User login

Are antibiotics effective for otitis media with effusion?

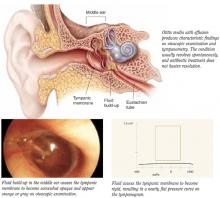

Antibiotics provide little or no long-term benefit for children with otitis media with effusion (OME), defined as fluid in the middle ear without signs or symptoms of infection.

Most meta-analyses show a modest, short-term reduction in effusion rates. However, the most rigorous meta-analysis shows no benefit (strength of recommendation [SOR]: D, based on conflicting meta-analyses). No significant effect was noted on longer-term (>1 month) outcomes after treatment (SOR: A, based on a meta-analysis of 8 trials). In addition, there is no reliable evidence regarding patient-oriented outcomes (hearing loss, speech delay).

Evidence summary

Longitudinal studies show spontaneous resolution in more than half of children within 3 months of the development of the effusion. After 3 months, the rate of spontaneous resolution remains constant, so that only a small percentage of children have OME a year or longer. There is a theoretical basis for the use of antibiotics for OME, since between 27%–50% of middle-ear aspirates of patients with OME contain bacteria.1

In the last 10 years, 4 meta-analyses reported mild short-term improvement in OME with antibiotic treatment (effusion clearance rates of 23%,2 16%,3 14%,1 and 4%,4 respectively—see Table). The last study was the only meta-analysis that restricted inclusion to only randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled trials. The small difference reported (4%) was not significant. None of the studies that assessed outcomes beyond a month showed a significant difference in the persistence of OME.

The meta-analyses vary significantly in methodology, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and interpretation, making a definitive conclusion on treatment results difficult. The included trials varied in antibiotics chosen, use of placebo, duration of therapy, time to measurement of OME resolution, and method of diagnosis (tympanography, otoscopy, audiometry).

The reviews commented on potential harms of antibiotic therapy, including medication cost and the development of antibiotic resistance. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea were reported in 2%–30% of children on antibiotic therapy.1 The reviews did not address the treatment of OME in the nonpediatric population or such long-term patient-oriented outcomes as hearing loss or speech delay.

Recommendations from others

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and the American Academy of Otolaryngology– Head and Neck Surgery participated in the meta-analysis by Stool et al,1 under contract with the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. The resulting clinical practice guideline has been adopted by the AAP, AAFP, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The guideline stresses that observation or antibiotics are treatment options for children with OME present less than 4 to 6 months. Antibiotic therapy is never considered a required treatment for OME of any duration. All published guidelines are applicable to the pediatric population only.

Conflicting evidence indicates short-term or no benefit for antibiotics, and complications such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and rash have been reported in 2%–32% of children. Long-term antibiotics lead to poor adherence, more office visits, and antibiotic resistance.5

Lynda Montgomery, MD

Case Western University School of Medicine Cleveland, Ohio

Conflicting meta-analyses and a guideline that hedges leaves the clinician who practices evidence-based medicine in the uncomfortable position of saying “maybe” when asked whether antibiotics are helpful. In the majority of cases of OME, I would seek to avoid the possible complications of antibiotics, given that there is no clear benefit. I await more data on speech and hearing outcomes in OME, as these studies will provide the most helpful evidence to primary care physicians.

TABLE

Meta-analyses of otitis media with effusion

| Meta-analysis | # of trials | Number of subjects | Description | Rate difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cantekin et al4 | 8 | 775 children | Includes only non-placebo-controlled RCTs. Variable timing of outcome measure | 32 (25.8–38.8) |

| Rosenfeld et al2 | 10 | 1325 children | Includes some nonblinded and nonplacebo-controlled RCTs. Variable timing | 22.8 (10.5–35.1) |

| Williams et al3 | 12 | 1697 children | Includes some nonblinded and nonplacebo-controlled RCTs. Short-term outcomes focused on bilateral resolution of OME within 1 month of starting therapy | 16 (3–29) |

| Williams et al3 | 8 | 2052 ears | Includes some nonblinded and nonplacebo-controlled RCTs. Short-term outcomes focused on unilateral resolution of OME within 1 month of starting therapy | 25 (10–40) |

| Williams et al3 | 8 | 1313 ears | Includes some nonblinded and nonplacebo-controlled RCTs. Long-term outcomes measured more than 1 month after treatment was completed | 6 (-3–14) |

| Stool et al1 | 10 | 1041 children | All blinded RCTs. Not all placebocontrolled. Variable timing | 14.0 (3.6–24.2) |

| Cantekin et al4 | 8 | 1292 children | Includes only blinded, placebo-controlled RCTs. Variable timing | 4.3 (-0.1–8.6) |

| RCT, randomized clinical trial; CI, confidence interval; OME, otitis media with effusion | ||||

Otitis media with effusion

1. Stool SE, Berg AO, Berman S, et al. Otitis media with effusion in young children. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 12. AHCPR Publication 94-0622. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, July 1994.

2. Rosenfeld RM, Post JC. Meta-analysis of antibiotics for the treatment of otitis media with effusion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;106:378-386.

3. Williams RL, Chalmers TC, Stange KC, Chalmers FT, Bowlin SJ. Use of antibiotics in preventing recurrent acute otitis media and in treating otitis media with effusion. A meta-analytic attempt to resolve to brouhaha. JAMA 1993;270:1344-351.

4. Cantekin EI, McGuire TW. Antibiotics are not effective for otitis media with effusion: reanalysis of meta-analyses. Otorhinolaryngol Nova 1998;8:214-222.

5. Williamson I. Otitis media with effusion. Clinical Evidence [online]. Available at: http://www.clinicalevidence.com. Accessed on February 24, 2003.

Antibiotics provide little or no long-term benefit for children with otitis media with effusion (OME), defined as fluid in the middle ear without signs or symptoms of infection.

Most meta-analyses show a modest, short-term reduction in effusion rates. However, the most rigorous meta-analysis shows no benefit (strength of recommendation [SOR]: D, based on conflicting meta-analyses). No significant effect was noted on longer-term (>1 month) outcomes after treatment (SOR: A, based on a meta-analysis of 8 trials). In addition, there is no reliable evidence regarding patient-oriented outcomes (hearing loss, speech delay).

Evidence summary

Longitudinal studies show spontaneous resolution in more than half of children within 3 months of the development of the effusion. After 3 months, the rate of spontaneous resolution remains constant, so that only a small percentage of children have OME a year or longer. There is a theoretical basis for the use of antibiotics for OME, since between 27%–50% of middle-ear aspirates of patients with OME contain bacteria.1

In the last 10 years, 4 meta-analyses reported mild short-term improvement in OME with antibiotic treatment (effusion clearance rates of 23%,2 16%,3 14%,1 and 4%,4 respectively—see Table). The last study was the only meta-analysis that restricted inclusion to only randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled trials. The small difference reported (4%) was not significant. None of the studies that assessed outcomes beyond a month showed a significant difference in the persistence of OME.

The meta-analyses vary significantly in methodology, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and interpretation, making a definitive conclusion on treatment results difficult. The included trials varied in antibiotics chosen, use of placebo, duration of therapy, time to measurement of OME resolution, and method of diagnosis (tympanography, otoscopy, audiometry).

The reviews commented on potential harms of antibiotic therapy, including medication cost and the development of antibiotic resistance. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea were reported in 2%–30% of children on antibiotic therapy.1 The reviews did not address the treatment of OME in the nonpediatric population or such long-term patient-oriented outcomes as hearing loss or speech delay.

Recommendations from others

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and the American Academy of Otolaryngology– Head and Neck Surgery participated in the meta-analysis by Stool et al,1 under contract with the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. The resulting clinical practice guideline has been adopted by the AAP, AAFP, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The guideline stresses that observation or antibiotics are treatment options for children with OME present less than 4 to 6 months. Antibiotic therapy is never considered a required treatment for OME of any duration. All published guidelines are applicable to the pediatric population only.

Conflicting evidence indicates short-term or no benefit for antibiotics, and complications such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and rash have been reported in 2%–32% of children. Long-term antibiotics lead to poor adherence, more office visits, and antibiotic resistance.5

Lynda Montgomery, MD

Case Western University School of Medicine Cleveland, Ohio

Conflicting meta-analyses and a guideline that hedges leaves the clinician who practices evidence-based medicine in the uncomfortable position of saying “maybe” when asked whether antibiotics are helpful. In the majority of cases of OME, I would seek to avoid the possible complications of antibiotics, given that there is no clear benefit. I await more data on speech and hearing outcomes in OME, as these studies will provide the most helpful evidence to primary care physicians.

TABLE

Meta-analyses of otitis media with effusion

| Meta-analysis | # of trials | Number of subjects | Description | Rate difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cantekin et al4 | 8 | 775 children | Includes only non-placebo-controlled RCTs. Variable timing of outcome measure | 32 (25.8–38.8) |

| Rosenfeld et al2 | 10 | 1325 children | Includes some nonblinded and nonplacebo-controlled RCTs. Variable timing | 22.8 (10.5–35.1) |

| Williams et al3 | 12 | 1697 children | Includes some nonblinded and nonplacebo-controlled RCTs. Short-term outcomes focused on bilateral resolution of OME within 1 month of starting therapy | 16 (3–29) |

| Williams et al3 | 8 | 2052 ears | Includes some nonblinded and nonplacebo-controlled RCTs. Short-term outcomes focused on unilateral resolution of OME within 1 month of starting therapy | 25 (10–40) |

| Williams et al3 | 8 | 1313 ears | Includes some nonblinded and nonplacebo-controlled RCTs. Long-term outcomes measured more than 1 month after treatment was completed | 6 (-3–14) |

| Stool et al1 | 10 | 1041 children | All blinded RCTs. Not all placebocontrolled. Variable timing | 14.0 (3.6–24.2) |

| Cantekin et al4 | 8 | 1292 children | Includes only blinded, placebo-controlled RCTs. Variable timing | 4.3 (-0.1–8.6) |

| RCT, randomized clinical trial; CI, confidence interval; OME, otitis media with effusion | ||||

Otitis media with effusion

Antibiotics provide little or no long-term benefit for children with otitis media with effusion (OME), defined as fluid in the middle ear without signs or symptoms of infection.

Most meta-analyses show a modest, short-term reduction in effusion rates. However, the most rigorous meta-analysis shows no benefit (strength of recommendation [SOR]: D, based on conflicting meta-analyses). No significant effect was noted on longer-term (>1 month) outcomes after treatment (SOR: A, based on a meta-analysis of 8 trials). In addition, there is no reliable evidence regarding patient-oriented outcomes (hearing loss, speech delay).

Evidence summary

Longitudinal studies show spontaneous resolution in more than half of children within 3 months of the development of the effusion. After 3 months, the rate of spontaneous resolution remains constant, so that only a small percentage of children have OME a year or longer. There is a theoretical basis for the use of antibiotics for OME, since between 27%–50% of middle-ear aspirates of patients with OME contain bacteria.1

In the last 10 years, 4 meta-analyses reported mild short-term improvement in OME with antibiotic treatment (effusion clearance rates of 23%,2 16%,3 14%,1 and 4%,4 respectively—see Table). The last study was the only meta-analysis that restricted inclusion to only randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled trials. The small difference reported (4%) was not significant. None of the studies that assessed outcomes beyond a month showed a significant difference in the persistence of OME.

The meta-analyses vary significantly in methodology, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and interpretation, making a definitive conclusion on treatment results difficult. The included trials varied in antibiotics chosen, use of placebo, duration of therapy, time to measurement of OME resolution, and method of diagnosis (tympanography, otoscopy, audiometry).

The reviews commented on potential harms of antibiotic therapy, including medication cost and the development of antibiotic resistance. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea were reported in 2%–30% of children on antibiotic therapy.1 The reviews did not address the treatment of OME in the nonpediatric population or such long-term patient-oriented outcomes as hearing loss or speech delay.

Recommendations from others

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and the American Academy of Otolaryngology– Head and Neck Surgery participated in the meta-analysis by Stool et al,1 under contract with the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. The resulting clinical practice guideline has been adopted by the AAP, AAFP, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The guideline stresses that observation or antibiotics are treatment options for children with OME present less than 4 to 6 months. Antibiotic therapy is never considered a required treatment for OME of any duration. All published guidelines are applicable to the pediatric population only.

Conflicting evidence indicates short-term or no benefit for antibiotics, and complications such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and rash have been reported in 2%–32% of children. Long-term antibiotics lead to poor adherence, more office visits, and antibiotic resistance.5

Lynda Montgomery, MD

Case Western University School of Medicine Cleveland, Ohio

Conflicting meta-analyses and a guideline that hedges leaves the clinician who practices evidence-based medicine in the uncomfortable position of saying “maybe” when asked whether antibiotics are helpful. In the majority of cases of OME, I would seek to avoid the possible complications of antibiotics, given that there is no clear benefit. I await more data on speech and hearing outcomes in OME, as these studies will provide the most helpful evidence to primary care physicians.

TABLE

Meta-analyses of otitis media with effusion

| Meta-analysis | # of trials | Number of subjects | Description | Rate difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cantekin et al4 | 8 | 775 children | Includes only non-placebo-controlled RCTs. Variable timing of outcome measure | 32 (25.8–38.8) |

| Rosenfeld et al2 | 10 | 1325 children | Includes some nonblinded and nonplacebo-controlled RCTs. Variable timing | 22.8 (10.5–35.1) |

| Williams et al3 | 12 | 1697 children | Includes some nonblinded and nonplacebo-controlled RCTs. Short-term outcomes focused on bilateral resolution of OME within 1 month of starting therapy | 16 (3–29) |

| Williams et al3 | 8 | 2052 ears | Includes some nonblinded and nonplacebo-controlled RCTs. Short-term outcomes focused on unilateral resolution of OME within 1 month of starting therapy | 25 (10–40) |

| Williams et al3 | 8 | 1313 ears | Includes some nonblinded and nonplacebo-controlled RCTs. Long-term outcomes measured more than 1 month after treatment was completed | 6 (-3–14) |

| Stool et al1 | 10 | 1041 children | All blinded RCTs. Not all placebocontrolled. Variable timing | 14.0 (3.6–24.2) |

| Cantekin et al4 | 8 | 1292 children | Includes only blinded, placebo-controlled RCTs. Variable timing | 4.3 (-0.1–8.6) |

| RCT, randomized clinical trial; CI, confidence interval; OME, otitis media with effusion | ||||

Otitis media with effusion

1. Stool SE, Berg AO, Berman S, et al. Otitis media with effusion in young children. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 12. AHCPR Publication 94-0622. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, July 1994.

2. Rosenfeld RM, Post JC. Meta-analysis of antibiotics for the treatment of otitis media with effusion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;106:378-386.

3. Williams RL, Chalmers TC, Stange KC, Chalmers FT, Bowlin SJ. Use of antibiotics in preventing recurrent acute otitis media and in treating otitis media with effusion. A meta-analytic attempt to resolve to brouhaha. JAMA 1993;270:1344-351.

4. Cantekin EI, McGuire TW. Antibiotics are not effective for otitis media with effusion: reanalysis of meta-analyses. Otorhinolaryngol Nova 1998;8:214-222.

5. Williamson I. Otitis media with effusion. Clinical Evidence [online]. Available at: http://www.clinicalevidence.com. Accessed on February 24, 2003.

1. Stool SE, Berg AO, Berman S, et al. Otitis media with effusion in young children. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 12. AHCPR Publication 94-0622. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, July 1994.

2. Rosenfeld RM, Post JC. Meta-analysis of antibiotics for the treatment of otitis media with effusion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;106:378-386.

3. Williams RL, Chalmers TC, Stange KC, Chalmers FT, Bowlin SJ. Use of antibiotics in preventing recurrent acute otitis media and in treating otitis media with effusion. A meta-analytic attempt to resolve to brouhaha. JAMA 1993;270:1344-351.

4. Cantekin EI, McGuire TW. Antibiotics are not effective for otitis media with effusion: reanalysis of meta-analyses. Otorhinolaryngol Nova 1998;8:214-222.

5. Williamson I. Otitis media with effusion. Clinical Evidence [online]. Available at: http://www.clinicalevidence.com. Accessed on February 24, 2003.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network