User login

Pemphigus Vulgaris in Pregnancy

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is a rare autoimmune bullous dermatosis that has not shown a predilection toward a particular race or sex.1 Autoantibodies for desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3, members of the cadherin family that are involved in cellular adhesion, have been linked to the pathogenesis of PV.2 These autoantibodies play a role in the loss of cell-to-cell adhesion in the basal and suprabasal layers of the deep epidermis while cellular adhesion in the superficial epidermis remains intact, leading to the clinical presentation of epidermal blistering and ulcerations most commonly found on the scalp, face, groin, and axillae. Diagnosis typically is made based on skin biopsy and confirmed by direct immunofluorescence. Histologically, PV displays acantholysis and suprabasal cleft formation. Immunofluorescence may show IgG antibodies against the PV antigen in the epidermis.3 Once a diagnosis has been made, treatment typically consists of systemic steroids, as the use of steroids has had great effect in preventing infections, sepsis, and fatality that were once associated with PV.4 Mortality rates associated with PV have decreased to 10% to 15% with systemic steroids from a mortality rate as high as 70% in the presteroid era.1,5 Treatment of PV during pregnancy, as in our patient, requires obstetric and pediatric consultations before therapy is initiated. Use of corticosteroids during pregnancy can be potentially dangerous to the fetus, particularly if high doses are necessary to control maternal disease.6,7

Case Report

A 34-year-old pregnant woman at 6 weeks’ gestation presented with widespread blistering dermatitis and associated burning and pruritus. Her obstetrical history was gravida 3, para 2. The patient reported a “rash” on the scalp that had developed 9 months prior. She had been treated as an outpatient at an outside institution with topical antibiotics and antifungal medications, yet the dermatitis progressed. Three weeks prior to hospitalization, the rash was present on the skin and mucosal surfaces, including the groin, chest, face, hard palate, buccal mucosa, lips (Figure 1), and back (Figure 2). Nontender bullae ruptured after 3 days, releasing clear, yellow, serous fluid with associated burning and pruritus. The bullae were hemorrhagic and erythematous at the base.

|

| Figure 1. Facial involvement with bullae, crusted hemorrhagic lesions, and eschar in a 34-year-old pregnant woman. |

|

| Figure 2. Involvement of the back with bullae in various stages. Some bullae were intact while others newly erupted. |

|

| Figure 3. Superinfected and flaking scalp. |

|

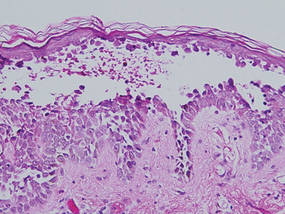

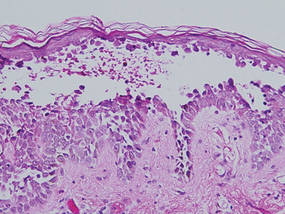

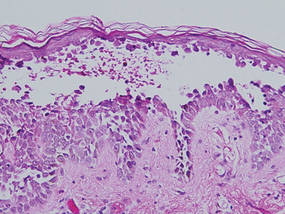

| Figure 4. Biopsy revealed suprabasal acantholysis with a tombstone effect of residual basal cells (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

At the current presentation, the patient had several excoriated 1- to 2-cm oval denudations; some were crusted with eschar. Nikolsky sign was negative. Multiple confluent bullous lesions had erupted on the entire scalp with a thick, impetiginous, yellow crust. She had a wet, boggy, foul-smelling, superinfected scalp that was mildly tender to touch with flaking tissue debris (Figure 3). A white blood cell count was 13.2×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L) with 5% eosinophils (reference range, 2.7%). The differential diagnosis included bullous impetigo, pemphigoid, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, dermatitis herpetiformis, and pemphigus vulgaris.

Biopsies of the scalp and back were taken and showed suprabasal acantholysis with a tombstone effect of residual basal cells standing up on the basement membrane without the characteristic acantholysis into skin appendages (Figure 4). The acantholytic cells in the bullous chamber did not round up as in Hailey-Hailey disease nor was there the dyskeratosis of Grover disease. Direct immunofluorescence on an elbow punch biopsy found diffuse 1+ intercellular IgG in the epidermis and diffuse 1+ basal intercellular C3, and was negative for IgA, IgM, and C1q, thus confirming a diagnosis of PV.

The patient was started on prednisone 20 mg once daily. An increase to prednisone 60 mg led to initial improvement of symptoms, but there was a relapse after several days, which is typical of PV in pregnancy,7 prompting the dose to be increased to 120 mg. Following alleviation of symptoms, the dose was later tapered back to 60 mg. No lesions were present at discharge or for 2.5 months thereafter, as the prednisone was tapered from 60 to 45 mg daily after discharge.

On follow-up, the patient’s PV was well controlled, but the prednisone dose was back up to 60 mg daily because of 2 new skin lesions that had developed since her last visit 2.5 months prior. Ultrasonography showed no fetal abnormalities as the pregnancy progressed to 28 weeks’ gestation. The patient developed hypertension and went into premature labor due to placenta previa. The neonate showed no skin lesions or anomalies while in the neonatal intensive care unit. The mother’s prednisone dose was tapered from 60 to 20 mg daily while the white blood cell count was 7.1×109/L with 2% eosinophils and a new scalp lesion appeared. Seven months after her initial discharge from the hospital for the dermatologic condition, she was no longer nursing and azathioprine was added to prednisone 60 mg daily.

Comment

Pemphigus vulgaris is associated with infertility in its active phase; therefore, PV during pregnancy is rare.8 Pregnancy may exacerbate PV, which has been a similar finding in other well-documented autoimmune diseases.7 One review of PV in pregnancy reported that 11 of 49 patients (22%) experienced an exacerbation of the disease.8 This finding pre-sents 2 problems: (1) severe active disease during pregnancy with high antibody titers has been shown to heighten risk for morbidity and mortality for the fetus, and (2) a patient with active PV during pregnancy may require systemic therapy with doses high enough to subdue the disease. The presence of PV was a challenge throughout our patient’s pregnancy. Transient skin lesions may occasionally appear in the neonate and seem to have an increased association with severe active PV in the mother; however, neonatal PV also has been present in mild cases in the mother.7 These lesions are secondary to passive transplacental transfer of PV antibodies but do not have long-lasting clinical implications because of an antibody’s brief half-life.9 The lesions either spontaneously resolve or can be treated with a topical corticosteroid.

Treatment with high-dose systemic corticosteroids or immunosuppressants can be problematic because of the risks posed to the fetus, especially if the mother must be treated when the embryo is particularly susceptible (eg, during organogenesis).10 If a woman with known PV is planning to become pregnant, it is recommended to first control and suppress the disease so that therapy can be minimal during the pregnancy. It also is recommended to use aggressive topical therapy if possible to control PV in a pregnant woman.8 This option would not have been efficacious in our patient because of her severe widespread disease.

Prednisone is considered one of the first-line treatments of PV and has been historically successful as a treatment for pregnant patients with PV if maintained at a low dosage. Prednisone, similar to other corticosteroids, can cross the placental barrier and can increase the chance of premature birth, infection, and mortality in high doses.7 Similar to prednisone, azathioprine is not recommended during pregnancy, but if use is necessary, it is suggested to keep the dose low to prevent fetal harm.11 Inadequate treatment and control of PV can be life threatening to the patient because of the severe infection that may ensue; thus it is necessary for the health of the patient and fetus to suppress the PV. One alternative to treatment with steroids and immunosuppressants is plasma exchange, which has been successful in the clinical context of pregnancy.12 The cons of plasma exchange are repeat procedures, the need to give the patient more immunosuppressants to prevent a rejection, and the return of the autoantibody.7

Several studies have evaluated the safety and efficacy of rituximab in the treatment of refractory PV. Multiple case reports state that both 1 and 2 courses of intravenous rituximab therapy at a dosage of 375 mg per square meter of body surface area affected once weekly for 4 weeks proved to be useful in clinical improvement for patients with refractory disease.13,14 Studies are currently underway to look at the effects of rituximab on pregnancy and the fetus. Preliminary findings show neonates may have B-cell abnormalities initially yet recover fully without infectious complications or sequelae.15 Rituximab currently is a pregnancy category C drug, and women are counseled to avoid pregnancy for at least 12 months after rituximab exposure and use contraception while actively taking the drug.16

Conclusion

Contrary to traditional thinking, PV itself may be associated with poor neonatal outcome, including prematurity and fetal death. These complications seem to be restricted to pregnancies with clinically severe PV.7 Our patient decided to progress with her pregnancy despite the potential risk to the fetus from the disease and treatment. Ultimately, the infant was delivered prematurely but was free of disease.

1. Fainaru O, Mashiach R, Kupferminc M, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy: a case report and review of literature. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1195-1197.

2. Joly P, Gilbert D, Thomine E, et al. Identification of a new antibody population directed against a desmosomal plaque antigen in pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:469-475.

3. Daniel Y, Shenhav M, Botchan A, et al. Pregnancy associated with pemphigus. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;102:667-669.

4. Ruach M, Ohel G, Rahav D, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris and pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1995;50:755-760.

5. Carson PJ, Hameed A, Ahmed AR. Influence of treatment on clinical course of pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:645-652.

6. Goldberg NS, DeFeo C, Kirshenbaum N. Pemphigus and pregnancy: risk factors and recommendations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(5, pt 2):877-879.

7. Lehman JS, Mueller KK, Schraith DF. Do safe and effective treatment options exist for patients with active pemphigus vulgaris who plan conception and pregnancy? Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:783-785.

8. Kardos M, Levine D, Gurcan H, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy: analysis of current data on the management and outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64:739-749.

9. Fenniche S, Benmously R, Marrak H, et al. Neonatal pemphigus vulgaris in an infant born to a mother with pemphigus vulgaris in remission. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:124-127.

10. Kalayciyan A, Engin B, Serdaroglu S, et al. A retrospective analysis of patients with pemphigus vulgaris associated with pregnancy. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:396-397.

11. Hup JM, Bruinsma RA, Boersma ER, et al. Neonatal pemphigus vulgaris: transplacental transmission of antibodies. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:468-472.

12. Piontek JO, Borberg H, Sollberg S, et al. Severe exacerbation of pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy: successful treatment with plasma exchange. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:455-456.

13. Faurschou A, Gniadecki R. Two courses of rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) for recalcitrant pemphigus vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:292-294.

14. Marzano AV, Fanoni D, Venegoni L, et al. Treatment of refractory pemphigus with the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab). Dermatology. 2007;214:310-318.

15. Braunstein I, Werth V. Treatment of dermatologic connective tissue disease and autoimmune blistering disorders in pregnancy. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:354-363.

16. Chakravarty EF, Murray ER, Kelman A, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to rituximab. Blood. 2011;117:1499-1506.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is a rare autoimmune bullous dermatosis that has not shown a predilection toward a particular race or sex.1 Autoantibodies for desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3, members of the cadherin family that are involved in cellular adhesion, have been linked to the pathogenesis of PV.2 These autoantibodies play a role in the loss of cell-to-cell adhesion in the basal and suprabasal layers of the deep epidermis while cellular adhesion in the superficial epidermis remains intact, leading to the clinical presentation of epidermal blistering and ulcerations most commonly found on the scalp, face, groin, and axillae. Diagnosis typically is made based on skin biopsy and confirmed by direct immunofluorescence. Histologically, PV displays acantholysis and suprabasal cleft formation. Immunofluorescence may show IgG antibodies against the PV antigen in the epidermis.3 Once a diagnosis has been made, treatment typically consists of systemic steroids, as the use of steroids has had great effect in preventing infections, sepsis, and fatality that were once associated with PV.4 Mortality rates associated with PV have decreased to 10% to 15% with systemic steroids from a mortality rate as high as 70% in the presteroid era.1,5 Treatment of PV during pregnancy, as in our patient, requires obstetric and pediatric consultations before therapy is initiated. Use of corticosteroids during pregnancy can be potentially dangerous to the fetus, particularly if high doses are necessary to control maternal disease.6,7

Case Report

A 34-year-old pregnant woman at 6 weeks’ gestation presented with widespread blistering dermatitis and associated burning and pruritus. Her obstetrical history was gravida 3, para 2. The patient reported a “rash” on the scalp that had developed 9 months prior. She had been treated as an outpatient at an outside institution with topical antibiotics and antifungal medications, yet the dermatitis progressed. Three weeks prior to hospitalization, the rash was present on the skin and mucosal surfaces, including the groin, chest, face, hard palate, buccal mucosa, lips (Figure 1), and back (Figure 2). Nontender bullae ruptured after 3 days, releasing clear, yellow, serous fluid with associated burning and pruritus. The bullae were hemorrhagic and erythematous at the base.

|

| Figure 1. Facial involvement with bullae, crusted hemorrhagic lesions, and eschar in a 34-year-old pregnant woman. |

|

| Figure 2. Involvement of the back with bullae in various stages. Some bullae were intact while others newly erupted. |

|

| Figure 3. Superinfected and flaking scalp. |

|

| Figure 4. Biopsy revealed suprabasal acantholysis with a tombstone effect of residual basal cells (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

At the current presentation, the patient had several excoriated 1- to 2-cm oval denudations; some were crusted with eschar. Nikolsky sign was negative. Multiple confluent bullous lesions had erupted on the entire scalp with a thick, impetiginous, yellow crust. She had a wet, boggy, foul-smelling, superinfected scalp that was mildly tender to touch with flaking tissue debris (Figure 3). A white blood cell count was 13.2×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L) with 5% eosinophils (reference range, 2.7%). The differential diagnosis included bullous impetigo, pemphigoid, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, dermatitis herpetiformis, and pemphigus vulgaris.

Biopsies of the scalp and back were taken and showed suprabasal acantholysis with a tombstone effect of residual basal cells standing up on the basement membrane without the characteristic acantholysis into skin appendages (Figure 4). The acantholytic cells in the bullous chamber did not round up as in Hailey-Hailey disease nor was there the dyskeratosis of Grover disease. Direct immunofluorescence on an elbow punch biopsy found diffuse 1+ intercellular IgG in the epidermis and diffuse 1+ basal intercellular C3, and was negative for IgA, IgM, and C1q, thus confirming a diagnosis of PV.

The patient was started on prednisone 20 mg once daily. An increase to prednisone 60 mg led to initial improvement of symptoms, but there was a relapse after several days, which is typical of PV in pregnancy,7 prompting the dose to be increased to 120 mg. Following alleviation of symptoms, the dose was later tapered back to 60 mg. No lesions were present at discharge or for 2.5 months thereafter, as the prednisone was tapered from 60 to 45 mg daily after discharge.

On follow-up, the patient’s PV was well controlled, but the prednisone dose was back up to 60 mg daily because of 2 new skin lesions that had developed since her last visit 2.5 months prior. Ultrasonography showed no fetal abnormalities as the pregnancy progressed to 28 weeks’ gestation. The patient developed hypertension and went into premature labor due to placenta previa. The neonate showed no skin lesions or anomalies while in the neonatal intensive care unit. The mother’s prednisone dose was tapered from 60 to 20 mg daily while the white blood cell count was 7.1×109/L with 2% eosinophils and a new scalp lesion appeared. Seven months after her initial discharge from the hospital for the dermatologic condition, she was no longer nursing and azathioprine was added to prednisone 60 mg daily.

Comment

Pemphigus vulgaris is associated with infertility in its active phase; therefore, PV during pregnancy is rare.8 Pregnancy may exacerbate PV, which has been a similar finding in other well-documented autoimmune diseases.7 One review of PV in pregnancy reported that 11 of 49 patients (22%) experienced an exacerbation of the disease.8 This finding pre-sents 2 problems: (1) severe active disease during pregnancy with high antibody titers has been shown to heighten risk for morbidity and mortality for the fetus, and (2) a patient with active PV during pregnancy may require systemic therapy with doses high enough to subdue the disease. The presence of PV was a challenge throughout our patient’s pregnancy. Transient skin lesions may occasionally appear in the neonate and seem to have an increased association with severe active PV in the mother; however, neonatal PV also has been present in mild cases in the mother.7 These lesions are secondary to passive transplacental transfer of PV antibodies but do not have long-lasting clinical implications because of an antibody’s brief half-life.9 The lesions either spontaneously resolve or can be treated with a topical corticosteroid.

Treatment with high-dose systemic corticosteroids or immunosuppressants can be problematic because of the risks posed to the fetus, especially if the mother must be treated when the embryo is particularly susceptible (eg, during organogenesis).10 If a woman with known PV is planning to become pregnant, it is recommended to first control and suppress the disease so that therapy can be minimal during the pregnancy. It also is recommended to use aggressive topical therapy if possible to control PV in a pregnant woman.8 This option would not have been efficacious in our patient because of her severe widespread disease.

Prednisone is considered one of the first-line treatments of PV and has been historically successful as a treatment for pregnant patients with PV if maintained at a low dosage. Prednisone, similar to other corticosteroids, can cross the placental barrier and can increase the chance of premature birth, infection, and mortality in high doses.7 Similar to prednisone, azathioprine is not recommended during pregnancy, but if use is necessary, it is suggested to keep the dose low to prevent fetal harm.11 Inadequate treatment and control of PV can be life threatening to the patient because of the severe infection that may ensue; thus it is necessary for the health of the patient and fetus to suppress the PV. One alternative to treatment with steroids and immunosuppressants is plasma exchange, which has been successful in the clinical context of pregnancy.12 The cons of plasma exchange are repeat procedures, the need to give the patient more immunosuppressants to prevent a rejection, and the return of the autoantibody.7

Several studies have evaluated the safety and efficacy of rituximab in the treatment of refractory PV. Multiple case reports state that both 1 and 2 courses of intravenous rituximab therapy at a dosage of 375 mg per square meter of body surface area affected once weekly for 4 weeks proved to be useful in clinical improvement for patients with refractory disease.13,14 Studies are currently underway to look at the effects of rituximab on pregnancy and the fetus. Preliminary findings show neonates may have B-cell abnormalities initially yet recover fully without infectious complications or sequelae.15 Rituximab currently is a pregnancy category C drug, and women are counseled to avoid pregnancy for at least 12 months after rituximab exposure and use contraception while actively taking the drug.16

Conclusion

Contrary to traditional thinking, PV itself may be associated with poor neonatal outcome, including prematurity and fetal death. These complications seem to be restricted to pregnancies with clinically severe PV.7 Our patient decided to progress with her pregnancy despite the potential risk to the fetus from the disease and treatment. Ultimately, the infant was delivered prematurely but was free of disease.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is a rare autoimmune bullous dermatosis that has not shown a predilection toward a particular race or sex.1 Autoantibodies for desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3, members of the cadherin family that are involved in cellular adhesion, have been linked to the pathogenesis of PV.2 These autoantibodies play a role in the loss of cell-to-cell adhesion in the basal and suprabasal layers of the deep epidermis while cellular adhesion in the superficial epidermis remains intact, leading to the clinical presentation of epidermal blistering and ulcerations most commonly found on the scalp, face, groin, and axillae. Diagnosis typically is made based on skin biopsy and confirmed by direct immunofluorescence. Histologically, PV displays acantholysis and suprabasal cleft formation. Immunofluorescence may show IgG antibodies against the PV antigen in the epidermis.3 Once a diagnosis has been made, treatment typically consists of systemic steroids, as the use of steroids has had great effect in preventing infections, sepsis, and fatality that were once associated with PV.4 Mortality rates associated with PV have decreased to 10% to 15% with systemic steroids from a mortality rate as high as 70% in the presteroid era.1,5 Treatment of PV during pregnancy, as in our patient, requires obstetric and pediatric consultations before therapy is initiated. Use of corticosteroids during pregnancy can be potentially dangerous to the fetus, particularly if high doses are necessary to control maternal disease.6,7

Case Report

A 34-year-old pregnant woman at 6 weeks’ gestation presented with widespread blistering dermatitis and associated burning and pruritus. Her obstetrical history was gravida 3, para 2. The patient reported a “rash” on the scalp that had developed 9 months prior. She had been treated as an outpatient at an outside institution with topical antibiotics and antifungal medications, yet the dermatitis progressed. Three weeks prior to hospitalization, the rash was present on the skin and mucosal surfaces, including the groin, chest, face, hard palate, buccal mucosa, lips (Figure 1), and back (Figure 2). Nontender bullae ruptured after 3 days, releasing clear, yellow, serous fluid with associated burning and pruritus. The bullae were hemorrhagic and erythematous at the base.

|

| Figure 1. Facial involvement with bullae, crusted hemorrhagic lesions, and eschar in a 34-year-old pregnant woman. |

|

| Figure 2. Involvement of the back with bullae in various stages. Some bullae were intact while others newly erupted. |

|

| Figure 3. Superinfected and flaking scalp. |

|

| Figure 4. Biopsy revealed suprabasal acantholysis with a tombstone effect of residual basal cells (H&E, original magnification ×200). |

At the current presentation, the patient had several excoriated 1- to 2-cm oval denudations; some were crusted with eschar. Nikolsky sign was negative. Multiple confluent bullous lesions had erupted on the entire scalp with a thick, impetiginous, yellow crust. She had a wet, boggy, foul-smelling, superinfected scalp that was mildly tender to touch with flaking tissue debris (Figure 3). A white blood cell count was 13.2×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L) with 5% eosinophils (reference range, 2.7%). The differential diagnosis included bullous impetigo, pemphigoid, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, dermatitis herpetiformis, and pemphigus vulgaris.

Biopsies of the scalp and back were taken and showed suprabasal acantholysis with a tombstone effect of residual basal cells standing up on the basement membrane without the characteristic acantholysis into skin appendages (Figure 4). The acantholytic cells in the bullous chamber did not round up as in Hailey-Hailey disease nor was there the dyskeratosis of Grover disease. Direct immunofluorescence on an elbow punch biopsy found diffuse 1+ intercellular IgG in the epidermis and diffuse 1+ basal intercellular C3, and was negative for IgA, IgM, and C1q, thus confirming a diagnosis of PV.

The patient was started on prednisone 20 mg once daily. An increase to prednisone 60 mg led to initial improvement of symptoms, but there was a relapse after several days, which is typical of PV in pregnancy,7 prompting the dose to be increased to 120 mg. Following alleviation of symptoms, the dose was later tapered back to 60 mg. No lesions were present at discharge or for 2.5 months thereafter, as the prednisone was tapered from 60 to 45 mg daily after discharge.

On follow-up, the patient’s PV was well controlled, but the prednisone dose was back up to 60 mg daily because of 2 new skin lesions that had developed since her last visit 2.5 months prior. Ultrasonography showed no fetal abnormalities as the pregnancy progressed to 28 weeks’ gestation. The patient developed hypertension and went into premature labor due to placenta previa. The neonate showed no skin lesions or anomalies while in the neonatal intensive care unit. The mother’s prednisone dose was tapered from 60 to 20 mg daily while the white blood cell count was 7.1×109/L with 2% eosinophils and a new scalp lesion appeared. Seven months after her initial discharge from the hospital for the dermatologic condition, she was no longer nursing and azathioprine was added to prednisone 60 mg daily.

Comment

Pemphigus vulgaris is associated with infertility in its active phase; therefore, PV during pregnancy is rare.8 Pregnancy may exacerbate PV, which has been a similar finding in other well-documented autoimmune diseases.7 One review of PV in pregnancy reported that 11 of 49 patients (22%) experienced an exacerbation of the disease.8 This finding pre-sents 2 problems: (1) severe active disease during pregnancy with high antibody titers has been shown to heighten risk for morbidity and mortality for the fetus, and (2) a patient with active PV during pregnancy may require systemic therapy with doses high enough to subdue the disease. The presence of PV was a challenge throughout our patient’s pregnancy. Transient skin lesions may occasionally appear in the neonate and seem to have an increased association with severe active PV in the mother; however, neonatal PV also has been present in mild cases in the mother.7 These lesions are secondary to passive transplacental transfer of PV antibodies but do not have long-lasting clinical implications because of an antibody’s brief half-life.9 The lesions either spontaneously resolve or can be treated with a topical corticosteroid.

Treatment with high-dose systemic corticosteroids or immunosuppressants can be problematic because of the risks posed to the fetus, especially if the mother must be treated when the embryo is particularly susceptible (eg, during organogenesis).10 If a woman with known PV is planning to become pregnant, it is recommended to first control and suppress the disease so that therapy can be minimal during the pregnancy. It also is recommended to use aggressive topical therapy if possible to control PV in a pregnant woman.8 This option would not have been efficacious in our patient because of her severe widespread disease.

Prednisone is considered one of the first-line treatments of PV and has been historically successful as a treatment for pregnant patients with PV if maintained at a low dosage. Prednisone, similar to other corticosteroids, can cross the placental barrier and can increase the chance of premature birth, infection, and mortality in high doses.7 Similar to prednisone, azathioprine is not recommended during pregnancy, but if use is necessary, it is suggested to keep the dose low to prevent fetal harm.11 Inadequate treatment and control of PV can be life threatening to the patient because of the severe infection that may ensue; thus it is necessary for the health of the patient and fetus to suppress the PV. One alternative to treatment with steroids and immunosuppressants is plasma exchange, which has been successful in the clinical context of pregnancy.12 The cons of plasma exchange are repeat procedures, the need to give the patient more immunosuppressants to prevent a rejection, and the return of the autoantibody.7

Several studies have evaluated the safety and efficacy of rituximab in the treatment of refractory PV. Multiple case reports state that both 1 and 2 courses of intravenous rituximab therapy at a dosage of 375 mg per square meter of body surface area affected once weekly for 4 weeks proved to be useful in clinical improvement for patients with refractory disease.13,14 Studies are currently underway to look at the effects of rituximab on pregnancy and the fetus. Preliminary findings show neonates may have B-cell abnormalities initially yet recover fully without infectious complications or sequelae.15 Rituximab currently is a pregnancy category C drug, and women are counseled to avoid pregnancy for at least 12 months after rituximab exposure and use contraception while actively taking the drug.16

Conclusion

Contrary to traditional thinking, PV itself may be associated with poor neonatal outcome, including prematurity and fetal death. These complications seem to be restricted to pregnancies with clinically severe PV.7 Our patient decided to progress with her pregnancy despite the potential risk to the fetus from the disease and treatment. Ultimately, the infant was delivered prematurely but was free of disease.

1. Fainaru O, Mashiach R, Kupferminc M, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy: a case report and review of literature. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1195-1197.

2. Joly P, Gilbert D, Thomine E, et al. Identification of a new antibody population directed against a desmosomal plaque antigen in pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:469-475.

3. Daniel Y, Shenhav M, Botchan A, et al. Pregnancy associated with pemphigus. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;102:667-669.

4. Ruach M, Ohel G, Rahav D, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris and pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1995;50:755-760.

5. Carson PJ, Hameed A, Ahmed AR. Influence of treatment on clinical course of pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:645-652.

6. Goldberg NS, DeFeo C, Kirshenbaum N. Pemphigus and pregnancy: risk factors and recommendations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(5, pt 2):877-879.

7. Lehman JS, Mueller KK, Schraith DF. Do safe and effective treatment options exist for patients with active pemphigus vulgaris who plan conception and pregnancy? Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:783-785.

8. Kardos M, Levine D, Gurcan H, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy: analysis of current data on the management and outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64:739-749.

9. Fenniche S, Benmously R, Marrak H, et al. Neonatal pemphigus vulgaris in an infant born to a mother with pemphigus vulgaris in remission. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:124-127.

10. Kalayciyan A, Engin B, Serdaroglu S, et al. A retrospective analysis of patients with pemphigus vulgaris associated with pregnancy. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:396-397.

11. Hup JM, Bruinsma RA, Boersma ER, et al. Neonatal pemphigus vulgaris: transplacental transmission of antibodies. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:468-472.

12. Piontek JO, Borberg H, Sollberg S, et al. Severe exacerbation of pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy: successful treatment with plasma exchange. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:455-456.

13. Faurschou A, Gniadecki R. Two courses of rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) for recalcitrant pemphigus vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:292-294.

14. Marzano AV, Fanoni D, Venegoni L, et al. Treatment of refractory pemphigus with the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab). Dermatology. 2007;214:310-318.

15. Braunstein I, Werth V. Treatment of dermatologic connective tissue disease and autoimmune blistering disorders in pregnancy. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:354-363.

16. Chakravarty EF, Murray ER, Kelman A, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to rituximab. Blood. 2011;117:1499-1506.

1. Fainaru O, Mashiach R, Kupferminc M, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy: a case report and review of literature. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1195-1197.

2. Joly P, Gilbert D, Thomine E, et al. Identification of a new antibody population directed against a desmosomal plaque antigen in pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:469-475.

3. Daniel Y, Shenhav M, Botchan A, et al. Pregnancy associated with pemphigus. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;102:667-669.

4. Ruach M, Ohel G, Rahav D, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris and pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1995;50:755-760.

5. Carson PJ, Hameed A, Ahmed AR. Influence of treatment on clinical course of pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:645-652.

6. Goldberg NS, DeFeo C, Kirshenbaum N. Pemphigus and pregnancy: risk factors and recommendations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(5, pt 2):877-879.

7. Lehman JS, Mueller KK, Schraith DF. Do safe and effective treatment options exist for patients with active pemphigus vulgaris who plan conception and pregnancy? Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:783-785.

8. Kardos M, Levine D, Gurcan H, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy: analysis of current data on the management and outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64:739-749.

9. Fenniche S, Benmously R, Marrak H, et al. Neonatal pemphigus vulgaris in an infant born to a mother with pemphigus vulgaris in remission. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:124-127.

10. Kalayciyan A, Engin B, Serdaroglu S, et al. A retrospective analysis of patients with pemphigus vulgaris associated with pregnancy. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:396-397.

11. Hup JM, Bruinsma RA, Boersma ER, et al. Neonatal pemphigus vulgaris: transplacental transmission of antibodies. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:468-472.

12. Piontek JO, Borberg H, Sollberg S, et al. Severe exacerbation of pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy: successful treatment with plasma exchange. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:455-456.

13. Faurschou A, Gniadecki R. Two courses of rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) for recalcitrant pemphigus vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:292-294.

14. Marzano AV, Fanoni D, Venegoni L, et al. Treatment of refractory pemphigus with the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab). Dermatology. 2007;214:310-318.

15. Braunstein I, Werth V. Treatment of dermatologic connective tissue disease and autoimmune blistering disorders in pregnancy. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:354-363.

16. Chakravarty EF, Murray ER, Kelman A, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to rituximab. Blood. 2011;117:1499-1506.

Practice Points

- Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy is paramount in protecting the health of the mother and fetus.

- Management of autoimmune diseases during pregnancy continues to present numerous challenges for physicians due to the pathology of the diseases as well as the sensitive nature of pregnancy and lack of robust data in this patient population.