User login

Unmasking Our Grief

Since the start of the pandemic, health care systems have requested many in-services for staff on self-care and stress management to help health care workers (HCWs) cope with the heavy toll of COVID-19. The pandemic has set off a global mental health crisis, with unprecedented numbers of individuals meeting criteria for anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders in response to the intense stressors of living through a pandemic. These calls to assist staff with self-care and burnout prevention have been especially salient for psychologists working in palliative care and geriatrics, where fears of COVID-19 infection and numbers of patient deaths have been high.

Throughout these painful times, we have been grateful for an online community of palliative care psychologists within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) from across the continuum of care and across the country. This community brought together many of us who were both struggling ourselves and striving to support the teams and HCWs around us. We are psychologists who provide home-care services in North Carolina, inpatient hospice and long-term care services in California, and long-term care and outpatient palliative care services in Massachusetts. Through our shared struggles and challenges navigating the pandemic, we realized that our respective teams requested similar services, all focused on staff support.

The psychological impact of COVID-19 on HCWs was clear from the beginning. Early in the pandemic our respective teams requested us to provide staff support and education about coping to our local HCWs. Soon national groups for long-term care staff requested education programs. Through this work, we realized that the emotional needs of HCWs ran much deeper than simple self-care. At the onset of the pandemic, before realizing its chronicity, the trainings we offered focused on stress and coping strategies. We cited several frameworks for staff support and eagerly shared anything that might help us, and our colleagues, survive the immediate anxiety and tumult surrounding us.1-3 In this paper, we briefly discuss the distress affecting the geriatric care workforce, reflect on our efforts to cope as HCWs, and offer recommendations at individual and organization levels to help address our collective grief.

Impact of COVID-19

As the death toll mounted and hospitals were pushed to the brink, we saw the suffering of our fellow HCWs. The lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing supplies led to evolving and increasing anxiety for HCWs about contracting COVID-19, potentially spreading it to one’s social circle or family, fears of becoming sick and dying, and fears of inadvertently spreading the virus to medically-vulnerable patients. Increasing demands on staff required many to work outside their areas of expertise. Clinical practice guidelines changed frequently as information emerged about the virus. Staff members struggled to keep pace with the increasing number of patients, many of whom died despite heroic efforts to save them.

As the medical crisis grew, so too did social uprisings as the general public gained a strengthened awareness of the legacy and ongoing effects of systemic oppression, racism, and social inequities in the United States. Individuals grappled with their own privileges, which often hid such disparities from view. Many HCWs and clinicians of color had to navigate unsolicited questions and discussions about racial injustices while also trying to survive. As psychologists, we strove to support the HCWs around us while also struggling with our own stressors. As the magnitude of the pandemic and ongoing social injustices came into view, we realized that presentations on self-care and burnout prevention did not suffice. We needed discussions on unmasking our grief, acknowledging our traumas, and working toward collective healing.

Geriatric Care Workers

Experiences of grief and trauma hit the geriatric care workforce and especially long-term care facilities particularly hard given the high morbidity and mortality rates of COVID-19.4 The geriatric care workforce itself suffers from institutional vulnerabilities. Individuals are often underpaid, undertrained, and work within a system that continually experiences staffing shortages, high burnout, and consequently high levels of turnover.5,6 Recent immigrants and racial/ethnic minorities disproportionately make up this workforce, who often live in multigenerational households and work in multiple facilities to get by.7,8 Amid the pandemic these HCWs continued to work despite demoralizing negative media coverage of nursing homes.9 Notably, facilities with unionized staff were less likely to need second or third jobs to survive, thus reducing spread across facilities. This along with better access to PPE may have contributed to their lower COVID-19 infection and mortality rates relative to non-unionized staff.10

Similar to long-term care workers, home-care staff had related fears and anxieties, magnified by the need to enter multiple homes. This often overlooked but growing sector of the geriatric care workforce faced the added anxiety of the unknown as they entered multiple homes to provide care to their patients. These staff have little control over who may be in the home when they arrive, the sanitation/PPE practices of the patient/family, and therefore little control over their potential exposure to COVID-19. This also applies to home health aides who, although not providing medical services, are a critical part of home-care services and allow older adults to remain living independently in their home.

Reflection on Grief

As we witnessed the interactive effects of the pandemic and social inequities in geriatrics and palliative care, we frequently sought solace in online communities of psychologists working in similar settings. Over time, our regular community meetings developed a different tone: discussions about caring for others shifted to caring for ourselves. It seemed that in holding others’ pain, many of us neglected to address our own. We needed emotional support. We needed to acknowledge that we were not all okay; that the masks we wear for protection also reveal our vulnerabilities; and that protective equipment in hospitals do not protect us from the hate and bias targeting many of us face everywhere we go.

As we let ourselves be vulnerable with each other, we saw the true face of our pain: it was not stress, it was grief. We were sad, broken, mourning innumerable losses, and grieving, mostly alone. It felt overwhelming. Our minds and hearts often grew numb to find respite from pain. At times we found ourselves seeking haven in our offices, convincing ourselves that paperwork needed to be done when in reality we had no space to hold anyone else’s pain; we could barely contain our own. We could only take so much.

Without space to process, grief festers and eats away at our remaining compassion. How do we hold grace for ourselves, dare to be vulnerable, and allow ourselves to feel, when doing so opens the door to our own grief? How do we allow room for emotional processing when we learned to numb-out in order to function? And as women with diverse intersectional identities, how do we honor our humanity when we live in a society that reflects its indifference? We needed to process our pain in order to heal in the slow and uneven way that grief heals.

Caring During Tough Times

The pain we feel is real and it tears at us over time. Pushing it away disenfranchises ourselves of the opportunity to heal and grow. Our collective grief and trauma demand collective healing and acknowledgment of our individual suffering. We must honor our shared humanity and find commonality amid our differences. Typical self-care (healthy eating, sleep, basic hygiene) may not be enough to mitigate the enormity of these stressors. A glass of wine or a virtual dinner with friends may distract but does not heal our wounds.

Self-care, by definition, centers the self and ignores the larger systemic factors that maintain our struggles. It keeps the focus on the individual and in so doing, risks inducing self-blame should we continue feeling burnout. We must do more. We can advocate that systems acknowledge our grief and suffering as well as our strengths and resiliencies. We can demand that organizations recognize human limits and provide support, rather than promote environments that encourage silent perseverance. And we can deconstruct the cultural narrative that vulnerability is weakness or that we are the “heroes.” Heroism suggests superhuman qualities or extreme courage and often negates the fear and trepidation in its midst.11,12 We can also recognize how intersectional aspects of our identities make navigating the pandemic and systemic racism harder and more dangerous for some than for others.

As noted by President Biden in a speech honoring those lost to COVID-19, “We have to resist becoming numb to the sorrow.”13 The nature of our work (and that of most clinicians) is that it is expected and sometimes necessary to compartmentalize and turn off the emotions so that we can function in a professional manner. But this way of being also serves to hold us back. It does not make space for the very real emotions of trauma and grief that have pervaded HCWs during this pandemic. We must learn a different way of functioning—one where grief is acknowledged and even actively processed while still going about our work. Grief therapist Megan Devine proposes to “tend to pain and grief by bearing witness” and notes that “when we allow the reality of grief to exist, we can focus on helping ourselves—and one another—survive inside pain.”14 She advocates for self-compassion and directs us to “find ways to show our grief to others, in ways that honor the truth of our experience” saying, “we have to be willing to stop diminishing our own pain so that others can be comfortable around us.” But what does this look like among health care teams who are traumatized and grieving?

In our experience, caring for ourselves and our teams in times of prolonged stress, trauma, and grief is essential to maintain functioning over time. We strongly believe that it must occur at both the organizational and individual levels. In the throes of a crisis, teams need support immediately. To offer a timely response, we gathered knowledge of team-based care and collaboration to develop practical strategies that can be implemented swiftly to provide support across the team.15-19

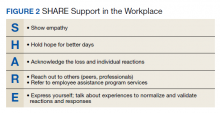

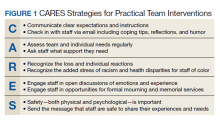

The strategies we developed offer steps for creating and maintaining a supportive, compassionate, and psychologically safe work environment. First, the CARES Strategies for Practical Team Intervention highlights the importance of clear communication, assessing team needs regularly, recognizing the stress that is occurring, engaging staff in discussions, and ensuring psychological safety and comfort (Figure 1). Next, the SHARE approach is laid out to allow for interpersonal support among team members (Figure 2). Showing each other empathy, hoping for better days, acknowledging each other’s pain, reaching out for assistance, and expressing our needs allow HCWs to open up about their grief, stress, and trauma. Of note, we found these sets of strategies interdependent: a team that does not believe the leader/organization CARES is not likely to SHARE. Therefore, we also feel that it is especially important that team leaders work to create or enhance the sense of psychological safety for the team. If team members do not feel safe, they will not disclose their grief and remain stuck in the old mode of suffering in silence.

Conclusions

This pandemic and the collective efforts toward social justice advocacy have revealed our vulnerabilities as well as our strengths. These experiences have forced us to reckon with our past and consider possible futures. It has revealed the inequities in our health care system, including our failure to protect those on the ground who keep our systems running, and prompted us to consider new ways of operating in low-resourced and high-demand environments. These experiences also present us with opportunities to be better and do better as both professionals and people; to reflect on our past and consider what we want different in our lives. As we yearn for better days and brace ourselves for what is to come, we hope that teams and organizations will take advantage of these opportunities for self-reflection and continue unmasking our grief, healing our wounds, and honoring our shared humanity.

1. Blake H, Bermingham F. Psychological wellbeing for health care workers: mitigating the impact of covid-19. Version 2.0. Updated June 18, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/toolkits/play_22794

2. Harris R. FACE COVID: how to respond effectively to the corona crisis. Published 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. http://louisville.edu/counseling/coping-with-covid-19/face-covid-by-dr-russ-harris/view

3. Norcross JC, Phillips CM. Psychologist self-care during the pandemic: now more than ever [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 2]. J Health Serv Psychol. 2020;1-5. doi:10.1007/s42843-020-00010-5

4. Kaiser Family Foundation. State reports of long-term care facility cases and deaths related to COVID-19. 2020. Published April 23, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/state-reporting-of-cases-and-deaths-due-to-covid-19-in-long-term-care-facilities

5. Sterling MR, Tseng E, Poon A, et al. Experiences of home health care workers in New York City during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a qualitative analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1453-1459. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3930

6. Stone R, Wilhelm J, Bishop CE, Bryant NS, Hermer L, Squillace MR. Predictors of intent to leave the job among home health workers: analysis of the National Home Health Aide Survey. Gerontologist. 2017;57(5):890-899. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw075

7. Scales K. It’s time to care: a detailed profile of America’s direct care workforce. PHI. 2020. Published January 21, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://phinational.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Its-Time-to-Care-2020-PHI.pdf

8. Wolfe R, Harknett K, Schneider D. Inequities at work and the toll of COVID-19. Health Aff Health Policy Brief. Published June 4, 2021. doi: 10.1377/hpb20210428.863621

9. White EM, Wetle TF, Reddy A, Baier RR. Front-line nursing home staff experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic [published correction appears in J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021 May;22(5):1123]. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(1):199-203. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2020.11.022

10. Dean A, Venkataramani A, Kimmel S. Mortality rates from COVID-19 are lower In unionized nursing homes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):1993-2001.doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01011

11. Cox CL. ‘Healthcare Heroes’: problems with media focus on heroism from healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Ethics. 2020;46(8):510-513. doi:10.1136/medethics-2020-106398

12. Stokes-Parish J, Elliott R, Rolls K, Massey D. Angels and heroes: the unintended consequence of the hero narrative. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52(5):462-466. doi:10.1111/jnu.12591

13. Biden J. Remarks by President Biden on the more than 500,000 American lives lost to COVID-19. Published February 22, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/02/22/remarks-by-president-biden-on-the-more-than-500000-american-lives-lost-to-covid-19

14. Devine M. It’s Okay That You’re Not Okay: Meeting Grief and Loss in a Culture That Doesn’t Understand. Sounds True; 2017.

15. Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress. Grief leadership during COVID-19. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.cstsonline.org/assets/media/documents/CSTS_FS_Grief_Leadership_During_COVID19.pdf

16. Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress. Sustaining the well-being of healthcare personnel during coronavirus and other infectious disease outbreaks. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.cstsonline.org/assets/media/documents/CSTS_FS_Sustaining_Well_Being_Health care_Personnel_during.pdf

17. Fessell D, Cherniss C. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and beyond: micropractices for burnout prevention and emotional wellness. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(6):746-748. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.03.013

18. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for PTSD. Managing healthcare workers’ stress associated with the COVID-19 virus outbreak. Updated March 25, 2020, Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/covid/COVID_healthcare_workers.asp

19. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, National Center for Organization Development (NCOD). Team Development Guide. 2017. https://vaww.va.gov/NCOD/docs/Team_Development_Guide.docx [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

Since the start of the pandemic, health care systems have requested many in-services for staff on self-care and stress management to help health care workers (HCWs) cope with the heavy toll of COVID-19. The pandemic has set off a global mental health crisis, with unprecedented numbers of individuals meeting criteria for anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders in response to the intense stressors of living through a pandemic. These calls to assist staff with self-care and burnout prevention have been especially salient for psychologists working in palliative care and geriatrics, where fears of COVID-19 infection and numbers of patient deaths have been high.

Throughout these painful times, we have been grateful for an online community of palliative care psychologists within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) from across the continuum of care and across the country. This community brought together many of us who were both struggling ourselves and striving to support the teams and HCWs around us. We are psychologists who provide home-care services in North Carolina, inpatient hospice and long-term care services in California, and long-term care and outpatient palliative care services in Massachusetts. Through our shared struggles and challenges navigating the pandemic, we realized that our respective teams requested similar services, all focused on staff support.

The psychological impact of COVID-19 on HCWs was clear from the beginning. Early in the pandemic our respective teams requested us to provide staff support and education about coping to our local HCWs. Soon national groups for long-term care staff requested education programs. Through this work, we realized that the emotional needs of HCWs ran much deeper than simple self-care. At the onset of the pandemic, before realizing its chronicity, the trainings we offered focused on stress and coping strategies. We cited several frameworks for staff support and eagerly shared anything that might help us, and our colleagues, survive the immediate anxiety and tumult surrounding us.1-3 In this paper, we briefly discuss the distress affecting the geriatric care workforce, reflect on our efforts to cope as HCWs, and offer recommendations at individual and organization levels to help address our collective grief.

Impact of COVID-19

As the death toll mounted and hospitals were pushed to the brink, we saw the suffering of our fellow HCWs. The lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing supplies led to evolving and increasing anxiety for HCWs about contracting COVID-19, potentially spreading it to one’s social circle or family, fears of becoming sick and dying, and fears of inadvertently spreading the virus to medically-vulnerable patients. Increasing demands on staff required many to work outside their areas of expertise. Clinical practice guidelines changed frequently as information emerged about the virus. Staff members struggled to keep pace with the increasing number of patients, many of whom died despite heroic efforts to save them.

As the medical crisis grew, so too did social uprisings as the general public gained a strengthened awareness of the legacy and ongoing effects of systemic oppression, racism, and social inequities in the United States. Individuals grappled with their own privileges, which often hid such disparities from view. Many HCWs and clinicians of color had to navigate unsolicited questions and discussions about racial injustices while also trying to survive. As psychologists, we strove to support the HCWs around us while also struggling with our own stressors. As the magnitude of the pandemic and ongoing social injustices came into view, we realized that presentations on self-care and burnout prevention did not suffice. We needed discussions on unmasking our grief, acknowledging our traumas, and working toward collective healing.

Geriatric Care Workers

Experiences of grief and trauma hit the geriatric care workforce and especially long-term care facilities particularly hard given the high morbidity and mortality rates of COVID-19.4 The geriatric care workforce itself suffers from institutional vulnerabilities. Individuals are often underpaid, undertrained, and work within a system that continually experiences staffing shortages, high burnout, and consequently high levels of turnover.5,6 Recent immigrants and racial/ethnic minorities disproportionately make up this workforce, who often live in multigenerational households and work in multiple facilities to get by.7,8 Amid the pandemic these HCWs continued to work despite demoralizing negative media coverage of nursing homes.9 Notably, facilities with unionized staff were less likely to need second or third jobs to survive, thus reducing spread across facilities. This along with better access to PPE may have contributed to their lower COVID-19 infection and mortality rates relative to non-unionized staff.10

Similar to long-term care workers, home-care staff had related fears and anxieties, magnified by the need to enter multiple homes. This often overlooked but growing sector of the geriatric care workforce faced the added anxiety of the unknown as they entered multiple homes to provide care to their patients. These staff have little control over who may be in the home when they arrive, the sanitation/PPE practices of the patient/family, and therefore little control over their potential exposure to COVID-19. This also applies to home health aides who, although not providing medical services, are a critical part of home-care services and allow older adults to remain living independently in their home.

Reflection on Grief

As we witnessed the interactive effects of the pandemic and social inequities in geriatrics and palliative care, we frequently sought solace in online communities of psychologists working in similar settings. Over time, our regular community meetings developed a different tone: discussions about caring for others shifted to caring for ourselves. It seemed that in holding others’ pain, many of us neglected to address our own. We needed emotional support. We needed to acknowledge that we were not all okay; that the masks we wear for protection also reveal our vulnerabilities; and that protective equipment in hospitals do not protect us from the hate and bias targeting many of us face everywhere we go.

As we let ourselves be vulnerable with each other, we saw the true face of our pain: it was not stress, it was grief. We were sad, broken, mourning innumerable losses, and grieving, mostly alone. It felt overwhelming. Our minds and hearts often grew numb to find respite from pain. At times we found ourselves seeking haven in our offices, convincing ourselves that paperwork needed to be done when in reality we had no space to hold anyone else’s pain; we could barely contain our own. We could only take so much.

Without space to process, grief festers and eats away at our remaining compassion. How do we hold grace for ourselves, dare to be vulnerable, and allow ourselves to feel, when doing so opens the door to our own grief? How do we allow room for emotional processing when we learned to numb-out in order to function? And as women with diverse intersectional identities, how do we honor our humanity when we live in a society that reflects its indifference? We needed to process our pain in order to heal in the slow and uneven way that grief heals.

Caring During Tough Times

The pain we feel is real and it tears at us over time. Pushing it away disenfranchises ourselves of the opportunity to heal and grow. Our collective grief and trauma demand collective healing and acknowledgment of our individual suffering. We must honor our shared humanity and find commonality amid our differences. Typical self-care (healthy eating, sleep, basic hygiene) may not be enough to mitigate the enormity of these stressors. A glass of wine or a virtual dinner with friends may distract but does not heal our wounds.

Self-care, by definition, centers the self and ignores the larger systemic factors that maintain our struggles. It keeps the focus on the individual and in so doing, risks inducing self-blame should we continue feeling burnout. We must do more. We can advocate that systems acknowledge our grief and suffering as well as our strengths and resiliencies. We can demand that organizations recognize human limits and provide support, rather than promote environments that encourage silent perseverance. And we can deconstruct the cultural narrative that vulnerability is weakness or that we are the “heroes.” Heroism suggests superhuman qualities or extreme courage and often negates the fear and trepidation in its midst.11,12 We can also recognize how intersectional aspects of our identities make navigating the pandemic and systemic racism harder and more dangerous for some than for others.

As noted by President Biden in a speech honoring those lost to COVID-19, “We have to resist becoming numb to the sorrow.”13 The nature of our work (and that of most clinicians) is that it is expected and sometimes necessary to compartmentalize and turn off the emotions so that we can function in a professional manner. But this way of being also serves to hold us back. It does not make space for the very real emotions of trauma and grief that have pervaded HCWs during this pandemic. We must learn a different way of functioning—one where grief is acknowledged and even actively processed while still going about our work. Grief therapist Megan Devine proposes to “tend to pain and grief by bearing witness” and notes that “when we allow the reality of grief to exist, we can focus on helping ourselves—and one another—survive inside pain.”14 She advocates for self-compassion and directs us to “find ways to show our grief to others, in ways that honor the truth of our experience” saying, “we have to be willing to stop diminishing our own pain so that others can be comfortable around us.” But what does this look like among health care teams who are traumatized and grieving?

In our experience, caring for ourselves and our teams in times of prolonged stress, trauma, and grief is essential to maintain functioning over time. We strongly believe that it must occur at both the organizational and individual levels. In the throes of a crisis, teams need support immediately. To offer a timely response, we gathered knowledge of team-based care and collaboration to develop practical strategies that can be implemented swiftly to provide support across the team.15-19

The strategies we developed offer steps for creating and maintaining a supportive, compassionate, and psychologically safe work environment. First, the CARES Strategies for Practical Team Intervention highlights the importance of clear communication, assessing team needs regularly, recognizing the stress that is occurring, engaging staff in discussions, and ensuring psychological safety and comfort (Figure 1). Next, the SHARE approach is laid out to allow for interpersonal support among team members (Figure 2). Showing each other empathy, hoping for better days, acknowledging each other’s pain, reaching out for assistance, and expressing our needs allow HCWs to open up about their grief, stress, and trauma. Of note, we found these sets of strategies interdependent: a team that does not believe the leader/organization CARES is not likely to SHARE. Therefore, we also feel that it is especially important that team leaders work to create or enhance the sense of psychological safety for the team. If team members do not feel safe, they will not disclose their grief and remain stuck in the old mode of suffering in silence.

Conclusions

This pandemic and the collective efforts toward social justice advocacy have revealed our vulnerabilities as well as our strengths. These experiences have forced us to reckon with our past and consider possible futures. It has revealed the inequities in our health care system, including our failure to protect those on the ground who keep our systems running, and prompted us to consider new ways of operating in low-resourced and high-demand environments. These experiences also present us with opportunities to be better and do better as both professionals and people; to reflect on our past and consider what we want different in our lives. As we yearn for better days and brace ourselves for what is to come, we hope that teams and organizations will take advantage of these opportunities for self-reflection and continue unmasking our grief, healing our wounds, and honoring our shared humanity.

Since the start of the pandemic, health care systems have requested many in-services for staff on self-care and stress management to help health care workers (HCWs) cope with the heavy toll of COVID-19. The pandemic has set off a global mental health crisis, with unprecedented numbers of individuals meeting criteria for anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders in response to the intense stressors of living through a pandemic. These calls to assist staff with self-care and burnout prevention have been especially salient for psychologists working in palliative care and geriatrics, where fears of COVID-19 infection and numbers of patient deaths have been high.

Throughout these painful times, we have been grateful for an online community of palliative care psychologists within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) from across the continuum of care and across the country. This community brought together many of us who were both struggling ourselves and striving to support the teams and HCWs around us. We are psychologists who provide home-care services in North Carolina, inpatient hospice and long-term care services in California, and long-term care and outpatient palliative care services in Massachusetts. Through our shared struggles and challenges navigating the pandemic, we realized that our respective teams requested similar services, all focused on staff support.

The psychological impact of COVID-19 on HCWs was clear from the beginning. Early in the pandemic our respective teams requested us to provide staff support and education about coping to our local HCWs. Soon national groups for long-term care staff requested education programs. Through this work, we realized that the emotional needs of HCWs ran much deeper than simple self-care. At the onset of the pandemic, before realizing its chronicity, the trainings we offered focused on stress and coping strategies. We cited several frameworks for staff support and eagerly shared anything that might help us, and our colleagues, survive the immediate anxiety and tumult surrounding us.1-3 In this paper, we briefly discuss the distress affecting the geriatric care workforce, reflect on our efforts to cope as HCWs, and offer recommendations at individual and organization levels to help address our collective grief.

Impact of COVID-19

As the death toll mounted and hospitals were pushed to the brink, we saw the suffering of our fellow HCWs. The lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing supplies led to evolving and increasing anxiety for HCWs about contracting COVID-19, potentially spreading it to one’s social circle or family, fears of becoming sick and dying, and fears of inadvertently spreading the virus to medically-vulnerable patients. Increasing demands on staff required many to work outside their areas of expertise. Clinical practice guidelines changed frequently as information emerged about the virus. Staff members struggled to keep pace with the increasing number of patients, many of whom died despite heroic efforts to save them.

As the medical crisis grew, so too did social uprisings as the general public gained a strengthened awareness of the legacy and ongoing effects of systemic oppression, racism, and social inequities in the United States. Individuals grappled with their own privileges, which often hid such disparities from view. Many HCWs and clinicians of color had to navigate unsolicited questions and discussions about racial injustices while also trying to survive. As psychologists, we strove to support the HCWs around us while also struggling with our own stressors. As the magnitude of the pandemic and ongoing social injustices came into view, we realized that presentations on self-care and burnout prevention did not suffice. We needed discussions on unmasking our grief, acknowledging our traumas, and working toward collective healing.

Geriatric Care Workers

Experiences of grief and trauma hit the geriatric care workforce and especially long-term care facilities particularly hard given the high morbidity and mortality rates of COVID-19.4 The geriatric care workforce itself suffers from institutional vulnerabilities. Individuals are often underpaid, undertrained, and work within a system that continually experiences staffing shortages, high burnout, and consequently high levels of turnover.5,6 Recent immigrants and racial/ethnic minorities disproportionately make up this workforce, who often live in multigenerational households and work in multiple facilities to get by.7,8 Amid the pandemic these HCWs continued to work despite demoralizing negative media coverage of nursing homes.9 Notably, facilities with unionized staff were less likely to need second or third jobs to survive, thus reducing spread across facilities. This along with better access to PPE may have contributed to their lower COVID-19 infection and mortality rates relative to non-unionized staff.10

Similar to long-term care workers, home-care staff had related fears and anxieties, magnified by the need to enter multiple homes. This often overlooked but growing sector of the geriatric care workforce faced the added anxiety of the unknown as they entered multiple homes to provide care to their patients. These staff have little control over who may be in the home when they arrive, the sanitation/PPE practices of the patient/family, and therefore little control over their potential exposure to COVID-19. This also applies to home health aides who, although not providing medical services, are a critical part of home-care services and allow older adults to remain living independently in their home.

Reflection on Grief

As we witnessed the interactive effects of the pandemic and social inequities in geriatrics and palliative care, we frequently sought solace in online communities of psychologists working in similar settings. Over time, our regular community meetings developed a different tone: discussions about caring for others shifted to caring for ourselves. It seemed that in holding others’ pain, many of us neglected to address our own. We needed emotional support. We needed to acknowledge that we were not all okay; that the masks we wear for protection also reveal our vulnerabilities; and that protective equipment in hospitals do not protect us from the hate and bias targeting many of us face everywhere we go.

As we let ourselves be vulnerable with each other, we saw the true face of our pain: it was not stress, it was grief. We were sad, broken, mourning innumerable losses, and grieving, mostly alone. It felt overwhelming. Our minds and hearts often grew numb to find respite from pain. At times we found ourselves seeking haven in our offices, convincing ourselves that paperwork needed to be done when in reality we had no space to hold anyone else’s pain; we could barely contain our own. We could only take so much.

Without space to process, grief festers and eats away at our remaining compassion. How do we hold grace for ourselves, dare to be vulnerable, and allow ourselves to feel, when doing so opens the door to our own grief? How do we allow room for emotional processing when we learned to numb-out in order to function? And as women with diverse intersectional identities, how do we honor our humanity when we live in a society that reflects its indifference? We needed to process our pain in order to heal in the slow and uneven way that grief heals.

Caring During Tough Times

The pain we feel is real and it tears at us over time. Pushing it away disenfranchises ourselves of the opportunity to heal and grow. Our collective grief and trauma demand collective healing and acknowledgment of our individual suffering. We must honor our shared humanity and find commonality amid our differences. Typical self-care (healthy eating, sleep, basic hygiene) may not be enough to mitigate the enormity of these stressors. A glass of wine or a virtual dinner with friends may distract but does not heal our wounds.

Self-care, by definition, centers the self and ignores the larger systemic factors that maintain our struggles. It keeps the focus on the individual and in so doing, risks inducing self-blame should we continue feeling burnout. We must do more. We can advocate that systems acknowledge our grief and suffering as well as our strengths and resiliencies. We can demand that organizations recognize human limits and provide support, rather than promote environments that encourage silent perseverance. And we can deconstruct the cultural narrative that vulnerability is weakness or that we are the “heroes.” Heroism suggests superhuman qualities or extreme courage and often negates the fear and trepidation in its midst.11,12 We can also recognize how intersectional aspects of our identities make navigating the pandemic and systemic racism harder and more dangerous for some than for others.

As noted by President Biden in a speech honoring those lost to COVID-19, “We have to resist becoming numb to the sorrow.”13 The nature of our work (and that of most clinicians) is that it is expected and sometimes necessary to compartmentalize and turn off the emotions so that we can function in a professional manner. But this way of being also serves to hold us back. It does not make space for the very real emotions of trauma and grief that have pervaded HCWs during this pandemic. We must learn a different way of functioning—one where grief is acknowledged and even actively processed while still going about our work. Grief therapist Megan Devine proposes to “tend to pain and grief by bearing witness” and notes that “when we allow the reality of grief to exist, we can focus on helping ourselves—and one another—survive inside pain.”14 She advocates for self-compassion and directs us to “find ways to show our grief to others, in ways that honor the truth of our experience” saying, “we have to be willing to stop diminishing our own pain so that others can be comfortable around us.” But what does this look like among health care teams who are traumatized and grieving?

In our experience, caring for ourselves and our teams in times of prolonged stress, trauma, and grief is essential to maintain functioning over time. We strongly believe that it must occur at both the organizational and individual levels. In the throes of a crisis, teams need support immediately. To offer a timely response, we gathered knowledge of team-based care and collaboration to develop practical strategies that can be implemented swiftly to provide support across the team.15-19

The strategies we developed offer steps for creating and maintaining a supportive, compassionate, and psychologically safe work environment. First, the CARES Strategies for Practical Team Intervention highlights the importance of clear communication, assessing team needs regularly, recognizing the stress that is occurring, engaging staff in discussions, and ensuring psychological safety and comfort (Figure 1). Next, the SHARE approach is laid out to allow for interpersonal support among team members (Figure 2). Showing each other empathy, hoping for better days, acknowledging each other’s pain, reaching out for assistance, and expressing our needs allow HCWs to open up about their grief, stress, and trauma. Of note, we found these sets of strategies interdependent: a team that does not believe the leader/organization CARES is not likely to SHARE. Therefore, we also feel that it is especially important that team leaders work to create or enhance the sense of psychological safety for the team. If team members do not feel safe, they will not disclose their grief and remain stuck in the old mode of suffering in silence.

Conclusions

This pandemic and the collective efforts toward social justice advocacy have revealed our vulnerabilities as well as our strengths. These experiences have forced us to reckon with our past and consider possible futures. It has revealed the inequities in our health care system, including our failure to protect those on the ground who keep our systems running, and prompted us to consider new ways of operating in low-resourced and high-demand environments. These experiences also present us with opportunities to be better and do better as both professionals and people; to reflect on our past and consider what we want different in our lives. As we yearn for better days and brace ourselves for what is to come, we hope that teams and organizations will take advantage of these opportunities for self-reflection and continue unmasking our grief, healing our wounds, and honoring our shared humanity.

1. Blake H, Bermingham F. Psychological wellbeing for health care workers: mitigating the impact of covid-19. Version 2.0. Updated June 18, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/toolkits/play_22794

2. Harris R. FACE COVID: how to respond effectively to the corona crisis. Published 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. http://louisville.edu/counseling/coping-with-covid-19/face-covid-by-dr-russ-harris/view

3. Norcross JC, Phillips CM. Psychologist self-care during the pandemic: now more than ever [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 2]. J Health Serv Psychol. 2020;1-5. doi:10.1007/s42843-020-00010-5

4. Kaiser Family Foundation. State reports of long-term care facility cases and deaths related to COVID-19. 2020. Published April 23, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/state-reporting-of-cases-and-deaths-due-to-covid-19-in-long-term-care-facilities

5. Sterling MR, Tseng E, Poon A, et al. Experiences of home health care workers in New York City during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a qualitative analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1453-1459. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3930

6. Stone R, Wilhelm J, Bishop CE, Bryant NS, Hermer L, Squillace MR. Predictors of intent to leave the job among home health workers: analysis of the National Home Health Aide Survey. Gerontologist. 2017;57(5):890-899. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw075

7. Scales K. It’s time to care: a detailed profile of America’s direct care workforce. PHI. 2020. Published January 21, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://phinational.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Its-Time-to-Care-2020-PHI.pdf

8. Wolfe R, Harknett K, Schneider D. Inequities at work and the toll of COVID-19. Health Aff Health Policy Brief. Published June 4, 2021. doi: 10.1377/hpb20210428.863621

9. White EM, Wetle TF, Reddy A, Baier RR. Front-line nursing home staff experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic [published correction appears in J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021 May;22(5):1123]. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(1):199-203. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2020.11.022

10. Dean A, Venkataramani A, Kimmel S. Mortality rates from COVID-19 are lower In unionized nursing homes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):1993-2001.doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01011

11. Cox CL. ‘Healthcare Heroes’: problems with media focus on heroism from healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Ethics. 2020;46(8):510-513. doi:10.1136/medethics-2020-106398

12. Stokes-Parish J, Elliott R, Rolls K, Massey D. Angels and heroes: the unintended consequence of the hero narrative. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52(5):462-466. doi:10.1111/jnu.12591

13. Biden J. Remarks by President Biden on the more than 500,000 American lives lost to COVID-19. Published February 22, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/02/22/remarks-by-president-biden-on-the-more-than-500000-american-lives-lost-to-covid-19

14. Devine M. It’s Okay That You’re Not Okay: Meeting Grief and Loss in a Culture That Doesn’t Understand. Sounds True; 2017.

15. Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress. Grief leadership during COVID-19. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.cstsonline.org/assets/media/documents/CSTS_FS_Grief_Leadership_During_COVID19.pdf

16. Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress. Sustaining the well-being of healthcare personnel during coronavirus and other infectious disease outbreaks. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.cstsonline.org/assets/media/documents/CSTS_FS_Sustaining_Well_Being_Health care_Personnel_during.pdf

17. Fessell D, Cherniss C. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and beyond: micropractices for burnout prevention and emotional wellness. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(6):746-748. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.03.013

18. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for PTSD. Managing healthcare workers’ stress associated with the COVID-19 virus outbreak. Updated March 25, 2020, Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/covid/COVID_healthcare_workers.asp

19. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, National Center for Organization Development (NCOD). Team Development Guide. 2017. https://vaww.va.gov/NCOD/docs/Team_Development_Guide.docx [Nonpublic source, not verified.]

1. Blake H, Bermingham F. Psychological wellbeing for health care workers: mitigating the impact of covid-19. Version 2.0. Updated June 18, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/toolkits/play_22794

2. Harris R. FACE COVID: how to respond effectively to the corona crisis. Published 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. http://louisville.edu/counseling/coping-with-covid-19/face-covid-by-dr-russ-harris/view

3. Norcross JC, Phillips CM. Psychologist self-care during the pandemic: now more than ever [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 2]. J Health Serv Psychol. 2020;1-5. doi:10.1007/s42843-020-00010-5

4. Kaiser Family Foundation. State reports of long-term care facility cases and deaths related to COVID-19. 2020. Published April 23, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/state-reporting-of-cases-and-deaths-due-to-covid-19-in-long-term-care-facilities

5. Sterling MR, Tseng E, Poon A, et al. Experiences of home health care workers in New York City during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a qualitative analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1453-1459. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3930

6. Stone R, Wilhelm J, Bishop CE, Bryant NS, Hermer L, Squillace MR. Predictors of intent to leave the job among home health workers: analysis of the National Home Health Aide Survey. Gerontologist. 2017;57(5):890-899. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw075

7. Scales K. It’s time to care: a detailed profile of America’s direct care workforce. PHI. 2020. Published January 21, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://phinational.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Its-Time-to-Care-2020-PHI.pdf

8. Wolfe R, Harknett K, Schneider D. Inequities at work and the toll of COVID-19. Health Aff Health Policy Brief. Published June 4, 2021. doi: 10.1377/hpb20210428.863621

9. White EM, Wetle TF, Reddy A, Baier RR. Front-line nursing home staff experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic [published correction appears in J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021 May;22(5):1123]. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(1):199-203. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2020.11.022

10. Dean A, Venkataramani A, Kimmel S. Mortality rates from COVID-19 are lower In unionized nursing homes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(11):1993-2001.doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01011

11. Cox CL. ‘Healthcare Heroes’: problems with media focus on heroism from healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Ethics. 2020;46(8):510-513. doi:10.1136/medethics-2020-106398

12. Stokes-Parish J, Elliott R, Rolls K, Massey D. Angels and heroes: the unintended consequence of the hero narrative. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52(5):462-466. doi:10.1111/jnu.12591

13. Biden J. Remarks by President Biden on the more than 500,000 American lives lost to COVID-19. Published February 22, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/02/22/remarks-by-president-biden-on-the-more-than-500000-american-lives-lost-to-covid-19

14. Devine M. It’s Okay That You’re Not Okay: Meeting Grief and Loss in a Culture That Doesn’t Understand. Sounds True; 2017.

15. Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress. Grief leadership during COVID-19. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.cstsonline.org/assets/media/documents/CSTS_FS_Grief_Leadership_During_COVID19.pdf

16. Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress. Sustaining the well-being of healthcare personnel during coronavirus and other infectious disease outbreaks. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.cstsonline.org/assets/media/documents/CSTS_FS_Sustaining_Well_Being_Health care_Personnel_during.pdf

17. Fessell D, Cherniss C. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and beyond: micropractices for burnout prevention and emotional wellness. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(6):746-748. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.03.013

18. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for PTSD. Managing healthcare workers’ stress associated with the COVID-19 virus outbreak. Updated March 25, 2020, Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/covid/COVID_healthcare_workers.asp

19. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, National Center for Organization Development (NCOD). Team Development Guide. 2017. https://vaww.va.gov/NCOD/docs/Team_Development_Guide.docx [Nonpublic source, not verified.]