User login

Renal disease and the surgical patient: Minimizing the impact

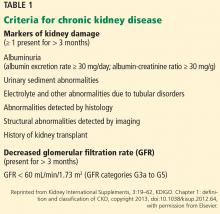

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is estimated to affect 14% of Americans, but it is likely underdiagnosed because it is often asymptomatic.1,2 Its prevalence is even higher in patients who undergo surgery—up to 30% in cardiac surgery.3 Its impact on surgical outcomes is substantial.4 Importantly, patients with CKD are at higher risk of postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI), which is also associated with adverse outcomes. Thus, it is important to recognize, assess, and manage abnormal renal function in surgical patients.

WHAT IS THE IMPACT ON POSTOPERATIVE OUTCOMES?

Cardiac surgery outcomes

Moreover, in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), the worse the renal dysfunction, the higher the long-term mortality rate. Patients with moderate (stage 3) CKD had a 3.5 times higher odds of in-hospital mortality compared with patients with normal renal function, rising to 8.8 with severe (stage 4) and to 9.6 with dialysis-dependent (stage 5) CKD.11

The mechanisms linking CKD with negative cardiac outcomes are unclear, but many possibilities exist. CKD is an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease and shares underlying risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes. Cardiac surgery patients with CKD are also more likely to have diabetes, left ventricular dysfunction, and peripheral vascular disease.

Noncardiac surgery outcomes

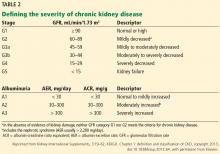

CKD is also associated with adverse outcomes in noncardiac surgery patients, especially at higher levels of renal dysfunction.12–14 For example, in patients who underwent major noncardiac surgery, compared with patients in stage 1 (estimated GFR > 90 mL/min/1.73 m2), the odds ratios for all-cause mortality were as follows:

- 0.8 for patients with stage 2 CKD

- 2.2 in stage 3a

- 2.8 in stage 3b

- 11.3 in stage 4

- 5.8 in stage 5.14

The association between estimated GFR and all-cause mortality was not statistically significant (P = .071), but statistically significant associations were observed between estimated GFR and major adverse cardiovascular events (P < .001) and hospital length of stay (P < .001).

The association of CKD with major adverse outcomes and death in both cardiac and noncardiac surgical patients demonstrates the importance of understanding this risk, identifying patients with CKD preoperatively, and taking steps to lower the risk.

WHAT IS THE IMPACT OF ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY?

AKI is a common and serious complication of surgery, especially cardiac surgery. It has been associated with higher rates of morbidity, mortality, and cardiovascular events, longer hospital length of stay, and higher cost.

Several groups have proposed criteria for defining AKI and its severity; the KDIGO criteria are the most widely accepted.15 These define AKI as an increase in serum creatinine concentration of 0.3 mg/dL or more within 48 hours or at least 1.5 times the baseline value within 7 days, or urine volume less than 0.5 mL/kg/hour for more than 6 hours. There are 3 stages of severity:

- Stage 1—an increase in serum creatinine of 1.5 to 1.9 times baseline, an absolute increase of at least 0.3 mg/dL, or urine output less than 0.5 mL/kg/hour for 6 to 12 hours

- Stage 2—an increase in serum creatinine of 2.0 to 2.9 times baseline or urine output less than 0.5 mmL/kg/hour for 12 or more hours

- Stage 3—an increase in serum creatinine of 3 times baseline, an absolute increase of at least 4 mg/dL, initiation of renal replacement therapy, urine output less than 0.3 mL/kg/hour for 24 or more hours, or anuria for 12 or more hours.15

Multiple factors associated with surgery may contribute to AKI, including hemodynamic instability, volume shifts, blood loss, use of heart-lung bypass, new medications, activation of the inflammatory cascade, oxidative stress, and anemia.

AKI in cardiac surgery

The incidence of AKI is high in cardiac surgery. In a meta-analysis of 46 studies (N = 242,000), its incidence in cardiopulmonary bypass surgery was about 18%, with 2.1% of patients needing renal replacement therapy.16 However, the incidence varied considerably from study to study, ranging from 1% to 53%, and was influenced by the definition of AKI, the type of cardiac surgery, and the patient population.16

Cardiac surgery-associated AKI adversely affects outcomes. Several studies have shown that cardiac surgery patients who develop AKI have higher rates of death and stroke.16–21 More severe AKI confers higher mortality rates, with the highest mortality rate in patients who need renal replacement therapy, approximately 37%.17 Patients with cardiac surgery-associated AKI also have a longer hospital length of stay and significantly higher costs of care.17,18

Long-term outcomes are also negatively affected by AKI. In cardiac surgery patients with AKI who had completely recovered renal function by the time they left the hospital, the 2-year incidence rate of CKD was 6.8%, significantly higher than the 0.2% rate in patients who did not develop AKI.19 The 2-year survival rates also were significantly worse for patients who developed postoperative AKI (82.3% vs 93.7%). Similarly, in patients undergoing CABG who had normal renal function before surgery, those who developed AKI postoperatively had significantly shorter long-term survival rates.20 The effect does not require a large change in renal function. An increase in creatinine as small as 0.3 mg/dL has been associated with a higher rate of death and a long-term risk of end-stage renal disease that is 3 times higher.21

WHAT ARE THE RISK FACTORS FOR ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY?

Cardiac surgery

CKD is a risk factor not only after cardiac surgery but also after percutaneous procedures. In a meta-analysis of 4,992 patients with CKD who underwent transcatheter aortic valve replacement, both moderate and severe CKD increased the odds of AKI, early stroke, the need for dialysis, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality at 1 year.22,23 Increased rates of AKI also have been found in patients with CKD undergoing CABG surgery.24 These results point to a synergistic effect between AKI and CKD, with outcomes much worse in combination than alone.

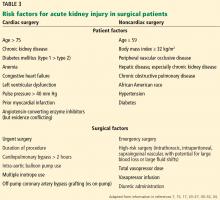

In cardiac surgery, the most important patient risk factors associated with a higher incidence of postoperative AKI are age older than 75, CKD, preoperative heart failure, and prior myocardial infarction.19,25 Diabetes is an additional independent risk factor, with type 1 conferring higher risk than type 2.26 Preoperative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors may or may not be a risk factor for cardiac surgery-associated AKI, with some studies finding increased risk and others finding reduced rates.27,28

Anemia, which may be related to either patient or surgical risk factors (eg, intraoperative blood loss), also increases the risk of AKI in cardiac surgery.29,30 A retrospective study of CABG surgery patients found that intraoperative hemoglobin levels below 8 g/dL were associated with a 25% to 30% incidence of AKI, compared with 15% to 20% with hemoglobin levels above 9 g/dL.29 Additionally, having severe hypotension (mean arterial pressure < 50 mm Hg) significantly increased the AKI rates in the low-hemoglobin group.29 Similar results were reported in a later study.30

Among surgical factors, several randomized controlled trials have shown that off-pump CABG is associated with a significantly lower risk of postoperative AKI than on-pump CABG; however, this difference did not translate into any long-term difference in mortality rates.31,32 Longer cardiopulmonary bypass time is strongly associated with a higher incidence of AKI and postoperative death.33

Noncardiac surgery

AKI is less common after noncardiac surgery; however, outcomes are severe in patients in whom it occurs. In a study of 15,102 noncardiac surgery patients, only 0.8% developed AKI and 0.1% required renal replacement therapy.34

Risk factors after noncardiac surgery are similar to those after cardiac surgery (Table 3).34–36 Factors with the greatest impact are older age, peripheral vascular occlusive disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease necessitating chronic bronchodilator therapy, high-risk surgery, hepatic disease, emergent or urgent surgery, and high body mass index.

Surgical risk factors include total vasopressor dose administered, use of a vasopressor infusion, and diuretic administration.34 In addition, intraoperative hypotension is associated with a higher risk of AKI, major adverse cardiac events, and 30-day mortality.37

Noncardiac surgery patients with postoperative AKI have significantly higher rates of 30-day readmissions, 1-year progression to end-stage renal disease, and mortality than patients who do not develop AKI.35 Additionally, patients with AKI have significantly higher rates of cardiovascular complications (33.3% vs 11.3%) and death (6.1% vs 0.9%), as well as a significantly longer length of hospital stay.34,36

CAN WE DECREASE THE IMPACT OF RENAL DISEASE IN SURGERY?

Before surgery, practitioners need to identify patients at risk of AKI, implement possible risk-reduction measures, and, afterward, treat it early in its course if it occurs.

The preoperative visit is the ideal time to assess a patient’s risk of postoperative renal dysfunction. Laboratory tests can identify risks based on surgery type, age, hypertension, the presence of CKD, and medications that affect renal function. However, the basic chemistry panel is abnormal in only 8.2% of patients and affects management in just 2.6%, requiring the clinician to target testing to patients at high risk.38

Patients with a significant degree of renal dysfunction, particularly those previously undiagnosed, may benefit from additional preoperative testing and medication management. Perioperative management of medications that could adversely affect renal function should be carefully considered during the preoperative visit. In addition, the postoperative inpatient team needs to be informed about potentially nephrotoxic medications and medications that are renally cleared. Attention needs to be given to the renal impact of common perioperative medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, intravenous contrast, low-molecular-weight heparins, diuretics, ACE inhibitors, and angiotensin II receptor blockers. With the emphasis on opioid-sparing analgesics, it is particularly important to assess the risk of AKI if nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are part of the pain control plan.

Nephrology referral may help, especially for patients with a GFR less than 45 mL/min. This information enables more informed decision-making regarding the risks of adverse outcomes related to kidney disease.

WHAT TOOLS DO WE HAVE TO DIAGNOSE RENAL INJURY?

Several risk-prediction models have been developed to assess the postoperative risk of AKI in both cardiac and major noncardiac surgery patients. Although these models can identify risk factors, their clinical accuracy and utility have been questioned.

Biomarkers

Early diagnosis is the first step in managing AKI, allowing time to implement measures to minimize its impact.

Serum creatinine testing is widely used to measure renal function and diagnose AKI; however, it does not detect small reductions in renal function, and there is a time lag between renal insult and a rise in creatinine. The result is a delay to diagnosis of AKI.

Biomarkers other than creatinine have been studied for early detection of intraoperative and postoperative renal insult. These novel renal injury markers include the following:

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL). Two studies looked at plasma NGAL as an early marker of AKI in patients with CKD who were undergoing cardiac surgery.39,40 One study found that by using NGAL instead of creatinine, postoperative AKI could be diagnosed an average of 20 hours earlier.39 In addition, NGAL helped detect renal recovery earlier than creatinine.40 The diagnostic cut-off values of NGAL were different for patients with CKD than for those without CKD.39,40

Other novel markers include:

- Kidney injury marker 1

- N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase

- Cysteine C.

Although these biomarkers show some ability to detect renal injury, they provide only modest discrimination and are not widely available for clinical use.41 Current evidence does not support routine use of these markers in clinical settings.

CAN WE PROTECT RENAL FUNCTION?

Interventions to prevent or ameliorate the impact of CKD and AKI on surgical outcomes have been studied most extensively in cardiac surgery patients.

Aspirin. A retrospective study of 3,585 cardiac surgery patients with CKD found that preoperative aspirin use significantly lowered the incidence of postoperative AKI and 30-day mortality compared with patients not using aspirin.42 Aspirin use reduced 30-day mortality in CKD stages 1, 2, and 3 by 23.3%, 58%, and 70%, respectively. On the other hand, in the Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation (POISE) trial, in noncardiac surgery patients, neither aspirin nor clonidine started 2 to 4 hours preoperatively and continued up to 30 days after surgery altered the risk of AKI significantly more than placebo.43

Statins have been ineffective in reducing the incidence of AKI in cardiac surgery patients. In fact, a meta-analysis of 8 interventional trials found an increased incidence of AKI in patients in whom statins were started perioperatively.44 Erythropoietin was also found to be ineffective in the prevention of perioperative AKI in cardiac surgery patients in a separate study.45

The evidence regarding other therapies has also varied.

N-acetylcysteine in high doses reduced the incidence of AKI in patients with CKD stage 3 and 4 undergoing CABG.46 Another meta-analysis of 10 studies in cardiac surgery patients published recently did not show any benefit of N-acetylcysteine in reducing AKI.47

Human atrial natriuretic peptide, given preoperatively to patients with CKD, reduced the acute and long-term creatinine rise as well as the number of cardiac events after CABG; however, it did not reduce mortality rates.48

Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, given preoperatively to patients with heart failure was associated with a decrease in the incidence of AKI in 1 study.49

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective alpha 2 adrenoreceptor agonist. A recent meta-analysis of 10 clinical trials found it beneficial in reducing the risk of perioperative AKI in cardiac surgery patients.50 An earlier meta-analysis had similar results.51

Levosimendan is an inotropic vasodilator that improves cardiac output and renal perfusion in patients with systolic heart failure, and it has been hypothesized to decrease the risk of AKI after cardiac surgery. Previous data demonstrated that this drug reduced AKI and mortality; however, analysis was limited by small sample size and varying definitions of AKI.52 A recent meta-analysis showed that levosimendan was associated with a lower incidence of AKI but was also associated with an increased incidence of atrial fibrillation and no reduction in 30-day mortality.53

Remote ischemic preconditioning is a procedure that subjects the kidneys to brief episodes of ischemia before surgery, protecting them when they are later subjected to prolonged ischemia or reperfusion injury. It has shown initial promising results in preventing AKI. In a randomized controlled trial in 240 patients at high risk of AKI, those who received remote ischemic preconditioning had an AKI incidence of 37.5% compared with 52.5% for controls (P = .02); however, the mortality rate was the same.54 Similarly, remote ischemic preconditioning significantly lowered the incidence of AKI in nondiabetic patients undergoing CABG surgery compared with controls.55

Fluid management. Renal perfusion is intimately related to the development of AKI, and there is evidence that both hypovolemia and excessive fluid resuscitation can increase the risk of AKI in noncardiac surgery patients.56 Because of this, fluid management has also received attention in perioperative AKI. Goal-directed fluid management has been evaluated in noncardiac surgery patients, and it did not show any benefit in preventing AKI.57 However, in a more recent retrospective study, postoperative positive fluid balance was associated with increased incidence of AKI compared with zero fluid balance. Negative fluid balance did not appear to have a detrimental effect.58

RECOMMENDATIONS

No prophylactic therapy has yet been shown to definitively decrease the risk of postoperative AKI in all patients. Nevertheless, it is important to identify patients at risk during the preoperative visit, especially those with CKD. Many patients undergoing surgery have CKD, placing them at high risk of developing AKI in the perioperative period. The risk is particularly high with cardiac surgery.

Serum creatinine and urine output should be closely monitored perioperatively in at-risk patients. If AKI is diagnosed, practitioners need to identify and ameliorate the cause as early as possible.

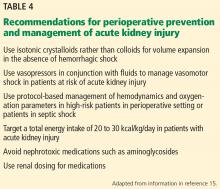

Recommendations from KDIGO for perioperative prevention and management of AKI are listed in Table 4.15 These include avoiding additional nephrotoxic medications and adjusting the doses of renally cleared medications. Also, some patients may benefit from preoperative counseling and specialist referral.

- Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 2007; 298(17):2038–2047. doi:10.1001/jama.298.17.2038

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States. www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/kidney-disease. Accessed June 11, 2018.

- Rosner MH, Okusa MD. Acute kidney injury associated with cardiac surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1(1):19–32. doi:10.2215/CJN.00240605

- Meersch M, Schmidt C, Zarbock A. Patient with chronic renal failure undergoing surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2016; 29(3):413–420. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000000329

- Stevens PE, Levin A; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group Members. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158(11):825–830. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00007

- Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Tsukamoto Y, et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 2005; 67(6):2089–2100. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00365.x

- Saitoh M, Takahashi T, Sakurada K, et al. Factors determining achievement of early postoperative cardiac rehabilitation goal in patients with or without preoperative kidney dysfunction undergoing isolated cardiac surgery. J Cardiol 2013; 61(4):299–303. doi:10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.12.014

- Minakata K, Bando K, Tanaka S, et al. Preoperative chronic kidney disease as a strong predictor of postoperative infection and mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting. Circ J 2014; 78(9):2225–2231. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-14-0328

- Domoto S, Tagusari O, Nakamura Y, et al. Preoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate as a significant predictor of long-term outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting in Japanese patients. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014; 62(2):95–102. doi:10.1007/s11748-013-0306-5

- Hedley AJ, Roberts MA, Hayward PA, et al. Impact of chronic kidney disease on patient outcome following cardiac surgery. Heart Lung Circ 2010; 19(8):453–459. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2010.03.005

- Boulton BJ, Kilgo P, Guyton RA, et al. Impact of preoperative renal dysfunction in patients undergoing off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 92(2):595–601. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.023

- Prowle JR, Kam EP, Ahmad T, Smith NC, Protopapa K, Pearse RM. Preoperative renal dysfunction and mortality after non-cardiac surgery. Br J Surg 2016; 103(10):1316–1325. doi:10.1002/bjs.10186

- Gaber AO, Moore LW, Aloia TA, et al. Cross-sectional and case-control analyses of the association of kidney function staging with adverse postoperative outcomes in general and vascular surgery. Ann Surg 2013; 258(1):169–177. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e318288e18e

- Mases A, Sabaté S, Guilera N, et al. Preoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate and the risk of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in non-cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 2014; 113(4):644–651. doi:10.1093/bja/aeu134

- Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clinical Practice 2012; 120(4):c179–c184. doi:10.1159/000339789

- Pickering JW, James MT, Palmer SC. Acute kidney injury and prognosis after cardiopulmonary bypass: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 65(2):283–293. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.09.008

- Dasta JF, Kane-Gill SL, Durtschi AJ, Pathak DS, Kellum JA. Costs and outcomes of acute kidney injury (AKI) following cardiac surgery. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008; 23(6):1970-1974. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfm908

- Karkouti K, Wijeysundera DN, Yau TM, et al. Acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery focus on modifiable risk factors. Circulation 2009; 119(4):495–502. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.786913

- Xu JR, Zhu JM, Jiang J, et al. Risk factors for long-term mortality and progressive chronic kidney disease associated with acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015; 94(45):e2025. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002025

- Chalmers J, Mediratta N, McShane J, Shaw M, Pullan M, Poullis M. The long-term effects of developing renal failure post-coronary artery bypass surgery, in patients with normal preoperative renal function. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013; 43(3):555–559. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezs329

- Ryden L, Sartipy U, Evans M, Holzmann MJ. Acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting and long-term risk of end-stage renal disease. Circulation 2014; 130(23):2005–2011. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010622

- Gargiulo G, Capodanno D, Sannino A, et al. Impact of moderate preoperative chronic kidney disease on mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Int J Cardiol 2015; 189:77–78. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.077

- Gargiulo G, Capodanno D, Sannino A, et al. Moderate and severe preoperative chronic kidney disease worsen clinical outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation meta-analysis of 4,992 patients. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2015; 8(2):e002220. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.002220

- Han SS, Shin N, Baek SH, et al. Effects of acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease on long-term mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am Heart J 2015; 169(3):419–425. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2014.12.019

- Aronson S, Fontes ML, Miao Y, Mangano DT; Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group; Ischemia Research and Education Foundation. Risk index for perioperative renal dysfunction/failure: critical dependence on pulse pressure hypertension. Circulation 2007; 115(6):733–742. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.623538

- Hertzberg D, Sartipy U, Holzmann MJ. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am Heart J 2015; 170(5):895–902. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2015.08.013

- Benedetto U, Sciarretta S, Roscitano A, et al. Preoperative angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 86(4):1160–1165. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.018

- Arora P, Rajagopalam S, Ranjan R, et al. Preoperative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers is associated with increased risk for acute kidney injury after cardiovascular surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3(5):1266–1273. doi:10.2215/CJN.05271107

- Haase M, Bellomo R, Story D, et al. Effect of mean arterial pressure, haemoglobin and blood transfusion during cardiopulmonary bypass on post-operative acute kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27(1):153–160. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfr275

- Ono M, Arnaoutakis GJ, Fine DM, et al. Blood pressure excursions below the cerebral autoregulation threshold during cardiac surgery are associated with acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med 2013; 41(2):464-471. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31826ab3a1

- Seabra VF, Alobaidi S, Balk EM, Poon AH, Jaber BL. Off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery and acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5(10):1734–1744. doi:10.2215/CJN.02800310

- Garg AX, Devereaux PJ, Yusuf S, et al; CORONARY Investigators. Kidney function after off-pump or on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014; 311(21):2191–2198. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.4952

- Kumar AB, Suneja M, Bayman EO, Weide GD, Tarasi M. Association between postoperative acute kidney injury and duration of cardiopulmonary bypass: a meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2012; 26(1):64–69. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2011.07.007

- Kheterpal S, Tremper KK, Englesbe MJ, et al. Predictors of postoperative acute renal failure after noncardiac surgery in patients with previously normal renal function. Anesthesiology 2007; 107(6):892–902. doi:10.1097/01.anes.0000290588.29668.38

- Grams ME, Sang Y, Coresh J, et al. Acute kidney injury after major surgery: a retrospective analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Am J Kidney Dis 2016; 67(6):872–880. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.022

- Biteker M, Dayan A, Tekkesin AI, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of perioperative acute kidney injury in noncardiac and nonvascular surgery. Am J Surg 2014: 207(1):53–59. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.04.006

- Gu W-J, Hou B-L, Kwong JS, et al. Association between intraoperative hypotension and 30-day mortality, major adverse cardiac events, and acute kidney injury after non-cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Cardiol 2018; 258:68–73. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.01.137

- Smetana GW, Macpherson DS. The case against routine preoperative laboratory testing. Med Clin North Am 2003; 87(1):7–40. pmid:12575882

- Perrotti A, Miltgen G, Chevet-Noel A, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as early predictor of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery in adults with chronic kidney failure. Ann Thorac Surg 2015; 99(3):864–869. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.10.011

- Doi K, Urata M, Katagiri D, et al. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in acute kidney injury superimposed on chronic kidney disease after cardiac surgery: a multicenter prospective study. Crit Care 2013; 17(6):R270. doi:10.1186/cc13104

- Ho J, Tangri N, Komenda P, et al. Urinary, plasma, and serum biomarkers’ utility for predicting acute kidney injury associated with cardiac surgery in adults: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66(6):993–1005. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.06.018

- Yao L, Young N, Liu H, et al. Evidence for preoperative aspirin improving major outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing cardiac surgery: a cohort study. Ann Surg 2015; 261(1):207–212. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000641

- Garg AX, Kurz A, Sessler DI, et al; POISE-2 Investigators. Aspirin and clonidine in non-cardiac surgery: acute kidney injury substudy protocol of the perioperative ischaemic evaluation (POISE) 2 randomised controlled trial. BMJ open 2014; 4(2):e004886. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004886

- He SJ, Liu Q, Li HQ, Tian F, Chen SY, Weng JX. Role of statins in preventing cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2018; 14:475–482. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S160298

- Tie HT, Luo MZ, Lin D, Zhang M, Wan JY, Wu QC. Erythropoietin administration for prevention of cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2015; 48(1):32–39. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezu378

- Santana-Santos E, Gowdak LH, Gaiotto FA, et al. High dose of N-acetylcystein prevents acute kidney injury in chronic kidney disease patients undergoing myocardial revascularization. Ann Thorac Surg 2014; 97(5):1617–1623. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.01.056

- Mei M, Zhao HW, Pan QG, Pu YM, Tang MZ, Shen BB. Efficacy of N-acetylcysteine in preventing acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis study. J Invest Surg 2018; 31(1):14–23. doi:10.1080/08941939.2016.1269853

- Sezai A, Hata M, Niino T, et al. Results of low-dose human atrial natriuretic peptide infusion in nondialysis patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: the NU-HIT (Nihon University working group study of low-dose HANP infusion therapy during cardiac surgery) trial for CKD. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58(9):897–903. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.056

- Xu N, Long Q, He T, et al. Association between preoperative renin-angiotensin system inhibitor use and postoperative acute kidney injury risk in patients with hypertension. Clin Nephrol 2018; 89(6):403–414. doi:10.5414/CN109319

- Liu Y, Sheng B, Wang S, Lu F, Zhen J, Chen W. Dexmedetomidine prevents acute kidney injury after adult cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Anesthesiol 2018; 18(1):7. doi:10.1186/s12871-018-0472-1

- Shi R, Tie H-T. Dexmedetomidine as a promising prevention strategy for cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis. Critical Care 2017; 21(1):198. doi:10.1186/s13054-017-1776-0

- Zhou C, Gong J, Chen D, Wang W, Liu M, Liu B. Levosimendan for prevention of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Kidney Dis 2016; 67(3):408–416. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.09.015

- Elbadawi A, Elgendy IY, Saad M, et al. Meta-analysis of trials on prophylactic use of levosimendan in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2018; 105(5):1403–1410. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.11.027

- Zarbock A, Schmidt C, Van Aken H, et al; RenalRIPC Investigators. Effect of remote ischemic preconditioning on kidney injury among high-risk patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 313(21):2133–2141. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.4189

- Venugopal V, Laing CM, Ludman A, Yellon DM, Hausenloy D. Effect of remote ischemic preconditioning on acute kidney injury in nondiabetic patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a secondary analysis of 2 small randomized trials. Am J Kidney Dis 2010; 56(6):1043–1049. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.07.014

- Futier E, Constantin JM, Petit A, et al. Conservative vs restrictive individualized goal-directed fluid replacement strategy in major abdominal surgery: a prospective randomized trial. Arch Surg 2010; 145(12):1193–1200. doi:10.1001/archsurg.2010.275

- Patel A, Prowle JR, Ackland GL. Postoperative goal-directed therapy and development of acute kidney injury following major elective noncardiac surgery: post-hoc analysis of POM-O randomized controlled trial. Clin Kidney J 2017; 10(3):348–356. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfw118

- Shen Y, Zhang W, Cheng X, Ying M. Association between postoperative fluid balance and acute kidney injury in patients after cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Crit Care 2018; 44:273–277. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.11.041

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is estimated to affect 14% of Americans, but it is likely underdiagnosed because it is often asymptomatic.1,2 Its prevalence is even higher in patients who undergo surgery—up to 30% in cardiac surgery.3 Its impact on surgical outcomes is substantial.4 Importantly, patients with CKD are at higher risk of postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI), which is also associated with adverse outcomes. Thus, it is important to recognize, assess, and manage abnormal renal function in surgical patients.

WHAT IS THE IMPACT ON POSTOPERATIVE OUTCOMES?

Cardiac surgery outcomes

Moreover, in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), the worse the renal dysfunction, the higher the long-term mortality rate. Patients with moderate (stage 3) CKD had a 3.5 times higher odds of in-hospital mortality compared with patients with normal renal function, rising to 8.8 with severe (stage 4) and to 9.6 with dialysis-dependent (stage 5) CKD.11

The mechanisms linking CKD with negative cardiac outcomes are unclear, but many possibilities exist. CKD is an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease and shares underlying risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes. Cardiac surgery patients with CKD are also more likely to have diabetes, left ventricular dysfunction, and peripheral vascular disease.

Noncardiac surgery outcomes

CKD is also associated with adverse outcomes in noncardiac surgery patients, especially at higher levels of renal dysfunction.12–14 For example, in patients who underwent major noncardiac surgery, compared with patients in stage 1 (estimated GFR > 90 mL/min/1.73 m2), the odds ratios for all-cause mortality were as follows:

- 0.8 for patients with stage 2 CKD

- 2.2 in stage 3a

- 2.8 in stage 3b

- 11.3 in stage 4

- 5.8 in stage 5.14

The association between estimated GFR and all-cause mortality was not statistically significant (P = .071), but statistically significant associations were observed between estimated GFR and major adverse cardiovascular events (P < .001) and hospital length of stay (P < .001).

The association of CKD with major adverse outcomes and death in both cardiac and noncardiac surgical patients demonstrates the importance of understanding this risk, identifying patients with CKD preoperatively, and taking steps to lower the risk.

WHAT IS THE IMPACT OF ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY?

AKI is a common and serious complication of surgery, especially cardiac surgery. It has been associated with higher rates of morbidity, mortality, and cardiovascular events, longer hospital length of stay, and higher cost.

Several groups have proposed criteria for defining AKI and its severity; the KDIGO criteria are the most widely accepted.15 These define AKI as an increase in serum creatinine concentration of 0.3 mg/dL or more within 48 hours or at least 1.5 times the baseline value within 7 days, or urine volume less than 0.5 mL/kg/hour for more than 6 hours. There are 3 stages of severity:

- Stage 1—an increase in serum creatinine of 1.5 to 1.9 times baseline, an absolute increase of at least 0.3 mg/dL, or urine output less than 0.5 mL/kg/hour for 6 to 12 hours

- Stage 2—an increase in serum creatinine of 2.0 to 2.9 times baseline or urine output less than 0.5 mmL/kg/hour for 12 or more hours

- Stage 3—an increase in serum creatinine of 3 times baseline, an absolute increase of at least 4 mg/dL, initiation of renal replacement therapy, urine output less than 0.3 mL/kg/hour for 24 or more hours, or anuria for 12 or more hours.15

Multiple factors associated with surgery may contribute to AKI, including hemodynamic instability, volume shifts, blood loss, use of heart-lung bypass, new medications, activation of the inflammatory cascade, oxidative stress, and anemia.

AKI in cardiac surgery

The incidence of AKI is high in cardiac surgery. In a meta-analysis of 46 studies (N = 242,000), its incidence in cardiopulmonary bypass surgery was about 18%, with 2.1% of patients needing renal replacement therapy.16 However, the incidence varied considerably from study to study, ranging from 1% to 53%, and was influenced by the definition of AKI, the type of cardiac surgery, and the patient population.16

Cardiac surgery-associated AKI adversely affects outcomes. Several studies have shown that cardiac surgery patients who develop AKI have higher rates of death and stroke.16–21 More severe AKI confers higher mortality rates, with the highest mortality rate in patients who need renal replacement therapy, approximately 37%.17 Patients with cardiac surgery-associated AKI also have a longer hospital length of stay and significantly higher costs of care.17,18

Long-term outcomes are also negatively affected by AKI. In cardiac surgery patients with AKI who had completely recovered renal function by the time they left the hospital, the 2-year incidence rate of CKD was 6.8%, significantly higher than the 0.2% rate in patients who did not develop AKI.19 The 2-year survival rates also were significantly worse for patients who developed postoperative AKI (82.3% vs 93.7%). Similarly, in patients undergoing CABG who had normal renal function before surgery, those who developed AKI postoperatively had significantly shorter long-term survival rates.20 The effect does not require a large change in renal function. An increase in creatinine as small as 0.3 mg/dL has been associated with a higher rate of death and a long-term risk of end-stage renal disease that is 3 times higher.21

WHAT ARE THE RISK FACTORS FOR ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY?

Cardiac surgery

CKD is a risk factor not only after cardiac surgery but also after percutaneous procedures. In a meta-analysis of 4,992 patients with CKD who underwent transcatheter aortic valve replacement, both moderate and severe CKD increased the odds of AKI, early stroke, the need for dialysis, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality at 1 year.22,23 Increased rates of AKI also have been found in patients with CKD undergoing CABG surgery.24 These results point to a synergistic effect between AKI and CKD, with outcomes much worse in combination than alone.

In cardiac surgery, the most important patient risk factors associated with a higher incidence of postoperative AKI are age older than 75, CKD, preoperative heart failure, and prior myocardial infarction.19,25 Diabetes is an additional independent risk factor, with type 1 conferring higher risk than type 2.26 Preoperative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors may or may not be a risk factor for cardiac surgery-associated AKI, with some studies finding increased risk and others finding reduced rates.27,28

Anemia, which may be related to either patient or surgical risk factors (eg, intraoperative blood loss), also increases the risk of AKI in cardiac surgery.29,30 A retrospective study of CABG surgery patients found that intraoperative hemoglobin levels below 8 g/dL were associated with a 25% to 30% incidence of AKI, compared with 15% to 20% with hemoglobin levels above 9 g/dL.29 Additionally, having severe hypotension (mean arterial pressure < 50 mm Hg) significantly increased the AKI rates in the low-hemoglobin group.29 Similar results were reported in a later study.30

Among surgical factors, several randomized controlled trials have shown that off-pump CABG is associated with a significantly lower risk of postoperative AKI than on-pump CABG; however, this difference did not translate into any long-term difference in mortality rates.31,32 Longer cardiopulmonary bypass time is strongly associated with a higher incidence of AKI and postoperative death.33

Noncardiac surgery

AKI is less common after noncardiac surgery; however, outcomes are severe in patients in whom it occurs. In a study of 15,102 noncardiac surgery patients, only 0.8% developed AKI and 0.1% required renal replacement therapy.34

Risk factors after noncardiac surgery are similar to those after cardiac surgery (Table 3).34–36 Factors with the greatest impact are older age, peripheral vascular occlusive disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease necessitating chronic bronchodilator therapy, high-risk surgery, hepatic disease, emergent or urgent surgery, and high body mass index.

Surgical risk factors include total vasopressor dose administered, use of a vasopressor infusion, and diuretic administration.34 In addition, intraoperative hypotension is associated with a higher risk of AKI, major adverse cardiac events, and 30-day mortality.37

Noncardiac surgery patients with postoperative AKI have significantly higher rates of 30-day readmissions, 1-year progression to end-stage renal disease, and mortality than patients who do not develop AKI.35 Additionally, patients with AKI have significantly higher rates of cardiovascular complications (33.3% vs 11.3%) and death (6.1% vs 0.9%), as well as a significantly longer length of hospital stay.34,36

CAN WE DECREASE THE IMPACT OF RENAL DISEASE IN SURGERY?

Before surgery, practitioners need to identify patients at risk of AKI, implement possible risk-reduction measures, and, afterward, treat it early in its course if it occurs.

The preoperative visit is the ideal time to assess a patient’s risk of postoperative renal dysfunction. Laboratory tests can identify risks based on surgery type, age, hypertension, the presence of CKD, and medications that affect renal function. However, the basic chemistry panel is abnormal in only 8.2% of patients and affects management in just 2.6%, requiring the clinician to target testing to patients at high risk.38

Patients with a significant degree of renal dysfunction, particularly those previously undiagnosed, may benefit from additional preoperative testing and medication management. Perioperative management of medications that could adversely affect renal function should be carefully considered during the preoperative visit. In addition, the postoperative inpatient team needs to be informed about potentially nephrotoxic medications and medications that are renally cleared. Attention needs to be given to the renal impact of common perioperative medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, intravenous contrast, low-molecular-weight heparins, diuretics, ACE inhibitors, and angiotensin II receptor blockers. With the emphasis on opioid-sparing analgesics, it is particularly important to assess the risk of AKI if nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are part of the pain control plan.

Nephrology referral may help, especially for patients with a GFR less than 45 mL/min. This information enables more informed decision-making regarding the risks of adverse outcomes related to kidney disease.

WHAT TOOLS DO WE HAVE TO DIAGNOSE RENAL INJURY?

Several risk-prediction models have been developed to assess the postoperative risk of AKI in both cardiac and major noncardiac surgery patients. Although these models can identify risk factors, their clinical accuracy and utility have been questioned.

Biomarkers

Early diagnosis is the first step in managing AKI, allowing time to implement measures to minimize its impact.

Serum creatinine testing is widely used to measure renal function and diagnose AKI; however, it does not detect small reductions in renal function, and there is a time lag between renal insult and a rise in creatinine. The result is a delay to diagnosis of AKI.

Biomarkers other than creatinine have been studied for early detection of intraoperative and postoperative renal insult. These novel renal injury markers include the following:

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL). Two studies looked at plasma NGAL as an early marker of AKI in patients with CKD who were undergoing cardiac surgery.39,40 One study found that by using NGAL instead of creatinine, postoperative AKI could be diagnosed an average of 20 hours earlier.39 In addition, NGAL helped detect renal recovery earlier than creatinine.40 The diagnostic cut-off values of NGAL were different for patients with CKD than for those without CKD.39,40

Other novel markers include:

- Kidney injury marker 1

- N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase

- Cysteine C.

Although these biomarkers show some ability to detect renal injury, they provide only modest discrimination and are not widely available for clinical use.41 Current evidence does not support routine use of these markers in clinical settings.

CAN WE PROTECT RENAL FUNCTION?

Interventions to prevent or ameliorate the impact of CKD and AKI on surgical outcomes have been studied most extensively in cardiac surgery patients.

Aspirin. A retrospective study of 3,585 cardiac surgery patients with CKD found that preoperative aspirin use significantly lowered the incidence of postoperative AKI and 30-day mortality compared with patients not using aspirin.42 Aspirin use reduced 30-day mortality in CKD stages 1, 2, and 3 by 23.3%, 58%, and 70%, respectively. On the other hand, in the Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation (POISE) trial, in noncardiac surgery patients, neither aspirin nor clonidine started 2 to 4 hours preoperatively and continued up to 30 days after surgery altered the risk of AKI significantly more than placebo.43

Statins have been ineffective in reducing the incidence of AKI in cardiac surgery patients. In fact, a meta-analysis of 8 interventional trials found an increased incidence of AKI in patients in whom statins were started perioperatively.44 Erythropoietin was also found to be ineffective in the prevention of perioperative AKI in cardiac surgery patients in a separate study.45

The evidence regarding other therapies has also varied.

N-acetylcysteine in high doses reduced the incidence of AKI in patients with CKD stage 3 and 4 undergoing CABG.46 Another meta-analysis of 10 studies in cardiac surgery patients published recently did not show any benefit of N-acetylcysteine in reducing AKI.47

Human atrial natriuretic peptide, given preoperatively to patients with CKD, reduced the acute and long-term creatinine rise as well as the number of cardiac events after CABG; however, it did not reduce mortality rates.48

Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, given preoperatively to patients with heart failure was associated with a decrease in the incidence of AKI in 1 study.49

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective alpha 2 adrenoreceptor agonist. A recent meta-analysis of 10 clinical trials found it beneficial in reducing the risk of perioperative AKI in cardiac surgery patients.50 An earlier meta-analysis had similar results.51

Levosimendan is an inotropic vasodilator that improves cardiac output and renal perfusion in patients with systolic heart failure, and it has been hypothesized to decrease the risk of AKI after cardiac surgery. Previous data demonstrated that this drug reduced AKI and mortality; however, analysis was limited by small sample size and varying definitions of AKI.52 A recent meta-analysis showed that levosimendan was associated with a lower incidence of AKI but was also associated with an increased incidence of atrial fibrillation and no reduction in 30-day mortality.53

Remote ischemic preconditioning is a procedure that subjects the kidneys to brief episodes of ischemia before surgery, protecting them when they are later subjected to prolonged ischemia or reperfusion injury. It has shown initial promising results in preventing AKI. In a randomized controlled trial in 240 patients at high risk of AKI, those who received remote ischemic preconditioning had an AKI incidence of 37.5% compared with 52.5% for controls (P = .02); however, the mortality rate was the same.54 Similarly, remote ischemic preconditioning significantly lowered the incidence of AKI in nondiabetic patients undergoing CABG surgery compared with controls.55

Fluid management. Renal perfusion is intimately related to the development of AKI, and there is evidence that both hypovolemia and excessive fluid resuscitation can increase the risk of AKI in noncardiac surgery patients.56 Because of this, fluid management has also received attention in perioperative AKI. Goal-directed fluid management has been evaluated in noncardiac surgery patients, and it did not show any benefit in preventing AKI.57 However, in a more recent retrospective study, postoperative positive fluid balance was associated with increased incidence of AKI compared with zero fluid balance. Negative fluid balance did not appear to have a detrimental effect.58

RECOMMENDATIONS

No prophylactic therapy has yet been shown to definitively decrease the risk of postoperative AKI in all patients. Nevertheless, it is important to identify patients at risk during the preoperative visit, especially those with CKD. Many patients undergoing surgery have CKD, placing them at high risk of developing AKI in the perioperative period. The risk is particularly high with cardiac surgery.

Serum creatinine and urine output should be closely monitored perioperatively in at-risk patients. If AKI is diagnosed, practitioners need to identify and ameliorate the cause as early as possible.

Recommendations from KDIGO for perioperative prevention and management of AKI are listed in Table 4.15 These include avoiding additional nephrotoxic medications and adjusting the doses of renally cleared medications. Also, some patients may benefit from preoperative counseling and specialist referral.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is estimated to affect 14% of Americans, but it is likely underdiagnosed because it is often asymptomatic.1,2 Its prevalence is even higher in patients who undergo surgery—up to 30% in cardiac surgery.3 Its impact on surgical outcomes is substantial.4 Importantly, patients with CKD are at higher risk of postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI), which is also associated with adverse outcomes. Thus, it is important to recognize, assess, and manage abnormal renal function in surgical patients.

WHAT IS THE IMPACT ON POSTOPERATIVE OUTCOMES?

Cardiac surgery outcomes

Moreover, in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), the worse the renal dysfunction, the higher the long-term mortality rate. Patients with moderate (stage 3) CKD had a 3.5 times higher odds of in-hospital mortality compared with patients with normal renal function, rising to 8.8 with severe (stage 4) and to 9.6 with dialysis-dependent (stage 5) CKD.11

The mechanisms linking CKD with negative cardiac outcomes are unclear, but many possibilities exist. CKD is an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease and shares underlying risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes. Cardiac surgery patients with CKD are also more likely to have diabetes, left ventricular dysfunction, and peripheral vascular disease.

Noncardiac surgery outcomes

CKD is also associated with adverse outcomes in noncardiac surgery patients, especially at higher levels of renal dysfunction.12–14 For example, in patients who underwent major noncardiac surgery, compared with patients in stage 1 (estimated GFR > 90 mL/min/1.73 m2), the odds ratios for all-cause mortality were as follows:

- 0.8 for patients with stage 2 CKD

- 2.2 in stage 3a

- 2.8 in stage 3b

- 11.3 in stage 4

- 5.8 in stage 5.14

The association between estimated GFR and all-cause mortality was not statistically significant (P = .071), but statistically significant associations were observed between estimated GFR and major adverse cardiovascular events (P < .001) and hospital length of stay (P < .001).

The association of CKD with major adverse outcomes and death in both cardiac and noncardiac surgical patients demonstrates the importance of understanding this risk, identifying patients with CKD preoperatively, and taking steps to lower the risk.

WHAT IS THE IMPACT OF ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY?

AKI is a common and serious complication of surgery, especially cardiac surgery. It has been associated with higher rates of morbidity, mortality, and cardiovascular events, longer hospital length of stay, and higher cost.

Several groups have proposed criteria for defining AKI and its severity; the KDIGO criteria are the most widely accepted.15 These define AKI as an increase in serum creatinine concentration of 0.3 mg/dL or more within 48 hours or at least 1.5 times the baseline value within 7 days, or urine volume less than 0.5 mL/kg/hour for more than 6 hours. There are 3 stages of severity:

- Stage 1—an increase in serum creatinine of 1.5 to 1.9 times baseline, an absolute increase of at least 0.3 mg/dL, or urine output less than 0.5 mL/kg/hour for 6 to 12 hours

- Stage 2—an increase in serum creatinine of 2.0 to 2.9 times baseline or urine output less than 0.5 mmL/kg/hour for 12 or more hours

- Stage 3—an increase in serum creatinine of 3 times baseline, an absolute increase of at least 4 mg/dL, initiation of renal replacement therapy, urine output less than 0.3 mL/kg/hour for 24 or more hours, or anuria for 12 or more hours.15

Multiple factors associated with surgery may contribute to AKI, including hemodynamic instability, volume shifts, blood loss, use of heart-lung bypass, new medications, activation of the inflammatory cascade, oxidative stress, and anemia.

AKI in cardiac surgery

The incidence of AKI is high in cardiac surgery. In a meta-analysis of 46 studies (N = 242,000), its incidence in cardiopulmonary bypass surgery was about 18%, with 2.1% of patients needing renal replacement therapy.16 However, the incidence varied considerably from study to study, ranging from 1% to 53%, and was influenced by the definition of AKI, the type of cardiac surgery, and the patient population.16

Cardiac surgery-associated AKI adversely affects outcomes. Several studies have shown that cardiac surgery patients who develop AKI have higher rates of death and stroke.16–21 More severe AKI confers higher mortality rates, with the highest mortality rate in patients who need renal replacement therapy, approximately 37%.17 Patients with cardiac surgery-associated AKI also have a longer hospital length of stay and significantly higher costs of care.17,18

Long-term outcomes are also negatively affected by AKI. In cardiac surgery patients with AKI who had completely recovered renal function by the time they left the hospital, the 2-year incidence rate of CKD was 6.8%, significantly higher than the 0.2% rate in patients who did not develop AKI.19 The 2-year survival rates also were significantly worse for patients who developed postoperative AKI (82.3% vs 93.7%). Similarly, in patients undergoing CABG who had normal renal function before surgery, those who developed AKI postoperatively had significantly shorter long-term survival rates.20 The effect does not require a large change in renal function. An increase in creatinine as small as 0.3 mg/dL has been associated with a higher rate of death and a long-term risk of end-stage renal disease that is 3 times higher.21

WHAT ARE THE RISK FACTORS FOR ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY?

Cardiac surgery

CKD is a risk factor not only after cardiac surgery but also after percutaneous procedures. In a meta-analysis of 4,992 patients with CKD who underwent transcatheter aortic valve replacement, both moderate and severe CKD increased the odds of AKI, early stroke, the need for dialysis, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality at 1 year.22,23 Increased rates of AKI also have been found in patients with CKD undergoing CABG surgery.24 These results point to a synergistic effect between AKI and CKD, with outcomes much worse in combination than alone.

In cardiac surgery, the most important patient risk factors associated with a higher incidence of postoperative AKI are age older than 75, CKD, preoperative heart failure, and prior myocardial infarction.19,25 Diabetes is an additional independent risk factor, with type 1 conferring higher risk than type 2.26 Preoperative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors may or may not be a risk factor for cardiac surgery-associated AKI, with some studies finding increased risk and others finding reduced rates.27,28

Anemia, which may be related to either patient or surgical risk factors (eg, intraoperative blood loss), also increases the risk of AKI in cardiac surgery.29,30 A retrospective study of CABG surgery patients found that intraoperative hemoglobin levels below 8 g/dL were associated with a 25% to 30% incidence of AKI, compared with 15% to 20% with hemoglobin levels above 9 g/dL.29 Additionally, having severe hypotension (mean arterial pressure < 50 mm Hg) significantly increased the AKI rates in the low-hemoglobin group.29 Similar results were reported in a later study.30

Among surgical factors, several randomized controlled trials have shown that off-pump CABG is associated with a significantly lower risk of postoperative AKI than on-pump CABG; however, this difference did not translate into any long-term difference in mortality rates.31,32 Longer cardiopulmonary bypass time is strongly associated with a higher incidence of AKI and postoperative death.33

Noncardiac surgery

AKI is less common after noncardiac surgery; however, outcomes are severe in patients in whom it occurs. In a study of 15,102 noncardiac surgery patients, only 0.8% developed AKI and 0.1% required renal replacement therapy.34

Risk factors after noncardiac surgery are similar to those after cardiac surgery (Table 3).34–36 Factors with the greatest impact are older age, peripheral vascular occlusive disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease necessitating chronic bronchodilator therapy, high-risk surgery, hepatic disease, emergent or urgent surgery, and high body mass index.

Surgical risk factors include total vasopressor dose administered, use of a vasopressor infusion, and diuretic administration.34 In addition, intraoperative hypotension is associated with a higher risk of AKI, major adverse cardiac events, and 30-day mortality.37

Noncardiac surgery patients with postoperative AKI have significantly higher rates of 30-day readmissions, 1-year progression to end-stage renal disease, and mortality than patients who do not develop AKI.35 Additionally, patients with AKI have significantly higher rates of cardiovascular complications (33.3% vs 11.3%) and death (6.1% vs 0.9%), as well as a significantly longer length of hospital stay.34,36

CAN WE DECREASE THE IMPACT OF RENAL DISEASE IN SURGERY?

Before surgery, practitioners need to identify patients at risk of AKI, implement possible risk-reduction measures, and, afterward, treat it early in its course if it occurs.

The preoperative visit is the ideal time to assess a patient’s risk of postoperative renal dysfunction. Laboratory tests can identify risks based on surgery type, age, hypertension, the presence of CKD, and medications that affect renal function. However, the basic chemistry panel is abnormal in only 8.2% of patients and affects management in just 2.6%, requiring the clinician to target testing to patients at high risk.38

Patients with a significant degree of renal dysfunction, particularly those previously undiagnosed, may benefit from additional preoperative testing and medication management. Perioperative management of medications that could adversely affect renal function should be carefully considered during the preoperative visit. In addition, the postoperative inpatient team needs to be informed about potentially nephrotoxic medications and medications that are renally cleared. Attention needs to be given to the renal impact of common perioperative medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, intravenous contrast, low-molecular-weight heparins, diuretics, ACE inhibitors, and angiotensin II receptor blockers. With the emphasis on opioid-sparing analgesics, it is particularly important to assess the risk of AKI if nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are part of the pain control plan.

Nephrology referral may help, especially for patients with a GFR less than 45 mL/min. This information enables more informed decision-making regarding the risks of adverse outcomes related to kidney disease.

WHAT TOOLS DO WE HAVE TO DIAGNOSE RENAL INJURY?

Several risk-prediction models have been developed to assess the postoperative risk of AKI in both cardiac and major noncardiac surgery patients. Although these models can identify risk factors, their clinical accuracy and utility have been questioned.

Biomarkers

Early diagnosis is the first step in managing AKI, allowing time to implement measures to minimize its impact.

Serum creatinine testing is widely used to measure renal function and diagnose AKI; however, it does not detect small reductions in renal function, and there is a time lag between renal insult and a rise in creatinine. The result is a delay to diagnosis of AKI.

Biomarkers other than creatinine have been studied for early detection of intraoperative and postoperative renal insult. These novel renal injury markers include the following:

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL). Two studies looked at plasma NGAL as an early marker of AKI in patients with CKD who were undergoing cardiac surgery.39,40 One study found that by using NGAL instead of creatinine, postoperative AKI could be diagnosed an average of 20 hours earlier.39 In addition, NGAL helped detect renal recovery earlier than creatinine.40 The diagnostic cut-off values of NGAL were different for patients with CKD than for those without CKD.39,40

Other novel markers include:

- Kidney injury marker 1

- N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase

- Cysteine C.

Although these biomarkers show some ability to detect renal injury, they provide only modest discrimination and are not widely available for clinical use.41 Current evidence does not support routine use of these markers in clinical settings.

CAN WE PROTECT RENAL FUNCTION?

Interventions to prevent or ameliorate the impact of CKD and AKI on surgical outcomes have been studied most extensively in cardiac surgery patients.

Aspirin. A retrospective study of 3,585 cardiac surgery patients with CKD found that preoperative aspirin use significantly lowered the incidence of postoperative AKI and 30-day mortality compared with patients not using aspirin.42 Aspirin use reduced 30-day mortality in CKD stages 1, 2, and 3 by 23.3%, 58%, and 70%, respectively. On the other hand, in the Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation (POISE) trial, in noncardiac surgery patients, neither aspirin nor clonidine started 2 to 4 hours preoperatively and continued up to 30 days after surgery altered the risk of AKI significantly more than placebo.43

Statins have been ineffective in reducing the incidence of AKI in cardiac surgery patients. In fact, a meta-analysis of 8 interventional trials found an increased incidence of AKI in patients in whom statins were started perioperatively.44 Erythropoietin was also found to be ineffective in the prevention of perioperative AKI in cardiac surgery patients in a separate study.45

The evidence regarding other therapies has also varied.

N-acetylcysteine in high doses reduced the incidence of AKI in patients with CKD stage 3 and 4 undergoing CABG.46 Another meta-analysis of 10 studies in cardiac surgery patients published recently did not show any benefit of N-acetylcysteine in reducing AKI.47

Human atrial natriuretic peptide, given preoperatively to patients with CKD, reduced the acute and long-term creatinine rise as well as the number of cardiac events after CABG; however, it did not reduce mortality rates.48

Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, given preoperatively to patients with heart failure was associated with a decrease in the incidence of AKI in 1 study.49

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective alpha 2 adrenoreceptor agonist. A recent meta-analysis of 10 clinical trials found it beneficial in reducing the risk of perioperative AKI in cardiac surgery patients.50 An earlier meta-analysis had similar results.51

Levosimendan is an inotropic vasodilator that improves cardiac output and renal perfusion in patients with systolic heart failure, and it has been hypothesized to decrease the risk of AKI after cardiac surgery. Previous data demonstrated that this drug reduced AKI and mortality; however, analysis was limited by small sample size and varying definitions of AKI.52 A recent meta-analysis showed that levosimendan was associated with a lower incidence of AKI but was also associated with an increased incidence of atrial fibrillation and no reduction in 30-day mortality.53

Remote ischemic preconditioning is a procedure that subjects the kidneys to brief episodes of ischemia before surgery, protecting them when they are later subjected to prolonged ischemia or reperfusion injury. It has shown initial promising results in preventing AKI. In a randomized controlled trial in 240 patients at high risk of AKI, those who received remote ischemic preconditioning had an AKI incidence of 37.5% compared with 52.5% for controls (P = .02); however, the mortality rate was the same.54 Similarly, remote ischemic preconditioning significantly lowered the incidence of AKI in nondiabetic patients undergoing CABG surgery compared with controls.55

Fluid management. Renal perfusion is intimately related to the development of AKI, and there is evidence that both hypovolemia and excessive fluid resuscitation can increase the risk of AKI in noncardiac surgery patients.56 Because of this, fluid management has also received attention in perioperative AKI. Goal-directed fluid management has been evaluated in noncardiac surgery patients, and it did not show any benefit in preventing AKI.57 However, in a more recent retrospective study, postoperative positive fluid balance was associated with increased incidence of AKI compared with zero fluid balance. Negative fluid balance did not appear to have a detrimental effect.58

RECOMMENDATIONS

No prophylactic therapy has yet been shown to definitively decrease the risk of postoperative AKI in all patients. Nevertheless, it is important to identify patients at risk during the preoperative visit, especially those with CKD. Many patients undergoing surgery have CKD, placing them at high risk of developing AKI in the perioperative period. The risk is particularly high with cardiac surgery.

Serum creatinine and urine output should be closely monitored perioperatively in at-risk patients. If AKI is diagnosed, practitioners need to identify and ameliorate the cause as early as possible.

Recommendations from KDIGO for perioperative prevention and management of AKI are listed in Table 4.15 These include avoiding additional nephrotoxic medications and adjusting the doses of renally cleared medications. Also, some patients may benefit from preoperative counseling and specialist referral.

- Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 2007; 298(17):2038–2047. doi:10.1001/jama.298.17.2038

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States. www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/kidney-disease. Accessed June 11, 2018.

- Rosner MH, Okusa MD. Acute kidney injury associated with cardiac surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1(1):19–32. doi:10.2215/CJN.00240605

- Meersch M, Schmidt C, Zarbock A. Patient with chronic renal failure undergoing surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2016; 29(3):413–420. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000000329

- Stevens PE, Levin A; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group Members. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158(11):825–830. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00007

- Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Tsukamoto Y, et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 2005; 67(6):2089–2100. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00365.x

- Saitoh M, Takahashi T, Sakurada K, et al. Factors determining achievement of early postoperative cardiac rehabilitation goal in patients with or without preoperative kidney dysfunction undergoing isolated cardiac surgery. J Cardiol 2013; 61(4):299–303. doi:10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.12.014

- Minakata K, Bando K, Tanaka S, et al. Preoperative chronic kidney disease as a strong predictor of postoperative infection and mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting. Circ J 2014; 78(9):2225–2231. doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-14-0328

- Domoto S, Tagusari O, Nakamura Y, et al. Preoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate as a significant predictor of long-term outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting in Japanese patients. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014; 62(2):95–102. doi:10.1007/s11748-013-0306-5

- Hedley AJ, Roberts MA, Hayward PA, et al. Impact of chronic kidney disease on patient outcome following cardiac surgery. Heart Lung Circ 2010; 19(8):453–459. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2010.03.005

- Boulton BJ, Kilgo P, Guyton RA, et al. Impact of preoperative renal dysfunction in patients undergoing off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 92(2):595–601. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.023

- Prowle JR, Kam EP, Ahmad T, Smith NC, Protopapa K, Pearse RM. Preoperative renal dysfunction and mortality after non-cardiac surgery. Br J Surg 2016; 103(10):1316–1325. doi:10.1002/bjs.10186

- Gaber AO, Moore LW, Aloia TA, et al. Cross-sectional and case-control analyses of the association of kidney function staging with adverse postoperative outcomes in general and vascular surgery. Ann Surg 2013; 258(1):169–177. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e318288e18e

- Mases A, Sabaté S, Guilera N, et al. Preoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate and the risk of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in non-cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 2014; 113(4):644–651. doi:10.1093/bja/aeu134

- Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clinical Practice 2012; 120(4):c179–c184. doi:10.1159/000339789

- Pickering JW, James MT, Palmer SC. Acute kidney injury and prognosis after cardiopulmonary bypass: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 65(2):283–293. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.09.008

- Dasta JF, Kane-Gill SL, Durtschi AJ, Pathak DS, Kellum JA. Costs and outcomes of acute kidney injury (AKI) following cardiac surgery. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008; 23(6):1970-1974. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfm908

- Karkouti K, Wijeysundera DN, Yau TM, et al. Acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery focus on modifiable risk factors. Circulation 2009; 119(4):495–502. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.786913

- Xu JR, Zhu JM, Jiang J, et al. Risk factors for long-term mortality and progressive chronic kidney disease associated with acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015; 94(45):e2025. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002025

- Chalmers J, Mediratta N, McShane J, Shaw M, Pullan M, Poullis M. The long-term effects of developing renal failure post-coronary artery bypass surgery, in patients with normal preoperative renal function. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013; 43(3):555–559. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezs329

- Ryden L, Sartipy U, Evans M, Holzmann MJ. Acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting and long-term risk of end-stage renal disease. Circulation 2014; 130(23):2005–2011. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010622

- Gargiulo G, Capodanno D, Sannino A, et al. Impact of moderate preoperative chronic kidney disease on mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Int J Cardiol 2015; 189:77–78. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.077

- Gargiulo G, Capodanno D, Sannino A, et al. Moderate and severe preoperative chronic kidney disease worsen clinical outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation meta-analysis of 4,992 patients. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2015; 8(2):e002220. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.002220

- Han SS, Shin N, Baek SH, et al. Effects of acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease on long-term mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am Heart J 2015; 169(3):419–425. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2014.12.019

- Aronson S, Fontes ML, Miao Y, Mangano DT; Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group; Ischemia Research and Education Foundation. Risk index for perioperative renal dysfunction/failure: critical dependence on pulse pressure hypertension. Circulation 2007; 115(6):733–742. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.623538

- Hertzberg D, Sartipy U, Holzmann MJ. Type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am Heart J 2015; 170(5):895–902. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2015.08.013

- Benedetto U, Sciarretta S, Roscitano A, et al. Preoperative angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 86(4):1160–1165. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.018

- Arora P, Rajagopalam S, Ranjan R, et al. Preoperative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers is associated with increased risk for acute kidney injury after cardiovascular surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3(5):1266–1273. doi:10.2215/CJN.05271107

- Haase M, Bellomo R, Story D, et al. Effect of mean arterial pressure, haemoglobin and blood transfusion during cardiopulmonary bypass on post-operative acute kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27(1):153–160. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfr275

- Ono M, Arnaoutakis GJ, Fine DM, et al. Blood pressure excursions below the cerebral autoregulation threshold during cardiac surgery are associated with acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med 2013; 41(2):464-471. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31826ab3a1

- Seabra VF, Alobaidi S, Balk EM, Poon AH, Jaber BL. Off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery and acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5(10):1734–1744. doi:10.2215/CJN.02800310

- Garg AX, Devereaux PJ, Yusuf S, et al; CORONARY Investigators. Kidney function after off-pump or on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014; 311(21):2191–2198. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.4952

- Kumar AB, Suneja M, Bayman EO, Weide GD, Tarasi M. Association between postoperative acute kidney injury and duration of cardiopulmonary bypass: a meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2012; 26(1):64–69. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2011.07.007

- Kheterpal S, Tremper KK, Englesbe MJ, et al. Predictors of postoperative acute renal failure after noncardiac surgery in patients with previously normal renal function. Anesthesiology 2007; 107(6):892–902. doi:10.1097/01.anes.0000290588.29668.38

- Grams ME, Sang Y, Coresh J, et al. Acute kidney injury after major surgery: a retrospective analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Am J Kidney Dis 2016; 67(6):872–880. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.022

- Biteker M, Dayan A, Tekkesin AI, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of perioperative acute kidney injury in noncardiac and nonvascular surgery. Am J Surg 2014: 207(1):53–59. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.04.006

- Gu W-J, Hou B-L, Kwong JS, et al. Association between intraoperative hypotension and 30-day mortality, major adverse cardiac events, and acute kidney injury after non-cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Cardiol 2018; 258:68–73. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.01.137

- Smetana GW, Macpherson DS. The case against routine preoperative laboratory testing. Med Clin North Am 2003; 87(1):7–40. pmid:12575882

- Perrotti A, Miltgen G, Chevet-Noel A, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as early predictor of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery in adults with chronic kidney failure. Ann Thorac Surg 2015; 99(3):864–869. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.10.011

- Doi K, Urata M, Katagiri D, et al. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in acute kidney injury superimposed on chronic kidney disease after cardiac surgery: a multicenter prospective study. Crit Care 2013; 17(6):R270. doi:10.1186/cc13104

- Ho J, Tangri N, Komenda P, et al. Urinary, plasma, and serum biomarkers’ utility for predicting acute kidney injury associated with cardiac surgery in adults: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66(6):993–1005. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.06.018

- Yao L, Young N, Liu H, et al. Evidence for preoperative aspirin improving major outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing cardiac surgery: a cohort study. Ann Surg 2015; 261(1):207–212. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000641

- Garg AX, Kurz A, Sessler DI, et al; POISE-2 Investigators. Aspirin and clonidine in non-cardiac surgery: acute kidney injury substudy protocol of the perioperative ischaemic evaluation (POISE) 2 randomised controlled trial. BMJ open 2014; 4(2):e004886. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004886

- He SJ, Liu Q, Li HQ, Tian F, Chen SY, Weng JX. Role of statins in preventing cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2018; 14:475–482. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S160298

- Tie HT, Luo MZ, Lin D, Zhang M, Wan JY, Wu QC. Erythropoietin administration for prevention of cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2015; 48(1):32–39. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezu378

- Santana-Santos E, Gowdak LH, Gaiotto FA, et al. High dose of N-acetylcystein prevents acute kidney injury in chronic kidney disease patients undergoing myocardial revascularization. Ann Thorac Surg 2014; 97(5):1617–1623. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.01.056

- Mei M, Zhao HW, Pan QG, Pu YM, Tang MZ, Shen BB. Efficacy of N-acetylcysteine in preventing acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis study. J Invest Surg 2018; 31(1):14–23. doi:10.1080/08941939.2016.1269853

- Sezai A, Hata M, Niino T, et al. Results of low-dose human atrial natriuretic peptide infusion in nondialysis patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: the NU-HIT (Nihon University working group study of low-dose HANP infusion therapy during cardiac surgery) trial for CKD. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58(9):897–903. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.056

- Xu N, Long Q, He T, et al. Association between preoperative renin-angiotensin system inhibitor use and postoperative acute kidney injury risk in patients with hypertension. Clin Nephrol 2018; 89(6):403–414. doi:10.5414/CN109319

- Liu Y, Sheng B, Wang S, Lu F, Zhen J, Chen W. Dexmedetomidine prevents acute kidney injury after adult cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Anesthesiol 2018; 18(1):7. doi:10.1186/s12871-018-0472-1

- Shi R, Tie H-T. Dexmedetomidine as a promising prevention strategy for cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis. Critical Care 2017; 21(1):198. doi:10.1186/s13054-017-1776-0