User login

Caring for outpatients during COVID-19: 4 themes

As a result of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the content of outpatient psychotherapy and psychopharmacology sessions has seen significant change, with many patients focusing on how the pandemic has altered their daily lives and emotional well-being. Most patients were suddenly limited in both the amount of time they spent, and in their interactions with people, outside of their homes. Additionally, employment-related stressors such as working from home and the potential loss of a job and/or income added to pandemic stress.1 Patients simultaneously processed their experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic while often striving to adapt to new virtual modes of mental health care delivery via phone or video conferencing.

The clinic staff at our large, multidisciplinary, urban outpatient mental health practice conducts weekly case consultation meetings. In meetings held during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, we noted 4 dominant clinical themes emerging across our patients’ experiences:

- isolation

- uncertainty

- household stress

- grief.

These themes occurred across many diagnostic categories, suggesting they reflect a dramatic shift brought on by the pandemic. Our group compared clinical experiences from the beginning of the pandemic through the end of May 2020. For this article, we considered several patients who expressed these 4 themes and created a “composite patient.” In the following sections, we describe the typical presentation of, and recommended interventions for, a composite patient for each of these 4 themes.

Isolation

Mr. J, a 60-year-old, single, African American man diagnosed with bipolar disorder with psychotic features, lives alone in an apartment in a densely populated area. Before COVID-19, he had been attending a day treatment program. His daily walks for coffee and cigarettes provided the scaffolding to his emotional stability and gave him a sense of belonging to a world outside of his home. Mr. J also had been able to engage in informal social activities in the common areas of his apartment complex.

The start of the COVID-19 pandemic ends his interpersonal interactions, from the passive and superficial conversations he had with strangers in coffee shops to the more intimate engagement with his peers in his treatment program. The common areas of Mr. J’s apartment building are closed, and his routine cigarette breaks with neighbors have become solitary events, with the added stress of having to schedule his use of the building’s designated smoking area. Before COVID-19, Mr. J had been regularly meeting his brother for coffee to talk about the recent death of their father, but these meetings end due to infection concerns by Mr. J and his brother, who cares for their ailing mother who is at high risk for COVID-19 infection.

Mr. J begins to report self-referential ideation when walking in public, citing his inability to see peoples’ facial expressions because they are wearing masks. As a result of the pandemic restrictions, he becomes depressed and develops increased paranoid ideation. Fortunately, Mr. J begins to participate in a virtual partial hospitalization program to address his paranoid ideation through intensive and clinically-based social interactions. He is unfamiliar with the technology used for virtual visits, but is given the necessary technical support. He is also able to begin virtual visits with his brother and mother. Mr. J soon reports his symptoms are reduced and his mood is more stable.

Engaging in interpersonal interactions can have a positive impact on mental health. Social isolation has demonstrated negative effects that are amplified in individuals with psychiatric disorders.2 Interpersonal interactions can provide a shared experience, promote positive feelings of social connection, and aid in the development of social skills.3,4 Among our patients, we have begun to see the effects of isolation manifest as loneliness and demoralization.

Continue to: Interventions

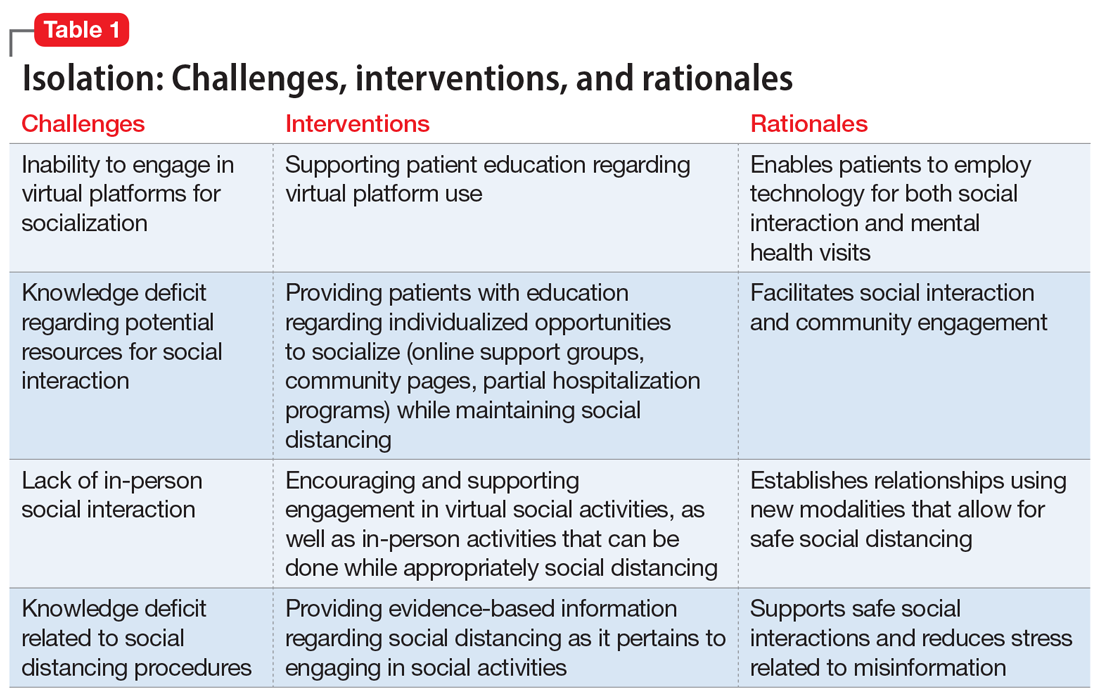

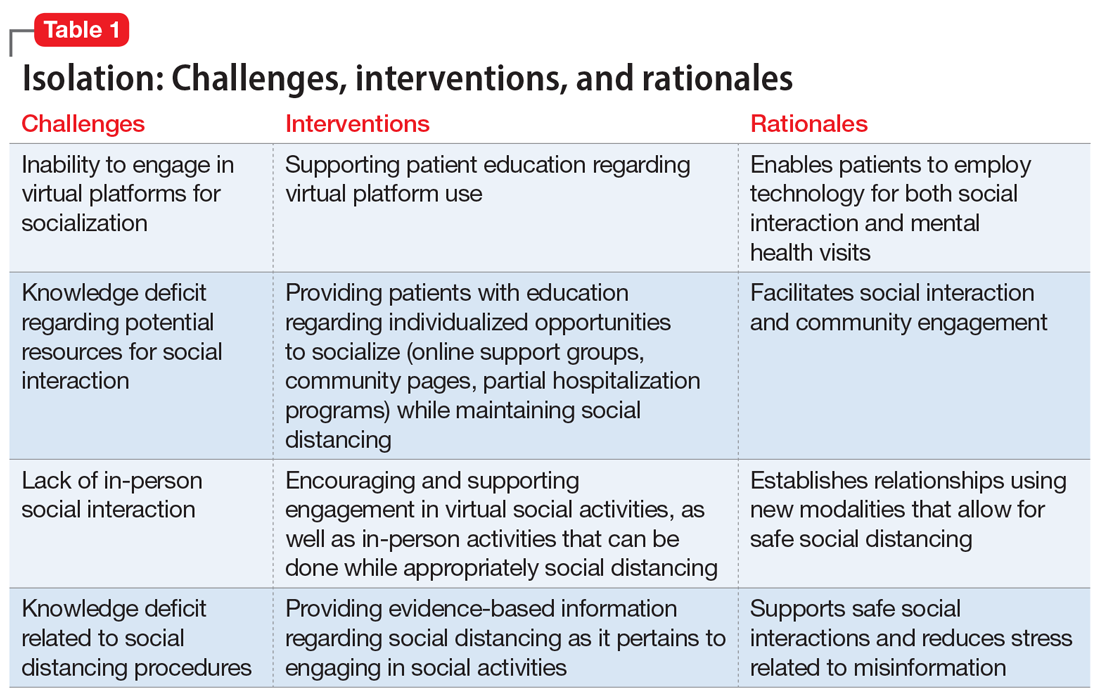

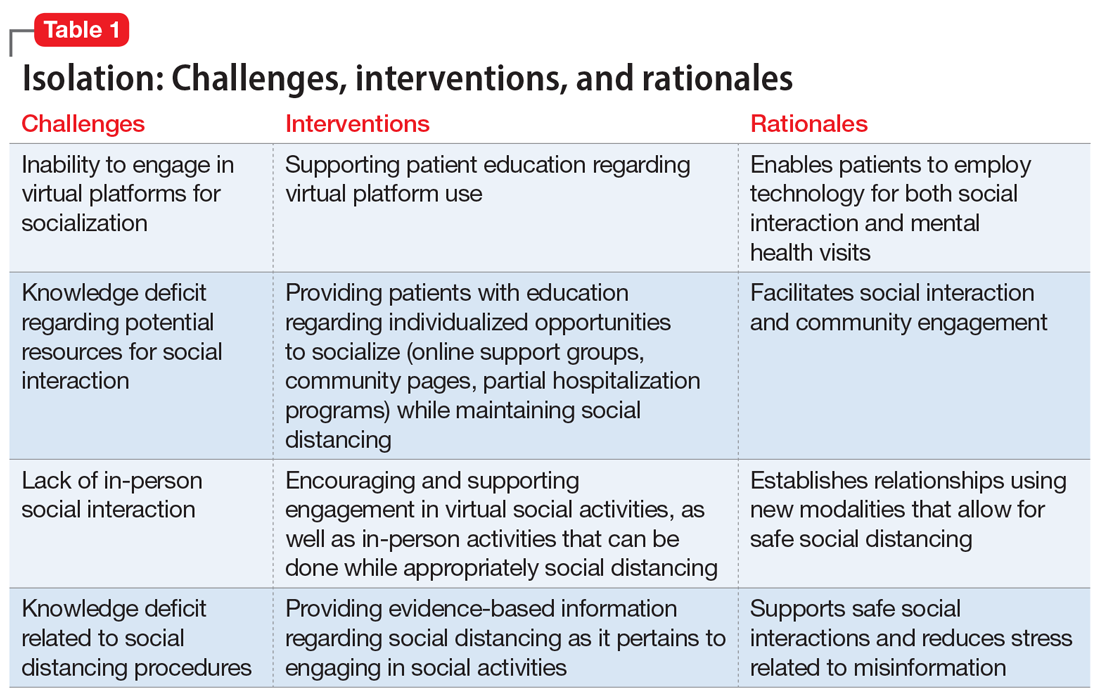

Interventions. Due to restrictions imposed to limit the spread of COVID-19, evidence-based interventions such as meeting a friend for a meal or participating in in-person support groups typically are not options, thus forcing clinicians to accommodate, adapt, and use technology to develop parallel interventions to provide the same therapeutic effects.5,6 These solutions need to be individualized to accommodate each patient’s unique social and clinical situation (Table 1). Engaging through technology can be problematic for patients with psychosis and paranoid ideation, or those with depressive symptoms. Psychopharmacology or therapy visit time has to be dedicated to helping patients become comfortable and confident when using technology to access their clinicians. Patients can use this same technology to establish virtual social connections. Providing patients with accurate, factual information about infection control during clinical visits ultimately supports their mental health. Delivering clinical care during COVID-19 has required creativity and flexibility to optimize available resources and capitalize on patients’ social supports. These strategies help decrease isolation, loneliness, and exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms.

Uncertainty

Ms. L, age 42, has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder and obstructive sleep apnea, for which she uses a continuous airway positive pressure (CPAP) device. She had been working as a part-time nanny when her employer furloughed her early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Her anxiety has gotten worse throughout the quarantine; she fears her unemployment benefits will run out and she will lose her job. Her anxiety manifests as somatic “pit-of-stomach” sensations. Her sleep has been disrupted; she reports more frequent nightmares, and her partner says that Ms. L has had apneic episodes and bruxism. The parameters of Ms. L’s CPAP device need to be adjusted, but a previously scheduled overnight polysomnography test is deemed a nonessential procedure and canceled. Ms. L has been reluctant to go to a food pantry because she is afraid of being exposed to COVID-19. In virtual sessions, Ms. L says she is uncertain if she will be able to pay her rent, buy food, or access medical care, and expresses overriding helplessness.

During COVID-19, anxiety and insomnia are driven by the sudden manifestation of uncertainty regarding being able to work, pay rent or mortgage, buy food and other provisions, or visit family and friends, including those who are hospitalized or live in nursing homes. Additional uncertainties include how long the quarantine will last, who will become ill, and when, or if, life will return to normal. Taken together, these uncertainties impart a pervasive dread to daily experience.

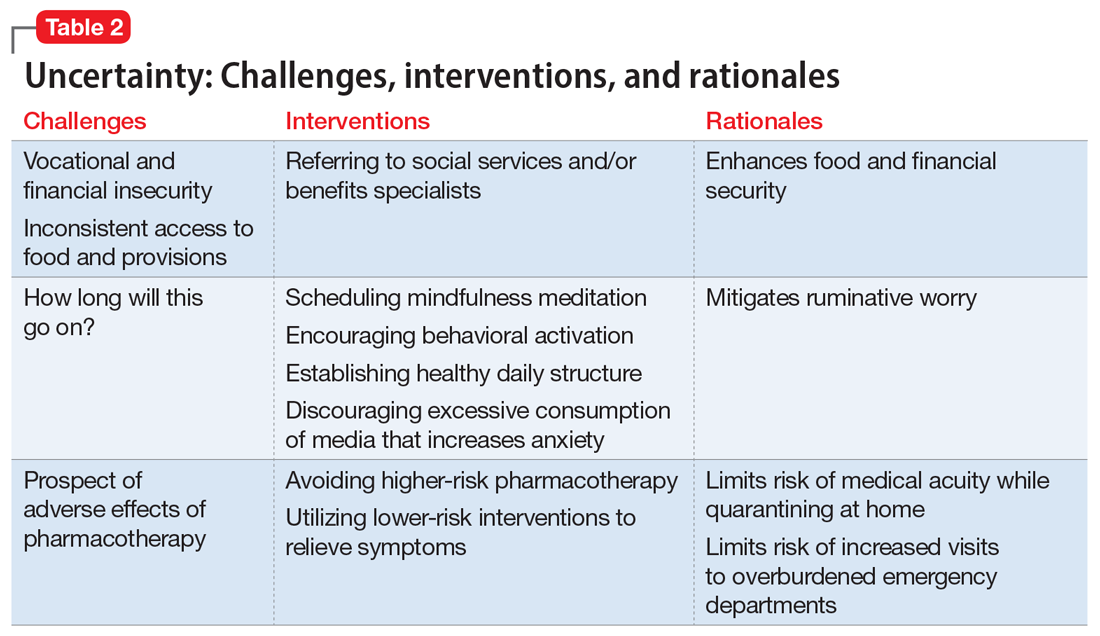

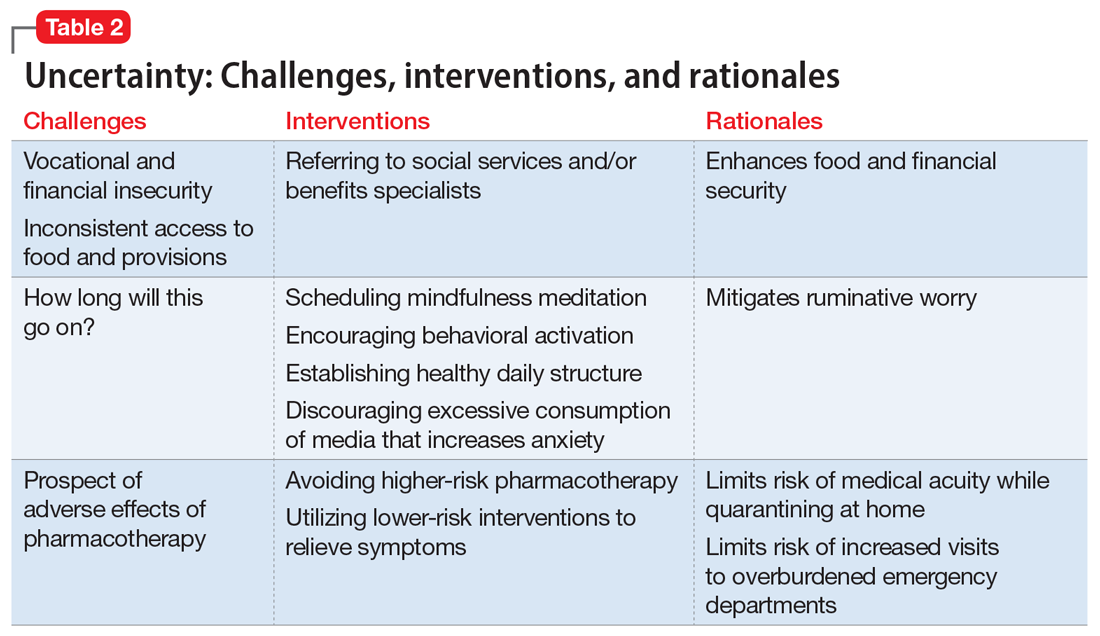

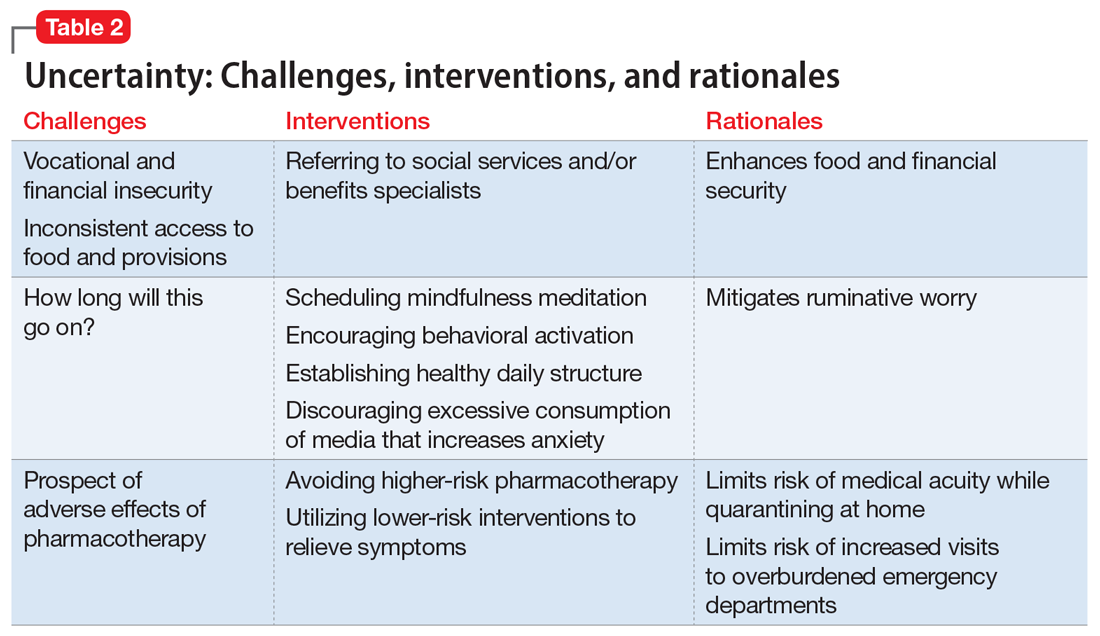

Interventions. Clinicians can facilitate access to services (eg, social services, benefits specialists) and help patients parse out what they should and can address practically, and which challenges are outside of their personal or communal control (Table 2). Patients can be encouraged to identify paralytic rumination and shift their mental focus to engage in constructive projects. They can be advised to limit their intake of media that increases their anxiety and replace it with phone calls or e-mails to family and friends. Scheduled practice of mindfulness meditation and diaphragmatic breathing can help reduce anxiety.7,8 Pharmacotherapeutic interventions should be low-risk to minimize burdening emergency departments saturated with patients who have COVID-19 and serve to reduce symptoms that interfere with behavioral activation. While the research on benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists (“Z-drugs” such as zolpidem and eszopiclone) in the setting of obstructive sleep apnea is complex, and there is some evidence that the latter may not exacerbate apnea,9 benzodiazepines and Z-drugs are associated with an array of risks, including tolerance, withdrawal, and traumatic falls, particularly in older adults.10 Sleep hygiene and cognitive-behavioral therapy are first-line therapies for insomnia.11

Household stress

Ms. M, a 45-year-old single mother with a history of generalized anxiety disorder, is suddenly thrust into homeschooling her 2 children, ages 10 and 8, while trying to remain productive at her job as a software engineer. She no longer has time for herself, and spends much of her day helping her children with schoolwork or planning activities to keep them engaged rather than arguing with each other. She feels intense pressure, heightened stress, and increased anxiety as she tries to navigate this new daily routine.

Continue to: New household dynamics...

New household dynamics abound when people are suddenly forced into atypical routines. In the context of COVID-19, working parents may be forced to balance the demands of their jobs with homeschooling their children. Couples may find themselves arguing more frequently. Adult children may find themselves needing to care for their ill parents. Limited space, a lack of leisure activities, and uncertainty about the future coalesce to increase conflict and stress. Research suggests that how people cope with a stressor is a more reliable determinant of health and well-being than the stressor itself.12

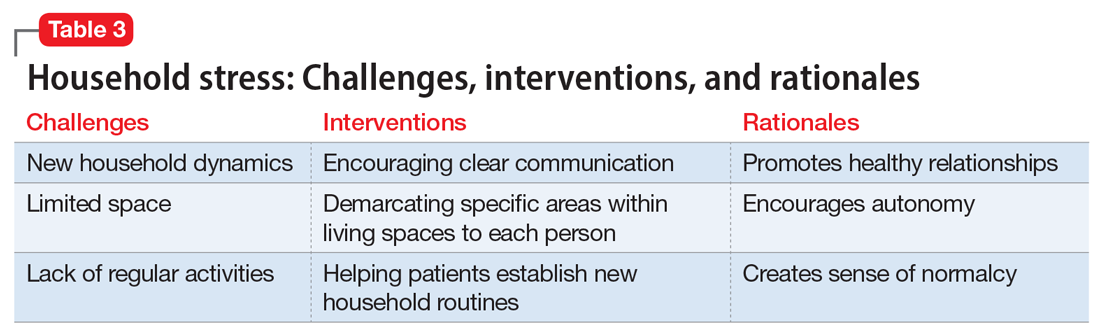

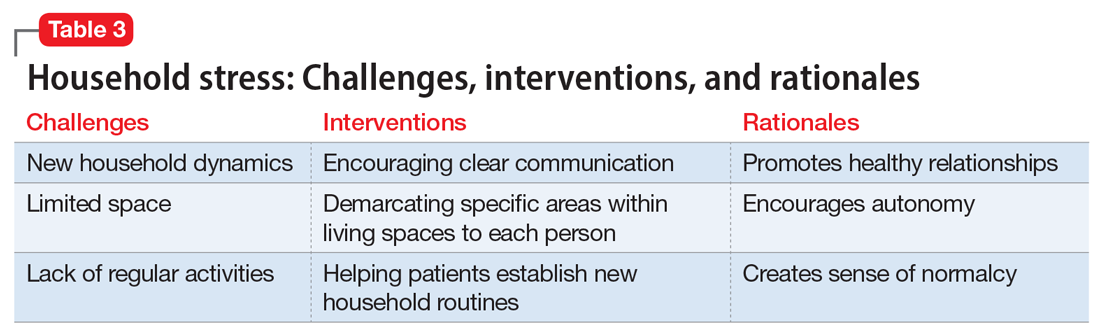

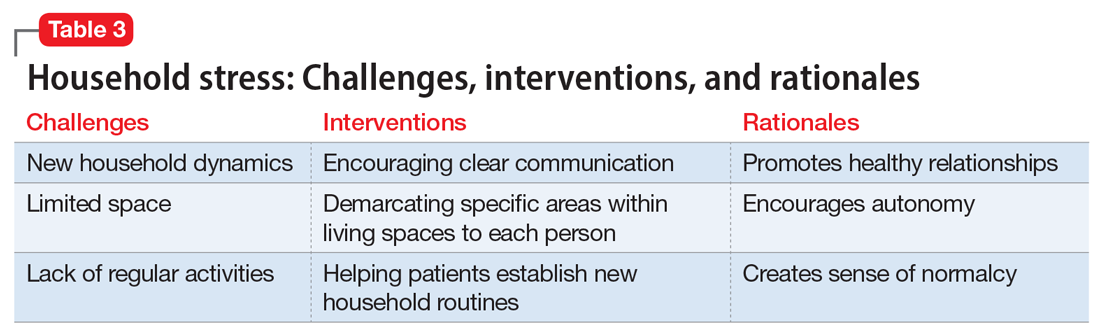

Interventions. Mental health clinicians can offer several recommendations to help patients cope with increased household stress (Table 3). We can encourage patients to have clear communication with their loved ones regarding new expectations, roles, and their feelings. Demarcating specific areas within living spaces to each person in the household can help each member feel a sense of autonomy, regardless of how small their area may be. Clinicians can help patients learn to take the time as a family to work on establishing new household routines. Telepsychiatry offers clinicians a unique window into patients’ lives and family dynamics, and we can use this perspective to deepen our understanding of the patient’s context and household relationships and help them navigate the situation thrust upon them.

Grief

Following a psychiatric hospitalization for an acute exacerbation of psychosis, Ms. S, age 79, is transferred to a rehabilitation facility, where she contracts COVID-19. Because Ms. S did not have a history of chronic medical illness, her family anticipates a full recovery. Early in the course of Ms. S’s admission, the rehabilitation facility restricts visitations, and her family is unable to see her. Ms. S dies in this facility without her family’s presence and without her family having the opportunity to say goodbye. Ms. S’s psychiatrist offers her family a virtual session to provide support. During the virtual session, the psychiatrist notes signs of complicated bereavement among Ms. S’s family members, including nonacceptance of the death, rumination about the circumstances of the death, and describing life as having no purpose.

The COVID-19 pandemic has complicated the natural process of loss and grief across multiple dimensions. Studies have shown that an inability to say goodbye before death, a lack of social support,13 and a lack of preparation for loss14 are associated with complicated bereavement and depression. Many people are experiencing the loss of loved ones without having a chance to appropriately mourn. Forbidding visits to family members who are hospitalized also prevents the practice of religious and spiritual rituals that typically occur at the end of life. This is worsened by truncated or absent funeral services. Support for those who are grieving may be offered from a distance, if at all. When surviving family members have been with the deceased prior to hospitalization, they may be required to self-quarantine, potentially exacerbating their grief and other symptoms associated with loss.

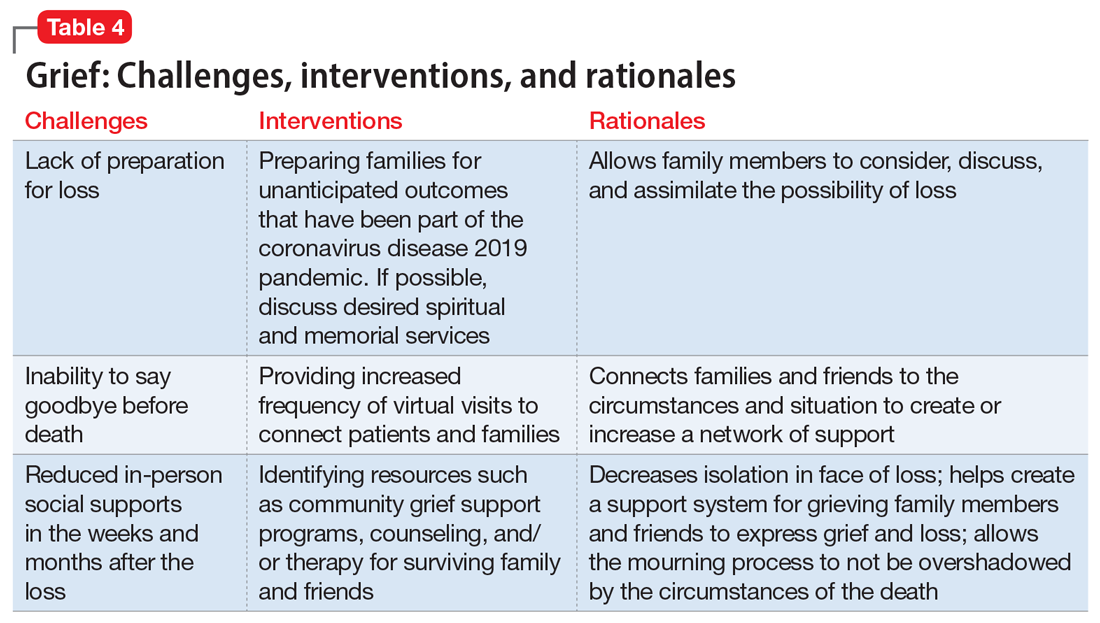

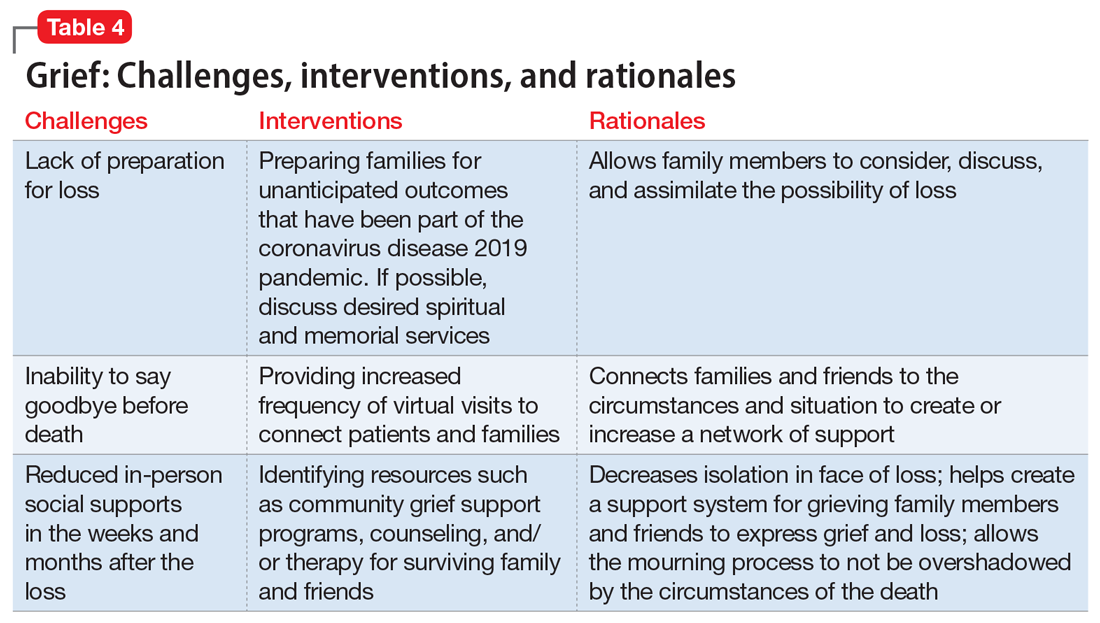

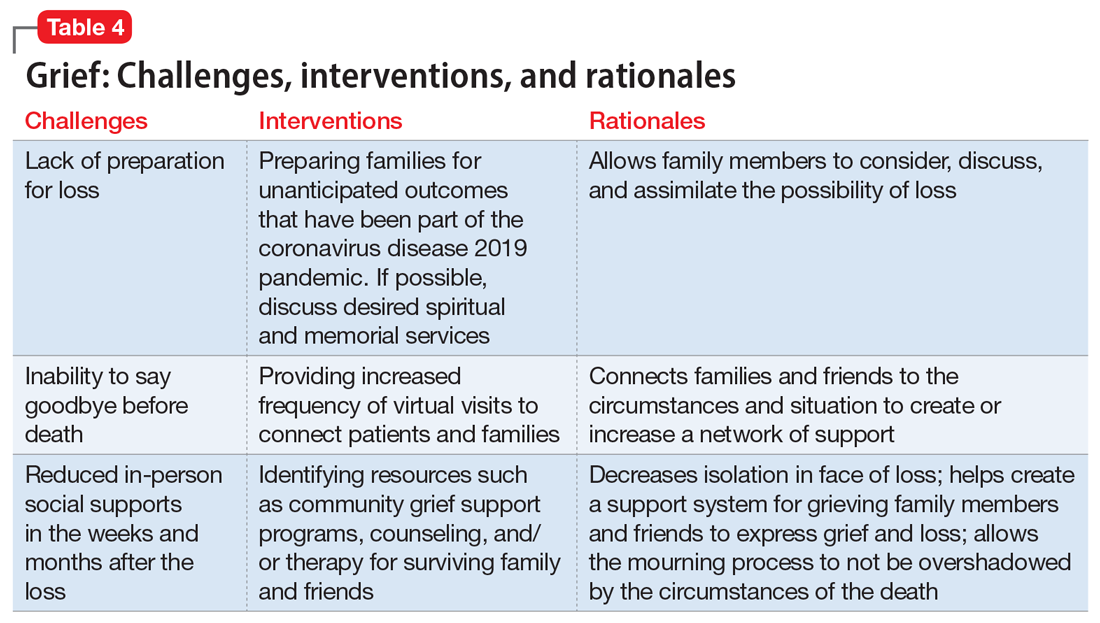

Interventions. Because social support is a protective factor against complicated grief,14 there are several recommendations for survivors as they work through the process of grief (Table 4). These include preparing families for a potential death; discussing desired spiritual and memorial services15; connecting families to resources such as community grief support programs, counseling/therapy, funeral services, video conferencing, and other communication tools; and planning for additional support for surviving family and friends, both immediately after the death and in the long term. It is also important to provide appropriate counseling and support for surviving family members to focus on their own well-being by exercising, eating nutritious meals, getting enough sleep, and abstaining from alcohol and drugs of abuse.16

Continue to: An ongoing challenge

An ongoing challenge

Our clinical team recommends further investigation to define additional psychotherapeutic themes arising from the COVID-19 pandemic and provide evidence-based interventions to address these categories, which we expect will increase in clinical salience in the months and years ahead. Close monitoring, follow-up by clinical and research staff, and evidence-based interventions will help address these dominant themes, with the goal of alleviating patient suffering.

Bottom Line

Our team identified 4 dominant clinical themes emerging across our patients’ experiences during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: isolation, uncertainty, household stress, and grief. Clinicians can implement specific interventions to reduce the impact of these themes, which we expect to remain clinically relevant in the upcoming months and years.

Related Resources

- Sharma RA, Maheshwari S, Bronsther R. COVID-19 in the era of loneliness. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):31-32,39.

- Carr D, Boerner K, Moorman S. Bereavement in the time of coronavirus: unprecedented challenges demand novel interventions. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32(4-5):425-431.

Drug Brand Names

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Bloom N. How working from home works out. Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research Policy Brief. https://siepr.stanford.edu/research/publications/how-working-home-works-out. Published June 2020. Accessed October 28, 2020.

2. Linz SJ, Sturm BA. The phenomenon of social isolation in the severely mentally ill. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2013;49(4):243-254.

3. Smith KP, Christakis NA. Social networks and health. Annual Review of Sociology. 2008;34(1):405-429.

4. Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(suppl):S54‐S66.

5. Mann F, Bone JK, Lloyd-Evans B. A life less lonely: the state of the art in interventions to reduce loneliness in people with mental health problems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(6):627-638.

6. Choi M, Kong S, Jung D. Computer and internet interventions for loneliness and depression in older adults: a meta-analysis. Healthc Inform Res. 2012;18(3):191‐198.

7. Chen YF, Huang ZY, Chien CH, et al. The effectiveness of diaphragmatic breathing relaxation training for reducing anxiety. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2017;53(4):329-336.

8. Hoge EA, Bui E, Marques L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(8):786‐792.

9. Carberry JC, Grunstein RR, Eckert DJ. The effects of zolpidem in obstructive sleep apnea - an open-label pilot study. Sleep Res. 2019;28(6):e12853. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12853.

10. Markota M, Rummans TA, Bostwick JM, et al. Benzodiazepine use in older adults: dangers, management, and alternative therapies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(11):1632-1639.

11. Matheson E, Hainer BL. Insomnia: pharmacologic therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(1):29-35.

12. Dijkstra MT, Homan AC. Engaging in rather than disengaging from stress: effective coping and perceived control. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1415.

13. Romero MM, Ott CH, Kelber ST. Predictors of grief in bereaved family caregivers of person’s with Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective study. Death Stud. 2014;38(6-10):395-403.

14. Lobb EA, Kristjanson LJ, Aoun SM, et al. Predictors of complicated grief: a systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud. 2010;34(8):673-698.

15. Wallace CL, Wladkowski SP, Gibson A, et al. Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for palliative care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(1):e70-e76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012

16. Selman LE, Chao D, Sowden R, et al. Bereavement support on the frontline of COVID-19: recommendations for hospital clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e81-e86. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.024

As a result of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the content of outpatient psychotherapy and psychopharmacology sessions has seen significant change, with many patients focusing on how the pandemic has altered their daily lives and emotional well-being. Most patients were suddenly limited in both the amount of time they spent, and in their interactions with people, outside of their homes. Additionally, employment-related stressors such as working from home and the potential loss of a job and/or income added to pandemic stress.1 Patients simultaneously processed their experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic while often striving to adapt to new virtual modes of mental health care delivery via phone or video conferencing.

The clinic staff at our large, multidisciplinary, urban outpatient mental health practice conducts weekly case consultation meetings. In meetings held during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, we noted 4 dominant clinical themes emerging across our patients’ experiences:

- isolation

- uncertainty

- household stress

- grief.

These themes occurred across many diagnostic categories, suggesting they reflect a dramatic shift brought on by the pandemic. Our group compared clinical experiences from the beginning of the pandemic through the end of May 2020. For this article, we considered several patients who expressed these 4 themes and created a “composite patient.” In the following sections, we describe the typical presentation of, and recommended interventions for, a composite patient for each of these 4 themes.

Isolation

Mr. J, a 60-year-old, single, African American man diagnosed with bipolar disorder with psychotic features, lives alone in an apartment in a densely populated area. Before COVID-19, he had been attending a day treatment program. His daily walks for coffee and cigarettes provided the scaffolding to his emotional stability and gave him a sense of belonging to a world outside of his home. Mr. J also had been able to engage in informal social activities in the common areas of his apartment complex.

The start of the COVID-19 pandemic ends his interpersonal interactions, from the passive and superficial conversations he had with strangers in coffee shops to the more intimate engagement with his peers in his treatment program. The common areas of Mr. J’s apartment building are closed, and his routine cigarette breaks with neighbors have become solitary events, with the added stress of having to schedule his use of the building’s designated smoking area. Before COVID-19, Mr. J had been regularly meeting his brother for coffee to talk about the recent death of their father, but these meetings end due to infection concerns by Mr. J and his brother, who cares for their ailing mother who is at high risk for COVID-19 infection.

Mr. J begins to report self-referential ideation when walking in public, citing his inability to see peoples’ facial expressions because they are wearing masks. As a result of the pandemic restrictions, he becomes depressed and develops increased paranoid ideation. Fortunately, Mr. J begins to participate in a virtual partial hospitalization program to address his paranoid ideation through intensive and clinically-based social interactions. He is unfamiliar with the technology used for virtual visits, but is given the necessary technical support. He is also able to begin virtual visits with his brother and mother. Mr. J soon reports his symptoms are reduced and his mood is more stable.

Engaging in interpersonal interactions can have a positive impact on mental health. Social isolation has demonstrated negative effects that are amplified in individuals with psychiatric disorders.2 Interpersonal interactions can provide a shared experience, promote positive feelings of social connection, and aid in the development of social skills.3,4 Among our patients, we have begun to see the effects of isolation manifest as loneliness and demoralization.

Continue to: Interventions

Interventions. Due to restrictions imposed to limit the spread of COVID-19, evidence-based interventions such as meeting a friend for a meal or participating in in-person support groups typically are not options, thus forcing clinicians to accommodate, adapt, and use technology to develop parallel interventions to provide the same therapeutic effects.5,6 These solutions need to be individualized to accommodate each patient’s unique social and clinical situation (Table 1). Engaging through technology can be problematic for patients with psychosis and paranoid ideation, or those with depressive symptoms. Psychopharmacology or therapy visit time has to be dedicated to helping patients become comfortable and confident when using technology to access their clinicians. Patients can use this same technology to establish virtual social connections. Providing patients with accurate, factual information about infection control during clinical visits ultimately supports their mental health. Delivering clinical care during COVID-19 has required creativity and flexibility to optimize available resources and capitalize on patients’ social supports. These strategies help decrease isolation, loneliness, and exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms.

Uncertainty

Ms. L, age 42, has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder and obstructive sleep apnea, for which she uses a continuous airway positive pressure (CPAP) device. She had been working as a part-time nanny when her employer furloughed her early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Her anxiety has gotten worse throughout the quarantine; she fears her unemployment benefits will run out and she will lose her job. Her anxiety manifests as somatic “pit-of-stomach” sensations. Her sleep has been disrupted; she reports more frequent nightmares, and her partner says that Ms. L has had apneic episodes and bruxism. The parameters of Ms. L’s CPAP device need to be adjusted, but a previously scheduled overnight polysomnography test is deemed a nonessential procedure and canceled. Ms. L has been reluctant to go to a food pantry because she is afraid of being exposed to COVID-19. In virtual sessions, Ms. L says she is uncertain if she will be able to pay her rent, buy food, or access medical care, and expresses overriding helplessness.

During COVID-19, anxiety and insomnia are driven by the sudden manifestation of uncertainty regarding being able to work, pay rent or mortgage, buy food and other provisions, or visit family and friends, including those who are hospitalized or live in nursing homes. Additional uncertainties include how long the quarantine will last, who will become ill, and when, or if, life will return to normal. Taken together, these uncertainties impart a pervasive dread to daily experience.

Interventions. Clinicians can facilitate access to services (eg, social services, benefits specialists) and help patients parse out what they should and can address practically, and which challenges are outside of their personal or communal control (Table 2). Patients can be encouraged to identify paralytic rumination and shift their mental focus to engage in constructive projects. They can be advised to limit their intake of media that increases their anxiety and replace it with phone calls or e-mails to family and friends. Scheduled practice of mindfulness meditation and diaphragmatic breathing can help reduce anxiety.7,8 Pharmacotherapeutic interventions should be low-risk to minimize burdening emergency departments saturated with patients who have COVID-19 and serve to reduce symptoms that interfere with behavioral activation. While the research on benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists (“Z-drugs” such as zolpidem and eszopiclone) in the setting of obstructive sleep apnea is complex, and there is some evidence that the latter may not exacerbate apnea,9 benzodiazepines and Z-drugs are associated with an array of risks, including tolerance, withdrawal, and traumatic falls, particularly in older adults.10 Sleep hygiene and cognitive-behavioral therapy are first-line therapies for insomnia.11

Household stress

Ms. M, a 45-year-old single mother with a history of generalized anxiety disorder, is suddenly thrust into homeschooling her 2 children, ages 10 and 8, while trying to remain productive at her job as a software engineer. She no longer has time for herself, and spends much of her day helping her children with schoolwork or planning activities to keep them engaged rather than arguing with each other. She feels intense pressure, heightened stress, and increased anxiety as she tries to navigate this new daily routine.

Continue to: New household dynamics...

New household dynamics abound when people are suddenly forced into atypical routines. In the context of COVID-19, working parents may be forced to balance the demands of their jobs with homeschooling their children. Couples may find themselves arguing more frequently. Adult children may find themselves needing to care for their ill parents. Limited space, a lack of leisure activities, and uncertainty about the future coalesce to increase conflict and stress. Research suggests that how people cope with a stressor is a more reliable determinant of health and well-being than the stressor itself.12

Interventions. Mental health clinicians can offer several recommendations to help patients cope with increased household stress (Table 3). We can encourage patients to have clear communication with their loved ones regarding new expectations, roles, and their feelings. Demarcating specific areas within living spaces to each person in the household can help each member feel a sense of autonomy, regardless of how small their area may be. Clinicians can help patients learn to take the time as a family to work on establishing new household routines. Telepsychiatry offers clinicians a unique window into patients’ lives and family dynamics, and we can use this perspective to deepen our understanding of the patient’s context and household relationships and help them navigate the situation thrust upon them.

Grief

Following a psychiatric hospitalization for an acute exacerbation of psychosis, Ms. S, age 79, is transferred to a rehabilitation facility, where she contracts COVID-19. Because Ms. S did not have a history of chronic medical illness, her family anticipates a full recovery. Early in the course of Ms. S’s admission, the rehabilitation facility restricts visitations, and her family is unable to see her. Ms. S dies in this facility without her family’s presence and without her family having the opportunity to say goodbye. Ms. S’s psychiatrist offers her family a virtual session to provide support. During the virtual session, the psychiatrist notes signs of complicated bereavement among Ms. S’s family members, including nonacceptance of the death, rumination about the circumstances of the death, and describing life as having no purpose.

The COVID-19 pandemic has complicated the natural process of loss and grief across multiple dimensions. Studies have shown that an inability to say goodbye before death, a lack of social support,13 and a lack of preparation for loss14 are associated with complicated bereavement and depression. Many people are experiencing the loss of loved ones without having a chance to appropriately mourn. Forbidding visits to family members who are hospitalized also prevents the practice of religious and spiritual rituals that typically occur at the end of life. This is worsened by truncated or absent funeral services. Support for those who are grieving may be offered from a distance, if at all. When surviving family members have been with the deceased prior to hospitalization, they may be required to self-quarantine, potentially exacerbating their grief and other symptoms associated with loss.

Interventions. Because social support is a protective factor against complicated grief,14 there are several recommendations for survivors as they work through the process of grief (Table 4). These include preparing families for a potential death; discussing desired spiritual and memorial services15; connecting families to resources such as community grief support programs, counseling/therapy, funeral services, video conferencing, and other communication tools; and planning for additional support for surviving family and friends, both immediately after the death and in the long term. It is also important to provide appropriate counseling and support for surviving family members to focus on their own well-being by exercising, eating nutritious meals, getting enough sleep, and abstaining from alcohol and drugs of abuse.16

Continue to: An ongoing challenge

An ongoing challenge

Our clinical team recommends further investigation to define additional psychotherapeutic themes arising from the COVID-19 pandemic and provide evidence-based interventions to address these categories, which we expect will increase in clinical salience in the months and years ahead. Close monitoring, follow-up by clinical and research staff, and evidence-based interventions will help address these dominant themes, with the goal of alleviating patient suffering.

Bottom Line

Our team identified 4 dominant clinical themes emerging across our patients’ experiences during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: isolation, uncertainty, household stress, and grief. Clinicians can implement specific interventions to reduce the impact of these themes, which we expect to remain clinically relevant in the upcoming months and years.

Related Resources

- Sharma RA, Maheshwari S, Bronsther R. COVID-19 in the era of loneliness. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):31-32,39.

- Carr D, Boerner K, Moorman S. Bereavement in the time of coronavirus: unprecedented challenges demand novel interventions. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32(4-5):425-431.

Drug Brand Names

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Zolpidem • Ambien

As a result of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the content of outpatient psychotherapy and psychopharmacology sessions has seen significant change, with many patients focusing on how the pandemic has altered their daily lives and emotional well-being. Most patients were suddenly limited in both the amount of time they spent, and in their interactions with people, outside of their homes. Additionally, employment-related stressors such as working from home and the potential loss of a job and/or income added to pandemic stress.1 Patients simultaneously processed their experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic while often striving to adapt to new virtual modes of mental health care delivery via phone or video conferencing.

The clinic staff at our large, multidisciplinary, urban outpatient mental health practice conducts weekly case consultation meetings. In meetings held during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, we noted 4 dominant clinical themes emerging across our patients’ experiences:

- isolation

- uncertainty

- household stress

- grief.

These themes occurred across many diagnostic categories, suggesting they reflect a dramatic shift brought on by the pandemic. Our group compared clinical experiences from the beginning of the pandemic through the end of May 2020. For this article, we considered several patients who expressed these 4 themes and created a “composite patient.” In the following sections, we describe the typical presentation of, and recommended interventions for, a composite patient for each of these 4 themes.

Isolation

Mr. J, a 60-year-old, single, African American man diagnosed with bipolar disorder with psychotic features, lives alone in an apartment in a densely populated area. Before COVID-19, he had been attending a day treatment program. His daily walks for coffee and cigarettes provided the scaffolding to his emotional stability and gave him a sense of belonging to a world outside of his home. Mr. J also had been able to engage in informal social activities in the common areas of his apartment complex.

The start of the COVID-19 pandemic ends his interpersonal interactions, from the passive and superficial conversations he had with strangers in coffee shops to the more intimate engagement with his peers in his treatment program. The common areas of Mr. J’s apartment building are closed, and his routine cigarette breaks with neighbors have become solitary events, with the added stress of having to schedule his use of the building’s designated smoking area. Before COVID-19, Mr. J had been regularly meeting his brother for coffee to talk about the recent death of their father, but these meetings end due to infection concerns by Mr. J and his brother, who cares for their ailing mother who is at high risk for COVID-19 infection.

Mr. J begins to report self-referential ideation when walking in public, citing his inability to see peoples’ facial expressions because they are wearing masks. As a result of the pandemic restrictions, he becomes depressed and develops increased paranoid ideation. Fortunately, Mr. J begins to participate in a virtual partial hospitalization program to address his paranoid ideation through intensive and clinically-based social interactions. He is unfamiliar with the technology used for virtual visits, but is given the necessary technical support. He is also able to begin virtual visits with his brother and mother. Mr. J soon reports his symptoms are reduced and his mood is more stable.

Engaging in interpersonal interactions can have a positive impact on mental health. Social isolation has demonstrated negative effects that are amplified in individuals with psychiatric disorders.2 Interpersonal interactions can provide a shared experience, promote positive feelings of social connection, and aid in the development of social skills.3,4 Among our patients, we have begun to see the effects of isolation manifest as loneliness and demoralization.

Continue to: Interventions

Interventions. Due to restrictions imposed to limit the spread of COVID-19, evidence-based interventions such as meeting a friend for a meal or participating in in-person support groups typically are not options, thus forcing clinicians to accommodate, adapt, and use technology to develop parallel interventions to provide the same therapeutic effects.5,6 These solutions need to be individualized to accommodate each patient’s unique social and clinical situation (Table 1). Engaging through technology can be problematic for patients with psychosis and paranoid ideation, or those with depressive symptoms. Psychopharmacology or therapy visit time has to be dedicated to helping patients become comfortable and confident when using technology to access their clinicians. Patients can use this same technology to establish virtual social connections. Providing patients with accurate, factual information about infection control during clinical visits ultimately supports their mental health. Delivering clinical care during COVID-19 has required creativity and flexibility to optimize available resources and capitalize on patients’ social supports. These strategies help decrease isolation, loneliness, and exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms.

Uncertainty

Ms. L, age 42, has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder and obstructive sleep apnea, for which she uses a continuous airway positive pressure (CPAP) device. She had been working as a part-time nanny when her employer furloughed her early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Her anxiety has gotten worse throughout the quarantine; she fears her unemployment benefits will run out and she will lose her job. Her anxiety manifests as somatic “pit-of-stomach” sensations. Her sleep has been disrupted; she reports more frequent nightmares, and her partner says that Ms. L has had apneic episodes and bruxism. The parameters of Ms. L’s CPAP device need to be adjusted, but a previously scheduled overnight polysomnography test is deemed a nonessential procedure and canceled. Ms. L has been reluctant to go to a food pantry because she is afraid of being exposed to COVID-19. In virtual sessions, Ms. L says she is uncertain if she will be able to pay her rent, buy food, or access medical care, and expresses overriding helplessness.

During COVID-19, anxiety and insomnia are driven by the sudden manifestation of uncertainty regarding being able to work, pay rent or mortgage, buy food and other provisions, or visit family and friends, including those who are hospitalized or live in nursing homes. Additional uncertainties include how long the quarantine will last, who will become ill, and when, or if, life will return to normal. Taken together, these uncertainties impart a pervasive dread to daily experience.

Interventions. Clinicians can facilitate access to services (eg, social services, benefits specialists) and help patients parse out what they should and can address practically, and which challenges are outside of their personal or communal control (Table 2). Patients can be encouraged to identify paralytic rumination and shift their mental focus to engage in constructive projects. They can be advised to limit their intake of media that increases their anxiety and replace it with phone calls or e-mails to family and friends. Scheduled practice of mindfulness meditation and diaphragmatic breathing can help reduce anxiety.7,8 Pharmacotherapeutic interventions should be low-risk to minimize burdening emergency departments saturated with patients who have COVID-19 and serve to reduce symptoms that interfere with behavioral activation. While the research on benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists (“Z-drugs” such as zolpidem and eszopiclone) in the setting of obstructive sleep apnea is complex, and there is some evidence that the latter may not exacerbate apnea,9 benzodiazepines and Z-drugs are associated with an array of risks, including tolerance, withdrawal, and traumatic falls, particularly in older adults.10 Sleep hygiene and cognitive-behavioral therapy are first-line therapies for insomnia.11

Household stress

Ms. M, a 45-year-old single mother with a history of generalized anxiety disorder, is suddenly thrust into homeschooling her 2 children, ages 10 and 8, while trying to remain productive at her job as a software engineer. She no longer has time for herself, and spends much of her day helping her children with schoolwork or planning activities to keep them engaged rather than arguing with each other. She feels intense pressure, heightened stress, and increased anxiety as she tries to navigate this new daily routine.

Continue to: New household dynamics...

New household dynamics abound when people are suddenly forced into atypical routines. In the context of COVID-19, working parents may be forced to balance the demands of their jobs with homeschooling their children. Couples may find themselves arguing more frequently. Adult children may find themselves needing to care for their ill parents. Limited space, a lack of leisure activities, and uncertainty about the future coalesce to increase conflict and stress. Research suggests that how people cope with a stressor is a more reliable determinant of health and well-being than the stressor itself.12

Interventions. Mental health clinicians can offer several recommendations to help patients cope with increased household stress (Table 3). We can encourage patients to have clear communication with their loved ones regarding new expectations, roles, and their feelings. Demarcating specific areas within living spaces to each person in the household can help each member feel a sense of autonomy, regardless of how small their area may be. Clinicians can help patients learn to take the time as a family to work on establishing new household routines. Telepsychiatry offers clinicians a unique window into patients’ lives and family dynamics, and we can use this perspective to deepen our understanding of the patient’s context and household relationships and help them navigate the situation thrust upon them.

Grief

Following a psychiatric hospitalization for an acute exacerbation of psychosis, Ms. S, age 79, is transferred to a rehabilitation facility, where she contracts COVID-19. Because Ms. S did not have a history of chronic medical illness, her family anticipates a full recovery. Early in the course of Ms. S’s admission, the rehabilitation facility restricts visitations, and her family is unable to see her. Ms. S dies in this facility without her family’s presence and without her family having the opportunity to say goodbye. Ms. S’s psychiatrist offers her family a virtual session to provide support. During the virtual session, the psychiatrist notes signs of complicated bereavement among Ms. S’s family members, including nonacceptance of the death, rumination about the circumstances of the death, and describing life as having no purpose.

The COVID-19 pandemic has complicated the natural process of loss and grief across multiple dimensions. Studies have shown that an inability to say goodbye before death, a lack of social support,13 and a lack of preparation for loss14 are associated with complicated bereavement and depression. Many people are experiencing the loss of loved ones without having a chance to appropriately mourn. Forbidding visits to family members who are hospitalized also prevents the practice of religious and spiritual rituals that typically occur at the end of life. This is worsened by truncated or absent funeral services. Support for those who are grieving may be offered from a distance, if at all. When surviving family members have been with the deceased prior to hospitalization, they may be required to self-quarantine, potentially exacerbating their grief and other symptoms associated with loss.

Interventions. Because social support is a protective factor against complicated grief,14 there are several recommendations for survivors as they work through the process of grief (Table 4). These include preparing families for a potential death; discussing desired spiritual and memorial services15; connecting families to resources such as community grief support programs, counseling/therapy, funeral services, video conferencing, and other communication tools; and planning for additional support for surviving family and friends, both immediately after the death and in the long term. It is also important to provide appropriate counseling and support for surviving family members to focus on their own well-being by exercising, eating nutritious meals, getting enough sleep, and abstaining from alcohol and drugs of abuse.16

Continue to: An ongoing challenge

An ongoing challenge

Our clinical team recommends further investigation to define additional psychotherapeutic themes arising from the COVID-19 pandemic and provide evidence-based interventions to address these categories, which we expect will increase in clinical salience in the months and years ahead. Close monitoring, follow-up by clinical and research staff, and evidence-based interventions will help address these dominant themes, with the goal of alleviating patient suffering.

Bottom Line

Our team identified 4 dominant clinical themes emerging across our patients’ experiences during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: isolation, uncertainty, household stress, and grief. Clinicians can implement specific interventions to reduce the impact of these themes, which we expect to remain clinically relevant in the upcoming months and years.

Related Resources

- Sharma RA, Maheshwari S, Bronsther R. COVID-19 in the era of loneliness. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):31-32,39.

- Carr D, Boerner K, Moorman S. Bereavement in the time of coronavirus: unprecedented challenges demand novel interventions. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32(4-5):425-431.

Drug Brand Names

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Bloom N. How working from home works out. Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research Policy Brief. https://siepr.stanford.edu/research/publications/how-working-home-works-out. Published June 2020. Accessed October 28, 2020.

2. Linz SJ, Sturm BA. The phenomenon of social isolation in the severely mentally ill. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2013;49(4):243-254.

3. Smith KP, Christakis NA. Social networks and health. Annual Review of Sociology. 2008;34(1):405-429.

4. Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(suppl):S54‐S66.

5. Mann F, Bone JK, Lloyd-Evans B. A life less lonely: the state of the art in interventions to reduce loneliness in people with mental health problems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(6):627-638.

6. Choi M, Kong S, Jung D. Computer and internet interventions for loneliness and depression in older adults: a meta-analysis. Healthc Inform Res. 2012;18(3):191‐198.

7. Chen YF, Huang ZY, Chien CH, et al. The effectiveness of diaphragmatic breathing relaxation training for reducing anxiety. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2017;53(4):329-336.

8. Hoge EA, Bui E, Marques L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(8):786‐792.

9. Carberry JC, Grunstein RR, Eckert DJ. The effects of zolpidem in obstructive sleep apnea - an open-label pilot study. Sleep Res. 2019;28(6):e12853. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12853.

10. Markota M, Rummans TA, Bostwick JM, et al. Benzodiazepine use in older adults: dangers, management, and alternative therapies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(11):1632-1639.

11. Matheson E, Hainer BL. Insomnia: pharmacologic therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(1):29-35.

12. Dijkstra MT, Homan AC. Engaging in rather than disengaging from stress: effective coping and perceived control. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1415.

13. Romero MM, Ott CH, Kelber ST. Predictors of grief in bereaved family caregivers of person’s with Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective study. Death Stud. 2014;38(6-10):395-403.

14. Lobb EA, Kristjanson LJ, Aoun SM, et al. Predictors of complicated grief: a systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud. 2010;34(8):673-698.

15. Wallace CL, Wladkowski SP, Gibson A, et al. Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for palliative care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(1):e70-e76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012

16. Selman LE, Chao D, Sowden R, et al. Bereavement support on the frontline of COVID-19: recommendations for hospital clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e81-e86. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.024

1. Bloom N. How working from home works out. Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research Policy Brief. https://siepr.stanford.edu/research/publications/how-working-home-works-out. Published June 2020. Accessed October 28, 2020.

2. Linz SJ, Sturm BA. The phenomenon of social isolation in the severely mentally ill. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2013;49(4):243-254.

3. Smith KP, Christakis NA. Social networks and health. Annual Review of Sociology. 2008;34(1):405-429.

4. Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(suppl):S54‐S66.

5. Mann F, Bone JK, Lloyd-Evans B. A life less lonely: the state of the art in interventions to reduce loneliness in people with mental health problems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(6):627-638.

6. Choi M, Kong S, Jung D. Computer and internet interventions for loneliness and depression in older adults: a meta-analysis. Healthc Inform Res. 2012;18(3):191‐198.

7. Chen YF, Huang ZY, Chien CH, et al. The effectiveness of diaphragmatic breathing relaxation training for reducing anxiety. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2017;53(4):329-336.

8. Hoge EA, Bui E, Marques L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(8):786‐792.

9. Carberry JC, Grunstein RR, Eckert DJ. The effects of zolpidem in obstructive sleep apnea - an open-label pilot study. Sleep Res. 2019;28(6):e12853. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12853.

10. Markota M, Rummans TA, Bostwick JM, et al. Benzodiazepine use in older adults: dangers, management, and alternative therapies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(11):1632-1639.

11. Matheson E, Hainer BL. Insomnia: pharmacologic therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(1):29-35.

12. Dijkstra MT, Homan AC. Engaging in rather than disengaging from stress: effective coping and perceived control. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1415.

13. Romero MM, Ott CH, Kelber ST. Predictors of grief in bereaved family caregivers of person’s with Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective study. Death Stud. 2014;38(6-10):395-403.

14. Lobb EA, Kristjanson LJ, Aoun SM, et al. Predictors of complicated grief: a systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud. 2010;34(8):673-698.

15. Wallace CL, Wladkowski SP, Gibson A, et al. Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for palliative care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(1):e70-e76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012

16. Selman LE, Chao D, Sowden R, et al. Bereavement support on the frontline of COVID-19: recommendations for hospital clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e81-e86. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.024