User login

Gender and Patient Satisfaction in a Veterans Health Administration Outpatient Chemotherapy Unit

Gender differences in patient satisfaction with medical care have been evaluated in multiple settings; however, studies specific to the unique population of women veterans with cancer are lacking. Women are reported to value privacy, psychosocial support, and communication to a higher degree compared with men.1 Factors affecting satisfaction include the following: discomfort in sharing treatment rooms with the opposite gender, a desire for privacy with treatment and restroom use, anatomic or illness differences, and a personal history of abuse.2-4 Regrettably, up to 1 in 3 women in the United States are victims of sexual trauma in their lifetimes, and up to 1 in 4 women in the military are victims of military sexual trauma. Incidence in both settings is suspected to be higher due to underreporting.5,6

Chemotherapy treatment units are often uniquely designed as an open space, with several patients sharing a treatment area. The design reduces isolation and facilitates quick nurse-patient access during potentially toxic treatments known to have frequent adverse effects. Data suggest that nursing staff prefer open models to facilitate quick patient assessments and interventions as needed; however, patients and families prefer private treatment rooms, especially among women patients or those receiving longer infusions.7

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient population is male predominant, comprised only of 10% female patients.8 Although the proportion of female patients in the VHA is expected to rise annually to about 16% by 2043, the low percentage of female veterans will persist for the foreseeable future.8 This low percentage of female veterans is reflected in the Veterans Affairs Portland Health Care System (VAPHCS) cancer patient population and in the use of the chemotherapy infusion unit, which is used for the ambulatory treatment of veterans undergoing cancer therapy.

The VHA has previously explored gender differences in health care, such as with cardiovascular disease, transgender care, and access to mental health.9-11 However, to the best of our knowledge, no analysis has explored gender differences within the outpatient cancer treatment experience. Patient satisfaction with outpatient cancer care may be magnified in the VHA setting due to the uniquely unequal gender populations, shared treatment space design, and high incidence of sexual abuse among women veterans. Given this, we aimed to identify gender-related preferences in outpatient cancer care in our chemotherapy infusion unit.

In our study, we used the terms male and female to reflect statistical data from the literature or labeled data from the electronic health record (EHR); whereas the terms men and women were used to describe and encompass the cultural implications and context of gender.12

Methods

This study was designated as a quality improvement (QI) project by the VAPHCS research office and Institutional Review Board in accordance with VHA policies.

The VAPHCS outpatient chemotherapy infusion unit is designed with 6 rooms for chemotherapy administration. One room is a large open space with 6 chairs for patients. The other rooms are smaller with glass dividers between the rooms, and 3 chairs inside each for patients. There are 2 private bathrooms, each gender neutral. Direct patient care is provided by physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), infusion unit nurses, and nurse coordinators. Men represent the majority of hematology and oncology physicians (13 of 20 total: 5 women fellow physicians and 2 women attending physicians), and 2 of 4 NPs. Women represent 10 of 12 infusion unit and cancer coordinator nurses. We used the VHA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) EHR, to create a list of veterans treated at the VAPHCS outpatient chemotherapy infusion unit for a 2-year period (January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2020).

Male and female patient lists were first generated based on CPRS categorization. We identified all female veterans treated in the ambulatory infusion unit during the study period. Male patients were then chosen at random, recording the most recent names for each year until a matched number per year compared with the female cohort was reached. Patients were recorded only once even though they had multiple infusion unit visits. Patients were excluded who were deceased, on hospice care, lost to follow-up, could not be reached by phone, refused to take the survey, had undeliverable email addresses, or lacked internet or email access.

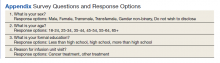

After filing the appropriate request through the VAPHCS Institutional Review Board committee in January 2021, patient records were reviewed for demographics data, contact information, and infusion treatment history. The survey was then conducted over a 2-week period during January and February 2021. Each patient was invited by phone to complete a 25-question anonymous online survey. The survey questions were created from patient-relayed experiences, then modeled into survey questions in a format similar to other patient satisfaction questionnaires described in cancer care and gender differences.2,13,14 The survey included self-identification of gender and was multiple choice for all except 2 questions, which allowed an open-ended response (Appendix). Only 1 answer per question was permitted. Only 1 survey link was sent to each veteran who gave permission for the survey. To protect anonymity for the small patient population, we excluded those identifying as gender nonbinary or transgender.

Statistical Analysis

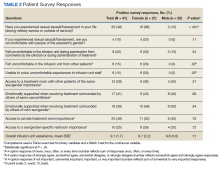

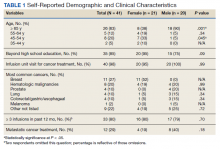

Patient, disease, and treatment features are separated by male and female cohorts to reflect information from the EHR (Table 1). Survey percentages were calculated to reflect the affirmative response of the question asked (Table 2). Questions with answer options of not important, minimally important, important, or very important were calculated to reflect the sum of any importance in both cohorts. Questions with answer options of never, once, often, or every time were calculated to reflect any occurrence (sum of once, often, or every time) in both patient groups. Questions with answer options of strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, and strongly disagree were calculated to reflect any agreement (somewhat agree and strongly agree summed together) for both groups. Comparisons between cohorts were then conducted using a Fisher exact test. A Welch t test was used to calculate the significance of the continuous variable and overall ranking of the infusion unit experience between groups.

Results

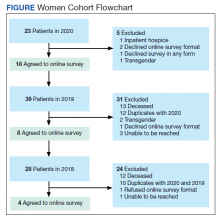

In 2020, 414 individual patients were treated at the VAPAHCS outpatient infusion unit. Of these, 23 (5.6%) were female, and 18 agreed to take the survey. After deceased and duplicate names from 2020 were removed, another 14 eligible 2019 female patients were invited and 6 agreed to participate; 6 eligible 2018 female patients were invited and 4 agreed to take the survey (Figure). Thirty female veterans were sent a survey link and 21 (70%) responses were collected. Twenty-one male 2020 patients were contacted and 18 agreed to take the survey. After removing duplicate names and deceased individuals, 17 of 21 eligible 2019 male patients and 4 of 6 eligible 2018 patients agreed to take the survey. Five additional male veterans declined the online-based survey method. In total, 39 male veterans were reached who agreed to have the survey link emailed, and 20 (51%) total responses were collected.

Most respondents answered all questions in the survey. The most frequently skipped questions included 3 questions that were contingent on a yes answer to a prior question, and 2 openended questions asking for a write-in response. Percentages for female and male respondents were adjusted for number of responses when applicable.

Thirteen (62%) female patients were aged < 65 years, while 18 (90%) of male patients were aged ≥ 65 years. Education beyond high school was reported in 20 female and 15 male respondents. Almost all treatment administered in the infusion unit was for cancer-directed treatment, with only 1 reporting a noncancer treatment (IV iron). The most common malignancy among female patients was breast cancer (n = 11, 52%); for male patients prostate cancer (n = 4, 20%) and hematologic malignancy (n = 4, 20%) were most common. Four (19%) female and 8 (40%) male respondents reported having a metastatic diagnosis. Overall patient satisfaction ranked high with an average score of 9.1 on a 10-point scale. The mean (SD) satisfaction score for female respondents was 1 point lower than that for men: 8.7 (2.2) vs 9.6 (0.6) in men (P = .11).

Eighteen (86%) women reported a history of sexual abuse or harassment compared with 2 (10%) men (P < .001). The sexual abuse assailant was a different gender for 17 of 18 female respondents and of the same gender for both male respondents. Of those with sexual abuse history, 4 women reported feeling uncomfortable around their assailant’s gender vs no men (P = .11), but this difference was not statistically significant. Six women (29%) and 2 (10%) men reported feeling uncomfortable during clinical examinations from comments made by the clinician or during treatment administration (P = .24). Six (29%) women and no men reported that they “felt uncomfortable in the infusion unit by other patients” (P = .02). Six (29%) women and no men reported feeling unable to “voice uncomfortable experiences” to the infusion unit clinician (P = .02).

Ten (48%) women and 6 (30%) men reported emotional support when receiving treatments provided by staff of the same gender (P = .34). Eight (38%) women and 4 (20%) men noted that access to treatment with the same gender was important (P = .31). Six (29%) women and 4 (20%) men indicated that access to a sex or gender-specific restroom was important (P = .72). No gender preferences were identified in the survey questions regarding importance of private treatment room access and level of emotional support when receiving treatment with others of the same malignancy. These relationships were not statistically significant.

In addition, 2 open-ended questions were asked. Seventeen women and 14 men responded. Contact the corresponding author for more information on the questions and responses.

Discussion

Overall patient satisfaction was high among the men and women veterans with cancer who received treatment in our outpatient infusion unit; however, notable gender differences existed. Three items in the survey revealed statistically significant differences in the patient experience between men and women veterans: history of sexual abuse or harassment, uncomfortable feelings among other patients, and discomfort in relaying uncomfortable feelings to a clinician. Other items in the survey did not reach statistical significance; however, we have included discussion of the findings as they may highlight important trends and be of clinical significance.

We suspect differences among genders in patient satisfaction to be related to the high incidence of sexual abuse or harassment history reported by women, much higher at 86% than the one-third to one-fourth incidence rates estimated by the existing literature for civilian or military sexual abuse in women.5,6 These high sexual abuse or harassment rates are present in a majority of women who receive cancer-directed treatment toward a gender-specific breast malignancy, surrounded predominantly among men in a shared treatment space. Together, these factors are likely key reasons behind the differences in satisfaction observed. This sentiment is expressed in our cohort, where one-fifth of women with a sexual abuse or harassment history continue to remain uncomfortable around men, and 29% of women reporting some uncomfortable feelings during their treatment experience compared with none of the men. Additionally, 6 (29%) women vs no men felt uncomfortable in reporting an uncomfortable experience with a clinician; this represents a significant barrier in providing care for these patients.

A key gender preference among women included access to shared treatment rooms with other women and that sharing a treatment space with other women resulted in feeling more emotional support during treatments. Access to gender-specific restrooms was also preferred by women more than men. Key findings in both genders were that about half of men and women valued access to a private treatment room and would derive more emotional support when surrounded by others with the same cancer.

Prior studies on gender and patient satisfaction in general medical care and cancer care have found women value privacy more than men.1-3 Wessels and colleagues performed an analysis of 386 patients with cancer in Europe and found gender to be the strongest influence in patient preferences within cancer care. Specifically, the highest statically significant association in care preferences among women included privacy, support/counseling/rehabilitation access, and decreased wait times.2 These findings were most pronounced in those with breast cancer compared with other malignancy type and highlights that malignancy type and gender predominance impact care satisfaction.

Traditionally a shared treatment space design has been used in outpatient chemotherapy units, similar to the design of the VAPHCS. However, recent data report on the patient preference for a private treatment space, which was especially prominent among women and those receiving longer infusions.7 In another study that evaluated 225 patients with cancer preferences in sharing a treatment space with those of a different sexual orientation or gender identify, differences were found. Both men and women had a similar level of comfort in sharing a treatment room with someone of a different sexual orientation; however, more women reported discomfort in sharing a treatment space with a transgender woman compared with men who felt more comfortable sharing a space with a transgender man.4 We noted a gender preference may be present to explain the difference. Within our cohort, women valued access to treatment with other women and derived more emotional support when with other women; however, we did not inquire about feelings in sharing a treatment space among transgender individuals or differing sexual orientation.

Gender differences for privacy and in shared room preferences may result from the lasting impacts of prior sexual abuse or harassment. A history of sexual abuse negatively impacts later medical care access and use.15 Those veterans who experienced sexual abuse/harrassment reported higher feelings of lack of control, vulnerability, depression, and pursued less medical care.15,16 Within cancer care, these feelings are most pronounced among women with gender-specific malignancies, such as gynecologic cancers or breast cancer. Treatment, screening, and physical examinations by clinicians who are of the same gender as the sexual abuse/harassment assailant can recreate traumatic feelings.15,16

A majority of women (n = 18, 86%) in our cohort reported a history of sexual abuse or harassment and breast malignancy was the most common cancer among women. However women represent just 5.6% of the VAPHCS infusion unit treatment population. This combination of factors may explain the reasons for women veterans’ preference for privacy during treatments, access to gender-specific restrooms, and feeling more emotional support when surrounded by other women. Strategies to help patients with a history of abuse have been described and include discussions from the clinician asking about abuse history, allowing time for the patient to express fears with an examination or test, and training on how to deliver sensitive care for those with trauma.17,18

Quality Improvement

Project In the VAPHCS infusion unit, several low-cost interventions have been undertaken as a result of our survey findings. We presented our survey data to the VAPHCS Cancer Committee, accredited through the national American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. The committee awarded support for a yearlong QI project, including a formal framework of quarterly multidisciplinary meetings to discuss project updates, challenges, and resources. The QI project centers on education to raise awareness of survey results as well as specific interventions for improvement.

Education efforts have been applied through multiple department-wide emails, in-person education to our chemotherapy unit staff, abstract submission to national oncology conferences, and grand rounds department presentations at VAPHCS and at other VHA-affiliated university programs. Additionally, education to clinicians with specific contact information for psychology and women’s health to support mental health, trauma, and sexual abuse histories has been given to each clinician who cares for veterans in the chemotherapy unit.

We also have implemented a mandatory cancer care navigation consultation for all women veterans who have a new cancer or infusion need. The cancer care navigator has received specialized training in sensitive history-taking and provides women veterans with a direct number to reach the cancer care navigation nurse. Cancer care navigation also provides a continuum of support and referral access for psychosocial needs as indicated between infusion or health care visits. Our hope is that these resources may help offset the sentiment reflected in our cohort of women feeling unable to voice concerns to a clinician.

Other interventions underway include offering designated scheduling time each week to women so they can receive infusions in an area with other women. This may help mitigate the finding that women veterans felt more uncomfortable around other patients during infusion treatments compared with how men felt in the chemotherapy unit. We also have implemented gender-specific restrooms labeled with a sign on each bathroom door so men and women can have access to a designated restroom. Offering private or semiprivate treatment rooms is currently limited by space and capacity; however, these may offer the greatest opportunity to improve patient satisfaction, especially among women veterans. Working with the support of the VAPHCS Cancer Committee, we aim to reevaluate the impact of the education and QI efforts on gender differences and patient satisfaction at completion of the 1-year award.

Limitations

Limitations to our study include the overall small sample size. This is due to the combination of the low number of women treated at VAPHCS and many with advanced cancer who, unfortunately, have a limited overall survival and hinders accrual of a larger sample size. Other limitations included age as a possible confounder in our findings, with women representing a younger demographic compared with men. We did not collect responses on duration of infusion time, which also may impact overall satisfaction and patient experience. We also acknowledge that biologic male or female sex may not correspond to a specific individual’s gender. Use of CPRS to obtain a matched number of male and female patients through random selection relied on labeled data from the EHR. This potentially may have excluded male patients who identify as another gender that would have been captured on the anonymous survey.

Last, we restricted survey responses to online only, which excluded a small percentage who declined this approach.

Conclusions

Our findings may have broad applications to other VHA facilities and other cancer-directed treatment centers where the patient demographic and open shared infusion unit design may be similar. The study also may serve as a model of survey design and implementation from which other centers may consider improving patient satisfaction. We hope these survey results and interventions can provide insight and be used to improve patient satisfaction among all cancer patients at infusion units serving veterans and nonveterans.

Acknowledgments

We are very thankful to our cancer patients who took the time to take the survey. We also are very grateful to the VHA infusion unit nurses, staff, nurse practitioners, and physicians who have embraced this project and welcomed any changes that may positively impact treatment of veterans. Also, thank you to Tia Kohs for statistical support and Sophie West for gender discussions. Last, we specifically thank Barbara, for her pursuit of better care for women and for all veterans.

1. Clarke SA, Booth L, Velikova G, Hewison J. Social support: gender differences in cancer patients in the United Kingdom. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(1):66-72. doi:10.1097/00002820-200601000-00012

2. Wessels H, de Graeff A, Wynia K, et al. Gender-related needs and preferences in cancer care indicate the need for an individualized approach to cancer patients. Oncologist. 2010;15(6):648-655. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0337

3. Hartigan SM, Bonnet K, Chisholm L, et al. Why do women not use the bathroom? Women’s attitudes and beliefs on using public restrooms. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2053. doi:10.3390/ijerph17062053

4. Alexander K, Walters CB, Banerjee SC. Oncology patients’ preferences regarding sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) disclosure and room sharing sharing. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(5):1041-1048. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2019.12.006

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about sexual violence. Updated July 5, 2022. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features /sexual-violence/index.html

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Military sexual trauma. Updated May 16, 2022. Accessed July 13, 2022. https:// www.mentalhealth.va.gov/mentalhealth/msthome/index.asp

7. Wang Z, Pukszta M. Private Rooms, Semi-open areas, or open areas for chemotherapy care: perspectives of cancer patients, families, and nursing staff. HERD. 2018;11(3):94- 108. doi:10.1177/1937586718758445

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Women veterans report: the past, present, and future of women veterans. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vetdata /docs/specialreports/women_veterans_2015_final.pdf

9. Driscoll MA, Higgins DM, Seng EK, et al. Trauma, social support, family conflict, and chronic pain in recent service veterans: does gender matter? Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1101- 1111. doi:10.1111/pme.12744

10. Fox AB, Meyer EC, Vogt D. Attitudes about the VA healthcare setting, mental illness, and mental health treatment and their relationship with VA mental health service use among female and male OEF/OIF veterans. Psychol Serv. 2015;12(1):49-58. doi:10.1037/a0038269

11. Virani SS, Woodard LD, Ramsey DJ, et al. Gender disparities in evidence-based statin therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(1):21-26. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.09.041

12. Tseng J. Sex, gender, and why the differences matter. Virtual Mentor. 2008;10(7):427-428. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2008.10.7.fred1-0807

13. Booij JC, Zegers M, Evers PMPJ, Hendricks M, Delnoij DMJ, Rademakers JJDJM. Improving cancer patient care: development of a generic cancer consumer quality index questionnaire for cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(203). doi:10.1186/1471-2407-13-203

14. Meropol NJ, Egleston BL, Buzaglo JS, et al. Cancer patient preferences for quality and length of life. Cancer. 2008;113(12):3459-3466. doi:10.1002/cncr.23968 1

5. Schnur JB, Dillon MJ, Goldsmith RE, Montgomery GH. Cancer treatment experiences among survivors of childhood sexual abuse: a qualitative investigation of triggers and reactions to cumulative trauma. Palliat Support Care. 2018;16(6):767-776. doi:10.1017/S147895151700075X

16. Cadman L, Waller J, Ashdown-Barr L, Szarewski A. Barriers to cervical screening in women who have experienced sexual abuse: an exploratory study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2012;38(4):214-220. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100378

17. Kelly S. The effects of childhood sexual abuse on women’s lives and their attitudes to cervical screening. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2012;38(4):212-213. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100418

18. McCloskey LA, Lichter E, Williams C, Gerber M, Wittenberg E, Ganz M. Assessing intimate partner violence in health care settings leads to women’s receipt of interventions and improved health. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(4):435-444. doi:10.1177/003335490612100412

Gender differences in patient satisfaction with medical care have been evaluated in multiple settings; however, studies specific to the unique population of women veterans with cancer are lacking. Women are reported to value privacy, psychosocial support, and communication to a higher degree compared with men.1 Factors affecting satisfaction include the following: discomfort in sharing treatment rooms with the opposite gender, a desire for privacy with treatment and restroom use, anatomic or illness differences, and a personal history of abuse.2-4 Regrettably, up to 1 in 3 women in the United States are victims of sexual trauma in their lifetimes, and up to 1 in 4 women in the military are victims of military sexual trauma. Incidence in both settings is suspected to be higher due to underreporting.5,6

Chemotherapy treatment units are often uniquely designed as an open space, with several patients sharing a treatment area. The design reduces isolation and facilitates quick nurse-patient access during potentially toxic treatments known to have frequent adverse effects. Data suggest that nursing staff prefer open models to facilitate quick patient assessments and interventions as needed; however, patients and families prefer private treatment rooms, especially among women patients or those receiving longer infusions.7

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient population is male predominant, comprised only of 10% female patients.8 Although the proportion of female patients in the VHA is expected to rise annually to about 16% by 2043, the low percentage of female veterans will persist for the foreseeable future.8 This low percentage of female veterans is reflected in the Veterans Affairs Portland Health Care System (VAPHCS) cancer patient population and in the use of the chemotherapy infusion unit, which is used for the ambulatory treatment of veterans undergoing cancer therapy.

The VHA has previously explored gender differences in health care, such as with cardiovascular disease, transgender care, and access to mental health.9-11 However, to the best of our knowledge, no analysis has explored gender differences within the outpatient cancer treatment experience. Patient satisfaction with outpatient cancer care may be magnified in the VHA setting due to the uniquely unequal gender populations, shared treatment space design, and high incidence of sexual abuse among women veterans. Given this, we aimed to identify gender-related preferences in outpatient cancer care in our chemotherapy infusion unit.

In our study, we used the terms male and female to reflect statistical data from the literature or labeled data from the electronic health record (EHR); whereas the terms men and women were used to describe and encompass the cultural implications and context of gender.12

Methods

This study was designated as a quality improvement (QI) project by the VAPHCS research office and Institutional Review Board in accordance with VHA policies.

The VAPHCS outpatient chemotherapy infusion unit is designed with 6 rooms for chemotherapy administration. One room is a large open space with 6 chairs for patients. The other rooms are smaller with glass dividers between the rooms, and 3 chairs inside each for patients. There are 2 private bathrooms, each gender neutral. Direct patient care is provided by physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), infusion unit nurses, and nurse coordinators. Men represent the majority of hematology and oncology physicians (13 of 20 total: 5 women fellow physicians and 2 women attending physicians), and 2 of 4 NPs. Women represent 10 of 12 infusion unit and cancer coordinator nurses. We used the VHA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) EHR, to create a list of veterans treated at the VAPHCS outpatient chemotherapy infusion unit for a 2-year period (January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2020).

Male and female patient lists were first generated based on CPRS categorization. We identified all female veterans treated in the ambulatory infusion unit during the study period. Male patients were then chosen at random, recording the most recent names for each year until a matched number per year compared with the female cohort was reached. Patients were recorded only once even though they had multiple infusion unit visits. Patients were excluded who were deceased, on hospice care, lost to follow-up, could not be reached by phone, refused to take the survey, had undeliverable email addresses, or lacked internet or email access.

After filing the appropriate request through the VAPHCS Institutional Review Board committee in January 2021, patient records were reviewed for demographics data, contact information, and infusion treatment history. The survey was then conducted over a 2-week period during January and February 2021. Each patient was invited by phone to complete a 25-question anonymous online survey. The survey questions were created from patient-relayed experiences, then modeled into survey questions in a format similar to other patient satisfaction questionnaires described in cancer care and gender differences.2,13,14 The survey included self-identification of gender and was multiple choice for all except 2 questions, which allowed an open-ended response (Appendix). Only 1 answer per question was permitted. Only 1 survey link was sent to each veteran who gave permission for the survey. To protect anonymity for the small patient population, we excluded those identifying as gender nonbinary or transgender.

Statistical Analysis

Patient, disease, and treatment features are separated by male and female cohorts to reflect information from the EHR (Table 1). Survey percentages were calculated to reflect the affirmative response of the question asked (Table 2). Questions with answer options of not important, minimally important, important, or very important were calculated to reflect the sum of any importance in both cohorts. Questions with answer options of never, once, often, or every time were calculated to reflect any occurrence (sum of once, often, or every time) in both patient groups. Questions with answer options of strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, and strongly disagree were calculated to reflect any agreement (somewhat agree and strongly agree summed together) for both groups. Comparisons between cohorts were then conducted using a Fisher exact test. A Welch t test was used to calculate the significance of the continuous variable and overall ranking of the infusion unit experience between groups.

Results

In 2020, 414 individual patients were treated at the VAPAHCS outpatient infusion unit. Of these, 23 (5.6%) were female, and 18 agreed to take the survey. After deceased and duplicate names from 2020 were removed, another 14 eligible 2019 female patients were invited and 6 agreed to participate; 6 eligible 2018 female patients were invited and 4 agreed to take the survey (Figure). Thirty female veterans were sent a survey link and 21 (70%) responses were collected. Twenty-one male 2020 patients were contacted and 18 agreed to take the survey. After removing duplicate names and deceased individuals, 17 of 21 eligible 2019 male patients and 4 of 6 eligible 2018 patients agreed to take the survey. Five additional male veterans declined the online-based survey method. In total, 39 male veterans were reached who agreed to have the survey link emailed, and 20 (51%) total responses were collected.

Most respondents answered all questions in the survey. The most frequently skipped questions included 3 questions that were contingent on a yes answer to a prior question, and 2 openended questions asking for a write-in response. Percentages for female and male respondents were adjusted for number of responses when applicable.

Thirteen (62%) female patients were aged < 65 years, while 18 (90%) of male patients were aged ≥ 65 years. Education beyond high school was reported in 20 female and 15 male respondents. Almost all treatment administered in the infusion unit was for cancer-directed treatment, with only 1 reporting a noncancer treatment (IV iron). The most common malignancy among female patients was breast cancer (n = 11, 52%); for male patients prostate cancer (n = 4, 20%) and hematologic malignancy (n = 4, 20%) were most common. Four (19%) female and 8 (40%) male respondents reported having a metastatic diagnosis. Overall patient satisfaction ranked high with an average score of 9.1 on a 10-point scale. The mean (SD) satisfaction score for female respondents was 1 point lower than that for men: 8.7 (2.2) vs 9.6 (0.6) in men (P = .11).

Eighteen (86%) women reported a history of sexual abuse or harassment compared with 2 (10%) men (P < .001). The sexual abuse assailant was a different gender for 17 of 18 female respondents and of the same gender for both male respondents. Of those with sexual abuse history, 4 women reported feeling uncomfortable around their assailant’s gender vs no men (P = .11), but this difference was not statistically significant. Six women (29%) and 2 (10%) men reported feeling uncomfortable during clinical examinations from comments made by the clinician or during treatment administration (P = .24). Six (29%) women and no men reported that they “felt uncomfortable in the infusion unit by other patients” (P = .02). Six (29%) women and no men reported feeling unable to “voice uncomfortable experiences” to the infusion unit clinician (P = .02).

Ten (48%) women and 6 (30%) men reported emotional support when receiving treatments provided by staff of the same gender (P = .34). Eight (38%) women and 4 (20%) men noted that access to treatment with the same gender was important (P = .31). Six (29%) women and 4 (20%) men indicated that access to a sex or gender-specific restroom was important (P = .72). No gender preferences were identified in the survey questions regarding importance of private treatment room access and level of emotional support when receiving treatment with others of the same malignancy. These relationships were not statistically significant.

In addition, 2 open-ended questions were asked. Seventeen women and 14 men responded. Contact the corresponding author for more information on the questions and responses.

Discussion

Overall patient satisfaction was high among the men and women veterans with cancer who received treatment in our outpatient infusion unit; however, notable gender differences existed. Three items in the survey revealed statistically significant differences in the patient experience between men and women veterans: history of sexual abuse or harassment, uncomfortable feelings among other patients, and discomfort in relaying uncomfortable feelings to a clinician. Other items in the survey did not reach statistical significance; however, we have included discussion of the findings as they may highlight important trends and be of clinical significance.

We suspect differences among genders in patient satisfaction to be related to the high incidence of sexual abuse or harassment history reported by women, much higher at 86% than the one-third to one-fourth incidence rates estimated by the existing literature for civilian or military sexual abuse in women.5,6 These high sexual abuse or harassment rates are present in a majority of women who receive cancer-directed treatment toward a gender-specific breast malignancy, surrounded predominantly among men in a shared treatment space. Together, these factors are likely key reasons behind the differences in satisfaction observed. This sentiment is expressed in our cohort, where one-fifth of women with a sexual abuse or harassment history continue to remain uncomfortable around men, and 29% of women reporting some uncomfortable feelings during their treatment experience compared with none of the men. Additionally, 6 (29%) women vs no men felt uncomfortable in reporting an uncomfortable experience with a clinician; this represents a significant barrier in providing care for these patients.

A key gender preference among women included access to shared treatment rooms with other women and that sharing a treatment space with other women resulted in feeling more emotional support during treatments. Access to gender-specific restrooms was also preferred by women more than men. Key findings in both genders were that about half of men and women valued access to a private treatment room and would derive more emotional support when surrounded by others with the same cancer.

Prior studies on gender and patient satisfaction in general medical care and cancer care have found women value privacy more than men.1-3 Wessels and colleagues performed an analysis of 386 patients with cancer in Europe and found gender to be the strongest influence in patient preferences within cancer care. Specifically, the highest statically significant association in care preferences among women included privacy, support/counseling/rehabilitation access, and decreased wait times.2 These findings were most pronounced in those with breast cancer compared with other malignancy type and highlights that malignancy type and gender predominance impact care satisfaction.

Traditionally a shared treatment space design has been used in outpatient chemotherapy units, similar to the design of the VAPHCS. However, recent data report on the patient preference for a private treatment space, which was especially prominent among women and those receiving longer infusions.7 In another study that evaluated 225 patients with cancer preferences in sharing a treatment space with those of a different sexual orientation or gender identify, differences were found. Both men and women had a similar level of comfort in sharing a treatment room with someone of a different sexual orientation; however, more women reported discomfort in sharing a treatment space with a transgender woman compared with men who felt more comfortable sharing a space with a transgender man.4 We noted a gender preference may be present to explain the difference. Within our cohort, women valued access to treatment with other women and derived more emotional support when with other women; however, we did not inquire about feelings in sharing a treatment space among transgender individuals or differing sexual orientation.

Gender differences for privacy and in shared room preferences may result from the lasting impacts of prior sexual abuse or harassment. A history of sexual abuse negatively impacts later medical care access and use.15 Those veterans who experienced sexual abuse/harrassment reported higher feelings of lack of control, vulnerability, depression, and pursued less medical care.15,16 Within cancer care, these feelings are most pronounced among women with gender-specific malignancies, such as gynecologic cancers or breast cancer. Treatment, screening, and physical examinations by clinicians who are of the same gender as the sexual abuse/harassment assailant can recreate traumatic feelings.15,16

A majority of women (n = 18, 86%) in our cohort reported a history of sexual abuse or harassment and breast malignancy was the most common cancer among women. However women represent just 5.6% of the VAPHCS infusion unit treatment population. This combination of factors may explain the reasons for women veterans’ preference for privacy during treatments, access to gender-specific restrooms, and feeling more emotional support when surrounded by other women. Strategies to help patients with a history of abuse have been described and include discussions from the clinician asking about abuse history, allowing time for the patient to express fears with an examination or test, and training on how to deliver sensitive care for those with trauma.17,18

Quality Improvement

Project In the VAPHCS infusion unit, several low-cost interventions have been undertaken as a result of our survey findings. We presented our survey data to the VAPHCS Cancer Committee, accredited through the national American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. The committee awarded support for a yearlong QI project, including a formal framework of quarterly multidisciplinary meetings to discuss project updates, challenges, and resources. The QI project centers on education to raise awareness of survey results as well as specific interventions for improvement.

Education efforts have been applied through multiple department-wide emails, in-person education to our chemotherapy unit staff, abstract submission to national oncology conferences, and grand rounds department presentations at VAPHCS and at other VHA-affiliated university programs. Additionally, education to clinicians with specific contact information for psychology and women’s health to support mental health, trauma, and sexual abuse histories has been given to each clinician who cares for veterans in the chemotherapy unit.

We also have implemented a mandatory cancer care navigation consultation for all women veterans who have a new cancer or infusion need. The cancer care navigator has received specialized training in sensitive history-taking and provides women veterans with a direct number to reach the cancer care navigation nurse. Cancer care navigation also provides a continuum of support and referral access for psychosocial needs as indicated between infusion or health care visits. Our hope is that these resources may help offset the sentiment reflected in our cohort of women feeling unable to voice concerns to a clinician.

Other interventions underway include offering designated scheduling time each week to women so they can receive infusions in an area with other women. This may help mitigate the finding that women veterans felt more uncomfortable around other patients during infusion treatments compared with how men felt in the chemotherapy unit. We also have implemented gender-specific restrooms labeled with a sign on each bathroom door so men and women can have access to a designated restroom. Offering private or semiprivate treatment rooms is currently limited by space and capacity; however, these may offer the greatest opportunity to improve patient satisfaction, especially among women veterans. Working with the support of the VAPHCS Cancer Committee, we aim to reevaluate the impact of the education and QI efforts on gender differences and patient satisfaction at completion of the 1-year award.

Limitations

Limitations to our study include the overall small sample size. This is due to the combination of the low number of women treated at VAPHCS and many with advanced cancer who, unfortunately, have a limited overall survival and hinders accrual of a larger sample size. Other limitations included age as a possible confounder in our findings, with women representing a younger demographic compared with men. We did not collect responses on duration of infusion time, which also may impact overall satisfaction and patient experience. We also acknowledge that biologic male or female sex may not correspond to a specific individual’s gender. Use of CPRS to obtain a matched number of male and female patients through random selection relied on labeled data from the EHR. This potentially may have excluded male patients who identify as another gender that would have been captured on the anonymous survey.

Last, we restricted survey responses to online only, which excluded a small percentage who declined this approach.

Conclusions

Our findings may have broad applications to other VHA facilities and other cancer-directed treatment centers where the patient demographic and open shared infusion unit design may be similar. The study also may serve as a model of survey design and implementation from which other centers may consider improving patient satisfaction. We hope these survey results and interventions can provide insight and be used to improve patient satisfaction among all cancer patients at infusion units serving veterans and nonveterans.

Acknowledgments

We are very thankful to our cancer patients who took the time to take the survey. We also are very grateful to the VHA infusion unit nurses, staff, nurse practitioners, and physicians who have embraced this project and welcomed any changes that may positively impact treatment of veterans. Also, thank you to Tia Kohs for statistical support and Sophie West for gender discussions. Last, we specifically thank Barbara, for her pursuit of better care for women and for all veterans.

Gender differences in patient satisfaction with medical care have been evaluated in multiple settings; however, studies specific to the unique population of women veterans with cancer are lacking. Women are reported to value privacy, psychosocial support, and communication to a higher degree compared with men.1 Factors affecting satisfaction include the following: discomfort in sharing treatment rooms with the opposite gender, a desire for privacy with treatment and restroom use, anatomic or illness differences, and a personal history of abuse.2-4 Regrettably, up to 1 in 3 women in the United States are victims of sexual trauma in their lifetimes, and up to 1 in 4 women in the military are victims of military sexual trauma. Incidence in both settings is suspected to be higher due to underreporting.5,6

Chemotherapy treatment units are often uniquely designed as an open space, with several patients sharing a treatment area. The design reduces isolation and facilitates quick nurse-patient access during potentially toxic treatments known to have frequent adverse effects. Data suggest that nursing staff prefer open models to facilitate quick patient assessments and interventions as needed; however, patients and families prefer private treatment rooms, especially among women patients or those receiving longer infusions.7

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient population is male predominant, comprised only of 10% female patients.8 Although the proportion of female patients in the VHA is expected to rise annually to about 16% by 2043, the low percentage of female veterans will persist for the foreseeable future.8 This low percentage of female veterans is reflected in the Veterans Affairs Portland Health Care System (VAPHCS) cancer patient population and in the use of the chemotherapy infusion unit, which is used for the ambulatory treatment of veterans undergoing cancer therapy.

The VHA has previously explored gender differences in health care, such as with cardiovascular disease, transgender care, and access to mental health.9-11 However, to the best of our knowledge, no analysis has explored gender differences within the outpatient cancer treatment experience. Patient satisfaction with outpatient cancer care may be magnified in the VHA setting due to the uniquely unequal gender populations, shared treatment space design, and high incidence of sexual abuse among women veterans. Given this, we aimed to identify gender-related preferences in outpatient cancer care in our chemotherapy infusion unit.

In our study, we used the terms male and female to reflect statistical data from the literature or labeled data from the electronic health record (EHR); whereas the terms men and women were used to describe and encompass the cultural implications and context of gender.12

Methods

This study was designated as a quality improvement (QI) project by the VAPHCS research office and Institutional Review Board in accordance with VHA policies.

The VAPHCS outpatient chemotherapy infusion unit is designed with 6 rooms for chemotherapy administration. One room is a large open space with 6 chairs for patients. The other rooms are smaller with glass dividers between the rooms, and 3 chairs inside each for patients. There are 2 private bathrooms, each gender neutral. Direct patient care is provided by physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), infusion unit nurses, and nurse coordinators. Men represent the majority of hematology and oncology physicians (13 of 20 total: 5 women fellow physicians and 2 women attending physicians), and 2 of 4 NPs. Women represent 10 of 12 infusion unit and cancer coordinator nurses. We used the VHA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) EHR, to create a list of veterans treated at the VAPHCS outpatient chemotherapy infusion unit for a 2-year period (January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2020).

Male and female patient lists were first generated based on CPRS categorization. We identified all female veterans treated in the ambulatory infusion unit during the study period. Male patients were then chosen at random, recording the most recent names for each year until a matched number per year compared with the female cohort was reached. Patients were recorded only once even though they had multiple infusion unit visits. Patients were excluded who were deceased, on hospice care, lost to follow-up, could not be reached by phone, refused to take the survey, had undeliverable email addresses, or lacked internet or email access.

After filing the appropriate request through the VAPHCS Institutional Review Board committee in January 2021, patient records were reviewed for demographics data, contact information, and infusion treatment history. The survey was then conducted over a 2-week period during January and February 2021. Each patient was invited by phone to complete a 25-question anonymous online survey. The survey questions were created from patient-relayed experiences, then modeled into survey questions in a format similar to other patient satisfaction questionnaires described in cancer care and gender differences.2,13,14 The survey included self-identification of gender and was multiple choice for all except 2 questions, which allowed an open-ended response (Appendix). Only 1 answer per question was permitted. Only 1 survey link was sent to each veteran who gave permission for the survey. To protect anonymity for the small patient population, we excluded those identifying as gender nonbinary or transgender.

Statistical Analysis

Patient, disease, and treatment features are separated by male and female cohorts to reflect information from the EHR (Table 1). Survey percentages were calculated to reflect the affirmative response of the question asked (Table 2). Questions with answer options of not important, minimally important, important, or very important were calculated to reflect the sum of any importance in both cohorts. Questions with answer options of never, once, often, or every time were calculated to reflect any occurrence (sum of once, often, or every time) in both patient groups. Questions with answer options of strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, and strongly disagree were calculated to reflect any agreement (somewhat agree and strongly agree summed together) for both groups. Comparisons between cohorts were then conducted using a Fisher exact test. A Welch t test was used to calculate the significance of the continuous variable and overall ranking of the infusion unit experience between groups.

Results

In 2020, 414 individual patients were treated at the VAPAHCS outpatient infusion unit. Of these, 23 (5.6%) were female, and 18 agreed to take the survey. After deceased and duplicate names from 2020 were removed, another 14 eligible 2019 female patients were invited and 6 agreed to participate; 6 eligible 2018 female patients were invited and 4 agreed to take the survey (Figure). Thirty female veterans were sent a survey link and 21 (70%) responses were collected. Twenty-one male 2020 patients were contacted and 18 agreed to take the survey. After removing duplicate names and deceased individuals, 17 of 21 eligible 2019 male patients and 4 of 6 eligible 2018 patients agreed to take the survey. Five additional male veterans declined the online-based survey method. In total, 39 male veterans were reached who agreed to have the survey link emailed, and 20 (51%) total responses were collected.

Most respondents answered all questions in the survey. The most frequently skipped questions included 3 questions that were contingent on a yes answer to a prior question, and 2 openended questions asking for a write-in response. Percentages for female and male respondents were adjusted for number of responses when applicable.

Thirteen (62%) female patients were aged < 65 years, while 18 (90%) of male patients were aged ≥ 65 years. Education beyond high school was reported in 20 female and 15 male respondents. Almost all treatment administered in the infusion unit was for cancer-directed treatment, with only 1 reporting a noncancer treatment (IV iron). The most common malignancy among female patients was breast cancer (n = 11, 52%); for male patients prostate cancer (n = 4, 20%) and hematologic malignancy (n = 4, 20%) were most common. Four (19%) female and 8 (40%) male respondents reported having a metastatic diagnosis. Overall patient satisfaction ranked high with an average score of 9.1 on a 10-point scale. The mean (SD) satisfaction score for female respondents was 1 point lower than that for men: 8.7 (2.2) vs 9.6 (0.6) in men (P = .11).

Eighteen (86%) women reported a history of sexual abuse or harassment compared with 2 (10%) men (P < .001). The sexual abuse assailant was a different gender for 17 of 18 female respondents and of the same gender for both male respondents. Of those with sexual abuse history, 4 women reported feeling uncomfortable around their assailant’s gender vs no men (P = .11), but this difference was not statistically significant. Six women (29%) and 2 (10%) men reported feeling uncomfortable during clinical examinations from comments made by the clinician or during treatment administration (P = .24). Six (29%) women and no men reported that they “felt uncomfortable in the infusion unit by other patients” (P = .02). Six (29%) women and no men reported feeling unable to “voice uncomfortable experiences” to the infusion unit clinician (P = .02).

Ten (48%) women and 6 (30%) men reported emotional support when receiving treatments provided by staff of the same gender (P = .34). Eight (38%) women and 4 (20%) men noted that access to treatment with the same gender was important (P = .31). Six (29%) women and 4 (20%) men indicated that access to a sex or gender-specific restroom was important (P = .72). No gender preferences were identified in the survey questions regarding importance of private treatment room access and level of emotional support when receiving treatment with others of the same malignancy. These relationships were not statistically significant.

In addition, 2 open-ended questions were asked. Seventeen women and 14 men responded. Contact the corresponding author for more information on the questions and responses.

Discussion

Overall patient satisfaction was high among the men and women veterans with cancer who received treatment in our outpatient infusion unit; however, notable gender differences existed. Three items in the survey revealed statistically significant differences in the patient experience between men and women veterans: history of sexual abuse or harassment, uncomfortable feelings among other patients, and discomfort in relaying uncomfortable feelings to a clinician. Other items in the survey did not reach statistical significance; however, we have included discussion of the findings as they may highlight important trends and be of clinical significance.

We suspect differences among genders in patient satisfaction to be related to the high incidence of sexual abuse or harassment history reported by women, much higher at 86% than the one-third to one-fourth incidence rates estimated by the existing literature for civilian or military sexual abuse in women.5,6 These high sexual abuse or harassment rates are present in a majority of women who receive cancer-directed treatment toward a gender-specific breast malignancy, surrounded predominantly among men in a shared treatment space. Together, these factors are likely key reasons behind the differences in satisfaction observed. This sentiment is expressed in our cohort, where one-fifth of women with a sexual abuse or harassment history continue to remain uncomfortable around men, and 29% of women reporting some uncomfortable feelings during their treatment experience compared with none of the men. Additionally, 6 (29%) women vs no men felt uncomfortable in reporting an uncomfortable experience with a clinician; this represents a significant barrier in providing care for these patients.

A key gender preference among women included access to shared treatment rooms with other women and that sharing a treatment space with other women resulted in feeling more emotional support during treatments. Access to gender-specific restrooms was also preferred by women more than men. Key findings in both genders were that about half of men and women valued access to a private treatment room and would derive more emotional support when surrounded by others with the same cancer.

Prior studies on gender and patient satisfaction in general medical care and cancer care have found women value privacy more than men.1-3 Wessels and colleagues performed an analysis of 386 patients with cancer in Europe and found gender to be the strongest influence in patient preferences within cancer care. Specifically, the highest statically significant association in care preferences among women included privacy, support/counseling/rehabilitation access, and decreased wait times.2 These findings were most pronounced in those with breast cancer compared with other malignancy type and highlights that malignancy type and gender predominance impact care satisfaction.

Traditionally a shared treatment space design has been used in outpatient chemotherapy units, similar to the design of the VAPHCS. However, recent data report on the patient preference for a private treatment space, which was especially prominent among women and those receiving longer infusions.7 In another study that evaluated 225 patients with cancer preferences in sharing a treatment space with those of a different sexual orientation or gender identify, differences were found. Both men and women had a similar level of comfort in sharing a treatment room with someone of a different sexual orientation; however, more women reported discomfort in sharing a treatment space with a transgender woman compared with men who felt more comfortable sharing a space with a transgender man.4 We noted a gender preference may be present to explain the difference. Within our cohort, women valued access to treatment with other women and derived more emotional support when with other women; however, we did not inquire about feelings in sharing a treatment space among transgender individuals or differing sexual orientation.

Gender differences for privacy and in shared room preferences may result from the lasting impacts of prior sexual abuse or harassment. A history of sexual abuse negatively impacts later medical care access and use.15 Those veterans who experienced sexual abuse/harrassment reported higher feelings of lack of control, vulnerability, depression, and pursued less medical care.15,16 Within cancer care, these feelings are most pronounced among women with gender-specific malignancies, such as gynecologic cancers or breast cancer. Treatment, screening, and physical examinations by clinicians who are of the same gender as the sexual abuse/harassment assailant can recreate traumatic feelings.15,16

A majority of women (n = 18, 86%) in our cohort reported a history of sexual abuse or harassment and breast malignancy was the most common cancer among women. However women represent just 5.6% of the VAPHCS infusion unit treatment population. This combination of factors may explain the reasons for women veterans’ preference for privacy during treatments, access to gender-specific restrooms, and feeling more emotional support when surrounded by other women. Strategies to help patients with a history of abuse have been described and include discussions from the clinician asking about abuse history, allowing time for the patient to express fears with an examination or test, and training on how to deliver sensitive care for those with trauma.17,18

Quality Improvement

Project In the VAPHCS infusion unit, several low-cost interventions have been undertaken as a result of our survey findings. We presented our survey data to the VAPHCS Cancer Committee, accredited through the national American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. The committee awarded support for a yearlong QI project, including a formal framework of quarterly multidisciplinary meetings to discuss project updates, challenges, and resources. The QI project centers on education to raise awareness of survey results as well as specific interventions for improvement.

Education efforts have been applied through multiple department-wide emails, in-person education to our chemotherapy unit staff, abstract submission to national oncology conferences, and grand rounds department presentations at VAPHCS and at other VHA-affiliated university programs. Additionally, education to clinicians with specific contact information for psychology and women’s health to support mental health, trauma, and sexual abuse histories has been given to each clinician who cares for veterans in the chemotherapy unit.

We also have implemented a mandatory cancer care navigation consultation for all women veterans who have a new cancer or infusion need. The cancer care navigator has received specialized training in sensitive history-taking and provides women veterans with a direct number to reach the cancer care navigation nurse. Cancer care navigation also provides a continuum of support and referral access for psychosocial needs as indicated between infusion or health care visits. Our hope is that these resources may help offset the sentiment reflected in our cohort of women feeling unable to voice concerns to a clinician.

Other interventions underway include offering designated scheduling time each week to women so they can receive infusions in an area with other women. This may help mitigate the finding that women veterans felt more uncomfortable around other patients during infusion treatments compared with how men felt in the chemotherapy unit. We also have implemented gender-specific restrooms labeled with a sign on each bathroom door so men and women can have access to a designated restroom. Offering private or semiprivate treatment rooms is currently limited by space and capacity; however, these may offer the greatest opportunity to improve patient satisfaction, especially among women veterans. Working with the support of the VAPHCS Cancer Committee, we aim to reevaluate the impact of the education and QI efforts on gender differences and patient satisfaction at completion of the 1-year award.

Limitations

Limitations to our study include the overall small sample size. This is due to the combination of the low number of women treated at VAPHCS and many with advanced cancer who, unfortunately, have a limited overall survival and hinders accrual of a larger sample size. Other limitations included age as a possible confounder in our findings, with women representing a younger demographic compared with men. We did not collect responses on duration of infusion time, which also may impact overall satisfaction and patient experience. We also acknowledge that biologic male or female sex may not correspond to a specific individual’s gender. Use of CPRS to obtain a matched number of male and female patients through random selection relied on labeled data from the EHR. This potentially may have excluded male patients who identify as another gender that would have been captured on the anonymous survey.

Last, we restricted survey responses to online only, which excluded a small percentage who declined this approach.

Conclusions

Our findings may have broad applications to other VHA facilities and other cancer-directed treatment centers where the patient demographic and open shared infusion unit design may be similar. The study also may serve as a model of survey design and implementation from which other centers may consider improving patient satisfaction. We hope these survey results and interventions can provide insight and be used to improve patient satisfaction among all cancer patients at infusion units serving veterans and nonveterans.

Acknowledgments

We are very thankful to our cancer patients who took the time to take the survey. We also are very grateful to the VHA infusion unit nurses, staff, nurse practitioners, and physicians who have embraced this project and welcomed any changes that may positively impact treatment of veterans. Also, thank you to Tia Kohs for statistical support and Sophie West for gender discussions. Last, we specifically thank Barbara, for her pursuit of better care for women and for all veterans.

1. Clarke SA, Booth L, Velikova G, Hewison J. Social support: gender differences in cancer patients in the United Kingdom. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(1):66-72. doi:10.1097/00002820-200601000-00012

2. Wessels H, de Graeff A, Wynia K, et al. Gender-related needs and preferences in cancer care indicate the need for an individualized approach to cancer patients. Oncologist. 2010;15(6):648-655. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0337

3. Hartigan SM, Bonnet K, Chisholm L, et al. Why do women not use the bathroom? Women’s attitudes and beliefs on using public restrooms. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2053. doi:10.3390/ijerph17062053

4. Alexander K, Walters CB, Banerjee SC. Oncology patients’ preferences regarding sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) disclosure and room sharing sharing. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(5):1041-1048. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2019.12.006

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about sexual violence. Updated July 5, 2022. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features /sexual-violence/index.html

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Military sexual trauma. Updated May 16, 2022. Accessed July 13, 2022. https:// www.mentalhealth.va.gov/mentalhealth/msthome/index.asp

7. Wang Z, Pukszta M. Private Rooms, Semi-open areas, or open areas for chemotherapy care: perspectives of cancer patients, families, and nursing staff. HERD. 2018;11(3):94- 108. doi:10.1177/1937586718758445

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Women veterans report: the past, present, and future of women veterans. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vetdata /docs/specialreports/women_veterans_2015_final.pdf

9. Driscoll MA, Higgins DM, Seng EK, et al. Trauma, social support, family conflict, and chronic pain in recent service veterans: does gender matter? Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1101- 1111. doi:10.1111/pme.12744

10. Fox AB, Meyer EC, Vogt D. Attitudes about the VA healthcare setting, mental illness, and mental health treatment and their relationship with VA mental health service use among female and male OEF/OIF veterans. Psychol Serv. 2015;12(1):49-58. doi:10.1037/a0038269

11. Virani SS, Woodard LD, Ramsey DJ, et al. Gender disparities in evidence-based statin therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(1):21-26. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.09.041

12. Tseng J. Sex, gender, and why the differences matter. Virtual Mentor. 2008;10(7):427-428. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2008.10.7.fred1-0807

13. Booij JC, Zegers M, Evers PMPJ, Hendricks M, Delnoij DMJ, Rademakers JJDJM. Improving cancer patient care: development of a generic cancer consumer quality index questionnaire for cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(203). doi:10.1186/1471-2407-13-203

14. Meropol NJ, Egleston BL, Buzaglo JS, et al. Cancer patient preferences for quality and length of life. Cancer. 2008;113(12):3459-3466. doi:10.1002/cncr.23968 1

5. Schnur JB, Dillon MJ, Goldsmith RE, Montgomery GH. Cancer treatment experiences among survivors of childhood sexual abuse: a qualitative investigation of triggers and reactions to cumulative trauma. Palliat Support Care. 2018;16(6):767-776. doi:10.1017/S147895151700075X

16. Cadman L, Waller J, Ashdown-Barr L, Szarewski A. Barriers to cervical screening in women who have experienced sexual abuse: an exploratory study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2012;38(4):214-220. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100378

17. Kelly S. The effects of childhood sexual abuse on women’s lives and their attitudes to cervical screening. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2012;38(4):212-213. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100418

18. McCloskey LA, Lichter E, Williams C, Gerber M, Wittenberg E, Ganz M. Assessing intimate partner violence in health care settings leads to women’s receipt of interventions and improved health. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(4):435-444. doi:10.1177/003335490612100412

1. Clarke SA, Booth L, Velikova G, Hewison J. Social support: gender differences in cancer patients in the United Kingdom. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(1):66-72. doi:10.1097/00002820-200601000-00012

2. Wessels H, de Graeff A, Wynia K, et al. Gender-related needs and preferences in cancer care indicate the need for an individualized approach to cancer patients. Oncologist. 2010;15(6):648-655. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0337

3. Hartigan SM, Bonnet K, Chisholm L, et al. Why do women not use the bathroom? Women’s attitudes and beliefs on using public restrooms. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2053. doi:10.3390/ijerph17062053

4. Alexander K, Walters CB, Banerjee SC. Oncology patients’ preferences regarding sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) disclosure and room sharing sharing. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(5):1041-1048. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2019.12.006

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about sexual violence. Updated July 5, 2022. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features /sexual-violence/index.html

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Military sexual trauma. Updated May 16, 2022. Accessed July 13, 2022. https:// www.mentalhealth.va.gov/mentalhealth/msthome/index.asp

7. Wang Z, Pukszta M. Private Rooms, Semi-open areas, or open areas for chemotherapy care: perspectives of cancer patients, families, and nursing staff. HERD. 2018;11(3):94- 108. doi:10.1177/1937586718758445

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Women veterans report: the past, present, and future of women veterans. Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vetdata /docs/specialreports/women_veterans_2015_final.pdf

9. Driscoll MA, Higgins DM, Seng EK, et al. Trauma, social support, family conflict, and chronic pain in recent service veterans: does gender matter? Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1101- 1111. doi:10.1111/pme.12744

10. Fox AB, Meyer EC, Vogt D. Attitudes about the VA healthcare setting, mental illness, and mental health treatment and their relationship with VA mental health service use among female and male OEF/OIF veterans. Psychol Serv. 2015;12(1):49-58. doi:10.1037/a0038269

11. Virani SS, Woodard LD, Ramsey DJ, et al. Gender disparities in evidence-based statin therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(1):21-26. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.09.041

12. Tseng J. Sex, gender, and why the differences matter. Virtual Mentor. 2008;10(7):427-428. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2008.10.7.fred1-0807

13. Booij JC, Zegers M, Evers PMPJ, Hendricks M, Delnoij DMJ, Rademakers JJDJM. Improving cancer patient care: development of a generic cancer consumer quality index questionnaire for cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(203). doi:10.1186/1471-2407-13-203

14. Meropol NJ, Egleston BL, Buzaglo JS, et al. Cancer patient preferences for quality and length of life. Cancer. 2008;113(12):3459-3466. doi:10.1002/cncr.23968 1

5. Schnur JB, Dillon MJ, Goldsmith RE, Montgomery GH. Cancer treatment experiences among survivors of childhood sexual abuse: a qualitative investigation of triggers and reactions to cumulative trauma. Palliat Support Care. 2018;16(6):767-776. doi:10.1017/S147895151700075X

16. Cadman L, Waller J, Ashdown-Barr L, Szarewski A. Barriers to cervical screening in women who have experienced sexual abuse: an exploratory study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2012;38(4):214-220. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100378

17. Kelly S. The effects of childhood sexual abuse on women’s lives and their attitudes to cervical screening. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2012;38(4):212-213. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100418

18. McCloskey LA, Lichter E, Williams C, Gerber M, Wittenberg E, Ganz M. Assessing intimate partner violence in health care settings leads to women’s receipt of interventions and improved health. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(4):435-444. doi:10.1177/003335490612100412

Leveraging Veterans Health Administration Clinical and Research Resources to Accelerate Discovery and Testing in Precision Oncology(FULL)

In May 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first 2 targeted treatments for prostate cancer, specifically, the poly-(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors rucaparib and olaparib.1,2 For these medications to work, the tumor must have a homologous recombination deficiency (HRD), which is a form of DNA repair deficiency. The PARP pathway is important for DNA repair, and PARP inhibition leads to “synthetic lethality” in cancer cells that already are deficient in DNA repair mechanisms.3 Now, there is evidence that patients with prostate cancer who have HRD tumors and receive PARP inhibitors live longer when compared with those who receive standard of care options.4 These findings offer hope for patients with prostate cancer. They also demonstrate the process and potential benefits of precision oncology efforts; namely, targeted treatments for specific tumor types in cancer patients.

This article discusses the challenges and opportunities of precision oncology for US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Health Administration (VHA). First, the article will discuss working with relatively rare mutations. Second, the article will examine how the trials of olaparib and rucaparib illuminate the VHA contribution to research on new therapies for patients with cancer. Finally, the article will explore the ways in which VHA is becoming a major national contributor in drug discovery and approval of precision medications.

Precision Oncology

Despite advances in screening and treatment, an estimated 600,000 people in the US will die of cancer in 2020.5 Meaningful advances in cancer care depend on both laboratory and clinical research. This combination, known as translational research, takes discoveries in the laboratory and applies them to patients and vice versa. Successful translational research requires many components. These include talented scientists to form hypotheses and perform the work; money for supplies and equipment; platforms for timely dissemination of knowledge; well-trained clinicians to treat patients and lead research teams; and patients to participate in clinical trials. In precision oncology, the ability to find patients for the trials can be daunting, particularly in cases where the frequency of the mutation of interest is low.

During the 20th century, with few exceptions, physicians caring for patients with cancer had blunt instruments at their disposal. Surgery and radiation could lead to survival if the cancer was caught early enough. Systemic therapies, such as chemotherapy, rarely cured but could prolong life in some patients. However, chemotherapy is imprecise and targets any cell growing rapidly, including blood, hair, and gastrointestinal tract cells, which often leads to adverse effects. Sometimes complications from chemotherapy may shorten a person’s life, and certainly the quality of life during and after these treatments could be diminished. The improvements in cancer care occurred more rapidly once scientists had the tools to learn about individual tumors.

In the summer of 2000, researchers announced that the human genome had been sequenced.6 The genome (ie, DNA) consists of introns and exons that form a map for human development. Exons can be converted to proteins that carry out specific actions, such as helping in cell growth, cell death, or DNA repair. Solving the human genome itself did not lead directly to cures, but it did represent a huge advance in medical research. As time passed, sequencing genomes became more affordable, and sequencing just the exome alone was even cheaper.7 Treatments for cancer began to expand with the help of these tools, but questions as to the true benefit of targeted therapy also grew.8

Physicians and scientists have amassed more information about cancer cells and have applied this knowledge to active drug development. In 2001, the FDA approved the first targeted therapy, imatinib, for the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). This rapidly improved patient survival through targeting the mutated protein that leads to CML, rather than just aiming for rapidly dividing cells.9 Those mutations for which there is a drug to target, such as the BCR-ABL translocation in CML, are called actionable mutations.

Precision Oncology Program for Prostate Cancer

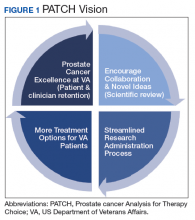

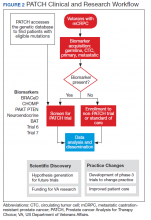

In 2016, the VA and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF) established the Precision Oncology Program for Prostate Cancer (POPCaP) Centers of Excellence (COE). This partnership was formed to accelerate treatment and cure for veterans with prostate cancer. The VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System in California and VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Washington led this effort, and their principal investigators continue to co-lead POPCaP. Since its inception, 9 additional funded POPCaP COEs have joined, each with a mandate to sequence the tumors of men with metastatic prostate cancer.

The more that is learned about a tumor, the more likely it is that researchers can find mutations that are that tumor’s Achilles heel and defeat it. In fact, many drugs that can target mutations are already available. For example, BRCA2 is an actionable mutation that can be exploited by knocking out another key DNA repair mechanism in the cell, PARP. Today, the effort of sequencing has led to a rich database of mutations present in men with metastatic prostate cancer.