User login

Climate change and mental illness: What psychiatrists can do

“ Hope is engagement with the act of mapping our destinies.” 1

—Valerie Braithwaite

Why should psychiatrists care about climate change and try to mitigate its effects? First, we are tasked by society with managing the psychological and neuropsychiatric sequelae from disasters, which include climate change. The American Psychiatric Association’s position statement on climate change includes it as a legitimate focus for our specialty.2 Second, as physicians, we are morally obligated to do no harm. Since the health care sector contributes significantly to climate change (8.5% of national carbon emissions stem from health care) and causes demonstrable health impacts,3 managing these impacts and decarbonizing the health care industry is morally imperative.4 And third, psychiatric clinicians have transferrable skills that can address fears of climate change, challenge climate change denialism,5 motivate people to adopt more pro-environmental behaviors, and help communities not only endure the emotional impact of climate change but become more psychologically resilient.6

Most psychiatrists, however, did not receive formal training on climate change and the related field of disaster preparedness. For example, Harvard Medical School did not include a course on climate change in their medical student curriculum until 2023.7 In this article, we provide a basic framework of climate change and its impact on mental health, with particular focus on patients with serious mental illness (SMI). We offer concrete steps clinicians can take to prevent or mitigate harm from climate change for their patients, prepare for disasters at the level of individual patient encounters, and strengthen their clinics and communities. We also encourage clinicians to take active leadership roles in their professional organizations to be part of climate solutions, building on the trust patients continue to have in their physicians.8 Even if clinicians do not view climate change concerns under their conceived clinical care mandate, having a working knowledge about it is important because patients, paraprofessional staff, or medical trainees are likely to bring it up.9

Climate change and mental health

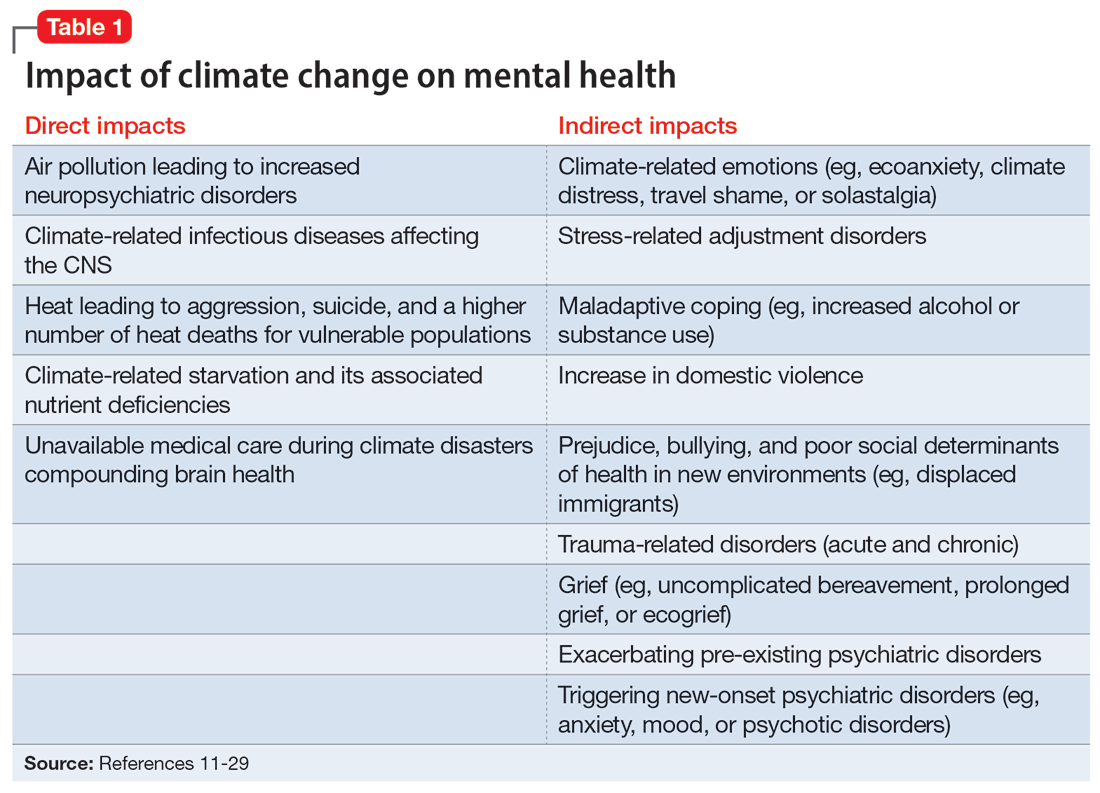

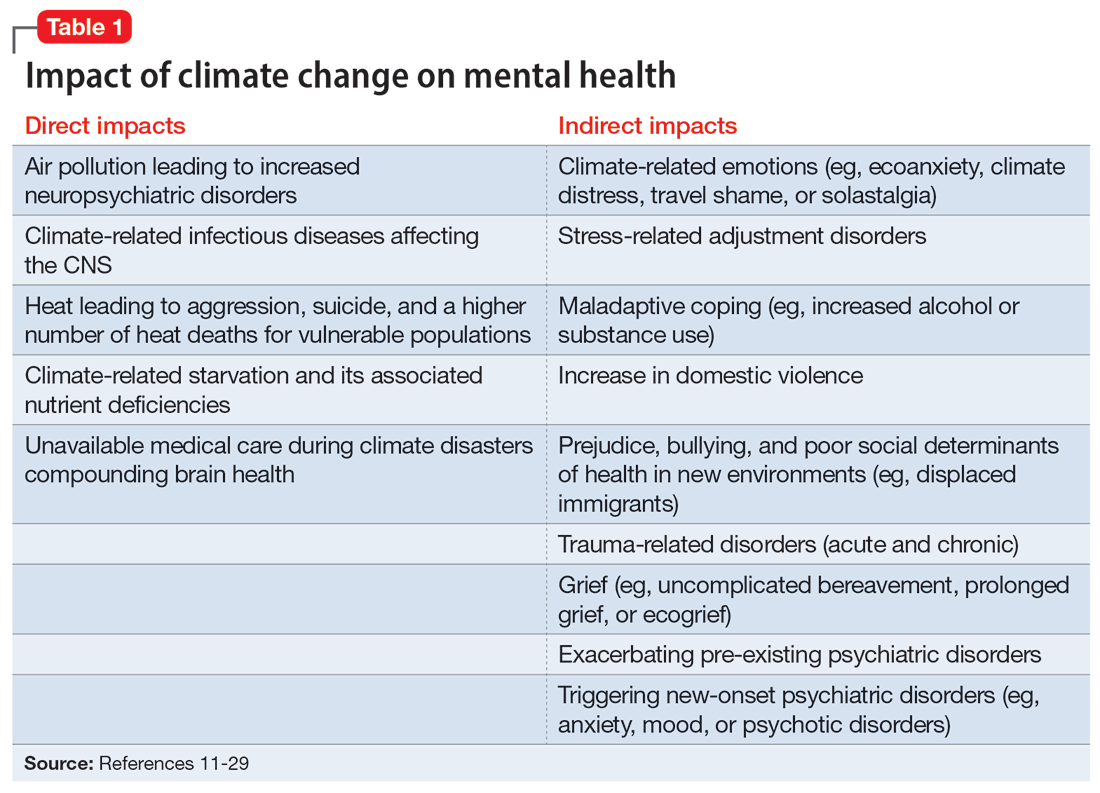

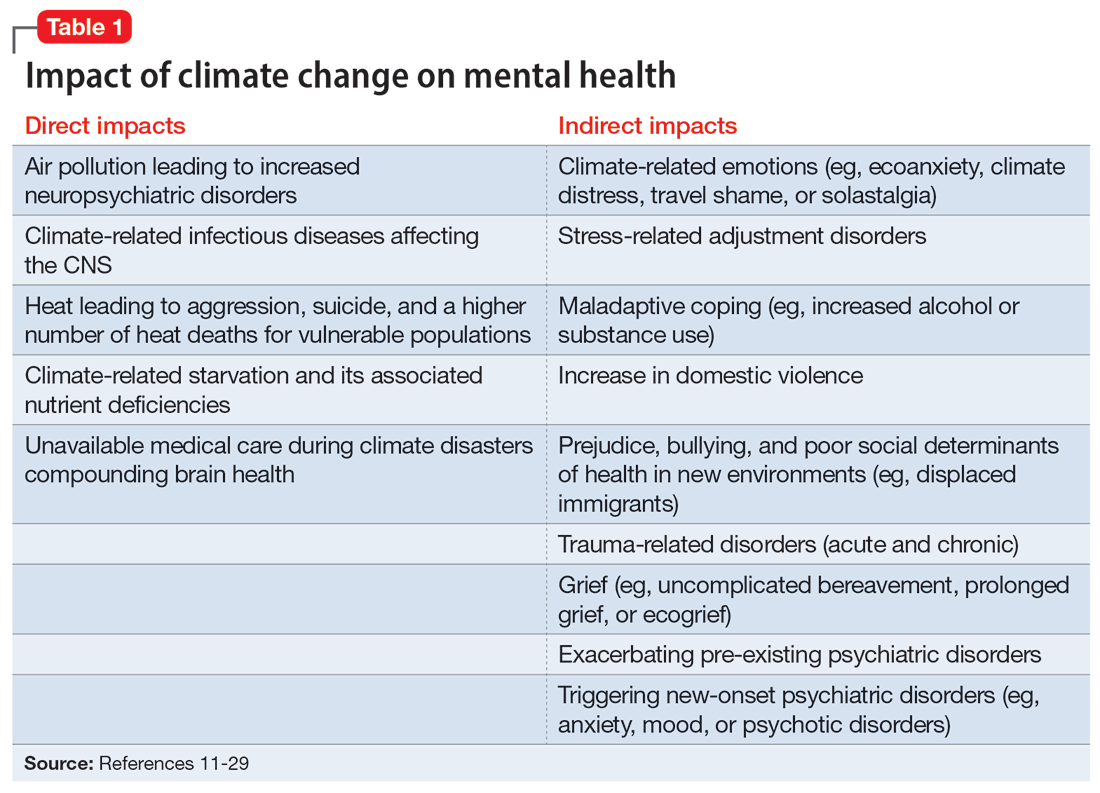

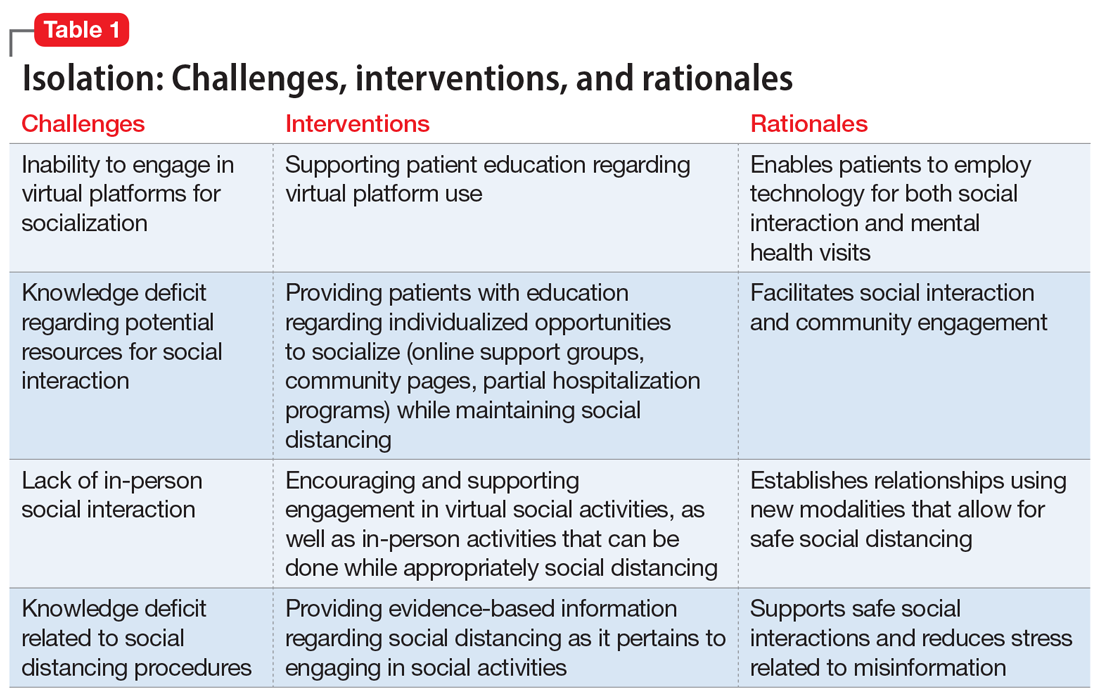

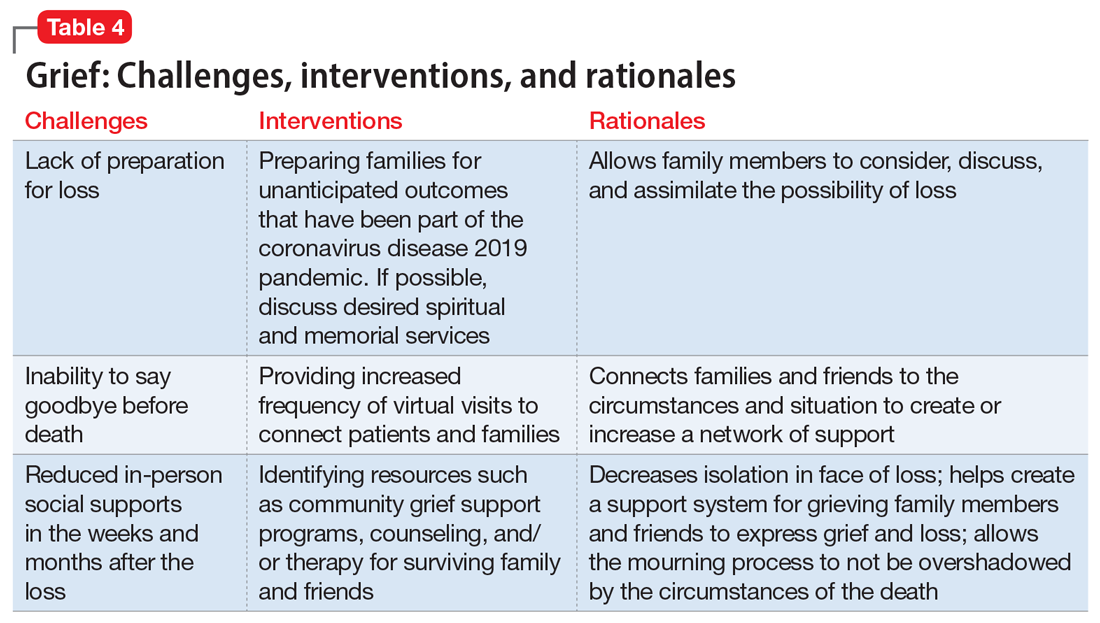

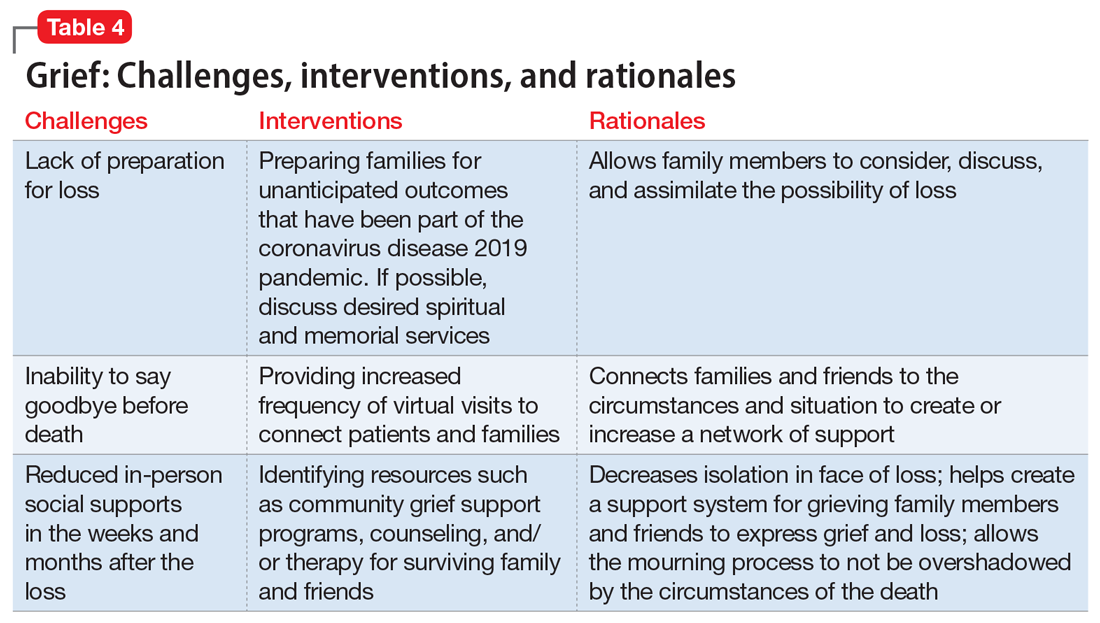

Climate change is harmful to human health, including mental health.10 It can impact mental health directly via its impact on brain function and neuropsychiatric sequelae, and indirectly via climate-related disasters leading to acute or chronic stress, losses, and displacement with psychiatric and psychological sequelae (Table 111-29).

Direct impact

The effects of air pollution, heat, infections, and starvation are examples of how climate change directly impacts mental health. Air pollution and brain health are a concern for psychiatry, given the well-described effects of air deterioration on the developing brain.11 In animal models, airborne pollutants lead to widespread neuroinflammation and cell loss via a multitude of mechanisms.12 This is consistent with worse cognitive and behavioral functions across a wide range of cognitive domains seen in children exposed to pollution compared to those who grew up in environments with healthy air.13 Even low-level exposure to air pollution increases the risk for later onset of depression, suicide, and anxiety.14 Hippocampal atrophy observed in patients with first-episode psychosis may also be partially attributable to air pollution.15 An association between heat and suicide (and to a lesser extent, aggression) has also been reported.16

Worse physical health (eg, strokes) due to excessive heat can further compound mental health via elevated rates of depression. Data from the United States and Mexico show that for each degree Celsius increase in ambient temperature, suicide rates may increase by approximately 1%.17 A meta-analysis by Frangione et al18 similarly concluded that each degree Celsius increase results in an overall risk ratio of 1.016 (95% CI, 1.012 to 1.019) for deaths by suicide and suicide attempts. Additionally, global warming is shifting the endemic areas for many infectious agents, particularly vector-borne diseases,19 to regions in which they had hitherto been unknown, increasing the risk for future outbreaks and even pandemics.20 These infectious illnesses often carry neuropsychiatric morbidity, with seizures, encephalopathy with incomplete recovery, and psychiatric syndromes occurring in many cases. Crop failure can lead to starvation during pregnancy and childhood, which has wide-ranging consequences for brain development and later physical and psychological health in adults.21,22 Mothers affected by starvation also experience negative impacts on childbearing and childrearing.23

Indirect impact

Climate change’s indirect impact on mental health can stem from the stress of living through a disaster such as an extreme weather event; from losses, including the death of friends and family members; and from becoming temporarily displaced.24 Some climate change–driven disasters can be viewed as slow-moving, such as drought and the rising of sea levels, where displacement becomes permanent. Managing mass migration from internally or externally displaced people who must abandon their communities because of climate change will have significant repercussions for all societies.25 The term “climate refugee” is not (yet) included in the United Nations’ official definition of refugees; it defines refugees as individuals who have fled their countries because of war, violence, or persecution.26 These and other bureaucratic issues can come up when clinicians are trying to help migrants with immigration-related paperwork.

Continue to: As the inevitability of climate change...

As the inevitability of climate change sinks in, its long-term ramifications have introduced a new lexicon of psychological suffering related to the crisis.27 Common terms for such distress include ecoanxiety (fear of what is happening and will happen with climate change), ecogrief (sadness about the destruction of species and natural habitats), solastalgia28 (the nostalgia an individual feels for emotionally treasured landscapes that have changed), and terrafuria or ecorage (the reaction to betrayal and inaction by governments and leaders).29 Climate-related emotions can lead to pessimism about the future and a nihilistic outlook on an individual’s ability to effect change and have agency over their life’s outcomes.

The categories of direct and indirect impacts are not mutually exclusive. A child may be starving due to weather-related crop failure as the family is forced to move to another country, then have to contend with prejudice and bullying as an immigrant, and later become anxiously preoccupied with climate change and its ability to cause further distress.

Effect on individuals with serious mental illness

Patients with SMI are particularly vulnerable to the impact of climate change. They are less resilient to climate change–related events, such as heat waves or temporary displacement from flooding, both at the personal level due to illness factors (eg, negative symptoms or cognitive impairment) and at the community level due to social factors (eg, weaker social support or poverty).

Recognizing the increased vulnerability to heat waves and preparing for them is particularly important for patients with SMI because they are at an increased risk for heat-related illnesses.30 For example, patients may not appreciate the danger from heat and live in conditions that put them at risk (ie, not having air conditioning in their home or living alone). Their illness alone impairs heat regulation31; patients with depression and anxiety also dissipate heat less effectively.32,33 Additionally, many psychiatric medications, particularly antipsychotics, impair key mechanisms of heat dissipation.34,35 Antipsychotics render organisms more poikilothermic (susceptible to environmental temperature, like cold-blooded animals) and can be anticholinergic, which impedes sweating. A recent analysis of heat-related deaths during a period of extreme and prolonged heat in British Columbia in 2021 affirmed these concerns, reporting that patients with schizophrenia had the highest odds of death during this heat-related event.36

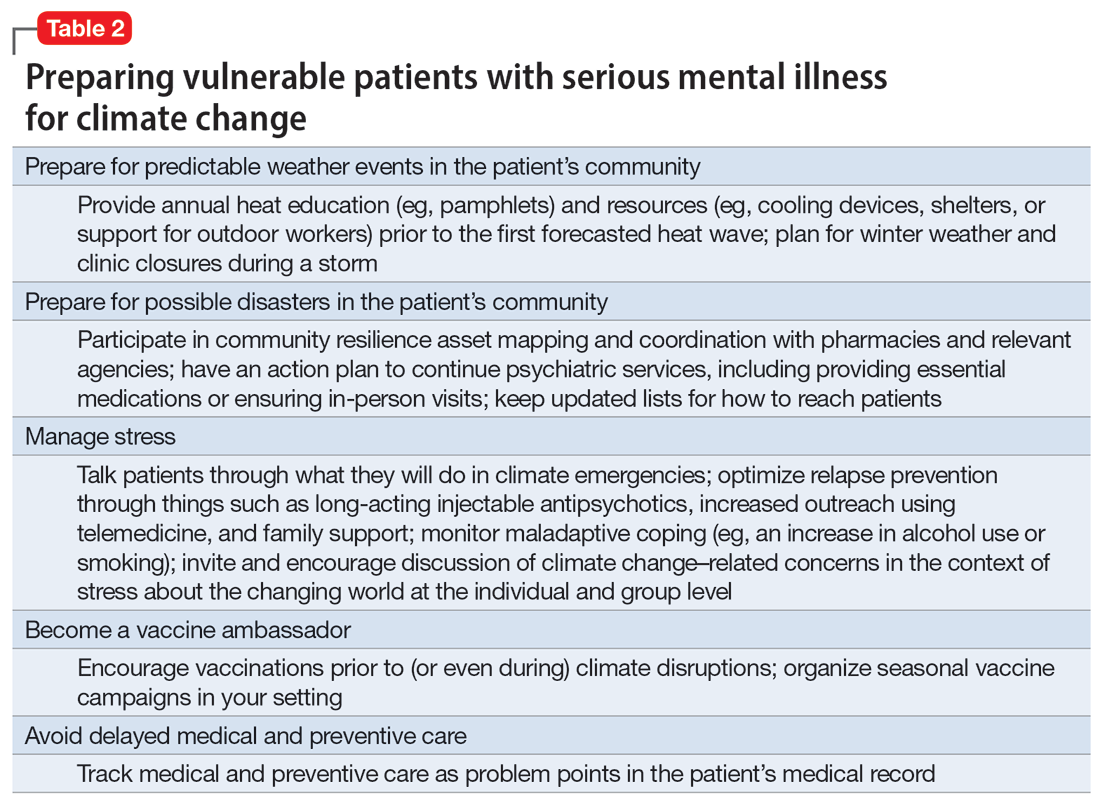

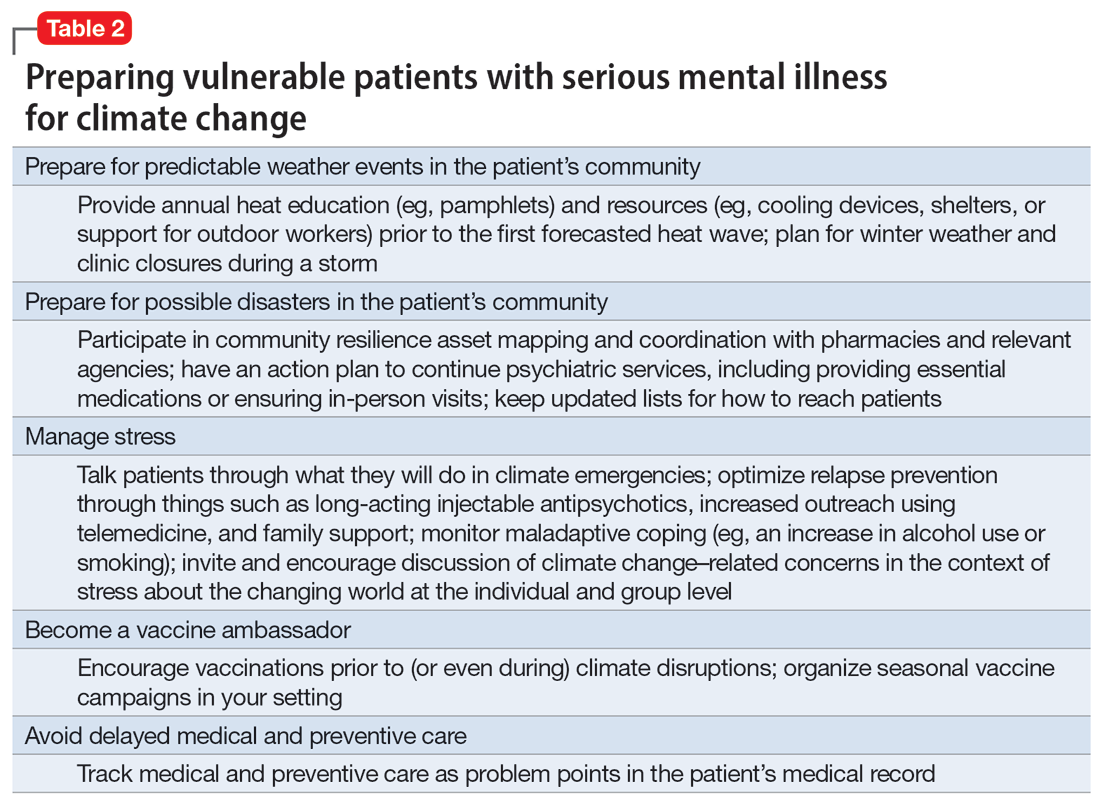

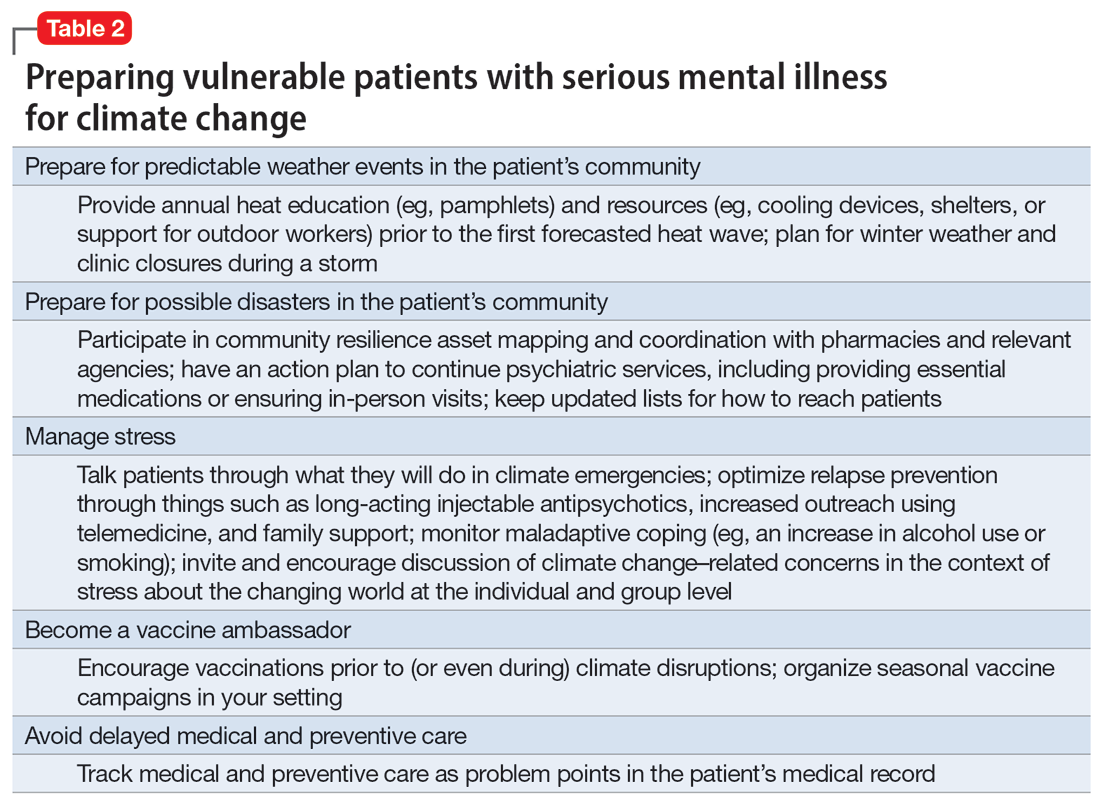

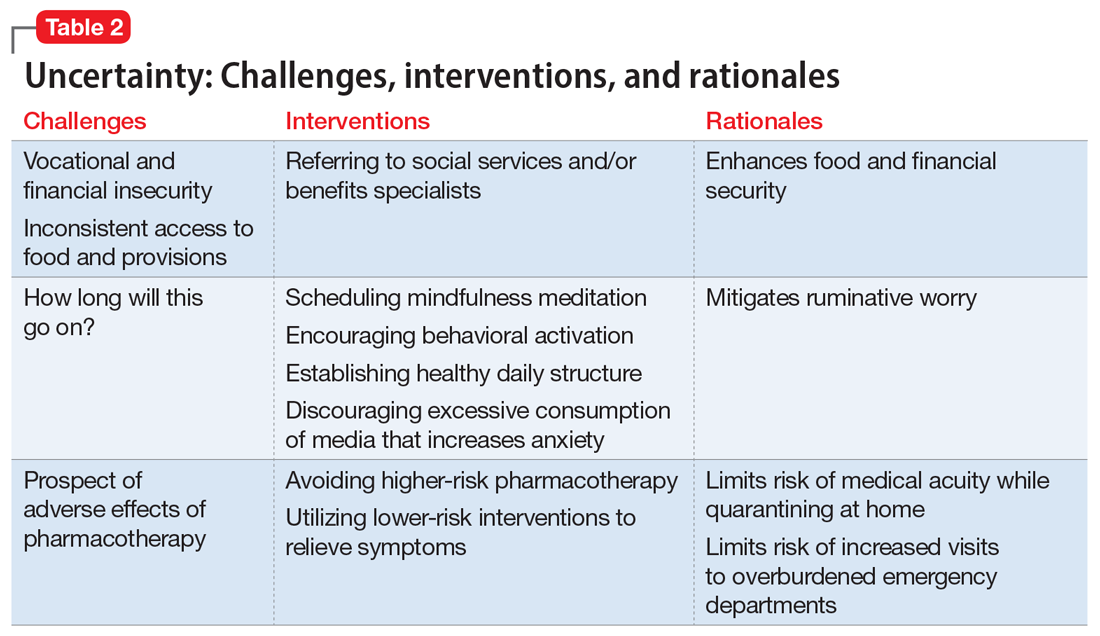

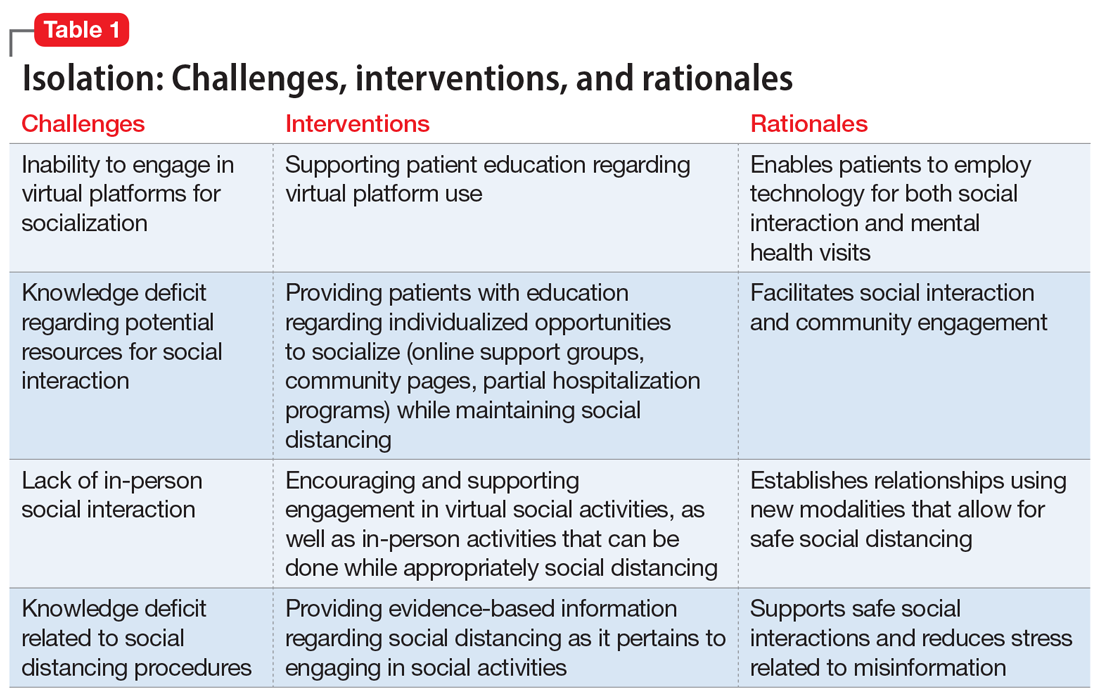

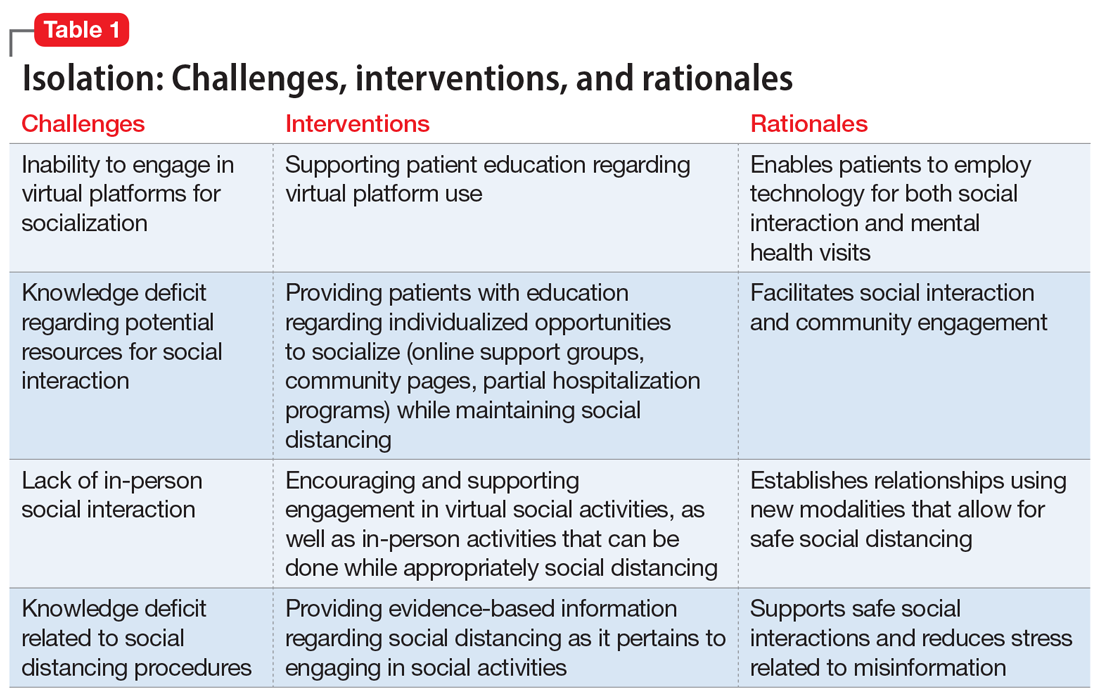

COVID-19 has shown that flexible models of care are needed to prevent disengagement from medical and psychiatric care37 and assure continued treatment with essential medications such as clozapine38 and long-acting injectable antipsychotics39 during periods of social change, as with climate change. While telehealth was critical during the COVID-19 pandemic40 and is here to stay, it alone may be insufficient given the digital divide (patients with SMI may be less likely to have access to or be proficient in the use of digital technologies). The pandemic has shown the importance of public health efforts, including benefits from targeted outreach, with regards to vaccinations for this patient group.41,42 Table 2 summarizes things clinicians should consider when preparing patients with SMI for the effects of climate change.

Continue to: The psychiatrist's role

The psychiatrist’s role

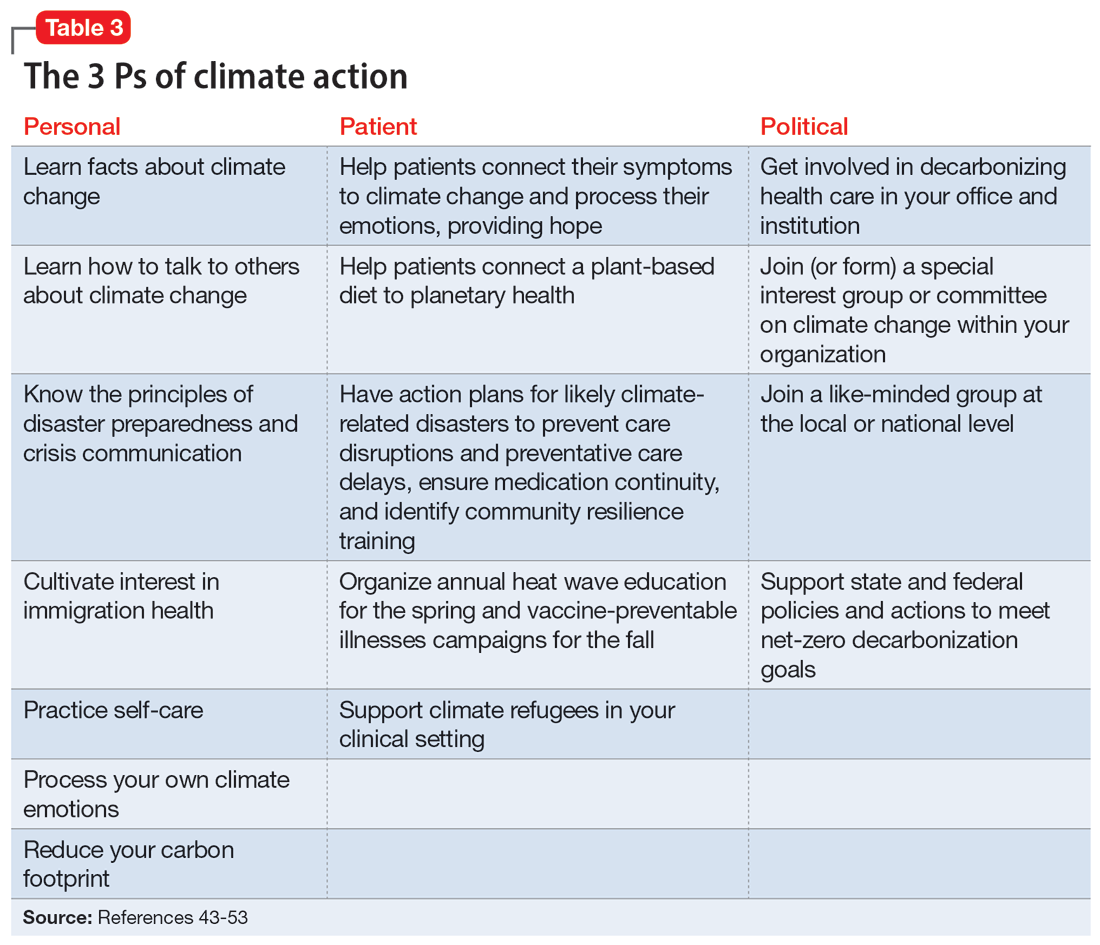

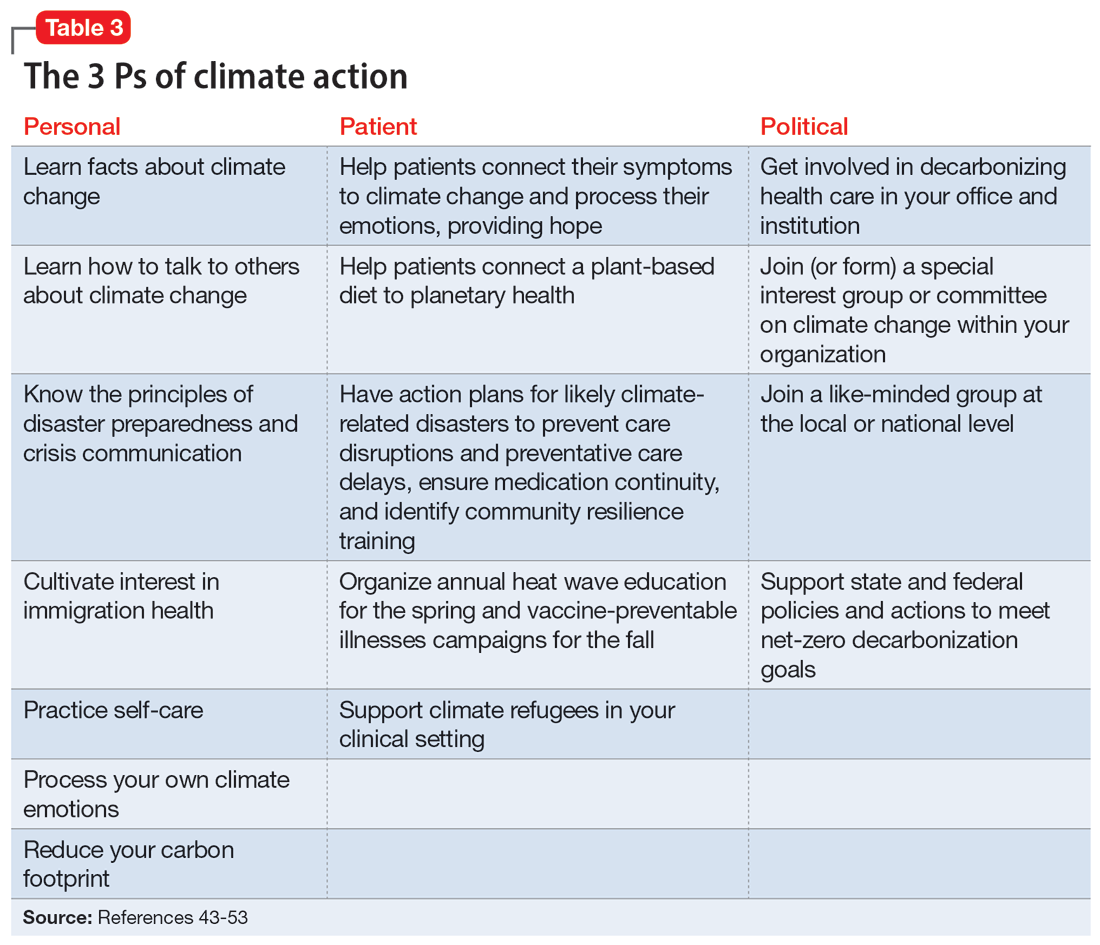

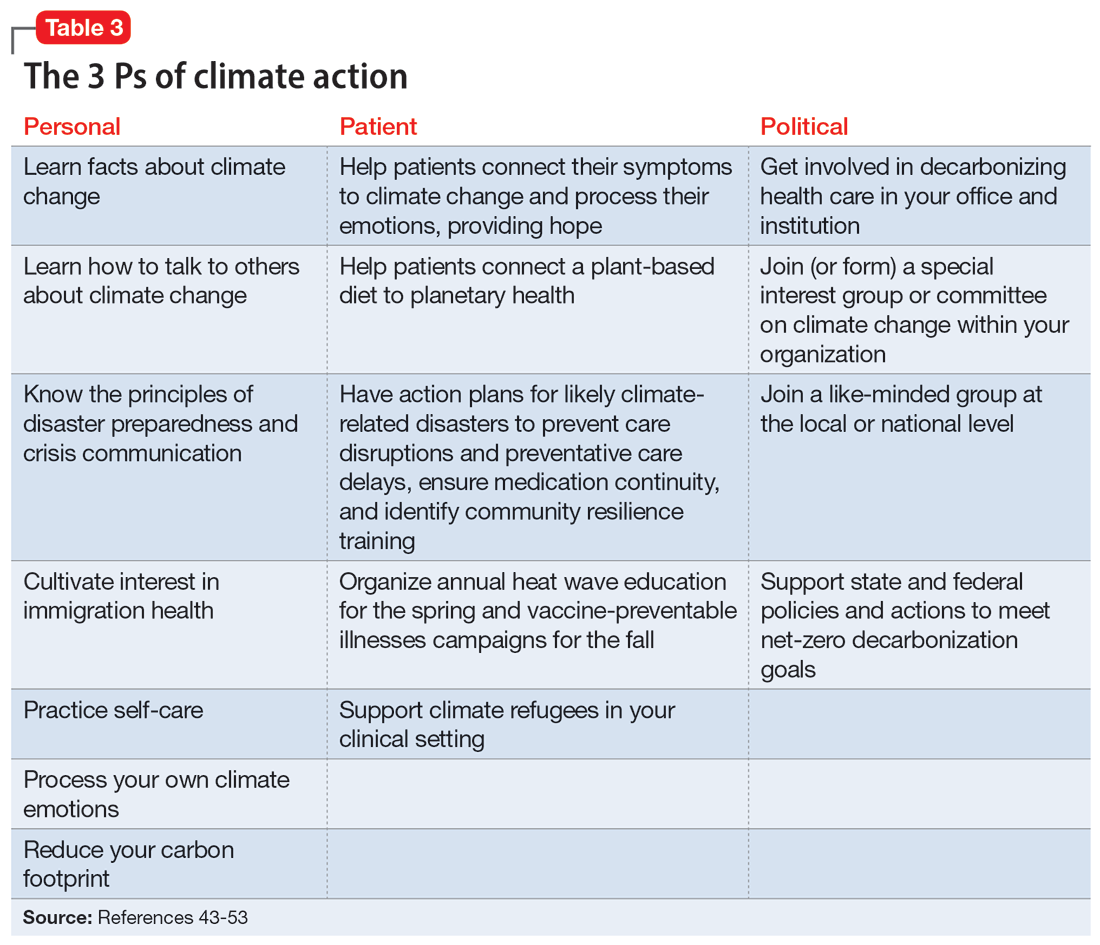

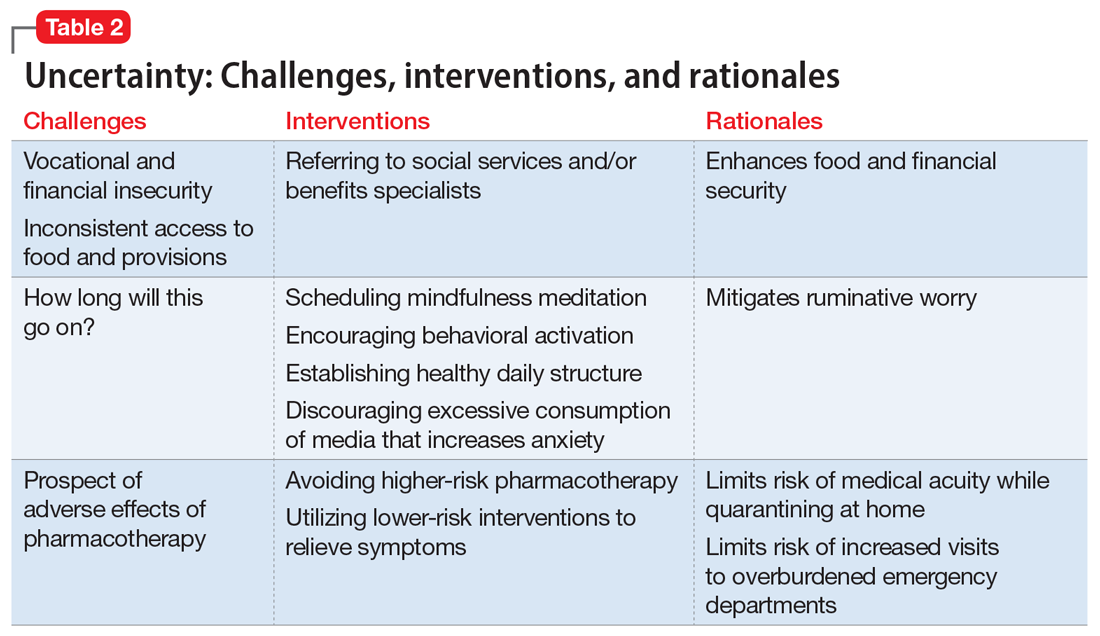

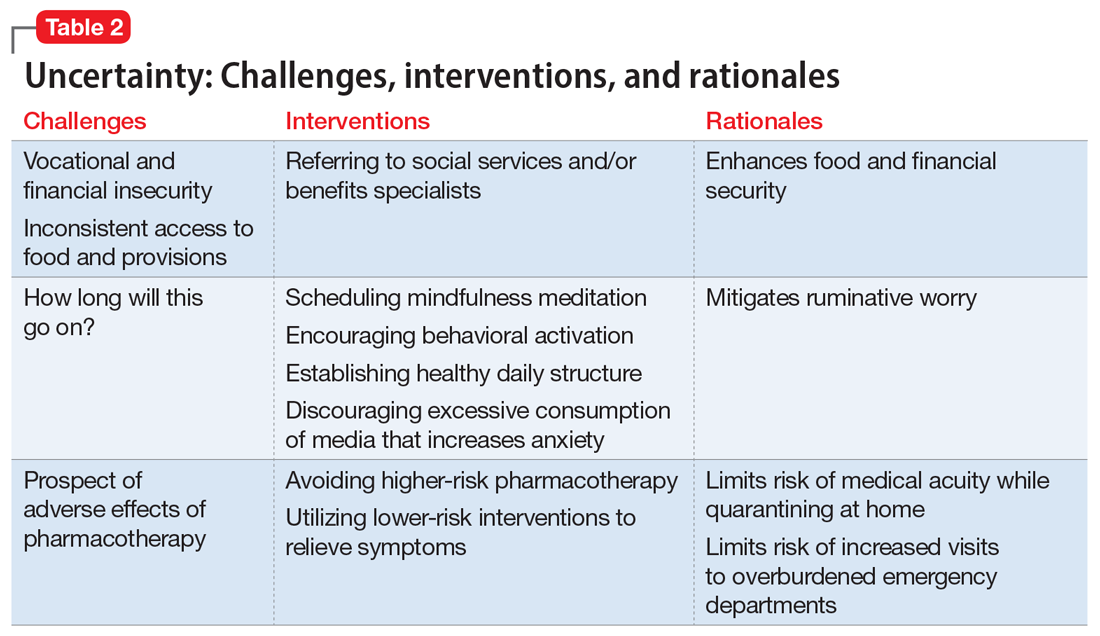

There are many ways a psychiatrist can professionally get involved in addressing climate change. Table 343-53 outlines the 3 Ps of climate action (taking actions to mitigate the effects of climate change): personal, patient (and clinic), and political (advocacy).

Personal

Even if clinicians believe climate change is important for their clinical work, they may still feel overwhelmed and unsure what to do in the context of competing responsibilities. A necessary first step is overcoming paralysis from the enormity of the problem, including the need to shift away from an expanding consumption model to environmental sustainability in a short period of time.

A good starting point is to get educated on the facts of climate change and how to discuss it in an office setting as well as in your personal life. A basic principle of climate change communication is that constructive hope (progress achieved despite everything) coupled with constructive doubt (the reality of the threat) can mobilize people towards action, whereas false hope or fatalistic doubt impedes action.43 The importance of optimal public health messaging cannot be overstated; well-meaning campaigns to change behavior can fail if they emphasize the wrong message. For example, in a study examining COVID-19 messaging in >80 countries, Dorison et al44 found that negatively framed messages mostly increased anxiety but had no benefit with regard to shifting people toward desired behaviors.

In addition, clinicians can learn how to confront climate disavowal and difficult emotions in themselves and even plan to shift to carbon neutrality, such as purchasing carbon offsets or green sources of energy and transportation. They may not be familiar with principles of disaster preparedness or crisis communication.46 Acquiring those professional skills may suggest next steps for action. Being familiar with the challenges and resources for immigrants, including individuals displaced due to climate change, may be necessary.47 Finally, to reduce the risk of burnout, it is important to practice self-care, including strategies to reduce feelings of being overwhelmed.

Patient

In clinical encounters, clinicians can be proactive in helping patients understand their climate-related anxieties around an uncertain future, including identifying barriers to climate action.48

Continue to: Clinics must prepare for disasters...

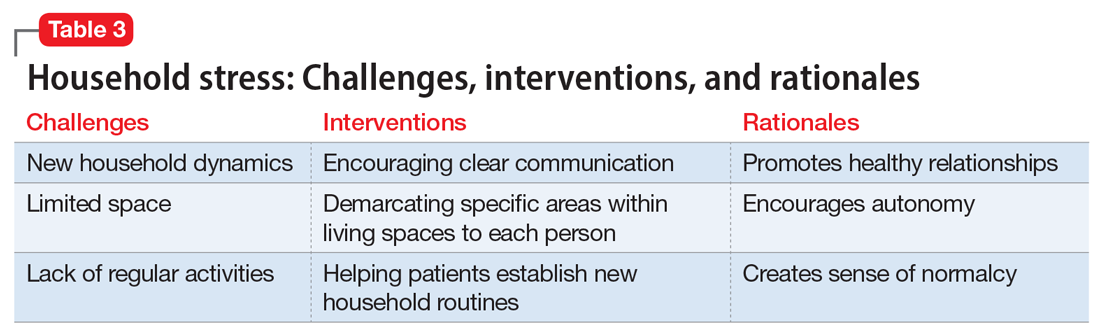

Clinics must prepare for disasters in their communities to prevent disruption of psychiatric care by having an action plan, including the provision of medications. Such action plans should be prioritized for the most likely scenarios in an individual’s setting (eg, heat waves, wildfires, hurricanes, or flooding).

It is important to educate clinic staff and include them in planning for emergencies, because an all-hands approach and buy-in from all team members is critical. Clinicians should review how patients would continue to receive services, particularly medications, in the event of a disaster. In some cases, providing a 90-day medication supply will suffice, while in others (eg, patients receiving long-acting antipsychotics or clozapine) more preparation is necessary. Some events are predictable and can be organized annually, such as clinicians becoming vaccine ambassadors and organizing vaccine campaigns every fall50; winter-related disaster preparation every fall; and heat wave education every spring (leaflets for patients, staff, and family members; review of safety of medications during heat waves). Plan for, monitor, and coordinate medical care and services for climate refugees and other populations that may otherwise delay medical care and impede illness prevention. Finally, support climate refugees, including connecting them to services or providing trauma-informed care.

Political

Some clinicians may feel compelled to become politically active to advocate for changes within the health care system. Two initiatives related to decarbonizing the health care sector are My Green Doctor51 and Health Care Without Harm,52 which offer help in shifting your office, clinic, or hospital towards carbon neutrality.

Climate change unevenly affects people and will continue to exacerbate inequalities in society, including individuals with mental illness.53 To work toward climate justice on behalf of their patients, clinicians could join (or form) climate committees of special interest groups in their professional organizations or setting. Joining like-minded groups working on climate change at the local or national level prevents an omission of a psychiatric voice and counteracts burnout. It is important to stay focused on the root causes of the problem during activism: doing something to reduce fossil fuel use is ultimately most important.54 The concrete goal of reaching the Paris 1.5-degree Celsius climate goal is a critical benchmark against which any other action can be measured.54

Planning for the future

Over the course of history, societies have always faced difficult periods in which they needed to rebuild after natural disasters or self-inflicted catastrophes such as terrorist attacks or wars. Since the advent of the nuclear age, people have lived under the existential threat of nuclear war. The Anthropocene is a proposed geological term that reflects the enormous and possibly disastrous impact human activity has had on our planet.55 While not yet formally adopted, this term has heuristic value, directing attention and reflection to our role and its now undisputed consequences. In the future, historians will debate if the scale of our current climate crisis has been different. It is, however, not controversial that humanity will be faced with the effects of climate change for the foreseeable future.10 Already, even “normal” weather events are fueled by energy in overcharged and altered weather systems due to global warming, leading to weather events ranging from droughts to floods and storms that are more severe, more frequent, and have longer-lasting effects on communities.56

Continue to: As physicians, we are tasked...

As physicians, we are tasked by society to create and maintain a health care system that addresses the needs of our patients and the communities in which they live. Increasingly, we are forced to contend with an addition to the traditional 5 phases of acute disaster management (prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery) to manage prolonged or even parallel disasters, where a series of disasters occurs before the community has recovered and healed. We must grapple with a sense of an “extended period of insecurity and instability” (permacrisis) and must better prepare for and prevent the polycrisis (many simultaneous crises) or the metacrisis of our “age of turmoil”57 in which we must limit global warming, mitigate its damage, and increase community resilience to adapt.

Leading by personal example and providing hope may be what some patients need, as the reality of climate change contributes to the general uneasiness about the future and doomsday scenarios to which many fall victim. At the level of professional societies, many are calling for leadership, including from mental health organizations, to bolster the “social climate,” to help us strengthen our emotional resilience and social bonds to better withstand climate change together.58 It is becoming harder to justify standing on the sidelines,59 and it may be better for both our world and a clinician’s own sanity to be engaged in professional and private hopeful action1 to address climate change. Without ecological or planetary health, there can be no mental health.

Bottom Line

Clinicians can prepare their patients for climate-related disruptions and manage the impact climate change has on their mental health. Addressing climate change at clinical and political levels is consistent with the leadership roles and professional ethics clinicians face in daily practice.

Related Resources

- Lim C, MacLaurin S, Freudenreich O. Preparing patients with serious mental illness for extreme HEAT. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(9):27-28. doi:10.12788/cp.0287

- My Green Doctor. https://mygreendoctor.org/

- The Climate Resilience for Frontline Clinics Toolkit from Americares. https://www.americares.org/what-we-do/community-health/climate-resilient-health-clinics

- Climate Psychiatry Alliance. https://www.climatepsychiatry.org/

Drug Brand Names

Clozapine • Clozaril

1. Kretz L. Hope in environmental philosophy. J Agricult Environ Ethics. 2013;26:925-944. doi:10.1007/s10806-012-9425-8

2. Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, Cooper R. Position statement on mental health and climate change. American Psychiatric Association. March 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.psychiatry.org/getattachment/0ce71f37-61a6-44d0-8fcd-c752b7e935fd/Position-Mental-Health-Climate-Change.pdf

3. Eckelman MJ, Huang K, Lagasse R, et al. Health care pollution and public health damage in the United States: an update. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39:2071-2079.

4. Dzau VJ, Levine R, Barrett G, et al. Decarbonizing the U.S. health sector - a call to action. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(23):2117-2119. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2115675

5. Haase E, Augustinavicius JH, K. Climate change and psychiatry. In: Tasman A, Riba MB, Alarcón RD, et al, eds. Tasman’s Psychiatry. 5th ed. Springer; 2023.

6. Belkin G. Mental health and the global race to resilience. Psychiatr Times. 2023;40(3):26.

7. Hu SR, Yang JQ. Harvard Medical School will integrate climate change into M.D. curriculum. The Harvard Crimson. February 3, 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2023/2/3/hms-climate-curriculum/#:~:text=The%20new%20climate%20change%20curriculum,in%20arriving%20at%20climate%20solutions

8. Funk C, Gramlich J. Amid coronavirus threat, Americans generally have a high level of trust in medical doctors. Pew Research Center. March 13, 2020. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/13/amid-coronavirus-threat-americans-generally-have-a-high-level-of-trust-in-medical-doctors/

9. Coverdale J, Balon R, Beresin EV, et al. Climate change: a call to action for the psychiatric profession. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(3):317-323. doi:10.1007/s40596-018-0885-7

10. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. AR6 synthesis report: climate change 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/

11. Perera FP. Multiple threats to child health from fossil fuel combustion: impacts of air pollution and climate change. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(2):141-148. doi:10.1289/EHP299

12. Hahad O, Lelieveldz J, Birklein F, et al. Ambient air pollution increases the risk of cerebrovascular and neuropsychiatric disorders through induction of inflammation and oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4306. doi:10.3390/ijms21124306

13. Brockmeyer S, D’Angiulli A. How air pollution alters brain development: the role of neuroinflammation. Translational Neurosci. 2016;7(1):24-30. doi:10.1515/tnsci-2016-0005

14. Yang T, Wang J, Huang J, et al. Long-term exposure to multiple ambient air pollutants and association with incident depression and anxiety. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80:305-313. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.4812

15. Worthington MA, Petkova E, Freudenreich O, et al. Air pollution and hippocampal atrophy in first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2020;218:63-69. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.03.001

16. Dumont C, Haase E, Dolber T, et al. Climate change and risk of completed suicide. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(7):559-565. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001162

17. Burke M, Gonzales F, Bayis P, et al. Higher temperatures increase suicide rates in the United States and Mexico. Nat Climate Change. 2018;8:723-729. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0222-x

18. Frangione B, Villamizar LAR, Lang JJ, et al. Short-term changes in meteorological conditions and suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2022;207:112230. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.112230

19. Rocklov J, Dubrow R. Climate change: an enduring challenge for vector-borne disease prevention and control. Nat Immunol. 2020;21(5):479-483. doi:10.1038/s41590-020-0648-y

20. Carlson CJ, Albery GF, Merow C, et al. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature. 2022;607(7919):555-562. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w

21. Roseboom TJ, Painter RC, van Abeelen AFM, et al. Hungry in the womb: what are the consequences? Lessons from the Dutch famine. Maturitas. 2011;70(2):141-145. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.06.017

22. Liu Y, Diao L, Xu L. The impact of childhood experience of starvations on the health of older adults: evidence from China. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2021;36(2):515-531. doi:10.1002/hpm.3099

23. Rothschild J, Haase E. The mental health of women and climate change: direct neuropsychiatric impacts and associated psychological concerns. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2023;160(2):405-413. doi:10.1002/ijgo.14479

24. Cianconi P, Betro S, Janiri L. The impact of climate change on mental health: a systematic descriptive review. Frontiers Psychiatry. 2020;11:74. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00074

25. World Economic Forum. Climate refugees – the world’s forgotten victims. June 18, 2021. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/climate-refugees-the-world-s-forgotten-victims

26. Climate Refugees. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.climate-refugees.org/why

27. Pihkala P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: an analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability. 2020;12(19):7836. doi:10.3390/su12197836

28. Galway LP, Beery T, Jones-Casey K, et al. Mapping the solastalgia literature: a scoping review study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(15):2662. doi:10.3390/ijerph16152662

29. Albrecht GA. Earth Emotions. New Words for a New World. Cornell University Press; 2019.

30. Sorensen C, Hess J. Treatment and prevention of heat-related illness. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(15):1404-1413. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp2210623

31. Chong TWH, Castle DJ. Layer upon layer: thermoregulation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;69(2-3):149-157. doi:10.1016/s0920-9964(03)00222-6

32. von Salis S, Ehlert U, Fischer S. Altered experienced thermoregulation in depression--no evidence for an effect of early life stress. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:620656. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.620656

33. Sarchiapone M, Gramaglia C, Iosue M, et al. The association between electrodermal activity (EDA), depression and suicidal behaviour: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1551-4

34. Martin-Latry K, Goumy MP, Latry P, et al. Psychotropic drugs use and risk of heat-related hospitalisation. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(6):335-338. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.03.007

35. Ebi KL, Capon A, Berry P, et al. Hot weather and heat extremes: health risks. Lancet. 2021;398(10301):698-708. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01208-3

36. Lee MJ, McLean KE, Kuo M, et al. Chronic diseases associated with mortality in British Columbia, Canada during the 2021 Western North America extreme heat event. Geohealth. 2023;7(3):e2022GH000729. doi:10.1029/2022GH000729

37. Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Raja P, et al. Disruptions in care for Medicare beneficiaries with severe mental illness during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2145677. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.45677

38. Siskind D, Honer WG, Clark S, et al. Consensus statement on the use of clozapine during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2020;45(3):222-223. doi:10.1503/jpn.200061

39. MacLaurin SA, Mulligan C, Van Alphen MU, et al. Optimal long-acting injectable antipsychotic management during COVID-19. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(1): 20l13730. doi:10.4088/JCP.20l13730

40. Bartels SJ, Baggett TP, Freudenreich O, et al. COVID-19 emergency reforms in Massachusetts to support behavioral health care and reduce mortality of people with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(10):1078-1081. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202000244

41. Van Alphen MU, Lim C, Freudenreich O. Mobile vaccine clinics for patients with serious mental illness and health care workers in outpatient mental health clinics. Psychiatr Serv. February 8, 2023. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.20220460

42. Lim C, Van Alphen MU, Maclaurin S, et al. Increasing COVID-19 vaccination rates among patients with serious mental illness: a pilot intervention study. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73(11):1274-1277. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202100702

43. Marlon JR, Bloodhart B, Ballew MT, et al. How hope and doubt affect climate change mobilization. Front Commun. May 21, 2019. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2019.00020

44. Dorison CA, Lerner JS, Heller BH, et al. In COVID-19 health messaging, loss framing increases anxiety with little-to-no concomitant benefits: experimental evidence from 84 countries. Affective Sci. 2022;3(3):577-602. doi:10.1007/s42761-022-00128-3

45. Maibach E. Increasing public awareness and facilitating behavior change: two guiding heuristics. George Mason University, Center for Climate Change Communication. September 2015. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.climatechangecommunication.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Maibach-Two-hueristics-September-2015-revised.pdf

46. Koh KA, Raviola G, Stoddard FJ Jr. Psychiatry and crisis communication during COVID-19: a view from the trenches. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72(5):615. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202000912

47. Velez G, Adam B, Shadid O, et al. The clock is ticking: are we prepared for mass climate migration? Psychiatr News. March 24, 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2023.04.4.3

48. Ingle HE, Mikulewicz M. Mental health and climate change: tackling invisible injustice. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4:e128-e130. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30081-4

49. Shah UA, Merlo G. Personal and planetary health--the connection with dietary choices. JAMA. 2023;329(21):1823-1824. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.6118

50. Lim C, Van Alphen MU, Freudenreich O. Becoming vaccine ambassadors: a new role for psychiatrists. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):10-11,17-21,26-28,38. doi:10.12788/cp.0155

51. My Green Doctor. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://mygreendoctor.org/

52. Healthcare Without Harm. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://noharm.org/

53. Levy BS, Patz JA. Climate change, human rights, and social justice. Ann Glob Health. 2015;81:310-322.

54. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Global warming of 1.5° C 2018. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

55. Steffen W, Crutzen J, McNeill JR. The Anthropocene: are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature? Ambio. 2007;36(8):614-621. doi:10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[614:taahno]2.0.co;2

56. American Meteorological Society. Explaining extreme events from a climate perspective. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.ametsoc.org/ams/index.cfm/publications/bulletin-of-the-american-meteorological-society-bams/explaining-extreme-events-from-a-climate-perspective/

57. Nierenberg AA. Coping in the age of turmoil. Psychiatr Ann. 2022;52(7):263. July 1, 2022. doi:10.3928/23258160-20220701-01

58. Belkin G. Leadership for the social climate. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1975-1977. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2001507

59. Skinner JR. Doctors and climate change: first do no harm. J Paediatr Child Health. 2021;57(11):1754-1758. doi:10.1111/jpc.15658

“ Hope is engagement with the act of mapping our destinies.” 1

—Valerie Braithwaite

Why should psychiatrists care about climate change and try to mitigate its effects? First, we are tasked by society with managing the psychological and neuropsychiatric sequelae from disasters, which include climate change. The American Psychiatric Association’s position statement on climate change includes it as a legitimate focus for our specialty.2 Second, as physicians, we are morally obligated to do no harm. Since the health care sector contributes significantly to climate change (8.5% of national carbon emissions stem from health care) and causes demonstrable health impacts,3 managing these impacts and decarbonizing the health care industry is morally imperative.4 And third, psychiatric clinicians have transferrable skills that can address fears of climate change, challenge climate change denialism,5 motivate people to adopt more pro-environmental behaviors, and help communities not only endure the emotional impact of climate change but become more psychologically resilient.6

Most psychiatrists, however, did not receive formal training on climate change and the related field of disaster preparedness. For example, Harvard Medical School did not include a course on climate change in their medical student curriculum until 2023.7 In this article, we provide a basic framework of climate change and its impact on mental health, with particular focus on patients with serious mental illness (SMI). We offer concrete steps clinicians can take to prevent or mitigate harm from climate change for their patients, prepare for disasters at the level of individual patient encounters, and strengthen their clinics and communities. We also encourage clinicians to take active leadership roles in their professional organizations to be part of climate solutions, building on the trust patients continue to have in their physicians.8 Even if clinicians do not view climate change concerns under their conceived clinical care mandate, having a working knowledge about it is important because patients, paraprofessional staff, or medical trainees are likely to bring it up.9

Climate change and mental health

Climate change is harmful to human health, including mental health.10 It can impact mental health directly via its impact on brain function and neuropsychiatric sequelae, and indirectly via climate-related disasters leading to acute or chronic stress, losses, and displacement with psychiatric and psychological sequelae (Table 111-29).

Direct impact

The effects of air pollution, heat, infections, and starvation are examples of how climate change directly impacts mental health. Air pollution and brain health are a concern for psychiatry, given the well-described effects of air deterioration on the developing brain.11 In animal models, airborne pollutants lead to widespread neuroinflammation and cell loss via a multitude of mechanisms.12 This is consistent with worse cognitive and behavioral functions across a wide range of cognitive domains seen in children exposed to pollution compared to those who grew up in environments with healthy air.13 Even low-level exposure to air pollution increases the risk for later onset of depression, suicide, and anxiety.14 Hippocampal atrophy observed in patients with first-episode psychosis may also be partially attributable to air pollution.15 An association between heat and suicide (and to a lesser extent, aggression) has also been reported.16

Worse physical health (eg, strokes) due to excessive heat can further compound mental health via elevated rates of depression. Data from the United States and Mexico show that for each degree Celsius increase in ambient temperature, suicide rates may increase by approximately 1%.17 A meta-analysis by Frangione et al18 similarly concluded that each degree Celsius increase results in an overall risk ratio of 1.016 (95% CI, 1.012 to 1.019) for deaths by suicide and suicide attempts. Additionally, global warming is shifting the endemic areas for many infectious agents, particularly vector-borne diseases,19 to regions in which they had hitherto been unknown, increasing the risk for future outbreaks and even pandemics.20 These infectious illnesses often carry neuropsychiatric morbidity, with seizures, encephalopathy with incomplete recovery, and psychiatric syndromes occurring in many cases. Crop failure can lead to starvation during pregnancy and childhood, which has wide-ranging consequences for brain development and later physical and psychological health in adults.21,22 Mothers affected by starvation also experience negative impacts on childbearing and childrearing.23

Indirect impact

Climate change’s indirect impact on mental health can stem from the stress of living through a disaster such as an extreme weather event; from losses, including the death of friends and family members; and from becoming temporarily displaced.24 Some climate change–driven disasters can be viewed as slow-moving, such as drought and the rising of sea levels, where displacement becomes permanent. Managing mass migration from internally or externally displaced people who must abandon their communities because of climate change will have significant repercussions for all societies.25 The term “climate refugee” is not (yet) included in the United Nations’ official definition of refugees; it defines refugees as individuals who have fled their countries because of war, violence, or persecution.26 These and other bureaucratic issues can come up when clinicians are trying to help migrants with immigration-related paperwork.

Continue to: As the inevitability of climate change...

As the inevitability of climate change sinks in, its long-term ramifications have introduced a new lexicon of psychological suffering related to the crisis.27 Common terms for such distress include ecoanxiety (fear of what is happening and will happen with climate change), ecogrief (sadness about the destruction of species and natural habitats), solastalgia28 (the nostalgia an individual feels for emotionally treasured landscapes that have changed), and terrafuria or ecorage (the reaction to betrayal and inaction by governments and leaders).29 Climate-related emotions can lead to pessimism about the future and a nihilistic outlook on an individual’s ability to effect change and have agency over their life’s outcomes.

The categories of direct and indirect impacts are not mutually exclusive. A child may be starving due to weather-related crop failure as the family is forced to move to another country, then have to contend with prejudice and bullying as an immigrant, and later become anxiously preoccupied with climate change and its ability to cause further distress.

Effect on individuals with serious mental illness

Patients with SMI are particularly vulnerable to the impact of climate change. They are less resilient to climate change–related events, such as heat waves or temporary displacement from flooding, both at the personal level due to illness factors (eg, negative symptoms or cognitive impairment) and at the community level due to social factors (eg, weaker social support or poverty).

Recognizing the increased vulnerability to heat waves and preparing for them is particularly important for patients with SMI because they are at an increased risk for heat-related illnesses.30 For example, patients may not appreciate the danger from heat and live in conditions that put them at risk (ie, not having air conditioning in their home or living alone). Their illness alone impairs heat regulation31; patients with depression and anxiety also dissipate heat less effectively.32,33 Additionally, many psychiatric medications, particularly antipsychotics, impair key mechanisms of heat dissipation.34,35 Antipsychotics render organisms more poikilothermic (susceptible to environmental temperature, like cold-blooded animals) and can be anticholinergic, which impedes sweating. A recent analysis of heat-related deaths during a period of extreme and prolonged heat in British Columbia in 2021 affirmed these concerns, reporting that patients with schizophrenia had the highest odds of death during this heat-related event.36

COVID-19 has shown that flexible models of care are needed to prevent disengagement from medical and psychiatric care37 and assure continued treatment with essential medications such as clozapine38 and long-acting injectable antipsychotics39 during periods of social change, as with climate change. While telehealth was critical during the COVID-19 pandemic40 and is here to stay, it alone may be insufficient given the digital divide (patients with SMI may be less likely to have access to or be proficient in the use of digital technologies). The pandemic has shown the importance of public health efforts, including benefits from targeted outreach, with regards to vaccinations for this patient group.41,42 Table 2 summarizes things clinicians should consider when preparing patients with SMI for the effects of climate change.

Continue to: The psychiatrist's role

The psychiatrist’s role

There are many ways a psychiatrist can professionally get involved in addressing climate change. Table 343-53 outlines the 3 Ps of climate action (taking actions to mitigate the effects of climate change): personal, patient (and clinic), and political (advocacy).

Personal

Even if clinicians believe climate change is important for their clinical work, they may still feel overwhelmed and unsure what to do in the context of competing responsibilities. A necessary first step is overcoming paralysis from the enormity of the problem, including the need to shift away from an expanding consumption model to environmental sustainability in a short period of time.

A good starting point is to get educated on the facts of climate change and how to discuss it in an office setting as well as in your personal life. A basic principle of climate change communication is that constructive hope (progress achieved despite everything) coupled with constructive doubt (the reality of the threat) can mobilize people towards action, whereas false hope or fatalistic doubt impedes action.43 The importance of optimal public health messaging cannot be overstated; well-meaning campaigns to change behavior can fail if they emphasize the wrong message. For example, in a study examining COVID-19 messaging in >80 countries, Dorison et al44 found that negatively framed messages mostly increased anxiety but had no benefit with regard to shifting people toward desired behaviors.

In addition, clinicians can learn how to confront climate disavowal and difficult emotions in themselves and even plan to shift to carbon neutrality, such as purchasing carbon offsets or green sources of energy and transportation. They may not be familiar with principles of disaster preparedness or crisis communication.46 Acquiring those professional skills may suggest next steps for action. Being familiar with the challenges and resources for immigrants, including individuals displaced due to climate change, may be necessary.47 Finally, to reduce the risk of burnout, it is important to practice self-care, including strategies to reduce feelings of being overwhelmed.

Patient

In clinical encounters, clinicians can be proactive in helping patients understand their climate-related anxieties around an uncertain future, including identifying barriers to climate action.48

Continue to: Clinics must prepare for disasters...

Clinics must prepare for disasters in their communities to prevent disruption of psychiatric care by having an action plan, including the provision of medications. Such action plans should be prioritized for the most likely scenarios in an individual’s setting (eg, heat waves, wildfires, hurricanes, or flooding).

It is important to educate clinic staff and include them in planning for emergencies, because an all-hands approach and buy-in from all team members is critical. Clinicians should review how patients would continue to receive services, particularly medications, in the event of a disaster. In some cases, providing a 90-day medication supply will suffice, while in others (eg, patients receiving long-acting antipsychotics or clozapine) more preparation is necessary. Some events are predictable and can be organized annually, such as clinicians becoming vaccine ambassadors and organizing vaccine campaigns every fall50; winter-related disaster preparation every fall; and heat wave education every spring (leaflets for patients, staff, and family members; review of safety of medications during heat waves). Plan for, monitor, and coordinate medical care and services for climate refugees and other populations that may otherwise delay medical care and impede illness prevention. Finally, support climate refugees, including connecting them to services or providing trauma-informed care.

Political

Some clinicians may feel compelled to become politically active to advocate for changes within the health care system. Two initiatives related to decarbonizing the health care sector are My Green Doctor51 and Health Care Without Harm,52 which offer help in shifting your office, clinic, or hospital towards carbon neutrality.

Climate change unevenly affects people and will continue to exacerbate inequalities in society, including individuals with mental illness.53 To work toward climate justice on behalf of their patients, clinicians could join (or form) climate committees of special interest groups in their professional organizations or setting. Joining like-minded groups working on climate change at the local or national level prevents an omission of a psychiatric voice and counteracts burnout. It is important to stay focused on the root causes of the problem during activism: doing something to reduce fossil fuel use is ultimately most important.54 The concrete goal of reaching the Paris 1.5-degree Celsius climate goal is a critical benchmark against which any other action can be measured.54

Planning for the future

Over the course of history, societies have always faced difficult periods in which they needed to rebuild after natural disasters or self-inflicted catastrophes such as terrorist attacks or wars. Since the advent of the nuclear age, people have lived under the existential threat of nuclear war. The Anthropocene is a proposed geological term that reflects the enormous and possibly disastrous impact human activity has had on our planet.55 While not yet formally adopted, this term has heuristic value, directing attention and reflection to our role and its now undisputed consequences. In the future, historians will debate if the scale of our current climate crisis has been different. It is, however, not controversial that humanity will be faced with the effects of climate change for the foreseeable future.10 Already, even “normal” weather events are fueled by energy in overcharged and altered weather systems due to global warming, leading to weather events ranging from droughts to floods and storms that are more severe, more frequent, and have longer-lasting effects on communities.56

Continue to: As physicians, we are tasked...

As physicians, we are tasked by society to create and maintain a health care system that addresses the needs of our patients and the communities in which they live. Increasingly, we are forced to contend with an addition to the traditional 5 phases of acute disaster management (prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery) to manage prolonged or even parallel disasters, where a series of disasters occurs before the community has recovered and healed. We must grapple with a sense of an “extended period of insecurity and instability” (permacrisis) and must better prepare for and prevent the polycrisis (many simultaneous crises) or the metacrisis of our “age of turmoil”57 in which we must limit global warming, mitigate its damage, and increase community resilience to adapt.

Leading by personal example and providing hope may be what some patients need, as the reality of climate change contributes to the general uneasiness about the future and doomsday scenarios to which many fall victim. At the level of professional societies, many are calling for leadership, including from mental health organizations, to bolster the “social climate,” to help us strengthen our emotional resilience and social bonds to better withstand climate change together.58 It is becoming harder to justify standing on the sidelines,59 and it may be better for both our world and a clinician’s own sanity to be engaged in professional and private hopeful action1 to address climate change. Without ecological or planetary health, there can be no mental health.

Bottom Line

Clinicians can prepare their patients for climate-related disruptions and manage the impact climate change has on their mental health. Addressing climate change at clinical and political levels is consistent with the leadership roles and professional ethics clinicians face in daily practice.

Related Resources

- Lim C, MacLaurin S, Freudenreich O. Preparing patients with serious mental illness for extreme HEAT. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(9):27-28. doi:10.12788/cp.0287

- My Green Doctor. https://mygreendoctor.org/

- The Climate Resilience for Frontline Clinics Toolkit from Americares. https://www.americares.org/what-we-do/community-health/climate-resilient-health-clinics

- Climate Psychiatry Alliance. https://www.climatepsychiatry.org/

Drug Brand Names

Clozapine • Clozaril

“ Hope is engagement with the act of mapping our destinies.” 1

—Valerie Braithwaite

Why should psychiatrists care about climate change and try to mitigate its effects? First, we are tasked by society with managing the psychological and neuropsychiatric sequelae from disasters, which include climate change. The American Psychiatric Association’s position statement on climate change includes it as a legitimate focus for our specialty.2 Second, as physicians, we are morally obligated to do no harm. Since the health care sector contributes significantly to climate change (8.5% of national carbon emissions stem from health care) and causes demonstrable health impacts,3 managing these impacts and decarbonizing the health care industry is morally imperative.4 And third, psychiatric clinicians have transferrable skills that can address fears of climate change, challenge climate change denialism,5 motivate people to adopt more pro-environmental behaviors, and help communities not only endure the emotional impact of climate change but become more psychologically resilient.6

Most psychiatrists, however, did not receive formal training on climate change and the related field of disaster preparedness. For example, Harvard Medical School did not include a course on climate change in their medical student curriculum until 2023.7 In this article, we provide a basic framework of climate change and its impact on mental health, with particular focus on patients with serious mental illness (SMI). We offer concrete steps clinicians can take to prevent or mitigate harm from climate change for their patients, prepare for disasters at the level of individual patient encounters, and strengthen their clinics and communities. We also encourage clinicians to take active leadership roles in their professional organizations to be part of climate solutions, building on the trust patients continue to have in their physicians.8 Even if clinicians do not view climate change concerns under their conceived clinical care mandate, having a working knowledge about it is important because patients, paraprofessional staff, or medical trainees are likely to bring it up.9

Climate change and mental health

Climate change is harmful to human health, including mental health.10 It can impact mental health directly via its impact on brain function and neuropsychiatric sequelae, and indirectly via climate-related disasters leading to acute or chronic stress, losses, and displacement with psychiatric and psychological sequelae (Table 111-29).

Direct impact

The effects of air pollution, heat, infections, and starvation are examples of how climate change directly impacts mental health. Air pollution and brain health are a concern for psychiatry, given the well-described effects of air deterioration on the developing brain.11 In animal models, airborne pollutants lead to widespread neuroinflammation and cell loss via a multitude of mechanisms.12 This is consistent with worse cognitive and behavioral functions across a wide range of cognitive domains seen in children exposed to pollution compared to those who grew up in environments with healthy air.13 Even low-level exposure to air pollution increases the risk for later onset of depression, suicide, and anxiety.14 Hippocampal atrophy observed in patients with first-episode psychosis may also be partially attributable to air pollution.15 An association between heat and suicide (and to a lesser extent, aggression) has also been reported.16

Worse physical health (eg, strokes) due to excessive heat can further compound mental health via elevated rates of depression. Data from the United States and Mexico show that for each degree Celsius increase in ambient temperature, suicide rates may increase by approximately 1%.17 A meta-analysis by Frangione et al18 similarly concluded that each degree Celsius increase results in an overall risk ratio of 1.016 (95% CI, 1.012 to 1.019) for deaths by suicide and suicide attempts. Additionally, global warming is shifting the endemic areas for many infectious agents, particularly vector-borne diseases,19 to regions in which they had hitherto been unknown, increasing the risk for future outbreaks and even pandemics.20 These infectious illnesses often carry neuropsychiatric morbidity, with seizures, encephalopathy with incomplete recovery, and psychiatric syndromes occurring in many cases. Crop failure can lead to starvation during pregnancy and childhood, which has wide-ranging consequences for brain development and later physical and psychological health in adults.21,22 Mothers affected by starvation also experience negative impacts on childbearing and childrearing.23

Indirect impact

Climate change’s indirect impact on mental health can stem from the stress of living through a disaster such as an extreme weather event; from losses, including the death of friends and family members; and from becoming temporarily displaced.24 Some climate change–driven disasters can be viewed as slow-moving, such as drought and the rising of sea levels, where displacement becomes permanent. Managing mass migration from internally or externally displaced people who must abandon their communities because of climate change will have significant repercussions for all societies.25 The term “climate refugee” is not (yet) included in the United Nations’ official definition of refugees; it defines refugees as individuals who have fled their countries because of war, violence, or persecution.26 These and other bureaucratic issues can come up when clinicians are trying to help migrants with immigration-related paperwork.

Continue to: As the inevitability of climate change...

As the inevitability of climate change sinks in, its long-term ramifications have introduced a new lexicon of psychological suffering related to the crisis.27 Common terms for such distress include ecoanxiety (fear of what is happening and will happen with climate change), ecogrief (sadness about the destruction of species and natural habitats), solastalgia28 (the nostalgia an individual feels for emotionally treasured landscapes that have changed), and terrafuria or ecorage (the reaction to betrayal and inaction by governments and leaders).29 Climate-related emotions can lead to pessimism about the future and a nihilistic outlook on an individual’s ability to effect change and have agency over their life’s outcomes.

The categories of direct and indirect impacts are not mutually exclusive. A child may be starving due to weather-related crop failure as the family is forced to move to another country, then have to contend with prejudice and bullying as an immigrant, and later become anxiously preoccupied with climate change and its ability to cause further distress.

Effect on individuals with serious mental illness

Patients with SMI are particularly vulnerable to the impact of climate change. They are less resilient to climate change–related events, such as heat waves or temporary displacement from flooding, both at the personal level due to illness factors (eg, negative symptoms or cognitive impairment) and at the community level due to social factors (eg, weaker social support or poverty).

Recognizing the increased vulnerability to heat waves and preparing for them is particularly important for patients with SMI because they are at an increased risk for heat-related illnesses.30 For example, patients may not appreciate the danger from heat and live in conditions that put them at risk (ie, not having air conditioning in their home or living alone). Their illness alone impairs heat regulation31; patients with depression and anxiety also dissipate heat less effectively.32,33 Additionally, many psychiatric medications, particularly antipsychotics, impair key mechanisms of heat dissipation.34,35 Antipsychotics render organisms more poikilothermic (susceptible to environmental temperature, like cold-blooded animals) and can be anticholinergic, which impedes sweating. A recent analysis of heat-related deaths during a period of extreme and prolonged heat in British Columbia in 2021 affirmed these concerns, reporting that patients with schizophrenia had the highest odds of death during this heat-related event.36

COVID-19 has shown that flexible models of care are needed to prevent disengagement from medical and psychiatric care37 and assure continued treatment with essential medications such as clozapine38 and long-acting injectable antipsychotics39 during periods of social change, as with climate change. While telehealth was critical during the COVID-19 pandemic40 and is here to stay, it alone may be insufficient given the digital divide (patients with SMI may be less likely to have access to or be proficient in the use of digital technologies). The pandemic has shown the importance of public health efforts, including benefits from targeted outreach, with regards to vaccinations for this patient group.41,42 Table 2 summarizes things clinicians should consider when preparing patients with SMI for the effects of climate change.

Continue to: The psychiatrist's role

The psychiatrist’s role

There are many ways a psychiatrist can professionally get involved in addressing climate change. Table 343-53 outlines the 3 Ps of climate action (taking actions to mitigate the effects of climate change): personal, patient (and clinic), and political (advocacy).

Personal

Even if clinicians believe climate change is important for their clinical work, they may still feel overwhelmed and unsure what to do in the context of competing responsibilities. A necessary first step is overcoming paralysis from the enormity of the problem, including the need to shift away from an expanding consumption model to environmental sustainability in a short period of time.

A good starting point is to get educated on the facts of climate change and how to discuss it in an office setting as well as in your personal life. A basic principle of climate change communication is that constructive hope (progress achieved despite everything) coupled with constructive doubt (the reality of the threat) can mobilize people towards action, whereas false hope or fatalistic doubt impedes action.43 The importance of optimal public health messaging cannot be overstated; well-meaning campaigns to change behavior can fail if they emphasize the wrong message. For example, in a study examining COVID-19 messaging in >80 countries, Dorison et al44 found that negatively framed messages mostly increased anxiety but had no benefit with regard to shifting people toward desired behaviors.

In addition, clinicians can learn how to confront climate disavowal and difficult emotions in themselves and even plan to shift to carbon neutrality, such as purchasing carbon offsets or green sources of energy and transportation. They may not be familiar with principles of disaster preparedness or crisis communication.46 Acquiring those professional skills may suggest next steps for action. Being familiar with the challenges and resources for immigrants, including individuals displaced due to climate change, may be necessary.47 Finally, to reduce the risk of burnout, it is important to practice self-care, including strategies to reduce feelings of being overwhelmed.

Patient

In clinical encounters, clinicians can be proactive in helping patients understand their climate-related anxieties around an uncertain future, including identifying barriers to climate action.48

Continue to: Clinics must prepare for disasters...

Clinics must prepare for disasters in their communities to prevent disruption of psychiatric care by having an action plan, including the provision of medications. Such action plans should be prioritized for the most likely scenarios in an individual’s setting (eg, heat waves, wildfires, hurricanes, or flooding).

It is important to educate clinic staff and include them in planning for emergencies, because an all-hands approach and buy-in from all team members is critical. Clinicians should review how patients would continue to receive services, particularly medications, in the event of a disaster. In some cases, providing a 90-day medication supply will suffice, while in others (eg, patients receiving long-acting antipsychotics or clozapine) more preparation is necessary. Some events are predictable and can be organized annually, such as clinicians becoming vaccine ambassadors and organizing vaccine campaigns every fall50; winter-related disaster preparation every fall; and heat wave education every spring (leaflets for patients, staff, and family members; review of safety of medications during heat waves). Plan for, monitor, and coordinate medical care and services for climate refugees and other populations that may otherwise delay medical care and impede illness prevention. Finally, support climate refugees, including connecting them to services or providing trauma-informed care.

Political

Some clinicians may feel compelled to become politically active to advocate for changes within the health care system. Two initiatives related to decarbonizing the health care sector are My Green Doctor51 and Health Care Without Harm,52 which offer help in shifting your office, clinic, or hospital towards carbon neutrality.

Climate change unevenly affects people and will continue to exacerbate inequalities in society, including individuals with mental illness.53 To work toward climate justice on behalf of their patients, clinicians could join (or form) climate committees of special interest groups in their professional organizations or setting. Joining like-minded groups working on climate change at the local or national level prevents an omission of a psychiatric voice and counteracts burnout. It is important to stay focused on the root causes of the problem during activism: doing something to reduce fossil fuel use is ultimately most important.54 The concrete goal of reaching the Paris 1.5-degree Celsius climate goal is a critical benchmark against which any other action can be measured.54

Planning for the future

Over the course of history, societies have always faced difficult periods in which they needed to rebuild after natural disasters or self-inflicted catastrophes such as terrorist attacks or wars. Since the advent of the nuclear age, people have lived under the existential threat of nuclear war. The Anthropocene is a proposed geological term that reflects the enormous and possibly disastrous impact human activity has had on our planet.55 While not yet formally adopted, this term has heuristic value, directing attention and reflection to our role and its now undisputed consequences. In the future, historians will debate if the scale of our current climate crisis has been different. It is, however, not controversial that humanity will be faced with the effects of climate change for the foreseeable future.10 Already, even “normal” weather events are fueled by energy in overcharged and altered weather systems due to global warming, leading to weather events ranging from droughts to floods and storms that are more severe, more frequent, and have longer-lasting effects on communities.56

Continue to: As physicians, we are tasked...

As physicians, we are tasked by society to create and maintain a health care system that addresses the needs of our patients and the communities in which they live. Increasingly, we are forced to contend with an addition to the traditional 5 phases of acute disaster management (prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery) to manage prolonged or even parallel disasters, where a series of disasters occurs before the community has recovered and healed. We must grapple with a sense of an “extended period of insecurity and instability” (permacrisis) and must better prepare for and prevent the polycrisis (many simultaneous crises) or the metacrisis of our “age of turmoil”57 in which we must limit global warming, mitigate its damage, and increase community resilience to adapt.

Leading by personal example and providing hope may be what some patients need, as the reality of climate change contributes to the general uneasiness about the future and doomsday scenarios to which many fall victim. At the level of professional societies, many are calling for leadership, including from mental health organizations, to bolster the “social climate,” to help us strengthen our emotional resilience and social bonds to better withstand climate change together.58 It is becoming harder to justify standing on the sidelines,59 and it may be better for both our world and a clinician’s own sanity to be engaged in professional and private hopeful action1 to address climate change. Without ecological or planetary health, there can be no mental health.

Bottom Line

Clinicians can prepare their patients for climate-related disruptions and manage the impact climate change has on their mental health. Addressing climate change at clinical and political levels is consistent with the leadership roles and professional ethics clinicians face in daily practice.

Related Resources

- Lim C, MacLaurin S, Freudenreich O. Preparing patients with serious mental illness for extreme HEAT. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(9):27-28. doi:10.12788/cp.0287

- My Green Doctor. https://mygreendoctor.org/

- The Climate Resilience for Frontline Clinics Toolkit from Americares. https://www.americares.org/what-we-do/community-health/climate-resilient-health-clinics

- Climate Psychiatry Alliance. https://www.climatepsychiatry.org/

Drug Brand Names

Clozapine • Clozaril

1. Kretz L. Hope in environmental philosophy. J Agricult Environ Ethics. 2013;26:925-944. doi:10.1007/s10806-012-9425-8

2. Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, Cooper R. Position statement on mental health and climate change. American Psychiatric Association. March 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.psychiatry.org/getattachment/0ce71f37-61a6-44d0-8fcd-c752b7e935fd/Position-Mental-Health-Climate-Change.pdf

3. Eckelman MJ, Huang K, Lagasse R, et al. Health care pollution and public health damage in the United States: an update. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39:2071-2079.

4. Dzau VJ, Levine R, Barrett G, et al. Decarbonizing the U.S. health sector - a call to action. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(23):2117-2119. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2115675

5. Haase E, Augustinavicius JH, K. Climate change and psychiatry. In: Tasman A, Riba MB, Alarcón RD, et al, eds. Tasman’s Psychiatry. 5th ed. Springer; 2023.

6. Belkin G. Mental health and the global race to resilience. Psychiatr Times. 2023;40(3):26.

7. Hu SR, Yang JQ. Harvard Medical School will integrate climate change into M.D. curriculum. The Harvard Crimson. February 3, 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2023/2/3/hms-climate-curriculum/#:~:text=The%20new%20climate%20change%20curriculum,in%20arriving%20at%20climate%20solutions

8. Funk C, Gramlich J. Amid coronavirus threat, Americans generally have a high level of trust in medical doctors. Pew Research Center. March 13, 2020. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/13/amid-coronavirus-threat-americans-generally-have-a-high-level-of-trust-in-medical-doctors/

9. Coverdale J, Balon R, Beresin EV, et al. Climate change: a call to action for the psychiatric profession. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(3):317-323. doi:10.1007/s40596-018-0885-7

10. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. AR6 synthesis report: climate change 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/

11. Perera FP. Multiple threats to child health from fossil fuel combustion: impacts of air pollution and climate change. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(2):141-148. doi:10.1289/EHP299

12. Hahad O, Lelieveldz J, Birklein F, et al. Ambient air pollution increases the risk of cerebrovascular and neuropsychiatric disorders through induction of inflammation and oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4306. doi:10.3390/ijms21124306

13. Brockmeyer S, D’Angiulli A. How air pollution alters brain development: the role of neuroinflammation. Translational Neurosci. 2016;7(1):24-30. doi:10.1515/tnsci-2016-0005

14. Yang T, Wang J, Huang J, et al. Long-term exposure to multiple ambient air pollutants and association with incident depression and anxiety. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80:305-313. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.4812

15. Worthington MA, Petkova E, Freudenreich O, et al. Air pollution and hippocampal atrophy in first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2020;218:63-69. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.03.001

16. Dumont C, Haase E, Dolber T, et al. Climate change and risk of completed suicide. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(7):559-565. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001162

17. Burke M, Gonzales F, Bayis P, et al. Higher temperatures increase suicide rates in the United States and Mexico. Nat Climate Change. 2018;8:723-729. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0222-x

18. Frangione B, Villamizar LAR, Lang JJ, et al. Short-term changes in meteorological conditions and suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2022;207:112230. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.112230

19. Rocklov J, Dubrow R. Climate change: an enduring challenge for vector-borne disease prevention and control. Nat Immunol. 2020;21(5):479-483. doi:10.1038/s41590-020-0648-y

20. Carlson CJ, Albery GF, Merow C, et al. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature. 2022;607(7919):555-562. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w

21. Roseboom TJ, Painter RC, van Abeelen AFM, et al. Hungry in the womb: what are the consequences? Lessons from the Dutch famine. Maturitas. 2011;70(2):141-145. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.06.017

22. Liu Y, Diao L, Xu L. The impact of childhood experience of starvations on the health of older adults: evidence from China. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2021;36(2):515-531. doi:10.1002/hpm.3099

23. Rothschild J, Haase E. The mental health of women and climate change: direct neuropsychiatric impacts and associated psychological concerns. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2023;160(2):405-413. doi:10.1002/ijgo.14479

24. Cianconi P, Betro S, Janiri L. The impact of climate change on mental health: a systematic descriptive review. Frontiers Psychiatry. 2020;11:74. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00074

25. World Economic Forum. Climate refugees – the world’s forgotten victims. June 18, 2021. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/climate-refugees-the-world-s-forgotten-victims

26. Climate Refugees. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.climate-refugees.org/why

27. Pihkala P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: an analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability. 2020;12(19):7836. doi:10.3390/su12197836

28. Galway LP, Beery T, Jones-Casey K, et al. Mapping the solastalgia literature: a scoping review study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(15):2662. doi:10.3390/ijerph16152662

29. Albrecht GA. Earth Emotions. New Words for a New World. Cornell University Press; 2019.

30. Sorensen C, Hess J. Treatment and prevention of heat-related illness. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(15):1404-1413. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp2210623

31. Chong TWH, Castle DJ. Layer upon layer: thermoregulation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;69(2-3):149-157. doi:10.1016/s0920-9964(03)00222-6

32. von Salis S, Ehlert U, Fischer S. Altered experienced thermoregulation in depression--no evidence for an effect of early life stress. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:620656. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.620656

33. Sarchiapone M, Gramaglia C, Iosue M, et al. The association between electrodermal activity (EDA), depression and suicidal behaviour: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1551-4

34. Martin-Latry K, Goumy MP, Latry P, et al. Psychotropic drugs use and risk of heat-related hospitalisation. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(6):335-338. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.03.007

35. Ebi KL, Capon A, Berry P, et al. Hot weather and heat extremes: health risks. Lancet. 2021;398(10301):698-708. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01208-3

36. Lee MJ, McLean KE, Kuo M, et al. Chronic diseases associated with mortality in British Columbia, Canada during the 2021 Western North America extreme heat event. Geohealth. 2023;7(3):e2022GH000729. doi:10.1029/2022GH000729

37. Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Raja P, et al. Disruptions in care for Medicare beneficiaries with severe mental illness during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2145677. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.45677

38. Siskind D, Honer WG, Clark S, et al. Consensus statement on the use of clozapine during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2020;45(3):222-223. doi:10.1503/jpn.200061

39. MacLaurin SA, Mulligan C, Van Alphen MU, et al. Optimal long-acting injectable antipsychotic management during COVID-19. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(1): 20l13730. doi:10.4088/JCP.20l13730

40. Bartels SJ, Baggett TP, Freudenreich O, et al. COVID-19 emergency reforms in Massachusetts to support behavioral health care and reduce mortality of people with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(10):1078-1081. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202000244

41. Van Alphen MU, Lim C, Freudenreich O. Mobile vaccine clinics for patients with serious mental illness and health care workers in outpatient mental health clinics. Psychiatr Serv. February 8, 2023. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.20220460

42. Lim C, Van Alphen MU, Maclaurin S, et al. Increasing COVID-19 vaccination rates among patients with serious mental illness: a pilot intervention study. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73(11):1274-1277. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202100702

43. Marlon JR, Bloodhart B, Ballew MT, et al. How hope and doubt affect climate change mobilization. Front Commun. May 21, 2019. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2019.00020

44. Dorison CA, Lerner JS, Heller BH, et al. In COVID-19 health messaging, loss framing increases anxiety with little-to-no concomitant benefits: experimental evidence from 84 countries. Affective Sci. 2022;3(3):577-602. doi:10.1007/s42761-022-00128-3

45. Maibach E. Increasing public awareness and facilitating behavior change: two guiding heuristics. George Mason University, Center for Climate Change Communication. September 2015. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.climatechangecommunication.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Maibach-Two-hueristics-September-2015-revised.pdf

46. Koh KA, Raviola G, Stoddard FJ Jr. Psychiatry and crisis communication during COVID-19: a view from the trenches. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72(5):615. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.202000912

47. Velez G, Adam B, Shadid O, et al. The clock is ticking: are we prepared for mass climate migration? Psychiatr News. March 24, 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2023.04.4.3

48. Ingle HE, Mikulewicz M. Mental health and climate change: tackling invisible injustice. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4:e128-e130. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30081-4

49. Shah UA, Merlo G. Personal and planetary health--the connection with dietary choices. JAMA. 2023;329(21):1823-1824. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.6118

50. Lim C, Van Alphen MU, Freudenreich O. Becoming vaccine ambassadors: a new role for psychiatrists. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):10-11,17-21,26-28,38. doi:10.12788/cp.0155

51. My Green Doctor. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://mygreendoctor.org/

52. Healthcare Without Harm. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://noharm.org/

53. Levy BS, Patz JA. Climate change, human rights, and social justice. Ann Glob Health. 2015;81:310-322.

54. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Global warming of 1.5° C 2018. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

55. Steffen W, Crutzen J, McNeill JR. The Anthropocene: are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature? Ambio. 2007;36(8):614-621. doi:10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[614:taahno]2.0.co;2

56. American Meteorological Society. Explaining extreme events from a climate perspective. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.ametsoc.org/ams/index.cfm/publications/bulletin-of-the-american-meteorological-society-bams/explaining-extreme-events-from-a-climate-perspective/

57. Nierenberg AA. Coping in the age of turmoil. Psychiatr Ann. 2022;52(7):263. July 1, 2022. doi:10.3928/23258160-20220701-01

58. Belkin G. Leadership for the social climate. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1975-1977. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2001507

59. Skinner JR. Doctors and climate change: first do no harm. J Paediatr Child Health. 2021;57(11):1754-1758. doi:10.1111/jpc.15658

1. Kretz L. Hope in environmental philosophy. J Agricult Environ Ethics. 2013;26:925-944. doi:10.1007/s10806-012-9425-8

2. Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, Cooper R. Position statement on mental health and climate change. American Psychiatric Association. March 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.psychiatry.org/getattachment/0ce71f37-61a6-44d0-8fcd-c752b7e935fd/Position-Mental-Health-Climate-Change.pdf

3. Eckelman MJ, Huang K, Lagasse R, et al. Health care pollution and public health damage in the United States: an update. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39:2071-2079.

4. Dzau VJ, Levine R, Barrett G, et al. Decarbonizing the U.S. health sector - a call to action. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(23):2117-2119. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2115675

5. Haase E, Augustinavicius JH, K. Climate change and psychiatry. In: Tasman A, Riba MB, Alarcón RD, et al, eds. Tasman’s Psychiatry. 5th ed. Springer; 2023.

6. Belkin G. Mental health and the global race to resilience. Psychiatr Times. 2023;40(3):26.

7. Hu SR, Yang JQ. Harvard Medical School will integrate climate change into M.D. curriculum. The Harvard Crimson. February 3, 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2023/2/3/hms-climate-curriculum/#:~:text=The%20new%20climate%20change%20curriculum,in%20arriving%20at%20climate%20solutions

8. Funk C, Gramlich J. Amid coronavirus threat, Americans generally have a high level of trust in medical doctors. Pew Research Center. March 13, 2020. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/13/amid-coronavirus-threat-americans-generally-have-a-high-level-of-trust-in-medical-doctors/

9. Coverdale J, Balon R, Beresin EV, et al. Climate change: a call to action for the psychiatric profession. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(3):317-323. doi:10.1007/s40596-018-0885-7

10. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. AR6 synthesis report: climate change 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/

11. Perera FP. Multiple threats to child health from fossil fuel combustion: impacts of air pollution and climate change. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(2):141-148. doi:10.1289/EHP299

12. Hahad O, Lelieveldz J, Birklein F, et al. Ambient air pollution increases the risk of cerebrovascular and neuropsychiatric disorders through induction of inflammation and oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4306. doi:10.3390/ijms21124306

13. Brockmeyer S, D’Angiulli A. How air pollution alters brain development: the role of neuroinflammation. Translational Neurosci. 2016;7(1):24-30. doi:10.1515/tnsci-2016-0005

14. Yang T, Wang J, Huang J, et al. Long-term exposure to multiple ambient air pollutants and association with incident depression and anxiety. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80:305-313. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.4812

15. Worthington MA, Petkova E, Freudenreich O, et al. Air pollution and hippocampal atrophy in first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2020;218:63-69. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.03.001

16. Dumont C, Haase E, Dolber T, et al. Climate change and risk of completed suicide. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(7):559-565. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001162

17. Burke M, Gonzales F, Bayis P, et al. Higher temperatures increase suicide rates in the United States and Mexico. Nat Climate Change. 2018;8:723-729. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0222-x

18. Frangione B, Villamizar LAR, Lang JJ, et al. Short-term changes in meteorological conditions and suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2022;207:112230. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.112230

19. Rocklov J, Dubrow R. Climate change: an enduring challenge for vector-borne disease prevention and control. Nat Immunol. 2020;21(5):479-483. doi:10.1038/s41590-020-0648-y

20. Carlson CJ, Albery GF, Merow C, et al. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature. 2022;607(7919):555-562. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w