User login

Implementing enhanced recovery protocols for gynecologic surgery

“Enhanced Recovery After Surgery” (ERAS) practices and protocols have been increasingly refined and adopted for the field of gynecology, and there is hope among gynecologic surgeons – and some recent evidence – that, with the ERAS movement, we are improving patient recoveries and outcomes and minimizing the need for opioids.

This applies not only to open surgeries but also to the minimally invasive procedures that already are prized for significant reductions in morbidity and length of stay. The overarching and guiding principle of ERAS is that any surgery – whether open or minimally invasive, major or minor – places stress on the body and is associated with risks and morbidity.

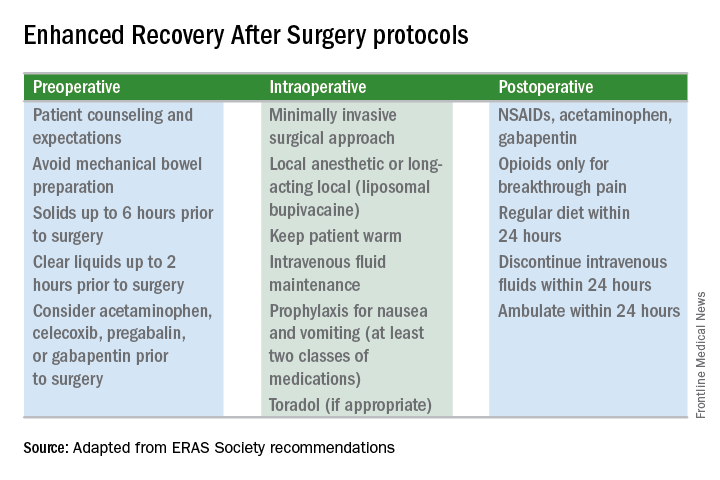

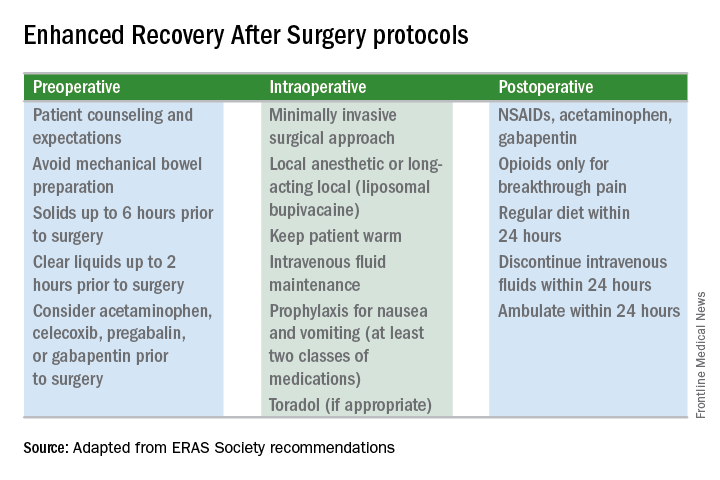

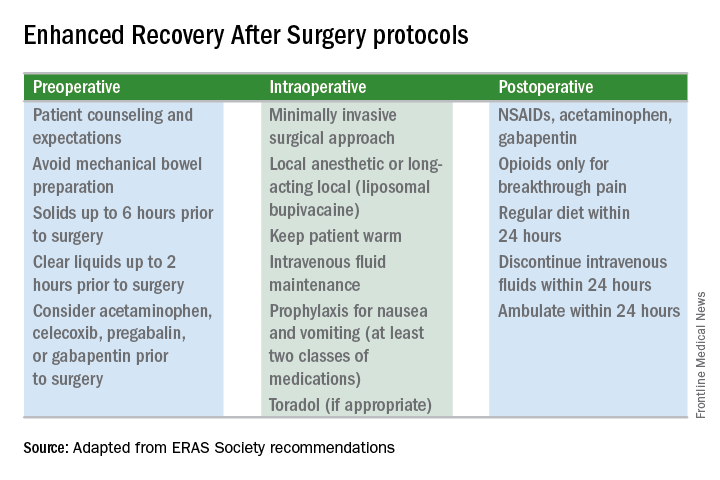

Enhanced recovery protocols are multidisciplinary, perioperative approaches designed to lessen the body’s stress response to surgery. The protocols and pathways offer us a menu of small changes that, in the aggregate, can lead to large and demonstrable benefits – especially when these small changes are chosen across the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative arenas and then standardized in one’s practice. Among the major components of ERAS practices and protocols are limiting preoperative fasting, employing multimodal analgesia, encouraging early ambulation and early postsurgical feeding, and creating culture shift that includes greater emphasis on patient expectations.

In our practice, we are incorporating ERAS practices not only in hopes of reducing the stress of all surgeries before, during, and after, but also with the goal of achieving a postoperative opioid-free hysterectomy, myomectomy, and extensive endometriosis surgery. (All of our advanced procedures are performed laparoscopically or robotically.)

Over the past 7 or so years, we have adopted a multimodal approach to pain control that includes a bundle of preoperative analgesics – acetaminophen, pregabalin, and celecoxib (we call it “TLC” for Tylenol, Lyrica, and Celebrex) – and the use of liposomal bupivacaine in our robotic surgeries. We are now turning toward ERAS nutritional changes, most of which run counter to traditional paradigms for surgical care. And in other areas, such as dedicated preoperative counseling, we continue to refine and improve our practices.

Improved Outcomes

The ERAS mindset notably intersected gynecology with the publication in 2016 of a two-part series of guidelines for gynecology/oncology surgery from the ERAS Society. The 8-year-old society has its roots in a study group of European surgeons and others who decided to examine surgical practices and the concept of multimodal surgical care put forth in the 1990s by Henrik Kehlet, MD, PhD, then a professor at the University of Copenhagen.

The first set of recommendations addressed pre- and intraoperative care (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:313-22), and the second set addressed postoperative care (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:323-32). Similar evidence-based recommendations were previously written for colonic resections, rectal and pelvic surgery, and other surgical specialties.

Most of the published outcomes of enhanced recovery protocols come from colorectal surgery. As noted in the ERAS Society gynecology/oncology guidelines, the benefits include an average reduction in length of stay of 2.5 days and a decrease in complications by as much as 50%.

There is growing evidence, however, that ERAS programs are also beneficial for patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery, and outcomes from gynecology – including minimally invasive surgery – are also being reported.

For instance, a retrospective case-control study of 55 consecutive gynecologic oncology patients treated at the University of California, San Francisco, with laparoscopic or robotic surgery and an enhanced recovery pathway – and 110 historical control patients matched on the basis of age and surgery type – found significant improvements in recovery time, decreased pain despite reduced opioid use, and overall lower hospital costs (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jul;128[1]:138-44).

The enhanced recovery pathway included patient education, multimodal antiemetics, multimodal analgesia, and balanced fluid administration. Early catheter removal, ambulation, and feeding were also components. Analgesia included routine preoperative gabapentin, diclofenac, and acetaminophen; routine postoperative gabapentin, NSAIDs, and acetaminophen; and transversus abdominis plane blocks in 32 of the ERAS patients.

ERAS patients were significantly more likely to be discharged on day 1 (91%, compared with 60% in the control group). Opioid use decreased by 30%, and pain scores on postoperative day 1 were significantly lower.

Another study looking at the effect of enhanced recovery implementation in gynecologic surgeries at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, (gynecologic oncology, urogynecology, and general gynecology) similarly reported benefits for vaginal and minimally invasive procedures, as well as for open procedures (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128[3]:457-66).

In the minimally invasive group, investigators compared 324 patients before ERAS implementation with 249 patients afterward and found that the median length of stay was unchanged (1 day). However, intraoperative and postoperative opioid consumption decreased significantly and – even though actual pain scores improved only slightly – patient satisfaction scores improved markedly among post-ERAS patients. Patients gave higher marks, for instance, to questions regarding pain control (“how well your pain was controlled”) and teamwork (“staff worked together to care for you”).

Reducing Opioids

New opioid use that persists after a surgical procedure is a postsurgical complication that we all should be working to prevent. It has been estimated that 6% of surgical patients – even those who’ve had relatively minor surgical procedures – will become long-term opioid users, developing a dependence on the drugs prescribed to them for postsurgical pain.

This was shown last year in a national study of insurance claims data from between 2013 and 2014; investigators identified adults without opioid use in the year prior to surgery (including hysterectomy) and found that 5.9%-6.5% were filling opioid prescriptions 90-180 days after their surgical procedure. The incidence in a nonoperative control cohort was 0.4% (JAMA Surg. 2017 Jun 21;152[6]:e170504). Notably, this prolonged use was greatest in patients with prior pain conditions, substance abuse, and mental health disorders – a finding that may have implications for the counseling we provide prior to surgery.

It’s not clear what the optimal analgesic regimen is for minimally invasive or other gynecologic surgeries. What is clearly recommended, however, is that the approach be multifaceted. In our practice, we believe that the preoperative use of acetaminophen, pregabalin, and celecoxib plays an important role in reducing postoperative pain and opioid use. But we also have striven to create a practice-wide culture shift (throughout the operating and recovery rooms), for instance, that encourages using the least amounts of narcotics possible and using the shortest-acting formulations possible.

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks are also often part of ERAS protocols; they have been shown in at least two randomized controlled trials of abdominal hysterectomy to reduce intraoperative fentanyl requirements and to reduce immediate postoperative pain scores and postoperative morphine requirements (Anesth Analg. 2008 Dec;107[6]:2056-60; J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014 Jul-Sep;30[3]:391-6).

More recently, liposomal bupivacaine, which is slowly released over several days, has gained traction as a substitute for standard bupivacaine and other agents in TAP blocks. In one recent retrospective study, abdominal incision infiltration with liposomal bupivacaine was associated with less opioid use (with no change in pain scores), compared with bupivacaine hydrochloride after laparotomy for gynecologic malignancies (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128[5]:1009-17). It’s significantly more expensive, however, making it likely that the formulation is being used more judiciously in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery than in open surgeries.

Because of costs, we currently are restricted to using liposomal bupivacaine in our robotic surgeries only. In our practice, the single 20 mL vial (266 mg of liposomal bupivacaine) is diluted with 20 mL of normal saline, but it can be further diluted without loss of efficacy. With a 16-gauge needle, the liposomal bupivacaine is distributed across the incisions (usually 20 mL in the umbilicus with a larger incision and 10 mL in each of the two lateral incisions). Patients are counseled that they may have more discomfort after 3 days, but by this point most are mobile and feeling relatively well with a combination of NSAIDs and acetaminophen.

With growing visibility of the problem of narcotic dependence in the United States, patients seem increasingly receptive and even eager to limit or avoid the use of opioids. Patients should be counseled that minimizing or avoiding opioids may also speed recovery. Narcotics cause gut motility to slow down, which may hinder mobilization. Early mobilization (within 24 hours) is among the enhanced recovery elements that the ERAS Society guidelines say is “of particular value” for minimally invasive surgery, along with maintenance of normothermia and normovolemia with maintenance of adequate cardiac output.

Selecting Steps

Our practice is also trying to reduce preoperative bowel preparation and preoperative fasting, both of which have been found to be stressful for the body without evidence of benefit. These practices can lead to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are associated with increased morbidity and length of stay.

It is now recommended that clear fluids be allowed up to 2 hours before surgery and solids up to 6 hours before. Some health systems and practices also recommend presurgical carbohydrate loading (for example, 10 ounces of apple juice 2 hours before surgery) – another small change on the ERAS menu – to further reduce postoperative insulin resistance and help the body cope with its stress response to surgery.

Along with nutritional changes are also various measures aimed at optimizing the body’s functionality before surgery (“prehabilitation”), from walking 30 minutes a day to abstaining from alcohol for patients who drink heavily.

Throughout the country, enhanced recovery protocols are taking shape in gynecologic surgery. ERAS was featured in an aptly titled panel session at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists: “Outpatient Hysterectomy, ERAS, and Same-Day Discharge: The Next Big Thing in Gyn Surgery.” Others are applying ERAS to scheduled cesarean sections. And in our practice, I believe that if we continue making small changes, we will reach our goal of opioid-free recoveries and a better surgical experience for our patients.

Kirsten Sasaki, MD, is an associate of the Advanced Gynecologic Surgery Institute. She reported that she has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

“Enhanced Recovery After Surgery” (ERAS) practices and protocols have been increasingly refined and adopted for the field of gynecology, and there is hope among gynecologic surgeons – and some recent evidence – that, with the ERAS movement, we are improving patient recoveries and outcomes and minimizing the need for opioids.

This applies not only to open surgeries but also to the minimally invasive procedures that already are prized for significant reductions in morbidity and length of stay. The overarching and guiding principle of ERAS is that any surgery – whether open or minimally invasive, major or minor – places stress on the body and is associated with risks and morbidity.

Enhanced recovery protocols are multidisciplinary, perioperative approaches designed to lessen the body’s stress response to surgery. The protocols and pathways offer us a menu of small changes that, in the aggregate, can lead to large and demonstrable benefits – especially when these small changes are chosen across the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative arenas and then standardized in one’s practice. Among the major components of ERAS practices and protocols are limiting preoperative fasting, employing multimodal analgesia, encouraging early ambulation and early postsurgical feeding, and creating culture shift that includes greater emphasis on patient expectations.

In our practice, we are incorporating ERAS practices not only in hopes of reducing the stress of all surgeries before, during, and after, but also with the goal of achieving a postoperative opioid-free hysterectomy, myomectomy, and extensive endometriosis surgery. (All of our advanced procedures are performed laparoscopically or robotically.)

Over the past 7 or so years, we have adopted a multimodal approach to pain control that includes a bundle of preoperative analgesics – acetaminophen, pregabalin, and celecoxib (we call it “TLC” for Tylenol, Lyrica, and Celebrex) – and the use of liposomal bupivacaine in our robotic surgeries. We are now turning toward ERAS nutritional changes, most of which run counter to traditional paradigms for surgical care. And in other areas, such as dedicated preoperative counseling, we continue to refine and improve our practices.

Improved Outcomes

The ERAS mindset notably intersected gynecology with the publication in 2016 of a two-part series of guidelines for gynecology/oncology surgery from the ERAS Society. The 8-year-old society has its roots in a study group of European surgeons and others who decided to examine surgical practices and the concept of multimodal surgical care put forth in the 1990s by Henrik Kehlet, MD, PhD, then a professor at the University of Copenhagen.

The first set of recommendations addressed pre- and intraoperative care (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:313-22), and the second set addressed postoperative care (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:323-32). Similar evidence-based recommendations were previously written for colonic resections, rectal and pelvic surgery, and other surgical specialties.

Most of the published outcomes of enhanced recovery protocols come from colorectal surgery. As noted in the ERAS Society gynecology/oncology guidelines, the benefits include an average reduction in length of stay of 2.5 days and a decrease in complications by as much as 50%.

There is growing evidence, however, that ERAS programs are also beneficial for patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery, and outcomes from gynecology – including minimally invasive surgery – are also being reported.

For instance, a retrospective case-control study of 55 consecutive gynecologic oncology patients treated at the University of California, San Francisco, with laparoscopic or robotic surgery and an enhanced recovery pathway – and 110 historical control patients matched on the basis of age and surgery type – found significant improvements in recovery time, decreased pain despite reduced opioid use, and overall lower hospital costs (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jul;128[1]:138-44).

The enhanced recovery pathway included patient education, multimodal antiemetics, multimodal analgesia, and balanced fluid administration. Early catheter removal, ambulation, and feeding were also components. Analgesia included routine preoperative gabapentin, diclofenac, and acetaminophen; routine postoperative gabapentin, NSAIDs, and acetaminophen; and transversus abdominis plane blocks in 32 of the ERAS patients.

ERAS patients were significantly more likely to be discharged on day 1 (91%, compared with 60% in the control group). Opioid use decreased by 30%, and pain scores on postoperative day 1 were significantly lower.

Another study looking at the effect of enhanced recovery implementation in gynecologic surgeries at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, (gynecologic oncology, urogynecology, and general gynecology) similarly reported benefits for vaginal and minimally invasive procedures, as well as for open procedures (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128[3]:457-66).

In the minimally invasive group, investigators compared 324 patients before ERAS implementation with 249 patients afterward and found that the median length of stay was unchanged (1 day). However, intraoperative and postoperative opioid consumption decreased significantly and – even though actual pain scores improved only slightly – patient satisfaction scores improved markedly among post-ERAS patients. Patients gave higher marks, for instance, to questions regarding pain control (“how well your pain was controlled”) and teamwork (“staff worked together to care for you”).

Reducing Opioids

New opioid use that persists after a surgical procedure is a postsurgical complication that we all should be working to prevent. It has been estimated that 6% of surgical patients – even those who’ve had relatively minor surgical procedures – will become long-term opioid users, developing a dependence on the drugs prescribed to them for postsurgical pain.

This was shown last year in a national study of insurance claims data from between 2013 and 2014; investigators identified adults without opioid use in the year prior to surgery (including hysterectomy) and found that 5.9%-6.5% were filling opioid prescriptions 90-180 days after their surgical procedure. The incidence in a nonoperative control cohort was 0.4% (JAMA Surg. 2017 Jun 21;152[6]:e170504). Notably, this prolonged use was greatest in patients with prior pain conditions, substance abuse, and mental health disorders – a finding that may have implications for the counseling we provide prior to surgery.

It’s not clear what the optimal analgesic regimen is for minimally invasive or other gynecologic surgeries. What is clearly recommended, however, is that the approach be multifaceted. In our practice, we believe that the preoperative use of acetaminophen, pregabalin, and celecoxib plays an important role in reducing postoperative pain and opioid use. But we also have striven to create a practice-wide culture shift (throughout the operating and recovery rooms), for instance, that encourages using the least amounts of narcotics possible and using the shortest-acting formulations possible.

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks are also often part of ERAS protocols; they have been shown in at least two randomized controlled trials of abdominal hysterectomy to reduce intraoperative fentanyl requirements and to reduce immediate postoperative pain scores and postoperative morphine requirements (Anesth Analg. 2008 Dec;107[6]:2056-60; J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014 Jul-Sep;30[3]:391-6).

More recently, liposomal bupivacaine, which is slowly released over several days, has gained traction as a substitute for standard bupivacaine and other agents in TAP blocks. In one recent retrospective study, abdominal incision infiltration with liposomal bupivacaine was associated with less opioid use (with no change in pain scores), compared with bupivacaine hydrochloride after laparotomy for gynecologic malignancies (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128[5]:1009-17). It’s significantly more expensive, however, making it likely that the formulation is being used more judiciously in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery than in open surgeries.

Because of costs, we currently are restricted to using liposomal bupivacaine in our robotic surgeries only. In our practice, the single 20 mL vial (266 mg of liposomal bupivacaine) is diluted with 20 mL of normal saline, but it can be further diluted without loss of efficacy. With a 16-gauge needle, the liposomal bupivacaine is distributed across the incisions (usually 20 mL in the umbilicus with a larger incision and 10 mL in each of the two lateral incisions). Patients are counseled that they may have more discomfort after 3 days, but by this point most are mobile and feeling relatively well with a combination of NSAIDs and acetaminophen.

With growing visibility of the problem of narcotic dependence in the United States, patients seem increasingly receptive and even eager to limit or avoid the use of opioids. Patients should be counseled that minimizing or avoiding opioids may also speed recovery. Narcotics cause gut motility to slow down, which may hinder mobilization. Early mobilization (within 24 hours) is among the enhanced recovery elements that the ERAS Society guidelines say is “of particular value” for minimally invasive surgery, along with maintenance of normothermia and normovolemia with maintenance of adequate cardiac output.

Selecting Steps

Our practice is also trying to reduce preoperative bowel preparation and preoperative fasting, both of which have been found to be stressful for the body without evidence of benefit. These practices can lead to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are associated with increased morbidity and length of stay.

It is now recommended that clear fluids be allowed up to 2 hours before surgery and solids up to 6 hours before. Some health systems and practices also recommend presurgical carbohydrate loading (for example, 10 ounces of apple juice 2 hours before surgery) – another small change on the ERAS menu – to further reduce postoperative insulin resistance and help the body cope with its stress response to surgery.

Along with nutritional changes are also various measures aimed at optimizing the body’s functionality before surgery (“prehabilitation”), from walking 30 minutes a day to abstaining from alcohol for patients who drink heavily.

Throughout the country, enhanced recovery protocols are taking shape in gynecologic surgery. ERAS was featured in an aptly titled panel session at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists: “Outpatient Hysterectomy, ERAS, and Same-Day Discharge: The Next Big Thing in Gyn Surgery.” Others are applying ERAS to scheduled cesarean sections. And in our practice, I believe that if we continue making small changes, we will reach our goal of opioid-free recoveries and a better surgical experience for our patients.

Kirsten Sasaki, MD, is an associate of the Advanced Gynecologic Surgery Institute. She reported that she has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

“Enhanced Recovery After Surgery” (ERAS) practices and protocols have been increasingly refined and adopted for the field of gynecology, and there is hope among gynecologic surgeons – and some recent evidence – that, with the ERAS movement, we are improving patient recoveries and outcomes and minimizing the need for opioids.

This applies not only to open surgeries but also to the minimally invasive procedures that already are prized for significant reductions in morbidity and length of stay. The overarching and guiding principle of ERAS is that any surgery – whether open or minimally invasive, major or minor – places stress on the body and is associated with risks and morbidity.

Enhanced recovery protocols are multidisciplinary, perioperative approaches designed to lessen the body’s stress response to surgery. The protocols and pathways offer us a menu of small changes that, in the aggregate, can lead to large and demonstrable benefits – especially when these small changes are chosen across the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative arenas and then standardized in one’s practice. Among the major components of ERAS practices and protocols are limiting preoperative fasting, employing multimodal analgesia, encouraging early ambulation and early postsurgical feeding, and creating culture shift that includes greater emphasis on patient expectations.

In our practice, we are incorporating ERAS practices not only in hopes of reducing the stress of all surgeries before, during, and after, but also with the goal of achieving a postoperative opioid-free hysterectomy, myomectomy, and extensive endometriosis surgery. (All of our advanced procedures are performed laparoscopically or robotically.)

Over the past 7 or so years, we have adopted a multimodal approach to pain control that includes a bundle of preoperative analgesics – acetaminophen, pregabalin, and celecoxib (we call it “TLC” for Tylenol, Lyrica, and Celebrex) – and the use of liposomal bupivacaine in our robotic surgeries. We are now turning toward ERAS nutritional changes, most of which run counter to traditional paradigms for surgical care. And in other areas, such as dedicated preoperative counseling, we continue to refine and improve our practices.

Improved Outcomes

The ERAS mindset notably intersected gynecology with the publication in 2016 of a two-part series of guidelines for gynecology/oncology surgery from the ERAS Society. The 8-year-old society has its roots in a study group of European surgeons and others who decided to examine surgical practices and the concept of multimodal surgical care put forth in the 1990s by Henrik Kehlet, MD, PhD, then a professor at the University of Copenhagen.

The first set of recommendations addressed pre- and intraoperative care (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:313-22), and the second set addressed postoperative care (Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Feb;140[2]:323-32). Similar evidence-based recommendations were previously written for colonic resections, rectal and pelvic surgery, and other surgical specialties.

Most of the published outcomes of enhanced recovery protocols come from colorectal surgery. As noted in the ERAS Society gynecology/oncology guidelines, the benefits include an average reduction in length of stay of 2.5 days and a decrease in complications by as much as 50%.

There is growing evidence, however, that ERAS programs are also beneficial for patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery, and outcomes from gynecology – including minimally invasive surgery – are also being reported.

For instance, a retrospective case-control study of 55 consecutive gynecologic oncology patients treated at the University of California, San Francisco, with laparoscopic or robotic surgery and an enhanced recovery pathway – and 110 historical control patients matched on the basis of age and surgery type – found significant improvements in recovery time, decreased pain despite reduced opioid use, and overall lower hospital costs (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jul;128[1]:138-44).

The enhanced recovery pathway included patient education, multimodal antiemetics, multimodal analgesia, and balanced fluid administration. Early catheter removal, ambulation, and feeding were also components. Analgesia included routine preoperative gabapentin, diclofenac, and acetaminophen; routine postoperative gabapentin, NSAIDs, and acetaminophen; and transversus abdominis plane blocks in 32 of the ERAS patients.

ERAS patients were significantly more likely to be discharged on day 1 (91%, compared with 60% in the control group). Opioid use decreased by 30%, and pain scores on postoperative day 1 were significantly lower.

Another study looking at the effect of enhanced recovery implementation in gynecologic surgeries at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, (gynecologic oncology, urogynecology, and general gynecology) similarly reported benefits for vaginal and minimally invasive procedures, as well as for open procedures (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;128[3]:457-66).

In the minimally invasive group, investigators compared 324 patients before ERAS implementation with 249 patients afterward and found that the median length of stay was unchanged (1 day). However, intraoperative and postoperative opioid consumption decreased significantly and – even though actual pain scores improved only slightly – patient satisfaction scores improved markedly among post-ERAS patients. Patients gave higher marks, for instance, to questions regarding pain control (“how well your pain was controlled”) and teamwork (“staff worked together to care for you”).

Reducing Opioids

New opioid use that persists after a surgical procedure is a postsurgical complication that we all should be working to prevent. It has been estimated that 6% of surgical patients – even those who’ve had relatively minor surgical procedures – will become long-term opioid users, developing a dependence on the drugs prescribed to them for postsurgical pain.

This was shown last year in a national study of insurance claims data from between 2013 and 2014; investigators identified adults without opioid use in the year prior to surgery (including hysterectomy) and found that 5.9%-6.5% were filling opioid prescriptions 90-180 days after their surgical procedure. The incidence in a nonoperative control cohort was 0.4% (JAMA Surg. 2017 Jun 21;152[6]:e170504). Notably, this prolonged use was greatest in patients with prior pain conditions, substance abuse, and mental health disorders – a finding that may have implications for the counseling we provide prior to surgery.

It’s not clear what the optimal analgesic regimen is for minimally invasive or other gynecologic surgeries. What is clearly recommended, however, is that the approach be multifaceted. In our practice, we believe that the preoperative use of acetaminophen, pregabalin, and celecoxib plays an important role in reducing postoperative pain and opioid use. But we also have striven to create a practice-wide culture shift (throughout the operating and recovery rooms), for instance, that encourages using the least amounts of narcotics possible and using the shortest-acting formulations possible.

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks are also often part of ERAS protocols; they have been shown in at least two randomized controlled trials of abdominal hysterectomy to reduce intraoperative fentanyl requirements and to reduce immediate postoperative pain scores and postoperative morphine requirements (Anesth Analg. 2008 Dec;107[6]:2056-60; J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014 Jul-Sep;30[3]:391-6).

More recently, liposomal bupivacaine, which is slowly released over several days, has gained traction as a substitute for standard bupivacaine and other agents in TAP blocks. In one recent retrospective study, abdominal incision infiltration with liposomal bupivacaine was associated with less opioid use (with no change in pain scores), compared with bupivacaine hydrochloride after laparotomy for gynecologic malignancies (Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128[5]:1009-17). It’s significantly more expensive, however, making it likely that the formulation is being used more judiciously in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery than in open surgeries.

Because of costs, we currently are restricted to using liposomal bupivacaine in our robotic surgeries only. In our practice, the single 20 mL vial (266 mg of liposomal bupivacaine) is diluted with 20 mL of normal saline, but it can be further diluted without loss of efficacy. With a 16-gauge needle, the liposomal bupivacaine is distributed across the incisions (usually 20 mL in the umbilicus with a larger incision and 10 mL in each of the two lateral incisions). Patients are counseled that they may have more discomfort after 3 days, but by this point most are mobile and feeling relatively well with a combination of NSAIDs and acetaminophen.

With growing visibility of the problem of narcotic dependence in the United States, patients seem increasingly receptive and even eager to limit or avoid the use of opioids. Patients should be counseled that minimizing or avoiding opioids may also speed recovery. Narcotics cause gut motility to slow down, which may hinder mobilization. Early mobilization (within 24 hours) is among the enhanced recovery elements that the ERAS Society guidelines say is “of particular value” for minimally invasive surgery, along with maintenance of normothermia and normovolemia with maintenance of adequate cardiac output.

Selecting Steps

Our practice is also trying to reduce preoperative bowel preparation and preoperative fasting, both of which have been found to be stressful for the body without evidence of benefit. These practices can lead to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are associated with increased morbidity and length of stay.

It is now recommended that clear fluids be allowed up to 2 hours before surgery and solids up to 6 hours before. Some health systems and practices also recommend presurgical carbohydrate loading (for example, 10 ounces of apple juice 2 hours before surgery) – another small change on the ERAS menu – to further reduce postoperative insulin resistance and help the body cope with its stress response to surgery.

Along with nutritional changes are also various measures aimed at optimizing the body’s functionality before surgery (“prehabilitation”), from walking 30 minutes a day to abstaining from alcohol for patients who drink heavily.

Throughout the country, enhanced recovery protocols are taking shape in gynecologic surgery. ERAS was featured in an aptly titled panel session at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists: “Outpatient Hysterectomy, ERAS, and Same-Day Discharge: The Next Big Thing in Gyn Surgery.” Others are applying ERAS to scheduled cesarean sections. And in our practice, I believe that if we continue making small changes, we will reach our goal of opioid-free recoveries and a better surgical experience for our patients.

Kirsten Sasaki, MD, is an associate of the Advanced Gynecologic Surgery Institute. She reported that she has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.