demonstrate staining similar to the “full house” seen in lupus nephritis (IgA, IgM, and C1q, in addition to IgG and C3).16 This explains the initial interpretation of this patient’s biopsy, as lupus nephritis would be a much more common etiology of secondary membranous nephropathy than is acute syphilis with this immunofluorescence pattern. However, the data in this case are highly suggestive of a causal relationship between secondary syphilis and membranous nephropathy.

► Dr. Li. Dr. Strymish, how should this patient be screened for syphilis reinfection, and at what intervals would you recommend?

► Dr. Strymish. He will need follow-up testing to make sure that his syphilis is effectively treated. If CSF pleocytosis was present initially, a CSF examination should be repeated every 6 months until the cell count is normal. He will also need follow-up for normalization of his RPR. Persons with HIV infection and primary or secondary syphilis should be evaluated clinically and serologically for treatment failure at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months after therapy according to US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.9

His treponemal test for syphilis will likely stay positive for life. His RPR should decrease significantly with effective treatment. It makes sense to screen with RPR alone as long as he continues to have risk factors for acquiring syphilis. Routine syphilis testing is recommended for pregnant women, sexually active men who have sex with men, sexually active persons with HIV, and persons taking PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) for HIV prevention. He should be screened at least yearly for syphilis.

► Dr. Li. Over the next several months, the patient’s creatinine normalized and his proteinuria resolved. His vision recovered, and he has had no further ophthalmologic complications.