User login

How to avoid abandonment claims when terminating care

Psychiatric clinicians may unilaterally decide to end a treatment relationship with a patient when the relationship is no longer therapeutic, such as when the patient does not adhere to treatment, repeatedly misses appointments, exhibits abusive behaviors, or fails to pay for treatment.1 Claims of abandonment can arise if ending the treatment relationship is not executed properly. Abandonment is the termination of a treatment relationship with a patient who remains in need of treatment, has no suitable substitute treatment, and subsequently experiences damages as a result of the termination.2 When a patient terminates a treatment relationship, there are no legal bases for abandonment claims.3 In this article, I provide a few practical tips for properly terminating the doctor-patient relationship to limit the likelihood of claims of abandonment.

Know your jurisdiction’s requirements for terminating the relationship. Each state has its own legal definition of a doctor-patient relationship as well as requirements for ending it. Abandonment claims are unfounded in the absence of a doctor-patient relationship.3 Contact the appropriate licensing board to determine what your state’s regulatory requirements are. If necessary, consult with your attorney or a risk management professional for guidance.4

Communicate clearly. Communicate with your patient about the end of the treatment relationship in a clear and consistent manner, both verbally and in writing, because a termination should be viewed as a formal, documented event.3 Except in situations requiring immediate termination, psychiatric clinicians should inform the patient about the reason(s) for termination,4 the need for continued treatment,3 and the type of recommended treatment.3 This discussion should be summarized in a termination letter given to the patient that includes termination language, referral sources, the end date of treatment, and a request for authorization to release a copy of the patient’s medical records to their new clinician.3,4

Give adequate time, set boundaries, and document. Thirty days is generally considered adequate time for a patient to find a new clinician,5 unless the patient lives in an area where there is a shortage of psychiatric clinicians, in which case a longer time period would be appropriate.3 Ensure your patient has a sufficient supply of medication(s) until they establish care with a new clinician.4 Offer to provide emergency care for a reasonable period of time during the termination process unless a safety concern requires immediate termination.4 Avoid situations in which the patient attempts to re-enter your care. Document the reason for the termination in your progress notes and keep a copy of the termination letter in the patient’s medical record.4

1. Mossman D. ‘Firing’ a patient: may a psychiatrist unilaterally terminate care? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(12):18,20,22,29.

2. Van Susteren L. Psychiatric abandonment: pitfalls and prevention. Psychiatric Times. 2001;18(8). Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/psychiatric-abandonment-pitfalls-and-prevention

3. Stankowski J, Sorrentino R. Abandonment and unnecessary commitment. In: Ash P, Frierson RL, Hatters Friedman S, eds. Malpractice and Liability in Psychiatry. Springer Nature Publishing; 2022:129-135.

4. Funicelli A. Avoiding abandonment claim: how to properly terminate patients from your practice. Psychiatric News. 2022;57(12):13,41. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2022.12.12.23

5. American Psychiatric Association. APA Quick Practice Guide: Ending the Physician/Patient Relationship. 2014. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/Practice-Management/Practice-Management-Guides/GeneralIssues-terminating-patient-relationships.pdf

Psychiatric clinicians may unilaterally decide to end a treatment relationship with a patient when the relationship is no longer therapeutic, such as when the patient does not adhere to treatment, repeatedly misses appointments, exhibits abusive behaviors, or fails to pay for treatment.1 Claims of abandonment can arise if ending the treatment relationship is not executed properly. Abandonment is the termination of a treatment relationship with a patient who remains in need of treatment, has no suitable substitute treatment, and subsequently experiences damages as a result of the termination.2 When a patient terminates a treatment relationship, there are no legal bases for abandonment claims.3 In this article, I provide a few practical tips for properly terminating the doctor-patient relationship to limit the likelihood of claims of abandonment.

Know your jurisdiction’s requirements for terminating the relationship. Each state has its own legal definition of a doctor-patient relationship as well as requirements for ending it. Abandonment claims are unfounded in the absence of a doctor-patient relationship.3 Contact the appropriate licensing board to determine what your state’s regulatory requirements are. If necessary, consult with your attorney or a risk management professional for guidance.4

Communicate clearly. Communicate with your patient about the end of the treatment relationship in a clear and consistent manner, both verbally and in writing, because a termination should be viewed as a formal, documented event.3 Except in situations requiring immediate termination, psychiatric clinicians should inform the patient about the reason(s) for termination,4 the need for continued treatment,3 and the type of recommended treatment.3 This discussion should be summarized in a termination letter given to the patient that includes termination language, referral sources, the end date of treatment, and a request for authorization to release a copy of the patient’s medical records to their new clinician.3,4

Give adequate time, set boundaries, and document. Thirty days is generally considered adequate time for a patient to find a new clinician,5 unless the patient lives in an area where there is a shortage of psychiatric clinicians, in which case a longer time period would be appropriate.3 Ensure your patient has a sufficient supply of medication(s) until they establish care with a new clinician.4 Offer to provide emergency care for a reasonable period of time during the termination process unless a safety concern requires immediate termination.4 Avoid situations in which the patient attempts to re-enter your care. Document the reason for the termination in your progress notes and keep a copy of the termination letter in the patient’s medical record.4

Psychiatric clinicians may unilaterally decide to end a treatment relationship with a patient when the relationship is no longer therapeutic, such as when the patient does not adhere to treatment, repeatedly misses appointments, exhibits abusive behaviors, or fails to pay for treatment.1 Claims of abandonment can arise if ending the treatment relationship is not executed properly. Abandonment is the termination of a treatment relationship with a patient who remains in need of treatment, has no suitable substitute treatment, and subsequently experiences damages as a result of the termination.2 When a patient terminates a treatment relationship, there are no legal bases for abandonment claims.3 In this article, I provide a few practical tips for properly terminating the doctor-patient relationship to limit the likelihood of claims of abandonment.

Know your jurisdiction’s requirements for terminating the relationship. Each state has its own legal definition of a doctor-patient relationship as well as requirements for ending it. Abandonment claims are unfounded in the absence of a doctor-patient relationship.3 Contact the appropriate licensing board to determine what your state’s regulatory requirements are. If necessary, consult with your attorney or a risk management professional for guidance.4

Communicate clearly. Communicate with your patient about the end of the treatment relationship in a clear and consistent manner, both verbally and in writing, because a termination should be viewed as a formal, documented event.3 Except in situations requiring immediate termination, psychiatric clinicians should inform the patient about the reason(s) for termination,4 the need for continued treatment,3 and the type of recommended treatment.3 This discussion should be summarized in a termination letter given to the patient that includes termination language, referral sources, the end date of treatment, and a request for authorization to release a copy of the patient’s medical records to their new clinician.3,4

Give adequate time, set boundaries, and document. Thirty days is generally considered adequate time for a patient to find a new clinician,5 unless the patient lives in an area where there is a shortage of psychiatric clinicians, in which case a longer time period would be appropriate.3 Ensure your patient has a sufficient supply of medication(s) until they establish care with a new clinician.4 Offer to provide emergency care for a reasonable period of time during the termination process unless a safety concern requires immediate termination.4 Avoid situations in which the patient attempts to re-enter your care. Document the reason for the termination in your progress notes and keep a copy of the termination letter in the patient’s medical record.4

1. Mossman D. ‘Firing’ a patient: may a psychiatrist unilaterally terminate care? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(12):18,20,22,29.

2. Van Susteren L. Psychiatric abandonment: pitfalls and prevention. Psychiatric Times. 2001;18(8). Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/psychiatric-abandonment-pitfalls-and-prevention

3. Stankowski J, Sorrentino R. Abandonment and unnecessary commitment. In: Ash P, Frierson RL, Hatters Friedman S, eds. Malpractice and Liability in Psychiatry. Springer Nature Publishing; 2022:129-135.

4. Funicelli A. Avoiding abandonment claim: how to properly terminate patients from your practice. Psychiatric News. 2022;57(12):13,41. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2022.12.12.23

5. American Psychiatric Association. APA Quick Practice Guide: Ending the Physician/Patient Relationship. 2014. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/Practice-Management/Practice-Management-Guides/GeneralIssues-terminating-patient-relationships.pdf

1. Mossman D. ‘Firing’ a patient: may a psychiatrist unilaterally terminate care? Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(12):18,20,22,29.

2. Van Susteren L. Psychiatric abandonment: pitfalls and prevention. Psychiatric Times. 2001;18(8). Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/psychiatric-abandonment-pitfalls-and-prevention

3. Stankowski J, Sorrentino R. Abandonment and unnecessary commitment. In: Ash P, Frierson RL, Hatters Friedman S, eds. Malpractice and Liability in Psychiatry. Springer Nature Publishing; 2022:129-135.

4. Funicelli A. Avoiding abandonment claim: how to properly terminate patients from your practice. Psychiatric News. 2022;57(12):13,41. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2022.12.12.23

5. American Psychiatric Association. APA Quick Practice Guide: Ending the Physician/Patient Relationship. 2014. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/Practice-Management/Practice-Management-Guides/GeneralIssues-terminating-patient-relationships.pdf

Medical record documentation: What to do, and what to avoid

Medical record documentation serves as a reminder of previous discussions with patients and what happened during their visits, a reimbursement justification for services, a communication tool to coordinate care with current and future clinicians, and a basis for defense in legal or regulatory matters.1,2 Documentation should be thorough, accurate, timely, and objective, with the ultimate goal of communicating our thoughts in an easily understood manner to other clinicians or attorneys.2 If we fail to achieve this goal, we may inadvertently give the impression that our care was hurried, incomplete, or thoughtless.2

Although not an exhaustive list, this article outlines strategies to employ and practices to avoid in our documentation efforts so we may enhance our defense in case of litigation and ensure the smooth transition of care for our patients.

Strategies to employ

Proper and accurate documentation details the course of patient care, and we should describe our thoughts in a clear and logical manner. Doing so minimizes the risk of misinterpretation by other clinicians or attorneys. Make sure the documentation of each appointment details the reason(s) for the patient’s visit, the effectiveness of treatment, possible treatment nonadherence, our clinical assessment, treatment consent, changes to the patient’s treatment plan, follow-up plans, reasons for not pursuing certain actions (eg, hospitalization), and a suicide risk assessment (and/or a violence risk assessment, if clinically indicated).2 Document missed or rescheduled appointments, and telephone and electronic contact with patients. Also be sure to use only commonly approved abbreviations.2 Document these items sooner rather than later because doing so improves the credibility of your charting.1 If you are handwriting notes, add the date and time to each encounter and make sure your handwriting is legible. Describe the behaviors of patients in objective and nonjudgmental terms.3 Documenting quotes from patients can convey crucial information about what was considered when making clinical decisions.1

Practices to avoid

If there is a need to make changes to previous entries, ensure these corrections are not mistaken for alterations. Each health care institution has its own policy for making corrections and addenda to medical records. Corrections to a patient’s medical record are acceptable, provided they are done appropriately, as I outlined in a previous Pearls article.4 Minimize or eliminate the copying and pasting of information; doing so can improve the efficiency of our documentation, but the practice can undermine the quality of the medical record, increase the risk of outdated and repetitive information being included, lead to clinical errors, and lead to overbilling of services.5 Finally, be sure to avoid speculation, personal commentary about patients and their family members, and language with negative connotations (unless such language is a direct quote from the patient).2,3

1. Mossman D. Tips to make documentation easier, faster, and more satisfying. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(2):80,84-86.

2. Staus C. Documentation: your very best defense. Psychiatric News. 2022;57(4):7,19.

3. Nelson KJ. How to use patient-centered language in documentation. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(10):70.

4. Joshi KG. Metadata, malpractice claims, and making changes to the EHR. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):e1-e3. doi:10.12788/cp.0106

5. Neal D. Do’s and don’ts of electronic documentation. Psychiatric News. 2021;56(8):7.

Medical record documentation serves as a reminder of previous discussions with patients and what happened during their visits, a reimbursement justification for services, a communication tool to coordinate care with current and future clinicians, and a basis for defense in legal or regulatory matters.1,2 Documentation should be thorough, accurate, timely, and objective, with the ultimate goal of communicating our thoughts in an easily understood manner to other clinicians or attorneys.2 If we fail to achieve this goal, we may inadvertently give the impression that our care was hurried, incomplete, or thoughtless.2

Although not an exhaustive list, this article outlines strategies to employ and practices to avoid in our documentation efforts so we may enhance our defense in case of litigation and ensure the smooth transition of care for our patients.

Strategies to employ

Proper and accurate documentation details the course of patient care, and we should describe our thoughts in a clear and logical manner. Doing so minimizes the risk of misinterpretation by other clinicians or attorneys. Make sure the documentation of each appointment details the reason(s) for the patient’s visit, the effectiveness of treatment, possible treatment nonadherence, our clinical assessment, treatment consent, changes to the patient’s treatment plan, follow-up plans, reasons for not pursuing certain actions (eg, hospitalization), and a suicide risk assessment (and/or a violence risk assessment, if clinically indicated).2 Document missed or rescheduled appointments, and telephone and electronic contact with patients. Also be sure to use only commonly approved abbreviations.2 Document these items sooner rather than later because doing so improves the credibility of your charting.1 If you are handwriting notes, add the date and time to each encounter and make sure your handwriting is legible. Describe the behaviors of patients in objective and nonjudgmental terms.3 Documenting quotes from patients can convey crucial information about what was considered when making clinical decisions.1

Practices to avoid

If there is a need to make changes to previous entries, ensure these corrections are not mistaken for alterations. Each health care institution has its own policy for making corrections and addenda to medical records. Corrections to a patient’s medical record are acceptable, provided they are done appropriately, as I outlined in a previous Pearls article.4 Minimize or eliminate the copying and pasting of information; doing so can improve the efficiency of our documentation, but the practice can undermine the quality of the medical record, increase the risk of outdated and repetitive information being included, lead to clinical errors, and lead to overbilling of services.5 Finally, be sure to avoid speculation, personal commentary about patients and their family members, and language with negative connotations (unless such language is a direct quote from the patient).2,3

Medical record documentation serves as a reminder of previous discussions with patients and what happened during their visits, a reimbursement justification for services, a communication tool to coordinate care with current and future clinicians, and a basis for defense in legal or regulatory matters.1,2 Documentation should be thorough, accurate, timely, and objective, with the ultimate goal of communicating our thoughts in an easily understood manner to other clinicians or attorneys.2 If we fail to achieve this goal, we may inadvertently give the impression that our care was hurried, incomplete, or thoughtless.2

Although not an exhaustive list, this article outlines strategies to employ and practices to avoid in our documentation efforts so we may enhance our defense in case of litigation and ensure the smooth transition of care for our patients.

Strategies to employ

Proper and accurate documentation details the course of patient care, and we should describe our thoughts in a clear and logical manner. Doing so minimizes the risk of misinterpretation by other clinicians or attorneys. Make sure the documentation of each appointment details the reason(s) for the patient’s visit, the effectiveness of treatment, possible treatment nonadherence, our clinical assessment, treatment consent, changes to the patient’s treatment plan, follow-up plans, reasons for not pursuing certain actions (eg, hospitalization), and a suicide risk assessment (and/or a violence risk assessment, if clinically indicated).2 Document missed or rescheduled appointments, and telephone and electronic contact with patients. Also be sure to use only commonly approved abbreviations.2 Document these items sooner rather than later because doing so improves the credibility of your charting.1 If you are handwriting notes, add the date and time to each encounter and make sure your handwriting is legible. Describe the behaviors of patients in objective and nonjudgmental terms.3 Documenting quotes from patients can convey crucial information about what was considered when making clinical decisions.1

Practices to avoid

If there is a need to make changes to previous entries, ensure these corrections are not mistaken for alterations. Each health care institution has its own policy for making corrections and addenda to medical records. Corrections to a patient’s medical record are acceptable, provided they are done appropriately, as I outlined in a previous Pearls article.4 Minimize or eliminate the copying and pasting of information; doing so can improve the efficiency of our documentation, but the practice can undermine the quality of the medical record, increase the risk of outdated and repetitive information being included, lead to clinical errors, and lead to overbilling of services.5 Finally, be sure to avoid speculation, personal commentary about patients and their family members, and language with negative connotations (unless such language is a direct quote from the patient).2,3

1. Mossman D. Tips to make documentation easier, faster, and more satisfying. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(2):80,84-86.

2. Staus C. Documentation: your very best defense. Psychiatric News. 2022;57(4):7,19.

3. Nelson KJ. How to use patient-centered language in documentation. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(10):70.

4. Joshi KG. Metadata, malpractice claims, and making changes to the EHR. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):e1-e3. doi:10.12788/cp.0106

5. Neal D. Do’s and don’ts of electronic documentation. Psychiatric News. 2021;56(8):7.

1. Mossman D. Tips to make documentation easier, faster, and more satisfying. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(2):80,84-86.

2. Staus C. Documentation: your very best defense. Psychiatric News. 2022;57(4):7,19.

3. Nelson KJ. How to use patient-centered language in documentation. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(10):70.

4. Joshi KG. Metadata, malpractice claims, and making changes to the EHR. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):e1-e3. doi:10.12788/cp.0106

5. Neal D. Do’s and don’ts of electronic documentation. Psychiatric News. 2021;56(8):7.

Risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury: A review of the evidence

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is the direct and deliberate destruction of body tissue without intent to die.1 Common forms of NSSI include cutting, burning, scraping/scratching skin, biting, hitting, and interfering with wound healing.2 Functional theories suggest that NSSI temporarily alleviates overwhelming negative emotions and can produce feelings of relief, resulting in a reinforcing effect.3

NSSI has been shown to be a risk factor for future suicide attempts.4 A 2018 study found that NSSI is associated with an increased risk of subsequent suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR] 2.8), suicide plan (OR 3.0), and suicide attempt (OR 5.5).5 NSSI is also associated with individuals who had suicidal ideation and formed a suicide plan, and individuals who had a suicide plan and attempted suicide (ORs 1.7 to 2.1).5 Another study found that 70% of adolescents who engage in NSSI have attempted suicide during their lifetime, and 55% have multiple attempts.6

Given the overlap between suicide attempts and NSSI, performing a thorough suicide risk assessment (which is beyond the scope of this article) is crucial. This article describes the static and dynamic risk factors for NSSI in adolescents and adults, which can help us perform a suicide risk assessment and allow us to formulate an appropriate treatment plan that includes safety-based interventions.

NSSI risk factors for adolescents

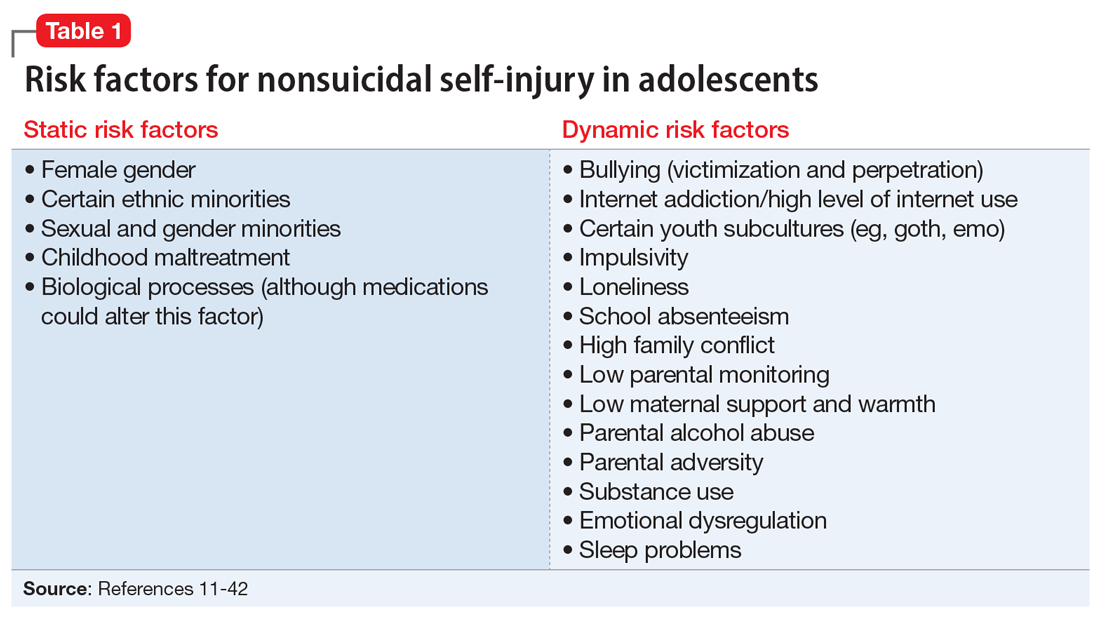

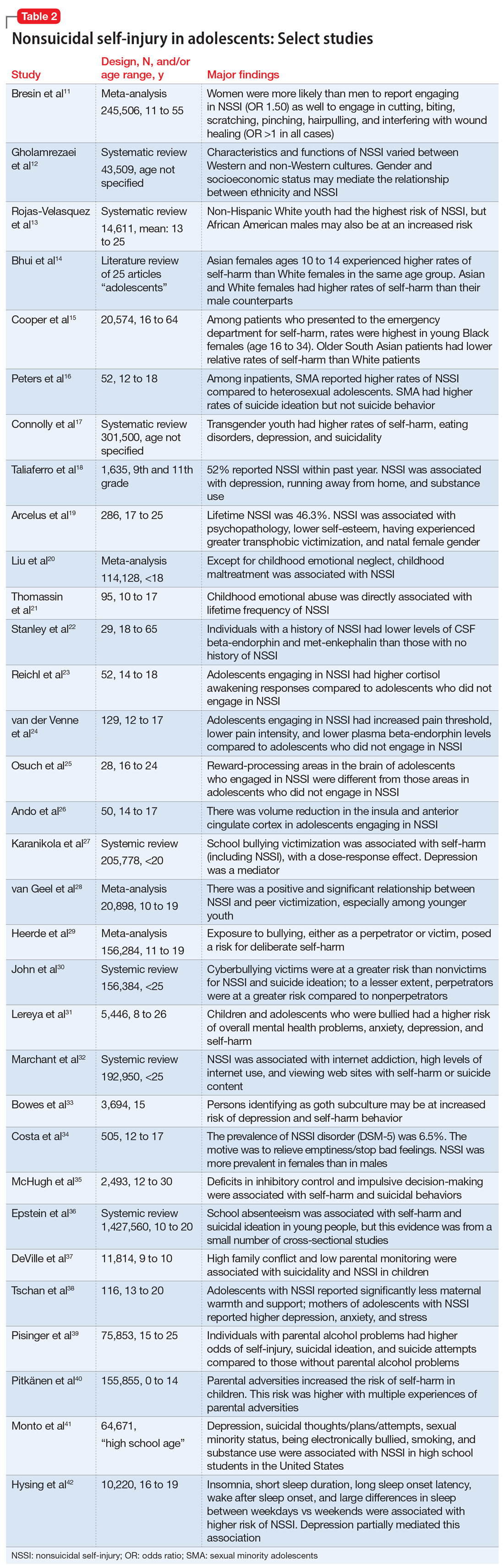

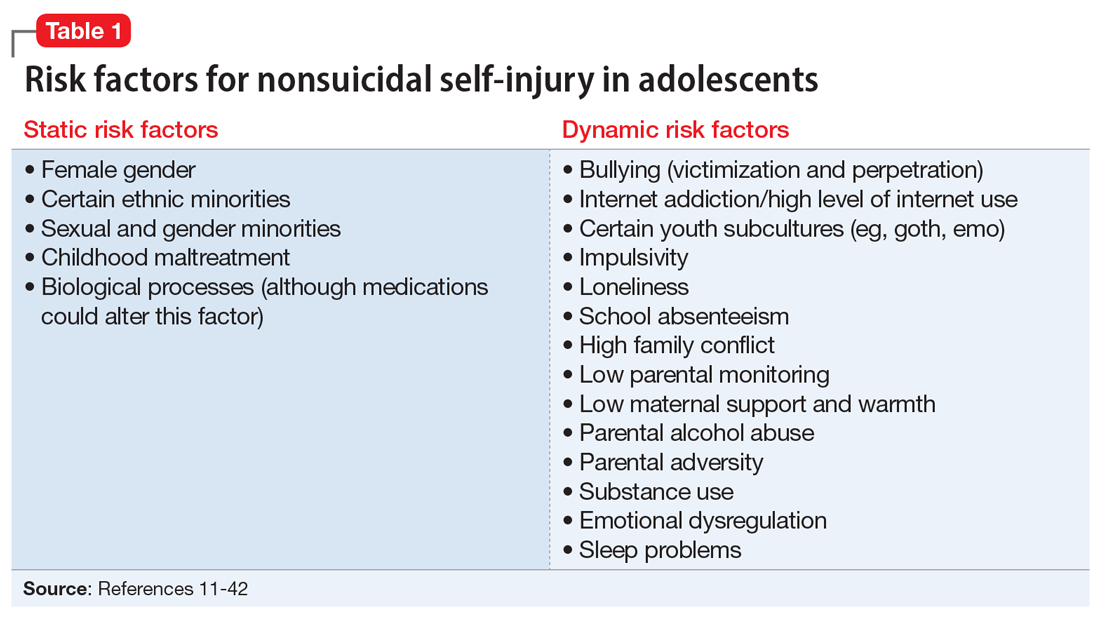

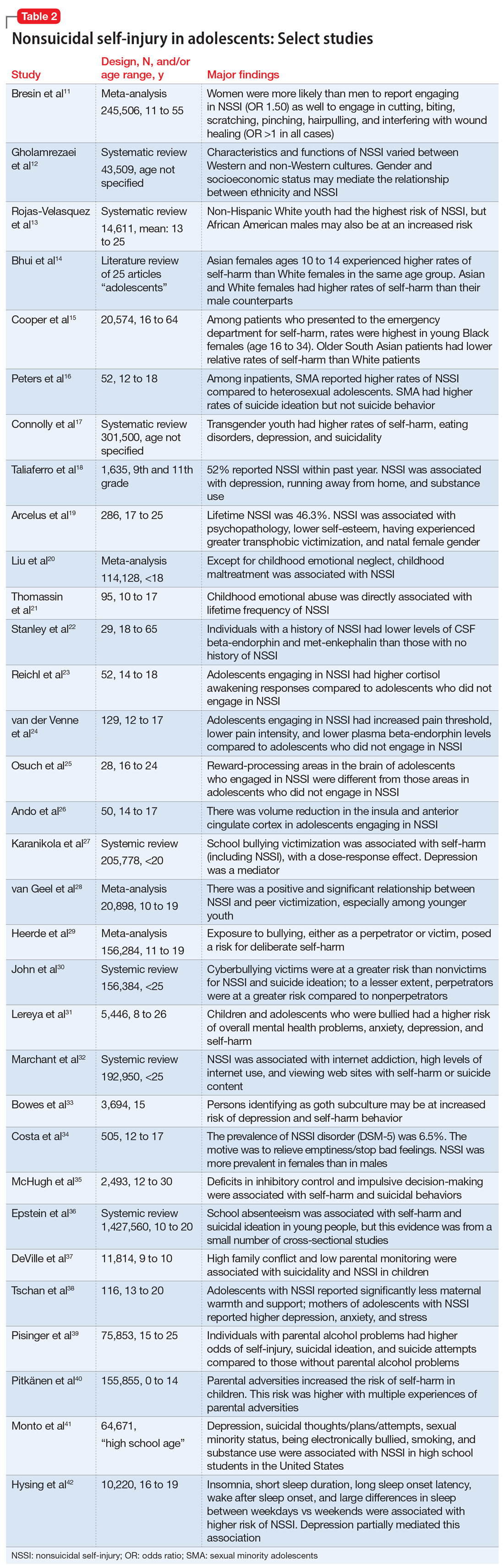

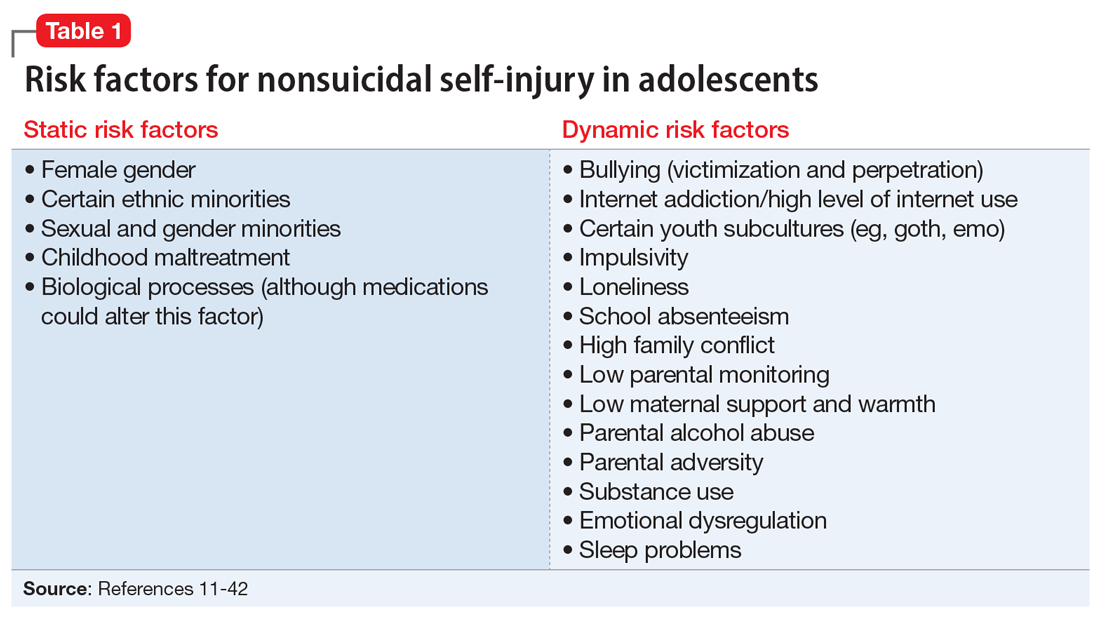

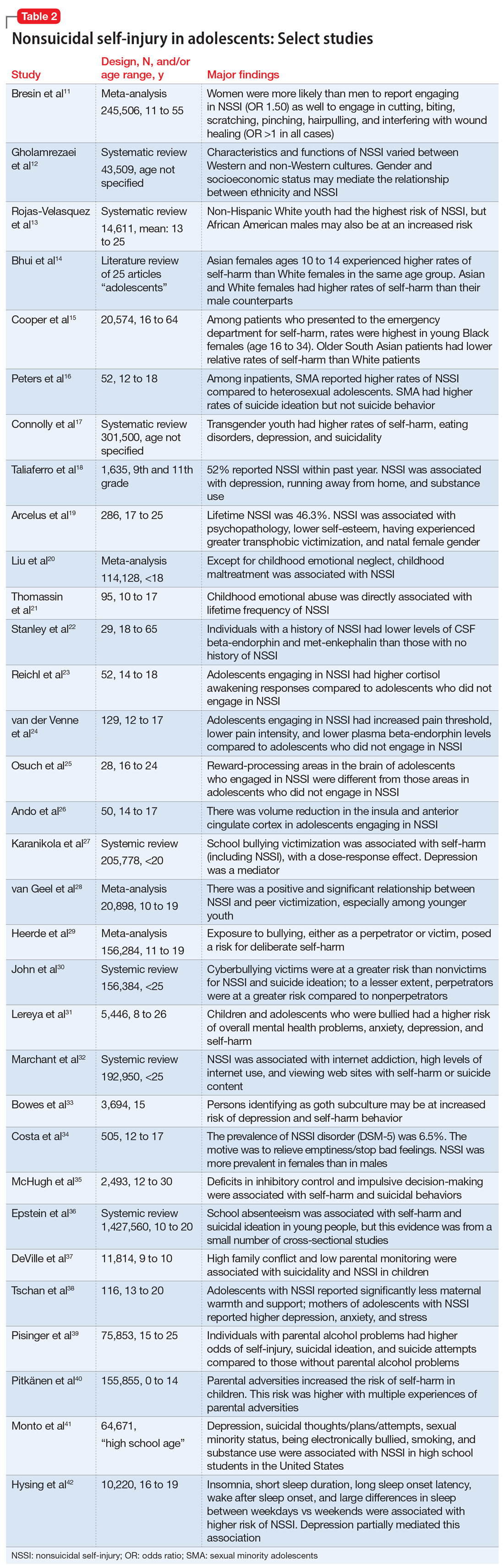

From developing sexual identity and undergoing puberty to achieving increased independence from their parents and developing a sense of autonomy, adolescents undergo many biological, psychological, and social changes before reaching adulthood.7 Data suggest that NSSI often begins in adolescence, with a typical onset at age 13 or 14.3 Community studies show that one-third to one-half of adolescents in the United States have engaged in NSSI.8,9 Previously, NSSI during adolescence was associated with 3 major diagnostic categories: eating disorders, developmental disabilities, and borderline personality disorder (BPD).10 However, recent data suggest that NSSI is also common outside of these categories. Here we describe static and dynamic risk factors for NSSI in adolescents (Table 111-42). Table 211-42 summarizes the studies of NSSI in adolescents that we reviewed.

Static risk factors

Female adolescents and adults engage in NSSI at higher rates than males. The difference is larger in clinical populations compared to the general population.11

A large portion of research about NSSI has been conducted in studies in which the majority of participants were White.12 Most studies report a higher prevalence of NSSI among non-Hispanic White youth,13 but some suggest other ethnic groups may also experience high rates of self-harm and NSSI.13-15 Several studies have demonstrated high rates of self-harm among South Asian adult females compared with White adult females, but this difference may be less pronounced in adolescents.14 One study in the United Kingdom found that White females age 10 to 14 had higher rates of self-harm compared to South Asian females,14 while another found that risk and rates of self-harm in young South Asian people varied by city and country of origin.15 Young Black females15 and young Black males13 also may be at an increased risk of self-harm. One review found that Black females were more likely to self-harm than Asian or White groups.15

Several studies suggest that sexual minority adolescents (SMA) (eg, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) are at greater risk for NSSI than heterosexual adolescents.16 SMA have been shown to engage in a significantly greater frequency of NSSI and more types of NSSI than heterosexual adolescents.16 Furthermore, on the Inventory of Statements about Self-Injury, SMA self-reported using NSSI for intrapersonal functions (eg, for affect regulation, antisuicide, self-punishment) significantly greater than their heterosexual peers; however, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups on interpersonal functions (eg, autonomy, interpersonal boundaries, peer bonding, sensation-seeking).16

Continue to: Transgender and gender nonconfirming...

Transgender and gender nonconfirming (GNC) youth are at a particularly high risk for NSSI; 30% to 45.5% of transgender adolescents report self-injury.17 Factors shown to distinguish transgender/GNC youth who engage in NSSI from those who do not include having a mental health problem, depression, running away from home, substance use, lower self-esteem/greater self-criticism, experiencing transphobia victimization, and having more interpersonal problems.18,19 Among transgender/GNC youth, those whose biological sex is female are more likely to report NSSI than those whose biological sex is male (ie, transgendered adolescent males are more likely to report NSSI than transgendered adolescent females).18,19

Most forms of childhood maltreatment have been associated with NSSI. In a recently published review, Liu et al20 found that childhood maltreatment (including sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and physical neglect) was associated with an increased risk for NSSI. However, conflicting evidence suggests that when confounders are removed, only childhood emotional abuse was directly associated with NSSI.21 Current evidence is modest for childhood emotional neglect as a risk factor for NSSI.20

Increasing research is investigating the biological processes that may be implicated in NSSI. Some studies suggest that endogenous opioids,22 monoamine neurotransmitters,22 and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis23 may play a role in NSSI. Compared to healthy controls, adolescents engaging in NSSI have been shown to have lower pain intensity (P = .036), higher pain thresholds (P = .040), and lower beta-endorphins (endogenous opioid hormones involved in mediating stress and pain) (P = .002).24 There may be alterations in the HPA axis among adolescents who engage in NSSI, more specifically stronger cortisol awakening responses.23 Both functional and standard MRI have been used to study the neurobiology of NSSI. One study demonstrated differences in functional connectivity between brain areas linked to neuroregulation of emotions in adolescents who engage in NSSI,25 while another found volume reduction in the insula of these adolescents, which suggests a possible neurobiological reason for impulsivity and the increased risk of suicidal behavior.26

Dynamic risk factors

Research has repeatedly shown bullying is a risk factor for NSSI.27 One study found that younger children who were victimized reported significantly more NSSI than older children.28 New data suggest that perpetrators of bullying are also at risk for deliberate self-harm behavior (SHB), which this study defined as a behavior that is intended to cause self-harm but without suicidal intent and having a nonfatal outcome.29 Victims of cyberbullying also are at a greater risk for self-harm, suicidal behaviors, and suicide attempt.30 To a lesser extent, cyberbullying perpetrators are at greater risk for suicidal behaviors and suicidal ideation.30 Bullying is a risk factor for NSSI not only in adolescence, but also in adulthood. Lereya et al31 found that victims of bullying in childhood and early adolescence were more likely to have mental health problems (including anxiety and depression) and more likely to engage in SHB—which this study defined as hurting oneself on purpose in any way—as adults.

The effects of internet use on adolescents’ mental health also has been investigated. A recent review that explored the relationship between all types of internet use (general use, internet addiction, social media, self-harm websites, forums, etc) and SHB/suicidal behavior found that young people with internet addiction, high levels of internet use, and a tendency to view websites with self-harm or suicidal content were at higher risk of engaging in SHB/suicidal behavior.32 This study did not use a specific definition for SHB or suicidal behavior.32

Continue to: Membership in certain youth...

Membership in certain youth subcultures (eg, emo or goth) has been evaluated as potential risk factors for depression and deliberate self-harm. Bowes et al33 found that for each unit increase in goth affiliation (not at all, not very much, somewhat, more than somewhat, very much), youth were 1.52 times more likely to engage in SHB; these researchers also reported a dose-response association between goth identification and future SHB. This study asked participants if they have ever tried to harm or hurt themselves in any manner, but did not distinguish between individuals who had harmed themselves with and without suicidal intent.33

Personality traits such as impulsiveness and loneliness have been linked to NSSI among adolescents.34,35 A recent study found that adolescents who met the proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for NSSI scored higher on the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, specifically in measures of:

- motor impulsiveness (ie, acting without thinking)

- attentional impulsiveness (ie, making decisions quickly)

- impulsiveness due to lack of planning (ie, failure to plan for the future).34

This study also found that adolescents who identified as being lonely based on scores on the Brazilian Loneliness Scale were at a higher risk for NSSI.34

A recent systematic review (32 studies) and meta-analysis (9 studies) found that school absenteeism was associated with a risk of self-harm (pooled aOR 1.37, P = .01) and suicidal ideation (pooled aOR 1.20, P = .03).36 This study suggested that school absenteeism, an important marker of social exclusion, was associated with both SHB and suicidal ideation in young people.36 It defined SHB as any act of self-injury or self-poisoning, regardless of intent.36

Finally, family-related factors have been associated with an increased risk of NSSI. One study of 11,814 children age 9 and 10 revealed that high family conflict (OR 1.09; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.14) and low parental monitoring (OR 0.95; 95% CI, 0.93 to 0.98) were associated with NSSI.37 A smaller, community-based study found that adolescents with NSSI reported significantly less maternal support and warmth than nonclinical controls, but a cause-and-effect relationship has not yet been determined.38 Parental history alone may influence adolescents’ risk of NSSI. A study that included nearly 76,000 youth found that adolescents with perceived parental alcohol problems had higher odds of self-injury, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts.39 Adolescents exposed to maternal or paternal adversities were also at a higher risk of self-harm (hazard ratio 1.5 to 5.4 among males, 1.7 to 3.9 among females).40

Continue to: NSSI risk factors for adults

NSSI risk factors for adults

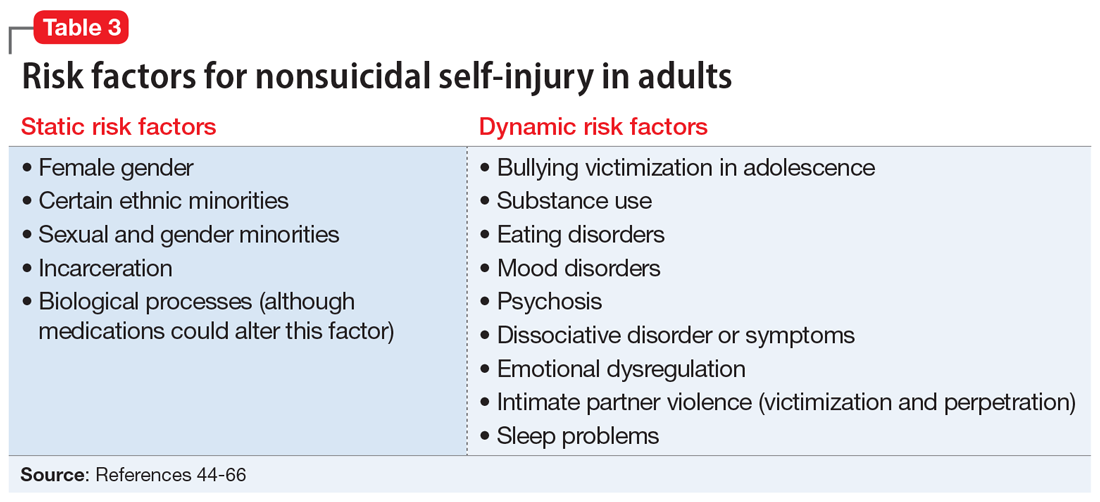

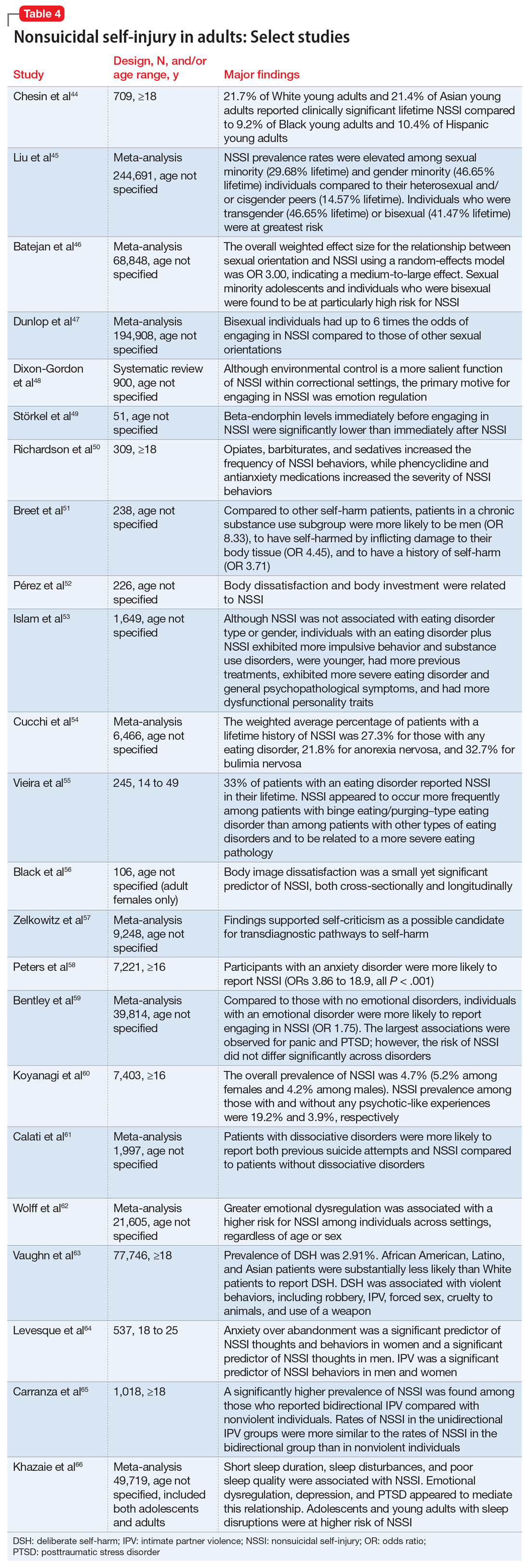

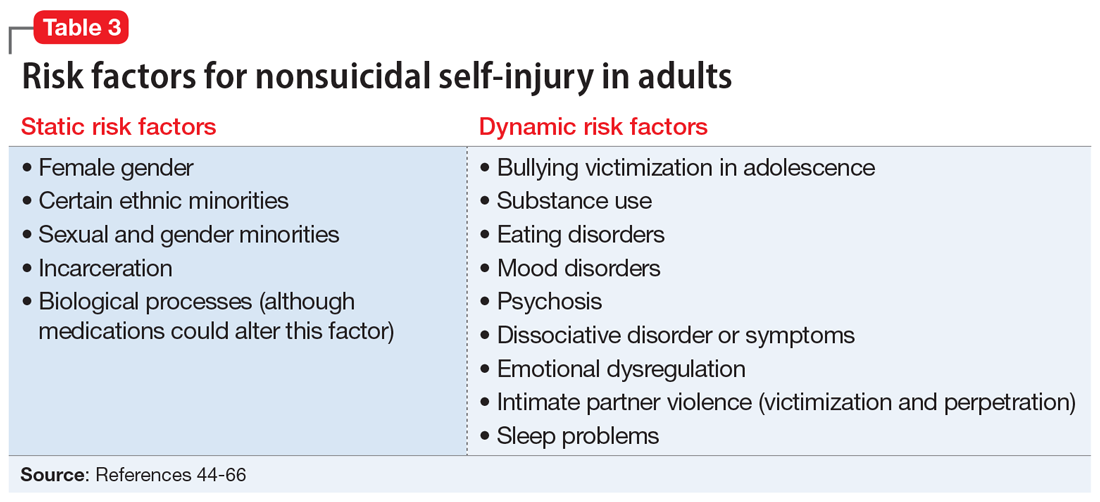

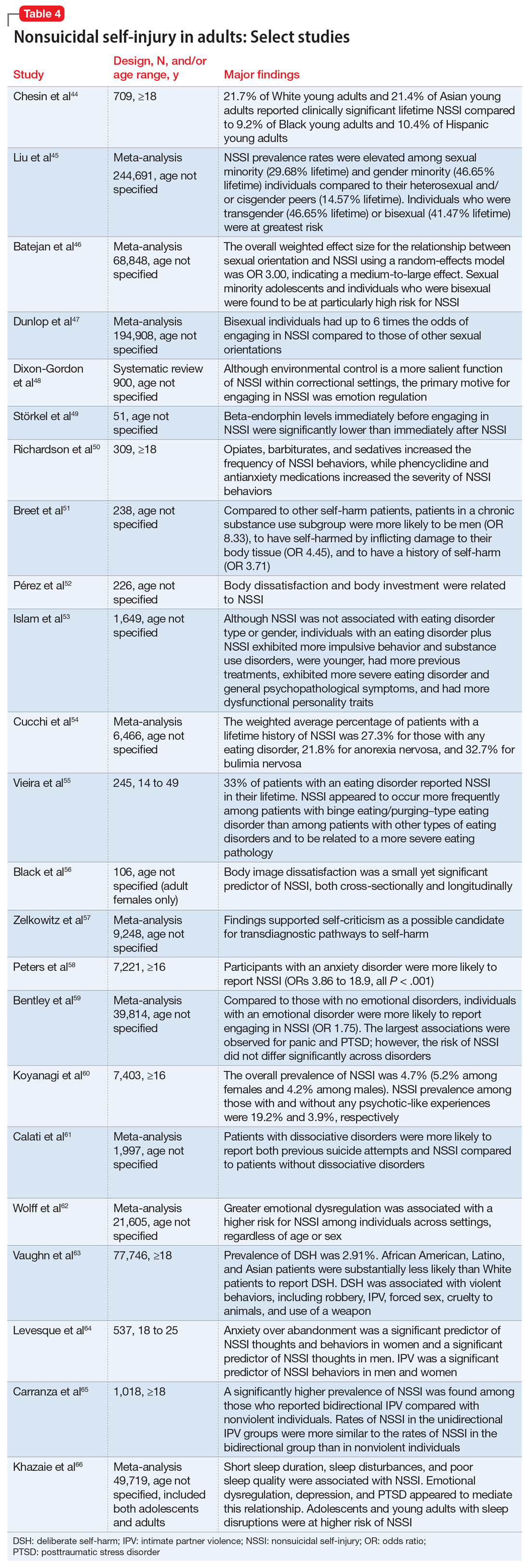

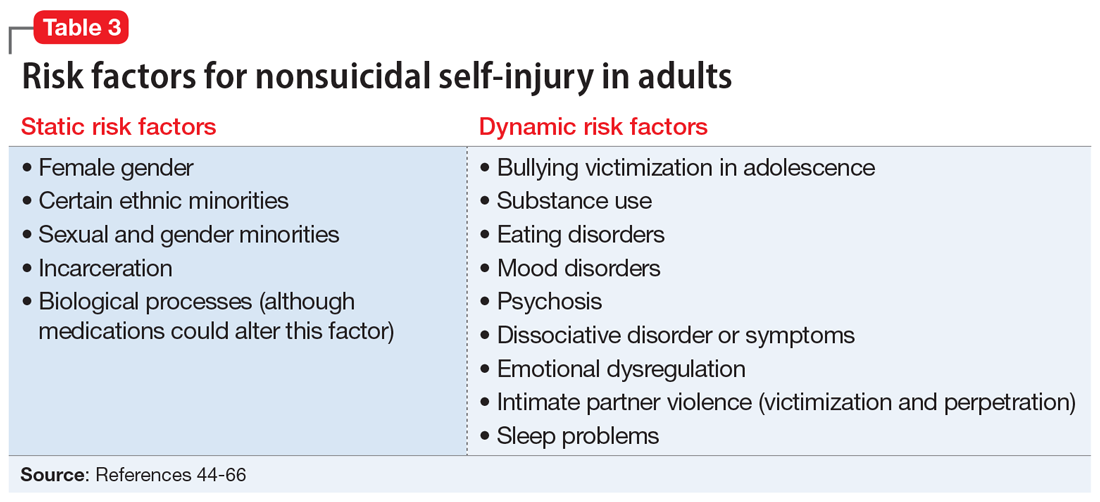

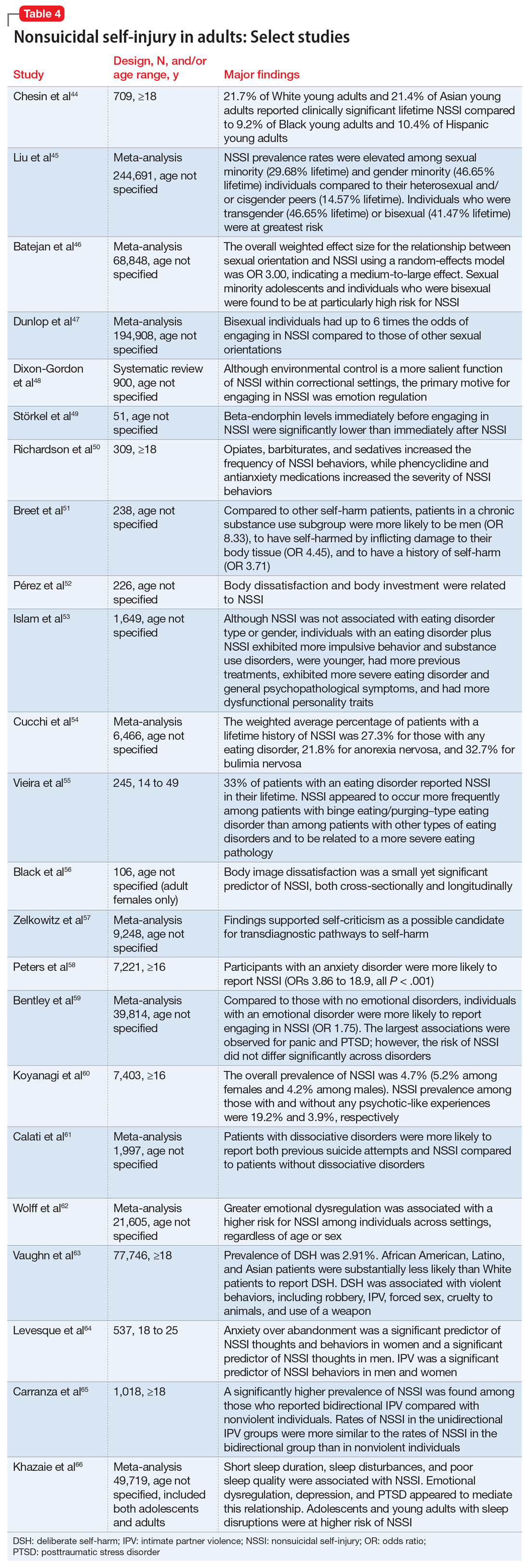

Although data regarding the prevalence of NSSI in adults are lacking, available studies report a 12-month prevalence of 0.9%2 and a lifetime prevalence of 5.5% to 5.9%.43 There is a significant overlap in risk factors for NSSI in adolescent and adult populations, but there are also many important differences. The static and dynamic risk factors for NSSI in adults are described in Table 3.44-66 Table 444-66 summarizes the studies of NSSI in adults that we reviewed.

Static risk factors

Research findings regarding the prevalence of NSSI based on gender are varied. For years, it has been believed that women are more likely to engage in NSSI than men. Recent meta-analyses that have examined this relationship closely found that the gender difference is larger for clinical samples compared to community samples and more pronounced in younger individuals.11

As is the case with adolescents, there may be ethnic variations in rates of self-harm and NSSI among adults. A 2013 study by Chesin et al44 found that Asian and White young adults experience higher rates of NSSI than their Hispanic and Black counterparts. Evidence suggests that relative rates of self-harm for older South Asian adults are lower than in older White adults.15

Compared to heterosexual or cisgender individuals, members of sexual and gender minorities have a higher past-year and lifetime prevalence of NSSI.45 One study found that the weighted effect size between sexual orientation and NSSI had an OR of 3 (95% CI, 2.46 to 3.66), indicating a medium-to-large effect.46 Bisexual and transgender individuals appear to be at the highest risk for NSSI when compared to members of other sexual and gender minority groups.45 One review that included mostly cross-sectional studies found that individuals identifying as bisexual had up to 6 times the odds of engaging in NSSI when compared to those of other sexual orientations.47

Incarceration is a risk factor for NSSI. The rates of NSSI in criminal justice settings are higher (up to 61%) than in the general adult population (approximately 4%).48 Recent research found that NSSI serves similar functions in correctional and non-correctional settings, primarily to regulate emotions.48 However, there is also evidence of higher rates of NSSI being motivated by an attempt to influence the environment (ie, engaging in NSSI in order to be transferred to another prison unit) compared to NSSI in community settings.48

Continue to: Though less robust than data...

Though less robust than data published regarding adolescents, the role of biological processes in adults engaging in NSSI has also been studied. A 2021 study by Störkel et al49 found that levels of salivary beta-endorphins were significantly lower in adults immediately before engaging in NSSI compared to after NSSI. Furthermore, adults who engage in NSSI have lower levels of met-enkephalin (P < .01), an opioid growth factor, compared to adults who have never engaged in NSSI.22

Dynamic risk factors

Individuals who engage in NSSI often report substance use, but there is little data on whether substance use is an independent risk factor for NSSI. Although limited, recent evidence suggests illicit substance use in both adolescents41 and adults50 increases risk for NSSI. Richardson et al50 found that the use of barbiturates, opiates, and sedatives significantly increased the frequency of NSSI, whereas use of marijuana, phencyclidine, and medications used to treat anxiety significantly increased the severity of NSSI. A smaller study conducted in South Africa found that individuals who engage in substance use and NSSI were more likely to be male (P < .001).51

Eating disorders and NSSI are highly comorbid.52 The lifetime prevalence of NSSI among individuals with eating disorders ranges from 20.6%to 37.1%.52,53 Results are inconsistent regarding which eating disorders (if any) are greater risk factors for NSSI. One study found that the prevalence of NSSI in patients with bulimia nervosa was 32.7% (95% CI, 26.9% to 39.1%) vs 21.8% in patients with anorexia nervosa (95% CI, 18.5% to 25.6%).54 Another study found that individuals with binge eating/purging–type eating disorders reported engaging in NSSI more frequently than those with other types of eating disorders.55 Among patients with eating disorders who reported NSSI, risk factors included younger age of onset, more negative self-evaluation, more impulsive behavior, concomitant substance use, history of suicide attempts, childhood abuse, and peer aggression.53,55 Body image dissatisfaction and self-criticism, even in individuals not formally diagnosed with an eating disorder, are small but significant predictors of NSSI.56,57

Mood disorders have also been linked to NSSI.58,59 Anxiety disorders (including generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, and agoraphobia) as well as anxiety-related disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorder have been significantly associated with NSSI (P < .001), but this relationship decreased in strength when mood instability was removed as a confounder.58 Among patients with anxiety and anxiety-related disorders, panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have shown the strongest association with NSSI, with pooled aORs of 2.67 and 2.06, respectively.59

Recent studies have examined the association of other mental health disorders and symptoms with NSSI, including psychosis60 and dissociative symptoms.61 One study found that paranoia, thought control, and auditory hallucinations were significantly associated with NSSI60; however, after controlling for concomitant BPD, only paranoia was significantly associated with NSSI.60 Individuals diagnosed with dissociative disorders were more likely than patients without such disorders to endorse NSSI and suicide attempts.61

Continue to: Emotional dysregulation...

Emotional dysregulation (EDR)—defined as difficulty understanding, recognizing, and managing one’s emotions—has been researched extensively in relation to NSSI.62 A recent review that included studies of both adolescents and adults reported a significant association between EDR and NSSI, with an OR of 2.40 (95% CI, 2.01 to 2.86).62 A larger effect size was observed between EDR and lifetime NSSI (OR 3.21; 95% CI, 2.63 to 3.91) compared to past-year NSSI (OR 2.32; 95% CI, 1.84 to 2.92).62 Patient age, sex, and sample type (clinical vs community) were not significant moderators of strength between the reported associations.62

Studies examining intimate partner violence (IPV) and NSSI have found that young adults who engage in IPV (both as victims and as perpetrators) are more likely to report NSSI.63-65 Researchers have proposed that anxiety over abandonment may explain this relationship.64 A recent study found that individuals with bidirectional IPV (ie, both victimization and perpetration) engaged in NSSI at a higher prevalence than those engaging in unidirectional IPV or no IPV.65 This suggests that relationship violence in general (rather than just being a victim of IPV) may be a risk factor for NSSI.65

Finally, studies suggest that adolescents and adults who have sleep problems (insomnia, short sleep duration, long sleep onset latency, waking after sleep onset, and poor quality sleep) are more likely to report self-harm or NSSI than those without sleep problems.42,66 In adults, this relationship is partially mediated by depressive symptoms, EDR, and PTSD.66 In adolescents, depressive symptoms are a mediator for this relationship.42

Bottom Line

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is a significant health concern due to its association with suicide attempts. Although there are similarities in NSSI risk factors between adolescents and adults, there are also important differences. Understanding these differences is necessary to develop appropriate treatment plans.

Related Resources

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. https://afsp.org/

- Cipriano A, Cella S, Cotrufo P. Nonsuicidal self-injury: a systematic review. Front Psych. 2017;8:1946. doi:10.3389/ fpsyg.2017.01946

- Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. Textbook of Suicide Risk Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

1. Nock MK. Self-injury. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:339-363.

2. Klonsky ED. Non-suicidal self-injury in United States adults: prevalence, sociodemographics, topography and functions. Psychol Med. 2011;41(9):1981-1986.

3. Klonsky ED. Nonsuicidal self-injury: what we know, and what we need to know. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(11):565-568.

4. Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, et al. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT). Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):495-501.

5. Kiekens G, Hasking P, Boyes M, et al. The associations between non-suicidal self-injury and first onset suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J Affect Disord. 2018;239:171-179.

6. Nock MK, Joiner TE, Gordon KH, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res. 2006;144(1):65-72.

7. Christie D, Viner R. Adolescent development. BMJ. 2005;330(7486):301-304.

8. Yates TM, Tracy AJ, Luthar SS. Nonsuicidal self-injury among “privileged” youths: longitudinal and cross-sectional approaches to developmental process. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(1):52-62.

9. Lloyd-Richardson EE, Perrine N, Dierker L, et al. Characteristics and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychol Med. 2007;37(8):1183-1192.

10. Peterson J, Freedenthal S, Sheldon C, et al. Nonsuicidal self injury in adolescents. Psychiatry(Edgmont). 2008;5(11):20-26.

11. Bresin K, Schoenleber M. Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;38:55-64.

12. Gholamrezaei M, Stefano JD, Heath NL. Nonsuicidal self-injury across cultures and ethnic and racial minorities: a review. Int J Psychol. 2015;52(4):316-326.

13. Rojas-Velasquez DA, Pluhar EI, Burns PA, et al. Nonsuicidal self-injury among African American and Hispanic adolescents and young adults: a systematic review. Prev Sci. 2021;22:367-377.

14. Bhui K, McKenzie K, Rasul F. Rates, risk factors & methods of self harm among minority ethnic groups in the UK: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:336.

15. Cooper J, Murphy E, Webb R, et al. Ethnic differences in self-harm, rates, characteristics and service provision: three-city cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(3):212-218.

16. Peters JR, Mereish EH, Krek MA, et al. Sexual orientation differences in non-suicidal self-injury, suicidality, and psychosocial factors among an inpatient psychiatric sample of adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284:112664.

17. Connolly MD, Zervos MJ, Barone 2nd CJ, et al. The mental health of transgender youth: advances in understanding. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(5):489-495.

18. Taliaferro LA, McMorris BJ, Rider GN, et al. Risk and protective factors for self-harm in a population-based sample of transgender youth. Archives Suicide Res. 2019;23(2):203-221.

19. Arcelus J, Claes L, Witcomb GL, et al. Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury among trans youth. J Sex Med. 2016;13(3):402-412.

20. Liu RT, Scopelliti KM, Pittman SK, et al. Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):51-64.

21. Thomassin K, Shaffer A, Madden A, et al. Specificity of childhood maltreatment and emotion deficit in nonsuicidal self-injury in an inpatient sample of youth. Psychiatry Res. 2016;244:103-108.

22. Stanley B, Sher L, Wilson S, et al. Non-suicidal self-injurious behavior, endogenous opioids and monoamine neurotransmitters. J Affect Disord. 2010;124(1-2):134-140.

23. Reichl C, Heyer A, Brunner R, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, childhood adversity and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;74:203-211.

24. van der Venne P, Balint A, Drews E, et al. Pain sensitivity and plasma beta-endorphin in adolescent non-suicidal self-injury. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:199-209.

25. Osuch E, Ford K, Wrath A, et al. Functional MRI of pain application in youth who engaged in repetitive non-suicidal self-injury vs. psychiatric controls. Psychiatry Res. 2014;223(2):104-112.

26. Ando A, Reichl C, Scheu F, et al. Regional grey matter volume reduction in adolescents engaging in non-suicidal self-injury. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2018;280:48-55.

27. Karanikola MNK, Lyberg A, Holm A-L, et al. The association between deliberate self-harm and school bullying victimization and the mediating effect of depressive symptoms and self-stigma: a systematic review. BioMed Res Int. 2018;4745791. doi: 10.1155/2018/4745791

28. van Geel M, Goemans A, Vedder P. A meta-analysis on the relation between peer victimization and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230(2):364-368.

29. Heerde JA, Hemphill SA. Are bullying perpetration and victimization associated with adolescent deliberate self-harm? A meta-analysis. Arch Suicide Res. 2019;23(3):353-381.

30. John A, Glendenning AC, Marchant A, et al. Self-harm, suicidal behaviours, and cyberbullying in children and young people: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(4):e129. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9044

31. Lereya ST, Copeland WE, Costello EJ, et al. Adult mental health consequences of peer bullying and maltreatment in childhood: two cohorts in two countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(6):524-531.

32. Marchant A, Hawton K, Stewart A, et al. A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: the good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0181722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181722

33. Bowes L, Carnegie R, Pearson R, et al. Risk of depression and self-harm in teenagers identifying with goth subculture: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):793-800.

34. Costa RPO, Peixoto ALRP, Lucas CCA, et al. Profile of non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: interface with impulsiveness and loneliness. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2021;97(2):184-190.

35. McHugh CM, Lee RSC, Hermens DF, et al. Impulsivity in the self-harm and suicidal behavior of young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;116:51-60.

36. Epstein S, Roberts E, Sedgwick R, et al. School absenteeism as a risk factor for self-harm and suicidal ideation in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29(9):1175-1194.

37. DeVille DC, Whalen D, Breslin FJ, et al. Prevalence and family-related factors associated with suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and self-injury in children aged 9 to 10 years. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920956. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20956

38. Tschan T, Schmid M, In-Albon T. Parenting behavior in families of female adolescents with nonsuicidal self-injury in comparison to a clinical and a nonclinical control group. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2015;9:17.

39. Pisinger V, Hawton K, Tolstrup JS. Self-injury and suicide behavior among young people with perceived parental alcohol problems in Denmark: a school-based survey. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(2):201-208.

40. Pitkänen J, Remes H, Aaltonen M, et al. Experience of maternal and paternal adversities in childhood as determinants of self-harm in adolescence and young adulthood. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2019;73(11):1040-1046.

41. Monto MA, McRee N, Deryck FS. Nonsuicidal self-injury among a representative sample of US adolescents, 2015. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(8):1042-1048.

42. Hysing M, Sivertsen B, Stormark KM, et al. Sleep problems and self-harm in adolescence. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(4):306-312.

43. Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, et al. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(3):273-303.

44. Chesin M, Moster A, Jeglic E. Non-suicidal self-injury among ethnically and racially diverse emerging adults: do factors unique to the minority experience matter? Current Psychology. 2013;32:318-328.

45. Liu RT, Sheehan AE, Walsh RFL, et al. Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;74:101-783. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101783

46. Batejan KL, Jarvi SM, Swenson LP. Sexual orientation and non-suicidal self-injury: a meta-analytic review. Arch Suicide Res. 2015;19(2):131-150.

47. Dunlop BJ, Hartley S, Oladokun O, et al. Bisexuality and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI): a narrative synthesis of associated variables and a meta-analysis of risk. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:1159-1172.

48. Dixon-Gordon K, Harrison N, Roesch R. Non-suicidal self-injury within offender populations: a systematic review. Int J Forensic Ment Health. 2012;11(1):33-50.

49. Störkel LM, Karabatsiakis A, Hepp K, et al. Salivary beta-endorphin in nonsuicidal self-injury: an ambulatory assessment study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46(7):1357-1363.

50. Richardson E, DePue MK, Therriault DJ, et al. The influence of substance use on engagement in non-suicidal self-injury (NSI) in adults. Subst Use Misuse. 2020;55(1):89-94.

51. Breet E, Bantjes J, Lewis I. Chronic substance use and self-harm in a primary health care setting. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2018;10(1):e1-e9. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1544

52. Pérez S, Marco JH, Cañabate M. Non-suicidal self-injury in patients with eating disorders: prevalence, forms, functions, and body image correlates. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;84:32-38.

53. Islam MA, Steiger H, Jimenez-Murcia S, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury in different eating disorder types: relevance of personality traits and gender. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23(6):553-560.

54. Cucchi A, Ryan D, Konstantakopoulos G, et al. Lifetime prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury in patients with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2016;46(7):1345-1358.

55. Vieira AI, Machado BC, Machado PPP, et al. Putative risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury in eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2017;25(6):544-550.

56. Black EB, Garratt M, Beccaria G, et al. Body image as a predictor of nonsuicidal self-injury in women: a longitudinal study. Compr Psychiatry. 2019;88:83-89.

57. Zelkowitz RL, Cole DA. Self-criticism as a transdiagnostic process in nonsuicidal self-injury and disordered eating: systematic review and meta-analysis. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;49(1):310-327.

58. Peters EM, Bowen R, Balbuena L. Mood instability contributes to impulsivity, non-suicidal self-injury, and binge eating/purging in people with anxiety disorders. Psychol Psychother. 2019;92(3):422-438.

59. Bentley KH, Cassiello-Robbins CF, Vittorio L, et al. The association between nonsuicidal self-injury and the emotional disorders: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;37:72-88.

60. Koyanagi A, Stickley A, Haro JM. Psychotic-like experiences and nonsuicidal self-injury in England: results from a national survey [corrected]. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0145533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145533

61. Calati R, Bensassi I, Courtet P. The link between dissociation and both suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury: meta-analyses. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:103-114.

62. Wolff JC, Thompson E, Thomas SA, et al. Emotion dysregulation and non-suicidal self-injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;59:25-36.

63. Vaughn MG, Salas-Wright CP, DeLisi M, et al. Deliberate self-harm and the nexus of violence, victimization, and mental health problems in the United States. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225(3):588-595.

64. Levesque C, Lafontaine M-F, Bureau J-F, et al. The influence of romantic attachment and intimate partner violence on nonsuicidal self-injury in young adults. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(5):474-483.

65. Carranza AB, Wallis CRD, Jonnson MR, et al. Nonsuicidal self-injury and intimate partner violence: directionality of violence and motives for self-injury. J Interpers Violence. 2020;886260520922372. doi: 10.1177/0886260520922372

66. Khazaie H, Zakiei A, McCall WV, et al. Relationship between sleep problems and self-injury: a systematic review. Behav Sleep Med. 2020;1-16. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2020.1822360

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is the direct and deliberate destruction of body tissue without intent to die.1 Common forms of NSSI include cutting, burning, scraping/scratching skin, biting, hitting, and interfering with wound healing.2 Functional theories suggest that NSSI temporarily alleviates overwhelming negative emotions and can produce feelings of relief, resulting in a reinforcing effect.3

NSSI has been shown to be a risk factor for future suicide attempts.4 A 2018 study found that NSSI is associated with an increased risk of subsequent suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR] 2.8), suicide plan (OR 3.0), and suicide attempt (OR 5.5).5 NSSI is also associated with individuals who had suicidal ideation and formed a suicide plan, and individuals who had a suicide plan and attempted suicide (ORs 1.7 to 2.1).5 Another study found that 70% of adolescents who engage in NSSI have attempted suicide during their lifetime, and 55% have multiple attempts.6

Given the overlap between suicide attempts and NSSI, performing a thorough suicide risk assessment (which is beyond the scope of this article) is crucial. This article describes the static and dynamic risk factors for NSSI in adolescents and adults, which can help us perform a suicide risk assessment and allow us to formulate an appropriate treatment plan that includes safety-based interventions.

NSSI risk factors for adolescents

From developing sexual identity and undergoing puberty to achieving increased independence from their parents and developing a sense of autonomy, adolescents undergo many biological, psychological, and social changes before reaching adulthood.7 Data suggest that NSSI often begins in adolescence, with a typical onset at age 13 or 14.3 Community studies show that one-third to one-half of adolescents in the United States have engaged in NSSI.8,9 Previously, NSSI during adolescence was associated with 3 major diagnostic categories: eating disorders, developmental disabilities, and borderline personality disorder (BPD).10 However, recent data suggest that NSSI is also common outside of these categories. Here we describe static and dynamic risk factors for NSSI in adolescents (Table 111-42). Table 211-42 summarizes the studies of NSSI in adolescents that we reviewed.

Static risk factors

Female adolescents and adults engage in NSSI at higher rates than males. The difference is larger in clinical populations compared to the general population.11

A large portion of research about NSSI has been conducted in studies in which the majority of participants were White.12 Most studies report a higher prevalence of NSSI among non-Hispanic White youth,13 but some suggest other ethnic groups may also experience high rates of self-harm and NSSI.13-15 Several studies have demonstrated high rates of self-harm among South Asian adult females compared with White adult females, but this difference may be less pronounced in adolescents.14 One study in the United Kingdom found that White females age 10 to 14 had higher rates of self-harm compared to South Asian females,14 while another found that risk and rates of self-harm in young South Asian people varied by city and country of origin.15 Young Black females15 and young Black males13 also may be at an increased risk of self-harm. One review found that Black females were more likely to self-harm than Asian or White groups.15

Several studies suggest that sexual minority adolescents (SMA) (eg, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) are at greater risk for NSSI than heterosexual adolescents.16 SMA have been shown to engage in a significantly greater frequency of NSSI and more types of NSSI than heterosexual adolescents.16 Furthermore, on the Inventory of Statements about Self-Injury, SMA self-reported using NSSI for intrapersonal functions (eg, for affect regulation, antisuicide, self-punishment) significantly greater than their heterosexual peers; however, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups on interpersonal functions (eg, autonomy, interpersonal boundaries, peer bonding, sensation-seeking).16

Continue to: Transgender and gender nonconfirming...

Transgender and gender nonconfirming (GNC) youth are at a particularly high risk for NSSI; 30% to 45.5% of transgender adolescents report self-injury.17 Factors shown to distinguish transgender/GNC youth who engage in NSSI from those who do not include having a mental health problem, depression, running away from home, substance use, lower self-esteem/greater self-criticism, experiencing transphobia victimization, and having more interpersonal problems.18,19 Among transgender/GNC youth, those whose biological sex is female are more likely to report NSSI than those whose biological sex is male (ie, transgendered adolescent males are more likely to report NSSI than transgendered adolescent females).18,19

Most forms of childhood maltreatment have been associated with NSSI. In a recently published review, Liu et al20 found that childhood maltreatment (including sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and physical neglect) was associated with an increased risk for NSSI. However, conflicting evidence suggests that when confounders are removed, only childhood emotional abuse was directly associated with NSSI.21 Current evidence is modest for childhood emotional neglect as a risk factor for NSSI.20

Increasing research is investigating the biological processes that may be implicated in NSSI. Some studies suggest that endogenous opioids,22 monoamine neurotransmitters,22 and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis23 may play a role in NSSI. Compared to healthy controls, adolescents engaging in NSSI have been shown to have lower pain intensity (P = .036), higher pain thresholds (P = .040), and lower beta-endorphins (endogenous opioid hormones involved in mediating stress and pain) (P = .002).24 There may be alterations in the HPA axis among adolescents who engage in NSSI, more specifically stronger cortisol awakening responses.23 Both functional and standard MRI have been used to study the neurobiology of NSSI. One study demonstrated differences in functional connectivity between brain areas linked to neuroregulation of emotions in adolescents who engage in NSSI,25 while another found volume reduction in the insula of these adolescents, which suggests a possible neurobiological reason for impulsivity and the increased risk of suicidal behavior.26

Dynamic risk factors

Research has repeatedly shown bullying is a risk factor for NSSI.27 One study found that younger children who were victimized reported significantly more NSSI than older children.28 New data suggest that perpetrators of bullying are also at risk for deliberate self-harm behavior (SHB), which this study defined as a behavior that is intended to cause self-harm but without suicidal intent and having a nonfatal outcome.29 Victims of cyberbullying also are at a greater risk for self-harm, suicidal behaviors, and suicide attempt.30 To a lesser extent, cyberbullying perpetrators are at greater risk for suicidal behaviors and suicidal ideation.30 Bullying is a risk factor for NSSI not only in adolescence, but also in adulthood. Lereya et al31 found that victims of bullying in childhood and early adolescence were more likely to have mental health problems (including anxiety and depression) and more likely to engage in SHB—which this study defined as hurting oneself on purpose in any way—as adults.

The effects of internet use on adolescents’ mental health also has been investigated. A recent review that explored the relationship between all types of internet use (general use, internet addiction, social media, self-harm websites, forums, etc) and SHB/suicidal behavior found that young people with internet addiction, high levels of internet use, and a tendency to view websites with self-harm or suicidal content were at higher risk of engaging in SHB/suicidal behavior.32 This study did not use a specific definition for SHB or suicidal behavior.32

Continue to: Membership in certain youth...

Membership in certain youth subcultures (eg, emo or goth) has been evaluated as potential risk factors for depression and deliberate self-harm. Bowes et al33 found that for each unit increase in goth affiliation (not at all, not very much, somewhat, more than somewhat, very much), youth were 1.52 times more likely to engage in SHB; these researchers also reported a dose-response association between goth identification and future SHB. This study asked participants if they have ever tried to harm or hurt themselves in any manner, but did not distinguish between individuals who had harmed themselves with and without suicidal intent.33

Personality traits such as impulsiveness and loneliness have been linked to NSSI among adolescents.34,35 A recent study found that adolescents who met the proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for NSSI scored higher on the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, specifically in measures of:

- motor impulsiveness (ie, acting without thinking)

- attentional impulsiveness (ie, making decisions quickly)

- impulsiveness due to lack of planning (ie, failure to plan for the future).34

This study also found that adolescents who identified as being lonely based on scores on the Brazilian Loneliness Scale were at a higher risk for NSSI.34

A recent systematic review (32 studies) and meta-analysis (9 studies) found that school absenteeism was associated with a risk of self-harm (pooled aOR 1.37, P = .01) and suicidal ideation (pooled aOR 1.20, P = .03).36 This study suggested that school absenteeism, an important marker of social exclusion, was associated with both SHB and suicidal ideation in young people.36 It defined SHB as any act of self-injury or self-poisoning, regardless of intent.36

Finally, family-related factors have been associated with an increased risk of NSSI. One study of 11,814 children age 9 and 10 revealed that high family conflict (OR 1.09; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.14) and low parental monitoring (OR 0.95; 95% CI, 0.93 to 0.98) were associated with NSSI.37 A smaller, community-based study found that adolescents with NSSI reported significantly less maternal support and warmth than nonclinical controls, but a cause-and-effect relationship has not yet been determined.38 Parental history alone may influence adolescents’ risk of NSSI. A study that included nearly 76,000 youth found that adolescents with perceived parental alcohol problems had higher odds of self-injury, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts.39 Adolescents exposed to maternal or paternal adversities were also at a higher risk of self-harm (hazard ratio 1.5 to 5.4 among males, 1.7 to 3.9 among females).40

Continue to: NSSI risk factors for adults

NSSI risk factors for adults

Although data regarding the prevalence of NSSI in adults are lacking, available studies report a 12-month prevalence of 0.9%2 and a lifetime prevalence of 5.5% to 5.9%.43 There is a significant overlap in risk factors for NSSI in adolescent and adult populations, but there are also many important differences. The static and dynamic risk factors for NSSI in adults are described in Table 3.44-66 Table 444-66 summarizes the studies of NSSI in adults that we reviewed.

Static risk factors

Research findings regarding the prevalence of NSSI based on gender are varied. For years, it has been believed that women are more likely to engage in NSSI than men. Recent meta-analyses that have examined this relationship closely found that the gender difference is larger for clinical samples compared to community samples and more pronounced in younger individuals.11

As is the case with adolescents, there may be ethnic variations in rates of self-harm and NSSI among adults. A 2013 study by Chesin et al44 found that Asian and White young adults experience higher rates of NSSI than their Hispanic and Black counterparts. Evidence suggests that relative rates of self-harm for older South Asian adults are lower than in older White adults.15

Compared to heterosexual or cisgender individuals, members of sexual and gender minorities have a higher past-year and lifetime prevalence of NSSI.45 One study found that the weighted effect size between sexual orientation and NSSI had an OR of 3 (95% CI, 2.46 to 3.66), indicating a medium-to-large effect.46 Bisexual and transgender individuals appear to be at the highest risk for NSSI when compared to members of other sexual and gender minority groups.45 One review that included mostly cross-sectional studies found that individuals identifying as bisexual had up to 6 times the odds of engaging in NSSI when compared to those of other sexual orientations.47

Incarceration is a risk factor for NSSI. The rates of NSSI in criminal justice settings are higher (up to 61%) than in the general adult population (approximately 4%).48 Recent research found that NSSI serves similar functions in correctional and non-correctional settings, primarily to regulate emotions.48 However, there is also evidence of higher rates of NSSI being motivated by an attempt to influence the environment (ie, engaging in NSSI in order to be transferred to another prison unit) compared to NSSI in community settings.48

Continue to: Though less robust than data...

Though less robust than data published regarding adolescents, the role of biological processes in adults engaging in NSSI has also been studied. A 2021 study by Störkel et al49 found that levels of salivary beta-endorphins were significantly lower in adults immediately before engaging in NSSI compared to after NSSI. Furthermore, adults who engage in NSSI have lower levels of met-enkephalin (P < .01), an opioid growth factor, compared to adults who have never engaged in NSSI.22

Dynamic risk factors

Individuals who engage in NSSI often report substance use, but there is little data on whether substance use is an independent risk factor for NSSI. Although limited, recent evidence suggests illicit substance use in both adolescents41 and adults50 increases risk for NSSI. Richardson et al50 found that the use of barbiturates, opiates, and sedatives significantly increased the frequency of NSSI, whereas use of marijuana, phencyclidine, and medications used to treat anxiety significantly increased the severity of NSSI. A smaller study conducted in South Africa found that individuals who engage in substance use and NSSI were more likely to be male (P < .001).51

Eating disorders and NSSI are highly comorbid.52 The lifetime prevalence of NSSI among individuals with eating disorders ranges from 20.6%to 37.1%.52,53 Results are inconsistent regarding which eating disorders (if any) are greater risk factors for NSSI. One study found that the prevalence of NSSI in patients with bulimia nervosa was 32.7% (95% CI, 26.9% to 39.1%) vs 21.8% in patients with anorexia nervosa (95% CI, 18.5% to 25.6%).54 Another study found that individuals with binge eating/purging–type eating disorders reported engaging in NSSI more frequently than those with other types of eating disorders.55 Among patients with eating disorders who reported NSSI, risk factors included younger age of onset, more negative self-evaluation, more impulsive behavior, concomitant substance use, history of suicide attempts, childhood abuse, and peer aggression.53,55 Body image dissatisfaction and self-criticism, even in individuals not formally diagnosed with an eating disorder, are small but significant predictors of NSSI.56,57

Mood disorders have also been linked to NSSI.58,59 Anxiety disorders (including generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, and agoraphobia) as well as anxiety-related disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorder have been significantly associated with NSSI (P < .001), but this relationship decreased in strength when mood instability was removed as a confounder.58 Among patients with anxiety and anxiety-related disorders, panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have shown the strongest association with NSSI, with pooled aORs of 2.67 and 2.06, respectively.59

Recent studies have examined the association of other mental health disorders and symptoms with NSSI, including psychosis60 and dissociative symptoms.61 One study found that paranoia, thought control, and auditory hallucinations were significantly associated with NSSI60; however, after controlling for concomitant BPD, only paranoia was significantly associated with NSSI.60 Individuals diagnosed with dissociative disorders were more likely than patients without such disorders to endorse NSSI and suicide attempts.61

Continue to: Emotional dysregulation...

Emotional dysregulation (EDR)—defined as difficulty understanding, recognizing, and managing one’s emotions—has been researched extensively in relation to NSSI.62 A recent review that included studies of both adolescents and adults reported a significant association between EDR and NSSI, with an OR of 2.40 (95% CI, 2.01 to 2.86).62 A larger effect size was observed between EDR and lifetime NSSI (OR 3.21; 95% CI, 2.63 to 3.91) compared to past-year NSSI (OR 2.32; 95% CI, 1.84 to 2.92).62 Patient age, sex, and sample type (clinical vs community) were not significant moderators of strength between the reported associations.62

Studies examining intimate partner violence (IPV) and NSSI have found that young adults who engage in IPV (both as victims and as perpetrators) are more likely to report NSSI.63-65 Researchers have proposed that anxiety over abandonment may explain this relationship.64 A recent study found that individuals with bidirectional IPV (ie, both victimization and perpetration) engaged in NSSI at a higher prevalence than those engaging in unidirectional IPV or no IPV.65 This suggests that relationship violence in general (rather than just being a victim of IPV) may be a risk factor for NSSI.65

Finally, studies suggest that adolescents and adults who have sleep problems (insomnia, short sleep duration, long sleep onset latency, waking after sleep onset, and poor quality sleep) are more likely to report self-harm or NSSI than those without sleep problems.42,66 In adults, this relationship is partially mediated by depressive symptoms, EDR, and PTSD.66 In adolescents, depressive symptoms are a mediator for this relationship.42

Bottom Line

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is a significant health concern due to its association with suicide attempts. Although there are similarities in NSSI risk factors between adolescents and adults, there are also important differences. Understanding these differences is necessary to develop appropriate treatment plans.

Related Resources

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. https://afsp.org/

- Cipriano A, Cella S, Cotrufo P. Nonsuicidal self-injury: a systematic review. Front Psych. 2017;8:1946. doi:10.3389/ fpsyg.2017.01946

- Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. Textbook of Suicide Risk Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is the direct and deliberate destruction of body tissue without intent to die.1 Common forms of NSSI include cutting, burning, scraping/scratching skin, biting, hitting, and interfering with wound healing.2 Functional theories suggest that NSSI temporarily alleviates overwhelming negative emotions and can produce feelings of relief, resulting in a reinforcing effect.3

NSSI has been shown to be a risk factor for future suicide attempts.4 A 2018 study found that NSSI is associated with an increased risk of subsequent suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR] 2.8), suicide plan (OR 3.0), and suicide attempt (OR 5.5).5 NSSI is also associated with individuals who had suicidal ideation and formed a suicide plan, and individuals who had a suicide plan and attempted suicide (ORs 1.7 to 2.1).5 Another study found that 70% of adolescents who engage in NSSI have attempted suicide during their lifetime, and 55% have multiple attempts.6

Given the overlap between suicide attempts and NSSI, performing a thorough suicide risk assessment (which is beyond the scope of this article) is crucial. This article describes the static and dynamic risk factors for NSSI in adolescents and adults, which can help us perform a suicide risk assessment and allow us to formulate an appropriate treatment plan that includes safety-based interventions.

NSSI risk factors for adolescents

From developing sexual identity and undergoing puberty to achieving increased independence from their parents and developing a sense of autonomy, adolescents undergo many biological, psychological, and social changes before reaching adulthood.7 Data suggest that NSSI often begins in adolescence, with a typical onset at age 13 or 14.3 Community studies show that one-third to one-half of adolescents in the United States have engaged in NSSI.8,9 Previously, NSSI during adolescence was associated with 3 major diagnostic categories: eating disorders, developmental disabilities, and borderline personality disorder (BPD).10 However, recent data suggest that NSSI is also common outside of these categories. Here we describe static and dynamic risk factors for NSSI in adolescents (Table 111-42). Table 211-42 summarizes the studies of NSSI in adolescents that we reviewed.

Static risk factors

Female adolescents and adults engage in NSSI at higher rates than males. The difference is larger in clinical populations compared to the general population.11

A large portion of research about NSSI has been conducted in studies in which the majority of participants were White.12 Most studies report a higher prevalence of NSSI among non-Hispanic White youth,13 but some suggest other ethnic groups may also experience high rates of self-harm and NSSI.13-15 Several studies have demonstrated high rates of self-harm among South Asian adult females compared with White adult females, but this difference may be less pronounced in adolescents.14 One study in the United Kingdom found that White females age 10 to 14 had higher rates of self-harm compared to South Asian females,14 while another found that risk and rates of self-harm in young South Asian people varied by city and country of origin.15 Young Black females15 and young Black males13 also may be at an increased risk of self-harm. One review found that Black females were more likely to self-harm than Asian or White groups.15

Several studies suggest that sexual minority adolescents (SMA) (eg, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) are at greater risk for NSSI than heterosexual adolescents.16 SMA have been shown to engage in a significantly greater frequency of NSSI and more types of NSSI than heterosexual adolescents.16 Furthermore, on the Inventory of Statements about Self-Injury, SMA self-reported using NSSI for intrapersonal functions (eg, for affect regulation, antisuicide, self-punishment) significantly greater than their heterosexual peers; however, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups on interpersonal functions (eg, autonomy, interpersonal boundaries, peer bonding, sensation-seeking).16

Continue to: Transgender and gender nonconfirming...

Transgender and gender nonconfirming (GNC) youth are at a particularly high risk for NSSI; 30% to 45.5% of transgender adolescents report self-injury.17 Factors shown to distinguish transgender/GNC youth who engage in NSSI from those who do not include having a mental health problem, depression, running away from home, substance use, lower self-esteem/greater self-criticism, experiencing transphobia victimization, and having more interpersonal problems.18,19 Among transgender/GNC youth, those whose biological sex is female are more likely to report NSSI than those whose biological sex is male (ie, transgendered adolescent males are more likely to report NSSI than transgendered adolescent females).18,19

Most forms of childhood maltreatment have been associated with NSSI. In a recently published review, Liu et al20 found that childhood maltreatment (including sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and physical neglect) was associated with an increased risk for NSSI. However, conflicting evidence suggests that when confounders are removed, only childhood emotional abuse was directly associated with NSSI.21 Current evidence is modest for childhood emotional neglect as a risk factor for NSSI.20